User login

Summer is over, more health care changes are afoot

CMS has released its proposed rule (see related articles and a commentary) and included changes as substantial as I have seen in the last two decades. Additionally, the Affordable Care Act has been under continued attack despite its majority support from our citizenry. Loss of the individual mandate, allowance of “skinny” health plans, a rewrite of association plan rules, elimination of cost-sharing reductions and premium support – all have contributed to a shifting away from socialized medical costs and toward a system of individual responsibility for health. Depending on one’s political philosophy (and income), that may be bad or good.

Our article list this month will be interesting to many. The AGA produced a Clinical Practice Update about tumor seeding with endoscopic procedures. This should give us pause and make us reconsider our endoscopic practices. My wife (an endoscopy nurse in Minneapolis) has been asking for years whether pulling a PEG tube past an esophageal cancer might cause tumor seeding, and physicians have reassured her that there is no cause for worry. Turns out she was right (as usual). Deaths from liver disease in the U.S. have seen a dramatic increase since 1999, driven substantially by increasing alcohol use. Fecal transplants in irritable bowel syndrome? Possibly helpful, as reported in an article from Digestive Disease Week.®

As summer comes to an end, we head into a tumultuous fall that will be dominated by November elections.

John I. Allen, MD, MBA, AGAF

Editor in Chief

CMS has released its proposed rule (see related articles and a commentary) and included changes as substantial as I have seen in the last two decades. Additionally, the Affordable Care Act has been under continued attack despite its majority support from our citizenry. Loss of the individual mandate, allowance of “skinny” health plans, a rewrite of association plan rules, elimination of cost-sharing reductions and premium support – all have contributed to a shifting away from socialized medical costs and toward a system of individual responsibility for health. Depending on one’s political philosophy (and income), that may be bad or good.

Our article list this month will be interesting to many. The AGA produced a Clinical Practice Update about tumor seeding with endoscopic procedures. This should give us pause and make us reconsider our endoscopic practices. My wife (an endoscopy nurse in Minneapolis) has been asking for years whether pulling a PEG tube past an esophageal cancer might cause tumor seeding, and physicians have reassured her that there is no cause for worry. Turns out she was right (as usual). Deaths from liver disease in the U.S. have seen a dramatic increase since 1999, driven substantially by increasing alcohol use. Fecal transplants in irritable bowel syndrome? Possibly helpful, as reported in an article from Digestive Disease Week.®

As summer comes to an end, we head into a tumultuous fall that will be dominated by November elections.

John I. Allen, MD, MBA, AGAF

Editor in Chief

CMS has released its proposed rule (see related articles and a commentary) and included changes as substantial as I have seen in the last two decades. Additionally, the Affordable Care Act has been under continued attack despite its majority support from our citizenry. Loss of the individual mandate, allowance of “skinny” health plans, a rewrite of association plan rules, elimination of cost-sharing reductions and premium support – all have contributed to a shifting away from socialized medical costs and toward a system of individual responsibility for health. Depending on one’s political philosophy (and income), that may be bad or good.

Our article list this month will be interesting to many. The AGA produced a Clinical Practice Update about tumor seeding with endoscopic procedures. This should give us pause and make us reconsider our endoscopic practices. My wife (an endoscopy nurse in Minneapolis) has been asking for years whether pulling a PEG tube past an esophageal cancer might cause tumor seeding, and physicians have reassured her that there is no cause for worry. Turns out she was right (as usual). Deaths from liver disease in the U.S. have seen a dramatic increase since 1999, driven substantially by increasing alcohol use. Fecal transplants in irritable bowel syndrome? Possibly helpful, as reported in an article from Digestive Disease Week.®

As summer comes to an end, we head into a tumultuous fall that will be dominated by November elections.

John I. Allen, MD, MBA, AGAF

Editor in Chief

Sometimes talk is useless

“Alex, I understand that you are upset that you left your little bulldozer at home. Let’s try to think of something else you can play with here at the restaurant that is kind of like a bulldozer.”

Sounds like a reasonable strategy to calm an unruly preschooler, and it might have been had it not been the fifth attempt in a 45-minute dialogue between a mother and her overtired, misbehaving 3-year-old. There had been a lot of “I understand how you feel” and “use your words” woven into a gag-worthy and futile effort to forge a collaborative parent-child solution to the problem of an exhausted preschooler who is up past his bedtime in a public place.

My wife and I enjoy a night out with friends and prefer a quiet dining atmosphere. However, some evenings we eat earlier and choose a restaurant we know appeals to families with young children. At those meals, we anticipate being serenaded by a loud background buzz punctuated by the occasional shriek or short bout of crying. We expect a degree of childish behavior to come with the territory, and watching the dramas unfold brings back fond “been there, done that” memories. But, listening to those behaviors being horribly mismanaged can ruin even the most tolerant adult’s appetite in less time than it takes a parent to say, “I can see you’re unhappy, and we need to talk about why.”

In an op-ed piece, a psychotherapist asks the legitimate question, and provides the correct quick answer (“Which Is Better, Rewards or Punishments? Neither,” New York Times, Aug. 21, 2018). I couldn’t agree more. In my experience, rewards have a very short half-life and can become disastrously inflationary in the blink of an eye. On the other hand, punishments can be either too heavy-handed or so irrational that the child fails to make a logical connection between his misbehavior and his sentence.

Unfortunately, many child behavior advisers, including the op-ed author, offer alternatives to rewards and punishment that are unworkable in real-world circumstances, such as the restaurant scenario my wife and I endured.

While it sounds very democratic to ask a 3-year-old why he is misbehaving, more often than not it should be the parent who is asking what he or she could have done differently to avoid the situation. It is likely the child has been allowed to become overtired and/or the parent may be in denial about his/her child’s intolerance for stimulating environments.

Too often the parent takes too long to realize that the water is spilling over the dam and it is time to head for shore. Children who are overtired and having a tantrum can’t participate in a rational discussion about their feelings. If that dialogue needs to happen, and that is seldom, it should be the next day after the parent has time to consider his or her own mistakes.

When it comes to managing misbehaving children, I prefer well-tailored consequences and my favorite is a humanely crafted time-out. When presented and executed properly, a time-out can break the cycle of misbehavior and give both parent and child a chance to reconsider their positions.

But at 7 p.m. on a Friday evening in a busy restaurant, neither a time-out nor philosophizing with a 3-year-old is going to work. It’s time to ask for the check and head home to bed.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

“Alex, I understand that you are upset that you left your little bulldozer at home. Let’s try to think of something else you can play with here at the restaurant that is kind of like a bulldozer.”

Sounds like a reasonable strategy to calm an unruly preschooler, and it might have been had it not been the fifth attempt in a 45-minute dialogue between a mother and her overtired, misbehaving 3-year-old. There had been a lot of “I understand how you feel” and “use your words” woven into a gag-worthy and futile effort to forge a collaborative parent-child solution to the problem of an exhausted preschooler who is up past his bedtime in a public place.

My wife and I enjoy a night out with friends and prefer a quiet dining atmosphere. However, some evenings we eat earlier and choose a restaurant we know appeals to families with young children. At those meals, we anticipate being serenaded by a loud background buzz punctuated by the occasional shriek or short bout of crying. We expect a degree of childish behavior to come with the territory, and watching the dramas unfold brings back fond “been there, done that” memories. But, listening to those behaviors being horribly mismanaged can ruin even the most tolerant adult’s appetite in less time than it takes a parent to say, “I can see you’re unhappy, and we need to talk about why.”

In an op-ed piece, a psychotherapist asks the legitimate question, and provides the correct quick answer (“Which Is Better, Rewards or Punishments? Neither,” New York Times, Aug. 21, 2018). I couldn’t agree more. In my experience, rewards have a very short half-life and can become disastrously inflationary in the blink of an eye. On the other hand, punishments can be either too heavy-handed or so irrational that the child fails to make a logical connection between his misbehavior and his sentence.

Unfortunately, many child behavior advisers, including the op-ed author, offer alternatives to rewards and punishment that are unworkable in real-world circumstances, such as the restaurant scenario my wife and I endured.

While it sounds very democratic to ask a 3-year-old why he is misbehaving, more often than not it should be the parent who is asking what he or she could have done differently to avoid the situation. It is likely the child has been allowed to become overtired and/or the parent may be in denial about his/her child’s intolerance for stimulating environments.

Too often the parent takes too long to realize that the water is spilling over the dam and it is time to head for shore. Children who are overtired and having a tantrum can’t participate in a rational discussion about their feelings. If that dialogue needs to happen, and that is seldom, it should be the next day after the parent has time to consider his or her own mistakes.

When it comes to managing misbehaving children, I prefer well-tailored consequences and my favorite is a humanely crafted time-out. When presented and executed properly, a time-out can break the cycle of misbehavior and give both parent and child a chance to reconsider their positions.

But at 7 p.m. on a Friday evening in a busy restaurant, neither a time-out nor philosophizing with a 3-year-old is going to work. It’s time to ask for the check and head home to bed.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

“Alex, I understand that you are upset that you left your little bulldozer at home. Let’s try to think of something else you can play with here at the restaurant that is kind of like a bulldozer.”

