User login

Small study finds high dose vitamin D relieved toxic erythema of chemotherapy

seen on an inpatient dermatology consultative service.

Currently, chemotherapy cessation, delay, or dose modification are the “only reliable methods of resolving TEC,” and supportive agents such as topical corticosteroids, topical keratolytics, and pain control are associated with variable and “relatively slow improvement involving 2 to 4 weeks of recovery after chemotherapy interruption,” Cuong V. Nguyen, MD, of the department of dermatology at Northwestern University, Chicago, and colleagues, wrote in a research letter.

Onset of TEC in the six patients occurred a mean of 8.5 days after chemotherapy. Vitamin D – 50,000 IU for one patient and 100,000 IU for the others – was administered a mean of 4.3 days from rash onset and again in 7 days. Triamcinolone, 0.1%, or clobetasol, 0.05%, ointments were also prescribed.

All patients experienced symptomatic improvement in pain, pruritus, or swelling within a day of the first vitamin D treatment, and improvement in redness within 1 to 4 days, the authors said. The second treatment was administered for residual symptoms.

Adam Friedman, MD, professor and chair of dermatology and director of the supportive oncodermatology clinic at George Washington University, Washington, said that supporting patients through the “expected, disabling and often treatment-limiting side effects of oncologic therapies” is an area that is “in its infancy” and is characterized by limited evidence-based approaches.

“Creativity is therefore a must,” he said, commenting on the research letter. “Practice starts with anecdote, and this is certainly an exciting finding ... I look forward to trialing this with our patients at GW.”

Five of the six patients had a hematologic condition that required induction chemotherapy before hematopoietic stem cell transplant, and one was receiving regorafenib for treatment of glioblastoma multiforme. Diagnosis of TEC was established by clinical presentation, and five of the six patients underwent a biopsy. Biopsy findings were consistent with a TEC diagnosis in three patients, and showed nonspecific perivascular dermatitis in two, the investigators reported.

Further research is needed to determine optimal dosing, “delineate safety concerns and potential role in cancer treatment, and establish whether a durable response in patients with continuous chemotherapy, such as in an outpatient setting, is possible,” they said.

Dr. Nguyen and his coauthors reported no conflict of interest disclosures.

seen on an inpatient dermatology consultative service.

Currently, chemotherapy cessation, delay, or dose modification are the “only reliable methods of resolving TEC,” and supportive agents such as topical corticosteroids, topical keratolytics, and pain control are associated with variable and “relatively slow improvement involving 2 to 4 weeks of recovery after chemotherapy interruption,” Cuong V. Nguyen, MD, of the department of dermatology at Northwestern University, Chicago, and colleagues, wrote in a research letter.

Onset of TEC in the six patients occurred a mean of 8.5 days after chemotherapy. Vitamin D – 50,000 IU for one patient and 100,000 IU for the others – was administered a mean of 4.3 days from rash onset and again in 7 days. Triamcinolone, 0.1%, or clobetasol, 0.05%, ointments were also prescribed.

All patients experienced symptomatic improvement in pain, pruritus, or swelling within a day of the first vitamin D treatment, and improvement in redness within 1 to 4 days, the authors said. The second treatment was administered for residual symptoms.

Adam Friedman, MD, professor and chair of dermatology and director of the supportive oncodermatology clinic at George Washington University, Washington, said that supporting patients through the “expected, disabling and often treatment-limiting side effects of oncologic therapies” is an area that is “in its infancy” and is characterized by limited evidence-based approaches.

“Creativity is therefore a must,” he said, commenting on the research letter. “Practice starts with anecdote, and this is certainly an exciting finding ... I look forward to trialing this with our patients at GW.”

Five of the six patients had a hematologic condition that required induction chemotherapy before hematopoietic stem cell transplant, and one was receiving regorafenib for treatment of glioblastoma multiforme. Diagnosis of TEC was established by clinical presentation, and five of the six patients underwent a biopsy. Biopsy findings were consistent with a TEC diagnosis in three patients, and showed nonspecific perivascular dermatitis in two, the investigators reported.

Further research is needed to determine optimal dosing, “delineate safety concerns and potential role in cancer treatment, and establish whether a durable response in patients with continuous chemotherapy, such as in an outpatient setting, is possible,” they said.

Dr. Nguyen and his coauthors reported no conflict of interest disclosures.

seen on an inpatient dermatology consultative service.

Currently, chemotherapy cessation, delay, or dose modification are the “only reliable methods of resolving TEC,” and supportive agents such as topical corticosteroids, topical keratolytics, and pain control are associated with variable and “relatively slow improvement involving 2 to 4 weeks of recovery after chemotherapy interruption,” Cuong V. Nguyen, MD, of the department of dermatology at Northwestern University, Chicago, and colleagues, wrote in a research letter.

Onset of TEC in the six patients occurred a mean of 8.5 days after chemotherapy. Vitamin D – 50,000 IU for one patient and 100,000 IU for the others – was administered a mean of 4.3 days from rash onset and again in 7 days. Triamcinolone, 0.1%, or clobetasol, 0.05%, ointments were also prescribed.

All patients experienced symptomatic improvement in pain, pruritus, or swelling within a day of the first vitamin D treatment, and improvement in redness within 1 to 4 days, the authors said. The second treatment was administered for residual symptoms.

Adam Friedman, MD, professor and chair of dermatology and director of the supportive oncodermatology clinic at George Washington University, Washington, said that supporting patients through the “expected, disabling and often treatment-limiting side effects of oncologic therapies” is an area that is “in its infancy” and is characterized by limited evidence-based approaches.

“Creativity is therefore a must,” he said, commenting on the research letter. “Practice starts with anecdote, and this is certainly an exciting finding ... I look forward to trialing this with our patients at GW.”

Five of the six patients had a hematologic condition that required induction chemotherapy before hematopoietic stem cell transplant, and one was receiving regorafenib for treatment of glioblastoma multiforme. Diagnosis of TEC was established by clinical presentation, and five of the six patients underwent a biopsy. Biopsy findings were consistent with a TEC diagnosis in three patients, and showed nonspecific perivascular dermatitis in two, the investigators reported.

Further research is needed to determine optimal dosing, “delineate safety concerns and potential role in cancer treatment, and establish whether a durable response in patients with continuous chemotherapy, such as in an outpatient setting, is possible,” they said.

Dr. Nguyen and his coauthors reported no conflict of interest disclosures.

FROM JAMA DERMATOLOGY

New osteoporosis guideline says start with a bisphosphonate

This is the first update for 5 years since the previous guidance was published in 2017.

It strongly recommends initial therapy with bisphosphonates for postmenopausal women with osteoporosis, as well as men with osteoporosis, among other recommendations.

However, the author of an accompanying editorial, Susan M. Ott, MD, says: “The decision to start a bisphosphonate is actually not that easy.”

She also queries some of the other recommendations in the guidance.

Her editorial, along with the guideline by Amir Qaseem, MD, PhD, MPH, and colleagues, and systematic review by Chelsea Ayers, MPH, and colleagues, were published in the Annals of Internal Medicine.

Ryan D. Mire, MD, MACP, president of the ACP, gave a brief overview of the new guidance in a video.

Systematic review

The ACP commissioned a review of the evidence because it says new data have emerged on the efficacy of newer medications for osteoporosis and low bone mass, as well as treatment comparisons, and treatment in men.

The review authors identified 34 randomized controlled trials (in 100 publications) and 36 observational studies, which evaluated the following pharmacologic interventions:

- Antiresorptive drugs: four bisphosphonates (alendronate, ibandronate, risedronate, zoledronate) and a RANK ligand inhibitor (denosumab).

- Anabolic drugs: an analog of human parathyroid hormone (PTH)–related protein (abaloparatide), recombinant human PTH (teriparatide), and a sclerostin inhibitor (romosozumab).

- Estrogen agonists: selective estrogen receptor modulators (bazedoxifene, raloxifene).

The authors focused on effectiveness and harms of active drugs compared with placebo or bisphosphonates.

Major changes from 2017 guidelines, some questions

“Though there are many nuanced changes in this [2023 guideline] version, perhaps the major change is the explicit hierarchy of pharmacologic recommendations: bisphosphonates first, then denosumab,” Thomas G. Cooney, MD, senior author of the clinical guideline, explained in an interview.

“Bisphosphonates had the most favorable balance among benefits, harms, patient values and preferences, and cost among the examined drugs in postmenopausal females with primary osteoporosis,” Dr. Cooney, professor of medicine, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, noted, as is stated in the guideline.

“Denosumab also had a favorable long-term net benefit, but bisphosphonates are much cheaper than other pharmacologic treatments and available in generic formulations,” the document states.

The new guideline suggests use of denosumab as second-line pharmacotherapy in adults who have contraindications to or experience adverse effects with bisphosphonates.

The choice among bisphosphonates (alendronate, risedronate, zoledronic acid) would be based on a patient-centered discussion between physician and patient, addressing costs (often related to insurance), delivery-mode preferences (oral versus intravenous), and “values,” which includes the patient’s priorities, concerns, and expectations regarding their health care, Dr. Cooney explained.

Another update in the new guideline is, “We also clarify the specific, albeit more limited, role of sclerostin inhibitors and recombinant PTH ‘to reduce the risk of fractures only in females with primary osteoporosis with very high-risk of fracture’,” Dr. Cooney noted.

In addition, the guideline now states, “treatment to reduce the risk of fractures in males rather than limiting it to ‘vertebral fracture’ in men,” as in the 2017 guideline.

It also explicitly includes denosumab as second-line therapy for men, Dr. Cooney noted, but as in 2017, the strength of evidence in men remains low.

“Finally, we also clarified that in females over the age of 65 with low bone mass or osteopenia that an individualized approach be taken to treatment (similar to last guideline), but if treatment is initiated, that a bisphosphonate be used (new content),” he said.

The use of estrogen, treatment duration, drug discontinuation, and serial bone mineral density monitoring were not addressed in this guideline, but will likely be evaluated within 2 to 3 years.

‘Osteoporosis treatment: Not easy’ – editorial

In her editorial, Dr. Ott writes: “The data about bisphosphonates may seem overwhelmingly positive, leading to strong recommendations for their use to treat osteoporosis, but the decision to start a bisphosphonate is actually not that easy.”

“A strong recommendation should be given only when future studies are unlikely to change it,” continues Dr. Ott, professor of medicine, University of Washington, Seattle.

“Yet, data already suggest that, in patients with serious osteoporosis, treatment should start with anabolic medications because previous treatment with either bisphosphonates or denosumab will prevent the anabolic response of newer medications.”

“Starting with bisphosphonate will change the bone so it will not respond to the newer medicines, and then a patient will lose the chance for getting the best improvement,” Dr. Ott clarified in an email to this news organization.

But, in fact, the new guidance does suggest that, to reduce the risk of fractures in females with primary osteoporosis at very high risk of fracture, one should consider use of the sclerostin inhibitor romosozumab (moderate-certainty evidence) or recombinant human parathyroid hormone (teriparatide) (low-certainty evidence) followed by a bisphosphonate (conditional recommendation).

Dr. Ott said: “If the [fracture] risk is high, then we should start with an anabolic medication for 1-2 years. If the risk is medium, then use a bisphosphonate for up to 5 years, and then stop and monitor the patient for signs that the medicine is wearing off,” based on blood and urine tests.

