User login

Hepatitis C Virus Infections Underreported

Formal surveillance reporting of acute hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection clinical diagnoses were grossly underascertained, according to a review of cases reported to the Massachusetts Department of Public Health (MDPH) and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Investigators assessed rates of electronic case reporting of acute HCV infection to MDPH and rate of subsequent confirmation according to the national case definition and found:

• Of 183 clinical cases, 149 were reported to MDPH.

• Of 149 reports, MDPH investigated 43 reports based on surveillance requirements.

• Only 1 case met the national criteria and was reported to the CDC.

The authors noted hurdles to accurate case ascertainment included incomplete clinician reporting, problematic case definitions, limitations of diagnostic testing, and imperfect data captures.

Citation: Onofrey S, Aneja J, Haney GA, et al. Underascertainment of acute hepatitis C virus infections in the U.S. Surveillance System: a case series and chart review. Ann Intern Med. 2015. doi:10.7326/M14-2939. [Epub ahead of print]

Commentary: Hepatitis C, for which there is now effective and well-tolerated treatment, is an important public health problem affecting over 180 million people worldwide. The USPSTF now recommends screening for Hep C in persons at high risk for infection and also a 1-time screening for HCV infection to adults born between 1945 and 1965.1 Unlike Hep A and Hep B, where the definition of an acute infection is clear with detection of IgM antibody, the definition of acute Hep C is based on a combination of symptoms, laboratory assessments including antibodies to HCV and nucleic acid testing, as well as elevated aminotransferase levels. This study shows that the current estimates of the incidence of new Hepatitis C infections are very inexact. —Neil Skolnik, MD

Citation: Hepatitis C: Screening. US Preventive Services Task Force website.www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Topic/recommendation-summary/hepatitis-c-screening. Updated June 2013. Accessed July 13, 2015.

Formal surveillance reporting of acute hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection clinical diagnoses were grossly underascertained, according to a review of cases reported to the Massachusetts Department of Public Health (MDPH) and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Investigators assessed rates of electronic case reporting of acute HCV infection to MDPH and rate of subsequent confirmation according to the national case definition and found:

• Of 183 clinical cases, 149 were reported to MDPH.

• Of 149 reports, MDPH investigated 43 reports based on surveillance requirements.

• Only 1 case met the national criteria and was reported to the CDC.

The authors noted hurdles to accurate case ascertainment included incomplete clinician reporting, problematic case definitions, limitations of diagnostic testing, and imperfect data captures.

Citation: Onofrey S, Aneja J, Haney GA, et al. Underascertainment of acute hepatitis C virus infections in the U.S. Surveillance System: a case series and chart review. Ann Intern Med. 2015. doi:10.7326/M14-2939. [Epub ahead of print]

Commentary: Hepatitis C, for which there is now effective and well-tolerated treatment, is an important public health problem affecting over 180 million people worldwide. The USPSTF now recommends screening for Hep C in persons at high risk for infection and also a 1-time screening for HCV infection to adults born between 1945 and 1965.1 Unlike Hep A and Hep B, where the definition of an acute infection is clear with detection of IgM antibody, the definition of acute Hep C is based on a combination of symptoms, laboratory assessments including antibodies to HCV and nucleic acid testing, as well as elevated aminotransferase levels. This study shows that the current estimates of the incidence of new Hepatitis C infections are very inexact. —Neil Skolnik, MD

Citation: Hepatitis C: Screening. US Preventive Services Task Force website.www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Topic/recommendation-summary/hepatitis-c-screening. Updated June 2013. Accessed July 13, 2015.

Formal surveillance reporting of acute hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection clinical diagnoses were grossly underascertained, according to a review of cases reported to the Massachusetts Department of Public Health (MDPH) and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Investigators assessed rates of electronic case reporting of acute HCV infection to MDPH and rate of subsequent confirmation according to the national case definition and found:

• Of 183 clinical cases, 149 were reported to MDPH.

• Of 149 reports, MDPH investigated 43 reports based on surveillance requirements.

• Only 1 case met the national criteria and was reported to the CDC.

The authors noted hurdles to accurate case ascertainment included incomplete clinician reporting, problematic case definitions, limitations of diagnostic testing, and imperfect data captures.

Citation: Onofrey S, Aneja J, Haney GA, et al. Underascertainment of acute hepatitis C virus infections in the U.S. Surveillance System: a case series and chart review. Ann Intern Med. 2015. doi:10.7326/M14-2939. [Epub ahead of print]

Commentary: Hepatitis C, for which there is now effective and well-tolerated treatment, is an important public health problem affecting over 180 million people worldwide. The USPSTF now recommends screening for Hep C in persons at high risk for infection and also a 1-time screening for HCV infection to adults born between 1945 and 1965.1 Unlike Hep A and Hep B, where the definition of an acute infection is clear with detection of IgM antibody, the definition of acute Hep C is based on a combination of symptoms, laboratory assessments including antibodies to HCV and nucleic acid testing, as well as elevated aminotransferase levels. This study shows that the current estimates of the incidence of new Hepatitis C infections are very inexact. —Neil Skolnik, MD

Citation: Hepatitis C: Screening. US Preventive Services Task Force website.www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Topic/recommendation-summary/hepatitis-c-screening. Updated June 2013. Accessed July 13, 2015.

Pharmacist Pain E-Consults That Result in a Therapy Change

The enormity of chronic pain among the veteran population makes pain management within the VA a critical issue. Of the veterans returning from Operation Enduring Freedom/Operation Iraqi Freedom (OEF/OIF), chronic pain is the most common report.1 Of equal concern is the lack of available pain specialists in the U.S. There are < 4,000 pain specialists in the U.S., and even fewer pain specialists are available within the VA system, making it difficult for veterans to access pain care and timely treatment.2

Furthermore, one of the biggest challenges surrounding pain management is the lack of proper training received by generalists and primary care providers (PCPs). Whereas opioid therapy was previously prescribed mainly by specialists and mainly to cancer patients, that is no longer the case. Today, nonspecialists frequently prescribe opioids, and 95% of long-acting opioids are for chronic, noncancer pain.1 In a majority of reviewed pain electronic consultations (e-consults) completed by the pain specialty pharmacist at the Bay Pines VA Healthcare System (BPVAHCS), the patient was not currently receiving opioid therapy, suggesting PCPs’ lack of comfort and training in chronic pain management. Effective and appropriate pain management from the patient perspective and confidence and reassurance from the prescriber standpoint cannot be successfully achieved without drastic improvements in education and training.

Related: Urologist Workforce Variation Across the VHA

The inception of the E-Consult Pain Service arose from a grant from VA National Innovations in Consult Management to 3 VA facilities in Florida: BPVAHCS; Orlando VAMC, and North Florida/South Georgia Veterans Health Systems.3 At the Orlando VAMC, PCPs needed advice on pain management for patients while they waited to see a pain clinic specialist, so a Pain Help Line was implemented to provide immediate consults, but miscommunication between recommendations given and their implementation limited its utility. That eventually led to an E-Consult Pain Service, which provided formal full chart reviews for pain management cases.

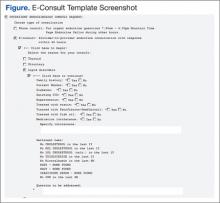

The E-Consult Pain Service program included 2 full-time pharmacists, a part-time pain psychologist, and a pain physician. Its goal was to assist PCPs with patient-specific pain management recommendations. The consult service did not replace specialty pain clinics, nor was it meant to provide continual pain management. Additional, separate pain e-consults could be scheduled as a follow-up to a previous consult or for new pain management issues. Although the recommendations in the consults were available for the provider’s use, it was at the provider’s discretion as to whether the recommendations were accepted and implemented.

The E-Consult Pain Service

The E-Consult Pain Service at the BPVAHCS started July 2011. Staffed by a full-time physician and pain specialty pharmacist, the program provides electronic chart review and recommendations to PCPs regarding complex pain management issues. About three-fourths of their time was spent directly on the consults, which took between 1 and 5 business days to complete. Their remaining time was spent on educational initiatives and administrative duties.

