User login

Letter from the Board of Editors: Call to action (again)

This editorial is the first to be published in GI & Hepatology News since the murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis. The corner of 38th and Chicago is 9 miles from my home in Bloomington, Minn. This corner became the epicenter of protests that have spread around the nation and world. Early on, protests were accompanied by widespread riots, looting, and destruction. In the ensuing weeks, this corner has become a memorial for Mr. Floyd and a place where people now go to reflect, pray, pay tribute, and pledge to work for change.

A coalition of willing businesses has formed in the area around 38th and Chicago. The largest employer in the area is Allina Health (I sit on the Governing Board of Allina Health). Our flagship hospital is 8 blocks from the site of George Floyd’s memorial. We will be a change leader by committing funds for local rebuilding, ensuring use of construction firms that promote minority workers (as was done when the Viking’s stadium was built), examining our investment portfolio with racial equity as one guiding principle, increasing our focus on barriers to access, enhancing equity education of our workforce, and working with city and state leaders to promote police reform.

As the Editor in Chief of the official newspaper of the AGA, I invited our board of editors to stand united in our condemnation of the racial injustices that led to the protests we now see. We each agree with the message from the combined Governing Boards of our GI societies (published June 2, 2020) stating “As health care providers, we have dedicated our lives to caring for our fellow human beings. Therefore, we are compelled to speak out against any treatment that results in unacceptable disparities that marginalize the vulnerable among us.”

Our responsibility as editors is to guide the content we deliver, ensuring its relevancy to our readers. In this light, we commit to delivering content that highlights racial injustices and health disparities for all people, as we seek to understand the many factors that result in barriers to health. We will emphasize content that leads to impactful change and will highlight progress we make as a specialty. We hope our collective work will help ensure that George Floyd’s memory, and the memories of all such victims, become a catalyst for permanent cultural change.

Editor in Chief, GI & Hepatology News

John I. Allen, MD, MBA, AGAF

Editor in Chief, The New Gastroenterologist

Vijaya L. Rao, MD

Associate Editors

Megan A. Adams, MD, JD, MSc

Ziad Gellad, MD, MPH, AGAF

Kim L. Isaacs, MD, PhD, AGAF

Charles J. Kahi, MD, MS, AGAF

Gyanprakash A. Ketwaroo, MD, MSc

Larry R. Kosinski, MD, MBA, AGAF

Sonia S. Kupfer, MD

Wajahat Mehal, MD, PhD

This editorial is the first to be published in GI & Hepatology News since the murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis. The corner of 38th and Chicago is 9 miles from my home in Bloomington, Minn. This corner became the epicenter of protests that have spread around the nation and world. Early on, protests were accompanied by widespread riots, looting, and destruction. In the ensuing weeks, this corner has become a memorial for Mr. Floyd and a place where people now go to reflect, pray, pay tribute, and pledge to work for change.

A coalition of willing businesses has formed in the area around 38th and Chicago. The largest employer in the area is Allina Health (I sit on the Governing Board of Allina Health). Our flagship hospital is 8 blocks from the site of George Floyd’s memorial. We will be a change leader by committing funds for local rebuilding, ensuring use of construction firms that promote minority workers (as was done when the Viking’s stadium was built), examining our investment portfolio with racial equity as one guiding principle, increasing our focus on barriers to access, enhancing equity education of our workforce, and working with city and state leaders to promote police reform.

As the Editor in Chief of the official newspaper of the AGA, I invited our board of editors to stand united in our condemnation of the racial injustices that led to the protests we now see. We each agree with the message from the combined Governing Boards of our GI societies (published June 2, 2020) stating “As health care providers, we have dedicated our lives to caring for our fellow human beings. Therefore, we are compelled to speak out against any treatment that results in unacceptable disparities that marginalize the vulnerable among us.”

Our responsibility as editors is to guide the content we deliver, ensuring its relevancy to our readers. In this light, we commit to delivering content that highlights racial injustices and health disparities for all people, as we seek to understand the many factors that result in barriers to health. We will emphasize content that leads to impactful change and will highlight progress we make as a specialty. We hope our collective work will help ensure that George Floyd’s memory, and the memories of all such victims, become a catalyst for permanent cultural change.

Editor in Chief, GI & Hepatology News

John I. Allen, MD, MBA, AGAF

Editor in Chief, The New Gastroenterologist

Vijaya L. Rao, MD

Associate Editors

Megan A. Adams, MD, JD, MSc

Ziad Gellad, MD, MPH, AGAF

Kim L. Isaacs, MD, PhD, AGAF

Charles J. Kahi, MD, MS, AGAF

Gyanprakash A. Ketwaroo, MD, MSc

Larry R. Kosinski, MD, MBA, AGAF

Sonia S. Kupfer, MD

Wajahat Mehal, MD, PhD

This editorial is the first to be published in GI & Hepatology News since the murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis. The corner of 38th and Chicago is 9 miles from my home in Bloomington, Minn. This corner became the epicenter of protests that have spread around the nation and world. Early on, protests were accompanied by widespread riots, looting, and destruction. In the ensuing weeks, this corner has become a memorial for Mr. Floyd and a place where people now go to reflect, pray, pay tribute, and pledge to work for change.

A coalition of willing businesses has formed in the area around 38th and Chicago. The largest employer in the area is Allina Health (I sit on the Governing Board of Allina Health). Our flagship hospital is 8 blocks from the site of George Floyd’s memorial. We will be a change leader by committing funds for local rebuilding, ensuring use of construction firms that promote minority workers (as was done when the Viking’s stadium was built), examining our investment portfolio with racial equity as one guiding principle, increasing our focus on barriers to access, enhancing equity education of our workforce, and working with city and state leaders to promote police reform.

As the Editor in Chief of the official newspaper of the AGA, I invited our board of editors to stand united in our condemnation of the racial injustices that led to the protests we now see. We each agree with the message from the combined Governing Boards of our GI societies (published June 2, 2020) stating “As health care providers, we have dedicated our lives to caring for our fellow human beings. Therefore, we are compelled to speak out against any treatment that results in unacceptable disparities that marginalize the vulnerable among us.”

Our responsibility as editors is to guide the content we deliver, ensuring its relevancy to our readers. In this light, we commit to delivering content that highlights racial injustices and health disparities for all people, as we seek to understand the many factors that result in barriers to health. We will emphasize content that leads to impactful change and will highlight progress we make as a specialty. We hope our collective work will help ensure that George Floyd’s memory, and the memories of all such victims, become a catalyst for permanent cultural change.

Editor in Chief, GI & Hepatology News

John I. Allen, MD, MBA, AGAF

Editor in Chief, The New Gastroenterologist

Vijaya L. Rao, MD

Associate Editors

Megan A. Adams, MD, JD, MSc

Ziad Gellad, MD, MPH, AGAF

Kim L. Isaacs, MD, PhD, AGAF

Charles J. Kahi, MD, MS, AGAF

Gyanprakash A. Ketwaroo, MD, MSc

Larry R. Kosinski, MD, MBA, AGAF

Sonia S. Kupfer, MD

Wajahat Mehal, MD, PhD

COVID-19’s effects on emergency psychiatry

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is affecting every aspect of medical care. Much has been written about overwhelmed hospital settings, the financial devastation to outpatient treatment centers, and an impending pandemic of mental illness that the existing underfunded and fragmented mental health system would not be prepared to weather. Although COVID-19 has undeniably affected the practice of emergency psychiatry, its impact has been surprising and complex. In this article, I describe the effects COVID-19 has had on our psychiatric emergency service, and how the pandemic has affected me personally.

How the pandemic affected our psychiatric ED

The Comprehensive Psychiatric Emergency Program (CPEP) in Buffalo, New York, is part of the emergency department (ED) in the local county hospital and is staffed by faculty from the Department of Psychiatry at the University at Buffalo. It was developed to provide evaluations of acutely psychiatrically ill individuals, to determine their treatment needs and facilitate access to the appropriate level of care.

Before COVID-19, as the only fully staffed psychiatric emergency service in the region, CPEP would routinely be called upon to serve many functions for which it was not designed. For example, people who had difficulty accessing psychiatric care in the community might come to CPEP expecting treatment for chronic conditions. Additionally, due to systemic deficiencies and limited resources, police and other community agencies refer individuals to CPEP who either have illnesses unrelated to current circumstances or who are not psychiatrically ill but unmanageable because of aggression or otherwise unresolvable social challenges such as homelessness, criminal behavior, poor parenting and other family strains, or general dissatisfaction with life. Parents unable to set limits with bored or defiant children might leave them in CPEP, hoping to transfer the parenting role, just as law enforcement officers who feel impotent to apply meaningful sanctions to non-felonious offenders might bring them to CPEP seeking containment. Labeling these problems as psychiatric emergencies has made it more palatable to leave these individuals in our care. These types of visits have contributed to the substantial growth of CPEP in recent years, in terms of annual patient visits, number of children abandoned and their lengths of stay in the CPEP, among other metrics.

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on an emergency psychiatry service that is expected to be all things to all people has been interesting. For the first few weeks of the societal shutdown, the patient flow was unchanged. However, during this time, the usual overcrowding created a feeling of vulnerability to contagion that sparked an urgency to minimize the census. Superhuman efforts were fueled by an unspoken sense of impending doom, and wait times dropped from approximately 17 hours to 3 or 4 hours. This state of hypervigilance was impossible to sustain indefinitely, and inevitably those efforts were exhausted. As adrenaline waned, the focus turned toward family and self-preservation. Nursing and social work staff began cancelling shifts, as did part-time physicians who contracted services with our department. Others, however, were drawn to join the front-line fight.

