User login

Older IBD patients are most at risk of postdischarge VTE

Hospitalized patients with inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) are most likely to be readmitted for venous thromboembolism (VTE) within 60 days of discharge, according to a new study that analyzed 5 years of U.S. readmissions data.

“Given increased thrombotic risk postdischarge, as well as overall safety of VTE prophylaxis, extending prophylaxis for those at highest risk may have significant benefits,” wrote Adam S. Faye, MD, of Columbia University, and coauthors. The study was published in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

To determine which IBD patients would be most in need of postdischarge VTE prophylaxis, as well as when to administer it, the researchers analyzed 2010-2014 data from the Nationwide Readmissions Database (NRD). They found a total of 872,122 index admissions for IBD patients; 4% of those patients had a prior VTE. Of the index admissions, 1,160 led to a VTE readmission within 90 days. Readmitted patients had a relatively equal proportion of ulcerative colitis (n = 522) and Crohn’s disease (n = 638).

More than 90% of VTE readmissions occurred within 60 days of discharge; the risk was highest over the first 10 days and then decreased in each ensuing 10-day period until a slight increase at the 81- to 90-day period. All patients over age 30 had higher rates of readmission than those of patients under age 18, with the highest risk in patients between the ages of 66 and 80 years (risk ratio 4.04; 95% confidence interval, 2.54-6.44, P less than .01). Women were at lower risk (RR 0.82; 95% CI, 0.73-0.92, P less than .01). Higher risks of readmission were also associated with being on Medicare (RR 1.39; 95% CI, 1.23-1.58, P less than .01) compared with being on private insurance and being cared for at a large hospital (RR 1.26; 95% CI, 1.04-1.52, P = .02) compared with a small hospital.

The highest risk of VTE readmission was associated with a prior history of VTE (RR 2.89; 95% CI, 2.40-3.48, P less than .01), having two or more comorbidities (RR 2.57; 95% CI, 2.11-3.12, P less than .01) and having a Clostridioides difficile infection as of index admission (RR 1.90; 95% CI, 1.51-2.38, P less than .01). In addition, increased risk was associated with being discharged to a nursing or care facility (RR 1.85; 95% CI, 1.56-2.20, P less than .01) or home with health services (RR 2.05; 95% CI, 1.78-2.38, P less than .01) compared with a routine discharge.

In their multivariable analysis, similar factors such as a history of VTE (adjusted RR 2.41; 95% CI, 1.99-2.90, P less than .01), two or more comorbidities (aRR 1.78; 95% CI, 1.44-2.20, P less than .01) and C. difficile infection (aRR 1.47; 95% CI, 1.17-1.85, P less than.01) continued to be associated with higher risk of VTE readmission.

Though they emphasized that the use of NRD data offered the impressive ability to “review over 15 million discharges across the U.S. annually,” Dr. Faye and coauthors acknowledged that their study did have limitations. These included the inability to verify via chart review the study’s outcomes and covariates. In addition, they were unable to assess potential contributing risk factors such as medication use, use of VTE prophylaxis during hospitalization, disease severity, and family history. Finally, though unlikely, they admitted the possibility that patients could be counted more than once if they were readmitted with a VTE each year of the study.

The authors reported being supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health and various pharmaceutical companies, as well as receiving honoraria and serving as consultants.

SOURCE: Faye AS et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019 July 20. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.07.028.

Hospitalized patients with inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) are most likely to be readmitted for venous thromboembolism (VTE) within 60 days of discharge, according to a new study that analyzed 5 years of U.S. readmissions data.

“Given increased thrombotic risk postdischarge, as well as overall safety of VTE prophylaxis, extending prophylaxis for those at highest risk may have significant benefits,” wrote Adam S. Faye, MD, of Columbia University, and coauthors. The study was published in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

To determine which IBD patients would be most in need of postdischarge VTE prophylaxis, as well as when to administer it, the researchers analyzed 2010-2014 data from the Nationwide Readmissions Database (NRD). They found a total of 872,122 index admissions for IBD patients; 4% of those patients had a prior VTE. Of the index admissions, 1,160 led to a VTE readmission within 90 days. Readmitted patients had a relatively equal proportion of ulcerative colitis (n = 522) and Crohn’s disease (n = 638).

More than 90% of VTE readmissions occurred within 60 days of discharge; the risk was highest over the first 10 days and then decreased in each ensuing 10-day period until a slight increase at the 81- to 90-day period. All patients over age 30 had higher rates of readmission than those of patients under age 18, with the highest risk in patients between the ages of 66 and 80 years (risk ratio 4.04; 95% confidence interval, 2.54-6.44, P less than .01). Women were at lower risk (RR 0.82; 95% CI, 0.73-0.92, P less than .01). Higher risks of readmission were also associated with being on Medicare (RR 1.39; 95% CI, 1.23-1.58, P less than .01) compared with being on private insurance and being cared for at a large hospital (RR 1.26; 95% CI, 1.04-1.52, P = .02) compared with a small hospital.

The highest risk of VTE readmission was associated with a prior history of VTE (RR 2.89; 95% CI, 2.40-3.48, P less than .01), having two or more comorbidities (RR 2.57; 95% CI, 2.11-3.12, P less than .01) and having a Clostridioides difficile infection as of index admission (RR 1.90; 95% CI, 1.51-2.38, P less than .01). In addition, increased risk was associated with being discharged to a nursing or care facility (RR 1.85; 95% CI, 1.56-2.20, P less than .01) or home with health services (RR 2.05; 95% CI, 1.78-2.38, P less than .01) compared with a routine discharge.

In their multivariable analysis, similar factors such as a history of VTE (adjusted RR 2.41; 95% CI, 1.99-2.90, P less than .01), two or more comorbidities (aRR 1.78; 95% CI, 1.44-2.20, P less than .01) and C. difficile infection (aRR 1.47; 95% CI, 1.17-1.85, P less than.01) continued to be associated with higher risk of VTE readmission.

Though they emphasized that the use of NRD data offered the impressive ability to “review over 15 million discharges across the U.S. annually,” Dr. Faye and coauthors acknowledged that their study did have limitations. These included the inability to verify via chart review the study’s outcomes and covariates. In addition, they were unable to assess potential contributing risk factors such as medication use, use of VTE prophylaxis during hospitalization, disease severity, and family history. Finally, though unlikely, they admitted the possibility that patients could be counted more than once if they were readmitted with a VTE each year of the study.

The authors reported being supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health and various pharmaceutical companies, as well as receiving honoraria and serving as consultants.

SOURCE: Faye AS et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019 July 20. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.07.028.

Hospitalized patients with inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) are most likely to be readmitted for venous thromboembolism (VTE) within 60 days of discharge, according to a new study that analyzed 5 years of U.S. readmissions data.

“Given increased thrombotic risk postdischarge, as well as overall safety of VTE prophylaxis, extending prophylaxis for those at highest risk may have significant benefits,” wrote Adam S. Faye, MD, of Columbia University, and coauthors. The study was published in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

To determine which IBD patients would be most in need of postdischarge VTE prophylaxis, as well as when to administer it, the researchers analyzed 2010-2014 data from the Nationwide Readmissions Database (NRD). They found a total of 872,122 index admissions for IBD patients; 4% of those patients had a prior VTE. Of the index admissions, 1,160 led to a VTE readmission within 90 days. Readmitted patients had a relatively equal proportion of ulcerative colitis (n = 522) and Crohn’s disease (n = 638).

More than 90% of VTE readmissions occurred within 60 days of discharge; the risk was highest over the first 10 days and then decreased in each ensuing 10-day period until a slight increase at the 81- to 90-day period. All patients over age 30 had higher rates of readmission than those of patients under age 18, with the highest risk in patients between the ages of 66 and 80 years (risk ratio 4.04; 95% confidence interval, 2.54-6.44, P less than .01). Women were at lower risk (RR 0.82; 95% CI, 0.73-0.92, P less than .01). Higher risks of readmission were also associated with being on Medicare (RR 1.39; 95% CI, 1.23-1.58, P less than .01) compared with being on private insurance and being cared for at a large hospital (RR 1.26; 95% CI, 1.04-1.52, P = .02) compared with a small hospital.

The highest risk of VTE readmission was associated with a prior history of VTE (RR 2.89; 95% CI, 2.40-3.48, P less than .01), having two or more comorbidities (RR 2.57; 95% CI, 2.11-3.12, P less than .01) and having a Clostridioides difficile infection as of index admission (RR 1.90; 95% CI, 1.51-2.38, P less than .01). In addition, increased risk was associated with being discharged to a nursing or care facility (RR 1.85; 95% CI, 1.56-2.20, P less than .01) or home with health services (RR 2.05; 95% CI, 1.78-2.38, P less than .01) compared with a routine discharge.

In their multivariable analysis, similar factors such as a history of VTE (adjusted RR 2.41; 95% CI, 1.99-2.90, P less than .01), two or more comorbidities (aRR 1.78; 95% CI, 1.44-2.20, P less than .01) and C. difficile infection (aRR 1.47; 95% CI, 1.17-1.85, P less than.01) continued to be associated with higher risk of VTE readmission.

Though they emphasized that the use of NRD data offered the impressive ability to “review over 15 million discharges across the U.S. annually,” Dr. Faye and coauthors acknowledged that their study did have limitations. These included the inability to verify via chart review the study’s outcomes and covariates. In addition, they were unable to assess potential contributing risk factors such as medication use, use of VTE prophylaxis during hospitalization, disease severity, and family history. Finally, though unlikely, they admitted the possibility that patients could be counted more than once if they were readmitted with a VTE each year of the study.

The authors reported being supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health and various pharmaceutical companies, as well as receiving honoraria and serving as consultants.

SOURCE: Faye AS et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019 July 20. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.07.028.

FROM CLINICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY AND HEPATOLOGY

Key clinical point: Readmission for VTE in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases most often occurs within 60 days of discharge.

Major finding: The highest readmission risk was in patients between the ages of 66 and 80 (risk ratio 4.04; 95% confidence interval, 2.54-6.44, P less than .01).

Study details: A retrospective cohort study of 1,160 IBD patients who had VTE readmissions via 2010-2014 data from the Nationwide Readmissions Database.

Disclosures: The authors reported being supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health and various pharmaceutical companies, as well as receiving honoraria and serving as consultants.

Source: Faye AS et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019 July 20. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.07.028.

Intranasal midazolam as first line for status epilepticus

BANGKOK – Lara Kay, MD, said at the International Epilepsy Congress.

Why? Because status epilepticus is a major medical emergency. It’s associated with substantial morbidity and mortality. And of the various factors that influence outcome in status epilepticus – including age, underlying etiology, and level of consciousness – only one is potentially within physician control: time to treatment, she noted at the congress sponsored by the International League Against Epilepsy.

“Time is brain,” observed Dr. Kay, a neurologist at the epilepsy center at University Hospital Frankfurt.

While intravenous benzodiazepines – for example, lorazepam at 2-4 mg – are widely accepted as the time-honored first-line treatment for status epilepticus, trying to place a line in a patient experiencing this emergency can be a tricky, time-consuming business. Multiple studies have demonstrated that various nonintravenous formulations of benzodiazepines, such as rectal diazepam or buccal or intramuscular midazolam, can be administered much faster and are as effective as intravenous benzodiazepines. But buccal midazolam is quite expensive in Germany, and the ready-to-use intramuscular midazolam applicator that’s available in the United States isn’t marketed in Germany. So several years ago Dr. Kay and her fellow neurologists started having their university hospital pharmacy manufacture intranasal midazolam.

Dr. Kay presented an observational study of 42 consecutive patients with status epilepticus who received intranasal midazolam as first-line treatment. The patients had a mean age of nearly 53 years and 23 were women. The starting dose was 2.5 mg per nostril, moving up to 5 mg per nostril after waiting 5 minutes in initial nonresponders.

Status epilepticus ceased both clinically and by EEG in 24 of the 42 patients, or 57%, in an average of 5 minutes after administration of the intranasal medication at a mean dose of 5.6 mg. Nonresponders received a mean dose of 7.5 mg. There were no significant differences between responders and nonresponders in terms of the proportion presenting with preexisting epilepsy or the epilepsy etiology. However, responders presented at a mean of 54 minutes in status epilepticus, while nonresponders had been in status for 17 minutes.

The 57% response rate with intranasal midazolam is comparable with other investigators’ reported success rates using other benzodiazepines and routes of administration, she noted.

Session cochair Gregory Krauss, MD, commented that he thought the Frankfurt neurologists may have been too cautious in their dosing of intranasal midazolam for status epilepticus.

“Often in the U.S. 5 mg is initially used in each nostril,” according to Dr. Krauss, professor of neurology at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

Dr. Kay reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding her study.

SOURCE: Kay L et al. IEC 2019, Abstract P029.

BANGKOK – Lara Kay, MD, said at the International Epilepsy Congress.

Why? Because status epilepticus is a major medical emergency. It’s associated with substantial morbidity and mortality. And of the various factors that influence outcome in status epilepticus – including age, underlying etiology, and level of consciousness – only one is potentially within physician control: time to treatment, she noted at the congress sponsored by the International League Against Epilepsy.