The BPVAHCS is a complexity level 1a facility providing comprehensive health care. The facility comprises a 192-acute care bed hospital (includes intensive care, medical, surgical, and psychiatric units); a 112-bed community living center; a 65-bed domiciliary; and a 34-bed residential treatment program.

Related: A Medical Specialty e-Consult Program in a VA Health Care System

Initially, the program was developed to provide pain management support to PCPs in the community-based outpatient clinics (CBOCs) but expanded to all BPVAHCS providers. With the expansion, the program helped reduce a 3-month delay for patients waiting to be seen in the pain clinic. Goals of the program included improving patient outcomes and safety while minimizing opioid therapy risks. These goals are met through an individual case consultation as well as formal educational programs for providers.

The purpose of this study was to obtain data evaluating the characteristics of recommendations made by a pharmacist through pain e-consults at the BPVAHCS and the percentage of consults that resulted in a change in therapy. Future research is warranted to provide clarity on why specific recommendations are or are not being accepted, patient outcomes, and PCPs’ perception on the program’s utility.

Methods

An institutional review board-exempt, retrospective chart review was conducted at the BPVAHCS to determine the percentage of patients whose pain regimen changed as a result of a pain e-consult completed by a pain specialty pharmacist. Although the BPVAHCS E-Consult Pain Service comprised a physician and a pain specialty pharmacist, this study was focused solely on the role and recommendations by the pharmacist. The characteristics of those recommendations and their acceptance/rejection rate were then recorded. Of note, the physician completed separate e-consults, and the frequency of input by the physician on pharmacist recommendations was not collected.

Patients who had a pain e-consult regarding chronic, noncancer pain between January 1, 2012, and March 31, 2012, were identified for inclusion in the study. Charts were selected based on consults submitted by providers. No consults for headaches were requested in the selected time frame.

Chronic pain is defined as persistent pain with or without an identifiable organic cause, lasting longer than 3 to 6 months.1 Use of the term chronic pain throughout this article refers to chronic, noncancer pain. Criteria for exclusion included patients who received a pain e-consult but died before September 30, 2012.

Data Collection

Patients identified for inclusion had their charts reviewed 6 months after completion of the consult in order to allow sufficient time for potential implementation of recommendations. Patient demographics, name and dose of pain medications, requesting practitioner, type of chronic pain, recommendation of pain e-consult, and consult outcome(s) were recorded for all participants.

The primary outcome of the study was the percentage of recommendations, both pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic, made by the pain specialty pharmacist and accepted and implemented by the consulting provider.

Results

A total of 127 patient charts were identified for inclusion. Five patients died prior to September 30, 2012, and were excluded from the study, leaving 122 charts for review. All 122 charts reviewed by the pain specialty pharmacist included recommendations. Most patients were male (95.1%) and white (75.6%). The most common source of chronic pain was back pain (66.4%) (Table).

Primary Outcome

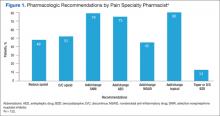

The pain specialty pharmacist pharmacologic treatment option recommendations varied significantly: add and/or change topical (80% of the 122 patients); add and/or change selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) (79%); add and/or change antiepileptic drug (AED) therapy (75%); discontinue opioid (52%); reduce opioid (48%); add and/or change nonsteroidal anti- inflammatory drug (NSAID) (45%); and taper/discontinue benzodiazepine (BZD) (13%) (Figure 1).

Primary care providers could choose to accept or ignore the recommendation, and of all the pharmacologic recommendations made, about 50% were implemented. The rate of PCP implementation of the pharmacist’s recommendations varied: add and/or change AED therapy (54%); add and/or change topical (44%); reduce opioid (42%); discontinue opioid (41%); taper/discontinue BZD (38%); add and/or change SNRI (36%); and add and/or change NSAID (33%).

Despite the most frequent recommendations made by pharmacists, the 3 most accepted and implemented by providers were addition and/or change in AED therapy, addition and/or change in topical therapy, and a decrease in opioid dose. Changes in therapy were identified as either a dose decrease or increase in the existing agent, whereas a new agent was considered an addition to existing pain therapy.

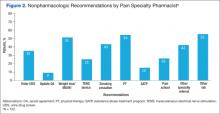

The rates of nonpharmacologic recommendations made by the pharmacist were as follows: ordering additional labs, primarily vitamin D and testosterone levels (55%); referral to physical therapy (PT) (54%); weight loss (51%); smoking cessation (43%); specialty referral (42%); order new urine drug screen (UDS) (35%); referral to pain school education program (26%); transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) (25%); referral to the substance abuse treatment program (SATP) (15%); and update opioid agreement (OA) (9%) (Figure 2).

Nonpharmacologic treatment acceptance rates were as follows: order new UDS (67%); update OA (45%); referral to SATP (33%); referral to PT (33%); order additional labs, primarily vitamin D and testosterone levels (27%); specialty referral (22%); TENS (19%); weight loss (18%); referral to pain school education program (16%); smoking cessation (6%); and music therapy (0%). The top 3 accepted recommendations were obtainment of a new UDS; updating the patient’s OA; and tied for third, referral to PT or the SATP.

Discussion

Including a pharmacist as part of a pain e-consult team may provide support to PCPs for managing chronic pain as well as for measuring improved adherence to VA/DoD guidelines for chronic pain. Pharmacists can offer recommendations for nontraditional pain therapies that PCPs may be unaware of or are unfamiliar with, such as the use of nonnarcotic agents and various nonpharmacologic options. For example, recommend testing for vitamin D levels. Vitamin D deficiency is common among the general population, and a project completed by Roesel and Engel specifically addressed vitamin D deficiency and pain in OEF/OIF veterans.4 Other studies have shown a correlation between vitamin D supplementation and a reduction in musculoskeletal pain or the association between low vitamin D levels and hypersensitivity in patients with chronic pain.5-7 Studies have also demonstrated a link between vitamin D deficiency and depression, which is well known to augment or increase patient awareness of somatic reports, like pain.8

Of all the pharmacologic recommendations made, about 50% were implemented. It is noteworthy to mention that although a change/ addition in SNRI therapy was recommended by the pharmacist 79% of the time, it was accepted and implemented by the PCP only one-third of the time. Many veterans have co-occurring mental health conditions, which are often managed by a psychiatrist, who is typically not the consulting provider (the PCP is). The PCP may be hesitant to change antidepressant therapy for fear of destabilizing the patient or because the PCP was not the antidepressant therapy prescriber. However, the incidence of co-occurring seizure disorders among veterans is much less than that of mental health disorders, making PCPs much more likely to accept and/or change AEDs. Interestingly, the majority of pain specialty pharmacist e-consults involved chronic pain management, further demonstrating the lack of comfort, time, and/or proper training for PCPs in general pain management.

Related: The Rapid Rise of e-Consults Across Specialty Care

Although the e-consult program at the BPVAHCS consisted solely of a physician and a pain specialty pharmacist, the purpose of this project was to evaluate the characteristics of recommendations made by a pharmacist and the percentage of consults that resulted in a therapy change. The physician was responsible for separate consults, and their recommendations were not collected. However, it is important to recognize that the pain specialty pharmacist and physician performed identical roles on the team, each recommending both pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic treatment options in every consult.

Related Programs

The VA Boston Healthcare System (VABHS) is composed of 3 main facilities and 5 CBOCs across eastern Massachusetts. Although veterans in the eastern part of the state are able to receive primary care at a CBOC, specialty care is provided primarily at 2 of the main locations in the Boston area. Therefore, the VABHS began an e-consult program in order to facilitate patient access to specialty providers for patients unable to participate in a face-to-face visit.

