User login

Type of insurance linked to length of survival after lung surgery

The study used public insurance status as a marker for low socioeconomic status (SES) and suggests that patients with combined insurance may constitute a separate population that deserves more attention.

Lower SES has been linked to later stage diagnoses and worse outcomes in NSCLC. Private insurance is a generally-accepted indicator of higher SES, while public insurance like Medicare or Medicaid, alone or in combination with private supplementary insurance, is an indicator of lower SES.

Although previous studies have found associations between patients having public health insurance and experiencing later-stage diagnoses and worse overall survival, there have been few studies of surgical outcomes, and almost no research has examined combination health insurance, according to Allison O. Dumitriu Carcoana, who presented the research during a poster session at the European Lung Cancer Congress 2023.

“This is an important insurance subgroup for us because the majority of our patients fall into this subgroup by being over 65 years old and thus qualifying for Medicare while also paying for a private supplement,” said Ms. Dumitriu Carcoana, who is a medical student at University of South Florida Health Morsani College of Medicine, Tampa.

A previous analysis by the group found an association between private insurance status and better discharge status, as well as higher 5-year overall survival. After accumulating an additional 278 patients, the researchers examined 10-year survival outcomes.

In the new analysis, 52% of 711 participants had combination insurance, while 28% had private insurance, and 20% had public insurance. The subgroups all had similar demographic and histological characteristics. The study was unique in that it found no between-group differences in higher stage at diagnosis, whereas previous studies have found a greater risk of higher stage diagnosis among individuals with public insurance. As expected, patients in the combined insurance group had a higher mean age (P less than .0001) and higher Charlson comorbidity index scores (P = .0014), which in turn was associated with lower 10-year survival. The group also had the highest percentage of former smokers, while the public insurance group had the highest percentage of current smokers (P = .0003).

At both 5 and 10 years, the private insurance group had better OS than the group with public (P less than .001) and the combination insurance group (P = .08). Public health insurance was associated with worse OS at 5 years (hazard ratio, 1.83; P less than .005) but not at 10 years (HR, 1.18; P = .51), while combination insurance was associated with worse OS at 10 years (HR, 1.72; P = .02).

“We think that patients with public health insurance having the worst 5-year overall survival, despite their lower ages and fewer comorbid conditions, compared with patients with combination insurance, highlights the impact of lower socioeconomic status on health outcomes. These patients had the same tumor characteristics, BMI, sex, and race as our patients in the other two insurance groups. The only other significant risk factor [the group had besides having a higher proportion of patients with lower socioeconomic status was that it had a higher proportion of current smokers]. But the multivariate analyses showed that insurance status was an independent predictor of survival, regardless of smoking status or other comorbidities,” said Ms. Dumitriu Carcoana.

“At 10 years post-operatively, the survival curves have shifted and the combination patients had the worst 10-year overall survival. We attribute this to their higher number of comorbid conditions and increased age. In practice, [this means that] the group of patients with public insurance type, but no supplement, should be identified clinically, and the clinical team can initiate a discussion,” Ms. Dumitriu Carcoana said.

“Do these patients feel that they can make follow-up appointments, keep up with medication costs, and make the right lifestyle decisions postoperatively on their current insurance plan? If not, can they afford a private supplement? In our cohort specifically, it may also be important to do more preoperative counseling on the importance of smoking cessation,” she added.

The study is interesting, but it has some important limitations, according to Raja Flores, MD, who was not involved with the study. The authors stated that there was no difference between the insurance groups with respect to mortality or cancer stage, which is the most important predictor of survival. However, the poster didn't include details of the authors' analysis, making it difficult to interpret, Dr. Flores said.

The fact that the study includes a single surgeon has some disadvantages in terms of broader applicability, but it also controls for surgical technique. “Different surgeons have different ways of doing things, so if you had the same surgeon doing it the same way every time, you can look at other variables like insurance (status) and stage,” said Dr. Flores.

The results may also provide an argument against using robotic surgery in patients who do not have insurance, especially since they have not been proven to be better than standard minimally invasive surgery with no robotic assistance. With uninsured patients, “you’re using taxpayer money for a more expensive procedure that isn’t proving to be any better,” Dr. Flores explained.

The study was performed at a single center and cannot prove causation due to its retrospective nature.

Ms. Dumitriu Carcoana and Dr. Flores have no relevant financial disclosures.

*This article was updated on 4/13/2023.

The study used public insurance status as a marker for low socioeconomic status (SES) and suggests that patients with combined insurance may constitute a separate population that deserves more attention.

Lower SES has been linked to later stage diagnoses and worse outcomes in NSCLC. Private insurance is a generally-accepted indicator of higher SES, while public insurance like Medicare or Medicaid, alone or in combination with private supplementary insurance, is an indicator of lower SES.

Although previous studies have found associations between patients having public health insurance and experiencing later-stage diagnoses and worse overall survival, there have been few studies of surgical outcomes, and almost no research has examined combination health insurance, according to Allison O. Dumitriu Carcoana, who presented the research during a poster session at the European Lung Cancer Congress 2023.

“This is an important insurance subgroup for us because the majority of our patients fall into this subgroup by being over 65 years old and thus qualifying for Medicare while also paying for a private supplement,” said Ms. Dumitriu Carcoana, who is a medical student at University of South Florida Health Morsani College of Medicine, Tampa.

A previous analysis by the group found an association between private insurance status and better discharge status, as well as higher 5-year overall survival. After accumulating an additional 278 patients, the researchers examined 10-year survival outcomes.

In the new analysis, 52% of 711 participants had combination insurance, while 28% had private insurance, and 20% had public insurance. The subgroups all had similar demographic and histological characteristics. The study was unique in that it found no between-group differences in higher stage at diagnosis, whereas previous studies have found a greater risk of higher stage diagnosis among individuals with public insurance. As expected, patients in the combined insurance group had a higher mean age (P less than .0001) and higher Charlson comorbidity index scores (P = .0014), which in turn was associated with lower 10-year survival. The group also had the highest percentage of former smokers, while the public insurance group had the highest percentage of current smokers (P = .0003).

At both 5 and 10 years, the private insurance group had better OS than the group with public (P less than .001) and the combination insurance group (P = .08). Public health insurance was associated with worse OS at 5 years (hazard ratio, 1.83; P less than .005) but not at 10 years (HR, 1.18; P = .51), while combination insurance was associated with worse OS at 10 years (HR, 1.72; P = .02).

“We think that patients with public health insurance having the worst 5-year overall survival, despite their lower ages and fewer comorbid conditions, compared with patients with combination insurance, highlights the impact of lower socioeconomic status on health outcomes. These patients had the same tumor characteristics, BMI, sex, and race as our patients in the other two insurance groups. The only other significant risk factor [the group had besides having a higher proportion of patients with lower socioeconomic status was that it had a higher proportion of current smokers]. But the multivariate analyses showed that insurance status was an independent predictor of survival, regardless of smoking status or other comorbidities,” said Ms. Dumitriu Carcoana.

“At 10 years post-operatively, the survival curves have shifted and the combination patients had the worst 10-year overall survival. We attribute this to their higher number of comorbid conditions and increased age. In practice, [this means that] the group of patients with public insurance type, but no supplement, should be identified clinically, and the clinical team can initiate a discussion,” Ms. Dumitriu Carcoana said.

“Do these patients feel that they can make follow-up appointments, keep up with medication costs, and make the right lifestyle decisions postoperatively on their current insurance plan? If not, can they afford a private supplement? In our cohort specifically, it may also be important to do more preoperative counseling on the importance of smoking cessation,” she added.

The study is interesting, but it has some important limitations, according to Raja Flores, MD, who was not involved with the study. The authors stated that there was no difference between the insurance groups with respect to mortality or cancer stage, which is the most important predictor of survival. However, the poster didn't include details of the authors' analysis, making it difficult to interpret, Dr. Flores said.

The fact that the study includes a single surgeon has some disadvantages in terms of broader applicability, but it also controls for surgical technique. “Different surgeons have different ways of doing things, so if you had the same surgeon doing it the same way every time, you can look at other variables like insurance (status) and stage,” said Dr. Flores.

The results may also provide an argument against using robotic surgery in patients who do not have insurance, especially since they have not been proven to be better than standard minimally invasive surgery with no robotic assistance. With uninsured patients, “you’re using taxpayer money for a more expensive procedure that isn’t proving to be any better,” Dr. Flores explained.

The study was performed at a single center and cannot prove causation due to its retrospective nature.

Ms. Dumitriu Carcoana and Dr. Flores have no relevant financial disclosures.

*This article was updated on 4/13/2023.

The study used public insurance status as a marker for low socioeconomic status (SES) and suggests that patients with combined insurance may constitute a separate population that deserves more attention.

Lower SES has been linked to later stage diagnoses and worse outcomes in NSCLC. Private insurance is a generally-accepted indicator of higher SES, while public insurance like Medicare or Medicaid, alone or in combination with private supplementary insurance, is an indicator of lower SES.

Although previous studies have found associations between patients having public health insurance and experiencing later-stage diagnoses and worse overall survival, there have been few studies of surgical outcomes, and almost no research has examined combination health insurance, according to Allison O. Dumitriu Carcoana, who presented the research during a poster session at the European Lung Cancer Congress 2023.

“This is an important insurance subgroup for us because the majority of our patients fall into this subgroup by being over 65 years old and thus qualifying for Medicare while also paying for a private supplement,” said Ms. Dumitriu Carcoana, who is a medical student at University of South Florida Health Morsani College of Medicine, Tampa.

A previous analysis by the group found an association between private insurance status and better discharge status, as well as higher 5-year overall survival. After accumulating an additional 278 patients, the researchers examined 10-year survival outcomes.

In the new analysis, 52% of 711 participants had combination insurance, while 28% had private insurance, and 20% had public insurance. The subgroups all had similar demographic and histological characteristics. The study was unique in that it found no between-group differences in higher stage at diagnosis, whereas previous studies have found a greater risk of higher stage diagnosis among individuals with public insurance. As expected, patients in the combined insurance group had a higher mean age (P less than .0001) and higher Charlson comorbidity index scores (P = .0014), which in turn was associated with lower 10-year survival. The group also had the highest percentage of former smokers, while the public insurance group had the highest percentage of current smokers (P = .0003).

At both 5 and 10 years, the private insurance group had better OS than the group with public (P less than .001) and the combination insurance group (P = .08). Public health insurance was associated with worse OS at 5 years (hazard ratio, 1.83; P less than .005) but not at 10 years (HR, 1.18; P = .51), while combination insurance was associated with worse OS at 10 years (HR, 1.72; P = .02).

“We think that patients with public health insurance having the worst 5-year overall survival, despite their lower ages and fewer comorbid conditions, compared with patients with combination insurance, highlights the impact of lower socioeconomic status on health outcomes. These patients had the same tumor characteristics, BMI, sex, and race as our patients in the other two insurance groups. The only other significant risk factor [the group had besides having a higher proportion of patients with lower socioeconomic status was that it had a higher proportion of current smokers]. But the multivariate analyses showed that insurance status was an independent predictor of survival, regardless of smoking status or other comorbidities,” said Ms. Dumitriu Carcoana.

“At 10 years post-operatively, the survival curves have shifted and the combination patients had the worst 10-year overall survival. We attribute this to their higher number of comorbid conditions and increased age. In practice, [this means that] the group of patients with public insurance type, but no supplement, should be identified clinically, and the clinical team can initiate a discussion,” Ms. Dumitriu Carcoana said.

“Do these patients feel that they can make follow-up appointments, keep up with medication costs, and make the right lifestyle decisions postoperatively on their current insurance plan? If not, can they afford a private supplement? In our cohort specifically, it may also be important to do more preoperative counseling on the importance of smoking cessation,” she added.

The study is interesting, but it has some important limitations, according to Raja Flores, MD, who was not involved with the study. The authors stated that there was no difference between the insurance groups with respect to mortality or cancer stage, which is the most important predictor of survival. However, the poster didn't include details of the authors' analysis, making it difficult to interpret, Dr. Flores said.

The fact that the study includes a single surgeon has some disadvantages in terms of broader applicability, but it also controls for surgical technique. “Different surgeons have different ways of doing things, so if you had the same surgeon doing it the same way every time, you can look at other variables like insurance (status) and stage,” said Dr. Flores.

The results may also provide an argument against using robotic surgery in patients who do not have insurance, especially since they have not been proven to be better than standard minimally invasive surgery with no robotic assistance. With uninsured patients, “you’re using taxpayer money for a more expensive procedure that isn’t proving to be any better,” Dr. Flores explained.

The study was performed at a single center and cannot prove causation due to its retrospective nature.

Ms. Dumitriu Carcoana and Dr. Flores have no relevant financial disclosures.

*This article was updated on 4/13/2023.

