User login

Abaloparatide works in ‘ignored population’: Men with osteoporosis

San Diego – The anabolic osteoporosis treatment abaloparatide (Tymlos, Radius Health) works in men as well as women, new data indicate.

Findings from the Abaloparatide for the Treatment of Men With Osteoporosis (ATOM) randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 study were presented last week at the American Association of Clinical Endocrinology (AACE) Annual Meeting 2022.

Abaloparatide, a subcutaneously administered parathyroid-hormone–related protein (PTHrP) analog, resulted in significant increases in bone mineral density by 12 months at the lumbar spine, total hip, and femoral neck, compared with placebo in men with osteoporosis, with no significant adverse effects.

“Osteoporosis is underdiagnosed in men. Abaloparatide is another option for an ignored population,” presenter Neil Binkley, MD, of the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health Madison, said in an interview.

Abaloparatide was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in 2017 for the treatment of postmenopausal women at high risk for fracture due to a history of osteoporotic fracture or multiple fracture risk factors, or who haven’t responded to or are intolerant of other osteoporosis therapies.

While postmenopausal women have mainly been the focus in osteoporosis, men account for approximately 30% of the societal burden of osteoporosis and have greater fracture-related morbidity and mortality than women.

About one in four men over the age of 50 years will have a fragility fracture in their lifetime. Yet, they’re far less likely to be diagnosed or to be included in osteoporosis treatment trials, Dr. Binkley noted.

Asked to comment, session moderator Thanh D. Hoang, DO, told this news organization, “I think it’s a great option to treat osteoporosis, and now we have evidence for treating osteoporosis in men. Mostly the data have come from postmenopausal women.”

Screen men with hypogonadism or those taking steroids

“This new medication is an addition to the very limited number of treatments that we have when patients don’t respond to [initial] medications. To have another anabolic bone-forming medication is very, very good,” said Dr. Hoang, who is professor and program director of the Endocrinology Fellowship Program at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, Bethesda, Maryland.

Radius Health filed a Supplemental New Drug Application with the FDA for abaloparatide (Tymlos) subcutaneous injection in men with osteoporosis at high risk for fracture in February. There is a 10-month review period.

Dr. Binkley advises bone screening for men who have conditions such as hypogonadism or who are taking glucocorticoids or chemotherapeutics.

But, he added, “I think that if we did nothing else good in the osteoporosis field, if we treated people after they fractured that would be a huge step forward. Even with a normal T score, when those people fracture, they [often] don’t have normal bone mineral density ... That’s a group of people we’re ignoring still. They’re not getting diagnosed, and they’re not getting treated.”

ATOM Study: Significant BMD increases at key sites

The approval of abaloparatide in women was based on the phase 3, 18-week ACTIVE trial of more than 2,000 high-risk women, in whom abaloparatide was associated with an 86% reduction in vertebral fracture incidence, compared with placebo, and also significantly greater reductions in nonvertebral fractures, compared with both placebo and teriparatide (Forteo, Eli Lilly).

The ATOM study involved a total of 228 men aged 40-85 years with primary or hypogonadism-associated osteoporosis randomized 2:1 to receive subcutaneous 80 μg abaloparatide or injected placebo daily for 12 months. All had T scores (based on male reference range) of ≤ −2.5 at the lumbar spine or hip, or ≤ −1.5 and with radiologic vertebral fracture or a history of low trauma nonvertebral fracture in the past 5 years, or T score ≤ −2.0 if older than 65 years.

Increases in bone mineral density from baseline were significantly greater with abaloparatide compared with placebo at the lumbar spine, total hip, and femoral neck at 3, 6, and 12 months. Mean percentage changes at 12 months were 8.5%, 2.1%, and 3.0%, for the three locations, respectively, compared with 1.2%, 0.01%, and 0.2% for placebo (all P ≤ .0001).

Three fractures occurred in those receiving placebo and one with abaloparatide.

For markers of bone turnover, median serum procollagen type I N-terminal propeptide (s-PINP) was 111.2 ng/mL after 1 month of abaloparatide treatment and 85.7 ng/mL at month 12. Median serum carboxy-terminal cross-linking telopeptide of type I collagen (s-CTX) was 0.48 ng/mL at month 6 and 0.45 ng/mL at month 12 in the abaloparatide group. Geometric mean relative to baseline s-PINP and s-CTX increased significantly at months 3, 6, and 12 (all P < .001 for relative treatment effect of abaloparatide vs. placebo).

The most commonly reported treatment-emergent adverse events were injection site erythema (12.8% vs. 5.1%), nasopharyngitis (8.7% vs. 7.6%), dizziness (8.7% vs. 1.3%), and arthralgia (6.7% vs. 1.3%), with abaloparatide versus placebo. Serious treatment-emergent adverse event rates were similar in both groups (5.4% vs. 5.1%). There was one death in the abaloparatide group, which was deemed unrelated to the drug.

Dr. Binkley has reported receiving consulting fees from Amgen and research support from Radius. Dr. Hoang has reported disclosures with Acella Pharmaceuticals and Horizon Therapeutics (no financial compensation).

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

San Diego – The anabolic osteoporosis treatment abaloparatide (Tymlos, Radius Health) works in men as well as women, new data indicate.

Findings from the Abaloparatide for the Treatment of Men With Osteoporosis (ATOM) randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 study were presented last week at the American Association of Clinical Endocrinology (AACE) Annual Meeting 2022.

Abaloparatide, a subcutaneously administered parathyroid-hormone–related protein (PTHrP) analog, resulted in significant increases in bone mineral density by 12 months at the lumbar spine, total hip, and femoral neck, compared with placebo in men with osteoporosis, with no significant adverse effects.

“Osteoporosis is underdiagnosed in men. Abaloparatide is another option for an ignored population,” presenter Neil Binkley, MD, of the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health Madison, said in an interview.

Abaloparatide was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in 2017 for the treatment of postmenopausal women at high risk for fracture due to a history of osteoporotic fracture or multiple fracture risk factors, or who haven’t responded to or are intolerant of other osteoporosis therapies.

While postmenopausal women have mainly been the focus in osteoporosis, men account for approximately 30% of the societal burden of osteoporosis and have greater fracture-related morbidity and mortality than women.

About one in four men over the age of 50 years will have a fragility fracture in their lifetime. Yet, they’re far less likely to be diagnosed or to be included in osteoporosis treatment trials, Dr. Binkley noted.

Asked to comment, session moderator Thanh D. Hoang, DO, told this news organization, “I think it’s a great option to treat osteoporosis, and now we have evidence for treating osteoporosis in men. Mostly the data have come from postmenopausal women.”

Screen men with hypogonadism or those taking steroids

“This new medication is an addition to the very limited number of treatments that we have when patients don’t respond to [initial] medications. To have another anabolic bone-forming medication is very, very good,” said Dr. Hoang, who is professor and program director of the Endocrinology Fellowship Program at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, Bethesda, Maryland.

Radius Health filed a Supplemental New Drug Application with the FDA for abaloparatide (Tymlos) subcutaneous injection in men with osteoporosis at high risk for fracture in February. There is a 10-month review period.

Dr. Binkley advises bone screening for men who have conditions such as hypogonadism or who are taking glucocorticoids or chemotherapeutics.

But, he added, “I think that if we did nothing else good in the osteoporosis field, if we treated people after they fractured that would be a huge step forward. Even with a normal T score, when those people fracture, they [often] don’t have normal bone mineral density ... That’s a group of people we’re ignoring still. They’re not getting diagnosed, and they’re not getting treated.”

ATOM Study: Significant BMD increases at key sites

The approval of abaloparatide in women was based on the phase 3, 18-week ACTIVE trial of more than 2,000 high-risk women, in whom abaloparatide was associated with an 86% reduction in vertebral fracture incidence, compared with placebo, and also significantly greater reductions in nonvertebral fractures, compared with both placebo and teriparatide (Forteo, Eli Lilly).

The ATOM study involved a total of 228 men aged 40-85 years with primary or hypogonadism-associated osteoporosis randomized 2:1 to receive subcutaneous 80 μg abaloparatide or injected placebo daily for 12 months. All had T scores (based on male reference range) of ≤ −2.5 at the lumbar spine or hip, or ≤ −1.5 and with radiologic vertebral fracture or a history of low trauma nonvertebral fracture in the past 5 years, or T score ≤ −2.0 if older than 65 years.

Increases in bone mineral density from baseline were significantly greater with abaloparatide compared with placebo at the lumbar spine, total hip, and femoral neck at 3, 6, and 12 months. Mean percentage changes at 12 months were 8.5%, 2.1%, and 3.0%, for the three locations, respectively, compared with 1.2%, 0.01%, and 0.2% for placebo (all P ≤ .0001).

Three fractures occurred in those receiving placebo and one with abaloparatide.

For markers of bone turnover, median serum procollagen type I N-terminal propeptide (s-PINP) was 111.2 ng/mL after 1 month of abaloparatide treatment and 85.7 ng/mL at month 12. Median serum carboxy-terminal cross-linking telopeptide of type I collagen (s-CTX) was 0.48 ng/mL at month 6 and 0.45 ng/mL at month 12 in the abaloparatide group. Geometric mean relative to baseline s-PINP and s-CTX increased significantly at months 3, 6, and 12 (all P < .001 for relative treatment effect of abaloparatide vs. placebo).

The most commonly reported treatment-emergent adverse events were injection site erythema (12.8% vs. 5.1%), nasopharyngitis (8.7% vs. 7.6%), dizziness (8.7% vs. 1.3%), and arthralgia (6.7% vs. 1.3%), with abaloparatide versus placebo. Serious treatment-emergent adverse event rates were similar in both groups (5.4% vs. 5.1%). There was one death in the abaloparatide group, which was deemed unrelated to the drug.

Dr. Binkley has reported receiving consulting fees from Amgen and research support from Radius. Dr. Hoang has reported disclosures with Acella Pharmaceuticals and Horizon Therapeutics (no financial compensation).

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

San Diego – The anabolic osteoporosis treatment abaloparatide (Tymlos, Radius Health) works in men as well as women, new data indicate.

Findings from the Abaloparatide for the Treatment of Men With Osteoporosis (ATOM) randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 study were presented last week at the American Association of Clinical Endocrinology (AACE) Annual Meeting 2022.

Abaloparatide, a subcutaneously administered parathyroid-hormone–related protein (PTHrP) analog, resulted in significant increases in bone mineral density by 12 months at the lumbar spine, total hip, and femoral neck, compared with placebo in men with osteoporosis, with no significant adverse effects.

“Osteoporosis is underdiagnosed in men. Abaloparatide is another option for an ignored population,” presenter Neil Binkley, MD, of the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health Madison, said in an interview.

Abaloparatide was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in 2017 for the treatment of postmenopausal women at high risk for fracture due to a history of osteoporotic fracture or multiple fracture risk factors, or who haven’t responded to or are intolerant of other osteoporosis therapies.

While postmenopausal women have mainly been the focus in osteoporosis, men account for approximately 30% of the societal burden of osteoporosis and have greater fracture-related morbidity and mortality than women.

About one in four men over the age of 50 years will have a fragility fracture in their lifetime. Yet, they’re far less likely to be diagnosed or to be included in osteoporosis treatment trials, Dr. Binkley noted.

Asked to comment, session moderator Thanh D. Hoang, DO, told this news organization, “I think it’s a great option to treat osteoporosis, and now we have evidence for treating osteoporosis in men. Mostly the data have come from postmenopausal women.”

Screen men with hypogonadism or those taking steroids

“This new medication is an addition to the very limited number of treatments that we have when patients don’t respond to [initial] medications. To have another anabolic bone-forming medication is very, very good,” said Dr. Hoang, who is professor and program director of the Endocrinology Fellowship Program at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, Bethesda, Maryland.

Radius Health filed a Supplemental New Drug Application with the FDA for abaloparatide (Tymlos) subcutaneous injection in men with osteoporosis at high risk for fracture in February. There is a 10-month review period.

Dr. Binkley advises bone screening for men who have conditions such as hypogonadism or who are taking glucocorticoids or chemotherapeutics.

But, he added, “I think that if we did nothing else good in the osteoporosis field, if we treated people after they fractured that would be a huge step forward. Even with a normal T score, when those people fracture, they [often] don’t have normal bone mineral density ... That’s a group of people we’re ignoring still. They’re not getting diagnosed, and they’re not getting treated.”

ATOM Study: Significant BMD increases at key sites

The approval of abaloparatide in women was based on the phase 3, 18-week ACTIVE trial of more than 2,000 high-risk women, in whom abaloparatide was associated with an 86% reduction in vertebral fracture incidence, compared with placebo, and also significantly greater reductions in nonvertebral fractures, compared with both placebo and teriparatide (Forteo, Eli Lilly).

The ATOM study involved a total of 228 men aged 40-85 years with primary or hypogonadism-associated osteoporosis randomized 2:1 to receive subcutaneous 80 μg abaloparatide or injected placebo daily for 12 months. All had T scores (based on male reference range) of ≤ −2.5 at the lumbar spine or hip, or ≤ −1.5 and with radiologic vertebral fracture or a history of low trauma nonvertebral fracture in the past 5 years, or T score ≤ −2.0 if older than 65 years.

