User login

Human frailty is a cash cow

Doctor, if you are caring for patients with diabetes, I sure hope you know more about it than I do. The longer I live, it seems, the less I understand.

In a free society, people can do what they want, and that’s great except when it isn’t. That’s why societies develop ethics and even public laws if ethics are not strong enough to protect us from ourselves and others.

Sugar, sugar

When I was growing up in small-town Alabama during the Depression and World War II, we called it sugar diabetes. Eat too much sugar, you got fat; your blood sugar went up, and you spilled sugar into your urine. Diabetes was fairly rare, and so was obesity. Doctors treated it by limiting the intake of sugar (and various sweet foods), along with attempting weight loss. If that didn’t do the trick, insulin injections.

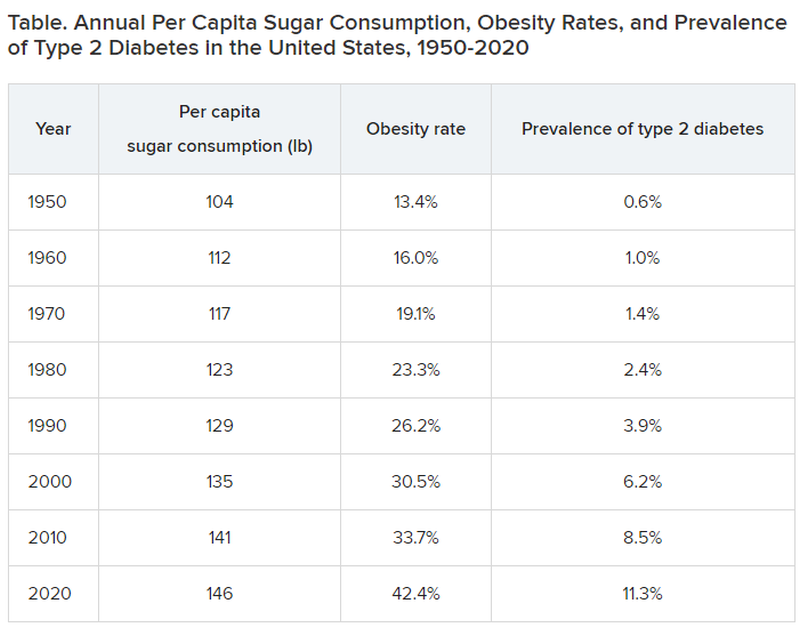

From then until now, note these trends.

Type 2 diabetes was diagnosed even more infrequently before 1950:

- 1920: 0.2% of the population

- 1930: 0.3% of the population

- 1940: 0.4% of the population

In 2020, although 11.3% of the population was diagnosed with type 2 diabetes, the unknown undiagnosed proportion could be much higher.

Notice a correlation between sugar consumption and prevalence of diabetes? Of course, correlation is not causation, but at the same time, it sure as hell is not negation. Such concordance can be considered hypothesis generating. It may not be true causation, but it’s a good bet when 89% of people with diabetes have overweight or obesity.

What did the entire medical, public health, government, agriculture, nursing, food manufacturing, marketing, advertising, restaurant, and education constituencies do about this as it was happening? They observed, documented, gave lip service, and wrung their hands in public a bit. I do not believe that this is an organized active conspiracy; it would take too many players cooperating over too long a period of time. But it certainly may be a passive conspiracy, and primary care physicians and their patients are trapped.

The proper daily practice of medicine consists of one patient, one physician, one moment, and one decision. Let it be a shared decision, informed by the best evidence and taking cost into consideration. That encounter represents an opportunity, a responsibility, and a conundrum.

Individual health is subsumed under the collective health of the public. As such, a patient’s health is out of the control of both physician and patient; instead, patients are the beneficiaries or victims of the “marketplace.” Humans are frail and easily taken advantage of by the brilliant and highly motivated strategic planning and execution of Big Agriculture, Big Food, Big Pharma, Big Marketing, and Big Money-Driven Medicine and generally failed by Big Government, Big Public Health, Big Education, Big Psychology, and Big Religion.

Rethinking diabetes

Consider diabetes as one of many examples. What a terrific deal for capitalism. then it discovers (invents) long-term, very expensive, compelling treatments to slim us down, with no end in sight, and still without ever understanding the true nature of diabetes.

Gary Taubes’s great new book, “Rethinking Diabetes: What Science Reveals About Diet, Insulin, and Successful Treatments,” is being published by Alfred A. Knopf in early 2024.

It is 404 pages of (dense) text, with 401 numbered references and footnotes, a bibliography of 790 references, alphabetically arranged for easy cross-checking, and a 25-page index.

Remember Mr. Taubes’s earlier definitive historical treatises: “Good Calories, Bad Calories” (2007), “Why We Get Fat” (2010), “The Case Against Sugar” (2016), and “The Case for Keto” (2020)?

This new book is more like “Good Calories, Bad Calories”: long, dense, detailed, definitive, and of great historical reference value, including original research information from other countries in other languages. The author told me that the many early research reference sources were available only in German and that his use of generative artificial intelligence as an assistant researcher was of great value.

Nonphysician author Mr. Taubes uses his deep understanding of science and history to inform his long-honed talents of impartial investigative journalism as he attempts to understand and then explain why after all these years, the medical scientific community still does not have a sound consensus about the essence of diabetes, diet, insulin, and proper prevention and treatment at a level that is actually effective – amazing and so sad.

To signal these evolved and evolving conflicts, the book includes the following chapters:

- “Rise of the Carbohydrate-Rich and Very-Low-Carbohydrate Diets”

- “The Fear of Fat and High-Fat Diets”

- “Insulin and The End of Carbohydrate Restriction and Low Blood Sugar”

Yes, it is difficult. Imagine the bookend segments: “The Nature of Medical Knowledge” and “The Conflicts of Evidence-Based Medicine.” There is also a detailed discussion of good versus bad science spanning three long chapters.

If all that reads like a greatly confused mess to you then you’re beginning to understand. If you are a fan of an unbiased explication of the evolution of understanding the ins and outs of scientific history in richly documented detail, this is a book for you. It’s not a quick nor easy read. And don’t expect to discover whether the newest wonder drugs for weight loss and control of diabetes will be the long-term solution for people with obesity and diabetes worldwide.

Obesity and overweight are major risk factors for type 2 diabetes. About 90% of patients with diabetes have either overweight or obesity. Thus, the complications of these two conditions, which largely overlap, include atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease; myocardial infarction; stroke; hypertension; metabolic syndrome; lower-extremity gangrene; chronic kidney disease; retinopathy; glaucoma; cataracts; disabling osteoarthritis; breast, endometrial, colon, and other cancers; fatty liver; sleep apnea; and peripheral neuropathy. These diseases create a major lucrative business for a wide swathe of medical and surgical specialties, plus hospital, clinic, device, pharmaceutical, and food industries.

In summary, we’ve just been through 40 years of failure to recognize the sugar-elephant in the room and intervene with serious preventive efforts. Forty years of fleshing out both the populace and the American medical-industrial complex (AMIC). Talk about a sweet spot. The only successful long-term treatment of obesity (and with it, diabetes) is prevention. Don’t emphasize losing weight. Focus on preventing excessive weight gain, right now, for the population, beginning with yourselves. Otherwise, we continue openly to perpetuate a terrific deal for the AMIC, a travesty for everyone else. Time for some industrial grade penance and a course correction.

Meanwhile, here we are living out Big Pharma’s dream of a big populace, produced by the agriculture and food industries, enjoyed by capitalism after failures of education, medicine, and public health: a seemingly endless supply of people living with big complications who are ready for big (expensive, new) medications to fix the world’s big health problems.

Dr. Lundberg is editor in chief, Cancer Commons. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Doctor, if you are caring for patients with diabetes, I sure hope you know more about it than I do. The longer I live, it seems, the less I understand.

In a free society, people can do what they want, and that’s great except when it isn’t. That’s why societies develop ethics and even public laws if ethics are not strong enough to protect us from ourselves and others.

Sugar, sugar

When I was growing up in small-town Alabama during the Depression and World War II, we called it sugar diabetes. Eat too much sugar, you got fat; your blood sugar went up, and you spilled sugar into your urine. Diabetes was fairly rare, and so was obesity. Doctors treated it by limiting the intake of sugar (and various sweet foods), along with attempting weight loss. If that didn’t do the trick, insulin injections.

