User login

42-year-old man • altered mental status • vomiting • agitation • Dx?

THE CASE

A 42-year-old man with a history of bipolar disorder with psychotic features, asthma, and chronic pain was brought to the emergency department (ED) by his father due to altered mental status, coughing, and vomiting. The patient was unable to recall events earlier in the day in detail but stated that he remembered using his inhaler for his cough, which seemed to precipitate his vomiting. The patient’s home medications were listed as albuterol 90 mcg, methadone 90 mg/d, and quetiapine 100 mg.

While in the ED, the patient was tachycardic (heart rate, 102 bpm), but all other vital signs were normal. He was agitated and at one point required restraints. On exam, he had epigastric tenderness to palpation, and his lungs were clear to auscultation bilaterally.

Blood work was notable for an elevated lipase level of 729 U/L (normal range, 0-160 U/L). Complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, urinalysis, chest x-ray, and alcohol levels were unremarkable. Computed tomography of the abdomen/pelvis and ultrasound of the abdomen showed excess stool and gallbladder sludge without cholecystitis.

The patient was treated symptomatically with intravenous fluids, ondansetron, and lorazepam. He was admitted with a working diagnosis of acute pancreatitis and possible acute psychosis in the setting of schizophrenia.

A few hours after presentation, the patient returned to his baseline mental status. Over the next 24 hours, his lipase level trended down to normal.

THE DIAGNOSIS

After the patient’s discharge, the pharmacist from his primary care provider’s office called as part of the routine post-hospital follow-up and a medication reconciliation was performed. During this call, the patient stated he had used 2 different nasal sprays prior to his ED presentation.

The pharmacist asked him to read the names of each medication. He related the first was naloxone and the second, fluticasone (neither of which was included on his medication list). Upon further questioning, the pharmacist elicited clarification from the patient that he had, in fact, taken 2 doses of naloxone, shortly after which his vomiting began.

Continue to: This additional history...

This additional history suggested the patient’s true diagnosis was acute opioid withdrawal precipitated by his accidental self-administration of naloxone.

DISCUSSION

Naloxone is a pure mu-opioid receptor antagonist that is used for opioid overdose.1 In the past decade, in response to the opioid epidemic, naloxone has become increasingly available in the community as a way of decreasing opioid-related deaths.1,2 The US Food and Drug Administration recommends that all patients who are prescribed opioids for pain or opioid use disorder, as well as those who are at increased risk for opioid overdose, should be prescribed naloxone and educated on its use. Patients who received a naloxone prescription from their primary care provider have been found to have 47% fewer opioid-related ED visits.3

Quick effects, potential for complications. Use of naloxone can rapidly induce opioid withdrawal symptoms, including gastrointestinal effects, tachycardia, and agitation, as well as diaphoresis, shivering, lacrimation, tremor, anxiety, mydriasis, and hypertension. Naloxone use can also lead to severe complications, such as violent behaviors, ventricular tachycardia or fibrillation, asystole, or pulmonary edema, in the period immediately following administration.4 These effects most often subside within 20 to 60 minutes after administration of naloxone, as the antagonist effect wears off.

The treatment of naloxone toxicity is supportive, with particular attention paid to the patient’s mental and respiratory status.

Our patient was advised by his primary care physician on the proper use of all of his medications, including nasal sprays. The clinic pharmacist also met with him for an additional educational session on the proper use of naloxone.

Continue to: THE TAKEAWAY

THE TAKEAWAY

Given the widespread use of naloxone, proper education and counselling regarding this medication is crucial. Patients should be advised of what to expect after its use. In addition, physicians should always maintain updated patient medication lists, ensuring that they include naloxone if it has been prescribed for use as needed for opioid reversal, to assist in the emergency treatment of affected patients.5

CORRESPONDENCE

Erik Weitz, DO, Troy Beaumont Family Medicine Residency, 44250 Dequindre Road, Sterling Heights, MI 48314; [email protected]

1. Parkin S, Neale J, Brown C, et al. Opioid overdose reversals using naloxone in New York City by people who use opioids: implications for public health and overdose harm reduction approaches from a qualitative study. Int J Drug Policy. 2020;79:102751. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2020.102751

2. Rzasa Lynn R, Galinkin JL. Naloxone dosage for opioid reversal: current evidence and clinical implications. Ther Adv Drug Saf. 2018;9:63-88. doi: 10.1177/2042098617744161

3. Coffin PO, Behar E, et al. Nonrandomized intervention study of naloxone coprescription for primary care patients receiving long-term opioid therapy for pain. Ann Intern Med. 2016;165:245-52. doi: 10.7326/M15-2771

4. Osterwalder JJ. Naloxone—for intoxications with intravenous heroin and heroin mixtures—harmless or hazardous? A prospective clinical study. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 1996;34:409-416. doi: 10.3109/15563659609013811

5. Kwan JL, Lo L, Sampson M, et al. Medication reconciliation during transitions of care as a patient safety strategy: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(5 pt 2):397-403. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-158-5-201303051-00006

THE CASE

A 42-year-old man with a history of bipolar disorder with psychotic features, asthma, and chronic pain was brought to the emergency department (ED) by his father due to altered mental status, coughing, and vomiting. The patient was unable to recall events earlier in the day in detail but stated that he remembered using his inhaler for his cough, which seemed to precipitate his vomiting. The patient’s home medications were listed as albuterol 90 mcg, methadone 90 mg/d, and quetiapine 100 mg.

While in the ED, the patient was tachycardic (heart rate, 102 bpm), but all other vital signs were normal. He was agitated and at one point required restraints. On exam, he had epigastric tenderness to palpation, and his lungs were clear to auscultation bilaterally.

Blood work was notable for an elevated lipase level of 729 U/L (normal range, 0-160 U/L). Complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, urinalysis, chest x-ray, and alcohol levels were unremarkable. Computed tomography of the abdomen/pelvis and ultrasound of the abdomen showed excess stool and gallbladder sludge without cholecystitis.

The patient was treated symptomatically with intravenous fluids, ondansetron, and lorazepam. He was admitted with a working diagnosis of acute pancreatitis and possible acute psychosis in the setting of schizophrenia.

A few hours after presentation, the patient returned to his baseline mental status. Over the next 24 hours, his lipase level trended down to normal.

THE DIAGNOSIS

After the patient’s discharge, the pharmacist from his primary care provider’s office called as part of the routine post-hospital follow-up and a medication reconciliation was performed. During this call, the patient stated he had used 2 different nasal sprays prior to his ED presentation.

The pharmacist asked him to read the names of each medication. He related the first was naloxone and the second, fluticasone (neither of which was included on his medication list). Upon further questioning, the pharmacist elicited clarification from the patient that he had, in fact, taken 2 doses of naloxone, shortly after which his vomiting began.

Continue to: This additional history...

This additional history suggested the patient’s true diagnosis was acute opioid withdrawal precipitated by his accidental self-administration of naloxone.

DISCUSSION

Naloxone is a pure mu-opioid receptor antagonist that is used for opioid overdose.1 In the past decade, in response to the opioid epidemic, naloxone has become increasingly available in the community as a way of decreasing opioid-related deaths.1,2 The US Food and Drug Administration recommends that all patients who are prescribed opioids for pain or opioid use disorder, as well as those who are at increased risk for opioid overdose, should be prescribed naloxone and educated on its use. Patients who received a naloxone prescription from their primary care provider have been found to have 47% fewer opioid-related ED visits.3

Quick effects, potential for complications. Use of naloxone can rapidly induce opioid withdrawal symptoms, including gastrointestinal effects, tachycardia, and agitation, as well as diaphoresis, shivering, lacrimation, tremor, anxiety, mydriasis, and hypertension. Naloxone use can also lead to severe complications, such as violent behaviors, ventricular tachycardia or fibrillation, asystole, or pulmonary edema, in the period immediately following administration.4 These effects most often subside within 20 to 60 minutes after administration of naloxone, as the antagonist effect wears off.

The treatment of naloxone toxicity is supportive, with particular attention paid to the patient’s mental and respiratory status.

Our patient was advised by his primary care physician on the proper use of all of his medications, including nasal sprays. The clinic pharmacist also met with him for an additional educational session on the proper use of naloxone.

Continue to: THE TAKEAWAY

THE TAKEAWAY

Given the widespread use of naloxone, proper education and counselling regarding this medication is crucial. Patients should be advised of what to expect after its use. In addition, physicians should always maintain updated patient medication lists, ensuring that they include naloxone if it has been prescribed for use as needed for opioid reversal, to assist in the emergency treatment of affected patients.5

CORRESPONDENCE

Erik Weitz, DO, Troy Beaumont Family Medicine Residency, 44250 Dequindre Road, Sterling Heights, MI 48314; [email protected]

THE CASE

A 42-year-old man with a history of bipolar disorder with psychotic features, asthma, and chronic pain was brought to the emergency department (ED) by his father due to altered mental status, coughing, and vomiting. The patient was unable to recall events earlier in the day in detail but stated that he remembered using his inhaler for his cough, which seemed to precipitate his vomiting. The patient’s home medications were listed as albuterol 90 mcg, methadone 90 mg/d, and quetiapine 100 mg.

While in the ED, the patient was tachycardic (heart rate, 102 bpm), but all other vital signs were normal. He was agitated and at one point required restraints. On exam, he had epigastric tenderness to palpation, and his lungs were clear to auscultation bilaterally.

Blood work was notable for an elevated lipase level of 729 U/L (normal range, 0-160 U/L). Complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, urinalysis, chest x-ray, and alcohol levels were unremarkable. Computed tomography of the abdomen/pelvis and ultrasound of the abdomen showed excess stool and gallbladder sludge without cholecystitis.

The patient was treated symptomatically with intravenous fluids, ondansetron, and lorazepam. He was admitted with a working diagnosis of acute pancreatitis and possible acute psychosis in the setting of schizophrenia.

A few hours after presentation, the patient returned to his baseline mental status. Over the next 24 hours, his lipase level trended down to normal.

THE DIAGNOSIS

After the patient’s discharge, the pharmacist from his primary care provider’s office called as part of the routine post-hospital follow-up and a medication reconciliation was performed. During this call, the patient stated he had used 2 different nasal sprays prior to his ED presentation.

The pharmacist asked him to read the names of each medication. He related the first was naloxone and the second, fluticasone (neither of which was included on his medication list). Upon further questioning, the pharmacist elicited clarification from the patient that he had, in fact, taken 2 doses of naloxone, shortly after which his vomiting began.

Continue to: This additional history...

This additional history suggested the patient’s true diagnosis was acute opioid withdrawal precipitated by his accidental self-administration of naloxone.

DISCUSSION

Naloxone is a pure mu-opioid receptor antagonist that is used for opioid overdose.1 In the past decade, in response to the opioid epidemic, naloxone has become increasingly available in the community as a way of decreasing opioid-related deaths.1,2 The US Food and Drug Administration recommends that all patients who are prescribed opioids for pain or opioid use disorder, as well as those who are at increased risk for opioid overdose, should be prescribed naloxone and educated on its use. Patients who received a naloxone prescription from their primary care provider have been found to have 47% fewer opioid-related ED visits.3

Quick effects, potential for complications. Use of naloxone can rapidly induce opioid withdrawal symptoms, including gastrointestinal effects, tachycardia, and agitation, as well as diaphoresis, shivering, lacrimation, tremor, anxiety, mydriasis, and hypertension. Naloxone use can also lead to severe complications, such as violent behaviors, ventricular tachycardia or fibrillation, asystole, or pulmonary edema, in the period immediately following administration.4 These effects most often subside within 20 to 60 minutes after administration of naloxone, as the antagonist effect wears off.

