User login

Defending the Home Planet

Like me, some of you may have been following the agonizing news about the unprecedented brushfires in Australia that have devastated human, animal, and vegetative life in that country so culturally akin to our own.1 For many people who believe the overwhelming majority of scientific reports on climate change, these apocalyptic fires are an empirical demonstration of the truth of the dire prophecies for the future of our planet. Scientists have demonstrated that although climate change may not have caused the worst fires in Australia’s history, they may have contributed to the conditions that enabled them to spread so far and wide and reach such a destructive intensity.2The heartbreaking pictures of singed koalas and displaced people and the helpless feeling that all I can do from here is donate money set me to thinking about the relationship between the military, health, and climate change, which is the subject of this column.

As I write this in mid-January of a new decade and glance at the weather headlines, I read about an earthquake in Puerto Rico and tornadoes in the southern US. This makes it quite plausible that our comfortable lifestyle and technological civilization could in the coming decades go the way of the dinosaurs, also victims of climate change.

Initially, my first thought about this relationship is a negative one—images of scorched earth policies that stretch back to ancient wars jump to mind. Reflection and research on the topic though suggest that the relationship may be more complicated and conflicted. Alas, I can only touch on a few of the themes in this brief format.

It may not be as obvious that climate change also threatens the military, which is the guardian of that civilization. In 2018, for example, Hurricane Michael caused nearly $5 billion in damages to Tyndall Air Force Base in Florida.3 A year later, the US Department of Defense (DoD) released a report on the effects of climate change as mandated by Congress.4 Even though some congressional critics expressed concern about the report’s lack of depth and detail,5 the report asserted that, “The effects of a changing climate are a national security issue with potential impacts to Department of Defense (DoD or the Department) missions, operational plans, and installations.”4

The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) is not immune either. Natural disasters have already disrupted the delivery of health care at its many aging facilities. Climate change was called the “engine”6 driving Hurricane Maria, which in 2017 slammed into Puerto Rico, including its VA medical center, and resulted in shortages of supplies, staff, and basic utilities.7 The facility and the island are still trying to rebuild. In response to weather-exposed vulnerability in VA infrastructure, Senator and presidential candidate Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) and Senator Brian Schatz (D-HI), the ranking member of the Subcommittee on Military Construction, sent a letter to VA leadership arguing that “Strengthening VA’s resilience to climate change is consistent with the agency’s mission to deliver timely, high-quality care and benefits to America’s veterans.”8

It has been reported that the current administration has countered initiatives to prepare for the challenges of providing health care to service members and veterans in a climate changed world.9 Sadly, but predictably, in the politicized federal health care arena, the safety of our service members and, in turn, the domestic and national security and peace that depend on them are caught in the partisan debate over global warming, though it is not likely Congress or federal agency leaders will abandon planning to safeguard service members who will see duty and combat in a radically altered ecology and veterans and who will need to have VA continue to be the reliable safety net despite an increasingly erratic environment.10

Climate change is a divisive political issue; there is a proud tradition of conservatism and self-reliance in military members, active duty and veteran alike. That was why I was surprised and impressed when I saw the results of a recent survey on climate change. In January 2019, 293 active-duty service members and veterans were surveyed.

Participants were selected to reflect the ethnic makeup, educational level, and political allegiance of the military population, which enhanced the validity of the findings.11Participants were asked to indicate whether they believed that the earth was warming secondary to human or natural processes; not growing warmer at all; or whether they were unsure. Similar to the general population, 46% agreed that climate change is anthropogenic.11 More than three-fourths believed it was likely climate change would adversely affect the places they worked, like military installations; 61% thought it likely that global warming could lead to armed conflict over resources. Seven in 10 respondents believed that climate is changing vs 46% who did not. Of respondents who believe climate change is real, 87% see it as a threat to military bases compared with 60% who do not accept the science that the earth is warming.11

This survey, though, is only a small study, and the military and VA are big tents under which a wide range of political persuasions and diverse beliefs co-exist. There are many readers of Federal Practitioner who will no doubt reject nearly every word I have written, in what I know is a controversial column. But it matters that the military and veteran constituency are thinking and speaking about the issue of climate change.11 Why? The answer takes us back to the disaster in Australia. When the fires and the devastation they wrought escalated beyond the powers of the civil authorities to handle, it was the military whose technical skill, coordinated readiness, and personal courage and dedication that was called on to rescue thousands of civilians from the inferno.12 So it will be in our country and around the world when disasters—manmade, natural, or both—threaten to engulf life in all its wondrous variety. Those who battle extreme weather will have unique health needs, and their valiant sacrifices deserve to have health care systems ready and able to treat them.

1. Thompson A. Australia’s bushfires have likely devastated wildlife–and the impact will only get worse. Scientific American. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/australias-bushfires-have-likely-devastated-wildlife-and-the-impact-will-only-get-worse. Published January 8, 2020. Accessed January 16, 2020.

2. Gibbens S. Intense ‘firestorms’ forming from Australia’s deadly wildfires. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/science/2020/01/australian-wildfires-cause-firestorms. Published January 9, 2020. Accessed January 15, 2020.

3. Shapiro A. Tyndall Air Force Base still faces challenges in recovering from Hurricane Michael. https://www.npr.org/2019/05/31/728754872/tyndall-air-force-base-still-faces-challenges-in-recovering-from-hurricane-micha. Published May 31, 2019. Accessed January 16, 2020.

4. US Department of Defense, Office of the Undersecretary for Acquisition and Sustainment. Report on effects of a changing climate to the Department of Defense. https://www.documentcloud.org/documents/5689153-DoD-Final-Climate-Report.html. Published January 2019. Accessed January 16, 2020.

5. Maucione S. DoD justifies climate change report, says response was mission-centric. https://federalnewsnetwork.com/defense-main/2019/03/dod-justifies-climate-change-report-says-response-was-mission-centric. Published March 28, 2019. Accessed January 16, 2020.

6. Shane L 3rd. Puerto Rico’s VA hospital weathers Maria, but challenges loom. https://www.armytimes.com/veterans/2017/09/22/puerto-ricos-va-hospital-weathers-hurricane-maria-but-challenges-loom. Published September 22, 2017. Accessed January 16, 2020.

7. Hersher R. Climate change was the engine that powered Hurricane Maria’s devastating rains. https://www.npr.org/2019/04/17/714098828/climate-change-was-the-engine-that-powered-hurricane-marias-devastating-rains. Published April 17, 2019. Accessed January 16, 2020.

8. Senators Warren and Schatz request an update from the Department of Veterans Affairs on efforts to build resilience to climate change [press release]. https://www.warren.senate.gov/oversight/letters/senators-warren-and-schatz-request-an-update-from-the-department-of-veterans-affairs-on-efforts-to-build-resilience-to-climate-change. Published October 1, 2019. Accessed January 16, 2020.

9. Simkins JD. Navy quietly ends climate change task force, reversing Obama initiative. https://www.navytimes.com/off-duty/military-culture/2019/08/26/navy-quietly-ends-climate-change-task-force-reversing-obama-initiative. Published August 26, 2019. Accessed January 16, 2020.

10. Eilperin J, Dennis B, Ryan M. As White House questions climate change, U.S. military is planning for it. https://www.washingtonpost.com/national/health-science/as-white-house-questions-climate-change-us-military-is-planning-for-it/2019/04/08/78142546-57c0-11e9-814f-e2f46684196e_story.html. Published April 8, 2019. Accessed January 16, 2020.

11. Motta M, Spindel J, Ralston R. Veterans are concerned about climate change and that matters. http://theconversation.com/veterans-are-concerned-about-climate-change-and-that-matters-110685. Published March 8, 2019. Accessed January 16, 2020.

12. Albeck-Ripka L, Kwai I, Fuller T, Tarabay J. ‘It’s an atomic bomb’: Australia deploys military as fires spread. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/01/04/world/australia/fires-military.html. Updated January 5, 2020. Accessed January 18, 2020.

