User login

Does the current age cutoff for screening miss too many cases of cervical cancer in older women?

Cooley JJ, Maguire FB, Morris CR, et al. Cervical cancer stage at diagnosis and survival among women ≥65 years in California. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2023;32:91-97. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-22-0793.

EXPERT COMMENTARY

Cervical cancer screening guidelines recommend screening cessation at age 65 once specific exit criteria are met. (According to the American Cancer Society, individuals aged >65 years who have no history of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia [CIN] grade 2 or more severe disease within the past 25 years, and who have documented adequate negative prior screening in the prior 10 years, discontinue all cervical cancer screening.)1 We know, however, that about one-fifth of all cervical cancer cases are diagnosed among individuals aged 65 or older, and for Black women that proportion is even higher when data are appropriately adjusted to account for the increased rate of hysterectomy among Black versus White women.2-4

Early-stage cervical cancer is largely a curable disease with very high 5-year overall survival rates. Unfortunately, more than half of all cervical cancer is diagnosed at a more advanced stage, and survival rates are much lower for this population.5

Cervical cancer incidence rates plummeted in the United States after the introduction of the Pap test for cervical cancer screening. However, the percentage of women who are not up to date with cervical cancer screening may now be increasing, from 14% in 2005 to 23% in 2019 according to one study from the US Preventive Services Task Force.6 When looking at cervical cancer screening rates by age, researchers from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimate that the proportion of patients who have not been recently screened goes up as patients get older, with approximately 845,000 American women aged 61 to 65 not adequately screened in 2015 alone.7

Details of the study

Cooley and colleagues sought to better characterize the cohort of women diagnosed with cervical cancer at a later age, specifically the stage at diagnosis and survival.8 They used data from the California Cancer Registry (CCR), a large state-mandated, population-based data repository that is affiliated with the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program.

The researchers identified 12,442 womenin the CCR who were newly diagnosed with cervical cancer from 2009 to 2018, 17.4% of whom were age 65 or older. They looked at cancer stage at diagnosis as it relates to relative survival rate (“the ratio of the observed survival rate among those who have cancer divided by the expected survival rate for people of the same sex, race/ethnicity, and age who do not have cancer”), Charlson comorbidity score, socioeconomic status, health insurance status, urbanicity, and race/ethnicity.

Results. In this study, 71% of women aged 65 or older presented with advanced-stage disease (FIGO [International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics] stage II–IV) as compared with only 48% in those aged 21 to 64. Five-year relative survival rates also were lower in the older cohort—23% to 37%, compared with 42% to 52% in the younger patients. In a sensitivity analysis, late-stage disease was associated with older age, increasing medical comorbidities, and nonadenocarcinoma histology.

Interestingly, older women of Hispanic ethnicity were less likely to be diagnosed with late-stage disease when compared with non-Hispanic White women.

Study strengths and limitations

Although this study’s conclusions—that patients with advanced-stage cancer are more likely to do poorly than those with early-stage cancer—may seem obvious to some even without the proven data, it is still important to highlight what a clinician may intuit with data to support that intuition. It is particularly important to emphasize this risk in older women in light of the aging population in the United States, with adults older than age 65 expected to account for more than 20% of the nation’s population by 2030.9

The study by Cooley and colleagues adds value to the existing literature due to its large study population, which included more than 12,000 patients diagnosed with cervical cancer.8 And although its results may not be completely generalizable as the data were gathered from only a California-specific population, the sample was diverse with significant portions of Hispanic and Black patients. This study supports previous data that showed high rates of advanced cervical cancer in women older than age 65, with resultant worse 5-year relative survival in this population of older women specifically.4 ●

Cervical cancer is both common and deadly in older women. Although current cervical cancer screening guidelines recommend screening cessation after age 65, remember that this is based on strict exit criteria. Consider screening older women (especially with human papillomavirus [HPV] testing) for cervical cancer if they have risk factors (such as smoking, multiple sexual partners, inconsistent or infrequent screening, history of abnormal Pap or HPV tests), and keep cervical cancer on your differential diagnosis in women who present with postmenopausal bleeding, vaginal discharge, pelvic pain, recurrent urinary tract infections, or other concerning symptoms.

SARAH DILLEY, MD, MPH, AND WARNER HUH, MD

- Fontham ETH, Wolf AMD, Church TR, et al. Cervical cancer screening for individuals at average risk: 2020 guideline update from the American Cancer Society. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70:321-346. doi:10.3322/caac.21628.

- Dilley S, Huh W, Blechter B, et al. It’s time to re-evaluate cervical cancer screening after age 65. Gynecol Oncol. 2021;162:200-202. doi:10.1016/j.ygyno.2021.04.027.

- Rositch AF, Nowak RG, Gravitt PE. Increased age and racespecific incidence of cervical cancer after correction for hysterectomy prevalence in the United States from 2000 to 2009. Cancer. 2014;120:2032-2038. doi:10.1002/cncr.28548.

- Beavis AL, Gravitt PE, Rositch AF. Hysterectomy-corrected cervical cancer mortality rates reveal a larger racial disparity in the United States. Cancer. 2017;123:1044-1050. doi:10.1002 /cncr.30507.

- Cancer Stat Facts. National Cancer Institute Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. https://seer.cancer .gov/statfacts/html/cervix.html

- Suk R, Hong YR, Rajan SS, et al. Assessment of US Preventive Services Task Force guideline-concordant cervical cancer screening rates and reasons for underscreening by age, race and ethnicity, sexual orientation, rurality, and insurance, 2005 to 2019. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5:e2143582. doi:10.1001 /jamanetworkopen.2021.43582.

- White MC, Shoemaker ML, Benard VB. Cervical cancer screening and incidence by age: unmet needs near and after the stopping age for screening. Am J Prev Med. 2017;53:392395. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2017.02.024.

- Cooley JJ, Maguire FB, Morris CR, et al. Cervical cancer stage at diagnosis and survival among women ≥65 years in California. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2023;32:91-97. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-22-0793.

- Ortman JM, Velkoff VA, Hogan H. An aging nation: the older population in the United States. May 2014. United States Census Bureau. Accessed April 12, 2023. https://www.census .gov/library/publications/2014/demo/p25-1140.html

Cooley JJ, Maguire FB, Morris CR, et al. Cervical cancer stage at diagnosis and survival among women ≥65 years in California. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2023;32:91-97. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-22-0793.

EXPERT COMMENTARY

Cervical cancer screening guidelines recommend screening cessation at age 65 once specific exit criteria are met. (According to the American Cancer Society, individuals aged >65 years who have no history of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia [CIN] grade 2 or more severe disease within the past 25 years, and who have documented adequate negative prior screening in the prior 10 years, discontinue all cervical cancer screening.)1 We know, however, that about one-fifth of all cervical cancer cases are diagnosed among individuals aged 65 or older, and for Black women that proportion is even higher when data are appropriately adjusted to account for the increased rate of hysterectomy among Black versus White women.2-4

Early-stage cervical cancer is largely a curable disease with very high 5-year overall survival rates. Unfortunately, more than half of all cervical cancer is diagnosed at a more advanced stage, and survival rates are much lower for this population.5

Cervical cancer incidence rates plummeted in the United States after the introduction of the Pap test for cervical cancer screening. However, the percentage of women who are not up to date with cervical cancer screening may now be increasing, from 14% in 2005 to 23% in 2019 according to one study from the US Preventive Services Task Force.6 When looking at cervical cancer screening rates by age, researchers from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimate that the proportion of patients who have not been recently screened goes up as patients get older, with approximately 845,000 American women aged 61 to 65 not adequately screened in 2015 alone.7

Details of the study

Cooley and colleagues sought to better characterize the cohort of women diagnosed with cervical cancer at a later age, specifically the stage at diagnosis and survival.8 They used data from the California Cancer Registry (CCR), a large state-mandated, population-based data repository that is affiliated with the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program.

