User login

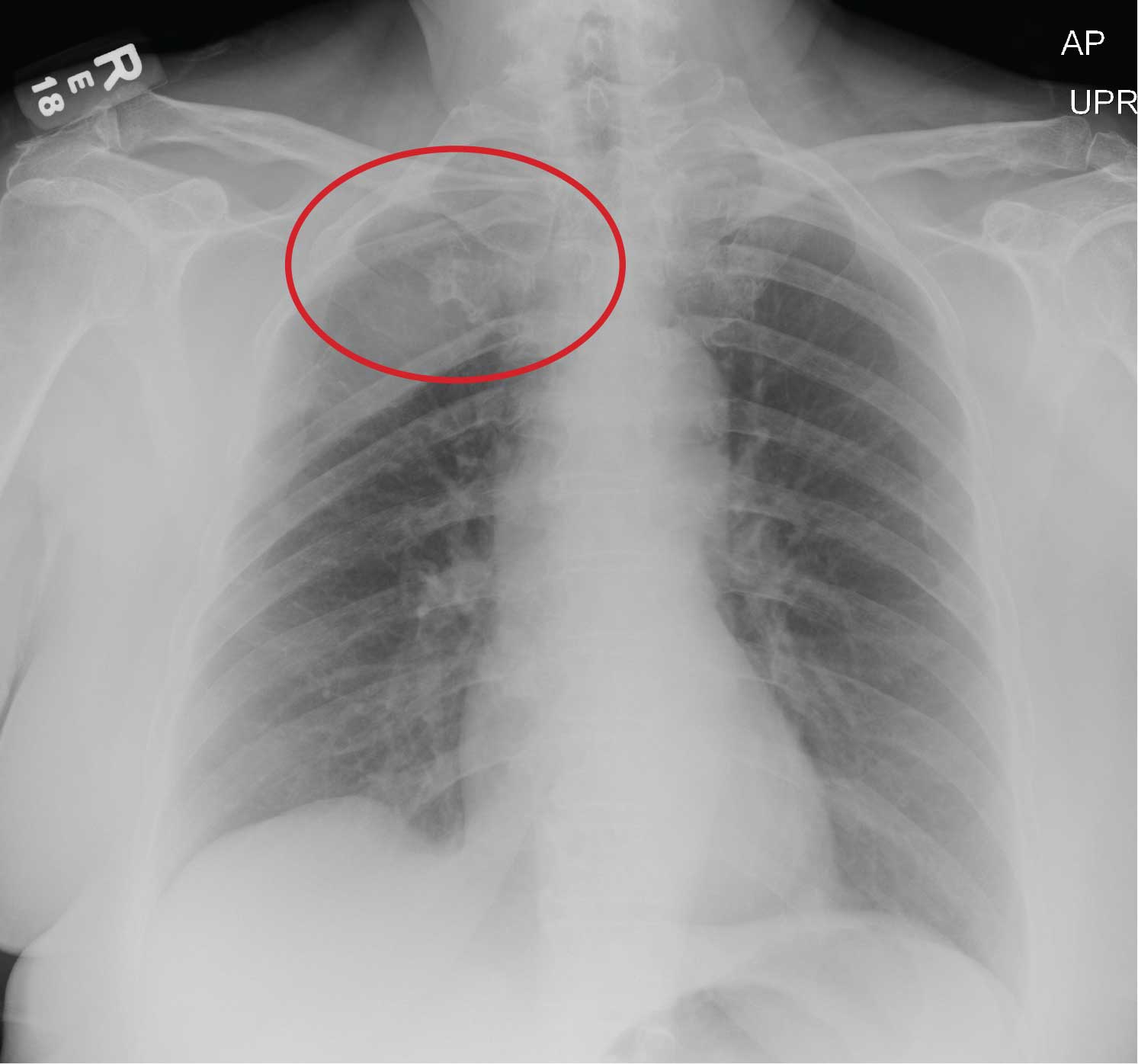

Is It More Than a Cold?

