User login

Surprising brain activity moments before death

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

All the participants in the study I am going to tell you about this week died. And three of them died twice. But their deaths provide us with a fascinating window into the complex electrochemistry of the dying brain. What we might be looking at, indeed, is the physiologic correlate of the near-death experience.

The concept of the near-death experience is culturally ubiquitous. And though the content seems to track along culture lines – Western Christians are more likely to report seeing guardian angels, while Hindus are more likely to report seeing messengers of the god of death – certain factors seem to transcend culture: an out-of-body experience; a feeling of peace; and, of course, the light at the end of the tunnel.

As a materialist, I won’t discuss the possibility that these commonalities reflect some metaphysical structure to the afterlife. More likely, it seems to me, is that the commonalities result from the fact that the experience is mediated by our brains, and our brains, when dying, may be more alike than different.

We are talking about this study, appearing in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, by Jimo Borjigin and her team.

Dr. Borjigin studies the neural correlates of consciousness, perhaps one of the biggest questions in all of science today. To wit,

The study in question follows four unconscious patients –comatose patients, really – as life-sustaining support was withdrawn, up until the moment of death. Three had suffered severe anoxic brain injury in the setting of prolonged cardiac arrest. Though the heart was restarted, the brain damage was severe. The fourth had a large brain hemorrhage. All four patients were thus comatose and, though not brain-dead, unresponsive – with the lowest possible Glasgow Coma Scale score. No response to outside stimuli.

The families had made the decision to withdraw life support – to remove the breathing tube – but agreed to enroll their loved one in the study.

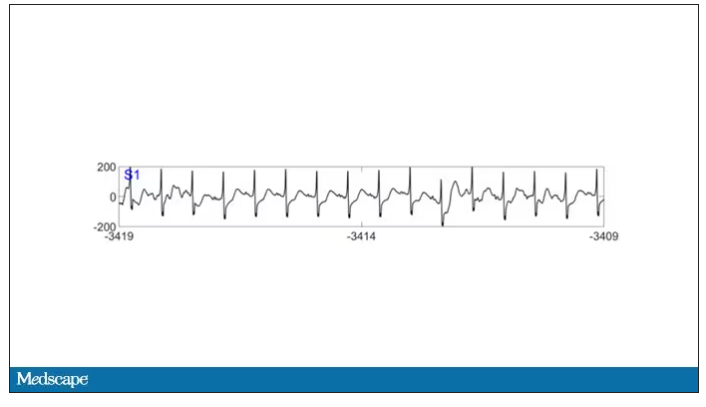

The team applied EEG leads to the head, EKG leads to the chest, and other monitoring equipment to observe the physiologic changes that occurred as the comatose and unresponsive patient died.

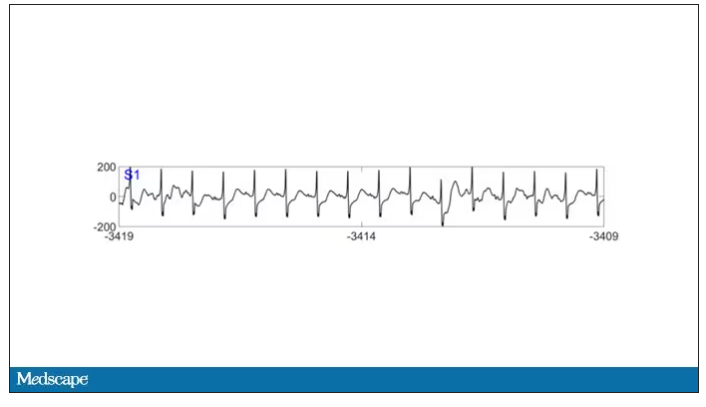

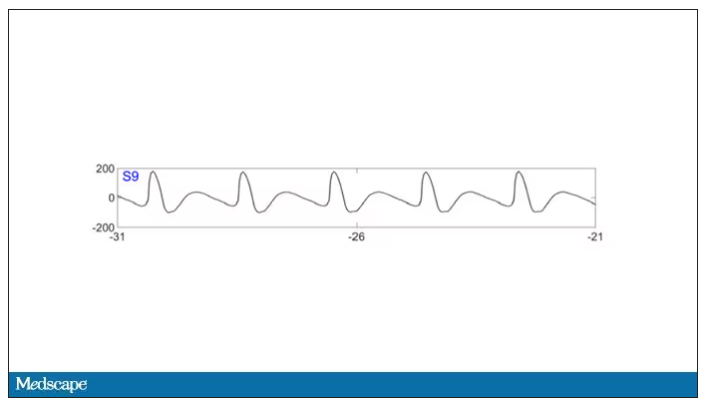

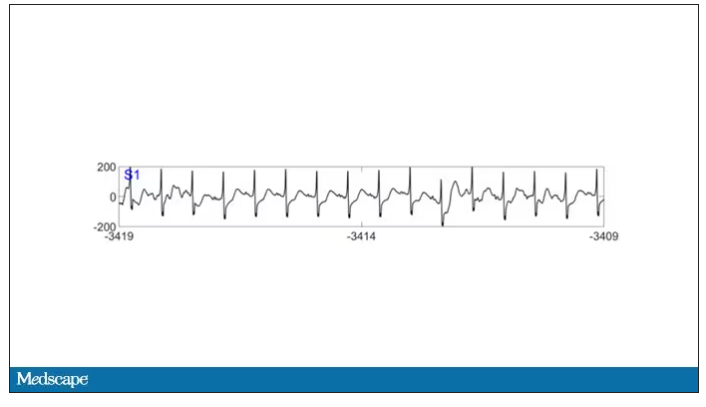

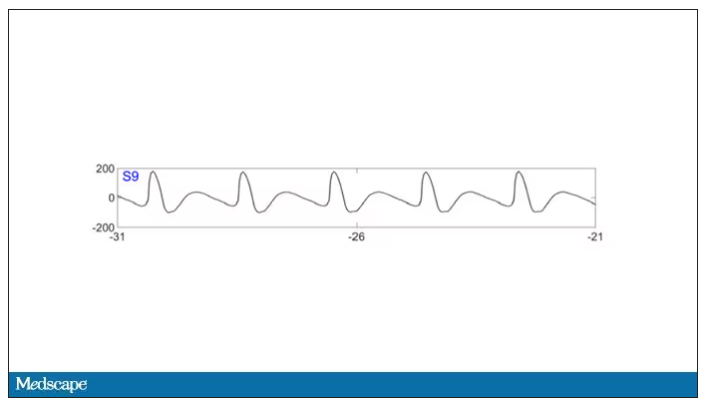

As the heart rhythm evolved from this:

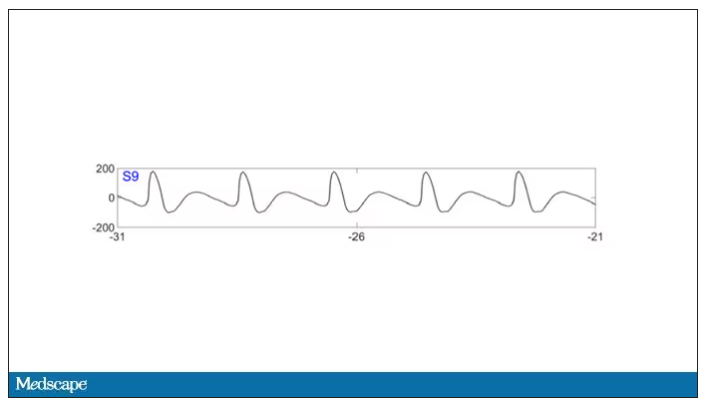

To this:

And eventually stopped.

But this is a study about the brain, not the heart.

