User login

ERRATUM

A recent letter, “Hypoglycemia in the elderly: Watch for atypical symptoms” (J Fam Pract. 2019;68:116) provided an incomplete list of the letter’s authors. The list should have read: Jan Brož, MD, Jana Urbanová, MD, PhD, Prague, Czech Republic; Brian M. Frier, MD, BSc, Edinburgh, United Kingdom.

A recent letter, “Hypoglycemia in the elderly: Watch for atypical symptoms” (J Fam Pract. 2019;68:116) provided an incomplete list of the letter’s authors. The list should have read: Jan Brož, MD, Jana Urbanová, MD, PhD, Prague, Czech Republic; Brian M. Frier, MD, BSc, Edinburgh, United Kingdom.

A recent letter, “Hypoglycemia in the elderly: Watch for atypical symptoms” (J Fam Pract. 2019;68:116) provided an incomplete list of the letter’s authors. The list should have read: Jan Brož, MD, Jana Urbanová, MD, PhD, Prague, Czech Republic; Brian M. Frier, MD, BSc, Edinburgh, United Kingdom.

Guidelines are not mandates

Just like the 2018 hypertension treatment guidelines, the 2018 Guidelines on the Management of Blood Cholesterol developed by the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) have made treatment decisions much more complicated. In this issue of JFP, Wójcik and Shapiro summarize the 70-page document to help family physicians and other primary health care professionals use these complex guidelines in everyday practice.

The good news is that not much has changed from the 2013 ACC/AHA cholesterol guidelines regarding the treatment of patients with established cardiovascular disease and diabetes mellitus, and those with familial hyperlipidemia—the groups at highest risk for major cardiovascular events. Most of these patients should be treated aggressively, and a target low-density lipoprotein of 70 mg/dL is recommended.

The new guidelines recommend using ezetimibe or a PCSK9 inhibitor if the goal of 70 mg/dL cannot be achieved with a statin alone. There is randomized trial evidence to support the benefit of this aggressive approach. Generic ezetimibe costs about $20 per month,1 but the PCSK9 inhibitors are about $500 per month,2,3 so cost may be a treatment barrier for the 2 monoclonal antibodies approved for cardiovascular prevention: evolocumab and alirocumab.

For primary prevention, the new guidelines are much more complicated. They divide cardiovascular risk into 4 tiers depending on the 10-year risk for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease calculated using the “pooled cohort equation.” Treatment recommendations are more aggressive for those at higher risk. Although it intuitively makes sense to treat those at higher risk more aggressively, there is no clinical trial evidence to support this approach’s superiority over the simpler approach recommended in the 2013 guidelines.

I find the recommendations for screening and primary prevention in adults ages 75 and older and for children and teens to be problematic. A meta-analysis of 28 studies found no statin treatment benefit for primary prevention in those older than 70.4 And there are no randomized trials showing benefit of screening and treating children and teens for hyperlipidemia.

On a positive note, most patients do not need to fast prior to having their lipids measured.

Read the 2018 cholesterol treatment guideline summary in this issue of JFP. But as you do so, remember that guidelines are guidelines; they are not mandates for treatment. You may need to customize these guidelines for your practice and your patients. In my opinion, the simpler 2013 cholesterol guidelines remain good guidelines.

1. Ezetimibe prices. GoodRx. www.goodrx.com/ezetimibe. Accessed April 24, 2019.

2. Dangi-Garimella S. Amgen announces 60% reduction in list price of PCSK9 inhibitor evolocumab. AJMC. October 24, 2018. https://www.ajmc.com/newsroom/amgen-announces-60-reduction-in-list-price-of-pcsk9-inhibitor-evolocumab. Accessed May 1, 2019.

3. Kuchler H. Sanofi and Regeneron cut price of Praluent by 60%. Financial Times. February 11, 2019. https://www.ft.com/content/d1b34cca-2e18-11e9-8744-e7016697f225. Accessed May 1, 2019.

4. Cholesterol Treatment Trialists’ Collaboration. Efficacy and safety of statin therapy in older people: a meta-analysis of individual participant data from 28 randomized controlled trials. Lancet. 2019;393:407-415.

Just like the 2018 hypertension treatment guidelines, the 2018 Guidelines on the Management of Blood Cholesterol developed by the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) have made treatment decisions much more complicated. In this issue of JFP, Wójcik and Shapiro summarize the 70-page document to help family physicians and other primary health care professionals use these complex guidelines in everyday practice.

The good news is that not much has changed from the 2013 ACC/AHA cholesterol guidelines regarding the treatment of patients with established cardiovascular disease and diabetes mellitus, and those with familial hyperlipidemia—the groups at highest risk for major cardiovascular events. Most of these patients should be treated aggressively, and a target low-density lipoprotein of 70 mg/dL is recommended.

The new guidelines recommend using ezetimibe or a PCSK9 inhibitor if the goal of 70 mg/dL cannot be achieved with a statin alone. There is randomized trial evidence to support the benefit of this aggressive approach. Generic ezetimibe costs about $20 per month,1 but the PCSK9 inhibitors are about $500 per month,2,3 so cost may be a treatment barrier for the 2 monoclonal antibodies approved for cardiovascular prevention: evolocumab and alirocumab.

For primary prevention, the new guidelines are much more complicated. They divide cardiovascular risk into 4 tiers depending on the 10-year risk for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease calculated using the “pooled cohort equation.” Treatment recommendations are more aggressive for those at higher risk. Although it intuitively makes sense to treat those at higher risk more aggressively, there is no clinical trial evidence to support this approach’s superiority over the simpler approach recommended in the 2013 guidelines.

I find the recommendations for screening and primary prevention in adults ages 75 and older and for children and teens to be problematic. A meta-analysis of 28 studies found no statin treatment benefit for primary prevention in those older than 70.4 And there are no randomized trials showing benefit of screening and treating children and teens for hyperlipidemia.

On a positive note, most patients do not need to fast prior to having their lipids measured.

Read the 2018 cholesterol treatment guideline summary in this issue of JFP. But as you do so, remember that guidelines are guidelines; they are not mandates for treatment. You may need to customize these guidelines for your practice and your patients. In my opinion, the simpler 2013 cholesterol guidelines remain good guidelines.

Just like the 2018 hypertension treatment guidelines, the 2018 Guidelines on the Management of Blood Cholesterol developed by the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) have made treatment decisions much more complicated. In this issue of JFP, Wójcik and Shapiro summarize the 70-page document to help family physicians and other primary health care professionals use these complex guidelines in everyday practice.

The good news is that not much has changed from the 2013 ACC/AHA cholesterol guidelines regarding the treatment of patients with established cardiovascular disease and diabetes mellitus, and those with familial hyperlipidemia—the groups at highest risk for major cardiovascular events. Most of these patients should be treated aggressively, and a target low-density lipoprotein of 70 mg/dL is recommended.

The new guidelines recommend using ezetimibe or a PCSK9 inhibitor if the goal of 70 mg/dL cannot be achieved with a statin alone. There is randomized trial evidence to support the benefit of this aggressive approach. Generic ezetimibe costs about $20 per month,1 but the PCSK9 inhibitors are about $500 per month,2,3 so cost may be a treatment barrier for the 2 monoclonal antibodies approved for cardiovascular prevention: evolocumab and alirocumab.

For primary prevention, the new guidelines are much more complicated. They divide cardiovascular risk into 4 tiers depending on the 10-year risk for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease calculated using the “pooled cohort equation.” Treatment recommendations are more aggressive for those at higher risk. Although it intuitively makes sense to treat those at higher risk more aggressively, there is no clinical trial evidence to support this approach’s superiority over the simpler approach recommended in the 2013 guidelines.

I find the recommendations for screening and primary prevention in adults ages 75 and older and for children and teens to be problematic. A meta-analysis of 28 studies found no statin treatment benefit for primary prevention in those older than 70.4 And there are no randomized trials showing benefit of screening and treating children and teens for hyperlipidemia.

On a positive note, most patients do not need to fast prior to having their lipids measured.

Read the 2018 cholesterol treatment guideline summary in this issue of JFP. But as you do so, remember that guidelines are guidelines; they are not mandates for treatment. You may need to customize these guidelines for your practice and your patients. In my opinion, the simpler 2013 cholesterol guidelines remain good guidelines.

1. Ezetimibe prices. GoodRx. www.goodrx.com/ezetimibe. Accessed April 24, 2019.

2. Dangi-Garimella S. Amgen announces 60% reduction in list price of PCSK9 inhibitor evolocumab. AJMC. October 24, 2018. https://www.ajmc.com/newsroom/amgen-announces-60-reduction-in-list-price-of-pcsk9-inhibitor-evolocumab. Accessed May 1, 2019.

3. Kuchler H. Sanofi and Regeneron cut price of Praluent by 60%. Financial Times. February 11, 2019. https://www.ft.com/content/d1b34cca-2e18-11e9-8744-e7016697f225. Accessed May 1, 2019.

4. Cholesterol Treatment Trialists’ Collaboration. Efficacy and safety of statin therapy in older people: a meta-analysis of individual participant data from 28 randomized controlled trials. Lancet. 2019;393:407-415.

1. Ezetimibe prices. GoodRx. www.goodrx.com/ezetimibe. Accessed April 24, 2019.

2. Dangi-Garimella S. Amgen announces 60% reduction in list price of PCSK9 inhibitor evolocumab. AJMC. October 24, 2018. https://www.ajmc.com/newsroom/amgen-announces-60-reduction-in-list-price-of-pcsk9-inhibitor-evolocumab. Accessed May 1, 2019.