ANSWER

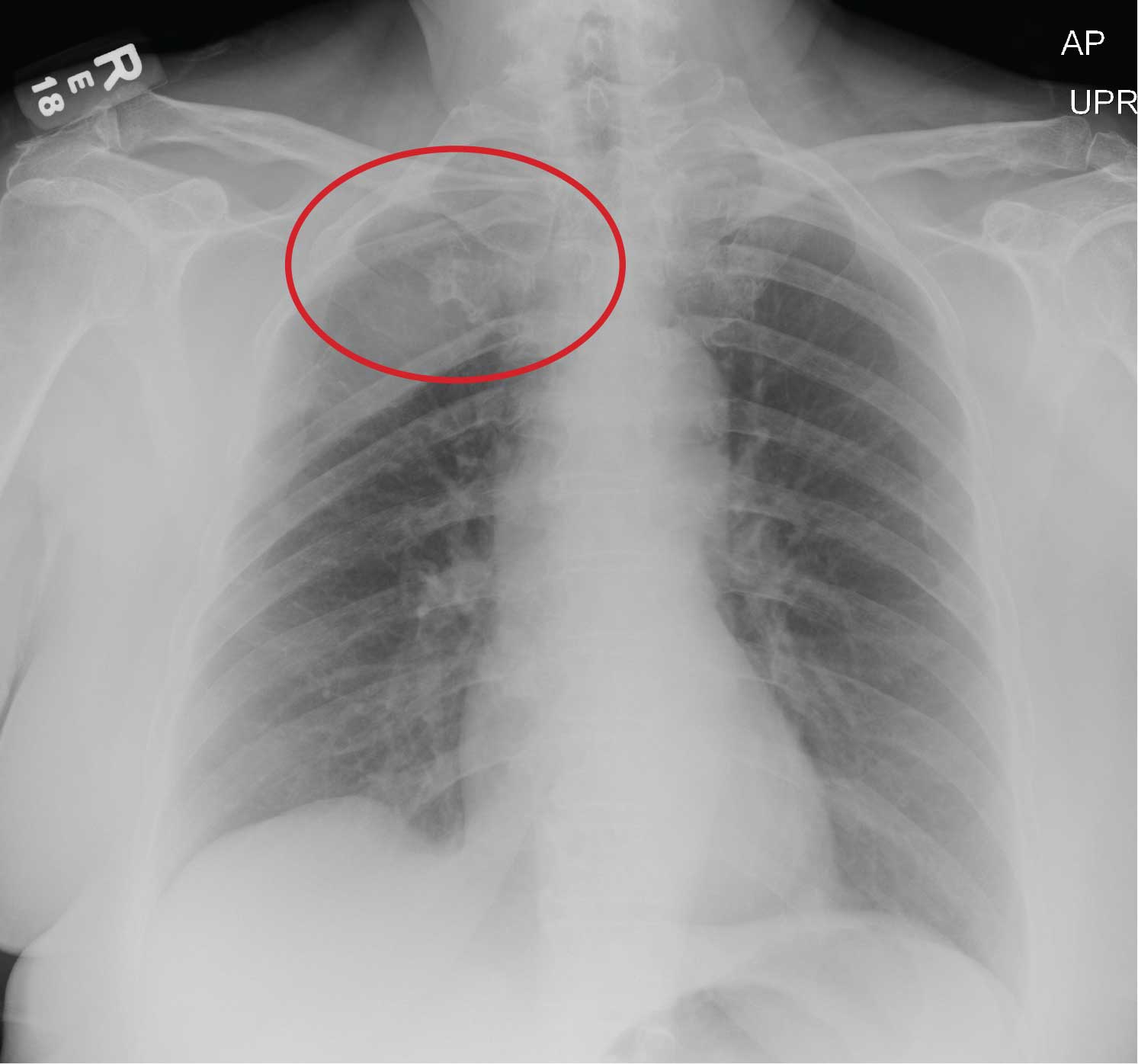

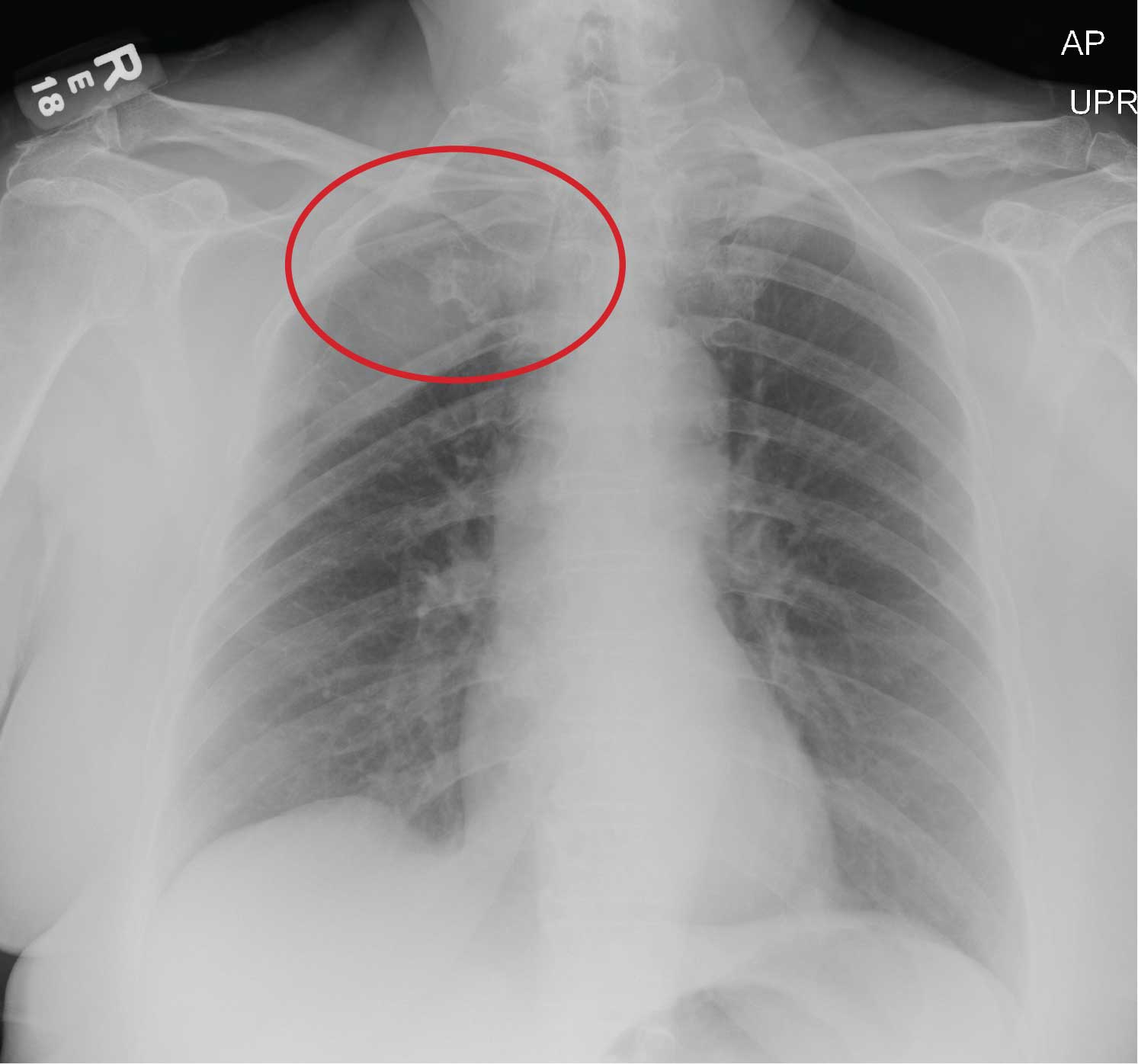

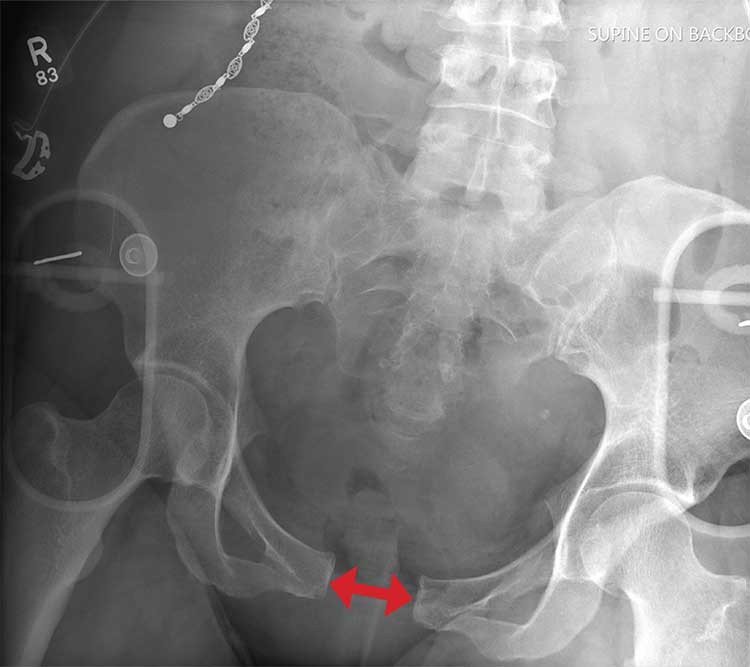

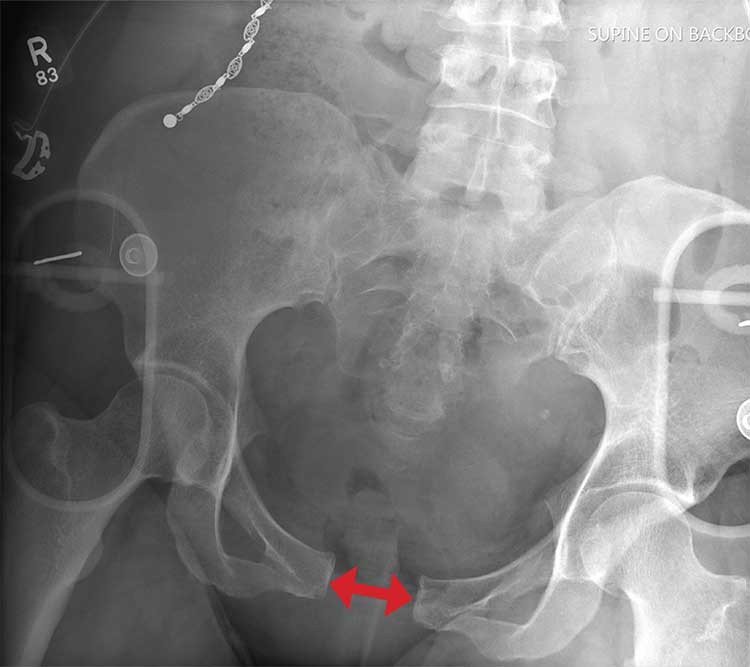

The radiograph does not demonstrate any evidence of infiltrate or pleural effusion. However, of note is a rather large lytic lesion involving the posterior aspect of the right fourth rib. This finding is very concerning for either a primary bone neoplasm or (more likely) a metastatic one.

The patient denied any history of cancer. She was promptly referred to Hematology/Oncology for further evaluation and workup. At last update, she had undergone a bone marrow biopsy, with preliminary pathology results suggestive of a plasma cell neoplasm.

ANSWER

The radiograph does not demonstrate any evidence of infiltrate or pleural effusion. However, of note is a rather large lytic lesion involving the posterior aspect of the right fourth rib. This finding is very concerning for either a primary bone neoplasm or (more likely) a metastatic one.

The patient denied any history of cancer. She was promptly referred to Hematology/Oncology for further evaluation and workup. At last update, she had undergone a bone marrow biopsy, with preliminary pathology results suggestive of a plasma cell neoplasm.

ANSWER

The radiograph does not demonstrate any evidence of infiltrate or pleural effusion. However, of note is a rather large lytic lesion involving the posterior aspect of the right fourth rib. This finding is very concerning for either a primary bone neoplasm or (more likely) a metastatic one.

The patient denied any history of cancer. She was promptly referred to Hematology/Oncology for further evaluation and workup. At last update, she had undergone a bone marrow biopsy, with preliminary pathology results suggestive of a plasma cell neoplasm.

A 70-year-old woman presents to the urgent care clinic with a week-long history of cold and cough that she feels is getting worse. She reports subjective fever and chills, as well as an occasional pain in the right side of her chest when she breathes. She has been taking OTC products with limited relief.

Her medical history is significant for mild hypertension. She denies smoking. On physical exam, you note an elderly female in no obvious distress. She is afebrile, with normal vital signs. Pulse oximetry reveals an O2 saturation of 98% on room air. Auscultation of her lungs demonstrates a little bit of mid bronchial congestion and perhaps some bibasilar crackles.

You order a complete blood count as well as a chest radiograph (shown). What is your impression?

Smokers with PE have higher rate of hospital readmission

NEW ORLEANS – , according to a retrospective study.

The rate of readmission was significantly higher among patients with tobacco dependence, and tobacco dependence was independently associated with an increased risk of readmission.

“This is the first study to quantify the increased rate of hospital readmission due to smoking,” said study investigator Kam Sing Ho, MD, of Mount Sinai St. Luke’s and Mount Sinai West, New York.

Dr. Ho and colleagues described this study and its results in a poster presented at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians.

The researchers analyzed data on 168,891 hospital admissions of adults with PE, 34.2% of whom had tobacco dependence. Patients with and without tobacco dependence were propensity matched for baseline characteristics (n = 24,262 in each group).

The 30-day readmission rate was significantly higher in patients with tobacco dependence than in those without it – 11.0% and 8.9%, respectively (P less than .001). The most common reason for readmission in both groups was PE.

Dr. Ho said the higher readmission rate among patients with tobacco dependence might be explained by the fact that smokers have a higher level of fibrinogen, which may affect blood viscosity and contribute to thrombus formation (Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2005;2[1]:71-7).

The investigators also found that tobacco dependence was an independent predictor of readmission (hazard ratio, 1.43; P less than .001). And the mortality rate was significantly higher after readmission than after index admission – 6.27% and 3.15%, respectively (P less than .001).

The increased risk of readmission and death among smokers highlights the importance of smoking cessation services. Dr. Ho cited previous research suggesting these services are underused in the hospital setting (BMJ Qual Improv Rep. 2014;3[1]:u204964.w2110).

“Given that smoking is a common phenomenon among patients admitted with pulmonary embolism, we suggest that more rigorous smoking cessation services are implemented prior to discharge for all active smokers,” Dr. Ho said. “[P]atients have the right to be informed on the benefits of smoking cessation and the autonomy to choose. Future research will focus on implementing inpatient smoking cessation at our hospital and its effect on local readmission rate, health resources utilization, and mortality.”

Dr. Ho has no relevant relationships to disclose.

SOURCE: Ho KS et al. CHEST 2019 October. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2019.08.1551.

NEW ORLEANS – , according to a retrospective study.

The rate of readmission was significantly higher among patients with tobacco dependence, and tobacco dependence was independently associated with an increased risk of readmission.

“This is the first study to quantify the increased rate of hospital readmission due to smoking,” said study investigator Kam Sing Ho, MD, of Mount Sinai St. Luke’s and Mount Sinai West, New York.

Dr. Ho and colleagues described this study and its results in a poster presented at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians.

The researchers analyzed data on 168,891 hospital admissions of adults with PE, 34.2% of whom had tobacco dependence. Patients with and without tobacco dependence were propensity matched for baseline characteristics (n = 24,262 in each group).

The 30-day readmission rate was significantly higher in patients with tobacco dependence than in those without it – 11.0% and 8.9%, respectively (P less than .001). The most common reason for readmission in both groups was PE.

Dr. Ho said the higher readmission rate among patients with tobacco dependence might be explained by the fact that smokers have a higher level of fibrinogen, which may affect blood viscosity and contribute to thrombus formation (Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2005;2[1]:71-7).

The investigators also found that tobacco dependence was an independent predictor of readmission (hazard ratio, 1.43; P less than .001). And the mortality rate was significantly higher after readmission than after index admission – 6.27% and 3.15%, respectively (P less than .001).

The increased risk of readmission and death among smokers highlights the importance of smoking cessation services. Dr. Ho cited previous research suggesting these services are underused in the hospital setting (BMJ Qual Improv Rep. 2014;3[1]:u204964.w2110).

“Given that smoking is a common phenomenon among patients admitted with pulmonary embolism, we suggest that more rigorous smoking cessation services are implemented prior to discharge for all active smokers,” Dr. Ho said. “[P]atients have the right to be informed on the benefits of smoking cessation and the autonomy to choose. Future research will focus on implementing inpatient smoking cessation at our hospital and its effect on local readmission rate, health resources utilization, and mortality.”

Dr. Ho has no relevant relationships to disclose.

SOURCE: Ho KS et al. CHEST 2019 October. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2019.08.1551.

NEW ORLEANS – , according to a retrospective study.

The rate of readmission was significantly higher among patients with tobacco dependence, and tobacco dependence was independently associated with an increased risk of readmission.

“This is the first study to quantify the increased rate of hospital readmission due to smoking,” said study investigator Kam Sing Ho, MD, of Mount Sinai St. Luke’s and Mount Sinai West, New York.

Dr. Ho and colleagues described this study and its results in a poster presented at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians.

The researchers analyzed data on 168,891 hospital admissions of adults with PE, 34.2% of whom had tobacco dependence. Patients with and without tobacco dependence were propensity matched for baseline characteristics (n = 24,262 in each group).

The 30-day readmission rate was significantly higher in patients with tobacco dependence than in those without it – 11.0% and 8.9%, respectively (P less than .001). The most common reason for readmission in both groups was PE.

Dr. Ho said the higher readmission rate among patients with tobacco dependence might be explained by the fact that smokers have a higher level of fibrinogen, which may affect blood viscosity and contribute to thrombus formation (Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2005;2[1]:71-7).

The investigators also found that tobacco dependence was an independent predictor of readmission (hazard ratio, 1.43; P less than .001). And the mortality rate was significantly higher after readmission than after index admission – 6.27% and 3.15%, respectively (P less than .001).

The increased risk of readmission and death among smokers highlights the importance of smoking cessation services. Dr. Ho cited previous research suggesting these services are underused in the hospital setting (BMJ Qual Improv Rep. 2014;3[1]:u204964.w2110).

“Given that smoking is a common phenomenon among patients admitted with pulmonary embolism, we suggest that more rigorous smoking cessation services are implemented prior to discharge for all active smokers,” Dr. Ho said. “[P]atients have the right to be informed on the benefits of smoking cessation and the autonomy to choose. Future research will focus on implementing inpatient smoking cessation at our hospital and its effect on local readmission rate, health resources utilization, and mortality.”