Like me, some of you may have been following the agonizing news about the unprecedented brushfires in Australia that have devastated human, animal, and vegetative life in that country so culturally akin to our own.1 For many people who believe the overwhelming majority of scientific reports on climate change, these apocalyptic fires are an empirical demonstration of the truth of the dire prophecies for the future of our planet. Scientists have demonstrated that although climate change may not have caused the worst fires in Australia’s history, they may have contributed to the conditions that enabled them to spread so far and wide and reach such a destructive intensity.2The heartbreaking pictures of singed koalas and displaced people and the helpless feeling that all I can do from here is donate money set me to thinking about the relationship between the military, health, and climate change, which is the subject of this column.

As I write this in mid-January of a new decade and glance at the weather headlines, I read about an earthquake in Puerto Rico and tornadoes in the southern US. This makes it quite plausible that our comfortable lifestyle and technological civilization could in the coming decades go the way of the dinosaurs, also victims of climate change.

Initially, my first thought about this relationship is a negative one—images of scorched earth policies that stretch back to ancient wars jump to mind. Reflection and research on the topic though suggest that the relationship may be more complicated and conflicted. Alas, I can only touch on a few of the themes in this brief format.

It may not be as obvious that climate change also threatens the military, which is the guardian of that civilization. In 2018, for example, Hurricane Michael caused nearly $5 billion in damages to Tyndall Air Force Base in Florida.3 A year later, the US Department of Defense (DoD) released a report on the effects of climate change as mandated by Congress.4 Even though some congressional critics expressed concern about the report’s lack of depth and detail,5 the report asserted that, “The effects of a changing climate are a national security issue with potential impacts to Department of Defense (DoD or the Department) missions, operational plans, and installations.”4

The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) is not immune either. Natural disasters have already disrupted the delivery of health care at its many aging facilities. Climate change was called the “engine”6 driving Hurricane Maria, which in 2017 slammed into Puerto Rico, including its VA medical center, and resulted in shortages of supplies, staff, and basic utilities.7 The facility and the island are still trying to rebuild. In response to weather-exposed vulnerability in VA infrastructure, Senator and presidential candidate Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) and Senator Brian Schatz (D-HI), the ranking member of the Subcommittee on Military Construction, sent a letter to VA leadership arguing that “Strengthening VA’s resilience to climate change is consistent with the agency’s mission to deliver timely, high-quality care and benefits to America’s veterans.”8

It has been reported that the current administration has countered initiatives to prepare for the challenges of providing health care to service members and veterans in a climate changed world.9 Sadly, but predictably, in the politicized federal health care arena, the safety of our service members and, in turn, the domestic and national security and peace that depend on them are caught in the partisan debate over global warming, though it is not likely Congress or federal agency leaders will abandon planning to safeguard service members who will see duty and combat in a radically altered ecology and veterans and who will need to have VA continue to be the reliable safety net despite an increasingly erratic environment.10

Climate change is a divisive political issue; there is a proud tradition of conservatism and self-reliance in military members, active duty and veteran alike. That was why I was surprised and impressed when I saw the results of a recent survey on climate change. In January 2019, 293 active-duty service members and veterans were surveyed.

Participants were selected to reflect the ethnic makeup, educational level, and political allegiance of the military population, which enhanced the validity of the findings.11Participants were asked to indicate whether they believed that the earth was warming secondary to human or natural processes; not growing warmer at all; or whether they were unsure. Similar to the general population, 46% agreed that climate change is anthropogenic.11 More than three-fourths believed it was likely climate change would adversely affect the places they worked, like military installations; 61% thought it likely that global warming could lead to armed conflict over resources. Seven in 10 respondents believed that climate is changing vs 46% who did not. Of respondents who believe climate change is real, 87% see it as a threat to military bases compared with 60% who do not accept the science that the earth is warming.11

This survey, though, is only a small study, and the military and VA are big tents under which a wide range of political persuasions and diverse beliefs co-exist. There are many readers of Federal Practitioner who will no doubt reject nearly every word I have written, in what I know is a controversial column. But it matters that the military and veteran constituency are thinking and speaking about the issue of climate change.11 Why? The answer takes us back to the disaster in Australia. When the fires and the devastation they wrought escalated beyond the powers of the civil authorities to handle, it was the military whose technical skill, coordinated readiness, and personal courage and dedication that was called on to rescue thousands of civilians from the inferno.12 So it will be in our country and around the world when disasters—manmade, natural, or both—threaten to engulf life in all its wondrous variety. Those who battle extreme weather will have unique health needs, and their valiant sacrifices deserve to have health care systems ready and able to treat them.

Like me, some of you may have been following the agonizing news about the unprecedented brushfires in Australia that have devastated human, animal, and vegetative life in that country so culturally akin to our own.1 For many people who believe the overwhelming majority of scientific reports on climate change, these apocalyptic fires are an empirical demonstration of the truth of the dire prophecies for the future of our planet. Scientists have demonstrated that although climate change may not have caused the worst fires in Australia’s history, they may have contributed to the conditions that enabled them to spread so far and wide and reach such a destructive intensity.2The heartbreaking pictures of singed koalas and displaced people and the helpless feeling that all I can do from here is donate money set me to thinking about the relationship between the military, health, and climate change, which is the subject of this column.

As I write this in mid-January of a new decade and glance at the weather headlines, I read about an earthquake in Puerto Rico and tornadoes in the southern US. This makes it quite plausible that our comfortable lifestyle and technological civilization could in the coming decades go the way of the dinosaurs, also victims of climate change.

Initially, my first thought about this relationship is a negative one—images of scorched earth policies that stretch back to ancient wars jump to mind. Reflection and research on the topic though suggest that the relationship may be more complicated and conflicted. Alas, I can only touch on a few of the themes in this brief format.

It may not be as obvious that climate change also threatens the military, which is the guardian of that civilization. In 2018, for example, Hurricane Michael caused nearly $5 billion in damages to Tyndall Air Force Base in Florida.3 A year later, the US Department of Defense (DoD) released a report on the effects of climate change as mandated by Congress.4 Even though some congressional critics expressed concern about the report’s lack of depth and detail,5 the report asserted that, “The effects of a changing climate are a national security issue with potential impacts to Department of Defense (DoD or the Department) missions, operational plans, and installations.”4

The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) is not immune either. Natural disasters have already disrupted the delivery of health care at its many aging facilities. Climate change was called the “engine”6 driving Hurricane Maria, which in 2017 slammed into Puerto Rico, including its VA medical center, and resulted in shortages of supplies, staff, and basic utilities.7 The facility and the island are still trying to rebuild. In response to weather-exposed vulnerability in VA infrastructure, Senator and presidential candidate Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) and Senator Brian Schatz (D-HI), the ranking member of the Subcommittee on Military Construction, sent a letter to VA leadership arguing that “Strengthening VA’s resilience to climate change is consistent with the agency’s mission to deliver timely, high-quality care and benefits to America’s veterans.”8

It has been reported that the current administration has countered initiatives to prepare for the challenges of providing health care to service members and veterans in a climate changed world.9 Sadly, but predictably, in the politicized federal health care arena, the safety of our service members and, in turn, the domestic and national security and peace that depend on them are caught in the partisan debate over global warming, though it is not likely Congress or federal agency leaders will abandon planning to safeguard service members who will see duty and combat in a radically altered ecology and veterans and who will need to have VA continue to be the reliable safety net despite an increasingly erratic environment.10

Climate change is a divisive political issue; there is a proud tradition of conservatism and self-reliance in military members, active duty and veteran alike. That was why I was surprised and impressed when I saw the results of a recent survey on climate change. In January 2019, 293 active-duty service members and veterans were surveyed.