The researchers identified 12,442 womenin the CCR who were newly diagnosed with cervical cancer from 2009 to 2018, 17.4% of whom were age 65 or older. They looked at cancer stage at diagnosis as it relates to relative survival rate (“the ratio of the observed survival rate among those who have cancer divided by the expected survival rate for people of the same sex, race/ethnicity, and age who do not have cancer”), Charlson comorbidity score, socioeconomic status, health insurance status, urbanicity, and race/ethnicity.

Results. In this study, 71% of women aged 65 or older presented with advanced-stage disease (FIGO [International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics] stage II–IV) as compared with only 48% in those aged 21 to 64. Five-year relative survival rates also were lower in the older cohort—23% to 37%, compared with 42% to 52% in the younger patients. In a sensitivity analysis, late-stage disease was associated with older age, increasing medical comorbidities, and nonadenocarcinoma histology.

Interestingly, older women of Hispanic ethnicity were less likely to be diagnosed with late-stage disease when compared with non-Hispanic White women.

Study strengths and limitations

Although this study’s conclusions—that patients with advanced-stage cancer are more likely to do poorly than those with early-stage cancer—may seem obvious to some even without the proven data, it is still important to highlight what a clinician may intuit with data to support that intuition. It is particularly important to emphasize this risk in older women in light of the aging population in the United States, with adults older than age 65 expected to account for more than 20% of the nation’s population by 2030.9

The study by Cooley and colleagues adds value to the existing literature due to its large study population, which included more than 12,000 patients diagnosed with cervical cancer.8 And although its results may not be completely generalizable as the data were gathered from only a California-specific population, the sample was diverse with significant portions of Hispanic and Black patients. This study supports previous data that showed high rates of advanced cervical cancer in women older than age 65, with resultant worse 5-year relative survival in this population of older women specifically.4 ●

Cervical cancer is both common and deadly in older women. Although current cervical cancer screening guidelines recommend screening cessation after age 65, remember that this is based on strict exit criteria. Consider screening older women (especially with human papillomavirus [HPV] testing) for cervical cancer if they have risk factors (such as smoking, multiple sexual partners, inconsistent or infrequent screening, history of abnormal Pap or HPV tests), and keep cervical cancer on your differential diagnosis in women who present with postmenopausal bleeding, vaginal discharge, pelvic pain, recurrent urinary tract infections, or other concerning symptoms.

SARAH DILLEY, MD, MPH, AND WARNER HUH, MD

Cooley JJ, Maguire FB, Morris CR, et al. Cervical cancer stage at diagnosis and survival among women ≥65 years in California. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2023;32:91-97. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-22-0793.

EXPERT COMMENTARY

Cervical cancer screening guidelines recommend screening cessation at age 65 once specific exit criteria are met. (According to the American Cancer Society, individuals aged >65 years who have no history of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia [CIN] grade 2 or more severe disease within the past 25 years, and who have documented adequate negative prior screening in the prior 10 years, discontinue all cervical cancer screening.)1 We know, however, that about one-fifth of all cervical cancer cases are diagnosed among individuals aged 65 or older, and for Black women that proportion is even higher when data are appropriately adjusted to account for the increased rate of hysterectomy among Black versus White women.2-4

Early-stage cervical cancer is largely a curable disease with very high 5-year overall survival rates. Unfortunately, more than half of all cervical cancer is diagnosed at a more advanced stage, and survival rates are much lower for this population.5

Cervical cancer incidence rates plummeted in the United States after the introduction of the Pap test for cervical cancer screening. However, the percentage of women who are not up to date with cervical cancer screening may now be increasing, from 14% in 2005 to 23% in 2019 according to one study from the US Preventive Services Task Force.6 When looking at cervical cancer screening rates by age, researchers from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimate that the proportion of patients who have not been recently screened goes up as patients get older, with approximately 845,000 American women aged 61 to 65 not adequately screened in 2015 alone.7

Details of the study

Cooley and colleagues sought to better characterize the cohort of women diagnosed with cervical cancer at a later age, specifically the stage at diagnosis and survival.8 They used data from the California Cancer Registry (CCR), a large state-mandated, population-based data repository that is affiliated with the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program.

The researchers identified 12,442 womenin the CCR who were newly diagnosed with cervical cancer from 2009 to 2018, 17.4% of whom were age 65 or older. They looked at cancer stage at diagnosis as it relates to relative survival rate (“the ratio of the observed survival rate among those who have cancer divided by the expected survival rate for people of the same sex, race/ethnicity, and age who do not have cancer”), Charlson comorbidity score, socioeconomic status, health insurance status, urbanicity, and race/ethnicity.

Results. In this study, 71% of women aged 65 or older presented with advanced-stage disease (FIGO [International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics] stage II–IV) as compared with only 48% in those aged 21 to 64. Five-year relative survival rates also were lower in the older cohort—23% to 37%, compared with 42% to 52% in the younger patients. In a sensitivity analysis, late-stage disease was associated with older age, increasing medical comorbidities, and nonadenocarcinoma histology.

Interestingly, older women of Hispanic ethnicity were less likely to be diagnosed with late-stage disease when compared with non-Hispanic White women.

Study strengths and limitations

Although this study’s conclusions—that patients with advanced-stage cancer are more likely to do poorly than those with early-stage cancer—may seem obvious to some even without the proven data, it is still important to highlight what a clinician may intuit with data to support that intuition. It is particularly important to emphasize this risk in older women in light of the aging population in the United States, with adults older than age 65 expected to account for more than 20% of the nation’s population by 2030.9

The study by Cooley and colleagues adds value to the existing literature due to its large study population, which included more than 12,000 patients diagnosed with cervical cancer.8 And although its results may not be completely generalizable as the data were gathered from only a California-specific population, the sample was diverse with significant portions of Hispanic and Black patients. This study supports previous data that showed high rates of advanced cervical cancer in women older than age 65, with resultant worse 5-year relative survival in this population of older women specifically.4 ●

Cervical cancer is both common and deadly in older women. Although current cervical cancer screening guidelines recommend screening cessation after age 65, remember that this is based on strict exit criteria. Consider screening older women (especially with human papillomavirus [HPV] testing) for cervical cancer if they have risk factors (such as smoking, multiple sexual partners, inconsistent or infrequent screening, history of abnormal Pap or HPV tests), and keep cervical cancer on your differential diagnosis in women who present with postmenopausal bleeding, vaginal discharge, pelvic pain, recurrent urinary tract infections, or other concerning symptoms.

SARAH DILLEY, MD, MPH, AND WARNER HUH, MD

- Fontham ETH, Wolf AMD, Church TR, et al. Cervical cancer screening for individuals at average risk: 2020 guideline update from the American Cancer Society. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70:321-346. doi:10.3322/caac.21628.

- Dilley S, Huh W, Blechter B, et al. It’s time to re-evaluate cervical cancer screening after age 65. Gynecol Oncol. 2021;162:200-202. doi:10.1016/j.ygyno.2021.04.027.

- Rositch AF, Nowak RG, Gravitt PE. Increased age and racespecific incidence of cervical cancer after correction for hysterectomy prevalence in the United States from 2000 to 2009. Cancer. 2014;120:2032-2038. doi:10.1002/cncr.28548.

- Beavis AL, Gravitt PE, Rositch AF. Hysterectomy-corrected cervical cancer mortality rates reveal a larger racial disparity in the United States. Cancer. 2017;123:1044-1050. doi:10.1002 /cncr.30507.

- Cancer Stat Facts. National Cancer Institute Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. https://seer.cancer .gov/statfacts/html/cervix.html

- Suk R, Hong YR, Rajan SS, et al. Assessment of US Preventive Services Task Force guideline-concordant cervical cancer screening rates and reasons for underscreening by age, race and ethnicity, sexual orientation, rurality, and insurance, 2005 to 2019. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5:e2143582. doi:10.1001 /jamanetworkopen.2021.43582.

