User login

Rheumatic diseases and assisted reproductive technology: Things to consider

The field of “reproductive rheumatology” has received growing attention in recent years as we learn more about how autoimmune rheumatic diseases and their treatment affect women of reproductive age. In 2020, the American College of Rheumatology published a comprehensive guideline that includes recommendations and supporting evidence for managing issues related to reproductive health in patients with rheumatic diseases and has since launched an ongoing Reproductive Health Initiative, with the goal of translating established guidelines into practice through various education and awareness campaigns. One area addressed by the guideline that comes up commonly in practice but receives less attention and research is the use of assisted reproductive technology (ART) in patients with rheumatic diseases.

Literature is conflicting regarding whether patients with autoimmune rheumatic diseases are inherently at increased risk for infertility, defined as failure to achieve a clinical pregnancy after 12 months or more of regular unprotected intercourse, or subfertility, defined as a delay in conception. Regardless, several factors indirectly contribute to a disproportionate risk for infertility or subfertility in this patient population, including active inflammatory disease, reduced ovarian reserve, and medications.

Patients with subfertility or infertility who desire pregnancy may pursue ovulation induction with timed intercourse or intrauterine insemination, in vitro fertilization (IVF)/intracytoplasmic sperm injection with either embryo transfer, or gestational surrogacy. Those who require treatment with cyclophosphamide or who plan to defer pregnancy for whatever reason can opt for oocyte cryopreservation (colloquially known as “egg freezing”). For IVF and oocyte cryopreservation, controlled ovarian stimulation is typically the first step (except in unstimulated, or “natural cycle,” IVF).

Various protocols are used for ovarian stimulation and ovulation induction, the nuances of which are beyond the scope of this article. In general, ovarian stimulation involves gonadotropin therapy (follicle-stimulating hormone and/or human menopausal gonadotropin) administered via scheduled subcutaneous injections to stimulate follicular growth, as well as gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists or antagonists to suppress luteinizing hormone, preventing ovulation. Adjunctive oral therapy (clomiphene citrate or letrozole, an aromatase inhibitor) may be used as well. The patient has frequent lab monitoring of hormone levels and transvaginal ultrasounds to measure follicle number and size and, when the timing is right, receives an “ovulation trigger” – either human chorionic gonadotropin or GnRH agonist, depending on the protocol. At this point, transvaginal ultrasound–guided egg retrieval is done under sedation. Recovered oocytes are then either frozen for later use or fertilized in the lab for embryo transfer. Lastly, exogenous hormones are often used: estrogen to support frozen embryo transfers and progesterone for so-called luteal phase support.

ART is not contraindicated in patients with autoimmune rheumatic diseases, but there may be additional factors to consider, particularly for those with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), antiphospholipid syndrome (APS), and antiphospholipid antibodies (aPL) without clinical APS.

Ovarian stimulation elevates estrogen levels to varying degrees depending on the patient and the medications used. In all cases, though, peak levels are significantly lower than levels reached during pregnancy. It is well established that elevated estrogen – whether from hormone therapies or pregnancy – significantly increases thrombotic risk, even in healthy people. High-risk patients should receive low-molecular-weight heparin – a prophylactic dose for patients with either positive aPL without clinical APS (including those with SLE) or with obstetric APS, and a therapeutic dose for those with thrombotic APS – during ART procedures.

In patients with SLE, another concern is that increased estrogen will cause disease flare. One case series published in 2017 reported 37 patients with SLE and/or APS who underwent 97 IVF cycles, of which 8% were complicated by flare or thrombotic events. Notably, half of these complications occurred in patients who stopped prescribed therapies (immunomodulatory therapy in two patients with SLE, anticoagulation in two patients with APS) after failure to conceive. In a separate study from 2000 including 19 patients with SLE, APS, or high-titer aPL who underwent 68 IVF cycles, 19% of cycles in patients with SLE were complicated by flare, and no thrombotic events occurred in the cohort. The authors concluded that ovulation induction does not exacerbate SLE or APS. In these studies, the overall pregnancy rates were felt to be consistent with those achieved by the general population through IVF. Although obstetric complications, such as preeclampsia and preterm delivery, were reported in about half of the pregnancies described, these are known to occur more frequently in those with SLE and APS, especially when active disease or other risk factors are present. There are no large-scale, controlled studies evaluating ART outcomes in patients with autoimmune rheumatic diseases to date.

Finally, ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS) is an increasingly rare but severe complication of ovarian stimulation. OHSS is characterized by capillary leak, fluid overload, and cytokine release syndrome and can lead to thromboembolic events. Comorbidities like hypertension and renal failure, which can go along with autoimmune rheumatic diseases, are risk factors for OHSS. The use of human chorionic gonadotropin to trigger ovulation is also associated with an increased risk for OHSS, so a GnRH agonist trigger may be preferable.

The ACR guideline recommends that individuals with any of these underlying conditions undergo ART only in expert centers. The ovarian stimulation protocol needs to be tailored to the individual patient to minimize risk and optimize outcomes. The overall goal when managing patients with autoimmune rheumatic diseases during ART is to establish and maintain disease control with pregnancy-compatible medications (when pregnancy is the goal). With adequate planning, appropriate treatment, and collaboration between obstetricians and rheumatologists, individuals with autoimmune rheumatic diseases can safely pursue ART and go on to have successful pregnancies.

Dr. Siegel is a 2022-2023 UCB Women’s Health rheumatology fellow in the rheumatology reproductive health program of the Barbara Volcker Center for Women and Rheumatic Diseases at Hospital for Special Surgery/Weill Cornell Medicine, New York. Her clinical and research focus is on reproductive health issues in individuals with rheumatic disease. Dr. Chan is an assistant professor at Weill Cornell Medical College and an attending physician at Hospital for Special Surgery and Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York. Before moving to New York City, she spent 7 years in private practice in Rhode Island and was a columnist for a monthly rheumatology publication, writing about the challenges of starting life as a full-fledged rheumatologist in a private practice. Follow Dr Chan on Twitter. Dr. Siegel and Dr. Chan disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article – an editorial collaboration between Medscape and the Hospital for Special Surgery – first appeared on Medscape.com.

The field of “reproductive rheumatology” has received growing attention in recent years as we learn more about how autoimmune rheumatic diseases and their treatment affect women of reproductive age. In 2020, the American College of Rheumatology published a comprehensive guideline that includes recommendations and supporting evidence for managing issues related to reproductive health in patients with rheumatic diseases and has since launched an ongoing Reproductive Health Initiative, with the goal of translating established guidelines into practice through various education and awareness campaigns. One area addressed by the guideline that comes up commonly in practice but receives less attention and research is the use of assisted reproductive technology (ART) in patients with rheumatic diseases.

Literature is conflicting regarding whether patients with autoimmune rheumatic diseases are inherently at increased risk for infertility, defined as failure to achieve a clinical pregnancy after 12 months or more of regular unprotected intercourse, or subfertility, defined as a delay in conception. Regardless, several factors indirectly contribute to a disproportionate risk for infertility or subfertility in this patient population, including active inflammatory disease, reduced ovarian reserve, and medications.

Patients with subfertility or infertility who desire pregnancy may pursue ovulation induction with timed intercourse or intrauterine insemination, in vitro fertilization (IVF)/intracytoplasmic sperm injection with either embryo transfer, or gestational surrogacy. Those who require treatment with cyclophosphamide or who plan to defer pregnancy for whatever reason can opt for oocyte cryopreservation (colloquially known as “egg freezing”). For IVF and oocyte cryopreservation, controlled ovarian stimulation is typically the first step (except in unstimulated, or “natural cycle,” IVF).

