User login

Phialophora verrucosa as a Cause of Deep Infection Following Total Knee Arthroplasty

Osteolytic Psuedotumor After Cemented Total Knee Arthroplasty

Neonatal Seizure: Sepsis or Toxic Syndrome?

A mother presents to the ED with her 4-day-old daughter after noting abnormal jerking movements of the neonate's upper extremities. She states the baby has had watery stools for the past day, but has been tolerating bottle formula feeds without vomiting and having appropriate urinary output. The patient was born full-term via normal spontaneous vaginal delivery, with Apgar scores of 8 at 1 minute and 9 at 5 minutes. The postdelivery course was uncomplicated, and both mother and baby were discharged home 2 days after delivery.

Initial vital signs are: heart rate, 135 beats/min; respiratory rate (RR), 48 breaths/min; and temperature, 98.7°F; blood glucose was normal. On physical examination, the baby is awake and well-appearing, with a nonbulging anterior fontanelle, soft, supple neck, and flexed and symmetrically mobile extremities. Moro, suck, rooting, and grasp reflexes are all intact. No abnormal movements are noted. The remainder of the examination is unremarkable.

Do the jerking movements indicate a focal seizure? What could cause these movements in a neonate?

As the length of the postpartum hospital stay has decreased over the past 20 years, EDs have experienced an increase in neonatal visits for conditions that traditionally manifested in newborn nurseries. While most presentations are for benign reasons (eg, issues related to feeding, irritability), patients with concerning conditions, including central nervous system (CNS) abnormalities, may also initially present to the ED. Causes of such clinical findings may be structural (eg, cerebral malformations, subdural hematomas, herpes encephalitis) and/or metabolic (eg, hypoglycemia, hypocalcemia, inborn errors). Many early-onset neonatal seizures are benign and resolve by several months of age, but it is essential to identify those that are consequential and treatable.

Case Continuation

In the evaluation of the neonatal patient with suspected seizure, it is important to take a detailed maternal and labor history, and to consider a broad differential in the face of nonspecific findings. In this case, the patient's mother disclosed a personal history of chronic pain, for which she took buprenorphine 2 mg orally in the morning and 4 mg orally at bedtime (total daily dose of 6mg/day) throughout her pregnancy.

How does drug withdrawal present in the neonate?

Neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS) is the clinical syndrome of withdrawal in a newborn exposed in utero to drugs capable of inducing dependence. Agents associated with NAS include opioids, benzodiazepines, ethanol, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), mood stabilizers, and nicotine.1,2

Over the past decade, there has been a 330% rise in the diagnosis of opioid-related NAS alone.3 In response to this increase, the US Food and Drug Administration recently added a black-box warning to all extended-release/long-acting opioid preparations detailing this risk.4

Presenting symptoms of NAS are protean, differ from patient to patient, and are a function of drug type, duration, and amount of drug exposure. NAS may mimic other severe life-threatening conditions such as those previously noted, and the inability to obtain an adequate symptom-based medical history from a neonate further complicates the diagnosis. Before making a diagnosis of NAS, other conditions should be carefully considered in the differential.

Neonatal opioid withdrawal manifests primarily with CNS and gastrointestinal (GI) effects since there are high concentrations of opioid receptors in these areas. Although clinical findings are generally similar among opioid agents, the onset and duration following abstinence varies—largely based on individual drug half-life; this helps to differentiate between opioid agents. For example, while babies exposed to heroin in utero present with signs of NAS within 24 hours of birth, those exposed to buprenorphine or methadone tend to present 2 to 6 days after delivery.1 Between 55% to 94% of neonates with in-utero opioid exposure develop NAS.5

Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors

SSRIs have also been associated with a neonatal syndrome, and largely involve similar signs and symptoms as NAS. Although the specific etiology is not clear, it has been suggested that this syndrome is the result of serotonin toxicity rather than withdrawal; as such, it is often referred to as "serotonin discontinuation syndrome." Clinical findings occur from several hours to several days after birth and usually resolve within 1 to 2 weeks.6

Cocaine Exposure

In-utero cocaine exposure is also associated with neurobehavioral abnormalities in neonates although a withdrawal syndrome is less clearly defined. Findings, however, are consistent with NAS and include increased irritability, tremors, and high-pitched cry—most frequently occurring between 24 and 48 hours postdelivery.6

Neonatal Alcohol Withdrawal Syndrome

Neonatal alcohol withdrawal syndrome, particularly in fetuses exposed to alcohol during the last trimester, is distinct from fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS). The latter is associated with typical dysmorphic features, growth deficiencies, and CNS findings reflective of permanent neurologic sequelae. Neonatal alcohol withdrawal presents with CNS findings similar to those listed for other in-utero exposures—eg, increased irritability, tremors, nystagmus hyperactive reflexes.7

Screening for NAS: The Finnegan Scale

The Finnegan Neonatal Abstinence Scoring System is one of the most commonly employed and validated tools used to screen for NAS. It comprises a 31-item scale, listing the clinical signs and symptoms of NAS, which are scored by severity and organized by system to include neurologic, metabolic, vasomotor, respiratory, and GI disturbances (Figure). Point allocation is based on mild, moderate, or severe symptoms as follows:

- Mild findings (eg, sweating, fever <101°F mottling, nasal stuffiness) each score 1 point.

- Moderate findings (eg, high-pitched cry, hyperactive moro reflex, increased muscle tone, fever >101°F, increased RR >60 with retractions, poor feeding, loose stools) each score 2 points.

- Severe findings (eg, myoclonic jerks, generalized convulsions, projectile vomiting, watery stools) each score 3 points.

While each of the above are independently nonspecific, the constellation of findings, together with the appropriate history, provide for a clinical diagnosis. The Finnegan Scale is therefore designed not only to aid in diagnosis, but also to quantify the severity of NAS and guide management.

Screening for NAS begins at birth in neonates with known in-utero exposure (ie, when risk of NAS is high) or at the time of initial presentation in other circumstances. Scoring is performed every 4 hours; the first two or three scores will determine the need for pharmacotherapy (see below).

| Pharmacotherapy is indicated in the following Finnegan scoring scenarios: |

|

|

|

How is NAS treated?

The two main goals of management in the treatment of opioid-related NAS are to relieve the signs and symptoms of withdrawal and to prevent complications (eg, fever, weight loss, seizures). Therapy should begin with nonpharmacologic measures that minimize excess external stimuli, such as swaddling, gentle handling, and minimizing noise and light. To prevent weight loss, small hypercaloric feeds may be helpful. If pharmacologic treatment is indicated, oral opioid replacement with morphine is considered by many to be the drug of choice. Oral morphine dosing may be guided by NAS severity based on the Finnegan score; alternatively, initial dosing at 0.1 mg/kg orally every 4 hours has also been recommended.1

Other agents, such methadone 0.1 mg/kg orally every 12 hours and buprenorphine 15.9 mcg/kg divided in three doses orally, may also be used. In patients whose symptoms persist despite opioid treatment, use of adjuncts such as phenobarbital and clonidine may be indicated.

Case Conclusion

The patient was admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit where she appropriately underwent a sepsis workup. Laboratory evaluation, including blood and urine cultures, was obtained. A brain ultrasound was unremarkable, and since lumbar puncture was unsuccessful, the patient was started empirically on meningitis doses of the cefotaxime, vancomycin, and acyclovir.

An initial Finnegan score was calculated. With the exception of soft stools, there were no other persistent symptoms, and patient did not achieve a score indicating a need for pharmacologic management. After 48 hours, she remained afebrile and soft stools resolved. All laboratory values, including cultures, were unremarkable. The patient was discharged on hospital day 3, with a scheduled well-baby follow-up appointment.

| Take Home Points |

|

- Cramton RE, Gruchala NE. Babies breaking bad: neonatal and iatrogenic withdrawal syndromes. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2013;25(4): 532-542.

- Kraft WK, Dysart K, Greenspan JS, Gibson E, Kaltenbach K, Ehrlich ME. Revised dose schema of sublingual buprenorphine in the treatment of the neonatal opioid abstinence syndrome. Addiction. 2011;106(3):574-580. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03170.x Accessed October 24, 2013.

- Patrick SW, Schumacher RE, Benneyworth BD, Krans EE, McAllister JM, Davis MM. Neonatal abstinence syndrome and associated health care expenditures: United States, 2000-2009. JAMA. 2012;307(18):1934-40.

- New safety measures announced for extended-release and long-acting opioids. US Food and Drug Administration Web site. www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/InformationbyDrugClass/ucm363722.htm. Accessed October 24, 2013.