Trends in psychiatric ED usage during the pandemic

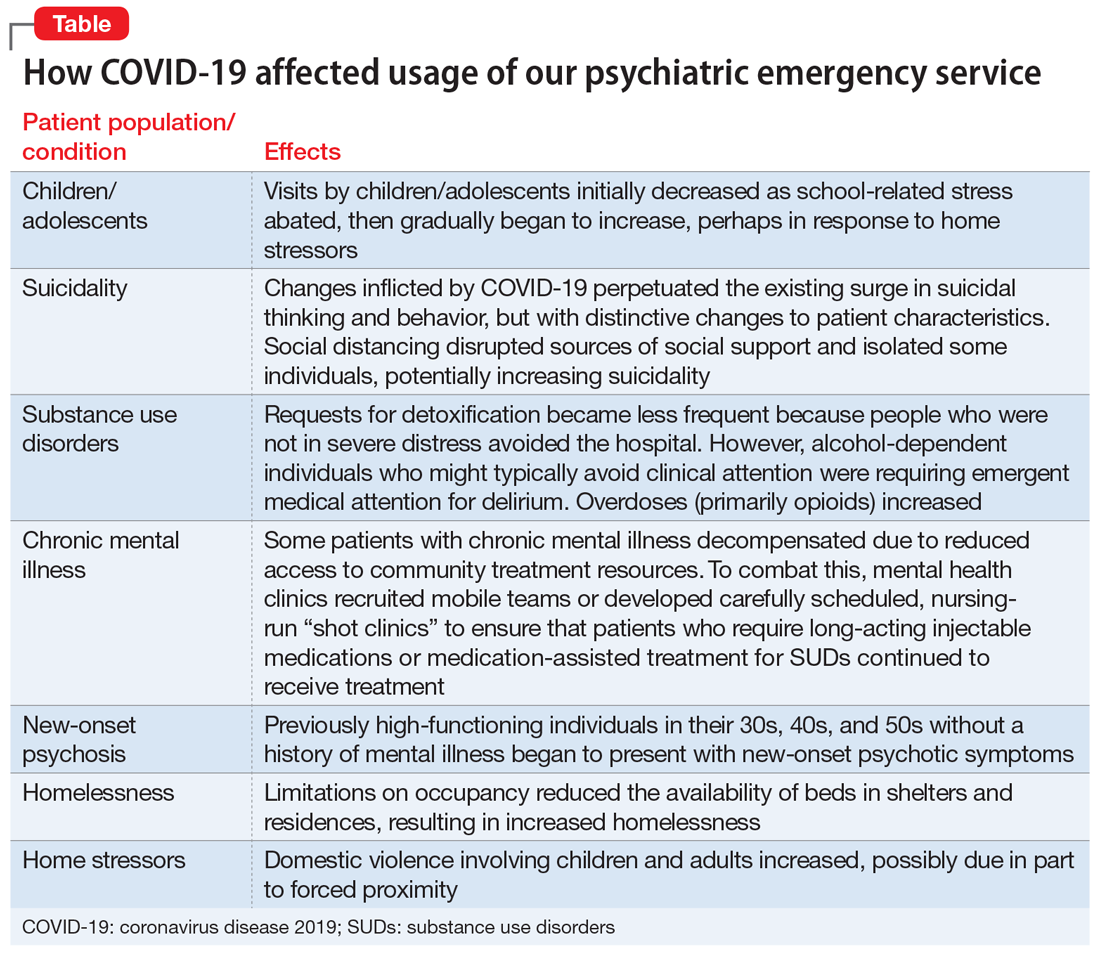

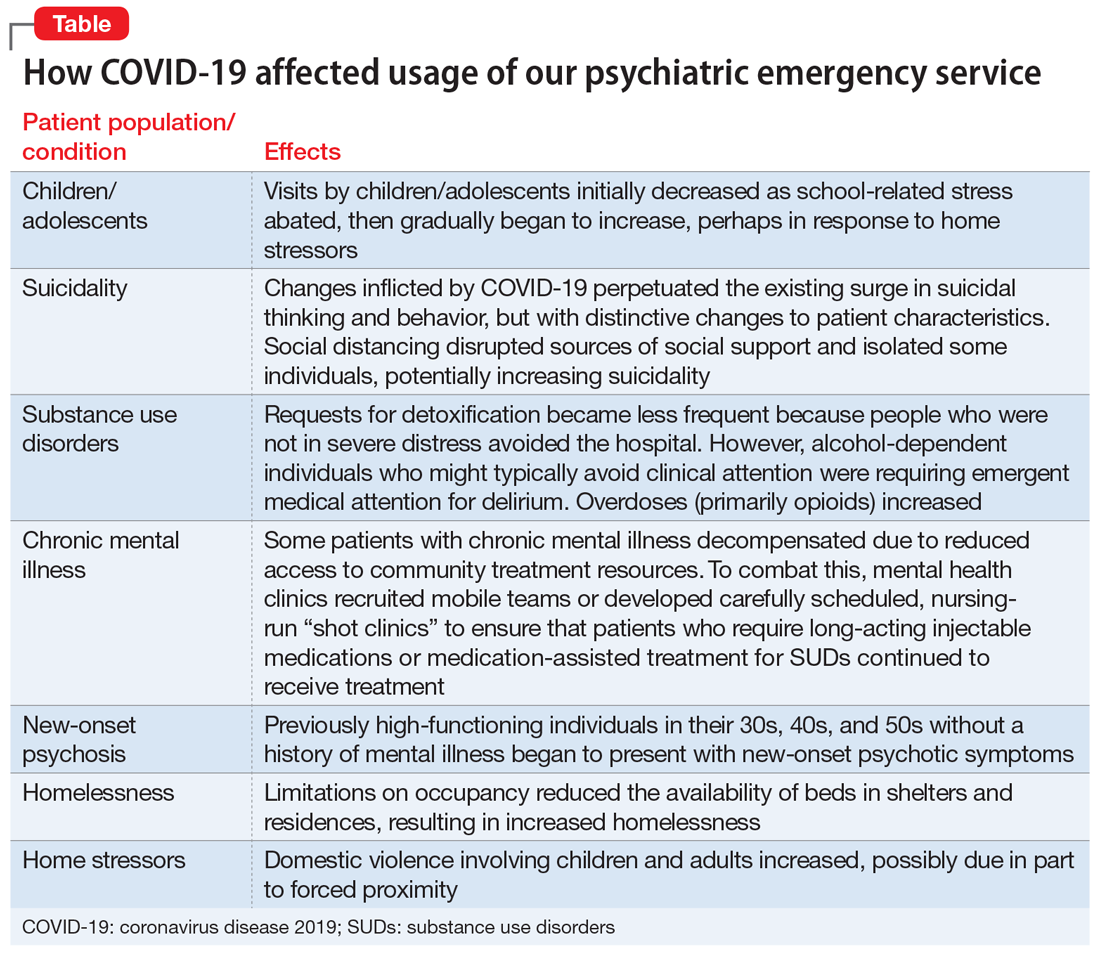

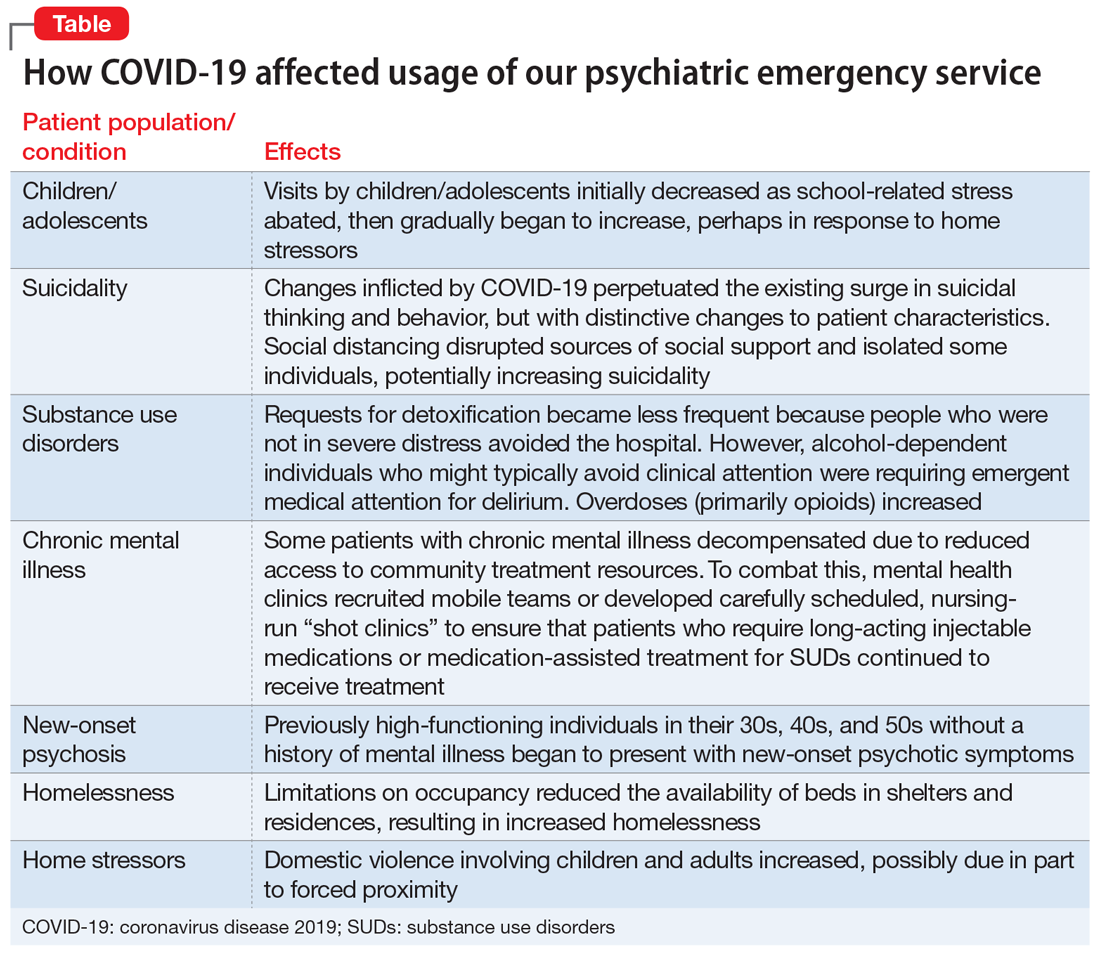

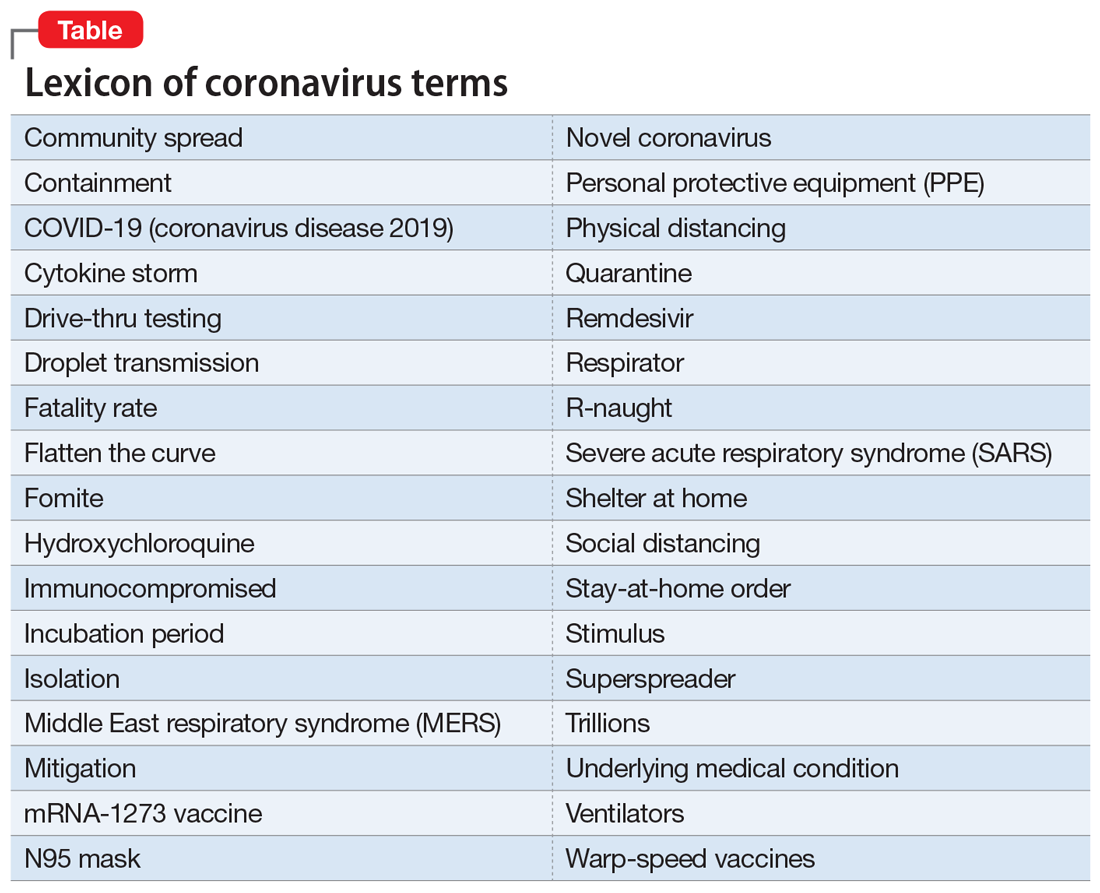

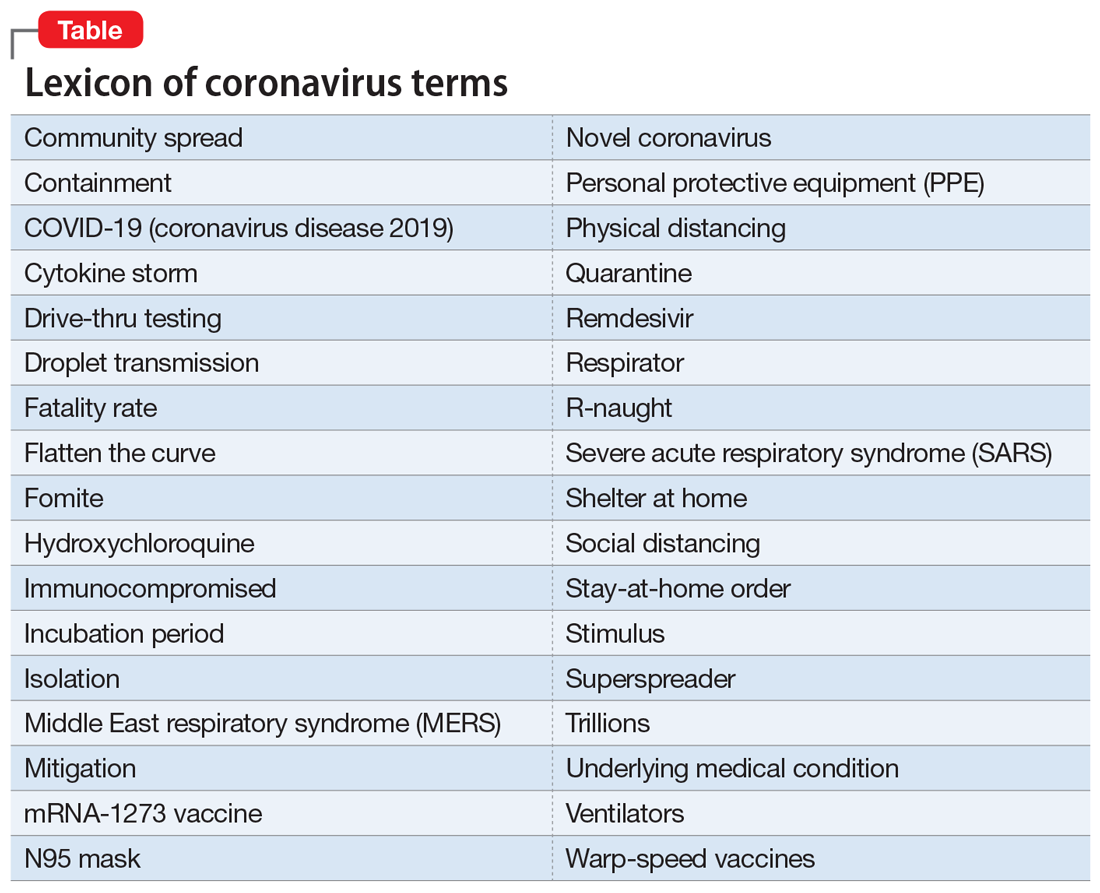

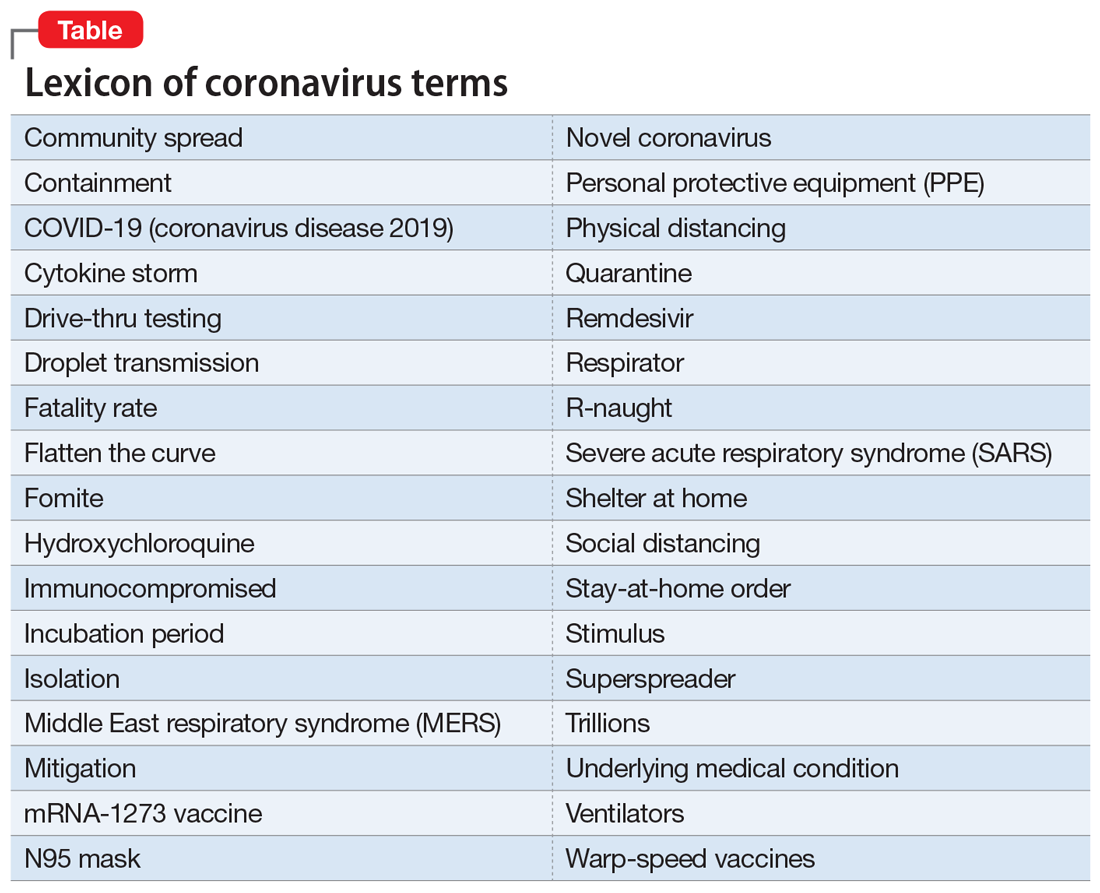

As COVID-19 spread, local media reported the paucity of personal protective equipment (PPE) and created the sense that no one would receive hospital treatment unless they were on the brink of death. Consequently, total visits to the ED began to slow. During April, CPEP saw 25% fewer visits than average. This reduction was partly attributable to cohorting patients with any suspicion of infection in a designated area within the medical ED, with access to remote evaluation by CPEP psychiatrists via telemedicine. In addition, the characteristics and circumstances of patients presenting to CPEP began to change (Table).