Various protocols are used for ovarian stimulation and ovulation induction, the nuances of which are beyond the scope of this article. In general, ovarian stimulation involves gonadotropin therapy (follicle-stimulating hormone and/or human menopausal gonadotropin) administered via scheduled subcutaneous injections to stimulate follicular growth, as well as gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists or antagonists to suppress luteinizing hormone, preventing ovulation. Adjunctive oral therapy (clomiphene citrate or letrozole, an aromatase inhibitor) may be used as well. The patient has frequent lab monitoring of hormone levels and transvaginal ultrasounds to measure follicle number and size and, when the timing is right, receives an “ovulation trigger” – either human chorionic gonadotropin or GnRH agonist, depending on the protocol. At this point, transvaginal ultrasound–guided egg retrieval is done under sedation. Recovered oocytes are then either frozen for later use or fertilized in the lab for embryo transfer. Lastly, exogenous hormones are often used: estrogen to support frozen embryo transfers and progesterone for so-called luteal phase support.

ART is not contraindicated in patients with autoimmune rheumatic diseases, but there may be additional factors to consider, particularly for those with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), antiphospholipid syndrome (APS), and antiphospholipid antibodies (aPL) without clinical APS.

Ovarian stimulation elevates estrogen levels to varying degrees depending on the patient and the medications used. In all cases, though, peak levels are significantly lower than levels reached during pregnancy. It is well established that elevated estrogen – whether from hormone therapies or pregnancy – significantly increases thrombotic risk, even in healthy people. High-risk patients should receive low-molecular-weight heparin – a prophylactic dose for patients with either positive aPL without clinical APS (including those with SLE) or with obstetric APS, and a therapeutic dose for those with thrombotic APS – during ART procedures.

In patients with SLE, another concern is that increased estrogen will cause disease flare. One case series published in 2017 reported 37 patients with SLE and/or APS who underwent 97 IVF cycles, of which 8% were complicated by flare or thrombotic events. Notably, half of these complications occurred in patients who stopped prescribed therapies (immunomodulatory therapy in two patients with SLE, anticoagulation in two patients with APS) after failure to conceive. In a separate study from 2000 including 19 patients with SLE, APS, or high-titer aPL who underwent 68 IVF cycles, 19% of cycles in patients with SLE were complicated by flare, and no thrombotic events occurred in the cohort. The authors concluded that ovulation induction does not exacerbate SLE or APS. In these studies, the overall pregnancy rates were felt to be consistent with those achieved by the general population through IVF. Although obstetric complications, such as preeclampsia and preterm delivery, were reported in about half of the pregnancies described, these are known to occur more frequently in those with SLE and APS, especially when active disease or other risk factors are present. There are no large-scale, controlled studies evaluating ART outcomes in patients with autoimmune rheumatic diseases to date.

Finally, ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS) is an increasingly rare but severe complication of ovarian stimulation. OHSS is characterized by capillary leak, fluid overload, and cytokine release syndrome and can lead to thromboembolic events. Comorbidities like hypertension and renal failure, which can go along with autoimmune rheumatic diseases, are risk factors for OHSS. The use of human chorionic gonadotropin to trigger ovulation is also associated with an increased risk for OHSS, so a GnRH agonist trigger may be preferable.

The ACR guideline recommends that individuals with any of these underlying conditions undergo ART only in expert centers. The ovarian stimulation protocol needs to be tailored to the individual patient to minimize risk and optimize outcomes. The overall goal when managing patients with autoimmune rheumatic diseases during ART is to establish and maintain disease control with pregnancy-compatible medications (when pregnancy is the goal). With adequate planning, appropriate treatment, and collaboration between obstetricians and rheumatologists, individuals with autoimmune rheumatic diseases can safely pursue ART and go on to have successful pregnancies.

Dr. Siegel is a 2022-2023 UCB Women’s Health rheumatology fellow in the rheumatology reproductive health program of the Barbara Volcker Center for Women and Rheumatic Diseases at Hospital for Special Surgery/Weill Cornell Medicine, New York. Her clinical and research focus is on reproductive health issues in individuals with rheumatic disease. Dr. Chan is an assistant professor at Weill Cornell Medical College and an attending physician at Hospital for Special Surgery and Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York. Before moving to New York City, she spent 7 years in private practice in Rhode Island and was a columnist for a monthly rheumatology publication, writing about the challenges of starting life as a full-fledged rheumatologist in a private practice. Follow Dr Chan on Twitter. Dr. Siegel and Dr. Chan disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article – an editorial collaboration between Medscape and the Hospital for Special Surgery – first appeared on Medscape.com.

The field of “reproductive rheumatology” has received growing attention in recent years as we learn more about how autoimmune rheumatic diseases and their treatment affect women of reproductive age. In 2020, the American College of Rheumatology published a comprehensive guideline that includes recommendations and supporting evidence for managing issues related to reproductive health in patients with rheumatic diseases and has since launched an ongoing Reproductive Health Initiative, with the goal of translating established guidelines into practice through various education and awareness campaigns. One area addressed by the guideline that comes up commonly in practice but receives less attention and research is the use of assisted reproductive technology (ART) in patients with rheumatic diseases.

Literature is conflicting regarding whether patients with autoimmune rheumatic diseases are inherently at increased risk for infertility, defined as failure to achieve a clinical pregnancy after 12 months or more of regular unprotected intercourse, or subfertility, defined as a delay in conception. Regardless, several factors indirectly contribute to a disproportionate risk for infertility or subfertility in this patient population, including active inflammatory disease, reduced ovarian reserve, and medications.

Patients with subfertility or infertility who desire pregnancy may pursue ovulation induction with timed intercourse or intrauterine insemination, in vitro fertilization (IVF)/intracytoplasmic sperm injection with either embryo transfer, or gestational surrogacy. Those who require treatment with cyclophosphamide or who plan to defer pregnancy for whatever reason can opt for oocyte cryopreservation (colloquially known as “egg freezing”). For IVF and oocyte cryopreservation, controlled ovarian stimulation is typically the first step (except in unstimulated, or “natural cycle,” IVF).

Various protocols are used for ovarian stimulation and ovulation induction, the nuances of which are beyond the scope of this article. In general, ovarian stimulation involves gonadotropin therapy (follicle-stimulating hormone and/or human menopausal gonadotropin) administered via scheduled subcutaneous injections to stimulate follicular growth, as well as gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists or antagonists to suppress luteinizing hormone, preventing ovulation. Adjunctive oral therapy (clomiphene citrate or letrozole, an aromatase inhibitor) may be used as well. The patient has frequent lab monitoring of hormone levels and transvaginal ultrasounds to measure follicle number and size and, when the timing is right, receives an “ovulation trigger” – either human chorionic gonadotropin or GnRH agonist, depending on the protocol. At this point, transvaginal ultrasound–guided egg retrieval is done under sedation. Recovered oocytes are then either frozen for later use or fertilized in the lab for embryo transfer. Lastly, exogenous hormones are often used: estrogen to support frozen embryo transfers and progesterone for so-called luteal phase support.

ART is not contraindicated in patients with autoimmune rheumatic diseases, but there may be additional factors to consider, particularly for those with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), antiphospholipid syndrome (APS), and antiphospholipid antibodies (aPL) without clinical APS.

Ovarian stimulation elevates estrogen levels to varying degrees depending on the patient and the medications used. In all cases, though, peak levels are significantly lower than levels reached during pregnancy. It is well established that elevated estrogen – whether from hormone therapies or pregnancy – significantly increases thrombotic risk, even in healthy people. High-risk patients should receive low-molecular-weight heparin – a prophylactic dose for patients with either positive aPL without clinical APS (including those with SLE) or with obstetric APS, and a therapeutic dose for those with thrombotic APS – during ART procedures.

