User login

Locking Plate Fixation for Proximal Humerus Fractures

4 EKG Abnormalities: What Are the Lifesaving Diagnoses?

› Consider placement of an automatic implantable cardioverter-defibrillator for all patients with a type 1 Brugada pattern on EKG accompanied by syncope, documented ventricular arrhythmia, or aborted sudden cardiac death. B

› Always look for EKG findings suggestive of Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome in otherwise healthy patients presenting with syncope. C

› Refer all patients with suspected hypertrophic cardiomyopathy to Cardiology for a transthoracic echocardiogram. B

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

When evaluating a patient with a history of chest pain, palpitations, syncope, and/or new-onset seizures, an electrocardiogram (EKG) may be the key to

identifying a potentially life-threatening condition. Here we present 4 cases in which EKG findings were the clue to underlying medical conditions that, if left untreated, could be fatal. Because each of these conditions may not have associated findings on a physical exam, early recognition of these EKG findings can be lifesaving.

CASE 1 › A 15-year-old boy suddenly collapses while walking, and bystanders report seizure-like activity. The patient doesn’t remember the event. Vital signs and physical exam are normal, and his blood glucose level is 86 mg/dL (normal: 70-100 mg/dL). He doesn’t take any medications and denies illicit drug use or recent illness.

What EKG abnormality (FIGURE 1) likely explains the cause of the patient’s collapse?

The EKG abnormality and diagnosis. The patient’s EKG revealed a prolonged QT interval (FIGURE 1, BRACKETS). His QTc (QT interval corrected for heart rate) was .470 seconds, which is at the high end of the normal range for his age and gender.1 The patient had no family history of syncope, sudden cardiac death (SCD), or seizure disorder. Evaluation uncovered a calcium level of 4.4 mEq/L (normal: 4.5-5.5 mEq/L) and a phosphate level of 7.8 mg/dL (normal: 2.4-4.1 mg/dL).

This patient had a low parathyroid hormone from primary hypoparathyroidism. His conduction abnormality was treated with both oral calcium and vitamin D supplements.

Etiology and epidemiology. A prolonged QT interval may be the result of a primary long QT syndrome (LQTS) or an acquired condition from electrolyte imbalance, medication effect, or toxin exposure.

In the United States, the incidence of a genetic mutation that causes LQTS is 1 in 2500 people.2 Patients with LQTS usually remain asymptomatic unless the QT interval is further prolonged by a condition or medication. There are several hundred congenital LQTS subtypes based on specific ion channel defects; the most common is LQTS1, with an inherited defect in the KCNQ1 gene, which regulates the slow potassium ion channel.

Acquired LQTS is much more common than congenital LQTS.3 Many drugs have been linked to an increased risk of LQTS, including certain antiarrhythmics, antibiotics, and antipsychotics (TABLE 1).4 In addition, electrolyte disturbances such as hypokalemia, hypocalcemia, and hypomagnesemia can be etiologic factors.

Be aware that an acquired LQTS may mask an underlying congenital LQTS. Therefore, patients in whom the offending agent or condition is corrected should still have a follow-up EKG. Screening family members for LQTS is worthwhile, even in those without symptoms.

Clinical features. Patients with symptomatic LQTS may have dizziness, palpitations, and syncope. SCD also is possible. These signs and symptoms may be triggered by strong emotions (in LQTS2) or physical activity (in LQTS1). They likely are caused by torsades de pointes and ventricular fibrillation. A brief aura may precede these arrhythmias, and patients may experience urinary or fecal incontinence.5

The key to making a diagnosis of LQTS is correctly measuring the QT interval. The QT interval is measured from the beginning of the Q-wave to the end of the T-wave as measured from the intersection of a line tangent to the downslope of the T-wave and the isoelectric line. This can be difficult to determine in EKGs showing bundle branch block or an irregular rhythm, such as atrial fibrillation (AF).6,7 A common error in measuring the QT interval occurs when clinicians inadvertently include a U-wave in the measurement.1 Some EKG machines may provide QT interval and QTc measurements. Normal QT intervals are ≤.450 seconds for men and ≤.470 seconds for women.8

It is essential to confirm the QT interval by using the Bazett formula (QTc equals the QT in seconds divided by the square root of the RR interval in seconds) for all patients with a history that suggests a possible arrhythmia.

Our patient had hypocalcemia, which on an EKG can cause T-wave widening with a normal ST segment, rather than a normal T-wave with a long ST segment, as is typically seen in LQTS. This distinction may be difficult to discern and should not preclude the search for either an acquired prolonged QTc or an underlying LQTS.9

Treatment. First rule out or treat any causes of acquired LQTS by taking a careful medication history and evaluating the patient’s electrolytes. Once these have been addressed, a beta-blocker is first-line therapy for symptomatic patients.5

Unfortunately, up to 20% of individuals treated with beta-blockers may continue to have syncope.5 For these patients, options include a left cardiac sympathetic denervation (LCSD) or placement of an automatic implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (AICD). An LCSD involves removal of the left-sided stellate and/or thoracic ganglia. This procedure can be used instead of, or in addition to, beta-blockers. If the patient’s syncope persists, AICDs are an option. AICDs can be lifesaving, but patients run the risk of adverse effects that include inappropriate shocks and infection.10 As the result of these therapies, mortality associated with LQTS has dropped to approximately 1%.11

CASE 2 › A 14-year-old boy has a syncopal episode while at rest. A similar event occurred 3 years earlier; at that time, an echocardiogram and EKG were normal. For 2 days, he’s had a cough and low-grade fever. His temperature is 102ºF and he has a productive cough. Based on this EKG (FIGURE 2), what is the likely diagnosis? What is the significance of his fever?

The EKG abnormality and diagnosis. This patient’s EKG showed a type 1 Brugada pattern (FIGURE 2, ARROWS), which strongly supported the diagnosis of Brugada syndrome (BS). BS is an inherited condition caused by a genetic defect in cardiac ion channel function that leads to characteristic EKG changes and a predisposition to ventricular fibrillation.12 In this case, the fever likely unmasked these EKG findings.

The patient was transferred to a local hospital for treatment of community-acquired pneumonia, and ultimately received an AICD.

Etiology and epidemiology. BS was first described in 199213 and is a major cause of SCD, responsible for up to 4% of all cases of SCD, and 20% of cases of patients without structural heart disease.14 BS is more common in men, and the mean age of diagnosis is 40 to 45.15-18

Mutations in at least 17 cardiac ion channel genes have been linked to BS.19 The SCN5A gene—a cardiac sodium channel—is the most commonly implicated, but accounts for only 11% to 24% of all BS cases.15

Clinical features. Patients with BS may present with syncope, nocturnal agonal respirations, or ventricular arrhythmias.12 EKG findings include partial or complete right bundle branch block (RBBB) and ST segment elevation in right precordial leads V1 to V3.12 There are 2 Brugada EKG patterns, a type 1 cloved pattern as seen in our patient’s EKG and a type 2 saddleback pattern.20 EKG findings are dynamic over time and may alternate between normal, type 1, and type 2.20 Factors that modulate EKG appearance include fever, intoxication, vagal tone, electrolyte imbalance, and sodium channel blockade.12,20

Diagnosis requires a type 1 Brugada pattern on EKG plus a family history of BS, documented ventricular arrhythmia, or arrhythmia-related symptoms such as syncope.12 Patients with a type 2 Brugada pattern may undergo electrophysiology (EP) testing with Class I antiarrhythmic drugs to induce a diagnostic type 1 Brugada pattern.12,21 Patients who have Brugada EKG findings but none of the other diagnostic criteria are considered to have a Brugada pattern (rather than Brugada syndrome).12

The most concerning outcome of BS is ventricular fibrillation. The estimated annual rate of cardiac events is 7.7% among patients who have experienced an aborted SCD, 1.9% among those who have experienced syncope, and 0.5% in asymptomatic patients.18

Treatment. The only effective treatment for BS is placement of an AICD; however, complications of AICD placement cause significant morbidity.6 Ten years after AICD placement, 37% of patients experienced inappropriate shocks and 29% experienced lead failure.22 Recent modifications in device programming and the addition of remote monitoring have decreased complication rates.12,22

The decision to place an AICD is based on the patient’s prior symptoms, EKG findings, and other factors. Recent guidelines recommend an AICD for all patients with a type 1 Brugada pattern (spontaneous or induced) who also have had an aborted SCD, syncope, or documented ventricular arrhythmia.12

Management of asymptomatic patients with type 1 Brugada pattern remains controversial because the rate of cardiac events is low, although such events can be fatal. Asymptomatic patients with type 1 Brugada findings should undergo further EP testing, and should receive AICD only upon demonstration of inducible ventricular arrhythmia.12

TABLE 2

Arrhythmias associated with Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome23

| Arrhythmia | EKG findings | Treatment—unstable patients | Treatment—stable patients (in preferred treatment order) |

| PSVT, orthodromic | Narrow QRS, loss of delta wave, rate 160-260 beats/min | Synchronized cardioversion | Vagal maneuvers, adenosine, calcium channel blockers, beta-blockers, digoxin, procainamide |

| PSVT, antidromic | Wide complex tachycardia | Synchronized cardioversion | Procainamide |

| Atrial fibrillation | Irregularly irregular (RR interval variable with no pattern), ventricular rates that can exceed 300 beats/min | Synchronized cardioversion | Synchronized cardioversion, procainamide |

| Atrial flutter | Flutter waves, rate normal to tachycardic depending on conduction rate | Synchronized cardioversion | Synchronized cardioversion, procainamide |

| Ventricular fibrillation | Rapid, erratic electrical impulses | Defibrillation | N/A |

EKG, electrocardiogram; N/A, not applicable; PSVT, paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia.

