User login

Retail neurosis

When I stopped by last August to pick up new eyeglass lenses, Harold the optician sat alone in his shop.

“Business slow in the summer?” I asked.

Harold looked morose. “I knew it would be like this when I bought the business,” he said. “We’re open Saturdays, but summers I close at 2. Everybody’s at the Cape.”

Working in retail makes people more neurotic than necessary. I should know. I’ve been in retail for 40 years.

My patient Myrtle once explained to me how retail induces neurosis by deforming incentives. Myrtle used to work in management at a big department store. (Older readers may recall going to stores in buildings to buy things. The same readers may recall newspapers.)

“The month between Thanksgiving and Christmas makes or breaks the whole year,” Myrtle said. “If you do worse than last year, you feel bad. But if you do better than last year you also feel bad, because you worry you won’t be able to top it next year.”

She paused. “I guess that’s not a very healthy way to live, is it?”

I was too polite to agree.

Early in my career I had few patients on my schedule, maybe five on a good day. Then three of them would cancel. That was the start of my retail neurosis. Of course, I was a solo practitioner who started my own practice. The likes of me will someday be found in a museum, stuffed and mounted, along with other extinct species, under the label Medicus Cutaneous Solipsisticus (North America c. 20th century).

Over time, I got busier and dropped each of my eleven part-time jobs. By now I’ve been busy for decades, even though I’ve never had much of a waiting list. Don’t know why that is, but it no longer matters.

Except it does, psychologically. You won’t find this code in the DSM, but my working definition for the malady I describe is as follows:

Retail Neurosis (billable ICD-10 code F48.8. Other unspecified nonpsychotic mental disorders, along with writer’s block and psychasthenia):

Definition: The unquenchable fear that even the tiniest break in an endless churn of patients means that all patients will disappear later this afternoon, reverting the practice to the empty, formless void from whence it came. Other than retirement, there is no treatment for this disorder. And maybe not then either.

You might think to classify Retail Neurosis under Financial Insecurity, but that disorder has a different code. (F40.248, Fear of Failing, Life-Circumstance Problem). After all, a single well-remunerated patient (53 actinic keratoses!) can outreimburse half a dozen others with only E/M codes and big deductibles. Treat one of the former, take the rest of the hour off, and you’re financially just as well off, or even better. Yes?

No. Taking the rest of the hour off leaves you with too much time to ponder what every retailer knows: Each idle minute is another lost chance to make another sale and generate revenue. That minute (and revenue) can never be retrieved. Never!

As Myrtle would say, “Not a very healthy way to live, is it?”

Maybe not, but here as elsewhere, knowing something and fixing it are different things. Besides, brisk retail business brings a buzz, along with a sense of mastery and accomplishment, which is pleasantly addictive. Until it isn’t.

New generations of physicians and other medical providers will work in different settings than mine; they will be wage-earners in large organizations. These conglomerations bring their own neurosis-inducing incentives. Their managers measure providers’ productivity in various deforming and crazy-making ways. (See RVU-penia, ICD-10 M26.56: “Nonworking side interference.” This is actually a dental code that refers to jaw position, but billing demands creativity.) Practitioner anxieties will center on being docked for not generating enough relative value units or for failure to bundle enough comorbidities for maximizing capitation payments (e.g., Plaque Psoriasis plus Morbid Obesity plus Writer’s Block). But the youngsters will learn to get along. They’ll have to.

“Taking any time off this summer?” I asked my optician Harold.

“My wife and daughter are going out to Michigan in mid-August,” he said.

“Aren’t you going with them?”

“I can’t swing it that week,” he said. “By then, people are coming back to town, getting their kids ready for school. If I go away, I would miss some customers.”

Harold, you are my kind of guy!

Dr. Rockoff practices dermatology in Brookline, Mass., and is a longtime contributor to Dermatology News. He serves on the clinical faculty at Tufts University, Boston, and has taught senior medical students and other trainees for 30 years. His second book, “Act Like a Doctor, Think Like a Patient,” is available at amazon.com and barnesandnoble.com. Write to him at [email protected].

When I stopped by last August to pick up new eyeglass lenses, Harold the optician sat alone in his shop.

“Business slow in the summer?” I asked.

Harold looked morose. “I knew it would be like this when I bought the business,” he said. “We’re open Saturdays, but summers I close at 2. Everybody’s at the Cape.”

Working in retail makes people more neurotic than necessary. I should know. I’ve been in retail for 40 years.

My patient Myrtle once explained to me how retail induces neurosis by deforming incentives. Myrtle used to work in management at a big department store. (Older readers may recall going to stores in buildings to buy things. The same readers may recall newspapers.)

“The month between Thanksgiving and Christmas makes or breaks the whole year,” Myrtle said. “If you do worse than last year, you feel bad. But if you do better than last year you also feel bad, because you worry you won’t be able to top it next year.”

She paused. “I guess that’s not a very healthy way to live, is it?”

I was too polite to agree.

Early in my career I had few patients on my schedule, maybe five on a good day. Then three of them would cancel. That was the start of my retail neurosis. Of course, I was a solo practitioner who started my own practice. The likes of me will someday be found in a museum, stuffed and mounted, along with other extinct species, under the label Medicus Cutaneous Solipsisticus (North America c. 20th century).

Over time, I got busier and dropped each of my eleven part-time jobs. By now I’ve been busy for decades, even though I’ve never had much of a waiting list. Don’t know why that is, but it no longer matters.

Except it does, psychologically. You won’t find this code in the DSM, but my working definition for the malady I describe is as follows:

Retail Neurosis (billable ICD-10 code F48.8. Other unspecified nonpsychotic mental disorders, along with writer’s block and psychasthenia):

Definition: The unquenchable fear that even the tiniest break in an endless churn of patients means that all patients will disappear later this afternoon, reverting the practice to the empty, formless void from whence it came. Other than retirement, there is no treatment for this disorder. And maybe not then either.

You might think to classify Retail Neurosis under Financial Insecurity, but that disorder has a different code. (F40.248, Fear of Failing, Life-Circumstance Problem). After all, a single well-remunerated patient (53 actinic keratoses!) can outreimburse half a dozen others with only E/M codes and big deductibles. Treat one of the former, take the rest of the hour off, and you’re financially just as well off, or even better. Yes?

No. Taking the rest of the hour off leaves you with too much time to ponder what every retailer knows: Each idle minute is another lost chance to make another sale and generate revenue. That minute (and revenue) can never be retrieved. Never!

As Myrtle would say, “Not a very healthy way to live, is it?”

Maybe not, but here as elsewhere, knowing something and fixing it are different things. Besides, brisk retail business brings a buzz, along with a sense of mastery and accomplishment, which is pleasantly addictive. Until it isn’t.

New generations of physicians and other medical providers will work in different settings than mine; they will be wage-earners in large organizations. These conglomerations bring their own neurosis-inducing incentives. Their managers measure providers’ productivity in various deforming and crazy-making ways. (See RVU-penia, ICD-10 M26.56: “Nonworking side interference.” This is actually a dental code that refers to jaw position, but billing demands creativity.) Practitioner anxieties will center on being docked for not generating enough relative value units or for failure to bundle enough comorbidities for maximizing capitation payments (e.g., Plaque Psoriasis plus Morbid Obesity plus Writer’s Block). But the youngsters will learn to get along. They’ll have to.

“Taking any time off this summer?” I asked my optician Harold.

“My wife and daughter are going out to Michigan in mid-August,” he said.

“Aren’t you going with them?”

“I can’t swing it that week,” he said. “By then, people are coming back to town, getting their kids ready for school. If I go away, I would miss some customers.”

Harold, you are my kind of guy!

Dr. Rockoff practices dermatology in Brookline, Mass., and is a longtime contributor to Dermatology News. He serves on the clinical faculty at Tufts University, Boston, and has taught senior medical students and other trainees for 30 years. His second book, “Act Like a Doctor, Think Like a Patient,” is available at amazon.com and barnesandnoble.com. Write to him at [email protected].

When I stopped by last August to pick up new eyeglass lenses, Harold the optician sat alone in his shop.

“Business slow in the summer?” I asked.

Harold looked morose. “I knew it would be like this when I bought the business,” he said. “We’re open Saturdays, but summers I close at 2. Everybody’s at the Cape.”

Working in retail makes people more neurotic than necessary. I should know. I’ve been in retail for 40 years.