Increases in bone mineral density from baseline were significantly greater with abaloparatide compared with placebo at the lumbar spine, total hip, and femoral neck at 3, 6, and 12 months. Mean percentage changes at 12 months were 8.5%, 2.1%, and 3.0%, for the three locations, respectively, compared with 1.2%, 0.01%, and 0.2% for placebo (all P ≤ .0001).

Three fractures occurred in those receiving placebo and one with abaloparatide.

For markers of bone turnover, median serum procollagen type I N-terminal propeptide (s-PINP) was 111.2 ng/mL after 1 month of abaloparatide treatment and 85.7 ng/mL at month 12. Median serum carboxy-terminal cross-linking telopeptide of type I collagen (s-CTX) was 0.48 ng/mL at month 6 and 0.45 ng/mL at month 12 in the abaloparatide group. Geometric mean relative to baseline s-PINP and s-CTX increased significantly at months 3, 6, and 12 (all P < .001 for relative treatment effect of abaloparatide vs. placebo).

The most commonly reported treatment-emergent adverse events were injection site erythema (12.8% vs. 5.1%), nasopharyngitis (8.7% vs. 7.6%), dizziness (8.7% vs. 1.3%), and arthralgia (6.7% vs. 1.3%), with abaloparatide versus placebo. Serious treatment-emergent adverse event rates were similar in both groups (5.4% vs. 5.1%). There was one death in the abaloparatide group, which was deemed unrelated to the drug.

Dr. Binkley has reported receiving consulting fees from Amgen and research support from Radius. Dr. Hoang has reported disclosures with Acella Pharmaceuticals and Horizon Therapeutics (no financial compensation).

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

AT AACE 2022

Study casts doubt on safety, efficacy of L-serine supplementation for AD

When given to patients with AD, L-serine supplements could be driving abnormally increased serine levels in the brain even higher, potentially accelerating neuronal death, according to study author Xu Chen, PhD, of the University of California, San Diego, and colleagues.

This conclusion conflicts with a 2020 study by Juliette Le Douce, PhD, and colleagues, who reported that oral L-serine supplementation may act as a “ready-to-use therapy” for AD, based on their findings that patients with AD had low levels of PHGDH, an enzyme necessary for synthesizing serine, and AD-like mice had low levels of serine.

Writing in Cell Metabolism, Dr. Chen and colleagues framed the present study, and their findings, in this context.

“In contrast to the work of Le Douce et al., here we report that PHGDH mRNA and protein levels are increased in the brains of two mouse models of AD and/or tauopathy, and are also progressively increased in human brains with no, early, and late AD pathology, as well as in people with no, asymptomatic, and symptomatic AD,” they wrote.

They suggested adjusting clinical recommendations for L-serine, the form of the amino acid commonly found in supplements. In the body, L-serine is converted to D-serine, which acts on the NMDA receptor (NMDAR).

‘Long-term use of D-serine contributes to neuronal death’ suggests research

“We feel oral L-serine as a ready-to-use therapy to AD warrants precaution,” Dr. Chen and colleagues wrote. “This is because despite being a cognitive enhancer, some [research] suggests that long-term use of D-serine contributes to neuronal death in AD through excitotoxicity. Furthermore, D-serine, as a co-agonist of NMDAR, would be expected to oppose NMDAR antagonists, which have proven clinical benefits in treating AD.”

According to principal author Sheng Zhong, PhD, of the University of California, San Diego, “Research is needed to test if targeting PHGDH can ameliorate cognitive decline in AD.”

Dr. Zhong also noted that the present findings support the “promise of using a specific RNA in blood as a biomarker for early detection of Alzheimer’s disease.” This approach is currently being validated at UCSD Shiley-Marcos Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center, he added.

Roles of PHGDH and serine in Alzheimer’s disease require further study

Commenting on both studies, Steve W. Barger, PhD, of the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, Little Rock, suggested that more work is needed to better understand the roles of PHGDH and serine in AD before clinical applications can be considered.

“In the end, these two studies fail to provide the clarity we need in designing evidence-based therapeutic hypotheses,” Dr. Barger said in an interview. “We still do not have a firm grasp on the role that D-serine plays in AD. Indeed, the evidence regarding even a single enzyme contributing to its levels is ambiguous.”

Dr. Barger, who has published extensively on the topic of neuronal death, with a particular focus on Alzheimer’s disease, noted that “determination of what happens to D-serine levels in AD has been of interest for decades,” but levels of the amino acid have been notoriously challenging to measure because “D-serine can disappear rapidly from the brain and its fluids after death.”

While Dr. Le Douce and colleagues did measure levels of serine in mice, Dr. Barger noted that the study by Dr. Chen and colleagues was conducted with more “quantitatively rigorous methods.” Even though Dr. Chen and colleagues “did not assay the levels of D-serine itself ... the implication of their findings is that PHGDH is poised to elevate this critical neurotransmitter,” leading to their conclusion that serine supplementation is “potentially dangerous.”

At this point, it may be too early to tell, according to Dr. Barger.

He suggested that conclusions drawn from PHGDH levels alone are “always limited,” and conclusions based on serine levels may be equally dubious, considering that the activities and effects of serine “are quite complex,” and may be influenced by other physiologic processes, including the effects of gut bacteria.

Instead, Dr. Barger suggested that changes in PHGDH and serine may be interpreted as signals coming from a more relevant process upstream: glucose metabolism.

“What we can say confidently is that the glucose metabolism that PHGDH connects to D-serine is most definitely a factor in AD,” he said. “Countless studies have documented what now appears to be a universal decline in glucose delivery to the cerebral cortex, even before frank dementia sets in.”

Dr. Barger noted that declining glucose delivery coincides with some of the earliest events in the development of AD, perhaps “linking accumulation of amyloid β-peptide to subsequent neurofibrillary tangles and tissue atrophy.”

Dr. Barger’s own work recently demonstrated that AD is associated with “an irregularity in the insertion of a specific glucose transporter (GLUT1) into the cell surface” of astrocytes.

“It could be more effective to direct therapeutic interventions at these events lying upstream of PHGDH or serine,” he concluded.

The study was partly supported by a Kreuger v. Wyeth research award. The investigators and Dr. Barger reported no conflicts of interest.

When given to patients with AD, L-serine supplements could be driving abnormally increased serine levels in the brain even higher, potentially accelerating neuronal death, according to study author Xu Chen, PhD, of the University of California, San Diego, and colleagues.

This conclusion conflicts with a 2020 study by Juliette Le Douce, PhD, and colleagues, who reported that oral L-serine supplementation may act as a “ready-to-use therapy” for AD, based on their findings that patients with AD had low levels of PHGDH, an enzyme necessary for synthesizing serine, and AD-like mice had low levels of serine.

Writing in Cell Metabolism, Dr. Chen and colleagues framed the present study, and their findings, in this context.

“In contrast to the work of Le Douce et al., here we report that PHGDH mRNA and protein levels are increased in the brains of two mouse models of AD and/or tauopathy, and are also progressively increased in human brains with no, early, and late AD pathology, as well as in people with no, asymptomatic, and symptomatic AD,” they wrote.

They suggested adjusting clinical recommendations for L-serine, the form of the amino acid commonly found in supplements. In the body, L-serine is converted to D-serine, which acts on the NMDA receptor (NMDAR).

‘Long-term use of D-serine contributes to neuronal death’ suggests research

“We feel oral L-serine as a ready-to-use therapy to AD warrants precaution,” Dr. Chen and colleagues wrote. “This is because despite being a cognitive enhancer, some [research] suggests that long-term use of D-serine contributes to neuronal death in AD through excitotoxicity. Furthermore, D-serine, as a co-agonist of NMDAR, would be expected to oppose NMDAR antagonists, which have proven clinical benefits in treating AD.”

According to principal author Sheng Zhong, PhD, of the University of California, San Diego, “Research is needed to test if targeting PHGDH can ameliorate cognitive decline in AD.”

Dr. Zhong also noted that the present findings support the “promise of using a specific RNA in blood as a biomarker for early detection of Alzheimer’s disease.” This approach is currently being validated at UCSD Shiley-Marcos Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center, he added.

Roles of PHGDH and serine in Alzheimer’s disease require further study

Commenting on both studies, Steve W. Barger, PhD, of the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, Little Rock, suggested that more work is needed to better understand the roles of PHGDH and serine in AD before clinical applications can be considered.

“In the end, these two studies fail to provide the clarity we need in designing evidence-based therapeutic hypotheses,” Dr. Barger said in an interview. “We still do not have a firm grasp on the role that D-serine plays in AD. Indeed, the evidence regarding even a single enzyme contributing to its levels is ambiguous.”

Dr. Barger, who has published extensively on the topic of neuronal death, with a particular focus on Alzheimer’s disease, noted that “determination of what happens to D-serine levels in AD has been of interest for decades,” but levels of the amino acid have been notoriously challenging to measure because “D-serine can disappear rapidly from the brain and its fluids after death.”

While Dr. Le Douce and colleagues did measure levels of serine in mice, Dr. Barger noted that the study by Dr. Chen and colleagues was conducted with more “quantitatively rigorous methods.” Even though Dr. Chen and colleagues “did not assay the levels of D-serine itself ... the implication of their findings is that PHGDH is poised to elevate this critical neurotransmitter,” leading to their conclusion that serine supplementation is “potentially dangerous.”

At this point, it may be too early to tell, according to Dr. Barger.

He suggested that conclusions drawn from PHGDH levels alone are “always limited,” and conclusions based on serine levels may be equally dubious, considering that the activities and effects of serine “are quite complex,” and may be influenced by other physiologic processes, including the effects of gut bacteria.

Instead, Dr. Barger suggested that changes in PHGDH and serine may be interpreted as signals coming from a more relevant process upstream: glucose metabolism.

“What we can say confidently is that the glucose metabolism that PHGDH connects to D-serine is most definitely a factor in AD,” he said. “Countless studies have documented what now appears to be a universal decline in glucose delivery to the cerebral cortex, even before frank dementia sets in.”

Dr. Barger noted that declining glucose delivery coincides with some of the earliest events in the development of AD, perhaps “linking accumulation of amyloid β-peptide to subsequent neurofibrillary tangles and tissue atrophy.”

Dr. Barger’s own work recently demonstrated that AD is associated with “an irregularity in the insertion of a specific glucose transporter (GLUT1) into the cell surface” of astrocytes.

“It could be more effective to direct therapeutic interventions at these events lying upstream of PHGDH or serine,” he concluded.

The study was partly supported by a Kreuger v. Wyeth research award. The investigators and Dr. Barger reported no conflicts of interest.

When given to patients with AD, L-serine supplements could be driving abnormally increased serine levels in the brain even higher, potentially accelerating neuronal death, according to study author Xu Chen, PhD, of the University of California, San Diego, and colleagues.

This conclusion conflicts with a 2020 study by Juliette Le Douce, PhD, and colleagues, who reported that oral L-serine supplementation may act as a “ready-to-use therapy” for AD, based on their findings that patients with AD had low levels of PHGDH, an enzyme necessary for synthesizing serine, and AD-like mice had low levels of serine.

Writing in Cell Metabolism, Dr. Chen and colleagues framed the present study, and their findings, in this context.

“In contrast to the work of Le Douce et al., here we report that PHGDH mRNA and protein levels are increased in the brains of two mouse models of AD and/or tauopathy, and are also progressively increased in human brains with no, early, and late AD pathology, as well as in people with no, asymptomatic, and symptomatic AD,” they wrote.

They suggested adjusting clinical recommendations for L-serine, the form of the amino acid commonly found in supplements. In the body, L-serine is converted to D-serine, which acts on the NMDA receptor (NMDAR).

‘Long-term use of D-serine contributes to neuronal death’ suggests research

“We feel oral L-serine as a ready-to-use therapy to AD warrants precaution,” Dr. Chen and colleagues wrote. “This is because despite being a cognitive enhancer, some [research] suggests that long-term use of D-serine contributes to neuronal death in AD through excitotoxicity. Furthermore, D-serine, as a co-agonist of NMDAR, would be expected to oppose NMDAR antagonists, which have proven clinical benefits in treating AD.”

According to principal author Sheng Zhong, PhD, of the University of California, San Diego, “Research is needed to test if targeting PHGDH can ameliorate cognitive decline in AD.”

Dr. Zhong also noted that the present findings support the “promise of using a specific RNA in blood as a biomarker for early detection of Alzheimer’s disease.” This approach is currently being validated at UCSD Shiley-Marcos Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center, he added.

Roles of PHGDH and serine in Alzheimer’s disease require further study

Commenting on both studies, Steve W. Barger, PhD, of the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, Little Rock, suggested that more work is needed to better understand the roles of PHGDH and serine in AD before clinical applications can be considered.

“In the end, these two studies fail to provide the clarity we need in designing evidence-based therapeutic hypotheses,” Dr. Barger said in an interview. “We still do not have a firm grasp on the role that D-serine plays in AD. Indeed, the evidence regarding even a single enzyme contributing to its levels is ambiguous.”

