User login

The older we are, the more unique we become

I was rounding at the nursing home and my day began as it often did. I reviewed the doctor communication book at the nursing station to see which patients I needed to visit and checked in with the floor nurse for any important updates.

A mother waiting for her son to visit

The first patient on my list was Rose. She had become increasingly withdrawn and less mobile. She used to walk the corridors asking when her son, Billy, would visit. We would all remind her that Billy visited her two or three times a week, but she never remembered the visits and blamed him for moving her out of her comfortable home in New Jersey where she’d lived with her husband before his death several years earlier.

Rose was declining, and we were trying to optimize her function and quality of life. She fell frequently while trying to get up at night to use the bathroom. None of our fall-reduction strategies had worked, and she had broken her hip a year prior. She’d fully recovered, but the combination of mental and physical frailty was becoming obvious to everyone, including her son. She had lost another five pounds and was approaching the end of her life.

“Good morning, Rose.” (She had demanded that I use her first name.) “How are you doing today?”

“I am doing okay, doctor. Have you seen Billy? When is he going to visit me?”

“I really can’t say when he’ll visit next, but I saw in a note that he was here yesterday.”

“No, he didn’t come to see me,” she said. “He doesn’t care about me. He spends more time with his wife and family than with his own mother.”

“Well, is there anything special that I can do for you?”

“Yes. Please tell Billy to visit his mother,” she said.

I completed her evaluation and made my way down the hall.

A wife ready to rejoin her husband

Next on my list was a widow named Violet. She reminded me of Whistler’s mother. As was her custom, she was sitting up in her chair reading her Bible when I came in. Her husband had been a minister, and she enjoyed reading the Bible or meditating for several hours each morning. Her bedside table had the most recent devotional and a picture of her husband in his vestments.

Violet was quiet and direct, and she had steely blue eyes that could communicate with your soul. Her nun-like quality was not overpowering; her manner was warm and welcoming.

“Good morning!” I said. “I hope I’m not bothering you.”

“Good morning, doctor. It’s always nice to see you.”

“I haven’t been by in a while, and I wanted to check your heart and lungs and make sure everything is going okay for you.”

“Of course; help yourself,” she said. “I feel fine. And as you know, I am ready to join my husband whenever the Lord calls me. I have lived a blessed life and do not wish to prolong it unless it is God’s will.”

“You certainly have made your wishes clear to me, and you are still in excellent health,” I said.

She really was in good health, and I made a quick note to call her daughter – who lived on the other side of the country – with an update.

A beauty queen ready for her close-up

Gabby was next on my list. She was a former beauty queen who had competed in local and state beauty contests. Her looks were the cornerstone of her identity, and she had done a truly remarkable job of maintaining her physical appearance.

Gabby had three attentive daughters who lived locally and supplied her with the latest makeup, beauty creams, and anti-aging nostrums. She always managed to look natural (and not like a caricature) with her face made up and her blond wig in place. Over the years, she’d made good use of the services offered by the local plastic surgeons and dermatologists. And to her credit – and theirs – she looked 30 years younger than her chronological age. In fairness, she had also taken good care of her overall health.

Gabby’s nickname was appropriate as she was chatty, to the extreme. She enjoyed being the center of attention.

When I entered her room, she was putting on her makeup. She was seated near her bedside table, which looked like it belonged in the backstage dressing room of a Broadway star. Lined up on the table were various bottles, brushes, and a mirror surrounded by lights.

“Oh, doctor, you can’t come in now. I’m a dreadful mess,” she said. “Please come back in 10 minutes. I am so embarrassed that you are seeing me this way. I just have a few things to fix, and then I will be presentable. My daughters are taking me out for lunch at the club, and I do not want to look like an old lady.”

“Gabby,” I said, “I have seen you before without your makeup. Do you remember last year when you developed pneumonia? You were really sick, and frankly, we were not sure you were going to pull through. One of the clues that you were getting ill was your smeared mascara and lipstick.”

I pressed on, and she let me examine her while she continued to apply her eyeliner.

“Everything sounds good. And I like your fresh pedicure,” I said. “Is there anything I can do for you?”

“No, thank you. Have a nice day, doctor!”

A mother devoted to her daughter’s care

Unlike my other patients, Mabel shared a room with a family member – her daughter, Hope. Mabel’s daughter had a congenital illness with significant physical, functional, and cognitive deficits. Mabel had considerable guilt regarding her daughter’s condition. Mabel’s husband had divorced her decades earlier, and she had devoted her life to caring for Hope. When Mabel’s health began to decline and she realized she could no longer care for Hope alone, the two moved into the facility together. Mabel told me that she simply couldn’t die before her daughter, because no one could oversee her care like she could.

Mabel was frail physically but sharp and vigilant mentally. Hope had had numerous hospitalizations, and Mabel had been with her through each experience. Hope could not communicate with others, but Mabel could express Hope’s concerns.

“How are you doing today?” I asked.

“Not well. I am concerned about Hope. She has not had a bowel movement in two days and does not want to eat breakfast.”

I checked out Hope, and her examination was reassuring. She looked up at me with her distorted features and managed a broad smile. I went back over to Mabel.

“She likes you, doctor. She thinks you smell good.”

I turned to Hope and thanked her for the compliment.

“I will check with the nurse and see if we can give you something simple to help your bowels.”

“Warm prune juice often works,” said Mabel. “Please come by again tomorrow to check on her. I don’t want this to progress. She is miserable.”

“I will be back tomorrow, and I will make a special trip to see you both.”

Upon reflection ...

When I sat down to write my clinical notes for the day, I realized that Rose, Violet, Gabby, and Mabel were each over 100 years old. I had seen four centenarians in a single day! Each of them manifested a fundamental principle of geriatrics: The older we are, the more unique and differentiated we become. A one-size approach to geriatric care does not fit all. Our care must be personalized to the unique individual in front of us.

Patients’ names and some details have been changed to protect their privacy. Dr. Williams is the Emeritus Ward K. Ensminger Distinguished Professor of Geriatric Medicine, University of Virginia, Charlottesville and attending physician, internal medicine and geriatrics, New Hanover Regional Medical Center, Wilmington, N.C. He disclosed no relevant financial disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

I was rounding at the nursing home and my day began as it often did. I reviewed the doctor communication book at the nursing station to see which patients I needed to visit and checked in with the floor nurse for any important updates.

A mother waiting for her son to visit

The first patient on my list was Rose. She had become increasingly withdrawn and less mobile. She used to walk the corridors asking when her son, Billy, would visit. We would all remind her that Billy visited her two or three times a week, but she never remembered the visits and blamed him for moving her out of her comfortable home in New Jersey where she’d lived with her husband before his death several years earlier.

Rose was declining, and we were trying to optimize her function and quality of life. She fell frequently while trying to get up at night to use the bathroom. None of our fall-reduction strategies had worked, and she had broken her hip a year prior. She’d fully recovered, but the combination of mental and physical frailty was becoming obvious to everyone, including her son. She had lost another five pounds and was approaching the end of her life.

“Good morning, Rose.” (She had demanded that I use her first name.) “How are you doing today?”

“I am doing okay, doctor. Have you seen Billy? When is he going to visit me?”

“I really can’t say when he’ll visit next, but I saw in a note that he was here yesterday.”

“No, he didn’t come to see me,” she said. “He doesn’t care about me. He spends more time with his wife and family than with his own mother.”

“Well, is there anything special that I can do for you?”

“Yes. Please tell Billy to visit his mother,” she said.

I completed her evaluation and made my way down the hall.

A wife ready to rejoin her husband

Next on my list was a widow named Violet. She reminded me of Whistler’s mother. As was her custom, she was sitting up in her chair reading her Bible when I came in. Her husband had been a minister, and she enjoyed reading the Bible or meditating for several hours each morning. Her bedside table had the most recent devotional and a picture of her husband in his vestments.

Violet was quiet and direct, and she had steely blue eyes that could communicate with your soul. Her nun-like quality was not overpowering; her manner was warm and welcoming.

“Good morning!” I said. “I hope I’m not bothering you.”

“Good morning, doctor. It’s always nice to see you.”

“I haven’t been by in a while, and I wanted to check your heart and lungs and make sure everything is going okay for you.”

“Of course; help yourself,” she said. “I feel fine. And as you know, I am ready to join my husband whenever the Lord calls me. I have lived a blessed life and do not wish to prolong it unless it is God’s will.”

