User login

Onychomycosis: New Developments in Diagnosis, Treatment, and Antifungal Medication Safety

Onychomycosis is the most prevalent nail condition worldwide and has a significant impact on quality of life.1 There were 10 million physician visits for nail fungal infections in the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey from 2007 to 2016, which was more than double the number of all other nail diagnoses combined.2 Therefore, it is important for dermatologists to be familiar with the most current data on diagnosis and treatment of this extremely common nail disease as well as antifungal medication safety.

Onychomycosis Diagnosis

Diagnosis of onychomycosis using clinical examination alone has poor sensitivity and specificity and may lead to progression of disease and unwanted side effects from inappropriate therapy.3,4 Dermoscopy is a useful adjunct but diagnostically is still inferior compared to mycologic testing.5 Classical methods of diagnosis include potassium hydroxide staining with microscopy, fungal culture, and histopathology. Polymerase chain reaction is a newer technique with wide accessibility and excellent sensitivity and specificity.6 Although these techniques have excellent diagnostic accuracy both alone and in combination, the ideal test would have 100% sensitivity and specificity and would not require nail sampling. Artificial intelligence recently has been studied for the diagnosis of onychomycosis. In a prospective study of 90 patients with onychodystrophy who had photographs of the nails taken by nonphysicians, deep neural networks showed comparable sensitivity (70.2% vs 73.0%) and specificity (72.7% vs 49.7%) for diagnosis of onychomycosis vs clinical examination by dermatologists with a mean of 5.6 years of experience.7 Therefore, artificial intelligence may be considered as a supplement to clinical examination for dermatology residents and junior attending dermatologists and may be superior to clinical examination by nondermatologists, but mycologic confirmation is still necessary before initiating onychomycosis treatment.

Treatment of Onychomycosis

There are 3 topical therapies (ciclopirox lacquer 8%, efinaconazole solution 10%, and tavaborole solution 5%) and 3 oral therapies (terbinafine, itraconazole, and griseofulvin) that are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for onychomycosis therapy. Griseofulvin rarely is used due to the availability of more efficacious treatment options. Fluconazole is an off-label treatment that often is used in the United States.8

There are new data on the efficacy and safety of topical onychomycosis treatments in children. A phase 4 open‐label study of efinaconazole solution 10% applied once daily for 48 weeks was performed in children aged 6 to 16 years with distal lateral subungual onychomycosis (N=62).9,10 The medication was both well tolerated and safe in children. The only treatment-related adverse event was onychocryptosis, which was reported by 2 patients. At week 52, mycologic cure was 65% and complete cure was 40% (N=50). In a pharmacokinetic assessment performed in a subset of 17 patients aged 12 to 16 years, efinaconazole was measured at very low levels in plasma.9

A phase 4 open-label study also was performed to evaluate the safety, pharmacokinetics, and efficacy of tavaborole for treatment of distal lateral subungual onychomycosis in children aged 6 years to under 17 years (N=55).11 Tavaborole solution 5% was applied once daily for 48 weeks; at week 52, mycologic and complete cures were 36.2% and 8.5%, respectively (N=47). Systemic exposure was low (Cmax=5.9 ng/mL [day 29]) in a subset of patients aged 12 years to under 17 years (N=37), and the medication demonstrated good safety and tolerability.11

Fosravuconazole was approved for treatment of onychomycosis in Japan in 2018. In a randomized, double-blind, phase 3 trial of oral fosravuconazole 100 mg once daily (n=101) vs placebo (n=52) for 12 weeks in patients with onychomycosis (mean age, 58.4 years), the complete cure rate at 48 weeks was 59.4%.12 In a small trial of 37 elderly patients (mean age, 78.1 years), complete cure rates were 5.0% in patients with a nail plate thickness of 3 mm or greater and 58.8% in those with a thickness lessthan 3 mm, and there were no severe adverse events.13 In addition to excellent efficacy and proven safety in elderly adults, the main advantage of fosravuconazole is less-potent inhibition of cytochrome P450 3A compared to other triazole antifungals, with no contraindicated drugs listed.

Safety of Antifungals

There are new data describing the safety of oral terbinafine in pregnant women and immunosuppressed patients. In a nationwide cohort study conducted in Denmark (1,650,649 pregnancies [942 oral terbinafine exposed, 9420 unexposed matched cohorts]), there was no association between oral or topical terbinafine exposure during pregnancy and risk of preterm birth, small-for-gestational-age birth weight, low birth weight, or stillbirth.14 In a small study of 13 kidney transplant recipients taking oral tacrolimus, cyclosporine, or everolimus who were treated with oral terbinafine, there were no severe drug interactions and no clinical consequences in renal grafts.15

There also is new information on laboratory abnormalities in adults, children, and patients with comorbidities who are taking oral terbinafine. In a retrospective study of 944 adult patients without pre-existing hepatic or hematologic conditions who were prescribed 3 months of oral terbinafine for onychomycosis, abnormal monitoring liver function tests (LFTs) and complete blood cell counts (CBCs) were uncommon (2.4% and 2.8%, respectively) and mild and resolved after treatment completion. In addition, patients with laboratory abnormalities were an average of 14.8 years older and approximately 3-times more likely to be 65 years or older compared to the overall study population.16 There were similar findings in a retrospective study of 134 children 18 years or younger who were prescribed oral terbinafine for superficial fungal infections. Abnormal monitoring LFTs and CBCs were uncommon (1.7% and 4.4%, respectively) and mild, resolving after after treatment completion.17 Finally, in a study of 255 patients with a pre-existing liver or hematologic condition who were prescribed oral terbinafine for onychomycosis, worsening of LFT or CBC values were rare, and all resolved after treatment completion or medication discontinuation.18

Final Thoughts

Mycologic confirmation is still necessary before treatment despite encouraging data on use of artificial intelligence for diagnosis of onychomycosis. Efinaconazole solution 10% and tavaborole solution 5% have shown good safety, tolerability, and efficacy in children with onychomycosis. Recent data suggest the safety of oral terbinafine in pregnant women and kidney transplant recipients, but these findings must be corroborated before its use in these populations. Fosravuconazole is a promising systemic treatment for onychomycosis with no drug-drug interactions reported to date. While baseline laboratory testing is recommended before prescribing terbinafine, interval laboratory monitoring may not be necessary in healthy adults.19 Prospective studies are necessary to corroborate these findings before formal recommendations can be made for prescribing terbinafine in the special populations discussed above, including children, and for interval laboratory monitoring.

- Stewart CR, Algu L, Kamran R, et al. Effect of onychomycosis and treatment on patient-reported quality-of-life outcomes: a systematic review [published online June 2, 2020]. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.05.143

- Lipner SR, Hancock JE, Fleischer AB. The ambulatory care burden of nail conditions in the United States [published online October 21, 2019]. J Dermatolog Treat. doi:10.1080/09546634.2019.1679337

- Lipner SR, Scher RK. Onychomycosis--a small step for quality of care. Curr Med Res Opin. 2016;32:865-867.

- Lipner SR, Scher RK. Confirmatory testing for onychomycosis. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:847.

- Piraccini BM, Balestri R, Starace M, et al. Nail digital dermoscopy (onychoscopy) in the diagnosis of onychomycosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:509-513.

- Lipner SR, Scher RK. Onychomycosis: clinical overview and diagnosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:835-851.

- Kim YJ, Han SS, Yang HJ, et al. Prospective, comparative evaluation of a deep neural network and dermoscopy in the diagnosis of onychomycosis. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0234334.

- Lipner SR, Scher RK. Onychomycosis: treatment and prevention of recurrence. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:853-867.

