User login

Coordination of Care Between Primary Care and Oncology for Patients With Prostate Cancer (FULL)

The following is a lightly edited transcript of a teleconference recorded in July 2018. The teleconference brought together health care providers from the Greater Los Angeles VA Health Care System (GLAVAHCS) to discuss the real-world processes for managing the treatment of patients with prostate cancer as they move between primary and specialist care.

William J. Aronson, MD. We are fortunate in having a superb medical record system at the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) where we can all communicate with each other through a number of methods. Let’s start our discussion by reviewing an index patient that we see in our practice who has been treated with either radical prostatectomy or radiation therapy. One question to address is: Is there a point when the Urology or Radiation Oncology service can transition the patient’s entire care back to the primary care team? And if so, what would be the optimal way to accomplish this?

Nick, is there some point at which you discharge the patient from the radiation oncology service and give specific directions to primary care, or is it primarily just back to urology in your case?

Nicholas G. Nickols, MD, PhD. I have not discharged any patient from my clinic after definitive prostate cancer treatment. During treatment, patients are seen every week. Subsequently, I see them 6 weeks posttreatment, and then every 4 months for the first year, then every 6 months for the next 4 years, and then yearly after that. Although I never formally discharged a patient from my clinic, you can see based on the frequency of visits, that the patient will see more often than their primary care provider (PCP) toward the beginning. And then, after some years, the patient sees their primary more than they me. So it’s not an immediate hand off but rather a gradual transition. It’s important that the PCP is aware of what to look for especially for the late recurrences, late potential side effects, probably more significantly than the early side effects, how to manage them when appropriate, and when to ask the patient to see our team more frequently in follow-up.

William Aronson. We have a number of patients who travel tremendous distances to see us, and I tend to think that many of our follow-up patients, once things are stabilized with regards to management of their side effects, really could see their primary care doctors if we can give them specific instructions on, for example, when to get a prostate-specific antigen (PSA) test and when to refer back to us.

Alison, can you think of some specific cases where you feel like we’ve successfully done that?

Alison Neymark, MS. For the most part we haven’t discharged people, either. What we have done is transitioned them over to a phone clinic. In our department, we have 4 nurse practitioners (NPs) who each have a half-day of phone clinic where they call patients with their test results. Some of those patients are prostate cancer patients that we have been following for years. We schedule them for a phone call, whether it’s every 3 months, every 6 months or every year, to review the updated PSA level and to just check in with them by phone. It’s a win-win because it’s a really quick phone call to reassure the veteran that the PSA level is being followed, and it frees up an in-person appointment slot for another veteran.

We still have patients that prefer face-to-face visits, even though they know we’re not doing anything except discussing a PSA level with them—they just want that security of seeing our face. Some patients are very nervous, and they don’t necessarily want to be discharged, so to speak, back to primary care. Also, for those patients that travel a long distance to clinic, we offer an appointment in the video chat clinic, with the community-based outpatient clinics in Bakersfield and Santa Maria, California.

PSA Levels

William Aronson. I probably see a patient about every 4 to 6 weeks who has a low PSA after about 10 years and has a long distance to travel and mobility and other problems that make it difficult to come in.

The challenge that I have is, what is that specific guideline to give with regards to the rise in PSA? I think it all depends on the patients prostate cancer clinical features and comorbidities.

Nicholas Nickols. If a patient has been seen by me in follow-up a number of times and there’s really no active issues and there’s a low suspicion of recurrence, then I offer the patient the option of a phone follow-up as an alternative to face to face. Some of them accept that, but I ask that they agree to also see either urology or their PCP face to face. I will also remotely ensure that they’re getting the right laboratory tests, and if not, I’ll put those orders in.

With regard to when to refer a patient back for a suspected recurrence after definitive radiation therapy, there is an accepted definition of biochemical failure called the Phoenix definition, which is an absolute rise in 2 ng/mL of PSA over their posttreatment nadir. Often the posttreatment nadir, especially if they were on hormone therapy, will be close to 0. If the PSA gets to 2, that is a good trigger for a referral back to me and/or urology to discuss restaging and workup for a suspected recurrence.

For patients that are postsurgery and then subsequently get salvage radiation, it is not as clear when a restaging workup should be initiated. Currently, the imaging that is routine care is not very sensitive for detecting PSA in that setting until the PSA is around 0.8 ng/mL, and that’s with the most modern imaging available. Over time that may improve.

William Aronson. The other index patient to think about would be the patient who is on watchful waiting for their prostate cancer, which is to be distinguished from active surveillance. If someone’s on active surveillance, we’re regularly doing prostate biopsies and doing very close monitoring; but we also have patients who have multiple other medical problems, have a limited life expectancy, don’t have aggressive prostate cancer, and it’s extremely reasonable not to do a biopsy in those patients.

Again, those are patients where we do follow the PSA generally every 6 months. And I think there’s also scenarios there where it’s reasonable to refer back to primary care with specific instructions. These, again, are patients who had difficulty getting in to see us or have mobility issues, but it is also a way to limit patient visits if that’s their desire.

Peter Glassman, MBBS, MSc: I’m trained as both a general internist and board certified in hospice and palliative medicine. I currently provide primary care as well as palliative care. I view prostate cancer from the diagnosis through the treatment spectrum as a continuum. It starts with the PCP with an elevated PSA level or if the digital rectal exam has an abnormality, and then the role of the genitourinary (GU) practitioner becomes more significant during the active treatment and diagnostic phases.

Primary care doesn’t disappear, and I think there are 2 major issues that go along with that. First of all, we in primary care, because we take care of patients that often have other comorbidities, need to work with the patient on those comorbidities. Secondly, we need the information shared between the GU and primary care providers so that we can answer questions from our patients and have an understanding of what they’re going through and when.

As time goes on, we go through various phases: We may reach a cure, a quiescent period, active therapy, watchful waiting, or recurrence. Primary care gets involved as time goes on when the disease either becomes quiescent, is just being followed, or is considered cured. Clearly when you have watchful waiting, active treatment, or are in a recurrence, then GU takes the forefront.

I view it as a wave function. Primary care to GU with primary in smaller letters and then primary, if you will, in larger letters, GU becomes a lesser participant unless there is active therapy, watchful waiting or recurrence.

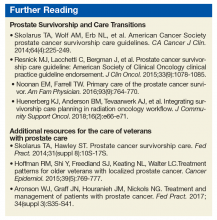

In doing a little bit of research, I found 2 very good and very helpful documents. One is the American Cancer Society (ACS) prostate cancer survivorship care guidelines (Box). And the other is a synopsis of the guidelines. What I liked was that the guidelines focused not only on what should be done for the initial period of prostate cancer, but also for many of the ancillary issues which we often don’t give voice to. The guidelines provide a structure, a foundation to work with our patients over time on their prostate cancer-related issues while, at the same time, being cognizant that we need to deal with their other comorbid conditions.

Modes of Communication

Alison Neymark. We find that including parameters for PSA monitoring in our Progress Notes in the electronic health record (EHR) the best way to communicate with other providers. We’ll say, “If PSA gets to this level, please refer back.” We try to make it clear because with the VA being a training facility, it could be a different resident/attending physician team that’s going to see the patient the next time he is in primary care.

Peter Glassman. Yes, we’re very lucky, as Bill talked about earlier and Alison just mentioned. We have the EHR, and Bill may remember this. Before the EHR, we were constantly fishing to find the most relevant notes. If a patient saw a GU practitioner the day before they saw me, I was often asking the patient what was said. Now we can just review the notes.

