User login

Part 4: We Can All Be Leaders

Personality quizzes abound on the Internet these days; you can find out everything from which Disney Princess you are to what type of fruit you would be. But there is a serious case to be made for how your personality type influences your work. It affects how you manage others, develop leadership skills, approach conflict resolution, and manage change.1 Understanding your personality type assists in identifying your strengths, weaknesses, and areas in need of development.

My personality type is ENTP: someone who is “resourceful in solving new and challenging problems.”1 At many points in my career, I found myself in a leadership role. But truthfully, I never set out to be a leader—my career goals set me on that path. You might call me an “accidental leader.”

Recall my story about the founding of the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners (AANP; see Part 2): In the beginning, we were all encouraged to contribute whatever time and energy we could to getting the organization off the ground. I had plenty of time and energy to give. I saw the need for an NP-dedicated organization as a challenge. While I did not know my personality type at the time, I understood that I had a drive to meet challenges—those arising from the status quo and those of moving the vision for this new organization forward.

Our leadership skills are derived from everyday experiences—both the good and the bad. But we only grow if we study the consequences of those experiences to gain insights and to find new ways to manage ourselves and the team.2 Understanding your own personality and skills helps you better appreciate the differences in those you lead and understand how to direct or utilize their particular skills.

Each team member brings a set of skills, range of ideas, and problem-solving approaches to a unique situation. You should identify your team members’ strengths and promote a culture in which the whole team feels comfortable, confident, supported, and encouraged to contribute.3

How do you do that? By initiating and maintaining effective working relationships within the team and demonstrating skills in care coordination and delegation. Everyone benefits when each team member’s unique abilities are used to progress toward the goal.

In my experience, a team is most effective when the leader

- knows each team members’ professional and personal goals

- sets real priorities and commitments

- establishes clear direction

- builds rapport

- is fair with everyone

- shares knowledge and resources

- mentors others to become effective leaders.

Continue to: Another thing that the most effective leaders do is...

Another thing that the most effective leaders do is manage their time and conserve their energy and focus. Think in both short- and long-term goals. Leaders are ordinary people with extraordinary determination, but they know when to stop working and how to recharge their batteries.3,4

It is also important for leaders to acknowledge their accomplishments. All too often, we downplay the contributions we have made, the barriers we have overcome, and the sacrifices we have made to get to where we are today. Our accomplishments add to our body of experience and serve as the foundation for our growth.

Contrary to popular belief, leaders can be made. Anybody can be a leader. One just has to take the time to understand the commitment and the responsibilities. Leadership is a function of who you are, what you can do, and how you do it. Find a mission that ignites your passion, and go for it!

1. The Myers & Briggs Foundation. MBTI® Type at Work. www.myersbriggs.org/type-use-for-everyday-life/mbti-type-at-work/. Accessed September 10, 2019.

2. AZquotes. John Dewey quotes. www.azquotes.com/quote/497608. Accessed September 10, 2019.

3. Knowledge@Wharton. Three big leadership clichés—and how to rethink them. Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania website. https://knowledge.wharton.upenn.edu/article/three-big-leadership-cliches-rethink/. Published November 26, 2018. Accessed September 10, 2019.

4. ForbesQuotes. Thoughts on the Business of Life. www.forbes.com/quotes/5477/. Accessed September 10, 2019.

Personality quizzes abound on the Internet these days; you can find out everything from which Disney Princess you are to what type of fruit you would be. But there is a serious case to be made for how your personality type influences your work. It affects how you manage others, develop leadership skills, approach conflict resolution, and manage change.1 Understanding your personality type assists in identifying your strengths, weaknesses, and areas in need of development.

My personality type is ENTP: someone who is “resourceful in solving new and challenging problems.”1 At many points in my career, I found myself in a leadership role. But truthfully, I never set out to be a leader—my career goals set me on that path. You might call me an “accidental leader.”

Recall my story about the founding of the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners (AANP; see Part 2): In the beginning, we were all encouraged to contribute whatever time and energy we could to getting the organization off the ground. I had plenty of time and energy to give. I saw the need for an NP-dedicated organization as a challenge. While I did not know my personality type at the time, I understood that I had a drive to meet challenges—those arising from the status quo and those of moving the vision for this new organization forward.

Our leadership skills are derived from everyday experiences—both the good and the bad. But we only grow if we study the consequences of those experiences to gain insights and to find new ways to manage ourselves and the team.2 Understanding your own personality and skills helps you better appreciate the differences in those you lead and understand how to direct or utilize their particular skills.

Each team member brings a set of skills, range of ideas, and problem-solving approaches to a unique situation. You should identify your team members’ strengths and promote a culture in which the whole team feels comfortable, confident, supported, and encouraged to contribute.3

How do you do that? By initiating and maintaining effective working relationships within the team and demonstrating skills in care coordination and delegation. Everyone benefits when each team member’s unique abilities are used to progress toward the goal.

In my experience, a team is most effective when the leader

- knows each team members’ professional and personal goals

- sets real priorities and commitments

- establishes clear direction

- builds rapport

- is fair with everyone

- shares knowledge and resources

- mentors others to become effective leaders.

Continue to: Another thing that the most effective leaders do is...

Another thing that the most effective leaders do is manage their time and conserve their energy and focus. Think in both short- and long-term goals. Leaders are ordinary people with extraordinary determination, but they know when to stop working and how to recharge their batteries.3,4

It is also important for leaders to acknowledge their accomplishments. All too often, we downplay the contributions we have made, the barriers we have overcome, and the sacrifices we have made to get to where we are today. Our accomplishments add to our body of experience and serve as the foundation for our growth.

Contrary to popular belief, leaders can be made. Anybody can be a leader. One just has to take the time to understand the commitment and the responsibilities. Leadership is a function of who you are, what you can do, and how you do it. Find a mission that ignites your passion, and go for it!

Personality quizzes abound on the Internet these days; you can find out everything from which Disney Princess you are to what type of fruit you would be. But there is a serious case to be made for how your personality type influences your work. It affects how you manage others, develop leadership skills, approach conflict resolution, and manage change.1 Understanding your personality type assists in identifying your strengths, weaknesses, and areas in need of development.

My personality type is ENTP: someone who is “resourceful in solving new and challenging problems.”1 At many points in my career, I found myself in a leadership role. But truthfully, I never set out to be a leader—my career goals set me on that path. You might call me an “accidental leader.”

Recall my story about the founding of the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners (AANP; see Part 2): In the beginning, we were all encouraged to contribute whatever time and energy we could to getting the organization off the ground. I had plenty of time and energy to give. I saw the need for an NP-dedicated organization as a challenge. While I did not know my personality type at the time, I understood that I had a drive to meet challenges—those arising from the status quo and those of moving the vision for this new organization forward.

Our leadership skills are derived from everyday experiences—both the good and the bad. But we only grow if we study the consequences of those experiences to gain insights and to find new ways to manage ourselves and the team.2 Understanding your own personality and skills helps you better appreciate the differences in those you lead and understand how to direct or utilize their particular skills.

Each team member brings a set of skills, range of ideas, and problem-solving approaches to a unique situation. You should identify your team members’ strengths and promote a culture in which the whole team feels comfortable, confident, supported, and encouraged to contribute.3

How do you do that? By initiating and maintaining effective working relationships within the team and demonstrating skills in care coordination and delegation. Everyone benefits when each team member’s unique abilities are used to progress toward the goal.

In my experience, a team is most effective when the leader

- knows each team members’ professional and personal goals

- sets real priorities and commitments

- establishes clear direction

- builds rapport

- is fair with everyone

- shares knowledge and resources

- mentors others to become effective leaders.

Continue to: Another thing that the most effective leaders do is...

Another thing that the most effective leaders do is manage their time and conserve their energy and focus. Think in both short- and long-term goals. Leaders are ordinary people with extraordinary determination, but they know when to stop working and how to recharge their batteries.3,4

It is also important for leaders to acknowledge their accomplishments. All too often, we downplay the contributions we have made, the barriers we have overcome, and the sacrifices we have made to get to where we are today. Our accomplishments add to our body of experience and serve as the foundation for our growth.

