User login

Scarring Head Wound

The Diagnosis: Brunsting-Perry Cicatricial Pemphigoid

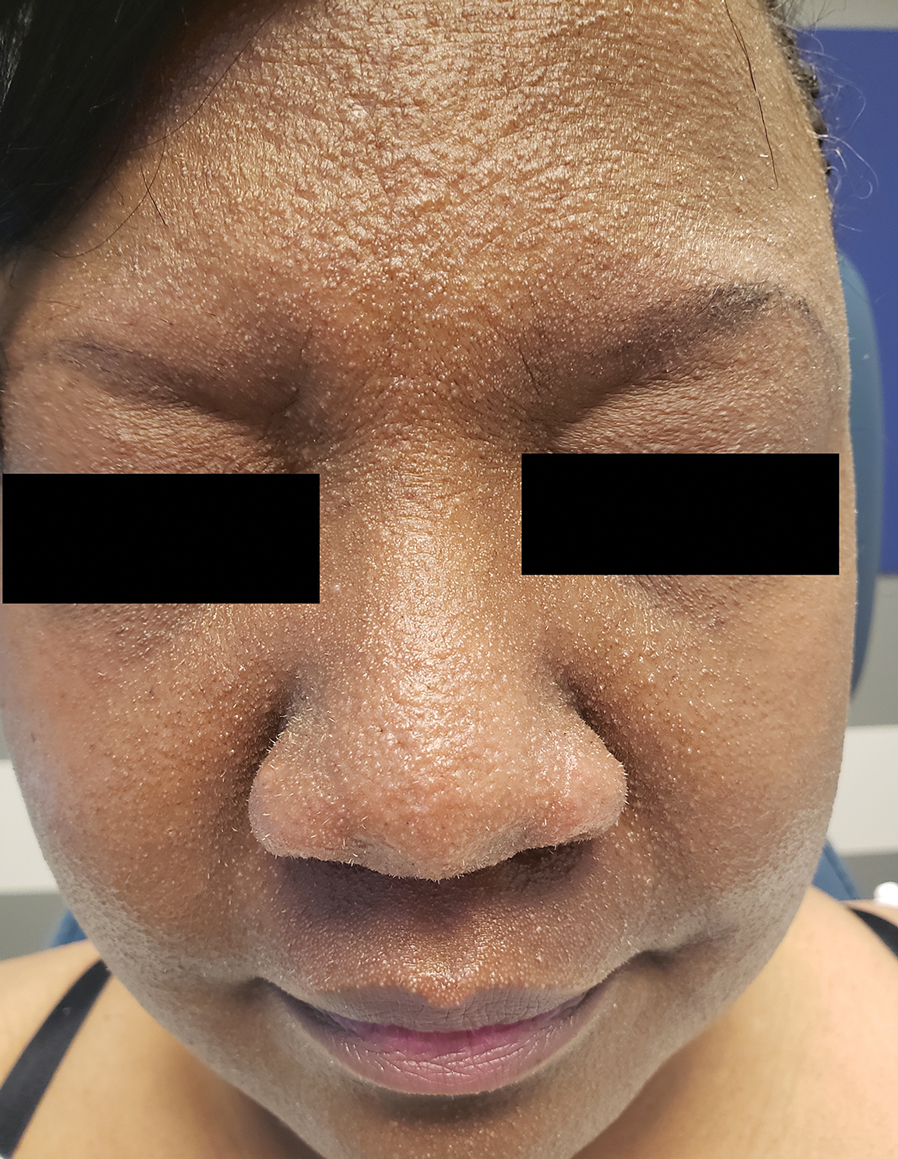

Physical examination and histopathology are paramount in diagnosing Brunsting-Perry cicatricial pemphigoid (BPCP). In our patient, histopathology showed subepidermal blistering with a mixed superficial dermal inflammatory cell infiltrate. Direct immunofluorescence was positive for linear IgG and C3 antibodies along the basement membrane. The scarring erosions on the scalp combined with the autoantibody findings on direct immunofluorescence were consistent with BPCP. He was started on dapsone 100 mg daily and demonstrated complete resolution of symptoms after 10 months, with the exception of persistent scarring hair loss (Figure).

Brunsting-Perry cicatricial pemphigoid is a rare dermatologic condition. It was first defined in 1957 when Brunsting and Perry1 examined 7 patients with cicatricial pemphigoid that predominantly affected the head and neck region, with occasional mucous membrane involvement but no mucosal scarring. Characteristically, BPCP manifests as scarring herpetiform plaques with varied blisters, erosions, crusts, and scarring.1 It primarily affects middle-aged men.2

Historically, BPCP has been considered a variant of cicatricial pemphigoid (now known as mucous membrane pemphigoid), bullous pemphigoid, or epidermolysis bullosa acquisita.3 The antigen target has not been established clearly; however, autoantibodies against laminin 332, collagen VII, and BP180 and BP230 have been proposed.2,4,5 Jacoby et al6 described BPCP on a spectrum with bullous pemphigoid and cicatricial pemphigoid, with primarily circulating autoantibodies on one end and tissue-fixed autoantibodies on the other.

The differential for BPCP also includes anti-p200 pemphigoid and anti–laminin 332 pemphigoid. Anti-p200 pemphigoid also is known as bullous pemphigoid with antibodies against the 200-kDa protein.7 It may clinically manifest similar to bullous pemphigoid and other subepidermal autoimmune blistering diseases; thus, immunopathologic differentiation can be helpful. Anti–laminin 332 pemphigoid (also known as anti–laminin gamma-1 pemphigoid) is characterized by autoantibodies targeting the laminin 332 protein in the basement membrane zone, resulting in blistering and erosions.8 Similar to BPCP and epidermolysis bullosa aquisita, anti–laminin 332 pemphigoid may affect cephalic regions and mucous membrane surfaces, resulting in scarring and cicatricial changes. Anti–laminin 332 pemphigoid also has been associated with internal malignancy.8 The use of the salt-split skin technique can be utilized to differentiate these entities based on their autoantibody-binding patterns in relation to the lamina densa.

Treatment options for mild BPCP include potent topical or intralesional steroids and dapsone, while more severe cases may require systemic therapy with rituximab, azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, or cyclophosphamide.4

This case highlights the importance of histopathologic examination of skin lesions with an unusual history or clinical presentation. Dermatologists should consider BPCP when presented with erosions, ulcerations, or blisters of the head and neck in middle-aged male patients.

- Brunsting LA, Perry HO. Benign pemphigoid? a report of seven cases with chronic, scarring, herpetiform plaques about the head and neck. AMA Arch Derm. 1957;75:489-501. doi:10.1001 /archderm.1957.01550160015002

- Jedlickova H, Neidermeier A, Zgažarová S, et al. Brunsting-Perry pemphigoid of the scalp with antibodies against laminin 332. Dermatology. 2011;222:193-195. doi:10.1159/000322842

- Eichhoff G. Brunsting-Perry pemphigoid as differential diagnosis of nonmelanoma skin cancer. Cureus. 2019;11:E5400. doi:10.7759/cureus.5400

- Asfour L, Chong H, Mee J, et al. Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita (Brunsting-Perry pemphigoid variant) localized to the face and diagnosed with antigen identification using skin deficient in type VII collagen. Am J Dermatopathol. 2017;39:e90-e96. doi:10.1097 /DAD.0000000000000829

- Zhou S, Zou Y, Pan M. Brunsting-Perry pemphigoid transitioning from previous bullous pemphigoid. JAAD Case Rep. 2020;6:192-194. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2019.12.018

- Jacoby WD Jr, Bartholome CW, Ramchand SC, et al. Cicatricial pemphigoid (Brunsting-Perry type). case report and immunofluorescence findings. Arch Dermatol. 1978;114:779-781. doi:10.1001/archderm.1978.01640170079018

- Kridin K, Ahmed AR. Anti-p200 pemphigoid: a systematic review. Front Immunol. 2019;10:2466. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2019.02466

- Shi L, Li X, Qian H. Anti-laminin 332-type mucous membrane pemphigoid. Biomolecules. 2022;12:1461. doi:10.3390/biom12101461

The Diagnosis: Brunsting-Perry Cicatricial Pemphigoid

Physical examination and histopathology are paramount in diagnosing Brunsting-Perry cicatricial pemphigoid (BPCP). In our patient, histopathology showed subepidermal blistering with a mixed superficial dermal inflammatory cell infiltrate. Direct immunofluorescence was positive for linear IgG and C3 antibodies along the basement membrane. The scarring erosions on the scalp combined with the autoantibody findings on direct immunofluorescence were consistent with BPCP. He was started on dapsone 100 mg daily and demonstrated complete resolution of symptoms after 10 months, with the exception of persistent scarring hair loss (Figure).

Brunsting-Perry cicatricial pemphigoid is a rare dermatologic condition. It was first defined in 1957 when Brunsting and Perry1 examined 7 patients with cicatricial pemphigoid that predominantly affected the head and neck region, with occasional mucous membrane involvement but no mucosal scarring. Characteristically, BPCP manifests as scarring herpetiform plaques with varied blisters, erosions, crusts, and scarring.1 It primarily affects middle-aged men.2

Historically, BPCP has been considered a variant of cicatricial pemphigoid (now known as mucous membrane pemphigoid), bullous pemphigoid, or epidermolysis bullosa acquisita.3 The antigen target has not been established clearly; however, autoantibodies against laminin 332, collagen VII, and BP180 and BP230 have been proposed.2,4,5 Jacoby et al6 described BPCP on a spectrum with bullous pemphigoid and cicatricial pemphigoid, with primarily circulating autoantibodies on one end and tissue-fixed autoantibodies on the other.

The differential for BPCP also includes anti-p200 pemphigoid and anti–laminin 332 pemphigoid. Anti-p200 pemphigoid also is known as bullous pemphigoid with antibodies against the 200-kDa protein.7 It may clinically manifest similar to bullous pemphigoid and other subepidermal autoimmune blistering diseases; thus, immunopathologic differentiation can be helpful. Anti–laminin 332 pemphigoid (also known as anti–laminin gamma-1 pemphigoid) is characterized by autoantibodies targeting the laminin 332 protein in the basement membrane zone, resulting in blistering and erosions.8 Similar to BPCP and epidermolysis bullosa aquisita, anti–laminin 332 pemphigoid may affect cephalic regions and mucous membrane surfaces, resulting in scarring and cicatricial changes. Anti–laminin 332 pemphigoid also has been associated with internal malignancy.8 The use of the salt-split skin technique can be utilized to differentiate these entities based on their autoantibody-binding patterns in relation to the lamina densa.

Treatment options for mild BPCP include potent topical or intralesional steroids and dapsone, while more severe cases may require systemic therapy with rituximab, azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, or cyclophosphamide.4

This case highlights the importance of histopathologic examination of skin lesions with an unusual history or clinical presentation. Dermatologists should consider BPCP when presented with erosions, ulcerations, or blisters of the head and neck in middle-aged male patients.

The Diagnosis: Brunsting-Perry Cicatricial Pemphigoid

Physical examination and histopathology are paramount in diagnosing Brunsting-Perry cicatricial pemphigoid (BPCP). In our patient, histopathology showed subepidermal blistering with a mixed superficial dermal inflammatory cell infiltrate. Direct immunofluorescence was positive for linear IgG and C3 antibodies along the basement membrane. The scarring erosions on the scalp combined with the autoantibody findings on direct immunofluorescence were consistent with BPCP. He was started on dapsone 100 mg daily and demonstrated complete resolution of symptoms after 10 months, with the exception of persistent scarring hair loss (Figure).

Brunsting-Perry cicatricial pemphigoid is a rare dermatologic condition. It was first defined in 1957 when Brunsting and Perry1 examined 7 patients with cicatricial pemphigoid that predominantly affected the head and neck region, with occasional mucous membrane involvement but no mucosal scarring. Characteristically, BPCP manifests as scarring herpetiform plaques with varied blisters, erosions, crusts, and scarring.1 It primarily affects middle-aged men.2

Historically, BPCP has been considered a variant of cicatricial pemphigoid (now known as mucous membrane pemphigoid), bullous pemphigoid, or epidermolysis bullosa acquisita.3 The antigen target has not been established clearly; however, autoantibodies against laminin 332, collagen VII, and BP180 and BP230 have been proposed.2,4,5 Jacoby et al6 described BPCP on a spectrum with bullous pemphigoid and cicatricial pemphigoid, with primarily circulating autoantibodies on one end and tissue-fixed autoantibodies on the other.