CASE 3 › A 21-year-old man with no medical history presents with sudden onset of lightheadedness followed by syncope. He denies any chest pain or other associated symptoms. At the time of evaluation, he is asymptomatic. His EKG (FIGURE 3) is diagnostic of what syndrome?

The EKG abnormality and diagnosis. The patient had a classic presentation for Wolff-Parkinson-White (WPW) syndrome, a common congenital disorder that alters normal cardiac conduction. He described 2 past instances of unexplained light-headedness and palpitations. Subsequent EP studies demonstrated that the patient had an accessory atrioventricular (AV) tract, causing electrical activity in the heart to bypass the AV node, resulting in a delta wave on EKG (FIGURE 3, GREEN ARROWS).

The patient opted for ablation therapy, which successfully eliminated the delta wave on EKG. Five years later he has had no recurrences.

Epidemiology. The prevalence of WPW syndrome is .1% to 3%.23 Accessory AV tracts are found in men twice as often as in women. Only half of individuals with confirmed tracts develop a tachyarrhythmia. The estimated risk of sudden death due to WPW syndrome is .5% to 4%.24

Pathophysiology. Normally cardiac conduction originates from the sinus node and travels to the AV node, where conduction is slowed, and then proceeds to the His-Purkinje system, and finally to the rest of the ventricular myocardium. In WPW syndrome, ventricular depolarization occurs first by an accessory AV tract called the bundle of Kent, followed shortly thereafter by the His-Purkinje system. This sequence of depolarization is what leads to the EKG findings characteristic of WPW syndrome: a PR interval <.12 seconds, presence of a delta wave, widened QRS complex (>.12 seconds), and repolarization changes seen as ST segment and T-wave changes discordant to (opposite direction) the delta wave and QRS complex (FIGURE 3, RED ARROW).

Factors that influence electrical conduction through the bundle of Kent include cardioactive medications, physiological stress, circulating catecholamines, coronary ischemia, and aging. The end result is a propensity for the heart to convert to one of 4 arrhythmias: paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia (PSVT), AF, atrial flutter, or ventricular fibrillation (TABLE 2).23

The most common arrhythmia in WPW syndrome is PSVT.23 This rhythm is induced by the formation of a reentry circuit—a pattern in which the heart’s electrical signal loops back on itself—involving the normal conduction pathway and the bundle of Kent. Reentry progressing down the His-Purkinje system and traveling up the bundle of Kent is referred to as orthodromic (anterograde) PSVT. Antidromic (retrograde) PSVT is due to a reentry circuit conducting from the bundle of Kent to the ventricles, and then retrograde through the His-Purkinje system and AV node to the atria.

Clinical features. Under normal circumstances, patients with WPW syndrome are asymptomatic. As was the case with our patient, individuals who develop one of the 4 characteristic arrhythmias can experience light-headedness and syncope.

Treatment. An unstable patient who is experiencing PSVT, AF, or atrial flutter should receive synchronized cardioversion; those experiencing ventricular fibrillation should receive defibrillation (TABLE 2).23 For stable patients, therapy is tailored to the type of arrhythmia. Calcium channel blockers, beta-blockers, and adenosine might be appropriate for patients with orthodromic PSVT but should be avoided in patients with antidromic PSVT, AF, or atrial flutter because these medications block AV node conduction and thus facilitate conduction down the bundle of Kent, which can result in potentially unstable arrhythmias. In general, the longer an arrhythmia has been present, the less effective the pharmacologic intervention because of the increasing sympathetic tone.

Preventive long-term therapies for WPW patients who have experienced arrhythmia include antiarrhythmic medications or ablative procedures. Long-term antiarrhythmic therapy often is reserved for older, more sedentary individuals with less frequent arrhythmias that are not life-threatening. Radiofrequency ablation is a popular option, with long-term success rates as high as 95% and complication rates <1%.23 Patients in whom a WPW pattern is identified incidentally on EKG should be referred to cardiology for EP studies and risk stratification.25

CASE 4 › A 61-year-old woman has an episode of substernal exertional chest pressure that lasted approximately 2 hours but resolved before she arrived at her physician’s office. She also experienced mild nausea. She has no history of coronary artery disease but says that she has experienced similar episodes of chest pressure. What abnormality is seen on her EKG (FIGURE 4)? What is the most likely cause of her symptoms?

The EKG abnormality and diagnosis. Although classically associated with syncope, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) often presents similarly to acute coronary syndromes, with chest pain and dyspnea on exertion.26 This patient had no history of cardiac disease or family history of SCD or cardiomyopathy; however, her EKG showed changes indicating left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH), which is consistent with HCM (FIGURE 4, ARROWS). Echocardiography identified myocardial hypertrophy, normal left ventricular ejection fraction, but severe left ventricular outflow obstruction and mild diastolic dysfunction. She was treated with metoprolol and verapamil.

Etiology and epidemiology. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy is an autosomal dominant intrinsic myocardial disorder resulting in LVH that is commonly associated with SCD during extreme physical activity.26,27 The prevalence of HCM is approximately 1 in 500.26 Although it can present at any age, it is the most common cause of SCD in young people (under age 30), responsible for 33% of deaths during athletic events.28

TABLE 3

4 diagnoses and what you'll see on EKG

| Diagnosis | EKG finding |

| Prolonged QT interval | QTc interval >.450 sec (men) or >.470 sec (women) |

| Brugada syndrome | Partial or complete RBBB, and ST segment elevation in right precordial leads V1-V3 |

| Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome | Delta wave, widened QRS, short PR interval, ST segment and T-wave changes |

| Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy | No definitive finding; may have left ventricular hypertrophy or abnormal Q-waves |

EKG, electrocardiogram; RBBB, right bundle branch block.

Clinical features. The severity of HCM ranges from asymptomatic to fatal. Symptoms of HCM include chest pain, dyspnea, and syncope. The disorder causes morbidity and mortality in at least one of 3 ways: ventricular tachyarrhythmias (often in younger patients), heart failure (from left ventricular outflow obstruction), and/or thromboembolism.27

Although echocardiography typically is used to make the diagnosis,27 an EKG often is the initial screening tool. EKG changes are seen in 75% to 95% of affected patients and include the presence of Q-waves and increased voltages related to LVH.27,29 Infarct-like patterns may be present before wall thickening on echocardiogram. Abnormal Q-waves are found in 20% to 50% of HCM patients, and are more common in younger patients. Konno et al30 have shown that Q-waves >3 mm in depth and/or >.040 seconds in duration in at least 2 leads other than aVR is specific (90%) in identifying carriers of HCM genes before they develop clinical symptoms.

Ambulatory monitoring may be useful for risk stratifying HCM patients; those with nonsustained ventricular tachycardia (NSVT) are at higher risk of SCD. Holter monitoring is recommended in initial evaluation because evidence of ventricular tachyarrhythmias may warrant AICD placement.26

Treatment. The risk of SCD in HCM is approximately 1%, but higher in those with a family history of SCD, syncope, NSVT, hypotension during exercise, or severe LVH (left ventricle thickness >30 mm).26 AICDs are recommended for HCM patients with prior cardiac arrest, patients with ≥2 of these risk factors, or patients with one risk factor who have experienced syncope related to arrhythmia.26

For patients who are symptomatic but have <2 risk factors, beta-blockers are firstline therapy.26 Verapamil is used as a second line treatment. Both beta-blockers and calcium channel blockers reduce dyspnea, palpitations, and chest pain.27

For patients who don’t respond to medical therapy, septal reduction therapy may be performed, either by septal myectomy or alcohol septal ablation.27 It is also important to consider genetic screening and counseling for the family.

A summary of all 4 diagnoses described in this article, their associated EKG findings, and their pathophysiology appears in TABLE 3.

CORRESPONDENCE

Samir Haydar, DO, MPH, FACEP, Tufts University School of Medicine, Maine Medical Center, Department of Emergency Medicine, 47 Bramhall St., Portland, ME 04103; [email protected]

1. Taggart NW, Haglund CM, Tester DJ, et al. Diagnostic miscues in congenital long-QT syndrome. Circulation. 2007;115:2613-2620.

2. Schwartz PJ, Stramba-Badiale M, Crotti L, et al. Prevalance of the congenital long QT syndrome. Circulation. 2009;120:1761-1767.

