User login

Micronychia of the Index Finger

Congenital onychodysplasia of the index finger (COIF), or Iso-Kikuchi syndrome, is a rare disorder characterized by malformation of one or both nails of the index fingers. The various anomalies described are anonychia, micronychia, polyonychia, malalignment, or hemi-onychogryphosis. It may be associated with abnormalities of the underlying phalangeal bone, the most masked being bifurcation of the terminal phalange.1 Initially thought to be nonhereditary and nonfamilial,2 it is now known that COIF can be inherited in an autosomal-dominant fashion.3 Millman and Strier3 described a family of 9 patients with COIF. It rarely is described outside of Japan. Padmavathy et al4 described a case in an Indian patient with COIF that was associated with the absence of a ring finger in addition to anomalies of the metacarpal bones.

Congenital onychodysplasia of the index finger has a broad spectrum regarding its etiology and clinical features.5 The pathogenesis of COIF still is poorly understood. Deficient circulation in digital arteries is thought to be a putative mechanism for developing a deformed nail. The nail is affected on the radial side of the index finger, likely because of the smaller caliber of the artery on that side.5 Hereditary as well as nonhereditary sporadic cases have been reported. In addition to the various fingernail anomalies, skeletal abnormalities also have been reported. Baran and Stroud6 have reported deformed lunulae as a manifestation of COIF.

The Diagnosis: Congenital Onychodysplasia of the Index Finger

The differential diagnosis of COIF includes hidrotic ectodermal dysplasia, nail-patella syndrome, Poland syndrome, and DOOR syndrome. Hidrotic ectodermal dysplasia exhibits onychodystrophy, generalized hypotrichosis, palmoplantar keratoderma, and dental anomalies.7 Nail-patella syndrome presents with hypoplasia of the fingernails and toenails, triangular nail lunulae, absent or hypoplastic patellae, and elbow and iliac horn dysplasia. Poland syndrome is distinguished from COIF by the congenital absence of the pectoralis major muscle on the ipsilateral side of the involved digits. The DOOR syndrome tetrad is comprised of deafness, onychodystrophy, osteodystrophy, and mental retardation.8 Unlike these conditions, COIF does not involve systems other than the nails and phalanges.

Treatment of this condition is mainly conservative, as patients typically do not have symptoms.9 Surgical interventions can be considered for cosmetic concerns. Knowledge of this congenital entity and its clinical findings is essential to prevent unnecessary procedures and workup.

- De Berker AR, Baran R. Science of the nail apparatus. Diseases of the Nails and Their Management. In: Baran R, De Berker AR, Holzberg M, et al, eds. 4th ed. Willey-Blackwell; 2012:1-50.

- Kikuchi I, Horikawa S, Amano F. Congenital onychodysplasia of the index fingers. Arch Dermatol. 1974;110:743-746.

- Millman AJ, Strier RP. Congenital onychodysplasia of the index fingers: report of a family. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1982;7:57-65.

- Padmavathy L, Rao L, Ethirajan N, et al. Iso-Kikuchi syndrome with absence of ring fingers and metacarpal bone abnormality. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2008;74:513.

- Hadj-Rabia S, Juhlin L, Baran R. Hereditary and congenital nail disorders. In: Baran R, De Berker AR, Holzberg M, et al, eds. Diseases of the Nails and Their Management. 4th ed. Wiley-Blackwell; 2012:485-490.

- Baran R, Stroud JD. Congenital onychodysplasia of the index fingers: Iso and Kikuchi syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 1984;120:243-244.

- Valerio E, Favot F, Mattei I, et al. Congenital isolated Iso-Kikuchi syndrome in a newborn. Clin Case Rep. 2015;3:866.

- Danarti R, Rahmayani S, Wirohadidjojo YW, et al. Deafness, onychodystrophy, osteodystrophy, mental retardation, and seizures (DOORS) syndrome: a new case report from Indonesia and review of the literature. Eur J Dermatol. 2020;30:404-407.

- Milani-Nejad N, Mosser-Goldfarb J. Congenital onychodysplasia of index fingers: Iso-Kikuchi syndrome. J Pediatr. 2020;218:254.

Congenital onychodysplasia of the index finger (COIF), or Iso-Kikuchi syndrome, is a rare disorder characterized by malformation of one or both nails of the index fingers. The various anomalies described are anonychia, micronychia, polyonychia, malalignment, or hemi-onychogryphosis. It may be associated with abnormalities of the underlying phalangeal bone, the most masked being bifurcation of the terminal phalange.1 Initially thought to be nonhereditary and nonfamilial,2 it is now known that COIF can be inherited in an autosomal-dominant fashion.3 Millman and Strier3 described a family of 9 patients with COIF. It rarely is described outside of Japan. Padmavathy et al4 described a case in an Indian patient with COIF that was associated with the absence of a ring finger in addition to anomalies of the metacarpal bones.

Congenital onychodysplasia of the index finger has a broad spectrum regarding its etiology and clinical features.5 The pathogenesis of COIF still is poorly understood. Deficient circulation in digital arteries is thought to be a putative mechanism for developing a deformed nail. The nail is affected on the radial side of the index finger, likely because of the smaller caliber of the artery on that side.5 Hereditary as well as nonhereditary sporadic cases have been reported. In addition to the various fingernail anomalies, skeletal abnormalities also have been reported. Baran and Stroud6 have reported deformed lunulae as a manifestation of COIF.

The Diagnosis: Congenital Onychodysplasia of the Index Finger

The differential diagnosis of COIF includes hidrotic ectodermal dysplasia, nail-patella syndrome, Poland syndrome, and DOOR syndrome. Hidrotic ectodermal dysplasia exhibits onychodystrophy, generalized hypotrichosis, palmoplantar keratoderma, and dental anomalies.7 Nail-patella syndrome presents with hypoplasia of the fingernails and toenails, triangular nail lunulae, absent or hypoplastic patellae, and elbow and iliac horn dysplasia. Poland syndrome is distinguished from COIF by the congenital absence of the pectoralis major muscle on the ipsilateral side of the involved digits. The DOOR syndrome tetrad is comprised of deafness, onychodystrophy, osteodystrophy, and mental retardation.8 Unlike these conditions, COIF does not involve systems other than the nails and phalanges.

Treatment of this condition is mainly conservative, as patients typically do not have symptoms.9 Surgical interventions can be considered for cosmetic concerns. Knowledge of this congenital entity and its clinical findings is essential to prevent unnecessary procedures and workup.

Congenital onychodysplasia of the index finger (COIF), or Iso-Kikuchi syndrome, is a rare disorder characterized by malformation of one or both nails of the index fingers. The various anomalies described are anonychia, micronychia, polyonychia, malalignment, or hemi-onychogryphosis. It may be associated with abnormalities of the underlying phalangeal bone, the most masked being bifurcation of the terminal phalange.1 Initially thought to be nonhereditary and nonfamilial,2 it is now known that COIF can be inherited in an autosomal-dominant fashion.3 Millman and Strier3 described a family of 9 patients with COIF. It rarely is described outside of Japan. Padmavathy et al4 described a case in an Indian patient with COIF that was associated with the absence of a ring finger in addition to anomalies of the metacarpal bones.

Congenital onychodysplasia of the index finger has a broad spectrum regarding its etiology and clinical features.5 The pathogenesis of COIF still is poorly understood. Deficient circulation in digital arteries is thought to be a putative mechanism for developing a deformed nail. The nail is affected on the radial side of the index finger, likely because of the smaller caliber of the artery on that side.5 Hereditary as well as nonhereditary sporadic cases have been reported. In addition to the various fingernail anomalies, skeletal abnormalities also have been reported. Baran and Stroud6 have reported deformed lunulae as a manifestation of COIF.

The Diagnosis: Congenital Onychodysplasia of the Index Finger

The differential diagnosis of COIF includes hidrotic ectodermal dysplasia, nail-patella syndrome, Poland syndrome, and DOOR syndrome. Hidrotic ectodermal dysplasia exhibits onychodystrophy, generalized hypotrichosis, palmoplantar keratoderma, and dental anomalies.7 Nail-patella syndrome presents with hypoplasia of the fingernails and toenails, triangular nail lunulae, absent or hypoplastic patellae, and elbow and iliac horn dysplasia. Poland syndrome is distinguished from COIF by the congenital absence of the pectoralis major muscle on the ipsilateral side of the involved digits. The DOOR syndrome tetrad is comprised of deafness, onychodystrophy, osteodystrophy, and mental retardation.8 Unlike these conditions, COIF does not involve systems other than the nails and phalanges.

Treatment of this condition is mainly conservative, as patients typically do not have symptoms.9 Surgical interventions can be considered for cosmetic concerns. Knowledge of this congenital entity and its clinical findings is essential to prevent unnecessary procedures and workup.

- De Berker AR, Baran R. Science of the nail apparatus. Diseases of the Nails and Their Management. In: Baran R, De Berker AR, Holzberg M, et al, eds. 4th ed. Willey-Blackwell; 2012:1-50.

- Kikuchi I, Horikawa S, Amano F. Congenital onychodysplasia of the index fingers. Arch Dermatol. 1974;110:743-746.

- Millman AJ, Strier RP. Congenital onychodysplasia of the index fingers: report of a family. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1982;7:57-65.

- Padmavathy L, Rao L, Ethirajan N, et al. Iso-Kikuchi syndrome with absence of ring fingers and metacarpal bone abnormality. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2008;74:513.

- Hadj-Rabia S, Juhlin L, Baran R. Hereditary and congenital nail disorders. In: Baran R, De Berker AR, Holzberg M, et al, eds. Diseases of the Nails and Their Management. 4th ed. Wiley-Blackwell; 2012:485-490.

- Baran R, Stroud JD. Congenital onychodysplasia of the index fingers: Iso and Kikuchi syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 1984;120:243-244.

- Valerio E, Favot F, Mattei I, et al. Congenital isolated Iso-Kikuchi syndrome in a newborn. Clin Case Rep. 2015;3:866.

- Danarti R, Rahmayani S, Wirohadidjojo YW, et al. Deafness, onychodystrophy, osteodystrophy, mental retardation, and seizures (DOORS) syndrome: a new case report from Indonesia and review of the literature. Eur J Dermatol. 2020;30:404-407.

- Milani-Nejad N, Mosser-Goldfarb J. Congenital onychodysplasia of index fingers: Iso-Kikuchi syndrome. J Pediatr. 2020;218:254.

- De Berker AR, Baran R. Science of the nail apparatus. Diseases of the Nails and Their Management. In: Baran R, De Berker AR, Holzberg M, et al, eds. 4th ed. Willey-Blackwell; 2012:1-50.

- Kikuchi I, Horikawa S, Amano F. Congenital onychodysplasia of the index fingers. Arch Dermatol. 1974;110:743-746.

- Millman AJ, Strier RP. Congenital onychodysplasia of the index fingers: report of a family. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1982;7:57-65.

- Padmavathy L, Rao L, Ethirajan N, et al. Iso-Kikuchi syndrome with absence of ring fingers and metacarpal bone abnormality. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2008;74:513.

- Hadj-Rabia S, Juhlin L, Baran R. Hereditary and congenital nail disorders. In: Baran R, De Berker AR, Holzberg M, et al, eds. Diseases of the Nails and Their Management. 4th ed. Wiley-Blackwell; 2012:485-490.

- Baran R, Stroud JD. Congenital onychodysplasia of the index fingers: Iso and Kikuchi syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 1984;120:243-244.

- Valerio E, Favot F, Mattei I, et al. Congenital isolated Iso-Kikuchi syndrome in a newborn. Clin Case Rep. 2015;3:866.

- Danarti R, Rahmayani S, Wirohadidjojo YW, et al. Deafness, onychodystrophy, osteodystrophy, mental retardation, and seizures (DOORS) syndrome: a new case report from Indonesia and review of the literature. Eur J Dermatol. 2020;30:404-407.

- Milani-Nejad N, Mosser-Goldfarb J. Congenital onychodysplasia of index fingers: Iso-Kikuchi syndrome. J Pediatr. 2020;218:254.

A 21-year-old Indian woman who was initially seeking dermatology consultation for acne also was noted to have micronychia of the nail of the left index finger. The affected nail was narrow and half as broad as the unaffected normal nail on the right index finger. The patient confirmed that this finding had been present since birth; she faced no cosmetic disability and had not sought medical care for diagnosis or treatment. There was no history of trauma, complications during pregnancy, family history of micronychia or similar eruptions, or any other inciting event. The teeth, hair, and skin as well as the patient’s height, weight, and physical and mental development were normal. Systemic examination revealed no abnormalities. Radiography of the hands did not reveal any apparent bony abnormalities.