- Eichenfield LF, Elewski B, Sugarman JL, et al. Efinaconazole 10% topical solution for the treatment of onychomycosis in pediatric patients: open-label phase 4 study [published online July 2, 2020]. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.06.1004

- Eichenfield LF, Elewski B, Sugarman JL, et al. Safety, pharmacokinetics, and efficacy of efinaconazole 10% topical solution for onychomycosis treatment in pediatric patients. J Drugs Dermatol. 2020;19:867-872.

- Rich P, Spellman M, Purohit V, et al. Tavaborole 5% topical solution for the treatment of toenail onychomycosis in pediatric patients: results from a phase 4 open-label study. J Drugs Dermatol. 2019;18:190-195.

- Watanabe S, Tsubouchi I, Okubo A. Efficacy and safety of fosravuconazole L-lysine ethanolate, a novel oral triazole antifungal agent, for the treatment of onychomycosis: a multicenter, double-blind, randomized phase III study. J Dermatol. 2018;45:1151-1159.

- Noguchi H, Matsumoto T, Kimura U, et al. Fosravuconazole to treat severe onychomycosis in the elderly [published online October 25, 2020]. J Dermatol. doi:10.1111/1346-8138.15651

- Andersson NW, Thomsen SF, Andersen JT. Exposure to terbinafine in pregnancy and risk of preterm birth, small for gestational age, low birth weight, and stillbirth: a nationwide cohort study [published online October 22, 2020]. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.10.034

- Moreno-Sabater A, Ouali N, Chasset F, et al. Severe onychomycosis management with oral terbinafine in a kidney transplantation setting: clinical follow-up by image analysis [published online November 27, 2020]. Mycoses. doi:10.1111/myc.13220

- Wang Y, Geizhals S, Lipner SR. Retrospective analysis of laboratory abnormalities in patients prescribed terbinafine for onychomycosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:497-499.

- Wang Y, Lipner SR. Retrospective analysis of laboratory abnormalities in pediatric patients prescribed terbinafine for superficial fungal infections [published online January 27, 2021]. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.01.073

- Wang Y, Lipner SR. Retrospective analysis of laboratory abnormalities in patients with preexisting liver and hematologic diseases prescribed terbinafine for onychomycosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:220-221.

- Lamisil. Prescribing information. Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; 2010. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2010/022071s003lbl.pdf

Onychomycosis is the most prevalent nail condition worldwide and has a significant impact on quality of life.1 There were 10 million physician visits for nail fungal infections in the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey from 2007 to 2016, which was more than double the number of all other nail diagnoses combined.2 Therefore, it is important for dermatologists to be familiar with the most current data on diagnosis and treatment of this extremely common nail disease as well as antifungal medication safety.

Onychomycosis Diagnosis

Diagnosis of onychomycosis using clinical examination alone has poor sensitivity and specificity and may lead to progression of disease and unwanted side effects from inappropriate therapy.3,4 Dermoscopy is a useful adjunct but diagnostically is still inferior compared to mycologic testing.5 Classical methods of diagnosis include potassium hydroxide staining with microscopy, fungal culture, and histopathology. Polymerase chain reaction is a newer technique with wide accessibility and excellent sensitivity and specificity.6 Although these techniques have excellent diagnostic accuracy both alone and in combination, the ideal test would have 100% sensitivity and specificity and would not require nail sampling. Artificial intelligence recently has been studied for the diagnosis of onychomycosis. In a prospective study of 90 patients with onychodystrophy who had photographs of the nails taken by nonphysicians, deep neural networks showed comparable sensitivity (70.2% vs 73.0%) and specificity (72.7% vs 49.7%) for diagnosis of onychomycosis vs clinical examination by dermatologists with a mean of 5.6 years of experience.7 Therefore, artificial intelligence may be considered as a supplement to clinical examination for dermatology residents and junior attending dermatologists and may be superior to clinical examination by nondermatologists, but mycologic confirmation is still necessary before initiating onychomycosis treatment.

Treatment of Onychomycosis

There are 3 topical therapies (ciclopirox lacquer 8%, efinaconazole solution 10%, and tavaborole solution 5%) and 3 oral therapies (terbinafine, itraconazole, and griseofulvin) that are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for onychomycosis therapy. Griseofulvin rarely is used due to the availability of more efficacious treatment options. Fluconazole is an off-label treatment that often is used in the United States.8

There are new data on the efficacy and safety of topical onychomycosis treatments in children. A phase 4 open‐label study of efinaconazole solution 10% applied once daily for 48 weeks was performed in children aged 6 to 16 years with distal lateral subungual onychomycosis (N=62).9,10 The medication was both well tolerated and safe in children. The only treatment-related adverse event was onychocryptosis, which was reported by 2 patients. At week 52, mycologic cure was 65% and complete cure was 40% (N=50). In a pharmacokinetic assessment performed in a subset of 17 patients aged 12 to 16 years, efinaconazole was measured at very low levels in plasma.9

A phase 4 open-label study also was performed to evaluate the safety, pharmacokinetics, and efficacy of tavaborole for treatment of distal lateral subungual onychomycosis in children aged 6 years to under 17 years (N=55).11 Tavaborole solution 5% was applied once daily for 48 weeks; at week 52, mycologic and complete cures were 36.2% and 8.5%, respectively (N=47). Systemic exposure was low (Cmax=5.9 ng/mL [day 29]) in a subset of patients aged 12 years to under 17 years (N=37), and the medication demonstrated good safety and tolerability.11

Fosravuconazole was approved for treatment of onychomycosis in Japan in 2018. In a randomized, double-blind, phase 3 trial of oral fosravuconazole 100 mg once daily (n=101) vs placebo (n=52) for 12 weeks in patients with onychomycosis (mean age, 58.4 years), the complete cure rate at 48 weeks was 59.4%.12 In a small trial of 37 elderly patients (mean age, 78.1 years), complete cure rates were 5.0% in patients with a nail plate thickness of 3 mm or greater and 58.8% in those with a thickness lessthan 3 mm, and there were no severe adverse events.13 In addition to excellent efficacy and proven safety in elderly adults, the main advantage of fosravuconazole is less-potent inhibition of cytochrome P450 3A compared to other triazole antifungals, with no contraindicated drugs listed.

Safety of Antifungals

There are new data describing the safety of oral terbinafine in pregnant women and immunosuppressed patients. In a nationwide cohort study conducted in Denmark (1,650,649 pregnancies [942 oral terbinafine exposed, 9420 unexposed matched cohorts]), there was no association between oral or topical terbinafine exposure during pregnancy and risk of preterm birth, small-for-gestational-age birth weight, low birth weight, or stillbirth.14 In a small study of 13 kidney transplant recipients taking oral tacrolimus, cyclosporine, or everolimus who were treated with oral terbinafine, there were no severe drug interactions and no clinical consequences in renal grafts.15

There also is new information on laboratory abnormalities in adults, children, and patients with comorbidities who are taking oral terbinafine. In a retrospective study of 944 adult patients without pre-existing hepatic or hematologic conditions who were prescribed 3 months of oral terbinafine for onychomycosis, abnormal monitoring liver function tests (LFTs) and complete blood cell counts (CBCs) were uncommon (2.4% and 2.8%, respectively) and mild and resolved after treatment completion. In addition, patients with laboratory abnormalities were an average of 14.8 years older and approximately 3-times more likely to be 65 years or older compared to the overall study population.16 There were similar findings in a retrospective study of 134 children 18 years or younger who were prescribed oral terbinafine for superficial fungal infections. Abnormal monitoring LFTs and CBCs were uncommon (1.7% and 4.4%, respectively) and mild, resolving after after treatment completion.17 Finally, in a study of 255 patients with a pre-existing liver or hematologic condition who were prescribed oral terbinafine for onychomycosis, worsening of LFT or CBC values were rare, and all resolved after treatment completion or medication discontinuation.18

Final Thoughts

Mycologic confirmation is still necessary before treatment despite encouraging data on use of artificial intelligence for diagnosis of onychomycosis. Efinaconazole solution 10% and tavaborole solution 5% have shown good safety, tolerability, and efficacy in children with onychomycosis. Recent data suggest the safety of oral terbinafine in pregnant women and kidney transplant recipients, but these findings must be corroborated before its use in these populations. Fosravuconazole is a promising systemic treatment for onychomycosis with no drug-drug interactions reported to date. While baseline laboratory testing is recommended before prescribing terbinafine, interval laboratory monitoring may not be necessary in healthy adults.19 Prospective studies are necessary to corroborate these findings before formal recommendations can be made for prescribing terbinafine in the special populations discussed above, including children, and for interval laboratory monitoring.