The differential for BPCP also includes anti-p200 pemphigoid and anti–laminin 332 pemphigoid. Anti-p200 pemphigoid also is known as bullous pemphigoid with antibodies against the 200-kDa protein.7 It may clinically manifest similar to bullous pemphigoid and other subepidermal autoimmune blistering diseases; thus, immunopathologic differentiation can be helpful. Anti–laminin 332 pemphigoid (also known as anti–laminin gamma-1 pemphigoid) is characterized by autoantibodies targeting the laminin 332 protein in the basement membrane zone, resulting in blistering and erosions.8 Similar to BPCP and epidermolysis bullosa aquisita, anti–laminin 332 pemphigoid may affect cephalic regions and mucous membrane surfaces, resulting in scarring and cicatricial changes. Anti–laminin 332 pemphigoid also has been associated with internal malignancy.8 The use of the salt-split skin technique can be utilized to differentiate these entities based on their autoantibody-binding patterns in relation to the lamina densa.

Treatment options for mild BPCP include potent topical or intralesional steroids and dapsone, while more severe cases may require systemic therapy with rituximab, azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, or cyclophosphamide.4

This case highlights the importance of histopathologic examination of skin lesions with an unusual history or clinical presentation. Dermatologists should consider BPCP when presented with erosions, ulcerations, or blisters of the head and neck in middle-aged male patients.

- Brunsting LA, Perry HO. Benign pemphigoid? a report of seven cases with chronic, scarring, herpetiform plaques about the head and neck. AMA Arch Derm. 1957;75:489-501. doi:10.1001 /archderm.1957.01550160015002

- Jedlickova H, Neidermeier A, Zgažarová S, et al. Brunsting-Perry pemphigoid of the scalp with antibodies against laminin 332. Dermatology. 2011;222:193-195. doi:10.1159/000322842

- Eichhoff G. Brunsting-Perry pemphigoid as differential diagnosis of nonmelanoma skin cancer. Cureus. 2019;11:E5400. doi:10.7759/cureus.5400

- Asfour L, Chong H, Mee J, et al. Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita (Brunsting-Perry pemphigoid variant) localized to the face and diagnosed with antigen identification using skin deficient in type VII collagen. Am J Dermatopathol. 2017;39:e90-e96. doi:10.1097 /DAD.0000000000000829

- Zhou S, Zou Y, Pan M. Brunsting-Perry pemphigoid transitioning from previous bullous pemphigoid. JAAD Case Rep. 2020;6:192-194. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2019.12.018

- Jacoby WD Jr, Bartholome CW, Ramchand SC, et al. Cicatricial pemphigoid (Brunsting-Perry type). case report and immunofluorescence findings. Arch Dermatol. 1978;114:779-781. doi:10.1001/archderm.1978.01640170079018

- Kridin K, Ahmed AR. Anti-p200 pemphigoid: a systematic review. Front Immunol. 2019;10:2466. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2019.02466

- Shi L, Li X, Qian H. Anti-laminin 332-type mucous membrane pemphigoid. Biomolecules. 2022;12:1461. doi:10.3390/biom12101461

- Brunsting LA, Perry HO. Benign pemphigoid? a report of seven cases with chronic, scarring, herpetiform plaques about the head and neck. AMA Arch Derm. 1957;75:489-501. doi:10.1001 /archderm.1957.01550160015002

- Jedlickova H, Neidermeier A, Zgažarová S, et al. Brunsting-Perry pemphigoid of the scalp with antibodies against laminin 332. Dermatology. 2011;222:193-195. doi:10.1159/000322842

- Eichhoff G. Brunsting-Perry pemphigoid as differential diagnosis of nonmelanoma skin cancer. Cureus. 2019;11:E5400. doi:10.7759/cureus.5400

- Asfour L, Chong H, Mee J, et al. Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita (Brunsting-Perry pemphigoid variant) localized to the face and diagnosed with antigen identification using skin deficient in type VII collagen. Am J Dermatopathol. 2017;39:e90-e96. doi:10.1097 /DAD.0000000000000829

- Zhou S, Zou Y, Pan M. Brunsting-Perry pemphigoid transitioning from previous bullous pemphigoid. JAAD Case Rep. 2020;6:192-194. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2019.12.018

- Jacoby WD Jr, Bartholome CW, Ramchand SC, et al. Cicatricial pemphigoid (Brunsting-Perry type). case report and immunofluorescence findings. Arch Dermatol. 1978;114:779-781. doi:10.1001/archderm.1978.01640170079018

- Kridin K, Ahmed AR. Anti-p200 pemphigoid: a systematic review. Front Immunol. 2019;10:2466. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2019.02466

- Shi L, Li X, Qian H. Anti-laminin 332-type mucous membrane pemphigoid. Biomolecules. 2022;12:1461. doi:10.3390/biom12101461

A 60-year-old man presented to a dermatology clinic with a wound on the scalp that had persisted for 11 months. The lesion started as a small erosion that eventually progressed to involve the entire parietal scalp. He had a history of type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and Graves disease. Physical examination demonstrated a large scar over the vertex scalp with central erosion, overlying crust, peripheral scalp atrophy, hypopigmentation at the periphery, and exaggerated superficial vasculature. Some oral erosions also were observed. A review of systems was negative for any constitutional symptoms. A month prior, the patient had been started on dapsone 50 mg with a prednisone taper by an outside dermatologist and noticed some improvement.

Painful Plaque on the Forearm

The Diagnosis: Mycobacterium marinum Infection

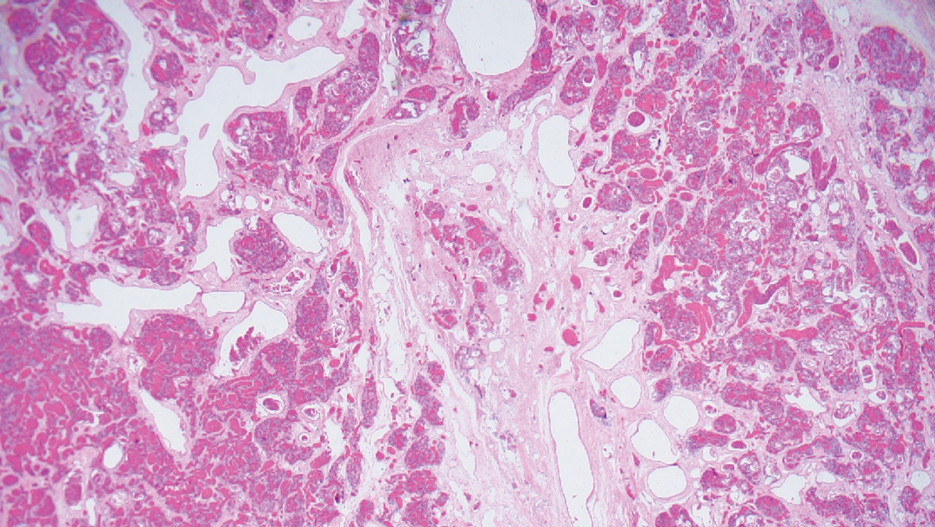

A repeat excisional biopsy showed suppurative granulomatous dermatitis with negative stains for infectious organisms; however, tissue culture grew Mycobacterium marinum. The patient had a history of exposure to fish tanks, which are a potential habitat for nontuberculous mycobacteria. These bacteria can enter the body through a minor laceration or cut in the skin, which was likely due to her occupation and pet care activities.1 Her fish tank exposure combined with the cutaneous findings of a long-standing indurated plaque with proximal nodular lymphangitis made M marinum infection the most likely diagnosis.2

Due to the limited specificity and sensitivity of patient symptoms, histologic staining, and direct microscopy, the gold standard for diagnosing acid-fast bacilli is tissue culture. 3 Tissue polymerase chain reaction testing is most useful in identifying the species of mycobacteria when histologic stains identify acid-fast bacilli but repeated tissue cultures are negative.4 With M marinum, a high clinical suspicion is needed to acquire a positive tissue culture because it needs to be grown for several weeks and at a temperature of 30 °C.5 Therefore, the physician should inform the laboratory if there is any suspicion for M marinum to increase the likelihood of obtaining a positive culture.

The differential diagnosis for M marinum infection includes other skin diseases that can cause nodular lymphangitis (also known as sporotrichoid spread) such as sporotrichosis, leishmaniasis, and certain bacterial and fungal infections. Although cat scratch disease, which is caused by Bartonella henselae, can appear similar to M marinum on histopathology, it clinically manifests with a single papulovesicular lesion at the site of inoculation that then forms a central eschar and resolves within a few weeks. Cat scratch disease typically causes painful lymphadenopathy, but it does not cause nodular lymphangitis or sporotrichoid spread.6 Sporotrichosis can have a similar clinical and histologic manifestation to M marinum infection, but the patient history typically includes exposure to Sporothrix schenckii through gardening or other contact with thorns, plants, or soil.2 Cutaneous sarcoidosis can have a similar clinical appearance to M marinum infection, but nodular lymphangitis does not occur and histopathology would demonstrate noncaseating epithelioid cell granulomas.7 Lastly, although vegetative pyoderma gangrenosum can have some of the same histologic findings as M marinum, it typically also demonstrates sinus tract formation, which was not present in our case. Additionally, vegetative pyoderma gangrenosum manifests with a verrucous and pustular plaque that would not have lymphocutaneous spread.8

Treatment of cutaneous M marinum infection is guided by antibiotic susceptibility testing. One regimen is clarithromycin (500 mg twice daily9) plus ethambutol. 10 Treatment often entails a multidrug combination due to the high rates of antibiotic resistance. Other antibiotics that potentially can be used include rifampin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, minocycline, and quinolones. The treatment duration typically is more than 3 months, and therapy is continued for 4 to 6 weeks after the skin lesions resolve.11 Excision of the lesion is reserved for patients with M marinum infection that fails to respond to antibiotic therapy.5

- Wayne LG, Sramek HA. Agents of newly recognized or infrequently encountered mycobacterial diseases. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1992;5:1-25. doi:10.1128/CMR.5.1.1

- Tobin EH, Jih WW. Sporotrichoid lymphocutaneous infections: etiology, diagnosis and therapy. Am Fam Physician. 2001;63:326-332.

- van Ingen J. Diagnosis of nontuberculous mycobacterial infections. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;34:103-109. doi:10.1055/s-0033-1333569

- Williamson H, Phillips R, Sarfo S, et al. Genetic diversity of PCR-positive, culture-negative and culture-positive Mycobacterium ulcerans isolated from Buruli ulcer patients in Ghana. PLoS One. 2014;9:E88007. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0088007

- Aubry A, Mougari F, Reibel F, et al. Mycobacterium marinum. Microbiol Spectr. 2017;5. doi:10.1128/microbiolspec.TNMI7-0038-2016

- Baranowski K, Huang B. Cat scratch disease. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated June 12, 2023. Accessed July 15, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm .nih.gov/books/NBK482139/

- Sanchez M, Haimovic A, Prystowsky S. Sarcoidosis. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:389-416. doi:10.1016/j.det.2015.03.006

- Borg Grech S, Vella Baldacchino A, Corso R, et al. Superficial granulomatous pyoderma successfully treated with intravenous immunoglobulin. Eur J Case Rep Intern Med. 2021;8:002656. doi:10.12890/2021_002656

- Krooks J, Weatherall A, Markowitz S. Complete resolution of Mycobacterium marinum infection with clarithromycin and ethambutol: a case report and a review of the literature. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2018;11:48-51.

