User login

Making one key connection may increase HPV vax uptake

The understanding that human papillomavirus (HPV) causes oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma (OPSCC) has been linked with increased likelihood of adults having been vaccinated for HPV, new research indicates.

In a study published online in JAMA Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery, most of the 288 adults surveyed with validated questions were not aware that HPV causes OPSCC and had not been told of the relationship by their health care provider.

Researchers found that when participants knew about the relationship between HPV infection and OPSCC they were more than three times as likely to be vaccinated (odds ratio, 3.7; 95% confidence interval, 1.8-7.6) as those without the knowledge.

The survey was paired with a novel point-of-care adult vaccination program within an otolaryngology clinic.

“Targeted education aimed at unvaccinated adults establishing the relationship between HPV infection and OPSCC, paired with point-of-care vaccination, may be an innovative strategy for increasing HPV vaccination rates in adults,” write the authors, led by Jacob C. Bloom, MD, with the department of otolaryngology–head and neck surgery at Boston Medical Center.

Current HPV vaccination recommendations include three parts:

- Routine vaccination at age 11 or 12 years

- Catch-up vaccination at ages 13-26 years if not adequately vaccinated

- Shared clinical decision-making in adults aged 27-45 years if the vaccine series has not been completed.

Despite proven efficacy and safety of the HPV vaccine, vaccination rates are low for adults. Although 75% of adolescents aged 13-17 years have initiated the HPV vaccine, recent studies show only 16% of U.S. men aged 18-21 years have received at least 1 dose of the HPV vaccine, the authors write.

Christiana Zhang, MD, with the division of internal medicine at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, who was not part of the study, said she was not surprised by the lack of knowledge about the HPV-OPSCC link.

Patients are often counseled on the relationship between HPV and genital warts or anogenital cancers like cervical cancer, she says, but there is less patient education surrounding the relationship between HPV and oropharyngeal cancers.

She says she does counsel patients on the link with OPSCC, but not all providers do and provider knowledge in general surrounding HPV is low.

“Research has shown that knowledge and confidence among health care providers surrounding HPV vaccination is generally low, and this corresponds with a low vaccination recommendation rate,” she says.

She adds, “Patient education on HPV infection and its relationship with OPSCC, paired with point-of-care vaccination for qualifying patients, is a great approach.”

But the education needs to go beyond patients, she says.

“Given the important role that health care providers play in vaccine uptake, I think further efforts are needed to educate providers on HPV vaccination as well,” she says.

The study included patients aged 18-45 years who sought routine outpatient care at the otolaryngology clinic at Boston Medical Center from Sept. 1, 2020, to May 19, 2021.

Limitations of this study include studying a population from a single otolaryngology clinic in an urban, academic medical center. The population was more racially and ethnically diverse than the U.S. population with 60.3% identifying as racial and ethnic minorities. Gender and educational levels were also not reflective of U.S. demographics as half (50.8%) of the participants had a college degree or higher and 58.3% were women.

Dr. Bloom reports grants from the American Head and Neck Cancer Society during the conduct of the study. Coauthor Dr. Faden reports personal fees from Merck, Neotic, Focus, BMS, Chrystalis Biomedical Advisors, and Guidepoint; receiving nonfinancial support from BostonGene and Predicine; and receiving grants from Calico outside the submitted work. Dr. Zhang reports no relevant financial relationships.

The understanding that human papillomavirus (HPV) causes oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma (OPSCC) has been linked with increased likelihood of adults having been vaccinated for HPV, new research indicates.

In a study published online in JAMA Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery, most of the 288 adults surveyed with validated questions were not aware that HPV causes OPSCC and had not been told of the relationship by their health care provider.

Researchers found that when participants knew about the relationship between HPV infection and OPSCC they were more than three times as likely to be vaccinated (odds ratio, 3.7; 95% confidence interval, 1.8-7.6) as those without the knowledge.

The survey was paired with a novel point-of-care adult vaccination program within an otolaryngology clinic.

“Targeted education aimed at unvaccinated adults establishing the relationship between HPV infection and OPSCC, paired with point-of-care vaccination, may be an innovative strategy for increasing HPV vaccination rates in adults,” write the authors, led by Jacob C. Bloom, MD, with the department of otolaryngology–head and neck surgery at Boston Medical Center.

Current HPV vaccination recommendations include three parts:

- Routine vaccination at age 11 or 12 years

- Catch-up vaccination at ages 13-26 years if not adequately vaccinated

- Shared clinical decision-making in adults aged 27-45 years if the vaccine series has not been completed.

Despite proven efficacy and safety of the HPV vaccine, vaccination rates are low for adults. Although 75% of adolescents aged 13-17 years have initiated the HPV vaccine, recent studies show only 16% of U.S. men aged 18-21 years have received at least 1 dose of the HPV vaccine, the authors write.

Christiana Zhang, MD, with the division of internal medicine at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, who was not part of the study, said she was not surprised by the lack of knowledge about the HPV-OPSCC link.

Patients are often counseled on the relationship between HPV and genital warts or anogenital cancers like cervical cancer, she says, but there is less patient education surrounding the relationship between HPV and oropharyngeal cancers.

She says she does counsel patients on the link with OPSCC, but not all providers do and provider knowledge in general surrounding HPV is low.

“Research has shown that knowledge and confidence among health care providers surrounding HPV vaccination is generally low, and this corresponds with a low vaccination recommendation rate,” she says.

She adds, “Patient education on HPV infection and its relationship with OPSCC, paired with point-of-care vaccination for qualifying patients, is a great approach.”

But the education needs to go beyond patients, she says.

“Given the important role that health care providers play in vaccine uptake, I think further efforts are needed to educate providers on HPV vaccination as well,” she says.

The study included patients aged 18-45 years who sought routine outpatient care at the otolaryngology clinic at Boston Medical Center from Sept. 1, 2020, to May 19, 2021.

Limitations of this study include studying a population from a single otolaryngology clinic in an urban, academic medical center. The population was more racially and ethnically diverse than the U.S. population with 60.3% identifying as racial and ethnic minorities. Gender and educational levels were also not reflective of U.S. demographics as half (50.8%) of the participants had a college degree or higher and 58.3% were women.

Dr. Bloom reports grants from the American Head and Neck Cancer Society during the conduct of the study. Coauthor Dr. Faden reports personal fees from Merck, Neotic, Focus, BMS, Chrystalis Biomedical Advisors, and Guidepoint; receiving nonfinancial support from BostonGene and Predicine; and receiving grants from Calico outside the submitted work. Dr. Zhang reports no relevant financial relationships.

The understanding that human papillomavirus (HPV) causes oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma (OPSCC) has been linked with increased likelihood of adults having been vaccinated for HPV, new research indicates.

In a study published online in JAMA Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery, most of the 288 adults surveyed with validated questions were not aware that HPV causes OPSCC and had not been told of the relationship by their health care provider.

Researchers found that when participants knew about the relationship between HPV infection and OPSCC they were more than three times as likely to be vaccinated (odds ratio, 3.7; 95% confidence interval, 1.8-7.6) as those without the knowledge.

The survey was paired with a novel point-of-care adult vaccination program within an otolaryngology clinic.

“Targeted education aimed at unvaccinated adults establishing the relationship between HPV infection and OPSCC, paired with point-of-care vaccination, may be an innovative strategy for increasing HPV vaccination rates in adults,” write the authors, led by Jacob C. Bloom, MD, with the department of otolaryngology–head and neck surgery at Boston Medical Center.

Current HPV vaccination recommendations include three parts:

- Routine vaccination at age 11 or 12 years

- Catch-up vaccination at ages 13-26 years if not adequately vaccinated

- Shared clinical decision-making in adults aged 27-45 years if the vaccine series has not been completed.

Despite proven efficacy and safety of the HPV vaccine, vaccination rates are low for adults. Although 75% of adolescents aged 13-17 years have initiated the HPV vaccine, recent studies show only 16% of U.S. men aged 18-21 years have received at least 1 dose of the HPV vaccine, the authors write.

Christiana Zhang, MD, with the division of internal medicine at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, who was not part of the study, said she was not surprised by the lack of knowledge about the HPV-OPSCC link.

Patients are often counseled on the relationship between HPV and genital warts or anogenital cancers like cervical cancer, she says, but there is less patient education surrounding the relationship between HPV and oropharyngeal cancers.

She says she does counsel patients on the link with OPSCC, but not all providers do and provider knowledge in general surrounding HPV is low.

“Research has shown that knowledge and confidence among health care providers surrounding HPV vaccination is generally low, and this corresponds with a low vaccination recommendation rate,” she says.

She adds, “Patient education on HPV infection and its relationship with OPSCC, paired with point-of-care vaccination for qualifying patients, is a great approach.”

But the education needs to go beyond patients, she says.

“Given the important role that health care providers play in vaccine uptake, I think further efforts are needed to educate providers on HPV vaccination as well,” she says.

