User login

Take Your Statins, for Heaven’s Sake

It’s an extremely common scenario. A patient’s screening tests return, showing a significant elevation of the calculated low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), known to the lay public as bad cholesterol. To a physician like myself, someone who prides himself on a modest bit of expertise in lipids, it’s an absolute no-brainer. The patient should be placed on statin therapy pronto to reduce the major risks of heart attack, stroke, and other vascular misfortunes that are clearly associated with an elevated LDL-C level.

The tremendous ability of statins to reduce cardiovascular risk is among the best-demonstrated therapeutic effects of any class of medication in any branch of medical practice. The first major trial to show definitive benefits with the use of statins was the Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study, which came out in 1994 and showed a 30% relative reduction in cardiovascular events in a high-risk secondary prevention population, meaning that the subjects already had documented vascular disease before entering the trial.

Related: Did Niacin Get a Bum Rap?

Similar results were reported soon after in primary prevention populations in the WOSCOPS study in the United Kingdom (UK), and from the AFCAPS/TexCAPS studies in the U.S. Then the large UK-based Heart Protection Study showed that statins reduce cardiovascular risk regardless of the initial LDL-C level. Some experts suspected that many of the protective effects of statins were due not only to the LDL-C reduction per se, but also the so-called pleiotropic benefits, which included vasodilation, antithrombotic effects, and improved function of the endothelial cells that line the walls of blood vessels.

A number of additional studies have since markedly expanded the role of statins. The CARDS study showed that patients with diabetes had fewer events on statins. The ASCOT study suggested that statins reduce risk in patients with hypertension. And the SPARCL study revealed fewer recurrent events in patients on statins who had experienced a stroke or transient ischemic attack. Perhaps an even greater advance came with the JUPITER study, which showed that patients with elevated C-reactive protein levels—a marker of systemic inflammation—had fewer cardiovascular events when treated with statins than with placebo.

As you can imagine, there are plenty of times when I reach for my prescription pad (actually, my mouse) with the intention of ordering a statin to reduce a patient’s cardiovascular risk. But unfortunately, many times the patient catches me up short by objecting to such a plan. I can’t tell you how many times a patient responds by asking rather pointedly about the adverse effects (AEs) of statins. Now, I’ll readily admit that a small number of patients ask about AEs with any medication, but I would submit that the question comes up far more commonly with statins than it does with almost any other class of medication. Why?

I firmly believe that a huge driver of my patients’ irrational suspicions of statins is the drivel that is found on countless unreliable and unscientific websites. Antistatin nonsense is readily available, and many patients have thoroughly marinated themselves in a toxic slurry of misinformation and medical fantasy. Most of these sites emphasize known statin AEs, such as myalgias and myopathies, liver damage, and rhabdomyolysis, but then grossly exaggerate the severity and frequency. Other sites hammer on the modest number of patients who are nudged from prediabetes to full-fledged diabetes by the statins or rant about medically unsubstantiated AEs of statins, such as worsened mentation and depression.

Related: Are Statins Safe to Use in Pregnancy? (Clinical Edge)

That’s all bad enough, but what’s even worse is when patients attack the very medical foundation for prescribing statins, claiming that their online “research” causes them to doubt the reported association between LDL-C levels and cardiovascular risk. They also hint darkly at a vast medical-industrial conspiracy to inflate the true importance of LDL-C, thus allowing for more sales of the highly questionable statins and increased drug company profits. No patient has directly accused me of personally benefitting financially by overprescribing statins, but some have certainly hinted at it.

Another large group of patients declines to take the proffered statins by insisting that they would much rather pursue diet and exercise to bring down their high levels of LDL-C. They are invariably surprised when I tell them that even the most aggressive approaches are unlikely to reduce LDL-C by more than a negligible amount. I suspect that they think that their tired old doctor has bought into a reflexive pills-cure-all mentality and does not appreciate the wondrous benefits of a holistic approach.

The most annoying patients tell me they will instead take red yeast rice to bring down their LDL-C, because they prefer a “natural” remedy to some monstrous artificial chemical produced in a pharmaceutical company laboratory. When I try to tell them that red yeast rice contains a varying but unknown amount of a natural inhibitor of hMG-coA reductase, the same enzyme targeted with precisely dosed statins, they gape at me with unhidden disgust for completely missing the point: The naturally occurring remedy is inherently superior, precisely because it is naturally occurring!

Of course, I have to remind myself that a good number of patients simply do not want to take statins because it is a reminder of their vulnerability, status as a cardiac patient, or as a potential future victim of a heart attack or stroke. Some patients find that concept so upsetting that they would rather ignore it altogether.

Reluctantly, I admit that statins are not perfect drugs. But I would still submit that they’re the closest things we have to wonder drugs today. Yes, a fair number of patients do develop myalgias, but these are often mild and transient and can be managed. Very infrequently, patients may manifest some degree of hepatotoxicity, and very rarely rhabdomyolysis can rear its ugly head. Statins can sometimes nudge prediabetes into diabetes, just as thiazide diuretics and beta-blockers will sometimes do. However, on balance, the risk-benefit analysis of taking statins in both primary and secondary prevention settings is very much in favor of taking the drugs.

So my message to my patients (and to your patients as well) is a very simple one. Take advantage of the phenomenal life-saving benefits of these near-wonder drugs, ignore the unscientific online nonsense authored by individuals practicing medicine without a license, and do what your tired but well-meaning doctor urges: take your statins, for Heaven’s sake!

Author disclosures

The author reports no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

It’s an extremely common scenario. A patient’s screening tests return, showing a significant elevation of the calculated low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), known to the lay public as bad cholesterol. To a physician like myself, someone who prides himself on a modest bit of expertise in lipids, it’s an absolute no-brainer. The patient should be placed on statin therapy pronto to reduce the major risks of heart attack, stroke, and other vascular misfortunes that are clearly associated with an elevated LDL-C level.

The tremendous ability of statins to reduce cardiovascular risk is among the best-demonstrated therapeutic effects of any class of medication in any branch of medical practice. The first major trial to show definitive benefits with the use of statins was the Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study, which came out in 1994 and showed a 30% relative reduction in cardiovascular events in a high-risk secondary prevention population, meaning that the subjects already had documented vascular disease before entering the trial.

Related: Did Niacin Get a Bum Rap?

Similar results were reported soon after in primary prevention populations in the WOSCOPS study in the United Kingdom (UK), and from the AFCAPS/TexCAPS studies in the U.S. Then the large UK-based Heart Protection Study showed that statins reduce cardiovascular risk regardless of the initial LDL-C level. Some experts suspected that many of the protective effects of statins were due not only to the LDL-C reduction per se, but also the so-called pleiotropic benefits, which included vasodilation, antithrombotic effects, and improved function of the endothelial cells that line the walls of blood vessels.

A number of additional studies have since markedly expanded the role of statins. The CARDS study showed that patients with diabetes had fewer events on statins. The ASCOT study suggested that statins reduce risk in patients with hypertension. And the SPARCL study revealed fewer recurrent events in patients on statins who had experienced a stroke or transient ischemic attack. Perhaps an even greater advance came with the JUPITER study, which showed that patients with elevated C-reactive protein levels—a marker of systemic inflammation—had fewer cardiovascular events when treated with statins than with placebo.

As you can imagine, there are plenty of times when I reach for my prescription pad (actually, my mouse) with the intention of ordering a statin to reduce a patient’s cardiovascular risk. But unfortunately, many times the patient catches me up short by objecting to such a plan. I can’t tell you how many times a patient responds by asking rather pointedly about the adverse effects (AEs) of statins. Now, I’ll readily admit that a small number of patients ask about AEs with any medication, but I would submit that the question comes up far more commonly with statins than it does with almost any other class of medication. Why?