- White MC, Shoemaker ML, Benard VB. Cervical cancer screening and incidence by age: unmet needs near and after the stopping age for screening. Am J Prev Med. 2017;53:392395. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2017.02.024.

- Cooley JJ, Maguire FB, Morris CR, et al. Cervical cancer stage at diagnosis and survival among women ≥65 years in California. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2023;32:91-97. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-22-0793.

- Ortman JM, Velkoff VA, Hogan H. An aging nation: the older population in the United States. May 2014. United States Census Bureau. Accessed April 12, 2023. https://www.census .gov/library/publications/2014/demo/p25-1140.html

- Fontham ETH, Wolf AMD, Church TR, et al. Cervical cancer screening for individuals at average risk: 2020 guideline update from the American Cancer Society. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70:321-346. doi:10.3322/caac.21628.

- Dilley S, Huh W, Blechter B, et al. It’s time to re-evaluate cervical cancer screening after age 65. Gynecol Oncol. 2021;162:200-202. doi:10.1016/j.ygyno.2021.04.027.

- Rositch AF, Nowak RG, Gravitt PE. Increased age and racespecific incidence of cervical cancer after correction for hysterectomy prevalence in the United States from 2000 to 2009. Cancer. 2014;120:2032-2038. doi:10.1002/cncr.28548.

- Beavis AL, Gravitt PE, Rositch AF. Hysterectomy-corrected cervical cancer mortality rates reveal a larger racial disparity in the United States. Cancer. 2017;123:1044-1050. doi:10.1002 /cncr.30507.

- Cancer Stat Facts. National Cancer Institute Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. https://seer.cancer .gov/statfacts/html/cervix.html

- Suk R, Hong YR, Rajan SS, et al. Assessment of US Preventive Services Task Force guideline-concordant cervical cancer screening rates and reasons for underscreening by age, race and ethnicity, sexual orientation, rurality, and insurance, 2005 to 2019. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5:e2143582. doi:10.1001 /jamanetworkopen.2021.43582.

- White MC, Shoemaker ML, Benard VB. Cervical cancer screening and incidence by age: unmet needs near and after the stopping age for screening. Am J Prev Med. 2017;53:392395. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2017.02.024.

- Cooley JJ, Maguire FB, Morris CR, et al. Cervical cancer stage at diagnosis and survival among women ≥65 years in California. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2023;32:91-97. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-22-0793.

- Ortman JM, Velkoff VA, Hogan H. An aging nation: the older population in the United States. May 2014. United States Census Bureau. Accessed April 12, 2023. https://www.census .gov/library/publications/2014/demo/p25-1140.html

Doctor spots a gunshot victim staggering down his street

It was a quiet day. I got up around 3 o’clock in the afternoon for my shift at 6 p.m. I was shaking off the cobwebs and making coffee at our front window that overlooked Brown Street in North Philadelphia. There was nobody else around so I went outside to see what was going on.

He was in his 50s or 60s, bleeding and obviously in distress. I had him sit down. Then I ran back inside and grabbed a dish towel and some exam gloves that I had in the house.

I ran back out and assessed him. A bullet had gone through one of his hands, but he had other wounds. I had to expose him, so I trauma stripped him on the sidewalk. I got his pants and his shirt off and saw a gunshot going through his lower pelvis. He was bleeding out from there.

I got the towel and started applying deep pressure down into the iliac vein in case they hit something, which I found out later, they had. I held it there. The man was just lying there begging not to die.

I’m someone who is very calm, maybe abnormally calm, as people tell me. I try to use that during my resuscitations and traumas. Just keeping everybody calm makes the situation easier. Afterwards, people asked me, “Weren’t you worried that you were going to get shot?” That does happen in North Philadelphia. But it didn’t even cross my mind.

I didn’t have to think at all about what I was doing. We saw so many gunshots, especially at Einstein Medical Center. We saw them daily. I’d sometimes get more than half a dozen gunshots in one shift.

So, I was holding pressure and some people started to come over. I got somebody to call 911 and asked the man about his medical history. I found out he had diabetes. Five or 10 minutes later, EMS showed up. They looked pretty stunned when I was able to give the handoff presentation to them. I told them what happened and his back-story. I wanted to make sure they would check his sugar and take extra precautions.

They got him on the stretcher, and he eventually made it to the hospital where he had surgery. They had to have a vascular surgeon work on him. I called later, and they told me, “Yeah, he’s alive.” But that’s about the extent of the update I got.

After the ambulance left, it was kind of chaos. All the neighbors poured out of their houses. People were panicked, talking and getting excited about it. I didn’t know, but everyone else had actually been home the whole time. They didn’t come out until then.

I went back inside and tried to get ready for work. I wasn’t planning on talking to the media, but my next door neighbor just walked the news camera crew over to my house and knocked on my door. I wasn’t exactly dressed to be on TV, but they talked to me on camera, and it was on the news later that night.

I went to work and didn’t say anything about it. To be honest, I was trying to avoid telling anyone. Our team had a close-knit bond, and we would often tease each other when we received any type of recognition.

Naturally one of my attendings saw it on the local news and told everybody. So, I got a lot of happy harassment for quite some time. Someone baked me a cake that said, “Hero of Fairmount” (the Philly neighborhood in which I live). Someone else printed out a photo of me that said, “Stop the Bleed Hero of Fairmount,” and put it on every single computer screen.

The man came to see me about 2 weeks later (a neighbor told him where I lived). The man was very tearful and gave me a big hug. We just embraced for a while, and he said how thankful he was. He brought me a bottle of wine, which I thought was really nice.

He told me what happened to him: There was a lot of construction on our street and he was the contractor overseeing a couple of home remodels and demolitions. Sometimes he paid workers in cash and carried it with him. Somebody had tipped off somebody else that he was going to be there that day. The contractor walked into one of the houses and a guy in a ski mask waited there with a gun. The guy shot him and took the cash. The bullet went through his hand into his pelvis.

I had never had to deal with something that intense before outside of work. Most of it really comes down to the basics – the ABCs and bleeding control. You do whatever you can with what you have. In this case, it was just a dish towel, gloves, and my hands to put as much pressure as possible.

It really was strange that I happened to be looking out the window at that moment. I don’t know if it was just a coincidence. The man told me he believed God had put somebody there at the right place at the right time to save his life. I just felt very fortunate to have been able to help him. I never saw him again.

I think something like this gives you a little confidence that you can actually do something and make a meaningful impact anywhere when it’s needed. It lets you know that you’re capable of doing it. You always think about it, but you don’t know until it happens.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

It was a quiet day. I got up around 3 o’clock in the afternoon for my shift at 6 p.m. I was shaking off the cobwebs and making coffee at our front window that overlooked Brown Street in North Philadelphia. There was nobody else around so I went outside to see what was going on.

He was in his 50s or 60s, bleeding and obviously in distress. I had him sit down. Then I ran back inside and grabbed a dish towel and some exam gloves that I had in the house.

I ran back out and assessed him. A bullet had gone through one of his hands, but he had other wounds. I had to expose him, so I trauma stripped him on the sidewalk. I got his pants and his shirt off and saw a gunshot going through his lower pelvis. He was bleeding out from there.

I got the towel and started applying deep pressure down into the iliac vein in case they hit something, which I found out later, they had. I held it there. The man was just lying there begging not to die.

I’m someone who is very calm, maybe abnormally calm, as people tell me. I try to use that during my resuscitations and traumas. Just keeping everybody calm makes the situation easier. Afterwards, people asked me, “Weren’t you worried that you were going to get shot?” That does happen in North Philadelphia. But it didn’t even cross my mind.

I didn’t have to think at all about what I was doing. We saw so many gunshots, especially at Einstein Medical Center. We saw them daily. I’d sometimes get more than half a dozen gunshots in one shift.

So, I was holding pressure and some people started to come over. I got somebody to call 911 and asked the man about his medical history. I found out he had diabetes. Five or 10 minutes later, EMS showed up. They looked pretty stunned when I was able to give the handoff presentation to them. I told them what happened and his back-story. I wanted to make sure they would check his sugar and take extra precautions.

