User login

Noninvasive prenatal testing: Where we are and where we’re going

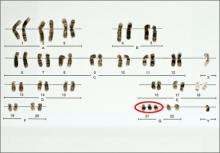

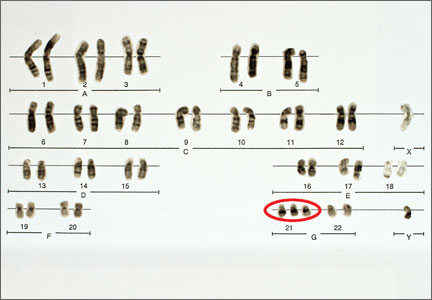

The introduction of amniocentesis in the 1960s brought to prenatal diagnosticians the ability to detect fetal chromosome abnormalities and certain structural defects (including neural tube defects). Since that time, a goal for these practitioners has been the development of effective screening algorithms to better identify women at high risk for detectable fetal abnormalities in concert with the advent of safer and more accessible diagnostic tests, with the eventual aim being the development of a noninvasive prenatal diagnostic test.

Postamniocentesis advancements have included the identification of maternal serum analytes as well as the incorporation of first-trimester ultrasonographic measurements of the fetal nuchal translucency (NT) and nasal bone, all associated with an improved ability to identify women at increased risk for fetal trisomies 21 and 18 as well as some other fetal abnormalities. In addition, targeted ultrasound has greatly improved the ability to detect fetal structural and growth abnormalities in women of all risk levels, although it remains a highly subjective process with considerable inter/intraoperator and equipment variability.

Related article: NIPT is expanding rapidly--but don't throw out that CVS kit just yet! (Update on Obstetrics; Jaimey M. Pauli, MD, and John T. Repke, MD; January 2014)

Noninvasive prenatal screening has the advantages of being noninvasive and carrying no increased risk for fetal loss compared with chorionic villus sampling (CVS) and amniocentesis, which are associated with a small increased risk for pregnancy loss (1/500 to 1/1,500 over baseline risk for loss). However, noninvasive screening is limited compared with diagnostic procedures because it provides only a risk adjustment rather than a definitive diagnostic outcome and is mostly limited to assessment for fetal trisomies 18 and 21.

Targeted ultrasound can identify structural abnormalities associated with other chromosomal, genetic, and genomic abnormalities, but again depends on operator experience, equipment used, maternal habitus, and fetal position. Accordingly, considerable interest has remained in developing a more effective approach for detecting fetal aneuploidy and other fetal abnormalities, including assays that eventually could serve to provide noninvasive prenatal diagnosis.

RECENT ADVANCES BRING US CLOSER TO OUR ULTIMATE GOAL

The recent introduction of circulating cell-free nucleic acids (ccfna) technologies for prenatal screening for common fetal aneuploidies, better known as noninvasive prenatal testing, or NIPT, has presented a far more effective prenatal screening protocol for certain groups of women compared with the aforementioned screening algorithms that rely on measurements of the fetal NT in the late first trimester and maternal serum measurements of analytes in the first and second trimesters.

Currently, four NIPT screening products are available commercially in the United States: MaterniT21 Plus (Sequenom, San Diego, California); Verifi (Illumina, San Diego, California); Harmony Prenatal Test (Ariosa Diagnostics, San Jose, California); and Panorama Prenatal Test (Natera, San Carlos, California). While the technologies and algorithms used by each of the companies differ, they all rely on the premise that 5% to 10% of ccfna in maternal blood are fetal in nature.1 Calculating the ratios of the expected amount of each chromosome-specific nucleic acid to that actually measured in the sample, a prediction of a normal or abnormal complement for that specific chromosome is then made. None of the commercially available tests specifically identify fetal DNA or differentiate fetal from maternal DNA.

Current validation studies have thus far limited the offering of NIPT to women at increased risk for fetal aneuploidy, including those:2–6

- of advanced maternal age

- with a positive conventional screening test

- with abnormal ultrasound results suggestive of aneuploidy, or

- who have had a prior pregnancy with a chromosome aneuploidy found in the NIPT panel.

Studies of all available technologies tested on women at increased risk for fetal aneuploidy have thus far shown considerably higher sensitivities and specificities and detection rates for fetal trisomies 21, 18, and 13 than conventional screening algorithms, although detection rates for trisomy 13 are slightly lower than those observed for trisomies 21 and 18.

WE STILL HAVE MANY HURDLES TO LEAP

However, the groups of women at high risk for fetal aneuploidy just outlined represent only a small segment of the community of pregnant women. A multicenter study involving 1,914 women published February 2014 in the New England Journal of Medicine7 showed considerably and significantly lower false-positive rates and higher positive predictive values for the detection of trisomies 21 and 18 by NIPT compared with conventional fetal aneuploidy screening. This study incorporated women at low risk for fetal aneuploidies in the study cohort, although women at high risk (based on the stated range of maternal age) also were included in the cohort. Unfortunately, no information was provided in the report about the percentage of low-risk women among the study participants.

Related articles:

Noninvasive prenatal DNA testing: Who is using it, and how? Audiocast, June 2013

Noninvasive prenatal DNA tests are unproven and costly David A. Carpenter, MD (Comment & Controversy; September 2013)

Another concern about the published accuracy of NIPT clinical assays was recently sounded by Menutti and colleagues.8 The authors cited recent cases of positive NIPT outcomes for fetal trisomies 18 and 13 that were not confirmed by diagnostic testing of the pregnancies in question. The authors pondered whether such cases may reflect a limitation of the positive predictive values attributed to NIPT assays and that such limitations may carry profound inaccuracies in determining the accuracy of such protocols for rare aneuploidies.

While the improved detection rates for NIPT compared with conventional screening are not surprising, guidelines published by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists still do not recommend the use of NIPT for the screening of low-risk women because of insufficient evaluation of ccfna technologies in the screening of such pregnancies.3 This also applies to twin pregnancies, despite preliminary studies showing comparable detection of trisomies 18 and 21 in such pregnancies compared with singleton pregnancies.3,9

There are no direct comparative studies of the four commercially available screening products, thus precluding a robust comparison and determination of the best existing method to use.

SO, WHERE ARE WE WITH NIPT EXACTLY?

The recent introduction of NIPT into routine obstetric care has left many clinicians with a wide range of questions, many of which cannot be answered because of little or no information, robust or otherwise, to formulate an accurate and cogent response. So let’s state what we know based on the available evidence, recognizing that this will likely change, perhaps considerably, in the weeks and months ahead.

NIPT is a far superior approach, compared with conventional screening approaches, to screening for fetal trisomies 21, 18, and 13 in women carrying singleton pregnancies who are at an increased risk for fetal chromosome abnormalities.

In our current understanding of prenatal screening and diagnosis, NIPT does not provide either the comprehensive approach or the diagnostic accuracy associated with CVS and amniocentesis. As such, NIPT is not a suitable replacement for prenatal diagnostic procedures.

However, its application to screening a low-risk population for the common fetal aneuploidies, as well as in twin pregnancies, has been supported by initial studies, and the inclusion of other clinical outcomes—including other chromosome abnormalities, such as X and Y aneuploidies, trisomy 16, and triploidy10,11 and certain genomic abnormalities (eg, 22q deletions)—in the screening algorithm will expand the future clinical applications of NIPT screening.

DOES NIPT CHANGE OUR CONCEPTS OF SCREENING AND DIAGNOSIS?

This question is simple but profound and is perhaps the most important to be asked and addressed. Is a screening algorithm that has a similar sensitivity and specificity to that of CVS and amniocentesis for the most common fetal trisomies in the first and second trimesters sufficient to replace invasive testing for most women? Does the ability to detect fetal genomic abnormalities with microarray analyses of fetal cells obtained by CVS or amniocentesis provide a far greater benefit than that possible with any screening algorithm?

With renewed interest in the cost of health-care screening and diagnosis, we need to consider how comprehensive and accurate our prenatal screening and diagnostic tests should be and whether such improvements are desired or even possible from a clinical or economic viewpoint. In addition, the development of new technologies, such as the capture and analysis of fetal cells in maternal blood, presents the potential for a direct diagnostic fetal assay without the risks of an invasive procedure.

BIAS-FREE COUNSELING CANNOT BE OVERLOOKED

That being said, the current role of NIPT and other screening protocols in obstetric care needs to be clearly communicated to women who are considering their fetal assessment options, with emphasis placed on the capabilities and limitations of prenatal screening (even the newer ccfna-based options), the actual risks associated with invasive testing, and the ability of invasive testing to provide expanded fetal information with the use of microarray analyses.