3. van Noord C, Eijgelsheim M, Stricker BH. Drug- and nondrug-associated QT interval prolongation. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2010;70:16-23.

4. Credible Meds Web site. Available at: http://crediblemeds.org. Accessed April 8, 2014.

5. Schwartz PJ, Priori SG, Spazzolini C, et al. Genotype-phenotype correlation in the long QT syndrome: gene specific triggers for life threatening arrhythmias. Circulation. 2001;103:89.

6. Chiladakis JK, Kalogeropoulos A, Koutsogiannis N, et al. Optimal QT/JT interval assessment in patients with complete bundle branch block. Ann Noninvasive Electrocardiol. 2012;17:268-276.

7. Ercan S, Altunbas G, Oylumlu M, et al. Congenital long QT syndrome masked by atrial fibrillation and unmasked by hypokalemia. Am J Emerg Med. 2013;31:451.e3-451.e6.

8. Goldenberg I, Moss AJ, Zareba W. QT interval: how to measure it and what is “normal.” J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2006;17:333-336.

9. Podrid PJ. ECG Response: August 20, 2013. Circulation. 2013;128:869.

10. Olde Nordkamp LR, Wilde AA, Tijssen JG, et al. The ICD for primary prevention in patients with inherited cardiac diseases: indications, use, and outcome: a comparison with secondary prevention. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2013;6:91-100.

11. Schwartz PJ. Pharmacological and non-pharmacological management of the congenital long QT syndrome: the rationale. Pharmacol Ther. 2011;131:171-177.

12. Berne P, Brugada J. Brugada syndrome 2012. Circ J. 2012;76:1563-1571.

13. Brugada P, Brugada J. Right bundle branch block, persistent ST segment elevation and sudden cardiac death: a distinct clinical and electrocardiographic syndrome. A multicenter report. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1992;20:1391-1396.

14. Antzelevitch C, Brugada P, Borggrefe M, et al. Brugada syndrome: report of the second consensus conference: endorsed by the Heart Rhythm Society and the European Heart Rhythm Association. Circulation. 2005;111:659-670.

15. Brugada J, Brugada R, Antzelevitch C, et al. Long-term followup of individuals with the electrocardiographic pattern of right bundle-branch block and ST-segment elevation in precordial leads V1 to V3. Circulation. 2002;105:73-78.

16. Eckardt L, Probst V, Smits JP, et al. Long-term prognosis of individuals with right precordial ST-segment-elevation Brugada syndrome. Circulation. 2005;111:257-263.

17. Giustetto C, Drago S, Demarchi PG, et al; Italian Association of Arrhythmology and Cardiostimulation (AIAC)-Piedmont Section. Risk stratification of the patients with Brugada type electrocardiogram: a community-based prospective study. Europace. 2009;11:507-513.

18. Probst V, Veltmann C, Eckardt L, et al. Long-term prognosis of patients diagnosed with Brugada syndrome: Results from the FINGER Brugada Syndrome Registry. Circulation. 2010;121:635-643.

19. Nielsen MW, Holst AG, Olesen SP, et al. The genetic component of Brugada syndrome. Front Physiol. 2013;4:179.

20. Bayés de Luna A, Brugada J, Baranchuk A, et al. Current electrocardiographic criteria for diagnosis of Brugada pattern: a consensus report. J Electrocardiol. 2012;45:433-442.

21. Veltmann C, Schimpf R, Echternach C, et al. A prospective study on spontaneous fluctuations between diagnostic and non-diagnostic ECGs in Brugada syndrome: implications for correct phenotyping and risk stratification. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:2544-2552.

22. Sacher F, Probst V, Maury P, et al. Outcome after implantation of a cardioverter-defibrillator in patients with Brugada syndrome: a multicenter study-part 2. Circulation. 2013;128:1739-1747.

23. Rosner MH, Brady WJ Jr, Kefer MP, et al. Electrocardiography in the patient with the Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome: diagnostic and initial therapeutic issues. Am J Emerg Med. 1999;17:705-714.

24. Keating L, Morris FP, Brady WJ. Electrocardiographic features of Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome. Emerg Med J. 2003;20:491-493.

25. Blomström-Lundqvist C, Scheinman MM, Aliot EM, et al; European Society of Cardiology Committee, NASPE-Heart Rhythm Society. ACC/AHA/ESC guidelines for the management of patients with supraventricular arrhythmias—executive summary. A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the European Society of Cardiology Committee for Practice Guidelines (writing committee to develop guidelines for the management of patients with supraventricular arrhythmias) developed in collaboration with NASPE-Heart Rhythm Society. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42:1493-1531.

26. Ho CY. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in 2012. Circulation. 2012;125:1432-1438.

27. Gersh BJ, Maron BJ, Bonow RO, et al; American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines; American Association for Thoracic Surgery; American Society of Echocardiography; American Society of Nuclear Cardiology; Heart Failure Society of America; Heart Rhythm Society; Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions; Society of Thoracic Surgeons. 2011 ACCF/AHA guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2011;124:e783-e831.

28. Paterick TE, Jan MF, Paterick ZR, et al. Cardiac evaluation of collegiate student athletes: a medical and legal perspective. Am J Med. 2012;125:742-752.

29. Maron BJ. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. In: Bonow RO, Mann DL, Zipes DP, et al (eds). Braunwald’s Heart Disease: A Textbook of Cardiovascular Medicine. 9th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2011:1582-1594.

30. Konno T, Shimizu M, Ino H, et al. Diagnostic value of abnormal Q waves for identification of preclinical carriers of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy based on molecular genetic diagnosis. Eur Heart J. 2004;25:246-251.

› Consider placement of an automatic implantable cardioverter-defibrillator for all patients with a type 1 Brugada pattern on EKG accompanied by syncope, documented ventricular arrhythmia, or aborted sudden cardiac death. B

› Always look for EKG findings suggestive of Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome in otherwise healthy patients presenting with syncope. C

› Refer all patients with suspected hypertrophic cardiomyopathy to Cardiology for a transthoracic echocardiogram. B

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

When evaluating a patient with a history of chest pain, palpitations, syncope, and/or new-onset seizures, an electrocardiogram (EKG) may be the key to

identifying a potentially life-threatening condition. Here we present 4 cases in which EKG findings were the clue to underlying medical conditions that, if left untreated, could be fatal. Because each of these conditions may not have associated findings on a physical exam, early recognition of these EKG findings can be lifesaving.

CASE 1 › A 15-year-old boy suddenly collapses while walking, and bystanders report seizure-like activity. The patient doesn’t remember the event. Vital signs and physical exam are normal, and his blood glucose level is 86 mg/dL (normal: 70-100 mg/dL). He doesn’t take any medications and denies illicit drug use or recent illness.

What EKG abnormality (FIGURE 1) likely explains the cause of the patient’s collapse?

The EKG abnormality and diagnosis. The patient’s EKG revealed a prolonged QT interval (FIGURE 1, BRACKETS). His QTc (QT interval corrected for heart rate) was .470 seconds, which is at the high end of the normal range for his age and gender.1 The patient had no family history of syncope, sudden cardiac death (SCD), or seizure disorder. Evaluation uncovered a calcium level of 4.4 mEq/L (normal: 4.5-5.5 mEq/L) and a phosphate level of 7.8 mg/dL (normal: 2.4-4.1 mg/dL).

This patient had a low parathyroid hormone from primary hypoparathyroidism. His conduction abnormality was treated with both oral calcium and vitamin D supplements.

Etiology and epidemiology. A prolonged QT interval may be the result of a primary long QT syndrome (LQTS) or an acquired condition from electrolyte imbalance, medication effect, or toxin exposure.

In the United States, the incidence of a genetic mutation that causes LQTS is 1 in 2500 people.2 Patients with LQTS usually remain asymptomatic unless the QT interval is further prolonged by a condition or medication. There are several hundred congenital LQTS subtypes based on specific ion channel defects; the most common is LQTS1, with an inherited defect in the KCNQ1 gene, which regulates the slow potassium ion channel.

Acquired LQTS is much more common than congenital LQTS.3 Many drugs have been linked to an increased risk of LQTS, including certain antiarrhythmics, antibiotics, and antipsychotics (TABLE 1).4 In addition, electrolyte disturbances such as hypokalemia, hypocalcemia, and hypomagnesemia can be etiologic factors.

Be aware that an acquired LQTS may mask an underlying congenital LQTS. Therefore, patients in whom the offending agent or condition is corrected should still have a follow-up EKG. Screening family members for LQTS is worthwhile, even in those without symptoms.