They got him on the stretcher, and he eventually made it to the hospital where he had surgery. They had to have a vascular surgeon work on him. I called later, and they told me, “Yeah, he’s alive.” But that’s about the extent of the update I got.

After the ambulance left, it was kind of chaos. All the neighbors poured out of their houses. People were panicked, talking and getting excited about it. I didn’t know, but everyone else had actually been home the whole time. They didn’t come out until then.

I went back inside and tried to get ready for work. I wasn’t planning on talking to the media, but my next door neighbor just walked the news camera crew over to my house and knocked on my door. I wasn’t exactly dressed to be on TV, but they talked to me on camera, and it was on the news later that night.

I went to work and didn’t say anything about it. To be honest, I was trying to avoid telling anyone. Our team had a close-knit bond, and we would often tease each other when we received any type of recognition.

Naturally one of my attendings saw it on the local news and told everybody. So, I got a lot of happy harassment for quite some time. Someone baked me a cake that said, “Hero of Fairmount” (the Philly neighborhood in which I live). Someone else printed out a photo of me that said, “Stop the Bleed Hero of Fairmount,” and put it on every single computer screen.

The man came to see me about 2 weeks later (a neighbor told him where I lived). The man was very tearful and gave me a big hug. We just embraced for a while, and he said how thankful he was. He brought me a bottle of wine, which I thought was really nice.

He told me what happened to him: There was a lot of construction on our street and he was the contractor overseeing a couple of home remodels and demolitions. Sometimes he paid workers in cash and carried it with him. Somebody had tipped off somebody else that he was going to be there that day. The contractor walked into one of the houses and a guy in a ski mask waited there with a gun. The guy shot him and took the cash. The bullet went through his hand into his pelvis.

I had never had to deal with something that intense before outside of work. Most of it really comes down to the basics – the ABCs and bleeding control. You do whatever you can with what you have. In this case, it was just a dish towel, gloves, and my hands to put as much pressure as possible.

It really was strange that I happened to be looking out the window at that moment. I don’t know if it was just a coincidence. The man told me he believed God had put somebody there at the right place at the right time to save his life. I just felt very fortunate to have been able to help him. I never saw him again.

I think something like this gives you a little confidence that you can actually do something and make a meaningful impact anywhere when it’s needed. It lets you know that you’re capable of doing it. You always think about it, but you don’t know until it happens.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

It was a quiet day. I got up around 3 o’clock in the afternoon for my shift at 6 p.m. I was shaking off the cobwebs and making coffee at our front window that overlooked Brown Street in North Philadelphia. There was nobody else around so I went outside to see what was going on.

He was in his 50s or 60s, bleeding and obviously in distress. I had him sit down. Then I ran back inside and grabbed a dish towel and some exam gloves that I had in the house.

I ran back out and assessed him. A bullet had gone through one of his hands, but he had other wounds. I had to expose him, so I trauma stripped him on the sidewalk. I got his pants and his shirt off and saw a gunshot going through his lower pelvis. He was bleeding out from there.

I got the towel and started applying deep pressure down into the iliac vein in case they hit something, which I found out later, they had. I held it there. The man was just lying there begging not to die.

I’m someone who is very calm, maybe abnormally calm, as people tell me. I try to use that during my resuscitations and traumas. Just keeping everybody calm makes the situation easier. Afterwards, people asked me, “Weren’t you worried that you were going to get shot?” That does happen in North Philadelphia. But it didn’t even cross my mind.

I didn’t have to think at all about what I was doing. We saw so many gunshots, especially at Einstein Medical Center. We saw them daily. I’d sometimes get more than half a dozen gunshots in one shift.

So, I was holding pressure and some people started to come over. I got somebody to call 911 and asked the man about his medical history. I found out he had diabetes. Five or 10 minutes later, EMS showed up. They looked pretty stunned when I was able to give the handoff presentation to them. I told them what happened and his back-story. I wanted to make sure they would check his sugar and take extra precautions.

They got him on the stretcher, and he eventually made it to the hospital where he had surgery. They had to have a vascular surgeon work on him. I called later, and they told me, “Yeah, he’s alive.” But that’s about the extent of the update I got.

After the ambulance left, it was kind of chaos. All the neighbors poured out of their houses. People were panicked, talking and getting excited about it. I didn’t know, but everyone else had actually been home the whole time. They didn’t come out until then.

I went back inside and tried to get ready for work. I wasn’t planning on talking to the media, but my next door neighbor just walked the news camera crew over to my house and knocked on my door. I wasn’t exactly dressed to be on TV, but they talked to me on camera, and it was on the news later that night.

I went to work and didn’t say anything about it. To be honest, I was trying to avoid telling anyone. Our team had a close-knit bond, and we would often tease each other when we received any type of recognition.

Naturally one of my attendings saw it on the local news and told everybody. So, I got a lot of happy harassment for quite some time. Someone baked me a cake that said, “Hero of Fairmount” (the Philly neighborhood in which I live). Someone else printed out a photo of me that said, “Stop the Bleed Hero of Fairmount,” and put it on every single computer screen.

The man came to see me about 2 weeks later (a neighbor told him where I lived). The man was very tearful and gave me a big hug. We just embraced for a while, and he said how thankful he was. He brought me a bottle of wine, which I thought was really nice.

He told me what happened to him: There was a lot of construction on our street and he was the contractor overseeing a couple of home remodels and demolitions. Sometimes he paid workers in cash and carried it with him. Somebody had tipped off somebody else that he was going to be there that day. The contractor walked into one of the houses and a guy in a ski mask waited there with a gun. The guy shot him and took the cash. The bullet went through his hand into his pelvis.

I had never had to deal with something that intense before outside of work. Most of it really comes down to the basics – the ABCs and bleeding control. You do whatever you can with what you have. In this case, it was just a dish towel, gloves, and my hands to put as much pressure as possible.

It really was strange that I happened to be looking out the window at that moment. I don’t know if it was just a coincidence. The man told me he believed God had put somebody there at the right place at the right time to save his life. I just felt very fortunate to have been able to help him. I never saw him again.

I think something like this gives you a little confidence that you can actually do something and make a meaningful impact anywhere when it’s needed. It lets you know that you’re capable of doing it. You always think about it, but you don’t know until it happens.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A legacy of unfair admissions

This is where people related to successful alumni and/or big donors can get preferential admission, possibly over more qualified people.

All of us likely experienced this from one side or another, though realistically I haven’t thought about it years. My kids went to the same state school I did, but I’m pretty sure I had nothing to do with their being accepted. I never gave the school a single donation, nor did I call anyone there to try and get them in. Not that anyone would have known who I was if I’d tried. I’m just another one of many who went there, preserved only in some filing cabinet of transcripts somewhere.

I’m all for the legacy system ending, though, for one simple reason: It’s not fair.

If someone is qualified, great. They should be admitted on their own merits. But if they’re not, they shouldn’t get into medical school just because one (or both) of their parents went there, or is a VIP, or paid for a new library wing.

The reason I’m writing this is because the recent reporting did bring back a memory.

A long time ago, when I was in college, I hung out with other premed students. We knew we were all competing with each other for the same spots at the state medical school, but also knew that we wouldn’t all get in there. That didn’t make us enemies, it was just the truth. It’s that point in life where ANY medical school admission is all you want.

Pete (not his real name) was a nice guy, but his grades weren’t the best. His MCAT scores lagged behind the rest of us in the clique, and ... he didn’t care.

Pete’s dad had graduated from the state medical school, and was still on staff there. He was now on the teaching staff ... and on the school’s admissions board. To Pete, tests and grades didn’t matter. His admission was assured.

So it was no surprise when he got in ahead of the rest of us with better qualifications. Most of us, including me, did get in somewhere, so we were still happy. We just had to move farther and pay more, but that’s life.

I really didn’t think much about Pete again after that. I was now in medical school, I had a whole new social group, and more importantly I didn’t really have time to think of much beyond when the next exam was.