“You certainly have made your wishes clear to me, and you are still in excellent health,” I said.

She really was in good health, and I made a quick note to call her daughter – who lived on the other side of the country – with an update.

A beauty queen ready for her close-up

Gabby was next on my list. She was a former beauty queen who had competed in local and state beauty contests. Her looks were the cornerstone of her identity, and she had done a truly remarkable job of maintaining her physical appearance.

Gabby had three attentive daughters who lived locally and supplied her with the latest makeup, beauty creams, and anti-aging nostrums. She always managed to look natural (and not like a caricature) with her face made up and her blond wig in place. Over the years, she’d made good use of the services offered by the local plastic surgeons and dermatologists. And to her credit – and theirs – she looked 30 years younger than her chronological age. In fairness, she had also taken good care of her overall health.

Gabby’s nickname was appropriate as she was chatty, to the extreme. She enjoyed being the center of attention.

When I entered her room, she was putting on her makeup. She was seated near her bedside table, which looked like it belonged in the backstage dressing room of a Broadway star. Lined up on the table were various bottles, brushes, and a mirror surrounded by lights.

“Oh, doctor, you can’t come in now. I’m a dreadful mess,” she said. “Please come back in 10 minutes. I am so embarrassed that you are seeing me this way. I just have a few things to fix, and then I will be presentable. My daughters are taking me out for lunch at the club, and I do not want to look like an old lady.”

“Gabby,” I said, “I have seen you before without your makeup. Do you remember last year when you developed pneumonia? You were really sick, and frankly, we were not sure you were going to pull through. One of the clues that you were getting ill was your smeared mascara and lipstick.”

I pressed on, and she let me examine her while she continued to apply her eyeliner.

“Everything sounds good. And I like your fresh pedicure,” I said. “Is there anything I can do for you?”

“No, thank you. Have a nice day, doctor!”

A mother devoted to her daughter’s care

Unlike my other patients, Mabel shared a room with a family member – her daughter, Hope. Mabel’s daughter had a congenital illness with significant physical, functional, and cognitive deficits. Mabel had considerable guilt regarding her daughter’s condition. Mabel’s husband had divorced her decades earlier, and she had devoted her life to caring for Hope. When Mabel’s health began to decline and she realized she could no longer care for Hope alone, the two moved into the facility together. Mabel told me that she simply couldn’t die before her daughter, because no one could oversee her care like she could.

Mabel was frail physically but sharp and vigilant mentally. Hope had had numerous hospitalizations, and Mabel had been with her through each experience. Hope could not communicate with others, but Mabel could express Hope’s concerns.

“How are you doing today?” I asked.

“Not well. I am concerned about Hope. She has not had a bowel movement in two days and does not want to eat breakfast.”

I checked out Hope, and her examination was reassuring. She looked up at me with her distorted features and managed a broad smile. I went back over to Mabel.

“She likes you, doctor. She thinks you smell good.”

I turned to Hope and thanked her for the compliment.

“I will check with the nurse and see if we can give you something simple to help your bowels.”

“Warm prune juice often works,” said Mabel. “Please come by again tomorrow to check on her. I don’t want this to progress. She is miserable.”

“I will be back tomorrow, and I will make a special trip to see you both.”

Upon reflection ...

When I sat down to write my clinical notes for the day, I realized that Rose, Violet, Gabby, and Mabel were each over 100 years old. I had seen four centenarians in a single day! Each of them manifested a fundamental principle of geriatrics: The older we are, the more unique and differentiated we become. A one-size approach to geriatric care does not fit all. Our care must be personalized to the unique individual in front of us.

Patients’ names and some details have been changed to protect their privacy. Dr. Williams is the Emeritus Ward K. Ensminger Distinguished Professor of Geriatric Medicine, University of Virginia, Charlottesville and attending physician, internal medicine and geriatrics, New Hanover Regional Medical Center, Wilmington, N.C. He disclosed no relevant financial disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

I was rounding at the nursing home and my day began as it often did. I reviewed the doctor communication book at the nursing station to see which patients I needed to visit and checked in with the floor nurse for any important updates.

A mother waiting for her son to visit

The first patient on my list was Rose. She had become increasingly withdrawn and less mobile. She used to walk the corridors asking when her son, Billy, would visit. We would all remind her that Billy visited her two or three times a week, but she never remembered the visits and blamed him for moving her out of her comfortable home in New Jersey where she’d lived with her husband before his death several years earlier.

Rose was declining, and we were trying to optimize her function and quality of life. She fell frequently while trying to get up at night to use the bathroom. None of our fall-reduction strategies had worked, and she had broken her hip a year prior. She’d fully recovered, but the combination of mental and physical frailty was becoming obvious to everyone, including her son. She had lost another five pounds and was approaching the end of her life.

“Good morning, Rose.” (She had demanded that I use her first name.) “How are you doing today?”

“I am doing okay, doctor. Have you seen Billy? When is he going to visit me?”

“I really can’t say when he’ll visit next, but I saw in a note that he was here yesterday.”

“No, he didn’t come to see me,” she said. “He doesn’t care about me. He spends more time with his wife and family than with his own mother.”

“Well, is there anything special that I can do for you?”

“Yes. Please tell Billy to visit his mother,” she said.

I completed her evaluation and made my way down the hall.

A wife ready to rejoin her husband

Next on my list was a widow named Violet. She reminded me of Whistler’s mother. As was her custom, she was sitting up in her chair reading her Bible when I came in. Her husband had been a minister, and she enjoyed reading the Bible or meditating for several hours each morning. Her bedside table had the most recent devotional and a picture of her husband in his vestments.

Violet was quiet and direct, and she had steely blue eyes that could communicate with your soul. Her nun-like quality was not overpowering; her manner was warm and welcoming.

“Good morning!” I said. “I hope I’m not bothering you.”

“Good morning, doctor. It’s always nice to see you.”

“I haven’t been by in a while, and I wanted to check your heart and lungs and make sure everything is going okay for you.”

“Of course; help yourself,” she said. “I feel fine. And as you know, I am ready to join my husband whenever the Lord calls me. I have lived a blessed life and do not wish to prolong it unless it is God’s will.”

“You certainly have made your wishes clear to me, and you are still in excellent health,” I said.

She really was in good health, and I made a quick note to call her daughter – who lived on the other side of the country – with an update.

A beauty queen ready for her close-up

Gabby was next on my list. She was a former beauty queen who had competed in local and state beauty contests. Her looks were the cornerstone of her identity, and she had done a truly remarkable job of maintaining her physical appearance.

Gabby had three attentive daughters who lived locally and supplied her with the latest makeup, beauty creams, and anti-aging nostrums. She always managed to look natural (and not like a caricature) with her face made up and her blond wig in place. Over the years, she’d made good use of the services offered by the local plastic surgeons and dermatologists. And to her credit – and theirs – she looked 30 years younger than her chronological age. In fairness, she had also taken good care of her overall health.

Gabby’s nickname was appropriate as she was chatty, to the extreme. She enjoyed being the center of attention.

When I entered her room, she was putting on her makeup. She was seated near her bedside table, which looked like it belonged in the backstage dressing room of a Broadway star. Lined up on the table were various bottles, brushes, and a mirror surrounded by lights.

“Oh, doctor, you can’t come in now. I’m a dreadful mess,” she said. “Please come back in 10 minutes. I am so embarrassed that you are seeing me this way. I just have a few things to fix, and then I will be presentable. My daughters are taking me out for lunch at the club, and I do not want to look like an old lady.”

“Gabby,” I said, “I have seen you before without your makeup. Do you remember last year when you developed pneumonia? You were really sick, and frankly, we were not sure you were going to pull through. One of the clues that you were getting ill was your smeared mascara and lipstick.”

I pressed on, and she let me examine her while she continued to apply her eyeliner.

“Everything sounds good. And I like your fresh pedicure,” I said. “Is there anything I can do for you?”

“No, thank you. Have a nice day, doctor!”

A mother devoted to her daughter’s care

Unlike my other patients, Mabel shared a room with a family member – her daughter, Hope. Mabel’s daughter had a congenital illness with significant physical, functional, and cognitive deficits. Mabel had considerable guilt regarding her daughter’s condition. Mabel’s husband had divorced her decades earlier, and she had devoted her life to caring for Hope. When Mabel’s health began to decline and she realized she could no longer care for Hope alone, the two moved into the facility together. Mabel told me that she simply couldn’t die before her daughter, because no one could oversee her care like she could.