“Time is brain,” observed Dr. Kay, a neurologist at the epilepsy center at University Hospital Frankfurt.

While intravenous benzodiazepines – for example, lorazepam at 2-4 mg – are widely accepted as the time-honored first-line treatment for status epilepticus, trying to place a line in a patient experiencing this emergency can be a tricky, time-consuming business. Multiple studies have demonstrated that various nonintravenous formulations of benzodiazepines, such as rectal diazepam or buccal or intramuscular midazolam, can be administered much faster and are as effective as intravenous benzodiazepines. But buccal midazolam is quite expensive in Germany, and the ready-to-use intramuscular midazolam applicator that’s available in the United States isn’t marketed in Germany. So several years ago Dr. Kay and her fellow neurologists started having their university hospital pharmacy manufacture intranasal midazolam.

Dr. Kay presented an observational study of 42 consecutive patients with status epilepticus who received intranasal midazolam as first-line treatment. The patients had a mean age of nearly 53 years and 23 were women. The starting dose was 2.5 mg per nostril, moving up to 5 mg per nostril after waiting 5 minutes in initial nonresponders.

Status epilepticus ceased both clinically and by EEG in 24 of the 42 patients, or 57%, in an average of 5 minutes after administration of the intranasal medication at a mean dose of 5.6 mg. Nonresponders received a mean dose of 7.5 mg. There were no significant differences between responders and nonresponders in terms of the proportion presenting with preexisting epilepsy or the epilepsy etiology. However, responders presented at a mean of 54 minutes in status epilepticus, while nonresponders had been in status for 17 minutes.

The 57% response rate with intranasal midazolam is comparable with other investigators’ reported success rates using other benzodiazepines and routes of administration, she noted.

Session cochair Gregory Krauss, MD, commented that he thought the Frankfurt neurologists may have been too cautious in their dosing of intranasal midazolam for status epilepticus.

“Often in the U.S. 5 mg is initially used in each nostril,” according to Dr. Krauss, professor of neurology at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

Dr. Kay reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding her study.

SOURCE: Kay L et al. IEC 2019, Abstract P029.

BANGKOK – Lara Kay, MD, said at the International Epilepsy Congress.

Why? Because status epilepticus is a major medical emergency. It’s associated with substantial morbidity and mortality. And of the various factors that influence outcome in status epilepticus – including age, underlying etiology, and level of consciousness – only one is potentially within physician control: time to treatment, she noted at the congress sponsored by the International League Against Epilepsy.

“Time is brain,” observed Dr. Kay, a neurologist at the epilepsy center at University Hospital Frankfurt.

While intravenous benzodiazepines – for example, lorazepam at 2-4 mg – are widely accepted as the time-honored first-line treatment for status epilepticus, trying to place a line in a patient experiencing this emergency can be a tricky, time-consuming business. Multiple studies have demonstrated that various nonintravenous formulations of benzodiazepines, such as rectal diazepam or buccal or intramuscular midazolam, can be administered much faster and are as effective as intravenous benzodiazepines. But buccal midazolam is quite expensive in Germany, and the ready-to-use intramuscular midazolam applicator that’s available in the United States isn’t marketed in Germany. So several years ago Dr. Kay and her fellow neurologists started having their university hospital pharmacy manufacture intranasal midazolam.

Dr. Kay presented an observational study of 42 consecutive patients with status epilepticus who received intranasal midazolam as first-line treatment. The patients had a mean age of nearly 53 years and 23 were women. The starting dose was 2.5 mg per nostril, moving up to 5 mg per nostril after waiting 5 minutes in initial nonresponders.

Status epilepticus ceased both clinically and by EEG in 24 of the 42 patients, or 57%, in an average of 5 minutes after administration of the intranasal medication at a mean dose of 5.6 mg. Nonresponders received a mean dose of 7.5 mg. There were no significant differences between responders and nonresponders in terms of the proportion presenting with preexisting epilepsy or the epilepsy etiology. However, responders presented at a mean of 54 minutes in status epilepticus, while nonresponders had been in status for 17 minutes.

The 57% response rate with intranasal midazolam is comparable with other investigators’ reported success rates using other benzodiazepines and routes of administration, she noted.

Session cochair Gregory Krauss, MD, commented that he thought the Frankfurt neurologists may have been too cautious in their dosing of intranasal midazolam for status epilepticus.

“Often in the U.S. 5 mg is initially used in each nostril,” according to Dr. Krauss, professor of neurology at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

Dr. Kay reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding her study.

SOURCE: Kay L et al. IEC 2019, Abstract P029.

REPORTING FROM IEC 2019

Is Diagnosis Up in the Air?

ANSWER

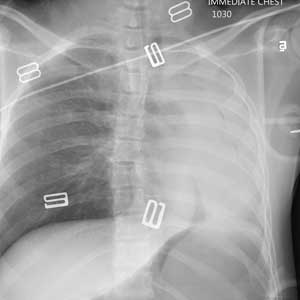

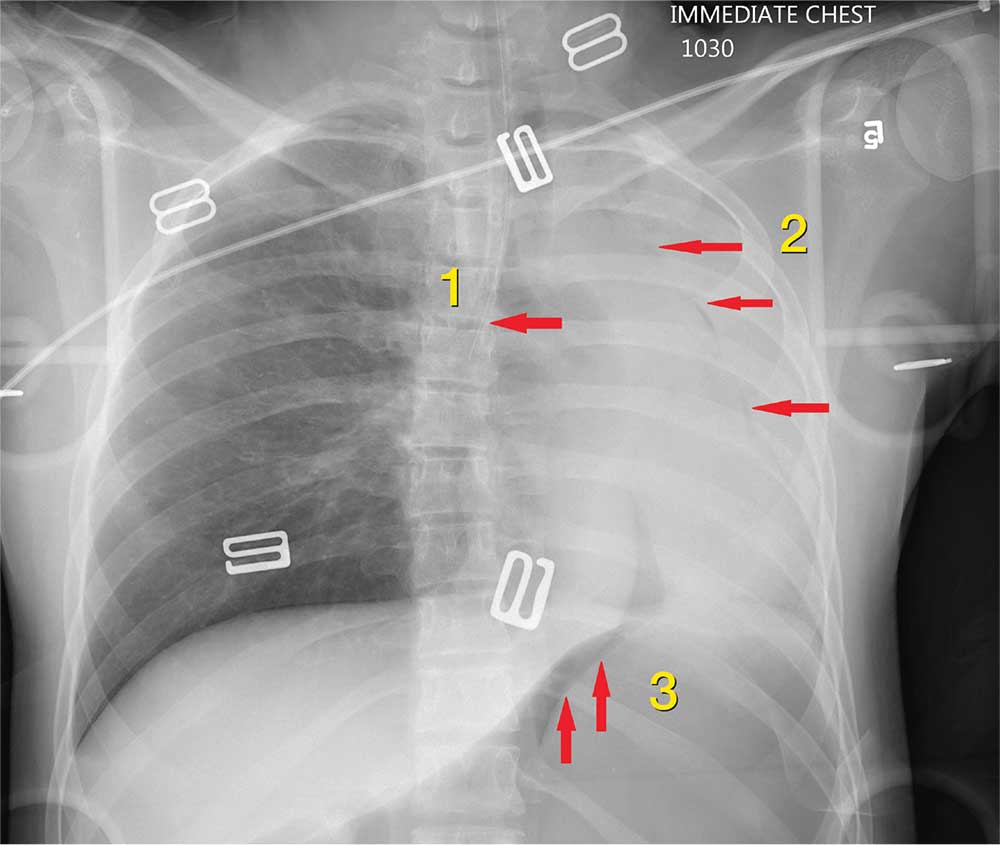

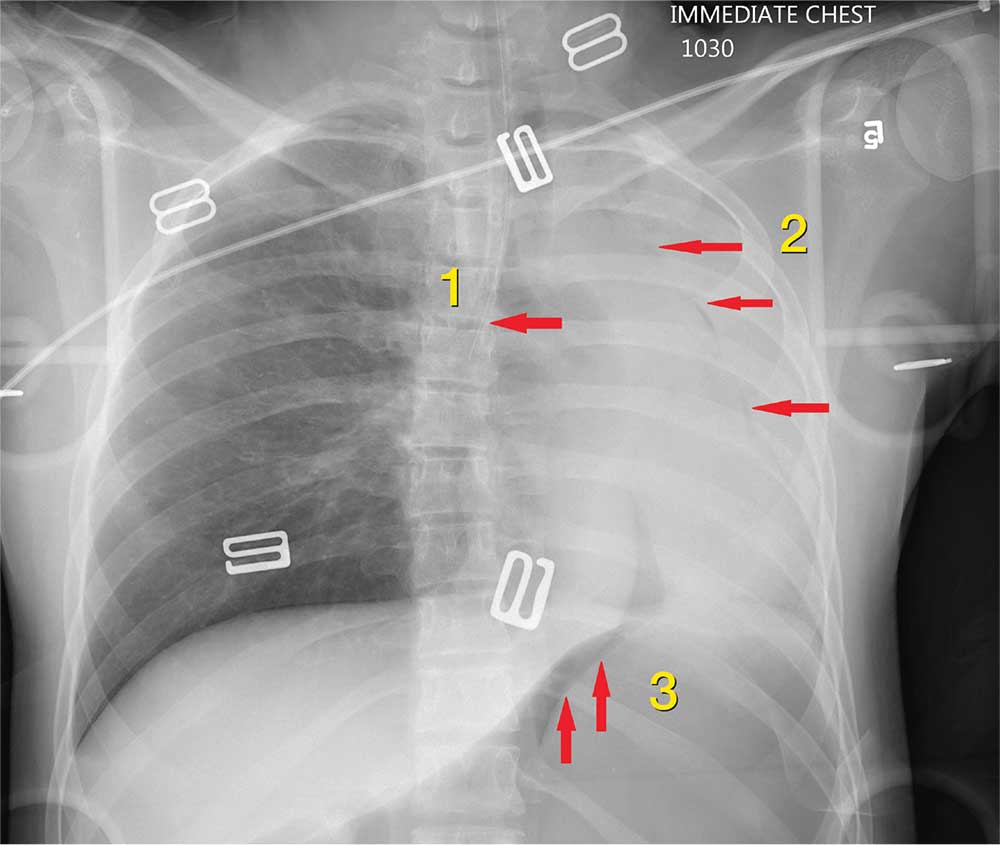

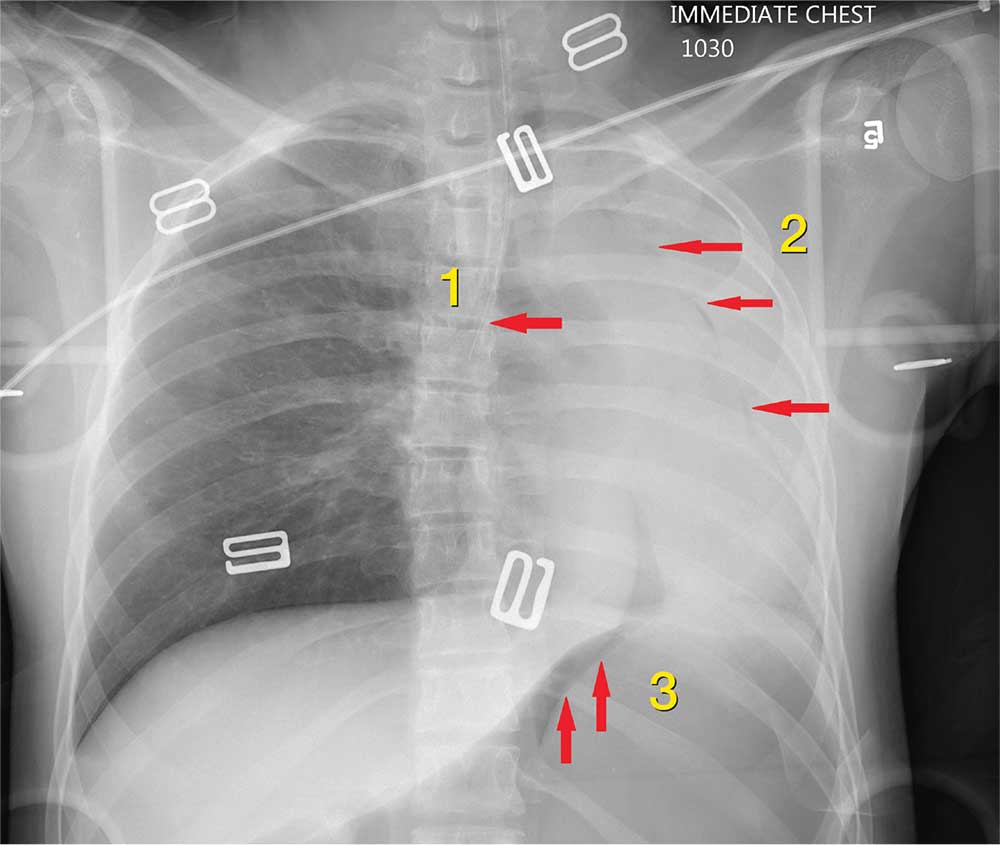

The radiograph shows 3 abnormalities:

(1) The endotracheal tube is in the right mainstem bronchus—a finding that in part leads to

(2) A whiteout of the left lung; the latter is due partly to collapse and atelectasis and partly to a possible pneumothorax.

