User login

Supreme Court Case: Dobbs v Jackson Women’s Health Organization: What you need to know

This fall, the Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) will announce when they will hear oral arguments for Dobbs v Jackson Women’s Health Organization. The court will examine a Mississippi law, known as the “Gestational Age Act,” originally passed in 2018, that sought to “limit abortions to fifteen weeks’ gestation except in a medical emergency or in cases of severe fetal abnormality.”1 This sets the stage for SCOTUS to make a major ruling on abortion, one which could affirm or upend landmark decisions and nearly 50 years of abortion legislative precedent. Additionally, SCOTUS’ recent decision to not intervene on Texas’ Senate Bill 8 (SB8), which essentially bans all abortions after 6 weeks’ gestational age, may foreshadow how this case will be decided. The current abortion restrictions in Texas and the implications of SB8 will be discussed in a forthcoming column.

SCOTUS and abortion rights

The decision to hear this case comes on the heels of another recent decision regarding a Louisiana law in June Medical Services v Russo. This case examined Louisiana Act 620, which would have required physicians to have hospital admitting privileges within 30 miles of where they provide abortion services.2 The law was deemed constitutionally invalid, with the majority noting the law would have drastically burdened a woman’s right to access abortion services. The Court ruled similarly in 2016 in Whole Women’s Health (WWH) v Hellerstedt, in which WWH challenged Texas House Bill 2, a nearly identical law requiring admitting privileges for abortion care providers. In both of these cases, SCOTUS pointed to precedent set by Southeastern Pennsylvania v Casey, which established that it is unconstitutional for a state to create an “undue burden” on a woman’s right to abortion prior to fetal viability.3 The precedent to this, Roe v Wade, and 5 decades of abortion legislation set may be upended by a SCOTUS decision this next term.

Dobbs v Jackson

On March 19, 2018, Mississippi enacted the “Gestational Age Act” into law. The newly enacted law would limit abortions to 15 weeks’ gestation except in a medical emergency or in cases of severe fetal anomalies. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, the only licensed abortion provider in the state, challenged the constitutionality of the law with legal support from Center for Reproductive Rights (CRR). The US District Court for the Southern District of Mississippi granted summary judgement in favor of the clinic and placed an injunction on the law’s enforcement. The state appealed to the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals, which upheld the district court decision in a 3-0 decision in November 2019. Mississippi appealed to the Supreme Court, with their petition focusing on multiple questions from the appeals process. After repeatedly rescheduling the case, and multiple reviews in conference, SCOTUS agreed to hear the case. Most recently, the state has narrowed its argument, changing course, and attacking Roe v Wade directly. In a brief submitted in July 2021, the state argues the court should hold that all pre-viability prohibitions on elective abortions are constitutional.

Interestingly, during this time the Mississippi legislature also passed a law, House Bill 2116, also known as the “fetal heartbeat bill,” banning abortion with gestational ages after detection of a fetal heartbeat. This was also challenged, deemed unconstitutional, and affirmed on appeal by the Fifth US Circuit Court.

While recent challenges have focused on the “undue burden” state laws placed on those trying to access abortion care, this case will bring the issue of “viability” and gestational age limits to the forefront.4,5 In addition to Roe v Wade, the Court will have the opportunity to reexamine other relevant precedent, such as Southeastern Pennsylvania v Casey, in considering the most recent arguments of the state. In this most recent brief, the state argues that the Court should, “reject viability as a barrier to prohibiting elective abortions” and that a “viability rule has no constitutional basis.” The state goes on to argue the “Constitution does not protect a right to abortion or limit States’ authority to restrict it.”6 The language and tone in this brief are more direct and aggressive than the states’ petition submitted last June.

However, the composition of the Court is different than in the past. This case will be argued with Justice Amy Coney Barrett seated in place of Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, who was a strong advocate for women’s rights.7 She joins Justices Neil Gorsuch and Brett Kavanaugh, also appointed by President Donald Trump and widely viewed as conservative judges, tipping the scales to a more conservative Supreme Court. This case will also be argued in a polarized political environment.8,9 Given the conservative Supreme Court in the setting of an increasingly politically charged environment, reproductive right advocates are understandably worried that members of the anti-abortion movement view this as an opportunity to weaken or remove federal constitutional protections for abortion.

Continue to: Potential outcome of Dobbs v Jackson...

Potential outcome of Dobbs v Jackson

Should SCOTUS choose to rule in favor of Mississippi, it could severely weaken, or even overturn Roe v Wade. This would leave a legal path for states with pre-Roe abortion bans and currently unenforced post-Roe bans to take effect. These “trigger” laws are bans or severe restrictions on abortion providers and patients intended to take effect if Roe were to be overturned. Alternatively, the Court may overturn Southeastern Pennsylvania v Casey, but maintain Roe v Wade, essentially leaving the regulation of pre-viability abortion care to individual states. Currently 21 states have laws that would restrict the legal status of abortion.10 In addition, state legislatures are aggressively introducing abortion restrictions. As of June 2021, there have been 561 abortion restrictions, including 165 abortion bans, introduced across 47 states, putting 2021 on course to be the most devastating anti-abortion state legislative session in decades.11

The damage caused by such restriction on abortion care would be significant. It would block or push access out of reach for many. The negative effects of such legislative action would most heavily burden those already marginalized by systemic, structural inequalities including those of low socioeconomic status, people of color, young people, those in rural communities, and members of the LGBTQ community. The medical community has long recognized the harm caused by restricting access to abortion care. Restriction of access to safe abortion care paradoxically has been shown not to decrease the incidence of abortion, but rather increases the number of unsafe abortions.12 The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) acknowledge “individuals require access to safe, legal abortion” and that this represents “a necessary component for comprehensive health care.”13,14 They joined the American Medical Association and other professional groups in a 2019 amicus brief to SCOTUS opposing restrictions on abortion access.15 In addition, government laws restricting access to abortion care undermine the fundamental relationship between a person and their physician, limiting a physician’s obligation to honor patient autonomy and provide appropriate medical care.

By taking up the question whether all pre-viability bans on elective abortions violate the Constitution, SCOTUS is indicating a possible willingness to revisit the central holding of abortion jurisprudence. Their decision regarding this case will likely be the most significant ruling regarding the legal status of abortion care in decades, and will significantly affect the delivery of abortion care in the future.

Action items

- Reach out to your representatives to support the Women’s Health Protection Act, an initiative introduced to Congress to protect access to abortion care. If you reside in a state where your federal representatives support the Women’s Health Protection Act, reach out to friends and colleagues in states without supportive elected officials and ask them to call their representatives and ask them to support the bill.

- Get involved with local grassroots groups fighting to protect abortion access.

- Continue to speak out against laws and policies designed to limit access to safe abortion care.

- Connect with your local ACOG chapter for more ways to become involved.

- As always, make sure you are registered to vote, and exercise your right whenever you can.

- HB1510 (As Introduced) - 2018 Regular Session. http://billstatus.ls.state.ms.us/documents/2018/html/HB/1500-1599/HB1510IN.htm Accessed August 13, 2021.

- HB338. Louisiana State Legislature. 2014. http://www.legis.la.gov/legis/BillInfo.aspx?s=14RS&b=ACT620&sbi=y. Accessed August 13, 2021.

- Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pennsylvania v. Casey. Cornell Law School Legal Information Institute. https://www.law.cornell.edu/supremecourt/text/505/833. Accessed August 13, 2021.

- 15-274 Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt (06/27/2016). Published online 2016:107.

- 18-1323 June Medical Services L. L. C. v. Russo (06/29/2020). Published online 2020:138.

- 19-1392 Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization (07/22/2021). Published online 2021.

- What Ruth Bader Ginsburg said about abortion and Roe v. Wade. Time. August 2, 2018. https://time.com/5354490/ruth-bader-ginsburg-roe-v-wade/. Accessed August 13, 2021.

- Montanaro D. Poll: majority want to keep abortion legal, but they also want restrictions. NPR. June 7, 2019. https://www.npr.org/2019/06/07/730183531/poll-majority-want-to-keep-abortion-legal-but-they-also-want-restrictions. Accessed August 13, 2021.

- Abortion support remains steady despite growing partisan divide, survey finds. Washington Post. August 13, 2019. https://www.washingtonpost.com/health/2019/08/13/one-largest-ever-abortion-surveys-shows-growing-partisan-divide/. Accessed August 13, 2021.