As it has been from the beginning of prenatal testing in the 1960s, counseling continues to be the most important part of the prenatal screening and diagnostic process and it is needed to facilitate clinical decisions made by women and couples. Counseling must include an accurate communication of the risks, benefits, and limitations of the aforementioned options and issues, and should be provided in a manner that strives to be free of bias, direction, and the personal opinions of the counselor.

In order to provide such counseling, we must remain informed of the ongoing work in the field of prenatal testing, a task that has become more challenging with the rapid release of a considerable amount of new information on prenatal screening technologies over the past 2 years. This will likely continue, and perhaps become even more frenetic, with the expected release of additional information on the clinical applications of ccfna technologies in the near future as well as the development of new technologies applicable for the screening and diagnosis of fetal abnormalities.

WE WANT TO HEAR FROM YOU!

Share your thoughts on this article. Send your letter to: [email protected] Please include the city and state in which you practice.

- Lo YM, Corbetta N, Chamberlain PF, et al. Presence of fetal DNA in maternal plasma and serum. Lancet. 1997;350(9076):485–487.

- Ashoor G, Syngelaki A, Wagner M, Birdir C, Nicolaides KH. Chromosome-selective sequencing of maternal plasma cell–free DNA for first-trimester detection of trisomy 21 and trisomy 18. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;206(4):322.e1–e5.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Genetics. Committee Opinion No. 545: Noninvasive prenatal testing for fetal aneuploidy. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120(6):1532–1534.

- Bianchi DW, Platt LD, Goldberg JD, et al; MatErnal Blood IS Source to Accurately diagnose fetal aneuploidy (MELISSA) Study Group. Genome-wide fetal aneuploidy detection by maternal plasma DNA-sequencing. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;119(5):890–901.

- Palomaki GE, Kloza EM, Lambert-Messerlian GM, et al. DNA sequencing of maternal plasma to detect Down syndrome: An international clinical validation study. Genet Med. 2011;13(11):913–920.

- Palomaki GE, Deciu C, Kloza EM, et al. DNA sequencing of maternal plasma reliably identifies trisomy 18 and trisomy 13 as well as Down syndrome: An international collaborative study. Genet Med. 2012;14(3):296–305.

- Bianchi DW, Parker RL, Wentworth J, et al; CARE Study Group. DNA sequencing versus standard prenatal aneuploidy screening. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(9):799–808.

- Menutti MT, Cherry AM, Morrissette JJ, Dugoff L. Is it time to sound an alarm about false-positive cell-free DNA testing for fetal aneuploidy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;209(5):415−419.

- Canick JA, Kloza EM, Lambert-Messerlian GM, et al. DNA sequencing of maternal plasma to identify Down syndrome and other trisomies in multiple gestations. Prenat Diagn. 2012;32(8):730–734.

- Nicolaides KH, Syngelaki A, Gil MM, Quezada MS, Zinevich Y. Prenatal detection of fetal triploidy from cell-free DNA testing in maternal blood [published online ahead of print October 10, 2013]. Fetal Diagn Ther.

- Semango-Sprouse C, Banjevic M, Ryan A, et al. SNP-based non-invasive prenatal testing detects sex chromosome aneuploidies with high accuracy. Prenat Diagn. 2013;33(7):643–649.

The introduction of amniocentesis in the 1960s brought to prenatal diagnosticians the ability to detect fetal chromosome abnormalities and certain structural defects (including neural tube defects). Since that time, a goal for these practitioners has been the development of effective screening algorithms to better identify women at high risk for detectable fetal abnormalities in concert with the advent of safer and more accessible diagnostic tests, with the eventual aim being the development of a noninvasive prenatal diagnostic test.

Postamniocentesis advancements have included the identification of maternal serum analytes as well as the incorporation of first-trimester ultrasonographic measurements of the fetal nuchal translucency (NT) and nasal bone, all associated with an improved ability to identify women at increased risk for fetal trisomies 21 and 18 as well as some other fetal abnormalities. In addition, targeted ultrasound has greatly improved the ability to detect fetal structural and growth abnormalities in women of all risk levels, although it remains a highly subjective process with considerable inter/intraoperator and equipment variability.

Related article: NIPT is expanding rapidly--but don't throw out that CVS kit just yet! (Update on Obstetrics; Jaimey M. Pauli, MD, and John T. Repke, MD; January 2014)

Noninvasive prenatal screening has the advantages of being noninvasive and carrying no increased risk for fetal loss compared with chorionic villus sampling (CVS) and amniocentesis, which are associated with a small increased risk for pregnancy loss (1/500 to 1/1,500 over baseline risk for loss). However, noninvasive screening is limited compared with diagnostic procedures because it provides only a risk adjustment rather than a definitive diagnostic outcome and is mostly limited to assessment for fetal trisomies 18 and 21.

Targeted ultrasound can identify structural abnormalities associated with other chromosomal, genetic, and genomic abnormalities, but again depends on operator experience, equipment used, maternal habitus, and fetal position. Accordingly, considerable interest has remained in developing a more effective approach for detecting fetal aneuploidy and other fetal abnormalities, including assays that eventually could serve to provide noninvasive prenatal diagnosis.

RECENT ADVANCES BRING US CLOSER TO OUR ULTIMATE GOAL

The recent introduction of circulating cell-free nucleic acids (ccfna) technologies for prenatal screening for common fetal aneuploidies, better known as noninvasive prenatal testing, or NIPT, has presented a far more effective prenatal screening protocol for certain groups of women compared with the aforementioned screening algorithms that rely on measurements of the fetal NT in the late first trimester and maternal serum measurements of analytes in the first and second trimesters.

Currently, four NIPT screening products are available commercially in the United States: MaterniT21 Plus (Sequenom, San Diego, California); Verifi (Illumina, San Diego, California); Harmony Prenatal Test (Ariosa Diagnostics, San Jose, California); and Panorama Prenatal Test (Natera, San Carlos, California). While the technologies and algorithms used by each of the companies differ, they all rely on the premise that 5% to 10% of ccfna in maternal blood are fetal in nature.1 Calculating the ratios of the expected amount of each chromosome-specific nucleic acid to that actually measured in the sample, a prediction of a normal or abnormal complement for that specific chromosome is then made. None of the commercially available tests specifically identify fetal DNA or differentiate fetal from maternal DNA.

Current validation studies have thus far limited the offering of NIPT to women at increased risk for fetal aneuploidy, including those:2–6

- of advanced maternal age

- with a positive conventional screening test

- with abnormal ultrasound results suggestive of aneuploidy, or

- who have had a prior pregnancy with a chromosome aneuploidy found in the NIPT panel.

Studies of all available technologies tested on women at increased risk for fetal aneuploidy have thus far shown considerably higher sensitivities and specificities and detection rates for fetal trisomies 21, 18, and 13 than conventional screening algorithms, although detection rates for trisomy 13 are slightly lower than those observed for trisomies 21 and 18.

WE STILL HAVE MANY HURDLES TO LEAP

However, the groups of women at high risk for fetal aneuploidy just outlined represent only a small segment of the community of pregnant women. A multicenter study involving 1,914 women published February 2014 in the New England Journal of Medicine7 showed considerably and significantly lower false-positive rates and higher positive predictive values for the detection of trisomies 21 and 18 by NIPT compared with conventional fetal aneuploidy screening. This study incorporated women at low risk for fetal aneuploidies in the study cohort, although women at high risk (based on the stated range of maternal age) also were included in the cohort. Unfortunately, no information was provided in the report about the percentage of low-risk women among the study participants.

Related articles:

Noninvasive prenatal DNA testing: Who is using it, and how? Audiocast, June 2013

Noninvasive prenatal DNA tests are unproven and costly David A. Carpenter, MD (Comment & Controversy; September 2013)

Another concern about the published accuracy of NIPT clinical assays was recently sounded by Menutti and colleagues.8 The authors cited recent cases of positive NIPT outcomes for fetal trisomies 18 and 13 that were not confirmed by diagnostic testing of the pregnancies in question. The authors pondered whether such cases may reflect a limitation of the positive predictive values attributed to NIPT assays and that such limitations may carry profound inaccuracies in determining the accuracy of such protocols for rare aneuploidies.

While the improved detection rates for NIPT compared with conventional screening are not surprising, guidelines published by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists still do not recommend the use of NIPT for the screening of low-risk women because of insufficient evaluation of ccfna technologies in the screening of such pregnancies.3 This also applies to twin pregnancies, despite preliminary studies showing comparable detection of trisomies 18 and 21 in such pregnancies compared with singleton pregnancies.3,9

There are no direct comparative studies of the four commercially available screening products, thus precluding a robust comparison and determination of the best existing method to use.

SO, WHERE ARE WE WITH NIPT EXACTLY?

