User login

Accelerated Hepatitis A and B Immunization in a Substance Abuse Treatment Program

Homeless individuals and IV drug users are susceptible to hepatitis A, B, and C infections, and co-infection with these diseases may complicate treatment and result in poor medical outcomes.1 Vaccination offers the best protection against hepatitis A and B, particularly among high-risk populations.2,3 Immunization against hepatitis A and B is of even greater importance for patients with hepatitis C, because there is no specific hepatitis C vaccine, and concomitant infections of B with C are damaging to the liver.4

Veterans have a rate of hepatitis C infection that is 3 times that of the general population.5 Some evidence exists that veterans with serious mental illness (SMI) have a higher rate of hepatitis C infection relative to patients without SMI. Co-occurring substance abuse may add another layer of vulnerability to hepatitis C infection, particularly for homeless veterans.5-7

Mental Health and Primary Care Integration

Substance abuse and dual-diagnosis treatment programs (ie, those programs that treat both substance abuse and co-occurring serious mental health problems, such as bipolar disorder, severe major depressive disorder, psychotic disorders, and posttraumatic stress disorder [PTSD]) that have integrated mental health and primary care into their treatment programs may offer a window of opportunity for risk-reducing interventions. These interventions include testing and education of patients regarding infectious diseases, such as viral hepatitis and HIV, and completion of the hepatitis A/B immunization series.

The James A. Haley Veterans’ Hospital (JAHVH) in Tampa, Florida, has demonstrated some limited success in the past with integrating a standard dosing schedule for hepatitis A/B vaccination into its substance abuse treatment program (SATP), though recent evidence points to more promising results using an accelerated regimen as indicated by a high completion rate for hepatitis B vaccination in a methadone clinic.8,9 A relatively low proportion of SATPs in the U.S. provide testing, education, or vaccination for hepatitis A and B, especially considering the public health importance of controlling these diseases in the substance abusing populations.10,11

Related: Combination Pill Approved for HCV

In 1999, a primary care team was added to the alcohol and drug abuse treatment program at JAHVH.In 2005, the nurses in the program began scheduling vaccinations and screening patients for medical and psychiatric issues, pain, hypertension, diabetes, hepatitis C, alcohol use, depression, PTSD, prostate and colorectal cancers.12 Such a multidisciplinary approach provides many treatment advantages for patients and may save lives.13

Even with a multidisciplinary approach, the nurses found it difficult to provide adequate hepatitis A/B immunization within the 3- to 6-week intensive SATP, because standard immunization dosing regimens are spread over 6 months.14 As with all types of immunizations, long dosing schedules may reduce patient adherence and result in inadequate seroprotection.15 Thus, there is a need to provide a completed immunization series in a more expeditious fashion, and an accelerated dosing regimen makes that possible.15,16

Hepatitis A/B Vaccination

Twinrix (GlaxoSmithKline, Brentford, United Kingdom) is a vaccine that provides dual immunization for hepatitis A and B. Whereas the standard vaccination schedule takes 6 months to complete, the accelerated dosing schedule can be used to complete the first 3 doses in less than a month. The accelerated dosing schedule was incorporated into the JAHVH clinic to capture as many patients as possible in the 3- to 6-week time frame: The first dose is administered and followed by a second dose 7 days later. The third dose is administered 21 to 30 days after the first dose. Twelve months after the first dose, a booster dose is given.

After the first 3 accelerated doses, > 98% of patients show a sustained immune response to hepatitis A, and > 63% demonstrate immunity to hepatitis B. If a 12-month booster injection is given, 100% of patients may receive immunity to hepatitis A and > 96% may have immunity to hepatitis B.16 Another study of the combined vaccine showed even greater seroprotection for hepatitis A and B after only 1 month, 100% and 82%, respectively.17

Related: Viral Hepatitis Awareness

This JAHVH retrospective feasibility study describes a risk-reduction program for hepatitis A/B prevention that was implemented within a 3- to 4-week intensive outpatient SATP and a 6-week dual-diagnosis treatment program. The study includes the development and implementation of the program, designed to vaccinate patients using the accelerated Twinrix schedule. To ascertain the feasibility of this vaccination approach, historical medical records were used to describe and examine the vaccination initiation and follow-up rates of the treatment program participants who received the hepatitis A/B immunization series during their intensive SATP.

Study Design

A retrospective review of medical records was conducted for all participants who were admitted to the intensive JAHVH SATP between October 1, 2008, and September 30, 2009. This study was reviewed and approved by the JAHVH research and development committee and its associated University of South Florida institutional review board. Informed consent to participate was not obtained, because the study was retrospective.

Patient Identification and Education

All program participants were offered testing for HIV and hepatitis A, B, and C. Program participants were educated about hepatitis and HIV transmission, as well as about the long-term effects of continued substance abuse on the progression of hepatitis C. Education about hepatitis, HIV, and substance abuse was provided in a group setting by a member of the program’s nursing staff. One-on-one risk education counseling was also provided when requested or otherwise indicated.

Laboratory testing was performed following each participant’s initial physical examination (within 3 to 5 days of program admission), and the nursing staff reviewed the results before vaccination. Explanation of laboratory results and an individualized immunization regimen were provided to each participant. On review of participants’ laboratory results, those with seroconversion of both hepatitis A and B were not given the combined immunization. Participants who had seroconversion of hepatitis A were offered the hepatitis B vaccination series, and vice versa.

Immunization Process

Participants who lacked prior immunization for hepatitis A and B and had no seroconversion of either hepatitis A or B were offered vaccination. Some patients declined vaccination, even though they were eligible. Their reasons were not formally assessed.

Related: Nivolumab Approved for Expanded Indication

Patients who accepted the vaccination were given the accelerated regimen.16 Participants were educated on the importance of compliance with the vaccination series and provided with follow-up immunization dates and a reminder for the 1-year booster vaccine. The immunizations were ordered by the program’s primary care NP and administered by a licensed practical nurse. The nurse who administered the injections took responsibility for scheduling the patients for all their subsequent injections, including the 1-year booster.

Follow-up Care

If the third injection was not completed before discharge, patients were given a follow-up appointment with the nurse if they remained in the JAHVH service area. If they were leaving the area, they were given instructions on how to follow-up at another VA facility to continue their immunization schedule. A note was written in the electronic medical record documenting their abbreviated hepatitis A/B immunization schedule, which could be accessed by other providers at other VA facilities. Patients who did not show up for any follow-up appointments (third injection or the 1-year booster injection) were contacted and reminded about the importance of completing the immunization series and to schedule an appointment.

Statistical Analysis

All data were analyzed using IBM Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (IBM SPSS, Armonk, New York) with a focus on identifying differences between vaccination-eligible patients (n = 269) who did (n = 128) and did not (n = 141) initiate the immunization schedule during the treatment program. Chi-square and Fisher exact tests were used to assess statistical differences in initiation of the immunization schedule related to categoric variables (ie, marital status, race, history of IV drug abuse, cigarette smoking status, housing status, legal status, history of combat, having a psychiatric or medical diagnosis, and program track). Independent sample t tests were used to test for differences between these 2 groups on the continuous variables, including age, number of previous treatment programs, Global Assessment of Functioning score, severity of smoking dependence as measured by the Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence, and the Addiction Severity Index scales.18-20

Results

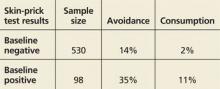

The sample consisted of 284 successive admissions to an intensive outpatient program for veterans with substance use disorders. About one-third of the patients were homeless at the time of admission to the treatment, and 87% required contracted housing while completing treatment for reasons related to lack of housing, transportation, clinical necessity, or a combination of those factors (Table 1). The most common substance problems were alcohol and cocaine dependence, and 21% (n = 59) of the patients acknowledged a history of IV drug use during their initial psychiatric evaluation. Seventy percent were dually diagnosed with some other Axis I disorder, and 40% had a history of serious mental illness. More than one-fourth (n = 77) of the patients admitted to the intensive outpatient SATP were seropositive for hepatitis A, B and/or C, and the most common hepatitis diagnosis was hepatitis C (n = 71).