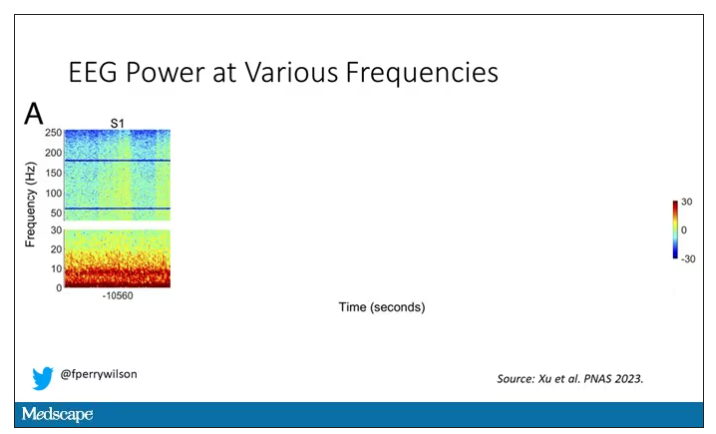

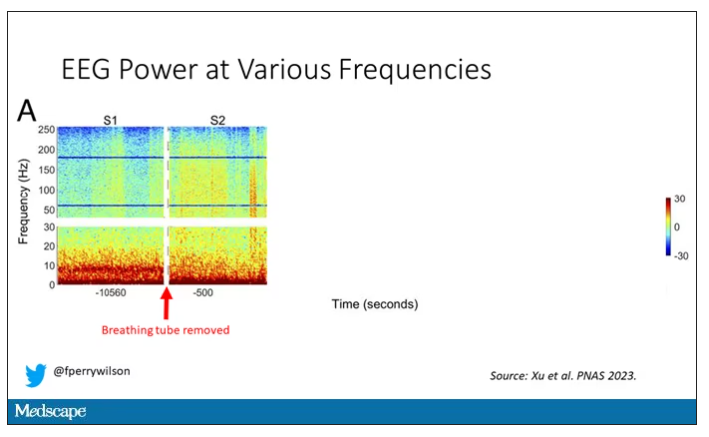

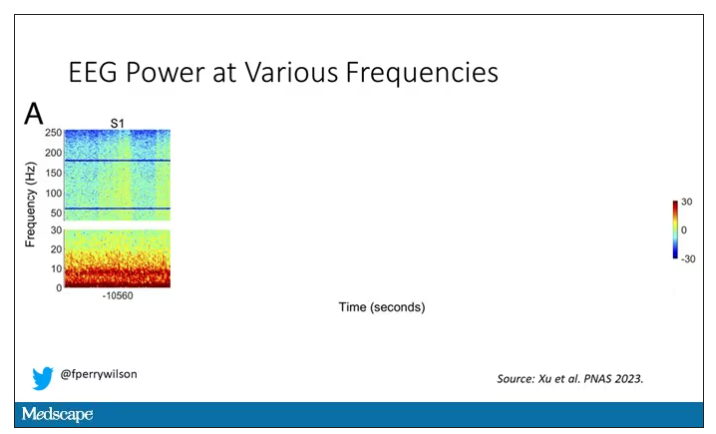

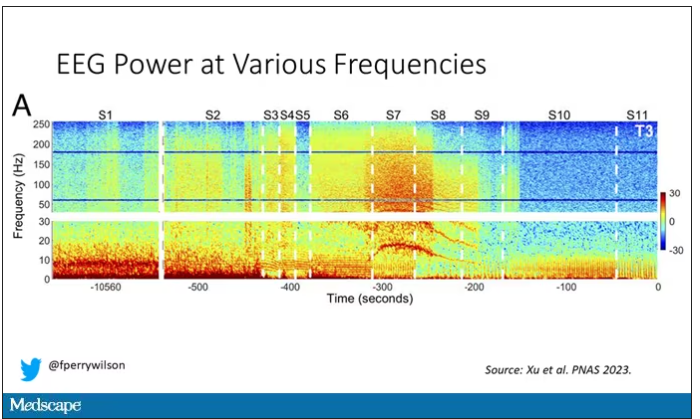

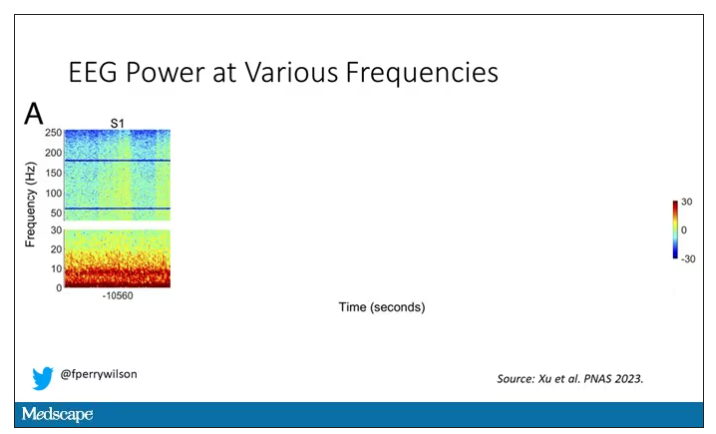

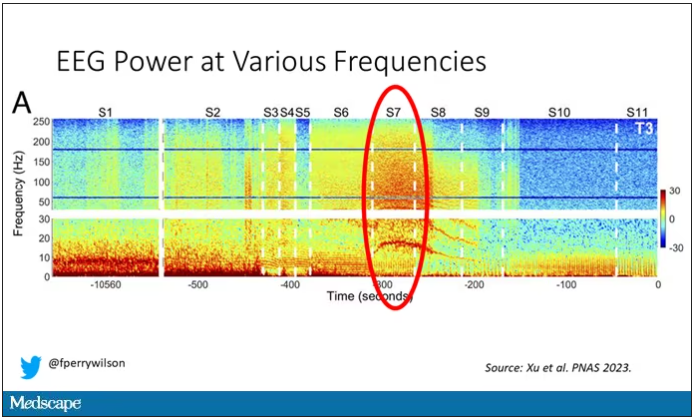

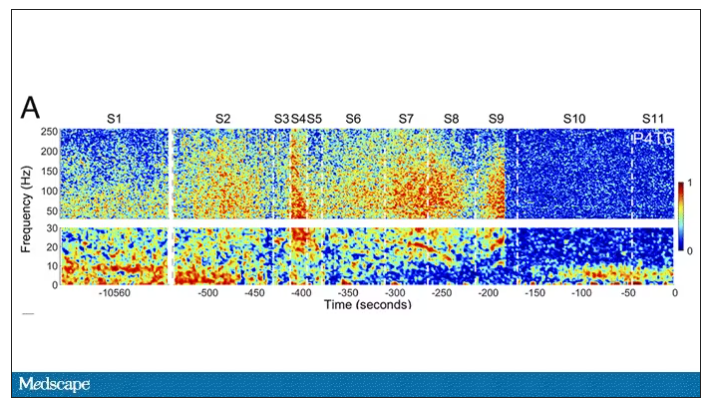

Prior to the withdrawal of life support, the brain electrical signals looked like this:

What you see is the EEG power at various frequencies, with red being higher. All the red was down at the low frequencies. Consciousness, at least as we understand it, is a higher-frequency phenomenon.

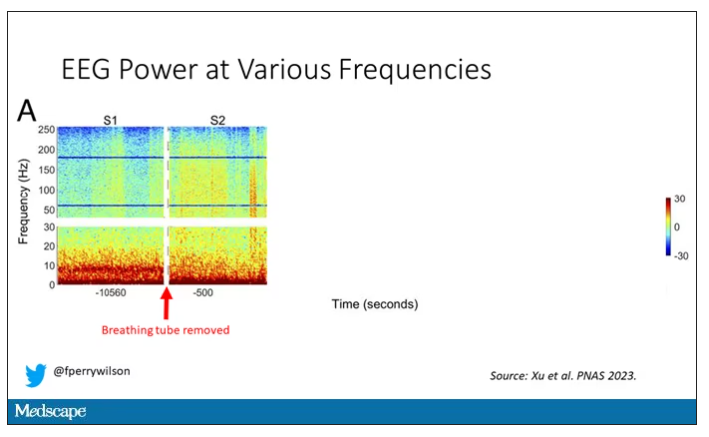

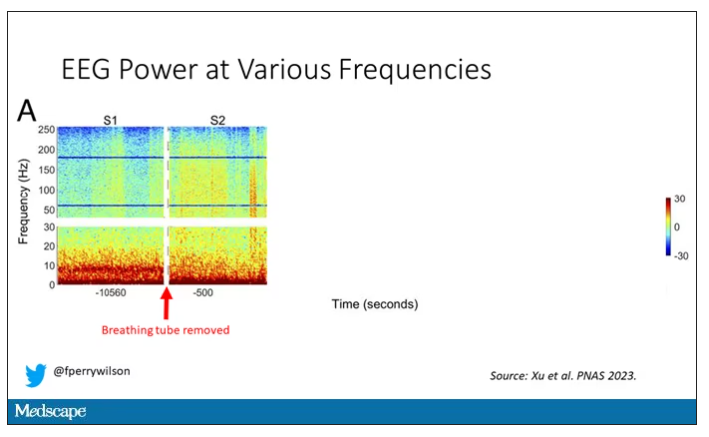

Right after the breathing tube was removed, the power didn’t change too much, but you can see some increased activity at the higher frequencies.

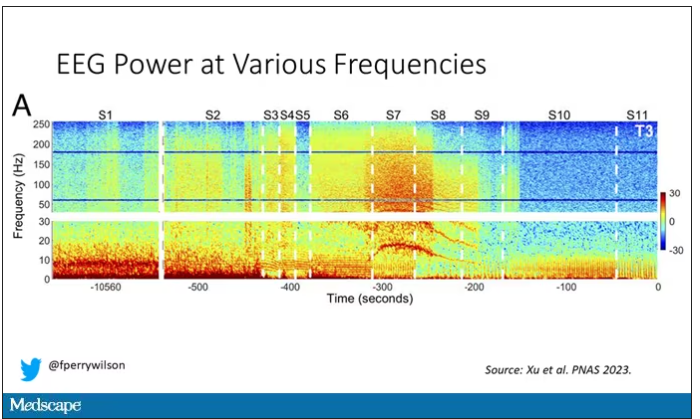

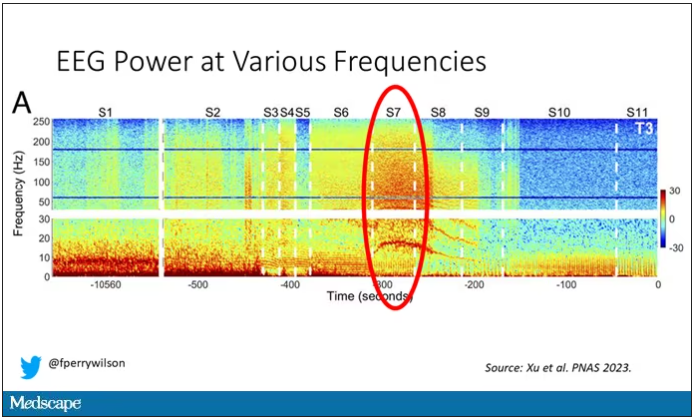

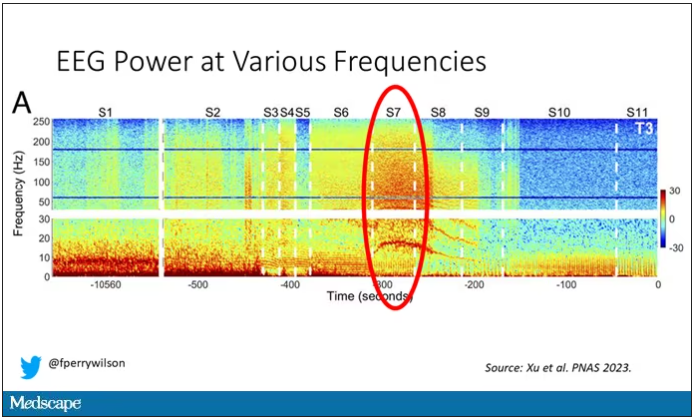

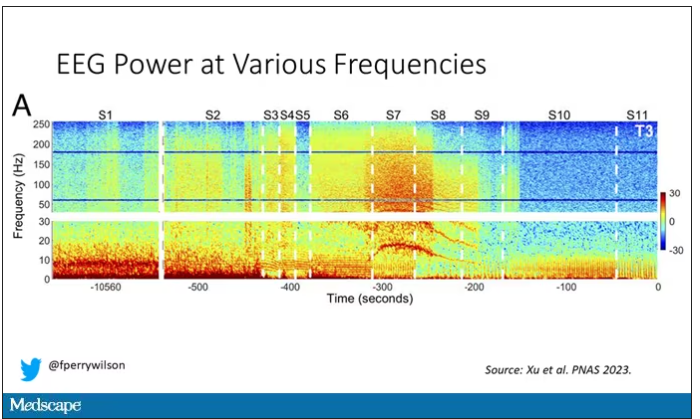

But in two of the four patients, something really surprising happened. Watch what happens as the brain gets closer and closer to death.