The recent introduction of NIPT into routine obstetric care has left many clinicians with a wide range of questions, many of which cannot be answered because of little or no information, robust or otherwise, to formulate an accurate and cogent response. So let’s state what we know based on the available evidence, recognizing that this will likely change, perhaps considerably, in the weeks and months ahead.

NIPT is a far superior approach, compared with conventional screening approaches, to screening for fetal trisomies 21, 18, and 13 in women carrying singleton pregnancies who are at an increased risk for fetal chromosome abnormalities.

In our current understanding of prenatal screening and diagnosis, NIPT does not provide either the comprehensive approach or the diagnostic accuracy associated with CVS and amniocentesis. As such, NIPT is not a suitable replacement for prenatal diagnostic procedures.

However, its application to screening a low-risk population for the common fetal aneuploidies, as well as in twin pregnancies, has been supported by initial studies, and the inclusion of other clinical outcomes—including other chromosome abnormalities, such as X and Y aneuploidies, trisomy 16, and triploidy10,11 and certain genomic abnormalities (eg, 22q deletions)—in the screening algorithm will expand the future clinical applications of NIPT screening.

DOES NIPT CHANGE OUR CONCEPTS OF SCREENING AND DIAGNOSIS?

This question is simple but profound and is perhaps the most important to be asked and addressed. Is a screening algorithm that has a similar sensitivity and specificity to that of CVS and amniocentesis for the most common fetal trisomies in the first and second trimesters sufficient to replace invasive testing for most women? Does the ability to detect fetal genomic abnormalities with microarray analyses of fetal cells obtained by CVS or amniocentesis provide a far greater benefit than that possible with any screening algorithm?

With renewed interest in the cost of health-care screening and diagnosis, we need to consider how comprehensive and accurate our prenatal screening and diagnostic tests should be and whether such improvements are desired or even possible from a clinical or economic viewpoint. In addition, the development of new technologies, such as the capture and analysis of fetal cells in maternal blood, presents the potential for a direct diagnostic fetal assay without the risks of an invasive procedure.

BIAS-FREE COUNSELING CANNOT BE OVERLOOKED

That being said, the current role of NIPT and other screening protocols in obstetric care needs to be clearly communicated to women who are considering their fetal assessment options, with emphasis placed on the capabilities and limitations of prenatal screening (even the newer ccfna-based options), the actual risks associated with invasive testing, and the ability of invasive testing to provide expanded fetal information with the use of microarray analyses.

As it has been from the beginning of prenatal testing in the 1960s, counseling continues to be the most important part of the prenatal screening and diagnostic process and it is needed to facilitate clinical decisions made by women and couples. Counseling must include an accurate communication of the risks, benefits, and limitations of the aforementioned options and issues, and should be provided in a manner that strives to be free of bias, direction, and the personal opinions of the counselor.

In order to provide such counseling, we must remain informed of the ongoing work in the field of prenatal testing, a task that has become more challenging with the rapid release of a considerable amount of new information on prenatal screening technologies over the past 2 years. This will likely continue, and perhaps become even more frenetic, with the expected release of additional information on the clinical applications of ccfna technologies in the near future as well as the development of new technologies applicable for the screening and diagnosis of fetal abnormalities.

WE WANT TO HEAR FROM YOU!

Share your thoughts on this article. Send your letter to: [email protected] Please include the city and state in which you practice.

The introduction of amniocentesis in the 1960s brought to prenatal diagnosticians the ability to detect fetal chromosome abnormalities and certain structural defects (including neural tube defects). Since that time, a goal for these practitioners has been the development of effective screening algorithms to better identify women at high risk for detectable fetal abnormalities in concert with the advent of safer and more accessible diagnostic tests, with the eventual aim being the development of a noninvasive prenatal diagnostic test.

Postamniocentesis advancements have included the identification of maternal serum analytes as well as the incorporation of first-trimester ultrasonographic measurements of the fetal nuchal translucency (NT) and nasal bone, all associated with an improved ability to identify women at increased risk for fetal trisomies 21 and 18 as well as some other fetal abnormalities. In addition, targeted ultrasound has greatly improved the ability to detect fetal structural and growth abnormalities in women of all risk levels, although it remains a highly subjective process with considerable inter/intraoperator and equipment variability.

Related article: NIPT is expanding rapidly--but don't throw out that CVS kit just yet! (Update on Obstetrics; Jaimey M. Pauli, MD, and John T. Repke, MD; January 2014)

Noninvasive prenatal screening has the advantages of being noninvasive and carrying no increased risk for fetal loss compared with chorionic villus sampling (CVS) and amniocentesis, which are associated with a small increased risk for pregnancy loss (1/500 to 1/1,500 over baseline risk for loss). However, noninvasive screening is limited compared with diagnostic procedures because it provides only a risk adjustment rather than a definitive diagnostic outcome and is mostly limited to assessment for fetal trisomies 18 and 21.

Targeted ultrasound can identify structural abnormalities associated with other chromosomal, genetic, and genomic abnormalities, but again depends on operator experience, equipment used, maternal habitus, and fetal position. Accordingly, considerable interest has remained in developing a more effective approach for detecting fetal aneuploidy and other fetal abnormalities, including assays that eventually could serve to provide noninvasive prenatal diagnosis.

RECENT ADVANCES BRING US CLOSER TO OUR ULTIMATE GOAL

The recent introduction of circulating cell-free nucleic acids (ccfna) technologies for prenatal screening for common fetal aneuploidies, better known as noninvasive prenatal testing, or NIPT, has presented a far more effective prenatal screening protocol for certain groups of women compared with the aforementioned screening algorithms that rely on measurements of the fetal NT in the late first trimester and maternal serum measurements of analytes in the first and second trimesters.

Currently, four NIPT screening products are available commercially in the United States: MaterniT21 Plus (Sequenom, San Diego, California); Verifi (Illumina, San Diego, California); Harmony Prenatal Test (Ariosa Diagnostics, San Jose, California); and Panorama Prenatal Test (Natera, San Carlos, California). While the technologies and algorithms used by each of the companies differ, they all rely on the premise that 5% to 10% of ccfna in maternal blood are fetal in nature.1 Calculating the ratios of the expected amount of each chromosome-specific nucleic acid to that actually measured in the sample, a prediction of a normal or abnormal complement for that specific chromosome is then made. None of the commercially available tests specifically identify fetal DNA or differentiate fetal from maternal DNA.

Current validation studies have thus far limited the offering of NIPT to women at increased risk for fetal aneuploidy, including those:2–6

- of advanced maternal age

- with a positive conventional screening test

- with abnormal ultrasound results suggestive of aneuploidy, or

- who have had a prior pregnancy with a chromosome aneuploidy found in the NIPT panel.

Studies of all available technologies tested on women at increased risk for fetal aneuploidy have thus far shown considerably higher sensitivities and specificities and detection rates for fetal trisomies 21, 18, and 13 than conventional screening algorithms, although detection rates for trisomy 13 are slightly lower than those observed for trisomies 21 and 18.

WE STILL HAVE MANY HURDLES TO LEAP

However, the groups of women at high risk for fetal aneuploidy just outlined represent only a small segment of the community of pregnant women. A multicenter study involving 1,914 women published February 2014 in the New England Journal of Medicine7 showed considerably and significantly lower false-positive rates and higher positive predictive values for the detection of trisomies 21 and 18 by NIPT compared with conventional fetal aneuploidy screening. This study incorporated women at low risk for fetal aneuploidies in the study cohort, although women at high risk (based on the stated range of maternal age) also were included in the cohort. Unfortunately, no information was provided in the report about the percentage of low-risk women among the study participants.

Related articles:

Noninvasive prenatal DNA testing: Who is using it, and how? Audiocast, June 2013

Noninvasive prenatal DNA tests are unproven and costly David A. Carpenter, MD (Comment & Controversy; September 2013)

Another concern about the published accuracy of NIPT clinical assays was recently sounded by Menutti and colleagues.8 The authors cited recent cases of positive NIPT outcomes for fetal trisomies 18 and 13 that were not confirmed by diagnostic testing of the pregnancies in question. The authors pondered whether such cases may reflect a limitation of the positive predictive values attributed to NIPT assays and that such limitations may carry profound inaccuracies in determining the accuracy of such protocols for rare aneuploidies.

While the improved detection rates for NIPT compared with conventional screening are not surprising, guidelines published by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists still do not recommend the use of NIPT for the screening of low-risk women because of insufficient evaluation of ccfna technologies in the screening of such pregnancies.3 This also applies to twin pregnancies, despite preliminary studies showing comparable detection of trisomies 18 and 21 in such pregnancies compared with singleton pregnancies.3,9

There are no direct comparative studies of the four commercially available screening products, thus precluding a robust comparison and determination of the best existing method to use.