3. Kuchler H. Sanofi and Regeneron cut price of Praluent by 60%. Financial Times. February 11, 2019. https://www.ft.com/content/d1b34cca-2e18-11e9-8744-e7016697f225. Accessed May 1, 2019.

4. Cholesterol Treatment Trialists’ Collaboration. Efficacy and safety of statin therapy in older people: a meta-analysis of individual participant data from 28 randomized controlled trials. Lancet. 2019;393:407-415.

Can Medicine Bring Good Out of War?

The title of this essay is more often posed as “Is War Good for Medicine?”2 The career VA physician in me, and the daughter and granddaughter of combat veterans, finds this question historically accurate, but ethically problematic. So I have rewritten the question to one that enables us to examine the historic relationship of medical advances and war from a more ethically justifiable posture. I am by no means ascribing to authors of other publications with this title anything but the highest motives of education and edification.

Yet the more I read and thought about the question(s), I realized that the moral assumptions underlying and supporting each concept are significantly different. What led me to that realization was a story my father told me when I was young which in my youthful ignorance I either dismissed or ignored. I now see that the narrative captured a profound truth about how war is not good especially for those who must wage it, but good may come from it for those who now live in peace.

My father was one of the founders of military pediatrics. Surprisingly, pediatricians were valuable members of the military medical forces because of their knowledge of infectious diseases.3 My father had gone in to the then new specialty of pediatrics because in the 1930s, infectious diseases were the primary cause of death in children. Before antibiotics, children would often die of common infections. Service as a combat medical officer in World War II stationed in the European Theater, my father had experience with and access to penicillin. After returning from the war to work in an Army hospital, he and his staff went into the acute pediatric ward and gave the drug to several very sick children, many of whom were likely to die. The next morning on rounds, they noted that many of the children were feeling much better, some even bouncing on their beds.

Perhaps either his telling or my remembering of these events is partly apocryphal, but the reality is that those lethal microbes had no idea what had hit them. Before human physicians overused the new drugs and nature struck back with antibiotic resistance, penicillin seemed miraculous.

Most likely, in 1945 those children would never have been prescribed penicillin, much less survived, if not for the unprecedented and war-driven consortium of industry and government that mass-produced penicillin to treat the troops with infections. Without a doubt then, from the sacrifice and devastation of World War II came the benefits and boons of the antibiotic era—one of the greatest discoveries in medical science.4

Penicillin is but one of legions of scientific discoveries that emerged during wartime. Many of these dramatic improvements, especially those in surgical techniques and emergency medicine, quickly entered the civilian sector. The French surgeon Amboise Paré, for example, revived an old Roman Army practice of using ligatures or tourniquets to stop excessive blood loss, now a staple of emergency responders in disasters. The ambulance services that transported wounded troops to the hospital began on the battlefields of the Civil War.5

These impressive contributions are the direct result of military medicine intended to preserve fighting strength. There are also indirect, although just as revolutionary, efforts of DoD and VA scientists and health care professionals to minimize disability and prevent progression especially of service-connected injuries and illnesses. Among the most groundbreaking is the VA’s 3D-printed artificial lung. I have to admit at first I thought that it was futuristic, but quickly I learned that it was a realistic possibility for the coming decades.6 VA researchers hope the lung will offer a treatment option for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), a lung condition more prevalent in veterans than in the civilian population.7 One contributing factor to the increased risk of COPD among former military is the higher rate of smoking among both active duty and veterans than that in the civilian population.8 And the last chain in the link of causation is that smoking is more common in those service members who have posttraumatic stress disorder.9

However, there also is a very dark side to the link between wartime research and medicine—most infamously the Nazi hypothermia experiments conducted at concentration camps. The proposed publication aroused a decades long ethical controversy regarding whether the data should be published, much less used, in research and practice even if it could save the lives of present or future warriors. In 1990, Marcia Angel, MD, then editor-in-chief of the prestigious New England Journal of Medicine, published the information with an accompanying ethical justification. “Finally, refusal to publish the unethical work serves notice to society at large that even scientists do not consider science the primary measure of a civilization. Knowledge, although important, may be less important to a decent society than the way it is obtained.”10 Ethicist Stephen Post writing on behalf of Holocaust victims strenuously disagreed with the decision to publish the research, “Because the Nazi experiments on human beings were so appallingly unethical, it follows, prima facie, that the use of the records is unethical.”11

This debate is key to the distinction between the 2 questions posed at the beginning of this column. Few who have been on a battlefield or who have cared for those who were can suggest or defend that wars should be fought as a catalyst for scientific research or an impetus to medical advancement. Such an instrumentalist view justifies the end of healing with the means of death, which is an intrinsic contradiction that would eventually corrode the integrity of the medical and scientific professions. Conversely, the second question challenges all of us in federal practice to assume a mantle of obligation to take the interventions that enabled combat medicine to save soldiers and apply them to improve the health and save the lives of veterans and civilians alike. It summons scientists laboring in the hundreds of DoD and VA laboratories to use the unparalleled funding and infrastructure of the institutions to develop promising therapeutics to treat the psychological toll and physical cost of war. And finally it charges the citizens whose family and friends have and will serve in uniform to enlist in a political process that enables military medicine and science to achieve the greatest good-health in peace.

1. Remarque EM. All Quiet on the Western Front. New York, NY: Fawcett Books; 1929:228.

2. Connell C. Is war good for medicine: war’s medical legacy? http://sm.stanford.edu/archive/stanmed/2007summer/main.html. Published 2007. Accessed April 18, 2019.

3. Burnett MW, Callahan CW. American pediatricians at war; a legacy of service. Pediatrics. 2012;129(suppl 1):S33-S49.

4. Ligon BL. Penicillin: its discovery and early development. Semin Pediatr Infect Dis. 2004;15(1):52-57.

5. Samuel L. 6 medical innovations that moved from the battlefield to mainstream medicine. https://www.scientificamercan.com/article/6-medical-innovations-that-moved-from-the-battlefield-to-mainstream-medicine. Published November 11, 2017. Accessed April 18, 2019.

6. Richman M. Breathing easier. https://www.research.va.gov/currents/0818-Researchers-strive-to-make-3D-printed-artificial-lung-to-help-Vets-with-respiratory-disease.cfm. Published August 1, 2018. Accessed April 18, 2019.

7. Murphy DE, Chaudry Z, Almoosa KF, Panos RJ. High prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease among veterans in the urban Midwest. Mill Med. 2011;176(5):552-560.

8. Thompson WH, St-Hilaire C. Prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and tobacco use in veterans at Boise Veterans Affairs Medical Center. Respir Care. 2010;55(5):555-560.

9. Cook J, Jakupcak M, Rosenheck R, Fontana A, McFall M. Influence of PTSD symptom clusters on smoking status among help-seeking Iraq and Afghanistan veterans. Nicotine Tob Res. 2009;11(10):1189-1195.

10. Angell M. The Nazi hypothermia experiments and unethical research today. N Eng J Med 1990;322(20):1462-1464.

11. Post SG. The echo of Nuremberg: Nazi data and ethics. J Med Ethics. 1991;17(1):42-44.

The title of this essay is more often posed as “Is War Good for Medicine?”2 The career VA physician in me, and the daughter and granddaughter of combat veterans, finds this question historically accurate, but ethically problematic. So I have rewritten the question to one that enables us to examine the historic relationship of medical advances and war from a more ethically justifiable posture. I am by no means ascribing to authors of other publications with this title anything but the highest motives of education and edification.

Yet the more I read and thought about the question(s), I realized that the moral assumptions underlying and supporting each concept are significantly different. What led me to that realization was a story my father told me when I was young which in my youthful ignorance I either dismissed or ignored. I now see that the narrative captured a profound truth about how war is not good especially for those who must wage it, but good may come from it for those who now live in peace.

My father was one of the founders of military pediatrics. Surprisingly, pediatricians were valuable members of the military medical forces because of their knowledge of infectious diseases.3 My father had gone in to the then new specialty of pediatrics because in the 1930s, infectious diseases were the primary cause of death in children. Before antibiotics, children would often die of common infections. Service as a combat medical officer in World War II stationed in the European Theater, my father had experience with and access to penicillin. After returning from the war to work in an Army hospital, he and his staff went into the acute pediatric ward and gave the drug to several very sick children, many of whom were likely to die. The next morning on rounds, they noted that many of the children were feeling much better, some even bouncing on their beds.

Perhaps either his telling or my remembering of these events is partly apocryphal, but the reality is that those lethal microbes had no idea what had hit them. Before human physicians overused the new drugs and nature struck back with antibiotic resistance, penicillin seemed miraculous.