Contrary to popular belief, leaders can be made. Anybody can be a leader. One just has to take the time to understand the commitment and the responsibilities. Leadership is a function of who you are, what you can do, and how you do it. Find a mission that ignites your passion, and go for it!

1. The Myers & Briggs Foundation. MBTI® Type at Work. www.myersbriggs.org/type-use-for-everyday-life/mbti-type-at-work/. Accessed September 10, 2019.

2. AZquotes. John Dewey quotes. www.azquotes.com/quote/497608. Accessed September 10, 2019.

3. Knowledge@Wharton. Three big leadership clichés—and how to rethink them. Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania website. https://knowledge.wharton.upenn.edu/article/three-big-leadership-cliches-rethink/. Published November 26, 2018. Accessed September 10, 2019.

4. ForbesQuotes. Thoughts on the Business of Life. www.forbes.com/quotes/5477/. Accessed September 10, 2019.

1. The Myers & Briggs Foundation. MBTI® Type at Work. www.myersbriggs.org/type-use-for-everyday-life/mbti-type-at-work/. Accessed September 10, 2019.

2. AZquotes. John Dewey quotes. www.azquotes.com/quote/497608. Accessed September 10, 2019.

3. Knowledge@Wharton. Three big leadership clichés—and how to rethink them. Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania website. https://knowledge.wharton.upenn.edu/article/three-big-leadership-cliches-rethink/. Published November 26, 2018. Accessed September 10, 2019.

4. ForbesQuotes. Thoughts on the Business of Life. www.forbes.com/quotes/5477/. Accessed September 10, 2019.

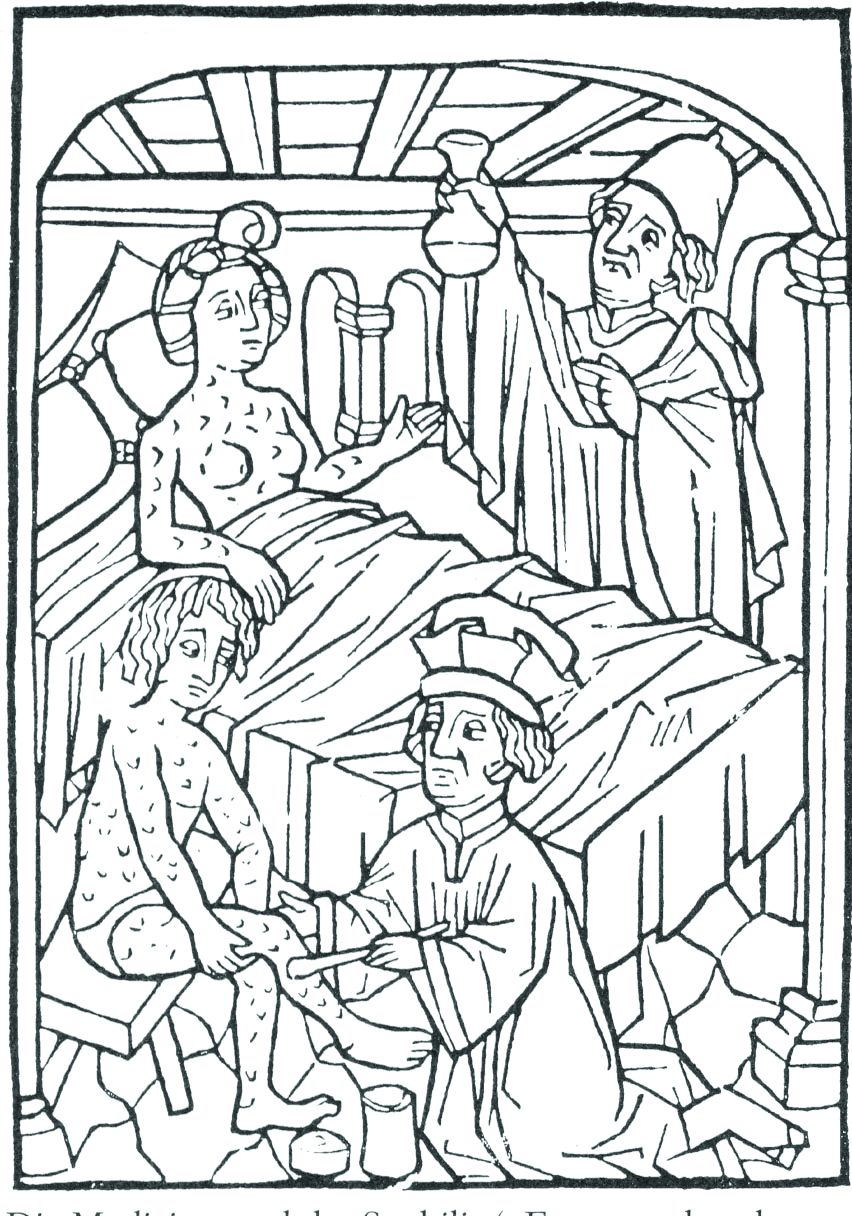

ID Blog: The story of syphilis, part II

From epidemic to endemic curse

Evolution is an amazing thing, and its more fascinating aspects are never more apparent than in the endless genetic dance between host and pathogen. And certainly, our fascination with the dance is not merely an intellectual exercise. The evolution of disease is perhaps one of the starkest examples of human misery writ large across the pages of recorded history.

In particular, the evolution of syphilis from dramatically visible, epidemic terror to silent, endemic, and long-term killer is one of the most striking examples of host-pathogen evolution. It is an example noteworthy not only for the profound transformation that occurred, but for the speed of the change, beginning so fast that it was noticed and detailed by physicians at the time as occurring over less than a human generation rather than centuries.

This very speed of the change makes it relatively certain that it was not the human species that evolved resistance, but rather that the syphilis-causing spirochetes transformed in virulence within almost the blink of an evolutionary eye – an epidemiologic mystery of profound importance to the countless lives involved.

Syphilis was a dramatic new phenomenon in the Old World of the late 15th and early 16th centuries – a hitherto unknown disease of terrible guise and rapid dissemination. It was noted and discussed throughout many of the writings of the time, so much so that one of the first detailed patient accounts in recorded history of the experience of a disease was written in response to a syphilis infection.

In 1498, Tommaso di Silvestro, an Italian notary, described his symptoms in depth: “I remember how I, Ser Tomaso, during the day 27th of April 1498, coming back from the fair in Foligno, started to feel pain in the virga [a contemporary euphemism for penis]. And then the pain grew in intensity. Then in June I started to feel the pains of the French disease. And all my body filled with pustules and crusts. I had pains in the right and left arms, in the entire arm, from the shoulder to the hand, I was filled with pain to the bones and I never found peace. And then I had pains in the right knee and all my body got full of boils, at the back at the front and behind.”

Alessandro Benedetti (1450-1512), a military surgeon and chronicler of the expedition of Charles VIII, wrote in 1497 that sufferers lost hands, feet, eyes, and noses to the disease, such that it made “the entire body so repulsive to look at and causes such great suffering.”Another common characteristic was a foul smell typical of the infected.

Careful analysis by historians has shown that, according to records from the time period, 10-15 years after the start of the epidemic in the late 15th century, there was a noticeable decline in disease virulence.

As one historian put it: “Many physicians and contemporary observers noticed the progressive decline in the severity of the disease. Many symptoms were less severe, and the rash, of a reddish color, did not cause itching.” Girolamo Fracastoro writes about some of these transformations, stating that “in the first epidemic periods the pustules were filthier,’ while they were ‘harder and drier’ afterwards.” Similarly, the historian and scholar Bernardino Cirillo dell’Aquila (1500-1575), writing in the 1530s, stated: “This horrible disease in different periods (1494) till the present had different alterations and different effects depending on the complications, and now many people just lose their hair and nothing else.”