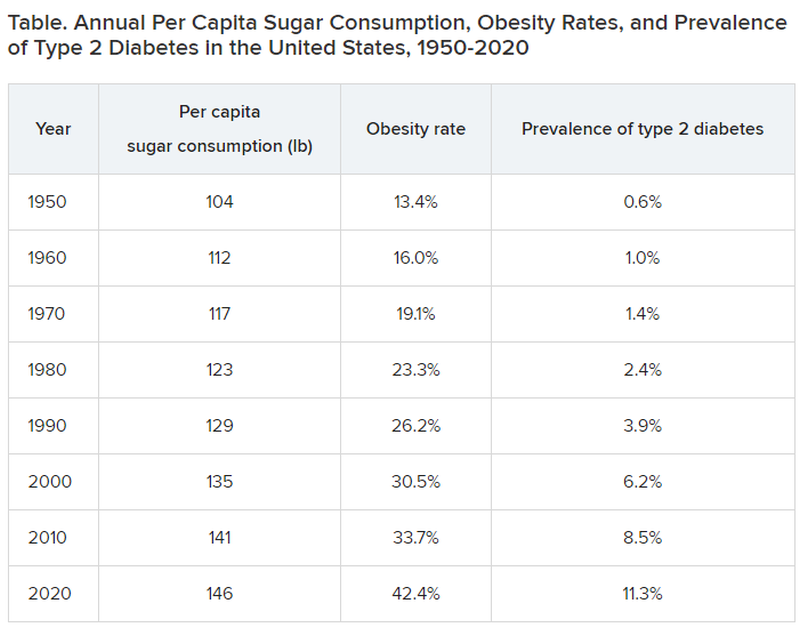

From then until now, note these trends.

Type 2 diabetes was diagnosed even more infrequently before 1950:

- 1920: 0.2% of the population

- 1930: 0.3% of the population

- 1940: 0.4% of the population

In 2020, although 11.3% of the population was diagnosed with type 2 diabetes, the unknown undiagnosed proportion could be much higher.

Notice a correlation between sugar consumption and prevalence of diabetes? Of course, correlation is not causation, but at the same time, it sure as hell is not negation. Such concordance can be considered hypothesis generating. It may not be true causation, but it’s a good bet when 89% of people with diabetes have overweight or obesity.

What did the entire medical, public health, government, agriculture, nursing, food manufacturing, marketing, advertising, restaurant, and education constituencies do about this as it was happening? They observed, documented, gave lip service, and wrung their hands in public a bit. I do not believe that this is an organized active conspiracy; it would take too many players cooperating over too long a period of time. But it certainly may be a passive conspiracy, and primary care physicians and their patients are trapped.

The proper daily practice of medicine consists of one patient, one physician, one moment, and one decision. Let it be a shared decision, informed by the best evidence and taking cost into consideration. That encounter represents an opportunity, a responsibility, and a conundrum.

Individual health is subsumed under the collective health of the public. As such, a patient’s health is out of the control of both physician and patient; instead, patients are the beneficiaries or victims of the “marketplace.” Humans are frail and easily taken advantage of by the brilliant and highly motivated strategic planning and execution of Big Agriculture, Big Food, Big Pharma, Big Marketing, and Big Money-Driven Medicine and generally failed by Big Government, Big Public Health, Big Education, Big Psychology, and Big Religion.

Rethinking diabetes

Consider diabetes as one of many examples. What a terrific deal for capitalism. then it discovers (invents) long-term, very expensive, compelling treatments to slim us down, with no end in sight, and still without ever understanding the true nature of diabetes.

Gary Taubes’s great new book, “Rethinking Diabetes: What Science Reveals About Diet, Insulin, and Successful Treatments,” is being published by Alfred A. Knopf in early 2024.

It is 404 pages of (dense) text, with 401 numbered references and footnotes, a bibliography of 790 references, alphabetically arranged for easy cross-checking, and a 25-page index.

Remember Mr. Taubes’s earlier definitive historical treatises: “Good Calories, Bad Calories” (2007), “Why We Get Fat” (2010), “The Case Against Sugar” (2016), and “The Case for Keto” (2020)?

This new book is more like “Good Calories, Bad Calories”: long, dense, detailed, definitive, and of great historical reference value, including original research information from other countries in other languages. The author told me that the many early research reference sources were available only in German and that his use of generative artificial intelligence as an assistant researcher was of great value.

Nonphysician author Mr. Taubes uses his deep understanding of science and history to inform his long-honed talents of impartial investigative journalism as he attempts to understand and then explain why after all these years, the medical scientific community still does not have a sound consensus about the essence of diabetes, diet, insulin, and proper prevention and treatment at a level that is actually effective – amazing and so sad.

To signal these evolved and evolving conflicts, the book includes the following chapters:

- “Rise of the Carbohydrate-Rich and Very-Low-Carbohydrate Diets”

- “The Fear of Fat and High-Fat Diets”

- “Insulin and The End of Carbohydrate Restriction and Low Blood Sugar”

Yes, it is difficult. Imagine the bookend segments: “The Nature of Medical Knowledge” and “The Conflicts of Evidence-Based Medicine.” There is also a detailed discussion of good versus bad science spanning three long chapters.

If all that reads like a greatly confused mess to you then you’re beginning to understand. If you are a fan of an unbiased explication of the evolution of understanding the ins and outs of scientific history in richly documented detail, this is a book for you. It’s not a quick nor easy read. And don’t expect to discover whether the newest wonder drugs for weight loss and control of diabetes will be the long-term solution for people with obesity and diabetes worldwide.

Obesity and overweight are major risk factors for type 2 diabetes. About 90% of patients with diabetes have either overweight or obesity. Thus, the complications of these two conditions, which largely overlap, include atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease; myocardial infarction; stroke; hypertension; metabolic syndrome; lower-extremity gangrene; chronic kidney disease; retinopathy; glaucoma; cataracts; disabling osteoarthritis; breast, endometrial, colon, and other cancers; fatty liver; sleep apnea; and peripheral neuropathy. These diseases create a major lucrative business for a wide swathe of medical and surgical specialties, plus hospital, clinic, device, pharmaceutical, and food industries.

In summary, we’ve just been through 40 years of failure to recognize the sugar-elephant in the room and intervene with serious preventive efforts. Forty years of fleshing out both the populace and the American medical-industrial complex (AMIC). Talk about a sweet spot. The only successful long-term treatment of obesity (and with it, diabetes) is prevention. Don’t emphasize losing weight. Focus on preventing excessive weight gain, right now, for the population, beginning with yourselves. Otherwise, we continue openly to perpetuate a terrific deal for the AMIC, a travesty for everyone else. Time for some industrial grade penance and a course correction.

Meanwhile, here we are living out Big Pharma’s dream of a big populace, produced by the agriculture and food industries, enjoyed by capitalism after failures of education, medicine, and public health: a seemingly endless supply of people living with big complications who are ready for big (expensive, new) medications to fix the world’s big health problems.

Dr. Lundberg is editor in chief, Cancer Commons. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Doctor, if you are caring for patients with diabetes, I sure hope you know more about it than I do. The longer I live, it seems, the less I understand.

In a free society, people can do what they want, and that’s great except when it isn’t. That’s why societies develop ethics and even public laws if ethics are not strong enough to protect us from ourselves and others.

Sugar, sugar

When I was growing up in small-town Alabama during the Depression and World War II, we called it sugar diabetes. Eat too much sugar, you got fat; your blood sugar went up, and you spilled sugar into your urine. Diabetes was fairly rare, and so was obesity. Doctors treated it by limiting the intake of sugar (and various sweet foods), along with attempting weight loss. If that didn’t do the trick, insulin injections.

