User login

Identifying CMV infection in asymptomatic newborns – one step closer?

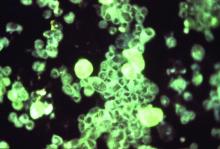

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection is the most common congenital viral infection in U.S. children, with a frequency between 0.5% and 1% of newborn infants resulting in approximately 30,000 infected children annually. A small minority (approximately 10%) can be identified in the neonatal period as symptomatic with jaundice (from direct hyperbilirubinemia), petechiae (from thrombocytopenia), hepatosplenomegaly, microcephaly, or other manifestations. The vast majority are asymptomatic at birth, yet 15% will have or develop sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL) during the first few years of life; others (1%-2%) will develop vision loss associated with retinal scars. Congenital CMV accounts for 20% of those with SNHL detected at birth and 25% of children with SNHL at 4 years of age.

Screening for congenital CMV has been an ongoing subject of debate. The challenges of implementing screening programs are related both to the diagnostics (collecting urine samples on newborns) as well as with the question of whether we have treatment and interventions to offer babies diagnosed with congenital CMV across the complete spectrum of clinical presentations.

Current screening programs implemented in some hospitals, called “targeted screening,” in which babies who fail newborn screening programs are tested for CMV, are not sufficient to achieve the goal of identifying babies who will need follow-up for early detection of SNHL or vision abnormalities, or possibly early antiviral therapy (Valcyte; valganciclovir), because only a small portion of those who eventually develop SNHL are currently identified by the targeted screening programs.1

However, its availability only has added to the debate as to whether the time has arrived for universal screening.

Vertical transmission of CMV occurs in utero (during any of the trimesters), at birth by passage through the birth canal, or postnatally by ingestion of breast milk. Neonatal infection (in utero and postnatal) occurs in both mothers with primary CMV infection during gestation and in those with recurrent infection (from a different viral strain) or reactivation of infection. Severe clinically symptomatic disease and sequelae is associated with primary maternal infection and early transmission to the fetus. However, it is estimated that nonprimary maternal infection accounts for 75% of neonatal infections. Transmission by breast milk to full-term, healthy infants does not appear to be associated with clinical illness or sequelae; however, preterm infants or those with birth weights less than 1,500 g have a small risk of developing clinical disease.

The polymerase chain reaction–based saliva CMV test (Alethia CMV Assay Test System) was licensed by the Food and Drug Administration in November 2018 after studies demonstrated high sensitivity and specificity, compared with viral culture (the gold standard). In one study, 17,327 infants were screened with the liquid-saliva PCR assay, and 0.5% tested positive for CMV on both the saliva test and culture. Sensitivity and specificity of the liquid-saliva PCR assay were 100% and 99.9%, respectively.2 The availability of an approved saliva-based assay that is both highly sensitive and specific overcomes the challenge of collecting urine, which has been a limiting factor in development of pragmatic universal screening programs. To date, most of the focus in identification of congenital CMV infection has been linking newborn hearing testing programs with CMV testing. For some, these have been labeled “targeted screening programs for CMV.” To us, these appear to be best practice for medical evaluations of an infant with identified SNHL. The availability of saliva-based CMV testing should enable virtually all children who fail newborn screening to be tested for CMV. In multiple studies,3,4 6% of infants with confirmed hearing screen failure tested positive for CMV. A recent study5 identified only 1 infant among the 171 infants who failed newborn screening, however only approximately 15% of the infants were eventually confirmed as hearing impaired at audiology follow-up, suggesting that programmatically testing for CMV might be limited to those with confirmed hearing loss if such can be accomplished within a narrow window of time.

The major challenge with linking CMV testing with newborn hearing screening is whether treatment with valganciclovir would be of value in congenital CMV infection and isolated hearing loss. Studies of children with symptomatic central nervous system congenital CMV disease provide evidence of improvement (or lack of progression) in hearing loss in those treated with valganciclovir. Few, if any of these children had isolated hearing loss in this pivotal study.6 An observational study reported improved outcomes in 55 of 59 (93%) children with congenital CMV and isolated SNHL treated with valganciclovir between birth to 12 weeks of life.7 Hearing improved in nearly 70% of ears, 27% showed no change, and only 3% demonstrated progression of hearing loss; most of the improved ears returned to normal hearing. Currently, a National Institutes of Health study (ValEAR) is recruiting CMV-infected infants with isolated SNHL and randomizing them to treatment with valganciclovir or placebo. The goal is to determine if infants treated with valganciclovir will have better hearing and language outcomes.

Linking CMV testing to those who fail newborn hearing screening programs is an important step, as it appears such children are at least five times more likely to be infected with CMV than is the overall birth cohort. However, such strategies fall short of identifying the majority of newborns with congenital CMV infection, who are completely asymptomatic yet are at risk for development of complications that potentially have substantial impact on their quality of life. Although the availability of sensitive and specific PCR testing in saliva provides a pragmatic approach to identify infected children, many questions remain. First, would a confirmatory test be necessary, such as urine PCR (now considered the gold standard by many CMV experts)? Second, once identified, what regimen for follow-up testing would be indicated to identify those with early SNHL or retinopathy, and until what age? Third, is there a role for treatment in asymptomatic infection? Would that treatment be prophylactic, prior to the development of clinical signs, or implemented once early evidence of SNHL or retinopathy is present?

The Valgan Toddler study – sponsored by NIH and the University of Alabama as part of the Collaborative Antiviral Study Group – will enroll children who are aged 1 month through 3 years and who had a recent diagnosis of hearing loss (within the prior 12 weeks) and evidence of congenital CMV infection. The purpose of this study is to compare the effect on hearing and neurologic outcomes in infants aged 1 month through 4 years with recent onset SNHL who receive 6 weeks of valganciclovir versus children who do not receive this drug. The results of such studies will be critical for the development of best practices.

In summary, the licensure of a rapid PCR-based tool for diagnosis of CMV infection from saliva adds to our ability to develop screening programs to detect asymptomatic infants with congenital CMV infection. The ability to link newborns who fail hearing screening programs with CMV testing will lead to more detection of CMV-infected neonates, both with isolated hearing loss, and subsequently with no signs or symptoms of infection. There is an urgent need for evidence from randomized clinical trials to enable the development of best practices for such infants.

Dr. Pelton is professor of pediatrics and epidemiology at Boston University and senior attending physician at Boston Medical Center. Dr. Lapidot is a senior fellow in pediatric infectious diseases, Boston Medical Center. Neither Dr. Pelton nor Dr. Lapidot have any relevant financial disclosures. Email them at [email protected].

References

1. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 2019 Mar 28;8(1):55-9.

2. N Engl J Med 2011 Jun 2; 364:2111-8.

3. Pediatrics. 2008 May;121(5):970-5

4. J Clin Virol. 2018 May;102:110-5.

5. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 2019 Mar;8(1):55-9.

6. J Pediatr. 2003 Jul;143(1):16-25.

7. J Pediatr. 2018 Aug;199:166-70.

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection is the most common congenital viral infection in U.S. children, with a frequency between 0.5% and 1% of newborn infants resulting in approximately 30,000 infected children annually. A small minority (approximately 10%) can be identified in the neonatal period as symptomatic with jaundice (from direct hyperbilirubinemia), petechiae (from thrombocytopenia), hepatosplenomegaly, microcephaly, or other manifestations. The vast majority are asymptomatic at birth, yet 15% will have or develop sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL) during the first few years of life; others (1%-2%) will develop vision loss associated with retinal scars. Congenital CMV accounts for 20% of those with SNHL detected at birth and 25% of children with SNHL at 4 years of age.