Sounds like a reasonable strategy to calm an unruly preschooler, and it might have been had it not been the fifth attempt in a 45-minute dialogue between a mother and her overtired, misbehaving 3-year-old. There had been a lot of “I understand how you feel” and “use your words” woven into a gag-worthy and futile effort to forge a collaborative parent-child solution to the problem of an exhausted preschooler who is up past his bedtime in a public place.

My wife and I enjoy a night out with friends and prefer a quiet dining atmosphere. However, some evenings we eat earlier and choose a restaurant we know appeals to families with young children. At those meals, we anticipate being serenaded by a loud background buzz punctuated by the occasional shriek or short bout of crying. We expect a degree of childish behavior to come with the territory, and watching the dramas unfold brings back fond “been there, done that” memories. But, listening to those behaviors being horribly mismanaged can ruin even the most tolerant adult’s appetite in less time than it takes a parent to say, “I can see you’re unhappy, and we need to talk about why.”

In an op-ed piece, a psychotherapist asks the legitimate question, and provides the correct quick answer (“Which Is Better, Rewards or Punishments? Neither,” New York Times, Aug. 21, 2018). I couldn’t agree more. In my experience, rewards have a very short half-life and can become disastrously inflationary in the blink of an eye. On the other hand, punishments can be either too heavy-handed or so irrational that the child fails to make a logical connection between his misbehavior and his sentence.

Unfortunately, many child behavior advisers, including the op-ed author, offer alternatives to rewards and punishment that are unworkable in real-world circumstances, such as the restaurant scenario my wife and I endured.

While it sounds very democratic to ask a 3-year-old why he is misbehaving, more often than not it should be the parent who is asking what he or she could have done differently to avoid the situation. It is likely the child has been allowed to become overtired and/or the parent may be in denial about his/her child’s intolerance for stimulating environments.

Too often the parent takes too long to realize that the water is spilling over the dam and it is time to head for shore. Children who are overtired and having a tantrum can’t participate in a rational discussion about their feelings. If that dialogue needs to happen, and that is seldom, it should be the next day after the parent has time to consider his or her own mistakes.

When it comes to managing misbehaving children, I prefer well-tailored consequences and my favorite is a humanely crafted time-out. When presented and executed properly, a time-out can break the cycle of misbehavior and give both parent and child a chance to reconsider their positions.

But at 7 p.m. on a Friday evening in a busy restaurant, neither a time-out nor philosophizing with a 3-year-old is going to work. It’s time to ask for the check and head home to bed.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

Artificial Intelligence for Clinical Decision Support

There is abundant research being conducted on the use of artificial intelligence (AI) to improve diagnosis in dermatology. Recently, convolutional neural networks trained using large image libraries have achieved parity with dermatologists in discriminating between benign and malignant lesions.1 There are expectations that these systems, as they improve and are implemented in mobile electronic devices, will revolutionize diagnosis. Substantially less attention has been given to the use of AI to guide management options following a diagnosis. There are several reasons this area lends itself to the application of AI.

In 2015, the National Library of Medicine indexed more than 800,000 articles.2 Medical literature is growing at an overwhelming pace that makes it challenging for health care professionals to read, retain, and appropriately implement the latest research into their care. One survey found that physicians spend no more than 4 hours per week reading medical journals, and for the majority of articles, only the abstracts are read.3 Conversely, AI networks today are able to interpret millions of pages of data within seconds. It is worth investigating how AI can be used to improve treatment and management decisions made by physicians.

Cognitive computing is a modern approach to AI that incorporates natural language processing, machine learning, and other techniques to answer questions. One cognitive computing system developed by IBM research in 2007, Watson, can interpret a user’s query using natural language processing and then generate hypotheses. It searches data sources extensively to find and score evidence for each candidate hypothesis.4 This information is synthesized to provide a simple output: ranked answers with associated confidence scores. Machine learning is used to improve the answers with feedback, training, and repetition.4,5

Watson Oncology, an ongoing collaboration between IBM and Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, is an application of cognitive computing to medicine. At Memorial Sloan Kettering, Watson has been trained by expert clinicians to provide an individualized, evidence-based list of therapeutic options for oncologists and patients to discuss. Furthermore, Watson is capable of taking patient preferences into consideration.4

In the near future, there also may be a role that cognitive computing could play in aiding dermatologists. Dermatologists manage a multitude of conditions requiring systemic therapies such as chemotherapeutics, biologics, and immunosuppressant medications. Frequently, the patient population has a complicated medical history with multiple comorbidities. Although current electronic health record (EHR) systems are able to assist physicians with structured numerical data such as vitals and laboratory results, cognitive computing systems could interpret the natural language of journal articles, textbooks, and published guidelines, as well as the narrative components of EHR notes. Outcomes from similar patients also could be used as inputs. With enough data, cognitive computing systems may be able to identify associations and epidemiologic trends that would not otherwise be noticed. As described by Miotto et al,6 one system, “deep patient,” was able to accurately predict the development of schizophrenia, diabetes mellitus, and various cancers based on EHR data. Patient genetic information also could one day be used to generate new insights into pharmacogenomics.

The benefit of a cognitive computing decision support system is that ineffective treatments and adverse reactions could be minimized, which may improve outcomes and reduce costs. Artificial intelligence also could help to decrease work burden so that physicians can spend more time with their patients, resulting in improved patient satisfaction and overall increased access to the specialty.

As with other clinical decision support systems, a number of challenges exist with the integration of cognitive computing into real care. One obstacle unique to machine learning algorithms is the black box problem. For instance, the skin lesion–identifying neural network cannot be questioned to determine which factors it used to arrive at its diagnosis. This shortcoming can lead to dangerous situations, such as the one reported by Caruana et al.7 A predictive model classified patients with pneumonia and a history of asthma as having a lower mortality risk than those with pneumonia alone because the model was unable to recognize the confounder that asthmatic patients were preemptively admitted to the intensive care unit and treated more aggressively, which is another reason that AI recommendations must always be evaluated by a physician.7 Physician and patient input also will be integral to incorporate contextual and qualitative information that may not be accessible to computers.8

As cognitive computing decision support systems are primarily used in oncology, they will need to be adjusted to optimize them for dermatologic conditions. It also will be up to health care providers to benchmark the performance of these systems.

Current clinical decision support systems that do not use AI have struggled to improve major patient outcomes such as mortality. These systems have been hobbled by poor usability and human-computer integration. Clinicians find their alerts and warnings to be a nuisance. The adoption of cognitive computing systems has the potential to give clinicians an intelligent partner. Their natural language processing, ability to comprehend questions, and easily understandable output give them an inherent ease of use that simplifies interactions with clinicians. Rather than replacing physicians, these systems will free clinicians to spend more of their time on the components of care that only a human can provide.

- Esteva A, Kuprel B, Novoa RA, et al. Dermatologist-level classification of skin cancer with deep neural networks. Nature. 2017;542:115-118.

- The National Library of Medicine fact sheet. U.S. National Library of Medicine website https://www.nlm.nih.gov/pubs/factsheets/nlm.html. Updated October 20, 2016. Accessed June 18, 2018.

- Saint S, Christakis DA, Saha S, et al. Journal reading habits of internists. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15:881-884.

- Kelly JE III, Hamm S. Smart Machines: IBM’s Watson and the Era of Cognitive Computing. New York, NY: Columbia University Press; 2013.

- Ferrucci D, Levas A, Bagchi S, et al. Watson: beyond Jeopardy! Artificial Intelligence. 2013;199:93-105.

- Miotto R, Li L, Kidd BA, et al. Deep patient: an unsupervised representation to predict the future of patients from the electronic health records. Sci Rep. 2016;6:26094.

- Caruana R, Lou Y, Gehrke J, et al. Intelligible models for healthcare: predicting pneumonia risk and hospital 30-day readmission. Paper presented at: 21st ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining 2015; August 10-13, 2015; Sydney, Australia.

- Verghese A, Shah NH, Harrington RA. What this computer needs is a physician: humanism and artificial intelligence. JAMA. 2018;319:19-20.

There is abundant research being conducted on the use of artificial intelligence (AI) to improve diagnosis in dermatology. Recently, convolutional neural networks trained using large image libraries have achieved parity with dermatologists in discriminating between benign and malignant lesions.1 There are expectations that these systems, as they improve and are implemented in mobile electronic devices, will revolutionize diagnosis. Substantially less attention has been given to the use of AI to guide management options following a diagnosis. There are several reasons this area lends itself to the application of AI.

In 2015, the National Library of Medicine indexed more than 800,000 articles.2 Medical literature is growing at an overwhelming pace that makes it challenging for health care professionals to read, retain, and appropriately implement the latest research into their care. One survey found that physicians spend no more than 4 hours per week reading medical journals, and for the majority of articles, only the abstracts are read.3 Conversely, AI networks today are able to interpret millions of pages of data within seconds. It is worth investigating how AI can be used to improve treatment and management decisions made by physicians.

