User login

Four Physicians Presented SHM’s 2005 National Awards of Excellence

Enter text here

Enter text here

Enter text here

SHM Inducts New Officers at Annual Meeting

Enter text here

Enter text here

Enter text here

Other Pediatric Literature of Interest

1. Bender B, Skae C, Ozuah P. Oral rehydration therapy: the clear solution to fluid loss. Contemp Pediatr. 2005;22:72-6.

Acute diarrhea leads to more than 1.5 million outpatient visits, 200,000 hospital visits, and 300 deaths per year in the United States. Oral rehydration therapy (ORT) is the preferred approach to treat mild to moderate dehydration due to acute gastroenteritis that includes diarrhea and vomiting. Mild dehydration is defined as a fluid deficit of less than 3%–5%, moderated dehydration is 5%–10%, and severe dehydration is greater than 9%–10%.

The practice of oral rehydration can be traced back more than 150 years. Studies have shown that more than 90% of children can be successfully rehydrated orally and that these children have a lower complication rate than those treated with IV fluids. The key to successful rehydration is to use the appropriate rehydration fluid. These fluids include Pedialyte, Enfalyte, Rehydralyte, or any other “lyte” fluid. Parents should be discouraged from using soda, juice, and chicken broth, because these liquids can cause electrolyte abnormalities.

There are 2 components of ORT: rehydration and maintenance. For rehydration, a child should receive 50–100 ml/kg of oral rehydration solution over a 3–4 hour period. Replacement fluids are estimated at 10 mL/kg for each stool and 2 mL/kg for each episode of vomiting. The most important consideration in successfully rehydrating a child who is vomiting is to offer a small volume frequently. ORT should start with one teaspoon every 1–2 minutes. Severely dehydrated children should receive IV fluid boluses until perfusion and mental status is normal, and then ORT can be initiated.

Treatment of ORT remains widely underused. Stated barriers include lack of convenience, inadequately trained staff , children’s unwillingness to take the solution, parents and staff preference for IV therapy, lower reimbursement for ORT, cost of ORT to parents, extended length of stay in the emergency department compared with IV therapy, and persistent vomiting that prevents administration of ORT. Recent data show that in the emergency department ORT actually requires less time than IV therapy and is less painful. In addition, the data showed that parents were more satisfied with the ED visit when ORT was used. ORT is less expensive than IV therapy. Children who refuse oral rehydration solution are usually not dehydrated and therefore do not crave the high salt concentration found in oral rehydration solutions.

- Concise Reviews of Pediatric Infectious Diseases: Treatment of community-associated methicillinresistant Staphylococcus aureus infections. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2005;24:45760.

Supplements

Supplement to Pediatric Critical Care Medicine. 2005;6. This supplement is devoted to sepsis in infants and children.

1. Bender B, Skae C, Ozuah P. Oral rehydration therapy: the clear solution to fluid loss. Contemp Pediatr. 2005;22:72-6.

Acute diarrhea leads to more than 1.5 million outpatient visits, 200,000 hospital visits, and 300 deaths per year in the United States. Oral rehydration therapy (ORT) is the preferred approach to treat mild to moderate dehydration due to acute gastroenteritis that includes diarrhea and vomiting. Mild dehydration is defined as a fluid deficit of less than 3%–5%, moderated dehydration is 5%–10%, and severe dehydration is greater than 9%–10%.

The practice of oral rehydration can be traced back more than 150 years. Studies have shown that more than 90% of children can be successfully rehydrated orally and that these children have a lower complication rate than those treated with IV fluids. The key to successful rehydration is to use the appropriate rehydration fluid. These fluids include Pedialyte, Enfalyte, Rehydralyte, or any other “lyte” fluid. Parents should be discouraged from using soda, juice, and chicken broth, because these liquids can cause electrolyte abnormalities.

There are 2 components of ORT: rehydration and maintenance. For rehydration, a child should receive 50–100 ml/kg of oral rehydration solution over a 3–4 hour period. Replacement fluids are estimated at 10 mL/kg for each stool and 2 mL/kg for each episode of vomiting. The most important consideration in successfully rehydrating a child who is vomiting is to offer a small volume frequently. ORT should start with one teaspoon every 1–2 minutes. Severely dehydrated children should receive IV fluid boluses until perfusion and mental status is normal, and then ORT can be initiated.

Treatment of ORT remains widely underused. Stated barriers include lack of convenience, inadequately trained staff , children’s unwillingness to take the solution, parents and staff preference for IV therapy, lower reimbursement for ORT, cost of ORT to parents, extended length of stay in the emergency department compared with IV therapy, and persistent vomiting that prevents administration of ORT. Recent data show that in the emergency department ORT actually requires less time than IV therapy and is less painful. In addition, the data showed that parents were more satisfied with the ED visit when ORT was used. ORT is less expensive than IV therapy. Children who refuse oral rehydration solution are usually not dehydrated and therefore do not crave the high salt concentration found in oral rehydration solutions.

- Concise Reviews of Pediatric Infectious Diseases: Treatment of community-associated methicillinresistant Staphylococcus aureus infections. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2005;24:45760.

Supplements

Supplement to Pediatric Critical Care Medicine. 2005;6. This supplement is devoted to sepsis in infants and children.

1. Bender B, Skae C, Ozuah P. Oral rehydration therapy: the clear solution to fluid loss. Contemp Pediatr. 2005;22:72-6.

Acute diarrhea leads to more than 1.5 million outpatient visits, 200,000 hospital visits, and 300 deaths per year in the United States. Oral rehydration therapy (ORT) is the preferred approach to treat mild to moderate dehydration due to acute gastroenteritis that includes diarrhea and vomiting. Mild dehydration is defined as a fluid deficit of less than 3%–5%, moderated dehydration is 5%–10%, and severe dehydration is greater than 9%–10%.

The practice of oral rehydration can be traced back more than 150 years. Studies have shown that more than 90% of children can be successfully rehydrated orally and that these children have a lower complication rate than those treated with IV fluids. The key to successful rehydration is to use the appropriate rehydration fluid. These fluids include Pedialyte, Enfalyte, Rehydralyte, or any other “lyte” fluid. Parents should be discouraged from using soda, juice, and chicken broth, because these liquids can cause electrolyte abnormalities.

There are 2 components of ORT: rehydration and maintenance. For rehydration, a child should receive 50–100 ml/kg of oral rehydration solution over a 3–4 hour period. Replacement fluids are estimated at 10 mL/kg for each stool and 2 mL/kg for each episode of vomiting. The most important consideration in successfully rehydrating a child who is vomiting is to offer a small volume frequently. ORT should start with one teaspoon every 1–2 minutes. Severely dehydrated children should receive IV fluid boluses until perfusion and mental status is normal, and then ORT can be initiated.

Treatment of ORT remains widely underused. Stated barriers include lack of convenience, inadequately trained staff , children’s unwillingness to take the solution, parents and staff preference for IV therapy, lower reimbursement for ORT, cost of ORT to parents, extended length of stay in the emergency department compared with IV therapy, and persistent vomiting that prevents administration of ORT. Recent data show that in the emergency department ORT actually requires less time than IV therapy and is less painful. In addition, the data showed that parents were more satisfied with the ED visit when ORT was used. ORT is less expensive than IV therapy. Children who refuse oral rehydration solution are usually not dehydrated and therefore do not crave the high salt concentration found in oral rehydration solutions.

- Concise Reviews of Pediatric Infectious Diseases: Treatment of community-associated methicillinresistant Staphylococcus aureus infections. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2005;24:45760.

Supplements

Supplement to Pediatric Critical Care Medicine. 2005;6. This supplement is devoted to sepsis in infants and children.

Pediatric in the Literature

Hospital “Report Cards”: Variation in the Management of Bronchiolitis

Christakis DA, Cowan CA, Garrison MM, Molteni R, Marcuse E, Zerr DM. Variation in Inpatient Diagnostic Testing and Management of Bronchiolitis. Pediatrics. 2005;115:878-4.

