User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

First target doesn’t affect survival in NSCLC with brain metastases

“The findings of our study highlight the importance of adopting a personalized, case-based approach when treating each patient” instead of always treating the brain or lung first, lead author Arvind Kumar, a medical student at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, said in an interview.

The study was released at European Lung Cancer Congress 2023.

According to the author, current guidelines recommend treating the brain first in patients with non–small cell lung cancer and a tumor that has spread to the brain.

“Determining whether the brain or body gets treated first depends on where the symptoms are coming from, how severe the symptoms are, how bulky the disease is, and how long the treatment to each is expected to take,” radiation oncologist Henry S. Park, MD, MPH, chief of the thoracic radiotherapy program at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., said in an interview. “Often the brain is treated first since surgery is used for both diagnosis of metastatic disease as well as removal of the brain metastasis, especially if it is causing symptoms. The radiosurgery that follows tends to occur within a day or a few days.”

However, he said, “if the brain disease is small and not causing symptoms, and the lung disease is more problematic, then we will often treat the body first and fit in the brain treatment later.”

For the new study, researchers identified 1,044 patients in the National Cancer Database with non–small cell lung cancer and brain metastases who received systemic therapy plus surgery, brain stereotactic radiosurgery, or lung radiation. All were treated from 2010 to 2019; 79.0% received brain treatment first, and the other 21.0% received lung treatment first.

There was no statistically significant difference in overall survival between those whose brains were treated first and those whose lungs were treated first (hazard ratio, 1.24, 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.91-1.70, P = .17). A propensity score–matched analysis turned up no difference in 5-year survival (38.2% of those whose brains were treated first, 95% CI, 27.5-34.4, vs. 38.0% of those whose lungs were treated first, 95% CI, 29.9-44.7, P = .32.)

“These results were consistent regardless of which combination of treatment modalities the patient received – neurosurgery versus brain stereotactic radiosurgery, thoracic surgery versus thoracic radiation,” the author said.

He cautioned that “our study only included patients who were considered candidates for either surgery or radiation to both the brain and lung. The results of our study should therefore be cautiously interpreted for patients who may have contraindications to such treatment.”

Dr. Park, who didn’t take part in the study, said “the results are consistent with what I would generally expect.”

He added: “The take-home message for clinicians should be that there is no one correct answer in how to manage non–small cell lung cancer with synchronous limited metastatic disease in only the brain. If the brain disease is bulky and/or causes symptoms while the body disease isn’t – or if a biopsy or surgery is required to prove that the patient in fact has metastatic disease – then the brain disease should be treated first. On the other hand, if the body disease is bulky and/or causing symptoms while the brain disease isn’t – and there is no need for surgery but rather only a biopsy of the brain – then the body disease can be treated first.”

No funding was reported. The study authors and Dr. Park reported no financial conflicts or other disclosures.

“The findings of our study highlight the importance of adopting a personalized, case-based approach when treating each patient” instead of always treating the brain or lung first, lead author Arvind Kumar, a medical student at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, said in an interview.

The study was released at European Lung Cancer Congress 2023.

According to the author, current guidelines recommend treating the brain first in patients with non–small cell lung cancer and a tumor that has spread to the brain.

“Determining whether the brain or body gets treated first depends on where the symptoms are coming from, how severe the symptoms are, how bulky the disease is, and how long the treatment to each is expected to take,” radiation oncologist Henry S. Park, MD, MPH, chief of the thoracic radiotherapy program at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., said in an interview. “Often the brain is treated first since surgery is used for both diagnosis of metastatic disease as well as removal of the brain metastasis, especially if it is causing symptoms. The radiosurgery that follows tends to occur within a day or a few days.”

However, he said, “if the brain disease is small and not causing symptoms, and the lung disease is more problematic, then we will often treat the body first and fit in the brain treatment later.”

For the new study, researchers identified 1,044 patients in the National Cancer Database with non–small cell lung cancer and brain metastases who received systemic therapy plus surgery, brain stereotactic radiosurgery, or lung radiation. All were treated from 2010 to 2019; 79.0% received brain treatment first, and the other 21.0% received lung treatment first.

There was no statistically significant difference in overall survival between those whose brains were treated first and those whose lungs were treated first (hazard ratio, 1.24, 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.91-1.70, P = .17). A propensity score–matched analysis turned up no difference in 5-year survival (38.2% of those whose brains were treated first, 95% CI, 27.5-34.4, vs. 38.0% of those whose lungs were treated first, 95% CI, 29.9-44.7, P = .32.)

“These results were consistent regardless of which combination of treatment modalities the patient received – neurosurgery versus brain stereotactic radiosurgery, thoracic surgery versus thoracic radiation,” the author said.

He cautioned that “our study only included patients who were considered candidates for either surgery or radiation to both the brain and lung. The results of our study should therefore be cautiously interpreted for patients who may have contraindications to such treatment.”

Dr. Park, who didn’t take part in the study, said “the results are consistent with what I would generally expect.”

He added: “The take-home message for clinicians should be that there is no one correct answer in how to manage non–small cell lung cancer with synchronous limited metastatic disease in only the brain. If the brain disease is bulky and/or causes symptoms while the body disease isn’t – or if a biopsy or surgery is required to prove that the patient in fact has metastatic disease – then the brain disease should be treated first. On the other hand, if the body disease is bulky and/or causing symptoms while the brain disease isn’t – and there is no need for surgery but rather only a biopsy of the brain – then the body disease can be treated first.”

No funding was reported. The study authors and Dr. Park reported no financial conflicts or other disclosures.

“The findings of our study highlight the importance of adopting a personalized, case-based approach when treating each patient” instead of always treating the brain or lung first, lead author Arvind Kumar, a medical student at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, said in an interview.

The study was released at European Lung Cancer Congress 2023.

According to the author, current guidelines recommend treating the brain first in patients with non–small cell lung cancer and a tumor that has spread to the brain.

“Determining whether the brain or body gets treated first depends on where the symptoms are coming from, how severe the symptoms are, how bulky the disease is, and how long the treatment to each is expected to take,” radiation oncologist Henry S. Park, MD, MPH, chief of the thoracic radiotherapy program at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., said in an interview. “Often the brain is treated first since surgery is used for both diagnosis of metastatic disease as well as removal of the brain metastasis, especially if it is causing symptoms. The radiosurgery that follows tends to occur within a day or a few days.”

However, he said, “if the brain disease is small and not causing symptoms, and the lung disease is more problematic, then we will often treat the body first and fit in the brain treatment later.”

For the new study, researchers identified 1,044 patients in the National Cancer Database with non–small cell lung cancer and brain metastases who received systemic therapy plus surgery, brain stereotactic radiosurgery, or lung radiation. All were treated from 2010 to 2019; 79.0% received brain treatment first, and the other 21.0% received lung treatment first.

There was no statistically significant difference in overall survival between those whose brains were treated first and those whose lungs were treated first (hazard ratio, 1.24, 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.91-1.70, P = .17). A propensity score–matched analysis turned up no difference in 5-year survival (38.2% of those whose brains were treated first, 95% CI, 27.5-34.4, vs. 38.0% of those whose lungs were treated first, 95% CI, 29.9-44.7, P = .32.)

“These results were consistent regardless of which combination of treatment modalities the patient received – neurosurgery versus brain stereotactic radiosurgery, thoracic surgery versus thoracic radiation,” the author said.

He cautioned that “our study only included patients who were considered candidates for either surgery or radiation to both the brain and lung. The results of our study should therefore be cautiously interpreted for patients who may have contraindications to such treatment.”

Dr. Park, who didn’t take part in the study, said “the results are consistent with what I would generally expect.”

He added: “The take-home message for clinicians should be that there is no one correct answer in how to manage non–small cell lung cancer with synchronous limited metastatic disease in only the brain. If the brain disease is bulky and/or causes symptoms while the body disease isn’t – or if a biopsy or surgery is required to prove that the patient in fact has metastatic disease – then the brain disease should be treated first. On the other hand, if the body disease is bulky and/or causing symptoms while the brain disease isn’t – and there is no need for surgery but rather only a biopsy of the brain – then the body disease can be treated first.”