- Burgos AE, Burke BL Jr. Neonatal abstinence syndrome. NeoReviews. 2009;10(5):e222-e228. http://dx.doi.org/10.1542/neo.10-5-e222. Accessed October 24, 2013.

- Hudak ML, Tan RC. Committee on Drugs. Committee on Fetus and Newborn. Neonatal drug withdrawal. Pediatrics. 2012;129(2):e540-e560.

- Coles CD, Smith IE, Fernhoff PM, Falek A. Neonatal ethanol withdrawal: Characteristics in clinically normal nondysmorphic neonates. J Pediatr. 1984;105(3):445-451.

A mother presents to the ED with her 4-day-old daughter after noting abnormal jerking movements of the neonate's upper extremities. She states the baby has had watery stools for the past day, but has been tolerating bottle formula feeds without vomiting and having appropriate urinary output. The patient was born full-term via normal spontaneous vaginal delivery, with Apgar scores of 8 at 1 minute and 9 at 5 minutes. The postdelivery course was uncomplicated, and both mother and baby were discharged home 2 days after delivery.

Initial vital signs are: heart rate, 135 beats/min; respiratory rate (RR), 48 breaths/min; and temperature, 98.7°F; blood glucose was normal. On physical examination, the baby is awake and well-appearing, with a nonbulging anterior fontanelle, soft, supple neck, and flexed and symmetrically mobile extremities. Moro, suck, rooting, and grasp reflexes are all intact. No abnormal movements are noted. The remainder of the examination is unremarkable.

Do the jerking movements indicate a focal seizure? What could cause these movements in a neonate?

As the length of the postpartum hospital stay has decreased over the past 20 years, EDs have experienced an increase in neonatal visits for conditions that traditionally manifested in newborn nurseries. While most presentations are for benign reasons (eg, issues related to feeding, irritability), patients with concerning conditions, including central nervous system (CNS) abnormalities, may also initially present to the ED. Causes of such clinical findings may be structural (eg, cerebral malformations, subdural hematomas, herpes encephalitis) and/or metabolic (eg, hypoglycemia, hypocalcemia, inborn errors). Many early-onset neonatal seizures are benign and resolve by several months of age, but it is essential to identify those that are consequential and treatable.

Case Continuation

In the evaluation of the neonatal patient with suspected seizure, it is important to take a detailed maternal and labor history, and to consider a broad differential in the face of nonspecific findings. In this case, the patient's mother disclosed a personal history of chronic pain, for which she took buprenorphine 2 mg orally in the morning and 4 mg orally at bedtime (total daily dose of 6mg/day) throughout her pregnancy.

How does drug withdrawal present in the neonate?

Neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS) is the clinical syndrome of withdrawal in a newborn exposed in utero to drugs capable of inducing dependence. Agents associated with NAS include opioids, benzodiazepines, ethanol, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), mood stabilizers, and nicotine.1,2

Over the past decade, there has been a 330% rise in the diagnosis of opioid-related NAS alone.3 In response to this increase, the US Food and Drug Administration recently added a black-box warning to all extended-release/long-acting opioid preparations detailing this risk.4

Presenting symptoms of NAS are protean, differ from patient to patient, and are a function of drug type, duration, and amount of drug exposure. NAS may mimic other severe life-threatening conditions such as those previously noted, and the inability to obtain an adequate symptom-based medical history from a neonate further complicates the diagnosis. Before making a diagnosis of NAS, other conditions should be carefully considered in the differential.

Neonatal opioid withdrawal manifests primarily with CNS and gastrointestinal (GI) effects since there are high concentrations of opioid receptors in these areas. Although clinical findings are generally similar among opioid agents, the onset and duration following abstinence varies—largely based on individual drug half-life; this helps to differentiate between opioid agents. For example, while babies exposed to heroin in utero present with signs of NAS within 24 hours of birth, those exposed to buprenorphine or methadone tend to present 2 to 6 days after delivery.1 Between 55% to 94% of neonates with in-utero opioid exposure develop NAS.5

Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors

SSRIs have also been associated with a neonatal syndrome, and largely involve similar signs and symptoms as NAS. Although the specific etiology is not clear, it has been suggested that this syndrome is the result of serotonin toxicity rather than withdrawal; as such, it is often referred to as "serotonin discontinuation syndrome." Clinical findings occur from several hours to several days after birth and usually resolve within 1 to 2 weeks.6

Cocaine Exposure

In-utero cocaine exposure is also associated with neurobehavioral abnormalities in neonates although a withdrawal syndrome is less clearly defined. Findings, however, are consistent with NAS and include increased irritability, tremors, and high-pitched cry—most frequently occurring between 24 and 48 hours postdelivery.6

Neonatal Alcohol Withdrawal Syndrome

Neonatal alcohol withdrawal syndrome, particularly in fetuses exposed to alcohol during the last trimester, is distinct from fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS). The latter is associated with typical dysmorphic features, growth deficiencies, and CNS findings reflective of permanent neurologic sequelae. Neonatal alcohol withdrawal presents with CNS findings similar to those listed for other in-utero exposures—eg, increased irritability, tremors, nystagmus hyperactive reflexes.7

Screening for NAS: The Finnegan Scale

The Finnegan Neonatal Abstinence Scoring System is one of the most commonly employed and validated tools used to screen for NAS. It comprises a 31-item scale, listing the clinical signs and symptoms of NAS, which are scored by severity and organized by system to include neurologic, metabolic, vasomotor, respiratory, and GI disturbances (Figure). Point allocation is based on mild, moderate, or severe symptoms as follows:

- Mild findings (eg, sweating, fever <101°F mottling, nasal stuffiness) each score 1 point.

- Moderate findings (eg, high-pitched cry, hyperactive moro reflex, increased muscle tone, fever >101°F, increased RR >60 with retractions, poor feeding, loose stools) each score 2 points.

- Severe findings (eg, myoclonic jerks, generalized convulsions, projectile vomiting, watery stools) each score 3 points.

While each of the above are independently nonspecific, the constellation of findings, together with the appropriate history, provide for a clinical diagnosis. The Finnegan Scale is therefore designed not only to aid in diagnosis, but also to quantify the severity of NAS and guide management.

Screening for NAS begins at birth in neonates with known in-utero exposure (ie, when risk of NAS is high) or at the time of initial presentation in other circumstances. Scoring is performed every 4 hours; the first two or three scores will determine the need for pharmacotherapy (see below).

| Pharmacotherapy is indicated in the following Finnegan scoring scenarios: |

|

|

|

How is NAS treated?

The two main goals of management in the treatment of opioid-related NAS are to relieve the signs and symptoms of withdrawal and to prevent complications (eg, fever, weight loss, seizures). Therapy should begin with nonpharmacologic measures that minimize excess external stimuli, such as swaddling, gentle handling, and minimizing noise and light. To prevent weight loss, small hypercaloric feeds may be helpful. If pharmacologic treatment is indicated, oral opioid replacement with morphine is considered by many to be the drug of choice. Oral morphine dosing may be guided by NAS severity based on the Finnegan score; alternatively, initial dosing at 0.1 mg/kg orally every 4 hours has also been recommended.1

Other agents, such methadone 0.1 mg/kg orally every 12 hours and buprenorphine 15.9 mcg/kg divided in three doses orally, may also be used. In patients whose symptoms persist despite opioid treatment, use of adjuncts such as phenobarbital and clonidine may be indicated.

Case Conclusion

The patient was admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit where she appropriately underwent a sepsis workup. Laboratory evaluation, including blood and urine cultures, was obtained. A brain ultrasound was unremarkable, and since lumbar puncture was unsuccessful, the patient was started empirically on meningitis doses of the cefotaxime, vancomycin, and acyclovir.

An initial Finnegan score was calculated. With the exception of soft stools, there were no other persistent symptoms, and patient did not achieve a score indicating a need for pharmacologic management. After 48 hours, she remained afebrile and soft stools resolved. All laboratory values, including cultures, were unremarkable. The patient was discharged on hospital day 3, with a scheduled well-baby follow-up appointment.

| Take Home Points |

|

A mother presents to the ED with her 4-day-old daughter after noting abnormal jerking movements of the neonate's upper extremities. She states the baby has had watery stools for the past day, but has been tolerating bottle formula feeds without vomiting and having appropriate urinary output. The patient was born full-term via normal spontaneous vaginal delivery, with Apgar scores of 8 at 1 minute and 9 at 5 minutes. The postdelivery course was uncomplicated, and both mother and baby were discharged home 2 days after delivery.

