User login

Interventional psychiatry (Part 1)

Advances in the understanding of neurobiological and neuropsychiatric pathophysiology have opened new avenues of treatment for psychiatric patients. Historically, with a few exceptions, most psychiatric medications have been administered orally. However, many of the newer treatments require some form of specialized administration because they cannot be taken orally due to their chemical property (such as aducanumab); because there is the need to produce stable blood levels of the medication (such as brexanolone); because oral administration greatly diminished efficacy (such as oral vs IV magnesium or scopolamine), or because the treatment is focused on specific brain structures. This need for specialized administration has created a subspecialty called interventional psychiatry.

Part 1 of this 2-part article provides an overview of 1 type of interventional psychiatry: parenterally administered medications, including those administered via IV. We also describe 3 other interventional approaches to treatment: stellate ganglion blocks, glabellar botulinum toxin (BT) injections, and trigger point injections. In Part 2 we will review interventional approaches that involve neuromodulation.

Parenteral medications in psychiatry

In general, IV and IM medications can be more potent that oral medications due to their overall faster onset of action and higher blood concentrations. These more invasive forms of administration can have significant limitations, such as a risk of infection at the injection site, the need to be administered in a medical setting, additional time, and patient discomfort.

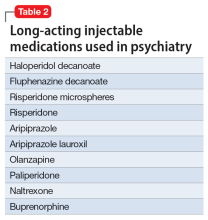

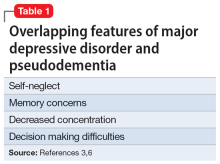

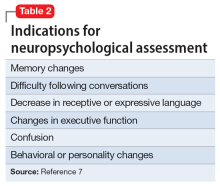

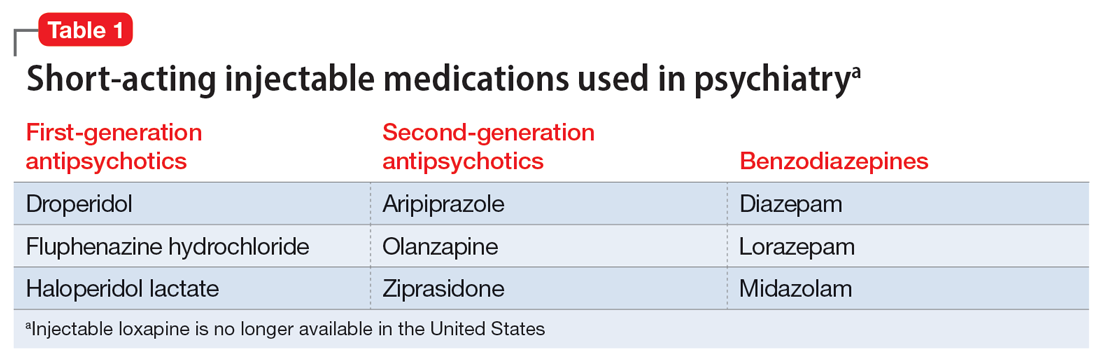

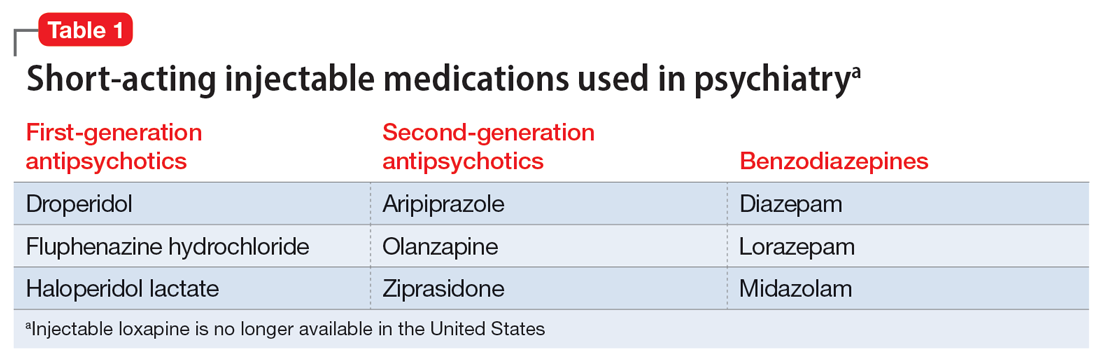

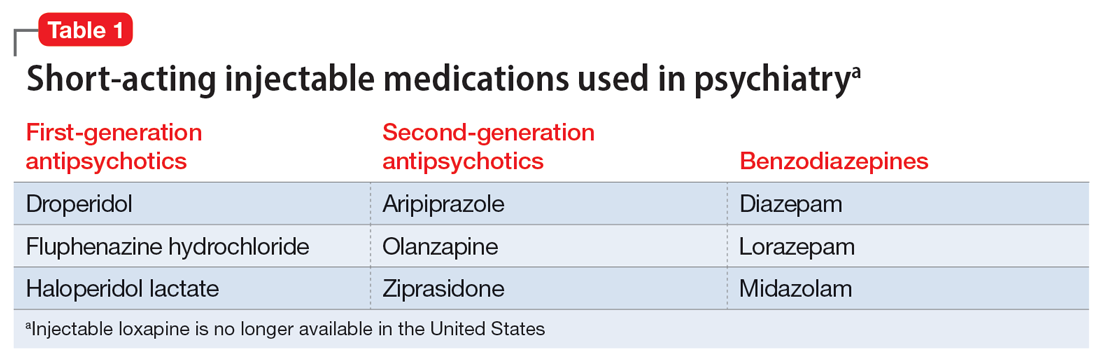

Table 1 lists short-acting injectable medications used in psychiatry, and Table 2 lists long-acting injectable medications. Parenteral administration of antipsychotics is performed to alleviate acute agitation or for chronic symptom control. These medications generally are not considered interventional treatments, but could be classified as such due to their invasive nature.1 Furthermore, inhalable loxapine—which is indicated for managing acute agitation—requires a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy program consisting of 2 hours observation and monitoring of respiratory status.2,3 Other indications for parenteral treatments include IM naltrexone extended release4 and subcutaneous injections of buprenorphine extended release5 and risperidone.6

IV administration

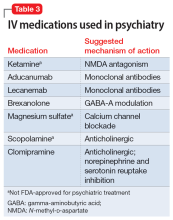

Most IV treatments described in this article are not FDA-approved for psychiatric treatment. Despite this, many interventional psychiatric treatments are part of clinical practice. IV infusion of ketamine is the most widely known and most researched of these. Table 3 lists other IV treatments that could be used as psychiatric treatment.

Ketamine

Since the early 1960s, ketamine has been used as a surgical anesthetic for animals. In the United States, it was approved for human surgical anesthesia in 1970. It was widely used during the Vietnam War due to its lack of inhibition of respiratory drive; medical staff first noticed an improvement in depressive symptoms and the resolution of suicidal ideation in patients who received ketamine. This led to further research on ketamine, particularly to determine its application in treatment-resistant depression (TRD) and other conditions.7 IV ketamine administration is most widely researched, but IM injections, intranasal sprays, and lozenges are also available. The dissociative properties of ketamine have led to its recreational use.8

Hypotheses for the mechanism of action of ketamine as an antidepressant include direct synaptic or extrasynaptic (GluN2B-selective), N-methyl-

Continue to: Ketamine is a schedule...

Ketamine is a schedule III medication with addictive properties. Delirium, panic attacks, hallucinations, nightmares, dysphoria, and paranoia may occur during and after use.13 Premedication with benzodiazepines, most notably lorazepam, is occasionally used to minimize ketamine’s adverse effects, but this generally is not recommended because doing so reduces ketamine’s antidepressant effects.14 Driving and operating heavy machinery is contraindicated after IV infusion. The usual protocol involves an IV infusion of ketamine 0.4 mg/kg to 1 mg/kg dosing over 1 hour. Doses between 0.4 mg/kg and 0.6 mg/kg are most common. Ketamine has a therapeutic window; doses >0.5 mg/kg are progressively less effective.15 Unlike the recommendation after esketamine administration, after receiving ketamine, patients remain in the care of their treatment team for <2 hours.

Esketamine, the S enantiomer of ketamine, was FDA-approved for TRD as an intranasal formulation. Esketamine is more commonly used than IV ketamine because it is FDA-approved and typically covered by insurance, but it may not be as effective.16 An economic analysis by Brendle et al17 suggested insurance companies would lower costs if they covered ketamine infusions vs intranasal esketamine.

Aducanumab and lecanemab

The most recent FDA-approved interventional agents are aducanumab and lecanemab, which are indicated for treating Alzheimer disease.18,19 Both are human monoclonal antibodies that bind selectively and with high affinity to amyloid beta plaque aggregates and promote their removal by Fc receptor–mediated phagocytosis.20

FDA approval of aducanumab and lecanemab was controversial. Initially, aducanumab’s safety monitoring board performed a futility analysis that suggested aducanumab was unlikely to separate from placebo, and the research was stopped.21 The manufacturer petitioned the FDA to consider the medication for accelerated approval on the basis of biomarker data showing that amyloid beta plaque aggregates become smaller. Current FDA approval is temporary to allow patients access to this potentially beneficial agent, but the manufacturer must supply clinical evidence that the reduction of amyloid beta plaques is associated with desirable changes in the course of Alzheimer disease, or risk losing the approval.