Mabel was frail physically but sharp and vigilant mentally. Hope had had numerous hospitalizations, and Mabel had been with her through each experience. Hope could not communicate with others, but Mabel could express Hope’s concerns.

“How are you doing today?” I asked.

“Not well. I am concerned about Hope. She has not had a bowel movement in two days and does not want to eat breakfast.”

I checked out Hope, and her examination was reassuring. She looked up at me with her distorted features and managed a broad smile. I went back over to Mabel.

“She likes you, doctor. She thinks you smell good.”

I turned to Hope and thanked her for the compliment.

“I will check with the nurse and see if we can give you something simple to help your bowels.”

“Warm prune juice often works,” said Mabel. “Please come by again tomorrow to check on her. I don’t want this to progress. She is miserable.”

“I will be back tomorrow, and I will make a special trip to see you both.”

Upon reflection ...

When I sat down to write my clinical notes for the day, I realized that Rose, Violet, Gabby, and Mabel were each over 100 years old. I had seen four centenarians in a single day! Each of them manifested a fundamental principle of geriatrics: The older we are, the more unique and differentiated we become. A one-size approach to geriatric care does not fit all. Our care must be personalized to the unique individual in front of us.

Patients’ names and some details have been changed to protect their privacy. Dr. Williams is the Emeritus Ward K. Ensminger Distinguished Professor of Geriatric Medicine, University of Virginia, Charlottesville and attending physician, internal medicine and geriatrics, New Hanover Regional Medical Center, Wilmington, N.C. He disclosed no relevant financial disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Low depression scores may miss seniors with suicidal intent

Older adults may have a high degree of suicidal intent yet still have low scores on scales measuring psychiatric symptoms, such as depression, new research suggests.

In a cross-sectional cohort study of more than 800 adults who presented with self-harm to psychiatric EDs in Sweden, participants aged 65 years and older scored higher than younger and middle-aged adults on measures of suicidal intent.

However, only half of the older group fulfilled criteria for major depression, compared with three-quarters of both the middle-aged and young adult–aged groups.

“Suicidal older persons show a somewhat different clinical picture with relatively low levels of psychopathology but with high suicide intent compared to younger persons,” lead author Stefan Wiktorsson, PhD, University of Gothenburg (Sweden), said in an interview.

“It is therefore of importance for clinicians to carefully evaluate suicidal thinking in this age group. he said.

The findings were published online Aug. 9, 2021, in the American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry.

Research by age groups ‘lacking’

“While there are large age differences in the prevalence of suicidal behavior, research studies that compare symptomatology and diagnostics in different age groups are lacking,” Dr. Wiktorsson said.

He and his colleagues “wanted to compare psychopathology in young, middle-aged, and older adults in order to increase knowledge about potential differences in symptomatology related to suicidal behavior over the life span.”

The researchers recruited patients aged 18 years and older who had sought or had been referred to emergency psychiatric services for self-harm at three psychiatric hospitals in Sweden between April 2012 and March 2016.

Among all patients, 821 fit inclusion criteria and agreed to participate. The researchers excluded participants who had engaged in nonsuicidal self-injury (NNSI), as determined on the basis of the Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS). The remaining 683 participants, who had attempted suicide, were included in the analysis.

The participants were then divided into the following three groups: older (n = 96; age, 65-97 years; mean age, 77.2 years; 57% women), middle-aged (n = 164; age, 45-64 years; mean age, 53.4 years; 57% women), and younger (n = 423; age, 18-44 years; mean age, 28.3 years; 64% women)

Mental health staff interviewed participants within 7 days of the index episode. They collected information about sociodemographics, health, and contact with health care professionals. They used the C-SSRS to identify characteristics of the suicide attempts, and they used the Suicide Intent Scale (SIS) to evaluate circumstances surrounding the suicide attempt, such as active preparation.

Investigators also used the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI), the Suicide Assessment Scale (SUAS), and the Karolinska Affective and Borderline Symptoms Scale.

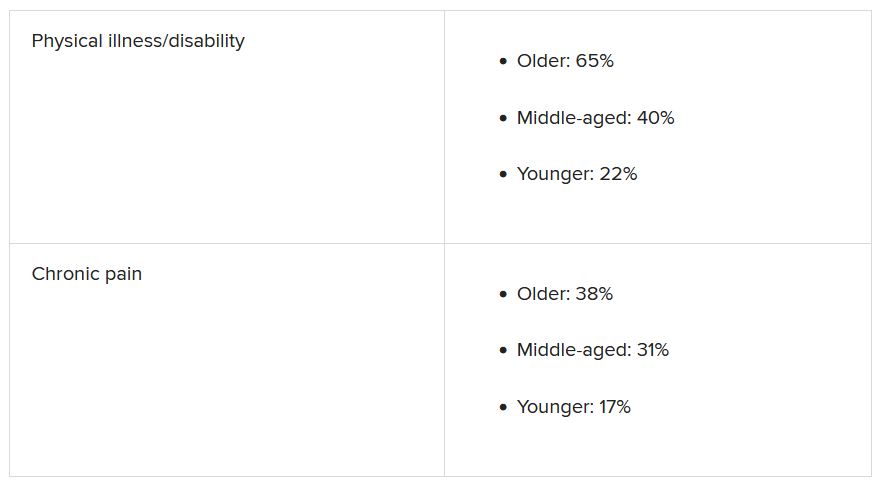

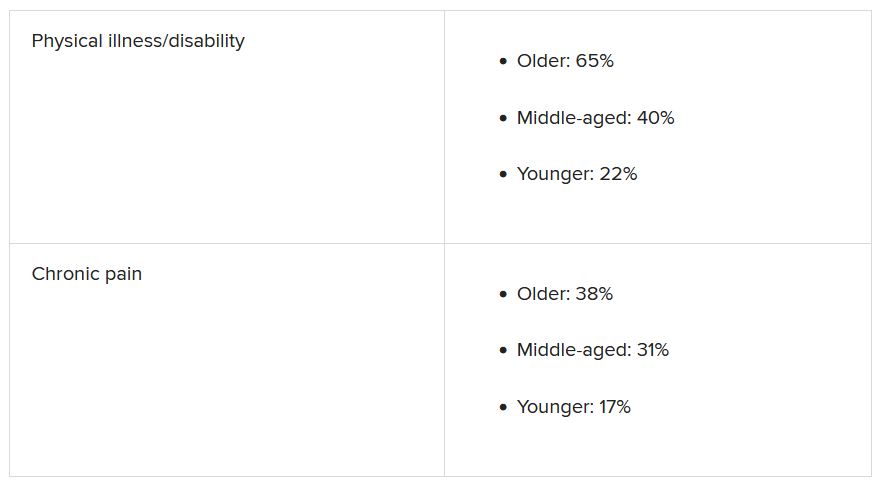

Greater disability, pain

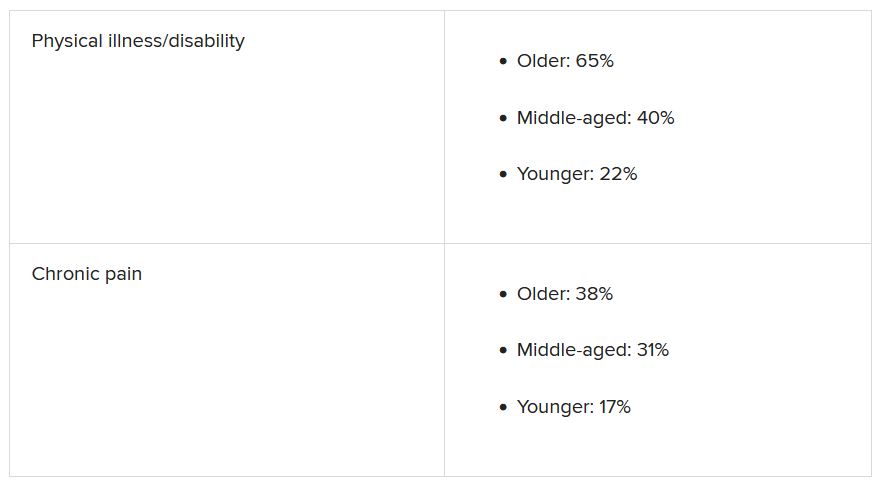

Of the older patients, 75% lived alone; 88% of the middle-aged and 48% of the younger participants lived alone. A higher proportion of older participants had severe physical illness/disability and severe chronic pain compared with younger participants (all comparisons, P < .001).