Initial vital signs are: heart rate, 135 beats/min; respiratory rate (RR), 48 breaths/min; and temperature, 98.7°F; blood glucose was normal. On physical examination, the baby is awake and well-appearing, with a nonbulging anterior fontanelle, soft, supple neck, and flexed and symmetrically mobile extremities. Moro, suck, rooting, and grasp reflexes are all intact. No abnormal movements are noted. The remainder of the examination is unremarkable.

Do the jerking movements indicate a focal seizure? What could cause these movements in a neonate?

As the length of the postpartum hospital stay has decreased over the past 20 years, EDs have experienced an increase in neonatal visits for conditions that traditionally manifested in newborn nurseries. While most presentations are for benign reasons (eg, issues related to feeding, irritability), patients with concerning conditions, including central nervous system (CNS) abnormalities, may also initially present to the ED. Causes of such clinical findings may be structural (eg, cerebral malformations, subdural hematomas, herpes encephalitis) and/or metabolic (eg, hypoglycemia, hypocalcemia, inborn errors). Many early-onset neonatal seizures are benign and resolve by several months of age, but it is essential to identify those that are consequential and treatable.

Case Continuation

In the evaluation of the neonatal patient with suspected seizure, it is important to take a detailed maternal and labor history, and to consider a broad differential in the face of nonspecific findings. In this case, the patient's mother disclosed a personal history of chronic pain, for which she took buprenorphine 2 mg orally in the morning and 4 mg orally at bedtime (total daily dose of 6mg/day) throughout her pregnancy.

How does drug withdrawal present in the neonate?

Neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS) is the clinical syndrome of withdrawal in a newborn exposed in utero to drugs capable of inducing dependence. Agents associated with NAS include opioids, benzodiazepines, ethanol, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), mood stabilizers, and nicotine.1,2

Over the past decade, there has been a 330% rise in the diagnosis of opioid-related NAS alone.3 In response to this increase, the US Food and Drug Administration recently added a black-box warning to all extended-release/long-acting opioid preparations detailing this risk.4

Presenting symptoms of NAS are protean, differ from patient to patient, and are a function of drug type, duration, and amount of drug exposure. NAS may mimic other severe life-threatening conditions such as those previously noted, and the inability to obtain an adequate symptom-based medical history from a neonate further complicates the diagnosis. Before making a diagnosis of NAS, other conditions should be carefully considered in the differential.

Neonatal opioid withdrawal manifests primarily with CNS and gastrointestinal (GI) effects since there are high concentrations of opioid receptors in these areas. Although clinical findings are generally similar among opioid agents, the onset and duration following abstinence varies—largely based on individual drug half-life; this helps to differentiate between opioid agents. For example, while babies exposed to heroin in utero present with signs of NAS within 24 hours of birth, those exposed to buprenorphine or methadone tend to present 2 to 6 days after delivery.1 Between 55% to 94% of neonates with in-utero opioid exposure develop NAS.5

Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors

SSRIs have also been associated with a neonatal syndrome, and largely involve similar signs and symptoms as NAS. Although the specific etiology is not clear, it has been suggested that this syndrome is the result of serotonin toxicity rather than withdrawal; as such, it is often referred to as "serotonin discontinuation syndrome." Clinical findings occur from several hours to several days after birth and usually resolve within 1 to 2 weeks.6

Cocaine Exposure

In-utero cocaine exposure is also associated with neurobehavioral abnormalities in neonates although a withdrawal syndrome is less clearly defined. Findings, however, are consistent with NAS and include increased irritability, tremors, and high-pitched cry—most frequently occurring between 24 and 48 hours postdelivery.6

Neonatal Alcohol Withdrawal Syndrome

Neonatal alcohol withdrawal syndrome, particularly in fetuses exposed to alcohol during the last trimester, is distinct from fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS). The latter is associated with typical dysmorphic features, growth deficiencies, and CNS findings reflective of permanent neurologic sequelae. Neonatal alcohol withdrawal presents with CNS findings similar to those listed for other in-utero exposures—eg, increased irritability, tremors, nystagmus hyperactive reflexes.7

Screening for NAS: The Finnegan Scale

The Finnegan Neonatal Abstinence Scoring System is one of the most commonly employed and validated tools used to screen for NAS. It comprises a 31-item scale, listing the clinical signs and symptoms of NAS, which are scored by severity and organized by system to include neurologic, metabolic, vasomotor, respiratory, and GI disturbances (Figure). Point allocation is based on mild, moderate, or severe symptoms as follows:

- Mild findings (eg, sweating, fever <101°F mottling, nasal stuffiness) each score 1 point.

- Moderate findings (eg, high-pitched cry, hyperactive moro reflex, increased muscle tone, fever >101°F, increased RR >60 with retractions, poor feeding, loose stools) each score 2 points.

- Severe findings (eg, myoclonic jerks, generalized convulsions, projectile vomiting, watery stools) each score 3 points.

While each of the above are independently nonspecific, the constellation of findings, together with the appropriate history, provide for a clinical diagnosis. The Finnegan Scale is therefore designed not only to aid in diagnosis, but also to quantify the severity of NAS and guide management.

Screening for NAS begins at birth in neonates with known in-utero exposure (ie, when risk of NAS is high) or at the time of initial presentation in other circumstances. Scoring is performed every 4 hours; the first two or three scores will determine the need for pharmacotherapy (see below).

| Pharmacotherapy is indicated in the following Finnegan scoring scenarios: |

|

|

|

How is NAS treated?

The two main goals of management in the treatment of opioid-related NAS are to relieve the signs and symptoms of withdrawal and to prevent complications (eg, fever, weight loss, seizures). Therapy should begin with nonpharmacologic measures that minimize excess external stimuli, such as swaddling, gentle handling, and minimizing noise and light. To prevent weight loss, small hypercaloric feeds may be helpful. If pharmacologic treatment is indicated, oral opioid replacement with morphine is considered by many to be the drug of choice. Oral morphine dosing may be guided by NAS severity based on the Finnegan score; alternatively, initial dosing at 0.1 mg/kg orally every 4 hours has also been recommended.1

Other agents, such methadone 0.1 mg/kg orally every 12 hours and buprenorphine 15.9 mcg/kg divided in three doses orally, may also be used. In patients whose symptoms persist despite opioid treatment, use of adjuncts such as phenobarbital and clonidine may be indicated.

Case Conclusion

The patient was admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit where she appropriately underwent a sepsis workup. Laboratory evaluation, including blood and urine cultures, was obtained. A brain ultrasound was unremarkable, and since lumbar puncture was unsuccessful, the patient was started empirically on meningitis doses of the cefotaxime, vancomycin, and acyclovir.

An initial Finnegan score was calculated. With the exception of soft stools, there were no other persistent symptoms, and patient did not achieve a score indicating a need for pharmacologic management. After 48 hours, she remained afebrile and soft stools resolved. All laboratory values, including cultures, were unremarkable. The patient was discharged on hospital day 3, with a scheduled well-baby follow-up appointment.

| Take Home Points |

|

- Cramton RE, Gruchala NE. Babies breaking bad: neonatal and iatrogenic withdrawal syndromes. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2013;25(4): 532-542.

- Kraft WK, Dysart K, Greenspan JS, Gibson E, Kaltenbach K, Ehrlich ME. Revised dose schema of sublingual buprenorphine in the treatment of the neonatal opioid abstinence syndrome. Addiction. 2011;106(3):574-580. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03170.x Accessed October 24, 2013.

- Patrick SW, Schumacher RE, Benneyworth BD, Krans EE, McAllister JM, Davis MM. Neonatal abstinence syndrome and associated health care expenditures: United States, 2000-2009. JAMA. 2012;307(18):1934-40.

- New safety measures announced for extended-release and long-acting opioids. US Food and Drug Administration Web site. www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/InformationbyDrugClass/ucm363722.htm. Accessed October 24, 2013.

- Burgos AE, Burke BL Jr. Neonatal abstinence syndrome. NeoReviews. 2009;10(5):e222-e228. http://dx.doi.org/10.1542/neo.10-5-e222. Accessed October 24, 2013.

- Hudak ML, Tan RC. Committee on Drugs. Committee on Fetus and Newborn. Neonatal drug withdrawal. Pediatrics. 2012;129(2):e540-e560.

- Coles CD, Smith IE, Fernhoff PM, Falek A. Neonatal ethanol withdrawal: Characteristics in clinically normal nondysmorphic neonates. J Pediatr. 1984;105(3):445-451.

- Cramton RE, Gruchala NE. Babies breaking bad: neonatal and iatrogenic withdrawal syndromes. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2013;25(4): 532-542.

