User login

Your patients are talking: Isn’t it time you take responsibility for your online reputation?

In a web-focused world, it should not take much convincing that monitoring your online reputation is time well spent. For some of us, it may be hard to believe that online reviews have evolved beyond restaurants and plumbers, but today your patients are flocking to the Internet to read and leave reviews about you, your staff, and your services. What can you do to protect your online reputation?

We first addressed this topic in December 2014 (“Using the Internet in your practice. Part 4: Reputation management—how to gather kudos and combat negative online reviews”1). Have you implemented any of the tactics we offered then? We hope that you do take proactive steps to protect your online image.

What is a physician’s most precious asset?

You might answer this question with, “my patients” or “the training and education that I have obtained to practice my craft.” But the real answer is that your most precious asset is your reputation.

Physicians live and die by their reputations. We spend our entire medical careers polishing and protecting this status. The Internet dramatically has altered the way people gather information. It is sad but true that a single comment that only takes a few seconds and a single mouse-click to post can be seen by thousands and ruin that life-long effort.

How are physicians rated on the web?

Online physician reviews are positive 70% to 90% of the time.2 Most physicians have 5 or fewer reviews on any one site.3 Of the approximately 30 sites that monitor physicians and hospitals online, one of the most popular is AngiesList.com. This site requires registration and a fee; a member can review a physician every 6 months. On free websites such as Yelp.com and doctorsscorecard.com the reviewer can comment once. Other sites such as vitals.com or DrScore.com limit the reviews from 1 source, which prevents an angry patient from stuffing the ballot box.2

Pay attention

At a minimum, physicians should be monitoring their reputation by conducting periodic searches—“Googling” their name and practice name—to identify what information is already online. You may find that 3, 4, or even 10 reviews appear on various sites. If you are lucky, these reviews will be positive. Don’t be surprised, however, if 1 or 2 are not. Let’s face it: even the most accredited and experienced physician cannot possibly satisfy every patient who walks through the door.

Neil Baum, MD, and Ron Romano have offered tips on ways to manage online reputations in the past,1 and they urge Ob-Gyns to take an active role in this process in order to increase positive exposure to patients and maintain an active practice. Is active reputation management something that ObGyns are spending their valuable time on? To find out, OBG Management reached out to its Virtual Editorial Board. We found that many readers are paying attention to patient satisfaction. Some are soliciting online reviews and maintaining active upkeep on their online reputation. Here are a few responses we received from practicing ObGyns across the United States.

William E. McGrath Jr, MD, of Fernandina Beach, Florida, says that his office provides patients with a list of 5 popular review websites during their visits, and that approximately 1 in 10 will follow up with a review. Patient reviews are also prominently posted on his practice’s website. The large, private, single-specialty group to which his practice belongs requires patient satisfaction surveys for quality assurance review and insurance contract negotiations. “It is all about physician-patient communication,” he says.

Keith S. Merlin, MD, of Brockton, Massachusetts, says that he has checked online reviews to ensure their accuracy. His practice uses surveys, a suggestion box, and a mystery shopper to measure patient satisfaction, a worthwhile effort he says to understand where the practice is doing well and what needs to be done better.

Wesley Hambright, MD, of Jacksonville, North Carolina, reports that he has established a Google Alert to monitor for new content relating to his practice.

Patrick Pevoto, MD, MBA, of Austin, Texas, informs us that he has just started to think about ways to manage his online reputation. He has created a website and is writing a monthly blog, which he posts on his site. He acknowledges the importance of assessing patient satisfaction in his practice but is not applying large-scale measurement techniques yet. To keep his patients happy, he handles concerns that arise on a personal, case-by-case basis.

John Armstrong, MD, MS, of Napa, California, also reports that management of his online reputation is in the beginning stages. He uses focus groups and feels that listening to his patients when they do comment on their experience is important to his overall practice. Listening helps to “identify areas to improve and reaffirms when we are doing well,” he says. To keep his patients happy, he strives to “give extraordinary care and simply be nice to people.” When issues arise, making it right and being polite are important elements, he asserts.

Delos J. Clow, DO, MS, of Chillicothe, Missouri, does measure patient satisfaction, and feels this is very important to his practice in order to identify and correct any negative trends. He does not actively monitor his practice reputation online.

Robert del Rosario, MD, of Camp Hill, Pennsylvania, similarly does not actively manage an online reputation, but does focus on patient satisfaction. To enhance satisfaction, he tries to de-emphasize the electronic medical record to “make visits more personal and less interrogative.” Additionally, his practice objectively gauges aspects of care that might be able to be improved upon.

Reference

- Romano R, Baum NH. Using the Internet in your practice. Part 4: Reputation management—how to gather kudos and combat negative online reviews. OBG Manag. 2014;26(12):23,24,26,28.

Tell your own story

As physicians, you may not have control over what others say about you, but you can take ownership of your online presence by establishing a website, blog, and social media platforms, ensuring your story is being properly communicated. Without an online presence, you are entirely at the mercy of directory and review sites.

Optimize your website

A site that successfully uses search engine optimization (SEO) will have the upper hand when patients hunt for a physician in your area because the information will be posted at the top of the search page, well above the reviews and listings left by patients and other third-party sources. This is a critical step for your online brand because it will be difficult for other sites to mask your credibility. This should motivate you to develop an online presence, regularly update information, and participate in Internet dialog with other sites.

Generate quality, natural reviews

If your site is in good standing in search results, the next step is to implement a patient reviews strategy to start acquiring positive online reviews. A third-party provider can work with you to launch a local search engine optimization strategy and a natural reviews management program tailored for your practice’s needs. For the most part, however, we do not recommend using an online reputation management company. It is far better and more economical to ask satisfied patients to provide reviews.

At first, you may be tempted to actively petition or solicit reviews through survey software, but this method is manipulative and can lead to reputation problems for your practice. Google actively tracks where reviews originate and uses advanced algorithms to determine the review’s integrity. A petitioned review is classified as less valid, and therefore Google will assume it was not written under the same pretense as a natural, unsolicited review.

Quality customer service and outstanding patient care are often what achieve the organic reviews you are striving for. To encourage a steady flow, administer a process that encourages your most satisfied, loyal patients to review your practice.

