User login

Borderline personality disorder: The lability of psychiatric diagnosis

Not everyone agrees that borderline personality disorder (BPD) should be a diagnostic category. BPD became “official” with DSM-III in 1980, although the term had been used for 40 years to describe various patient groups. Being listed in DSM-III legitimized BPD, which was thought to represent a specific—though not necessarily distinct—diagnostic category.

The history of the BPD diagnosis and opinions as to its usefulness can be viewed as a microcosm of psychiatric diagnosis in general. Before DSM-III, diagnoses were broadly defined and did not contain specific inclusion or exclusion criteria.1 For the 5 to 10 years prior to DSM-III, however, two assumptions developed:

- distinct diagnostic categories did, in fact, exist

- by rigorously defining and studying those categories we could develop more specific and effective treatments for our patients.2

The specificity and exclusivity that we assumed we could achieve by categorical diagnoses, however, remain a distant wish. Comorbidity appears more common in psychiatry than was originally thought and confounds both treatment and outcome.3 Also, many patients appear treatment-resistant, despite fitting neatly into diagnostic categories.4

Miss A, age 35, presents to the emergency room with a long history of intermittent depression and self-mutilation. She has never been hospitalized nor on psychotropic medication but has been in and out of psychotherapy for years. She has had intermittent depressive episodes for many years, though the episodes often lasted 2 to 3 weeks and appeared to correct themselves spontaneously.

Agitated and afraid. She is extremely agitated when she arrives at the emergency department. She has hardly slept or eaten but insists she is not hungry. She reports that she cannot concentrate or do her work as an accountant. She says she is hearing voices, knows they are in her head, but nonetheless is terrified that something horrible is about to happen—though she cannot say what it might be.

Voice ‘calling my name.’ When the psychiatric resident inquires further, Miss A says a male voice is calling her name and mumbling some short phrase she cannot understand. She says she has heard the voice the last few days, perhaps for 10 to 15 minutes every few hours, particularly when she ruminates about how she messed up a relationship with her now ex-boyfriend. The breakup occurred 1 week ago.

Feeling detached. She claims she has never heard voices before but describes periods when she has felt detached and unreal. Often these were short-term dissociative episodes that occurred in the wake of what she perceived as a personal failure or a distressful interpersonal encounter (often with a man). Relationships frequently were very difficult for her, and she felt she could easily go from infatuation to detesting someone.

Diagnosis? Talking appears to calm her down. After being in the emergency room for 2 hours, she says she no longer hears the voice. The resident tells the attending psychiatrist he believes the patient is in a major depressive episode, perhaps a psychotic depression, and proposes starting antidepressant treatment. The attending argues that the patient appears to have borderline personality disorder and suggests that she be sent home without medication and given an appointment to the outpatient clinic within the next few days.

As psychiatry considers DSM-V, questions linger as to whether BPD (and personality disorder in general) should remain as a categorical diagnosis or if dimensional measures may be more appropriate. Dimensions imply that no one ever fits into a given box because no specific box exists. Rather, patients are described as being closer to or more distant from a prototypic model of the diagnosis. In personality disorders, the dimensions most often mentioned are cognition, impulsivity, emotional lability, environmental hyperreactivity, and anxiety. The case report (above) illustrates the interplay of these dimensions in a typical patient with presumed BPD.

What’s in a name?

The symptom complex or syndrome that bears the name borderline personality disorder has probably existed for as long as people have thought about patients in psychopathologic terms.5 Before 1980, the term “borderline” applied primarily to two separate but overlapping concepts:

- Patients thought to reside on the “border” with psychosis, such as the patient in our case example. They seemed to have an underlying psychotic disorder, but the psychosis—if it surfaced—appeared briefly, was not exceptionally deep or firmly held, and was not regularly evident or immediately accessible to the clinician.

- Patients who appeared to occupy the space between neurosis and psychosis. This concept evolved into the idea of a character or personality disorder distinguished primarily by unstable interpersonal relationships, a confused or inconsistent sense of identity, and emotional instability.

How DSM is changing. Comparing the disorders listed in DSM-IV (1994)6 versus DSM-II (1968)1 suggests that psychiatry has become enamored of the naming process. For example, DSM-II lists anxiety neurosis (300.0), phobic neurosis (300.2), and obsessive-compulsive neurosis (300.3), whereas DSM-IV lists 11 different categories of anxiety disorders.

But beyond naming, subsequent DSMs have differed even more dramatically from DSM-II. We have seen a shift from describing a diagnostic category with a simple explanatory paragraph to lists of specific inclusion and exclusion criteria. These more-specific lists imply that they define categories closer to some reality or authenticity than did previous definitions.

Before DSM-III, the borderline concept was conceived in broad object relational and psychodynamic terms. In contrast, DSM-III produced a definitive set of criteria and required that a subset be met before the diagnosis could be made.7 An example of this criteria-based model is shown in Box 1, which lists the DSM-IV-TR criteria for BPD.

Some psychiatrists objected that BPD was solely a psychoanalytic construct and too theoretical for inclusion in DSM-III. Others argued that if BPD were not defined, it would be difficult to study the clinical usefulness of that definition or any other. Nonetheless, many have argued that BPD does not exist, though to what category BPD patients should belong has changed over the years:

- Is BPD nothing more than a milder or unusual presentation of an affective disorder8 or actually bipolar II disorder?9

- Is it a presentation of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) called “complex PTSD,”10-11 or an adult presentation of attention-deficit/ hyperactivity or other brain disorder?12

- Is it a stigmatizing diagnosis that we apply to patients whom we do not like?13

In truth, the diagnosis of BPD reflects a particular clinical presentation no more or less accurately than many of the well-accepted axis I disorders. Despite recent advances in the neurosciences, the dilemma we face as psychiatrists is that we make a diagnosis based upon what we see in the clinical setting (i.e., a phenotype). Yet in labeling what we believe is a specific psychiatric disorder, we make assumptions—for better or for worse, consciously or unconsciously—about pathophysiology and indirectly about genotype.

A pervasive pattern of instability of interpersonal relationships, self-image, and affects and marked impulsivity beginning by early adulthood and present in a variety of contexts, as indicated by five (or more) of the following:

- Frantic efforts to avoid real or imagined abandonment

- A pattern of unstable and intense interpersonal relationships characterized by alternating between extremes of idealization and devaluation

- Identity disturbance: markedly and persistent unstable self-image or sense of self

- Impulsivity in at least two areas that are potentially self-damaging (spending, sex, substance abuse, binge eating, reckless driving)

- Recurrent suicidal behavior, gestures, or threats; self-mutilating behavior

- Affective instability due to a marked reactivity of mood

- Chronic feelings of emptiness

- Inappropriate, intense anger or difficulty controlling anger

- Transient, stress-related paranoid ideation or severe dissociative symptoms

Source: DSM-IV6

Defining the borderline personality

Stern first used the term “borderline” in 1938 to describe patients who appeared to occupy the border between neurosis and psychosis.14 In 1942, Deutsch described the “as if” personality in patients who seemed chameleon-like. They could adapt or play the role demanded of them in specific situations, yet elsewhere—as in the analyst’s office—they had little sense of themselves and were thought to be internally disorganized and probably psychotic.15

Border to psychosis. The idea that borderline-type patients were psychotic continued in Hoch and Polatin’s description of the “pseudoneurotic schizophrenic,”16 a patient who appeared severely neurotic but was thought to employ many defenses and interpersonal styles to ward off a fundamental inner psychosis. Knight used the label “borderline states”17 to describe severely ill patients who were not frankly psychotic but fell within the realm of psychosis without qualifying for a diagnosis of schizophrenia. Knight was the first person to use the term “borderline” as a diagnostic entity, though simultaneously he argued against its use as a label because the term lacked precision.

Psychotic character. About the same time, Schmideberg characterized a group of patients whose emotional lability or affective reactivity seemed to be a consistent aspect of their clinical presentation. She believed this appearance of “stable instability”18 represented the patient’s characterologic adaptation to the world.

Frosch coined the term “psychotic character”19 that aptly captured both the characterologic and the border-to-psychosis aspects of these patients’ clinical picture. According to Frosch, these patients appeared to regress readily into psychotic thinking, yet they did not lose their ability to test reality.

Affective and emotional instability. Thus until the 1960s, the term borderline was applied primarily to patients who appeared to occupy the border between neurosis and psychosis but were thought to be closer to psychotic than neurotic. And this sitting close to the edge of psychosis appeared to be a stable condition.