(3) There is evidence of free air under the left hemidiaphragm, which is concerning for an intra-abdominal injury, such as a perforated viscus.

The patient’s endotracheal tube was partially withdrawn, and a left chest tube was placed. Subsequent CT of the abdomen confirmed the finding of free air. She was then taken to the operating room for an emergent laparotomy.

ANSWER

The radiograph shows 3 abnormalities:

(1) The endotracheal tube is in the right mainstem bronchus—a finding that in part leads to

(2) A whiteout of the left lung; the latter is due partly to collapse and atelectasis and partly to a possible pneumothorax.

(3) There is evidence of free air under the left hemidiaphragm, which is concerning for an intra-abdominal injury, such as a perforated viscus.

The patient’s endotracheal tube was partially withdrawn, and a left chest tube was placed. Subsequent CT of the abdomen confirmed the finding of free air. She was then taken to the operating room for an emergent laparotomy.

ANSWER

The radiograph shows 3 abnormalities:

(1) The endotracheal tube is in the right mainstem bronchus—a finding that in part leads to

(2) A whiteout of the left lung; the latter is due partly to collapse and atelectasis and partly to a possible pneumothorax.

(3) There is evidence of free air under the left hemidiaphragm, which is concerning for an intra-abdominal injury, such as a perforated viscus.

The patient’s endotracheal tube was partially withdrawn, and a left chest tube was placed. Subsequent CT of the abdomen confirmed the finding of free air. She was then taken to the operating room for an emergent laparotomy.

An air ambulance emergently transports a young woman from the scene of a motor vehicle collision to your facility. The details of the accident and age of the patient are unknown. The air ambulance crew had intubated her en route for a decreased level of responsiveness and for airway protection.

The patient is brought to your trauma bay, where you note an intubated female teenager who is unresponsive, with a Glasgow Coma Sc

Her pupils are equal and react bilaterally, albeit sluggishly. Her right leg was placed in an immobilizer by the air ambulance crew because they had noted a right thigh deformity.

Before completing your primary survey, you obtain a portable chest radiograph (shown). What is your impression?

Man, 46, With Wrist Laceration

A right hand–dominant 46-year-old man presents to the emergency department (ED) with a 1-cm laceration of his volar right wrist that occurred after he slipped on a wet floor while carrying a ceramic dish. The patient fell with his hand outstretched and landed on the dish as it broke against the floor. The patient has no pain but complains of tingling in his fingers. Past medical history is negative for diabetes, hypertension, or any neurologic disorders. Social history includes smoking one-half pack of cigarettes per day and drinking 6 to 10 12-oz beers each weekend. He works as a machinist.

Physical examination shows no bony tenderness. There is a 1.0-cm transverse laceration at the base of the hand at the midline of the volar wrist crease. Flexion, extension, and strength of the fingers are intact, as are dull and sharp discrimination to the thumb and other fingers. A cotton-tip applicator is used for gross sensory testing. No other neuromuscular assessment of the hand is performed. An x-ray of the hand to rule out a fracture or ceramic foreign body is negative.

The wound is locally anesthetized with 1% xylocaine without epinephrine. The laceration is irrigated with normal saline solution and closed with 4-0 nylon sutures using conventional bedside-suturing technique. A sterile bandage is applied. After-care instructions include wound care and follow-up with the patient’s family physician in 1 week for suture removal.

The patient returns to the ED 4 days later, complaining of increased tingling and weakness of the thumb and index and middle fingers. Repeat neuromuscular examination shows decreased sensation and dull/sharp discrimination, and abnormal static 2-point discrimination of the thumb and index and middle fingers. Based on the location of the laceration, the follow-up provider suspects a median nerve injury. After a telephone consultation with a hand surgeon, the patient is told to come into the office in 2 days.

Subsequent follow-up by the hospital’s risk manager indicates that the hand surgeon found a transected median nerve, requiring surgery to repair it. The patient has resulting deficits in sensation and strength and requires extensive occupational therapy. The risk management team learns that the patient intends to file a malpractice suit.

DISCUSSION

Hand and finger injuries represent about 20% of ED visits and are among the most costly injuries for the employed population.1 Knife and glass lacerations of the fingers are most common.2 Failure to diagnose significant hand and finger injuries is also a major contributor to malpractice claims in the ED.3 It is imperative for the PA or NP working in a high-stress/high-volume environment to perform a thorough neuromuscular and vascular examination when encountering a traumatic hand injury or a laceration. This applies to all frontline practices, including urgent care, ED, and primary care and family practices.

Volar surface lacerations of the wrist and fingers are especially high risk.2 Small lacerations (< 2 cm for fingers and < 3 cm for wrist and forearm) may lead a provider to consider the injury minor; however, these have the greatest potential for missed significant deep injuries.2 Missed median nerve lacerations can result in major complications if not surgically repaired soon after the injury.4

Continue to: With our case patient...

With our case patient, a small glass cut at the volar wrist crease did not cause tendon lacerations or flexor deficits. The patient complained only of mild tingling to the fingers, and a detailed hand-and-finger examination was not performed to isolate further nerve injury.4