From Buns to Braids and Ponytails: Entering a New Era of Female Military Hair-Grooming Standards

Professional appearance of servicemembers has been a long-standing custom in the US Military. Specific standards are determined by each branch. Initially, men dominated the military.1,2 As the number of women as well as racial diversity increased in the military, modifications to grooming standards were slow to change and resulted in female hair standards requiring a uniform tight and sleek style or short haircut. Clinicians can be attuned to these occupational standards and their implications on the diagnosis and management of common diseases of the hair and scalp.

History of Hairstyle Standards for Female Servicemembers

For half a century, female servicemembers had limited hairstyle choices. They were not authorized to have hair shorter than one-quarter inch in length. They could choose either short hair worn down or long hair with neatly secured loose ends in the form of a bun or a tucked braid—both of which could not extend past the bottom edge of the uniform collar.3-5 Female navy sailors and air force airmen with long hair were only allowed to wear ponytails during physical training; however, army soldiers previously were limited to wearing a bun.3,6,7 Cornrows and microbraids were authorized in the mid-1990s for the US Air Force, but policy stated that locs were prohibited due to their “unkempt” and “matted” nature. Furthermore, the size of hair bulk in the air force was restricted to no more than 3 inches and could not obstruct wear of the uniform cap.5 Based on these regulations, female servicemembers with longer hair had to utilize tight hairstyles that caused prolonged traction and pressure along the scalp, which contributed to headaches, a sore scalp, and alopecia over time. Normalization of these symptoms led to underreporting, as women lived with the consequences or turned to shorter hairstyles.