Older adults had less contact with psychiatric services, but they had more contact than the other age groups with primary care for mental health problems. Older adults were prescribed antidepressants at the time of the suicide attempt at a lower rate, compared with the middle-aged and younger groups (50% vs. 73% and 66%).

Slightly less than half (44%) of the older adults had a previous history of a suicide attempt – a proportion considerably lower than was reported by patients in the middle-aged and young adult groups (63% and 75%, respectively). Few older adults had a history of a previous NNSI (6% vs. 23% and 63%).

Three-quarters of older adults employed poisoning as the single method of suicide attempt at their index episode, compared with 67% and 59% of the middle-aged and younger groups.

Notably, only half of older adults (52%) met criteria for major depression, determined on the basis of the MINI, compared with three quarters of participants in the other groups (73% and 76%, respectively). Fewer members of the older group met criteria for other psychiatric conditions.

Clouded judgment

The mean total SUAS score was “considerably lower” in the older-adult group than in the other groups. This was also the case for the SUAS subscales for affect, bodily states, control, coping, and emotional reactivity.

Importantly, however, older adults scored higher than younger adults on the SIS total score and the subjective subscale, indicating a higher level of suicidal intent.

The mean SIS total score was 17.8 in the older group, 17.4 in the middle-aged group, and 15.9 in the younger group. The SIS subjective suicide intent score was 10.9 versus 10.6 and 9.4.

“While subjective suicidal intent was higher, compared to the young group, older adults were less likely to fulfill criteria for major depression and several other mental disorders and lower scores were observed on all symptom rating scales, compared to both middle-aged and younger adults,” the investigators wrote.

“Low levels of psychopathology may cloud the clinician’s assessment of the serious nature of suicide attempts in older patients,” they added.

‘Silent generation’

Commenting on the findings, Marnin Heisel, PhD, CPsych, associate professor, departments of psychiatry and of epidemiology and biostatistics, University of Western Ontario, London, said an important takeaway from the study is that, if health care professionals look only for depression or only consider suicide risk in individuals who present with depression, “they might miss older adults who are contemplating suicide or engaging in suicidal behavior.”

Dr. Heisel, who was not involved with the study, observed that older adults are sometimes called the “silent generation” because they often tend to downplay or underreport depressive symptoms, partially because of having been socialized to “keep things to themselves and not to air emotional laundry.”

He recommended that, when assessing potentially suicidal older adults, clinicians select tools specifically designed for use in this age group, particularly the Geriatric Suicide Ideation Scale and the Geriatric Depression Scale. Dr. Heisel also recommended the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale–Revised Version.

“Beyond a specific scale, the question is to walk into a clinical encounter with a much broader viewpoint, understand who the client is, where they come from, their attitudes, life experience, and what in their experience is going on, their reason for coming to see someone and what they’re struggling with,” he said.

“What we’re seeing with this study is that standard clinical tools don’t necessarily identify some of these richer issues that might contribute to emotional pain, so sometimes the best way to go is a broader clinical interview with a humanistic perspective,” Dr. Heisel concluded.

The study was funded by the Swedish Research Council, the Swedish Research Council for Health, Working Life and Welfare, and the Swedish state, Stockholm County Council and Västerbotten County Council. The investigators and Dr. Heisel have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Older adults may have a high degree of suicidal intent yet still have low scores on scales measuring psychiatric symptoms, such as depression, new research suggests.

In a cross-sectional cohort study of more than 800 adults who presented with self-harm to psychiatric EDs in Sweden, participants aged 65 years and older scored higher than younger and middle-aged adults on measures of suicidal intent.

However, only half of the older group fulfilled criteria for major depression, compared with three-quarters of both the middle-aged and young adult–aged groups.

“Suicidal older persons show a somewhat different clinical picture with relatively low levels of psychopathology but with high suicide intent compared to younger persons,” lead author Stefan Wiktorsson, PhD, University of Gothenburg (Sweden), said in an interview.

“It is therefore of importance for clinicians to carefully evaluate suicidal thinking in this age group. he said.

The findings were published online Aug. 9, 2021, in the American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry.

Research by age groups ‘lacking’

“While there are large age differences in the prevalence of suicidal behavior, research studies that compare symptomatology and diagnostics in different age groups are lacking,” Dr. Wiktorsson said.

He and his colleagues “wanted to compare psychopathology in young, middle-aged, and older adults in order to increase knowledge about potential differences in symptomatology related to suicidal behavior over the life span.”

The researchers recruited patients aged 18 years and older who had sought or had been referred to emergency psychiatric services for self-harm at three psychiatric hospitals in Sweden between April 2012 and March 2016.

Among all patients, 821 fit inclusion criteria and agreed to participate. The researchers excluded participants who had engaged in nonsuicidal self-injury (NNSI), as determined on the basis of the Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS). The remaining 683 participants, who had attempted suicide, were included in the analysis.

The participants were then divided into the following three groups: older (n = 96; age, 65-97 years; mean age, 77.2 years; 57% women), middle-aged (n = 164; age, 45-64 years; mean age, 53.4 years; 57% women), and younger (n = 423; age, 18-44 years; mean age, 28.3 years; 64% women)

Mental health staff interviewed participants within 7 days of the index episode. They collected information about sociodemographics, health, and contact with health care professionals. They used the C-SSRS to identify characteristics of the suicide attempts, and they used the Suicide Intent Scale (SIS) to evaluate circumstances surrounding the suicide attempt, such as active preparation.

Investigators also used the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI), the Suicide Assessment Scale (SUAS), and the Karolinska Affective and Borderline Symptoms Scale.

Greater disability, pain

Of the older patients, 75% lived alone; 88% of the middle-aged and 48% of the younger participants lived alone. A higher proportion of older participants had severe physical illness/disability and severe chronic pain compared with younger participants (all comparisons, P < .001).

Older adults had less contact with psychiatric services, but they had more contact than the other age groups with primary care for mental health problems. Older adults were prescribed antidepressants at the time of the suicide attempt at a lower rate, compared with the middle-aged and younger groups (50% vs. 73% and 66%).

Slightly less than half (44%) of the older adults had a previous history of a suicide attempt – a proportion considerably lower than was reported by patients in the middle-aged and young adult groups (63% and 75%, respectively). Few older adults had a history of a previous NNSI (6% vs. 23% and 63%).

Three-quarters of older adults employed poisoning as the single method of suicide attempt at their index episode, compared with 67% and 59% of the middle-aged and younger groups.

Notably, only half of older adults (52%) met criteria for major depression, determined on the basis of the MINI, compared with three quarters of participants in the other groups (73% and 76%, respectively). Fewer members of the older group met criteria for other psychiatric conditions.

Clouded judgment

The mean total SUAS score was “considerably lower” in the older-adult group than in the other groups. This was also the case for the SUAS subscales for affect, bodily states, control, coping, and emotional reactivity.

Importantly, however, older adults scored higher than younger adults on the SIS total score and the subjective subscale, indicating a higher level of suicidal intent.

The mean SIS total score was 17.8 in the older group, 17.4 in the middle-aged group, and 15.9 in the younger group. The SIS subjective suicide intent score was 10.9 versus 10.6 and 9.4.

“While subjective suicidal intent was higher, compared to the young group, older adults were less likely to fulfill criteria for major depression and several other mental disorders and lower scores were observed on all symptom rating scales, compared to both middle-aged and younger adults,” the investigators wrote.

“Low levels of psychopathology may cloud the clinician’s assessment of the serious nature of suicide attempts in older patients,” they added.

‘Silent generation’

Commenting on the findings, Marnin Heisel, PhD, CPsych, associate professor, departments of psychiatry and of epidemiology and biostatistics, University of Western Ontario, London, said an important takeaway from the study is that, if health care professionals look only for depression or only consider suicide risk in individuals who present with depression, “they might miss older adults who are contemplating suicide or engaging in suicidal behavior.”