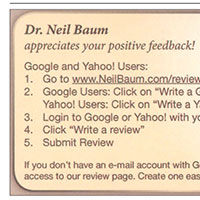

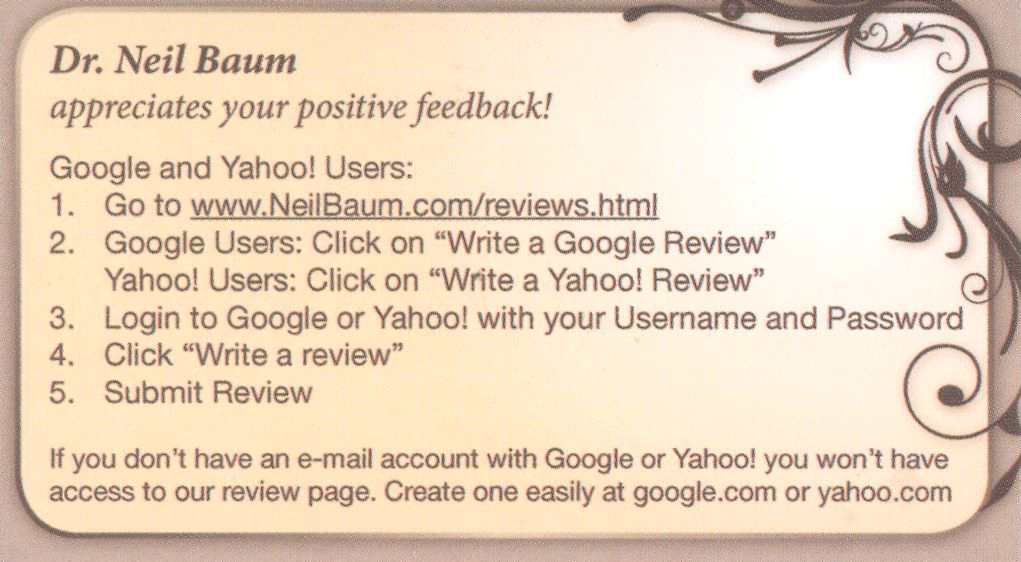

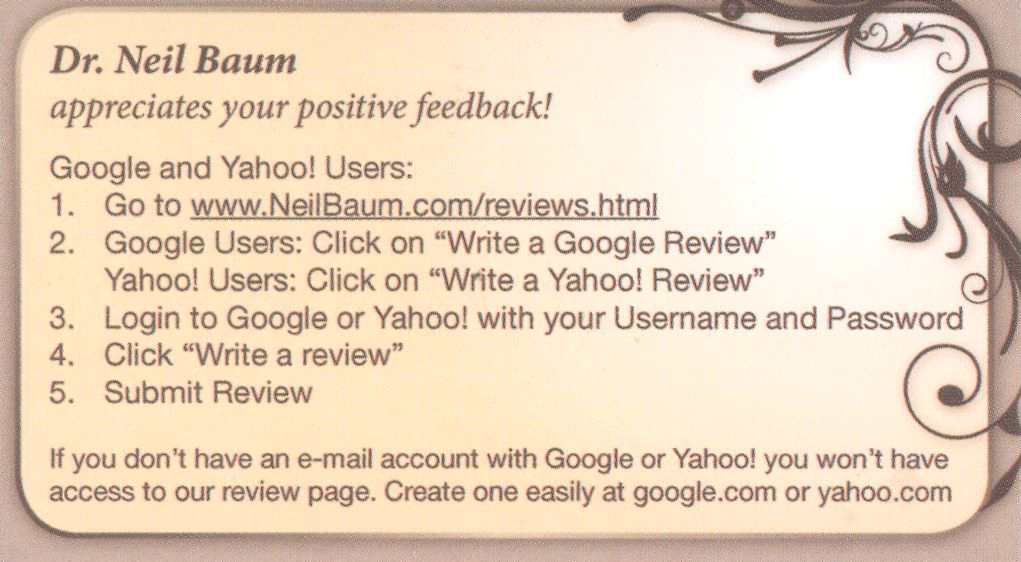

Keep the process simple. Capture positive compliments at the point of service. Before a patient leaves your office, hand her a card (FIGURE) with easy steps for posting an online review, or offer her a tablet that links directly to your website review section. If your patient is not computer savvy, ask her to complete a 4- to 5-question survey and give her a clipboard and a pen. Then have a staff member post it on your website.

In Dr. Baum’s practice, there is a poster in every exam room and in the reception area where patients can scan the quick response (QR) code and immediately submit a testimonial. Using this system, the practice is able to collect 3 to 5 positive reviews every day.

A patient pleased with your staff’s service will happily take 5 minutes to submit a review. Acquire 5 to 10 reviews monthly and within a year’s time you will have generated enough positive reviews to negate any damaging comments that inevitably will emerge from time to time.

CASE Patient criticizes physician in a review forum

A physician with a robust Internet presence will have his or her name and the practice appear at the top of search engine results pages (as is the case with Dr. Neil Baum when “urologist” plus “New Orleans” is typed into the Google search engine window). By far most of Dr. Baum’s reviews are positive. In one instance, however, a patient on a physician review website referred to Dr. Baum as “technologically advanced but more motivated to increase his income by performing too many diagnostic tests.”

If you find a negative comment in an online directory or review website, what should you do?

The Office for Civil Rights (OCR) within the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) is responsible for handling Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA)1 complaints. Deven McGraw, OCR’s deputy director of health information privacy, states that “just because patients have rated their health provider publicly doesn’t give their health provider permission to rate them in return.”2,3 In fact, some health care providers who responded to poor online reviews ran into trouble with privacy rules established by HIPAA.2,3

Mr. McGraw notes that, when responding to online reviews, health professionals should speak generally about the way they treat patients while complying with HIPAA regulations. He suggests, “If the complaint is about poor patient care … say, ‘I provide all of my patients with good patient care’ and ‘I’ve been reviewed in other contexts and have good reviews.’”2,3

According to Yelp’s senior director of litigation, Aaron Schur, most patient complaints center on practice-based concerns such as wait times, office staff, and billing, not about the medical service delivered. Although most physicians do not respond, says Mr. Schur, those who do, tend to ask patients to discuss the matter in private or to apologize.2,3

What are the consequences of a HIPAA violation?

OCR Director Jocelyn Samuels says that the office’s primary role is to help health providers follow HIPAA regulations.2,5 The OCR can resolve HIPPA violations privately and informally, impose fines of up to $50,000 per violation, or it can file criminal charges against violators.2,4

The majority of the office’s investigation and enforcement of HIPAA has been against large medical data breaches.2,5 Small privacy breaches by large health care providers (eg, CVS, Walmart, Lab Corp, Quest Diagnostics, and others) generally do not result in legal consequences; the providers are privately warned. According to ProPublica, even repeated HIPAA violations tend not to be fined.2,4

Small-scale infractions can be more damaging on a personal level to both patients and physicians. However, the OCR does not typically become involved in privacy breaches that include only a few individuals. Health care providers are rarely punished for small HIPPA breaches; instead, the OCR typically settles for pledges to fix any problems and issues reminders of HIPPA requirements.2,5

Although the OCR is often the only place patients can go to seek vindication, HIPAA does not support the right to sue for violation of personal privacy. People who seek a legal remedy must find another means, which is easier in some states than in others.2,5

Health care providers have tried myriad ways to attempt to combat negative reviews. Some have sued patients, attracting a flood of attention but achieving little legal success. Others have asked patients to remove their complaints.2,3

Best practices

Create and circulate a policy. Medical privacy breaches involving sensitive health details can occur when office or hospital staff share patient information due to personal hostility or lack of understanding of HIPPA policy.2,5 Have a practice policy for responding to online reviews by patients, and make sure the staff members who have access to the practice’s online accounts understand your policy and the possible repercussions of not following it. Teach and continue to remind your staff about HIPPA regulations and hold them to a high ethical level of privacy.

Solicit reviews on an ongoing basis. Jeffrey Segal, a review site critic, says that all reviews are valuable. Physicians should respond carefully to negative comments and encourage satisfied patients to post positive reviews. “’For doctors who get bent out of shape to get rid of negative reviews, it’s a denominator problem,’ he said. ‘If they only have three reviews and two are negative, the denominator is the problem. … If you can figure out a way to cultivate reviews from hundreds of patients rather than a few patients, the problem is solved.’”2,3

CASE Resolved

Dr. Baum never responded directly to the negative patient review, and others he has received. He balances the rare negative response with numerous and plentiful positive responses by making it a practice to encourage reviews from all of his patients.

References

- HIPAA for Professionals. US Department of Health & Human Services. http://www.hhs.gov/hipaa/for-professionals/index.html. Accessed October 11, 2016.

- Hall SD. Providers responding to Yelp reviews must be mindful of HIPAA. FierceHealthcare. http://www.fiercehealthcare.com/it/providers-responding-to-yelp-reviews-must-be-mindful-hipaa. Published May 31, 2016. Accessed October 7, 2016.

- Ornstein C. Stung by Yelp reviews, health providers spill patient secrets. ProPublica. https://www.propublica.org/article/stung-by-yelp-reviews-health -providers-spill-patient-secrets. Published May 27, 2016. Accessed October 11, 2016.

- Ornstein C, Waldman A. Few consequences for health privacy law’s repeat offenders. ProPublica. https://www.propublica.org/article/few-consequences-for-health-privacy-law-repeat-offenders. Published December 29, 2015. Accessed October 11, 2016.

- Ornstein C. Small-scale violations of medical privacy often cause the most harm. ProPublica. https://www.propublica.org/article/small-scale-violations-of-medical-privacy-often-cause-the-most-harm. Published December 10, 2015. Accessed October 11, 2016.

The bottom line

Patients are seeking and leaving reviews about you and your practice online and you need to actively manage your online reputation. Do not let one disgruntled patient ruin your reputation. Our advice: Do not wait for a negative review to begin your reputation management. Take an active role and generate positive reviews to drown out negative remarks made by an occasional patient. This is an inexpensive process that does work.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Romano R, Baum NH. Using the Internet in your practice. Part 4: Reputation management-how to gather kudos and combat negative online reviews. OBG Manag. 2014;26(12):23,24,26,28.

- Lagu T, Hannon NS, Rothberg MB, Lindenauer PK. Patients' evaluations of health care providers in the era of social networking: an analysis of physician rating websites. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(9):942-946.

- Gunter J. For better or maybe, worse, patients are judging your care online. OBG Manag. 2011;23(3):47-51.

In a web-focused world, it should not take much convincing that monitoring your online reputation is time well spent. For some of us, it may be hard to believe that online reviews have evolved beyond restaurants and plumbers, but today your patients are flocking to the Internet to read and leave reviews about you, your staff, and your services. What can you do to protect your online reputation?