Cognitive computing is a modern approach to AI that incorporates natural language processing, machine learning, and other techniques to answer questions. One cognitive computing system developed by IBM research in 2007, Watson, can interpret a user’s query using natural language processing and then generate hypotheses. It searches data sources extensively to find and score evidence for each candidate hypothesis.4 This information is synthesized to provide a simple output: ranked answers with associated confidence scores. Machine learning is used to improve the answers with feedback, training, and repetition.4,5

Watson Oncology, an ongoing collaboration between IBM and Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, is an application of cognitive computing to medicine. At Memorial Sloan Kettering, Watson has been trained by expert clinicians to provide an individualized, evidence-based list of therapeutic options for oncologists and patients to discuss. Furthermore, Watson is capable of taking patient preferences into consideration.4

In the near future, there also may be a role that cognitive computing could play in aiding dermatologists. Dermatologists manage a multitude of conditions requiring systemic therapies such as chemotherapeutics, biologics, and immunosuppressant medications. Frequently, the patient population has a complicated medical history with multiple comorbidities. Although current electronic health record (EHR) systems are able to assist physicians with structured numerical data such as vitals and laboratory results, cognitive computing systems could interpret the natural language of journal articles, textbooks, and published guidelines, as well as the narrative components of EHR notes. Outcomes from similar patients also could be used as inputs. With enough data, cognitive computing systems may be able to identify associations and epidemiologic trends that would not otherwise be noticed. As described by Miotto et al,6 one system, “deep patient,” was able to accurately predict the development of schizophrenia, diabetes mellitus, and various cancers based on EHR data. Patient genetic information also could one day be used to generate new insights into pharmacogenomics.

The benefit of a cognitive computing decision support system is that ineffective treatments and adverse reactions could be minimized, which may improve outcomes and reduce costs. Artificial intelligence also could help to decrease work burden so that physicians can spend more time with their patients, resulting in improved patient satisfaction and overall increased access to the specialty.

As with other clinical decision support systems, a number of challenges exist with the integration of cognitive computing into real care. One obstacle unique to machine learning algorithms is the black box problem. For instance, the skin lesion–identifying neural network cannot be questioned to determine which factors it used to arrive at its diagnosis. This shortcoming can lead to dangerous situations, such as the one reported by Caruana et al.7 A predictive model classified patients with pneumonia and a history of asthma as having a lower mortality risk than those with pneumonia alone because the model was unable to recognize the confounder that asthmatic patients were preemptively admitted to the intensive care unit and treated more aggressively, which is another reason that AI recommendations must always be evaluated by a physician.7 Physician and patient input also will be integral to incorporate contextual and qualitative information that may not be accessible to computers.8

As cognitive computing decision support systems are primarily used in oncology, they will need to be adjusted to optimize them for dermatologic conditions. It also will be up to health care providers to benchmark the performance of these systems.

Current clinical decision support systems that do not use AI have struggled to improve major patient outcomes such as mortality. These systems have been hobbled by poor usability and human-computer integration. Clinicians find their alerts and warnings to be a nuisance. The adoption of cognitive computing systems has the potential to give clinicians an intelligent partner. Their natural language processing, ability to comprehend questions, and easily understandable output give them an inherent ease of use that simplifies interactions with clinicians. Rather than replacing physicians, these systems will free clinicians to spend more of their time on the components of care that only a human can provide.

There is abundant research being conducted on the use of artificial intelligence (AI) to improve diagnosis in dermatology. Recently, convolutional neural networks trained using large image libraries have achieved parity with dermatologists in discriminating between benign and malignant lesions.1 There are expectations that these systems, as they improve and are implemented in mobile electronic devices, will revolutionize diagnosis. Substantially less attention has been given to the use of AI to guide management options following a diagnosis. There are several reasons this area lends itself to the application of AI.

In 2015, the National Library of Medicine indexed more than 800,000 articles.2 Medical literature is growing at an overwhelming pace that makes it challenging for health care professionals to read, retain, and appropriately implement the latest research into their care. One survey found that physicians spend no more than 4 hours per week reading medical journals, and for the majority of articles, only the abstracts are read.3 Conversely, AI networks today are able to interpret millions of pages of data within seconds. It is worth investigating how AI can be used to improve treatment and management decisions made by physicians.

Cognitive computing is a modern approach to AI that incorporates natural language processing, machine learning, and other techniques to answer questions. One cognitive computing system developed by IBM research in 2007, Watson, can interpret a user’s query using natural language processing and then generate hypotheses. It searches data sources extensively to find and score evidence for each candidate hypothesis.4 This information is synthesized to provide a simple output: ranked answers with associated confidence scores. Machine learning is used to improve the answers with feedback, training, and repetition.4,5

Watson Oncology, an ongoing collaboration between IBM and Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, is an application of cognitive computing to medicine. At Memorial Sloan Kettering, Watson has been trained by expert clinicians to provide an individualized, evidence-based list of therapeutic options for oncologists and patients to discuss. Furthermore, Watson is capable of taking patient preferences into consideration.4

In the near future, there also may be a role that cognitive computing could play in aiding dermatologists. Dermatologists manage a multitude of conditions requiring systemic therapies such as chemotherapeutics, biologics, and immunosuppressant medications. Frequently, the patient population has a complicated medical history with multiple comorbidities. Although current electronic health record (EHR) systems are able to assist physicians with structured numerical data such as vitals and laboratory results, cognitive computing systems could interpret the natural language of journal articles, textbooks, and published guidelines, as well as the narrative components of EHR notes. Outcomes from similar patients also could be used as inputs. With enough data, cognitive computing systems may be able to identify associations and epidemiologic trends that would not otherwise be noticed. As described by Miotto et al,6 one system, “deep patient,” was able to accurately predict the development of schizophrenia, diabetes mellitus, and various cancers based on EHR data. Patient genetic information also could one day be used to generate new insights into pharmacogenomics.

The benefit of a cognitive computing decision support system is that ineffective treatments and adverse reactions could be minimized, which may improve outcomes and reduce costs. Artificial intelligence also could help to decrease work burden so that physicians can spend more time with their patients, resulting in improved patient satisfaction and overall increased access to the specialty.

As with other clinical decision support systems, a number of challenges exist with the integration of cognitive computing into real care. One obstacle unique to machine learning algorithms is the black box problem. For instance, the skin lesion–identifying neural network cannot be questioned to determine which factors it used to arrive at its diagnosis. This shortcoming can lead to dangerous situations, such as the one reported by Caruana et al.7 A predictive model classified patients with pneumonia and a history of asthma as having a lower mortality risk than those with pneumonia alone because the model was unable to recognize the confounder that asthmatic patients were preemptively admitted to the intensive care unit and treated more aggressively, which is another reason that AI recommendations must always be evaluated by a physician.7 Physician and patient input also will be integral to incorporate contextual and qualitative information that may not be accessible to computers.8

As cognitive computing decision support systems are primarily used in oncology, they will need to be adjusted to optimize them for dermatologic conditions. It also will be up to health care providers to benchmark the performance of these systems.

Current clinical decision support systems that do not use AI have struggled to improve major patient outcomes such as mortality. These systems have been hobbled by poor usability and human-computer integration. Clinicians find their alerts and warnings to be a nuisance. The adoption of cognitive computing systems has the potential to give clinicians an intelligent partner. Their natural language processing, ability to comprehend questions, and easily understandable output give them an inherent ease of use that simplifies interactions with clinicians. Rather than replacing physicians, these systems will free clinicians to spend more of their time on the components of care that only a human can provide.

- Esteva A, Kuprel B, Novoa RA, et al. Dermatologist-level classification of skin cancer with deep neural networks. Nature. 2017;542:115-118.

- The National Library of Medicine fact sheet. U.S. National Library of Medicine website https://www.nlm.nih.gov/pubs/factsheets/nlm.html. Updated October 20, 2016. Accessed June 18, 2018.

- Saint S, Christakis DA, Saha S, et al. Journal reading habits of internists. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15:881-884.

- Kelly JE III, Hamm S. Smart Machines: IBM’s Watson and the Era of Cognitive Computing. New York, NY: Columbia University Press; 2013.

- Ferrucci D, Levas A, Bagchi S, et al. Watson: beyond Jeopardy! Artificial Intelligence. 2013;199:93-105.

- Miotto R, Li L, Kidd BA, et al. Deep patient: an unsupervised representation to predict the future of patients from the electronic health records. Sci Rep. 2016;6:26094.

- Caruana R, Lou Y, Gehrke J, et al. Intelligible models for healthcare: predicting pneumonia risk and hospital 30-day readmission. Paper presented at: 21st ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining 2015; August 10-13, 2015; Sydney, Australia.

- Verghese A, Shah NH, Harrington RA. What this computer needs is a physician: humanism and artificial intelligence. JAMA. 2018;319:19-20.

- Esteva A, Kuprel B, Novoa RA, et al. Dermatologist-level classification of skin cancer with deep neural networks. Nature. 2017;542:115-118.

- The National Library of Medicine fact sheet. U.S. National Library of Medicine website https://www.nlm.nih.gov/pubs/factsheets/nlm.html. Updated October 20, 2016. Accessed June 18, 2018.

- Saint S, Christakis DA, Saha S, et al. Journal reading habits of internists. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15:881-884.

- Kelly JE III, Hamm S. Smart Machines: IBM’s Watson and the Era of Cognitive Computing. New York, NY: Columbia University Press; 2013.

- Ferrucci D, Levas A, Bagchi S, et al. Watson: beyond Jeopardy! Artificial Intelligence. 2013;199:93-105.

- Miotto R, Li L, Kidd BA, et al. Deep patient: an unsupervised representation to predict the future of patients from the electronic health records. Sci Rep. 2016;6:26094.