Screening for congenital CMV has been an ongoing subject of debate. The challenges of implementing screening programs are related both to the diagnostics (collecting urine samples on newborns) as well as with the question of whether we have treatment and interventions to offer babies diagnosed with congenital CMV across the complete spectrum of clinical presentations.

Current screening programs implemented in some hospitals, called “targeted screening,” in which babies who fail newborn screening programs are tested for CMV, are not sufficient to achieve the goal of identifying babies who will need follow-up for early detection of SNHL or vision abnormalities, or possibly early antiviral therapy (Valcyte; valganciclovir), because only a small portion of those who eventually develop SNHL are currently identified by the targeted screening programs.1

However, its availability only has added to the debate as to whether the time has arrived for universal screening.

Vertical transmission of CMV occurs in utero (during any of the trimesters), at birth by passage through the birth canal, or postnatally by ingestion of breast milk. Neonatal infection (in utero and postnatal) occurs in both mothers with primary CMV infection during gestation and in those with recurrent infection (from a different viral strain) or reactivation of infection. Severe clinically symptomatic disease and sequelae is associated with primary maternal infection and early transmission to the fetus. However, it is estimated that nonprimary maternal infection accounts for 75% of neonatal infections. Transmission by breast milk to full-term, healthy infants does not appear to be associated with clinical illness or sequelae; however, preterm infants or those with birth weights less than 1,500 g have a small risk of developing clinical disease.

The polymerase chain reaction–based saliva CMV test (Alethia CMV Assay Test System) was licensed by the Food and Drug Administration in November 2018 after studies demonstrated high sensitivity and specificity, compared with viral culture (the gold standard). In one study, 17,327 infants were screened with the liquid-saliva PCR assay, and 0.5% tested positive for CMV on both the saliva test and culture. Sensitivity and specificity of the liquid-saliva PCR assay were 100% and 99.9%, respectively.2 The availability of an approved saliva-based assay that is both highly sensitive and specific overcomes the challenge of collecting urine, which has been a limiting factor in development of pragmatic universal screening programs. To date, most of the focus in identification of congenital CMV infection has been linking newborn hearing testing programs with CMV testing. For some, these have been labeled “targeted screening programs for CMV.” To us, these appear to be best practice for medical evaluations of an infant with identified SNHL. The availability of saliva-based CMV testing should enable virtually all children who fail newborn screening to be tested for CMV. In multiple studies,3,4 6% of infants with confirmed hearing screen failure tested positive for CMV. A recent study5 identified only 1 infant among the 171 infants who failed newborn screening, however only approximately 15% of the infants were eventually confirmed as hearing impaired at audiology follow-up, suggesting that programmatically testing for CMV might be limited to those with confirmed hearing loss if such can be accomplished within a narrow window of time.

The major challenge with linking CMV testing with newborn hearing screening is whether treatment with valganciclovir would be of value in congenital CMV infection and isolated hearing loss. Studies of children with symptomatic central nervous system congenital CMV disease provide evidence of improvement (or lack of progression) in hearing loss in those treated with valganciclovir. Few, if any of these children had isolated hearing loss in this pivotal study.6 An observational study reported improved outcomes in 55 of 59 (93%) children with congenital CMV and isolated SNHL treated with valganciclovir between birth to 12 weeks of life.7 Hearing improved in nearly 70% of ears, 27% showed no change, and only 3% demonstrated progression of hearing loss; most of the improved ears returned to normal hearing. Currently, a National Institutes of Health study (ValEAR) is recruiting CMV-infected infants with isolated SNHL and randomizing them to treatment with valganciclovir or placebo. The goal is to determine if infants treated with valganciclovir will have better hearing and language outcomes.

Linking CMV testing to those who fail newborn hearing screening programs is an important step, as it appears such children are at least five times more likely to be infected with CMV than is the overall birth cohort. However, such strategies fall short of identifying the majority of newborns with congenital CMV infection, who are completely asymptomatic yet are at risk for development of complications that potentially have substantial impact on their quality of life. Although the availability of sensitive and specific PCR testing in saliva provides a pragmatic approach to identify infected children, many questions remain. First, would a confirmatory test be necessary, such as urine PCR (now considered the gold standard by many CMV experts)? Second, once identified, what regimen for follow-up testing would be indicated to identify those with early SNHL or retinopathy, and until what age? Third, is there a role for treatment in asymptomatic infection? Would that treatment be prophylactic, prior to the development of clinical signs, or implemented once early evidence of SNHL or retinopathy is present?

The Valgan Toddler study – sponsored by NIH and the University of Alabama as part of the Collaborative Antiviral Study Group – will enroll children who are aged 1 month through 3 years and who had a recent diagnosis of hearing loss (within the prior 12 weeks) and evidence of congenital CMV infection. The purpose of this study is to compare the effect on hearing and neurologic outcomes in infants aged 1 month through 4 years with recent onset SNHL who receive 6 weeks of valganciclovir versus children who do not receive this drug. The results of such studies will be critical for the development of best practices.

In summary, the licensure of a rapid PCR-based tool for diagnosis of CMV infection from saliva adds to our ability to develop screening programs to detect asymptomatic infants with congenital CMV infection. The ability to link newborns who fail hearing screening programs with CMV testing will lead to more detection of CMV-infected neonates, both with isolated hearing loss, and subsequently with no signs or symptoms of infection. There is an urgent need for evidence from randomized clinical trials to enable the development of best practices for such infants.

Dr. Pelton is professor of pediatrics and epidemiology at Boston University and senior attending physician at Boston Medical Center. Dr. Lapidot is a senior fellow in pediatric infectious diseases, Boston Medical Center. Neither Dr. Pelton nor Dr. Lapidot have any relevant financial disclosures. Email them at [email protected].

References

1. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 2019 Mar 28;8(1):55-9.

2. N Engl J Med 2011 Jun 2; 364:2111-8.

3. Pediatrics. 2008 May;121(5):970-5

4. J Clin Virol. 2018 May;102:110-5.

5. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 2019 Mar;8(1):55-9.

6. J Pediatr. 2003 Jul;143(1):16-25.

7. J Pediatr. 2018 Aug;199:166-70.

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection is the most common congenital viral infection in U.S. children, with a frequency between 0.5% and 1% of newborn infants resulting in approximately 30,000 infected children annually. A small minority (approximately 10%) can be identified in the neonatal period as symptomatic with jaundice (from direct hyperbilirubinemia), petechiae (from thrombocytopenia), hepatosplenomegaly, microcephaly, or other manifestations. The vast majority are asymptomatic at birth, yet 15% will have or develop sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL) during the first few years of life; others (1%-2%) will develop vision loss associated with retinal scars. Congenital CMV accounts for 20% of those with SNHL detected at birth and 25% of children with SNHL at 4 years of age.

Screening for congenital CMV has been an ongoing subject of debate. The challenges of implementing screening programs are related both to the diagnostics (collecting urine samples on newborns) as well as with the question of whether we have treatment and interventions to offer babies diagnosed with congenital CMV across the complete spectrum of clinical presentations.

Current screening programs implemented in some hospitals, called “targeted screening,” in which babies who fail newborn screening programs are tested for CMV, are not sufficient to achieve the goal of identifying babies who will need follow-up for early detection of SNHL or vision abnormalities, or possibly early antiviral therapy (Valcyte; valganciclovir), because only a small portion of those who eventually develop SNHL are currently identified by the targeted screening programs.1

However, its availability only has added to the debate as to whether the time has arrived for universal screening.