No funding was reported. The study authors and Dr. Park reported no financial conflicts or other disclosures.

FROM ELCC 2023

Type of insurance linked to length of survival after lung surgery

The study used public insurance status as a marker for low socioeconomic status (SES) and suggests that patients with combined insurance may constitute a separate population that deserves more attention.

Lower SES has been linked to later stage diagnoses and worse outcomes in NSCLC. Private insurance is a generally-accepted indicator of higher SES, while public insurance like Medicare or Medicaid, alone or in combination with private supplementary insurance, is an indicator of lower SES.

Although previous studies have found associations between patients having public health insurance and experiencing later-stage diagnoses and worse overall survival, there have been few studies of surgical outcomes, and almost no research has examined combination health insurance, according to Allison O. Dumitriu Carcoana, who presented the research during a poster session at the European Lung Cancer Congress 2023.

“This is an important insurance subgroup for us because the majority of our patients fall into this subgroup by being over 65 years old and thus qualifying for Medicare while also paying for a private supplement,” said Ms. Dumitriu Carcoana, who is a medical student at University of South Florida Health Morsani College of Medicine, Tampa.

A previous analysis by the group found an association between private insurance status and better discharge status, as well as higher 5-year overall survival. After accumulating an additional 278 patients, the researchers examined 10-year survival outcomes.

In the new analysis, 52% of 711 participants had combination insurance, while 28% had private insurance, and 20% had public insurance. The subgroups all had similar demographic and histological characteristics. The study was unique in that it found no between-group differences in higher stage at diagnosis, whereas previous studies have found a greater risk of higher stage diagnosis among individuals with public insurance. As expected, patients in the combined insurance group had a higher mean age (P less than .0001) and higher Charlson comorbidity index scores (P = .0014), which in turn was associated with lower 10-year survival. The group also had the highest percentage of former smokers, while the public insurance group had the highest percentage of current smokers (P = .0003).

At both 5 and 10 years, the private insurance group had better OS than the group with public (P less than .001) and the combination insurance group (P = .08). Public health insurance was associated with worse OS at 5 years (hazard ratio, 1.83; P less than .005) but not at 10 years (HR, 1.18; P = .51), while combination insurance was associated with worse OS at 10 years (HR, 1.72; P = .02).

“We think that patients with public health insurance having the worst 5-year overall survival, despite their lower ages and fewer comorbid conditions, compared with patients with combination insurance, highlights the impact of lower socioeconomic status on health outcomes. These patients had the same tumor characteristics, BMI, sex, and race as our patients in the other two insurance groups. The only other significant risk factor [the group had besides having a higher proportion of patients with lower socioeconomic status was that it had a higher proportion of current smokers]. But the multivariate analyses showed that insurance status was an independent predictor of survival, regardless of smoking status or other comorbidities,” said Ms. Dumitriu Carcoana.

“At 10 years post-operatively, the survival curves have shifted and the combination patients had the worst 10-year overall survival. We attribute this to their higher number of comorbid conditions and increased age. In practice, [this means that] the group of patients with public insurance type, but no supplement, should be identified clinically, and the clinical team can initiate a discussion,” Ms. Dumitriu Carcoana said.

“Do these patients feel that they can make follow-up appointments, keep up with medication costs, and make the right lifestyle decisions postoperatively on their current insurance plan? If not, can they afford a private supplement? In our cohort specifically, it may also be important to do more preoperative counseling on the importance of smoking cessation,” she added.

The study is interesting, but it has some important limitations, according to Raja Flores, MD, who was not involved with the study. The authors stated that there was no difference between the insurance groups with respect to mortality or cancer stage, which is the most important predictor of survival. However, the poster didn't include details of the authors' analysis, making it difficult to interpret, Dr. Flores said.

The fact that the study includes a single surgeon has some disadvantages in terms of broader applicability, but it also controls for surgical technique. “Different surgeons have different ways of doing things, so if you had the same surgeon doing it the same way every time, you can look at other variables like insurance (status) and stage,” said Dr. Flores.

The results may also provide an argument against using robotic surgery in patients who do not have insurance, especially since they have not been proven to be better than standard minimally invasive surgery with no robotic assistance. With uninsured patients, “you’re using taxpayer money for a more expensive procedure that isn’t proving to be any better,” Dr. Flores explained.

The study was performed at a single center and cannot prove causation due to its retrospective nature.

Ms. Dumitriu Carcoana and Dr. Flores have no relevant financial disclosures.

*This article was updated on 4/13/2023.

The study used public insurance status as a marker for low socioeconomic status (SES) and suggests that patients with combined insurance may constitute a separate population that deserves more attention.

Lower SES has been linked to later stage diagnoses and worse outcomes in NSCLC. Private insurance is a generally-accepted indicator of higher SES, while public insurance like Medicare or Medicaid, alone or in combination with private supplementary insurance, is an indicator of lower SES.

Although previous studies have found associations between patients having public health insurance and experiencing later-stage diagnoses and worse overall survival, there have been few studies of surgical outcomes, and almost no research has examined combination health insurance, according to Allison O. Dumitriu Carcoana, who presented the research during a poster session at the European Lung Cancer Congress 2023.

“This is an important insurance subgroup for us because the majority of our patients fall into this subgroup by being over 65 years old and thus qualifying for Medicare while also paying for a private supplement,” said Ms. Dumitriu Carcoana, who is a medical student at University of South Florida Health Morsani College of Medicine, Tampa.

A previous analysis by the group found an association between private insurance status and better discharge status, as well as higher 5-year overall survival. After accumulating an additional 278 patients, the researchers examined 10-year survival outcomes.

In the new analysis, 52% of 711 participants had combination insurance, while 28% had private insurance, and 20% had public insurance. The subgroups all had similar demographic and histological characteristics. The study was unique in that it found no between-group differences in higher stage at diagnosis, whereas previous studies have found a greater risk of higher stage diagnosis among individuals with public insurance. As expected, patients in the combined insurance group had a higher mean age (P less than .0001) and higher Charlson comorbidity index scores (P = .0014), which in turn was associated with lower 10-year survival. The group also had the highest percentage of former smokers, while the public insurance group had the highest percentage of current smokers (P = .0003).

At both 5 and 10 years, the private insurance group had better OS than the group with public (P less than .001) and the combination insurance group (P = .08). Public health insurance was associated with worse OS at 5 years (hazard ratio, 1.83; P less than .005) but not at 10 years (HR, 1.18; P = .51), while combination insurance was associated with worse OS at 10 years (HR, 1.72; P = .02).

“We think that patients with public health insurance having the worst 5-year overall survival, despite their lower ages and fewer comorbid conditions, compared with patients with combination insurance, highlights the impact of lower socioeconomic status on health outcomes. These patients had the same tumor characteristics, BMI, sex, and race as our patients in the other two insurance groups. The only other significant risk factor [the group had besides having a higher proportion of patients with lower socioeconomic status was that it had a higher proportion of current smokers]. But the multivariate analyses showed that insurance status was an independent predictor of survival, regardless of smoking status or other comorbidities,” said Ms. Dumitriu Carcoana.

“At 10 years post-operatively, the survival curves have shifted and the combination patients had the worst 10-year overall survival. We attribute this to their higher number of comorbid conditions and increased age. In practice, [this means that] the group of patients with public insurance type, but no supplement, should be identified clinically, and the clinical team can initiate a discussion,” Ms. Dumitriu Carcoana said.

“Do these patients feel that they can make follow-up appointments, keep up with medication costs, and make the right lifestyle decisions postoperatively on their current insurance plan? If not, can they afford a private supplement? In our cohort specifically, it may also be important to do more preoperative counseling on the importance of smoking cessation,” she added.

The study is interesting, but it has some important limitations, according to Raja Flores, MD, who was not involved with the study. The authors stated that there was no difference between the insurance groups with respect to mortality or cancer stage, which is the most important predictor of survival. However, the poster didn't include details of the authors' analysis, making it difficult to interpret, Dr. Flores said.