It’s a double-edged sword though because there are, of course, many notes in a medical record; and you have to look for the specific items. The EHR and documenting the medical record probably plays the primary role in getting information across. When you want to have an active handoff, or you need to communicate with each other, we have a variety of mechanisms, ranging from the phone to the Microsoft Skype Link (Redmond, WA) system that allows us to tap a message to a colleague.

And I’ve been here long enough that I’ve seen most permutations of how prostate cancer is diagnosed as well as shared among providers. Bill and I have shared patients. Alison and I have shared patients, not necessarily with prostate cancer, although that too. But we know how to communicate with each other. And of course, there’s paging if you need something more urgently.

William Aronson. We also use Microsoft Outlook e-mail, and encrypt the messages to keep them confidential and private. The other nice thing we have is there is a nationwide urology Outlook e-mail, so if any of us have any specific questions, through one e-mail we can send it around the country; and there’s usually multiple very useful responses. That’s another real strength of our system within the VA that helps patient care enormously.

Nicholas Nickols. Sometimes, if there’s a critical note that I absolutely want someone on the care team to read, I’ll add them as a cosigner; and that will pop up when they log in to the Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS) as something that they need to read.

If the patient lives particularly far or gets his care at another VA medical center and laboratory tests are needed, then I will reach out to their PCP via e-mail. If contact is not confirmed, I will reach out via phone or Skype.

Peter Glassman. The most helpful notes are those that are very specific as to what primary care is being asked to do and/or what urology is going to be doing. So, the more specific we get in the notes as to what is being addressed, I think that’s very helpful.

I have been here long enough that I’ve known both Alison and Bill; and if they have an issue, they will tap me a message. It wasn’t long ago that Bill sent a message to me, and we worked on a patient with prostate cancer who was going to be on long-term hormone therapy. We talked about osteoporosis management, and between us we worked out who was going to do what. Those are the kind of shared decision-making situations that are very, very helpful.

Alison Neymark. Also, GLAVAHCS has a home-based primary care team (HBPC), and a lot of the PCPs for that team are NPs. They know that they can contact me for their patients because a lot of those patients are on watchful waiting, and we do not necessarily need to see them face to face in clinic. Our urology team just needs to review updated lab results and how they are doing clinically. The HBPC NP who knows them best can contact me every 6 months or so, and we’ll discuss the case, which avoids making the patient come in, especially when they’re homebound. Those of us that have been working at the VA for many years have established good relationships. We feel very comfortable reaching out and talking to each other about these patients

Peter Glassman. Alison, I agree. When I can talk to my patients and say, “You know, we had that question about,” whatever the question might be, “and I contacted urology, and this is what they said.” It gives the patient confidence that we’re following up on the issues that they have and that we’re communicating with each other in a way that is to their benefit. And I think it’s very appreciated both by the provider as well as the patient.

William Aronson. Not infrequently I’ll have patients who have nonurologic issues, which I may first detect, or who have specific issues with their prostate cancer that can be comanaged. And I have found that when I send an encrypted e-mail to the PCP, it has been an extremely satisfying interaction; and we really get to the heart of the matter quickly for the sake of the veteran.

Veterans With Comorbidities

William Aronson. Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a very significant and unique aspect of our patients, which is enormously important to recognize. For example, the side effects of prostate treatments can be very significant, whether radiation or surgery. Our patients understandably can be very fearful of the prostate cancer diagnosis and treatment side effects.

We know, for example, after a patient gets a diagnosis of prostate cancer, they’re at increased risk of cardiac death. That’s an especially important issue for our patients that there be an ongoing interaction between urology and primary care.

The ACS guidelines that Dr. Glassman referred to were enlightening. In many cases, primary care can look at the whole patient and their circumstances better than we can and may detect, for example, specific psychological issues that either they can manage or refer to other specialists.

Peter Glassman. One of the things that was highlighted in the ACS guideline is that in any population of men who have this disease, there’s going to be distress, anxiety, and full-fledged depression. Of course, there are psychosocial aspects of prostate cancer, such as sexual activity and intimacy with a partner that we often don’t explore but are probably playing an important role in the overall health of our patients. We need to be mindful of these psychosocial aspects and at least periodically ask them, “How are you doing with this? How are things at home?” And of course, we already use screeners for depression. As the article noted, distress and anxiety and other factors can make somebody’s life less optimal with poorer quality of life.

Dual Care Patients

Alison Neymark. Many patients whether they have Medicare, insurance through their spouse, or Kaiser Permanente through their job, choose to go to both places. The challenge is communicating with the non-VA providers because here at the VA we can communicate easily through Skype, Outlook e-mail, or CPRS, but for dual care patients who’s in charge? I encourage the veterans to choose whom they want to manage their care; we’re always here and happy to treat them, but they need to decide who’s in charge because I don’t want them to get into a situation where the differing opinions lead to a delay in care.

Nicholas Nickols. The communication when the patient is receiving care outside VA, either on a continuous basis or temporarily, is more of a challenge. We obviously can’t rely upon the messaging system, face-to-face contact is difficult, and they may not be able to use e-mail as well. So in those situations, usually a phone call is the best approach. I have found that the outside providers are happy to speak on the phone to coordinate care.

Peter Glassman. I agree, it does add a layer of complexity because we don’t readily have the notes, any information in front of us. That said, a lot of our patients can and do bring in information from outside specialists, and I’m hopeful that they share the information that we provide back to their outside doctors as well.

William Aronson. Some patient get nervous. They might decide they want care elsewhere, but they still want the VA available for them. I always let them know they should proceed in whatever way they prefer, but we’re always available and here for them. I try to empower them to make their own decisions and feel comfortable with them.

Nicholas Nickols. Notes from the outside, if they’re being referred for VA Choice or community care, do get uploaded into VistA Imaging and can be accessed, although it’s not instantaneous. Sometimes there’s a delay, but I have been able to access outside notes most of the time. If a patient goes through a clinic at the VA, the note is written in real time, and you can read it immediately.

Peter Glassman. That is true for patients that are within the VA system who receive contracted care either through Choice or through non-VA care that is contracted through VA. For somebody who is choosing to use 2 health care systems, that can provide more of a challenge because those notes don’t come to us. Over time, most of my patients have brought test results to me.

The thing with oncologic care, of course, is it’s a lot more complex. And it’s hard to know without reasonable documentation what’s been going on. At some level, you have to trust that the outside provider is doing whatever they need to do, or you have to take it upon yourself to do it within the system.

Alison Neymark. In my experience with the Choice Program, it really depends on the outside providers and how comfortable they are with the system that has been established to share records. Not all providers are going into that system and accessing it. I have had cases where I will see the non-VA provider’s note and it’ll say, “No documentation available for this consultation.” It just happens that they didn’t go into the system to review it. So it can be a challenge.

I’ve had good communication with the providers who use the system correctly. In some cases, just to make it easier, I will go ahead and communicate with them through encrypted e-mail, or I’ll talk to their care coordinators directly by phone.

Peter Glassman. Many, if not most, PCPs are going to take care of these patients, certainly within the VA, with their GU colleagues. And most of us feel comfortable using the current documentation system in a way that allows us to share information or at least to gather information about these patients.

One of the things that I think came out for me in looking at this was that there are guidelines or there are ideas out there on how to take better care of these patients. And I for one learned a fair bit just by going through these documents, which I’m very appreciative of. But it does highlight to me that we can give good care and provide good shared care for prostate cancer survivors. I think that is something that perhaps this discussion will highlight that not only are people doing that, but there are resources they can utilize that will help them get a more comprehensive picture of taking care of prostate cancer survivors in the primary care clinic.