In patients with SLE, another concern is that increased estrogen will cause disease flare. One case series published in 2017 reported 37 patients with SLE and/or APS who underwent 97 IVF cycles, of which 8% were complicated by flare or thrombotic events. Notably, half of these complications occurred in patients who stopped prescribed therapies (immunomodulatory therapy in two patients with SLE, anticoagulation in two patients with APS) after failure to conceive. In a separate study from 2000 including 19 patients with SLE, APS, or high-titer aPL who underwent 68 IVF cycles, 19% of cycles in patients with SLE were complicated by flare, and no thrombotic events occurred in the cohort. The authors concluded that ovulation induction does not exacerbate SLE or APS. In these studies, the overall pregnancy rates were felt to be consistent with those achieved by the general population through IVF. Although obstetric complications, such as preeclampsia and preterm delivery, were reported in about half of the pregnancies described, these are known to occur more frequently in those with SLE and APS, especially when active disease or other risk factors are present. There are no large-scale, controlled studies evaluating ART outcomes in patients with autoimmune rheumatic diseases to date.

Finally, ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS) is an increasingly rare but severe complication of ovarian stimulation. OHSS is characterized by capillary leak, fluid overload, and cytokine release syndrome and can lead to thromboembolic events. Comorbidities like hypertension and renal failure, which can go along with autoimmune rheumatic diseases, are risk factors for OHSS. The use of human chorionic gonadotropin to trigger ovulation is also associated with an increased risk for OHSS, so a GnRH agonist trigger may be preferable.

The ACR guideline recommends that individuals with any of these underlying conditions undergo ART only in expert centers. The ovarian stimulation protocol needs to be tailored to the individual patient to minimize risk and optimize outcomes. The overall goal when managing patients with autoimmune rheumatic diseases during ART is to establish and maintain disease control with pregnancy-compatible medications (when pregnancy is the goal). With adequate planning, appropriate treatment, and collaboration between obstetricians and rheumatologists, individuals with autoimmune rheumatic diseases can safely pursue ART and go on to have successful pregnancies.

Dr. Siegel is a 2022-2023 UCB Women’s Health rheumatology fellow in the rheumatology reproductive health program of the Barbara Volcker Center for Women and Rheumatic Diseases at Hospital for Special Surgery/Weill Cornell Medicine, New York. Her clinical and research focus is on reproductive health issues in individuals with rheumatic disease. Dr. Chan is an assistant professor at Weill Cornell Medical College and an attending physician at Hospital for Special Surgery and Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York. Before moving to New York City, she spent 7 years in private practice in Rhode Island and was a columnist for a monthly rheumatology publication, writing about the challenges of starting life as a full-fledged rheumatologist in a private practice. Follow Dr Chan on Twitter. Dr. Siegel and Dr. Chan disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article – an editorial collaboration between Medscape and the Hospital for Special Surgery – first appeared on Medscape.com.

Is evolution’s greatest triumph its worst blunder?

Of all the dazzling achievements of evolution, the most glorious by far is the emergence of the advanced human brain, especially the prefrontal cortex. Homo sapiens (the wise humans) are without doubt the most transformative development in the consequential annals of evolution. It was evolution’s spectacular “moonshot.” Ironically, it may also have been the seed of its destruction.

The unprecedented growth of the human brain over the past 7 million years (tripling in size) was a monumental tipping point in evolution that ultimately disrupted the entire orderly cascade of evolution on Planet Earth. Because of their superior intelligence, Homo sapiens have substantially “tinkered” with the foundations of evolution, such as “natural selection” and “survival of the fittest,” and may eventually change the course of evolution, or even reverse it. It should also be recognized that 20% of the human genome is Neanderthal, and the 2022 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine was awarded to Svante Pääbo, the founder of the field of paleogenetics, who demonstrated genetically that Homo sapiens interbred with Homo neanderthalensis (who disappeared 30,000 years ago).

The majestic evolution of the human brain, in both size and complexity, led to monumental changes in the history of humankind compared to their primitive predecessors. Thanks to a superior cerebral cortex, humans developed traits and abilities that were nonexistent, even unimaginable, in the rest of animal kingdom, including primates and other mammals. These include thoughts; speech (hundreds of languages), spoken and written, to communicate among themselves; composed music and created numerous instruments to play it; invented mathematics, physics, and chemistry; developed agriculture to sustain and feed the masses; built homes, palaces, and pyramids, with water and sewage systems; hatched hundreds of religions and built thousands of houses of worship; built machines to transport themselves (cars, trains, ships, planes, and space shuttles); paved airports and countless miles of roads and railways; established companies, universities, hospitals, and research laboratories; built sports facilities such as stadiums for Olympic games and all its athletics; created hotels, restaurants, coffee shops, newspapers, and magazines; discovered the amazing DNA double helix and its genome with 23,000 coding genes containing instructions to build the brain and 200 other body tissues; developed surgeries and invented medications for diseases that would have killed millions every year; and established paper money to replace gold and silver coins. Humans established governments that included monarchies, dictatorships, democracies, and pseudodemocracies; stipulated constitutions, laws, and regulations to maintain various societies; and created several civilizations around the world that thrived and then faded. Over the past century, the advanced human brain elevated human existence to a higher sophistication with technologies such as electricity, phones, computers, internet, artificial intelligence, and machine learning. Using powerful rockets and space stations, humans have begun to expand their influence to the moon and planets of the solar system. Humans are very likely to continue achieving what evolution could never have done without evolving the human brain to become the most powerful force in nature.

The key ingredient of the brain that has enabled humans to achieve so much is the development of an advanced cognition, with superior functions that far exceed those of other living organisms. These include neurocognitive functions such as memory and attention, and executive functions that include planning, problem-solving, decision-making, abstract thinking, and insight. Those cognitive functions generate lofty prose, splendiferous poetry, and heavenly symphonies that inspire those who create it and others. The human brain also developed social cognition, with empathy, theory of mind, recognition of facial expressions, and courtship rituals that can trigger infatuation and love. Homo sapiens can experience a wide range of emotions in addition to love and attachment (necessary for procreation), including shame, guilt, surprise, embarrassment, disgust, and indifference, and a unique sense of right and wrong.

Perhaps the most distinctive human attribute, generated by an advanced prefrontal cortex, is a belief system that includes philosophy, politics, religion, and faith. Hundreds of different religions sprouted throughout human history (each claiming a monopoly on “the truth”), mandating rituals and behaviors, but also promoting a profound and unshakable belief in a divine “higher being” and an afterlife that mitigates the fear of death. Humans, unlike other animals, are painfully aware of mortality and the inevitability of death. Faith is an antidote for thanatophobia. Unfortunately, religious beliefs often generated severe and protracted schisms and warfare, with fatal consequences for their followers.

The anti-evolution aspect of the advanced brain

Despite remarkable talents and achievements, the unprecedented evolutionary expansion of the human brain also has a detrimental downside. The same intellectual power that led to astonishing positive accomplishments has a wicked side as well. While most animals have a predator, humans have become the “omni-predator” that preys on all living things. The balanced ecosystems of animals and plants has been dominated and disrupted by humans. Thousands of species that evolution had so ingeniously spawned became extinct because of human actions. The rainforests, jewels of nature’s plantation system, were victimized by human indifference to the deleterious effects on nature and climate. The excavation of coal and oil, exploited as necessary sources of energy for societal infrastructure, came back to haunt humans with climate consequences. In many ways, human “progress” corrupted evolution and dismantled its components. Survival of the fittest among various species was whittled down to “survival of humans” (and their domesticated animals) at the expense of all other organisms, animals, or plants.

Among Homo sapiens, momentous scientific, medical, and technological advances completely undermined the principle of survival of the fittest. Very premature infants, who would have certainly died, were kept alive. Children with disabling genetic disorders who would have perished in childhood were kept alive into the age of procreation, perpetuating the genetic mutations. The discovery of antibiotic and antiviral medications, and especially vaccines, ensured the survival of millions of humans who would have succumbed to infections. With evolution’s natural selection, humans who survived severe infections without medications would have passed on their “infection-resistant genes” to their progeny. The triumph of human medical progress can be conceptualized as a setback for the principles of evolution.