The fact that the study includes a single surgeon has some disadvantages in terms of broader applicability, but it also controls for surgical technique. “Different surgeons have different ways of doing things, so if you had the same surgeon doing it the same way every time, you can look at other variables like insurance (status) and stage,” said Dr. Flores.

The results may also provide an argument against using robotic surgery in patients who do not have insurance, especially since they have not been proven to be better than standard minimally invasive surgery with no robotic assistance. With uninsured patients, “you’re using taxpayer money for a more expensive procedure that isn’t proving to be any better,” Dr. Flores explained.

The study was performed at a single center and cannot prove causation due to its retrospective nature.

Ms. Dumitriu Carcoana and Dr. Flores have no relevant financial disclosures.

*This article was updated on 4/13/2023.

The study used public insurance status as a marker for low socioeconomic status (SES) and suggests that patients with combined insurance may constitute a separate population that deserves more attention.

Lower SES has been linked to later stage diagnoses and worse outcomes in NSCLC. Private insurance is a generally-accepted indicator of higher SES, while public insurance like Medicare or Medicaid, alone or in combination with private supplementary insurance, is an indicator of lower SES.

Although previous studies have found associations between patients having public health insurance and experiencing later-stage diagnoses and worse overall survival, there have been few studies of surgical outcomes, and almost no research has examined combination health insurance, according to Allison O. Dumitriu Carcoana, who presented the research during a poster session at the European Lung Cancer Congress 2023.

“This is an important insurance subgroup for us because the majority of our patients fall into this subgroup by being over 65 years old and thus qualifying for Medicare while also paying for a private supplement,” said Ms. Dumitriu Carcoana, who is a medical student at University of South Florida Health Morsani College of Medicine, Tampa.

A previous analysis by the group found an association between private insurance status and better discharge status, as well as higher 5-year overall survival. After accumulating an additional 278 patients, the researchers examined 10-year survival outcomes.

In the new analysis, 52% of 711 participants had combination insurance, while 28% had private insurance, and 20% had public insurance. The subgroups all had similar demographic and histological characteristics. The study was unique in that it found no between-group differences in higher stage at diagnosis, whereas previous studies have found a greater risk of higher stage diagnosis among individuals with public insurance. As expected, patients in the combined insurance group had a higher mean age (P less than .0001) and higher Charlson comorbidity index scores (P = .0014), which in turn was associated with lower 10-year survival. The group also had the highest percentage of former smokers, while the public insurance group had the highest percentage of current smokers (P = .0003).

At both 5 and 10 years, the private insurance group had better OS than the group with public (P less than .001) and the combination insurance group (P = .08). Public health insurance was associated with worse OS at 5 years (hazard ratio, 1.83; P less than .005) but not at 10 years (HR, 1.18; P = .51), while combination insurance was associated with worse OS at 10 years (HR, 1.72; P = .02).

“We think that patients with public health insurance having the worst 5-year overall survival, despite their lower ages and fewer comorbid conditions, compared with patients with combination insurance, highlights the impact of lower socioeconomic status on health outcomes. These patients had the same tumor characteristics, BMI, sex, and race as our patients in the other two insurance groups. The only other significant risk factor [the group had besides having a higher proportion of patients with lower socioeconomic status was that it had a higher proportion of current smokers]. But the multivariate analyses showed that insurance status was an independent predictor of survival, regardless of smoking status or other comorbidities,” said Ms. Dumitriu Carcoana.

“At 10 years post-operatively, the survival curves have shifted and the combination patients had the worst 10-year overall survival. We attribute this to their higher number of comorbid conditions and increased age. In practice, [this means that] the group of patients with public insurance type, but no supplement, should be identified clinically, and the clinical team can initiate a discussion,” Ms. Dumitriu Carcoana said.

“Do these patients feel that they can make follow-up appointments, keep up with medication costs, and make the right lifestyle decisions postoperatively on their current insurance plan? If not, can they afford a private supplement? In our cohort specifically, it may also be important to do more preoperative counseling on the importance of smoking cessation,” she added.

The study is interesting, but it has some important limitations, according to Raja Flores, MD, who was not involved with the study. The authors stated that there was no difference between the insurance groups with respect to mortality or cancer stage, which is the most important predictor of survival. However, the poster didn't include details of the authors' analysis, making it difficult to interpret, Dr. Flores said.

The fact that the study includes a single surgeon has some disadvantages in terms of broader applicability, but it also controls for surgical technique. “Different surgeons have different ways of doing things, so if you had the same surgeon doing it the same way every time, you can look at other variables like insurance (status) and stage,” said Dr. Flores.

The results may also provide an argument against using robotic surgery in patients who do not have insurance, especially since they have not been proven to be better than standard minimally invasive surgery with no robotic assistance. With uninsured patients, “you’re using taxpayer money for a more expensive procedure that isn’t proving to be any better,” Dr. Flores explained.

The study was performed at a single center and cannot prove causation due to its retrospective nature.

Ms. Dumitriu Carcoana and Dr. Flores have no relevant financial disclosures.

*This article was updated on 4/13/2023.

FROM ELCC 2023

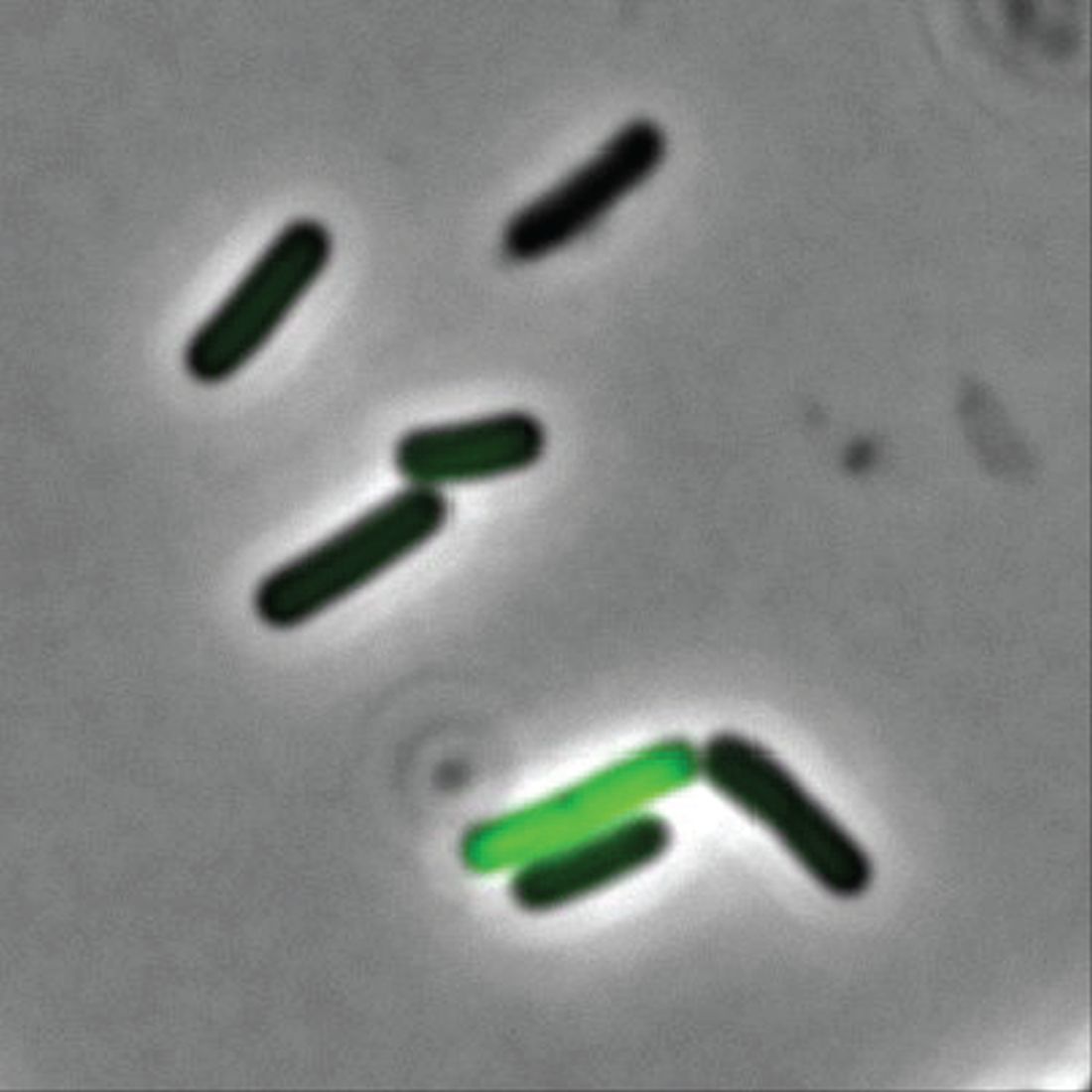

Lack of food for thought: Starve a bacterium, feed an infection

A whole new, tiny level of hangry

Ever been so hungry that everything just got on your nerves? Maybe you feel a little snappy right now? Like you’ll just lash out unless you get something to eat? Been there. And so have bacteria.

