User login

Asian patients with psoriasis have shortest visits, study shows

(NAMCS) from 2010 to 2016.

Yet the reasons for the difference are unclear and in need of further research, said the investigators and dermatologists who were asked to comment on the research.

The study covered over 4 million visits for psoriasis and found that the mean duration of visits for Asian patients was 9.2 minutes, compared with 15.7 minutes for Hispanic or Latino patients, 20.7 minutes for non-Hispanic Black patients, and 15.4 minutes for non-Hispanic White patients.

The mean duration of visits with Asian patients was 39.9% shorter, compared with visits with White patients (beta coefficient, –5,747; 95% confidence interval, –11.026 to –0.469; P = .03), and 40.6% shorter, compared with visits with non-Asian patients combined (beta coefficient, –5.908; 95% CI, –11.147 to –0.669, P = .03), April W. Armstrong, MD, MPH, professor of dermatology and director of the psoriasis program at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, and Kevin K. Wu, MD, a dermatology resident at USC, said in a research letter published in JAMA Dermatology.

“The etiology of these differences is unclear,” they wrote. “It is possible that factors such as unconscious bias, cultural differences in communication, or residual confounding may be responsible for the observed findings.”

Their findings came from multivariable linear regression analyses that adjusted for age, sex, type of visit (new or follow-up), visit complexity based on the number of reasons for the visit, insurance status (such as private insurance or Medicaid), psoriasis severity on the basis of systemic psoriasis treatment or phototherapy, and complex topical regimens (three or more topical agents).

Commenting on the results, Deborah A. Scott, MD, codirector of the skin of color dermatology program at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and assistant professor at Harvard Medical School, both in Boston, said in an interview that visit length “is a reasonable parameter to look at among many others” when investigating potential disparities in care.

“They’re equating [shorter visit times] with lack of time spent counseling patients,” said Dr. Scott, who was not involved in the research. But there are “many variables” that can affect visit time, such as language differences, time spent with interpreters, and differences in patient educational levels.

Clarissa Yang, MD, dermatologist-in-chief at Tufts Medical Center, Boston, agreed. “We’re worried about there being a quality of care issue. However, there could also be differences culturally in how [the patients] interact with their physicians – their styles and the questions they ask,” she said in an interview. “The study is a good first step to noting that there may be a disparity,” and there is a need to break down the differences “into more granularity.”

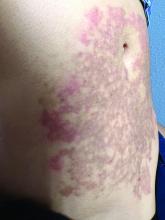

Previous research, the authors wrote, has found that Asian patients were less likely to receive counseling from physicians, compared with White patients. And “paradoxically,” they noted, Asian individuals tend to present with more severe psoriasis than patients of other races and ethnicities.

Dr. Scott said the tendency to present with more severe psoriasis has been documented in patients with skin of color broadly – likely because of delays in recognition and treatment.

Race and ethnicity in the study were self-reported by patients, and missing data were imputed by NAMCS researchers using a sequential regression method. Patients who did not report race and ethnicity may have different characteristics affecting visit duration than those who did report the information, Dr. Armstrong and Dr. Wu said in describing their study’s limitations.

Other differences found

In addition to visit length, they found significant differences in mean age and in the use of complex topical regimens. The mean ages of Asian, Hispanic or Latino, and non-Hispanic Black patients were 37.2, 44.7, and 33.3 years, respectively. Complex topical regimens were prescribed to 11.8% of Asian patients, compared with 1.5% of Black and 1.1% of White patients.

For practicing dermatologists, knowing for now that Asian patients have shorter visits “may bring to light some consciousness to how we practice,” Dr. Yang noted. “We may counsel differently, we may spend differing amounts of time – for reasons still unknown. But being generally aware can help us to shift any unconscious bias that may be there.”

Dermatologists, Dr. Armstrong and Dr. Wu wrote, “need to allow sufficient time to develop strong physician-patient communication regardless of patient background.”

The NAMCS – administered by the Center for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Center for Health Statistics – collects data on a sample of visits provided by non–federally employed office-based physicians.

Dr. Armstrong disclosed receiving personal fees from AbbVie and Regeneron for research funding and serving as a scientific adviser and speaker for additional pharmaceutical and therapeutic companies. Dr. Wu, Dr. Scott, and Dr. Yang did not report any disclosures.

(NAMCS) from 2010 to 2016.

Yet the reasons for the difference are unclear and in need of further research, said the investigators and dermatologists who were asked to comment on the research.

The study covered over 4 million visits for psoriasis and found that the mean duration of visits for Asian patients was 9.2 minutes, compared with 15.7 minutes for Hispanic or Latino patients, 20.7 minutes for non-Hispanic Black patients, and 15.4 minutes for non-Hispanic White patients.

The mean duration of visits with Asian patients was 39.9% shorter, compared with visits with White patients (beta coefficient, –5,747; 95% confidence interval, –11.026 to –0.469; P = .03), and 40.6% shorter, compared with visits with non-Asian patients combined (beta coefficient, –5.908; 95% CI, –11.147 to –0.669, P = .03), April W. Armstrong, MD, MPH, professor of dermatology and director of the psoriasis program at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, and Kevin K. Wu, MD, a dermatology resident at USC, said in a research letter published in JAMA Dermatology.

“The etiology of these differences is unclear,” they wrote. “It is possible that factors such as unconscious bias, cultural differences in communication, or residual confounding may be responsible for the observed findings.”

Their findings came from multivariable linear regression analyses that adjusted for age, sex, type of visit (new or follow-up), visit complexity based on the number of reasons for the visit, insurance status (such as private insurance or Medicaid), psoriasis severity on the basis of systemic psoriasis treatment or phototherapy, and complex topical regimens (three or more topical agents).

Commenting on the results, Deborah A. Scott, MD, codirector of the skin of color dermatology program at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and assistant professor at Harvard Medical School, both in Boston, said in an interview that visit length “is a reasonable parameter to look at among many others” when investigating potential disparities in care.

“They’re equating [shorter visit times] with lack of time spent counseling patients,” said Dr. Scott, who was not involved in the research. But there are “many variables” that can affect visit time, such as language differences, time spent with interpreters, and differences in patient educational levels.

Clarissa Yang, MD, dermatologist-in-chief at Tufts Medical Center, Boston, agreed. “We’re worried about there being a quality of care issue. However, there could also be differences culturally in how [the patients] interact with their physicians – their styles and the questions they ask,” she said in an interview. “The study is a good first step to noting that there may be a disparity,” and there is a need to break down the differences “into more granularity.”

Previous research, the authors wrote, has found that Asian patients were less likely to receive counseling from physicians, compared with White patients. And “paradoxically,” they noted, Asian individuals tend to present with more severe psoriasis than patients of other races and ethnicities.

Dr. Scott said the tendency to present with more severe psoriasis has been documented in patients with skin of color broadly – likely because of delays in recognition and treatment.

Race and ethnicity in the study were self-reported by patients, and missing data were imputed by NAMCS researchers using a sequential regression method. Patients who did not report race and ethnicity may have different characteristics affecting visit duration than those who did report the information, Dr. Armstrong and Dr. Wu said in describing their study’s limitations.

Other differences found

In addition to visit length, they found significant differences in mean age and in the use of complex topical regimens. The mean ages of Asian, Hispanic or Latino, and non-Hispanic Black patients were 37.2, 44.7, and 33.3 years, respectively. Complex topical regimens were prescribed to 11.8% of Asian patients, compared with 1.5% of Black and 1.1% of White patients.

For practicing dermatologists, knowing for now that Asian patients have shorter visits “may bring to light some consciousness to how we practice,” Dr. Yang noted. “We may counsel differently, we may spend differing amounts of time – for reasons still unknown. But being generally aware can help us to shift any unconscious bias that may be there.”

Dermatologists, Dr. Armstrong and Dr. Wu wrote, “need to allow sufficient time to develop strong physician-patient communication regardless of patient background.”

The NAMCS – administered by the Center for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Center for Health Statistics – collects data on a sample of visits provided by non–federally employed office-based physicians.