- Medel-Plaza M., Esteban J. Current treatment options for Mycobacterium marinum cutaneous infections. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2023;24:1113-1123. doi:10.1080/14656566.2023.2211258

- Tirado-Sánchez A, Bonifaz A. Nodular lymphangitis (sporotrichoid lymphocutaneous infections): clues to differential diagnosis. J Fungi (Basel). 2018;4:56. doi:10.3390/jof4020056

The Diagnosis: Mycobacterium marinum Infection

A repeat excisional biopsy showed suppurative granulomatous dermatitis with negative stains for infectious organisms; however, tissue culture grew Mycobacterium marinum. The patient had a history of exposure to fish tanks, which are a potential habitat for nontuberculous mycobacteria. These bacteria can enter the body through a minor laceration or cut in the skin, which was likely due to her occupation and pet care activities.1 Her fish tank exposure combined with the cutaneous findings of a long-standing indurated plaque with proximal nodular lymphangitis made M marinum infection the most likely diagnosis.2

Due to the limited specificity and sensitivity of patient symptoms, histologic staining, and direct microscopy, the gold standard for diagnosing acid-fast bacilli is tissue culture. 3 Tissue polymerase chain reaction testing is most useful in identifying the species of mycobacteria when histologic stains identify acid-fast bacilli but repeated tissue cultures are negative.4 With M marinum, a high clinical suspicion is needed to acquire a positive tissue culture because it needs to be grown for several weeks and at a temperature of 30 °C.5 Therefore, the physician should inform the laboratory if there is any suspicion for M marinum to increase the likelihood of obtaining a positive culture.

The differential diagnosis for M marinum infection includes other skin diseases that can cause nodular lymphangitis (also known as sporotrichoid spread) such as sporotrichosis, leishmaniasis, and certain bacterial and fungal infections. Although cat scratch disease, which is caused by Bartonella henselae, can appear similar to M marinum on histopathology, it clinically manifests with a single papulovesicular lesion at the site of inoculation that then forms a central eschar and resolves within a few weeks. Cat scratch disease typically causes painful lymphadenopathy, but it does not cause nodular lymphangitis or sporotrichoid spread.6 Sporotrichosis can have a similar clinical and histologic manifestation to M marinum infection, but the patient history typically includes exposure to Sporothrix schenckii through gardening or other contact with thorns, plants, or soil.2 Cutaneous sarcoidosis can have a similar clinical appearance to M marinum infection, but nodular lymphangitis does not occur and histopathology would demonstrate noncaseating epithelioid cell granulomas.7 Lastly, although vegetative pyoderma gangrenosum can have some of the same histologic findings as M marinum, it typically also demonstrates sinus tract formation, which was not present in our case. Additionally, vegetative pyoderma gangrenosum manifests with a verrucous and pustular plaque that would not have lymphocutaneous spread.8

Treatment of cutaneous M marinum infection is guided by antibiotic susceptibility testing. One regimen is clarithromycin (500 mg twice daily9) plus ethambutol. 10 Treatment often entails a multidrug combination due to the high rates of antibiotic resistance. Other antibiotics that potentially can be used include rifampin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, minocycline, and quinolones. The treatment duration typically is more than 3 months, and therapy is continued for 4 to 6 weeks after the skin lesions resolve.11 Excision of the lesion is reserved for patients with M marinum infection that fails to respond to antibiotic therapy.5

The Diagnosis: Mycobacterium marinum Infection

A repeat excisional biopsy showed suppurative granulomatous dermatitis with negative stains for infectious organisms; however, tissue culture grew Mycobacterium marinum. The patient had a history of exposure to fish tanks, which are a potential habitat for nontuberculous mycobacteria. These bacteria can enter the body through a minor laceration or cut in the skin, which was likely due to her occupation and pet care activities.1 Her fish tank exposure combined with the cutaneous findings of a long-standing indurated plaque with proximal nodular lymphangitis made M marinum infection the most likely diagnosis.2

Due to the limited specificity and sensitivity of patient symptoms, histologic staining, and direct microscopy, the gold standard for diagnosing acid-fast bacilli is tissue culture. 3 Tissue polymerase chain reaction testing is most useful in identifying the species of mycobacteria when histologic stains identify acid-fast bacilli but repeated tissue cultures are negative.4 With M marinum, a high clinical suspicion is needed to acquire a positive tissue culture because it needs to be grown for several weeks and at a temperature of 30 °C.5 Therefore, the physician should inform the laboratory if there is any suspicion for M marinum to increase the likelihood of obtaining a positive culture.

The differential diagnosis for M marinum infection includes other skin diseases that can cause nodular lymphangitis (also known as sporotrichoid spread) such as sporotrichosis, leishmaniasis, and certain bacterial and fungal infections. Although cat scratch disease, which is caused by Bartonella henselae, can appear similar to M marinum on histopathology, it clinically manifests with a single papulovesicular lesion at the site of inoculation that then forms a central eschar and resolves within a few weeks. Cat scratch disease typically causes painful lymphadenopathy, but it does not cause nodular lymphangitis or sporotrichoid spread.6 Sporotrichosis can have a similar clinical and histologic manifestation to M marinum infection, but the patient history typically includes exposure to Sporothrix schenckii through gardening or other contact with thorns, plants, or soil.2 Cutaneous sarcoidosis can have a similar clinical appearance to M marinum infection, but nodular lymphangitis does not occur and histopathology would demonstrate noncaseating epithelioid cell granulomas.7 Lastly, although vegetative pyoderma gangrenosum can have some of the same histologic findings as M marinum, it typically also demonstrates sinus tract formation, which was not present in our case. Additionally, vegetative pyoderma gangrenosum manifests with a verrucous and pustular plaque that would not have lymphocutaneous spread.8

Treatment of cutaneous M marinum infection is guided by antibiotic susceptibility testing. One regimen is clarithromycin (500 mg twice daily9) plus ethambutol. 10 Treatment often entails a multidrug combination due to the high rates of antibiotic resistance. Other antibiotics that potentially can be used include rifampin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, minocycline, and quinolones. The treatment duration typically is more than 3 months, and therapy is continued for 4 to 6 weeks after the skin lesions resolve.11 Excision of the lesion is reserved for patients with M marinum infection that fails to respond to antibiotic therapy.5

- Wayne LG, Sramek HA. Agents of newly recognized or infrequently encountered mycobacterial diseases. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1992;5:1-25. doi:10.1128/CMR.5.1.1

- Tobin EH, Jih WW. Sporotrichoid lymphocutaneous infections: etiology, diagnosis and therapy. Am Fam Physician. 2001;63:326-332.

- van Ingen J. Diagnosis of nontuberculous mycobacterial infections. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;34:103-109. doi:10.1055/s-0033-1333569

- Williamson H, Phillips R, Sarfo S, et al. Genetic diversity of PCR-positive, culture-negative and culture-positive Mycobacterium ulcerans isolated from Buruli ulcer patients in Ghana. PLoS One. 2014;9:E88007. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0088007

- Aubry A, Mougari F, Reibel F, et al. Mycobacterium marinum. Microbiol Spectr. 2017;5. doi:10.1128/microbiolspec.TNMI7-0038-2016

- Baranowski K, Huang B. Cat scratch disease. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated June 12, 2023. Accessed July 15, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm .nih.gov/books/NBK482139/

- Sanchez M, Haimovic A, Prystowsky S. Sarcoidosis. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:389-416. doi:10.1016/j.det.2015.03.006

- Borg Grech S, Vella Baldacchino A, Corso R, et al. Superficial granulomatous pyoderma successfully treated with intravenous immunoglobulin. Eur J Case Rep Intern Med. 2021;8:002656. doi:10.12890/2021_002656

- Krooks J, Weatherall A, Markowitz S. Complete resolution of Mycobacterium marinum infection with clarithromycin and ethambutol: a case report and a review of the literature. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2018;11:48-51.

- Medel-Plaza M., Esteban J. Current treatment options for Mycobacterium marinum cutaneous infections. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2023;24:1113-1123. doi:10.1080/14656566.2023.2211258

- Tirado-Sánchez A, Bonifaz A. Nodular lymphangitis (sporotrichoid lymphocutaneous infections): clues to differential diagnosis. J Fungi (Basel). 2018;4:56. doi:10.3390/jof4020056

- Wayne LG, Sramek HA. Agents of newly recognized or infrequently encountered mycobacterial diseases. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1992;5:1-25. doi:10.1128/CMR.5.1.1

- Tobin EH, Jih WW. Sporotrichoid lymphocutaneous infections: etiology, diagnosis and therapy. Am Fam Physician. 2001;63:326-332.

- van Ingen J. Diagnosis of nontuberculous mycobacterial infections. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;34:103-109. doi:10.1055/s-0033-1333569

- Williamson H, Phillips R, Sarfo S, et al. Genetic diversity of PCR-positive, culture-negative and culture-positive Mycobacterium ulcerans isolated from Buruli ulcer patients in Ghana. PLoS One. 2014;9:E88007. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0088007

- Aubry A, Mougari F, Reibel F, et al. Mycobacterium marinum. Microbiol Spectr. 2017;5. doi:10.1128/microbiolspec.TNMI7-0038-2016

- Baranowski K, Huang B. Cat scratch disease. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated June 12, 2023. Accessed July 15, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm .nih.gov/books/NBK482139/

- Sanchez M, Haimovic A, Prystowsky S. Sarcoidosis. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:389-416. doi:10.1016/j.det.2015.03.006

- Borg Grech S, Vella Baldacchino A, Corso R, et al. Superficial granulomatous pyoderma successfully treated with intravenous immunoglobulin. Eur J Case Rep Intern Med. 2021;8:002656. doi:10.12890/2021_002656

- Krooks J, Weatherall A, Markowitz S. Complete resolution of Mycobacterium marinum infection with clarithromycin and ethambutol: a case report and a review of the literature. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2018;11:48-51.

- Medel-Plaza M., Esteban J. Current treatment options for Mycobacterium marinum cutaneous infections. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2023;24:1113-1123. doi:10.1080/14656566.2023.2211258

- Tirado-Sánchez A, Bonifaz A. Nodular lymphangitis (sporotrichoid lymphocutaneous infections): clues to differential diagnosis. J Fungi (Basel). 2018;4:56. doi:10.3390/jof4020056

A 30-year-old woman presented to the dermatology clinic with lesions on the right forearm of 2 years’ duration. Her medical history was unremarkable. She reported working as a chef and caring for multiple pets in her home, including 3 cats, 6 fish tanks, 3 dogs, and 3 lizards. Physical examination revealed a painful, indurated, red-violaceous plaque on the right forearm with satellite pink nodules that had been slowly migrating proximally up the forearm. An outside excisional biopsy performed 1 year prior had shown suppurative granulomatous dermatitis with negative stains for infectious organisms and negative tissue cultures. At that time, the patient was diagnosed with ruptured folliculitis; however, a subsequent lack of clinical improvement prompted her to seek a second opinion at our clinic.