Most likely, in 1945 those children would never have been prescribed penicillin, much less survived, if not for the unprecedented and war-driven consortium of industry and government that mass-produced penicillin to treat the troops with infections. Without a doubt then, from the sacrifice and devastation of World War II came the benefits and boons of the antibiotic era—one of the greatest discoveries in medical science.4

Penicillin is but one of legions of scientific discoveries that emerged during wartime. Many of these dramatic improvements, especially those in surgical techniques and emergency medicine, quickly entered the civilian sector. The French surgeon Amboise Paré, for example, revived an old Roman Army practice of using ligatures or tourniquets to stop excessive blood loss, now a staple of emergency responders in disasters. The ambulance services that transported wounded troops to the hospital began on the battlefields of the Civil War.5

These impressive contributions are the direct result of military medicine intended to preserve fighting strength. There are also indirect, although just as revolutionary, efforts of DoD and VA scientists and health care professionals to minimize disability and prevent progression especially of service-connected injuries and illnesses. Among the most groundbreaking is the VA’s 3D-printed artificial lung. I have to admit at first I thought that it was futuristic, but quickly I learned that it was a realistic possibility for the coming decades.6 VA researchers hope the lung will offer a treatment option for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), a lung condition more prevalent in veterans than in the civilian population.7 One contributing factor to the increased risk of COPD among former military is the higher rate of smoking among both active duty and veterans than that in the civilian population.8 And the last chain in the link of causation is that smoking is more common in those service members who have posttraumatic stress disorder.9

However, there also is a very dark side to the link between wartime research and medicine—most infamously the Nazi hypothermia experiments conducted at concentration camps. The proposed publication aroused a decades long ethical controversy regarding whether the data should be published, much less used, in research and practice even if it could save the lives of present or future warriors. In 1990, Marcia Angel, MD, then editor-in-chief of the prestigious New England Journal of Medicine, published the information with an accompanying ethical justification. “Finally, refusal to publish the unethical work serves notice to society at large that even scientists do not consider science the primary measure of a civilization. Knowledge, although important, may be less important to a decent society than the way it is obtained.”10 Ethicist Stephen Post writing on behalf of Holocaust victims strenuously disagreed with the decision to publish the research, “Because the Nazi experiments on human beings were so appallingly unethical, it follows, prima facie, that the use of the records is unethical.”11

This debate is key to the distinction between the 2 questions posed at the beginning of this column. Few who have been on a battlefield or who have cared for those who were can suggest or defend that wars should be fought as a catalyst for scientific research or an impetus to medical advancement. Such an instrumentalist view justifies the end of healing with the means of death, which is an intrinsic contradiction that would eventually corrode the integrity of the medical and scientific professions. Conversely, the second question challenges all of us in federal practice to assume a mantle of obligation to take the interventions that enabled combat medicine to save soldiers and apply them to improve the health and save the lives of veterans and civilians alike. It summons scientists laboring in the hundreds of DoD and VA laboratories to use the unparalleled funding and infrastructure of the institutions to develop promising therapeutics to treat the psychological toll and physical cost of war. And finally it charges the citizens whose family and friends have and will serve in uniform to enlist in a political process that enables military medicine and science to achieve the greatest good-health in peace.

The title of this essay is more often posed as “Is War Good for Medicine?”2 The career VA physician in me, and the daughter and granddaughter of combat veterans, finds this question historically accurate, but ethically problematic. So I have rewritten the question to one that enables us to examine the historic relationship of medical advances and war from a more ethically justifiable posture. I am by no means ascribing to authors of other publications with this title anything but the highest motives of education and edification.

Yet the more I read and thought about the question(s), I realized that the moral assumptions underlying and supporting each concept are significantly different. What led me to that realization was a story my father told me when I was young which in my youthful ignorance I either dismissed or ignored. I now see that the narrative captured a profound truth about how war is not good especially for those who must wage it, but good may come from it for those who now live in peace.

My father was one of the founders of military pediatrics. Surprisingly, pediatricians were valuable members of the military medical forces because of their knowledge of infectious diseases.3 My father had gone in to the then new specialty of pediatrics because in the 1930s, infectious diseases were the primary cause of death in children. Before antibiotics, children would often die of common infections. Service as a combat medical officer in World War II stationed in the European Theater, my father had experience with and access to penicillin. After returning from the war to work in an Army hospital, he and his staff went into the acute pediatric ward and gave the drug to several very sick children, many of whom were likely to die. The next morning on rounds, they noted that many of the children were feeling much better, some even bouncing on their beds.

Perhaps either his telling or my remembering of these events is partly apocryphal, but the reality is that those lethal microbes had no idea what had hit them. Before human physicians overused the new drugs and nature struck back with antibiotic resistance, penicillin seemed miraculous.

Most likely, in 1945 those children would never have been prescribed penicillin, much less survived, if not for the unprecedented and war-driven consortium of industry and government that mass-produced penicillin to treat the troops with infections. Without a doubt then, from the sacrifice and devastation of World War II came the benefits and boons of the antibiotic era—one of the greatest discoveries in medical science.4

Penicillin is but one of legions of scientific discoveries that emerged during wartime. Many of these dramatic improvements, especially those in surgical techniques and emergency medicine, quickly entered the civilian sector. The French surgeon Amboise Paré, for example, revived an old Roman Army practice of using ligatures or tourniquets to stop excessive blood loss, now a staple of emergency responders in disasters. The ambulance services that transported wounded troops to the hospital began on the battlefields of the Civil War.5

These impressive contributions are the direct result of military medicine intended to preserve fighting strength. There are also indirect, although just as revolutionary, efforts of DoD and VA scientists and health care professionals to minimize disability and prevent progression especially of service-connected injuries and illnesses. Among the most groundbreaking is the VA’s 3D-printed artificial lung. I have to admit at first I thought that it was futuristic, but quickly I learned that it was a realistic possibility for the coming decades.6 VA researchers hope the lung will offer a treatment option for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), a lung condition more prevalent in veterans than in the civilian population.7 One contributing factor to the increased risk of COPD among former military is the higher rate of smoking among both active duty and veterans than that in the civilian population.8 And the last chain in the link of causation is that smoking is more common in those service members who have posttraumatic stress disorder.9

However, there also is a very dark side to the link between wartime research and medicine—most infamously the Nazi hypothermia experiments conducted at concentration camps. The proposed publication aroused a decades long ethical controversy regarding whether the data should be published, much less used, in research and practice even if it could save the lives of present or future warriors. In 1990, Marcia Angel, MD, then editor-in-chief of the prestigious New England Journal of Medicine, published the information with an accompanying ethical justification. “Finally, refusal to publish the unethical work serves notice to society at large that even scientists do not consider science the primary measure of a civilization. Knowledge, although important, may be less important to a decent society than the way it is obtained.”10 Ethicist Stephen Post writing on behalf of Holocaust victims strenuously disagreed with the decision to publish the research, “Because the Nazi experiments on human beings were so appallingly unethical, it follows, prima facie, that the use of the records is unethical.”11

This debate is key to the distinction between the 2 questions posed at the beginning of this column. Few who have been on a battlefield or who have cared for those who were can suggest or defend that wars should be fought as a catalyst for scientific research or an impetus to medical advancement. Such an instrumentalist view justifies the end of healing with the means of death, which is an intrinsic contradiction that would eventually corrode the integrity of the medical and scientific professions. Conversely, the second question challenges all of us in federal practice to assume a mantle of obligation to take the interventions that enabled combat medicine to save soldiers and apply them to improve the health and save the lives of veterans and civilians alike. It summons scientists laboring in the hundreds of DoD and VA laboratories to use the unparalleled funding and infrastructure of the institutions to develop promising therapeutics to treat the psychological toll and physical cost of war. And finally it charges the citizens whose family and friends have and will serve in uniform to enlist in a political process that enables military medicine and science to achieve the greatest good-health in peace.

1. Remarque EM. All Quiet on the Western Front. New York, NY: Fawcett Books; 1929:228.

2. Connell C. Is war good for medicine: war’s medical legacy? http://sm.stanford.edu/archive/stanmed/2007summer/main.html. Published 2007. Accessed April 18, 2019.

3. Burnett MW, Callahan CW. American pediatricians at war; a legacy of service. Pediatrics. 2012;129(suppl 1):S33-S49.

4. Ligon BL. Penicillin: its discovery and early development. Semin Pediatr Infect Dis. 2004;15(1):52-57.

5. Samuel L. 6 medical innovations that moved from the battlefield to mainstream medicine. https://www.scientificamercan.com/article/6-medical-innovations-that-moved-from-the-battlefield-to-mainstream-medicine. Published November 11, 2017. Accessed April 18, 2019.

6. Richman M. Breathing easier. https://www.research.va.gov/currents/0818-Researchers-strive-to-make-3D-printed-artificial-lung-to-help-Vets-with-respiratory-disease.cfm. Published August 1, 2018. Accessed April 18, 2019.

7. Murphy DE, Chaudry Z, Almoosa KF, Panos RJ. High prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease among veterans in the urban Midwest. Mill Med. 2011;176(5):552-560.

8. Thompson WH, St-Hilaire C. Prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and tobacco use in veterans at Boise Veterans Affairs Medical Center. Respir Care. 2010;55(5):555-560.

9. Cook J, Jakupcak M, Rosenheck R, Fontana A, McFall M. Influence of PTSD symptom clusters on smoking status among help-seeking Iraq and Afghanistan veterans. Nicotine Tob Res. 2009;11(10):1189-1195.

10. Angell M. The Nazi hypothermia experiments and unethical research today. N Eng J Med 1990;322(20):1462-1464.

11. Post SG. The echo of Nuremberg: Nazi data and ethics. J Med Ethics. 1991;17(1):42-44.

1. Remarque EM. All Quiet on the Western Front. New York, NY: Fawcett Books; 1929:228.

2. Connell C. Is war good for medicine: war’s medical legacy? http://sm.stanford.edu/archive/stanmed/2007summer/main.html. Published 2007. Accessed April 18, 2019.