Dr. Armstrong disclosed receiving personal fees from AbbVie and Regeneron for research funding and serving as a scientific adviser and speaker for additional pharmaceutical and therapeutic companies. Dr. Wu, Dr. Scott, and Dr. Yang did not report any disclosures.

(NAMCS) from 2010 to 2016.

Yet the reasons for the difference are unclear and in need of further research, said the investigators and dermatologists who were asked to comment on the research.

The study covered over 4 million visits for psoriasis and found that the mean duration of visits for Asian patients was 9.2 minutes, compared with 15.7 minutes for Hispanic or Latino patients, 20.7 minutes for non-Hispanic Black patients, and 15.4 minutes for non-Hispanic White patients.

The mean duration of visits with Asian patients was 39.9% shorter, compared with visits with White patients (beta coefficient, –5,747; 95% confidence interval, –11.026 to –0.469; P = .03), and 40.6% shorter, compared with visits with non-Asian patients combined (beta coefficient, –5.908; 95% CI, –11.147 to –0.669, P = .03), April W. Armstrong, MD, MPH, professor of dermatology and director of the psoriasis program at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, and Kevin K. Wu, MD, a dermatology resident at USC, said in a research letter published in JAMA Dermatology.

“The etiology of these differences is unclear,” they wrote. “It is possible that factors such as unconscious bias, cultural differences in communication, or residual confounding may be responsible for the observed findings.”

Their findings came from multivariable linear regression analyses that adjusted for age, sex, type of visit (new or follow-up), visit complexity based on the number of reasons for the visit, insurance status (such as private insurance or Medicaid), psoriasis severity on the basis of systemic psoriasis treatment or phototherapy, and complex topical regimens (three or more topical agents).

Commenting on the results, Deborah A. Scott, MD, codirector of the skin of color dermatology program at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and assistant professor at Harvard Medical School, both in Boston, said in an interview that visit length “is a reasonable parameter to look at among many others” when investigating potential disparities in care.

“They’re equating [shorter visit times] with lack of time spent counseling patients,” said Dr. Scott, who was not involved in the research. But there are “many variables” that can affect visit time, such as language differences, time spent with interpreters, and differences in patient educational levels.

Clarissa Yang, MD, dermatologist-in-chief at Tufts Medical Center, Boston, agreed. “We’re worried about there being a quality of care issue. However, there could also be differences culturally in how [the patients] interact with their physicians – their styles and the questions they ask,” she said in an interview. “The study is a good first step to noting that there may be a disparity,” and there is a need to break down the differences “into more granularity.”

Previous research, the authors wrote, has found that Asian patients were less likely to receive counseling from physicians, compared with White patients. And “paradoxically,” they noted, Asian individuals tend to present with more severe psoriasis than patients of other races and ethnicities.

Dr. Scott said the tendency to present with more severe psoriasis has been documented in patients with skin of color broadly – likely because of delays in recognition and treatment.

Race and ethnicity in the study were self-reported by patients, and missing data were imputed by NAMCS researchers using a sequential regression method. Patients who did not report race and ethnicity may have different characteristics affecting visit duration than those who did report the information, Dr. Armstrong and Dr. Wu said in describing their study’s limitations.

Other differences found

In addition to visit length, they found significant differences in mean age and in the use of complex topical regimens. The mean ages of Asian, Hispanic or Latino, and non-Hispanic Black patients were 37.2, 44.7, and 33.3 years, respectively. Complex topical regimens were prescribed to 11.8% of Asian patients, compared with 1.5% of Black and 1.1% of White patients.

For practicing dermatologists, knowing for now that Asian patients have shorter visits “may bring to light some consciousness to how we practice,” Dr. Yang noted. “We may counsel differently, we may spend differing amounts of time – for reasons still unknown. But being generally aware can help us to shift any unconscious bias that may be there.”

Dermatologists, Dr. Armstrong and Dr. Wu wrote, “need to allow sufficient time to develop strong physician-patient communication regardless of patient background.”

The NAMCS – administered by the Center for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Center for Health Statistics – collects data on a sample of visits provided by non–federally employed office-based physicians.

Dr. Armstrong disclosed receiving personal fees from AbbVie and Regeneron for research funding and serving as a scientific adviser and speaker for additional pharmaceutical and therapeutic companies. Dr. Wu, Dr. Scott, and Dr. Yang did not report any disclosures.

FROM JAMA DERMATOLOGY

Second opinions on melanocytic lesions swayed when first opinion is known

, diminishing the value and accuracy of an independent analysis.

In a novel effort to determine whether previous interpretations sway second opinions, 149 dermatopathologists were asked to read melanocytic skin biopsy specimens without access to the initial pathology report. A year or more later they read them again but now with access to the initial reading.

The study showed that the participants, independent of many variables, such as years of experience or frequency with which they offered second options, were more likely to upgrade or downgrade the severity of the specimens in accordance with the initial report even if their original reading was correct.

If the goal of a second dermatopathologist opinion is to obtain an independent diagnostic opinion, the message from this study is that they “should be blinded to first opinions,” according to the authors of this study, led by Joann G. Elmore, MD, professor of medicine, University of California, Los Angeles. The study was published online in JAMA Dermatology.

Two-phase study has 1-year washout

The study was conducted in two phases. In phase 1, a nationally representative sample of volunteer dermatopathologists performed 878 interpretations. In phase 2, conducted after a washout period of 12 months or more, the dermatopathologists read a random subset of the same cases evaluated in phase 1, but this time, unlike the first, they were first exposed to prior pathology reports.

Ultimately, “the dermatologists provided more than 5,000 interpretations of study cases, which was a big contribution of time,” Dr. Elmore said in an interview. Grateful for their critical contribution, she speculated that they were driven by the importance of the question being asked.

When categorized by the Melanocytic Pathology Assessment Tool (MPAT), which rates specimens from benign (class 1) to pT1b invasive melanoma (class 4), the influence of the prior report went in both directions, so that the likelihood of upgrading or downgrading went in accordance with the grading in the original dermatopathology report.

As a result, the risk of a less severe interpretation on the second relative to the first reading was 38% greater if the initial dermatopathology report had a lower grade (relative risk, 1.38; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.19-1.59). The risk of upgrading the second report if the initial pathology report had a higher grade was increased by more than 50% (RR, 1.52; 95% CI, 1.34-1.73).

The greater likelihood of upgrading than downgrading is “understandable,” Dr. Elmore said. “I think this is consistent with the concern about missing something,” she explained.

According to Dr. Elmore, one of the greatest concerns regarding the bias imposed by the original pathology report is that the switch of opinions often went from one that was accurate to one that was inaccurate.

If the phase 1 diagnosis was accurate but upgraded in the phase 2 diagnosis, the risk of inaccuracy was almost doubled (RR, 1.96; 95% CI, 1.31-2.93). If the phase 1 report was inaccurate, the relative risk of changing the phase 2 diagnosis was still high but lower than if it was accurate (RR, 1.46; 95% CI, 1.27-1.68).

“That is, even when the phase 1 diagnoses agreed with the consensus reference diagnosis, they were swayed away from the correct diagnosis in phase 2 [when the initial pathology report characterized the specimen as higher grade],” Dr. Elmore reported.

Conversely, the risk of downgrading was about the same whether the phase 1 evaluation was accurate (RR, 1.37; 95% CI, 1.14-1.64) or inaccurate (RR 1.32; 95% CI, 1.07-1.64).

Downward and upward shifts in severity from an accurate diagnosis are concerning because of the likelihood they will lead to overtreatment or undertreatment. The problem, according to data from this study, is that dermatologists making a second opinion cannot judge their own susceptibility to being swayed by the original report.

Pathologists might be unaware of bias

At baseline, the participants were asked whether they thought they were influenced by the first interpretation when providing a second opinion. Although 69% acknowledged that they might be “somewhat influenced,” 31% maintained that they do not take initial reports into consideration. When the two groups were compared, the risk of downgrading was nearly identical. The risk of upgrading was lower in those claiming to disregard initial reports (RR, 1.29) relative to those who said they were “somewhat influenced” by a previous diagnosis (RR, 1.64), but the difference was not significant.