Continue to: The most malignant...

The most malignant consequence of the exceptional human brain is the evil of which it is capable. Human ingenuity led to the development of weapons of individual killing (guns), large-scale murder (machine guns), and massive destruction (nuclear weapons). And because aggression and warfare are an inherent part of human nature, the most potent predator for a human is another human. The history of humans is riddled with conflict and death on a large scale. Ironically, many wars were instigated by various religious groups around the world, who developed intense hostility towards one another.

There are other downsides to the advanced human brain. It can channel its talents and skills into unimaginably wicked and depraved behaviors, such as premeditated and well-planned murder, slavery, cults, child abuse, domestic abuse, pornography, fascism, dictatorships, and political corruption. Astonishingly, the same brain that can be loving, kind, friendly, and empathetic can suddenly become hateful, vengeful, cruel, vile, sinister, vicious, diabolical, and capable of unimaginable violence and atrocities. The advanced human brain definitely has a very dark side.

Finally, unlike other members of the animal kingdom, the human brain generates its virtual counterpart: the highly complex human mind, which is prone to various maladies, labeled as “psychiatric disorders.” No other animal species develops delusions, hallucinations, thought disorders, melancholia, mania, obsessive-compulsive disorder, generalized anxiety, panic attacks, posttraumatic stress disorder, psychopathy, narcissistic and borderline personality disorders, alcohol addiction, and drug abuse. Homo sapiens are the only species whose members decide to end their own life in large numbers. About 25% of human minds are afflicted with one or more of those psychiatric ailments.1,2 The redeeming grace of the large human brain is that it led to the development of pharmacologic and somatic treatments for most of them, including psychotherapy, which is a uniquely human treatment strategy that can mend many psychiatric disorders.

Evolution may not realize what it hath wrought when it evolved the dramatically expanded human brain, with its extraordinary cognition. This awe-inspiring “biological computer” can be creative and adaptive, with superlative survival abilities, but it can also degenerate and become nefarious, villainous, murderous, and even demonic. The human brain has essentially brought evolution to a screeching halt and may at some point end up destroying Earth and all of its Homo sapien inhabitants, who may foolishly use their weapons of mass destruction. The historic achievement of evolution has become the ultimate example of “the law of unintended consequences.”

1. Robin LN, Regier DA. Psychiatric Disorders in America: The Epidemiologic Catchment Area Study. Free Press; 1990.

2. Johns Hopkins Medicine. Mental Health Disorder Statistics. Accessed October 12, 2022. https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/wellness-and-prevention/mental-health-disorder-statistics

Of all the dazzling achievements of evolution, the most glorious by far is the emergence of the advanced human brain, especially the prefrontal cortex. Homo sapiens (the wise humans) are without doubt the most transformative development in the consequential annals of evolution. It was evolution’s spectacular “moonshot.” Ironically, it may also have been the seed of its destruction.

The unprecedented growth of the human brain over the past 7 million years (tripling in size) was a monumental tipping point in evolution that ultimately disrupted the entire orderly cascade of evolution on Planet Earth. Because of their superior intelligence, Homo sapiens have substantially “tinkered” with the foundations of evolution, such as “natural selection” and “survival of the fittest,” and may eventually change the course of evolution, or even reverse it. It should also be recognized that 20% of the human genome is Neanderthal, and the 2022 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine was awarded to Svante Pääbo, the founder of the field of paleogenetics, who demonstrated genetically that Homo sapiens interbred with Homo neanderthalensis (who disappeared 30,000 years ago).

The majestic evolution of the human brain, in both size and complexity, led to monumental changes in the history of humankind compared to their primitive predecessors. Thanks to a superior cerebral cortex, humans developed traits and abilities that were nonexistent, even unimaginable, in the rest of animal kingdom, including primates and other mammals. These include thoughts; speech (hundreds of languages), spoken and written, to communicate among themselves; composed music and created numerous instruments to play it; invented mathematics, physics, and chemistry; developed agriculture to sustain and feed the masses; built homes, palaces, and pyramids, with water and sewage systems; hatched hundreds of religions and built thousands of houses of worship; built machines to transport themselves (cars, trains, ships, planes, and space shuttles); paved airports and countless miles of roads and railways; established companies, universities, hospitals, and research laboratories; built sports facilities such as stadiums for Olympic games and all its athletics; created hotels, restaurants, coffee shops, newspapers, and magazines; discovered the amazing DNA double helix and its genome with 23,000 coding genes containing instructions to build the brain and 200 other body tissues; developed surgeries and invented medications for diseases that would have killed millions every year; and established paper money to replace gold and silver coins. Humans established governments that included monarchies, dictatorships, democracies, and pseudodemocracies; stipulated constitutions, laws, and regulations to maintain various societies; and created several civilizations around the world that thrived and then faded. Over the past century, the advanced human brain elevated human existence to a higher sophistication with technologies such as electricity, phones, computers, internet, artificial intelligence, and machine learning. Using powerful rockets and space stations, humans have begun to expand their influence to the moon and planets of the solar system. Humans are very likely to continue achieving what evolution could never have done without evolving the human brain to become the most powerful force in nature.

The key ingredient of the brain that has enabled humans to achieve so much is the development of an advanced cognition, with superior functions that far exceed those of other living organisms. These include neurocognitive functions such as memory and attention, and executive functions that include planning, problem-solving, decision-making, abstract thinking, and insight. Those cognitive functions generate lofty prose, splendiferous poetry, and heavenly symphonies that inspire those who create it and others. The human brain also developed social cognition, with empathy, theory of mind, recognition of facial expressions, and courtship rituals that can trigger infatuation and love. Homo sapiens can experience a wide range of emotions in addition to love and attachment (necessary for procreation), including shame, guilt, surprise, embarrassment, disgust, and indifference, and a unique sense of right and wrong.

Perhaps the most distinctive human attribute, generated by an advanced prefrontal cortex, is a belief system that includes philosophy, politics, religion, and faith. Hundreds of different religions sprouted throughout human history (each claiming a monopoly on “the truth”), mandating rituals and behaviors, but also promoting a profound and unshakable belief in a divine “higher being” and an afterlife that mitigates the fear of death. Humans, unlike other animals, are painfully aware of mortality and the inevitability of death. Faith is an antidote for thanatophobia. Unfortunately, religious beliefs often generated severe and protracted schisms and warfare, with fatal consequences for their followers.

The anti-evolution aspect of the advanced brain

Despite remarkable talents and achievements, the unprecedented evolutionary expansion of the human brain also has a detrimental downside. The same intellectual power that led to astonishing positive accomplishments has a wicked side as well. While most animals have a predator, humans have become the “omni-predator” that preys on all living things. The balanced ecosystems of animals and plants has been dominated and disrupted by humans. Thousands of species that evolution had so ingeniously spawned became extinct because of human actions. The rainforests, jewels of nature’s plantation system, were victimized by human indifference to the deleterious effects on nature and climate. The excavation of coal and oil, exploited as necessary sources of energy for societal infrastructure, came back to haunt humans with climate consequences. In many ways, human “progress” corrupted evolution and dismantled its components. Survival of the fittest among various species was whittled down to “survival of humans” (and their domesticated animals) at the expense of all other organisms, animals, or plants.

Among Homo sapiens, momentous scientific, medical, and technological advances completely undermined the principle of survival of the fittest. Very premature infants, who would have certainly died, were kept alive. Children with disabling genetic disorders who would have perished in childhood were kept alive into the age of procreation, perpetuating the genetic mutations. The discovery of antibiotic and antiviral medications, and especially vaccines, ensured the survival of millions of humans who would have succumbed to infections. With evolution’s natural selection, humans who survived severe infections without medications would have passed on their “infection-resistant genes” to their progeny. The triumph of human medical progress can be conceptualized as a setback for the principles of evolution.