The beauty of the VA system as a system is that as these issues come up that might affect the overall health of the veteran with prostate cancer, for example, psychosocial issues, we have many people that can address this that are experts in their area. And one of the great beauties of having an all-encompassing healthcare system is being able to use resources within the system, whether that be for other medical problems or other social or other psychological issues, that we ourselves are not expert in. We can reach out to our other colleagues and ask them for assistance. We have that available to help the patients. It’s really holistic.

We even have integrated medicine where we can help patients, hopefully, get back into a healthy lifestyle, for example, whereas we may not have that expertise or knowledge. We often think of this as sort of a shared decision between GU and primary care. But, in fact, it’s really the responsibility of many, many people of the system at large. We are very lucky to have that.

The following is a lightly edited transcript of a teleconference recorded in July 2018. The teleconference brought together health care providers from the Greater Los Angeles VA Health Care System (GLAVAHCS) to discuss the real-world processes for managing the treatment of patients with prostate cancer as they move between primary and specialist care.

William J. Aronson, MD. We are fortunate in having a superb medical record system at the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) where we can all communicate with each other through a number of methods. Let’s start our discussion by reviewing an index patient that we see in our practice who has been treated with either radical prostatectomy or radiation therapy. One question to address is: Is there a point when the Urology or Radiation Oncology service can transition the patient’s entire care back to the primary care team? And if so, what would be the optimal way to accomplish this?

Nick, is there some point at which you discharge the patient from the radiation oncology service and give specific directions to primary care, or is it primarily just back to urology in your case?

Nicholas G. Nickols, MD, PhD. I have not discharged any patient from my clinic after definitive prostate cancer treatment. During treatment, patients are seen every week. Subsequently, I see them 6 weeks posttreatment, and then every 4 months for the first year, then every 6 months for the next 4 years, and then yearly after that. Although I never formally discharged a patient from my clinic, you can see based on the frequency of visits, that the patient will see more often than their primary care provider (PCP) toward the beginning. And then, after some years, the patient sees their primary more than they me. So it’s not an immediate hand off but rather a gradual transition. It’s important that the PCP is aware of what to look for especially for the late recurrences, late potential side effects, probably more significantly than the early side effects, how to manage them when appropriate, and when to ask the patient to see our team more frequently in follow-up.

William Aronson. We have a number of patients who travel tremendous distances to see us, and I tend to think that many of our follow-up patients, once things are stabilized with regards to management of their side effects, really could see their primary care doctors if we can give them specific instructions on, for example, when to get a prostate-specific antigen (PSA) test and when to refer back to us.

Alison, can you think of some specific cases where you feel like we’ve successfully done that?

Alison Neymark, MS. For the most part we haven’t discharged people, either. What we have done is transitioned them over to a phone clinic. In our department, we have 4 nurse practitioners (NPs) who each have a half-day of phone clinic where they call patients with their test results. Some of those patients are prostate cancer patients that we have been following for years. We schedule them for a phone call, whether it’s every 3 months, every 6 months or every year, to review the updated PSA level and to just check in with them by phone. It’s a win-win because it’s a really quick phone call to reassure the veteran that the PSA level is being followed, and it frees up an in-person appointment slot for another veteran.

We still have patients that prefer face-to-face visits, even though they know we’re not doing anything except discussing a PSA level with them—they just want that security of seeing our face. Some patients are very nervous, and they don’t necessarily want to be discharged, so to speak, back to primary care. Also, for those patients that travel a long distance to clinic, we offer an appointment in the video chat clinic, with the community-based outpatient clinics in Bakersfield and Santa Maria, California.

PSA Levels

William Aronson. I probably see a patient about every 4 to 6 weeks who has a low PSA after about 10 years and has a long distance to travel and mobility and other problems that make it difficult to come in.

The challenge that I have is, what is that specific guideline to give with regards to the rise in PSA? I think it all depends on the patients prostate cancer clinical features and comorbidities.

Nicholas Nickols. If a patient has been seen by me in follow-up a number of times and there’s really no active issues and there’s a low suspicion of recurrence, then I offer the patient the option of a phone follow-up as an alternative to face to face. Some of them accept that, but I ask that they agree to also see either urology or their PCP face to face. I will also remotely ensure that they’re getting the right laboratory tests, and if not, I’ll put those orders in.

With regard to when to refer a patient back for a suspected recurrence after definitive radiation therapy, there is an accepted definition of biochemical failure called the Phoenix definition, which is an absolute rise in 2 ng/mL of PSA over their posttreatment nadir. Often the posttreatment nadir, especially if they were on hormone therapy, will be close to 0. If the PSA gets to 2, that is a good trigger for a referral back to me and/or urology to discuss restaging and workup for a suspected recurrence.

For patients that are postsurgery and then subsequently get salvage radiation, it is not as clear when a restaging workup should be initiated. Currently, the imaging that is routine care is not very sensitive for detecting PSA in that setting until the PSA is around 0.8 ng/mL, and that’s with the most modern imaging available. Over time that may improve.

William Aronson. The other index patient to think about would be the patient who is on watchful waiting for their prostate cancer, which is to be distinguished from active surveillance. If someone’s on active surveillance, we’re regularly doing prostate biopsies and doing very close monitoring; but we also have patients who have multiple other medical problems, have a limited life expectancy, don’t have aggressive prostate cancer, and it’s extremely reasonable not to do a biopsy in those patients.

Again, those are patients where we do follow the PSA generally every 6 months. And I think there’s also scenarios there where it’s reasonable to refer back to primary care with specific instructions. These, again, are patients who had difficulty getting in to see us or have mobility issues, but it is also a way to limit patient visits if that’s their desire.

Peter Glassman, MBBS, MSc: I’m trained as both a general internist and board certified in hospice and palliative medicine. I currently provide primary care as well as palliative care. I view prostate cancer from the diagnosis through the treatment spectrum as a continuum. It starts with the PCP with an elevated PSA level or if the digital rectal exam has an abnormality, and then the role of the genitourinary (GU) practitioner becomes more significant during the active treatment and diagnostic phases.

Primary care doesn’t disappear, and I think there are 2 major issues that go along with that. First of all, we in primary care, because we take care of patients that often have other comorbidities, need to work with the patient on those comorbidities. Secondly, we need the information shared between the GU and primary care providers so that we can answer questions from our patients and have an understanding of what they’re going through and when.

As time goes on, we go through various phases: We may reach a cure, a quiescent period, active therapy, watchful waiting, or recurrence. Primary care gets involved as time goes on when the disease either becomes quiescent, is just being followed, or is considered cured. Clearly when you have watchful waiting, active treatment, or are in a recurrence, then GU takes the forefront.

I view it as a wave function. Primary care to GU with primary in smaller letters and then primary, if you will, in larger letters, GU becomes a lesser participant unless there is active therapy, watchful waiting or recurrence.

In doing a little bit of research, I found 2 very good and very helpful documents. One is the American Cancer Society (ACS) prostate cancer survivorship care guidelines (Box). And the other is a synopsis of the guidelines. What I liked was that the guidelines focused not only on what should be done for the initial period of prostate cancer, but also for many of the ancillary issues which we often don’t give voice to. The guidelines provide a structure, a foundation to work with our patients over time on their prostate cancer-related issues while, at the same time, being cognizant that we need to deal with their other comorbid conditions.