The actual risk of bias incurred by prior pathology reports might be greater than that captured in this study for several reasons, according to the investigators. They pointed out that all participants were experienced and board-certified and might therefore be expected to be more confident in their interpretations than an unselected group of dermatopathologists. In addition, participants might have been more careful in their interpretations knowing they were participating in a study.

“There are a lot of data to support the value of second opinions [in dermatopathology and other areas], but we need to consider the process of how they are being obtained,” Dr. Elmore said. “There needs to be a greater emphasis on providing an independent analysis.”

More than 60% of the dermatologists participating in this study reported that they agreed or strongly agreed with the premise that they prefer to have the original dermatopathology report when they offer a second opinion. Dr. Elmore said that the desire of those offering a second opinion to have as much information in front of them as possible is understandable, but the bias imposed by the original report weakens the value of the second opinion.

Blind reading of pathology reports needed

“These data suggest that seeing the original report sways opinions and that includes swaying opinions away from an accurate reading,” Dr. Elmore said. She thinks that for dermatopathologists to render a valuable and independent second opinion, the specimens should be examined “at least initially” without access to the first report.

The results of this study were not surprising to Vishal Anil Patel, MD, director of the Cutaneous Oncology Program, George Washington University Cancer Center, Washington. He made the point that physicians “are human first and foremost and not perfect machines.” As a result, he suggested bias and error are inevitable.

Although strategies to avoid bias are likely to offer some protection against inaccuracy, he said that diagnostic support tools such as artificial intelligence might be the right direction for improving inter- and intra-rater reliability.

Ruifeng Guo, MD, PhD, a consultant in the division of anatomic pathology at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., agreed with the basic premise of the study, but he cautioned that restricting access to the initial pathology report might not always be the right approach.

It is true that “dermatopathologists providing a second opinion in diagnosing cutaneous melanoma are mostly unaware of the risk of bias if they read the initial pathology report,” said Dr. Guo, but restricting access comes with risks.

“There are also times critical information may be contained in the initial pathology report that needs to be considered when providing a second opinion consultation,” he noted. Ultimately, the decision to read or not read the initial report should be decided “on an individual basis.”

The study was funded by grants from the National Cancer Institute. Dr. Elmore, Dr. Patel, and Dr. Guo reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, diminishing the value and accuracy of an independent analysis.

In a novel effort to determine whether previous interpretations sway second opinions, 149 dermatopathologists were asked to read melanocytic skin biopsy specimens without access to the initial pathology report. A year or more later they read them again but now with access to the initial reading.

The study showed that the participants, independent of many variables, such as years of experience or frequency with which they offered second options, were more likely to upgrade or downgrade the severity of the specimens in accordance with the initial report even if their original reading was correct.

If the goal of a second dermatopathologist opinion is to obtain an independent diagnostic opinion, the message from this study is that they “should be blinded to first opinions,” according to the authors of this study, led by Joann G. Elmore, MD, professor of medicine, University of California, Los Angeles. The study was published online in JAMA Dermatology.

Two-phase study has 1-year washout

The study was conducted in two phases. In phase 1, a nationally representative sample of volunteer dermatopathologists performed 878 interpretations. In phase 2, conducted after a washout period of 12 months or more, the dermatopathologists read a random subset of the same cases evaluated in phase 1, but this time, unlike the first, they were first exposed to prior pathology reports.

Ultimately, “the dermatologists provided more than 5,000 interpretations of study cases, which was a big contribution of time,” Dr. Elmore said in an interview. Grateful for their critical contribution, she speculated that they were driven by the importance of the question being asked.

When categorized by the Melanocytic Pathology Assessment Tool (MPAT), which rates specimens from benign (class 1) to pT1b invasive melanoma (class 4), the influence of the prior report went in both directions, so that the likelihood of upgrading or downgrading went in accordance with the grading in the original dermatopathology report.

As a result, the risk of a less severe interpretation on the second relative to the first reading was 38% greater if the initial dermatopathology report had a lower grade (relative risk, 1.38; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.19-1.59). The risk of upgrading the second report if the initial pathology report had a higher grade was increased by more than 50% (RR, 1.52; 95% CI, 1.34-1.73).

The greater likelihood of upgrading than downgrading is “understandable,” Dr. Elmore said. “I think this is consistent with the concern about missing something,” she explained.

According to Dr. Elmore, one of the greatest concerns regarding the bias imposed by the original pathology report is that the switch of opinions often went from one that was accurate to one that was inaccurate.

If the phase 1 diagnosis was accurate but upgraded in the phase 2 diagnosis, the risk of inaccuracy was almost doubled (RR, 1.96; 95% CI, 1.31-2.93). If the phase 1 report was inaccurate, the relative risk of changing the phase 2 diagnosis was still high but lower than if it was accurate (RR, 1.46; 95% CI, 1.27-1.68).

“That is, even when the phase 1 diagnoses agreed with the consensus reference diagnosis, they were swayed away from the correct diagnosis in phase 2 [when the initial pathology report characterized the specimen as higher grade],” Dr. Elmore reported.

Conversely, the risk of downgrading was about the same whether the phase 1 evaluation was accurate (RR, 1.37; 95% CI, 1.14-1.64) or inaccurate (RR 1.32; 95% CI, 1.07-1.64).

Downward and upward shifts in severity from an accurate diagnosis are concerning because of the likelihood they will lead to overtreatment or undertreatment. The problem, according to data from this study, is that dermatologists making a second opinion cannot judge their own susceptibility to being swayed by the original report.

Pathologists might be unaware of bias

At baseline, the participants were asked whether they thought they were influenced by the first interpretation when providing a second opinion. Although 69% acknowledged that they might be “somewhat influenced,” 31% maintained that they do not take initial reports into consideration. When the two groups were compared, the risk of downgrading was nearly identical. The risk of upgrading was lower in those claiming to disregard initial reports (RR, 1.29) relative to those who said they were “somewhat influenced” by a previous diagnosis (RR, 1.64), but the difference was not significant.

The actual risk of bias incurred by prior pathology reports might be greater than that captured in this study for several reasons, according to the investigators. They pointed out that all participants were experienced and board-certified and might therefore be expected to be more confident in their interpretations than an unselected group of dermatopathologists. In addition, participants might have been more careful in their interpretations knowing they were participating in a study.

“There are a lot of data to support the value of second opinions [in dermatopathology and other areas], but we need to consider the process of how they are being obtained,” Dr. Elmore said. “There needs to be a greater emphasis on providing an independent analysis.”

More than 60% of the dermatologists participating in this study reported that they agreed or strongly agreed with the premise that they prefer to have the original dermatopathology report when they offer a second opinion. Dr. Elmore said that the desire of those offering a second opinion to have as much information in front of them as possible is understandable, but the bias imposed by the original report weakens the value of the second opinion.

Blind reading of pathology reports needed

“These data suggest that seeing the original report sways opinions and that includes swaying opinions away from an accurate reading,” Dr. Elmore said. She thinks that for dermatopathologists to render a valuable and independent second opinion, the specimens should be examined “at least initially” without access to the first report.

The results of this study were not surprising to Vishal Anil Patel, MD, director of the Cutaneous Oncology Program, George Washington University Cancer Center, Washington. He made the point that physicians “are human first and foremost and not perfect machines.” As a result, he suggested bias and error are inevitable.

Although strategies to avoid bias are likely to offer some protection against inaccuracy, he said that diagnostic support tools such as artificial intelligence might be the right direction for improving inter- and intra-rater reliability.

Ruifeng Guo, MD, PhD, a consultant in the division of anatomic pathology at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., agreed with the basic premise of the study, but he cautioned that restricting access to the initial pathology report might not always be the right approach.

It is true that “dermatopathologists providing a second opinion in diagnosing cutaneous melanoma are mostly unaware of the risk of bias if they read the initial pathology report,” said Dr. Guo, but restricting access comes with risks.