I firmly believe that a huge driver of my patients’ irrational suspicions of statins is the drivel that is found on countless unreliable and unscientific websites. Antistatin nonsense is readily available, and many patients have thoroughly marinated themselves in a toxic slurry of misinformation and medical fantasy. Most of these sites emphasize known statin AEs, such as myalgias and myopathies, liver damage, and rhabdomyolysis, but then grossly exaggerate the severity and frequency. Other sites hammer on the modest number of patients who are nudged from prediabetes to full-fledged diabetes by the statins or rant about medically unsubstantiated AEs of statins, such as worsened mentation and depression.

Related: Are Statins Safe to Use in Pregnancy? (Clinical Edge)

That’s all bad enough, but what’s even worse is when patients attack the very medical foundation for prescribing statins, claiming that their online “research” causes them to doubt the reported association between LDL-C levels and cardiovascular risk. They also hint darkly at a vast medical-industrial conspiracy to inflate the true importance of LDL-C, thus allowing for more sales of the highly questionable statins and increased drug company profits. No patient has directly accused me of personally benefitting financially by overprescribing statins, but some have certainly hinted at it.

Another large group of patients declines to take the proffered statins by insisting that they would much rather pursue diet and exercise to bring down their high levels of LDL-C. They are invariably surprised when I tell them that even the most aggressive approaches are unlikely to reduce LDL-C by more than a negligible amount. I suspect that they think that their tired old doctor has bought into a reflexive pills-cure-all mentality and does not appreciate the wondrous benefits of a holistic approach.

The most annoying patients tell me they will instead take red yeast rice to bring down their LDL-C, because they prefer a “natural” remedy to some monstrous artificial chemical produced in a pharmaceutical company laboratory. When I try to tell them that red yeast rice contains a varying but unknown amount of a natural inhibitor of hMG-coA reductase, the same enzyme targeted with precisely dosed statins, they gape at me with unhidden disgust for completely missing the point: The naturally occurring remedy is inherently superior, precisely because it is naturally occurring!

Of course, I have to remind myself that a good number of patients simply do not want to take statins because it is a reminder of their vulnerability, status as a cardiac patient, or as a potential future victim of a heart attack or stroke. Some patients find that concept so upsetting that they would rather ignore it altogether.

Reluctantly, I admit that statins are not perfect drugs. But I would still submit that they’re the closest things we have to wonder drugs today. Yes, a fair number of patients do develop myalgias, but these are often mild and transient and can be managed. Very infrequently, patients may manifest some degree of hepatotoxicity, and very rarely rhabdomyolysis can rear its ugly head. Statins can sometimes nudge prediabetes into diabetes, just as thiazide diuretics and beta-blockers will sometimes do. However, on balance, the risk-benefit analysis of taking statins in both primary and secondary prevention settings is very much in favor of taking the drugs.

So my message to my patients (and to your patients as well) is a very simple one. Take advantage of the phenomenal life-saving benefits of these near-wonder drugs, ignore the unscientific online nonsense authored by individuals practicing medicine without a license, and do what your tired but well-meaning doctor urges: take your statins, for Heaven’s sake!

Author disclosures

The author reports no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

It’s an extremely common scenario. A patient’s screening tests return, showing a significant elevation of the calculated low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), known to the lay public as bad cholesterol. To a physician like myself, someone who prides himself on a modest bit of expertise in lipids, it’s an absolute no-brainer. The patient should be placed on statin therapy pronto to reduce the major risks of heart attack, stroke, and other vascular misfortunes that are clearly associated with an elevated LDL-C level.

The tremendous ability of statins to reduce cardiovascular risk is among the best-demonstrated therapeutic effects of any class of medication in any branch of medical practice. The first major trial to show definitive benefits with the use of statins was the Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study, which came out in 1994 and showed a 30% relative reduction in cardiovascular events in a high-risk secondary prevention population, meaning that the subjects already had documented vascular disease before entering the trial.

Related: Did Niacin Get a Bum Rap?

Similar results were reported soon after in primary prevention populations in the WOSCOPS study in the United Kingdom (UK), and from the AFCAPS/TexCAPS studies in the U.S. Then the large UK-based Heart Protection Study showed that statins reduce cardiovascular risk regardless of the initial LDL-C level. Some experts suspected that many of the protective effects of statins were due not only to the LDL-C reduction per se, but also the so-called pleiotropic benefits, which included vasodilation, antithrombotic effects, and improved function of the endothelial cells that line the walls of blood vessels.

A number of additional studies have since markedly expanded the role of statins. The CARDS study showed that patients with diabetes had fewer events on statins. The ASCOT study suggested that statins reduce risk in patients with hypertension. And the SPARCL study revealed fewer recurrent events in patients on statins who had experienced a stroke or transient ischemic attack. Perhaps an even greater advance came with the JUPITER study, which showed that patients with elevated C-reactive protein levels—a marker of systemic inflammation—had fewer cardiovascular events when treated with statins than with placebo.

As you can imagine, there are plenty of times when I reach for my prescription pad (actually, my mouse) with the intention of ordering a statin to reduce a patient’s cardiovascular risk. But unfortunately, many times the patient catches me up short by objecting to such a plan. I can’t tell you how many times a patient responds by asking rather pointedly about the adverse effects (AEs) of statins. Now, I’ll readily admit that a small number of patients ask about AEs with any medication, but I would submit that the question comes up far more commonly with statins than it does with almost any other class of medication. Why?

I firmly believe that a huge driver of my patients’ irrational suspicions of statins is the drivel that is found on countless unreliable and unscientific websites. Antistatin nonsense is readily available, and many patients have thoroughly marinated themselves in a toxic slurry of misinformation and medical fantasy. Most of these sites emphasize known statin AEs, such as myalgias and myopathies, liver damage, and rhabdomyolysis, but then grossly exaggerate the severity and frequency. Other sites hammer on the modest number of patients who are nudged from prediabetes to full-fledged diabetes by the statins or rant about medically unsubstantiated AEs of statins, such as worsened mentation and depression.

Related: Are Statins Safe to Use in Pregnancy? (Clinical Edge)

That’s all bad enough, but what’s even worse is when patients attack the very medical foundation for prescribing statins, claiming that their online “research” causes them to doubt the reported association between LDL-C levels and cardiovascular risk. They also hint darkly at a vast medical-industrial conspiracy to inflate the true importance of LDL-C, thus allowing for more sales of the highly questionable statins and increased drug company profits. No patient has directly accused me of personally benefitting financially by overprescribing statins, but some have certainly hinted at it.

Another large group of patients declines to take the proffered statins by insisting that they would much rather pursue diet and exercise to bring down their high levels of LDL-C. They are invariably surprised when I tell them that even the most aggressive approaches are unlikely to reduce LDL-C by more than a negligible amount. I suspect that they think that their tired old doctor has bought into a reflexive pills-cure-all mentality and does not appreciate the wondrous benefits of a holistic approach.

The most annoying patients tell me they will instead take red yeast rice to bring down their LDL-C, because they prefer a “natural” remedy to some monstrous artificial chemical produced in a pharmaceutical company laboratory. When I try to tell them that red yeast rice contains a varying but unknown amount of a natural inhibitor of hMG-coA reductase, the same enzyme targeted with precisely dosed statins, they gape at me with unhidden disgust for completely missing the point: The naturally occurring remedy is inherently superior, precisely because it is naturally occurring!

Of course, I have to remind myself that a good number of patients simply do not want to take statins because it is a reminder of their vulnerability, status as a cardiac patient, or as a potential future victim of a heart attack or stroke. Some patients find that concept so upsetting that they would rather ignore it altogether.