Dr. Barger, who has published extensively on the topic of neuronal death, with a particular focus on Alzheimer’s disease, noted that “determination of what happens to D-serine levels in AD has been of interest for decades,” but levels of the amino acid have been notoriously challenging to measure because “D-serine can disappear rapidly from the brain and its fluids after death.”

While Dr. Le Douce and colleagues did measure levels of serine in mice, Dr. Barger noted that the study by Dr. Chen and colleagues was conducted with more “quantitatively rigorous methods.” Even though Dr. Chen and colleagues “did not assay the levels of D-serine itself ... the implication of their findings is that PHGDH is poised to elevate this critical neurotransmitter,” leading to their conclusion that serine supplementation is “potentially dangerous.”

At this point, it may be too early to tell, according to Dr. Barger.

He suggested that conclusions drawn from PHGDH levels alone are “always limited,” and conclusions based on serine levels may be equally dubious, considering that the activities and effects of serine “are quite complex,” and may be influenced by other physiologic processes, including the effects of gut bacteria.

Instead, Dr. Barger suggested that changes in PHGDH and serine may be interpreted as signals coming from a more relevant process upstream: glucose metabolism.

“What we can say confidently is that the glucose metabolism that PHGDH connects to D-serine is most definitely a factor in AD,” he said. “Countless studies have documented what now appears to be a universal decline in glucose delivery to the cerebral cortex, even before frank dementia sets in.”

Dr. Barger noted that declining glucose delivery coincides with some of the earliest events in the development of AD, perhaps “linking accumulation of amyloid β-peptide to subsequent neurofibrillary tangles and tissue atrophy.”

Dr. Barger’s own work recently demonstrated that AD is associated with “an irregularity in the insertion of a specific glucose transporter (GLUT1) into the cell surface” of astrocytes.

“It could be more effective to direct therapeutic interventions at these events lying upstream of PHGDH or serine,” he concluded.

The study was partly supported by a Kreuger v. Wyeth research award. The investigators and Dr. Barger reported no conflicts of interest.

FROM CELL METABOLISM

Higher industriousness reduces risk of predementia syndrome in older adults

Higher industriousness was associated with a 25% reduced risk of concurrent motoric cognitive risk syndrome (MCR), based on data from approximately 6,000 individuals.

Previous research supports an association between conscientiousness and a lower risk of MCR, a form of predementia that involves slow gait speed and cognitive complaints, wrote Yannick Stephan, PhD, of the University of Montpellier (France), and colleagues. However, the specific facets of conscientiousness that impact MCR have not been examined.

In a study published in the Journal of Psychiatric Research, the authors reviewed data from 6,001 dementia-free adults aged 65-99 years who were enrolled in the Health and Retirement Study, a nationally representative longitudinal study of adults aged 50 years and older in the United States.

Baseline data were collected between 2008 and 2010, and participants were assessed for MCR at follow-up points during 2012-2014 and 2016-2018. Six facets of conscientiousness were assessed using a 24-item scale that has been used in previous studies. The six facets were industriousness, self-control, order, traditionalism, virtue, and responsibility. The researchers controlled for variables including demographic factors, cognition, physical activity, disease burden, depressive symptoms, and body mass index.

Overall, increased industriousness was significantly associated with a lower likelihood of concurrent MCR (odds ratio, 0.75) and a reduced risk of incident MCR (hazard ratio, 0.63,; P < .001 for both).

The conscientiousness facets of order, self-control, and responsibility also were associated with a lower likelihood of both concurrent and incident MCR, with ORs ranging from 0.82-0.88 for concurrent and HRs ranging from 0.72-0.82 for incident.

Traditionalism and virtue were significantly associated with a lower risk of incident MCR, but not concurrent MCR (HR, 0.84; P < .01 for both).

The mechanism of action for the association may be explained by several cognitive, health-related, behavioral, and psychological pathways, the researchers wrote. With regard to industriousness, the relationship could be partly explained by cognition, physical activity, disease burden, BMI, and depressive symptoms. However, industriousness also has been associated with a reduced risk of systemic inflammation, which may in turn reduce MCR risk. Also, data suggest that industriousness and MCR share a common genetic cause.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the observational design and the positive selection effect from patients with complete follow-up data, as these patients likely have higher levels of order, industriousness, and responsibility, the researchers noted. However, the results support those from previous studies and were strengthened by the large sample and examination of six facets of conscientiousness.

“This study thus provides a more detailed understanding of the specific components of conscientiousness that are associated with risk of MCR among older adults,” and the facets could be targeted in interventions to reduce both MCR and dementia, they concluded.

The Health and Retirement Study is supported by the National Institute on Aging and conducted by the University of Michigan. The current study was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Higher industriousness was associated with a 25% reduced risk of concurrent motoric cognitive risk syndrome (MCR), based on data from approximately 6,000 individuals.

Previous research supports an association between conscientiousness and a lower risk of MCR, a form of predementia that involves slow gait speed and cognitive complaints, wrote Yannick Stephan, PhD, of the University of Montpellier (France), and colleagues. However, the specific facets of conscientiousness that impact MCR have not been examined.

In a study published in the Journal of Psychiatric Research, the authors reviewed data from 6,001 dementia-free adults aged 65-99 years who were enrolled in the Health and Retirement Study, a nationally representative longitudinal study of adults aged 50 years and older in the United States.

Baseline data were collected between 2008 and 2010, and participants were assessed for MCR at follow-up points during 2012-2014 and 2016-2018. Six facets of conscientiousness were assessed using a 24-item scale that has been used in previous studies. The six facets were industriousness, self-control, order, traditionalism, virtue, and responsibility. The researchers controlled for variables including demographic factors, cognition, physical activity, disease burden, depressive symptoms, and body mass index.

Overall, increased industriousness was significantly associated with a lower likelihood of concurrent MCR (odds ratio, 0.75) and a reduced risk of incident MCR (hazard ratio, 0.63,; P < .001 for both).

The conscientiousness facets of order, self-control, and responsibility also were associated with a lower likelihood of both concurrent and incident MCR, with ORs ranging from 0.82-0.88 for concurrent and HRs ranging from 0.72-0.82 for incident.

Traditionalism and virtue were significantly associated with a lower risk of incident MCR, but not concurrent MCR (HR, 0.84; P < .01 for both).

The mechanism of action for the association may be explained by several cognitive, health-related, behavioral, and psychological pathways, the researchers wrote. With regard to industriousness, the relationship could be partly explained by cognition, physical activity, disease burden, BMI, and depressive symptoms. However, industriousness also has been associated with a reduced risk of systemic inflammation, which may in turn reduce MCR risk. Also, data suggest that industriousness and MCR share a common genetic cause.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the observational design and the positive selection effect from patients with complete follow-up data, as these patients likely have higher levels of order, industriousness, and responsibility, the researchers noted. However, the results support those from previous studies and were strengthened by the large sample and examination of six facets of conscientiousness.

“This study thus provides a more detailed understanding of the specific components of conscientiousness that are associated with risk of MCR among older adults,” and the facets could be targeted in interventions to reduce both MCR and dementia, they concluded.

The Health and Retirement Study is supported by the National Institute on Aging and conducted by the University of Michigan. The current study was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Higher industriousness was associated with a 25% reduced risk of concurrent motoric cognitive risk syndrome (MCR), based on data from approximately 6,000 individuals.

Previous research supports an association between conscientiousness and a lower risk of MCR, a form of predementia that involves slow gait speed and cognitive complaints, wrote Yannick Stephan, PhD, of the University of Montpellier (France), and colleagues. However, the specific facets of conscientiousness that impact MCR have not been examined.

In a study published in the Journal of Psychiatric Research, the authors reviewed data from 6,001 dementia-free adults aged 65-99 years who were enrolled in the Health and Retirement Study, a nationally representative longitudinal study of adults aged 50 years and older in the United States.

Baseline data were collected between 2008 and 2010, and participants were assessed for MCR at follow-up points during 2012-2014 and 2016-2018. Six facets of conscientiousness were assessed using a 24-item scale that has been used in previous studies. The six facets were industriousness, self-control, order, traditionalism, virtue, and responsibility. The researchers controlled for variables including demographic factors, cognition, physical activity, disease burden, depressive symptoms, and body mass index.

Overall, increased industriousness was significantly associated with a lower likelihood of concurrent MCR (odds ratio, 0.75) and a reduced risk of incident MCR (hazard ratio, 0.63,; P < .001 for both).

The conscientiousness facets of order, self-control, and responsibility also were associated with a lower likelihood of both concurrent and incident MCR, with ORs ranging from 0.82-0.88 for concurrent and HRs ranging from 0.72-0.82 for incident.

Traditionalism and virtue were significantly associated with a lower risk of incident MCR, but not concurrent MCR (HR, 0.84; P < .01 for both).

The mechanism of action for the association may be explained by several cognitive, health-related, behavioral, and psychological pathways, the researchers wrote. With regard to industriousness, the relationship could be partly explained by cognition, physical activity, disease burden, BMI, and depressive symptoms. However, industriousness also has been associated with a reduced risk of systemic inflammation, which may in turn reduce MCR risk. Also, data suggest that industriousness and MCR share a common genetic cause.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the observational design and the positive selection effect from patients with complete follow-up data, as these patients likely have higher levels of order, industriousness, and responsibility, the researchers noted. However, the results support those from previous studies and were strengthened by the large sample and examination of six facets of conscientiousness.

“This study thus provides a more detailed understanding of the specific components of conscientiousness that are associated with risk of MCR among older adults,” and the facets could be targeted in interventions to reduce both MCR and dementia, they concluded.

The Health and Retirement Study is supported by the National Institute on Aging and conducted by the University of Michigan. The current study was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

FROM PSYCHIATRIC RESEARCH

Atypical knee pain

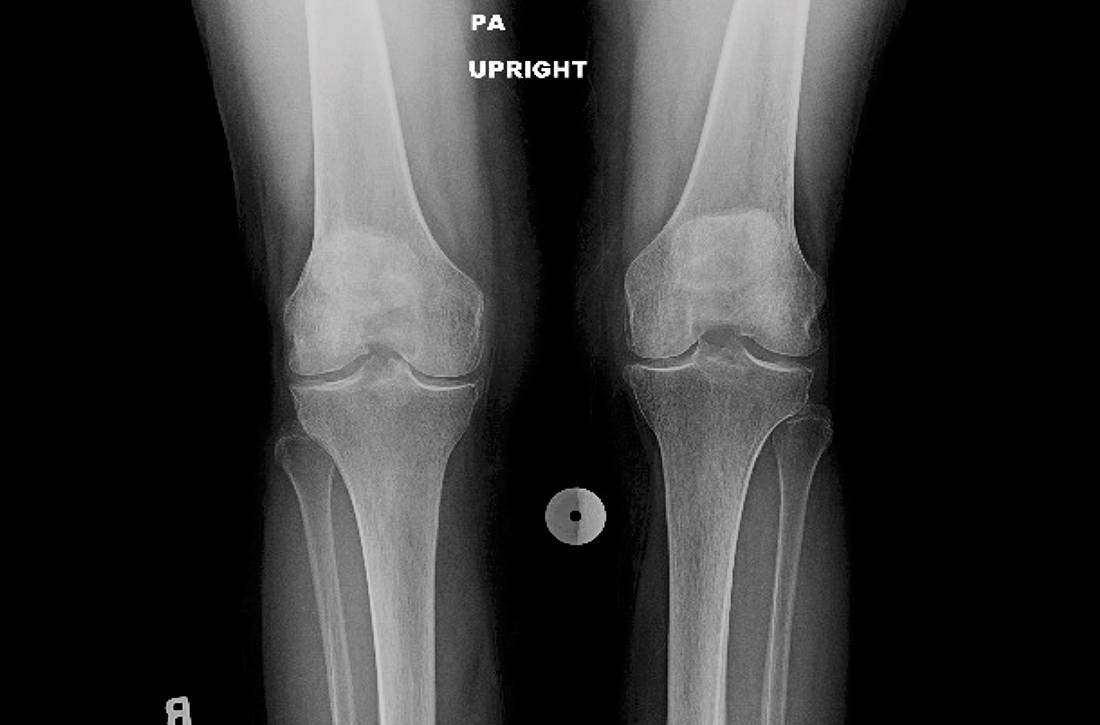

An 83-year-old woman, with an otherwise noncontributory past medical history, presented with chronic right knee pain. Over the prior 4 years, she had undergone evaluation by an outside physician and received several corticosteroid and hyaluronic acid intra-articular injections, without symptom resolution. She described the pain as a 4/10 at rest and as “severe” when climbing stairs and exercising. The pain was localized to her lower back and right groin and extended to her right knee. She also said that she found it difficult to put on her socks. An outside orthopedic surgeon recommended right total knee arthroplasty, prompting her to seek a second opinion.

Examination of her right knee was unrevealing. However, during the hip examination, there was a pronounced loss of range of motion and concordant pain reproduction with the FABER (combined flexion, abduction, external rotation) and FADIR (combined flexion, adduction, and internal rotation) maneuvers.