Dr. Ho has no relevant relationships to disclose.

SOURCE: Ho KS et al. CHEST 2019 October. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2019.08.1551.

REPORTING FROM CHEST 2019

One in five chest tube placements/removals goes awry

SAN FRANCISCO – , according to a prospective observational study conducted at 14 adult trauma centers.

“The sad part is, I don’t know if it was surprisingly high, but I’m glad somebody has taken the time to document it,” said Robert Sawyer, MD, professor of surgery at Western Michigan University, Kalamazoo, Mich., who comoderated the session at the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons, where the study was presented.

The researchers examined error rates in both insertions and removals, and compared some of the practices and characteristics of trauma centers with unusually good or poor records. The work could begin to inform quality improvement initiatives. “That’s very parallel to where we were 20 or 25 years ago with central venous catheters. We used to put them in and thought it was never a problem, and then we started taking a close look at it and found out, yeah, there was a problem. We systematically made our procedures more consistent and had better outcomes. I think chest tubes is going to be ripe for that,” Dr. Sawyer said in an interview.

“In some ways we have been lying to ourselves. We acknowledge that trainees have a high rate of complications in chest tube insertion and removal, but we haven’t fixed it as a systematic problem. We’re behind in our work to reduce complications for this bedside procedure,” echoed the session’s other comoderator, Tam Pham, MD, professor of surgery at the University of Washington, Seattle, in an interview.

The researchers defined chest tube errors as anything that resulted in a need to manipulate, replace, or revise an existing tube; a worsening of the condition that the tube was intended to address; or complications that resulted in additional length of stay or interventions. A total of 381 chest tubes were placed in 273 patients over a 3-month period, about 55% by residents and about 28% by trauma attending physicians. Around 80% were traditional chest tubes, and most of the rest were Pigtail, with a very small fraction of Trocar chest tubes, according to a pie chart displayed by Michaela West, MD, a trauma surgeon at North Memorial Health, Robbinsdale, Minn., who presented the research.

Dr. West reported a wide range of complication rates among the 14 institutions, ranging from under 10% to nearly 60%, and some centers reported far more complications with removal or insertion, while some had closer to an even split. The overall average rate of insertion complications was 18.7%, and the average for removal was 17.7%.

When the researchers looked at some of the best and worst performing centers, they identified some trends. A total of 98.6% of chest tubes were tunneled in the best-performing centers, while 14.3% were tunneled in the worst. An initial air leak was more common in the best performing centers (52.5% versus 21.7%). Higher performing centers had a greater percentage of patients with gunshot wounds (24.3% versus 13%), and had a longer duration of stay (5.3 days versus 3.4 days; P less than .05 for all).

In the single highest performing center, all chest tubes were removed by midlevel individuals, and the other two best performing centers relied on an attending physician or resident. The worst performing centers often had postgraduate year 1 and 2 residents removing the chest tubes.

Dr. West, Dr. Pham, and Dr. Sawyer have no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: West M et al. Clinical Congress 2019 Abstract.

SAN FRANCISCO – , according to a prospective observational study conducted at 14 adult trauma centers.

“The sad part is, I don’t know if it was surprisingly high, but I’m glad somebody has taken the time to document it,” said Robert Sawyer, MD, professor of surgery at Western Michigan University, Kalamazoo, Mich., who comoderated the session at the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons, where the study was presented.

The researchers examined error rates in both insertions and removals, and compared some of the practices and characteristics of trauma centers with unusually good or poor records. The work could begin to inform quality improvement initiatives. “That’s very parallel to where we were 20 or 25 years ago with central venous catheters. We used to put them in and thought it was never a problem, and then we started taking a close look at it and found out, yeah, there was a problem. We systematically made our procedures more consistent and had better outcomes. I think chest tubes is going to be ripe for that,” Dr. Sawyer said in an interview.

“In some ways we have been lying to ourselves. We acknowledge that trainees have a high rate of complications in chest tube insertion and removal, but we haven’t fixed it as a systematic problem. We’re behind in our work to reduce complications for this bedside procedure,” echoed the session’s other comoderator, Tam Pham, MD, professor of surgery at the University of Washington, Seattle, in an interview.

The researchers defined chest tube errors as anything that resulted in a need to manipulate, replace, or revise an existing tube; a worsening of the condition that the tube was intended to address; or complications that resulted in additional length of stay or interventions. A total of 381 chest tubes were placed in 273 patients over a 3-month period, about 55% by residents and about 28% by trauma attending physicians. Around 80% were traditional chest tubes, and most of the rest were Pigtail, with a very small fraction of Trocar chest tubes, according to a pie chart displayed by Michaela West, MD, a trauma surgeon at North Memorial Health, Robbinsdale, Minn., who presented the research.

Dr. West reported a wide range of complication rates among the 14 institutions, ranging from under 10% to nearly 60%, and some centers reported far more complications with removal or insertion, while some had closer to an even split. The overall average rate of insertion complications was 18.7%, and the average for removal was 17.7%.

When the researchers looked at some of the best and worst performing centers, they identified some trends. A total of 98.6% of chest tubes were tunneled in the best-performing centers, while 14.3% were tunneled in the worst. An initial air leak was more common in the best performing centers (52.5% versus 21.7%). Higher performing centers had a greater percentage of patients with gunshot wounds (24.3% versus 13%), and had a longer duration of stay (5.3 days versus 3.4 days; P less than .05 for all).

In the single highest performing center, all chest tubes were removed by midlevel individuals, and the other two best performing centers relied on an attending physician or resident. The worst performing centers often had postgraduate year 1 and 2 residents removing the chest tubes.

Dr. West, Dr. Pham, and Dr. Sawyer have no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: West M et al. Clinical Congress 2019 Abstract.

SAN FRANCISCO – , according to a prospective observational study conducted at 14 adult trauma centers.

“The sad part is, I don’t know if it was surprisingly high, but I’m glad somebody has taken the time to document it,” said Robert Sawyer, MD, professor of surgery at Western Michigan University, Kalamazoo, Mich., who comoderated the session at the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons, where the study was presented.

The researchers examined error rates in both insertions and removals, and compared some of the practices and characteristics of trauma centers with unusually good or poor records. The work could begin to inform quality improvement initiatives. “That’s very parallel to where we were 20 or 25 years ago with central venous catheters. We used to put them in and thought it was never a problem, and then we started taking a close look at it and found out, yeah, there was a problem. We systematically made our procedures more consistent and had better outcomes. I think chest tubes is going to be ripe for that,” Dr. Sawyer said in an interview.

“In some ways we have been lying to ourselves. We acknowledge that trainees have a high rate of complications in chest tube insertion and removal, but we haven’t fixed it as a systematic problem. We’re behind in our work to reduce complications for this bedside procedure,” echoed the session’s other comoderator, Tam Pham, MD, professor of surgery at the University of Washington, Seattle, in an interview.

The researchers defined chest tube errors as anything that resulted in a need to manipulate, replace, or revise an existing tube; a worsening of the condition that the tube was intended to address; or complications that resulted in additional length of stay or interventions. A total of 381 chest tubes were placed in 273 patients over a 3-month period, about 55% by residents and about 28% by trauma attending physicians. Around 80% were traditional chest tubes, and most of the rest were Pigtail, with a very small fraction of Trocar chest tubes, according to a pie chart displayed by Michaela West, MD, a trauma surgeon at North Memorial Health, Robbinsdale, Minn., who presented the research.

Dr. West reported a wide range of complication rates among the 14 institutions, ranging from under 10% to nearly 60%, and some centers reported far more complications with removal or insertion, while some had closer to an even split. The overall average rate of insertion complications was 18.7%, and the average for removal was 17.7%.

When the researchers looked at some of the best and worst performing centers, they identified some trends. A total of 98.6% of chest tubes were tunneled in the best-performing centers, while 14.3% were tunneled in the worst. An initial air leak was more common in the best performing centers (52.5% versus 21.7%). Higher performing centers had a greater percentage of patients with gunshot wounds (24.3% versus 13%), and had a longer duration of stay (5.3 days versus 3.4 days; P less than .05 for all).

In the single highest performing center, all chest tubes were removed by midlevel individuals, and the other two best performing centers relied on an attending physician or resident. The worst performing centers often had postgraduate year 1 and 2 residents removing the chest tubes.

Dr. West, Dr. Pham, and Dr. Sawyer have no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: West M et al. Clinical Congress 2019 Abstract.

REPORTING FROM CLINICAL CONGRESS 2019

Getting high heightens stroke, arrhythmia risks

Stoners, beware: , and people with cannabis use disorder are at a 50% greater risk of being hospitalized for arrhythmias, according to new research presented at the American Heart Association Scientific Sessions 2019.

An analysis of pooled data on nearly 44,000 participants in a cross-sectional survey showed that, among the 13.6% who reported using marijuana within the last 30 days, the adjusted odds ratio for young-onset stroke (aged 18-44 years), compared with non-users, was 2.75, reported Tarang Parekh, MBBS, a health policy researcher of George Mason University in Fairfax, Va., and colleagues.

In a separate study, a retrospective analysis of national inpatient data showed that people diagnosed with cannabis use disorder – a pathological pattern of impaired control, social impairment, risky behavior or physiological adaptation similar in nature to alcoholism – had a 47%-52% increased likelihood of hospitalization for an arrhythmia, reported Rikinkumar S. Patel, MD, a psychiatry resident at Griffin Memorial Hospital in Norman, Okla.

“As these [cannabis] products become increasingly used across the country, getting clearer, scientifically rigorous data is going to be important as we try to understand the overall health effects of cannabis,” said AHA President Robert Harrington, MD, of Stanford (Calif.) University in a statement.

Currently, use of both medical and recreational marijuana is fully legal in 11 U.S. states and the District of Columbia. Medical marijuana is legal with recreational use decriminalized (or penalties reduced) in 28 other states, and totally illegal in 11 other states, according to employee screening firm DISA Global Solutions.

Stroke study

In an oral presentation with simultaneous publication in the AHA journal Stroke, Dr. Parekh and colleagues presented an analysis of pooled data from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS), a nationally representative cross-sectional survey collected by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in 2016 and 2017.

They looked at baseline sociodemographic data and created multivariable logistic regression models with state fixed effects to determine whether marijuana use within the last 30 days was associated with young-onset stroke.

They identified 43,860 participants representing a weighted sample of 35.5 million Americans. Of the sample, 63.3% were male, and 13.6 % of all participants reported using marijuana in the last 30 days.

They found in an unadjusted model that marijuana users had an odds ratio for stroke, compared with nonusers, of 1.59 (P less than.1), and in a model adjusted for demographic factors (gender, race, ethnicity, and education) the OR increased to 1.76 (P less than .05).

When they threw risk behavior into the model (physical activity, body mass index, heavy drinking, and cigarette smoking), they saw that the OR for stroke shot up to 2.75 (P less than .01).

“Physicians should ask patients if they use cannabis and counsel them about its potential stroke risk as part of regular doctor visits,” Dr. Parekh said in a statement.

Arrhythmias study

Based on recent studies suggesting that cannabis use may trigger cardiovascular events, Dr. Patel and colleagues studied whether cannabis use disorder may be related to arrhythmias, approaching the question through hospital records.

“The effects of using cannabis are seen within 15 minutes and last for around 3 hours. At lower doses, it is linked to a rapid heartbeat. At higher doses, it is linked to a too-slow heartbeat,” he said in a statement.