Then I moved home, and started residency. During my PGY-2 year we had a changing group of medical students assigned to my wards rotation.

And, as you probably guessed, one of them was Pete.

Pete was in his last year of medical school. But we’d both started in the same year, and now I was 2 years ahead of him. I didn’t ask him what happened, but another medical student told me he wasn’t known to be the best student, but the university refused to drop him, and just kept setting him back a class here, a year there.

Maybe they’d have done the same for anyone, but I doubt it.

I never saw Pete again after that. When I looked him up online tonight he’s not listed as being a doctor, and isn’t even in medicine. Granted, a lot of doctors have left medicine, and maybe he did too.

But the more likely reason is that Pete never should have been there in the first place. He got in as a legacy, taking a medical school slot from someone who may have been more capable and driven.

And that just doesn’t seem right to me. It didn’t then and it doesn’t now.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

This is where people related to successful alumni and/or big donors can get preferential admission, possibly over more qualified people.

All of us likely experienced this from one side or another, though realistically I haven’t thought about it years. My kids went to the same state school I did, but I’m pretty sure I had nothing to do with their being accepted. I never gave the school a single donation, nor did I call anyone there to try and get them in. Not that anyone would have known who I was if I’d tried. I’m just another one of many who went there, preserved only in some filing cabinet of transcripts somewhere.

I’m all for the legacy system ending, though, for one simple reason: It’s not fair.

If someone is qualified, great. They should be admitted on their own merits. But if they’re not, they shouldn’t get into medical school just because one (or both) of their parents went there, or is a VIP, or paid for a new library wing.

The reason I’m writing this is because the recent reporting did bring back a memory.

A long time ago, when I was in college, I hung out with other premed students. We knew we were all competing with each other for the same spots at the state medical school, but also knew that we wouldn’t all get in there. That didn’t make us enemies, it was just the truth. It’s that point in life where ANY medical school admission is all you want.

Pete (not his real name) was a nice guy, but his grades weren’t the best. His MCAT scores lagged behind the rest of us in the clique, and ... he didn’t care.

Pete’s dad had graduated from the state medical school, and was still on staff there. He was now on the teaching staff ... and on the school’s admissions board. To Pete, tests and grades didn’t matter. His admission was assured.

So it was no surprise when he got in ahead of the rest of us with better qualifications. Most of us, including me, did get in somewhere, so we were still happy. We just had to move farther and pay more, but that’s life.

I really didn’t think much about Pete again after that. I was now in medical school, I had a whole new social group, and more importantly I didn’t really have time to think of much beyond when the next exam was.

Then I moved home, and started residency. During my PGY-2 year we had a changing group of medical students assigned to my wards rotation.

And, as you probably guessed, one of them was Pete.

Pete was in his last year of medical school. But we’d both started in the same year, and now I was 2 years ahead of him. I didn’t ask him what happened, but another medical student told me he wasn’t known to be the best student, but the university refused to drop him, and just kept setting him back a class here, a year there.

Maybe they’d have done the same for anyone, but I doubt it.

I never saw Pete again after that. When I looked him up online tonight he’s not listed as being a doctor, and isn’t even in medicine. Granted, a lot of doctors have left medicine, and maybe he did too.

But the more likely reason is that Pete never should have been there in the first place. He got in as a legacy, taking a medical school slot from someone who may have been more capable and driven.

And that just doesn’t seem right to me. It didn’t then and it doesn’t now.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

This is where people related to successful alumni and/or big donors can get preferential admission, possibly over more qualified people.

All of us likely experienced this from one side or another, though realistically I haven’t thought about it years. My kids went to the same state school I did, but I’m pretty sure I had nothing to do with their being accepted. I never gave the school a single donation, nor did I call anyone there to try and get them in. Not that anyone would have known who I was if I’d tried. I’m just another one of many who went there, preserved only in some filing cabinet of transcripts somewhere.

I’m all for the legacy system ending, though, for one simple reason: It’s not fair.

If someone is qualified, great. They should be admitted on their own merits. But if they’re not, they shouldn’t get into medical school just because one (or both) of their parents went there, or is a VIP, or paid for a new library wing.

The reason I’m writing this is because the recent reporting did bring back a memory.

A long time ago, when I was in college, I hung out with other premed students. We knew we were all competing with each other for the same spots at the state medical school, but also knew that we wouldn’t all get in there. That didn’t make us enemies, it was just the truth. It’s that point in life where ANY medical school admission is all you want.

Pete (not his real name) was a nice guy, but his grades weren’t the best. His MCAT scores lagged behind the rest of us in the clique, and ... he didn’t care.

Pete’s dad had graduated from the state medical school, and was still on staff there. He was now on the teaching staff ... and on the school’s admissions board. To Pete, tests and grades didn’t matter. His admission was assured.

So it was no surprise when he got in ahead of the rest of us with better qualifications. Most of us, including me, did get in somewhere, so we were still happy. We just had to move farther and pay more, but that’s life.

I really didn’t think much about Pete again after that. I was now in medical school, I had a whole new social group, and more importantly I didn’t really have time to think of much beyond when the next exam was.

Then I moved home, and started residency. During my PGY-2 year we had a changing group of medical students assigned to my wards rotation.

And, as you probably guessed, one of them was Pete.

Pete was in his last year of medical school. But we’d both started in the same year, and now I was 2 years ahead of him. I didn’t ask him what happened, but another medical student told me he wasn’t known to be the best student, but the university refused to drop him, and just kept setting him back a class here, a year there.

Maybe they’d have done the same for anyone, but I doubt it.

I never saw Pete again after that. When I looked him up online tonight he’s not listed as being a doctor, and isn’t even in medicine. Granted, a lot of doctors have left medicine, and maybe he did too.

But the more likely reason is that Pete never should have been there in the first place. He got in as a legacy, taking a medical school slot from someone who may have been more capable and driven.

And that just doesn’t seem right to me. It didn’t then and it doesn’t now.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Fatigue is a monster for patients with pulmonary disease

If you’re looking for it, you’ll find fatigue almost everywhere. It’s so common that it hides in plain sight, never dealt with because it’s present for good reason: the inevitable consequence of age, whatever disease you’re treating, poor lifestyle choices, and the daily grind of twenty-first–century life. Its impact is so ubiquitous and pernicious that it’s considered acceptable.

Is it though? After all, fatigue can be debilitating. Not every symptom is worthy of a chronic syndrome bearing its name. Furthermore, what if its relationship to the disease you’re treating is bidirectional?

Outside of sleep medicine, I see little focus on fatigue among pulmonologists. This despite the existing data on fatigue related to sarcoidosis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and interstitial lung disease. Even when we do pay it lip service, “addressing” fatigue or sleep is essentially a euphemism for ordering a sleep study.

As with fatigue, if you look for obstructive sleep apnea, it’ll be there, although with OSA, it’s related to the incredibly low, nonevidence-based threshold the American Academy of Sleep Medicine has established for making the diagnosis. With continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) in hand, the patient has a new disease to worry about and a difficult behavioral change (wearing, cleaning, and resupplying their CPAP equipment) to make. Too often, the CPAP isn’t used – or is – and the fatigue persists. But it’s okay, because we followed somebody’s guideline.

The American Thoracic Society just published a research statement on cancer-related fatigue. It is comprehensive and highlights the high prevalence and poor recognition of cancer-related fatigue. The authors note that among cancers, those of the lung are associated with a higher comorbid disease burden, older age, and cigarette smoking. All these factors make patients with lung cancer particularly prone to fatigue. Interactions between these factors, lung cancer histology, and specific chemotherapy regimens are poorly understood. True to its title, the “research statement” serves more as a call to action than an evidence-based blueprint for diagnosis and management.