Bronchiolitis remains 1 of the most common causes of hospitalization in children within the first 2 years of life. In this analysis, the authors conducted a large retrospective descriptive study of infants who were admitted with bronchiolitis to children’s hospitals across the United States. The study examined the variability in length of stay (LOS), diagnostic testing, medications used, and readmission rates. The authors reviewed data on a total of 17,397 infants younger than 1 year of age. Information was obtained from the Pediatric Health Information System, which includes demographic and diagnostic data on 36 freestanding, noncompeting children’s hospitals. The authors found significant and wide variation in LOS, readmission rates, treatment approaches, and use of diagnostic tests for inpatient management of bronchiolitis.

Results indicated that 72% of patients received chest radiographs, 45% received antibiotics, and 25% received systemic steroids. The mean LOS varied considerably across hospitals, with a range of 2.40–3.90 days. The use of antibiotics varied from 28% to 62%, and the use of chest radiographs varied from 38% to 89%. There was also significant difference in readmission rates, which varied from 0% to 2.7%. The variation between hospitals remained a significant contributor even after controlling for multiple potential confounding factors.

Decreasing LOS and unnecessary medication and test utilization is supportive of pediatric patient safety initiatives. The authors suggest that chest radiographs may be leading to unnecessary use of antibiotics due to presumptive treatment based on nonspecific findings. In addition, the authors hypothesize that increased virologic testing may be cost-effective if it leads to decreased use of antibiotics.

The study concludes that there are considerable, unexplained variations that exist in the inpatient management of bronchiolitis. Development of national guidelines and controlled trials of new therapies and different approaches are indicated. Hospitals need to direct resources at analyzing and improving their inpatient care by implementing a more evidence-based approach to management of this common problem.

Maternal Group B Streptococcal Positivity: Risk factor or not?

Puopolo KM, Madoff LC, Eichenwald EC. Early-onset group B streptococcal disease in the era of maternal screening. Pediatrics. 2005;115:1240-6.

Despite implementation of intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis (IAP) based on maternal screening for group B streptococcus (GBS) colonization, cases of early-onset neonatal GBS disease (EOGBS) continue to occur with significant morbidity and mortality. Researchers at the Brigham and Woman’s Hospital in Boston, MA devised this retrospective analysis to determine which attributes of maternal screening, provision of IAP, or evaluation of newborns for sepsis might influence the persistence of EOGBS cases. A retrospective review of all cases of culture proven EOGBS between 1997 and 2003 identified 25 cases of EOGBS among the 67,260 live births, for an overall incidence of 0.37 per 1000 live births. The incidence in infants of very low birth weight was 3.3 cases per 1,000 live births. Among the mothers of term infants with EOGBS, 14 of 17 (82%) had been screened GBS negative; 1 was GBS unknown. Eight of these 14 GBS negative mothers had at least 1 intrapartum risk factor for neonatal sepsis but did not receive IAP. The authors hypothesize that the negative GBS status in these cases may have provided a false sense of reassurance to obstetricians.

Ten of the 17 term infants were evaluated for sepsis due to clinical signs of illness, while the remaining infants were evaluated based on intrapartum risk factors alone. Interestingly, the retrospective analysis demonstrated that 5 of the 25 bacterial isolates were resistant to clindamycin and/or erythromycin, with another 5 isolates partially resistant to 1 or both of these medications. One case of EOGBS disease was found in the child of a penicillin-allergic mother who received clindamycin for IAP. This article highlights the importance of reviewing intrapartum risk factors other than GBS colonization—i.e., delivery at <37 weeks’ gestation,

intrapartum temperature >100.4°C, or signs of clinical chorioamnionitis, in addition to documenting if IAP was provided and with which antibiotic in evaluation of neonates for possible EOGBS.

Treating Refractory Kawasaki Syndrome with Infliximab

Burns JC, Mason, WH, Hauger SB, et al. Infliximab treatment for refractory Kawasaki syndrome. J Pediatr. 2005;146: 662-7.

Citing a 10% to 20% failure rate for intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) in combination with high-dose aspirin (ASA) for treating Kawasaki syndrome (KS), these authors present a case series of patients with refractory KS who were treated with infliximab. Several treatments have been suggested for KS patients with persistent or recrudescent fever after IVIG and ASA; however, no clinical trials have established an optimal treatment. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) has been shown not only to be elevated in patients with KS but also to correlate with development of coronary artery aneurysms. Infliximab, a TNF-α antagonist licensed for clinical use (Remicade, Centocor, Malvern, PA), is used in several immunologic diseases with inflammation mediated by this proinflammatory cytokine. In this poorly controlled case series, 17 patients with acute KS received infliximab after at least 2 doses of IVIG (2 g/kg) and daily ASA (80–100 mg/kg/day) because they were either persistently febrile (16 patients) or had severe arthritis without fever (1 patient). Fourteen of 16 febrile patients became afebrile. C-reactive protein was lower after infliximab in all patients with elevated CRP when remeasured within 48 hours of treatment. In addition to these signs of inflammation, the researchers also studied patient outcomes.

Of 12 patients with coronary artery abnormalities before treatment with infliximab, 4 had dilatation that resolved after treatment. The remaining 8 had either aneurysms or ectasia that were unchanged after therapy. No patients in the series had complications attributed to infliximab. The authors note that the cost of treatment with infliximab compares favorably with a 2 g/kg dose of IVIG. Appropriately, they also specifically address the potential adverse effects of infliximab, for which the pharmacodynamics, pharmacokinetics and safety have not been established in children <5 years of age. Data with regard to possible complications is inadequate and comes from studies of children and adults who typically receive multiple doses of infliximab for chronic inflammatory conditions that inherently can produce multiorgan symptoms. Of note, infliximab does not carry the risk of possible infectious contamination that treatment with IVIG poses. There are several important limitations to the study that are adequately addressed by the authors. Nonetheless, the series highlights the significance of current and future randomized, controlled clinical trials defining the role of TNF-α antagonism in the treatment of KS.

Do Freestanding Children’s Hospitals Improve Care?

Merenstein D, Egleston B, Diener-West M. Lengths of stay and costs associated with children’s hospitals. Pediatrics. 2005;115: 839-44.

Adult literature has shown that access to more subspecialty oriented care results in higher costs and more procedures but does not guarantee improved outcomes. Researchers from Johns Hopkins School of Medicine and Johns Hopkins School of Public Health hypothesized that freestanding children’s hospitals would have longer lengths of stay (LOS) and higher costs compared with other hospitals with regard to similar diagnoses. To test the hypothesis, they studied 24,322 inpatient encounters for pneumonia, gastroenteritis, respiratory syncytial virus, dehydration, or asthma from the Heathcare Cost and Utilization Project Kids’ Inpatient database 2000. Of these encounters, 3,408 were from 23 different freestanding children’s hospitals, and the remaining 20,194 encounters were from 1,749 non-children’s hospitals. The children’s hospitals were all urban teaching hospitals. After adjusting for potentially confounding variables, the researchers found no significant difference in the LOS by hospital type. In this study, the median cost for an admission at a freestanding hospital was $1,294 more per hospitalization after adjustment for LOS and other potential confounder variables. In addition, the results showed that children’s hospitals were more likely to care for minority patients, patients with Medicaid, patients with multiple diagnoses, and patients transferred from other hospitals. The study design did not include direct measures of quality of care, so it is unclear if the increased cost of admission to a children’s hospital leads to improved care.

Asthma and Invasive Pneumococcal Infections

Talbot RT, Hartert TV Mitchel E, et al. Asthma as a risk factor for invasive pneumococcal disease. N Engl J Med. 2005; 352: 2082-90.

Current guidelines for pneumococcal vaccination exclude people with asthma, nor do the most recently published guidelines for management of asthma include pneumococcal vaccination. The authors of this study utilized public health databases to perform a nested case-controlled cohort study to determine the risk of pneumococcal disease among people with asthma. By combining a database of active surveillance for invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD) with a state-based managed healthcare program, researchers identified 635 cases of IPD in people with asthma and paired them with 6,350 age-matched controls. The age range of test subjects was 2 to 49 years (mean, 28.5). After adjustment for race and other conditions with high risk for IPD, asthma was significantly associated with increased risk of IPD (OR: 2.4; 95% CI: 1.9 to 3.1). This finding was consistent in analyses stratified for age (2 to 4 years and 5 to 17 years). Of the isolates causing IPD, 56.9% were among the 7 serotypes included in the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine, with an additional 29.1% found only in the 23-valent polysaccharide vaccine. The authors hypothesize that obstruction caused by increased production and decreased clearance of mucus and the chronic airway inflammation found in asthma are plausible etiologies for the increased risk of IPD. They conclude that consideration should be given for the addition of asthma to the list of conditions warranting pneumococcal vaccination, particularly for the younger population in the study, who are less likely to have other high-risk conditions for which vaccination is already recommended.