Here, about 300 seconds before death, there was a power surge at the high gamma frequencies.

This spike in power occurred in the somatosensory cortex and the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, areas that are associated with conscious experience. It seems that this patient, 5 minutes before death, was experiencing something.

But I know what you’re thinking. This is a brain that is not receiving oxygen. Cells are going to become disordered quickly and start firing randomly – a last gasp, so to speak, before the end. Meaningless noise.

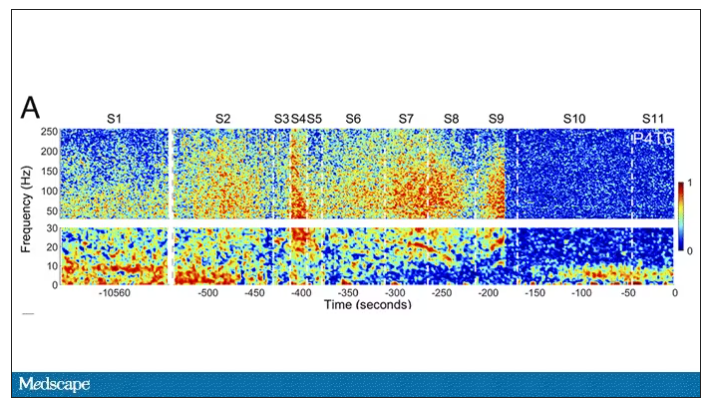

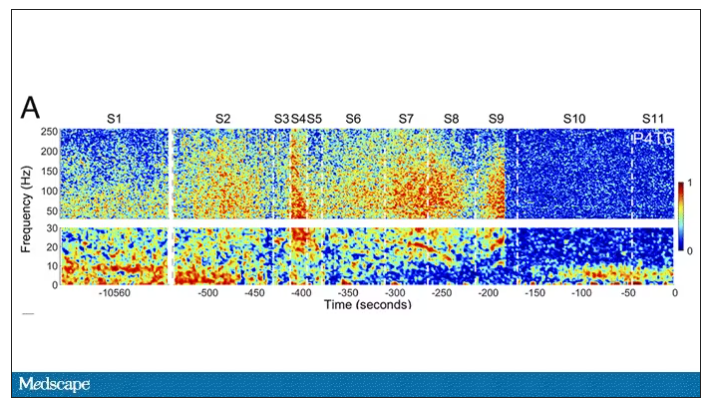

But connectivity mapping tells a different story. The signals seem to have structure.

Those high-frequency power surges increased connectivity in the posterior cortical “hot zone,” an area of the brain many researchers feel is necessary for conscious perception. This figure is not a map of raw brain electrical output like the one I showed before, but of coherence between brain regions in the consciousness hot zone. Those red areas indicate cross-talk – not the disordered scream of dying neurons, but a last set of messages passing back and forth from the parietal and posterior temporal lobes.

In fact, the electrical patterns of the brains in these patients looked very similar to the patterns seen in dreaming humans, as well as in patients with epilepsy who report sensations of out-of-body experiences.

It’s critical to realize two things here. First, these signals of consciousness were not present before life support was withdrawn. These comatose patients had minimal brain activity; there was no evidence that they were experiencing anything before the process of dying began. These brains are behaving fundamentally differently near death.

But second, we must realize that, although the brains of these individuals, in their last moments, appeared to be acting in a way that conscious brains act, we have no way of knowing if the patients were truly having a conscious experience. As I said, all the patients in the study died. Short of those metaphysics I alluded to earlier, we will have no way to ask them how they experienced their final moments.

Let’s be clear: This study doesn’t answer the question of what happens when we die. It says nothing about life after death or the existence or persistence of the soul. But what it does do is shed light on an incredibly difficult problem in neuroscience: the problem of consciousness. And as studies like this move forward, we may discover that the root of consciousness comes not from the breath of God or the energy of a living universe, but from very specific parts of the very complicated machine that is the brain, acting together to produce something transcendent. And to me, that is no less sublime.

Dr. Wilson is an associate professor of medicine and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator, Yale University, New Haven, Conn. His science communication work can be found in the Huffington Post, on NPR, and on Medscape. He tweets @fperrywilson and his new book, How Medicine Works and When It Doesn’t, is available now. Dr. Wilson has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

All the participants in the study I am going to tell you about this week died. And three of them died twice. But their deaths provide us with a fascinating window into the complex electrochemistry of the dying brain. What we might be looking at, indeed, is the physiologic correlate of the near-death experience.

The concept of the near-death experience is culturally ubiquitous. And though the content seems to track along culture lines – Western Christians are more likely to report seeing guardian angels, while Hindus are more likely to report seeing messengers of the god of death – certain factors seem to transcend culture: an out-of-body experience; a feeling of peace; and, of course, the light at the end of the tunnel.

As a materialist, I won’t discuss the possibility that these commonalities reflect some metaphysical structure to the afterlife. More likely, it seems to me, is that the commonalities result from the fact that the experience is mediated by our brains, and our brains, when dying, may be more alike than different.

We are talking about this study, appearing in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, by Jimo Borjigin and her team.

Dr. Borjigin studies the neural correlates of consciousness, perhaps one of the biggest questions in all of science today. To wit,

The study in question follows four unconscious patients –comatose patients, really – as life-sustaining support was withdrawn, up until the moment of death. Three had suffered severe anoxic brain injury in the setting of prolonged cardiac arrest. Though the heart was restarted, the brain damage was severe. The fourth had a large brain hemorrhage. All four patients were thus comatose and, though not brain-dead, unresponsive – with the lowest possible Glasgow Coma Scale score. No response to outside stimuli.

The families had made the decision to withdraw life support – to remove the breathing tube – but agreed to enroll their loved one in the study.

The team applied EEG leads to the head, EKG leads to the chest, and other monitoring equipment to observe the physiologic changes that occurred as the comatose and unresponsive patient died.

As the heart rhythm evolved from this:

To this:

And eventually stopped.

But this is a study about the brain, not the heart.

Prior to the withdrawal of life support, the brain electrical signals looked like this:

What you see is the EEG power at various frequencies, with red being higher. All the red was down at the low frequencies. Consciousness, at least as we understand it, is a higher-frequency phenomenon.

Right after the breathing tube was removed, the power didn’t change too much, but you can see some increased activity at the higher frequencies.

But in two of the four patients, something really surprising happened. Watch what happens as the brain gets closer and closer to death.

Here, about 300 seconds before death, there was a power surge at the high gamma frequencies.

This spike in power occurred in the somatosensory cortex and the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, areas that are associated with conscious experience. It seems that this patient, 5 minutes before death, was experiencing something.

But I know what you’re thinking. This is a brain that is not receiving oxygen. Cells are going to become disordered quickly and start firing randomly – a last gasp, so to speak, before the end. Meaningless noise.

But connectivity mapping tells a different story. The signals seem to have structure.

Those high-frequency power surges increased connectivity in the posterior cortical “hot zone,” an area of the brain many researchers feel is necessary for conscious perception. This figure is not a map of raw brain electrical output like the one I showed before, but of coherence between brain regions in the consciousness hot zone. Those red areas indicate cross-talk – not the disordered scream of dying neurons, but a last set of messages passing back and forth from the parietal and posterior temporal lobes.

In fact, the electrical patterns of the brains in these patients looked very similar to the patterns seen in dreaming humans, as well as in patients with epilepsy who report sensations of out-of-body experiences.

It’s critical to realize two things here. First, these signals of consciousness were not present before life support was withdrawn. These comatose patients had minimal brain activity; there was no evidence that they were experiencing anything before the process of dying began. These brains are behaving fundamentally differently near death.

But second, we must realize that, although the brains of these individuals, in their last moments, appeared to be acting in a way that conscious brains act, we have no way of knowing if the patients were truly having a conscious experience. As I said, all the patients in the study died. Short of those metaphysics I alluded to earlier, we will have no way to ask them how they experienced their final moments.

Let’s be clear: This study doesn’t answer the question of what happens when we die. It says nothing about life after death or the existence or persistence of the soul. But what it does do is shed light on an incredibly difficult problem in neuroscience: the problem of consciousness. And as studies like this move forward, we may discover that the root of consciousness comes not from the breath of God or the energy of a living universe, but from very specific parts of the very complicated machine that is the brain, acting together to produce something transcendent. And to me, that is no less sublime.

Dr. Wilson is an associate professor of medicine and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator, Yale University, New Haven, Conn. His science communication work can be found in the Huffington Post, on NPR, and on Medscape. He tweets @fperrywilson and his new book, How Medicine Works and When It Doesn’t, is available now. Dr. Wilson has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

All the participants in the study I am going to tell you about this week died. And three of them died twice. But their deaths provide us with a fascinating window into the complex electrochemistry of the dying brain. What we might be looking at, indeed, is the physiologic correlate of the near-death experience.

The concept of the near-death experience is culturally ubiquitous. And though the content seems to track along culture lines – Western Christians are more likely to report seeing guardian angels, while Hindus are more likely to report seeing messengers of the god of death – certain factors seem to transcend culture: an out-of-body experience; a feeling of peace; and, of course, the light at the end of the tunnel.