Continue to: The most malignant...

The most malignant consequence of the exceptional human brain is the evil of which it is capable. Human ingenuity led to the development of weapons of individual killing (guns), large-scale murder (machine guns), and massive destruction (nuclear weapons). And because aggression and warfare are an inherent part of human nature, the most potent predator for a human is another human. The history of humans is riddled with conflict and death on a large scale. Ironically, many wars were instigated by various religious groups around the world, who developed intense hostility towards one another.

There are other downsides to the advanced human brain. It can channel its talents and skills into unimaginably wicked and depraved behaviors, such as premeditated and well-planned murder, slavery, cults, child abuse, domestic abuse, pornography, fascism, dictatorships, and political corruption. Astonishingly, the same brain that can be loving, kind, friendly, and empathetic can suddenly become hateful, vengeful, cruel, vile, sinister, vicious, diabolical, and capable of unimaginable violence and atrocities. The advanced human brain definitely has a very dark side.

Finally, unlike other members of the animal kingdom, the human brain generates its virtual counterpart: the highly complex human mind, which is prone to various maladies, labeled as “psychiatric disorders.” No other animal species develops delusions, hallucinations, thought disorders, melancholia, mania, obsessive-compulsive disorder, generalized anxiety, panic attacks, posttraumatic stress disorder, psychopathy, narcissistic and borderline personality disorders, alcohol addiction, and drug abuse. Homo sapiens are the only species whose members decide to end their own life in large numbers. About 25% of human minds are afflicted with one or more of those psychiatric ailments.1,2 The redeeming grace of the large human brain is that it led to the development of pharmacologic and somatic treatments for most of them, including psychotherapy, which is a uniquely human treatment strategy that can mend many psychiatric disorders.

Evolution may not realize what it hath wrought when it evolved the dramatically expanded human brain, with its extraordinary cognition. This awe-inspiring “biological computer” can be creative and adaptive, with superlative survival abilities, but it can also degenerate and become nefarious, villainous, murderous, and even demonic. The human brain has essentially brought evolution to a screeching halt and may at some point end up destroying Earth and all of its Homo sapien inhabitants, who may foolishly use their weapons of mass destruction. The historic achievement of evolution has become the ultimate example of “the law of unintended consequences.”

Of all the dazzling achievements of evolution, the most glorious by far is the emergence of the advanced human brain, especially the prefrontal cortex. Homo sapiens (the wise humans) are without doubt the most transformative development in the consequential annals of evolution. It was evolution’s spectacular “moonshot.” Ironically, it may also have been the seed of its destruction.

The unprecedented growth of the human brain over the past 7 million years (tripling in size) was a monumental tipping point in evolution that ultimately disrupted the entire orderly cascade of evolution on Planet Earth. Because of their superior intelligence, Homo sapiens have substantially “tinkered” with the foundations of evolution, such as “natural selection” and “survival of the fittest,” and may eventually change the course of evolution, or even reverse it. It should also be recognized that 20% of the human genome is Neanderthal, and the 2022 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine was awarded to Svante Pääbo, the founder of the field of paleogenetics, who demonstrated genetically that Homo sapiens interbred with Homo neanderthalensis (who disappeared 30,000 years ago).

The majestic evolution of the human brain, in both size and complexity, led to monumental changes in the history of humankind compared to their primitive predecessors. Thanks to a superior cerebral cortex, humans developed traits and abilities that were nonexistent, even unimaginable, in the rest of animal kingdom, including primates and other mammals. These include thoughts; speech (hundreds of languages), spoken and written, to communicate among themselves; composed music and created numerous instruments to play it; invented mathematics, physics, and chemistry; developed agriculture to sustain and feed the masses; built homes, palaces, and pyramids, with water and sewage systems; hatched hundreds of religions and built thousands of houses of worship; built machines to transport themselves (cars, trains, ships, planes, and space shuttles); paved airports and countless miles of roads and railways; established companies, universities, hospitals, and research laboratories; built sports facilities such as stadiums for Olympic games and all its athletics; created hotels, restaurants, coffee shops, newspapers, and magazines; discovered the amazing DNA double helix and its genome with 23,000 coding genes containing instructions to build the brain and 200 other body tissues; developed surgeries and invented medications for diseases that would have killed millions every year; and established paper money to replace gold and silver coins. Humans established governments that included monarchies, dictatorships, democracies, and pseudodemocracies; stipulated constitutions, laws, and regulations to maintain various societies; and created several civilizations around the world that thrived and then faded. Over the past century, the advanced human brain elevated human existence to a higher sophistication with technologies such as electricity, phones, computers, internet, artificial intelligence, and machine learning. Using powerful rockets and space stations, humans have begun to expand their influence to the moon and planets of the solar system. Humans are very likely to continue achieving what evolution could never have done without evolving the human brain to become the most powerful force in nature.

The key ingredient of the brain that has enabled humans to achieve so much is the development of an advanced cognition, with superior functions that far exceed those of other living organisms. These include neurocognitive functions such as memory and attention, and executive functions that include planning, problem-solving, decision-making, abstract thinking, and insight. Those cognitive functions generate lofty prose, splendiferous poetry, and heavenly symphonies that inspire those who create it and others. The human brain also developed social cognition, with empathy, theory of mind, recognition of facial expressions, and courtship rituals that can trigger infatuation and love. Homo sapiens can experience a wide range of emotions in addition to love and attachment (necessary for procreation), including shame, guilt, surprise, embarrassment, disgust, and indifference, and a unique sense of right and wrong.

Perhaps the most distinctive human attribute, generated by an advanced prefrontal cortex, is a belief system that includes philosophy, politics, religion, and faith. Hundreds of different religions sprouted throughout human history (each claiming a monopoly on “the truth”), mandating rituals and behaviors, but also promoting a profound and unshakable belief in a divine “higher being” and an afterlife that mitigates the fear of death. Humans, unlike other animals, are painfully aware of mortality and the inevitability of death. Faith is an antidote for thanatophobia. Unfortunately, religious beliefs often generated severe and protracted schisms and warfare, with fatal consequences for their followers.

The anti-evolution aspect of the advanced brain

Despite remarkable talents and achievements, the unprecedented evolutionary expansion of the human brain also has a detrimental downside. The same intellectual power that led to astonishing positive accomplishments has a wicked side as well. While most animals have a predator, humans have become the “omni-predator” that preys on all living things. The balanced ecosystems of animals and plants has been dominated and disrupted by humans. Thousands of species that evolution had so ingeniously spawned became extinct because of human actions. The rainforests, jewels of nature’s plantation system, were victimized by human indifference to the deleterious effects on nature and climate. The excavation of coal and oil, exploited as necessary sources of energy for societal infrastructure, came back to haunt humans with climate consequences. In many ways, human “progress” corrupted evolution and dismantled its components. Survival of the fittest among various species was whittled down to “survival of humans” (and their domesticated animals) at the expense of all other organisms, animals, or plants.

Among Homo sapiens, momentous scientific, medical, and technological advances completely undermined the principle of survival of the fittest. Very premature infants, who would have certainly died, were kept alive. Children with disabling genetic disorders who would have perished in childhood were kept alive into the age of procreation, perpetuating the genetic mutations. The discovery of antibiotic and antiviral medications, and especially vaccines, ensured the survival of millions of humans who would have succumbed to infections. With evolution’s natural selection, humans who survived severe infections without medications would have passed on their “infection-resistant genes” to their progeny. The triumph of human medical progress can be conceptualized as a setback for the principles of evolution.

Continue to: The most malignant...