As added documentation of the change, the chaplain of the infamous conquistador Hernàn Cortés reported that syphilis was less severe in his time than earlier. He wrote that: “at the beginning this disease was very violent, dirty and indecent; now it is no longer so severe and so indecent.”

The medical literature of the time confirmed that the fever, characteristic of the second stage of the disease, “was less violent, while even the rashes were just a ‘reddening.’ Moreover, the gummy tumors appeared only in a limited number of cases.”

According to another historian, “By the middle of the 16th century, the generation of physicians born between the end of the 15th century and the first decades of the 16th century considered the exceptional virulence manifested by syphilis when it first appeared to be ancient history.”

And Ambroise Paré (1510-1590), a renowned French surgeon, stated: “Today it is much less serious and easier to heal than it was in the past... It is obviously becoming much milder … so that it seems it should disappear in the future.”

Lacking detailed genetic analysis of the changing pathogen, if one were to speculate on why the virulence of syphilis decreased so rapidly, I suggest, in a Just-So story fashion, that one might merely speculate on the evolutionary wisdom of an STD that commonly turned its victims into foul-smelling, scabrous, agonized, and lethargic individuals who lost body parts, including their genitals, according to some reports. None of these outcomes, of course, would be conducive to the natural spread of the disease. In addition, this is a good case for sexual selection as well as early death of the host, which are two main engineers of evolutionary change.

But for whatever reason, the presentation of syphilis changed dramatically over a relatively short period of time, and as the disease was still spreading through a previously unexposed population, a change in pathogenicity rather than host immunity seems the most logical explanation.

As syphilis evolved from its initial onslaught, it showed new and hitherto unseen symptoms, including the aforementioned hair loss, and other manifestations such as tinnitus. Soon it was presenting so many systemic phenotypes similar to the effects of other diseases that Sir William Osler (1849-1919) ultimately proposed that syphilis should be described as the “Great Imitator.”

The evolution of syphilis from epidemic to endemic does not diminish the horrors of those afflicted with active tertiary syphilis, but as the disease transformed, these effects were greatly postponed and occurred less commonly, compared with their relatively rapid onset in an earlier era and in a greater proportion of the infected individuals.

Although still lethal, especially in its congenital form, by the end of the 16th century, syphilis had completed its rapid evolution from a devastating, highly visible plague to the covert disease “so sinful that it could not be discussed by name.” It would remain so until the rise of modern antibiotics finally provided a reliable cure. Active tertiary syphilis remained a severe affliction, but the effects were postponed from their relatively rapid onset in an earlier era and in a greater proportion of the infected individuals.

So, syphilis remains a unique example of host-pathogen evolution, an endemic part of the global human condition, battled by physicians in mostly futile efforts for nearly 500 years, and a disease tracking closely with the rise of modern medicine.

References

Frith J. 2012. Syphilis – Its Early History and Treatment Until Penicillin and the Debate on its Origins. J Military and Veteran’s Health. 20(4):49-58.

Tognoti B. 2009. The Rise and Fall of Syphilis in Renaissance Italy. J Med Humanit. 30(2):99-113.

Mark Lesney is the managing editor of MDedge.com/IDPractioner. He has a PhD in plant virology and a PhD in the history of science, with a focus on the history of biotechnology and medicine. He has served as an adjunct assistant professor of the department of biochemistry and molecular & celluar biology at Georgetown University, Washington, D.C.

From epidemic to endemic curse

From epidemic to endemic curse

Evolution is an amazing thing, and its more fascinating aspects are never more apparent than in the endless genetic dance between host and pathogen. And certainly, our fascination with the dance is not merely an intellectual exercise. The evolution of disease is perhaps one of the starkest examples of human misery writ large across the pages of recorded history.

In particular, the evolution of syphilis from dramatically visible, epidemic terror to silent, endemic, and long-term killer is one of the most striking examples of host-pathogen evolution. It is an example noteworthy not only for the profound transformation that occurred, but for the speed of the change, beginning so fast that it was noticed and detailed by physicians at the time as occurring over less than a human generation rather than centuries.

This very speed of the change makes it relatively certain that it was not the human species that evolved resistance, but rather that the syphilis-causing spirochetes transformed in virulence within almost the blink of an evolutionary eye – an epidemiologic mystery of profound importance to the countless lives involved.

Syphilis was a dramatic new phenomenon in the Old World of the late 15th and early 16th centuries – a hitherto unknown disease of terrible guise and rapid dissemination. It was noted and discussed throughout many of the writings of the time, so much so that one of the first detailed patient accounts in recorded history of the experience of a disease was written in response to a syphilis infection.

In 1498, Tommaso di Silvestro, an Italian notary, described his symptoms in depth: “I remember how I, Ser Tomaso, during the day 27th of April 1498, coming back from the fair in Foligno, started to feel pain in the virga [a contemporary euphemism for penis]. And then the pain grew in intensity. Then in June I started to feel the pains of the French disease. And all my body filled with pustules and crusts. I had pains in the right and left arms, in the entire arm, from the shoulder to the hand, I was filled with pain to the bones and I never found peace. And then I had pains in the right knee and all my body got full of boils, at the back at the front and behind.”

Alessandro Benedetti (1450-1512), a military surgeon and chronicler of the expedition of Charles VIII, wrote in 1497 that sufferers lost hands, feet, eyes, and noses to the disease, such that it made “the entire body so repulsive to look at and causes such great suffering.”Another common characteristic was a foul smell typical of the infected.

Careful analysis by historians has shown that, according to records from the time period, 10-15 years after the start of the epidemic in the late 15th century, there was a noticeable decline in disease virulence.

As one historian put it: “Many physicians and contemporary observers noticed the progressive decline in the severity of the disease. Many symptoms were less severe, and the rash, of a reddish color, did not cause itching.” Girolamo Fracastoro writes about some of these transformations, stating that “in the first epidemic periods the pustules were filthier,’ while they were ‘harder and drier’ afterwards.” Similarly, the historian and scholar Bernardino Cirillo dell’Aquila (1500-1575), writing in the 1530s, stated: “This horrible disease in different periods (1494) till the present had different alterations and different effects depending on the complications, and now many people just lose their hair and nothing else.”

As added documentation of the change, the chaplain of the infamous conquistador Hernàn Cortés reported that syphilis was less severe in his time than earlier. He wrote that: “at the beginning this disease was very violent, dirty and indecent; now it is no longer so severe and so indecent.”

The medical literature of the time confirmed that the fever, characteristic of the second stage of the disease, “was less violent, while even the rashes were just a ‘reddening.’ Moreover, the gummy tumors appeared only in a limited number of cases.”

According to another historian, “By the middle of the 16th century, the generation of physicians born between the end of the 15th century and the first decades of the 16th century considered the exceptional virulence manifested by syphilis when it first appeared to be ancient history.”

And Ambroise Paré (1510-1590), a renowned French surgeon, stated: “Today it is much less serious and easier to heal than it was in the past... It is obviously becoming much milder … so that it seems it should disappear in the future.”

Lacking detailed genetic analysis of the changing pathogen, if one were to speculate on why the virulence of syphilis decreased so rapidly, I suggest, in a Just-So story fashion, that one might merely speculate on the evolutionary wisdom of an STD that commonly turned its victims into foul-smelling, scabrous, agonized, and lethargic individuals who lost body parts, including their genitals, according to some reports. None of these outcomes, of course, would be conducive to the natural spread of the disease. In addition, this is a good case for sexual selection as well as early death of the host, which are two main engineers of evolutionary change.

But for whatever reason, the presentation of syphilis changed dramatically over a relatively short period of time, and as the disease was still spreading through a previously unexposed population, a change in pathogenicity rather than host immunity seems the most logical explanation.

As syphilis evolved from its initial onslaught, it showed new and hitherto unseen symptoms, including the aforementioned hair loss, and other manifestations such as tinnitus. Soon it was presenting so many systemic phenotypes similar to the effects of other diseases that Sir William Osler (1849-1919) ultimately proposed that syphilis should be described as the “Great Imitator.”