Lecanemab is also a human monoclonal antibody intended to remove amyloid beta plaques that was FDA-approved under the accelerated approval pathway.22 Unlike aducanumab, lecanemab demonstrated a statistically significant (although clinically imperceptible) reduction in the rate of cognitive decline; it did not show cognitive improvement.23 Lecanemab also significantly reduced amyloid beta plaques.23

Continue to: Aducanumab and lecanemab are generally...

Aducanumab and lecanemab are generally not covered by insurance and typically cost >$26,000 annually. Both are administered by IV infusion once a month. More monoclonal antibody medications for treating early Alzheimer disease are in the late stages of development, most notably donanebab.24 Observations during clinical trials found that in the later stages of Alzheimer disease, forceful removal of plaques by the autoimmune process damages neurons, while in less dense deposits of early dementia such removal is not harmful to the cells and prevents amyloid buildup.

Brexanolone is an aqueous formulation of allopregnanolone, a major metabolite of progesterone and a positive allosteric modulator of GABA-A receptors.25 Its levels are maximal at the end of the third trimester of pregnancy and fall rapidly following delivery. Research showed a 3-day infusion was rapidly and significantly effective for treating postpartum depression26 and brexanolone received FDA approval for this indication in March 2019.27 However, various administrative, economic, insurance, and other hurdles make it difficult for patients to access this treatment. Despite its rapid onset of action (usually 48 hours), brexanolone takes an average of 15 days to go through the prior authorization process.28 In addition to the need for prior authorization, the main impediment to the use of brexanolone is the 3-day infusion schedule, which greatly magnifies the cost but is partially circumvented by the availability of dedicated outpatient centers.

Magnesium

Magnesium is on the World Health Organization’s Model List of Essential Medicines.29 There has been extensive research on the use of magnesium sulfate for psychiatric indications, especially for depression.30 Magnesium functions similarly to calcium channel blockers by competitively blocking intracellular calcium channels, decreasing calcium availability, and inhibiting smooth muscle contractility.31 It also competes with calcium at the motor end plate, reducing excitation by inhibiting the release of acetylcholine.32 This property is used for high-dose IV magnesium treatment of impending preterm labor in obstetrics. Magnesium sulfate is the drug of choice in treating eclamptic seizures and preventing seizures in severe preeclampsia or gestational hypertension with severe features.33 It is also used to treat torsade de pointes, severe asthma exacerbations, constipation, and barium poisoning.34 Beneficial use in asthma treatment35 and the treatment of migraine36 have also been reported.

IV magnesium in myocardial infarction may be harmful,37 though outside of acute cardiac events, magnesium is found to be safe.38

Oral magnesium sulfate is a common over-the-counter anxiety remedy. As a general cell stabilizer (mediated by the reduction of intracellular calcium), magnesium is potentially beneficial outside of its muscle-relaxing properties, although muscle relaxing can benefit anxious patients. It is used to treat anxiety,39 alcohol withdrawal,40 and fear.41 Low magnesium blood levels are found in patients with depression, schizophrenia,42 and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.43 However, it is important to note that the therapeutic effect of magnesium when treating anxiety and headache is independent of preinfusion magnesium blood levels.43

Continue to: The efficacy of oral magnesium...

The efficacy of oral magnesium is not robust. However, IV administration has a pronounced beneficial effect as an abortive and preventative treatment in many patients with anxiety.44

IV administration of magnesium can produce adverse effects, including flushing, sweating, hypotension, depressed reflexes, flaccid paralysis, hypothermia, circulatory collapse, and cardiac and CNS depression. These complications are very rare and dose-dependent.45 Magnesium is excreted by the kidneys, and dosing must be decreased in patients with kidney failure. The most common adverse effect is local burning along the vein upon infusion; small doses of IV lidocaine can remedy this. Hot flashes are also common.45

Various dosing strategies are available. In patients with anxiety, application dosing is based on the recommended preeclampsia IV dose of 4 g diluted in 250 mL of 5% dextrose. Much higher doses may be used in obstetrics. Unlike in obstetrics, for psychiatric indications, magnesium is administered over 60 to 90 minutes. Heart monitoring is recommended.

Scopolamine

Scopolamine is primarily used to relieve nausea, vomiting, and dizziness associated with motion sickness and recovery from anesthesia. It is also used in ophthalmology and in patients with excessive sweating. In off-label and experimental applications, scopolamine has been used in patients with TRD.46

Scopolamine is an anticholinergic medication. It is a nonselective antagonist at muscarinic receptors.47 Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) possess strong anticholinergic function. Newer generations of antidepressants were designed specifically not to have this function because it was believed to be an unwanted and potentially dangerous adverse effect. However, data suggest that anticholinergic action is important in decreasing depressive symptoms. Several hypotheses of anticholinergic effects on depression have been published since the 1970s. They include the cholinergic-adrenergic hypothesis,48 acetylcholine predominance relative to adrenergic action hypothesis,49 and insecticide poisoning observations.50 Centrally acting physostigmine (but not peripherally acting neostigmine) was reported to control mania.48,51 A genetic connection between the M2 acetylcholine receptor in patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) and alcohol use disorder is also suggestive.52

Continue to: Multiple animal studies show...

Multiple animal studies show direct improvement in mobility and a decrease in despair upon introducing anticholinergic substances.53-55 The cholinergic theory of depression has been studied in several controlled clinical human studies.56,57 Use of a short-acting anticholinergic glycopyrrolate during electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) may contribute to the procedure’s efficacy.

Human research shows scopolamine has a higher efficacy as an antidepressant and anti-anxiety medication in women than in men,58 possibly because estrogen increases the activity of choline acetyltransferase and release of acetylcholine.59,60 M2 receptors mediate estrogen influence on the NMDAR, which may explain the anticholinergic effects of depression treatments in women.61

Another proposed mechanism of action of scopolamine is a potent inhibition of the NMDAR.62 Rapid treatments of depression may be based on this mechanism. Examples of such treatments include IV ketamine and sleep deprivation.63 IV scopolamine shows potency in treating MDD and bipolar depression. This treatment should be reserved for patients who do not respond to or are not candidates for other usual treatment modalities of MDD and for the most severe cases. Scopolamine is 30 times more potent than amitriptyline in anticholinergic effect and reportedly produces sustained improvement in MDD.64

Scopolamine has no black-box warnings. It has not been studied in pregnant women and is not recommended for use during pregnancy. Due to possible negative cardiovascular effects, a normal electrocardiogram is required before the start of treatment. Exercise caution in patients with glaucoma, benign prostatic enlargement, gastroparesis, unstable cardiovascular status, or severe renal impairment.

Treatment with scopolamine is not indicated for patients with myasthenia gravis, psychosis, or seizures. Patients must be off potassium for 3 days before beginning scopolamine treatment. Patients should consult with their cardiologist before having a scopolamine infusion. Adverse reactions may include psychosis, tachycardia, seizures, paralytic ileus, and glaucoma exacerbation. The most common adverse effects of scopolamine infusion treatment include drowsiness, dry mouth, blurred vision, lightheadedness, and dizziness. Due to possible drowsiness, operating motor vehicles or heavy machinery must be avoided on the day of treatment.65 Overall, the adverse effects of scopolamine are preventable and manageable, and its antidepressant efficacy is noteworthy.66

Continue to: Treatment typically consists of 3 consecutive infusions...

Treatment typically consists of 3 consecutive infusions of 4 mcg/kg separated by 3 to 5 days.56 It is possible to have a longer treatment course if the patient experiences only partial improvement. Repeated courses or maintenance treatment (similar to ECT maintenance) are utilized in some patients if indicated. Cardiac monitoring is mandatory.

Clomipramine

Clomipramine, a TCA, acts as a preferential inhibitor of 5-hydroxytryptamine uptake and has proven effective in managing depression, TRD, and obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD).67 Although this medication has reported treatment benefits for patients with phobia, panic disorder,15 chronic pain,68 Tourette syndrome,69 premature ejaculation, anorexia nervosa,70 cataplexy,49 and enuresis,71 it is FDA-approved only for the treatment of OCD.72 Clomipramine may also be beneficial for pain and headache, possibly because of its anti-inflammatory action.73 The anticholinergic effects of clomipramine may add to its efficacy in depression.

The pathophysiology of MDD is connected to hyperactivity of the HPA axis and elevated cortisol levels. Higher clomipramine plasma levels show a linear correlation with lower cortisol secretion and levels, possibly aiding in the treatment of MDD and anxiety.74 The higher the blood level, the more pronounced clomipramine’s therapeutic effect across multiple domains.75

IV infusion of clomipramine produces the highest concentration in the shortest time, but overall, research does not necessarily support increased efficacy of IV over oral administration. There is evidence suggesting that subgroups of patients with severe, treatment-refractory OCD may benefit from IV agents and research suggests a faster onset of action.76 Faster onset of symptom relief is the basis for IV clomipramine use. In patients with OCD, it can take several months for oral medications to produce therapeutic benefits; not all patients can tolerate this. In such scenarios, IV administration may be considered, though it is not appropriate for routine use until more research is available. Patients with treatment-resistant OCD who have exhausted other means of symptom relief may also be candidates for IV treatment.