Accelerated Immunization Regimen

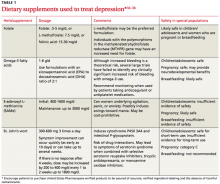

Patients were eligible to receive the accelerated vaccination schedule only if they had no prior immunization for hepatitis A or B and if they had no seroconversion for either hepatitis A or B. Six people had hepatitis B alone, 7 had hepatitis B and C, 1 had hepatitis A and C, and 1 had all 3 (Table 2). Thus, 15 participants were ineligible to receive the accelerated hepatitis A/B immunization. Chi-square, Fisher exact, and independent sample t tests showed that among those who were vaccination-eligible (269), there were no significant differences in any of the demographic or clinical characteristics between those who initiated the vaccination schedule and those who did not. Among those who completed the first 3 vaccine injections, those who received the 1-year booster injection (54) did not differ (on any demographic or clinical variables) from those who did not (58).

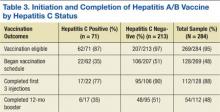

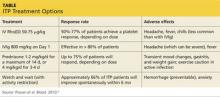

Nearly half (48%) of all the eligible patients admitted to the program began the accelerated immunization schedule for hepatitis A and B. Of those, 88% completed the first 3 injections in the series. Among the patients who received the first 3 injections, 48% received the 1-year booster injection—a 20% completion rate for the vaccination-eligible sample overall (Table 3).

Of the 74 patients who did not complete their vaccinations once initiating the accelerated schedule, the most common reason identified was that the patient moved away (37), or no reason could be identified (33). It was uncommon for a patient not to complete the vaccination schedule because of terminating treatment prematurely (4).

Compared with the vaccine-eligible patients without hepatitis C (207), patients with hepatitis C were less likely to receive any vaccination injections (Table 3). Specifically, 51% of the vaccination-eligible patients who did not have hepatitis C began the vaccination regimen. However, only 22 patients with hepatitis C, or

35% of all vaccination-eligible patients with hepatitis C, began the vaccination regimen. Patients with hepatitis C were also less likely than those without hepatitis C to complete the first 3 injections of the vaccination series once they had initiated it (77%, vs 90%, respectively). This difference continued to be apparent at the time of the 12-month booster injection. Only 35% of vaccine-eligible individuals with hepatitis C received the 12-month booster injection, whereas 51% of vaccination-eligible individuals without hepatitis C received the 12-month booster injection. As with the sample overall, the most common reason patients with hepatitis C did not complete the vaccination regimen was because they moved away (9), followed by no identified reason (5), and premature termination of treatment (2).

Discussion

Individuals abusing alcohol and drugs have an increased vulnerability for infectious diseases, and homeless veterans with substance use disorders may be at a particularly heightened risk.21,22 This study describes a sample of veterans, many were homeless and most were dually diagnosed, in an intensive outpatient SATP that offered an accelerated dosing regimen for hepatitis A and B vaccination. Almost half (48%) of the vaccination-eligible patients began the accelerated regimen for hepatitis A/B vaccination. Moreover, 88% of those who started the vaccination regimen received the first 3 injections of the series, thus possibly conferring substantial immunity to hepatitis A and B and demonstrating the feasibility of an accelerated vaccination schedule in an intensive outpatient SATP.

It is especially important to demonstrate the successful integration of a hepatitis screening and immunization program within a SATP, given that many such programs do not offer screening or immunization for hepatitis, even though substance abusers are disproportionately affected by the disease and contribute greatly to the ongoing hepatitis epidemic.10,11 This study’s results were in line with another study of rapid vaccination for hepatitis B in IV drug users being treated in a methadone clinic, where 83% of the vaccination initiators completed the first 3 injections of the series.9

Unvaccinated Patients

The treatment team in the current study seemed to be less effective at reaching the subset of vaccination-eligible veterans with hepatitis C (almost one-quarter of the sample) in order to administer the accelerated vaccination schedule, as indicated by the lower rate of vaccination initiation as well as a lower rate of completion of the vaccination series among those patients. This replicates a finding from another study that also indicated a low rate of hepatitis A and B vaccination among patients with hepatitis C.23 Only 35% of the vaccination-eligible patients with hepatitis C in the current study initiated the vaccination series, compared with 51% of the patients without hepatitis C. However, the rate of completion of the first 3 injections of the series in the hepatitis C group was respectably high (77%), especially given the high relapse rate and psychosocial instability of individuals with addictive disorders. Initiation seems to be a bigger obstacle than completion of at least the first 3 injections of the vaccination series in both patients with and without hepatitis C.

The study investigators did not formally assess the reasons that more than half the patients in the study did not begin the vaccination series, but anecdotal evidence from the nurses indicated that many patients were afraid of needles. In addition, other patients felt that they simply did not need the vaccination. Some also insisted that they had already had the vaccination despite a blood test showing no evidence for either hepatitis A or B immunization.

Although the nursing team provided group and individual risk-based education as well as information about the effects of continued substance abuse on hepatitis C, it is possible that patients still underestimated their own risk of hepatitis infection and its consequences, or perhaps the information was simply not retained.24

Patient Education

A recent study showed that there is a positive relationship between the amount of hepatitis counseling received and knowledge of hepatitis.25 Possibly, increased intensity of education efforts may make an impact on initiation rates. Encouragingly, there is also evidence that prompting people to predict their future vaccination behavior may increase vaccination initiation rates despite a high-degree of short-term barriers, such as perceived pain or inconvenience.26 A brief intervention to induce people to formulate their future intentions would be relatively easy to incorporate into a vaccination program, and the study team is considering options for this to improve vaccination initiation rates.

Patients can expect to achieve substantial immunity from hepatitis A and, to a lesser degree, hepatitis B after completing the first 3 injections of the series, although the best seroprotection from both is obtained by completing the 12-month booster injection as well.17 Overall, about half of all patients who completed the first 3 injections returned for the booster shot, but only 35% of the patients with hepatitis C did so. The most common known cause of any patient not receiving the booster was movement out of the geographic area. However, much of the time the investigators were unable to determine the reasons patients did not return for the booster shot.

Medication adherence is a difficult problem with vaccination in high-risk samples, although Stitzer and colleagues found a significant improvement in follow-up for a 6-month vaccination protocol by using monetary incentives.27 In addition to ensuring medication adherence, it would also be of value for future immunization efforts to include testing to assess whether seroconversion has occurred once the vaccinations are complete, which is the ultimate measure of the success of a vaccination program. Most patients in the current study did not receive such testing at the completion of their vaccination schedules, and thus, seroconversion rates could not be determined. However, existing studies suggest high rates of seroprotection after the first 3 doses of the combined vaccine.10,17

Limitations

The retrospective nature of the study is its most significant limitation. Any conclusions about the results must be made with caution. However, this design allowed for a naturalistic and potentially generalizable investigation into the application of a vaccination program in a real-world treatment setting. As such, the investigators were able to demonstrate the feasibility of conducting a rapid vaccination program within a 3- to 6-week SATP.

The retrospective nature of the study also limited a full investigation into the reasons behind the lack of vaccination initiation and vaccination noncompletion among the study’s treatment population, especially with regard to the follow-up booster injection. Initial statistical comparisons of initiators and noninitiators and completers and noncompleters showed no significant statistical differences between the groups. Future prospective designs should take into account the need to successfully initiate and complete vaccinations for all eligible patients and include assessment measures to determine the specific reasons that patients did not initiate or complete their vaccinations.