Painful Anal Lesions in a Patient With HIV

The Diagnosis: Condyloma Latum

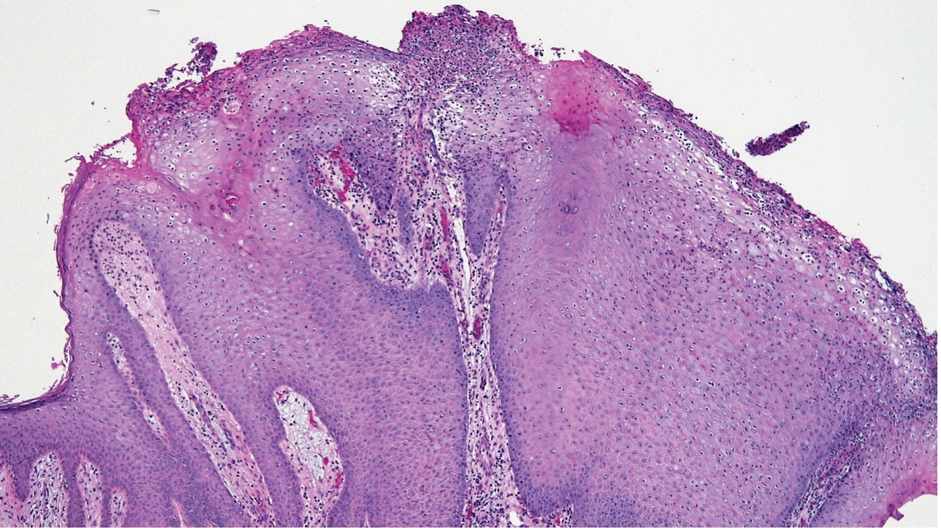

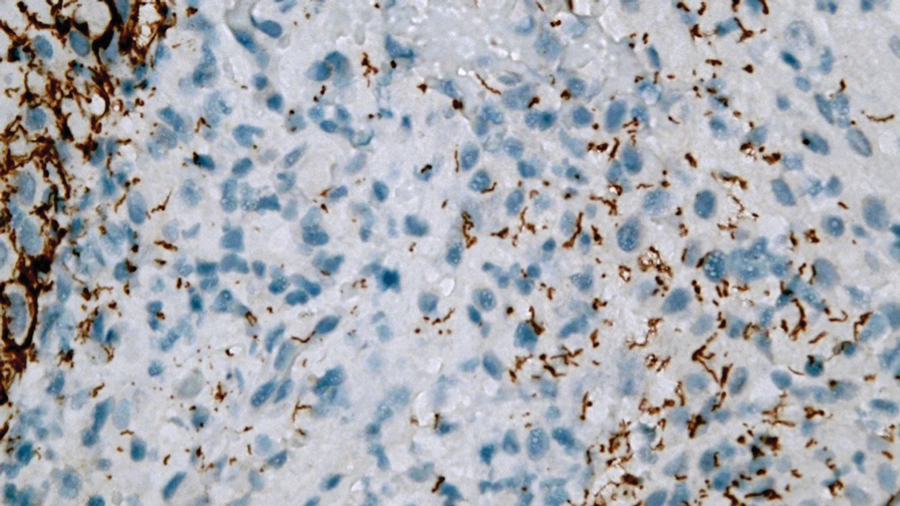

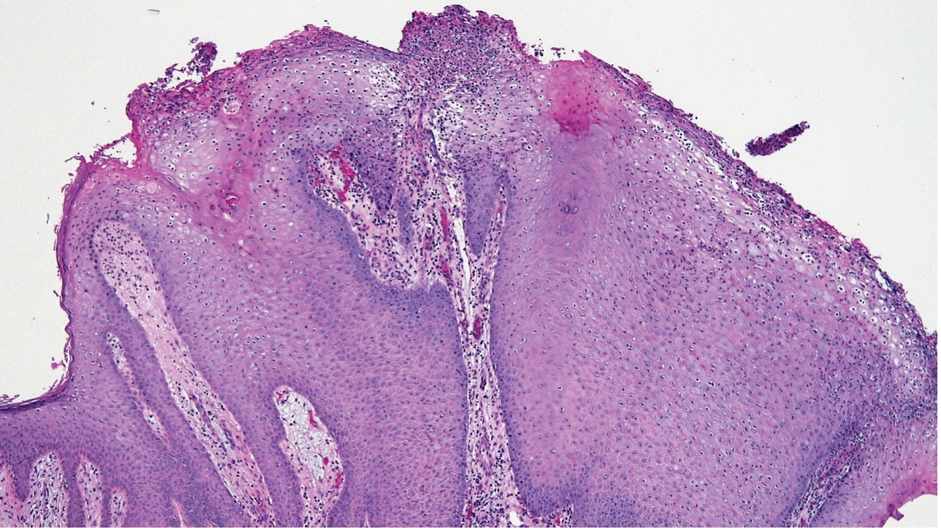

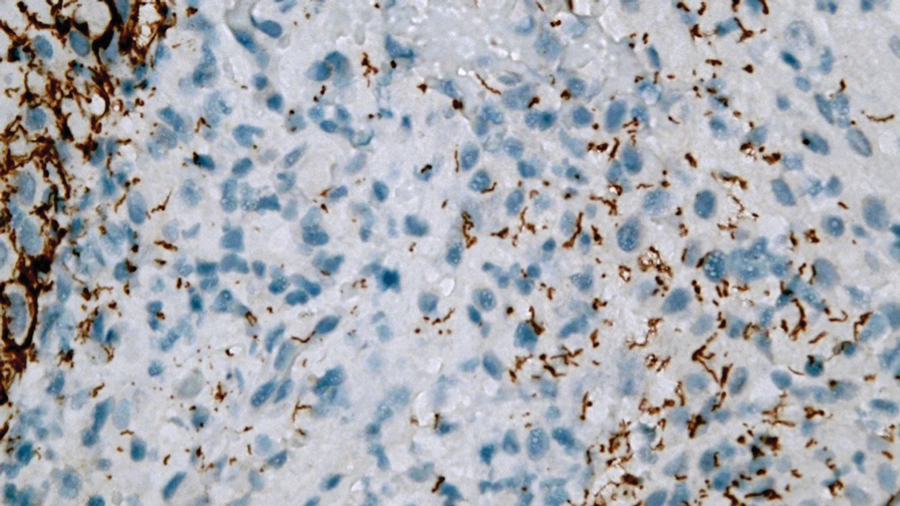

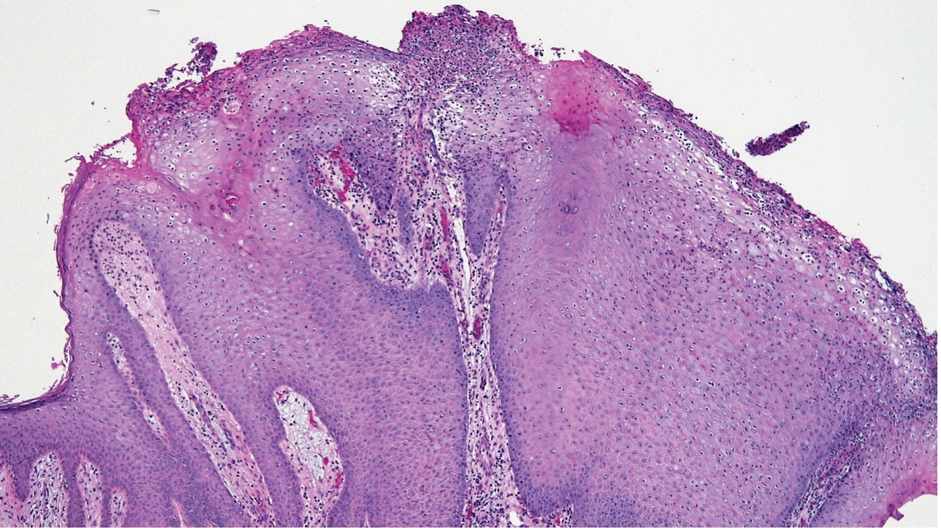

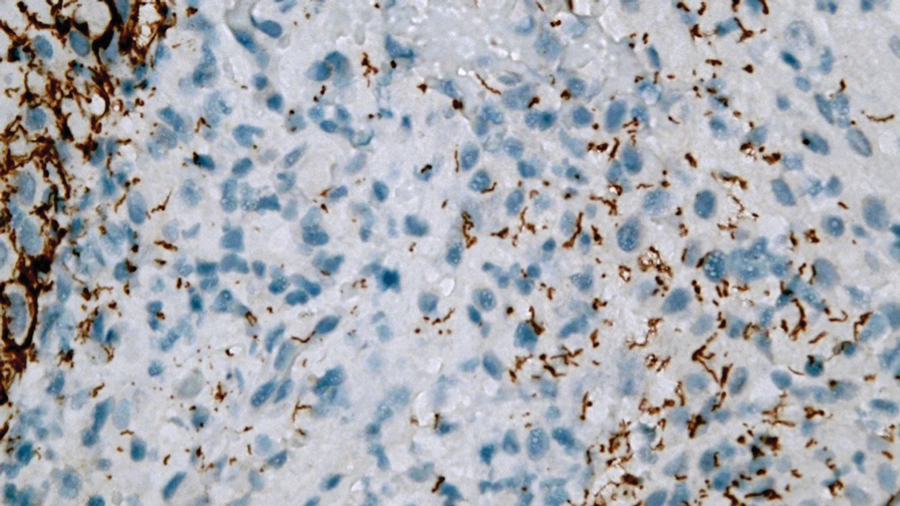

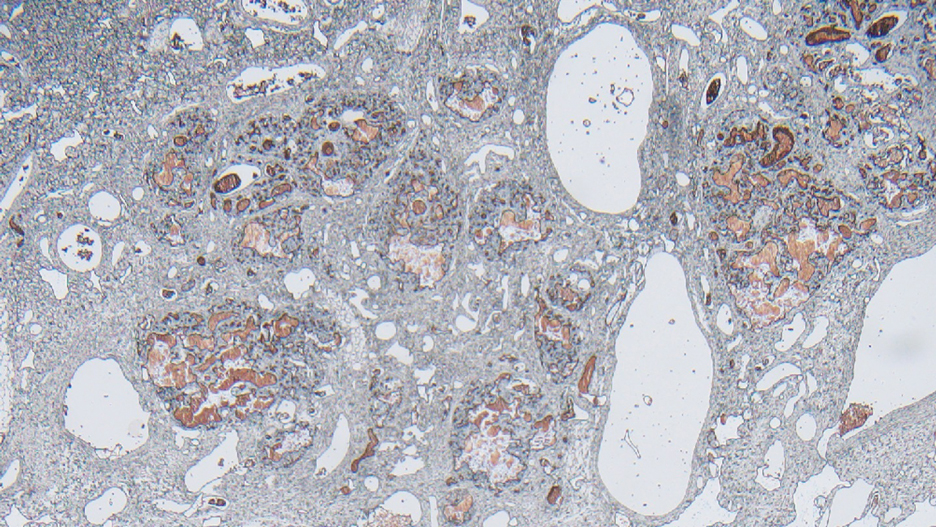

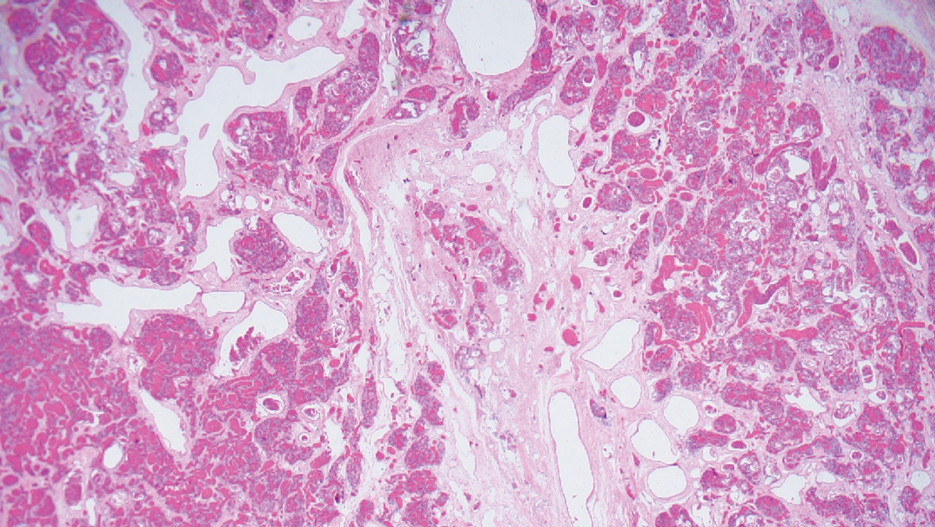

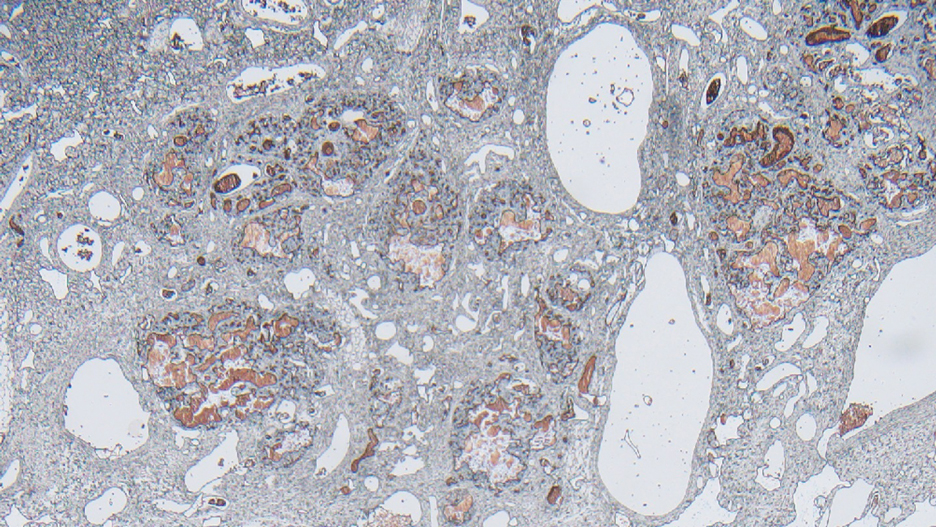

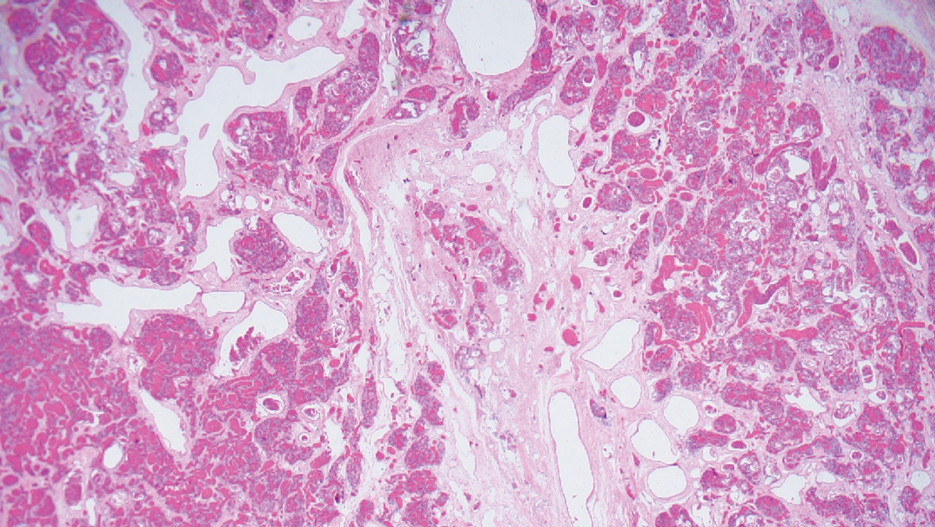

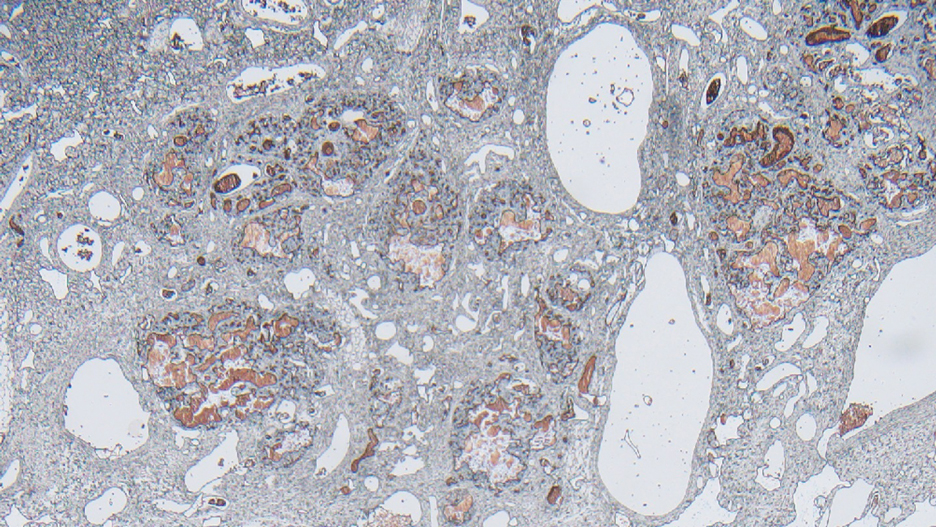

Laboratory test results were notable for a rapid plasma reagin titer of 1:512, a positive Treponema pallidum particle agglutination test, negative rectal nucleic acid amplification tests for gonorrhea and chlamydia, and a negative herpes simplex virus polymerase chain reaction. A VDRL test of cerebrospinal fluid from a lumbar puncture was negative. Histopathology of the punch biopsy sample revealed marked verrucous epidermal hyperplasia without keratinocytic atypia and with mixed inflammation (Figure 1), while immunohistochemical staining showed numerus T pallidum organisms (Figure 2). A diagnosis of condyloma latum was made based on the laboratory, lumbar puncture, and punch biopsy results. Due to a penicillin allergy, the patient was treated with oral doxycycline for 14 days. On follow-up at day 12 of therapy, he reported cessation of rectal pain, and resolution of anal lesions was noted on physical examination.

Condylomata lata are highly infectious cutaneous lesions that can manifest during secondary syphilis.1 They typically are described as white or gray, raised, flatappearing plaques and occur in moist areas or skin folds including the anus, scrotum, and vulva. However, these lesions also have been reported in the axillae, umbilicus, nasolabial folds, and other anatomic areas.1,2 The lesions can be painful and often manifest in multiples, especially in patients living with HIV.3

Condylomata lata can have a verrucous appearance and may mimic other anogenital lesions, such as condylomata acuminata, genital herpes, and malignant tumors, leading to an initial misdiagnosis.1,2 Condylomata lata should always be included in the differential when evaluating anogenital lesions. Other conditions in the differential diagnosis include psoriasis, typically manifesting as erythematous plaques with silver scale, and molluscum contagiosum, appearing as small umbilicated papules on physical examination.

Condylomata lata have been reported to occur in 6% to 23% of patients with secondary syphilis.1 Although secondary syphilis more typically manifests with a diffuse maculopapular rash, condylomata lata may be the sole dermatologic manifestation.4

Histopathology of condylomata lata consists of epithelial hyperplasia as well as lymphocytic and plasma cell infiltrates. It is diagnosed by serologic testing as well as immunohistochemical staining or dark-field microscopy.

First-line treatment of secondary syphilis is a single dose of benzathine penicillin G administered intramuscularly.5 However, a 14-day course of oral doxycycline can be used in patients with a penicillin allergy. When compliance and follow-up cannot be guaranteed, penicillin desensitization and treatment with benzathine penicillin G is recommended. Clinical evaluation and repeat serologic testing should be performed at 6 and 12 months follow-up, or more frequently if clinically indicated.5

- Pourang A, Fung MA, Tartar D, et al. Condyloma lata in secondary syphilis. JAAD Case Rep. 2021;10:18-21. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2021.01.025

- Liu Z, Wang L, Zhang G, et al. Warty mucosal lesions: oral condyloma lata of secondary syphilis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2017;83:277. doi:10.4103/0378-6323.191129

- Rompalo AM, Joesoef MR, O’Donnell JA, et al; Syphilis and HIV Study Group. Clinical manifestations of early syphilis by HIV status and gender: results of the syphilis and HIV study. Sex Transm Dis.2001;28:158-165.

- Kumar P, Das A, Mondal A. Secondary syphilis: an unusual presentation. Indian J Sex Transm Dis AIDS. 2017;38:98-99. doi:10.4103/0253-7184.194318

- Workowski KA, Bachmann LH, Chan PA, et al. Sexually transmitted infections treatment guidelines, 2021. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2021;70:1-187. doi:10.15585/mmwr.rr7004a1

The Diagnosis: Condyloma Latum

Laboratory test results were notable for a rapid plasma reagin titer of 1:512, a positive Treponema pallidum particle agglutination test, negative rectal nucleic acid amplification tests for gonorrhea and chlamydia, and a negative herpes simplex virus polymerase chain reaction. A VDRL test of cerebrospinal fluid from a lumbar puncture was negative. Histopathology of the punch biopsy sample revealed marked verrucous epidermal hyperplasia without keratinocytic atypia and with mixed inflammation (Figure 1), while immunohistochemical staining showed numerus T pallidum organisms (Figure 2). A diagnosis of condyloma latum was made based on the laboratory, lumbar puncture, and punch biopsy results. Due to a penicillin allergy, the patient was treated with oral doxycycline for 14 days. On follow-up at day 12 of therapy, he reported cessation of rectal pain, and resolution of anal lesions was noted on physical examination.