The most malignant consequence of the exceptional human brain is the evil of which it is capable. Human ingenuity led to the development of weapons of individual killing (guns), large-scale murder (machine guns), and massive destruction (nuclear weapons). And because aggression and warfare are an inherent part of human nature, the most potent predator for a human is another human. The history of humans is riddled with conflict and death on a large scale. Ironically, many wars were instigated by various religious groups around the world, who developed intense hostility towards one another.

There are other downsides to the advanced human brain. It can channel its talents and skills into unimaginably wicked and depraved behaviors, such as premeditated and well-planned murder, slavery, cults, child abuse, domestic abuse, pornography, fascism, dictatorships, and political corruption. Astonishingly, the same brain that can be loving, kind, friendly, and empathetic can suddenly become hateful, vengeful, cruel, vile, sinister, vicious, diabolical, and capable of unimaginable violence and atrocities. The advanced human brain definitely has a very dark side.

Finally, unlike other members of the animal kingdom, the human brain generates its virtual counterpart: the highly complex human mind, which is prone to various maladies, labeled as “psychiatric disorders.” No other animal species develops delusions, hallucinations, thought disorders, melancholia, mania, obsessive-compulsive disorder, generalized anxiety, panic attacks, posttraumatic stress disorder, psychopathy, narcissistic and borderline personality disorders, alcohol addiction, and drug abuse. Homo sapiens are the only species whose members decide to end their own life in large numbers. About 25% of human minds are afflicted with one or more of those psychiatric ailments.1,2 The redeeming grace of the large human brain is that it led to the development of pharmacologic and somatic treatments for most of them, including psychotherapy, which is a uniquely human treatment strategy that can mend many psychiatric disorders.

Evolution may not realize what it hath wrought when it evolved the dramatically expanded human brain, with its extraordinary cognition. This awe-inspiring “biological computer” can be creative and adaptive, with superlative survival abilities, but it can also degenerate and become nefarious, villainous, murderous, and even demonic. The human brain has essentially brought evolution to a screeching halt and may at some point end up destroying Earth and all of its Homo sapien inhabitants, who may foolishly use their weapons of mass destruction. The historic achievement of evolution has become the ultimate example of “the law of unintended consequences.”

1. Robin LN, Regier DA. Psychiatric Disorders in America: The Epidemiologic Catchment Area Study. Free Press; 1990.

2. Johns Hopkins Medicine. Mental Health Disorder Statistics. Accessed October 12, 2022. https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/wellness-and-prevention/mental-health-disorder-statistics

1. Robin LN, Regier DA. Psychiatric Disorders in America: The Epidemiologic Catchment Area Study. Free Press; 1990.

2. Johns Hopkins Medicine. Mental Health Disorder Statistics. Accessed October 12, 2022. https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/wellness-and-prevention/mental-health-disorder-statistics

Warning: Watch out for ‘medication substitution reaction’

Editor’s note: Readers’ Forum is a department for correspondence from readers that is not in response to articles published in

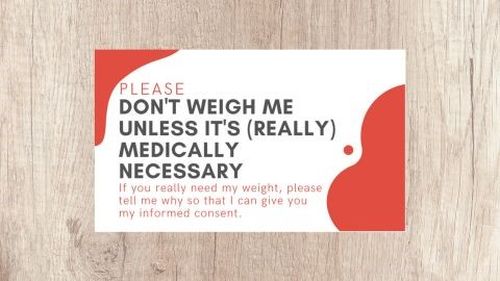

I (MZP) recently started medical school, and one of the first things we learned in our Human Dimension class was to listen to our patients. While this may seem prosaic to seasoned practitioners, I quickly realized the important, real-world consequences of doing so.

Clinicians rightfully presume that when they send a prescription to a pharmacy, the patient will receive what they have ordered or the generic equivalent unless it is ordered “Dispense as written.” Unfortunately, a confluence of increased demand and supply chain disruptions has produced nationwide shortages of generic Adderall extended-release (XR) and Adderall, which are commonly prescribed to patients with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).1 While pharmacies should notify patients when they do not have these medications in stock, we have encountered numerous cases where due to shortages, prescriptions for generic dextroamphetamine/amphetamine salts XR or immediate-release (IR) have been filled with the same milligrams of only dextroamphetamine XR or IR, respectively, without notifying the patient or the prescribing clinician. Pharmacies have included several national chains and local independent stores in the New York/New Jersey region.

Over the past several months, we have encountered patients who had been well stabilized on their ADHD medication regimen who began to report anxiety, jitteriness, agitation, fatigue, poor concentration, and/or hyperactivity, and who also reported that their pills “look different.” First, we considered their symptoms could be attributed to a switch between generic manufacturers. However, upon further inspection, we discovered that the medication name printed on the label was different from what had been prescribed. We confirmed this by checking the Prescription Monitoring Program database.

Pharmacists have recently won prescribing privileges for nirmatrelvir/ritonavir (Paxlovid) to treat COVID-19, but they certainly are not permitted to fill prescriptions for psychoactive controlled substances that have different pharmacologic profiles than the medication the clinician ordered. Adderall contains D-amphetamine and L-amphetamine in a ratio of 3:1, which makes it different in potency from dextroamphetamine alone and requires adjustment to the dosage and potentially to the frequency to achieve near equivalency.

Once we realized the issue and helped our patients locate a pharmacy that had generic Adderall XR and Adderall in stock so they could resume their previous regimen, their symptoms resolved.

It is important for all clinicians to add “medication substitution reaction” to their differential diagnosis of new-onset ADHD-related symptoms in previously stable patients.

1. Pharmaceutical Commerce. Innovative solutions for pandemic-driven pharmacy drug shortages. Published February 28, 2022. Accessed September 8, 2022. https://www.pharmaceuticalcommerce.com/view/innovative-solutions-for-pandemic-driven-pharmacy-drug-shortages

Editor’s note: Readers’ Forum is a department for correspondence from readers that is not in response to articles published in

I (MZP) recently started medical school, and one of the first things we learned in our Human Dimension class was to listen to our patients. While this may seem prosaic to seasoned practitioners, I quickly realized the important, real-world consequences of doing so.

Clinicians rightfully presume that when they send a prescription to a pharmacy, the patient will receive what they have ordered or the generic equivalent unless it is ordered “Dispense as written.” Unfortunately, a confluence of increased demand and supply chain disruptions has produced nationwide shortages of generic Adderall extended-release (XR) and Adderall, which are commonly prescribed to patients with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).1 While pharmacies should notify patients when they do not have these medications in stock, we have encountered numerous cases where due to shortages, prescriptions for generic dextroamphetamine/amphetamine salts XR or immediate-release (IR) have been filled with the same milligrams of only dextroamphetamine XR or IR, respectively, without notifying the patient or the prescribing clinician. Pharmacies have included several national chains and local independent stores in the New York/New Jersey region.

Over the past several months, we have encountered patients who had been well stabilized on their ADHD medication regimen who began to report anxiety, jitteriness, agitation, fatigue, poor concentration, and/or hyperactivity, and who also reported that their pills “look different.” First, we considered their symptoms could be attributed to a switch between generic manufacturers. However, upon further inspection, we discovered that the medication name printed on the label was different from what had been prescribed. We confirmed this by checking the Prescription Monitoring Program database.

Pharmacists have recently won prescribing privileges for nirmatrelvir/ritonavir (Paxlovid) to treat COVID-19, but they certainly are not permitted to fill prescriptions for psychoactive controlled substances that have different pharmacologic profiles than the medication the clinician ordered. Adderall contains D-amphetamine and L-amphetamine in a ratio of 3:1, which makes it different in potency from dextroamphetamine alone and requires adjustment to the dosage and potentially to the frequency to achieve near equivalency.

Once we realized the issue and helped our patients locate a pharmacy that had generic Adderall XR and Adderall in stock so they could resume their previous regimen, their symptoms resolved.

It is important for all clinicians to add “medication substitution reaction” to their differential diagnosis of new-onset ADHD-related symptoms in previously stable patients.