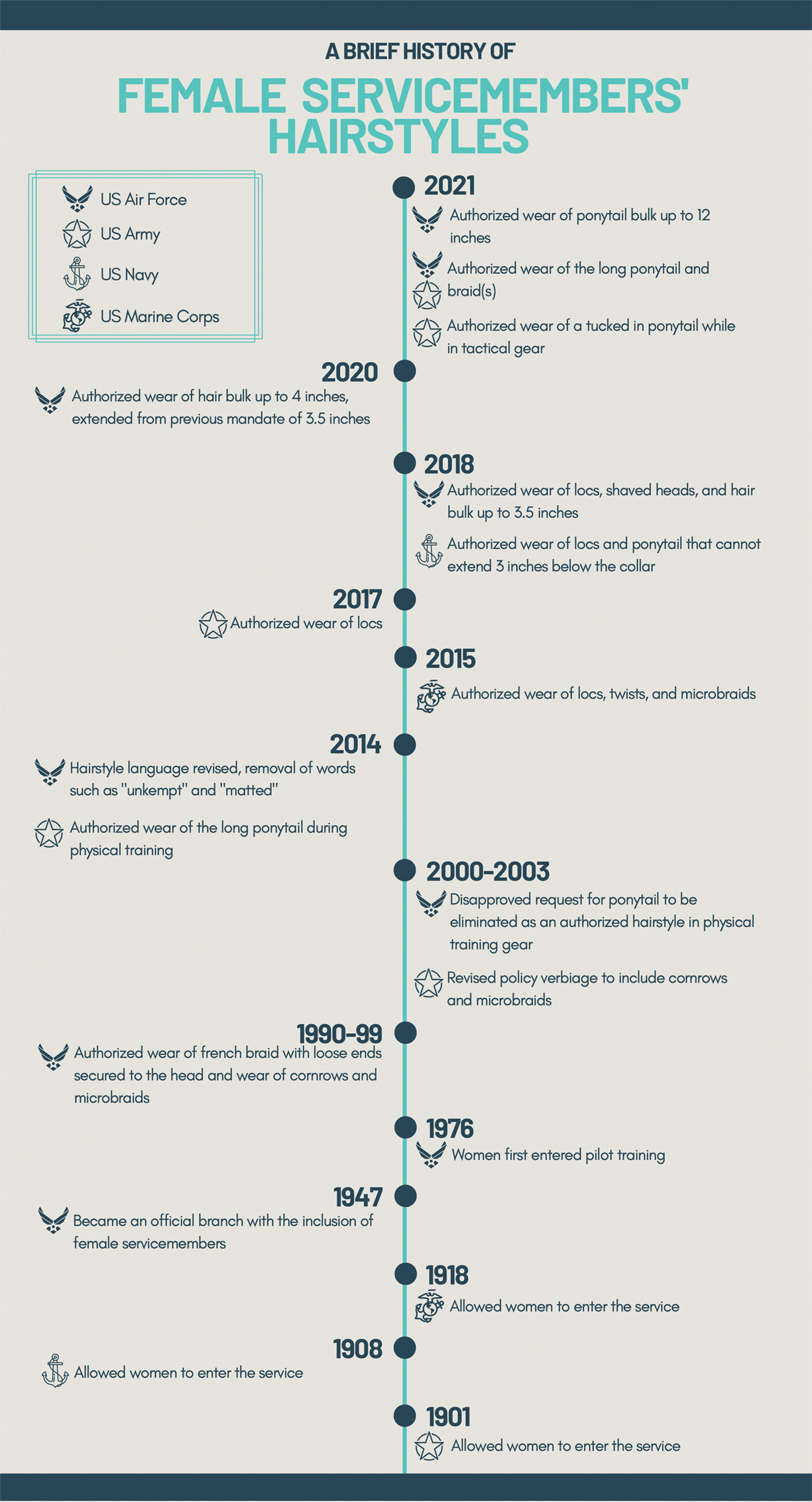

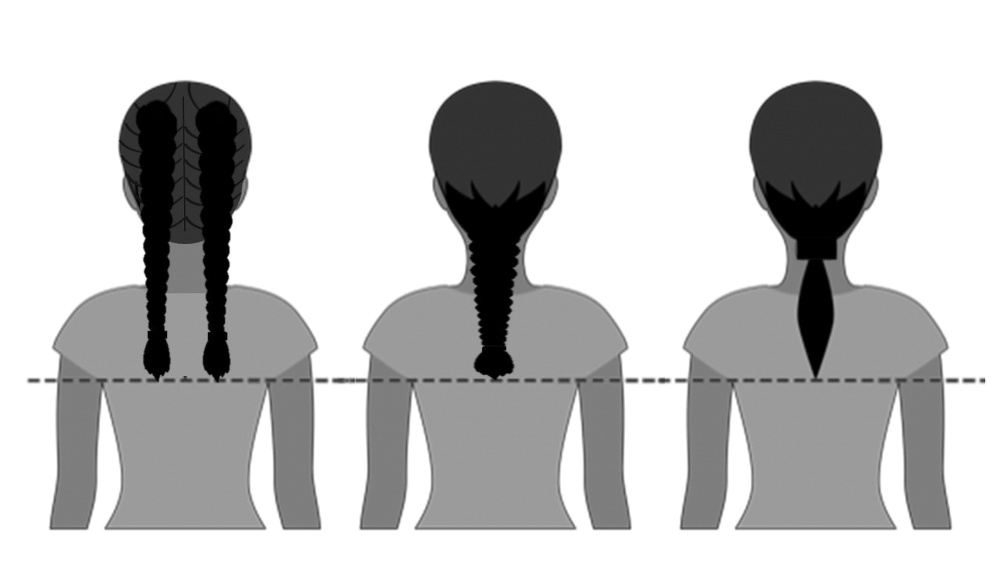

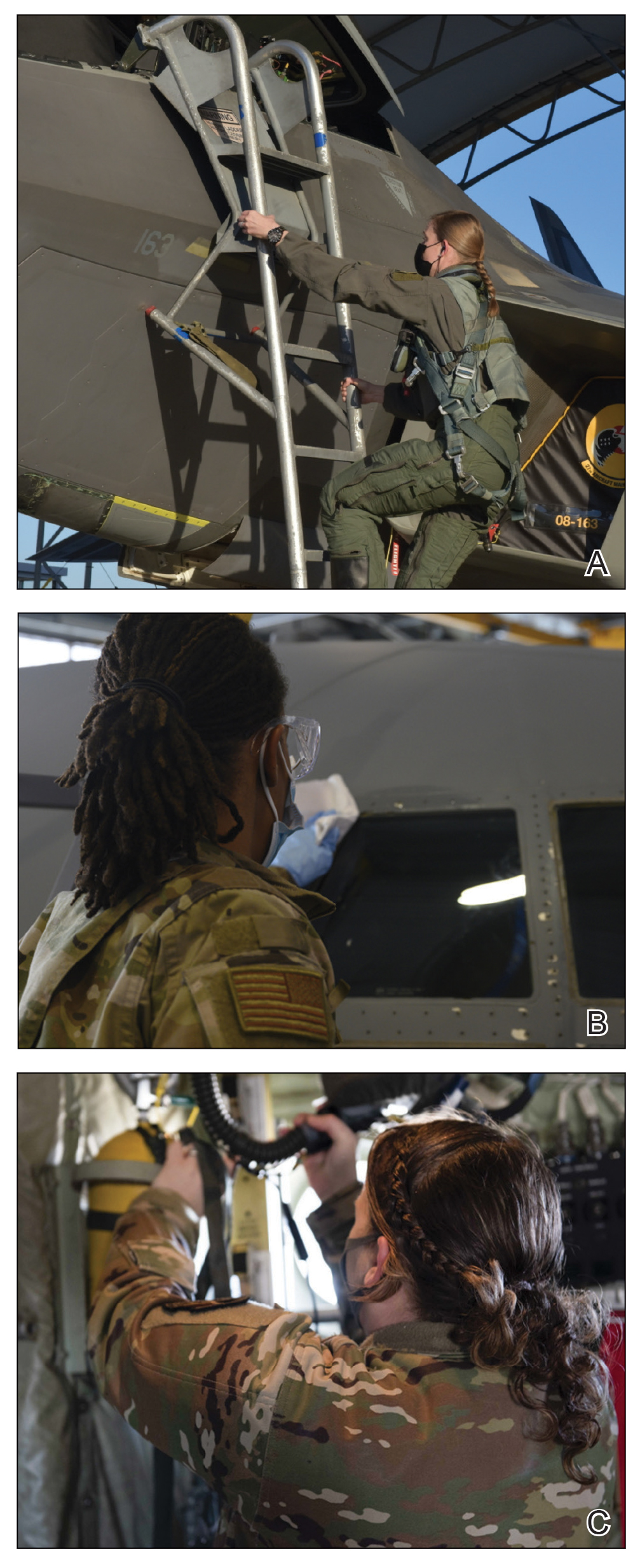

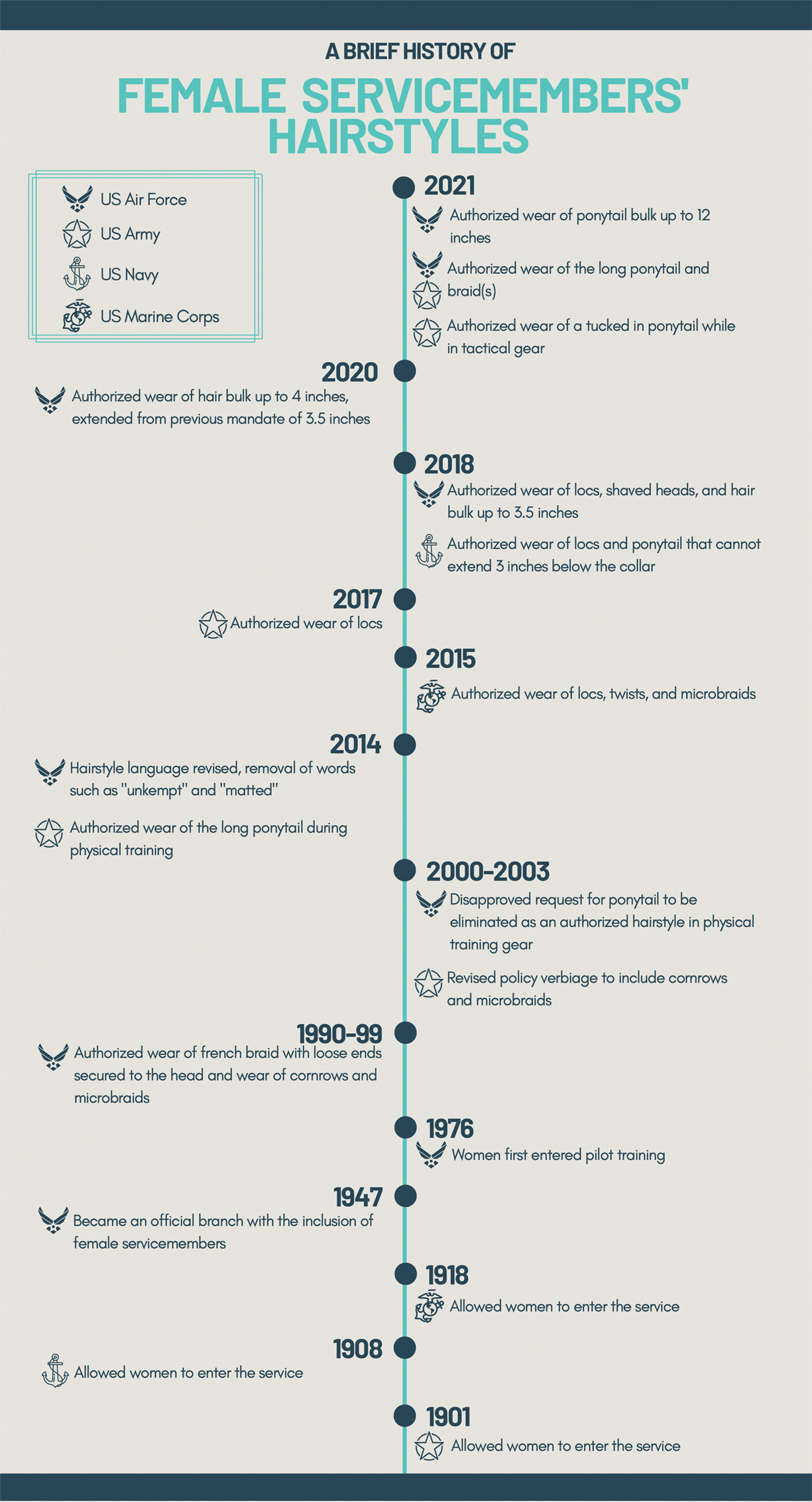

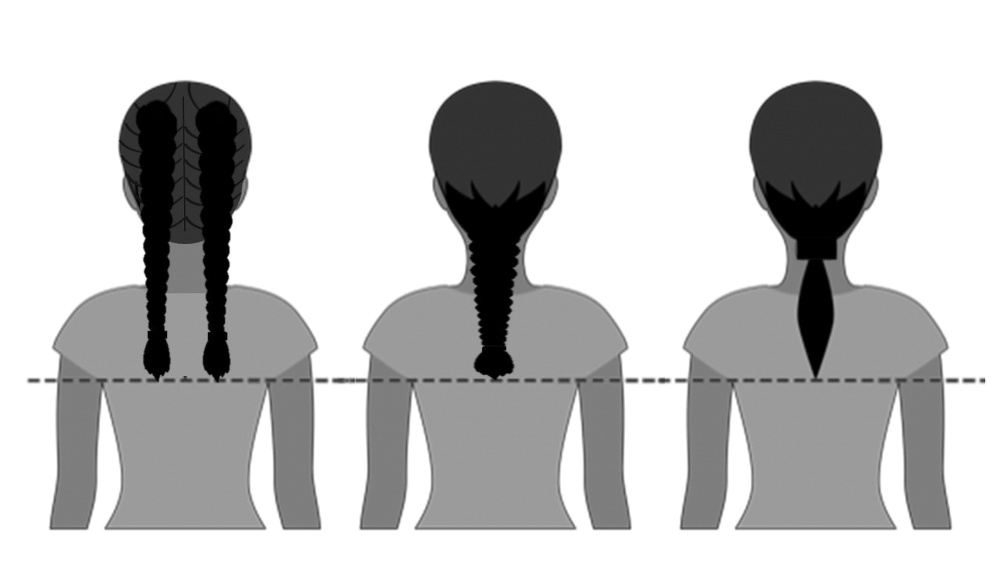

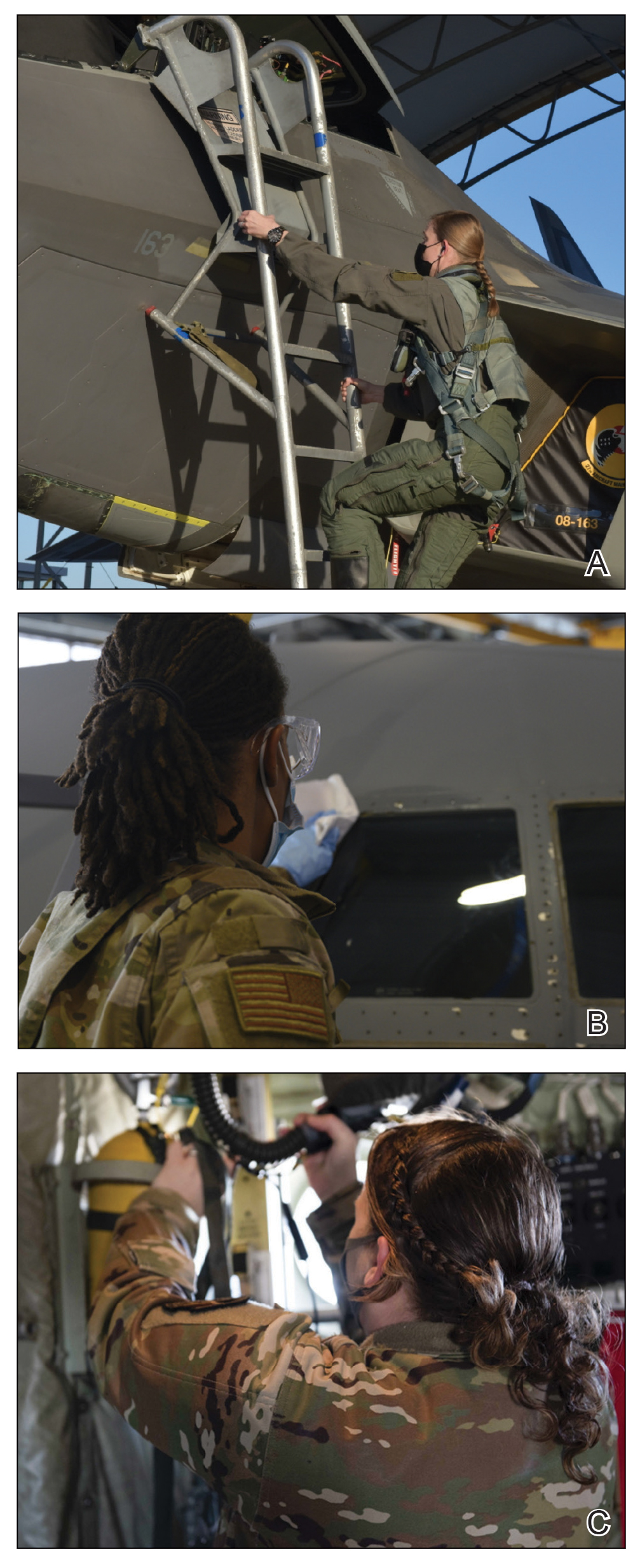

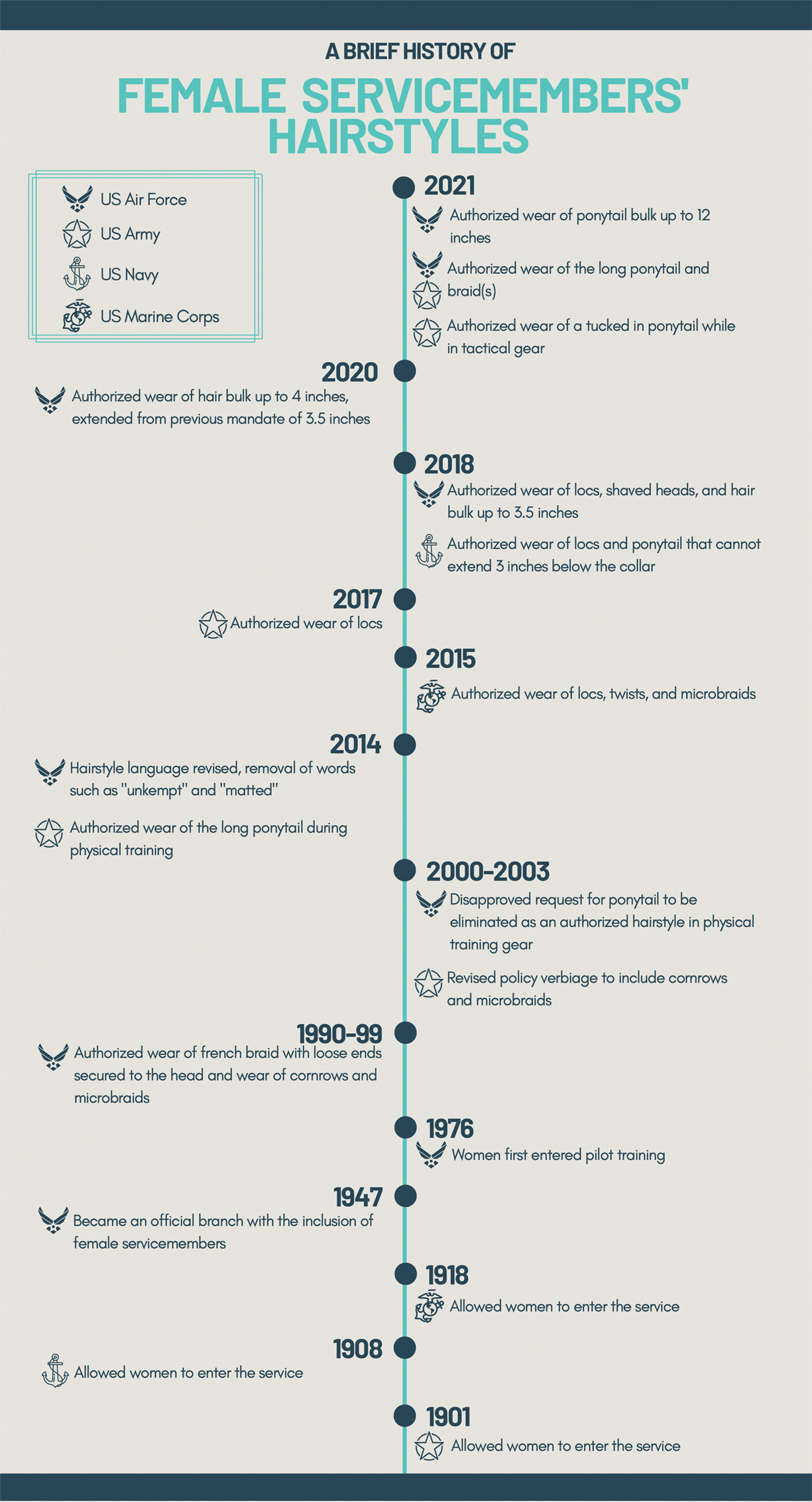

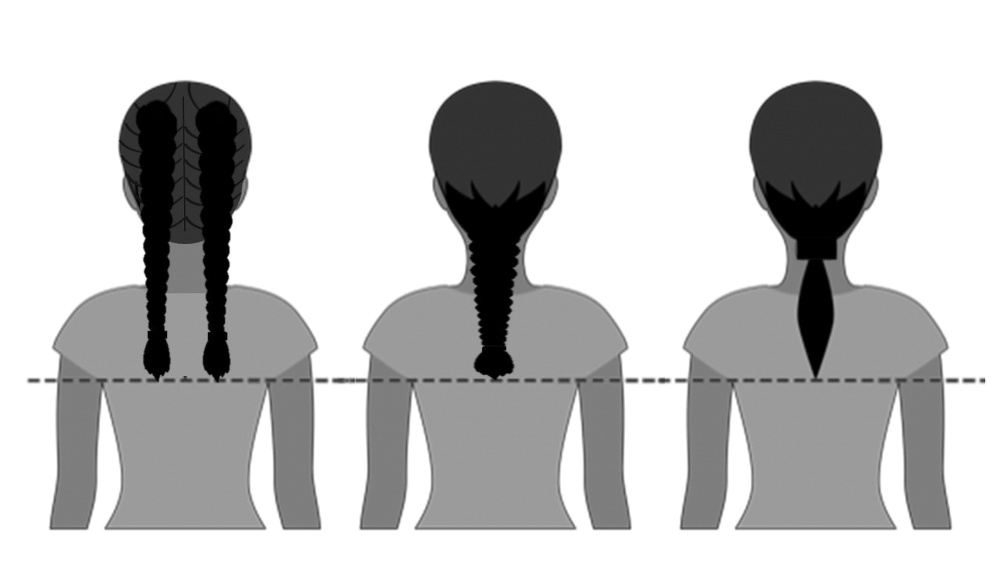

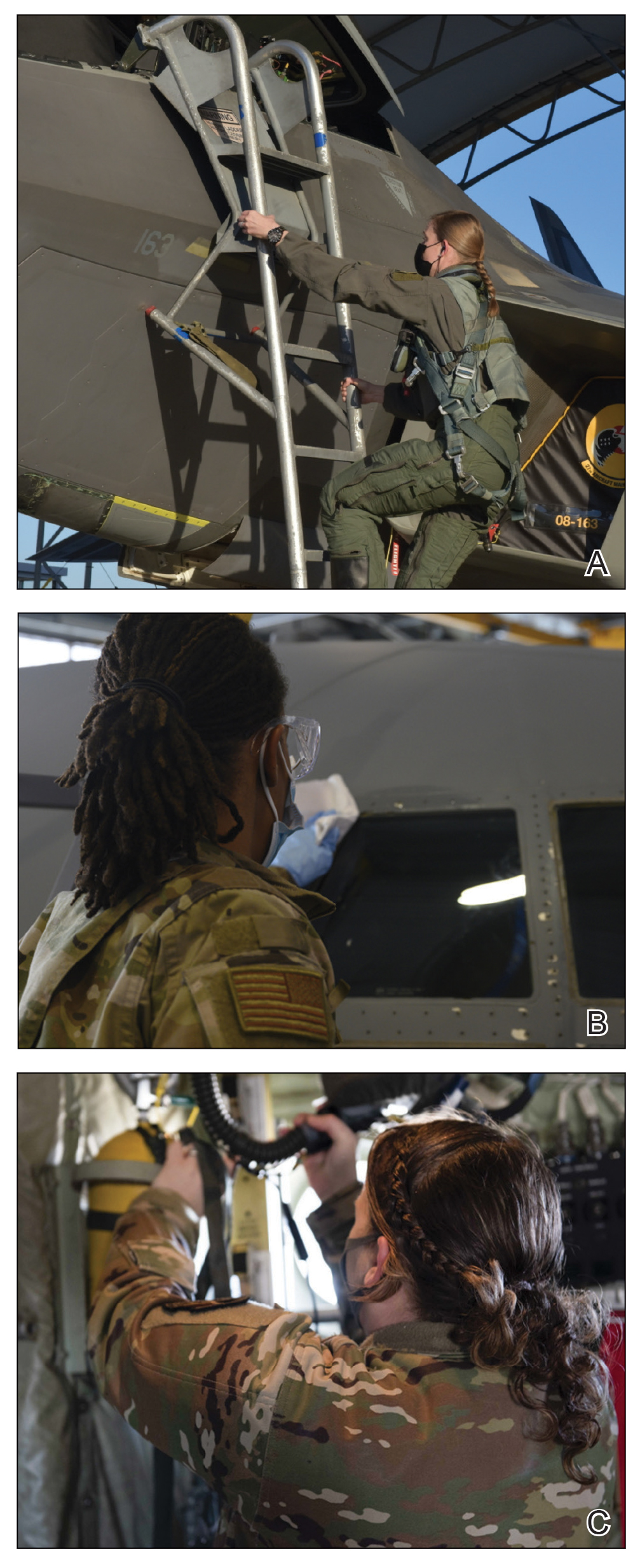

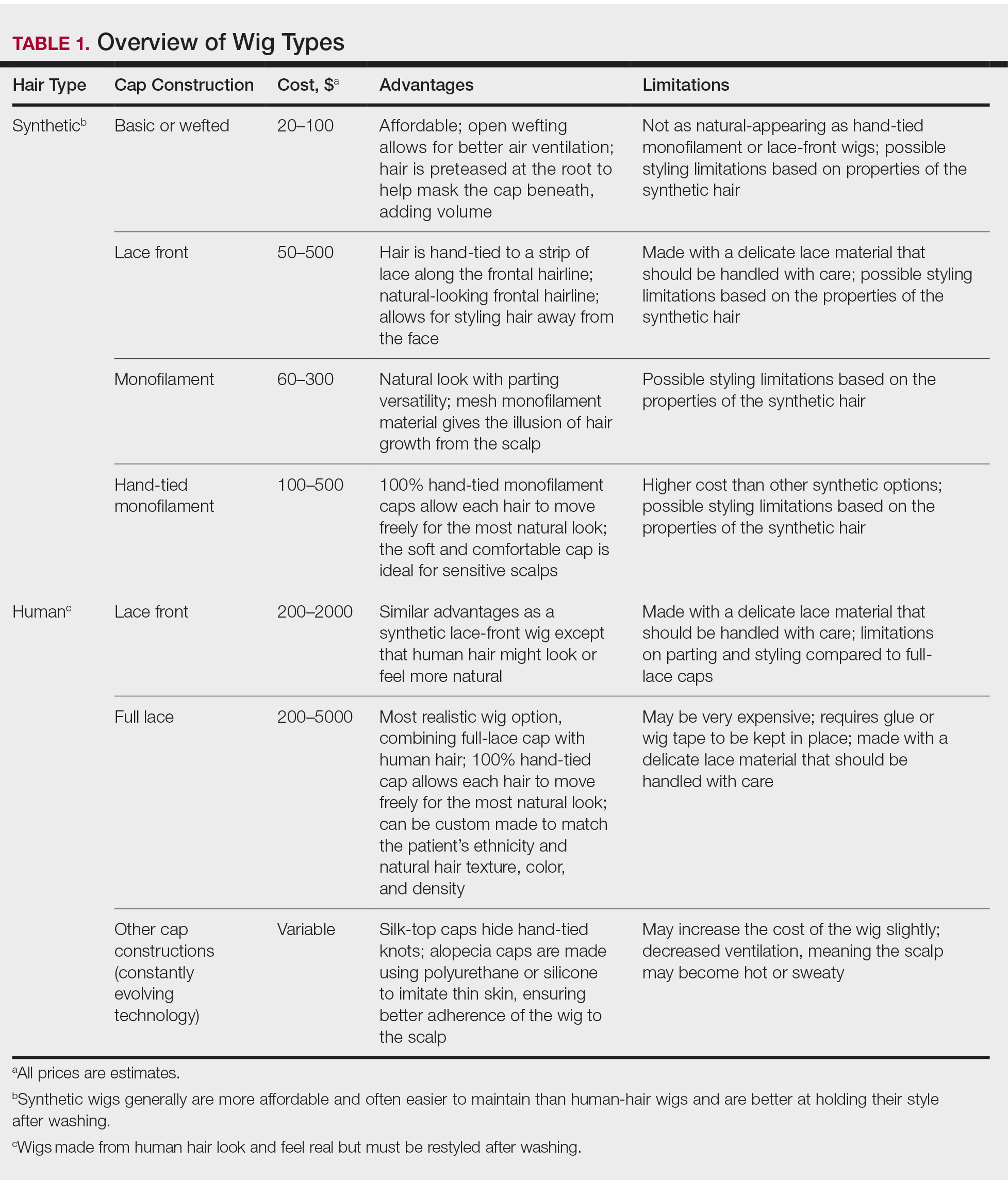

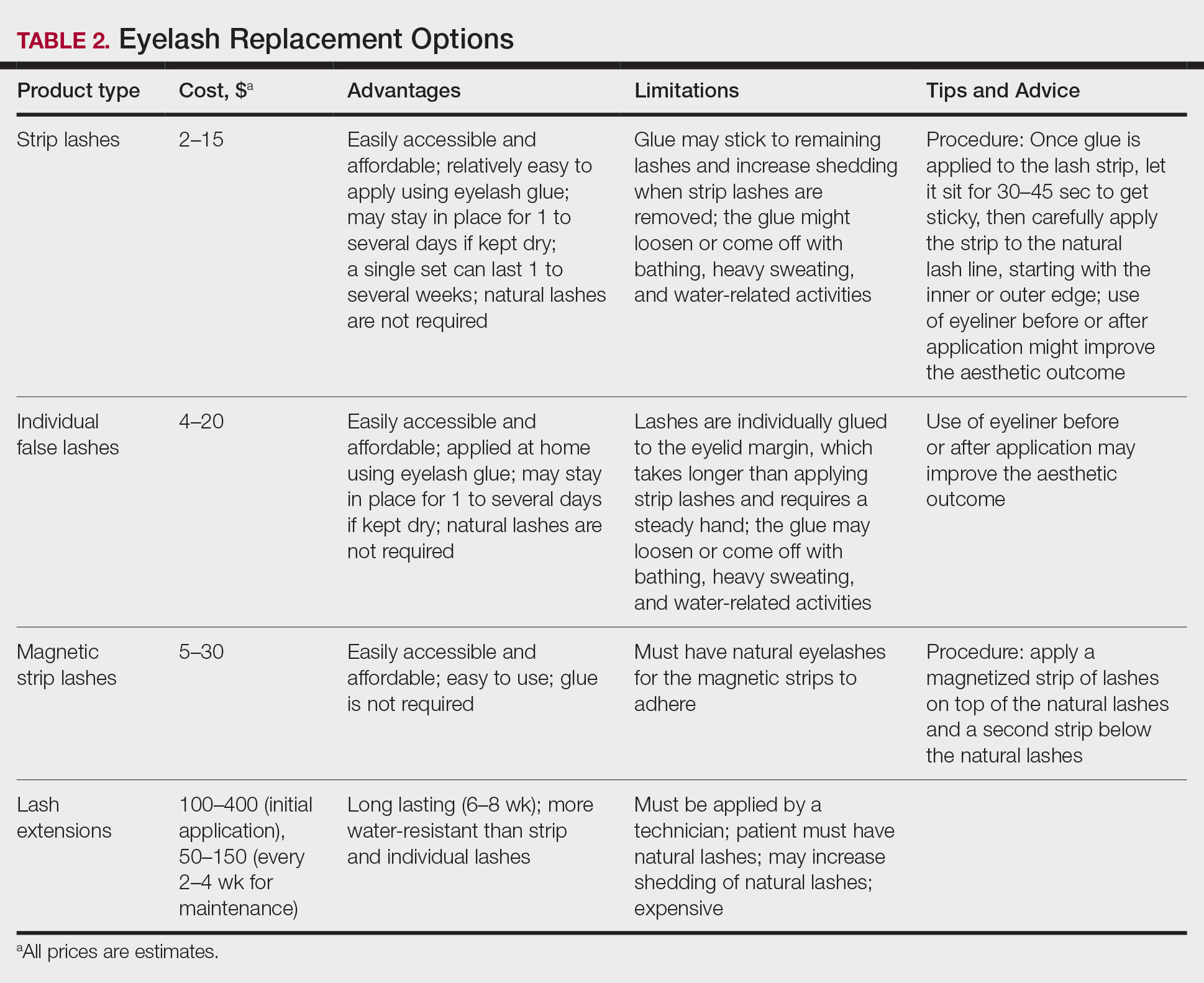

In the last decade alone, female servicemembers have witnessed the greatest number of changes in authorized hairstyles despite being part of the military for more than 50 years (Figure 1).1-11 In 2014, the language used in the air force instructions to describe locs was revised to remove ethnically offensive terms.4,5 This same year, the army allowed female soldiers to wear ponytails during physical training, a privilege that had been authorized by other services years prior.3,6,7 By the end of 2018, locs were authorized by all services, and female sailors could wear a ponytail in all navy uniforms as long as it did not extend 3 inches below the collar.3,4,6-8 In 2018, the air force increased authorized hair bulk up to 3.5 inches from the previous mandate of 3 inches and approved female buzz cuts6,9; in 2020, it allowed hair bulk up to 4 inches. As of 2021, female airmen can wear a ponytail and/or braid(s) as long as it starts below the crown of the head and the length does not extend below a horizontal line running between the top of each sleeve inseam at the underarm (Figures 2–4).6 In an ongoing effort to be more inclusive of hair density differences, female airmen will be authorized to wear a ponytail not exceeding a maximum width bulk of 1 ft starting June 25, 