Modes of Communication

Alison Neymark. We find that including parameters for PSA monitoring in our Progress Notes in the electronic health record (EHR) the best way to communicate with other providers. We’ll say, “If PSA gets to this level, please refer back.” We try to make it clear because with the VA being a training facility, it could be a different resident/attending physician team that’s going to see the patient the next time he is in primary care.

Peter Glassman. Yes, we’re very lucky, as Bill talked about earlier and Alison just mentioned. We have the EHR, and Bill may remember this. Before the EHR, we were constantly fishing to find the most relevant notes. If a patient saw a GU practitioner the day before they saw me, I was often asking the patient what was said. Now we can just review the notes.

It’s a double-edged sword though because there are, of course, many notes in a medical record; and you have to look for the specific items. The EHR and documenting the medical record probably plays the primary role in getting information across. When you want to have an active handoff, or you need to communicate with each other, we have a variety of mechanisms, ranging from the phone to the Microsoft Skype Link (Redmond, WA) system that allows us to tap a message to a colleague.

And I’ve been here long enough that I’ve seen most permutations of how prostate cancer is diagnosed as well as shared among providers. Bill and I have shared patients. Alison and I have shared patients, not necessarily with prostate cancer, although that too. But we know how to communicate with each other. And of course, there’s paging if you need something more urgently.

William Aronson. We also use Microsoft Outlook e-mail, and encrypt the messages to keep them confidential and private. The other nice thing we have is there is a nationwide urology Outlook e-mail, so if any of us have any specific questions, through one e-mail we can send it around the country; and there’s usually multiple very useful responses. That’s another real strength of our system within the VA that helps patient care enormously.

Nicholas Nickols. Sometimes, if there’s a critical note that I absolutely want someone on the care team to read, I’ll add them as a cosigner; and that will pop up when they log in to the Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS) as something that they need to read.

If the patient lives particularly far or gets his care at another VA medical center and laboratory tests are needed, then I will reach out to their PCP via e-mail. If contact is not confirmed, I will reach out via phone or Skype.

Peter Glassman. The most helpful notes are those that are very specific as to what primary care is being asked to do and/or what urology is going to be doing. So, the more specific we get in the notes as to what is being addressed, I think that’s very helpful.

I have been here long enough that I’ve known both Alison and Bill; and if they have an issue, they will tap me a message. It wasn’t long ago that Bill sent a message to me, and we worked on a patient with prostate cancer who was going to be on long-term hormone therapy. We talked about osteoporosis management, and between us we worked out who was going to do what. Those are the kind of shared decision-making situations that are very, very helpful.

Alison Neymark. Also, GLAVAHCS has a home-based primary care team (HBPC), and a lot of the PCPs for that team are NPs. They know that they can contact me for their patients because a lot of those patients are on watchful waiting, and we do not necessarily need to see them face to face in clinic. Our urology team just needs to review updated lab results and how they are doing clinically. The HBPC NP who knows them best can contact me every 6 months or so, and we’ll discuss the case, which avoids making the patient come in, especially when they’re homebound. Those of us that have been working at the VA for many years have established good relationships. We feel very comfortable reaching out and talking to each other about these patients

Peter Glassman. Alison, I agree. When I can talk to my patients and say, “You know, we had that question about,” whatever the question might be, “and I contacted urology, and this is what they said.” It gives the patient confidence that we’re following up on the issues that they have and that we’re communicating with each other in a way that is to their benefit. And I think it’s very appreciated both by the provider as well as the patient.

William Aronson. Not infrequently I’ll have patients who have nonurologic issues, which I may first detect, or who have specific issues with their prostate cancer that can be comanaged. And I have found that when I send an encrypted e-mail to the PCP, it has been an extremely satisfying interaction; and we really get to the heart of the matter quickly for the sake of the veteran.

Veterans With Comorbidities

William Aronson. Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a very significant and unique aspect of our patients, which is enormously important to recognize. For example, the side effects of prostate treatments can be very significant, whether radiation or surgery. Our patients understandably can be very fearful of the prostate cancer diagnosis and treatment side effects.

We know, for example, after a patient gets a diagnosis of prostate cancer, they’re at increased risk of cardiac death. That’s an especially important issue for our patients that there be an ongoing interaction between urology and primary care.

The ACS guidelines that Dr. Glassman referred to were enlightening. In many cases, primary care can look at the whole patient and their circumstances better than we can and may detect, for example, specific psychological issues that either they can manage or refer to other specialists.

Peter Glassman. One of the things that was highlighted in the ACS guideline is that in any population of men who have this disease, there’s going to be distress, anxiety, and full-fledged depression. Of course, there are psychosocial aspects of prostate cancer, such as sexual activity and intimacy with a partner that we often don’t explore but are probably playing an important role in the overall health of our patients. We need to be mindful of these psychosocial aspects and at least periodically ask them, “How are you doing with this? How are things at home?” And of course, we already use screeners for depression. As the article noted, distress and anxiety and other factors can make somebody’s life less optimal with poorer quality of life.

Dual Care Patients

Alison Neymark. Many patients whether they have Medicare, insurance through their spouse, or Kaiser Permanente through their job, choose to go to both places. The challenge is communicating with the non-VA providers because here at the VA we can communicate easily through Skype, Outlook e-mail, or CPRS, but for dual care patients who’s in charge? I encourage the veterans to choose whom they want to manage their care; we’re always here and happy to treat them, but they need to decide who’s in charge because I don’t want them to get into a situation where the differing opinions lead to a delay in care.

Nicholas Nickols. The communication when the patient is receiving care outside VA, either on a continuous basis or temporarily, is more of a challenge. We obviously can’t rely upon the messaging system, face-to-face contact is difficult, and they may not be able to use e-mail as well. So in those situations, usually a phone call is the best approach. I have found that the outside providers are happy to speak on the phone to coordinate care.

Peter Glassman. I agree, it does add a layer of complexity because we don’t readily have the notes, any information in front of us. That said, a lot of our patients can and do bring in information from outside specialists, and I’m hopeful that they share the information that we provide back to their outside doctors as well.

William Aronson. Some patient get nervous. They might decide they want care elsewhere, but they still want the VA available for them. I always let them know they should proceed in whatever way they prefer, but we’re always available and here for them. I try to empower them to make their own decisions and feel comfortable with them.

Nicholas Nickols. Notes from the outside, if they’re being referred for VA Choice or community care, do get uploaded into VistA Imaging and can be accessed, although it’s not instantaneous. Sometimes there’s a delay, but I have been able to access outside notes most of the time. If a patient goes through a clinic at the VA, the note is written in real time, and you can read it immediately.

Peter Glassman. That is true for patients that are within the VA system who receive contracted care either through Choice or through non-VA care that is contracted through VA. For somebody who is choosing to use 2 health care systems, that can provide more of a challenge because those notes don’t come to us. Over time, most of my patients have brought test results to me.

The thing with oncologic care, of course, is it’s a lot more complex. And it’s hard to know without reasonable documentation what’s been going on. At some level, you have to trust that the outside provider is doing whatever they need to do, or you have to take it upon yourself to do it within the system.

Alison Neymark. In my experience with the Choice Program, it really depends on the outside providers and how comfortable they are with the system that has been established to share records. Not all providers are going into that system and accessing it. I have had cases where I will see the non-VA provider’s note and it’ll say, “No documentation available for this consultation.” It just happens that they didn’t go into the system to review it. So it can be a challenge.