3. Burnett MW, Callahan CW. American pediatricians at war; a legacy of service. Pediatrics. 2012;129(suppl 1):S33-S49.

4. Ligon BL. Penicillin: its discovery and early development. Semin Pediatr Infect Dis. 2004;15(1):52-57.

5. Samuel L. 6 medical innovations that moved from the battlefield to mainstream medicine. https://www.scientificamercan.com/article/6-medical-innovations-that-moved-from-the-battlefield-to-mainstream-medicine. Published November 11, 2017. Accessed April 18, 2019.

6. Richman M. Breathing easier. https://www.research.va.gov/currents/0818-Researchers-strive-to-make-3D-printed-artificial-lung-to-help-Vets-with-respiratory-disease.cfm. Published August 1, 2018. Accessed April 18, 2019.

7. Murphy DE, Chaudry Z, Almoosa KF, Panos RJ. High prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease among veterans in the urban Midwest. Mill Med. 2011;176(5):552-560.

8. Thompson WH, St-Hilaire C. Prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and tobacco use in veterans at Boise Veterans Affairs Medical Center. Respir Care. 2010;55(5):555-560.

9. Cook J, Jakupcak M, Rosenheck R, Fontana A, McFall M. Influence of PTSD symptom clusters on smoking status among help-seeking Iraq and Afghanistan veterans. Nicotine Tob Res. 2009;11(10):1189-1195.

10. Angell M. The Nazi hypothermia experiments and unethical research today. N Eng J Med 1990;322(20):1462-1464.

11. Post SG. The echo of Nuremberg: Nazi data and ethics. J Med Ethics. 1991;17(1):42-44.

Topical Chemotherapy for Numerous Superficial Basal Cell Carcinomas Years After Isolated Limb Perfusion for Melanoma

Isolated limb perfusion (ILP) for the adjuvant treatment of melanoma involves isolating the blood flow of a limb from the rest of the body to allow for high concentrations of chemotherapeutic agents locally. Chemotherapy with nitrogen mustard is the preferred chemotherapeutic agent in ILP for the adjuvant treatment of locally advanced melanoma.1 Systemic exposure to nitrogen mustard has shown to be carcinogenic, and its topical application has been associated with the development of actinic keratosis, basal cell carcinoma (BCC), and squamous cell carcinoma.2,3 However, the long-term effects of ILP with nitrogen mustard are not well defined. In 1998, one of the authors (R.L.M.) described a patient with melanoma of the left leg that was treated with ILP with nitrogen mustard who subsequently developed numerous BCCs on the same leg.4 This same patient has since been successfully managed with only topical chemotherapeutic agents for the last 21 years.