“There are also times critical information may be contained in the initial pathology report that needs to be considered when providing a second opinion consultation,” he noted. Ultimately, the decision to read or not read the initial report should be decided “on an individual basis.”

The study was funded by grants from the National Cancer Institute. Dr. Elmore, Dr. Patel, and Dr. Guo reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, diminishing the value and accuracy of an independent analysis.

In a novel effort to determine whether previous interpretations sway second opinions, 149 dermatopathologists were asked to read melanocytic skin biopsy specimens without access to the initial pathology report. A year or more later they read them again but now with access to the initial reading.

The study showed that the participants, independent of many variables, such as years of experience or frequency with which they offered second options, were more likely to upgrade or downgrade the severity of the specimens in accordance with the initial report even if their original reading was correct.

If the goal of a second dermatopathologist opinion is to obtain an independent diagnostic opinion, the message from this study is that they “should be blinded to first opinions,” according to the authors of this study, led by Joann G. Elmore, MD, professor of medicine, University of California, Los Angeles. The study was published online in JAMA Dermatology.

Two-phase study has 1-year washout

The study was conducted in two phases. In phase 1, a nationally representative sample of volunteer dermatopathologists performed 878 interpretations. In phase 2, conducted after a washout period of 12 months or more, the dermatopathologists read a random subset of the same cases evaluated in phase 1, but this time, unlike the first, they were first exposed to prior pathology reports.

Ultimately, “the dermatologists provided more than 5,000 interpretations of study cases, which was a big contribution of time,” Dr. Elmore said in an interview. Grateful for their critical contribution, she speculated that they were driven by the importance of the question being asked.

When categorized by the Melanocytic Pathology Assessment Tool (MPAT), which rates specimens from benign (class 1) to pT1b invasive melanoma (class 4), the influence of the prior report went in both directions, so that the likelihood of upgrading or downgrading went in accordance with the grading in the original dermatopathology report.

As a result, the risk of a less severe interpretation on the second relative to the first reading was 38% greater if the initial dermatopathology report had a lower grade (relative risk, 1.38; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.19-1.59). The risk of upgrading the second report if the initial pathology report had a higher grade was increased by more than 50% (RR, 1.52; 95% CI, 1.34-1.73).

The greater likelihood of upgrading than downgrading is “understandable,” Dr. Elmore said. “I think this is consistent with the concern about missing something,” she explained.

According to Dr. Elmore, one of the greatest concerns regarding the bias imposed by the original pathology report is that the switch of opinions often went from one that was accurate to one that was inaccurate.

If the phase 1 diagnosis was accurate but upgraded in the phase 2 diagnosis, the risk of inaccuracy was almost doubled (RR, 1.96; 95% CI, 1.31-2.93). If the phase 1 report was inaccurate, the relative risk of changing the phase 2 diagnosis was still high but lower than if it was accurate (RR, 1.46; 95% CI, 1.27-1.68).

“That is, even when the phase 1 diagnoses agreed with the consensus reference diagnosis, they were swayed away from the correct diagnosis in phase 2 [when the initial pathology report characterized the specimen as higher grade],” Dr. Elmore reported.

Conversely, the risk of downgrading was about the same whether the phase 1 evaluation was accurate (RR, 1.37; 95% CI, 1.14-1.64) or inaccurate (RR 1.32; 95% CI, 1.07-1.64).

Downward and upward shifts in severity from an accurate diagnosis are concerning because of the likelihood they will lead to overtreatment or undertreatment. The problem, according to data from this study, is that dermatologists making a second opinion cannot judge their own susceptibility to being swayed by the original report.

Pathologists might be unaware of bias

At baseline, the participants were asked whether they thought they were influenced by the first interpretation when providing a second opinion. Although 69% acknowledged that they might be “somewhat influenced,” 31% maintained that they do not take initial reports into consideration. When the two groups were compared, the risk of downgrading was nearly identical. The risk of upgrading was lower in those claiming to disregard initial reports (RR, 1.29) relative to those who said they were “somewhat influenced” by a previous diagnosis (RR, 1.64), but the difference was not significant.

The actual risk of bias incurred by prior pathology reports might be greater than that captured in this study for several reasons, according to the investigators. They pointed out that all participants were experienced and board-certified and might therefore be expected to be more confident in their interpretations than an unselected group of dermatopathologists. In addition, participants might have been more careful in their interpretations knowing they were participating in a study.

“There are a lot of data to support the value of second opinions [in dermatopathology and other areas], but we need to consider the process of how they are being obtained,” Dr. Elmore said. “There needs to be a greater emphasis on providing an independent analysis.”

More than 60% of the dermatologists participating in this study reported that they agreed or strongly agreed with the premise that they prefer to have the original dermatopathology report when they offer a second opinion. Dr. Elmore said that the desire of those offering a second opinion to have as much information in front of them as possible is understandable, but the bias imposed by the original report weakens the value of the second opinion.

Blind reading of pathology reports needed

“These data suggest that seeing the original report sways opinions and that includes swaying opinions away from an accurate reading,” Dr. Elmore said. She thinks that for dermatopathologists to render a valuable and independent second opinion, the specimens should be examined “at least initially” without access to the first report.

The results of this study were not surprising to Vishal Anil Patel, MD, director of the Cutaneous Oncology Program, George Washington University Cancer Center, Washington. He made the point that physicians “are human first and foremost and not perfect machines.” As a result, he suggested bias and error are inevitable.

Although strategies to avoid bias are likely to offer some protection against inaccuracy, he said that diagnostic support tools such as artificial intelligence might be the right direction for improving inter- and intra-rater reliability.

Ruifeng Guo, MD, PhD, a consultant in the division of anatomic pathology at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., agreed with the basic premise of the study, but he cautioned that restricting access to the initial pathology report might not always be the right approach.

It is true that “dermatopathologists providing a second opinion in diagnosing cutaneous melanoma are mostly unaware of the risk of bias if they read the initial pathology report,” said Dr. Guo, but restricting access comes with risks.

“There are also times critical information may be contained in the initial pathology report that needs to be considered when providing a second opinion consultation,” he noted. Ultimately, the decision to read or not read the initial report should be decided “on an individual basis.”

The study was funded by grants from the National Cancer Institute. Dr. Elmore, Dr. Patel, and Dr. Guo reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Abrocitinib evaluated in patients with and without prior dupilumab treatment

an industry-sponsored study reports.

“In this post hoc analysis, both the efficacy and the safety profiles of abrocitinib were consistent in patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis, regardless of prior biologic therapy use,” lead author Melinda Gooderham, MD, medical director of the SKiN Centre for Dermatology, Peterborough, Ont., said during an oral presentation at the Society for Investigative Dermatology (SID) 2022 Annual Meeting.

“These results ... support the use of abrocitinib in patients who might have received biologic therapy prior,” she added.

“Prior biologic use did not reveal any new safety signals ... keeping in mind the key limitation of this analysis is that it was done post hoc,” she noted.

Guidelines for moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis refractory to topical or systemic therapy include systemic immunosuppressants and dupilumab, a monoclonal antibody that inhibits interleukin-4 and interleukin-13 cytokine-induced responses, Dr. Gooderham said.

The Food and Drug Administration recently approved abrocitinib, an oral once-a-day Janus kinase 1 (JAK1) inhibitor, to treat the disease. The approval came with a boxed warning about increased risk for serious infections, mortality, malignancy, and lymphoproliferative disorders, major adverse cardiovascular events, thrombosis, and laboratory abnormalities.

Comparing the bio-experienced with the bio-naive

Dr. Gooderham and colleagues investigated whether patients who’d been treated with a biologic would respond to abrocitinib differently than patients who had not received prior biologic treatment.

Researchers pooled data from two phase 3 placebo-controlled trials of abrocitinib that led to approval and an earlier phase 2b study. They identified 67 patients previously treated with dupilumab and 867 patients who were bio-naive. They repeated their analysis using data from another phase 3 study of abrocitinib on 86 patients previously treated with dupilumab and 1,147 who were bio-naive. On average, the bio-experienced patients were in their mid-30s to early 40s, and the bio-naive group was several years younger.