Most of the attention up until this point had been paid to how these patients thought—with little attention to their affective lability or emotional instability, save for Schmideberg’s comments. In the 1960s, however, the term borderline was applied somewhat differently—not completely divorced from previous concepts but with greater emphasis on borderline as a stable but psychopathologic functioning of the personality that included affective and emotional instability and an impaired sense of self.

- Intense affect, usually depressive or hostile

- History of impulsive, often self-destructive behavior

- Social adaptiveness that may mask a disturbed identity

- Brief psychotic episodes, often paranoid and evident in unstructured situations

- “Loose thinking” or primitive answers on unstructured psychological tests

- Relationships vacillate between transient superficiality and intense dependency

Impaired personality organization. In 1967, Kernberg published a seminal article in the history of BPD diagnosis. Although he did not discuss the diagnosis of BPD, Kernberg did develop a concept concerning a specific organization of the personality based upon impaired object relations. This impaired organization could apply across several personality disorders. The construct, named borderline personality organization (BPO),20 was defined by:

- an impaired sense of identity and lack of integration of one’s own identity

- use of primitive defenses, including splitting, rage, and regression

- ability to test reality.

Kernberg’s theory is too complex to summarize here, but he—along with Roy Grinker—is responsible for placing BPD on the diagnostic map. He was the first to describe BPO (and by extension BPD) in terms of a personality disorder.

Grinker’s ‘core’ group. Almost simultaneously (in 1968), Grinker published a careful study of 50 hospitalized patients. His work on the “borderline syndrome”21 revealed four subgroups to which the label of borderline had been applied:

- those occupying the border with psychosis

- those occupying the border with neurosis

- those similar to Deutsch’s “as if” group

- the “core” borderline group.

The core group—with its symptoms of anger and loneliness, a nonintegrated sense of self, and labile and oscillating interpersonal relationships— defined patients closest to our current definition.

Six criteria for BPD. In 1975, Gunderson and Singer published an article that greatly influenced our definition of BPD. They reviewed major descriptive accounts of BPD or BPD-like syndromes22 and proposed six diagnostic criteria (Box 2), though they did not identify a specific number or subset of the criteria as needing to be met for the diagnosis. (It is important to note that the term BPD did not become official for 5 more years.)

DSM-IV’s definition of BPD retains four of Gunderson and Singer‘s criteria among the nine it lists (five being necessary for a diagnosis of BPD). Missing are:

- social adaptiveness—though DSM-IV does say that social adaptiveness may be superficial (as in the “as if” personality) and may hide a disturbed identity6

- and the criterion relating to psychological test performance (this omission reflects a movement since 1980 away from listing “psychological” or psychodynamic criteria in the DSM).

DSM-III. BPD was included in DSM-III7 following an important study that tried to determine whether the term “borderline” refers to patients at the border of psychosis or to a stable group with mood instability and affective lability as part of a personality disorder. Spitzer et al23 asked 808 clinicians to describe patients they would label as borderline and to use 22 items gleaned from the literature to score two of their own patients:

- one patient who the clinician felt truly had borderline personality, borderline personality organization, or borderline schizophrenia

- and a control patient who was not diagnosed as psychotic and did not fall into any borderline category.

- The concept of abandonment, introduced in DSM-III-R, replaced the concept of aloneness in DSM-III.

- In DSM-III and DSM-III-R, a patient needed to meet 5 of 8 criteria for a diagnosis of BPD.

- DSM-IV introduced the ninth criterion, “transient, stress-related paranoid ideation or severe dissociative symptoms.” Since then, a patient has needed to meet 5 of 9 criteria for a diagnosis of BPD.

Their responses showed that BPD and schizotypal personality disorder (SPD) were separate, independent (though not mutually exclusive) disorders. Spitzer et al preserved the “schizotypal” label in DSM-III to describe the personality disorder that closely matched the border-to-psychosis subset. The other criteria set, which they labeled the “unstable personality item set,” was renamed “borderline” in DSM-III to describe the personality disorder that closely matched the emotional lability subset.

From one DSM edition to another, the concept of brief transient psychotic episodes has been included in and excluded from the diagnosis of borderline personality disorder (BPD).

In DSM-III. Because of work by Spitzer et al, these “experiences” were placed within schizotypal personality disorder (SPD) in DSM-III in 1980, though historically they had always been within the borderline concept and were one of Gunderson and Singer’s six criteria for diagnosing BPD (Box 2).22

Out of DSM-III-R. Research in the late 1980s suggested that when patients with BPD were depressed, they had a greater tendency to have psychotic–like episodes.24 Evidence indicated that attributing these psychotic and dissociative phenomena to SPD, rather than—perhaps more appropriately—to BPD, was one of the main reasons for the overlap between the definitions of BPD and SPD.25 Therefore, in DSM-III-R, the transient psychotic/dissociative criterion was removed from the SPD criteria set.

Back in DSM-IV. The criterion “transient stress-related paranoid ideation or severe dissociative symptoms” was placed into the BPD criteria set in DSM-IV. In DSM-IV, these symptoms were further characterized as usually not of “sufficient severity or duration to warrant an additional diagnosis.”

What is “sufficient” duration? The psychotic episodes of BPD last for minutes to hours and often appear when the patient imagines being (or actually is) abandoned by others. Not all agree that the criteria for BPD are met if these episodes last longer (e.g.,a day or two). In that case, they may exceed the transient time frame. More research is needed to better understand the quality and duration of these psychotic-like phenomena.

Not everyone agrees with renaming the unstable set “borderline” because the word:

- has always been ambiguous

- does not connote or denote any specific criteria or characteristic of patients who bear the label

- brands the patient as untreatable, defiant, or just “bad.”

Post-DSM-III: Where are we now?

From DSM-III evolved the hope that psychiatry could describe valid, well-defined diagnostic categories. Lost in the DSM-III enthusiasm was the fact that the categories were based upon theoretic constructs—theories no more or less valid than other theories that had preceded them. Because some of these categories were based upon empiric data— such as the Spitzer et al study—these diagnoses were perceived as more valid and more related to pathophysiology and perhaps genotype than prior constructs and definitions.

In the 1980s and early 1990s, a proliferation of studies attempted to examine the validity and reliability of DSM-III definitions, and BPD became the most studied of the personality disorders. The BPD concept took hold, even though several studies did not support it and despite refinements in subsequent DSM editions (Box 3).

One refinement in the BPD construct applied to transient psychotic or psychotic-like experiences, including dissociative phenomena. Yet questions remain about the duration of these transient episodes (Box 4).

Categorical versus dimensional

The categorical concept of BPD is facing new scrutiny,26,27 as recent studies have implied that biological disturbances may be spread across a number of personality disorders.28 If biological findings are found to be more closely allied with genotypic variations (alleles),29 then perhaps a dimensional classification system is needed for BPD and personality disorders in general.

On the other hand, categories provide a well-defined population that we can study and try to delineate from other populations, whereas dimensions—while perhaps closer to the reality of clinical presentation—may allow too much variability for research to proceed without confounding restraints.

BPD will continue to evolve, as will all psychiatric diagnostic categories, but the need to modify its definition does not negate its usefulness and clinical applicability. Most of our patients do not read the DSM before coming to us. They present with symptom complexes and problems that demand that we listen to what they say and understand who they are while we also try to fit them—as best we can—into categories or dimensions30 that help us choose the most appropriate interventions.

Related resources

- BPD Sanctuary (borderline personality disorder education, communities, support, books, and resources) http://www.mhsanctuary.com/borderline/ Borderline Central (resources for people who care about someone with borderline personality disorder) http://www.bpdcentral.com/

- Gunderson JG. Borderline personality disorder: a clinical guide. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc., 200l.

- Paris J (ed). Borderline personality disorder. Psych Clin N Am 2000;23:1 (entire volume devoted to BPD).

- Silk KR (ed). Biological and neurobehavioral studies of borderline personality disorder. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, 1994.

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (2nd ed). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 1968.

2. Feighner JP, Robins E, Guze SB, et al. Diagnostic criteria for use in psychiatric research. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1972;26:57-63.

3. Merikangas KR, Angst J, Eaton W, et al. Comorbidity and boundaries of affective disorders with anxiety disorders and substance misuse: results of an international task force. Br J Psychiatry 1996;30(suppl):58-67.