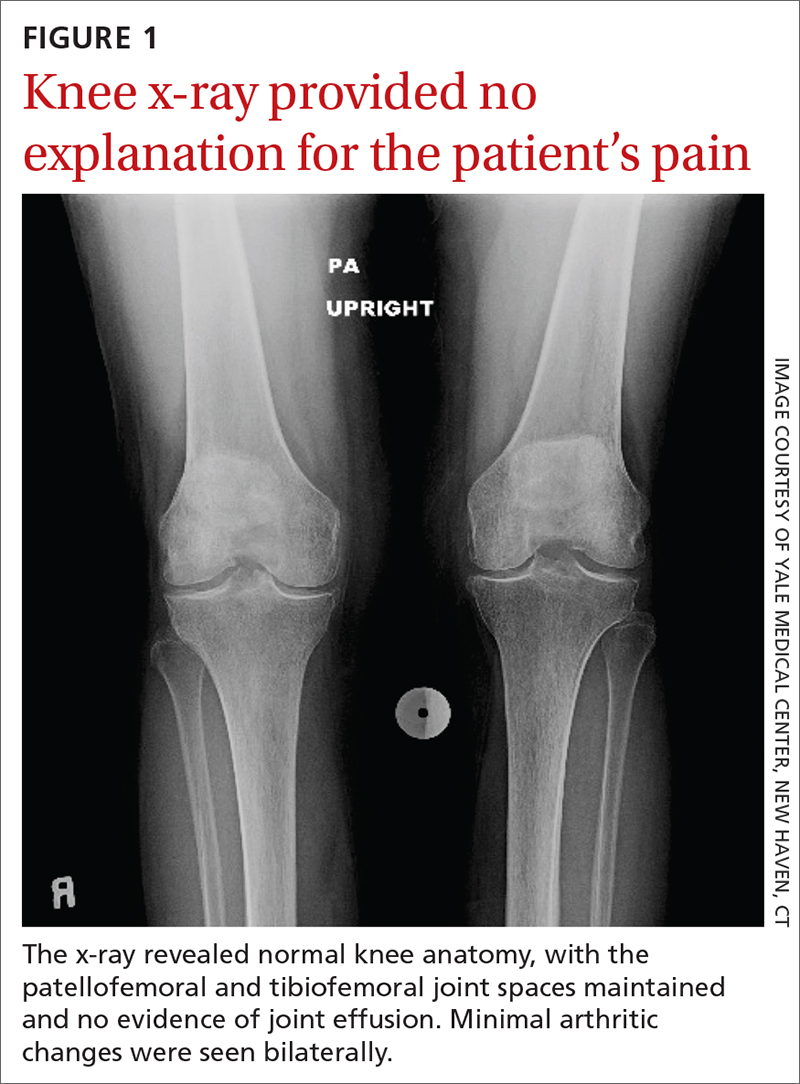

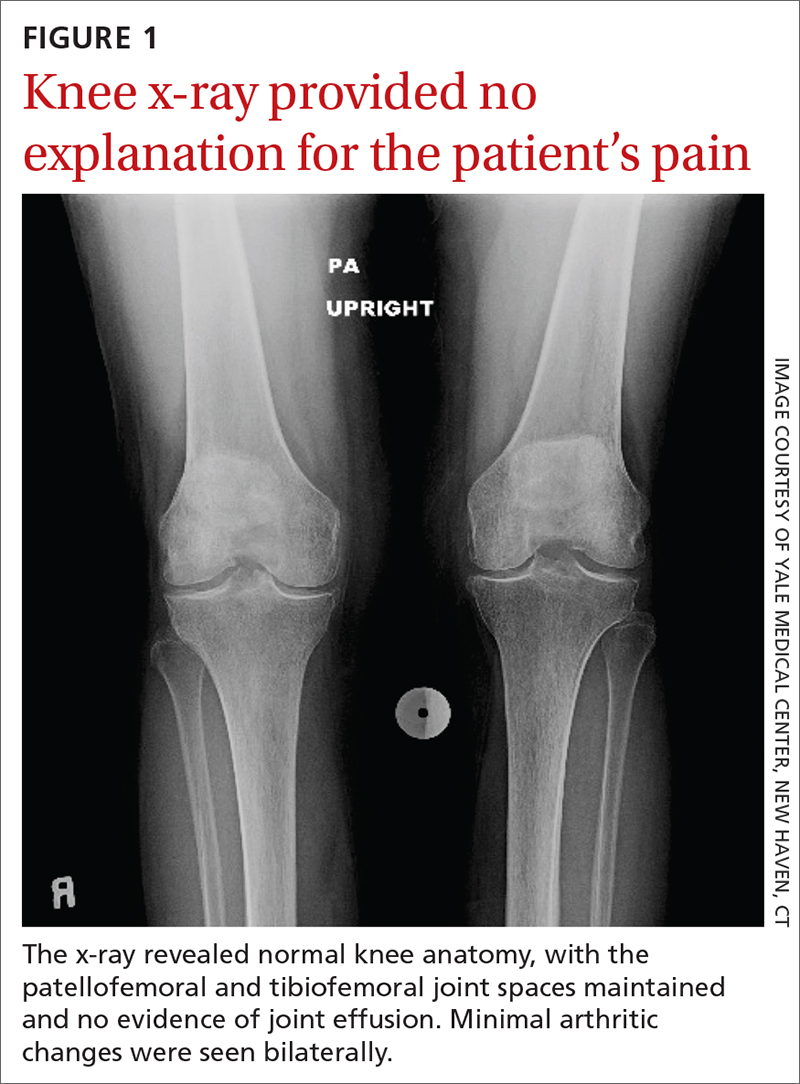

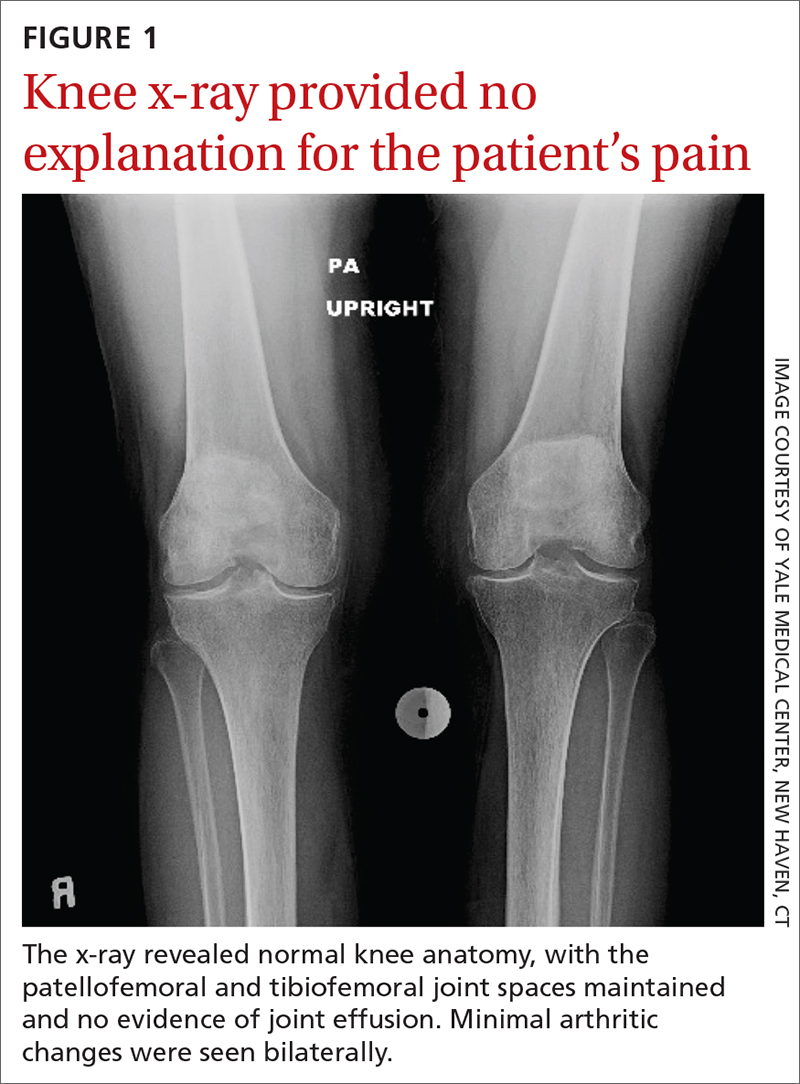

The patient’s extensive clinical and diagnostic history, combined with benign knee examination and imaging (FIGURE 1), ruled out isolated knee pathology.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Dx: Right hip OA with referred knee pain