We first addressed this topic in December 2014 (“Using the Internet in your practice. Part 4: Reputation management—how to gather kudos and combat negative online reviews”1). Have you implemented any of the tactics we offered then? We hope that you do take proactive steps to protect your online image.

What is a physician’s most precious asset?

You might answer this question with, “my patients” or “the training and education that I have obtained to practice my craft.” But the real answer is that your most precious asset is your reputation.

Physicians live and die by their reputations. We spend our entire medical careers polishing and protecting this status. The Internet dramatically has altered the way people gather information. It is sad but true that a single comment that only takes a few seconds and a single mouse-click to post can be seen by thousands and ruin that life-long effort.

How are physicians rated on the web?

Online physician reviews are positive 70% to 90% of the time.2 Most physicians have 5 or fewer reviews on any one site.3 Of the approximately 30 sites that monitor physicians and hospitals online, one of the most popular is AngiesList.com. This site requires registration and a fee; a member can review a physician every 6 months. On free websites such as Yelp.com and doctorsscorecard.com the reviewer can comment once. Other sites such as vitals.com or DrScore.com limit the reviews from 1 source, which prevents an angry patient from stuffing the ballot box.2

Pay attention

At a minimum, physicians should be monitoring their reputation by conducting periodic searches—“Googling” their name and practice name—to identify what information is already online. You may find that 3, 4, or even 10 reviews appear on various sites. If you are lucky, these reviews will be positive. Don’t be surprised, however, if 1 or 2 are not. Let’s face it: even the most accredited and experienced physician cannot possibly satisfy every patient who walks through the door.

Neil Baum, MD, and Ron Romano have offered tips on ways to manage online reputations in the past,1 and they urge Ob-Gyns to take an active role in this process in order to increase positive exposure to patients and maintain an active practice. Is active reputation management something that ObGyns are spending their valuable time on? To find out, OBG Management reached out to its Virtual Editorial Board. We found that many readers are paying attention to patient satisfaction. Some are soliciting online reviews and maintaining active upkeep on their online reputation. Here are a few responses we received from practicing ObGyns across the United States.

William E. McGrath Jr, MD, of Fernandina Beach, Florida, says that his office provides patients with a list of 5 popular review websites during their visits, and that approximately 1 in 10 will follow up with a review. Patient reviews are also prominently posted on his practice’s website. The large, private, single-specialty group to which his practice belongs requires patient satisfaction surveys for quality assurance review and insurance contract negotiations. “It is all about physician-patient communication,” he says.

Keith S. Merlin, MD, of Brockton, Massachusetts, says that he has checked online reviews to ensure their accuracy. His practice uses surveys, a suggestion box, and a mystery shopper to measure patient satisfaction, a worthwhile effort he says to understand where the practice is doing well and what needs to be done better.

Wesley Hambright, MD, of Jacksonville, North Carolina, reports that he has established a Google Alert to monitor for new content relating to his practice.

Patrick Pevoto, MD, MBA, of Austin, Texas, informs us that he has just started to think about ways to manage his online reputation. He has created a website and is writing a monthly blog, which he posts on his site. He acknowledges the importance of assessing patient satisfaction in his practice but is not applying large-scale measurement techniques yet. To keep his patients happy, he handles concerns that arise on a personal, case-by-case basis.

John Armstrong, MD, MS, of Napa, California, also reports that management of his online reputation is in the beginning stages. He uses focus groups and feels that listening to his patients when they do comment on their experience is important to his overall practice. Listening helps to “identify areas to improve and reaffirms when we are doing well,” he says. To keep his patients happy, he strives to “give extraordinary care and simply be nice to people.” When issues arise, making it right and being polite are important elements, he asserts.

Delos J. Clow, DO, MS, of Chillicothe, Missouri, does measure patient satisfaction, and feels this is very important to his practice in order to identify and correct any negative trends. He does not actively monitor his practice reputation online.

Robert del Rosario, MD, of Camp Hill, Pennsylvania, similarly does not actively manage an online reputation, but does focus on patient satisfaction. To enhance satisfaction, he tries to de-emphasize the electronic medical record to “make visits more personal and less interrogative.” Additionally, his practice objectively gauges aspects of care that might be able to be improved upon.

Reference

- Romano R, Baum NH. Using the Internet in your practice. Part 4: Reputation management—how to gather kudos and combat negative online reviews. OBG Manag. 2014;26(12):23,24,26,28.

Tell your own story

As physicians, you may not have control over what others say about you, but you can take ownership of your online presence by establishing a website, blog, and social media platforms, ensuring your story is being properly communicated. Without an online presence, you are entirely at the mercy of directory and review sites.

Optimize your website

A site that successfully uses search engine optimization (SEO) will have the upper hand when patients hunt for a physician in your area because the information will be posted at the top of the search page, well above the reviews and listings left by patients and other third-party sources. This is a critical step for your online brand because it will be difficult for other sites to mask your credibility. This should motivate you to develop an online presence, regularly update information, and participate in Internet dialog with other sites.

Generate quality, natural reviews

If your site is in good standing in search results, the next step is to implement a patient reviews strategy to start acquiring positive online reviews. A third-party provider can work with you to launch a local search engine optimization strategy and a natural reviews management program tailored for your practice’s needs. For the most part, however, we do not recommend using an online reputation management company. It is far better and more economical to ask satisfied patients to provide reviews.

At first, you may be tempted to actively petition or solicit reviews through survey software, but this method is manipulative and can lead to reputation problems for your practice. Google actively tracks where reviews originate and uses advanced algorithms to determine the review’s integrity. A petitioned review is classified as less valid, and therefore Google will assume it was not written under the same pretense as a natural, unsolicited review.

Quality customer service and outstanding patient care are often what achieve the organic reviews you are striving for. To encourage a steady flow, administer a process that encourages your most satisfied, loyal patients to review your practice.

Keep the process simple. Capture positive compliments at the point of service. Before a patient leaves your office, hand her a card (FIGURE) with easy steps for posting an online review, or offer her a tablet that links directly to your website review section. If your patient is not computer savvy, ask her to complete a 4- to 5-question survey and give her a clipboard and a pen. Then have a staff member post it on your website.

In Dr. Baum’s practice, there is a poster in every exam room and in the reception area where patients can scan the quick response (QR) code and immediately submit a testimonial. Using this system, the practice is able to collect 3 to 5 positive reviews every day.

A patient pleased with your staff’s service will happily take 5 minutes to submit a review. Acquire 5 to 10 reviews monthly and within a year’s time you will have generated enough positive reviews to negate any damaging comments that inevitably will emerge from time to time.

CASE Patient criticizes physician in a review forum

A physician with a robust Internet presence will have his or her name and the practice appear at the top of search engine results pages (as is the case with Dr. Neil Baum when “urologist” plus “New Orleans” is typed into the Google search engine window). By far most of Dr. Baum’s reviews are positive. In one instance, however, a patient on a physician review website referred to Dr. Baum as “technologically advanced but more motivated to increase his income by performing too many diagnostic tests.”

If you find a negative comment in an online directory or review website, what should you do?

The Office for Civil Rights (OCR) within the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) is responsible for handling Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA)1 complaints. Deven McGraw, OCR’s deputy director of health information privacy, states that “just because patients have rated their health provider publicly doesn’t give their health provider permission to rate them in return.”2,3 In fact, some health care providers who responded to poor online reviews ran into trouble with privacy rules established by HIPAA.2,3

Mr. McGraw notes that, when responding to online reviews, health professionals should speak generally about the way they treat patients while complying with HIPAA regulations. He suggests, “If the complaint is about poor patient care … say, ‘I provide all of my patients with good patient care’ and ‘I’ve been reviewed in other contexts and have good reviews.’”2,3

According to Yelp’s senior director of litigation, Aaron Schur, most patient complaints center on practice-based concerns such as wait times, office staff, and billing, not about the medical service delivered. Although most physicians do not respond, says Mr. Schur, those who do, tend to ask patients to discuss the matter in private or to apologize.2,3

What are the consequences of a HIPAA violation?