- Caruana R, Lou Y, Gehrke J, et al. Intelligible models for healthcare: predicting pneumonia risk and hospital 30-day readmission. Paper presented at: 21st ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining 2015; August 10-13, 2015; Sydney, Australia.

- Verghese A, Shah NH, Harrington RA. What this computer needs is a physician: humanism and artificial intelligence. JAMA. 2018;319:19-20.

Outcomes Associated With Shorter Wait Times at a County Hospital Outpatient Dermatology Clinic

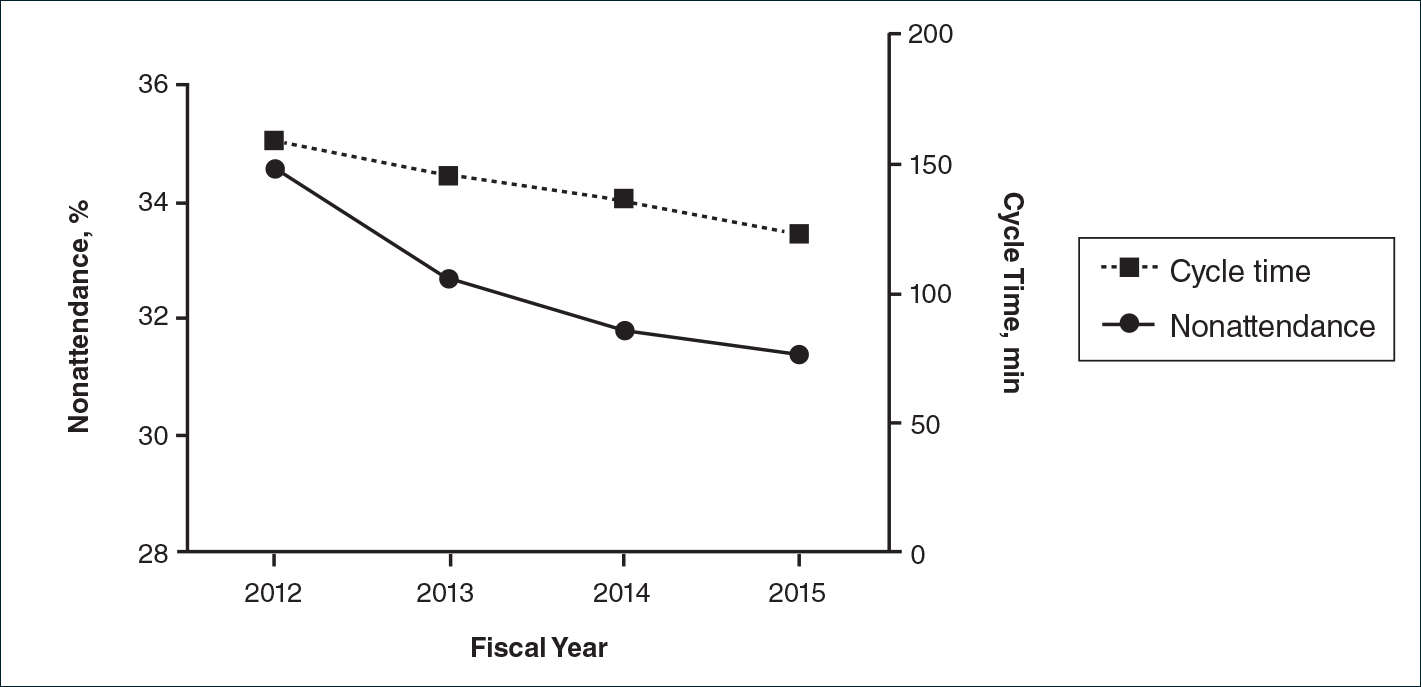

Maximizing productivity is prudent for outpatient subspecialty clinics to improve access to care. The outpatient dermatology clinic at Parkland Health and Hospital System in Dallas, Texas, which is a safety-net hospital in Dallas County, decreased wait times for new patients (from 377 to 48 days) and follow-up patients (from 95 to 34 days) from May 2012 to September 2015.1 Changes in clinic productivity measures that occur with decreased wait times are not well characterized; therefore, we sought to address this knowledge gap. We propose that decreased wait times are associated with improvement in additional clinic productivity measures, specifically decreases in nonattendance and cycle times (defined as time between patient check-in and discharge) as well as increases in referrals.

In our retrospective cohort study of patients seen in the Parkland outpatient dermatology clinic between fiscal year (FY) 2012 and FY 2015 (between October 2011 and September 2015), we collected data on patient nonattendance rates, cycle times, and referral volumes. Categorical variables were compared using χ2 tests, and changes in cycle times were analyzed using 2-way analysis of variance. P<.05 was considered statistically significant.

There were 52,775 scheduled clinic visits from FY 2012 to FY 2015. The overall proportion of patient nonattendance rates decreased from 34.6% (4202/12,141) to 31.4% (4429/14,119)(P<.001)(Figure), despite an increase in completed patient visits during the study period (7939 vs 9690). New patient nonattendance rates decreased from 42.9% (1831/4269) to 30.2% (1474/4874)(P<.001). The number of completed visits for new patients increased from 2438 in FY 2012 to 3400 in FY 2015. Follow-up nonattendance rates increased from 30.1% (2371/7872) to 32.0% (2955/9245)(P<.001). Follow-up completed visits increased from 5501 in FY 2012 to 6290 in FY 2015. Overall, average cycle time showed a trend to decrease from 159 to 123 minutes (22.6%)(Figure). Average cycle times were reduced from 159 to 128 minutes (19.5%) for new patients and from 161 to 115 minutes (28.6%) for follow-up patients (P=.02). Overall, referrals increased by 14.1% (816/5799)(P<.001), which was largely due to the increase in volume of referrals observed between FY 2014 (n=5770) and FY 2015 (n=6615).

We have demonstrated that decreased wait times can be associated with improvements in clinic productivity measures, namely decreased nonattendance rates and cycle times and increased referrals. Patient nonattendance is a burden on clinic resources and has been described in the dermatology clinic setting.2-6 Increased likelihood of nonattendance has been associated with prolonged wait times.3,7 We propose that decreased wait times can lead to diminished nonattendance rates, as patients are more likely to keep their appointments rather than seek other providers for dermatologic care. The difference in trends between new patient and follow-up nonattendance rates may be attributed to the larger relative increase in completed new patient visits compared to follow-ups during the study period.

Furthermore, the decrease in average cycle time reflected our clinic’s ability to see a larger number of patients per clinic, with subsequently shorter wait times. The greater reduction in cycle times for follow-up patients may be attributed to the increased continuity of providers who had previously seen these patients. Although the cycle times may seem high in our clinic compared to other practice settings, we believe that this marker of productivity is widely applicable to various clinic settings, including private practices and other outpatient specialty clinics. Increased clinic referrals can be a downstream effect of decreased wait times due to improvements in access to care, as shown in other specialty clinics.8 Effects of confounding variables on referral volumes, including nationwide health insurance changes during our study period, could not be ruled out.

Limitations of this study include unavailable data on patient and provider satisfaction and changes in patients’ health insurance. This study provides evidence of changes in clinical productivity measures associated with decreased wait times that can demonstrate widespread benefits to the health system.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Michael Estabrooks, RN, and Trung Vu for providing aggregate data, as well as Linda Hynan, PhD, for statistical advice (all Dallas, Texas).

- O’Brien JC, Chong BF. Reducing outpatient dermatology clinic wait times in a safety net health system in Dallas, Texas. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:631-632.

- Canizares MJ, Penneys NS. The incidence of nonattendance at an urgent care dermatology clinic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:457-459.

- Cohen AD, Dreiher J, Vardy DA, et al. Nonattendance in a dermatology clinic—a large sample analysis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:1178-1183.

- Resneck JS Jr, Lipton S, Pletcher MJ. Short wait times for patients seeking cosmetic botulinum toxin appointments with dermatologists. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:985-989.

- Tsang MW, Resneck JS Jr. Even patients with changing moles face long dermatology appointment wait-times: a study of simulated patient calls to dermatologists. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:54-58.

- Rosenbach M, Kagan S, Leventhal S. Dermatology urgent care clinic: a survey of referring physician satisfaction. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:1067-1069.e1.

- Dickey W, Morrow JI. Can outpatient non-attendance be predicted from the referral letter? an audit of default at neurology clinics. J R Soc Med. 1991;8:662-663.

- Bungard TJ, Smigorowsky MJ, Lalonde LD, et al. Cardiac EASE (Ensuring Access and Speedy Evaluation)—the impact of a single-point-of-entry multidisciplinary outpatient cardiology consultation program on wait times in Canada. Can J Cardiol. 2009;25:697-702.