I’ve had good communication with the providers who use the system correctly. In some cases, just to make it easier, I will go ahead and communicate with them through encrypted e-mail, or I’ll talk to their care coordinators directly by phone.

Peter Glassman. Many, if not most, PCPs are going to take care of these patients, certainly within the VA, with their GU colleagues. And most of us feel comfortable using the current documentation system in a way that allows us to share information or at least to gather information about these patients.

One of the things that I think came out for me in looking at this was that there are guidelines or there are ideas out there on how to take better care of these patients. And I for one learned a fair bit just by going through these documents, which I’m very appreciative of. But it does highlight to me that we can give good care and provide good shared care for prostate cancer survivors. I think that is something that perhaps this discussion will highlight that not only are people doing that, but there are resources they can utilize that will help them get a more comprehensive picture of taking care of prostate cancer survivors in the primary care clinic.

The beauty of the VA system as a system is that as these issues come up that might affect the overall health of the veteran with prostate cancer, for example, psychosocial issues, we have many people that can address this that are experts in their area. And one of the great beauties of having an all-encompassing healthcare system is being able to use resources within the system, whether that be for other medical problems or other social or other psychological issues, that we ourselves are not expert in. We can reach out to our other colleagues and ask them for assistance. We have that available to help the patients. It’s really holistic.

We even have integrated medicine where we can help patients, hopefully, get back into a healthy lifestyle, for example, whereas we may not have that expertise or knowledge. We often think of this as sort of a shared decision between GU and primary care. But, in fact, it’s really the responsibility of many, many people of the system at large. We are very lucky to have that.

The following is a lightly edited transcript of a teleconference recorded in July 2018. The teleconference brought together health care providers from the Greater Los Angeles VA Health Care System (GLAVAHCS) to discuss the real-world processes for managing the treatment of patients with prostate cancer as they move between primary and specialist care.

William J. Aronson, MD. We are fortunate in having a superb medical record system at the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) where we can all communicate with each other through a number of methods. Let’s start our discussion by reviewing an index patient that we see in our practice who has been treated with either radical prostatectomy or radiation therapy. One question to address is: Is there a point when the Urology or Radiation Oncology service can transition the patient’s entire care back to the primary care team? And if so, what would be the optimal way to accomplish this?

Nick, is there some point at which you discharge the patient from the radiation oncology service and give specific directions to primary care, or is it primarily just back to urology in your case?

Nicholas G. Nickols, MD, PhD. I have not discharged any patient from my clinic after definitive prostate cancer treatment. During treatment, patients are seen every week. Subsequently, I see them 6 weeks posttreatment, and then every 4 months for the first year, then every 6 months for the next 4 years, and then yearly after that. Although I never formally discharged a patient from my clinic, you can see based on the frequency of visits, that the patient will see more often than their primary care provider (PCP) toward the beginning. And then, after some years, the patient sees their primary more than they me. So it’s not an immediate hand off but rather a gradual transition. It’s important that the PCP is aware of what to look for especially for the late recurrences, late potential side effects, probably more significantly than the early side effects, how to manage them when appropriate, and when to ask the patient to see our team more frequently in follow-up.

William Aronson. We have a number of patients who travel tremendous distances to see us, and I tend to think that many of our follow-up patients, once things are stabilized with regards to management of their side effects, really could see their primary care doctors if we can give them specific instructions on, for example, when to get a prostate-specific antigen (PSA) test and when to refer back to us.

Alison, can you think of some specific cases where you feel like we’ve successfully done that?

Alison Neymark, MS. For the most part we haven’t discharged people, either. What we have done is transitioned them over to a phone clinic. In our department, we have 4 nurse practitioners (NPs) who each have a half-day of phone clinic where they call patients with their test results. Some of those patients are prostate cancer patients that we have been following for years. We schedule them for a phone call, whether it’s every 3 months, every 6 months or every year, to review the updated PSA level and to just check in with them by phone. It’s a win-win because it’s a really quick phone call to reassure the veteran that the PSA level is being followed, and it frees up an in-person appointment slot for another veteran.

We still have patients that prefer face-to-face visits, even though they know we’re not doing anything except discussing a PSA level with them—they just want that security of seeing our face. Some patients are very nervous, and they don’t necessarily want to be discharged, so to speak, back to primary care. Also, for those patients that travel a long distance to clinic, we offer an appointment in the video chat clinic, with the community-based outpatient clinics in Bakersfield and Santa Maria, California.

PSA Levels

William Aronson. I probably see a patient about every 4 to 6 weeks who has a low PSA after about 10 years and has a long distance to travel and mobility and other problems that make it difficult to come in.

The challenge that I have is, what is that specific guideline to give with regards to the rise in PSA? I think it all depends on the patients prostate cancer clinical features and comorbidities.

Nicholas Nickols. If a patient has been seen by me in follow-up a number of times and there’s really no active issues and there’s a low suspicion of recurrence, then I offer the patient the option of a phone follow-up as an alternative to face to face. Some of them accept that, but I ask that they agree to also see either urology or their PCP face to face. I will also remotely ensure that they’re getting the right laboratory tests, and if not, I’ll put those orders in.

With regard to when to refer a patient back for a suspected recurrence after definitive radiation therapy, there is an accepted definition of biochemical failure called the Phoenix definition, which is an absolute rise in 2 ng/mL of PSA over their posttreatment nadir. Often the posttreatment nadir, especially if they were on hormone therapy, will be close to 0. If the PSA gets to 2, that is a good trigger for a referral back to me and/or urology to discuss restaging and workup for a suspected recurrence.

For patients that are postsurgery and then subsequently get salvage radiation, it is not as clear when a restaging workup should be initiated. Currently, the imaging that is routine care is not very sensitive for detecting PSA in that setting until the PSA is around 0.8 ng/mL, and that’s with the most modern imaging available. Over time that may improve.

William Aronson. The other index patient to think about would be the patient who is on watchful waiting for their prostate cancer, which is to be distinguished from active surveillance. If someone’s on active surveillance, we’re regularly doing prostate biopsies and doing very close monitoring; but we also have patients who have multiple other medical problems, have a limited life expectancy, don’t have aggressive prostate cancer, and it’s extremely reasonable not to do a biopsy in those patients.

Again, those are patients where we do follow the PSA generally every 6 months. And I think there’s also scenarios there where it’s reasonable to refer back to primary care with specific instructions. These, again, are patients who had difficulty getting in to see us or have mobility issues, but it is also a way to limit patient visits if that’s their desire.

Peter Glassman, MBBS, MSc: I’m trained as both a general internist and board certified in hospice and palliative medicine. I currently provide primary care as well as palliative care. I view prostate cancer from the diagnosis through the treatment spectrum as a continuum. It starts with the PCP with an elevated PSA level or if the digital rectal exam has an abnormality, and then the role of the genitourinary (GU) practitioner becomes more significant during the active treatment and diagnostic phases.

Primary care doesn’t disappear, and I think there are 2 major issues that go along with that. First of all, we in primary care, because we take care of patients that often have other comorbidities, need to work with the patient on those comorbidities. Secondly, we need the information shared between the GU and primary care providers so that we can answer questions from our patients and have an understanding of what they’re going through and when.

As time goes on, we go through various phases: We may reach a cure, a quiescent period, active therapy, watchful waiting, or recurrence. Primary care gets involved as time goes on when the disease either becomes quiescent, is just being followed, or is considered cured. Clearly when you have watchful waiting, active treatment, or are in a recurrence, then GU takes the forefront.