OCR Director Jocelyn Samuels says that the office’s primary role is to help health providers follow HIPAA regulations.2,5 The OCR can resolve HIPPA violations privately and informally, impose fines of up to $50,000 per violation, or it can file criminal charges against violators.2,4

The majority of the office’s investigation and enforcement of HIPAA has been against large medical data breaches.2,5 Small privacy breaches by large health care providers (eg, CVS, Walmart, Lab Corp, Quest Diagnostics, and others) generally do not result in legal consequences; the providers are privately warned. According to ProPublica, even repeated HIPAA violations tend not to be fined.2,4

Small-scale infractions can be more damaging on a personal level to both patients and physicians. However, the OCR does not typically become involved in privacy breaches that include only a few individuals. Health care providers are rarely punished for small HIPPA breaches; instead, the OCR typically settles for pledges to fix any problems and issues reminders of HIPPA requirements.2,5

Although the OCR is often the only place patients can go to seek vindication, HIPAA does not support the right to sue for violation of personal privacy. People who seek a legal remedy must find another means, which is easier in some states than in others.2,5

Health care providers have tried myriad ways to attempt to combat negative reviews. Some have sued patients, attracting a flood of attention but achieving little legal success. Others have asked patients to remove their complaints.2,3

Best practices

Create and circulate a policy. Medical privacy breaches involving sensitive health details can occur when office or hospital staff share patient information due to personal hostility or lack of understanding of HIPPA policy.2,5 Have a practice policy for responding to online reviews by patients, and make sure the staff members who have access to the practice’s online accounts understand your policy and the possible repercussions of not following it. Teach and continue to remind your staff about HIPPA regulations and hold them to a high ethical level of privacy.

Solicit reviews on an ongoing basis. Jeffrey Segal, a review site critic, says that all reviews are valuable. Physicians should respond carefully to negative comments and encourage satisfied patients to post positive reviews. “’For doctors who get bent out of shape to get rid of negative reviews, it’s a denominator problem,’ he said. ‘If they only have three reviews and two are negative, the denominator is the problem. … If you can figure out a way to cultivate reviews from hundreds of patients rather than a few patients, the problem is solved.’”2,3

CASE Resolved

Dr. Baum never responded directly to the negative patient review, and others he has received. He balances the rare negative response with numerous and plentiful positive responses by making it a practice to encourage reviews from all of his patients.

References

- HIPAA for Professionals. US Department of Health & Human Services. http://www.hhs.gov/hipaa/for-professionals/index.html. Accessed October 11, 2016.

- Hall SD. Providers responding to Yelp reviews must be mindful of HIPAA. FierceHealthcare. http://www.fiercehealthcare.com/it/providers-responding-to-yelp-reviews-must-be-mindful-hipaa. Published May 31, 2016. Accessed October 7, 2016.

- Ornstein C. Stung by Yelp reviews, health providers spill patient secrets. ProPublica. https://www.propublica.org/article/stung-by-yelp-reviews-health -providers-spill-patient-secrets. Published May 27, 2016. Accessed October 11, 2016.

- Ornstein C, Waldman A. Few consequences for health privacy law’s repeat offenders. ProPublica. https://www.propublica.org/article/few-consequences-for-health-privacy-law-repeat-offenders. Published December 29, 2015. Accessed October 11, 2016.

- Ornstein C. Small-scale violations of medical privacy often cause the most harm. ProPublica. https://www.propublica.org/article/small-scale-violations-of-medical-privacy-often-cause-the-most-harm. Published December 10, 2015. Accessed October 11, 2016.

The bottom line

Patients are seeking and leaving reviews about you and your practice online and you need to actively manage your online reputation. Do not let one disgruntled patient ruin your reputation. Our advice: Do not wait for a negative review to begin your reputation management. Take an active role and generate positive reviews to drown out negative remarks made by an occasional patient. This is an inexpensive process that does work.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

In a web-focused world, it should not take much convincing that monitoring your online reputation is time well spent. For some of us, it may be hard to believe that online reviews have evolved beyond restaurants and plumbers, but today your patients are flocking to the Internet to read and leave reviews about you, your staff, and your services. What can you do to protect your online reputation?

We first addressed this topic in December 2014 (“Using the Internet in your practice. Part 4: Reputation management—how to gather kudos and combat negative online reviews”1). Have you implemented any of the tactics we offered then? We hope that you do take proactive steps to protect your online image.

What is a physician’s most precious asset?

You might answer this question with, “my patients” or “the training and education that I have obtained to practice my craft.” But the real answer is that your most precious asset is your reputation.

Physicians live and die by their reputations. We spend our entire medical careers polishing and protecting this status. The Internet dramatically has altered the way people gather information. It is sad but true that a single comment that only takes a few seconds and a single mouse-click to post can be seen by thousands and ruin that life-long effort.

How are physicians rated on the web?

Online physician reviews are positive 70% to 90% of the time.2 Most physicians have 5 or fewer reviews on any one site.3 Of the approximately 30 sites that monitor physicians and hospitals online, one of the most popular is AngiesList.com. This site requires registration and a fee; a member can review a physician every 6 months. On free websites such as Yelp.com and doctorsscorecard.com the reviewer can comment once. Other sites such as vitals.com or DrScore.com limit the reviews from 1 source, which prevents an angry patient from stuffing the ballot box.2

Pay attention

At a minimum, physicians should be monitoring their reputation by conducting periodic searches—“Googling” their name and practice name—to identify what information is already online. You may find that 3, 4, or even 10 reviews appear on various sites. If you are lucky, these reviews will be positive. Don’t be surprised, however, if 1 or 2 are not. Let’s face it: even the most accredited and experienced physician cannot possibly satisfy every patient who walks through the door.

Neil Baum, MD, and Ron Romano have offered tips on ways to manage online reputations in the past,1 and they urge Ob-Gyns to take an active role in this process in order to increase positive exposure to patients and maintain an active practice. Is active reputation management something that ObGyns are spending their valuable time on? To find out, OBG Management reached out to its Virtual Editorial Board. We found that many readers are paying attention to patient satisfaction. Some are soliciting online reviews and maintaining active upkeep on their online reputation. Here are a few responses we received from practicing ObGyns across the United States.

William E. McGrath Jr, MD, of Fernandina Beach, Florida, says that his office provides patients with a list of 5 popular review websites during their visits, and that approximately 1 in 10 will follow up with a review. Patient reviews are also prominently posted on his practice’s website. The large, private, single-specialty group to which his practice belongs requires patient satisfaction surveys for quality assurance review and insurance contract negotiations. “It is all about physician-patient communication,” he says.

Keith S. Merlin, MD, of Brockton, Massachusetts, says that he has checked online reviews to ensure their accuracy. His practice uses surveys, a suggestion box, and a mystery shopper to measure patient satisfaction, a worthwhile effort he says to understand where the practice is doing well and what needs to be done better.

Wesley Hambright, MD, of Jacksonville, North Carolina, reports that he has established a Google Alert to monitor for new content relating to his practice.

Patrick Pevoto, MD, MBA, of Austin, Texas, informs us that he has just started to think about ways to manage his online reputation. He has created a website and is writing a monthly blog, which he posts on his site. He acknowledges the importance of assessing patient satisfaction in his practice but is not applying large-scale measurement techniques yet. To keep his patients happy, he handles concerns that arise on a personal, case-by-case basis.

John Armstrong, MD, MS, of Napa, California, also reports that management of his online reputation is in the beginning stages. He uses focus groups and feels that listening to his patients when they do comment on their experience is important to his overall practice. Listening helps to “identify areas to improve and reaffirms when we are doing well,” he says. To keep his patients happy, he strives to “give extraordinary care and simply be nice to people.” When issues arise, making it right and being polite are important elements, he asserts.

Delos J. Clow, DO, MS, of Chillicothe, Missouri, does measure patient satisfaction, and feels this is very important to his practice in order to identify and correct any negative trends. He does not actively monitor his practice reputation online.

Robert del Rosario, MD, of Camp Hill, Pennsylvania, similarly does not actively manage an online reputation, but does focus on patient satisfaction. To enhance satisfaction, he tries to de-emphasize the electronic medical record to “make visits more personal and less interrogative.” Additionally, his practice objectively gauges aspects of care that might be able to be improved upon.

Reference

- Romano R, Baum NH. Using the Internet in your practice. Part 4: Reputation management—how to gather kudos and combat negative online reviews. OBG Manag. 2014;26(12):23,24,26,28.

Tell your own story

As physicians, you may not have control over what others say about you, but you can take ownership of your online presence by establishing a website, blog, and social media platforms, ensuring your story is being properly communicated. Without an online presence, you are entirely at the mercy of directory and review sites.