Vertical transmission of CMV occurs in utero (during any of the trimesters), at birth by passage through the birth canal, or postnatally by ingestion of breast milk. Neonatal infection (in utero and postnatal) occurs in both mothers with primary CMV infection during gestation and in those with recurrent infection (from a different viral strain) or reactivation of infection. Severe clinically symptomatic disease and sequelae is associated with primary maternal infection and early transmission to the fetus. However, it is estimated that nonprimary maternal infection accounts for 75% of neonatal infections. Transmission by breast milk to full-term, healthy infants does not appear to be associated with clinical illness or sequelae; however, preterm infants or those with birth weights less than 1,500 g have a small risk of developing clinical disease.

The polymerase chain reaction–based saliva CMV test (Alethia CMV Assay Test System) was licensed by the Food and Drug Administration in November 2018 after studies demonstrated high sensitivity and specificity, compared with viral culture (the gold standard). In one study, 17,327 infants were screened with the liquid-saliva PCR assay, and 0.5% tested positive for CMV on both the saliva test and culture. Sensitivity and specificity of the liquid-saliva PCR assay were 100% and 99.9%, respectively.2 The availability of an approved saliva-based assay that is both highly sensitive and specific overcomes the challenge of collecting urine, which has been a limiting factor in development of pragmatic universal screening programs. To date, most of the focus in identification of congenital CMV infection has been linking newborn hearing testing programs with CMV testing. For some, these have been labeled “targeted screening programs for CMV.” To us, these appear to be best practice for medical evaluations of an infant with identified SNHL. The availability of saliva-based CMV testing should enable virtually all children who fail newborn screening to be tested for CMV. In multiple studies,3,4 6% of infants with confirmed hearing screen failure tested positive for CMV. A recent study5 identified only 1 infant among the 171 infants who failed newborn screening, however only approximately 15% of the infants were eventually confirmed as hearing impaired at audiology follow-up, suggesting that programmatically testing for CMV might be limited to those with confirmed hearing loss if such can be accomplished within a narrow window of time.

The major challenge with linking CMV testing with newborn hearing screening is whether treatment with valganciclovir would be of value in congenital CMV infection and isolated hearing loss. Studies of children with symptomatic central nervous system congenital CMV disease provide evidence of improvement (or lack of progression) in hearing loss in those treated with valganciclovir. Few, if any of these children had isolated hearing loss in this pivotal study.6 An observational study reported improved outcomes in 55 of 59 (93%) children with congenital CMV and isolated SNHL treated with valganciclovir between birth to 12 weeks of life.7 Hearing improved in nearly 70% of ears, 27% showed no change, and only 3% demonstrated progression of hearing loss; most of the improved ears returned to normal hearing. Currently, a National Institutes of Health study (ValEAR) is recruiting CMV-infected infants with isolated SNHL and randomizing them to treatment with valganciclovir or placebo. The goal is to determine if infants treated with valganciclovir will have better hearing and language outcomes.

Linking CMV testing to those who fail newborn hearing screening programs is an important step, as it appears such children are at least five times more likely to be infected with CMV than is the overall birth cohort. However, such strategies fall short of identifying the majority of newborns with congenital CMV infection, who are completely asymptomatic yet are at risk for development of complications that potentially have substantial impact on their quality of life. Although the availability of sensitive and specific PCR testing in saliva provides a pragmatic approach to identify infected children, many questions remain. First, would a confirmatory test be necessary, such as urine PCR (now considered the gold standard by many CMV experts)? Second, once identified, what regimen for follow-up testing would be indicated to identify those with early SNHL or retinopathy, and until what age? Third, is there a role for treatment in asymptomatic infection? Would that treatment be prophylactic, prior to the development of clinical signs, or implemented once early evidence of SNHL or retinopathy is present?

The Valgan Toddler study – sponsored by NIH and the University of Alabama as part of the Collaborative Antiviral Study Group – will enroll children who are aged 1 month through 3 years and who had a recent diagnosis of hearing loss (within the prior 12 weeks) and evidence of congenital CMV infection. The purpose of this study is to compare the effect on hearing and neurologic outcomes in infants aged 1 month through 4 years with recent onset SNHL who receive 6 weeks of valganciclovir versus children who do not receive this drug. The results of such studies will be critical for the development of best practices.

In summary, the licensure of a rapid PCR-based tool for diagnosis of CMV infection from saliva adds to our ability to develop screening programs to detect asymptomatic infants with congenital CMV infection. The ability to link newborns who fail hearing screening programs with CMV testing will lead to more detection of CMV-infected neonates, both with isolated hearing loss, and subsequently with no signs or symptoms of infection. There is an urgent need for evidence from randomized clinical trials to enable the development of best practices for such infants.

Dr. Pelton is professor of pediatrics and epidemiology at Boston University and senior attending physician at Boston Medical Center. Dr. Lapidot is a senior fellow in pediatric infectious diseases, Boston Medical Center. Neither Dr. Pelton nor Dr. Lapidot have any relevant financial disclosures. Email them at [email protected].

References

1. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 2019 Mar 28;8(1):55-9.

2. N Engl J Med 2011 Jun 2; 364:2111-8.

3. Pediatrics. 2008 May;121(5):970-5

4. J Clin Virol. 2018 May;102:110-5.

5. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 2019 Mar;8(1):55-9.

6. J Pediatr. 2003 Jul;143(1):16-25.

7. J Pediatr. 2018 Aug;199:166-70.

Part 3: Getting to the Scope of the Problem

Nurse practitioners (and PAs, I would submit) have been the most researched group of health care professionals since the inception of the role. Much of that research has focused on evaluating our contributions to primary care. Numerous studies of NP performance in various settings have concluded that we perform as well as physicians with respect to patient outcomes, proper diagnosis, management of specific medical conditions, and patient satisfaction.1

Over the past 10 years, however, the interest in our roles has shifted from the primary care arena to the emergency department (ED). Even before the introduction of the Affordable Care Act (ACA), two-thirds of all EDs utilized NPs and PAs.2 The ACA increased the number of Americans with insurance coverage, resulting in a greater demand for health care services—including ED utilization. Faced with an already strained system, hospital administrators looked for a solution and found one: hiring NPs and PAs to augment the clinician workforce.

This decision to (increasingly) employ NPs and PAs in ED settings was based on a desire to reduce wait times, increase throughput, improve access to care, and control costs. For the most part, these goals have been achieved. A systematic review of the impact of NPs in the ED on quality of care and patient satisfaction demonstrated a reduction in wait times.3 Moreover, in a national survey that included a review of the types of visits made to the ED, NPs and PAs were comparable to MDs in terms of reasons for care, diagnosis, and treatment.4

Given these results, I again ask: What was the intent of the research by Bai et al?5 Surely proper and prompt care is the goal of every ED provider. So the decision to examine only the billing is confounding.

Are the authors suggesting that hospital administrators prefer employing NPs and PAs over MDs? Are we replacing physicians in certain areas or filling voids where the physician workforce is inadequate to meet the community demands? Maybe yes to both. But, if the goal is to improve access, then we should focus on meeting the needs and on the quality of the care, not on who bills for it.

My cynical self says the goal of Bai et al was to establish that NPs and PAs are taking the jobs of ED physicians, and we must be stopped! Am I tilting at windmills with this train of thought? Next week, we’ll conclude our examination and draw our own conclusions! You can join the conversation by writing to [email protected].

1. Congressional Budget Office. Physician extenders: their current and future role in medical care delivery. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office; 1979.

2. Wiler JL, Rooks, SP, Ginde AA. Update on midlevel provider utilization in US emergency departments, 2006 to 2009. Academic Emerg Med. 2012;19(8):986-989.

3. Carter A, Chochinov A. A systematic review of the impact of nurse practitioners on cost, quality of care, satisfaction, and wait times in the emergency department. Can J Emerg Med. 2007;9(4):286-295.

4. Hooker RS, McCaig L. Emergency department uses of physician assistants and nurse practitioners: a national survey. Am J Emerg Med. 1996;14:245-249.