SO, WHERE ARE WE WITH NIPT EXACTLY?

The recent introduction of NIPT into routine obstetric care has left many clinicians with a wide range of questions, many of which cannot be answered because of little or no information, robust or otherwise, to formulate an accurate and cogent response. So let’s state what we know based on the available evidence, recognizing that this will likely change, perhaps considerably, in the weeks and months ahead.

NIPT is a far superior approach, compared with conventional screening approaches, to screening for fetal trisomies 21, 18, and 13 in women carrying singleton pregnancies who are at an increased risk for fetal chromosome abnormalities.

In our current understanding of prenatal screening and diagnosis, NIPT does not provide either the comprehensive approach or the diagnostic accuracy associated with CVS and amniocentesis. As such, NIPT is not a suitable replacement for prenatal diagnostic procedures.

However, its application to screening a low-risk population for the common fetal aneuploidies, as well as in twin pregnancies, has been supported by initial studies, and the inclusion of other clinical outcomes—including other chromosome abnormalities, such as X and Y aneuploidies, trisomy 16, and triploidy10,11 and certain genomic abnormalities (eg, 22q deletions)—in the screening algorithm will expand the future clinical applications of NIPT screening.

DOES NIPT CHANGE OUR CONCEPTS OF SCREENING AND DIAGNOSIS?

This question is simple but profound and is perhaps the most important to be asked and addressed. Is a screening algorithm that has a similar sensitivity and specificity to that of CVS and amniocentesis for the most common fetal trisomies in the first and second trimesters sufficient to replace invasive testing for most women? Does the ability to detect fetal genomic abnormalities with microarray analyses of fetal cells obtained by CVS or amniocentesis provide a far greater benefit than that possible with any screening algorithm?

With renewed interest in the cost of health-care screening and diagnosis, we need to consider how comprehensive and accurate our prenatal screening and diagnostic tests should be and whether such improvements are desired or even possible from a clinical or economic viewpoint. In addition, the development of new technologies, such as the capture and analysis of fetal cells in maternal blood, presents the potential for a direct diagnostic fetal assay without the risks of an invasive procedure.

BIAS-FREE COUNSELING CANNOT BE OVERLOOKED

That being said, the current role of NIPT and other screening protocols in obstetric care needs to be clearly communicated to women who are considering their fetal assessment options, with emphasis placed on the capabilities and limitations of prenatal screening (even the newer ccfna-based options), the actual risks associated with invasive testing, and the ability of invasive testing to provide expanded fetal information with the use of microarray analyses.

As it has been from the beginning of prenatal testing in the 1960s, counseling continues to be the most important part of the prenatal screening and diagnostic process and it is needed to facilitate clinical decisions made by women and couples. Counseling must include an accurate communication of the risks, benefits, and limitations of the aforementioned options and issues, and should be provided in a manner that strives to be free of bias, direction, and the personal opinions of the counselor.

In order to provide such counseling, we must remain informed of the ongoing work in the field of prenatal testing, a task that has become more challenging with the rapid release of a considerable amount of new information on prenatal screening technologies over the past 2 years. This will likely continue, and perhaps become even more frenetic, with the expected release of additional information on the clinical applications of ccfna technologies in the near future as well as the development of new technologies applicable for the screening and diagnosis of fetal abnormalities.

WE WANT TO HEAR FROM YOU!

Share your thoughts on this article. Send your letter to: [email protected] Please include the city and state in which you practice.

- Lo YM, Corbetta N, Chamberlain PF, et al. Presence of fetal DNA in maternal plasma and serum. Lancet. 1997;350(9076):485–487.

- Ashoor G, Syngelaki A, Wagner M, Birdir C, Nicolaides KH. Chromosome-selective sequencing of maternal plasma cell–free DNA for first-trimester detection of trisomy 21 and trisomy 18. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;206(4):322.e1–e5.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Genetics. Committee Opinion No. 545: Noninvasive prenatal testing for fetal aneuploidy. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120(6):1532–1534.

- Bianchi DW, Platt LD, Goldberg JD, et al; MatErnal Blood IS Source to Accurately diagnose fetal aneuploidy (MELISSA) Study Group. Genome-wide fetal aneuploidy detection by maternal plasma DNA-sequencing. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;119(5):890–901.

- Palomaki GE, Kloza EM, Lambert-Messerlian GM, et al. DNA sequencing of maternal plasma to detect Down syndrome: An international clinical validation study. Genet Med. 2011;13(11):913–920.

- Palomaki GE, Deciu C, Kloza EM, et al. DNA sequencing of maternal plasma reliably identifies trisomy 18 and trisomy 13 as well as Down syndrome: An international collaborative study. Genet Med. 2012;14(3):296–305.

- Bianchi DW, Parker RL, Wentworth J, et al; CARE Study Group. DNA sequencing versus standard prenatal aneuploidy screening. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(9):799–808.

- Menutti MT, Cherry AM, Morrissette JJ, Dugoff L. Is it time to sound an alarm about false-positive cell-free DNA testing for fetal aneuploidy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;209(5):415−419.

- Canick JA, Kloza EM, Lambert-Messerlian GM, et al. DNA sequencing of maternal plasma to identify Down syndrome and other trisomies in multiple gestations. Prenat Diagn. 2012;32(8):730–734.

- Nicolaides KH, Syngelaki A, Gil MM, Quezada MS, Zinevich Y. Prenatal detection of fetal triploidy from cell-free DNA testing in maternal blood [published online ahead of print October 10, 2013]. Fetal Diagn Ther.

- Semango-Sprouse C, Banjevic M, Ryan A, et al. SNP-based non-invasive prenatal testing detects sex chromosome aneuploidies with high accuracy. Prenat Diagn. 2013;33(7):643–649.

- Lo YM, Corbetta N, Chamberlain PF, et al. Presence of fetal DNA in maternal plasma and serum. Lancet. 1997;350(9076):485–487.

- Ashoor G, Syngelaki A, Wagner M, Birdir C, Nicolaides KH. Chromosome-selective sequencing of maternal plasma cell–free DNA for first-trimester detection of trisomy 21 and trisomy 18. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;206(4):322.e1–e5.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Genetics. Committee Opinion No. 545: Noninvasive prenatal testing for fetal aneuploidy. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120(6):1532–1534.

- Bianchi DW, Platt LD, Goldberg JD, et al; MatErnal Blood IS Source to Accurately diagnose fetal aneuploidy (MELISSA) Study Group. Genome-wide fetal aneuploidy detection by maternal plasma DNA-sequencing. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;119(5):890–901.

- Palomaki GE, Kloza EM, Lambert-Messerlian GM, et al. DNA sequencing of maternal plasma to detect Down syndrome: An international clinical validation study. Genet Med. 2011;13(11):913–920.

- Palomaki GE, Deciu C, Kloza EM, et al. DNA sequencing of maternal plasma reliably identifies trisomy 18 and trisomy 13 as well as Down syndrome: An international collaborative study. Genet Med. 2012;14(3):296–305.

- Bianchi DW, Parker RL, Wentworth J, et al; CARE Study Group. DNA sequencing versus standard prenatal aneuploidy screening. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(9):799–808.

- Menutti MT, Cherry AM, Morrissette JJ, Dugoff L. Is it time to sound an alarm about false-positive cell-free DNA testing for fetal aneuploidy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;209(5):415−419.

- Canick JA, Kloza EM, Lambert-Messerlian GM, et al. DNA sequencing of maternal plasma to identify Down syndrome and other trisomies in multiple gestations. Prenat Diagn. 2012;32(8):730–734.

- Nicolaides KH, Syngelaki A, Gil MM, Quezada MS, Zinevich Y. Prenatal detection of fetal triploidy from cell-free DNA testing in maternal blood [published online ahead of print October 10, 2013]. Fetal Diagn Ther.

- Semango-Sprouse C, Banjevic M, Ryan A, et al. SNP-based non-invasive prenatal testing detects sex chromosome aneuploidies with high accuracy. Prenat Diagn. 2013;33(7):643–649.

Does your obstetric unit have a protocol for treating amniotic fluid embolism?

Amniotic fluid embolism (AFE) occurs in about 1 in 20,000 to 1 in 40,000 deliveries.1,2 Although the condition is rare, the case fatality rate is high, and AFE is a common cause of maternal death in developed countries. AFE cannot be predicted or prevented. Moreover, the condition is difficult to precisely define and is often a diagnosis of exclusion.