FROM ELCC 2023

Melasma

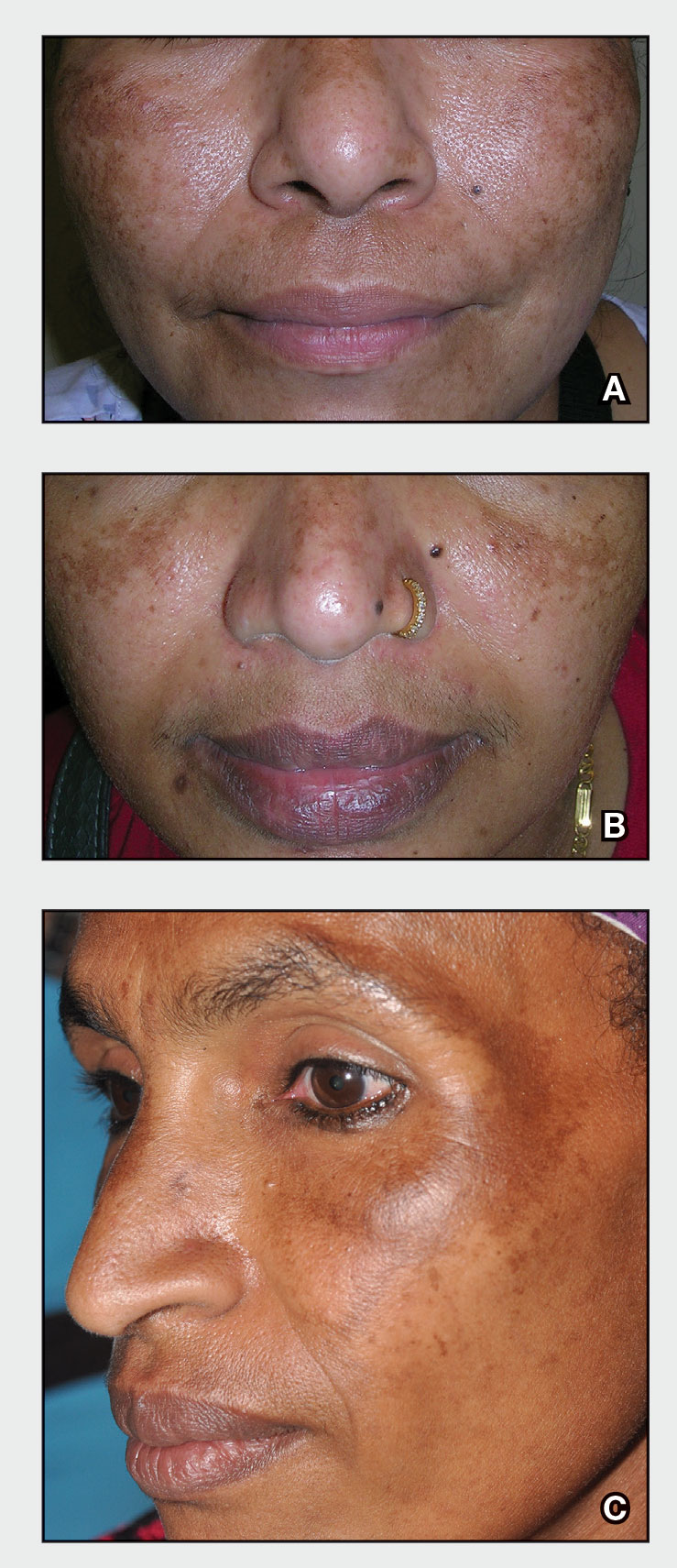

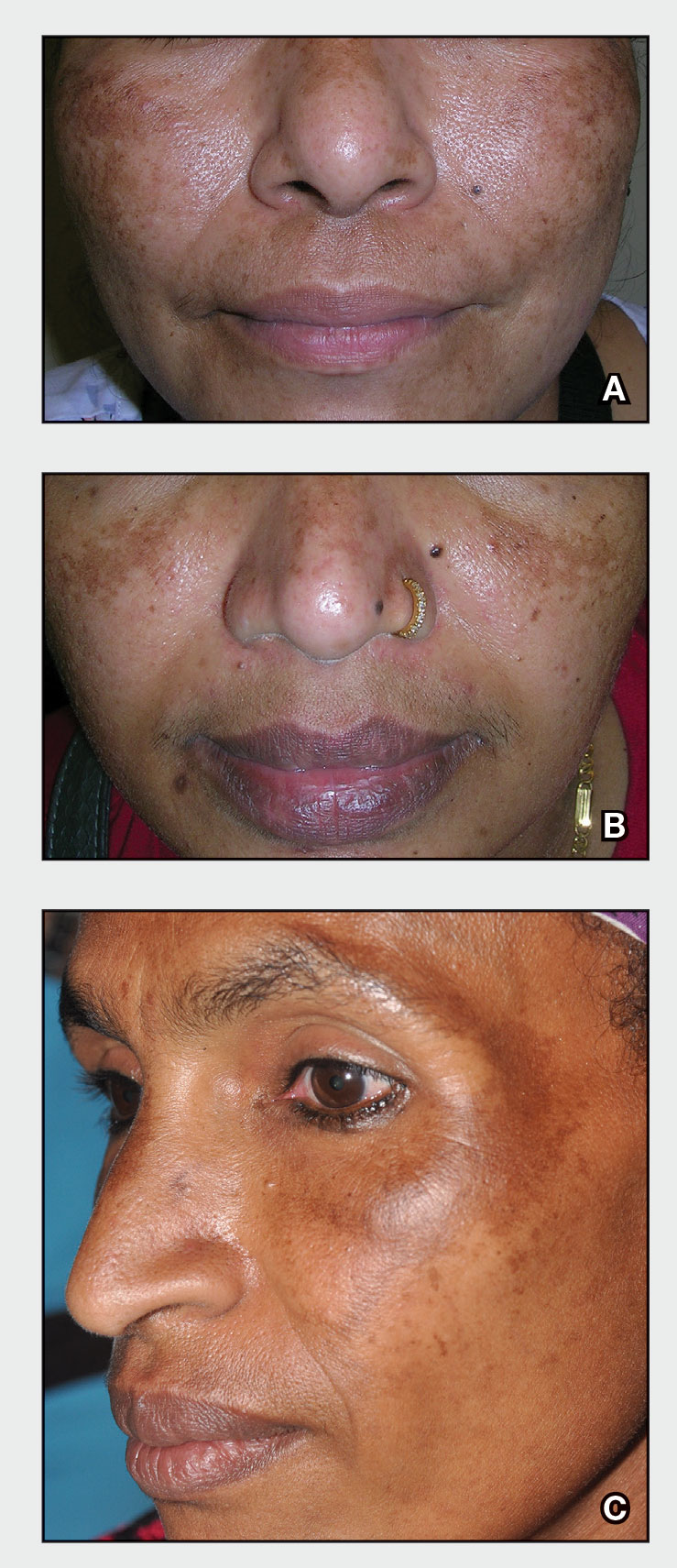

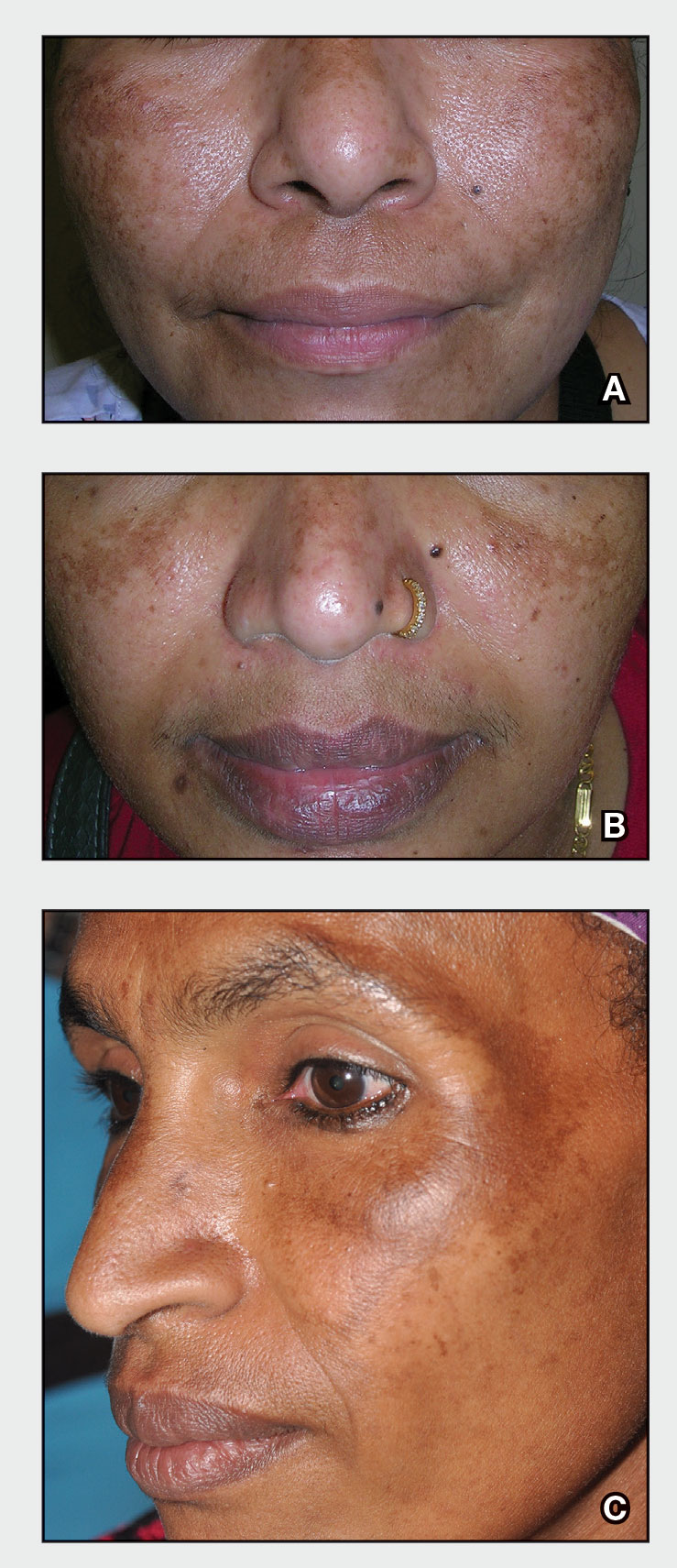

THE COMPARISON

A Melasma on the face of a Hispanic woman, with hyperpigmentation on the cheeks, bridge of the nose, and upper lip.

B Melasma on the face of a Malaysian woman, with hyperpigmentation on the upper cheeks and bridge of the nose.

C Melasma on the face of an African woman, with hyperpigmentation on the upper cheeks and lateral to the eyes.

Melasma (also known as chloasma) is a pigmentary disorder that causes chronic symmetric hyperpigmentation on the face. In patients with darker skin tones, centrofacial areas are affected.1 Increased deposition of melanin distributed in the dermis leads to dermal melanosis. Newer research suggests that mast cell and keratinocyte interactions, altered gene regulation, neovascularization, and disruptions in the basement membrane cause melasma.2 Patients present with epidermal or dermal melasma or a combination of both (mixed melasma).3 Wood lamp examination is helpful to distinguish between epidermal and dermal melasma. Dermal and mixed melasma can be difficult to treat and require multimodal treatments.

Epidemiology

Melasma commonly affects women aged 20 to 40 years,4 with a female to male ratio of 9:1.5 Potential triggers of melasma include hormones (eg, pregnancy, oral contraceptives, hormone replacement therapy) and exposure to UV light.2,5 Melasma occurs in patients of all racial and ethnic backgrounds; however, the prevalence is higher in patients with darker skin tones.2

Key clinical features in people with darker skin tones

Melasma commonly manifests as symmetrically distributed, reticulated (lacy), dark brown to grayish brown patches on the cheeks, nose, forehead, upper lip, and chin in patients with darker skin tones.5 The pigment can be tan brown in patients with lighter skin tones. Given that postinflammatory hyperpigmentation and other pigmentary disorders can cause a similar appearance, a biopsy sometimes is needed to confirm the diagnosis, but melasma is diagnosed via physical examination in most patients. Melasma can be misdiagnosed as postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, solar lentigines, exogenous ochronosis, and Hori nevus.5

Worth noting

Prevention

• Daily sunscreen use is critical to prevent worsening of melasma. Sunscreen may not appear cosmetically elegant on darker skin tones, which creates a barrier to its use.6 Protection from both sunlight and visible light is necessary. Visible light, including light from light bulbs and device-emitted blue light, can worsen melasma. Iron oxides in tinted sunscreen offer protection from visible light.

• Physicians can recommend sunscreens that are more transparent or tinted for a better cosmetic match.