4. Nierenberg AA. DeCecco LM.Definitions of antidepressant treatment response, remission, nonresponse, partial response, and other relevant outcomes: a focus on treatment-resistant depression. J Clin Psychiatry 2001;62(suppl 16):5-9.

5. Stone MH (ed). Essential papers on borderline disorders: one hundred years at the border. New York: New York University Press, 1986.

6. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 1994.

7. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (3rd ed). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 1980.

8. Akiskal HS. Subaffective disorders: dysthymic, cyclothymic and bipolar II disorders in the “borderline” realm. Psychiatric Clin N Am 1981;4:25-46.

9. Henry C, Mitropoulou V, New AS, et al. Affective instability and impulsivity in borderline personality and bipolar II disorders: similarities and differences. J Psychiatric Res 2001;35:307-12.

10. Herman JL, van der Kolk BA. Traumatic antecedents of borderline personality disorder. In: van der Kolk, BA. Psychological trauma. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, 1987;111-26.

11. Silk KR, Lee S, Hill EM, Lohr NE. Borderline symptoms and severity of sexual abuse. Am J Psychiatry 1995;152:1059-64.

12. Streeter CC, Van Reekum R, Shorr RI, Bachman DL. Prior head injury in male veterans with borderline personality disorder. J Nerv Ment Dis 1995;183:577-81.

13. Maltsberger JT. Countertransference in borderline conditions: some further notes. Int J Psychoanal Psychother 1982-83;9:125-34.

14. Stern A. Psychoanalytic investigation and therapy in the borderline group of neuroses. Psychoanal Q 1938;7:467-89.

15. Deutsch H. Some forms of emotional disturbance and their relationship to schizophrenia. Psychoanal Q 1942;11:301-21.

16. Hoch P, Polatin P. Pseudoneurotic forms of schizophrenia. Psychiatric Q 1949;23:248-76.

17. Knight R. Borderline states. Bull Menn Clin 1953;17:1-12.

18. Schmideberg M. The treatment of psychopaths and borderline patients. Am J Psychotherapy 1947;1:45-70.

19. Frosch J. The psychotic character: clinical psychiatric considerations. Psychiatric Q 1964;38:81-96.

20. Kernberg O. Borderline personality organization. J Am Psychoanal Assoc 1967;15:641-85.

21. Grinker RR, Werble B, Drye R. The borderline syndrome: a behavioral study of ego functions. New York: Basic Books, 1968.

22. Gunderson JG, Singer MT. Defining borderline patients: an overview. Am J Psychiatry 1975;132:1-10.

23. Spitzer RL, Endicott J, Gibbon M. Crossing the border into borderline personality and borderline schizophrenia: the development of criteria. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1979;36:17-24.

24. Silk KR, Lohr NE, Westen D, Goodrich S. Psychosis in borderline patients with depression. J Personality Disord 1989;3:92-100.

25. Silk KR, Westen D, Lohr NE, et al. DSM-III and DSM-III-R schizotypal symptoms in borderline personality disorder. Comprehen Psychiatry 1990;31:103-10.

26. Livesley WJ, Jang KL, Vernon PA. Phenotypic and genetic structure of traits delineating personality disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1998;55:941-8.

27. McCrae RR, Yang J, Costa PT, Jr, et al. Personality profiles and the prediction of categorical personality disorders. J Personality 2001;69:155-74.

28. Siever LJ, Davis KL. A psychobiological perspective on the personality disorders. Am J Psychiatry 1991;148:1647-58.

29. New AS, Gelernter J, Goodman M, et al. Suicide, impulsive aggression, and HTR1B genotype. Biolog Psychiatry 2001;50:62-5.

30. Oldham JM, Skodol AE. Charting the future of axis II. J Personality Disord 2000;14:17-29.

Not everyone agrees that borderline personality disorder (BPD) should be a diagnostic category. BPD became “official” with DSM-III in 1980, although the term had been used for 40 years to describe various patient groups. Being listed in DSM-III legitimized BPD, which was thought to represent a specific—though not necessarily distinct—diagnostic category.

The history of the BPD diagnosis and opinions as to its usefulness can be viewed as a microcosm of psychiatric diagnosis in general. Before DSM-III, diagnoses were broadly defined and did not contain specific inclusion or exclusion criteria.1 For the 5 to 10 years prior to DSM-III, however, two assumptions developed:

- distinct diagnostic categories did, in fact, exist

- by rigorously defining and studying those categories we could develop more specific and effective treatments for our patients.2

The specificity and exclusivity that we assumed we could achieve by categorical diagnoses, however, remain a distant wish. Comorbidity appears more common in psychiatry than was originally thought and confounds both treatment and outcome.3 Also, many patients appear treatment-resistant, despite fitting neatly into diagnostic categories.4

Miss A, age 35, presents to the emergency room with a long history of intermittent depression and self-mutilation. She has never been hospitalized nor on psychotropic medication but has been in and out of psychotherapy for years. She has had intermittent depressive episodes for many years, though the episodes often lasted 2 to 3 weeks and appeared to correct themselves spontaneously.

Agitated and afraid. She is extremely agitated when she arrives at the emergency department. She has hardly slept or eaten but insists she is not hungry. She reports that she cannot concentrate or do her work as an accountant. She says she is hearing voices, knows they are in her head, but nonetheless is terrified that something horrible is about to happen—though she cannot say what it might be.

Voice ‘calling my name.’ When the psychiatric resident inquires further, Miss A says a male voice is calling her name and mumbling some short phrase she cannot understand. She says she has heard the voice the last few days, perhaps for 10 to 15 minutes every few hours, particularly when she ruminates about how she messed up a relationship with her now ex-boyfriend. The breakup occurred 1 week ago.

Feeling detached. She claims she has never heard voices before but describes periods when she has felt detached and unreal. Often these were short-term dissociative episodes that occurred in the wake of what she perceived as a personal failure or a distressful interpersonal encounter (often with a man). Relationships frequently were very difficult for her, and she felt she could easily go from infatuation to detesting someone.

Diagnosis? Talking appears to calm her down. After being in the emergency room for 2 hours, she says she no longer hears the voice. The resident tells the attending psychiatrist he believes the patient is in a major depressive episode, perhaps a psychotic depression, and proposes starting antidepressant treatment. The attending argues that the patient appears to have borderline personality disorder and suggests that she be sent home without medication and given an appointment to the outpatient clinic within the next few days.

As psychiatry considers DSM-V, questions linger as to whether BPD (and personality disorder in general) should remain as a categorical diagnosis or if dimensional measures may be more appropriate. Dimensions imply that no one ever fits into a given box because no specific box exists. Rather, patients are described as being closer to or more distant from a prototypic model of the diagnosis. In personality disorders, the dimensions most often mentioned are cognition, impulsivity, emotional lability, environmental hyperreactivity, and anxiety. The case report (above) illustrates the interplay of these dimensions in a typical patient with presumed BPD.

What’s in a name?

The symptom complex or syndrome that bears the name borderline personality disorder has probably existed for as long as people have thought about patients in psychopathologic terms.5 Before 1980, the term “borderline” applied primarily to two separate but overlapping concepts:

- Patients thought to reside on the “border” with psychosis, such as the patient in our case example. They seemed to have an underlying psychotic disorder, but the psychosis—if it surfaced—appeared briefly, was not exceptionally deep or firmly held, and was not regularly evident or immediately accessible to the clinician.

- Patients who appeared to occupy the space between neurosis and psychosis. This concept evolved into the idea of a character or personality disorder distinguished primarily by unstable interpersonal relationships, a confused or inconsistent sense of identity, and emotional instability.

How DSM is changing. Comparing the disorders listed in DSM-IV (1994)6 versus DSM-II (1968)1 suggests that psychiatry has become enamored of the naming process. For example, DSM-II lists anxiety neurosis (300.0), phobic neurosis (300.2), and obsessive-compulsive neurosis (300.3), whereas DSM-IV lists 11 different categories of anxiety disorders.

But beyond naming, subsequent DSMs have differed even more dramatically from DSM-II. We have seen a shift from describing a diagnostic category with a simple explanatory paragraph to lists of specific inclusion and exclusion criteria. These more-specific lists imply that they define categories closer to some reality or authenticity than did previous definitions.

Before DSM-III, the borderline concept was conceived in broad object relational and psychodynamic terms. In contrast, DSM-III produced a definitive set of criteria and required that a subset be met before the diagnosis could be made.7 An example of this criteria-based model is shown in Box 1, which lists the DSM-IV-TR criteria for BPD.