2021, so long as they can comply with the above regulations.11 The army now allows ponytails and braids across all uniforms, as long they do not extend past the bottom of the shoulder blades. This change came just months after authorizing the wearing of ponytails tucked under the uniform blouse with tactical headgear.10 These changes allow for a variety of hairstyles for members to practice while avoiding the physical consequences that develop from repetitive traction and pressure along the same areas of the hair and scalp.

Common Hair Disorders in Female Servicemembers

Herein, we discuss 3 of the most common hair and scalp disorders linked to grooming practices utilized by women to meet prior military regulations: trichorrhexis nodosa (TN), extracranial headaches, and traction alopecia (TA). It is essential that health care providers are able to promptly recognize these conditions, understand their risk factors, and be familiar with first-line treatment options. With these new standards, the hope is that the incidence of the following conditions decreases, thus improving servicemembers’ medical readiness and overall quality of life.

Trichorrhexis Nodosa

Acquired TN is a defect in the hair shaft that causes the hair to break easily secondary to chemical, thermal, or mechanical trauma. This can include but is not limited to chemical relaxers, blow-dryers, excessive brushing or styling, flat irons, and tightly packed hairstyles. The condition is characterized by a thickened hair diameter and splitting at the tip. Clinically, it may present as brittle, lusterless, broken hair with split ends, as well as a positive tug test.14 Management includes gentle hair care and avoidance of harsh hair care practices and treatments.