• Severe flares of melasma can occur with sun exposure despite good control with medications and laser modalities.

Treatment

• First-line therapies include topical hydroquinone 2% to 4%, tretinoin, azelaic acid, kojic acid, or ascorbic acid (vitamin C). A popular topical compound is a steroid, tretinoin, and hydroquinone.1,5 Over-the-counter hydroquinone has been removed from the market due to safety concerns; however, it is still first line in the treatment of melasma. If hydroquinone is prescribed, treatment intervals of 6 to 8 weeks followed by a hydroquinone-free period is advised to reduce the risk for exogenous ochronosis (a paradoxical darkening of the skin).

• Chemical peels are second-line treatments that are effective for melasma. Improvement in epidermal melasma has been shown with chemical peels containing Jessner solution, salicylic acid, or α-hydroxy acid. Patients with dermal and mixed melasma have seen improvement with trichloroacetic acid 25% to 35% with or without Jessner solution.1

• Cysteamine is a topical treatment created from the degradation of coenzyme A. It disrupts the synthesis of melanin to create a more even skin tone. It may be recommended in combination with sunscreen as a first-line or second-line topical therapy.

• Oral tranexamic acid is a third-line treatment that is an analogue for lysine. It decreases prostaglandin production, which leads to a lower number of tyrosine precursors available for the creation of melanin. Tranexamic acid has been shown to lighten the appearance of melasma.7 The most common and dangerous adverse effect of tranexamic acid is blood clots and this treatment should be avoided in those on combination (estrogen and progestin) contraceptives or those with a personal or family history of clotting disorders.8

• Fourth-line treatments such as lasers (performed by dermatologists) can destroy the deposition of pigment while avoiding destruction of epidermal keratinocytes.1,9,10 They also are commonly employed in refractive melasma. The most common lasers are nonablative fractionated lasers and low-fluence Q-switched lasers. The Q-switched Nd:YAG and picosecond lasers are safe for treating melasma in darker skin tones. Ablative fractionated lasers such as CO2 lasers and erbium:YAG lasers also have been used in the treatment of melasma; however, there is still an extremely high risk for postinflammatory dyspigmentation 1 to 2 months after the procedure.10

• Although there is still a risk for rebound hyperpigmentation after laser treatment, use of topical hydroquinone pretreatment may help decrease postoperative hyperpigmentation.1,5 Patients who are treated with the incorrect laser or overtreated may develop postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, rebound hyperpigmentation, or hypopigmentation.

Health disparity highlight

Melasma, most common in patients with skin of color, is a common chronic pigmentation disorder that is cosmetically and psychologically burdensome,11 leading to decreased quality of life, emotional functioning, and selfesteem.12 Clinicians should counsel patients and work closely on long-term management. The treatment options for melasma are considered cosmetic and may be cost prohibitive for many to cover out-of-pocket. Topical treatments have been found to be the most cost-effective.13 Some compounding pharmacies and drug discount programs provide more affordable treatment pricing; however, some patients are still unable to afford these options.

- Cunha PR, Kroumpouzos G. Melasma and vitiligo: novel and experimental therapies. J Clin Exp Derm Res. 2016;7:2. doi:10.4172/2155-9554.1000e106

- Rajanala S, Maymone MBC, Vashi NA. Melasma pathogenesis: a review of the latest research, pathological findings, and investigational therapies. Dermatol Online J. 2019;25:13030/qt47b7r28c.

- Grimes PE, Yamada N, Bhawan J. Light microscopic, immunohistochemical, and ultrastructural alterations in patients with melasma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005;27:96-101.

- Achar A, Rathi SK. Melasma: a clinico-epidemiological study of 312 cases. Indian J Dermatol. 2011;56:380-382.

- Ogbechie-Godec OA, Elbuluk N. Melasma: an up-to-date comprehensive review. Dermatol Ther. 2017;7:305-318.

- Morquette AJ, Waples ER, Heath CR. The importance of cosmetically elegant sunscreen in skin of color populations. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2022;21:1337-1338.

- Taraz M, Nikham S, Ehsani AH. Tranexamic acid in treatment of melasma: a comprehensive review of clinical studies [published online January 30, 2017]. Dermatol Ther. doi:10.1111/dth.12465

- Bala HR, Lee S, Wong C, et al. Oral tranexamic acid for the treatment of melasma: a review. Dermatol Surg. 2018;44:814-825.

- Castanedo-Cazares JP, Hernandez-Blanco D, Carlos-Ortega B, et al. Near-visible light and UV photoprotection in the treatment of melasma: a double-blind randomized trial. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2014;30:35-42.

- Trivedi MK, Yang FC, Cho BK. A review of laser and light therapy in melasma. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2017;3:11-20.

- Dodmani PN, Deshmukh AR. Assessment of quality of life of melasma patients as per melasma quality of life scale (MELASQoL). Pigment Int. 2020;7:75-79.

- Balkrishnan R, McMichael A, Camacho FT, et al. Development and validation of a health‐related quality of life instrument for women with melasma. Br J Dermatol. 2003;149:572-577.

- Alikhan A, Daly M, Wu J, et al. Cost-effectiveness of a hydroquinone /tretinoin/fluocinolone acetonide cream combination in treating melasma in the United States. J Dermatolog Treat. 2010;21:276-281.

THE COMPARISON

A Melasma on the face of a Hispanic woman, with hyperpigmentation on the cheeks, bridge of the nose, and upper lip.

B Melasma on the face of a Malaysian woman, with hyperpigmentation on the upper cheeks and bridge of the nose.

C Melasma on the face of an African woman, with hyperpigmentation on the upper cheeks and lateral to the eyes.

Melasma (also known as chloasma) is a pigmentary disorder that causes chronic symmetric hyperpigmentation on the face. In patients with darker skin tones, centrofacial areas are affected.1 Increased deposition of melanin distributed in the dermis leads to dermal melanosis. Newer research suggests that mast cell and keratinocyte interactions, altered gene regulation, neovascularization, and disruptions in the basement membrane cause melasma.2 Patients present with epidermal or dermal melasma or a combination of both (mixed melasma).3 Wood lamp examination is helpful to distinguish between epidermal and dermal melasma. Dermal and mixed melasma can be difficult to treat and require multimodal treatments.

Epidemiology

Melasma commonly affects women aged 20 to 40 years,4 with a female to male ratio of 9:1.5 Potential triggers of melasma include hormones (eg, pregnancy, oral contraceptives, hormone replacement therapy) and exposure to UV light.2,5 Melasma occurs in patients of all racial and ethnic backgrounds; however, the prevalence is higher in patients with darker skin tones.2

Key clinical features in people with darker skin tones

Melasma commonly manifests as symmetrically distributed, reticulated (lacy), dark brown to grayish brown patches on the cheeks, nose, forehead, upper lip, and chin in patients with darker skin tones.5 The pigment can be tan brown in patients with lighter skin tones. Given that postinflammatory hyperpigmentation and other pigmentary disorders can cause a similar appearance, a biopsy sometimes is needed to confirm the diagnosis, but melasma is diagnosed via physical examination in most patients. Melasma can be misdiagnosed as postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, solar lentigines, exogenous ochronosis, and Hori nevus.5

Worth noting

Prevention

• Daily sunscreen use is critical to prevent worsening of melasma. Sunscreen may not appear cosmetically elegant on darker skin tones, which creates a barrier to its use.6 Protection from both sunlight and visible light is necessary. Visible light, including light from light bulbs and device-emitted blue light, can worsen melasma. Iron oxides in tinted sunscreen offer protection from visible light.

• Physicians can recommend sunscreens that are more transparent or tinted for a better cosmetic match.

• Severe flares of melasma can occur with sun exposure despite good control with medications and laser modalities.

Treatment

• First-line therapies include topical hydroquinone 2% to 4%, tretinoin, azelaic acid, kojic acid, or ascorbic acid (vitamin C). A popular topical compound is a steroid, tretinoin, and hydroquinone.1,5 Over-the-counter hydroquinone has been removed from the market due to safety concerns; however, it is still first line in the treatment of melasma. If hydroquinone is prescribed, treatment intervals of 6 to 8 weeks followed by a hydroquinone-free period is advised to reduce the risk for exogenous ochronosis (a paradoxical darkening of the skin).

• Chemical peels are second-line treatments that are effective for melasma. Improvement in epidermal melasma has been shown with chemical peels containing Jessner solution, salicylic acid, or α-hydroxy acid. Patients with dermal and mixed melasma have seen improvement with trichloroacetic acid 25% to 35% with or without Jessner solution.1

• Cysteamine is a topical treatment created from the degradation of coenzyme A. It disrupts the synthesis of melanin to create a more even skin tone. It may be recommended in combination with sunscreen as a first-line or second-line topical therapy.

• Oral tranexamic acid is a third-line treatment that is an analogue for lysine. It decreases prostaglandin production, which leads to a lower number of tyrosine precursors available for the creation of melanin. Tranexamic acid has been shown to lighten the appearance of melasma.7 The most common and dangerous adverse effect of tranexamic acid is blood clots and this treatment should be avoided in those on combination (estrogen and progestin) contraceptives or those with a personal or family history of clotting disorders.8

• Fourth-line treatments such as lasers (performed by dermatologists) can destroy the deposition of pigment while avoiding destruction of epidermal keratinocytes.1,9,10 They also are commonly employed in refractive melasma. The most common lasers are nonablative fractionated lasers and low-fluence Q-switched lasers. The Q-switched Nd:YAG and picosecond lasers are safe for treating melasma in darker skin tones. Ablative fractionated lasers such as CO2 lasers and erbium:YAG lasers also have been used in the treatment of melasma; however, there is still an extremely high risk for postinflammatory dyspigmentation 1 to 2 months after the procedure.10

• Although there is still a risk for rebound hyperpigmentation after laser treatment, use of topical hydroquinone pretreatment may help decrease postoperative hyperpigmentation.1,5 Patients who are treated with the incorrect laser or overtreated may develop postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, rebound hyperpigmentation, or hypopigmentation.

Health disparity highlight

Melasma, most common in patients with skin of color, is a common chronic pigmentation disorder that is cosmetically and psychologically burdensome,11 leading to decreased quality of life, emotional functioning, and selfesteem.12 Clinicians should counsel patients and work closely on long-term management. The treatment options for melasma are considered cosmetic and may be cost prohibitive for many to cover out-of-pocket. Topical treatments have been found to be the most cost-effective.13 Some compounding pharmacies and drug discount programs provide more affordable treatment pricing; however, some patients are still unable to afford these options.

THE COMPARISON

A Melasma on the face of a Hispanic woman, with hyperpigmentation on the cheeks, bridge of the nose, and upper lip.

B Melasma on the face of a Malaysian woman, with hyperpigmentation on the upper cheeks and bridge of the nose.

C Melasma on the face of an African woman, with hyperpigmentation on the upper cheeks and lateral to the eyes.

Melasma (also known as chloasma) is a pigmentary disorder that causes chronic symmetric hyperpigmentation on the face. In patients with darker skin tones, centrofacial areas are affected.1 Increased deposition of melanin distributed in the dermis leads to dermal melanosis. Newer research suggests that mast cell and keratinocyte interactions, altered gene regulation, neovascularization, and disruptions in the basement membrane cause melasma.2 Patients present with epidermal or dermal melasma or a combination of both (mixed melasma).3 Wood lamp examination is helpful to distinguish between epidermal and dermal melasma. Dermal and mixed melasma can be difficult to treat and require multimodal treatments.

Epidemiology

Melasma commonly affects women aged 20 to 40 years,4 with a female to male ratio of 9:1.5 Potential triggers of melasma include hormones (eg, pregnancy, oral contraceptives, hormone replacement therapy) and exposure to UV light.2,5 Melasma occurs in patients of all racial and ethnic backgrounds; however, the prevalence is higher in patients with darker skin tones.2

Key clinical features in people with darker skin tones

Melasma commonly manifests as symmetrically distributed, reticulated (lacy), dark brown to grayish brown patches on the cheeks, nose, forehead, upper lip, and chin in patients with darker skin tones.5 The pigment can be tan brown in patients with lighter skin tones. Given that postinflammatory hyperpigmentation and other pigmentary disorders can cause a similar appearance, a biopsy sometimes is needed to confirm the diagnosis, but melasma is diagnosed via physical examination in most patients. Melasma can be misdiagnosed as postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, solar lentigines, exogenous ochronosis, and Hori nevus.5

Worth noting

Prevention

• Daily sunscreen use is critical to prevent worsening of melasma. Sunscreen may not appear cosmetically elegant on darker skin tones, which creates a barrier to its use.6 Protection from both sunlight and visible light is necessary. Visible light, including light from light bulbs and device-emitted blue light, can worsen melasma. Iron oxides in tinted sunscreen offer protection from visible light.