- Abortion policy in the absence of Roe. Guttmacher Institute. September 1, 2021. https://www.guttmacher.org/state-policy/explore/abortion-policy-absence-roe#. Accessed September 8, 2021.

- 2021 is on track to become the most devastating antiabortion state legislative session in decades. Guttmacher Institute. Published April 30, 2021. Updated June 14, 2021. https://www.guttmacher.org/article/2021/04/2021-track-become-most-devastating-antiabortion-state-legislative-session-decades. Accessed August 13, 2021.

- Facts and consequences: legality, incidence and safety of abortion worldwide. Guttmacher Institute. November 20, 2009. https://www.guttmacher.org/gpr/2009/11/facts-and-consequences-legality-incidence-and-safety-abortion-worldwide. Accessed August 13, 2021.

- Increasing access to abortion. https://www.acog.org/en/clinical/clinical-guidance/committee-opinion/articles/2020/12/increasing-access-to-abortion. Accessed August 13, 2021.

- ACOG statement on Dobbs vs. Jackson Women’s Health. May 17, 2021. https://www.acog.org/en/news/news-releases/2021/05/acog-statement-dobbs-vs-jackson-womens-health. Accessed August 13, 2021.

- Perryman SL, Parker KA, Hickman SA. Brief of amici curiae American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, American Medical Associations, American Academy of Family Physicians, American Academy of Nursing, American Academy of Pediatrics, et al. In support of June Medical Services, LLC, et al. https://www.supremecourt.gov/

DocketPDF/18/18-1323/124091/ . Accessed August 13, 2021.20191202145531124_18-1323% 2018-1460%20tsac%20American% 20College%20of% 20Obstetricians%20and% 20Gynecologists%20et%20al.pdf

This fall, the Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) will announce when they will hear oral arguments for Dobbs v Jackson Women’s Health Organization. The court will examine a Mississippi law, known as the “Gestational Age Act,” originally passed in 2018, that sought to “limit abortions to fifteen weeks’ gestation except in a medical emergency or in cases of severe fetal abnormality.”1 This sets the stage for SCOTUS to make a major ruling on abortion, one which could affirm or upend landmark decisions and nearly 50 years of abortion legislative precedent. Additionally, SCOTUS’ recent decision to not intervene on Texas’ Senate Bill 8 (SB8), which essentially bans all abortions after 6 weeks’ gestational age, may foreshadow how this case will be decided. The current abortion restrictions in Texas and the implications of SB8 will be discussed in a forthcoming column.

SCOTUS and abortion rights

The decision to hear this case comes on the heels of another recent decision regarding a Louisiana law in June Medical Services v Russo. This case examined Louisiana Act 620, which would have required physicians to have hospital admitting privileges within 30 miles of where they provide abortion services.2 The law was deemed constitutionally invalid, with the majority noting the law would have drastically burdened a woman’s right to access abortion services. The Court ruled similarly in 2016 in Whole Women’s Health (WWH) v Hellerstedt, in which WWH challenged Texas House Bill 2, a nearly identical law requiring admitting privileges for abortion care providers. In both of these cases, SCOTUS pointed to precedent set by Southeastern Pennsylvania v Casey, which established that it is unconstitutional for a state to create an “undue burden” on a woman’s right to abortion prior to fetal viability.3 The precedent to this, Roe v Wade, and 5 decades of abortion legislation set may be upended by a SCOTUS decision this next term.

Dobbs v Jackson

On March 19, 2018, Mississippi enacted the “Gestational Age Act” into law. The newly enacted law would limit abortions to 15 weeks’ gestation except in a medical emergency or in cases of severe fetal anomalies. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, the only licensed abortion provider in the state, challenged the constitutionality of the law with legal support from Center for Reproductive Rights (CRR). The US District Court for the Southern District of Mississippi granted summary judgement in favor of the clinic and placed an injunction on the law’s enforcement. The state appealed to the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals, which upheld the district court decision in a 3-0 decision in November 2019. Mississippi appealed to the Supreme Court, with their petition focusing on multiple questions from the appeals process. After repeatedly rescheduling the case, and multiple reviews in conference, SCOTUS agreed to hear the case. Most recently, the state has narrowed its argument, changing course, and attacking Roe v Wade directly. In a brief submitted in July 2021, the state argues the court should hold that all pre-viability prohibitions on elective abortions are constitutional.

Interestingly, during this time the Mississippi legislature also passed a law, House Bill 2116, also known as the “fetal heartbeat bill,” banning abortion with gestational ages after detection of a fetal heartbeat. This was also challenged, deemed unconstitutional, and affirmed on appeal by the Fifth US Circuit Court.

While recent challenges have focused on the “undue burden” state laws placed on those trying to access abortion care, this case will bring the issue of “viability” and gestational age limits to the forefront.4,5 In addition to Roe v Wade, the Court will have the opportunity to reexamine other relevant precedent, such as Southeastern Pennsylvania v Casey, in considering the most recent arguments of the state. In this most recent brief, the state argues that the Court should, “reject viability as a barrier to prohibiting elective abortions” and that a “viability rule has no constitutional basis.” The state goes on to argue the “Constitution does not protect a right to abortion or limit States’ authority to restrict it.”6 The language and tone in this brief are more direct and aggressive than the states’ petition submitted last June.

However, the composition of the Court is different than in the past. This case will be argued with Justice Amy Coney Barrett seated in place of Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, who was a strong advocate for women’s rights.7 She joins Justices Neil Gorsuch and Brett Kavanaugh, also appointed by President Donald Trump and widely viewed as conservative judges, tipping the scales to a more conservative Supreme Court. This case will also be argued in a polarized political environment.8,9 Given the conservative Supreme Court in the setting of an increasingly politically charged environment, reproductive right advocates are understandably worried that members of the anti-abortion movement view this as an opportunity to weaken or remove federal constitutional protections for abortion.

Continue to: Potential outcome of Dobbs v Jackson...

Potential outcome of Dobbs v Jackson

Should SCOTUS choose to rule in favor of Mississippi, it could severely weaken, or even overturn Roe v Wade. This would leave a legal path for states with pre-Roe abortion bans and currently unenforced post-Roe bans to take effect. These “trigger” laws are bans or severe restrictions on abortion providers and patients intended to take effect if Roe were to be overturned. Alternatively, the Court may overturn Southeastern Pennsylvania v Casey, but maintain Roe v Wade, essentially leaving the regulation of pre-viability abortion care to individual states. Currently 21 states have laws that would restrict the legal status of abortion.10 In addition, state legislatures are aggressively introducing abortion restrictions. As of June 2021, there have been 561 abortion restrictions, including 165 abortion bans, introduced across 47 states, putting 2021 on course to be the most devastating anti-abortion state legislative session in decades.11

The damage caused by such restriction on abortion care would be significant. It would block or push access out of reach for many. The negative effects of such legislative action would most heavily burden those already marginalized by systemic, structural inequalities including those of low socioeconomic status, people of color, young people, those in rural communities, and members of the LGBTQ community. The medical community has long recognized the harm caused by restricting access to abortion care. Restriction of access to safe abortion care paradoxically has been shown not to decrease the incidence of abortion, but rather increases the number of unsafe abortions.12 The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) acknowledge “individuals require access to safe, legal abortion” and that this represents “a necessary component for comprehensive health care.”13,14 They joined the American Medical Association and other professional groups in a 2019 amicus brief to SCOTUS opposing restrictions on abortion access.15 In addition, government laws restricting access to abortion care undermine the fundamental relationship between a person and their physician, limiting a physician’s obligation to honor patient autonomy and provide appropriate medical care.

By taking up the question whether all pre-viability bans on elective abortions violate the Constitution, SCOTUS is indicating a possible willingness to revisit the central holding of abortion jurisprudence. Their decision regarding this case will likely be the most significant ruling regarding the legal status of abortion care in decades, and will significantly affect the delivery of abortion care in the future.

Action items

- Reach out to your representatives to support the Women’s Health Protection Act, an initiative introduced to Congress to protect access to abortion care. If you reside in a state where your federal representatives support the Women’s Health Protection Act, reach out to friends and colleagues in states without supportive elected officials and ask them to call their representatives and ask them to support the bill.

- Get involved with local grassroots groups fighting to protect abortion access.

- Continue to speak out against laws and policies designed to limit access to safe abortion care.

- Connect with your local ACOG chapter for more ways to become involved.

- As always, make sure you are registered to vote, and exercise your right whenever you can.