‘We need medicines that will stop bone aging’

Osteopenia is defined by an arbitrary bone density measurement, Dr. Ott explained. “About half of women over 65 will have osteopenia, and by age 85 there are hardly any ‘normal’ women left.”

“We need medicines that will stop bone aging, which might sound impossible, but we should still try,” she continued.

“In the meantime, while waiting on new discoveries,” Dr. Ott said, “I would not use bisphosphonates in patients who did not already have a fracture or whose bone density T-score was better than –2.5 because, in the major study, alendronate did not prevent fractures in this group.”

Many people are worried about bisphosphonates because of problems with the jaw or femur. These are real, but they are very rare during the first 5 years of treatment, Dr. Ott noted. Then the risk starts to rise, up to more than 1 in 1,000 after 8 years. So people can get the benefits of these drugs with very low risk for 5 years.

“An immediate [guideline] update is necessary to address the severity of bone loss and the high risk for vertebral fractures after discontinuation of denosumab,” Dr. Ott urged.

“I don’t agree with using denosumab for osteoporosis as a second-line treatment,” she said. “I would use it only in patients who have cancer or unusually high bone resorption. You have to get a dose strictly every 6 months, and if you need to stop, it is recommended to treat with bisphosphonates. Denosumab is a poor choice for somebody who does not want to take a bisphosphonate. Many patients and even too many doctors do not realize how serious it can be to skip a dose.”

“I also think that men could be treated with anabolic medications,” Dr. Ott said. “Clinical trials show they respond the same as women. Many men have osteoporosis as a consequence of low testosterone, and then they can usually be treated with testosterone. Osteoporosis in men is a serious problem that is too often ignored – almost reverse discrimination.”

It is also unfortunate that the review and recommendations do not address estrogen, one of the most effective medications to prevent osteoporotic fractures, according to Dr. Ott.

Clinical considerations in addition to drug types

The new guideline also advises:

- Clinicians treating adults with osteoporosis should encourage adherence to recommended treatments and healthy lifestyle habits, including exercise, and counseling to evaluate and prevent falls.

- All adults with osteopenia or osteoporosis should have adequate calcium and vitamin D intake, as part of fracture prevention.

- Clinicians should assess baseline fracture risk based on bone density, fracture history, fracture risk factors, and response to prior osteoporosis treatments.

- Current evidence suggests that more than 3-5 years of bisphosphonate therapy reduces risk for new vertebral but not other fractures; however, it also increases risk for long-term harms. Therefore, clinicians should consider stopping bisphosphonate treatment after 5 years unless the patient has a strong indication for treatment continuation.

- The decision for a bisphosphonate holiday (temporary discontinuation) and its duration should be based on baseline fracture risk, medication half-life in bone, and benefits and harms.

- Women treated with an anabolic agent who discontinue it should be offered an antiresorptive agent to preserve gains and because of serious risk for rebound and multiple vertebral fractures.

- Adults older than 65 years with osteoporosis may be at increased risk for falls or other adverse events because of drug interactions.

- Transgender persons have variable risk for low bone mass.

The review and guideline were funded by the ACP. Dr. Ott has reported no relevant disclosures. Relevant financial disclosures for other authors are listed with the guideline and review.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This is the first update for 5 years since the previous guidance was published in 2017.

It strongly recommends initial therapy with bisphosphonates for postmenopausal women with osteoporosis, as well as men with osteoporosis, among other recommendations.

However, the author of an accompanying editorial, Susan M. Ott, MD, says: “The decision to start a bisphosphonate is actually not that easy.”

She also queries some of the other recommendations in the guidance.

Her editorial, along with the guideline by Amir Qaseem, MD, PhD, MPH, and colleagues, and systematic review by Chelsea Ayers, MPH, and colleagues, were published in the Annals of Internal Medicine.

Ryan D. Mire, MD, MACP, president of the ACP, gave a brief overview of the new guidance in a video.

Systematic review

The ACP commissioned a review of the evidence because it says new data have emerged on the efficacy of newer medications for osteoporosis and low bone mass, as well as treatment comparisons, and treatment in men.

The review authors identified 34 randomized controlled trials (in 100 publications) and 36 observational studies, which evaluated the following pharmacologic interventions:

- Antiresorptive drugs: four bisphosphonates (alendronate, ibandronate, risedronate, zoledronate) and a RANK ligand inhibitor (denosumab).

- Anabolic drugs: an analog of human parathyroid hormone (PTH)–related protein (abaloparatide), recombinant human PTH (teriparatide), and a sclerostin inhibitor (romosozumab).

- Estrogen agonists: selective estrogen receptor modulators (bazedoxifene, raloxifene).

The authors focused on effectiveness and harms of active drugs compared with placebo or bisphosphonates.

Major changes from 2017 guidelines, some questions

“Though there are many nuanced changes in this [2023 guideline] version, perhaps the major change is the explicit hierarchy of pharmacologic recommendations: bisphosphonates first, then denosumab,” Thomas G. Cooney, MD, senior author of the clinical guideline, explained in an interview.

“Bisphosphonates had the most favorable balance among benefits, harms, patient values and preferences, and cost among the examined drugs in postmenopausal females with primary osteoporosis,” Dr. Cooney, professor of medicine, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, noted, as is stated in the guideline.

“Denosumab also had a favorable long-term net benefit, but bisphosphonates are much cheaper than other pharmacologic treatments and available in generic formulations,” the document states.

The new guideline suggests use of denosumab as second-line pharmacotherapy in adults who have contraindications to or experience adverse effects with bisphosphonates.

The choice among bisphosphonates (alendronate, risedronate, zoledronic acid) would be based on a patient-centered discussion between physician and patient, addressing costs (often related to insurance), delivery-mode preferences (oral versus intravenous), and “values,” which includes the patient’s priorities, concerns, and expectations regarding their health care, Dr. Cooney explained.

Another update in the new guideline is, “We also clarify the specific, albeit more limited, role of sclerostin inhibitors and recombinant PTH ‘to reduce the risk of fractures only in females with primary osteoporosis with very high-risk of fracture’,” Dr. Cooney noted.

In addition, the guideline now states, “treatment to reduce the risk of fractures in males rather than limiting it to ‘vertebral fracture’ in men,” as in the 2017 guideline.

It also explicitly includes denosumab as second-line therapy for men, Dr. Cooney noted, but as in 2017, the strength of evidence in men remains low.

“Finally, we also clarified that in females over the age of 65 with low bone mass or osteopenia that an individualized approach be taken to treatment (similar to last guideline), but if treatment is initiated, that a bisphosphonate be used (new content),” he said.

The use of estrogen, treatment duration, drug discontinuation, and serial bone mineral density monitoring were not addressed in this guideline, but will likely be evaluated within 2 to 3 years.

‘Osteoporosis treatment: Not easy’ – editorial

In her editorial, Dr. Ott writes: “The data about bisphosphonates may seem overwhelmingly positive, leading to strong recommendations for their use to treat osteoporosis, but the decision to start a bisphosphonate is actually not that easy.”

“A strong recommendation should be given only when future studies are unlikely to change it,” continues Dr. Ott, professor of medicine, University of Washington, Seattle.

“Yet, data already suggest that, in patients with serious osteoporosis, treatment should start with anabolic medications because previous treatment with either bisphosphonates or denosumab will prevent the anabolic response of newer medications.”

“Starting with bisphosphonate will change the bone so it will not respond to the newer medicines, and then a patient will lose the chance for getting the best improvement,” Dr. Ott clarified in an email to this news organization.

But, in fact, the new guidance does suggest that, to reduce the risk of fractures in females with primary osteoporosis at very high risk of fracture, one should consider use of the sclerostin inhibitor romosozumab (moderate-certainty evidence) or recombinant human parathyroid hormone (teriparatide) (low-certainty evidence) followed by a bisphosphonate (conditional recommendation).

Dr. Ott said: “If the [fracture] risk is high, then we should start with an anabolic medication for 1-2 years. If the risk is medium, then use a bisphosphonate for up to 5 years, and then stop and monitor the patient for signs that the medicine is wearing off,” based on blood and urine tests.

‘We need medicines that will stop bone aging’

Osteopenia is defined by an arbitrary bone density measurement, Dr. Ott explained. “About half of women over 65 will have osteopenia, and by age 85 there are hardly any ‘normal’ women left.”

“We need medicines that will stop bone aging, which might sound impossible, but we should still try,” she continued.

“In the meantime, while waiting on new discoveries,” Dr. Ott said, “I would not use bisphosphonates in patients who did not already have a fracture or whose bone density T-score was better than –2.5 because, in the major study, alendronate did not prevent fractures in this group.”

Many people are worried about bisphosphonates because of problems with the jaw or femur. These are real, but they are very rare during the first 5 years of treatment, Dr. Ott noted. Then the risk starts to rise, up to more than 1 in 1,000 after 8 years. So people can get the benefits of these drugs with very low risk for 5 years.

“An immediate [guideline] update is necessary to address the severity of bone loss and the high risk for vertebral fractures after discontinuation of denosumab,” Dr. Ott urged.

“I don’t agree with using denosumab for osteoporosis as a second-line treatment,” she said. “I would use it only in patients who have cancer or unusually high bone resorption. You have to get a dose strictly every 6 months, and if you need to stop, it is recommended to treat with bisphosphonates. Denosumab is a poor choice for somebody who does not want to take a bisphosphonate. Many patients and even too many doctors do not realize how serious it can be to skip a dose.”

“I also think that men could be treated with anabolic medications,” Dr. Ott said. “Clinical trials show they respond the same as women. Many men have osteoporosis as a consequence of low testosterone, and then they can usually be treated with testosterone. Osteoporosis in men is a serious problem that is too often ignored – almost reverse discrimination.”

It is also unfortunate that the review and recommendations do not address estrogen, one of the most effective medications to prevent osteoporotic fractures, according to Dr. Ott.

Clinical considerations in addition to drug types

The new guideline also advises:

- Clinicians treating adults with osteoporosis should encourage adherence to recommended treatments and healthy lifestyle habits, including exercise, and counseling to evaluate and prevent falls.

- All adults with osteopenia or osteoporosis should have adequate calcium and vitamin D intake, as part of fracture prevention.

- Clinicians should assess baseline fracture risk based on bone density, fracture history, fracture risk factors, and response to prior osteoporosis treatments.

- Current evidence suggests that more than 3-5 years of bisphosphonate therapy reduces risk for new vertebral but not other fractures; however, it also increases risk for long-term harms. Therefore, clinicians should consider stopping bisphosphonate treatment after 5 years unless the patient has a strong indication for treatment continuation.

- The decision for a bisphosphonate holiday (temporary discontinuation) and its duration should be based on baseline fracture risk, medication half-life in bone, and benefits and harms.

- Women treated with an anabolic agent who discontinue it should be offered an antiresorptive agent to preserve gains and because of serious risk for rebound and multiple vertebral fractures.

- Adults older than 65 years with osteoporosis may be at increased risk for falls or other adverse events because of drug interactions.

- Transgender persons have variable risk for low bone mass.

The review and guideline were funded by the ACP. Dr. Ott has reported no relevant disclosures. Relevant financial disclosures for other authors are listed with the guideline and review.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This is the first update for 5 years since the previous guidance was published in 2017.