Condylomata lata are highly infectious cutaneous lesions that can manifest during secondary syphilis.1 They typically are described as white or gray, raised, flatappearing plaques and occur in moist areas or skin folds including the anus, scrotum, and vulva. However, these lesions also have been reported in the axillae, umbilicus, nasolabial folds, and other anatomic areas.1,2 The lesions can be painful and often manifest in multiples, especially in patients living with HIV.3

Condylomata lata can have a verrucous appearance and may mimic other anogenital lesions, such as condylomata acuminata, genital herpes, and malignant tumors, leading to an initial misdiagnosis.1,2 Condylomata lata should always be included in the differential when evaluating anogenital lesions. Other conditions in the differential diagnosis include psoriasis, typically manifesting as erythematous plaques with silver scale, and molluscum contagiosum, appearing as small umbilicated papules on physical examination.

Condylomata lata have been reported to occur in 6% to 23% of patients with secondary syphilis.1 Although secondary syphilis more typically manifests with a diffuse maculopapular rash, condylomata lata may be the sole dermatologic manifestation.4

Histopathology of condylomata lata consists of epithelial hyperplasia as well as lymphocytic and plasma cell infiltrates. It is diagnosed by serologic testing as well as immunohistochemical staining or dark-field microscopy.

First-line treatment of secondary syphilis is a single dose of benzathine penicillin G administered intramuscularly.5 However, a 14-day course of oral doxycycline can be used in patients with a penicillin allergy. When compliance and follow-up cannot be guaranteed, penicillin desensitization and treatment with benzathine penicillin G is recommended. Clinical evaluation and repeat serologic testing should be performed at 6 and 12 months follow-up, or more frequently if clinically indicated.5

The Diagnosis: Condyloma Latum

Laboratory test results were notable for a rapid plasma reagin titer of 1:512, a positive Treponema pallidum particle agglutination test, negative rectal nucleic acid amplification tests for gonorrhea and chlamydia, and a negative herpes simplex virus polymerase chain reaction. A VDRL test of cerebrospinal fluid from a lumbar puncture was negative. Histopathology of the punch biopsy sample revealed marked verrucous epidermal hyperplasia without keratinocytic atypia and with mixed inflammation (Figure 1), while immunohistochemical staining showed numerus T pallidum organisms (Figure 2). A diagnosis of condyloma latum was made based on the laboratory, lumbar puncture, and punch biopsy results. Due to a penicillin allergy, the patient was treated with oral doxycycline for 14 days. On follow-up at day 12 of therapy, he reported cessation of rectal pain, and resolution of anal lesions was noted on physical examination.

Condylomata lata are highly infectious cutaneous lesions that can manifest during secondary syphilis.1 They typically are described as white or gray, raised, flatappearing plaques and occur in moist areas or skin folds including the anus, scrotum, and vulva. However, these lesions also have been reported in the axillae, umbilicus, nasolabial folds, and other anatomic areas.1,2 The lesions can be painful and often manifest in multiples, especially in patients living with HIV.3

Condylomata lata can have a verrucous appearance and may mimic other anogenital lesions, such as condylomata acuminata, genital herpes, and malignant tumors, leading to an initial misdiagnosis.1,2 Condylomata lata should always be included in the differential when evaluating anogenital lesions. Other conditions in the differential diagnosis include psoriasis, typically manifesting as erythematous plaques with silver scale, and molluscum contagiosum, appearing as small umbilicated papules on physical examination.

Condylomata lata have been reported to occur in 6% to 23% of patients with secondary syphilis.1 Although secondary syphilis more typically manifests with a diffuse maculopapular rash, condylomata lata may be the sole dermatologic manifestation.4

Histopathology of condylomata lata consists of epithelial hyperplasia as well as lymphocytic and plasma cell infiltrates. It is diagnosed by serologic testing as well as immunohistochemical staining or dark-field microscopy.