5. Bai G, Kelen GD, Frick KD, Anderson GF. Nurse practitioners and physician assistants in emergency medical services who billed independently, 2012-2016. Am J Emerg Med. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2019.01.052. Accessed April 1, 2019.

Nurse practitioners (and PAs, I would submit) have been the most researched group of health care professionals since the inception of the role. Much of that research has focused on evaluating our contributions to primary care. Numerous studies of NP performance in various settings have concluded that we perform as well as physicians with respect to patient outcomes, proper diagnosis, management of specific medical conditions, and patient satisfaction.1

Over the past 10 years, however, the interest in our roles has shifted from the primary care arena to the emergency department (ED). Even before the introduction of the Affordable Care Act (ACA), two-thirds of all EDs utilized NPs and PAs.2 The ACA increased the number of Americans with insurance coverage, resulting in a greater demand for health care services—including ED utilization. Faced with an already strained system, hospital administrators looked for a solution and found one: hiring NPs and PAs to augment the clinician workforce.

This decision to (increasingly) employ NPs and PAs in ED settings was based on a desire to reduce wait times, increase throughput, improve access to care, and control costs. For the most part, these goals have been achieved. A systematic review of the impact of NPs in the ED on quality of care and patient satisfaction demonstrated a reduction in wait times.3 Moreover, in a national survey that included a review of the types of visits made to the ED, NPs and PAs were comparable to MDs in terms of reasons for care, diagnosis, and treatment.4

Given these results, I again ask: What was the intent of the research by Bai et al?5 Surely proper and prompt care is the goal of every ED provider. So the decision to examine only the billing is confounding.

Are the authors suggesting that hospital administrators prefer employing NPs and PAs over MDs? Are we replacing physicians in certain areas or filling voids where the physician workforce is inadequate to meet the community demands? Maybe yes to both. But, if the goal is to improve access, then we should focus on meeting the needs and on the quality of the care, not on who bills for it.

My cynical self says the goal of Bai et al was to establish that NPs and PAs are taking the jobs of ED physicians, and we must be stopped! Am I tilting at windmills with this train of thought? Next week, we’ll conclude our examination and draw our own conclusions! You can join the conversation by writing to [email protected].

Nurse practitioners (and PAs, I would submit) have been the most researched group of health care professionals since the inception of the role. Much of that research has focused on evaluating our contributions to primary care. Numerous studies of NP performance in various settings have concluded that we perform as well as physicians with respect to patient outcomes, proper diagnosis, management of specific medical conditions, and patient satisfaction.1

Over the past 10 years, however, the interest in our roles has shifted from the primary care arena to the emergency department (ED). Even before the introduction of the Affordable Care Act (ACA), two-thirds of all EDs utilized NPs and PAs.2 The ACA increased the number of Americans with insurance coverage, resulting in a greater demand for health care services—including ED utilization. Faced with an already strained system, hospital administrators looked for a solution and found one: hiring NPs and PAs to augment the clinician workforce.

This decision to (increasingly) employ NPs and PAs in ED settings was based on a desire to reduce wait times, increase throughput, improve access to care, and control costs. For the most part, these goals have been achieved. A systematic review of the impact of NPs in the ED on quality of care and patient satisfaction demonstrated a reduction in wait times.3 Moreover, in a national survey that included a review of the types of visits made to the ED, NPs and PAs were comparable to MDs in terms of reasons for care, diagnosis, and treatment.4

Given these results, I again ask: What was the intent of the research by Bai et al?5 Surely proper and prompt care is the goal of every ED provider. So the decision to examine only the billing is confounding.

Are the authors suggesting that hospital administrators prefer employing NPs and PAs over MDs? Are we replacing physicians in certain areas or filling voids where the physician workforce is inadequate to meet the community demands? Maybe yes to both. But, if the goal is to improve access, then we should focus on meeting the needs and on the quality of the care, not on who bills for it.

My cynical self says the goal of Bai et al was to establish that NPs and PAs are taking the jobs of ED physicians, and we must be stopped! Am I tilting at windmills with this train of thought? Next week, we’ll conclude our examination and draw our own conclusions! You can join the conversation by writing to [email protected].

1. Congressional Budget Office. Physician extenders: their current and future role in medical care delivery. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office; 1979.

2. Wiler JL, Rooks, SP, Ginde AA. Update on midlevel provider utilization in US emergency departments, 2006 to 2009. Academic Emerg Med. 2012;19(8):986-989.

3. Carter A, Chochinov A. A systematic review of the impact of nurse practitioners on cost, quality of care, satisfaction, and wait times in the emergency department. Can J Emerg Med. 2007;9(4):286-295.

4. Hooker RS, McCaig L. Emergency department uses of physician assistants and nurse practitioners: a national survey. Am J Emerg Med. 1996;14:245-249.

5. Bai G, Kelen GD, Frick KD, Anderson GF. Nurse practitioners and physician assistants in emergency medical services who billed independently, 2012-2016. Am J Emerg Med. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2019.01.052. Accessed April 1, 2019.

1. Congressional Budget Office. Physician extenders: their current and future role in medical care delivery. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office; 1979.

2. Wiler JL, Rooks, SP, Ginde AA. Update on midlevel provider utilization in US emergency departments, 2006 to 2009. Academic Emerg Med. 2012;19(8):986-989.

3. Carter A, Chochinov A. A systematic review of the impact of nurse practitioners on cost, quality of care, satisfaction, and wait times in the emergency department. Can J Emerg Med. 2007;9(4):286-295.

4. Hooker RS, McCaig L. Emergency department uses of physician assistants and nurse practitioners: a national survey. Am J Emerg Med. 1996;14:245-249.

5. Bai G, Kelen GD, Frick KD, Anderson GF. Nurse practitioners and physician assistants in emergency medical services who billed independently, 2012-2016. Am J Emerg Med. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2019.01.052. Accessed April 1, 2019.

Acute psychosis: Is it schizophrenia or bipolar disorder?

Patients’ functional outcome assessment results are critical

I have been amazed at psychiatrists who could see a patient who was obviously acutely psychotic and tell whether they had schizophrenia or bipolar disorder while the patient was acutely psychotic. I am amazed because I cannot do it, although I used to think I could.

Earlier in my career, I would see patients who were floridly psychotic who would have all the symptoms of schizophrenia, and I would think “Yep, they have schizophrenia, all right.” After all, when I was starting out in psychiatry, I thought that Schneiderian first-rank symptoms were pathognomonic of schizophrenia, but research later showed that these first-rank symptoms could also be characteristic of dissociative disorder.

I quickly learned that some of the patients I thought had schizophrenia would recover and return to their premorbid level of functioning after the psychotic episode. Accordingly, by definition – for example, there was not a deterioration of psychosocial functioning after their psychotic episode – I would have to revise their diagnosis to bipolar disorder.

Finally, I got hip and realized that I could not determine patients’ diagnoses when they were acutely psychotic, and I started diagnosing patients as having a psychosis not otherwise specified (NOS).

Of course, using the NOS designation made many of my academic colleagues scoff at my diagnostic skills, but then I read the DSM-IV Guidebook by Frances, First, and Pincus (1995), and it was explained the NOS designation was wrongly maligned. Apparently, it was learned that there was extensive comorbidity between various diagnostic categories, and, it was explicated, approximately 50% of patients could not fit neatly into any specific diagnostic category. In fact, regarding psychotic and affective disorders, depending on how good a history patients and/or their family could deliver, it would sometimes take the resolution of the patients’ psychosis before it became clear that they were or were not going to return to premorbid functioning or continue to show significant psychosocial deterioration.

Since psychiatrists do not yet have objective diagnostic tests to determine whether a psychotic patient has some form of schizophrenia or bipolar disorder, because I do not think we can tell the patients’ post psychotic outcomes.