Optimize your website

A site that successfully uses search engine optimization (SEO) will have the upper hand when patients hunt for a physician in your area because the information will be posted at the top of the search page, well above the reviews and listings left by patients and other third-party sources. This is a critical step for your online brand because it will be difficult for other sites to mask your credibility. This should motivate you to develop an online presence, regularly update information, and participate in Internet dialog with other sites.

Generate quality, natural reviews

If your site is in good standing in search results, the next step is to implement a patient reviews strategy to start acquiring positive online reviews. A third-party provider can work with you to launch a local search engine optimization strategy and a natural reviews management program tailored for your practice’s needs. For the most part, however, we do not recommend using an online reputation management company. It is far better and more economical to ask satisfied patients to provide reviews.

At first, you may be tempted to actively petition or solicit reviews through survey software, but this method is manipulative and can lead to reputation problems for your practice. Google actively tracks where reviews originate and uses advanced algorithms to determine the review’s integrity. A petitioned review is classified as less valid, and therefore Google will assume it was not written under the same pretense as a natural, unsolicited review.

Quality customer service and outstanding patient care are often what achieve the organic reviews you are striving for. To encourage a steady flow, administer a process that encourages your most satisfied, loyal patients to review your practice.

Keep the process simple. Capture positive compliments at the point of service. Before a patient leaves your office, hand her a card (FIGURE) with easy steps for posting an online review, or offer her a tablet that links directly to your website review section. If your patient is not computer savvy, ask her to complete a 4- to 5-question survey and give her a clipboard and a pen. Then have a staff member post it on your website.

In Dr. Baum’s practice, there is a poster in every exam room and in the reception area where patients can scan the quick response (QR) code and immediately submit a testimonial. Using this system, the practice is able to collect 3 to 5 positive reviews every day.

A patient pleased with your staff’s service will happily take 5 minutes to submit a review. Acquire 5 to 10 reviews monthly and within a year’s time you will have generated enough positive reviews to negate any damaging comments that inevitably will emerge from time to time.

CASE Patient criticizes physician in a review forum

A physician with a robust Internet presence will have his or her name and the practice appear at the top of search engine results pages (as is the case with Dr. Neil Baum when “urologist” plus “New Orleans” is typed into the Google search engine window). By far most of Dr. Baum’s reviews are positive. In one instance, however, a patient on a physician review website referred to Dr. Baum as “technologically advanced but more motivated to increase his income by performing too many diagnostic tests.”

If you find a negative comment in an online directory or review website, what should you do?

The Office for Civil Rights (OCR) within the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) is responsible for handling Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA)1 complaints. Deven McGraw, OCR’s deputy director of health information privacy, states that “just because patients have rated their health provider publicly doesn’t give their health provider permission to rate them in return.”2,3 In fact, some health care providers who responded to poor online reviews ran into trouble with privacy rules established by HIPAA.2,3

Mr. McGraw notes that, when responding to online reviews, health professionals should speak generally about the way they treat patients while complying with HIPAA regulations. He suggests, “If the complaint is about poor patient care … say, ‘I provide all of my patients with good patient care’ and ‘I’ve been reviewed in other contexts and have good reviews.’”2,3

According to Yelp’s senior director of litigation, Aaron Schur, most patient complaints center on practice-based concerns such as wait times, office staff, and billing, not about the medical service delivered. Although most physicians do not respond, says Mr. Schur, those who do, tend to ask patients to discuss the matter in private or to apologize.2,3

What are the consequences of a HIPAA violation?

OCR Director Jocelyn Samuels says that the office’s primary role is to help health providers follow HIPAA regulations.2,5 The OCR can resolve HIPPA violations privately and informally, impose fines of up to $50,000 per violation, or it can file criminal charges against violators.2,4

The majority of the office’s investigation and enforcement of HIPAA has been against large medical data breaches.2,5 Small privacy breaches by large health care providers (eg, CVS, Walmart, Lab Corp, Quest Diagnostics, and others) generally do not result in legal consequences; the providers are privately warned. According to ProPublica, even repeated HIPAA violations tend not to be fined.2,4

Small-scale infractions can be more damaging on a personal level to both patients and physicians. However, the OCR does not typically become involved in privacy breaches that include only a few individuals. Health care providers are rarely punished for small HIPPA breaches; instead, the OCR typically settles for pledges to fix any problems and issues reminders of HIPPA requirements.2,5

Although the OCR is often the only place patients can go to seek vindication, HIPAA does not support the right to sue for violation of personal privacy. People who seek a legal remedy must find another means, which is easier in some states than in others.2,5

Health care providers have tried myriad ways to attempt to combat negative reviews. Some have sued patients, attracting a flood of attention but achieving little legal success. Others have asked patients to remove their complaints.2,3

Best practices

Create and circulate a policy. Medical privacy breaches involving sensitive health details can occur when office or hospital staff share patient information due to personal hostility or lack of understanding of HIPPA policy.2,5 Have a practice policy for responding to online reviews by patients, and make sure the staff members who have access to the practice’s online accounts understand your policy and the possible repercussions of not following it. Teach and continue to remind your staff about HIPPA regulations and hold them to a high ethical level of privacy.

Solicit reviews on an ongoing basis. Jeffrey Segal, a review site critic, says that all reviews are valuable. Physicians should respond carefully to negative comments and encourage satisfied patients to post positive reviews. “’For doctors who get bent out of shape to get rid of negative reviews, it’s a denominator problem,’ he said. ‘If they only have three reviews and two are negative, the denominator is the problem. … If you can figure out a way to cultivate reviews from hundreds of patients rather than a few patients, the problem is solved.’”2,3

CASE Resolved

Dr. Baum never responded directly to the negative patient review, and others he has received. He balances the rare negative response with numerous and plentiful positive responses by making it a practice to encourage reviews from all of his patients.

References

- HIPAA for Professionals. US Department of Health & Human Services. http://www.hhs.gov/hipaa/for-professionals/index.html. Accessed October 11, 2016.

- Hall SD. Providers responding to Yelp reviews must be mindful of HIPAA. FierceHealthcare. http://www.fiercehealthcare.com/it/providers-responding-to-yelp-reviews-must-be-mindful-hipaa. Published May 31, 2016. Accessed October 7, 2016.

- Ornstein C. Stung by Yelp reviews, health providers spill patient secrets. ProPublica. https://www.propublica.org/article/stung-by-yelp-reviews-health -providers-spill-patient-secrets. Published May 27, 2016. Accessed October 11, 2016.

- Ornstein C, Waldman A. Few consequences for health privacy law’s repeat offenders. ProPublica. https://www.propublica.org/article/few-consequences-for-health-privacy-law-repeat-offenders. Published December 29, 2015. Accessed October 11, 2016.

- Ornstein C. Small-scale violations of medical privacy often cause the most harm. ProPublica. https://www.propublica.org/article/small-scale-violations-of-medical-privacy-often-cause-the-most-harm. Published December 10, 2015. Accessed October 11, 2016.

The bottom line

Patients are seeking and leaving reviews about you and your practice online and you need to actively manage your online reputation. Do not let one disgruntled patient ruin your reputation. Our advice: Do not wait for a negative review to begin your reputation management. Take an active role and generate positive reviews to drown out negative remarks made by an occasional patient. This is an inexpensive process that does work.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Romano R, Baum NH. Using the Internet in your practice. Part 4: Reputation management-how to gather kudos and combat negative online reviews. OBG Manag. 2014;26(12):23,24,26,28.

- Lagu T, Hannon NS, Rothberg MB, Lindenauer PK. Patients' evaluations of health care providers in the era of social networking: an analysis of physician rating websites. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(9):942-946.

- Gunter J. For better or maybe, worse, patients are judging your care online. OBG Manag. 2011;23(3):47-51.

- Romano R, Baum NH. Using the Internet in your practice. Part 4: Reputation management-how to gather kudos and combat negative online reviews. OBG Manag. 2014;26(12):23,24,26,28.

- Lagu T, Hannon NS, Rothberg MB, Lindenauer PK. Patients' evaluations of health care providers in the era of social networking: an analysis of physician rating websites. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(9):942-946.

- Gunter J. For better or maybe, worse, patients are judging your care online. OBG Manag. 2011;23(3):47-51.

In this Article

- How your peers manage online reputation

- Should you respond to a negative review?