Participants were selected to reflect the ethnic makeup, educational level, and political allegiance of the military population, which enhanced the validity of the findings.11Participants were asked to indicate whether they believed that the earth was warming secondary to human or natural processes; not growing warmer at all; or whether they were unsure. Similar to the general population, 46% agreed that climate change is anthropogenic.11 More than three-fourths believed it was likely climate change would adversely affect the places they worked, like military installations; 61% thought it likely that global warming could lead to armed conflict over resources. Seven in 10 respondents believed that climate is changing vs 46% who did not. Of respondents who believe climate change is real, 87% see it as a threat to military bases compared with 60% who do not accept the science that the earth is warming.11

This survey, though, is only a small study, and the military and VA are big tents under which a wide range of political persuasions and diverse beliefs co-exist. There are many readers of Federal Practitioner who will no doubt reject nearly every word I have written, in what I know is a controversial column. But it matters that the military and veteran constituency are thinking and speaking about the issue of climate change.11 Why? The answer takes us back to the disaster in Australia. When the fires and the devastation they wrought escalated beyond the powers of the civil authorities to handle, it was the military whose technical skill, coordinated readiness, and personal courage and dedication that was called on to rescue thousands of civilians from the inferno.12 So it will be in our country and around the world when disasters—manmade, natural, or both—threaten to engulf life in all its wondrous variety. Those who battle extreme weather will have unique health needs, and their valiant sacrifices deserve to have health care systems ready and able to treat them.

1. Thompson A. Australia’s bushfires have likely devastated wildlife–and the impact will only get worse. Scientific American. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/australias-bushfires-have-likely-devastated-wildlife-and-the-impact-will-only-get-worse. Published January 8, 2020. Accessed January 16, 2020.

2. Gibbens S. Intense ‘firestorms’ forming from Australia’s deadly wildfires. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/science/2020/01/australian-wildfires-cause-firestorms. Published January 9, 2020. Accessed January 15, 2020.

3. Shapiro A. Tyndall Air Force Base still faces challenges in recovering from Hurricane Michael. https://www.npr.org/2019/05/31/728754872/tyndall-air-force-base-still-faces-challenges-in-recovering-from-hurricane-micha. Published May 31, 2019. Accessed January 16, 2020.

4. US Department of Defense, Office of the Undersecretary for Acquisition and Sustainment. Report on effects of a changing climate to the Department of Defense. https://www.documentcloud.org/documents/5689153-DoD-Final-Climate-Report.html. Published January 2019. Accessed January 16, 2020.

5. Maucione S. DoD justifies climate change report, says response was mission-centric. https://federalnewsnetwork.com/defense-main/2019/03/dod-justifies-climate-change-report-says-response-was-mission-centric. Published March 28, 2019. Accessed January 16, 2020.

6. Shane L 3rd. Puerto Rico’s VA hospital weathers Maria, but challenges loom. https://www.armytimes.com/veterans/2017/09/22/puerto-ricos-va-hospital-weathers-hurricane-maria-but-challenges-loom. Published September 22, 2017. Accessed January 16, 2020.

7. Hersher R. Climate change was the engine that powered Hurricane Maria’s devastating rains. https://www.npr.org/2019/04/17/714098828/climate-change-was-the-engine-that-powered-hurricane-marias-devastating-rains. Published April 17, 2019. Accessed January 16, 2020.

8. Senators Warren and Schatz request an update from the Department of Veterans Affairs on efforts to build resilience to climate change [press release]. https://www.warren.senate.gov/oversight/letters/senators-warren-and-schatz-request-an-update-from-the-department-of-veterans-affairs-on-efforts-to-build-resilience-to-climate-change. Published October 1, 2019. Accessed January 16, 2020.

9. Simkins JD. Navy quietly ends climate change task force, reversing Obama initiative. https://www.navytimes.com/off-duty/military-culture/2019/08/26/navy-quietly-ends-climate-change-task-force-reversing-obama-initiative. Published August 26, 2019. Accessed January 16, 2020.

10. Eilperin J, Dennis B, Ryan M. As White House questions climate change, U.S. military is planning for it. https://www.washingtonpost.com/national/health-science/as-white-house-questions-climate-change-us-military-is-planning-for-it/2019/04/08/78142546-57c0-11e9-814f-e2f46684196e_story.html. Published April 8, 2019. Accessed January 16, 2020.

11. Motta M, Spindel J, Ralston R. Veterans are concerned about climate change and that matters. http://theconversation.com/veterans-are-concerned-about-climate-change-and-that-matters-110685. Published March 8, 2019. Accessed January 16, 2020.

12. Albeck-Ripka L, Kwai I, Fuller T, Tarabay J. ‘It’s an atomic bomb’: Australia deploys military as fires spread. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/01/04/world/australia/fires-military.html. Updated January 5, 2020. Accessed January 18, 2020.

1. Thompson A. Australia’s bushfires have likely devastated wildlife–and the impact will only get worse. Scientific American. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/australias-bushfires-have-likely-devastated-wildlife-and-the-impact-will-only-get-worse. Published January 8, 2020. Accessed January 16, 2020.

2. Gibbens S. Intense ‘firestorms’ forming from Australia’s deadly wildfires. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/science/2020/01/australian-wildfires-cause-firestorms. Published January 9, 2020. Accessed January 15, 2020.

3. Shapiro A. Tyndall Air Force Base still faces challenges in recovering from Hurricane Michael. https://www.npr.org/2019/05/31/728754872/tyndall-air-force-base-still-faces-challenges-in-recovering-from-hurricane-micha. Published May 31, 2019. Accessed January 16, 2020.

4. US Department of Defense, Office of the Undersecretary for Acquisition and Sustainment. Report on effects of a changing climate to the Department of Defense. https://www.documentcloud.org/documents/5689153-DoD-Final-Climate-Report.html. Published January 2019. Accessed January 16, 2020.

5. Maucione S. DoD justifies climate change report, says response was mission-centric. https://federalnewsnetwork.com/defense-main/2019/03/dod-justifies-climate-change-report-says-response-was-mission-centric. Published March 28, 2019. Accessed January 16, 2020.

6. Shane L 3rd. Puerto Rico’s VA hospital weathers Maria, but challenges loom. https://www.armytimes.com/veterans/2017/09/22/puerto-ricos-va-hospital-weathers-hurricane-maria-but-challenges-loom. Published September 22, 2017. Accessed January 16, 2020.

7. Hersher R. Climate change was the engine that powered Hurricane Maria’s devastating rains. https://www.npr.org/2019/04/17/714098828/climate-change-was-the-engine-that-powered-hurricane-marias-devastating-rains. Published April 17, 2019. Accessed January 16, 2020.

8. Senators Warren and Schatz request an update from the Department of Veterans Affairs on efforts to build resilience to climate change [press release]. https://www.warren.senate.gov/oversight/letters/senators-warren-and-schatz-request-an-update-from-the-department-of-veterans-affairs-on-efforts-to-build-resilience-to-climate-change. Published October 1, 2019. Accessed January 16, 2020.

9. Simkins JD. Navy quietly ends climate change task force, reversing Obama initiative. https://www.navytimes.com/off-duty/military-culture/2019/08/26/navy-quietly-ends-climate-change-task-force-reversing-obama-initiative. Published August 26, 2019. Accessed January 16, 2020.

10. Eilperin J, Dennis B, Ryan M. As White House questions climate change, U.S. military is planning for it. https://www.washingtonpost.com/national/health-science/as-white-house-questions-climate-change-us-military-is-planning-for-it/2019/04/08/78142546-57c0-11e9-814f-e2f46684196e_story.html. Published April 8, 2019. Accessed January 16, 2020.

11. Motta M, Spindel J, Ralston R. Veterans are concerned about climate change and that matters. http://theconversation.com/veterans-are-concerned-about-climate-change-and-that-matters-110685. Published March 8, 2019. Accessed January 16, 2020.

12. Albeck-Ripka L, Kwai I, Fuller T, Tarabay J. ‘It’s an atomic bomb’: Australia deploys military as fires spread. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/01/04/world/australia/fires-military.html. Updated January 5, 2020. Accessed January 18, 2020.

Understanding postpartum psychosis: From course to treatment

Although the last decade has brought appropriate increased interest in the diagnosis and treatment of postpartum depression, with screening initiatives across more than 40 states in place and even new medications being brought to market for treatment, far less attention has been given to diagnosis and treatment of a particularly serious psychiatric illness: postpartum psychosis.

Clinically, women can experience rapid mood changes, most often with the presentation that is consistent with a manic-like psychosis, with associated symptoms of delusional thinking, hallucinations, paranoia and either depression or elation, or an amalgam of these so-called “mixed symptoms.” Onset of symptoms typically is early, within 72 hours as is classically described, but may have a somewhat later time of onset in some women.