My patient Myrtle once explained to me how retail induces neurosis by deforming incentives. Myrtle used to work in management at a big department store. (Older readers may recall going to stores in buildings to buy things. The same readers may recall newspapers.)

“The month between Thanksgiving and Christmas makes or breaks the whole year,” Myrtle said. “If you do worse than last year, you feel bad. But if you do better than last year you also feel bad, because you worry you won’t be able to top it next year.”

She paused. “I guess that’s not a very healthy way to live, is it?”

I was too polite to agree.

Early in my career I had few patients on my schedule, maybe five on a good day. Then three of them would cancel. That was the start of my retail neurosis. Of course, I was a solo practitioner who started my own practice. The likes of me will someday be found in a museum, stuffed and mounted, along with other extinct species, under the label Medicus Cutaneous Solipsisticus (North America c. 20th century).

Over time, I got busier and dropped each of my eleven part-time jobs. By now I’ve been busy for decades, even though I’ve never had much of a waiting list. Don’t know why that is, but it no longer matters.

Except it does, psychologically. You won’t find this code in the DSM, but my working definition for the malady I describe is as follows:

Retail Neurosis (billable ICD-10 code F48.8. Other unspecified nonpsychotic mental disorders, along with writer’s block and psychasthenia):

Definition: The unquenchable fear that even the tiniest break in an endless churn of patients means that all patients will disappear later this afternoon, reverting the practice to the empty, formless void from whence it came. Other than retirement, there is no treatment for this disorder. And maybe not then either.

You might think to classify Retail Neurosis under Financial Insecurity, but that disorder has a different code. (F40.248, Fear of Failing, Life-Circumstance Problem). After all, a single well-remunerated patient (53 actinic keratoses!) can outreimburse half a dozen others with only E/M codes and big deductibles. Treat one of the former, take the rest of the hour off, and you’re financially just as well off, or even better. Yes?

No. Taking the rest of the hour off leaves you with too much time to ponder what every retailer knows: Each idle minute is another lost chance to make another sale and generate revenue. That minute (and revenue) can never be retrieved. Never!

As Myrtle would say, “Not a very healthy way to live, is it?”

Maybe not, but here as elsewhere, knowing something and fixing it are different things. Besides, brisk retail business brings a buzz, along with a sense of mastery and accomplishment, which is pleasantly addictive. Until it isn’t.

New generations of physicians and other medical providers will work in different settings than mine; they will be wage-earners in large organizations. These conglomerations bring their own neurosis-inducing incentives. Their managers measure providers’ productivity in various deforming and crazy-making ways. (See RVU-penia, ICD-10 M26.56: “Nonworking side interference.” This is actually a dental code that refers to jaw position, but billing demands creativity.) Practitioner anxieties will center on being docked for not generating enough relative value units or for failure to bundle enough comorbidities for maximizing capitation payments (e.g., Plaque Psoriasis plus Morbid Obesity plus Writer’s Block). But the youngsters will learn to get along. They’ll have to.

“Taking any time off this summer?” I asked my optician Harold.

“My wife and daughter are going out to Michigan in mid-August,” he said.

“Aren’t you going with them?”

“I can’t swing it that week,” he said. “By then, people are coming back to town, getting their kids ready for school. If I go away, I would miss some customers.”

Harold, you are my kind of guy!

Dr. Rockoff practices dermatology in Brookline, Mass., and is a longtime contributor to Dermatology News. He serves on the clinical faculty at Tufts University, Boston, and has taught senior medical students and other trainees for 30 years. His second book, “Act Like a Doctor, Think Like a Patient,” is available at amazon.com and barnesandnoble.com. Write to him at [email protected].

Navigating the Oncology Care Model

Care of the cancer patient is complex and expensive. During 2001-2011, medical spending to treat cancer increased from $56.8 billion to $88.3 billion in the United States. During this time, ambulatory expenditures for care and treatment increased while inpatient hospital expenditures decreased.1,2 Treatments for cancer have advanced, but costs do not correlate with outcomes. Advanced payment models aimed at ensuring high quality while lowering costs may be the vehicle to help mitigate the financial burden of cancer treatment on patients and society at large.

Oncology Care Model

The Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation designed the Oncology Care Model (OCM), which allows practices and payers in the United States to partner with the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. The goal of the OCM is to provide high quality, highly coordinated cancer care at the same or lower cost. Practice partnerships with the CMS involve payment arrangements that include financial and performance accountability for episodes of cancer care surrounding chemotherapy delivery to patients.3

Practices that have been selected by the CMS have attested to providing a number of enhanced services from 24/7 patient access to an appropriate clinician who can access medical records to having a documented care plan for every patient.4

Payment methodology

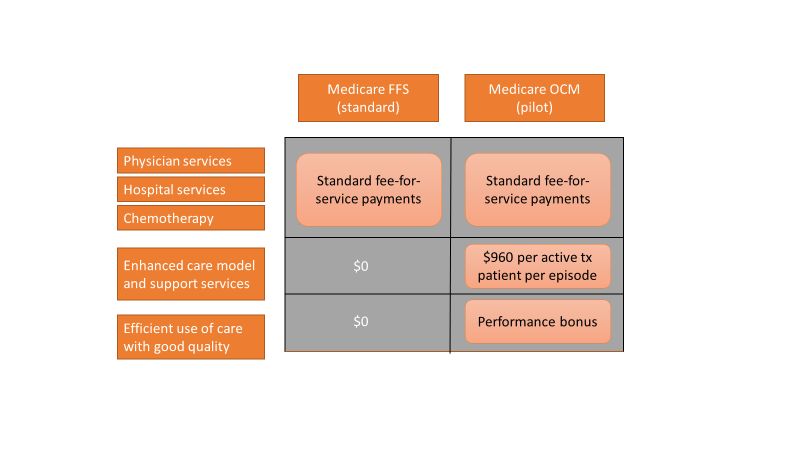

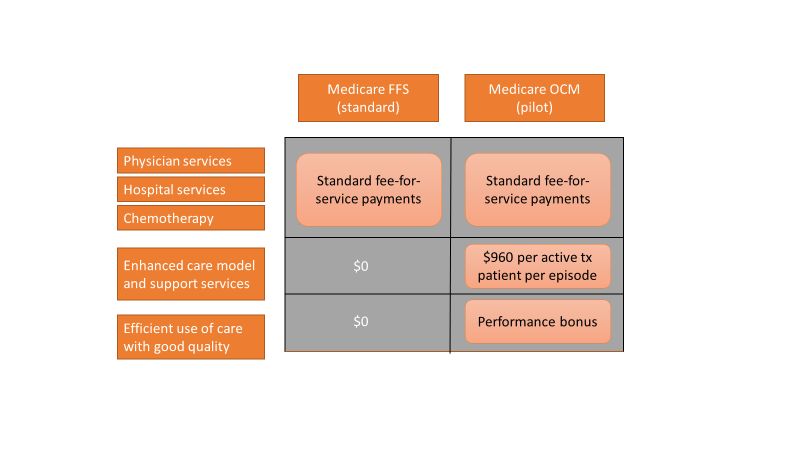

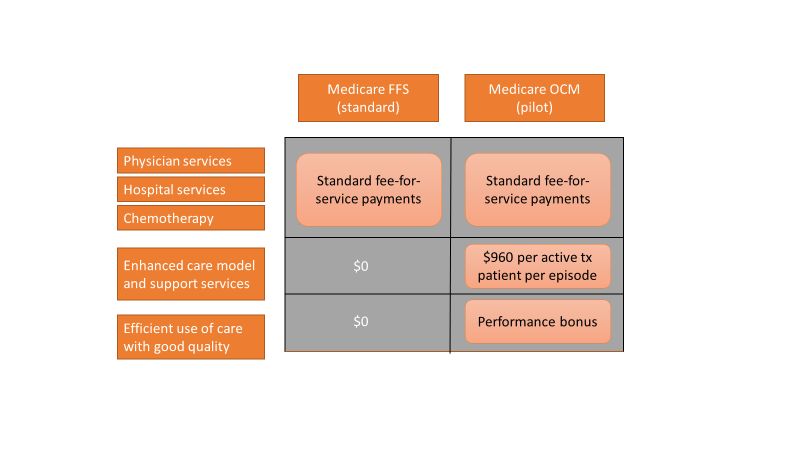

An episode of care is defined as a 6-month period that starts at the time of chemotherapy administration. In addition to the standard fee-for-service payment, practices have the ability to earn two other types of payments during an oncology episode.