- Generate quality, natural reviews

Public speaking fundamentals. Presentation follow-up: What to do after the last slide is shown

This third article in a series on public speaking describes steps you can take immediately following the program to strengthen the impact of your diligent preparation (“Preparation: Tips that lead to a solid, engaging presentation.” OBG Manag. 2016;28[7]:31–36) and honed presentation (“The program: Key elements in capturing and holding audience attention.” OBG Manag. 2016;28[9]:46–50). Don’t overlook these details.

Find ways to stay in touch

You have concluded your talk. The audience response was enthusiastic and the brief Q&A session productive. But it is not over yet. Postpone putting away your computer and disconnecting the audiovisual equipment. Instead, mingle with the attendees—as you also did, we hope, before the program began. There is always more you can learn about your listeners. And, importantly, a few of them would undoubtedly like to ask you one-on-one about a case related to the topic you covered or about another problem in your area of expertise.

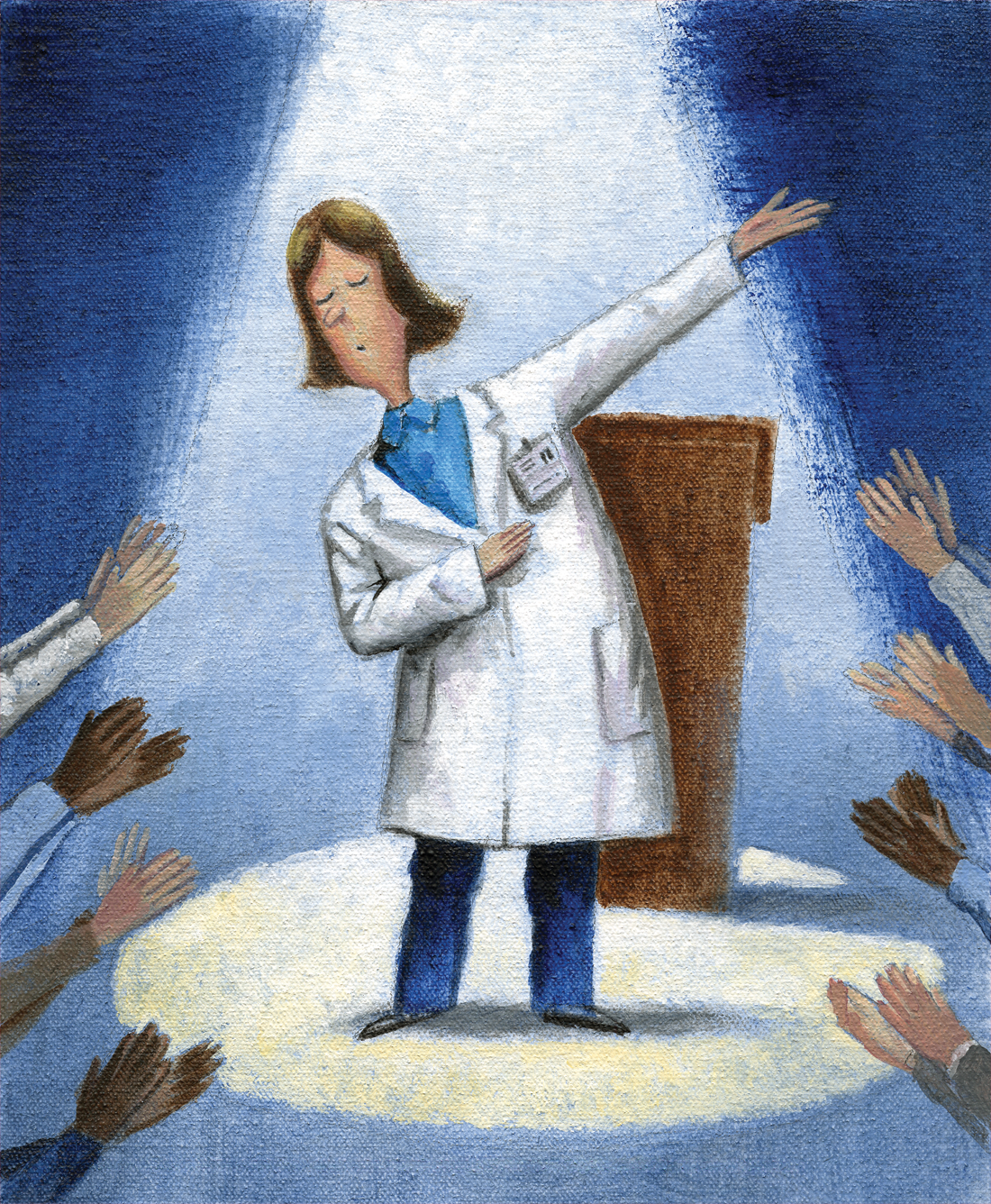

We suggest that, as part of your follow-up, you take the names of attendees you speak with. Make a note relevant to each one and plan to send a personal letter that perhaps includes an article you wrote or one published by a credible source. For example, if one of us (MK) gives a talk for a physician audience on a clinical topic, I will send the inquiring physician a note and an article on the topic, with the key sentences related to his or her question highlighted. A sticky note on the article’s front page directs the physician’s attention to the page containing the answer to his or her question (FIGURE). Using this simple technique can make you a value-added resource long after your presentation.

Alternatively, you could e-mail the article to a representative for the organization that you were speaking for. This makes you an asset to the representative, who will likely tell colleagues about your assistance, which could earn you a return speaking engagement.

Make sure, too, that you have an ample supply of business cards—the quickest and easiest way to give out your contact information.

You may also want to distribute a handout of your presentation. This could of course be a printout of your slide show presentation (assuming there are no copyright concerns). But we think it is better to distribute a single page with salient points you would like the audience to take away from your program. However you prepare your handout, be certain each page displays your name, address, phone numbers, and e-mail and website addresses.

Another suggestion: An unobtrusive way to obtain the names of those who attend your program is to collect their business cards in a container before the presentation and hold a drawing for a prize at the end of the program. We often give away a copy of one of our books, but any small gift would work.

Ask for feedback

If you are speaking on behalf of an organization or another sponsoring entity, it is helpful to ask the meeting planner what they thought of the program. Ask for constructive criticism and input on how you might improve the program. Also ask if you were able to get across your most important points.

Finally, send a note to the meeting planner or representative expressing your thanks for the invitation and offering to provide any additional information they might need or want.

Extend the reach of your message

If your talk would be appropriate for a broader audience, you could consider adapting it for publication. Be sure to understand the audience of the publication and review the selected journal’s guidance for authors.

If you do write an article, share it with your colleagues and perhaps your patients. You might also consider posting the article on your website. Yet another option would be to videotape your presentation, keeping it under 10 minutes, and upload it to the video-sharing website YouTube.

Bottom line. The payoff for your research and preparation need not end with the speaking engagement.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

This third article in a series on public speaking describes steps you can take immediately following the program to strengthen the impact of your diligent preparation (“Preparation: Tips that lead to a solid, engaging presentation.” OBG Manag. 2016;28[7]:31–36) and honed presentation (“The program: Key elements in capturing and holding audience attention.” OBG Manag. 2016;28[9]:46–50). Don’t overlook these details.

Find ways to stay in touch

You have concluded your talk. The audience response was enthusiastic and the brief Q&A session productive. But it is not over yet. Postpone putting away your computer and disconnecting the audiovisual equipment. Instead, mingle with the attendees—as you also did, we hope, before the program began. There is always more you can learn about your listeners. And, importantly, a few of them would undoubtedly like to ask you one-on-one about a case related to the topic you covered or about another problem in your area of expertise.

We suggest that, as part of your follow-up, you take the names of attendees you speak with. Make a note relevant to each one and plan to send a personal letter that perhaps includes an article you wrote or one published by a credible source. For example, if one of us (MK) gives a talk for a physician audience on a clinical topic, I will send the inquiring physician a note and an article on the topic, with the key sentences related to his or her question highlighted. A sticky note on the article’s front page directs the physician’s attention to the page containing the answer to his or her question (FIGURE). Using this simple technique can make you a value-added resource long after your presentation.

Alternatively, you could e-mail the article to a representative for the organization that you were speaking for. This makes you an asset to the representative, who will likely tell colleagues about your assistance, which could earn you a return speaking engagement.

Make sure, too, that you have an ample supply of business cards—the quickest and easiest way to give out your contact information.

You may also want to distribute a handout of your presentation. This could of course be a printout of your slide show presentation (assuming there are no copyright concerns). But we think it is better to distribute a single page with salient points you would like the audience to take away from your program. However you prepare your handout, be certain each page displays your name, address, phone numbers, and e-mail and website addresses.