• Physicians can recommend sunscreens that are more transparent or tinted for a better cosmetic match.

• Severe flares of melasma can occur with sun exposure despite good control with medications and laser modalities.

Treatment

• First-line therapies include topical hydroquinone 2% to 4%, tretinoin, azelaic acid, kojic acid, or ascorbic acid (vitamin C). A popular topical compound is a steroid, tretinoin, and hydroquinone.1,5 Over-the-counter hydroquinone has been removed from the market due to safety concerns; however, it is still first line in the treatment of melasma. If hydroquinone is prescribed, treatment intervals of 6 to 8 weeks followed by a hydroquinone-free period is advised to reduce the risk for exogenous ochronosis (a paradoxical darkening of the skin).

• Chemical peels are second-line treatments that are effective for melasma. Improvement in epidermal melasma has been shown with chemical peels containing Jessner solution, salicylic acid, or α-hydroxy acid. Patients with dermal and mixed melasma have seen improvement with trichloroacetic acid 25% to 35% with or without Jessner solution.1

• Cysteamine is a topical treatment created from the degradation of coenzyme A. It disrupts the synthesis of melanin to create a more even skin tone. It may be recommended in combination with sunscreen as a first-line or second-line topical therapy.

• Oral tranexamic acid is a third-line treatment that is an analogue for lysine. It decreases prostaglandin production, which leads to a lower number of tyrosine precursors available for the creation of melanin. Tranexamic acid has been shown to lighten the appearance of melasma.7 The most common and dangerous adverse effect of tranexamic acid is blood clots and this treatment should be avoided in those on combination (estrogen and progestin) contraceptives or those with a personal or family history of clotting disorders.8

• Fourth-line treatments such as lasers (performed by dermatologists) can destroy the deposition of pigment while avoiding destruction of epidermal keratinocytes.1,9,10 They also are commonly employed in refractive melasma. The most common lasers are nonablative fractionated lasers and low-fluence Q-switched lasers. The Q-switched Nd:YAG and picosecond lasers are safe for treating melasma in darker skin tones. Ablative fractionated lasers such as CO2 lasers and erbium:YAG lasers also have been used in the treatment of melasma; however, there is still an extremely high risk for postinflammatory dyspigmentation 1 to 2 months after the procedure.10

• Although there is still a risk for rebound hyperpigmentation after laser treatment, use of topical hydroquinone pretreatment may help decrease postoperative hyperpigmentation.1,5 Patients who are treated with the incorrect laser or overtreated may develop postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, rebound hyperpigmentation, or hypopigmentation.

Health disparity highlight

Melasma, most common in patients with skin of color, is a common chronic pigmentation disorder that is cosmetically and psychologically burdensome,11 leading to decreased quality of life, emotional functioning, and selfesteem.12 Clinicians should counsel patients and work closely on long-term management. The treatment options for melasma are considered cosmetic and may be cost prohibitive for many to cover out-of-pocket. Topical treatments have been found to be the most cost-effective.13 Some compounding pharmacies and drug discount programs provide more affordable treatment pricing; however, some patients are still unable to afford these options.

- Cunha PR, Kroumpouzos G. Melasma and vitiligo: novel and experimental therapies. J Clin Exp Derm Res. 2016;7:2. doi:10.4172/2155-9554.1000e106

- Rajanala S, Maymone MBC, Vashi NA. Melasma pathogenesis: a review of the latest research, pathological findings, and investigational therapies. Dermatol Online J. 2019;25:13030/qt47b7r28c.

- Grimes PE, Yamada N, Bhawan J. Light microscopic, immunohistochemical, and ultrastructural alterations in patients with melasma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005;27:96-101.

- Achar A, Rathi SK. Melasma: a clinico-epidemiological study of 312 cases. Indian J Dermatol. 2011;56:380-382.

- Ogbechie-Godec OA, Elbuluk N. Melasma: an up-to-date comprehensive review. Dermatol Ther. 2017;7:305-318.

- Morquette AJ, Waples ER, Heath CR. The importance of cosmetically elegant sunscreen in skin of color populations. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2022;21:1337-1338.

- Taraz M, Nikham S, Ehsani AH. Tranexamic acid in treatment of melasma: a comprehensive review of clinical studies [published online January 30, 2017]. Dermatol Ther. doi:10.1111/dth.12465

- Bala HR, Lee S, Wong C, et al. Oral tranexamic acid for the treatment of melasma: a review. Dermatol Surg. 2018;44:814-825.

- Castanedo-Cazares JP, Hernandez-Blanco D, Carlos-Ortega B, et al. Near-visible light and UV photoprotection in the treatment of melasma: a double-blind randomized trial. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2014;30:35-42.

- Trivedi MK, Yang FC, Cho BK. A review of laser and light therapy in melasma. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2017;3:11-20.

- Dodmani PN, Deshmukh AR. Assessment of quality of life of melasma patients as per melasma quality of life scale (MELASQoL). Pigment Int. 2020;7:75-79.

- Balkrishnan R, McMichael A, Camacho FT, et al. Development and validation of a health‐related quality of life instrument for women with melasma. Br J Dermatol. 2003;149:572-577.

- Alikhan A, Daly M, Wu J, et al. Cost-effectiveness of a hydroquinone /tretinoin/fluocinolone acetonide cream combination in treating melasma in the United States. J Dermatolog Treat. 2010;21:276-281.

- Cunha PR, Kroumpouzos G. Melasma and vitiligo: novel and experimental therapies. J Clin Exp Derm Res. 2016;7:2. doi:10.4172/2155-9554.1000e106

- Rajanala S, Maymone MBC, Vashi NA. Melasma pathogenesis: a review of the latest research, pathological findings, and investigational therapies. Dermatol Online J. 2019;25:13030/qt47b7r28c.

- Grimes PE, Yamada N, Bhawan J. Light microscopic, immunohistochemical, and ultrastructural alterations in patients with melasma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005;27:96-101.

- Achar A, Rathi SK. Melasma: a clinico-epidemiological study of 312 cases. Indian J Dermatol. 2011;56:380-382.

- Ogbechie-Godec OA, Elbuluk N. Melasma: an up-to-date comprehensive review. Dermatol Ther. 2017;7:305-318.

- Morquette AJ, Waples ER, Heath CR. The importance of cosmetically elegant sunscreen in skin of color populations. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2022;21:1337-1338.

- Taraz M, Nikham S, Ehsani AH. Tranexamic acid in treatment of melasma: a comprehensive review of clinical studies [published online January 30, 2017]. Dermatol Ther. doi:10.1111/dth.12465

- Bala HR, Lee S, Wong C, et al. Oral tranexamic acid for the treatment of melasma: a review. Dermatol Surg. 2018;44:814-825.

- Castanedo-Cazares JP, Hernandez-Blanco D, Carlos-Ortega B, et al. Near-visible light and UV photoprotection in the treatment of melasma: a double-blind randomized trial. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2014;30:35-42.

- Trivedi MK, Yang FC, Cho BK. A review of laser and light therapy in melasma. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2017;3:11-20.

- Dodmani PN, Deshmukh AR. Assessment of quality of life of melasma patients as per melasma quality of life scale (MELASQoL). Pigment Int. 2020;7:75-79.

- Balkrishnan R, McMichael A, Camacho FT, et al. Development and validation of a health‐related quality of life instrument for women with melasma. Br J Dermatol. 2003;149:572-577.

- Alikhan A, Daly M, Wu J, et al. Cost-effectiveness of a hydroquinone /tretinoin/fluocinolone acetonide cream combination in treating melasma in the United States. J Dermatolog Treat. 2010;21:276-281.