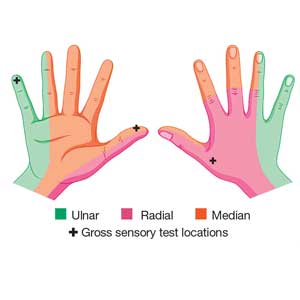

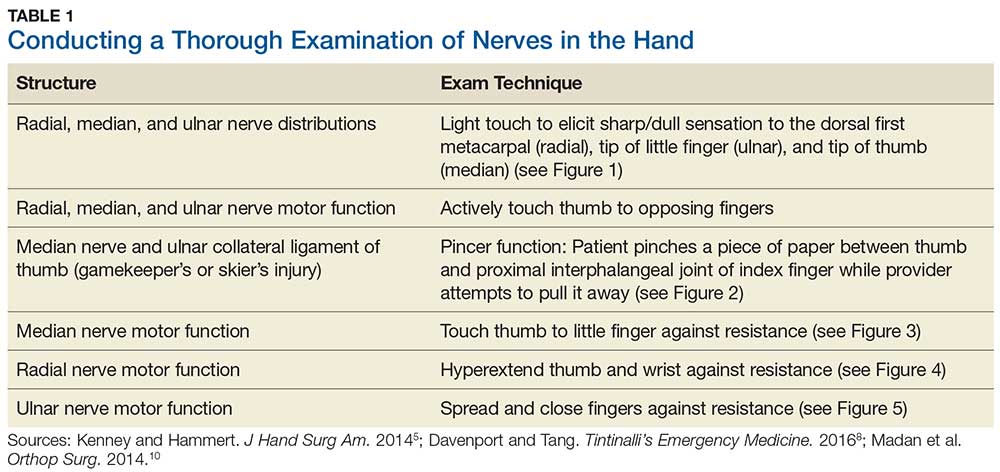

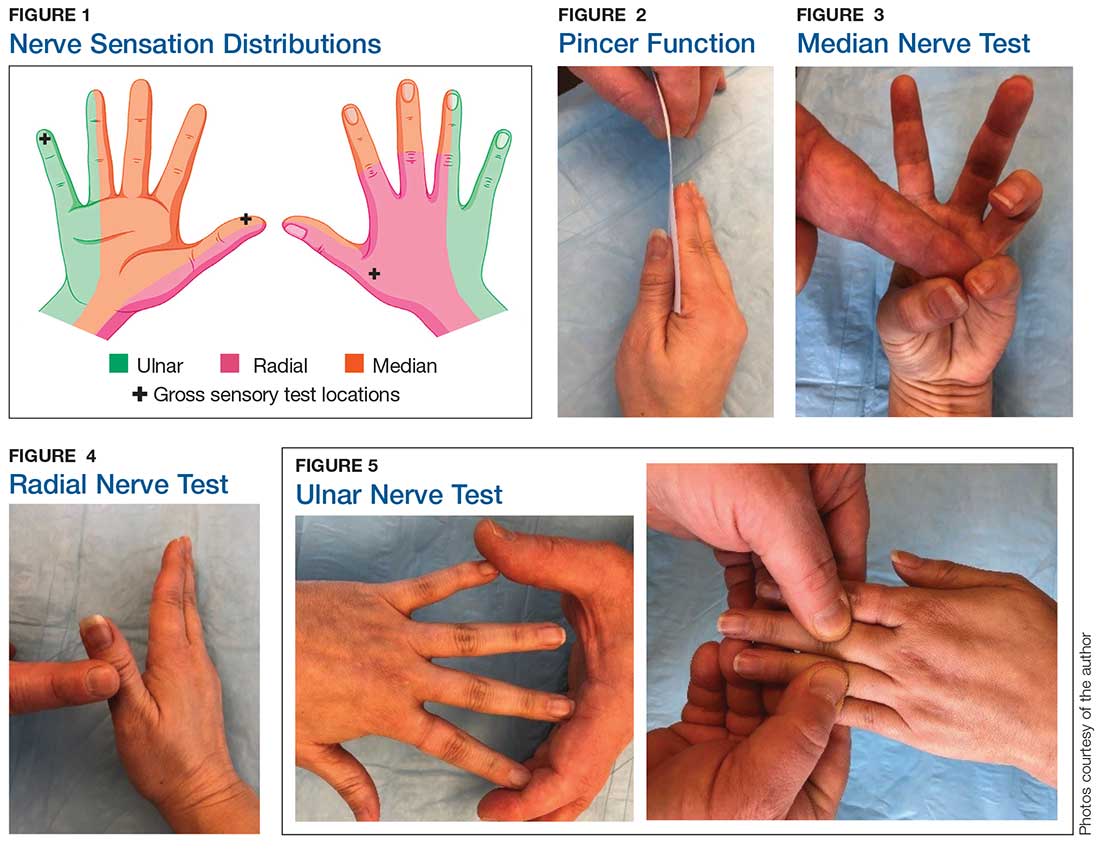

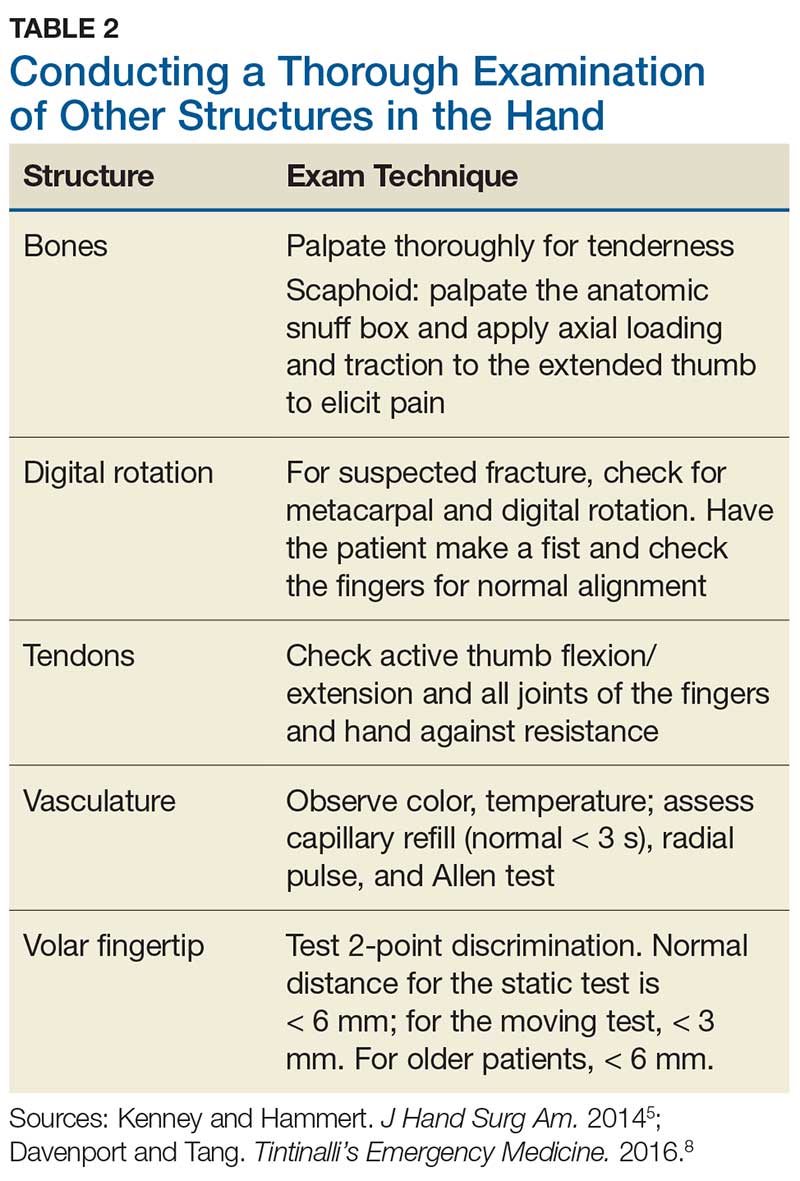

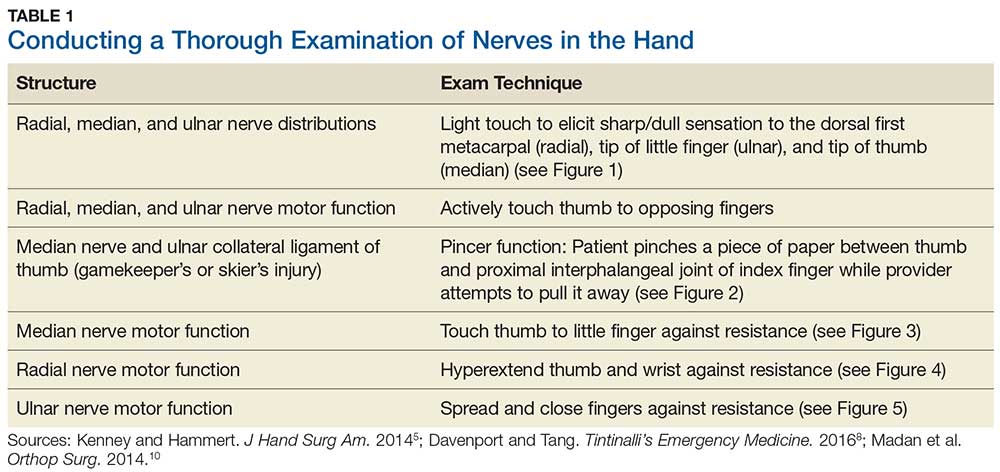

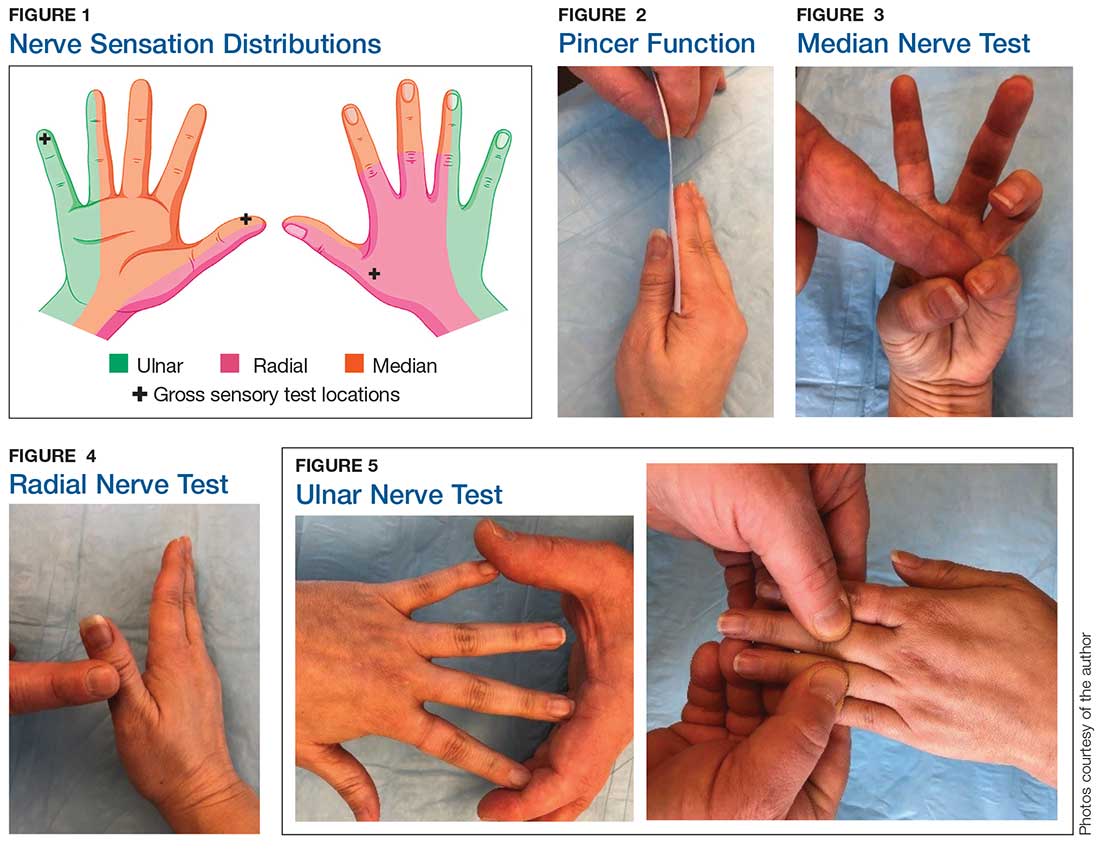

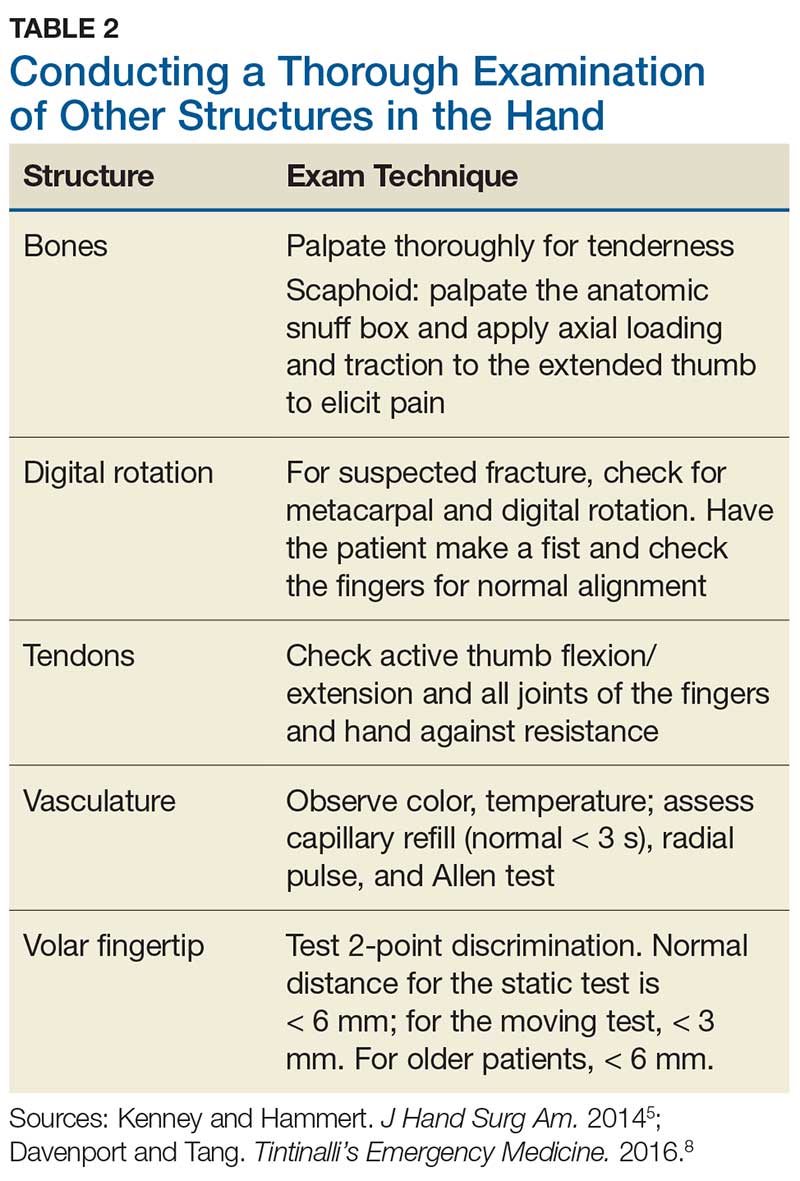

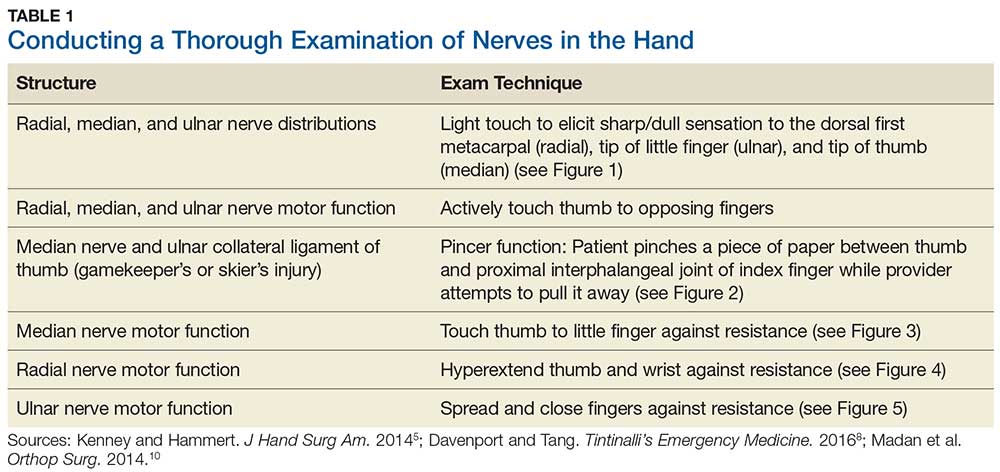

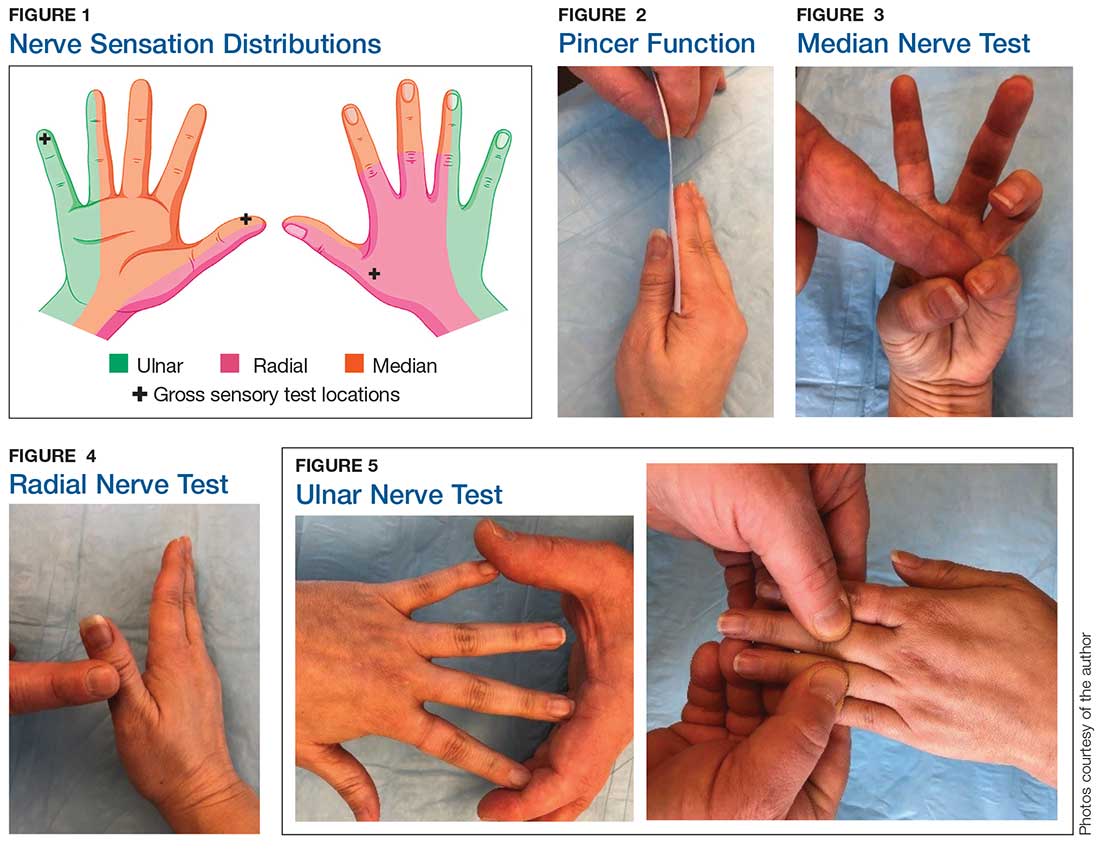

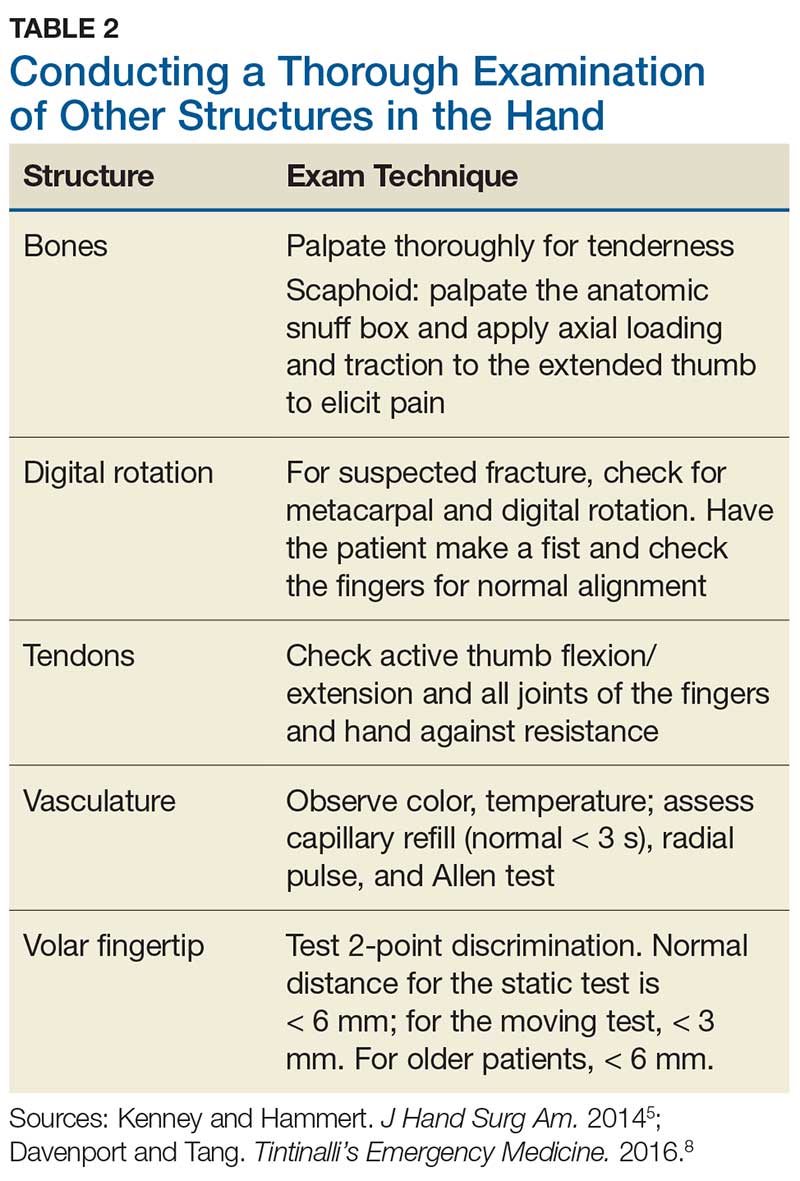

Although most nerve injuries result in a loss in sensory function, motor function must also be evaluated.5 With partial nerve lacerations, subtle loss of motor or sensory function can be missed by the examiner.4 It is imperative to conduct a thorough hand examination (outlined in Tables 1 and 2) to decrease the likelihood of missing a significant nerve or tendon injury.

Sensory testing basics

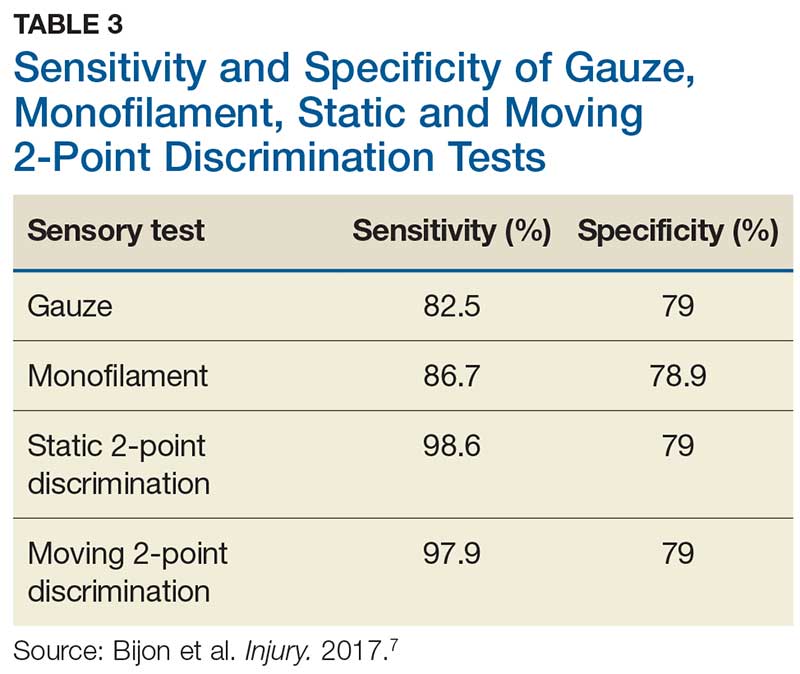

Nerve laceration vs nerve compression disorder. It is important to distinguish sensory testing for a nerve injury or laceration from testing for a nerve compression disorder, such as carpal tunnel syndrome. When examining compression neuropathies, light touch, tuning fork vibration, and monofilament testing are used. When a nerve injury or laceration is suspected, light touch and 2-point discrimination are used.5 Static 2-point discrimination (also known as the Weber static test) will be immediately abnormal if a nerve is lacerated. In a nerve compression disorder, 2-point discrimination is decreased progressively.5

Sensory testing evidence

Comparing light touch, monofilament, and 2-point discrimination. As seen with our case patient, testing dull-sharp discrimination using the cotton-tip applicator for “dull” and the broken end of the wooden applicator stick for “sharp” may not be the most complete way to assess sensation in the hand and fingers. The physical examination should include light touch and 2-point discrimination.5

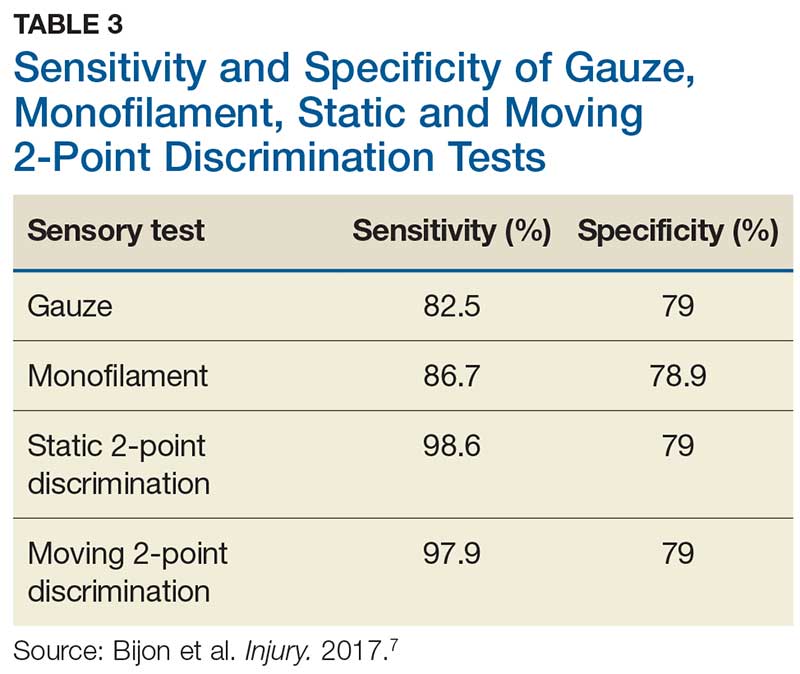

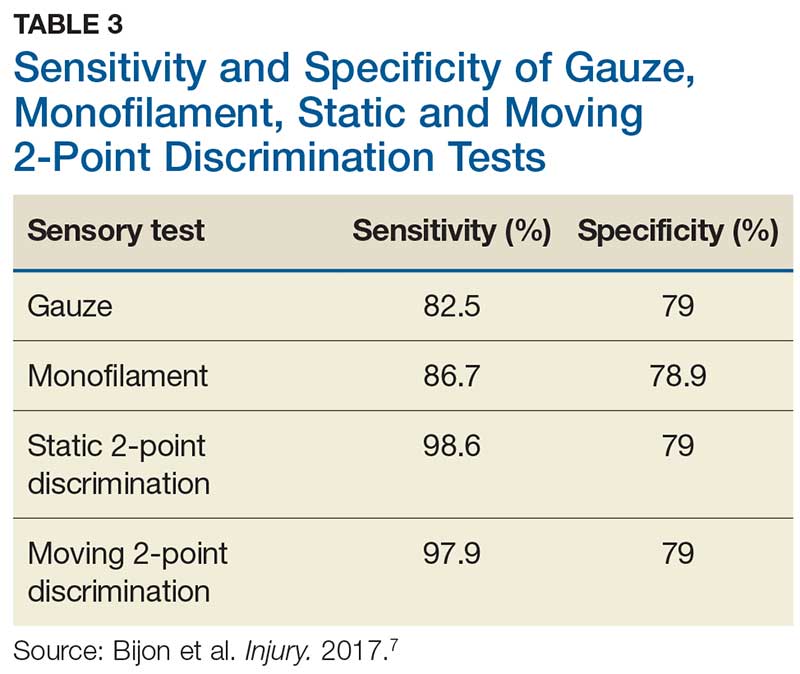

In one study, tests for sensation compared the gauze test (light touch), the static 2-point discrimination, the moving 2-point discrimination (m2PD; also known as the Weber dynamic test),6 and the monofilament test. The static and m2PD tests were statistically superior to the gauze and monofilament tests (see Table 3).7 Two-point discrimination abnormalities are detected immediately after a nerve is lacerated.5 This suggests performing 2-point discrimination, either moving or static, is superior to dull-sensation testing alone (gauze or cotton-tip applicator). This should be included in the motor and sensory examinations of the hand and fingers seen in Tables 1 and 2.

Continue to: Moving 2-point discrimination test

Moving 2-point discrimination test

The m2PD requires a 2-pointed instrument that can maintain a fixed 5 mm of width, such as a bent paperclip or EKG calipers. Commercially available devices specifically for 2-point discrimination can also be used.

When performing the m2PD test, the provider strokes 1 point in the proximal to distal direction in 5-mm increments on the finger and asks whether the patient feels “1 moving point.” The provider then holds 2 points and moves them in the proximal to distal direction in 5-mm increments and asks whether the patient feels “2 moving points.”