The treatment of naloxone toxicity is supportive, with particular attention paid to the patient’s mental and respiratory status.

Our patient was advised by his primary care physician on the proper use of all of his medications, including nasal sprays. The clinic pharmacist also met with him for an additional educational session on the proper use of naloxone.

Continue to: THE TAKEAWAY

THE TAKEAWAY

Given the widespread use of naloxone, proper education and counselling regarding this medication is crucial. Patients should be advised of what to expect after its use. In addition, physicians should always maintain updated patient medication lists, ensuring that they include naloxone if it has been prescribed for use as needed for opioid reversal, to assist in the emergency treatment of affected patients.5

CORRESPONDENCE

Erik Weitz, DO, Troy Beaumont Family Medicine Residency, 44250 Dequindre Road, Sterling Heights, MI 48314; [email protected]

1. Parkin S, Neale J, Brown C, et al. Opioid overdose reversals using naloxone in New York City by people who use opioids: implications for public health and overdose harm reduction approaches from a qualitative study. Int J Drug Policy. 2020;79:102751. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2020.102751

2. Rzasa Lynn R, Galinkin JL. Naloxone dosage for opioid reversal: current evidence and clinical implications. Ther Adv Drug Saf. 2018;9:63-88. doi: 10.1177/2042098617744161

3. Coffin PO, Behar E, et al. Nonrandomized intervention study of naloxone coprescription for primary care patients receiving long-term opioid therapy for pain. Ann Intern Med. 2016;165:245-52. doi: 10.7326/M15-2771

4. Osterwalder JJ. Naloxone—for intoxications with intravenous heroin and heroin mixtures—harmless or hazardous? A prospective clinical study. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 1996;34:409-416. doi: 10.3109/15563659609013811

5. Kwan JL, Lo L, Sampson M, et al. Medication reconciliation during transitions of care as a patient safety strategy: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(5 pt 2):397-403. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-158-5-201303051-00006

1. Parkin S, Neale J, Brown C, et al. Opioid overdose reversals using naloxone in New York City by people who use opioids: implications for public health and overdose harm reduction approaches from a qualitative study. Int J Drug Policy. 2020;79:102751. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2020.102751

2. Rzasa Lynn R, Galinkin JL. Naloxone dosage for opioid reversal: current evidence and clinical implications. Ther Adv Drug Saf. 2018;9:63-88. doi: 10.1177/2042098617744161

3. Coffin PO, Behar E, et al. Nonrandomized intervention study of naloxone coprescription for primary care patients receiving long-term opioid therapy for pain. Ann Intern Med. 2016;165:245-52. doi: 10.7326/M15-2771

4. Osterwalder JJ. Naloxone—for intoxications with intravenous heroin and heroin mixtures—harmless or hazardous? A prospective clinical study. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 1996;34:409-416. doi: 10.3109/15563659609013811

5. Kwan JL, Lo L, Sampson M, et al. Medication reconciliation during transitions of care as a patient safety strategy: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(5 pt 2):397-403. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-158-5-201303051-00006

Kikuchi-Fujimoto Disease: A Case Report of Fever and Lymphadenopathy in a Young White Man

Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease (KFD) is a rare, usually self-limited cause of cervical lymphadenitis that is more prevalent among patients of Asian descent.1 The pathogenesis of KFD remains unknown. Clinically, KFD may mimic malignant lymphoproliferative disorders, autoimmune diseases such as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) lymphadenitis, and infectious conditions such as HIV and tuberculous lymphadenitis. The most common presentation of KFD involves fever and rapidly evolving cervical lymphadenopathy.2,3 Due to its rarity, KFD is not always considered in the differential diagnosis for fever with tender lymphadenopathy, and up to one-third of cases are initially misdiagnosed.2

Definitive diagnosis requires lymph node biopsy. It is critical to achieving a timely diagnosis of KFD to exclude more serious conditions, initiate appropriate treatment, and minimize undue stress for patients. We describe a case of KFD in a patient who was met with delays in obtaining a definitive diagnosis for his symptoms.

Case Presentation

A 27-year-old previously healthy White man presented to the emergency department with subacute, progressive right-sided neck pain and swelling. In the week leading up to presentation, he also noted intermittent fevers, night sweats, and abdominal pain. His symptoms were unrelieved with acetaminophen and aspirin. He reported no sick contacts, recent travel, or animal exposures. He had no known history of autoimmune disease, malignancy, or immunocompromising conditions. Vital signs at the time of presentation were notable for a temperature of 39.0 °C. On examination, he had several firm, mobile, and exquisitely tender lymph nodes in the right upper anterior cervical chain. Abdominal examination was notable for left upper quadrant tenderness with palpable splenomegaly. Due to initial concern that his symptoms represented bacterial lymphadenitis, he was started on broad-spectrum antibiotics and admitted to the hospital for an expedited infectious workup.

Initial laboratory studies were notable for a white blood cell count of 3.7 × 109/L with 57.5% neutrophils and 27.0% lymphocytes on differential.

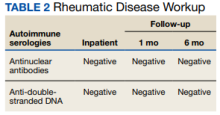

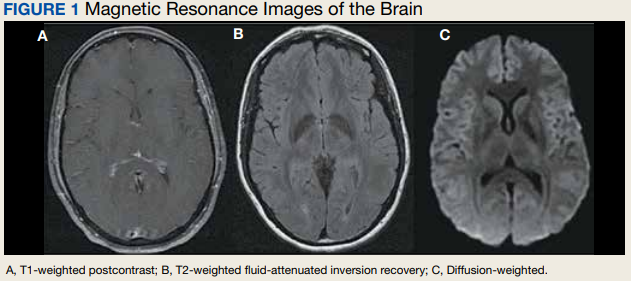

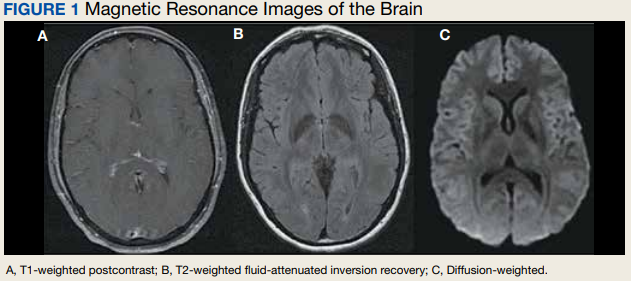

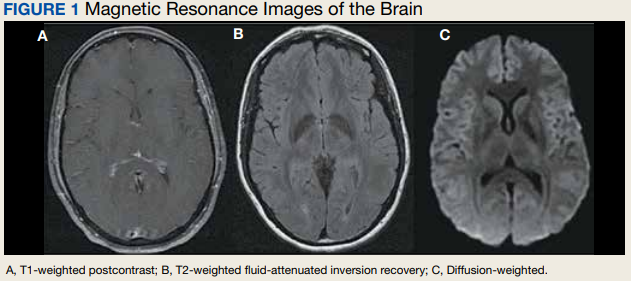

Computed tomography (CT) of the neck revealed multiple heterogeneously enlarged lymph nodes along the right anterior cervical chain with necrotic changes (Figure 1).

A core needle biopsy of a right-sided cervical lymph node was initially pursued, demonstrating necrotic tissue with minimal residual lymphoid tissue and no definitive evidence of lymphoma. Because these results were nondiagnostic, an excisional biopsy of the right-sided cervical lymph node was pursued 10 days later. Due to the stress of his 2-week hospitalization without a unifying diagnosis, the patient then elected to discharge home with close outpatient follow-up while awaiting his biopsy results. Antibiotics were not continued at the time of discharge as our broad infectious workup failed to yield a causative organism.

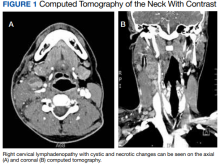

Two weeks postdischarge, the patient’s excisional lymph node biopsy returned demonstrating lymphohistiocytic inflammation with plasmacytoid dendritic cells, areas of necrosis, and scattered karyorrhectic nuclear debris, consistent with a diagnosis of KFD (Figure 2).

After 4 months of hydroxychloroquine therapy, the patient’s KFD symptoms resolved, prompting his dose to be reduced and eventually tapered. Repeat testing of his ANA and anti-dsDNA were performed at 1 and 6 months posthospitalization and returned within normal limits. A repeat PET-CT was performed 6 months posthospitalization showing resolution of his hypermetabolic right neck and right supraclavicular lymphadenopathy as well as his splenomegaly. It has now been more than a year since the patient’s initial presentation to the hospital, and he remains symptom-free and off prednisone and hydroxychloroquine.

Discussion

KFD is a rare cause of cervical lymphadenitis that was first described in 1972. Although cases have been reported worldwide, it is seen with higher prevalence in Asian countries. KFD was previously thought to have a female predominance, but recent reviews suggest a female to male ratio close to 1:1.1 The pathogenesis of KFD remains unknown, though some studies have suggested Epstein-Barr virus infection as a potential trigger.4,5 Human herpesvirus (HHV) 6, HHV 7, HHV 8, HSV, HIV, and parvovirus B19 also have been implicated as potential triggers, though no causative relationship has been established.2,5,6 Autoimmunity may also play a role in the pathogenesis of KFD given its histopathologic overlap with SLE lymphadenitis.1,7

The most common presenting symptoms of KFD include fever and tender cervical lymphadenopathy. Many patients also experience constitutional symptoms such as weight loss, night sweats, and fatigue.2 KFD is characterized by enlarged cervical lymph nodes, typically > 2 cm in diameter.3 Cutaneous manifestations of KFD are common and may manifest as nonspecific papules, plaques, nodules, or facial malar erythema.1,2 Case reports also have described KFD manifesting with ataxia, arthritis, parotitis, or ocular pathologies such as conjunctivitis and uveitis.1,2,8,9 Hepatosplenomegaly is a relatively rare manifestation of KFD seen in approximately 3% of cases.10 When present, hepatosplenomegaly may make the diagnosis of KFD especially difficult to distinguish from lymphoproliferative disorders such as lymphoma. Laboratory findings in KFD are nonspecific and include elevated levels of lactate dehydrogenase, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, and liver enzymes.3 Both lymphocytosis and lymphopenia have been described.3Definitive diagnosis of KFD is achieved through lymph node biopsy and histologic examination. Histopathologic findings of KFD include areas of coagulative necrosis and histiocytic proliferation within the cortical and paracortical regions of the lymph node. Scattered nuclear debris also may be seen, though this histologic finding also is seen with lymphoma. The absence of neutrophils is characteristic of KFD.2 In our patient, a core needle biopsy was initially pursued but returned nondiagnostic. A PET-CT also was obtained, though KFD may mimic lymphoma on PET as was seen in this patient’s case as well as in prior case reports.11 An excisional lymph node biopsy was ultimately performed and secured the diagnosis of KFD.

Although ultrasound-guided core needle biopsy was unable to yield the diagnosis for our patient, its diagnostic accuracy is still superior to that of fine needle aspiration and is therefore suggested as the primary diagnostic modality when KFD is suspected.12 Core needle biopsy also is less invasive, less time consuming, and perhaps more cost-effective than an open excisional biopsy, which often requires the use of an operating room and monitored anesthesia care.12 Understandably, our patient experienced significant stress while awaiting a final diagnosis. Whenever possible, lymph node biopsy should be prioritized over other diagnostic modalities to achieve a timely and definitive diagnosis.