I recently had one patient who had been hospitalized for 39 days, and, who was so acutely floridly psychotic, I did not think she was going to recover. She was on antipsychotic medication at bedtime and other mood stabilizers during the day, but she had to be in soft restraints for a significant period of time and was getting several antipsychotic medication injections daily because she was extremely rambunctious and dangerously disruptive on the medical-surgical/psychiatric floor. Finally, when I reluctantly added lithium to her treatment regimen (I was unenthusiastic about putting her on lithium, which had worked for her in the past, because her kidneys were not functioning well and she had arrived at the hospital with lithium toxicity), she recovered. The transformation was remarkable.

So, it seems to me that a functional outcome assessment should determine the difference between patients who have bipolar disorder and schizophrenia as, by definition, if you do not have a deterioration in your psychosocial functioning you probably have bipolar disorder, and if you do have a deterioration in your psychosocial functioning you probably have schizophrenia. From a practical standpoint, post psychotic functioning is a major distinction between these two diagnoses by definition, and, since we don’t have objective measures to delineate bipolar disorder from schizophrenia (some studies have shown there is remarkable overlap between these two disorders), it seems to me we should give more consideration to post psychotic functioning, instead of trying to nail the patients’ diagnoses when they are acutely psychotic.

Dr. Bell is a staff psychiatrist at Jackson Park Hospital’s medical/surgical-psychiatry inpatient unit in Chicago, clinical psychiatrist emeritus in the department of psychiatry at the University of Illinois at Chicago, former president/CEO of Community Mental Health Council, and former director of the Institute for Juvenile Research (birthplace of child psychiatry), also in Chicago. Be sure to check out Dr. Bell’s new book Fetal Alcohol Exposure in the African-American Community.

Patients’ functional outcome assessment results are critical

Patients’ functional outcome assessment results are critical

I have been amazed at psychiatrists who could see a patient who was obviously acutely psychotic and tell whether they had schizophrenia or bipolar disorder while the patient was acutely psychotic. I am amazed because I cannot do it, although I used to think I could.

Earlier in my career, I would see patients who were floridly psychotic who would have all the symptoms of schizophrenia, and I would think “Yep, they have schizophrenia, all right.” After all, when I was starting out in psychiatry, I thought that Schneiderian first-rank symptoms were pathognomonic of schizophrenia, but research later showed that these first-rank symptoms could also be characteristic of dissociative disorder.

I quickly learned that some of the patients I thought had schizophrenia would recover and return to their premorbid level of functioning after the psychotic episode. Accordingly, by definition – for example, there was not a deterioration of psychosocial functioning after their psychotic episode – I would have to revise their diagnosis to bipolar disorder.

Finally, I got hip and realized that I could not determine patients’ diagnoses when they were acutely psychotic, and I started diagnosing patients as having a psychosis not otherwise specified (NOS).

Of course, using the NOS designation made many of my academic colleagues scoff at my diagnostic skills, but then I read the DSM-IV Guidebook by Frances, First, and Pincus (1995), and it was explained the NOS designation was wrongly maligned. Apparently, it was learned that there was extensive comorbidity between various diagnostic categories, and, it was explicated, approximately 50% of patients could not fit neatly into any specific diagnostic category. In fact, regarding psychotic and affective disorders, depending on how good a history patients and/or their family could deliver, it would sometimes take the resolution of the patients’ psychosis before it became clear that they were or were not going to return to premorbid functioning or continue to show significant psychosocial deterioration.

Since psychiatrists do not yet have objective diagnostic tests to determine whether a psychotic patient has some form of schizophrenia or bipolar disorder, because I do not think we can tell the patients’ post psychotic outcomes.

I recently had one patient who had been hospitalized for 39 days, and, who was so acutely floridly psychotic, I did not think she was going to recover. She was on antipsychotic medication at bedtime and other mood stabilizers during the day, but she had to be in soft restraints for a significant period of time and was getting several antipsychotic medication injections daily because she was extremely rambunctious and dangerously disruptive on the medical-surgical/psychiatric floor. Finally, when I reluctantly added lithium to her treatment regimen (I was unenthusiastic about putting her on lithium, which had worked for her in the past, because her kidneys were not functioning well and she had arrived at the hospital with lithium toxicity), she recovered. The transformation was remarkable.

So, it seems to me that a functional outcome assessment should determine the difference between patients who have bipolar disorder and schizophrenia as, by definition, if you do not have a deterioration in your psychosocial functioning you probably have bipolar disorder, and if you do have a deterioration in your psychosocial functioning you probably have schizophrenia. From a practical standpoint, post psychotic functioning is a major distinction between these two diagnoses by definition, and, since we don’t have objective measures to delineate bipolar disorder from schizophrenia (some studies have shown there is remarkable overlap between these two disorders), it seems to me we should give more consideration to post psychotic functioning, instead of trying to nail the patients’ diagnoses when they are acutely psychotic.

Dr. Bell is a staff psychiatrist at Jackson Park Hospital’s medical/surgical-psychiatry inpatient unit in Chicago, clinical psychiatrist emeritus in the department of psychiatry at the University of Illinois at Chicago, former president/CEO of Community Mental Health Council, and former director of the Institute for Juvenile Research (birthplace of child psychiatry), also in Chicago. Be sure to check out Dr. Bell’s new book Fetal Alcohol Exposure in the African-American Community.

I have been amazed at psychiatrists who could see a patient who was obviously acutely psychotic and tell whether they had schizophrenia or bipolar disorder while the patient was acutely psychotic. I am amazed because I cannot do it, although I used to think I could.

Earlier in my career, I would see patients who were floridly psychotic who would have all the symptoms of schizophrenia, and I would think “Yep, they have schizophrenia, all right.” After all, when I was starting out in psychiatry, I thought that Schneiderian first-rank symptoms were pathognomonic of schizophrenia, but research later showed that these first-rank symptoms could also be characteristic of dissociative disorder.

I quickly learned that some of the patients I thought had schizophrenia would recover and return to their premorbid level of functioning after the psychotic episode. Accordingly, by definition – for example, there was not a deterioration of psychosocial functioning after their psychotic episode – I would have to revise their diagnosis to bipolar disorder.

Finally, I got hip and realized that I could not determine patients’ diagnoses when they were acutely psychotic, and I started diagnosing patients as having a psychosis not otherwise specified (NOS).

Of course, using the NOS designation made many of my academic colleagues scoff at my diagnostic skills, but then I read the DSM-IV Guidebook by Frances, First, and Pincus (1995), and it was explained the NOS designation was wrongly maligned. Apparently, it was learned that there was extensive comorbidity between various diagnostic categories, and, it was explicated, approximately 50% of patients could not fit neatly into any specific diagnostic category. In fact, regarding psychotic and affective disorders, depending on how good a history patients and/or their family could deliver, it would sometimes take the resolution of the patients’ psychosis before it became clear that they were or were not going to return to premorbid functioning or continue to show significant psychosocial deterioration.

Since psychiatrists do not yet have objective diagnostic tests to determine whether a psychotic patient has some form of schizophrenia or bipolar disorder, because I do not think we can tell the patients’ post psychotic outcomes.

I recently had one patient who had been hospitalized for 39 days, and, who was so acutely floridly psychotic, I did not think she was going to recover. She was on antipsychotic medication at bedtime and other mood stabilizers during the day, but she had to be in soft restraints for a significant period of time and was getting several antipsychotic medication injections daily because she was extremely rambunctious and dangerously disruptive on the medical-surgical/psychiatric floor. Finally, when I reluctantly added lithium to her treatment regimen (I was unenthusiastic about putting her on lithium, which had worked for her in the past, because her kidneys were not functioning well and she had arrived at the hospital with lithium toxicity), she recovered. The transformation was remarkable.