Reluctantly, I admit that statins are not perfect drugs. But I would still submit that they’re the closest things we have to wonder drugs today. Yes, a fair number of patients do develop myalgias, but these are often mild and transient and can be managed. Very infrequently, patients may manifest some degree of hepatotoxicity, and very rarely rhabdomyolysis can rear its ugly head. Statins can sometimes nudge prediabetes into diabetes, just as thiazide diuretics and beta-blockers will sometimes do. However, on balance, the risk-benefit analysis of taking statins in both primary and secondary prevention settings is very much in favor of taking the drugs.

So my message to my patients (and to your patients as well) is a very simple one. Take advantage of the phenomenal life-saving benefits of these near-wonder drugs, ignore the unscientific online nonsense authored by individuals practicing medicine without a license, and do what your tired but well-meaning doctor urges: take your statins, for Heaven’s sake!

Author disclosures

The author reports no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

No Man Is an Island in the Public Health Service

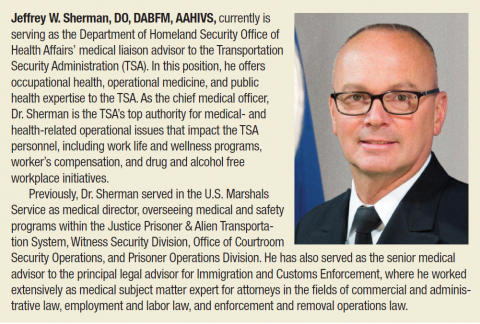

Below is an edited and condensed version of the Federal Practitioner interview with Jeffrey W. Sherman, DO, chief medical officer of the Department of Homeland Security’s Transportation Security Administration. Dr. Sherman recently received the Outstanding Service Medal from PHS. To hear the complete interview, visit: http://www.fedprac.com/multimedia/multimedia-library.html.

The Transportation Security Administration

Jeffrey W. Sherman, DO. I’m primarily responsible for providing expert opinion to the senior leadership of the Transportation Security Administration (TSA) as it relates to occupational health, preventive medicine, and other medical topics. The position of chief medical officer at the TSA has been on the books for quite a while. However, it hasn’t been filled on a permanent basis until the time that I came over from the Office of Health Affairs…. For the most part, the marching orders that I was given from the senior leadership was to take a fairly neutral look at the agency’s ability to manage the health and wellness of its workforce and find both positive areas and areas for improvement where the TSA could impact the welfare of the TSA population.

Related: Committed to Showing Results at the VA

Programs that we were able to identify that were already in existence and working really well for the TSA were in abundance. However, there were a number of programs that I found would probably enhance the TSA’ s ability to manage its workforce better and to provide a more comfortable, safe workplace. The main one was an ability to measure the transportation security officers’ medical capability and aptitude over a period of time, so more or less to manage them periodically and allow us to review the requirements and assessments for that particular workforce from an occupational health standpoint.

Having a Career in the PHS

Dr. Sherman. My previous work with the PHS included being a director for a number of different medical programs in other government agencies, including Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), where I was acting director of the Division of Immigration Health Services for a period of time. I moved on to be the senior medical advisor to the principal legal advisor at ICE; and again, working with the attorneys on various medical issues allowed me to build greater confidence in my ability to manage the interface between what’s appropriate legally from the medical standpoint and what’s appropriate from the clinical practice of medicine in occupational health. So that was very vital and important.

Just prior to coming to the TSA, I was the medical director for a number of programs for the U.S. Marshals Services. Working alongside law enforcement in their unique roles and managing programs that are variously clinical and nonclinical gives good insight as to how to come into a large organization such as the TSA, with more than 48,000 transportation security officers, and put in place programs in a preexisting organization. To retrofit programs into an organization of that size requires some tact and ability. So all that time previously spent has allowed me to gain those skills.

Joining the PHS

Dr. Sherman. We are a group of dedicated professionals; we have a very close connection and a close network of collegial interactions. I was the Professional Advisory Committee (PAC) chair for the Physicians PAC for a year and vice chair before that. Meeting all the individuals and working with them on various cross-agency public health and professional projects has absolutely brought a lot of their wealth into what I do here at the TSA specifically. No man is an island; and certainly, in the PHS, you never feel that way…

Related: Pharmacist Management of Adult Asthma at an Indian Health Service Facility

I was in private practice in rural upstate New York in 2005 when Hurricane Katrina and Hurricane Rita came ashore, and I was part of the National Health Service Corps at that time. Part of my response as a National Health Service Corps Scholar was to join colleagues—some of whom were PHS officers—down in the recovery area in Louisiana; that is where I met my first uniformed Commissioned Corps officer, 2 of them, in fact. I worked with them for several weeks and was so incredibly impressed with the work of the PHS that while I was there, I applied for my commission. So I was hit pretty hard and pretty heavy, and I haven’t looked back…

It’s, of course, very satisfying to hear your uniformed service spoken highly of in a public forum and especially by elected officials such as the president. I mean it’s difficult not to smile when you hear that. I will say, as one of the 7 uniformed services of the U.S., we do take a lot of knuckling under from our sister services that are more well known. But frankly, at the end of the day, we work beside them regardless of the notoriety or note that we get from them or from anyone else.

I’ve served alongside the Navy on the USNS Mercy, and I’ve been out with Air Force and Coast Guard on their vessels as well. So I’m very comfortable, and I think most of the PHS officers are comfortable working with our sister uniformed services. It is nice to hear the recognition.

The PHS Outstanding Service Medal

Dr. Sherman. It’s a real honor and a privilege to have received that medal…. There are things you do in your professional career that you do not do for notoriety; you do it because it’s the right thing to do, and you know it’s in the greater service to your profession.

In this case, our profession is also a uniformed service. And so for the uniformed service itself to take note and to give recognition for what I would do anyway and the manner in which I do it, it’s again, very satisfying; and it’s very humbling.

Mentoring Junior Officers

Dr. Sherman. The PHS has a very robust program of mentoring junior officers; and I think one of the things that has been most satisfying in my time in uniform, outside of the obvious professional things, has really been mentoring junior officers on their way up through the ranks and as they find their pathway forward in a career as a Commissioned Corps officer. And if I can say one thing to any new officer coming into the organization, it’s make sure that you reach out to your senior officers, and make sure you learn from both their successes and their errors so that by the time you finish your career, you can look back and say you’ve done everything you’ve wanted to.

I still maintain relationships with [my] mentors. I don’t think you’re ever too old or ever too experienced to have a mentor. There’s always something you can learn from another individual. So you know, you never stop learning, and you never stop appreciating the people who you’re working beside who come before you and who are coming behind you. And please don’t ask me to state names, because there are too many.

Below is an edited and condensed version of the Federal Practitioner interview with Jeffrey W. Sherman, DO, chief medical officer of the Department of Homeland Security’s Transportation Security Administration. Dr. Sherman recently received the Outstanding Service Medal from PHS. To hear the complete interview, visit: http://www.fedprac.com/multimedia/multimedia-library.html.

The Transportation Security Administration

Jeffrey W. Sherman, DO. I’m primarily responsible for providing expert opinion to the senior leadership of the Transportation Security Administration (TSA) as it relates to occupational health, preventive medicine, and other medical topics. The position of chief medical officer at the TSA has been on the books for quite a while. However, it hasn’t been filled on a permanent basis until the time that I came over from the Office of Health Affairs…. For the most part, the marching orders that I was given from the senior leadership was to take a fairly neutral look at the agency’s ability to manage the health and wellness of its workforce and find both positive areas and areas for improvement where the TSA could impact the welfare of the TSA population.