It strongly recommends initial therapy with bisphosphonates for postmenopausal women with osteoporosis, as well as men with osteoporosis, among other recommendations.

However, the author of an accompanying editorial, Susan M. Ott, MD, says: “The decision to start a bisphosphonate is actually not that easy.”

She also queries some of the other recommendations in the guidance.

Her editorial, along with the guideline by Amir Qaseem, MD, PhD, MPH, and colleagues, and systematic review by Chelsea Ayers, MPH, and colleagues, were published in the Annals of Internal Medicine.

Ryan D. Mire, MD, MACP, president of the ACP, gave a brief overview of the new guidance in a video.

Systematic review

The ACP commissioned a review of the evidence because it says new data have emerged on the efficacy of newer medications for osteoporosis and low bone mass, as well as treatment comparisons, and treatment in men.

The review authors identified 34 randomized controlled trials (in 100 publications) and 36 observational studies, which evaluated the following pharmacologic interventions:

- Antiresorptive drugs: four bisphosphonates (alendronate, ibandronate, risedronate, zoledronate) and a RANK ligand inhibitor (denosumab).

- Anabolic drugs: an analog of human parathyroid hormone (PTH)–related protein (abaloparatide), recombinant human PTH (teriparatide), and a sclerostin inhibitor (romosozumab).

- Estrogen agonists: selective estrogen receptor modulators (bazedoxifene, raloxifene).

The authors focused on effectiveness and harms of active drugs compared with placebo or bisphosphonates.

Major changes from 2017 guidelines, some questions

“Though there are many nuanced changes in this [2023 guideline] version, perhaps the major change is the explicit hierarchy of pharmacologic recommendations: bisphosphonates first, then denosumab,” Thomas G. Cooney, MD, senior author of the clinical guideline, explained in an interview.

“Bisphosphonates had the most favorable balance among benefits, harms, patient values and preferences, and cost among the examined drugs in postmenopausal females with primary osteoporosis,” Dr. Cooney, professor of medicine, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, noted, as is stated in the guideline.

“Denosumab also had a favorable long-term net benefit, but bisphosphonates are much cheaper than other pharmacologic treatments and available in generic formulations,” the document states.

The new guideline suggests use of denosumab as second-line pharmacotherapy in adults who have contraindications to or experience adverse effects with bisphosphonates.

The choice among bisphosphonates (alendronate, risedronate, zoledronic acid) would be based on a patient-centered discussion between physician and patient, addressing costs (often related to insurance), delivery-mode preferences (oral versus intravenous), and “values,” which includes the patient’s priorities, concerns, and expectations regarding their health care, Dr. Cooney explained.

Another update in the new guideline is, “We also clarify the specific, albeit more limited, role of sclerostin inhibitors and recombinant PTH ‘to reduce the risk of fractures only in females with primary osteoporosis with very high-risk of fracture’,” Dr. Cooney noted.

In addition, the guideline now states, “treatment to reduce the risk of fractures in males rather than limiting it to ‘vertebral fracture’ in men,” as in the 2017 guideline.

It also explicitly includes denosumab as second-line therapy for men, Dr. Cooney noted, but as in 2017, the strength of evidence in men remains low.

“Finally, we also clarified that in females over the age of 65 with low bone mass or osteopenia that an individualized approach be taken to treatment (similar to last guideline), but if treatment is initiated, that a bisphosphonate be used (new content),” he said.

The use of estrogen, treatment duration, drug discontinuation, and serial bone mineral density monitoring were not addressed in this guideline, but will likely be evaluated within 2 to 3 years.

‘Osteoporosis treatment: Not easy’ – editorial

In her editorial, Dr. Ott writes: “The data about bisphosphonates may seem overwhelmingly positive, leading to strong recommendations for their use to treat osteoporosis, but the decision to start a bisphosphonate is actually not that easy.”

“A strong recommendation should be given only when future studies are unlikely to change it,” continues Dr. Ott, professor of medicine, University of Washington, Seattle.

“Yet, data already suggest that, in patients with serious osteoporosis, treatment should start with anabolic medications because previous treatment with either bisphosphonates or denosumab will prevent the anabolic response of newer medications.”

“Starting with bisphosphonate will change the bone so it will not respond to the newer medicines, and then a patient will lose the chance for getting the best improvement,” Dr. Ott clarified in an email to this news organization.

But, in fact, the new guidance does suggest that, to reduce the risk of fractures in females with primary osteoporosis at very high risk of fracture, one should consider use of the sclerostin inhibitor romosozumab (moderate-certainty evidence) or recombinant human parathyroid hormone (teriparatide) (low-certainty evidence) followed by a bisphosphonate (conditional recommendation).

Dr. Ott said: “If the [fracture] risk is high, then we should start with an anabolic medication for 1-2 years. If the risk is medium, then use a bisphosphonate for up to 5 years, and then stop and monitor the patient for signs that the medicine is wearing off,” based on blood and urine tests.

‘We need medicines that will stop bone aging’

Osteopenia is defined by an arbitrary bone density measurement, Dr. Ott explained. “About half of women over 65 will have osteopenia, and by age 85 there are hardly any ‘normal’ women left.”

“We need medicines that will stop bone aging, which might sound impossible, but we should still try,” she continued.

“In the meantime, while waiting on new discoveries,” Dr. Ott said, “I would not use bisphosphonates in patients who did not already have a fracture or whose bone density T-score was better than –2.5 because, in the major study, alendronate did not prevent fractures in this group.”

Many people are worried about bisphosphonates because of problems with the jaw or femur. These are real, but they are very rare during the first 5 years of treatment, Dr. Ott noted. Then the risk starts to rise, up to more than 1 in 1,000 after 8 years. So people can get the benefits of these drugs with very low risk for 5 years.

“An immediate [guideline] update is necessary to address the severity of bone loss and the high risk for vertebral fractures after discontinuation of denosumab,” Dr. Ott urged.

“I don’t agree with using denosumab for osteoporosis as a second-line treatment,” she said. “I would use it only in patients who have cancer or unusually high bone resorption. You have to get a dose strictly every 6 months, and if you need to stop, it is recommended to treat with bisphosphonates. Denosumab is a poor choice for somebody who does not want to take a bisphosphonate. Many patients and even too many doctors do not realize how serious it can be to skip a dose.”

“I also think that men could be treated with anabolic medications,” Dr. Ott said. “Clinical trials show they respond the same as women. Many men have osteoporosis as a consequence of low testosterone, and then they can usually be treated with testosterone. Osteoporosis in men is a serious problem that is too often ignored – almost reverse discrimination.”

It is also unfortunate that the review and recommendations do not address estrogen, one of the most effective medications to prevent osteoporotic fractures, according to Dr. Ott.

Clinical considerations in addition to drug types

The new guideline also advises:

- Clinicians treating adults with osteoporosis should encourage adherence to recommended treatments and healthy lifestyle habits, including exercise, and counseling to evaluate and prevent falls.

- All adults with osteopenia or osteoporosis should have adequate calcium and vitamin D intake, as part of fracture prevention.

- Clinicians should assess baseline fracture risk based on bone density, fracture history, fracture risk factors, and response to prior osteoporosis treatments.

- Current evidence suggests that more than 3-5 years of bisphosphonate therapy reduces risk for new vertebral but not other fractures; however, it also increases risk for long-term harms. Therefore, clinicians should consider stopping bisphosphonate treatment after 5 years unless the patient has a strong indication for treatment continuation.

- The decision for a bisphosphonate holiday (temporary discontinuation) and its duration should be based on baseline fracture risk, medication half-life in bone, and benefits and harms.

- Women treated with an anabolic agent who discontinue it should be offered an antiresorptive agent to preserve gains and because of serious risk for rebound and multiple vertebral fractures.

- Adults older than 65 years with osteoporosis may be at increased risk for falls or other adverse events because of drug interactions.

- Transgender persons have variable risk for low bone mass.

The review and guideline were funded by the ACP. Dr. Ott has reported no relevant disclosures. Relevant financial disclosures for other authors are listed with the guideline and review.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE ANNALS OF INTERNAL MEDICINE

FDA considers regulating CBD products

The products can have drug-like effects on the body and contain CBD (cannabidiol) and THC (tetrahydrocannabinol). Both CBD and THC can be derived from hemp, which was legalized by Congress in 2018.

“Given what we know about the safety of CBD so far, it raises concerns for FDA about whether these existing regulatory pathways for food and dietary supplements are appropriate for this substance,” FDA Principal Deputy Commissioner Janet Woodcock, MD, told The Wall Street Journal.

A 2021 FDA report valued the CBD market at $4.6 billion and projected it to quadruple by 2026. The only FDA-approved CBD product is an oil called Epidiolex, which can be prescribed for the seizure-associated disease epilepsy. Research on CBD to treat other diseases is ongoing.

Food, beverage, and beauty products containing CBD are sold in stores and online in many forms, including oils, vaporized liquids, and oil-based capsules, but “research supporting the drug’s benefits is still limited,” the Mayo Clinic said.

Recently, investigations have found that many CBD products also contain THC, which can be derived from legal hemp in a form that is referred to as Delta 8 and produces a psychoactive high. The CDC warned in 2022 that people “mistook” THC products for CBD products, which are often sold at the same stores, and experienced “adverse events.”

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and FDA warn that much is unknown about CBD and delta-8 products. The CDC says known CBD risks include liver damage; interference with other drugs you are taking, which may lead to injury or serious side effects; drowsiness or sleepiness; diarrhea or changes in appetite; changes in mood, such as crankiness; potential negative effects on fetuses during pregnancy or on babies during breastfeeding; or unintentional poisoning of children when mistaking THC products for CBD products or due to containing other ingredients such as THC or pesticides.

“I don’t think that we can have the perfect be the enemy of the good when we’re looking at such a vast market that is so available and utilized,” Norman Birenbaum, a senior FDA adviser who is working on the regulatory issue, told the Journal. “You’ve got a widely unregulated market.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

The products can have drug-like effects on the body and contain CBD (cannabidiol) and THC (tetrahydrocannabinol). Both CBD and THC can be derived from hemp, which was legalized by Congress in 2018.

“Given what we know about the safety of CBD so far, it raises concerns for FDA about whether these existing regulatory pathways for food and dietary supplements are appropriate for this substance,” FDA Principal Deputy Commissioner Janet Woodcock, MD, told The Wall Street Journal.

A 2021 FDA report valued the CBD market at $4.6 billion and projected it to quadruple by 2026. The only FDA-approved CBD product is an oil called Epidiolex, which can be prescribed for the seizure-associated disease epilepsy. Research on CBD to treat other diseases is ongoing.

Food, beverage, and beauty products containing CBD are sold in stores and online in many forms, including oils, vaporized liquids, and oil-based capsules, but “research supporting the drug’s benefits is still limited,” the Mayo Clinic said.

Recently, investigations have found that many CBD products also contain THC, which can be derived from legal hemp in a form that is referred to as Delta 8 and produces a psychoactive high. The CDC warned in 2022 that people “mistook” THC products for CBD products, which are often sold at the same stores, and experienced “adverse events.”

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and FDA warn that much is unknown about CBD and delta-8 products. The CDC says known CBD risks include liver damage; interference with other drugs you are taking, which may lead to injury or serious side effects; drowsiness or sleepiness; diarrhea or changes in appetite; changes in mood, such as crankiness; potential negative effects on fetuses during pregnancy or on babies during breastfeeding; or unintentional poisoning of children when mistaking THC products for CBD products or due to containing other ingredients such as THC or pesticides.