Many investigators have studied risk factors for postpartum psychosis, and it has been well established that a history of mood disorder, particularly bipolar disorder, is one of the strongest predictors of risk for postpartum psychosis. Women with histories of postpartum psychosis are at very high risk of recurrence, with as many as 70%-90% of women experiencing recurrence if not prophylaxed with an appropriate agent. From a clinical point of view, women with postpartum psychosis typically are hospitalized, given that this is both a psychiatric and potential obstetrical emergency. In fact, the data would suggest that although postpartum suicide and infanticide are not common, they can be a tragic concomitant of postpartum psychosis (Am J Psychiatry. 2016 Dec 1;173[12]:1179-88).

A great amount of interest has been placed on the etiology of postpartum psychosis, as it’s a dramatic presentation with very rapid onset in the acute postpartum period. A rich evidence base with respect to an algorithm of treatment that maximizes likelihood of full recovery or sustaining of euthymia after recovery is limited. Few studies have looked systematically at the optimum way to treat postpartum psychosis. Clinical wisdom has dictated that, given the dramatic symptoms with which these patients present, most patients are treated with lithium and an antipsychotic medication as if they have a manic-like psychosis. It may take brief or extended periods of time for patients to stabilize. Once they are stabilized, one of the most challenging questions for clinicians is how long to treat. Again, an evidence base clearly informing this question is lacking.

Over the years, many clinicians have treated patients with postpartum psychosis as if they have bipolar disorder, given the index presentation of the illness, so some of these patients are treated with antimanic drugs indefinitely. However, clinical experience from several centers that treat women with postpartum psychosis suggests that in remitted patients, a proportion of them may be able to taper and discontinue treatment, then sustain well-being for protracted periods.

One obstacle with respect to treatment of postpartum psychosis derives from the short length of stay after delivery for many women. Some women who present with symptoms of postpartum psychosis in the first 24-48 hours frequently are managed with direct admission to an inpatient psychiatric service. But others may not develop symptoms until they are home, which may place both mother and newborn at risk.

Given that the risk for recurrent postpartum psychosis is so great (70%-90%), women with histories of postpartum psychosis invariably are prophylaxed with mood stabilizer prior to delivery in a subsequent pregnancy. In our own center, we have published on the value of such prophylactic intervention, not just in women with postpartum psychosis, but in women with bipolar disorder, who are, as noted, at great risk for developing postpartum psychotic symptoms (Am J Psychiatry. 1995 Nov;152[11]:1641-5.)

Although postpartum psychosis may be rare, over the last 3 decades we have seen a substantial number of women with postpartum psychosis and have been fascinated with the spectrum of symptoms with which some women with postpartum psychotic illness present. We also have been impressed with the time required for some women to recompensate from their illness and the course of their disorder after they have seemingly remitted. Some women appear to be able to discontinue treatment as noted above; others, particularly if there is any history of bipolar disorder, need to be maintained on treatment with mood stabilizer indefinitely.

To better understand the phenomenology of postpartum psychosis, as well as the longitudinal course of the illness, in 2019, the Mass General Hospital Postpartum Psychosis Project (MGHP3) was established. The project is conducted as a hospital-based registry where women with histories of postpartum psychosis over the last decade are invited to participate in an in-depth interview to understand both symptoms and course of underlying illness. This is complemented by obtaining a sample of saliva, which is used for genetic testing to try to identify a genetic underpinning associated with postpartum psychosis, as the question of genetic etiology of postpartum psychosis is still an open one.

As part of the MGHP3 project, clinicians across the country are able to contact perinatal psychiatrists in our center with expertise in the treatment of postpartum psychosis. Our psychiatrists also can counsel clinicians on issues regarding long-term management of postpartum psychosis because for many, knowledge of precisely how to manage this disorder or the follow-up treatment may be incomplete.

From a clinical point of view, the relevant questions really include not only acute treatment, which has already been outlined, but also the issue of duration of treatment. While some patients may be able to taper and discontinue treatment after, for example, a year of being totally well, to date we are unable to know who those patients are. We tend to be more conservative in our own center and treat patients with puerperal psychosis for a more protracted period of time, usually over several years. We also ask women about their family history of bipolar disorder or postpartum psychosis. Depending on the clinical course (if the patient really has sustained euthymia), we consider slow taper and ultimate discontinuation. As always, treatment decisions are tailored to individual clinical history, course, and patient wishes.

Postpartum psychosis remains one of the most serious illnesses that we find in reproductive psychiatry, and incomplete attention has been given to this devastating illness, which we read about periodically in newspapers and magazines. Greater understanding of postpartum psychosis will lead to a more precision-like psychiatric approach, tailoring treatment to the invariable heterogeneity of this illness.

Dr. Cohen is the director of the Ammon-Pinizzotto Center for Women’s Mental Health at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, which provides information resources and conducts clinical care and research in reproductive mental health. He has been a consultant to manufacturers of psychiatric medications. Email Dr. Cohen at [email protected].

Although the last decade has brought appropriate increased interest in the diagnosis and treatment of postpartum depression, with screening initiatives across more than 40 states in place and even new medications being brought to market for treatment, far less attention has been given to diagnosis and treatment of a particularly serious psychiatric illness: postpartum psychosis.

Clinically, women can experience rapid mood changes, most often with the presentation that is consistent with a manic-like psychosis, with associated symptoms of delusional thinking, hallucinations, paranoia and either depression or elation, or an amalgam of these so-called “mixed symptoms.” Onset of symptoms typically is early, within 72 hours as is classically described, but may have a somewhat later time of onset in some women.

Many investigators have studied risk factors for postpartum psychosis, and it has been well established that a history of mood disorder, particularly bipolar disorder, is one of the strongest predictors of risk for postpartum psychosis. Women with histories of postpartum psychosis are at very high risk of recurrence, with as many as 70%-90% of women experiencing recurrence if not prophylaxed with an appropriate agent. From a clinical point of view, women with postpartum psychosis typically are hospitalized, given that this is both a psychiatric and potential obstetrical emergency. In fact, the data would suggest that although postpartum suicide and infanticide are not common, they can be a tragic concomitant of postpartum psychosis (Am J Psychiatry. 2016 Dec 1;173[12]:1179-88).

A great amount of interest has been placed on the etiology of postpartum psychosis, as it’s a dramatic presentation with very rapid onset in the acute postpartum period. A rich evidence base with respect to an algorithm of treatment that maximizes likelihood of full recovery or sustaining of euthymia after recovery is limited. Few studies have looked systematically at the optimum way to treat postpartum psychosis. Clinical wisdom has dictated that, given the dramatic symptoms with which these patients present, most patients are treated with lithium and an antipsychotic medication as if they have a manic-like psychosis. It may take brief or extended periods of time for patients to stabilize. Once they are stabilized, one of the most challenging questions for clinicians is how long to treat. Again, an evidence base clearly informing this question is lacking.

Over the years, many clinicians have treated patients with postpartum psychosis as if they have bipolar disorder, given the index presentation of the illness, so some of these patients are treated with antimanic drugs indefinitely. However, clinical experience from several centers that treat women with postpartum psychosis suggests that in remitted patients, a proportion of them may be able to taper and discontinue treatment, then sustain well-being for protracted periods.

One obstacle with respect to treatment of postpartum psychosis derives from the short length of stay after delivery for many women. Some women who present with symptoms of postpartum psychosis in the first 24-48 hours frequently are managed with direct admission to an inpatient psychiatric service. But others may not develop symptoms until they are home, which may place both mother and newborn at risk.

Given that the risk for recurrent postpartum psychosis is so great (70%-90%), women with histories of postpartum psychosis invariably are prophylaxed with mood stabilizer prior to delivery in a subsequent pregnancy. In our own center, we have published on the value of such prophylactic intervention, not just in women with postpartum psychosis, but in women with bipolar disorder, who are, as noted, at great risk for developing postpartum psychotic symptoms (Am J Psychiatry. 1995 Nov;152[11]:1641-5.)