KFD has no established treatment guidelines. Supportive care with antipyretics and analgesics is the most common initial approach, as KFD is typically a self-limited disease that resolves in 1 to 4 months.2 Patients with severe, persistent symptoms have been successfully treated with corticosteroids and hydroxychloroquine, with monotherapy typically trialed before concomitant use.2,13 After 2 courses of prednisone, our patient was prescribed single-agent hydroxychloroquine due to his recurrent symptoms and debilitating AEs from the steroids. Other case reports have described hydroxychloroquine as a treatment option when steroids fail to provide symptom relief or when there are recurrences of KFD.14-19 Retinopathy can occur as a result of long-term hydroxychloroquine use. As such, patients anticipated to require long-term hydroxychloroquine therapy should receive a baseline eye examination within months of drug initiation and repeat examination after 5 years of therapy.20

After symptom resolution, continued follow-up with a health care professional is recommended due to the potential for KFD recurrence or the development of a new autoimmune disease. The rate of KFD recurrence was previously described as 3%, but a more recent review found the rate of recurrence to be approximately 15% at > 6 months follow-up.1,3 Recurrence is often described during or shortly after the tapering of steroids.13,16,21,22 Recurrent KFD can be diagnosed with repeat lymph node biopsy, which also serves to exclude other disease processes.13,16 However, recurrence also has been diagnosed clinically based on the patient’s symptoms and laboratory investigations.21,22Continued surveillance of patients with KFD is also necessary to monitor for the development of new autoimmune diseases, especially SLE. SLE lymphadenitis shares many histopathologic characteristics with KFD. Case reports have described the development of SLE in patients with a history of KFD.2,7 Other autoimmune conditions described in patients with prior KFD include Sjögren syndrome, Hashimoto thyroiditis, Graves disease, mixed connective tissue disease, and antiphospholipid syndrome.3,23 Among patients with KFD, female sex, painful adenopathy, and cytopenias are significantly associated with the later development of autoimmune disease.23

Patient Perspective

This began for me in September 2020 out of the blue. I woke up one day with a random lymph node in my neck but otherwise felt completely healthy, and within 2 to 3 weeks I had never been more sick in my entire life. It came with bouts of fevers, neck pain from the swelling, stomach pain (I later learned an enlarged spleen was the source), terrible night sweats, violent chills where the shaking was uncontrollable for hours at a time, loss of appetite, and countless other symptoms that have come and gone over the past year.

It did take a little while to get a diagnosis, but I understand the autoimmune field is tricky. For about 4 to 5 weeks, I was told to prepare for a lymphoma diagnosis. I ended up doing 2 rounds of prednisone, one for 3 weeks at the end of 2020 and one for 2 months from March to May. The initial round helped quite a bit, but the second round did not have any effect on the lingering symptoms. In my opinion, prednisone is miserable to be on long term and I do not recommend it. The daily AEs that came with it included mood swings, insomnia, weight gain, and more. I have been on hydroxychloroquine now for almost 2 months and although it has some AEs of its own, it is nowhere near as rough as the prednisone and has helped manage my remaining symptoms quite a bit.

This certainly has not been a fun experience, but I was under great care during my time in the hospital and continue to be under good care through the rheumatology clinic. The one thing that could have made a huge difference would have been the issues involved in getting my surgery scheduled while I was still inpatient, which took quite a while. The pain during that time was so intense and unlike anything I have ever experienced before, and it was only the surgery that finally brought me some relief. To paint you a picture, I have broken bones, split my leg open, and have roughly 40 to 50 hours of tattoo work on me, and I have never experienced the level of pain like I felt in my neck and stomach. I remember feeling like someone had wound up and hit me with a baseball bat. The surgery brought me immense relief and if it had occurred when it was originally supposed to, I would have been spared 3 or so days of this type of pain.

It has been almost 10 months since my surgery and diagnosis, and life has mostly returned to normal for me. I am still on long-term medication as I mentioned, and I still deal with fatigue, spleen pain, and several other symptoms, but it is much more under control these days. I feel very fortunate to have been under and continue to be under such great care.

Conclusions

This case report highlights the importance of recognizing KFD as a rare but possible cause of fever and necrotizing cervical lymphadenopathy. KFD often mimics malignant lymphoproliferative disorders, autoimmune diseases such as SLE lymphadenitis, and infectious conditions such as HIV and tuberculous lymphadenitis. While KFD is seen with higher prevalence in Asian countries and was previously thought to be more predominant in females, the diagnosis should still be considered irrespective of geographic location or patient sex. Lymph node biopsy is the preferred diagnostic approach for patients with suspected KFD. Treatment is typically supportive but may consist of glucocorticoids in severe cases. Hydroxychloroquine may be used in refractory cases or as a steroid-sparing regimen when steroid AEs are poorly tolerated. Long-term follow-up is critical for patients with KFD to monitor for both disease recurrence and the development of autoimmune disease, especially SLE.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Jacob Pilley for his detailed review of the patient’s pathology results. The authors also extend their gratitude to the patient, who deepened our understanding of this condition and what it is like to live with it.

1. Bosch X, Guilabert A, Miquel R, Campo E. Enigmatic Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease: a comprehensive review. Am J Clin Pathol. 2004;122(1):141-152. doi:10.1309/YF08-1L4T-KYWV-YVPQ

2. Deaver D, Horna P, Cualing H, Sokol L. Pathogenesis, diagnosis, and management of Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease. Cancer Control. 2014;21(4):313-321. doi:10.1177/107327481402100407

3. Cheng CY, Sheng WH, Lo YC, Chung CS, Chen YC, Chang SC. Clinical presentations, laboratory results and outcomes of patients with Kikuchi’s disease: emphasis on the association between recurrent Kikuchi’s disease and autoimmune diseases. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2010;43(5):366-371. doi:10.1016/S1684-1182(10)60058-8

4. Stéphan JL, Jeannoël P, Chanoz J, Gentil-Përret A. Epstein-Barr virus-associated Kikuchi disease in two children. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2001;23(4):240-243. doi:10.1097/00043426-200105000-00012

5. Chiu CF, Chow KC, Lin TY, Tsai MH, Shih CM, Chen LM. Virus infection in patients with histiocytic necrotizing lymphadenitis in Taiwan. Detection of Epstein-Barr virus, type I human T-cell lymphotropic virus, and parvovirus B19. Am J Clin Pathol. 2000;113(6):774-781. doi:10.1309/1A6Y-YCKP-5AVF-QTYR

6. Rosado FG, Tang YW, Hasserjian RP, McClain CM, Wang B, Mosse CA. Kikuchi-Fujimoto lymphadenitis: role of parvovirus B-19, Epstein-Barr virus, human herpesvirus 6, and human herpesvirus 8. Hum Pathol. 2013;44(2):255-259. doi:10.1016/j.humpath.2012.05.016

7. Gordon JK, Magro C, Lu T, et al. Overlap between systemic lupus erythematosus and Kikuchi Fujimoto disease: a clinical pathology conference held by the Department of Rheumatology at Hospital for Special Surgery. HSS J. 2009;5(2):169-177. doi:10.1007/s11420-009-9123-x

8. Lo KB, Papazoglou A, Chua L, Candelario N. Case Report: Kikuchi: The great mimicker. F1000Res. 2018;7:520. Published 2018 Apr 30. doi:10.12688/f1000research.14758.1

9. Galor A, Georgy M, Leder HA, Dunn JP, Peters GB 3rd. Papillary conjunctivitis associated with Kikuchi disease. Cornea. 2008;27(8):944-946. doi:10.1097/ICO.0b013e31816bf488

10. Kucukardali Y, Solmazgul E, Kunter E, Oncul O, Yildirim S, Kaplan M. Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease: analysis of 244 cases. Clin Rheumatol. 2007;26(1):50-54. doi:10.1007/s10067-006-0230-5

11. Lee DH, Lee JH, Shim EJ, et al. Disseminated Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease mimicking malignant lymphoma on positron emission tomography in a child. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2009;31(9):687-689. doi:10.1097/MPH.0b013e31819a5d77

12. Park SG, Koo HR, Jang K, et al. Efficacy of ultrasound-guided needle biopsy in the diagnosis of Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease. Laryngoscope. 2021;131(5):E1519-E1523. doi:10.1002/lary.29160

13. Honda F, Tsuboi H, Toko H, et al. Recurrent Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease successfully treated by the concomitant use of hydroxychloroquine and corticosteroids. Intern Med. 2017;56(24):3373-3377. doi:10.2169/internalmedicine.9205-17

14. Rezayat T, Carroll MB, Ramsey BC, Smith A. A case of relapsing Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease. Case Rep Otolaryngol. 2013;2013:364795. doi:10.1155/2013/364795

15. Rezai K, Kuchipudi S, Chundi V, Ariga R, Loew J, Sha BE. Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease: hydroxychloroquine as a treatment. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39(12):e124-e126. doi:10.1086/426144

16. Hyun M, So IT, Kim HA, Jung H, Ryu SY. Recurrent Kikuchi’s disease treated by hydroxychloroquine. Infect Chemother. 2016;48(2):127-131. doi:10.3947/ic.2016.48.2.127

17. Lin YC, Huang HH, Nong BR, et al. Pediatric Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease: A clinicopathologic study and the therapeutic effects of hydroxychloroquine. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2019;52(3):395-401. doi:10.1016/j.jmii.2017.08.023

18. Lin DY, Villegas MS, Tan PL, Wang S, Shek LP. Severe Kikuchi’s disease responsive to immune modulation. Singapore Med J. 2010;51(1):e18-e21.

19. Quintás-Cardama A, Fraga M, Cozzi SN, Caparrini A, Maceiras F, Forteza J. Fatal Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease: the lupus connection. Ann Hematol. 2003;82(3):186-188. doi:10.1007/s00277-003-0611-7

20. American Academy of Ophthalmology. ACR, AAD, RDS, and AAO 2020 Joint Statement on Hydroxychloroquine Use with Respect to Retinal Toxicity. Updated February 2021. Accessed November 28, 2022. https://www.aao.org/clinical-statement/acr-aad-rds-aao-2020-joint-statement-on-hydroxychl-2

21. Gerwig U, Weidmann RG, Lindner G. Relapsing Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease requiring prolonged steroid therapy. Case Rep Emerg Med. 2019;2019:6405687. Published 2019 Mar 7. doi:10.1155/2019/6405687

22. Faheem B, Kumar V, Ashkar H, Komal F, Sultana Y. Recurrent Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease masquerading as lymphoma successfully treated by anakinra. Cureus. 2020;12(11):e11655. Published 2020 Nov 23. doi:10.7759/cureus.11655

23. Sopeña B, Rivera A, Vázquez-Triñanes C, et al. Autoimmune manifestations of Kikuchi disease. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2012;41(6):900-906. doi:10.1016/j.semarthrit.2011.11.001

Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease (KFD) is a rare, usually self-limited cause of cervical lymphadenitis that is more prevalent among patients of Asian descent.1 The pathogenesis of KFD remains unknown. Clinically, KFD may mimic malignant lymphoproliferative disorders, autoimmune diseases such as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) lymphadenitis, and infectious conditions such as HIV and tuberculous lymphadenitis. The most common presentation of KFD involves fever and rapidly evolving cervical lymphadenopathy.2,3 Due to its rarity, KFD is not always considered in the differential diagnosis for fever with tender lymphadenopathy, and up to one-third of cases are initially misdiagnosed.2

Definitive diagnosis requires lymph node biopsy. It is critical to achieving a timely diagnosis of KFD to exclude more serious conditions, initiate appropriate treatment, and minimize undue stress for patients. We describe a case of KFD in a patient who was met with delays in obtaining a definitive diagnosis for his symptoms.