I view it as a wave function. Primary care to GU with primary in smaller letters and then primary, if you will, in larger letters, GU becomes a lesser participant unless there is active therapy, watchful waiting or recurrence.

In doing a little bit of research, I found 2 very good and very helpful documents. One is the American Cancer Society (ACS) prostate cancer survivorship care guidelines (Box). And the other is a synopsis of the guidelines. What I liked was that the guidelines focused not only on what should be done for the initial period of prostate cancer, but also for many of the ancillary issues which we often don’t give voice to. The guidelines provide a structure, a foundation to work with our patients over time on their prostate cancer-related issues while, at the same time, being cognizant that we need to deal with their other comorbid conditions.

Modes of Communication

Alison Neymark. We find that including parameters for PSA monitoring in our Progress Notes in the electronic health record (EHR) the best way to communicate with other providers. We’ll say, “If PSA gets to this level, please refer back.” We try to make it clear because with the VA being a training facility, it could be a different resident/attending physician team that’s going to see the patient the next time he is in primary care.

Peter Glassman. Yes, we’re very lucky, as Bill talked about earlier and Alison just mentioned. We have the EHR, and Bill may remember this. Before the EHR, we were constantly fishing to find the most relevant notes. If a patient saw a GU practitioner the day before they saw me, I was often asking the patient what was said. Now we can just review the notes.

It’s a double-edged sword though because there are, of course, many notes in a medical record; and you have to look for the specific items. The EHR and documenting the medical record probably plays the primary role in getting information across. When you want to have an active handoff, or you need to communicate with each other, we have a variety of mechanisms, ranging from the phone to the Microsoft Skype Link (Redmond, WA) system that allows us to tap a message to a colleague.

And I’ve been here long enough that I’ve seen most permutations of how prostate cancer is diagnosed as well as shared among providers. Bill and I have shared patients. Alison and I have shared patients, not necessarily with prostate cancer, although that too. But we know how to communicate with each other. And of course, there’s paging if you need something more urgently.

William Aronson. We also use Microsoft Outlook e-mail, and encrypt the messages to keep them confidential and private. The other nice thing we have is there is a nationwide urology Outlook e-mail, so if any of us have any specific questions, through one e-mail we can send it around the country; and there’s usually multiple very useful responses. That’s another real strength of our system within the VA that helps patient care enormously.

Nicholas Nickols. Sometimes, if there’s a critical note that I absolutely want someone on the care team to read, I’ll add them as a cosigner; and that will pop up when they log in to the Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS) as something that they need to read.

If the patient lives particularly far or gets his care at another VA medical center and laboratory tests are needed, then I will reach out to their PCP via e-mail. If contact is not confirmed, I will reach out via phone or Skype.

Peter Glassman. The most helpful notes are those that are very specific as to what primary care is being asked to do and/or what urology is going to be doing. So, the more specific we get in the notes as to what is being addressed, I think that’s very helpful.

I have been here long enough that I’ve known both Alison and Bill; and if they have an issue, they will tap me a message. It wasn’t long ago that Bill sent a message to me, and we worked on a patient with prostate cancer who was going to be on long-term hormone therapy. We talked about osteoporosis management, and between us we worked out who was going to do what. Those are the kind of shared decision-making situations that are very, very helpful.

Alison Neymark. Also, GLAVAHCS has a home-based primary care team (HBPC), and a lot of the PCPs for that team are NPs. They know that they can contact me for their patients because a lot of those patients are on watchful waiting, and we do not necessarily need to see them face to face in clinic. Our urology team just needs to review updated lab results and how they are doing clinically. The HBPC NP who knows them best can contact me every 6 months or so, and we’ll discuss the case, which avoids making the patient come in, especially when they’re homebound. Those of us that have been working at the VA for many years have established good relationships. We feel very comfortable reaching out and talking to each other about these patients

Peter Glassman. Alison, I agree. When I can talk to my patients and say, “You know, we had that question about,” whatever the question might be, “and I contacted urology, and this is what they said.” It gives the patient confidence that we’re following up on the issues that they have and that we’re communicating with each other in a way that is to their benefit. And I think it’s very appreciated both by the provider as well as the patient.

William Aronson. Not infrequently I’ll have patients who have nonurologic issues, which I may first detect, or who have specific issues with their prostate cancer that can be comanaged. And I have found that when I send an encrypted e-mail to the PCP, it has been an extremely satisfying interaction; and we really get to the heart of the matter quickly for the sake of the veteran.

Veterans With Comorbidities

William Aronson. Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a very significant and unique aspect of our patients, which is enormously important to recognize. For example, the side effects of prostate treatments can be very significant, whether radiation or surgery. Our patients understandably can be very fearful of the prostate cancer diagnosis and treatment side effects.

We know, for example, after a patient gets a diagnosis of prostate cancer, they’re at increased risk of cardiac death. That’s an especially important issue for our patients that there be an ongoing interaction between urology and primary care.

The ACS guidelines that Dr. Glassman referred to were enlightening. In many cases, primary care can look at the whole patient and their circumstances better than we can and may detect, for example, specific psychological issues that either they can manage or refer to other specialists.

Peter Glassman. One of the things that was highlighted in the ACS guideline is that in any population of men who have this disease, there’s going to be distress, anxiety, and full-fledged depression. Of course, there are psychosocial aspects of prostate cancer, such as sexual activity and intimacy with a partner that we often don’t explore but are probably playing an important role in the overall health of our patients. We need to be mindful of these psychosocial aspects and at least periodically ask them, “How are you doing with this? How are things at home?” And of course, we already use screeners for depression. As the article noted, distress and anxiety and other factors can make somebody’s life less optimal with poorer quality of life.

Dual Care Patients

Alison Neymark. Many patients whether they have Medicare, insurance through their spouse, or Kaiser Permanente through their job, choose to go to both places. The challenge is communicating with the non-VA providers because here at the VA we can communicate easily through Skype, Outlook e-mail, or CPRS, but for dual care patients who’s in charge? I encourage the veterans to choose whom they want to manage their care; we’re always here and happy to treat them, but they need to decide who’s in charge because I don’t want them to get into a situation where the differing opinions lead to a delay in care.

Nicholas Nickols. The communication when the patient is receiving care outside VA, either on a continuous basis or temporarily, is more of a challenge. We obviously can’t rely upon the messaging system, face-to-face contact is difficult, and they may not be able to use e-mail as well. So in those situations, usually a phone call is the best approach. I have found that the outside providers are happy to speak on the phone to coordinate care.

Peter Glassman. I agree, it does add a layer of complexity because we don’t readily have the notes, any information in front of us. That said, a lot of our patients can and do bring in information from outside specialists, and I’m hopeful that they share the information that we provide back to their outside doctors as well.

William Aronson. Some patient get nervous. They might decide they want care elsewhere, but they still want the VA available for them. I always let them know they should proceed in whatever way they prefer, but we’re always available and here for them. I try to empower them to make their own decisions and feel comfortable with them.

Nicholas Nickols. Notes from the outside, if they’re being referred for VA Choice or community care, do get uploaded into VistA Imaging and can be accessed, although it’s not instantaneous. Sometimes there’s a delay, but I have been able to access outside notes most of the time. If a patient goes through a clinic at the VA, the note is written in real time, and you can read it immediately.

Peter Glassman. That is true for patients that are within the VA system who receive contracted care either through Choice or through non-VA care that is contracted through VA. For somebody who is choosing to use 2 health care systems, that can provide more of a challenge because those notes don’t come to us. Over time, most of my patients have brought test results to me.