The study included patients aged 18-45 years who sought routine outpatient care at the otolaryngology clinic at Boston Medical Center from Sept. 1, 2020, to May 19, 2021.

Limitations of this study include studying a population from a single otolaryngology clinic in an urban, academic medical center. The population was more racially and ethnically diverse than the U.S. population with 60.3% identifying as racial and ethnic minorities. Gender and educational levels were also not reflective of U.S. demographics as half (50.8%) of the participants had a college degree or higher and 58.3% were women.

Dr. Bloom reports grants from the American Head and Neck Cancer Society during the conduct of the study. Coauthor Dr. Faden reports personal fees from Merck, Neotic, Focus, BMS, Chrystalis Biomedical Advisors, and Guidepoint; receiving nonfinancial support from BostonGene and Predicine; and receiving grants from Calico outside the submitted work. Dr. Zhang reports no relevant financial relationships.

FROM JAMA OTOLARYNGOLOGY–HEAD AND NECK SURGERY

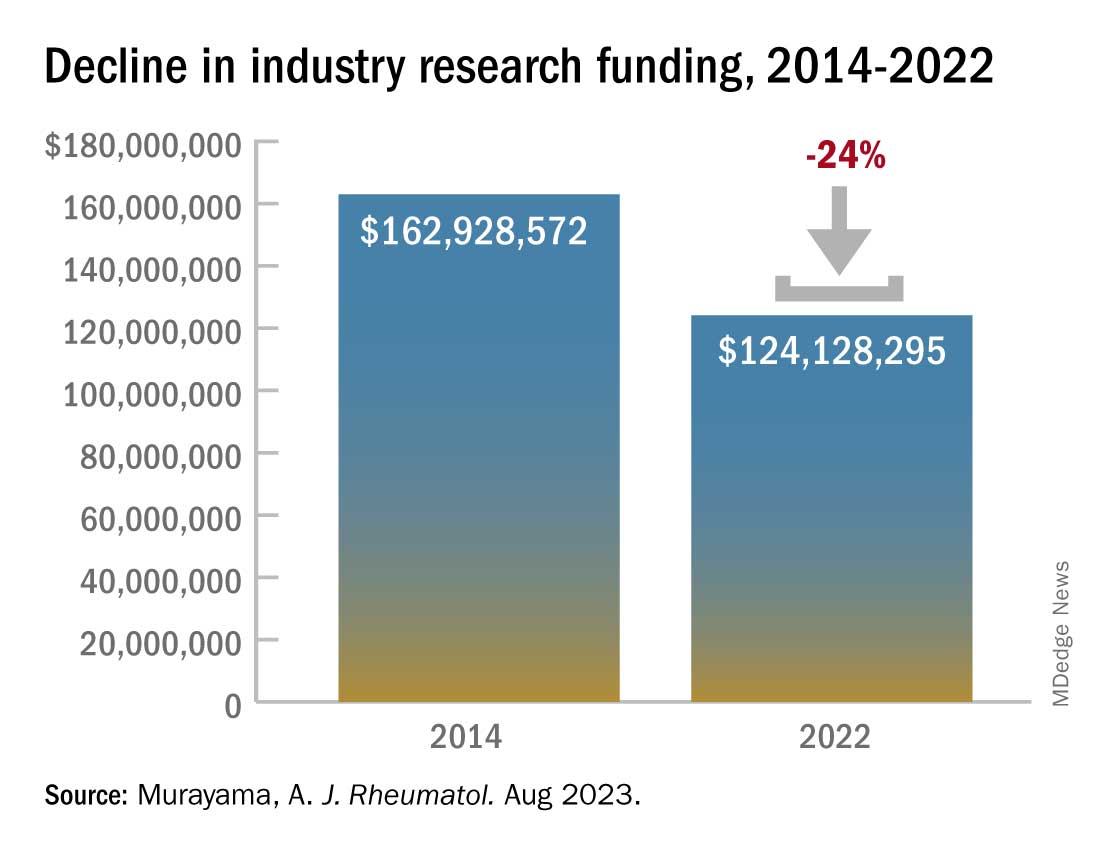

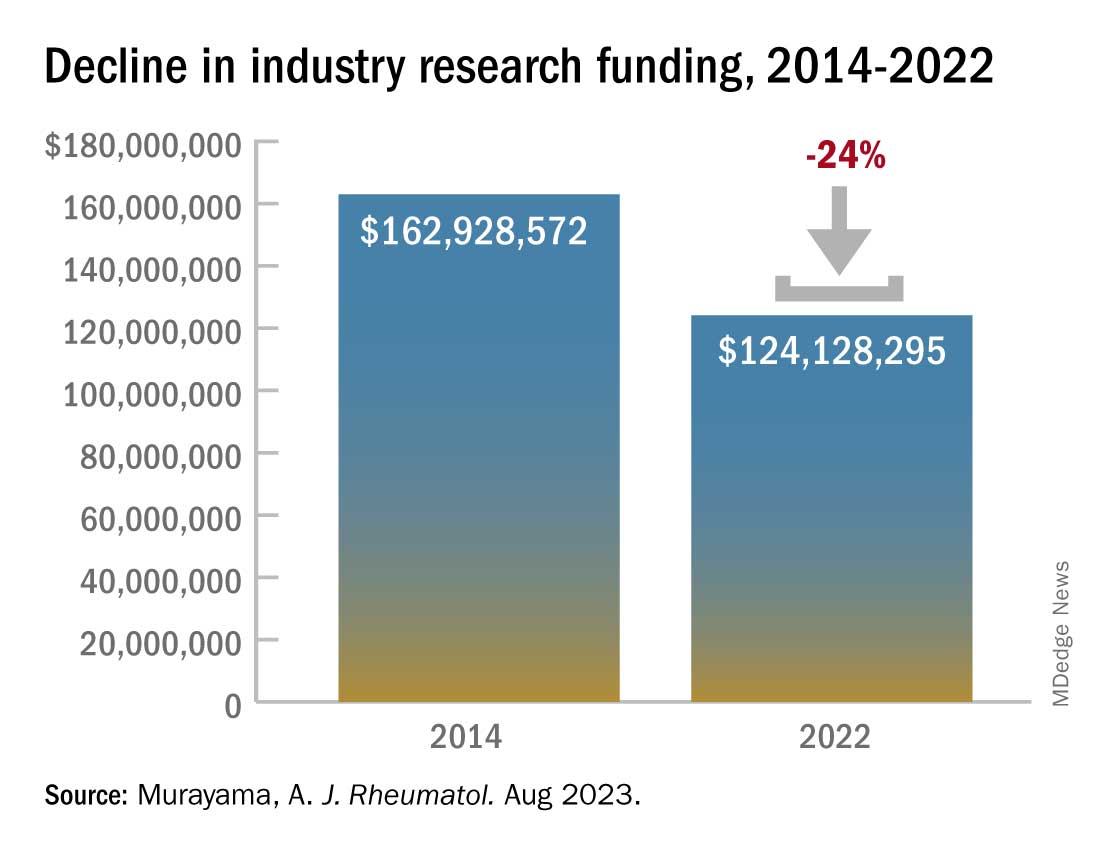

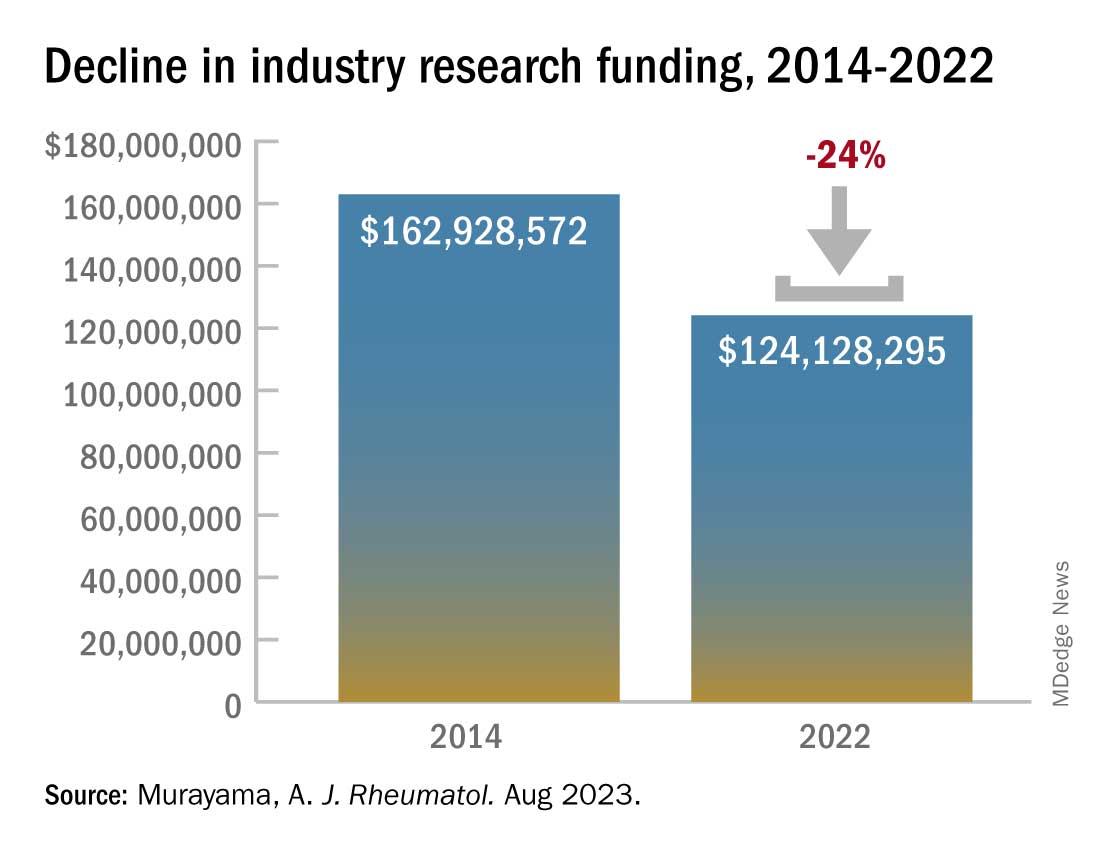

Industry funding falls for rheumatology research

Industry-sponsored research funding has fallen by more than 20% from 2014 to 2022, according to a new analysis.