The adverse effects of IV clomipramine are no different from oral use, though they may be more pronounced. A pretreatment cardiac exam is desirable because clomipramine, like other TCAs, may be cardiotoxic. The anticholinergic adverse effects of TCAs are well known to clinicians77 and partially explained in the scopolamine section of this article. It is not advisable to combine clomipramine with other TCAs or serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Clomipramine also should not be combined with monoamine oxidase inhibitors, though such a combination was reported in medical literature.78 Combination with antiarrhythmics such as lidocaine or opioids such as fentanyl or and tramadol is highly discouraged (fentanyl and tramadol also have serotonergic effects).79

Continue to: Clomipramine for IV use is not commercially available...

Clomipramine for IV use is not commercially available and must be sterilely compounded. The usual course of treatment is a series of 3 infusions: 150 mg on Day 1, 200 mg on Day 2 or Day 3, and 250 mg on Day 3, Day 4, or Day 5, depending on tolerability. A protocol with a 50 mg/d starting dose and titration up to a maximum dose of 225 mg/d over 5 to 7 days has been suggested for inpatient settings.67 Titration to 250 mg is more common.80

A longer series may be performed, but this increases the likelihood of adverse effects. Booster and maintenance treatments are also completed when required. Cardiac monitoring is mandatory.

Vortioxetine and citalopram

IV treatment of depression with

Injections and blocks

Three interventional approaches to treatment that possess psychotherapeutic potential include stellate ganglion blocks (SGBs), glabellar BT injections, and trigger point injections (TPIs). None of these are FDA-approved for psychiatric treatment.

Stellate ganglion blocks

The sympathetic nervous system is involved in autonomic hyperarousal and is at the core of posttraumatic symptomatology.83 Insomnia, anxiety, irritability, hypervigilance, and other excitatory CNS events are connected to the sympathetic nervous system and amygdala activation is commonly observed in those exposed to extreme stress or traumatic events.84

Continue to: SGBs were first performed 100 years ago...

SGBs were first performed 100 years ago and reported to have beneficial psychiatric effects at the end of the 1940s. In 1998 in Finland, improvement of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms was observed accidentally via thoracic level spine blocks.85 In 2006, cervical level sympathetic blocks were shown to be effective for PTSD symptom control.86 By the end of 2010, Veterans Administration hospitals adopted SGBs to treat veterans with PTSD.87,88 The first multisite, randomized clinical trial of

Since the stellate ganglion is connected to the amygdala, SGB has also been assessed for treating anxiety and depression.89,90 Outside of PTSD, SGBs are used to treat complex regional pain syndrome,91 phantom limb pain, trigeminal neuralgia,92 intractable angina,93 and postherpetic neuralgia in the head, neck, upper chest, or arms.94 The procedure consists of an injection of a local anesthetic through a 25-gauge needle into the stellate sympathetic ganglion at the C6 or C7 vertebral levels. An injection into C6 is considered safer because of specific cervical spine anatomy. Ideally, fluoroscopic guidance or ultrasound is used to guide needle insertion.95

A severe drop in blood pressure may be associated with SGBs and is mitigated by IV hydration. Other adverse effects include red eyes, drooping of the eyelids, nasal congestion, hoarseness, difficulty swallowing, a sensation of a “lump” in the throat, and a sensation of warmth or tingling in the arm or hand. Bilateral SGB is contraindicated due to the danger of respiratory arrest.96

Glabellar BT injections

OnabotulinumtoxinA (BT) injection was first approved for therapeutic use in 1989 for eye muscle disorders such as strabismus97 and blepharospasm.98 It was later approved for several other indications, including cosmetic use, hyperhidrosis, migraine prevention, neurogenic bladder disorder, overactive bladder, urinary incontinence, and spasticity.99-104 BT is used off-label for achalasia and sialorrhea.105,106 Its mechanism of action is primarily attributed to muscle paralysis by blocking presynaptic acetylcholine release into neuromuscular junctions.107

Facial BT injections are usually administered for cosmetic purposes, but smoothing forehead wrinkles and frown lines (the glabellar region of the face) both have antidepressant effects.108 BT injections into the glabellar region also demonstrate antidepressant effects, particularly in patients with comorbid migraines and MDD.109 Early case observations supported the independent benefit of the toxin on MDD when the toxin was injected into the glabellar region.110,111 The most frequent protocol involves injections in the procerus and corrugator muscles.

Continue to: The facial feedback/emotional proprioception hypothesis...

The facial feedback/emotional proprioception hypothesis has dominated thinking about the mood-improving effects of BT. The theory is that blocking muscular expression of sadness (especially in the face) interrupts the experience of sadness; therefore, depression subsides.112,113 However, BT injections in the muscles involved in the smile and an expression of positive emotions (lateral part of the musculus orbicularis oculi) have been associated with increased MDD scores.114 Thus, the mechanism clearly involves more than the cosmetic effect, since facial muscle injections in rats also have antidepressant effects.115

The use of progressive muscle relaxation is well-established in psychiatric treatment. The investigated conditions of increased muscle tone, especially torticollis and blepharospasm, are associated with MDD, and it may be speculated that proprioceptive feedback from the affected muscles may be causally involved in this association.116-118 Activity of the corrugator muscle has been positively associated with increased amygdala activity.119 This suggests a potential similar mechanism to that hypothesized for SGB.

Alternatively, BT is commonly used to treat chronic conditions that may contribute to depression; its success in relieving the underlying problem may indirectly relieve MDD. Thus, in a postmarketing safety evaluation of BT, MDD was demonstrated 40% to 88% less often by patients treated with BT for 6 of the 8 conditions and injection sites, such as in spasms and spasticity of arms and legs, torticollis and neck pain, and axilla and palm injections for hyperhidrosis. In a parotid and submandibular glands BT injection subcohort, no patients experienced depressive symptoms.120

Medicinal BT is generally considered safe. The most common adverse effects are hypersensitivity, injection site reactions, and other adverse effects specific to the injection site.121 Additionally, the cosmetic effects are transient, given the nature of the medication.

Trigger point injections

TPIs in the neck and shoulders are frequently used to treat tension headaches and various referred pain locations in the face and arms. Tension and depression frequently overlap in clinical practice.122 Relieving muscle tension (with resulting trigger points) improves muscle function and mood.

Continue to: The higher the number of active...

The higher the number of active trigger points (TPs), the greater the physical burden of headache and the higher the anxiety level. Gender differences in TP prevalence and TPI efficacy have been described in the literature. For example, the number of active TPs seems directly associated with anxiety levels in women but not in men.123 Although TPs appear to be more closely associated with anxiety than depression,124 depression associated with muscle tension does improve with TPIs. European studies have demonstrated a decrease in scores on the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale and Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale following TPI treatment.125 The effect may be indirect, as when a patient’s pain is relieved, sleep and other psychiatric symptoms improve.126

A randomized controlled trial by Castro Sánchez et al127 demonstrated that dry needling therapy in patients with fibromyalgia syndrome (FMS) showed improvements in pain pressure thresholds, body pain, vitality, and social function, as well as total FMS symptoms, quality of sleep, anxiety, hospital anxiety and depression, general pain intensity, and fatigue.

Myofascial pain syndrome, catastrophizing, and muscle tension are common in patients with depression, anxiety, and somatization. Local TPI therapy aimed at inactivating pain generators is supported by moderate quality evidence. All manner of therapies have been described, including injection of saline, corticosteroids, local anesthetic agents, and dry needling. BT injections in chronic TPs are also practiced, though no specific injection therapy has been reliably shown to be more advantageous than another. The benefits of TPIs may be derived from the needle itself rather than from any specific substance injected. Stimulation of a local twitch response with direct needling of the TP appears of importance. There is no established consensus regarding the number of injection points, frequency of administration, and volume or type of injectate.128

Adverse effects of TPIs relate to the nature of the invasive therapy, with the risk of tissue damage and bleeding. Pneumothorax risk is present with needle insertion at the neck and thorax.129 Patients with diabetes may experience variations in blood sugar control if steroids are used.

Bottom Line

Interventional treatment modalities that may have a role in psychiatric treatment include IV administration of ketamine, aducanumab, lecanemab, brexanolone, magnesium, scopolamine, and clomipramine. Other interventional approaches include stellate ganglion blocks, glabellar botulinum toxin injections, and trigger point injections.

Related Resources

- Dokucu ME, Janicak PG. Nontraditional therapies for treatment-resistant depression. Current Psychiatry. 2021; 20(9):38-43,49. doi:10.12788/cp.0166

- Kim J, Khoury R, Grossberg GT. Botulinum toxin: emerging psychiatric indications. Current Psychiatry. 2018;17(12):8-18.

Drug Brand Names

Aducanumab • Aduhelm

Aripiprazole • Abilify

Aripiprazole lauroxil • Aristada

Brexanolone • Zulresso

Buprenorphine • Sublocade

Citalopram • Celexa

Clomipramine • Anafranil

Diazepam • Valium

Droperidol • Inapsine

Esketamine • Spravato

Fentanyl • Actiq

Fluphenazine decanoate • Modecate

Fluphenazine hydrochloride • Prolixin

Haloperidol decanoate • Haldol decanoate

Haloperidol lactate • Haldol

Ketamine • Ketalar

Lecanemab • Leqembi

Lidocaine • Xylocaine

Lorazepam • Ativan

Loxapine inhaled • Adasuve

Naltrexone • Vivitrol

Magnesium sulfate • Sulfamag

Midazolam • Versed

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

OnabotulinumtoxinA injection • Botox

Paliperidone • Invega Hafyera, Invega Sustenna, Invega Trinza

Rapamycin • Rapamune, Sirolimus

Risperidone • Perseris

Risperidone microspheres • Risperdal Consta, Rykindo

Scopolamine • Hyoscine

Tramadol • Conzip

Vortioxetine • Trintellix

Ziprasidone • Geodon

1. Vincent KM, Ryan M, Palmer E, et al. Interventional psychiatry. Postgrad Med. 2020;132(7):573-574.

2. Allen MH, Feifel D, Lesem MD, et al. Efficacy and safety of loxapine for inhalation in the treatment of agitation in patients with schizophrenia: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72(10):1313-1321.