“I don’t think that we can have the perfect be the enemy of the good when we’re looking at such a vast market that is so available and utilized,” Norman Birenbaum, a senior FDA adviser who is working on the regulatory issue, told the Journal. “You’ve got a widely unregulated market.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

The products can have drug-like effects on the body and contain CBD (cannabidiol) and THC (tetrahydrocannabinol). Both CBD and THC can be derived from hemp, which was legalized by Congress in 2018.

“Given what we know about the safety of CBD so far, it raises concerns for FDA about whether these existing regulatory pathways for food and dietary supplements are appropriate for this substance,” FDA Principal Deputy Commissioner Janet Woodcock, MD, told The Wall Street Journal.

A 2021 FDA report valued the CBD market at $4.6 billion and projected it to quadruple by 2026. The only FDA-approved CBD product is an oil called Epidiolex, which can be prescribed for the seizure-associated disease epilepsy. Research on CBD to treat other diseases is ongoing.

Food, beverage, and beauty products containing CBD are sold in stores and online in many forms, including oils, vaporized liquids, and oil-based capsules, but “research supporting the drug’s benefits is still limited,” the Mayo Clinic said.

Recently, investigations have found that many CBD products also contain THC, which can be derived from legal hemp in a form that is referred to as Delta 8 and produces a psychoactive high. The CDC warned in 2022 that people “mistook” THC products for CBD products, which are often sold at the same stores, and experienced “adverse events.”

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and FDA warn that much is unknown about CBD and delta-8 products. The CDC says known CBD risks include liver damage; interference with other drugs you are taking, which may lead to injury or serious side effects; drowsiness or sleepiness; diarrhea or changes in appetite; changes in mood, such as crankiness; potential negative effects on fetuses during pregnancy or on babies during breastfeeding; or unintentional poisoning of children when mistaking THC products for CBD products or due to containing other ingredients such as THC or pesticides.

“I don’t think that we can have the perfect be the enemy of the good when we’re looking at such a vast market that is so available and utilized,” Norman Birenbaum, a senior FDA adviser who is working on the regulatory issue, told the Journal. “You’ve got a widely unregulated market.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Patient With Severe Headache After IV Immunoglobulin

A 35-year-old woman with a history of hypothyroidism and idiopathic small fiber autonomic and sensory neuropathy presented to the emergency department (ED) 48 hours after IV immunoglobulin (IG) infusion with a severe headache, nausea, neck stiffness, photophobia, and episodes of intense positional eye pressure. The patient reported previous episodes of headaches post-IVIG infusion but not nearly as severe. On ED arrival, the patient was afebrile with vital signs within normal limits. Initial laboratory results were notable for levels within reference range parameters: 5.9 × 109/L white blood cell (WBC) count, 13.3 g/dL hemoglobin, 38.7% hematocrit, and 279 × 109/L platelet count; there were no abnormal urinalysis findings, and she was negative for human chorionic gonadotropin.

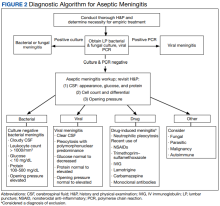

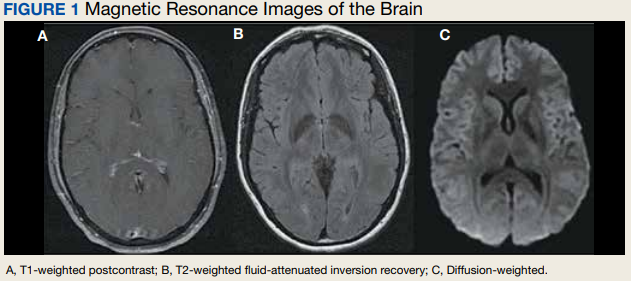

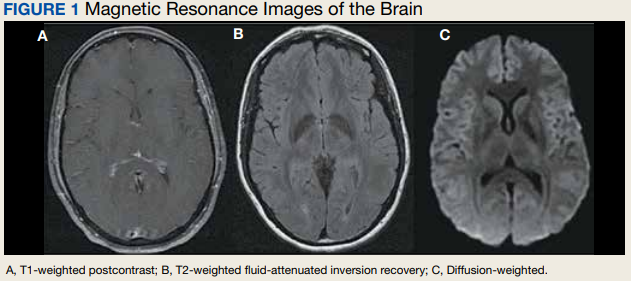

Due to the patient’s symptoms concerning for an acute intracranial process, a brain computed tomography (CT) without contrast was ordered. The CT demonstrated no intracranial abnormalities, but the patient’s symptoms continued to worsen. The patient was started on IV fluids and 1 g IV acetaminophen and underwent a lumbar puncture (LP). Her opening pressure was elevated at 29 cm H2O (reference range, 6-20 cm), and the fluid was notably clear. During the LP, 25 mL of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) was collected for laboratory analysis to include a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) panel and cultures, and a closing pressure of 12 cm H2O was recorded at the end of the procedure with the patient reporting some relief of pressure. The patient was admitted to the medicine ward for further workup and observations.The patient’s meningitis/encephalitis PCR panel detected no pathogens in the CSF, but her WBC count was 84 × 109/L (reference range, 4-11) with 30 segmented neutrophils (reference range, 0-6) and red blood cell count of 24 (reference range, 0-1); her normal glucose at 60 mg/dL (reference range, 40-70) and protein of 33 mg/dL (reference range, 15-45) were within normal parameters. Brain magnetic resonance images with and without contrast was inconsistent with any acute intracranial pathology to include subarachnoid hemorrhage or central nervous system neoplasm (Figure 1). Bacterial and fungal cultures were negative.

- What is your diagnosis?

- How would you treat this patient?

Discussion

Aseptic meningitis presents with a typical clinical picture of meningitis to include headache, stiffened neck, and photophobia. In the event of negative CSF bacterial and fungal cultures and negative viral PCR, a diagnosis of aseptic meningitis is considered.1 Though the differential for aseptic meningitis is broad, in the immunocompetent patient, the most common etiology of aseptic meningitis in the United States is by far viral, and specifically, enterovirus (50.9%). It is less commonly caused by herpes simplex virus (8.3%), varicella zoster virus, and finally, the mosquito-borne St. Louis encephalitis and West Nile viruses typically acquired in the summer or early fall months. Other infectious agents that can present with aseptic meningitis are spirochetes (Lyme disease and syphilis), tuberculous meningitis, fungal infections (cryptococcal meningitis), and other bacterial infections that have a negative culture.

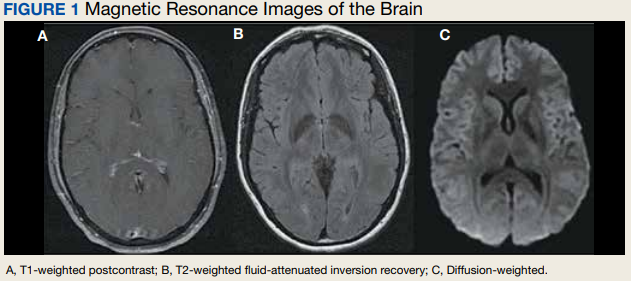

The patient’s history, physical examination, vital signs, imaging, and lumbar puncture findings were most concerning for drug-induced aseptic meningitis (DIAM) secondary to her recent IVIG infusion. An algorithm can be used to work through the diagnostic approach (Figure 2).3,4

Immediate and delayed adverse reactions to IVIG are known risks for IVIG therapy. About 1% to 15% of patients who receive IVIG will experience mild immediate reactions to the infusion.6 These immediate reactions include fever (78.6%), acrocyanosis (71.4%), rash (64.3%), headache (57.1%), shortness of breath (42.8%), hypotension (35.7%), and chest pain (21.4%).

IVIG is an increasingly used biologic pharmacologic agent used for a variety of medical conditions. This can be attributed to its multifaceted properties and ability to fight infection when given as replacement therapy and provide immunomodulation in conjunction with its more well-known anti-inflammatory properties.8 The number of conditions that can potentially benefit from IVIG is so vast that the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology had to divide the indication for IVIG therapy into definitely beneficial, probably beneficial, may provide benefit, and unlikely to provide benefit categories.8

Conclusions

We encourage heightened clinical suspicion of DIAM in patients who have recently undergone IVIG infusion and present with meningeal signs (stiff neck, headache, photophobia, and ear/eye pressure) without any evidence of infection on physical examination or laboratory results. With such, we hope to improve clinician suspicion, detection, as well as patient education and outcomes in cases of DIAM.

1. Kareva L, Mironska K, Stavric K, Hasani A. Adverse reactions to intravenous immunoglobulins—our experience. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2018;6(12):2359-2362. doi:10.3889/oamjms.2018.513

2. Mount HR, Boyle SD. Aseptic and bacterial meningitis: evaluation, treatment, and prevention. Am Fam Physician. 2017;96(5):314-322.

3. Seehusen DA, Reeves MM, Fomin DA. Cerebrospinal fluid analysis. Am Fam Physician. 2003;68(6):1103-1108.

4. Connolly KJ, Hammer SM. The acute aseptic meningitis syndrome. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 1990;4(4):599-622.

5. Jolles S, Sewell WA, Leighton C. Drug-induced aseptic meningitis: diagnosis and management. Drug Saf. 2000;22(3):215-226. doi:10.2165/00002018-200022030-00005

6. Yelehe-Okouma M, Czmil-Garon J, Pape E, Petitpain N, Gillet P. Drug-induced aseptic meningitis: a mini-review. Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 2018;32(3):252-260. doi:10.1111/fcp.12349

7. Kepa L, Oczko-Grzesik B, Stolarz W, Sobala-Szczygiel B. Drug-induced aseptic meningitis in suspected central nervous system infections. J Clin Neurosci. 2005;12(5):562-564. doi:10.1016/j.jocn.2004.08.024

8. Perez EE, Orange JS, Bonilla F, et al. Update on the use of immunoglobulin in human disease: a review of evidence. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;139(3S):S1-S46. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2016.09.023

9. Kaarthigeyan K, Burli VV. Aseptic meningitis following intravenous immunoglobulin therapy of common variable immunodeficiency. J Pediatr Neurosci. 2011;6(2):160-161. doi:10.4103/1817-1745.92858

A 35-year-old woman with a history of hypothyroidism and idiopathic small fiber autonomic and sensory neuropathy presented to the emergency department (ED) 48 hours after IV immunoglobulin (IG) infusion with a severe headache, nausea, neck stiffness, photophobia, and episodes of intense positional eye pressure. The patient reported previous episodes of headaches post-IVIG infusion but not nearly as severe. On ED arrival, the patient was afebrile with vital signs within normal limits. Initial laboratory results were notable for levels within reference range parameters: 5.9 × 109/L white blood cell (WBC) count, 13.3 g/dL hemoglobin, 38.7% hematocrit, and 279 × 109/L platelet count; there were no abnormal urinalysis findings, and she was negative for human chorionic gonadotropin.