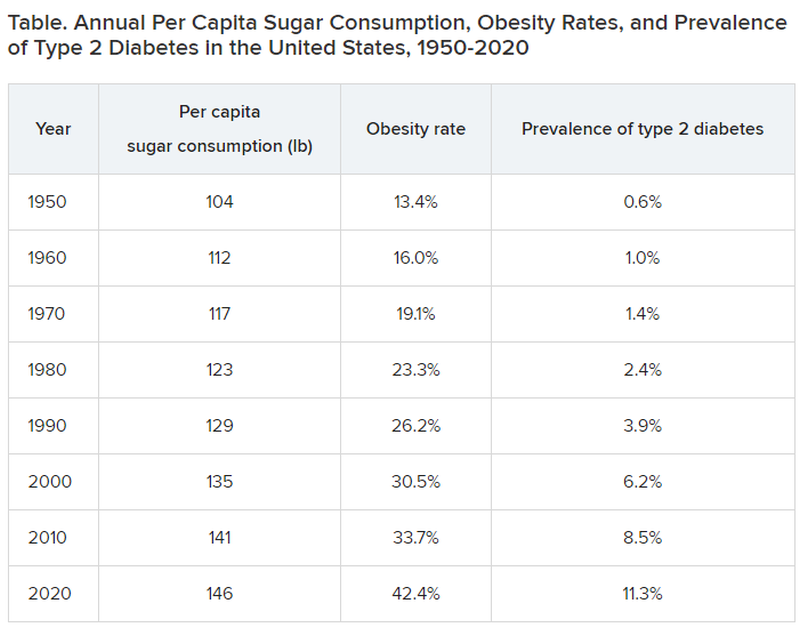

From then until now, note these trends.

Type 2 diabetes was diagnosed even more infrequently before 1950:

- 1920: 0.2% of the population

- 1930: 0.3% of the population

- 1940: 0.4% of the population

In 2020, although 11.3% of the population was diagnosed with type 2 diabetes, the unknown undiagnosed proportion could be much higher.

Notice a correlation between sugar consumption and prevalence of diabetes? Of course, correlation is not causation, but at the same time, it sure as hell is not negation. Such concordance can be considered hypothesis generating. It may not be true causation, but it’s a good bet when 89% of people with diabetes have overweight or obesity.

What did the entire medical, public health, government, agriculture, nursing, food manufacturing, marketing, advertising, restaurant, and education constituencies do about this as it was happening? They observed, documented, gave lip service, and wrung their hands in public a bit. I do not believe that this is an organized active conspiracy; it would take too many players cooperating over too long a period of time. But it certainly may be a passive conspiracy, and primary care physicians and their patients are trapped.

The proper daily practice of medicine consists of one patient, one physician, one moment, and one decision. Let it be a shared decision, informed by the best evidence and taking cost into consideration. That encounter represents an opportunity, a responsibility, and a conundrum.

Individual health is subsumed under the collective health of the public. As such, a patient’s health is out of the control of both physician and patient; instead, patients are the beneficiaries or victims of the “marketplace.” Humans are frail and easily taken advantage of by the brilliant and highly motivated strategic planning and execution of Big Agriculture, Big Food, Big Pharma, Big Marketing, and Big Money-Driven Medicine and generally failed by Big Government, Big Public Health, Big Education, Big Psychology, and Big Religion.

Rethinking diabetes

Consider diabetes as one of many examples. What a terrific deal for capitalism. then it discovers (invents) long-term, very expensive, compelling treatments to slim us down, with no end in sight, and still without ever understanding the true nature of diabetes.

Gary Taubes’s great new book, “Rethinking Diabetes: What Science Reveals About Diet, Insulin, and Successful Treatments,” is being published by Alfred A. Knopf in early 2024.

It is 404 pages of (dense) text, with 401 numbered references and footnotes, a bibliography of 790 references, alphabetically arranged for easy cross-checking, and a 25-page index.

Remember Mr. Taubes’s earlier definitive historical treatises: “Good Calories, Bad Calories” (2007), “Why We Get Fat” (2010), “The Case Against Sugar” (2016), and “The Case for Keto” (2020)?

This new book is more like “Good Calories, Bad Calories”: long, dense, detailed, definitive, and of great historical reference value, including original research information from other countries in other languages. The author told me that the many early research reference sources were available only in German and that his use of generative artificial intelligence as an assistant researcher was of great value.

Nonphysician author Mr. Taubes uses his deep understanding of science and history to inform his long-honed talents of impartial investigative journalism as he attempts to understand and then explain why after all these years, the medical scientific community still does not have a sound consensus about the essence of diabetes, diet, insulin, and proper prevention and treatment at a level that is actually effective – amazing and so sad.

To signal these evolved and evolving conflicts, the book includes the following chapters:

- “Rise of the Carbohydrate-Rich and Very-Low-Carbohydrate Diets”

- “The Fear of Fat and High-Fat Diets”

- “Insulin and The End of Carbohydrate Restriction and Low Blood Sugar”

Yes, it is difficult. Imagine the bookend segments: “The Nature of Medical Knowledge” and “The Conflicts of Evidence-Based Medicine.” There is also a detailed discussion of good versus bad science spanning three long chapters.

If all that reads like a greatly confused mess to you then you’re beginning to understand. If you are a fan of an unbiased explication of the evolution of understanding the ins and outs of scientific history in richly documented detail, this is a book for you. It’s not a quick nor easy read. And don’t expect to discover whether the newest wonder drugs for weight loss and control of diabetes will be the long-term solution for people with obesity and diabetes worldwide.

Obesity and overweight are major risk factors for type 2 diabetes. About 90% of patients with diabetes have either overweight or obesity. Thus, the complications of these two conditions, which largely overlap, include atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease; myocardial infarction; stroke; hypertension; metabolic syndrome; lower-extremity gangrene; chronic kidney disease; retinopathy; glaucoma; cataracts; disabling osteoarthritis; breast, endometrial, colon, and other cancers; fatty liver; sleep apnea; and peripheral neuropathy. These diseases create a major lucrative business for a wide swathe of medical and surgical specialties, plus hospital, clinic, device, pharmaceutical, and food industries.

In summary, we’ve just been through 40 years of failure to recognize the sugar-elephant in the room and intervene with serious preventive efforts. Forty years of fleshing out both the populace and the American medical-industrial complex (AMIC). Talk about a sweet spot. The only successful long-term treatment of obesity (and with it, diabetes) is prevention. Don’t emphasize losing weight. Focus on preventing excessive weight gain, right now, for the population, beginning with yourselves. Otherwise, we continue openly to perpetuate a terrific deal for the AMIC, a travesty for everyone else. Time for some industrial grade penance and a course correction.

Meanwhile, here we are living out Big Pharma’s dream of a big populace, produced by the agriculture and food industries, enjoyed by capitalism after failures of education, medicine, and public health: a seemingly endless supply of people living with big complications who are ready for big (expensive, new) medications to fix the world’s big health problems.

Dr. Lundberg is editor in chief, Cancer Commons. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Mothers in medicine: What can we learn when worlds collide?

Across all industries, studies by the U.S. Department of Labor have shown that women, on average, earn 83.7 percent of what their male peers earn. While a lot has been written about the struggles women face in medicine, there have been decidedly fewer analyses that focus on women who choose to become mothers while working in medicine.

I’ve been privileged to work with medical students and residents for the last 8 years as the director of graduate and medical student mental health at Rowan-Virtua School of Osteopathic Medicine in Mt. Laurel, N.J. Often, the women I see as patients speak about their struggles with the elusive goal of “having it all.” While both men and women in medicine have difficulty maintaining a work-life balance, I’ve learned, both personally and professionally, that many women face a unique set of challenges.

No matter what their professional status, our society often views a woman as the default parent. For example, the teacher often calls the mothers first. The camp nurse calls me first, not my husband, when our child scrapes a knee. After-school play dates are arranged by the mothers, not fathers.

But mothers also bring to medicine a wealth of unique experiences, ideas, and viewpoints. They learn firsthand how to foster affect regulation and frustration tolerance in their kids and become efficient at managing the constant, conflicting tug of war of demands.

Some may argue that, over time, women end up earning significantly less than their male counterparts because they leave the workforce while on maternity leave, ultimately delaying their upward career progression. It’s likely a much more complex problem. Many of my patients believe that, in our male-dominated society (and workforce), women are punished for being aggressive or stating bold opinions, while men are rewarded for the same actions. While a man may sound forceful and in charge, a women will likely be thought of as brusque and unappreciative.

Outside of work, many women may have more on their plate. A 2020 Gallup poll of more than 3,000 heterosexual couples found that women are responsible for the majority of household chores. Women continue to handle more of the emotional labor within their families, regardless of income, age, or professional status. This is sometimes called the “Mental Load’ or “Second Shift.” As our society continues to view women as the default parent for childcare, medical issues, and overarching social and emotional tasks vital to raising happy, healthy children, the struggle a female medical professional feels is palpable.

Raising kids requires a parent to consistently dole out control, predictability, and reassurance for a child to thrive. Good limit and boundary setting leads to healthy development from a young age.