The per-beneficiary Monthly Enhanced Oncology Services payment is $960 for the entire episode but is paid to practices at $160 per month.

Practices have the potential to earn additional performance-based payments (PBP) based on the difference in cost between the projected and actual cost of the episode. The PBP also incorporates performance on quality metrics, based on Medicare claims and other information submitted by the practice. For example, claims-based measures include hospital, emergency department (ED), and hospice utilization.

To participate in the OCM, practices must choose either a one-sided or two-sided risk model. In the one-sided risk model, practices take on no downside risk but need to achieve a greater reduction in expenditures (4% below the benchmark price). In the two-side risk model, practices need only to reduce expenditures by 2.75% below the benchmark price. But if they fail to meet their savings goals, they must pay the difference to the CMS. The recoupment is capped at 20% of the benchmark amount.

Feedback reports

The CMS sends quarterly feedback reports that contain information on practice demographics, outcomes, expenditures, chemotherapy use, and patient satisfaction. The outcomes include the mortality rate for Medicare beneficiaries treated at the practice, compared with other practices nationally. In addition, the reports include end-of-life metrics and patient satisfaction, as well as details of expenditures on drugs, hospital use, imaging and laboratory services, and a description of chemotherapy usage.

These reports can be a helpful tool for measuring your own use of services, as well as benchmarking it against national figures.

Practice modifications

According to CMS feedback reports, the cost of care per beneficiary per month has increased across all practices since the inception of the OCM. However, there are practices that have been successful in reducing cost of care without negatively affecting mortality.

Drugs, hospital, and ED visits, along with imaging and laboratory evaluation, account for 75% of the cost. Some strategies to reduce expenditure involve targeting those areas.

Consider prescribing drugs conservatively without affecting outcomes. For instance, bisphosphonates for bone metastasis can be given every 12 weeks instead of 4 weeks.5 Similarly, adjuvant chemotherapy can be given for 3 months, instead of 6 months in appropriate stage 3 colon cancer patients.6

Another potential opportunity for savings is the judicious use of pertuzumab in early-stage breast cancer patients.7 These are all evidence-based recommendations with potential for cost savings. Clinical pathways can aid in this process, but physician buy-in is imperative.

In terms of imaging, avoid PET scans when they will not affect your clinical decision making, avoid staging scans in early-stage breast and prostate cancer patients, and avoid surveillance scans among early-stage breast cancer and lymphoma patients. The Choosing Wisely campaign can help guide some of these decisions.8

Another area where good care meets cost effective care is in the early engagement of palliative care. Several studies have shown that early involvement of palliative care improves survival and quality of life.9,10 Palliative care involvement also decreases the emotional burden for patients and oncologists. Appropriate symptom control, particularly of pain, decreases hospitalizations during treatment.

Investing in a robust supportive care team – financial advocates, social work, nutrition, behavioral health, as well as various community services – can help reduce the financial, physical, and emotional distress levels for patients. All of these services ultimately lead to reduced hospitalizations.11 The Monthly Enhanced Oncology Services payment can be put toward these expenses.

Care teams working at the highest level of competence and license can also save time and money. Consider using registered nurses to implement triage pathways to assess side effects and symptom management, or using nurse practitioners, registered nurses, and physician assistants for same-day appointments and to assess symptoms rather than referring patients to the emergency department.

Avoid the ED and hospitalizations by using the infusion center to provide hydration and blood transfusions in a timely fashion.

Telemedicine can be used for symptom management as well as leveraging supportive care services.

Cost for cancer care is very difficult to sustain. The OCM provides early insights into expenditures, challenges, and opportunities. Practices should use this information to build infrastructure and provide high quality, cost-effective care. Value-based cancer care should be the overarching goal for oncology practices and health care organizations.

Dr. Mahesh is the director of hematology-oncology and program director of the Oncology Care Model at Summa Health in Akron, Ohio.

References

1. Siegel RL et al. Cancer statistics, 2018. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018 Jan;68(1):7-30.

2. Medical Expenditure Panel Survey, Statistical Brief #443. 2014 Jun.

3. CMS: Oncology Care Model.

4. CMS: OCM Frequently Asked Questions.

5. Himelstein AL et al. Effect of longer-interval vs. standard dosing of zoledronic acid on skeletal events in patients with bone metastases. JAMA. 2017 Jan 3;317(1):48-58.

6. Grothey A et al. Duration of adjuvant chemotherapy for stage III colon cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(13):1177-88.

7. Von Minckwitz G et al. Adjuvant pertuzumab and trastuzumab in early HER2-positive breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(2):122-31.

8. American Society of Clinical Oncology: Ten Things Physician and Patients Should Question.

9. Temel JS et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non–small cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(8):733-42.

10. Blayney DW et al. Critical lessons from high-value oncology practices. JAMA Oncol. 2018 Feb 1;4(2):164-71.

11. Sherman DE. Transforming practices through the oncology care model: financial toxicity and counseling. J Oncol Pract. 2017 Aug;13(8):519-22.

Care of the cancer patient is complex and expensive. During 2001-2011, medical spending to treat cancer increased from $56.8 billion to $88.3 billion in the United States. During this time, ambulatory expenditures for care and treatment increased while inpatient hospital expenditures decreased.1,2 Treatments for cancer have advanced, but costs do not correlate with outcomes. Advanced payment models aimed at ensuring high quality while lowering costs may be the vehicle to help mitigate the financial burden of cancer treatment on patients and society at large.

Oncology Care Model

The Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation designed the Oncology Care Model (OCM), which allows practices and payers in the United States to partner with the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. The goal of the OCM is to provide high quality, highly coordinated cancer care at the same or lower cost. Practice partnerships with the CMS involve payment arrangements that include financial and performance accountability for episodes of cancer care surrounding chemotherapy delivery to patients.3

Practices that have been selected by the CMS have attested to providing a number of enhanced services from 24/7 patient access to an appropriate clinician who can access medical records to having a documented care plan for every patient.4

Payment methodology

An episode of care is defined as a 6-month period that starts at the time of chemotherapy administration. In addition to the standard fee-for-service payment, practices have the ability to earn two other types of payments during an oncology episode.

The per-beneficiary Monthly Enhanced Oncology Services payment is $960 for the entire episode but is paid to practices at $160 per month.

Practices have the potential to earn additional performance-based payments (PBP) based on the difference in cost between the projected and actual cost of the episode. The PBP also incorporates performance on quality metrics, based on Medicare claims and other information submitted by the practice. For example, claims-based measures include hospital, emergency department (ED), and hospice utilization.

To participate in the OCM, practices must choose either a one-sided or two-sided risk model. In the one-sided risk model, practices take on no downside risk but need to achieve a greater reduction in expenditures (4% below the benchmark price). In the two-side risk model, practices need only to reduce expenditures by 2.75% below the benchmark price. But if they fail to meet their savings goals, they must pay the difference to the CMS. The recoupment is capped at 20% of the benchmark amount.

Feedback reports

The CMS sends quarterly feedback reports that contain information on practice demographics, outcomes, expenditures, chemotherapy use, and patient satisfaction. The outcomes include the mortality rate for Medicare beneficiaries treated at the practice, compared with other practices nationally. In addition, the reports include end-of-life metrics and patient satisfaction, as well as details of expenditures on drugs, hospital use, imaging and laboratory services, and a description of chemotherapy usage.

These reports can be a helpful tool for measuring your own use of services, as well as benchmarking it against national figures.

Practice modifications

According to CMS feedback reports, the cost of care per beneficiary per month has increased across all practices since the inception of the OCM. However, there are practices that have been successful in reducing cost of care without negatively affecting mortality.

Drugs, hospital, and ED visits, along with imaging and laboratory evaluation, account for 75% of the cost. Some strategies to reduce expenditure involve targeting those areas.

Consider prescribing drugs conservatively without affecting outcomes. For instance, bisphosphonates for bone metastasis can be given every 12 weeks instead of 4 weeks.5 Similarly, adjuvant chemotherapy can be given for 3 months, instead of 6 months in appropriate stage 3 colon cancer patients.6

Another potential opportunity for savings is the judicious use of pertuzumab in early-stage breast cancer patients.7 These are all evidence-based recommendations with potential for cost savings. Clinical pathways can aid in this process, but physician buy-in is imperative.