Clinical features. Patients with symptomatic LQTS may have dizziness, palpitations, and syncope. SCD also is possible. These signs and symptoms may be triggered by strong emotions (in LQTS2) or physical activity (in LQTS1). They likely are caused by torsades de pointes and ventricular fibrillation. A brief aura may precede these arrhythmias, and patients may experience urinary or fecal incontinence.5

The key to making a diagnosis of LQTS is correctly measuring the QT interval. The QT interval is measured from the beginning of the Q-wave to the end of the T-wave as measured from the intersection of a line tangent to the downslope of the T-wave and the isoelectric line. This can be difficult to determine in EKGs showing bundle branch block or an irregular rhythm, such as atrial fibrillation (AF).6,7 A common error in measuring the QT interval occurs when clinicians inadvertently include a U-wave in the measurement.1 Some EKG machines may provide QT interval and QTc measurements. Normal QT intervals are ≤.450 seconds for men and ≤.470 seconds for women.8

It is essential to confirm the QT interval by using the Bazett formula (QTc equals the QT in seconds divided by the square root of the RR interval in seconds) for all patients with a history that suggests a possible arrhythmia.

Our patient had hypocalcemia, which on an EKG can cause T-wave widening with a normal ST segment, rather than a normal T-wave with a long ST segment, as is typically seen in LQTS. This distinction may be difficult to discern and should not preclude the search for either an acquired prolonged QTc or an underlying LQTS.9

Treatment. First rule out or treat any causes of acquired LQTS by taking a careful medication history and evaluating the patient’s electrolytes. Once these have been addressed, a beta-blocker is first-line therapy for symptomatic patients.5

Unfortunately, up to 20% of individuals treated with beta-blockers may continue to have syncope.5 For these patients, options include a left cardiac sympathetic denervation (LCSD) or placement of an automatic implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (AICD). An LCSD involves removal of the left-sided stellate and/or thoracic ganglia. This procedure can be used instead of, or in addition to, beta-blockers. If the patient’s syncope persists, AICDs are an option. AICDs can be lifesaving, but patients run the risk of adverse effects that include inappropriate shocks and infection.10 As the result of these therapies, mortality associated with LQTS has dropped to approximately 1%.11

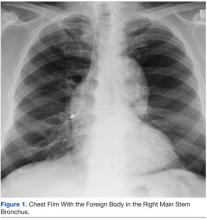

CASE 2 › A 14-year-old boy has a syncopal episode while at rest. A similar event occurred 3 years earlier; at that time, an echocardiogram and EKG were normal. For 2 days, he’s had a cough and low-grade fever. His temperature is 102ºF and he has a productive cough. Based on this EKG (FIGURE 2), what is the likely diagnosis? What is the significance of his fever?

The EKG abnormality and diagnosis. This patient’s EKG showed a type 1 Brugada pattern (FIGURE 2, ARROWS), which strongly supported the diagnosis of Brugada syndrome (BS). BS is an inherited condition caused by a genetic defect in cardiac ion channel function that leads to characteristic EKG changes and a predisposition to ventricular fibrillation.12 In this case, the fever likely unmasked these EKG findings.

The patient was transferred to a local hospital for treatment of community-acquired pneumonia, and ultimately received an AICD.

Etiology and epidemiology. BS was first described in 199213 and is a major cause of SCD, responsible for up to 4% of all cases of SCD, and 20% of cases of patients without structural heart disease.14 BS is more common in men, and the mean age of diagnosis is 40 to 45.15-18

Mutations in at least 17 cardiac ion channel genes have been linked to BS.19 The SCN5A gene—a cardiac sodium channel—is the most commonly implicated, but accounts for only 11% to 24% of all BS cases.15

Clinical features. Patients with BS may present with syncope, nocturnal agonal respirations, or ventricular arrhythmias.12 EKG findings include partial or complete right bundle branch block (RBBB) and ST segment elevation in right precordial leads V1 to V3.12 There are 2 Brugada EKG patterns, a type 1 cloved pattern as seen in our patient’s EKG and a type 2 saddleback pattern.20 EKG findings are dynamic over time and may alternate between normal, type 1, and type 2.20 Factors that modulate EKG appearance include fever, intoxication, vagal tone, electrolyte imbalance, and sodium channel blockade.12,20

Diagnosis requires a type 1 Brugada pattern on EKG plus a family history of BS, documented ventricular arrhythmia, or arrhythmia-related symptoms such as syncope.12 Patients with a type 2 Brugada pattern may undergo electrophysiology (EP) testing with Class I antiarrhythmic drugs to induce a diagnostic type 1 Brugada pattern.12,21 Patients who have Brugada EKG findings but none of the other diagnostic criteria are considered to have a Brugada pattern (rather than Brugada syndrome).12

The most concerning outcome of BS is ventricular fibrillation. The estimated annual rate of cardiac events is 7.7% among patients who have experienced an aborted SCD, 1.9% among those who have experienced syncope, and 0.5% in asymptomatic patients.18

Treatment. The only effective treatment for BS is placement of an AICD; however, complications of AICD placement cause significant morbidity.6 Ten years after AICD placement, 37% of patients experienced inappropriate shocks and 29% experienced lead failure.22 Recent modifications in device programming and the addition of remote monitoring have decreased complication rates.12,22

The decision to place an AICD is based on the patient’s prior symptoms, EKG findings, and other factors. Recent guidelines recommend an AICD for all patients with a type 1 Brugada pattern (spontaneous or induced) who also have had an aborted SCD, syncope, or documented ventricular arrhythmia.12

Management of asymptomatic patients with type 1 Brugada pattern remains controversial because the rate of cardiac events is low, although such events can be fatal. Asymptomatic patients with type 1 Brugada findings should undergo further EP testing, and should receive AICD only upon demonstration of inducible ventricular arrhythmia.12

TABLE 2

Arrhythmias associated with Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome23

| Arrhythmia | EKG findings | Treatment—unstable patients | Treatment—stable patients (in preferred treatment order) |

| PSVT, orthodromic | Narrow QRS, loss of delta wave, rate 160-260 beats/min | Synchronized cardioversion | Vagal maneuvers, adenosine, calcium channel blockers, beta-blockers, digoxin, procainamide |

| PSVT, antidromic | Wide complex tachycardia | Synchronized cardioversion | Procainamide |

| Atrial fibrillation | Irregularly irregular (RR interval variable with no pattern), ventricular rates that can exceed 300 beats/min | Synchronized cardioversion | Synchronized cardioversion, procainamide |

| Atrial flutter | Flutter waves, rate normal to tachycardic depending on conduction rate | Synchronized cardioversion | Synchronized cardioversion, procainamide |

| Ventricular fibrillation | Rapid, erratic electrical impulses | Defibrillation | N/A |

EKG, electrocardiogram; N/A, not applicable; PSVT, paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia.

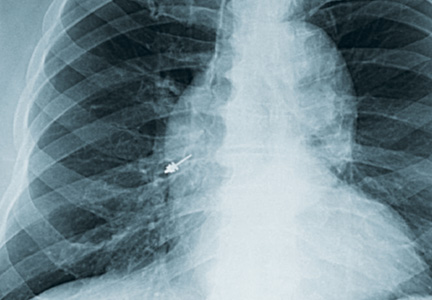

CASE 3 › A 21-year-old man with no medical history presents with sudden onset of lightheadedness followed by syncope. He denies any chest pain or other associated symptoms. At the time of evaluation, he is asymptomatic. His EKG (FIGURE 3) is diagnostic of what syndrome?

The EKG abnormality and diagnosis. The patient had a classic presentation for Wolff-Parkinson-White (WPW) syndrome, a common congenital disorder that alters normal cardiac conduction. He described 2 past instances of unexplained light-headedness and palpitations. Subsequent EP studies demonstrated that the patient had an accessory atrioventricular (AV) tract, causing electrical activity in the heart to bypass the AV node, resulting in a delta wave on EKG (FIGURE 3, GREEN ARROWS).

The patient opted for ablation therapy, which successfully eliminated the delta wave on EKG. Five years later he has had no recurrences.

Epidemiology. The prevalence of WPW syndrome is .1% to 3%.23 Accessory AV tracts are found in men twice as often as in women. Only half of individuals with confirmed tracts develop a tachyarrhythmia. The estimated risk of sudden death due to WPW syndrome is .5% to 4%.24

Pathophysiology. Normally cardiac conduction originates from the sinus node and travels to the AV node, where conduction is slowed, and then proceeds to the His-Purkinje system, and finally to the rest of the ventricular myocardium. In WPW syndrome, ventricular depolarization occurs first by an accessory AV tract called the bundle of Kent, followed shortly thereafter by the His-Purkinje system. This sequence of depolarization is what leads to the EKG findings characteristic of WPW syndrome: a PR interval <.12 seconds, presence of a delta wave, widened QRS complex (>.12 seconds), and repolarization changes seen as ST segment and T-wave changes discordant to (opposite direction) the delta wave and QRS complex (FIGURE 3, RED ARROW).

Factors that influence electrical conduction through the bundle of Kent include cardioactive medications, physiological stress, circulating catecholamines, coronary ischemia, and aging. The end result is a propensity for the heart to convert to one of 4 arrhythmias: paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia (PSVT), AF, atrial flutter, or ventricular fibrillation (TABLE 2).23

The most common arrhythmia in WPW syndrome is PSVT.23 This rhythm is induced by the formation of a reentry circuit—a pattern in which the heart’s electrical signal loops back on itself—involving the normal conduction pathway and the bundle of Kent. Reentry progressing down the His-Purkinje system and traveling up the bundle of Kent is referred to as orthodromic (anterograde) PSVT. Antidromic (retrograde) PSVT is due to a reentry circuit conducting from the bundle of Kent to the ventricles, and then retrograde through the His-Purkinje system and AV node to the atria.