“Despite the growing partnerships and networks between rheumatologists, the public sector, and the health care industry to optimize research funding allocations, the declining trend in industry-sponsored research payments is a concerning sign for all rheumatologists,” writes study author Anju Murayama, an undergraduate medical student at the Tohoku University School of Medicine in Sendai City, Japan. The data suggest that “more and more rheumatologists are facing difficulties in obtaining research funding from the health care industry.”

Dr. Murayama used the Open Payments Database, which contains records of payments made by drug and pharmaceutical companies to health care providers. The analysis included research payments provided directly to rheumatologists (direct-research payments) and payments given to clinicians or health care organizations related to research whose principal investigator was a rheumatologist (associated-research payments). These associated payments included costs for study enrollment and screening, safety monitoring committees, research publication, and more.

The research was published August 15 in The Journal of Rheumatology .

In 2014, the total direct payments to rheumatologists from industry were $1.4 million. These payments jumped to nearly $4.6 million in 2016 but have declined since. In 2022, there were $976,481 in total payments, a 31% drop from 9 years before.

This decline comes after an observed drop in research funding from the public sector. From 2014 to 2017, public-sector research funding to members of the American College of Rheumatology fell by 7.5%. Timothy Niewold, MD, a rheumatologist and vice chair for research in the department of medicine at Hospital for Special Surgery, New York, said that he and colleagues have felt the funding squeeze from both public and industry sectors. “The budgets for trials have seemed tight,” he told this news organization. With the overhead and cost of doing a trial at an academic institution like HSS, “sometimes you can’t make the budget work,” and researchers must pass on industry-funded trials.

The analysis also found a larger discrepancy between average and median associated-research payments. Of the $1.4 billion in associated-research payments combined over the 9-year period, the median payments per physician ($173,022) were much smaller than the mean payments ($989,753), which indicates that “only a very small number of rheumatologists received substantial amounts of research funding from the industry,” Dr. Murayama wrote in an email to this news organization. “This finding might support statements published by Scher and Schett in Nature Review Rheumatology suggesting that many industry-initiated clinical trials are conducted and authored by a small number of influential rheumatologists, often referred to as key opinion leaders.”

The analysis also found that of all associated payments, less than 3% ($39.2 million) went to funding preclinical research, which is “more disappointing than surprising,” Dr. Niewold said. Though clinical trials are expensive and require larger amounts of investment, industry partnerships at preclinical phases of research are important for devising novel solutions for these complex rheumatic diseases, he noted. “The clinical trials are one piece,” he added, “but you need the whole [research] continuum.”

Dr. Niewold reports receiving research grants from EMD Serono and Zenas Biopharma and consulting for Thermo Fisher Scientific, Progentec Diagnostics, Roivant Sciences, Ventus, S3 Connected Health, AstraZeneca, and Inova. Dr. Murayama reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Industry-sponsored research funding has fallen by more than 20% from 2014 to 2022, according to a new analysis.

“Despite the growing partnerships and networks between rheumatologists, the public sector, and the health care industry to optimize research funding allocations, the declining trend in industry-sponsored research payments is a concerning sign for all rheumatologists,” writes study author Anju Murayama, an undergraduate medical student at the Tohoku University School of Medicine in Sendai City, Japan. The data suggest that “more and more rheumatologists are facing difficulties in obtaining research funding from the health care industry.”

Dr. Murayama used the Open Payments Database, which contains records of payments made by drug and pharmaceutical companies to health care providers. The analysis included research payments provided directly to rheumatologists (direct-research payments) and payments given to clinicians or health care organizations related to research whose principal investigator was a rheumatologist (associated-research payments). These associated payments included costs for study enrollment and screening, safety monitoring committees, research publication, and more.

The research was published August 15 in The Journal of Rheumatology .

In 2014, the total direct payments to rheumatologists from industry were $1.4 million. These payments jumped to nearly $4.6 million in 2016 but have declined since. In 2022, there were $976,481 in total payments, a 31% drop from 9 years before.

This decline comes after an observed drop in research funding from the public sector. From 2014 to 2017, public-sector research funding to members of the American College of Rheumatology fell by 7.5%. Timothy Niewold, MD, a rheumatologist and vice chair for research in the department of medicine at Hospital for Special Surgery, New York, said that he and colleagues have felt the funding squeeze from both public and industry sectors. “The budgets for trials have seemed tight,” he told this news organization. With the overhead and cost of doing a trial at an academic institution like HSS, “sometimes you can’t make the budget work,” and researchers must pass on industry-funded trials.

The analysis also found a larger discrepancy between average and median associated-research payments. Of the $1.4 billion in associated-research payments combined over the 9-year period, the median payments per physician ($173,022) were much smaller than the mean payments ($989,753), which indicates that “only a very small number of rheumatologists received substantial amounts of research funding from the industry,” Dr. Murayama wrote in an email to this news organization. “This finding might support statements published by Scher and Schett in Nature Review Rheumatology suggesting that many industry-initiated clinical trials are conducted and authored by a small number of influential rheumatologists, often referred to as key opinion leaders.”

The analysis also found that of all associated payments, less than 3% ($39.2 million) went to funding preclinical research, which is “more disappointing than surprising,” Dr. Niewold said. Though clinical trials are expensive and require larger amounts of investment, industry partnerships at preclinical phases of research are important for devising novel solutions for these complex rheumatic diseases, he noted. “The clinical trials are one piece,” he added, “but you need the whole [research] continuum.”

Dr. Niewold reports receiving research grants from EMD Serono and Zenas Biopharma and consulting for Thermo Fisher Scientific, Progentec Diagnostics, Roivant Sciences, Ventus, S3 Connected Health, AstraZeneca, and Inova. Dr. Murayama reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Industry-sponsored research funding has fallen by more than 20% from 2014 to 2022, according to a new analysis.

“Despite the growing partnerships and networks between rheumatologists, the public sector, and the health care industry to optimize research funding allocations, the declining trend in industry-sponsored research payments is a concerning sign for all rheumatologists,” writes study author Anju Murayama, an undergraduate medical student at the Tohoku University School of Medicine in Sendai City, Japan. The data suggest that “more and more rheumatologists are facing difficulties in obtaining research funding from the health care industry.”

Dr. Murayama used the Open Payments Database, which contains records of payments made by drug and pharmaceutical companies to health care providers. The analysis included research payments provided directly to rheumatologists (direct-research payments) and payments given to clinicians or health care organizations related to research whose principal investigator was a rheumatologist (associated-research payments). These associated payments included costs for study enrollment and screening, safety monitoring committees, research publication, and more.

The research was published August 15 in The Journal of Rheumatology .

In 2014, the total direct payments to rheumatologists from industry were $1.4 million. These payments jumped to nearly $4.6 million in 2016 but have declined since. In 2022, there were $976,481 in total payments, a 31% drop from 9 years before.

This decline comes after an observed drop in research funding from the public sector. From 2014 to 2017, public-sector research funding to members of the American College of Rheumatology fell by 7.5%. Timothy Niewold, MD, a rheumatologist and vice chair for research in the department of medicine at Hospital for Special Surgery, New York, said that he and colleagues have felt the funding squeeze from both public and industry sectors. “The budgets for trials have seemed tight,” he told this news organization. With the overhead and cost of doing a trial at an academic institution like HSS, “sometimes you can’t make the budget work,” and researchers must pass on industry-funded trials.

The analysis also found a larger discrepancy between average and median associated-research payments. Of the $1.4 billion in associated-research payments combined over the 9-year period, the median payments per physician ($173,022) were much smaller than the mean payments ($989,753), which indicates that “only a very small number of rheumatologists received substantial amounts of research funding from the industry,” Dr. Murayama wrote in an email to this news organization. “This finding might support statements published by Scher and Schett in Nature Review Rheumatology suggesting that many industry-initiated clinical trials are conducted and authored by a small number of influential rheumatologists, often referred to as key opinion leaders.”