Some psychiatrists objected that BPD was solely a psychoanalytic construct and too theoretical for inclusion in DSM-III. Others argued that if BPD were not defined, it would be difficult to study the clinical usefulness of that definition or any other. Nonetheless, many have argued that BPD does not exist, though to what category BPD patients should belong has changed over the years:

- Is BPD nothing more than a milder or unusual presentation of an affective disorder8 or actually bipolar II disorder?9

- Is it a presentation of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) called “complex PTSD,”10-11 or an adult presentation of attention-deficit/ hyperactivity or other brain disorder?12

- Is it a stigmatizing diagnosis that we apply to patients whom we do not like?13

In truth, the diagnosis of BPD reflects a particular clinical presentation no more or less accurately than many of the well-accepted axis I disorders. Despite recent advances in the neurosciences, the dilemma we face as psychiatrists is that we make a diagnosis based upon what we see in the clinical setting (i.e., a phenotype). Yet in labeling what we believe is a specific psychiatric disorder, we make assumptions—for better or for worse, consciously or unconsciously—about pathophysiology and indirectly about genotype.

A pervasive pattern of instability of interpersonal relationships, self-image, and affects and marked impulsivity beginning by early adulthood and present in a variety of contexts, as indicated by five (or more) of the following:

- Frantic efforts to avoid real or imagined abandonment

- A pattern of unstable and intense interpersonal relationships characterized by alternating between extremes of idealization and devaluation

- Identity disturbance: markedly and persistent unstable self-image or sense of self

- Impulsivity in at least two areas that are potentially self-damaging (spending, sex, substance abuse, binge eating, reckless driving)

- Recurrent suicidal behavior, gestures, or threats; self-mutilating behavior

- Affective instability due to a marked reactivity of mood

- Chronic feelings of emptiness

- Inappropriate, intense anger or difficulty controlling anger

- Transient, stress-related paranoid ideation or severe dissociative symptoms

Source: DSM-IV6

Defining the borderline personality

Stern first used the term “borderline” in 1938 to describe patients who appeared to occupy the border between neurosis and psychosis.14 In 1942, Deutsch described the “as if” personality in patients who seemed chameleon-like. They could adapt or play the role demanded of them in specific situations, yet elsewhere—as in the analyst’s office—they had little sense of themselves and were thought to be internally disorganized and probably psychotic.15

Border to psychosis. The idea that borderline-type patients were psychotic continued in Hoch and Polatin’s description of the “pseudoneurotic schizophrenic,”16 a patient who appeared severely neurotic but was thought to employ many defenses and interpersonal styles to ward off a fundamental inner psychosis. Knight used the label “borderline states”17 to describe severely ill patients who were not frankly psychotic but fell within the realm of psychosis without qualifying for a diagnosis of schizophrenia. Knight was the first person to use the term “borderline” as a diagnostic entity, though simultaneously he argued against its use as a label because the term lacked precision.

Psychotic character. About the same time, Schmideberg characterized a group of patients whose emotional lability or affective reactivity seemed to be a consistent aspect of their clinical presentation. She believed this appearance of “stable instability”18 represented the patient’s characterologic adaptation to the world.

Frosch coined the term “psychotic character”19 that aptly captured both the characterologic and the border-to-psychosis aspects of these patients’ clinical picture. According to Frosch, these patients appeared to regress readily into psychotic thinking, yet they did not lose their ability to test reality.

Affective and emotional instability. Thus until the 1960s, the term borderline was applied primarily to patients who appeared to occupy the border between neurosis and psychosis but were thought to be closer to psychotic than neurotic. And this sitting close to the edge of psychosis appeared to be a stable condition.

Most of the attention up until this point had been paid to how these patients thought—with little attention to their affective lability or emotional instability, save for Schmideberg’s comments. In the 1960s, however, the term borderline was applied somewhat differently—not completely divorced from previous concepts but with greater emphasis on borderline as a stable but psychopathologic functioning of the personality that included affective and emotional instability and an impaired sense of self.

- Intense affect, usually depressive or hostile

- History of impulsive, often self-destructive behavior

- Social adaptiveness that may mask a disturbed identity

- Brief psychotic episodes, often paranoid and evident in unstructured situations

- “Loose thinking” or primitive answers on unstructured psychological tests

- Relationships vacillate between transient superficiality and intense dependency

Impaired personality organization. In 1967, Kernberg published a seminal article in the history of BPD diagnosis. Although he did not discuss the diagnosis of BPD, Kernberg did develop a concept concerning a specific organization of the personality based upon impaired object relations. This impaired organization could apply across several personality disorders. The construct, named borderline personality organization (BPO),20 was defined by:

- an impaired sense of identity and lack of integration of one’s own identity

- use of primitive defenses, including splitting, rage, and regression

- ability to test reality.

Kernberg’s theory is too complex to summarize here, but he—along with Roy Grinker—is responsible for placing BPD on the diagnostic map. He was the first to describe BPO (and by extension BPD) in terms of a personality disorder.

Grinker’s ‘core’ group. Almost simultaneously (in 1968), Grinker published a careful study of 50 hospitalized patients. His work on the “borderline syndrome”21 revealed four subgroups to which the label of borderline had been applied:

- those occupying the border with psychosis

- those occupying the border with neurosis

- those similar to Deutsch’s “as if” group

- the “core” borderline group.

The core group—with its symptoms of anger and loneliness, a nonintegrated sense of self, and labile and oscillating interpersonal relationships— defined patients closest to our current definition.

Six criteria for BPD. In 1975, Gunderson and Singer published an article that greatly influenced our definition of BPD. They reviewed major descriptive accounts of BPD or BPD-like syndromes22 and proposed six diagnostic criteria (Box 2), though they did not identify a specific number or subset of the criteria as needing to be met for the diagnosis. (It is important to note that the term BPD did not become official for 5 more years.)

DSM-IV’s definition of BPD retains four of Gunderson and Singer‘s criteria among the nine it lists (five being necessary for a diagnosis of BPD). Missing are:

- social adaptiveness—though DSM-IV does say that social adaptiveness may be superficial (as in the “as if” personality) and may hide a disturbed identity6

- and the criterion relating to psychological test performance (this omission reflects a movement since 1980 away from listing “psychological” or psychodynamic criteria in the DSM).

DSM-III. BPD was included in DSM-III7 following an important study that tried to determine whether the term “borderline” refers to patients at the border of psychosis or to a stable group with mood instability and affective lability as part of a personality disorder. Spitzer et al23 asked 808 clinicians to describe patients they would label as borderline and to use 22 items gleaned from the literature to score two of their own patients:

- one patient who the clinician felt truly had borderline personality, borderline personality organization, or borderline schizophrenia

- and a control patient who was not diagnosed as psychotic and did not fall into any borderline category.

- The concept of abandonment, introduced in DSM-III-R, replaced the concept of aloneness in DSM-III.

- In DSM-III and DSM-III-R, a patient needed to meet 5 of 8 criteria for a diagnosis of BPD.

- DSM-IV introduced the ninth criterion, “transient, stress-related paranoid ideation or severe dissociative symptoms.” Since then, a patient has needed to meet 5 of 9 criteria for a diagnosis of BPD.

Their responses showed that BPD and schizotypal personality disorder (SPD) were separate, independent (though not mutually exclusive) disorders. Spitzer et al preserved the “schizotypal” label in DSM-III to describe the personality disorder that closely matched the border-to-psychosis subset. The other criteria set, which they labeled the “unstable personality item set,” was renamed “borderline” in DSM-III to describe the personality disorder that closely matched the emotional lability subset.

From one DSM edition to another, the concept of brief transient psychotic episodes has been included in and excluded from the diagnosis of borderline personality disorder (BPD).

In DSM-III. Because of work by Spitzer et al, these “experiences” were placed within schizotypal personality disorder (SPD) in DSM-III in 1980, though historically they had always been within the borderline concept and were one of Gunderson and Singer’s six criteria for diagnosing BPD (Box 2).22

Out of DSM-III-R. Research in the late 1980s suggested that when patients with BPD were depressed, they had a greater tendency to have psychotic–like episodes.24 Evidence indicated that attributing these psychotic and dissociative phenomena to SPD, rather than—perhaps more appropriately—to BPD, was one of the main reasons for the overlap between the definitions of BPD and SPD.25 Therefore, in DSM-III-R, the transient psychotic/dissociative criterion was removed from the SPD criteria set.