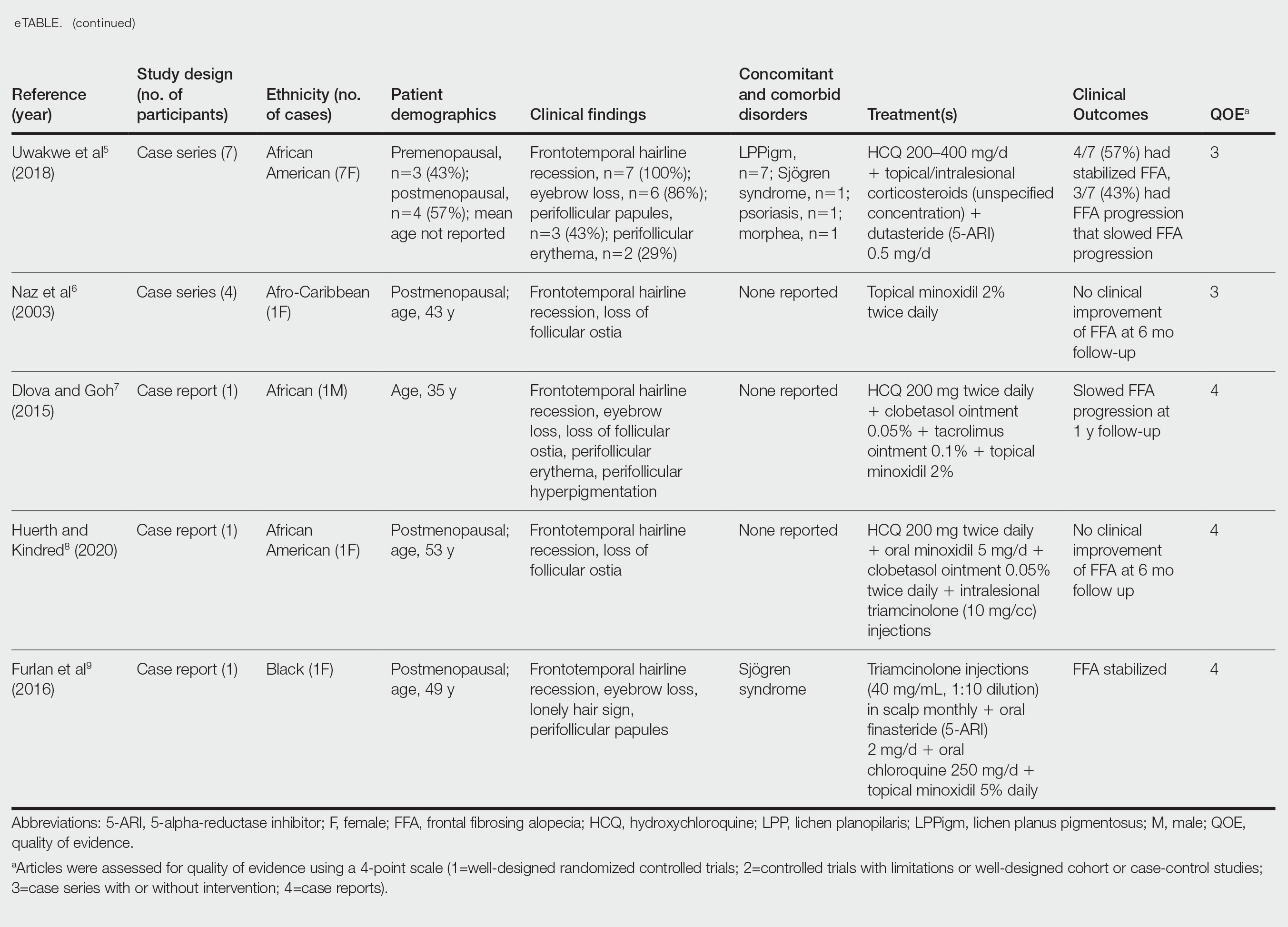

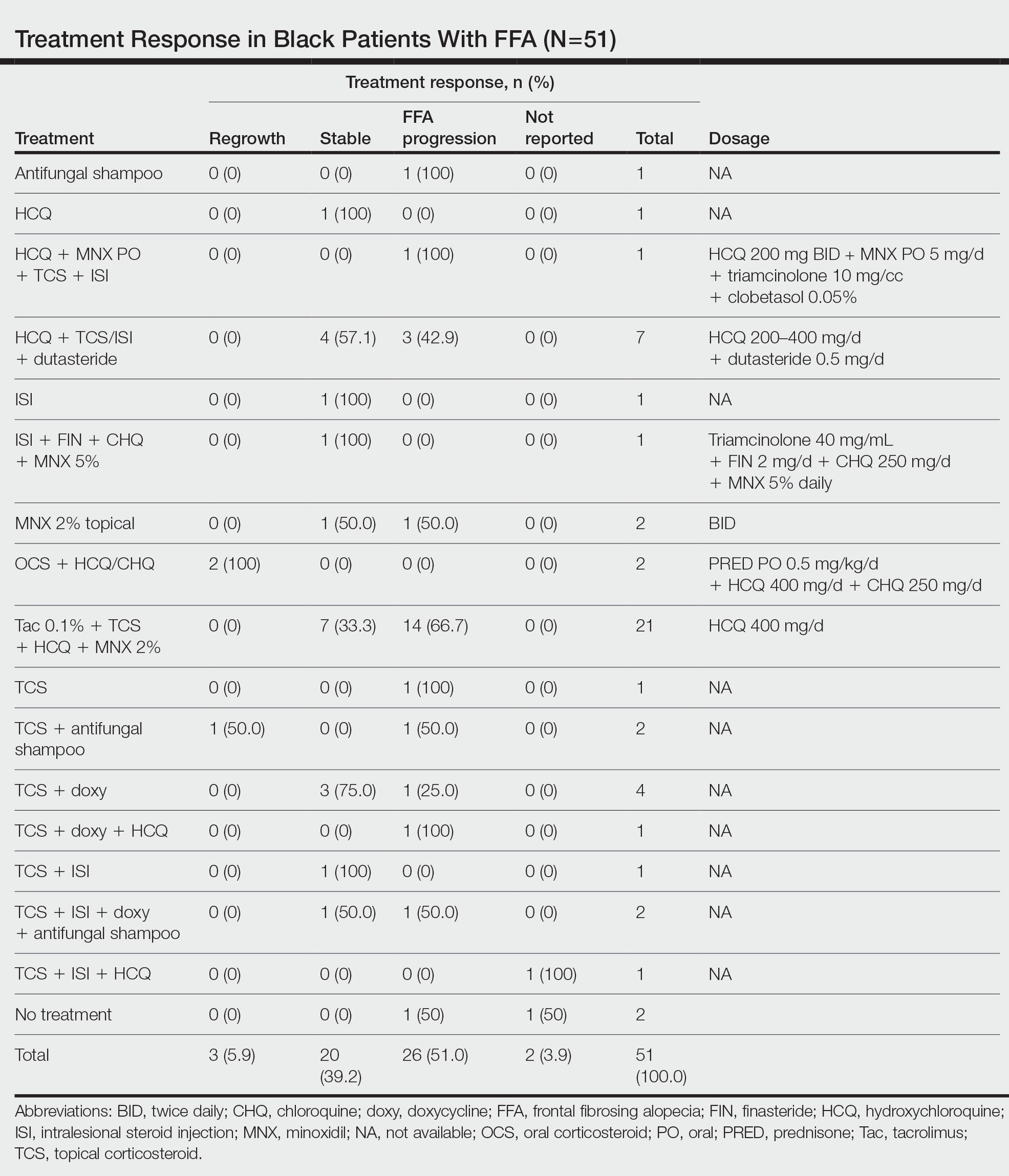

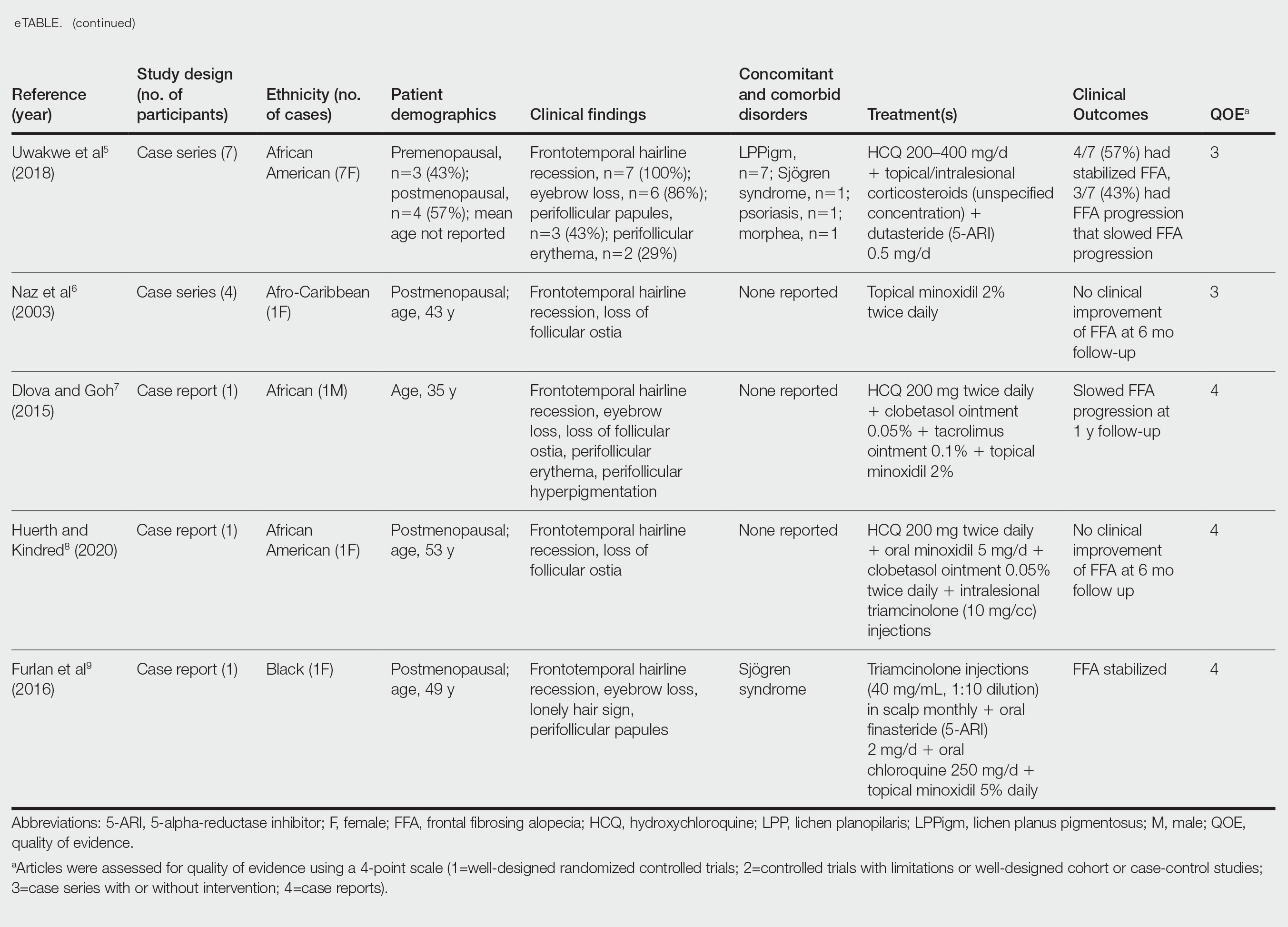

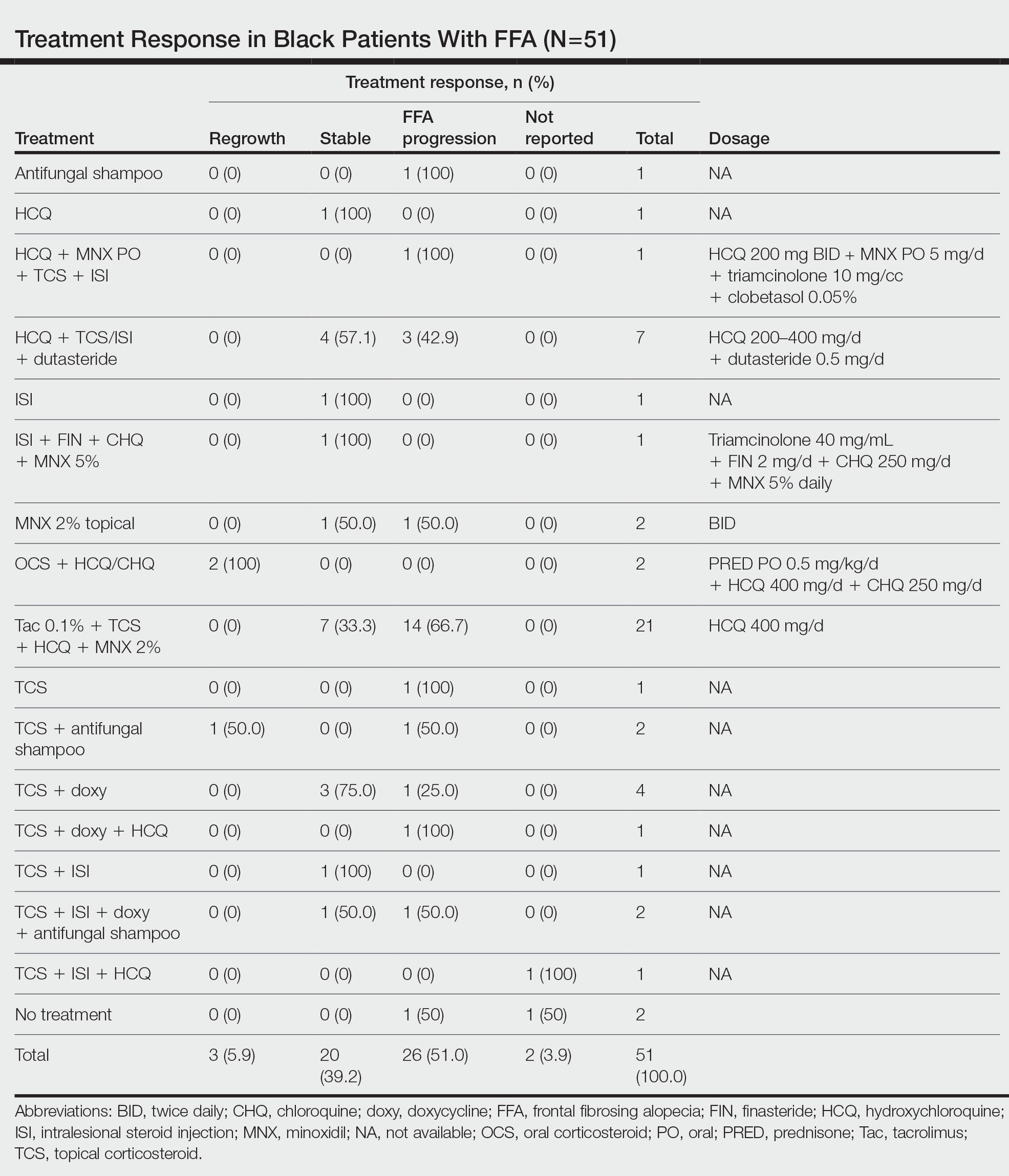

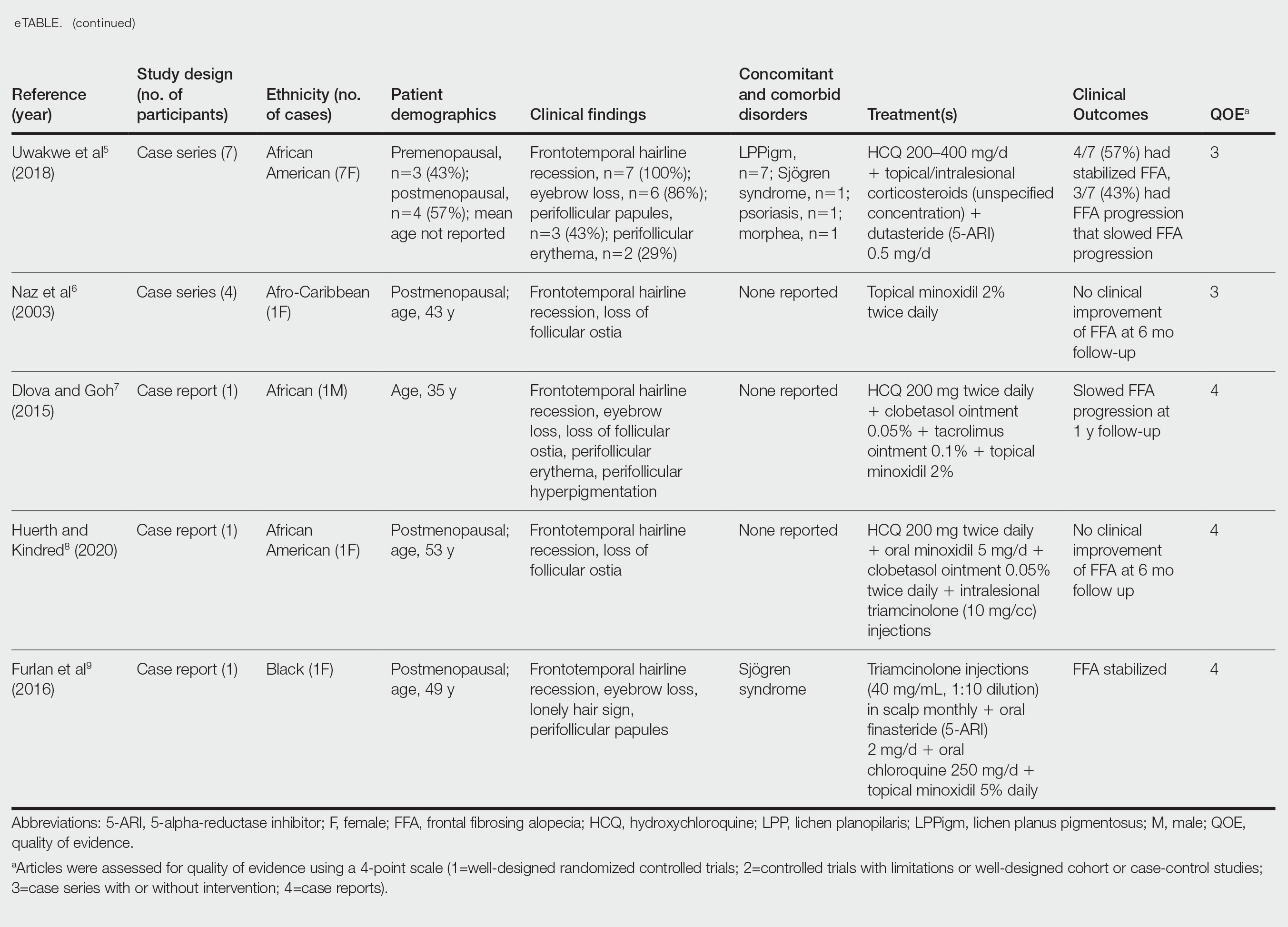

Treatment of Frontal Fibrosing Alopecia in Black Patients: A Systematic Review

Frontal fibrosing alopecia (FFA) is a lymphocytic cicatricial alopecia that primarily affects postmenopausal women. Considered a subtype of lichen planopilaris (LPP), FFA is histologically identical but presents as symmetric frontotemporal hairline recession rather than the multifocal distribution typical of LPP (Figure 1). Patients also may experience symptoms such as itching, facial papules, and eyebrow loss. As a progressive and scarring alopecia, early management of FFA is necessary to prevent permanent hair loss; however, there still are no clear guidelines regarding the efficacy of different treatment options for FFA due to a lack of randomized controlled studies in the literature. Patients with skin of color (SOC) also may have varying responses to treatment, further complicating the establishment of any treatment algorithm. Furthermore, symptoms, clinical findings, and demographics of FFA have been observed to vary across different ethnicities, especially among Black individuals. We conducted a systematic review of the literature on FFA in Black patients, with an analysis of demographics, clinical findings, concomitant skin conditions, treatments given, and treatment responses.

Methods

A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE was conducted of studies investigating FFA in patients with SOC from January 1, 2000, through November 30, 2020, using the terms frontal fibrosing alopecia, ethnicity, African, Black, Asian, Indian, Hispanic, and Latino. Articles were included if they were available in English and discussed treatment and clinical outcomes of FFA in Black individuals. The reference lists of included studies also were reviewed. Articles were assessed for quality of evidence using a 4-point scale (1=well-designed randomized controlled trials; 2=controlled trials with limitations or well-designed cohort or case-control studies; 3=case series with or without intervention; 4=case reports). Variables related to study type, patient demographics, treatments, and clinical outcomes were recorded.

Results

Of the 69 search results, 8 studies—2 retrospective cohort studies, 3 case series, and 3 case reports—describing 51 Black individuals with FFA were included in our review (eTable). Of these, 49 (96.1%) were female and 2 (3.9%) were male. Of the 45 females with data available for menopausal status, 24 (53.3%) were premenopausal and 21 (46.7%) were postmenopausal; data were not available for 4 females. Patients identified as African or African American in 27 (52.9%) cases, South African in 19 (37.3%), Black in 3 (5.9%), Indian in 1 (2.0%), and Afro-Caribbean in 1 (2.0%). The average age of FFA onset was 43.8 years in females (raw data available in 24 patients) and 35 years in males (raw data available in 2 patients). A family history of hair loss was reported in 15.7% (8/51) of patients.

Involved areas of hair loss included the frontotemporal hairline (51/51 [100%]), eyebrows (32/51 [62.7%]), limbs (4/51 [7.8%]), occiput (4/51 [7.8%]), facial hair (2/51 [3.9%]), vertex scalp (1/51 [2.0%]), and eyelashes (1/51 [2.0%]). Patchy alopecia suggestive of LPP was reported in 2 (3.9%) patients.

Patients frequently presented with scalp pruritus (26/51 [51.0%]), perifollicular papules or pustules (9/51 [17.6%]), and perifollicular hyperpigmentation (9/51 [17.6%]). Other associated symptoms included perifollicular erythema (6/51 [11.8%]), scalp pain (5/51 [9.8%]), hyperkeratosis or flaking (3/51 [5.9%]), and facial papules (2/51 [3.9%]). Loss of follicular ostia, prominent follicular ostia, and the lonely hair sign (Figure 2) was described in 21 (41.2%), 5 (9.8%), and 15 (29.4%) of patients, respectively. Hairstyles that involve scalp traction (19/51 [37.3%]) and/or chemicals (28/51 [54.9%]), such as hair dye or chemical relaxers, commonly were reported in patients prior to the onset of FFA.

The most commonly reported dermatologic comorbidities included traction alopecia (17/51 [33.3%]), followed by lichen planus pigmentosus (LLPigm)(7/51 [13.7%]), LPP (2/51 [3.9%]), psoriasis (1/51 [2.0%]), and morphea (1/51 [2.0%]). Reported comorbid diseases included Sjögren syndrome (2/51 [3.9%]), hypothyroidism (2/51 [3.9%]), HIV (1/51 [2.0%]), and diabetes mellitus (1/51 [2.0%]).