Dr. Patel and colleagues conducted a retrospective analysis of the Nationwide Inpatient Sample from 2010-2014, a period during which medical marijuana became legal in several states and recreational marijuana became legal in Colorado and Washington. The sample is a database maintained by the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project of the U.S. Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion.

They identified 570,557 patients aged 15-54 years with a primary diagnosis of arrhythmia, and compared them with a sample of 67,662,082 patients hospitalized with no arrhythmia diagnosed during the same period.

They found a 2.6% incidence of cannabis use disorder among patients hospitalized for arrhythmias. Patients with cannabis use disorder tended to be younger (15- to 24-years-old; OR, 4.23), male (OR, 1.70) and African American (OR, 2.70).

In regression analysis adjusted for demographics and comorbidities, cannabis use disorder was associated with higher odds of arrhythmia hospitalization in young patients, at 1.28 times among 15- to 24-year-olds (95% confidence interval, 1.229-1.346) and 1.52 times for 25- to 34-year-olds (95% CI, 1.469-1.578).

“As medical and recreational cannabis is legalized in many states, it is important to know the difference between therapeutic cannabis dosing for medical purposes and the consequences of cannabis abuse. We urgently need additional research to understand these issues,” Dr. Patel said.

“It’s not proving that there’s a direct link, but it’s raising a suggestion in an observational analysis that [this] indeed might be the case. What that means for clinicians is that, if you’re seeing a patient who is presenting with a symptomatic arrhythmia, adding cannabis usage to your list of questions as you begin to try to understand possible precipitating factors for this arrhythmia seems to be a reasonable thing to do,” Dr. Harrington commented.

Stoners, beware: , and people with cannabis use disorder are at a 50% greater risk of being hospitalized for arrhythmias, according to new research presented at the American Heart Association Scientific Sessions 2019.

An analysis of pooled data on nearly 44,000 participants in a cross-sectional survey showed that, among the 13.6% who reported using marijuana within the last 30 days, the adjusted odds ratio for young-onset stroke (aged 18-44 years), compared with non-users, was 2.75, reported Tarang Parekh, MBBS, a health policy researcher of George Mason University in Fairfax, Va., and colleagues.

In a separate study, a retrospective analysis of national inpatient data showed that people diagnosed with cannabis use disorder – a pathological pattern of impaired control, social impairment, risky behavior or physiological adaptation similar in nature to alcoholism – had a 47%-52% increased likelihood of hospitalization for an arrhythmia, reported Rikinkumar S. Patel, MD, a psychiatry resident at Griffin Memorial Hospital in Norman, Okla.

“As these [cannabis] products become increasingly used across the country, getting clearer, scientifically rigorous data is going to be important as we try to understand the overall health effects of cannabis,” said AHA President Robert Harrington, MD, of Stanford (Calif.) University in a statement.

Currently, use of both medical and recreational marijuana is fully legal in 11 U.S. states and the District of Columbia. Medical marijuana is legal with recreational use decriminalized (or penalties reduced) in 28 other states, and totally illegal in 11 other states, according to employee screening firm DISA Global Solutions.

Stroke study

In an oral presentation with simultaneous publication in the AHA journal Stroke, Dr. Parekh and colleagues presented an analysis of pooled data from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS), a nationally representative cross-sectional survey collected by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in 2016 and 2017.

They looked at baseline sociodemographic data and created multivariable logistic regression models with state fixed effects to determine whether marijuana use within the last 30 days was associated with young-onset stroke.

They identified 43,860 participants representing a weighted sample of 35.5 million Americans. Of the sample, 63.3% were male, and 13.6 % of all participants reported using marijuana in the last 30 days.

They found in an unadjusted model that marijuana users had an odds ratio for stroke, compared with nonusers, of 1.59 (P less than.1), and in a model adjusted for demographic factors (gender, race, ethnicity, and education) the OR increased to 1.76 (P less than .05).

When they threw risk behavior into the model (physical activity, body mass index, heavy drinking, and cigarette smoking), they saw that the OR for stroke shot up to 2.75 (P less than .01).

“Physicians should ask patients if they use cannabis and counsel them about its potential stroke risk as part of regular doctor visits,” Dr. Parekh said in a statement.

Arrhythmias study

Based on recent studies suggesting that cannabis use may trigger cardiovascular events, Dr. Patel and colleagues studied whether cannabis use disorder may be related to arrhythmias, approaching the question through hospital records.

“The effects of using cannabis are seen within 15 minutes and last for around 3 hours. At lower doses, it is linked to a rapid heartbeat. At higher doses, it is linked to a too-slow heartbeat,” he said in a statement.

Dr. Patel and colleagues conducted a retrospective analysis of the Nationwide Inpatient Sample from 2010-2014, a period during which medical marijuana became legal in several states and recreational marijuana became legal in Colorado and Washington. The sample is a database maintained by the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project of the U.S. Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion.

They identified 570,557 patients aged 15-54 years with a primary diagnosis of arrhythmia, and compared them with a sample of 67,662,082 patients hospitalized with no arrhythmia diagnosed during the same period.

They found a 2.6% incidence of cannabis use disorder among patients hospitalized for arrhythmias. Patients with cannabis use disorder tended to be younger (15- to 24-years-old; OR, 4.23), male (OR, 1.70) and African American (OR, 2.70).

In regression analysis adjusted for demographics and comorbidities, cannabis use disorder was associated with higher odds of arrhythmia hospitalization in young patients, at 1.28 times among 15- to 24-year-olds (95% confidence interval, 1.229-1.346) and 1.52 times for 25- to 34-year-olds (95% CI, 1.469-1.578).

“As medical and recreational cannabis is legalized in many states, it is important to know the difference between therapeutic cannabis dosing for medical purposes and the consequences of cannabis abuse. We urgently need additional research to understand these issues,” Dr. Patel said.

“It’s not proving that there’s a direct link, but it’s raising a suggestion in an observational analysis that [this] indeed might be the case. What that means for clinicians is that, if you’re seeing a patient who is presenting with a symptomatic arrhythmia, adding cannabis usage to your list of questions as you begin to try to understand possible precipitating factors for this arrhythmia seems to be a reasonable thing to do,” Dr. Harrington commented.

Stoners, beware: , and people with cannabis use disorder are at a 50% greater risk of being hospitalized for arrhythmias, according to new research presented at the American Heart Association Scientific Sessions 2019.

An analysis of pooled data on nearly 44,000 participants in a cross-sectional survey showed that, among the 13.6% who reported using marijuana within the last 30 days, the adjusted odds ratio for young-onset stroke (aged 18-44 years), compared with non-users, was 2.75, reported Tarang Parekh, MBBS, a health policy researcher of George Mason University in Fairfax, Va., and colleagues.

In a separate study, a retrospective analysis of national inpatient data showed that people diagnosed with cannabis use disorder – a pathological pattern of impaired control, social impairment, risky behavior or physiological adaptation similar in nature to alcoholism – had a 47%-52% increased likelihood of hospitalization for an arrhythmia, reported Rikinkumar S. Patel, MD, a psychiatry resident at Griffin Memorial Hospital in Norman, Okla.

“As these [cannabis] products become increasingly used across the country, getting clearer, scientifically rigorous data is going to be important as we try to understand the overall health effects of cannabis,” said AHA President Robert Harrington, MD, of Stanford (Calif.) University in a statement.

Currently, use of both medical and recreational marijuana is fully legal in 11 U.S. states and the District of Columbia. Medical marijuana is legal with recreational use decriminalized (or penalties reduced) in 28 other states, and totally illegal in 11 other states, according to employee screening firm DISA Global Solutions.

Stroke study

In an oral presentation with simultaneous publication in the AHA journal Stroke, Dr. Parekh and colleagues presented an analysis of pooled data from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS), a nationally representative cross-sectional survey collected by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in 2016 and 2017.

They looked at baseline sociodemographic data and created multivariable logistic regression models with state fixed effects to determine whether marijuana use within the last 30 days was associated with young-onset stroke.

They identified 43,860 participants representing a weighted sample of 35.5 million Americans. Of the sample, 63.3% were male, and 13.6 % of all participants reported using marijuana in the last 30 days.

They found in an unadjusted model that marijuana users had an odds ratio for stroke, compared with nonusers, of 1.59 (P less than.1), and in a model adjusted for demographic factors (gender, race, ethnicity, and education) the OR increased to 1.76 (P less than .05).

When they threw risk behavior into the model (physical activity, body mass index, heavy drinking, and cigarette smoking), they saw that the OR for stroke shot up to 2.75 (P less than .01).

“Physicians should ask patients if they use cannabis and counsel them about its potential stroke risk as part of regular doctor visits,” Dr. Parekh said in a statement.

Arrhythmias study

Based on recent studies suggesting that cannabis use may trigger cardiovascular events, Dr. Patel and colleagues studied whether cannabis use disorder may be related to arrhythmias, approaching the question through hospital records.

“The effects of using cannabis are seen within 15 minutes and last for around 3 hours. At lower doses, it is linked to a rapid heartbeat. At higher doses, it is linked to a too-slow heartbeat,” he said in a statement.

Dr. Patel and colleagues conducted a retrospective analysis of the Nationwide Inpatient Sample from 2010-2014, a period during which medical marijuana became legal in several states and recreational marijuana became legal in Colorado and Washington. The sample is a database maintained by the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project of the U.S. Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion.

They identified 570,557 patients aged 15-54 years with a primary diagnosis of arrhythmia, and compared them with a sample of 67,662,082 patients hospitalized with no arrhythmia diagnosed during the same period.

They found a 2.6% incidence of cannabis use disorder among patients hospitalized for arrhythmias. Patients with cannabis use disorder tended to be younger (15- to 24-years-old; OR, 4.23), male (OR, 1.70) and African American (OR, 2.70).

In regression analysis adjusted for demographics and comorbidities, cannabis use disorder was associated with higher odds of arrhythmia hospitalization in young patients, at 1.28 times among 15- to 24-year-olds (95% confidence interval, 1.229-1.346) and 1.52 times for 25- to 34-year-olds (95% CI, 1.469-1.578).

“As medical and recreational cannabis is legalized in many states, it is important to know the difference between therapeutic cannabis dosing for medical purposes and the consequences of cannabis abuse. We urgently need additional research to understand these issues,” Dr. Patel said.

“It’s not proving that there’s a direct link, but it’s raising a suggestion in an observational analysis that [this] indeed might be the case. What that means for clinicians is that, if you’re seeing a patient who is presenting with a symptomatic arrhythmia, adding cannabis usage to your list of questions as you begin to try to understand possible precipitating factors for this arrhythmia seems to be a reasonable thing to do,” Dr. Harrington commented.

REPORTING FROM AHA 2019

Previously healthy patients hospitalized for sepsis show increased mortality

WASHINGTON – Although severe, community-acquired sepsis in previously healthy U.S. adults is relatively uncommon, it occurs often enough to strike about 40,000 people annually, and when previously healthy people are hospitalized for severe sepsis, their rate of in-hospital mortality was double the rate in people with one or more comorbidities who have severe, community-acquired sepsis, based on a review of almost 7 million Americans hospitalized for sepsis.

The findings “underscore the importance of improving public awareness of sepsis and emphasizing early sepsis recognition and treatment in all patients,” including those without comorbidities, Chanu Rhee, MD, said at an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases. He hypothesized that the increased sepsis mortality among previously healthy patients may have stemmed from factors such as delayed sepsis recognition resulting in hospitalization at a more advanced stage and less aggressive management.