The purpose of the VABHS study was to examine the implementation and provider perception of an e-consult program within a large VA system, to provide timely patient access to specialty care. The pilot program was initiated in 2 specialty clinics in 2011 but expanded to 12 specialty clinics within 9 months. The specialty clinics included allergy, cardiology, endocrinology, gastroenterology, hematology, infectious disease, nephrology, oncology, palliative care, pulmonary disease, rheumatology, and sleep medicine. Outcomes of the VABHS e-consult program revealed that a majority of PCPs were satisfied with the use of e-consults, whereas specialists were less satisfied. The PCP-perceived benefits to patients included avoidance of unnecessary travel, faster clinical input, and avoidance of unnecessary copays.9

Like the VABHS, the use of pain e-consults at BPVAHCS helps reduce the burden of face-to-face clinic visits and eliminate accessibility barriers for veterans. This study differs from the VABHS in that PCPs requested onetime consults focused solely on pain management. The pain specialty pharmacist at BPVAHCS did not provide longitudinal care; measure patient outcomes, such as satisfaction, reduction in pain, or improved functionally; or examine provider satisfaction. Additionally, unlike the BPVAHCS program, there was no indication whether a pharmacist played a role in the program.9

Other studies have explored the role of a pain pharmacist in the inpatient setting offering consults on patient-controlled analgesia and in patients with a history of substance abuse.10,11 Another recent study similarly looked at the effectiveness of a pharmacist-led medication review in chronic pain management. The aim was to assess patient outcomes: decrease in pain intensity and improvement in physical functioning.12 Another study involving a nurse and pharmacist-led chronic pain clinic in a primary care setting conducted in England showed improvement in patient-reported pain and reduction in secondary referrals.13

Limitations

Limitations of the study included short study duration (6 months); use of a newly implemented E-Consult Pain Service; lack of pharmacist follow-up on acceptance/rejection of their recommendation; inability to determine patient outcome(s), as consults were for a single point in time, regarding a therapy recommendation; lack of access to non-VA medications; and patient refusal to change current pain regimen.

Patient refusal inhibited providers from implementing therapy changes recommended by the pharmacist and therefore could have negatively impacted study outcomes. Raw data were used for this study, and there were no statistical analyses conducted. Furthermore, lack of other formal e-consult programs within BPVAHCS to compare the acceptance/rejection of pharmacist recommendations for other conditions and lack of a third-party review of pharmacist recommendations to ensure standard of care may have limited this study.

Future Research

As the E-Consult Pain Service continues, research regarding the value of the pain specialty pharmacist may be warranted. Additional research is needed to identify the reasons that recommendations were accepted or ignored, whether the recommendations were beneficial to the patients, and the PCPs’ perception on the usefulness of a pain e-consult program. When the program started, 14% of patients at BPVAHCS were taking opioids. The pain e-consult program handled a small percentage of these patients.

The authors considered proactively reviewing all patients on > 100 mg morphine equivalents of opioids daily but did not have adequate staff to support the review. It may be helpful to identify those patients taking opioids but do not have a consult. The role of the pain e-consult pharmacist may be expanded to assist PCPs, including leading patient education classes to explain the concept and purpose of the opioid treatment agreement; reinforcing expected behaviors and outcomes of patients prescribed opioids; assisting providers with interpreting UDSs and notifying providers of aberrant behaviors; and educating providers on opioid risk mitigation through seminars or academic detailing.

Furthermore, future research may be warranted to determine the prospective role of a pain specialty pharmacist on longitudinal measures, such as pain outcomes, patient satisfaction, improvement in quality of life and/or function, as well as to determine provider perspective and satisfaction of the program. Finally, it would be interesting to compare and contrast the recommendations and outcomes between the pharmacist and physician team at the BPVAHCS.

Conclusion

The addition of a pain specialty pharmacist as part of the E-Consult Pain Service seems to provide support to prescribing PCPs in general chronic pain management, as well as measuring improved adherence to VA/DoD guidelines for chronic pain.

Acknowledgments

This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the Bay Pines VA Healthcare System.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review the complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

1. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Management of opioid therapy for chronic pain. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Website. http://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/Pain/cot. Published May 2010. Accessed May 25, 2015.

2. Boyle AM. VA ahead of schedule in improving chronic pain care. U.S. Medicine. 2012. http://www.usmedicine.com/agencies/department-of-veterans-affairs/va-ahead-of-schedule-in-improving -chronic-pain-care. Accessed June 16, 2015.

3. Sproul RD. Bridging the gap: e-consult pain service for the primary care physician. Am Soc Pain Educ. 2012;8(1).

4. Roesel T, Engel C. Vitamin D levels and their correlation to pain, fatigue, anxiety, and other co-morbidities in specialized care program service members seen at the Deployment Health Clinical Center. In: Deployment Health Clinical Center Annual Report 2011: pp28-29. http://www.pdhealth.mil/downloads/DHCC_AR_2011.pdf. Accessed May 25, 2015.

5. Le Goaziou MF, Kellou N, Flori M, et al. Vitamin D supplementation for diffuse musculoskeletal pain: results of a before-and-after study. Eur J Gen Pract. 2014;20(1):3-9.

6. Abbasi M, Hashemipour S, Hajmanuchehri F, Kazemifar AM. Is vitamin D deficiency associated with non specific musculoskeletal pain? Glob J Health Sci. 2012;11;5(1):107-111.

7. Von Känel R, Müller-Hartmannsgruber V, Kokinogenis G, Egloff N. Vitamin D and central hypersensitivity in patients with chronic pain. Pain Med. 2014;15(9):1609-1618.

8. Anglin RE, Samaan Z, Walter SD, McDonald SD. Vitamin D deficiency and depression in adults: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2013;202:100-107.

9. McAdams M, Cannavo L, Orlander JD. A medical specialty e-consult program in a VA healthcare system. Fed Pract. 2014;31(5):26-31.

10. Fan T, Elgourt T. Pain management pharmacy service in a community hospital. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2008;65(16):1560-1565.

11. Andrews LB, Bridgeman MB, Dalal KS, et al. Implementation of pharmacist-driven pain management consultation service for hospitalised adults with a history of substance abuse. Int J Clin Pract. 2013;67(12):1342-1349.

12. Hadi M, Alldred D, Briggs M, Munyombwe T, Closs SJ. Effectiveness of pharmacist-led medication review in chronic pain management: systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin J Pain. 2014;30(11):1006-1014.

13. Briggs M, Closs SJ, Marczewski K, Barratt J. A feasibility study of a combined nurse/pharmacist-led chronic pain clinic in primary care. Qual Prim Care. 2008;16(2):91-94.

The enormity of chronic pain among the veteran population makes pain management within the VA a critical issue. Of the veterans returning from Operation Enduring Freedom/Operation Iraqi Freedom (OEF/OIF), chronic pain is the most common report.1 Of equal concern is the lack of available pain specialists in the U.S. There are < 4,000 pain specialists in the U.S., and even fewer pain specialists are available within the VA system, making it difficult for veterans to access pain care and timely treatment.2

Furthermore, one of the biggest challenges surrounding pain management is the lack of proper training received by generalists and primary care providers (PCPs). Whereas opioid therapy was previously prescribed mainly by specialists and mainly to cancer patients, that is no longer the case. Today, nonspecialists frequently prescribe opioids, and 95% of long-acting opioids are for chronic, noncancer pain.1 In a majority of reviewed pain electronic consultations (e-consults) completed by the pain specialty pharmacist at the Bay Pines VA Healthcare System (BPVAHCS), the patient was not currently receiving opioid therapy, suggesting PCPs’ lack of comfort and training in chronic pain management. Effective and appropriate pain management from the patient perspective and confidence and reassurance from the prescriber standpoint cannot be successfully achieved without drastic improvements in education and training.

Related: Urologist Workforce Variation Across the VHA

The inception of the E-Consult Pain Service arose from a grant from VA National Innovations in Consult Management to 3 VA facilities in Florida: BPVAHCS; Orlando VAMC, and North Florida/South Georgia Veterans Health Systems.3 At the Orlando VAMC, PCPs needed advice on pain management for patients while they waited to see a pain clinic specialist, so a Pain Help Line was implemented to provide immediate consults, but miscommunication between recommendations given and their implementation limited its utility. That eventually led to an E-Consult Pain Service, which provided formal full chart reviews for pain management cases.