Related: Committed to Showing Results at the VA

Programs that we were able to identify that were already in existence and working really well for the TSA were in abundance. However, there were a number of programs that I found would probably enhance the TSA’ s ability to manage its workforce better and to provide a more comfortable, safe workplace. The main one was an ability to measure the transportation security officers’ medical capability and aptitude over a period of time, so more or less to manage them periodically and allow us to review the requirements and assessments for that particular workforce from an occupational health standpoint.

Having a Career in the PHS

Dr. Sherman. My previous work with the PHS included being a director for a number of different medical programs in other government agencies, including Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), where I was acting director of the Division of Immigration Health Services for a period of time. I moved on to be the senior medical advisor to the principal legal advisor at ICE; and again, working with the attorneys on various medical issues allowed me to build greater confidence in my ability to manage the interface between what’s appropriate legally from the medical standpoint and what’s appropriate from the clinical practice of medicine in occupational health. So that was very vital and important.

Just prior to coming to the TSA, I was the medical director for a number of programs for the U.S. Marshals Services. Working alongside law enforcement in their unique roles and managing programs that are variously clinical and nonclinical gives good insight as to how to come into a large organization such as the TSA, with more than 48,000 transportation security officers, and put in place programs in a preexisting organization. To retrofit programs into an organization of that size requires some tact and ability. So all that time previously spent has allowed me to gain those skills.

Joining the PHS

Dr. Sherman. We are a group of dedicated professionals; we have a very close connection and a close network of collegial interactions. I was the Professional Advisory Committee (PAC) chair for the Physicians PAC for a year and vice chair before that. Meeting all the individuals and working with them on various cross-agency public health and professional projects has absolutely brought a lot of their wealth into what I do here at the TSA specifically. No man is an island; and certainly, in the PHS, you never feel that way…

Related: Pharmacist Management of Adult Asthma at an Indian Health Service Facility

I was in private practice in rural upstate New York in 2005 when Hurricane Katrina and Hurricane Rita came ashore, and I was part of the National Health Service Corps at that time. Part of my response as a National Health Service Corps Scholar was to join colleagues—some of whom were PHS officers—down in the recovery area in Louisiana; that is where I met my first uniformed Commissioned Corps officer, 2 of them, in fact. I worked with them for several weeks and was so incredibly impressed with the work of the PHS that while I was there, I applied for my commission. So I was hit pretty hard and pretty heavy, and I haven’t looked back…

It’s, of course, very satisfying to hear your uniformed service spoken highly of in a public forum and especially by elected officials such as the president. I mean it’s difficult not to smile when you hear that. I will say, as one of the 7 uniformed services of the U.S., we do take a lot of knuckling under from our sister services that are more well known. But frankly, at the end of the day, we work beside them regardless of the notoriety or note that we get from them or from anyone else.

I’ve served alongside the Navy on the USNS Mercy, and I’ve been out with Air Force and Coast Guard on their vessels as well. So I’m very comfortable, and I think most of the PHS officers are comfortable working with our sister uniformed services. It is nice to hear the recognition.

The PHS Outstanding Service Medal

Dr. Sherman. It’s a real honor and a privilege to have received that medal…. There are things you do in your professional career that you do not do for notoriety; you do it because it’s the right thing to do, and you know it’s in the greater service to your profession.

In this case, our profession is also a uniformed service. And so for the uniformed service itself to take note and to give recognition for what I would do anyway and the manner in which I do it, it’s again, very satisfying; and it’s very humbling.

Mentoring Junior Officers

Dr. Sherman. The PHS has a very robust program of mentoring junior officers; and I think one of the things that has been most satisfying in my time in uniform, outside of the obvious professional things, has really been mentoring junior officers on their way up through the ranks and as they find their pathway forward in a career as a Commissioned Corps officer. And if I can say one thing to any new officer coming into the organization, it’s make sure that you reach out to your senior officers, and make sure you learn from both their successes and their errors so that by the time you finish your career, you can look back and say you’ve done everything you’ve wanted to.

I still maintain relationships with [my] mentors. I don’t think you’re ever too old or ever too experienced to have a mentor. There’s always something you can learn from another individual. So you know, you never stop learning, and you never stop appreciating the people who you’re working beside who come before you and who are coming behind you. And please don’t ask me to state names, because there are too many.

Below is an edited and condensed version of the Federal Practitioner interview with Jeffrey W. Sherman, DO, chief medical officer of the Department of Homeland Security’s Transportation Security Administration. Dr. Sherman recently received the Outstanding Service Medal from PHS. To hear the complete interview, visit: http://www.fedprac.com/multimedia/multimedia-library.html.

The Transportation Security Administration

Jeffrey W. Sherman, DO. I’m primarily responsible for providing expert opinion to the senior leadership of the Transportation Security Administration (TSA) as it relates to occupational health, preventive medicine, and other medical topics. The position of chief medical officer at the TSA has been on the books for quite a while. However, it hasn’t been filled on a permanent basis until the time that I came over from the Office of Health Affairs…. For the most part, the marching orders that I was given from the senior leadership was to take a fairly neutral look at the agency’s ability to manage the health and wellness of its workforce and find both positive areas and areas for improvement where the TSA could impact the welfare of the TSA population.

Related: Committed to Showing Results at the VA

Programs that we were able to identify that were already in existence and working really well for the TSA were in abundance. However, there were a number of programs that I found would probably enhance the TSA’ s ability to manage its workforce better and to provide a more comfortable, safe workplace. The main one was an ability to measure the transportation security officers’ medical capability and aptitude over a period of time, so more or less to manage them periodically and allow us to review the requirements and assessments for that particular workforce from an occupational health standpoint.

Having a Career in the PHS

Dr. Sherman. My previous work with the PHS included being a director for a number of different medical programs in other government agencies, including Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), where I was acting director of the Division of Immigration Health Services for a period of time. I moved on to be the senior medical advisor to the principal legal advisor at ICE; and again, working with the attorneys on various medical issues allowed me to build greater confidence in my ability to manage the interface between what’s appropriate legally from the medical standpoint and what’s appropriate from the clinical practice of medicine in occupational health. So that was very vital and important.

Just prior to coming to the TSA, I was the medical director for a number of programs for the U.S. Marshals Services. Working alongside law enforcement in their unique roles and managing programs that are variously clinical and nonclinical gives good insight as to how to come into a large organization such as the TSA, with more than 48,000 transportation security officers, and put in place programs in a preexisting organization. To retrofit programs into an organization of that size requires some tact and ability. So all that time previously spent has allowed me to gain those skills.

Joining the PHS

Dr. Sherman. We are a group of dedicated professionals; we have a very close connection and a close network of collegial interactions. I was the Professional Advisory Committee (PAC) chair for the Physicians PAC for a year and vice chair before that. Meeting all the individuals and working with them on various cross-agency public health and professional projects has absolutely brought a lot of their wealth into what I do here at the TSA specifically. No man is an island; and certainly, in the PHS, you never feel that way…

Related: Pharmacist Management of Adult Asthma at an Indian Health Service Facility

I was in private practice in rural upstate New York in 2005 when Hurricane Katrina and Hurricane Rita came ashore, and I was part of the National Health Service Corps at that time. Part of my response as a National Health Service Corps Scholar was to join colleagues—some of whom were PHS officers—down in the recovery area in Louisiana; that is where I met my first uniformed Commissioned Corps officer, 2 of them, in fact. I worked with them for several weeks and was so incredibly impressed with the work of the PHS that while I was there, I applied for my commission. So I was hit pretty hard and pretty heavy, and I haven’t looked back…

It’s, of course, very satisfying to hear your uniformed service spoken highly of in a public forum and especially by elected officials such as the president. I mean it’s difficult not to smile when you hear that. I will say, as one of the 7 uniformed services of the U.S., we do take a lot of knuckling under from our sister services that are more well known. But frankly, at the end of the day, we work beside them regardless of the notoriety or note that we get from them or from anyone else.