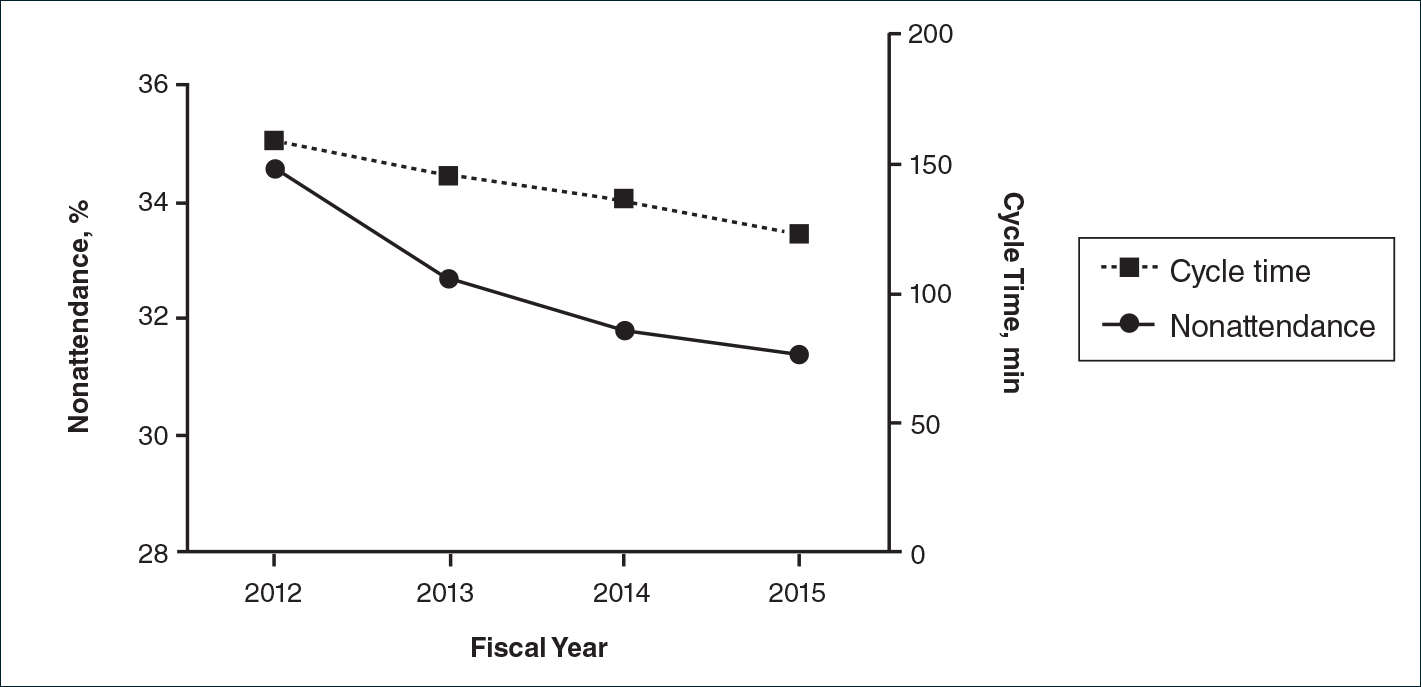

Maximizing productivity is prudent for outpatient subspecialty clinics to improve access to care. The outpatient dermatology clinic at Parkland Health and Hospital System in Dallas, Texas, which is a safety-net hospital in Dallas County, decreased wait times for new patients (from 377 to 48 days) and follow-up patients (from 95 to 34 days) from May 2012 to September 2015.1 Changes in clinic productivity measures that occur with decreased wait times are not well characterized; therefore, we sought to address this knowledge gap. We propose that decreased wait times are associated with improvement in additional clinic productivity measures, specifically decreases in nonattendance and cycle times (defined as time between patient check-in and discharge) as well as increases in referrals.

In our retrospective cohort study of patients seen in the Parkland outpatient dermatology clinic between fiscal year (FY) 2012 and FY 2015 (between October 2011 and September 2015), we collected data on patient nonattendance rates, cycle times, and referral volumes. Categorical variables were compared using χ2 tests, and changes in cycle times were analyzed using 2-way analysis of variance. P<.05 was considered statistically significant.

There were 52,775 scheduled clinic visits from FY 2012 to FY 2015. The overall proportion of patient nonattendance rates decreased from 34.6% (4202/12,141) to 31.4% (4429/14,119)(P<.001)(Figure), despite an increase in completed patient visits during the study period (7939 vs 9690). New patient nonattendance rates decreased from 42.9% (1831/4269) to 30.2% (1474/4874)(P<.001). The number of completed visits for new patients increased from 2438 in FY 2012 to 3400 in FY 2015. Follow-up nonattendance rates increased from 30.1% (2371/7872) to 32.0% (2955/9245)(P<.001). Follow-up completed visits increased from 5501 in FY 2012 to 6290 in FY 2015. Overall, average cycle time showed a trend to decrease from 159 to 123 minutes (22.6%)(Figure). Average cycle times were reduced from 159 to 128 minutes (19.5%) for new patients and from 161 to 115 minutes (28.6%) for follow-up patients (P=.02). Overall, referrals increased by 14.1% (816/5799)(P<.001), which was largely due to the increase in volume of referrals observed between FY 2014 (n=5770) and FY 2015 (n=6615).

We have demonstrated that decreased wait times can be associated with improvements in clinic productivity measures, namely decreased nonattendance rates and cycle times and increased referrals. Patient nonattendance is a burden on clinic resources and has been described in the dermatology clinic setting.2-6 Increased likelihood of nonattendance has been associated with prolonged wait times.3,7 We propose that decreased wait times can lead to diminished nonattendance rates, as patients are more likely to keep their appointments rather than seek other providers for dermatologic care. The difference in trends between new patient and follow-up nonattendance rates may be attributed to the larger relative increase in completed new patient visits compared to follow-ups during the study period.

Furthermore, the decrease in average cycle time reflected our clinic’s ability to see a larger number of patients per clinic, with subsequently shorter wait times. The greater reduction in cycle times for follow-up patients may be attributed to the increased continuity of providers who had previously seen these patients. Although the cycle times may seem high in our clinic compared to other practice settings, we believe that this marker of productivity is widely applicable to various clinic settings, including private practices and other outpatient specialty clinics. Increased clinic referrals can be a downstream effect of decreased wait times due to improvements in access to care, as shown in other specialty clinics.8 Effects of confounding variables on referral volumes, including nationwide health insurance changes during our study period, could not be ruled out.

Limitations of this study include unavailable data on patient and provider satisfaction and changes in patients’ health insurance. This study provides evidence of changes in clinical productivity measures associated with decreased wait times that can demonstrate widespread benefits to the health system.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Michael Estabrooks, RN, and Trung Vu for providing aggregate data, as well as Linda Hynan, PhD, for statistical advice (all Dallas, Texas).

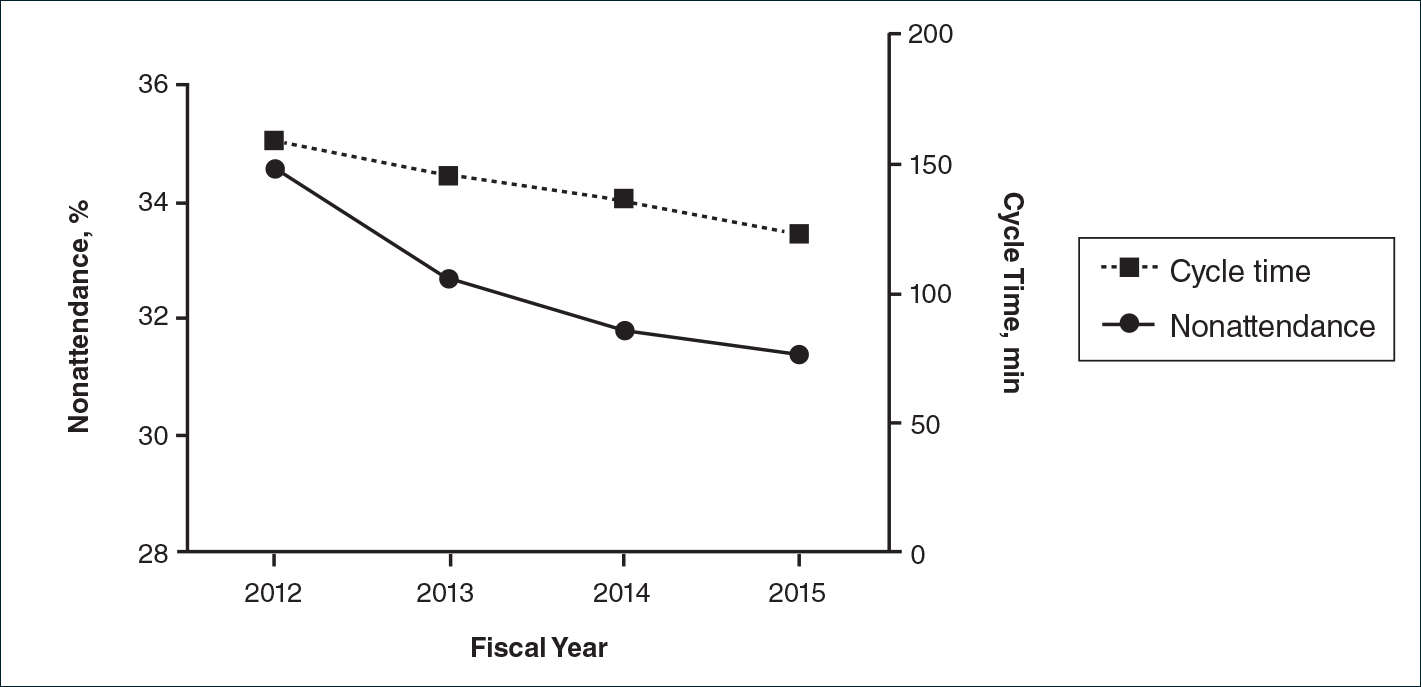

Maximizing productivity is prudent for outpatient subspecialty clinics to improve access to care. The outpatient dermatology clinic at Parkland Health and Hospital System in Dallas, Texas, which is a safety-net hospital in Dallas County, decreased wait times for new patients (from 377 to 48 days) and follow-up patients (from 95 to 34 days) from May 2012 to September 2015.1 Changes in clinic productivity measures that occur with decreased wait times are not well characterized; therefore, we sought to address this knowledge gap. We propose that decreased wait times are associated with improvement in additional clinic productivity measures, specifically decreases in nonattendance and cycle times (defined as time between patient check-in and discharge) as well as increases in referrals.