The m2PD test is then conducted comparing the ulnar and radial side of the injured finger with the ipsilateral noninjured finger. This should be done at least 4 times.8 The test is positive if there is a ≥ 2-mm difference between the affected and the unaffected side.7

Wound exploration

Data from a French insurance company indicate that 10% of ED malpractice claims in 2013 were related to inadequately examined hand lacerations. In an analysis of these claims, Mouton et al found that most injuries resulting in claims affected the thumb or the volar aspects of the fingers. Reasons for malpractice claims included residual stiffness, weakness, sensory deficit, retained foreign body, and wound infection. The researchers concluded that inadequate examination of hand wounds “carries a risk of lasting and sometimes severe residual impairment, and generates considerable societal costs.”3

In particular, small penetrating lacerations from broken glass or a knife should be considered high-risk injuries.2 In a study of small (< 2 cm) lacerations of the hand and fingers, 59% of the patients were found to have deep-structure injuries.2 Tuncali et al concluded that small lacerations increase the likelihood of missing deeper structural injuries because of failure to examine the wound.2 Furthermore, with glass lacerations, examiners tend to prioritize ruling out a foreign body and then fail to examine the wound. If a careful examination of the hand and fingers prompts suspicion of a tendon or nerve injury, referral to hand surgery for direct surgical exploration is indicated.

Continue to: CONCLUSION

CONCLUSION

Busy health care providers must be aware that approximately 10% to 15% of the negative outcomes in patient care result from diagnostic errors and are most common in the internal medicine, family medicine, and emergency medicine clinical environments.9 With hand and finger lacerations, small size can give a provider a false sense that the laceration is minor, resulting in a failure to diagnose a deeper injury (eg, tendon or nerve).1

When evaluating a traumatic injury or laceration to the hand or fingers, it is important to conduct a thorough sensory and motor examination. Experts recommend light touch and 2-point discrimination be included in the sensory exam to avoid missing nerve injuries. If a deeper structural injury is suspected, the patient should be referred to hand surgery and the wound surgically explored.2

1. Robinson LS, Sarkies M, Brown T, et al. Direct, indirect and intangible costs of acute hand and wrist injuries: a systematic review. Injury. 2016;47:2614-2626.

2. Tuncali D, Yavuz N, Terzioglu A, Aslan G. The rate of upper-extremity deep-structure injuries through small penetrating lacerations. Ann Plast Surg. 2005;55:146-148.

3. Mouton J, Houdre H, Beccari R, et al. Surgical exploration of hand wounds in the emergency room: preliminary study of 80 personal injury claims. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2016;102:1009-1012.

4. Pederson WC. Median nerve injury and repair. J Hand Surg Am. 2014;39(6): 1216-1222.

5. Kenney RJ, Hammert WC. Physical examination of the hand. J Hand Surg Am. 2014;39(11):2324-2334.

6. Dellon AL. The moving two-point discrimination test: clinical evaluation of the quickly adapting fiber/receptor system. J Hand Surg. 1978;3(5):474-481.