Children/adolescents. In the months before COVID-19’s spread to the United States, there had been an exponential surge in child visits to CPEP, with >200 such visits in January 2020. When schools closed on March 13, school-related stress abruptly abated, and during April, child visits dropped to 89. This reduction might have been due in part to increased access to outpatient treatment via telemedicine or telephone appointments. In our affiliated clinics, both new patient visits and remote attendance to appointments by established patients increased substantially, likely contributing to a decreased reliance on the CPEP for treatment. Limited Family Court operations, though, left already-frustrated police without much recourse when called to intervene with adolescent offenders. CPEP once again served an untraditional role, facilitating the removal of these disruptive individuals from potentially dangerous circumstances, under the guise of behavioral emergencies.

Suicidality. While nonemergent visits declined, presentations related to suicidality persisted. In the United States, suicide rates have increased annually for decades. This trend has also been observed locally, with early evidence suggesting that the changes inflicted by COVID-19 perpetuated the surge in suicidal thinking and behavior, but with a change in character. Some of this is likely related to financial stress and social disruption, though job loss seems more likely to result in increased substance use than suicidality. Even more distressing to those coming to CPEP was anxiety about the illness itself, social isolation, and loss. The death of a loved one is painful enough, but disrupting the grief process by preventing people from visiting family members dying in hospitals or gathering for funerals has been devastating. Reports of increased gun sales undoubtedly associated with fears of social decay caused by the pandemic are concerning with regard to patients with suicidality, because shooting has emerged as the means most likely to result in completed suicide.1 The imposition of social distancing directly isolated some individuals, increasing suicidality. Limitations on gathering in groups disrupted other sources of social support as well, such as religious services, clubhouses, and meetings of 12-step programs such as Alcoholics Anonymous. This could increase suicidality, either directly for more vulnerable patients or indirectly by compromising sobriety and thereby adding to the risk for suicide.

Continue to: Substance use disorders (SUDs)

Substance use disorders (SUDs). Presentations to CPEP by patients with SUDs surged, but the patient profile changed, undoubtedly influenced by the pandemic. Requests for detoxification became less frequent because people who were not in severe distress avoided the hospital. At the same time, alcohol-dependent individuals who might typically avoid clinical attention were requiring emergent medical attention for delirium. This is attributable to a combination of factors, including nutritional depletion, and a lack of access to alcohol leading to abrupt withdrawal or consumption of unconventional sources of alcohol, such as hand sanitizer, or hard liquor (over beer). Amphetamine use appears to have increased, although the observed surge may simply be related to the conspicuousness of stimulant intoxication for someone who is sheltering in place. There was a noticeable uptick in overdoses (primarily with opioids) requiring CPEP evaluation, which was possibly related to a reduction of available beds in inpatient rehabilitation facilities as a result of social distancing rules.

Patients with chronic mental illness. Many experts anticipated an increase in hospital visits by individuals with chronic mental illness expected to decompensate as a result of reduced access to community treatment resources.2 Closing courts did not prevent remote sessions for inpatient retention and treatment over objection, but did result in the expiration of many Assisted Outpatient Treatment orders by restricting renewal hearings, which is circuitously beginning to fulfill this prediction. On the other hand, an impressive community response has managed to continue meeting the needs of most of these patients. Dedicated mental health clinics have recruited mobile teams or developed carefully scheduled, nursing-run “shot clinics” to ensure that patients who require long-acting injectable medications or medication-assisted treatment for SUDs continue to receive treatment.

New-onset psychosis. A new population of patients with acute mania and psychosis also seems to have surfaced during this pandemic. Previously high-functioning individuals in their 30s, 40s, and 50s without a history of mental illness were presenting with new-onset psychotic symptoms. These are individuals who may have been characteristically anxious, or had a “Type A personality,” but were social and employed. The cause is unclear, but given the extreme uncertainty and the political climate COVID-19 brings, it is possible that the pandemic may have triggered these episodes. These individuals and their families now have the stress of learning to navigate the mental health system added to the anxiety COVID-19 brings to most households.

Homelessness. Limitations on occupancy have reduced the availability of beds in shelters and residences, resulting in increased homelessness. Locally, authorities estimated that the homeless population has grown nearly threefold as a result of bussing in from neighboring counties with fewer resources, flight from New York City, and the urgent release from jail of nonviolent offenders, many of whom had no place to go for shelter. New emergency shelter beds have not fully compensated for the relative shortage, leading individuals who had been avoiding the hospital due to fear of infection to CPEP looking for a place to stay.

Home stressors. Whereas CPEP visits by children initially decreased, after 6 weeks, the relief from school pressures appears to have been replaced by weariness from stresses at home, and the number of children presenting with depression, SUDs, and behavioral disruptions has increased. Domestic violence involving children and adults increased. Factors that might be contributing to this include the forced proximity of family members who would typically need intermittent interpersonal distance, and an obligation to care for children who would normally be in school or for disabled loved ones now unable to attend day programs or respite services. After months of enduring the pressure of these conflicts and the resulting emotional strain, patient volumes in CPEP have begun slowly returning toward the expected average, particularly since the perceived threat of coming to the hospital has attenuated.

Continue to: Personal challenges

Personal challenges

For me, COVID-19 has brought the chance to grow and learn, fumbling at times to provide the best care when crisis abounds and when not much can be said to ease the appropriate emotional distress our patients experience. The lines between what is pathological anxiety, what level of anxiety causes functional impairment, and what can realistically be expected to respond to psychiatric treatment have become blurred. At the same time, I have come across some of the sickest patients I have ever encountered.

In some ways, my passion for psychiatry has been rekindled by COVID-19, sparking an enthusiasm to teach and inspire students to pursue careers in this wonderful field of medicine. Helping to care for patients in the absence of a cure can necessitate the application of creativity and thoughtfulness to relieve suffering, thereby teaching the art of healing above offering treatment alone. Unfortunately, replacing actual patient contact with remote learning deprives students of this unique educational opportunity. Residents who attempt to continue training while limiting exposure to patients may mitigate their own risk but could also be missing an opportunity to learn how to balance their needs with making their patients’ well-being a priority. This raises the question of how the next generation of medical students and residents will learn to navigate future crises. Gruesome media depictions of haunting experiences witnessed by medical professionals exposed to an enormity of loss and death, magnified by the suicide deaths of 2 front-line workers in New York City, undoubtedly contribute to the instinct driving the protection of students and residents in this way.

The gratitude the public expresses toward me for simply continuing to do my job brings an expectation of heroism I did not seek, and with which I am uncomfortable. For me, exceptionally poised to analyze and over-analyze myriad aspects of an internal conflict that is exhausting to balance, it all generates frustration and guilt more than anything.

I am theoretically at lower risk than intubating anesthesiologists, emergency medicine physicians, and emergency medical technicians who face patients with active COVID-19. Nevertheless, daily proximity to so many patients naturally generates fear. I convince myself that performing video consultations to the medical ED is an adaptation necessary to preserve PPE, to keep me healthy through reduced exposure, to be available to patients longer, and to support the emotional health of the medical staff who are handing over that headset to patients “under investigation.” At the same time, I am secretly relieved to avoid entering those rooms and taunting death, or even worse, risking exposing my family to the virus. The threat of COVID-19 can be so consuming that it becomes easy to forget that most individuals infected are asymptomatic and therefore difficult to quickly identify.

So I continue to sit with patients face-to-face all day. Many of them are not capable of following masking and distancing recommendations, and are more prone to spitting and biting than their counterparts in the medical ED. I must ignore this threat and convince myself I am safe to be able to place my responsibility to patient care above my own needs and do my job.

Continue to: Most of my colleagues exhibit...

Most of my colleagues exhibit an effortless bravery, even if we all naturally waver briefly at times. I am proud to stand shoulder-to-shoulder every day with these clinicians, and other staff, from police to custodians, as we continue to care for the people of this community. Despite the lower clinical burden, each day we expend significant emotional energy struggling with unexpected and unique challenges, including the burden of facing the unknown. Everyone is under stress right now. For most, the effects will be transient. For some, the damage might be permanent. For others, this stress has brought out the best in us. But knowing that physicians are particularly prone to burnout, how long can the current state of hypervigilance be maintained?

What will the future hold?

The COVID-19 era has brought fewer patients through the door of my psychiatric ED; however, just like everywhere else in the world, everything has changed. The only thing that is certain is that further change is inevitable, and we must adapt to the challenge and learn from it. As unsettling as disruptions to the status quo can be, human behavior dictates that we have the option to seize opportunities created by instability to produce superior outcomes, which can be accomplished only by looking at things anew. The question is whether we will revert to the pre-COVID-19 dysfunctional use of psychiatric emergency services, or can we use what we have learned—particularly about the value of telepsychiatry—to pursue a more effective system based on an improved understanding of the mental health treatment needs of our community. While technology is proving that social distancing requires only space between people, and not necessarily social separation, there is a risk that excessive use of remote treatment could compromise the therapeutic relationship with our patients. Despite emerging opportunities, it is difficult to direct change in a productive way when the future is uncertain.

The continuous outpouring of respect for clinicians is morale-boosting. Behind closed doors, however, news that this county hospital failed to qualify for any of the second round of federal support funding because the management of COVID-19 patients has been too effective brought a new layer of unanticipated stress. This is the only hospital in 7 counties operating a psychiatric emergency service. The mandatory, “voluntary” furloughs expected of nursing and social work staff are only now being scheduled to occur over the next couple of months. And just in time for patient volumes to return to normal. How can we continue to provide quality care, let alone build changes into practice, with reduced nursing and support staff?

It is promising, however, that in the midst of social distancing, the shared experience of endeavoring to overcome COVID-19 has promoted a connectedness among individuals who might otherwise never cross paths. This observation has bolstered my confidence in the capacity for resilience of the mental health system and the individuals within it. The reality is that we are all in this together. Differences should matter less in the face of altered perceptions of mortality. Despite the stress, suicide becomes a less reasonable choice when the value of life is magnified by pandemic circumstances. Maybe there will be even less of a need for psychiatric emergency services in the wake of COVID-19, rather than the anticipated wave of mental health crises. Until we know for sure, it is only through fellowship and continued dedication to healing that the ED experience will continue to be a positive one.

Bottom Line

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) led to changes in the characteristics and circumstances of patients presenting to our psychiatric emergency service. Despite a lower clinical burden, each day we expended significant emotional energy struggling with unexpected and unique challenges. We can use what we have learned from COVID-19 to pursue a more effective system based on an improved understanding of the mental health treatment needs of our community.