In addition, “the findings provide context for high-profile reports about sepsis death in previously healthy people,” said Dr. Rhee, an infectious diseases and critical care physician at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. Dr. Rhee and associates found that, among patients hospitalized with what the researchers defined as “community-acquired” sepsis, 3% were judged previously healthy by having no identified major or minor comorbidity or pregnancy at the time of hospitalization, a percentage that – while small – still translates into roughly 40,000 such cases annually in the United States. That helps explain why every so often a headline appears about a famous person who died suddenly and unexpectedly from sepsis, he noted.

The study used data collected on hospitalized U.S. patients in the Cerner Health Facts, HCA Healthcare, and Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation databases, which included about 6.7 million people total including 337,983 identified as having community-acquired sepsis, defined as patients who met the criteria for adult sepsis advanced by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention within 2 days of their hospital admission. The researchers looked further into the hospital records of these patients and divided them into patients with one or more major comorbidities (96% of the cohort), patients who were pregnant or had a “minor” comorbidity such as a lipid disorder, benign neoplasm, or obesity (1% of the study group), or those with no chronic comorbidity (3%; the subgroup the researchers deemed previously healthy).

In a multivariate analysis that adjusted for patients’ age, sex, race, infection site, and illness severity at the time of hospital admission the researchers found that the rate of in-hospital death among the previously healthy patients was exactly twice the rate of those who had at least one major chronic comorbidity, Dr. Rhee reported. Differences in the treatment received by the previously-healthy patients or in their medical status compared with patients with a major comorbidity suggested that the previously health patients were sicker. They had a higher rate of mechanical ventilation, 30%, compared with about 18% for those with a comorbidity; a higher rate of acute kidney injury, about 43% in those previously healthy and 28% in those with a comorbidity; and a higher percentage had an elevated lactate level, about 41% among the previously healthy patients and about 22% among those with a comorbidity.

SOURCE: Alrawashdeh M et al. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2019 Oct 23;6. Abstract 891.

WASHINGTON – Although severe, community-acquired sepsis in previously healthy U.S. adults is relatively uncommon, it occurs often enough to strike about 40,000 people annually, and when previously healthy people are hospitalized for severe sepsis, their rate of in-hospital mortality was double the rate in people with one or more comorbidities who have severe, community-acquired sepsis, based on a review of almost 7 million Americans hospitalized for sepsis.

The findings “underscore the importance of improving public awareness of sepsis and emphasizing early sepsis recognition and treatment in all patients,” including those without comorbidities, Chanu Rhee, MD, said at an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases. He hypothesized that the increased sepsis mortality among previously healthy patients may have stemmed from factors such as delayed sepsis recognition resulting in hospitalization at a more advanced stage and less aggressive management.

In addition, “the findings provide context for high-profile reports about sepsis death in previously healthy people,” said Dr. Rhee, an infectious diseases and critical care physician at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. Dr. Rhee and associates found that, among patients hospitalized with what the researchers defined as “community-acquired” sepsis, 3% were judged previously healthy by having no identified major or minor comorbidity or pregnancy at the time of hospitalization, a percentage that – while small – still translates into roughly 40,000 such cases annually in the United States. That helps explain why every so often a headline appears about a famous person who died suddenly and unexpectedly from sepsis, he noted.

The study used data collected on hospitalized U.S. patients in the Cerner Health Facts, HCA Healthcare, and Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation databases, which included about 6.7 million people total including 337,983 identified as having community-acquired sepsis, defined as patients who met the criteria for adult sepsis advanced by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention within 2 days of their hospital admission. The researchers looked further into the hospital records of these patients and divided them into patients with one or more major comorbidities (96% of the cohort), patients who were pregnant or had a “minor” comorbidity such as a lipid disorder, benign neoplasm, or obesity (1% of the study group), or those with no chronic comorbidity (3%; the subgroup the researchers deemed previously healthy).

In a multivariate analysis that adjusted for patients’ age, sex, race, infection site, and illness severity at the time of hospital admission the researchers found that the rate of in-hospital death among the previously healthy patients was exactly twice the rate of those who had at least one major chronic comorbidity, Dr. Rhee reported. Differences in the treatment received by the previously-healthy patients or in their medical status compared with patients with a major comorbidity suggested that the previously health patients were sicker. They had a higher rate of mechanical ventilation, 30%, compared with about 18% for those with a comorbidity; a higher rate of acute kidney injury, about 43% in those previously healthy and 28% in those with a comorbidity; and a higher percentage had an elevated lactate level, about 41% among the previously healthy patients and about 22% among those with a comorbidity.

SOURCE: Alrawashdeh M et al. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2019 Oct 23;6. Abstract 891.

WASHINGTON – Although severe, community-acquired sepsis in previously healthy U.S. adults is relatively uncommon, it occurs often enough to strike about 40,000 people annually, and when previously healthy people are hospitalized for severe sepsis, their rate of in-hospital mortality was double the rate in people with one or more comorbidities who have severe, community-acquired sepsis, based on a review of almost 7 million Americans hospitalized for sepsis.

The findings “underscore the importance of improving public awareness of sepsis and emphasizing early sepsis recognition and treatment in all patients,” including those without comorbidities, Chanu Rhee, MD, said at an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases. He hypothesized that the increased sepsis mortality among previously healthy patients may have stemmed from factors such as delayed sepsis recognition resulting in hospitalization at a more advanced stage and less aggressive management.

In addition, “the findings provide context for high-profile reports about sepsis death in previously healthy people,” said Dr. Rhee, an infectious diseases and critical care physician at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. Dr. Rhee and associates found that, among patients hospitalized with what the researchers defined as “community-acquired” sepsis, 3% were judged previously healthy by having no identified major or minor comorbidity or pregnancy at the time of hospitalization, a percentage that – while small – still translates into roughly 40,000 such cases annually in the United States. That helps explain why every so often a headline appears about a famous person who died suddenly and unexpectedly from sepsis, he noted.

The study used data collected on hospitalized U.S. patients in the Cerner Health Facts, HCA Healthcare, and Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation databases, which included about 6.7 million people total including 337,983 identified as having community-acquired sepsis, defined as patients who met the criteria for adult sepsis advanced by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention within 2 days of their hospital admission. The researchers looked further into the hospital records of these patients and divided them into patients with one or more major comorbidities (96% of the cohort), patients who were pregnant or had a “minor” comorbidity such as a lipid disorder, benign neoplasm, or obesity (1% of the study group), or those with no chronic comorbidity (3%; the subgroup the researchers deemed previously healthy).

In a multivariate analysis that adjusted for patients’ age, sex, race, infection site, and illness severity at the time of hospital admission the researchers found that the rate of in-hospital death among the previously healthy patients was exactly twice the rate of those who had at least one major chronic comorbidity, Dr. Rhee reported. Differences in the treatment received by the previously-healthy patients or in their medical status compared with patients with a major comorbidity suggested that the previously health patients were sicker. They had a higher rate of mechanical ventilation, 30%, compared with about 18% for those with a comorbidity; a higher rate of acute kidney injury, about 43% in those previously healthy and 28% in those with a comorbidity; and a higher percentage had an elevated lactate level, about 41% among the previously healthy patients and about 22% among those with a comorbidity.

SOURCE: Alrawashdeh M et al. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2019 Oct 23;6. Abstract 891.

REPORTING FROM ID WEEK 2019

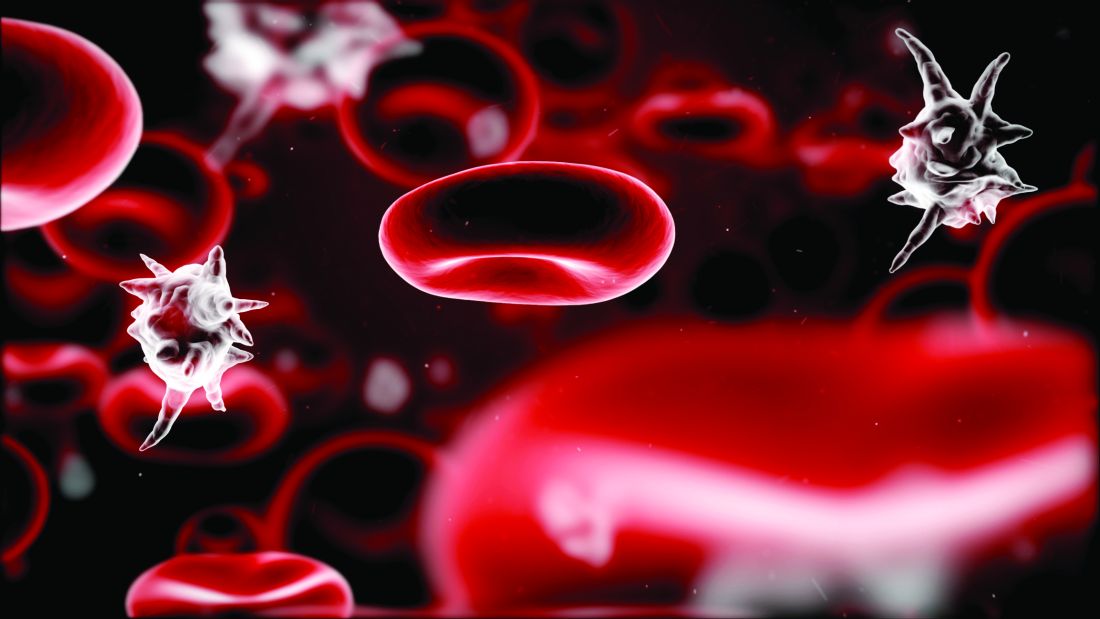

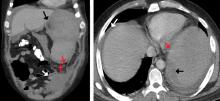

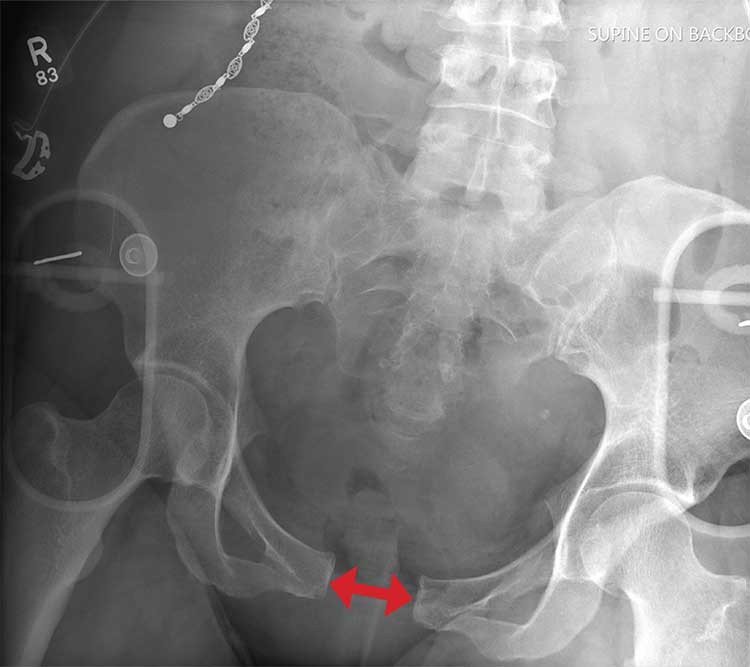

Atraumatic splenic rupture in acute myeloid leukemia

A 50-year-old man with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) with a complex karyotype was admitted to the hospital with several days of dull, left-sided abdominal pain. His most recent bone marrow biopsy showed 30% blasts, and immunophenotyping was suggestive of persistent AML (CD13+, CD34+, CD117+, CD33+, CD7+, MPO–). He was on treatment with venetoclax and cytarabine after induction therapy had failed.