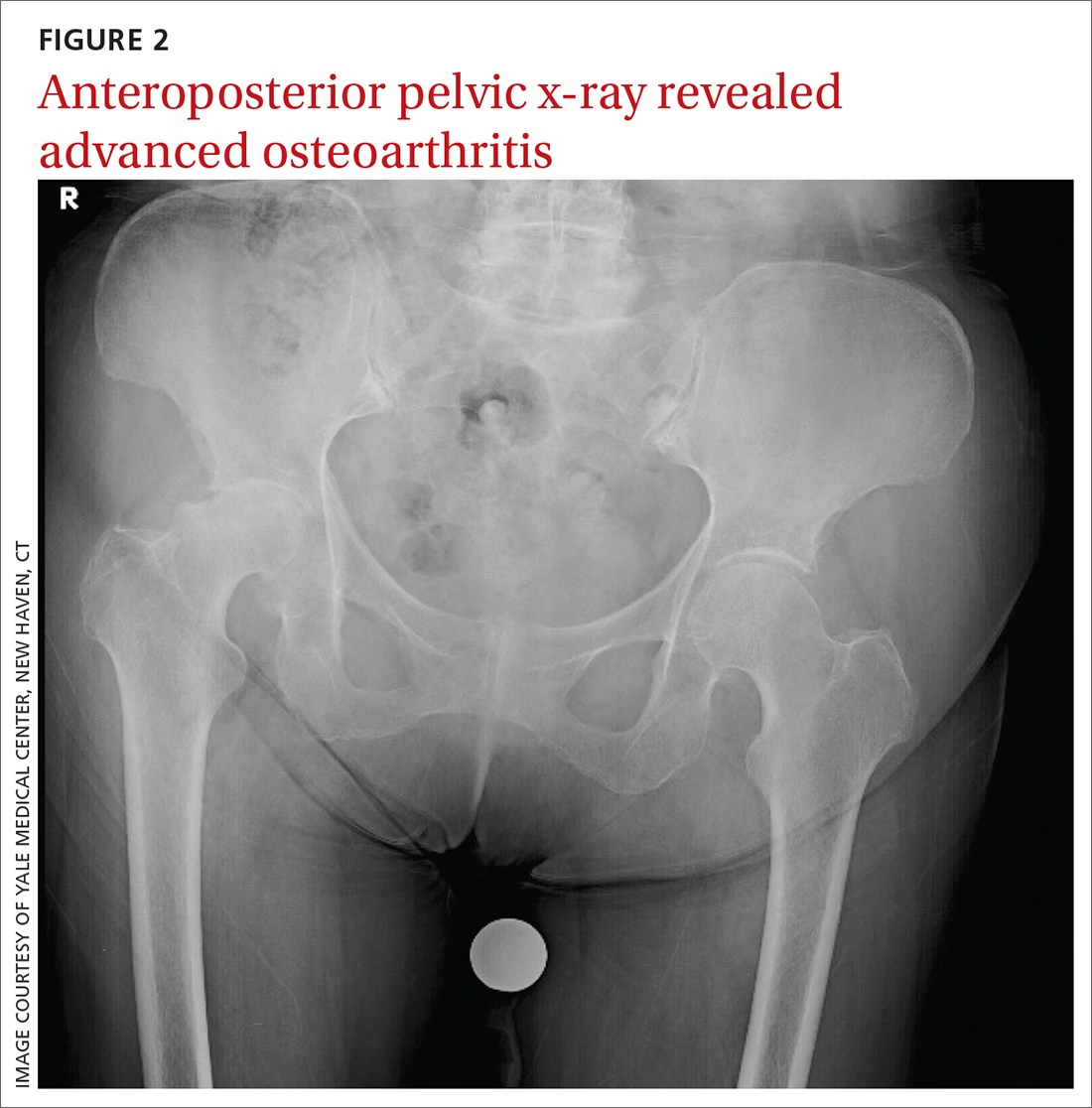

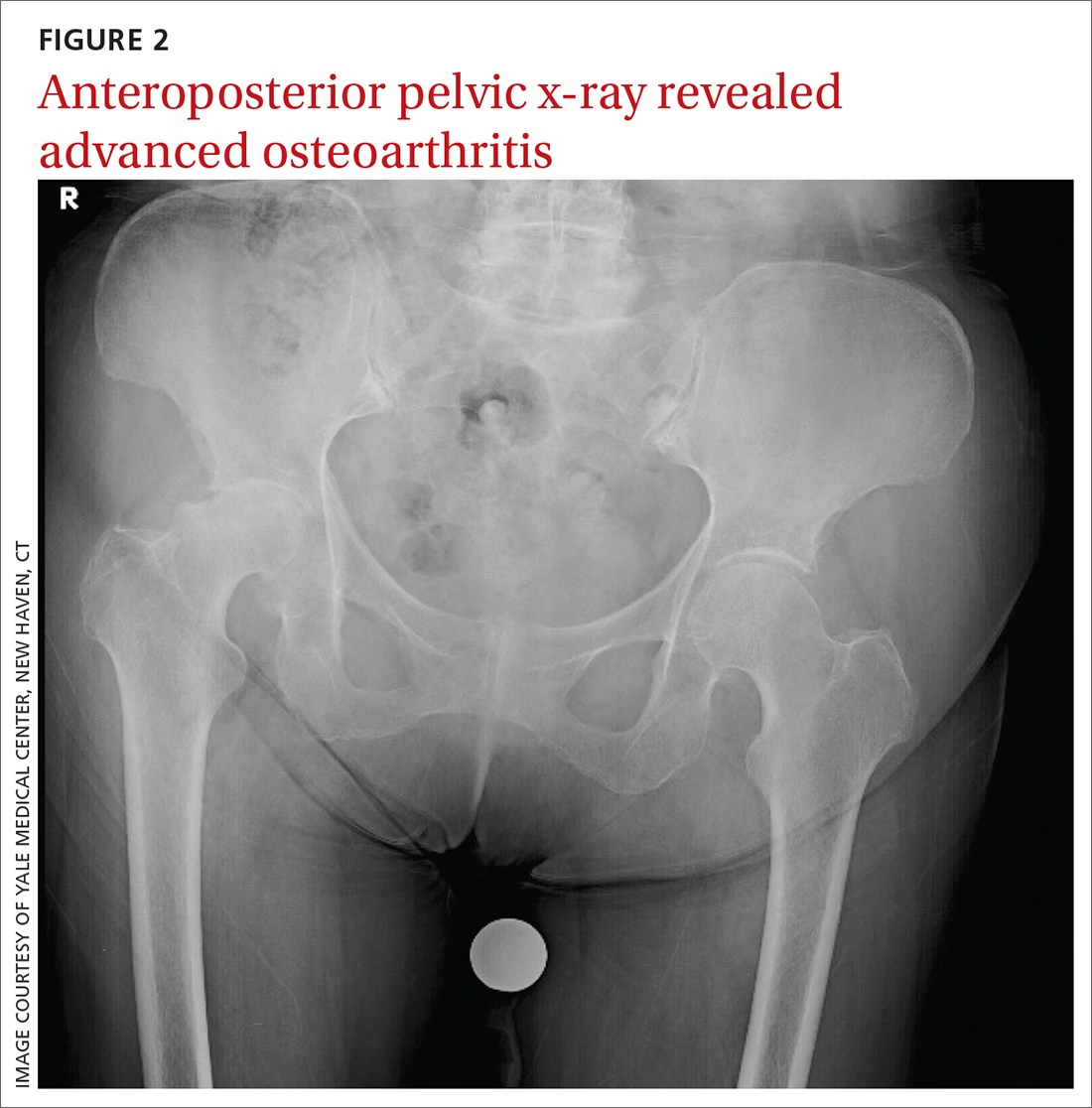

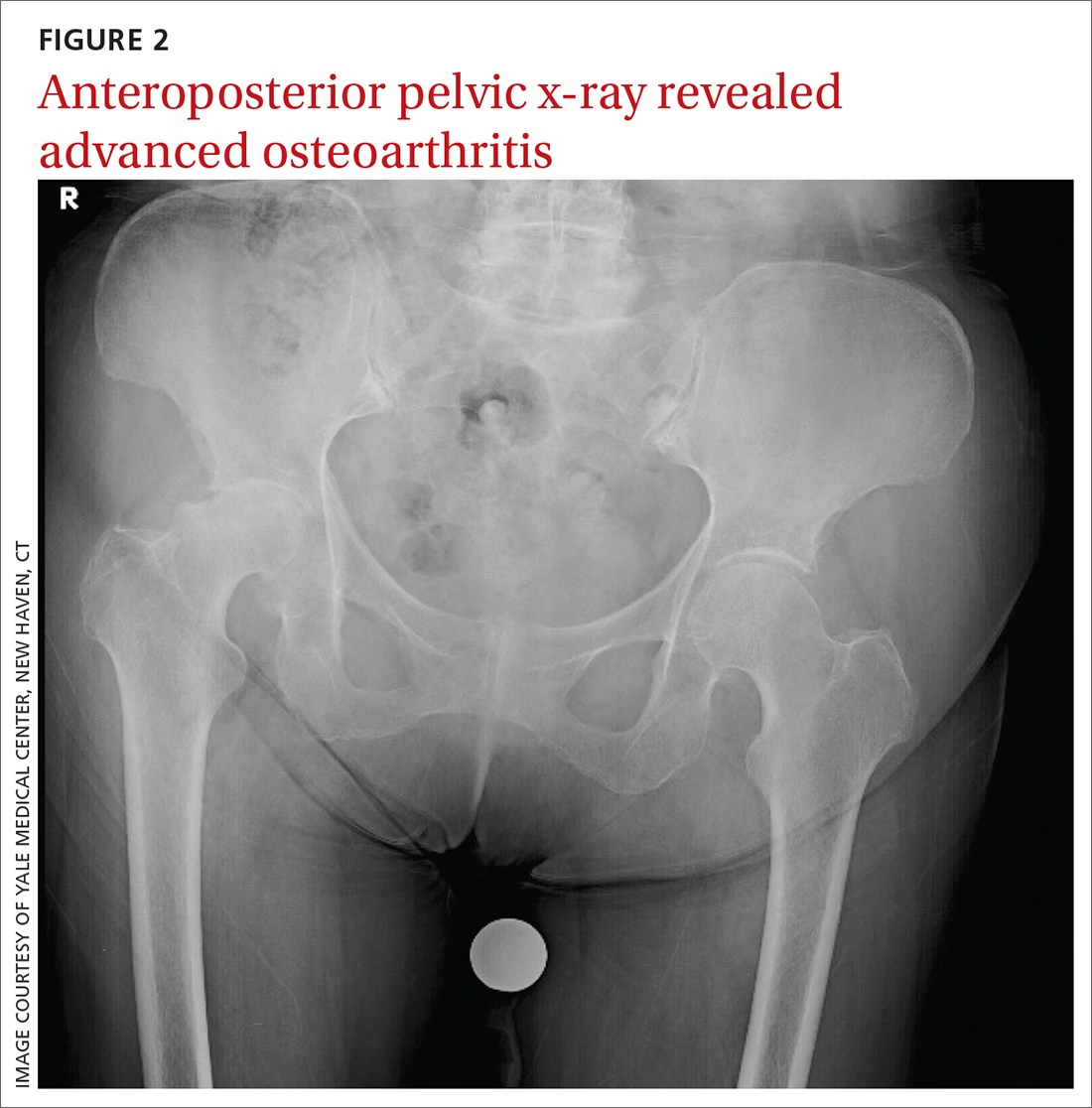

The patient’s history and physical exam prompted us to suspect right hip osteoarthritis (OA) with referred pain to the right knee. This suspicion was confirmed with hip radiographs (FIGURE 2), which revealed significant OA of the right hip, as evidenced by marked joint space narrowing, subchondral sclerosis, and osteophytes. There was also superior migration of the right femoral head relative to the acetabulum. Additionally, there was loss of sphericity of the right femoral head, suggesting avascular necrosis with collapse.

Hip and knee OA are among the most common causes of disability worldwide. Knee and hip pain are estimated to affect up to 27% and 15% of the general population, respectively.1,2 Referred knee pain secondary to hip pathology, also known as atypical knee pain, has been cited at highly variable rates, ranging from 2% to 27%.3

Eighty-six percent of patients with atypical knee pain experience a delay in diagnosis of more than 1 year.4 Half of these patients require the use of a wheelchair or walker for community navigation.4 These findings highlight the impact that a delay in diagnosis can have on the day-to-day quality of life for these patients. Also, delayed or missed diagnoses may have contributed to the doubling in the rate of knee replacement surgery from 2000 to 2010 and the reports that up to one-third of knee replacement surgeries did not meet appropriate criteria to be performed.5,6

Convergence confusion

Referred pain is likely explained by the convergence of nociceptive and non-nociceptive nerve fibers.7 Both of these fiber types conduct action potentials that terminate at second order neurons. Occasionally, nociceptive nerve fibers from different parts of the body (ie, knee and hip) terminate at the same second order fiber. At this point of convergence, higher brain centers lose their ability to discriminate the anatomic location of origin. This results in the perception of pain in a different location, where there is no intrinsic pathology.

Patients with hip OA report that the most common locations of pain are the groin, anterior thigh, buttock, anterior knee, and greater trochanter.3 One small study revealed that 85% of patients with referred pain who underwent total hip arthroplasty (THA) reported complete resolution of pain symptoms within 4 days of the procedure.3