Related Resource

- American Association for Emergency Psychiatry, American College of Emergency Physicians, American Psychiatric Association, Coalition on Psychiatric Emergencies, Crisis Residential Association, and the Emergency Nurses Association. Joint statement for care of patients with behavioral health emergencies and suspected or confirmed COVID-19. https://aaep.memberclicks.net/assets/joint-statement-covid-behavioral-health.pdf.

1. Wang J, Sumner SA, Simon TR, et al. Trends in the incidence and lethality of suicidal acts in the United States, 2006-2015 [published online April 22, 2020]. JAMA Psychiatry. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.0596.

2. Reger MA, Stanley IH, Joiner TE. Suicide mortality and coronavirus disease 2019--a perfect storm? [published online April 10, 2020]. JAMA Psychiatry. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.1060.

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is affecting every aspect of medical care. Much has been written about overwhelmed hospital settings, the financial devastation to outpatient treatment centers, and an impending pandemic of mental illness that the existing underfunded and fragmented mental health system would not be prepared to weather. Although COVID-19 has undeniably affected the practice of emergency psychiatry, its impact has been surprising and complex. In this article, I describe the effects COVID-19 has had on our psychiatric emergency service, and how the pandemic has affected me personally.

How the pandemic affected our psychiatric ED

The Comprehensive Psychiatric Emergency Program (CPEP) in Buffalo, New York, is part of the emergency department (ED) in the local county hospital and is staffed by faculty from the Department of Psychiatry at the University at Buffalo. It was developed to provide evaluations of acutely psychiatrically ill individuals, to determine their treatment needs and facilitate access to the appropriate level of care.

Before COVID-19, as the only fully staffed psychiatric emergency service in the region, CPEP would routinely be called upon to serve many functions for which it was not designed. For example, people who had difficulty accessing psychiatric care in the community might come to CPEP expecting treatment for chronic conditions. Additionally, due to systemic deficiencies and limited resources, police and other community agencies refer individuals to CPEP who either have illnesses unrelated to current circumstances or who are not psychiatrically ill but unmanageable because of aggression or otherwise unresolvable social challenges such as homelessness, criminal behavior, poor parenting and other family strains, or general dissatisfaction with life. Parents unable to set limits with bored or defiant children might leave them in CPEP, hoping to transfer the parenting role, just as law enforcement officers who feel impotent to apply meaningful sanctions to non-felonious offenders might bring them to CPEP seeking containment. Labeling these problems as psychiatric emergencies has made it more palatable to leave these individuals in our care. These types of visits have contributed to the substantial growth of CPEP in recent years, in terms of annual patient visits, number of children abandoned and their lengths of stay in the CPEP, among other metrics.

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on an emergency psychiatry service that is expected to be all things to all people has been interesting. For the first few weeks of the societal shutdown, the patient flow was unchanged. However, during this time, the usual overcrowding created a feeling of vulnerability to contagion that sparked an urgency to minimize the census. Superhuman efforts were fueled by an unspoken sense of impending doom, and wait times dropped from approximately 17 hours to 3 or 4 hours. This state of hypervigilance was impossible to sustain indefinitely, and inevitably those efforts were exhausted. As adrenaline waned, the focus turned toward family and self-preservation. Nursing and social work staff began cancelling shifts, as did part-time physicians who contracted services with our department. Others, however, were drawn to join the front-line fight.

Trends in psychiatric ED usage during the pandemic

As COVID-19 spread, local media reported the paucity of personal protective equipment (PPE) and created the sense that no one would receive hospital treatment unless they were on the brink of death. Consequently, total visits to the ED began to slow. During April, CPEP saw 25% fewer visits than average. This reduction was partly attributable to cohorting patients with any suspicion of infection in a designated area within the medical ED, with access to remote evaluation by CPEP psychiatrists via telemedicine. In addition, the characteristics and circumstances of patients presenting to CPEP began to change (Table).

Children/adolescents. In the months before COVID-19’s spread to the United States, there had been an exponential surge in child visits to CPEP, with >200 such visits in January 2020. When schools closed on March 13, school-related stress abruptly abated, and during April, child visits dropped to 89. This reduction might have been due in part to increased access to outpatient treatment via telemedicine or telephone appointments. In our affiliated clinics, both new patient visits and remote attendance to appointments by established patients increased substantially, likely contributing to a decreased reliance on the CPEP for treatment. Limited Family Court operations, though, left already-frustrated police without much recourse when called to intervene with adolescent offenders. CPEP once again served an untraditional role, facilitating the removal of these disruptive individuals from potentially dangerous circumstances, under the guise of behavioral emergencies.

Suicidality. While nonemergent visits declined, presentations related to suicidality persisted. In the United States, suicide rates have increased annually for decades. This trend has also been observed locally, with early evidence suggesting that the changes inflicted by COVID-19 perpetuated the surge in suicidal thinking and behavior, but with a change in character. Some of this is likely related to financial stress and social disruption, though job loss seems more likely to result in increased substance use than suicidality. Even more distressing to those coming to CPEP was anxiety about the illness itself, social isolation, and loss. The death of a loved one is painful enough, but disrupting the grief process by preventing people from visiting family members dying in hospitals or gathering for funerals has been devastating. Reports of increased gun sales undoubtedly associated with fears of social decay caused by the pandemic are concerning with regard to patients with suicidality, because shooting has emerged as the means most likely to result in completed suicide.1 The imposition of social distancing directly isolated some individuals, increasing suicidality. Limitations on gathering in groups disrupted other sources of social support as well, such as religious services, clubhouses, and meetings of 12-step programs such as Alcoholics Anonymous. This could increase suicidality, either directly for more vulnerable patients or indirectly by compromising sobriety and thereby adding to the risk for suicide.

Continue to: Substance use disorders (SUDs)

Substance use disorders (SUDs). Presentations to CPEP by patients with SUDs surged, but the patient profile changed, undoubtedly influenced by the pandemic. Requests for detoxification became less frequent because people who were not in severe distress avoided the hospital. At the same time, alcohol-dependent individuals who might typically avoid clinical attention were requiring emergent medical attention for delirium. This is attributable to a combination of factors, including nutritional depletion, and a lack of access to alcohol leading to abrupt withdrawal or consumption of unconventional sources of alcohol, such as hand sanitizer, or hard liquor (over beer). Amphetamine use appears to have increased, although the observed surge may simply be related to the conspicuousness of stimulant intoxication for someone who is sheltering in place. There was a noticeable uptick in overdoses (primarily with opioids) requiring CPEP evaluation, which was possibly related to a reduction of available beds in inpatient rehabilitation facilities as a result of social distancing rules.

Patients with chronic mental illness. Many experts anticipated an increase in hospital visits by individuals with chronic mental illness expected to decompensate as a result of reduced access to community treatment resources.2 Closing courts did not prevent remote sessions for inpatient retention and treatment over objection, but did result in the expiration of many Assisted Outpatient Treatment orders by restricting renewal hearings, which is circuitously beginning to fulfill this prediction. On the other hand, an impressive community response has managed to continue meeting the needs of most of these patients. Dedicated mental health clinics have recruited mobile teams or developed carefully scheduled, nursing-run “shot clinics” to ensure that patients who require long-acting injectable medications or medication-assisted treatment for SUDs continue to receive treatment.

New-onset psychosis. A new population of patients with acute mania and psychosis also seems to have surfaced during this pandemic. Previously high-functioning individuals in their 30s, 40s, and 50s without a history of mental illness were presenting with new-onset psychotic symptoms. These are individuals who may have been characteristically anxious, or had a “Type A personality,” but were social and employed. The cause is unclear, but given the extreme uncertainty and the political climate COVID-19 brings, it is possible that the pandemic may have triggered these episodes. These individuals and their families now have the stress of learning to navigate the mental health system added to the anxiety COVID-19 brings to most households.

Homelessness. Limitations on occupancy have reduced the availability of beds in shelters and residences, resulting in increased homelessness. Locally, authorities estimated that the homeless population has grown nearly threefold as a result of bussing in from neighboring counties with fewer resources, flight from New York City, and the urgent release from jail of nonviolent offenders, many of whom had no place to go for shelter. New emergency shelter beds have not fully compensated for the relative shortage, leading individuals who had been avoiding the hospital due to fear of infection to CPEP looking for a place to stay.

Home stressors. Whereas CPEP visits by children initially decreased, after 6 weeks, the relief from school pressures appears to have been replaced by weariness from stresses at home, and the number of children presenting with depression, SUDs, and behavioral disruptions has increased. Domestic violence involving children and adults increased. Factors that might be contributing to this include the forced proximity of family members who would typically need intermittent interpersonal distance, and an obligation to care for children who would normally be in school or for disabled loved ones now unable to attend day programs or respite services. After months of enduring the pressure of these conflicts and the resulting emotional strain, patient volumes in CPEP have begun slowly returning toward the expected average, particularly since the perceived threat of coming to the hospital has attenuated.

Continue to: Personal challenges

Personal challenges

For me, COVID-19 has brought the chance to grow and learn, fumbling at times to provide the best care when crisis abounds and when not much can be said to ease the appropriate emotional distress our patients experience. The lines between what is pathological anxiety, what level of anxiety causes functional impairment, and what can realistically be expected to respond to psychiatric treatment have become blurred. At the same time, I have come across some of the sickest patients I have ever encountered.

In some ways, my passion for psychiatry has been rekindled by COVID-19, sparking an enthusiasm to teach and inspire students to pursue careers in this wonderful field of medicine. Helping to care for patients in the absence of a cure can necessitate the application of creativity and thoughtfulness to relieve suffering, thereby teaching the art of healing above offering treatment alone. Unfortunately, replacing actual patient contact with remote learning deprives students of this unique educational opportunity. Residents who attempt to continue training while limiting exposure to patients may mitigate their own risk but could also be missing an opportunity to learn how to balance their needs with making their patients’ well-being a priority. This raises the question of how the next generation of medical students and residents will learn to navigate future crises. Gruesome media depictions of haunting experiences witnessed by medical professionals exposed to an enormity of loss and death, magnified by the suicide deaths of 2 front-line workers in New York City, undoubtedly contribute to the instinct driving the protection of students and residents in this way.