Although postpartum psychosis may be rare, over the last 3 decades we have seen a substantial number of women with postpartum psychosis and have been fascinated with the spectrum of symptoms with which some women with postpartum psychotic illness present. We also have been impressed with the time required for some women to recompensate from their illness and the course of their disorder after they have seemingly remitted. Some women appear to be able to discontinue treatment as noted above; others, particularly if there is any history of bipolar disorder, need to be maintained on treatment with mood stabilizer indefinitely.

To better understand the phenomenology of postpartum psychosis, as well as the longitudinal course of the illness, in 2019, the Mass General Hospital Postpartum Psychosis Project (MGHP3) was established. The project is conducted as a hospital-based registry where women with histories of postpartum psychosis over the last decade are invited to participate in an in-depth interview to understand both symptoms and course of underlying illness. This is complemented by obtaining a sample of saliva, which is used for genetic testing to try to identify a genetic underpinning associated with postpartum psychosis, as the question of genetic etiology of postpartum psychosis is still an open one.

As part of the MGHP3 project, clinicians across the country are able to contact perinatal psychiatrists in our center with expertise in the treatment of postpartum psychosis. Our psychiatrists also can counsel clinicians on issues regarding long-term management of postpartum psychosis because for many, knowledge of precisely how to manage this disorder or the follow-up treatment may be incomplete.

From a clinical point of view, the relevant questions really include not only acute treatment, which has already been outlined, but also the issue of duration of treatment. While some patients may be able to taper and discontinue treatment after, for example, a year of being totally well, to date we are unable to know who those patients are. We tend to be more conservative in our own center and treat patients with puerperal psychosis for a more protracted period of time, usually over several years. We also ask women about their family history of bipolar disorder or postpartum psychosis. Depending on the clinical course (if the patient really has sustained euthymia), we consider slow taper and ultimate discontinuation. As always, treatment decisions are tailored to individual clinical history, course, and patient wishes.

Postpartum psychosis remains one of the most serious illnesses that we find in reproductive psychiatry, and incomplete attention has been given to this devastating illness, which we read about periodically in newspapers and magazines. Greater understanding of postpartum psychosis will lead to a more precision-like psychiatric approach, tailoring treatment to the invariable heterogeneity of this illness.

Dr. Cohen is the director of the Ammon-Pinizzotto Center for Women’s Mental Health at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, which provides information resources and conducts clinical care and research in reproductive mental health. He has been a consultant to manufacturers of psychiatric medications. Email Dr. Cohen at [email protected].

Although the last decade has brought appropriate increased interest in the diagnosis and treatment of postpartum depression, with screening initiatives across more than 40 states in place and even new medications being brought to market for treatment, far less attention has been given to diagnosis and treatment of a particularly serious psychiatric illness: postpartum psychosis.

Clinically, women can experience rapid mood changes, most often with the presentation that is consistent with a manic-like psychosis, with associated symptoms of delusional thinking, hallucinations, paranoia and either depression or elation, or an amalgam of these so-called “mixed symptoms.” Onset of symptoms typically is early, within 72 hours as is classically described, but may have a somewhat later time of onset in some women.

Many investigators have studied risk factors for postpartum psychosis, and it has been well established that a history of mood disorder, particularly bipolar disorder, is one of the strongest predictors of risk for postpartum psychosis. Women with histories of postpartum psychosis are at very high risk of recurrence, with as many as 70%-90% of women experiencing recurrence if not prophylaxed with an appropriate agent. From a clinical point of view, women with postpartum psychosis typically are hospitalized, given that this is both a psychiatric and potential obstetrical emergency. In fact, the data would suggest that although postpartum suicide and infanticide are not common, they can be a tragic concomitant of postpartum psychosis (Am J Psychiatry. 2016 Dec 1;173[12]:1179-88).

A great amount of interest has been placed on the etiology of postpartum psychosis, as it’s a dramatic presentation with very rapid onset in the acute postpartum period. A rich evidence base with respect to an algorithm of treatment that maximizes likelihood of full recovery or sustaining of euthymia after recovery is limited. Few studies have looked systematically at the optimum way to treat postpartum psychosis. Clinical wisdom has dictated that, given the dramatic symptoms with which these patients present, most patients are treated with lithium and an antipsychotic medication as if they have a manic-like psychosis. It may take brief or extended periods of time for patients to stabilize. Once they are stabilized, one of the most challenging questions for clinicians is how long to treat. Again, an evidence base clearly informing this question is lacking.

Over the years, many clinicians have treated patients with postpartum psychosis as if they have bipolar disorder, given the index presentation of the illness, so some of these patients are treated with antimanic drugs indefinitely. However, clinical experience from several centers that treat women with postpartum psychosis suggests that in remitted patients, a proportion of them may be able to taper and discontinue treatment, then sustain well-being for protracted periods.

One obstacle with respect to treatment of postpartum psychosis derives from the short length of stay after delivery for many women. Some women who present with symptoms of postpartum psychosis in the first 24-48 hours frequently are managed with direct admission to an inpatient psychiatric service. But others may not develop symptoms until they are home, which may place both mother and newborn at risk.

Given that the risk for recurrent postpartum psychosis is so great (70%-90%), women with histories of postpartum psychosis invariably are prophylaxed with mood stabilizer prior to delivery in a subsequent pregnancy. In our own center, we have published on the value of such prophylactic intervention, not just in women with postpartum psychosis, but in women with bipolar disorder, who are, as noted, at great risk for developing postpartum psychotic symptoms (Am J Psychiatry. 1995 Nov;152[11]:1641-5.)

Although postpartum psychosis may be rare, over the last 3 decades we have seen a substantial number of women with postpartum psychosis and have been fascinated with the spectrum of symptoms with which some women with postpartum psychotic illness present. We also have been impressed with the time required for some women to recompensate from their illness and the course of their disorder after they have seemingly remitted. Some women appear to be able to discontinue treatment as noted above; others, particularly if there is any history of bipolar disorder, need to be maintained on treatment with mood stabilizer indefinitely.

To better understand the phenomenology of postpartum psychosis, as well as the longitudinal course of the illness, in 2019, the Mass General Hospital Postpartum Psychosis Project (MGHP3) was established. The project is conducted as a hospital-based registry where women with histories of postpartum psychosis over the last decade are invited to participate in an in-depth interview to understand both symptoms and course of underlying illness. This is complemented by obtaining a sample of saliva, which is used for genetic testing to try to identify a genetic underpinning associated with postpartum psychosis, as the question of genetic etiology of postpartum psychosis is still an open one.

As part of the MGHP3 project, clinicians across the country are able to contact perinatal psychiatrists in our center with expertise in the treatment of postpartum psychosis. Our psychiatrists also can counsel clinicians on issues regarding long-term management of postpartum psychosis because for many, knowledge of precisely how to manage this disorder or the follow-up treatment may be incomplete.

From a clinical point of view, the relevant questions really include not only acute treatment, which has already been outlined, but also the issue of duration of treatment. While some patients may be able to taper and discontinue treatment after, for example, a year of being totally well, to date we are unable to know who those patients are. We tend to be more conservative in our own center and treat patients with puerperal psychosis for a more protracted period of time, usually over several years. We also ask women about their family history of bipolar disorder or postpartum psychosis. Depending on the clinical course (if the patient really has sustained euthymia), we consider slow taper and ultimate discontinuation. As always, treatment decisions are tailored to individual clinical history, course, and patient wishes.

Postpartum psychosis remains one of the most serious illnesses that we find in reproductive psychiatry, and incomplete attention has been given to this devastating illness, which we read about periodically in newspapers and magazines. Greater understanding of postpartum psychosis will lead to a more precision-like psychiatric approach, tailoring treatment to the invariable heterogeneity of this illness.

Dr. Cohen is the director of the Ammon-Pinizzotto Center for Women’s Mental Health at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, which provides information resources and conducts clinical care and research in reproductive mental health. He has been a consultant to manufacturers of psychiatric medications. Email Dr. Cohen at [email protected].

Docs weigh pulling out of MIPS over paltry payments

If you’ve knocked yourself out to earn a Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) bonus payment, it’s pretty safe to say that getting a 1.68% payment boost probably didn’t feel like a “win” that was worth the effort.