Hospital “Report Cards”: Variation in the Management of Bronchiolitis

Christakis DA, Cowan CA, Garrison MM, Molteni R, Marcuse E, Zerr DM. Variation in Inpatient Diagnostic Testing and Management of Bronchiolitis. Pediatrics. 2005;115:878-4.

Bronchiolitis remains 1 of the most common causes of hospitalization in children within the first 2 years of life. In this analysis, the authors conducted a large retrospective descriptive study of infants who were admitted with bronchiolitis to children’s hospitals across the United States. The study examined the variability in length of stay (LOS), diagnostic testing, medications used, and readmission rates. The authors reviewed data on a total of 17,397 infants younger than 1 year of age. Information was obtained from the Pediatric Health Information System, which includes demographic and diagnostic data on 36 freestanding, noncompeting children’s hospitals. The authors found significant and wide variation in LOS, readmission rates, treatment approaches, and use of diagnostic tests for inpatient management of bronchiolitis.

Results indicated that 72% of patients received chest radiographs, 45% received antibiotics, and 25% received systemic steroids. The mean LOS varied considerably across hospitals, with a range of 2.40–3.90 days. The use of antibiotics varied from 28% to 62%, and the use of chest radiographs varied from 38% to 89%. There was also significant difference in readmission rates, which varied from 0% to 2.7%. The variation between hospitals remained a significant contributor even after controlling for multiple potential confounding factors.

Decreasing LOS and unnecessary medication and test utilization is supportive of pediatric patient safety initiatives. The authors suggest that chest radiographs may be leading to unnecessary use of antibiotics due to presumptive treatment based on nonspecific findings. In addition, the authors hypothesize that increased virologic testing may be cost-effective if it leads to decreased use of antibiotics.

The study concludes that there are considerable, unexplained variations that exist in the inpatient management of bronchiolitis. Development of national guidelines and controlled trials of new therapies and different approaches are indicated. Hospitals need to direct resources at analyzing and improving their inpatient care by implementing a more evidence-based approach to management of this common problem.

Maternal Group B Streptococcal Positivity: Risk factor or not?

Puopolo KM, Madoff LC, Eichenwald EC. Early-onset group B streptococcal disease in the era of maternal screening. Pediatrics. 2005;115:1240-6.

Despite implementation of intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis (IAP) based on maternal screening for group B streptococcus (GBS) colonization, cases of early-onset neonatal GBS disease (EOGBS) continue to occur with significant morbidity and mortality. Researchers at the Brigham and Woman’s Hospital in Boston, MA devised this retrospective analysis to determine which attributes of maternal screening, provision of IAP, or evaluation of newborns for sepsis might influence the persistence of EOGBS cases. A retrospective review of all cases of culture proven EOGBS between 1997 and 2003 identified 25 cases of EOGBS among the 67,260 live births, for an overall incidence of 0.37 per 1000 live births. The incidence in infants of very low birth weight was 3.3 cases per 1,000 live births. Among the mothers of term infants with EOGBS, 14 of 17 (82%) had been screened GBS negative; 1 was GBS unknown. Eight of these 14 GBS negative mothers had at least 1 intrapartum risk factor for neonatal sepsis but did not receive IAP. The authors hypothesize that the negative GBS status in these cases may have provided a false sense of reassurance to obstetricians.

Ten of the 17 term infants were evaluated for sepsis due to clinical signs of illness, while the remaining infants were evaluated based on intrapartum risk factors alone. Interestingly, the retrospective analysis demonstrated that 5 of the 25 bacterial isolates were resistant to clindamycin and/or erythromycin, with another 5 isolates partially resistant to 1 or both of these medications. One case of EOGBS disease was found in the child of a penicillin-allergic mother who received clindamycin for IAP. This article highlights the importance of reviewing intrapartum risk factors other than GBS colonization—i.e., delivery at <37 weeks’ gestation,

intrapartum temperature >100.4°C, or signs of clinical chorioamnionitis, in addition to documenting if IAP was provided and with which antibiotic in evaluation of neonates for possible EOGBS.

Treating Refractory Kawasaki Syndrome with Infliximab

Burns JC, Mason, WH, Hauger SB, et al. Infliximab treatment for refractory Kawasaki syndrome. J Pediatr. 2005;146: 662-7.

Citing a 10% to 20% failure rate for intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) in combination with high-dose aspirin (ASA) for treating Kawasaki syndrome (KS), these authors present a case series of patients with refractory KS who were treated with infliximab. Several treatments have been suggested for KS patients with persistent or recrudescent fever after IVIG and ASA; however, no clinical trials have established an optimal treatment. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) has been shown not only to be elevated in patients with KS but also to correlate with development of coronary artery aneurysms. Infliximab, a TNF-α antagonist licensed for clinical use (Remicade, Centocor, Malvern, PA), is used in several immunologic diseases with inflammation mediated by this proinflammatory cytokine. In this poorly controlled case series, 17 patients with acute KS received infliximab after at least 2 doses of IVIG (2 g/kg) and daily ASA (80–100 mg/kg/day) because they were either persistently febrile (16 patients) or had severe arthritis without fever (1 patient). Fourteen of 16 febrile patients became afebrile. C-reactive protein was lower after infliximab in all patients with elevated CRP when remeasured within 48 hours of treatment. In addition to these signs of inflammation, the researchers also studied patient outcomes.

Of 12 patients with coronary artery abnormalities before treatment with infliximab, 4 had dilatation that resolved after treatment. The remaining 8 had either aneurysms or ectasia that were unchanged after therapy. No patients in the series had complications attributed to infliximab. The authors note that the cost of treatment with infliximab compares favorably with a 2 g/kg dose of IVIG. Appropriately, they also specifically address the potential adverse effects of infliximab, for which the pharmacodynamics, pharmacokinetics and safety have not been established in children <5 years of age. Data with regard to possible complications is inadequate and comes from studies of children and adults who typically receive multiple doses of infliximab for chronic inflammatory conditions that inherently can produce multiorgan symptoms. Of note, infliximab does not carry the risk of possible infectious contamination that treatment with IVIG poses. There are several important limitations to the study that are adequately addressed by the authors. Nonetheless, the series highlights the significance of current and future randomized, controlled clinical trials defining the role of TNF-α antagonism in the treatment of KS.

Do Freestanding Children’s Hospitals Improve Care?

Merenstein D, Egleston B, Diener-West M. Lengths of stay and costs associated with children’s hospitals. Pediatrics. 2005;115: 839-44.

Adult literature has shown that access to more subspecialty oriented care results in higher costs and more procedures but does not guarantee improved outcomes. Researchers from Johns Hopkins School of Medicine and Johns Hopkins School of Public Health hypothesized that freestanding children’s hospitals would have longer lengths of stay (LOS) and higher costs compared with other hospitals with regard to similar diagnoses. To test the hypothesis, they studied 24,322 inpatient encounters for pneumonia, gastroenteritis, respiratory syncytial virus, dehydration, or asthma from the Heathcare Cost and Utilization Project Kids’ Inpatient database 2000. Of these encounters, 3,408 were from 23 different freestanding children’s hospitals, and the remaining 20,194 encounters were from 1,749 non-children’s hospitals. The children’s hospitals were all urban teaching hospitals. After adjusting for potentially confounding variables, the researchers found no significant difference in the LOS by hospital type. In this study, the median cost for an admission at a freestanding hospital was $1,294 more per hospitalization after adjustment for LOS and other potential confounder variables. In addition, the results showed that children’s hospitals were more likely to care for minority patients, patients with Medicaid, patients with multiple diagnoses, and patients transferred from other hospitals. The study design did not include direct measures of quality of care, so it is unclear if the increased cost of admission to a children’s hospital leads to improved care.