This fall, the Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) will announce when they will hear oral arguments for Dobbs v Jackson Women’s Health Organization. The court will examine a Mississippi law, known as the “Gestational Age Act,” originally passed in 2018, that sought to “limit abortions to fifteen weeks’ gestation except in a medical emergency or in cases of severe fetal abnormality.”1 This sets the stage for SCOTUS to make a major ruling on abortion, one which could affirm or upend landmark decisions and nearly 50 years of abortion legislative precedent. Additionally, SCOTUS’ recent decision to not intervene on Texas’ Senate Bill 8 (SB8), which essentially bans all abortions after 6 weeks’ gestational age, may foreshadow how this case will be decided. The current abortion restrictions in Texas and the implications of SB8 will be discussed in a forthcoming column.

SCOTUS and abortion rights

The decision to hear this case comes on the heels of another recent decision regarding a Louisiana law in June Medical Services v Russo. This case examined Louisiana Act 620, which would have required physicians to have hospital admitting privileges within 30 miles of where they provide abortion services.2 The law was deemed constitutionally invalid, with the majority noting the law would have drastically burdened a woman’s right to access abortion services. The Court ruled similarly in 2016 in Whole Women’s Health (WWH) v Hellerstedt, in which WWH challenged Texas House Bill 2, a nearly identical law requiring admitting privileges for abortion care providers. In both of these cases, SCOTUS pointed to precedent set by Southeastern Pennsylvania v Casey, which established that it is unconstitutional for a state to create an “undue burden” on a woman’s right to abortion prior to fetal viability.3 The precedent to this, Roe v Wade, and 5 decades of abortion legislation set may be upended by a SCOTUS decision this next term.

Dobbs v Jackson

On March 19, 2018, Mississippi enacted the “Gestational Age Act” into law. The newly enacted law would limit abortions to 15 weeks’ gestation except in a medical emergency or in cases of severe fetal anomalies. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, the only licensed abortion provider in the state, challenged the constitutionality of the law with legal support from Center for Reproductive Rights (CRR). The US District Court for the Southern District of Mississippi granted summary judgement in favor of the clinic and placed an injunction on the law’s enforcement. The state appealed to the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals, which upheld the district court decision in a 3-0 decision in November 2019. Mississippi appealed to the Supreme Court, with their petition focusing on multiple questions from the appeals process. After repeatedly rescheduling the case, and multiple reviews in conference, SCOTUS agreed to hear the case. Most recently, the state has narrowed its argument, changing course, and attacking Roe v Wade directly. In a brief submitted in July 2021, the state argues the court should hold that all pre-viability prohibitions on elective abortions are constitutional.

Interestingly, during this time the Mississippi legislature also passed a law, House Bill 2116, also known as the “fetal heartbeat bill,” banning abortion with gestational ages after detection of a fetal heartbeat. This was also challenged, deemed unconstitutional, and affirmed on appeal by the Fifth US Circuit Court.

While recent challenges have focused on the “undue burden” state laws placed on those trying to access abortion care, this case will bring the issue of “viability” and gestational age limits to the forefront.4,5 In addition to Roe v Wade, the Court will have the opportunity to reexamine other relevant precedent, such as Southeastern Pennsylvania v Casey, in considering the most recent arguments of the state. In this most recent brief, the state argues that the Court should, “reject viability as a barrier to prohibiting elective abortions” and that a “viability rule has no constitutional basis.” The state goes on to argue the “Constitution does not protect a right to abortion or limit States’ authority to restrict it.”6 The language and tone in this brief are more direct and aggressive than the states’ petition submitted last June.

However, the composition of the Court is different than in the past. This case will be argued with Justice Amy Coney Barrett seated in place of Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, who was a strong advocate for women’s rights.7 She joins Justices Neil Gorsuch and Brett Kavanaugh, also appointed by President Donald Trump and widely viewed as conservative judges, tipping the scales to a more conservative Supreme Court. This case will also be argued in a polarized political environment.8,9 Given the conservative Supreme Court in the setting of an increasingly politically charged environment, reproductive right advocates are understandably worried that members of the anti-abortion movement view this as an opportunity to weaken or remove federal constitutional protections for abortion.

Continue to: Potential outcome of Dobbs v Jackson...

Potential outcome of Dobbs v Jackson

Should SCOTUS choose to rule in favor of Mississippi, it could severely weaken, or even overturn Roe v Wade. This would leave a legal path for states with pre-Roe abortion bans and currently unenforced post-Roe bans to take effect. These “trigger” laws are bans or severe restrictions on abortion providers and patients intended to take effect if Roe were to be overturned. Alternatively, the Court may overturn Southeastern Pennsylvania v Casey, but maintain Roe v Wade, essentially leaving the regulation of pre-viability abortion care to individual states. Currently 21 states have laws that would restrict the legal status of abortion.10 In addition, state legislatures are aggressively introducing abortion restrictions. As of June 2021, there have been 561 abortion restrictions, including 165 abortion bans, introduced across 47 states, putting 2021 on course to be the most devastating anti-abortion state legislative session in decades.11

The damage caused by such restriction on abortion care would be significant. It would block or push access out of reach for many. The negative effects of such legislative action would most heavily burden those already marginalized by systemic, structural inequalities including those of low socioeconomic status, people of color, young people, those in rural communities, and members of the LGBTQ community. The medical community has long recognized the harm caused by restricting access to abortion care. Restriction of access to safe abortion care paradoxically has been shown not to decrease the incidence of abortion, but rather increases the number of unsafe abortions.12 The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) acknowledge “individuals require access to safe, legal abortion” and that this represents “a necessary component for comprehensive health care.”13,14 They joined the American Medical Association and other professional groups in a 2019 amicus brief to SCOTUS opposing restrictions on abortion access.15 In addition, government laws restricting access to abortion care undermine the fundamental relationship between a person and their physician, limiting a physician’s obligation to honor patient autonomy and provide appropriate medical care.

By taking up the question whether all pre-viability bans on elective abortions violate the Constitution, SCOTUS is indicating a possible willingness to revisit the central holding of abortion jurisprudence. Their decision regarding this case will likely be the most significant ruling regarding the legal status of abortion care in decades, and will significantly affect the delivery of abortion care in the future.

Action items

- Reach out to your representatives to support the Women’s Health Protection Act, an initiative introduced to Congress to protect access to abortion care. If you reside in a state where your federal representatives support the Women’s Health Protection Act, reach out to friends and colleagues in states without supportive elected officials and ask them to call their representatives and ask them to support the bill.

- Get involved with local grassroots groups fighting to protect abortion access.

- Continue to speak out against laws and policies designed to limit access to safe abortion care.

- Connect with your local ACOG chapter for more ways to become involved.

- As always, make sure you are registered to vote, and exercise your right whenever you can.

- HB1510 (As Introduced) - 2018 Regular Session. http://billstatus.ls.state.ms.us/documents/2018/html/HB/1500-1599/HB1510IN.htm Accessed August 13, 2021.

- HB338. Louisiana State Legislature. 2014. http://www.legis.la.gov/legis/BillInfo.aspx?s=14RS&b=ACT620&sbi=y. Accessed August 13, 2021.

- Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pennsylvania v. Casey. Cornell Law School Legal Information Institute. https://www.law.cornell.edu/supremecourt/text/505/833. Accessed August 13, 2021.

- 15-274 Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt (06/27/2016). Published online 2016:107.

- 18-1323 June Medical Services L. L. C. v. Russo (06/29/2020). Published online 2020:138.

- 19-1392 Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization (07/22/2021). Published online 2021.

- What Ruth Bader Ginsburg said about abortion and Roe v. Wade. Time. August 2, 2018. https://time.com/5354490/ruth-bader-ginsburg-roe-v-wade/. Accessed August 13, 2021.

- Montanaro D. Poll: majority want to keep abortion legal, but they also want restrictions. NPR. June 7, 2019. https://www.npr.org/2019/06/07/730183531/poll-majority-want-to-keep-abortion-legal-but-they-also-want-restrictions. Accessed August 13, 2021.

- Abortion support remains steady despite growing partisan divide, survey finds. Washington Post. August 13, 2019. https://www.washingtonpost.com/health/2019/08/13/one-largest-ever-abortion-surveys-shows-growing-partisan-divide/. Accessed August 13, 2021.

- Abortion policy in the absence of Roe. Guttmacher Institute. September 1, 2021. https://www.guttmacher.org/state-policy/explore/abortion-policy-absence-roe#. Accessed September 8, 2021.