On admission, his heart rate was 101 beats per minute and his blood pressure was 122/85 mm Hg. Abdominal examination revealed mild distention, hepatomegaly, and previously known massive splenomegaly, with the splenic tip extending to the umbilicus, and mild tenderness.

Results of laboratory testing revealed persistent pancytopenia:

- Hemoglobin level 6.8 g/dL (reference range 13.0–17.0)

- Total white blood cell count 0.8 × 109/L (4.5–11.0)

- Platelet count 8 × 109/L (150–400).

The next day, he developed severe, acute-onset left-sided abdominal pain. A check of vital signs showed worsening sinus tachycardia at 132 beats per minute and a drop in blood pressure to 90/56 mm Hg. He had worsening diffuse abdominal tenderness with sluggish bowel sounds. His hemoglobin concentration was 6.4 g/dL and platelet count 12 × 109/L.

He received supportive transfusions of blood products. Surgical exploration was deemed risky, given his overall condition and severe thrombocytopenia. Splenic angiography showed no evidence of pseudoaneurysm or focal contrast extravasation. He underwent empiric embolization of the midsplenic artery, after which his hemodynamic status stabilized. He died 4 weeks later of acute respiratory failure from pneumonia.

SPLENIC RUPTURE IN AML

Atraumatic splenic rupture is rare but potentially life-threatening, especially if the diagnosis is delayed. Conditions that can cause splenomegaly and predispose to rupture include infection (infectious mononucleosis, malaria), malignant hematologic disorders (leukemia, lymphoma), other neoplasms, and amyloidosis.1

The literature includes a few reports of splenic rupture in patients with AML.2–4 The proposed mechanisms include bleeding from infarction sites or tumor foci, dysregulated hemostasis, and leukostasis.

The classic presentation of splenic rupture is acute-onset left-sided abdominal pain associated with hypotension and decreasing hemoglobin levels. CT of the abdomen is confirmatory, and resuscitation with crystalloids and blood products is a vital initial step in management. Choice of treatment depends on the patient’s surgical risk and hemodynamic status; options include conservative medical management, splenic artery embolization, and exploratory laparotomy.

In patients with AML and splenomegaly presenting with acute abdominal pain, clinicians need to be aware of this potential hematologic emergency.

- Renzulli P, Hostettler A, Schoepfer AM, Gloor B, Candinas D. Systematic review of atraumatic splenic rupture. Br J Surg 2009; 96(10):1114–1121. doi:10.1002/bjs.6737

- Gardner JA, Bao L, Ornstein DL. Spontaneous splenic rupture in acute myeloid leukemia with mixed-lineage leukemia gene rearrangement. Med Rep Case Stud 2016; 1:119. doi:10.4172/2572-5130.1000119

- Zeidan AM, Mitchell M, Khatri R, et al. Spontaneous splenic rupture during induction chemotherapy for acute myeloid leukemia. Leuk Lymphoma 2014; 55(1):209–212. doi:10.3109/10428194.2013.796060

- Fahmi Y, Elabbasi T, Khaiz D, et al. Splenic spontaneous rupture associated with acute myeloïd leukemia: report of a case and literature review. Surgery Curr Res 2014; 4:170. doi:10.4172/2161-1076.1000170

A 50-year-old man with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) with a complex karyotype was admitted to the hospital with several days of dull, left-sided abdominal pain. His most recent bone marrow biopsy showed 30% blasts, and immunophenotyping was suggestive of persistent AML (CD13+, CD34+, CD117+, CD33+, CD7+, MPO–). He was on treatment with venetoclax and cytarabine after induction therapy had failed.

On admission, his heart rate was 101 beats per minute and his blood pressure was 122/85 mm Hg. Abdominal examination revealed mild distention, hepatomegaly, and previously known massive splenomegaly, with the splenic tip extending to the umbilicus, and mild tenderness.

Results of laboratory testing revealed persistent pancytopenia:

- Hemoglobin level 6.8 g/dL (reference range 13.0–17.0)

- Total white blood cell count 0.8 × 109/L (4.5–11.0)

- Platelet count 8 × 109/L (150–400).

The next day, he developed severe, acute-onset left-sided abdominal pain. A check of vital signs showed worsening sinus tachycardia at 132 beats per minute and a drop in blood pressure to 90/56 mm Hg. He had worsening diffuse abdominal tenderness with sluggish bowel sounds. His hemoglobin concentration was 6.4 g/dL and platelet count 12 × 109/L.

He received supportive transfusions of blood products. Surgical exploration was deemed risky, given his overall condition and severe thrombocytopenia. Splenic angiography showed no evidence of pseudoaneurysm or focal contrast extravasation. He underwent empiric embolization of the midsplenic artery, after which his hemodynamic status stabilized. He died 4 weeks later of acute respiratory failure from pneumonia.

SPLENIC RUPTURE IN AML

Atraumatic splenic rupture is rare but potentially life-threatening, especially if the diagnosis is delayed. Conditions that can cause splenomegaly and predispose to rupture include infection (infectious mononucleosis, malaria), malignant hematologic disorders (leukemia, lymphoma), other neoplasms, and amyloidosis.1

The literature includes a few reports of splenic rupture in patients with AML.2–4 The proposed mechanisms include bleeding from infarction sites or tumor foci, dysregulated hemostasis, and leukostasis.

The classic presentation of splenic rupture is acute-onset left-sided abdominal pain associated with hypotension and decreasing hemoglobin levels. CT of the abdomen is confirmatory, and resuscitation with crystalloids and blood products is a vital initial step in management. Choice of treatment depends on the patient’s surgical risk and hemodynamic status; options include conservative medical management, splenic artery embolization, and exploratory laparotomy.

In patients with AML and splenomegaly presenting with acute abdominal pain, clinicians need to be aware of this potential hematologic emergency.

A 50-year-old man with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) with a complex karyotype was admitted to the hospital with several days of dull, left-sided abdominal pain. His most recent bone marrow biopsy showed 30% blasts, and immunophenotyping was suggestive of persistent AML (CD13+, CD34+, CD117+, CD33+, CD7+, MPO–). He was on treatment with venetoclax and cytarabine after induction therapy had failed.

On admission, his heart rate was 101 beats per minute and his blood pressure was 122/85 mm Hg. Abdominal examination revealed mild distention, hepatomegaly, and previously known massive splenomegaly, with the splenic tip extending to the umbilicus, and mild tenderness.

Results of laboratory testing revealed persistent pancytopenia:

- Hemoglobin level 6.8 g/dL (reference range 13.0–17.0)

- Total white blood cell count 0.8 × 109/L (4.5–11.0)

- Platelet count 8 × 109/L (150–400).

The next day, he developed severe, acute-onset left-sided abdominal pain. A check of vital signs showed worsening sinus tachycardia at 132 beats per minute and a drop in blood pressure to 90/56 mm Hg. He had worsening diffuse abdominal tenderness with sluggish bowel sounds. His hemoglobin concentration was 6.4 g/dL and platelet count 12 × 109/L.

He received supportive transfusions of blood products. Surgical exploration was deemed risky, given his overall condition and severe thrombocytopenia. Splenic angiography showed no evidence of pseudoaneurysm or focal contrast extravasation. He underwent empiric embolization of the midsplenic artery, after which his hemodynamic status stabilized. He died 4 weeks later of acute respiratory failure from pneumonia.

SPLENIC RUPTURE IN AML

Atraumatic splenic rupture is rare but potentially life-threatening, especially if the diagnosis is delayed. Conditions that can cause splenomegaly and predispose to rupture include infection (infectious mononucleosis, malaria), malignant hematologic disorders (leukemia, lymphoma), other neoplasms, and amyloidosis.1

The literature includes a few reports of splenic rupture in patients with AML.2–4 The proposed mechanisms include bleeding from infarction sites or tumor foci, dysregulated hemostasis, and leukostasis.

The classic presentation of splenic rupture is acute-onset left-sided abdominal pain associated with hypotension and decreasing hemoglobin levels. CT of the abdomen is confirmatory, and resuscitation with crystalloids and blood products is a vital initial step in management. Choice of treatment depends on the patient’s surgical risk and hemodynamic status; options include conservative medical management, splenic artery embolization, and exploratory laparotomy.

In patients with AML and splenomegaly presenting with acute abdominal pain, clinicians need to be aware of this potential hematologic emergency.

- Renzulli P, Hostettler A, Schoepfer AM, Gloor B, Candinas D. Systematic review of atraumatic splenic rupture. Br J Surg 2009; 96(10):1114–1121. doi:10.1002/bjs.6737

- Gardner JA, Bao L, Ornstein DL. Spontaneous splenic rupture in acute myeloid leukemia with mixed-lineage leukemia gene rearrangement. Med Rep Case Stud 2016; 1:119. doi:10.4172/2572-5130.1000119

- Zeidan AM, Mitchell M, Khatri R, et al. Spontaneous splenic rupture during induction chemotherapy for acute myeloid leukemia. Leuk Lymphoma 2014; 55(1):209–212. doi:10.3109/10428194.2013.796060

- Fahmi Y, Elabbasi T, Khaiz D, et al. Splenic spontaneous rupture associated with acute myeloïd leukemia: report of a case and literature review. Surgery Curr Res 2014; 4:170. doi:10.4172/2161-1076.1000170

- Renzulli P, Hostettler A, Schoepfer AM, Gloor B, Candinas D. Systematic review of atraumatic splenic rupture. Br J Surg 2009; 96(10):1114–1121. doi:10.1002/bjs.6737

- Gardner JA, Bao L, Ornstein DL. Spontaneous splenic rupture in acute myeloid leukemia with mixed-lineage leukemia gene rearrangement. Med Rep Case Stud 2016; 1:119. doi:10.4172/2572-5130.1000119

- Zeidan AM, Mitchell M, Khatri R, et al. Spontaneous splenic rupture during induction chemotherapy for acute myeloid leukemia. Leuk Lymphoma 2014; 55(1):209–212. doi:10.3109/10428194.2013.796060

- Fahmi Y, Elabbasi T, Khaiz D, et al. Splenic spontaneous rupture associated with acute myeloïd leukemia: report of a case and literature review. Surgery Curr Res 2014; 4:170. doi:10.4172/2161-1076.1000170

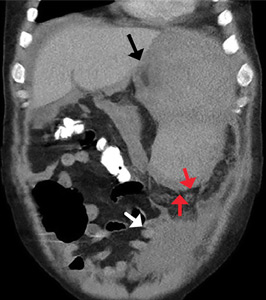

Severe hypercalcemia in a 54-year-old woman

A morbidly obese 54-year-old woman presented to the emergency department after experiencing generalized abdominal pain for 3 days. She rated the pain as 5 on a scale of 10 and described it as dull, cramping, waxing and waning, not radiating, and not relieved with changes of position—in fact, not alleviated by anything she had tried. Her pain was associated with nausea and 1 episode of vomiting. She also experienced constipation before the onset of pain.