The analysis also found that of all associated payments, less than 3% ($39.2 million) went to funding preclinical research, which is “more disappointing than surprising,” Dr. Niewold said. Though clinical trials are expensive and require larger amounts of investment, industry partnerships at preclinical phases of research are important for devising novel solutions for these complex rheumatic diseases, he noted. “The clinical trials are one piece,” he added, “but you need the whole [research] continuum.”

Dr. Niewold reports receiving research grants from EMD Serono and Zenas Biopharma and consulting for Thermo Fisher Scientific, Progentec Diagnostics, Roivant Sciences, Ventus, S3 Connected Health, AstraZeneca, and Inova. Dr. Murayama reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF RHEUMATOLOGY

Medicare announces 10 drugs targeted for price cuts in 2026

People on Medicare may in 2026 see prices drop for 10 medicines, including pricey diabetes, cancer, blood clot, and arthritis treatments, if advocates for federal drug-price negotiations can implement their plans amid tough opposition.

It’s unclear at this time, though, how these negotiations will play out. The Chamber of Commerce has sided with pharmaceutical companies in bids to block direct Medicare negotiation of drug prices. Many influential Republicans in Congress oppose this plan, which has deep support from both Democrats and AARP.

While facing strong opposition to negotiations, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services sought in its announcement to illustrate the high costs of the selected medicines.

CMS provided data on total Part D costs for selected medicines for the period from June 2022 to May 2023, along with tallies of the number of people taking these drugs. The 10 selected medicines are as follows:

- Eliquis (generic name: apixaban), used to prevent and treat serious blood clots. It is taken by about 3.7 million people through Part D plans. The estimated cost is $16.4 billion.

- Jardiance (generic name: empagliflozin), used for diabetes and heart failure. It is taken by almost 1.6 million people through Part D plans. The estimated cost is $7.06 billion.

- Xarelto (generic name: rivaroxaban), used for blood clots. It is taken by about 1.3 million people through Part D plans. The estimated cost is $6 billion.

- Januvia (generic name: sitagliptin), used for diabetes. It is taken by about 869,00 people through Part D plans. The estimated cost is $4.1 billion.

- Farxiga (generic name: dapagliflozin), used for diabetes, heart failure, and chronic kidney disease. It is taken by about 799,000 people through Part D plans. The estimated cost is almost $3.3 billion.

- Entresto (generic name: sacubitril/valsartan), used to treat heart failure. It is taken by 587,000 people through Part D plans. The estimated cost is $2.9 billion.

- Enbrel( generic name: etanercept), used for rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis, and psoriatic arthritis. It is taken by 48,000 people through Part D plans. The estimated cost is $2.8 billion.

- Imbruvica (generic name: ibrutinib), used to treat some blood cancers. It is taken by about 20,000 people in Part D plans. The estimated cost is $2.7 billion.

- Stelara (generic name: ustekinumab), used to treat plaque psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, or certain bowel conditions (Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis). It is used by about 22,000 people through Part D plans. The estimated cost is $2.6 billion.

- Fiasp; Fiasp FlexTouch; Fiasp PenFill; NovoLog; NovoLog FlexPen; NovoLog PenFill. These are forms of insulin used to treat diabetes. They are used by about 777,000 people through Part D plans. The estimated cost is $2.6 billion.

A vocal critic of Medicare drug negotiations, Joel White, president of the Council for Affordable Health Coverage, called the announcement of the 10 drugs selected for negotiation “a hollow victory lap.” A former Republican staffer on the House Ways and Means Committee, Mr. White aided with the development of the Medicare Part D plans and has kept tabs on the pharmacy programs since its launch in 2006.

“No one’s costs will go down now or for years because of this announcement” about Part D negotiations, Mr. White said in a statement.

According to its website, CAHC includes among its members the American Academy of Ophthalmology as well as some patient groups, drugmakers, such as Johnson & Johnson, and insurers and industry groups, such as the National Association of Manufacturers.

Separately, the influential Chamber of Commerce is making a strong push to at least delay the implementation of the Medicare Part D drug negotiations. On Aug. 28, the chamber released a letter sent to the Biden administration, raising concerns about a “rush” to implement the provisions of the Inflation Reduction Act.

The chamber also has filed suit to challenge the drug negotiation provisions of the Inflation Reduction Act, requesting that the court issue a preliminary injunction by Oct. 1, 2023.

Other pending legal challenges to direct Medicare drug negotiations include suits filed by Merck, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Johnson & Johnson, Boehringer Ingelheim, and AstraZeneca, according to an email from Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America. PhRMA also said it is a party to a case.

In addition, the three congressional Republicans with most direct influence over Medicare policy issued on Aug. 29 a joint statement outlining their objections to the planned negotiations on drug prices.

This drug-negotiation proposal is “an unworkable, legally dubious scheme that will lead to higher prices for new drugs coming to market, stifle the development of new cures, and destroy jobs,” said House Energy and Commerce Committee Chair Cathy McMorris Rodgers (R-Wash.), House Ways and Means Committee Chair Jason Smith (R-Mo.), and Senate Finance Committee Ranking Member Mike Crapo (R-Idaho).

Democrats were equally firm and vocal in their support of the negotiations. Senate Finance Chairman Ron Wyden (D-Ore.) issued a statement on Aug. 29 that said the release of the list of the 10 drugs selected for Medicare drug negotiations is part of a “seismic shift in the relationship between Big Pharma, the federal government, and seniors who are counting on lower prices.

“I will be following the negotiation process closely and will fight any attempt by Big Pharma to undo or undermine the progress that’s been made,” Mr. Wyden said.

In addition, AARP issued a statement of its continued support for Medicare drug negotiations.

“The No. 1 reason seniors skip or ration their prescriptions is because they can’t afford them. This must stop,” said AARP executive vice president and chief advocacy and engagement officer Nancy LeaMond in the statement. “The big drug companies and their allies continue suing to overturn the Medicare drug price negotiation program to keep up their price gouging. We can’t allow seniors to be Big Pharma’s cash machine anymore.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

People on Medicare may in 2026 see prices drop for 10 medicines, including pricey diabetes, cancer, blood clot, and arthritis treatments, if advocates for federal drug-price negotiations can implement their plans amid tough opposition.

It’s unclear at this time, though, how these negotiations will play out. The Chamber of Commerce has sided with pharmaceutical companies in bids to block direct Medicare negotiation of drug prices. Many influential Republicans in Congress oppose this plan, which has deep support from both Democrats and AARP.

While facing strong opposition to negotiations, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services sought in its announcement to illustrate the high costs of the selected medicines.

CMS provided data on total Part D costs for selected medicines for the period from June 2022 to May 2023, along with tallies of the number of people taking these drugs. The 10 selected medicines are as follows:

- Eliquis (generic name: apixaban), used to prevent and treat serious blood clots. It is taken by about 3.7 million people through Part D plans. The estimated cost is $16.4 billion.

- Jardiance (generic name: empagliflozin), used for diabetes and heart failure. It is taken by almost 1.6 million people through Part D plans. The estimated cost is $7.06 billion.

- Xarelto (generic name: rivaroxaban), used for blood clots. It is taken by about 1.3 million people through Part D plans. The estimated cost is $6 billion.

- Januvia (generic name: sitagliptin), used for diabetes. It is taken by about 869,00 people through Part D plans. The estimated cost is $4.1 billion.

- Farxiga (generic name: dapagliflozin), used for diabetes, heart failure, and chronic kidney disease. It is taken by about 799,000 people through Part D plans. The estimated cost is almost $3.3 billion.

- Entresto (generic name: sacubitril/valsartan), used to treat heart failure. It is taken by 587,000 people through Part D plans. The estimated cost is $2.9 billion.

- Enbrel( generic name: etanercept), used for rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis, and psoriatic arthritis. It is taken by 48,000 people through Part D plans. The estimated cost is $2.8 billion.

- Imbruvica (generic name: ibrutinib), used to treat some blood cancers. It is taken by about 20,000 people in Part D plans. The estimated cost is $2.7 billion.

- Stelara (generic name: ustekinumab), used to treat plaque psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, or certain bowel conditions (Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis). It is used by about 22,000 people through Part D plans. The estimated cost is $2.6 billion.

- Fiasp; Fiasp FlexTouch; Fiasp PenFill; NovoLog; NovoLog FlexPen; NovoLog PenFill. These are forms of insulin used to treat diabetes. They are used by about 777,000 people through Part D plans. The estimated cost is $2.6 billion.

A vocal critic of Medicare drug negotiations, Joel White, president of the Council for Affordable Health Coverage, called the announcement of the 10 drugs selected for negotiation “a hollow victory lap.” A former Republican staffer on the House Ways and Means Committee, Mr. White aided with the development of the Medicare Part D plans and has kept tabs on the pharmacy programs since its launch in 2006.