The cancer-related fatigue data that does exist suggests treatment starts with recognition followed by a focus on sleep, exercise, and nutrition. This should surprise no one. The data on fatigue in general (not specific to cancer-related fatigue) shows that although fatigue is not synonymous with poor quality or insufficient sleep, sleep is usually a major factor. The cancer-related conditions affecting sleep include anxiety, depression, insufficient sleep, insomnia, medication side effects, and OSA. The intersecting web is complex, but across underlying conditions (cancer or otherwise), the quickest most efficient method for mitigating fatigue is optimizing sleep.

Exercise and nutrition are also important. Again, across disease processes (interstitial lung disease, COPD, lung cancer, and so on), no drug comes close to aerobic exercise for reducing symptoms, including fatigue. If an exercise prescription could be delivered in pill-form, it’d be a blockbuster. But it can’t be, and the ATS lung cancer–related fatigue research statement nicely outlines the evidence for increased activity levels and the barriers to obtaining support and compliance. As is the case with exercise, support for improving nutrition is limited by cost, access, and patient education.

Perhaps most importantly, sleep, exercise, and nutrition require time for counseling and a behavior change for the physician and patient. Both are in short supply, and commitment is always ephemeral. Incentivization could perhaps be re-structured, but the ATS document notes this will be challenging. With respect to pulmonary rehabilitation (about 50% of patients with lung cancer have comorbid COPD), for example, reimbursement is poor, which serves as a disincentive. Their suggestions? Early integration and repeated introduction to rehabilitation and exercise concepts. Sounds great.

In summary, in my opinion, fatigue doesn’t receive the attention level commensurate with its impact. It’s easy to understand why, but I’m glad the ATS is highlighting the problem. Unbeknownst to me, multiple cancer guidelines already recommend screening for fatigue. The recent sarcoidosis treatment guideline published by the European Respiratory Society dedicated a PICO (Patients, Intervention, Comparison, Outcomes) to the topic and recommended exercise (pulmonary rehabilitation). That said, consensus statements on COPD mention it only in passing in relation to severe disease and end-of-life care, and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis guidelines ignore it entirely. So, recognition is improving, but we’ve got ways to go.

Dr. Holley is professor of medicine at Uniformed Services University, Bethesda, Md., and a pulmonary/sleep and critical care medicine physician at MedStar Washington Hospital Center in Washington. He disclosed ties with Metapharm, CHEST College, and WebMD.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

If you’re looking for it, you’ll find fatigue almost everywhere. It’s so common that it hides in plain sight, never dealt with because it’s present for good reason: the inevitable consequence of age, whatever disease you’re treating, poor lifestyle choices, and the daily grind of twenty-first–century life. Its impact is so ubiquitous and pernicious that it’s considered acceptable.

Is it though? After all, fatigue can be debilitating. Not every symptom is worthy of a chronic syndrome bearing its name. Furthermore, what if its relationship to the disease you’re treating is bidirectional?

Outside of sleep medicine, I see little focus on fatigue among pulmonologists. This despite the existing data on fatigue related to sarcoidosis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and interstitial lung disease. Even when we do pay it lip service, “addressing” fatigue or sleep is essentially a euphemism for ordering a sleep study.

As with fatigue, if you look for obstructive sleep apnea, it’ll be there, although with OSA, it’s related to the incredibly low, nonevidence-based threshold the American Academy of Sleep Medicine has established for making the diagnosis. With continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) in hand, the patient has a new disease to worry about and a difficult behavioral change (wearing, cleaning, and resupplying their CPAP equipment) to make. Too often, the CPAP isn’t used – or is – and the fatigue persists. But it’s okay, because we followed somebody’s guideline.

The American Thoracic Society just published a research statement on cancer-related fatigue. It is comprehensive and highlights the high prevalence and poor recognition of cancer-related fatigue. The authors note that among cancers, those of the lung are associated with a higher comorbid disease burden, older age, and cigarette smoking. All these factors make patients with lung cancer particularly prone to fatigue. Interactions between these factors, lung cancer histology, and specific chemotherapy regimens are poorly understood. True to its title, the “research statement” serves more as a call to action than an evidence-based blueprint for diagnosis and management.

The cancer-related fatigue data that does exist suggests treatment starts with recognition followed by a focus on sleep, exercise, and nutrition. This should surprise no one. The data on fatigue in general (not specific to cancer-related fatigue) shows that although fatigue is not synonymous with poor quality or insufficient sleep, sleep is usually a major factor. The cancer-related conditions affecting sleep include anxiety, depression, insufficient sleep, insomnia, medication side effects, and OSA. The intersecting web is complex, but across underlying conditions (cancer or otherwise), the quickest most efficient method for mitigating fatigue is optimizing sleep.

Exercise and nutrition are also important. Again, across disease processes (interstitial lung disease, COPD, lung cancer, and so on), no drug comes close to aerobic exercise for reducing symptoms, including fatigue. If an exercise prescription could be delivered in pill-form, it’d be a blockbuster. But it can’t be, and the ATS lung cancer–related fatigue research statement nicely outlines the evidence for increased activity levels and the barriers to obtaining support and compliance. As is the case with exercise, support for improving nutrition is limited by cost, access, and patient education.

Perhaps most importantly, sleep, exercise, and nutrition require time for counseling and a behavior change for the physician and patient. Both are in short supply, and commitment is always ephemeral. Incentivization could perhaps be re-structured, but the ATS document notes this will be challenging. With respect to pulmonary rehabilitation (about 50% of patients with lung cancer have comorbid COPD), for example, reimbursement is poor, which serves as a disincentive. Their suggestions? Early integration and repeated introduction to rehabilitation and exercise concepts. Sounds great.

In summary, in my opinion, fatigue doesn’t receive the attention level commensurate with its impact. It’s easy to understand why, but I’m glad the ATS is highlighting the problem. Unbeknownst to me, multiple cancer guidelines already recommend screening for fatigue. The recent sarcoidosis treatment guideline published by the European Respiratory Society dedicated a PICO (Patients, Intervention, Comparison, Outcomes) to the topic and recommended exercise (pulmonary rehabilitation). That said, consensus statements on COPD mention it only in passing in relation to severe disease and end-of-life care, and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis guidelines ignore it entirely. So, recognition is improving, but we’ve got ways to go.

Dr. Holley is professor of medicine at Uniformed Services University, Bethesda, Md., and a pulmonary/sleep and critical care medicine physician at MedStar Washington Hospital Center in Washington. He disclosed ties with Metapharm, CHEST College, and WebMD.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

If you’re looking for it, you’ll find fatigue almost everywhere. It’s so common that it hides in plain sight, never dealt with because it’s present for good reason: the inevitable consequence of age, whatever disease you’re treating, poor lifestyle choices, and the daily grind of twenty-first–century life. Its impact is so ubiquitous and pernicious that it’s considered acceptable.

Is it though? After all, fatigue can be debilitating. Not every symptom is worthy of a chronic syndrome bearing its name. Furthermore, what if its relationship to the disease you’re treating is bidirectional?

Outside of sleep medicine, I see little focus on fatigue among pulmonologists. This despite the existing data on fatigue related to sarcoidosis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and interstitial lung disease. Even when we do pay it lip service, “addressing” fatigue or sleep is essentially a euphemism for ordering a sleep study.

As with fatigue, if you look for obstructive sleep apnea, it’ll be there, although with OSA, it’s related to the incredibly low, nonevidence-based threshold the American Academy of Sleep Medicine has established for making the diagnosis. With continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) in hand, the patient has a new disease to worry about and a difficult behavioral change (wearing, cleaning, and resupplying their CPAP equipment) to make. Too often, the CPAP isn’t used – or is – and the fatigue persists. But it’s okay, because we followed somebody’s guideline.

The American Thoracic Society just published a research statement on cancer-related fatigue. It is comprehensive and highlights the high prevalence and poor recognition of cancer-related fatigue. The authors note that among cancers, those of the lung are associated with a higher comorbid disease burden, older age, and cigarette smoking. All these factors make patients with lung cancer particularly prone to fatigue. Interactions between these factors, lung cancer histology, and specific chemotherapy regimens are poorly understood. True to its title, the “research statement” serves more as a call to action than an evidence-based blueprint for diagnosis and management.