In the pooled phase 2b and phase 3 JADE MONO-1 and JADE MONO-2 monotherapy trials, patients received once-daily abrocitinib 100 or 200 mg or placebo for 12 weeks. In the phase 3 JADE REGIMEN, which they analyzed separately, eligible patients were enrolled in a 12-week open-label run-in period during which they received an induction treatment of abrocitinib 200 mg once a day.

Researchers compared results of two assessments: the IGA (Investigator Global Assessment) and EASI-75 (Eczema Area and Severity Index, 75% or greater improvement from baseline).

- At week 12, IGA 0/1 dose-dependent response rates were similar in the pooled groups, regardless of whether they had received prior biologic therapy. With abrocitinib 200 mg, 43.5% of those with prior dupilumab therapy responded versus 41.4% of bio-naive patients; with abrocitinib 100 mg, 24.1% versus 26.7% responded. In JADE REGIMEN, corresponding response rates with abrocitinib 200 mg were 53.5% versus 66.9%, respectively.

- At week 12, EASI-75 responses were also comparable. In the pooled groups by dose, with abrocitinib 200 mg, EASI-75 response rates were 65.2% in patients with prior dupilumab therapy versus 62.4% in those without; at abrocitinib 100 mg, 34.5% versus 42.7% responded. Corresponding rates in JADE REGIMEN were 64.0% versus 76.4%, respectively.

- Treatment-emergent adverse event rates among patients with versus without prior biologic therapy were, respectively, 71.7% versus 69.9% (abrocitinib 200 mg + 100 mg groups) in the pooled population. Rates in JADE REGIMEN with abrocitinib 200 mg were, respectively, 66.3% versus 66.5%.

- Abrocitinib efficacy and safety were consistent in patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis, regardless of prior biologic therapy. Adverse events in the pooled monotherapy trials and in JADE REGIMEN included acne, atopic dermatitis, diarrhea, headache, nasopharyngitis, nausea, upper abdominal pain, and upper respiratory tract infection.

The authors acknowledge that the post hoc study design is a limitation and recommend confirming these findings in a large, long-term prospective study.

JAK inhibitors expand treatment options

The results will help doctors treat their patients, Jami L. Miller, MD, associate professor of dermatology and dermatology clinic medical director at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn., told this news organization.

“Because JAK inhibitors have potentially more side effects than inhibitors of interleukin-4 and interleukin-13, in clinical practice most dermatologists are more likely to treat patients first with dupilumab or similar meds and step up to a JAK inhibitor if they do not respond,” she added in an email.

“With more meds coming out to meet the needs of this population, this is an exciting time for patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis,” she commented.

Lindsay C. Strowd, MD, associate professor and vice chair of the department of dermatology at Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, N.C., said JAK inhibitors are increasingly being studied and approved for use in various dermatologic diseases.

An oral JAK inhibitor (upadacitinib) is currently FDA approved for moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis, and a topical JAK inhibitor (ruxolitinib) is also approved for use in atopic dermatitis, Dr. Strowd noted.

“The study results give providers important practical information,” added Dr. Strowd, who also was not involved with the study. “Those of us who care for patients with severe atopic dermatitis need to know how patients with prior biologic exposure will respond as newer agents come to market and the options for biologic use in atopic dermatitis continue to grow.”

The study was sponsored by Pfizer. All study authors have reported relevant financial relationships with, and several authors are employees of, Pfizer, the developer of abrocitinib. Dr. Strowd and Dr. Miller have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

an industry-sponsored study reports.

“In this post hoc analysis, both the efficacy and the safety profiles of abrocitinib were consistent in patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis, regardless of prior biologic therapy use,” lead author Melinda Gooderham, MD, medical director of the SKiN Centre for Dermatology, Peterborough, Ont., said during an oral presentation at the Society for Investigative Dermatology (SID) 2022 Annual Meeting.

“These results ... support the use of abrocitinib in patients who might have received biologic therapy prior,” she added.

“Prior biologic use did not reveal any new safety signals ... keeping in mind the key limitation of this analysis is that it was done post hoc,” she noted.

Guidelines for moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis refractory to topical or systemic therapy include systemic immunosuppressants and dupilumab, a monoclonal antibody that inhibits interleukin-4 and interleukin-13 cytokine-induced responses, Dr. Gooderham said.

The Food and Drug Administration recently approved abrocitinib, an oral once-a-day Janus kinase 1 (JAK1) inhibitor, to treat the disease. The approval came with a boxed warning about increased risk for serious infections, mortality, malignancy, and lymphoproliferative disorders, major adverse cardiovascular events, thrombosis, and laboratory abnormalities.

Comparing the bio-experienced with the bio-naive

Dr. Gooderham and colleagues investigated whether patients who’d been treated with a biologic would respond to abrocitinib differently than patients who had not received prior biologic treatment.

Researchers pooled data from two phase 3 placebo-controlled trials of abrocitinib that led to approval and an earlier phase 2b study. They identified 67 patients previously treated with dupilumab and 867 patients who were bio-naive. They repeated their analysis using data from another phase 3 study of abrocitinib on 86 patients previously treated with dupilumab and 1,147 who were bio-naive. On average, the bio-experienced patients were in their mid-30s to early 40s, and the bio-naive group was several years younger.

In the pooled phase 2b and phase 3 JADE MONO-1 and JADE MONO-2 monotherapy trials, patients received once-daily abrocitinib 100 or 200 mg or placebo for 12 weeks. In the phase 3 JADE REGIMEN, which they analyzed separately, eligible patients were enrolled in a 12-week open-label run-in period during which they received an induction treatment of abrocitinib 200 mg once a day.

Researchers compared results of two assessments: the IGA (Investigator Global Assessment) and EASI-75 (Eczema Area and Severity Index, 75% or greater improvement from baseline).

- At week 12, IGA 0/1 dose-dependent response rates were similar in the pooled groups, regardless of whether they had received prior biologic therapy. With abrocitinib 200 mg, 43.5% of those with prior dupilumab therapy responded versus 41.4% of bio-naive patients; with abrocitinib 100 mg, 24.1% versus 26.7% responded. In JADE REGIMEN, corresponding response rates with abrocitinib 200 mg were 53.5% versus 66.9%, respectively.

- At week 12, EASI-75 responses were also comparable. In the pooled groups by dose, with abrocitinib 200 mg, EASI-75 response rates were 65.2% in patients with prior dupilumab therapy versus 62.4% in those without; at abrocitinib 100 mg, 34.5% versus 42.7% responded. Corresponding rates in JADE REGIMEN were 64.0% versus 76.4%, respectively.

- Treatment-emergent adverse event rates among patients with versus without prior biologic therapy were, respectively, 71.7% versus 69.9% (abrocitinib 200 mg + 100 mg groups) in the pooled population. Rates in JADE REGIMEN with abrocitinib 200 mg were, respectively, 66.3% versus 66.5%.

- Abrocitinib efficacy and safety were consistent in patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis, regardless of prior biologic therapy. Adverse events in the pooled monotherapy trials and in JADE REGIMEN included acne, atopic dermatitis, diarrhea, headache, nasopharyngitis, nausea, upper abdominal pain, and upper respiratory tract infection.

The authors acknowledge that the post hoc study design is a limitation and recommend confirming these findings in a large, long-term prospective study.

JAK inhibitors expand treatment options

The results will help doctors treat their patients, Jami L. Miller, MD, associate professor of dermatology and dermatology clinic medical director at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn., told this news organization.

“Because JAK inhibitors have potentially more side effects than inhibitors of interleukin-4 and interleukin-13, in clinical practice most dermatologists are more likely to treat patients first with dupilumab or similar meds and step up to a JAK inhibitor if they do not respond,” she added in an email.

“With more meds coming out to meet the needs of this population, this is an exciting time for patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis,” she commented.

Lindsay C. Strowd, MD, associate professor and vice chair of the department of dermatology at Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, N.C., said JAK inhibitors are increasingly being studied and approved for use in various dermatologic diseases.