7. Bijon C, Hidalgo-Diaz JJ, Chiara P, et al. Nerve injuries to the volar aspect of the hand: a comparison of the reliability of the Weber static test versus the gauze test. Injury. 2017;48:2582-2585.

8. Davenport M, Tang P. Injuries to the hand and digits. In: Tintinalli JE, Stapczynski J, Ma OJ, et al, eds. Tintinalli’s Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide. 8th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2016:1667.

9. Croskerry P, Nimmo GR. Better clinical decision making and reducing diagnostic error. J R Coll Physicians Edinb. 2011;41:155-162.

10. Madan SS, Pai DR, Kaur A, Dixit R. Injury to the ulnar collateral ligament of thumb. Orthop Surg. 2014;6:1-7.

A right hand–dominant 46-year-old man presents to the emergency department (ED) with a 1-cm laceration of his volar right wrist that occurred after he slipped on a wet floor while carrying a ceramic dish. The patient fell with his hand outstretched and landed on the dish as it broke against the floor. The patient has no pain but complains of tingling in his fingers. Past medical history is negative for diabetes, hypertension, or any neurologic disorders. Social history includes smoking one-half pack of cigarettes per day and drinking 6 to 10 12-oz beers each weekend. He works as a machinist.

Physical examination shows no bony tenderness. There is a 1.0-cm transverse laceration at the base of the hand at the midline of the volar wrist crease. Flexion, extension, and strength of the fingers are intact, as are dull and sharp discrimination to the thumb and other fingers. A cotton-tip applicator is used for gross sensory testing. No other neuromuscular assessment of the hand is performed. An x-ray of the hand to rule out a fracture or ceramic foreign body is negative.

The wound is locally anesthetized with 1% xylocaine without epinephrine. The laceration is irrigated with normal saline solution and closed with 4-0 nylon sutures using conventional bedside-suturing technique. A sterile bandage is applied. After-care instructions include wound care and follow-up with the patient’s family physician in 1 week for suture removal.

The patient returns to the ED 4 days later, complaining of increased tingling and weakness of the thumb and index and middle fingers. Repeat neuromuscular examination shows decreased sensation and dull/sharp discrimination, and abnormal static 2-point discrimination of the thumb and index and middle fingers. Based on the location of the laceration, the follow-up provider suspects a median nerve injury. After a telephone consultation with a hand surgeon, the patient is told to come into the office in 2 days.

Subsequent follow-up by the hospital’s risk manager indicates that the hand surgeon found a transected median nerve, requiring surgery to repair it. The patient has resulting deficits in sensation and strength and requires extensive occupational therapy. The risk management team learns that the patient intends to file a malpractice suit.

DISCUSSION

Hand and finger injuries represent about 20% of ED visits and are among the most costly injuries for the employed population.1 Knife and glass lacerations of the fingers are most common.2 Failure to diagnose significant hand and finger injuries is also a major contributor to malpractice claims in the ED.3 It is imperative for the PA or NP working in a high-stress/high-volume environment to perform a thorough neuromuscular and vascular examination when encountering a traumatic hand injury or a laceration. This applies to all frontline practices, including urgent care, ED, and primary care and family practices.

Volar surface lacerations of the wrist and fingers are especially high risk.2 Small lacerations (< 2 cm for fingers and < 3 cm for wrist and forearm) may lead a provider to consider the injury minor; however, these have the greatest potential for missed significant deep injuries.2 Missed median nerve lacerations can result in major complications if not surgically repaired soon after the injury.4

Continue to: With our case patient...

With our case patient, a small glass cut at the volar wrist crease did not cause tendon lacerations or flexor deficits. The patient complained only of mild tingling to the fingers, and a detailed hand-and-finger examination was not performed to isolate further nerve injury.4

Although most nerve injuries result in a loss in sensory function, motor function must also be evaluated.5 With partial nerve lacerations, subtle loss of motor or sensory function can be missed by the examiner.4 It is imperative to conduct a thorough hand examination (outlined in Tables 1 and 2) to decrease the likelihood of missing a significant nerve or tendon injury.

Sensory testing basics

Nerve laceration vs nerve compression disorder. It is important to distinguish sensory testing for a nerve injury or laceration from testing for a nerve compression disorder, such as carpal tunnel syndrome. When examining compression neuropathies, light touch, tuning fork vibration, and monofilament testing are used. When a nerve injury or laceration is suspected, light touch and 2-point discrimination are used.5 Static 2-point discrimination (also known as the Weber static test) will be immediately abnormal if a nerve is lacerated. In a nerve compression disorder, 2-point discrimination is decreased progressively.5

Sensory testing evidence

Comparing light touch, monofilament, and 2-point discrimination. As seen with our case patient, testing dull-sharp discrimination using the cotton-tip applicator for “dull” and the broken end of the wooden applicator stick for “sharp” may not be the most complete way to assess sensation in the hand and fingers. The physical examination should include light touch and 2-point discrimination.5

In one study, tests for sensation compared the gauze test (light touch), the static 2-point discrimination, the moving 2-point discrimination (m2PD; also known as the Weber dynamic test),6 and the monofilament test. The static and m2PD tests were statistically superior to the gauze and monofilament tests (see Table 3).7 Two-point discrimination abnormalities are detected immediately after a nerve is lacerated.5 This suggests performing 2-point discrimination, either moving or static, is superior to dull-sensation testing alone (gauze or cotton-tip applicator). This should be included in the motor and sensory examinations of the hand and fingers seen in Tables 1 and 2.

Continue to: Moving 2-point discrimination test

Moving 2-point discrimination test

The m2PD requires a 2-pointed instrument that can maintain a fixed 5 mm of width, such as a bent paperclip or EKG calipers. Commercially available devices specifically for 2-point discrimination can also be used.

When performing the m2PD test, the provider strokes 1 point in the proximal to distal direction in 5-mm increments on the finger and asks whether the patient feels “1 moving point.” The provider then holds 2 points and moves them in the proximal to distal direction in 5-mm increments and asks whether the patient feels “2 moving points.”

The m2PD test is then conducted comparing the ulnar and radial side of the injured finger with the ipsilateral noninjured finger. This should be done at least 4 times.8 The test is positive if there is a ≥ 2-mm difference between the affected and the unaffected side.7

Wound exploration

Data from a French insurance company indicate that 10% of ED malpractice claims in 2013 were related to inadequately examined hand lacerations. In an analysis of these claims, Mouton et al found that most injuries resulting in claims affected the thumb or the volar aspects of the fingers. Reasons for malpractice claims included residual stiffness, weakness, sensory deficit, retained foreign body, and wound infection. The researchers concluded that inadequate examination of hand wounds “carries a risk of lasting and sometimes severe residual impairment, and generates considerable societal costs.”3

In particular, small penetrating lacerations from broken glass or a knife should be considered high-risk injuries.2 In a study of small (< 2 cm) lacerations of the hand and fingers, 59% of the patients were found to have deep-structure injuries.2 Tuncali et al concluded that small lacerations increase the likelihood of missing deeper structural injuries because of failure to examine the wound.2 Furthermore, with glass lacerations, examiners tend to prioritize ruling out a foreign body and then fail to examine the wound. If a careful examination of the hand and fingers prompts suspicion of a tendon or nerve injury, referral to hand surgery for direct surgical exploration is indicated.

Continue to: CONCLUSION

CONCLUSION

Busy health care providers must be aware that approximately 10% to 15% of the negative outcomes in patient care result from diagnostic errors and are most common in the internal medicine, family medicine, and emergency medicine clinical environments.9 With hand and finger lacerations, small size can give a provider a false sense that the laceration is minor, resulting in a failure to diagnose a deeper injury (eg, tendon or nerve).1

When evaluating a traumatic injury or laceration to the hand or fingers, it is important to conduct a thorough sensory and motor examination. Experts recommend light touch and 2-point discrimination be included in the sensory exam to avoid missing nerve injuries. If a deeper structural injury is suspected, the patient should be referred to hand surgery and the wound surgically explored.2

A right hand–dominant 46-year-old man presents to the emergency department (ED) with a 1-cm laceration of his volar right wrist that occurred after he slipped on a wet floor while carrying a ceramic dish. The patient fell with his hand outstretched and landed on the dish as it broke against the floor. The patient has no pain but complains of tingling in his fingers. Past medical history is negative for diabetes, hypertension, or any neurologic disorders. Social history includes smoking one-half pack of cigarettes per day and drinking 6 to 10 12-oz beers each weekend. He works as a machinist.

Physical examination shows no bony tenderness. There is a 1.0-cm transverse laceration at the base of the hand at the midline of the volar wrist crease. Flexion, extension, and strength of the fingers are intact, as are dull and sharp discrimination to the thumb and other fingers. A cotton-tip applicator is used for gross sensory testing. No other neuromuscular assessment of the hand is performed. An x-ray of the hand to rule out a fracture or ceramic foreign body is negative.

The wound is locally anesthetized with 1% xylocaine without epinephrine. The laceration is irrigated with normal saline solution and closed with 4-0 nylon sutures using conventional bedside-suturing technique. A sterile bandage is applied. After-care instructions include wound care and follow-up with the patient’s family physician in 1 week for suture removal.

The patient returns to the ED 4 days later, complaining of increased tingling and weakness of the thumb and index and middle fingers. Repeat neuromuscular examination shows decreased sensation and dull/sharp discrimination, and abnormal static 2-point discrimination of the thumb and index and middle fingers. Based on the location of the laceration, the follow-up provider suspects a median nerve injury. After a telephone consultation with a hand surgeon, the patient is told to come into the office in 2 days.

Subsequent follow-up by the hospital’s risk manager indicates that the hand surgeon found a transected median nerve, requiring surgery to repair it. The patient has resulting deficits in sensation and strength and requires extensive occupational therapy. The risk management team learns that the patient intends to file a malpractice suit.

DISCUSSION

Hand and finger injuries represent about 20% of ED visits and are among the most costly injuries for the employed population.1 Knife and glass lacerations of the fingers are most common.2 Failure to diagnose significant hand and finger injuries is also a major contributor to malpractice claims in the ED.3 It is imperative for the PA or NP working in a high-stress/high-volume environment to perform a thorough neuromuscular and vascular examination when encountering a traumatic hand injury or a laceration. This applies to all frontline practices, including urgent care, ED, and primary care and family practices.

Volar surface lacerations of the wrist and fingers are especially high risk.2 Small lacerations (< 2 cm for fingers and < 3 cm for wrist and forearm) may lead a provider to consider the injury minor; however, these have the greatest potential for missed significant deep injuries.2 Missed median nerve lacerations can result in major complications if not surgically repaired soon after the injury.4

Continue to: With our case patient...

With our case patient, a small glass cut at the volar wrist crease did not cause tendon lacerations or flexor deficits. The patient complained only of mild tingling to the fingers, and a detailed hand-and-finger examination was not performed to isolate further nerve injury.4

Although most nerve injuries result in a loss in sensory function, motor function must also be evaluated.5 With partial nerve lacerations, subtle loss of motor or sensory function can be missed by the examiner.4 It is imperative to conduct a thorough hand examination (outlined in Tables 1 and 2) to decrease the likelihood of missing a significant nerve or tendon injury.

Sensory testing basics

Nerve laceration vs nerve compression disorder. It is important to distinguish sensory testing for a nerve injury or laceration from testing for a nerve compression disorder, such as carpal tunnel syndrome. When examining compression neuropathies, light touch, tuning fork vibration, and monofilament testing are used. When a nerve injury or laceration is suspected, light touch and 2-point discrimination are used.5 Static 2-point discrimination (also known as the Weber static test) will be immediately abnormal if a nerve is lacerated. In a nerve compression disorder, 2-point discrimination is decreased progressively.5

Sensory testing evidence

Comparing light touch, monofilament, and 2-point discrimination. As seen with our case patient, testing dull-sharp discrimination using the cotton-tip applicator for “dull” and the broken end of the wooden applicator stick for “sharp” may not be the most complete way to assess sensation in the hand and fingers. The physical examination should include light touch and 2-point discrimination.5

In one study, tests for sensation compared the gauze test (light touch), the static 2-point discrimination, the moving 2-point discrimination (m2PD; also known as the Weber dynamic test),6 and the monofilament test. The static and m2PD tests were statistically superior to the gauze and monofilament tests (see Table 3).7 Two-point discrimination abnormalities are detected immediately after a nerve is lacerated.5 This suggests performing 2-point discrimination, either moving or static, is superior to dull-sensation testing alone (gauze or cotton-tip applicator). This should be included in the motor and sensory examinations of the hand and fingers seen in Tables 1 and 2.

Continue to: Moving 2-point discrimination test

Moving 2-point discrimination test

The m2PD requires a 2-pointed instrument that can maintain a fixed 5 mm of width, such as a bent paperclip or EKG calipers. Commercially available devices specifically for 2-point discrimination can also be used.

When performing the m2PD test, the provider strokes 1 point in the proximal to distal direction in 5-mm increments on the finger and asks whether the patient feels “1 moving point.” The provider then holds 2 points and moves them in the proximal to distal direction in 5-mm increments and asks whether the patient feels “2 moving points.”