I’ve served alongside the Navy on the USNS Mercy, and I’ve been out with Air Force and Coast Guard on their vessels as well. So I’m very comfortable, and I think most of the PHS officers are comfortable working with our sister uniformed services. It is nice to hear the recognition.

The PHS Outstanding Service Medal

Dr. Sherman. It’s a real honor and a privilege to have received that medal…. There are things you do in your professional career that you do not do for notoriety; you do it because it’s the right thing to do, and you know it’s in the greater service to your profession.

In this case, our profession is also a uniformed service. And so for the uniformed service itself to take note and to give recognition for what I would do anyway and the manner in which I do it, it’s again, very satisfying; and it’s very humbling.

Mentoring Junior Officers

Dr. Sherman. The PHS has a very robust program of mentoring junior officers; and I think one of the things that has been most satisfying in my time in uniform, outside of the obvious professional things, has really been mentoring junior officers on their way up through the ranks and as they find their pathway forward in a career as a Commissioned Corps officer. And if I can say one thing to any new officer coming into the organization, it’s make sure that you reach out to your senior officers, and make sure you learn from both their successes and their errors so that by the time you finish your career, you can look back and say you’ve done everything you’ve wanted to.

I still maintain relationships with [my] mentors. I don’t think you’re ever too old or ever too experienced to have a mentor. There’s always something you can learn from another individual. So you know, you never stop learning, and you never stop appreciating the people who you’re working beside who come before you and who are coming behind you. And please don’t ask me to state names, because there are too many.

Be true to yourself

How often have nonphysicians told you that they could never work the hours you do?

Most people think physicians are a unique breed, and in some respects, we are. But in important ways we are just like everyone else. When we work long hours under stressful conditions and go without adequate sleep or nourishment, we cannot function at peak performance. Just like everyone else, we can become irritable, grumpy, and cynical when our basic needs are not met. We are human too, and we are at higher risk than most people for burnout, depression, and even suicide.

An article in the Journal of Hospital Medicine in 2014 noted that slightly over 50% of hospitalists were affected by burnout. We scored high on the emotional exhaustion subscale, and 40.3% of us had symptoms of depression, with a surprising 9.2% rate of recent suicidality. Hospital medicine definitely has its advantages over many other fields of medicine, but as this study demonstrates, there is still much to be desired in our “work-life balance.”

Each practice has its own perks and negatives, and what will enhance the lives of hospitalists in one group may make intolerable the lives of members of another group. For instance, it is no surprise that 12-hour shifts with 7-on, 7-off block scheduling can be exhausting. If you have a family, this schedule leaves plenty of fun time on the weeks you are off, but you may still be missing 50% of your family’s life if you leave for work before your kids wake up and return after they go to bed.

Whatever your concerns and stressors may be, rest assured, you are not alone, and if enough of the members of your group have similar issues, you may be successful addressing them with your director or hospital administrator. Retaining good hospitalists is vital to the financial success of many hospitals, and being flexible enough to truly meet their reasonable needs can literally make or break a hospitalist team.

How often have nonphysicians told you that they could never work the hours you do?

Most people think physicians are a unique breed, and in some respects, we are. But in important ways we are just like everyone else. When we work long hours under stressful conditions and go without adequate sleep or nourishment, we cannot function at peak performance. Just like everyone else, we can become irritable, grumpy, and cynical when our basic needs are not met. We are human too, and we are at higher risk than most people for burnout, depression, and even suicide.

An article in the Journal of Hospital Medicine in 2014 noted that slightly over 50% of hospitalists were affected by burnout. We scored high on the emotional exhaustion subscale, and 40.3% of us had symptoms of depression, with a surprising 9.2% rate of recent suicidality. Hospital medicine definitely has its advantages over many other fields of medicine, but as this study demonstrates, there is still much to be desired in our “work-life balance.”

Each practice has its own perks and negatives, and what will enhance the lives of hospitalists in one group may make intolerable the lives of members of another group. For instance, it is no surprise that 12-hour shifts with 7-on, 7-off block scheduling can be exhausting. If you have a family, this schedule leaves plenty of fun time on the weeks you are off, but you may still be missing 50% of your family’s life if you leave for work before your kids wake up and return after they go to bed.

Whatever your concerns and stressors may be, rest assured, you are not alone, and if enough of the members of your group have similar issues, you may be successful addressing them with your director or hospital administrator. Retaining good hospitalists is vital to the financial success of many hospitals, and being flexible enough to truly meet their reasonable needs can literally make or break a hospitalist team.

How often have nonphysicians told you that they could never work the hours you do?

Most people think physicians are a unique breed, and in some respects, we are. But in important ways we are just like everyone else. When we work long hours under stressful conditions and go without adequate sleep or nourishment, we cannot function at peak performance. Just like everyone else, we can become irritable, grumpy, and cynical when our basic needs are not met. We are human too, and we are at higher risk than most people for burnout, depression, and even suicide.

An article in the Journal of Hospital Medicine in 2014 noted that slightly over 50% of hospitalists were affected by burnout. We scored high on the emotional exhaustion subscale, and 40.3% of us had symptoms of depression, with a surprising 9.2% rate of recent suicidality. Hospital medicine definitely has its advantages over many other fields of medicine, but as this study demonstrates, there is still much to be desired in our “work-life balance.”

Each practice has its own perks and negatives, and what will enhance the lives of hospitalists in one group may make intolerable the lives of members of another group. For instance, it is no surprise that 12-hour shifts with 7-on, 7-off block scheduling can be exhausting. If you have a family, this schedule leaves plenty of fun time on the weeks you are off, but you may still be missing 50% of your family’s life if you leave for work before your kids wake up and return after they go to bed.

Whatever your concerns and stressors may be, rest assured, you are not alone, and if enough of the members of your group have similar issues, you may be successful addressing them with your director or hospital administrator. Retaining good hospitalists is vital to the financial success of many hospitals, and being flexible enough to truly meet their reasonable needs can literally make or break a hospitalist team.

Eat slowly to reduce consumed calories

I freely admit I am obsessed with research articles about eating habits. I hold out hope that this will eventually unlock the magic bullet to cure us of the modern plague of obesity. At a certain level, our patients need us to be captivated by such literature. We should feel fairly comfortable with the common knowledge that diets are effective if you stay on them and reducing the caloric density of foods can result in meaningful weight loss.

But what about how quickly we eat? In our fast-paced, heavily caffeinated society, we seem to shovel rather than chew. Ever since I was a medical resident, I have practically inhaled my food. Perchance I am operating under the erroneous and illogical assumption that if I don’t taste the food it won’t register as calories. True science has now enlightened me to the error in my thinking.

Dr. Eric Robinson and his colleagues conducted a brilliant systematic review of the impact of eating rate on energy intake and hunger (Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2014;100:123-51). They included studies for which there was at least one study arm in which participants ate a meal at a statistically significant slower rate than that of a different arm. Twenty-two studies met the criteria for inclusion.

Available evidence suggests that a slower eating rate is associated with lower intake, compared with faster eating. The effect on caloric intake was observed regardless of the intervention used to modify the eating rate, such as modifying food from soft (fast rate) to hard (slow rate) or verbal instruction. No relationship was observed between eating rate and hunger at the end of the meal or several hours later.

Intriguing to me is the hypothesis that eating rate likely affects intake through the duration and intensity of oral exposure to taste. Previous studies have shown that, when eating rate is held constant, increasing sensory exposure leads to a lower energy intake. This seems to relate to our innate wiring that gives us a “sensory specific satiety.” In my understanding, sensory specific satiety turns off appetitive drive when you have had too much chocolate or too many potato chips and you feel slightly ill. Unfortunately, the food industry is on to this game and they have designed foods to be perfectly balanced to not render satiety. These foods can tragically be eaten ceaselessly.