The E-Consult Pain Service program included 2 full-time pharmacists, a part-time pain psychologist, and a pain physician. Its goal was to assist PCPs with patient-specific pain management recommendations. The consult service did not replace specialty pain clinics, nor was it meant to provide continual pain management. Additional, separate pain e-consults could be scheduled as a follow-up to a previous consult or for new pain management issues. Although the recommendations in the consults were available for the provider’s use, it was at the provider’s discretion as to whether the recommendations were accepted and implemented.

The E-Consult Pain Service

The E-Consult Pain Service at the BPVAHCS started July 2011. Staffed by a full-time physician and pain specialty pharmacist, the program provides electronic chart review and recommendations to PCPs regarding complex pain management issues. About three-fourths of their time was spent directly on the consults, which took between 1 and 5 business days to complete. Their remaining time was spent on educational initiatives and administrative duties.

The BPVAHCS is a complexity level 1a facility providing comprehensive health care. The facility comprises a 192-acute care bed hospital (includes intensive care, medical, surgical, and psychiatric units); a 112-bed community living center; a 65-bed domiciliary; and a 34-bed residential treatment program.

Related: A Medical Specialty e-Consult Program in a VA Health Care System

Initially, the program was developed to provide pain management support to PCPs in the community-based outpatient clinics (CBOCs) but expanded to all BPVAHCS providers. With the expansion, the program helped reduce a 3-month delay for patients waiting to be seen in the pain clinic. Goals of the program included improving patient outcomes and safety while minimizing opioid therapy risks. These goals are met through an individual case consultation as well as formal educational programs for providers.

The purpose of this study was to obtain data evaluating the characteristics of recommendations made by a pharmacist through pain e-consults at the BPVAHCS and the percentage of consults that resulted in a change in therapy. Future research is warranted to provide clarity on why specific recommendations are or are not being accepted, patient outcomes, and PCPs’ perception on the program’s utility.

Methods

An institutional review board-exempt, retrospective chart review was conducted at the BPVAHCS to determine the percentage of patients whose pain regimen changed as a result of a pain e-consult completed by a pain specialty pharmacist. Although the BPVAHCS E-Consult Pain Service comprised a physician and a pain specialty pharmacist, this study was focused solely on the role and recommendations by the pharmacist. The characteristics of those recommendations and their acceptance/rejection rate were then recorded. Of note, the physician completed separate e-consults, and the frequency of input by the physician on pharmacist recommendations was not collected.

Patients who had a pain e-consult regarding chronic, noncancer pain between January 1, 2012, and March 31, 2012, were identified for inclusion in the study. Charts were selected based on consults submitted by providers. No consults for headaches were requested in the selected time frame.

Chronic pain is defined as persistent pain with or without an identifiable organic cause, lasting longer than 3 to 6 months.1 Use of the term chronic pain throughout this article refers to chronic, noncancer pain. Criteria for exclusion included patients who received a pain e-consult but died before September 30, 2012.

Data Collection

Patients identified for inclusion had their charts reviewed 6 months after completion of the consult in order to allow sufficient time for potential implementation of recommendations. Patient demographics, name and dose of pain medications, requesting practitioner, type of chronic pain, recommendation of pain e-consult, and consult outcome(s) were recorded for all participants.

The primary outcome of the study was the percentage of recommendations, both pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic, made by the pain specialty pharmacist and accepted and implemented by the consulting provider.

Results

A total of 127 patient charts were identified for inclusion. Five patients died prior to September 30, 2012, and were excluded from the study, leaving 122 charts for review. All 122 charts reviewed by the pain specialty pharmacist included recommendations. Most patients were male (95.1%) and white (75.6%). The most common source of chronic pain was back pain (66.4%) (Table).

Primary Outcome

The pain specialty pharmacist pharmacologic treatment option recommendations varied significantly: add and/or change topical (80% of the 122 patients); add and/or change selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) (79%); add and/or change antiepileptic drug (AED) therapy (75%); discontinue opioid (52%); reduce opioid (48%); add and/or change nonsteroidal anti- inflammatory drug (NSAID) (45%); and taper/discontinue benzodiazepine (BZD) (13%) (Figure 1).

Primary care providers could choose to accept or ignore the recommendation, and of all the pharmacologic recommendations made, about 50% were implemented. The rate of PCP implementation of the pharmacist’s recommendations varied: add and/or change AED therapy (54%); add and/or change topical (44%); reduce opioid (42%); discontinue opioid (41%); taper/discontinue BZD (38%); add and/or change SNRI (36%); and add and/or change NSAID (33%).

Despite the most frequent recommendations made by pharmacists, the 3 most accepted and implemented by providers were addition and/or change in AED therapy, addition and/or change in topical therapy, and a decrease in opioid dose. Changes in therapy were identified as either a dose decrease or increase in the existing agent, whereas a new agent was considered an addition to existing pain therapy.

The rates of nonpharmacologic recommendations made by the pharmacist were as follows: ordering additional labs, primarily vitamin D and testosterone levels (55%); referral to physical therapy (PT) (54%); weight loss (51%); smoking cessation (43%); specialty referral (42%); order new urine drug screen (UDS) (35%); referral to pain school education program (26%); transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) (25%); referral to the substance abuse treatment program (SATP) (15%); and update opioid agreement (OA) (9%) (Figure 2).

Nonpharmacologic treatment acceptance rates were as follows: order new UDS (67%); update OA (45%); referral to SATP (33%); referral to PT (33%); order additional labs, primarily vitamin D and testosterone levels (27%); specialty referral (22%); TENS (19%); weight loss (18%); referral to pain school education program (16%); smoking cessation (6%); and music therapy (0%). The top 3 accepted recommendations were obtainment of a new UDS; updating the patient’s OA; and tied for third, referral to PT or the SATP.

Discussion

Including a pharmacist as part of a pain e-consult team may provide support to PCPs for managing chronic pain as well as for measuring improved adherence to VA/DoD guidelines for chronic pain. Pharmacists can offer recommendations for nontraditional pain therapies that PCPs may be unaware of or are unfamiliar with, such as the use of nonnarcotic agents and various nonpharmacologic options. For example, recommend testing for vitamin D levels. Vitamin D deficiency is common among the general population, and a project completed by Roesel and Engel specifically addressed vitamin D deficiency and pain in OEF/OIF veterans.4 Other studies have shown a correlation between vitamin D supplementation and a reduction in musculoskeletal pain or the association between low vitamin D levels and hypersensitivity in patients with chronic pain.5-7 Studies have also demonstrated a link between vitamin D deficiency and depression, which is well known to augment or increase patient awareness of somatic reports, like pain.8

Of all the pharmacologic recommendations made, about 50% were implemented. It is noteworthy to mention that although a change/ addition in SNRI therapy was recommended by the pharmacist 79% of the time, it was accepted and implemented by the PCP only one-third of the time. Many veterans have co-occurring mental health conditions, which are often managed by a psychiatrist, who is typically not the consulting provider (the PCP is). The PCP may be hesitant to change antidepressant therapy for fear of destabilizing the patient or because the PCP was not the antidepressant therapy prescriber. However, the incidence of co-occurring seizure disorders among veterans is much less than that of mental health disorders, making PCPs much more likely to accept and/or change AEDs. Interestingly, the majority of pain specialty pharmacist e-consults involved chronic pain management, further demonstrating the lack of comfort, time, and/or proper training for PCPs in general pain management.

Related: The Rapid Rise of e-Consults Across Specialty Care

Although the e-consult program at the BPVAHCS consisted solely of a physician and a pain specialty pharmacist, the purpose of this project was to evaluate the characteristics of recommendations made by a pharmacist and the percentage of consults that resulted in a therapy change. The physician was responsible for separate consults, and their recommendations were not collected. However, it is important to recognize that the pain specialty pharmacist and physician performed identical roles on the team, each recommending both pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic treatment options in every consult.