Continue to: A comprehensive exam can reveal a different origin of pain

A comprehensive exam can reveal a different origin of pain

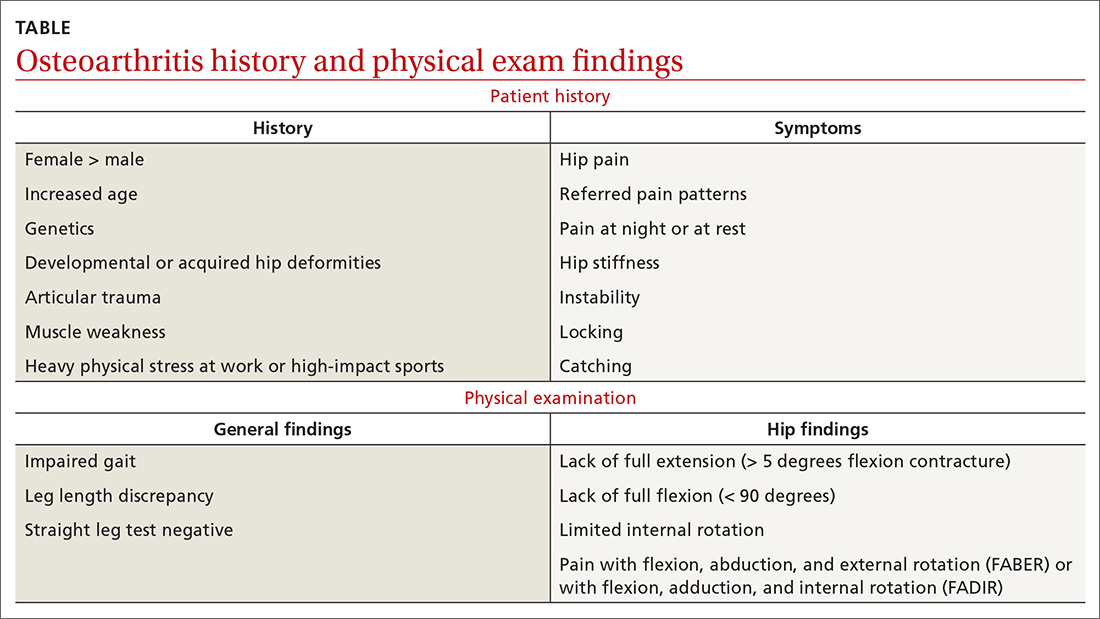

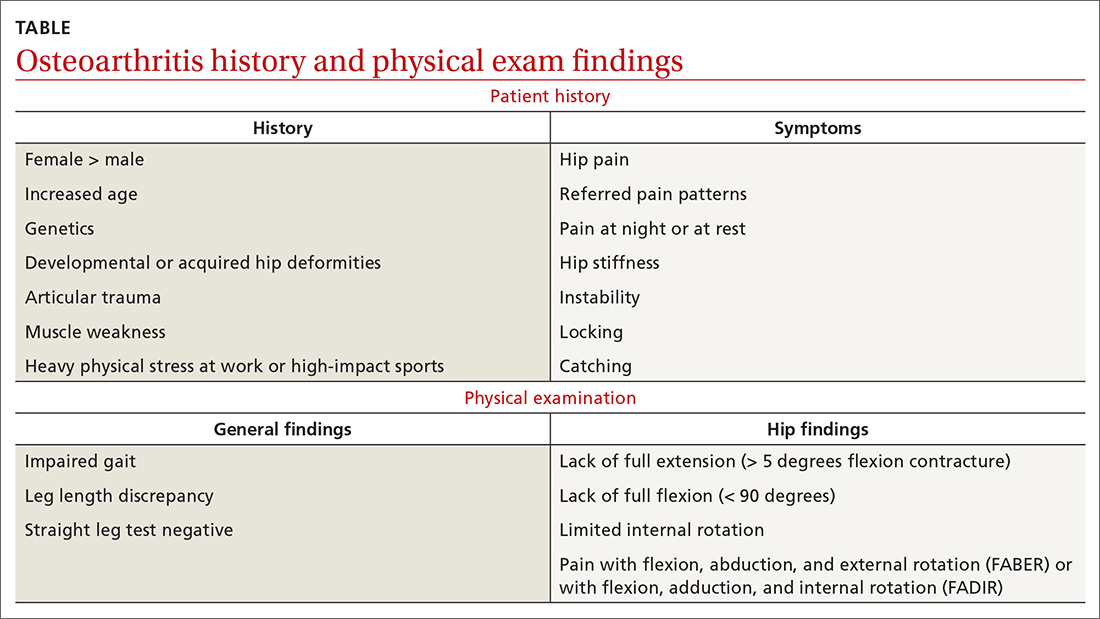

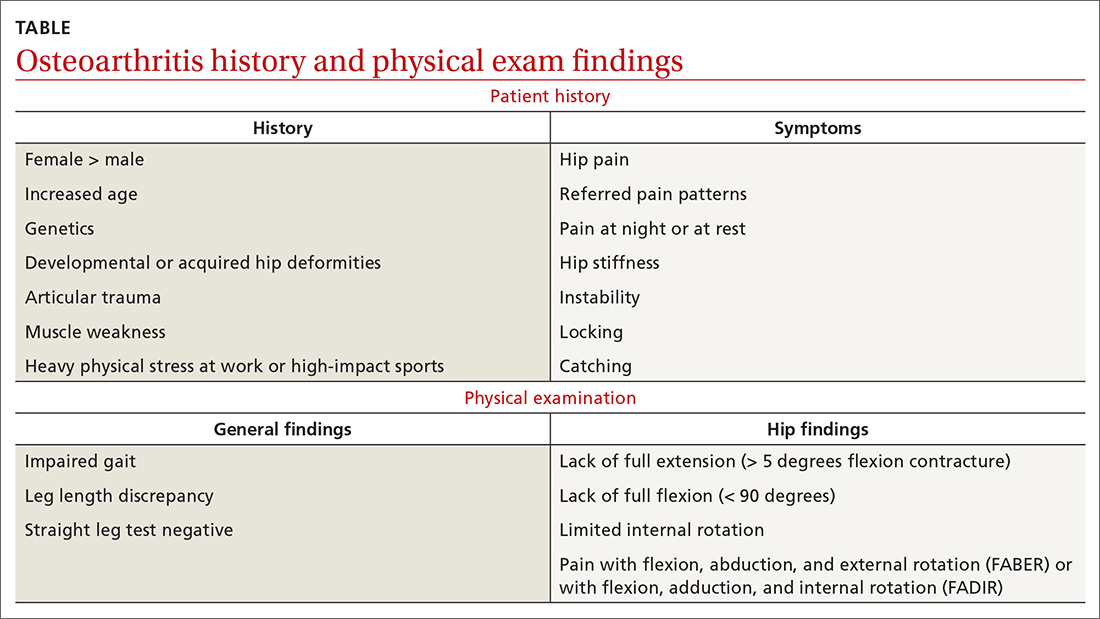

As with any musculoskeletal complaint, history and physical examination should include a focus on the joints proximal and distal to the purported joint of concern. When the hip is in consideration, historical inquiry should focus on degree and timeline of pain, stiffness, and traumatic history. Our patient reported difficulty donning socks, an excellent screening question to evaluate loss of range of motion in the hip. On physical examination, the FABER and FADIR maneuvers are quite specific to hip OA. A comprehensive list of history and physical examination findings can be found in the TABLE.

The differential includes a broad range of musculoskeletal diagnoses

The differential diagnosis for knee pain includes knee OA, spinopelvic pathology, infection, and rheumatologic disease.

Knee OA can be confirmed with knee radiographs, but one must also assess the joint above and below, as with all musculoskeletal complaints.

Spinopelvic pathology may be established with radiographs and a thorough nervous system exam.

Infection, such as septic arthritis or gout, can be diagnosed through radiographs, physical exam, and lab tests to evaluate white blood cell count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and C-reactive protein levels. High clinical suspicion may warrant a joint aspiration.

Continue to: Rheumatologic disease

Rheumatologic disease can be evaluated with a comprehensive physical exam, as well as lab work.

Management includes both surgical and nonsurgical options

Hip OA can be managed much like OA in other areas of the body. The Osteoarthritis Research Society International guidelines provide direction and insight concerning outpatient nonsurgical management.8 Weight loss and land-based, low-impact exercise programs are excellent first-line options. Second-line therapies include symptomatic management with systemic nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) in patients without contraindications. (Topical NSAIDs, while useful in the treatment of knee OA, are not as effective for hip OA due to thickness of soft tissue in this area of the body.)

Patients who do not achieve symptomatic relief with these first- and second-line therapies may benefit from other nonoperative measures, such as intra-articular corticosteroid injections. If pain persists, patients may need a referral to an orthopedic surgeon to discuss surgical candidacy.

Following the x-ray, our patient received a fluoroscopic guided intra-articular hip joint anesthetic and corticosteroid injection. Her pain level went from a reported6/10 prior to the procedure to complete pain relief after it.

However, at her follow-up visit 4 weeks later, the patient reported return of functionally limiting pain. The orthopedic surgeon talked to the patient about the potential risks and benefits of THA. She elected to proceed with a right THA.