3. Kwentus J, Riesenberg RA, Marandi M, et al. Rapid acute treatment of agitation in patients with bipolar I disorder: a multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial with inhaled loxapine. Bipolar Disord. 2012;14(1):31-40.

4. Lee JD, Nunes EV Jr, Novo P, et al. Comparative effectiveness of extended-release naltrexone versus buprenorphine-naloxone for opioid relapse prevention (X:BOT): a multicentre, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2018;391(10118):309-318.

5. Haight BR, Learned SM, Laffont CM, et al. Efficacy and safety of a monthly buprenorphine depot injection for opioid use disorder: a multicentre, randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2019;393(10173):778-790.

6. Andorn A, Graham J, Csernansky J, et al. Monthly extended-release risperidone (RBP-7000) in the treatment of schizophrenia: results from the phase 3 program. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2019;39(5):428-433.

7. Dundee TW. Twenty-five years of ketamine. A report of an international meeting. Anaesthesia. 1990;45(2):159. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2044.1990.tb14287.x

8. White PF, Way WL, Trevor AJ. Ketamine--its pharmacology and therapeutic uses. Anesthesiology. 1982;56(2):119-136. doi:10.1097/00000542-198202000-00007

9. Zanos P, Gould TD. Mechanisms of ketamine action as an antidepressant. Mol Psychiatry. 2018;23(4):801-811.

10. Molero P, Ramos-Quiroga JA, Martin-Santos R, et al. Antidepressant efficacy and tolerability of ketamine and esketamine: a critical review. CNS Drugs. 2018;32(5):411-420. doi:10.1007/s40263-018-0519-3

11. Williams NR, Heifets BD, Blasey C, et al. Attenuation of antidepressant effects of ketamine by opioid receptor antagonism. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(12):1205-1215.

12. Witkin JM, Martin AE, Golani LK, et al. Rapid-acting antidepressants. Adv Pharmacol. 2019;86:47-96.

13. Strayer RJ, Nelson LS. Adverse events associated with ketamine for procedural sedation in adults. Am J Emerg Med. 2008;26(9):985-1028. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2007.12.005

14. Frye MA, Blier P, Tye SJ. Concomitant benzodiazepine use attenuates ketamine response: implications for large scale study design and clinical development. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2015;35(3):334-336.

15. Fava M, Freeman MP, Flynn M, et al. Double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging trial of intravenous ketamine as adjunctive therapy in treatment-resistant depression (TRD). Mol Psychiatry. 2020;25(7):1592-1603.

16. Bahji A, Vazquez GH, Zarate CA Jr. Comparative efficacy of racemic ketamine and esketamine for depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2021;278:542-555. Erratum in: J Affect Disord. 2021;281:1001.

17. Brendle M, Robison R, Malone DC. Cost-effectiveness of esketamine nasal spray compared to intravenous ketamine for patients with treatment-resistant depression in the US utilizing clinical trial efficacy and real-world effectiveness estimates. J Affect Disord. 2022;319:388-396.

18. Dhillon S. Aducanumab: first approval. Drugs. 2021;81(12):1437-1443. Erratum in: Drugs. 2021;81(14):1701.

19. van Dyck CH, Swanson CJ, Aisen P, et al. Lecanemab in early Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2023;388(1):9-21. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2212948

20. Sevigny J, Chiao P, Bussière T, et al. The antibody aducanumab reduces Aβ plaques in Alzheimer’s disease. Nature. 2016;537(7618):50-56. Update in: Nature. 2017;546(7659):564.

21. Fillit H, Green A. Aducanumab and the FDA – where are we now? Nat Rev Neurol. 2021;17(3):129-130.

22. Reardon S. FDA approves Alzheimer’s drug lecanemab amid safety concerns. Nature. 2023;613(7943):227-228. doi:10.1038/d41586-023-00030-3

23. McDade E, Cummings JL, Dhadda S, et al. Lecanemab in patients with early Alzheimer’s disease: detailed results on biomarker, cognitive, and clinical effects from the randomized and open-label extension of the phase 2 proof-of-concept study. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2022;14(1):191. doi:10.1186/s13195-022-01124-2

24. Mintun MA, Lo AC, Evans CD, et al. Donanemab in early Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(18):1691-1704.

25. Luisi S, Petraglia F, Benedetto C, et al. Serum allopregnanolone levels in pregnant women: changes during pregnancy, at delivery, and in hypertensive patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85(7):2429-2433.

26. Meltzer-Brody S, Colquhoun H, Riesenberg R, et al. Brexanolone injection in post-partum depression: two multicentre, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trials. Lancet. 2018;392(10152):1058-1070.

27. Powell JG, Garland S, Preston K, et al. Brexanolone (Zulresso): finally, an FDA-approved treatment for postpartum depression. Ann Pharmacother. 2020;54(2):157-163.

28. Patterson R, Krohn H, Richardson E, et al. A brexanolone treatment program at an academic medical center: patient selection, 90-day posttreatment outcomes, and lessons learned. J Acad Consult Liaison Psychiatry. 2022;63(1):14-22.

29. World Health Organization. WHO model list of essential medicines - 22nd list (2021). World Health Organization. September 30, 2021. Accessed April 7, 2023. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-MHP-HPS-EML-2021.02

30. Eby GA, Eby KL, Mruk H. Magnesium and major depression. In: Vink R, Nechifor M, eds. Magnesium in the Central Nervous System. University of Adelaide Press; 2011.

31. Plant TM, Zeleznik AJ. Knobil and Neill’s Physiology of Reproduction. 4th ed. Elsevier Inc.; 2015:2503-2550.

32. Sidebotham D, Le Grice IJ. Physiology and pathophysiology. In: Sidebotham D, McKee A, Gillham M, Levy J. Cardiothoracic Critical Care. Elsevier, Inc.; 2007:3-27.

33. Duley L, Gülmezoglu AM, Henderson-Smart DJ, et al. Magnesium sulphate and other anticonvulsants for women with pre-eclampsia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;2010(11):CD000025.

34. Emergency supply of medicines. In: British National Formulary. British Medical Association, Royal Pharmaceutical Society; 2015:6. Accessed April 7, 2023. https://www.academia.edu/35076015/british_national_formulary_2015_pdf

35. Kwofie K, Wolfson AB. Intravenous magnesium sulfate for acute asthma exacerbation in children and adults. Am Fam Physician. 2021;103(4):245-246.

36. Patniyot IR, Gelfand AA. Acute treatment therapies for pediatric migraine: a qualitative systematic review. Headache. 2016;56(1):49-70.

37. Wang X, Du X, Yang H, et al. Use of intravenous magnesium sulfate among patients with acute myocardial infarction in China from 2001 to 2015: China PEACE-Retrospective AMI Study. BMJ Open. 2020;10(3):e033269.

38. Karhu E, Atlas SE, Jinrun G, et al. Intravenous infusion of magnesium sulfate is not associated with cardiovascular, liver, kidney, and metabolic toxicity in adults. J Clin Transl Res. 2018;4(1):47-55.

39. Noah L, Pickering G, Mazur A, et al. Impact of magnesium supplementation, in combination with vitamin B6, on stress and magnesium status: secondary data from a randomized controlled trial. Magnes Res. 2020;33(3):45-57.

40. Erstad BL, Cotugno CL. Management of alcohol withdrawal. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 1995;52(7):697-709.

41. Abumaria N, Luo L, Ahn M, et al. Magnesium supplement enhances spatial-context pattern separation and prevents fear overgeneralization. Behav Pharmacol. 2013;24(4):255-263.

42. Kirov GK, Tsachev KN. Magnesium, schizophrenia and manic-depressive disease. Neuropsychobiology. 1990;23(2):79-81.

43. Botturi A, Ciappolino V, Delvecchio G, et al. The role and the effect of magnesium in mental disorders: a systematic review. Nutrients. 2020;12(6):1661.

44. Kirkland AE, Sarlo GL, Holton KF. The role of magnesium in neurological disorders. Nutrients. 2018;10(6):730.

45. Magnesium sulfate intravenous side effects by likelihood and severity. WebMD. Accessed April 9, 2023. https://www.webmd.com/drugs/2/drug-149570/magnesium-sulfate-intravenous/details/list-sideeffects

46. Scopolamine base transdermal system – uses, side effects, and more. WebMD. Accessed April 9, 2023. https://www.webmd.com/drugs/2/drug-14032/scopolamine-transdermal/details

47. Bolden C, Cusack B, Richelson E. Antagonism by antimuscarinic and neuroleptic compounds at the five cloned human muscarinic cholinergic receptors expressed in Chinese hamster ovary cells. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1992;260(2):576-580.