Onychomycosis is the most prevalent nail condition worldwide and has a significant impact on quality of life.1 There were 10 million physician visits for nail fungal infections in the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey from 2007 to 2016, which was more than double the number of all other nail diagnoses combined.2 Therefore, it is important for dermatologists to be familiar with the most current data on diagnosis and treatment of this extremely common nail disease as well as antifungal medication safety.

Onychomycosis Diagnosis

Diagnosis of onychomycosis using clinical examination alone has poor sensitivity and specificity and may lead to progression of disease and unwanted side effects from inappropriate therapy.3,4 Dermoscopy is a useful adjunct but diagnostically is still inferior compared to mycologic testing.5 Classical methods of diagnosis include potassium hydroxide staining with microscopy, fungal culture, and histopathology. Polymerase chain reaction is a newer technique with wide accessibility and excellent sensitivity and specificity.6 Although these techniques have excellent diagnostic accuracy both alone and in combination, the ideal test would have 100% sensitivity and specificity and would not require nail sampling. Artificial intelligence recently has been studied for the diagnosis of onychomycosis. In a prospective study of 90 patients with onychodystrophy who had photographs of the nails taken by nonphysicians, deep neural networks showed comparable sensitivity (70.2% vs 73.0%) and specificity (72.7% vs 49.7%) for diagnosis of onychomycosis vs clinical examination by dermatologists with a mean of 5.6 years of experience.7 Therefore, artificial intelligence may be considered as a supplement to clinical examination for dermatology residents and junior attending dermatologists and may be superior to clinical examination by nondermatologists, but mycologic confirmation is still necessary before initiating onychomycosis treatment.

Treatment of Onychomycosis

There are 3 topical therapies (ciclopirox lacquer 8%, efinaconazole solution 10%, and tavaborole solution 5%) and 3 oral therapies (terbinafine, itraconazole, and griseofulvin) that are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for onychomycosis therapy. Griseofulvin rarely is used due to the availability of more efficacious treatment options. Fluconazole is an off-label treatment that often is used in the United States.8

There are new data on the efficacy and safety of topical onychomycosis treatments in children. A phase 4 open‐label study of efinaconazole solution 10% applied once daily for 48 weeks was performed in children aged 6 to 16 years with distal lateral subungual onychomycosis (N=62).9,10 The medication was both well tolerated and safe in children. The only treatment-related adverse event was onychocryptosis, which was reported by 2 patients. At week 52, mycologic cure was 65% and complete cure was 40% (N=50). In a pharmacokinetic assessment performed in a subset of 17 patients aged 12 to 16 years, efinaconazole was measured at very low levels in plasma.9

A phase 4 open-label study also was performed to evaluate the safety, pharmacokinetics, and efficacy of tavaborole for treatment of distal lateral subungual onychomycosis in children aged 6 years to under 17 years (N=55).11 Tavaborole solution 5% was applied once daily for 48 weeks; at week 52, mycologic and complete cures were 36.2% and 8.5%, respectively (N=47). Systemic exposure was low (Cmax=5.9 ng/mL [day 29]) in a subset of patients aged 12 years to under 17 years (N=37), and the medication demonstrated good safety and tolerability.11

Fosravuconazole was approved for treatment of onychomycosis in Japan in 2018. In a randomized, double-blind, phase 3 trial of oral fosravuconazole 100 mg once daily (n=101) vs placebo (n=52) for 12 weeks in patients with onychomycosis (mean age, 58.4 years), the complete cure rate at 48 weeks was 59.4%.12 In a small trial of 37 elderly patients (mean age, 78.1 years), complete cure rates were 5.0% in patients with a nail plate thickness of 3 mm or greater and 58.8% in those with a thickness lessthan 3 mm, and there were no severe adverse events.13 In addition to excellent efficacy and proven safety in elderly adults, the main advantage of fosravuconazole is less-potent inhibition of cytochrome P450 3A compared to other triazole antifungals, with no contraindicated drugs listed.

Safety of Antifungals

There are new data describing the safety of oral terbinafine in pregnant women and immunosuppressed patients. In a nationwide cohort study conducted in Denmark (1,650,649 pregnancies [942 oral terbinafine exposed, 9420 unexposed matched cohorts]), there was no association between oral or topical terbinafine exposure during pregnancy and risk of preterm birth, small-for-gestational-age birth weight, low birth weight, or stillbirth.14 In a small study of 13 kidney transplant recipients taking oral tacrolimus, cyclosporine, or everolimus who were treated with oral terbinafine, there were no severe drug interactions and no clinical consequences in renal grafts.15

There also is new information on laboratory abnormalities in adults, children, and patients with comorbidities who are taking oral terbinafine. In a retrospective study of 944 adult patients without pre-existing hepatic or hematologic conditions who were prescribed 3 months of oral terbinafine for onychomycosis, abnormal monitoring liver function tests (LFTs) and complete blood cell counts (CBCs) were uncommon (2.4% and 2.8%, respectively) and mild and resolved after treatment completion. In addition, patients with laboratory abnormalities were an average of 14.8 years older and approximately 3-times more likely to be 65 years or older compared to the overall study population.16 There were similar findings in a retrospective study of 134 children 18 years or younger who were prescribed oral terbinafine for superficial fungal infections. Abnormal monitoring LFTs and CBCs were uncommon (1.7% and 4.4%, respectively) and mild, resolving after after treatment completion.17 Finally, in a study of 255 patients with a pre-existing liver or hematologic condition who were prescribed oral terbinafine for onychomycosis, worsening of LFT or CBC values were rare, and all resolved after treatment completion or medication discontinuation.18

Final Thoughts

Mycologic confirmation is still necessary before treatment despite encouraging data on use of artificial intelligence for diagnosis of onychomycosis. Efinaconazole solution 10% and tavaborole solution 5% have shown good safety, tolerability, and efficacy in children with onychomycosis. Recent data suggest the safety of oral terbinafine in pregnant women and kidney transplant recipients, but these findings must be corroborated before its use in these populations. Fosravuconazole is a promising systemic treatment for onychomycosis with no drug-drug interactions reported to date. While baseline laboratory testing is recommended before prescribing terbinafine, interval laboratory monitoring may not be necessary in healthy adults.19 Prospective studies are necessary to corroborate these findings before formal recommendations can be made for prescribing terbinafine in the special populations discussed above, including children, and for interval laboratory monitoring.

- Stewart CR, Algu L, Kamran R, et al. Effect of onychomycosis and treatment on patient-reported quality-of-life outcomes: a systematic review [published online June 2, 2020]. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.05.143

- Lipner SR, Hancock JE, Fleischer AB. The ambulatory care burden of nail conditions in the United States [published online October 21, 2019]. J Dermatolog Treat. doi:10.1080/09546634.2019.1679337

- Lipner SR, Scher RK. Onychomycosis--a small step for quality of care. Curr Med Res Opin. 2016;32:865-867.