Related Programs

The VA Boston Healthcare System (VABHS) is composed of 3 main facilities and 5 CBOCs across eastern Massachusetts. Although veterans in the eastern part of the state are able to receive primary care at a CBOC, specialty care is provided primarily at 2 of the main locations in the Boston area. Therefore, the VABHS began an e-consult program in order to facilitate patient access to specialty providers for patients unable to participate in a face-to-face visit.

The purpose of the VABHS study was to examine the implementation and provider perception of an e-consult program within a large VA system, to provide timely patient access to specialty care. The pilot program was initiated in 2 specialty clinics in 2011 but expanded to 12 specialty clinics within 9 months. The specialty clinics included allergy, cardiology, endocrinology, gastroenterology, hematology, infectious disease, nephrology, oncology, palliative care, pulmonary disease, rheumatology, and sleep medicine. Outcomes of the VABHS e-consult program revealed that a majority of PCPs were satisfied with the use of e-consults, whereas specialists were less satisfied. The PCP-perceived benefits to patients included avoidance of unnecessary travel, faster clinical input, and avoidance of unnecessary copays.9

Like the VABHS, the use of pain e-consults at BPVAHCS helps reduce the burden of face-to-face clinic visits and eliminate accessibility barriers for veterans. This study differs from the VABHS in that PCPs requested onetime consults focused solely on pain management. The pain specialty pharmacist at BPVAHCS did not provide longitudinal care; measure patient outcomes, such as satisfaction, reduction in pain, or improved functionally; or examine provider satisfaction. Additionally, unlike the BPVAHCS program, there was no indication whether a pharmacist played a role in the program.9

Other studies have explored the role of a pain pharmacist in the inpatient setting offering consults on patient-controlled analgesia and in patients with a history of substance abuse.10,11 Another recent study similarly looked at the effectiveness of a pharmacist-led medication review in chronic pain management. The aim was to assess patient outcomes: decrease in pain intensity and improvement in physical functioning.12 Another study involving a nurse and pharmacist-led chronic pain clinic in a primary care setting conducted in England showed improvement in patient-reported pain and reduction in secondary referrals.13

Limitations

Limitations of the study included short study duration (6 months); use of a newly implemented E-Consult Pain Service; lack of pharmacist follow-up on acceptance/rejection of their recommendation; inability to determine patient outcome(s), as consults were for a single point in time, regarding a therapy recommendation; lack of access to non-VA medications; and patient refusal to change current pain regimen.

Patient refusal inhibited providers from implementing therapy changes recommended by the pharmacist and therefore could have negatively impacted study outcomes. Raw data were used for this study, and there were no statistical analyses conducted. Furthermore, lack of other formal e-consult programs within BPVAHCS to compare the acceptance/rejection of pharmacist recommendations for other conditions and lack of a third-party review of pharmacist recommendations to ensure standard of care may have limited this study.

Future Research

As the E-Consult Pain Service continues, research regarding the value of the pain specialty pharmacist may be warranted. Additional research is needed to identify the reasons that recommendations were accepted or ignored, whether the recommendations were beneficial to the patients, and the PCPs’ perception on the usefulness of a pain e-consult program. When the program started, 14% of patients at BPVAHCS were taking opioids. The pain e-consult program handled a small percentage of these patients.

The authors considered proactively reviewing all patients on > 100 mg morphine equivalents of opioids daily but did not have adequate staff to support the review. It may be helpful to identify those patients taking opioids but do not have a consult. The role of the pain e-consult pharmacist may be expanded to assist PCPs, including leading patient education classes to explain the concept and purpose of the opioid treatment agreement; reinforcing expected behaviors and outcomes of patients prescribed opioids; assisting providers with interpreting UDSs and notifying providers of aberrant behaviors; and educating providers on opioid risk mitigation through seminars or academic detailing.

Furthermore, future research may be warranted to determine the prospective role of a pain specialty pharmacist on longitudinal measures, such as pain outcomes, patient satisfaction, improvement in quality of life and/or function, as well as to determine provider perspective and satisfaction of the program. Finally, it would be interesting to compare and contrast the recommendations and outcomes between the pharmacist and physician team at the BPVAHCS.

Conclusion

The addition of a pain specialty pharmacist as part of the E-Consult Pain Service seems to provide support to prescribing PCPs in general chronic pain management, as well as measuring improved adherence to VA/DoD guidelines for chronic pain.

Acknowledgments

This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the Bay Pines VA Healthcare System.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review the complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

The enormity of chronic pain among the veteran population makes pain management within the VA a critical issue. Of the veterans returning from Operation Enduring Freedom/Operation Iraqi Freedom (OEF/OIF), chronic pain is the most common report.1 Of equal concern is the lack of available pain specialists in the U.S. There are < 4,000 pain specialists in the U.S., and even fewer pain specialists are available within the VA system, making it difficult for veterans to access pain care and timely treatment.2

Furthermore, one of the biggest challenges surrounding pain management is the lack of proper training received by generalists and primary care providers (PCPs). Whereas opioid therapy was previously prescribed mainly by specialists and mainly to cancer patients, that is no longer the case. Today, nonspecialists frequently prescribe opioids, and 95% of long-acting opioids are for chronic, noncancer pain.1 In a majority of reviewed pain electronic consultations (e-consults) completed by the pain specialty pharmacist at the Bay Pines VA Healthcare System (BPVAHCS), the patient was not currently receiving opioid therapy, suggesting PCPs’ lack of comfort and training in chronic pain management. Effective and appropriate pain management from the patient perspective and confidence and reassurance from the prescriber standpoint cannot be successfully achieved without drastic improvements in education and training.

Related: Urologist Workforce Variation Across the VHA

The inception of the E-Consult Pain Service arose from a grant from VA National Innovations in Consult Management to 3 VA facilities in Florida: BPVAHCS; Orlando VAMC, and North Florida/South Georgia Veterans Health Systems.3 At the Orlando VAMC, PCPs needed advice on pain management for patients while they waited to see a pain clinic specialist, so a Pain Help Line was implemented to provide immediate consults, but miscommunication between recommendations given and their implementation limited its utility. That eventually led to an E-Consult Pain Service, which provided formal full chart reviews for pain management cases.

The E-Consult Pain Service program included 2 full-time pharmacists, a part-time pain psychologist, and a pain physician. Its goal was to assist PCPs with patient-specific pain management recommendations. The consult service did not replace specialty pain clinics, nor was it meant to provide continual pain management. Additional, separate pain e-consults could be scheduled as a follow-up to a previous consult or for new pain management issues. Although the recommendations in the consults were available for the provider’s use, it was at the provider’s discretion as to whether the recommendations were accepted and implemented.

The E-Consult Pain Service

The E-Consult Pain Service at the BPVAHCS started July 2011. Staffed by a full-time physician and pain specialty pharmacist, the program provides electronic chart review and recommendations to PCPs regarding complex pain management issues. About three-fourths of their time was spent directly on the consults, which took between 1 and 5 business days to complete. Their remaining time was spent on educational initiatives and administrative duties.

The BPVAHCS is a complexity level 1a facility providing comprehensive health care. The facility comprises a 192-acute care bed hospital (includes intensive care, medical, surgical, and psychiatric units); a 112-bed community living center; a 65-bed domiciliary; and a 34-bed residential treatment program.

Related: A Medical Specialty e-Consult Program in a VA Health Care System

Initially, the program was developed to provide pain management support to PCPs in the community-based outpatient clinics (CBOCs) but expanded to all BPVAHCS providers. With the expansion, the program helped reduce a 3-month delay for patients waiting to be seen in the pain clinic. Goals of the program included improving patient outcomes and safety while minimizing opioid therapy risks. These goals are met through an individual case consultation as well as formal educational programs for providers.

The purpose of this study was to obtain data evaluating the characteristics of recommendations made by a pharmacist through pain e-consults at the BPVAHCS and the percentage of consults that resulted in a change in therapy. Future research is warranted to provide clarity on why specific recommendations are or are not being accepted, patient outcomes, and PCPs’ perception on the program’s utility.