So, it seems to me that a functional outcome assessment should determine the difference between patients who have bipolar disorder and schizophrenia as, by definition, if you do not have a deterioration in your psychosocial functioning you probably have bipolar disorder, and if you do have a deterioration in your psychosocial functioning you probably have schizophrenia. From a practical standpoint, post psychotic functioning is a major distinction between these two diagnoses by definition, and, since we don’t have objective measures to delineate bipolar disorder from schizophrenia (some studies have shown there is remarkable overlap between these two disorders), it seems to me we should give more consideration to post psychotic functioning, instead of trying to nail the patients’ diagnoses when they are acutely psychotic.

Dr. Bell is a staff psychiatrist at Jackson Park Hospital’s medical/surgical-psychiatry inpatient unit in Chicago, clinical psychiatrist emeritus in the department of psychiatry at the University of Illinois at Chicago, former president/CEO of Community Mental Health Council, and former director of the Institute for Juvenile Research (birthplace of child psychiatry), also in Chicago. Be sure to check out Dr. Bell’s new book Fetal Alcohol Exposure in the African-American Community.

The type II error and black holes

An international group of scientists have announced they have an image of a black hole. This feat of scientific achievement and teamwork is another giant step in humankind’s understanding of the universe. It isn’t easy to find something that isn’t there. Black holes exist and this one is about 6.5 billion times more massive than Earth’s sun. That is a lot of “there.”

In medical research, most articles are about discovering something new. Lately, it is also common to publish studies that claim that something doesn’t exist. No difference is found between treatment A and treatment B. Two decades ago those negative studies rarely were published, but there was merit in the idea that more of them should be published. However, that merit presupposed that the negative studies worthy of publication would be well designed, robust, and, most importantly, contain a power calculation showing that the methodology would have detected the phenomenon if the phenomenon were large enough to be clinically important. Alas, the literature has been flooded with negative studies finding no effect because the studies were hopelessly underpowered and never had a realistic chance of detecting anything. This fake news pollutes our medical knowledge.

To clarify, let me provide a simple example. With my myopia, at 100 yards and without my glasses, I can’t detect the difference between Lebron James and Megan Rapinoe, although I know Megan is better at corner kicks.

Now let me give a second, more complex example that obfuscates the same detection issue. Are there moons circling Jupiter? I go out each night, find Jupiter, take a picture with my trusty cell phone, and examine the picture for any evidence of an object(s) circling the planet. I do this many times. How many? Well, if I only do it three times, people will doubt my science, but doing it 1,000 times would take too long. In my experience, most negative studies seem to involve about 30-50 patients. So one picture a week for a year will produce 52 observations. That is a lot of cold nights under the stars. I will use my scientific knowledge and ability to read sky charts to locate Jupiter. (There is an app for that.) I will use my experience to distinguish Jupiter from Venus and Mars. There will be cloudy days, so maybe only 30 clear pictures will be obtained. I will have a second observer examine the photos. We will calculate a kappa statistic for inter-rater agreement. There will be pictures and tables of numbers. When I’m done, I will publish an article saying that Jupiter doesn’t have moons because I didn’t find any. Trust me, I’m a doctor.

Science doesn’t work that way. Science doesn’t care how smart I am, how dedicated I am, how expensive my cell phone is, or how much work I put into the project, science wants empiric proof. My failure to find moons does not refute their existence. A claim that something does NOT exist cannot be correctly made by simply showing that the P value is greater than .05. A statistically insignificant P value also might also mean that my experiment, despite all my time, effort, commitment, and data collection, is simply inadequate to detect the phenomenon. My cell phone has enough pixels to see Jupiter but not its moons. The phone isn’t powerful enough. My claim is a type II error.

One needs to specify the threshold size of a clinically important effect and then show that your methods and results were powerful enough to have detected something that small. Only then may you correctly publish a conclusion that there is nothing there, a donut hole in the black void of space.

I invite you to do your own survey. As you read journal articles, identify the next 10 times you read a conclusion that claims no effect was found. Scour that article carefully for any indication of the size of effect that those methods and results would have been able to detect. Look for a power calculation. Grade the article with a simple pass/fail on that point. Did the authors provide that information in a way you can understand, or do you just have to trust them? Take President Reagan’s advice, “Trust, but verify.” Most of the 10 articles will lack the calculation and many negative claims are type II errors.

Dr. Powell is a pediatric hospitalist and clinical ethics consultant living in St. Louis. Email him at [email protected].

An international group of scientists have announced they have an image of a black hole. This feat of scientific achievement and teamwork is another giant step in humankind’s understanding of the universe. It isn’t easy to find something that isn’t there. Black holes exist and this one is about 6.5 billion times more massive than Earth’s sun. That is a lot of “there.”

In medical research, most articles are about discovering something new. Lately, it is also common to publish studies that claim that something doesn’t exist. No difference is found between treatment A and treatment B. Two decades ago those negative studies rarely were published, but there was merit in the idea that more of them should be published. However, that merit presupposed that the negative studies worthy of publication would be well designed, robust, and, most importantly, contain a power calculation showing that the methodology would have detected the phenomenon if the phenomenon were large enough to be clinically important. Alas, the literature has been flooded with negative studies finding no effect because the studies were hopelessly underpowered and never had a realistic chance of detecting anything. This fake news pollutes our medical knowledge.

To clarify, let me provide a simple example. With my myopia, at 100 yards and without my glasses, I can’t detect the difference between Lebron James and Megan Rapinoe, although I know Megan is better at corner kicks.

Now let me give a second, more complex example that obfuscates the same detection issue. Are there moons circling Jupiter? I go out each night, find Jupiter, take a picture with my trusty cell phone, and examine the picture for any evidence of an object(s) circling the planet. I do this many times. How many? Well, if I only do it three times, people will doubt my science, but doing it 1,000 times would take too long. In my experience, most negative studies seem to involve about 30-50 patients. So one picture a week for a year will produce 52 observations. That is a lot of cold nights under the stars. I will use my scientific knowledge and ability to read sky charts to locate Jupiter. (There is an app for that.) I will use my experience to distinguish Jupiter from Venus and Mars. There will be cloudy days, so maybe only 30 clear pictures will be obtained. I will have a second observer examine the photos. We will calculate a kappa statistic for inter-rater agreement. There will be pictures and tables of numbers. When I’m done, I will publish an article saying that Jupiter doesn’t have moons because I didn’t find any. Trust me, I’m a doctor.

Science doesn’t work that way. Science doesn’t care how smart I am, how dedicated I am, how expensive my cell phone is, or how much work I put into the project, science wants empiric proof. My failure to find moons does not refute their existence. A claim that something does NOT exist cannot be correctly made by simply showing that the P value is greater than .05. A statistically insignificant P value also might also mean that my experiment, despite all my time, effort, commitment, and data collection, is simply inadequate to detect the phenomenon. My cell phone has enough pixels to see Jupiter but not its moons. The phone isn’t powerful enough. My claim is a type II error.

One needs to specify the threshold size of a clinically important effect and then show that your methods and results were powerful enough to have detected something that small. Only then may you correctly publish a conclusion that there is nothing there, a donut hole in the black void of space.

I invite you to do your own survey. As you read journal articles, identify the next 10 times you read a conclusion that claims no effect was found. Scour that article carefully for any indication of the size of effect that those methods and results would have been able to detect. Look for a power calculation. Grade the article with a simple pass/fail on that point. Did the authors provide that information in a way you can understand, or do you just have to trust them? Take President Reagan’s advice, “Trust, but verify.” Most of the 10 articles will lack the calculation and many negative claims are type II errors.