As a materialist, I won’t discuss the possibility that these commonalities reflect some metaphysical structure to the afterlife. More likely, it seems to me, is that the commonalities result from the fact that the experience is mediated by our brains, and our brains, when dying, may be more alike than different.

We are talking about this study, appearing in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, by Jimo Borjigin and her team.

Dr. Borjigin studies the neural correlates of consciousness, perhaps one of the biggest questions in all of science today. To wit,

The study in question follows four unconscious patients –comatose patients, really – as life-sustaining support was withdrawn, up until the moment of death. Three had suffered severe anoxic brain injury in the setting of prolonged cardiac arrest. Though the heart was restarted, the brain damage was severe. The fourth had a large brain hemorrhage. All four patients were thus comatose and, though not brain-dead, unresponsive – with the lowest possible Glasgow Coma Scale score. No response to outside stimuli.

The families had made the decision to withdraw life support – to remove the breathing tube – but agreed to enroll their loved one in the study.

The team applied EEG leads to the head, EKG leads to the chest, and other monitoring equipment to observe the physiologic changes that occurred as the comatose and unresponsive patient died.

As the heart rhythm evolved from this:

To this:

And eventually stopped.

But this is a study about the brain, not the heart.

Prior to the withdrawal of life support, the brain electrical signals looked like this:

What you see is the EEG power at various frequencies, with red being higher. All the red was down at the low frequencies. Consciousness, at least as we understand it, is a higher-frequency phenomenon.

Right after the breathing tube was removed, the power didn’t change too much, but you can see some increased activity at the higher frequencies.

But in two of the four patients, something really surprising happened. Watch what happens as the brain gets closer and closer to death.

Here, about 300 seconds before death, there was a power surge at the high gamma frequencies.

This spike in power occurred in the somatosensory cortex and the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, areas that are associated with conscious experience. It seems that this patient, 5 minutes before death, was experiencing something.

But I know what you’re thinking. This is a brain that is not receiving oxygen. Cells are going to become disordered quickly and start firing randomly – a last gasp, so to speak, before the end. Meaningless noise.

But connectivity mapping tells a different story. The signals seem to have structure.

Those high-frequency power surges increased connectivity in the posterior cortical “hot zone,” an area of the brain many researchers feel is necessary for conscious perception. This figure is not a map of raw brain electrical output like the one I showed before, but of coherence between brain regions in the consciousness hot zone. Those red areas indicate cross-talk – not the disordered scream of dying neurons, but a last set of messages passing back and forth from the parietal and posterior temporal lobes.

In fact, the electrical patterns of the brains in these patients looked very similar to the patterns seen in dreaming humans, as well as in patients with epilepsy who report sensations of out-of-body experiences.

It’s critical to realize two things here. First, these signals of consciousness were not present before life support was withdrawn. These comatose patients had minimal brain activity; there was no evidence that they were experiencing anything before the process of dying began. These brains are behaving fundamentally differently near death.

But second, we must realize that, although the brains of these individuals, in their last moments, appeared to be acting in a way that conscious brains act, we have no way of knowing if the patients were truly having a conscious experience. As I said, all the patients in the study died. Short of those metaphysics I alluded to earlier, we will have no way to ask them how they experienced their final moments.

Let’s be clear: This study doesn’t answer the question of what happens when we die. It says nothing about life after death or the existence or persistence of the soul. But what it does do is shed light on an incredibly difficult problem in neuroscience: the problem of consciousness. And as studies like this move forward, we may discover that the root of consciousness comes not from the breath of God or the energy of a living universe, but from very specific parts of the very complicated machine that is the brain, acting together to produce something transcendent. And to me, that is no less sublime.

Dr. Wilson is an associate professor of medicine and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator, Yale University, New Haven, Conn. His science communication work can be found in the Huffington Post, on NPR, and on Medscape. He tweets @fperrywilson and his new book, How Medicine Works and When It Doesn’t, is available now. Dr. Wilson has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Malaria: Not just someone else’s problem

What is the most dangerous animal on Earth? Which one has killed more humans since we first began walking upright?

The mind leaps to the vicious and dangerous – great white sharks. lions. tigers. crocodiles. The fearsome predators of the planet But realistically, more people are killed and injured by large herbivores each year than predators. Just watch news updates from Yellowstone during their busy season.

Anyway, the correct answer is ... none of the above.

It’s the mosquito, and the many microbes it’s a vector for. Malaria, in particular. Even the once-devastating bubonic plague is no longer a major concern.

What do Presidents Washington, Kennedy, Eisenhower, Lincoln, Monroe, Grant, Garfield, Jackson, Teddy Roosevelt, and other historical VIPs like Oliver Cromwell, King Tut, and numerous kings, queens, and popes all have in common? They all had malaria. Cromwell, Tut, and many royal and religious figures died of it.

You can make a solid argument that malaria is the disease that’s affected the course of history more than any other (you could make a good case for the plague, too, but it’s less relevant today). The control of malaria is what allowed the Panama canal to happen.

I’m bringing this up because, mostly overlooked in the news recently as we argued about light beer endorsements, TV pundits, and the NFL draft, is the approval and gradual increase in use of a malaria vaccine.

This is a pretty big deal given the scope of the problem and the fact that the most effective prevention up until recently was a mosquito net.

We tend to see malaria as someone else’s problem, something that affects the tropics, but forget that as recently as the 1940s it was still common in the U.S. During the Civil War as many as 1 million soldiers were infected with it. Given the right conditions it could easily return here.

Which is why we should be more aware of these things. As COVID showed, infectious diseases are never some other country’s, or continent’s, problem. They affect all of us either directly or indirectly. In the interconnected economies of the world illnesses in one area can spread to others. Even if they don’t they can still have significant effects on supply chains, since so much of what we depend on comes from somewhere else.

COVID, by comparison, is small beer. Just think about smallpox, or the plague, or polio, as to what an unchecked disease can do to a society until medicine catches up with it.

There will always be new diseases. Microbes and humans have been in a state of hostilities for a few million years now, and likely always will be. But every victory along the way is a victory for everyone, regardless of who they are or where they live.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

What is the most dangerous animal on Earth? Which one has killed more humans since we first began walking upright?

The mind leaps to the vicious and dangerous – great white sharks. lions. tigers. crocodiles. The fearsome predators of the planet But realistically, more people are killed and injured by large herbivores each year than predators. Just watch news updates from Yellowstone during their busy season.

Anyway, the correct answer is ... none of the above.

It’s the mosquito, and the many microbes it’s a vector for. Malaria, in particular. Even the once-devastating bubonic plague is no longer a major concern.

What do Presidents Washington, Kennedy, Eisenhower, Lincoln, Monroe, Grant, Garfield, Jackson, Teddy Roosevelt, and other historical VIPs like Oliver Cromwell, King Tut, and numerous kings, queens, and popes all have in common? They all had malaria. Cromwell, Tut, and many royal and religious figures died of it.

You can make a solid argument that malaria is the disease that’s affected the course of history more than any other (you could make a good case for the plague, too, but it’s less relevant today). The control of malaria is what allowed the Panama canal to happen.

I’m bringing this up because, mostly overlooked in the news recently as we argued about light beer endorsements, TV pundits, and the NFL draft, is the approval and gradual increase in use of a malaria vaccine.

This is a pretty big deal given the scope of the problem and the fact that the most effective prevention up until recently was a mosquito net.

We tend to see malaria as someone else’s problem, something that affects the tropics, but forget that as recently as the 1940s it was still common in the U.S. During the Civil War as many as 1 million soldiers were infected with it. Given the right conditions it could easily return here.

Which is why we should be more aware of these things. As COVID showed, infectious diseases are never some other country’s, or continent’s, problem. They affect all of us either directly or indirectly. In the interconnected economies of the world illnesses in one area can spread to others. Even if they don’t they can still have significant effects on supply chains, since so much of what we depend on comes from somewhere else.

COVID, by comparison, is small beer. Just think about smallpox, or the plague, or polio, as to what an unchecked disease can do to a society until medicine catches up with it.

There will always be new diseases. Microbes and humans have been in a state of hostilities for a few million years now, and likely always will be. But every victory along the way is a victory for everyone, regardless of who they are or where they live.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

What is the most dangerous animal on Earth? Which one has killed more humans since we first began walking upright?

The mind leaps to the vicious and dangerous – great white sharks. lions. tigers. crocodiles. The fearsome predators of the planet But realistically, more people are killed and injured by large herbivores each year than predators. Just watch news updates from Yellowstone during their busy season.

Anyway, the correct answer is ... none of the above.

It’s the mosquito, and the many microbes it’s a vector for. Malaria, in particular. Even the once-devastating bubonic plague is no longer a major concern.

What do Presidents Washington, Kennedy, Eisenhower, Lincoln, Monroe, Grant, Garfield, Jackson, Teddy Roosevelt, and other historical VIPs like Oliver Cromwell, King Tut, and numerous kings, queens, and popes all have in common? They all had malaria. Cromwell, Tut, and many royal and religious figures died of it.

You can make a solid argument that malaria is the disease that’s affected the course of history more than any other (you could make a good case for the plague, too, but it’s less relevant today). The control of malaria is what allowed the Panama canal to happen.

I’m bringing this up because, mostly overlooked in the news recently as we argued about light beer endorsements, TV pundits, and the NFL draft, is the approval and gradual increase in use of a malaria vaccine.

This is a pretty big deal given the scope of the problem and the fact that the most effective prevention up until recently was a mosquito net.

We tend to see malaria as someone else’s problem, something that affects the tropics, but forget that as recently as the 1940s it was still common in the U.S. During the Civil War as many as 1 million soldiers were infected with it. Given the right conditions it could easily return here.

Which is why we should be more aware of these things. As COVID showed, infectious diseases are never some other country’s, or continent’s, problem. They affect all of us either directly or indirectly. In the interconnected economies of the world illnesses in one area can spread to others. Even if they don’t they can still have significant effects on supply chains, since so much of what we depend on comes from somewhere else.