Psychiatric patients (and perhaps all patients) also require control, predictability, and reassurance from their doctor. The lessons learned in being a good mother can be directly applied in patient care, and vice versa. The cross-pollination of this relationship continues to grow more powerful as a woman’s children grow and her career matures.

Pediatrician and psychoanalyst Donald Winnicott’s idea of a “good enough” mother cannot be a one-size-fits-all approach. Women who self-select into the world of medicine often hold themselves to a higher standard than “good enough.” Acknowledging that the demands from both home and work will fluctuate is key to achieving success both personally and professionally, and lessons from home can and should be utilized to become a more effective physician. The notion of having it all, and the definition of success, must evolve over time.

Dr. Maymind is director of medical and graduate student mental health at Rowan-Virtua School of Osteopathic Medicine in Mt. Laurel, N.J. She has no relevant disclosures.

Across all industries, studies by the U.S. Department of Labor have shown that women, on average, earn 83.7 percent of what their male peers earn. While a lot has been written about the struggles women face in medicine, there have been decidedly fewer analyses that focus on women who choose to become mothers while working in medicine.

I’ve been privileged to work with medical students and residents for the last 8 years as the director of graduate and medical student mental health at Rowan-Virtua School of Osteopathic Medicine in Mt. Laurel, N.J. Often, the women I see as patients speak about their struggles with the elusive goal of “having it all.” While both men and women in medicine have difficulty maintaining a work-life balance, I’ve learned, both personally and professionally, that many women face a unique set of challenges.

No matter what their professional status, our society often views a woman as the default parent. For example, the teacher often calls the mothers first. The camp nurse calls me first, not my husband, when our child scrapes a knee. After-school play dates are arranged by the mothers, not fathers.

But mothers also bring to medicine a wealth of unique experiences, ideas, and viewpoints. They learn firsthand how to foster affect regulation and frustration tolerance in their kids and become efficient at managing the constant, conflicting tug of war of demands.

Some may argue that, over time, women end up earning significantly less than their male counterparts because they leave the workforce while on maternity leave, ultimately delaying their upward career progression. It’s likely a much more complex problem. Many of my patients believe that, in our male-dominated society (and workforce), women are punished for being aggressive or stating bold opinions, while men are rewarded for the same actions. While a man may sound forceful and in charge, a women will likely be thought of as brusque and unappreciative.

Outside of work, many women may have more on their plate. A 2020 Gallup poll of more than 3,000 heterosexual couples found that women are responsible for the majority of household chores. Women continue to handle more of the emotional labor within their families, regardless of income, age, or professional status. This is sometimes called the “Mental Load’ or “Second Shift.” As our society continues to view women as the default parent for childcare, medical issues, and overarching social and emotional tasks vital to raising happy, healthy children, the struggle a female medical professional feels is palpable.

Raising kids requires a parent to consistently dole out control, predictability, and reassurance for a child to thrive. Good limit and boundary setting leads to healthy development from a young age.

Psychiatric patients (and perhaps all patients) also require control, predictability, and reassurance from their doctor. The lessons learned in being a good mother can be directly applied in patient care, and vice versa. The cross-pollination of this relationship continues to grow more powerful as a woman’s children grow and her career matures.

Pediatrician and psychoanalyst Donald Winnicott’s idea of a “good enough” mother cannot be a one-size-fits-all approach. Women who self-select into the world of medicine often hold themselves to a higher standard than “good enough.” Acknowledging that the demands from both home and work will fluctuate is key to achieving success both personally and professionally, and lessons from home can and should be utilized to become a more effective physician. The notion of having it all, and the definition of success, must evolve over time.

Dr. Maymind is director of medical and graduate student mental health at Rowan-Virtua School of Osteopathic Medicine in Mt. Laurel, N.J. She has no relevant disclosures.

Across all industries, studies by the U.S. Department of Labor have shown that women, on average, earn 83.7 percent of what their male peers earn. While a lot has been written about the struggles women face in medicine, there have been decidedly fewer analyses that focus on women who choose to become mothers while working in medicine.

I’ve been privileged to work with medical students and residents for the last 8 years as the director of graduate and medical student mental health at Rowan-Virtua School of Osteopathic Medicine in Mt. Laurel, N.J. Often, the women I see as patients speak about their struggles with the elusive goal of “having it all.” While both men and women in medicine have difficulty maintaining a work-life balance, I’ve learned, both personally and professionally, that many women face a unique set of challenges.

No matter what their professional status, our society often views a woman as the default parent. For example, the teacher often calls the mothers first. The camp nurse calls me first, not my husband, when our child scrapes a knee. After-school play dates are arranged by the mothers, not fathers.

But mothers also bring to medicine a wealth of unique experiences, ideas, and viewpoints. They learn firsthand how to foster affect regulation and frustration tolerance in their kids and become efficient at managing the constant, conflicting tug of war of demands.

Some may argue that, over time, women end up earning significantly less than their male counterparts because they leave the workforce while on maternity leave, ultimately delaying their upward career progression. It’s likely a much more complex problem. Many of my patients believe that, in our male-dominated society (and workforce), women are punished for being aggressive or stating bold opinions, while men are rewarded for the same actions. While a man may sound forceful and in charge, a women will likely be thought of as brusque and unappreciative.

Outside of work, many women may have more on their plate. A 2020 Gallup poll of more than 3,000 heterosexual couples found that women are responsible for the majority of household chores. Women continue to handle more of the emotional labor within their families, regardless of income, age, or professional status. This is sometimes called the “Mental Load’ or “Second Shift.” As our society continues to view women as the default parent for childcare, medical issues, and overarching social and emotional tasks vital to raising happy, healthy children, the struggle a female medical professional feels is palpable.

Raising kids requires a parent to consistently dole out control, predictability, and reassurance for a child to thrive. Good limit and boundary setting leads to healthy development from a young age.

Psychiatric patients (and perhaps all patients) also require control, predictability, and reassurance from their doctor. The lessons learned in being a good mother can be directly applied in patient care, and vice versa. The cross-pollination of this relationship continues to grow more powerful as a woman’s children grow and her career matures.

Pediatrician and psychoanalyst Donald Winnicott’s idea of a “good enough” mother cannot be a one-size-fits-all approach. Women who self-select into the world of medicine often hold themselves to a higher standard than “good enough.” Acknowledging that the demands from both home and work will fluctuate is key to achieving success both personally and professionally, and lessons from home can and should be utilized to become a more effective physician. The notion of having it all, and the definition of success, must evolve over time.

Dr. Maymind is director of medical and graduate student mental health at Rowan-Virtua School of Osteopathic Medicine in Mt. Laurel, N.J. She has no relevant disclosures.

Buyer beware

The invitation came to my house, addressed to “residential customer.” It was for my wife and me to attend a free dinner at a swanky local restaurant to learn about “revolutionary” treatments for memory loss. It was presented by a “wellness expert.”

Of course, I just had to check out the website.

The dinner was hosted by an internist pushing an unproven (except for the usual small noncontrolled studies) treatment. Although not stated, I’m sure when you call you’ll find out this is not covered by insurance; not Food and Drug Administration approved to treat, cure, diagnose, prevent any disease; your mileage may vary, etc.

The website was full of testimonials as to how well the treatments worked, primarily from people in their 20s-40s who are, realistically, unlikely to have a pathologically serious cause for memory problems. The site also mentions that you can use it to treat traumatic brain injury, ADHD, learning disorders, obsessive-compulsive disorder, PTSD, Parkinson’s disease, autism, dementia, and stroke, though it does clearly state that such use is not FDA approved.

Prices (I assume all cash pay) for the treatment weren’t listed. I guess you have to come to the “free” dinner for those, or submit an online form to the office.

I’m not going to say the advertised treatment doesn’t work. It might, for at least some of those things. A PubMed search tells me it’s under investigation for several of them.

But that doesn’t mean it works. It might, but a lot of things that look promising in early trials end up failing in the long run. So, at least to me, this is no different than people selling various over-the-counter supplements online with all kinds of extravagant claims and testimonials.

I also have to question a treatment targeting young people for memory loss. In neurology we see a lot of that, and know that true pathology is rare. Most of these patients have root issues with depression, or anxiety, or stress that are affecting their memory. That doesn’t make their memory issues any less real, but they shouldn’t be lumped in with neurodegenerative diseases. They need to be correctly diagnosed and treated for what they are.