AFE should be considered in the differential diagnosis of a pregnant woman with sudden onset of shortness of breath, hypotension, or cardiac arrhythmia or arrest, followed by coagulopathy and hemorrhage. Premonitory symptoms, including restlessness, confusion, disorientation, agitation, chills, nausea, numbness, and tingling, are commonly reported just before the cardiorespiratory collapse. AFE is less likely if the initial obstetric event is hemorrhage in the absence of cardiorespiratory compromise or a preceding coagulopathy.3

Typically, the onset is just before birth, during birth, or within the first few hours after delivery. In the United Kingdom, which has a robust centralized registry for reporting AFE, about 56% of cases occur before birth and 44% after birth.4

Related article: Is the incidence of amniotic fluid embolism rising? John T. Repke, MD (Examining the Evidence, August 2010)

The resources available to obstetric units vary greatly. Each unit needs to assess its resources and develop an AFE treatment protocol that builds on the unique strengths of the unit. Treatment of AFE requires the coordinated actions of anesthesiologists, obstetricians, nurses, the blood bank, pharmacy, and cardiovascular specialists. Coordinated activity among the members of such a large multidisciplinary team requires a written protocol that is practiced on a regular basis.

Six important components of a multidisciplinary response to AFE treatment protocol are:

- high-quality cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR)

- a protocol for massive transfusion

- treatment of diffuse bleeding and coagulopathy

- treatment of uterine and pelvic bleeding

- extracorporeal lung and heart support

- post-AFE intensive care.

1. Initiate high-quality CPR

Hypotension and hypoxemia due to cardiac and pulmonary dysfunction are prominent features of AFE. Dysrythmias such as pulseless electrical activity, bradycardia, ventricular fibrillation, and asystole are common. Rapid institution of high-quality CPR is critical to the survival of women with AFE.

Interventions often used in CPR of patients with AFE include initiation of high-quality chest compressions, early defibrillation if indicated, immediate administration of 100% oxygen by mask ventilation followed by early intubation, and rapid establishment of peripheral, arterial, and central venous access. Volume assessment, fluid replacement, and administration of vasopressors and inotropes are also important.

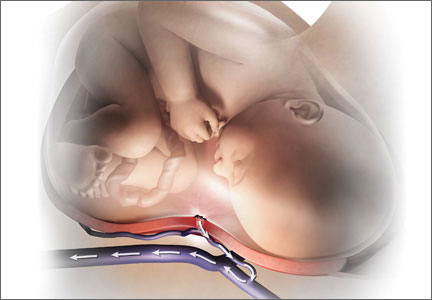

CPR of pregnant women requires special interventions, including maximal left lateral displacement of the uterus to reduce compression of the descending aorta and vena cava. Lateral displacement of the uterus can be accomplished by left lateral tilt or by manual uterine displacement. To optimize the effectiveness of chest compressions, many experts recommend placing the woman in a supine position and using manual uterine displacement rather than a left lateral tilt.5 For chest compressions, the hands should be placed just above the center of the sternum to adjust for the elevation of the diaphragm caused by the gravid uterus.

The gravid uterus can compromise the effectiveness of CPR. Fetal viability and neurologic outcome are best if delivery occurs within 5 minutes of the onset of cardiopulmonary arrest. If the gestational age of the fetus is consistent with extrauterine viability and initial CPR has not restored cardiac function, it is best to initiate fetal delivery within 4 minutes of the onset of cardiopulmonary arrest with the intent to deliver the fetus within 5 minutes.6,7 If the fetus is beyond 20 weeks’ gestational age, delivery early in the course of CPR improves the effectiveness of maternal resuscitation and may increase the probability of maternal survival.

In one study of the response of anesthesiologists, obstetricians, and nurses to a simulated cardiac arrest caused by an AFE, the participants did not routinely use defibrillation when indicated, did not place a firm support under the back for chest compressions, and did not switch the provider of chest compressions every 2 minutes.8 This study indicates that additional training and routinely scheduled multidisciplinary simulation of the response to cardiopulmonary arrest could improve the quality of our CPR.

2. Use a massive transfusion protocol

Severe coagulopathy and diffuse bleeding are commonly encountered in AFE. Target goals for the replacement of blood products include:

- hemoglobin concentration ≥8 g/dL

- fibrinogen ≥150 to 200 mg/dL

- platelets ≥50,000/μL

- prothrombin time international normalized ratio (INR) ≤1.5.

Most massive transfusion protocols provide for the rapid delivery of 4 to 8 units of red blood cells and a similar number of units of fresh frozen plasma to the patient’s bedside. In the management of AFE, 20 to 30 units of red blood cells and a similar quantity of fresh frozen plasma may need to be transfused. Cryoprecipitate takes 20 to 30 minutes to thaw, so preparations to transfuse cryoprecipitate should be initiated as soon as the massive transfusion protocol is triggered. A case of AFE can completely empty the blood bank of all available blood products and necessitate the use of alternative agents.

Lyophilized fibrinogen concentrate (RiaSTAP) is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of congenital hypofibrinogenemia and also may be useful to replace fibrinogen in cases of AFE. In many hospitals, large quantities of fresh frozen plasma are not immediately available; lyophilized fibrinogen concentrate may be especially useful in these settings. Another advantage of fibrinogen concentrate is that large amounts of fibrinogen can be administered in a small volume of intravenous fluid. Fibrinogen concentrate typically is used at a dose of 70 mg/kg of body weight.9,10

Intraoperative red cell salvage occasionally is used in cases of obstetric hemorrhage. In one case report of the use of red cell salvage with leukocyte depletion filtration during treatment of an AFE, acute hypotension developed in the patient after the transfusion of salvaged red cells.11 This case report raises safety concerns about the use of salvaged cells in women with severe AFE.

Related article: 10 practical, evidence-based recommendations for the management of severe postpartum hemorrhage Baha M. Sibai, MD (June 2011)

3. Treat diffuse bleeding and coagulopathy

In addition to the initiation of the massive transfusion protocol, additional treatments that may be helpful in managing the coagulopathy of AFE include tranexamic acid, recombinant factor VIIa (rFVIIa), and exchange transfusion.

AFE is often associated with hyperfibrinolysis, which can cause excessive bleeding.12 Tranexamic acid blocks the lysine binding sites on plasminogen and thereby reduces the lysis of fibrin clots. Clinical trials in patients who have undergone trauma have demonstrated that the administration of tranexamic acid reduces blood loss.13 The dose of tranexamic acid is approximately 10 to 20 mg/kg of body weight, or approximately 1 g.

Controversy exists about the use of rFVIIa to treat the coagulopathy and bleeding caused by AFE. Some authorities believe that rFVIIa is associated with an increased AFE case fatality rate.14 Other authorities believe rFVIIa may be useful in the treatment of AFE coagulopathy, especially when bleeding persists despite aggressive blood and component replacement.”15 The dose of rFVIIa is approximately 90 µg/kg of body weight. rFVIIa is extremely expensive.

Exchange transfusion has been used successfully to treat AFE.16 In women with AFE, exchange transfusion removes circulating cells, cell fragments, and substances that trigger systemic anaphylaxis and coagulopathy, thereby enhancing rapid recovery.

Related article: Act fast when confronted by a coagulopathy postpartum Robert L. Barbieri, MD (Editorial; March 2012)

4. Treat uterine and pelvic bleeding

Obstetrician-gynecologists are experts in the control of uterine and pelvic bleeding. Interventions that commonly are used to control uterine and pelvic bleeding in cases of postpartum hemorrhage, uterine rupture, or placenta accreta also can be applied in cases of AFE with uncontrolled uterine and pelvic bleeding. These techniques include:

- use of uterine compression sutures

- the Bakri balloon

- a uterine tourniquet

- vascular clamps on the ovarian vessels.17,18

In many cases of AFE, total or supracervical hysterectomy is necessary to control uterine bleeding. Uterine artery embolization, if available, has been reported to be helpful in select cases. However, many women with AFE are too unstable to survive transfer to an interventional radiology suite. Additional interventions to control bleeding include hypogastric artery ligation, infrarenal aortic compression, and pelvic packing.