Of available reports (n=32), the most common histologic findings included perifollicular fibrosis (23/32 [71.9%]), lichenoid lymphocytic inflammation (22/23 [95.7%]) primarily affecting the isthmus and infundibular areas of the follicles, and decreased follicular density (21/23 [91.3%]).

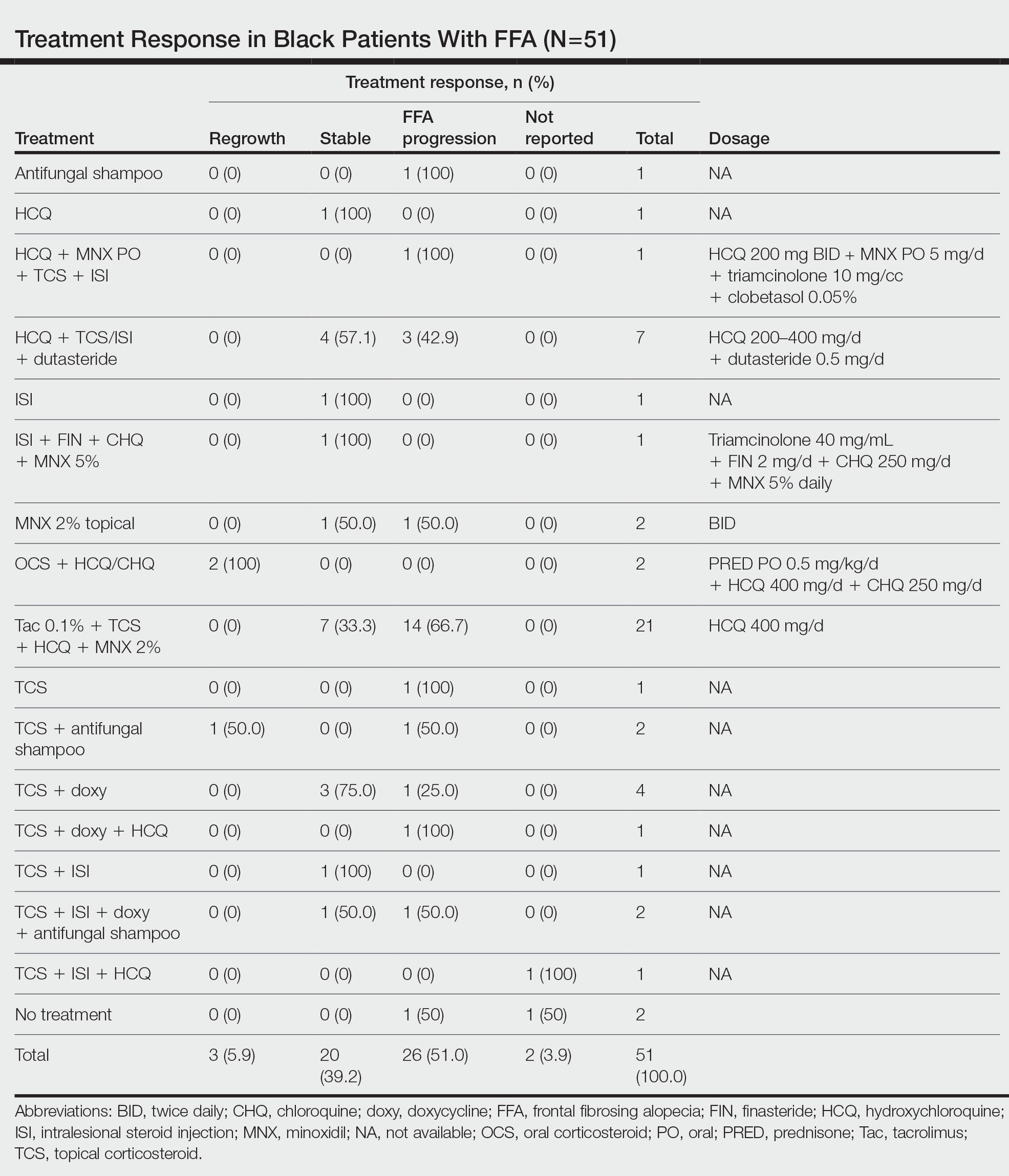

The average time interval from treatment initiation to treatment assessment in available reports (n=25) was 1.8 years (range, 0.5–2 years). Response to treatment included regrowth of hair in 5.9% (3/51) of patients, FFA stabilization in 39.2% (20/51), FFA progression in 51.0% (26/51), and not reported in 3.9% (2/51). Combination therapy was used in 84.3% (43/51) of patients, while monotherapy was used in 11.8% (6/51), and 3.9% (2/51) did not have any treatment reported. Response to treatment was highly variable among patients, as were the combinations of therapeutic agents used (Table). Regrowth of hair was rare, occurring in only 2 (100%) patients treated with oral prednisone plus hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) or chloroquine (CHQ), and in 1 (50.0%) patient treated with topical corticosteroids plus antifungal shampoo, while there was no response in the other patient treated with this combination.

Improvement in hair loss, defined as having at least slowed progression of FFA, was observed in 100% (2/2) of patients who had oral steroids as part of their treatment regimen, followed by 5-alpha-reductase inhibitors (5-ARIs)(finasteride and dutasteride; 62.5% [5/8]), intralesional steroids (57.1% [8/14]), HCQ/CHQ (42.9% [15/35]), topical steroids (41.5% [17/41]), antifungal shampoo (40.0% [2/5]), topical/oral minoxidil (36.0% [9/25]), and tacrolimus (33.3% [7/21]).

Comment

Frontal fibrosing alopecia is a progressive scarring alopecia and a clinical variant of LPP. First described in 1994 by Kossard,1 it initially was thought to be a disease of postmenopausal White women. Although still most prevalent in White individuals, there has been a growing number of reports describing FFA in patients with SOC, including Black individuals.10 Despite the increasing number of cases over the years, studies on the treatment of FFA remain sparse. Without expert guidelines, treatments usually are chosen based on clinician preferences. Few observational studies on these treatment modalities and their clinical outcomes exist, and the cohorts largely are composed of White patients.10-12 However, Black individuals may respond differently to these treatments, just as they have been shown to exhibit unique features of FFA.3

Demographics of Patients With FFA—Consistent with our findings, prior studies have found that Black patients are more likely to be younger and premenopausal at FFA onset than their White counterparts.13-15 Among the Black individuals included in our review, the majority were premenopausal (53%) with an average age of FFA onset of 46.7 years. Conversely, only 5% of 60 White females with FFA reported in a retrospective review were premenopausal and had an older mean age of FFA onset of 64 years,1 substantiating prior reports.

Clinical Findings in Patients With FFA—The clinical findings observed in our cohort were consistent with what has previously been described in Black patients, including loss of follicular ostia (41.2%), lonely hair sign (29.4%), perifollicular erythema (11.8%), perifollicular papules (17.6%), and hyperkeratosis or flaking (5.9%). In comparing these findings with a review of 932 patients, 86% of whom were White, the observed frequencies of follicular ostia loss (38.3%) and lonely hair sign (26.7%) were similar; however, perifollicular erythema (44.2%), and hyperkeratosis (44.4%) were more prevalent in this group, while perifollicular papules (6.2%) were less common compared to our Black cohort.16 An explanation for this discrepancy in perifollicular erythema may be the increased skin pigmentation diminishing the appearance of erythema in Black individuals. Our cohort of Black individuals noted the presence of follicular hyperpigmentation (17.6%) and a high prevalence of scalp pruritus (51.0%), which appear to be more common in Black patients.3,17 Although it is unclear why these differences in FFA presentation exist, it may be helpful for clinicians to be aware of these unique features when examining Black patients with suspected FFA.