Maybe it’s just me, but I often see this sort of thing as kind of sketchy – generating business for unproven treatments by selling fear – you need to do something NOW to keep from getting worse. And, of course there’s always the mysterious “they.” The treatments “they” offer don’t work. Why aren’t “they” telling you what really does?

Looking at the restaurant’s online menu, dinners are around $75 per person and the invitation says “seats are limited.” Doing some mental math gives you an idea how many diners need to come, what percentage of them need to sign up for the treatment, and how much it costs to recoup the investment.

Let the buyer beware.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

The invitation came to my house, addressed to “residential customer.” It was for my wife and me to attend a free dinner at a swanky local restaurant to learn about “revolutionary” treatments for memory loss. It was presented by a “wellness expert.”

Of course, I just had to check out the website.

The dinner was hosted by an internist pushing an unproven (except for the usual small noncontrolled studies) treatment. Although not stated, I’m sure when you call you’ll find out this is not covered by insurance; not Food and Drug Administration approved to treat, cure, diagnose, prevent any disease; your mileage may vary, etc.

The website was full of testimonials as to how well the treatments worked, primarily from people in their 20s-40s who are, realistically, unlikely to have a pathologically serious cause for memory problems. The site also mentions that you can use it to treat traumatic brain injury, ADHD, learning disorders, obsessive-compulsive disorder, PTSD, Parkinson’s disease, autism, dementia, and stroke, though it does clearly state that such use is not FDA approved.

Prices (I assume all cash pay) for the treatment weren’t listed. I guess you have to come to the “free” dinner for those, or submit an online form to the office.

I’m not going to say the advertised treatment doesn’t work. It might, for at least some of those things. A PubMed search tells me it’s under investigation for several of them.

But that doesn’t mean it works. It might, but a lot of things that look promising in early trials end up failing in the long run. So, at least to me, this is no different than people selling various over-the-counter supplements online with all kinds of extravagant claims and testimonials.

I also have to question a treatment targeting young people for memory loss. In neurology we see a lot of that, and know that true pathology is rare. Most of these patients have root issues with depression, or anxiety, or stress that are affecting their memory. That doesn’t make their memory issues any less real, but they shouldn’t be lumped in with neurodegenerative diseases. They need to be correctly diagnosed and treated for what they are.

Maybe it’s just me, but I often see this sort of thing as kind of sketchy – generating business for unproven treatments by selling fear – you need to do something NOW to keep from getting worse. And, of course there’s always the mysterious “they.” The treatments “they” offer don’t work. Why aren’t “they” telling you what really does?

Looking at the restaurant’s online menu, dinners are around $75 per person and the invitation says “seats are limited.” Doing some mental math gives you an idea how many diners need to come, what percentage of them need to sign up for the treatment, and how much it costs to recoup the investment.

Let the buyer beware.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

The invitation came to my house, addressed to “residential customer.” It was for my wife and me to attend a free dinner at a swanky local restaurant to learn about “revolutionary” treatments for memory loss. It was presented by a “wellness expert.”

Of course, I just had to check out the website.

The dinner was hosted by an internist pushing an unproven (except for the usual small noncontrolled studies) treatment. Although not stated, I’m sure when you call you’ll find out this is not covered by insurance; not Food and Drug Administration approved to treat, cure, diagnose, prevent any disease; your mileage may vary, etc.

The website was full of testimonials as to how well the treatments worked, primarily from people in their 20s-40s who are, realistically, unlikely to have a pathologically serious cause for memory problems. The site also mentions that you can use it to treat traumatic brain injury, ADHD, learning disorders, obsessive-compulsive disorder, PTSD, Parkinson’s disease, autism, dementia, and stroke, though it does clearly state that such use is not FDA approved.

Prices (I assume all cash pay) for the treatment weren’t listed. I guess you have to come to the “free” dinner for those, or submit an online form to the office.

I’m not going to say the advertised treatment doesn’t work. It might, for at least some of those things. A PubMed search tells me it’s under investigation for several of them.

But that doesn’t mean it works. It might, but a lot of things that look promising in early trials end up failing in the long run. So, at least to me, this is no different than people selling various over-the-counter supplements online with all kinds of extravagant claims and testimonials.

I also have to question a treatment targeting young people for memory loss. In neurology we see a lot of that, and know that true pathology is rare. Most of these patients have root issues with depression, or anxiety, or stress that are affecting their memory. That doesn’t make their memory issues any less real, but they shouldn’t be lumped in with neurodegenerative diseases. They need to be correctly diagnosed and treated for what they are.

Maybe it’s just me, but I often see this sort of thing as kind of sketchy – generating business for unproven treatments by selling fear – you need to do something NOW to keep from getting worse. And, of course there’s always the mysterious “they.” The treatments “they” offer don’t work. Why aren’t “they” telling you what really does?

Looking at the restaurant’s online menu, dinners are around $75 per person and the invitation says “seats are limited.” Doing some mental math gives you an idea how many diners need to come, what percentage of them need to sign up for the treatment, and how much it costs to recoup the investment.

Let the buyer beware.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

The three pillars of perinatal care: Babies, parents, dyadic relationships

Perinatal depression (PND) is the most common obstetric complication in the United States. Even when screening results are positive, mothers often do not receive further evaluation, and even when PND is diagnosed, mothers do not receive evidence-based treatments.

Meta-analytic estimates show that pregnant women suffer from PND at rates from 6.5% to 12.9% across pregnancy to 3-months post partum.1 Women from low-income families and adolescent mothers are at highest risk, where rates are double and triple respectively.

Fathers also suffer from PND, with a prevalence rate from 2% to 25%, increasing to 50% when the mother experiences PND.

The American Academy of Pediatrics issued a Policy Statement (January 2019) about the need to recognize and manage PND. They recommended that pediatric medical homes establish a system to implement the screening of mothers at the 1-, 2-, 4-, and 6-month well-child visits, to use community resources for the treatment and referral of the mother with depression, and to provide support for the maternal-child relationship.2

The American Academy of Pediatrics also recommends advocacy for workforce development for mental health professionals who care for young children and mother-infant dyads, and for promotion of evidence-based interventions focused on healthy attachment and parent-child relationships.

Family research

There is a bidirectional association between family relational stress and PND. Lack of family support is both a predictor and a consequence of perinatal depression. Frequent arguments, conflict because one or both partners did not want the pregnancy, division of labor, poor support following stressful life events, lack of partner availability, and low intimacy are associated with increased perinatal depressive symptoms.

Gender role stress is also included as a risk factor. For example, men may fear performance failure related to work and sex, and women may fear disruption in the couple relationship due to the introduction of a child.

When depressed and nondepressed women at 2 months post delivery were compared, the women with depressive symptoms perceived that their partners did not share similar interests, provided little companionship, expressed disinterest in infant care, did not provide a feeling of connection, did not encourage them to get assistance to cope with difficulties, and expressed disagreement in infant care.3

A high-quality intimate relationship is protective for many illnesses and PND is no exception.4

Assessment

Despite the availability of effective treatments, perinatal mental health utilization rates are strikingly low. There are limited providers and a general lack of awareness of the need for this care. The stigma for assessing and treating PND is high because the perception is that pregnancy is supposed to be a joyous time and with time, PND will pass.

The first step is a timely and accurate assessment of the mother, which should, if possible, include the father and other family support people. The preferred standard for women is the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS), a checklist of 10 items (listed below) with a maximum score of 30, and any score over 10 warrants further assessment.5 This scale is used worldwide in obstetric clinics and has been used to identify PND in fathers.

- I have been able to laugh and see the funny side of things.

- I have looked forward with enjoyment to things.

- I have blamed myself unnecessarily when things went wrong.

- I have been anxious or worried for no good reason.

- I have felt scared or panicky for no good reason.

- Things have been getting to me.

- I have been so unhappy that I have had difficulty sleeping.

- I have felt sad or miserable.

- I have been so unhappy that I have been crying.

- The thought of harming myself has occurred to me.

A new ultrabrief tool with only four questions is the Brief Multidimensional Assessment Scale (BMAS), which measures the ability to get things done, emotional support in important relationships, quality of life, and sense of purpose in life. It demonstrates concurrent validity with other measures and discriminates between nonclinical participants and participants from most clinical contexts.6

For those interested in assessing family health, an easy-to-use assessment tool is the 12-item Family Assessment Device (FAD).7

Family therapy interventions

A systematic review and meta-analysis of the current evidence on the usefulness of family therapy interventions in the prevention and treatment of PND identified seven studies.