Cross-clamping the aorta below the renal vessels can reduce blood flow to the pelvis and provide time for cardiopulmonary and volume resuscitation. Alternatively, placing pressure on the infrarenal aorta with a sponge or directly by hand can help reduce blood flow to the pelvis.19

In many cases of AFE, pelvic hemorrhage is difficult to control. Even if surgical pedicles are ligated securely, the coagulopathy of AFE may cause persistent oozing from areas of minor tissue trauma. Uncontrolled blood loss can be a proximate cause of death in women with AFE. All written protocols for responding to an AFE should include a plan to use pelvic packing for patients in whom standard operative procedures do not produce adequate control of bleeding. A “mushroom,” “parachute,” or “umbrella” pack has been reported to help stabilize the severely ill patient with pelvic bleeding and permit effective resuscitation and blood product replacement.20

Related articles:

A stitch in time: The B-Lynch, Hayman and Pereira uterine compression sutures Robert L. Barbieri, MD (Editorial, December 2012)

Have you made the best use of the Bakri balloon in PPH? Robert L. Barbieri, MD (Editorial, July 2011)

5. Consider extracorporeal lung and heart support

In many cases of AFE, both lung and cardiac function are severely compromised. Both veno-arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (VA-ECMO) and full cardiopulmonary bypass provide support for the failing lung and heart. Based on a small number of case reports, extracorporeal lung and heart support appear to be useful in the treatment of AFE.21–26 Using the Seldinger technique,27 it is technically feasible to rapidly access a major vein and artery to provide the input and output ports for VA-ECMO. Unlike the cardiopulmonary bypass pump, the VA-ECMO pump does not have a reservoir that needs to be primed with blood and is smaller and more portable. To provide a patient with VA-ECMO or cardiopulmonary bypass, a cardiac interventionist and a perfusionist must be available. Extracorporeal lung and heart support require heparinization of the patient’s blood, which may result in increased bleeding. Both VA-ECMO and cardiopulmonary bypass, along with the diseases for which they are used, may cause renal dysfunction, neurologic injury, and infection.28

Alternative approaches that provide support of the heart—but not lung—are the Impella pump, TandemHeart, and the intra-aortic balloon pump. An alternative that provides lung support—but not cardiac support—is veno-venous ECMO.

In developing a written protocol for responding to an AFE, obstetricians should explore the potential availability of VA-ECMO, cardiopulmonary bypass, or other cardiopulmonary support devices as options for patients who have not responded to standard treatment of AFE and are at high risk of death.

6. Post-AFE intensive care

After stabilization, most women with AFE will require intensive care for 48 to 96 hours. Some experts have proposed that all survivors of cardiopulmonary arrest who are successfully resuscitated and stabilized be transferred to hospitals that specialize in post−cardiac arrest care to improve outcomes.

Assessment of organ injury is important after an AFE. In addition, encephalopathy is a common complication of AFE, and sequential neurologic examination is a priority. Therapeutic hypothermia (TH) may help to preserve neurologic function after AFE.29 However, TH may cause a mild coagulopathy by inhibiting platelet activation and enzyme activity of clotting factors. Because coagulopathy is a prominent feature of AFE, TH may be contraindicated if the patient has a clinically significant baseline coagulopathy.30

DEVELOP AN AFE PROTOCOL AND PRACTICE THE COMPONENTS

Practicing the components of obstetric protocols can improve unit performance and patient outcomes.31 The components of an AFE protocol, as described in this article, include high-quality CPR, a protocol for massive transfusion, treatment of diffuse bleeding and coagulopathy, treatment of uterine and pelvic bleeding, extracorporeal lung and heart support, and post-AFE intensive care. Practicing these components of an AFE protocol will enhance performance across many common obstetric complications including postpartum hemorrhage, uterine rupture, placenta accreta, and pulmonary embolism.

When Chesley “Sully” Sullenberger and his copilot landed Flight 1549 in the Hudson River in New York, he had never practiced that specific response to twin engine failure, but he had practiced many emergency responses involving related scenarios. The combination of exceptional flight experience and years of practicing the response to emergency scenarios in simulation exercises permitted him and his copilot to execute a uniquely clever plan to solve a life-threatening

emergency. In a related way, practicing the components of AFE treatment will help obstetricians, obstetric anesthesiologists, and their multidisciplinary team to improve the responses to all major obstetric emergencies.

INSTANT POLL

Does your obstetric unit have a written protocol for treating an amniotic fluid embolism (AFE)? Has your obstetric unit practiced any of the components of the AFE treatment protocol: 1) high-quality cardiopulmonary resuscitation, 2) a protocol for massive transfusion protocol, 3) treatment of diffuse bleeding and coagulopathy, 4) treatment of uterine and pelvic bleeding, 5) extracorporeal lung and heart support, and 6) post-AFE intensive care?

Tell us—at [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Kramer MS, Rouleau J, Baskett TF, Joseph KS; Maternal Health Study Group of the Canadian Perinatal Surveillance System. Amniotic-fluid embolism and medical induction of labour: A retrospective, population-based cohort study. Lancet. 2006;368(9545):1444–1448.

- Abenhaim HA, Azoulay L, Kramer MS, Leduc L. Incidence and risk factors of amniotic fluid embolism: A population-based study on 3 million births in the United States. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;199(1):49.e1–49.e8.

- Tuffnell D, Knight M, Plaat F. Amniotic fluid embolism—An update. Anaesthesia. 2011;66(1):3–6.

- Knight M, Tuffnell D, Brocklehurst P, Spark P, Kurinczuk JJ; UK Obstetric Surveillance System. Incidence and risk factors for amniotic-fluid embolism. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115(5):910–917.

- Kundra P, Khanna S, Habeebullahg S, Ravishankar M. Manual displacement of the uterus during Caesarean section. Anaesthesia. 2007;62(5):460–465.

- Katz VL, Dotters DJ, Droegemueller W. Perimortem cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 1986;68(4):571–576.

- Katz V, Balderston K, DeFreest M. Perimortem cesarean delivery: Were our assumptions correct? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192(6):1916–1920.

- Lipman SS, Daniels KI, Carvalho B, et al. Deficits in the provision of cardiopulmonary resuscitation during simulated obstetric crises. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;203(2):179.e1–179.e5.

- Bell SF, Rayment R, Collins PW, Collis RE. The use of fibrinogen concentrate to correct hypofibrinogenaemia rapidly during obstetric haemorrhage. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2010;19(2):218–223.

- Sorensen B, Tang M, Larsen OH, Laursen PN, Fenger-Eriksen C, Rea CJ. The role of fibrinogen: A new paradigm in the treatment of coagulopathic bleeding. Thromb Res. 2011;128(Suppl 1):S13–S16.

- Rogers WK, Wernimont SA, Kumar GC, Bennett E, Chestnut DH. Acute hypotension associated with intraoperative cell salvage using a leukocyte depletion filter during management of obstetric hemorrhage due to amniotic fluid embolism. Anesth Analg. 2013;117(2):449–452.

- Collins NF, Bloor M, McDonnell NJ. Hyperfibrinolysis diagnosed by rotational thromboelastometry in a case of suspected amniotic fluid embolism. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2013;22(1):71–76.

- Ker K, Edwards P, Perel P, Shakur H, Roberts I. Effect of tranexamic acid on surgical bleeding: Systematic review and cumulative meta-analysis. BMJ. 2012;344:e3054.

- Leighton BL, Wall MH, Lockhart EM, Phillips LE, Zatta AJ. Use of recombinant factor VIIa in patients with amniotic fluid embolism: A systematic review of case reports. Anesthesiology. 2011;115(6):1201–1208.

- Huber AW, Raio L, Alberio L, Ghezzi F, Surbek DV. Recombinant human factor VIIa prevents hysterectomy in severe postpartum hemorrhage: single center study. J Perinat Med. 2011;40(1):43–49.

- Dodgson J, Martin J, Boswell J, Goodall HB, Smith R. Probable amniotic fluid embolism precipitated by amniocentesis and treated by exchange transfusion. Brit Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1987;294(6583):1322–1323.

- Barbieri RL. A stitch in time: The B-Lynch, Hayman and Pereira uterine compression sutures. OBG Manage. 2012;24(12):6, 8, 10, 11.

- Barbieri RL. Have you made the best use of the Bakri balloon in PPH? OBG Manage. 2011;23(7):6, 8, 9.

- Belfort MA, Zimmerman J, Schemmer G, Oldroyd R, Smilanich R, Pearce M. Aortic compression and cross clamping in a case of placenta percreta and amniotic fluid embolism: A case report. AJP Rep. 2011;1(1):33–36.

- Dildy GA, Scott JR, Saffer CS, Belfort MA. An

effective pressure pack for severe pelvic hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108(5):1222–1226. - Stanten RD, Iverson LI, Daugharty TM, Lovett SM, Terry C, Blumenstock E. Amniotic fluid embolism causing catastrophic pulmonary vasoconstriction: Diagnosis by transesophageal echocardiogram and treatment by cardiopulmonary bypass. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102(3):496–498.

- Ho CH, Chen KB, Liu SK, Liu YF, Cheng HC, Wu RS. Early application of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in a patient with amniotic fluid embolism. Acta Anaesthesiol Taiwan. 2009;47(2):99–102.

- Shen HP, Chang WC, Yeh LS, Ho M. Amniotic fluid embolism treated with emergency extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: A case report.