“No one’s costs will go down now or for years because of this announcement” about Part D negotiations, Mr. White said in a statement.

According to its website, CAHC includes among its members the American Academy of Ophthalmology as well as some patient groups, drugmakers, such as Johnson & Johnson, and insurers and industry groups, such as the National Association of Manufacturers.

Separately, the influential Chamber of Commerce is making a strong push to at least delay the implementation of the Medicare Part D drug negotiations. On Aug. 28, the chamber released a letter sent to the Biden administration, raising concerns about a “rush” to implement the provisions of the Inflation Reduction Act.

The chamber also has filed suit to challenge the drug negotiation provisions of the Inflation Reduction Act, requesting that the court issue a preliminary injunction by Oct. 1, 2023.

Other pending legal challenges to direct Medicare drug negotiations include suits filed by Merck, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Johnson & Johnson, Boehringer Ingelheim, and AstraZeneca, according to an email from Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America. PhRMA also said it is a party to a case.

In addition, the three congressional Republicans with most direct influence over Medicare policy issued on Aug. 29 a joint statement outlining their objections to the planned negotiations on drug prices.

This drug-negotiation proposal is “an unworkable, legally dubious scheme that will lead to higher prices for new drugs coming to market, stifle the development of new cures, and destroy jobs,” said House Energy and Commerce Committee Chair Cathy McMorris Rodgers (R-Wash.), House Ways and Means Committee Chair Jason Smith (R-Mo.), and Senate Finance Committee Ranking Member Mike Crapo (R-Idaho).

Democrats were equally firm and vocal in their support of the negotiations. Senate Finance Chairman Ron Wyden (D-Ore.) issued a statement on Aug. 29 that said the release of the list of the 10 drugs selected for Medicare drug negotiations is part of a “seismic shift in the relationship between Big Pharma, the federal government, and seniors who are counting on lower prices.

“I will be following the negotiation process closely and will fight any attempt by Big Pharma to undo or undermine the progress that’s been made,” Mr. Wyden said.

In addition, AARP issued a statement of its continued support for Medicare drug negotiations.

“The No. 1 reason seniors skip or ration their prescriptions is because they can’t afford them. This must stop,” said AARP executive vice president and chief advocacy and engagement officer Nancy LeaMond in the statement. “The big drug companies and their allies continue suing to overturn the Medicare drug price negotiation program to keep up their price gouging. We can’t allow seniors to be Big Pharma’s cash machine anymore.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

People on Medicare may in 2026 see prices drop for 10 medicines, including pricey diabetes, cancer, blood clot, and arthritis treatments, if advocates for federal drug-price negotiations can implement their plans amid tough opposition.

It’s unclear at this time, though, how these negotiations will play out. The Chamber of Commerce has sided with pharmaceutical companies in bids to block direct Medicare negotiation of drug prices. Many influential Republicans in Congress oppose this plan, which has deep support from both Democrats and AARP.

While facing strong opposition to negotiations, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services sought in its announcement to illustrate the high costs of the selected medicines.

CMS provided data on total Part D costs for selected medicines for the period from June 2022 to May 2023, along with tallies of the number of people taking these drugs. The 10 selected medicines are as follows:

- Eliquis (generic name: apixaban), used to prevent and treat serious blood clots. It is taken by about 3.7 million people through Part D plans. The estimated cost is $16.4 billion.

- Jardiance (generic name: empagliflozin), used for diabetes and heart failure. It is taken by almost 1.6 million people through Part D plans. The estimated cost is $7.06 billion.

- Xarelto (generic name: rivaroxaban), used for blood clots. It is taken by about 1.3 million people through Part D plans. The estimated cost is $6 billion.

- Januvia (generic name: sitagliptin), used for diabetes. It is taken by about 869,00 people through Part D plans. The estimated cost is $4.1 billion.

- Farxiga (generic name: dapagliflozin), used for diabetes, heart failure, and chronic kidney disease. It is taken by about 799,000 people through Part D plans. The estimated cost is almost $3.3 billion.

- Entresto (generic name: sacubitril/valsartan), used to treat heart failure. It is taken by 587,000 people through Part D plans. The estimated cost is $2.9 billion.

- Enbrel( generic name: etanercept), used for rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis, and psoriatic arthritis. It is taken by 48,000 people through Part D plans. The estimated cost is $2.8 billion.

- Imbruvica (generic name: ibrutinib), used to treat some blood cancers. It is taken by about 20,000 people in Part D plans. The estimated cost is $2.7 billion.

- Stelara (generic name: ustekinumab), used to treat plaque psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, or certain bowel conditions (Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis). It is used by about 22,000 people through Part D plans. The estimated cost is $2.6 billion.

- Fiasp; Fiasp FlexTouch; Fiasp PenFill; NovoLog; NovoLog FlexPen; NovoLog PenFill. These are forms of insulin used to treat diabetes. They are used by about 777,000 people through Part D plans. The estimated cost is $2.6 billion.

A vocal critic of Medicare drug negotiations, Joel White, president of the Council for Affordable Health Coverage, called the announcement of the 10 drugs selected for negotiation “a hollow victory lap.” A former Republican staffer on the House Ways and Means Committee, Mr. White aided with the development of the Medicare Part D plans and has kept tabs on the pharmacy programs since its launch in 2006.

“No one’s costs will go down now or for years because of this announcement” about Part D negotiations, Mr. White said in a statement.

According to its website, CAHC includes among its members the American Academy of Ophthalmology as well as some patient groups, drugmakers, such as Johnson & Johnson, and insurers and industry groups, such as the National Association of Manufacturers.

Separately, the influential Chamber of Commerce is making a strong push to at least delay the implementation of the Medicare Part D drug negotiations. On Aug. 28, the chamber released a letter sent to the Biden administration, raising concerns about a “rush” to implement the provisions of the Inflation Reduction Act.

The chamber also has filed suit to challenge the drug negotiation provisions of the Inflation Reduction Act, requesting that the court issue a preliminary injunction by Oct. 1, 2023.

Other pending legal challenges to direct Medicare drug negotiations include suits filed by Merck, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Johnson & Johnson, Boehringer Ingelheim, and AstraZeneca, according to an email from Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America. PhRMA also said it is a party to a case.

In addition, the three congressional Republicans with most direct influence over Medicare policy issued on Aug. 29 a joint statement outlining their objections to the planned negotiations on drug prices.

This drug-negotiation proposal is “an unworkable, legally dubious scheme that will lead to higher prices for new drugs coming to market, stifle the development of new cures, and destroy jobs,” said House Energy and Commerce Committee Chair Cathy McMorris Rodgers (R-Wash.), House Ways and Means Committee Chair Jason Smith (R-Mo.), and Senate Finance Committee Ranking Member Mike Crapo (R-Idaho).

Democrats were equally firm and vocal in their support of the negotiations. Senate Finance Chairman Ron Wyden (D-Ore.) issued a statement on Aug. 29 that said the release of the list of the 10 drugs selected for Medicare drug negotiations is part of a “seismic shift in the relationship between Big Pharma, the federal government, and seniors who are counting on lower prices.

“I will be following the negotiation process closely and will fight any attempt by Big Pharma to undo or undermine the progress that’s been made,” Mr. Wyden said.

In addition, AARP issued a statement of its continued support for Medicare drug negotiations.

“The No. 1 reason seniors skip or ration their prescriptions is because they can’t afford them. This must stop,” said AARP executive vice president and chief advocacy and engagement officer Nancy LeaMond in the statement. “The big drug companies and their allies continue suing to overturn the Medicare drug price negotiation program to keep up their price gouging. We can’t allow seniors to be Big Pharma’s cash machine anymore.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

It’s not an assembly line

A lot of businesses benefit from being in private equity funds.

Health care isn’t one of them, and a recent report found that

This really shouldn’t surprise anyone. Such funds may offer glittering phrases like “improved technology” and “greater efficiency” but the bottom line is that they’re run by – and for – the shareholders. The majority of them aren’t going to be medical people or realize that you can’t run a medical practice like it’s a clothing retailer or electronic car manufacturer.

I’m not saying medicine isn’t a business – it is. I depend on my little practice to support three families, so keeping it in the black is important. But it also needs to run well to do that. Measures to increase revenue, like cutting my staff down (there are only two of them) or overbooking patients would seriously impact me effectively doing my part, which is playing doctor.

You can predict pretty accurately how long it will take to put a motor and bumper assembly on a specific model of car, but you can’t do that in medicine because people aren’t standardized. Even if you control variables such as same sex, age, and diagnosis, personalities vary widely, as do treatment decisions, questions they’ll have, and the “oh, another thing” factor.

That doesn’t happen at a bottling plant.

In the business model of health care, you’re hoping revenue will pay overhead and a reasonable salary for everyone. But when you add a private equity firm in, the shareholders also expect to be paid. Which means either revenue has to go up significantly, or costs have to be cut (layoffs, short staffing, reduced benefits, etc.), or a combination of both.