In these studies, there were statistically significant reductions in depressive symptoms at postintervention in intervention group mothers. Intervention intensity and level of family involvement moderated the impacts of intervention on maternal depression, and there was a trend in improved family functioning in intervention group couples.8

Evidence-based interventions are usually psychoeducational or cognitive-behavioral family therapy models where focused interventions target the following three areas:

- Communication skills related to expectations (including those that pertain to gender roles and the transition to parenthood) and emotional support.

- Conflict management.

- Problem-solving skills related to shared responsibility in infant care and household activities.

Intensive day program for mothers and babies

There is a growing awareness of the effectiveness of specialized mother-baby day hospital programs for women with psychiatric distress during the peripartum period.9

The Women & Infants’ Hospital (WIH) in Providence, R.I., established a mother-baby postpartum depression day program in 2000, adjacent to the obstetrical hospital, the ninth largest obstetrical service in the United States. The day program is integrated with the hospital’s obstetric medicine team and referrals are also accepted from the perinatal practices in the surrounding community. The treatment day includes group, individual, and milieu treatment, as well as consultation with psychiatrists, nutritionists, social workers, lactation specialists and others.

The primary theoretical model utilized by the program is interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT), with essential elements of the program incorporating cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), and experiential strategies (for instance, mindfulness, breathing, progressive muscle relaxation) to improve self-care and relaxation skills. Patient satisfaction surveys collected from 800 women, (54% identified as White) treated at the program between 2007 and 2012 found that women were highly satisfied with the treatment received, noting that the inclusion of the baby in their treatment is a highly valued aspect of care.

A similar program in Minnesota reported that 328 women who consented to participation in research had significant improvements (P < .001) in self-report scales assessing depression, anxiety, and maternal functioning, improving mental health and parenting functioning.10

Lastly, a recent study out of Brussels, on the benefit of a mother-baby day program analyzed patient data from 2015 and 2020. This clinical population of 92 patients (43% identifying as North African) was comparable to the population of the inpatient mother-baby units in terms of psychosocial fragility except that the parents entering the day program had less severe illnesses, more anxiety disorder, and less postpartum psychosis. In the day program, all the babies improved in terms of symptoms and relationships, except for those with significant developmental difficulties.

The dyadic relationship was measured using “levels of adaptation of the parent–child relationship” scale which has four general levels of adjustment, from well-adjusted to troubled or dangerous relationship. Unlike programs in the United States, this program takes children up to 2.5 years old and the assessment period is up to 8 weeks.11

Prevention of mental illness is best achieved by reducing the known determinants of illness. For PND, the research is clear, so why not start at the earliest possible stage, when we know that change is possible? Pushing health care systems to change is not easy, but as the research accumulates and the positive results grow, our arguments become stronger.

Dr. Heru is a psychiatrist in Aurora, Colo. She is editor of “Working With Families in Medical Settings: A Multidisciplinary Guide for Psychiatrists and Other Health Professionals” (New York: Routledge, 2013). She has no conflicts of interest to disclose. Contact Dr. Heru at [email protected].

References

1. Gavin NI et al. Perinatal depression: a systematic review of prevalence and incidence. Obstet Gynecol. 2005 Nov;106(5 Pt 1):1071-83. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000183597.31630.db.

2. Rafferty J et al. Incorporating recognition and management of perinatal depression into pediatric practice. Pediatrics. 2019 Jan;143(1):e20183260. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-3260.

3. Cluxton-Keller F, Bruce ML. Clinical effectiveness of family therapeutic interventions in the prevention and treatment of perinatal depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2018 Jun 14;13(6):e0198730. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0198730.

4. Kumar SA et al. Promoting resilience to depression among couples during pregnancy: The protective functions of intimate relationship satisfaction and self-compassion. Family Process. 2022 May;62(1):387-405. doi: 10.1111/famp.12788.

5. Cox JL et al. Detection of postnatal depression: Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Br J Psychiatry. 1987 Jun;150:782-6. doi: 10.1192/bjp.150.6.782.

6. Keitner GI et al. The Brief Multidimensional Assessment Scale (BMAS): A broad measure of patient well-being. Am J Psychother. 2023 Feb 1;76(2):75-81. doi: 10.1176/appi.psychotherapy.20220032.

7. Boterhoven de Haan KL et al. Reliability and validity of a short version of the general functioning subscale of the McMaster Family Assessment Device. Fam Process. 2015 Mar;54(1):116-23. doi: 10.1111/famp.12113.

8. Cluxton-Keller F, Bruce ML. Clinical effectiveness of family therapeutic interventions in the prevention and treatment of perinatal depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2018 Jun 14;13(6):e0198730. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0198730.

9. Battle CL, Howard MM. A mother-baby psychiatric day hospital: History, rationale, and why perinatal mental health is important for obstetric medicine. Obstet Med. 2014 Jun;7(2):66-70. doi: 10.1177/1753495X13514402.

10. Kim HG et al. Keeping Parent, Child, and Relationship in Mind: Clinical Effectiveness of a Trauma-informed, Multigenerational, Attachment-Based, Mother-Baby Partial Hospital Program in an Urban Safety Net Hospital. Matern Child Health J. 2021 Nov;25(11):1776-86. doi: 10.1007/s10995-021-03221-4.

11. Moureau A et al. A 5 years’ experience of a parent-baby day unit: impact on baby’s development. Front Psychiatry. 2023 June 15;14. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1121894.

Perinatal depression (PND) is the most common obstetric complication in the United States. Even when screening results are positive, mothers often do not receive further evaluation, and even when PND is diagnosed, mothers do not receive evidence-based treatments.

Meta-analytic estimates show that pregnant women suffer from PND at rates from 6.5% to 12.9% across pregnancy to 3-months post partum.1 Women from low-income families and adolescent mothers are at highest risk, where rates are double and triple respectively.

Fathers also suffer from PND, with a prevalence rate from 2% to 25%, increasing to 50% when the mother experiences PND.

The American Academy of Pediatrics issued a Policy Statement (January 2019) about the need to recognize and manage PND. They recommended that pediatric medical homes establish a system to implement the screening of mothers at the 1-, 2-, 4-, and 6-month well-child visits, to use community resources for the treatment and referral of the mother with depression, and to provide support for the maternal-child relationship.2

The American Academy of Pediatrics also recommends advocacy for workforce development for mental health professionals who care for young children and mother-infant dyads, and for promotion of evidence-based interventions focused on healthy attachment and parent-child relationships.

Family research

There is a bidirectional association between family relational stress and PND. Lack of family support is both a predictor and a consequence of perinatal depression. Frequent arguments, conflict because one or both partners did not want the pregnancy, division of labor, poor support following stressful life events, lack of partner availability, and low intimacy are associated with increased perinatal depressive symptoms.

Gender role stress is also included as a risk factor. For example, men may fear performance failure related to work and sex, and women may fear disruption in the couple relationship due to the introduction of a child.

When depressed and nondepressed women at 2 months post delivery were compared, the women with depressive symptoms perceived that their partners did not share similar interests, provided little companionship, expressed disinterest in infant care, did not provide a feeling of connection, did not encourage them to get assistance to cope with difficulties, and expressed disagreement in infant care.3

A high-quality intimate relationship is protective for many illnesses and PND is no exception.4

Assessment

Despite the availability of effective treatments, perinatal mental health utilization rates are strikingly low. There are limited providers and a general lack of awareness of the need for this care. The stigma for assessing and treating PND is high because the perception is that pregnancy is supposed to be a joyous time and with time, PND will pass.

The first step is a timely and accurate assessment of the mother, which should, if possible, include the father and other family support people. The preferred standard for women is the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS), a checklist of 10 items (listed below) with a maximum score of 30, and any score over 10 warrants further assessment.5 This scale is used worldwide in obstetric clinics and has been used to identify PND in fathers.

- I have been able to laugh and see the funny side of things.

- I have looked forward with enjoyment to things.

- I have blamed myself unnecessarily when things went wrong.

- I have been anxious or worried for no good reason.

- I have felt scared or panicky for no good reason.

- Things have been getting to me.

- I have been so unhappy that I have had difficulty sleeping.

- I have felt sad or miserable.