Extracranial Headaches

Headaches are a common concern among military servicemembers15 and generally are classified as primary or secondary. A less commonly discussed primary headache disorder includes external-pressure headaches, which result from either sustained compression or traction of the soft tissues of the scalp, usually from wearing headbands, helmets, or tight hairstyles.16 Additional at-risk groups include those who chronically wear surgical scrub caps or flight caps, especially if clipped or pinned to the hair. In our 38 years of combined military clinical experience, we can attest that these types of headaches are common among female servicemembers. The diagnostic criteria for an external-pressure headache, commonly referred to by patients as a “ponytail headache,” includes at least 2 headache episodes triggered within 1 hour of sustained traction on the scalp, maximal at the site of traction and resolving within 1 hour after relieving the traction.16 Management includes removal of the pressure-causing source, usually a tight ponytail or bun.

Traction Alopecia

Traction alopecia is hair loss caused by repetitive or prolonged tension on the hair secondary to tight hairstyles. It can be clinically classified into 2 types: marginal and nonmarginal patchy alopecia (Figure 5).13,17,18 Traction alopecia most commonly is found in individuals with ethnic hair, predominantly Black women. Hairstyles with the highest risk for causing TA include tight buns, ponytails, cornrows, weaves, and locs—all of which are utilized by female servicemembers to maintain a professional appearance and adhere to grooming regulations.13,18 Other groups at risk include athletes (eg, ballerinas, gymnasts) and those with chronic headwear use (eg, turbans, helmets, nurse caps, wigs).18 Early TA typically presents with perifollicular erythema followed by follicular-based papules or pustules.13,18 Marginal TA classically includes frontotemporal hair loss or thinning with or without a fringe sign.17,18 Nonmarginal TA includes patchy alopecia most commonly involving the parietal or occipital scalp, seen with chignons, buns, ponytails, or the use of clips, extensions, or bobby pins.18 The first line in management is avoidance of traction-causing hairstyles or headgear. Medical therapy may be warranted and consists of a single agent or combination regimen to include oral or topical antibiotics, topical or intralesional steroids, and topical minoxidil.13,18

Final Thoughts

Military hair-grooming standards have evolved over time. Recent changes show that the US Department of Defense is seriously evaluating policies that may be inherently exclusive. Prior grooming standards resulted in the widespread use of tight hairstyles and harsh hair treatments among female servicemembers with long hair. These practices resulted in TN, extracranial headaches, and TA, among other hair and scalp disorders. These occupational-related hair conditions impact female servicemembers’ mental and physical well-being and thus impact military readiness. Physicians should recognize that these conditions can be related to occupational grooming standards that may impact hair care practices.

The challenge that remains is a lack of standardized documentation for hair and scalp symptoms in the medical record. Due to a paucity in reporting and documentation, limited objective data exist to guide future recommendations for military grooming standards. Another obstacle is the lack of knowledge of hair diseases among primary care providers and patients, especially due to the underrepresentation of ethnic hair in medical textbooks.19 As a result, women frequently accept their hair symptoms as normal and either suffer through them, cut their hair short, or wear wigs before considering a visit to the doctor. Furthermore, hair-grooming standards can expose racial disparities, which are the driving force behind the current policy changes. Clinicians can strive to ask about hair and scalp symptoms and document the following in relation to hair and scalp disorders: occupational grooming requirements; skin and hair type; location, number, and size of scalp lesion(s); onset; duration; current and prior hair care practices; history of treatment; and clinical course accompanied with photographic documentation. Ultimately, improved awareness in patients, collaboration between physicians, and consistent clinical documentation can help create positive change and continued improvement in hair-grooming standards within the military. Improved reporting and documentation will facilitate further study into the effectiveness of the updated hair-grooming standards in female servicemembers.

- United States Air Force Statistical Digest FY 1999. United States Air Force; 2000. Accessed June 8, 2021. https://media.defense.gov/2011/Apr/14/2001330240/-1/-1/0/AFD-110414-048.pdf

- Air Force demographics. Air Force Personnel Center website. Accessed June 8, 2021. https://www.afpc.af.mil/About/Air-Force-Demographics/

- US Department of the Army. Wear and Appearance of Army Uniforms and Insignia: Army Regulation 670-1. Department of the Army; 2021. Accessed June 8, 2021. https://armypubs.army.mil/epubs/DR_pubs/DR_a/ARN30302-AR_670-1-000-WEB-1.pdf

- Losey S. Loc hairstyles, off-duty earrings for men ok’d in new dress regs. Air Force Times. Published July 16, 2018. Accessed June 8, 2021. https://www.airforcetimes.com/news/your-air-force/2018/07/16/loc-hairstyles-off-duty-earrings-for-men-okd-in-new-dress-regs/

- Department of the Air Force. AFT 36-2903, Dress and Personal Appearance of Air Force Personnel. Department of the Air Force; 2011. Accessed June 8, 2021. https://www.uc.edu/content/dam/uc/afrotc/docs/Documents/AFI36-2903.pdf

- Department of the Air Force. AFT 36-2903, Dress and Personal Appearance of Air Force Personnel. Department of the Air Force; 2021. Accessed June 8, 2021. https://static.e-publishing.af.mil/production/1/af_a1/publication/afi36-2903/afi36-2903.pdf

- U.S. Navy uniform regulations: summary of changes (26 February 2020). Navy Personnel Command website. Accessed June 8, 2021. https://www.mynavyhr.navy.mil/Portals/55/Navy%20Uniforms/Uniform%20Regulations/Documents/SOC_2020_02_26.pdf?ver=y8Wd0ykVXgISfFpOy8qHkg%3d%3d

- US Headquarters Marine Corps. Marine Corps Uniform Regulations: Marine Corps Order 1020.34H. United States Marine Corps, 2018. Accessed June 8, 2021. https://www.marines.mil/portals/1/Publications/MCO%201020.34H%20v2.pdf?ver=2018-06-26-094038-137

- Secretary of the Air Force Public Affairs. Air Force to allow longer braids, ponytails, bangs for women. United States Air Force website. Published January 21, 2021. Accessed June 8, 2021. https://www.af.mil/News/Article-Display/Article/2478173/air-force-to-allow-longer-braids-ponytails-bangs-for-women/

- Britzky H. The Army will now allow women to wear ponytails in all uniforms. Task & Purpose. Published May 6, 2021. Accessed June 8, 2021. https://taskandpurpose.com/news/army-women-ponytails-all-uniforms/

- Secretary of the Air Force Public Affairs. Air Force readdresses women’s hair standard after feedback. US Air Force website. Published June 11, 2021. Accessed June 27, 2021. https://www.af.mil/News/Article-Display/Article/2654774/air-force-readdresses-womens-hair-standard-after-feedback/

- Myers M. Esper direct services to review racial bias in grooming standards, training and more. Air Force Times. Published July 15, 2020. Accessed June 8, 2021. https://www.airforcetimes.com/news/your-military/2020/07/15/esper-directs-services-to-review-racial-bias-in-grooming-standards-training-and-more/

- Madu P, Kundu RV. Follicular and scarring disorders in skin of color: presentation and management. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2014;15:307-321.

- Quaresma M, Martinez Velasco M, Tosti A. Hair breakage in patients of African descent: role of dermoscopy. Skin Appendage Disord. 2015;1:99-104.

- Burch RC, Loder S, Loder E, et al. The prevalence and burden of migraine and severe headache in the United States: updated statistics from government health surveillance studies. Headache. 2015;55:21-34.

- Kararizou E, Bougea AM, Giotopoulou D, et al. An update on the less-known group of other primary headaches—a review. Eur Neurol Rev. 2014;9:71-77.

- Sperling L, Cowper S, Knopp E. An Atlas of Hair Pathology with Clinical Correlations. CRC Press; 2012:67-68.

- Billero V, Miteva M. Traction alopecia: the root of the problem. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2018;11:149-159.

- Adelekun A, Onyekaba G, Lipoff JB. Skin color in dermatology textbooks: an updated evaluation and analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:194-196.

Professional appearance of servicemembers has been a long-standing custom in the US Military. Specific standards are determined by each branch. Initially, men dominated the military.1,2 As the number of women as well as racial diversity increased in the military, modifications to grooming standards were slow to change and resulted in female hair standards requiring a uniform tight and sleek style or short haircut. Clinicians can be attuned to these occupational standards and their implications on the diagnosis and management of common diseases of the hair and scalp.

History of Hairstyle Standards for Female Servicemembers

For half a century, female servicemembers had limited hairstyle choices. They were not authorized to have hair shorter than one-quarter inch in length. They could choose either short hair worn down or long hair with neatly secured loose ends in the form of a bun or a tucked braid—both of which could not extend past the bottom edge of the uniform collar.3-5 Female navy sailors and air force airmen with long hair were only allowed to wear ponytails during physical training; however, army soldiers previously were limited to wearing a bun.3,6,7 Cornrows and microbraids were authorized in the mid-1990s for the US Air Force, but policy stated that locs were prohibited due to their “unkempt” and “matted” nature. Furthermore, the size of hair bulk in the air force was restricted to no more than 3 inches and could not obstruct wear of the uniform cap.5 Based on these regulations, female servicemembers with longer hair had to utilize tight hairstyles that caused prolonged traction and pressure along the scalp, which contributed to headaches, a sore scalp, and alopecia over time. Normalization of these symptoms led to underreporting, as women lived with the consequences or turned to shorter hairstyles.

In the last decade alone, female servicemembers have witnessed the greatest number of changes in authorized hairstyles despite being part of the military for more than 50 years (Figure 1).1-11 In 2014, the language used in the air force instructions to describe locs was revised to remove ethnically offensive terms.4,5 This same year, the army allowed female soldiers to wear ponytails during physical training, a privilege that had been authorized by other services years prior.3,6,7 By the end of 2018, locs were authorized by all services, and female sailors could wear a ponytail in all navy uniforms as long as it did not extend 3 inches below the collar.3,4,6-8 In 2018, the air force increased authorized hair bulk up to 3.5 inches from the previous mandate of 3 inches and approved female buzz cuts6,9; in 2020, it allowed hair bulk up to 4 inches. As of 2021, female airmen can wear a ponytail and/or braid(s) as long as it starts below the crown of the head and the length does not extend below a horizontal line running between the top of each sleeve inseam at the underarm (Figures 2–4).6 In an ongoing effort to be more inclusive of hair density differences, female airmen will be authorized to wear a ponytail not exceeding a maximum width bulk of 1 ft starting June 25, 2021, so long as they can comply with the above regulations.11 The army now allows ponytails and braids across all uniforms, as long they do not extend past the bottom of the shoulder blades. This change came just months after authorizing the wearing of ponytails tucked under the uniform blouse with tactical headgear.10 These changes allow for a variety of hairstyles for members to practice while avoiding the physical consequences that develop from repetitive traction and pressure along the same areas of the hair and scalp.

Common Hair Disorders in Female Servicemembers

Herein, we discuss 3 of the most common hair and scalp disorders linked to grooming practices utilized by women to meet prior military regulations: trichorrhexis nodosa (TN), extracranial headaches, and traction alopecia (TA). It is essential that health care providers are able to promptly recognize these conditions, understand their risk factors, and be familiar with first-line treatment options. With these new standards, the hope is that the incidence of the following conditions decreases, thus improving servicemembers’ medical readiness and overall quality of life.

Trichorrhexis Nodosa

Acquired TN is a defect in the hair shaft that causes the hair to break easily secondary to chemical, thermal, or mechanical trauma. This can include but is not limited to chemical relaxers, blow-dryers, excessive brushing or styling, flat irons, and tightly packed hairstyles. The condition is characterized by a thickened hair diameter and splitting at the tip. Clinically, it may present as brittle, lusterless, broken hair with split ends, as well as a positive tug test.14 Management includes gentle hair care and avoidance of harsh hair care practices and treatments.

Extracranial Headaches

Headaches are a common concern among military servicemembers15 and generally are classified as primary or secondary. A less commonly discussed primary headache disorder includes external-pressure headaches, which result from either sustained compression or traction of the soft tissues of the scalp, usually from wearing headbands, helmets, or tight hairstyles.16 Additional at-risk groups include those who chronically wear surgical scrub caps or flight caps, especially if clipped or pinned to the hair. In our 38 years of combined military clinical experience, we can attest that these types of headaches are common among female servicemembers. The diagnostic criteria for an external-pressure headache, commonly referred to by patients as a “ponytail headache,” includes at least 2 headache episodes triggered within 1 hour of sustained traction on the scalp, maximal at the site of traction and resolving within 1 hour after relieving the traction.16 Management includes removal of the pressure-causing source, usually a tight ponytail or bun.