Asthma and Invasive Pneumococcal Infections

Talbot RT, Hartert TV Mitchel E, et al. Asthma as a risk factor for invasive pneumococcal disease. N Engl J Med. 2005; 352: 2082-90.

Current guidelines for pneumococcal vaccination exclude people with asthma, nor do the most recently published guidelines for management of asthma include pneumococcal vaccination. The authors of this study utilized public health databases to perform a nested case-controlled cohort study to determine the risk of pneumococcal disease among people with asthma. By combining a database of active surveillance for invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD) with a state-based managed healthcare program, researchers identified 635 cases of IPD in people with asthma and paired them with 6,350 age-matched controls. The age range of test subjects was 2 to 49 years (mean, 28.5). After adjustment for race and other conditions with high risk for IPD, asthma was significantly associated with increased risk of IPD (OR: 2.4; 95% CI: 1.9 to 3.1). This finding was consistent in analyses stratified for age (2 to 4 years and 5 to 17 years). Of the isolates causing IPD, 56.9% were among the 7 serotypes included in the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine, with an additional 29.1% found only in the 23-valent polysaccharide vaccine. The authors hypothesize that obstruction caused by increased production and decreased clearance of mucus and the chronic airway inflammation found in asthma are plausible etiologies for the increased risk of IPD. They conclude that consideration should be given for the addition of asthma to the list of conditions warranting pneumococcal vaccination, particularly for the younger population in the study, who are less likely to have other high-risk conditions for which vaccination is already recommended.

Hospital “Report Cards”: Variation in the Management of Bronchiolitis

Christakis DA, Cowan CA, Garrison MM, Molteni R, Marcuse E, Zerr DM. Variation in Inpatient Diagnostic Testing and Management of Bronchiolitis. Pediatrics. 2005;115:878-4.

Bronchiolitis remains 1 of the most common causes of hospitalization in children within the first 2 years of life. In this analysis, the authors conducted a large retrospective descriptive study of infants who were admitted with bronchiolitis to children’s hospitals across the United States. The study examined the variability in length of stay (LOS), diagnostic testing, medications used, and readmission rates. The authors reviewed data on a total of 17,397 infants younger than 1 year of age. Information was obtained from the Pediatric Health Information System, which includes demographic and diagnostic data on 36 freestanding, noncompeting children’s hospitals. The authors found significant and wide variation in LOS, readmission rates, treatment approaches, and use of diagnostic tests for inpatient management of bronchiolitis.

Results indicated that 72% of patients received chest radiographs, 45% received antibiotics, and 25% received systemic steroids. The mean LOS varied considerably across hospitals, with a range of 2.40–3.90 days. The use of antibiotics varied from 28% to 62%, and the use of chest radiographs varied from 38% to 89%. There was also significant difference in readmission rates, which varied from 0% to 2.7%. The variation between hospitals remained a significant contributor even after controlling for multiple potential confounding factors.

Decreasing LOS and unnecessary medication and test utilization is supportive of pediatric patient safety initiatives. The authors suggest that chest radiographs may be leading to unnecessary use of antibiotics due to presumptive treatment based on nonspecific findings. In addition, the authors hypothesize that increased virologic testing may be cost-effective if it leads to decreased use of antibiotics.

The study concludes that there are considerable, unexplained variations that exist in the inpatient management of bronchiolitis. Development of national guidelines and controlled trials of new therapies and different approaches are indicated. Hospitals need to direct resources at analyzing and improving their inpatient care by implementing a more evidence-based approach to management of this common problem.

Maternal Group B Streptococcal Positivity: Risk factor or not?

Puopolo KM, Madoff LC, Eichenwald EC. Early-onset group B streptococcal disease in the era of maternal screening. Pediatrics. 2005;115:1240-6.

Despite implementation of intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis (IAP) based on maternal screening for group B streptococcus (GBS) colonization, cases of early-onset neonatal GBS disease (EOGBS) continue to occur with significant morbidity and mortality. Researchers at the Brigham and Woman’s Hospital in Boston, MA devised this retrospective analysis to determine which attributes of maternal screening, provision of IAP, or evaluation of newborns for sepsis might influence the persistence of EOGBS cases. A retrospective review of all cases of culture proven EOGBS between 1997 and 2003 identified 25 cases of EOGBS among the 67,260 live births, for an overall incidence of 0.37 per 1000 live births. The incidence in infants of very low birth weight was 3.3 cases per 1,000 live births. Among the mothers of term infants with EOGBS, 14 of 17 (82%) had been screened GBS negative; 1 was GBS unknown. Eight of these 14 GBS negative mothers had at least 1 intrapartum risk factor for neonatal sepsis but did not receive IAP. The authors hypothesize that the negative GBS status in these cases may have provided a false sense of reassurance to obstetricians.

Ten of the 17 term infants were evaluated for sepsis due to clinical signs of illness, while the remaining infants were evaluated based on intrapartum risk factors alone. Interestingly, the retrospective analysis demonstrated that 5 of the 25 bacterial isolates were resistant to clindamycin and/or erythromycin, with another 5 isolates partially resistant to 1 or both of these medications. One case of EOGBS disease was found in the child of a penicillin-allergic mother who received clindamycin for IAP. This article highlights the importance of reviewing intrapartum risk factors other than GBS colonization—i.e., delivery at <37 weeks’ gestation,

intrapartum temperature >100.4°C, or signs of clinical chorioamnionitis, in addition to documenting if IAP was provided and with which antibiotic in evaluation of neonates for possible EOGBS.

Treating Refractory Kawasaki Syndrome with Infliximab

Burns JC, Mason, WH, Hauger SB, et al. Infliximab treatment for refractory Kawasaki syndrome. J Pediatr. 2005;146: 662-7.

Citing a 10% to 20% failure rate for intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) in combination with high-dose aspirin (ASA) for treating Kawasaki syndrome (KS), these authors present a case series of patients with refractory KS who were treated with infliximab. Several treatments have been suggested for KS patients with persistent or recrudescent fever after IVIG and ASA; however, no clinical trials have established an optimal treatment. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) has been shown not only to be elevated in patients with KS but also to correlate with development of coronary artery aneurysms. Infliximab, a TNF-α antagonist licensed for clinical use (Remicade, Centocor, Malvern, PA), is used in several immunologic diseases with inflammation mediated by this proinflammatory cytokine. In this poorly controlled case series, 17 patients with acute KS received infliximab after at least 2 doses of IVIG (2 g/kg) and daily ASA (80–100 mg/kg/day) because they were either persistently febrile (16 patients) or had severe arthritis without fever (1 patient). Fourteen of 16 febrile patients became afebrile. C-reactive protein was lower after infliximab in all patients with elevated CRP when remeasured within 48 hours of treatment. In addition to these signs of inflammation, the researchers also studied patient outcomes.

Of 12 patients with coronary artery abnormalities before treatment with infliximab, 4 had dilatation that resolved after treatment. The remaining 8 had either aneurysms or ectasia that were unchanged after therapy. No patients in the series had complications attributed to infliximab. The authors note that the cost of treatment with infliximab compares favorably with a 2 g/kg dose of IVIG. Appropriately, they also specifically address the potential adverse effects of infliximab, for which the pharmacodynamics, pharmacokinetics and safety have not been established in children <5 years of age. Data with regard to possible complications is inadequate and comes from studies of children and adults who typically receive multiple doses of infliximab for chronic inflammatory conditions that inherently can produce multiorgan symptoms. Of note, infliximab does not carry the risk of possible infectious contamination that treatment with IVIG poses. There are several important limitations to the study that are adequately addressed by the authors. Nonetheless, the series highlights the significance of current and future randomized, controlled clinical trials defining the role of TNF-α antagonism in the treatment of KS.

Do Freestanding Children’s Hospitals Improve Care?

Merenstein D, Egleston B, Diener-West M. Lengths of stay and costs associated with children’s hospitals. Pediatrics. 2005;115: 839-44.