The cancer-related fatigue data that does exist suggests treatment starts with recognition followed by a focus on sleep, exercise, and nutrition. This should surprise no one. The data on fatigue in general (not specific to cancer-related fatigue) shows that although fatigue is not synonymous with poor quality or insufficient sleep, sleep is usually a major factor. The cancer-related conditions affecting sleep include anxiety, depression, insufficient sleep, insomnia, medication side effects, and OSA. The intersecting web is complex, but across underlying conditions (cancer or otherwise), the quickest most efficient method for mitigating fatigue is optimizing sleep.

Exercise and nutrition are also important. Again, across disease processes (interstitial lung disease, COPD, lung cancer, and so on), no drug comes close to aerobic exercise for reducing symptoms, including fatigue. If an exercise prescription could be delivered in pill-form, it’d be a blockbuster. But it can’t be, and the ATS lung cancer–related fatigue research statement nicely outlines the evidence for increased activity levels and the barriers to obtaining support and compliance. As is the case with exercise, support for improving nutrition is limited by cost, access, and patient education.

Perhaps most importantly, sleep, exercise, and nutrition require time for counseling and a behavior change for the physician and patient. Both are in short supply, and commitment is always ephemeral. Incentivization could perhaps be re-structured, but the ATS document notes this will be challenging. With respect to pulmonary rehabilitation (about 50% of patients with lung cancer have comorbid COPD), for example, reimbursement is poor, which serves as a disincentive. Their suggestions? Early integration and repeated introduction to rehabilitation and exercise concepts. Sounds great.

In summary, in my opinion, fatigue doesn’t receive the attention level commensurate with its impact. It’s easy to understand why, but I’m glad the ATS is highlighting the problem. Unbeknownst to me, multiple cancer guidelines already recommend screening for fatigue. The recent sarcoidosis treatment guideline published by the European Respiratory Society dedicated a PICO (Patients, Intervention, Comparison, Outcomes) to the topic and recommended exercise (pulmonary rehabilitation). That said, consensus statements on COPD mention it only in passing in relation to severe disease and end-of-life care, and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis guidelines ignore it entirely. So, recognition is improving, but we’ve got ways to go.

Dr. Holley is professor of medicine at Uniformed Services University, Bethesda, Md., and a pulmonary/sleep and critical care medicine physician at MedStar Washington Hospital Center in Washington. He disclosed ties with Metapharm, CHEST College, and WebMD.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Boys may carry the weight, or overweight, of adults’ infertility

Overweight boy, infertile man?

When it comes to causes of infertility, history and science have generally focused on women. A lot of the research overlooks men, but some previous studies have suggested that male infertility contributes to about half of the cases of couple infertility. The reason for much of that male infertility, however, has been a mystery. Until now.

A group of Italian investigators looked at the declining trend in sperm counts over the past 40 years and the increase of childhood obesity. Is there a correlation? The researchers think so. Childhood obesity can be linked to multiple causes, but the researchers zeroed in on the effect that obesity has on metabolic rates and, therefore, testicular growth.

Collecting data on testicular volume, body mass index (BMI), and insulin resistance from 268 boys aged 2-18 years, the researchers discovered that those with normal weight and normal insulin levels had testicular volumes 1.5 times higher than their overweight counterparts and 1.5-2 times higher than those with hyperinsulinemia, building a case for obesity being a factor for infertility later in life.

Since low testicular volume is associated with lower sperm count and production as an adult, putting two and two together makes a compelling argument for childhood obesity being a major male infertility culprit. It also creates even more urgency for the health care industry and community decision makers to focus on childhood obesity.

It sure would be nice to be able to take one of the many risk factors for future human survival off the table. Maybe by taking something, like cake, off the table.

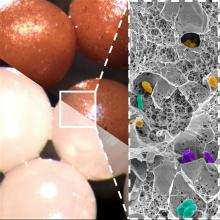

Fecal transplantation moves to the kitchen

Fecal microbiota transplantation is an effective way to treat Clostridioides difficile infection, but, in the end, it’s still a transplantation procedure involving a nasogastric or colorectal tube or rather large oral capsules with a demanding (30-40 capsules over 2 days) dosage. Please, Science, tell us there’s a better way.

Science, in the form of investigators at the University of Geneva and Lausanne University Hospital in Switzerland, has spoken, and there may be a better way. Presenting fecal beads: All the bacterial goodness of donor stool without the tubal insertions or massive quantities of giant capsules.

We know you’re scoffing out there, but it’s true. All you need is a little alginate, which is a “biocompatible polysaccharide isolated from brown algae” of the Phaeophyceae family. The donor feces is microencapsulated by mixing it with the alginate, dropping that mixture into water containing calcium chloride, turning it into a gel, and then freeze-drying the gel into small (just 2 mm), solid beads.

Sounds plausible enough, but what do you do with them? “These brownish beads can be easily dispersed in a liquid or food that is pleasant to eat. They also have no taste,” senior author Eric Allémann, PhD, said in a statement released by the University of Geneva.

Pleasant to eat? No taste? So which is it? If you really want to know, watch fecal beads week on the new season of “The Great British Baking Show,” when Paul and Prue judge poop baked into crumpets, crepes, and crostatas. Yum.

We’re on the low-oxygen diet

Nine out of ten doctors agree: Oxygen is more important to your continued well-being than food. After all, a human can go weeks without food, but just minutes without oxygen. However, ten out of ten doctors agree that the United States has an obesity problem. They all also agree that previous research has shown soldiers who train at high altitudes lose more weight than those training at lower altitudes.

So, on the one hand, we have a country full of overweight people, and on the other, we have low oxygen levels causing weight loss. The solution, then, is obvious: Stop breathing.

More specifically (and somewhat less facetiously), researchers from Louisiana have launched the Low Oxygen and Weight Status trial and are currently recruiting individuals with BMIs of 30-40 to, uh, suffocate themselves. No, no, it’s okay, it’s just when they’re sleeping.

Fine, straight face. Participants in the LOWS trial will undergo an 8-week period when they will consume a controlled weight-loss diet and spend their nights in a hypoxic sealed tent, where they will sleep in an environment with an oxygen level equivalent to 8,500 feet above sea level (roughly equivalent to Aspen, Colo.). They will be compared with people on the same diet who sleep in a normal, sea-level oxygen environment.

The study’s goal is to determine whether or not spending time in a low-oxygen environment will suppress appetite, increase energy expenditure, and improve weight loss and insulin sensitivity. Excessive weight loss in high-altitude environments isn’t a good thing for soldiers – they kind of need their muscles and body weight to do the whole soldiering thing – but it could be great for people struggling to lose those last few pounds. And it also may prove LOTME’s previous thesis: Air is not good.

Overweight boy, infertile man?

When it comes to causes of infertility, history and science have generally focused on women. A lot of the research overlooks men, but some previous studies have suggested that male infertility contributes to about half of the cases of couple infertility. The reason for much of that male infertility, however, has been a mystery. Until now.

A group of Italian investigators looked at the declining trend in sperm counts over the past 40 years and the increase of childhood obesity. Is there a correlation? The researchers think so. Childhood obesity can be linked to multiple causes, but the researchers zeroed in on the effect that obesity has on metabolic rates and, therefore, testicular growth.

Collecting data on testicular volume, body mass index (BMI), and insulin resistance from 268 boys aged 2-18 years, the researchers discovered that those with normal weight and normal insulin levels had testicular volumes 1.5 times higher than their overweight counterparts and 1.5-2 times higher than those with hyperinsulinemia, building a case for obesity being a factor for infertility later in life.

Since low testicular volume is associated with lower sperm count and production as an adult, putting two and two together makes a compelling argument for childhood obesity being a major male infertility culprit. It also creates even more urgency for the health care industry and community decision makers to focus on childhood obesity.