- Kraft WK, Dysart K, Greenspan JS, Gibson E, Kaltenbach K, Ehrlich ME. Revised dose schema of sublingual buprenorphine in the treatment of the neonatal opioid abstinence syndrome. Addiction. 2011;106(3):574-580. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03170.x Accessed October 24, 2013.

- Patrick SW, Schumacher RE, Benneyworth BD, Krans EE, McAllister JM, Davis MM. Neonatal abstinence syndrome and associated health care expenditures: United States, 2000-2009. JAMA. 2012;307(18):1934-40.

- New safety measures announced for extended-release and long-acting opioids. US Food and Drug Administration Web site. www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/InformationbyDrugClass/ucm363722.htm. Accessed October 24, 2013.

- Burgos AE, Burke BL Jr. Neonatal abstinence syndrome. NeoReviews. 2009;10(5):e222-e228. http://dx.doi.org/10.1542/neo.10-5-e222. Accessed October 24, 2013.

- Hudak ML, Tan RC. Committee on Drugs. Committee on Fetus and Newborn. Neonatal drug withdrawal. Pediatrics. 2012;129(2):e540-e560.

- Coles CD, Smith IE, Fernhoff PM, Falek A. Neonatal ethanol withdrawal: Characteristics in clinically normal nondysmorphic neonates. J Pediatr. 1984;105(3):445-451.

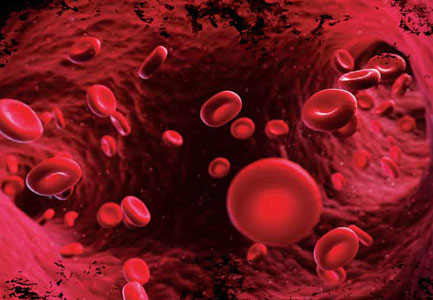

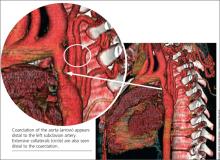

Direct Thrombin and Factor Xa Inhibitors

Parenteral direct thrombin inhibitors (DTI), such as bivalirudin, have been used for more than a decade in the hospital setting. Over the past few years, new DTIs have received US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval, most notably dabigatran etexilate, an orally active DTI touted as a viable alternative for anticoagulation in patients previously taking warfarin or enoxaparin. In addition to the DTIs, oral factor Xa (FXa) inhibitors have also received FDA approval. As these drugs begin to appear on the medication lists of many patients in the ED, a review—especially of the newer, oral agents—is essential. This article provides an overview of the parenteral DTIs and oral DTI dabigatran etexilate, as well as the oral FXa inhibitors, with a focus on proper monitoring of anticoagulation and common problems encountered in patients taking these medications.

Parenteral Direct Thrombin Inhibitors

Hirudin

Hirudin, a bivalent DTI, was the first parenteral anticoagulant of its kind approved for use in humans.1 Commercially available analogs, including lepirudin, bivalirudin, and desirudin, have since become available. Anticoagulation in patients taking hirudin can be monitored effectively in the ED via activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT).2 However, there are significant disadvantages to its use, including high cost, lack of a reversal agent, and the potential development of antibodies to hirudin and its derivatives. In addition, since anaphylactoid reactions have been reported, current recommendations contraindicate its use in patients previously treated with hirudin derivatives.3

Lepirudin

Lepirudin is a hirudin analog derived from yeast cells, and is ideal for patients with heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT). With respect to thromboembolic complications in patients with a previous history of HIT, Greinacher et al,4 demonstrated its relative safety and effectiveness. Their study showed a significant reduction in thromboembolic complications per patient day from 6.1% to 1.3%.4 Bleeding events in study participants occurred at an increased rate compared to controls, but these events were greatly decreased when aPTT levels were maintained between 1.5 to 2.5-fold above baseline.4 Since lepirudin is renally excreted and no reversal agent currently exists, clinicians must use caution when administering it to patients with renal insufficiency.

Bivalirudin

Bivalirudin is another hirudin analog and has an important niche among patients requiring percutaneous coronary intervention, primarily due to its favorable pharmacokinetic profile. In contrast to other DTIs, bivalirudin does not undergo organ-specific clearance, but rather proteolysis—an excellent option for patients with other comorbidities. Additionally, its short half-life of 25 minutes makes it an appropriate choice in cases warranting only a brief period of anticoagulation.5

Argatroban

Argatroban, another parenteral DTI, differs from hirudin, lepirudin, and bivalirudin in that it is a univalent molecule. Anticoagulation is monitored by aPTT, though dose-dependent changes may be seen in prothrombin time (PT). Since argatroban undergoes hepatic clearance, dose adjustments are required in patients with hepatic dysfunction—but not in those with renal insufficiency.6 Similar to lepirudin, argatroban is also indicated for patients with a history of HIT. In recent studies, argatroban achieved patency more frequently than heparin in patients with acute myocardial infarction—without differences in clinical outcomes.7

Dabigatran Etexilate

With the increased number of patients presenting to the ED with venous and arterial thromboembolic disorders, emergency physicians should be familiar with the orally active prodrug, dabigatran. This DTI is taken twice daily and converts to it active form after administration, binding to thrombin with great specificity and affinity.8 Its half-life ranges from 12 to 24 hours in patients with normal renal function; reduced dosing schedules are recommended in patients older than age 75 years and in those with renal impairment. Dabigatran is contraindicated if creatinine clearance is less than 30 mL/min. Even though dabigatran is not cleared by the cytochrome P450 system, it does utilize the P-glycoprotein efflux transporter and is thus vulnerable to both inducers and inhibitors, including systemic antifungals and other medications.9

Monitoring Anticoagulation

Unlike warfarin, dabigatran does not require extensive monitoring. However, thrombin and aPPT assays are often less predictable at supertherapeutic levels of dabigatran, and results vary depending on last administration time of the drug.10 Strangier et al11 identified some weaknesses in aPTT measurement, concluding that while measurement of aPTT may provide a qualitative indication of anticoagulant activity, it is not suitable for the precise quantification of anticoagulant effect—especially at high plasma concentrations of dabigatran.11 Furthermore, since PT time is not significantly affected by DTIs, this assay is a poor monitoring choice for these medications.12

The thrombin time (TT) assay test, which is usually accessible in routine clinical practice, directly assesses thrombin activity, providing a direct measure of dabigatran concentration. The TT is particularly sensitive to the effects of dabigatran and displays a linear dose-response even at supratherapeutic concentrations, making it the most useful and sensitive method for determining the anticoagulation effect of dabigatran.13

When treating patients in the ED who could potentially benefit from thrombolytic agents, monitoring dabigatran anticoagulation can present a challenge. There is very little information regarding the use of tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) in patients on dabigatran, with only one published case on the subject. In this case, intravenous (IV) tPA was administered just less than 4.5 hours after onset of neurologic symptoms and 7 hours after the last intake of dabigatran, with no complications and improved neurology function.14

The Interventional Management Stroke (IMS) III trial has suggested clinicians consider IV tPA in patients with acute stroke if the last dose of dabigatran was greater than 48 hours prior to presentation in the ED.15 Until further evidence becomes available, the decision to administer thrombolytics to stroke patients taking dabigatran should be made on a case-by-case basis and in consultation with a neurologist.

Noninferiority Studies

Dabigatran has been compared to enoxaparin and showed noninferiority for venous thromboembolism (VTE) prophylaxis, with a similar safety profile.16 The RE-COVER study in 2009 demonstrated the noninferiority of dabigatran compared to warfarin. In this study, patients received either the standard dose of dabigatran (150 mg orally, twice daily) or traditional dose-adjusted warfarin. In patients on the dabigatran regimen, recurrent VTE complications occurred at a rate of 2.4%, compared with the 2.1% observed in the warfarin group.17 The safety profile was also similar, with major bleeding episodes occurring in 1.6% and 1.9%, respectively.17

Another study, the RE-LY trial, also sought to prove noninferiority between dabigatran and warfarin, specifically in patients with a known history of atrial fibrillation requiring anticoagulation.18 The authors of the study concluded a clinical net benefit of dabigatran over warfarin with respect to reduction in both hemorrhagic and ischemic stroke and bleeding versus the increase of myocardial infarction.19 Further studies, however, are needed to determine the safety profile of dabigatran.

Dabigatran Reversal

Perhaps the most pressing question for the emergency physician is how to approach the bleeding patient on dabigatran. Although well-known protocols exist for the reversal of other anticoagulants such as warfarin and heparin, no clear, effective reversal agent is currently available for dabigatran. Given its relatively short half-life (12 to 24 hours), the first line of treatment should be to discontinue its use, followed by mechanical pressure or surgical hemostatic, if indicated. Transfusion of blood products (eg, packed red blood cells, fresh frozen plasma, platelets) should be administered based on the extent of the patient’s bleeding.