COVID, by comparison, is small beer. Just think about smallpox, or the plague, or polio, as to what an unchecked disease can do to a society until medicine catches up with it.

There will always be new diseases. Microbes and humans have been in a state of hostilities for a few million years now, and likely always will be. But every victory along the way is a victory for everyone, regardless of who they are or where they live.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Getting a white-bagging exemption: A win for the patient, employer, and rheumatologist

Whether it’s filling out a prior authorization form or testifying before Congress, it is an action we perform that ultimately helps our patients achieve that care. We are familiar with many of the obstacles that block the path to the best care and interfere with our patient-doctor relationships. Much work has been done to pass legislation in the states to mitigate some of those obstacles, such as unreasonable step therapy regimens, nonmedical switching, and copay accumulators.

Unfortunately, that state legislation does not cover patients who work for companies that are self-insured. Self-insured employers, which account for about 60% of America’s workers, directly pay for the health benefits offered to employees instead of buying “fully funded” insurance plans. Most of those self-funded plans fall under “ERISA” protections and are regulated by the federal Department of Labor. ERISA stands for Employee Retirement Income Security Act. The law, which was enacted in 1974, also covers employee health plans. These plans must act as a fiduciary, meaning they must look after the well-being of the employees, including their finances and those of the plan itself.

The Coalition of State Rheumatology Organizations (CSRO) has learned of a number of issues involving patients who work for self-funded companies, regulated by ERISA. One such issue is that of mandated “white bagging.” White bagging has been discussed in “Rheum for Action” in the past. There is a long list of white-bagging problems, including dosing issues, lack of “chain of custody” with the medications, delays in treatment, mandatory up-front payments by the patient, and wastage of unused medication. However, there is another issue that is of concern not only to the employees (our patients) but to the employer as well.

Employers’ fiduciary responsibility

As mentioned earlier, the employers who self insure are responsible for the financial well-being of their employee and the plan itself. Therefore, if certain practices are mandated within the health plan that harm our patients or the plan financially, the company could be in violation of their fiduciary duty. Rheumatologists have said that buying and billing the drug to the medical side of the health plan in many cases costs much less than white bagging. Conceivably, that could result in breach of an employer’s fiduciary duty to their employee.

Evidence for violating fiduciary duty

CSRO recently received redacted receipts comparing costs between the two models of drug acquisition for a patient in an ERISA plan. White bagging for the patient occurred in 2021, and in 2022 an exemption was granted for the rheumatologist to buy and bill the administered medication. Unfortunately, the exemption to buy and bill in 2023 was denied and continues to be denied (as of this writing). A comparison of the receipts revealed the company was charged over $40,000 for the white-bagged medication in 2021, and the patient’s cost share for that year was $525. Under the traditional buy-and-bill acquisition model in 2022, the company was charged around $12,000 for the medication and the patient’s cost share was $30. There is a clear difference in cost to the employee and plan between the two acquisition models.

Is this major company unknowingly violating its fiduciary duty by mandating white bagging as per their contract with one of the three big pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs)? If so, how does something like this happen with a large national company that has ERISA attorneys looking over the contracts with the PBMs?

Why is white bagging mandated?

Often, white bagging is mandated because the cost of infusions in a hospital outpatient facility can be very high. Nationally, it has been shown that hospitals charge four to five times the cost they paid for the drug, and the 100 most expensive hospitals charge 10-18 times the cost of their drugs. With these up-charges, white bagging could easily be a lower cost for employee and company. But across-the-board mandating of white bagging ignores that physician office–based infusions may offer a much lower cost to employees and the employer.

Another reason large and small self-funded companies may unknowingly sign contracts that are often more profitable to the PBM than to the employer is that the employer pharmacy benefit consultants are paid handsomely by the big PBMs and have been known to “rig” the contract in favor of the PBM, according to Paul Holmes, an ERISA attorney with a focus in pharmacy health plan contracts. Clearly, the PBM profits more with white-bagged medicines billed through the pharmacy (PBM) side of insurance as opposed to buy-and-bill medications that are billed on the medical side of insurance. So mandated white bagging is often included in these contracts, ignoring the lower cost in an infusion suite at a physician’s office.

Suggestions for employers

Employers and employees should be able to obtain the costs of mandated, white-bagged drugs from their PBMs because the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2021 (CAA) mandates that group health plans ensure access to cost data. The employer should also have access to their consultant’s compensation from the PBM as Section 202 in the CAA states that employer benefit consultants must “disclose actual and anticipated cash and non-cash compensation they expect to earn in connection with the sale, renewal, and extension of group health insurance.”

It would be wise for all self-insured companies to use this section to see how much their consultants are being influenced by the company that they are recommending. Additionally, the companies should consider hiring ERISA attorneys that understand not only the legalese of the contract with a PBM but also the pharmacy lingo, such as the difference between maximum allowable cost, average wholesale price, average sales price, and average manufacturer’s price.

Suggestion for the rheumatologist

This leads to a suggestion to rheumatologists trying to get an exemption from mandated white bagging. If a patient has already had white-bagged medication, have them obtain a receipt from the PBM for their charges to the plan for the medication. If the patient has not gone through the white bagging yet, the PBM should be able to tell the plan the cost of the white-bagged medication and the cost to the patient. Compare those costs with what would be charged through buy and bill, and if it is less, present that evidence to the employer and remind them of their fiduciary responsibility to their employees.

Granted, this process may take more effort than filling out a prior authorization, but getting the white-bag exemption will help the patient, the employer, and the rheumatologist in the long run. A win-win-win!

Dr. Feldman is a rheumatologist in private practice with The Rheumatology Group in New Orleans. She is the CSRO’s Vice President of Advocacy and Government Affairs and its immediate Past President, as well as past chair of the Alliance for Safe Biologic Medicines and a past member of the American College of Rheumatology insurance subcommittee. You can reach her at [email protected].

Whether it’s filling out a prior authorization form or testifying before Congress, it is an action we perform that ultimately helps our patients achieve that care. We are familiar with many of the obstacles that block the path to the best care and interfere with our patient-doctor relationships. Much work has been done to pass legislation in the states to mitigate some of those obstacles, such as unreasonable step therapy regimens, nonmedical switching, and copay accumulators.

Unfortunately, that state legislation does not cover patients who work for companies that are self-insured. Self-insured employers, which account for about 60% of America’s workers, directly pay for the health benefits offered to employees instead of buying “fully funded” insurance plans. Most of those self-funded plans fall under “ERISA” protections and are regulated by the federal Department of Labor. ERISA stands for Employee Retirement Income Security Act. The law, which was enacted in 1974, also covers employee health plans. These plans must act as a fiduciary, meaning they must look after the well-being of the employees, including their finances and those of the plan itself.

The Coalition of State Rheumatology Organizations (CSRO) has learned of a number of issues involving patients who work for self-funded companies, regulated by ERISA. One such issue is that of mandated “white bagging.” White bagging has been discussed in “Rheum for Action” in the past. There is a long list of white-bagging problems, including dosing issues, lack of “chain of custody” with the medications, delays in treatment, mandatory up-front payments by the patient, and wastage of unused medication. However, there is another issue that is of concern not only to the employees (our patients) but to the employer as well.

Employers’ fiduciary responsibility

As mentioned earlier, the employers who self insure are responsible for the financial well-being of their employee and the plan itself. Therefore, if certain practices are mandated within the health plan that harm our patients or the plan financially, the company could be in violation of their fiduciary duty. Rheumatologists have said that buying and billing the drug to the medical side of the health plan in many cases costs much less than white bagging. Conceivably, that could result in breach of an employer’s fiduciary duty to their employee.

Evidence for violating fiduciary duty

CSRO recently received redacted receipts comparing costs between the two models of drug acquisition for a patient in an ERISA plan. White bagging for the patient occurred in 2021, and in 2022 an exemption was granted for the rheumatologist to buy and bill the administered medication. Unfortunately, the exemption to buy and bill in 2023 was denied and continues to be denied (as of this writing). A comparison of the receipts revealed the company was charged over $40,000 for the white-bagged medication in 2021, and the patient’s cost share for that year was $525. Under the traditional buy-and-bill acquisition model in 2022, the company was charged around $12,000 for the medication and the patient’s cost share was $30. There is a clear difference in cost to the employee and plan between the two acquisition models.

Is this major company unknowingly violating its fiduciary duty by mandating white bagging as per their contract with one of the three big pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs)? If so, how does something like this happen with a large national company that has ERISA attorneys looking over the contracts with the PBMs?

Why is white bagging mandated?

Often, white bagging is mandated because the cost of infusions in a hospital outpatient facility can be very high. Nationally, it has been shown that hospitals charge four to five times the cost they paid for the drug, and the 100 most expensive hospitals charge 10-18 times the cost of their drugs. With these up-charges, white bagging could easily be a lower cost for employee and company. But across-the-board mandating of white bagging ignores that physician office–based infusions may offer a much lower cost to employees and the employer.

Another reason large and small self-funded companies may unknowingly sign contracts that are often more profitable to the PBM than to the employer is that the employer pharmacy benefit consultants are paid handsomely by the big PBMs and have been known to “rig” the contract in favor of the PBM, according to Paul Holmes, an ERISA attorney with a focus in pharmacy health plan contracts. Clearly, the PBM profits more with white-bagged medicines billed through the pharmacy (PBM) side of insurance as opposed to buy-and-bill medications that are billed on the medical side of insurance. So mandated white bagging is often included in these contracts, ignoring the lower cost in an infusion suite at a physician’s office.

Suggestions for employers

Employers and employees should be able to obtain the costs of mandated, white-bagged drugs from their PBMs because the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2021 (CAA) mandates that group health plans ensure access to cost data. The employer should also have access to their consultant’s compensation from the PBM as Section 202 in the CAA states that employer benefit consultants must “disclose actual and anticipated cash and non-cash compensation they expect to earn in connection with the sale, renewal, and extension of group health insurance.”