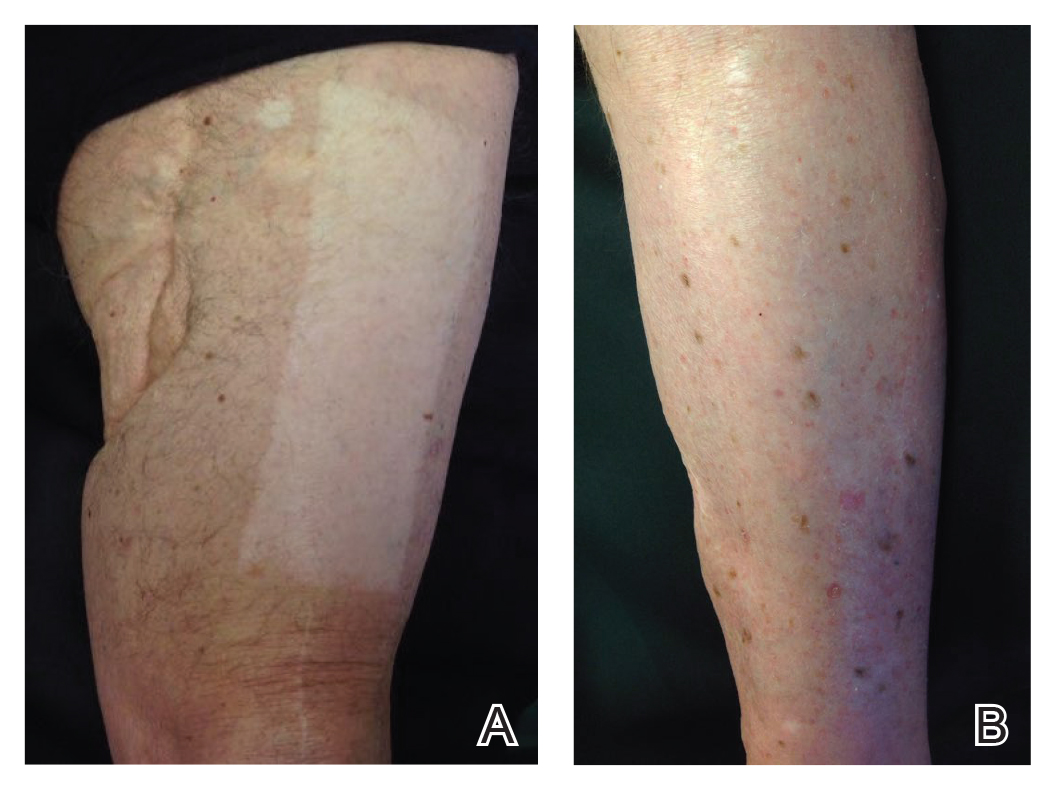

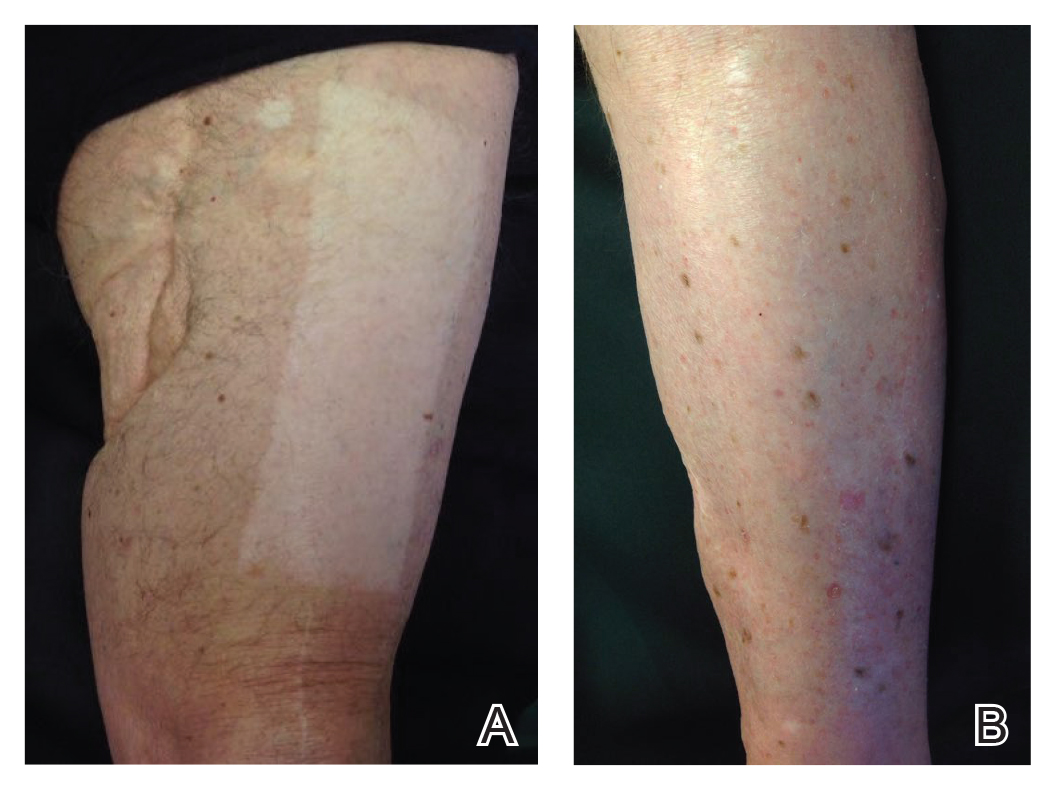

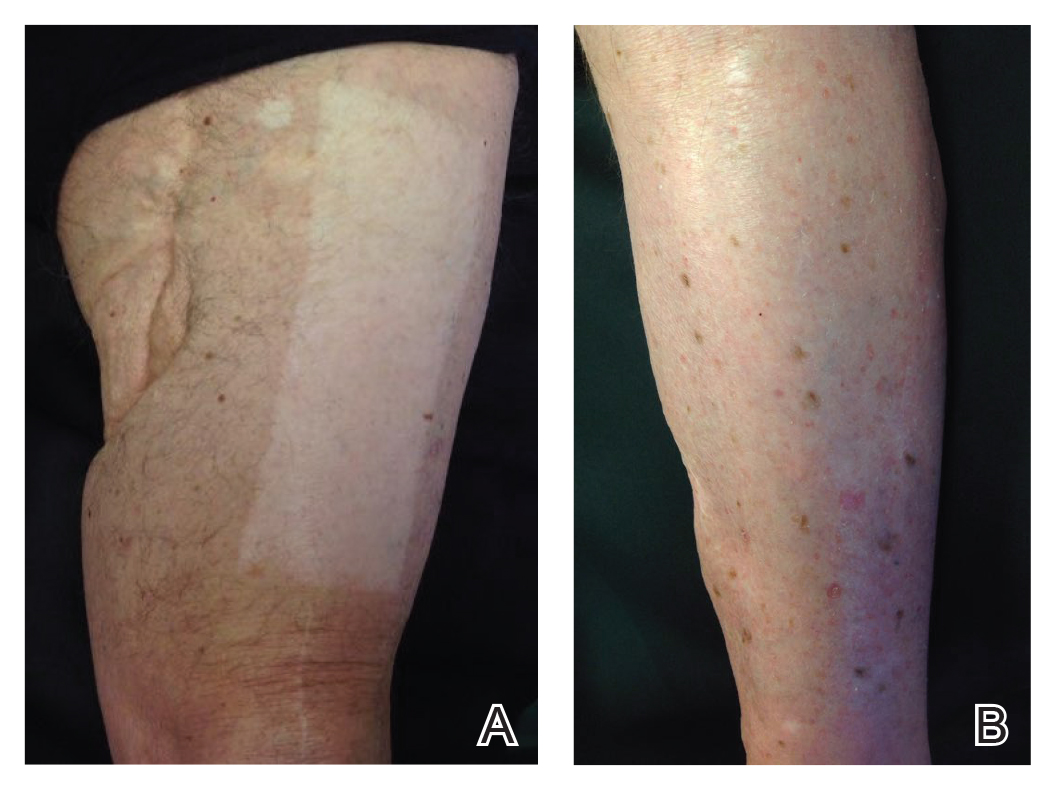

An 86-year-old man with a history of melanoma underwent wide resection, lymph node dissection, and adjuvant ILP with nitrogen mustard for the treatment of melanoma of the medial left thigh approximately 50 years ago. He denied any prior radiation treatment. He subsequently presented years later to our dermatology clinic with many biopsy-proven superficial and nodular BCCs of the left leg over the course of the last 30 years. On physical examination, the patient had several pink papules and macules on the left lower leg (Figure). The patient had previously undergone multiple invasive excisions with grafting for the treatment of BCCs by a plastic surgeon prior to presentation to our clinic but has since had many years of control under our care with only topical chemotherapeutic agents. His current medication regimen consists of 5-fluorouracil twice daily, which he tolerates without serious side effects. He also has used imiquimod in the past.

Isolated limb perfusion was first described by Creech et al5 in 1958. Chemotherapy in ILP is designed to maximize limb perfusion while minimizing systemic absorption.1 Meta

Topical use of nitrogen mustard has been linked to the development of nonmelanoma skin cancer (NMSC)2,3; however, a 30-year population-based study found no significant increase in secondary malignancies, including NMSC or melanoma, following use of topical nitrogen mustard.6 There also have been reported cases of secondary cancers following ILP reported in the literature, including pleomorphic sarcoma and Merkel cell carcinoma.7 We hypothesize that our patient’s exposure to nitrogen mustard during ILP led to the development of numerous BCCs, but further research is necessary to confirm this relationship.

Treatment modalities for NMSC include surgical excision with defined margins, Mohs micrographic surgery, radiotherapy, electrodesiccation and curettage, cryotherapy, photodynamic therapy, and topical therapy. Our patient experienced such a high volume of superficial BCCs that the decision was made to avoid frequent surgical procedures and to treat with topical chemotherapeutic agents. He had an excellent response to topical 5-fluorouracil, and the treatment has been well tolerated. This case is valuable for clinicians, as it demonstrates that topical chemotherapy can be a well-tolerated option for patients who present with frequent superficial BCCs to prevent numerous invasive surgical treatments.

- Benckhuijsen C, Kroon BB, van Geel AN, et al. Regional perfusion treatment with melphalan for melanoma in a limb: an evaluation of drug kinetics. Eur J Surg Oncol. 1988;14:157-163.

- Abel EA, Sendagorta E, Hoppe RT. Cutaneous malignancies and metastatic squamous cell carcinoma following topical therapy for mycosis fungoides. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1986;14:1029-1038.

- Lee LA, Fritz KA, Golitz L, et al. Second cutaneous malignancies in patients with mycosis fungoides treated with topical nitrogen mustard. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1982;7:590-598.

- Lamb PM, Menaker GM, Moy RL. Multiple basal cell carcinomas of the limb after adjuvant treatment of melanoma with isolated limb perfusion. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;38:767-768.

- Creech O Jr, Krementz ET, Ryan RF, et al. Chemotherapy of cancer: regional perfusion utilizing an extracorporal circuit. Ann Surg. 1958;148:616-632.

- Lindahl L, Fenger-Grøn M, Iversen L. Secondary cancers, comorbidities and mortality associated with nitrogen mustard therapy in patients with mycosis fungoides: a 30-year population-based cohort study. Br J Dermatol. 2014;170:699-704.

- Lenormand C, Pelletier C, Goeldel AL, et al. Second malignant neoplasm occurring years after hyperthermic isolated limb perfusion for melanoma. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:319-321.

Isolated limb perfusion (ILP) for the adjuvant treatment of melanoma involves isolating the blood flow of a limb from the rest of the body to allow for high concentrations of chemotherapeutic agents locally. Chemotherapy with nitrogen mustard is the preferred chemotherapeutic agent in ILP for the adjuvant treatment of locally advanced melanoma.1 Systemic exposure to nitrogen mustard has shown to be carcinogenic, and its topical application has been associated with the development of actinic keratosis, basal cell carcinoma (BCC), and squamous cell carcinoma.2,3 However, the long-term effects of ILP with nitrogen mustard are not well defined. In 1998, one of the authors (R.L.M.) described a patient with melanoma of the left leg that was treated with ILP with nitrogen mustard who subsequently developed numerous BCCs on the same leg.4 This same patient has since been successfully managed with only topical chemotherapeutic agents for the last 21 years.

An 86-year-old man with a history of melanoma underwent wide resection, lymph node dissection, and adjuvant ILP with nitrogen mustard for the treatment of melanoma of the medial left thigh approximately 50 years ago. He denied any prior radiation treatment. He subsequently presented years later to our dermatology clinic with many biopsy-proven superficial and nodular BCCs of the left leg over the course of the last 30 years. On physical examination, the patient had several pink papules and macules on the left lower leg (Figure). The patient had previously undergone multiple invasive excisions with grafting for the treatment of BCCs by a plastic surgeon prior to presentation to our clinic but has since had many years of control under our care with only topical chemotherapeutic agents. His current medication regimen consists of 5-fluorouracil twice daily, which he tolerates without serious side effects. He also has used imiquimod in the past.

Isolated limb perfusion was first described by Creech et al5 in 1958. Chemotherapy in ILP is designed to maximize limb perfusion while minimizing systemic absorption.1 Meta

Topical use of nitrogen mustard has been linked to the development of nonmelanoma skin cancer (NMSC)2,3; however, a 30-year population-based study found no significant increase in secondary malignancies, including NMSC or melanoma, following use of topical nitrogen mustard.6 There also have been reported cases of secondary cancers following ILP reported in the literature, including pleomorphic sarcoma and Merkel cell carcinoma.7 We hypothesize that our patient’s exposure to nitrogen mustard during ILP led to the development of numerous BCCs, but further research is necessary to confirm this relationship.

Treatment modalities for NMSC include surgical excision with defined margins, Mohs micrographic surgery, radiotherapy, electrodesiccation and curettage, cryotherapy, photodynamic therapy, and topical therapy. Our patient experienced such a high volume of superficial BCCs that the decision was made to avoid frequent surgical procedures and to treat with topical chemotherapeutic agents. He had an excellent response to topical 5-fluorouracil, and the treatment has been well tolerated. This case is valuable for clinicians, as it demonstrates that topical chemotherapy can be a well-tolerated option for patients who present with frequent superficial BCCs to prevent numerous invasive surgical treatments.

Isolated limb perfusion (ILP) for the adjuvant treatment of melanoma involves isolating the blood flow of a limb from the rest of the body to allow for high concentrations of chemotherapeutic agents locally. Chemotherapy with nitrogen mustard is the preferred chemotherapeutic agent in ILP for the adjuvant treatment of locally advanced melanoma.1 Systemic exposure to nitrogen mustard has shown to be carcinogenic, and its topical application has been associated with the development of actinic keratosis, basal cell carcinoma (BCC), and squamous cell carcinoma.2,3 However, the long-term effects of ILP with nitrogen mustard are not well defined. In 1998, one of the authors (R.L.M.) described a patient with melanoma of the left leg that was treated with ILP with nitrogen mustard who subsequently developed numerous BCCs on the same leg.4 This same patient has since been successfully managed with only topical chemotherapeutic agents for the last 21 years.

An 86-year-old man with a history of melanoma underwent wide resection, lymph node dissection, and adjuvant ILP with nitrogen mustard for the treatment of melanoma of the medial left thigh approximately 50 years ago. He denied any prior radiation treatment. He subsequently presented years later to our dermatology clinic with many biopsy-proven superficial and nodular BCCs of the left leg over the course of the last 30 years. On physical examination, the patient had several pink papules and macules on the left lower leg (Figure). The patient had previously undergone multiple invasive excisions with grafting for the treatment of BCCs by a plastic surgeon prior to presentation to our clinic but has since had many years of control under our care with only topical chemotherapeutic agents. His current medication regimen consists of 5-fluorouracil twice daily, which he tolerates without serious side effects. He also has used imiquimod in the past.