If these measures fail, dialysis may be considered, particularly in patients with renal insufficiency that may have bleeding secondary to dabigatran toxicity. In cases of suspected overdose, although activated charcoal is still being evaluated, Van Ryn and colleagues noted "preliminary in vitro data indicate that dabigatran etexilate can be successfully adsorbed by classical activated charcoal therapy. However, this has not been tested in vivo or in patients…additional clinically relevant models are required before this can be recommended in patients."10

Managing Dti-Associated Bleeding

Factor VII

Since recombinant activated factor VII directly activates thrombin on the surface of platelets, it is an option in cases of life-threatening DTI-associated bleeding. While laboratory data has supported this use, human studies have been less convincing, with conflicting results in two separate studies.20,21 Moreover, financial considerations may also affect the decision to use factor VII as its dollar cost is in the thousands at most institutions.22 Since the role of factor VII in life-threatening bleeding related to DTIs has yet to be defined, it is prudent to consider this option when other measures fail, understanding the variable rates of success in reversal of anticoagulation.

Prothrombin Complex Concentrates

Prothrombin complex concentrates (PCCs) have a significant place in reversing bleeding in patients on certain anticoagulants. Since these products contain all of the vitamin K-dependent clotting factors and proteins C and S, they have been used in the treatment of warfarin toxicity.

PCCs can be divided into activated and nonactivated categories. Among the nonactivated PCCs are PCC3 and PCC4. Both contain factors II, VII, IX, and X, but PCC3 products have lower concentrations of factor VII. To augment factor VII activity, it has been proposed that fresh frozen plasma or packed red blood cells be given in conjunction with a PCC3.23

Activated prothrombin complex concentrates (APCC) contain activated factor VII, along with inactivated forms of factors II, IX, X, and protein C. Animal studies appear promising for the use of PCCs in DTI-associated bleeding; however, this treatment has not yet been fully evaluated in human studies.24

A recent randomized, placebo-controlled crossover study by Eerenberg et al25 evaluated 12 healthy volunteers treated with PCC4 after receiving either dabigatran or rivaroxaban. While the PCC completely reversed anticoagulation in the rivaroxaban group, there was no reversal of anticoagulation in the dabigatran group.25 The authors made note of the study limitations, which include small sample size and the fact that healthy volunteers were used as surrogates as opposed to patients with major bleeding complications. The authors stated that "although this trial may have important clinical implications, the effect of PCC has yet to be confirmed in patients with bleeding events treated with these anticoagulants."25 This is the only human study available and serves as a starting point from which further human research can be initiated.25

Oral Factor Xa Inhibitors

Apixaban

The FXa inhibitors are a new class of prophylactic anticoagulants. Apixaban, one of the more recent oral FXa inhibitors, has a half-life of approximately 12 hours, predictable pharmacokinetics, and is cleared primarily via the GI tract. Given its hepatic metabolism, patients taking apixaban along with cytochrome P3A4 inhibitors (eg, certain antibiotics and antifungals) may be at increased risk of bleeding.26 As evidenced by the ARISTOTLE trial, compared to standard treatment with warfarin, apixaban is an effective alternative therapy for patients with atrial fibrillation.27 Of note, however, the ADOPT trial showed increased rates of bleeding in patients with comorbid conditions taking apixaban compared to standard enoxaparin dosing.28

Rivaroxaban

Rivaroxaban is another oral FXa inhibitor, with similar pharmacokinetics as apixaban and a half-life ranging from 8 hours in young healthy subjects to 12 hours in elderly patients. Since one third of the drug is renally cleared, rivaroxaban should be prescribed with caution in patients who have impaired creatinine clearance. Moreover, as the remaining two thirds undergo hepatic clearance, as with apixaban, its use is contraindicated in patients taking other cytochrome P-inhibiting medications.29

The MAGELLAN trial found rivaroxaban to be an effective means of DVT prophylaxis compared to control subjects who received enoxaparin injections, but there was in increased rate of clinically significant bleeding in the rivaroxaban group—arguably one of the more important outcome measures for the emergency provider.30 The ROCKET-AF trial, however, showed reduced rates of stroke in patients who received rivaroxaban versus warfarin. Both drugs had similar rates of major and minor bleeding, but rivaroxaban showed a decrease in intracranial hemorrhage and fatal bleeding.31

Monitoring and Reversal

As with the DTIs, monitoring the anticoagulant activity of factor Xa inhibitors can be a challenge, though various factor X assays have been proposed.31 Similar difficulties likewise exist in terms of reversal. There is no specific reversal agent for the FXa inhibitors, and current treatment guidelines recommend the use of PCCs, APCCs, or recombinant factor VIIa—though limited data exist on which agent to base clinical practice. In contrast to the DTIs, neither apixaban nor rivaroxaban are dialyzable.32 The relatively short half-life of these products, however, can prove beneficial, with cessation of the medication being the first line therapy in the case of any clinically significant bleeding.33

Conclusion

Parenteral DTIs have been utilized for years in the ED setting. With the increasing use of newer oral DTIs and FXa inhibitors, emergency physicians must also become familiar with the drug profile of these products, including appropriate anticoagulation monitoring and effective methods to treat DTI- and FXa-associated bleeding. Many questions remain unanswered about these drugs, necessitating further research—specifically in areas of practical monitoring of anticoagulation and possible reversal protocols in the bleeding patient.

Dr Byrne is a clinical instructor in the department of emergency medicine, Eastern Virginia Medical School, Norfolk. Dr Byars is an associate professor in the department of emergency medicine, Eastern Virginia Medical School, Norfolk.

Disclosure: The authors report no conflict of interest.

- Greinacher A, Warkentin TE. The direct thrombin inhibitor hirudin. Thromb Haemost. 2008;99(5):819-829.

- Greinacher A, Eichler P, Albrecht D, Strobel U, Pötzsch B, Eriksson BI. Antihirudin antibodies following low-dose subcutaneous treatment with desirudin for thrombosis prophylaxis after hip-replacement surgery: incidence and clinical relevance. Blood. 2003;101(7):2617-2619.

- Desirudin (Iprivask) for DVT prevention. Med Lett Drugs Ther. 2010;52(1350):85,86.

- Greinacher A, Völpel H, Janssens U, et al. Recombinant hirudin (lepirudin) provides safe and effective anticoagulation in patients with heparin-induced thrombocytopenia: a prospective study. Circulation. 1999;99(1):73-80.

- Warkentin TE, Greinacher A, Koster A. Bivalirudin. Thromb Haemost. 2008;99(5):830-839.

- Swan SK, Hursting MJ. The pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of argatroban: effects of age, gender, and hepatic or renal dysfunction. Pharmacotherapy. 2000;20(3):318-329.

- Jang IK, Brown DF, Giugliano RP, et al. A multicenter, randomized study of argatroban versus heparin as adjunct to tissue plasminogen activator (TPA) in acute myocardial infarction: myocardial infarction with novastan and TPA (MINT) study. J Am Coll Cardiol 1999;33(7):1879-1885.

- Blech S, Ebner T, Ludwig-Schwellinger E, Stangier J, Roth W. The metabolism and disposition of the oral direct thrombin inhibitor, dabigatran, in humans. Drug Metab Dispos. 2008;36(2):386-399.

- Stangier J, Rathgen K, Stähle H, Gansser D, Roth W. The pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics and tolerability of dabigatran etexilate, a new oral direct thrombin inhibitor, in healthy male subjects. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2007;64(3):292-303.

- van Ryn J, Stangier J, Haertter S, et al. Dabigatran etexilate—a novel, reversible, oral direct thrombin inhibitor: interpretation of coagulation assays and reversal of anticoagulant activity.Thromb Haemost. 2010;103(6):1116-1127.

- Stangier J, Rathgen K, Stähle H, Mazur D. Influence of renal impairment on the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of oral dabigatran etexilate: an open-label, parallel-group, single-centre study. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2010;49(4):259-268.

- Nowak G. The ecarin clotting time, a universal method to quantify direct thrombin inhibitors. Pathophysiol Haemost Thromb. 2003;33(4):173-183.

- Watanabe M, Siddiqui FM, Qureshi AI. Incidence and management of ischemic stroke and intracerebral hemorrhage in patients on dabigatran etexilate treatment. Neurocrit Care. 2012;16(1):203-209.

- De Smedt A, De Raedt S, Nieboer K, De Keyser J, Brouns R. Intravenous thrombolysis with recombinant tissue plasminogen activator in a stroke patient treated with dabigatran. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2010;30(5):533,534.