The m2PD test is then conducted comparing the ulnar and radial side of the injured finger with the ipsilateral noninjured finger. This should be done at least 4 times.8 The test is positive if there is a ≥ 2-mm difference between the affected and the unaffected side.7

Wound exploration

Data from a French insurance company indicate that 10% of ED malpractice claims in 2013 were related to inadequately examined hand lacerations. In an analysis of these claims, Mouton et al found that most injuries resulting in claims affected the thumb or the volar aspects of the fingers. Reasons for malpractice claims included residual stiffness, weakness, sensory deficit, retained foreign body, and wound infection. The researchers concluded that inadequate examination of hand wounds “carries a risk of lasting and sometimes severe residual impairment, and generates considerable societal costs.”3

In particular, small penetrating lacerations from broken glass or a knife should be considered high-risk injuries.2 In a study of small (< 2 cm) lacerations of the hand and fingers, 59% of the patients were found to have deep-structure injuries.2 Tuncali et al concluded that small lacerations increase the likelihood of missing deeper structural injuries because of failure to examine the wound.2 Furthermore, with glass lacerations, examiners tend to prioritize ruling out a foreign body and then fail to examine the wound. If a careful examination of the hand and fingers prompts suspicion of a tendon or nerve injury, referral to hand surgery for direct surgical exploration is indicated.

Continue to: CONCLUSION

CONCLUSION

Busy health care providers must be aware that approximately 10% to 15% of the negative outcomes in patient care result from diagnostic errors and are most common in the internal medicine, family medicine, and emergency medicine clinical environments.9 With hand and finger lacerations, small size can give a provider a false sense that the laceration is minor, resulting in a failure to diagnose a deeper injury (eg, tendon or nerve).1

When evaluating a traumatic injury or laceration to the hand or fingers, it is important to conduct a thorough sensory and motor examination. Experts recommend light touch and 2-point discrimination be included in the sensory exam to avoid missing nerve injuries. If a deeper structural injury is suspected, the patient should be referred to hand surgery and the wound surgically explored.2

1. Robinson LS, Sarkies M, Brown T, et al. Direct, indirect and intangible costs of acute hand and wrist injuries: a systematic review. Injury. 2016;47:2614-2626.

2. Tuncali D, Yavuz N, Terzioglu A, Aslan G. The rate of upper-extremity deep-structure injuries through small penetrating lacerations. Ann Plast Surg. 2005;55:146-148.

3. Mouton J, Houdre H, Beccari R, et al. Surgical exploration of hand wounds in the emergency room: preliminary study of 80 personal injury claims. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2016;102:1009-1012.

4. Pederson WC. Median nerve injury and repair. J Hand Surg Am. 2014;39(6): 1216-1222.

5. Kenney RJ, Hammert WC. Physical examination of the hand. J Hand Surg Am. 2014;39(11):2324-2334.

6. Dellon AL. The moving two-point discrimination test: clinical evaluation of the quickly adapting fiber/receptor system. J Hand Surg. 1978;3(5):474-481.

7. Bijon C, Hidalgo-Diaz JJ, Chiara P, et al. Nerve injuries to the volar aspect of the hand: a comparison of the reliability of the Weber static test versus the gauze test. Injury. 2017;48:2582-2585.

8. Davenport M, Tang P. Injuries to the hand and digits. In: Tintinalli JE, Stapczynski J, Ma OJ, et al, eds. Tintinalli’s Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide. 8th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2016:1667.

9. Croskerry P, Nimmo GR. Better clinical decision making and reducing diagnostic error. J R Coll Physicians Edinb. 2011;41:155-162.

10. Madan SS, Pai DR, Kaur A, Dixit R. Injury to the ulnar collateral ligament of thumb. Orthop Surg. 2014;6:1-7.

1. Robinson LS, Sarkies M, Brown T, et al. Direct, indirect and intangible costs of acute hand and wrist injuries: a systematic review. Injury. 2016;47:2614-2626.

2. Tuncali D, Yavuz N, Terzioglu A, Aslan G. The rate of upper-extremity deep-structure injuries through small penetrating lacerations. Ann Plast Surg. 2005;55:146-148.

3. Mouton J, Houdre H, Beccari R, et al. Surgical exploration of hand wounds in the emergency room: preliminary study of 80 personal injury claims. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2016;102:1009-1012.

4. Pederson WC. Median nerve injury and repair. J Hand Surg Am. 2014;39(6): 1216-1222.

5. Kenney RJ, Hammert WC. Physical examination of the hand. J Hand Surg Am. 2014;39(11):2324-2334.

6. Dellon AL. The moving two-point discrimination test: clinical evaluation of the quickly adapting fiber/receptor system. J Hand Surg. 1978;3(5):474-481.

7. Bijon C, Hidalgo-Diaz JJ, Chiara P, et al. Nerve injuries to the volar aspect of the hand: a comparison of the reliability of the Weber static test versus the gauze test. Injury. 2017;48:2582-2585.

8. Davenport M, Tang P. Injuries to the hand and digits. In: Tintinalli JE, Stapczynski J, Ma OJ, et al, eds. Tintinalli’s Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide. 8th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2016:1667.

9. Croskerry P, Nimmo GR. Better clinical decision making and reducing diagnostic error. J R Coll Physicians Edinb. 2011;41:155-162.

10. Madan SS, Pai DR, Kaur A, Dixit R. Injury to the ulnar collateral ligament of thumb. Orthop Surg. 2014;6:1-7.

There’s Mischief Afoot

ANSWER

The radiograph demonstrates no evidence of an acute fracture or soft-tissue gas to suggest an abscess. Of note, though, within the tibiotalar joint, the patient has bony destruction and settling of the articular surfaces of both the distal tibia and fibula into the talus and calcaneus.

This finding is typically associated with neuropathic arthropathy (also known as a Charcot joint). This pathologic process is typically seen in a weight-bearing joint that develops progressive degeneration from chronic loss of sensation.

ANSWER

The radiograph demonstrates no evidence of an acute fracture or soft-tissue gas to suggest an abscess. Of note, though, within the tibiotalar joint, the patient has bony destruction and settling of the articular surfaces of both the distal tibia and fibula into the talus and calcaneus.

This finding is typically associated with neuropathic arthropathy (also known as a Charcot joint). This pathologic process is typically seen in a weight-bearing joint that develops progressive degeneration from chronic loss of sensation.

ANSWER

The radiograph demonstrates no evidence of an acute fracture or soft-tissue gas to suggest an abscess. Of note, though, within the tibiotalar joint, the patient has bony destruction and settling of the articular surfaces of both the distal tibia and fibula into the talus and calcaneus.

This finding is typically associated with neuropathic arthropathy (also known as a Charcot joint). This pathologic process is typically seen in a weight-bearing joint that develops progressive degeneration from chronic loss of sensation.

A 70-year-old man presents for evaluation of left foot pain, redness, and swelling. He reports injuring the foot a week ago; he went to the emergency department for evaluation of the cut he had sustained, which required stapling.

The patient has a chronic foot ulcer for which a home health aide provides wound care and dressing changes. His medical history is significant for hypertension, stroke with chronic left-sided weakness, congestive heart failure, and chronic renal insufficiency. He admits to daily tobacco use, and his medical record reflects a history of drug use.

On physical exam, you note an elderly, chronically ill male in no obvious distress. His vital signs are stable, and he is afebrile. Inspection of his left foot shows generalized swelling and redness. Good distal pulses are appreciated. On the dorsal aspect, there is a healing wound with a single staple present. On the heel is a 2-cm stage 2 ulcer with some scant purulent drainage.

Bloodwork and a radiograph of the left foot are ordered; lateral view is shown. What is your impression?

Giant cell arteritis: An updated review of an old disease

Giant cell arteritis (GCA) is a systemic vasculitis involving medium-sized and large arteries, most commonly the temporal, ophthalmic, occipital, vertebral, posterior ciliary, and proximal vertebral arteries. Moreover, involvement of the ophthalmic artery and its branches results in loss of vision. GCA can also involve the aorta and its proximal branches, especially in the upper extremities.

GCA is the most common systemic vasculitis in adults. It occurs almost exclusively in patients over age 50 and affects women more than men. It is most frequent in populations of northern European ancestry, especially Scandinavian. In a retrospective cohort study in Norway, the average annual cumulative incidence rate of GCA was 16.7 per 100,000 people over age 50.1 Risk factors include older age, history of smoking, current smoking, early menopause, and, possibly, stress-related disorders.2

PATHOGENESIS IS NOT COMPLETELY UNDERSTOOD

The pathogenesis of GCA is not completely understood, but there is evidence of immune activation in the arterial wall leading to activation of macrophages and formation of multinucleated giant cells (which may not always be present in biopsies).

The most relevant cytokines in the ongoing pathogenesis are still being defined, but the presence of interferon gamma and interleukin 6 (IL-6) seem to be critical for the expression of the disease. The primary immunogenic triggers for the elaboration of these cytokines and the arteritis remain elusive.

A SPECTRUM OF PRESENTATIONS

The initial symptoms of GCA may be vague, such as malaise, fever, and night sweats, and are likely due to systemic inflammation. Features of vascular involvement include headache, scalp tenderness, and jaw claudication (cramping pain in the jaw while chewing).

A less common but serious feature associated with GCA is partial or complete vision loss affecting 1 or both eyes.3 Some patients suddenly go completely blind without any visual prodrome.

Overlapping GCA phenotypes exist, with a spectrum of presentations that include classic cranial arteritis, extracranial GCA (also called large-vessel GCA), and polymyalgia rheumatica.2

Cranial GCA, the best-characterized clinical presentation, causes symptoms such as headache or signs such as tenderness of the temporal artery. On examination, the temporal arteries may be tender or nodular, and the pulses may be felt above the zygomatic arch, above and in front of the tragus of the ear. About two-thirds of patients with cranial GCA present with new-onset headache, most often in the temporal area, but possibly anywhere throughout the head.

Visual disturbance, jaw claudication, and tongue pain are less common but, if present, increase the likelihood of this diagnosis.2

Large-vessel involvement in GCA is common and refers to involvement of the aorta and its proximal branches. Imaging methods used in diagnosing large-vessel GCA include color Doppler ultrasonography, computed tomography with angiography, magnetic resonance imaging with angiography, and positron emission tomography. In some centers, such imaging is performed in all patients diagnosed with GCA to survey for large-vessel involvement.

Depending on the imaging study, large-vessel involvement has been found in 30% to 80% of cases of GCA.4,5 It is often associated with nonspecific symptoms such as fever, weight loss, chills, and malaise, but it can also cause more specific symptoms such as unilateral extremity claudication. In contrast to patients with cranial GCA, patients with large-vessel GCA were younger at onset, less likely to have headaches, and more likely to have arm claudication at presentation.6 Aortitis of the ascending aorta can occur with a histopathologic pattern of GCA but without the clinical stigmata of GCA.

The finding of aortitis should prompt the clinician to question the patient about other symptoms of GCA and to order imaging of the whole vascular tree. Ultrasonography and biopsy of the temporal arteries can be considered. Whether idiopathic aortitis is part of the GCA spectrum remains to be seen.

Laboratory tests often show anemia, leukocytosis, and thrombocytosis. Acute-phase reactants such as C-reactive protein and the erythrocyte sedimentation rate are often elevated. The sedimentation rate often exceeds 50 mm/hour and sometimes 100 mm/hour.

In 2 retrospective studies, the number of patients with GCA whose sedimentation rate was less than 50 mm/hour ranged between 5% and 11%.7,8 However, a small percentage of patients with GCA have normal inflammatory markers. Therefore, if the suspicion for GCA is high, treatment should be started and biopsy pursued.9 In patients with paraproteinemia or other causes of a spuriously elevated or low erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein is a more reliable test.

Polymyalgia rheumatica is another rheumatologic condition that can occur independently or in conjunction with GCA. It is characterized by stiffness and pain in the proximal joints such as the hips and shoulders, typically worse in the morning and better with activity. Although the patient may subjectively feel weak, a close neurologic examination will reveal normal muscle strength.

Polymyalgia rheumatica is observed in 40% to 60% of patients with GCA at the time of diagnosis; 16% to 21% of patients with polymyalgia rheumatica may develop GCA, especially if untreated.2,10

Differential diagnosis

Other vasculitides (eg, Takayasu arteritis) can also present with unexplained fever, anemia, and constitutional symptoms.

Infection should be considered if fever is present. An infectious disease accompanied by fever, headache, and elevated inflammatory markers can mimic GCA.

Nonarteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy can present with sudden vision loss, prompting concern for underlying GCA. Risk factors include hypertension and diabetes mellitus; other features of GCA, including elevated inflammatory markers, are generally absent.

TEMPORAL ARTERY BIOPSY: THE GOLD STANDARD FOR DIAGNOSIS

Temporal artery biopsy remains the standard to confirm the diagnosis. However, because inflammation in the temporal arteries can affect some segments but not others, biopsy results on conventional hematoxylin and eosin staining can be falsely negative in patients with GCA. In one study,11 the mean sensitivity of unilateral temporal artery biopsy was 86.9%.