New research shows that some bacteria go into a full-on Hulk smash if they’re not getting the nutrients they need by releasing toxins into the body. Sounds like a bacterial temper tantrum.

Even though two cells may be genetically identical, they don’t always behave the same in a bacterial community. Some do their job and stay in line, but some evil twins rage out and make people sick by releasing toxins into the environment, Adam Rosenthal, PhD, of the University of North Carolina and his colleagues discovered.

To figure out why some cells were all business as usual while others were not, the investigators looked at Clostridium perfringens, a bacterium found in the intestines of humans and other vertebrates. When the C. perfringens cells were fed a little acetate to munch on, the hangry cells calmed down faster than a kid with a bag of fruit snacks, reducing toxin levels. Some cells even disappeared, falling in line with their model-citizen counterparts.

So what does this really mean? More research, duh. Now that we know nutrients play a role in toxicity, it may open the door to finding a way to fight against antibiotic resistance in humans and reduce antibiotic use in the food industry.

So think to yourself. Are you bothered for no reason? Getting a little testy with your friends and coworkers? Maybe you just haven’t eaten in a while. You’re literally not alone. Even a single-cell organism can behave based on its hunger levels.

Now go have a snack. Your bacteria are getting restless.

The very hangry iguana?

Imagine yourself on a warm, sunny tropical beach. You are enjoying a piece of cake as you take in the slow beat of the waves lapping against the shore. Life is as good as it could be.

Then you feel a presence nearby. Hostility. Hunger. A set of feral, covetous eyes in the nearby jungle. A reptilian beast stalks you, and its all-encompassing sweet tooth desires your cake.

Wait, hold on, what?

As an unfortunate 3-year-old on vacation in Costa Rica found out, there’s at least one iguana in the world out there with a taste for sugar (better than a taste for blood, we suppose).

While out on the beach, the lizard darted out of nowhere, bit the girl on the back of the hand, and stole her cake. Still not the worst party guest ever. The child was taken to a local clinic, where the wound was cleaned and a 5-day antibiotic treatment (lizards carry salmonella) was provided. Things seemed fine, and the girl returned home without incident.

But of course, that’s not the end of the story. Five months later, the girl’s parents noticed a red bump at the wound site. Over the next 3 months, the surrounding skin grew red and painful. A trip to the hospital in California revealed that she had a ganglion cyst and a discharge of pus. Turns out our cake-obsessed lizard friend did give the little girl a gift: the first known human case of Mycobacterium marinum infection following an iguana bite on record.

M. marinum, which causes a disease similar to tuberculosis, typically infects fish but can infect humans if skin wounds are exposed to contaminated water. It’s also resistant to most antibiotics, which is why the first round didn’t clear up the infection. A second round of more-potent antibiotics seems to be working well.

So, to sum up, this poor child got bitten by a lizard, had her cake stolen, and contracted a rare illness in exchange. For a 3-year-old, that’s gotta be in the top-10 worst days ever. Unless, of course, we’re actually living in the Marvel universe (sorry, multiverse at this point). Then we’re totally going to see the emergence of the new superhero Iguana Girl in 15 years or so. Keep your eyes open.

No allergies? Let them give up cake

Allergy season is already here – starting earlier every year, it seems – and many people are not happy about it. So unhappy, actually, that there’s a list of things they would be willing to give up for a year to get rid of their of allergies, according to a survey conducted by OnePoll on behalf of Flonase.

Nearly 40% of 2,000 respondents with allergies would go a year without eating cake or chocolate or playing video games in exchange for allergy-free status, the survey results show. Almost as many would forgo coffee (38%) or pizza (37%) for a year, while 36% would stay off social media and 31% would take a pay cut or give up their smartphones, the Independent reported.

More than half of the allergic Americans – 54%, to be exact – who were polled this past winter – Feb. 24 to March 1, to be exact – consider allergy symptoms to be the most frustrating part of the spring. Annoying things that were less frustrating to the group included mosquitoes (41%), filing tax returns (38%), and daylight savings time (37%).

The Trump arraignment circus, of course, occurred too late to make the list, as did the big “We’re going back to the office! No wait, we’re closing the office forever!” email extravaganza and emotional roller coaster. That second one, however, did not get nearly as much media coverage.

A whole new, tiny level of hangry

Ever been so hungry that everything just got on your nerves? Maybe you feel a little snappy right now? Like you’ll just lash out unless you get something to eat? Been there. And so have bacteria.

New research shows that some bacteria go into a full-on Hulk smash if they’re not getting the nutrients they need by releasing toxins into the body. Sounds like a bacterial temper tantrum.

Even though two cells may be genetically identical, they don’t always behave the same in a bacterial community. Some do their job and stay in line, but some evil twins rage out and make people sick by releasing toxins into the environment, Adam Rosenthal, PhD, of the University of North Carolina and his colleagues discovered.

To figure out why some cells were all business as usual while others were not, the investigators looked at Clostridium perfringens, a bacterium found in the intestines of humans and other vertebrates. When the C. perfringens cells were fed a little acetate to munch on, the hangry cells calmed down faster than a kid with a bag of fruit snacks, reducing toxin levels. Some cells even disappeared, falling in line with their model-citizen counterparts.

So what does this really mean? More research, duh. Now that we know nutrients play a role in toxicity, it may open the door to finding a way to fight against antibiotic resistance in humans and reduce antibiotic use in the food industry.

So think to yourself. Are you bothered for no reason? Getting a little testy with your friends and coworkers? Maybe you just haven’t eaten in a while. You’re literally not alone. Even a single-cell organism can behave based on its hunger levels.

Now go have a snack. Your bacteria are getting restless.

The very hangry iguana?

Imagine yourself on a warm, sunny tropical beach. You are enjoying a piece of cake as you take in the slow beat of the waves lapping against the shore. Life is as good as it could be.

Then you feel a presence nearby. Hostility. Hunger. A set of feral, covetous eyes in the nearby jungle. A reptilian beast stalks you, and its all-encompassing sweet tooth desires your cake.

Wait, hold on, what?

As an unfortunate 3-year-old on vacation in Costa Rica found out, there’s at least one iguana in the world out there with a taste for sugar (better than a taste for blood, we suppose).

While out on the beach, the lizard darted out of nowhere, bit the girl on the back of the hand, and stole her cake. Still not the worst party guest ever. The child was taken to a local clinic, where the wound was cleaned and a 5-day antibiotic treatment (lizards carry salmonella) was provided. Things seemed fine, and the girl returned home without incident.

But of course, that’s not the end of the story. Five months later, the girl’s parents noticed a red bump at the wound site. Over the next 3 months, the surrounding skin grew red and painful. A trip to the hospital in California revealed that she had a ganglion cyst and a discharge of pus. Turns out our cake-obsessed lizard friend did give the little girl a gift: the first known human case of Mycobacterium marinum infection following an iguana bite on record.