Another suggestion: An unobtrusive way to obtain the names of those who attend your program is to collect their business cards in a container before the presentation and hold a drawing for a prize at the end of the program. We often give away a copy of one of our books, but any small gift would work.

Ask for feedback

If you are speaking on behalf of an organization or another sponsoring entity, it is helpful to ask the meeting planner what they thought of the program. Ask for constructive criticism and input on how you might improve the program. Also ask if you were able to get across your most important points.

Finally, send a note to the meeting planner or representative expressing your thanks for the invitation and offering to provide any additional information they might need or want.

Extend the reach of your message

If your talk would be appropriate for a broader audience, you could consider adapting it for publication. Be sure to understand the audience of the publication and review the selected journal’s guidance for authors.

If you do write an article, share it with your colleagues and perhaps your patients. You might also consider posting the article on your website. Yet another option would be to videotape your presentation, keeping it under 10 minutes, and upload it to the video-sharing website YouTube.

Bottom line. The payoff for your research and preparation need not end with the speaking engagement.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

This third article in a series on public speaking describes steps you can take immediately following the program to strengthen the impact of your diligent preparation (“Preparation: Tips that lead to a solid, engaging presentation.” OBG Manag. 2016;28[7]:31–36) and honed presentation (“The program: Key elements in capturing and holding audience attention.” OBG Manag. 2016;28[9]:46–50). Don’t overlook these details.

Find ways to stay in touch

You have concluded your talk. The audience response was enthusiastic and the brief Q&A session productive. But it is not over yet. Postpone putting away your computer and disconnecting the audiovisual equipment. Instead, mingle with the attendees—as you also did, we hope, before the program began. There is always more you can learn about your listeners. And, importantly, a few of them would undoubtedly like to ask you one-on-one about a case related to the topic you covered or about another problem in your area of expertise.

We suggest that, as part of your follow-up, you take the names of attendees you speak with. Make a note relevant to each one and plan to send a personal letter that perhaps includes an article you wrote or one published by a credible source. For example, if one of us (MK) gives a talk for a physician audience on a clinical topic, I will send the inquiring physician a note and an article on the topic, with the key sentences related to his or her question highlighted. A sticky note on the article’s front page directs the physician’s attention to the page containing the answer to his or her question (FIGURE). Using this simple technique can make you a value-added resource long after your presentation.

Alternatively, you could e-mail the article to a representative for the organization that you were speaking for. This makes you an asset to the representative, who will likely tell colleagues about your assistance, which could earn you a return speaking engagement.

Make sure, too, that you have an ample supply of business cards—the quickest and easiest way to give out your contact information.

You may also want to distribute a handout of your presentation. This could of course be a printout of your slide show presentation (assuming there are no copyright concerns). But we think it is better to distribute a single page with salient points you would like the audience to take away from your program. However you prepare your handout, be certain each page displays your name, address, phone numbers, and e-mail and website addresses.

Another suggestion: An unobtrusive way to obtain the names of those who attend your program is to collect their business cards in a container before the presentation and hold a drawing for a prize at the end of the program. We often give away a copy of one of our books, but any small gift would work.

Ask for feedback

If you are speaking on behalf of an organization or another sponsoring entity, it is helpful to ask the meeting planner what they thought of the program. Ask for constructive criticism and input on how you might improve the program. Also ask if you were able to get across your most important points.

Finally, send a note to the meeting planner or representative expressing your thanks for the invitation and offering to provide any additional information they might need or want.

Extend the reach of your message

If your talk would be appropriate for a broader audience, you could consider adapting it for publication. Be sure to understand the audience of the publication and review the selected journal’s guidance for authors.

If you do write an article, share it with your colleagues and perhaps your patients. You might also consider posting the article on your website. Yet another option would be to videotape your presentation, keeping it under 10 minutes, and upload it to the video-sharing website YouTube.

Bottom line. The payoff for your research and preparation need not end with the speaking engagement.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

CMS offering educational webinars on MACRA

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services is offering a pair of webinars aimed at helping physicians navigate the new regulation that operationalizes the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act (MACRA).

The first webinar, scheduled for Oct. 26, will provide an overview of the two components of the Quality Payment Program – the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) and advanced Alternative Payment Models (APMs).

The second webinar, scheduled for Nov. 15, is targeted to Medicare Part B fee-for-service clinicians, office managers and administrators, state and national associations that represent health care providers, and other stakeholders and will feature a question-and-answer session.

The webinars are part of the agency’s ongoing efforts to help educate practitioners on the provisions of the final MACRA regulation, which was issued on Oct. 14. CMS also recently launched a website to help in that regard.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services is offering a pair of webinars aimed at helping physicians navigate the new regulation that operationalizes the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act (MACRA).

The first webinar, scheduled for Oct. 26, will provide an overview of the two components of the Quality Payment Program – the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) and advanced Alternative Payment Models (APMs).

The second webinar, scheduled for Nov. 15, is targeted to Medicare Part B fee-for-service clinicians, office managers and administrators, state and national associations that represent health care providers, and other stakeholders and will feature a question-and-answer session.

The webinars are part of the agency’s ongoing efforts to help educate practitioners on the provisions of the final MACRA regulation, which was issued on Oct. 14. CMS also recently launched a website to help in that regard.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services is offering a pair of webinars aimed at helping physicians navigate the new regulation that operationalizes the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act (MACRA).

The first webinar, scheduled for Oct. 26, will provide an overview of the two components of the Quality Payment Program – the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) and advanced Alternative Payment Models (APMs).

The second webinar, scheduled for Nov. 15, is targeted to Medicare Part B fee-for-service clinicians, office managers and administrators, state and national associations that represent health care providers, and other stakeholders and will feature a question-and-answer session.

The webinars are part of the agency’s ongoing efforts to help educate practitioners on the provisions of the final MACRA regulation, which was issued on Oct. 14. CMS also recently launched a website to help in that regard.

MACRA

Given the copious amount of printed and blog space that has been devoted in recent months to MACRA – the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 – I felt no particular obligation to add to the din. Then I was startled to read a recent poll from Deloitte that found that half of all private-practice physicians had never heard of MACRA. Furthermore, only 21% of solo or small-group physicians, and 9% of those employed by hospitals or larger groups, were even somewhat familiar with its financial implications.

Since yet another significant percentage of your Medicare reimbursements will be at risk under this new bureaucracy, an introduction is in order.

When the new system is implemented in 2019, physicians must choose between two payment tracks: the Merit-Based Incentive System (MIPS) or one of the so-called Alternate Payment Models (APM).

The MIPS track will use the four reporting programs just mentioned to compile a composite score between 0 and 100 each year for every practitioner, based on four performance metrics: quality measures listed in Qualified Clinical Data Registries, such as Approved Quality Improvement; total resources used by each practitioner, as measured by VBM; “improvement activities” (MOC); and MU, in some new, as-yet-undefined form. You can earn a bonus of 4% of reimbursement in 2019, rising to 5% in 2020, 7% in 2021, and 9% in 2022 – or you can be penalized those amounts (“negative adjustments”) if your performance doesn’t measure up.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services initially estimated that most physicians in groups of 24 or fewer on the MIPS track would incur a penalty in 2019; but the final MACRA regulations, issued in mid-October, allow a more gradual implementation that should decrease the penalty burden for small practices, at least initially. For example, you can avoid a penalty – but not qualify for a bonus – in 2019 by reporting your performance in only one quality-of-care or practice-improvement category, or by reporting for only a portion of the year. A decrease in penalties, however, means a smaller pot for bonuses – and reprieves will be temporary.

The alternative, APM, is difficult to discuss at present as very few models have been presented, or even defined, to date. Only Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs) have been introduced in any quantity, and most have failed miserably in real-world settings. The Episode of Care model, which pays providers a fixed amount for all services rendered in a bundle (“episode”) of care, has been discussed at some length, but remains untested, and in the end, may turn out to be just another variant of capitation.

So, which to choose? Long term, I strongly suggest that everyone prepare for the APM track as soon as better, more efficient APMs become available, as it appears that there will be more financial security, with less risk of penalties; but you will probably need to start in the MIPS program, as most projections indicate that the great majority of practitioners, particularly those in smaller operations, will do.

While some may be prompted to join a larger organization or network to decrease their risk of MIPS penalties and gain quicker access to the APM track – which may well be one of CMS’ surreptitious goals in introducing MACRA in the first place – there are steps that those individuals and small groups who choose to remain independent can take now to maximize their chances of landing on the bonus side of the MIPS ledger.