Dr. Powell is a pediatric hospitalist and clinical ethics consultant living in St. Louis. Email him at [email protected].

An international group of scientists have announced they have an image of a black hole. This feat of scientific achievement and teamwork is another giant step in humankind’s understanding of the universe. It isn’t easy to find something that isn’t there. Black holes exist and this one is about 6.5 billion times more massive than Earth’s sun. That is a lot of “there.”

In medical research, most articles are about discovering something new. Lately, it is also common to publish studies that claim that something doesn’t exist. No difference is found between treatment A and treatment B. Two decades ago those negative studies rarely were published, but there was merit in the idea that more of them should be published. However, that merit presupposed that the negative studies worthy of publication would be well designed, robust, and, most importantly, contain a power calculation showing that the methodology would have detected the phenomenon if the phenomenon were large enough to be clinically important. Alas, the literature has been flooded with negative studies finding no effect because the studies were hopelessly underpowered and never had a realistic chance of detecting anything. This fake news pollutes our medical knowledge.

To clarify, let me provide a simple example. With my myopia, at 100 yards and without my glasses, I can’t detect the difference between Lebron James and Megan Rapinoe, although I know Megan is better at corner kicks.

Now let me give a second, more complex example that obfuscates the same detection issue. Are there moons circling Jupiter? I go out each night, find Jupiter, take a picture with my trusty cell phone, and examine the picture for any evidence of an object(s) circling the planet. I do this many times. How many? Well, if I only do it three times, people will doubt my science, but doing it 1,000 times would take too long. In my experience, most negative studies seem to involve about 30-50 patients. So one picture a week for a year will produce 52 observations. That is a lot of cold nights under the stars. I will use my scientific knowledge and ability to read sky charts to locate Jupiter. (There is an app for that.) I will use my experience to distinguish Jupiter from Venus and Mars. There will be cloudy days, so maybe only 30 clear pictures will be obtained. I will have a second observer examine the photos. We will calculate a kappa statistic for inter-rater agreement. There will be pictures and tables of numbers. When I’m done, I will publish an article saying that Jupiter doesn’t have moons because I didn’t find any. Trust me, I’m a doctor.

Science doesn’t work that way. Science doesn’t care how smart I am, how dedicated I am, how expensive my cell phone is, or how much work I put into the project, science wants empiric proof. My failure to find moons does not refute their existence. A claim that something does NOT exist cannot be correctly made by simply showing that the P value is greater than .05. A statistically insignificant P value also might also mean that my experiment, despite all my time, effort, commitment, and data collection, is simply inadequate to detect the phenomenon. My cell phone has enough pixels to see Jupiter but not its moons. The phone isn’t powerful enough. My claim is a type II error.

One needs to specify the threshold size of a clinically important effect and then show that your methods and results were powerful enough to have detected something that small. Only then may you correctly publish a conclusion that there is nothing there, a donut hole in the black void of space.

I invite you to do your own survey. As you read journal articles, identify the next 10 times you read a conclusion that claims no effect was found. Scour that article carefully for any indication of the size of effect that those methods and results would have been able to detect. Look for a power calculation. Grade the article with a simple pass/fail on that point. Did the authors provide that information in a way you can understand, or do you just have to trust them? Take President Reagan’s advice, “Trust, but verify.” Most of the 10 articles will lack the calculation and many negative claims are type II errors.

Dr. Powell is a pediatric hospitalist and clinical ethics consultant living in St. Louis. Email him at [email protected].

A chance to unite

Is America coming apart at the seams? According to the press, there are more things that divide us than bind us together. It’s red state versus blue state, it’s the privileged versus the disadvantaged, people of color versus the white majority. Could the great melting pot have cooled and its contents settled out into a dozen stratified layers?

Despite the image of a divided America that we see portrayed in the newspapers and on television, I continue to believe that there is more that we share in common than separate us, but it’s a struggle. The media operate on the assumption that conflict draws more readers than good news about cooperation and compromise. The situation is compounded by the apparent absence of a leader from either party who wants to unite us.

However, when one scratches the surface, there is surprising amount of agreement among Americans. For example, according to John Gramlich (“7 facts about guns in the U.S.,” Pew Research Center, Dec. 27, 2018), 89% of both Republicans and Democrats feel that people with mental illness should not be allowed to purchase a gun. And 79% of Republicans and 91% of Democrats favor background checks at gun shows and for private sales for purchase of a gun. As of 2018, 58% of Americans feel that abortion should be legal in all or most cases, and only 37% feel it should be illegal in all or most cases. (“Public Opinion on Abortion,” Pew Research Center, Oct. 15, 2018).

At the core of many of our struggles to unite is a question that has bedeviled democracies for millennia: How does one balance a citizen’s freedom of choice with the health and safety of the society in which that person lives? While resolutions on gun control and abortion seem unlikely in the foreseeable future, the current outbreaks of measles offer America a rare opportunity to unite on an issue that pits personal freedom against societal safety.

According to Virginia Villa (“5 facts about vaccines in the U.S.,” Pew Research Center, Mar. 19, 2019), 82% of adults in the United States believe that the MMR vaccine should be required for public school attendance, while only 17% believe that parents should be allowed to leave their child unvaccinated even if their decision creates a health risk for other children and adults.

Why should we expect the government to respond to protect the population from the risk posed by the unvaccinated minority when it has done very little to further gun control? Obviously a key difference is that the antivaccination minority lacks the financial resources and political muscle of a large organization such as the National Rifle Association. While we must never underestimate the power of social media, the publicity surfacing from the mainstream media as the measles outbreaks in the United States have continued has prompted several states to rethink their policies regarding vaccination requirements and school attendance. Here in Maine, there has been strong support among the legislature for eliminating exemptions for philosophic or religious exemptions.

It is probably unrealistic to expect the federal government to act on the health threat caused by the antivaccine movement. However, it is encouraging that, at least at the local level, there is hope for closing one of the wounds that divide us. As providers who care for children, we should seize this opportunity created by the measles outbreaks to promote legislation and policies that strike a sensible balance between the right of the individual and the safety of the society at large.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

Is America coming apart at the seams? According to the press, there are more things that divide us than bind us together. It’s red state versus blue state, it’s the privileged versus the disadvantaged, people of color versus the white majority. Could the great melting pot have cooled and its contents settled out into a dozen stratified layers?

Despite the image of a divided America that we see portrayed in the newspapers and on television, I continue to believe that there is more that we share in common than separate us, but it’s a struggle. The media operate on the assumption that conflict draws more readers than good news about cooperation and compromise. The situation is compounded by the apparent absence of a leader from either party who wants to unite us.

However, when one scratches the surface, there is surprising amount of agreement among Americans. For example, according to John Gramlich (“7 facts about guns in the U.S.,” Pew Research Center, Dec. 27, 2018), 89% of both Republicans and Democrats feel that people with mental illness should not be allowed to purchase a gun. And 79% of Republicans and 91% of Democrats favor background checks at gun shows and for private sales for purchase of a gun. As of 2018, 58% of Americans feel that abortion should be legal in all or most cases, and only 37% feel it should be illegal in all or most cases. (“Public Opinion on Abortion,” Pew Research Center, Oct. 15, 2018).

At the core of many of our struggles to unite is a question that has bedeviled democracies for millennia: How does one balance a citizen’s freedom of choice with the health and safety of the society in which that person lives? While resolutions on gun control and abortion seem unlikely in the foreseeable future, the current outbreaks of measles offer America a rare opportunity to unite on an issue that pits personal freedom against societal safety.

According to Virginia Villa (“5 facts about vaccines in the U.S.,” Pew Research Center, Mar. 19, 2019), 82% of adults in the United States believe that the MMR vaccine should be required for public school attendance, while only 17% believe that parents should be allowed to leave their child unvaccinated even if their decision creates a health risk for other children and adults.