Dr. Heisel, who was not involved with the study, observed that older adults are sometimes called the “silent generation” because they often tend to downplay or underreport depressive symptoms, partially because of having been socialized to “keep things to themselves and not to air emotional laundry.”

He recommended that, when assessing potentially suicidal older adults, clinicians select tools specifically designed for use in this age group, particularly the Geriatric Suicide Ideation Scale and the Geriatric Depression Scale. Dr. Heisel also recommended the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale–Revised Version.

“Beyond a specific scale, the question is to walk into a clinical encounter with a much broader viewpoint, understand who the client is, where they come from, their attitudes, life experience, and what in their experience is going on, their reason for coming to see someone and what they’re struggling with,” he said.

“What we’re seeing with this study is that standard clinical tools don’t necessarily identify some of these richer issues that might contribute to emotional pain, so sometimes the best way to go is a broader clinical interview with a humanistic perspective,” Dr. Heisel concluded.

The study was funded by the Swedish Research Council, the Swedish Research Council for Health, Working Life and Welfare, and the Swedish state, Stockholm County Council and Västerbotten County Council. The investigators and Dr. Heisel have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Older adults may have a high degree of suicidal intent yet still have low scores on scales measuring psychiatric symptoms, such as depression, new research suggests.

In a cross-sectional cohort study of more than 800 adults who presented with self-harm to psychiatric EDs in Sweden, participants aged 65 years and older scored higher than younger and middle-aged adults on measures of suicidal intent.

However, only half of the older group fulfilled criteria for major depression, compared with three-quarters of both the middle-aged and young adult–aged groups.

“Suicidal older persons show a somewhat different clinical picture with relatively low levels of psychopathology but with high suicide intent compared to younger persons,” lead author Stefan Wiktorsson, PhD, University of Gothenburg (Sweden), said in an interview.

“It is therefore of importance for clinicians to carefully evaluate suicidal thinking in this age group. he said.

The findings were published online Aug. 9, 2021, in the American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry.

Research by age groups ‘lacking’

“While there are large age differences in the prevalence of suicidal behavior, research studies that compare symptomatology and diagnostics in different age groups are lacking,” Dr. Wiktorsson said.

He and his colleagues “wanted to compare psychopathology in young, middle-aged, and older adults in order to increase knowledge about potential differences in symptomatology related to suicidal behavior over the life span.”

The researchers recruited patients aged 18 years and older who had sought or had been referred to emergency psychiatric services for self-harm at three psychiatric hospitals in Sweden between April 2012 and March 2016.

Among all patients, 821 fit inclusion criteria and agreed to participate. The researchers excluded participants who had engaged in nonsuicidal self-injury (NNSI), as determined on the basis of the Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS). The remaining 683 participants, who had attempted suicide, were included in the analysis.

The participants were then divided into the following three groups: older (n = 96; age, 65-97 years; mean age, 77.2 years; 57% women), middle-aged (n = 164; age, 45-64 years; mean age, 53.4 years; 57% women), and younger (n = 423; age, 18-44 years; mean age, 28.3 years; 64% women)

Mental health staff interviewed participants within 7 days of the index episode. They collected information about sociodemographics, health, and contact with health care professionals. They used the C-SSRS to identify characteristics of the suicide attempts, and they used the Suicide Intent Scale (SIS) to evaluate circumstances surrounding the suicide attempt, such as active preparation.

Investigators also used the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI), the Suicide Assessment Scale (SUAS), and the Karolinska Affective and Borderline Symptoms Scale.

Greater disability, pain

Of the older patients, 75% lived alone; 88% of the middle-aged and 48% of the younger participants lived alone. A higher proportion of older participants had severe physical illness/disability and severe chronic pain compared with younger participants (all comparisons, P < .001).

Older adults had less contact with psychiatric services, but they had more contact than the other age groups with primary care for mental health problems. Older adults were prescribed antidepressants at the time of the suicide attempt at a lower rate, compared with the middle-aged and younger groups (50% vs. 73% and 66%).

Slightly less than half (44%) of the older adults had a previous history of a suicide attempt – a proportion considerably lower than was reported by patients in the middle-aged and young adult groups (63% and 75%, respectively). Few older adults had a history of a previous NNSI (6% vs. 23% and 63%).

Three-quarters of older adults employed poisoning as the single method of suicide attempt at their index episode, compared with 67% and 59% of the middle-aged and younger groups.

Notably, only half of older adults (52%) met criteria for major depression, determined on the basis of the MINI, compared with three quarters of participants in the other groups (73% and 76%, respectively). Fewer members of the older group met criteria for other psychiatric conditions.

Clouded judgment

The mean total SUAS score was “considerably lower” in the older-adult group than in the other groups. This was also the case for the SUAS subscales for affect, bodily states, control, coping, and emotional reactivity.

Importantly, however, older adults scored higher than younger adults on the SIS total score and the subjective subscale, indicating a higher level of suicidal intent.

The mean SIS total score was 17.8 in the older group, 17.4 in the middle-aged group, and 15.9 in the younger group. The SIS subjective suicide intent score was 10.9 versus 10.6 and 9.4.

“While subjective suicidal intent was higher, compared to the young group, older adults were less likely to fulfill criteria for major depression and several other mental disorders and lower scores were observed on all symptom rating scales, compared to both middle-aged and younger adults,” the investigators wrote.

“Low levels of psychopathology may cloud the clinician’s assessment of the serious nature of suicide attempts in older patients,” they added.

‘Silent generation’

Commenting on the findings, Marnin Heisel, PhD, CPsych, associate professor, departments of psychiatry and of epidemiology and biostatistics, University of Western Ontario, London, said an important takeaway from the study is that, if health care professionals look only for depression or only consider suicide risk in individuals who present with depression, “they might miss older adults who are contemplating suicide or engaging in suicidal behavior.”

Dr. Heisel, who was not involved with the study, observed that older adults are sometimes called the “silent generation” because they often tend to downplay or underreport depressive symptoms, partially because of having been socialized to “keep things to themselves and not to air emotional laundry.”

He recommended that, when assessing potentially suicidal older adults, clinicians select tools specifically designed for use in this age group, particularly the Geriatric Suicide Ideation Scale and the Geriatric Depression Scale. Dr. Heisel also recommended the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale–Revised Version.

“Beyond a specific scale, the question is to walk into a clinical encounter with a much broader viewpoint, understand who the client is, where they come from, their attitudes, life experience, and what in their experience is going on, their reason for coming to see someone and what they’re struggling with,” he said.

“What we’re seeing with this study is that standard clinical tools don’t necessarily identify some of these richer issues that might contribute to emotional pain, so sometimes the best way to go is a broader clinical interview with a humanistic perspective,” Dr. Heisel concluded.

The study was funded by the Swedish Research Council, the Swedish Research Council for Health, Working Life and Welfare, and the Swedish state, Stockholm County Council and Västerbotten County Council. The investigators and Dr. Heisel have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Managing sleep in the elderly

Sleep problems are prevalent in older adults, and overmedication is a common cause. Insomnia is a concern, and it might not look the same in older adults as it does in younger populations, especially when neurodegenerative disorders may be present. “There’s often not only the inability to get to sleep and stay asleep in older adults but also changes in their biological rhythms, which is why treatments really need to be focused on both,” Ruth M. Benca, MD, PhD, said in an interview.

Dr. Benca spoke on the topic of insomnia in the elderly at a virtual meeting presented by Current Psychiatry and the American Academy of Clinical Psychiatrists. She is chair of psychiatry at Wake Forest Baptist Health, Winston-Salem, N.C.

Sleep issues strongly affect quality of life and health outcomes in the elderly, and there isn’t a lot of clear guidance for physicians to manage these issues. who spoke at the meeting presented by MedscapeLive. MedscapeLive and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

Behavioral approaches are important, because quality of sleep is often affected by daytime activities, such as exercise and light exposure, according to Dr. Benca, who said that those factors can and should be addressed by behavioral interventions. Medications should be used as an adjunct to those treatments. “When we do need to use medications, we need to use ones that have been tested and found to be more helpful than harmful in older adults,” Dr. Benca said.

Many Food and Drug Administration–approved drugs should be used with caution or avoided in the elderly. The Beers criteria provide a useful list of potentially problematic drugs, and removing those drugs from consideration leaves just a few options, including the melatonin receptor agonist ramelteon, low doses of the tricyclic antidepressant doxepin, and dual orexin receptor antagonists, which are being tested in older adults, including some with dementia, Dr. Benca said.