Isolated limb perfusion was first described by Creech et al5 in 1958. Chemotherapy in ILP is designed to maximize limb perfusion while minimizing systemic absorption.1 Meta

Topical use of nitrogen mustard has been linked to the development of nonmelanoma skin cancer (NMSC)2,3; however, a 30-year population-based study found no significant increase in secondary malignancies, including NMSC or melanoma, following use of topical nitrogen mustard.6 There also have been reported cases of secondary cancers following ILP reported in the literature, including pleomorphic sarcoma and Merkel cell carcinoma.7 We hypothesize that our patient’s exposure to nitrogen mustard during ILP led to the development of numerous BCCs, but further research is necessary to confirm this relationship.

Treatment modalities for NMSC include surgical excision with defined margins, Mohs micrographic surgery, radiotherapy, electrodesiccation and curettage, cryotherapy, photodynamic therapy, and topical therapy. Our patient experienced such a high volume of superficial BCCs that the decision was made to avoid frequent surgical procedures and to treat with topical chemotherapeutic agents. He had an excellent response to topical 5-fluorouracil, and the treatment has been well tolerated. This case is valuable for clinicians, as it demonstrates that topical chemotherapy can be a well-tolerated option for patients who present with frequent superficial BCCs to prevent numerous invasive surgical treatments.

- Benckhuijsen C, Kroon BB, van Geel AN, et al. Regional perfusion treatment with melphalan for melanoma in a limb: an evaluation of drug kinetics. Eur J Surg Oncol. 1988;14:157-163.

- Abel EA, Sendagorta E, Hoppe RT. Cutaneous malignancies and metastatic squamous cell carcinoma following topical therapy for mycosis fungoides. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1986;14:1029-1038.

- Lee LA, Fritz KA, Golitz L, et al. Second cutaneous malignancies in patients with mycosis fungoides treated with topical nitrogen mustard. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1982;7:590-598.

- Lamb PM, Menaker GM, Moy RL. Multiple basal cell carcinomas of the limb after adjuvant treatment of melanoma with isolated limb perfusion. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;38:767-768.

- Creech O Jr, Krementz ET, Ryan RF, et al. Chemotherapy of cancer: regional perfusion utilizing an extracorporal circuit. Ann Surg. 1958;148:616-632.

- Lindahl L, Fenger-Grøn M, Iversen L. Secondary cancers, comorbidities and mortality associated with nitrogen mustard therapy in patients with mycosis fungoides: a 30-year population-based cohort study. Br J Dermatol. 2014;170:699-704.

- Lenormand C, Pelletier C, Goeldel AL, et al. Second malignant neoplasm occurring years after hyperthermic isolated limb perfusion for melanoma. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:319-321.

- Benckhuijsen C, Kroon BB, van Geel AN, et al. Regional perfusion treatment with melphalan for melanoma in a limb: an evaluation of drug kinetics. Eur J Surg Oncol. 1988;14:157-163.

- Abel EA, Sendagorta E, Hoppe RT. Cutaneous malignancies and metastatic squamous cell carcinoma following topical therapy for mycosis fungoides. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1986;14:1029-1038.

- Lee LA, Fritz KA, Golitz L, et al. Second cutaneous malignancies in patients with mycosis fungoides treated with topical nitrogen mustard. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1982;7:590-598.

- Lamb PM, Menaker GM, Moy RL. Multiple basal cell carcinomas of the limb after adjuvant treatment of melanoma with isolated limb perfusion. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;38:767-768.

- Creech O Jr, Krementz ET, Ryan RF, et al. Chemotherapy of cancer: regional perfusion utilizing an extracorporal circuit. Ann Surg. 1958;148:616-632.

- Lindahl L, Fenger-Grøn M, Iversen L. Secondary cancers, comorbidities and mortality associated with nitrogen mustard therapy in patients with mycosis fungoides: a 30-year population-based cohort study. Br J Dermatol. 2014;170:699-704.

- Lenormand C, Pelletier C, Goeldel AL, et al. Second malignant neoplasm occurring years after hyperthermic isolated limb perfusion for melanoma. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:319-321.

The Dayanara Effect: Increasing Skin Cancer Awareness in the Hispanic Community

In February 2019, Dayanara Torres announced that she had been diagnosed with metastatic melanoma. Ms. Torres, a Puerto Rican–born former Miss Universe who has more than 1 million followers on Instagram (@dayanarapr), seemed an unlikely candidate for skin cancer, which often is associated with fair-skinned and light-eyed individuals. She shared the news of her diagnosis in an Instagram video that has now received more than 850,000 views. In the video, Ms. Torres described a new mole with uneven surface that had developed on her leg and noted that she had ignored it, even though it had been growing for years. Ultimately, she was diagnosed with melanoma that had already metastasized to regional lymph nodes in her leg. Ms. Torres concluded the video by urging fans and viewers to be mindful of new or changing skin lesions and to be aware of the seriousness of skin cancer. In March 2019, Ms. Torres posted a follow-up educational video on Instagram highlighting the features of melanoma that has now received more than 300,000 views.

Since her announcement, we have noticed that more Hispanic patients with concerns about skin cancer are presenting to our dermatology clinic, which is located in a highly diverse city (New Brunswick, New Jersey) with approximately 50% of residents identifying as Hispanic.1 Most Hispanic patients typically present to our dermatology clinic for non–skin cancer–related concerns, such as acne, rash, and dyschromia; however, following Ms. Torres’ announcement, many have cited her diagnosis of metastatic melanoma as a cause for concern and a motivating factor in having their skin examined. The diagnosis in a prominent celebrity and Hispanic woman has given a new face to metastatic melanoma.

Although melanoma most commonly occurs in white patients, Hispanic patients experience disproportionately greater morbidity and mortality when diagnosed with melanoma.2 Poor prognosis in patients with skin of color is multifactorial and may be due to poor use of sun protection, misconceptions about melanoma risk, atypical clinical presentation, impaired access to care, and delay in diagnosis. The Hispanic community encompasses a wide variety of individuals with varying levels of skin pigmentation and sun sensitivity.3 However, Hispanics report low levels of sun-protective behaviors. They also may have misconceptions that sunscreen is ineffective in preventing skin cancer and that little can be done to decrease the risk for developing skin cancer.4,5 Additionally, Hispanic patients often have lower perceptions of their personal risk for melanoma and report low rates of clinical and self-examinations compared to non-Hispanic white patients.6-8 Many Hispanic patients have reported that they were not instructed to perform self-examinations of their skin regularly by dermatologists or other providers and did not know the signs of skin cancer.7 Furthermore, a language barrier also may impede communication and education regarding melanoma risk.9

Similar to white patients, superficial spreading melanoma is the most common histologic subtype in Hispanic patients, followed by acral lentiginous melanoma, which is the most common subtype in black and Asian patients.2,4 Compared to non-Hispanic white patients, who most commonly present with truncal melanomas, Hispanic patients (particularly those from Puerto Rico, such as Ms. Torres) are more likely to present with melanoma on the lower extremities.4,10 Additionally, Hispanic patients have high rates of head, neck, and mucosal melanomas compared to all other racial and ethnic groups.2

Hispanic patients diagnosed with melanoma are more likely to present with thicker primary tumors, later stages of disease, and distant metastases compared to non-Hispanic white patients, all of which are associated with poor prognosis.2,4,11 Five-year survival rates for melanoma are lower in Hispanic patients compared to non-Hispanic white patients.12 Although the Hispanic community is diverse in socioeconomic and immigration status as well as occupation, lack of insurance also may contribute to decreased access to care, delayed diagnosis, and ultimately worse survival.

These disparities have spurred suggestions for increased education about skin cancer and the signs and symptoms of melanoma, encouragement of self-examinations, and routine clinical skin examinations for Hispanic patients by dermatologists and other providers.8 There is evidence that knowledge-based interventions, especially when presented in Spanish, produce statistically significant improvements in knowledge of skin cancer risk and sun-protective behavior among Hispanic patients.12 Similarly, we have observed that the videos shared by Ms. Torres regarding her melanoma diagnosis and the features of melanoma, in which she spoke in Spanish, have compelled many Hispanic patients to examine their own skin and have led to increased concern for skin cancer in this patient population. In our practice, we refer to the increase in spot checks and skin examinations requested by Hispanic patients as “The Dayanara Effect,” and we hypothesize that this same effect may be taking place throughout the dermatology community.

- New Brunswick, NJ. Data USA website. https://datausa.io/profile/geo/new-brunswick-nj. Accessed April 17, 2019.

- Higgins S, Nazemi A, Feinstein S, et al. Clinical presentations of melanoma in African Americans, Hispanics, and Asians [published online January 4, 2019]. Dermatol Surg. doi:10.1097/dss.0000000000001759.

- Robinson JK, Penedo FJ, Hay JL, et al. Recognizing Latinos’ range of skin pigment and phototypes to enhance skin cancer prevention [published online July 4, 2017]. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2017;30:488-492.

- Garnett E, Townsend J, Steele B, et al. Characteristics, rates, and trends of melanoma incidence among Hispanics in the USA. Cancer Causes Control. 2016;27:647-659.

- Agbai ON, Buster K, Sanchez M, et al. Skin cancer and photoprotection in people of color: a review and recommendations for physicians and the public. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:748-762.