- I have been so unhappy that I have been crying.

- The thought of harming myself has occurred to me.

A new ultrabrief tool with only four questions is the Brief Multidimensional Assessment Scale (BMAS), which measures the ability to get things done, emotional support in important relationships, quality of life, and sense of purpose in life. It demonstrates concurrent validity with other measures and discriminates between nonclinical participants and participants from most clinical contexts.6

For those interested in assessing family health, an easy-to-use assessment tool is the 12-item Family Assessment Device (FAD).7

Family therapy interventions

A systematic review and meta-analysis of the current evidence on the usefulness of family therapy interventions in the prevention and treatment of PND identified seven studies.

In these studies, there were statistically significant reductions in depressive symptoms at postintervention in intervention group mothers. Intervention intensity and level of family involvement moderated the impacts of intervention on maternal depression, and there was a trend in improved family functioning in intervention group couples.8

Evidence-based interventions are usually psychoeducational or cognitive-behavioral family therapy models where focused interventions target the following three areas:

- Communication skills related to expectations (including those that pertain to gender roles and the transition to parenthood) and emotional support.

- Conflict management.

- Problem-solving skills related to shared responsibility in infant care and household activities.

Intensive day program for mothers and babies

There is a growing awareness of the effectiveness of specialized mother-baby day hospital programs for women with psychiatric distress during the peripartum period.9

The Women & Infants’ Hospital (WIH) in Providence, R.I., established a mother-baby postpartum depression day program in 2000, adjacent to the obstetrical hospital, the ninth largest obstetrical service in the United States. The day program is integrated with the hospital’s obstetric medicine team and referrals are also accepted from the perinatal practices in the surrounding community. The treatment day includes group, individual, and milieu treatment, as well as consultation with psychiatrists, nutritionists, social workers, lactation specialists and others.

The primary theoretical model utilized by the program is interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT), with essential elements of the program incorporating cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), and experiential strategies (for instance, mindfulness, breathing, progressive muscle relaxation) to improve self-care and relaxation skills. Patient satisfaction surveys collected from 800 women, (54% identified as White) treated at the program between 2007 and 2012 found that women were highly satisfied with the treatment received, noting that the inclusion of the baby in their treatment is a highly valued aspect of care.

A similar program in Minnesota reported that 328 women who consented to participation in research had significant improvements (P < .001) in self-report scales assessing depression, anxiety, and maternal functioning, improving mental health and parenting functioning.10

Lastly, a recent study out of Brussels, on the benefit of a mother-baby day program analyzed patient data from 2015 and 2020. This clinical population of 92 patients (43% identifying as North African) was comparable to the population of the inpatient mother-baby units in terms of psychosocial fragility except that the parents entering the day program had less severe illnesses, more anxiety disorder, and less postpartum psychosis. In the day program, all the babies improved in terms of symptoms and relationships, except for those with significant developmental difficulties.

The dyadic relationship was measured using “levels of adaptation of the parent–child relationship” scale which has four general levels of adjustment, from well-adjusted to troubled or dangerous relationship. Unlike programs in the United States, this program takes children up to 2.5 years old and the assessment period is up to 8 weeks.11

Prevention of mental illness is best achieved by reducing the known determinants of illness. For PND, the research is clear, so why not start at the earliest possible stage, when we know that change is possible? Pushing health care systems to change is not easy, but as the research accumulates and the positive results grow, our arguments become stronger.

Dr. Heru is a psychiatrist in Aurora, Colo. She is editor of “Working With Families in Medical Settings: A Multidisciplinary Guide for Psychiatrists and Other Health Professionals” (New York: Routledge, 2013). She has no conflicts of interest to disclose. Contact Dr. Heru at [email protected].

References

1. Gavin NI et al. Perinatal depression: a systematic review of prevalence and incidence. Obstet Gynecol. 2005 Nov;106(5 Pt 1):1071-83. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000183597.31630.db.

2. Rafferty J et al. Incorporating recognition and management of perinatal depression into pediatric practice. Pediatrics. 2019 Jan;143(1):e20183260. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-3260.

3. Cluxton-Keller F, Bruce ML. Clinical effectiveness of family therapeutic interventions in the prevention and treatment of perinatal depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2018 Jun 14;13(6):e0198730. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0198730.

4. Kumar SA et al. Promoting resilience to depression among couples during pregnancy: The protective functions of intimate relationship satisfaction and self-compassion. Family Process. 2022 May;62(1):387-405. doi: 10.1111/famp.12788.

5. Cox JL et al. Detection of postnatal depression: Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Br J Psychiatry. 1987 Jun;150:782-6. doi: 10.1192/bjp.150.6.782.

6. Keitner GI et al. The Brief Multidimensional Assessment Scale (BMAS): A broad measure of patient well-being. Am J Psychother. 2023 Feb 1;76(2):75-81. doi: 10.1176/appi.psychotherapy.20220032.

7. Boterhoven de Haan KL et al. Reliability and validity of a short version of the general functioning subscale of the McMaster Family Assessment Device. Fam Process. 2015 Mar;54(1):116-23. doi: 10.1111/famp.12113.

8. Cluxton-Keller F, Bruce ML. Clinical effectiveness of family therapeutic interventions in the prevention and treatment of perinatal depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2018 Jun 14;13(6):e0198730. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0198730.

9. Battle CL, Howard MM. A mother-baby psychiatric day hospital: History, rationale, and why perinatal mental health is important for obstetric medicine. Obstet Med. 2014 Jun;7(2):66-70. doi: 10.1177/1753495X13514402.

10. Kim HG et al. Keeping Parent, Child, and Relationship in Mind: Clinical Effectiveness of a Trauma-informed, Multigenerational, Attachment-Based, Mother-Baby Partial Hospital Program in an Urban Safety Net Hospital. Matern Child Health J. 2021 Nov;25(11):1776-86. doi: 10.1007/s10995-021-03221-4.

11. Moureau A et al. A 5 years’ experience of a parent-baby day unit: impact on baby’s development. Front Psychiatry. 2023 June 15;14. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1121894.

Perinatal depression (PND) is the most common obstetric complication in the United States. Even when screening results are positive, mothers often do not receive further evaluation, and even when PND is diagnosed, mothers do not receive evidence-based treatments.

Meta-analytic estimates show that pregnant women suffer from PND at rates from 6.5% to 12.9% across pregnancy to 3-months post partum.1 Women from low-income families and adolescent mothers are at highest risk, where rates are double and triple respectively.

Fathers also suffer from PND, with a prevalence rate from 2% to 25%, increasing to 50% when the mother experiences PND.

The American Academy of Pediatrics issued a Policy Statement (January 2019) about the need to recognize and manage PND. They recommended that pediatric medical homes establish a system to implement the screening of mothers at the 1-, 2-, 4-, and 6-month well-child visits, to use community resources for the treatment and referral of the mother with depression, and to provide support for the maternal-child relationship.2

The American Academy of Pediatrics also recommends advocacy for workforce development for mental health professionals who care for young children and mother-infant dyads, and for promotion of evidence-based interventions focused on healthy attachment and parent-child relationships.

Family research

There is a bidirectional association between family relational stress and PND. Lack of family support is both a predictor and a consequence of perinatal depression. Frequent arguments, conflict because one or both partners did not want the pregnancy, division of labor, poor support following stressful life events, lack of partner availability, and low intimacy are associated with increased perinatal depressive symptoms.

Gender role stress is also included as a risk factor. For example, men may fear performance failure related to work and sex, and women may fear disruption in the couple relationship due to the introduction of a child.

When depressed and nondepressed women at 2 months post delivery were compared, the women with depressive symptoms perceived that their partners did not share similar interests, provided little companionship, expressed disinterest in infant care, did not provide a feeling of connection, did not encourage them to get assistance to cope with difficulties, and expressed disagreement in infant care.3

A high-quality intimate relationship is protective for many illnesses and PND is no exception.4

Assessment

Despite the availability of effective treatments, perinatal mental health utilization rates are strikingly low. There are limited providers and a general lack of awareness of the need for this care. The stigma for assessing and treating PND is high because the perception is that pregnancy is supposed to be a joyous time and with time, PND will pass.

The first step is a timely and accurate assessment of the mother, which should, if possible, include the father and other family support people. The preferred standard for women is the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS), a checklist of 10 items (listed below) with a maximum score of 30, and any score over 10 warrants further assessment.5 This scale is used worldwide in obstetric clinics and has been used to identify PND in fathers.