Due to the patient’s symptoms concerning for an acute intracranial process, a brain computed tomography (CT) without contrast was ordered. The CT demonstrated no intracranial abnormalities, but the patient’s symptoms continued to worsen. The patient was started on IV fluids and 1 g IV acetaminophen and underwent a lumbar puncture (LP). Her opening pressure was elevated at 29 cm H2O (reference range, 6-20 cm), and the fluid was notably clear. During the LP, 25 mL of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) was collected for laboratory analysis to include a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) panel and cultures, and a closing pressure of 12 cm H2O was recorded at the end of the procedure with the patient reporting some relief of pressure. The patient was admitted to the medicine ward for further workup and observations.The patient’s meningitis/encephalitis PCR panel detected no pathogens in the CSF, but her WBC count was 84 × 109/L (reference range, 4-11) with 30 segmented neutrophils (reference range, 0-6) and red blood cell count of 24 (reference range, 0-1); her normal glucose at 60 mg/dL (reference range, 40-70) and protein of 33 mg/dL (reference range, 15-45) were within normal parameters. Brain magnetic resonance images with and without contrast was inconsistent with any acute intracranial pathology to include subarachnoid hemorrhage or central nervous system neoplasm (Figure 1). Bacterial and fungal cultures were negative.

- What is your diagnosis?

- How would you treat this patient?

Discussion

Aseptic meningitis presents with a typical clinical picture of meningitis to include headache, stiffened neck, and photophobia. In the event of negative CSF bacterial and fungal cultures and negative viral PCR, a diagnosis of aseptic meningitis is considered.1 Though the differential for aseptic meningitis is broad, in the immunocompetent patient, the most common etiology of aseptic meningitis in the United States is by far viral, and specifically, enterovirus (50.9%). It is less commonly caused by herpes simplex virus (8.3%), varicella zoster virus, and finally, the mosquito-borne St. Louis encephalitis and West Nile viruses typically acquired in the summer or early fall months. Other infectious agents that can present with aseptic meningitis are spirochetes (Lyme disease and syphilis), tuberculous meningitis, fungal infections (cryptococcal meningitis), and other bacterial infections that have a negative culture.

The patient’s history, physical examination, vital signs, imaging, and lumbar puncture findings were most concerning for drug-induced aseptic meningitis (DIAM) secondary to her recent IVIG infusion. An algorithm can be used to work through the diagnostic approach (Figure 2).3,4

Immediate and delayed adverse reactions to IVIG are known risks for IVIG therapy. About 1% to 15% of patients who receive IVIG will experience mild immediate reactions to the infusion.6 These immediate reactions include fever (78.6%), acrocyanosis (71.4%), rash (64.3%), headache (57.1%), shortness of breath (42.8%), hypotension (35.7%), and chest pain (21.4%).

IVIG is an increasingly used biologic pharmacologic agent used for a variety of medical conditions. This can be attributed to its multifaceted properties and ability to fight infection when given as replacement therapy and provide immunomodulation in conjunction with its more well-known anti-inflammatory properties.8 The number of conditions that can potentially benefit from IVIG is so vast that the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology had to divide the indication for IVIG therapy into definitely beneficial, probably beneficial, may provide benefit, and unlikely to provide benefit categories.8

Conclusions

We encourage heightened clinical suspicion of DIAM in patients who have recently undergone IVIG infusion and present with meningeal signs (stiff neck, headache, photophobia, and ear/eye pressure) without any evidence of infection on physical examination or laboratory results. With such, we hope to improve clinician suspicion, detection, as well as patient education and outcomes in cases of DIAM.

A 35-year-old woman with a history of hypothyroidism and idiopathic small fiber autonomic and sensory neuropathy presented to the emergency department (ED) 48 hours after IV immunoglobulin (IG) infusion with a severe headache, nausea, neck stiffness, photophobia, and episodes of intense positional eye pressure. The patient reported previous episodes of headaches post-IVIG infusion but not nearly as severe. On ED arrival, the patient was afebrile with vital signs within normal limits. Initial laboratory results were notable for levels within reference range parameters: 5.9 × 109/L white blood cell (WBC) count, 13.3 g/dL hemoglobin, 38.7% hematocrit, and 279 × 109/L platelet count; there were no abnormal urinalysis findings, and she was negative for human chorionic gonadotropin.

Due to the patient’s symptoms concerning for an acute intracranial process, a brain computed tomography (CT) without contrast was ordered. The CT demonstrated no intracranial abnormalities, but the patient’s symptoms continued to worsen. The patient was started on IV fluids and 1 g IV acetaminophen and underwent a lumbar puncture (LP). Her opening pressure was elevated at 29 cm H2O (reference range, 6-20 cm), and the fluid was notably clear. During the LP, 25 mL of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) was collected for laboratory analysis to include a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) panel and cultures, and a closing pressure of 12 cm H2O was recorded at the end of the procedure with the patient reporting some relief of pressure. The patient was admitted to the medicine ward for further workup and observations.The patient’s meningitis/encephalitis PCR panel detected no pathogens in the CSF, but her WBC count was 84 × 109/L (reference range, 4-11) with 30 segmented neutrophils (reference range, 0-6) and red blood cell count of 24 (reference range, 0-1); her normal glucose at 60 mg/dL (reference range, 40-70) and protein of 33 mg/dL (reference range, 15-45) were within normal parameters. Brain magnetic resonance images with and without contrast was inconsistent with any acute intracranial pathology to include subarachnoid hemorrhage or central nervous system neoplasm (Figure 1). Bacterial and fungal cultures were negative.

- What is your diagnosis?

- How would you treat this patient?

Discussion

Aseptic meningitis presents with a typical clinical picture of meningitis to include headache, stiffened neck, and photophobia. In the event of negative CSF bacterial and fungal cultures and negative viral PCR, a diagnosis of aseptic meningitis is considered.1 Though the differential for aseptic meningitis is broad, in the immunocompetent patient, the most common etiology of aseptic meningitis in the United States is by far viral, and specifically, enterovirus (50.9%). It is less commonly caused by herpes simplex virus (8.3%), varicella zoster virus, and finally, the mosquito-borne St. Louis encephalitis and West Nile viruses typically acquired in the summer or early fall months. Other infectious agents that can present with aseptic meningitis are spirochetes (Lyme disease and syphilis), tuberculous meningitis, fungal infections (cryptococcal meningitis), and other bacterial infections that have a negative culture.

The patient’s history, physical examination, vital signs, imaging, and lumbar puncture findings were most concerning for drug-induced aseptic meningitis (DIAM) secondary to her recent IVIG infusion. An algorithm can be used to work through the diagnostic approach (Figure 2).3,4

Immediate and delayed adverse reactions to IVIG are known risks for IVIG therapy. About 1% to 15% of patients who receive IVIG will experience mild immediate reactions to the infusion.6 These immediate reactions include fever (78.6%), acrocyanosis (71.4%), rash (64.3%), headache (57.1%), shortness of breath (42.8%), hypotension (35.7%), and chest pain (21.4%).

IVIG is an increasingly used biologic pharmacologic agent used for a variety of medical conditions. This can be attributed to its multifaceted properties and ability to fight infection when given as replacement therapy and provide immunomodulation in conjunction with its more well-known anti-inflammatory properties.8 The number of conditions that can potentially benefit from IVIG is so vast that the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology had to divide the indication for IVIG therapy into definitely beneficial, probably beneficial, may provide benefit, and unlikely to provide benefit categories.8

Conclusions

We encourage heightened clinical suspicion of DIAM in patients who have recently undergone IVIG infusion and present with meningeal signs (stiff neck, headache, photophobia, and ear/eye pressure) without any evidence of infection on physical examination or laboratory results. With such, we hope to improve clinician suspicion, detection, as well as patient education and outcomes in cases of DIAM.

1. Kareva L, Mironska K, Stavric K, Hasani A. Adverse reactions to intravenous immunoglobulins—our experience. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2018;6(12):2359-2362. doi:10.3889/oamjms.2018.513

2. Mount HR, Boyle SD. Aseptic and bacterial meningitis: evaluation, treatment, and prevention. Am Fam Physician. 2017;96(5):314-322.

3. Seehusen DA, Reeves MM, Fomin DA. Cerebrospinal fluid analysis. Am Fam Physician. 2003;68(6):1103-1108.

4. Connolly KJ, Hammer SM. The acute aseptic meningitis syndrome. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 1990;4(4):599-622.

5. Jolles S, Sewell WA, Leighton C. Drug-induced aseptic meningitis: diagnosis and management. Drug Saf. 2000;22(3):215-226. doi:10.2165/00002018-200022030-00005

6. Yelehe-Okouma M, Czmil-Garon J, Pape E, Petitpain N, Gillet P. Drug-induced aseptic meningitis: a mini-review. Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 2018;32(3):252-260. doi:10.1111/fcp.12349

7. Kepa L, Oczko-Grzesik B, Stolarz W, Sobala-Szczygiel B. Drug-induced aseptic meningitis in suspected central nervous system infections. J Clin Neurosci. 2005;12(5):562-564. doi:10.1016/j.jocn.2004.08.024

8. Perez EE, Orange JS, Bonilla F, et al. Update on the use of immunoglobulin in human disease: a review of evidence. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;139(3S):S1-S46. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2016.09.023

9. Kaarthigeyan K, Burli VV. Aseptic meningitis following intravenous immunoglobulin therapy of common variable immunodeficiency. J Pediatr Neurosci. 2011;6(2):160-161. doi:10.4103/1817-1745.92858

1. Kareva L, Mironska K, Stavric K, Hasani A. Adverse reactions to intravenous immunoglobulins—our experience. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2018;6(12):2359-2362. doi:10.3889/oamjms.2018.513

2. Mount HR, Boyle SD. Aseptic and bacterial meningitis: evaluation, treatment, and prevention. Am Fam Physician. 2017;96(5):314-322.

3. Seehusen DA, Reeves MM, Fomin DA. Cerebrospinal fluid analysis. Am Fam Physician. 2003;68(6):1103-1108.

4. Connolly KJ, Hammer SM. The acute aseptic meningitis syndrome. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 1990;4(4):599-622.

5. Jolles S, Sewell WA, Leighton C. Drug-induced aseptic meningitis: diagnosis and management. Drug Saf. 2000;22(3):215-226. doi:10.2165/00002018-200022030-00005

6. Yelehe-Okouma M, Czmil-Garon J, Pape E, Petitpain N, Gillet P. Drug-induced aseptic meningitis: a mini-review. Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 2018;32(3):252-260. doi:10.1111/fcp.12349

7. Kepa L, Oczko-Grzesik B, Stolarz W, Sobala-Szczygiel B. Drug-induced aseptic meningitis in suspected central nervous system infections. J Clin Neurosci. 2005;12(5):562-564. doi:10.1016/j.jocn.2004.08.024

8. Perez EE, Orange JS, Bonilla F, et al. Update on the use of immunoglobulin in human disease: a review of evidence. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;139(3S):S1-S46. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2016.09.023

9. Kaarthigeyan K, Burli VV. Aseptic meningitis following intravenous immunoglobulin therapy of common variable immunodeficiency. J Pediatr Neurosci. 2011;6(2):160-161. doi:10.4103/1817-1745.92858

HIV vaccine trial makes pivotal leap toward making ‘super antibodies’

The announcement comes from the journal Science, which published phase 1 results of a small clinical trial for a vaccine technology that aims to cause the body to create a rare kind of cell.

“At the most general level, the trial results show that one can design vaccines that induce antibodies with prespecified genetic features, and this may herald a new era of precision vaccines,” William Schief, PhD, a researcher at the Scripps Research Institute and study coauthor, told the American Association for the Advancement of Science.