48. Janowsky DS, el-Yousef MK, Davis JM, et al. A cholinergic-adrenergic hypothesis of mania and depression. Lancet. 1972;2(7778):632-635.

49. Janowsky DS, Risch SC, Gillin JC. Adrenergic-cholinergic balance and the treatment of affective disorders. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 1983;7(2-3):297-307.

50. Gershon S, Shaw FH. Psychiatric sequelae of chronic exposure to organophosphorous insecticides. Lancet. 1972;1(7191):1371-1374.

51. Davis KL, Berger PA, Hollister LE, et al. Physostigmine in mania. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1978;35(1):119-122.

52. Wang JC, Hinrichs AL, Stock H, et al. Evidence of common and specific genetic effects: association of the muscarinic acetylcholine receptor M2 (CHRM2) gene with alcohol dependence and major depressive syndrome. Hum Mol Genet. 2004;13(17):1903-1911.

53. Brown RG. Effects of antidepressants and anticholinergics in a mouse “behavioral despair” test. Eur J Pharmacol. 1979;58(3):331-334.

54. Porsolt RD, Le Pichon M, Jalfre M. Depression: a new animal model sensitive to antidepressant treatments. Nature. 1977;266(5604):730-732.

55. Ji CX, Zhang JJ. Effect of scopolamine on depression in mice. Abstract in English. Yao Xue Xue Bao. 2011;46(4):400-405.

56. Furey ML, Drevets WC. Antidepressant efficacy of the antimuscarinic drug scopolamine: a randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63(10):1121-1129.

57. Drevets WC, Furey ML. Replication of scopolamine’s antidepressant efficacy in major depressive disorder: a randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;67(5):432-438.

58. Furey ML, Khanna A, Hoffman EM, et al. Scopolamine produces larger antidepressant and antianxiety effects in women than in men. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35(12):2479-2488.

59. Gibbs RB, Gabor R, Cox T, et al. Effects of raloxifene and estradiol on hippocampal acetylcholine release and spatial learning in the rat. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2004;29(6):741-748.

60. Pongrac JL, Gibbs RB, Defranco DB. Estrogen-mediated regulation of cholinergic expression in basal forebrain neurons requires extracellular-signal-regulated kinase activity. Neuroscience. 2004;124(4):809-816.

61. Daniel JM, Dohanich GP. Acetylcholine mediates the estrogen-induced increase in NMDA receptor binding in CA1 of the hippocampus and the associated improvement in working memory. J Neurosci. 2001;21(17):6949-6956.

62. Gerhard DM, Wohleb ES, Duman RS. Emerging treatment mechanisms for depression: focus on glutamate and synaptic plasticity. Drug Discov Today. 2016;21(3):454-464.

63. Voderholzer U. Sleep deprivation and antidepressant treatment. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2003;5(4):366-369.

64. Hasselmann H. Scopolamine and depression: a role for muscarinic antagonism? CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 2014;13(4):673-683.

65. Transderm scopolamine [prescribing information]. Warren, NJ: GSK Consumer Healthcare; 2019.

66. Jaffe RJ, Novakovic V, Peselow ED. Scopolamine as an antidepressant: a systematic review. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2013;36(1):24-26.

67. Karameh WK, Khani M. Intravenous clomipramine for treatment-resistant obsessive-compulsive disorder. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2015;19(2):pyv084.

68. Andrews ET, Beattie RM, Tighe MP. Functional abdominal pain: what clinicians need to know. Arch Dis Child. 2020;105(10):938-944. doi:10.1136/archdischild-2020-318825

69. Aliane V, Pérez S, Bohren Y, et al. Key role of striatal cholinergic interneurons in processes leading to arrest of motor stereotypies. Brain. 2011;134(Pt 1):110-118. doi:10.1093/brain/awq285

70. Tzavara ET, Bymaster FP, Davis RJ, et al. M4 muscarinic receptors regulate the dynamics of cholinergic and dopaminergic neurotransmission: relevance to the pathophysiology and treatment of related CNS pathologies. FASEB J. 2004;18(12):1410-1412. doi:10.1096/fj.04-1575fje

71. Korczyn AD, Kish I. The mechanism of imipramine in enuresis nocturna. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 1979;6(1):31-35. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1681.1979.tb00004.x

72. Trimble MR. Worldwide use of clomipramine. J Clin Psychiatry. 1990;51(Suppl):51-54; discussion 55-58.

73. Gong W, Zhang S, Zong Y, et al. Involvement of the microglial NLRP3 inflammasome in the anti-inflammatory effect of the antidepressant clomipramine. J Affect Disord. 2019;254:15-25.

74. Piwowarska J, Wrzosek M, Radziwon’-Zaleska M. Serum cortisol concentration in patients with major depression after treatment with clomipramine. Pharmacol Rep. 2009;61(4):604-611.

75. Danish University Antidepressant Group (DUAG). Clomipramine dose-effect study in patients with depression: clinical end points and pharmacokinetics. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1999;66(2):152-165.

76. Moukaddam NJ, Hirschfeld RMA. Intravenous antidepressants: a review. Depress Anxiety. 2004;19(1):1-9.

77. Gerretsen P, Pollock BG. Rediscovering adverse anticholinergic effects. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72(6):869-870. doi:10.4088/JCP.11ac07093

78. Thomas SJ, Shin M, McInnis MG, et al. Combination therapy with monoamine oxidase inhibitors and other antidepressants or stimulants: strategies for the management of treatment-resistant depression. Pharmacotherapy. 2015;35(4):433-449. doi:10.1002/phar.1576

79. Robles LA. Serotonin syndrome induced by fentanyl in a child: case report. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2015;38(5):206-208. doi:10.1097/WNF.0000000000000100

80. Fallon BA, Liebowitz MR, Campeas R, et al. Intravenous clomipramine for obsessive-compulsive disorder refractory to oral clomipramine: a placebo-controlled study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55(10):918-924.

81. Vieta E, Florea I, Schmidt SN, et al. Intravenous vortioxetine to accelerate onset of effect in major depressive disorder: a 2-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2019;34(4):153-160.

82. Kasper S, Müller-Spahn F. Intravenous antidepressant treatment: focus on citalopram. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2002;252(3):105-109.

83. Togay B, El-Mallakh RS. Posttraumatic stress disorder: from pathophysiology to pharmacology. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(5):33-39.

84. Adhikari A, Lerner TN, Finkelstein J, et al. Basomedial amygdala mediates top-down control of anxiety and fear. Nature. 2015;527(7577):179-185. doi:10.1038/nature15698

85. Lipov E. In search of an effective treatment for combat-related post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD): can the stellate ganglion block be the answer? Pain Pract. 2010;10(4):265-266.

86. Lipov E, Ritchie EC. A review of the use of stellate ganglion block in the treatment of PTSD. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2015;17(8):599.

87. Olmsted KLR, Bartoszek M, McLean B, et al. Effect of stellate ganglion block treatment on posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2020;77(2):130-138.

88. Lipov E, Candido K. The successful use of left-sided stellate ganglion block in patients that fail to respond to right-sided stellate ganglion block for the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms: a retrospective analysis of 205 patients. Mil Med. 2021;186(11-12):319-320.

89. Li Y, Loshak H. Stellate ganglion block for the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, and anxiety. Canadian J Health Technol. 2021;1(3):1-30.

90. Kerzner J, Liu H, Demchenko I, et al. Stellate ganglion block for psychiatric disorders: a systematic review of the clinical research landscape. Chronic Stress (Thousand Oaks). 2021;5:24705470211055176.

91. Wie C, Gupta R, Maloney J, et al. Interventional modalities to treat complex regional pain syndrome. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2021;25(2):10. doi:10.1007/s11916-020-00904-5

92. Chaturvedi A, Dash HH. Sympathetic blockade for the relief of chronic pain. J Indian Med Assoc. 2001;99(12):698-703.

93. Chester M, Hammond C. Leach A. Long-term benefits of stellate ganglion block in severe chronic refractory angina. Pain. 2000;87(1):103-105. doi:10.1016/S0304-3959(00)00270-0

94. Jeon Y. Therapeutic potential of stellate ganglion block in orofacial pain: a mini review. J Dent Anesth Pain Med. 2016;16(3):159-163. doi:10.17245/jdapm.2016.16.3.159

95. Shan HH, Chen HF, Ni Y, et al. Effects of stellate ganglion block through different approaches under guidance of ultrasound. Front Surg. 2022;8:797793. doi:10.3389/fsurg.2021.797793

96. Goel V, Patwardhan AM, Ibrahim M, et al. Complications associated with stellate ganglion nerve block: a systematic review. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2019;rapm-2018-100127. doi:10.1136/rapm-2018-100127

97. Rowe FJ, Noonan CP. Botulinum toxin for the treatment of strabismus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;3(3):CD006499.

98. Roggenkämper P, Jost WH, Bihari K, et al. Efficacy and safety of a new botulinum toxin type A free of complexing proteins in the treatment of blepharospasm. J Neural Transm (Vienna). 2006;113(3):303-312.

99. Heckmann M, Ceballos-Baumann AO, Plewig G; Hyperhidrosis Study Group. Botulinum toxin A for axillary hyperhidrosis (excessive sweating). N Engl J Med. 2001;344(7):488-493.