It sure would be nice to be able to take one of the many risk factors for future human survival off the table. Maybe by taking something, like cake, off the table.

Fecal transplantation moves to the kitchen

Fecal microbiota transplantation is an effective way to treat Clostridioides difficile infection, but, in the end, it’s still a transplantation procedure involving a nasogastric or colorectal tube or rather large oral capsules with a demanding (30-40 capsules over 2 days) dosage. Please, Science, tell us there’s a better way.

Science, in the form of investigators at the University of Geneva and Lausanne University Hospital in Switzerland, has spoken, and there may be a better way. Presenting fecal beads: All the bacterial goodness of donor stool without the tubal insertions or massive quantities of giant capsules.

We know you’re scoffing out there, but it’s true. All you need is a little alginate, which is a “biocompatible polysaccharide isolated from brown algae” of the Phaeophyceae family. The donor feces is microencapsulated by mixing it with the alginate, dropping that mixture into water containing calcium chloride, turning it into a gel, and then freeze-drying the gel into small (just 2 mm), solid beads.

Sounds plausible enough, but what do you do with them? “These brownish beads can be easily dispersed in a liquid or food that is pleasant to eat. They also have no taste,” senior author Eric Allémann, PhD, said in a statement released by the University of Geneva.

Pleasant to eat? No taste? So which is it? If you really want to know, watch fecal beads week on the new season of “The Great British Baking Show,” when Paul and Prue judge poop baked into crumpets, crepes, and crostatas. Yum.

We’re on the low-oxygen diet

Nine out of ten doctors agree: Oxygen is more important to your continued well-being than food. After all, a human can go weeks without food, but just minutes without oxygen. However, ten out of ten doctors agree that the United States has an obesity problem. They all also agree that previous research has shown soldiers who train at high altitudes lose more weight than those training at lower altitudes.

So, on the one hand, we have a country full of overweight people, and on the other, we have low oxygen levels causing weight loss. The solution, then, is obvious: Stop breathing.

More specifically (and somewhat less facetiously), researchers from Louisiana have launched the Low Oxygen and Weight Status trial and are currently recruiting individuals with BMIs of 30-40 to, uh, suffocate themselves. No, no, it’s okay, it’s just when they’re sleeping.

Fine, straight face. Participants in the LOWS trial will undergo an 8-week period when they will consume a controlled weight-loss diet and spend their nights in a hypoxic sealed tent, where they will sleep in an environment with an oxygen level equivalent to 8,500 feet above sea level (roughly equivalent to Aspen, Colo.). They will be compared with people on the same diet who sleep in a normal, sea-level oxygen environment.

The study’s goal is to determine whether or not spending time in a low-oxygen environment will suppress appetite, increase energy expenditure, and improve weight loss and insulin sensitivity. Excessive weight loss in high-altitude environments isn’t a good thing for soldiers – they kind of need their muscles and body weight to do the whole soldiering thing – but it could be great for people struggling to lose those last few pounds. And it also may prove LOTME’s previous thesis: Air is not good.

Overweight boy, infertile man?

When it comes to causes of infertility, history and science have generally focused on women. A lot of the research overlooks men, but some previous studies have suggested that male infertility contributes to about half of the cases of couple infertility. The reason for much of that male infertility, however, has been a mystery. Until now.

A group of Italian investigators looked at the declining trend in sperm counts over the past 40 years and the increase of childhood obesity. Is there a correlation? The researchers think so. Childhood obesity can be linked to multiple causes, but the researchers zeroed in on the effect that obesity has on metabolic rates and, therefore, testicular growth.

Collecting data on testicular volume, body mass index (BMI), and insulin resistance from 268 boys aged 2-18 years, the researchers discovered that those with normal weight and normal insulin levels had testicular volumes 1.5 times higher than their overweight counterparts and 1.5-2 times higher than those with hyperinsulinemia, building a case for obesity being a factor for infertility later in life.

Since low testicular volume is associated with lower sperm count and production as an adult, putting two and two together makes a compelling argument for childhood obesity being a major male infertility culprit. It also creates even more urgency for the health care industry and community decision makers to focus on childhood obesity.

It sure would be nice to be able to take one of the many risk factors for future human survival off the table. Maybe by taking something, like cake, off the table.

Fecal transplantation moves to the kitchen

Fecal microbiota transplantation is an effective way to treat Clostridioides difficile infection, but, in the end, it’s still a transplantation procedure involving a nasogastric or colorectal tube or rather large oral capsules with a demanding (30-40 capsules over 2 days) dosage. Please, Science, tell us there’s a better way.

Science, in the form of investigators at the University of Geneva and Lausanne University Hospital in Switzerland, has spoken, and there may be a better way. Presenting fecal beads: All the bacterial goodness of donor stool without the tubal insertions or massive quantities of giant capsules.

We know you’re scoffing out there, but it’s true. All you need is a little alginate, which is a “biocompatible polysaccharide isolated from brown algae” of the Phaeophyceae family. The donor feces is microencapsulated by mixing it with the alginate, dropping that mixture into water containing calcium chloride, turning it into a gel, and then freeze-drying the gel into small (just 2 mm), solid beads.

Sounds plausible enough, but what do you do with them? “These brownish beads can be easily dispersed in a liquid or food that is pleasant to eat. They also have no taste,” senior author Eric Allémann, PhD, said in a statement released by the University of Geneva.

Pleasant to eat? No taste? So which is it? If you really want to know, watch fecal beads week on the new season of “The Great British Baking Show,” when Paul and Prue judge poop baked into crumpets, crepes, and crostatas. Yum.

We’re on the low-oxygen diet

Nine out of ten doctors agree: Oxygen is more important to your continued well-being than food. After all, a human can go weeks without food, but just minutes without oxygen. However, ten out of ten doctors agree that the United States has an obesity problem. They all also agree that previous research has shown soldiers who train at high altitudes lose more weight than those training at lower altitudes.

So, on the one hand, we have a country full of overweight people, and on the other, we have low oxygen levels causing weight loss. The solution, then, is obvious: Stop breathing.

More specifically (and somewhat less facetiously), researchers from Louisiana have launched the Low Oxygen and Weight Status trial and are currently recruiting individuals with BMIs of 30-40 to, uh, suffocate themselves. No, no, it’s okay, it’s just when they’re sleeping.

Fine, straight face. Participants in the LOWS trial will undergo an 8-week period when they will consume a controlled weight-loss diet and spend their nights in a hypoxic sealed tent, where they will sleep in an environment with an oxygen level equivalent to 8,500 feet above sea level (roughly equivalent to Aspen, Colo.). They will be compared with people on the same diet who sleep in a normal, sea-level oxygen environment.

The study’s goal is to determine whether or not spending time in a low-oxygen environment will suppress appetite, increase energy expenditure, and improve weight loss and insulin sensitivity. Excessive weight loss in high-altitude environments isn’t a good thing for soldiers – they kind of need their muscles and body weight to do the whole soldiering thing – but it could be great for people struggling to lose those last few pounds. And it also may prove LOTME’s previous thesis: Air is not good.

Nurses: The unsung heroes

Try practicing inpatient medicine without nurses.

You can’t.

We blow in and out of the rooms, write notes, check results and vitals, then move on to the next person.

But the nurses are the ones who actually make this all happen. And, amazingly, can do all that work with a smile.

But in our current postpandemic world, we’re facing a serious shortage. A recent survey of registered nurses found that only 15% of hospital nurses were planning on being there in 1 year. Thirty percent said they were planning on changing careers entirely in the aftermath of the pandemic. Their job satisfaction scores have dropped 15% from 2019 to 2023. Their stress scores, and concerns that the job is affecting their health, have increased 15%-20%.

The problem reflects a combination of things intersecting at a bad time: Staffing shortages resulting in more patients per nurse, hospital administrators cutting corners on staffing and pay, and the ongoing state of incivility.

The last one is a particularly new issue. Difficult patients and their families are nothing new. We all encounter them, and learn to deal with them in our own way. It’s part of the territory.