J Reprod Med. 2009;54(11–12):706–708. - Lee PH, Shulman MS, Vellayappan U, Symes JF, Olenchock SA Jr. Surgical treatment of amniotic fluid embolism with cardiopulmonary collapse. Ann Thorac Surg. 2010;90(5):1694–1696.

- Firstenberg MS, Abel E, Blais D, et al. Temporary extracorporeal circulatory support and pulmonary embolectomy for catastrophic amniotic fluid embolism. Heart Surg Forum. 2011;14(3):E157–E159.

- Ecker JL, Solt K, Fitzsimons MG, MacGillivray TE. Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Case 40-2012: A 43-year-old woman with cardiorespiratory arrest after a cesarean section. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(26):2528–2536.

- Seldinger SI. Catheter replacement of the needle in percutaneous arteriography; a new technique. Acta Radiol. 1953;39(5):368–376.

- Cheng R, Hachamovitch R, Kittelson M, et al. Complications of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for treatment of cardiogenic shock and cardiac arrest: A meta-analysis of 1,866 adult patients. Ann Thorac Surg. 2013; epub Nov 8.

- Rittenberger JC, Kelly E, Jang D, Greer K, Heffner A. Successful outcome utilizing hypothermia after cardiac arrest in pregnancy: A case report. Crit Care Med. 2008;36(4):1354–1356.

- Michelson AD, MacGregor H, Barnard MR, Krestin AS, Rohrer MJ, Valeri CR. Reversible inhibition of human platelet activation by hypothermia in vivo and in vitro. Thromb Haemost. 1994;71(5):633–640.

- Rivzi F, Mackey R, Barrett T, McKenna P, Geary M. Successful reduction of massive postpartum haemorrhage by use of guidelines and staff education. BJOG. 2004;111(5):495–498.

Amniotic fluid embolism (AFE) occurs in about 1 in 20,000 to 1 in 40,000 deliveries.1,2 Although the condition is rare, the case fatality rate is high, and AFE is a common cause of maternal death in developed countries. AFE cannot be predicted or prevented. Moreover, the condition is difficult to precisely define and is often a diagnosis of exclusion.

AFE should be considered in the differential diagnosis of a pregnant woman with sudden onset of shortness of breath, hypotension, or cardiac arrhythmia or arrest, followed by coagulopathy and hemorrhage. Premonitory symptoms, including restlessness, confusion, disorientation, agitation, chills, nausea, numbness, and tingling, are commonly reported just before the cardiorespiratory collapse. AFE is less likely if the initial obstetric event is hemorrhage in the absence of cardiorespiratory compromise or a preceding coagulopathy.3

Typically, the onset is just before birth, during birth, or within the first few hours after delivery. In the United Kingdom, which has a robust centralized registry for reporting AFE, about 56% of cases occur before birth and 44% after birth.4

Related article: Is the incidence of amniotic fluid embolism rising? John T. Repke, MD (Examining the Evidence, August 2010)

The resources available to obstetric units vary greatly. Each unit needs to assess its resources and develop an AFE treatment protocol that builds on the unique strengths of the unit. Treatment of AFE requires the coordinated actions of anesthesiologists, obstetricians, nurses, the blood bank, pharmacy, and cardiovascular specialists. Coordinated activity among the members of such a large multidisciplinary team requires a written protocol that is practiced on a regular basis.

Six important components of a multidisciplinary response to AFE treatment protocol are:

- high-quality cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR)

- a protocol for massive transfusion

- treatment of diffuse bleeding and coagulopathy

- treatment of uterine and pelvic bleeding

- extracorporeal lung and heart support

- post-AFE intensive care.

1. Initiate high-quality CPR

Hypotension and hypoxemia due to cardiac and pulmonary dysfunction are prominent features of AFE. Dysrythmias such as pulseless electrical activity, bradycardia, ventricular fibrillation, and asystole are common. Rapid institution of high-quality CPR is critical to the survival of women with AFE.

Interventions often used in CPR of patients with AFE include initiation of high-quality chest compressions, early defibrillation if indicated, immediate administration of 100% oxygen by mask ventilation followed by early intubation, and rapid establishment of peripheral, arterial, and central venous access. Volume assessment, fluid replacement, and administration of vasopressors and inotropes are also important.

CPR of pregnant women requires special interventions, including maximal left lateral displacement of the uterus to reduce compression of the descending aorta and vena cava. Lateral displacement of the uterus can be accomplished by left lateral tilt or by manual uterine displacement. To optimize the effectiveness of chest compressions, many experts recommend placing the woman in a supine position and using manual uterine displacement rather than a left lateral tilt.5 For chest compressions, the hands should be placed just above the center of the sternum to adjust for the elevation of the diaphragm caused by the gravid uterus.

The gravid uterus can compromise the effectiveness of CPR. Fetal viability and neurologic outcome are best if delivery occurs within 5 minutes of the onset of cardiopulmonary arrest. If the gestational age of the fetus is consistent with extrauterine viability and initial CPR has not restored cardiac function, it is best to initiate fetal delivery within 4 minutes of the onset of cardiopulmonary arrest with the intent to deliver the fetus within 5 minutes.6,7 If the fetus is beyond 20 weeks’ gestational age, delivery early in the course of CPR improves the effectiveness of maternal resuscitation and may increase the probability of maternal survival.

In one study of the response of anesthesiologists, obstetricians, and nurses to a simulated cardiac arrest caused by an AFE, the participants did not routinely use defibrillation when indicated, did not place a firm support under the back for chest compressions, and did not switch the provider of chest compressions every 2 minutes.8 This study indicates that additional training and routinely scheduled multidisciplinary simulation of the response to cardiopulmonary arrest could improve the quality of our CPR.

2. Use a massive transfusion protocol

Severe coagulopathy and diffuse bleeding are commonly encountered in AFE. Target goals for the replacement of blood products include:

- hemoglobin concentration ≥8 g/dL

- fibrinogen ≥150 to 200 mg/dL

- platelets ≥50,000/μL

- prothrombin time international normalized ratio (INR) ≤1.5.

Most massive transfusion protocols provide for the rapid delivery of 4 to 8 units of red blood cells and a similar number of units of fresh frozen plasma to the patient’s bedside. In the management of AFE, 20 to 30 units of red blood cells and a similar quantity of fresh frozen plasma may need to be transfused. Cryoprecipitate takes 20 to 30 minutes to thaw, so preparations to transfuse cryoprecipitate should be initiated as soon as the massive transfusion protocol is triggered. A case of AFE can completely empty the blood bank of all available blood products and necessitate the use of alternative agents.

Lyophilized fibrinogen concentrate (RiaSTAP) is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of congenital hypofibrinogenemia and also may be useful to replace fibrinogen in cases of AFE. In many hospitals, large quantities of fresh frozen plasma are not immediately available; lyophilized fibrinogen concentrate may be especially useful in these settings. Another advantage of fibrinogen concentrate is that large amounts of fibrinogen can be administered in a small volume of intravenous fluid. Fibrinogen concentrate typically is used at a dose of 70 mg/kg of body weight.9,10

Intraoperative red cell salvage occasionally is used in cases of obstetric hemorrhage. In one case report of the use of red cell salvage with leukocyte depletion filtration during treatment of an AFE, acute hypotension developed in the patient after the transfusion of salvaged red cells.11 This case report raises safety concerns about the use of salvaged cells in women with severe AFE.

Related article: 10 practical, evidence-based recommendations for the management of severe postpartum hemorrhage Baha M. Sibai, MD (June 2011)

3. Treat diffuse bleeding and coagulopathy

In addition to the initiation of the massive transfusion protocol, additional treatments that may be helpful in managing the coagulopathy of AFE include tranexamic acid, recombinant factor VIIa (rFVIIa), and exchange transfusion.

AFE is often associated with hyperfibrinolysis, which can cause excessive bleeding.12 Tranexamic acid blocks the lysine binding sites on plasminogen and thereby reduces the lysis of fibrin clots. Clinical trials in patients who have undergone trauma have demonstrated that the administration of tranexamic acid reduces blood loss.13 The dose of tranexamic acid is approximately 10 to 20 mg/kg of body weight, or approximately 1 g.

Controversy exists about the use of rFVIIa to treat the coagulopathy and bleeding caused by AFE. Some authorities believe that rFVIIa is associated with an increased AFE case fatality rate.14 Other authorities believe rFVIIa may be useful in the treatment of AFE coagulopathy, especially when bleeding persists despite aggressive blood and component replacement.”15 The dose of rFVIIa is approximately 90 µg/kg of body weight. rFVIIa is extremely expensive.

Exchange transfusion has been used successfully to treat AFE.16 In women with AFE, exchange transfusion removes circulating cells, cell fragments, and substances that trigger systemic anaphylaxis and coagulopathy, thereby enhancing rapid recovery.