100. Carruthers JA, Lowe NJ, Menter MA, et al. A multicenter, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study of the efficacy and safety of botulinum toxin type A in the treatment of glabellar lines. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46(6):840-849.

101. Schurch B, de Sèze M, Denys P, et al. Botulinum toxin type A is a safe and effective treatment for neurogenic urinary incontinence: results of a single treatment, randomized, placebo controlled 6-month study. J Urol. 2005;174:196–200.

102. Aurora SK, Winner P, Freeman MC, et al. OnabotulinumtoxinA for treatment of chronic migraine: Pooled analyses of the 56-week PREEMPT clinical program. Headache. 2011;51(9):1358-1373.

103. Dashtipour K, Chen JJ, Walker HW, et al. Systematic literature review of abobotulinumtoxinA in clinical trials for adult upper limb spasticity. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2015;94(3):229-238.

104. Nitti VW, Dmochowski R, Herschorn S, et al. OnabotulinumtoxinA for the treatment of patients with overactive bladder and urinary incontinence: results of a phase 3, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J Urol. 2017;197(2S):S216-S223.

105. Jongerius PH, van den Hoogen FJA, van Limbeek J, et al. Effect of botulinum toxin in the treatment of drooling: a controlled clinical trial. Pediatrics. 2004;114(3):620-627.

106. Zaninotto, G. Annese V, Costantini M, et al. Randomized controlled trial of botulinum toxin versus laparoscopic heller myotomy for esophageal achalasia. Ann Surg. 2004;239(3):364-370.

107. Dressler D, Adib Saberi F. Botulinum toxin: mechanisms of action. Eur Neurol. 2005;53:3-9.

108. Lewis MB, Bowler PJ. Botulinum toxin cosmetic therapy correlates with a more positive mood. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2009;8(1):24-26.

109. Affatato O, Moulin TC, Pisanu C, et al. High efficacy of onabotulinumtoxinA treatment in patients with comorbid migraine and depression: a meta-analysis. J Transl Med. 2021;19(1):133.

110. Finzi E, Wasserman E. Treatment of depression with botulinum toxin A: a case series. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32(5):645-649; discussion 649-650.

111. Schulze J, Neumann I, Magid M, et al. Botulinum toxin for the management of depression: an updated review of the evidence and meta-analysis. J Psychiatr Res. 2021;135:332-340.

112. Finzi E, Rosenthal NE. Emotional proprioception: treatment of depression with afferent facial feedback. J Psychiatr Res. 2016;80:93-96.

113. Söderkvist S, Ohlén K, Dimberg U. How the experience of emotion is modulated by facial feedback. J Nonverbal Behav. 2018;42(1):129-151.

114. Lewis, MB. The interactions between botulinum-toxin-based facial treatments and embodied emotions. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):14720.

115. Li Y, Liu J, Liu X, et al. Antidepressant-like action of single facial injection of botulinum neurotoxin A is associated with augmented 5-HT levels and BDNF/ERK/CREB pathways in mouse brain. Neurosci Bull. 2019;35(4):661-672. Erratum in: Neurosci Bull. 2019;35(4):779-780.

116. Gündel H, Wolf A, Xidara V, et al. High psychiatric comorbidity in spasmodic torticollis: a controlled study. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2003;191(7):465-473.

117. Hall TA, McGwin G Jr, Searcey K, et al. Health-related quality of life and psychosocial characteristics of patients with benign essential blepharospasm. Arch Ophthalmol. 2006;124(1):116-119.

118. Ceylan D, Erer S, Zarifog˘lu M, et al. Evaluation of anxiety and depression scales and quality of life in cervical dystonia patients on botulinum toxin therapy and their relatives. Neurol Sci. 2019;40(4):725-731.

119. Heller AS, Lapate RC, Mayer KE, et al. The face of negative affect: trial-by-trial corrugator responses to negative pictures are positively associated with amygdala and negatively associated with ventromedial prefrontal cortex activity. J Cogn Neurosci. 2014;26(9):2102-2110.

120. Makunts T, Wollmer MA, Abagyan R. Postmarketing safety surveillance data reveals antidepressant effects of botulinum toxin across various indications and injection sites. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):12851.

121. Ahsanuddin S, Roy S, Nasser W, et al. Adverse events associated with botox as reported in a Food and Drug Administration database. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2021;45(3):1201-1209. doi:10.1007/s00266-020-02027-z

122. Kashif M, Tahir S, Ashfaq F, et al. Association of myofascial trigger points in neck and shoulder region with depression, anxiety, and stress among university students. J Pak Med Assoc. 2021;71(9):2139-2142.

123. Cigarán-Méndez M, Jiménez-Antona C, Parás-Bravo P, et al. Active trigger points are associated with anxiety and widespread pressure pain sensitivity in women, but not men, with tension type headache. Pain Pract. 2019;19(5):522-529.

124. Palacios-Ceña M, Castaldo M, Wang K, et al. Relationship of active trigger points with related disability and anxiety in people with tension-type headache. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96(13):e6548.

125. Karadas Ö, Inan LE, Ulas Ü, et al. Efficacy of local lidocaine application on anxiety and depression and its curative effect on patients with chronic tension-type headache. Eur Neurol. 2013;70(1-2):95-101.

126. Gerwin RD. Classification, epidemiology and natural history of myofascial pain syndrome. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2001;5(5):412-420.

127. Castro Sánchez AM, García López H, Fernández Sánchez M, et al. Improvement in clinical outcomes after dry needling versus myofascial release on pain pressure thresholds, quality of life, fatigue, pain intensity, quality of sleep, anxiety, and depression in patients with fibromyalgia syndrome. Disabil Rehabil. 2019;41(19):2235-2246.

128. Healy GM, Finn DP, O’Gorman DA, et al. Pretreatment anxiety and pain acceptance are associated with response to trigger point injection therapy for chronic myofascial pain. Pain Med. 2015;16(10):1955-1966.

129. Morjaria JB, Lakshminarayana UB, Liu-Shiu-Cheong P, et al. Pneumothorax: a tale of pain or spontaneity. Ther Adv Chronic Dis. 2014;5(6):269-273.

Advances in the understanding of neurobiological and neuropsychiatric pathophysiology have opened new avenues of treatment for psychiatric patients. Historically, with a few exceptions, most psychiatric medications have been administered orally. However, many of the newer treatments require some form of specialized administration because they cannot be taken orally due to their chemical property (such as aducanumab); because there is the need to produce stable blood levels of the medication (such as brexanolone); because oral administration greatly diminished efficacy (such as oral vs IV magnesium or scopolamine), or because the treatment is focused on specific brain structures. This need for specialized administration has created a subspecialty called interventional psychiatry.

Part 1 of this 2-part article provides an overview of 1 type of interventional psychiatry: parenterally administered medications, including those administered via IV. We also describe 3 other interventional approaches to treatment: stellate ganglion blocks, glabellar botulinum toxin (BT) injections, and trigger point injections. In Part 2 we will review interventional approaches that involve neuromodulation.

Parenteral medications in psychiatry

In general, IV and IM medications can be more potent that oral medications due to their overall faster onset of action and higher blood concentrations. These more invasive forms of administration can have significant limitations, such as a risk of infection at the injection site, the need to be administered in a medical setting, additional time, and patient discomfort.

Table 1 lists short-acting injectable medications used in psychiatry, and Table 2 lists long-acting injectable medications. Parenteral administration of antipsychotics is performed to alleviate acute agitation or for chronic symptom control. These medications generally are not considered interventional treatments, but could be classified as such due to their invasive nature.1 Furthermore, inhalable loxapine—which is indicated for managing acute agitation—requires a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy program consisting of 2 hours observation and monitoring of respiratory status.2,3 Other indications for parenteral treatments include IM naltrexone extended release4 and subcutaneous injections of buprenorphine extended release5 and risperidone.6

IV administration

Most IV treatments described in this article are not FDA-approved for psychiatric treatment. Despite this, many interventional psychiatric treatments are part of clinical practice. IV infusion of ketamine is the most widely known and most researched of these. Table 3 lists other IV treatments that could be used as psychiatric treatment.

Ketamine

Since the early 1960s, ketamine has been used as a surgical anesthetic for animals. In the United States, it was approved for human surgical anesthesia in 1970. It was widely used during the Vietnam War due to its lack of inhibition of respiratory drive; medical staff first noticed an improvement in depressive symptoms and the resolution of suicidal ideation in patients who received ketamine. This led to further research on ketamine, particularly to determine its application in treatment-resistant depression (TRD) and other conditions.7 IV ketamine administration is most widely researched, but IM injections, intranasal sprays, and lozenges are also available. The dissociative properties of ketamine have led to its recreational use.8

Hypotheses for the mechanism of action of ketamine as an antidepressant include direct synaptic or extrasynaptic (GluN2B-selective), N-methyl-

Continue to: Ketamine is a schedule...

Ketamine is a schedule III medication with addictive properties. Delirium, panic attacks, hallucinations, nightmares, dysphoria, and paranoia may occur during and after use.13 Premedication with benzodiazepines, most notably lorazepam, is occasionally used to minimize ketamine’s adverse effects, but this generally is not recommended because doing so reduces ketamine’s antidepressant effects.14 Driving and operating heavy machinery is contraindicated after IV infusion. The usual protocol involves an IV infusion of ketamine 0.4 mg/kg to 1 mg/kg dosing over 1 hour. Doses between 0.4 mg/kg and 0.6 mg/kg are most common. Ketamine has a therapeutic window; doses >0.5 mg/kg are progressively less effective.15 Unlike the recommendation after esketamine administration, after receiving ketamine, patients remain in the care of their treatment team for <2 hours.