Clinical features. Under normal circumstances, patients with WPW syndrome are asymptomatic. As was the case with our patient, individuals who develop one of the 4 characteristic arrhythmias can experience light-headedness and syncope.

Treatment. An unstable patient who is experiencing PSVT, AF, or atrial flutter should receive synchronized cardioversion; those experiencing ventricular fibrillation should receive defibrillation (TABLE 2).23 For stable patients, therapy is tailored to the type of arrhythmia. Calcium channel blockers, beta-blockers, and adenosine might be appropriate for patients with orthodromic PSVT but should be avoided in patients with antidromic PSVT, AF, or atrial flutter because these medications block AV node conduction and thus facilitate conduction down the bundle of Kent, which can result in potentially unstable arrhythmias. In general, the longer an arrhythmia has been present, the less effective the pharmacologic intervention because of the increasing sympathetic tone.

Preventive long-term therapies for WPW patients who have experienced arrhythmia include antiarrhythmic medications or ablative procedures. Long-term antiarrhythmic therapy often is reserved for older, more sedentary individuals with less frequent arrhythmias that are not life-threatening. Radiofrequency ablation is a popular option, with long-term success rates as high as 95% and complication rates <1%.23 Patients in whom a WPW pattern is identified incidentally on EKG should be referred to cardiology for EP studies and risk stratification.25

CASE 4 › A 61-year-old woman has an episode of substernal exertional chest pressure that lasted approximately 2 hours but resolved before she arrived at her physician’s office. She also experienced mild nausea. She has no history of coronary artery disease but says that she has experienced similar episodes of chest pressure. What abnormality is seen on her EKG (FIGURE 4)? What is the most likely cause of her symptoms?

The EKG abnormality and diagnosis. Although classically associated with syncope, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) often presents similarly to acute coronary syndromes, with chest pain and dyspnea on exertion.26 This patient had no history of cardiac disease or family history of SCD or cardiomyopathy; however, her EKG showed changes indicating left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH), which is consistent with HCM (FIGURE 4, ARROWS). Echocardiography identified myocardial hypertrophy, normal left ventricular ejection fraction, but severe left ventricular outflow obstruction and mild diastolic dysfunction. She was treated with metoprolol and verapamil.

Etiology and epidemiology. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy is an autosomal dominant intrinsic myocardial disorder resulting in LVH that is commonly associated with SCD during extreme physical activity.26,27 The prevalence of HCM is approximately 1 in 500.26 Although it can present at any age, it is the most common cause of SCD in young people (under age 30), responsible for 33% of deaths during athletic events.28

TABLE 3

4 diagnoses and what you'll see on EKG

| Diagnosis | EKG finding |

| Prolonged QT interval | QTc interval >.450 sec (men) or >.470 sec (women) |

| Brugada syndrome | Partial or complete RBBB, and ST segment elevation in right precordial leads V1-V3 |

| Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome | Delta wave, widened QRS, short PR interval, ST segment and T-wave changes |

| Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy | No definitive finding; may have left ventricular hypertrophy or abnormal Q-waves |

EKG, electrocardiogram; RBBB, right bundle branch block.

Clinical features. The severity of HCM ranges from asymptomatic to fatal. Symptoms of HCM include chest pain, dyspnea, and syncope. The disorder causes morbidity and mortality in at least one of 3 ways: ventricular tachyarrhythmias (often in younger patients), heart failure (from left ventricular outflow obstruction), and/or thromboembolism.27

Although echocardiography typically is used to make the diagnosis,27 an EKG often is the initial screening tool. EKG changes are seen in 75% to 95% of affected patients and include the presence of Q-waves and increased voltages related to LVH.27,29 Infarct-like patterns may be present before wall thickening on echocardiogram. Abnormal Q-waves are found in 20% to 50% of HCM patients, and are more common in younger patients. Konno et al30 have shown that Q-waves >3 mm in depth and/or >.040 seconds in duration in at least 2 leads other than aVR is specific (90%) in identifying carriers of HCM genes before they develop clinical symptoms.

Ambulatory monitoring may be useful for risk stratifying HCM patients; those with nonsustained ventricular tachycardia (NSVT) are at higher risk of SCD. Holter monitoring is recommended in initial evaluation because evidence of ventricular tachyarrhythmias may warrant AICD placement.26

Treatment. The risk of SCD in HCM is approximately 1%, but higher in those with a family history of SCD, syncope, NSVT, hypotension during exercise, or severe LVH (left ventricle thickness >30 mm).26 AICDs are recommended for HCM patients with prior cardiac arrest, patients with ≥2 of these risk factors, or patients with one risk factor who have experienced syncope related to arrhythmia.26

For patients who are symptomatic but have <2 risk factors, beta-blockers are firstline therapy.26 Verapamil is used as a second line treatment. Both beta-blockers and calcium channel blockers reduce dyspnea, palpitations, and chest pain.27

For patients who don’t respond to medical therapy, septal reduction therapy may be performed, either by septal myectomy or alcohol septal ablation.27 It is also important to consider genetic screening and counseling for the family.

A summary of all 4 diagnoses described in this article, their associated EKG findings, and their pathophysiology appears in TABLE 3.

CORRESPONDENCE

Samir Haydar, DO, MPH, FACEP, Tufts University School of Medicine, Maine Medical Center, Department of Emergency Medicine, 47 Bramhall St., Portland, ME 04103; [email protected]

› Consider placement of an automatic implantable cardioverter-defibrillator for all patients with a type 1 Brugada pattern on EKG accompanied by syncope, documented ventricular arrhythmia, or aborted sudden cardiac death. B

› Always look for EKG findings suggestive of Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome in otherwise healthy patients presenting with syncope. C

› Refer all patients with suspected hypertrophic cardiomyopathy to Cardiology for a transthoracic echocardiogram. B

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

When evaluating a patient with a history of chest pain, palpitations, syncope, and/or new-onset seizures, an electrocardiogram (EKG) may be the key to

identifying a potentially life-threatening condition. Here we present 4 cases in which EKG findings were the clue to underlying medical conditions that, if left untreated, could be fatal. Because each of these conditions may not have associated findings on a physical exam, early recognition of these EKG findings can be lifesaving.

CASE 1 › A 15-year-old boy suddenly collapses while walking, and bystanders report seizure-like activity. The patient doesn’t remember the event. Vital signs and physical exam are normal, and his blood glucose level is 86 mg/dL (normal: 70-100 mg/dL). He doesn’t take any medications and denies illicit drug use or recent illness.

What EKG abnormality (FIGURE 1) likely explains the cause of the patient’s collapse?

The EKG abnormality and diagnosis. The patient’s EKG revealed a prolonged QT interval (FIGURE 1, BRACKETS). His QTc (QT interval corrected for heart rate) was .470 seconds, which is at the high end of the normal range for his age and gender.1 The patient had no family history of syncope, sudden cardiac death (SCD), or seizure disorder. Evaluation uncovered a calcium level of 4.4 mEq/L (normal: 4.5-5.5 mEq/L) and a phosphate level of 7.8 mg/dL (normal: 2.4-4.1 mg/dL).

This patient had a low parathyroid hormone from primary hypoparathyroidism. His conduction abnormality was treated with both oral calcium and vitamin D supplements.

Etiology and epidemiology. A prolonged QT interval may be the result of a primary long QT syndrome (LQTS) or an acquired condition from electrolyte imbalance, medication effect, or toxin exposure.

In the United States, the incidence of a genetic mutation that causes LQTS is 1 in 2500 people.2 Patients with LQTS usually remain asymptomatic unless the QT interval is further prolonged by a condition or medication. There are several hundred congenital LQTS subtypes based on specific ion channel defects; the most common is LQTS1, with an inherited defect in the KCNQ1 gene, which regulates the slow potassium ion channel.

Acquired LQTS is much more common than congenital LQTS.3 Many drugs have been linked to an increased risk of LQTS, including certain antiarrhythmics, antibiotics, and antipsychotics (TABLE 1).4 In addition, electrolyte disturbances such as hypokalemia, hypocalcemia, and hypomagnesemia can be etiologic factors.

Be aware that an acquired LQTS may mask an underlying congenital LQTS. Therefore, patients in whom the offending agent or condition is corrected should still have a follow-up EKG. Screening family members for LQTS is worthwhile, even in those without symptoms.