Related article: Act fast when confronted by a coagulopathy postpartum Robert L. Barbieri, MD (Editorial; March 2012)

4. Treat uterine and pelvic bleeding

Obstetrician-gynecologists are experts in the control of uterine and pelvic bleeding. Interventions that commonly are used to control uterine and pelvic bleeding in cases of postpartum hemorrhage, uterine rupture, or placenta accreta also can be applied in cases of AFE with uncontrolled uterine and pelvic bleeding. These techniques include:

- use of uterine compression sutures

- the Bakri balloon

- a uterine tourniquet

- vascular clamps on the ovarian vessels.17,18

In many cases of AFE, total or supracervical hysterectomy is necessary to control uterine bleeding. Uterine artery embolization, if available, has been reported to be helpful in select cases. However, many women with AFE are too unstable to survive transfer to an interventional radiology suite. Additional interventions to control bleeding include hypogastric artery ligation, infrarenal aortic compression, and pelvic packing.

Cross-clamping the aorta below the renal vessels can reduce blood flow to the pelvis and provide time for cardiopulmonary and volume resuscitation. Alternatively, placing pressure on the infrarenal aorta with a sponge or directly by hand can help reduce blood flow to the pelvis.19

In many cases of AFE, pelvic hemorrhage is difficult to control. Even if surgical pedicles are ligated securely, the coagulopathy of AFE may cause persistent oozing from areas of minor tissue trauma. Uncontrolled blood loss can be a proximate cause of death in women with AFE. All written protocols for responding to an AFE should include a plan to use pelvic packing for patients in whom standard operative procedures do not produce adequate control of bleeding. A “mushroom,” “parachute,” or “umbrella” pack has been reported to help stabilize the severely ill patient with pelvic bleeding and permit effective resuscitation and blood product replacement.20

Related articles:

A stitch in time: The B-Lynch, Hayman and Pereira uterine compression sutures Robert L. Barbieri, MD (Editorial, December 2012)

Have you made the best use of the Bakri balloon in PPH? Robert L. Barbieri, MD (Editorial, July 2011)

5. Consider extracorporeal lung and heart support

In many cases of AFE, both lung and cardiac function are severely compromised. Both veno-arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (VA-ECMO) and full cardiopulmonary bypass provide support for the failing lung and heart. Based on a small number of case reports, extracorporeal lung and heart support appear to be useful in the treatment of AFE.21–26 Using the Seldinger technique,27 it is technically feasible to rapidly access a major vein and artery to provide the input and output ports for VA-ECMO. Unlike the cardiopulmonary bypass pump, the VA-ECMO pump does not have a reservoir that needs to be primed with blood and is smaller and more portable. To provide a patient with VA-ECMO or cardiopulmonary bypass, a cardiac interventionist and a perfusionist must be available. Extracorporeal lung and heart support require heparinization of the patient’s blood, which may result in increased bleeding. Both VA-ECMO and cardiopulmonary bypass, along with the diseases for which they are used, may cause renal dysfunction, neurologic injury, and infection.28

Alternative approaches that provide support of the heart—but not lung—are the Impella pump, TandemHeart, and the intra-aortic balloon pump. An alternative that provides lung support—but not cardiac support—is veno-venous ECMO.

In developing a written protocol for responding to an AFE, obstetricians should explore the potential availability of VA-ECMO, cardiopulmonary bypass, or other cardiopulmonary support devices as options for patients who have not responded to standard treatment of AFE and are at high risk of death.

6. Post-AFE intensive care

After stabilization, most women with AFE will require intensive care for 48 to 96 hours. Some experts have proposed that all survivors of cardiopulmonary arrest who are successfully resuscitated and stabilized be transferred to hospitals that specialize in post−cardiac arrest care to improve outcomes.

Assessment of organ injury is important after an AFE. In addition, encephalopathy is a common complication of AFE, and sequential neurologic examination is a priority. Therapeutic hypothermia (TH) may help to preserve neurologic function after AFE.29 However, TH may cause a mild coagulopathy by inhibiting platelet activation and enzyme activity of clotting factors. Because coagulopathy is a prominent feature of AFE, TH may be contraindicated if the patient has a clinically significant baseline coagulopathy.30

DEVELOP AN AFE PROTOCOL AND PRACTICE THE COMPONENTS

Practicing the components of obstetric protocols can improve unit performance and patient outcomes.31 The components of an AFE protocol, as described in this article, include high-quality CPR, a protocol for massive transfusion, treatment of diffuse bleeding and coagulopathy, treatment of uterine and pelvic bleeding, extracorporeal lung and heart support, and post-AFE intensive care. Practicing these components of an AFE protocol will enhance performance across many common obstetric complications including postpartum hemorrhage, uterine rupture, placenta accreta, and pulmonary embolism.

When Chesley “Sully” Sullenberger and his copilot landed Flight 1549 in the Hudson River in New York, he had never practiced that specific response to twin engine failure, but he had practiced many emergency responses involving related scenarios. The combination of exceptional flight experience and years of practicing the response to emergency scenarios in simulation exercises permitted him and his copilot to execute a uniquely clever plan to solve a life-threatening

emergency. In a related way, practicing the components of AFE treatment will help obstetricians, obstetric anesthesiologists, and their multidisciplinary team to improve the responses to all major obstetric emergencies.

INSTANT POLL

Does your obstetric unit have a written protocol for treating an amniotic fluid embolism (AFE)? Has your obstetric unit practiced any of the components of the AFE treatment protocol: 1) high-quality cardiopulmonary resuscitation, 2) a protocol for massive transfusion protocol, 3) treatment of diffuse bleeding and coagulopathy, 4) treatment of uterine and pelvic bleeding, 5) extracorporeal lung and heart support, and 6) post-AFE intensive care?

Tell us—at [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Amniotic fluid embolism (AFE) occurs in about 1 in 20,000 to 1 in 40,000 deliveries.1,2 Although the condition is rare, the case fatality rate is high, and AFE is a common cause of maternal death in developed countries. AFE cannot be predicted or prevented. Moreover, the condition is difficult to precisely define and is often a diagnosis of exclusion.

AFE should be considered in the differential diagnosis of a pregnant woman with sudden onset of shortness of breath, hypotension, or cardiac arrhythmia or arrest, followed by coagulopathy and hemorrhage. Premonitory symptoms, including restlessness, confusion, disorientation, agitation, chills, nausea, numbness, and tingling, are commonly reported just before the cardiorespiratory collapse. AFE is less likely if the initial obstetric event is hemorrhage in the absence of cardiorespiratory compromise or a preceding coagulopathy.3

Typically, the onset is just before birth, during birth, or within the first few hours after delivery. In the United Kingdom, which has a robust centralized registry for reporting AFE, about 56% of cases occur before birth and 44% after birth.4

Related article: Is the incidence of amniotic fluid embolism rising? John T. Repke, MD (Examining the Evidence, August 2010)

The resources available to obstetric units vary greatly. Each unit needs to assess its resources and develop an AFE treatment protocol that builds on the unique strengths of the unit. Treatment of AFE requires the coordinated actions of anesthesiologists, obstetricians, nurses, the blood bank, pharmacy, and cardiovascular specialists. Coordinated activity among the members of such a large multidisciplinary team requires a written protocol that is practiced on a regular basis.

Six important components of a multidisciplinary response to AFE treatment protocol are:

- high-quality cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR)

- a protocol for massive transfusion

- treatment of diffuse bleeding and coagulopathy

- treatment of uterine and pelvic bleeding

- extracorporeal lung and heart support

- post-AFE intensive care.

1. Initiate high-quality CPR

Hypotension and hypoxemia due to cardiac and pulmonary dysfunction are prominent features of AFE. Dysrythmias such as pulseless electrical activity, bradycardia, ventricular fibrillation, and asystole are common. Rapid institution of high-quality CPR is critical to the survival of women with AFE.

Interventions often used in CPR of patients with AFE include initiation of high-quality chest compressions, early defibrillation if indicated, immediate administration of 100% oxygen by mask ventilation followed by early intubation, and rapid establishment of peripheral, arterial, and central venous access. Volume assessment, fluid replacement, and administration of vasopressors and inotropes are also important.

CPR of pregnant women requires special interventions, including maximal left lateral displacement of the uterus to reduce compression of the descending aorta and vena cava. Lateral displacement of the uterus can be accomplished by left lateral tilt or by manual uterine displacement. To optimize the effectiveness of chest compressions, many experts recommend placing the woman in a supine position and using manual uterine displacement rather than a left lateral tilt.5 For chest compressions, the hands should be placed just above the center of the sternum to adjust for the elevation of the diaphragm caused by the gravid uterus.