The evolution of syphilis from epidemic to endemic does not diminish the horrors of those afflicted with active tertiary syphilis, but as the disease transformed, these effects were greatly postponed and occurred less commonly, compared with their relatively rapid onset in an earlier era and in a greater proportion of the infected individuals.

Although still lethal, especially in its congenital form, by the end of the 16th century, syphilis had completed its rapid evolution from a devastating, highly visible plague to the covert disease “so sinful that it could not be discussed by name.” It would remain so until the rise of modern antibiotics finally provided a reliable cure. Active tertiary syphilis remained a severe affliction, but the effects were postponed from their relatively rapid onset in an earlier era and in a greater proportion of the infected individuals.

So, syphilis remains a unique example of host-pathogen evolution, an endemic part of the global human condition, battled by physicians in mostly futile efforts for nearly 500 years, and a disease tracking closely with the rise of modern medicine.

References

Frith J. 2012. Syphilis – Its Early History and Treatment Until Penicillin and the Debate on its Origins. J Military and Veteran’s Health. 20(4):49-58.

Tognoti B. 2009. The Rise and Fall of Syphilis in Renaissance Italy. J Med Humanit. 30(2):99-113.

Mark Lesney is the managing editor of MDedge.com/IDPractioner. He has a PhD in plant virology and a PhD in the history of science, with a focus on the history of biotechnology and medicine. He has served as an adjunct assistant professor of the department of biochemistry and molecular & celluar biology at Georgetown University, Washington, D.C.

Evolution is an amazing thing, and its more fascinating aspects are never more apparent than in the endless genetic dance between host and pathogen. And certainly, our fascination with the dance is not merely an intellectual exercise. The evolution of disease is perhaps one of the starkest examples of human misery writ large across the pages of recorded history.

In particular, the evolution of syphilis from dramatically visible, epidemic terror to silent, endemic, and long-term killer is one of the most striking examples of host-pathogen evolution. It is an example noteworthy not only for the profound transformation that occurred, but for the speed of the change, beginning so fast that it was noticed and detailed by physicians at the time as occurring over less than a human generation rather than centuries.

This very speed of the change makes it relatively certain that it was not the human species that evolved resistance, but rather that the syphilis-causing spirochetes transformed in virulence within almost the blink of an evolutionary eye – an epidemiologic mystery of profound importance to the countless lives involved.

Syphilis was a dramatic new phenomenon in the Old World of the late 15th and early 16th centuries – a hitherto unknown disease of terrible guise and rapid dissemination. It was noted and discussed throughout many of the writings of the time, so much so that one of the first detailed patient accounts in recorded history of the experience of a disease was written in response to a syphilis infection.

In 1498, Tommaso di Silvestro, an Italian notary, described his symptoms in depth: “I remember how I, Ser Tomaso, during the day 27th of April 1498, coming back from the fair in Foligno, started to feel pain in the virga [a contemporary euphemism for penis]. And then the pain grew in intensity. Then in June I started to feel the pains of the French disease. And all my body filled with pustules and crusts. I had pains in the right and left arms, in the entire arm, from the shoulder to the hand, I was filled with pain to the bones and I never found peace. And then I had pains in the right knee and all my body got full of boils, at the back at the front and behind.”

Alessandro Benedetti (1450-1512), a military surgeon and chronicler of the expedition of Charles VIII, wrote in 1497 that sufferers lost hands, feet, eyes, and noses to the disease, such that it made “the entire body so repulsive to look at and causes such great suffering.”Another common characteristic was a foul smell typical of the infected.

Careful analysis by historians has shown that, according to records from the time period, 10-15 years after the start of the epidemic in the late 15th century, there was a noticeable decline in disease virulence.

As one historian put it: “Many physicians and contemporary observers noticed the progressive decline in the severity of the disease. Many symptoms were less severe, and the rash, of a reddish color, did not cause itching.” Girolamo Fracastoro writes about some of these transformations, stating that “in the first epidemic periods the pustules were filthier,’ while they were ‘harder and drier’ afterwards.” Similarly, the historian and scholar Bernardino Cirillo dell’Aquila (1500-1575), writing in the 1530s, stated: “This horrible disease in different periods (1494) till the present had different alterations and different effects depending on the complications, and now many people just lose their hair and nothing else.”

As added documentation of the change, the chaplain of the infamous conquistador Hernàn Cortés reported that syphilis was less severe in his time than earlier. He wrote that: “at the beginning this disease was very violent, dirty and indecent; now it is no longer so severe and so indecent.”

The medical literature of the time confirmed that the fever, characteristic of the second stage of the disease, “was less violent, while even the rashes were just a ‘reddening.’ Moreover, the gummy tumors appeared only in a limited number of cases.”

According to another historian, “By the middle of the 16th century, the generation of physicians born between the end of the 15th century and the first decades of the 16th century considered the exceptional virulence manifested by syphilis when it first appeared to be ancient history.”

And Ambroise Paré (1510-1590), a renowned French surgeon, stated: “Today it is much less serious and easier to heal than it was in the past... It is obviously becoming much milder … so that it seems it should disappear in the future.”

Lacking detailed genetic analysis of the changing pathogen, if one were to speculate on why the virulence of syphilis decreased so rapidly, I suggest, in a Just-So story fashion, that one might merely speculate on the evolutionary wisdom of an STD that commonly turned its victims into foul-smelling, scabrous, agonized, and lethargic individuals who lost body parts, including their genitals, according to some reports. None of these outcomes, of course, would be conducive to the natural spread of the disease. In addition, this is a good case for sexual selection as well as early death of the host, which are two main engineers of evolutionary change.

But for whatever reason, the presentation of syphilis changed dramatically over a relatively short period of time, and as the disease was still spreading through a previously unexposed population, a change in pathogenicity rather than host immunity seems the most logical explanation.

As syphilis evolved from its initial onslaught, it showed new and hitherto unseen symptoms, including the aforementioned hair loss, and other manifestations such as tinnitus. Soon it was presenting so many systemic phenotypes similar to the effects of other diseases that Sir William Osler (1849-1919) ultimately proposed that syphilis should be described as the “Great Imitator.”

The evolution of syphilis from epidemic to endemic does not diminish the horrors of those afflicted with active tertiary syphilis, but as the disease transformed, these effects were greatly postponed and occurred less commonly, compared with their relatively rapid onset in an earlier era and in a greater proportion of the infected individuals.

Although still lethal, especially in its congenital form, by the end of the 16th century, syphilis had completed its rapid evolution from a devastating, highly visible plague to the covert disease “so sinful that it could not be discussed by name.” It would remain so until the rise of modern antibiotics finally provided a reliable cure. Active tertiary syphilis remained a severe affliction, but the effects were postponed from their relatively rapid onset in an earlier era and in a greater proportion of the infected individuals.

So, syphilis remains a unique example of host-pathogen evolution, an endemic part of the global human condition, battled by physicians in mostly futile efforts for nearly 500 years, and a disease tracking closely with the rise of modern medicine.

References

Frith J. 2012. Syphilis – Its Early History and Treatment Until Penicillin and the Debate on its Origins. J Military and Veteran’s Health. 20(4):49-58.

Tognoti B. 2009. The Rise and Fall of Syphilis in Renaissance Italy. J Med Humanit. 30(2):99-113.

Mark Lesney is the managing editor of MDedge.com/IDPractioner. He has a PhD in plant virology and a PhD in the history of science, with a focus on the history of biotechnology and medicine. He has served as an adjunct assistant professor of the department of biochemistry and molecular & celluar biology at Georgetown University, Washington, D.C.

Mid-career advice

You’ve arrived at an important milestone when someone asks you to give a grand rounds titled ... “Mid-Career Advice.” Yes, I’ve been asked.