Case Presentation

A 27-year-old previously healthy White man presented to the emergency department with subacute, progressive right-sided neck pain and swelling. In the week leading up to presentation, he also noted intermittent fevers, night sweats, and abdominal pain. His symptoms were unrelieved with acetaminophen and aspirin. He reported no sick contacts, recent travel, or animal exposures. He had no known history of autoimmune disease, malignancy, or immunocompromising conditions. Vital signs at the time of presentation were notable for a temperature of 39.0 °C. On examination, he had several firm, mobile, and exquisitely tender lymph nodes in the right upper anterior cervical chain. Abdominal examination was notable for left upper quadrant tenderness with palpable splenomegaly. Due to initial concern that his symptoms represented bacterial lymphadenitis, he was started on broad-spectrum antibiotics and admitted to the hospital for an expedited infectious workup.

Initial laboratory studies were notable for a white blood cell count of 3.7 × 109/L with 57.5% neutrophils and 27.0% lymphocytes on differential.

Computed tomography (CT) of the neck revealed multiple heterogeneously enlarged lymph nodes along the right anterior cervical chain with necrotic changes (Figure 1).

A core needle biopsy of a right-sided cervical lymph node was initially pursued, demonstrating necrotic tissue with minimal residual lymphoid tissue and no definitive evidence of lymphoma. Because these results were nondiagnostic, an excisional biopsy of the right-sided cervical lymph node was pursued 10 days later. Due to the stress of his 2-week hospitalization without a unifying diagnosis, the patient then elected to discharge home with close outpatient follow-up while awaiting his biopsy results. Antibiotics were not continued at the time of discharge as our broad infectious workup failed to yield a causative organism.

Two weeks postdischarge, the patient’s excisional lymph node biopsy returned demonstrating lymphohistiocytic inflammation with plasmacytoid dendritic cells, areas of necrosis, and scattered karyorrhectic nuclear debris, consistent with a diagnosis of KFD (Figure 2).

After 4 months of hydroxychloroquine therapy, the patient’s KFD symptoms resolved, prompting his dose to be reduced and eventually tapered. Repeat testing of his ANA and anti-dsDNA were performed at 1 and 6 months posthospitalization and returned within normal limits. A repeat PET-CT was performed 6 months posthospitalization showing resolution of his hypermetabolic right neck and right supraclavicular lymphadenopathy as well as his splenomegaly. It has now been more than a year since the patient’s initial presentation to the hospital, and he remains symptom-free and off prednisone and hydroxychloroquine.

Discussion

KFD is a rare cause of cervical lymphadenitis that was first described in 1972. Although cases have been reported worldwide, it is seen with higher prevalence in Asian countries. KFD was previously thought to have a female predominance, but recent reviews suggest a female to male ratio close to 1:1.1 The pathogenesis of KFD remains unknown, though some studies have suggested Epstein-Barr virus infection as a potential trigger.4,5 Human herpesvirus (HHV) 6, HHV 7, HHV 8, HSV, HIV, and parvovirus B19 also have been implicated as potential triggers, though no causative relationship has been established.2,5,6 Autoimmunity may also play a role in the pathogenesis of KFD given its histopathologic overlap with SLE lymphadenitis.1,7

The most common presenting symptoms of KFD include fever and tender cervical lymphadenopathy. Many patients also experience constitutional symptoms such as weight loss, night sweats, and fatigue.2 KFD is characterized by enlarged cervical lymph nodes, typically > 2 cm in diameter.3 Cutaneous manifestations of KFD are common and may manifest as nonspecific papules, plaques, nodules, or facial malar erythema.1,2 Case reports also have described KFD manifesting with ataxia, arthritis, parotitis, or ocular pathologies such as conjunctivitis and uveitis.1,2,8,9 Hepatosplenomegaly is a relatively rare manifestation of KFD seen in approximately 3% of cases.10 When present, hepatosplenomegaly may make the diagnosis of KFD especially difficult to distinguish from lymphoproliferative disorders such as lymphoma. Laboratory findings in KFD are nonspecific and include elevated levels of lactate dehydrogenase, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, and liver enzymes.3 Both lymphocytosis and lymphopenia have been described.3Definitive diagnosis of KFD is achieved through lymph node biopsy and histologic examination. Histopathologic findings of KFD include areas of coagulative necrosis and histiocytic proliferation within the cortical and paracortical regions of the lymph node. Scattered nuclear debris also may be seen, though this histologic finding also is seen with lymphoma. The absence of neutrophils is characteristic of KFD.2 In our patient, a core needle biopsy was initially pursued but returned nondiagnostic. A PET-CT also was obtained, though KFD may mimic lymphoma on PET as was seen in this patient’s case as well as in prior case reports.11 An excisional lymph node biopsy was ultimately performed and secured the diagnosis of KFD.

Although ultrasound-guided core needle biopsy was unable to yield the diagnosis for our patient, its diagnostic accuracy is still superior to that of fine needle aspiration and is therefore suggested as the primary diagnostic modality when KFD is suspected.12 Core needle biopsy also is less invasive, less time consuming, and perhaps more cost-effective than an open excisional biopsy, which often requires the use of an operating room and monitored anesthesia care.12 Understandably, our patient experienced significant stress while awaiting a final diagnosis. Whenever possible, lymph node biopsy should be prioritized over other diagnostic modalities to achieve a timely and definitive diagnosis.

KFD has no established treatment guidelines. Supportive care with antipyretics and analgesics is the most common initial approach, as KFD is typically a self-limited disease that resolves in 1 to 4 months.2 Patients with severe, persistent symptoms have been successfully treated with corticosteroids and hydroxychloroquine, with monotherapy typically trialed before concomitant use.2,13 After 2 courses of prednisone, our patient was prescribed single-agent hydroxychloroquine due to his recurrent symptoms and debilitating AEs from the steroids. Other case reports have described hydroxychloroquine as a treatment option when steroids fail to provide symptom relief or when there are recurrences of KFD.14-19 Retinopathy can occur as a result of long-term hydroxychloroquine use. As such, patients anticipated to require long-term hydroxychloroquine therapy should receive a baseline eye examination within months of drug initiation and repeat examination after 5 years of therapy.20

After symptom resolution, continued follow-up with a health care professional is recommended due to the potential for KFD recurrence or the development of a new autoimmune disease. The rate of KFD recurrence was previously described as 3%, but a more recent review found the rate of recurrence to be approximately 15% at > 6 months follow-up.1,3 Recurrence is often described during or shortly after the tapering of steroids.13,16,21,22 Recurrent KFD can be diagnosed with repeat lymph node biopsy, which also serves to exclude other disease processes.13,16 However, recurrence also has been diagnosed clinically based on the patient’s symptoms and laboratory investigations.21,22Continued surveillance of patients with KFD is also necessary to monitor for the development of new autoimmune diseases, especially SLE. SLE lymphadenitis shares many histopathologic characteristics with KFD. Case reports have described the development of SLE in patients with a history of KFD.2,7 Other autoimmune conditions described in patients with prior KFD include Sjögren syndrome, Hashimoto thyroiditis, Graves disease, mixed connective tissue disease, and antiphospholipid syndrome.3,23 Among patients with KFD, female sex, painful adenopathy, and cytopenias are significantly associated with the later development of autoimmune disease.23

Patient Perspective

This began for me in September 2020 out of the blue. I woke up one day with a random lymph node in my neck but otherwise felt completely healthy, and within 2 to 3 weeks I had never been more sick in my entire life. It came with bouts of fevers, neck pain from the swelling, stomach pain (I later learned an enlarged spleen was the source), terrible night sweats, violent chills where the shaking was uncontrollable for hours at a time, loss of appetite, and countless other symptoms that have come and gone over the past year.

It did take a little while to get a diagnosis, but I understand the autoimmune field is tricky. For about 4 to 5 weeks, I was told to prepare for a lymphoma diagnosis. I ended up doing 2 rounds of prednisone, one for 3 weeks at the end of 2020 and one for 2 months from March to May. The initial round helped quite a bit, but the second round did not have any effect on the lingering symptoms. In my opinion, prednisone is miserable to be on long term and I do not recommend it. The daily AEs that came with it included mood swings, insomnia, weight gain, and more. I have been on hydroxychloroquine now for almost 2 months and although it has some AEs of its own, it is nowhere near as rough as the prednisone and has helped manage my remaining symptoms quite a bit.

This certainly has not been a fun experience, but I was under great care during my time in the hospital and continue to be under good care through the rheumatology clinic. The one thing that could have made a huge difference would have been the issues involved in getting my surgery scheduled while I was still inpatient, which took quite a while. The pain during that time was so intense and unlike anything I have ever experienced before, and it was only the surgery that finally brought me some relief. To paint you a picture, I have broken bones, split my leg open, and have roughly 40 to 50 hours of tattoo work on me, and I have never experienced the level of pain like I felt in my neck and stomach. I remember feeling like someone had wound up and hit me with a baseball bat. The surgery brought me immense relief and if it had occurred when it was originally supposed to, I would have been spared 3 or so days of this type of pain.

It has been almost 10 months since my surgery and diagnosis, and life has mostly returned to normal for me. I am still on long-term medication as I mentioned, and I still deal with fatigue, spleen pain, and several other symptoms, but it is much more under control these days. I feel very fortunate to have been under and continue to be under such great care.

Conclusions

This case report highlights the importance of recognizing KFD as a rare but possible cause of fever and necrotizing cervical lymphadenopathy. KFD often mimics malignant lymphoproliferative disorders, autoimmune diseases such as SLE lymphadenitis, and infectious conditions such as HIV and tuberculous lymphadenitis. While KFD is seen with higher prevalence in Asian countries and was previously thought to be more predominant in females, the diagnosis should still be considered irrespective of geographic location or patient sex. Lymph node biopsy is the preferred diagnostic approach for patients with suspected KFD. Treatment is typically supportive but may consist of glucocorticoids in severe cases. Hydroxychloroquine may be used in refractory cases or as a steroid-sparing regimen when steroid AEs are poorly tolerated. Long-term follow-up is critical for patients with KFD to monitor for both disease recurrence and the development of autoimmune disease, especially SLE.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Jacob Pilley for his detailed review of the patient’s pathology results. The authors also extend their gratitude to the patient, who deepened our understanding of this condition and what it is like to live with it.

Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease (KFD) is a rare, usually self-limited cause of cervical lymphadenitis that is more prevalent among patients of Asian descent.1 The pathogenesis of KFD remains unknown. Clinically, KFD may mimic malignant lymphoproliferative disorders, autoimmune diseases such as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) lymphadenitis, and infectious conditions such as HIV and tuberculous lymphadenitis. The most common presentation of KFD involves fever and rapidly evolving cervical lymphadenopathy.2,3 Due to its rarity, KFD is not always considered in the differential diagnosis for fever with tender lymphadenopathy, and up to one-third of cases are initially misdiagnosed.2

Definitive diagnosis requires lymph node biopsy. It is critical to achieving a timely diagnosis of KFD to exclude more serious conditions, initiate appropriate treatment, and minimize undue stress for patients. We describe a case of KFD in a patient who was met with delays in obtaining a definitive diagnosis for his symptoms.