Adult literature has shown that access to more subspecialty oriented care results in higher costs and more procedures but does not guarantee improved outcomes. Researchers from Johns Hopkins School of Medicine and Johns Hopkins School of Public Health hypothesized that freestanding children’s hospitals would have longer lengths of stay (LOS) and higher costs compared with other hospitals with regard to similar diagnoses. To test the hypothesis, they studied 24,322 inpatient encounters for pneumonia, gastroenteritis, respiratory syncytial virus, dehydration, or asthma from the Heathcare Cost and Utilization Project Kids’ Inpatient database 2000. Of these encounters, 3,408 were from 23 different freestanding children’s hospitals, and the remaining 20,194 encounters were from 1,749 non-children’s hospitals. The children’s hospitals were all urban teaching hospitals. After adjusting for potentially confounding variables, the researchers found no significant difference in the LOS by hospital type. In this study, the median cost for an admission at a freestanding hospital was $1,294 more per hospitalization after adjustment for LOS and other potential confounder variables. In addition, the results showed that children’s hospitals were more likely to care for minority patients, patients with Medicaid, patients with multiple diagnoses, and patients transferred from other hospitals. The study design did not include direct measures of quality of care, so it is unclear if the increased cost of admission to a children’s hospital leads to improved care.

Asthma and Invasive Pneumococcal Infections

Talbot RT, Hartert TV Mitchel E, et al. Asthma as a risk factor for invasive pneumococcal disease. N Engl J Med. 2005; 352: 2082-90.

Current guidelines for pneumococcal vaccination exclude people with asthma, nor do the most recently published guidelines for management of asthma include pneumococcal vaccination. The authors of this study utilized public health databases to perform a nested case-controlled cohort study to determine the risk of pneumococcal disease among people with asthma. By combining a database of active surveillance for invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD) with a state-based managed healthcare program, researchers identified 635 cases of IPD in people with asthma and paired them with 6,350 age-matched controls. The age range of test subjects was 2 to 49 years (mean, 28.5). After adjustment for race and other conditions with high risk for IPD, asthma was significantly associated with increased risk of IPD (OR: 2.4; 95% CI: 1.9 to 3.1). This finding was consistent in analyses stratified for age (2 to 4 years and 5 to 17 years). Of the isolates causing IPD, 56.9% were among the 7 serotypes included in the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine, with an additional 29.1% found only in the 23-valent polysaccharide vaccine. The authors hypothesize that obstruction caused by increased production and decreased clearance of mucus and the chronic airway inflammation found in asthma are plausible etiologies for the increased risk of IPD. They conclude that consideration should be given for the addition of asthma to the list of conditions warranting pneumococcal vaccination, particularly for the younger population in the study, who are less likely to have other high-risk conditions for which vaccination is already recommended.

Pediatric Practice Profile

Contact

Marcus C. Hermansen, MD

Southern New Hampshire Medical Center

8 Prospect Street

Nashua, NH 03061

603-577-2609

E-mail: [email protected]

Physician Staff (FTE)

Valeria Atkins, MD, Neonatologist and Pediatric Hospitalist

Suzanne Fetter, MD, Pediatric Hospitalist

Anshula Greene, MD, Pediatric Hospitalist

Marcus C. Hermansen, MD, Neonatologist and Pediatric Hospitalist

Sumana Myneni, MD, Pediatric Hospitalist

Cynthia Wright-Devine, CRNP, Neonatal Nurse Practitioner

Other Staff

Lisa Ormond, Practice Manager

The Original Challenge and Solution

The Southern New Hampshire Medical Center maintained a relatively small neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) and pediatric ward. Neither was large enough to justify the desired 24/7 in-house coverage. A combined neonatal-pediatric hospitalist program has been developed and staffed by a combination of neonatologists and pediatric hospitalists. 24/7 in-house coverage is now provided.

History and Background

The Southern New Hampshire Medical Center traditionally staffed its Level 3A NICU with 1 or 2 neonatologists. Approximately 1,500 deliveries take place annually at the medical center; however, these tend to be relatively low-risk deliveries and do not provide enough clinical activity to support a larger group of neonatologists. This prevented the neonatologists from providing the desired 24/7 in-house coverage. To increase clinical activity, the program expanded to include pediatric hospitalist services in 1999. Within 2 years, the combined neonatal-pediatric hospitalist program had grown to allow for 24/7 in-house coverage.

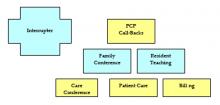

Clinical and Educational Services

The neonatal-pediatric hospitalist team provides services for both the hospital’s neonatology and the pediatric practices. Prior to the team’s development, all community pediatricians were expected to attend high-risk deliveries with availability upon 30 minutes request. Since the development of the in-house neonatal-pediatric hospitalist team, only these team members attend high-risk deliveries. The team attends approximately half of all births at the hospital and has a goal of availability upon 2 minutes notice. Members of the neonatal-pediatric hospitalist team are certified in both neonatal and pediatric resuscitation.

The neonatal-pediatric hospitalist team serves as the attending physician for all admissions to the NICU. Prior to the team’s establishment, it was not possible to care for critically ill infants in the NICU requiring 24/7 in-house attendance; however, with the current team, the NICU can care for smaller and more acutely ill neonates. Additionally, the hospital’s obstetrics department has been able to improve recruitment of high-risk obstetrical patients based upon the improved neonatal staffing.

The team’s non-neonatal pediatric care includes providing consultations in the emergency department and services on the 8-bed pediatric ward. Nearly all of the community pediatricians and family practitioners have asked the hospitalist team to perform the necessary pediatric inpatient history and physical examinations. The unique circumstances of each case determine whether the hospitalist or the PCP serves as the attending physician in the hospital. Additionally, the neonatal-pediatric hospitalist team currently serves as the attending physician in the normal new-born nursery for approximately 25% of all newborns.

Staffing and Schedule

Each day is divided into 2 12-hour shifts: 7:30 a.m. to 7:30 p.m., and 7:30 p.m. to 7:30 a.m. Each fulltime clinician is expected to work 3 or 4 shifts each week. A physician is always available as “back-up” coverage when the neonatal nurse practitioner is providing the in-house coverage. The typical patient load consists of 8–12 NICU patients, 2–4 pediatric ward patients, and 2–5 normal newborns. Each member of the team is employed by The Medical Center and receives a guaranteed salary and benefits.

Philosophic Principles

Certain principles have been followed during the development of the program. These include:

- All services are offered to community PCPs on a voluntary basis. No hospitalist service is mandatory.

- Close communication with the PCP is of primary importance. Telephone, email, and transcribed summaries are provided throughout the hospital stay and at discharge.

- High-quality patient care must be provided. The team members recognize that some patients are too sick for care at The medical center and are better served at one of the nearby tertiary academic centers.

Ongoing Challenges

The primary challenge stems from the relatively small neonatal and pediatric services. Combining the neonatal and pediatric programs to provide 24/7 coverage required the difficult task of recruiting of neonatologists willing to provide pediatric care and pediatric hospitalists willing to provide care in the NICU. Additionally, because of the small services, there is limited pediatric subspecialty support available at the Medical Center. The hospitalist occasionally serves as consultant to community PCPs on issues related to pediatric cardiology, neurology, endocrinology, and other disciplines for which there are no other consulting specialists available.

Although the team has grown to include 5 full-time healthcare providers, the small size of the team still provides challenges. There is little flexibility in scheduling, making it difficult for 2 providers to take an extended vacation at the same time. Finally, the small size of the group prevents the ability to provide back-up coverage to the in-house hospitalist. Community pediatricians fulfill this function.

Every year the team is producing improved financial results but still does not generate revenues to support the team’s salaries; a hospital subsidy provides the difference.

Future Opportunities

The neonatal-hospital team continues to explore opportunities for growth. Opportunities under consideration include provision of pediatric conscious sedation, developing Level II pediatric intensive care unit services, performance of circumcisions on normal newborns, marketing the NICU to nearby primary care community hospitals to obtain more neonatal, pediatric, and obstetric referrals and provision of expanded services in the emergency department.