I’m flattered to be asked (although I hope I’m not halfway). Mid-career “crisis!” is what Google expected me to talk about when I searched on this topic. Apparently, I’d rather be me today than me in residency – you learn an awful lot in 40K patient visits. Here are a few notes from my journey:

1. Knowing how to care for patients is as important as knowing medicine. The bulk of work to be done in outpatient care depends on bonding, trust, and affecting change efficiently and effectively. Sometimes great diagnostic acumen and procedural skills are needed. Yet, for most, this isn’t hard. Access to differential diagnoses, recommended work-ups, and best practice treatments are easily accessible, just in time. In contrast, it’s often hard to convince patients of their diagnosis and to help them adhere to the best plan.

2. You can do everything right and still have it end up wrong. Medicine is more like poker than chess. In chess, most information is knowable, and there is always one best move. In poker, much is unknown, and a lot depends on chance. You might perform surgery with perfect sterile technique and still, the patient develops an infection. You could prescribe all the best treatments for pyoderma gangrenosum and the disease might still progress. Thinking probabilistically helps me make better choices and sleep better at night, especially when the outcome was not commensurate with the quality of care.

3. Patients are sometimes impertinent, sometimes wrong, sometimes stubborn, sometimes rude. “Restrain your indignation,” Dr. Osler advised his medical students in 1889, and remember that “offences of this kind come; expect them, and do not be vexed.” You might give the best care, the most compassionate, time-generous appointment, and still your patient files a grievance, posts a bad review, fails to follow through, chooses CBD oil instead. Remember, they are just people with all our shortcomings. Do your best to serve and know in your heart that you are enough and have done enough. Then move on; patients are waiting.

4. Adverse outcomes can be devastating, to us as well as to our patients. Any harm caused to a patient or an angry complaint against you can trigger anxiety, regret, and endless ruminating. Sometimes these thoughts become intrusive. Try setting boundaries. Take the time to absorb the discomfort, still knowing you are strong, you are not alone, and failure is sometimes inevitable. Learn what you can, then when you find you’re unable to stop your thoughts, choose an activity (like AngryBirds!) to break your thoughts. You will be a healthier human and provide better care if you can find your equanimity often and early.

5. Amor fati, or “love your fate.” You cannot know what life has planned. Small, seemingly insignificant events in my life changed my path dramatically. I could have been a store manager in Attleboro, Mass., an orthopedic surgeon in Winston-Salem, or a psychologist in Denver. I could never have known then that I’d end up here, as chief of dermatology in San Diego. Rather than depend only on a deliberate strategy with happiness at your destination being “find the job you love,” rely more on an evolving strategy. Do your job and then exploit opportunities as they develop. Forget sunk costs and move ahead. Don’t depend on fate for your happiness or search for a career to fulfill you. Close your eyes and find the happiness in you, then open your eyes and be so right there. Love your fate.

Dr. Benabio is director of healthcare transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at [email protected].

You’ve arrived at an important milestone when someone asks you to give a grand rounds titled ... “Mid-Career Advice.” Yes, I’ve been asked.

I’m flattered to be asked (although I hope I’m not halfway). Mid-career “crisis!” is what Google expected me to talk about when I searched on this topic. Apparently, I’d rather be me today than me in residency – you learn an awful lot in 40K patient visits. Here are a few notes from my journey:

1. Knowing how to care for patients is as important as knowing medicine. The bulk of work to be done in outpatient care depends on bonding, trust, and affecting change efficiently and effectively. Sometimes great diagnostic acumen and procedural skills are needed. Yet, for most, this isn’t hard. Access to differential diagnoses, recommended work-ups, and best practice treatments are easily accessible, just in time. In contrast, it’s often hard to convince patients of their diagnosis and to help them adhere to the best plan.

2. You can do everything right and still have it end up wrong. Medicine is more like poker than chess. In chess, most information is knowable, and there is always one best move. In poker, much is unknown, and a lot depends on chance. You might perform surgery with perfect sterile technique and still, the patient develops an infection. You could prescribe all the best treatments for pyoderma gangrenosum and the disease might still progress. Thinking probabilistically helps me make better choices and sleep better at night, especially when the outcome was not commensurate with the quality of care.

3. Patients are sometimes impertinent, sometimes wrong, sometimes stubborn, sometimes rude. “Restrain your indignation,” Dr. Osler advised his medical students in 1889, and remember that “offences of this kind come; expect them, and do not be vexed.” You might give the best care, the most compassionate, time-generous appointment, and still your patient files a grievance, posts a bad review, fails to follow through, chooses CBD oil instead. Remember, they are just people with all our shortcomings. Do your best to serve and know in your heart that you are enough and have done enough. Then move on; patients are waiting.

4. Adverse outcomes can be devastating, to us as well as to our patients. Any harm caused to a patient or an angry complaint against you can trigger anxiety, regret, and endless ruminating. Sometimes these thoughts become intrusive. Try setting boundaries. Take the time to absorb the discomfort, still knowing you are strong, you are not alone, and failure is sometimes inevitable. Learn what you can, then when you find you’re unable to stop your thoughts, choose an activity (like AngryBirds!) to break your thoughts. You will be a healthier human and provide better care if you can find your equanimity often and early.

5. Amor fati, or “love your fate.” You cannot know what life has planned. Small, seemingly insignificant events in my life changed my path dramatically. I could have been a store manager in Attleboro, Mass., an orthopedic surgeon in Winston-Salem, or a psychologist in Denver. I could never have known then that I’d end up here, as chief of dermatology in San Diego. Rather than depend only on a deliberate strategy with happiness at your destination being “find the job you love,” rely more on an evolving strategy. Do your job and then exploit opportunities as they develop. Forget sunk costs and move ahead. Don’t depend on fate for your happiness or search for a career to fulfill you. Close your eyes and find the happiness in you, then open your eyes and be so right there. Love your fate.

Dr. Benabio is director of healthcare transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at [email protected].

You’ve arrived at an important milestone when someone asks you to give a grand rounds titled ... “Mid-Career Advice.” Yes, I’ve been asked.

I’m flattered to be asked (although I hope I’m not halfway). Mid-career “crisis!” is what Google expected me to talk about when I searched on this topic. Apparently, I’d rather be me today than me in residency – you learn an awful lot in 40K patient visits. Here are a few notes from my journey:

1. Knowing how to care for patients is as important as knowing medicine. The bulk of work to be done in outpatient care depends on bonding, trust, and affecting change efficiently and effectively. Sometimes great diagnostic acumen and procedural skills are needed. Yet, for most, this isn’t hard. Access to differential diagnoses, recommended work-ups, and best practice treatments are easily accessible, just in time. In contrast, it’s often hard to convince patients of their diagnosis and to help them adhere to the best plan.

2. You can do everything right and still have it end up wrong. Medicine is more like poker than chess. In chess, most information is knowable, and there is always one best move. In poker, much is unknown, and a lot depends on chance. You might perform surgery with perfect sterile technique and still, the patient develops an infection. You could prescribe all the best treatments for pyoderma gangrenosum and the disease might still progress. Thinking probabilistically helps me make better choices and sleep better at night, especially when the outcome was not commensurate with the quality of care.

3. Patients are sometimes impertinent, sometimes wrong, sometimes stubborn, sometimes rude. “Restrain your indignation,” Dr. Osler advised his medical students in 1889, and remember that “offences of this kind come; expect them, and do not be vexed.” You might give the best care, the most compassionate, time-generous appointment, and still your patient files a grievance, posts a bad review, fails to follow through, chooses CBD oil instead. Remember, they are just people with all our shortcomings. Do your best to serve and know in your heart that you are enough and have done enough. Then move on; patients are waiting.

4. Adverse outcomes can be devastating, to us as well as to our patients. Any harm caused to a patient or an angry complaint against you can trigger anxiety, regret, and endless ruminating. Sometimes these thoughts become intrusive. Try setting boundaries. Take the time to absorb the discomfort, still knowing you are strong, you are not alone, and failure is sometimes inevitable. Learn what you can, then when you find you’re unable to stop your thoughts, choose an activity (like AngryBirds!) to break your thoughts. You will be a healthier human and provide better care if you can find your equanimity often and early.