First-line treatment of secondary syphilis is a single dose of benzathine penicillin G administered intramuscularly.5 However, a 14-day course of oral doxycycline can be used in patients with a penicillin allergy. When compliance and follow-up cannot be guaranteed, penicillin desensitization and treatment with benzathine penicillin G is recommended. Clinical evaluation and repeat serologic testing should be performed at 6 and 12 months follow-up, or more frequently if clinically indicated.5

- Pourang A, Fung MA, Tartar D, et al. Condyloma lata in secondary syphilis. JAAD Case Rep. 2021;10:18-21. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2021.01.025

- Liu Z, Wang L, Zhang G, et al. Warty mucosal lesions: oral condyloma lata of secondary syphilis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2017;83:277. doi:10.4103/0378-6323.191129

- Rompalo AM, Joesoef MR, O’Donnell JA, et al; Syphilis and HIV Study Group. Clinical manifestations of early syphilis by HIV status and gender: results of the syphilis and HIV study. Sex Transm Dis.2001;28:158-165.

- Kumar P, Das A, Mondal A. Secondary syphilis: an unusual presentation. Indian J Sex Transm Dis AIDS. 2017;38:98-99. doi:10.4103/0253-7184.194318

- Workowski KA, Bachmann LH, Chan PA, et al. Sexually transmitted infections treatment guidelines, 2021. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2021;70:1-187. doi:10.15585/mmwr.rr7004a1

- Pourang A, Fung MA, Tartar D, et al. Condyloma lata in secondary syphilis. JAAD Case Rep. 2021;10:18-21. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2021.01.025

- Liu Z, Wang L, Zhang G, et al. Warty mucosal lesions: oral condyloma lata of secondary syphilis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2017;83:277. doi:10.4103/0378-6323.191129

- Rompalo AM, Joesoef MR, O’Donnell JA, et al; Syphilis and HIV Study Group. Clinical manifestations of early syphilis by HIV status and gender: results of the syphilis and HIV study. Sex Transm Dis.2001;28:158-165.

- Kumar P, Das A, Mondal A. Secondary syphilis: an unusual presentation. Indian J Sex Transm Dis AIDS. 2017;38:98-99. doi:10.4103/0253-7184.194318

- Workowski KA, Bachmann LH, Chan PA, et al. Sexually transmitted infections treatment guidelines, 2021. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2021;70:1-187. doi:10.15585/mmwr.rr7004a1

A 24-year-old man presented to the emergency department with rectal pain and lesions of 3 weeks’ duration that were progressively worsening. He had a medical history of poorly controlled HIV, cerebral toxoplasmosis, and genital herpes, as well as a social history of sexual activity with other men.

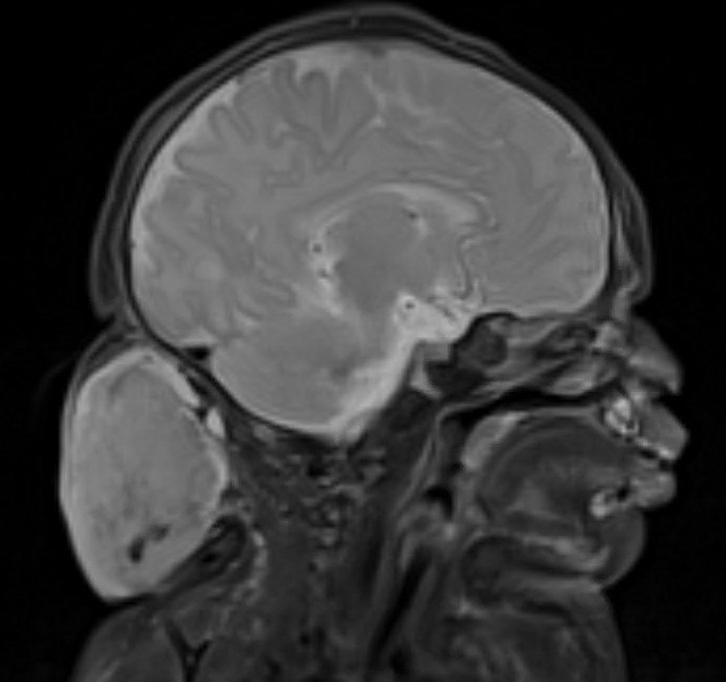

He had been diagnosed with HIV 7 years prior and had been off therapy until 1 year prior to the current presentation, when he was hospitalized with encephalopathy (CD4 count, <50 cells/mm3). A diagnosis of cerebral toxoplasmosis was made, and he began a treatment regimen of sulfadiazine, pyrimethamine, and leucovorin, as well as bictegravir, emtricitabine, and tenofovir alafenamide. Since then, the patient admitted to difficulty with medication adherence.

Rapid plasma reagin, gonorrhea, and chlamydia testing were negative during a routine workup 6 months prior to the current presentation. He initially presented to an urgent care clinic for evaluation of the rectal pain and lesions and was treated empirically with topical podofilox. He presented to the emergency department 1 week later (3 weeks after symptom onset) with anal warts and apparent vesicular lesions. Empiric treatment with oral valacyclovir was prescribed.

Despite these treatments, the rectal pain became severe—especially upon sitting, defecation, and physical exertion—prompting further evaluation. Physical examination revealed soft, flat-topped, moist-appearing, gray plaques with minimal surrounding erythema at the anus. Laboratory test results demonstrated a CD4 count of 161 cells/mm3 and an HIV viral load of 137 copies/mL.

Pruritic Rash on the Neck and Back

The Diagnosis: Prurigo Pigmentosa

A comprehensive metabolic panel collected from our patient 1 month earlier did not reveal any abnormalities. Serum methylmalonic acid and homocysteine were both elevated at 417 nmol/L (reference range [for those aged 2–59 years], 55–335 nmol/L) and 23 μmol/L (reference range, 5–15 μmol/L), respectively. Serum folate and 25-hydroxyvitamin D were low at 3.1 ng/mL (reference range, >4.8 ng/mL) and 5 ng/mL (reference range, 30–80 ng/mL), respectively. Vitamin B12 was within reference range. Two 4-mm punch biopsies collected from the upper back showed spongiotic dermatitis.

Our patient’s histopathology results along with the rash distribution and medical history of anorexia increased suspicion for prurigo pigmentosa. A trial of oral doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 2 weeks was prescribed. At 2-week follow-up, the patient’s mother revealed a history of ketosis in her daughter, solidifying the diagnosis. The patient was counseled on maintaining a healthy diet to prevent future breakouts. The patient’s rash resolved with diet modification and doxycycline; however, it recurred upon relapse of anorexia 4 months later.

Prurigo pigmentosa, originally identified in Japan by Nagashima et al,1 is an uncommon recurrent inflammatory disorder predominantly observed in young adults of Asian descent. Subsequently, it was reported to occur among individuals from different ethnic backgrounds, indicating potential underdiagnosis or misdiagnosis in Western countries.2 Although a direct pathogenic cause for prurigo pigmentosa has not been identified, a strong association has been linked to diet, specifically when ketosis is induced, such as in ketogenic diets and anorexia nervosa.3-5 Other possible causes include sunlight exposure, clothing friction, and sweating.1,5 The disease course is characterized by intermittent flares and spontaneous resolution, with recurrence in most cases. During the active phase, intensely pruritic, papulovesicular or urticarial papules are predominant and most often are localized to the upper body and torso, including the back, shoulders, neck, and chest.5 These flares can persist for several days but eventually subside, leaving behind a characteristic reticular pigmentation that can persist for months.5 First-line treatment often involves the use of tetracycline antibiotics, such as minocycline or doxycycline. 2,4,5 Dapsone often is used with successful resolution. 6 Dietary modifications also have been found to be effective in treating prurigo pigmentosa, particularly in patients presenting with dietary insufficiency.6,7 Increased carbohydrate intake has been shown to promote resolution. 6 Topical corticosteroids demonstrate limited efficacy in controlling flares.6,8

Histopathology has been variably described, with initial findings reported as nonspecific.1 However, it was later described as a distinct inflammatory disease of the skin with histologically distinct stages.2,9 Early stages reveal scattered dermal, dermal papillary, and perivascular neutrophilic infiltration.9 The lesions then progress and become fully developed, at which point neutrophilic infiltration becomes more prominent, accompanied by the presence of intraepidermal neutrophils and spongiosis. As the lesions resolve, the infiltration transitions to lymphocytic, and lichenoid changes can sometimes be appreciated along with epidermal hyperplasia, hyperpigmentation, and dermal melanophages.9 Although these findings aid in the diagnosis of prurigo pigmentosa, a clinicopathologic correlation is necessary to establish a definitive diagnosis.

Because prurigo pigmentosa is rare, it often is misdiagnosed as another condition with a similar presentation and nonspecific biopsy findings.6 Allergic contact dermatitis is a common type IV delayed hypersensitivity reaction that manifests similar to prurigo pigmentosa with pruritus and a well-demarcated distribution10 that is related to the pattern of allergen exposure; in the case of allergic contact dermatitis related to textiles, a well-demarcated rash will appear in the distribution area of the associated clothing (eg, shirt, pants, shorts).11 Development of allergy involves exposure and sensitization to an allergen, followed by subsequent re-exposure that results in cutaneous T-cell activation and inflammation. 10 Histopathology shows nonspecific spongiotic inflammation, and the gold standard for diagnosis is patch testing to identify the causative substance(s). Definitive treatment includes avoidance of identified allergies; however, if patients are unable to avoid the allergen or the cause is unknown, then corticosteroids, antihistamines, and/or calcineurin inhibitors are beneficial in controlling symptoms and flares.10

Pityrosporum folliculitis (also known as Malassezia folliculitis) is a fungal acneform condition that arises from overgrowth of normal skin flora Malassezia yeast,12 which may be due to occlusion of follicles or disruption of the normal flora composition. Clinically, the manifestation may resemble prurigo pigmentosa in distribution and presence of intense pruritus. However, pustular lesions and involvement of the face can aid in differentiating Pityrosporum from prurigo pigmentosa, which can be confirmed via periodic acid–Schiff staining with numerous round yeasts within affected follicles. Oral antifungal therapy typically yields rapid improvement and resolution of symptoms.12

Urticaria and prurigo pigmentosa share similar clinical characteristics, with symptoms of intense pruritus and urticarial lesions on the trunk.2,13 Urticaria is an IgEmediated type I hypersensitivity reaction characterized by wheals (ie, edematous red or pink lesions of variable size and shape that typically resolve spontaneously within 24–48 hours).13 Notably, urticaria will improve and in some cases completely resolve with antihistamines or anti-IgE antibody treatment, which may aid in distinguishing it from prurigo pigmentosa, as the latter typically exhibits limited response to such treatment.2 Histopathology also can assist in the diagnosis by ruling out other causes of similar rash; however, biopsies are not routinely done unless other inflammatory conditions are of high suspicion.13

Bullous pemphigoid is an autoimmune, subepidermal, blistering dermatosis that is most common among the elderly.14 It is characterized by the presence of IgG antibodies that target BP180 and BP230, which initiate inflammatory cascades that lead to tissue damage and blister formation. It typically manifests as pruritic blistering eruptions, primarily on the limbs and trunk, but may involve the head, neck, or palmoplantar regions.14 Although blistering eruptions are the prodrome of the disease, some cases may present with nonspecific urticarial or eczematous lesions14,15 that may resemble prurigo pigmentosa. The diagnosis is confirmed through direct immunofluorescence microscopy of biopsied lesions, which reveals IgG and/or C3 deposits along the dermoepidermal junction.14 Management of bullous pemphigoid involves timely initiation of dapsone or systemic corticosteroids, which have demonstrated high efficacy in controlling the disease and its associated symptoms.15

Our patient achieved a favorable response to diet modification and doxycycline therapy consistent with the diagnosis of prurigo pigmentosa. Unfortunately, the condition recurred following a relapse of anorexia. Management of prurigo pigmentosa necessitates not only accurate diagnosis but also addressing any underlying factors that may contribute to disease exacerbation. We anticipate the eating disorder will pose a major challenge in achieving long-term control of prurigo pigmentosa.

- Nagashima M, Ohshiro A, Shimizu N. A peculiar pruriginous dermatosis with gross reticular pigmentation. Jpn J Dermatol. 1971;81:38-39.