In our retrospective cohort study of patients seen in the Parkland outpatient dermatology clinic between fiscal year (FY) 2012 and FY 2015 (between October 2011 and September 2015), we collected data on patient nonattendance rates, cycle times, and referral volumes. Categorical variables were compared using χ2 tests, and changes in cycle times were analyzed using 2-way analysis of variance. P<.05 was considered statistically significant.

There were 52,775 scheduled clinic visits from FY 2012 to FY 2015. The overall proportion of patient nonattendance rates decreased from 34.6% (4202/12,141) to 31.4% (4429/14,119)(P<.001)(Figure), despite an increase in completed patient visits during the study period (7939 vs 9690). New patient nonattendance rates decreased from 42.9% (1831/4269) to 30.2% (1474/4874)(P<.001). The number of completed visits for new patients increased from 2438 in FY 2012 to 3400 in FY 2015. Follow-up nonattendance rates increased from 30.1% (2371/7872) to 32.0% (2955/9245)(P<.001). Follow-up completed visits increased from 5501 in FY 2012 to 6290 in FY 2015. Overall, average cycle time showed a trend to decrease from 159 to 123 minutes (22.6%)(Figure). Average cycle times were reduced from 159 to 128 minutes (19.5%) for new patients and from 161 to 115 minutes (28.6%) for follow-up patients (P=.02). Overall, referrals increased by 14.1% (816/5799)(P<.001), which was largely due to the increase in volume of referrals observed between FY 2014 (n=5770) and FY 2015 (n=6615).

We have demonstrated that decreased wait times can be associated with improvements in clinic productivity measures, namely decreased nonattendance rates and cycle times and increased referrals. Patient nonattendance is a burden on clinic resources and has been described in the dermatology clinic setting.2-6 Increased likelihood of nonattendance has been associated with prolonged wait times.3,7 We propose that decreased wait times can lead to diminished nonattendance rates, as patients are more likely to keep their appointments rather than seek other providers for dermatologic care. The difference in trends between new patient and follow-up nonattendance rates may be attributed to the larger relative increase in completed new patient visits compared to follow-ups during the study period.

Furthermore, the decrease in average cycle time reflected our clinic’s ability to see a larger number of patients per clinic, with subsequently shorter wait times. The greater reduction in cycle times for follow-up patients may be attributed to the increased continuity of providers who had previously seen these patients. Although the cycle times may seem high in our clinic compared to other practice settings, we believe that this marker of productivity is widely applicable to various clinic settings, including private practices and other outpatient specialty clinics. Increased clinic referrals can be a downstream effect of decreased wait times due to improvements in access to care, as shown in other specialty clinics.8 Effects of confounding variables on referral volumes, including nationwide health insurance changes during our study period, could not be ruled out.

Limitations of this study include unavailable data on patient and provider satisfaction and changes in patients’ health insurance. This study provides evidence of changes in clinical productivity measures associated with decreased wait times that can demonstrate widespread benefits to the health system.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Michael Estabrooks, RN, and Trung Vu for providing aggregate data, as well as Linda Hynan, PhD, for statistical advice (all Dallas, Texas).

- O’Brien JC, Chong BF. Reducing outpatient dermatology clinic wait times in a safety net health system in Dallas, Texas. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:631-632.

- Canizares MJ, Penneys NS. The incidence of nonattendance at an urgent care dermatology clinic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:457-459.

- Cohen AD, Dreiher J, Vardy DA, et al. Nonattendance in a dermatology clinic—a large sample analysis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:1178-1183.

- Resneck JS Jr, Lipton S, Pletcher MJ. Short wait times for patients seeking cosmetic botulinum toxin appointments with dermatologists. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:985-989.

- Tsang MW, Resneck JS Jr. Even patients with changing moles face long dermatology appointment wait-times: a study of simulated patient calls to dermatologists. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:54-58.

- Rosenbach M, Kagan S, Leventhal S. Dermatology urgent care clinic: a survey of referring physician satisfaction. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:1067-1069.e1.

- Dickey W, Morrow JI. Can outpatient non-attendance be predicted from the referral letter? an audit of default at neurology clinics. J R Soc Med. 1991;8:662-663.

- Bungard TJ, Smigorowsky MJ, Lalonde LD, et al. Cardiac EASE (Ensuring Access and Speedy Evaluation)—the impact of a single-point-of-entry multidisciplinary outpatient cardiology consultation program on wait times in Canada. Can J Cardiol. 2009;25:697-702.

- O’Brien JC, Chong BF. Reducing outpatient dermatology clinic wait times in a safety net health system in Dallas, Texas. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:631-632.

- Canizares MJ, Penneys NS. The incidence of nonattendance at an urgent care dermatology clinic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:457-459.

- Cohen AD, Dreiher J, Vardy DA, et al. Nonattendance in a dermatology clinic—a large sample analysis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:1178-1183.

- Resneck JS Jr, Lipton S, Pletcher MJ. Short wait times for patients seeking cosmetic botulinum toxin appointments with dermatologists. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:985-989.

- Tsang MW, Resneck JS Jr. Even patients with changing moles face long dermatology appointment wait-times: a study of simulated patient calls to dermatologists. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:54-58.

- Rosenbach M, Kagan S, Leventhal S. Dermatology urgent care clinic: a survey of referring physician satisfaction. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:1067-1069.e1.

- Dickey W, Morrow JI. Can outpatient non-attendance be predicted from the referral letter? an audit of default at neurology clinics. J R Soc Med. 1991;8:662-663.

- Bungard TJ, Smigorowsky MJ, Lalonde LD, et al. Cardiac EASE (Ensuring Access and Speedy Evaluation)—the impact of a single-point-of-entry multidisciplinary outpatient cardiology consultation program on wait times in Canada. Can J Cardiol. 2009;25:697-702.

Atopic Dermatitis Pipeline

Just when you might have thought dermatologic therapies were peaking, along came another banner year in atopic dermatitis (AD). Last year we saw the landmark launch of dupilumab, the first US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved biologic therapy for AD. Dupilumab addresses a novel mechanism of AD in adults by blocking IL-4 and IL-13, which both play a central role in the type 2 helper T cell (TH2) axis on the dual development of barrier-impaired skin and aberrant immune response including IgE to cutaneous aggravating agents with resultant inflammation. Additional information has shown direct effects to reduce itch in AD.1 A 12-week study of dupilumab monotherapy showed that 85% (47/55) of treated patients had at least a 50% reduction in Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) score and 40% (22/55) were clear or almost clear on the investigator global assessment. With concomitant corticosteroid therapy, 100% of patients achieved EASI-50.2 Also notable, 2017 ushered in the appearance of a novel iteration of the 30-year-old concept of phosphodiesterase inhibition with the approval of the topical agent crisaborole for AD treatment in patients 2 years and older, which has been shown to be effective in both children and adults.3,4 However, despite these leaps of advancement in the care of AD, by no means has the condition been cured.

Atopic dermatitis has remained an incurable disease due to many factors: (1) variable immunologic and environmental triggers and patient disease course; (2) intolerance to therapeutic agents, including an enhanced sense of stinging and/or reactivity; (3) poor access to novel therapies among underserved patient populations; (4) lack of available data and information on variable treatment response by ethnicity and race; and (5) the absence of biologic treatments for severe childhood AD to modify long-term recurrence and progression of atopy, which is probably the most important issue, as the majority of AD cases start in children 5 years and younger.

Instituting a treatment today to provide children with disease-free skin for a lifetime truly is the Holy Grail in pediatric dermatology. To aid in the progress toward this goal, a deeper understanding of the manifestation of pediatric versus adult AD is now being investigated. It is clear that with adult chronicity, type 1 helper T cell (TH1) axis activity and prolonged defects are triggered in barrier maturation; however, recent data have started to demonstrate that the youngest patients have different issues in lipid maturation and lack TH1 activation. In particular, fatty acyl-CoA reductase 2 and fatty acid 2-hydroxylase is preferentially downregulated in children.5 It appears that the young immune system may be ripe for immune modification, which previously has been demonstrated with wild-type viral infections of varicella in children.6 However, future research will focus on what kind of tweaks to the immune system are required.

To encapsulate the AD pipeline, we will review drug trials that are in active recruitment as well as recently published data, which constitute an exciting group full of modifications of current therapies and agents with novel mechanisms of action.