Back in DSM-IV. The criterion “transient stress-related paranoid ideation or severe dissociative symptoms” was placed into the BPD criteria set in DSM-IV. In DSM-IV, these symptoms were further characterized as usually not of “sufficient severity or duration to warrant an additional diagnosis.”

What is “sufficient” duration? The psychotic episodes of BPD last for minutes to hours and often appear when the patient imagines being (or actually is) abandoned by others. Not all agree that the criteria for BPD are met if these episodes last longer (e.g.,a day or two). In that case, they may exceed the transient time frame. More research is needed to better understand the quality and duration of these psychotic-like phenomena.

Not everyone agrees with renaming the unstable set “borderline” because the word:

- has always been ambiguous

- does not connote or denote any specific criteria or characteristic of patients who bear the label

- brands the patient as untreatable, defiant, or just “bad.”

Post-DSM-III: Where are we now?

From DSM-III evolved the hope that psychiatry could describe valid, well-defined diagnostic categories. Lost in the DSM-III enthusiasm was the fact that the categories were based upon theoretic constructs—theories no more or less valid than other theories that had preceded them. Because some of these categories were based upon empiric data— such as the Spitzer et al study—these diagnoses were perceived as more valid and more related to pathophysiology and perhaps genotype than prior constructs and definitions.

In the 1980s and early 1990s, a proliferation of studies attempted to examine the validity and reliability of DSM-III definitions, and BPD became the most studied of the personality disorders. The BPD concept took hold, even though several studies did not support it and despite refinements in subsequent DSM editions (Box 3).

One refinement in the BPD construct applied to transient psychotic or psychotic-like experiences, including dissociative phenomena. Yet questions remain about the duration of these transient episodes (Box 4).

Categorical versus dimensional

The categorical concept of BPD is facing new scrutiny,26,27 as recent studies have implied that biological disturbances may be spread across a number of personality disorders.28 If biological findings are found to be more closely allied with genotypic variations (alleles),29 then perhaps a dimensional classification system is needed for BPD and personality disorders in general.

On the other hand, categories provide a well-defined population that we can study and try to delineate from other populations, whereas dimensions—while perhaps closer to the reality of clinical presentation—may allow too much variability for research to proceed without confounding restraints.

BPD will continue to evolve, as will all psychiatric diagnostic categories, but the need to modify its definition does not negate its usefulness and clinical applicability. Most of our patients do not read the DSM before coming to us. They present with symptom complexes and problems that demand that we listen to what they say and understand who they are while we also try to fit them—as best we can—into categories or dimensions30 that help us choose the most appropriate interventions.

Related resources

- BPD Sanctuary (borderline personality disorder education, communities, support, books, and resources) http://www.mhsanctuary.com/borderline/ Borderline Central (resources for people who care about someone with borderline personality disorder) http://www.bpdcentral.com/

- Gunderson JG. Borderline personality disorder: a clinical guide. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc., 200l.

- Paris J (ed). Borderline personality disorder. Psych Clin N Am 2000;23:1 (entire volume devoted to BPD).

- Silk KR (ed). Biological and neurobehavioral studies of borderline personality disorder. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, 1994.

Not everyone agrees that borderline personality disorder (BPD) should be a diagnostic category. BPD became “official” with DSM-III in 1980, although the term had been used for 40 years to describe various patient groups. Being listed in DSM-III legitimized BPD, which was thought to represent a specific—though not necessarily distinct—diagnostic category.

The history of the BPD diagnosis and opinions as to its usefulness can be viewed as a microcosm of psychiatric diagnosis in general. Before DSM-III, diagnoses were broadly defined and did not contain specific inclusion or exclusion criteria.1 For the 5 to 10 years prior to DSM-III, however, two assumptions developed:

- distinct diagnostic categories did, in fact, exist

- by rigorously defining and studying those categories we could develop more specific and effective treatments for our patients.2

The specificity and exclusivity that we assumed we could achieve by categorical diagnoses, however, remain a distant wish. Comorbidity appears more common in psychiatry than was originally thought and confounds both treatment and outcome.3 Also, many patients appear treatment-resistant, despite fitting neatly into diagnostic categories.4

Miss A, age 35, presents to the emergency room with a long history of intermittent depression and self-mutilation. She has never been hospitalized nor on psychotropic medication but has been in and out of psychotherapy for years. She has had intermittent depressive episodes for many years, though the episodes often lasted 2 to 3 weeks and appeared to correct themselves spontaneously.

Agitated and afraid. She is extremely agitated when she arrives at the emergency department. She has hardly slept or eaten but insists she is not hungry. She reports that she cannot concentrate or do her work as an accountant. She says she is hearing voices, knows they are in her head, but nonetheless is terrified that something horrible is about to happen—though she cannot say what it might be.

Voice ‘calling my name.’ When the psychiatric resident inquires further, Miss A says a male voice is calling her name and mumbling some short phrase she cannot understand. She says she has heard the voice the last few days, perhaps for 10 to 15 minutes every few hours, particularly when she ruminates about how she messed up a relationship with her now ex-boyfriend. The breakup occurred 1 week ago.

Feeling detached. She claims she has never heard voices before but describes periods when she has felt detached and unreal. Often these were short-term dissociative episodes that occurred in the wake of what she perceived as a personal failure or a distressful interpersonal encounter (often with a man). Relationships frequently were very difficult for her, and she felt she could easily go from infatuation to detesting someone.

Diagnosis? Talking appears to calm her down. After being in the emergency room for 2 hours, she says she no longer hears the voice. The resident tells the attending psychiatrist he believes the patient is in a major depressive episode, perhaps a psychotic depression, and proposes starting antidepressant treatment. The attending argues that the patient appears to have borderline personality disorder and suggests that she be sent home without medication and given an appointment to the outpatient clinic within the next few days.

As psychiatry considers DSM-V, questions linger as to whether BPD (and personality disorder in general) should remain as a categorical diagnosis or if dimensional measures may be more appropriate. Dimensions imply that no one ever fits into a given box because no specific box exists. Rather, patients are described as being closer to or more distant from a prototypic model of the diagnosis. In personality disorders, the dimensions most often mentioned are cognition, impulsivity, emotional lability, environmental hyperreactivity, and anxiety. The case report (above) illustrates the interplay of these dimensions in a typical patient with presumed BPD.

What’s in a name?

The symptom complex or syndrome that bears the name borderline personality disorder has probably existed for as long as people have thought about patients in psychopathologic terms.5 Before 1980, the term “borderline” applied primarily to two separate but overlapping concepts:

- Patients thought to reside on the “border” with psychosis, such as the patient in our case example. They seemed to have an underlying psychotic disorder, but the psychosis—if it surfaced—appeared briefly, was not exceptionally deep or firmly held, and was not regularly evident or immediately accessible to the clinician.

- Patients who appeared to occupy the space between neurosis and psychosis. This concept evolved into the idea of a character or personality disorder distinguished primarily by unstable interpersonal relationships, a confused or inconsistent sense of identity, and emotional instability.

How DSM is changing. Comparing the disorders listed in DSM-IV (1994)6 versus DSM-II (1968)1 suggests that psychiatry has become enamored of the naming process. For example, DSM-II lists anxiety neurosis (300.0), phobic neurosis (300.2), and obsessive-compulsive neurosis (300.3), whereas DSM-IV lists 11 different categories of anxiety disorders.

But beyond naming, subsequent DSMs have differed even more dramatically from DSM-II. We have seen a shift from describing a diagnostic category with a simple explanatory paragraph to lists of specific inclusion and exclusion criteria. These more-specific lists imply that they define categories closer to some reality or authenticity than did previous definitions.

Before DSM-III, the borderline concept was conceived in broad object relational and psychodynamic terms. In contrast, DSM-III produced a definitive set of criteria and required that a subset be met before the diagnosis could be made.7 An example of this criteria-based model is shown in Box 1, which lists the DSM-IV-TR criteria for BPD.

Some psychiatrists objected that BPD was solely a psychoanalytic construct and too theoretical for inclusion in DSM-III. Others argued that if BPD were not defined, it would be difficult to study the clinical usefulness of that definition or any other. Nonetheless, many have argued that BPD does not exist, though to what category BPD patients should belong has changed over the years:

- Is BPD nothing more than a milder or unusual presentation of an affective disorder8 or actually bipolar II disorder?9

- Is it a presentation of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) called “complex PTSD,”10-11 or an adult presentation of attention-deficit/ hyperactivity or other brain disorder?12

- Is it a stigmatizing diagnosis that we apply to patients whom we do not like?13

In truth, the diagnosis of BPD reflects a particular clinical presentation no more or less accurately than many of the well-accepted axis I disorders. Despite recent advances in the neurosciences, the dilemma we face as psychiatrists is that we make a diagnosis based upon what we see in the clinical setting (i.e., a phenotype). Yet in labeling what we believe is a specific psychiatric disorder, we make assumptions—for better or for worse, consciously or unconsciously—about pathophysiology and indirectly about genotype.