Concomitant Cutaneous Disorders—A notable proportion of our cohort also had concomitant traction alopecia, which presents with frontotemporal alopecia, similar to FFA, making the diagnosis more challenging; however, the presence of perifollicular hyperpigmentation and facial hyperpigmentation in FFA may aid in differentiating these 2 entities.3 Other concomitant conditions noted in our review included androgenic alopecia, Sjögren syndrome, psoriasis, hypothyroidism, morphea, and HIV, suggesting a potential interplay between autoimmune, genetic, hormonal, and environmental components in the etiology of FFA. In fact, a recent study found that a persistent inflammatory response, loss of immune privilege, and a genetic susceptibility are some of the key processes in the pathogenesis of FFA.18 Although the authors speculated that there may be other triggers in initiating the onset of FFA, such as steroid hormones, sun exposure, and topical allergens, more evidence and controlled studies are needed

Additionally, concomitant LPPigm occurred in 13.7% of our FFA cohort, which appears to be more common in patients with darker skin types.5,19-21 Lichen planus pigmentosus is a rare variant of LPP, and previous reports suggest that it may be associated with FFA.5 Similar to FFA, the pathogenesis of LPPigm also is unclear, and its treatment may be just as difficult.22 Because LPPigm may occur before, during, or after onset of FFA,23 it may be helpful for clinicians to search for the signs of LPPigm in patients with darker skin types patients presenting with hair loss both as a diagnostic clue and so that treatment may be tailored to both conditions.

Response to Treatment—Similar to the varying clinical pictures, the response to treatment also can vary between patients of different ethnicities. For Black patients, treatment outcomes did not seem as successful as they did for other patients with SOC described in the literature. A retrospective cohort of 58 Asian individuals with FFA found that up to 90% had improvement or stabilization of FFA after treatment,23 while only 45.1% (23/51) of the Black patients included in our study had improvement or stabilization. One reason may be that a greater proportion of Black patients are premenopausal at FFA onset (53%) compared to what is reported in Asian patients (28%),23 and women who are premenopausal at FFA onset often face more severe disease.15 Although there may be additional explanations for these differences in treatment outcomes between ethnic groups, further investigation is needed.

All patients included in our study received either monotherapy or combination therapy of topical/intralesional/oral steroids, HCQ or CHQ, 5-ARIs, topical/oral minoxidil, antifungal shampoo, and/or a calcineurin inhibitor; however, most patients (51.0%) did not see a response to treatment, while only 45.1% showed slowed or halted progression of FFA. Hair regrowth was rare, occurring in only 3 (5.9%) patients; 2 of them were the only patients treated with oral prednisone, making for a potentially promising therapeutic for Black patients that should be further investigated in larger controlled cohort studies. In a prior study, intramuscular steroids (40 mg every 3 weeks) plus topical minoxidil were unsuccessful in slowing the progression of FFA in 3 postmenopausal women,24 which may be explained by the racial differences in the response to FFA treatments and perhaps also menopausal status. Although not included in any of the regimens in our review, isotretinoin was shown to be effective in an ethnically unspecified group of patients (n=16) and also may be efficacious in Black individuals.25 Although FFA may stabilize with time,26 this was not observed in any of the patients included in our study; however, we only included patients who were treated, making it impossible to discern whether resolution was idiopathic or due to treatment.

Future Research—Research on treatments for FFA is lacking, especially in patients with SOC. Although we observed that there may be differences in the treatment response among Black individuals compared to other patients with SOC, additional studies are needed to delineate these racial differences, which can help guide management. More randomized controlled trials evaluating the various treatment regimens also are required to establish treatment guidelines. Frontal fibrosing alopecia likely is underdiagnosed in Black individuals, contributing to the lack of research in this group. Darker skin can obscure some of the clinical and dermoscopic features that are more visible in fair skin. Furthermore, it may be challenging to distinguish clinical features of FFA in the setting of concomitant traction alopecia, which is more common in Black patients.27 Frontal fibrosing alopecia presenting in Black women also is less likely to be biopsied, contributing to the tendency to miss FFA in favor of traction or androgenic alopecia, which often are assumed to be more common in this population.2,27 Therefore, histologic evaluation through biopsy is paramount in securing an accurate diagnosis for Black patients with frontotemporal alopecia.

Study Limitations—The studies included in our review were limited by a lack of control comparison groups, especially among the retrospective cohort studies. Additionally, some of the studies included cases refractory to prior treatment modalities, possibly leading to a selection bias of more severe cases that were not representative of FFA in the general population. Thus, further studies involving larger populations of those with SOC are needed to fully evaluate the clinical utility of the current treatment modalities in this group.

- Kossard S. Postmenopausal frontal fibrosing alopecia. scarring alopecia in a pattern distribution. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:770-774.

- Dlova NC, Jordaan HF, Skenjane A, et al. Frontal fibrosing alopecia: a clinical review of 20 black patients from South Africa. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:939-941. doi:10.1111/bjd.12424

- Callender VD, Reid SD, Obayan O, et al. Diagnostic clues to frontal fibrosing alopecia in patients of African descent. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2016;9:45-51.

- Donati A, Molina L, Doche I, et al. Facial papules in frontal fibrosing alopecia: evidence of vellus follicle involvement. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:1424-1427. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2011.321

- Uwakwe LN, Cardwell LA, Dothard EH, et al. Frontal fibrosing alopecia and concomitant lichen planus pigmentosus: a case series of seven African American women. J Drugs Dermatol. 2018;17:397-400.

- Naz E, Vidaurrázaga C, Hernández-Cano N, et al. Postmenopausal frontal fibrosing alopecia. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2003;28:25-27. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2230.2003.01131.x

- Dlova NC, Goh CL. Frontal fibrosing alopecia in an African man. Int J Dermatol. 2015;54:81-83. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2012.05821.x

- Huerth K, Kindred C. Frontal fibrosing alopecia presenting as androgenetic alopecia in an African American woman. J Drugs Dermatol. 2020;19:794-795. doi:10.36849/jdd.2020.4682

- Furlan KC, Kakizaki P, Chartuni JC, et al. Frontal fibrosing alopecia in association with Sjögren’s syndrome: more than a simple coincidence. An Bras Dermatol. 2016;91(5 suppl 1):14-16. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20164526

- Zhang M, Zhang L, Rosman IS, et al. Frontal fibrosing alopecia demographics: a survey of 29 patients. Cutis. 2019;103:E16-E22.

- MacDonald A, Clark C, Holmes S. Frontal fibrosing alopecia: a review of 60 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:955-961. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2011.12.038

- Starace M, Brandi N, Alessandrini A, et al. Frontal fibrosing alopecia: a case series of 65 patients seen in a single Italian centre. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019;33:433-438. doi:10.1111/jdv.15372

- Dlova NC. Frontal fibrosing alopecia and lichen planus pigmentosus: is there a link? Br J Dermatol. 2013;168:439-442. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2012.11146.x

- Petrof G, Cuell A, Rajkomar VV, et al. Retrospective review of 18 British South Asian women with frontal fibrosing alopecia. Int J Dermatol. 2018;57:490-491. doi:10.1111/ijd.13929

- Mervis JS, Borda LJ, Miteva M. Facial and extrafacial lesions in an ethnically diverse series of 91 patients with frontal fibrosing alopecia followed at a single center. Dermatology. 2019;235:112-119. doi:10.1159/000494603

- Valesky EM, Maier MD, Kippenberger S, et al. Frontal fibrosing alopecia - review of recent case reports and case series in PubMed. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. Aug 2018;16:992-999. doi:10.1111/ddg.13601

- Adotama P, Callender V, Kolla A, et al. Comparing the clinical differences in white and black women with frontal fibrosing alopecia. Br J Dermatol. 2021;185:1074-1076. doi:10.1111/bjd.20605

- Miao YJ, Jing J, Du XF, et al. Frontal fibrosing alopecia: a review of disease pathogenesis. Front Med (Lausanne). 2022;9:911944. doi:10.3389/fmed.2022.911944

- Pirmez R, Duque-Estrada B, Donati A, et al. Clinical and dermoscopic features of lichen planus pigmentosus in 37 patients with frontal fibrosing alopecia. Br J Dermatol. 2016;175:1387-1390. doi:10.1111/bjd.14722

- Berliner JG, McCalmont TH, Price VH, et al. Frontal fibrosing alopecia and lichen planus pigmentosus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:E26-E27. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2013.12.031

- Romiti R, Biancardi Gavioli CF, et al. Clinical and histopathological findings of frontal fibrosing alopecia-associated lichen planus pigmentosus. Skin Appendage Disord. 2017;3:59-63. doi:10.1159/000456038

- Mulinari-Brenner FA, Guilherme MR, Peretti MC, et al. Frontal fibrosing alopecia and lichen planus pigmentosus: diagnosis and therapeutic challenge. An Bras Dermatol. 2017;92(5 suppl 1):79-81. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20175833

- Panchaprateep R, Ruxrungtham P, Chancheewa B, et al. Clinical characteristics, trichoscopy, histopathology and treatment outcomes of frontal fibrosing alopecia in an Asian population: a retro-prospective cohort study. J Dermatol. 2020;47:1301-1311. doi:10.1111/1346-8138.15517

- Tosti A, Piraccini BM, Iorizzo M, et al. Frontal fibrosing alopecia in postmenopausal women. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:55-60. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2004.05.014

- Rokni GR, Emadi SN, Dabbaghzade A, et al. Evaluating the combined efficacy of oral isotretinoin and topical tacrolimus versus oral finasteride and topical tacrolimus in frontal fibrosing alopecia—a randomized controlled trial. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2023;22:613-619. doi:10.1111/jocd.15232

- Kossard S, Lee MS, Wilkinson B. Postmenopausal frontal fibrosing alopecia: a frontal variant of lichen planopilaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;36:59-66. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(97)70326-8

- Miteva M, Whiting D, Harries M, et al. Frontal fibrosing alopecia in black patients. Br J Dermatol. 2012;167:208-210. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2012.10809.x

Frontal fibrosing alopecia (FFA) is a lymphocytic cicatricial alopecia that primarily affects postmenopausal women. Considered a subtype of lichen planopilaris (LPP), FFA is histologically identical but presents as symmetric frontotemporal hairline recession rather than the multifocal distribution typical of LPP (Figure 1). Patients also may experience symptoms such as itching, facial papules, and eyebrow loss. As a progressive and scarring alopecia, early management of FFA is necessary to prevent permanent hair loss; however, there still are no clear guidelines regarding the efficacy of different treatment options for FFA due to a lack of randomized controlled studies in the literature. Patients with skin of color (SOC) also may have varying responses to treatment, further complicating the establishment of any treatment algorithm. Furthermore, symptoms, clinical findings, and demographics of FFA have been observed to vary across different ethnicities, especially among Black individuals. We conducted a systematic review of the literature on FFA in Black patients, with an analysis of demographics, clinical findings, concomitant skin conditions, treatments given, and treatment responses.

Methods

A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE was conducted of studies investigating FFA in patients with SOC from January 1, 2000, through November 30, 2020, using the terms frontal fibrosing alopecia, ethnicity, African, Black, Asian, Indian, Hispanic, and Latino. Articles were included if they were available in English and discussed treatment and clinical outcomes of FFA in Black individuals. The reference lists of included studies also were reviewed. Articles were assessed for quality of evidence using a 4-point scale (1=well-designed randomized controlled trials; 2=controlled trials with limitations or well-designed cohort or case-control studies; 3=case series with or without intervention; 4=case reports). Variables related to study type, patient demographics, treatments, and clinical outcomes were recorded.

Results

Of the 69 search results, 8 studies—2 retrospective cohort studies, 3 case series, and 3 case reports—describing 51 Black individuals with FFA were included in our review (eTable). Of these, 49 (96.1%) were female and 2 (3.9%) were male. Of the 45 females with data available for menopausal status, 24 (53.3%) were premenopausal and 21 (46.7%) were postmenopausal; data were not available for 4 females. Patients identified as African or African American in 27 (52.9%) cases, South African in 19 (37.3%), Black in 3 (5.9%), Indian in 1 (2.0%), and Afro-Caribbean in 1 (2.0%). The average age of FFA onset was 43.8 years in females (raw data available in 24 patients) and 35 years in males (raw data available in 2 patients). A family history of hair loss was reported in 15.7% (8/51) of patients.