Conclusions

Many patients began and completed the accelerated vaccination schedule for hepatitis A and B in the context of a 3- to 6-week SATP at JAHVH. The overall vaccination rate, including the 12-month booster injection, was one-fifth of the entire vaccination-eligible sample. Additionally, 88% of the vaccination-eligible patients who began the vaccination schedule (or 42% of the whole sample) completed at least the first 3 doses, which may confer substantial immunity from hepatitis A and B. For reasons not entirely clear, a little less than half the vaccination-eligible patients began the vaccination schedule, and only about 50% of those returned to receive their 12-month booster injection. Future prospective studies may be able to determine barriers to both the initiation of and adherence to the vaccination protocol.

The results of this study are also a testament to having primary care nursing staff available and actively involved in the care of patients in a SATP. It seems likely that additional interventions might be needed for outreach to and retention of patients in need of vaccination for hepatitis A and B, and particularly those patients with hepatitis C. It is important to find ways to increase the rates of 12-month booster vaccinations, both for veterans who continue to receive services at JAHVH and for those who transfer care to other VA facilities. Finally, testing to confirm serologic immunity to hepatitis A and hepatitis B would be the next step in the effort to eliminate the risk of hepatitis A and hepatitis B and minimize additional harm for those with hepatitis C in the population receiving treatment for addictive disorders.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review the complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

1. Nyamathi A, Liu Y, Marfisee M, et al. Effects of a nurse-managed program on hepatitis A and B vaccine completion among homeless adults. Nurs Res. 2009;58(1):13-22.

2. Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). A comprehensive immunization strategy to eliminate transmission of hepatitis B virus infection in the United States. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2006;55(RR16):1-25.

3. Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), Fiore AE, Wasley A, Bell BP. Prevention of hepatitis A through active or passive immunization: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2006;55(RR07):1-23.

4. Weltman MD, Brotodihardjo A, Crewe EB, et al. Coinfection with hepatitis B and C or B, C and delta viruses results in severe chronic liver disease and responds poorly to interferon-alpha treatment. J Viral Hepat. 1995;2(1):39-45.

5. Groessl EJ, Weingart KR, Kaplan RM, et al. Living with hepatitis C: qualitative interviews with hepatitis C-infected veterans. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(12):1959-1965.

6. Dominitz JA, Boyko EJ, Koepsell TD, et al. Elevated prevalence of hepatitis C infection in users of United States veterans medical centers. Hepatology. 2005;41(1):88-96.

7. Himeloch S, McCarthy JF, Ganoczy D, et al. Understanding associations between serious mental illness and hepatitis C virus among veterans: a national multivariate analysis. Psychosomatics. 2009;50(1):30-37.

8. Hagedorn H, Dieperink E, Dingmann D, et al. Integrating hepatitis prevention services into a substance use disorder clinic. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2007;32(4):391-398.

9. Ramasamy P, Lintzeris N, Sutton Y, Taylor H, Day CA, Haber PS. The outcome of a rapid hepatitis B vaccination programme in a methadone treatment clinic. Addiction. 2010;105(2):329-334.

10. Bini EJ, Kritz S, Brown LS Jr, et al. Hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus services offered by substance abuse treatment programs in the United States. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2012;42(4):438-445.

11. Recommendations for prevention and control of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection and HCV-related chronic disease. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1998;47(RR-19):1-39.

12. Francis E, Gonzales-Nolas CL, Markowitz J, Phillips S. Integration of preventive health screening into mental health clinics. Fed Pract. 2008;25(2):39-50.

13. Vreeland B. Bridging the gap between mental and physical health: a multidisciplinary approach. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68(suppl 4):26-33.

14. Brim N, Zaller N, Taylor LE, Feller E. Twinrix vaccination schedules among injecting drug users. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2007;7(3):379-389.

15. Zuckerman J. The place of accelerated schedules for hepatitis A and B vaccinations. Drugs. 2003;63(17):1779-1784.

16. Connor BA, Blatter MM, Beran J, Zou B, Trofa AF. Rapid and sustained immune response against hepatitis A and B achieved with combined vaccine using an accelerated administration schedule. J Travel Med. 2007;14(1):9-15.

17. Nothdurft HD, Dietrich M, Zuckerman JN, et al. A new accelerated vaccination schedule for rapid protection against hepatitis A and B. Vaccine. 2002;20(7-8):1157-1162.

18. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

19. Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerström KO. The Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence: a revision of the Fagerström Tolerance Questionnaire. Br J Addict. 1991;86(9):1119-1127.

20. McLellan AT, Kushner H, Metzger D, et al. The Fifth Edition of the Addiction Severity Index. J Subst Abuse Treat. 1992;9(3):199-213.

21. Batki SL, Nathan KI. HIV/AIDS and Hepatitis C. In: Galanter M, Kleber HD, Brady KT, eds. The American Psychiatric Publishing Textbook of Substance Abuse Treatment. 5th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2015.

22. Gelberg L, Robertson MJ, Leake B, et al. Hepatitis B among homeless and other impoverished US military veterans in residential care in Los Angeles. Public Health. 2001;115(4):286-291.

23. Felsen UR, Fishbein DA, Litwin AH. Low rates of hepatitis A and B vaccination in patients with chronic hepatitis C at an urban methadone maintenance program. J Addict Dis. 2010;29(4):461-465.

24. Brewer NT, Chapman GB, Gibbons FX, Gerrard M, McCaul KD, Weinstein ND. Meta-analysis of the relationship between risk perception and health behavior: the example of vaccination. Health Psychol. 2007;26(2):136-145.

25. Soto-Salgado M, Suárez E, Ortiz AP, et al. Knowledge of viral hepatitis among Puerto Rican adults: implications for prevention. J Community Health. 2011;36(4):565-573.

26. Cox AD, Cox D, Cyrier R, Graham-Dotson Y, Zimet GD. Can self-prediction overcome barriers to hepatitis B vaccination? A randomized controlled trial. Health Psychol. 2012;31(1):97-105.

27. Stitzer ML, Polk T, Bowles S, Kosten T. Drug users’ adherence to a 6-month vaccination protocol: effects of motivational incentives. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010;107(1):76-79.

Homeless individuals and IV drug users are susceptible to hepatitis A, B, and C infections, and co-infection with these diseases may complicate treatment and result in poor medical outcomes.1 Vaccination offers the best protection against hepatitis A and B, particularly among high-risk populations.2,3 Immunization against hepatitis A and B is of even greater importance for patients with hepatitis C, because there is no specific hepatitis C vaccine, and concomitant infections of B with C are damaging to the liver.4

Veterans have a rate of hepatitis C infection that is 3 times that of the general population.5 Some evidence exists that veterans with serious mental illness (SMI) have a higher rate of hepatitis C infection relative to patients without SMI. Co-occurring substance abuse may add another layer of vulnerability to hepatitis C infection, particularly for homeless veterans.5-7

Mental Health and Primary Care Integration

Substance abuse and dual-diagnosis treatment programs (ie, those programs that treat both substance abuse and co-occurring serious mental health problems, such as bipolar disorder, severe major depressive disorder, psychotic disorders, and posttraumatic stress disorder [PTSD]) that have integrated mental health and primary care into their treatment programs may offer a window of opportunity for risk-reducing interventions. These interventions include testing and education of patients regarding infectious diseases, such as viral hepatitis and HIV, and completion of the hepatitis A/B immunization series.