Why should we expect the government to respond to protect the population from the risk posed by the unvaccinated minority when it has done very little to further gun control? Obviously a key difference is that the antivaccination minority lacks the financial resources and political muscle of a large organization such as the National Rifle Association. While we must never underestimate the power of social media, the publicity surfacing from the mainstream media as the measles outbreaks in the United States have continued has prompted several states to rethink their policies regarding vaccination requirements and school attendance. Here in Maine, there has been strong support among the legislature for eliminating exemptions for philosophic or religious exemptions.

It is probably unrealistic to expect the federal government to act on the health threat caused by the antivaccine movement. However, it is encouraging that, at least at the local level, there is hope for closing one of the wounds that divide us. As providers who care for children, we should seize this opportunity created by the measles outbreaks to promote legislation and policies that strike a sensible balance between the right of the individual and the safety of the society at large.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

Is America coming apart at the seams? According to the press, there are more things that divide us than bind us together. It’s red state versus blue state, it’s the privileged versus the disadvantaged, people of color versus the white majority. Could the great melting pot have cooled and its contents settled out into a dozen stratified layers?

Despite the image of a divided America that we see portrayed in the newspapers and on television, I continue to believe that there is more that we share in common than separate us, but it’s a struggle. The media operate on the assumption that conflict draws more readers than good news about cooperation and compromise. The situation is compounded by the apparent absence of a leader from either party who wants to unite us.

However, when one scratches the surface, there is surprising amount of agreement among Americans. For example, according to John Gramlich (“7 facts about guns in the U.S.,” Pew Research Center, Dec. 27, 2018), 89% of both Republicans and Democrats feel that people with mental illness should not be allowed to purchase a gun. And 79% of Republicans and 91% of Democrats favor background checks at gun shows and for private sales for purchase of a gun. As of 2018, 58% of Americans feel that abortion should be legal in all or most cases, and only 37% feel it should be illegal in all or most cases. (“Public Opinion on Abortion,” Pew Research Center, Oct. 15, 2018).

At the core of many of our struggles to unite is a question that has bedeviled democracies for millennia: How does one balance a citizen’s freedom of choice with the health and safety of the society in which that person lives? While resolutions on gun control and abortion seem unlikely in the foreseeable future, the current outbreaks of measles offer America a rare opportunity to unite on an issue that pits personal freedom against societal safety.

According to Virginia Villa (“5 facts about vaccines in the U.S.,” Pew Research Center, Mar. 19, 2019), 82% of adults in the United States believe that the MMR vaccine should be required for public school attendance, while only 17% believe that parents should be allowed to leave their child unvaccinated even if their decision creates a health risk for other children and adults.

Why should we expect the government to respond to protect the population from the risk posed by the unvaccinated minority when it has done very little to further gun control? Obviously a key difference is that the antivaccination minority lacks the financial resources and political muscle of a large organization such as the National Rifle Association. While we must never underestimate the power of social media, the publicity surfacing from the mainstream media as the measles outbreaks in the United States have continued has prompted several states to rethink their policies regarding vaccination requirements and school attendance. Here in Maine, there has been strong support among the legislature for eliminating exemptions for philosophic or religious exemptions.

It is probably unrealistic to expect the federal government to act on the health threat caused by the antivaccine movement. However, it is encouraging that, at least at the local level, there is hope for closing one of the wounds that divide us. As providers who care for children, we should seize this opportunity created by the measles outbreaks to promote legislation and policies that strike a sensible balance between the right of the individual and the safety of the society at large.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

A state of mind

Are you happy with your current situation? Do you enjoy your job and look forward to getting home at the end of the day? Or, do you find your work unrewarding? Do you consider your home simply a place to wait impatiently until you can hop on a plane for your next getaway vacation?

Maybe you should consider relocating to Montana. According to the headline in an article by Richard Franki in Pediatric News (“Montana named ‘best state to practice medicine’ in 2019,” Mar. 28, 2019) the Treasure State is currently the best state to practice medicine. Big Sky Country earned this distinction by outdistancing 49 states and Washington, D.C., in a ranking by WalletHub. The personal finance website used 18 metrics ranging from average annual wage adjusted for cost of living to malpractice award payment per capita. One category of metrics grouped data related to “competition and opportunity” and the other “medical environment.”

I suspect that you are as skeptical as I am of surveys that claim to rank complex entities across broad geographic landscapes. I hope you are neither depressed or elated when your alma mater moves three positions on U.S. News and World Report’s ranking of colleges and universities. However, there are a few pearls hidden in this WalletHub attempt at choosing the most physician-friendly states.

New York was again ranked the worst state to practice medicine, a distinction it had “earned” in 2017 with a highest cost of malpractice insurance. This consistency suggests that there is a litigious atmosphere, at least in some parts of New York, that could make forging a trusting doctor-patient relationship difficult. Heading off to work each morning under the dark cloud of malpractice must take a lot of the fun out of practicing medicine.

The other interesting association buried in the ranking is that Montana is at the top of the list because it also was the state with the highest percentage of “medical residents retained.” This concurrence suggests that living and working in Big Sky Country provided a balance that young physicians found not just tolerable but so enjoyable they wanted to stay. I have been unable to find a complete listing of the raw data, but I suspect that Maine also could boast a high percentage of medical residents who choose to remain at the end of their training. It has been and continues to be a wonderful place to live and raise a family.

While there may be days when you feel as though the practice of medicine has consumed your every waking moment, the truth is that there is more to life than being a physician. Of course, one must be able to earn enough to support oneself and family, but this survey that purports to rank the best place to practice is too heavily weighted to the financial side of the equation and ignores the more difficult to quantify lifestyle qualities.

You may have found a position that pays well enough but requires a time-gobbling and stress-inducing commute to a place you feel comfortable living. Or, you may like your work, but find the community where you have settled lacks the suite of recreational and/or cultural opportunities you enjoy. Not everyone gets it right the first time. Sometimes it is a matter of making compromises and then continuing to reassess whether these compromises have been the best ones.

Regardless of its ranking on any survey, every state has multiple communities in which a physician can have a satisfying career and a lifestyle he or she enjoys. However, achieving this balanced mix may require the physician to invest something of him or herself into making that community one that feels like home.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

Are you happy with your current situation? Do you enjoy your job and look forward to getting home at the end of the day? Or, do you find your work unrewarding? Do you consider your home simply a place to wait impatiently until you can hop on a plane for your next getaway vacation?

Maybe you should consider relocating to Montana. According to the headline in an article by Richard Franki in Pediatric News (“Montana named ‘best state to practice medicine’ in 2019,” Mar. 28, 2019) the Treasure State is currently the best state to practice medicine. Big Sky Country earned this distinction by outdistancing 49 states and Washington, D.C., in a ranking by WalletHub. The personal finance website used 18 metrics ranging from average annual wage adjusted for cost of living to malpractice award payment per capita. One category of metrics grouped data related to “competition and opportunity” and the other “medical environment.”

I suspect that you are as skeptical as I am of surveys that claim to rank complex entities across broad geographic landscapes. I hope you are neither depressed or elated when your alma mater moves three positions on U.S. News and World Report’s ranking of colleges and universities. However, there are a few pearls hidden in this WalletHub attempt at choosing the most physician-friendly states.

New York was again ranked the worst state to practice medicine, a distinction it had “earned” in 2017 with a highest cost of malpractice insurance. This consistency suggests that there is a litigious atmosphere, at least in some parts of New York, that could make forging a trusting doctor-patient relationship difficult. Heading off to work each morning under the dark cloud of malpractice must take a lot of the fun out of practicing medicine.