Clinical features. Patients with symptomatic LQTS may have dizziness, palpitations, and syncope. SCD also is possible. These signs and symptoms may be triggered by strong emotions (in LQTS2) or physical activity (in LQTS1). They likely are caused by torsades de pointes and ventricular fibrillation. A brief aura may precede these arrhythmias, and patients may experience urinary or fecal incontinence.5

The key to making a diagnosis of LQTS is correctly measuring the QT interval. The QT interval is measured from the beginning of the Q-wave to the end of the T-wave as measured from the intersection of a line tangent to the downslope of the T-wave and the isoelectric line. This can be difficult to determine in EKGs showing bundle branch block or an irregular rhythm, such as atrial fibrillation (AF).6,7 A common error in measuring the QT interval occurs when clinicians inadvertently include a U-wave in the measurement.1 Some EKG machines may provide QT interval and QTc measurements. Normal QT intervals are ≤.450 seconds for men and ≤.470 seconds for women.8

It is essential to confirm the QT interval by using the Bazett formula (QTc equals the QT in seconds divided by the square root of the RR interval in seconds) for all patients with a history that suggests a possible arrhythmia.

Our patient had hypocalcemia, which on an EKG can cause T-wave widening with a normal ST segment, rather than a normal T-wave with a long ST segment, as is typically seen in LQTS. This distinction may be difficult to discern and should not preclude the search for either an acquired prolonged QTc or an underlying LQTS.9

Treatment. First rule out or treat any causes of acquired LQTS by taking a careful medication history and evaluating the patient’s electrolytes. Once these have been addressed, a beta-blocker is first-line therapy for symptomatic patients.5

Unfortunately, up to 20% of individuals treated with beta-blockers may continue to have syncope.5 For these patients, options include a left cardiac sympathetic denervation (LCSD) or placement of an automatic implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (AICD). An LCSD involves removal of the left-sided stellate and/or thoracic ganglia. This procedure can be used instead of, or in addition to, beta-blockers. If the patient’s syncope persists, AICDs are an option. AICDs can be lifesaving, but patients run the risk of adverse effects that include inappropriate shocks and infection.10 As the result of these therapies, mortality associated with LQTS has dropped to approximately 1%.11

CASE 2 › A 14-year-old boy has a syncopal episode while at rest. A similar event occurred 3 years earlier; at that time, an echocardiogram and EKG were normal. For 2 days, he’s had a cough and low-grade fever. His temperature is 102ºF and he has a productive cough. Based on this EKG (FIGURE 2), what is the likely diagnosis? What is the significance of his fever?

The EKG abnormality and diagnosis. This patient’s EKG showed a type 1 Brugada pattern (FIGURE 2, ARROWS), which strongly supported the diagnosis of Brugada syndrome (BS). BS is an inherited condition caused by a genetic defect in cardiac ion channel function that leads to characteristic EKG changes and a predisposition to ventricular fibrillation.12 In this case, the fever likely unmasked these EKG findings.

The patient was transferred to a local hospital for treatment of community-acquired pneumonia, and ultimately received an AICD.

Etiology and epidemiology. BS was first described in 199213 and is a major cause of SCD, responsible for up to 4% of all cases of SCD, and 20% of cases of patients without structural heart disease.14 BS is more common in men, and the mean age of diagnosis is 40 to 45.15-18

Mutations in at least 17 cardiac ion channel genes have been linked to BS.19 The SCN5A gene—a cardiac sodium channel—is the most commonly implicated, but accounts for only 11% to 24% of all BS cases.15

Clinical features. Patients with BS may present with syncope, nocturnal agonal respirations, or ventricular arrhythmias.12 EKG findings include partial or complete right bundle branch block (RBBB) and ST segment elevation in right precordial leads V1 to V3.12 There are 2 Brugada EKG patterns, a type 1 cloved pattern as seen in our patient’s EKG and a type 2 saddleback pattern.20 EKG findings are dynamic over time and may alternate between normal, type 1, and type 2.20 Factors that modulate EKG appearance include fever, intoxication, vagal tone, electrolyte imbalance, and sodium channel blockade.12,20

Diagnosis requires a type 1 Brugada pattern on EKG plus a family history of BS, documented ventricular arrhythmia, or arrhythmia-related symptoms such as syncope.12 Patients with a type 2 Brugada pattern may undergo electrophysiology (EP) testing with Class I antiarrhythmic drugs to induce a diagnostic type 1 Brugada pattern.12,21 Patients who have Brugada EKG findings but none of the other diagnostic criteria are considered to have a Brugada pattern (rather than Brugada syndrome).12

The most concerning outcome of BS is ventricular fibrillation. The estimated annual rate of cardiac events is 7.7% among patients who have experienced an aborted SCD, 1.9% among those who have experienced syncope, and 0.5% in asymptomatic patients.18

Treatment. The only effective treatment for BS is placement of an AICD; however, complications of AICD placement cause significant morbidity.6 Ten years after AICD placement, 37% of patients experienced inappropriate shocks and 29% experienced lead failure.22 Recent modifications in device programming and the addition of remote monitoring have decreased complication rates.12,22

The decision to place an AICD is based on the patient’s prior symptoms, EKG findings, and other factors. Recent guidelines recommend an AICD for all patients with a type 1 Brugada pattern (spontaneous or induced) who also have had an aborted SCD, syncope, or documented ventricular arrhythmia.12

Management of asymptomatic patients with type 1 Brugada pattern remains controversial because the rate of cardiac events is low, although such events can be fatal. Asymptomatic patients with type 1 Brugada findings should undergo further EP testing, and should receive AICD only upon demonstration of inducible ventricular arrhythmia.12

TABLE 2

Arrhythmias associated with Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome23

| Arrhythmia | EKG findings | Treatment—unstable patients | Treatment—stable patients (in preferred treatment order) |

| PSVT, orthodromic | Narrow QRS, loss of delta wave, rate 160-260 beats/min | Synchronized cardioversion | Vagal maneuvers, adenosine, calcium channel blockers, beta-blockers, digoxin, procainamide |

| PSVT, antidromic | Wide complex tachycardia | Synchronized cardioversion | Procainamide |

| Atrial fibrillation | Irregularly irregular (RR interval variable with no pattern), ventricular rates that can exceed 300 beats/min | Synchronized cardioversion | Synchronized cardioversion, procainamide |

| Atrial flutter | Flutter waves, rate normal to tachycardic depending on conduction rate | Synchronized cardioversion | Synchronized cardioversion, procainamide |

| Ventricular fibrillation | Rapid, erratic electrical impulses | Defibrillation | N/A |

EKG, electrocardiogram; N/A, not applicable; PSVT, paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia.

CASE 3 › A 21-year-old man with no medical history presents with sudden onset of lightheadedness followed by syncope. He denies any chest pain or other associated symptoms. At the time of evaluation, he is asymptomatic. His EKG (FIGURE 3) is diagnostic of what syndrome?

The EKG abnormality and diagnosis. The patient had a classic presentation for Wolff-Parkinson-White (WPW) syndrome, a common congenital disorder that alters normal cardiac conduction. He described 2 past instances of unexplained light-headedness and palpitations. Subsequent EP studies demonstrated that the patient had an accessory atrioventricular (AV) tract, causing electrical activity in the heart to bypass the AV node, resulting in a delta wave on EKG (FIGURE 3, GREEN ARROWS).

The patient opted for ablation therapy, which successfully eliminated the delta wave on EKG. Five years later he has had no recurrences.

Epidemiology. The prevalence of WPW syndrome is .1% to 3%.23 Accessory AV tracts are found in men twice as often as in women. Only half of individuals with confirmed tracts develop a tachyarrhythmia. The estimated risk of sudden death due to WPW syndrome is .5% to 4%.24

Pathophysiology. Normally cardiac conduction originates from the sinus node and travels to the AV node, where conduction is slowed, and then proceeds to the His-Purkinje system, and finally to the rest of the ventricular myocardium. In WPW syndrome, ventricular depolarization occurs first by an accessory AV tract called the bundle of Kent, followed shortly thereafter by the His-Purkinje system. This sequence of depolarization is what leads to the EKG findings characteristic of WPW syndrome: a PR interval <.12 seconds, presence of a delta wave, widened QRS complex (>.12 seconds), and repolarization changes seen as ST segment and T-wave changes discordant to (opposite direction) the delta wave and QRS complex (FIGURE 3, RED ARROW).

Factors that influence electrical conduction through the bundle of Kent include cardioactive medications, physiological stress, circulating catecholamines, coronary ischemia, and aging. The end result is a propensity for the heart to convert to one of 4 arrhythmias: paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia (PSVT), AF, atrial flutter, or ventricular fibrillation (TABLE 2).23

The most common arrhythmia in WPW syndrome is PSVT.23 This rhythm is induced by the formation of a reentry circuit—a pattern in which the heart’s electrical signal loops back on itself—involving the normal conduction pathway and the bundle of Kent. Reentry progressing down the His-Purkinje system and traveling up the bundle of Kent is referred to as orthodromic (anterograde) PSVT. Antidromic (retrograde) PSVT is due to a reentry circuit conducting from the bundle of Kent to the ventricles, and then retrograde through the His-Purkinje system and AV node to the atria.