Case Presentation

A 27-year-old previously healthy White man presented to the emergency department with subacute, progressive right-sided neck pain and swelling. In the week leading up to presentation, he also noted intermittent fevers, night sweats, and abdominal pain. His symptoms were unrelieved with acetaminophen and aspirin. He reported no sick contacts, recent travel, or animal exposures. He had no known history of autoimmune disease, malignancy, or immunocompromising conditions. Vital signs at the time of presentation were notable for a temperature of 39.0 °C. On examination, he had several firm, mobile, and exquisitely tender lymph nodes in the right upper anterior cervical chain. Abdominal examination was notable for left upper quadrant tenderness with palpable splenomegaly. Due to initial concern that his symptoms represented bacterial lymphadenitis, he was started on broad-spectrum antibiotics and admitted to the hospital for an expedited infectious workup.

Initial laboratory studies were notable for a white blood cell count of 3.7 × 109/L with 57.5% neutrophils and 27.0% lymphocytes on differential.

Computed tomography (CT) of the neck revealed multiple heterogeneously enlarged lymph nodes along the right anterior cervical chain with necrotic changes (Figure 1).

A core needle biopsy of a right-sided cervical lymph node was initially pursued, demonstrating necrotic tissue with minimal residual lymphoid tissue and no definitive evidence of lymphoma. Because these results were nondiagnostic, an excisional biopsy of the right-sided cervical lymph node was pursued 10 days later. Due to the stress of his 2-week hospitalization without a unifying diagnosis, the patient then elected to discharge home with close outpatient follow-up while awaiting his biopsy results. Antibiotics were not continued at the time of discharge as our broad infectious workup failed to yield a causative organism.

Two weeks postdischarge, the patient’s excisional lymph node biopsy returned demonstrating lymphohistiocytic inflammation with plasmacytoid dendritic cells, areas of necrosis, and scattered karyorrhectic nuclear debris, consistent with a diagnosis of KFD (Figure 2).

After 4 months of hydroxychloroquine therapy, the patient’s KFD symptoms resolved, prompting his dose to be reduced and eventually tapered. Repeat testing of his ANA and anti-dsDNA were performed at 1 and 6 months posthospitalization and returned within normal limits. A repeat PET-CT was performed 6 months posthospitalization showing resolution of his hypermetabolic right neck and right supraclavicular lymphadenopathy as well as his splenomegaly. It has now been more than a year since the patient’s initial presentation to the hospital, and he remains symptom-free and off prednisone and hydroxychloroquine.

Discussion

KFD is a rare cause of cervical lymphadenitis that was first described in 1972. Although cases have been reported worldwide, it is seen with higher prevalence in Asian countries. KFD was previously thought to have a female predominance, but recent reviews suggest a female to male ratio close to 1:1.1 The pathogenesis of KFD remains unknown, though some studies have suggested Epstein-Barr virus infection as a potential trigger.4,5 Human herpesvirus (HHV) 6, HHV 7, HHV 8, HSV, HIV, and parvovirus B19 also have been implicated as potential triggers, though no causative relationship has been established.2,5,6 Autoimmunity may also play a role in the pathogenesis of KFD given its histopathologic overlap with SLE lymphadenitis.1,7

The most common presenting symptoms of KFD include fever and tender cervical lymphadenopathy. Many patients also experience constitutional symptoms such as weight loss, night sweats, and fatigue.2 KFD is characterized by enlarged cervical lymph nodes, typically > 2 cm in diameter.3 Cutaneous manifestations of KFD are common and may manifest as nonspecific papules, plaques, nodules, or facial malar erythema.1,2 Case reports also have described KFD manifesting with ataxia, arthritis, parotitis, or ocular pathologies such as conjunctivitis and uveitis.1,2,8,9 Hepatosplenomegaly is a relatively rare manifestation of KFD seen in approximately 3% of cases.10 When present, hepatosplenomegaly may make the diagnosis of KFD especially difficult to distinguish from lymphoproliferative disorders such as lymphoma. Laboratory findings in KFD are nonspecific and include elevated levels of lactate dehydrogenase, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, and liver enzymes.3 Both lymphocytosis and lymphopenia have been described.3Definitive diagnosis of KFD is achieved through lymph node biopsy and histologic examination. Histopathologic findings of KFD include areas of coagulative necrosis and histiocytic proliferation within the cortical and paracortical regions of the lymph node. Scattered nuclear debris also may be seen, though this histologic finding also is seen with lymphoma. The absence of neutrophils is characteristic of KFD.2 In our patient, a core needle biopsy was initially pursued but returned nondiagnostic. A PET-CT also was obtained, though KFD may mimic lymphoma on PET as was seen in this patient’s case as well as in prior case reports.11 An excisional lymph node biopsy was ultimately performed and secured the diagnosis of KFD.

Although ultrasound-guided core needle biopsy was unable to yield the diagnosis for our patient, its diagnostic accuracy is still superior to that of fine needle aspiration and is therefore suggested as the primary diagnostic modality when KFD is suspected.12 Core needle biopsy also is less invasive, less time consuming, and perhaps more cost-effective than an open excisional biopsy, which often requires the use of an operating room and monitored anesthesia care.12 Understandably, our patient experienced significant stress while awaiting a final diagnosis. Whenever possible, lymph node biopsy should be prioritized over other diagnostic modalities to achieve a timely and definitive diagnosis.

KFD has no established treatment guidelines. Supportive care with antipyretics and analgesics is the most common initial approach, as KFD is typically a self-limited disease that resolves in 1 to 4 months.2 Patients with severe, persistent symptoms have been successfully treated with corticosteroids and hydroxychloroquine, with monotherapy typically trialed before concomitant use.2,13 After 2 courses of prednisone, our patient was prescribed single-agent hydroxychloroquine due to his recurrent symptoms and debilitating AEs from the steroids. Other case reports have described hydroxychloroquine as a treatment option when steroids fail to provide symptom relief or when there are recurrences of KFD.14-19 Retinopathy can occur as a result of long-term hydroxychloroquine use. As such, patients anticipated to require long-term hydroxychloroquine therapy should receive a baseline eye examination within months of drug initiation and repeat examination after 5 years of therapy.20

After symptom resolution, continued follow-up with a health care professional is recommended due to the potential for KFD recurrence or the development of a new autoimmune disease. The rate of KFD recurrence was previously described as 3%, but a more recent review found the rate of recurrence to be approximately 15% at > 6 months follow-up.1,3 Recurrence is often described during or shortly after the tapering of steroids.13,16,21,22 Recurrent KFD can be diagnosed with repeat lymph node biopsy, which also serves to exclude other disease processes.13,16 However, recurrence also has been diagnosed clinically based on the patient’s symptoms and laboratory investigations.21,22Continued surveillance of patients with KFD is also necessary to monitor for the development of new autoimmune diseases, especially SLE. SLE lymphadenitis shares many histopathologic characteristics with KFD. Case reports have described the development of SLE in patients with a history of KFD.2,7 Other autoimmune conditions described in patients with prior KFD include Sjögren syndrome, Hashimoto thyroiditis, Graves disease, mixed connective tissue disease, and antiphospholipid syndrome.3,23 Among patients with KFD, female sex, painful adenopathy, and cytopenias are significantly associated with the later development of autoimmune disease.23

Patient Perspective

This began for me in September 2020 out of the blue. I woke up one day with a random lymph node in my neck but otherwise felt completely healthy, and within 2 to 3 weeks I had never been more sick in my entire life. It came with bouts of fevers, neck pain from the swelling, stomach pain (I later learned an enlarged spleen was the source), terrible night sweats, violent chills where the shaking was uncontrollable for hours at a time, loss of appetite, and countless other symptoms that have come and gone over the past year.

It did take a little while to get a diagnosis, but I understand the autoimmune field is tricky. For about 4 to 5 weeks, I was told to prepare for a lymphoma diagnosis. I ended up doing 2 rounds of prednisone, one for 3 weeks at the end of 2020 and one for 2 months from March to May. The initial round helped quite a bit, but the second round did not have any effect on the lingering symptoms. In my opinion, prednisone is miserable to be on long term and I do not recommend it. The daily AEs that came with it included mood swings, insomnia, weight gain, and more. I have been on hydroxychloroquine now for almost 2 months and although it has some AEs of its own, it is nowhere near as rough as the prednisone and has helped manage my remaining symptoms quite a bit.

This certainly has not been a fun experience, but I was under great care during my time in the hospital and continue to be under good care through the rheumatology clinic. The one thing that could have made a huge difference would have been the issues involved in getting my surgery scheduled while I was still inpatient, which took quite a while. The pain during that time was so intense and unlike anything I have ever experienced before, and it was only the surgery that finally brought me some relief. To paint you a picture, I have broken bones, split my leg open, and have roughly 40 to 50 hours of tattoo work on me, and I have never experienced the level of pain like I felt in my neck and stomach. I remember feeling like someone had wound up and hit me with a baseball bat. The surgery brought me immense relief and if it had occurred when it was originally supposed to, I would have been spared 3 or so days of this type of pain.

It has been almost 10 months since my surgery and diagnosis, and life has mostly returned to normal for me. I am still on long-term medication as I mentioned, and I still deal with fatigue, spleen pain, and several other symptoms, but it is much more under control these days. I feel very fortunate to have been under and continue to be under such great care.

Conclusions

This case report highlights the importance of recognizing KFD as a rare but possible cause of fever and necrotizing cervical lymphadenopathy. KFD often mimics malignant lymphoproliferative disorders, autoimmune diseases such as SLE lymphadenitis, and infectious conditions such as HIV and tuberculous lymphadenitis. While KFD is seen with higher prevalence in Asian countries and was previously thought to be more predominant in females, the diagnosis should still be considered irrespective of geographic location or patient sex. Lymph node biopsy is the preferred diagnostic approach for patients with suspected KFD. Treatment is typically supportive but may consist of glucocorticoids in severe cases. Hydroxychloroquine may be used in refractory cases or as a steroid-sparing regimen when steroid AEs are poorly tolerated. Long-term follow-up is critical for patients with KFD to monitor for both disease recurrence and the development of autoimmune disease, especially SLE.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Jacob Pilley for his detailed review of the patient’s pathology results. The authors also extend their gratitude to the patient, who deepened our understanding of this condition and what it is like to live with it.