Esketamine, the S enantiomer of ketamine, was FDA-approved for TRD as an intranasal formulation. Esketamine is more commonly used than IV ketamine because it is FDA-approved and typically covered by insurance, but it may not be as effective.16 An economic analysis by Brendle et al17 suggested insurance companies would lower costs if they covered ketamine infusions vs intranasal esketamine.

Aducanumab and lecanemab

The most recent FDA-approved interventional agents are aducanumab and lecanemab, which are indicated for treating Alzheimer disease.18,19 Both are human monoclonal antibodies that bind selectively and with high affinity to amyloid beta plaque aggregates and promote their removal by Fc receptor–mediated phagocytosis.20

FDA approval of aducanumab and lecanemab was controversial. Initially, aducanumab’s safety monitoring board performed a futility analysis that suggested aducanumab was unlikely to separate from placebo, and the research was stopped.21 The manufacturer petitioned the FDA to consider the medication for accelerated approval on the basis of biomarker data showing that amyloid beta plaque aggregates become smaller. Current FDA approval is temporary to allow patients access to this potentially beneficial agent, but the manufacturer must supply clinical evidence that the reduction of amyloid beta plaques is associated with desirable changes in the course of Alzheimer disease, or risk losing the approval.

Lecanemab is also a human monoclonal antibody intended to remove amyloid beta plaques that was FDA-approved under the accelerated approval pathway.22 Unlike aducanumab, lecanemab demonstrated a statistically significant (although clinically imperceptible) reduction in the rate of cognitive decline; it did not show cognitive improvement.23 Lecanemab also significantly reduced amyloid beta plaques.23

Continue to: Aducanumab and lecanemab are generally...

Aducanumab and lecanemab are generally not covered by insurance and typically cost >$26,000 annually. Both are administered by IV infusion once a month. More monoclonal antibody medications for treating early Alzheimer disease are in the late stages of development, most notably donanebab.24 Observations during clinical trials found that in the later stages of Alzheimer disease, forceful removal of plaques by the autoimmune process damages neurons, while in less dense deposits of early dementia such removal is not harmful to the cells and prevents amyloid buildup.

Brexanolone is an aqueous formulation of allopregnanolone, a major metabolite of progesterone and a positive allosteric modulator of GABA-A receptors.25 Its levels are maximal at the end of the third trimester of pregnancy and fall rapidly following delivery. Research showed a 3-day infusion was rapidly and significantly effective for treating postpartum depression26 and brexanolone received FDA approval for this indication in March 2019.27 However, various administrative, economic, insurance, and other hurdles make it difficult for patients to access this treatment. Despite its rapid onset of action (usually 48 hours), brexanolone takes an average of 15 days to go through the prior authorization process.28 In addition to the need for prior authorization, the main impediment to the use of brexanolone is the 3-day infusion schedule, which greatly magnifies the cost but is partially circumvented by the availability of dedicated outpatient centers.

Magnesium

Magnesium is on the World Health Organization’s Model List of Essential Medicines.29 There has been extensive research on the use of magnesium sulfate for psychiatric indications, especially for depression.30 Magnesium functions similarly to calcium channel blockers by competitively blocking intracellular calcium channels, decreasing calcium availability, and inhibiting smooth muscle contractility.31 It also competes with calcium at the motor end plate, reducing excitation by inhibiting the release of acetylcholine.32 This property is used for high-dose IV magnesium treatment of impending preterm labor in obstetrics. Magnesium sulfate is the drug of choice in treating eclamptic seizures and preventing seizures in severe preeclampsia or gestational hypertension with severe features.33 It is also used to treat torsade de pointes, severe asthma exacerbations, constipation, and barium poisoning.34 Beneficial use in asthma treatment35 and the treatment of migraine36 have also been reported.

IV magnesium in myocardial infarction may be harmful,37 though outside of acute cardiac events, magnesium is found to be safe.38

Oral magnesium sulfate is a common over-the-counter anxiety remedy. As a general cell stabilizer (mediated by the reduction of intracellular calcium), magnesium is potentially beneficial outside of its muscle-relaxing properties, although muscle relaxing can benefit anxious patients. It is used to treat anxiety,39 alcohol withdrawal,40 and fear.41 Low magnesium blood levels are found in patients with depression, schizophrenia,42 and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.43 However, it is important to note that the therapeutic effect of magnesium when treating anxiety and headache is independent of preinfusion magnesium blood levels.43

Continue to: The efficacy of oral magnesium...

The efficacy of oral magnesium is not robust. However, IV administration has a pronounced beneficial effect as an abortive and preventative treatment in many patients with anxiety.44

IV administration of magnesium can produce adverse effects, including flushing, sweating, hypotension, depressed reflexes, flaccid paralysis, hypothermia, circulatory collapse, and cardiac and CNS depression. These complications are very rare and dose-dependent.45 Magnesium is excreted by the kidneys, and dosing must be decreased in patients with kidney failure. The most common adverse effect is local burning along the vein upon infusion; small doses of IV lidocaine can remedy this. Hot flashes are also common.45

Various dosing strategies are available. In patients with anxiety, application dosing is based on the recommended preeclampsia IV dose of 4 g diluted in 250 mL of 5% dextrose. Much higher doses may be used in obstetrics. Unlike in obstetrics, for psychiatric indications, magnesium is administered over 60 to 90 minutes. Heart monitoring is recommended.

Scopolamine

Scopolamine is primarily used to relieve nausea, vomiting, and dizziness associated with motion sickness and recovery from anesthesia. It is also used in ophthalmology and in patients with excessive sweating. In off-label and experimental applications, scopolamine has been used in patients with TRD.46

Scopolamine is an anticholinergic medication. It is a nonselective antagonist at muscarinic receptors.47 Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) possess strong anticholinergic function. Newer generations of antidepressants were designed specifically not to have this function because it was believed to be an unwanted and potentially dangerous adverse effect. However, data suggest that anticholinergic action is important in decreasing depressive symptoms. Several hypotheses of anticholinergic effects on depression have been published since the 1970s. They include the cholinergic-adrenergic hypothesis,48 acetylcholine predominance relative to adrenergic action hypothesis,49 and insecticide poisoning observations.50 Centrally acting physostigmine (but not peripherally acting neostigmine) was reported to control mania.48,51 A genetic connection between the M2 acetylcholine receptor in patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) and alcohol use disorder is also suggestive.52

Continue to: Multiple animal studies show...

Multiple animal studies show direct improvement in mobility and a decrease in despair upon introducing anticholinergic substances.53-55 The cholinergic theory of depression has been studied in several controlled clinical human studies.56,57 Use of a short-acting anticholinergic glycopyrrolate during electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) may contribute to the procedure’s efficacy.

Human research shows scopolamine has a higher efficacy as an antidepressant and anti-anxiety medication in women than in men,58 possibly because estrogen increases the activity of choline acetyltransferase and release of acetylcholine.59,60 M2 receptors mediate estrogen influence on the NMDAR, which may explain the anticholinergic effects of depression treatments in women.61

Another proposed mechanism of action of scopolamine is a potent inhibition of the NMDAR.62 Rapid treatments of depression may be based on this mechanism. Examples of such treatments include IV ketamine and sleep deprivation.63 IV scopolamine shows potency in treating MDD and bipolar depression. This treatment should be reserved for patients who do not respond to or are not candidates for other usual treatment modalities of MDD and for the most severe cases. Scopolamine is 30 times more potent than amitriptyline in anticholinergic effect and reportedly produces sustained improvement in MDD.64

Scopolamine has no black-box warnings. It has not been studied in pregnant women and is not recommended for use during pregnancy. Due to possible negative cardiovascular effects, a normal electrocardiogram is required before the start of treatment. Exercise caution in patients with glaucoma, benign prostatic enlargement, gastroparesis, unstable cardiovascular status, or severe renal impairment.

Treatment with scopolamine is not indicated for patients with myasthenia gravis, psychosis, or seizures. Patients must be off potassium for 3 days before beginning scopolamine treatment. Patients should consult with their cardiologist before having a scopolamine infusion. Adverse reactions may include psychosis, tachycardia, seizures, paralytic ileus, and glaucoma exacerbation. The most common adverse effects of scopolamine infusion treatment include drowsiness, dry mouth, blurred vision, lightheadedness, and dizziness. Due to possible drowsiness, operating motor vehicles or heavy machinery must be avoided on the day of treatment.65 Overall, the adverse effects of scopolamine are preventable and manageable, and its antidepressant efficacy is noteworthy.66

Continue to: Treatment typically consists of 3 consecutive infusions...

Treatment typically consists of 3 consecutive infusions of 4 mcg/kg separated by 3 to 5 days.56 It is possible to have a longer treatment course if the patient experiences only partial improvement. Repeated courses or maintenance treatment (similar to ECT maintenance) are utilized in some patients if indicated. Cardiac monitoring is mandatory.