- 2021 is on track to become the most devastating antiabortion state legislative session in decades. Guttmacher Institute. Published April 30, 2021. Updated June 14, 2021. https://www.guttmacher.org/article/2021/04/2021-track-become-most-devastating-antiabortion-state-legislative-session-decades. Accessed August 13, 2021.

- Facts and consequences: legality, incidence and safety of abortion worldwide. Guttmacher Institute. November 20, 2009. https://www.guttmacher.org/gpr/2009/11/facts-and-consequences-legality-incidence-and-safety-abortion-worldwide. Accessed August 13, 2021.

- Increasing access to abortion. https://www.acog.org/en/clinical/clinical-guidance/committee-opinion/articles/2020/12/increasing-access-to-abortion. Accessed August 13, 2021.

- ACOG statement on Dobbs vs. Jackson Women’s Health. May 17, 2021. https://www.acog.org/en/news/news-releases/2021/05/acog-statement-dobbs-vs-jackson-womens-health. Accessed August 13, 2021.

- Perryman SL, Parker KA, Hickman SA. Brief of amici curiae American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, American Medical Associations, American Academy of Family Physicians, American Academy of Nursing, American Academy of Pediatrics, et al. In support of June Medical Services, LLC, et al. https://www.supremecourt.gov/

DocketPDF/18/18-1323/124091/ . Accessed August 13, 2021.20191202145531124_18-1323% 2018-1460%20tsac%20American% 20College%20of% 20Obstetricians%20and% 20Gynecologists%20et%20al.pdf

- HB1510 (As Introduced) - 2018 Regular Session. http://billstatus.ls.state.ms.us/documents/2018/html/HB/1500-1599/HB1510IN.htm Accessed August 13, 2021.

- HB338. Louisiana State Legislature. 2014. http://www.legis.la.gov/legis/BillInfo.aspx?s=14RS&b=ACT620&sbi=y. Accessed August 13, 2021.

- Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pennsylvania v. Casey. Cornell Law School Legal Information Institute. https://www.law.cornell.edu/supremecourt/text/505/833. Accessed August 13, 2021.

- 15-274 Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt (06/27/2016). Published online 2016:107.

- 18-1323 June Medical Services L. L. C. v. Russo (06/29/2020). Published online 2020:138.

- 19-1392 Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization (07/22/2021). Published online 2021.

- What Ruth Bader Ginsburg said about abortion and Roe v. Wade. Time. August 2, 2018. https://time.com/5354490/ruth-bader-ginsburg-roe-v-wade/. Accessed August 13, 2021.

- Montanaro D. Poll: majority want to keep abortion legal, but they also want restrictions. NPR. June 7, 2019. https://www.npr.org/2019/06/07/730183531/poll-majority-want-to-keep-abortion-legal-but-they-also-want-restrictions. Accessed August 13, 2021.

- Abortion support remains steady despite growing partisan divide, survey finds. Washington Post. August 13, 2019. https://www.washingtonpost.com/health/2019/08/13/one-largest-ever-abortion-surveys-shows-growing-partisan-divide/. Accessed August 13, 2021.

- Abortion policy in the absence of Roe. Guttmacher Institute. September 1, 2021. https://www.guttmacher.org/state-policy/explore/abortion-policy-absence-roe#. Accessed September 8, 2021.

- 2021 is on track to become the most devastating antiabortion state legislative session in decades. Guttmacher Institute. Published April 30, 2021. Updated June 14, 2021. https://www.guttmacher.org/article/2021/04/2021-track-become-most-devastating-antiabortion-state-legislative-session-decades. Accessed August 13, 2021.

- Facts and consequences: legality, incidence and safety of abortion worldwide. Guttmacher Institute. November 20, 2009. https://www.guttmacher.org/gpr/2009/11/facts-and-consequences-legality-incidence-and-safety-abortion-worldwide. Accessed August 13, 2021.

- Increasing access to abortion. https://www.acog.org/en/clinical/clinical-guidance/committee-opinion/articles/2020/12/increasing-access-to-abortion. Accessed August 13, 2021.

- ACOG statement on Dobbs vs. Jackson Women’s Health. May 17, 2021. https://www.acog.org/en/news/news-releases/2021/05/acog-statement-dobbs-vs-jackson-womens-health. Accessed August 13, 2021.

- Perryman SL, Parker KA, Hickman SA. Brief of amici curiae American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, American Medical Associations, American Academy of Family Physicians, American Academy of Nursing, American Academy of Pediatrics, et al. In support of June Medical Services, LLC, et al. https://www.supremecourt.gov/

DocketPDF/18/18-1323/124091/ . Accessed August 13, 2021.20191202145531124_18-1323% 2018-1460%20tsac%20American% 20College%20of% 20Obstetricians%20and% 20Gynecologists%20et%20al.pdf

Volunteer Opportunities Within Dermatology: More than Skin Deep

The adage “so much to do, so little time” aptly describes the daily challenges facing dermatologists and dermatology residents. The time and attention required by direct patient care, writing notes, navigating electronic health records, and engaging in education and research as well as family commitments can drain even the most tireless clinician. In addition, dermatologists are expected to play a critical role in clinic and practice management to successfully curate an online presence and adapt their skills to successfully manage a teledermatology practice. Coupled with the time spent socializing with friends or colleagues and time for personal hobbies or exercise, it’s easy to see how sleep deprivation is common in many of our colleagues.

What’s being left out of these jam-packed schedules? Increasingly, it is the time and expertise dedicated to volunteering in our local communities. Two recent research letters highlighted how a dramatic increase in the number of research projects and publications is not mirrored by a similar increase in volunteer experiences as dermatology residency selection becomes more competitive.1,2

Although the rate of volunteerism among practicing dermatologists has yet to be studied, a brief review suggests a component of unmet dermatology need within our communities. It’s estimated that approximately 5% to 10% of all emergency department visits are for dermatologic concerns.3-5 In many cases, the reason for the visit is nonurgent and instead reflects a lack of other options for care. However, the need for dermatologists extends beyond the emergency department setting. A review of the prevalence of patients presenting for care to a group of regional free clinics found that 8% (N=5553) of all visitors sought care for dermatologic concerns.6 The benefit is not just for those seated on the examination table; research has shown that while many of the underlying factors resulting in physician burnout stem from systemic issues, participating in volunteer opportunities helps combat burnout in ourselves and our colleagues.7-9 Herein, opportunities that exist for dermatologists to reconnect with their communities, advocate for causes distinctive to the specialty, and care for neighbors most in need are highlighted.

Camp Wonder

Every year, children from across the United States living with chronic and debilitating skin conditions get the opportunity to join fellow campers and spend a week just being kids without the constant focus on being a patient. Camp Wonder’s founder and director, Francesca Tenconi, describes the camp as a place where kids “can form a community and can feel free to be themselves, without judgment, without stares. They get the chance to forget about their skin disease and be themselves” (oral communication, June 18, 2021). Tenconi and the camp’s cofounders and medical directors, Drs. Jenny Kim and Stefani Takahashi, envisioned the camp as a place for all campers regardless of their skin condition to feel safe and welcome. This overall mission guides camp leadership and staff every year over the course of the camp week where campers participate in a mix of traditional and nontraditional summer activities that are safe and accessible for all, from spending time in the pool to arts and crafts and a ropes course.

Camp Wonder is in its 21st year of hosting children and adolescents from across North America at its camp in Livermore, California. This year, Tenconi expects about 100 campers during the last week in July. Camp Wonder relies on medical staff volunteers to make the camp setting safe, inclusive, and fun. “Our dermatology residents and dermatology volunteers are a huge part of why we’re able to have camp,” said Tenconi. “A lot of our kids require very specific medical care throughout the week. We are able to provide this camp experience for them because we have this medical support system available, this specialized dermatology knowledge.” She also noted the benefit to the volunteers themselves, saying,“The feedback we get a lot from residents and dermatologists is that camp gave them a chance to understand the true-life impact of some of the skin diseases these kids and families are living with. Kids will open up to them and tell them how their disease has impacted them personally” (oral communication, June 18, 2021).