It would be wise for all self-insured companies to use this section to see how much their consultants are being influenced by the company that they are recommending. Additionally, the companies should consider hiring ERISA attorneys that understand not only the legalese of the contract with a PBM but also the pharmacy lingo, such as the difference between maximum allowable cost, average wholesale price, average sales price, and average manufacturer’s price.

Suggestion for the rheumatologist

This leads to a suggestion to rheumatologists trying to get an exemption from mandated white bagging. If a patient has already had white-bagged medication, have them obtain a receipt from the PBM for their charges to the plan for the medication. If the patient has not gone through the white bagging yet, the PBM should be able to tell the plan the cost of the white-bagged medication and the cost to the patient. Compare those costs with what would be charged through buy and bill, and if it is less, present that evidence to the employer and remind them of their fiduciary responsibility to their employees.

Granted, this process may take more effort than filling out a prior authorization, but getting the white-bag exemption will help the patient, the employer, and the rheumatologist in the long run. A win-win-win!

Dr. Feldman is a rheumatologist in private practice with The Rheumatology Group in New Orleans. She is the CSRO’s Vice President of Advocacy and Government Affairs and its immediate Past President, as well as past chair of the Alliance for Safe Biologic Medicines and a past member of the American College of Rheumatology insurance subcommittee. You can reach her at [email protected].

Whether it’s filling out a prior authorization form or testifying before Congress, it is an action we perform that ultimately helps our patients achieve that care. We are familiar with many of the obstacles that block the path to the best care and interfere with our patient-doctor relationships. Much work has been done to pass legislation in the states to mitigate some of those obstacles, such as unreasonable step therapy regimens, nonmedical switching, and copay accumulators.

Unfortunately, that state legislation does not cover patients who work for companies that are self-insured. Self-insured employers, which account for about 60% of America’s workers, directly pay for the health benefits offered to employees instead of buying “fully funded” insurance plans. Most of those self-funded plans fall under “ERISA” protections and are regulated by the federal Department of Labor. ERISA stands for Employee Retirement Income Security Act. The law, which was enacted in 1974, also covers employee health plans. These plans must act as a fiduciary, meaning they must look after the well-being of the employees, including their finances and those of the plan itself.

The Coalition of State Rheumatology Organizations (CSRO) has learned of a number of issues involving patients who work for self-funded companies, regulated by ERISA. One such issue is that of mandated “white bagging.” White bagging has been discussed in “Rheum for Action” in the past. There is a long list of white-bagging problems, including dosing issues, lack of “chain of custody” with the medications, delays in treatment, mandatory up-front payments by the patient, and wastage of unused medication. However, there is another issue that is of concern not only to the employees (our patients) but to the employer as well.

Employers’ fiduciary responsibility

As mentioned earlier, the employers who self insure are responsible for the financial well-being of their employee and the plan itself. Therefore, if certain practices are mandated within the health plan that harm our patients or the plan financially, the company could be in violation of their fiduciary duty. Rheumatologists have said that buying and billing the drug to the medical side of the health plan in many cases costs much less than white bagging. Conceivably, that could result in breach of an employer’s fiduciary duty to their employee.

Evidence for violating fiduciary duty

CSRO recently received redacted receipts comparing costs between the two models of drug acquisition for a patient in an ERISA plan. White bagging for the patient occurred in 2021, and in 2022 an exemption was granted for the rheumatologist to buy and bill the administered medication. Unfortunately, the exemption to buy and bill in 2023 was denied and continues to be denied (as of this writing). A comparison of the receipts revealed the company was charged over $40,000 for the white-bagged medication in 2021, and the patient’s cost share for that year was $525. Under the traditional buy-and-bill acquisition model in 2022, the company was charged around $12,000 for the medication and the patient’s cost share was $30. There is a clear difference in cost to the employee and plan between the two acquisition models.

Is this major company unknowingly violating its fiduciary duty by mandating white bagging as per their contract with one of the three big pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs)? If so, how does something like this happen with a large national company that has ERISA attorneys looking over the contracts with the PBMs?

Why is white bagging mandated?

Often, white bagging is mandated because the cost of infusions in a hospital outpatient facility can be very high. Nationally, it has been shown that hospitals charge four to five times the cost they paid for the drug, and the 100 most expensive hospitals charge 10-18 times the cost of their drugs. With these up-charges, white bagging could easily be a lower cost for employee and company. But across-the-board mandating of white bagging ignores that physician office–based infusions may offer a much lower cost to employees and the employer.

Another reason large and small self-funded companies may unknowingly sign contracts that are often more profitable to the PBM than to the employer is that the employer pharmacy benefit consultants are paid handsomely by the big PBMs and have been known to “rig” the contract in favor of the PBM, according to Paul Holmes, an ERISA attorney with a focus in pharmacy health plan contracts. Clearly, the PBM profits more with white-bagged medicines billed through the pharmacy (PBM) side of insurance as opposed to buy-and-bill medications that are billed on the medical side of insurance. So mandated white bagging is often included in these contracts, ignoring the lower cost in an infusion suite at a physician’s office.

Suggestions for employers

Employers and employees should be able to obtain the costs of mandated, white-bagged drugs from their PBMs because the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2021 (CAA) mandates that group health plans ensure access to cost data. The employer should also have access to their consultant’s compensation from the PBM as Section 202 in the CAA states that employer benefit consultants must “disclose actual and anticipated cash and non-cash compensation they expect to earn in connection with the sale, renewal, and extension of group health insurance.”

It would be wise for all self-insured companies to use this section to see how much their consultants are being influenced by the company that they are recommending. Additionally, the companies should consider hiring ERISA attorneys that understand not only the legalese of the contract with a PBM but also the pharmacy lingo, such as the difference between maximum allowable cost, average wholesale price, average sales price, and average manufacturer’s price.

Suggestion for the rheumatologist

This leads to a suggestion to rheumatologists trying to get an exemption from mandated white bagging. If a patient has already had white-bagged medication, have them obtain a receipt from the PBM for their charges to the plan for the medication. If the patient has not gone through the white bagging yet, the PBM should be able to tell the plan the cost of the white-bagged medication and the cost to the patient. Compare those costs with what would be charged through buy and bill, and if it is less, present that evidence to the employer and remind them of their fiduciary responsibility to their employees.

Granted, this process may take more effort than filling out a prior authorization, but getting the white-bag exemption will help the patient, the employer, and the rheumatologist in the long run. A win-win-win!

Dr. Feldman is a rheumatologist in private practice with The Rheumatology Group in New Orleans. She is the CSRO’s Vice President of Advocacy and Government Affairs and its immediate Past President, as well as past chair of the Alliance for Safe Biologic Medicines and a past member of the American College of Rheumatology insurance subcommittee. You can reach her at [email protected].

Some decisions aren’t right or wrong; they’re just devastating

There is one situation, while not common, that is often among the most difficult for me: the person who must be told at diagnosis that they are already dying. I am still reminded of a patient I saw early in my career.

A woman in her 40s was admitted to the hospital complaining of severe shortness of breath. In retrospect, she had been sick for months. She had not sought help because she was young and thought it would pass – the results of a “bad bug” that she just couldn’t shake.

But in the past few weeks, the persistence of symptoms became associated with weight loss, profound fatigue, loss of appetite, and nausea.

By the time she was hospitalized she was emaciated, though she appeared pregnant – a sign of the fluid that had built up in her abdomen. Imaging showed that her abdomen was filled with disease (carcinomatosis) and her liver and lungs were nearly replaced with metastatic disease.

A biopsy revealed an aggressive cancer that had no identifying histologic marker: carcinoma, not otherwise specified, or cancer of unknown primary.

I still remember seeing her. She had a deer-in-headlights stare that held me as I approached. I introduced myself and sat down so we were eye to eye.

“Tell me what you know,” I said.

“I know I have cancer and they don’t know where it started. I know surgery is not an option and that’s why they’ve asked you to come. Whatever. I’m ready. I want to fight this because I know I can beat it,” she said.

I remember that she looked very sick; her thin face and arms contrasted with her large, distended abdomen. Her breathing was labored, her skin almost gray. For a moment I didn’t know what to say.

As doctors, we like to believe that our decisions are guided by data: the randomized trials and meta-analyses that set standards of care; phase 2 trials that establish evidence (or lack thereof) of activity; case-control studies that suggest the impacts of treatment; and at the very least, case studies that document that “N of 1” experience. We have expert panels and pathways that lay out what treatments we should be using to help ensure access to quality care in every clinic on every corner of every cancer center in the United States.

These data and pathways tell us objectively what we can expect from therapy, who is at most risk for toxicities, and profiles of patients for whom treatment is not likely to be of benefit. In an ideal world, this objectivity would help us help people decide on an approach. But life is not objective, and sometimes individualizing care is as important as data.

In this scenario, I knew only one thing: She was dying. She had an overwhelming tumor burden. But I still asked myself a question that many in, and outside of, oncology ask themselves: Could she be saved?

This question was made even more difficult because she was young. She had her whole life ahead of her. It seemed incongruous that she would be here now, facing the gravity of her situation.

Looking at her, I saw the person, not a data point in a trial or a statistic in a textbook. She was terrified. And she was not ready to die.

I sat down and reviewed what I knew about her cancer and what I did not know. I went through potential treatments we could try and the toxicities associated with each. I made clear that these treatments, based on how sick she was, could kill her.

“Whatever we do,” I said, “you do not have disease that I can cure.”

She cried then, realizing what a horrible situation she was in and that she would no longer go back to her normal life. Indeed, she seemed to grasp that she was probably facing the end of her life and that it could be short.

“My concern is,” I continued, “that treatment could do the exact opposite of what I hope it would do. It could kill you sooner than this cancer will.”

Instead of making a treatment plan, I decided that it would be best to come back another day, so I said my goodbyes and left. Still, I could not stop thinking about her and what I should suggest as her next steps.

I asked colleagues what they would suggest. Some recommended hospice care, others recommended treatment. Clearly, there was no one way to proceed.

One might wonder: Why is it so hard to do the right thing?