A pervasive pattern of instability of interpersonal relationships, self-image, and affects and marked impulsivity beginning by early adulthood and present in a variety of contexts, as indicated by five (or more) of the following:

- Frantic efforts to avoid real or imagined abandonment

- A pattern of unstable and intense interpersonal relationships characterized by alternating between extremes of idealization and devaluation

- Identity disturbance: markedly and persistent unstable self-image or sense of self

- Impulsivity in at least two areas that are potentially self-damaging (spending, sex, substance abuse, binge eating, reckless driving)

- Recurrent suicidal behavior, gestures, or threats; self-mutilating behavior

- Affective instability due to a marked reactivity of mood

- Chronic feelings of emptiness

- Inappropriate, intense anger or difficulty controlling anger

- Transient, stress-related paranoid ideation or severe dissociative symptoms

Source: DSM-IV6

Defining the borderline personality

Stern first used the term “borderline” in 1938 to describe patients who appeared to occupy the border between neurosis and psychosis.14 In 1942, Deutsch described the “as if” personality in patients who seemed chameleon-like. They could adapt or play the role demanded of them in specific situations, yet elsewhere—as in the analyst’s office—they had little sense of themselves and were thought to be internally disorganized and probably psychotic.15

Border to psychosis. The idea that borderline-type patients were psychotic continued in Hoch and Polatin’s description of the “pseudoneurotic schizophrenic,”16 a patient who appeared severely neurotic but was thought to employ many defenses and interpersonal styles to ward off a fundamental inner psychosis. Knight used the label “borderline states”17 to describe severely ill patients who were not frankly psychotic but fell within the realm of psychosis without qualifying for a diagnosis of schizophrenia. Knight was the first person to use the term “borderline” as a diagnostic entity, though simultaneously he argued against its use as a label because the term lacked precision.

Psychotic character. About the same time, Schmideberg characterized a group of patients whose emotional lability or affective reactivity seemed to be a consistent aspect of their clinical presentation. She believed this appearance of “stable instability”18 represented the patient’s characterologic adaptation to the world.

Frosch coined the term “psychotic character”19 that aptly captured both the characterologic and the border-to-psychosis aspects of these patients’ clinical picture. According to Frosch, these patients appeared to regress readily into psychotic thinking, yet they did not lose their ability to test reality.

Affective and emotional instability. Thus until the 1960s, the term borderline was applied primarily to patients who appeared to occupy the border between neurosis and psychosis but were thought to be closer to psychotic than neurotic. And this sitting close to the edge of psychosis appeared to be a stable condition.

Most of the attention up until this point had been paid to how these patients thought—with little attention to their affective lability or emotional instability, save for Schmideberg’s comments. In the 1960s, however, the term borderline was applied somewhat differently—not completely divorced from previous concepts but with greater emphasis on borderline as a stable but psychopathologic functioning of the personality that included affective and emotional instability and an impaired sense of self.

- Intense affect, usually depressive or hostile

- History of impulsive, often self-destructive behavior

- Social adaptiveness that may mask a disturbed identity

- Brief psychotic episodes, often paranoid and evident in unstructured situations

- “Loose thinking” or primitive answers on unstructured psychological tests

- Relationships vacillate between transient superficiality and intense dependency

Impaired personality organization. In 1967, Kernberg published a seminal article in the history of BPD diagnosis. Although he did not discuss the diagnosis of BPD, Kernberg did develop a concept concerning a specific organization of the personality based upon impaired object relations. This impaired organization could apply across several personality disorders. The construct, named borderline personality organization (BPO),20 was defined by:

- an impaired sense of identity and lack of integration of one’s own identity

- use of primitive defenses, including splitting, rage, and regression

- ability to test reality.

Kernberg’s theory is too complex to summarize here, but he—along with Roy Grinker—is responsible for placing BPD on the diagnostic map. He was the first to describe BPO (and by extension BPD) in terms of a personality disorder.

Grinker’s ‘core’ group. Almost simultaneously (in 1968), Grinker published a careful study of 50 hospitalized patients. His work on the “borderline syndrome”21 revealed four subgroups to which the label of borderline had been applied:

- those occupying the border with psychosis

- those occupying the border with neurosis

- those similar to Deutsch’s “as if” group

- the “core” borderline group.

The core group—with its symptoms of anger and loneliness, a nonintegrated sense of self, and labile and oscillating interpersonal relationships— defined patients closest to our current definition.

Six criteria for BPD. In 1975, Gunderson and Singer published an article that greatly influenced our definition of BPD. They reviewed major descriptive accounts of BPD or BPD-like syndromes22 and proposed six diagnostic criteria (Box 2), though they did not identify a specific number or subset of the criteria as needing to be met for the diagnosis. (It is important to note that the term BPD did not become official for 5 more years.)

DSM-IV’s definition of BPD retains four of Gunderson and Singer‘s criteria among the nine it lists (five being necessary for a diagnosis of BPD). Missing are:

- social adaptiveness—though DSM-IV does say that social adaptiveness may be superficial (as in the “as if” personality) and may hide a disturbed identity6

- and the criterion relating to psychological test performance (this omission reflects a movement since 1980 away from listing “psychological” or psychodynamic criteria in the DSM).

DSM-III. BPD was included in DSM-III7 following an important study that tried to determine whether the term “borderline” refers to patients at the border of psychosis or to a stable group with mood instability and affective lability as part of a personality disorder. Spitzer et al23 asked 808 clinicians to describe patients they would label as borderline and to use 22 items gleaned from the literature to score two of their own patients:

- one patient who the clinician felt truly had borderline personality, borderline personality organization, or borderline schizophrenia

- and a control patient who was not diagnosed as psychotic and did not fall into any borderline category.

- The concept of abandonment, introduced in DSM-III-R, replaced the concept of aloneness in DSM-III.

- In DSM-III and DSM-III-R, a patient needed to meet 5 of 8 criteria for a diagnosis of BPD.

- DSM-IV introduced the ninth criterion, “transient, stress-related paranoid ideation or severe dissociative symptoms.” Since then, a patient has needed to meet 5 of 9 criteria for a diagnosis of BPD.

Their responses showed that BPD and schizotypal personality disorder (SPD) were separate, independent (though not mutually exclusive) disorders. Spitzer et al preserved the “schizotypal” label in DSM-III to describe the personality disorder that closely matched the border-to-psychosis subset. The other criteria set, which they labeled the “unstable personality item set,” was renamed “borderline” in DSM-III to describe the personality disorder that closely matched the emotional lability subset.

From one DSM edition to another, the concept of brief transient psychotic episodes has been included in and excluded from the diagnosis of borderline personality disorder (BPD).

In DSM-III. Because of work by Spitzer et al, these “experiences” were placed within schizotypal personality disorder (SPD) in DSM-III in 1980, though historically they had always been within the borderline concept and were one of Gunderson and Singer’s six criteria for diagnosing BPD (Box 2).22

Out of DSM-III-R. Research in the late 1980s suggested that when patients with BPD were depressed, they had a greater tendency to have psychotic–like episodes.24 Evidence indicated that attributing these psychotic and dissociative phenomena to SPD, rather than—perhaps more appropriately—to BPD, was one of the main reasons for the overlap between the definitions of BPD and SPD.25 Therefore, in DSM-III-R, the transient psychotic/dissociative criterion was removed from the SPD criteria set.

Back in DSM-IV. The criterion “transient stress-related paranoid ideation or severe dissociative symptoms” was placed into the BPD criteria set in DSM-IV. In DSM-IV, these symptoms were further characterized as usually not of “sufficient severity or duration to warrant an additional diagnosis.”

What is “sufficient” duration? The psychotic episodes of BPD last for minutes to hours and often appear when the patient imagines being (or actually is) abandoned by others. Not all agree that the criteria for BPD are met if these episodes last longer (e.g.,a day or two). In that case, they may exceed the transient time frame. More research is needed to better understand the quality and duration of these psychotic-like phenomena.