5. Amor fati, or “love your fate.” You cannot know what life has planned. Small, seemingly insignificant events in my life changed my path dramatically. I could have been a store manager in Attleboro, Mass., an orthopedic surgeon in Winston-Salem, or a psychologist in Denver. I could never have known then that I’d end up here, as chief of dermatology in San Diego. Rather than depend only on a deliberate strategy with happiness at your destination being “find the job you love,” rely more on an evolving strategy. Do your job and then exploit opportunities as they develop. Forget sunk costs and move ahead. Don’t depend on fate for your happiness or search for a career to fulfill you. Close your eyes and find the happiness in you, then open your eyes and be so right there. Love your fate.

Dr. Benabio is director of healthcare transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at [email protected].

Part 3: Leadership Is a Team Effort

“Lead, follow, or get out of the way” sounds pejorative—even arrogant—but it ultimately speaks truth about most situations involving a team. A leader must know, or at least sense, the right action to take at any given moment; sometimes that action entails yielding leadership to another team member. So let’s break down this quote to identify the functional behavioral requirements of leadership.

Northouse presents the notion that leadership is a relationship or process of collaboration in which each team member is needed. The leader should be cognizant of each member’s interests, ideas, passions, attitudes, and motivations.1

As a leader, you must reflect on all of your output. This includes how you relate to those you lead; how you collaborate with and affect the actions of your teammates; and how you communicate the process and influence a team toward a goal—which is crucial to the entire team’s success. Allow me to illustrate these core principles.

Relating

Early in the NP movement, it was necessary to develop a collective vision for the profession’s future. What was the purpose of an NP? What could we add to the existing health care landscape? The founders and early proponents of our profession, recognizing that there was power in numbers and strength in collaboration, identified a mission: Provide health care services for those who were underserved. Working as a group, NPs leveraged strength in numbers, creating a more efficient way to move forward and achieve that mission.2 In those early NP pioneers, I recognize the leadership skills—ability to engage individuals and coordinate activities to move an agenda forward—that are key components of any relationship.

Collaborating

Later, in 1984, a small group of like-minded NPs (of which I was one) joined together to investigate the possibility of a starting an organization dedicated to NPs. As a profession, we were woefully underrepresented nationally. Our role was not fully understood, especially by legislators, and there were laws in place that impeded patients’ access to care by NPs. The existing nursing organizations were in no position to dedicate their resources to represent us professionally or politically.

Several colleagues and I were willing to take a risk to move our profession forward, even if it meant alienating other NPs. Each of us was able to work autonomously, as well as in a team, and we all viewed adversity as an opportunity. This gave us the impetus and motivation to carry out the footwork needed to achieve our goal. These skills—determination, energy, persistence—are essential for anyone looking to start a business or get involved in an organization.

Maybe when my colleagues and I formed the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners (AANP), we weren’t all leaders … but our relationship consisted of the passion and collective vision needed to work together and achieve. We knew we had to build on each other’s strengths and remain open and respectful of each other’s ideas. We believed we had nothing to lose and everything to gain and—honestly—we succeeded on all fronts!

Continue to: Influencing

Influencing

One success story happened in 1988 when Title VIII of the Public Health Service Act—the Nurse Education Act—was under review. New provisions in the bill included specific penalties for NPs and nurses if they defaulted on their student loans—penalties that did not apply to other health care professionals. My colleagues and I were outraged! Like many others, I had such a loan, which had allowed me to pursue my dream of becoming an NP.

The AANP got the word out, and we bombarded our legislators’ offices with calls and a threat to “march on Washington.” For my part, I personally spoke with Senator Edward “Ted” Kennedy and asked him if he realized the revisions made him look like a “loan shark.” I told him that NPs were in direct competition with physicians in settings identified as “loan repayments sites” and that physicians were more apt to be hired in these settings than NPs. I quickly offered up alternatives to increase the number of eligible sites where NPs could work for loan repayment, such as community health centers—a system for which he had secured funding decades earlier.

The end result of our influence? Community health centers throughout the country would be considered “loan repayment” sites, which helped to expand the opportunities for NPs to fulfill their financial obligations. If that doesn’t show you that being a leader requires you to challenge unfairness and identify solutions to correct inequity, I don’t know what does.

In a health care organization, we all have multiple roles that require us to be leaders. We are collaborators, providers of care, advocates for our patients, problem-solvers, and idealists. We are also role models for nascent health care providers. A leader’s responsibility spans the breadth of the organization, and today’s health care system continues to demand strong leaders capable of utilizing a variety of skills.

Next Thursday, I will continue my investigation of how to become an effective leader. In our fourth and final part of this series, we will discuss how acknowledging our specific personality traits can strengthen the efforts of a leader.

1. Northouse PG. Introduction to Leadership: Concepts and Practice. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications; 2009.

2. Resnick B, Sheer B, McArthur DB, et al. The world is our oyster: celebrating our past and anticipating our future. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2002;14(11):484-491.

“Lead, follow, or get out of the way” sounds pejorative—even arrogant—but it ultimately speaks truth about most situations involving a team. A leader must know, or at least sense, the right action to take at any given moment; sometimes that action entails yielding leadership to another team member. So let’s break down this quote to identify the functional behavioral requirements of leadership.

Northouse presents the notion that leadership is a relationship or process of collaboration in which each team member is needed. The leader should be cognizant of each member’s interests, ideas, passions, attitudes, and motivations.1

As a leader, you must reflect on all of your output. This includes how you relate to those you lead; how you collaborate with and affect the actions of your teammates; and how you communicate the process and influence a team toward a goal—which is crucial to the entire team’s success. Allow me to illustrate these core principles.

Relating

Early in the NP movement, it was necessary to develop a collective vision for the profession’s future. What was the purpose of an NP? What could we add to the existing health care landscape? The founders and early proponents of our profession, recognizing that there was power in numbers and strength in collaboration, identified a mission: Provide health care services for those who were underserved. Working as a group, NPs leveraged strength in numbers, creating a more efficient way to move forward and achieve that mission.2 In those early NP pioneers, I recognize the leadership skills—ability to engage individuals and coordinate activities to move an agenda forward—that are key components of any relationship.

Collaborating

Later, in 1984, a small group of like-minded NPs (of which I was one) joined together to investigate the possibility of a starting an organization dedicated to NPs. As a profession, we were woefully underrepresented nationally. Our role was not fully understood, especially by legislators, and there were laws in place that impeded patients’ access to care by NPs. The existing nursing organizations were in no position to dedicate their resources to represent us professionally or politically.

Several colleagues and I were willing to take a risk to move our profession forward, even if it meant alienating other NPs. Each of us was able to work autonomously, as well as in a team, and we all viewed adversity as an opportunity. This gave us the impetus and motivation to carry out the footwork needed to achieve our goal. These skills—determination, energy, persistence—are essential for anyone looking to start a business or get involved in an organization.

Maybe when my colleagues and I formed the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners (AANP), we weren’t all leaders … but our relationship consisted of the passion and collective vision needed to work together and achieve. We knew we had to build on each other’s strengths and remain open and respectful of each other’s ideas. We believed we had nothing to lose and everything to gain and—honestly—we succeeded on all fronts!

Continue to: Influencing

Influencing

One success story happened in 1988 when Title VIII of the Public Health Service Act—the Nurse Education Act—was under review. New provisions in the bill included specific penalties for NPs and nurses if they defaulted on their student loans—penalties that did not apply to other health care professionals. My colleagues and I were outraged! Like many others, I had such a loan, which had allowed me to pursue my dream of becoming an NP.

The AANP got the word out, and we bombarded our legislators’ offices with calls and a threat to “march on Washington.” For my part, I personally spoke with Senator Edward “Ted” Kennedy and asked him if he realized the revisions made him look like a “loan shark.” I told him that NPs were in direct competition with physicians in settings identified as “loan repayments sites” and that physicians were more apt to be hired in these settings than NPs. I quickly offered up alternatives to increase the number of eligible sites where NPs could work for loan repayment, such as community health centers—a system for which he had secured funding decades earlier.