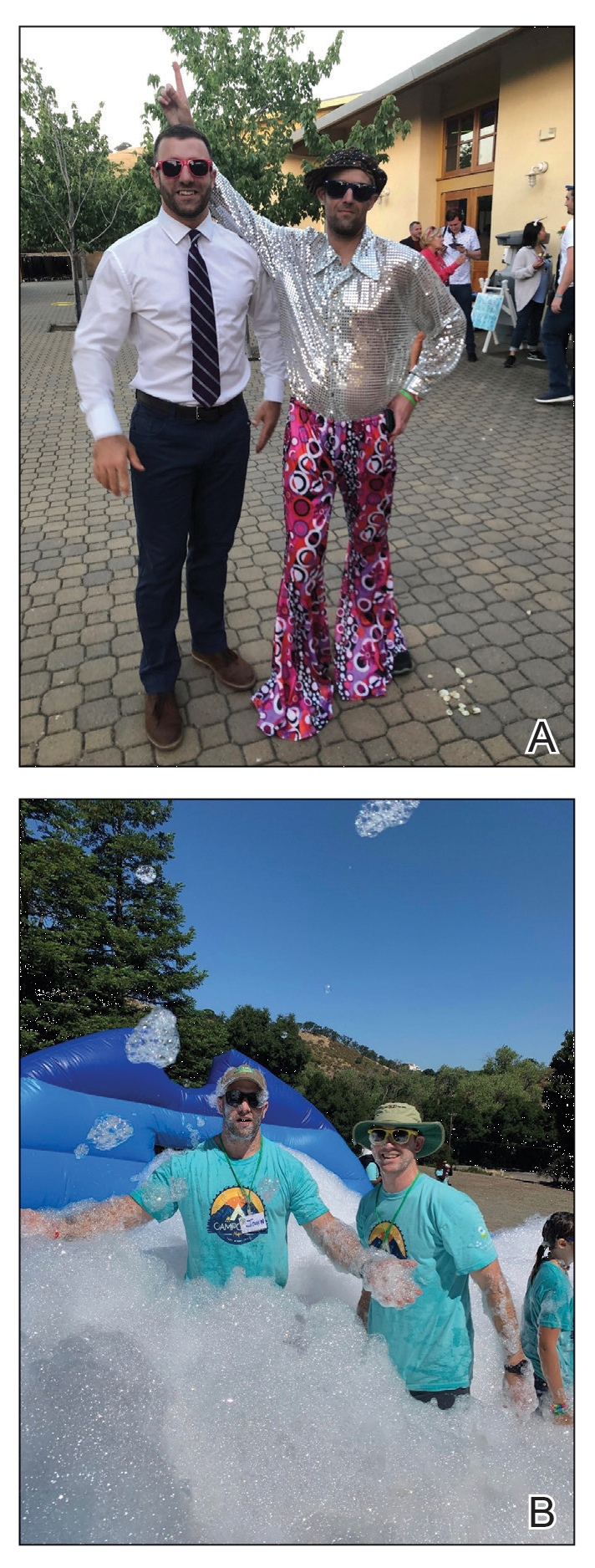

Volunteer medical providers help manage the medical needs of the campers beginning at check-in and work shifts in the infirmary as well as help with dispensing and administering medications, changing dressings, and applying ointments or other topical medications. When not assisting with medical care, medical staff can get to know the campers; help out with arts and crafts, games, sports, and other camp activities; and put on skits and plays for campers at nightly camp hangouts (Figure 1).

How to Get Involved

Visit the website (https://www.csdf.org/camp-wonder) for information on becoming a medical volunteer for 2022. Donations to help keep the camp running also are greatly appreciated, as attendance, including travel costs, is free for families through the Children’s Skin Disease Foundation. Finally, dermatologists can help by keeping their young patients with skin disease in mind as future campers. The camp welcomes kids from across the United States and Canada and invites questions from dermatologists and families on how to become a camper and what the experience is like.

Native American Health Services Rotation

Located in the southwestern United States, the Navajo Nation is North America’s largest Native American tribe by enrollment and resides on the largest reservation in the United States.10 Comprised of 27,000 square miles within portions of Arizona, New Mexico, and Utah, the reservation’s total area is greater than that of Massachusetts, Vermont, and New Hampshire combined.11 The reservation is home to an estimated 180,000 Navajo people, a population roughly the size of Salt Lake City, Utah. Yet, many homes on the reservation are without electricity, running water, telephones, or broadband access, and many roads on the reservation remain unpaved. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, 4 dermatology residents were selected each year to travel to this unique and remote location to work with the staff of the Chinle Comprehensive Health Care Facility (Chinle, Arizona), an Indian Health Service facility, as part of the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD)–sponsored Native American Health Services Resident Rotation (NAHSRR).

Dr. Lucinda Kohn, Assistant Professor of Dermatology at the University of Colorado and the director of the NAHSRR program discovered the value of this rotation firsthand as a dermatology resident. In 2017, she traveled to the area to spend 2 weeks serving within the community. “I went because of a personal connection. My husband is Native American, although not Navajo. I wanted to experience what it was like to provide dermatologic care for Native Americans. I found the Navajo people to be so friendly and so grateful for our care. The clinicians we worked with at Chinle were excited to have us share our expertise and to pass on their knowledge to us,” said Dr. Kohn (personal communication, June 24, 2021).

Rotating residents provide dermatologic care for the Navajo people and share their unique medical skill set to local primary care clinicians serving as preceptors. They also may have an opportunity to learn from Native healers about traditional Navajo beliefs and ceremonies used as part of a holistic approach to healing.

The program, similar to volunteer programs across the country, was put on hold during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic. “The Navajo nation witnessed a really tragic surge of COVID cases that required that limited medical resources be diverted to help cope with the pandemic,” says Dr. Kohn. “It really wasn’t safe for residents to travel to the reservation either, so the rotation had to be put on hold.” However, in April 2021, the health care staff of the Chinle Comprehensive Care Facility reached out to revive the program, which is now pending the green light from the AAD. It is unclear if or when AAD leadership will allow this rotation to restart. Dr. Kohn hopes to be able to start accepting new applications soon. “This rotation provides a wealth of benefits to all those involved, from the residents who get the chance to work with a unique population in need to the clinicians who gain a diverse understanding of dermatology treatment techniques. And of course, for the patients, who are so appreciative of the care they receive from our volunteers” (personal communication, June 25, 2021).

How to Get Involved

Dr. Kohn is happy to field questions regarding the rotation and requests for more information via email ([email protected]). Residents interested in this program also may reach out to the AAD’s Education and Volunteers Abroad Committee to express interest in the NAHSRR program’s reinstatement.

Destination Healthy Skin

Since 2017, the Skin Cancer Foundation’s Destination Healthy Skin (DHS) RV has been the setting for more than 3800 free skin cancer screenings provided by volunteers within underserved populations across the United States (Figure 2). After a year hiatus due to the pandemic, DHS hit the road again, starting in New York City on August 1 to 3, 2021. From there, the DHS RV will traverse the country in one large loop, starting with visits to large and small cities in the Midwest and the West Coast. Following a visit to San Diego, California, in early October, the RV will turn east, with stops in Arizona, Texas, and several southern states before ending in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Dr. Elizabeth Hale, Senior Vice President of the Skin Cancer Foundation, feels that increasing awareness of the importance of regular skin cancer screening for those at risk is more important than ever. “We know that many people in the past year put routine cancer screening on the back burner, but we’re beginning to appreciate that this has led to significant delays in skin cancer diagnosis and potentially more significant disease when cases are diagnosed.” Dr. Hale noted that as the country continues to return to a degree of normalcy, the backlog of patients now seeking their routine screening has led to longer wait times. She expects DHS may offer some relief. “There are no appointments necessary. If the RV is close to their hometown, patients have an advantage in being able to be seen first come, first served, without having to wait for an appointment or make sure their insurance is accepted. It’s a free screening that can increase access to dermatologists” (personal communication, June 21, 2021).

The program’s organizers acknowledge that DHS is not a long-term solution for improving dermatology access in the United States and recognize that more needs to be done to raise awareness, both of the value that screenings can provide and the importance of sun-protective behavior. “This is an important first step,” says Dr. Hale. “It’s important that we disseminate that no one is immune to skin cancer. It’s about education, and this is a tool to educate patients that everyone should have a skin check once a year, regardless of where you live or what your skin type is” (personal communication, June 21, 2021).

Volunteer dermatologists are needed to assist with screenings when the DHS RV arrives in their community. Providers complete a screening form identifying any concerning lesions and can document specific lesions using the patient’s cell phone. Following the screenings, participating dermatologists are welcome to invite participants to make appointments at their practices or suggest local clinics for follow-up care.