Ask any clinician and I think you will hear the same answer: Because we do not have the luxury of certainty.

Am I certain that this person will not benefit from intubation? Am I certain that she has only weeks to live? Am I sure that there are no treatments that will work?

The answer to these questions is no – I am not certain. It is that uncertainty that always makes me pause because it reminds me of my own humanity.

I stopped by the next day to see her surrounded by family. After some pleasantries I took the opportunity to reiterate much of our conversation from the other day. After some questions, I looked at her and asked if she wanted to talk more about her options. I was prepared to suggest treatment, anticipating that she would want it. Instead, she told me she didn’t want to proceed.

“I feel like I’m dying, and if what you have to give me isn’t going to cure me, then I’d prefer not to suffer while it happens. You said it’s up to me. I don’t want it.”

First, do no harm. It’s one of the tenets of medicine – to provide care that will benefit the people who have trusted us with their lives, whether that be longevity, relief of symptoms, or helping them achieve their last wishes. Throughout one’s life, goals might change but that edict remains the same.

But that can be difficult, especially in oncology and especially when one is not prepared for their own end of life. It can be hard for doctors to discuss the end of life; it’s easier to focus on the next treatment, instilling hope that there’s more that can be done. And there are people with end-stage cancer who insist on continuing treatment in the same circumstances, preferring to “die fighting” than to “give up.” Involving supportive and palliative care specialists early has helped in both situations, which is certainly a good thing.

We talked a while more and then arranged for our palliative care team to see her. I wish I could say I was at peace with her decision, but I wasn’t. The truth is, whatever she decided would probably have the same impact: I wouldn’t be able to stop thinking about it.

Dr. Dizon is professor of medicine, department of medicine, at Brown University and director of medical oncology at Rhode Island Hospital, both in Providence, R.I. He disclosed conflicts of interest with Regeneron, AstraZeneca, Clovis, Bristol Myers Squibb, and Kazia.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

There is one situation, while not common, that is often among the most difficult for me: the person who must be told at diagnosis that they are already dying. I am still reminded of a patient I saw early in my career.

A woman in her 40s was admitted to the hospital complaining of severe shortness of breath. In retrospect, she had been sick for months. She had not sought help because she was young and thought it would pass – the results of a “bad bug” that she just couldn’t shake.

But in the past few weeks, the persistence of symptoms became associated with weight loss, profound fatigue, loss of appetite, and nausea.

By the time she was hospitalized she was emaciated, though she appeared pregnant – a sign of the fluid that had built up in her abdomen. Imaging showed that her abdomen was filled with disease (carcinomatosis) and her liver and lungs were nearly replaced with metastatic disease.

A biopsy revealed an aggressive cancer that had no identifying histologic marker: carcinoma, not otherwise specified, or cancer of unknown primary.

I still remember seeing her. She had a deer-in-headlights stare that held me as I approached. I introduced myself and sat down so we were eye to eye.

“Tell me what you know,” I said.

“I know I have cancer and they don’t know where it started. I know surgery is not an option and that’s why they’ve asked you to come. Whatever. I’m ready. I want to fight this because I know I can beat it,” she said.

I remember that she looked very sick; her thin face and arms contrasted with her large, distended abdomen. Her breathing was labored, her skin almost gray. For a moment I didn’t know what to say.

As doctors, we like to believe that our decisions are guided by data: the randomized trials and meta-analyses that set standards of care; phase 2 trials that establish evidence (or lack thereof) of activity; case-control studies that suggest the impacts of treatment; and at the very least, case studies that document that “N of 1” experience. We have expert panels and pathways that lay out what treatments we should be using to help ensure access to quality care in every clinic on every corner of every cancer center in the United States.

These data and pathways tell us objectively what we can expect from therapy, who is at most risk for toxicities, and profiles of patients for whom treatment is not likely to be of benefit. In an ideal world, this objectivity would help us help people decide on an approach. But life is not objective, and sometimes individualizing care is as important as data.

In this scenario, I knew only one thing: She was dying. She had an overwhelming tumor burden. But I still asked myself a question that many in, and outside of, oncology ask themselves: Could she be saved?

This question was made even more difficult because she was young. She had her whole life ahead of her. It seemed incongruous that she would be here now, facing the gravity of her situation.

Looking at her, I saw the person, not a data point in a trial or a statistic in a textbook. She was terrified. And she was not ready to die.

I sat down and reviewed what I knew about her cancer and what I did not know. I went through potential treatments we could try and the toxicities associated with each. I made clear that these treatments, based on how sick she was, could kill her.

“Whatever we do,” I said, “you do not have disease that I can cure.”

She cried then, realizing what a horrible situation she was in and that she would no longer go back to her normal life. Indeed, she seemed to grasp that she was probably facing the end of her life and that it could be short.

“My concern is,” I continued, “that treatment could do the exact opposite of what I hope it would do. It could kill you sooner than this cancer will.”

Instead of making a treatment plan, I decided that it would be best to come back another day, so I said my goodbyes and left. Still, I could not stop thinking about her and what I should suggest as her next steps.

I asked colleagues what they would suggest. Some recommended hospice care, others recommended treatment. Clearly, there was no one way to proceed.

One might wonder: Why is it so hard to do the right thing?

Ask any clinician and I think you will hear the same answer: Because we do not have the luxury of certainty.

Am I certain that this person will not benefit from intubation? Am I certain that she has only weeks to live? Am I sure that there are no treatments that will work?

The answer to these questions is no – I am not certain. It is that uncertainty that always makes me pause because it reminds me of my own humanity.

I stopped by the next day to see her surrounded by family. After some pleasantries I took the opportunity to reiterate much of our conversation from the other day. After some questions, I looked at her and asked if she wanted to talk more about her options. I was prepared to suggest treatment, anticipating that she would want it. Instead, she told me she didn’t want to proceed.

“I feel like I’m dying, and if what you have to give me isn’t going to cure me, then I’d prefer not to suffer while it happens. You said it’s up to me. I don’t want it.”

First, do no harm. It’s one of the tenets of medicine – to provide care that will benefit the people who have trusted us with their lives, whether that be longevity, relief of symptoms, or helping them achieve their last wishes. Throughout one’s life, goals might change but that edict remains the same.

But that can be difficult, especially in oncology and especially when one is not prepared for their own end of life. It can be hard for doctors to discuss the end of life; it’s easier to focus on the next treatment, instilling hope that there’s more that can be done. And there are people with end-stage cancer who insist on continuing treatment in the same circumstances, preferring to “die fighting” than to “give up.” Involving supportive and palliative care specialists early has helped in both situations, which is certainly a good thing.

We talked a while more and then arranged for our palliative care team to see her. I wish I could say I was at peace with her decision, but I wasn’t. The truth is, whatever she decided would probably have the same impact: I wouldn’t be able to stop thinking about it.

Dr. Dizon is professor of medicine, department of medicine, at Brown University and director of medical oncology at Rhode Island Hospital, both in Providence, R.I. He disclosed conflicts of interest with Regeneron, AstraZeneca, Clovis, Bristol Myers Squibb, and Kazia.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

There is one situation, while not common, that is often among the most difficult for me: the person who must be told at diagnosis that they are already dying. I am still reminded of a patient I saw early in my career.

A woman in her 40s was admitted to the hospital complaining of severe shortness of breath. In retrospect, she had been sick for months. She had not sought help because she was young and thought it would pass – the results of a “bad bug” that she just couldn’t shake.

But in the past few weeks, the persistence of symptoms became associated with weight loss, profound fatigue, loss of appetite, and nausea.

By the time she was hospitalized she was emaciated, though she appeared pregnant – a sign of the fluid that had built up in her abdomen. Imaging showed that her abdomen was filled with disease (carcinomatosis) and her liver and lungs were nearly replaced with metastatic disease.

A biopsy revealed an aggressive cancer that had no identifying histologic marker: carcinoma, not otherwise specified, or cancer of unknown primary.

I still remember seeing her. She had a deer-in-headlights stare that held me as I approached. I introduced myself and sat down so we were eye to eye.

“Tell me what you know,” I said.

“I know I have cancer and they don’t know where it started. I know surgery is not an option and that’s why they’ve asked you to come. Whatever. I’m ready. I want to fight this because I know I can beat it,” she said.

I remember that she looked very sick; her thin face and arms contrasted with her large, distended abdomen. Her breathing was labored, her skin almost gray. For a moment I didn’t know what to say.

As doctors, we like to believe that our decisions are guided by data: the randomized trials and meta-analyses that set standards of care; phase 2 trials that establish evidence (or lack thereof) of activity; case-control studies that suggest the impacts of treatment; and at the very least, case studies that document that “N of 1” experience. We have expert panels and pathways that lay out what treatments we should be using to help ensure access to quality care in every clinic on every corner of every cancer center in the United States.

These data and pathways tell us objectively what we can expect from therapy, who is at most risk for toxicities, and profiles of patients for whom treatment is not likely to be of benefit. In an ideal world, this objectivity would help us help people decide on an approach. But life is not objective, and sometimes individualizing care is as important as data.

In this scenario, I knew only one thing: She was dying. She had an overwhelming tumor burden. But I still asked myself a question that many in, and outside of, oncology ask themselves: Could she be saved?

This question was made even more difficult because she was young. She had her whole life ahead of her. It seemed incongruous that she would be here now, facing the gravity of her situation.

Looking at her, I saw the person, not a data point in a trial or a statistic in a textbook. She was terrified. And she was not ready to die.

I sat down and reviewed what I knew about her cancer and what I did not know. I went through potential treatments we could try and the toxicities associated with each. I made clear that these treatments, based on how sick she was, could kill her.

“Whatever we do,” I said, “you do not have disease that I can cure.”

She cried then, realizing what a horrible situation she was in and that she would no longer go back to her normal life. Indeed, she seemed to grasp that she was probably facing the end of her life and that it could be short.

“My concern is,” I continued, “that treatment could do the exact opposite of what I hope it would do. It could kill you sooner than this cancer will.”