Clomipramine

Clomipramine, a TCA, acts as a preferential inhibitor of 5-hydroxytryptamine uptake and has proven effective in managing depression, TRD, and obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD).67 Although this medication has reported treatment benefits for patients with phobia, panic disorder,15 chronic pain,68 Tourette syndrome,69 premature ejaculation, anorexia nervosa,70 cataplexy,49 and enuresis,71 it is FDA-approved only for the treatment of OCD.72 Clomipramine may also be beneficial for pain and headache, possibly because of its anti-inflammatory action.73 The anticholinergic effects of clomipramine may add to its efficacy in depression.

The pathophysiology of MDD is connected to hyperactivity of the HPA axis and elevated cortisol levels. Higher clomipramine plasma levels show a linear correlation with lower cortisol secretion and levels, possibly aiding in the treatment of MDD and anxiety.74 The higher the blood level, the more pronounced clomipramine’s therapeutic effect across multiple domains.75

IV infusion of clomipramine produces the highest concentration in the shortest time, but overall, research does not necessarily support increased efficacy of IV over oral administration. There is evidence suggesting that subgroups of patients with severe, treatment-refractory OCD may benefit from IV agents and research suggests a faster onset of action.76 Faster onset of symptom relief is the basis for IV clomipramine use. In patients with OCD, it can take several months for oral medications to produce therapeutic benefits; not all patients can tolerate this. In such scenarios, IV administration may be considered, though it is not appropriate for routine use until more research is available. Patients with treatment-resistant OCD who have exhausted other means of symptom relief may also be candidates for IV treatment.

The adverse effects of IV clomipramine are no different from oral use, though they may be more pronounced. A pretreatment cardiac exam is desirable because clomipramine, like other TCAs, may be cardiotoxic. The anticholinergic adverse effects of TCAs are well known to clinicians77 and partially explained in the scopolamine section of this article. It is not advisable to combine clomipramine with other TCAs or serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Clomipramine also should not be combined with monoamine oxidase inhibitors, though such a combination was reported in medical literature.78 Combination with antiarrhythmics such as lidocaine or opioids such as fentanyl or and tramadol is highly discouraged (fentanyl and tramadol also have serotonergic effects).79

Continue to: Clomipramine for IV use is not commercially available...

Clomipramine for IV use is not commercially available and must be sterilely compounded. The usual course of treatment is a series of 3 infusions: 150 mg on Day 1, 200 mg on Day 2 or Day 3, and 250 mg on Day 3, Day 4, or Day 5, depending on tolerability. A protocol with a 50 mg/d starting dose and titration up to a maximum dose of 225 mg/d over 5 to 7 days has been suggested for inpatient settings.67 Titration to 250 mg is more common.80

A longer series may be performed, but this increases the likelihood of adverse effects. Booster and maintenance treatments are also completed when required. Cardiac monitoring is mandatory.

Vortioxetine and citalopram

IV treatment of depression with

Injections and blocks

Three interventional approaches to treatment that possess psychotherapeutic potential include stellate ganglion blocks (SGBs), glabellar BT injections, and trigger point injections (TPIs). None of these are FDA-approved for psychiatric treatment.

Stellate ganglion blocks

The sympathetic nervous system is involved in autonomic hyperarousal and is at the core of posttraumatic symptomatology.83 Insomnia, anxiety, irritability, hypervigilance, and other excitatory CNS events are connected to the sympathetic nervous system and amygdala activation is commonly observed in those exposed to extreme stress or traumatic events.84

Continue to: SGBs were first performed 100 years ago...

SGBs were first performed 100 years ago and reported to have beneficial psychiatric effects at the end of the 1940s. In 1998 in Finland, improvement of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms was observed accidentally via thoracic level spine blocks.85 In 2006, cervical level sympathetic blocks were shown to be effective for PTSD symptom control.86 By the end of 2010, Veterans Administration hospitals adopted SGBs to treat veterans with PTSD.87,88 The first multisite, randomized clinical trial of

Since the stellate ganglion is connected to the amygdala, SGB has also been assessed for treating anxiety and depression.89,90 Outside of PTSD, SGBs are used to treat complex regional pain syndrome,91 phantom limb pain, trigeminal neuralgia,92 intractable angina,93 and postherpetic neuralgia in the head, neck, upper chest, or arms.94 The procedure consists of an injection of a local anesthetic through a 25-gauge needle into the stellate sympathetic ganglion at the C6 or C7 vertebral levels. An injection into C6 is considered safer because of specific cervical spine anatomy. Ideally, fluoroscopic guidance or ultrasound is used to guide needle insertion.95

A severe drop in blood pressure may be associated with SGBs and is mitigated by IV hydration. Other adverse effects include red eyes, drooping of the eyelids, nasal congestion, hoarseness, difficulty swallowing, a sensation of a “lump” in the throat, and a sensation of warmth or tingling in the arm or hand. Bilateral SGB is contraindicated due to the danger of respiratory arrest.96

Glabellar BT injections

OnabotulinumtoxinA (BT) injection was first approved for therapeutic use in 1989 for eye muscle disorders such as strabismus97 and blepharospasm.98 It was later approved for several other indications, including cosmetic use, hyperhidrosis, migraine prevention, neurogenic bladder disorder, overactive bladder, urinary incontinence, and spasticity.99-104 BT is used off-label for achalasia and sialorrhea.105,106 Its mechanism of action is primarily attributed to muscle paralysis by blocking presynaptic acetylcholine release into neuromuscular junctions.107

Facial BT injections are usually administered for cosmetic purposes, but smoothing forehead wrinkles and frown lines (the glabellar region of the face) both have antidepressant effects.108 BT injections into the glabellar region also demonstrate antidepressant effects, particularly in patients with comorbid migraines and MDD.109 Early case observations supported the independent benefit of the toxin on MDD when the toxin was injected into the glabellar region.110,111 The most frequent protocol involves injections in the procerus and corrugator muscles.

Continue to: The facial feedback/emotional proprioception hypothesis...

The facial feedback/emotional proprioception hypothesis has dominated thinking about the mood-improving effects of BT. The theory is that blocking muscular expression of sadness (especially in the face) interrupts the experience of sadness; therefore, depression subsides.112,113 However, BT injections in the muscles involved in the smile and an expression of positive emotions (lateral part of the musculus orbicularis oculi) have been associated with increased MDD scores.114 Thus, the mechanism clearly involves more than the cosmetic effect, since facial muscle injections in rats also have antidepressant effects.115

The use of progressive muscle relaxation is well-established in psychiatric treatment. The investigated conditions of increased muscle tone, especially torticollis and blepharospasm, are associated with MDD, and it may be speculated that proprioceptive feedback from the affected muscles may be causally involved in this association.116-118 Activity of the corrugator muscle has been positively associated with increased amygdala activity.119 This suggests a potential similar mechanism to that hypothesized for SGB.

Alternatively, BT is commonly used to treat chronic conditions that may contribute to depression; its success in relieving the underlying problem may indirectly relieve MDD. Thus, in a postmarketing safety evaluation of BT, MDD was demonstrated 40% to 88% less often by patients treated with BT for 6 of the 8 conditions and injection sites, such as in spasms and spasticity of arms and legs, torticollis and neck pain, and axilla and palm injections for hyperhidrosis. In a parotid and submandibular glands BT injection subcohort, no patients experienced depressive symptoms.120

Medicinal BT is generally considered safe. The most common adverse effects are hypersensitivity, injection site reactions, and other adverse effects specific to the injection site.121 Additionally, the cosmetic effects are transient, given the nature of the medication.

Trigger point injections

TPIs in the neck and shoulders are frequently used to treat tension headaches and various referred pain locations in the face and arms. Tension and depression frequently overlap in clinical practice.122 Relieving muscle tension (with resulting trigger points) improves muscle function and mood.

Continue to: The higher the number of active...

The higher the number of active trigger points (TPs), the greater the physical burden of headache and the higher the anxiety level. Gender differences in TP prevalence and TPI efficacy have been described in the literature. For example, the number of active TPs seems directly associated with anxiety levels in women but not in men.123 Although TPs appear to be more closely associated with anxiety than depression,124 depression associated with muscle tension does improve with TPIs. European studies have demonstrated a decrease in scores on the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale and Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale following TPI treatment.125 The effect may be indirect, as when a patient’s pain is relieved, sleep and other psychiatric symptoms improve.126

A randomized controlled trial by Castro Sánchez et al127 demonstrated that dry needling therapy in patients with fibromyalgia syndrome (FMS) showed improvements in pain pressure thresholds, body pain, vitality, and social function, as well as total FMS symptoms, quality of sleep, anxiety, hospital anxiety and depression, general pain intensity, and fatigue.

Myofascial pain syndrome, catastrophizing, and muscle tension are common in patients with depression, anxiety, and somatization. Local TPI therapy aimed at inactivating pain generators is supported by moderate quality evidence. All manner of therapies have been described, including injection of saline, corticosteroids, local anesthetic agents, and dry needling. BT injections in chronic TPs are also practiced, though no specific injection therapy has been reliably shown to be more advantageous than another. The benefits of TPIs may be derived from the needle itself rather than from any specific substance injected. Stimulation of a local twitch response with direct needling of the TP appears of importance. There is no established consensus regarding the number of injection points, frequency of administration, and volume or type of injectate.128

Adverse effects of TPIs relate to the nature of the invasive therapy, with the risk of tissue damage and bleeding. Pneumothorax risk is present with needle insertion at the neck and thorax.129 Patients with diabetes may experience variations in blood sugar control if steroids are used.

Bottom Line