Take-home message: If your patients cannot control the bad foods they eat, they should try to eat them more slowly.

Dr. Ebbert is professor of medicine, a general internist at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., and a diplomate of the American Board of Addiction Medicine. The opinions expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views and opinions of the Mayo Clinic. The opinions expressed in this article should not be used to diagnose or treat any medical condition nor should they be used as a substitute for medical advice from a qualified, board-certified practicing clinician.

I freely admit I am obsessed with research articles about eating habits. I hold out hope that this will eventually unlock the magic bullet to cure us of the modern plague of obesity. At a certain level, our patients need us to be captivated by such literature. We should feel fairly comfortable with the common knowledge that diets are effective if you stay on them and reducing the caloric density of foods can result in meaningful weight loss.

But what about how quickly we eat? In our fast-paced, heavily caffeinated society, we seem to shovel rather than chew. Ever since I was a medical resident, I have practically inhaled my food. Perchance I am operating under the erroneous and illogical assumption that if I don’t taste the food it won’t register as calories. True science has now enlightened me to the error in my thinking.

Dr. Eric Robinson and his colleagues conducted a brilliant systematic review of the impact of eating rate on energy intake and hunger (Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2014;100:123-51). They included studies for which there was at least one study arm in which participants ate a meal at a statistically significant slower rate than that of a different arm. Twenty-two studies met the criteria for inclusion.

Available evidence suggests that a slower eating rate is associated with lower intake, compared with faster eating. The effect on caloric intake was observed regardless of the intervention used to modify the eating rate, such as modifying food from soft (fast rate) to hard (slow rate) or verbal instruction. No relationship was observed between eating rate and hunger at the end of the meal or several hours later.

Intriguing to me is the hypothesis that eating rate likely affects intake through the duration and intensity of oral exposure to taste. Previous studies have shown that, when eating rate is held constant, increasing sensory exposure leads to a lower energy intake. This seems to relate to our innate wiring that gives us a “sensory specific satiety.” In my understanding, sensory specific satiety turns off appetitive drive when you have had too much chocolate or too many potato chips and you feel slightly ill. Unfortunately, the food industry is on to this game and they have designed foods to be perfectly balanced to not render satiety. These foods can tragically be eaten ceaselessly.

Take-home message: If your patients cannot control the bad foods they eat, they should try to eat them more slowly.

Dr. Ebbert is professor of medicine, a general internist at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., and a diplomate of the American Board of Addiction Medicine. The opinions expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views and opinions of the Mayo Clinic. The opinions expressed in this article should not be used to diagnose or treat any medical condition nor should they be used as a substitute for medical advice from a qualified, board-certified practicing clinician.

I freely admit I am obsessed with research articles about eating habits. I hold out hope that this will eventually unlock the magic bullet to cure us of the modern plague of obesity. At a certain level, our patients need us to be captivated by such literature. We should feel fairly comfortable with the common knowledge that diets are effective if you stay on them and reducing the caloric density of foods can result in meaningful weight loss.

But what about how quickly we eat? In our fast-paced, heavily caffeinated society, we seem to shovel rather than chew. Ever since I was a medical resident, I have practically inhaled my food. Perchance I am operating under the erroneous and illogical assumption that if I don’t taste the food it won’t register as calories. True science has now enlightened me to the error in my thinking.

Dr. Eric Robinson and his colleagues conducted a brilliant systematic review of the impact of eating rate on energy intake and hunger (Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2014;100:123-51). They included studies for which there was at least one study arm in which participants ate a meal at a statistically significant slower rate than that of a different arm. Twenty-two studies met the criteria for inclusion.

Available evidence suggests that a slower eating rate is associated with lower intake, compared with faster eating. The effect on caloric intake was observed regardless of the intervention used to modify the eating rate, such as modifying food from soft (fast rate) to hard (slow rate) or verbal instruction. No relationship was observed between eating rate and hunger at the end of the meal or several hours later.

Intriguing to me is the hypothesis that eating rate likely affects intake through the duration and intensity of oral exposure to taste. Previous studies have shown that, when eating rate is held constant, increasing sensory exposure leads to a lower energy intake. This seems to relate to our innate wiring that gives us a “sensory specific satiety.” In my understanding, sensory specific satiety turns off appetitive drive when you have had too much chocolate or too many potato chips and you feel slightly ill. Unfortunately, the food industry is on to this game and they have designed foods to be perfectly balanced to not render satiety. These foods can tragically be eaten ceaselessly.

Take-home message: If your patients cannot control the bad foods they eat, they should try to eat them more slowly.

Dr. Ebbert is professor of medicine, a general internist at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., and a diplomate of the American Board of Addiction Medicine. The opinions expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views and opinions of the Mayo Clinic. The opinions expressed in this article should not be used to diagnose or treat any medical condition nor should they be used as a substitute for medical advice from a qualified, board-certified practicing clinician.

Physician Advocacy for Zoster Vaccination

Herpes zoster (HZ) infection occurs when the varicella-zoster virus (VZV) is reactivated due to waning cellular immunity associated with age or immunosuppression. It results in a painful blistering cutaneous eruption.1 The incidence and rate of complications from HZ infection increase with age.2 The most common complication of HZ infection is postherpetic neuralgia (PHN), which can be extremely debilitating.1

In 2006 the US Food and Drug Administration approved a live attenuated HZ vaccine that boosts VZV cell-mediated immunity and largely reduces HZ disease burden. The HZ vaccine contains the same strain of VZV as the varicella vaccine but contains 14 times more virus particles.3 In a study of the efficacy and safety of the HZ vaccine, HZ vaccination was associated with a 51% reduction in HZ incidence, a 61% reduction in HZ disease burden, and a 67% reduction in PHN incidence at 3-year follow-up.4 In adults aged 60 to 69 years, the benefit of the HZ vaccine resulted from the reduction in HZ incidence.5 However, in adults 70 years and older, the benefit resulted from the reduction in PHN incidence and severity. Overall, the absolute benefit of the HZ vaccine was greatest in the older age group, as the severity and incidence of HZ and PHN are highest in these patients.5 Although efficacy declines with time, a long-term persistence substudy demonstrated that the HZ vaccine still reduced the incidence and severity of HZ.6

The HZ vaccine currently is approved for adults aged 50 years or older.3 Antivirals that are active against VZV (eg, acyclovir, valacyclovir, famciclovir) should not be administered 24 hours before or 14 days after vaccination.1 Concurrent administration of the HZ vaccine and the pneumococcal vaccine is not recommended due to risk for reduced immunogenicity of the zoster vaccine.5 Because it is a live vaccine, the HZ vaccine is not recommended in immunocompromised patients. However, the HZ vaccine can be safely given to moderately immunosuppressed patients. The HZ vaccine also is well tolerated and stimulates a strong cell-mediated immune response in adults who have had prior HZ infections. Herpes zoster vaccination is recommended in patients with a history of shingles, though there are no published data showing that it reduces the already low rate of recurrent HZ infections.7

Despite strong efficacy data and established guidelines, a low vaccination rate has been reported8 due to doubts about its long-term efficacy, failure of both physicians and patients to recognize the burden of disease imposed by HZ infection and PHN, and concerns about reimbursement and out-of-pocket costs for the patient.5 Furthermore, many patients who are eligible to receive the HZ vaccine may not do so because they do not remember having chickenpox and therefore do not feel they are at risk for developing shingles.

The HZ vaccine is an important factor in public health prevention strategy, as HZ infection and PHN are common, incurable, and incapacitating. The HZ vaccine is the most efficacious agent currently available on the market for prevention. It is important for dermatologists to educate our patients and encourage them to receive the HZ vaccine to safeguard their long-term health.