Not everyone agrees with renaming the unstable set “borderline” because the word:

- has always been ambiguous

- does not connote or denote any specific criteria or characteristic of patients who bear the label

- brands the patient as untreatable, defiant, or just “bad.”

Post-DSM-III: Where are we now?

From DSM-III evolved the hope that psychiatry could describe valid, well-defined diagnostic categories. Lost in the DSM-III enthusiasm was the fact that the categories were based upon theoretic constructs—theories no more or less valid than other theories that had preceded them. Because some of these categories were based upon empiric data— such as the Spitzer et al study—these diagnoses were perceived as more valid and more related to pathophysiology and perhaps genotype than prior constructs and definitions.

In the 1980s and early 1990s, a proliferation of studies attempted to examine the validity and reliability of DSM-III definitions, and BPD became the most studied of the personality disorders. The BPD concept took hold, even though several studies did not support it and despite refinements in subsequent DSM editions (Box 3).

One refinement in the BPD construct applied to transient psychotic or psychotic-like experiences, including dissociative phenomena. Yet questions remain about the duration of these transient episodes (Box 4).

Categorical versus dimensional

The categorical concept of BPD is facing new scrutiny,26,27 as recent studies have implied that biological disturbances may be spread across a number of personality disorders.28 If biological findings are found to be more closely allied with genotypic variations (alleles),29 then perhaps a dimensional classification system is needed for BPD and personality disorders in general.

On the other hand, categories provide a well-defined population that we can study and try to delineate from other populations, whereas dimensions—while perhaps closer to the reality of clinical presentation—may allow too much variability for research to proceed without confounding restraints.

BPD will continue to evolve, as will all psychiatric diagnostic categories, but the need to modify its definition does not negate its usefulness and clinical applicability. Most of our patients do not read the DSM before coming to us. They present with symptom complexes and problems that demand that we listen to what they say and understand who they are while we also try to fit them—as best we can—into categories or dimensions30 that help us choose the most appropriate interventions.

Related resources

- BPD Sanctuary (borderline personality disorder education, communities, support, books, and resources) http://www.mhsanctuary.com/borderline/ Borderline Central (resources for people who care about someone with borderline personality disorder) http://www.bpdcentral.com/

- Gunderson JG. Borderline personality disorder: a clinical guide. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc., 200l.

- Paris J (ed). Borderline personality disorder. Psych Clin N Am 2000;23:1 (entire volume devoted to BPD).

- Silk KR (ed). Biological and neurobehavioral studies of borderline personality disorder. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, 1994.

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (2nd ed). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 1968.

2. Feighner JP, Robins E, Guze SB, et al. Diagnostic criteria for use in psychiatric research. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1972;26:57-63.

3. Merikangas KR, Angst J, Eaton W, et al. Comorbidity and boundaries of affective disorders with anxiety disorders and substance misuse: results of an international task force. Br J Psychiatry 1996;30(suppl):58-67.

4. Nierenberg AA. DeCecco LM.Definitions of antidepressant treatment response, remission, nonresponse, partial response, and other relevant outcomes: a focus on treatment-resistant depression. J Clin Psychiatry 2001;62(suppl 16):5-9.

5. Stone MH (ed). Essential papers on borderline disorders: one hundred years at the border. New York: New York University Press, 1986.

6. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 1994.

7. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (3rd ed). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 1980.

8. Akiskal HS. Subaffective disorders: dysthymic, cyclothymic and bipolar II disorders in the “borderline” realm. Psychiatric Clin N Am 1981;4:25-46.

9. Henry C, Mitropoulou V, New AS, et al. Affective instability and impulsivity in borderline personality and bipolar II disorders: similarities and differences. J Psychiatric Res 2001;35:307-12.

10. Herman JL, van der Kolk BA. Traumatic antecedents of borderline personality disorder. In: van der Kolk, BA. Psychological trauma. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, 1987;111-26.

11. Silk KR, Lee S, Hill EM, Lohr NE. Borderline symptoms and severity of sexual abuse. Am J Psychiatry 1995;152:1059-64.

12. Streeter CC, Van Reekum R, Shorr RI, Bachman DL. Prior head injury in male veterans with borderline personality disorder. J Nerv Ment Dis 1995;183:577-81.

13. Maltsberger JT. Countertransference in borderline conditions: some further notes. Int J Psychoanal Psychother 1982-83;9:125-34.

14. Stern A. Psychoanalytic investigation and therapy in the borderline group of neuroses. Psychoanal Q 1938;7:467-89.

15. Deutsch H. Some forms of emotional disturbance and their relationship to schizophrenia. Psychoanal Q 1942;11:301-21.

16. Hoch P, Polatin P. Pseudoneurotic forms of schizophrenia. Psychiatric Q 1949;23:248-76.

17. Knight R. Borderline states. Bull Menn Clin 1953;17:1-12.

18. Schmideberg M. The treatment of psychopaths and borderline patients. Am J Psychotherapy 1947;1:45-70.

19. Frosch J. The psychotic character: clinical psychiatric considerations. Psychiatric Q 1964;38:81-96.

20. Kernberg O. Borderline personality organization. J Am Psychoanal Assoc 1967;15:641-85.

21. Grinker RR, Werble B, Drye R. The borderline syndrome: a behavioral study of ego functions. New York: Basic Books, 1968.

22. Gunderson JG, Singer MT. Defining borderline patients: an overview. Am J Psychiatry 1975;132:1-10.

23. Spitzer RL, Endicott J, Gibbon M. Crossing the border into borderline personality and borderline schizophrenia: the development of criteria. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1979;36:17-24.

24. Silk KR, Lohr NE, Westen D, Goodrich S. Psychosis in borderline patients with depression. J Personality Disord 1989;3:92-100.

25. Silk KR, Westen D, Lohr NE, et al. DSM-III and DSM-III-R schizotypal symptoms in borderline personality disorder. Comprehen Psychiatry 1990;31:103-10.

26. Livesley WJ, Jang KL, Vernon PA. Phenotypic and genetic structure of traits delineating personality disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1998;55:941-8.

27. McCrae RR, Yang J, Costa PT, Jr, et al. Personality profiles and the prediction of categorical personality disorders. J Personality 2001;69:155-74.

28. Siever LJ, Davis KL. A psychobiological perspective on the personality disorders. Am J Psychiatry 1991;148:1647-58.

29. New AS, Gelernter J, Goodman M, et al. Suicide, impulsive aggression, and HTR1B genotype. Biolog Psychiatry 2001;50:62-5.

30. Oldham JM, Skodol AE. Charting the future of axis II. J Personality Disord 2000;14:17-29.

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (2nd ed). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 1968.

2. Feighner JP, Robins E, Guze SB, et al. Diagnostic criteria for use in psychiatric research. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1972;26:57-63.

3. Merikangas KR, Angst J, Eaton W, et al. Comorbidity and boundaries of affective disorders with anxiety disorders and substance misuse: results of an international task force. Br J Psychiatry 1996;30(suppl):58-67.

4. Nierenberg AA. DeCecco LM.Definitions of antidepressant treatment response, remission, nonresponse, partial response, and other relevant outcomes: a focus on treatment-resistant depression. J Clin Psychiatry 2001;62(suppl 16):5-9.

5. Stone MH (ed). Essential papers on borderline disorders: one hundred years at the border. New York: New York University Press, 1986.

6. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 1994.

7. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (3rd ed). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 1980.

8. Akiskal HS. Subaffective disorders: dysthymic, cyclothymic and bipolar II disorders in the “borderline” realm. Psychiatric Clin N Am 1981;4:25-46.

9. Henry C, Mitropoulou V, New AS, et al. Affective instability and impulsivity in borderline personality and bipolar II disorders: similarities and differences. J Psychiatric Res 2001;35:307-12.

10. Herman JL, van der Kolk BA. Traumatic antecedents of borderline personality disorder. In: van der Kolk, BA. Psychological trauma. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, 1987;111-26.

11. Silk KR, Lee S, Hill EM, Lohr NE. Borderline symptoms and severity of sexual abuse. Am J Psychiatry 1995;152:1059-64.

12. Streeter CC, Van Reekum R, Shorr RI, Bachman DL. Prior head injury in male veterans with borderline personality disorder. J Nerv Ment Dis 1995;183:577-81.

13. Maltsberger JT. Countertransference in borderline conditions: some further notes. Int J Psychoanal Psychother 1982-83;9:125-34.