Other drugs like benzodiazepines and related “Z” drugs can cause problems like amnesia, confusion, and psychomotor issues. “They’re advised against because there are some concerns about those side effects,” Dr. Benca said.

Sleep disturbance itself can be the result of polypharmacy. Even something as simple as a diuretic can interrupt slumber because of nocturnal bathroom visits. Antihypertensives and drugs that affect the central nervous system, including antidepressants, can affect sleep. “I’ve had patients get horrible dreams and nightmares from antihypertensive drugs. So there’s a very long laundry list of drugs that can affect sleep in a negative way,” said Dr. Benca.

Physicians have a tendency to prescribe more drugs to a patient without eliminating any, which can result in complex situations. “We see this sort of chasing the tail: You give a drug, it may have a positive effect on the primary thing you want to treat, but it has a side effect. When you give another drug to treat that side effect, it in turn has its own side effect. We keep piling on drugs,” Dr. Benca said.

“So if [a patient is] on medications for an indication, and particularly for sleep or other things, and the patient isn’t getting better, what we might want to do is slowly to withdraw things. Even for older adults who are on sleeping medications and maybe are doing better, sometimes we can decrease the dose [of the other drugs], or get them off those drugs or put them on something that might be less likely to have side effects,” Dr. Benca said.

To do that, she suggests taking a history to determine when the sleep problem began, and whether it coincided with adding or changing a medication. Another approach is to look at the list of current medications, and look for drugs that are prescribed for a problem and where the problem still persists. “You might want to take that away first, before you start adding something else,” said Dr. Benca.

Another challenge is that physicians are often unwilling to investigate sleep disorders, which are more common in older adults. Physicians can be reluctant to prescribe sleep medications, and may also be unfamiliar with behavioral interventions. “For a lot of providers, getting into sleep issues is like opening a Pandora’s Box. I think mostly physicians are taught: Don’t do this, and don’t do that. They’re not as well versed in the things that they can and should do,” said Dr. Benca.

If attempts to treat insomnia don’t succeed, or if the physician suspects a movement disorder or primary sleep disorder like sleep apnea, then the patients should be referred to a sleep specialist, according to Dr. Benca.

During the question-and-answer period following her talk, a questioner brought up the increasingly common use of cannabis to improve sleep. That can be tricky because it can be difficult to stop cannabis use, because of the rebound insomnia that may persist. She noted that there are ongoing studies on the potential impact of cannabidiol oil.

Dr. Benca was also asked about patients who take sedatives chronically and seem to be doing well. She emphasized the need for finding the lowest effective dose of a short-acting medication. “Patients should be monitored frequently, at least every 6 months. Just monitor your patient carefully.”

Dr. Benca is a consultant for Eisai, Genomind, Idorsia, Jazz, Merck, Sage, and Sunovion.

Sleep problems are prevalent in older adults, and overmedication is a common cause. Insomnia is a concern, and it might not look the same in older adults as it does in younger populations, especially when neurodegenerative disorders may be present. “There’s often not only the inability to get to sleep and stay asleep in older adults but also changes in their biological rhythms, which is why treatments really need to be focused on both,” Ruth M. Benca, MD, PhD, said in an interview.

Dr. Benca spoke on the topic of insomnia in the elderly at a virtual meeting presented by Current Psychiatry and the American Academy of Clinical Psychiatrists. She is chair of psychiatry at Wake Forest Baptist Health, Winston-Salem, N.C.

Sleep issues strongly affect quality of life and health outcomes in the elderly, and there isn’t a lot of clear guidance for physicians to manage these issues. who spoke at the meeting presented by MedscapeLive. MedscapeLive and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

Behavioral approaches are important, because quality of sleep is often affected by daytime activities, such as exercise and light exposure, according to Dr. Benca, who said that those factors can and should be addressed by behavioral interventions. Medications should be used as an adjunct to those treatments. “When we do need to use medications, we need to use ones that have been tested and found to be more helpful than harmful in older adults,” Dr. Benca said.

Many Food and Drug Administration–approved drugs should be used with caution or avoided in the elderly. The Beers criteria provide a useful list of potentially problematic drugs, and removing those drugs from consideration leaves just a few options, including the melatonin receptor agonist ramelteon, low doses of the tricyclic antidepressant doxepin, and dual orexin receptor antagonists, which are being tested in older adults, including some with dementia, Dr. Benca said.

Other drugs like benzodiazepines and related “Z” drugs can cause problems like amnesia, confusion, and psychomotor issues. “They’re advised against because there are some concerns about those side effects,” Dr. Benca said.

Sleep disturbance itself can be the result of polypharmacy. Even something as simple as a diuretic can interrupt slumber because of nocturnal bathroom visits. Antihypertensives and drugs that affect the central nervous system, including antidepressants, can affect sleep. “I’ve had patients get horrible dreams and nightmares from antihypertensive drugs. So there’s a very long laundry list of drugs that can affect sleep in a negative way,” said Dr. Benca.

Physicians have a tendency to prescribe more drugs to a patient without eliminating any, which can result in complex situations. “We see this sort of chasing the tail: You give a drug, it may have a positive effect on the primary thing you want to treat, but it has a side effect. When you give another drug to treat that side effect, it in turn has its own side effect. We keep piling on drugs,” Dr. Benca said.

“So if [a patient is] on medications for an indication, and particularly for sleep or other things, and the patient isn’t getting better, what we might want to do is slowly to withdraw things. Even for older adults who are on sleeping medications and maybe are doing better, sometimes we can decrease the dose [of the other drugs], or get them off those drugs or put them on something that might be less likely to have side effects,” Dr. Benca said.

To do that, she suggests taking a history to determine when the sleep problem began, and whether it coincided with adding or changing a medication. Another approach is to look at the list of current medications, and look for drugs that are prescribed for a problem and where the problem still persists. “You might want to take that away first, before you start adding something else,” said Dr. Benca.

Another challenge is that physicians are often unwilling to investigate sleep disorders, which are more common in older adults. Physicians can be reluctant to prescribe sleep medications, and may also be unfamiliar with behavioral interventions. “For a lot of providers, getting into sleep issues is like opening a Pandora’s Box. I think mostly physicians are taught: Don’t do this, and don’t do that. They’re not as well versed in the things that they can and should do,” said Dr. Benca.

If attempts to treat insomnia don’t succeed, or if the physician suspects a movement disorder or primary sleep disorder like sleep apnea, then the patients should be referred to a sleep specialist, according to Dr. Benca.

During the question-and-answer period following her talk, a questioner brought up the increasingly common use of cannabis to improve sleep. That can be tricky because it can be difficult to stop cannabis use, because of the rebound insomnia that may persist. She noted that there are ongoing studies on the potential impact of cannabidiol oil.

Dr. Benca was also asked about patients who take sedatives chronically and seem to be doing well. She emphasized the need for finding the lowest effective dose of a short-acting medication. “Patients should be monitored frequently, at least every 6 months. Just monitor your patient carefully.”

Dr. Benca is a consultant for Eisai, Genomind, Idorsia, Jazz, Merck, Sage, and Sunovion.

Sleep problems are prevalent in older adults, and overmedication is a common cause. Insomnia is a concern, and it might not look the same in older adults as it does in younger populations, especially when neurodegenerative disorders may be present. “There’s often not only the inability to get to sleep and stay asleep in older adults but also changes in their biological rhythms, which is why treatments really need to be focused on both,” Ruth M. Benca, MD, PhD, said in an interview.

Dr. Benca spoke on the topic of insomnia in the elderly at a virtual meeting presented by Current Psychiatry and the American Academy of Clinical Psychiatrists. She is chair of psychiatry at Wake Forest Baptist Health, Winston-Salem, N.C.

Sleep issues strongly affect quality of life and health outcomes in the elderly, and there isn’t a lot of clear guidance for physicians to manage these issues. who spoke at the meeting presented by MedscapeLive. MedscapeLive and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

Behavioral approaches are important, because quality of sleep is often affected by daytime activities, such as exercise and light exposure, according to Dr. Benca, who said that those factors can and should be addressed by behavioral interventions. Medications should be used as an adjunct to those treatments. “When we do need to use medications, we need to use ones that have been tested and found to be more helpful than harmful in older adults,” Dr. Benca said.