The James A. Haley Veterans’ Hospital (JAHVH) in Tampa, Florida, has demonstrated some limited success in the past with integrating a standard dosing schedule for hepatitis A/B vaccination into its substance abuse treatment program (SATP), though recent evidence points to more promising results using an accelerated regimen as indicated by a high completion rate for hepatitis B vaccination in a methadone clinic.8,9 A relatively low proportion of SATPs in the U.S. provide testing, education, or vaccination for hepatitis A and B, especially considering the public health importance of controlling these diseases in the substance abusing populations.10,11

Related: Combination Pill Approved for HCV

In 1999, a primary care team was added to the alcohol and drug abuse treatment program at JAHVH.In 2005, the nurses in the program began scheduling vaccinations and screening patients for medical and psychiatric issues, pain, hypertension, diabetes, hepatitis C, alcohol use, depression, PTSD, prostate and colorectal cancers.12 Such a multidisciplinary approach provides many treatment advantages for patients and may save lives.13

Even with a multidisciplinary approach, the nurses found it difficult to provide adequate hepatitis A/B immunization within the 3- to 6-week intensive SATP, because standard immunization dosing regimens are spread over 6 months.14 As with all types of immunizations, long dosing schedules may reduce patient adherence and result in inadequate seroprotection.15 Thus, there is a need to provide a completed immunization series in a more expeditious fashion, and an accelerated dosing regimen makes that possible.15,16

Hepatitis A/B Vaccination

Twinrix (GlaxoSmithKline, Brentford, United Kingdom) is a vaccine that provides dual immunization for hepatitis A and B. Whereas the standard vaccination schedule takes 6 months to complete, the accelerated dosing schedule can be used to complete the first 3 doses in less than a month. The accelerated dosing schedule was incorporated into the JAHVH clinic to capture as many patients as possible in the 3- to 6-week time frame: The first dose is administered and followed by a second dose 7 days later. The third dose is administered 21 to 30 days after the first dose. Twelve months after the first dose, a booster dose is given.

After the first 3 accelerated doses, > 98% of patients show a sustained immune response to hepatitis A, and > 63% demonstrate immunity to hepatitis B. If a 12-month booster injection is given, 100% of patients may receive immunity to hepatitis A and > 96% may have immunity to hepatitis B.16 Another study of the combined vaccine showed even greater seroprotection for hepatitis A and B after only 1 month, 100% and 82%, respectively.17

Related: Viral Hepatitis Awareness

This JAHVH retrospective feasibility study describes a risk-reduction program for hepatitis A/B prevention that was implemented within a 3- to 4-week intensive outpatient SATP and a 6-week dual-diagnosis treatment program. The study includes the development and implementation of the program, designed to vaccinate patients using the accelerated Twinrix schedule. To ascertain the feasibility of this vaccination approach, historical medical records were used to describe and examine the vaccination initiation and follow-up rates of the treatment program participants who received the hepatitis A/B immunization series during their intensive SATP.

Study Design

A retrospective review of medical records was conducted for all participants who were admitted to the intensive JAHVH SATP between October 1, 2008, and September 30, 2009. This study was reviewed and approved by the JAHVH research and development committee and its associated University of South Florida institutional review board. Informed consent to participate was not obtained, because the study was retrospective.

Patient Identification and Education

All program participants were offered testing for HIV and hepatitis A, B, and C. Program participants were educated about hepatitis and HIV transmission, as well as about the long-term effects of continued substance abuse on the progression of hepatitis C. Education about hepatitis, HIV, and substance abuse was provided in a group setting by a member of the program’s nursing staff. One-on-one risk education counseling was also provided when requested or otherwise indicated.

Laboratory testing was performed following each participant’s initial physical examination (within 3 to 5 days of program admission), and the nursing staff reviewed the results before vaccination. Explanation of laboratory results and an individualized immunization regimen were provided to each participant. On review of participants’ laboratory results, those with seroconversion of both hepatitis A and B were not given the combined immunization. Participants who had seroconversion of hepatitis A were offered the hepatitis B vaccination series, and vice versa.

Immunization Process

Participants who lacked prior immunization for hepatitis A and B and had no seroconversion of either hepatitis A or B were offered vaccination. Some patients declined vaccination, even though they were eligible. Their reasons were not formally assessed.

Related: Nivolumab Approved for Expanded Indication

Patients who accepted the vaccination were given the accelerated regimen.16 Participants were educated on the importance of compliance with the vaccination series and provided with follow-up immunization dates and a reminder for the 1-year booster vaccine. The immunizations were ordered by the program’s primary care NP and administered by a licensed practical nurse. The nurse who administered the injections took responsibility for scheduling the patients for all their subsequent injections, including the 1-year booster.

Follow-up Care

If the third injection was not completed before discharge, patients were given a follow-up appointment with the nurse if they remained in the JAHVH service area. If they were leaving the area, they were given instructions on how to follow-up at another VA facility to continue their immunization schedule. A note was written in the electronic medical record documenting their abbreviated hepatitis A/B immunization schedule, which could be accessed by other providers at other VA facilities. Patients who did not show up for any follow-up appointments (third injection or the 1-year booster injection) were contacted and reminded about the importance of completing the immunization series and to schedule an appointment.

Statistical Analysis

All data were analyzed using IBM Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (IBM SPSS, Armonk, New York) with a focus on identifying differences between vaccination-eligible patients (n = 269) who did (n = 128) and did not (n = 141) initiate the immunization schedule during the treatment program. Chi-square and Fisher exact tests were used to assess statistical differences in initiation of the immunization schedule related to categoric variables (ie, marital status, race, history of IV drug abuse, cigarette smoking status, housing status, legal status, history of combat, having a psychiatric or medical diagnosis, and program track). Independent sample t tests were used to test for differences between these 2 groups on the continuous variables, including age, number of previous treatment programs, Global Assessment of Functioning score, severity of smoking dependence as measured by the Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence, and the Addiction Severity Index scales.18-20

Results

The sample consisted of 284 successive admissions to an intensive outpatient program for veterans with substance use disorders. About one-third of the patients were homeless at the time of admission to the treatment, and 87% required contracted housing while completing treatment for reasons related to lack of housing, transportation, clinical necessity, or a combination of those factors (Table 1). The most common substance problems were alcohol and cocaine dependence, and 21% (n = 59) of the patients acknowledged a history of IV drug use during their initial psychiatric evaluation. Seventy percent were dually diagnosed with some other Axis I disorder, and 40% had a history of serious mental illness. More than one-fourth (n = 77) of the patients admitted to the intensive outpatient SATP were seropositive for hepatitis A, B and/or C, and the most common hepatitis diagnosis was hepatitis C (n = 71).

Accelerated Immunization Regimen

Patients were eligible to receive the accelerated vaccination schedule only if they had no prior immunization for hepatitis A or B and if they had no seroconversion for either hepatitis A or B. Six people had hepatitis B alone, 7 had hepatitis B and C, 1 had hepatitis A and C, and 1 had all 3 (Table 2). Thus, 15 participants were ineligible to receive the accelerated hepatitis A/B immunization. Chi-square, Fisher exact, and independent sample t tests showed that among those who were vaccination-eligible (269), there were no significant differences in any of the demographic or clinical characteristics between those who initiated the vaccination schedule and those who did not. Among those who completed the first 3 vaccine injections, those who received the 1-year booster injection (54) did not differ (on any demographic or clinical variables) from those who did not (58).

Nearly half (48%) of all the eligible patients admitted to the program began the accelerated immunization schedule for hepatitis A and B. Of those, 88% completed the first 3 injections in the series. Among the patients who received the first 3 injections, 48% received the 1-year booster injection—a 20% completion rate for the vaccination-eligible sample overall (Table 3).

Of the 74 patients who did not complete their vaccinations once initiating the accelerated schedule, the most common reason identified was that the patient moved away (37), or no reason could be identified (33). It was uncommon for a patient not to complete the vaccination schedule because of terminating treatment prematurely (4).