Regardless of which option is chosen, it isn’t good for the medical staff or the patients. Increasing the number of people seen in a given amount of time per doctor may be good for the shareholders, but it’s not good for the doctor or the person being cared for. Think of Lucy and Ethyl at the chocolate factory.

Even in an auto factory, if you speed up the rate of cars going through the assembly line, sooner or later mistakes will be made. Humans can’t keep up, and even robots will make errors if things aren’t aligned correctly, or are a few seconds ahead or behind the program. This is why they (hopefully) have quality control, to try and catch those things before they’re on the road.

Of course, cars are more easily fixable. When the mistake is found you repair or replace the part. You can’t do that as easily in people, and when serious mistakes happen it’s the doctor who’s held at fault – not the shareholders who pressured him or her to see patients faster and with less support.

Unfortunately, this is the way the current trend is going. The more people who are involved in the practice of medicine, in person or behind the scenes, the smaller each slice of the pie gets.

That’s not good for the patient, who’s the person at the center of it all and the reason why we’re here.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

A lot of businesses benefit from being in private equity funds.

Health care isn’t one of them, and a recent report found that

This really shouldn’t surprise anyone. Such funds may offer glittering phrases like “improved technology” and “greater efficiency” but the bottom line is that they’re run by – and for – the shareholders. The majority of them aren’t going to be medical people or realize that you can’t run a medical practice like it’s a clothing retailer or electronic car manufacturer.

I’m not saying medicine isn’t a business – it is. I depend on my little practice to support three families, so keeping it in the black is important. But it also needs to run well to do that. Measures to increase revenue, like cutting my staff down (there are only two of them) or overbooking patients would seriously impact me effectively doing my part, which is playing doctor.

You can predict pretty accurately how long it will take to put a motor and bumper assembly on a specific model of car, but you can’t do that in medicine because people aren’t standardized. Even if you control variables such as same sex, age, and diagnosis, personalities vary widely, as do treatment decisions, questions they’ll have, and the “oh, another thing” factor.

That doesn’t happen at a bottling plant.

In the business model of health care, you’re hoping revenue will pay overhead and a reasonable salary for everyone. But when you add a private equity firm in, the shareholders also expect to be paid. Which means either revenue has to go up significantly, or costs have to be cut (layoffs, short staffing, reduced benefits, etc.), or a combination of both.

Regardless of which option is chosen, it isn’t good for the medical staff or the patients. Increasing the number of people seen in a given amount of time per doctor may be good for the shareholders, but it’s not good for the doctor or the person being cared for. Think of Lucy and Ethyl at the chocolate factory.

Even in an auto factory, if you speed up the rate of cars going through the assembly line, sooner or later mistakes will be made. Humans can’t keep up, and even robots will make errors if things aren’t aligned correctly, or are a few seconds ahead or behind the program. This is why they (hopefully) have quality control, to try and catch those things before they’re on the road.

Of course, cars are more easily fixable. When the mistake is found you repair or replace the part. You can’t do that as easily in people, and when serious mistakes happen it’s the doctor who’s held at fault – not the shareholders who pressured him or her to see patients faster and with less support.

Unfortunately, this is the way the current trend is going. The more people who are involved in the practice of medicine, in person or behind the scenes, the smaller each slice of the pie gets.

That’s not good for the patient, who’s the person at the center of it all and the reason why we’re here.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

A lot of businesses benefit from being in private equity funds.

Health care isn’t one of them, and a recent report found that

This really shouldn’t surprise anyone. Such funds may offer glittering phrases like “improved technology” and “greater efficiency” but the bottom line is that they’re run by – and for – the shareholders. The majority of them aren’t going to be medical people or realize that you can’t run a medical practice like it’s a clothing retailer or electronic car manufacturer.

I’m not saying medicine isn’t a business – it is. I depend on my little practice to support three families, so keeping it in the black is important. But it also needs to run well to do that. Measures to increase revenue, like cutting my staff down (there are only two of them) or overbooking patients would seriously impact me effectively doing my part, which is playing doctor.

You can predict pretty accurately how long it will take to put a motor and bumper assembly on a specific model of car, but you can’t do that in medicine because people aren’t standardized. Even if you control variables such as same sex, age, and diagnosis, personalities vary widely, as do treatment decisions, questions they’ll have, and the “oh, another thing” factor.

That doesn’t happen at a bottling plant.

In the business model of health care, you’re hoping revenue will pay overhead and a reasonable salary for everyone. But when you add a private equity firm in, the shareholders also expect to be paid. Which means either revenue has to go up significantly, or costs have to be cut (layoffs, short staffing, reduced benefits, etc.), or a combination of both.

Regardless of which option is chosen, it isn’t good for the medical staff or the patients. Increasing the number of people seen in a given amount of time per doctor may be good for the shareholders, but it’s not good for the doctor or the person being cared for. Think of Lucy and Ethyl at the chocolate factory.

Even in an auto factory, if you speed up the rate of cars going through the assembly line, sooner or later mistakes will be made. Humans can’t keep up, and even robots will make errors if things aren’t aligned correctly, or are a few seconds ahead or behind the program. This is why they (hopefully) have quality control, to try and catch those things before they’re on the road.

Of course, cars are more easily fixable. When the mistake is found you repair or replace the part. You can’t do that as easily in people, and when serious mistakes happen it’s the doctor who’s held at fault – not the shareholders who pressured him or her to see patients faster and with less support.

Unfortunately, this is the way the current trend is going. The more people who are involved in the practice of medicine, in person or behind the scenes, the smaller each slice of the pie gets.

That’s not good for the patient, who’s the person at the center of it all and the reason why we’re here.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Use of mental health services soared during pandemic

By the end of August 2022, overall use of mental health services was almost 40% higher than before the COVID-19 pandemic, while spending increased by 54%, according to a new study by researchers at the RAND Corporation.

During the early phase of the pandemic, from mid-March to mid-December 2020, before the vaccine was available, in-person visits decreased by 40%, while telehealth visits increased by 1,000%, reported Jonathan H. Cantor, PhD, and colleagues at RAND, and at Castlight Health, a benefit coordination provider, in a paper published online in JAMA Health Forum.

Between December 2020 and August 2022, telehealth visits stayed stable, but in-person visits creeped back up, eventually reaching 80% of prepandemic levels. However, “total utilization was higher than before the pandemic,” Dr. Cantor, a policy researcher at RAND, told this news organization.

“It could be that it’s easier for individuals to receive care via telehealth, but it could also just be that there’s a greater demand or need since the pandemic,” said Dr. Cantor. “We’ll just need more research to actually unpack what’s going on,” he said.

Initial per capita spending increased by about a third and was up overall by more than half. But it’s not clear how much of that is due to utilization or to price of services, said Dr. Cantor. Spending for telehealth services remained stable in the post-vaccine period, while spending on in-person visits returned to prepandemic levels.

Dr. Cantor and his colleagues were not able to determine whether utilization was by new or existing patients, but he said that would be good data to have. “It would be really important to know whether or not folks are initiating care because telehealth is making it easier,” he said.

The authors analyzed about 1.5 million claims for anxiety disorders, major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, and posttraumatic stress disorder, out of claims submitted by 7 million commercially insured adults whose self-insured employers used the Castlight benefit.

Dr. Cantor noted that this is just a small subset of the U.S. population. He said he’d like to have data from Medicare and Medicaid to fully assess the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health and of telehealth visits.

“This is a still-burgeoning field,” he said about telehealth. “We’re still trying to get a handle on how things are operating, given that there’s been so much change so rapidly.”

Meanwhile, 152 major employers responding to a large national survey this summer said that they’ve been grappling with how COVID-19 has affected workers. The employers include 72 Fortune 100 companies and provide health coverage for more than 60 million workers, retirees, and their families.

Seventy-seven percent said they are currently seeing an increase in depression, anxiety, and substance use disorders as a result of the pandemic, according to the Business Group on Health’s survey. That’s up from 44% in 2022.

Going forward, employers will focus on increasing access to mental health services, the survey reported.

“Our survey found that in 2024 and for the near future, employers will be acutely focused on addressing employees’ mental health needs while ensuring access and lowering cost barriers,” Ellen Kelsay, president and CEO of Business Group on Health, said in a statement.

The study was supported by grants from the National Institute of Mental Health and the National Institute on Aging. Coauthor Dena Bravata, MD, a Castlight employee, reported receiving personal fees from Castlight Health during the conduct of the study. Coauthor Christopher M. Whaley, a RAND employee, reported receiving personal fees from Castlight Health outside the submitted work.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

By the end of August 2022, overall use of mental health services was almost 40% higher than before the COVID-19 pandemic, while spending increased by 54%, according to a new study by researchers at the RAND Corporation.

During the early phase of the pandemic, from mid-March to mid-December 2020, before the vaccine was available, in-person visits decreased by 40%, while telehealth visits increased by 1,000%, reported Jonathan H. Cantor, PhD, and colleagues at RAND, and at Castlight Health, a benefit coordination provider, in a paper published online in JAMA Health Forum.