The gratitude the public expresses toward me for simply continuing to do my job brings an expectation of heroism I did not seek, and with which I am uncomfortable. For me, exceptionally poised to analyze and over-analyze myriad aspects of an internal conflict that is exhausting to balance, it all generates frustration and guilt more than anything.

I am theoretically at lower risk than intubating anesthesiologists, emergency medicine physicians, and emergency medical technicians who face patients with active COVID-19. Nevertheless, daily proximity to so many patients naturally generates fear. I convince myself that performing video consultations to the medical ED is an adaptation necessary to preserve PPE, to keep me healthy through reduced exposure, to be available to patients longer, and to support the emotional health of the medical staff who are handing over that headset to patients “under investigation.” At the same time, I am secretly relieved to avoid entering those rooms and taunting death, or even worse, risking exposing my family to the virus. The threat of COVID-19 can be so consuming that it becomes easy to forget that most individuals infected are asymptomatic and therefore difficult to quickly identify.

So I continue to sit with patients face-to-face all day. Many of them are not capable of following masking and distancing recommendations, and are more prone to spitting and biting than their counterparts in the medical ED. I must ignore this threat and convince myself I am safe to be able to place my responsibility to patient care above my own needs and do my job.

Continue to: Most of my colleagues exhibit...

Most of my colleagues exhibit an effortless bravery, even if we all naturally waver briefly at times. I am proud to stand shoulder-to-shoulder every day with these clinicians, and other staff, from police to custodians, as we continue to care for the people of this community. Despite the lower clinical burden, each day we expend significant emotional energy struggling with unexpected and unique challenges, including the burden of facing the unknown. Everyone is under stress right now. For most, the effects will be transient. For some, the damage might be permanent. For others, this stress has brought out the best in us. But knowing that physicians are particularly prone to burnout, how long can the current state of hypervigilance be maintained?

What will the future hold?

The COVID-19 era has brought fewer patients through the door of my psychiatric ED; however, just like everywhere else in the world, everything has changed. The only thing that is certain is that further change is inevitable, and we must adapt to the challenge and learn from it. As unsettling as disruptions to the status quo can be, human behavior dictates that we have the option to seize opportunities created by instability to produce superior outcomes, which can be accomplished only by looking at things anew. The question is whether we will revert to the pre-COVID-19 dysfunctional use of psychiatric emergency services, or can we use what we have learned—particularly about the value of telepsychiatry—to pursue a more effective system based on an improved understanding of the mental health treatment needs of our community. While technology is proving that social distancing requires only space between people, and not necessarily social separation, there is a risk that excessive use of remote treatment could compromise the therapeutic relationship with our patients. Despite emerging opportunities, it is difficult to direct change in a productive way when the future is uncertain.

The continuous outpouring of respect for clinicians is morale-boosting. Behind closed doors, however, news that this county hospital failed to qualify for any of the second round of federal support funding because the management of COVID-19 patients has been too effective brought a new layer of unanticipated stress. This is the only hospital in 7 counties operating a psychiatric emergency service. The mandatory, “voluntary” furloughs expected of nursing and social work staff are only now being scheduled to occur over the next couple of months. And just in time for patient volumes to return to normal. How can we continue to provide quality care, let alone build changes into practice, with reduced nursing and support staff?

It is promising, however, that in the midst of social distancing, the shared experience of endeavoring to overcome COVID-19 has promoted a connectedness among individuals who might otherwise never cross paths. This observation has bolstered my confidence in the capacity for resilience of the mental health system and the individuals within it. The reality is that we are all in this together. Differences should matter less in the face of altered perceptions of mortality. Despite the stress, suicide becomes a less reasonable choice when the value of life is magnified by pandemic circumstances. Maybe there will be even less of a need for psychiatric emergency services in the wake of COVID-19, rather than the anticipated wave of mental health crises. Until we know for sure, it is only through fellowship and continued dedication to healing that the ED experience will continue to be a positive one.

Bottom Line

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) led to changes in the characteristics and circumstances of patients presenting to our psychiatric emergency service. Despite a lower clinical burden, each day we expended significant emotional energy struggling with unexpected and unique challenges. We can use what we have learned from COVID-19 to pursue a more effective system based on an improved understanding of the mental health treatment needs of our community.

Related Resource

- American Association for Emergency Psychiatry, American College of Emergency Physicians, American Psychiatric Association, Coalition on Psychiatric Emergencies, Crisis Residential Association, and the Emergency Nurses Association. Joint statement for care of patients with behavioral health emergencies and suspected or confirmed COVID-19. https://aaep.memberclicks.net/assets/joint-statement-covid-behavioral-health.pdf.

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is affecting every aspect of medical care. Much has been written about overwhelmed hospital settings, the financial devastation to outpatient treatment centers, and an impending pandemic of mental illness that the existing underfunded and fragmented mental health system would not be prepared to weather. Although COVID-19 has undeniably affected the practice of emergency psychiatry, its impact has been surprising and complex. In this article, I describe the effects COVID-19 has had on our psychiatric emergency service, and how the pandemic has affected me personally.

How the pandemic affected our psychiatric ED

The Comprehensive Psychiatric Emergency Program (CPEP) in Buffalo, New York, is part of the emergency department (ED) in the local county hospital and is staffed by faculty from the Department of Psychiatry at the University at Buffalo. It was developed to provide evaluations of acutely psychiatrically ill individuals, to determine their treatment needs and facilitate access to the appropriate level of care.

Before COVID-19, as the only fully staffed psychiatric emergency service in the region, CPEP would routinely be called upon to serve many functions for which it was not designed. For example, people who had difficulty accessing psychiatric care in the community might come to CPEP expecting treatment for chronic conditions. Additionally, due to systemic deficiencies and limited resources, police and other community agencies refer individuals to CPEP who either have illnesses unrelated to current circumstances or who are not psychiatrically ill but unmanageable because of aggression or otherwise unresolvable social challenges such as homelessness, criminal behavior, poor parenting and other family strains, or general dissatisfaction with life. Parents unable to set limits with bored or defiant children might leave them in CPEP, hoping to transfer the parenting role, just as law enforcement officers who feel impotent to apply meaningful sanctions to non-felonious offenders might bring them to CPEP seeking containment. Labeling these problems as psychiatric emergencies has made it more palatable to leave these individuals in our care. These types of visits have contributed to the substantial growth of CPEP in recent years, in terms of annual patient visits, number of children abandoned and their lengths of stay in the CPEP, among other metrics.

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on an emergency psychiatry service that is expected to be all things to all people has been interesting. For the first few weeks of the societal shutdown, the patient flow was unchanged. However, during this time, the usual overcrowding created a feeling of vulnerability to contagion that sparked an urgency to minimize the census. Superhuman efforts were fueled by an unspoken sense of impending doom, and wait times dropped from approximately 17 hours to 3 or 4 hours. This state of hypervigilance was impossible to sustain indefinitely, and inevitably those efforts were exhausted. As adrenaline waned, the focus turned toward family and self-preservation. Nursing and social work staff began cancelling shifts, as did part-time physicians who contracted services with our department. Others, however, were drawn to join the front-line fight.

Trends in psychiatric ED usage during the pandemic

As COVID-19 spread, local media reported the paucity of personal protective equipment (PPE) and created the sense that no one would receive hospital treatment unless they were on the brink of death. Consequently, total visits to the ED began to slow. During April, CPEP saw 25% fewer visits than average. This reduction was partly attributable to cohorting patients with any suspicion of infection in a designated area within the medical ED, with access to remote evaluation by CPEP psychiatrists via telemedicine. In addition, the characteristics and circumstances of patients presenting to CPEP began to change (Table).

Children/adolescents. In the months before COVID-19’s spread to the United States, there had been an exponential surge in child visits to CPEP, with >200 such visits in January 2020. When schools closed on March 13, school-related stress abruptly abated, and during April, child visits dropped to 89. This reduction might have been due in part to increased access to outpatient treatment via telemedicine or telephone appointments. In our affiliated clinics, both new patient visits and remote attendance to appointments by established patients increased substantially, likely contributing to a decreased reliance on the CPEP for treatment. Limited Family Court operations, though, left already-frustrated police without much recourse when called to intervene with adolescent offenders. CPEP once again served an untraditional role, facilitating the removal of these disruptive individuals from potentially dangerous circumstances, under the guise of behavioral emergencies.

Suicidality. While nonemergent visits declined, presentations related to suicidality persisted. In the United States, suicide rates have increased annually for decades. This trend has also been observed locally, with early evidence suggesting that the changes inflicted by COVID-19 perpetuated the surge in suicidal thinking and behavior, but with a change in character. Some of this is likely related to financial stress and social disruption, though job loss seems more likely to result in increased substance use than suicidality. Even more distressing to those coming to CPEP was anxiety about the illness itself, social isolation, and loss. The death of a loved one is painful enough, but disrupting the grief process by preventing people from visiting family members dying in hospitals or gathering for funerals has been devastating. Reports of increased gun sales undoubtedly associated with fears of social decay caused by the pandemic are concerning with regard to patients with suicidality, because shooting has emerged as the means most likely to result in completed suicide.1 The imposition of social distancing directly isolated some individuals, increasing suicidality. Limitations on gathering in groups disrupted other sources of social support as well, such as religious services, clubhouses, and meetings of 12-step programs such as Alcoholics Anonymous. This could increase suicidality, either directly for more vulnerable patients or indirectly by compromising sobriety and thereby adding to the risk for suicide.

Continue to: Substance use disorders (SUDs)

Substance use disorders (SUDs). Presentations to CPEP by patients with SUDs surged, but the patient profile changed, undoubtedly influenced by the pandemic. Requests for detoxification became less frequent because people who were not in severe distress avoided the hospital. At the same time, alcohol-dependent individuals who might typically avoid clinical attention were requiring emergent medical attention for delirium. This is attributable to a combination of factors, including nutritional depletion, and a lack of access to alcohol leading to abrupt withdrawal or consumption of unconventional sources of alcohol, such as hand sanitizer, or hard liquor (over beer). Amphetamine use appears to have increased, although the observed surge may simply be related to the conspicuousness of stimulant intoxication for someone who is sheltering in place. There was a noticeable uptick in overdoses (primarily with opioids) requiring CPEP evaluation, which was possibly related to a reduction of available beds in inpatient rehabilitation facilities as a result of social distancing rules.