M. marinum, which causes a disease similar to tuberculosis, typically infects fish but can infect humans if skin wounds are exposed to contaminated water. It’s also resistant to most antibiotics, which is why the first round didn’t clear up the infection. A second round of more-potent antibiotics seems to be working well.

So, to sum up, this poor child got bitten by a lizard, had her cake stolen, and contracted a rare illness in exchange. For a 3-year-old, that’s gotta be in the top-10 worst days ever. Unless, of course, we’re actually living in the Marvel universe (sorry, multiverse at this point). Then we’re totally going to see the emergence of the new superhero Iguana Girl in 15 years or so. Keep your eyes open.

No allergies? Let them give up cake

Allergy season is already here – starting earlier every year, it seems – and many people are not happy about it. So unhappy, actually, that there’s a list of things they would be willing to give up for a year to get rid of their of allergies, according to a survey conducted by OnePoll on behalf of Flonase.

Nearly 40% of 2,000 respondents with allergies would go a year without eating cake or chocolate or playing video games in exchange for allergy-free status, the survey results show. Almost as many would forgo coffee (38%) or pizza (37%) for a year, while 36% would stay off social media and 31% would take a pay cut or give up their smartphones, the Independent reported.

More than half of the allergic Americans – 54%, to be exact – who were polled this past winter – Feb. 24 to March 1, to be exact – consider allergy symptoms to be the most frustrating part of the spring. Annoying things that were less frustrating to the group included mosquitoes (41%), filing tax returns (38%), and daylight savings time (37%).

The Trump arraignment circus, of course, occurred too late to make the list, as did the big “We’re going back to the office! No wait, we’re closing the office forever!” email extravaganza and emotional roller coaster. That second one, however, did not get nearly as much media coverage.

A whole new, tiny level of hangry

Ever been so hungry that everything just got on your nerves? Maybe you feel a little snappy right now? Like you’ll just lash out unless you get something to eat? Been there. And so have bacteria.

New research shows that some bacteria go into a full-on Hulk smash if they’re not getting the nutrients they need by releasing toxins into the body. Sounds like a bacterial temper tantrum.

Even though two cells may be genetically identical, they don’t always behave the same in a bacterial community. Some do their job and stay in line, but some evil twins rage out and make people sick by releasing toxins into the environment, Adam Rosenthal, PhD, of the University of North Carolina and his colleagues discovered.

To figure out why some cells were all business as usual while others were not, the investigators looked at Clostridium perfringens, a bacterium found in the intestines of humans and other vertebrates. When the C. perfringens cells were fed a little acetate to munch on, the hangry cells calmed down faster than a kid with a bag of fruit snacks, reducing toxin levels. Some cells even disappeared, falling in line with their model-citizen counterparts.

So what does this really mean? More research, duh. Now that we know nutrients play a role in toxicity, it may open the door to finding a way to fight against antibiotic resistance in humans and reduce antibiotic use in the food industry.

So think to yourself. Are you bothered for no reason? Getting a little testy with your friends and coworkers? Maybe you just haven’t eaten in a while. You’re literally not alone. Even a single-cell organism can behave based on its hunger levels.

Now go have a snack. Your bacteria are getting restless.

The very hangry iguana?

Imagine yourself on a warm, sunny tropical beach. You are enjoying a piece of cake as you take in the slow beat of the waves lapping against the shore. Life is as good as it could be.

Then you feel a presence nearby. Hostility. Hunger. A set of feral, covetous eyes in the nearby jungle. A reptilian beast stalks you, and its all-encompassing sweet tooth desires your cake.

Wait, hold on, what?

As an unfortunate 3-year-old on vacation in Costa Rica found out, there’s at least one iguana in the world out there with a taste for sugar (better than a taste for blood, we suppose).

While out on the beach, the lizard darted out of nowhere, bit the girl on the back of the hand, and stole her cake. Still not the worst party guest ever. The child was taken to a local clinic, where the wound was cleaned and a 5-day antibiotic treatment (lizards carry salmonella) was provided. Things seemed fine, and the girl returned home without incident.

But of course, that’s not the end of the story. Five months later, the girl’s parents noticed a red bump at the wound site. Over the next 3 months, the surrounding skin grew red and painful. A trip to the hospital in California revealed that she had a ganglion cyst and a discharge of pus. Turns out our cake-obsessed lizard friend did give the little girl a gift: the first known human case of Mycobacterium marinum infection following an iguana bite on record.

M. marinum, which causes a disease similar to tuberculosis, typically infects fish but can infect humans if skin wounds are exposed to contaminated water. It’s also resistant to most antibiotics, which is why the first round didn’t clear up the infection. A second round of more-potent antibiotics seems to be working well.

So, to sum up, this poor child got bitten by a lizard, had her cake stolen, and contracted a rare illness in exchange. For a 3-year-old, that’s gotta be in the top-10 worst days ever. Unless, of course, we’re actually living in the Marvel universe (sorry, multiverse at this point). Then we’re totally going to see the emergence of the new superhero Iguana Girl in 15 years or so. Keep your eyes open.

No allergies? Let them give up cake

Allergy season is already here – starting earlier every year, it seems – and many people are not happy about it. So unhappy, actually, that there’s a list of things they would be willing to give up for a year to get rid of their of allergies, according to a survey conducted by OnePoll on behalf of Flonase.

Nearly 40% of 2,000 respondents with allergies would go a year without eating cake or chocolate or playing video games in exchange for allergy-free status, the survey results show. Almost as many would forgo coffee (38%) or pizza (37%) for a year, while 36% would stay off social media and 31% would take a pay cut or give up their smartphones, the Independent reported.

More than half of the allergic Americans – 54%, to be exact – who were polled this past winter – Feb. 24 to March 1, to be exact – consider allergy symptoms to be the most frustrating part of the spring. Annoying things that were less frustrating to the group included mosquitoes (41%), filing tax returns (38%), and daylight savings time (37%).

The Trump arraignment circus, of course, occurred too late to make the list, as did the big “We’re going back to the office! No wait, we’re closing the office forever!” email extravaganza and emotional roller coaster. That second one, however, did not get nearly as much media coverage.

SBRT: Alternative to surgery in early stage lung cancer?

, according to population-based data from a German cancer registry.

“From a public health perspective, SBRT is a good therapeutic option in terms of survival, especially for elderly and inoperable patients,” noted the study authors, led by Jörg Andreas Müller, MD, department of radiation oncology, University Hospital of Halle, Germany.

The analysis was published online in the journal Strahlentherapie Und Onkologie.

Surgery remains the standard of care for early stage NSCLC. However, many patients are not eligible for surgery because of the tumor’s location, age, frailty, or comorbidities.

Before the introduction of SBRT, conventional radiation therapy was the only reasonable option for inoperable patients, with study data showing only a small survival improvement in treated vs. untreated patients.

High-precision, image-guided SBRT offers better tumor control with limited toxicity. And while many radiation oncology centers in Germany adopted SBRT as an alternative treatment for surgery after 2000, few population-based studies evaluating SBRT’s impact on overall survival exist.

Using the German clinical cancer registry of Berlin-Brandenburg, Dr. Müller and colleagues assessed SBRT as an alternative to surgery in 558 patients with stage I and II NSCLC, diagnosed between 2000 and 2015.

More patients received surgery than SBRT (74% vs. 26%). Those who received SBRT were younger than those in the surgery group and had better Karnofsky performance status.

Among patients in the SBRT group, median survival was 19 months overall and 27 months in patients over age 75. In the surgery group, median survival was 22 months overall and 24 months in those over 75.

In a univariate survival model of a propensity-matched sample of 292 patients – half of whom received SBRT – survival rates were similar among those who underwent SBRT versus surgery (hazard ratio [HR], 1.2; P = .2).

Survival was also similar in the two treatment groups in a T1 subanalysis (HR, 1.12; P = .7) as well as in patients over age 75 (HR, 0.86; P = .5).