In terms of imaging, avoid PET scans when they will not affect your clinical decision making, avoid staging scans in early-stage breast and prostate cancer patients, and avoid surveillance scans among early-stage breast cancer and lymphoma patients. The Choosing Wisely campaign can help guide some of these decisions.8

Another area where good care meets cost effective care is in the early engagement of palliative care. Several studies have shown that early involvement of palliative care improves survival and quality of life.9,10 Palliative care involvement also decreases the emotional burden for patients and oncologists. Appropriate symptom control, particularly of pain, decreases hospitalizations during treatment.

Investing in a robust supportive care team – financial advocates, social work, nutrition, behavioral health, as well as various community services – can help reduce the financial, physical, and emotional distress levels for patients. All of these services ultimately lead to reduced hospitalizations.11 The Monthly Enhanced Oncology Services payment can be put toward these expenses.

Care teams working at the highest level of competence and license can also save time and money. Consider using registered nurses to implement triage pathways to assess side effects and symptom management, or using nurse practitioners, registered nurses, and physician assistants for same-day appointments and to assess symptoms rather than referring patients to the emergency department.

Avoid the ED and hospitalizations by using the infusion center to provide hydration and blood transfusions in a timely fashion.

Telemedicine can be used for symptom management as well as leveraging supportive care services.

Cost for cancer care is very difficult to sustain. The OCM provides early insights into expenditures, challenges, and opportunities. Practices should use this information to build infrastructure and provide high quality, cost-effective care. Value-based cancer care should be the overarching goal for oncology practices and health care organizations.

Dr. Mahesh is the director of hematology-oncology and program director of the Oncology Care Model at Summa Health in Akron, Ohio.

References

1. Siegel RL et al. Cancer statistics, 2018. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018 Jan;68(1):7-30.

2. Medical Expenditure Panel Survey, Statistical Brief #443. 2014 Jun.

3. CMS: Oncology Care Model.

4. CMS: OCM Frequently Asked Questions.

5. Himelstein AL et al. Effect of longer-interval vs. standard dosing of zoledronic acid on skeletal events in patients with bone metastases. JAMA. 2017 Jan 3;317(1):48-58.

6. Grothey A et al. Duration of adjuvant chemotherapy for stage III colon cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(13):1177-88.

7. Von Minckwitz G et al. Adjuvant pertuzumab and trastuzumab in early HER2-positive breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(2):122-31.

8. American Society of Clinical Oncology: Ten Things Physician and Patients Should Question.

9. Temel JS et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non–small cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(8):733-42.

10. Blayney DW et al. Critical lessons from high-value oncology practices. JAMA Oncol. 2018 Feb 1;4(2):164-71.

11. Sherman DE. Transforming practices through the oncology care model: financial toxicity and counseling. J Oncol Pract. 2017 Aug;13(8):519-22.

Care of the cancer patient is complex and expensive. During 2001-2011, medical spending to treat cancer increased from $56.8 billion to $88.3 billion in the United States. During this time, ambulatory expenditures for care and treatment increased while inpatient hospital expenditures decreased.1,2 Treatments for cancer have advanced, but costs do not correlate with outcomes. Advanced payment models aimed at ensuring high quality while lowering costs may be the vehicle to help mitigate the financial burden of cancer treatment on patients and society at large.

Oncology Care Model

The Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation designed the Oncology Care Model (OCM), which allows practices and payers in the United States to partner with the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. The goal of the OCM is to provide high quality, highly coordinated cancer care at the same or lower cost. Practice partnerships with the CMS involve payment arrangements that include financial and performance accountability for episodes of cancer care surrounding chemotherapy delivery to patients.3

Practices that have been selected by the CMS have attested to providing a number of enhanced services from 24/7 patient access to an appropriate clinician who can access medical records to having a documented care plan for every patient.4

Payment methodology

An episode of care is defined as a 6-month period that starts at the time of chemotherapy administration. In addition to the standard fee-for-service payment, practices have the ability to earn two other types of payments during an oncology episode.

The per-beneficiary Monthly Enhanced Oncology Services payment is $960 for the entire episode but is paid to practices at $160 per month.

Practices have the potential to earn additional performance-based payments (PBP) based on the difference in cost between the projected and actual cost of the episode. The PBP also incorporates performance on quality metrics, based on Medicare claims and other information submitted by the practice. For example, claims-based measures include hospital, emergency department (ED), and hospice utilization.

To participate in the OCM, practices must choose either a one-sided or two-sided risk model. In the one-sided risk model, practices take on no downside risk but need to achieve a greater reduction in expenditures (4% below the benchmark price). In the two-side risk model, practices need only to reduce expenditures by 2.75% below the benchmark price. But if they fail to meet their savings goals, they must pay the difference to the CMS. The recoupment is capped at 20% of the benchmark amount.

Feedback reports

The CMS sends quarterly feedback reports that contain information on practice demographics, outcomes, expenditures, chemotherapy use, and patient satisfaction. The outcomes include the mortality rate for Medicare beneficiaries treated at the practice, compared with other practices nationally. In addition, the reports include end-of-life metrics and patient satisfaction, as well as details of expenditures on drugs, hospital use, imaging and laboratory services, and a description of chemotherapy usage.

These reports can be a helpful tool for measuring your own use of services, as well as benchmarking it against national figures.

Practice modifications

According to CMS feedback reports, the cost of care per beneficiary per month has increased across all practices since the inception of the OCM. However, there are practices that have been successful in reducing cost of care without negatively affecting mortality.

Drugs, hospital, and ED visits, along with imaging and laboratory evaluation, account for 75% of the cost. Some strategies to reduce expenditure involve targeting those areas.

Consider prescribing drugs conservatively without affecting outcomes. For instance, bisphosphonates for bone metastasis can be given every 12 weeks instead of 4 weeks.5 Similarly, adjuvant chemotherapy can be given for 3 months, instead of 6 months in appropriate stage 3 colon cancer patients.6

Another potential opportunity for savings is the judicious use of pertuzumab in early-stage breast cancer patients.7 These are all evidence-based recommendations with potential for cost savings. Clinical pathways can aid in this process, but physician buy-in is imperative.

In terms of imaging, avoid PET scans when they will not affect your clinical decision making, avoid staging scans in early-stage breast and prostate cancer patients, and avoid surveillance scans among early-stage breast cancer and lymphoma patients. The Choosing Wisely campaign can help guide some of these decisions.8

Another area where good care meets cost effective care is in the early engagement of palliative care. Several studies have shown that early involvement of palliative care improves survival and quality of life.9,10 Palliative care involvement also decreases the emotional burden for patients and oncologists. Appropriate symptom control, particularly of pain, decreases hospitalizations during treatment.

Investing in a robust supportive care team – financial advocates, social work, nutrition, behavioral health, as well as various community services – can help reduce the financial, physical, and emotional distress levels for patients. All of these services ultimately lead to reduced hospitalizations.11 The Monthly Enhanced Oncology Services payment can be put toward these expenses.

Care teams working at the highest level of competence and license can also save time and money. Consider using registered nurses to implement triage pathways to assess side effects and symptom management, or using nurse practitioners, registered nurses, and physician assistants for same-day appointments and to assess symptoms rather than referring patients to the emergency department.

Avoid the ED and hospitalizations by using the infusion center to provide hydration and blood transfusions in a timely fashion.

Telemedicine can be used for symptom management as well as leveraging supportive care services.

Cost for cancer care is very difficult to sustain. The OCM provides early insights into expenditures, challenges, and opportunities. Practices should use this information to build infrastructure and provide high quality, cost-effective care. Value-based cancer care should be the overarching goal for oncology practices and health care organizations.

Dr. Mahesh is the director of hematology-oncology and program director of the Oncology Care Model at Summa Health in Akron, Ohio.

References

1. Siegel RL et al. Cancer statistics, 2018. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018 Jan;68(1):7-30.

2. Medical Expenditure Panel Survey, Statistical Brief #443. 2014 Jun.

3. CMS: Oncology Care Model.

4. CMS: OCM Frequently Asked Questions.

5. Himelstein AL et al. Effect of longer-interval vs. standard dosing of zoledronic acid on skeletal events in patients with bone metastases. JAMA. 2017 Jan 3;317(1):48-58.

6. Grothey A et al. Duration of adjuvant chemotherapy for stage III colon cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(13):1177-88.