The end result of our influence? Community health centers throughout the country would be considered “loan repayment” sites, which helped to expand the opportunities for NPs to fulfill their financial obligations. If that doesn’t show you that being a leader requires you to challenge unfairness and identify solutions to correct inequity, I don’t know what does.

In a health care organization, we all have multiple roles that require us to be leaders. We are collaborators, providers of care, advocates for our patients, problem-solvers, and idealists. We are also role models for nascent health care providers. A leader’s responsibility spans the breadth of the organization, and today’s health care system continues to demand strong leaders capable of utilizing a variety of skills.

Next Thursday, I will continue my investigation of how to become an effective leader. In our fourth and final part of this series, we will discuss how acknowledging our specific personality traits can strengthen the efforts of a leader.

“Lead, follow, or get out of the way” sounds pejorative—even arrogant—but it ultimately speaks truth about most situations involving a team. A leader must know, or at least sense, the right action to take at any given moment; sometimes that action entails yielding leadership to another team member. So let’s break down this quote to identify the functional behavioral requirements of leadership.

Northouse presents the notion that leadership is a relationship or process of collaboration in which each team member is needed. The leader should be cognizant of each member’s interests, ideas, passions, attitudes, and motivations.1

As a leader, you must reflect on all of your output. This includes how you relate to those you lead; how you collaborate with and affect the actions of your teammates; and how you communicate the process and influence a team toward a goal—which is crucial to the entire team’s success. Allow me to illustrate these core principles.

Relating

Early in the NP movement, it was necessary to develop a collective vision for the profession’s future. What was the purpose of an NP? What could we add to the existing health care landscape? The founders and early proponents of our profession, recognizing that there was power in numbers and strength in collaboration, identified a mission: Provide health care services for those who were underserved. Working as a group, NPs leveraged strength in numbers, creating a more efficient way to move forward and achieve that mission.2 In those early NP pioneers, I recognize the leadership skills—ability to engage individuals and coordinate activities to move an agenda forward—that are key components of any relationship.

Collaborating

Later, in 1984, a small group of like-minded NPs (of which I was one) joined together to investigate the possibility of a starting an organization dedicated to NPs. As a profession, we were woefully underrepresented nationally. Our role was not fully understood, especially by legislators, and there were laws in place that impeded patients’ access to care by NPs. The existing nursing organizations were in no position to dedicate their resources to represent us professionally or politically.

Several colleagues and I were willing to take a risk to move our profession forward, even if it meant alienating other NPs. Each of us was able to work autonomously, as well as in a team, and we all viewed adversity as an opportunity. This gave us the impetus and motivation to carry out the footwork needed to achieve our goal. These skills—determination, energy, persistence—are essential for anyone looking to start a business or get involved in an organization.

Maybe when my colleagues and I formed the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners (AANP), we weren’t all leaders … but our relationship consisted of the passion and collective vision needed to work together and achieve. We knew we had to build on each other’s strengths and remain open and respectful of each other’s ideas. We believed we had nothing to lose and everything to gain and—honestly—we succeeded on all fronts!

Continue to: Influencing

Influencing

One success story happened in 1988 when Title VIII of the Public Health Service Act—the Nurse Education Act—was under review. New provisions in the bill included specific penalties for NPs and nurses if they defaulted on their student loans—penalties that did not apply to other health care professionals. My colleagues and I were outraged! Like many others, I had such a loan, which had allowed me to pursue my dream of becoming an NP.

The AANP got the word out, and we bombarded our legislators’ offices with calls and a threat to “march on Washington.” For my part, I personally spoke with Senator Edward “Ted” Kennedy and asked him if he realized the revisions made him look like a “loan shark.” I told him that NPs were in direct competition with physicians in settings identified as “loan repayments sites” and that physicians were more apt to be hired in these settings than NPs. I quickly offered up alternatives to increase the number of eligible sites where NPs could work for loan repayment, such as community health centers—a system for which he had secured funding decades earlier.

The end result of our influence? Community health centers throughout the country would be considered “loan repayment” sites, which helped to expand the opportunities for NPs to fulfill their financial obligations. If that doesn’t show you that being a leader requires you to challenge unfairness and identify solutions to correct inequity, I don’t know what does.

In a health care organization, we all have multiple roles that require us to be leaders. We are collaborators, providers of care, advocates for our patients, problem-solvers, and idealists. We are also role models for nascent health care providers. A leader’s responsibility spans the breadth of the organization, and today’s health care system continues to demand strong leaders capable of utilizing a variety of skills.

Next Thursday, I will continue my investigation of how to become an effective leader. In our fourth and final part of this series, we will discuss how acknowledging our specific personality traits can strengthen the efforts of a leader.

1. Northouse PG. Introduction to Leadership: Concepts and Practice. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications; 2009.

2. Resnick B, Sheer B, McArthur DB, et al. The world is our oyster: celebrating our past and anticipating our future. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2002;14(11):484-491.

1. Northouse PG. Introduction to Leadership: Concepts and Practice. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications; 2009.

2. Resnick B, Sheer B, McArthur DB, et al. The world is our oyster: celebrating our past and anticipating our future. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2002;14(11):484-491.

Health Policy Q&A

Being the optimistic physician

Is your glass always half full? Is that because you’re so busy that you never have time to finish drinking it? Or is it because you are an optimist? Have you always been someone who could see a glimmer at the end of even the darkest, longest tunnels? Do you think your positive outlook is something you inherited? Or did you model it after continued exposure to an optimistic parent or medical school mentor?

Are you aware that your optimism makes it more likely that you will live to a ripe old age? A recent study of 69,744 women and 1,429 men initiated by researchers at the Harvard School T.H. Chan School of Public Health in Boston, Boston University Medical School, and the National Center for PTSD at Veterans Affairs Boston Health Care System found that “individuals with greater optimism are more likely to live longer and to achieve ‘exceptional longevity,’ that is, living to 85 or older” (“New Evidence that optimists live longer.” Harvard T.C. Chan School of Public Health. August 27, 2019).

Do you think your optimism has been a positive contribution to your success as a physician? Or have there been times when it has been a liability?

Because I’m not going to wait for you to answer, I’ll share my own observations. I sense that optimism is something with a strong genetic component, just as is the vulnerability to anxiety and depression. My mother was an optimist. However, I suspect that being around an individual who exudes a high degree of optimism can have a positive influence on a person who already has a partly cloudy disposition.

On the other hand, I’ve found that it is very difficult for even the most optimistic people to induce a positive outlook in individuals born with a chronically half empty glass simply by radiating their own aura of optimism. In my own experience, I have found that being an optimist has definitely been an asset in my role as a physician. – tension that may be exacerbating their ability to cope with the presenting problem. However, I have had to learn to recognize more quickly that there are situations when my optimism isn’t going to be effective and not become frustrated by its inadequacy.

Are there downsides to being an optimistic physician? Of course; there can be a fine line between being an optimist and sounding like a Pollyanna. To avoid stepping over the line, optimists must choose their words carefully. And more importantly, they must be reading the patient’s and family’s response to attempts at injecting positivity into the situation. Optimism also can be mistaken for a nonchalant attitude that signals a lack of caring and concern.

However, the most dangerous liability of optimism occurs when it slips into the swift running and turbulent waters of denial. I have almost killed myself on a couple of occasions when my “optimistic” interpretation of my symptoms has prompted me to “tough out” a potentially fatal situation instead of seeking timely advice from my physician.

My optimism sometimes has made it difficult for me to be appropriately objective when assessing the seriousness of a patient’s condition. Given a list of positives and negatives, my tendency might be focus more on the positives. As far as I know, my overly positive attitude has never killed any of my patients, but I fear a few diagnoses and remedies may have been delayed when the Prince of Optimism became the Queen of Denial.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

Is your glass always half full? Is that because you’re so busy that you never have time to finish drinking it? Or is it because you are an optimist? Have you always been someone who could see a glimmer at the end of even the darkest, longest tunnels? Do you think your positive outlook is something you inherited? Or did you model it after continued exposure to an optimistic parent or medical school mentor?