- Andreeva VA, Cockburn MG. Cutaneous melanoma and other skin cancer screening among Hispanics in the United States: a review of the evidence, disparities, and need for expanding the intervention and research agendas. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:743-745.

- Roman C, Lugo-Somolinos A, Thomas N. Skin cancer knowledge and skin self-examinations in the Hispanic population of North Carolina: the patient’s perspective. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:103-104.

- Jaimes N, Oliveria S, Halpern A. A cautionary note on melanoma screening in the Hispanic/Latino population. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:396-397.

- Wich LG, Ma MW, Price LS, et al. Impact of socioeconomic status and sociodemographic factors on melanoma presentation among ethnic minorities. J Community Health. 2011;36:461-468.

- Rouhani P, Hu S, Kirsner RS. Melanoma in Hispanic and black Americans. Cancer Control. 2008;15:248-253.

- Dawes SM, Tsai S, Gittleman H, et al. Racial disparities in melanoma survival. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:983-991.

- Kailas A, Botwin AL, Pritchett EN, et al. Assessing the effectiveness of knowledge-based interventions in increasing skin cancer awareness, knowledge, and protective behaviors in skin of color populations. Cutis. 2017;100:235-240.

In February 2019, Dayanara Torres announced that she had been diagnosed with metastatic melanoma. Ms. Torres, a Puerto Rican–born former Miss Universe who has more than 1 million followers on Instagram (@dayanarapr), seemed an unlikely candidate for skin cancer, which often is associated with fair-skinned and light-eyed individuals. She shared the news of her diagnosis in an Instagram video that has now received more than 850,000 views. In the video, Ms. Torres described a new mole with uneven surface that had developed on her leg and noted that she had ignored it, even though it had been growing for years. Ultimately, she was diagnosed with melanoma that had already metastasized to regional lymph nodes in her leg. Ms. Torres concluded the video by urging fans and viewers to be mindful of new or changing skin lesions and to be aware of the seriousness of skin cancer. In March 2019, Ms. Torres posted a follow-up educational video on Instagram highlighting the features of melanoma that has now received more than 300,000 views.

Since her announcement, we have noticed that more Hispanic patients with concerns about skin cancer are presenting to our dermatology clinic, which is located in a highly diverse city (New Brunswick, New Jersey) with approximately 50% of residents identifying as Hispanic.1 Most Hispanic patients typically present to our dermatology clinic for non–skin cancer–related concerns, such as acne, rash, and dyschromia; however, following Ms. Torres’ announcement, many have cited her diagnosis of metastatic melanoma as a cause for concern and a motivating factor in having their skin examined. The diagnosis in a prominent celebrity and Hispanic woman has given a new face to metastatic melanoma.

Although melanoma most commonly occurs in white patients, Hispanic patients experience disproportionately greater morbidity and mortality when diagnosed with melanoma.2 Poor prognosis in patients with skin of color is multifactorial and may be due to poor use of sun protection, misconceptions about melanoma risk, atypical clinical presentation, impaired access to care, and delay in diagnosis. The Hispanic community encompasses a wide variety of individuals with varying levels of skin pigmentation and sun sensitivity.3 However, Hispanics report low levels of sun-protective behaviors. They also may have misconceptions that sunscreen is ineffective in preventing skin cancer and that little can be done to decrease the risk for developing skin cancer.4,5 Additionally, Hispanic patients often have lower perceptions of their personal risk for melanoma and report low rates of clinical and self-examinations compared to non-Hispanic white patients.6-8 Many Hispanic patients have reported that they were not instructed to perform self-examinations of their skin regularly by dermatologists or other providers and did not know the signs of skin cancer.7 Furthermore, a language barrier also may impede communication and education regarding melanoma risk.9

Similar to white patients, superficial spreading melanoma is the most common histologic subtype in Hispanic patients, followed by acral lentiginous melanoma, which is the most common subtype in black and Asian patients.2,4 Compared to non-Hispanic white patients, who most commonly present with truncal melanomas, Hispanic patients (particularly those from Puerto Rico, such as Ms. Torres) are more likely to present with melanoma on the lower extremities.4,10 Additionally, Hispanic patients have high rates of head, neck, and mucosal melanomas compared to all other racial and ethnic groups.2

Hispanic patients diagnosed with melanoma are more likely to present with thicker primary tumors, later stages of disease, and distant metastases compared to non-Hispanic white patients, all of which are associated with poor prognosis.2,4,11 Five-year survival rates for melanoma are lower in Hispanic patients compared to non-Hispanic white patients.12 Although the Hispanic community is diverse in socioeconomic and immigration status as well as occupation, lack of insurance also may contribute to decreased access to care, delayed diagnosis, and ultimately worse survival.

These disparities have spurred suggestions for increased education about skin cancer and the signs and symptoms of melanoma, encouragement of self-examinations, and routine clinical skin examinations for Hispanic patients by dermatologists and other providers.8 There is evidence that knowledge-based interventions, especially when presented in Spanish, produce statistically significant improvements in knowledge of skin cancer risk and sun-protective behavior among Hispanic patients.12 Similarly, we have observed that the videos shared by Ms. Torres regarding her melanoma diagnosis and the features of melanoma, in which she spoke in Spanish, have compelled many Hispanic patients to examine their own skin and have led to increased concern for skin cancer in this patient population. In our practice, we refer to the increase in spot checks and skin examinations requested by Hispanic patients as “The Dayanara Effect,” and we hypothesize that this same effect may be taking place throughout the dermatology community.

In February 2019, Dayanara Torres announced that she had been diagnosed with metastatic melanoma. Ms. Torres, a Puerto Rican–born former Miss Universe who has more than 1 million followers on Instagram (@dayanarapr), seemed an unlikely candidate for skin cancer, which often is associated with fair-skinned and light-eyed individuals. She shared the news of her diagnosis in an Instagram video that has now received more than 850,000 views. In the video, Ms. Torres described a new mole with uneven surface that had developed on her leg and noted that she had ignored it, even though it had been growing for years. Ultimately, she was diagnosed with melanoma that had already metastasized to regional lymph nodes in her leg. Ms. Torres concluded the video by urging fans and viewers to be mindful of new or changing skin lesions and to be aware of the seriousness of skin cancer. In March 2019, Ms. Torres posted a follow-up educational video on Instagram highlighting the features of melanoma that has now received more than 300,000 views.

Since her announcement, we have noticed that more Hispanic patients with concerns about skin cancer are presenting to our dermatology clinic, which is located in a highly diverse city (New Brunswick, New Jersey) with approximately 50% of residents identifying as Hispanic.1 Most Hispanic patients typically present to our dermatology clinic for non–skin cancer–related concerns, such as acne, rash, and dyschromia; however, following Ms. Torres’ announcement, many have cited her diagnosis of metastatic melanoma as a cause for concern and a motivating factor in having their skin examined. The diagnosis in a prominent celebrity and Hispanic woman has given a new face to metastatic melanoma.

Although melanoma most commonly occurs in white patients, Hispanic patients experience disproportionately greater morbidity and mortality when diagnosed with melanoma.2 Poor prognosis in patients with skin of color is multifactorial and may be due to poor use of sun protection, misconceptions about melanoma risk, atypical clinical presentation, impaired access to care, and delay in diagnosis. The Hispanic community encompasses a wide variety of individuals with varying levels of skin pigmentation and sun sensitivity.3 However, Hispanics report low levels of sun-protective behaviors. They also may have misconceptions that sunscreen is ineffective in preventing skin cancer and that little can be done to decrease the risk for developing skin cancer.4,5 Additionally, Hispanic patients often have lower perceptions of their personal risk for melanoma and report low rates of clinical and self-examinations compared to non-Hispanic white patients.6-8 Many Hispanic patients have reported that they were not instructed to perform self-examinations of their skin regularly by dermatologists or other providers and did not know the signs of skin cancer.7 Furthermore, a language barrier also may impede communication and education regarding melanoma risk.9

Similar to white patients, superficial spreading melanoma is the most common histologic subtype in Hispanic patients, followed by acral lentiginous melanoma, which is the most common subtype in black and Asian patients.2,4 Compared to non-Hispanic white patients, who most commonly present with truncal melanomas, Hispanic patients (particularly those from Puerto Rico, such as Ms. Torres) are more likely to present with melanoma on the lower extremities.4,10 Additionally, Hispanic patients have high rates of head, neck, and mucosal melanomas compared to all other racial and ethnic groups.2

Hispanic patients diagnosed with melanoma are more likely to present with thicker primary tumors, later stages of disease, and distant metastases compared to non-Hispanic white patients, all of which are associated with poor prognosis.2,4,11 Five-year survival rates for melanoma are lower in Hispanic patients compared to non-Hispanic white patients.12 Although the Hispanic community is diverse in socioeconomic and immigration status as well as occupation, lack of insurance also may contribute to decreased access to care, delayed diagnosis, and ultimately worse survival.

These disparities have spurred suggestions for increased education about skin cancer and the signs and symptoms of melanoma, encouragement of self-examinations, and routine clinical skin examinations for Hispanic patients by dermatologists and other providers.8 There is evidence that knowledge-based interventions, especially when presented in Spanish, produce statistically significant improvements in knowledge of skin cancer risk and sun-protective behavior among Hispanic patients.12 Similarly, we have observed that the videos shared by Ms. Torres regarding her melanoma diagnosis and the features of melanoma, in which she spoke in Spanish, have compelled many Hispanic patients to examine their own skin and have led to increased concern for skin cancer in this patient population. In our practice, we refer to the increase in spot checks and skin examinations requested by Hispanic patients as “The Dayanara Effect,” and we hypothesize that this same effect may be taking place throughout the dermatology community.