The thing with oncologic care, of course, is it’s a lot more complex. And it’s hard to know without reasonable documentation what’s been going on. At some level, you have to trust that the outside provider is doing whatever they need to do, or you have to take it upon yourself to do it within the system.

Alison Neymark. In my experience with the Choice Program, it really depends on the outside providers and how comfortable they are with the system that has been established to share records. Not all providers are going into that system and accessing it. I have had cases where I will see the non-VA provider’s note and it’ll say, “No documentation available for this consultation.” It just happens that they didn’t go into the system to review it. So it can be a challenge.

I’ve had good communication with the providers who use the system correctly. In some cases, just to make it easier, I will go ahead and communicate with them through encrypted e-mail, or I’ll talk to their care coordinators directly by phone.

Peter Glassman. Many, if not most, PCPs are going to take care of these patients, certainly within the VA, with their GU colleagues. And most of us feel comfortable using the current documentation system in a way that allows us to share information or at least to gather information about these patients.

One of the things that I think came out for me in looking at this was that there are guidelines or there are ideas out there on how to take better care of these patients. And I for one learned a fair bit just by going through these documents, which I’m very appreciative of. But it does highlight to me that we can give good care and provide good shared care for prostate cancer survivors. I think that is something that perhaps this discussion will highlight that not only are people doing that, but there are resources they can utilize that will help them get a more comprehensive picture of taking care of prostate cancer survivors in the primary care clinic.

The beauty of the VA system as a system is that as these issues come up that might affect the overall health of the veteran with prostate cancer, for example, psychosocial issues, we have many people that can address this that are experts in their area. And one of the great beauties of having an all-encompassing healthcare system is being able to use resources within the system, whether that be for other medical problems or other social or other psychological issues, that we ourselves are not expert in. We can reach out to our other colleagues and ask them for assistance. We have that available to help the patients. It’s really holistic.

We even have integrated medicine where we can help patients, hopefully, get back into a healthy lifestyle, for example, whereas we may not have that expertise or knowledge. We often think of this as sort of a shared decision between GU and primary care. But, in fact, it’s really the responsibility of many, many people of the system at large. We are very lucky to have that.

Cognitive Biases Influence Decision-Making Regarding Postacute Care in a Skilled Nursing Facility

The combination of decreasing hospital lengths of stay and increasing age and comorbidity of the United States population is a principal driver of the increased use of postacute care in the US.1-3 Postacute care refers to care in long-term acute care hospitals, inpatient rehabilitation facilities, skilled nursing facilities (SNFs), and care provided by home health agencies after an acute hospitalization. In 2016, 43% of Medicare beneficiaries received postacute care after hospital discharge at the cost of $60 billion annually; nearly half of these received care in an SNF.4 Increasing recognition of the significant cost and poor outcomes of postacute care led to payment reforms, such as bundled payments, that incentivized less expensive forms of postacute care and improvements in outcomes.5-9 Early evaluations suggested that hospitals are sensitive to these reforms and responded by significantly decreasing SNF utilization.10,11 It remains unclear whether this was safe and effective.

In this context, increased attention to how hospital clinicians and hospitalized patients decide whether to use postacute care (and what form to use) is appropriate since the effect of payment reforms could negatively impact vulnerable populations of older adults without adequate protection.12 Suboptimal decision-making can drive both overuse and inappropriate underuse of this expensive medical resource. Initial evidence suggests that patients and clinicians are poorly equipped to make high-quality decisions about postacute care, with significant deficits in both the decision-making process and content.13-16 While these gaps are important to address, they may only be part of the problem. The fields of cognitive psychology and behavioral economics have revealed new insights into decision-making, demonstrating that people deviate from rational decision-making in predictable ways, termed decision heuristics, or cognitive biases.17 This growing field of research suggests heuristics or biases play important roles in decision-making and determining behavior, particularly in situations where there may be little information provided and the patient is stressed, tired, and ill—precisely like deciding on postacute care.18 However, it is currently unknown whether cognitive biases are at play when making hospital discharge decisions.

We sought to identify the most salient heuristics or cognitive biases patients may utilize when making decisions about postacute care at the end of their hospitalization and ways clinicians may contribute to these biases. The overall goal was to derive insights for improving postacute care decision-making.

METHODS

Study Design

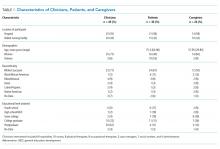

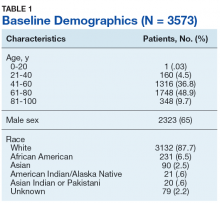

We conducted a secondary analysis on interviews with hospital and SNF clinicians as well as patients and their caregivers who were either leaving the hospital for an SNF or newly arrived in an SNF from the hospital to understand if cognitive biases were present and how they manifested themselves in a real-world clinical context.19 These interviews were part of a larger qualitative study that sought to understand how clinicians, patients, and their caregivers made decisions about postacute care, particularly related to SNFs.13,14 This study represents the analysis of all our interviews, specifically examining decision-making bias. Participating sites, clinical roles, and both patient and caregiver characteristics (Table 1) in our cohort have been previously described.13,14

Analysis

We used a team-based approach to framework analysis, which has been used in other decision-making studies14, including those measuring cognitive bias.20 A limitation in cognitive bias research is the lack of a standardized list or categorization of cognitive biases. We reviewed prior systematic17,21 and narrative reviews18,22, as well as prior studies describing examples of cognitive biases playing a role in decision-making about therapy20 to construct a list of possible cognitive biases to evaluate and narrow these a priori to potential biases relevant to the decision about postacute care based on our prior work (Table 2).

We applied this framework to analyze transcripts through an iterative process of deductive coding and reviewing across four reviewers (ML, RA, AL, CL) and a hospitalist physician with expertise leading qualitative studies (REB).

Intercoder consensus was built through team discussion by resolving points of disagreement.23 Consistency of coding was regularly checked by having more than one investigator code individual manuscripts and comparing coding, and discrepancies were resolved through team discussion. We triangulated the data (shared our preliminary results) using a larger study team, including an expert in behavioral economics (SRG), physicians at study sites (EC, RA), and an anthropologist with expertise in qualitative methods (CL). We did this to ensure credibility (to what extent the findings are credible or believable) and confirmability of findings (ensuring the findings are based on participant narratives rather than researcher biases).

RESULTS

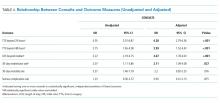

We reviewed a total of 105 interviews with 25 hospital clinicians, 20 SNF clinicians, 21 patients and 14 caregivers in the hospital, and 15 patients and 10 caregivers in the SNF setting (Table 1). We found authority bias/halo effect; default/status quo bias, anchoring bias, and framing was commonly present in decision-making about postacute care in a SNF, whereas there were few if any examples of ambiguity aversion, availability heuristic, confirmation bias, optimism bias, or false consensus effect (Table 2).

Authority Bias/Halo Effect

While most patients deferred to their inpatient teams when it came to decision-making, this effect seemed to differ across VA and non-VA settings. Veterans expressed a higher degree of potential authority bias regarding the VA as an institution, whereas older adults in non-VA settings saw physicians as the authority figure making decisions in their best interests.