And although it saved you from having a negative 5% payment adjustment, many physicians don’t feel that it was worth the effort.

On Jan. 6, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services announced the 2020 payouts for MIPS.

Based on 2018 participation, the bonus for those who scored a perfect 100 is only a 1.68% boost in Medicare reimbursement, slightly lower than last year’s 1.88%. This decline comes as no surprise as the agency leader admits: “As the program matures, we expect that the increases in the performance thresholds in future program years will create a smaller distribution of positive payment adjustments.” Overall, more than 97% of participants avoided having a negative 5% payment adjustment.

Indeed, these bonus monies are based on a short-term appropriation of extra funds from Congress. After these temporary funds are no longer available, there will be little, if any, monies to distribute as the program is based on a “losers-feed-the-winners” construct.

It may be very tempting for many physicians to decide to ignore MIPS, with the rationale that 1.68% is not worth the effort. But don’t let your foot off the gas pedal yet, since the penalty for not participating in 2020 is a substantial 9%.

However, it is certainly time to reconsider efforts to participate at the highest level.

Should you or shouldn’t you bother with MIPS?

Let’s say you have $75,000 in revenue from Medicare Part B per year. Depending on the services you offer in your practice, that equates to 500-750 encounters with Medicare beneficiaries per year. (A reminder that MIPS affects only Part B; Medicare Advantage plans do not partake in the program.)

The recent announcement reveals that perfection would equate to an additional $1,260 per year. That’s only if you received the full 100 points; if you were simply an “exceptional performer,” the government will allot an additional $157. That’s less than you get paid for a single office visit.

The difference between perfection and compliance is approximately $1,000. Failure to participate, however, knocks $6,750 off your bottom line. Clearly, that’s a substantial financial loss that would affect most practices. Obviously, the numbers change if you have higher – or lower – Medicare revenue, but it’s important to do the math.

Why? Physicians are spending a significant amount of money to comply with the program requirements. This includes substantial payments to registries – typically $200 to >$1,000 per year – to report the quality measures for the program; electronic health record (EHR) systems, many of which require additional funding for the “upgrade” to a MIPS-compatible system, are also a sizable investment.

These hard costs pale in comparison with the time spent on understanding the ever-changing requirements of the program and the process by which your practice will implement them. Take, for example, something as innocuous as the required “Support Electronic Referral Loops by Receiving and Incorporating Health Information.”

You first must understand the elements of the measure: What is a “referral loop?” When do we need to generate one? To whom shall it be sent? What needs to be included in “health information?” What is the electronic address to which we should route the information? How do we obtain that address? Then you must determine how your EHR system captures and reports it.

Only then comes the hard part: How are we going to implement this? That’s only one of more than a dozen required elements: six quality measures, two (to four) improvement activities, and four promoting interoperability requirements. Each one of these elements has a host of requirements, all listed on multipage specification sheets.

The government does not seem to be listening. John Cullen, MD, president of the American Academy of Family Physicians, testified at the Senate Finance Committee in May 2019 that MIPS “has created a burdensome and extremely complex program that has increased practice costs ... ” Yet, later that year, CMS issued another hefty ruling that outlines significant changes to the program, despite the fact that it’s in its fourth performance year.

Turning frustration into action

Frustration or even anger may be one reaction, but now is an opportune time to determine your investment in the program. At a minimum, it’s vital to understand and meet the threshold to avoid the penalty. It’s been shifting to date, but it’s now set at 9% for perpetuity.

First, it’s crucial to check on your participation status. CMS revealed that the participation database was recently corrected for so-called inconsistencies, so it pays to double-check. It only takes seconds: Insert your NPI in the QPP Participation Status Tool to determine your eligibility for 2020.

In 2020, the threshold to avoid the penalty is 45 points. To get the 45 points, practices must participate in two improvement activities, which is not difficult as there are 118 options. That will garner 15 points. Then there are 45 points available from the quality category; you need at least 30 to reach the 45-point threshold for penalty avoidance.

Smart MIPS hacks that can help you

To obtain the additional 30 points, turn your attention to the quality category. There are 268 quality measures; choose at least six to measure. If you report directly from your EHR system, you’ll get a bonus point for each reported measure, plus one just for trying. (There are a few other opportunities for bonus points, such as improving your scores over last year.) Those bonus points give you a base with which to work, but getting to 45 will require effort to report successfully on at least a couple of the measures.

The quality category has a total of 100 points available, which are converted to 45 toward your composite score. Since you need 30 to reach that magical 45 (if 15 were attained from improvement activities), that means you must come up with 75 points in the quality category. Between the bonus points and measuring a handful of measures successfully through the year, you’ll achieve this threshold.

There are two other categories in the program: promoting interoperability (PI) and cost. The PI category mirrors the old “meaningful use” program; however, it has become increasingly difficult over the years. If you think that you can meet the required elements, you can pick up 25 more points toward your composite score.

Cost is a bit of an unknown, as the scoring is based on a retrospective review of your claims. You’ll likely pick up a few more points on this 15-point category, but there’s no method to determine performance until after the reporting period. Therefore, be cautious about relying on this category.

The best MIPS hack, however, is if you are a small practice. CMS – remarkably – defines a “small practice” as 15 or fewer eligible professionals. If you qualify under this paradigm, you have multiple options to ease compliance:

Apply for a “hardship exemption” simply on the basis of being small; the exemption relates to the promoting operability category, shifting those points to the quality category.

Gain three points per quality measure, regardless of data completeness; this compares to just one point for other physicians.

Capture all of the points available from the Improvement Activities category by confirming participation with just a single activity. (This also applies to all physicians in rural or Health Professional Shortage Areas.)

In the event that you don’t qualify as a “small practice” or you’re still falling short of the requirements, CMS allows for the ultimate “out”: You can apply for exemption on the basis of an “extreme and uncontrollable circumstance.” The applications for these exceptions open this summer.

Unless you qualify for the program exemption, it’s important to keep pace with the program to ensure that you reach the 45-point threshold. It may not, however, be worthwhile to gear up for all 100 points unless your estimate of the potential return – and what it costs you to get there – reveals otherwise. MIPS is not going anywhere; the program is written into the law.

But that doesn’t mean that CMS can’t make tweaks and updates. Hopefully, the revisions won’t create even more administrative burden as the program is quickly turning into a big stick with only a small carrot at the end.

Elizabeth Woodcock is president of Woodcock & Associates in Atlanta. She has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

If you’ve knocked yourself out to earn a Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) bonus payment, it’s pretty safe to say that getting a 1.68% payment boost probably didn’t feel like a “win” that was worth the effort.

And although it saved you from having a negative 5% payment adjustment, many physicians don’t feel that it was worth the effort.

On Jan. 6, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services announced the 2020 payouts for MIPS.

Based on 2018 participation, the bonus for those who scored a perfect 100 is only a 1.68% boost in Medicare reimbursement, slightly lower than last year’s 1.88%. This decline comes as no surprise as the agency leader admits: “As the program matures, we expect that the increases in the performance thresholds in future program years will create a smaller distribution of positive payment adjustments.” Overall, more than 97% of participants avoided having a negative 5% payment adjustment.

Indeed, these bonus monies are based on a short-term appropriation of extra funds from Congress. After these temporary funds are no longer available, there will be little, if any, monies to distribute as the program is based on a “losers-feed-the-winners” construct.

It may be very tempting for many physicians to decide to ignore MIPS, with the rationale that 1.68% is not worth the effort. But don’t let your foot off the gas pedal yet, since the penalty for not participating in 2020 is a substantial 9%.

However, it is certainly time to reconsider efforts to participate at the highest level.

Should you or shouldn’t you bother with MIPS?

Let’s say you have $75,000 in revenue from Medicare Part B per year. Depending on the services you offer in your practice, that equates to 500-750 encounters with Medicare beneficiaries per year. (A reminder that MIPS affects only Part B; Medicare Advantage plans do not partake in the program.)

The recent announcement reveals that perfection would equate to an additional $1,260 per year. That’s only if you received the full 100 points; if you were simply an “exceptional performer,” the government will allot an additional $157. That’s less than you get paid for a single office visit.