First, make sure your practice data is accurate on the Medicare Provider Enrollment, Chain, and Ownership System (PECOS) – where CMS will gather data for the VBM and Physician Feedback Reports. Study the quality benchmarks, and review your Quality Resource and Use Report (QRUR), which gathers information about each practice’s quality and performance rates for the VBM. (Both PECOS and QRUR can be downloaded at CMS.gov.) And, of course, report successfully for PQRS, which will avoid an automatic penalty of 4% 2 years hence.

If the alphabet soup above has your head swimming, join the club – you’re far from alone; but don’t be discouraged. CMS has already indicated its willingness to make changes aimed at decreasing the administrative burden and, in its words, “making the transition to MACRA as simple and as flexible as possible.”

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J. He is the author of numerous articles and textbook chapters, and is a longtime monthly columnist for Dermatology News. Write to him at [email protected] .

Given the copious amount of printed and blog space that has been devoted in recent months to MACRA – the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 – I felt no particular obligation to add to the din. Then I was startled to read a recent poll from Deloitte that found that half of all private-practice physicians had never heard of MACRA. Furthermore, only 21% of solo or small-group physicians, and 9% of those employed by hospitals or larger groups, were even somewhat familiar with its financial implications.

Since yet another significant percentage of your Medicare reimbursements will be at risk under this new bureaucracy, an introduction is in order.

When the new system is implemented in 2019, physicians must choose between two payment tracks: the Merit-Based Incentive System (MIPS) or one of the so-called Alternate Payment Models (APM).

The MIPS track will use the four reporting programs just mentioned to compile a composite score between 0 and 100 each year for every practitioner, based on four performance metrics: quality measures listed in Qualified Clinical Data Registries, such as Approved Quality Improvement; total resources used by each practitioner, as measured by VBM; “improvement activities” (MOC); and MU, in some new, as-yet-undefined form. You can earn a bonus of 4% of reimbursement in 2019, rising to 5% in 2020, 7% in 2021, and 9% in 2022 – or you can be penalized those amounts (“negative adjustments”) if your performance doesn’t measure up.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services initially estimated that most physicians in groups of 24 or fewer on the MIPS track would incur a penalty in 2019; but the final MACRA regulations, issued in mid-October, allow a more gradual implementation that should decrease the penalty burden for small practices, at least initially. For example, you can avoid a penalty – but not qualify for a bonus – in 2019 by reporting your performance in only one quality-of-care or practice-improvement category, or by reporting for only a portion of the year. A decrease in penalties, however, means a smaller pot for bonuses – and reprieves will be temporary.

The alternative, APM, is difficult to discuss at present as very few models have been presented, or even defined, to date. Only Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs) have been introduced in any quantity, and most have failed miserably in real-world settings. The Episode of Care model, which pays providers a fixed amount for all services rendered in a bundle (“episode”) of care, has been discussed at some length, but remains untested, and in the end, may turn out to be just another variant of capitation.

So, which to choose? Long term, I strongly suggest that everyone prepare for the APM track as soon as better, more efficient APMs become available, as it appears that there will be more financial security, with less risk of penalties; but you will probably need to start in the MIPS program, as most projections indicate that the great majority of practitioners, particularly those in smaller operations, will do.

While some may be prompted to join a larger organization or network to decrease their risk of MIPS penalties and gain quicker access to the APM track – which may well be one of CMS’ surreptitious goals in introducing MACRA in the first place – there are steps that those individuals and small groups who choose to remain independent can take now to maximize their chances of landing on the bonus side of the MIPS ledger.

First, make sure your practice data is accurate on the Medicare Provider Enrollment, Chain, and Ownership System (PECOS) – where CMS will gather data for the VBM and Physician Feedback Reports. Study the quality benchmarks, and review your Quality Resource and Use Report (QRUR), which gathers information about each practice’s quality and performance rates for the VBM. (Both PECOS and QRUR can be downloaded at CMS.gov.) And, of course, report successfully for PQRS, which will avoid an automatic penalty of 4% 2 years hence.

If the alphabet soup above has your head swimming, join the club – you’re far from alone; but don’t be discouraged. CMS has already indicated its willingness to make changes aimed at decreasing the administrative burden and, in its words, “making the transition to MACRA as simple and as flexible as possible.”

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J. He is the author of numerous articles and textbook chapters, and is a longtime monthly columnist for Dermatology News. Write to him at [email protected] .

Given the copious amount of printed and blog space that has been devoted in recent months to MACRA – the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 – I felt no particular obligation to add to the din. Then I was startled to read a recent poll from Deloitte that found that half of all private-practice physicians had never heard of MACRA. Furthermore, only 21% of solo or small-group physicians, and 9% of those employed by hospitals or larger groups, were even somewhat familiar with its financial implications.

Since yet another significant percentage of your Medicare reimbursements will be at risk under this new bureaucracy, an introduction is in order.

When the new system is implemented in 2019, physicians must choose between two payment tracks: the Merit-Based Incentive System (MIPS) or one of the so-called Alternate Payment Models (APM).

The MIPS track will use the four reporting programs just mentioned to compile a composite score between 0 and 100 each year for every practitioner, based on four performance metrics: quality measures listed in Qualified Clinical Data Registries, such as Approved Quality Improvement; total resources used by each practitioner, as measured by VBM; “improvement activities” (MOC); and MU, in some new, as-yet-undefined form. You can earn a bonus of 4% of reimbursement in 2019, rising to 5% in 2020, 7% in 2021, and 9% in 2022 – or you can be penalized those amounts (“negative adjustments”) if your performance doesn’t measure up.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services initially estimated that most physicians in groups of 24 or fewer on the MIPS track would incur a penalty in 2019; but the final MACRA regulations, issued in mid-October, allow a more gradual implementation that should decrease the penalty burden for small practices, at least initially. For example, you can avoid a penalty – but not qualify for a bonus – in 2019 by reporting your performance in only one quality-of-care or practice-improvement category, or by reporting for only a portion of the year. A decrease in penalties, however, means a smaller pot for bonuses – and reprieves will be temporary.

The alternative, APM, is difficult to discuss at present as very few models have been presented, or even defined, to date. Only Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs) have been introduced in any quantity, and most have failed miserably in real-world settings. The Episode of Care model, which pays providers a fixed amount for all services rendered in a bundle (“episode”) of care, has been discussed at some length, but remains untested, and in the end, may turn out to be just another variant of capitation.

So, which to choose? Long term, I strongly suggest that everyone prepare for the APM track as soon as better, more efficient APMs become available, as it appears that there will be more financial security, with less risk of penalties; but you will probably need to start in the MIPS program, as most projections indicate that the great majority of practitioners, particularly those in smaller operations, will do.

While some may be prompted to join a larger organization or network to decrease their risk of MIPS penalties and gain quicker access to the APM track – which may well be one of CMS’ surreptitious goals in introducing MACRA in the first place – there are steps that those individuals and small groups who choose to remain independent can take now to maximize their chances of landing on the bonus side of the MIPS ledger.

First, make sure your practice data is accurate on the Medicare Provider Enrollment, Chain, and Ownership System (PECOS) – where CMS will gather data for the VBM and Physician Feedback Reports. Study the quality benchmarks, and review your Quality Resource and Use Report (QRUR), which gathers information about each practice’s quality and performance rates for the VBM. (Both PECOS and QRUR can be downloaded at CMS.gov.) And, of course, report successfully for PQRS, which will avoid an automatic penalty of 4% 2 years hence.

If the alphabet soup above has your head swimming, join the club – you’re far from alone; but don’t be discouraged. CMS has already indicated its willingness to make changes aimed at decreasing the administrative burden and, in its words, “making the transition to MACRA as simple and as flexible as possible.”

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J. He is the author of numerous articles and textbook chapters, and is a longtime monthly columnist for Dermatology News. Write to him at [email protected] .

Observation Status Utilization by Hospitalist Groups Is Increasing

Editor's Note: Listen to Dr. Smith share more of his views on the State of Hospital Medicine report.

Hospitalist groups and their stakeholders must continually adapt to evolving reimbursement models and their attendant financial foci on quality. Even in the midst of care models that rely less heavily on volume of care as a marker for reimbursement, the use of criteria by insurers to separate hospital stays into inpatient or observation status remains widespread. Hospitalist groups vary in the reimbursement model environment they work in, and different reimbursement models can drive hospitalist group behavior in different ways.