Compared with the vaccine-eligible patients without hepatitis C (207), patients with hepatitis C were less likely to receive any vaccination injections (Table 3). Specifically, 51% of the vaccination-eligible patients who did not have hepatitis C began the vaccination regimen. However, only 22 patients with hepatitis C, or

35% of all vaccination-eligible patients with hepatitis C, began the vaccination regimen. Patients with hepatitis C were also less likely than those without hepatitis C to complete the first 3 injections of the vaccination series once they had initiated it (77%, vs 90%, respectively). This difference continued to be apparent at the time of the 12-month booster injection. Only 35% of vaccine-eligible individuals with hepatitis C received the 12-month booster injection, whereas 51% of vaccination-eligible individuals without hepatitis C received the 12-month booster injection. As with the sample overall, the most common reason patients with hepatitis C did not complete the vaccination regimen was because they moved away (9), followed by no identified reason (5), and premature termination of treatment (2).

Discussion

Individuals abusing alcohol and drugs have an increased vulnerability for infectious diseases, and homeless veterans with substance use disorders may be at a particularly heightened risk.21,22 This study describes a sample of veterans, many were homeless and most were dually diagnosed, in an intensive outpatient SATP that offered an accelerated dosing regimen for hepatitis A and B vaccination. Almost half (48%) of the vaccination-eligible patients began the accelerated regimen for hepatitis A/B vaccination. Moreover, 88% of those who started the vaccination regimen received the first 3 injections of the series, thus possibly conferring substantial immunity to hepatitis A and B and demonstrating the feasibility of an accelerated vaccination schedule in an intensive outpatient SATP.

It is especially important to demonstrate the successful integration of a hepatitis screening and immunization program within a SATP, given that many such programs do not offer screening or immunization for hepatitis, even though substance abusers are disproportionately affected by the disease and contribute greatly to the ongoing hepatitis epidemic.10,11 This study’s results were in line with another study of rapid vaccination for hepatitis B in IV drug users being treated in a methadone clinic, where 83% of the vaccination initiators completed the first 3 injections of the series.9

Unvaccinated Patients

The treatment team in the current study seemed to be less effective at reaching the subset of vaccination-eligible veterans with hepatitis C (almost one-quarter of the sample) in order to administer the accelerated vaccination schedule, as indicated by the lower rate of vaccination initiation as well as a lower rate of completion of the vaccination series among those patients. This replicates a finding from another study that also indicated a low rate of hepatitis A and B vaccination among patients with hepatitis C.23 Only 35% of the vaccination-eligible patients with hepatitis C in the current study initiated the vaccination series, compared with 51% of the patients without hepatitis C. However, the rate of completion of the first 3 injections of the series in the hepatitis C group was respectably high (77%), especially given the high relapse rate and psychosocial instability of individuals with addictive disorders. Initiation seems to be a bigger obstacle than completion of at least the first 3 injections of the vaccination series in both patients with and without hepatitis C.

The study investigators did not formally assess the reasons that more than half the patients in the study did not begin the vaccination series, but anecdotal evidence from the nurses indicated that many patients were afraid of needles. In addition, other patients felt that they simply did not need the vaccination. Some also insisted that they had already had the vaccination despite a blood test showing no evidence for either hepatitis A or B immunization.

Although the nursing team provided group and individual risk-based education as well as information about the effects of continued substance abuse on hepatitis C, it is possible that patients still underestimated their own risk of hepatitis infection and its consequences, or perhaps the information was simply not retained.24

Patient Education

A recent study showed that there is a positive relationship between the amount of hepatitis counseling received and knowledge of hepatitis.25 Possibly, increased intensity of education efforts may make an impact on initiation rates. Encouragingly, there is also evidence that prompting people to predict their future vaccination behavior may increase vaccination initiation rates despite a high-degree of short-term barriers, such as perceived pain or inconvenience.26 A brief intervention to induce people to formulate their future intentions would be relatively easy to incorporate into a vaccination program, and the study team is considering options for this to improve vaccination initiation rates.

Patients can expect to achieve substantial immunity from hepatitis A and, to a lesser degree, hepatitis B after completing the first 3 injections of the series, although the best seroprotection from both is obtained by completing the 12-month booster injection as well.17 Overall, about half of all patients who completed the first 3 injections returned for the booster shot, but only 35% of the patients with hepatitis C did so. The most common known cause of any patient not receiving the booster was movement out of the geographic area. However, much of the time the investigators were unable to determine the reasons patients did not return for the booster shot.

Medication adherence is a difficult problem with vaccination in high-risk samples, although Stitzer and colleagues found a significant improvement in follow-up for a 6-month vaccination protocol by using monetary incentives.27 In addition to ensuring medication adherence, it would also be of value for future immunization efforts to include testing to assess whether seroconversion has occurred once the vaccinations are complete, which is the ultimate measure of the success of a vaccination program. Most patients in the current study did not receive such testing at the completion of their vaccination schedules, and thus, seroconversion rates could not be determined. However, existing studies suggest high rates of seroprotection after the first 3 doses of the combined vaccine.10,17

Limitations

The retrospective nature of the study is its most significant limitation. Any conclusions about the results must be made with caution. However, this design allowed for a naturalistic and potentially generalizable investigation into the application of a vaccination program in a real-world treatment setting. As such, the investigators were able to demonstrate the feasibility of conducting a rapid vaccination program within a 3- to 6-week SATP.

The retrospective nature of the study also limited a full investigation into the reasons behind the lack of vaccination initiation and vaccination noncompletion among the study’s treatment population, especially with regard to the follow-up booster injection. Initial statistical comparisons of initiators and noninitiators and completers and noncompleters showed no significant statistical differences between the groups. Future prospective designs should take into account the need to successfully initiate and complete vaccinations for all eligible patients and include assessment measures to determine the specific reasons that patients did not initiate or complete their vaccinations.

Conclusions

Many patients began and completed the accelerated vaccination schedule for hepatitis A and B in the context of a 3- to 6-week SATP at JAHVH. The overall vaccination rate, including the 12-month booster injection, was one-fifth of the entire vaccination-eligible sample. Additionally, 88% of the vaccination-eligible patients who began the vaccination schedule (or 42% of the whole sample) completed at least the first 3 doses, which may confer substantial immunity from hepatitis A and B. For reasons not entirely clear, a little less than half the vaccination-eligible patients began the vaccination schedule, and only about 50% of those returned to receive their 12-month booster injection. Future prospective studies may be able to determine barriers to both the initiation of and adherence to the vaccination protocol.

The results of this study are also a testament to having primary care nursing staff available and actively involved in the care of patients in a SATP. It seems likely that additional interventions might be needed for outreach to and retention of patients in need of vaccination for hepatitis A and B, and particularly those patients with hepatitis C. It is important to find ways to increase the rates of 12-month booster vaccinations, both for veterans who continue to receive services at JAHVH and for those who transfer care to other VA facilities. Finally, testing to confirm serologic immunity to hepatitis A and hepatitis B would be the next step in the effort to eliminate the risk of hepatitis A and hepatitis B and minimize additional harm for those with hepatitis C in the population receiving treatment for addictive disorders.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review the complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

Homeless individuals and IV drug users are susceptible to hepatitis A, B, and C infections, and co-infection with these diseases may complicate treatment and result in poor medical outcomes.1 Vaccination offers the best protection against hepatitis A and B, particularly among high-risk populations.2,3 Immunization against hepatitis A and B is of even greater importance for patients with hepatitis C, because there is no specific hepatitis C vaccine, and concomitant infections of B with C are damaging to the liver.4

Veterans have a rate of hepatitis C infection that is 3 times that of the general population.5 Some evidence exists that veterans with serious mental illness (SMI) have a higher rate of hepatitis C infection relative to patients without SMI. Co-occurring substance abuse may add another layer of vulnerability to hepatitis C infection, particularly for homeless veterans.5-7

Mental Health and Primary Care Integration

Substance abuse and dual-diagnosis treatment programs (ie, those programs that treat both substance abuse and co-occurring serious mental health problems, such as bipolar disorder, severe major depressive disorder, psychotic disorders, and posttraumatic stress disorder [PTSD]) that have integrated mental health and primary care into their treatment programs may offer a window of opportunity for risk-reducing interventions. These interventions include testing and education of patients regarding infectious diseases, such as viral hepatitis and HIV, and completion of the hepatitis A/B immunization series.