Instead of making a treatment plan, I decided that it would be best to come back another day, so I said my goodbyes and left. Still, I could not stop thinking about her and what I should suggest as her next steps.

I asked colleagues what they would suggest. Some recommended hospice care, others recommended treatment. Clearly, there was no one way to proceed.

One might wonder: Why is it so hard to do the right thing?

Ask any clinician and I think you will hear the same answer: Because we do not have the luxury of certainty.

Am I certain that this person will not benefit from intubation? Am I certain that she has only weeks to live? Am I sure that there are no treatments that will work?

The answer to these questions is no – I am not certain. It is that uncertainty that always makes me pause because it reminds me of my own humanity.

I stopped by the next day to see her surrounded by family. After some pleasantries I took the opportunity to reiterate much of our conversation from the other day. After some questions, I looked at her and asked if she wanted to talk more about her options. I was prepared to suggest treatment, anticipating that she would want it. Instead, she told me she didn’t want to proceed.

“I feel like I’m dying, and if what you have to give me isn’t going to cure me, then I’d prefer not to suffer while it happens. You said it’s up to me. I don’t want it.”

First, do no harm. It’s one of the tenets of medicine – to provide care that will benefit the people who have trusted us with their lives, whether that be longevity, relief of symptoms, or helping them achieve their last wishes. Throughout one’s life, goals might change but that edict remains the same.

But that can be difficult, especially in oncology and especially when one is not prepared for their own end of life. It can be hard for doctors to discuss the end of life; it’s easier to focus on the next treatment, instilling hope that there’s more that can be done. And there are people with end-stage cancer who insist on continuing treatment in the same circumstances, preferring to “die fighting” than to “give up.” Involving supportive and palliative care specialists early has helped in both situations, which is certainly a good thing.

We talked a while more and then arranged for our palliative care team to see her. I wish I could say I was at peace with her decision, but I wasn’t. The truth is, whatever she decided would probably have the same impact: I wouldn’t be able to stop thinking about it.

Dr. Dizon is professor of medicine, department of medicine, at Brown University and director of medical oncology at Rhode Island Hospital, both in Providence, R.I. He disclosed conflicts of interest with Regeneron, AstraZeneca, Clovis, Bristol Myers Squibb, and Kazia.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Pancreas cysts – What’s the best approach?

Dear colleagues,

Pancreas cysts have become almost ubiquitous in this era of high-resolution cross-sectional imaging. They are a common GI consult with patients and providers worried about the potential risk of malignant transformation. Despite significant research over the past few decades, predicting the natural history of these cysts, especially the side-branch intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms (IPMNs), remains difficult. There have been a variety of expert recommendations and guidelines, but heterogeneity exists in management especially regarding timing of endoscopic ultrasound, imaging surveillance, and cessation of surveillance. Some centers will present these cysts at multidisciplinary conferences, while others will follow general or local algorithms. In this issue of Perspectives, Dr. Lauren G. Khanna, assistant professor of medicine at NYU Langone Health, New York, and Dr. Santhi Vege, professor of medicine at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., present updated and differing approaches to managing these cysts. Which side of the debate are you on? We welcome your thoughts, questions and input– share with us on Twitter @AGA_GIHN

Gyanprakash A. Ketwaroo, MD, MSc, is associate professor of medicine, Yale University, New Haven, Conn., and chief of endoscopy at West Haven (Conn.) VA Medical Center. He is an associate editor for GI & Hepatology News.

Continuing pancreas cyst surveillance indefinitely is reasonable

BY LAUREN G. KHANNA, MD, MS

Pancreas cysts remain a clinical challenge. The true incidence of pancreas cysts is unknown, but from MRI and autopsy series, may be up to 50%. Patients presenting with a pancreas cyst often have significant anxiety about their risk of pancreas cancer. We as a medical community initially did too; but over the past few decades as we have gathered more data, we have become more comfortable observing many pancreas cysts. Yet our recommendations for how, how often, and for how long to evaluate pancreas cysts are still very much under debate; there are multiple guidelines with discordant recommendations. In this article, I will discuss my approach to patients with a pancreas cyst.

At the first evaluation, I review available imaging to see if there are characteristic features to determine the type of pancreas cyst: IPMN (including main duct, branch duct, or mixed type), serous cystic neoplasm (SCA), mucinous cystic neoplasm (MCN), solid pseudopapillary neoplasm (SPN), cystic neuroendocrine tumor (NET), or pseudocyst. I also review symptoms, including abdominal pain, weight loss, history of pancreatitis, and onset of diabetes, and check hemoglobin A1c and Ca19-9. I often recommend magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) if it has not already been obtained and is feasible (that is, if a patient does not have severe claustrophobia or a medical device incompatible with MRI). If a patient is not a candidate for treatment should a pancreatic malignancy be identified, because of age, comorbidities, or preference, I recommend no further evaluation.

Where cyst type remains unclear despite MRCP, and for cysts over 2 cm, I recommend endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) for fluid sampling to assist in determining cyst type and to rule out any other high-risk features. In accordance with international guidelines, if a patient has any concerning imaging features, including main pancreatic duct dilation >5 mm, solid component or mural nodule, or thickened or enhancing duct walls, regardless of cyst size, I recommend EUS to assess for and biopsy any solid component and to sample cyst fluid to examine for dysplasia. Given the lower sensitivity of CT for high-risk features, if MRCP is not feasible, for cysts 1-2 cm, I recommend EUS for better evaluation.

If a cyst is determined to be a cystic NET; main duct or mixed-type IPMN; MCN; or SPN; or a branch duct IPMN with mural nodule, high-grade dysplasia, or adenocarcinoma, and the patient is a surgical candidate, I refer the patient for surgical evaluation. If a cyst is determined to be an SCA, the malignant potential is minimal, and patients do not require follow-up. Patients with a pseudocyst are managed according to their clinical scenario.

Many patients have a proven or suspected branch duct IPMN, an indeterminate cyst, or multiple cysts. Cyst management during surveillance is then determined by the size of the largest cyst and stability of the cyst(s). Of note, patients with an IPMN also have been shown to have an elevated risk of concurrent pancreas adenocarcinoma, which I believe is one of the strongest arguments for heightened surveillance of the entire pancreas in pancreas cyst patients. EUS in particular can identify small or subtle lesions that are not detected by cross-sectional imaging.

If a patient has no prior imaging, in accordance with international and European guidelines, I recommend the first surveillance MRCP at a 6-month interval for cysts <2 cm, which may offer the opportunity to identify rapidly progressing cysts. If a patient has previous imaging available demonstrating stability, I recommend surveillance on an annual basis for cysts <2 cm. For patients with a cyst >2 cm, as above, I recommend EUS, and if there are no concerning features on imaging or EUS, I then recommend annual surveillance.

While the patient is under surveillance, if there is more than minimal cyst growth, a change in cyst appearance, or development of any imaging high-risk feature, pancreatitis, new onset or worsening diabetes, or elevation of Ca19-9, I recommend EUS for further evaluation and consideration of surgery based on EUS findings. If an asymptomatic cyst <2 cm remains stable for 5 years, I offer patients the option to extend imaging to every 2 years, if they are comfortable. In my experience, though, many patients prefer to continue annual imaging. The American Gastroenterological Association guidelines promote stopping surveillance after 5 years of stability, however there are studies demonstrating development of malignancy in cysts that were initially stable over the first 5 years of surveillance. Therefore, I discuss with patients that it is reasonable to continue cyst surveillance indefinitely, until they would no longer be interested in pursuing treatment of any kind if a malignant lesion were to be identified.

There are two special groups of pancreas cyst patients who warrant specific attention. Patients who are at elevated risk of pancreas adenocarcinoma because of an associated genetic mutation or a family history of pancreatic cancer already may be undergoing annual pancreas cancer screening with either MRCP, EUS, or alternating MRCP and EUS. When these high-risk patients also have pancreas cysts, I utilize whichever strategy would image their pancreas most frequently and do not extend beyond 1-year intervals. Another special group is patients who have undergone partial pancreatectomy for IPMN. As discussed above, given the elevated risk of concurrent pancreas adenocarcinoma in IPMN patients, I recommend indefinite continued surveillance of the remaining pancreas parenchyma in these patients.

Given the prevalence of pancreas cysts, it certainly would be convenient if guidelines were straightforward enough for primary care physicians to manage pancreas cyst surveillance, as they do for breast cancer screening. However, the complexities of pancreas cysts necessitate the expertise of gastroenterologists and pancreas surgeons, and a multidisciplinary team approach is best where possible.

Dr. Khanna is chief, advanced endoscopy, Tisch Hospital; director, NYU Advanced Endoscopy Fellowship; assistant professor of medicine, NYU Langone Health. Email: [email protected]. There are no relevant conflicts to disclose.

References

Tanaka M et al. Pancreatology. 2017 Sep-Oct;17(5):738-75.

Sahora K et al. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2016 Feb;42(2):197-204.

Del Chiaro M et al. Gut. 2018 May;67(5):789-804

Vege SS et al. Gastroenterology. 2015 Apr;148(4):819-22

Petrone MC et al. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2018 Jun 13;9(6):158

Pancreas cysts: More is not necessarily better!

BY SANTHI SWAROOP VEGE, MD

Pancreas cysts (PC) are very common, incidental findings on cross-sectional imaging, performed for non–pancreas-related symptoms. The important issues in management of patients with PC in my practice are the prevalence, natural history, frequency of occurrence of high-grade dysplasia (HGD) and/or pancreatic cancer (PDAC), concerning clinical symptoms and imaging findings, indications for EUS and fine-needle aspiration cytology, ideal method and frequency of surveillance, indications for surgery (up front and during follow-up), follow-up after surgery, stopping surveillance, costs, and unintentional harms of management. Good population-based evidence regarding many of the issues described above does not exist, and all information is from selected clinic, radiology, EUS, and surgical cohorts (very important when trying to assess the publications). Cohort studies should start with all PC undergoing surveillance and assess various outcomes, rather than looking backward from EUS or surgical cohorts.