Editor’s note: Readers’ Forum is a department for correspondence from readers that is not in response to articles published in

I (MZP) recently started medical school, and one of the first things we learned in our Human Dimension class was to listen to our patients. While this may seem prosaic to seasoned practitioners, I quickly realized the important, real-world consequences of doing so.

Clinicians rightfully presume that when they send a prescription to a pharmacy, the patient will receive what they have ordered or the generic equivalent unless it is ordered “Dispense as written.” Unfortunately, a confluence of increased demand and supply chain disruptions has produced nationwide shortages of generic Adderall extended-release (XR) and Adderall, which are commonly prescribed to patients with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).1 While pharmacies should notify patients when they do not have these medications in stock, we have encountered numerous cases where due to shortages, prescriptions for generic dextroamphetamine/amphetamine salts XR or immediate-release (IR) have been filled with the same milligrams of only dextroamphetamine XR or IR, respectively, without notifying the patient or the prescribing clinician. Pharmacies have included several national chains and local independent stores in the New York/New Jersey region.

Over the past several months, we have encountered patients who had been well stabilized on their ADHD medication regimen who began to report anxiety, jitteriness, agitation, fatigue, poor concentration, and/or hyperactivity, and who also reported that their pills “look different.” First, we considered their symptoms could be attributed to a switch between generic manufacturers. However, upon further inspection, we discovered that the medication name printed on the label was different from what had been prescribed. We confirmed this by checking the Prescription Monitoring Program database.

Pharmacists have recently won prescribing privileges for nirmatrelvir/ritonavir (Paxlovid) to treat COVID-19, but they certainly are not permitted to fill prescriptions for psychoactive controlled substances that have different pharmacologic profiles than the medication the clinician ordered. Adderall contains D-amphetamine and L-amphetamine in a ratio of 3:1, which makes it different in potency from dextroamphetamine alone and requires adjustment to the dosage and potentially to the frequency to achieve near equivalency.

Once we realized the issue and helped our patients locate a pharmacy that had generic Adderall XR and Adderall in stock so they could resume their previous regimen, their symptoms resolved.

It is important for all clinicians to add “medication substitution reaction” to their differential diagnosis of new-onset ADHD-related symptoms in previously stable patients.

1. Pharmaceutical Commerce. Innovative solutions for pandemic-driven pharmacy drug shortages. Published February 28, 2022. Accessed September 8, 2022. https://www.pharmaceuticalcommerce.com/view/innovative-solutions-for-pandemic-driven-pharmacy-drug-shortages

1. Pharmaceutical Commerce. Innovative solutions for pandemic-driven pharmacy drug shortages. Published February 28, 2022. Accessed September 8, 2022. https://www.pharmaceuticalcommerce.com/view/innovative-solutions-for-pandemic-driven-pharmacy-drug-shortages

The light at the end of the tunnel: Reflecting on a 7-year training journey

Throughout my training, a common refrain from more senior colleagues was that training “goes by quickly.” At the risk of sounding cliché, and even after a 7-year journey spanning psychiatry and preventive medicine residencies as well as a consultation-liaison psychiatry fellowship, I agree without reservations that it does indeed go quickly. In the waning days of my training, reflection and nostalgia have become commonplace, as one might expect after such a meaningful pursuit. In sharing my reflections, I hope others progressing through training will also reflect on elements that added meaning to their experience and how they might improve the journey for future trainees.

Residency is a team sport

One realization that quickly struck me was that residency is a team sport, and finding supportive communities is essential to survival. Other residents, colleagues, and mentors played integral roles in making my experience rewarding. Training might be considered a shared traumatic experience, but having peers to commiserate with at each step has been among its greatest rewards. Residency automatically provided a cohort of colleagues who shared and validated my experiences. Additionally, having mentors who have been through it themselves and find ways to improve the training experience made mine superlative. Mentors assisted me in tailoring my training and developing interests that I could integrate into my future practice. The interpersonal connections I made were critical in helping me survive and thrive during training.

See one, do one, teach one

Residency and fellowship programs might be considered “see one, do one, teach one”1 at large scale. Since their inception, these programs—designed to develop junior physicians—have been inherently educational in nature. The structure is elegant, allowing trainees to continue learning while incrementally gaining more autonomy and teaching responsibility.2 Naively, I did not understand that implicit within my education was an expectation to become an educator and hone my teaching skills. Initially, being a newly minted resident receiving brand-new 3rd-year medical students charged me with apprehension. Thoughts I internalized, such as “these students probably know more than me” or “how can I be responsible for patients and students simultaneously,” may have resulted from a paucity of instruction about teaching available during medical school.3,4 I quickly found, though, that teaching was among the most rewarding facets of training. Helping other learners grow became one of my passions and added to my experience.

Iron sharpens iron

Although my experience was enjoyable, I would be remiss without also considering accompanying trials and tribulations. Seemingly interminable night shifts, sleep deprivation, lack of autonomy, and system inefficiencies frustrated me. Eventually, these frustrations seemed less bothersome. These challenges likely had not vanished with time, but perhaps my capacity to tolerate distress improved—likely corresponding with increasing skill and confidence. These challenges allowed me to hone my clinical decision-making abilities while under duress. My struggles and frustrations were not unique but perhaps lessons themselves.

Residency is not meant to be easy. The crucible of residency taught me that I had resilience to draw upon during challenging times. “Iron sharpens iron,” as the adage goes, and I believe adversity ultimately helped me become a better psychiatrist.

Self-reflection is part of completing training

Reminders that my journey is at an end are everywhere. Seeing notes written by past residents or fellows reminds me that soon I too will merely be a name in the chart to future trainees. Perhaps this line of thought is unfair, reducing my training experience to notes I signed—whereas my training experience was defined by connections made with colleagues and mentors, opportunities to teach junior learners, and confidence gained by overcoming adversity.

While becoming an attending psychiatrist fills me with trepidation, fear need not be an inherent aspect of new beginnings. Reflection has been a powerful practice, allowing me to realize what made my experience so meaningful, and that training is meant to be process-oriented rather than outcome-oriented. My reflection has underscored the realization that challenges are inherent in training, although not without purpose. I believe these struggles were meant to allow me to build meaningful relationships with colleagues, discover joy in teaching, and build resiliency.

The purpose of residencies and fellowships should be to produce clinically excellent psychiatrists, but I feel the journey was as important as the destination. Psychiatrists likely understand this better than most, as we were trained to thoughtfully approach the process of termination with patients.5 While the conclusion of our training journeys may seem unceremonious or anticlimactic, the termination process should include self-reflection on meaningful facets of training. For me, this reflection has itself been invaluable, while also making me hopeful to contribute value to the training journeys of future psychiatrists.

1. Gorrindo T, Beresin EV. Is “See one, do one, teach one” dead? Implications for the professionalization of medical educators in the twenty-first century. Acad Psychiatry. 2015;39(6):613-614. doi:10.1007/s40596-015-0424-8

2. Wright Jr. JR, Schachar NS. Necessity is the mother of invention: William Stewart Halsted’s addiction and its influence on the development of residency training in North America. Can J Surg. 2020;63(1):E13-E19. doi:10.1503/cjs.003319

3. Dandavino M, Snell L, Wiseman J. Why medical students should learn how to teach. Med Teach. 2007;29(6):558-565. doi:10.1080/01421590701477449

4. Liu AC, Liu M, Dannaway J, et al. Are Australian medical students being taught to teach? Clin Teach. 2017;14(5):330-335. doi:10.1111/tct.12591

5. Vasquez MJ, Bingham RP, Barnett JE. Psychotherapy termination: clinical and ethical responsibilities. J Clin Psychol. 2008;64(5):653-665. doi:10.1002/jclp.20478

Throughout my training, a common refrain from more senior colleagues was that training “goes by quickly.” At the risk of sounding cliché, and even after a 7-year journey spanning psychiatry and preventive medicine residencies as well as a consultation-liaison psychiatry fellowship, I agree without reservations that it does indeed go quickly. In the waning days of my training, reflection and nostalgia have become commonplace, as one might expect after such a meaningful pursuit. In sharing my reflections, I hope others progressing through training will also reflect on elements that added meaning to their experience and how they might improve the journey for future trainees.