Methods

An institutional review board-exempt, retrospective chart review was conducted at the BPVAHCS to determine the percentage of patients whose pain regimen changed as a result of a pain e-consult completed by a pain specialty pharmacist. Although the BPVAHCS E-Consult Pain Service comprised a physician and a pain specialty pharmacist, this study was focused solely on the role and recommendations by the pharmacist. The characteristics of those recommendations and their acceptance/rejection rate were then recorded. Of note, the physician completed separate e-consults, and the frequency of input by the physician on pharmacist recommendations was not collected.

Patients who had a pain e-consult regarding chronic, noncancer pain between January 1, 2012, and March 31, 2012, were identified for inclusion in the study. Charts were selected based on consults submitted by providers. No consults for headaches were requested in the selected time frame.

Chronic pain is defined as persistent pain with or without an identifiable organic cause, lasting longer than 3 to 6 months.1 Use of the term chronic pain throughout this article refers to chronic, noncancer pain. Criteria for exclusion included patients who received a pain e-consult but died before September 30, 2012.

Data Collection

Patients identified for inclusion had their charts reviewed 6 months after completion of the consult in order to allow sufficient time for potential implementation of recommendations. Patient demographics, name and dose of pain medications, requesting practitioner, type of chronic pain, recommendation of pain e-consult, and consult outcome(s) were recorded for all participants.

The primary outcome of the study was the percentage of recommendations, both pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic, made by the pain specialty pharmacist and accepted and implemented by the consulting provider.

Results

A total of 127 patient charts were identified for inclusion. Five patients died prior to September 30, 2012, and were excluded from the study, leaving 122 charts for review. All 122 charts reviewed by the pain specialty pharmacist included recommendations. Most patients were male (95.1%) and white (75.6%). The most common source of chronic pain was back pain (66.4%) (Table).

Primary Outcome

The pain specialty pharmacist pharmacologic treatment option recommendations varied significantly: add and/or change topical (80% of the 122 patients); add and/or change selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) (79%); add and/or change antiepileptic drug (AED) therapy (75%); discontinue opioid (52%); reduce opioid (48%); add and/or change nonsteroidal anti- inflammatory drug (NSAID) (45%); and taper/discontinue benzodiazepine (BZD) (13%) (Figure 1).

Primary care providers could choose to accept or ignore the recommendation, and of all the pharmacologic recommendations made, about 50% were implemented. The rate of PCP implementation of the pharmacist’s recommendations varied: add and/or change AED therapy (54%); add and/or change topical (44%); reduce opioid (42%); discontinue opioid (41%); taper/discontinue BZD (38%); add and/or change SNRI (36%); and add and/or change NSAID (33%).

Despite the most frequent recommendations made by pharmacists, the 3 most accepted and implemented by providers were addition and/or change in AED therapy, addition and/or change in topical therapy, and a decrease in opioid dose. Changes in therapy were identified as either a dose decrease or increase in the existing agent, whereas a new agent was considered an addition to existing pain therapy.

The rates of nonpharmacologic recommendations made by the pharmacist were as follows: ordering additional labs, primarily vitamin D and testosterone levels (55%); referral to physical therapy (PT) (54%); weight loss (51%); smoking cessation (43%); specialty referral (42%); order new urine drug screen (UDS) (35%); referral to pain school education program (26%); transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) (25%); referral to the substance abuse treatment program (SATP) (15%); and update opioid agreement (OA) (9%) (Figure 2).

Nonpharmacologic treatment acceptance rates were as follows: order new UDS (67%); update OA (45%); referral to SATP (33%); referral to PT (33%); order additional labs, primarily vitamin D and testosterone levels (27%); specialty referral (22%); TENS (19%); weight loss (18%); referral to pain school education program (16%); smoking cessation (6%); and music therapy (0%). The top 3 accepted recommendations were obtainment of a new UDS; updating the patient’s OA; and tied for third, referral to PT or the SATP.

Discussion

Including a pharmacist as part of a pain e-consult team may provide support to PCPs for managing chronic pain as well as for measuring improved adherence to VA/DoD guidelines for chronic pain. Pharmacists can offer recommendations for nontraditional pain therapies that PCPs may be unaware of or are unfamiliar with, such as the use of nonnarcotic agents and various nonpharmacologic options. For example, recommend testing for vitamin D levels. Vitamin D deficiency is common among the general population, and a project completed by Roesel and Engel specifically addressed vitamin D deficiency and pain in OEF/OIF veterans.4 Other studies have shown a correlation between vitamin D supplementation and a reduction in musculoskeletal pain or the association between low vitamin D levels and hypersensitivity in patients with chronic pain.5-7 Studies have also demonstrated a link between vitamin D deficiency and depression, which is well known to augment or increase patient awareness of somatic reports, like pain.8

Of all the pharmacologic recommendations made, about 50% were implemented. It is noteworthy to mention that although a change/ addition in SNRI therapy was recommended by the pharmacist 79% of the time, it was accepted and implemented by the PCP only one-third of the time. Many veterans have co-occurring mental health conditions, which are often managed by a psychiatrist, who is typically not the consulting provider (the PCP is). The PCP may be hesitant to change antidepressant therapy for fear of destabilizing the patient or because the PCP was not the antidepressant therapy prescriber. However, the incidence of co-occurring seizure disorders among veterans is much less than that of mental health disorders, making PCPs much more likely to accept and/or change AEDs. Interestingly, the majority of pain specialty pharmacist e-consults involved chronic pain management, further demonstrating the lack of comfort, time, and/or proper training for PCPs in general pain management.

Related: The Rapid Rise of e-Consults Across Specialty Care

Although the e-consult program at the BPVAHCS consisted solely of a physician and a pain specialty pharmacist, the purpose of this project was to evaluate the characteristics of recommendations made by a pharmacist and the percentage of consults that resulted in a therapy change. The physician was responsible for separate consults, and their recommendations were not collected. However, it is important to recognize that the pain specialty pharmacist and physician performed identical roles on the team, each recommending both pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic treatment options in every consult.

Related Programs

The VA Boston Healthcare System (VABHS) is composed of 3 main facilities and 5 CBOCs across eastern Massachusetts. Although veterans in the eastern part of the state are able to receive primary care at a CBOC, specialty care is provided primarily at 2 of the main locations in the Boston area. Therefore, the VABHS began an e-consult program in order to facilitate patient access to specialty providers for patients unable to participate in a face-to-face visit.

The purpose of the VABHS study was to examine the implementation and provider perception of an e-consult program within a large VA system, to provide timely patient access to specialty care. The pilot program was initiated in 2 specialty clinics in 2011 but expanded to 12 specialty clinics within 9 months. The specialty clinics included allergy, cardiology, endocrinology, gastroenterology, hematology, infectious disease, nephrology, oncology, palliative care, pulmonary disease, rheumatology, and sleep medicine. Outcomes of the VABHS e-consult program revealed that a majority of PCPs were satisfied with the use of e-consults, whereas specialists were less satisfied. The PCP-perceived benefits to patients included avoidance of unnecessary travel, faster clinical input, and avoidance of unnecessary copays.9

Like the VABHS, the use of pain e-consults at BPVAHCS helps reduce the burden of face-to-face clinic visits and eliminate accessibility barriers for veterans. This study differs from the VABHS in that PCPs requested onetime consults focused solely on pain management. The pain specialty pharmacist at BPVAHCS did not provide longitudinal care; measure patient outcomes, such as satisfaction, reduction in pain, or improved functionally; or examine provider satisfaction. Additionally, unlike the BPVAHCS program, there was no indication whether a pharmacist played a role in the program.9

Other studies have explored the role of a pain pharmacist in the inpatient setting offering consults on patient-controlled analgesia and in patients with a history of substance abuse.10,11 Another recent study similarly looked at the effectiveness of a pharmacist-led medication review in chronic pain management. The aim was to assess patient outcomes: decrease in pain intensity and improvement in physical functioning.12 Another study involving a nurse and pharmacist-led chronic pain clinic in a primary care setting conducted in England showed improvement in patient-reported pain and reduction in secondary referrals.13

Limitations

Limitations of the study included short study duration (6 months); use of a newly implemented E-Consult Pain Service; lack of pharmacist follow-up on acceptance/rejection of their recommendation; inability to determine patient outcome(s), as consults were for a single point in time, regarding a therapy recommendation; lack of access to non-VA medications; and patient refusal to change current pain regimen.