- Broderick J; National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS). Interventional management of stroke (IMS) III trial (IMS III). http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00359424. Accessed October 29, 2013.

- Wolowacz SE, Roskell NS, Plumb JM, Caprini JA, Eriksson BI. Efficacy and safety of dabigatran etexilate for the prevention of venous thromboembolism following total hip or knee arthoplasty. A meta-analysis. Thromb Haemost. 2009;101(1):77-85.

- Schulman S, Kearon C, Kakkar AK, et al; RE-COVER Study Group. Dabigatran versus warfarin in the treatment of acute venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(24):2342-2352.

- Connolly SJ, Ezekowitz MD, Yusuf S, et al; RE-LY Steering Committee and Investigators. Dabigatran versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2009; 361(12):1139-1151.

- Hughes S. Dabigatran: New data on MI and ischemic events. Medscape. 2012. http://www.theheart.org/article/1338427.do Accessed October 29, 2013.

- Wolzt M, Levi M, Sarich TC, et al. Effect of recombinant factor VIIa on melagatran-induced inhibition of thrombin generation and platelet activation in health volunteers. Thromb Haemost. 2004;91(6):1090-1096.

- Sørensen B, Ingerslev J. A direct thrombin inhibitor studied by dynamic whole blood clot formation. Haemostatic response to ex-vivo addition of recombinant factor VIIa or activated prothrombin complex concentrate. Thromb Haemost. 2006;96(4):446-453.

- Kissela BM, Eckman MH. Cost effectiveness of recombinant factor VIIa for treatment of intracerebral hemorrhage. BMC Neurology. 2008;8:17.

- Dager WE. Using prothrombin complex concentrates to rapidly reverse oral anticoagulant effects. Ann Pharmacother. 2011;45(7-8):1016-1020.

- Uchino K, Hernandez AV. Dabigatran association with higher risk of acute coronary events: meta-analysis of noninferiority randomized controlled trials. Arch Inter Med. 2012;172(5):397-402.

- Eerenberg ES, Kamphuisen PW, Sijpkens MK, Meijers JC, Buller HR, Levi M. Reversal of rivaroxaban and dabigatran by prothrombin complex concentrate: a randomized, placebo-controlled, crossover study in healthy subjects. Circulation. 2011;124(14):1573-1579.

- Tahir F, Riaz H, Riaz T, et al. The new oral anti-coagulants and the phase 3 clinical trials - a systematic review of the literature. Thromb J. 2013;11(1):18.

- Granger C, Alexander J, McMurray JJ, et al; ARISTOTLE Committees and Investigators. Apixaban versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(11):981-992.

- Goldhaber SZ, Leizorovicz A, Kakkar AK, et al; ADOPT Trial Investigators. Apixaban versus enoxaparin for thromboprophylaxis in medically ill patients. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(23):2167-2177.

- Mueck W, Stampfuss J, Kubitza D, Becka M. Clinical pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic profile of rivaroxaban. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2013.

- Cohen AT, Spiro TE, Büller HR, et al; MAGELLAN Investigators. Rivaroxaban for thromboprophylaxis in acutely ill medical patients. N Engl J Med. 2013; 368(6):513-523.

- Patel MR, Mahaffey KW, Garg J, et al; ROCKET AF Investigators. Rivaroxaban versus warfarin in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(10):883-991.

- Samama MM, Contant G, Spiro TE, et al; Rivaroxaban Anti-Factor Xa Chromogenic Assay Field Trial Laboratories. Evaluation of the anti-factor Xa chromogenic assay for the measurement of rivaroxaban plasma concentrations using calibrators and controls. Thromb Haemost. 2012;107(2):379-387.

- Goldstein P, Elalamy I, Huber K, Danchin N, Wiel E. Rivaroxaban and other non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants in the emergency treatment of thromboembolism. Int J Emerg Med. 2013;6(1):25.

- Fawole A, Daw HA, Crowther MA. Practical management of bleeding due to the anticoagulants dabigatran, rivaroxaban, and apixaban. Cleve Clin J Med. 2013; 80(7):443-451.

Parenteral direct thrombin inhibitors (DTI), such as bivalirudin, have been used for more than a decade in the hospital setting. Over the past few years, new DTIs have received US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval, most notably dabigatran etexilate, an orally active DTI touted as a viable alternative for anticoagulation in patients previously taking warfarin or enoxaparin. In addition to the DTIs, oral factor Xa (FXa) inhibitors have also received FDA approval. As these drugs begin to appear on the medication lists of many patients in the ED, a review—especially of the newer, oral agents—is essential. This article provides an overview of the parenteral DTIs and oral DTI dabigatran etexilate, as well as the oral FXa inhibitors, with a focus on proper monitoring of anticoagulation and common problems encountered in patients taking these medications.

Parenteral Direct Thrombin Inhibitors

Hirudin

Hirudin, a bivalent DTI, was the first parenteral anticoagulant of its kind approved for use in humans.1 Commercially available analogs, including lepirudin, bivalirudin, and desirudin, have since become available. Anticoagulation in patients taking hirudin can be monitored effectively in the ED via activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT).2 However, there are significant disadvantages to its use, including high cost, lack of a reversal agent, and the potential development of antibodies to hirudin and its derivatives. In addition, since anaphylactoid reactions have been reported, current recommendations contraindicate its use in patients previously treated with hirudin derivatives.3

Lepirudin

Lepirudin is a hirudin analog derived from yeast cells, and is ideal for patients with heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT). With respect to thromboembolic complications in patients with a previous history of HIT, Greinacher et al,4 demonstrated its relative safety and effectiveness. Their study showed a significant reduction in thromboembolic complications per patient day from 6.1% to 1.3%.4 Bleeding events in study participants occurred at an increased rate compared to controls, but these events were greatly decreased when aPTT levels were maintained between 1.5 to 2.5-fold above baseline.4 Since lepirudin is renally excreted and no reversal agent currently exists, clinicians must use caution when administering it to patients with renal insufficiency.

Bivalirudin

Bivalirudin is another hirudin analog and has an important niche among patients requiring percutaneous coronary intervention, primarily due to its favorable pharmacokinetic profile. In contrast to other DTIs, bivalirudin does not undergo organ-specific clearance, but rather proteolysis—an excellent option for patients with other comorbidities. Additionally, its short half-life of 25 minutes makes it an appropriate choice in cases warranting only a brief period of anticoagulation.5

Argatroban

Argatroban, another parenteral DTI, differs from hirudin, lepirudin, and bivalirudin in that it is a univalent molecule. Anticoagulation is monitored by aPTT, though dose-dependent changes may be seen in prothrombin time (PT). Since argatroban undergoes hepatic clearance, dose adjustments are required in patients with hepatic dysfunction—but not in those with renal insufficiency.6 Similar to lepirudin, argatroban is also indicated for patients with a history of HIT. In recent studies, argatroban achieved patency more frequently than heparin in patients with acute myocardial infarction—without differences in clinical outcomes.7

Dabigatran Etexilate

With the increased number of patients presenting to the ED with venous and arterial thromboembolic disorders, emergency physicians should be familiar with the orally active prodrug, dabigatran. This DTI is taken twice daily and converts to it active form after administration, binding to thrombin with great specificity and affinity.8 Its half-life ranges from 12 to 24 hours in patients with normal renal function; reduced dosing schedules are recommended in patients older than age 75 years and in those with renal impairment. Dabigatran is contraindicated if creatinine clearance is less than 30 mL/min. Even though dabigatran is not cleared by the cytochrome P450 system, it does utilize the P-glycoprotein efflux transporter and is thus vulnerable to both inducers and inhibitors, including systemic antifungals and other medications.9

Monitoring Anticoagulation

Unlike warfarin, dabigatran does not require extensive monitoring. However, thrombin and aPPT assays are often less predictable at supertherapeutic levels of dabigatran, and results vary depending on last administration time of the drug.10 Strangier et al11 identified some weaknesses in aPTT measurement, concluding that while measurement of aPTT may provide a qualitative indication of anticoagulant activity, it is not suitable for the precise quantification of anticoagulant effect—especially at high plasma concentrations of dabigatran.11 Furthermore, since PT time is not significantly affected by DTIs, this assay is a poor monitoring choice for these medications.12

The thrombin time (TT) assay test, which is usually accessible in routine clinical practice, directly assesses thrombin activity, providing a direct measure of dabigatran concentration. The TT is particularly sensitive to the effects of dabigatran and displays a linear dose-response even at supratherapeutic concentrations, making it the most useful and sensitive method for determining the anticoagulation effect of dabigatran.13

When treating patients in the ED who could potentially benefit from thrombolytic agents, monitoring dabigatran anticoagulation can present a challenge. There is very little information regarding the use of tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) in patients on dabigatran, with only one published case on the subject. In this case, intravenous (IV) tPA was administered just less than 4.5 hours after onset of neurologic symptoms and 7 hours after the last intake of dabigatran, with no complications and improved neurology function.14

The Interventional Management Stroke (IMS) III trial has suggested clinicians consider IV tPA in patients with acute stroke if the last dose of dabigatran was greater than 48 hours prior to presentation in the ED.15 Until further evidence becomes available, the decision to administer thrombolytics to stroke patients taking dabigatran should be made on a case-by-case basis and in consultation with a neurologist.