The James A. Haley Veterans’ Hospital (JAHVH) in Tampa, Florida, has demonstrated some limited success in the past with integrating a standard dosing schedule for hepatitis A/B vaccination into its substance abuse treatment program (SATP), though recent evidence points to more promising results using an accelerated regimen as indicated by a high completion rate for hepatitis B vaccination in a methadone clinic.8,9 A relatively low proportion of SATPs in the U.S. provide testing, education, or vaccination for hepatitis A and B, especially considering the public health importance of controlling these diseases in the substance abusing populations.10,11

Related: Combination Pill Approved for HCV

In 1999, a primary care team was added to the alcohol and drug abuse treatment program at JAHVH.In 2005, the nurses in the program began scheduling vaccinations and screening patients for medical and psychiatric issues, pain, hypertension, diabetes, hepatitis C, alcohol use, depression, PTSD, prostate and colorectal cancers.12 Such a multidisciplinary approach provides many treatment advantages for patients and may save lives.13

Even with a multidisciplinary approach, the nurses found it difficult to provide adequate hepatitis A/B immunization within the 3- to 6-week intensive SATP, because standard immunization dosing regimens are spread over 6 months.14 As with all types of immunizations, long dosing schedules may reduce patient adherence and result in inadequate seroprotection.15 Thus, there is a need to provide a completed immunization series in a more expeditious fashion, and an accelerated dosing regimen makes that possible.15,16

Hepatitis A/B Vaccination

Twinrix (GlaxoSmithKline, Brentford, United Kingdom) is a vaccine that provides dual immunization for hepatitis A and B. Whereas the standard vaccination schedule takes 6 months to complete, the accelerated dosing schedule can be used to complete the first 3 doses in less than a month. The accelerated dosing schedule was incorporated into the JAHVH clinic to capture as many patients as possible in the 3- to 6-week time frame: The first dose is administered and followed by a second dose 7 days later. The third dose is administered 21 to 30 days after the first dose. Twelve months after the first dose, a booster dose is given.

After the first 3 accelerated doses, > 98% of patients show a sustained immune response to hepatitis A, and > 63% demonstrate immunity to hepatitis B. If a 12-month booster injection is given, 100% of patients may receive immunity to hepatitis A and > 96% may have immunity to hepatitis B.16 Another study of the combined vaccine showed even greater seroprotection for hepatitis A and B after only 1 month, 100% and 82%, respectively.17

Related: Viral Hepatitis Awareness

This JAHVH retrospective feasibility study describes a risk-reduction program for hepatitis A/B prevention that was implemented within a 3- to 4-week intensive outpatient SATP and a 6-week dual-diagnosis treatment program. The study includes the development and implementation of the program, designed to vaccinate patients using the accelerated Twinrix schedule. To ascertain the feasibility of this vaccination approach, historical medical records were used to describe and examine the vaccination initiation and follow-up rates of the treatment program participants who received the hepatitis A/B immunization series during their intensive SATP.

Study Design

A retrospective review of medical records was conducted for all participants who were admitted to the intensive JAHVH SATP between October 1, 2008, and September 30, 2009. This study was reviewed and approved by the JAHVH research and development committee and its associated University of South Florida institutional review board. Informed consent to participate was not obtained, because the study was retrospective.

Patient Identification and Education

All program participants were offered testing for HIV and hepatitis A, B, and C. Program participants were educated about hepatitis and HIV transmission, as well as about the long-term effects of continued substance abuse on the progression of hepatitis C. Education about hepatitis, HIV, and substance abuse was provided in a group setting by a member of the program’s nursing staff. One-on-one risk education counseling was also provided when requested or otherwise indicated.

Laboratory testing was performed following each participant’s initial physical examination (within 3 to 5 days of program admission), and the nursing staff reviewed the results before vaccination. Explanation of laboratory results and an individualized immunization regimen were provided to each participant. On review of participants’ laboratory results, those with seroconversion of both hepatitis A and B were not given the combined immunization. Participants who had seroconversion of hepatitis A were offered the hepatitis B vaccination series, and vice versa.

Immunization Process

Participants who lacked prior immunization for hepatitis A and B and had no seroconversion of either hepatitis A or B were offered vaccination. Some patients declined vaccination, even though they were eligible. Their reasons were not formally assessed.

Related: Nivolumab Approved for Expanded Indication

Patients who accepted the vaccination were given the accelerated regimen.16 Participants were educated on the importance of compliance with the vaccination series and provided with follow-up immunization dates and a reminder for the 1-year booster vaccine. The immunizations were ordered by the program’s primary care NP and administered by a licensed practical nurse. The nurse who administered the injections took responsibility for scheduling the patients for all their subsequent injections, including the 1-year booster.

Follow-up Care

If the third injection was not completed before discharge, patients were given a follow-up appointment with the nurse if they remained in the JAHVH service area. If they were leaving the area, they were given instructions on how to follow-up at another VA facility to continue their immunization schedule. A note was written in the electronic medical record documenting their abbreviated hepatitis A/B immunization schedule, which could be accessed by other providers at other VA facilities. Patients who did not show up for any follow-up appointments (third injection or the 1-year booster injection) were contacted and reminded about the importance of completing the immunization series and to schedule an appointment.

Statistical Analysis

All data were analyzed using IBM Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (IBM SPSS, Armonk, New York) with a focus on identifying differences between vaccination-eligible patients (n = 269) who did (n = 128) and did not (n = 141) initiate the immunization schedule during the treatment program. Chi-square and Fisher exact tests were used to assess statistical differences in initiation of the immunization schedule related to categoric variables (ie, marital status, race, history of IV drug abuse, cigarette smoking status, housing status, legal status, history of combat, having a psychiatric or medical diagnosis, and program track). Independent sample t tests were used to test for differences between these 2 groups on the continuous variables, including age, number of previous treatment programs, Global Assessment of Functioning score, severity of smoking dependence as measured by the Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence, and the Addiction Severity Index scales.18-20

Results

The sample consisted of 284 successive admissions to an intensive outpatient program for veterans with substance use disorders. About one-third of the patients were homeless at the time of admission to the treatment, and 87% required contracted housing while completing treatment for reasons related to lack of housing, transportation, clinical necessity, or a combination of those factors (Table 1). The most common substance problems were alcohol and cocaine dependence, and 21% (n = 59) of the patients acknowledged a history of IV drug use during their initial psychiatric evaluation. Seventy percent were dually diagnosed with some other Axis I disorder, and 40% had a history of serious mental illness. More than one-fourth (n = 77) of the patients admitted to the intensive outpatient SATP were seropositive for hepatitis A, B and/or C, and the most common hepatitis diagnosis was hepatitis C (n = 71).

Accelerated Immunization Regimen

Patients were eligible to receive the accelerated vaccination schedule only if they had no prior immunization for hepatitis A or B and if they had no seroconversion for either hepatitis A or B. Six people had hepatitis B alone, 7 had hepatitis B and C, 1 had hepatitis A and C, and 1 had all 3 (Table 2). Thus, 15 participants were ineligible to receive the accelerated hepatitis A/B immunization. Chi-square, Fisher exact, and independent sample t tests showed that among those who were vaccination-eligible (269), there were no significant differences in any of the demographic or clinical characteristics between those who initiated the vaccination schedule and those who did not. Among those who completed the first 3 vaccine injections, those who received the 1-year booster injection (54) did not differ (on any demographic or clinical variables) from those who did not (58).