Better performance status scores were associated with improved survival, and higher histological grades and TNM stages were linked to higher mortality risk. The availability of histological data did not have a significant impact on survival outcomes.

Overall, the findings suggest that SBRT and surgery offer comparable survival outcomes in early stage NSCLC and “the availability of histological data might not be decisive for treatment planning,” Dr. Müller and colleagues said.

Drew Moghanaki, MD, chief of the thoracic oncology service at UCLA Health Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center, Los Angeles, highlighted the findings on Twitter.

A thoracic surgeon from Germany responded with several concerns about the study, including the use of statistics with univariate modeling and undiagnosed lymph node (N) status.

Dr. Moghanaki replied that these “concerns summarize how we USED to think. It increasingly seems they aren’t as important as our teachers once thought they were. As we move into the future we need to reassess the data that supported these recommendations as they seem more academic than patient centered.”

The study authors reported no specific funding, and no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, according to population-based data from a German cancer registry.

“From a public health perspective, SBRT is a good therapeutic option in terms of survival, especially for elderly and inoperable patients,” noted the study authors, led by Jörg Andreas Müller, MD, department of radiation oncology, University Hospital of Halle, Germany.

The analysis was published online in the journal Strahlentherapie Und Onkologie.

Surgery remains the standard of care for early stage NSCLC. However, many patients are not eligible for surgery because of the tumor’s location, age, frailty, or comorbidities.

Before the introduction of SBRT, conventional radiation therapy was the only reasonable option for inoperable patients, with study data showing only a small survival improvement in treated vs. untreated patients.

High-precision, image-guided SBRT offers better tumor control with limited toxicity. And while many radiation oncology centers in Germany adopted SBRT as an alternative treatment for surgery after 2000, few population-based studies evaluating SBRT’s impact on overall survival exist.

Using the German clinical cancer registry of Berlin-Brandenburg, Dr. Müller and colleagues assessed SBRT as an alternative to surgery in 558 patients with stage I and II NSCLC, diagnosed between 2000 and 2015.

More patients received surgery than SBRT (74% vs. 26%). Those who received SBRT were younger than those in the surgery group and had better Karnofsky performance status.

Among patients in the SBRT group, median survival was 19 months overall and 27 months in patients over age 75. In the surgery group, median survival was 22 months overall and 24 months in those over 75.

In a univariate survival model of a propensity-matched sample of 292 patients – half of whom received SBRT – survival rates were similar among those who underwent SBRT versus surgery (hazard ratio [HR], 1.2; P = .2).

Survival was also similar in the two treatment groups in a T1 subanalysis (HR, 1.12; P = .7) as well as in patients over age 75 (HR, 0.86; P = .5).

Better performance status scores were associated with improved survival, and higher histological grades and TNM stages were linked to higher mortality risk. The availability of histological data did not have a significant impact on survival outcomes.

Overall, the findings suggest that SBRT and surgery offer comparable survival outcomes in early stage NSCLC and “the availability of histological data might not be decisive for treatment planning,” Dr. Müller and colleagues said.

Drew Moghanaki, MD, chief of the thoracic oncology service at UCLA Health Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center, Los Angeles, highlighted the findings on Twitter.

A thoracic surgeon from Germany responded with several concerns about the study, including the use of statistics with univariate modeling and undiagnosed lymph node (N) status.

Dr. Moghanaki replied that these “concerns summarize how we USED to think. It increasingly seems they aren’t as important as our teachers once thought they were. As we move into the future we need to reassess the data that supported these recommendations as they seem more academic than patient centered.”

The study authors reported no specific funding, and no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, according to population-based data from a German cancer registry.

“From a public health perspective, SBRT is a good therapeutic option in terms of survival, especially for elderly and inoperable patients,” noted the study authors, led by Jörg Andreas Müller, MD, department of radiation oncology, University Hospital of Halle, Germany.

The analysis was published online in the journal Strahlentherapie Und Onkologie.

Surgery remains the standard of care for early stage NSCLC. However, many patients are not eligible for surgery because of the tumor’s location, age, frailty, or comorbidities.

Before the introduction of SBRT, conventional radiation therapy was the only reasonable option for inoperable patients, with study data showing only a small survival improvement in treated vs. untreated patients.

High-precision, image-guided SBRT offers better tumor control with limited toxicity. And while many radiation oncology centers in Germany adopted SBRT as an alternative treatment for surgery after 2000, few population-based studies evaluating SBRT’s impact on overall survival exist.

Using the German clinical cancer registry of Berlin-Brandenburg, Dr. Müller and colleagues assessed SBRT as an alternative to surgery in 558 patients with stage I and II NSCLC, diagnosed between 2000 and 2015.

More patients received surgery than SBRT (74% vs. 26%). Those who received SBRT were younger than those in the surgery group and had better Karnofsky performance status.

Among patients in the SBRT group, median survival was 19 months overall and 27 months in patients over age 75. In the surgery group, median survival was 22 months overall and 24 months in those over 75.

In a univariate survival model of a propensity-matched sample of 292 patients – half of whom received SBRT – survival rates were similar among those who underwent SBRT versus surgery (hazard ratio [HR], 1.2; P = .2).

Survival was also similar in the two treatment groups in a T1 subanalysis (HR, 1.12; P = .7) as well as in patients over age 75 (HR, 0.86; P = .5).

Better performance status scores were associated with improved survival, and higher histological grades and TNM stages were linked to higher mortality risk. The availability of histological data did not have a significant impact on survival outcomes.

Overall, the findings suggest that SBRT and surgery offer comparable survival outcomes in early stage NSCLC and “the availability of histological data might not be decisive for treatment planning,” Dr. Müller and colleagues said.

Drew Moghanaki, MD, chief of the thoracic oncology service at UCLA Health Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center, Los Angeles, highlighted the findings on Twitter.

A thoracic surgeon from Germany responded with several concerns about the study, including the use of statistics with univariate modeling and undiagnosed lymph node (N) status.

Dr. Moghanaki replied that these “concerns summarize how we USED to think. It increasingly seems they aren’t as important as our teachers once thought they were. As we move into the future we need to reassess the data that supported these recommendations as they seem more academic than patient centered.”

The study authors reported no specific funding, and no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM STRAHLENTHERAPIE UND ONKOLOGIE

‘Excess’ deaths surging, but why?

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

“Excess deaths.” You’ve heard the phrase countless times by now. It is one of the myriad of previously esoteric epidemiology terms that the pandemic brought squarely into the zeitgeist.

As a sort of standard candle of the performance of a state or a region or a country in terms of health care, it has a lot of utility – if for nothing more than Monday-morning quarterbacking. But this week, I want to dig in on the concept a bit because, according to a new study, the excess death gap between the United States and Western Europe has never been higher.

You might imagine that the best way to figure this out is for some group of intelligent people to review each death and decide, somehow, whether it was expected or not. But aside from being impractical, this would end up being somewhat subjective. That older person who died from pneumonia – was that an expected death? Could it have been avoided?

Rather, the calculation of excess mortality relies on large numbers and statistical inference to compare an expected number of deaths with those that are observed.

The difference is excess mortality, even if you can never be sure whether any particular death was expected or not.

As always, however, the devil is in the details. What data do you use to define the expected number of deaths?

There are options here. Probably the most straightforward analysis uses past data from the country of interest. You look at annual deaths over some historical period of time and compare those numbers with the rates today. Two issues need to be accounted for here: population growth – a larger population will have more deaths, so you need to adjust the historical population with current levels, and demographic shifts – an older or more male population will have more deaths, so you need to adjust for that as well.

But provided you take care of those factors, you can estimate fairly well how many deaths you can expect to see in any given period of time.

Still, you should see right away that excess mortality is a relative concept. If you think that, just perhaps, the United States has some systematic failure to deliver care that has been stable and persistent over time, you wouldn’t capture that failing in an excess mortality calculation that uses U.S. historical data as the baseline.

The best way to get around that is to use data from other countries, and that’s just what this article – a rare single-author piece by Patrick Heuveline – does, calculating excess deaths in the United States by standardizing our mortality rates to the five largest Western European countries: the United Kingdom, France, Germany, Italy, and Spain.