1. Sampathkumar P, Drage LA, Martin DP. Herpes zoster (shingles) and postherpetic neuralgia. Mayo Clin Proc. 2009;84:274-280.

2. Gilden D. Efficacy of live zoster vaccine in preventing zoster and postherpetic neuralgia. J Intern Med. 2011;269:496-506.

3. Javed S, Javed SA, Trying SK. Varicella vaccines. Curr Open Infect Dis. 2012;25:135-140.

4. Oxman MN, Levin MJ, Johnson GR, et al. A vaccine to prevent herpes zoster and postherpetic neuralgia in older adults. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2271-2284.

5. Oxman MN. Zoster vaccine: current status and future prospects. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;51:197-213.

6. Keating GM. Shingles (herpes zoster) vaccine (Zostavax®): a review of its use in the prevention of herpes zoster and postherpetic neuralgia in adults aged >50 years. Drugs. 2013;73:1227-1244.

7. Herpes zoster vaccination. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/vpd-vac/shingles/hcp-vaccination.htm. Updated March 12, 2015. Accessed April 21, 2015.

8. Langan SM, Smeeth L, Margolis D, et al. Herpes zoster vaccine effectiveness against herpes zoster and post-herpetic neuralgia in an older US population: a cohort study. PLoS Med. 2013;10:e1001420.

Herpes zoster (HZ) infection occurs when the varicella-zoster virus (VZV) is reactivated due to waning cellular immunity associated with age or immunosuppression. It results in a painful blistering cutaneous eruption.1 The incidence and rate of complications from HZ infection increase with age.2 The most common complication of HZ infection is postherpetic neuralgia (PHN), which can be extremely debilitating.1

In 2006 the US Food and Drug Administration approved a live attenuated HZ vaccine that boosts VZV cell-mediated immunity and largely reduces HZ disease burden. The HZ vaccine contains the same strain of VZV as the varicella vaccine but contains 14 times more virus particles.3 In a study of the efficacy and safety of the HZ vaccine, HZ vaccination was associated with a 51% reduction in HZ incidence, a 61% reduction in HZ disease burden, and a 67% reduction in PHN incidence at 3-year follow-up.4 In adults aged 60 to 69 years, the benefit of the HZ vaccine resulted from the reduction in HZ incidence.5 However, in adults 70 years and older, the benefit resulted from the reduction in PHN incidence and severity. Overall, the absolute benefit of the HZ vaccine was greatest in the older age group, as the severity and incidence of HZ and PHN are highest in these patients.5 Although efficacy declines with time, a long-term persistence substudy demonstrated that the HZ vaccine still reduced the incidence and severity of HZ.6

The HZ vaccine currently is approved for adults aged 50 years or older.3 Antivirals that are active against VZV (eg, acyclovir, valacyclovir, famciclovir) should not be administered 24 hours before or 14 days after vaccination.1 Concurrent administration of the HZ vaccine and the pneumococcal vaccine is not recommended due to risk for reduced immunogenicity of the zoster vaccine.5 Because it is a live vaccine, the HZ vaccine is not recommended in immunocompromised patients. However, the HZ vaccine can be safely given to moderately immunosuppressed patients. The HZ vaccine also is well tolerated and stimulates a strong cell-mediated immune response in adults who have had prior HZ infections. Herpes zoster vaccination is recommended in patients with a history of shingles, though there are no published data showing that it reduces the already low rate of recurrent HZ infections.7

Despite strong efficacy data and established guidelines, a low vaccination rate has been reported8 due to doubts about its long-term efficacy, failure of both physicians and patients to recognize the burden of disease imposed by HZ infection and PHN, and concerns about reimbursement and out-of-pocket costs for the patient.5 Furthermore, many patients who are eligible to receive the HZ vaccine may not do so because they do not remember having chickenpox and therefore do not feel they are at risk for developing shingles.

The HZ vaccine is an important factor in public health prevention strategy, as HZ infection and PHN are common, incurable, and incapacitating. The HZ vaccine is the most efficacious agent currently available on the market for prevention. It is important for dermatologists to educate our patients and encourage them to receive the HZ vaccine to safeguard their long-term health.

Herpes zoster (HZ) infection occurs when the varicella-zoster virus (VZV) is reactivated due to waning cellular immunity associated with age or immunosuppression. It results in a painful blistering cutaneous eruption.1 The incidence and rate of complications from HZ infection increase with age.2 The most common complication of HZ infection is postherpetic neuralgia (PHN), which can be extremely debilitating.1

In 2006 the US Food and Drug Administration approved a live attenuated HZ vaccine that boosts VZV cell-mediated immunity and largely reduces HZ disease burden. The HZ vaccine contains the same strain of VZV as the varicella vaccine but contains 14 times more virus particles.3 In a study of the efficacy and safety of the HZ vaccine, HZ vaccination was associated with a 51% reduction in HZ incidence, a 61% reduction in HZ disease burden, and a 67% reduction in PHN incidence at 3-year follow-up.4 In adults aged 60 to 69 years, the benefit of the HZ vaccine resulted from the reduction in HZ incidence.5 However, in adults 70 years and older, the benefit resulted from the reduction in PHN incidence and severity. Overall, the absolute benefit of the HZ vaccine was greatest in the older age group, as the severity and incidence of HZ and PHN are highest in these patients.5 Although efficacy declines with time, a long-term persistence substudy demonstrated that the HZ vaccine still reduced the incidence and severity of HZ.6

The HZ vaccine currently is approved for adults aged 50 years or older.3 Antivirals that are active against VZV (eg, acyclovir, valacyclovir, famciclovir) should not be administered 24 hours before or 14 days after vaccination.1 Concurrent administration of the HZ vaccine and the pneumococcal vaccine is not recommended due to risk for reduced immunogenicity of the zoster vaccine.5 Because it is a live vaccine, the HZ vaccine is not recommended in immunocompromised patients. However, the HZ vaccine can be safely given to moderately immunosuppressed patients. The HZ vaccine also is well tolerated and stimulates a strong cell-mediated immune response in adults who have had prior HZ infections. Herpes zoster vaccination is recommended in patients with a history of shingles, though there are no published data showing that it reduces the already low rate of recurrent HZ infections.7

Despite strong efficacy data and established guidelines, a low vaccination rate has been reported8 due to doubts about its long-term efficacy, failure of both physicians and patients to recognize the burden of disease imposed by HZ infection and PHN, and concerns about reimbursement and out-of-pocket costs for the patient.5 Furthermore, many patients who are eligible to receive the HZ vaccine may not do so because they do not remember having chickenpox and therefore do not feel they are at risk for developing shingles.

The HZ vaccine is an important factor in public health prevention strategy, as HZ infection and PHN are common, incurable, and incapacitating. The HZ vaccine is the most efficacious agent currently available on the market for prevention. It is important for dermatologists to educate our patients and encourage them to receive the HZ vaccine to safeguard their long-term health.

1. Sampathkumar P, Drage LA, Martin DP. Herpes zoster (shingles) and postherpetic neuralgia. Mayo Clin Proc. 2009;84:274-280.

2. Gilden D. Efficacy of live zoster vaccine in preventing zoster and postherpetic neuralgia. J Intern Med. 2011;269:496-506.

3. Javed S, Javed SA, Trying SK. Varicella vaccines. Curr Open Infect Dis. 2012;25:135-140.

4. Oxman MN, Levin MJ, Johnson GR, et al. A vaccine to prevent herpes zoster and postherpetic neuralgia in older adults. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2271-2284.

5. Oxman MN. Zoster vaccine: current status and future prospects. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;51:197-213.