- New Brunswick, NJ. Data USA website. https://datausa.io/profile/geo/new-brunswick-nj. Accessed April 17, 2019.

- Higgins S, Nazemi A, Feinstein S, et al. Clinical presentations of melanoma in African Americans, Hispanics, and Asians [published online January 4, 2019]. Dermatol Surg. doi:10.1097/dss.0000000000001759.

- Robinson JK, Penedo FJ, Hay JL, et al. Recognizing Latinos’ range of skin pigment and phototypes to enhance skin cancer prevention [published online July 4, 2017]. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2017;30:488-492.

- Garnett E, Townsend J, Steele B, et al. Characteristics, rates, and trends of melanoma incidence among Hispanics in the USA. Cancer Causes Control. 2016;27:647-659.

- Agbai ON, Buster K, Sanchez M, et al. Skin cancer and photoprotection in people of color: a review and recommendations for physicians and the public. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:748-762.

- Andreeva VA, Cockburn MG. Cutaneous melanoma and other skin cancer screening among Hispanics in the United States: a review of the evidence, disparities, and need for expanding the intervention and research agendas. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:743-745.

- Roman C, Lugo-Somolinos A, Thomas N. Skin cancer knowledge and skin self-examinations in the Hispanic population of North Carolina: the patient’s perspective. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:103-104.

- Jaimes N, Oliveria S, Halpern A. A cautionary note on melanoma screening in the Hispanic/Latino population. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:396-397.

- Wich LG, Ma MW, Price LS, et al. Impact of socioeconomic status and sociodemographic factors on melanoma presentation among ethnic minorities. J Community Health. 2011;36:461-468.

- Rouhani P, Hu S, Kirsner RS. Melanoma in Hispanic and black Americans. Cancer Control. 2008;15:248-253.

- Dawes SM, Tsai S, Gittleman H, et al. Racial disparities in melanoma survival. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:983-991.

- Kailas A, Botwin AL, Pritchett EN, et al. Assessing the effectiveness of knowledge-based interventions in increasing skin cancer awareness, knowledge, and protective behaviors in skin of color populations. Cutis. 2017;100:235-240.

- New Brunswick, NJ. Data USA website. https://datausa.io/profile/geo/new-brunswick-nj. Accessed April 17, 2019.

- Higgins S, Nazemi A, Feinstein S, et al. Clinical presentations of melanoma in African Americans, Hispanics, and Asians [published online January 4, 2019]. Dermatol Surg. doi:10.1097/dss.0000000000001759.

- Robinson JK, Penedo FJ, Hay JL, et al. Recognizing Latinos’ range of skin pigment and phototypes to enhance skin cancer prevention [published online July 4, 2017]. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2017;30:488-492.

- Garnett E, Townsend J, Steele B, et al. Characteristics, rates, and trends of melanoma incidence among Hispanics in the USA. Cancer Causes Control. 2016;27:647-659.

- Agbai ON, Buster K, Sanchez M, et al. Skin cancer and photoprotection in people of color: a review and recommendations for physicians and the public. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:748-762.

- Andreeva VA, Cockburn MG. Cutaneous melanoma and other skin cancer screening among Hispanics in the United States: a review of the evidence, disparities, and need for expanding the intervention and research agendas. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:743-745.

- Roman C, Lugo-Somolinos A, Thomas N. Skin cancer knowledge and skin self-examinations in the Hispanic population of North Carolina: the patient’s perspective. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:103-104.

- Jaimes N, Oliveria S, Halpern A. A cautionary note on melanoma screening in the Hispanic/Latino population. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:396-397.

- Wich LG, Ma MW, Price LS, et al. Impact of socioeconomic status and sociodemographic factors on melanoma presentation among ethnic minorities. J Community Health. 2011;36:461-468.

- Rouhani P, Hu S, Kirsner RS. Melanoma in Hispanic and black Americans. Cancer Control. 2008;15:248-253.

- Dawes SM, Tsai S, Gittleman H, et al. Racial disparities in melanoma survival. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:983-991.

- Kailas A, Botwin AL, Pritchett EN, et al. Assessing the effectiveness of knowledge-based interventions in increasing skin cancer awareness, knowledge, and protective behaviors in skin of color populations. Cutis. 2017;100:235-240.

A telemedicine compromise

It’s late on a Thursday afternoon. Even through the six walls that separate you from the waiting room you can feel the impatient throng of families as you struggle to see the tympanic membrane of a feverish and uncooperative 3-year-old. You already have scraped his auditory canal once with your curette. Your gut tells you that he must have an otitis but deeper in your soul there are other voices reminding you that to make the diagnosis you must visualize his ear drum. Your skill and the technology on hand has failed you.

It’s a Sunday morning, weekend hours, and you are seeing a 12-year-old with a sore throat and fever. Her physical exam suggests that she has strep pharyngitis but the team member in charge of restocking supplies has forgotten to reorder rapid strep kits and you used the last one yesterday afternoon.

Do you ignore your training and treat these sick children with antibiotics?

If you are someone who perceives the world in black and white, your response to these scenarios is simple because you NEVER prescribe antibiotics without seeing a tympanic membrane or confirming your suspicion with a rapid strep test. There are unrealistic solutions that could include requesting an immediate ear/nose/throat consult or sending the patient on an hour-long odyssey to the hospital lab. But for the rest of us who see in shades of gray, we may have to compromise our principles and temporarily become poor antibiotic stewards. The question is, how often do you compromise? Once a week, once a month, twice a year, or twice a day?

A study published in Pediatrics looks at the issue of antibiotic stewardship as it relates to telemedicine (“Antibiotic Prescribing During Pediatrics Direct-to-Consumer Telemedicine Visits,” Pediatrics. 2019 May. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-2491).

The investigators found that children with acute respiratory infections were more likely to receive antibiotics and less likely to receive guideline concordant management at direct-to-consumer (DTC) telemedicine visits than when they were seen by their primary care physician or at an urgent care center.

In their discussion, the researchers note several possible explanations for the discrepancies they observed. DTC telemedicine visits are limited by the devices used by the families and physicians and generally lack availability of otoscopy and strep testing. The authors also wonder whether “there may be differential expectations for antibiotics among children and parents who use DTC telemedicine versus in person care.” Does this mean that families who utilize DTC telemedicine undervalue in-person care and/or are willing to compromise by accepting what they may suspect is substandard care for the convenience of DTC telemedicine?

Which brings me to my point. A physician who accepts the challenge of seeing pediatric patients with acute respiratory illnesses knowing that he or she will not be able to visualize tympanic membranes or perform strep testing also has accepted the fact that he or she will be compromising the principles of antibiotic stewardship he or she must have – or maybe should have – learned in medical school or residency.

We all occasionally compromise our principles when technology fails us or when the situations are extraordinary. But I am troubled that there some physicians who are willing to practice in an environment in which they are aware that they will be compromising their antibiotic stewardship on a daily or even hourly basis.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

It’s late on a Thursday afternoon. Even through the six walls that separate you from the waiting room you can feel the impatient throng of families as you struggle to see the tympanic membrane of a feverish and uncooperative 3-year-old. You already have scraped his auditory canal once with your curette. Your gut tells you that he must have an otitis but deeper in your soul there are other voices reminding you that to make the diagnosis you must visualize his ear drum. Your skill and the technology on hand has failed you.

It’s a Sunday morning, weekend hours, and you are seeing a 12-year-old with a sore throat and fever. Her physical exam suggests that she has strep pharyngitis but the team member in charge of restocking supplies has forgotten to reorder rapid strep kits and you used the last one yesterday afternoon.

Do you ignore your training and treat these sick children with antibiotics?

If you are someone who perceives the world in black and white, your response to these scenarios is simple because you NEVER prescribe antibiotics without seeing a tympanic membrane or confirming your suspicion with a rapid strep test. There are unrealistic solutions that could include requesting an immediate ear/nose/throat consult or sending the patient on an hour-long odyssey to the hospital lab. But for the rest of us who see in shades of gray, we may have to compromise our principles and temporarily become poor antibiotic stewards. The question is, how often do you compromise? Once a week, once a month, twice a year, or twice a day?

A study published in Pediatrics looks at the issue of antibiotic stewardship as it relates to telemedicine (“Antibiotic Prescribing During Pediatrics Direct-to-Consumer Telemedicine Visits,” Pediatrics. 2019 May. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-2491).

The investigators found that children with acute respiratory infections were more likely to receive antibiotics and less likely to receive guideline concordant management at direct-to-consumer (DTC) telemedicine visits than when they were seen by their primary care physician or at an urgent care center.

In their discussion, the researchers note several possible explanations for the discrepancies they observed. DTC telemedicine visits are limited by the devices used by the families and physicians and generally lack availability of otoscopy and strep testing. The authors also wonder whether “there may be differential expectations for antibiotics among children and parents who use DTC telemedicine versus in person care.” Does this mean that families who utilize DTC telemedicine undervalue in-person care and/or are willing to compromise by accepting what they may suspect is substandard care for the convenience of DTC telemedicine?