Typical positive histologic findings are inflammation with panarteritis, CD4-positive lymphocytes, macrophages, giant cells, and fragmentation of the internal elastic lamina.12

When GCA is suspected, treatment with glucocorticoids should be started immediately and biopsy performed as soon as possible. Delaying biopsy for 14 days or more may not affect the accuracy of biopsy study.13 Treatment should never be withheld while awaiting the results of biopsy study.

Biopsy is usually performed unilaterally, on the same side as the symptoms or abnormal findings on examination. Bilateral temporal artery biopsy is also performed and compared with unilateral biopsy; this approach increases the diagnostic yield by about 5%.14

IMAGING

In patients with suspected GCA, imaging is recommended early to complement the clinical criteria for the diagnosis of GCA.15 Positron emission tomography, computed tomography angiography, magnetic resonance angiography, or Doppler ultrasonography can reveal inflammation of the arteries in the proximal upper or lower limbs or the aorta.2

In patients with suspected cranial GCA, ultrasonography of the temporal and axillary arteries is recommended first. If ultrasonography is not available or is inconclusive, high-resolution magnetic resonance imaging of the cranial arteries can be used as an alternative. Computed tomography and positron emission tomography of the cranial arteries are not recommended.

In patients with suspected large-vessel GCA, ultrasonography, positron emission tomography, computed tomography, and magnetic resonance imaging may be used to screen for vessel wall inflammation, edema, and luminal narrowing in extracranial arteries. Ultrasonography is of limited value in assessing aortitis.

Color duplex ultrasonography can be applied to assess for vascular inflammation of the temporal or large arteries. The typical finding of the “halo” sign, a hypoechoic ring around the arterial lumen, represents the inflammation-induced thickening of the arterial wall. The “compression sign,” the persistence of the “halo” during compression of the vessel lumen by the ultrasound probe, has high specificity for the diagnosis.16

Ultrasonography of suspected GCA has yielded sensitivities of 55% to 100% and specificities of 78% to 100%. However, its sensitivity depends on the user’s level of expertise, so it should be done only in medical centers with a high number of GCA cases and with highly experienced sonographers. High-resolution magnetic resonance imaging is an alternative to ultrasonography and has shown similar sensitivity and specificity.3

TREATMENT WITH GLUCOCORTICOIDS

Glucocorticoids remain the standard for treatment of GCA. The therapeutic effect of glucocorticoids in GCA has been established by years of clinical experience, but has never been proven in a placebo-controlled trial. When started appropriately and expeditiously, glucocorticoids produce exquisite resolution of signs and symptoms and prevent the serious complication of vision loss. Rapid resolution of symptoms is so typical of GCA that if the patient’s symptoms persist more than a few days after starting a glucocorticoid, the diagnosis of GCA should be reconsidered.

In a retrospective study of 245 patients with biopsy-proven GCA treated with glucocorticoids, 34 had permanent loss of sight.17 In 32 (94%) of the 34, the vision loss occurred before glucocorticoids were started. Of the remaining 2 patients, 1 lost vision 8 days into treatment, and the other lost vision 3 years after diagnosis and 1 year after discontinuation of glucocorticoids.

In a series of 144 patients with biopsy-proven GCA, 51 had no vision loss at presentation and no vision loss after starting glucocorticoids, and 93 had vision loss at presentation. In the latter group, symptoms worsened within 5 days of starting glucocorticoids in 9 patients.18 If vision was intact at the time of presentation, prompt initiation of glucocorticoids reduced the risk of vision loss to less than 1%.

High doses, slowly tapered

The European League Against Rheumatism recommends early initiation of high-dose glucocorticoids for patients with large-vessel vasculitis,19 and it also recommends glucocorticoids for patients with polymyalgia rheumatica.20 The optimal initial and tapering dosage has never been formally evaluated, but regimens have been devised on the basis of expert opinion.21

For patients with GCA who do not have vision loss at the time of diagnosis, the initial dose is prednisone 1 mg/kg or its equivalent daily for 2 to 4 weeks, after which it is tapered.21 If the initial dosage is prednisone 60 mg orally daily for 2 to 4 weeks, our practice is to taper it to 50 mg daily for 2 weeks, then 40 mg daily for 2 weeks. Then, it is decreased by 5 mg every 2 weeks until it is 20 mg daily, and then by 2.5 mg every 2 weeks until it is 10 mg orally daily. Thereafter, the dosage is decreased by 1 mg every 2 to 4 weeks.

For patients with GCA who experience transient vision loss or diplopia at the time of diagnosis, intravenous pulse glucocorticoid therapy should be initiated to reduce the risk of vision loss as rapidly as possible.22 A typical pulse regimen is methylprednisolone 1 g intravenously daily for 3 days. Though not rigorously validated in studies, such an approach is used to avoid vision impairment due to GCA, which is rarely reversible.

RELAPSE OF DISEASE

Suspect a relapse of GCA if the patient’s initial symptoms recur, if inflammatory markers become elevated, or if classic symptoms of GCA or polymyalgia rheumatica occur. Elevations in inflammatory markers do not definitely indicate a flare of GCA, but they should trigger close monitoring of the patient’s symptoms.

Relapse is treated by increasing the glucocorticoid dosage as appropriate to the nature of the relapse. If vision is affected or the patient has symptoms of GCA, then increments of 30 to 60 mg of prednisone are warranted, whereas if the patient has symptoms of polymyalgia rheumatica, then increments of 5 to 10 mg of prednisone are usually used.

The incidence of relapses of GCA in multiple tertiary care centers has been reported to vary between 34% and 75%.23,24 Most relapses occur at prednisone dosages of less than 20 mg orally daily and within the first year after diagnosis. The most common symptoms are limb ischemia, jaw claudication, constitutional symptoms, headaches, and polymyalgia rheumatica. In a review of 286 patients,25 213 (74%) had at least 1 relapse. The first relapse occurred in the first year in 50%, by 2 years in 68%, and by 5 years in 79%.

ADVERSE EFFECTS OF GLUCOCORTICOIDS

In high doses, glucocorticoids have well-known adverse effects. In a population-based study of 120 patients, each patient treated with glucocorticoids experienced at least 1 adverse effect (cataract, fracture, infection, osteonecrosis, diabetes, hypertension, weight gain, capillary fragility, or hair loss).26 The effects were related to aging and cumulative dosage of prednisone but not to the initial dosage.

Glucocorticoids can affect many organs and systems:

- Eyes (cataracts, increased intraocular pressure, exophthalmos)

- Heart (premature atherosclerotic disease, hypertension, fluid retention, hyperlipidemia, arrhythmias)

- Gastrointestinal system (ulcer, gastrointestinal bleeding, gastritis, visceral perforation, hepatic steatosis, acute pancreatitis)

- Bone and muscle (osteopenia, osteoporosis, osteonecrosis, myopathy)

- Brain (mood disorder, psychosis, memory impairment)

- Endocrine system (hyperglycemia, hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis suppression)

- Immune system (immunosuppression, leading to infection and leukocytosis).

Patients receiving a glucocorticoid dose equivalent to 20 mg or more of prednisone daily for 1 month or more who also have another cause of immunocompromise need prophylaxis against Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia.27 They should also receive appropriate immunizations before starting glucocorticoids. Live-virus vaccines should not be given to these patients until they have been off glucocorticoids for 1 month.

Glucocorticoids and bone loss

Glucocorticoids are associated with bone loss and fracture, which can occur within the first few months of use and with dosages as low as 2.5 to 7.5 mg orally daily.28 Therefore, glucocorticoid-induced bone loss has to be treated aggressively, particularly in patients who are older and have a history of fragility fracture.

For patients with GCA who need glucocorticoids in doses greater than 5 mg orally daily for more than 3 months, the following measures are advised to decrease the risk of bone loss:

- Weight-bearing exercise

- Smoking cessation

- Moderation in alcohol intake

- Measures to prevent falls29

- Supplementation with 1,200 mg of calcium and 800 IU of vitamin D.30

Pharmacologic therapy should be initiated in men over age 50 who have established osteoporosis and in postmenopausal women with established osteoporosis or osteopenia. For men over age 50 with established osteopenia, risk assessment with the glucocorticoid-corrected FRAX score (www.sheffield.ac.uk/FRAX) should be performed to identify those at high risk in whom pharmacologic therapy is warranted.31

Bisphosphonates are the first-line therapy for glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis.32

Teriparatide is the second-line therapy and is used in patients who cannot tolerate bisphosphonates or other osteoporosis therapies, and in those who have severe osteoporosis, with T scores of –3.5 and below if they have not had a fracture, and –2.5 and below if they have had a fragility fracture.33

Denosumab, a monoclonal antibody to an osteoclast differentiating factor, may be beneficial for some patients with glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis.34

To assess the efficacy of therapy, measuring bone mineral density at baseline and at 1 year of therapy is recommended. If density is stable or improved, then repeating the measurement at 2- to 3-year intervals is suggested.

TOCILIZUMAB: A STEROID-SPARING MEDICATION

Due to the adverse effects of long-term use of glucocorticoids and high rates of relapse, there is a pressing need for medications that are more efficacious and less toxic to treat GCA.

The European League Against Rheumatism, in its 2009 management guidelines for large-vessel vasculitis, recommend using an adjunctive immunosuppressant agent.19 In the case of GCA, they recommend using methotrexate 10 to 15 mg/week, which has shown modest evidence of reducing the relapse rate and lowering the cumulative doses of glucocorticoids needed.35,36

Studies of tumor necrosis factor inhibitors and abatacept have not yielded significant reductions in the relapse rate or decreased cumulative doses of prednisone.37,38

Advances in treatment for GCA have stagnated, but recent trials39,40 have evaluated the IL-6 receptor alpha inhibitor tocilizumab, given the central role of IL-6 in the pathogenesis of GCA. Case reports have revealed rapid induction and maintenance of remission in GCA using tocilizumab.41,42

Villiger et al39 performed a randomized, placebo-controlled trial to study the efficacy and safety of tocilizumab in induction and maintenance of disease remission in 30 patients with newly diagnosed GCA. The primary outcome, complete remission at 12 weeks, was achieved in 85% of patients who received tocilizumab plus tapered prednisolone, compared with 40% of patients who received placebo plus tapering prednisolone. The tocilizumab group also had favorable results in secondary outcomes including relapse-free survival at 52 weeks, time to first relapse after induction of remission, and cumulative dose of prednisolone.

The GiACTA trial. Stone et al40 studied the effect of tocilizumab on rates of relapse during glucocorticoid tapering in 251 GCA patients over the course of 52 weeks. Patients were randomized in a 2:1:1:1 ratio to 4 treatment groups:

- Tocilizumab weekly plus prednisone, with prednisone tapered over 26 weeks

- Tocilizumab every other week plus prednisone tapered over 26 weeks

- Placebo plus prednisone tapered over 26 weeks

- Placebo plus prednisone tapered over 52 weeks.

The primary outcome was the rate of sustained glucocorticoid-free remission at 52 weeks. Secondary outcomes included the remission rate, the cumulative glucocorticoid dose, and safety measures. At 52 weeks, the rates of sustained remission were:

- 56% with tocilizumab weekly

- 53% with tocilizumab every other week

- 14% with placebo plus 26-week prednisone taper

- 18% with placebo plus 52-week taper.

Differences between the active treatment groups and the placebo groups were statistically significant (P < .001).

The cumulative dose of prednisone in tocilizumab recipients was significantly less than in placebo recipients. Rates of adverse events were similar. Ultimately, the study showed that tocilizumab, either weekly or every other week, was more effective than prednisone alone at sustaining glucocorticoid-free remission in patients with GCA.

However, the study also raised questions about tocilizumab’s toxic effect profile and its long-term efficacy, as well as who are the optimal candidates for this therapy. Data on long-term use of tocilizumab are primarily taken from its use in rheumatoid arthritis.43 As of this writing, Stone et al are conducting an open-label trial to help provide long-term safety and efficacy data in patients with GCA. In the meantime, we must extrapolate data from the long-term use of tocilizumab in rheumatoid arthritis.

Tocilizumab and lower gastrointestinal tract perforation

One of the major adverse effects of long-term use of tocilizumab is lower gastrointestinal tract perforation.

Xie et al,44 in 2016, reported that the risk of perforation in patients on tocilizumab for rheumatoid arthritis was more than 2 times higher than in patients taking a tumor necrosis factor inhibitor. However, the absolute rates of perforation were low overall, roughly 1 to 3 per 1,000 patient-years in the tocilizumab group. Risk factors for perforation included older age, history of diverticulitis or other gastrointestinal tract condition, and prednisone doses of 7.5 mg or more a day.

Does tocilizumab prevent blindness?

Another consideration is that tocilizumab may not prevent optic neuropathy. In the GiACTA trial, 1 patient in the group receiving tocilizumab every other week developed optic neuropathy.40 Prednisone had been completely tapered off at the time, and the condition resolved when glucocorticoids were restarted. Thus, it is unknown if tocilizumab would be effective on its own without concomitant use of glucocorticoids.