Noninferiority Studies

Dabigatran has been compared to enoxaparin and showed noninferiority for venous thromboembolism (VTE) prophylaxis, with a similar safety profile.16 The RE-COVER study in 2009 demonstrated the noninferiority of dabigatran compared to warfarin. In this study, patients received either the standard dose of dabigatran (150 mg orally, twice daily) or traditional dose-adjusted warfarin. In patients on the dabigatran regimen, recurrent VTE complications occurred at a rate of 2.4%, compared with the 2.1% observed in the warfarin group.17 The safety profile was also similar, with major bleeding episodes occurring in 1.6% and 1.9%, respectively.17

Another study, the RE-LY trial, also sought to prove noninferiority between dabigatran and warfarin, specifically in patients with a known history of atrial fibrillation requiring anticoagulation.18 The authors of the study concluded a clinical net benefit of dabigatran over warfarin with respect to reduction in both hemorrhagic and ischemic stroke and bleeding versus the increase of myocardial infarction.19 Further studies, however, are needed to determine the safety profile of dabigatran.

Dabigatran Reversal

Perhaps the most pressing question for the emergency physician is how to approach the bleeding patient on dabigatran. Although well-known protocols exist for the reversal of other anticoagulants such as warfarin and heparin, no clear, effective reversal agent is currently available for dabigatran. Given its relatively short half-life (12 to 24 hours), the first line of treatment should be to discontinue its use, followed by mechanical pressure or surgical hemostatic, if indicated. Transfusion of blood products (eg, packed red blood cells, fresh frozen plasma, platelets) should be administered based on the extent of the patient’s bleeding.

If these measures fail, dialysis may be considered, particularly in patients with renal insufficiency that may have bleeding secondary to dabigatran toxicity. In cases of suspected overdose, although activated charcoal is still being evaluated, Van Ryn and colleagues noted "preliminary in vitro data indicate that dabigatran etexilate can be successfully adsorbed by classical activated charcoal therapy. However, this has not been tested in vivo or in patients…additional clinically relevant models are required before this can be recommended in patients."10

Managing Dti-Associated Bleeding

Factor VII

Since recombinant activated factor VII directly activates thrombin on the surface of platelets, it is an option in cases of life-threatening DTI-associated bleeding. While laboratory data has supported this use, human studies have been less convincing, with conflicting results in two separate studies.20,21 Moreover, financial considerations may also affect the decision to use factor VII as its dollar cost is in the thousands at most institutions.22 Since the role of factor VII in life-threatening bleeding related to DTIs has yet to be defined, it is prudent to consider this option when other measures fail, understanding the variable rates of success in reversal of anticoagulation.

Prothrombin Complex Concentrates

Prothrombin complex concentrates (PCCs) have a significant place in reversing bleeding in patients on certain anticoagulants. Since these products contain all of the vitamin K-dependent clotting factors and proteins C and S, they have been used in the treatment of warfarin toxicity.

PCCs can be divided into activated and nonactivated categories. Among the nonactivated PCCs are PCC3 and PCC4. Both contain factors II, VII, IX, and X, but PCC3 products have lower concentrations of factor VII. To augment factor VII activity, it has been proposed that fresh frozen plasma or packed red blood cells be given in conjunction with a PCC3.23

Activated prothrombin complex concentrates (APCC) contain activated factor VII, along with inactivated forms of factors II, IX, X, and protein C. Animal studies appear promising for the use of PCCs in DTI-associated bleeding; however, this treatment has not yet been fully evaluated in human studies.24

A recent randomized, placebo-controlled crossover study by Eerenberg et al25 evaluated 12 healthy volunteers treated with PCC4 after receiving either dabigatran or rivaroxaban. While the PCC completely reversed anticoagulation in the rivaroxaban group, there was no reversal of anticoagulation in the dabigatran group.25 The authors made note of the study limitations, which include small sample size and the fact that healthy volunteers were used as surrogates as opposed to patients with major bleeding complications. The authors stated that "although this trial may have important clinical implications, the effect of PCC has yet to be confirmed in patients with bleeding events treated with these anticoagulants."25 This is the only human study available and serves as a starting point from which further human research can be initiated.25

Oral Factor Xa Inhibitors

Apixaban

The FXa inhibitors are a new class of prophylactic anticoagulants. Apixaban, one of the more recent oral FXa inhibitors, has a half-life of approximately 12 hours, predictable pharmacokinetics, and is cleared primarily via the GI tract. Given its hepatic metabolism, patients taking apixaban along with cytochrome P3A4 inhibitors (eg, certain antibiotics and antifungals) may be at increased risk of bleeding.26 As evidenced by the ARISTOTLE trial, compared to standard treatment with warfarin, apixaban is an effective alternative therapy for patients with atrial fibrillation.27 Of note, however, the ADOPT trial showed increased rates of bleeding in patients with comorbid conditions taking apixaban compared to standard enoxaparin dosing.28

Rivaroxaban

Rivaroxaban is another oral FXa inhibitor, with similar pharmacokinetics as apixaban and a half-life ranging from 8 hours in young healthy subjects to 12 hours in elderly patients. Since one third of the drug is renally cleared, rivaroxaban should be prescribed with caution in patients who have impaired creatinine clearance. Moreover, as the remaining two thirds undergo hepatic clearance, as with apixaban, its use is contraindicated in patients taking other cytochrome P-inhibiting medications.29

The MAGELLAN trial found rivaroxaban to be an effective means of DVT prophylaxis compared to control subjects who received enoxaparin injections, but there was in increased rate of clinically significant bleeding in the rivaroxaban group—arguably one of the more important outcome measures for the emergency provider.30 The ROCKET-AF trial, however, showed reduced rates of stroke in patients who received rivaroxaban versus warfarin. Both drugs had similar rates of major and minor bleeding, but rivaroxaban showed a decrease in intracranial hemorrhage and fatal bleeding.31

Monitoring and Reversal

As with the DTIs, monitoring the anticoagulant activity of factor Xa inhibitors can be a challenge, though various factor X assays have been proposed.31 Similar difficulties likewise exist in terms of reversal. There is no specific reversal agent for the FXa inhibitors, and current treatment guidelines recommend the use of PCCs, APCCs, or recombinant factor VIIa—though limited data exist on which agent to base clinical practice. In contrast to the DTIs, neither apixaban nor rivaroxaban are dialyzable.32 The relatively short half-life of these products, however, can prove beneficial, with cessation of the medication being the first line therapy in the case of any clinically significant bleeding.33

Conclusion

Parenteral DTIs have been utilized for years in the ED setting. With the increasing use of newer oral DTIs and FXa inhibitors, emergency physicians must also become familiar with the drug profile of these products, including appropriate anticoagulation monitoring and effective methods to treat DTI- and FXa-associated bleeding. Many questions remain unanswered about these drugs, necessitating further research—specifically in areas of practical monitoring of anticoagulation and possible reversal protocols in the bleeding patient.

Dr Byrne is a clinical instructor in the department of emergency medicine, Eastern Virginia Medical School, Norfolk. Dr Byars is an associate professor in the department of emergency medicine, Eastern Virginia Medical School, Norfolk.

Disclosure: The authors report no conflict of interest.

Parenteral direct thrombin inhibitors (DTI), such as bivalirudin, have been used for more than a decade in the hospital setting. Over the past few years, new DTIs have received US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval, most notably dabigatran etexilate, an orally active DTI touted as a viable alternative for anticoagulation in patients previously taking warfarin or enoxaparin. In addition to the DTIs, oral factor Xa (FXa) inhibitors have also received FDA approval. As these drugs begin to appear on the medication lists of many patients in the ED, a review—especially of the newer, oral agents—is essential. This article provides an overview of the parenteral DTIs and oral DTI dabigatran etexilate, as well as the oral FXa inhibitors, with a focus on proper monitoring of anticoagulation and common problems encountered in patients taking these medications.