The difference between perfection and compliance is approximately $1,000. Failure to participate, however, knocks $6,750 off your bottom line. Clearly, that’s a substantial financial loss that would affect most practices. Obviously, the numbers change if you have higher – or lower – Medicare revenue, but it’s important to do the math.

Why? Physicians are spending a significant amount of money to comply with the program requirements. This includes substantial payments to registries – typically $200 to >$1,000 per year – to report the quality measures for the program; electronic health record (EHR) systems, many of which require additional funding for the “upgrade” to a MIPS-compatible system, are also a sizable investment.

These hard costs pale in comparison with the time spent on understanding the ever-changing requirements of the program and the process by which your practice will implement them. Take, for example, something as innocuous as the required “Support Electronic Referral Loops by Receiving and Incorporating Health Information.”

You first must understand the elements of the measure: What is a “referral loop?” When do we need to generate one? To whom shall it be sent? What needs to be included in “health information?” What is the electronic address to which we should route the information? How do we obtain that address? Then you must determine how your EHR system captures and reports it.

Only then comes the hard part: How are we going to implement this? That’s only one of more than a dozen required elements: six quality measures, two (to four) improvement activities, and four promoting interoperability requirements. Each one of these elements has a host of requirements, all listed on multipage specification sheets.

The government does not seem to be listening. John Cullen, MD, president of the American Academy of Family Physicians, testified at the Senate Finance Committee in May 2019 that MIPS “has created a burdensome and extremely complex program that has increased practice costs ... ” Yet, later that year, CMS issued another hefty ruling that outlines significant changes to the program, despite the fact that it’s in its fourth performance year.

Turning frustration into action

Frustration or even anger may be one reaction, but now is an opportune time to determine your investment in the program. At a minimum, it’s vital to understand and meet the threshold to avoid the penalty. It’s been shifting to date, but it’s now set at 9% for perpetuity.

First, it’s crucial to check on your participation status. CMS revealed that the participation database was recently corrected for so-called inconsistencies, so it pays to double-check. It only takes seconds: Insert your NPI in the QPP Participation Status Tool to determine your eligibility for 2020.

In 2020, the threshold to avoid the penalty is 45 points. To get the 45 points, practices must participate in two improvement activities, which is not difficult as there are 118 options. That will garner 15 points. Then there are 45 points available from the quality category; you need at least 30 to reach the 45-point threshold for penalty avoidance.

Smart MIPS hacks that can help you

To obtain the additional 30 points, turn your attention to the quality category. There are 268 quality measures; choose at least six to measure. If you report directly from your EHR system, you’ll get a bonus point for each reported measure, plus one just for trying. (There are a few other opportunities for bonus points, such as improving your scores over last year.) Those bonus points give you a base with which to work, but getting to 45 will require effort to report successfully on at least a couple of the measures.

The quality category has a total of 100 points available, which are converted to 45 toward your composite score. Since you need 30 to reach that magical 45 (if 15 were attained from improvement activities), that means you must come up with 75 points in the quality category. Between the bonus points and measuring a handful of measures successfully through the year, you’ll achieve this threshold.

There are two other categories in the program: promoting interoperability (PI) and cost. The PI category mirrors the old “meaningful use” program; however, it has become increasingly difficult over the years. If you think that you can meet the required elements, you can pick up 25 more points toward your composite score.

Cost is a bit of an unknown, as the scoring is based on a retrospective review of your claims. You’ll likely pick up a few more points on this 15-point category, but there’s no method to determine performance until after the reporting period. Therefore, be cautious about relying on this category.

The best MIPS hack, however, is if you are a small practice. CMS – remarkably – defines a “small practice” as 15 or fewer eligible professionals. If you qualify under this paradigm, you have multiple options to ease compliance:

Apply for a “hardship exemption” simply on the basis of being small; the exemption relates to the promoting operability category, shifting those points to the quality category.

Gain three points per quality measure, regardless of data completeness; this compares to just one point for other physicians.

Capture all of the points available from the Improvement Activities category by confirming participation with just a single activity. (This also applies to all physicians in rural or Health Professional Shortage Areas.)

In the event that you don’t qualify as a “small practice” or you’re still falling short of the requirements, CMS allows for the ultimate “out”: You can apply for exemption on the basis of an “extreme and uncontrollable circumstance.” The applications for these exceptions open this summer.

Unless you qualify for the program exemption, it’s important to keep pace with the program to ensure that you reach the 45-point threshold. It may not, however, be worthwhile to gear up for all 100 points unless your estimate of the potential return – and what it costs you to get there – reveals otherwise. MIPS is not going anywhere; the program is written into the law.

But that doesn’t mean that CMS can’t make tweaks and updates. Hopefully, the revisions won’t create even more administrative burden as the program is quickly turning into a big stick with only a small carrot at the end.

Elizabeth Woodcock is president of Woodcock & Associates in Atlanta. She has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

If you’ve knocked yourself out to earn a Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) bonus payment, it’s pretty safe to say that getting a 1.68% payment boost probably didn’t feel like a “win” that was worth the effort.

And although it saved you from having a negative 5% payment adjustment, many physicians don’t feel that it was worth the effort.

On Jan. 6, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services announced the 2020 payouts for MIPS.

Based on 2018 participation, the bonus for those who scored a perfect 100 is only a 1.68% boost in Medicare reimbursement, slightly lower than last year’s 1.88%. This decline comes as no surprise as the agency leader admits: “As the program matures, we expect that the increases in the performance thresholds in future program years will create a smaller distribution of positive payment adjustments.” Overall, more than 97% of participants avoided having a negative 5% payment adjustment.

Indeed, these bonus monies are based on a short-term appropriation of extra funds from Congress. After these temporary funds are no longer available, there will be little, if any, monies to distribute as the program is based on a “losers-feed-the-winners” construct.

It may be very tempting for many physicians to decide to ignore MIPS, with the rationale that 1.68% is not worth the effort. But don’t let your foot off the gas pedal yet, since the penalty for not participating in 2020 is a substantial 9%.

However, it is certainly time to reconsider efforts to participate at the highest level.

Should you or shouldn’t you bother with MIPS?

Let’s say you have $75,000 in revenue from Medicare Part B per year. Depending on the services you offer in your practice, that equates to 500-750 encounters with Medicare beneficiaries per year. (A reminder that MIPS affects only Part B; Medicare Advantage plans do not partake in the program.)

The recent announcement reveals that perfection would equate to an additional $1,260 per year. That’s only if you received the full 100 points; if you were simply an “exceptional performer,” the government will allot an additional $157. That’s less than you get paid for a single office visit.

The difference between perfection and compliance is approximately $1,000. Failure to participate, however, knocks $6,750 off your bottom line. Clearly, that’s a substantial financial loss that would affect most practices. Obviously, the numbers change if you have higher – or lower – Medicare revenue, but it’s important to do the math.

Why? Physicians are spending a significant amount of money to comply with the program requirements. This includes substantial payments to registries – typically $200 to >$1,000 per year – to report the quality measures for the program; electronic health record (EHR) systems, many of which require additional funding for the “upgrade” to a MIPS-compatible system, are also a sizable investment.

These hard costs pale in comparison with the time spent on understanding the ever-changing requirements of the program and the process by which your practice will implement them. Take, for example, something as innocuous as the required “Support Electronic Referral Loops by Receiving and Incorporating Health Information.”

You first must understand the elements of the measure: What is a “referral loop?” When do we need to generate one? To whom shall it be sent? What needs to be included in “health information?” What is the electronic address to which we should route the information? How do we obtain that address? Then you must determine how your EHR system captures and reports it.

Only then comes the hard part: How are we going to implement this? That’s only one of more than a dozen required elements: six quality measures, two (to four) improvement activities, and four promoting interoperability requirements. Each one of these elements has a host of requirements, all listed on multipage specification sheets.

The government does not seem to be listening. John Cullen, MD, president of the American Academy of Family Physicians, testified at the Senate Finance Committee in May 2019 that MIPS “has created a burdensome and extremely complex program that has increased practice costs ... ” Yet, later that year, CMS issued another hefty ruling that outlines significant changes to the program, despite the fact that it’s in its fourth performance year.