- I have been able to laugh and see the funny side of things.

- I have looked forward with enjoyment to things.

- I have blamed myself unnecessarily when things went wrong.

- I have been anxious or worried for no good reason.

- I have felt scared or panicky for no good reason.

- Things have been getting to me.

- I have been so unhappy that I have had difficulty sleeping.

- I have felt sad or miserable.

- I have been so unhappy that I have been crying.

- The thought of harming myself has occurred to me.

A new ultrabrief tool with only four questions is the Brief Multidimensional Assessment Scale (BMAS), which measures the ability to get things done, emotional support in important relationships, quality of life, and sense of purpose in life. It demonstrates concurrent validity with other measures and discriminates between nonclinical participants and participants from most clinical contexts.6

For those interested in assessing family health, an easy-to-use assessment tool is the 12-item Family Assessment Device (FAD).7

Family therapy interventions

A systematic review and meta-analysis of the current evidence on the usefulness of family therapy interventions in the prevention and treatment of PND identified seven studies.

In these studies, there were statistically significant reductions in depressive symptoms at postintervention in intervention group mothers. Intervention intensity and level of family involvement moderated the impacts of intervention on maternal depression, and there was a trend in improved family functioning in intervention group couples.8

Evidence-based interventions are usually psychoeducational or cognitive-behavioral family therapy models where focused interventions target the following three areas:

- Communication skills related to expectations (including those that pertain to gender roles and the transition to parenthood) and emotional support.

- Conflict management.

- Problem-solving skills related to shared responsibility in infant care and household activities.

Intensive day program for mothers and babies

There is a growing awareness of the effectiveness of specialized mother-baby day hospital programs for women with psychiatric distress during the peripartum period.9

The Women & Infants’ Hospital (WIH) in Providence, R.I., established a mother-baby postpartum depression day program in 2000, adjacent to the obstetrical hospital, the ninth largest obstetrical service in the United States. The day program is integrated with the hospital’s obstetric medicine team and referrals are also accepted from the perinatal practices in the surrounding community. The treatment day includes group, individual, and milieu treatment, as well as consultation with psychiatrists, nutritionists, social workers, lactation specialists and others.

The primary theoretical model utilized by the program is interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT), with essential elements of the program incorporating cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), and experiential strategies (for instance, mindfulness, breathing, progressive muscle relaxation) to improve self-care and relaxation skills. Patient satisfaction surveys collected from 800 women, (54% identified as White) treated at the program between 2007 and 2012 found that women were highly satisfied with the treatment received, noting that the inclusion of the baby in their treatment is a highly valued aspect of care.

A similar program in Minnesota reported that 328 women who consented to participation in research had significant improvements (P < .001) in self-report scales assessing depression, anxiety, and maternal functioning, improving mental health and parenting functioning.10

Lastly, a recent study out of Brussels, on the benefit of a mother-baby day program analyzed patient data from 2015 and 2020. This clinical population of 92 patients (43% identifying as North African) was comparable to the population of the inpatient mother-baby units in terms of psychosocial fragility except that the parents entering the day program had less severe illnesses, more anxiety disorder, and less postpartum psychosis. In the day program, all the babies improved in terms of symptoms and relationships, except for those with significant developmental difficulties.

The dyadic relationship was measured using “levels of adaptation of the parent–child relationship” scale which has four general levels of adjustment, from well-adjusted to troubled or dangerous relationship. Unlike programs in the United States, this program takes children up to 2.5 years old and the assessment period is up to 8 weeks.11

Prevention of mental illness is best achieved by reducing the known determinants of illness. For PND, the research is clear, so why not start at the earliest possible stage, when we know that change is possible? Pushing health care systems to change is not easy, but as the research accumulates and the positive results grow, our arguments become stronger.

Dr. Heru is a psychiatrist in Aurora, Colo. She is editor of “Working With Families in Medical Settings: A Multidisciplinary Guide for Psychiatrists and Other Health Professionals” (New York: Routledge, 2013). She has no conflicts of interest to disclose. Contact Dr. Heru at [email protected].

References

1. Gavin NI et al. Perinatal depression: a systematic review of prevalence and incidence. Obstet Gynecol. 2005 Nov;106(5 Pt 1):1071-83. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000183597.31630.db.

2. Rafferty J et al. Incorporating recognition and management of perinatal depression into pediatric practice. Pediatrics. 2019 Jan;143(1):e20183260. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-3260.

3. Cluxton-Keller F, Bruce ML. Clinical effectiveness of family therapeutic interventions in the prevention and treatment of perinatal depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2018 Jun 14;13(6):e0198730. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0198730.

4. Kumar SA et al. Promoting resilience to depression among couples during pregnancy: The protective functions of intimate relationship satisfaction and self-compassion. Family Process. 2022 May;62(1):387-405. doi: 10.1111/famp.12788.

5. Cox JL et al. Detection of postnatal depression: Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Br J Psychiatry. 1987 Jun;150:782-6. doi: 10.1192/bjp.150.6.782.

6. Keitner GI et al. The Brief Multidimensional Assessment Scale (BMAS): A broad measure of patient well-being. Am J Psychother. 2023 Feb 1;76(2):75-81. doi: 10.1176/appi.psychotherapy.20220032.

7. Boterhoven de Haan KL et al. Reliability and validity of a short version of the general functioning subscale of the McMaster Family Assessment Device. Fam Process. 2015 Mar;54(1):116-23. doi: 10.1111/famp.12113.

8. Cluxton-Keller F, Bruce ML. Clinical effectiveness of family therapeutic interventions in the prevention and treatment of perinatal depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2018 Jun 14;13(6):e0198730. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0198730.

9. Battle CL, Howard MM. A mother-baby psychiatric day hospital: History, rationale, and why perinatal mental health is important for obstetric medicine. Obstet Med. 2014 Jun;7(2):66-70. doi: 10.1177/1753495X13514402.

10. Kim HG et al. Keeping Parent, Child, and Relationship in Mind: Clinical Effectiveness of a Trauma-informed, Multigenerational, Attachment-Based, Mother-Baby Partial Hospital Program in an Urban Safety Net Hospital. Matern Child Health J. 2021 Nov;25(11):1776-86. doi: 10.1007/s10995-021-03221-4.

11. Moureau A et al. A 5 years’ experience of a parent-baby day unit: impact on baby’s development. Front Psychiatry. 2023 June 15;14. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1121894.

Morning vs. afternoon exercise debate: A false dichotomy

Should we be exercising in the morning or afternoon? Before a meal or after a meal?

Popular media outlets, researchers, and clinicians seem to love these debates. I hate them. For me, it’s a false dichotomy. A false dichotomy is when people argue two sides as if only one option exists. A winner must be crowned, and a loser exists. But

Some but not all research suggests that morning fasted exercise may be the best time of day and condition to work out for weight control and training adaptations. Morning exercise may be a bit better for logistical reasons if you like to get up early. Some of us are indeed early chronotypes who rise early, get as much done as we can, including all our fitness and work-related activities, and then head to bed early (for me that is about 10 PM). Getting an early morning workout seems to fit with our schedules as morning larks.

But if you are a late-day chronotype, early exercise may not be in sync with your low morning energy levels or your preference for leisure-time activities later in the day. And lots of people with diabetes prefer to eat and then exercise. Late chronotypes are less physically active in general, compared with early chronotypes, and those who train in the morning tend to have better training adherence and expend more energy overall throughout the day. According to Dr. Normand Boulé from the University of Alberta, Edmonton, who presented on the topic of exercise time of day at the recent scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association in San Diego, morning exercise in the fasted state tends to be associated with higher rates of fat oxidation, better weight control, and better skeletal muscle adaptations over time, compared with exercise performed later in the day. Dr Boulé also proposed that fasted exercise might be superior for training adaptations and long-term glycemia if you have type 2 diabetes.

But the argument for morning-only exercise falls short when we look specifically at postmeal glycemia, according to Dr. Jenna Gillen from the University of Toronto, who faced off against Dr. Boulé at a debate at the meeting and also publishes on the topic. She pointed out that mild to moderate intensity exercising done soon after meals typically results in fewer glucose spikes after meals in people with diabetes, and her argument is supported by at least one recent meta-analysis where postmeal walking was best for improving glycemia in those with prediabetes and type 2 diabetes.