Therapies targeting new mechanisms of action include Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors, which have shown promising results for alopecia areata and vitiligo vulgaris. These agents may create selective modification of the immune system and are being tested topically and orally (Clinicaltrials.gov identifier NCT03011892).

Another mechanism that currently is being studied includes a topical IL-4 and IL-13 inhibitor, which would hopefully mimic the efficacy of dupilumab, antioxidant therapies, and antimicrobials (NCT03351777, NCT03381625, NCT02910011).

Data on the outcome of a phase 3 trial of dupilumab in adolescents has been released but not yet published by the manufacturer and shows promising results in children aged 12 to 17 years, both in reduction of EASI score and in achieving clear or almost clear skin.11 Interestingly, limited data available from a press release reported similar results with dupilumab injection every 2 weeks versus every 4 weeks, which may give alternative dosing regimens in this age group once approved11; however, publication has yet to occur for the latter data.

Other mechanistic agents include blockade of cytokines and interleukins, particularly those involved in type 2 helper T cell (TH2) activity, such as thymic stromal lymphopoietin (a cytokine), as well as targeted single inhibition of IL-4, IL-5, IL-13, and IL-31 and/or their receptors. Nemolizumab, an anti–IL-31 receptor A antibody, is showing promise in the control of AD-associated itch and reduction in EASI

The future of AD therapy is anyone’s guess. Having entered the biologic era with dupilumab, we have a high bar set for efficacy and safety of AD therapies, yet there remains a core group of AD patients who have not yet achieved clearance or refuse injectables; therefore, adjunctive or alternative therapeutics are still needed. Furthermore, we still have not identified who will best benefit long-term from systemic intervention and how to best effect long-term disease control with biologics or novel agents, and choosing the therapy based on patient disease characteristics or serotyping has not yet come of age. It is exciting to think about what next year will bring!

- Xu X, Zheng Y, Zhang X, et al. Efficacy and safety of dupilumab for the treatment of moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis in adults. Oncotarget. 2017;8:108480-108491.

- Beck LA, Thaçi D, Hamilton JD, et al. Dupilumab treatment in adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:130-139.

- Murrell D, Gebauer K, Spelman L, et al. Crisaborole topical ointment, 2% in adults with atopic dermatitis: a phase 2a, vehicle-controlled, proof-of-concept study. J Drugs Dermatol. 2015;14:1108-1112.

- Paller AS, Tom WL, Lebwohl MG, et al. Efficacy and safety of crisaborole ointment, a novel, nonsteroidal phosphodiesterase 4 (PDE4) inhibitor for the topical treatment of atopic dermatitis (AD) in children and adults. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:494-503.e6.

- Brunner PM, Israel A, Zhang N, et al. Early-onset pediatric atopic dermatitis is characterized by TH2/TH17/TH22-centered inflammation and lipid alterations. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018;141:2094-2106.

- Silverberg JI, Kleiman E, Silverberg NB, et al. Chickenpox in childhood is associated with decreased atopic disorders, IgE, allergic sensitization, and leukocyte subsets. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2012;23:50-58.

- Paller AS, Kabashima K, Bieber T. Therapeutic pipeline for atopic dermatitis: end of the drought? Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;140:633-643.

- Renert-Yuval Y, Guttman-Yassky E. Systemic therapies in atopic dermatitis: the pipeline. Clin Dermatol. 2017;35:387-397.

- Bissonnette R, Papp KA, Poulin Y, et al. Topical tofacitinib for atopic dermatitis: a phase IIa randomized trial. Br J Dermatol. 2016;175:902-911.

- Guttman-Yassky E, Silverberg JI, Nemoto O, et al. Baricitinib in adult patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: a phase 2 parallel, double-blinded, randomized placebo-controlled multiple-dose study [published online February 1, 2018]. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.01.018.

- Dupixent (dupilumab) showed positive phase 3 results in adolescents with inadequately controlled moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis [press release]. Tarrytown, NY: Sanofi; May 16, 2018. https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/dupixent-dupilumab-showed-positive-phase-3-results-in-adolescents-with-inadequately-controlled-moderate-to-severe-atopic-dermatitis-300649146.html. Accessed July 11, 2018.

- Ruzicka T, Hanifin JM, Furue M, et al. Anti–interleukin-31 receptor A antibody for atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:826-835.

Just when you might have thought dermatologic therapies were peaking, along came another banner year in atopic dermatitis (AD). Last year we saw the landmark launch of dupilumab, the first US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved biologic therapy for AD. Dupilumab addresses a novel mechanism of AD in adults by blocking IL-4 and IL-13, which both play a central role in the type 2 helper T cell (TH2) axis on the dual development of barrier-impaired skin and aberrant immune response including IgE to cutaneous aggravating agents with resultant inflammation. Additional information has shown direct effects to reduce itch in AD.1 A 12-week study of dupilumab monotherapy showed that 85% (47/55) of treated patients had at least a 50% reduction in Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) score and 40% (22/55) were clear or almost clear on the investigator global assessment. With concomitant corticosteroid therapy, 100% of patients achieved EASI-50.2 Also notable, 2017 ushered in the appearance of a novel iteration of the 30-year-old concept of phosphodiesterase inhibition with the approval of the topical agent crisaborole for AD treatment in patients 2 years and older, which has been shown to be effective in both children and adults.3,4 However, despite these leaps of advancement in the care of AD, by no means has the condition been cured.

Atopic dermatitis has remained an incurable disease due to many factors: (1) variable immunologic and environmental triggers and patient disease course; (2) intolerance to therapeutic agents, including an enhanced sense of stinging and/or reactivity; (3) poor access to novel therapies among underserved patient populations; (4) lack of available data and information on variable treatment response by ethnicity and race; and (5) the absence of biologic treatments for severe childhood AD to modify long-term recurrence and progression of atopy, which is probably the most important issue, as the majority of AD cases start in children 5 years and younger.

Instituting a treatment today to provide children with disease-free skin for a lifetime truly is the Holy Grail in pediatric dermatology. To aid in the progress toward this goal, a deeper understanding of the manifestation of pediatric versus adult AD is now being investigated. It is clear that with adult chronicity, type 1 helper T cell (TH1) axis activity and prolonged defects are triggered in barrier maturation; however, recent data have started to demonstrate that the youngest patients have different issues in lipid maturation and lack TH1 activation. In particular, fatty acyl-CoA reductase 2 and fatty acid 2-hydroxylase is preferentially downregulated in children.5 It appears that the young immune system may be ripe for immune modification, which previously has been demonstrated with wild-type viral infections of varicella in children.6 However, future research will focus on what kind of tweaks to the immune system are required.

To encapsulate the AD pipeline, we will review drug trials that are in active recruitment as well as recently published data, which constitute an exciting group full of modifications of current therapies and agents with novel mechanisms of action.

Therapies targeting new mechanisms of action include Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors, which have shown promising results for alopecia areata and vitiligo vulgaris. These agents may create selective modification of the immune system and are being tested topically and orally (Clinicaltrials.gov identifier NCT03011892).

Another mechanism that currently is being studied includes a topical IL-4 and IL-13 inhibitor, which would hopefully mimic the efficacy of dupilumab, antioxidant therapies, and antimicrobials (NCT03351777, NCT03381625, NCT02910011).

Data on the outcome of a phase 3 trial of dupilumab in adolescents has been released but not yet published by the manufacturer and shows promising results in children aged 12 to 17 years, both in reduction of EASI score and in achieving clear or almost clear skin.11 Interestingly, limited data available from a press release reported similar results with dupilumab injection every 2 weeks versus every 4 weeks, which may give alternative dosing regimens in this age group once approved11; however, publication has yet to occur for the latter data.

Other mechanistic agents include blockade of cytokines and interleukins, particularly those involved in type 2 helper T cell (TH2) activity, such as thymic stromal lymphopoietin (a cytokine), as well as targeted single inhibition of IL-4, IL-5, IL-13, and IL-31 and/or their receptors. Nemolizumab, an anti–IL-31 receptor A antibody, is showing promise in the control of AD-associated itch and reduction in EASI

The future of AD therapy is anyone’s guess. Having entered the biologic era with dupilumab, we have a high bar set for efficacy and safety of AD therapies, yet there remains a core group of AD patients who have not yet achieved clearance or refuse injectables; therefore, adjunctive or alternative therapeutics are still needed. Furthermore, we still have not identified who will best benefit long-term from systemic intervention and how to best effect long-term disease control with biologics or novel agents, and choosing the therapy based on patient disease characteristics or serotyping has not yet come of age. It is exciting to think about what next year will bring!

Just when you might have thought dermatologic therapies were peaking, along came another banner year in atopic dermatitis (AD). Last year we saw the landmark launch of dupilumab, the first US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved biologic therapy for AD. Dupilumab addresses a novel mechanism of AD in adults by blocking IL-4 and IL-13, which both play a central role in the type 2 helper T cell (TH2) axis on the dual development of barrier-impaired skin and aberrant immune response including IgE to cutaneous aggravating agents with resultant inflammation. Additional information has shown direct effects to reduce itch in AD.1 A 12-week study of dupilumab monotherapy showed that 85% (47/55) of treated patients had at least a 50% reduction in Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) score and 40% (22/55) were clear or almost clear on the investigator global assessment. With concomitant corticosteroid therapy, 100% of patients achieved EASI-50.2 Also notable, 2017 ushered in the appearance of a novel iteration of the 30-year-old concept of phosphodiesterase inhibition with the approval of the topical agent crisaborole for AD treatment in patients 2 years and older, which has been shown to be effective in both children and adults.3,4 However, despite these leaps of advancement in the care of AD, by no means has the condition been cured.