The study was the first to test the approach in humans and was effective in 97% – or 35 of 36 – participants. The vaccine technology is called “germline targeting.” Trial results show that “one can design a vaccine that elicits made-to-order antibodies in humans,” Dr. Schief said in a news release.

In addition to possibly being a breakthrough for the treatment of HIV, the vaccine technology could also impact the development of treatments for flu, hepatitis C, and coronaviruses, study authors wrote.

There is no cure for HIV, but there are treatments to manage how the disease progresses. HIV attacks the body’s immune system, destroys white blood cells, and increases susceptibility to other infections, AAAS summarized. More than 1 million people in the United States and 38 million people worldwide have HIV.

Previous HIV vaccine attempts were not able to cause the production of specialized cells known as “broadly neutralizing antibodies,” CNN reported.

“Call them super antibodies, if you want,” University of Minnesota HIV researcher Timothy Schacker, MD, who was not involved in the research, told CNN. “The hope is that if you can induce this kind of immunity in people, you can protect them from some of these viruses that we’ve had a very hard time designing vaccines for that are effective. So this is an important step forward.”

Study authors said this is just the first step in the multiphase vaccine design, which so far is a theory. Further study is needed to see if the next steps also work in humans, and then if all the steps can be linked together and can be effective against HIV.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

The announcement comes from the journal Science, which published phase 1 results of a small clinical trial for a vaccine technology that aims to cause the body to create a rare kind of cell.

“At the most general level, the trial results show that one can design vaccines that induce antibodies with prespecified genetic features, and this may herald a new era of precision vaccines,” William Schief, PhD, a researcher at the Scripps Research Institute and study coauthor, told the American Association for the Advancement of Science.

The study was the first to test the approach in humans and was effective in 97% – or 35 of 36 – participants. The vaccine technology is called “germline targeting.” Trial results show that “one can design a vaccine that elicits made-to-order antibodies in humans,” Dr. Schief said in a news release.

In addition to possibly being a breakthrough for the treatment of HIV, the vaccine technology could also impact the development of treatments for flu, hepatitis C, and coronaviruses, study authors wrote.

There is no cure for HIV, but there are treatments to manage how the disease progresses. HIV attacks the body’s immune system, destroys white blood cells, and increases susceptibility to other infections, AAAS summarized. More than 1 million people in the United States and 38 million people worldwide have HIV.

Previous HIV vaccine attempts were not able to cause the production of specialized cells known as “broadly neutralizing antibodies,” CNN reported.

“Call them super antibodies, if you want,” University of Minnesota HIV researcher Timothy Schacker, MD, who was not involved in the research, told CNN. “The hope is that if you can induce this kind of immunity in people, you can protect them from some of these viruses that we’ve had a very hard time designing vaccines for that are effective. So this is an important step forward.”

Study authors said this is just the first step in the multiphase vaccine design, which so far is a theory. Further study is needed to see if the next steps also work in humans, and then if all the steps can be linked together and can be effective against HIV.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

The announcement comes from the journal Science, which published phase 1 results of a small clinical trial for a vaccine technology that aims to cause the body to create a rare kind of cell.

“At the most general level, the trial results show that one can design vaccines that induce antibodies with prespecified genetic features, and this may herald a new era of precision vaccines,” William Schief, PhD, a researcher at the Scripps Research Institute and study coauthor, told the American Association for the Advancement of Science.

The study was the first to test the approach in humans and was effective in 97% – or 35 of 36 – participants. The vaccine technology is called “germline targeting.” Trial results show that “one can design a vaccine that elicits made-to-order antibodies in humans,” Dr. Schief said in a news release.

In addition to possibly being a breakthrough for the treatment of HIV, the vaccine technology could also impact the development of treatments for flu, hepatitis C, and coronaviruses, study authors wrote.

There is no cure for HIV, but there are treatments to manage how the disease progresses. HIV attacks the body’s immune system, destroys white blood cells, and increases susceptibility to other infections, AAAS summarized. More than 1 million people in the United States and 38 million people worldwide have HIV.

Previous HIV vaccine attempts were not able to cause the production of specialized cells known as “broadly neutralizing antibodies,” CNN reported.

“Call them super antibodies, if you want,” University of Minnesota HIV researcher Timothy Schacker, MD, who was not involved in the research, told CNN. “The hope is that if you can induce this kind of immunity in people, you can protect them from some of these viruses that we’ve had a very hard time designing vaccines for that are effective. So this is an important step forward.”

Study authors said this is just the first step in the multiphase vaccine design, which so far is a theory. Further study is needed to see if the next steps also work in humans, and then if all the steps can be linked together and can be effective against HIV.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

FROM SCIENCE

The new obesity breakthrough drugs

This article was originally published December 10 on Medscape editor-in-chief Eric Topol’s Substack ”Ground Truths.”

– achieving a substantial amount of weight loss without serious side effects. Many attempts to get there now fill a graveyard of failed drugs, such as fen-phen in the 1990s when a single small study of this drug combination in 121 people unleashed millions of prescriptions, some leading to serious heart valve lesions that resulted in withdrawal of the drug in 1995. The drug rimonabant, an endocannabinoid receptor blocker (think of blocking the munchies after marijuana) looked encouraging in randomized trials. However, subsequently, in a trial that I led of nearly 19,000 participants in 42 countries around the world, there was a significant excess of depression, neuropsychiatric side-effects and suicidal ideation which spelled the end of that drug’s life.

In the United States, where there had not been an antiobesity drug approved by the Food and Drug Administration since 2014, Wegovy (semaglutide), a once-weekly injection was approved in June 2021. The same drug, at a lower dose, is known as Ozempic (as in O-O-O, Ozempic, the ubiquitous commercial that you undoubtedly hear and see on TV) and had already been approved in January 2020 for improving glucose regulation in diabetes. The next drug on fast track at FDA to be imminently approved is tirzepatide (Mounjaro) following its approval for diabetes in May 2022. It is noteworthy that the discovery of these drugs for weight loss was serendipitous: they were being developed for improving glucose regulation and unexpectedly were found to achieve significant weight reduction.