1. Bosch X, Guilabert A, Miquel R, Campo E. Enigmatic Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease: a comprehensive review. Am J Clin Pathol. 2004;122(1):141-152. doi:10.1309/YF08-1L4T-KYWV-YVPQ

2. Deaver D, Horna P, Cualing H, Sokol L. Pathogenesis, diagnosis, and management of Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease. Cancer Control. 2014;21(4):313-321. doi:10.1177/107327481402100407

3. Cheng CY, Sheng WH, Lo YC, Chung CS, Chen YC, Chang SC. Clinical presentations, laboratory results and outcomes of patients with Kikuchi’s disease: emphasis on the association between recurrent Kikuchi’s disease and autoimmune diseases. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2010;43(5):366-371. doi:10.1016/S1684-1182(10)60058-8

4. Stéphan JL, Jeannoël P, Chanoz J, Gentil-Përret A. Epstein-Barr virus-associated Kikuchi disease in two children. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2001;23(4):240-243. doi:10.1097/00043426-200105000-00012

5. Chiu CF, Chow KC, Lin TY, Tsai MH, Shih CM, Chen LM. Virus infection in patients with histiocytic necrotizing lymphadenitis in Taiwan. Detection of Epstein-Barr virus, type I human T-cell lymphotropic virus, and parvovirus B19. Am J Clin Pathol. 2000;113(6):774-781. doi:10.1309/1A6Y-YCKP-5AVF-QTYR

6. Rosado FG, Tang YW, Hasserjian RP, McClain CM, Wang B, Mosse CA. Kikuchi-Fujimoto lymphadenitis: role of parvovirus B-19, Epstein-Barr virus, human herpesvirus 6, and human herpesvirus 8. Hum Pathol. 2013;44(2):255-259. doi:10.1016/j.humpath.2012.05.016

7. Gordon JK, Magro C, Lu T, et al. Overlap between systemic lupus erythematosus and Kikuchi Fujimoto disease: a clinical pathology conference held by the Department of Rheumatology at Hospital for Special Surgery. HSS J. 2009;5(2):169-177. doi:10.1007/s11420-009-9123-x

8. Lo KB, Papazoglou A, Chua L, Candelario N. Case Report: Kikuchi: The great mimicker. F1000Res. 2018;7:520. Published 2018 Apr 30. doi:10.12688/f1000research.14758.1

9. Galor A, Georgy M, Leder HA, Dunn JP, Peters GB 3rd. Papillary conjunctivitis associated with Kikuchi disease. Cornea. 2008;27(8):944-946. doi:10.1097/ICO.0b013e31816bf488

10. Kucukardali Y, Solmazgul E, Kunter E, Oncul O, Yildirim S, Kaplan M. Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease: analysis of 244 cases. Clin Rheumatol. 2007;26(1):50-54. doi:10.1007/s10067-006-0230-5

11. Lee DH, Lee JH, Shim EJ, et al. Disseminated Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease mimicking malignant lymphoma on positron emission tomography in a child. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2009;31(9):687-689. doi:10.1097/MPH.0b013e31819a5d77

12. Park SG, Koo HR, Jang K, et al. Efficacy of ultrasound-guided needle biopsy in the diagnosis of Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease. Laryngoscope. 2021;131(5):E1519-E1523. doi:10.1002/lary.29160

13. Honda F, Tsuboi H, Toko H, et al. Recurrent Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease successfully treated by the concomitant use of hydroxychloroquine and corticosteroids. Intern Med. 2017;56(24):3373-3377. doi:10.2169/internalmedicine.9205-17

14. Rezayat T, Carroll MB, Ramsey BC, Smith A. A case of relapsing Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease. Case Rep Otolaryngol. 2013;2013:364795. doi:10.1155/2013/364795

15. Rezai K, Kuchipudi S, Chundi V, Ariga R, Loew J, Sha BE. Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease: hydroxychloroquine as a treatment. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39(12):e124-e126. doi:10.1086/426144

16. Hyun M, So IT, Kim HA, Jung H, Ryu SY. Recurrent Kikuchi’s disease treated by hydroxychloroquine. Infect Chemother. 2016;48(2):127-131. doi:10.3947/ic.2016.48.2.127

17. Lin YC, Huang HH, Nong BR, et al. Pediatric Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease: A clinicopathologic study and the therapeutic effects of hydroxychloroquine. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2019;52(3):395-401. doi:10.1016/j.jmii.2017.08.023

18. Lin DY, Villegas MS, Tan PL, Wang S, Shek LP. Severe Kikuchi’s disease responsive to immune modulation. Singapore Med J. 2010;51(1):e18-e21.

19. Quintás-Cardama A, Fraga M, Cozzi SN, Caparrini A, Maceiras F, Forteza J. Fatal Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease: the lupus connection. Ann Hematol. 2003;82(3):186-188. doi:10.1007/s00277-003-0611-7

20. American Academy of Ophthalmology. ACR, AAD, RDS, and AAO 2020 Joint Statement on Hydroxychloroquine Use with Respect to Retinal Toxicity. Updated February 2021. Accessed November 28, 2022. https://www.aao.org/clinical-statement/acr-aad-rds-aao-2020-joint-statement-on-hydroxychl-2

21. Gerwig U, Weidmann RG, Lindner G. Relapsing Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease requiring prolonged steroid therapy. Case Rep Emerg Med. 2019;2019:6405687. Published 2019 Mar 7. doi:10.1155/2019/6405687

22. Faheem B, Kumar V, Ashkar H, Komal F, Sultana Y. Recurrent Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease masquerading as lymphoma successfully treated by anakinra. Cureus. 2020;12(11):e11655. Published 2020 Nov 23. doi:10.7759/cureus.11655

23. Sopeña B, Rivera A, Vázquez-Triñanes C, et al. Autoimmune manifestations of Kikuchi disease. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2012;41(6):900-906. doi:10.1016/j.semarthrit.2011.11.001

1. Bosch X, Guilabert A, Miquel R, Campo E. Enigmatic Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease: a comprehensive review. Am J Clin Pathol. 2004;122(1):141-152. doi:10.1309/YF08-1L4T-KYWV-YVPQ

2. Deaver D, Horna P, Cualing H, Sokol L. Pathogenesis, diagnosis, and management of Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease. Cancer Control. 2014;21(4):313-321. doi:10.1177/107327481402100407

3. Cheng CY, Sheng WH, Lo YC, Chung CS, Chen YC, Chang SC. Clinical presentations, laboratory results and outcomes of patients with Kikuchi’s disease: emphasis on the association between recurrent Kikuchi’s disease and autoimmune diseases. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2010;43(5):366-371. doi:10.1016/S1684-1182(10)60058-8

4. Stéphan JL, Jeannoël P, Chanoz J, Gentil-Përret A. Epstein-Barr virus-associated Kikuchi disease in two children. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2001;23(4):240-243. doi:10.1097/00043426-200105000-00012

5. Chiu CF, Chow KC, Lin TY, Tsai MH, Shih CM, Chen LM. Virus infection in patients with histiocytic necrotizing lymphadenitis in Taiwan. Detection of Epstein-Barr virus, type I human T-cell lymphotropic virus, and parvovirus B19. Am J Clin Pathol. 2000;113(6):774-781. doi:10.1309/1A6Y-YCKP-5AVF-QTYR

6. Rosado FG, Tang YW, Hasserjian RP, McClain CM, Wang B, Mosse CA. Kikuchi-Fujimoto lymphadenitis: role of parvovirus B-19, Epstein-Barr virus, human herpesvirus 6, and human herpesvirus 8. Hum Pathol. 2013;44(2):255-259. doi:10.1016/j.humpath.2012.05.016

7. Gordon JK, Magro C, Lu T, et al. Overlap between systemic lupus erythematosus and Kikuchi Fujimoto disease: a clinical pathology conference held by the Department of Rheumatology at Hospital for Special Surgery. HSS J. 2009;5(2):169-177. doi:10.1007/s11420-009-9123-x

8. Lo KB, Papazoglou A, Chua L, Candelario N. Case Report: Kikuchi: The great mimicker. F1000Res. 2018;7:520. Published 2018 Apr 30. doi:10.12688/f1000research.14758.1

9. Galor A, Georgy M, Leder HA, Dunn JP, Peters GB 3rd. Papillary conjunctivitis associated with Kikuchi disease. Cornea. 2008;27(8):944-946. doi:10.1097/ICO.0b013e31816bf488

10. Kucukardali Y, Solmazgul E, Kunter E, Oncul O, Yildirim S, Kaplan M. Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease: analysis of 244 cases. Clin Rheumatol. 2007;26(1):50-54. doi:10.1007/s10067-006-0230-5

11. Lee DH, Lee JH, Shim EJ, et al. Disseminated Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease mimicking malignant lymphoma on positron emission tomography in a child. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2009;31(9):687-689. doi:10.1097/MPH.0b013e31819a5d77

12. Park SG, Koo HR, Jang K, et al. Efficacy of ultrasound-guided needle biopsy in the diagnosis of Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease. Laryngoscope. 2021;131(5):E1519-E1523. doi:10.1002/lary.29160

13. Honda F, Tsuboi H, Toko H, et al. Recurrent Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease successfully treated by the concomitant use of hydroxychloroquine and corticosteroids. Intern Med. 2017;56(24):3373-3377. doi:10.2169/internalmedicine.9205-17

14. Rezayat T, Carroll MB, Ramsey BC, Smith A. A case of relapsing Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease. Case Rep Otolaryngol. 2013;2013:364795. doi:10.1155/2013/364795

15. Rezai K, Kuchipudi S, Chundi V, Ariga R, Loew J, Sha BE. Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease: hydroxychloroquine as a treatment. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39(12):e124-e126. doi:10.1086/426144

16. Hyun M, So IT, Kim HA, Jung H, Ryu SY. Recurrent Kikuchi’s disease treated by hydroxychloroquine. Infect Chemother. 2016;48(2):127-131. doi:10.3947/ic.2016.48.2.127

17. Lin YC, Huang HH, Nong BR, et al. Pediatric Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease: A clinicopathologic study and the therapeutic effects of hydroxychloroquine. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2019;52(3):395-401. doi:10.1016/j.jmii.2017.08.023

18. Lin DY, Villegas MS, Tan PL, Wang S, Shek LP. Severe Kikuchi’s disease responsive to immune modulation. Singapore Med J. 2010;51(1):e18-e21.

19. Quintás-Cardama A, Fraga M, Cozzi SN, Caparrini A, Maceiras F, Forteza J. Fatal Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease: the lupus connection. Ann Hematol. 2003;82(3):186-188. doi:10.1007/s00277-003-0611-7

20. American Academy of Ophthalmology. ACR, AAD, RDS, and AAO 2020 Joint Statement on Hydroxychloroquine Use with Respect to Retinal Toxicity. Updated February 2021. Accessed November 28, 2022. https://www.aao.org/clinical-statement/acr-aad-rds-aao-2020-joint-statement-on-hydroxychl-2

21. Gerwig U, Weidmann RG, Lindner G. Relapsing Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease requiring prolonged steroid therapy. Case Rep Emerg Med. 2019;2019:6405687. Published 2019 Mar 7. doi:10.1155/2019/6405687

22. Faheem B, Kumar V, Ashkar H, Komal F, Sultana Y. Recurrent Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease masquerading as lymphoma successfully treated by anakinra. Cureus. 2020;12(11):e11655. Published 2020 Nov 23. doi:10.7759/cureus.11655

23. Sopeña B, Rivera A, Vázquez-Triñanes C, et al. Autoimmune manifestations of Kikuchi disease. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2012;41(6):900-906. doi:10.1016/j.semarthrit.2011.11.001

Pyostomatitis Vegetans With Orofacial and Vulvar Granulomatosis in a Pediatric Patient