- Lipner SR, Scher RK. Confirmatory testing for onychomycosis. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:847.

- Piraccini BM, Balestri R, Starace M, et al. Nail digital dermoscopy (onychoscopy) in the diagnosis of onychomycosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:509-513.

- Lipner SR, Scher RK. Onychomycosis: clinical overview and diagnosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:835-851.

- Kim YJ, Han SS, Yang HJ, et al. Prospective, comparative evaluation of a deep neural network and dermoscopy in the diagnosis of onychomycosis. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0234334.

- Lipner SR, Scher RK. Onychomycosis: treatment and prevention of recurrence. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:853-867.

- Eichenfield LF, Elewski B, Sugarman JL, et al. Efinaconazole 10% topical solution for the treatment of onychomycosis in pediatric patients: open-label phase 4 study [published online July 2, 2020]. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.06.1004

- Eichenfield LF, Elewski B, Sugarman JL, et al. Safety, pharmacokinetics, and efficacy of efinaconazole 10% topical solution for onychomycosis treatment in pediatric patients. J Drugs Dermatol. 2020;19:867-872.

- Rich P, Spellman M, Purohit V, et al. Tavaborole 5% topical solution for the treatment of toenail onychomycosis in pediatric patients: results from a phase 4 open-label study. J Drugs Dermatol. 2019;18:190-195.

- Watanabe S, Tsubouchi I, Okubo A. Efficacy and safety of fosravuconazole L-lysine ethanolate, a novel oral triazole antifungal agent, for the treatment of onychomycosis: a multicenter, double-blind, randomized phase III study. J Dermatol. 2018;45:1151-1159.

- Noguchi H, Matsumoto T, Kimura U, et al. Fosravuconazole to treat severe onychomycosis in the elderly [published online October 25, 2020]. J Dermatol. doi:10.1111/1346-8138.15651

- Andersson NW, Thomsen SF, Andersen JT. Exposure to terbinafine in pregnancy and risk of preterm birth, small for gestational age, low birth weight, and stillbirth: a nationwide cohort study [published online October 22, 2020]. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.10.034

- Moreno-Sabater A, Ouali N, Chasset F, et al. Severe onychomycosis management with oral terbinafine in a kidney transplantation setting: clinical follow-up by image analysis [published online November 27, 2020]. Mycoses. doi:10.1111/myc.13220

- Wang Y, Geizhals S, Lipner SR. Retrospective analysis of laboratory abnormalities in patients prescribed terbinafine for onychomycosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:497-499.

- Wang Y, Lipner SR. Retrospective analysis of laboratory abnormalities in pediatric patients prescribed terbinafine for superficial fungal infections [published online January 27, 2021]. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.01.073

- Wang Y, Lipner SR. Retrospective analysis of laboratory abnormalities in patients with preexisting liver and hematologic diseases prescribed terbinafine for onychomycosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:220-221.

- Lamisil. Prescribing information. Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; 2010. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2010/022071s003lbl.pdf

- Stewart CR, Algu L, Kamran R, et al. Effect of onychomycosis and treatment on patient-reported quality-of-life outcomes: a systematic review [published online June 2, 2020]. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.05.143

- Lipner SR, Hancock JE, Fleischer AB. The ambulatory care burden of nail conditions in the United States [published online October 21, 2019]. J Dermatolog Treat. doi:10.1080/09546634.2019.1679337

- Lipner SR, Scher RK. Onychomycosis--a small step for quality of care. Curr Med Res Opin. 2016;32:865-867.

- Lipner SR, Scher RK. Confirmatory testing for onychomycosis. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:847.

- Piraccini BM, Balestri R, Starace M, et al. Nail digital dermoscopy (onychoscopy) in the diagnosis of onychomycosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:509-513.

- Lipner SR, Scher RK. Onychomycosis: clinical overview and diagnosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:835-851.

- Kim YJ, Han SS, Yang HJ, et al. Prospective, comparative evaluation of a deep neural network and dermoscopy in the diagnosis of onychomycosis. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0234334.

- Lipner SR, Scher RK. Onychomycosis: treatment and prevention of recurrence. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:853-867.

- Eichenfield LF, Elewski B, Sugarman JL, et al. Efinaconazole 10% topical solution for the treatment of onychomycosis in pediatric patients: open-label phase 4 study [published online July 2, 2020]. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.06.1004

- Eichenfield LF, Elewski B, Sugarman JL, et al. Safety, pharmacokinetics, and efficacy of efinaconazole 10% topical solution for onychomycosis treatment in pediatric patients. J Drugs Dermatol. 2020;19:867-872.

- Rich P, Spellman M, Purohit V, et al. Tavaborole 5% topical solution for the treatment of toenail onychomycosis in pediatric patients: results from a phase 4 open-label study. J Drugs Dermatol. 2019;18:190-195.

- Watanabe S, Tsubouchi I, Okubo A. Efficacy and safety of fosravuconazole L-lysine ethanolate, a novel oral triazole antifungal agent, for the treatment of onychomycosis: a multicenter, double-blind, randomized phase III study. J Dermatol. 2018;45:1151-1159.

- Noguchi H, Matsumoto T, Kimura U, et al. Fosravuconazole to treat severe onychomycosis in the elderly [published online October 25, 2020]. J Dermatol. doi:10.1111/1346-8138.15651

- Andersson NW, Thomsen SF, Andersen JT. Exposure to terbinafine in pregnancy and risk of preterm birth, small for gestational age, low birth weight, and stillbirth: a nationwide cohort study [published online October 22, 2020]. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.10.034

- Moreno-Sabater A, Ouali N, Chasset F, et al. Severe onychomycosis management with oral terbinafine in a kidney transplantation setting: clinical follow-up by image analysis [published online November 27, 2020]. Mycoses. doi:10.1111/myc.13220

- Wang Y, Geizhals S, Lipner SR. Retrospective analysis of laboratory abnormalities in patients prescribed terbinafine for onychomycosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:497-499.

- Wang Y, Lipner SR. Retrospective analysis of laboratory abnormalities in pediatric patients prescribed terbinafine for superficial fungal infections [published online January 27, 2021]. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.01.073

- Wang Y, Lipner SR. Retrospective analysis of laboratory abnormalities in patients with preexisting liver and hematologic diseases prescribed terbinafine for onychomycosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:220-221.

- Lamisil. Prescribing information. Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; 2010. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2010/022071s003lbl.pdf

Crusted Scabies Presenting as White Superficial Onychomycosislike Lesions

To the Editor:

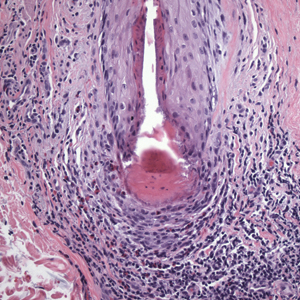

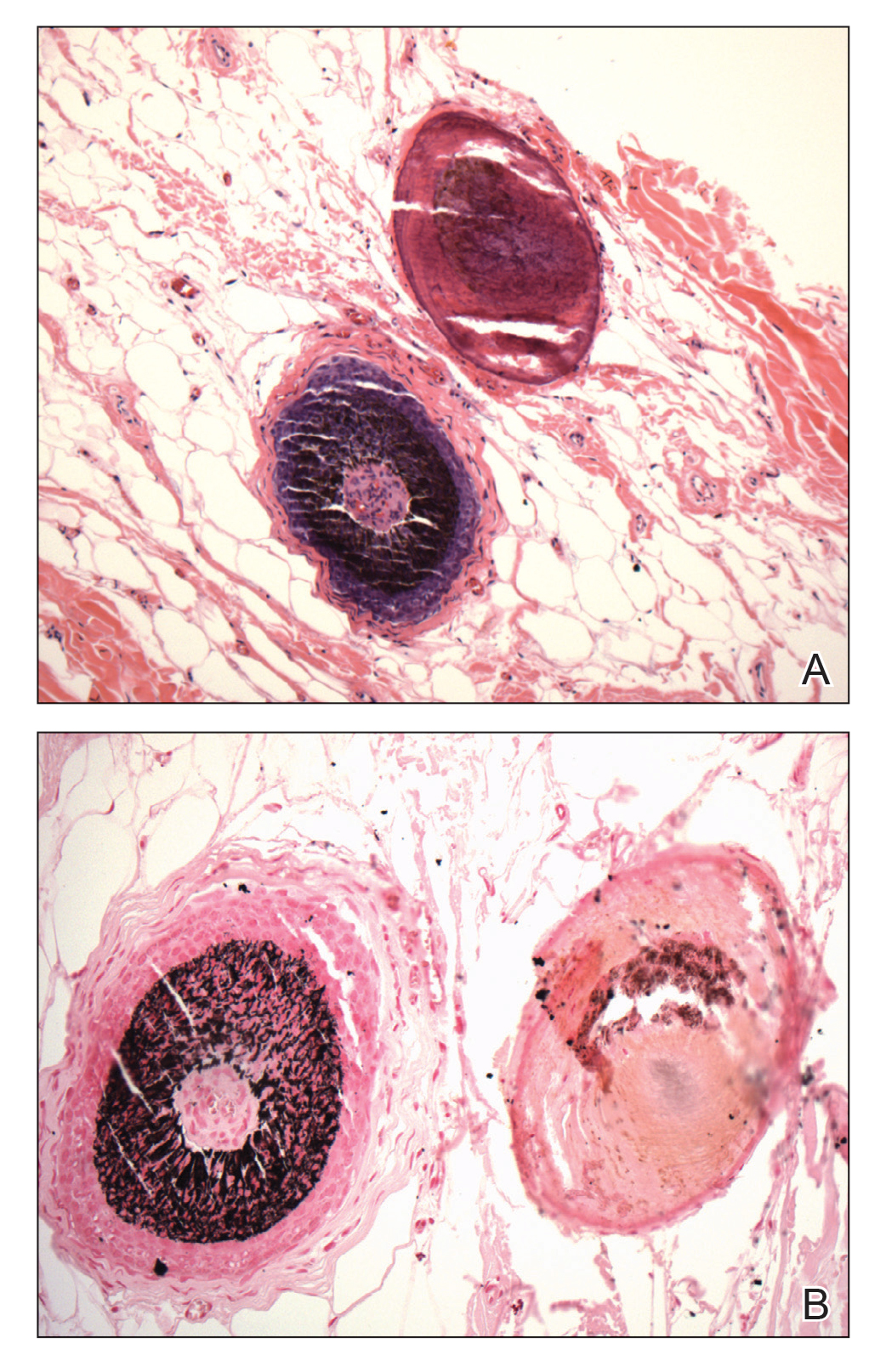

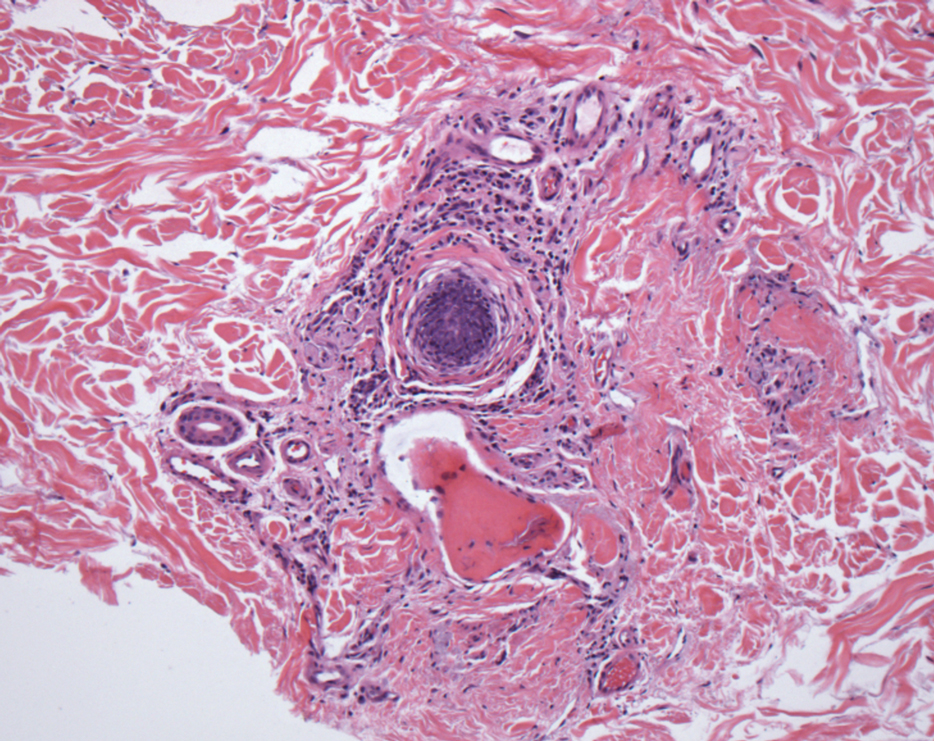

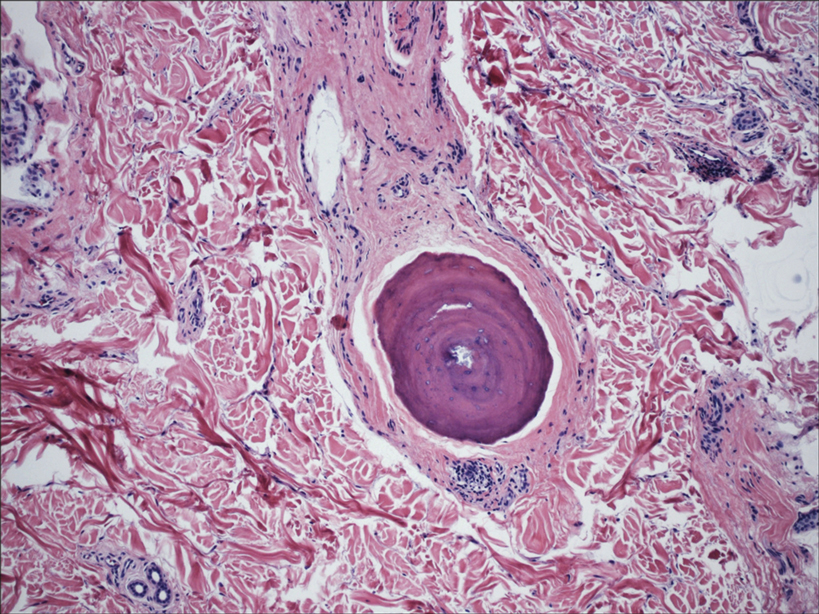

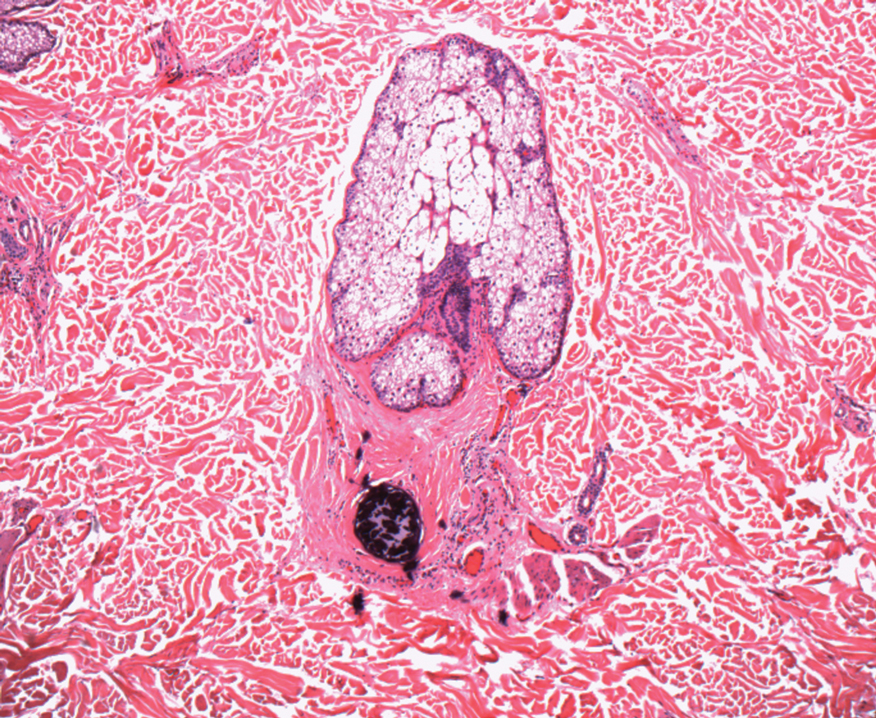

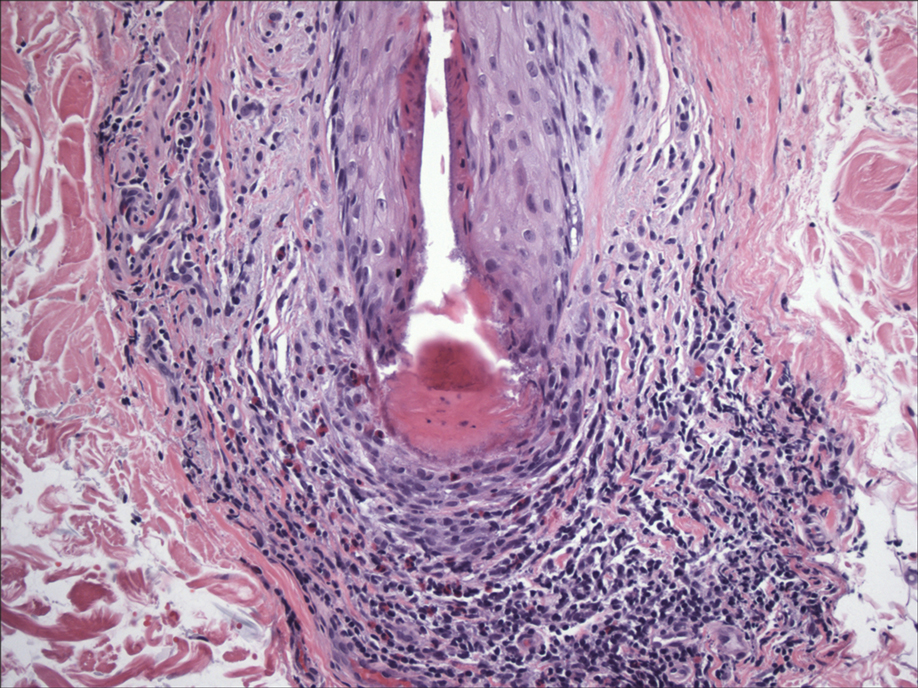

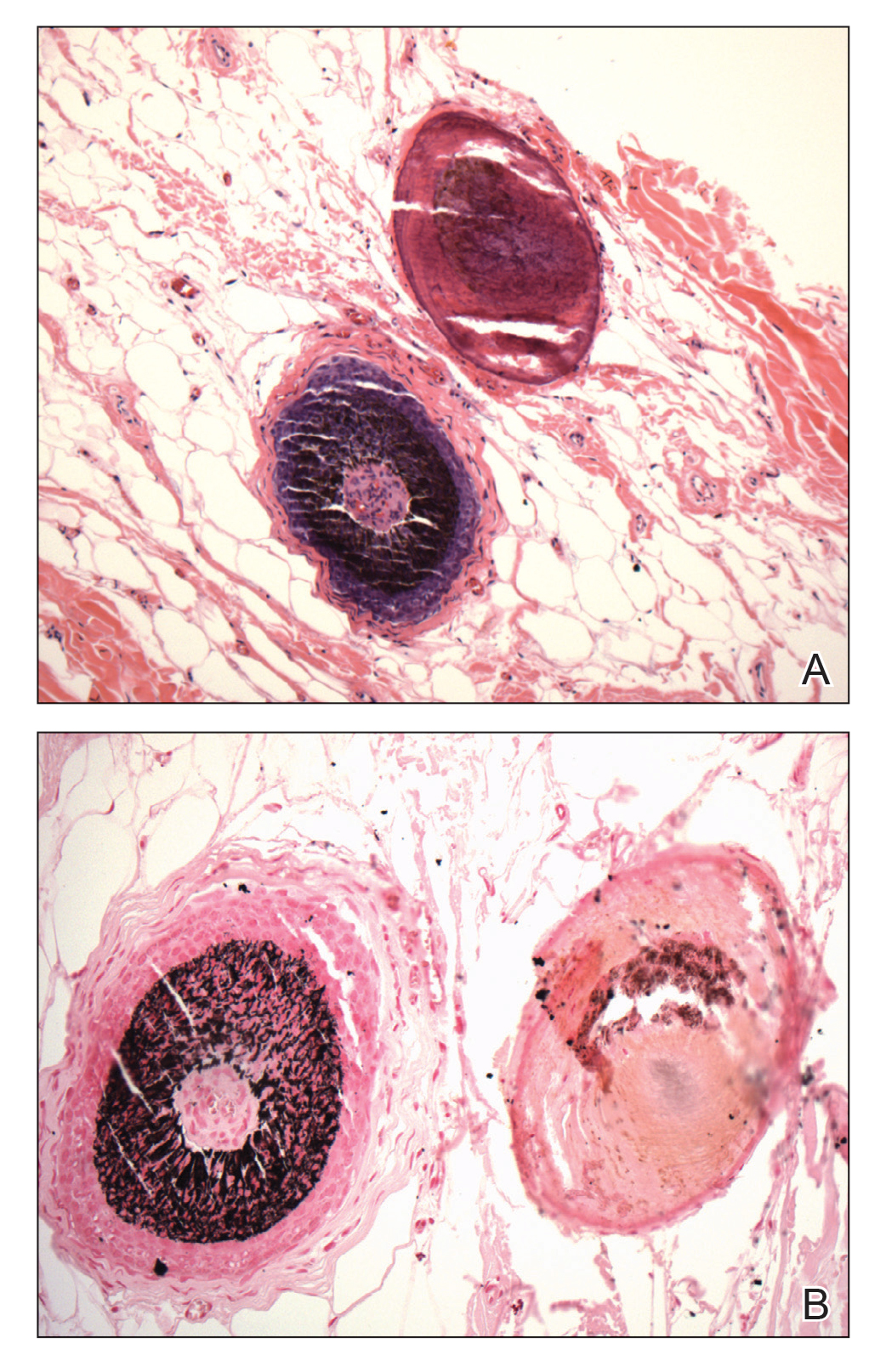

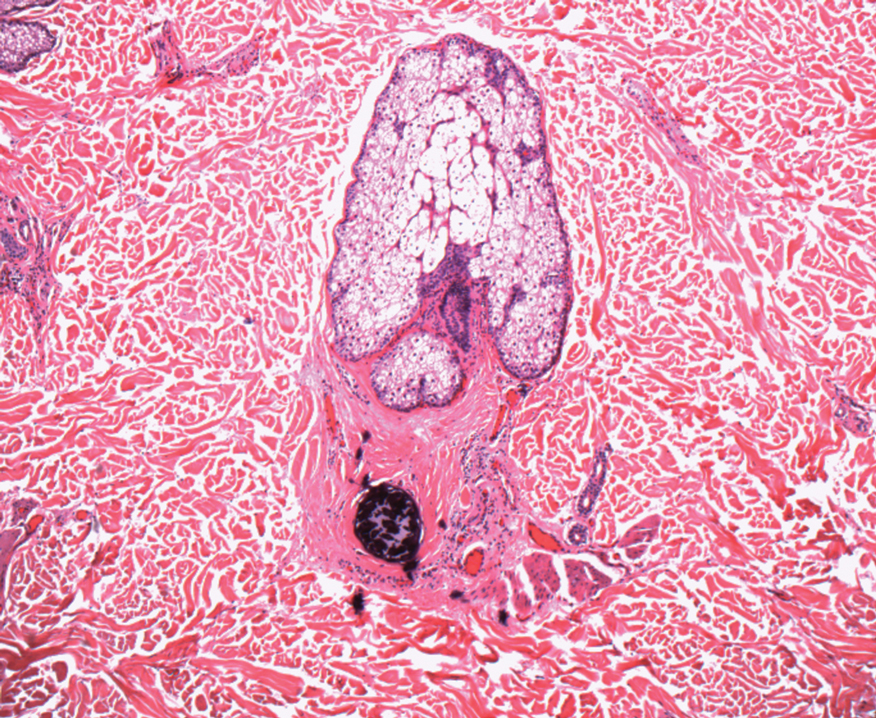

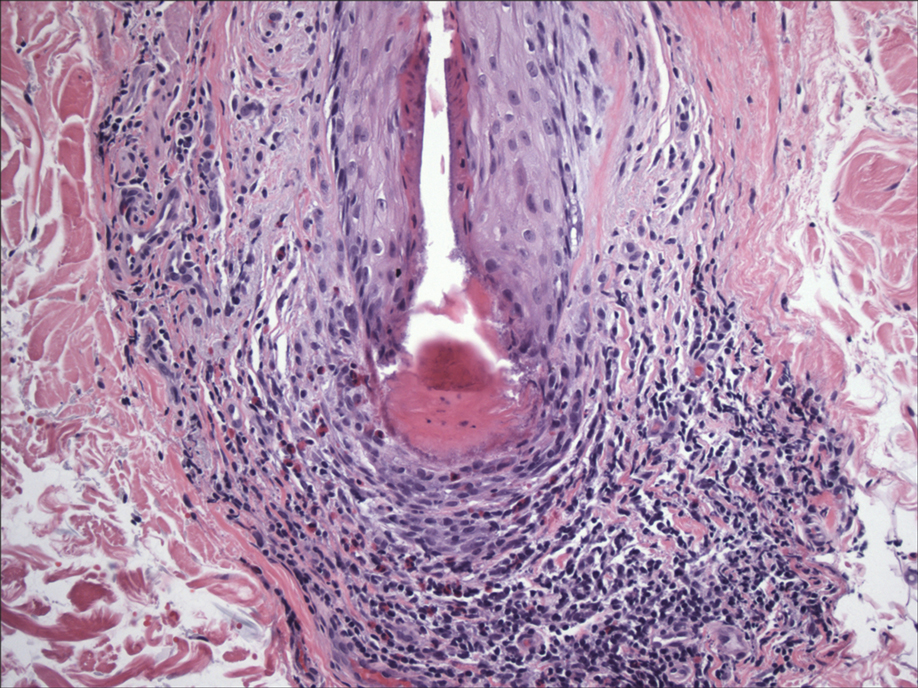

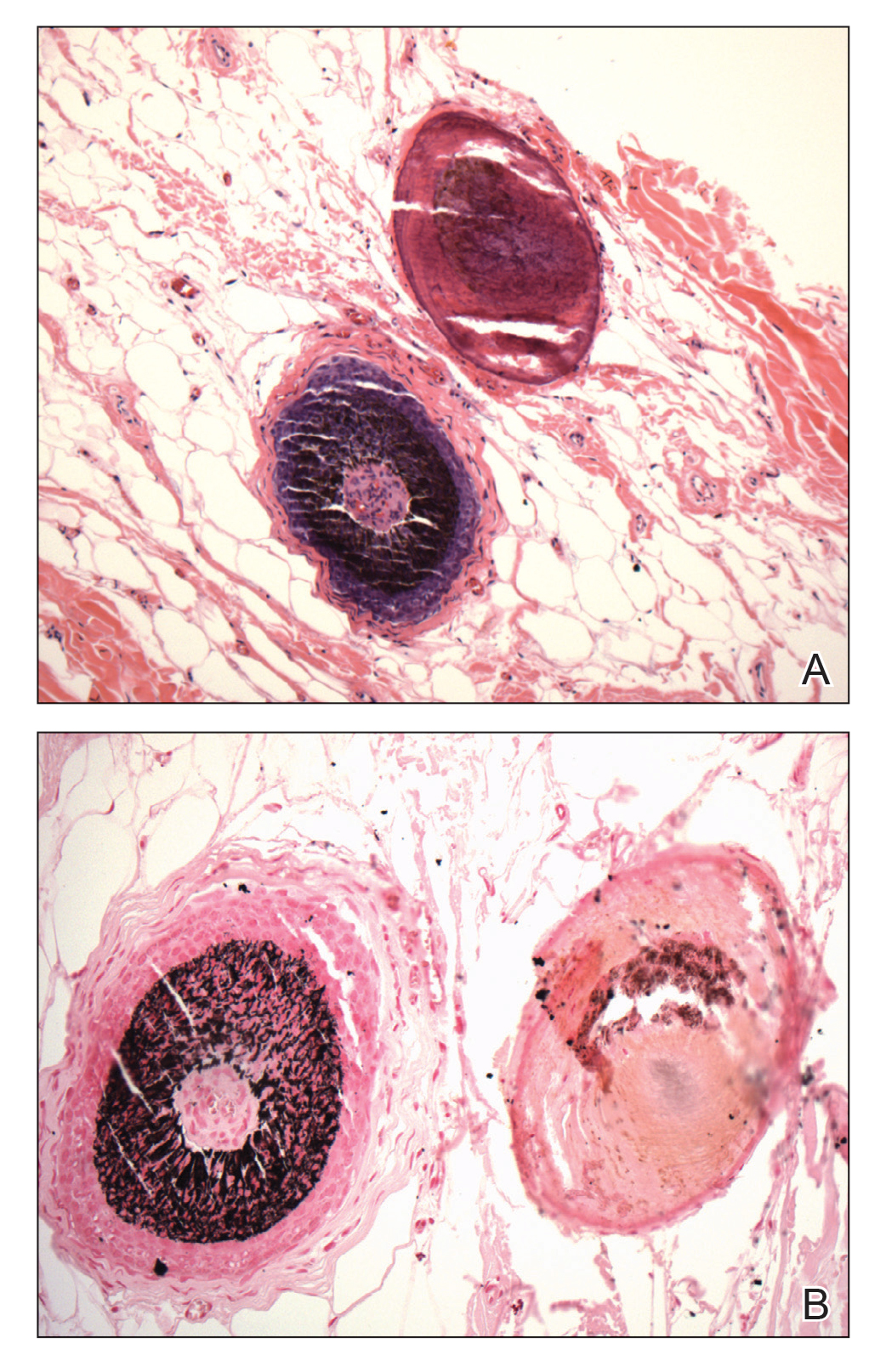

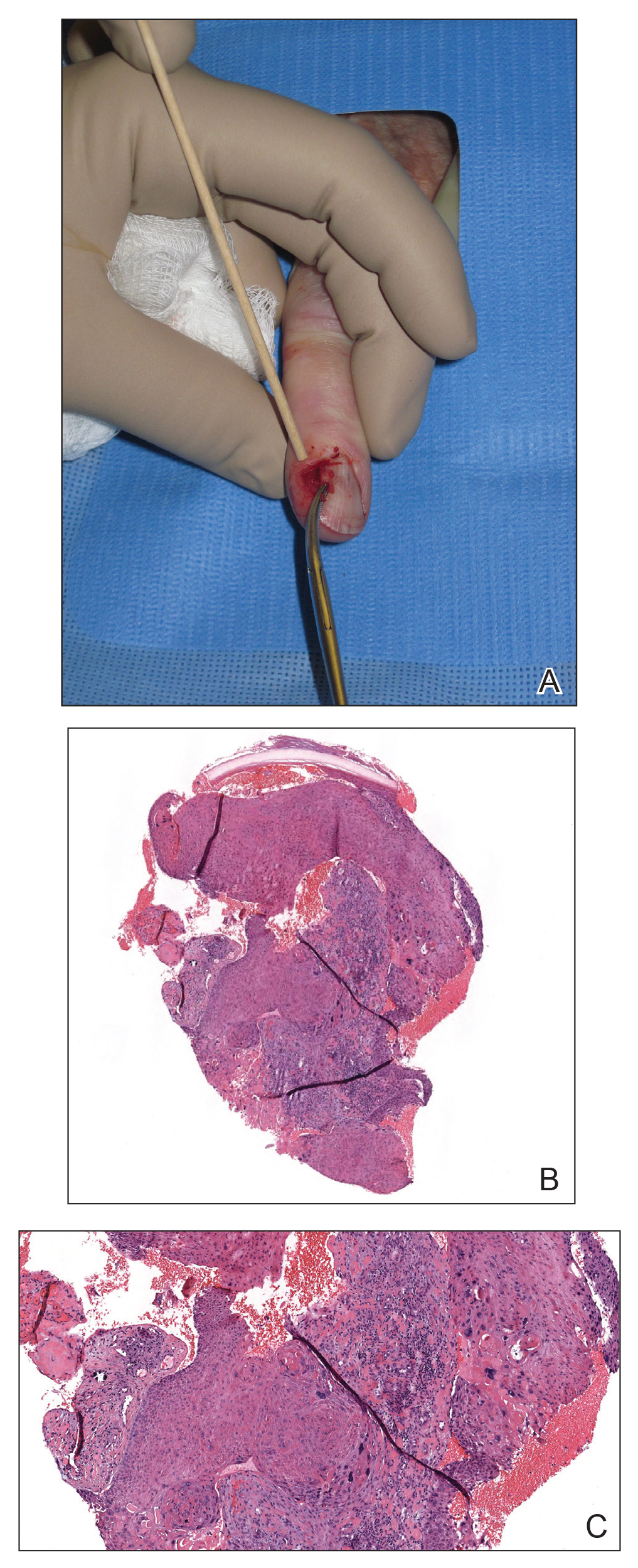

We report the case of an 83-year-old male nursing home resident with a history of end-stage renal disease who presented with multiple small white islands on the surface of the nail plate, similar to those seen in white superficial onychomycosis (Figure 1). Minimal subungual hyperkeratosis of the fingernails also was observed. Three digits were affected with no toenail involvement. Wet mount examination with potassium hydroxide 20% showed a mite (Figure 2A) and multiple eggs (Figure 2B). Treatment consisted of oral ivermectin 3 mg immediately and permethrin solution 5% applied under occlusion to each of the affected nails for 5 consecutive nights, which resulted in complete clearance of the lesion on the nail plate after 2 weeks.