How to Get Involved

The schedule for this year’s screening events can be found online (https://www.skincancer.org/early-detection/destination-healthy-skin/). Consider volunteering (https://www.skincancer.org/early-detection/destination-healthy-skin/physician-volunteers/) or helping to raise awareness by reaching out to local dermatology societies or free clinics in your area. Residents and physician’s assistants are welcome to volunteer as well, as long as they are under the on-site supervision of a board-certified dermatologist.

Final Thoughts

As medical professionals, we all recognize there are valuable contributions we can make to groups and organizations that need our help. The stresses and pressure of work and everyday life can make finding the time to offer that help seem impossible. Although it may seem counterintuitive, volunteering our time to help others can help us better navigate the professional burnout that many medical professionals experience today.

- Ezekor M, Pona A, Cline A, et al. An increasing trend in the number of publications and research projects among dermatology residency applicants. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:214-216.

- Atluri S, Seivright JR, Shi VY, et al. Volunteer and work experiences among dermatology residency applicants. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:E97-E98.

- Abokwidir M, Davis SA, Fleischer AB, et al. Use of the emergency department for dermatologic care in the United States by ethnic group. J Dermatolog Treat. 2015;26:392-394.

- Uscher-Pines L, Pines J, Kellermann A, et al. Emergency department visits for nonurgent conditions: systematic literature review. Am J Manag Care. 2013;19:47-59.

- Jack AR, Spence AA, Nichols BJ, et al. Cutaneous conditions leading to dermatology consultations in the emergency department. West J Emerg Med. 2011;12:551-555.

- Ayoubi N, Mirza A-S, Swanson J, et al. Dermatologic care of uninsured patients managed at free clinics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:433-437.

- Wright AA, Katz IT. Beyond burnout—redesigning care to restore meaning and sanity for physicians. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:309-311.

- Bull C, Aucoin JB. Voluntary association participation and life satisfaction: a replication note. J Gerontol. 1975;30:73-76.

- Iserson KV. Burnout syndrome: global medicine volunteering as a possible treatment strategy. J Emerg Med. 2018;54:516-521.

- Romero S. Navajo Nation becomes largest tribe in U.S. after pandemic enrollment surge. New York Times. May 21, 2021. Accessed August 19, 2021. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/05/21/us/navajo-cherokee-population.html

- Moore GR, Benally J, Tuttle S. The Navajo Nation: quick facts. University of Arizona website. Accessed August 19, 2021. https://extension.arizona.edu/sites/extension.arizona.edu/files/pubs/az1471.pdf

The adage “so much to do, so little time” aptly describes the daily challenges facing dermatologists and dermatology residents. The time and attention required by direct patient care, writing notes, navigating electronic health records, and engaging in education and research as well as family commitments can drain even the most tireless clinician. In addition, dermatologists are expected to play a critical role in clinic and practice management to successfully curate an online presence and adapt their skills to successfully manage a teledermatology practice. Coupled with the time spent socializing with friends or colleagues and time for personal hobbies or exercise, it’s easy to see how sleep deprivation is common in many of our colleagues.

What’s being left out of these jam-packed schedules? Increasingly, it is the time and expertise dedicated to volunteering in our local communities. Two recent research letters highlighted how a dramatic increase in the number of research projects and publications is not mirrored by a similar increase in volunteer experiences as dermatology residency selection becomes more competitive.1,2

Although the rate of volunteerism among practicing dermatologists has yet to be studied, a brief review suggests a component of unmet dermatology need within our communities. It’s estimated that approximately 5% to 10% of all emergency department visits are for dermatologic concerns.3-5 In many cases, the reason for the visit is nonurgent and instead reflects a lack of other options for care. However, the need for dermatologists extends beyond the emergency department setting. A review of the prevalence of patients presenting for care to a group of regional free clinics found that 8% (N=5553) of all visitors sought care for dermatologic concerns.6 The benefit is not just for those seated on the examination table; research has shown that while many of the underlying factors resulting in physician burnout stem from systemic issues, participating in volunteer opportunities helps combat burnout in ourselves and our colleagues.7-9 Herein, opportunities that exist for dermatologists to reconnect with their communities, advocate for causes distinctive to the specialty, and care for neighbors most in need are highlighted.

Camp Wonder

Every year, children from across the United States living with chronic and debilitating skin conditions get the opportunity to join fellow campers and spend a week just being kids without the constant focus on being a patient. Camp Wonder’s founder and director, Francesca Tenconi, describes the camp as a place where kids “can form a community and can feel free to be themselves, without judgment, without stares. They get the chance to forget about their skin disease and be themselves” (oral communication, June 18, 2021). Tenconi and the camp’s cofounders and medical directors, Drs. Jenny Kim and Stefani Takahashi, envisioned the camp as a place for all campers regardless of their skin condition to feel safe and welcome. This overall mission guides camp leadership and staff every year over the course of the camp week where campers participate in a mix of traditional and nontraditional summer activities that are safe and accessible for all, from spending time in the pool to arts and crafts and a ropes course.

Camp Wonder is in its 21st year of hosting children and adolescents from across North America at its camp in Livermore, California. This year, Tenconi expects about 100 campers during the last week in July. Camp Wonder relies on medical staff volunteers to make the camp setting safe, inclusive, and fun. “Our dermatology residents and dermatology volunteers are a huge part of why we’re able to have camp,” said Tenconi. “A lot of our kids require very specific medical care throughout the week. We are able to provide this camp experience for them because we have this medical support system available, this specialized dermatology knowledge.” She also noted the benefit to the volunteers themselves, saying,“The feedback we get a lot from residents and dermatologists is that camp gave them a chance to understand the true-life impact of some of the skin diseases these kids and families are living with. Kids will open up to them and tell them how their disease has impacted them personally” (oral communication, June 18, 2021).

Volunteer medical providers help manage the medical needs of the campers beginning at check-in and work shifts in the infirmary as well as help with dispensing and administering medications, changing dressings, and applying ointments or other topical medications. When not assisting with medical care, medical staff can get to know the campers; help out with arts and crafts, games, sports, and other camp activities; and put on skits and plays for campers at nightly camp hangouts (Figure 1).

How to Get Involved

Visit the website (https://www.csdf.org/camp-wonder) for information on becoming a medical volunteer for 2022. Donations to help keep the camp running also are greatly appreciated, as attendance, including travel costs, is free for families through the Children’s Skin Disease Foundation. Finally, dermatologists can help by keeping their young patients with skin disease in mind as future campers. The camp welcomes kids from across the United States and Canada and invites questions from dermatologists and families on how to become a camper and what the experience is like.

Native American Health Services Rotation

Located in the southwestern United States, the Navajo Nation is North America’s largest Native American tribe by enrollment and resides on the largest reservation in the United States.10 Comprised of 27,000 square miles within portions of Arizona, New Mexico, and Utah, the reservation’s total area is greater than that of Massachusetts, Vermont, and New Hampshire combined.11 The reservation is home to an estimated 180,000 Navajo people, a population roughly the size of Salt Lake City, Utah. Yet, many homes on the reservation are without electricity, running water, telephones, or broadband access, and many roads on the reservation remain unpaved. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, 4 dermatology residents were selected each year to travel to this unique and remote location to work with the staff of the Chinle Comprehensive Health Care Facility (Chinle, Arizona), an Indian Health Service facility, as part of the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD)–sponsored Native American Health Services Resident Rotation (NAHSRR).

Dr. Lucinda Kohn, Assistant Professor of Dermatology at the University of Colorado and the director of the NAHSRR program discovered the value of this rotation firsthand as a dermatology resident. In 2017, she traveled to the area to spend 2 weeks serving within the community. “I went because of a personal connection. My husband is Native American, although not Navajo. I wanted to experience what it was like to provide dermatologic care for Native Americans. I found the Navajo people to be so friendly and so grateful for our care. The clinicians we worked with at Chinle were excited to have us share our expertise and to pass on their knowledge to us,” said Dr. Kohn (personal communication, June 24, 2021).

Rotating residents provide dermatologic care for the Navajo people and share their unique medical skill set to local primary care clinicians serving as preceptors. They also may have an opportunity to learn from Native healers about traditional Navajo beliefs and ceremonies used as part of a holistic approach to healing.