She denied recent trauma, recent travel, diarrhea, fevers, weakness, shortness of breath, chest pain, other muscle pains, or recent changes in diet. She also denied having this pain in the past. She said she had unintentionally lost some weight but was not certain how much. She denied tobacco, alcohol, or illicit drug use. She had no history of surgery.

Her medical history included hypertension, anemia, and uterine fibroids. Her current medications included losartan, hydrochlorothiazide, and albuterol. She had no family history of significant disease.

INITIAL EVALUATION AND MANAGEMENT

On admission, her temperature was 97.8°F (36.6°C), heart rate 100 beats per minute, blood pressure 136/64 mm Hg, respiratory rate 18 breaths per minute, oxygen saturation 97% on room air, weight 130.6 kg, and body mass index 35 kg/m2.

She was alert and oriented to person, place, and time. She was in mild discomfort but no distress. Her lungs were clear to auscultation, with no wheezing or crackles. Heart rate and rhythm were regular, with no extra heart sounds or murmurs. Bowel sounds were normal in all 4 quadrants, with tenderness to palpation of the epigastric area, but with no guarding or rebound tenderness.

Laboratory test results

Notable results of blood testing at presentation were as follows:

- Hemoglobin 8.2 g/dL (reference range 12.3–15.3)

- Hematocrit 26% (41–50)

- Mean corpuscular volume 107 fL (80–100)

- Blood urea nitrogen 33 mg/dL (8–21); 6 months earlier it was 16

- Serum creatinine 3.6 mg/dL (0.58–0.96); 6 months earlier, it was 0.75

- Albumin 3.3 g/dL (3.5–5)

- Calcium 18.4 mg/dL (8.4–10.2); 6 months earlier, it was 9.6

- Corrected calcium 19 mg/dL.

Findings on imaging, electrocardiography

Chest radiography showed no acute cardiopulmonary abnormalities. Abdominal computed tomography without contrast showed no abnormalities within the pancreas and no evidence of inflammation or obstruction. Electrocardiography showed sinus tachycardia.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

1. Which is the most likely cause of this patient’s symptoms?

- Primary hyperparathyroidism

- Malignancy

- Her drug therapy

- Familial hypercalcemic hypocalciuria

In total, her laboratory results were consistent with macrocytic anemia, severe hypercalcemia, and acute kidney injury, and she had generalized symptoms.

Primary hyperparathyroidism

A main cause of hypercalcemia is primary hyperparathyroidism, and this needs to be ruled out. Benign adenomas are the most common cause of primary hyperparathyroidism, and a risk factor for benign adenoma is exposure to therapeutic levels of radiation.3

In hyperparathyroidism, there is an increased secretion of parathyroid hormone (PTH), which has multiple effects including increased reabsorption of calcium from the urine, increased excretion of phosphate, and increased expression of 1,25-hydroxyvitamin D hydroxylase to activate vitamin D. PTH also stimulates osteoclasts to increase their expression of receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa B ligand (RANKL), which has a downstream effect on osteoclast precursors to cause bone reabsorption.3

Inherited primary hyperparathyroidism tends to present at a younger age, with multiple overactive parathyroid glands.3 Given our patient’s age, inherited primary hyparathyroidism is thus less likely.

Malignancy

The probability that malignancy is causing the hypercalcemia increases with calcium levels greater than 13 mg/dL. Epidemiologically, in hospitalized patients with hypercalcemia, the source tends to be malignancy.4 Typically, patients who develop hypercalcemia from malignancy have a worse prognosis.5

Solid tumors and leukemias can cause hypercalcemia. The mechanisms include humoral factors secreted by the malignancy, local osteolysis due to tumor invasion of bone, and excessive absorption of calcium due to excess vitamin D produced by malignancies.5 The cancers that most frequently cause an increase in calcium resorption are lung cancer, renal cancer, breast cancer, and multiple myeloma.1

Solid tumors with no bone metastasis and non-Hodgkin lymphoma that release PTH-related protein (PTHrP) cause humoral hypercalcemia in malignancy. The patient is typically in an advanced stage of disease. PTHrP increases serum calcium levels by decreasing the kidney’s ability to excrete calcium and by increasing bone turnover. It has no effect on intestinal absorption because of its inability to stimulate activated vitamin D3. Thus, the increase in systemic calcium comes directly from breakdown of bone and inability to excrete the excess.

PTHrP has a unique role in breast cancer: it is released locally in areas where cancer cells have metastasized to bone, but it does not cause a systemic effect. Bone resorption occurs in areas of metastasis and results from an increase in expression of RANKL and RANK in osteoclasts in response to the effects of PTHrP, leading to an increase in the production of osteoclastic cells.1

Tamoxifen, an endocrine therapy often used in breast cancer, also causes a release of bone-reabsorbing factors from tumor cells, which can partially contribute to hypercalcemia.5

Myeloma cells secrete RANKL, which stimulates osteoclastic activity, and they also release interleukin 6 (IL-6) and activating macrophage inflammatory protein alpha. Serum testing usually shows low or normal intact PTH, PTHrP, and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D.1

Patients with multiple myeloma have a worse prognosis if they have a high red blood cell distribution width, a condition shown to correlate with malnutrition, leading to deficiencies in vitamin B12 and to poor response to treatment.6 Up to 14% of patients with multiple myeloma have vitamin B12 deficiency.7

Our patient’s recent weight loss and severe hypercalcemia raise suspicion of malignancy. Further, her obesity makes proper routine breast examination difficult and thus increases the chance of undiagnosed breast cancer.8 Her decrease in renal function and her anemia complicated by hypercalcemia also raise suspicion of multiple myeloma.

Hypercalcemia due to drug therapy

Thiazide diuretics, lithium, teriparatide, and vitamin A in excessive amounts can raise the serum calcium concentration.5 Our patient was taking a thiazide for hypertension, but her extremely high calcium level places drug-induced hypercalcemia as the sole cause lower on the differential list.

Familial hypercalcemic hypocalciuria

Familial hypercalcemic hypocalciuria is a rare autosomal-dominant cause of hypercalcemia in which the ability of the body (and especially the kidneys) to sense levels of calcium is impaired, leading to a decrease in excretion of calcium in the urine.3 Very high calcium levels are rare in hypercalcemic hypocalciuria.3 In our patient with a corrected calcium concentration of nearly 19 mg/dL, familial hypercalcemic hypocalciuria is very unlikely to be the cause of the hypercalcemia.

WHAT ARE THE NEXT STEPS IN THE WORKUP?

As hypercalcemia has been confirmed, the intact PTH level should be checked to determine whether the patient’s condition is PTH-mediated. If the PTH level is in the upper range of normal or is minimally elevated, primary hyperparathyroidism is likely. Elevated PTH confirms primary hyperparathyroidism. A low-normal or low intact PTH confirms a non-PTH-mediated process, and once this is confirmed, PTHrP levels should be checked. An elevated PTHrP suggests humoral hypercalcemia of malignancy. Serum protein electrophoresis, urine protein electrophoresis, and a serum light chain assay should be performed to rule out multiple myeloma.

Vitamin D toxicity is associated with high concentrations of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D and 25-hydroxyvitamin D metabolites. These levels should be checked in this patient.

Other disorders that cause hypercalcemia are vitamin A toxicity and hyperthyroidism, so vitamin A and thyroid-stimulating hormone levels should also be checked.5

CASE CONTINUED

After further questioning, the patient said that she had had lower back pain about 1 to 2 weeks before coming to the emergency room; her primary care doctor had said the pain was likely from muscle strain. The pain had almost resolved but was still present.

The results of further laboratory testing were as follows:

- Serum PTH 11 pg/mL (15–65)

- PTHrP 3.4 pmol/L (< 2.0)

- Protein electrophoresis showed a monoclonal (M) spike of 0.2 g/dL (0)

- Activated vitamin D < 5 ng/mL (19.9–79.3)

- Vitamin A 7.2 mg/dL (33.1–100)

- Vitamin B12 194 pg/mL (239–931)

- Thyroid-stimulating hormone 1.21 mIU/ L (0.47–4.68

- Free thyroxine 1.27 ng/dL (0.78–2.19)

- Iron 103 µg/dL (37–170)

- Total iron-binding capacity 335 µg/dL (265–497)

- Transferrin 248 mg/dL (206–381)

- Ferritin 66 ng/mL (11.1–264)

- Urine protein (random) 100 mg/dL (0–20)

- Urine microalbumin (random) 5.9 mg/dL (0–1.6)

- Urine creatinine clearance 88.5 mL/min (88–128)

- Urine albumin-creatinine ratio 66.66 mg/g (< 30).

Imaging reports

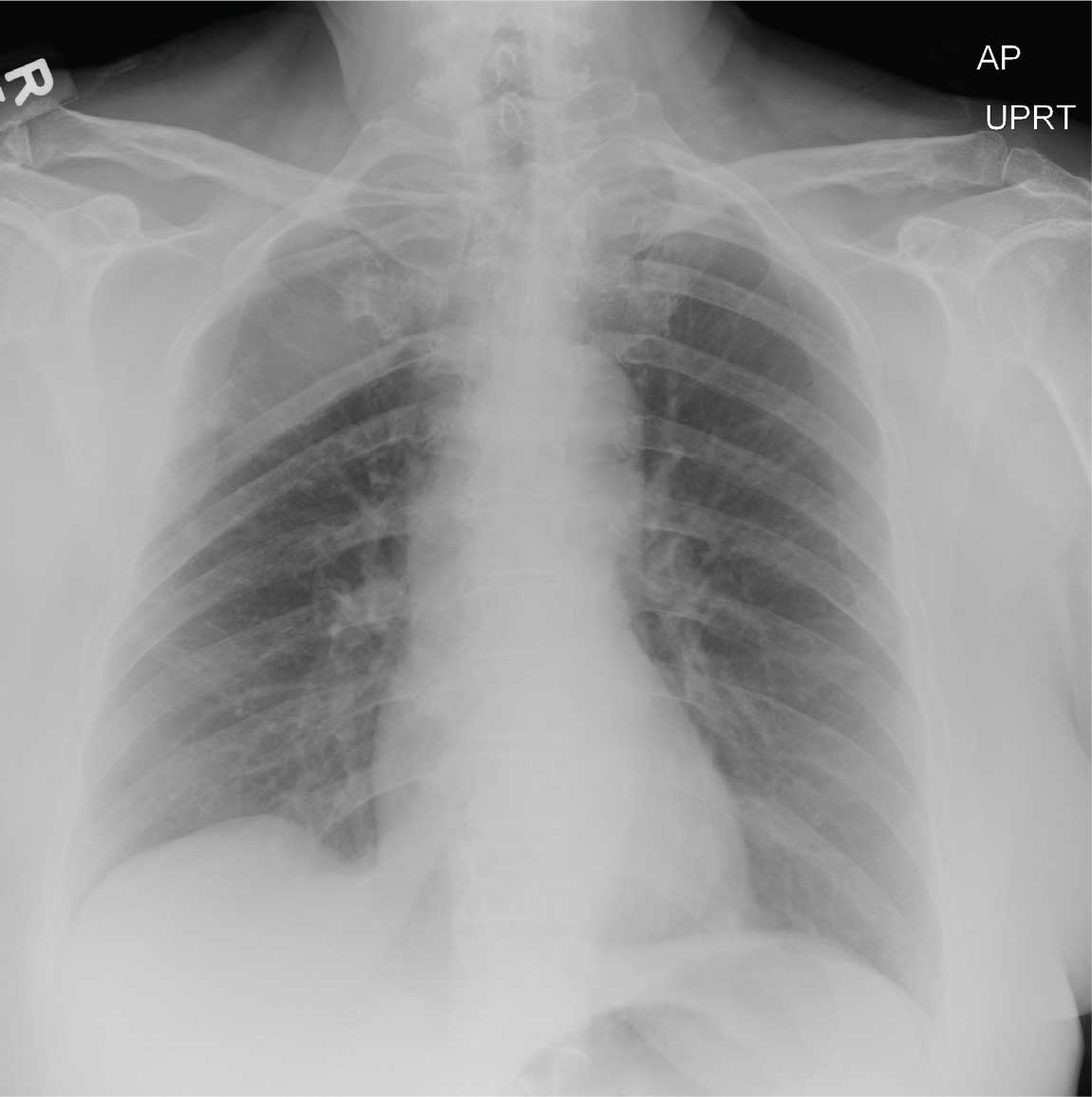

A nuclear bone scan showed increased bone uptake in the hip and both shoulders, consistent with arthritis, and increased activity in 2 of the lower left ribs, associated with rib fractures secondary to lytic lesions. A skeletal survey at a later date showed multiple well-circumscribed “punched-out” lytic lesions in both forearms and both femurs.