- Boer A, Asgari M. Prurigo pigmentosa: an underdiagnosed disease? Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2006;72:405-409. doi:10.4103/0378-6323.29334

- Michaels JD, Hoss E, DiCaudo DJ, et al. Prurigo pigmentosa after a strict ketogenic diet. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;32:248-251. doi:10.1111/pde.12275

- Teraki Y, Teraki E, Kawashima M, et al. Ketosis is involved in the origin of prurigo pigmentosa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;34:509-511. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(96)90460-0

- Böer A, Misago N, Wolter M, et al. Prurigo pigmentosa: a distinctive inflammatory disease of the skin. Am J Dermatopathol. 2003;25:117-129. doi:10.1097/00000372-200304000-00005

- Mufti A, Mirali S, Abduelmula A, et al. Clinical manifestations and treatment outcomes in prurigo pigmentosa (Nagashima disease): a systematic review of the literature. JAAD Int. 2021;3:79-87. doi:10.1016/j.jdin.2021.03.003

- Wong M, Lee E, Wu Y, et al. Treatment of prurigo pigmentosa with diet modification: a medical case study. Hawaii J Med Public Health. 2018;77:114-117.

- Almaani N, Al-Tarawneh AH, Msallam H. Prurigo pigmentosa: a clinicopathological report of three Middle Eastern patients. Case Rep Dermatol Med. 2018;2018:9406797. doi:10.1155/2018/9406797

- Kim JK, Chung WK, Chang SE, et al. Prurigo pigmentosa: clinicopathological study and analysis of 50 cases in Korea. J Dermatol. 2012;39:891-897. doi:10.1111/j.1346-8138.2012.01640.x

- Mowad CM, Anderson B, Scheinman P, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis: patient diagnosis and evaluation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:1029-1040. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.02.1139

- Lazarov A, Cordoba M, Plosk N, et al. Atypical and unusual clinical manifestations of contact dermatitis to clothing (textile contact dermatitis)—case presentation and review of the literature. Dermatol Online J. 2003;9. doi:10.5070/d30kd1d259

- Rubenstein RM, Malerich SA. Malassezia (Pityrosporum) folliculitis. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7:37-41.

- Bernstein JA, Lang DM, Khan DA, et al. The diagnosis and management of acute and chronic urticaria: 2014 update. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133:1270-1277. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2014.02.036

- della Torre R, Combescure C, Cortés B, et al. Clinical presentation and diagnostic delay in bullous pemphigoid: a prospective nationwide cohort. Br J Dermatol. 2012;167:1111-1117. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2012.11108.x

- Alonso-Llamazares J, Rogers RS 3rd, Oursler JR, et al. Bullous pemphigoid presenting as generalized pruritus: observations in six patients. Int J Dermatol. 1998;37:508-514.

The Diagnosis: Prurigo Pigmentosa

A comprehensive metabolic panel collected from our patient 1 month earlier did not reveal any abnormalities. Serum methylmalonic acid and homocysteine were both elevated at 417 nmol/L (reference range [for those aged 2–59 years], 55–335 nmol/L) and 23 μmol/L (reference range, 5–15 μmol/L), respectively. Serum folate and 25-hydroxyvitamin D were low at 3.1 ng/mL (reference range, >4.8 ng/mL) and 5 ng/mL (reference range, 30–80 ng/mL), respectively. Vitamin B12 was within reference range. Two 4-mm punch biopsies collected from the upper back showed spongiotic dermatitis.

Our patient’s histopathology results along with the rash distribution and medical history of anorexia increased suspicion for prurigo pigmentosa. A trial of oral doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 2 weeks was prescribed. At 2-week follow-up, the patient’s mother revealed a history of ketosis in her daughter, solidifying the diagnosis. The patient was counseled on maintaining a healthy diet to prevent future breakouts. The patient’s rash resolved with diet modification and doxycycline; however, it recurred upon relapse of anorexia 4 months later.

Prurigo pigmentosa, originally identified in Japan by Nagashima et al,1 is an uncommon recurrent inflammatory disorder predominantly observed in young adults of Asian descent. Subsequently, it was reported to occur among individuals from different ethnic backgrounds, indicating potential underdiagnosis or misdiagnosis in Western countries.2 Although a direct pathogenic cause for prurigo pigmentosa has not been identified, a strong association has been linked to diet, specifically when ketosis is induced, such as in ketogenic diets and anorexia nervosa.3-5 Other possible causes include sunlight exposure, clothing friction, and sweating.1,5 The disease course is characterized by intermittent flares and spontaneous resolution, with recurrence in most cases. During the active phase, intensely pruritic, papulovesicular or urticarial papules are predominant and most often are localized to the upper body and torso, including the back, shoulders, neck, and chest.5 These flares can persist for several days but eventually subside, leaving behind a characteristic reticular pigmentation that can persist for months.5 First-line treatment often involves the use of tetracycline antibiotics, such as minocycline or doxycycline. 2,4,5 Dapsone often is used with successful resolution. 6 Dietary modifications also have been found to be effective in treating prurigo pigmentosa, particularly in patients presenting with dietary insufficiency.6,7 Increased carbohydrate intake has been shown to promote resolution. 6 Topical corticosteroids demonstrate limited efficacy in controlling flares.6,8

Histopathology has been variably described, with initial findings reported as nonspecific.1 However, it was later described as a distinct inflammatory disease of the skin with histologically distinct stages.2,9 Early stages reveal scattered dermal, dermal papillary, and perivascular neutrophilic infiltration.9 The lesions then progress and become fully developed, at which point neutrophilic infiltration becomes more prominent, accompanied by the presence of intraepidermal neutrophils and spongiosis. As the lesions resolve, the infiltration transitions to lymphocytic, and lichenoid changes can sometimes be appreciated along with epidermal hyperplasia, hyperpigmentation, and dermal melanophages.9 Although these findings aid in the diagnosis of prurigo pigmentosa, a clinicopathologic correlation is necessary to establish a definitive diagnosis.

Because prurigo pigmentosa is rare, it often is misdiagnosed as another condition with a similar presentation and nonspecific biopsy findings.6 Allergic contact dermatitis is a common type IV delayed hypersensitivity reaction that manifests similar to prurigo pigmentosa with pruritus and a well-demarcated distribution10 that is related to the pattern of allergen exposure; in the case of allergic contact dermatitis related to textiles, a well-demarcated rash will appear in the distribution area of the associated clothing (eg, shirt, pants, shorts).11 Development of allergy involves exposure and sensitization to an allergen, followed by subsequent re-exposure that results in cutaneous T-cell activation and inflammation. 10 Histopathology shows nonspecific spongiotic inflammation, and the gold standard for diagnosis is patch testing to identify the causative substance(s). Definitive treatment includes avoidance of identified allergies; however, if patients are unable to avoid the allergen or the cause is unknown, then corticosteroids, antihistamines, and/or calcineurin inhibitors are beneficial in controlling symptoms and flares.10

Pityrosporum folliculitis (also known as Malassezia folliculitis) is a fungal acneform condition that arises from overgrowth of normal skin flora Malassezia yeast,12 which may be due to occlusion of follicles or disruption of the normal flora composition. Clinically, the manifestation may resemble prurigo pigmentosa in distribution and presence of intense pruritus. However, pustular lesions and involvement of the face can aid in differentiating Pityrosporum from prurigo pigmentosa, which can be confirmed via periodic acid–Schiff staining with numerous round yeasts within affected follicles. Oral antifungal therapy typically yields rapid improvement and resolution of symptoms.12

Urticaria and prurigo pigmentosa share similar clinical characteristics, with symptoms of intense pruritus and urticarial lesions on the trunk.2,13 Urticaria is an IgEmediated type I hypersensitivity reaction characterized by wheals (ie, edematous red or pink lesions of variable size and shape that typically resolve spontaneously within 24–48 hours).13 Notably, urticaria will improve and in some cases completely resolve with antihistamines or anti-IgE antibody treatment, which may aid in distinguishing it from prurigo pigmentosa, as the latter typically exhibits limited response to such treatment.2 Histopathology also can assist in the diagnosis by ruling out other causes of similar rash; however, biopsies are not routinely done unless other inflammatory conditions are of high suspicion.13

Bullous pemphigoid is an autoimmune, subepidermal, blistering dermatosis that is most common among the elderly.14 It is characterized by the presence of IgG antibodies that target BP180 and BP230, which initiate inflammatory cascades that lead to tissue damage and blister formation. It typically manifests as pruritic blistering eruptions, primarily on the limbs and trunk, but may involve the head, neck, or palmoplantar regions.14 Although blistering eruptions are the prodrome of the disease, some cases may present with nonspecific urticarial or eczematous lesions14,15 that may resemble prurigo pigmentosa. The diagnosis is confirmed through direct immunofluorescence microscopy of biopsied lesions, which reveals IgG and/or C3 deposits along the dermoepidermal junction.14 Management of bullous pemphigoid involves timely initiation of dapsone or systemic corticosteroids, which have demonstrated high efficacy in controlling the disease and its associated symptoms.15

Our patient achieved a favorable response to diet modification and doxycycline therapy consistent with the diagnosis of prurigo pigmentosa. Unfortunately, the condition recurred following a relapse of anorexia. Management of prurigo pigmentosa necessitates not only accurate diagnosis but also addressing any underlying factors that may contribute to disease exacerbation. We anticipate the eating disorder will pose a major challenge in achieving long-term control of prurigo pigmentosa.

The Diagnosis: Prurigo Pigmentosa

A comprehensive metabolic panel collected from our patient 1 month earlier did not reveal any abnormalities. Serum methylmalonic acid and homocysteine were both elevated at 417 nmol/L (reference range [for those aged 2–59 years], 55–335 nmol/L) and 23 μmol/L (reference range, 5–15 μmol/L), respectively. Serum folate and 25-hydroxyvitamin D were low at 3.1 ng/mL (reference range, >4.8 ng/mL) and 5 ng/mL (reference range, 30–80 ng/mL), respectively. Vitamin B12 was within reference range. Two 4-mm punch biopsies collected from the upper back showed spongiotic dermatitis.

Our patient’s histopathology results along with the rash distribution and medical history of anorexia increased suspicion for prurigo pigmentosa. A trial of oral doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 2 weeks was prescribed. At 2-week follow-up, the patient’s mother revealed a history of ketosis in her daughter, solidifying the diagnosis. The patient was counseled on maintaining a healthy diet to prevent future breakouts. The patient’s rash resolved with diet modification and doxycycline; however, it recurred upon relapse of anorexia 4 months later.

Prurigo pigmentosa, originally identified in Japan by Nagashima et al,1 is an uncommon recurrent inflammatory disorder predominantly observed in young adults of Asian descent. Subsequently, it was reported to occur among individuals from different ethnic backgrounds, indicating potential underdiagnosis or misdiagnosis in Western countries.2 Although a direct pathogenic cause for prurigo pigmentosa has not been identified, a strong association has been linked to diet, specifically when ketosis is induced, such as in ketogenic diets and anorexia nervosa.3-5 Other possible causes include sunlight exposure, clothing friction, and sweating.1,5 The disease course is characterized by intermittent flares and spontaneous resolution, with recurrence in most cases. During the active phase, intensely pruritic, papulovesicular or urticarial papules are predominant and most often are localized to the upper body and torso, including the back, shoulders, neck, and chest.5 These flares can persist for several days but eventually subside, leaving behind a characteristic reticular pigmentation that can persist for months.5 First-line treatment often involves the use of tetracycline antibiotics, such as minocycline or doxycycline. 2,4,5 Dapsone often is used with successful resolution. 6 Dietary modifications also have been found to be effective in treating prurigo pigmentosa, particularly in patients presenting with dietary insufficiency.6,7 Increased carbohydrate intake has been shown to promote resolution. 6 Topical corticosteroids demonstrate limited efficacy in controlling flares.6,8

Histopathology has been variably described, with initial findings reported as nonspecific.1 However, it was later described as a distinct inflammatory disease of the skin with histologically distinct stages.2,9 Early stages reveal scattered dermal, dermal papillary, and perivascular neutrophilic infiltration.9 The lesions then progress and become fully developed, at which point neutrophilic infiltration becomes more prominent, accompanied by the presence of intraepidermal neutrophils and spongiosis. As the lesions resolve, the infiltration transitions to lymphocytic, and lichenoid changes can sometimes be appreciated along with epidermal hyperplasia, hyperpigmentation, and dermal melanophages.9 Although these findings aid in the diagnosis of prurigo pigmentosa, a clinicopathologic correlation is necessary to establish a definitive diagnosis.