Residency is a team sport

One realization that quickly struck me was that residency is a team sport, and finding supportive communities is essential to survival. Other residents, colleagues, and mentors played integral roles in making my experience rewarding. Training might be considered a shared traumatic experience, but having peers to commiserate with at each step has been among its greatest rewards. Residency automatically provided a cohort of colleagues who shared and validated my experiences. Additionally, having mentors who have been through it themselves and find ways to improve the training experience made mine superlative. Mentors assisted me in tailoring my training and developing interests that I could integrate into my future practice. The interpersonal connections I made were critical in helping me survive and thrive during training.

See one, do one, teach one

Residency and fellowship programs might be considered “see one, do one, teach one”1 at large scale. Since their inception, these programs—designed to develop junior physicians—have been inherently educational in nature. The structure is elegant, allowing trainees to continue learning while incrementally gaining more autonomy and teaching responsibility.2 Naively, I did not understand that implicit within my education was an expectation to become an educator and hone my teaching skills. Initially, being a newly minted resident receiving brand-new 3rd-year medical students charged me with apprehension. Thoughts I internalized, such as “these students probably know more than me” or “how can I be responsible for patients and students simultaneously,” may have resulted from a paucity of instruction about teaching available during medical school.3,4 I quickly found, though, that teaching was among the most rewarding facets of training. Helping other learners grow became one of my passions and added to my experience.

Iron sharpens iron

Although my experience was enjoyable, I would be remiss without also considering accompanying trials and tribulations. Seemingly interminable night shifts, sleep deprivation, lack of autonomy, and system inefficiencies frustrated me. Eventually, these frustrations seemed less bothersome. These challenges likely had not vanished with time, but perhaps my capacity to tolerate distress improved—likely corresponding with increasing skill and confidence. These challenges allowed me to hone my clinical decision-making abilities while under duress. My struggles and frustrations were not unique but perhaps lessons themselves.

Residency is not meant to be easy. The crucible of residency taught me that I had resilience to draw upon during challenging times. “Iron sharpens iron,” as the adage goes, and I believe adversity ultimately helped me become a better psychiatrist.

Self-reflection is part of completing training

Reminders that my journey is at an end are everywhere. Seeing notes written by past residents or fellows reminds me that soon I too will merely be a name in the chart to future trainees. Perhaps this line of thought is unfair, reducing my training experience to notes I signed—whereas my training experience was defined by connections made with colleagues and mentors, opportunities to teach junior learners, and confidence gained by overcoming adversity.

While becoming an attending psychiatrist fills me with trepidation, fear need not be an inherent aspect of new beginnings. Reflection has been a powerful practice, allowing me to realize what made my experience so meaningful, and that training is meant to be process-oriented rather than outcome-oriented. My reflection has underscored the realization that challenges are inherent in training, although not without purpose. I believe these struggles were meant to allow me to build meaningful relationships with colleagues, discover joy in teaching, and build resiliency.

The purpose of residencies and fellowships should be to produce clinically excellent psychiatrists, but I feel the journey was as important as the destination. Psychiatrists likely understand this better than most, as we were trained to thoughtfully approach the process of termination with patients.5 While the conclusion of our training journeys may seem unceremonious or anticlimactic, the termination process should include self-reflection on meaningful facets of training. For me, this reflection has itself been invaluable, while also making me hopeful to contribute value to the training journeys of future psychiatrists.

Throughout my training, a common refrain from more senior colleagues was that training “goes by quickly.” At the risk of sounding cliché, and even after a 7-year journey spanning psychiatry and preventive medicine residencies as well as a consultation-liaison psychiatry fellowship, I agree without reservations that it does indeed go quickly. In the waning days of my training, reflection and nostalgia have become commonplace, as one might expect after such a meaningful pursuit. In sharing my reflections, I hope others progressing through training will also reflect on elements that added meaning to their experience and how they might improve the journey for future trainees.

Residency is a team sport

One realization that quickly struck me was that residency is a team sport, and finding supportive communities is essential to survival. Other residents, colleagues, and mentors played integral roles in making my experience rewarding. Training might be considered a shared traumatic experience, but having peers to commiserate with at each step has been among its greatest rewards. Residency automatically provided a cohort of colleagues who shared and validated my experiences. Additionally, having mentors who have been through it themselves and find ways to improve the training experience made mine superlative. Mentors assisted me in tailoring my training and developing interests that I could integrate into my future practice. The interpersonal connections I made were critical in helping me survive and thrive during training.

See one, do one, teach one

Residency and fellowship programs might be considered “see one, do one, teach one”1 at large scale. Since their inception, these programs—designed to develop junior physicians—have been inherently educational in nature. The structure is elegant, allowing trainees to continue learning while incrementally gaining more autonomy and teaching responsibility.2 Naively, I did not understand that implicit within my education was an expectation to become an educator and hone my teaching skills. Initially, being a newly minted resident receiving brand-new 3rd-year medical students charged me with apprehension. Thoughts I internalized, such as “these students probably know more than me” or “how can I be responsible for patients and students simultaneously,” may have resulted from a paucity of instruction about teaching available during medical school.3,4 I quickly found, though, that teaching was among the most rewarding facets of training. Helping other learners grow became one of my passions and added to my experience.

Iron sharpens iron

Although my experience was enjoyable, I would be remiss without also considering accompanying trials and tribulations. Seemingly interminable night shifts, sleep deprivation, lack of autonomy, and system inefficiencies frustrated me. Eventually, these frustrations seemed less bothersome. These challenges likely had not vanished with time, but perhaps my capacity to tolerate distress improved—likely corresponding with increasing skill and confidence. These challenges allowed me to hone my clinical decision-making abilities while under duress. My struggles and frustrations were not unique but perhaps lessons themselves.

Residency is not meant to be easy. The crucible of residency taught me that I had resilience to draw upon during challenging times. “Iron sharpens iron,” as the adage goes, and I believe adversity ultimately helped me become a better psychiatrist.

Self-reflection is part of completing training

Reminders that my journey is at an end are everywhere. Seeing notes written by past residents or fellows reminds me that soon I too will merely be a name in the chart to future trainees. Perhaps this line of thought is unfair, reducing my training experience to notes I signed—whereas my training experience was defined by connections made with colleagues and mentors, opportunities to teach junior learners, and confidence gained by overcoming adversity.

While becoming an attending psychiatrist fills me with trepidation, fear need not be an inherent aspect of new beginnings. Reflection has been a powerful practice, allowing me to realize what made my experience so meaningful, and that training is meant to be process-oriented rather than outcome-oriented. My reflection has underscored the realization that challenges are inherent in training, although not without purpose. I believe these struggles were meant to allow me to build meaningful relationships with colleagues, discover joy in teaching, and build resiliency.

The purpose of residencies and fellowships should be to produce clinically excellent psychiatrists, but I feel the journey was as important as the destination. Psychiatrists likely understand this better than most, as we were trained to thoughtfully approach the process of termination with patients.5 While the conclusion of our training journeys may seem unceremonious or anticlimactic, the termination process should include self-reflection on meaningful facets of training. For me, this reflection has itself been invaluable, while also making me hopeful to contribute value to the training journeys of future psychiatrists.

1. Gorrindo T, Beresin EV. Is “See one, do one, teach one” dead? Implications for the professionalization of medical educators in the twenty-first century. Acad Psychiatry. 2015;39(6):613-614. doi:10.1007/s40596-015-0424-8