Patients with chronic mental illness. Many experts anticipated an increase in hospital visits by individuals with chronic mental illness expected to decompensate as a result of reduced access to community treatment resources.2 Closing courts did not prevent remote sessions for inpatient retention and treatment over objection, but did result in the expiration of many Assisted Outpatient Treatment orders by restricting renewal hearings, which is circuitously beginning to fulfill this prediction. On the other hand, an impressive community response has managed to continue meeting the needs of most of these patients. Dedicated mental health clinics have recruited mobile teams or developed carefully scheduled, nursing-run “shot clinics” to ensure that patients who require long-acting injectable medications or medication-assisted treatment for SUDs continue to receive treatment.

New-onset psychosis. A new population of patients with acute mania and psychosis also seems to have surfaced during this pandemic. Previously high-functioning individuals in their 30s, 40s, and 50s without a history of mental illness were presenting with new-onset psychotic symptoms. These are individuals who may have been characteristically anxious, or had a “Type A personality,” but were social and employed. The cause is unclear, but given the extreme uncertainty and the political climate COVID-19 brings, it is possible that the pandemic may have triggered these episodes. These individuals and their families now have the stress of learning to navigate the mental health system added to the anxiety COVID-19 brings to most households.

Homelessness. Limitations on occupancy have reduced the availability of beds in shelters and residences, resulting in increased homelessness. Locally, authorities estimated that the homeless population has grown nearly threefold as a result of bussing in from neighboring counties with fewer resources, flight from New York City, and the urgent release from jail of nonviolent offenders, many of whom had no place to go for shelter. New emergency shelter beds have not fully compensated for the relative shortage, leading individuals who had been avoiding the hospital due to fear of infection to CPEP looking for a place to stay.

Home stressors. Whereas CPEP visits by children initially decreased, after 6 weeks, the relief from school pressures appears to have been replaced by weariness from stresses at home, and the number of children presenting with depression, SUDs, and behavioral disruptions has increased. Domestic violence involving children and adults increased. Factors that might be contributing to this include the forced proximity of family members who would typically need intermittent interpersonal distance, and an obligation to care for children who would normally be in school or for disabled loved ones now unable to attend day programs or respite services. After months of enduring the pressure of these conflicts and the resulting emotional strain, patient volumes in CPEP have begun slowly returning toward the expected average, particularly since the perceived threat of coming to the hospital has attenuated.

Continue to: Personal challenges

Personal challenges

For me, COVID-19 has brought the chance to grow and learn, fumbling at times to provide the best care when crisis abounds and when not much can be said to ease the appropriate emotional distress our patients experience. The lines between what is pathological anxiety, what level of anxiety causes functional impairment, and what can realistically be expected to respond to psychiatric treatment have become blurred. At the same time, I have come across some of the sickest patients I have ever encountered.

In some ways, my passion for psychiatry has been rekindled by COVID-19, sparking an enthusiasm to teach and inspire students to pursue careers in this wonderful field of medicine. Helping to care for patients in the absence of a cure can necessitate the application of creativity and thoughtfulness to relieve suffering, thereby teaching the art of healing above offering treatment alone. Unfortunately, replacing actual patient contact with remote learning deprives students of this unique educational opportunity. Residents who attempt to continue training while limiting exposure to patients may mitigate their own risk but could also be missing an opportunity to learn how to balance their needs with making their patients’ well-being a priority. This raises the question of how the next generation of medical students and residents will learn to navigate future crises. Gruesome media depictions of haunting experiences witnessed by medical professionals exposed to an enormity of loss and death, magnified by the suicide deaths of 2 front-line workers in New York City, undoubtedly contribute to the instinct driving the protection of students and residents in this way.

The gratitude the public expresses toward me for simply continuing to do my job brings an expectation of heroism I did not seek, and with which I am uncomfortable. For me, exceptionally poised to analyze and over-analyze myriad aspects of an internal conflict that is exhausting to balance, it all generates frustration and guilt more than anything.

I am theoretically at lower risk than intubating anesthesiologists, emergency medicine physicians, and emergency medical technicians who face patients with active COVID-19. Nevertheless, daily proximity to so many patients naturally generates fear. I convince myself that performing video consultations to the medical ED is an adaptation necessary to preserve PPE, to keep me healthy through reduced exposure, to be available to patients longer, and to support the emotional health of the medical staff who are handing over that headset to patients “under investigation.” At the same time, I am secretly relieved to avoid entering those rooms and taunting death, or even worse, risking exposing my family to the virus. The threat of COVID-19 can be so consuming that it becomes easy to forget that most individuals infected are asymptomatic and therefore difficult to quickly identify.

So I continue to sit with patients face-to-face all day. Many of them are not capable of following masking and distancing recommendations, and are more prone to spitting and biting than their counterparts in the medical ED. I must ignore this threat and convince myself I am safe to be able to place my responsibility to patient care above my own needs and do my job.

Continue to: Most of my colleagues exhibit...

Most of my colleagues exhibit an effortless bravery, even if we all naturally waver briefly at times. I am proud to stand shoulder-to-shoulder every day with these clinicians, and other staff, from police to custodians, as we continue to care for the people of this community. Despite the lower clinical burden, each day we expend significant emotional energy struggling with unexpected and unique challenges, including the burden of facing the unknown. Everyone is under stress right now. For most, the effects will be transient. For some, the damage might be permanent. For others, this stress has brought out the best in us. But knowing that physicians are particularly prone to burnout, how long can the current state of hypervigilance be maintained?

What will the future hold?

The COVID-19 era has brought fewer patients through the door of my psychiatric ED; however, just like everywhere else in the world, everything has changed. The only thing that is certain is that further change is inevitable, and we must adapt to the challenge and learn from it. As unsettling as disruptions to the status quo can be, human behavior dictates that we have the option to seize opportunities created by instability to produce superior outcomes, which can be accomplished only by looking at things anew. The question is whether we will revert to the pre-COVID-19 dysfunctional use of psychiatric emergency services, or can we use what we have learned—particularly about the value of telepsychiatry—to pursue a more effective system based on an improved understanding of the mental health treatment needs of our community. While technology is proving that social distancing requires only space between people, and not necessarily social separation, there is a risk that excessive use of remote treatment could compromise the therapeutic relationship with our patients. Despite emerging opportunities, it is difficult to direct change in a productive way when the future is uncertain.

The continuous outpouring of respect for clinicians is morale-boosting. Behind closed doors, however, news that this county hospital failed to qualify for any of the second round of federal support funding because the management of COVID-19 patients has been too effective brought a new layer of unanticipated stress. This is the only hospital in 7 counties operating a psychiatric emergency service. The mandatory, “voluntary” furloughs expected of nursing and social work staff are only now being scheduled to occur over the next couple of months. And just in time for patient volumes to return to normal. How can we continue to provide quality care, let alone build changes into practice, with reduced nursing and support staff?

It is promising, however, that in the midst of social distancing, the shared experience of endeavoring to overcome COVID-19 has promoted a connectedness among individuals who might otherwise never cross paths. This observation has bolstered my confidence in the capacity for resilience of the mental health system and the individuals within it. The reality is that we are all in this together. Differences should matter less in the face of altered perceptions of mortality. Despite the stress, suicide becomes a less reasonable choice when the value of life is magnified by pandemic circumstances. Maybe there will be even less of a need for psychiatric emergency services in the wake of COVID-19, rather than the anticipated wave of mental health crises. Until we know for sure, it is only through fellowship and continued dedication to healing that the ED experience will continue to be a positive one.

Bottom Line

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) led to changes in the characteristics and circumstances of patients presenting to our psychiatric emergency service. Despite a lower clinical burden, each day we expended significant emotional energy struggling with unexpected and unique challenges. We can use what we have learned from COVID-19 to pursue a more effective system based on an improved understanding of the mental health treatment needs of our community.

Related Resource

- American Association for Emergency Psychiatry, American College of Emergency Physicians, American Psychiatric Association, Coalition on Psychiatric Emergencies, Crisis Residential Association, and the Emergency Nurses Association. Joint statement for care of patients with behavioral health emergencies and suspected or confirmed COVID-19. https://aaep.memberclicks.net/assets/joint-statement-covid-behavioral-health.pdf.

1. Wang J, Sumner SA, Simon TR, et al. Trends in the incidence and lethality of suicidal acts in the United States, 2006-2015 [published online April 22, 2020]. JAMA Psychiatry. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.0596.

2. Reger MA, Stanley IH, Joiner TE. Suicide mortality and coronavirus disease 2019--a perfect storm? [published online April 10, 2020]. JAMA Psychiatry. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.1060.

1. Wang J, Sumner SA, Simon TR, et al. Trends in the incidence and lethality of suicidal acts in the United States, 2006-2015 [published online April 22, 2020]. JAMA Psychiatry. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.0596.

2. Reger MA, Stanley IH, Joiner TE. Suicide mortality and coronavirus disease 2019--a perfect storm? [published online April 10, 2020]. JAMA Psychiatry. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.1060.

The hidden dangers of supplements: A case of substance-induced psychosis

“You are what you eat,” my mother always said, and structured our dinner plates according to the USDA food pyramid. We dutifully consumed leafy greens, and prior to medical school I invested time and money into healthy diet choices. I drank green smoothies, pureed baby food for my children, read up on the pH balancing diet, grew sprouts on windowsills, bought organic.

With the stressors and time constraints of managing medical school and a family, nutrition tumbled down the ladder of priorities until eventually my family was subsisting on chicken nuggets, pizza, and peanut butter. Intern year has only added the occasional candy bar from the doctors’ lounge. I experienced a vague sense of loss for something I had once valued, but simultaneously felt dismissive of trendy topics such as omega-3 fatty acids and antioxidants in the face of myocardial infarctions and liver failure. A biochemistry professor once scoffed at “the laypeople’s obsession with toxins,” and nutrition received zero attention in our medical school curriculum or board exams.