Involved areas of hair loss included the frontotemporal hairline (51/51 [100%]), eyebrows (32/51 [62.7%]), limbs (4/51 [7.8%]), occiput (4/51 [7.8%]), facial hair (2/51 [3.9%]), vertex scalp (1/51 [2.0%]), and eyelashes (1/51 [2.0%]). Patchy alopecia suggestive of LPP was reported in 2 (3.9%) patients.

Patients frequently presented with scalp pruritus (26/51 [51.0%]), perifollicular papules or pustules (9/51 [17.6%]), and perifollicular hyperpigmentation (9/51 [17.6%]). Other associated symptoms included perifollicular erythema (6/51 [11.8%]), scalp pain (5/51 [9.8%]), hyperkeratosis or flaking (3/51 [5.9%]), and facial papules (2/51 [3.9%]). Loss of follicular ostia, prominent follicular ostia, and the lonely hair sign (Figure 2) was described in 21 (41.2%), 5 (9.8%), and 15 (29.4%) of patients, respectively. Hairstyles that involve scalp traction (19/51 [37.3%]) and/or chemicals (28/51 [54.9%]), such as hair dye or chemical relaxers, commonly were reported in patients prior to the onset of FFA.

The most commonly reported dermatologic comorbidities included traction alopecia (17/51 [33.3%]), followed by lichen planus pigmentosus (LLPigm)(7/51 [13.7%]), LPP (2/51 [3.9%]), psoriasis (1/51 [2.0%]), and morphea (1/51 [2.0%]). Reported comorbid diseases included Sjögren syndrome (2/51 [3.9%]), hypothyroidism (2/51 [3.9%]), HIV (1/51 [2.0%]), and diabetes mellitus (1/51 [2.0%]).

Of available reports (n=32), the most common histologic findings included perifollicular fibrosis (23/32 [71.9%]), lichenoid lymphocytic inflammation (22/23 [95.7%]) primarily affecting the isthmus and infundibular areas of the follicles, and decreased follicular density (21/23 [91.3%]).

The average time interval from treatment initiation to treatment assessment in available reports (n=25) was 1.8 years (range, 0.5–2 years). Response to treatment included regrowth of hair in 5.9% (3/51) of patients, FFA stabilization in 39.2% (20/51), FFA progression in 51.0% (26/51), and not reported in 3.9% (2/51). Combination therapy was used in 84.3% (43/51) of patients, while monotherapy was used in 11.8% (6/51), and 3.9% (2/51) did not have any treatment reported. Response to treatment was highly variable among patients, as were the combinations of therapeutic agents used (Table). Regrowth of hair was rare, occurring in only 2 (100%) patients treated with oral prednisone plus hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) or chloroquine (CHQ), and in 1 (50.0%) patient treated with topical corticosteroids plus antifungal shampoo, while there was no response in the other patient treated with this combination.

Improvement in hair loss, defined as having at least slowed progression of FFA, was observed in 100% (2/2) of patients who had oral steroids as part of their treatment regimen, followed by 5-alpha-reductase inhibitors (5-ARIs)(finasteride and dutasteride; 62.5% [5/8]), intralesional steroids (57.1% [8/14]), HCQ/CHQ (42.9% [15/35]), topical steroids (41.5% [17/41]), antifungal shampoo (40.0% [2/5]), topical/oral minoxidil (36.0% [9/25]), and tacrolimus (33.3% [7/21]).

Comment

Frontal fibrosing alopecia is a progressive scarring alopecia and a clinical variant of LPP. First described in 1994 by Kossard,1 it initially was thought to be a disease of postmenopausal White women. Although still most prevalent in White individuals, there has been a growing number of reports describing FFA in patients with SOC, including Black individuals.10 Despite the increasing number of cases over the years, studies on the treatment of FFA remain sparse. Without expert guidelines, treatments usually are chosen based on clinician preferences. Few observational studies on these treatment modalities and their clinical outcomes exist, and the cohorts largely are composed of White patients.10-12 However, Black individuals may respond differently to these treatments, just as they have been shown to exhibit unique features of FFA.3

Demographics of Patients With FFA—Consistent with our findings, prior studies have found that Black patients are more likely to be younger and premenopausal at FFA onset than their White counterparts.13-15 Among the Black individuals included in our review, the majority were premenopausal (53%) with an average age of FFA onset of 46.7 years. Conversely, only 5% of 60 White females with FFA reported in a retrospective review were premenopausal and had an older mean age of FFA onset of 64 years,1 substantiating prior reports.

Clinical Findings in Patients With FFA—The clinical findings observed in our cohort were consistent with what has previously been described in Black patients, including loss of follicular ostia (41.2%), lonely hair sign (29.4%), perifollicular erythema (11.8%), perifollicular papules (17.6%), and hyperkeratosis or flaking (5.9%). In comparing these findings with a review of 932 patients, 86% of whom were White, the observed frequencies of follicular ostia loss (38.3%) and lonely hair sign (26.7%) were similar; however, perifollicular erythema (44.2%), and hyperkeratosis (44.4%) were more prevalent in this group, while perifollicular papules (6.2%) were less common compared to our Black cohort.16 An explanation for this discrepancy in perifollicular erythema may be the increased skin pigmentation diminishing the appearance of erythema in Black individuals. Our cohort of Black individuals noted the presence of follicular hyperpigmentation (17.6%) and a high prevalence of scalp pruritus (51.0%), which appear to be more common in Black patients.3,17 Although it is unclear why these differences in FFA presentation exist, it may be helpful for clinicians to be aware of these unique features when examining Black patients with suspected FFA.

Concomitant Cutaneous Disorders—A notable proportion of our cohort also had concomitant traction alopecia, which presents with frontotemporal alopecia, similar to FFA, making the diagnosis more challenging; however, the presence of perifollicular hyperpigmentation and facial hyperpigmentation in FFA may aid in differentiating these 2 entities.3 Other concomitant conditions noted in our review included androgenic alopecia, Sjögren syndrome, psoriasis, hypothyroidism, morphea, and HIV, suggesting a potential interplay between autoimmune, genetic, hormonal, and environmental components in the etiology of FFA. In fact, a recent study found that a persistent inflammatory response, loss of immune privilege, and a genetic susceptibility are some of the key processes in the pathogenesis of FFA.18 Although the authors speculated that there may be other triggers in initiating the onset of FFA, such as steroid hormones, sun exposure, and topical allergens, more evidence and controlled studies are needed

Additionally, concomitant LPPigm occurred in 13.7% of our FFA cohort, which appears to be more common in patients with darker skin types.5,19-21 Lichen planus pigmentosus is a rare variant of LPP, and previous reports suggest that it may be associated with FFA.5 Similar to FFA, the pathogenesis of LPPigm also is unclear, and its treatment may be just as difficult.22 Because LPPigm may occur before, during, or after onset of FFA,23 it may be helpful for clinicians to search for the signs of LPPigm in patients with darker skin types patients presenting with hair loss both as a diagnostic clue and so that treatment may be tailored to both conditions.

Response to Treatment—Similar to the varying clinical pictures, the response to treatment also can vary between patients of different ethnicities. For Black patients, treatment outcomes did not seem as successful as they did for other patients with SOC described in the literature. A retrospective cohort of 58 Asian individuals with FFA found that up to 90% had improvement or stabilization of FFA after treatment,23 while only 45.1% (23/51) of the Black patients included in our study had improvement or stabilization. One reason may be that a greater proportion of Black patients are premenopausal at FFA onset (53%) compared to what is reported in Asian patients (28%),23 and women who are premenopausal at FFA onset often face more severe disease.15 Although there may be additional explanations for these differences in treatment outcomes between ethnic groups, further investigation is needed.

All patients included in our study received either monotherapy or combination therapy of topical/intralesional/oral steroids, HCQ or CHQ, 5-ARIs, topical/oral minoxidil, antifungal shampoo, and/or a calcineurin inhibitor; however, most patients (51.0%) did not see a response to treatment, while only 45.1% showed slowed or halted progression of FFA. Hair regrowth was rare, occurring in only 3 (5.9%) patients; 2 of them were the only patients treated with oral prednisone, making for a potentially promising therapeutic for Black patients that should be further investigated in larger controlled cohort studies. In a prior study, intramuscular steroids (40 mg every 3 weeks) plus topical minoxidil were unsuccessful in slowing the progression of FFA in 3 postmenopausal women,24 which may be explained by the racial differences in the response to FFA treatments and perhaps also menopausal status. Although not included in any of the regimens in our review, isotretinoin was shown to be effective in an ethnically unspecified group of patients (n=16) and also may be efficacious in Black individuals.25 Although FFA may stabilize with time,26 this was not observed in any of the patients included in our study; however, we only included patients who were treated, making it impossible to discern whether resolution was idiopathic or due to treatment.

Future Research—Research on treatments for FFA is lacking, especially in patients with SOC. Although we observed that there may be differences in the treatment response among Black individuals compared to other patients with SOC, additional studies are needed to delineate these racial differences, which can help guide management. More randomized controlled trials evaluating the various treatment regimens also are required to establish treatment guidelines. Frontal fibrosing alopecia likely is underdiagnosed in Black individuals, contributing to the lack of research in this group. Darker skin can obscure some of the clinical and dermoscopic features that are more visible in fair skin. Furthermore, it may be challenging to distinguish clinical features of FFA in the setting of concomitant traction alopecia, which is more common in Black patients.27 Frontal fibrosing alopecia presenting in Black women also is less likely to be biopsied, contributing to the tendency to miss FFA in favor of traction or androgenic alopecia, which often are assumed to be more common in this population.2,27 Therefore, histologic evaluation through biopsy is paramount in securing an accurate diagnosis for Black patients with frontotemporal alopecia.

Study Limitations—The studies included in our review were limited by a lack of control comparison groups, especially among the retrospective cohort studies. Additionally, some of the studies included cases refractory to prior treatment modalities, possibly leading to a selection bias of more severe cases that were not representative of FFA in the general population. Thus, further studies involving larger populations of those with SOC are needed to fully evaluate the clinical utility of the current treatment modalities in this group.

Frontal fibrosing alopecia (FFA) is a lymphocytic cicatricial alopecia that primarily affects postmenopausal women. Considered a subtype of lichen planopilaris (LPP), FFA is histologically identical but presents as symmetric frontotemporal hairline recession rather than the multifocal distribution typical of LPP (Figure 1). Patients also may experience symptoms such as itching, facial papules, and eyebrow loss. As a progressive and scarring alopecia, early management of FFA is necessary to prevent permanent hair loss; however, there still are no clear guidelines regarding the efficacy of different treatment options for FFA due to a lack of randomized controlled studies in the literature. Patients with skin of color (SOC) also may have varying responses to treatment, further complicating the establishment of any treatment algorithm. Furthermore, symptoms, clinical findings, and demographics of FFA have been observed to vary across different ethnicities, especially among Black individuals. We conducted a systematic review of the literature on FFA in Black patients, with an analysis of demographics, clinical findings, concomitant skin conditions, treatments given, and treatment responses.

Methods

A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE was conducted of studies investigating FFA in patients with SOC from January 1, 2000, through November 30, 2020, using the terms frontal fibrosing alopecia, ethnicity, African, Black, Asian, Indian, Hispanic, and Latino. Articles were included if they were available in English and discussed treatment and clinical outcomes of FFA in Black individuals. The reference lists of included studies also were reviewed. Articles were assessed for quality of evidence using a 4-point scale (1=well-designed randomized controlled trials; 2=controlled trials with limitations or well-designed cohort or case-control studies; 3=case series with or without intervention; 4=case reports). Variables related to study type, patient demographics, treatments, and clinical outcomes were recorded.

Results

Of the 69 search results, 8 studies—2 retrospective cohort studies, 3 case series, and 3 case reports—describing 51 Black individuals with FFA were included in our review (eTable). Of these, 49 (96.1%) were female and 2 (3.9%) were male. Of the 45 females with data available for menopausal status, 24 (53.3%) were premenopausal and 21 (46.7%) were postmenopausal; data were not available for 4 females. Patients identified as African or African American in 27 (52.9%) cases, South African in 19 (37.3%), Black in 3 (5.9%), Indian in 1 (2.0%), and Afro-Caribbean in 1 (2.0%). The average age of FFA onset was 43.8 years in females (raw data available in 24 patients) and 35 years in males (raw data available in 2 patients). A family history of hair loss was reported in 15.7% (8/51) of patients.

Involved areas of hair loss included the frontotemporal hairline (51/51 [100%]), eyebrows (32/51 [62.7%]), limbs (4/51 [7.8%]), occiput (4/51 [7.8%]), facial hair (2/51 [3.9%]), vertex scalp (1/51 [2.0%]), and eyelashes (1/51 [2.0%]). Patchy alopecia suggestive of LPP was reported in 2 (3.9%) patients.