Between December 2020 and August 2022, telehealth visits stayed stable, but in-person visits creeped back up, eventually reaching 80% of prepandemic levels. However, “total utilization was higher than before the pandemic,” Dr. Cantor, a policy researcher at RAND, told this news organization.

“It could be that it’s easier for individuals to receive care via telehealth, but it could also just be that there’s a greater demand or need since the pandemic,” said Dr. Cantor. “We’ll just need more research to actually unpack what’s going on,” he said.

Initial per capita spending increased by about a third and was up overall by more than half. But it’s not clear how much of that is due to utilization or to price of services, said Dr. Cantor. Spending for telehealth services remained stable in the post-vaccine period, while spending on in-person visits returned to prepandemic levels.

Dr. Cantor and his colleagues were not able to determine whether utilization was by new or existing patients, but he said that would be good data to have. “It would be really important to know whether or not folks are initiating care because telehealth is making it easier,” he said.

The authors analyzed about 1.5 million claims for anxiety disorders, major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, and posttraumatic stress disorder, out of claims submitted by 7 million commercially insured adults whose self-insured employers used the Castlight benefit.

Dr. Cantor noted that this is just a small subset of the U.S. population. He said he’d like to have data from Medicare and Medicaid to fully assess the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health and of telehealth visits.

“This is a still-burgeoning field,” he said about telehealth. “We’re still trying to get a handle on how things are operating, given that there’s been so much change so rapidly.”

Meanwhile, 152 major employers responding to a large national survey this summer said that they’ve been grappling with how COVID-19 has affected workers. The employers include 72 Fortune 100 companies and provide health coverage for more than 60 million workers, retirees, and their families.

Seventy-seven percent said they are currently seeing an increase in depression, anxiety, and substance use disorders as a result of the pandemic, according to the Business Group on Health’s survey. That’s up from 44% in 2022.

Going forward, employers will focus on increasing access to mental health services, the survey reported.

“Our survey found that in 2024 and for the near future, employers will be acutely focused on addressing employees’ mental health needs while ensuring access and lowering cost barriers,” Ellen Kelsay, president and CEO of Business Group on Health, said in a statement.

The study was supported by grants from the National Institute of Mental Health and the National Institute on Aging. Coauthor Dena Bravata, MD, a Castlight employee, reported receiving personal fees from Castlight Health during the conduct of the study. Coauthor Christopher M. Whaley, a RAND employee, reported receiving personal fees from Castlight Health outside the submitted work.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

By the end of August 2022, overall use of mental health services was almost 40% higher than before the COVID-19 pandemic, while spending increased by 54%, according to a new study by researchers at the RAND Corporation.

During the early phase of the pandemic, from mid-March to mid-December 2020, before the vaccine was available, in-person visits decreased by 40%, while telehealth visits increased by 1,000%, reported Jonathan H. Cantor, PhD, and colleagues at RAND, and at Castlight Health, a benefit coordination provider, in a paper published online in JAMA Health Forum.

Between December 2020 and August 2022, telehealth visits stayed stable, but in-person visits creeped back up, eventually reaching 80% of prepandemic levels. However, “total utilization was higher than before the pandemic,” Dr. Cantor, a policy researcher at RAND, told this news organization.

“It could be that it’s easier for individuals to receive care via telehealth, but it could also just be that there’s a greater demand or need since the pandemic,” said Dr. Cantor. “We’ll just need more research to actually unpack what’s going on,” he said.

Initial per capita spending increased by about a third and was up overall by more than half. But it’s not clear how much of that is due to utilization or to price of services, said Dr. Cantor. Spending for telehealth services remained stable in the post-vaccine period, while spending on in-person visits returned to prepandemic levels.

Dr. Cantor and his colleagues were not able to determine whether utilization was by new or existing patients, but he said that would be good data to have. “It would be really important to know whether or not folks are initiating care because telehealth is making it easier,” he said.

The authors analyzed about 1.5 million claims for anxiety disorders, major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, and posttraumatic stress disorder, out of claims submitted by 7 million commercially insured adults whose self-insured employers used the Castlight benefit.

Dr. Cantor noted that this is just a small subset of the U.S. population. He said he’d like to have data from Medicare and Medicaid to fully assess the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health and of telehealth visits.

“This is a still-burgeoning field,” he said about telehealth. “We’re still trying to get a handle on how things are operating, given that there’s been so much change so rapidly.”

Meanwhile, 152 major employers responding to a large national survey this summer said that they’ve been grappling with how COVID-19 has affected workers. The employers include 72 Fortune 100 companies and provide health coverage for more than 60 million workers, retirees, and their families.

Seventy-seven percent said they are currently seeing an increase in depression, anxiety, and substance use disorders as a result of the pandemic, according to the Business Group on Health’s survey. That’s up from 44% in 2022.

Going forward, employers will focus on increasing access to mental health services, the survey reported.

“Our survey found that in 2024 and for the near future, employers will be acutely focused on addressing employees’ mental health needs while ensuring access and lowering cost barriers,” Ellen Kelsay, president and CEO of Business Group on Health, said in a statement.

The study was supported by grants from the National Institute of Mental Health and the National Institute on Aging. Coauthor Dena Bravata, MD, a Castlight employee, reported receiving personal fees from Castlight Health during the conduct of the study. Coauthor Christopher M. Whaley, a RAND employee, reported receiving personal fees from Castlight Health outside the submitted work.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

National Practitioner Data Bank should go public, group says

arguing that extra public scrutiny could pressure state medical boards to be more aggressive watchdogs.

Public Citizen’s report includes an analysis of how frequently medical boards sanctioned physicians in 2019, 2020, and 2021. These sanctions include license revocations, suspensions, voluntary surrenders of licenses, and limitations on practice while under investigation.

The report used data from the National Practitioner Data Bank (NPDB), a federal repository of reports about state licensure, discipline, and certification actions as well as medical malpractice payments. The database is closed to the public, but hospitals, malpractice insurers, and investigators can query it.

According to Public Citizen’s calculations, states most likely to take serious disciplinary action against physicians were:

- Michigan: 1.74 serious disciplinary actions per 1,000 physicians per year

- Ohio: 1.61

- North Dakota: 1.60

- Colorado: 1.55

- Arizona: 1.53

- The states least likely to do so were:

- Nevada: 0.24 serious disciplinary actions per 1,000 physicians per year

- New Hampshire: 0.25

- Georgia: 0.27

- Indiana: 0.28

- Nebraska: 0.32

- California, the largest U.S. state by both population and number of physicians, landed near the middle, ranking 27th with a rate of 0.83 serious actions per 1,000 physicians, Public Citizen said.

“There is no evidence that physicians in any state are, overall, more or less likely to be incompetent or miscreant than the physicians in any other state,” said Robert Oshel, PhD, a former NPDB associate director for research and an author of the report.

The differences instead reflect variations in boards’ enforcement of medical practice laws, domination of licensing boards by physicians, and inadequate budgets, he noted.

Public Citizen said Congress should change federal law to let members of the public get information from the NPDB to do a background check on physicians whom they are considering seeing or are already seeing. This would not only help individuals but also would spur state licensing boards to do their own checks with the NPDB, the group said.

“If licensing boards routinely queried the NPDB, they would not be faulted by the public and state legislators for not knowing about malpractice payments or disciplinary actions affecting their licensees and therefore not taking reasonable actions concerning their licensees found to have poor records,” the report said.

Questioning NPDB access for consumers

Michelle Mello, JD, PhD, a professor of law and health policy at Stanford (Calif.) University, has studied the current applications of the NPDB. In 2019, she published an article in The New England Journal of Medicine examining changes in practice patterns for clinicians who faced multiple malpractice claims.

Dr. Mello questioned what benefit consumers would get from direct access to the NPDB’s information.

“It provides almost no context for the information it reports, making it even harder for patients to make sense of what they see there,” Dr. Mello said in an interview.

Hospitals are already required to routinely query the NPDB. This legal requirement should be expanded to include licensing boards, which the report called “the last line of defense for the public from incompetent and miscreant physicians,” Public Citizen said.

“Ideally, this amendment should include free continuous query access by medical boards for all their licensees,” the report said. “In the absence of any action by Congress, individual state legislatures should require their licensing boards to query all their licensees or enroll in continuous query, as a few states already do.”

The Federation of State Medical Boards agreed with some of the other suggestions Public Citizen offered in the report. The two concur on the need for increased funding to state medical boards to ensure that they have adequate resources and staffing to fulfill their duties, FSMB said in a statement.

But FSMB disagreed with Public Citizens’ approach to ranking boards, saying it could mislead. The report lacks context about how boards’ funding and authority vary, Humayun Chaudhry, DO, FSMB’s chief executive officer, said. He also questioned the decision to focus only on serious disciplinary actions.