6. Keating GM. Shingles (herpes zoster) vaccine (Zostavax®): a review of its use in the prevention of herpes zoster and postherpetic neuralgia in adults aged >50 years. Drugs. 2013;73:1227-1244.

7. Herpes zoster vaccination. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/vpd-vac/shingles/hcp-vaccination.htm. Updated March 12, 2015. Accessed April 21, 2015.

8. Langan SM, Smeeth L, Margolis D, et al. Herpes zoster vaccine effectiveness against herpes zoster and post-herpetic neuralgia in an older US population: a cohort study. PLoS Med. 2013;10:e1001420.

1. Sampathkumar P, Drage LA, Martin DP. Herpes zoster (shingles) and postherpetic neuralgia. Mayo Clin Proc. 2009;84:274-280.

2. Gilden D. Efficacy of live zoster vaccine in preventing zoster and postherpetic neuralgia. J Intern Med. 2011;269:496-506.

3. Javed S, Javed SA, Trying SK. Varicella vaccines. Curr Open Infect Dis. 2012;25:135-140.

4. Oxman MN, Levin MJ, Johnson GR, et al. A vaccine to prevent herpes zoster and postherpetic neuralgia in older adults. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2271-2284.

5. Oxman MN. Zoster vaccine: current status and future prospects. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;51:197-213.

6. Keating GM. Shingles (herpes zoster) vaccine (Zostavax®): a review of its use in the prevention of herpes zoster and postherpetic neuralgia in adults aged >50 years. Drugs. 2013;73:1227-1244.

7. Herpes zoster vaccination. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/vpd-vac/shingles/hcp-vaccination.htm. Updated March 12, 2015. Accessed April 21, 2015.

8. Langan SM, Smeeth L, Margolis D, et al. Herpes zoster vaccine effectiveness against herpes zoster and post-herpetic neuralgia in an older US population: a cohort study. PLoS Med. 2013;10:e1001420.

Trauma center verification

Despite the many changes in medicine over the past century, traumatic injury remains a surgical disease.

Trauma injury is a major public health concern in rural areas, where death rates from unintentional injuries are higher than in metropolitan areas (Am. J. Public Health 2004;10:1689-93). The rural surgeon sees more than his or her fair share of victims of automobile accidents, falls, unintentional firearms injuries, and occupational accidents (think tractor accidents and injuries involving machinery and animals).

Another reality of the rural areas of the United States is that the number of broadly trained general surgeons who can treat a wide variety of trauma injuries is shrinking. Aging and retirements of the “old school rural surgeons” are accelerating and precipitating a lack of surgical coverage crisis, including trauma, in rural areas (Arch. Surg. 2005;140:74-9).

These well-documented developments have combined to reduce the availability of rural surgeons to manage injured patients in planned and consistent ways. Because of the current training paradigm of increasing subspecialization, injured rural patients may be cared for at rural hospitals with reduced capabilities and by rural surgeons with limited trauma training and experience.

What is the action plan to help counteract these developments and to provide the highest-quality patient care at facilities staffed by surgeons who have sworn to “serve all with skill and fidelity”?

The most straightforward and well-established action plan to achieve those goals is the verification process developed by the ACS Verification, Review, and Consultation Program (VRC) in 1987 to help hospitals improve trauma care. The process involves a pre-review questionnaire, a site visit, and report of findings. Verification as a trauma center guarantees that the facility has the required resources listed in the current, evidence-based guide, Resources for Optimal Care of the Injured Patient (2014). If successful, the trauma center receives a certificate of verification that is valid for 3 years.

Most rural hospitals are designated as Level III and IV verified trauma centers on the basis of their available resources. ACS verification confirms that these centers have the commitments and capabilities to manage the initial care of injured patients by providing stabilization and instituting life-saving maneuvers. In addition, verification confirms that protocols and agreements with higher-level trauma centers within a system enable the safe and efficient transfer of injured patients.

During many years of practice in the rural hospitals verified as trauma centers, including being the medical director of a Level II and Level III facility, I provided care to injured patients who presented to the emergency departments (EDs). My experiences confirmed the unequivocal value of practicing in those facilities, and I can attest to the benefits of verification within a system, like Iowa’s state program.

The following case report validates such assertions. A helicopter, unable to complete the transfer to a Level I center for a deteriorating patient with a left chest gunshot wound, landed at my Level III hospital. There was a “Hot Off Load,” which was followed by a full trauma alert for the patient in profound shock. After placing a chest tube during a 20-minute ED stay, the patient transferred to the OR for further resuscitation, and stabilization with required operative treatment. With the patient stabilized and fully resuscitated, according to established agreements, I contacted the Level I center from the OR. After 3 hours, the patient returned to the helicopter and completed the transfer to the Level I trauma center. The patient survived because of the local trauma team’s commitment, organization, and skill brought about by the trauma center verification.

Most research to date has focused on higher-level trauma centers, but recent studies have shown that ACS verification was an independent predictor of survival of trauma patients at Level II centers (J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2013;75:44-9; J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2010;69:1362-6).

I have firsthand experience with the verification process. Following my involvement with the ACS Committee on Trauma, I became a national site surveyor for the ACSVRC. I became an Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS) instructor and then worked as a course director. ATLS is an essential component for trauma center verification. It supports the rural surgeon by giving the local trauma team a format for consistent, life-saving care for the most severely injured patients. I subsequently completed the ACS Advanced Trauma Operative Management course and elected to become an instructor.

I have made site visits to many rural hospitals as a part of the ACSVRC process and have met with a wide range of reactions from “Let’s show off how good we are” to “We really don’t know why we’re doing this” to “Just give us the merit badge and then get out of our hair.” I am gratified to note that ACS Fellows are uniformly supportive. They understand the need for organization, standards, and performance improvement.

Opposition to the ACSVRC process by hospitals and staff is no doubt rooted in cost concerns and general resistance to change. But, as most of us know, demonstrated benefits for patient care can be highly persuasive to most medical professionals.

It is also worth noting that in an effort to decrease stress, the ACSVRC takes significant steps to support facilities that seek verification by eliminating ambiguity from application to on-site visit, by defining criteria deficiencies, and by providing evidence for the entire verification process. The complete VRC program along with an FAQ is available on the ACS website (facs.org/quality-programs/trauma/vrc).

For me, trauma care has always been about what is best for the injured patient. I often ask colleagues this question: “What care do you want for an injured member of your family?” I then answer my own question: “I want the best care possible. That means organized, efficient, and life-saving [care] if needed.” Fortunately, I experienced these benefits at my verified trauma center hospital when my second son was in a rollover motor vehicle crash. He survived.

Verified rural trauma centers do indeed offer the best opportunities for high-quality patient care and for support of the rural surgeons who render that care to “serve all with skill and fidelity.” I know. I have been there.

Dr. Caropreso is a general surgeon at Keokuk (Iowa) Area Hospital and clinical professor of surgery at the University of Iowa Carver College of Medicine, Iowa City. He has practiced surgery in the rural communities of Mason City, Iowa; Keokuk, Iowa; and Carthage, Ill., for 37 years.

Despite the many changes in medicine over the past century, traumatic injury remains a surgical disease.

Trauma injury is a major public health concern in rural areas, where death rates from unintentional injuries are higher than in metropolitan areas (Am. J. Public Health 2004;10:1689-93). The rural surgeon sees more than his or her fair share of victims of automobile accidents, falls, unintentional firearms injuries, and occupational accidents (think tractor accidents and injuries involving machinery and animals).

Another reality of the rural areas of the United States is that the number of broadly trained general surgeons who can treat a wide variety of trauma injuries is shrinking. Aging and retirements of the “old school rural surgeons” are accelerating and precipitating a lack of surgical coverage crisis, including trauma, in rural areas (Arch. Surg. 2005;140:74-9).