7. Von Minckwitz G et al. Adjuvant pertuzumab and trastuzumab in early HER2-positive breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(2):122-31.

8. American Society of Clinical Oncology: Ten Things Physician and Patients Should Question.

9. Temel JS et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non–small cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(8):733-42.

10. Blayney DW et al. Critical lessons from high-value oncology practices. JAMA Oncol. 2018 Feb 1;4(2):164-71.

11. Sherman DE. Transforming practices through the oncology care model: financial toxicity and counseling. J Oncol Pract. 2017 Aug;13(8):519-22.

Part 4: Misguided Research or Missed Opportunities?

I have been ruminating about the Bai et al article on independent billing in the emergency department (ED) for weeks.1 I keep wondering why the data analysis seems so off base. Don’t get me wrong: The data gathered from Medicare is what it is—but a key piece of information is not present in the pure numbers input to the Medicare database.

So, I continued to probe this study with my colleagues. To a person, their comments supported that the intent of the study is unclear. The authors posit their objective to be an examination of the “involvement of NPs and PAs” in emergency services, using billing data. But to use billing data as a measure of “involvement” does not tell the whole story.

Independence in billing does not mean that the care NPs and PAs are providing is “beyond their scope of practice.” Moreover, the billing does not capture whether, or to what extent, physician consultation or assistance was involved. If the NP or PA dictated the chart, then they are by default the “only” (independent) provider. However, billing independently does not mean a physician (or other provider) was not consulted about the plan of care.

Case in point: Years ago, I had a young woman present to the ED with a sore throat. Her presenting complaint was a symptom of a peritonsillar abscess. So I phoned an ENT colleague (a physician) and asked him about the best treatment and follow-up in this case. Did he make a note in or sign the chart? No. Was I the only provider of record? Yes. Was that care “independent,” if you only look at the billing (done by a coder, for the record)? Yes.

Admittedly, Bai and colleagues do add in their conclusion that “independence in billing … does not necessarily indicate [NPs’/PAs’] independence in care delivery.”1 And they do note that the true challenge in the ED is determining how best to “blend” the expertise of the three professions (MD, NP, and PA) to provide efficient and cost-effective care.

However, throughout the article, there is an underpinning of inference that NPs and PAs are potentially practicing beyond their scope. Their comment that the increase in billing for NP and PA services results in a “reduction of the proportion of emergency physicians” speaks volumes.1 Perhaps there is more concern here about ED physician job security than about independent billing!

Regardless of the intention by Bai et al—and acknowledging that the analysis they presented is somewhat interesting—I see two missed opportunities to “actionalize” the data.2 One is to use the information to identify whether a problem with billing exists (ie, is there upcharging as a result of more details contained within the electronic health record?). The second is to use the data to investigate innovative ways to improve access to care across the continuum. Essentially, how do we use the results of any data analysis in a way that can be useful? That is the real challenge.

Continue to: The biggest conclusion I've drawn...

The biggest conclusion I’ve drawn from my exploration of these study findings? The opportunity to investigate the competencies of all ED providers, with the goal of improving access and controlling costs, is there. And as the NPs and PAs providing the care, we should undertake the next research study or data analysis and not leave the research on us to other professions!

I’d love to hear your thoughts on the Bai et al study or any aspect of this 4-part discussion! Drop me a line at [email protected].

1. Bai G, Kelen GD, Frick KD, Anderson GF. Nurse practitioners and physician assistants in emergency medical services who billed independently, 2012-2016. Am J Emerg Med. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2019.01.052. Accessed April 1, 2019.

2. The Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania. Big data’s biggest challenge: how to avoid getting lost in the weeds. Knowledge@Wharton podcast. March 14, 2019. http://knowledge.wharton.upenn.edu/article/data-analytics-challenges. Accessed April 1, 2019.

I have been ruminating about the Bai et al article on independent billing in the emergency department (ED) for weeks.1 I keep wondering why the data analysis seems so off base. Don’t get me wrong: The data gathered from Medicare is what it is—but a key piece of information is not present in the pure numbers input to the Medicare database.

So, I continued to probe this study with my colleagues. To a person, their comments supported that the intent of the study is unclear. The authors posit their objective to be an examination of the “involvement of NPs and PAs” in emergency services, using billing data. But to use billing data as a measure of “involvement” does not tell the whole story.

Independence in billing does not mean that the care NPs and PAs are providing is “beyond their scope of practice.” Moreover, the billing does not capture whether, or to what extent, physician consultation or assistance was involved. If the NP or PA dictated the chart, then they are by default the “only” (independent) provider. However, billing independently does not mean a physician (or other provider) was not consulted about the plan of care.

Case in point: Years ago, I had a young woman present to the ED with a sore throat. Her presenting complaint was a symptom of a peritonsillar abscess. So I phoned an ENT colleague (a physician) and asked him about the best treatment and follow-up in this case. Did he make a note in or sign the chart? No. Was I the only provider of record? Yes. Was that care “independent,” if you only look at the billing (done by a coder, for the record)? Yes.

Admittedly, Bai and colleagues do add in their conclusion that “independence in billing … does not necessarily indicate [NPs’/PAs’] independence in care delivery.”1 And they do note that the true challenge in the ED is determining how best to “blend” the expertise of the three professions (MD, NP, and PA) to provide efficient and cost-effective care.

However, throughout the article, there is an underpinning of inference that NPs and PAs are potentially practicing beyond their scope. Their comment that the increase in billing for NP and PA services results in a “reduction of the proportion of emergency physicians” speaks volumes.1 Perhaps there is more concern here about ED physician job security than about independent billing!

Regardless of the intention by Bai et al—and acknowledging that the analysis they presented is somewhat interesting—I see two missed opportunities to “actionalize” the data.2 One is to use the information to identify whether a problem with billing exists (ie, is there upcharging as a result of more details contained within the electronic health record?). The second is to use the data to investigate innovative ways to improve access to care across the continuum. Essentially, how do we use the results of any data analysis in a way that can be useful? That is the real challenge.

Continue to: The biggest conclusion I've drawn...

The biggest conclusion I’ve drawn from my exploration of these study findings? The opportunity to investigate the competencies of all ED providers, with the goal of improving access and controlling costs, is there. And as the NPs and PAs providing the care, we should undertake the next research study or data analysis and not leave the research on us to other professions!

I’d love to hear your thoughts on the Bai et al study or any aspect of this 4-part discussion! Drop me a line at [email protected].

I have been ruminating about the Bai et al article on independent billing in the emergency department (ED) for weeks.1 I keep wondering why the data analysis seems so off base. Don’t get me wrong: The data gathered from Medicare is what it is—but a key piece of information is not present in the pure numbers input to the Medicare database.

So, I continued to probe this study with my colleagues. To a person, their comments supported that the intent of the study is unclear. The authors posit their objective to be an examination of the “involvement of NPs and PAs” in emergency services, using billing data. But to use billing data as a measure of “involvement” does not tell the whole story.

Independence in billing does not mean that the care NPs and PAs are providing is “beyond their scope of practice.” Moreover, the billing does not capture whether, or to what extent, physician consultation or assistance was involved. If the NP or PA dictated the chart, then they are by default the “only” (independent) provider. However, billing independently does not mean a physician (or other provider) was not consulted about the plan of care.

Case in point: Years ago, I had a young woman present to the ED with a sore throat. Her presenting complaint was a symptom of a peritonsillar abscess. So I phoned an ENT colleague (a physician) and asked him about the best treatment and follow-up in this case. Did he make a note in or sign the chart? No. Was I the only provider of record? Yes. Was that care “independent,” if you only look at the billing (done by a coder, for the record)? Yes.

Admittedly, Bai and colleagues do add in their conclusion that “independence in billing … does not necessarily indicate [NPs’/PAs’] independence in care delivery.”1 And they do note that the true challenge in the ED is determining how best to “blend” the expertise of the three professions (MD, NP, and PA) to provide efficient and cost-effective care.

However, throughout the article, there is an underpinning of inference that NPs and PAs are potentially practicing beyond their scope. Their comment that the increase in billing for NP and PA services results in a “reduction of the proportion of emergency physicians” speaks volumes.1 Perhaps there is more concern here about ED physician job security than about independent billing!

Regardless of the intention by Bai et al—and acknowledging that the analysis they presented is somewhat interesting—I see two missed opportunities to “actionalize” the data.2 One is to use the information to identify whether a problem with billing exists (ie, is there upcharging as a result of more details contained within the electronic health record?). The second is to use the data to investigate innovative ways to improve access to care across the continuum. Essentially, how do we use the results of any data analysis in a way that can be useful? That is the real challenge.