Clinical features. Under normal circumstances, patients with WPW syndrome are asymptomatic. As was the case with our patient, individuals who develop one of the 4 characteristic arrhythmias can experience light-headedness and syncope.

Treatment. An unstable patient who is experiencing PSVT, AF, or atrial flutter should receive synchronized cardioversion; those experiencing ventricular fibrillation should receive defibrillation (TABLE 2).23 For stable patients, therapy is tailored to the type of arrhythmia. Calcium channel blockers, beta-blockers, and adenosine might be appropriate for patients with orthodromic PSVT but should be avoided in patients with antidromic PSVT, AF, or atrial flutter because these medications block AV node conduction and thus facilitate conduction down the bundle of Kent, which can result in potentially unstable arrhythmias. In general, the longer an arrhythmia has been present, the less effective the pharmacologic intervention because of the increasing sympathetic tone.

Preventive long-term therapies for WPW patients who have experienced arrhythmia include antiarrhythmic medications or ablative procedures. Long-term antiarrhythmic therapy often is reserved for older, more sedentary individuals with less frequent arrhythmias that are not life-threatening. Radiofrequency ablation is a popular option, with long-term success rates as high as 95% and complication rates <1%.23 Patients in whom a WPW pattern is identified incidentally on EKG should be referred to cardiology for EP studies and risk stratification.25

CASE 4 › A 61-year-old woman has an episode of substernal exertional chest pressure that lasted approximately 2 hours but resolved before she arrived at her physician’s office. She also experienced mild nausea. She has no history of coronary artery disease but says that she has experienced similar episodes of chest pressure. What abnormality is seen on her EKG (FIGURE 4)? What is the most likely cause of her symptoms?

The EKG abnormality and diagnosis. Although classically associated with syncope, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) often presents similarly to acute coronary syndromes, with chest pain and dyspnea on exertion.26 This patient had no history of cardiac disease or family history of SCD or cardiomyopathy; however, her EKG showed changes indicating left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH), which is consistent with HCM (FIGURE 4, ARROWS). Echocardiography identified myocardial hypertrophy, normal left ventricular ejection fraction, but severe left ventricular outflow obstruction and mild diastolic dysfunction. She was treated with metoprolol and verapamil.

Etiology and epidemiology. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy is an autosomal dominant intrinsic myocardial disorder resulting in LVH that is commonly associated with SCD during extreme physical activity.26,27 The prevalence of HCM is approximately 1 in 500.26 Although it can present at any age, it is the most common cause of SCD in young people (under age 30), responsible for 33% of deaths during athletic events.28

TABLE 3

4 diagnoses and what you'll see on EKG

| Diagnosis | EKG finding |

| Prolonged QT interval | QTc interval >.450 sec (men) or >.470 sec (women) |

| Brugada syndrome | Partial or complete RBBB, and ST segment elevation in right precordial leads V1-V3 |

| Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome | Delta wave, widened QRS, short PR interval, ST segment and T-wave changes |

| Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy | No definitive finding; may have left ventricular hypertrophy or abnormal Q-waves |

EKG, electrocardiogram; RBBB, right bundle branch block.

Clinical features. The severity of HCM ranges from asymptomatic to fatal. Symptoms of HCM include chest pain, dyspnea, and syncope. The disorder causes morbidity and mortality in at least one of 3 ways: ventricular tachyarrhythmias (often in younger patients), heart failure (from left ventricular outflow obstruction), and/or thromboembolism.27

Although echocardiography typically is used to make the diagnosis,27 an EKG often is the initial screening tool. EKG changes are seen in 75% to 95% of affected patients and include the presence of Q-waves and increased voltages related to LVH.27,29 Infarct-like patterns may be present before wall thickening on echocardiogram. Abnormal Q-waves are found in 20% to 50% of HCM patients, and are more common in younger patients. Konno et al30 have shown that Q-waves >3 mm in depth and/or >.040 seconds in duration in at least 2 leads other than aVR is specific (90%) in identifying carriers of HCM genes before they develop clinical symptoms.

Ambulatory monitoring may be useful for risk stratifying HCM patients; those with nonsustained ventricular tachycardia (NSVT) are at higher risk of SCD. Holter monitoring is recommended in initial evaluation because evidence of ventricular tachyarrhythmias may warrant AICD placement.26

Treatment. The risk of SCD in HCM is approximately 1%, but higher in those with a family history of SCD, syncope, NSVT, hypotension during exercise, or severe LVH (left ventricle thickness >30 mm).26 AICDs are recommended for HCM patients with prior cardiac arrest, patients with ≥2 of these risk factors, or patients with one risk factor who have experienced syncope related to arrhythmia.26

For patients who are symptomatic but have <2 risk factors, beta-blockers are firstline therapy.26 Verapamil is used as a second line treatment. Both beta-blockers and calcium channel blockers reduce dyspnea, palpitations, and chest pain.27

For patients who don’t respond to medical therapy, septal reduction therapy may be performed, either by septal myectomy or alcohol septal ablation.27 It is also important to consider genetic screening and counseling for the family.

A summary of all 4 diagnoses described in this article, their associated EKG findings, and their pathophysiology appears in TABLE 3.

CORRESPONDENCE

Samir Haydar, DO, MPH, FACEP, Tufts University School of Medicine, Maine Medical Center, Department of Emergency Medicine, 47 Bramhall St., Portland, ME 04103; [email protected]

1. Taggart NW, Haglund CM, Tester DJ, et al. Diagnostic miscues in congenital long-QT syndrome. Circulation. 2007;115:2613-2620.

2. Schwartz PJ, Stramba-Badiale M, Crotti L, et al. Prevalance of the congenital long QT syndrome. Circulation. 2009;120:1761-1767.

3. van Noord C, Eijgelsheim M, Stricker BH. Drug- and nondrug-associated QT interval prolongation. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2010;70:16-23.

4. Credible Meds Web site. Available at: http://crediblemeds.org. Accessed April 8, 2014.

5. Schwartz PJ, Priori SG, Spazzolini C, et al. Genotype-phenotype correlation in the long QT syndrome: gene specific triggers for life threatening arrhythmias. Circulation. 2001;103:89.

6. Chiladakis JK, Kalogeropoulos A, Koutsogiannis N, et al. Optimal QT/JT interval assessment in patients with complete bundle branch block. Ann Noninvasive Electrocardiol. 2012;17:268-276.

7. Ercan S, Altunbas G, Oylumlu M, et al. Congenital long QT syndrome masked by atrial fibrillation and unmasked by hypokalemia. Am J Emerg Med. 2013;31:451.e3-451.e6.

8. Goldenberg I, Moss AJ, Zareba W. QT interval: how to measure it and what is “normal.” J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2006;17:333-336.

9. Podrid PJ. ECG Response: August 20, 2013. Circulation. 2013;128:869.

10. Olde Nordkamp LR, Wilde AA, Tijssen JG, et al. The ICD for primary prevention in patients with inherited cardiac diseases: indications, use, and outcome: a comparison with secondary prevention. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2013;6:91-100.

11. Schwartz PJ. Pharmacological and non-pharmacological management of the congenital long QT syndrome: the rationale. Pharmacol Ther. 2011;131:171-177.

12. Berne P, Brugada J. Brugada syndrome 2012. Circ J. 2012;76:1563-1571.

13. Brugada P, Brugada J. Right bundle branch block, persistent ST segment elevation and sudden cardiac death: a distinct clinical and electrocardiographic syndrome. A multicenter report. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1992;20:1391-1396.

14. Antzelevitch C, Brugada P, Borggrefe M, et al. Brugada syndrome: report of the second consensus conference: endorsed by the Heart Rhythm Society and the European Heart Rhythm Association. Circulation. 2005;111:659-670.

15. Brugada J, Brugada R, Antzelevitch C, et al. Long-term followup of individuals with the electrocardiographic pattern of right bundle-branch block and ST-segment elevation in precordial leads V1 to V3. Circulation. 2002;105:73-78.

16. Eckardt L, Probst V, Smits JP, et al. Long-term prognosis of individuals with right precordial ST-segment-elevation Brugada syndrome. Circulation. 2005;111:257-263.

17. Giustetto C, Drago S, Demarchi PG, et al; Italian Association of Arrhythmology and Cardiostimulation (AIAC)-Piedmont Section. Risk stratification of the patients with Brugada type electrocardiogram: a community-based prospective study. Europace. 2009;11:507-513.

18. Probst V, Veltmann C, Eckardt L, et al. Long-term prognosis of patients diagnosed with Brugada syndrome: Results from the FINGER Brugada Syndrome Registry. Circulation. 2010;121:635-643.

19. Nielsen MW, Holst AG, Olesen SP, et al. The genetic component of Brugada syndrome. Front Physiol. 2013;4:179.

20. Bayés de Luna A, Brugada J, Baranchuk A, et al. Current electrocardiographic criteria for diagnosis of Brugada pattern: a consensus report. J Electrocardiol. 2012;45:433-442.