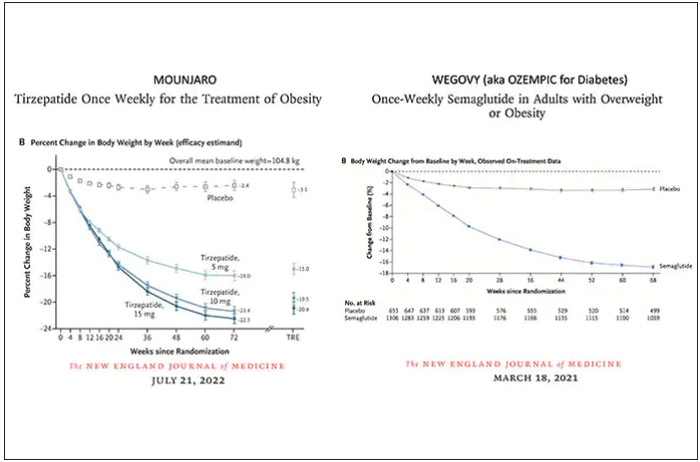

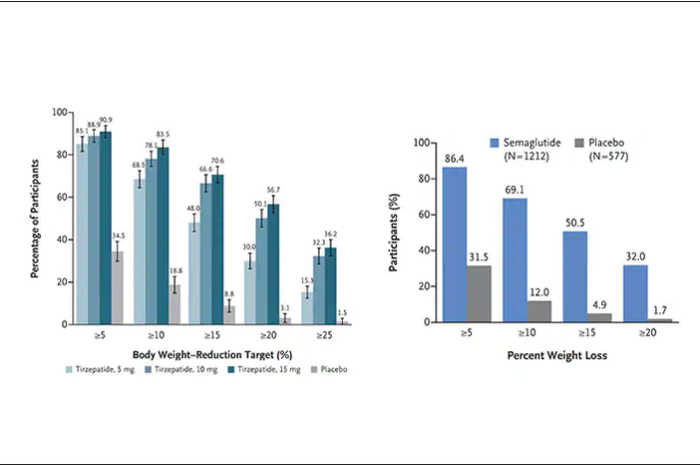

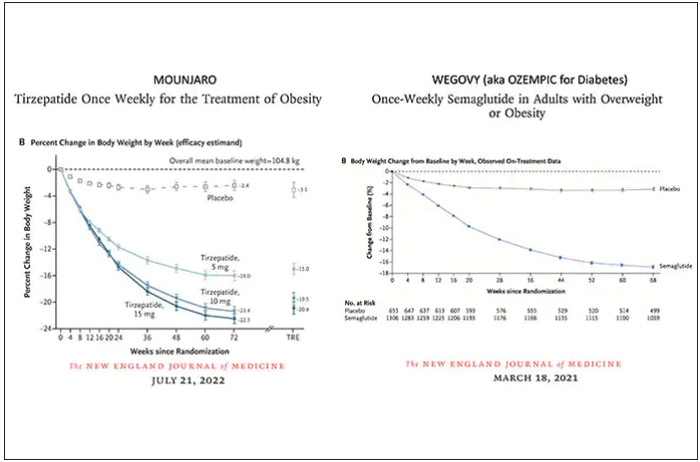

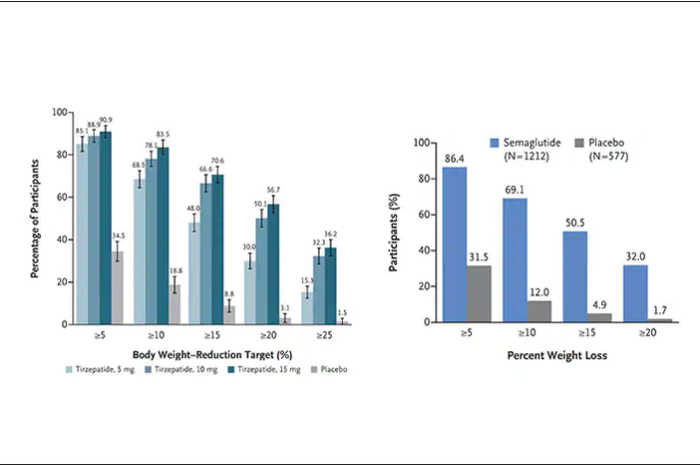

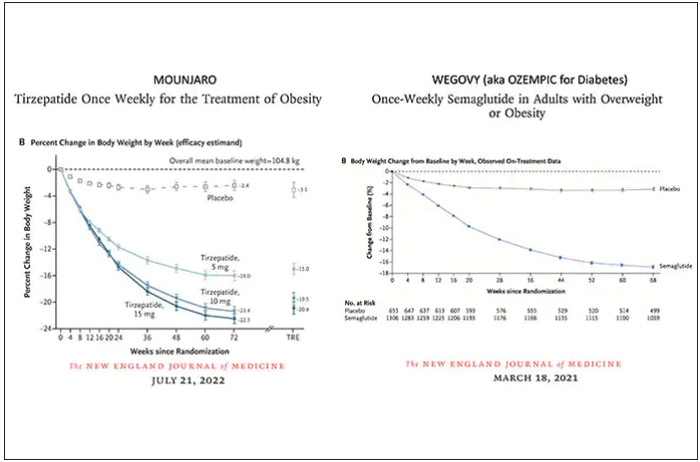

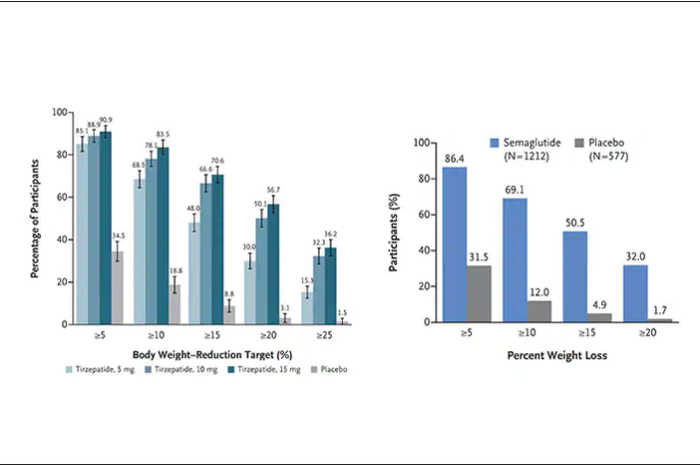

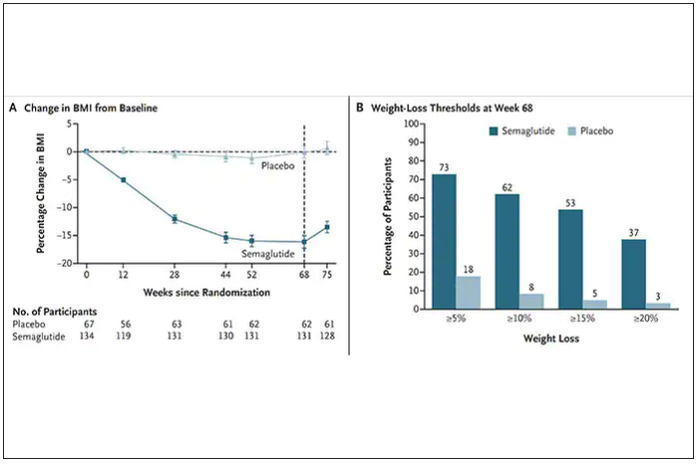

Both semaglutide and tirzepatide underwent randomized, placebo-controlled trials for obesity, with marked reduction of weight as shown below. Tirzepatide at dose of 10-15 mg per week achieved greater than 20% body weight reduction. Semaglutide at a dose of 2.4 mg achieved about 17% reduction. These per cent changes in body weight are 7-9 fold more than seen with placebo (2%-3% reduction). Note: these levels of percent body-weight reduction resemble what is typically achieved with the different types of bariatric surgery, such as gastric bypass.

Another way to present the data for the two trials is shown here, with an edge for tirzepatide at high (10-15 mg) doses, extending to greater than 25% body-weight reduction

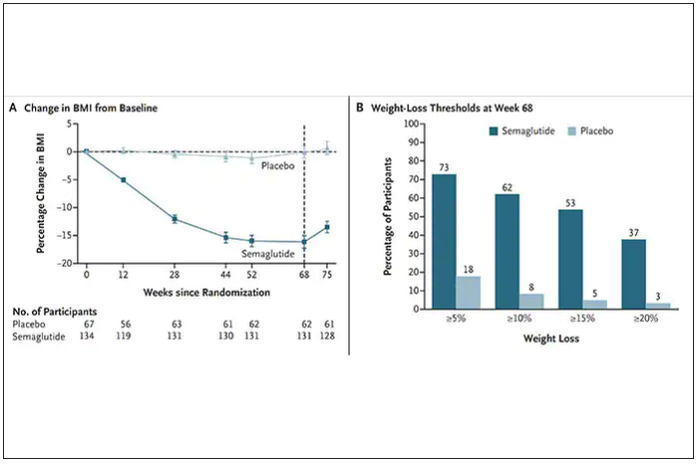

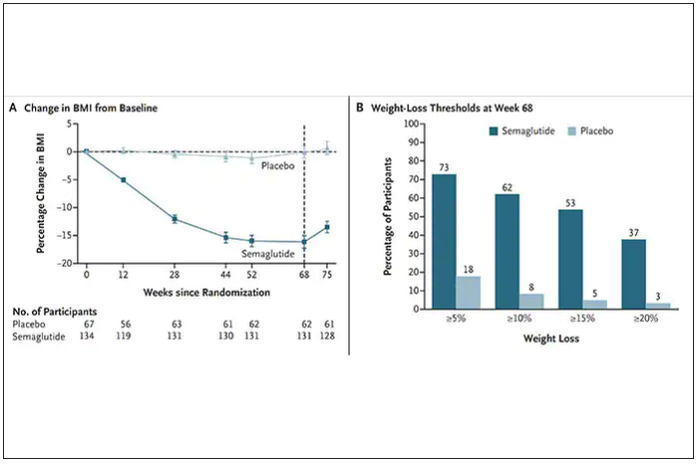

The results with semaglutide were extended to teens in a randomized trial (as shown below), and a similar trial with tirzepatide is in progress.

How do these drugs work?

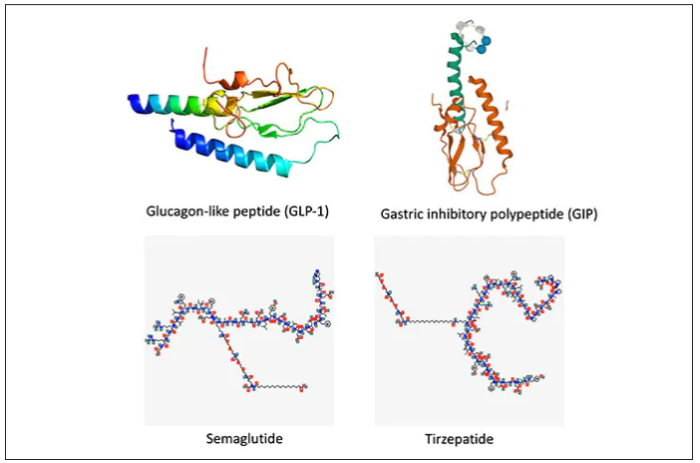

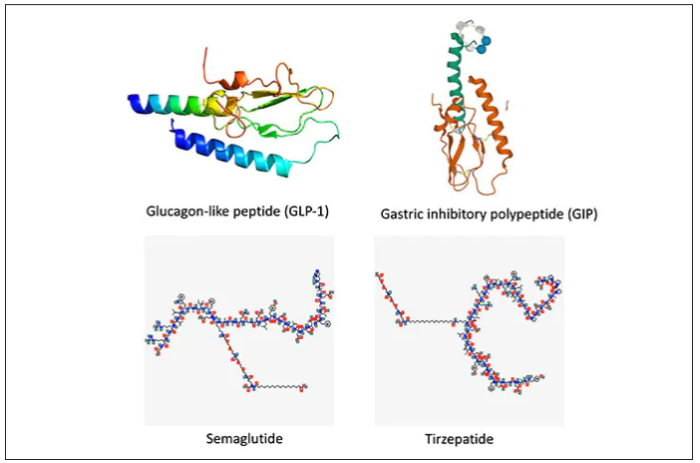

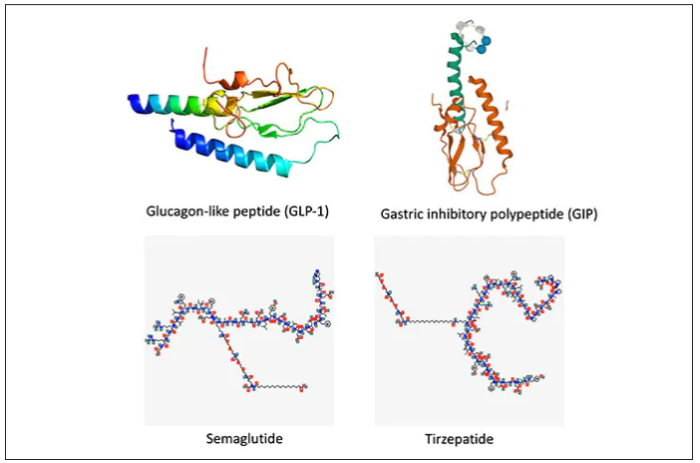

These are peptides in the class of incretins, mimicking gut hormones that are secreted after food intake which stimulate insulin secretion.