However, a clinical experience on the inpatient psychiatric unit made me reevaluate the importance nutrition should have in both our personal lives and the practice of medicine. This is the case of an otherwise healthy young man with no psychiatric history who suffered a psychotic break after ingesting an excess of a supplement he purchased online with the purpose of improving his performance at a high-stress job.

CASE REPORT

Mr. K, a 28-year-old computer programmer, was voluntarily admitted to the inpatient psychiatry unit for paranoia and persecutory delusions along with auditory hallucinations. His father reported that Mr. K had been behaving erratically for several days prior to admission and was subsequently found wandering in the street.

On admission, Mr. K was not oriented to place or situation. He was unkempt and guarded, and claimed people were following him. His urine toxicology screen and blood alcohol levels were negative.

While hospitalized, Mr. K was hyperverbal and delusional. He related that at work he had been developing programs to make slaves in the computer, “algorithms for orchestration,” and that he was uncomfortable with the ethical implications. He eventually endorsed having purchased the supplement phenylethylamine (PEA) to improve his focus, and ingesting “two substantial scoops of the crystalline substance.”

We did not initiate any psychiatric medications. On the third day of his hospitalization, Mr. K was alert, oriented, euthymic, relaxed, and had a full range of affect; upon discharge we advised him to discard the PEA and avoid stimulants. He complied, quit his high-stress job, and had no subsequent psychotic symptoms in the 7 months since discharge.

Continue to: Dietary supplements carry risks

Dietary supplements carry risks

According to the FDA, dietary supplements are regulated as food, but many have strong biologic effects or may even contain drugs.1 More than 18% of Americans use herbal or nutritional therapies as part of their health regimen.2 However, many over-the-counter remedies have been found to exhibit psychotropic effects,3 and many more are purported to impact mental and physical health with little to no scientific research into these claims or potential adverse effects.

Phenylethylamine is sold as a nutritional supplement and marketed for its purported beneficial effects on weight loss, mood, and focus.4 However, PEA is known to act as a natural amphetamine and to play a role in the development of neuropsychiatric disorders.5 It is an endogenous psychotogenic molecule that has been previously theorized as a cause for primary psychosis.6 Phenylethylamine interacts with the same receptor ligand that responds to amphetamine and related compounds (such as methamphetamine and 3,4-methylenedioxy-methamphetamine [MDMA]), the genetic coding for which is located in an area of DNA associated with schizophrenia: chromosome 6q23.2.7 While the mechanisms and details of these interactions remain poorly understood, this case of PEA-induced psychosis represents a glimpse into the potential psychoactive properties of this readily available nutritional supplement.

This patient’s cautionary tale has given me pause regarding both my family’s nutrition and the oft-neglected dietary portion of the social history. Also, several subsequent patient experiences hearken back to my mother’s words regarding the importance of healthy eating. A patient with phenylketonuria presented with psychosis after running out of her formula and consuming junk food. Another patient with severely elevated blood glucose levels presented with confusion. I have come to realize that ingestion impacts presentation, or, in other words, you are what you eat.

1. US Food and Drug Administration. Dietary supplements. https://www.fda.gov/consumers/consumer-updates/dietary-supplements. Accessed December 11, 2019.

2. Tindle H, Davis R, Philips R, et al. Trends in use of complementary and alternative medicine by US adults: 1997-2002. Altern Ther Health Med. 2005;11(1):42-49.

3. Sarris J. Herbal medicines in the treatment of psychiatric disorders: 10-year updated review. Phytotherapy Research. 2018;32(7):1147-1162.

4. Irsfeld M, Spadafore M, Prüß BM. β-phenylethylamine, a small molecule with a large impact. WebmedCentral. 2013;4(9):4409.

5. Wolf M, Mosnaim A. Phenylethylamine in neuropsychiatric disorders. Gen Pharmacol. 1983;14(4):385-390.

6. Janssen P, Leysen J, Megens A, et al. Does phenylethylamine act as an endogenous amphetamine in some patients? In J Neuropsychopharmacol. 1999;2(3):229-240.

7. Zucchi R, Chiellini G, Scanlan TS, et al. Trace amine-associated receptors and their ligands. Br J Pharmacol. 2006;149(8):967-978.

“You are what you eat,” my mother always said, and structured our dinner plates according to the USDA food pyramid. We dutifully consumed leafy greens, and prior to medical school I invested time and money into healthy diet choices. I drank green smoothies, pureed baby food for my children, read up on the pH balancing diet, grew sprouts on windowsills, bought organic.

With the stressors and time constraints of managing medical school and a family, nutrition tumbled down the ladder of priorities until eventually my family was subsisting on chicken nuggets, pizza, and peanut butter. Intern year has only added the occasional candy bar from the doctors’ lounge. I experienced a vague sense of loss for something I had once valued, but simultaneously felt dismissive of trendy topics such as omega-3 fatty acids and antioxidants in the face of myocardial infarctions and liver failure. A biochemistry professor once scoffed at “the laypeople’s obsession with toxins,” and nutrition received zero attention in our medical school curriculum or board exams.

However, a clinical experience on the inpatient psychiatric unit made me reevaluate the importance nutrition should have in both our personal lives and the practice of medicine. This is the case of an otherwise healthy young man with no psychiatric history who suffered a psychotic break after ingesting an excess of a supplement he purchased online with the purpose of improving his performance at a high-stress job.

CASE REPORT

Mr. K, a 28-year-old computer programmer, was voluntarily admitted to the inpatient psychiatry unit for paranoia and persecutory delusions along with auditory hallucinations. His father reported that Mr. K had been behaving erratically for several days prior to admission and was subsequently found wandering in the street.

On admission, Mr. K was not oriented to place or situation. He was unkempt and guarded, and claimed people were following him. His urine toxicology screen and blood alcohol levels were negative.

While hospitalized, Mr. K was hyperverbal and delusional. He related that at work he had been developing programs to make slaves in the computer, “algorithms for orchestration,” and that he was uncomfortable with the ethical implications. He eventually endorsed having purchased the supplement phenylethylamine (PEA) to improve his focus, and ingesting “two substantial scoops of the crystalline substance.”

We did not initiate any psychiatric medications. On the third day of his hospitalization, Mr. K was alert, oriented, euthymic, relaxed, and had a full range of affect; upon discharge we advised him to discard the PEA and avoid stimulants. He complied, quit his high-stress job, and had no subsequent psychotic symptoms in the 7 months since discharge.

Continue to: Dietary supplements carry risks

Dietary supplements carry risks

According to the FDA, dietary supplements are regulated as food, but many have strong biologic effects or may even contain drugs.1 More than 18% of Americans use herbal or nutritional therapies as part of their health regimen.2 However, many over-the-counter remedies have been found to exhibit psychotropic effects,3 and many more are purported to impact mental and physical health with little to no scientific research into these claims or potential adverse effects.

Phenylethylamine is sold as a nutritional supplement and marketed for its purported beneficial effects on weight loss, mood, and focus.4 However, PEA is known to act as a natural amphetamine and to play a role in the development of neuropsychiatric disorders.5 It is an endogenous psychotogenic molecule that has been previously theorized as a cause for primary psychosis.6 Phenylethylamine interacts with the same receptor ligand that responds to amphetamine and related compounds (such as methamphetamine and 3,4-methylenedioxy-methamphetamine [MDMA]), the genetic coding for which is located in an area of DNA associated with schizophrenia: chromosome 6q23.2.7 While the mechanisms and details of these interactions remain poorly understood, this case of PEA-induced psychosis represents a glimpse into the potential psychoactive properties of this readily available nutritional supplement.

This patient’s cautionary tale has given me pause regarding both my family’s nutrition and the oft-neglected dietary portion of the social history. Also, several subsequent patient experiences hearken back to my mother’s words regarding the importance of healthy eating. A patient with phenylketonuria presented with psychosis after running out of her formula and consuming junk food. Another patient with severely elevated blood glucose levels presented with confusion. I have come to realize that ingestion impacts presentation, or, in other words, you are what you eat.

“You are what you eat,” my mother always said, and structured our dinner plates according to the USDA food pyramid. We dutifully consumed leafy greens, and prior to medical school I invested time and money into healthy diet choices. I drank green smoothies, pureed baby food for my children, read up on the pH balancing diet, grew sprouts on windowsills, bought organic.

With the stressors and time constraints of managing medical school and a family, nutrition tumbled down the ladder of priorities until eventually my family was subsisting on chicken nuggets, pizza, and peanut butter. Intern year has only added the occasional candy bar from the doctors’ lounge. I experienced a vague sense of loss for something I had once valued, but simultaneously felt dismissive of trendy topics such as omega-3 fatty acids and antioxidants in the face of myocardial infarctions and liver failure. A biochemistry professor once scoffed at “the laypeople’s obsession with toxins,” and nutrition received zero attention in our medical school curriculum or board exams.

However, a clinical experience on the inpatient psychiatric unit made me reevaluate the importance nutrition should have in both our personal lives and the practice of medicine. This is the case of an otherwise healthy young man with no psychiatric history who suffered a psychotic break after ingesting an excess of a supplement he purchased online with the purpose of improving his performance at a high-stress job.

CASE REPORT

Mr. K, a 28-year-old computer programmer, was voluntarily admitted to the inpatient psychiatry unit for paranoia and persecutory delusions along with auditory hallucinations. His father reported that Mr. K had been behaving erratically for several days prior to admission and was subsequently found wandering in the street.

On admission, Mr. K was not oriented to place or situation. He was unkempt and guarded, and claimed people were following him. His urine toxicology screen and blood alcohol levels were negative.

While hospitalized, Mr. K was hyperverbal and delusional. He related that at work he had been developing programs to make slaves in the computer, “algorithms for orchestration,” and that he was uncomfortable with the ethical implications. He eventually endorsed having purchased the supplement phenylethylamine (PEA) to improve his focus, and ingesting “two substantial scoops of the crystalline substance.”