Patient refusal inhibited providers from implementing therapy changes recommended by the pharmacist and therefore could have negatively impacted study outcomes. Raw data were used for this study, and there were no statistical analyses conducted. Furthermore, lack of other formal e-consult programs within BPVAHCS to compare the acceptance/rejection of pharmacist recommendations for other conditions and lack of a third-party review of pharmacist recommendations to ensure standard of care may have limited this study.

Future Research

As the E-Consult Pain Service continues, research regarding the value of the pain specialty pharmacist may be warranted. Additional research is needed to identify the reasons that recommendations were accepted or ignored, whether the recommendations were beneficial to the patients, and the PCPs’ perception on the usefulness of a pain e-consult program. When the program started, 14% of patients at BPVAHCS were taking opioids. The pain e-consult program handled a small percentage of these patients.

The authors considered proactively reviewing all patients on > 100 mg morphine equivalents of opioids daily but did not have adequate staff to support the review. It may be helpful to identify those patients taking opioids but do not have a consult. The role of the pain e-consult pharmacist may be expanded to assist PCPs, including leading patient education classes to explain the concept and purpose of the opioid treatment agreement; reinforcing expected behaviors and outcomes of patients prescribed opioids; assisting providers with interpreting UDSs and notifying providers of aberrant behaviors; and educating providers on opioid risk mitigation through seminars or academic detailing.

Furthermore, future research may be warranted to determine the prospective role of a pain specialty pharmacist on longitudinal measures, such as pain outcomes, patient satisfaction, improvement in quality of life and/or function, as well as to determine provider perspective and satisfaction of the program. Finally, it would be interesting to compare and contrast the recommendations and outcomes between the pharmacist and physician team at the BPVAHCS.

Conclusion

The addition of a pain specialty pharmacist as part of the E-Consult Pain Service seems to provide support to prescribing PCPs in general chronic pain management, as well as measuring improved adherence to VA/DoD guidelines for chronic pain.

Acknowledgments

This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the Bay Pines VA Healthcare System.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review the complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

1. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Management of opioid therapy for chronic pain. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Website. http://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/Pain/cot. Published May 2010. Accessed May 25, 2015.

2. Boyle AM. VA ahead of schedule in improving chronic pain care. U.S. Medicine. 2012. http://www.usmedicine.com/agencies/department-of-veterans-affairs/va-ahead-of-schedule-in-improving -chronic-pain-care. Accessed June 16, 2015.

3. Sproul RD. Bridging the gap: e-consult pain service for the primary care physician. Am Soc Pain Educ. 2012;8(1).

4. Roesel T, Engel C. Vitamin D levels and their correlation to pain, fatigue, anxiety, and other co-morbidities in specialized care program service members seen at the Deployment Health Clinical Center. In: Deployment Health Clinical Center Annual Report 2011: pp28-29. http://www.pdhealth.mil/downloads/DHCC_AR_2011.pdf. Accessed May 25, 2015.

5. Le Goaziou MF, Kellou N, Flori M, et al. Vitamin D supplementation for diffuse musculoskeletal pain: results of a before-and-after study. Eur J Gen Pract. 2014;20(1):3-9.

6. Abbasi M, Hashemipour S, Hajmanuchehri F, Kazemifar AM. Is vitamin D deficiency associated with non specific musculoskeletal pain? Glob J Health Sci. 2012;11;5(1):107-111.

7. Von Känel R, Müller-Hartmannsgruber V, Kokinogenis G, Egloff N. Vitamin D and central hypersensitivity in patients with chronic pain. Pain Med. 2014;15(9):1609-1618.

8. Anglin RE, Samaan Z, Walter SD, McDonald SD. Vitamin D deficiency and depression in adults: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2013;202:100-107.

9. McAdams M, Cannavo L, Orlander JD. A medical specialty e-consult program in a VA healthcare system. Fed Pract. 2014;31(5):26-31.

10. Fan T, Elgourt T. Pain management pharmacy service in a community hospital. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2008;65(16):1560-1565.

11. Andrews LB, Bridgeman MB, Dalal KS, et al. Implementation of pharmacist-driven pain management consultation service for hospitalised adults with a history of substance abuse. Int J Clin Pract. 2013;67(12):1342-1349.

12. Hadi M, Alldred D, Briggs M, Munyombwe T, Closs SJ. Effectiveness of pharmacist-led medication review in chronic pain management: systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin J Pain. 2014;30(11):1006-1014.

13. Briggs M, Closs SJ, Marczewski K, Barratt J. A feasibility study of a combined nurse/pharmacist-led chronic pain clinic in primary care. Qual Prim Care. 2008;16(2):91-94.

1. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Management of opioid therapy for chronic pain. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Website. http://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/Pain/cot. Published May 2010. Accessed May 25, 2015.

2. Boyle AM. VA ahead of schedule in improving chronic pain care. U.S. Medicine. 2012. http://www.usmedicine.com/agencies/department-of-veterans-affairs/va-ahead-of-schedule-in-improving -chronic-pain-care. Accessed June 16, 2015.

3. Sproul RD. Bridging the gap: e-consult pain service for the primary care physician. Am Soc Pain Educ. 2012;8(1).

4. Roesel T, Engel C. Vitamin D levels and their correlation to pain, fatigue, anxiety, and other co-morbidities in specialized care program service members seen at the Deployment Health Clinical Center. In: Deployment Health Clinical Center Annual Report 2011: pp28-29. http://www.pdhealth.mil/downloads/DHCC_AR_2011.pdf. Accessed May 25, 2015.

5. Le Goaziou MF, Kellou N, Flori M, et al. Vitamin D supplementation for diffuse musculoskeletal pain: results of a before-and-after study. Eur J Gen Pract. 2014;20(1):3-9.

6. Abbasi M, Hashemipour S, Hajmanuchehri F, Kazemifar AM. Is vitamin D deficiency associated with non specific musculoskeletal pain? Glob J Health Sci. 2012;11;5(1):107-111.

7. Von Känel R, Müller-Hartmannsgruber V, Kokinogenis G, Egloff N. Vitamin D and central hypersensitivity in patients with chronic pain. Pain Med. 2014;15(9):1609-1618.

8. Anglin RE, Samaan Z, Walter SD, McDonald SD. Vitamin D deficiency and depression in adults: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2013;202:100-107.

9. McAdams M, Cannavo L, Orlander JD. A medical specialty e-consult program in a VA healthcare system. Fed Pract. 2014;31(5):26-31.

10. Fan T, Elgourt T. Pain management pharmacy service in a community hospital. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2008;65(16):1560-1565.

11. Andrews LB, Bridgeman MB, Dalal KS, et al. Implementation of pharmacist-driven pain management consultation service for hospitalised adults with a history of substance abuse. Int J Clin Pract. 2013;67(12):1342-1349.

12. Hadi M, Alldred D, Briggs M, Munyombwe T, Closs SJ. Effectiveness of pharmacist-led medication review in chronic pain management: systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin J Pain. 2014;30(11):1006-1014.

13. Briggs M, Closs SJ, Marczewski K, Barratt J. A feasibility study of a combined nurse/pharmacist-led chronic pain clinic in primary care. Qual Prim Care. 2008;16(2):91-94.

Development of a Virtual Pharmacy Resident Conference

The VHA is the nation’s largest provider of pharmacy residency programs offering > 150 programs.1 The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP) is the accreditation body for these pharmacy residency programs. One of the several ASHP residency standards is the presentation of a resident project at an annual conference.2,3 To meet the requirement, U.S. residency programs send pharmacy residents to regional conferences to present their projects.

Often only pharmacy residents and their project preceptors attend the regional conferences. Most pharmacists who work at each institution are not able to attend and do not have the opportunity to benefit from resident research directly related to the pharmacy profession and the facilities where the research is conducted.