Controlling for the differences in the demographics of that European population, here is the expected number of deaths in the United States over the past 5 years.

Note that there is a small uptick in expected deaths in 2020, reflecting the pandemic, which returns to baseline levels by 2021. This is because that’s what happened in Europe; by 2021, the excess mortality due to COVID-19 was quite low.

Here are the actual deaths in the US during that time.

Highlighted here in green, then, is the excess mortality over time in the United States.

There are some fascinating and concerning findings here.

First of all, you can see that even before the pandemic, the United States has an excess mortality problem. This is not entirely a surprise; we’ve known that so-called “deaths of despair,” those due to alcohol abuse, drug overdoses, and suicide, are at an all-time high and tend to affect a “prime of life” population that would not otherwise be expected to die. In fact, fully 50% of the excess deaths in the United States occur in those between ages 15 and 64.

Excess deaths are also a concerning percentage of total deaths. In 2017, 17% of total deaths in the United States could be considered “excess.” In 2021, that number had doubled to 35%. Nearly 900,000 individuals in the United States died in 2021 who perhaps didn’t need to.

The obvious culprit to blame here is COVID, but COVID-associated excess deaths only explain about 50% of the excess we see in 2021. The rest reflect something even more concerning: a worsening of the failures of the past, perhaps exacerbated by the pandemic but not due to the virus itself.

Of course, we started this discussion acknowledging that the calculation of excess mortality is exquisitely dependent on how you model the expected number of deaths, and I’m sure some will take issue with the use of European numbers when applied to Americans. After all, Europe has, by and large, a robust public health service, socialized medicine, and healthcare that does not run the risk of bankrupting its citizens. How can we compare our outcomes to a place like that?

How indeed.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and director of Yale University’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator in New Haven,Conn. He reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

“Excess deaths.” You’ve heard the phrase countless times by now. It is one of the myriad of previously esoteric epidemiology terms that the pandemic brought squarely into the zeitgeist.

As a sort of standard candle of the performance of a state or a region or a country in terms of health care, it has a lot of utility – if for nothing more than Monday-morning quarterbacking. But this week, I want to dig in on the concept a bit because, according to a new study, the excess death gap between the United States and Western Europe has never been higher.

You might imagine that the best way to figure this out is for some group of intelligent people to review each death and decide, somehow, whether it was expected or not. But aside from being impractical, this would end up being somewhat subjective. That older person who died from pneumonia – was that an expected death? Could it have been avoided?

Rather, the calculation of excess mortality relies on large numbers and statistical inference to compare an expected number of deaths with those that are observed.

The difference is excess mortality, even if you can never be sure whether any particular death was expected or not.

As always, however, the devil is in the details. What data do you use to define the expected number of deaths?

There are options here. Probably the most straightforward analysis uses past data from the country of interest. You look at annual deaths over some historical period of time and compare those numbers with the rates today. Two issues need to be accounted for here: population growth – a larger population will have more deaths, so you need to adjust the historical population with current levels, and demographic shifts – an older or more male population will have more deaths, so you need to adjust for that as well.

But provided you take care of those factors, you can estimate fairly well how many deaths you can expect to see in any given period of time.

Still, you should see right away that excess mortality is a relative concept. If you think that, just perhaps, the United States has some systematic failure to deliver care that has been stable and persistent over time, you wouldn’t capture that failing in an excess mortality calculation that uses U.S. historical data as the baseline.

The best way to get around that is to use data from other countries, and that’s just what this article – a rare single-author piece by Patrick Heuveline – does, calculating excess deaths in the United States by standardizing our mortality rates to the five largest Western European countries: the United Kingdom, France, Germany, Italy, and Spain.

Controlling for the differences in the demographics of that European population, here is the expected number of deaths in the United States over the past 5 years.

Note that there is a small uptick in expected deaths in 2020, reflecting the pandemic, which returns to baseline levels by 2021. This is because that’s what happened in Europe; by 2021, the excess mortality due to COVID-19 was quite low.

Here are the actual deaths in the US during that time.

Highlighted here in green, then, is the excess mortality over time in the United States.

There are some fascinating and concerning findings here.

First of all, you can see that even before the pandemic, the United States has an excess mortality problem. This is not entirely a surprise; we’ve known that so-called “deaths of despair,” those due to alcohol abuse, drug overdoses, and suicide, are at an all-time high and tend to affect a “prime of life” population that would not otherwise be expected to die. In fact, fully 50% of the excess deaths in the United States occur in those between ages 15 and 64.

Excess deaths are also a concerning percentage of total deaths. In 2017, 17% of total deaths in the United States could be considered “excess.” In 2021, that number had doubled to 35%. Nearly 900,000 individuals in the United States died in 2021 who perhaps didn’t need to.

The obvious culprit to blame here is COVID, but COVID-associated excess deaths only explain about 50% of the excess we see in 2021. The rest reflect something even more concerning: a worsening of the failures of the past, perhaps exacerbated by the pandemic but not due to the virus itself.

Of course, we started this discussion acknowledging that the calculation of excess mortality is exquisitely dependent on how you model the expected number of deaths, and I’m sure some will take issue with the use of European numbers when applied to Americans. After all, Europe has, by and large, a robust public health service, socialized medicine, and healthcare that does not run the risk of bankrupting its citizens. How can we compare our outcomes to a place like that?

How indeed.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and director of Yale University’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator in New Haven,Conn. He reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

“Excess deaths.” You’ve heard the phrase countless times by now. It is one of the myriad of previously esoteric epidemiology terms that the pandemic brought squarely into the zeitgeist.

As a sort of standard candle of the performance of a state or a region or a country in terms of health care, it has a lot of utility – if for nothing more than Monday-morning quarterbacking. But this week, I want to dig in on the concept a bit because, according to a new study, the excess death gap between the United States and Western Europe has never been higher.

You might imagine that the best way to figure this out is for some group of intelligent people to review each death and decide, somehow, whether it was expected or not. But aside from being impractical, this would end up being somewhat subjective. That older person who died from pneumonia – was that an expected death? Could it have been avoided?

Rather, the calculation of excess mortality relies on large numbers and statistical inference to compare an expected number of deaths with those that are observed.

The difference is excess mortality, even if you can never be sure whether any particular death was expected or not.

As always, however, the devil is in the details. What data do you use to define the expected number of deaths?

There are options here. Probably the most straightforward analysis uses past data from the country of interest. You look at annual deaths over some historical period of time and compare those numbers with the rates today. Two issues need to be accounted for here: population growth – a larger population will have more deaths, so you need to adjust the historical population with current levels, and demographic shifts – an older or more male population will have more deaths, so you need to adjust for that as well.

But provided you take care of those factors, you can estimate fairly well how many deaths you can expect to see in any given period of time.

Still, you should see right away that excess mortality is a relative concept. If you think that, just perhaps, the United States has some systematic failure to deliver care that has been stable and persistent over time, you wouldn’t capture that failing in an excess mortality calculation that uses U.S. historical data as the baseline.

The best way to get around that is to use data from other countries, and that’s just what this article – a rare single-author piece by Patrick Heuveline – does, calculating excess deaths in the United States by standardizing our mortality rates to the five largest Western European countries: the United Kingdom, France, Germany, Italy, and Spain.

Controlling for the differences in the demographics of that European population, here is the expected number of deaths in the United States over the past 5 years.

Note that there is a small uptick in expected deaths in 2020, reflecting the pandemic, which returns to baseline levels by 2021. This is because that’s what happened in Europe; by 2021, the excess mortality due to COVID-19 was quite low.

Here are the actual deaths in the US during that time.

Highlighted here in green, then, is the excess mortality over time in the United States.

There are some fascinating and concerning findings here.

First of all, you can see that even before the pandemic, the United States has an excess mortality problem. This is not entirely a surprise; we’ve known that so-called “deaths of despair,” those due to alcohol abuse, drug overdoses, and suicide, are at an all-time high and tend to affect a “prime of life” population that would not otherwise be expected to die. In fact, fully 50% of the excess deaths in the United States occur in those between ages 15 and 64.