An oral JAK inhibitor (upadacitinib) is currently FDA approved for moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis, and a topical JAK inhibitor (ruxolitinib) is also approved for use in atopic dermatitis, Dr. Strowd noted.

“The study results give providers important practical information,” added Dr. Strowd, who also was not involved with the study. “Those of us who care for patients with severe atopic dermatitis need to know how patients with prior biologic exposure will respond as newer agents come to market and the options for biologic use in atopic dermatitis continue to grow.”

The study was sponsored by Pfizer. All study authors have reported relevant financial relationships with, and several authors are employees of, Pfizer, the developer of abrocitinib. Dr. Strowd and Dr. Miller have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

an industry-sponsored study reports.

“In this post hoc analysis, both the efficacy and the safety profiles of abrocitinib were consistent in patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis, regardless of prior biologic therapy use,” lead author Melinda Gooderham, MD, medical director of the SKiN Centre for Dermatology, Peterborough, Ont., said during an oral presentation at the Society for Investigative Dermatology (SID) 2022 Annual Meeting.

“These results ... support the use of abrocitinib in patients who might have received biologic therapy prior,” she added.

“Prior biologic use did not reveal any new safety signals ... keeping in mind the key limitation of this analysis is that it was done post hoc,” she noted.

Guidelines for moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis refractory to topical or systemic therapy include systemic immunosuppressants and dupilumab, a monoclonal antibody that inhibits interleukin-4 and interleukin-13 cytokine-induced responses, Dr. Gooderham said.

The Food and Drug Administration recently approved abrocitinib, an oral once-a-day Janus kinase 1 (JAK1) inhibitor, to treat the disease. The approval came with a boxed warning about increased risk for serious infections, mortality, malignancy, and lymphoproliferative disorders, major adverse cardiovascular events, thrombosis, and laboratory abnormalities.

Comparing the bio-experienced with the bio-naive

Dr. Gooderham and colleagues investigated whether patients who’d been treated with a biologic would respond to abrocitinib differently than patients who had not received prior biologic treatment.

Researchers pooled data from two phase 3 placebo-controlled trials of abrocitinib that led to approval and an earlier phase 2b study. They identified 67 patients previously treated with dupilumab and 867 patients who were bio-naive. They repeated their analysis using data from another phase 3 study of abrocitinib on 86 patients previously treated with dupilumab and 1,147 who were bio-naive. On average, the bio-experienced patients were in their mid-30s to early 40s, and the bio-naive group was several years younger.

In the pooled phase 2b and phase 3 JADE MONO-1 and JADE MONO-2 monotherapy trials, patients received once-daily abrocitinib 100 or 200 mg or placebo for 12 weeks. In the phase 3 JADE REGIMEN, which they analyzed separately, eligible patients were enrolled in a 12-week open-label run-in period during which they received an induction treatment of abrocitinib 200 mg once a day.

Researchers compared results of two assessments: the IGA (Investigator Global Assessment) and EASI-75 (Eczema Area and Severity Index, 75% or greater improvement from baseline).

- At week 12, IGA 0/1 dose-dependent response rates were similar in the pooled groups, regardless of whether they had received prior biologic therapy. With abrocitinib 200 mg, 43.5% of those with prior dupilumab therapy responded versus 41.4% of bio-naive patients; with abrocitinib 100 mg, 24.1% versus 26.7% responded. In JADE REGIMEN, corresponding response rates with abrocitinib 200 mg were 53.5% versus 66.9%, respectively.

- At week 12, EASI-75 responses were also comparable. In the pooled groups by dose, with abrocitinib 200 mg, EASI-75 response rates were 65.2% in patients with prior dupilumab therapy versus 62.4% in those without; at abrocitinib 100 mg, 34.5% versus 42.7% responded. Corresponding rates in JADE REGIMEN were 64.0% versus 76.4%, respectively.

- Treatment-emergent adverse event rates among patients with versus without prior biologic therapy were, respectively, 71.7% versus 69.9% (abrocitinib 200 mg + 100 mg groups) in the pooled population. Rates in JADE REGIMEN with abrocitinib 200 mg were, respectively, 66.3% versus 66.5%.

- Abrocitinib efficacy and safety were consistent in patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis, regardless of prior biologic therapy. Adverse events in the pooled monotherapy trials and in JADE REGIMEN included acne, atopic dermatitis, diarrhea, headache, nasopharyngitis, nausea, upper abdominal pain, and upper respiratory tract infection.

The authors acknowledge that the post hoc study design is a limitation and recommend confirming these findings in a large, long-term prospective study.

JAK inhibitors expand treatment options

The results will help doctors treat their patients, Jami L. Miller, MD, associate professor of dermatology and dermatology clinic medical director at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn., told this news organization.

“Because JAK inhibitors have potentially more side effects than inhibitors of interleukin-4 and interleukin-13, in clinical practice most dermatologists are more likely to treat patients first with dupilumab or similar meds and step up to a JAK inhibitor if they do not respond,” she added in an email.

“With more meds coming out to meet the needs of this population, this is an exciting time for patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis,” she commented.

Lindsay C. Strowd, MD, associate professor and vice chair of the department of dermatology at Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, N.C., said JAK inhibitors are increasingly being studied and approved for use in various dermatologic diseases.

An oral JAK inhibitor (upadacitinib) is currently FDA approved for moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis, and a topical JAK inhibitor (ruxolitinib) is also approved for use in atopic dermatitis, Dr. Strowd noted.

“The study results give providers important practical information,” added Dr. Strowd, who also was not involved with the study. “Those of us who care for patients with severe atopic dermatitis need to know how patients with prior biologic exposure will respond as newer agents come to market and the options for biologic use in atopic dermatitis continue to grow.”

The study was sponsored by Pfizer. All study authors have reported relevant financial relationships with, and several authors are employees of, Pfizer, the developer of abrocitinib. Dr. Strowd and Dr. Miller have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Consider essential oil allergy in patient with dermatitis

PORTLAND, ORE. – When patients present to Brandon L. Adler, MD, with dermatitis on the eyelid, face, or neck, he routinely asks them if they apply essential oils on their skin, or if they have an essential oil diffuser or nebulizer in their home.

“The answer is frequently ‘yes,’ ” Dr. Adler, clinical assistant professor of dermatology at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, said at the annual meeting of the Pacific Dermatologic Association. “Essential oils are widely used throughout the wellness industry. They are contained in personal care products, beauty products, natural cleaning products, and they’re being diffused by our patients into the air. More than 75 essential oils are reported to cause allergic contact dermatitis.”

“Linalool is most classically associated with lavender, while limonene is associated with citrus, but they’re found in many different plants,” said Dr. Adler, who directs USC’s contact dermatitis clinic. “On their own, linalool and limonene are not particularly allergenic; they’re not a big deal in the patch test clinic. The problem comes when we add air to the mix, because they oxidize to hydroperoxides of linalool and limonene. These are quite potent allergens.”

According to the most recent North American Contact Dermatitis Group data, 8.9% of patients undergoing patch testing tested positive to linalool hydroperoxides and 2.6% were positive to limonene hydroperoxides.

Dr. Adler discussed the case of a female massage therapist who presented with refractory hand dermatitis and was on methotrexate and dupilumab at the time of consultation but was still symptomatic. She patch-tested positive to limonene and linalool hydroperoxides as well as multiple essential oils that she had been using with her clients, ranging from sacred frankincense oil to basil oil, and she was advised to massage using only coconut or vegetable oils.

Essential oil allergy may also be related to cannabis allergy. According to Dr. Adler, allergic contact dermatitis to cannabis has been rarely reported, but in an analysis of 103 commercial topical cannabinoid preparations that he published with Vincent DeLeo, MD, also with USC, 84% contained a NACDG allergen, frequently essential oils.

More recently, Dr. Adler and colleagues reported the case of a 40-year-old woman who was referred for patch testing for nummular dermatitis that wasn’t responding to treatment. The patient was found to be using topical cannabis and also grew cannabis at home. “She asked to be patch-tested to her homegrown cannabis and had a strong positive patch test to the cannabis, linalool and limonene hydroperoxides, and other essential oils,” Dr. Adler recalled. “We sent her cannabis sample for analysis at a commercial lab and found that it contained limonene and other allergenic terpene chemicals.