Case Report

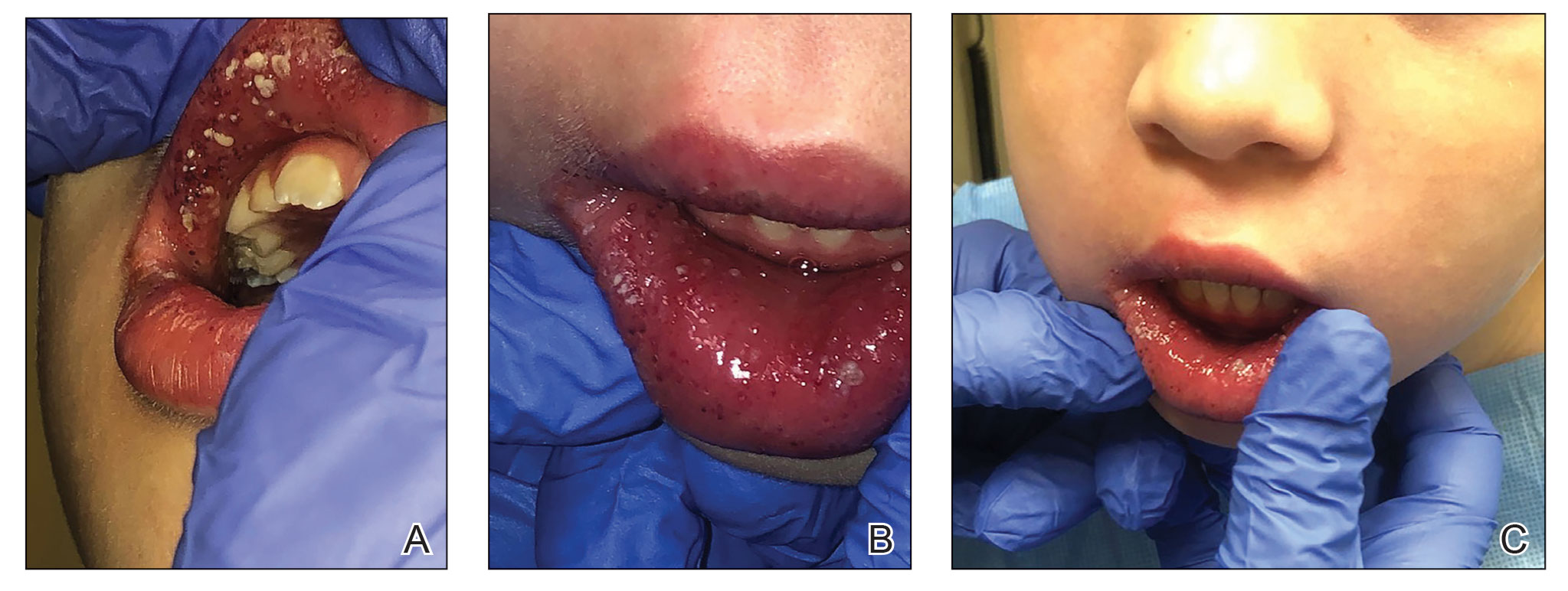

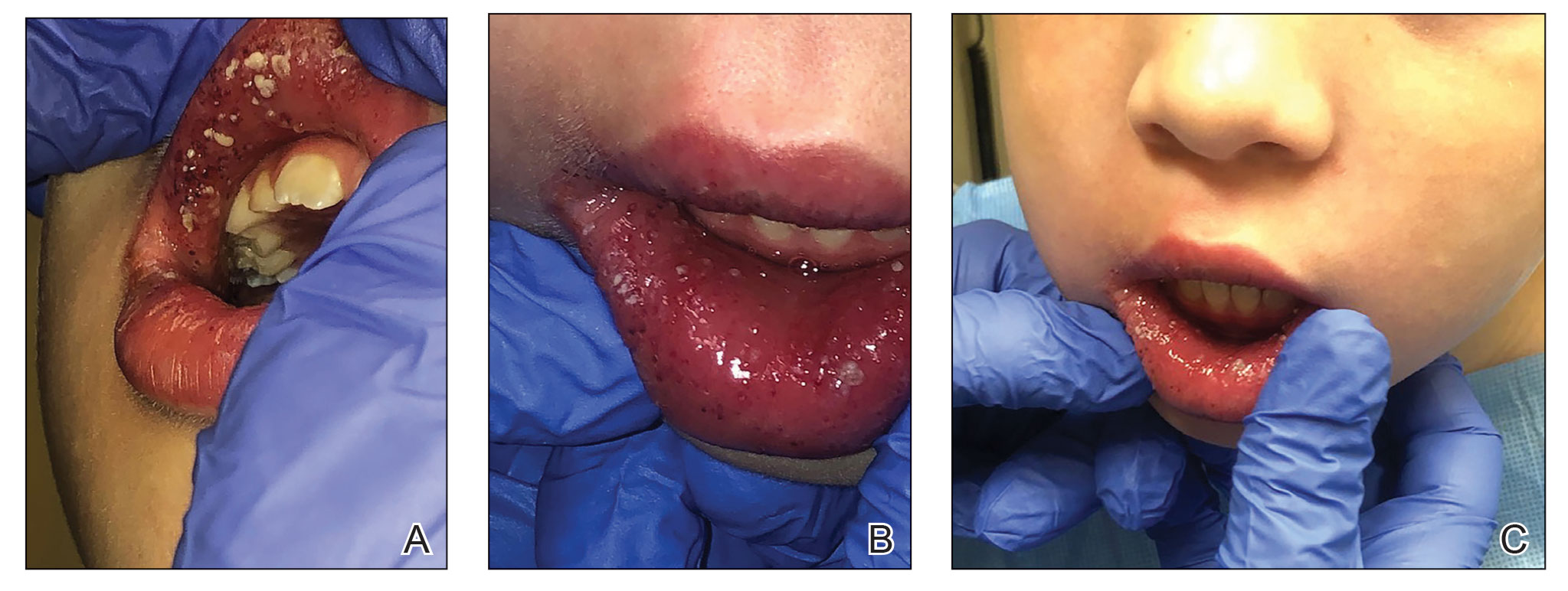

A 7-year-old girl who was otherwise healthy was referred by pediatric gastroenterology for evaluation of cutaneous Crohn disease (CD). The patient had a 4-year history of persistent lip swelling and a 3-year history of asymmetric erythematous labial swelling and perianal erythema with skin tags. She had been applying the calcineurin inhibitor tacrolimus ointment 0.03% 1 or 2 times daily to her lesions with minimal improvement. She did not have a medical history of recurrent or unusual infectious diseases. There was no family history of autoimmune disease.

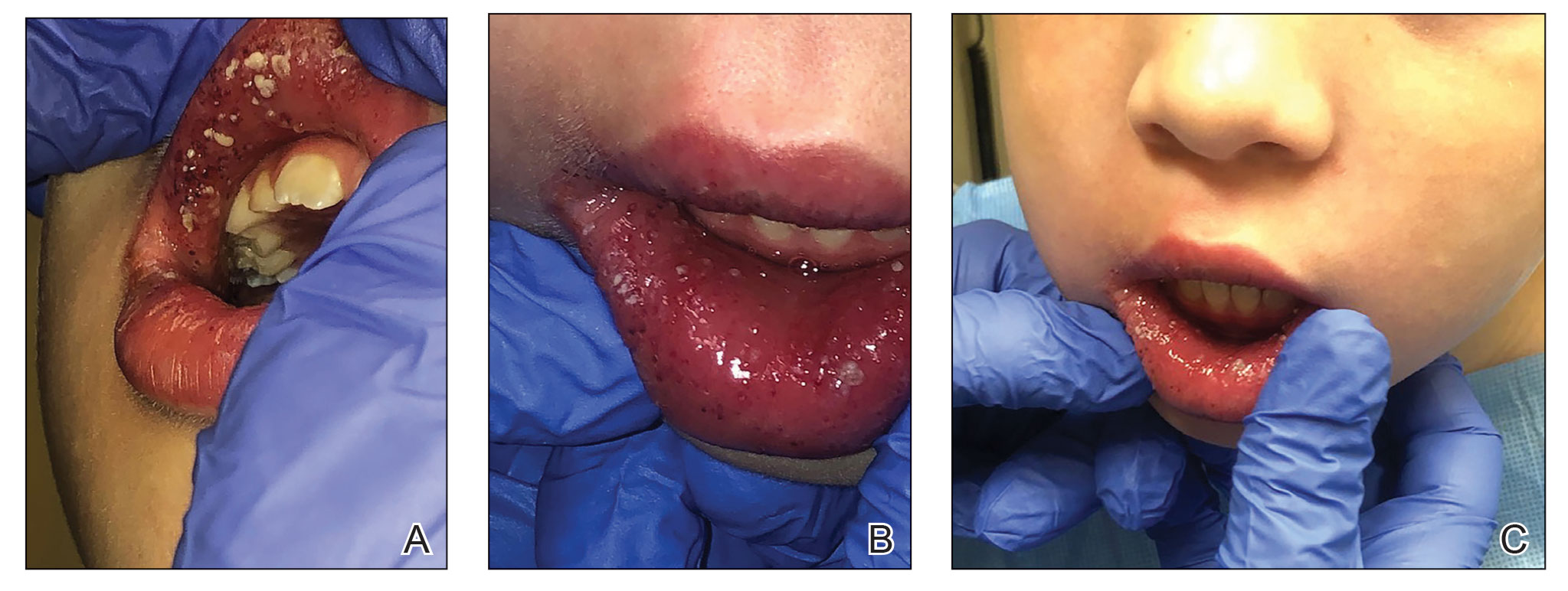

The patient and her guardian reported intermittent perianal pain but denied constipation, diarrhea, abdominal pain, and blood in the stool. She denied throat and tongue swelling, dysphagia, dyspnea, drooling, facial paralysis, and eyelid edema. She was a well-nourished child whose height and weight percentiles tracked at 30% and 25%, respectively. Physical examination revealed confluent symmetric lip swelling with mild angular cheilitis. Multiple 1- to 2-mm white pustules with pinpoint erosions covered the upper and lower labial mucosa and extended onto the buccal mucosa (Figure 1). She had symmetric erythema and swelling of the left labia majora extending to and involving the left perianal mucosa. Three perianal erythematous skin tags and a perianal fissure were identified.

The patient had been assessed 2 years earlier by pediatric dermatology and gastroenterology with an extensive evaluation that favored a diagnosis of cutaneous CD because the combination of orofacial granulomatosis (OFG), vulvar edema, and perianal skin tags is strongly associated.1-3 Contact dermatitis affecting the mouth was considered; however, allergen testing did not demonstrate a trigger.

A trial of a benzoate- and cinnamon-free diet, which has been reported to improve OFG,4 did not provide symptomatic improvement. Topical corticosteroids and tacrolimus reduced the perioral erythema, but the swelling persisted. An infectious cause was considered; however, topical mupirocin had no effect, and amoxicillin resulted in oral candidiasis.

A perianal biopsy revealed a granulomatous dermatitis. Fungal and bacterial cultures were negative. Upper and lower gastrointestinal (GI) endoscopy and a fecal calprotectin assay were not suggestive of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). A complete blood cell count and QuantiFERON-TB Gold test measuring the immune response to tuberculosis antigens were normal. Chronic granulomatous disease, RAG1/RAG2 deficiency, common variable immunodeficiency, and NOD2 defects were ruled out with normal tests of dihydrorhodamine, quantitative immunoglobulins, and toll-like receptors.

Because of the discomfort associated with the patient’s lesions, she was offered treatment with tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors, including infliximab and adalimumab. These agents had been offered since the onset of symptoms; however, her parents declined systemic medication unless she developed GI involvement. Instead, the tacrolimus concentration was increased to 0.1% applied to the lips, labia, and perianal area, and fluocinonide gel 0.05% applied nightly to the oral pustules was added.

Two months later the patient had notably fewer oral pustules and diminished erythema but only slightly reduced oral, vulvar, and perianal swelling. A trial of oral metronidazole, which has been reported to clear a patient with cutaneous CD,5 was discontinued by her parents after 6 weeks because of a lack of interval improvement.

One year later, a pre-existing perianal skin tag doubled in size and became exquisitely tender. The calprotectin level—previously within reference range at less than 16 μg/g—was now elevated at 149 μg/g (reference range, 1–120 μg/g) and increased to 336 μg/g 3 weeks later. Testing for C-reactive protein, zinc, and stool occult blood; a comprehensive metabolic panel; and a complete blood cell count were unremarkable.