Contact

Marcus C. Hermansen, MD

Southern New Hampshire Medical Center

8 Prospect Street

Nashua, NH 03061

603-577-2609

E-mail: [email protected]

Physician Staff (FTE)

Valeria Atkins, MD, Neonatologist and Pediatric Hospitalist

Suzanne Fetter, MD, Pediatric Hospitalist

Anshula Greene, MD, Pediatric Hospitalist

Marcus C. Hermansen, MD, Neonatologist and Pediatric Hospitalist

Sumana Myneni, MD, Pediatric Hospitalist

Cynthia Wright-Devine, CRNP, Neonatal Nurse Practitioner

Other Staff

Lisa Ormond, Practice Manager

The Original Challenge and Solution

The Southern New Hampshire Medical Center maintained a relatively small neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) and pediatric ward. Neither was large enough to justify the desired 24/7 in-house coverage. A combined neonatal-pediatric hospitalist program has been developed and staffed by a combination of neonatologists and pediatric hospitalists. 24/7 in-house coverage is now provided.

History and Background

The Southern New Hampshire Medical Center traditionally staffed its Level 3A NICU with 1 or 2 neonatologists. Approximately 1,500 deliveries take place annually at the medical center; however, these tend to be relatively low-risk deliveries and do not provide enough clinical activity to support a larger group of neonatologists. This prevented the neonatologists from providing the desired 24/7 in-house coverage. To increase clinical activity, the program expanded to include pediatric hospitalist services in 1999. Within 2 years, the combined neonatal-pediatric hospitalist program had grown to allow for 24/7 in-house coverage.

Clinical and Educational Services

The neonatal-pediatric hospitalist team provides services for both the hospital’s neonatology and the pediatric practices. Prior to the team’s development, all community pediatricians were expected to attend high-risk deliveries with availability upon 30 minutes request. Since the development of the in-house neonatal-pediatric hospitalist team, only these team members attend high-risk deliveries. The team attends approximately half of all births at the hospital and has a goal of availability upon 2 minutes notice. Members of the neonatal-pediatric hospitalist team are certified in both neonatal and pediatric resuscitation.

The neonatal-pediatric hospitalist team serves as the attending physician for all admissions to the NICU. Prior to the team’s establishment, it was not possible to care for critically ill infants in the NICU requiring 24/7 in-house attendance; however, with the current team, the NICU can care for smaller and more acutely ill neonates. Additionally, the hospital’s obstetrics department has been able to improve recruitment of high-risk obstetrical patients based upon the improved neonatal staffing.

The team’s non-neonatal pediatric care includes providing consultations in the emergency department and services on the 8-bed pediatric ward. Nearly all of the community pediatricians and family practitioners have asked the hospitalist team to perform the necessary pediatric inpatient history and physical examinations. The unique circumstances of each case determine whether the hospitalist or the PCP serves as the attending physician in the hospital. Additionally, the neonatal-pediatric hospitalist team currently serves as the attending physician in the normal new-born nursery for approximately 25% of all newborns.

Staffing and Schedule

Each day is divided into 2 12-hour shifts: 7:30 a.m. to 7:30 p.m., and 7:30 p.m. to 7:30 a.m. Each fulltime clinician is expected to work 3 or 4 shifts each week. A physician is always available as “back-up” coverage when the neonatal nurse practitioner is providing the in-house coverage. The typical patient load consists of 8–12 NICU patients, 2–4 pediatric ward patients, and 2–5 normal newborns. Each member of the team is employed by The Medical Center and receives a guaranteed salary and benefits.

Philosophic Principles

Certain principles have been followed during the development of the program. These include:

- All services are offered to community PCPs on a voluntary basis. No hospitalist service is mandatory.

- Close communication with the PCP is of primary importance. Telephone, email, and transcribed summaries are provided throughout the hospital stay and at discharge.

- High-quality patient care must be provided. The team members recognize that some patients are too sick for care at The medical center and are better served at one of the nearby tertiary academic centers.

Ongoing Challenges

The primary challenge stems from the relatively small neonatal and pediatric services. Combining the neonatal and pediatric programs to provide 24/7 coverage required the difficult task of recruiting of neonatologists willing to provide pediatric care and pediatric hospitalists willing to provide care in the NICU. Additionally, because of the small services, there is limited pediatric subspecialty support available at the Medical Center. The hospitalist occasionally serves as consultant to community PCPs on issues related to pediatric cardiology, neurology, endocrinology, and other disciplines for which there are no other consulting specialists available.

Although the team has grown to include 5 full-time healthcare providers, the small size of the team still provides challenges. There is little flexibility in scheduling, making it difficult for 2 providers to take an extended vacation at the same time. Finally, the small size of the group prevents the ability to provide back-up coverage to the in-house hospitalist. Community pediatricians fulfill this function.

Every year the team is producing improved financial results but still does not generate revenues to support the team’s salaries; a hospital subsidy provides the difference.

Future Opportunities

The neonatal-hospital team continues to explore opportunities for growth. Opportunities under consideration include provision of pediatric conscious sedation, developing Level II pediatric intensive care unit services, performance of circumcisions on normal newborns, marketing the NICU to nearby primary care community hospitals to obtain more neonatal, pediatric, and obstetric referrals and provision of expanded services in the emergency department.

Contact

Marcus C. Hermansen, MD

Southern New Hampshire Medical Center

8 Prospect Street

Nashua, NH 03061

603-577-2609

E-mail: [email protected]

Physician Staff (FTE)

Valeria Atkins, MD, Neonatologist and Pediatric Hospitalist

Suzanne Fetter, MD, Pediatric Hospitalist

Anshula Greene, MD, Pediatric Hospitalist

Marcus C. Hermansen, MD, Neonatologist and Pediatric Hospitalist

Sumana Myneni, MD, Pediatric Hospitalist

Cynthia Wright-Devine, CRNP, Neonatal Nurse Practitioner

Other Staff

Lisa Ormond, Practice Manager

The Original Challenge and Solution

The Southern New Hampshire Medical Center maintained a relatively small neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) and pediatric ward. Neither was large enough to justify the desired 24/7 in-house coverage. A combined neonatal-pediatric hospitalist program has been developed and staffed by a combination of neonatologists and pediatric hospitalists. 24/7 in-house coverage is now provided.

History and Background

The Southern New Hampshire Medical Center traditionally staffed its Level 3A NICU with 1 or 2 neonatologists. Approximately 1,500 deliveries take place annually at the medical center; however, these tend to be relatively low-risk deliveries and do not provide enough clinical activity to support a larger group of neonatologists. This prevented the neonatologists from providing the desired 24/7 in-house coverage. To increase clinical activity, the program expanded to include pediatric hospitalist services in 1999. Within 2 years, the combined neonatal-pediatric hospitalist program had grown to allow for 24/7 in-house coverage.

Clinical and Educational Services

The neonatal-pediatric hospitalist team provides services for both the hospital’s neonatology and the pediatric practices. Prior to the team’s development, all community pediatricians were expected to attend high-risk deliveries with availability upon 30 minutes request. Since the development of the in-house neonatal-pediatric hospitalist team, only these team members attend high-risk deliveries. The team attends approximately half of all births at the hospital and has a goal of availability upon 2 minutes notice. Members of the neonatal-pediatric hospitalist team are certified in both neonatal and pediatric resuscitation.

The neonatal-pediatric hospitalist team serves as the attending physician for all admissions to the NICU. Prior to the team’s establishment, it was not possible to care for critically ill infants in the NICU requiring 24/7 in-house attendance; however, with the current team, the NICU can care for smaller and more acutely ill neonates. Additionally, the hospital’s obstetrics department has been able to improve recruitment of high-risk obstetrical patients based upon the improved neonatal staffing.

The team’s non-neonatal pediatric care includes providing consultations in the emergency department and services on the 8-bed pediatric ward. Nearly all of the community pediatricians and family practitioners have asked the hospitalist team to perform the necessary pediatric inpatient history and physical examinations. The unique circumstances of each case determine whether the hospitalist or the PCP serves as the attending physician in the hospital. Additionally, the neonatal-pediatric hospitalist team currently serves as the attending physician in the normal new-born nursery for approximately 25% of all newborns.

Staffing and Schedule

Each day is divided into 2 12-hour shifts: 7:30 a.m. to 7:30 p.m., and 7:30 p.m. to 7:30 a.m. Each fulltime clinician is expected to work 3 or 4 shifts each week. A physician is always available as “back-up” coverage when the neonatal nurse practitioner is providing the in-house coverage. The typical patient load consists of 8–12 NICU patients, 2–4 pediatric ward patients, and 2–5 normal newborns. Each member of the team is employed by The Medical Center and receives a guaranteed salary and benefits.