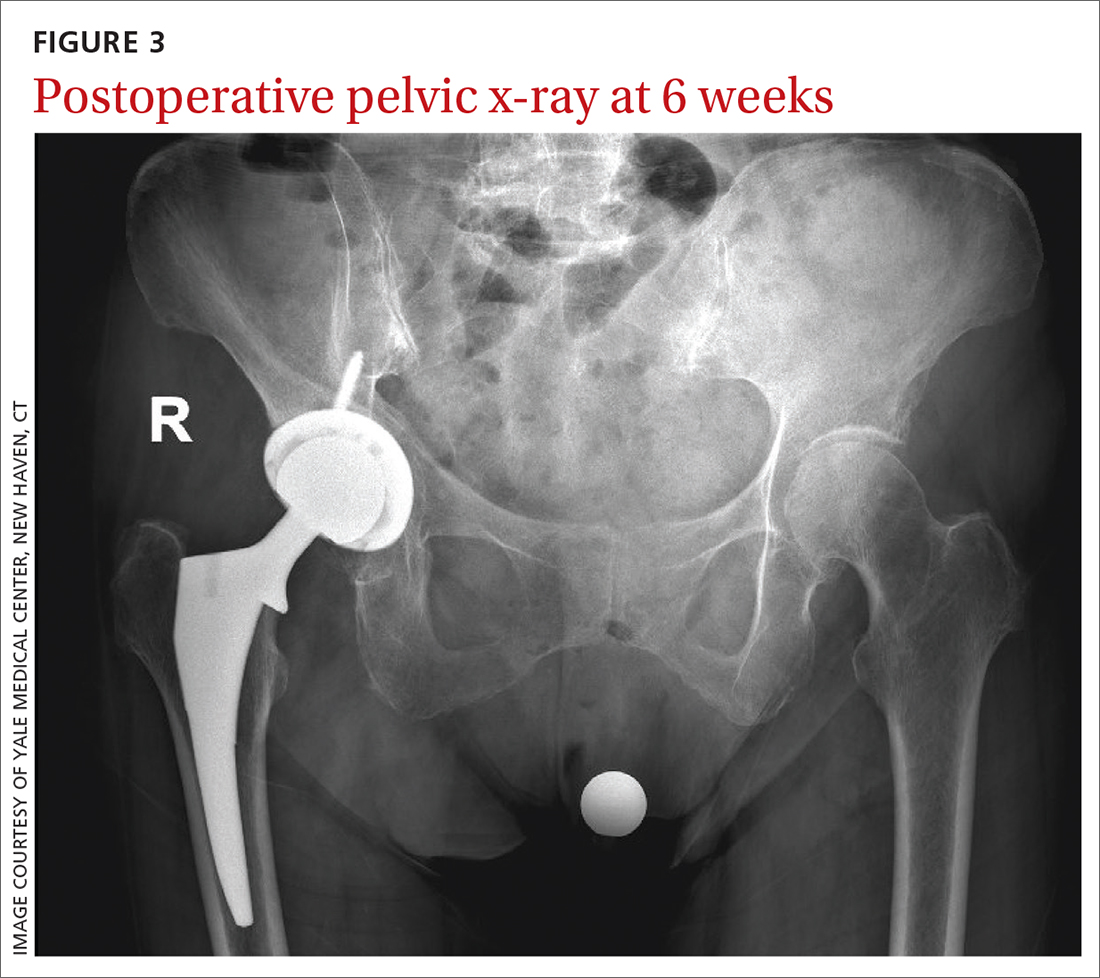

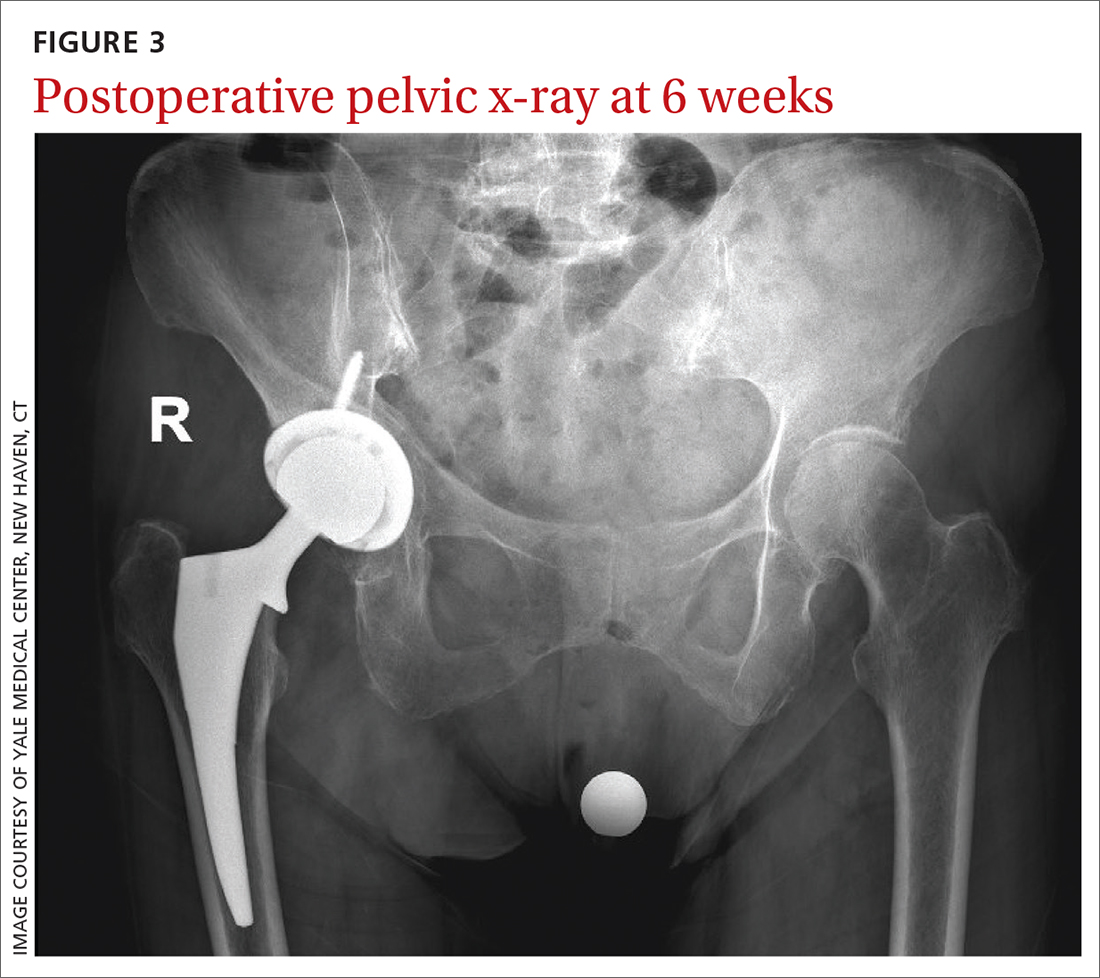

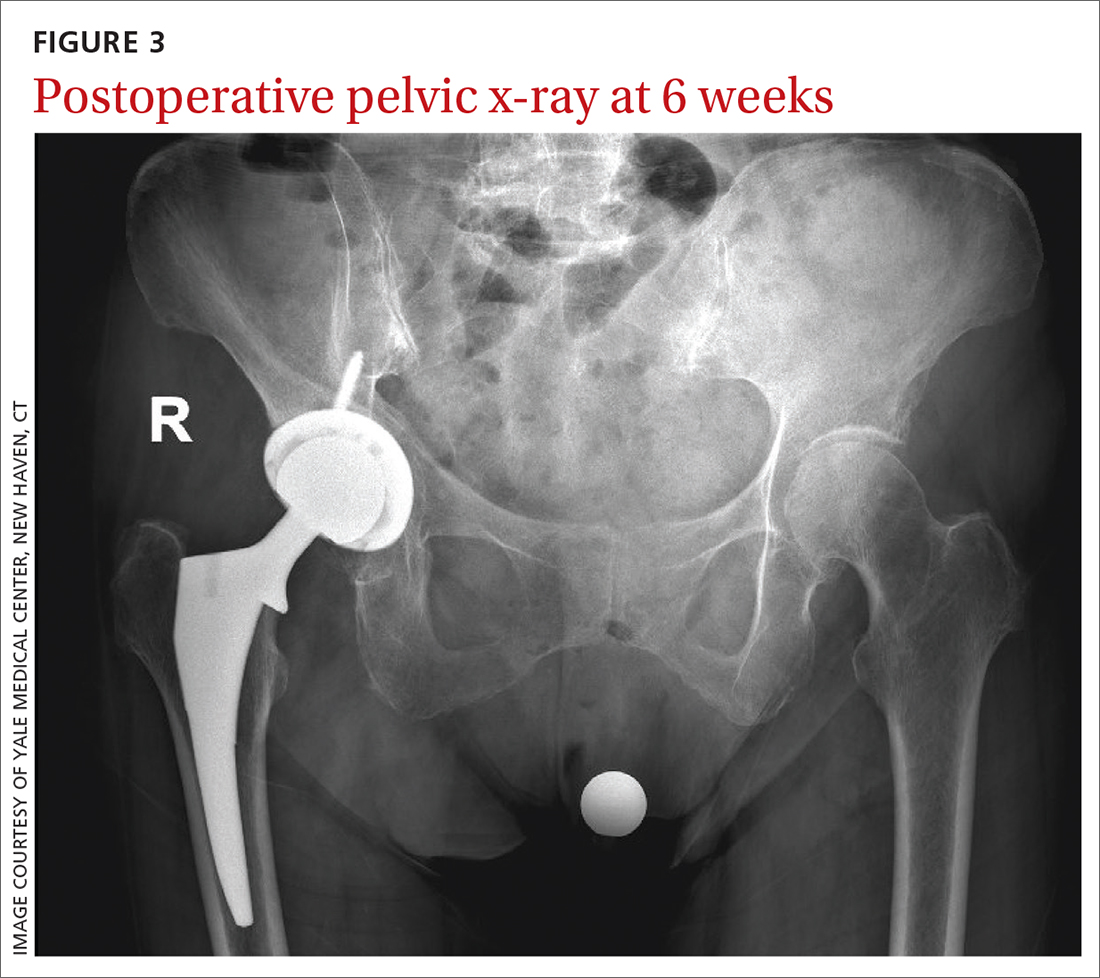

Six weeks after the surgery, the patient presented for follow-up with minimal hip pain and complete resolution of her knee pain (FIGURE 3). Functionally, she found it much easier to stand straight, and she was able to climb the stairs in her house independently.

1. Fernandes GS, Parekh SM, Moses J, et al. Prevalence of knee pain, radiographic osteoarthritis and arthroplasty in retired professional footballers compared with men in the general population: a cross-sectional study. Br J Sports Med. 2018;52:678-683. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2017-097503

2. Christmas C, Crespo CJ, Franckowiak SC, et al. How common is hip pain among older adults? Results from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. J Fam Pract. 2002;51:345-348.

3. Hsieh PH, Chang Y, Chen DW, et al. Pain distribution and response to total hip arthroplasty: a prospective observational study in 113 patients with end-stage hip disease. J Orthop Sci. 2012;17:213-218. doi: 10.1007/s00776-012-0204-1

4. Dibra FF, Prietao HA, Gray CF, et al. Don’t forget the hip! Hip arthritis masquerading as knee pain. Arthroplast Today. 2017;4:118-124. doi: 10.1016/j.artd.2017.06.008

5. Cross M, Smith E, Hoy D, et al. The global burden of hip and knee osteoarthritis: estimates from the global burden of disease 2010 study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73:1323-1330. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204763

6. Maradit Kremers H, Larson DR, Crowson CS, et al. Prevalence of total hip and knee replacement in the United States. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2015;97:1386-1397. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.N.01141

7. Sessle BJ. Central mechanisms of craniofacial musculoskeletal pain: a review. In: Graven-Nielsen T, Arendt-Nielsen L, Mense S, eds. Fundamentals of musculoskeletal pain. 1st ed. IASP Press; 2008:87-103.

8. Bannuru RR, Osani MC, Vaysbrot EE, et al. OARSI guidelines for the non-surgical management of knee, hip, and polyarticular osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2019;27:1578-1589. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2019.06.011

An 83-year-old woman, with an otherwise noncontributory past medical history, presented with chronic right knee pain. Over the prior 4 years, she had undergone evaluation by an outside physician and received several corticosteroid and hyaluronic acid intra-articular injections, without symptom resolution. She described the pain as a 4/10 at rest and as “severe” when climbing stairs and exercising. The pain was localized to her lower back and right groin and extended to her right knee. She also said that she found it difficult to put on her socks. An outside orthopedic surgeon recommended right total knee arthroplasty, prompting her to seek a second opinion.

Examination of her right knee was unrevealing. However, during the hip examination, there was a pronounced loss of range of motion and concordant pain reproduction with the FABER (combined flexion, abduction, external rotation) and FADIR (combined flexion, adduction, and internal rotation) maneuvers.

The patient’s extensive clinical and diagnostic history, combined with benign knee examination and imaging (FIGURE 1), ruled out isolated knee pathology.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Dx: Right hip OA with referred knee pain

The patient’s history and physical exam prompted us to suspect right hip osteoarthritis (OA) with referred pain to the right knee. This suspicion was confirmed with hip radiographs (FIGURE 2), which revealed significant OA of the right hip, as evidenced by marked joint space narrowing, subchondral sclerosis, and osteophytes. There was also superior migration of the right femoral head relative to the acetabulum. Additionally, there was loss of sphericity of the right femoral head, suggesting avascular necrosis with collapse.

Hip and knee OA are among the most common causes of disability worldwide. Knee and hip pain are estimated to affect up to 27% and 15% of the general population, respectively.1,2 Referred knee pain secondary to hip pathology, also known as atypical knee pain, has been cited at highly variable rates, ranging from 2% to 27%.3

Eighty-six percent of patients with atypical knee pain experience a delay in diagnosis of more than 1 year.4 Half of these patients require the use of a wheelchair or walker for community navigation.4 These findings highlight the impact that a delay in diagnosis can have on the day-to-day quality of life for these patients. Also, delayed or missed diagnoses may have contributed to the doubling in the rate of knee replacement surgery from 2000 to 2010 and the reports that up to one-third of knee replacement surgeries did not meet appropriate criteria to be performed.5,6

Convergence confusion

Referred pain is likely explained by the convergence of nociceptive and non-nociceptive nerve fibers.7 Both of these fiber types conduct action potentials that terminate at second order neurons. Occasionally, nociceptive nerve fibers from different parts of the body (ie, knee and hip) terminate at the same second order fiber. At this point of convergence, higher brain centers lose their ability to discriminate the anatomic location of origin. This results in the perception of pain in a different location, where there is no intrinsic pathology.

Patients with hip OA report that the most common locations of pain are the groin, anterior thigh, buttock, anterior knee, and greater trochanter.3 One small study revealed that 85% of patients with referred pain who underwent total hip arthroplasty (THA) reported complete resolution of pain symptoms within 4 days of the procedure.3

Continue to: A comprehensive exam can reveal a different origin of pain

A comprehensive exam can reveal a different origin of pain

As with any musculoskeletal complaint, history and physical examination should include a focus on the joints proximal and distal to the purported joint of concern. When the hip is in consideration, historical inquiry should focus on degree and timeline of pain, stiffness, and traumatic history. Our patient reported difficulty donning socks, an excellent screening question to evaluate loss of range of motion in the hip. On physical examination, the FABER and FADIR maneuvers are quite specific to hip OA. A comprehensive list of history and physical examination findings can be found in the TABLE.

The differential includes a broad range of musculoskeletal diagnoses

The differential diagnosis for knee pain includes knee OA, spinopelvic pathology, infection, and rheumatologic disease.

Knee OA can be confirmed with knee radiographs, but one must also assess the joint above and below, as with all musculoskeletal complaints.

Spinopelvic pathology may be established with radiographs and a thorough nervous system exam.

Infection, such as septic arthritis or gout, can be diagnosed through radiographs, physical exam, and lab tests to evaluate white blood cell count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and C-reactive protein levels. High clinical suspicion may warrant a joint aspiration.

Continue to: Rheumatologic disease

Rheumatologic disease can be evaluated with a comprehensive physical exam, as well as lab work.

Management includes both surgical and nonsurgical options

Hip OA can be managed much like OA in other areas of the body. The Osteoarthritis Research Society International guidelines provide direction and insight concerning outpatient nonsurgical management.8 Weight loss and land-based, low-impact exercise programs are excellent first-line options. Second-line therapies include symptomatic management with systemic nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) in patients without contraindications. (Topical NSAIDs, while useful in the treatment of knee OA, are not as effective for hip OA due to thickness of soft tissue in this area of the body.)

Patients who do not achieve symptomatic relief with these first- and second-line therapies may benefit from other nonoperative measures, such as intra-articular corticosteroid injections. If pain persists, patients may need a referral to an orthopedic surgeon to discuss surgical candidacy.

Following the x-ray, our patient received a fluoroscopic guided intra-articular hip joint anesthetic and corticosteroid injection. Her pain level went from a reported6/10 prior to the procedure to complete pain relief after it.

However, at her follow-up visit 4 weeks later, the patient reported return of functionally limiting pain. The orthopedic surgeon talked to the patient about the potential risks and benefits of THA. She elected to proceed with a right THA.

Six weeks after the surgery, the patient presented for follow-up with minimal hip pain and complete resolution of her knee pain (FIGURE 3). Functionally, she found it much easier to stand straight, and she was able to climb the stairs in her house independently.

An 83-year-old woman, with an otherwise noncontributory past medical history, presented with chronic right knee pain. Over the prior 4 years, she had undergone evaluation by an outside physician and received several corticosteroid and hyaluronic acid intra-articular injections, without symptom resolution. She described the pain as a 4/10 at rest and as “severe” when climbing stairs and exercising. The pain was localized to her lower back and right groin and extended to her right knee. She also said that she found it difficult to put on her socks. An outside orthopedic surgeon recommended right total knee arthroplasty, prompting her to seek a second opinion.

Examination of her right knee was unrevealing. However, during the hip examination, there was a pronounced loss of range of motion and concordant pain reproduction with the FABER (combined flexion, abduction, external rotation) and FADIR (combined flexion, adduction, and internal rotation) maneuvers.

The patient’s extensive clinical and diagnostic history, combined with benign knee examination and imaging (FIGURE 1), ruled out isolated knee pathology.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Dx: Right hip OA with referred knee pain

The patient’s history and physical exam prompted us to suspect right hip osteoarthritis (OA) with referred pain to the right knee. This suspicion was confirmed with hip radiographs (FIGURE 2), which revealed significant OA of the right hip, as evidenced by marked joint space narrowing, subchondral sclerosis, and osteophytes. There was also superior migration of the right femoral head relative to the acetabulum. Additionally, there was loss of sphericity of the right femoral head, suggesting avascular necrosis with collapse.

Hip and knee OA are among the most common causes of disability worldwide. Knee and hip pain are estimated to affect up to 27% and 15% of the general population, respectively.1,2 Referred knee pain secondary to hip pathology, also known as atypical knee pain, has been cited at highly variable rates, ranging from 2% to 27%.3

Eighty-six percent of patients with atypical knee pain experience a delay in diagnosis of more than 1 year.4 Half of these patients require the use of a wheelchair or walker for community navigation.4 These findings highlight the impact that a delay in diagnosis can have on the day-to-day quality of life for these patients. Also, delayed or missed diagnoses may have contributed to the doubling in the rate of knee replacement surgery from 2000 to 2010 and the reports that up to one-third of knee replacement surgeries did not meet appropriate criteria to be performed.5,6

Convergence confusion

Referred pain is likely explained by the convergence of nociceptive and non-nociceptive nerve fibers.7 Both of these fiber types conduct action potentials that terminate at second order neurons. Occasionally, nociceptive nerve fibers from different parts of the body (ie, knee and hip) terminate at the same second order fiber. At this point of convergence, higher brain centers lose their ability to discriminate the anatomic location of origin. This results in the perception of pain in a different location, where there is no intrinsic pathology.

Patients with hip OA report that the most common locations of pain are the groin, anterior thigh, buttock, anterior knee, and greater trochanter.3 One small study revealed that 85% of patients with referred pain who underwent total hip arthroplasty (THA) reported complete resolution of pain symptoms within 4 days of the procedure.3

Continue to: A comprehensive exam can reveal a different origin of pain

A comprehensive exam can reveal a different origin of pain

As with any musculoskeletal complaint, history and physical examination should include a focus on the joints proximal and distal to the purported joint of concern. When the hip is in consideration, historical inquiry should focus on degree and timeline of pain, stiffness, and traumatic history. Our patient reported difficulty donning socks, an excellent screening question to evaluate loss of range of motion in the hip. On physical examination, the FABER and FADIR maneuvers are quite specific to hip OA. A comprehensive list of history and physical examination findings can be found in the TABLE.

The differential includes a broad range of musculoskeletal diagnoses

The differential diagnosis for knee pain includes knee OA, spinopelvic pathology, infection, and rheumatologic disease.