Veterans expressed confidence in the VA regarding both whether to go to a SNF and where to go:

“The VA wouldn’t license [an SNF] if they didn’t have a good reputation for care, cleanliness, things of that nature” (Veteran, VA CLC)

“I just knew the VA would have my best interests at heart” (Veteran, VA CLC)

Their caregivers expressed similar confidence:

“I’m not gonna decide [on whether the patient they care for goes to postacute care], like I told you, that’s totally up to the VA. I have trust and faith in them…so wherever they send him, that’s where he’s going” (Caregiver, VA hospital)

In some cases, this perspective was closer to the halo effect: a positive experience with the care provider or the care team led the decision-makers to believe that their recommendations about postacute care would be similarly positive.

“I think we were very trusting in the sense that whatever happened the last time around, he survived it…they took care of him…he got back home, and he started his life again, you know, so why would we question what they’re telling us to do? (Caregiver, VA hospital)

In contrast to Veterans, non-Veteran patients seemed to experience authority bias when it came to the inpatient team.

“Well, I’d like to know more about the PTs [Physical Therapists] there, but I assume since they were recommended, they will be good.” (Patient, University hospital)

This perspective was especially apparent when it came to physicians:

“The level of trust that they [patients] put in their doctor is gonna outweigh what anyone else would say.” (Clinical liaison, SNF)

“[In response to a question about influences on the decision to go to rehab] I don’t…that’s not my decision to make, that’s the doctor’s decision.” (Patient, University hospital)

“They said so…[the doctor] said I needed to go to rehab, so I guess I do because it’s the doctor’s decision.” (Patient, University hospital)

Default/Status quo Bias

In a related way, patients and caregivers with exposure to a SNF seemed to default to the same SNF with which they had previous experience. This bias seems to be primarily related to knowing what to expect.

“He thinks it’s [a particular SNF] the right place for him now…he was there before and he knew, again, it was the right place for him to be” (Caregiver, VA hospital)

“It’s the only one I’ve ever been in…but they have a lot of activities; you have a lot of freedom, staff was good” (Patient, VA hospital)

“I’ve been [to this SNF] before and I kind of know what the program involves…so it was kind of like going home, not, going home is the wrong way to put it…I mean coming here is like something I know, you know, I didn’t need anybody to explain it to me.” (Patient, VA hospital)

“Anybody that’s been to [SNF], that would be their choice to go back to, and I guess I must’ve liked it that first time because I asked to go back again.” (Patient, University hospital)

Anchoring Bias

While anchoring bias was less frequent, it came up in two domains: first, related to costs of care, and second, related to facility characteristics. Costs came up most frequently for Veterans who preferred to move their care to the VA for cost reasons, which appeared in these cases to overshadow other considerations:

“I kept emphasizing that the VA could do all the same things at a lot more reasonable price. The whole purpose of having the VA is for the Veteran, so that…we can get the healthcare that we need at a more reasonable [sic] or a reasonable price.” (Veteran, CLC)

“I think the CLC [VA SNF] is going to take care of her probably the same way any other facility of its type would, unless she were in a private facility, but you know, that costs a lot more money.” (Caregiver, VA hospital)

Patients occasionally had striking responses to particular characteristics of SNFs, regardless of whether this was a central feature or related to their rehabilitation:

“The social worker comes and talks to me about the nursing home where cats are running around, you know, to infect my leg or spin their little cat hairs into my lungs and make my asthma worse…I’m going to have to beg the nurses or the aides or the family or somebody to clean the cat…” (Veteran, VA hospital)

Framing

Framing was the strongest theme among clinician interviews in our sample. Clinicians most frequently described the SNF as a place where patients could recover function (a positive frame), explaining risks (eg, rehospitalization) associated with alternative postacute care options besides the SNF in great detail.

“Aside from explaining the benefits of going and…having that 24-hour care, having the therapies provided to them [the patients], talking about them getting stronger, phrasing it in such a way that patients sometimes are more agreeable, like not calling it a skilled nursing facility, calling it a rehab you know, for them to get physically stronger so they can be the most independent that they can once they do go home, and also explaining … we think that this would be the best plan to prevent them from coming back to the hospital, so those are some of the things that we’ll mention to patients to try and educate them and get them to be agreeable for placement.” (Social worker, University hospital)

Clinicians avoided negative associations with “nursing home” (even though all SNFs are nursing homes) and tended to use more positive frames such as “rehabilitation facility.”

“Use the word rehab….we definitely use the word rehab, to get more therapy, to go home; it’s not a, we really emphasize it’s not a nursing home, it’s not to go to stay forever.” (Physical therapist, safety-net hospital)

Clinicians used a frame of “safety” when discussing the SNF and used a frame of “risk” when discussing alternative postacute care options such as returning home. We did not find examples of clinicians discussing similar risks in going to a SNF even for risks, such as falling, which exist in both settings.

“I’ve talked to them primarily on an avenue of safety because I think people want and they value independence, they value making sure they can get home, but you know, a lot of the times they understand safety is, it can be a concern and outlining that our goal is to make sure that they’re safe and they stay home, and I tend to broach the subject saying that our therapists believe that they might not be safe at home in the moment, but they have potential goals to be safe later on if we continue therapy. I really highlight safety being the major driver of our discussion.” (Physician, VA hospital)

In some cases, framing was so overt that other risk-mitigating options (eg, home healthcare) are not discussed.

“I definitely tend to explain the ideal first. I’m not going to bring up home care when we really think somebody should go to rehab, however, once people say I don’t want to do that, I’m not going, then that’s when I’m like OK, well, let’s talk to the doctors, but we can see about other supports in the home.” (Social worker, VA hospital)

DISCUSSION

In a large sample of patients and their caregivers, as well as multidisciplinary clinicians at three different hospitals and three SNFs, we found authority bias/halo effect and framing biases were most common and seemed most impactful. Default/status quo bias and anchoring bias were also present in decision-making about a SNF. The combination of authority bias/halo effect and framing biases could synergistically interact to augment the likelihood of patients accepting a SNF for postacute care. Patients who had been to a SNF before seemed more likely to choose the SNF they had experienced previously even if they had no other postacute care experiences, and could be highly influenced by isolated characteristics of that facility (such as the physical environment or cost of care).

It is important to mention that cognitive biases do not necessarily have a negative impact: indeed, as Kahneman and Tversky point out, these are useful heuristics from “fast” thinking that are often effective.24 For example, clinicians may be trying to act in the best interests of the patient when framing the decision in terms of regaining function and averting loss of safety and independence. However, the evidence base regarding the outcomes of an SNF versus other postacute options is not robust, and this decision-making is complex. While this decision was most commonly framed in terms of rehabilitation and returning home, the fact that only about half of patients have returned to the community by 100 days4 was not discussed in any interview. In fact, initial evidence suggests replacing the SNF with home healthcare in patients with hip and knee arthroplasty may reduce costs without worsening clinical outcomes.6 However, across a broader population, SNFs significantly reduce 30-day readmissions when directly compared with home healthcare, but other clinical outcomes are similar.25 This evidence suggests that the “right” postacute care option for an individual patient is not clear, highlighting a key role biases may play in decision-making. Further, the nebulous concept of “safety” could introduce potential disparities related to social determinants of health.12 The observed inclination to accept an SNF with which the individual had prior experience may be influenced by the acceptability of this choice because of personal factors or prior research, even if it also represents a bias by limiting the consideration of current alternatives.

Our findings complement those of others in the literature which have also identified profound gaps in discharge decision-making among patients and clinicians,13-16,26-31 though to our knowledge the role of cognitive biases in these decisions has not been explored. This study also addresses gaps in the cognitive bias literature, including the need for real-world data rather than hypothetical vignettes,17 and evaluation of treatment and management decisions rather than diagnoses, which have been more commonly studied.21