Continue to: The biggest conclusion I've drawn...

The biggest conclusion I’ve drawn from my exploration of these study findings? The opportunity to investigate the competencies of all ED providers, with the goal of improving access and controlling costs, is there. And as the NPs and PAs providing the care, we should undertake the next research study or data analysis and not leave the research on us to other professions!

I’d love to hear your thoughts on the Bai et al study or any aspect of this 4-part discussion! Drop me a line at [email protected].

1. Bai G, Kelen GD, Frick KD, Anderson GF. Nurse practitioners and physician assistants in emergency medical services who billed independently, 2012-2016. Am J Emerg Med. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2019.01.052. Accessed April 1, 2019.

2. The Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania. Big data’s biggest challenge: how to avoid getting lost in the weeds. Knowledge@Wharton podcast. March 14, 2019. http://knowledge.wharton.upenn.edu/article/data-analytics-challenges. Accessed April 1, 2019.

1. Bai G, Kelen GD, Frick KD, Anderson GF. Nurse practitioners and physician assistants in emergency medical services who billed independently, 2012-2016. Am J Emerg Med. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2019.01.052. Accessed April 1, 2019.

2. The Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania. Big data’s biggest challenge: how to avoid getting lost in the weeds. Knowledge@Wharton podcast. March 14, 2019. http://knowledge.wharton.upenn.edu/article/data-analytics-challenges. Accessed April 1, 2019.

Suicide barriers on the Golden Gate Bridge: Will they save lives?

Ultimately, we need to find better treatments for depression and anxiety

San Francisco entrances people. Photographers capture more images of the Golden Gate Bridge than any other bridge in the world.1 And only the Nanjing Yangtze River Bridge in China surpasses the Golden Gate as a destination for dying by suicide.2 At least 1,700 people reportedly have plunged from the bridge to their deaths since its opening in 1937.3

Despite concerted efforts by bridge security, the local mental health community, and a volunteer organization – Bridgewatch Angels – suicides continue at the pace of about 1 every 2 weeks. After more than 60 years of discussion, transportation officials allocated funding and have started building a suicide prevention barrier system on the Golden Gate.

Extrapolating from the success of barriers built on other bridges that were “suicide magnets,” we should be able to assure people that suicide deaths from the Golden Gate will dramatically decrease, and perhaps cease completely.4 Certainly, some in the mental health community think this barrier will save lives. They support this claim by citing research showing that removing highly accessible and lethal means of suicide reduces overall suicide rates, and that suicidal individuals, when thwarted, do not seek alternate modes of death.

I support building the Golden Gate suicide barrier, partly because symbolically, it should deliver a powerful message that we value all human life. But will the barrier save lives? I don’t think it will. As the American Psychiatric Association prepares to gather for its annual meeting in San Francisco, I would like to share my reasoning.

What the evidence shows

The most robust evidence that restricting availability of highly lethal and accessible means of suicide reduces overall suicide deaths comes from studies looking at self-poisoning in Asian countries and Great Britain. In many parts of Asia, ingestion of pesticides constitutes a significant proportion of suicide deaths, and several studies have found that, in localities where sales of highly lethal pesticides were restricted, overall suicide deaths decreased.5,6 Conversely, suicide rates increased when more lethal varieties of pesticides became more available. In Great Britain, overall suicide rates decreased when natural gas replaced coal gas for home heating and cooking.7 For decades preceding this change, more Britons had killed themselves by inhaling coal gas than by any other method.

Strong correlations exist between regional levels of gun ownership and suicide rates by shooting,8 but several potentially confounding sociopolitical factors explain some portion of this connection. Stronger evidence of gun availability affecting suicide rates has been demonstrated by decreases in suicide rates after restrictions in gun access in Switzerland,9 Israel,10 and other areas. These studies show correlations – not causality. However, the number of studies, links between increases and decreases in suicide rates with changes in access to guns, absence of changes in suicide rates during the same time periods among ostensibly similar control populations, and lack of other compelling explanations support the argument that restricting access to highly lethal and accessible means of suicide prevents suicide deaths overall.

The installation of suicide barriers on bridges that have been the sites of multiple suicides robustly reduces or even eliminates suicide deaths from those bridges,11 but the effect on overall suicide rates remains less clear. Various studies have found subsequent increases or no changes12-14 in suicide deaths from other bridges or tall buildings in the vicinity after the installation of suicide barriers on a “suicide magnet.” Many of the studies failed to find any impact on overall suicide rates in the regions investigated. Deaths from jumping off tall structures constitute a tiny proportion of total suicide deaths, making it difficult to detect any changes in overall suicide rates. In the United States, suicides by jumping/falling constituted 1%-2% of total suicides over the last several decades.15

If we know that restricting highly lethal and accessible methods of killing reduces suicide deaths, why would I question the value of the Golden Gate suicide barrier in preventing overall suicide deaths?

Unique aspects of the bridge

The World High Dive Federation recommends keeping dives to less than 20 meters (65.5 feet), with a few exceptions.16 The rail of the Golden Gate Bridge stands 67 meters (220 feet) above the water, and assuming minimal wind resistance, a falling person traverses that distance in about 3.7 seconds and lands with an impact of 130 km/hour (81 miles per hour).17 Only about 1%-2% of those jumping from the Golden Gate survive that fall.18

A 99% likelihood of death sounds pretty lethal; however, death by jumping from the Golden Gate inherently takes place in a public space, with the opportunity for interventions by other people. A more realistic calculation of the lethality would start the instant that someone initiates a sequence of behaviors leading to the intended death. By that criteria, measuring the lethality of the Golden Gate would begin when an individual enters a vehicle or sets off on foot with the plan of going over the railing.

Unless our surveillance-oriented society makes substantially greater advances (which I oppose), we will remain unable to assess suicide lethality by starting at the moment of inception. However, we do have data showing what happens once someone with suicidal intentions walks onto the bridge.

Between 2000 and 2018, observers noted 2,546 people on the Golden Gate who appeared to be considering a suicide attempt, the San Francisco Chronicle has reported. Five hundred sixty-four confirmed suicides occurred. In an additional 71 cases, suicide is presumed but bodies were not recovered. In the 1,911 remaining instances, mental health interventions were made, with individuals taken to local hospitals and psychiatric wards, and released when no longer overtly suicidal. Interventions successfully diverted 75% (1,911/2,546) of those intending to end their own lives, which suggests that the current lethality of the Golden Gate as a means of suicide is only 25%. Even in the bridge’s first half-century, without constant camera monitoring, and a cadre of volunteers and professionals scanning for those attempting suicide, the lethality rate approached about 50%.19

We face even more difficulties measuring accessibility than in determining lethality. The Golden Gate appears to be accessible to almost anyone – drivers have to pay a toll only when traveling from the north, and then only after they have traversed the span. Pedestrians retain unfettered admittance to the east sidewalk (facing San Francisco city and bay) throughout daylight hours. But any determination of accessibility must include how quickly and easily one can make use of an opportunity.

Both entrances to the Golden Gate are embedded in the Golden Gate National Recreational Area, part of the National Park system. The south entrance to the bridge arises from The Presidio, a former military installation that housed about 4,000 people.20 Even fewer people live in the parklands at the north end of the bridge. The Presidio extends far enough so that the closest San Francisco neighborhoods outside of the park are a full 2.2 km (1.36 miles) from the bridge railing. A brisk walk would still require a minimum of about 20 minutes to get to the bridge; it is difficult to arrive at the bridge without a trek.

Researchers define impulsivity, like accessibility, inconsistently – and often imprecisely. Impulsivity, which clearly exists on a spectrum, connotes overvaluing of immediate feelings and thoughts at the expense of longer term goals and aspirations. Some suicide research appears to define impulsivity as the antithesis of planned behavior;21,22 others define it pragmatically as behaviors executed within 5 minutes of a decision,23 and still others contend that “suicidal behavior is rarely if ever impulsive.”24 Furthermore, when we assess impulsivity, we must acknowledge a fundamental difference between “impulsive” shootings and poisonings that are accomplished at home and within seconds or minutes, from “impulsive” Golden Gate Bridge suicide attempts, which require substantial travel and time commitments, and inherently involve the potential for others to intervene.