Turning frustration into action

Frustration or even anger may be one reaction, but now is an opportune time to determine your investment in the program. At a minimum, it’s vital to understand and meet the threshold to avoid the penalty. It’s been shifting to date, but it’s now set at 9% for perpetuity.

First, it’s crucial to check on your participation status. CMS revealed that the participation database was recently corrected for so-called inconsistencies, so it pays to double-check. It only takes seconds: Insert your NPI in the QPP Participation Status Tool to determine your eligibility for 2020.

In 2020, the threshold to avoid the penalty is 45 points. To get the 45 points, practices must participate in two improvement activities, which is not difficult as there are 118 options. That will garner 15 points. Then there are 45 points available from the quality category; you need at least 30 to reach the 45-point threshold for penalty avoidance.

Smart MIPS hacks that can help you

To obtain the additional 30 points, turn your attention to the quality category. There are 268 quality measures; choose at least six to measure. If you report directly from your EHR system, you’ll get a bonus point for each reported measure, plus one just for trying. (There are a few other opportunities for bonus points, such as improving your scores over last year.) Those bonus points give you a base with which to work, but getting to 45 will require effort to report successfully on at least a couple of the measures.

The quality category has a total of 100 points available, which are converted to 45 toward your composite score. Since you need 30 to reach that magical 45 (if 15 were attained from improvement activities), that means you must come up with 75 points in the quality category. Between the bonus points and measuring a handful of measures successfully through the year, you’ll achieve this threshold.

There are two other categories in the program: promoting interoperability (PI) and cost. The PI category mirrors the old “meaningful use” program; however, it has become increasingly difficult over the years. If you think that you can meet the required elements, you can pick up 25 more points toward your composite score.

Cost is a bit of an unknown, as the scoring is based on a retrospective review of your claims. You’ll likely pick up a few more points on this 15-point category, but there’s no method to determine performance until after the reporting period. Therefore, be cautious about relying on this category.

The best MIPS hack, however, is if you are a small practice. CMS – remarkably – defines a “small practice” as 15 or fewer eligible professionals. If you qualify under this paradigm, you have multiple options to ease compliance:

Apply for a “hardship exemption” simply on the basis of being small; the exemption relates to the promoting operability category, shifting those points to the quality category.

Gain three points per quality measure, regardless of data completeness; this compares to just one point for other physicians.

Capture all of the points available from the Improvement Activities category by confirming participation with just a single activity. (This also applies to all physicians in rural or Health Professional Shortage Areas.)

In the event that you don’t qualify as a “small practice” or you’re still falling short of the requirements, CMS allows for the ultimate “out”: You can apply for exemption on the basis of an “extreme and uncontrollable circumstance.” The applications for these exceptions open this summer.

Unless you qualify for the program exemption, it’s important to keep pace with the program to ensure that you reach the 45-point threshold. It may not, however, be worthwhile to gear up for all 100 points unless your estimate of the potential return – and what it costs you to get there – reveals otherwise. MIPS is not going anywhere; the program is written into the law.

But that doesn’t mean that CMS can’t make tweaks and updates. Hopefully, the revisions won’t create even more administrative burden as the program is quickly turning into a big stick with only a small carrot at the end.

Elizabeth Woodcock is president of Woodcock & Associates in Atlanta. She has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

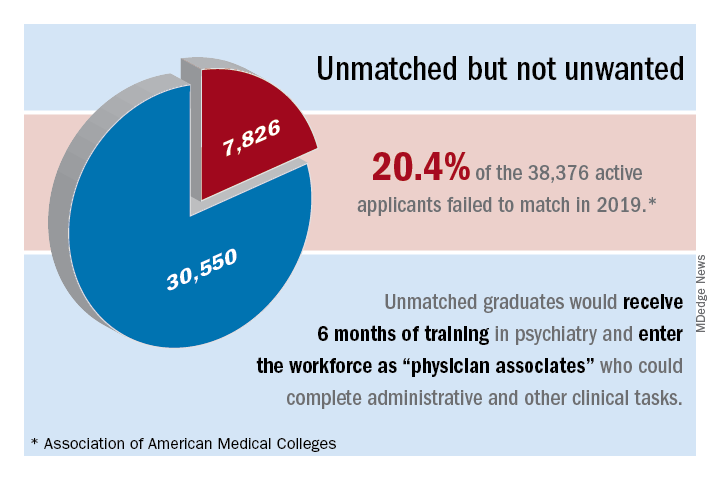

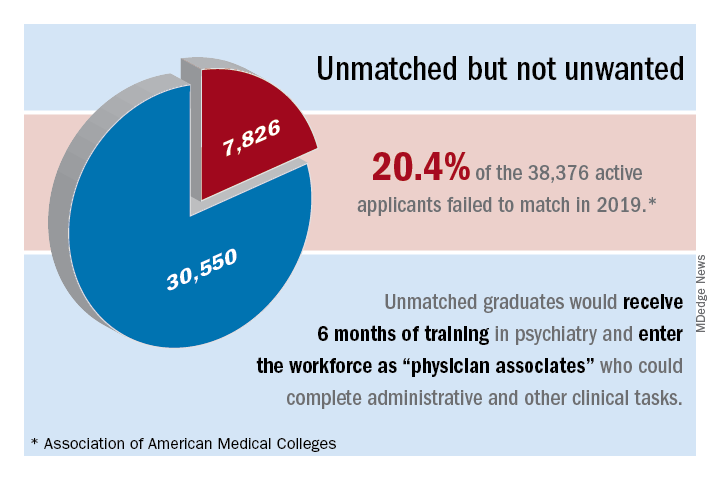

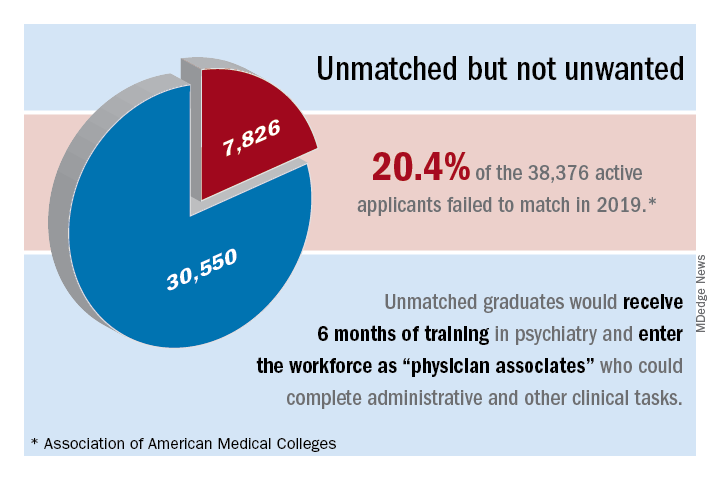

Are unmatched residency graduates a solution for ‘shrinking shrinks’?

‘Physician associates’ could be used to expand the reach of psychiatry

For many years now, we have been lamenting the shortage of psychiatrists practicing in the United States. At this point, we must identify possible solutions.1,2 Currently, the shortage of practicing psychiatrists in the United States could be as high as 45,000.3 The major problem is that the number of psychiatry residency positions will not increase in the foreseeable future, thus generating more psychiatrists is not an option.

Medicare pays about $150,000 per residency slot per year. To solve the mental health access problem, $27 billion (45,000 x $150,000 x 4 years)* would be required from Medicare, which is not feasible.4 The national average starting salary for psychiatrists from 2018-2019 was about $273,000 (much lower in academic institutions), according to Merritt Hawkins, the physician recruiting firm. That salary is modest, compared with those offered in other medical specialties. For this reason, many graduates choose other lucrative specialties. And we know that increasing the salaries of psychiatrists alone would not lead more people to choose psychiatry. On paper, it may say they work a 40-hour week, but they end up working 60 hours a week.

To make matters worse, family medicine and internal medicine doctors generally would rather not deal with people with mental illness and do “cherry-picking and lemon-dropping.” While many patients present to primary care with mental health issues, lack of time and education in psychiatric disorders and treatment hinder these physicians. In short, the mental health field cannot count on primary care physicians.