Parenteral Direct Thrombin Inhibitors

Hirudin

Hirudin, a bivalent DTI, was the first parenteral anticoagulant of its kind approved for use in humans.1 Commercially available analogs, including lepirudin, bivalirudin, and desirudin, have since become available. Anticoagulation in patients taking hirudin can be monitored effectively in the ED via activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT).2 However, there are significant disadvantages to its use, including high cost, lack of a reversal agent, and the potential development of antibodies to hirudin and its derivatives. In addition, since anaphylactoid reactions have been reported, current recommendations contraindicate its use in patients previously treated with hirudin derivatives.3

Lepirudin

Lepirudin is a hirudin analog derived from yeast cells, and is ideal for patients with heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT). With respect to thromboembolic complications in patients with a previous history of HIT, Greinacher et al,4 demonstrated its relative safety and effectiveness. Their study showed a significant reduction in thromboembolic complications per patient day from 6.1% to 1.3%.4 Bleeding events in study participants occurred at an increased rate compared to controls, but these events were greatly decreased when aPTT levels were maintained between 1.5 to 2.5-fold above baseline.4 Since lepirudin is renally excreted and no reversal agent currently exists, clinicians must use caution when administering it to patients with renal insufficiency.

Bivalirudin

Bivalirudin is another hirudin analog and has an important niche among patients requiring percutaneous coronary intervention, primarily due to its favorable pharmacokinetic profile. In contrast to other DTIs, bivalirudin does not undergo organ-specific clearance, but rather proteolysis—an excellent option for patients with other comorbidities. Additionally, its short half-life of 25 minutes makes it an appropriate choice in cases warranting only a brief period of anticoagulation.5

Argatroban

Argatroban, another parenteral DTI, differs from hirudin, lepirudin, and bivalirudin in that it is a univalent molecule. Anticoagulation is monitored by aPTT, though dose-dependent changes may be seen in prothrombin time (PT). Since argatroban undergoes hepatic clearance, dose adjustments are required in patients with hepatic dysfunction—but not in those with renal insufficiency.6 Similar to lepirudin, argatroban is also indicated for patients with a history of HIT. In recent studies, argatroban achieved patency more frequently than heparin in patients with acute myocardial infarction—without differences in clinical outcomes.7

Dabigatran Etexilate

With the increased number of patients presenting to the ED with venous and arterial thromboembolic disorders, emergency physicians should be familiar with the orally active prodrug, dabigatran. This DTI is taken twice daily and converts to it active form after administration, binding to thrombin with great specificity and affinity.8 Its half-life ranges from 12 to 24 hours in patients with normal renal function; reduced dosing schedules are recommended in patients older than age 75 years and in those with renal impairment. Dabigatran is contraindicated if creatinine clearance is less than 30 mL/min. Even though dabigatran is not cleared by the cytochrome P450 system, it does utilize the P-glycoprotein efflux transporter and is thus vulnerable to both inducers and inhibitors, including systemic antifungals and other medications.9

Monitoring Anticoagulation

Unlike warfarin, dabigatran does not require extensive monitoring. However, thrombin and aPPT assays are often less predictable at supertherapeutic levels of dabigatran, and results vary depending on last administration time of the drug.10 Strangier et al11 identified some weaknesses in aPTT measurement, concluding that while measurement of aPTT may provide a qualitative indication of anticoagulant activity, it is not suitable for the precise quantification of anticoagulant effect—especially at high plasma concentrations of dabigatran.11 Furthermore, since PT time is not significantly affected by DTIs, this assay is a poor monitoring choice for these medications.12

The thrombin time (TT) assay test, which is usually accessible in routine clinical practice, directly assesses thrombin activity, providing a direct measure of dabigatran concentration. The TT is particularly sensitive to the effects of dabigatran and displays a linear dose-response even at supratherapeutic concentrations, making it the most useful and sensitive method for determining the anticoagulation effect of dabigatran.13

When treating patients in the ED who could potentially benefit from thrombolytic agents, monitoring dabigatran anticoagulation can present a challenge. There is very little information regarding the use of tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) in patients on dabigatran, with only one published case on the subject. In this case, intravenous (IV) tPA was administered just less than 4.5 hours after onset of neurologic symptoms and 7 hours after the last intake of dabigatran, with no complications and improved neurology function.14

The Interventional Management Stroke (IMS) III trial has suggested clinicians consider IV tPA in patients with acute stroke if the last dose of dabigatran was greater than 48 hours prior to presentation in the ED.15 Until further evidence becomes available, the decision to administer thrombolytics to stroke patients taking dabigatran should be made on a case-by-case basis and in consultation with a neurologist.

Noninferiority Studies

Dabigatran has been compared to enoxaparin and showed noninferiority for venous thromboembolism (VTE) prophylaxis, with a similar safety profile.16 The RE-COVER study in 2009 demonstrated the noninferiority of dabigatran compared to warfarin. In this study, patients received either the standard dose of dabigatran (150 mg orally, twice daily) or traditional dose-adjusted warfarin. In patients on the dabigatran regimen, recurrent VTE complications occurred at a rate of 2.4%, compared with the 2.1% observed in the warfarin group.17 The safety profile was also similar, with major bleeding episodes occurring in 1.6% and 1.9%, respectively.17

Another study, the RE-LY trial, also sought to prove noninferiority between dabigatran and warfarin, specifically in patients with a known history of atrial fibrillation requiring anticoagulation.18 The authors of the study concluded a clinical net benefit of dabigatran over warfarin with respect to reduction in both hemorrhagic and ischemic stroke and bleeding versus the increase of myocardial infarction.19 Further studies, however, are needed to determine the safety profile of dabigatran.

Dabigatran Reversal

Perhaps the most pressing question for the emergency physician is how to approach the bleeding patient on dabigatran. Although well-known protocols exist for the reversal of other anticoagulants such as warfarin and heparin, no clear, effective reversal agent is currently available for dabigatran. Given its relatively short half-life (12 to 24 hours), the first line of treatment should be to discontinue its use, followed by mechanical pressure or surgical hemostatic, if indicated. Transfusion of blood products (eg, packed red blood cells, fresh frozen plasma, platelets) should be administered based on the extent of the patient’s bleeding.

If these measures fail, dialysis may be considered, particularly in patients with renal insufficiency that may have bleeding secondary to dabigatran toxicity. In cases of suspected overdose, although activated charcoal is still being evaluated, Van Ryn and colleagues noted "preliminary in vitro data indicate that dabigatran etexilate can be successfully adsorbed by classical activated charcoal therapy. However, this has not been tested in vivo or in patients…additional clinically relevant models are required before this can be recommended in patients."10

Managing Dti-Associated Bleeding

Factor VII

Since recombinant activated factor VII directly activates thrombin on the surface of platelets, it is an option in cases of life-threatening DTI-associated bleeding. While laboratory data has supported this use, human studies have been less convincing, with conflicting results in two separate studies.20,21 Moreover, financial considerations may also affect the decision to use factor VII as its dollar cost is in the thousands at most institutions.22 Since the role of factor VII in life-threatening bleeding related to DTIs has yet to be defined, it is prudent to consider this option when other measures fail, understanding the variable rates of success in reversal of anticoagulation.

Prothrombin Complex Concentrates

Prothrombin complex concentrates (PCCs) have a significant place in reversing bleeding in patients on certain anticoagulants. Since these products contain all of the vitamin K-dependent clotting factors and proteins C and S, they have been used in the treatment of warfarin toxicity.

PCCs can be divided into activated and nonactivated categories. Among the nonactivated PCCs are PCC3 and PCC4. Both contain factors II, VII, IX, and X, but PCC3 products have lower concentrations of factor VII. To augment factor VII activity, it has been proposed that fresh frozen plasma or packed red blood cells be given in conjunction with a PCC3.23

Activated prothrombin complex concentrates (APCC) contain activated factor VII, along with inactivated forms of factors II, IX, X, and protein C. Animal studies appear promising for the use of PCCs in DTI-associated bleeding; however, this treatment has not yet been fully evaluated in human studies.24

A recent randomized, placebo-controlled crossover study by Eerenberg et al25 evaluated 12 healthy volunteers treated with PCC4 after receiving either dabigatran or rivaroxaban. While the PCC completely reversed anticoagulation in the rivaroxaban group, there was no reversal of anticoagulation in the dabigatran group.25 The authors made note of the study limitations, which include small sample size and the fact that healthy volunteers were used as surrogates as opposed to patients with major bleeding complications. The authors stated that "although this trial may have important clinical implications, the effect of PCC has yet to be confirmed in patients with bleeding events treated with these anticoagulants."25 This is the only human study available and serves as a starting point from which further human research can be initiated.25

Oral Factor Xa Inhibitors

Apixaban