Traction Alopecia

Traction alopecia is hair loss caused by repetitive or prolonged tension on the hair secondary to tight hairstyles. It can be clinically classified into 2 types: marginal and nonmarginal patchy alopecia (Figure 5).13,17,18 Traction alopecia most commonly is found in individuals with ethnic hair, predominantly Black women. Hairstyles with the highest risk for causing TA include tight buns, ponytails, cornrows, weaves, and locs—all of which are utilized by female servicemembers to maintain a professional appearance and adhere to grooming regulations.13,18 Other groups at risk include athletes (eg, ballerinas, gymnasts) and those with chronic headwear use (eg, turbans, helmets, nurse caps, wigs).18 Early TA typically presents with perifollicular erythema followed by follicular-based papules or pustules.13,18 Marginal TA classically includes frontotemporal hair loss or thinning with or without a fringe sign.17,18 Nonmarginal TA includes patchy alopecia most commonly involving the parietal or occipital scalp, seen with chignons, buns, ponytails, or the use of clips, extensions, or bobby pins.18 The first line in management is avoidance of traction-causing hairstyles or headgear. Medical therapy may be warranted and consists of a single agent or combination regimen to include oral or topical antibiotics, topical or intralesional steroids, and topical minoxidil.13,18

Final Thoughts

Military hair-grooming standards have evolved over time. Recent changes show that the US Department of Defense is seriously evaluating policies that may be inherently exclusive. Prior grooming standards resulted in the widespread use of tight hairstyles and harsh hair treatments among female servicemembers with long hair. These practices resulted in TN, extracranial headaches, and TA, among other hair and scalp disorders. These occupational-related hair conditions impact female servicemembers’ mental and physical well-being and thus impact military readiness. Physicians should recognize that these conditions can be related to occupational grooming standards that may impact hair care practices.

The challenge that remains is a lack of standardized documentation for hair and scalp symptoms in the medical record. Due to a paucity in reporting and documentation, limited objective data exist to guide future recommendations for military grooming standards. Another obstacle is the lack of knowledge of hair diseases among primary care providers and patients, especially due to the underrepresentation of ethnic hair in medical textbooks.19 As a result, women frequently accept their hair symptoms as normal and either suffer through them, cut their hair short, or wear wigs before considering a visit to the doctor. Furthermore, hair-grooming standards can expose racial disparities, which are the driving force behind the current policy changes. Clinicians can strive to ask about hair and scalp symptoms and document the following in relation to hair and scalp disorders: occupational grooming requirements; skin and hair type; location, number, and size of scalp lesion(s); onset; duration; current and prior hair care practices; history of treatment; and clinical course accompanied with photographic documentation. Ultimately, improved awareness in patients, collaboration between physicians, and consistent clinical documentation can help create positive change and continued improvement in hair-grooming standards within the military. Improved reporting and documentation will facilitate further study into the effectiveness of the updated hair-grooming standards in female servicemembers.

Professional appearance of servicemembers has been a long-standing custom in the US Military. Specific standards are determined by each branch. Initially, men dominated the military.1,2 As the number of women as well as racial diversity increased in the military, modifications to grooming standards were slow to change and resulted in female hair standards requiring a uniform tight and sleek style or short haircut. Clinicians can be attuned to these occupational standards and their implications on the diagnosis and management of common diseases of the hair and scalp.

History of Hairstyle Standards for Female Servicemembers

For half a century, female servicemembers had limited hairstyle choices. They were not authorized to have hair shorter than one-quarter inch in length. They could choose either short hair worn down or long hair with neatly secured loose ends in the form of a bun or a tucked braid—both of which could not extend past the bottom edge of the uniform collar.3-5 Female navy sailors and air force airmen with long hair were only allowed to wear ponytails during physical training; however, army soldiers previously were limited to wearing a bun.3,6,7 Cornrows and microbraids were authorized in the mid-1990s for the US Air Force, but policy stated that locs were prohibited due to their “unkempt” and “matted” nature. Furthermore, the size of hair bulk in the air force was restricted to no more than 3 inches and could not obstruct wear of the uniform cap.5 Based on these regulations, female servicemembers with longer hair had to utilize tight hairstyles that caused prolonged traction and pressure along the scalp, which contributed to headaches, a sore scalp, and alopecia over time. Normalization of these symptoms led to underreporting, as women lived with the consequences or turned to shorter hairstyles.

In the last decade alone, female servicemembers have witnessed the greatest number of changes in authorized hairstyles despite being part of the military for more than 50 years (Figure 1).1-11 In 2014, the language used in the air force instructions to describe locs was revised to remove ethnically offensive terms.4,5 This same year, the army allowed female soldiers to wear ponytails during physical training, a privilege that had been authorized by other services years prior.3,6,7 By the end of 2018, locs were authorized by all services, and female sailors could wear a ponytail in all navy uniforms as long as it did not extend 3 inches below the collar.3,4,6-8 In 2018, the air force increased authorized hair bulk up to 3.5 inches from the previous mandate of 3 inches and approved female buzz cuts6,9; in 2020, it allowed hair bulk up to 4 inches. As of 2021, female airmen can wear a ponytail and/or braid(s) as long as it starts below the crown of the head and the length does not extend below a horizontal line running between the top of each sleeve inseam at the underarm (Figures 2–4).6 In an ongoing effort to be more inclusive of hair density differences, female airmen will be authorized to wear a ponytail not exceeding a maximum width bulk of 1 ft starting June 25, 2021, so long as they can comply with the above regulations.11 The army now allows ponytails and braids across all uniforms, as long they do not extend past the bottom of the shoulder blades. This change came just months after authorizing the wearing of ponytails tucked under the uniform blouse with tactical headgear.10 These changes allow for a variety of hairstyles for members to practice while avoiding the physical consequences that develop from repetitive traction and pressure along the same areas of the hair and scalp.

Common Hair Disorders in Female Servicemembers

Herein, we discuss 3 of the most common hair and scalp disorders linked to grooming practices utilized by women to meet prior military regulations: trichorrhexis nodosa (TN), extracranial headaches, and traction alopecia (TA). It is essential that health care providers are able to promptly recognize these conditions, understand their risk factors, and be familiar with first-line treatment options. With these new standards, the hope is that the incidence of the following conditions decreases, thus improving servicemembers’ medical readiness and overall quality of life.

Trichorrhexis Nodosa

Acquired TN is a defect in the hair shaft that causes the hair to break easily secondary to chemical, thermal, or mechanical trauma. This can include but is not limited to chemical relaxers, blow-dryers, excessive brushing or styling, flat irons, and tightly packed hairstyles. The condition is characterized by a thickened hair diameter and splitting at the tip. Clinically, it may present as brittle, lusterless, broken hair with split ends, as well as a positive tug test.14 Management includes gentle hair care and avoidance of harsh hair care practices and treatments.

Extracranial Headaches

Headaches are a common concern among military servicemembers15 and generally are classified as primary or secondary. A less commonly discussed primary headache disorder includes external-pressure headaches, which result from either sustained compression or traction of the soft tissues of the scalp, usually from wearing headbands, helmets, or tight hairstyles.16 Additional at-risk groups include those who chronically wear surgical scrub caps or flight caps, especially if clipped or pinned to the hair. In our 38 years of combined military clinical experience, we can attest that these types of headaches are common among female servicemembers. The diagnostic criteria for an external-pressure headache, commonly referred to by patients as a “ponytail headache,” includes at least 2 headache episodes triggered within 1 hour of sustained traction on the scalp, maximal at the site of traction and resolving within 1 hour after relieving the traction.16 Management includes removal of the pressure-causing source, usually a tight ponytail or bun.

Traction Alopecia

Traction alopecia is hair loss caused by repetitive or prolonged tension on the hair secondary to tight hairstyles. It can be clinically classified into 2 types: marginal and nonmarginal patchy alopecia (Figure 5).13,17,18 Traction alopecia most commonly is found in individuals with ethnic hair, predominantly Black women. Hairstyles with the highest risk for causing TA include tight buns, ponytails, cornrows, weaves, and locs—all of which are utilized by female servicemembers to maintain a professional appearance and adhere to grooming regulations.13,18 Other groups at risk include athletes (eg, ballerinas, gymnasts) and those with chronic headwear use (eg, turbans, helmets, nurse caps, wigs).18 Early TA typically presents with perifollicular erythema followed by follicular-based papules or pustules.13,18 Marginal TA classically includes frontotemporal hair loss or thinning with or without a fringe sign.17,18 Nonmarginal TA includes patchy alopecia most commonly involving the parietal or occipital scalp, seen with chignons, buns, ponytails, or the use of clips, extensions, or bobby pins.18 The first line in management is avoidance of traction-causing hairstyles or headgear. Medical therapy may be warranted and consists of a single agent or combination regimen to include oral or topical antibiotics, topical or intralesional steroids, and topical minoxidil.13,18

Final Thoughts

Military hair-grooming standards have evolved over time. Recent changes show that the US Department of Defense is seriously evaluating policies that may be inherently exclusive. Prior grooming standards resulted in the widespread use of tight hairstyles and harsh hair treatments among female servicemembers with long hair. These practices resulted in TN, extracranial headaches, and TA, among other hair and scalp disorders. These occupational-related hair conditions impact female servicemembers’ mental and physical well-being and thus impact military readiness. Physicians should recognize that these conditions can be related to occupational grooming standards that may impact hair care practices.

The challenge that remains is a lack of standardized documentation for hair and scalp symptoms in the medical record. Due to a paucity in reporting and documentation, limited objective data exist to guide future recommendations for military grooming standards. Another obstacle is the lack of knowledge of hair diseases among primary care providers and patients, especially due to the underrepresentation of ethnic hair in medical textbooks.19 As a result, women frequently accept their hair symptoms as normal and either suffer through them, cut their hair short, or wear wigs before considering a visit to the doctor. Furthermore, hair-grooming standards can expose racial disparities, which are the driving force behind the current policy changes. Clinicians can strive to ask about hair and scalp symptoms and document the following in relation to hair and scalp disorders: occupational grooming requirements; skin and hair type; location, number, and size of scalp lesion(s); onset; duration; current and prior hair care practices; history of treatment; and clinical course accompanied with photographic documentation. Ultimately, improved awareness in patients, collaboration between physicians, and consistent clinical documentation can help create positive change and continued improvement in hair-grooming standards within the military. Improved reporting and documentation will facilitate further study into the effectiveness of the updated hair-grooming standards in female servicemembers.

- United States Air Force Statistical Digest FY 1999. United States Air Force; 2000. Accessed June 8, 2021. https://media.defense.gov/2011/Apr/14/2001330240/-1/-1/0/AFD-110414-048.pdf

- Air Force demographics. Air Force Personnel Center website. Accessed June 8, 2021. https://www.afpc.af.mil/About/Air-Force-Demographics/

- US Department of the Army. Wear and Appearance of Army Uniforms and Insignia: Army Regulation 670-1. Department of the Army; 2021. Accessed June 8, 2021. https://armypubs.army.mil/epubs/DR_pubs/DR_a/ARN30302-AR_670-1-000-WEB-1.pdf

- Losey S. Loc hairstyles, off-duty earrings for men ok’d in new dress regs. Air Force Times. Published July 16, 2018. Accessed June 8, 2021. https://www.airforcetimes.com/news/your-air-force/2018/07/16/loc-hairstyles-off-duty-earrings-for-men-okd-in-new-dress-regs/

- Department of the Air Force. AFT 36-2903, Dress and Personal Appearance of Air Force Personnel. Department of the Air Force; 2011. Accessed June 8, 2021. https://www.uc.edu/content/dam/uc/afrotc/docs/Documents/AFI36-2903.pdf

- Department of the Air Force. AFT 36-2903, Dress and Personal Appearance of Air Force Personnel. Department of the Air Force; 2021. Accessed June 8, 2021. https://static.e-publishing.af.mil/production/1/af_a1/publication/afi36-2903/afi36-2903.pdf

- U.S. Navy uniform regulations: summary of changes (26 February 2020). Navy Personnel Command website. Accessed June 8, 2021. https://www.mynavyhr.navy.mil/Portals/55/Navy%20Uniforms/Uniform%20Regulations/Documents/SOC_2020_02_26.pdf?ver=y8Wd0ykVXgISfFpOy8qHkg%3d%3d

- US Headquarters Marine Corps. Marine Corps Uniform Regulations: Marine Corps Order 1020.34H. United States Marine Corps, 2018. Accessed June 8, 2021. https://www.marines.mil/portals/1/Publications/MCO%201020.34H%20v2.pdf?ver=2018-06-26-094038-137

- Secretary of the Air Force Public Affairs. Air Force to allow longer braids, ponytails, bangs for women. United States Air Force website. Published January 21, 2021. Accessed June 8, 2021. https://www.af.mil/News/Article-Display/Article/2478173/air-force-to-allow-longer-braids-ponytails-bangs-for-women/

- Britzky H. The Army will now allow women to wear ponytails in all uniforms. Task & Purpose. Published May 6, 2021. Accessed June 8, 2021. https://taskandpurpose.com/news/army-women-ponytails-all-uniforms/

- Secretary of the Air Force Public Affairs. Air Force readdresses women’s hair standard after feedback. US Air Force website. Published June 11, 2021. Accessed June 27, 2021. https://www.af.mil/News/Article-Display/Article/2654774/air-force-readdresses-womens-hair-standard-after-feedback/

- Myers M. Esper direct services to review racial bias in grooming standards, training and more. Air Force Times. Published July 15, 2020. Accessed June 8, 2021. https://www.airforcetimes.com/news/your-military/2020/07/15/esper-directs-services-to-review-racial-bias-in-grooming-standards-training-and-more/

- Madu P, Kundu RV. Follicular and scarring disorders in skin of color: presentation and management. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2014;15:307-321.