Those arguing that the bridge suicide barrier will save lives often bring up two additional sets of numbers to back up their assertions. They provide evidence that most of those people who were stopped in their attempts at suicide at the Golden Gate do not go on to commit suicide elsewhere, and that many of those who survived their attempts express regret at having tried to kill themselves. Specifically, 94% of those who were prevented from jumping from the Golden Gate had not committed suicide after a median follow-up of 26 years, according to a follow-up study published a few years ago. On the other hand, those who have made a serious suicide attempt have a substantially increased risk, relative to the general population, of dying from a later attempt,25,26 and the strongest predictor for death by suicide is having made a previous, serious suicide attempt.27

While all of these studies provide important and interesting information regarding suicide, none directly address the question of whether individuals will substitute attempts by other methods if the Golden Gate Bridge were no longer available. Many discussions blur the distinction between how individuals behave after a thwarted Golden Gate suicide attempt and how other people might act if we secured the bridge from any potential future suicide attempts. I hope that the following analogy makes this distinction clearer without trivializing: Imagine that we know that everyone who was interrupted while eating their dinner in a particular restaurant never went back and ate out anywhere, ever again. We could not conclude from this that another individual, who learned that the intended restaurant was indefinitely closed, would never dine out again. Once effective suicide barriers exist on the Golden Gate, this will likely become widely known, thereby greatly reducing the likelihood that any individuals will consider the possibility of jumping from the bridge. But it seems very unlikely that this would vanquish all suicidal impulses from the northern California population.

Lessons from patients

Two former patients of mine ended their lives by suicide from the Golden Gate. P, a solitary and lonely man in his 50s, was referred to me by his neighbor, Q, one of my long-term patients. P had a history of repeated assessments for lifelong depression, with minimal follow-up. I made a treatment plan with P that we hoped would address both his depression and his reluctance to engage with mental health professionals. He did not return for his follow-up appointment and ignored all my attempts to contact him.

P continued to have intermittent contact with Q. A decade after I had evaluated him, P was finally hospitalized for depression. Since P had no local family or friends, he asked Q to pick him up from the hospital at the time of his discharge. P asked Q to drive him to the Golden Gate Bridge, ostensibly to relish his release by partaking of the panoramic view of San Francisco from the bridge. They parked in the lot at the north end of the bridge, where Q stayed with the car at the vista point. The last that anyone saw of P was when Q noticed him walking on the bridge; nobody saw him go over and his body was not recovered.

In contrast to my brief connection with P, I worked with S over the course of 8 years to deal with her very severe attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and associated depression, which destroyed jobs and friendships, and estranged her from her family. She moved to Hawaii in hopes of “starting over with less baggage,” but I received a few phone calls over the next few years detailing suicide attempts, including driving her car off a bridge. Floundering in life, she returned to San Francisco and was hospitalized with suicidal ideation. The inpatient team sedated her heavily, ignored her past treatments and diagnoses, and discharged her after several days. Within a day of discharge, S’s sister called to say that S’s body had been recovered from the water below the bridge.

I don’t think that suicide was inevitable for either P or S, but I also lack any indication that either would be alive today had we installed suicide barriers on the Golden Gate years ago. Unless we eliminate access to guns, cars, trains, poisons, ropes, tall buildings and cliffs, people contemplating suicide will have numerous options at their disposal. We are likely to save lives by continuing to find ways to restrict access to means of death that can be used within seconds and have a high degree of lethality, and we should persist with such efforts. Buying a $5 trigger lock for every gun in California, and spending tens of millions on a public service campaign would cost less and may well save more lives than the Golden Gate suicide barrier. Unfortunately, we still possess very limited knowledge regarding which suicide prevention measures have an “impact on actual deaths or behavior.”28

To increase our efficacy in reducing suicide, we need to find better treatments for depression and anxiety. We also need to identify better ways of targeting those most at risk for suicide,29 improve our delivery of such treatments, and mitigate the social factors that contribute to such misery and unhappiness.

As a psychiatrist who has lost not only patients but also family members to suicide, I appreciate the hole in the soul these deaths create. I understand the drive to find ways to prevent additional deaths and save future survivors from such grief. But we must design psychiatric interventions that do the maximum good. To be imprecise in the lessons we learn from those who have killed themselves doubles down on the disservice to those lives already lost.

Dr. Kruse is a psychiatrist who practices in San Francisco. Several key details about the patients were changed to protect confidentiality.

References

1. Frommer’s Comprehensive Travel Guide, California. New York: Prentice Hall Travel, 1993.

2. “Chen Si, the ‘Angel of Nanjing,’ has saved more than 330 people from suicide,” by Matt Young, News.com.au. May 14, 2017.

3. “Finding Kyle,” by Lizzie Johnson, San Francisco Chronicle. Feb 8, 2019.

4. Beautrais A. Suicide by jumping. A review of research and prevention strategies. Crisis. 2007 Jan;28 Suppl 1:58-63. Crisis: The J of Crisis Interven Suicide Preven. 2007 Jan. (28)[Suppl1]:58-63.

5. Gunnell D et al. The global distribution of fatal pesticide self-poisoning: Systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2007 Dec. 21;7:357.

6. Vijayakumar L and Satheesh-Babu R. Does ‘no pesticide’ reduce suicides? Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2009 Jul 17;55:401-6.

7. Kreitman N. The coal gas story. United Kingdom suicide rates, 1960-71. Br J Prev Soc Med. 1976 Jun;30(2)86-93.

8. Ajdacic-Gross V et al. Changing times: A longitudinal analysis of international firearm suicide data. Am J Public Health. 2006 Oct;96(10):1752-5.

9. Reisch T et al. Change in suicide rates in Switzerland before and after firearm restriction resulting from the 2003 “Army XXI” reform. Am J Psychiatry. 2013 Sep170(9):977-84.

10. Lubin G et al. Decrease in suicide rates after a change of policy reducing access to firearms in adolescents: A naturalistic epidemiological study. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2010 Oct;40(5):421-4.

11. Sinyor M and Levitt A. Effect of a barrier at Bloor Street Viaduct on suicide rates in Toronto: Natural experiment BMJ. 2010;341. doi: 1136/bmjc2884.

12. O’Carroll P and Silverman M. Community suicide prevention: The effectiveness of bridge barriers. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 1994 Spring;24(1):89-91; discussion 91-9.

13. Pelletier A. Preventing suicide by jumping: The effect of a bridge safety fence. Inj Prev. 2007 Feb;13(1):57-9.

14. Bennewith O et al. Effect of barriers on the Clifton suspension bridge, England, on local patterns of suicide: Implications for prevention. Br J Psychiatry. 2007 Mar;190:266-7.

15. Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. 2004. “How do people most commonly complete suicide?”

16. “How cliff diving works,” by Heather Kolich, HowStuffWorks.com. Oct 5, 2009.

17. “Bridge design and construction statistics.” Goldengate.org

18. “How did teen survive fall from Golden Gate Bridge?” by Remy Molina, Live Science. Apr 19, 2011.

19. Seiden R. Where are they now? A follow-up study of suicide attempters from the Golden Gate Bridge. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 1978 Winter;8(4):203-16.

20. Presidio demographics. Point2homes.com.

21. Baca-García E et al. A prospective study of the paradoxical relationship between impulsivity and lethality of suicide attempts. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001 Jul;62(7):560-4.

22. Lim M et al. Differences between impulsive and non-impulsive suicide attempts among individuals treated in emergency rooms of South Korea. Psychiatry Investig. 2016 Jul;13(4):389-96.

23. Simon O et al. Characteristics of impulsive suicide attempts and attempters. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2001;32(1 Suppl):49-59.

24. Anestis M et al. Reconsidering the link between impulsivity and suicidal behavior. Pers Soc Psychol Rev. 2014 Nov;18(4):366-86.

25. Ostamo A et al. Excess mortality of suicide attempters. Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2001 Jan;36(1):29-35.

26. Leon A et al. Statistical issues in the identification of risk factors for suicidal behavior: The application of survival analysis. Psychiatry Res. 1990 Jan;31(1):99-108.

27. Bostwick J et al. Suicide attempt as a risk factor for completed suicide: Even more lethal than we knew. Am J Psychiatry. 2016 Nov 1;173(11):1094-100.

28. Stone D and Crosby A. Suicide prevention. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2014;8(6):404-20.

29. Belsher B et al. Prediction models for suicide attempts and deaths: A systematic review and simulation. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019 Mar 13. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.0174.