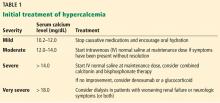

2. What should be the next step in this patient’s management?

- Intravenous (IV) fluids

- Calcitonin

- Bisphosphonate treatment

- Denosumab

- Hemodialysis

Initial treatment of severe hypercalcemia includes the following:

Start IV isotonic fluids at a rate of 150 mL/h (if the patient is making urine) to maintain urine output at more than 100 mL/h. Closely monitor urine output.

Give calcitonin 4 IU/kg in combination with IV fluids to reduce calcium levels within the first 12 to 48 hours of treatment.

Give a bisphosphonate, eg, zoledronic acid 4 mg over 15 minutes, or pamidronate 60 to 90 mg over 2 hours. Zoledronic acid is preferred in malignancy-induced hypercalcemia because it is more potent. Doses should be adjusted in patients with renal failure.

Give denosumab if hypercalcemia is refractory to bisphosphonates, or when bisphosphonates cannot be used in renal failure.9

Hemodialysis is performed in patients who have significant neurologic symptoms irrespective of acute renal insufficiency.

Our patient was started on 0.9% sodium chloride at a rate of 150 mL/h for severe hypercalcemia. Zoledronic acid 4 mg IV was given once. These measures lowered her calcium level and lessened her acute kidney injury.

ADDITIONAL FINDINGS

Urine testing was positive for Bence Jones protein. Immune electrophoresis, performed because of suspicion of multiple myeloma, showed an elevated level of kappa light chains at 806.7 mg/dL (0.33–1.94) and normal lambda light chains at 0.62 mg/dL (0.57–2.63). The immunoglobulin G level was low at 496 mg/dL (610–1,660). In patients with severe hypercalcemia, these results point to a diagnosis of malignancy. Bone marrow aspiration study showed greater than 10% plasma cells, confirming multiple myeloma.

MULTIPLE MYELOMA

The diagnosis of multiple myeloma is based in part on the presence of 10% or more of clonal bone marrow plasma cells10 and of specific end-organ damage (anemia, hypercalcemia, renal insufficiency, or bone lesions).9

Bone marrow clonality can be shown by the ratio of kappa to lambda light chains as detected with immunohistochemistry, immunofluorescence, or flow cytometry.11 The normal ratio is 0.26 to 1.65 for a patient with normal kidney function. In this patient, however, the ratio was 1,301.08 (806.67 kappa to 0.62 lambda), which was extremely out of range. The patient’s bone marrow biopsy results revealed the presence of 15% clonal bone marrow plasma cells.

Multiple myeloma causes osteolytic lesions through increased activation of osteoclast activating factor that stimulates the growth of osteoclast precursors. At the same time, it inhibits osteoblast formation via multiple pathways, including the action of sclerostin.11 Our patient had lytic lesions in 2 left lower ribs and in both forearms and femurs.

Hypercalcemia in multiple myeloma is attributed to 2 main factors: bone breakdown and macrophage overactivation. Multiple myeloma cells increase the release of macrophage inflammatory protein 1-alpha and tumor necrosis factor, which are inflammatory proteins that cause an increase in macrophages, which cause an increase in calcitriol.11 As noted, our patient’s calcium level at presentation was 18.4 mg/dL uncorrected and 18.96 mg/dL corrected.

Cast nephropathy can occur in the distal tubules from the increased free light chains circulating and combining with Tamm-Horsfall protein, which in turn causes obstruction and local inflammation,12 leading to a rise in creatinine levels and resulting in acute kidney injury,12 as in our patient.

TREATMENT CONSIDERATIONS IN MULTIPLE MYELOMA

Our patient was referred to an oncologist for management.

In the management of multiple myeloma, the patient’s quality of life needs to be considered. With the development of new agents to combat the damages of the osteolytic effects, there is hope for improving quality of life.13,14 New agents under study include anabolic agents such as antisclerostin and anti-Dickkopf-1, which promote osteoblastogenesis, leading to bone formation, with the possibility of repairing existing damage.15

TAKE-HOME POINTS

- If hypercalcemia is mild to moderate, consider primary hyperparathyroidism.

- Identify patients with severe symptoms of hypercalcemia such as volume depletion, acute kidney injury, arrhythmia, or seizures.

- Confirm severe cases of hypercalcemia and treat severe cases effectively.

- Severe hypercalcemia may need further investigation into a potential underlying malignancy.

- Sternlicht H, Glezerman IG. Hypercalcemia of malignancy and new treatment options. Ther Clin Risk Manag 2015; 11:1779–1788. doi:10.2147/TCRM.S83681

- Ahmed R, Hashiba K. Reliability of QT intervals as indicators of clinical hypercalcemia. Clin Cardiol 1988; 11(6):395–400. doi:10.1002/clc.4960110607

- Bilezikian JP, Cusano NE, Khan AA, Liu JM, Marcocci C, Bandeira F. Primary hyperparathyroidism. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2016; 2:16033. doi:10.1038/nrdp.2016.33

- Kuchay MS, Kaur P, Mishra SK, Mithal A. The changing profile of hypercalcemia in a tertiary care setting in North India: an 18-month retrospective study. Clin Cases Miner Bone Metab 2017; 14(2):131–135. doi:10.11138/ccmbm/2017.14.1.131

- Rosner MH, Dalkin AC. Onco-nephrology: the pathophysiology and treatment of malignancy-associated hypercalcemia. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2012; 7(10):1722–1729. doi:10.2215/CJN.02470312

- Ai L, Mu S, Hu Y. Prognostic role of RDW in hematological malignancies: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Cell Int 2018; 18:61. doi:10.1186/s12935-018-0558-3

- Baz R, Alemany C, Green R, Hussein MA. Prevalence of vitamin B12 deficiency in patients with plasma cell dyscrasias: a retrospective review. Cancer 2004; 101(4):790–795. doi:10.1002/cncr.20441

- Elmore JG, Carney PA, Abraham LA, et al. The association between obesity and screening mammography accuracy. Arch Intern Med 2004; 164(10):1140–1147. doi:10.1001/archinte.164.10.1140

- Gerecke C, Fuhrmann S, Strifler S, Schmidt-Hieber M, Einsele H, Knop S. The diagnosis and treatment of multiple myeloma. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2016; 113(27–28):470–476. doi:10.3238/arztebl.2016.0470

- Rajkumar SV. Multiple myeloma: 2016 update on diagnosis, risk-stratification, and management. Am J Hematol 2016; 91(7):719–734. doi:10.1002/ajh.24402

- Silbermann R, Roodman GD. Myeloma bone disease: pathophysiology and management. J Bone Oncol 2013; 2(2):59–69. doi:10.1016/j.jbo.2013.04.001

- Doshi M, Lahoti A, Danesh FR, Batuman V, Sanders PW; American Society of Nephrology Onco-Nephrology Forum. Paraprotein-related kidney disease: kidney injury from paraproteins—what determines the site of injury? Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2016; 11(12):2288–2294. doi:10.2215/CJN.02560316

- Reece D. Update on the initial therapy of multiple myeloma. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book 2013. doi:10.1200/EdBook_AM.2013.33.e307

- Nishida H. Bone-targeted agents in multiple myeloma. Hematol Rep 2018; 10(1):7401. doi:10.4081/hr.2018.7401

- Ring ES, Lawson MA, Snowden JA, Jolley I, Chantry AD. New agents in the treatment of myeloma bone disease. Calcif Tissue Int 2018; 102(2):196–209. doi:10.1007/s00223-017-0351-7

A morbidly obese 54-year-old woman presented to the emergency department after experiencing generalized abdominal pain for 3 days. She rated the pain as 5 on a scale of 10 and described it as dull, cramping, waxing and waning, not radiating, and not relieved with changes of position—in fact, not alleviated by anything she had tried. Her pain was associated with nausea and 1 episode of vomiting. She also experienced constipation before the onset of pain.

She denied recent trauma, recent travel, diarrhea, fevers, weakness, shortness of breath, chest pain, other muscle pains, or recent changes in diet. She also denied having this pain in the past. She said she had unintentionally lost some weight but was not certain how much. She denied tobacco, alcohol, or illicit drug use. She had no history of surgery.

Her medical history included hypertension, anemia, and uterine fibroids. Her current medications included losartan, hydrochlorothiazide, and albuterol. She had no family history of significant disease.

INITIAL EVALUATION AND MANAGEMENT

On admission, her temperature was 97.8°F (36.6°C), heart rate 100 beats per minute, blood pressure 136/64 mm Hg, respiratory rate 18 breaths per minute, oxygen saturation 97% on room air, weight 130.6 kg, and body mass index 35 kg/m2.

She was alert and oriented to person, place, and time. She was in mild discomfort but no distress. Her lungs were clear to auscultation, with no wheezing or crackles. Heart rate and rhythm were regular, with no extra heart sounds or murmurs. Bowel sounds were normal in all 4 quadrants, with tenderness to palpation of the epigastric area, but with no guarding or rebound tenderness.

Laboratory test results

Notable results of blood testing at presentation were as follows:

- Hemoglobin 8.2 g/dL (reference range 12.3–15.3)

- Hematocrit 26% (41–50)

- Mean corpuscular volume 107 fL (80–100)

- Blood urea nitrogen 33 mg/dL (8–21); 6 months earlier it was 16

- Serum creatinine 3.6 mg/dL (0.58–0.96); 6 months earlier, it was 0.75

- Albumin 3.3 g/dL (3.5–5)

- Calcium 18.4 mg/dL (8.4–10.2); 6 months earlier, it was 9.6

- Corrected calcium 19 mg/dL.

Findings on imaging, electrocardiography

Chest radiography showed no acute cardiopulmonary abnormalities. Abdominal computed tomography without contrast showed no abnormalities within the pancreas and no evidence of inflammation or obstruction. Electrocardiography showed sinus tachycardia.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

1. Which is the most likely cause of this patient’s symptoms?

- Primary hyperparathyroidism

- Malignancy

- Her drug therapy

- Familial hypercalcemic hypocalciuria

In total, her laboratory results were consistent with macrocytic anemia, severe hypercalcemia, and acute kidney injury, and she had generalized symptoms.

Primary hyperparathyroidism