- Quaresma M, Martinez Velasco M, Tosti A. Hair breakage in patients of African descent: role of dermoscopy. Skin Appendage Disord. 2015;1:99-104.

- Burch RC, Loder S, Loder E, et al. The prevalence and burden of migraine and severe headache in the United States: updated statistics from government health surveillance studies. Headache. 2015;55:21-34.

- Kararizou E, Bougea AM, Giotopoulou D, et al. An update on the less-known group of other primary headaches—a review. Eur Neurol Rev. 2014;9:71-77.

- Sperling L, Cowper S, Knopp E. An Atlas of Hair Pathology with Clinical Correlations. CRC Press; 2012:67-68.

- Billero V, Miteva M. Traction alopecia: the root of the problem. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2018;11:149-159.

- Adelekun A, Onyekaba G, Lipoff JB. Skin color in dermatology textbooks: an updated evaluation and analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:194-196.

- United States Air Force Statistical Digest FY 1999. United States Air Force; 2000. Accessed June 8, 2021. https://media.defense.gov/2011/Apr/14/2001330240/-1/-1/0/AFD-110414-048.pdf

- Air Force demographics. Air Force Personnel Center website. Accessed June 8, 2021. https://www.afpc.af.mil/About/Air-Force-Demographics/

- US Department of the Army. Wear and Appearance of Army Uniforms and Insignia: Army Regulation 670-1. Department of the Army; 2021. Accessed June 8, 2021. https://armypubs.army.mil/epubs/DR_pubs/DR_a/ARN30302-AR_670-1-000-WEB-1.pdf

- Losey S. Loc hairstyles, off-duty earrings for men ok’d in new dress regs. Air Force Times. Published July 16, 2018. Accessed June 8, 2021. https://www.airforcetimes.com/news/your-air-force/2018/07/16/loc-hairstyles-off-duty-earrings-for-men-okd-in-new-dress-regs/

- Department of the Air Force. AFT 36-2903, Dress and Personal Appearance of Air Force Personnel. Department of the Air Force; 2011. Accessed June 8, 2021. https://www.uc.edu/content/dam/uc/afrotc/docs/Documents/AFI36-2903.pdf

- Department of the Air Force. AFT 36-2903, Dress and Personal Appearance of Air Force Personnel. Department of the Air Force; 2021. Accessed June 8, 2021. https://static.e-publishing.af.mil/production/1/af_a1/publication/afi36-2903/afi36-2903.pdf

- U.S. Navy uniform regulations: summary of changes (26 February 2020). Navy Personnel Command website. Accessed June 8, 2021. https://www.mynavyhr.navy.mil/Portals/55/Navy%20Uniforms/Uniform%20Regulations/Documents/SOC_2020_02_26.pdf?ver=y8Wd0ykVXgISfFpOy8qHkg%3d%3d

- US Headquarters Marine Corps. Marine Corps Uniform Regulations: Marine Corps Order 1020.34H. United States Marine Corps, 2018. Accessed June 8, 2021. https://www.marines.mil/portals/1/Publications/MCO%201020.34H%20v2.pdf?ver=2018-06-26-094038-137

- Secretary of the Air Force Public Affairs. Air Force to allow longer braids, ponytails, bangs for women. United States Air Force website. Published January 21, 2021. Accessed June 8, 2021. https://www.af.mil/News/Article-Display/Article/2478173/air-force-to-allow-longer-braids-ponytails-bangs-for-women/

- Britzky H. The Army will now allow women to wear ponytails in all uniforms. Task & Purpose. Published May 6, 2021. Accessed June 8, 2021. https://taskandpurpose.com/news/army-women-ponytails-all-uniforms/

- Secretary of the Air Force Public Affairs. Air Force readdresses women’s hair standard after feedback. US Air Force website. Published June 11, 2021. Accessed June 27, 2021. https://www.af.mil/News/Article-Display/Article/2654774/air-force-readdresses-womens-hair-standard-after-feedback/

- Myers M. Esper direct services to review racial bias in grooming standards, training and more. Air Force Times. Published July 15, 2020. Accessed June 8, 2021. https://www.airforcetimes.com/news/your-military/2020/07/15/esper-directs-services-to-review-racial-bias-in-grooming-standards-training-and-more/

- Madu P, Kundu RV. Follicular and scarring disorders in skin of color: presentation and management. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2014;15:307-321.

- Quaresma M, Martinez Velasco M, Tosti A. Hair breakage in patients of African descent: role of dermoscopy. Skin Appendage Disord. 2015;1:99-104.

- Burch RC, Loder S, Loder E, et al. The prevalence and burden of migraine and severe headache in the United States: updated statistics from government health surveillance studies. Headache. 2015;55:21-34.

- Kararizou E, Bougea AM, Giotopoulou D, et al. An update on the less-known group of other primary headaches—a review. Eur Neurol Rev. 2014;9:71-77.

- Sperling L, Cowper S, Knopp E. An Atlas of Hair Pathology with Clinical Correlations. CRC Press; 2012:67-68.

- Billero V, Miteva M. Traction alopecia: the root of the problem. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2018;11:149-159.

- Adelekun A, Onyekaba G, Lipoff JB. Skin color in dermatology textbooks: an updated evaluation and analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:194-196.

Practice Points

- Military hair-grooming standards have undergone considerable changes to foster inclusivity and acknowledge racial diversity in hair and skin types.

- The chronic wearing of tight hairstyles can lead to hair breakage, headaches, and traction alopecia.

- A deliberate focus on diversity and inclusivity has started to drive policy change that eliminates racial and gender bias.

Gray hair goes away and squids go to space

Goodbye stress, goodbye gray hair

Last year was a doozy, so it wouldn’t be too surprising if we all had a few new gray strands in our hair. But what if we told you that you don’t need to start dying them or plucking them out? What if they could magically go back to the way they were? Well, it may be possible, sans magic and sans stress.

Investigators recently discovered that the age-old belief that stress will permanently turn your hair gray may not be true after all. There’s a strong possibility that it could turn back to its original color once the stressful agent is eliminated.

“Understanding the mechanisms that allow ‘old’ gray hairs to return to their ‘young’ pigmented states could yield new clues about the malleability of human aging in general and how it is influenced by stress,” said senior author Martin Picard, PhD, of Columbia University, New York.

For the study, 14 volunteers were asked to keep a stress diary and review their levels of stress throughout the week. The researchers used a new method of viewing and capturing the images of tiny parts of the hairs to see how much graying took place in each part of the strand. And what they found – some strands naturally turning back to the original color – had never been documented before.

How did it happen? Our good friend the mitochondria. We haven’t really heard that word since eighth-grade biology, but it’s actually the key link between stress hormones and hair pigmentation. Think of them as little radars picking up all different kinds of signals in your body, like mental/emotional stress. They get a big enough alert and they’re going to react, thus gray hair.

So that’s all it takes? Cut the stress and a full head of gray can go back to brown? Not exactly. The researchers said there may be a “threshold because of biological age and other factors.” They believe middle age is near that threshold and it could easily be pushed over due to stress and could potentially go back. But if you’ve been rocking the salt and pepper or silver fox for a number of years and are looking for change, you might want to just eliminate the stress and pick up a bottle of dye.

One small step for squid

Space does a number on the human body. Forget the obvious like going for a walk outside without a spacesuit, or even the well-known risks like the degradation of bone in microgravity; there are numerous smaller but still important changes to the body during spaceflight, like the disruption of the symbiotic relationship between gut bacteria and the human body. This causes the immune system to lose the ability to recognize threats, and illnesses spread more easily.

Naturally, if astronauts are going to undertake years-long journeys to Mars and beyond, a thorough understanding of this disturbance is necessary, and that’s why NASA has sent a bunch of squid to the International Space Station.

When it comes to animal studies, squid aren’t the usual culprits, but there’s a reason NASA chose calamari over the alternatives: The Hawaiian bobtail squid has a symbiotic relationship with bacteria that regulate their bioluminescence in much the same way that we have a symbiotic relationship with our gut bacteria, but the squid is a much simpler animal. If the bioluminescence-regulating bacteria are disturbed during their time in space, it will be much easier to figure out what’s going wrong.

The experiment is ongoing, but we should salute the brave squid who have taken a giant leap for squidkind. Though if NASA didn’t send them up in a giant bubble, we’re going to be very disappointed.

Less plastic, more vanilla

Have you been racked by guilt over the number of plastic water bottles you use? What about the amount of ice cream you eat? Well, this one’s for you.

Plastic isn’t the first thing you think about when you open up a pint of vanilla ice cream and catch the sweet, spicy vanilla scent, or when you smell those fresh vanilla scones coming out of the oven at the coffee shop, but a new study shows that the flavor of vanilla can come from water bottles.

Here’s the deal. A compound called vanillin is responsible for the scent of vanilla, and it can come naturally from the bean or it can be made synthetically. Believe it or not, 85% of vanillin is made synthetically from fossil fuels!

We’ve definitely grown accustomed to our favorite vanilla scents, foods, and cosmetics. In 2018, the global demand for vanillin was about 40,800 tons and is expected to grow to 65,000 tons by 2025, which far exceeds the supply of natural vanilla.

So what can we do? Well, we can use genetically engineered bacteria to turn plastic water bottles into vanillin, according to a study published in the journal Green Chemistry.

The plastic can be broken down into terephthalic acid, which is very similar, chemically speaking, to vanillin. Similar enough that a bit of bioengineering produced Escherichia coli that could convert the acid into the tasty treat, according to researchers at the University of Edinburgh.

A perfect solution? Decreasing plastic waste while producing a valued food product? The thought of consuming plastic isn’t appetizing, so just eat your ice cream and try to forget about it.

No withdrawals from this bank

Into each life, some milestones must fall: High school graduation, birth of a child, first house, 50th wedding anniversary, COVID-19. One LOTME staffer got really excited – way too excited, actually – when his Nissan Sentra reached 300,000 miles.

Well, there are milestones, and then there are milestones. “1,000 Reasons for Hope” is a report celebrating the first 1,000 brains donated to the VA-BU-CLF Brain Bank. For those of you keeping score at home, that would be the Department of Veterans Affairs, Boston University, and the Concussion Legacy Foundation.

The Brain Bank, created in 2008 to study concussions and chronic traumatic encephalopathy, is the brainchild – yes, we went there – of Chris Nowinski, PhD, a former professional wrestler, and Ann McKee, MD, an expert on neurogenerative disease. “Our discoveries have already inspired changes to sports that will prevent many future cases of CTE in the next generation of athletes,” Dr. Nowinski, the CEO of CLF, said in a written statement.

Data from the first thousand brains show that 706 men, including 305 former NFL players, had football as their primary exposure to head impacts. Women were underrepresented, making up only 2.8% of brain donations, so recruiting females is a priority. Anyone interested in pledging can go to PledgeMyBrain.org or call 617-992-0615 for the 24-hour emergency donation pager.

LOTME wanted to help, so we called the Brain Bank to find out about donating. They asked a few questions and we told them what we do for a living. “Oh, you’re with LOTME? Yeah, we’ve … um, seen that before. It’s, um … funny. Can we put you on hold?” We’re starting to get a little sick of the on-hold music by now.

Goodbye stress, goodbye gray hair

Last year was a doozy, so it wouldn’t be too surprising if we all had a few new gray strands in our hair. But what if we told you that you don’t need to start dying them or plucking them out? What if they could magically go back to the way they were? Well, it may be possible, sans magic and sans stress.

Investigators recently discovered that the age-old belief that stress will permanently turn your hair gray may not be true after all. There’s a strong possibility that it could turn back to its original color once the stressful agent is eliminated.

“Understanding the mechanisms that allow ‘old’ gray hairs to return to their ‘young’ pigmented states could yield new clues about the malleability of human aging in general and how it is influenced by stress,” said senior author Martin Picard, PhD, of Columbia University, New York.