The program, similar to volunteer programs across the country, was put on hold during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic. “The Navajo nation witnessed a really tragic surge of COVID cases that required that limited medical resources be diverted to help cope with the pandemic,” says Dr. Kohn. “It really wasn’t safe for residents to travel to the reservation either, so the rotation had to be put on hold.” However, in April 2021, the health care staff of the Chinle Comprehensive Care Facility reached out to revive the program, which is now pending the green light from the AAD. It is unclear if or when AAD leadership will allow this rotation to restart. Dr. Kohn hopes to be able to start accepting new applications soon. “This rotation provides a wealth of benefits to all those involved, from the residents who get the chance to work with a unique population in need to the clinicians who gain a diverse understanding of dermatology treatment techniques. And of course, for the patients, who are so appreciative of the care they receive from our volunteers” (personal communication, June 25, 2021).

How to Get Involved

Dr. Kohn is happy to field questions regarding the rotation and requests for more information via email ([email protected]). Residents interested in this program also may reach out to the AAD’s Education and Volunteers Abroad Committee to express interest in the NAHSRR program’s reinstatement.

Destination Healthy Skin

Since 2017, the Skin Cancer Foundation’s Destination Healthy Skin (DHS) RV has been the setting for more than 3800 free skin cancer screenings provided by volunteers within underserved populations across the United States (Figure 2). After a year hiatus due to the pandemic, DHS hit the road again, starting in New York City on August 1 to 3, 2021. From there, the DHS RV will traverse the country in one large loop, starting with visits to large and small cities in the Midwest and the West Coast. Following a visit to San Diego, California, in early October, the RV will turn east, with stops in Arizona, Texas, and several southern states before ending in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Dr. Elizabeth Hale, Senior Vice President of the Skin Cancer Foundation, feels that increasing awareness of the importance of regular skin cancer screening for those at risk is more important than ever. “We know that many people in the past year put routine cancer screening on the back burner, but we’re beginning to appreciate that this has led to significant delays in skin cancer diagnosis and potentially more significant disease when cases are diagnosed.” Dr. Hale noted that as the country continues to return to a degree of normalcy, the backlog of patients now seeking their routine screening has led to longer wait times. She expects DHS may offer some relief. “There are no appointments necessary. If the RV is close to their hometown, patients have an advantage in being able to be seen first come, first served, without having to wait for an appointment or make sure their insurance is accepted. It’s a free screening that can increase access to dermatologists” (personal communication, June 21, 2021).

The program’s organizers acknowledge that DHS is not a long-term solution for improving dermatology access in the United States and recognize that more needs to be done to raise awareness, both of the value that screenings can provide and the importance of sun-protective behavior. “This is an important first step,” says Dr. Hale. “It’s important that we disseminate that no one is immune to skin cancer. It’s about education, and this is a tool to educate patients that everyone should have a skin check once a year, regardless of where you live or what your skin type is” (personal communication, June 21, 2021).

Volunteer dermatologists are needed to assist with screenings when the DHS RV arrives in their community. Providers complete a screening form identifying any concerning lesions and can document specific lesions using the patient’s cell phone. Following the screenings, participating dermatologists are welcome to invite participants to make appointments at their practices or suggest local clinics for follow-up care.

How to Get Involved

The schedule for this year’s screening events can be found online (https://www.skincancer.org/early-detection/destination-healthy-skin/). Consider volunteering (https://www.skincancer.org/early-detection/destination-healthy-skin/physician-volunteers/) or helping to raise awareness by reaching out to local dermatology societies or free clinics in your area. Residents and physician’s assistants are welcome to volunteer as well, as long as they are under the on-site supervision of a board-certified dermatologist.

Final Thoughts

As medical professionals, we all recognize there are valuable contributions we can make to groups and organizations that need our help. The stresses and pressure of work and everyday life can make finding the time to offer that help seem impossible. Although it may seem counterintuitive, volunteering our time to help others can help us better navigate the professional burnout that many medical professionals experience today.

The adage “so much to do, so little time” aptly describes the daily challenges facing dermatologists and dermatology residents. The time and attention required by direct patient care, writing notes, navigating electronic health records, and engaging in education and research as well as family commitments can drain even the most tireless clinician. In addition, dermatologists are expected to play a critical role in clinic and practice management to successfully curate an online presence and adapt their skills to successfully manage a teledermatology practice. Coupled with the time spent socializing with friends or colleagues and time for personal hobbies or exercise, it’s easy to see how sleep deprivation is common in many of our colleagues.

What’s being left out of these jam-packed schedules? Increasingly, it is the time and expertise dedicated to volunteering in our local communities. Two recent research letters highlighted how a dramatic increase in the number of research projects and publications is not mirrored by a similar increase in volunteer experiences as dermatology residency selection becomes more competitive.1,2

Although the rate of volunteerism among practicing dermatologists has yet to be studied, a brief review suggests a component of unmet dermatology need within our communities. It’s estimated that approximately 5% to 10% of all emergency department visits are for dermatologic concerns.3-5 In many cases, the reason for the visit is nonurgent and instead reflects a lack of other options for care. However, the need for dermatologists extends beyond the emergency department setting. A review of the prevalence of patients presenting for care to a group of regional free clinics found that 8% (N=5553) of all visitors sought care for dermatologic concerns.6 The benefit is not just for those seated on the examination table; research has shown that while many of the underlying factors resulting in physician burnout stem from systemic issues, participating in volunteer opportunities helps combat burnout in ourselves and our colleagues.7-9 Herein, opportunities that exist for dermatologists to reconnect with their communities, advocate for causes distinctive to the specialty, and care for neighbors most in need are highlighted.

Camp Wonder

Every year, children from across the United States living with chronic and debilitating skin conditions get the opportunity to join fellow campers and spend a week just being kids without the constant focus on being a patient. Camp Wonder’s founder and director, Francesca Tenconi, describes the camp as a place where kids “can form a community and can feel free to be themselves, without judgment, without stares. They get the chance to forget about their skin disease and be themselves” (oral communication, June 18, 2021). Tenconi and the camp’s cofounders and medical directors, Drs. Jenny Kim and Stefani Takahashi, envisioned the camp as a place for all campers regardless of their skin condition to feel safe and welcome. This overall mission guides camp leadership and staff every year over the course of the camp week where campers participate in a mix of traditional and nontraditional summer activities that are safe and accessible for all, from spending time in the pool to arts and crafts and a ropes course.

Camp Wonder is in its 21st year of hosting children and adolescents from across North America at its camp in Livermore, California. This year, Tenconi expects about 100 campers during the last week in July. Camp Wonder relies on medical staff volunteers to make the camp setting safe, inclusive, and fun. “Our dermatology residents and dermatology volunteers are a huge part of why we’re able to have camp,” said Tenconi. “A lot of our kids require very specific medical care throughout the week. We are able to provide this camp experience for them because we have this medical support system available, this specialized dermatology knowledge.” She also noted the benefit to the volunteers themselves, saying,“The feedback we get a lot from residents and dermatologists is that camp gave them a chance to understand the true-life impact of some of the skin diseases these kids and families are living with. Kids will open up to them and tell them how their disease has impacted them personally” (oral communication, June 18, 2021).

Volunteer medical providers help manage the medical needs of the campers beginning at check-in and work shifts in the infirmary as well as help with dispensing and administering medications, changing dressings, and applying ointments or other topical medications. When not assisting with medical care, medical staff can get to know the campers; help out with arts and crafts, games, sports, and other camp activities; and put on skits and plays for campers at nightly camp hangouts (Figure 1).

How to Get Involved

Visit the website (https://www.csdf.org/camp-wonder) for information on becoming a medical volunteer for 2022. Donations to help keep the camp running also are greatly appreciated, as attendance, including travel costs, is free for families through the Children’s Skin Disease Foundation. Finally, dermatologists can help by keeping their young patients with skin disease in mind as future campers. The camp welcomes kids from across the United States and Canada and invites questions from dermatologists and families on how to become a camper and what the experience is like.

Native American Health Services Rotation

Located in the southwestern United States, the Navajo Nation is North America’s largest Native American tribe by enrollment and resides on the largest reservation in the United States.10 Comprised of 27,000 square miles within portions of Arizona, New Mexico, and Utah, the reservation’s total area is greater than that of Massachusetts, Vermont, and New Hampshire combined.11 The reservation is home to an estimated 180,000 Navajo people, a population roughly the size of Salt Lake City, Utah. Yet, many homes on the reservation are without electricity, running water, telephones, or broadband access, and many roads on the reservation remain unpaved. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, 4 dermatology residents were selected each year to travel to this unique and remote location to work with the staff of the Chinle Comprehensive Health Care Facility (Chinle, Arizona), an Indian Health Service facility, as part of the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD)–sponsored Native American Health Services Resident Rotation (NAHSRR).