Knee OA can be confirmed with knee radiographs, but one must also assess the joint above and below, as with all musculoskeletal complaints.

Spinopelvic pathology may be established with radiographs and a thorough nervous system exam.

Infection, such as septic arthritis or gout, can be diagnosed through radiographs, physical exam, and lab tests to evaluate white blood cell count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and C-reactive protein levels. High clinical suspicion may warrant a joint aspiration.

Continue to: Rheumatologic disease

Rheumatologic disease can be evaluated with a comprehensive physical exam, as well as lab work.

Management includes both surgical and nonsurgical options

Hip OA can be managed much like OA in other areas of the body. The Osteoarthritis Research Society International guidelines provide direction and insight concerning outpatient nonsurgical management.8 Weight loss and land-based, low-impact exercise programs are excellent first-line options. Second-line therapies include symptomatic management with systemic nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) in patients without contraindications. (Topical NSAIDs, while useful in the treatment of knee OA, are not as effective for hip OA due to thickness of soft tissue in this area of the body.)

Patients who do not achieve symptomatic relief with these first- and second-line therapies may benefit from other nonoperative measures, such as intra-articular corticosteroid injections. If pain persists, patients may need a referral to an orthopedic surgeon to discuss surgical candidacy.

Following the x-ray, our patient received a fluoroscopic guided intra-articular hip joint anesthetic and corticosteroid injection. Her pain level went from a reported6/10 prior to the procedure to complete pain relief after it.

However, at her follow-up visit 4 weeks later, the patient reported return of functionally limiting pain. The orthopedic surgeon talked to the patient about the potential risks and benefits of THA. She elected to proceed with a right THA.

Six weeks after the surgery, the patient presented for follow-up with minimal hip pain and complete resolution of her knee pain (FIGURE 3). Functionally, she found it much easier to stand straight, and she was able to climb the stairs in her house independently.

1. Fernandes GS, Parekh SM, Moses J, et al. Prevalence of knee pain, radiographic osteoarthritis and arthroplasty in retired professional footballers compared with men in the general population: a cross-sectional study. Br J Sports Med. 2018;52:678-683. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2017-097503

2. Christmas C, Crespo CJ, Franckowiak SC, et al. How common is hip pain among older adults? Results from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. J Fam Pract. 2002;51:345-348.

3. Hsieh PH, Chang Y, Chen DW, et al. Pain distribution and response to total hip arthroplasty: a prospective observational study in 113 patients with end-stage hip disease. J Orthop Sci. 2012;17:213-218. doi: 10.1007/s00776-012-0204-1

4. Dibra FF, Prietao HA, Gray CF, et al. Don’t forget the hip! Hip arthritis masquerading as knee pain. Arthroplast Today. 2017;4:118-124. doi: 10.1016/j.artd.2017.06.008

5. Cross M, Smith E, Hoy D, et al. The global burden of hip and knee osteoarthritis: estimates from the global burden of disease 2010 study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73:1323-1330. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204763

6. Maradit Kremers H, Larson DR, Crowson CS, et al. Prevalence of total hip and knee replacement in the United States. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2015;97:1386-1397. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.N.01141

7. Sessle BJ. Central mechanisms of craniofacial musculoskeletal pain: a review. In: Graven-Nielsen T, Arendt-Nielsen L, Mense S, eds. Fundamentals of musculoskeletal pain. 1st ed. IASP Press; 2008:87-103.

8. Bannuru RR, Osani MC, Vaysbrot EE, et al. OARSI guidelines for the non-surgical management of knee, hip, and polyarticular osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2019;27:1578-1589. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2019.06.011

1. Fernandes GS, Parekh SM, Moses J, et al. Prevalence of knee pain, radiographic osteoarthritis and arthroplasty in retired professional footballers compared with men in the general population: a cross-sectional study. Br J Sports Med. 2018;52:678-683. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2017-097503

2. Christmas C, Crespo CJ, Franckowiak SC, et al. How common is hip pain among older adults? Results from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. J Fam Pract. 2002;51:345-348.

3. Hsieh PH, Chang Y, Chen DW, et al. Pain distribution and response to total hip arthroplasty: a prospective observational study in 113 patients with end-stage hip disease. J Orthop Sci. 2012;17:213-218. doi: 10.1007/s00776-012-0204-1

4. Dibra FF, Prietao HA, Gray CF, et al. Don’t forget the hip! Hip arthritis masquerading as knee pain. Arthroplast Today. 2017;4:118-124. doi: 10.1016/j.artd.2017.06.008

5. Cross M, Smith E, Hoy D, et al. The global burden of hip and knee osteoarthritis: estimates from the global burden of disease 2010 study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73:1323-1330. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204763

6. Maradit Kremers H, Larson DR, Crowson CS, et al. Prevalence of total hip and knee replacement in the United States. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2015;97:1386-1397. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.N.01141

7. Sessle BJ. Central mechanisms of craniofacial musculoskeletal pain: a review. In: Graven-Nielsen T, Arendt-Nielsen L, Mense S, eds. Fundamentals of musculoskeletal pain. 1st ed. IASP Press; 2008:87-103.

8. Bannuru RR, Osani MC, Vaysbrot EE, et al. OARSI guidelines for the non-surgical management of knee, hip, and polyarticular osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2019;27:1578-1589. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2019.06.011

Transvaginal mesh, native tissue repair have similar outcomes in 3-year trial

Transvaginal mesh was found to be safe and effective for patients with pelvic organ prolapse (POP) when compared with native tissue repair (NTR) in a 3-year trial.

Researchers, led by Bruce S. Kahn, MD, with the department of obstetrics & gynecology at Scripps Clinic in San Diego evaluated the two surgical treatment methods and published their findings in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

At completion of the 3-year follow-up in 2016, there were 401 participants in the transvaginal mesh group and 171 in the NTR group.

The prospective, nonrandomized, parallel-cohort, 27-site trial used a primary composite endpoint of anatomical success; subjective success (vaginal bulging); retreatment measures; and serious device-related or serious procedure-related adverse events.

The secondary endpoint was a composite outcome similar to the primary composite outcome but with anatomical success more stringently defined as POP quantification (POP-Q) point Ba < 0 and/or C < 0.

The secondary outcome was added to this trial because investigators had criticized the primary endpoint, set by the Food and Drug Administration, because it included anatomic outcome measures that were the same for inclusion criteria (POP-Q point Ba < 0 and/or C < 0.)

The secondary-outcome composite also included quality-of-life measures, mesh exposure, and mesh- and procedure-related complications.

Outcomes similar for both groups

The primary outcome demonstrated transvaginal mesh was not superior to native tissue repair (P =.056).

In the secondary outcome, superiority of transvaginal mesh over native tissue repair was shown (P =.009), with a propensity score–adjusted difference of 10.6% (90% confidence interval, 3.3%-17.9%) in favor of transvaginal mesh.

The authors noted that subjective success regarding vaginal bulging, which is important in patient satisfaction, was high and not statistically different between the two groups.

Additionally, transvaginal mesh repair was as safe as NTR regarding serious device-related and/or serious procedure-related side effects.

For the primary safety endpoint, 3.1% in the mesh group and 2.7% in the native tissue repair group experienced serious adverse events, demonstrating that mesh was noninferior to NTR.

Research results have been mixed

Unanswered questions surround surgical options for POP, which, the authors wrote, “affects 3%-6% of women based on symptoms and up to 50% of women based on vaginal examination.”

The FDA in 2011 issued 522 postmarket surveillance study orders for companies that market transvaginal mesh for POP.

Research results have varied and contentious debate has continued in the field. Some studies have shown that mesh has better subjective and objective outcomes than NTR in the anterior compartment. Others have found more complications with transvaginal mesh, such as mesh exposure and painful intercourse.

Complicating comparisons, early versions of the mesh used were larger and denser than today’s versions.

In this postmarket study, patients received either the Uphold LITE brand of transvaginal mesh or native tissue repair for surgical treatment of POP.

Expert: This study unlikely to change minds

In an accompanying editorial, John O.L. DeLancey, MD, professor of gynecology at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, pointed out that so far there’s been a lack of randomized trials that could answer whether mesh surgeries result in fewer symptoms or result in sufficient improvements in anatomy to justify their additional risk.

This study may not help with the decision. Dr. DeLancey wrote: “Will this study change the minds of either side of this debate? Probably not. The two sides are deeply entrenched in their positions.”

Two considerations are important in thinking about the issue, he said. Surgical outcomes for POP are “not as good as we would hope.” Also, many women have had serious complications with mesh operations.

He wrote: “Mesh litigation has resulted in more $8 billion in settlements, which is many times the $1 billion annual national cost of providing care for prolapse. Those of us who practice in referral centers have seen women with devastating problems, even though they probably represent a small fraction of cases.”

Dr. DeLancey highlighted some limitations of the study by Dr. Kahn and colleagues, especially regarding differences in the groups studied and the design of the study.

“For example,” he explained, “65% of individuals in the mesh-repair group had a prior hysterectomy as opposed to 30% in the native tissue repair group. In addition, some of the operations in the native tissue group are not typical choices; for example, hysteropexy was used for some patients and had a 47% failure rate.”

He said the all-or-nothing approach to surgical solutions may be clouding the debate – in other words mesh or no mesh for women as a group.

“Rather than asking whether mesh is better than no mesh, knowing which women (if any) stand to benefit from mesh is the critical question. We need to understand, for each woman, what structural failures exist so that we can target our interventions to correct them,” he wrote.

This study was sponsored by Boston Scientific. Dr. Kahn disclosed research support from Solaire, payments from AbbVie and Douchenay as a speaker, payments from Caldera and Cytuity (Boston Scientific) as a medical consultant, and payment from Johnson & Johnson as an expert witness. One coauthor disclosed that money was paid to her institution from Medtronic and Boston Scientific (both unrestricted educational grants for cadaveric lab). Another is chief medical officer at Axonics. One study coauthor receives research funding from Axonics and is a consultant for Group Dynamics, Medpace, and FirstThought. One coauthor received research support, is a consultant for Boston Scientific, and is an expert witness for Johnson & Johnson. Dr. DeLancey declared no relevant financial relationships.

Transvaginal mesh was found to be safe and effective for patients with pelvic organ prolapse (POP) when compared with native tissue repair (NTR) in a 3-year trial.

Researchers, led by Bruce S. Kahn, MD, with the department of obstetrics & gynecology at Scripps Clinic in San Diego evaluated the two surgical treatment methods and published their findings in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

At completion of the 3-year follow-up in 2016, there were 401 participants in the transvaginal mesh group and 171 in the NTR group.

The prospective, nonrandomized, parallel-cohort, 27-site trial used a primary composite endpoint of anatomical success; subjective success (vaginal bulging); retreatment measures; and serious device-related or serious procedure-related adverse events.

The secondary endpoint was a composite outcome similar to the primary composite outcome but with anatomical success more stringently defined as POP quantification (POP-Q) point Ba < 0 and/or C < 0.

The secondary outcome was added to this trial because investigators had criticized the primary endpoint, set by the Food and Drug Administration, because it included anatomic outcome measures that were the same for inclusion criteria (POP-Q point Ba < 0 and/or C < 0.)

The secondary-outcome composite also included quality-of-life measures, mesh exposure, and mesh- and procedure-related complications.

Outcomes similar for both groups

The primary outcome demonstrated transvaginal mesh was not superior to native tissue repair (P =.056).

In the secondary outcome, superiority of transvaginal mesh over native tissue repair was shown (P =.009), with a propensity score–adjusted difference of 10.6% (90% confidence interval, 3.3%-17.9%) in favor of transvaginal mesh.

The authors noted that subjective success regarding vaginal bulging, which is important in patient satisfaction, was high and not statistically different between the two groups.

Additionally, transvaginal mesh repair was as safe as NTR regarding serious device-related and/or serious procedure-related side effects.

For the primary safety endpoint, 3.1% in the mesh group and 2.7% in the native tissue repair group experienced serious adverse events, demonstrating that mesh was noninferior to NTR.

Research results have been mixed

Unanswered questions surround surgical options for POP, which, the authors wrote, “affects 3%-6% of women based on symptoms and up to 50% of women based on vaginal examination.”

The FDA in 2011 issued 522 postmarket surveillance study orders for companies that market transvaginal mesh for POP.

Research results have varied and contentious debate has continued in the field. Some studies have shown that mesh has better subjective and objective outcomes than NTR in the anterior compartment. Others have found more complications with transvaginal mesh, such as mesh exposure and painful intercourse.

Complicating comparisons, early versions of the mesh used were larger and denser than today’s versions.

In this postmarket study, patients received either the Uphold LITE brand of transvaginal mesh or native tissue repair for surgical treatment of POP.

Expert: This study unlikely to change minds

In an accompanying editorial, John O.L. DeLancey, MD, professor of gynecology at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, pointed out that so far there’s been a lack of randomized trials that could answer whether mesh surgeries result in fewer symptoms or result in sufficient improvements in anatomy to justify their additional risk.

This study may not help with the decision. Dr. DeLancey wrote: “Will this study change the minds of either side of this debate? Probably not. The two sides are deeply entrenched in their positions.”