“We’re just starting to unravel what this means in terms of our patients and how to manage them, but many are using topical cannabis and topical CBD. I suspect this is a lot less rare than we realize.”

Another recent case from Europe reported allergic contact dermatitis to Cannabis sativa (hemp) seed oil following topical application, with positive patch testing.

Dr. Adler disclosed that he has received research grants from the American Contact Dermatitis Society. He is also an investigator for AbbVie and a consultant for the Skin Research Institute.

PORTLAND, ORE. – When patients present to Brandon L. Adler, MD, with dermatitis on the eyelid, face, or neck, he routinely asks them if they apply essential oils on their skin, or if they have an essential oil diffuser or nebulizer in their home.

“The answer is frequently ‘yes,’ ” Dr. Adler, clinical assistant professor of dermatology at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, said at the annual meeting of the Pacific Dermatologic Association. “Essential oils are widely used throughout the wellness industry. They are contained in personal care products, beauty products, natural cleaning products, and they’re being diffused by our patients into the air. More than 75 essential oils are reported to cause allergic contact dermatitis.”

“Linalool is most classically associated with lavender, while limonene is associated with citrus, but they’re found in many different plants,” said Dr. Adler, who directs USC’s contact dermatitis clinic. “On their own, linalool and limonene are not particularly allergenic; they’re not a big deal in the patch test clinic. The problem comes when we add air to the mix, because they oxidize to hydroperoxides of linalool and limonene. These are quite potent allergens.”

According to the most recent North American Contact Dermatitis Group data, 8.9% of patients undergoing patch testing tested positive to linalool hydroperoxides and 2.6% were positive to limonene hydroperoxides.

Dr. Adler discussed the case of a female massage therapist who presented with refractory hand dermatitis and was on methotrexate and dupilumab at the time of consultation but was still symptomatic. She patch-tested positive to limonene and linalool hydroperoxides as well as multiple essential oils that she had been using with her clients, ranging from sacred frankincense oil to basil oil, and she was advised to massage using only coconut or vegetable oils.

Essential oil allergy may also be related to cannabis allergy. According to Dr. Adler, allergic contact dermatitis to cannabis has been rarely reported, but in an analysis of 103 commercial topical cannabinoid preparations that he published with Vincent DeLeo, MD, also with USC, 84% contained a NACDG allergen, frequently essential oils.

More recently, Dr. Adler and colleagues reported the case of a 40-year-old woman who was referred for patch testing for nummular dermatitis that wasn’t responding to treatment. The patient was found to be using topical cannabis and also grew cannabis at home. “She asked to be patch-tested to her homegrown cannabis and had a strong positive patch test to the cannabis, linalool and limonene hydroperoxides, and other essential oils,” Dr. Adler recalled. “We sent her cannabis sample for analysis at a commercial lab and found that it contained limonene and other allergenic terpene chemicals.

“We’re just starting to unravel what this means in terms of our patients and how to manage them, but many are using topical cannabis and topical CBD. I suspect this is a lot less rare than we realize.”

Another recent case from Europe reported allergic contact dermatitis to Cannabis sativa (hemp) seed oil following topical application, with positive patch testing.

Dr. Adler disclosed that he has received research grants from the American Contact Dermatitis Society. He is also an investigator for AbbVie and a consultant for the Skin Research Institute.

PORTLAND, ORE. – When patients present to Brandon L. Adler, MD, with dermatitis on the eyelid, face, or neck, he routinely asks them if they apply essential oils on their skin, or if they have an essential oil diffuser or nebulizer in their home.

“The answer is frequently ‘yes,’ ” Dr. Adler, clinical assistant professor of dermatology at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, said at the annual meeting of the Pacific Dermatologic Association. “Essential oils are widely used throughout the wellness industry. They are contained in personal care products, beauty products, natural cleaning products, and they’re being diffused by our patients into the air. More than 75 essential oils are reported to cause allergic contact dermatitis.”

“Linalool is most classically associated with lavender, while limonene is associated with citrus, but they’re found in many different plants,” said Dr. Adler, who directs USC’s contact dermatitis clinic. “On their own, linalool and limonene are not particularly allergenic; they’re not a big deal in the patch test clinic. The problem comes when we add air to the mix, because they oxidize to hydroperoxides of linalool and limonene. These are quite potent allergens.”

According to the most recent North American Contact Dermatitis Group data, 8.9% of patients undergoing patch testing tested positive to linalool hydroperoxides and 2.6% were positive to limonene hydroperoxides.

Dr. Adler discussed the case of a female massage therapist who presented with refractory hand dermatitis and was on methotrexate and dupilumab at the time of consultation but was still symptomatic. She patch-tested positive to limonene and linalool hydroperoxides as well as multiple essential oils that she had been using with her clients, ranging from sacred frankincense oil to basil oil, and she was advised to massage using only coconut or vegetable oils.

Essential oil allergy may also be related to cannabis allergy. According to Dr. Adler, allergic contact dermatitis to cannabis has been rarely reported, but in an analysis of 103 commercial topical cannabinoid preparations that he published with Vincent DeLeo, MD, also with USC, 84% contained a NACDG allergen, frequently essential oils.

More recently, Dr. Adler and colleagues reported the case of a 40-year-old woman who was referred for patch testing for nummular dermatitis that wasn’t responding to treatment. The patient was found to be using topical cannabis and also grew cannabis at home. “She asked to be patch-tested to her homegrown cannabis and had a strong positive patch test to the cannabis, linalool and limonene hydroperoxides, and other essential oils,” Dr. Adler recalled. “We sent her cannabis sample for analysis at a commercial lab and found that it contained limonene and other allergenic terpene chemicals.

“We’re just starting to unravel what this means in terms of our patients and how to manage them, but many are using topical cannabis and topical CBD. I suspect this is a lot less rare than we realize.”

Another recent case from Europe reported allergic contact dermatitis to Cannabis sativa (hemp) seed oil following topical application, with positive patch testing.

Dr. Adler disclosed that he has received research grants from the American Contact Dermatitis Society. He is also an investigator for AbbVie and a consultant for the Skin Research Institute.

AT PDA 2022

Why it’s important for dermatologists to learn about JAK inhibitors

PORTLAND, ORE. – according to Andrew Blauvelt, MD, MBA.

“In dermatology, you need to know about JAK inhibitors, and you need to know how to use them,” Dr. Blauvelt, president of Oregon Medical Research Center, Portland, said at the annual meeting of the Pacific Dermatologic Association. “Making the choice, ‘I’m not going to use those drugs because of safety concerns,’ may be okay in 2022, but we are going to be getting a lot more indications for these drugs. So instead of avoiding JAK inhibitors, I would say try to learn [about] them, understand them, and get your messaging out on safety.”

It’s difficult to imagine a clinician-researcher who has more experience with the use of biologics and JAK inhibitors in AD than Dr. Blauvelt, who has been the international investigator on several important trials of treatments that include dupilumab, tralokinumab, abrocitinib, and upadacitinib for AD such as CHRONOS, ECZTEND, JADE REGIMEN, and HEADS UP. At the meeting, he discussed his clinical approach to selecting systemic agents for AD and shared prescribing tips. He began by noting that the approval of dupilumab for moderate to severe AD in 2017 ushered in a new era of treating the disease systemically.

“When it was approved, experts went right to dupilumab if they could, and avoided the use of cyclosporine or methotrexate,” said Dr. Blauvelt, who is also an elected member of the American Society for Clinical Investigation and the International Eczema Council. “I still think that dupilumab is a great agent to start with. We’ve had a bit of difficulty improving upon it.”

Following dupilumab’s approval, three other systemic options became available for patients with moderate to severe AD: the human IgG4 monoclonal antibody tralokinumab that binds to interleukin-13, which is administered subcutaneously; and, more recently, the oral JAK inhibitors abrocitinib and upadacitinib, approved in January for moderate to severe AD.