Because prurigo pigmentosa is rare, it often is misdiagnosed as another condition with a similar presentation and nonspecific biopsy findings.6 Allergic contact dermatitis is a common type IV delayed hypersensitivity reaction that manifests similar to prurigo pigmentosa with pruritus and a well-demarcated distribution10 that is related to the pattern of allergen exposure; in the case of allergic contact dermatitis related to textiles, a well-demarcated rash will appear in the distribution area of the associated clothing (eg, shirt, pants, shorts).11 Development of allergy involves exposure and sensitization to an allergen, followed by subsequent re-exposure that results in cutaneous T-cell activation and inflammation. 10 Histopathology shows nonspecific spongiotic inflammation, and the gold standard for diagnosis is patch testing to identify the causative substance(s). Definitive treatment includes avoidance of identified allergies; however, if patients are unable to avoid the allergen or the cause is unknown, then corticosteroids, antihistamines, and/or calcineurin inhibitors are beneficial in controlling symptoms and flares.10

Pityrosporum folliculitis (also known as Malassezia folliculitis) is a fungal acneform condition that arises from overgrowth of normal skin flora Malassezia yeast,12 which may be due to occlusion of follicles or disruption of the normal flora composition. Clinically, the manifestation may resemble prurigo pigmentosa in distribution and presence of intense pruritus. However, pustular lesions and involvement of the face can aid in differentiating Pityrosporum from prurigo pigmentosa, which can be confirmed via periodic acid–Schiff staining with numerous round yeasts within affected follicles. Oral antifungal therapy typically yields rapid improvement and resolution of symptoms.12

Urticaria and prurigo pigmentosa share similar clinical characteristics, with symptoms of intense pruritus and urticarial lesions on the trunk.2,13 Urticaria is an IgEmediated type I hypersensitivity reaction characterized by wheals (ie, edematous red or pink lesions of variable size and shape that typically resolve spontaneously within 24–48 hours).13 Notably, urticaria will improve and in some cases completely resolve with antihistamines or anti-IgE antibody treatment, which may aid in distinguishing it from prurigo pigmentosa, as the latter typically exhibits limited response to such treatment.2 Histopathology also can assist in the diagnosis by ruling out other causes of similar rash; however, biopsies are not routinely done unless other inflammatory conditions are of high suspicion.13

Bullous pemphigoid is an autoimmune, subepidermal, blistering dermatosis that is most common among the elderly.14 It is characterized by the presence of IgG antibodies that target BP180 and BP230, which initiate inflammatory cascades that lead to tissue damage and blister formation. It typically manifests as pruritic blistering eruptions, primarily on the limbs and trunk, but may involve the head, neck, or palmoplantar regions.14 Although blistering eruptions are the prodrome of the disease, some cases may present with nonspecific urticarial or eczematous lesions14,15 that may resemble prurigo pigmentosa. The diagnosis is confirmed through direct immunofluorescence microscopy of biopsied lesions, which reveals IgG and/or C3 deposits along the dermoepidermal junction.14 Management of bullous pemphigoid involves timely initiation of dapsone or systemic corticosteroids, which have demonstrated high efficacy in controlling the disease and its associated symptoms.15

Our patient achieved a favorable response to diet modification and doxycycline therapy consistent with the diagnosis of prurigo pigmentosa. Unfortunately, the condition recurred following a relapse of anorexia. Management of prurigo pigmentosa necessitates not only accurate diagnosis but also addressing any underlying factors that may contribute to disease exacerbation. We anticipate the eating disorder will pose a major challenge in achieving long-term control of prurigo pigmentosa.

- Nagashima M, Ohshiro A, Shimizu N. A peculiar pruriginous dermatosis with gross reticular pigmentation. Jpn J Dermatol. 1971;81:38-39.

- Boer A, Asgari M. Prurigo pigmentosa: an underdiagnosed disease? Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2006;72:405-409. doi:10.4103/0378-6323.29334

- Michaels JD, Hoss E, DiCaudo DJ, et al. Prurigo pigmentosa after a strict ketogenic diet. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;32:248-251. doi:10.1111/pde.12275

- Teraki Y, Teraki E, Kawashima M, et al. Ketosis is involved in the origin of prurigo pigmentosa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;34:509-511. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(96)90460-0

- Böer A, Misago N, Wolter M, et al. Prurigo pigmentosa: a distinctive inflammatory disease of the skin. Am J Dermatopathol. 2003;25:117-129. doi:10.1097/00000372-200304000-00005

- Mufti A, Mirali S, Abduelmula A, et al. Clinical manifestations and treatment outcomes in prurigo pigmentosa (Nagashima disease): a systematic review of the literature. JAAD Int. 2021;3:79-87. doi:10.1016/j.jdin.2021.03.003

- Wong M, Lee E, Wu Y, et al. Treatment of prurigo pigmentosa with diet modification: a medical case study. Hawaii J Med Public Health. 2018;77:114-117.

- Almaani N, Al-Tarawneh AH, Msallam H. Prurigo pigmentosa: a clinicopathological report of three Middle Eastern patients. Case Rep Dermatol Med. 2018;2018:9406797. doi:10.1155/2018/9406797

- Kim JK, Chung WK, Chang SE, et al. Prurigo pigmentosa: clinicopathological study and analysis of 50 cases in Korea. J Dermatol. 2012;39:891-897. doi:10.1111/j.1346-8138.2012.01640.x

- Mowad CM, Anderson B, Scheinman P, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis: patient diagnosis and evaluation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:1029-1040. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.02.1139

- Lazarov A, Cordoba M, Plosk N, et al. Atypical and unusual clinical manifestations of contact dermatitis to clothing (textile contact dermatitis)—case presentation and review of the literature. Dermatol Online J. 2003;9. doi:10.5070/d30kd1d259

- Rubenstein RM, Malerich SA. Malassezia (Pityrosporum) folliculitis. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7:37-41.

- Bernstein JA, Lang DM, Khan DA, et al. The diagnosis and management of acute and chronic urticaria: 2014 update. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133:1270-1277. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2014.02.036

- della Torre R, Combescure C, Cortés B, et al. Clinical presentation and diagnostic delay in bullous pemphigoid: a prospective nationwide cohort. Br J Dermatol. 2012;167:1111-1117. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2012.11108.x

- Alonso-Llamazares J, Rogers RS 3rd, Oursler JR, et al. Bullous pemphigoid presenting as generalized pruritus: observations in six patients. Int J Dermatol. 1998;37:508-514.

- Nagashima M, Ohshiro A, Shimizu N. A peculiar pruriginous dermatosis with gross reticular pigmentation. Jpn J Dermatol. 1971;81:38-39.

- Boer A, Asgari M. Prurigo pigmentosa: an underdiagnosed disease? Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2006;72:405-409. doi:10.4103/0378-6323.29334

- Michaels JD, Hoss E, DiCaudo DJ, et al. Prurigo pigmentosa after a strict ketogenic diet. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;32:248-251. doi:10.1111/pde.12275

- Teraki Y, Teraki E, Kawashima M, et al. Ketosis is involved in the origin of prurigo pigmentosa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;34:509-511. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(96)90460-0

- Böer A, Misago N, Wolter M, et al. Prurigo pigmentosa: a distinctive inflammatory disease of the skin. Am J Dermatopathol. 2003;25:117-129. doi:10.1097/00000372-200304000-00005

- Mufti A, Mirali S, Abduelmula A, et al. Clinical manifestations and treatment outcomes in prurigo pigmentosa (Nagashima disease): a systematic review of the literature. JAAD Int. 2021;3:79-87. doi:10.1016/j.jdin.2021.03.003

- Wong M, Lee E, Wu Y, et al. Treatment of prurigo pigmentosa with diet modification: a medical case study. Hawaii J Med Public Health. 2018;77:114-117.

- Almaani N, Al-Tarawneh AH, Msallam H. Prurigo pigmentosa: a clinicopathological report of three Middle Eastern patients. Case Rep Dermatol Med. 2018;2018:9406797. doi:10.1155/2018/9406797

- Kim JK, Chung WK, Chang SE, et al. Prurigo pigmentosa: clinicopathological study and analysis of 50 cases in Korea. J Dermatol. 2012;39:891-897. doi:10.1111/j.1346-8138.2012.01640.x

- Mowad CM, Anderson B, Scheinman P, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis: patient diagnosis and evaluation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:1029-1040. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.02.1139

- Lazarov A, Cordoba M, Plosk N, et al. Atypical and unusual clinical manifestations of contact dermatitis to clothing (textile contact dermatitis)—case presentation and review of the literature. Dermatol Online J. 2003;9. doi:10.5070/d30kd1d259

- Rubenstein RM, Malerich SA. Malassezia (Pityrosporum) folliculitis. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7:37-41.

- Bernstein JA, Lang DM, Khan DA, et al. The diagnosis and management of acute and chronic urticaria: 2014 update. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133:1270-1277. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2014.02.036

- della Torre R, Combescure C, Cortés B, et al. Clinical presentation and diagnostic delay in bullous pemphigoid: a prospective nationwide cohort. Br J Dermatol. 2012;167:1111-1117. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2012.11108.x

- Alonso-Llamazares J, Rogers RS 3rd, Oursler JR, et al. Bullous pemphigoid presenting as generalized pruritus: observations in six patients. Int J Dermatol. 1998;37:508-514.

A 43-year-old woman presented with a pruritic rash across the neck and back of 6 months’ duration that progressively worsened. She had a medical history of anorexia nervosa, herpes zoster with a recent flare, and peripheral neuropathy. Physical examination showed numerous red scaly papules across the upper back and shoulders that coalesced in a reticular pattern. No similar papules were seen elsewhere on the body.

Draining Nodule of the Hand

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Nocardiosis

The wound culture was positive for Nocardia farcinica. The patient received a 5-day course of intravenous sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim in the hospital and was transitioned to oral sulfamethoxazoletrimethoprim (800 mg/160 mg taken as 1 tablet twice daily) for 6 months. Complete resolution of the infection was noted at 6-month follow-up (Figure).

Nocardia is a gram-positive, aerobic bacterium that typically is found in soil, water, and decaying organic matter.1 There are more than 50 species; N farcinica, Nocardia nova, and Nocardia asteroides are the leading causes of infection in humans and animals. Nocardia asteroides is the most common cause of infection in humans.1,2 Nocardiosis is an uncommon opportunistic infection that usually targets the skin, lungs, and central nervous system.3 Although it mainly affects individuals who are immunocompromised, up to 30% of infections can be seen in immunocompetent hosts who can contract cutaneous nocardiosis after experiencing traumatic injury to the skin.1

Nocardiosis is difficult to diagnose due to its diverse clinical presentations. For example, cutaneous nocardiosis can manifest similar to mycetoma, sporotrichosis, spider bites, nontuberculous mycobacteria such as Mycobacterium marinum, or methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections, thus making cutaneous nocardiosis one of the great imitators.1 A culture is required for definitive diagnosis, as Nocardia grows well on nonselective media such as blood or Löwenstein-Jensen agar. It grows as waxy, pigmented, cerebriform colonies 3 to 5 days following incubation.3 The bacterium can be difficult to culture, and it is important to notify the microbiology laboratory if there is a high index of clinical suspicion for infection.

A history of exposure to gardening or handling animals can increase the risk for an individual contracting Nocardia.3 Although nocardiosis can be found across the world, it is native to tropical and subtropical climates such as those found in India, Africa, Latin America, and Southeast Asia.1 Infections mostly are observed in individuals aged 20 to 40 years and tend to affect men more than women. Lesions typically are seen on the lower extremities, but localized infections also can be found on the torso, neck, and upper extremities.1

Cutaneous nocardiosis is a granulomatous infection encompassing both cutaneous and subcutaneous tissue, which ultimately can lead to injury of bone and viscera.1 Primary cutaneous nocardiosis can manifest as tumors or nodules that have a sporotrichoid pattern, in which they ascend along the lymphatics. Histopathology of infected tissue frequently shows a subcutaneous dermal infiltrate of neutrophils accompanied with abscess formation, and everlasting lesions may show signs of chronic inflammation and nonspecific granulomas.3