Are you aware that your optimism makes it more likely that you will live to a ripe old age? A recent study of 69,744 women and 1,429 men initiated by researchers at the Harvard School T.H. Chan School of Public Health in Boston, Boston University Medical School, and the National Center for PTSD at Veterans Affairs Boston Health Care System found that “individuals with greater optimism are more likely to live longer and to achieve ‘exceptional longevity,’ that is, living to 85 or older” (“New Evidence that optimists live longer.” Harvard T.C. Chan School of Public Health. August 27, 2019).

Do you think your optimism has been a positive contribution to your success as a physician? Or have there been times when it has been a liability?

Because I’m not going to wait for you to answer, I’ll share my own observations. I sense that optimism is something with a strong genetic component, just as is the vulnerability to anxiety and depression. My mother was an optimist. However, I suspect that being around an individual who exudes a high degree of optimism can have a positive influence on a person who already has a partly cloudy disposition.

On the other hand, I’ve found that it is very difficult for even the most optimistic people to induce a positive outlook in individuals born with a chronically half empty glass simply by radiating their own aura of optimism. In my own experience, I have found that being an optimist has definitely been an asset in my role as a physician. – tension that may be exacerbating their ability to cope with the presenting problem. However, I have had to learn to recognize more quickly that there are situations when my optimism isn’t going to be effective and not become frustrated by its inadequacy.

Are there downsides to being an optimistic physician? Of course; there can be a fine line between being an optimist and sounding like a Pollyanna. To avoid stepping over the line, optimists must choose their words carefully. And more importantly, they must be reading the patient’s and family’s response to attempts at injecting positivity into the situation. Optimism also can be mistaken for a nonchalant attitude that signals a lack of caring and concern.

However, the most dangerous liability of optimism occurs when it slips into the swift running and turbulent waters of denial. I have almost killed myself on a couple of occasions when my “optimistic” interpretation of my symptoms has prompted me to “tough out” a potentially fatal situation instead of seeking timely advice from my physician.

My optimism sometimes has made it difficult for me to be appropriately objective when assessing the seriousness of a patient’s condition. Given a list of positives and negatives, my tendency might be focus more on the positives. As far as I know, my overly positive attitude has never killed any of my patients, but I fear a few diagnoses and remedies may have been delayed when the Prince of Optimism became the Queen of Denial.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

Is your glass always half full? Is that because you’re so busy that you never have time to finish drinking it? Or is it because you are an optimist? Have you always been someone who could see a glimmer at the end of even the darkest, longest tunnels? Do you think your positive outlook is something you inherited? Or did you model it after continued exposure to an optimistic parent or medical school mentor?

Are you aware that your optimism makes it more likely that you will live to a ripe old age? A recent study of 69,744 women and 1,429 men initiated by researchers at the Harvard School T.H. Chan School of Public Health in Boston, Boston University Medical School, and the National Center for PTSD at Veterans Affairs Boston Health Care System found that “individuals with greater optimism are more likely to live longer and to achieve ‘exceptional longevity,’ that is, living to 85 or older” (“New Evidence that optimists live longer.” Harvard T.C. Chan School of Public Health. August 27, 2019).

Do you think your optimism has been a positive contribution to your success as a physician? Or have there been times when it has been a liability?

Because I’m not going to wait for you to answer, I’ll share my own observations. I sense that optimism is something with a strong genetic component, just as is the vulnerability to anxiety and depression. My mother was an optimist. However, I suspect that being around an individual who exudes a high degree of optimism can have a positive influence on a person who already has a partly cloudy disposition.

On the other hand, I’ve found that it is very difficult for even the most optimistic people to induce a positive outlook in individuals born with a chronically half empty glass simply by radiating their own aura of optimism. In my own experience, I have found that being an optimist has definitely been an asset in my role as a physician. – tension that may be exacerbating their ability to cope with the presenting problem. However, I have had to learn to recognize more quickly that there are situations when my optimism isn’t going to be effective and not become frustrated by its inadequacy.

Are there downsides to being an optimistic physician? Of course; there can be a fine line between being an optimist and sounding like a Pollyanna. To avoid stepping over the line, optimists must choose their words carefully. And more importantly, they must be reading the patient’s and family’s response to attempts at injecting positivity into the situation. Optimism also can be mistaken for a nonchalant attitude that signals a lack of caring and concern.

However, the most dangerous liability of optimism occurs when it slips into the swift running and turbulent waters of denial. I have almost killed myself on a couple of occasions when my “optimistic” interpretation of my symptoms has prompted me to “tough out” a potentially fatal situation instead of seeking timely advice from my physician.

My optimism sometimes has made it difficult for me to be appropriately objective when assessing the seriousness of a patient’s condition. Given a list of positives and negatives, my tendency might be focus more on the positives. As far as I know, my overly positive attitude has never killed any of my patients, but I fear a few diagnoses and remedies may have been delayed when the Prince of Optimism became the Queen of Denial.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

Educating teens, young adults about dangers of vaping

Physicians have been alarmed about the vaping craze for quite some time. This alarm has grown louder in the wake of news that electronic cigarettes have been associated with a mysterious lung disease.

Public health officials have reported that there have been 530 cases of vaping-related respiratory disease,1 and as of press time at least seven deaths had been attributed to vaping*. On Sept. 6, 2019, the Food and Drug Administration, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and other health officials issued an investigation notice on vaping and e-cigarettes,2 cautioning teenagers, young adults, and pregnant women to avoid e-cigarettes completely and cautioning all users to never buy e-cigarettes off the street or from social sources.

A few days later, on Sept. 9, the FDA’s Center for Tobacco Products issued a warning letter to JUUL Labs, makers of a popular e-cigarette, for illegal marketing of modified-risk tobacco products.3 Then on Sept. 10, health officials in Kansas reported that a sixth person has died of a lung illness related to vaping.4

Researchers have found that 80% of those diagnosed with the vaping illness used products that contained THC, the psychoactive ingredient in marijuana, 61% had used nicotine products, and 7% used cannabidiol (CBD) products. Vitamin E acetate is another substance identified in press reports as tied to the severe lung disease.

Most of the patients affected are adolescents and young adults, with the average age of 19 years.5 This comes as vaping among high school students rose 78% between 2017 and 2018.6 According the U.S. surgeon general, one in five teens vapes. Other data show that teen use of e-cigarettes comes with most users having never smoked a traditional cigarette.7 Teens and young adults frequently borrow buy* e-cigarette “pods” from gas stations but borrow and purchase from friends or peers. In addition, young people are known to alter the pods to insert other liquids, such as CBD and other marijuana products.

Teens and young adults are at higher risk for vaping complications. Their respiratory and immune systems are still developing. In addition to concerns about the recent surge of respiratory illnesses, nicotine is known to also suppress the immune system, which makes people who use it more susceptible to viral and bacterial infections – and also making it harder for them to recover.

In addition nicotine hyperactivates the reward centers of the brain, which can trigger addictive behaviors. Because the brains of young adults are not yet fully developed until at or after age 26, nicotine use before this can “prime the pump” of a still-developing brain, thereby increasing the likelihood for addiction to harder drugs. Nicotine has been shown to disrupt sleep patterns, which are critical for mental and physical health. Lastly, research shows that smoking increases the risks of various psychiatric disorders, such as depression and anxiety. My teen and young adult patients have endlessly debated with me the idea that smoking – either nicotine or marijuana – eases their anxiety or helps them get to sleep. I tell them that, in the long run, the data show that smoking makes those problems worse.8-11

Nationally, we are seeing an explosion of multistate legislation pushing marijuana as a health food. E-cigarettes have followed as the “healthy” alternative to traditional tobacco. As clinicians, we must counter those messages.