Ultimately, we need to find better treatments for depression and anxiety

Ultimately, we need to find better treatments for depression and anxiety

San Francisco entrances people. Photographers capture more images of the Golden Gate Bridge than any other bridge in the world.1 And only the Nanjing Yangtze River Bridge in China surpasses the Golden Gate as a destination for dying by suicide.2 At least 1,700 people reportedly have plunged from the bridge to their deaths since its opening in 1937.3

Despite concerted efforts by bridge security, the local mental health community, and a volunteer organization – Bridgewatch Angels – suicides continue at the pace of about 1 every 2 weeks. After more than 60 years of discussion, transportation officials allocated funding and have started building a suicide prevention barrier system on the Golden Gate.

Extrapolating from the success of barriers built on other bridges that were “suicide magnets,” we should be able to assure people that suicide deaths from the Golden Gate will dramatically decrease, and perhaps cease completely.4 Certainly, some in the mental health community think this barrier will save lives. They support this claim by citing research showing that removing highly accessible and lethal means of suicide reduces overall suicide rates, and that suicidal individuals, when thwarted, do not seek alternate modes of death.

I support building the Golden Gate suicide barrier, partly because symbolically, it should deliver a powerful message that we value all human life. But will the barrier save lives? I don’t think it will. As the American Psychiatric Association prepares to gather for its annual meeting in San Francisco, I would like to share my reasoning.

What the evidence shows

The most robust evidence that restricting availability of highly lethal and accessible means of suicide reduces overall suicide deaths comes from studies looking at self-poisoning in Asian countries and Great Britain. In many parts of Asia, ingestion of pesticides constitutes a significant proportion of suicide deaths, and several studies have found that, in localities where sales of highly lethal pesticides were restricted, overall suicide deaths decreased.5,6 Conversely, suicide rates increased when more lethal varieties of pesticides became more available. In Great Britain, overall suicide rates decreased when natural gas replaced coal gas for home heating and cooking.7 For decades preceding this change, more Britons had killed themselves by inhaling coal gas than by any other method.

Strong correlations exist between regional levels of gun ownership and suicide rates by shooting,8 but several potentially confounding sociopolitical factors explain some portion of this connection. Stronger evidence of gun availability affecting suicide rates has been demonstrated by decreases in suicide rates after restrictions in gun access in Switzerland,9 Israel,10 and other areas. These studies show correlations – not causality. However, the number of studies, links between increases and decreases in suicide rates with changes in access to guns, absence of changes in suicide rates during the same time periods among ostensibly similar control populations, and lack of other compelling explanations support the argument that restricting access to highly lethal and accessible means of suicide prevents suicide deaths overall.

The installation of suicide barriers on bridges that have been the sites of multiple suicides robustly reduces or even eliminates suicide deaths from those bridges,11 but the effect on overall suicide rates remains less clear. Various studies have found subsequent increases or no changes12-14 in suicide deaths from other bridges or tall buildings in the vicinity after the installation of suicide barriers on a “suicide magnet.” Many of the studies failed to find any impact on overall suicide rates in the regions investigated. Deaths from jumping off tall structures constitute a tiny proportion of total suicide deaths, making it difficult to detect any changes in overall suicide rates. In the United States, suicides by jumping/falling constituted 1%-2% of total suicides over the last several decades.15

If we know that restricting highly lethal and accessible methods of killing reduces suicide deaths, why would I question the value of the Golden Gate suicide barrier in preventing overall suicide deaths?

Unique aspects of the bridge

The World High Dive Federation recommends keeping dives to less than 20 meters (65.5 feet), with a few exceptions.16 The rail of the Golden Gate Bridge stands 67 meters (220 feet) above the water, and assuming minimal wind resistance, a falling person traverses that distance in about 3.7 seconds and lands with an impact of 130 km/hour (81 miles per hour).17 Only about 1%-2% of those jumping from the Golden Gate survive that fall.18

A 99% likelihood of death sounds pretty lethal; however, death by jumping from the Golden Gate inherently takes place in a public space, with the opportunity for interventions by other people. A more realistic calculation of the lethality would start the instant that someone initiates a sequence of behaviors leading to the intended death. By that criteria, measuring the lethality of the Golden Gate would begin when an individual enters a vehicle or sets off on foot with the plan of going over the railing.

Unless our surveillance-oriented society makes substantially greater advances (which I oppose), we will remain unable to assess suicide lethality by starting at the moment of inception. However, we do have data showing what happens once someone with suicidal intentions walks onto the bridge.

Between 2000 and 2018, observers noted 2,546 people on the Golden Gate who appeared to be considering a suicide attempt, the San Francisco Chronicle has reported. Five hundred sixty-four confirmed suicides occurred. In an additional 71 cases, suicide is presumed but bodies were not recovered. In the 1,911 remaining instances, mental health interventions were made, with individuals taken to local hospitals and psychiatric wards, and released when no longer overtly suicidal. Interventions successfully diverted 75% (1,911/2,546) of those intending to end their own lives, which suggests that the current lethality of the Golden Gate as a means of suicide is only 25%. Even in the bridge’s first half-century, without constant camera monitoring, and a cadre of volunteers and professionals scanning for those attempting suicide, the lethality rate approached about 50%.19

We face even more difficulties measuring accessibility than in determining lethality. The Golden Gate appears to be accessible to almost anyone – drivers have to pay a toll only when traveling from the north, and then only after they have traversed the span. Pedestrians retain unfettered admittance to the east sidewalk (facing San Francisco city and bay) throughout daylight hours. But any determination of accessibility must include how quickly and easily one can make use of an opportunity.

Both entrances to the Golden Gate are embedded in the Golden Gate National Recreational Area, part of the National Park system. The south entrance to the bridge arises from The Presidio, a former military installation that housed about 4,000 people.20 Even fewer people live in the parklands at the north end of the bridge. The Presidio extends far enough so that the closest San Francisco neighborhoods outside of the park are a full 2.2 km (1.36 miles) from the bridge railing. A brisk walk would still require a minimum of about 20 minutes to get to the bridge; it is difficult to arrive at the bridge without a trek.

Researchers define impulsivity, like accessibility, inconsistently – and often imprecisely. Impulsivity, which clearly exists on a spectrum, connotes overvaluing of immediate feelings and thoughts at the expense of longer term goals and aspirations. Some suicide research appears to define impulsivity as the antithesis of planned behavior;21,22 others define it pragmatically as behaviors executed within 5 minutes of a decision,23 and still others contend that “suicidal behavior is rarely if ever impulsive.”24 Furthermore, when we assess impulsivity, we must acknowledge a fundamental difference between “impulsive” shootings and poisonings that are accomplished at home and within seconds or minutes, from “impulsive” Golden Gate Bridge suicide attempts, which require substantial travel and time commitments, and inherently involve the potential for others to intervene.

Those arguing that the bridge suicide barrier will save lives often bring up two additional sets of numbers to back up their assertions. They provide evidence that most of those people who were stopped in their attempts at suicide at the Golden Gate do not go on to commit suicide elsewhere, and that many of those who survived their attempts express regret at having tried to kill themselves. Specifically, 94% of those who were prevented from jumping from the Golden Gate had not committed suicide after a median follow-up of 26 years, according to a follow-up study published a few years ago. On the other hand, those who have made a serious suicide attempt have a substantially increased risk, relative to the general population, of dying from a later attempt,25,26 and the strongest predictor for death by suicide is having made a previous, serious suicide attempt.27

While all of these studies provide important and interesting information regarding suicide, none directly address the question of whether individuals will substitute attempts by other methods if the Golden Gate Bridge were no longer available. Many discussions blur the distinction between how individuals behave after a thwarted Golden Gate suicide attempt and how other people might act if we secured the bridge from any potential future suicide attempts. I hope that the following analogy makes this distinction clearer without trivializing: Imagine that we know that everyone who was interrupted while eating their dinner in a particular restaurant never went back and ate out anywhere, ever again. We could not conclude from this that another individual, who learned that the intended restaurant was indefinitely closed, would never dine out again. Once effective suicide barriers exist on the Golden Gate, this will likely become widely known, thereby greatly reducing the likelihood that any individuals will consider the possibility of jumping from the bridge. But it seems very unlikely that this would vanquish all suicidal impulses from the northern California population.

Lessons from patients