Dr. Lucinda Kohn, Assistant Professor of Dermatology at the University of Colorado and the director of the NAHSRR program discovered the value of this rotation firsthand as a dermatology resident. In 2017, she traveled to the area to spend 2 weeks serving within the community. “I went because of a personal connection. My husband is Native American, although not Navajo. I wanted to experience what it was like to provide dermatologic care for Native Americans. I found the Navajo people to be so friendly and so grateful for our care. The clinicians we worked with at Chinle were excited to have us share our expertise and to pass on their knowledge to us,” said Dr. Kohn (personal communication, June 24, 2021).

Rotating residents provide dermatologic care for the Navajo people and share their unique medical skill set to local primary care clinicians serving as preceptors. They also may have an opportunity to learn from Native healers about traditional Navajo beliefs and ceremonies used as part of a holistic approach to healing.

The program, similar to volunteer programs across the country, was put on hold during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic. “The Navajo nation witnessed a really tragic surge of COVID cases that required that limited medical resources be diverted to help cope with the pandemic,” says Dr. Kohn. “It really wasn’t safe for residents to travel to the reservation either, so the rotation had to be put on hold.” However, in April 2021, the health care staff of the Chinle Comprehensive Care Facility reached out to revive the program, which is now pending the green light from the AAD. It is unclear if or when AAD leadership will allow this rotation to restart. Dr. Kohn hopes to be able to start accepting new applications soon. “This rotation provides a wealth of benefits to all those involved, from the residents who get the chance to work with a unique population in need to the clinicians who gain a diverse understanding of dermatology treatment techniques. And of course, for the patients, who are so appreciative of the care they receive from our volunteers” (personal communication, June 25, 2021).

How to Get Involved

Dr. Kohn is happy to field questions regarding the rotation and requests for more information via email ([email protected]). Residents interested in this program also may reach out to the AAD’s Education and Volunteers Abroad Committee to express interest in the NAHSRR program’s reinstatement.

Destination Healthy Skin

Since 2017, the Skin Cancer Foundation’s Destination Healthy Skin (DHS) RV has been the setting for more than 3800 free skin cancer screenings provided by volunteers within underserved populations across the United States (Figure 2). After a year hiatus due to the pandemic, DHS hit the road again, starting in New York City on August 1 to 3, 2021. From there, the DHS RV will traverse the country in one large loop, starting with visits to large and small cities in the Midwest and the West Coast. Following a visit to San Diego, California, in early October, the RV will turn east, with stops in Arizona, Texas, and several southern states before ending in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Dr. Elizabeth Hale, Senior Vice President of the Skin Cancer Foundation, feels that increasing awareness of the importance of regular skin cancer screening for those at risk is more important than ever. “We know that many people in the past year put routine cancer screening on the back burner, but we’re beginning to appreciate that this has led to significant delays in skin cancer diagnosis and potentially more significant disease when cases are diagnosed.” Dr. Hale noted that as the country continues to return to a degree of normalcy, the backlog of patients now seeking their routine screening has led to longer wait times. She expects DHS may offer some relief. “There are no appointments necessary. If the RV is close to their hometown, patients have an advantage in being able to be seen first come, first served, without having to wait for an appointment or make sure their insurance is accepted. It’s a free screening that can increase access to dermatologists” (personal communication, June 21, 2021).

The program’s organizers acknowledge that DHS is not a long-term solution for improving dermatology access in the United States and recognize that more needs to be done to raise awareness, both of the value that screenings can provide and the importance of sun-protective behavior. “This is an important first step,” says Dr. Hale. “It’s important that we disseminate that no one is immune to skin cancer. It’s about education, and this is a tool to educate patients that everyone should have a skin check once a year, regardless of where you live or what your skin type is” (personal communication, June 21, 2021).

Volunteer dermatologists are needed to assist with screenings when the DHS RV arrives in their community. Providers complete a screening form identifying any concerning lesions and can document specific lesions using the patient’s cell phone. Following the screenings, participating dermatologists are welcome to invite participants to make appointments at their practices or suggest local clinics for follow-up care.

How to Get Involved

The schedule for this year’s screening events can be found online (https://www.skincancer.org/early-detection/destination-healthy-skin/). Consider volunteering (https://www.skincancer.org/early-detection/destination-healthy-skin/physician-volunteers/) or helping to raise awareness by reaching out to local dermatology societies or free clinics in your area. Residents and physician’s assistants are welcome to volunteer as well, as long as they are under the on-site supervision of a board-certified dermatologist.

Final Thoughts

As medical professionals, we all recognize there are valuable contributions we can make to groups and organizations that need our help. The stresses and pressure of work and everyday life can make finding the time to offer that help seem impossible. Although it may seem counterintuitive, volunteering our time to help others can help us better navigate the professional burnout that many medical professionals experience today.

- Ezekor M, Pona A, Cline A, et al. An increasing trend in the number of publications and research projects among dermatology residency applicants. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:214-216.

- Atluri S, Seivright JR, Shi VY, et al. Volunteer and work experiences among dermatology residency applicants. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:E97-E98.

- Abokwidir M, Davis SA, Fleischer AB, et al. Use of the emergency department for dermatologic care in the United States by ethnic group. J Dermatolog Treat. 2015;26:392-394.

- Uscher-Pines L, Pines J, Kellermann A, et al. Emergency department visits for nonurgent conditions: systematic literature review. Am J Manag Care. 2013;19:47-59.

- Jack AR, Spence AA, Nichols BJ, et al. Cutaneous conditions leading to dermatology consultations in the emergency department. West J Emerg Med. 2011;12:551-555.

- Ayoubi N, Mirza A-S, Swanson J, et al. Dermatologic care of uninsured patients managed at free clinics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:433-437.

- Wright AA, Katz IT. Beyond burnout—redesigning care to restore meaning and sanity for physicians. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:309-311.

- Bull C, Aucoin JB. Voluntary association participation and life satisfaction: a replication note. J Gerontol. 1975;30:73-76.

- Iserson KV. Burnout syndrome: global medicine volunteering as a possible treatment strategy. J Emerg Med. 2018;54:516-521.

- Romero S. Navajo Nation becomes largest tribe in U.S. after pandemic enrollment surge. New York Times. May 21, 2021. Accessed August 19, 2021. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/05/21/us/navajo-cherokee-population.html

- Moore GR, Benally J, Tuttle S. The Navajo Nation: quick facts. University of Arizona website. Accessed August 19, 2021. https://extension.arizona.edu/sites/extension.arizona.edu/files/pubs/az1471.pdf

- Ezekor M, Pona A, Cline A, et al. An increasing trend in the number of publications and research projects among dermatology residency applicants. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:214-216.

- Atluri S, Seivright JR, Shi VY, et al. Volunteer and work experiences among dermatology residency applicants. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:E97-E98.

- Abokwidir M, Davis SA, Fleischer AB, et al. Use of the emergency department for dermatologic care in the United States by ethnic group. J Dermatolog Treat. 2015;26:392-394.

- Uscher-Pines L, Pines J, Kellermann A, et al. Emergency department visits for nonurgent conditions: systematic literature review. Am J Manag Care. 2013;19:47-59.

- Jack AR, Spence AA, Nichols BJ, et al. Cutaneous conditions leading to dermatology consultations in the emergency department. West J Emerg Med. 2011;12:551-555.

- Ayoubi N, Mirza A-S, Swanson J, et al. Dermatologic care of uninsured patients managed at free clinics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:433-437.

- Wright AA, Katz IT. Beyond burnout—redesigning care to restore meaning and sanity for physicians. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:309-311.

- Bull C, Aucoin JB. Voluntary association participation and life satisfaction: a replication note. J Gerontol. 1975;30:73-76.

- Iserson KV. Burnout syndrome: global medicine volunteering as a possible treatment strategy. J Emerg Med. 2018;54:516-521.

- Romero S. Navajo Nation becomes largest tribe in U.S. after pandemic enrollment surge. New York Times. May 21, 2021. Accessed August 19, 2021. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/05/21/us/navajo-cherokee-population.html

- Moore GR, Benally J, Tuttle S. The Navajo Nation: quick facts. University of Arizona website. Accessed August 19, 2021. https://extension.arizona.edu/sites/extension.arizona.edu/files/pubs/az1471.pdf

Resident Pearl