14. Stern A. Psychoanalytic investigation and therapy in the borderline group of neuroses. Psychoanal Q 1938;7:467-89.

15. Deutsch H. Some forms of emotional disturbance and their relationship to schizophrenia. Psychoanal Q 1942;11:301-21.

16. Hoch P, Polatin P. Pseudoneurotic forms of schizophrenia. Psychiatric Q 1949;23:248-76.

17. Knight R. Borderline states. Bull Menn Clin 1953;17:1-12.

18. Schmideberg M. The treatment of psychopaths and borderline patients. Am J Psychotherapy 1947;1:45-70.

19. Frosch J. The psychotic character: clinical psychiatric considerations. Psychiatric Q 1964;38:81-96.

20. Kernberg O. Borderline personality organization. J Am Psychoanal Assoc 1967;15:641-85.

21. Grinker RR, Werble B, Drye R. The borderline syndrome: a behavioral study of ego functions. New York: Basic Books, 1968.

22. Gunderson JG, Singer MT. Defining borderline patients: an overview. Am J Psychiatry 1975;132:1-10.

23. Spitzer RL, Endicott J, Gibbon M. Crossing the border into borderline personality and borderline schizophrenia: the development of criteria. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1979;36:17-24.

24. Silk KR, Lohr NE, Westen D, Goodrich S. Psychosis in borderline patients with depression. J Personality Disord 1989;3:92-100.

25. Silk KR, Westen D, Lohr NE, et al. DSM-III and DSM-III-R schizotypal symptoms in borderline personality disorder. Comprehen Psychiatry 1990;31:103-10.

26. Livesley WJ, Jang KL, Vernon PA. Phenotypic and genetic structure of traits delineating personality disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1998;55:941-8.

27. McCrae RR, Yang J, Costa PT, Jr, et al. Personality profiles and the prediction of categorical personality disorders. J Personality 2001;69:155-74.

28. Siever LJ, Davis KL. A psychobiological perspective on the personality disorders. Am J Psychiatry 1991;148:1647-58.

29. New AS, Gelernter J, Goodman M, et al. Suicide, impulsive aggression, and HTR1B genotype. Biolog Psychiatry 2001;50:62-5.

30. Oldham JM, Skodol AE. Charting the future of axis II. J Personality Disord 2000;14:17-29.

ADHD and substance abuse: 4 therapeutic options for patients with addictions

Should you prescribe a stimulant to treat attention and hyperactivity problems in teenagers and adults with a history of substance abuse? Evidence suggests that using a stimulant to treat attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) may place such patients at risk for stimulant abuse or for relapse into abuse of other substances. But a stimulant may be the only option for patients whose ADHD symptoms do not respond to alternate medications, such as antidepressants.

Growing numbers of adults are being treated for ADHD. Because substance abuse problems are common in adults with ADHD (Box 1 ),1-3 prescribing an antidepressant instead of a stimulant in some cases may be prudent. Consider the following factors when choosing ADHD therapy for patients with a history of substance abuse.

Prevalence of stimulant use and abuse

In the United States, more than 95% of medications prescribed for children and adults with ADHD are stimulants—usually methylphenidate.4 Stimulant use has increased as more children and adults are diagnosed with ADHD. Methylphenidate prescriptions increased five-fold from 1990 to 1995.5 Visits to psychiatrists and physicians that included stimulant prescriptions grew from 570,000 to 2.86 million from 1985 to 1994, with most of that increase occurring during visits to primary care and other physicians.6

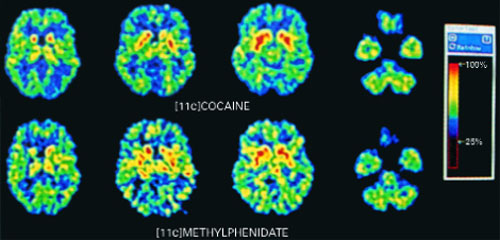

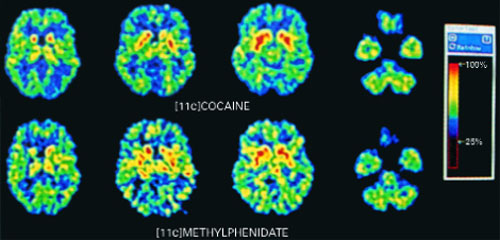

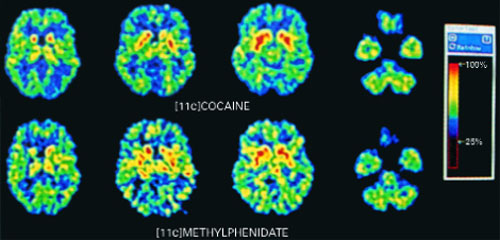

When used as prescribed, methylphenidate is safe and effective for treating most children and adults with ADHD. Methylphenidate’s pharmacologic properties, however, are similar to those of amphetamines and cocaine (Box 2, Figure 1),7,8 which is why methylphenidate is a schedule-II controlled substance.

Published data. Fifteen reports of methylphenidate abuse were published in the medical literature between 1960 and 1999,7 but little is known about the prevalence of stimulant abuse among patients with ADHD. Banov and colleagues recently published what may be the only data available, when they reported that 3 of 37 (8%) patients abused the stimulants they were prescribed for ADHD.9 The three patients who abused stimulants had histories of drug and alcohol abuse at study entry. In all three cases, stimulant abuse did not develop immediately but became apparent within 6 months after the study began.

In a study of 651 students ages 11 to 18 in Wisconsin and Minnesota, more than one-third of those taking stimulants reported being asked to sell or trade their medications. More than one-half of those not taking ADHD medications said they knew someone who sold or gave away his or her medication.10

Stimulant theft, recreational use. Methylphenidate has been identified as the third most abused prescribed substance in the United States.11 It was the 10th most frequently stolen controlled drug from pharmacies between 1990 and 1995, and 700,000 dosage units were reported stolen in 1996 and 1997.12

As many as 50% of adults with ADHD have substance abuse problems (including alcohol, cocaine, and marijuana), and as many as 30% have antisocial personality disorder (with increased potential for drug-seeking behaviors).1 Compared with the general population, persons with ADHD have an earlier onset of substance abuse that is less responsive to treatment and more likely to progress from alcohol to other drugs.2

The elevated risk of substance abuse in ADHD may be related to a subtle lack of response to normal positive and negative reinforcements. Hunt has outlined four neurobehavioral deficits that define ADHD.3 Besides inattention, hyperarousal, and impulsiveness, he proposes that persons with ADHD have a reward system deficit. They may gravitate toward substance abuse because drugs, alcohol, and nicotine provide stronger rewards than life’s more subtle social interactions.

The popular media have reported recreational use of methylphenidate—with street names such as “R-Ball” and “Vitamin R”—among teens and college students.13 Illegal stimulants are perceived to be easily accessible on college campuses, but no data have been reported.

The use of stimulant medication for ADHD patients with substance abuse problems remains controversial. For such patients, this author reserves stimulant medication for those:

- whose ADHD symptoms have not responded adequately to alternate treatments

- who have been reliable with prescription medications

- and whose functional level is seriously impaired by their ADHD.

Antidepressants vs. stimulants

Although few well-designed controlled studies have been published, four antidepressants appear to be reasonably equivalent in effectiveness for adults with ADHD and do not carry potential for stimulant abuse.14

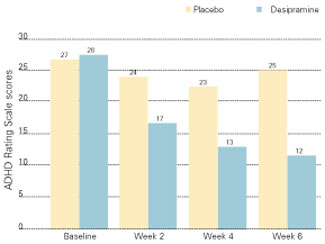

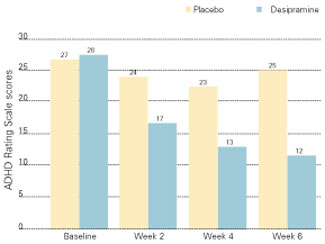

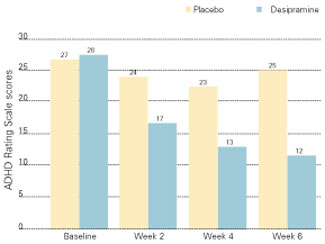

Desipraime, bupropion, venlafaxine, and the experimental drug atomoxetine (Table 1) all increase norepinephrine at the synapse by inhibiting presynaptic reuptake. Though dopamine has traditionally been considered the neurotransmitter of choice for ADHD treatment, norepinephrine may be equally potent.