“I’m a big fan of JAK inhibitors because I think they offer things that biologic and topical therapies can’t offer,” Dr. Blauvelt said. “Patients like the pills versus shots. They also like the speed; JAK inhibitors work faster than dupilumab and tralokinumab. So, if you have a patient with bad AD who wants to get better quickly, that would be a reason to choose a JAK inhibitor over a biologic if you can.”

When Dr. Blauvelt has asked AD clinical trial participants if they’d rather be treated with a biologic agent or with a JAK inhibitor, about half choose one over the other.

“Patients who shy away from the safety issues would choose the biologic trial while the ones who wanted the fast relief would choose the JAK trial,” he said. “But if you present both options and the patients prefer a pill, I think the JAK inhibitors do better with a rapid control of inflammation as well as pruritus – the latter within 2 days of taking the pills.”

When counseling patients initiating a JAK inhibitor, Dr. Blauvelt mentioned three advantages, compared with biologics: the pill formulation, the rapidity of response in pruritus control, and better efficacy. “The downside is the safety,” he said. “Safety is the elephant in the room for the JAK inhibitors.”

The risks listed in the boxed warning in the labeling for JAK inhibitors include: an increased risk of serious bacterial, fungal, and opportunistic infections such as TB; a higher rate of all-cause mortality, including cardiovascular death; a higher rate of MACE (major adverse cardiovascular events, defined as cardiovascular death, MI, and stroke); the potential for malignancy, including lymphoma; and the potential for thrombosis, including an increased incidence of pulmonary embolism (PE).

“Risk of thrombosis seems to be a class effect for all JAK inhibitors,” Dr. Blauvelt said. “As far as I know, it’s idiosyncratic. For nearly all the DVT [deep vein thrombosis] cases that have been reported, patients had baseline risk factors for DVT and PE, which are obesity, smoking, and use of oral contraceptives.”

Dr. Blauvelt pointed out that the boxed warning related to mortality, malignancies, and MACE stemmed from a long-term trial of the JAK inhibitor tofacitinib in RA patients. “Those patients had to be at least 50 years old, 75% of them were on concomitant methotrexate and/or prednisone, and they had to have at least one cardiac risk factor to get into the trial,” he said.

“I’m not saying those things can’t happen in dermatology patients, but if you look at the safety data of JAK inhibitors in the AD studies and in the alopecia areata studies, we are seeing a few cases of these things here and there, but not major signals,” he said. To date, “they look safer in dermatologic diseases compared to tofacitinib in RA data in older populations.”

He emphasized the importance of discussing each of the risks in the boxed warning with patients who are candidates for JAK inhibitor therapy.

Dr. Blauvelt likened the lab monitoring required for JAK inhibitors to that required for methotrexate. This means ordering at baseline, a CBC with differential, a chem-20, a lipid panel, and a QuantiFERON-TB Gold test. The JAK inhibitor labels do not include information on the frequency of monitoring, “but I have a distinct opinion on this because of my blood test monitoring experience in the trials for many years,” he said.

“I think it’s good to do follow-up testing at 1 month, then every 3 months in the first year. In my experience, the people who drop blood cell counts or increase their lipids tend to do it in the first year.”

After 1 year of treatment, he continued, follow-up testing once every 6 months is reasonable. “If CPK [creatine phosphokinase] goes up, I don’t worry about it; it’s not clinically relevant. There is no recommendation for CPK monitoring, so if you’re getting that on your chem-20, I’d say don’t worry about it.”

Dr. Blauvelt reported that he is an investigator and a scientific adviser for several pharmaceutical companies developing treatments for AD, including companies that are evaluating or marketing JAK inhibitors for AD, including AbbVie, Incyte, and Pfizer, as well as dupilumab’s joint developers Sanofi and Regeneron.

PORTLAND, ORE. – according to Andrew Blauvelt, MD, MBA.

“In dermatology, you need to know about JAK inhibitors, and you need to know how to use them,” Dr. Blauvelt, president of Oregon Medical Research Center, Portland, said at the annual meeting of the Pacific Dermatologic Association. “Making the choice, ‘I’m not going to use those drugs because of safety concerns,’ may be okay in 2022, but we are going to be getting a lot more indications for these drugs. So instead of avoiding JAK inhibitors, I would say try to learn [about] them, understand them, and get your messaging out on safety.”

It’s difficult to imagine a clinician-researcher who has more experience with the use of biologics and JAK inhibitors in AD than Dr. Blauvelt, who has been the international investigator on several important trials of treatments that include dupilumab, tralokinumab, abrocitinib, and upadacitinib for AD such as CHRONOS, ECZTEND, JADE REGIMEN, and HEADS UP. At the meeting, he discussed his clinical approach to selecting systemic agents for AD and shared prescribing tips. He began by noting that the approval of dupilumab for moderate to severe AD in 2017 ushered in a new era of treating the disease systemically.

“When it was approved, experts went right to dupilumab if they could, and avoided the use of cyclosporine or methotrexate,” said Dr. Blauvelt, who is also an elected member of the American Society for Clinical Investigation and the International Eczema Council. “I still think that dupilumab is a great agent to start with. We’ve had a bit of difficulty improving upon it.”

Following dupilumab’s approval, three other systemic options became available for patients with moderate to severe AD: the human IgG4 monoclonal antibody tralokinumab that binds to interleukin-13, which is administered subcutaneously; and, more recently, the oral JAK inhibitors abrocitinib and upadacitinib, approved in January for moderate to severe AD.

“I’m a big fan of JAK inhibitors because I think they offer things that biologic and topical therapies can’t offer,” Dr. Blauvelt said. “Patients like the pills versus shots. They also like the speed; JAK inhibitors work faster than dupilumab and tralokinumab. So, if you have a patient with bad AD who wants to get better quickly, that would be a reason to choose a JAK inhibitor over a biologic if you can.”

When Dr. Blauvelt has asked AD clinical trial participants if they’d rather be treated with a biologic agent or with a JAK inhibitor, about half choose one over the other.

“Patients who shy away from the safety issues would choose the biologic trial while the ones who wanted the fast relief would choose the JAK trial,” he said. “But if you present both options and the patients prefer a pill, I think the JAK inhibitors do better with a rapid control of inflammation as well as pruritus – the latter within 2 days of taking the pills.”

When counseling patients initiating a JAK inhibitor, Dr. Blauvelt mentioned three advantages, compared with biologics: the pill formulation, the rapidity of response in pruritus control, and better efficacy. “The downside is the safety,” he said. “Safety is the elephant in the room for the JAK inhibitors.”

The risks listed in the boxed warning in the labeling for JAK inhibitors include: an increased risk of serious bacterial, fungal, and opportunistic infections such as TB; a higher rate of all-cause mortality, including cardiovascular death; a higher rate of MACE (major adverse cardiovascular events, defined as cardiovascular death, MI, and stroke); the potential for malignancy, including lymphoma; and the potential for thrombosis, including an increased incidence of pulmonary embolism (PE).

“Risk of thrombosis seems to be a class effect for all JAK inhibitors,” Dr. Blauvelt said. “As far as I know, it’s idiosyncratic. For nearly all the DVT [deep vein thrombosis] cases that have been reported, patients had baseline risk factors for DVT and PE, which are obesity, smoking, and use of oral contraceptives.”

Dr. Blauvelt pointed out that the boxed warning related to mortality, malignancies, and MACE stemmed from a long-term trial of the JAK inhibitor tofacitinib in RA patients. “Those patients had to be at least 50 years old, 75% of them were on concomitant methotrexate and/or prednisone, and they had to have at least one cardiac risk factor to get into the trial,” he said.

“I’m not saying those things can’t happen in dermatology patients, but if you look at the safety data of JAK inhibitors in the AD studies and in the alopecia areata studies, we are seeing a few cases of these things here and there, but not major signals,” he said. To date, “they look safer in dermatologic diseases compared to tofacitinib in RA data in older populations.”

He emphasized the importance of discussing each of the risks in the boxed warning with patients who are candidates for JAK inhibitor therapy.