Related: Treatment of Ampicillin-Resistant Enterococcus faecium Urinary Tract Infections

Reasons for not being able to attend these regional resident conferences include financial limitations as well as staffing and work requirements. The expenses associated with attending regional resident conferences include conference registration, transportation, lodging, meals, and other incidental expenses. These expenses could easily surpass several hundred dollars per attendee.

The requirements to obtain travel reimbursement for VHA employees to attend conferences for professional development have become increasingly more complex. This has presented the VHA with a unique challenge to provide its employees with professional development opportunities that do not require travel.

One option is to develop virtual learning environments, which eliminate the need for travel and conference-related expenses. Virtual learning has been a successful and convenient platform for professional development and has recently emerged within the pharmacy profession.4 In 2012, the American College of Clinical Pharmacy hosted its first Virtual Poster Symposium, which allowed participants to visit posters and interact with presenters online.5 At the VHA, pharmacists also have the opportunity to deliver and attend virtual presentations through the VA Learning University system.

To provide increased exposure and understanding to pharmacy resident research within the limitations of the VHA employee travel reimbursement system, a virtual pharmacy resident conference was developed. This article describes the steps taken to develop a conference and its impact on the pharmacists and pharmacy residents of VISN 11.

Methods

Planning for the VISN 11 Virtual Pharmacy Resident Conference started in June 2013 during the annual call for education programming from the VHA Employee Education System (EES). A proposal for the virtual conference, explaining its purpose and structure, was submitted to EES at that time, and approval was granted in August 2013.

Planning Process

Once approved, an EES representative provided guidance through the planning process and serve as a liaison between the planning committee and the desired educational accreditation body, the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE). For any educational program receiving continuing education (CE) credit from ACPE, an ACPE Planning Committee must be formed that includes a licensed pharmacist.6

The ACPE credit approval process then requires a needs assessment. The needs assessment identified a current gap within the profession and highlighted how the proposed education programming filled this gap. For the VISN 11 Virtual Pharmacy Resident Conference, the needs assessment included the challenges surrounding professional travel reimbursement and the missed learning opportunity for VA pharmacists who were not able to learn from resident research projects. Developing a virtual conference was proposed to fill this gap; pharmacists within the VISN could attend presentations from their workstations in order to stay abreast of pharmacy resident projects while gaining required CE hours for license renewal.

After the needs assessment was approved, a brochure and a content alignment worksheet was developed. The brochure identified the date and time of the conference, the target audience, and included a statement of purpose. The content alignment worksheet listed the program (presentation) title, the faculty delivering the presentation, and objectives. The completed brochure and content alignment worksheet was submitted to ACPE for credit hours approval. In the VHA, it is a VHA employee who coordinates ACPE activities for the entire health system.

Gaining Support

Another important step was to gain the support of VHA pharmacy leadership. In September 2013, an informational meeting was held to discuss the proposal and request feedback from the pharmacy chiefs, supervisors, and residency program directors at each facility within VISN 11. Following this meeting, each facility was given 1 month to determine whether the pharmacy residents at each respective facility would participate in the virtual conference. Once the planning committee had a final list of participating residents, an official announcement of the virtual conference was made to the pharmacy residents, chiefs of pharmacy, supervisors, and residency pharmacy directors.

Participating pharmacy residents submitted presentation titles to the ACPE planning committee and identified which of the 3 content tracks the research fell into: ambulatory care, acute care, or pharmacy administration. A presentation schedule was then developed.

VISN 11 pharmacists were invited to register for each of the presentations. Registration took place through the VHA Talent Management System. Presentations were delivered through Microsoft Lync (Redmond, WA), a web-based communication and conferencing platform. The VA eHealth University could have been used to achieve the same outcome.

Statistical Analysis

Presentation content breakdown and attendance rates from the VISN 11 Virtual Pharmacy Resident Conference were analyzed using descriptive statistics. The comparison of attendance rates at the virtual conference with those expected for the regional face-to-face conference was analyzed using a single sample t test.

Results

The VISN 11 Virtual Pharmacy Resident Conference took place May 5-7, 2014. Twenty-six of the 29 pharmacy residents in VISN 11 delivered 23 presentations. Three presentations had 2 presenters each, as these had completed their research as a team. Each presentation was approved by ACPE for 0.5 CE hours for a total of 11.5 CE hours available to participants.

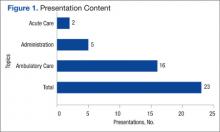

Of the 23 presentations, 16 (69.6%) focused on ambulatory care, 5 (21.7%) on pharmacy administration, and 2 (8.7%) on acute care (Figure 1). The ambulatory care presentations were divided into subgroups of diabetes (n = 6), mental health (n = 4), anticoagulation (n = 4), and cardiology (n = 2). Diabetes and cardiology presentations were delivered on day 1 of the conference, mental health and anticoagulation on day 2, and acute care and pharmacy administration on day 3.

A total of 386 VISN 11 pharmacists were invited to attend the virtual conference and 71 pharmacists (18.4%) registered for at least 1 presentation. VISN 11 pharmacy participation at the virtual conference was increased by 50% compared with the attendance at the 29th Annual Great Lakes Pharmacy Resident Conference, hosted by Purdue University, where only 47 VISN 11 pharmacists (12.2%) were expected to attend, based on results of a VISN-wide survey (95% confidence interval, 0.15-0.23; P < .001) (Figure 2).

On average, each participant attended 7 presentations and earned 3.5 hours of ACPE credit. Of the pharmacists who registered, 14 (19.7%) were pharmacy residents. Of note, registration was not required to deliver a presentation, which explains why the number of pharmacy residents registered to attend (14) was less than the number of pharmacy residents that delivered presentations (26).

More pharmacists registered for ambulatory care presentations (76.2%), followed by pharmacy administration (16.4%) and acute care (7.4%). These differences may be explained by the variability in the number of presentations within each content track. The registration for ambulatory care presentations, when stratified by content subgroup, was 45.7% for diabetes, 22.6% for mental health, 21.2% for anticoagulation, and 10.5% for cardiology.

The first day of the conference had the largest number of participants with 42.8% of all registrants, followed by 33.4% of registrants attending presentations on day 2 and 23.8% on day 3. The presentation with the largest number of registrants was in the diabetes subgroup, which was presented on the first day of the conference. The pharmacy administration presentation was held on the third and final day of the conference and had the lowest number of registrants. An average of 21.2 pharmacists registered for each presentation.

Discussion

The VISN 11 Virtual Pharmacy Resident Conference was structured in a way that offered benefits to multiple groups. First, the virtual conference served as a medium for pharmacy residents to present their yearlong research projects and meet an ASHP residency requirement. Second, the virtual conference greatly expanded the audience size and potential impact of the presentations. Traditionally, resident research projects have been available to the few pharmacists who are able to attend an in-person conference. Almost 20% of all VISN 11 pharmacists were able to attend at least 1 presentation over the course of the 3-day conference. Attendance may increase as the virtual conference becomes more familiar to the VISN 11 pharmacy staff.

Access to a larger audience may help more pharmacists understand veteran-specific research. The information discovered through these research projects may be valuable to advance the clinical and administrative role of pharmacy within each facility as well as the entire VISN. Previously, staff pharmacists could not easily learn about resident research projects taking place at their local and neighboring VA facilities. In addition to the increased impact having a larger audience size also increases staff buy-in and feedback toward the projects.

Related:Non–Daily-Dosed Rosuvastatin in Statin-Intolerant Veterans

Individual VHA facilities frequently try to find ways to increase collaboration between VISN sites. The virtual conference format can help this collaboration. Sharing information between sites through a virtual conference may decrease duplication of projects across facilities, and each facility can learn from the mistakes of the others as well as the successes.

The VHA has a standing contract with ACPE, and therefore, registration fees were not required for this conference. For health systems that may not have such a contract, an ACPE registration fee may be required; however, this fee would still be considerably lower than the travel costs of an in-person conference.