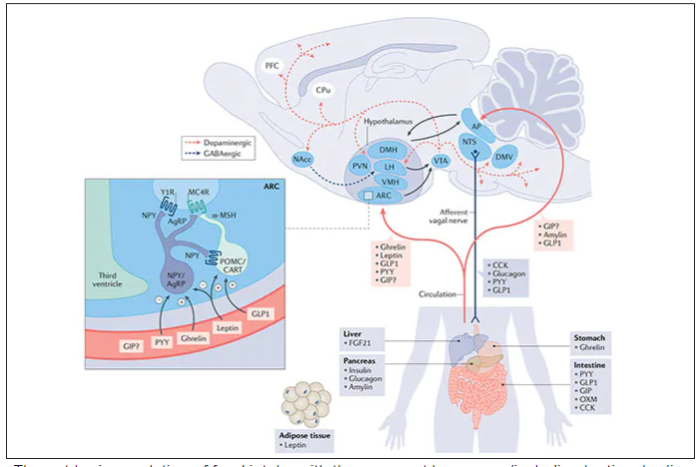

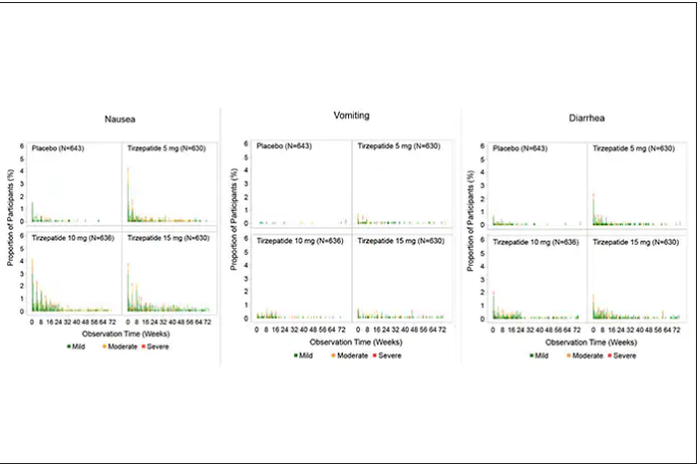

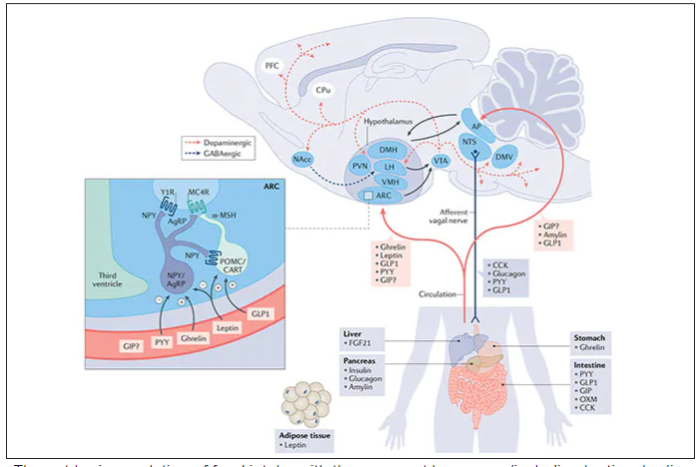

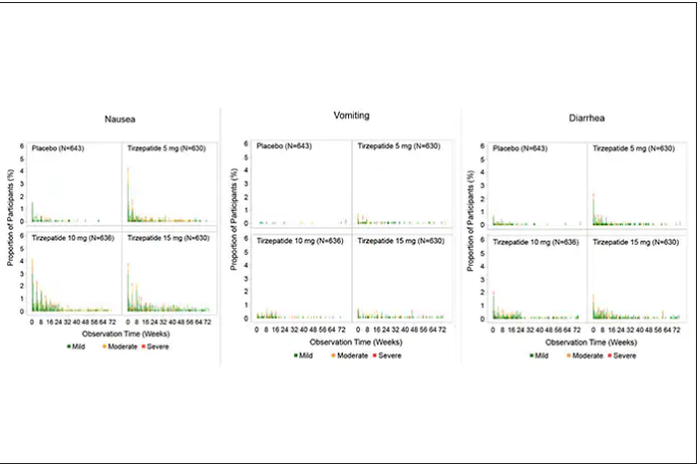

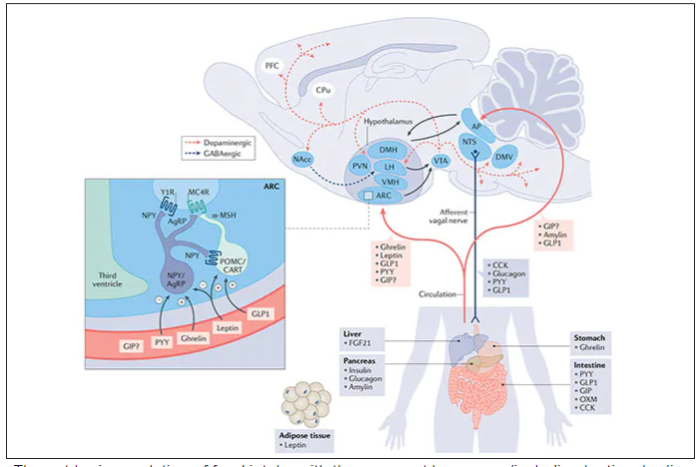

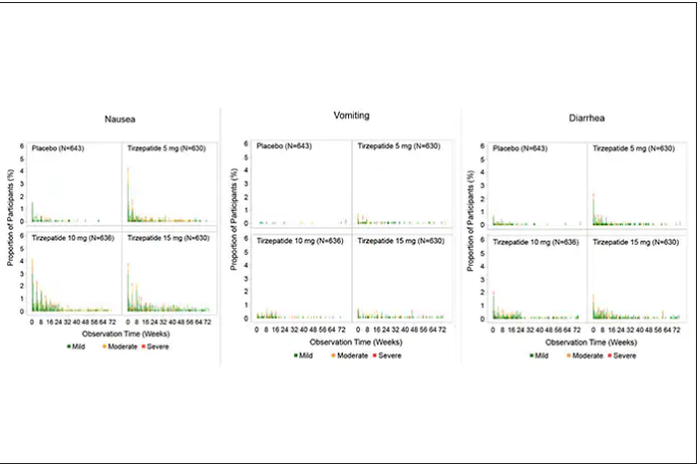

These two drugs have in common long half-lives (about 5 days), which affords once-weekly dosing, but have different mechanisms of action. Semaglutide activates (an agonist) the glucagonlike peptide–1 receptor, while tirzepatide is in a new class of dual agonists: It activates (mimics) both the GLP-1 receptor and GIP receptors (Gastric inhibit polypeptide is also known as glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide.) The potency of activation for tirzepatide is fivefold more for GIPR than GLP1. As seen below, there are body wide effects that include the brain, liver, pancreas, stomach, intestine, skeletal muscle and fat tissue. While their mode of action is somewhat different, their clinical effects are overlapping, which include enhancing satiety, delaying gastric emptying, increasing insulin and its sensitivity, decreasing glucagon, and, of course, reducing high glucose levels. The overlap extends to side effects of nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, constipation and diarrhea. Yet only 4%-6% of participants discontinued the drug in these trials, mostly owing to these GI side effects (and 1%-2% in the placebo group discontinued the study drug for the same reasons).

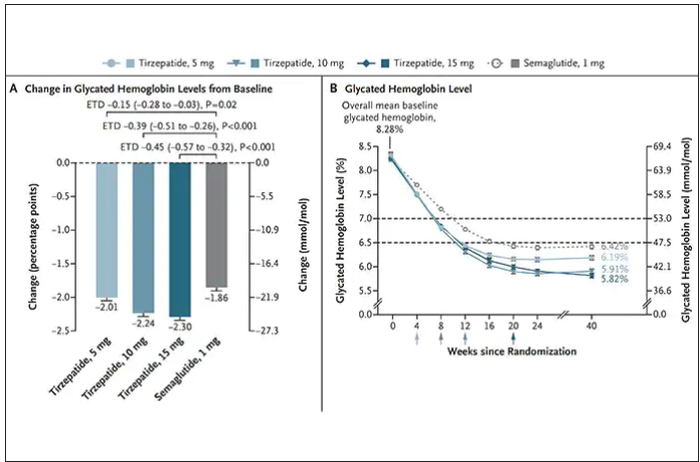

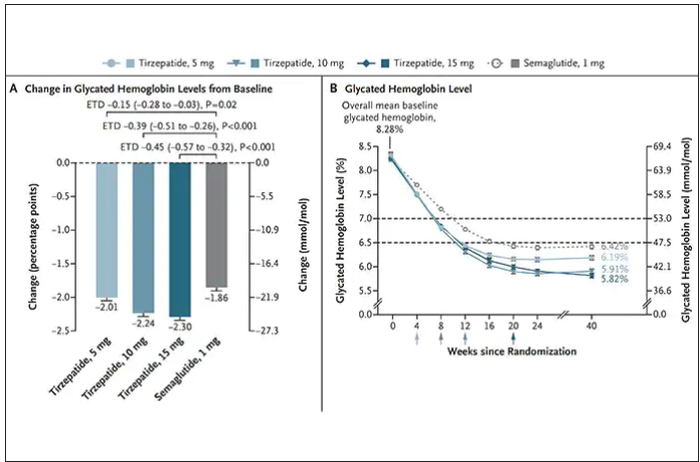

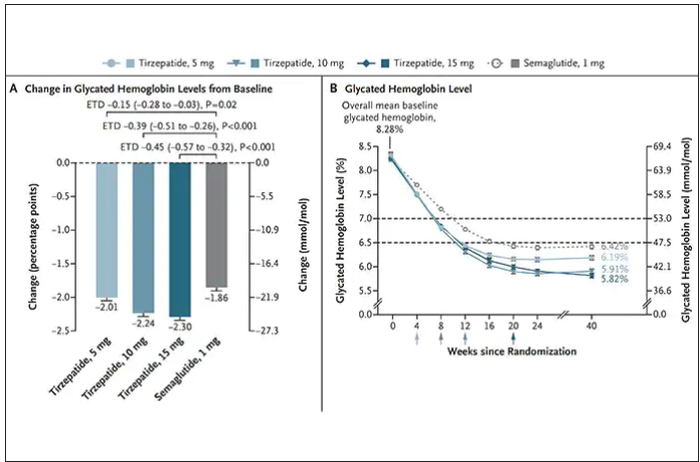

In randomized trials among people with type 2 diabetes, the drugs achieved hemoglobin A1c reduction of at least an absolute 2 percentage points which led to their FDA approvals (For semaglutide in January 2020, and for tirzepatide in May 2022). The edge that tirzepatide has exhibited for weight-loss reduction may be related to its dual agonist role, but the enhancement via GIP receptor activation is not fully resolved (as seen below with GIP? designation). The Amgen drug in development (AMG-133) has a marked weight loss effect but inhibits GIP rather than mimics it, clouding our precise understanding of the mechanism.

Nevertheless, when the two drugs were directly compared in a randomized trial for improving glucose regulation, tirzepatide was superior to semaglutide, as shown below. Of note, both drugs achieved very favorable effects on lipids, reducing triglycerides and LDL cholesterol and raising HDL cholesterol, along with reduction of blood pressure, an outgrowth of the indirect effect of weight reduction and direct metabolic effects of the drugs.

While there has been a concern about other side effects besides the GI ones noted above, review of all the trials to date in these classes of medication do not reinforce a risk of acute pancreatitis. Other rare side effects that have been noted with these drugs include allergic reactions, gallstones (which can occur with a large amount of weight loss), and potential of medullary thyroid cancer (so far only documented in rats, not people), which is why they are contraindicated in people with Type 2 multiple endocrine neoplasia syndrome.

How they are given and practical considerations

For semaglutide, which has FDA approval, the indication is a body mass index of 30 kg/m2 or greater than 27 and a weight-related medical condition (such as hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, or diabetes). To reduce the GI side effects, which mainly occur in the early dose escalation period, semaglutide is given in increasing doses by a prefilled pen by self-injection under the skin (abdomen, thigh, or arm) starting at 0.25 mg for a month and gradual increases each month reaching the maximum dose of 2.4 mg at month 5. The FDA label for dosing of tirzepatide has not been provided yet but in the weight loss trial there was a similar dose escalation from 2.5 mg up to 15 mg by month 5. The escalation is essential to reduce the frequent GI side effects, such as seen below in the tirzepatide trial.

Semaglutide is very expensive, about $1,500 per month, and not covered by Medicare. There are manufacturer starter coupons from Novo Nordisk, but that is just for the first month. These drugs have to be taken for a year to 18 months to have their full effect and without changes in lifestyle that are durable, it is likely that weight will be regained after stopping them.

What does this mean?

More than 650 million adults and 340 million children aged 5-18 are obese. The global obesity epidemic has been relentless, worsening each year, and a driver of “diabesity,” the combined dual epidemic. We now have a breakthrough class of drugs that can achieve profound weight loss equivalent to bariatric surgery, along with the side benefits of reducing cardiovascular risk factors (hypertension and hyperlipidemia), improving glucose regulation, reversing fatty liver, and the many detrimental long-term effects of obesity such as osteoarthritis and various cancers. That, in itself, is remarkable. Revolutionary.

But the downsides are also obvious. Self-injections, even though they are once a week, are not palatable for many. We have seen far more of these injectables in recent years such as the proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 inhibitors for hypercholesterolemia or the tumor necrosis factor blockers for autoimmune conditions. That still will not make them a popular item for such an enormous population of potential users.

That brings me to Rybelsus, the oral form of semaglutide, which is approved for glucose regulation improvement but not obesity. It effects for weight loss have been modest, compared with Wegovy (5 to 8 pounds for the 7- and 14-mg dose, respectively). But the potential for the very high efficacy of an injectable to be achievable via a pill represents an important path going forward—it could help markedly reduce the cost and uptake.

The problem of discontinuation of the drugs is big, since there are limited data and the likelihood is that the weight will be regained unless there are substantial changes in lifestyle. We know how hard it is to durably achieve such changes, along with the undesirability (and uncertainty with respect to unknown side effects) of having to take injectable drugs for many years, no less the cost of doing that.