Excess deaths are also a concerning percentage of total deaths. In 2017, 17% of total deaths in the United States could be considered “excess.” In 2021, that number had doubled to 35%. Nearly 900,000 individuals in the United States died in 2021 who perhaps didn’t need to.

The obvious culprit to blame here is COVID, but COVID-associated excess deaths only explain about 50% of the excess we see in 2021. The rest reflect something even more concerning: a worsening of the failures of the past, perhaps exacerbated by the pandemic but not due to the virus itself.

Of course, we started this discussion acknowledging that the calculation of excess mortality is exquisitely dependent on how you model the expected number of deaths, and I’m sure some will take issue with the use of European numbers when applied to Americans. After all, Europe has, by and large, a robust public health service, socialized medicine, and healthcare that does not run the risk of bankrupting its citizens. How can we compare our outcomes to a place like that?

How indeed.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and director of Yale University’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator in New Haven,Conn. He reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Sweaty treatment for social anxiety could pass the sniff test

Getting sweet on sweat

Are you the sort of person who struggles in social situations? Have the past 3 years been a secret respite from the terror and exhaustion of meeting new people? We understand your plight. People kind of suck. And you don’t have to look far to be reminded of it.

Unfortunately, on occasion we all have to interact with other human beings. If you suffer from social anxiety, this is not a fun thing to do. But new research indicates that there may be a way to alleviate the stress for those with social anxiety: armpits.

Specifically, sweat from the armpits of other people. Yes, this means a group of scientists gathered up some volunteers and collected their armpit sweat while the volunteers watched a variety of movies (horror, comedy, romance, etc.). Our condolences to the poor unpaid interns tasked with gathering the sweat.

Once they had their precious new medicine, the researchers took a group of women and administered a round of mindfulness therapy. Some of the participants then received the various sweats, while the rest were forced to smell only clean air. (The horror!) Lo and behold, the sweat groups had their anxiety scores reduced by about 40% after their therapy, compared with just 17% in the control group.

The researchers also found that the source of the sweat didn’t matter. Their study subjects responded the same to sweat excreted during a scary movie as they did to sweat from a comedy, a result that surprised the researchers. They suggested chemosignals in the sweat may affect the treatment response and advised further research. Which means more sweat collection! They plan on testing emotionally neutral movies next time, and if we can make a humble suggestion, they also should try the sweatiest movies.

Before the Food and Drug Administration can approve armpit sweat as a treatment for social anxiety, we have some advice for those shut-in introverts out there. Next time you have to interact with rabid extroverts, instead of shaking their hands, walk up to them and take a deep whiff of their armpits. Establish dominance. Someone will feel awkward, and science has proved it won’t be you.

The puff that vaccinates

Ever been shot with a Nerf gun or hit with a foam pool tube? More annoying than painful, right? If we asked if you’d rather get pelted with one of those than receive a traditional vaccine injection, you would choose the former. Maybe someday you actually will.

During the boredom of the early pandemic lockdown, Jeremiah Gassensmith, PhD, of the department of chemistry and biochemistry at the University of Texas, Dallas, ordered a compressed gas–powered jet injection system to fool around with at home. Hey, who didn’t? Anyway, when it was time to go back to the lab he handed it over to one of his grad students, Yalini Wijesundara, and asked her to see what could be done with it.

In her tinkering she found that the jet injector could deliver metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) that can hold a bunch of different materials, like proteins and nucleic acids, through the skin.

Thus the “MOF-Jet” was born!

Jet injectors are nothing new, but they hurt. The MOF-Jet, however, is practically painless and cheaper than the gene guns that veterinarians use to inject biological cargo attached to the surface of a metal microparticle.

Changing the carrier gas also changes the time needed to break down the MOF and thus alters delivery of the drug inside. “If you shoot it with carbon dioxide, it will release its cargo faster within cells; if you use regular air, it will take 4 or 5 days,” Ms. Wijesundara explained in a written statement. That means the same drug could be released over different timescales without changing its formulation.

While testing on onion cells and mice, Ms. Wijesundara noted that it was as easy as “pointing and shooting” to distribute the puff of gas into the cells. A saving grace to those with needle anxiety. Not that we would know anything about needle anxiety.

More testing needs to be done before bringing this technology to human use, obviously, but we’re looking forward to saying goodbye to that dreaded prick and hello to a puff.

Your hippocampus is showing

Brain anatomy is one of the many, many things that’s not really our thing, but we do know a cool picture when we see one. Case in point: The image just below, which happens to be a full-scale, single-cell resolution model of the CA1 region of the hippocampus that “replicates the structure and architecture of the area, along with the position and relative connectivity of the neurons,” according to a statement from the Human Brain Project.

“We have performed a data mining operation on high resolution images of the human hippocampus, obtained from the BigBrain database. The position of individual neurons has been derived from a detailed analysis of these images,” said senior author Michele Migliore, PhD, of the Italian National Research Council’s Institute of Biophysics in Palermo.

Yes, he did say BigBrain database. BigBrain is – we checked and it’s definitely not this – a 3D model of a brain that was sectioned into 7,404 slices just 20 micrometers thick and then scanned by MRI. Digital reconstruction of those slices was done by supercomputer and the results are now available for analysis.

Dr. Migliore and his associates developed an image-processing algorithm to obtain neuronal positioning distribution and an algorithm to generate neuronal connectivity by approximating the shapes of dendrites and axons. (Our brains are starting to hurt just trying to write this.) “Some fit into narrow cones, others have a broad complex extension that can be approximated by dedicated geometrical volumes, and the connectivity to nearby neurons changes accordingly,” explained lead author Daniela Gandolfi of the University of Modena (Italy) and Reggio Emilia.

The investigators have made their dataset and the extraction methodology available on the EBRAINS platform and through the Human Brain Project and are moving on to other brain regions. And then, once everyone can find their way in and around the old gray matter, it should bring an end to conversations like this, which no doubt occur between male and female neuroscientists every day:

“Arnold, I think we’re lost.”

“Don’t worry, Bev, I know where I’m going.”

“Stop and ask this lady for directions.”

“I said I can find it.”

“Just ask her.”

“Fine. Excuse me, ma’am, can you tell us how to get to the corpora quadrigemina from here?

Getting sweet on sweat

Are you the sort of person who struggles in social situations? Have the past 3 years been a secret respite from the terror and exhaustion of meeting new people? We understand your plight. People kind of suck. And you don’t have to look far to be reminded of it.

Unfortunately, on occasion we all have to interact with other human beings. If you suffer from social anxiety, this is not a fun thing to do. But new research indicates that there may be a way to alleviate the stress for those with social anxiety: armpits.

Specifically, sweat from the armpits of other people. Yes, this means a group of scientists gathered up some volunteers and collected their armpit sweat while the volunteers watched a variety of movies (horror, comedy, romance, etc.). Our condolences to the poor unpaid interns tasked with gathering the sweat.

Once they had their precious new medicine, the researchers took a group of women and administered a round of mindfulness therapy. Some of the participants then received the various sweats, while the rest were forced to smell only clean air. (The horror!) Lo and behold, the sweat groups had their anxiety scores reduced by about 40% after their therapy, compared with just 17% in the control group.

The researchers also found that the source of the sweat didn’t matter. Their study subjects responded the same to sweat excreted during a scary movie as they did to sweat from a comedy, a result that surprised the researchers. They suggested chemosignals in the sweat may affect the treatment response and advised further research. Which means more sweat collection! They plan on testing emotionally neutral movies next time, and if we can make a humble suggestion, they also should try the sweatiest movies.

Before the Food and Drug Administration can approve armpit sweat as a treatment for social anxiety, we have some advice for those shut-in introverts out there. Next time you have to interact with rabid extroverts, instead of shaking their hands, walk up to them and take a deep whiff of their armpits. Establish dominance. Someone will feel awkward, and science has proved it won’t be you.

The puff that vaccinates