Philosophic Principles

Certain principles have been followed during the development of the program. These include:

- All services are offered to community PCPs on a voluntary basis. No hospitalist service is mandatory.

- Close communication with the PCP is of primary importance. Telephone, email, and transcribed summaries are provided throughout the hospital stay and at discharge.

- High-quality patient care must be provided. The team members recognize that some patients are too sick for care at The medical center and are better served at one of the nearby tertiary academic centers.

Ongoing Challenges

The primary challenge stems from the relatively small neonatal and pediatric services. Combining the neonatal and pediatric programs to provide 24/7 coverage required the difficult task of recruiting of neonatologists willing to provide pediatric care and pediatric hospitalists willing to provide care in the NICU. Additionally, because of the small services, there is limited pediatric subspecialty support available at the Medical Center. The hospitalist occasionally serves as consultant to community PCPs on issues related to pediatric cardiology, neurology, endocrinology, and other disciplines for which there are no other consulting specialists available.

Although the team has grown to include 5 full-time healthcare providers, the small size of the team still provides challenges. There is little flexibility in scheduling, making it difficult for 2 providers to take an extended vacation at the same time. Finally, the small size of the group prevents the ability to provide back-up coverage to the in-house hospitalist. Community pediatricians fulfill this function.

Every year the team is producing improved financial results but still does not generate revenues to support the team’s salaries; a hospital subsidy provides the difference.

Future Opportunities

The neonatal-hospital team continues to explore opportunities for growth. Opportunities under consideration include provision of pediatric conscious sedation, developing Level II pediatric intensive care unit services, performance of circumcisions on normal newborns, marketing the NICU to nearby primary care community hospitals to obtain more neonatal, pediatric, and obstetric referrals and provision of expanded services in the emergency department.

Other Literature of Interest

1. Chimowitz MI, Lynn MJ, Howlett-Smith H, et al. Comparison of warfarin and aspirin for symptomatic intracranial arterial stenosis. N Engl J Med. 352:1305-16.

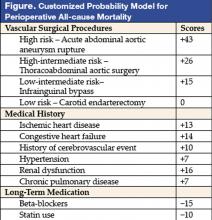

This is the first prospective study comparing antithrombotic therapies for patients with atherosclerotic stenosis of major intracranial arteries. This multicenter, NINDS-sponsored, placebo-controlled, blinded study randomized 569 patients to aspirin (650 mg twice daily) or warfarin (initially 5 mg daily, titrated to achieve an INR of 2.0–3.0) and followed them for nearly 2 years. The study was terminated early over safely concerns about patients in the warfarin group. Baseline characteristics between the 2 groups were not significantly different. Warfarin was not more effective than aspirin in its effect on the primary endpoints of ischemic stroke, brain hemorrhage, or vascular death other than from stroke (as defined in the study protocol). However, major cardiac events (myocardial infarction or sudden death) were significantly higher in the warfarin group, and major hemorrhage (defined as any intracranial or systemic hemorrhage requiring hospitalization, transfusion, or surgical intervention) was also significantly higher in the warfarin group. The authors note the difficulty maintaining the INR in the target range (achieved only 63.1 % of the time during the maintenance period, an observation in line with other anticoagulation studies). In an accompanying editorial, Dr. Koroshetz of the stroke service at the Massachusetts General Hospital also observed that difficulties in achieving the therapeutic goal with warfarin could have impacted the results. The authors also note that the dose of aspirin employed in this study is somewhat higher than in previous trials. Nevertheless, until other data emerge, this investigation’s results favor aspirin in preference to warfarin for this high-risk condition.

2. Cornish PL, Knowles, SR, Marchesano R, et al. Unintended medication discrepancies at the time of hospital admission Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:424-9

Of the various types of medical errors, medication errors are believed to be the most common. At the time of hospital admission, medication discrepancies may lead to unintended drug interactions, toxicity, or interruption of appropriate drug therapies. These investigators performed a prospective study to identify unintended medication discrepancies between the patient’s home medications and those ordered at the time of the patient’s admission and to evaluate the potential clinical significance of these discrepancies.

This study was conducted at a 1,000-bed tertiary care hospital in Canada on the general medicine teaching service. A member of the study team reviewed each medical record to ascertain the physician-recorded medication history, the nurse-recorded medication history, the admission medication orders, and demographic information. A comprehensive list of all of the patient’s prescription or nonprescription drugs was compiled by interviewing patients, families, and pharmacists, and by inspecting the bottles. A discrepancy was defined as any difference between this comprehensive list and the admission medication orders. These were categorized into omission or addition of a medication, substitution of an agent within the same drug class, and change in dose, route, and frequency of administration of an agent. The medical team caring for the patient was then asked whether or not these discrepancies were intended. The team then reconciled any unintended discrepancies. These unintended discrepancies were further classified according to their potential for harm by 3 medical hospitalists into Class 1, 2, 3, in increasing order of potential harm. One hundred fifty-one patients were included in the analysis. A total of 140 errors occurred in 81 patients (54%). The overall error rate was 0.93 per patient. Of the errors, 46% consisted of omission of a regularly prescribed medication, 25% involved discrepant doses, 17.1% involved discrepant frequency, and 11.4% were actually incorrect drugs. Breakdown of error severity resulted in designation of 61% as Class 1, 33% as Class 2, and 5.7% as Class 3. The interrater agreement was a kappa of 0.26. These discrepancies were not found to be associated with night or weekend admissions, high patient volume, or high numbers of medications.

Real-time clinical correlation with the responsible physicians allowed distinction of intended from unintended discrepancies. This presumably improved the accuracy of the error rate measurement. This study confirmed the relatively high rate previously reported. Further study can focus on possible intervention to minimize these errors.

3. Liperoti R, Gambassi G, Lapane KL, et al. Conventional and atypical antipsychotics and the risk of hospitalization for ventricular arrhythmias or cardiac arrest Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:696-701.

As the number of hospitalized elderly and demented patients increases, use of both typical and atypical antipsychotics has become prevalent. QT prolongation, ventricular arrhythmia, and cardiac arrest are more commonly associated with the older conventional antipsychotics than with newer atypical agents. This case-control study was conducted to estimate the effect of both conventional and atypical antipsychotics use on the risk of hospital admission for ventricular arrhythmia or cardiac arrest.

The patient population involved consisted of elderly nursing home residents in 6 US states. The investigators utilized Systematic Assessment of Geriatric Drug Use via Epidemiology database that contains data from minimum data set (MDS), a standardized data set required of all certified nursing homes in the United States. Case patients were selected by ICD-9 codes for cardiac arrest or ventricular arrhythmia. Control patients were selected via ICD-9 codes of 6 other common inpatient diagnoses. Antipsychotic exposure was determined by use of the most recent assessment in the nursing homes prior to admission. Exposed patients were those who received atypical antipsychotics such as risperidone, olanzapine, quetiapine, and clozapine, and those who used conventional agents such as haloperidol and others. After control for potential confounders, users of conventional antipsychotics showed an 86% increase in the risk of hospitalization for ventricular arrhythmias or cardiac arrest (OR: 1.86) compared with nonusers. No increased risk was reported for users of atypical antipsychotics. (OR: 0.87). When compared with atypical antipsychotic use, conventional antipsychotic use carries an OR of 2.13 for these cardiac outcomes. In patients using conventional antipsychotics, the presence and absence of cardiac diseases were 3.27 times and 2.05 times, respectively, more likely to be associated with hospitalization for ventricular arrhythmias and cardiac arrest, compared with nonusers without cardiac diseases.

These results suggest that atypical antipsychotics may carry less cardiac risk than conventional agents. In an inpatient population with advancing age and increasing prevalence of dementia and cardiac disease, use of atypical antipsychotic agents may be safer than older, typical agents.

4. Mayer SA, Brun NC, Begtrup K, et al. Recombinant activated factor VII for acute intracerebral hemorrhage. N Engl J Med. 352:777-85.