21. Veltmann C, Schimpf R, Echternach C, et al. A prospective study on spontaneous fluctuations between diagnostic and non-diagnostic ECGs in Brugada syndrome: implications for correct phenotyping and risk stratification. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:2544-2552.

22. Sacher F, Probst V, Maury P, et al. Outcome after implantation of a cardioverter-defibrillator in patients with Brugada syndrome: a multicenter study-part 2. Circulation. 2013;128:1739-1747.

23. Rosner MH, Brady WJ Jr, Kefer MP, et al. Electrocardiography in the patient with the Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome: diagnostic and initial therapeutic issues. Am J Emerg Med. 1999;17:705-714.

24. Keating L, Morris FP, Brady WJ. Electrocardiographic features of Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome. Emerg Med J. 2003;20:491-493.

25. Blomström-Lundqvist C, Scheinman MM, Aliot EM, et al; European Society of Cardiology Committee, NASPE-Heart Rhythm Society. ACC/AHA/ESC guidelines for the management of patients with supraventricular arrhythmias—executive summary. A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the European Society of Cardiology Committee for Practice Guidelines (writing committee to develop guidelines for the management of patients with supraventricular arrhythmias) developed in collaboration with NASPE-Heart Rhythm Society. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42:1493-1531.

26. Ho CY. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in 2012. Circulation. 2012;125:1432-1438.

27. Gersh BJ, Maron BJ, Bonow RO, et al; American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines; American Association for Thoracic Surgery; American Society of Echocardiography; American Society of Nuclear Cardiology; Heart Failure Society of America; Heart Rhythm Society; Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions; Society of Thoracic Surgeons. 2011 ACCF/AHA guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2011;124:e783-e831.

28. Paterick TE, Jan MF, Paterick ZR, et al. Cardiac evaluation of collegiate student athletes: a medical and legal perspective. Am J Med. 2012;125:742-752.

29. Maron BJ. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. In: Bonow RO, Mann DL, Zipes DP, et al (eds). Braunwald’s Heart Disease: A Textbook of Cardiovascular Medicine. 9th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2011:1582-1594.

30. Konno T, Shimizu M, Ino H, et al. Diagnostic value of abnormal Q waves for identification of preclinical carriers of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy based on molecular genetic diagnosis. Eur Heart J. 2004;25:246-251.

1. Taggart NW, Haglund CM, Tester DJ, et al. Diagnostic miscues in congenital long-QT syndrome. Circulation. 2007;115:2613-2620.

2. Schwartz PJ, Stramba-Badiale M, Crotti L, et al. Prevalance of the congenital long QT syndrome. Circulation. 2009;120:1761-1767.

3. van Noord C, Eijgelsheim M, Stricker BH. Drug- and nondrug-associated QT interval prolongation. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2010;70:16-23.

4. Credible Meds Web site. Available at: http://crediblemeds.org. Accessed April 8, 2014.

5. Schwartz PJ, Priori SG, Spazzolini C, et al. Genotype-phenotype correlation in the long QT syndrome: gene specific triggers for life threatening arrhythmias. Circulation. 2001;103:89.

6. Chiladakis JK, Kalogeropoulos A, Koutsogiannis N, et al. Optimal QT/JT interval assessment in patients with complete bundle branch block. Ann Noninvasive Electrocardiol. 2012;17:268-276.

7. Ercan S, Altunbas G, Oylumlu M, et al. Congenital long QT syndrome masked by atrial fibrillation and unmasked by hypokalemia. Am J Emerg Med. 2013;31:451.e3-451.e6.

8. Goldenberg I, Moss AJ, Zareba W. QT interval: how to measure it and what is “normal.” J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2006;17:333-336.

9. Podrid PJ. ECG Response: August 20, 2013. Circulation. 2013;128:869.

10. Olde Nordkamp LR, Wilde AA, Tijssen JG, et al. The ICD for primary prevention in patients with inherited cardiac diseases: indications, use, and outcome: a comparison with secondary prevention. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2013;6:91-100.

11. Schwartz PJ. Pharmacological and non-pharmacological management of the congenital long QT syndrome: the rationale. Pharmacol Ther. 2011;131:171-177.

12. Berne P, Brugada J. Brugada syndrome 2012. Circ J. 2012;76:1563-1571.

13. Brugada P, Brugada J. Right bundle branch block, persistent ST segment elevation and sudden cardiac death: a distinct clinical and electrocardiographic syndrome. A multicenter report. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1992;20:1391-1396.

14. Antzelevitch C, Brugada P, Borggrefe M, et al. Brugada syndrome: report of the second consensus conference: endorsed by the Heart Rhythm Society and the European Heart Rhythm Association. Circulation. 2005;111:659-670.

15. Brugada J, Brugada R, Antzelevitch C, et al. Long-term followup of individuals with the electrocardiographic pattern of right bundle-branch block and ST-segment elevation in precordial leads V1 to V3. Circulation. 2002;105:73-78.

16. Eckardt L, Probst V, Smits JP, et al. Long-term prognosis of individuals with right precordial ST-segment-elevation Brugada syndrome. Circulation. 2005;111:257-263.

17. Giustetto C, Drago S, Demarchi PG, et al; Italian Association of Arrhythmology and Cardiostimulation (AIAC)-Piedmont Section. Risk stratification of the patients with Brugada type electrocardiogram: a community-based prospective study. Europace. 2009;11:507-513.

18. Probst V, Veltmann C, Eckardt L, et al. Long-term prognosis of patients diagnosed with Brugada syndrome: Results from the FINGER Brugada Syndrome Registry. Circulation. 2010;121:635-643.

19. Nielsen MW, Holst AG, Olesen SP, et al. The genetic component of Brugada syndrome. Front Physiol. 2013;4:179.

20. Bayés de Luna A, Brugada J, Baranchuk A, et al. Current electrocardiographic criteria for diagnosis of Brugada pattern: a consensus report. J Electrocardiol. 2012;45:433-442.

21. Veltmann C, Schimpf R, Echternach C, et al. A prospective study on spontaneous fluctuations between diagnostic and non-diagnostic ECGs in Brugada syndrome: implications for correct phenotyping and risk stratification. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:2544-2552.

22. Sacher F, Probst V, Maury P, et al. Outcome after implantation of a cardioverter-defibrillator in patients with Brugada syndrome: a multicenter study-part 2. Circulation. 2013;128:1739-1747.

23. Rosner MH, Brady WJ Jr, Kefer MP, et al. Electrocardiography in the patient with the Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome: diagnostic and initial therapeutic issues. Am J Emerg Med. 1999;17:705-714.

24. Keating L, Morris FP, Brady WJ. Electrocardiographic features of Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome. Emerg Med J. 2003;20:491-493.

25. Blomström-Lundqvist C, Scheinman MM, Aliot EM, et al; European Society of Cardiology Committee, NASPE-Heart Rhythm Society. ACC/AHA/ESC guidelines for the management of patients with supraventricular arrhythmias—executive summary. A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the European Society of Cardiology Committee for Practice Guidelines (writing committee to develop guidelines for the management of patients with supraventricular arrhythmias) developed in collaboration with NASPE-Heart Rhythm Society. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42:1493-1531.

26. Ho CY. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in 2012. Circulation. 2012;125:1432-1438.

27. Gersh BJ, Maron BJ, Bonow RO, et al; American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines; American Association for Thoracic Surgery; American Society of Echocardiography; American Society of Nuclear Cardiology; Heart Failure Society of America; Heart Rhythm Society; Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions; Society of Thoracic Surgeons. 2011 ACCF/AHA guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2011;124:e783-e831.

28. Paterick TE, Jan MF, Paterick ZR, et al. Cardiac evaluation of collegiate student athletes: a medical and legal perspective. Am J Med. 2012;125:742-752.

29. Maron BJ. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. In: Bonow RO, Mann DL, Zipes DP, et al (eds). Braunwald’s Heart Disease: A Textbook of Cardiovascular Medicine. 9th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2011:1582-1594.

30. Konno T, Shimizu M, Ino H, et al. Diagnostic value of abnormal Q waves for identification of preclinical carriers of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy based on molecular genetic diagnosis. Eur Heart J. 2004;25:246-251.

Q&A: “Code Black” Offers Insider Look at ED Challenges

Interview by Mary Ellen Schneider

“Code Black,” the award-winning documentary about working in the ED at Los Angeles County Hospital, opened in theaters in 40 US cities this summer.

It’s the film debut for emergency physician Ryan McGarry, who both stars in and directs the feature-length documentary. It highlights the thrills and challenges of working in a busy ED through the eyes of senior residents, including Dr McGarry, who completed his training while working on the film. The young doctors start the film as fresh-faced idealists in the “C-Booth” trauma bay at LA County Hospital, the famed birthplace of emergency medicine. Later they move to the county’s newly built hospital, which, though state-of-the-art, lacks some of the camaraderie of the original ED.

“Code Black” was the Best Documentary winner at the Los Angeles Film Festival and the Hamptons International Film Festival. And it was the Audience Award winner at both the Starz Denver Film Festival and the Aspen Filmfest.