Many Food and Drug Administration–approved drugs should be used with caution or avoided in the elderly. The Beers criteria provide a useful list of potentially problematic drugs, and removing those drugs from consideration leaves just a few options, including the melatonin receptor agonist ramelteon, low doses of the tricyclic antidepressant doxepin, and dual orexin receptor antagonists, which are being tested in older adults, including some with dementia, Dr. Benca said.

Other drugs like benzodiazepines and related “Z” drugs can cause problems like amnesia, confusion, and psychomotor issues. “They’re advised against because there are some concerns about those side effects,” Dr. Benca said.

Sleep disturbance itself can be the result of polypharmacy. Even something as simple as a diuretic can interrupt slumber because of nocturnal bathroom visits. Antihypertensives and drugs that affect the central nervous system, including antidepressants, can affect sleep. “I’ve had patients get horrible dreams and nightmares from antihypertensive drugs. So there’s a very long laundry list of drugs that can affect sleep in a negative way,” said Dr. Benca.

Physicians have a tendency to prescribe more drugs to a patient without eliminating any, which can result in complex situations. “We see this sort of chasing the tail: You give a drug, it may have a positive effect on the primary thing you want to treat, but it has a side effect. When you give another drug to treat that side effect, it in turn has its own side effect. We keep piling on drugs,” Dr. Benca said.

“So if [a patient is] on medications for an indication, and particularly for sleep or other things, and the patient isn’t getting better, what we might want to do is slowly to withdraw things. Even for older adults who are on sleeping medications and maybe are doing better, sometimes we can decrease the dose [of the other drugs], or get them off those drugs or put them on something that might be less likely to have side effects,” Dr. Benca said.

To do that, she suggests taking a history to determine when the sleep problem began, and whether it coincided with adding or changing a medication. Another approach is to look at the list of current medications, and look for drugs that are prescribed for a problem and where the problem still persists. “You might want to take that away first, before you start adding something else,” said Dr. Benca.

Another challenge is that physicians are often unwilling to investigate sleep disorders, which are more common in older adults. Physicians can be reluctant to prescribe sleep medications, and may also be unfamiliar with behavioral interventions. “For a lot of providers, getting into sleep issues is like opening a Pandora’s Box. I think mostly physicians are taught: Don’t do this, and don’t do that. They’re not as well versed in the things that they can and should do,” said Dr. Benca.

If attempts to treat insomnia don’t succeed, or if the physician suspects a movement disorder or primary sleep disorder like sleep apnea, then the patients should be referred to a sleep specialist, according to Dr. Benca.

During the question-and-answer period following her talk, a questioner brought up the increasingly common use of cannabis to improve sleep. That can be tricky because it can be difficult to stop cannabis use, because of the rebound insomnia that may persist. She noted that there are ongoing studies on the potential impact of cannabidiol oil.

Dr. Benca was also asked about patients who take sedatives chronically and seem to be doing well. She emphasized the need for finding the lowest effective dose of a short-acting medication. “Patients should be monitored frequently, at least every 6 months. Just monitor your patient carefully.”

Dr. Benca is a consultant for Eisai, Genomind, Idorsia, Jazz, Merck, Sage, and Sunovion.

FROM FOCUS ON NEUROPSYCHIATRY 2021

Diet, exercise in older adults with knee OA have long-term payoff

Older patients with knee osteoarthritis (OA) who underwent lengthy diet and exercise interventions reported less pain and maintained some weight loss years after the program ended, according to a new study published in Arthritis Care & Research.

“These data imply that clinicians who treat people with knee osteoarthritis have a variety of nonpharmacologic options that preserve clinically important effects 3.5 years after the treatments end,” wrote lead author Stephen P. Messier, PhD, professor and director of the J.B. Snow Biomechanics Laboratory at Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, N.C.

The study involved patients with overweight or obesity aged 55 years or older who were previously enrolled in the 1.5-year Intensive Diet and Exercise for Arthritis (IDEA) trial.

“You have to remember, this is 3.5 years after the IDEA trial ended,” Dr. Messier said in an interview. “There was no contact with them for that entire time; you’d expect, based on the literature, that they’d revert back to where they were before they entered the trial. And certainly, there was some regression, there was some weight regain, but the important part of the study is that, even after 3.5 years, and even with some weight regain, there were some clinically important effects that lasted.”

“What we feel now is that if we can somehow prepare people better for that time after they finish a weight loss intervention, from a psychological standpoint, it will make a real difference,” he added. “We are very good at helping people have the confidence to lose weight. But having the confidence to lose weight is totally different than having confidence to maintain weight loss. If we can give folks an intervention that has a psychological component, hopefully we can increase their confidence to maintain the weight loss that they attained.”

Study details

Of the 184 participants who were contacted for a follow-up visit, 94 consented to participate, 67% of whom were females and 88% of whom were White. A total of 27 participants had completed the diet and exercise intervention, and another 35 completed the diet-only and 32 exercise-only interventions.

In the 3.5-year period between the IDEA trial’s end and follow-up, body weight increased by 5.9 kg in the diet and exercise group (P < .0001) and by 3.1 kg in the diet-only group (P = .0006) but decreased in the exercise-only group by 1.0 kg (P = .25). However, from baseline to 5-year follow-up, all groups saw a reduction in body weight. Mean weight loss was –3.7 kg for the diet and exercise group (P = .0007), –5.8 kg for the diet group (P < .0001), and –2.9 kg for the exercise group (P = .003). Body mass index also decreased in all groups: by –1.2 kg/m2 in the diet and exercise group (P = .001), by –2.0 kg/m2 in the diet group (P < .0001), and by –1.0 kg/m2 in the exercise group (P = .004).

Pain – as measured by the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Arthritis Index (WOMAC) score – was reduced in all groups across 5-year follow-up: –1.2 (P = .03) for the diet and exercise group, –1.5 (P = .001) for the diet-only group, and –1.6 (P = .0008) for the exercise-only group. WOMAC function also significantly improved relative to baseline by 6.2 (P = .0001) in the diet and exercise group, by 6.1 (P < .0001) in the diet group, and by 3.7 (P = .01) in the exercise-only group.

Finding time to advise on weight loss, exercise

“If exercise and weight loss were easy, this country wouldn’t be in the state we’re in,” Tuhina Neogi, MD, PhD, of Boston University said in an interview. “Shared decision-making and personalized medicine are important; unfortunately, for the majority of physicians – particularly primary care physicians, where a good deal of OA management is undertaken – they don’t have a lot of time in their 20 minutes with a patient who has OA to counsel individuals toward a healthy weight and physical activity program when they’re also addressing common comorbidities seen in OA such as diabetes and heart disease.

“But as we know,” she added, “when you do address weight loss and physical activity, it has wide-ranging health benefits. This study provides support for utilizing formal diet and exercise programs to achieve important and durable benefits for people with OA.”

Dr. Neogi did note one of the study’s acknowledged limitations: Only slightly more than half of the contacted participants returned for follow-up. Though the authors stated that the individuals who returned were representative of both the pool of potential participants and the IDEA cohort as a whole, “we don’t want to make too many inferences when you don’t have the whole study population available,” she said. “The people who have agreed to come back 3.5 years later for follow-up testing, maybe they are a little more health conscious, more resilient. Those people might be systematically different than the people who [did not return], even though most of the factors were not statistically different between the groups.

“Whatever positive attributes they may have, though, we need to understand more about them,” she added. “We need to know how they maintained the benefits they had 3.5 years prior. That kind of understanding is important to inform long-term strategies in OA management.”

Dr. Messier highlighted a related, ongoing study he’s leading in which more than 800 overweight patients in North Carolina who suffer from knee pain are being led through diet and exercise interventions in a community setting. The goal is to replicate the IDEA results outside of a clinical trial setting and show skeptical physicians that diet and exercise can be enacted and maintained in this subset of patients.

“I think we know how effective weight loss is, especially when combined with exercise, in reducing pain, improving function, improving quality of life in these patients,” he said. “The next step is to allow them to maintain those benefits for a long period of time after the intervention ends.”

The study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health and by General Nutrition Centers. Its authors reported no potential conflicts of interest.

Older patients with knee osteoarthritis (OA) who underwent lengthy diet and exercise interventions reported less pain and maintained some weight loss years after the program ended, according to a new study published in Arthritis Care & Research.