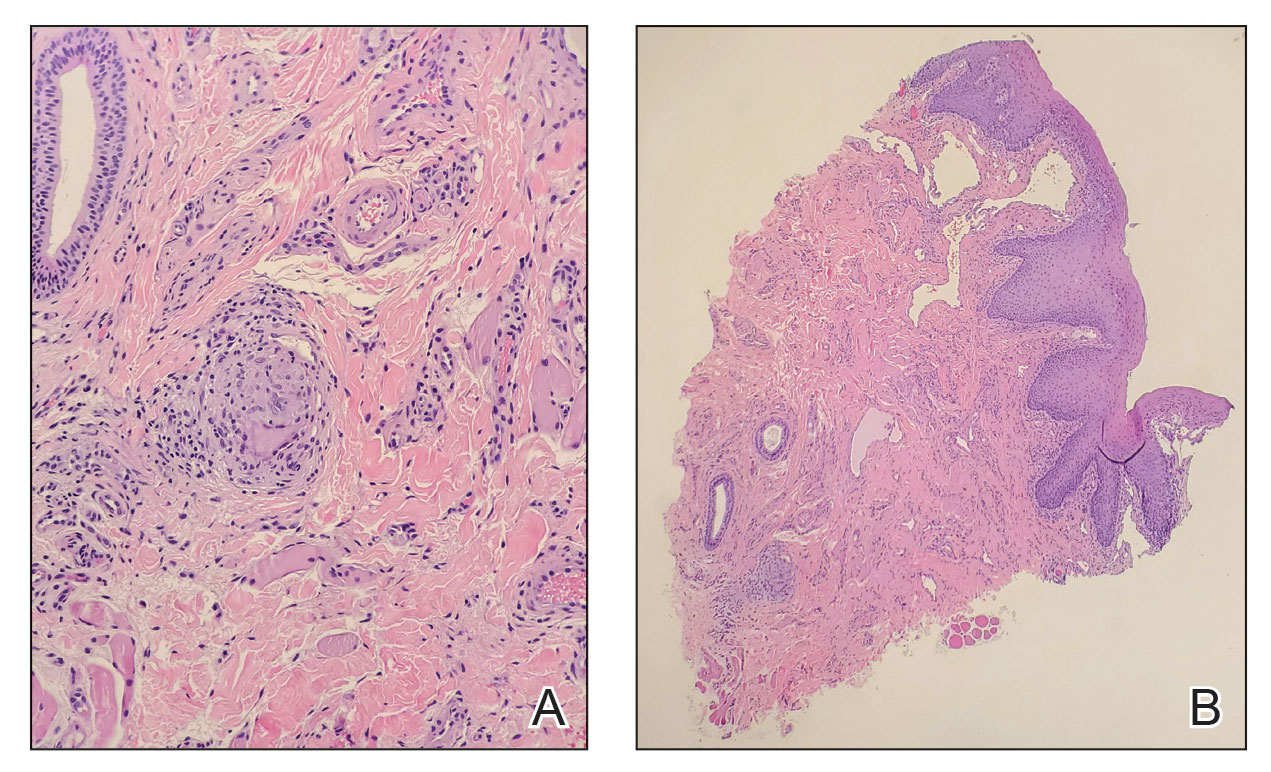

Repeat upper and lower GI endoscopy did not suggest CD. A biopsy using direct immunofluorescence (DIF) was obtained to evaluate for pyostomatitis vegetans (PSV) and rule out

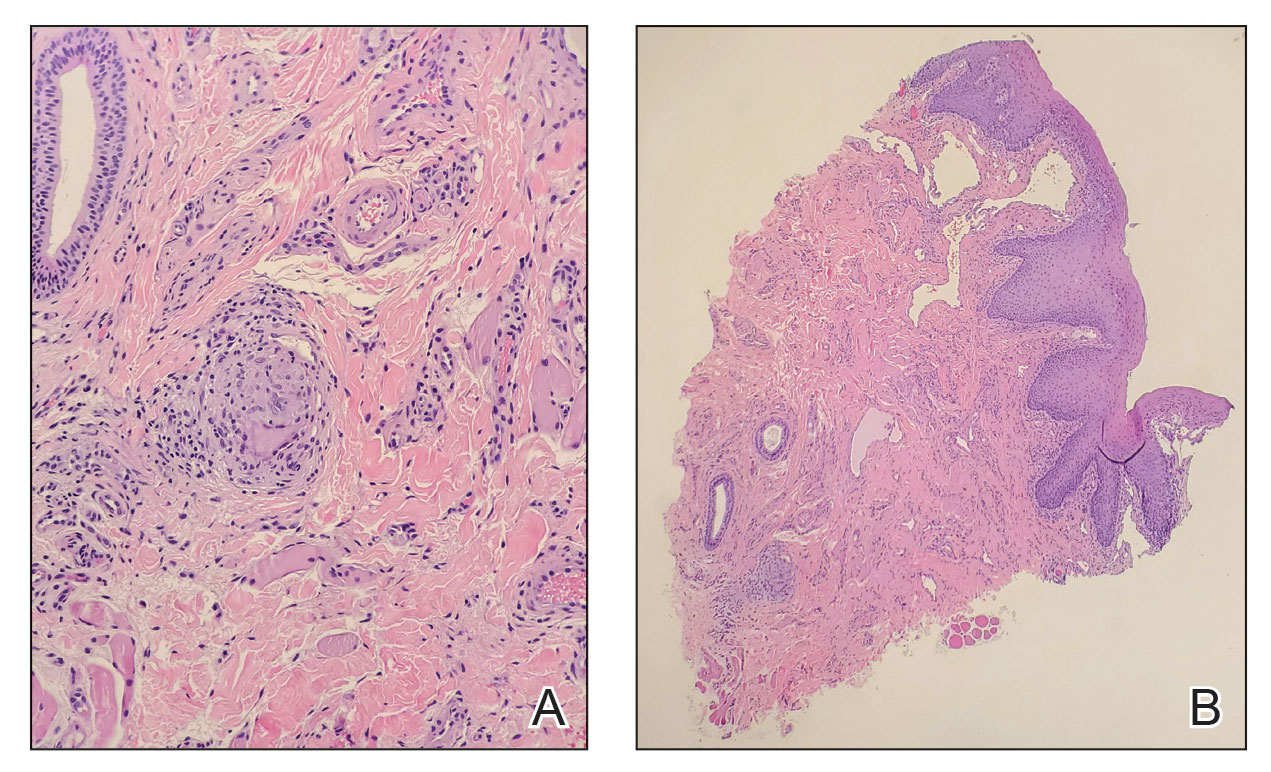

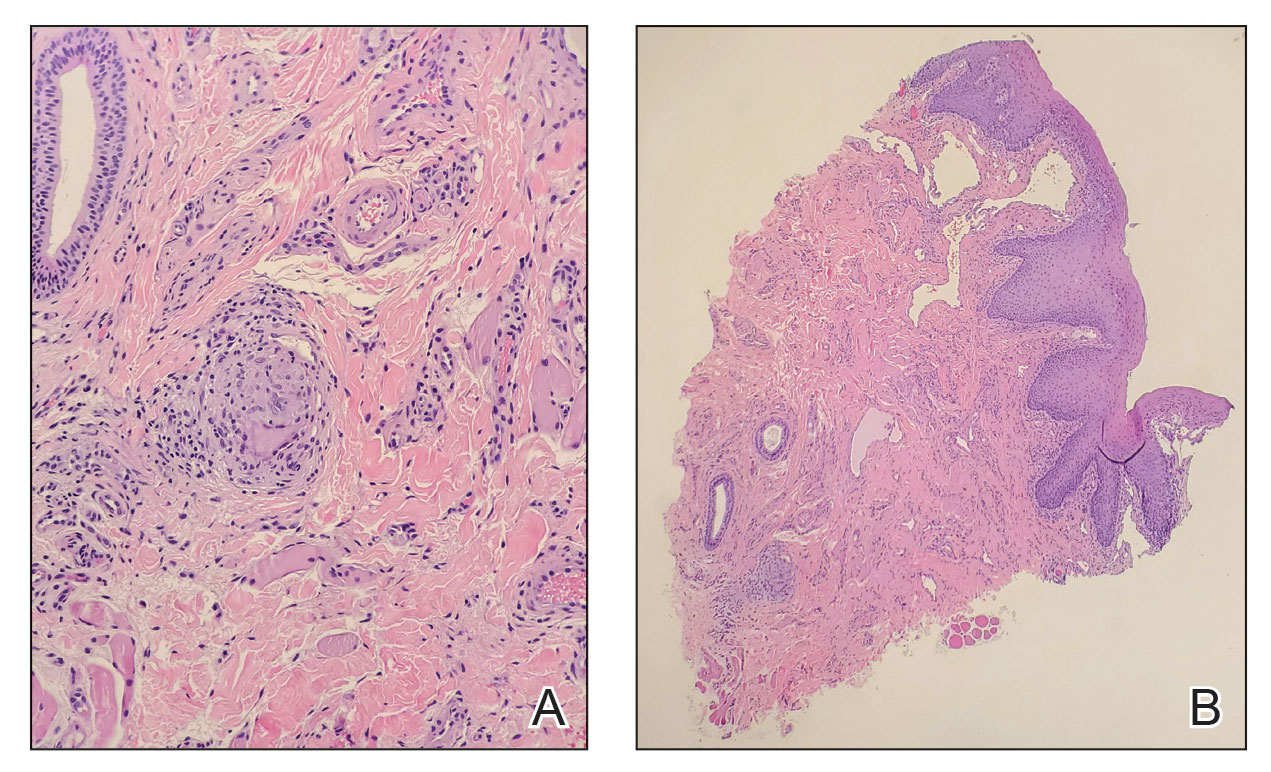

The captured biopsy did not demonstrate the intended pustule; instead, it included less-affected mucosa and was obtained during topical treatment when few pustules and erosions persisted. Pathologic analysis revealed noncaseating granulomas without an increase in microabscesses, neutrophils, or eosinophils (Figure 2). Direct immunofluorescence staining for IgG, IgA, and C3 and indirect immunofluorescence staining for desmoglein-1 and desmoglein-3 antibodies were negative. Although the biopsy did not capture the intended pustule, diagnosis of PV was made based on clinical features and the constellation of cutaneous findings associated with IBD.

Intralesional triamcinolone, which has been of benefit for pediatric patients with orofacial granulomatosis,1,6,7 was instituted and normalized the vulva and perianal mucosa; however, lip swelling improved only minimally.

Comment

Pyostomatitis vegetans is characterized by multiple white or yellow, friable, miliary pustules that rupture, leaving behind ulcerations and erosions that cause a varying degree of oral pain.8 The disorder can involve any area of the oral mucosa—most often the labia-attached gingiva, soft and hard palates, buccal mucosa, vestibule, and tonsillar areas—but often spares the floor of the mouth and tongue.8-11 The term pyostomatitis vegetans was proposed in 1949 by McCarthy12 when he noted in a patient who presented with the characteristic appearance of the oral mucosa, though cases of vaginal, nasal, and periocular involvement have been reported.8,13,14

Histopathology—Pyostomatitis vegetans displays pseudoepithelial hyperplasia with acanthosis, hyperkeratosis, and intraepithelial or subepithelial microabscesses (or both) with neutrophils and eosinophils.8,9,15 There are a few possible explanations for this patient’s lack of tissue eosinophilia. It has been theorized that the presence of granulomas could mask concurrent PSV16 or that tissue in PSV contains fewer eosinophils as the disorder progresses.11 The oral biopsy obtained from our patient did not capture a pustule, and the condition had noticeably improved with topical tacrolimus at the time of biopsy; therefore, neither neutrophils nor eosinophils were identified. Peripheral eosinophilia, which is present in 42% to 90% of cases of PSV,9,17 can be a diagnostic clue.18 However, PE is associated with IBD,24 which usually occurs with PSV, so the absence of peripheral eosinophilia in our patient may be explained by her lack of bowel disease.