Atopic dermatitis has remained an incurable disease due to many factors: (1) variable immunologic and environmental triggers and patient disease course; (2) intolerance to therapeutic agents, including an enhanced sense of stinging and/or reactivity; (3) poor access to novel therapies among underserved patient populations; (4) lack of available data and information on variable treatment response by ethnicity and race; and (5) the absence of biologic treatments for severe childhood AD to modify long-term recurrence and progression of atopy, which is probably the most important issue, as the majority of AD cases start in children 5 years and younger.

Instituting a treatment today to provide children with disease-free skin for a lifetime truly is the Holy Grail in pediatric dermatology. To aid in the progress toward this goal, a deeper understanding of the manifestation of pediatric versus adult AD is now being investigated. It is clear that with adult chronicity, type 1 helper T cell (TH1) axis activity and prolonged defects are triggered in barrier maturation; however, recent data have started to demonstrate that the youngest patients have different issues in lipid maturation and lack TH1 activation. In particular, fatty acyl-CoA reductase 2 and fatty acid 2-hydroxylase is preferentially downregulated in children.5 It appears that the young immune system may be ripe for immune modification, which previously has been demonstrated with wild-type viral infections of varicella in children.6 However, future research will focus on what kind of tweaks to the immune system are required.

To encapsulate the AD pipeline, we will review drug trials that are in active recruitment as well as recently published data, which constitute an exciting group full of modifications of current therapies and agents with novel mechanisms of action.

Therapies targeting new mechanisms of action include Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors, which have shown promising results for alopecia areata and vitiligo vulgaris. These agents may create selective modification of the immune system and are being tested topically and orally (Clinicaltrials.gov identifier NCT03011892).

Another mechanism that currently is being studied includes a topical IL-4 and IL-13 inhibitor, which would hopefully mimic the efficacy of dupilumab, antioxidant therapies, and antimicrobials (NCT03351777, NCT03381625, NCT02910011).

Data on the outcome of a phase 3 trial of dupilumab in adolescents has been released but not yet published by the manufacturer and shows promising results in children aged 12 to 17 years, both in reduction of EASI score and in achieving clear or almost clear skin.11 Interestingly, limited data available from a press release reported similar results with dupilumab injection every 2 weeks versus every 4 weeks, which may give alternative dosing regimens in this age group once approved11; however, publication has yet to occur for the latter data.

Other mechanistic agents include blockade of cytokines and interleukins, particularly those involved in type 2 helper T cell (TH2) activity, such as thymic stromal lymphopoietin (a cytokine), as well as targeted single inhibition of IL-4, IL-5, IL-13, and IL-31 and/or their receptors. Nemolizumab, an anti–IL-31 receptor A antibody, is showing promise in the control of AD-associated itch and reduction in EASI

The future of AD therapy is anyone’s guess. Having entered the biologic era with dupilumab, we have a high bar set for efficacy and safety of AD therapies, yet there remains a core group of AD patients who have not yet achieved clearance or refuse injectables; therefore, adjunctive or alternative therapeutics are still needed. Furthermore, we still have not identified who will best benefit long-term from systemic intervention and how to best effect long-term disease control with biologics or novel agents, and choosing the therapy based on patient disease characteristics or serotyping has not yet come of age. It is exciting to think about what next year will bring!

- Xu X, Zheng Y, Zhang X, et al. Efficacy and safety of dupilumab for the treatment of moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis in adults. Oncotarget. 2017;8:108480-108491.

- Beck LA, Thaçi D, Hamilton JD, et al. Dupilumab treatment in adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:130-139.

- Murrell D, Gebauer K, Spelman L, et al. Crisaborole topical ointment, 2% in adults with atopic dermatitis: a phase 2a, vehicle-controlled, proof-of-concept study. J Drugs Dermatol. 2015;14:1108-1112.

- Paller AS, Tom WL, Lebwohl MG, et al. Efficacy and safety of crisaborole ointment, a novel, nonsteroidal phosphodiesterase 4 (PDE4) inhibitor for the topical treatment of atopic dermatitis (AD) in children and adults. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:494-503.e6.

- Brunner PM, Israel A, Zhang N, et al. Early-onset pediatric atopic dermatitis is characterized by TH2/TH17/TH22-centered inflammation and lipid alterations. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018;141:2094-2106.

- Silverberg JI, Kleiman E, Silverberg NB, et al. Chickenpox in childhood is associated with decreased atopic disorders, IgE, allergic sensitization, and leukocyte subsets. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2012;23:50-58.

- Paller AS, Kabashima K, Bieber T. Therapeutic pipeline for atopic dermatitis: end of the drought? Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;140:633-643.

- Renert-Yuval Y, Guttman-Yassky E. Systemic therapies in atopic dermatitis: the pipeline. Clin Dermatol. 2017;35:387-397.

- Bissonnette R, Papp KA, Poulin Y, et al. Topical tofacitinib for atopic dermatitis: a phase IIa randomized trial. Br J Dermatol. 2016;175:902-911.

- Guttman-Yassky E, Silverberg JI, Nemoto O, et al. Baricitinib in adult patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: a phase 2 parallel, double-blinded, randomized placebo-controlled multiple-dose study [published online February 1, 2018]. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.01.018.

- Dupixent (dupilumab) showed positive phase 3 results in adolescents with inadequately controlled moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis [press release]. Tarrytown, NY: Sanofi; May 16, 2018. https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/dupixent-dupilumab-showed-positive-phase-3-results-in-adolescents-with-inadequately-controlled-moderate-to-severe-atopic-dermatitis-300649146.html. Accessed July 11, 2018.

- Ruzicka T, Hanifin JM, Furue M, et al. Anti–interleukin-31 receptor A antibody for atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:826-835.

- Xu X, Zheng Y, Zhang X, et al. Efficacy and safety of dupilumab for the treatment of moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis in adults. Oncotarget. 2017;8:108480-108491.

- Beck LA, Thaçi D, Hamilton JD, et al. Dupilumab treatment in adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:130-139.

- Murrell D, Gebauer K, Spelman L, et al. Crisaborole topical ointment, 2% in adults with atopic dermatitis: a phase 2a, vehicle-controlled, proof-of-concept study. J Drugs Dermatol. 2015;14:1108-1112.

- Paller AS, Tom WL, Lebwohl MG, et al. Efficacy and safety of crisaborole ointment, a novel, nonsteroidal phosphodiesterase 4 (PDE4) inhibitor for the topical treatment of atopic dermatitis (AD) in children and adults. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:494-503.e6.

- Brunner PM, Israel A, Zhang N, et al. Early-onset pediatric atopic dermatitis is characterized by TH2/TH17/TH22-centered inflammation and lipid alterations. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018;141:2094-2106.

- Silverberg JI, Kleiman E, Silverberg NB, et al. Chickenpox in childhood is associated with decreased atopic disorders, IgE, allergic sensitization, and leukocyte subsets. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2012;23:50-58.

- Paller AS, Kabashima K, Bieber T. Therapeutic pipeline for atopic dermatitis: end of the drought? Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;140:633-643.

- Renert-Yuval Y, Guttman-Yassky E. Systemic therapies in atopic dermatitis: the pipeline. Clin Dermatol. 2017;35:387-397.

- Bissonnette R, Papp KA, Poulin Y, et al. Topical tofacitinib for atopic dermatitis: a phase IIa randomized trial. Br J Dermatol. 2016;175:902-911.

- Guttman-Yassky E, Silverberg JI, Nemoto O, et al. Baricitinib in adult patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: a phase 2 parallel, double-blinded, randomized placebo-controlled multiple-dose study [published online February 1, 2018]. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.01.018.

- Dupixent (dupilumab) showed positive phase 3 results in adolescents with inadequately controlled moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis [press release]. Tarrytown, NY: Sanofi; May 16, 2018. https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/dupixent-dupilumab-showed-positive-phase-3-results-in-adolescents-with-inadequately-controlled-moderate-to-severe-atopic-dermatitis-300649146.html. Accessed July 11, 2018.

- Ruzicka T, Hanifin JM, Furue M, et al. Anti–interleukin-31 receptor A antibody for atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:826-835.

Speaking the unspeakable: Talking to children about parental mental illness

You probably think you know how to talk with a child about death. But somehow talking about a parent’s mental illness may seem more difficult. Even medical professionals, as most people, can find themselves feeling more judgmental or uneasy talking about mental illness than about physical problems. But with a prevalence of about one in four people having mental disorders, we need to be prepared for this discussion.

Sometimes family members, or even parents themselves, have asked me to tell a child about a parent’s mental illness or substance use. They know the child is confused and scared but don’t know what to say about this still-hushed issue. Other times, children’s behaviors show that they are struggling – by their aggression, depression, decline in school performance, anger, anxiety, or running away – and I find out only by asking that they are experiencing life with a mentally ill parent.