For the study, 14 volunteers were asked to keep a stress diary and review their levels of stress throughout the week. The researchers used a new method of viewing and capturing the images of tiny parts of the hairs to see how much graying took place in each part of the strand. And what they found – some strands naturally turning back to the original color – had never been documented before.

How did it happen? Our good friend the mitochondria. We haven’t really heard that word since eighth-grade biology, but it’s actually the key link between stress hormones and hair pigmentation. Think of them as little radars picking up all different kinds of signals in your body, like mental/emotional stress. They get a big enough alert and they’re going to react, thus gray hair.

So that’s all it takes? Cut the stress and a full head of gray can go back to brown? Not exactly. The researchers said there may be a “threshold because of biological age and other factors.” They believe middle age is near that threshold and it could easily be pushed over due to stress and could potentially go back. But if you’ve been rocking the salt and pepper or silver fox for a number of years and are looking for change, you might want to just eliminate the stress and pick up a bottle of dye.

One small step for squid

Space does a number on the human body. Forget the obvious like going for a walk outside without a spacesuit, or even the well-known risks like the degradation of bone in microgravity; there are numerous smaller but still important changes to the body during spaceflight, like the disruption of the symbiotic relationship between gut bacteria and the human body. This causes the immune system to lose the ability to recognize threats, and illnesses spread more easily.

Naturally, if astronauts are going to undertake years-long journeys to Mars and beyond, a thorough understanding of this disturbance is necessary, and that’s why NASA has sent a bunch of squid to the International Space Station.

When it comes to animal studies, squid aren’t the usual culprits, but there’s a reason NASA chose calamari over the alternatives: The Hawaiian bobtail squid has a symbiotic relationship with bacteria that regulate their bioluminescence in much the same way that we have a symbiotic relationship with our gut bacteria, but the squid is a much simpler animal. If the bioluminescence-regulating bacteria are disturbed during their time in space, it will be much easier to figure out what’s going wrong.

The experiment is ongoing, but we should salute the brave squid who have taken a giant leap for squidkind. Though if NASA didn’t send them up in a giant bubble, we’re going to be very disappointed.

Less plastic, more vanilla

Have you been racked by guilt over the number of plastic water bottles you use? What about the amount of ice cream you eat? Well, this one’s for you.

Plastic isn’t the first thing you think about when you open up a pint of vanilla ice cream and catch the sweet, spicy vanilla scent, or when you smell those fresh vanilla scones coming out of the oven at the coffee shop, but a new study shows that the flavor of vanilla can come from water bottles.

Here’s the deal. A compound called vanillin is responsible for the scent of vanilla, and it can come naturally from the bean or it can be made synthetically. Believe it or not, 85% of vanillin is made synthetically from fossil fuels!

We’ve definitely grown accustomed to our favorite vanilla scents, foods, and cosmetics. In 2018, the global demand for vanillin was about 40,800 tons and is expected to grow to 65,000 tons by 2025, which far exceeds the supply of natural vanilla.

So what can we do? Well, we can use genetically engineered bacteria to turn plastic water bottles into vanillin, according to a study published in the journal Green Chemistry.

The plastic can be broken down into terephthalic acid, which is very similar, chemically speaking, to vanillin. Similar enough that a bit of bioengineering produced Escherichia coli that could convert the acid into the tasty treat, according to researchers at the University of Edinburgh.

A perfect solution? Decreasing plastic waste while producing a valued food product? The thought of consuming plastic isn’t appetizing, so just eat your ice cream and try to forget about it.

No withdrawals from this bank

Into each life, some milestones must fall: High school graduation, birth of a child, first house, 50th wedding anniversary, COVID-19. One LOTME staffer got really excited – way too excited, actually – when his Nissan Sentra reached 300,000 miles.

Well, there are milestones, and then there are milestones. “1,000 Reasons for Hope” is a report celebrating the first 1,000 brains donated to the VA-BU-CLF Brain Bank. For those of you keeping score at home, that would be the Department of Veterans Affairs, Boston University, and the Concussion Legacy Foundation.

The Brain Bank, created in 2008 to study concussions and chronic traumatic encephalopathy, is the brainchild – yes, we went there – of Chris Nowinski, PhD, a former professional wrestler, and Ann McKee, MD, an expert on neurogenerative disease. “Our discoveries have already inspired changes to sports that will prevent many future cases of CTE in the next generation of athletes,” Dr. Nowinski, the CEO of CLF, said in a written statement.

Data from the first thousand brains show that 706 men, including 305 former NFL players, had football as their primary exposure to head impacts. Women were underrepresented, making up only 2.8% of brain donations, so recruiting females is a priority. Anyone interested in pledging can go to PledgeMyBrain.org or call 617-992-0615 for the 24-hour emergency donation pager.

LOTME wanted to help, so we called the Brain Bank to find out about donating. They asked a few questions and we told them what we do for a living. “Oh, you’re with LOTME? Yeah, we’ve … um, seen that before. It’s, um … funny. Can we put you on hold?” We’re starting to get a little sick of the on-hold music by now.

Goodbye stress, goodbye gray hair

Last year was a doozy, so it wouldn’t be too surprising if we all had a few new gray strands in our hair. But what if we told you that you don’t need to start dying them or plucking them out? What if they could magically go back to the way they were? Well, it may be possible, sans magic and sans stress.

Investigators recently discovered that the age-old belief that stress will permanently turn your hair gray may not be true after all. There’s a strong possibility that it could turn back to its original color once the stressful agent is eliminated.

“Understanding the mechanisms that allow ‘old’ gray hairs to return to their ‘young’ pigmented states could yield new clues about the malleability of human aging in general and how it is influenced by stress,” said senior author Martin Picard, PhD, of Columbia University, New York.

For the study, 14 volunteers were asked to keep a stress diary and review their levels of stress throughout the week. The researchers used a new method of viewing and capturing the images of tiny parts of the hairs to see how much graying took place in each part of the strand. And what they found – some strands naturally turning back to the original color – had never been documented before.

How did it happen? Our good friend the mitochondria. We haven’t really heard that word since eighth-grade biology, but it’s actually the key link between stress hormones and hair pigmentation. Think of them as little radars picking up all different kinds of signals in your body, like mental/emotional stress. They get a big enough alert and they’re going to react, thus gray hair.

So that’s all it takes? Cut the stress and a full head of gray can go back to brown? Not exactly. The researchers said there may be a “threshold because of biological age and other factors.” They believe middle age is near that threshold and it could easily be pushed over due to stress and could potentially go back. But if you’ve been rocking the salt and pepper or silver fox for a number of years and are looking for change, you might want to just eliminate the stress and pick up a bottle of dye.

One small step for squid

Space does a number on the human body. Forget the obvious like going for a walk outside without a spacesuit, or even the well-known risks like the degradation of bone in microgravity; there are numerous smaller but still important changes to the body during spaceflight, like the disruption of the symbiotic relationship between gut bacteria and the human body. This causes the immune system to lose the ability to recognize threats, and illnesses spread more easily.

Naturally, if astronauts are going to undertake years-long journeys to Mars and beyond, a thorough understanding of this disturbance is necessary, and that’s why NASA has sent a bunch of squid to the International Space Station.

When it comes to animal studies, squid aren’t the usual culprits, but there’s a reason NASA chose calamari over the alternatives: The Hawaiian bobtail squid has a symbiotic relationship with bacteria that regulate their bioluminescence in much the same way that we have a symbiotic relationship with our gut bacteria, but the squid is a much simpler animal. If the bioluminescence-regulating bacteria are disturbed during their time in space, it will be much easier to figure out what’s going wrong.

The experiment is ongoing, but we should salute the brave squid who have taken a giant leap for squidkind. Though if NASA didn’t send them up in a giant bubble, we’re going to be very disappointed.

Less plastic, more vanilla

Have you been racked by guilt over the number of plastic water bottles you use? What about the amount of ice cream you eat? Well, this one’s for you.

Plastic isn’t the first thing you think about when you open up a pint of vanilla ice cream and catch the sweet, spicy vanilla scent, or when you smell those fresh vanilla scones coming out of the oven at the coffee shop, but a new study shows that the flavor of vanilla can come from water bottles.

Here’s the deal. A compound called vanillin is responsible for the scent of vanilla, and it can come naturally from the bean or it can be made synthetically. Believe it or not, 85% of vanillin is made synthetically from fossil fuels!

We’ve definitely grown accustomed to our favorite vanilla scents, foods, and cosmetics. In 2018, the global demand for vanillin was about 40,800 tons and is expected to grow to 65,000 tons by 2025, which far exceeds the supply of natural vanilla.

So what can we do? Well, we can use genetically engineered bacteria to turn plastic water bottles into vanillin, according to a study published in the journal Green Chemistry.

The plastic can be broken down into terephthalic acid, which is very similar, chemically speaking, to vanillin. Similar enough that a bit of bioengineering produced Escherichia coli that could convert the acid into the tasty treat, according to researchers at the University of Edinburgh.

A perfect solution? Decreasing plastic waste while producing a valued food product? The thought of consuming plastic isn’t appetizing, so just eat your ice cream and try to forget about it.

No withdrawals from this bank

Into each life, some milestones must fall: High school graduation, birth of a child, first house, 50th wedding anniversary, COVID-19. One LOTME staffer got really excited – way too excited, actually – when his Nissan Sentra reached 300,000 miles.

Well, there are milestones, and then there are milestones. “1,000 Reasons for Hope” is a report celebrating the first 1,000 brains donated to the VA-BU-CLF Brain Bank. For those of you keeping score at home, that would be the Department of Veterans Affairs, Boston University, and the Concussion Legacy Foundation.

The Brain Bank, created in 2008 to study concussions and chronic traumatic encephalopathy, is the brainchild – yes, we went there – of Chris Nowinski, PhD, a former professional wrestler, and Ann McKee, MD, an expert on neurogenerative disease. “Our discoveries have already inspired changes to sports that will prevent many future cases of CTE in the next generation of athletes,” Dr. Nowinski, the CEO of CLF, said in a written statement.

Data from the first thousand brains show that 706 men, including 305 former NFL players, had football as their primary exposure to head impacts. Women were underrepresented, making up only 2.8% of brain donations, so recruiting females is a priority. Anyone interested in pledging can go to PledgeMyBrain.org or call 617-992-0615 for the 24-hour emergency donation pager.

LOTME wanted to help, so we called the Brain Bank to find out about donating. They asked a few questions and we told them what we do for a living. “Oh, you’re with LOTME? Yeah, we’ve … um, seen that before. It’s, um … funny. Can we put you on hold?” We’re starting to get a little sick of the on-hold music by now.

Argyria From a Topical Home Remedy

To the Editor:

Argyria is a rare disease caused by chronic exposure to products with high silver content (eg, oral ingestion, inhalation, percutaneous absorption). With time, the blood levels of silver surpass the body’s renal and hepatic excretory capacities that lead to silver granules being deposited in the skin and internal organs, including the liver, spleen, adrenal glands, and bone marrow.1 The cutaneous deposition results in a blue or blue-gray pigmentation of the skin, mucous membranes, and nails. Intervals of exposure that span from 8 months to 5 years prior to symptom onset have been described in the literature.2 The discoloration that results often is permanent, with no established way of effectively removing silver deposits from the tissue.3

A 22-year-old autistic man, who was completely dependent on his mother’s care, presented to the emergency department with a primary concern of abdominal pain. The mother reported that he was indicating abdominal pain by motioning to his stomach for the last 5 days. The mother also reported he did not have a bowel movement during this time, and she noticed his hands were shaking. Prior to presentation, the mother had given him 2 enemas and had him on a 3-day strict liquid fast consisting of water, lemon juice, cayenne pepper, honey, and orange juice. Notably, the mother had a strong history of using naturopathic remedies for treatment of her son’s ailments.

On admission, the patient was stable. There was a 2-point decrease in the patient’s body mass index over the last month. Initial serum electrolytes were highly abnormal with a serum sodium level of 124 mEq/L (reference range, 135–145 mEq/L), blood urea nitrogen of 3 mg/dL (reference range, 7–20 mg/dL), creatinine of 0.77 mg/dL (reference range, 0.74–1.35 mg/dL), and lactic acid of 2.1 mEq/L (reference range, 0.5–1 mEq/L). Serum osmolality was 272 mOsm/kg (reference range, 275–295 mOsm/kg). Urine osmolality was 114 mOsm/kg (reference range, 500–850 mOsm/kg) with a low-normal urine sodium level of 41 mmol/24 hr (reference range, 40–220 mmol/24 hr). Abnormalities were felt to be secondary to malnutrition from the strict liquid diet (blood urea nitrogen and creatinine ratio of 3:1 suggestive of notable protein calorie malnutrition). The patient was given 1 L of normal saline in the emergency department, with further fluids held so as not to increase serum sodium level too rapidly. A regular diet was started.