“These data imply that clinicians who treat people with knee osteoarthritis have a variety of nonpharmacologic options that preserve clinically important effects 3.5 years after the treatments end,” wrote lead author Stephen P. Messier, PhD, professor and director of the J.B. Snow Biomechanics Laboratory at Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, N.C.

The study involved patients with overweight or obesity aged 55 years or older who were previously enrolled in the 1.5-year Intensive Diet and Exercise for Arthritis (IDEA) trial.

“You have to remember, this is 3.5 years after the IDEA trial ended,” Dr. Messier said in an interview. “There was no contact with them for that entire time; you’d expect, based on the literature, that they’d revert back to where they were before they entered the trial. And certainly, there was some regression, there was some weight regain, but the important part of the study is that, even after 3.5 years, and even with some weight regain, there were some clinically important effects that lasted.”

“What we feel now is that if we can somehow prepare people better for that time after they finish a weight loss intervention, from a psychological standpoint, it will make a real difference,” he added. “We are very good at helping people have the confidence to lose weight. But having the confidence to lose weight is totally different than having confidence to maintain weight loss. If we can give folks an intervention that has a psychological component, hopefully we can increase their confidence to maintain the weight loss that they attained.”

Study details

Of the 184 participants who were contacted for a follow-up visit, 94 consented to participate, 67% of whom were females and 88% of whom were White. A total of 27 participants had completed the diet and exercise intervention, and another 35 completed the diet-only and 32 exercise-only interventions.

In the 3.5-year period between the IDEA trial’s end and follow-up, body weight increased by 5.9 kg in the diet and exercise group (P < .0001) and by 3.1 kg in the diet-only group (P = .0006) but decreased in the exercise-only group by 1.0 kg (P = .25). However, from baseline to 5-year follow-up, all groups saw a reduction in body weight. Mean weight loss was –3.7 kg for the diet and exercise group (P = .0007), –5.8 kg for the diet group (P < .0001), and –2.9 kg for the exercise group (P = .003). Body mass index also decreased in all groups: by –1.2 kg/m2 in the diet and exercise group (P = .001), by –2.0 kg/m2 in the diet group (P < .0001), and by –1.0 kg/m2 in the exercise group (P = .004).

Pain – as measured by the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Arthritis Index (WOMAC) score – was reduced in all groups across 5-year follow-up: –1.2 (P = .03) for the diet and exercise group, –1.5 (P = .001) for the diet-only group, and –1.6 (P = .0008) for the exercise-only group. WOMAC function also significantly improved relative to baseline by 6.2 (P = .0001) in the diet and exercise group, by 6.1 (P < .0001) in the diet group, and by 3.7 (P = .01) in the exercise-only group.

Finding time to advise on weight loss, exercise

“If exercise and weight loss were easy, this country wouldn’t be in the state we’re in,” Tuhina Neogi, MD, PhD, of Boston University said in an interview. “Shared decision-making and personalized medicine are important; unfortunately, for the majority of physicians – particularly primary care physicians, where a good deal of OA management is undertaken – they don’t have a lot of time in their 20 minutes with a patient who has OA to counsel individuals toward a healthy weight and physical activity program when they’re also addressing common comorbidities seen in OA such as diabetes and heart disease.

“But as we know,” she added, “when you do address weight loss and physical activity, it has wide-ranging health benefits. This study provides support for utilizing formal diet and exercise programs to achieve important and durable benefits for people with OA.”

Dr. Neogi did note one of the study’s acknowledged limitations: Only slightly more than half of the contacted participants returned for follow-up. Though the authors stated that the individuals who returned were representative of both the pool of potential participants and the IDEA cohort as a whole, “we don’t want to make too many inferences when you don’t have the whole study population available,” she said. “The people who have agreed to come back 3.5 years later for follow-up testing, maybe they are a little more health conscious, more resilient. Those people might be systematically different than the people who [did not return], even though most of the factors were not statistically different between the groups.

“Whatever positive attributes they may have, though, we need to understand more about them,” she added. “We need to know how they maintained the benefits they had 3.5 years prior. That kind of understanding is important to inform long-term strategies in OA management.”

Dr. Messier highlighted a related, ongoing study he’s leading in which more than 800 overweight patients in North Carolina who suffer from knee pain are being led through diet and exercise interventions in a community setting. The goal is to replicate the IDEA results outside of a clinical trial setting and show skeptical physicians that diet and exercise can be enacted and maintained in this subset of patients.

“I think we know how effective weight loss is, especially when combined with exercise, in reducing pain, improving function, improving quality of life in these patients,” he said. “The next step is to allow them to maintain those benefits for a long period of time after the intervention ends.”

The study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health and by General Nutrition Centers. Its authors reported no potential conflicts of interest.

Older patients with knee osteoarthritis (OA) who underwent lengthy diet and exercise interventions reported less pain and maintained some weight loss years after the program ended, according to a new study published in Arthritis Care & Research.

“These data imply that clinicians who treat people with knee osteoarthritis have a variety of nonpharmacologic options that preserve clinically important effects 3.5 years after the treatments end,” wrote lead author Stephen P. Messier, PhD, professor and director of the J.B. Snow Biomechanics Laboratory at Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, N.C.

The study involved patients with overweight or obesity aged 55 years or older who were previously enrolled in the 1.5-year Intensive Diet and Exercise for Arthritis (IDEA) trial.

“You have to remember, this is 3.5 years after the IDEA trial ended,” Dr. Messier said in an interview. “There was no contact with them for that entire time; you’d expect, based on the literature, that they’d revert back to where they were before they entered the trial. And certainly, there was some regression, there was some weight regain, but the important part of the study is that, even after 3.5 years, and even with some weight regain, there were some clinically important effects that lasted.”

“What we feel now is that if we can somehow prepare people better for that time after they finish a weight loss intervention, from a psychological standpoint, it will make a real difference,” he added. “We are very good at helping people have the confidence to lose weight. But having the confidence to lose weight is totally different than having confidence to maintain weight loss. If we can give folks an intervention that has a psychological component, hopefully we can increase their confidence to maintain the weight loss that they attained.”

Study details

Of the 184 participants who were contacted for a follow-up visit, 94 consented to participate, 67% of whom were females and 88% of whom were White. A total of 27 participants had completed the diet and exercise intervention, and another 35 completed the diet-only and 32 exercise-only interventions.

In the 3.5-year period between the IDEA trial’s end and follow-up, body weight increased by 5.9 kg in the diet and exercise group (P < .0001) and by 3.1 kg in the diet-only group (P = .0006) but decreased in the exercise-only group by 1.0 kg (P = .25). However, from baseline to 5-year follow-up, all groups saw a reduction in body weight. Mean weight loss was –3.7 kg for the diet and exercise group (P = .0007), –5.8 kg for the diet group (P < .0001), and –2.9 kg for the exercise group (P = .003). Body mass index also decreased in all groups: by –1.2 kg/m2 in the diet and exercise group (P = .001), by –2.0 kg/m2 in the diet group (P < .0001), and by –1.0 kg/m2 in the exercise group (P = .004).

Pain – as measured by the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Arthritis Index (WOMAC) score – was reduced in all groups across 5-year follow-up: –1.2 (P = .03) for the diet and exercise group, –1.5 (P = .001) for the diet-only group, and –1.6 (P = .0008) for the exercise-only group. WOMAC function also significantly improved relative to baseline by 6.2 (P = .0001) in the diet and exercise group, by 6.1 (P < .0001) in the diet group, and by 3.7 (P = .01) in the exercise-only group.

Finding time to advise on weight loss, exercise

“If exercise and weight loss were easy, this country wouldn’t be in the state we’re in,” Tuhina Neogi, MD, PhD, of Boston University said in an interview. “Shared decision-making and personalized medicine are important; unfortunately, for the majority of physicians – particularly primary care physicians, where a good deal of OA management is undertaken – they don’t have a lot of time in their 20 minutes with a patient who has OA to counsel individuals toward a healthy weight and physical activity program when they’re also addressing common comorbidities seen in OA such as diabetes and heart disease.

“But as we know,” she added, “when you do address weight loss and physical activity, it has wide-ranging health benefits. This study provides support for utilizing formal diet and exercise programs to achieve important and durable benefits for people with OA.”