Nearly half (48%) of all the eligible patients admitted to the program began the accelerated immunization schedule for hepatitis A and B. Of those, 88% completed the first 3 injections in the series. Among the patients who received the first 3 injections, 48% received the 1-year booster injection—a 20% completion rate for the vaccination-eligible sample overall (Table 3).

Of the 74 patients who did not complete their vaccinations once initiating the accelerated schedule, the most common reason identified was that the patient moved away (37), or no reason could be identified (33). It was uncommon for a patient not to complete the vaccination schedule because of terminating treatment prematurely (4).

Compared with the vaccine-eligible patients without hepatitis C (207), patients with hepatitis C were less likely to receive any vaccination injections (Table 3). Specifically, 51% of the vaccination-eligible patients who did not have hepatitis C began the vaccination regimen. However, only 22 patients with hepatitis C, or

35% of all vaccination-eligible patients with hepatitis C, began the vaccination regimen. Patients with hepatitis C were also less likely than those without hepatitis C to complete the first 3 injections of the vaccination series once they had initiated it (77%, vs 90%, respectively). This difference continued to be apparent at the time of the 12-month booster injection. Only 35% of vaccine-eligible individuals with hepatitis C received the 12-month booster injection, whereas 51% of vaccination-eligible individuals without hepatitis C received the 12-month booster injection. As with the sample overall, the most common reason patients with hepatitis C did not complete the vaccination regimen was because they moved away (9), followed by no identified reason (5), and premature termination of treatment (2).

Discussion

Individuals abusing alcohol and drugs have an increased vulnerability for infectious diseases, and homeless veterans with substance use disorders may be at a particularly heightened risk.21,22 This study describes a sample of veterans, many were homeless and most were dually diagnosed, in an intensive outpatient SATP that offered an accelerated dosing regimen for hepatitis A and B vaccination. Almost half (48%) of the vaccination-eligible patients began the accelerated regimen for hepatitis A/B vaccination. Moreover, 88% of those who started the vaccination regimen received the first 3 injections of the series, thus possibly conferring substantial immunity to hepatitis A and B and demonstrating the feasibility of an accelerated vaccination schedule in an intensive outpatient SATP.

It is especially important to demonstrate the successful integration of a hepatitis screening and immunization program within a SATP, given that many such programs do not offer screening or immunization for hepatitis, even though substance abusers are disproportionately affected by the disease and contribute greatly to the ongoing hepatitis epidemic.10,11 This study’s results were in line with another study of rapid vaccination for hepatitis B in IV drug users being treated in a methadone clinic, where 83% of the vaccination initiators completed the first 3 injections of the series.9

Unvaccinated Patients

The treatment team in the current study seemed to be less effective at reaching the subset of vaccination-eligible veterans with hepatitis C (almost one-quarter of the sample) in order to administer the accelerated vaccination schedule, as indicated by the lower rate of vaccination initiation as well as a lower rate of completion of the vaccination series among those patients. This replicates a finding from another study that also indicated a low rate of hepatitis A and B vaccination among patients with hepatitis C.23 Only 35% of the vaccination-eligible patients with hepatitis C in the current study initiated the vaccination series, compared with 51% of the patients without hepatitis C. However, the rate of completion of the first 3 injections of the series in the hepatitis C group was respectably high (77%), especially given the high relapse rate and psychosocial instability of individuals with addictive disorders. Initiation seems to be a bigger obstacle than completion of at least the first 3 injections of the vaccination series in both patients with and without hepatitis C.

The study investigators did not formally assess the reasons that more than half the patients in the study did not begin the vaccination series, but anecdotal evidence from the nurses indicated that many patients were afraid of needles. In addition, other patients felt that they simply did not need the vaccination. Some also insisted that they had already had the vaccination despite a blood test showing no evidence for either hepatitis A or B immunization.

Although the nursing team provided group and individual risk-based education as well as information about the effects of continued substance abuse on hepatitis C, it is possible that patients still underestimated their own risk of hepatitis infection and its consequences, or perhaps the information was simply not retained.24

Patient Education

A recent study showed that there is a positive relationship between the amount of hepatitis counseling received and knowledge of hepatitis.25 Possibly, increased intensity of education efforts may make an impact on initiation rates. Encouragingly, there is also evidence that prompting people to predict their future vaccination behavior may increase vaccination initiation rates despite a high-degree of short-term barriers, such as perceived pain or inconvenience.26 A brief intervention to induce people to formulate their future intentions would be relatively easy to incorporate into a vaccination program, and the study team is considering options for this to improve vaccination initiation rates.

Patients can expect to achieve substantial immunity from hepatitis A and, to a lesser degree, hepatitis B after completing the first 3 injections of the series, although the best seroprotection from both is obtained by completing the 12-month booster injection as well.17 Overall, about half of all patients who completed the first 3 injections returned for the booster shot, but only 35% of the patients with hepatitis C did so. The most common known cause of any patient not receiving the booster was movement out of the geographic area. However, much of the time the investigators were unable to determine the reasons patients did not return for the booster shot.

Medication adherence is a difficult problem with vaccination in high-risk samples, although Stitzer and colleagues found a significant improvement in follow-up for a 6-month vaccination protocol by using monetary incentives.27 In addition to ensuring medication adherence, it would also be of value for future immunization efforts to include testing to assess whether seroconversion has occurred once the vaccinations are complete, which is the ultimate measure of the success of a vaccination program. Most patients in the current study did not receive such testing at the completion of their vaccination schedules, and thus, seroconversion rates could not be determined. However, existing studies suggest high rates of seroprotection after the first 3 doses of the combined vaccine.10,17

Limitations

The retrospective nature of the study is its most significant limitation. Any conclusions about the results must be made with caution. However, this design allowed for a naturalistic and potentially generalizable investigation into the application of a vaccination program in a real-world treatment setting. As such, the investigators were able to demonstrate the feasibility of conducting a rapid vaccination program within a 3- to 6-week SATP.

The retrospective nature of the study also limited a full investigation into the reasons behind the lack of vaccination initiation and vaccination noncompletion among the study’s treatment population, especially with regard to the follow-up booster injection. Initial statistical comparisons of initiators and noninitiators and completers and noncompleters showed no significant statistical differences between the groups. Future prospective designs should take into account the need to successfully initiate and complete vaccinations for all eligible patients and include assessment measures to determine the specific reasons that patients did not initiate or complete their vaccinations.

Conclusions

Many patients began and completed the accelerated vaccination schedule for hepatitis A and B in the context of a 3- to 6-week SATP at JAHVH. The overall vaccination rate, including the 12-month booster injection, was one-fifth of the entire vaccination-eligible sample. Additionally, 88% of the vaccination-eligible patients who began the vaccination schedule (or 42% of the whole sample) completed at least the first 3 doses, which may confer substantial immunity from hepatitis A and B. For reasons not entirely clear, a little less than half the vaccination-eligible patients began the vaccination schedule, and only about 50% of those returned to receive their 12-month booster injection. Future prospective studies may be able to determine barriers to both the initiation of and adherence to the vaccination protocol.

The results of this study are also a testament to having primary care nursing staff available and actively involved in the care of patients in a SATP. It seems likely that additional interventions might be needed for outreach to and retention of patients in need of vaccination for hepatitis A and B, and particularly those patients with hepatitis C. It is important to find ways to increase the rates of 12-month booster vaccinations, both for veterans who continue to receive services at JAHVH and for those who transfer care to other VA facilities. Finally, testing to confirm serologic immunity to hepatitis A and hepatitis B would be the next step in the effort to eliminate the risk of hepatitis A and hepatitis B and minimize additional harm for those with hepatitis C in the population receiving treatment for addictive disorders.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review the complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

1. Nyamathi A, Liu Y, Marfisee M, et al. Effects of a nurse-managed program on hepatitis A and B vaccine completion among homeless adults. Nurs Res. 2009;58(1):13-22.

2. Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). A comprehensive immunization strategy to eliminate transmission of hepatitis B virus infection in the United States. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2006;55(RR16):1-25.

3. Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), Fiore AE, Wasley A, Bell BP. Prevention of hepatitis A through active or passive immunization: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2006;55(RR07):1-23.

4. Weltman MD, Brotodihardjo A, Crewe EB, et al. Coinfection with hepatitis B and C or B, C and delta viruses results in severe chronic liver disease and responds poorly to interferon-alpha treatment. J Viral Hepat. 1995;2(1):39-45.

5. Groessl EJ, Weingart KR, Kaplan RM, et al. Living with hepatitis C: qualitative interviews with hepatitis C-infected veterans. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(12):1959-1965.

6. Dominitz JA, Boyko EJ, Koepsell TD, et al. Elevated prevalence of hepatitis C infection in users of United States veterans medical centers. Hepatology. 2005;41(1):88-96.

7. Himeloch S, McCarthy JF, Ganoczy D, et al. Understanding associations between serious mental illness and hepatitis C virus among veterans: a national multivariate analysis. Psychosomatics. 2009;50(1):30-37.

8. Hagedorn H, Dieperink E, Dingmann D, et al. Integrating hepatitis prevention services into a substance use disorder clinic. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2007;32(4):391-398.

9. Ramasamy P, Lintzeris N, Sutton Y, Taylor H, Day CA, Haber PS. The outcome of a rapid hepatitis B vaccination programme in a methadone treatment clinic. Addiction. 2010;105(2):329-334.

10. Bini EJ, Kritz S, Brown LS Jr, et al. Hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus services offered by substance abuse treatment programs in the United States. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2012;42(4):438-445.

11. Recommendations for prevention and control of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection and HCV-related chronic disease. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1998;47(RR-19):1-39.

12. Francis E, Gonzales-Nolas CL, Markowitz J, Phillips S. Integration of preventive health screening into mental health clinics. Fed Pract. 2008;25(2):39-50.

13. Vreeland B. Bridging the gap between mental and physical health: a multidisciplinary approach. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68(suppl 4):26-33.

14. Brim N, Zaller N, Taylor LE, Feller E. Twinrix vaccination schedules among injecting drug users. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2007;7(3):379-389.

15. Zuckerman J. The place of accelerated schedules for hepatitis A and B vaccinations. Drugs. 2003;63(17):1779-1784.

16. Connor BA, Blatter MM, Beran J, Zou B, Trofa AF. Rapid and sustained immune response against hepatitis A and B achieved with combined vaccine using an accelerated administration schedule. J Travel Med. 2007;14(1):9-15.

17. Nothdurft HD, Dietrich M, Zuckerman JN, et al. A new accelerated vaccination schedule for rapid protection against hepatitis A and B. Vaccine. 2002;20(7-8):1157-1162.

18. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

19. Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerström KO. The Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence: a revision of the Fagerström Tolerance Questionnaire. Br J Addict. 1991;86(9):1119-1127.

20. McLellan AT, Kushner H, Metzger D, et al. The Fifth Edition of the Addiction Severity Index. J Subst Abuse Treat. 1992;9(3):199-213.

21. Batki SL, Nathan KI. HIV/AIDS and Hepatitis C. In: Galanter M, Kleber HD, Brady KT, eds. The American Psychiatric Publishing Textbook of Substance Abuse Treatment. 5th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2015.

22. Gelberg L, Robertson MJ, Leake B, et al. Hepatitis B among homeless and other impoverished US military veterans in residential care in Los Angeles. Public Health. 2001;115(4):286-291.

23. Felsen UR, Fishbein DA, Litwin AH. Low rates of hepatitis A and B vaccination in patients with chronic hepatitis C at an urban methadone maintenance program. J Addict Dis. 2010;29(4):461-465.

24. Brewer NT, Chapman GB, Gibbons FX, Gerrard M, McCaul KD, Weinstein ND. Meta-analysis of the relationship between risk perception and health behavior: the example of vaccination. Health Psychol. 2007;26(2):136-145.

25. Soto-Salgado M, Suárez E, Ortiz AP, et al. Knowledge of viral hepatitis among Puerto Rican adults: implications for prevention. J Community Health. 2011;36(4):565-573.

26. Cox AD, Cox D, Cyrier R, Graham-Dotson Y, Zimet GD. Can self-prediction overcome barriers to hepatitis B vaccination? A randomized controlled trial. Health Psychol. 2012;31(1):97-105.

27. Stitzer ML, Polk T, Bowles S, Kosten T. Drug users’ adherence to a 6-month vaccination protocol: effects of motivational incentives. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010;107(1):76-79.

1. Nyamathi A, Liu Y, Marfisee M, et al. Effects of a nurse-managed program on hepatitis A and B vaccine completion among homeless adults. Nurs Res. 2009;58(1):13-22.

2. Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). A comprehensive immunization strategy to eliminate transmission of hepatitis B virus infection in the United States. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2006;55(RR16):1-25.

3. Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), Fiore AE, Wasley A, Bell BP. Prevention of hepatitis A through active or passive immunization: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2006;55(RR07):1-23.

4. Weltman MD, Brotodihardjo A, Crewe EB, et al. Coinfection with hepatitis B and C or B, C and delta viruses results in severe chronic liver disease and responds poorly to interferon-alpha treatment. J Viral Hepat. 1995;2(1):39-45.

5. Groessl EJ, Weingart KR, Kaplan RM, et al. Living with hepatitis C: qualitative interviews with hepatitis C-infected veterans. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(12):1959-1965.

6. Dominitz JA, Boyko EJ, Koepsell TD, et al. Elevated prevalence of hepatitis C infection in users of United States veterans medical centers. Hepatology. 2005;41(1):88-96.

7. Himeloch S, McCarthy JF, Ganoczy D, et al. Understanding associations between serious mental illness and hepatitis C virus among veterans: a national multivariate analysis. Psychosomatics. 2009;50(1):30-37.

8. Hagedorn H, Dieperink E, Dingmann D, et al. Integrating hepatitis prevention services into a substance use disorder clinic. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2007;32(4):391-398.

9. Ramasamy P, Lintzeris N, Sutton Y, Taylor H, Day CA, Haber PS. The outcome of a rapid hepatitis B vaccination programme in a methadone treatment clinic. Addiction. 2010;105(2):329-334.

10. Bini EJ, Kritz S, Brown LS Jr, et al. Hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus services offered by substance abuse treatment programs in the United States. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2012;42(4):438-445.

11. Recommendations for prevention and control of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection and HCV-related chronic disease. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1998;47(RR-19):1-39.

12. Francis E, Gonzales-Nolas CL, Markowitz J, Phillips S. Integration of preventive health screening into mental health clinics. Fed Pract. 2008;25(2):39-50.

13. Vreeland B. Bridging the gap between mental and physical health: a multidisciplinary approach. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68(suppl 4):26-33.

14. Brim N, Zaller N, Taylor LE, Feller E. Twinrix vaccination schedules among injecting drug users. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2007;7(3):379-389.

15. Zuckerman J. The place of accelerated schedules for hepatitis A and B vaccinations. Drugs. 2003;63(17):1779-1784.

16. Connor BA, Blatter MM, Beran J, Zou B, Trofa AF. Rapid and sustained immune response against hepatitis A and B achieved with combined vaccine using an accelerated administration schedule. J Travel Med. 2007;14(1):9-15.

17. Nothdurft HD, Dietrich M, Zuckerman JN, et al. A new accelerated vaccination schedule for rapid protection against hepatitis A and B. Vaccine. 2002;20(7-8):1157-1162.

18. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.