“The Public Citizen report does not take into account the wide range of disciplinary steps boards can take such as letters of reprimand or fines, which are often enough to stop problem behaviors – preempting further problems in the future,” Dr. Chaudhry said.

D.C. gets worst rating

The District of Columbia earned the worst mark in the Public Citizen ranking, holding the 51st spot, the same place it held in the group’s similar ranking on actions taken in the 2017-2019 period. There were 0.19 serious disciplinary actions per 1,000 physicians a year in Washington, Public Citizen said.

In an email to this news organization, Dr. Oshel said that the Public Citizen analysis focused on the number of licensed physicians in each state and D.C. that can be obtained and compared reliably. It avoided using the term “practicing physicians” owing in part to doubts about the reliability of these counts, he said.

As many as 20% of physicians nationwide are focused primarily on work outside of clinical care, Dr. Oshel estimated. In D.C., perhaps 40% of physicians may fall into this category. Of the more than 13,700 physicians licensed in D.C., there may be only about 8,126 actively practicing, according to Dr. Oshel.

But even using that lower estimate of practicing physicians would only raise D.C.’s ranking to 46, signaling a need for stepped-up enforcement, Dr. Oshel said.

“[Whether it’s] 46th or 51st, both are bad,” Dr. Oshel said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

arguing that extra public scrutiny could pressure state medical boards to be more aggressive watchdogs.

Public Citizen’s report includes an analysis of how frequently medical boards sanctioned physicians in 2019, 2020, and 2021. These sanctions include license revocations, suspensions, voluntary surrenders of licenses, and limitations on practice while under investigation.

The report used data from the National Practitioner Data Bank (NPDB), a federal repository of reports about state licensure, discipline, and certification actions as well as medical malpractice payments. The database is closed to the public, but hospitals, malpractice insurers, and investigators can query it.

According to Public Citizen’s calculations, states most likely to take serious disciplinary action against physicians were:

- Michigan: 1.74 serious disciplinary actions per 1,000 physicians per year

- Ohio: 1.61

- North Dakota: 1.60

- Colorado: 1.55

- Arizona: 1.53

- The states least likely to do so were:

- Nevada: 0.24 serious disciplinary actions per 1,000 physicians per year

- New Hampshire: 0.25

- Georgia: 0.27

- Indiana: 0.28

- Nebraska: 0.32

- California, the largest U.S. state by both population and number of physicians, landed near the middle, ranking 27th with a rate of 0.83 serious actions per 1,000 physicians, Public Citizen said.

“There is no evidence that physicians in any state are, overall, more or less likely to be incompetent or miscreant than the physicians in any other state,” said Robert Oshel, PhD, a former NPDB associate director for research and an author of the report.

The differences instead reflect variations in boards’ enforcement of medical practice laws, domination of licensing boards by physicians, and inadequate budgets, he noted.

Public Citizen said Congress should change federal law to let members of the public get information from the NPDB to do a background check on physicians whom they are considering seeing or are already seeing. This would not only help individuals but also would spur state licensing boards to do their own checks with the NPDB, the group said.

“If licensing boards routinely queried the NPDB, they would not be faulted by the public and state legislators for not knowing about malpractice payments or disciplinary actions affecting their licensees and therefore not taking reasonable actions concerning their licensees found to have poor records,” the report said.

Questioning NPDB access for consumers

Michelle Mello, JD, PhD, a professor of law and health policy at Stanford (Calif.) University, has studied the current applications of the NPDB. In 2019, she published an article in The New England Journal of Medicine examining changes in practice patterns for clinicians who faced multiple malpractice claims.

Dr. Mello questioned what benefit consumers would get from direct access to the NPDB’s information.

“It provides almost no context for the information it reports, making it even harder for patients to make sense of what they see there,” Dr. Mello said in an interview.

Hospitals are already required to routinely query the NPDB. This legal requirement should be expanded to include licensing boards, which the report called “the last line of defense for the public from incompetent and miscreant physicians,” Public Citizen said.

“Ideally, this amendment should include free continuous query access by medical boards for all their licensees,” the report said. “In the absence of any action by Congress, individual state legislatures should require their licensing boards to query all their licensees or enroll in continuous query, as a few states already do.”

The Federation of State Medical Boards agreed with some of the other suggestions Public Citizen offered in the report. The two concur on the need for increased funding to state medical boards to ensure that they have adequate resources and staffing to fulfill their duties, FSMB said in a statement.

But FSMB disagreed with Public Citizens’ approach to ranking boards, saying it could mislead. The report lacks context about how boards’ funding and authority vary, Humayun Chaudhry, DO, FSMB’s chief executive officer, said. He also questioned the decision to focus only on serious disciplinary actions.

“The Public Citizen report does not take into account the wide range of disciplinary steps boards can take such as letters of reprimand or fines, which are often enough to stop problem behaviors – preempting further problems in the future,” Dr. Chaudhry said.

D.C. gets worst rating

The District of Columbia earned the worst mark in the Public Citizen ranking, holding the 51st spot, the same place it held in the group’s similar ranking on actions taken in the 2017-2019 period. There were 0.19 serious disciplinary actions per 1,000 physicians a year in Washington, Public Citizen said.

In an email to this news organization, Dr. Oshel said that the Public Citizen analysis focused on the number of licensed physicians in each state and D.C. that can be obtained and compared reliably. It avoided using the term “practicing physicians” owing in part to doubts about the reliability of these counts, he said.

As many as 20% of physicians nationwide are focused primarily on work outside of clinical care, Dr. Oshel estimated. In D.C., perhaps 40% of physicians may fall into this category. Of the more than 13,700 physicians licensed in D.C., there may be only about 8,126 actively practicing, according to Dr. Oshel.

But even using that lower estimate of practicing physicians would only raise D.C.’s ranking to 46, signaling a need for stepped-up enforcement, Dr. Oshel said.

“[Whether it’s] 46th or 51st, both are bad,” Dr. Oshel said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

arguing that extra public scrutiny could pressure state medical boards to be more aggressive watchdogs.

Public Citizen’s report includes an analysis of how frequently medical boards sanctioned physicians in 2019, 2020, and 2021. These sanctions include license revocations, suspensions, voluntary surrenders of licenses, and limitations on practice while under investigation.

The report used data from the National Practitioner Data Bank (NPDB), a federal repository of reports about state licensure, discipline, and certification actions as well as medical malpractice payments. The database is closed to the public, but hospitals, malpractice insurers, and investigators can query it.

According to Public Citizen’s calculations, states most likely to take serious disciplinary action against physicians were:

- Michigan: 1.74 serious disciplinary actions per 1,000 physicians per year

- Ohio: 1.61

- North Dakota: 1.60

- Colorado: 1.55

- Arizona: 1.53

- The states least likely to do so were:

- Nevada: 0.24 serious disciplinary actions per 1,000 physicians per year

- New Hampshire: 0.25

- Georgia: 0.27

- Indiana: 0.28

- Nebraska: 0.32

- California, the largest U.S. state by both population and number of physicians, landed near the middle, ranking 27th with a rate of 0.83 serious actions per 1,000 physicians, Public Citizen said.

“There is no evidence that physicians in any state are, overall, more or less likely to be incompetent or miscreant than the physicians in any other state,” said Robert Oshel, PhD, a former NPDB associate director for research and an author of the report.

The differences instead reflect variations in boards’ enforcement of medical practice laws, domination of licensing boards by physicians, and inadequate budgets, he noted.

Public Citizen said Congress should change federal law to let members of the public get information from the NPDB to do a background check on physicians whom they are considering seeing or are already seeing. This would not only help individuals but also would spur state licensing boards to do their own checks with the NPDB, the group said.

“If licensing boards routinely queried the NPDB, they would not be faulted by the public and state legislators for not knowing about malpractice payments or disciplinary actions affecting their licensees and therefore not taking reasonable actions concerning their licensees found to have poor records,” the report said.

Questioning NPDB access for consumers

Michelle Mello, JD, PhD, a professor of law and health policy at Stanford (Calif.) University, has studied the current applications of the NPDB. In 2019, she published an article in The New England Journal of Medicine examining changes in practice patterns for clinicians who faced multiple malpractice claims.

Dr. Mello questioned what benefit consumers would get from direct access to the NPDB’s information.

“It provides almost no context for the information it reports, making it even harder for patients to make sense of what they see there,” Dr. Mello said in an interview.

Hospitals are already required to routinely query the NPDB. This legal requirement should be expanded to include licensing boards, which the report called “the last line of defense for the public from incompetent and miscreant physicians,” Public Citizen said.

“Ideally, this amendment should include free continuous query access by medical boards for all their licensees,” the report said. “In the absence of any action by Congress, individual state legislatures should require their licensing boards to query all their licensees or enroll in continuous query, as a few states already do.”

The Federation of State Medical Boards agreed with some of the other suggestions Public Citizen offered in the report. The two concur on the need for increased funding to state medical boards to ensure that they have adequate resources and staffing to fulfill their duties, FSMB said in a statement.