This placebo-controlled, double-blind, multicenter, industry-sponsored trial of early treatment of hemorrhagic stroke with rFVIIa at 3 escalating doses, evaluated stroke hematoma growth, mortality, and functional outcomes up to 90 days. The authors note the substantial mortality and high morbidity of this condition, which currently lacks definitive treatment. Patients within 3 hours of symptoms with intracerebral hemorrhage on CT and who met study criteria were randomized to receive either placebo or a single intravenous dose of 40, 80, or 160 mcg/kg of rFVIIa within 1 hour of baseline CT and no more than 4 hours after symptoms. Follow-up CTs at 24 and 72 hours were obtained and functional assessments were performed serially at frequent intervals throughout the study period. Three hundred ninety-nine patients were analyzed and were found similar in their baseline characteristics. Lesion volume was significantly less with treatment, in a dose-dependent fashion. Mortality at 3 months was significantly less (29% vs. 18%) with treatment, and all 4 of the global functional outcome scales utilized were favorable, 3 of them (modified Rankin Scale for all doses, NIH Stroke Scale for all doses, and the Barthel Index at the 80 and 160 mcg/kg doses) in a statistically significant fashion. However, the authors noted an increase in serious thromboembolic events in the treatment groups, with a statistically significant increased frequency of arterial thromboembolic events. These included myocardial ischemic events and cerebral infarction, and most occurred within 3 days of rFVIIa treatment. Of note, the majority of patients who suffered these events made recovery from their complications, and the overall rates of fatal or disabling thromboembolic occurrences between the treatment and placebo groups were similar. This study offers new and exciting insights into potential therapy for this serious form of stroke, although safety concerns merit further study.

5. Siguret V, Gouin I, Debray M, et al. Initiation of warfarin therapy in elderly medical inpatients: a safe and accurate regimen. Am J Med. 2005; 118:137-142.

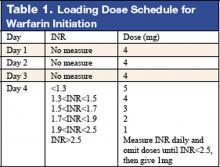

Warfarin therapy is widely used in geriatric populations. Sometimes over-anticoagulation occurs when warfarin therapy is initiated based on standard loading and maintenance dose in the hospital setting. This is mainly due to decreased hepatic clearance and polypharmacy in the geriatric population. A recent study in France demonstrated a useful and simple low-dose regimen for starting warfarin therapy (target INR: 2.0–3.0) in the elderly without over-anticoagulation. The patients enrolled in this study were typical geriatric patients with multiple comorbid conditions. These patients also received concomitant medications known to potentiate the effect of warfarin. One hundred six consecutive inpatients (age %70, mean age of 85 years) were given a 4-mg induction dose of warfarin for 3 days, and INR levels were measured on the 4th day. From this point, the daily warfarin dose was adjusted according to an algorithm (see Table 1), and INR values were obtained every 2–3 days until actual maintenance doses were determined. The maintenance dose was defined as the amount of warfarin required to yield an INR in 2.0 to 3.0 range on 2 consecutive samples obtained 48–72 hours apart in the absence of any dosage change for at least 4 days. Based on this algorithm, the predicted daily warfarin dose (3.1 ± 1.6 mg/day) correlated closely with the actual maintenance dose (3.2 ± 1.7 mg/day). The average time needed to achieve a therapeutic INR was 6.7 ± 3.3 days. None of the patients had an INR >4.0 during the induction period. This regimen also required fewer INR measurements.

Intracranial hemorrhage and gastrointestinal bleeding are serious complications of over-anticoagulation. The majority of gastrointestinal bleeding episodes respond to withholding warfarin and reversing anticoagulation. However, intracranial hemorrhage frequently leads to devastating outcomes. A recent report suggested that an age over 85 and INR of 3.5 or greater were associated with increased risk of intracranial hemorrhage. The warfarin algorithm proposed in this study provides a simple, safe, and effective tool to predict warfarin dosing in elderly hospitalized patients without over-anticoagulation. Although this regimen still needs to be validated in a large patient population in the future, it can be incorporated into computer-based dosing entry programs in the hospital setting to guide physicians in initiating warfarin therapy.

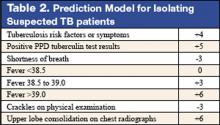

6. Wisnivesky JP, Henschke C, Balentine J, Willner, C, Deloire AM, McGinn TG. Prospective validation of a prediction model for isolating inpatients with suspected pulmonary tuberculosis. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:453-7.

Whether to isolate a patient for suspected pulmonary tuberculosis (TB) is often a balancing act between clinical risk assessment and optimal hospital resource utilitization. Practitioners need a relatively simple but sophisticated tool that they can use at the bedside to more precisely assess the likelihood of TB for more efficient and effective triage.

These authors previously developed such a tool with a sensitivity of 98% and specificity of 46%. (See Table 2 for details) This study was designed to validate this decision rule in a new set of patients. Patients were enrolled in 2 tertiary-care hospitals in New York City area over a 21-month period. They were all admitted and isolated because of clinical suspicion for pulmonary TB, not utilizing the decision rule under study. Study team members collected demographic, clinical risk factors, presenting symptoms, and signs, laboratory, and radiographic findings. Chest x-ray findings were reviewed by investigators who were blinded to the other clinical and demographical information. The gold standard of diagnosis was at least 1 sputum culture that was positive for Mycobacterium tuberculosis.

A total of 516 patients were enrolled in this study. Of the 516, 19 (3.7%) were found to have culture-proven pulmonary TB. Univariate analyses showed that history of positive PPD, higher (98% vs. 95%) oxygen saturation, upper-lobe consolidation (not upper lobe cavity), and lymphadenopathy (hilar, mediastinal, or paratracheal) were all associated with the presence of pulmonary TB. Shortness of breath was associated with the absence of TB. A total score of 1 or higher in the prediction rule had a sensitivity of 95% for pulmonary TB, and score of less than 1 had a specificity of 35%. The investigators estimated a prevalence of 3.7%, thereby yielding a positive predictive value of 9.6% but a negative predictive value of 99.7%. They estimated that 35% of patients isolated would not have been with this prediction rule.

Though validated scientifically, this tool still has a false-negative rate of 5%. In a less endemic area, the false-negative rate would be correspondingly lower and thus more acceptable from a public health perspective. This is one step closer to a balance of optimal bed utilization and reasoned clinical assessment.

1. Chimowitz MI, Lynn MJ, Howlett-Smith H, et al. Comparison of warfarin and aspirin for symptomatic intracranial arterial stenosis. N Engl J Med. 352:1305-16.

This is the first prospective study comparing antithrombotic therapies for patients with atherosclerotic stenosis of major intracranial arteries. This multicenter, NINDS-sponsored, placebo-controlled, blinded study randomized 569 patients to aspirin (650 mg twice daily) or warfarin (initially 5 mg daily, titrated to achieve an INR of 2.0–3.0) and followed them for nearly 2 years. The study was terminated early over safely concerns about patients in the warfarin group. Baseline characteristics between the 2 groups were not significantly different. Warfarin was not more effective than aspirin in its effect on the primary endpoints of ischemic stroke, brain hemorrhage, or vascular death other than from stroke (as defined in the study protocol). However, major cardiac events (myocardial infarction or sudden death) were significantly higher in the warfarin group, and major hemorrhage (defined as any intracranial or systemic hemorrhage requiring hospitalization, transfusion, or surgical intervention) was also significantly higher in the warfarin group. The authors note the difficulty maintaining the INR in the target range (achieved only 63.1 % of the time during the maintenance period, an observation in line with other anticoagulation studies). In an accompanying editorial, Dr. Koroshetz of the stroke service at the Massachusetts General Hospital also observed that difficulties in achieving the therapeutic goal with warfarin could have impacted the results. The authors also note that the dose of aspirin employed in this study is somewhat higher than in previous trials. Nevertheless, until other data emerge, this investigation’s results favor aspirin in preference to warfarin for this high-risk condition.

2. Cornish PL, Knowles, SR, Marchesano R, et al. Unintended medication discrepancies at the time of hospital admission Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:424-9

Of the various types of medical errors, medication errors are believed to be the most common. At the time of hospital admission, medication discrepancies may lead to unintended drug interactions, toxicity, or interruption of appropriate drug therapies. These investigators performed a prospective study to identify unintended medication discrepancies between the patient’s home medications and those ordered at the time of the patient’s admission and to evaluate the potential clinical significance of these discrepancies.