Crusted scabies was first described as Norwegian scabies in 1848 by Danielsen and Boeck,1 and the name was later changed to crusted scabies in 1976 by Parish and Lumholt2 because there was no inherent connection between Norway and Norwegian scabies. It is a skin infestation of Sarcoptes scabiei var hominis and more commonly is seen in immunocompromised individuals such as the elderly and malnourished patients as well as those with diabetes mellitus and alcoholism.3,4 Patients typically present with widespread hyperkeratosis, mostly involving the palms and soles. Subungual hyperkeratosis and nail dystrophy also can be seen when nail involvement is present, and the scalp rarely is involved.5 Unlike common scabies, skin burrows and pruritus may be minimal or absent, thus making the diagnosis of crusted scabies more difficult than normal scabies.6 Diagnosis of crusted scabies is confirmed by direct microscopy, which demonstrates mites, eggs, or feces. Strict isolation of the patient is necessary, as the disease is very contagious. Treatment with oral ivermectin (1–3 doses of 3 mg at 14-day intervals) in combination with topical permethrin is effective.7

We present a case of crusted scabies with nail involvement that presented with white superficial onychomycosislike lesions. The patient’s nails were successfully treated with a combination of oral ivermectin and topical permethrin occlusion of the nails. In cases with subungual hyperkeratosis, nonsurgical nail avulsion with 40% urea cream or ointment has been used to improve the penetration of permethrin. Partial nail avulsion may be necessary if subungual hyperkeratosis or nail dystrophy becomes extreme.8

- Danielsen DG, Boeck W. Treatment of Leprosy or Greek Elephantiasis. JB Balliere; 1848.

- Parish L, Lumholt G. Crusted scabies: alias Norwegian scabies. Int J Dermatol. 1976;15:747-748.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Parasites: scabies. Updated November 2, 2010. Accessed January 17, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/scabies/

- Roberts LJ, Huffam SE, Walton SF, et al. Crusted scabies: clinical and immunological findings in seventy-eight patient and a review of the literature. J Infect. 2005;50:375-381.

- Dourmisher AL, Serafimova DK, Dourmisher LA, et al. Crusted scabies of the scalp in dermatomyositis patients: three cases treated with oral ivermectin. Int J Dermatol. 1998;37:231-234.

- Barnes L, McCallister RE, Lucky AW. Crusted (Norwegian) scabies: occurrence in a child undergoing a bone marrow transplant. Arch Dermatol. 1987;123:95-97.

- Huffam SE, Currie BJ. Ivermectin for Sarcoptes scabiei hyperinfestation. Int J Infect Dis. 1998;2:152-154.

- De Paoli R, Mark SV. Crusted (Norwegian) scabies: treatment of nail involvement. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;17:136-138.

To the Editor:

We report the case of an 83-year-old male nursing home resident with a history of end-stage renal disease who presented with multiple small white islands on the surface of the nail plate, similar to those seen in white superficial onychomycosis (Figure 1). Minimal subungual hyperkeratosis of the fingernails also was observed. Three digits were affected with no toenail involvement. Wet mount examination with potassium hydroxide 20% showed a mite (Figure 2A) and multiple eggs (Figure 2B). Treatment consisted of oral ivermectin 3 mg immediately and permethrin solution 5% applied under occlusion to each of the affected nails for 5 consecutive nights, which resulted in complete clearance of the lesion on the nail plate after 2 weeks.

Crusted scabies was first described as Norwegian scabies in 1848 by Danielsen and Boeck,1 and the name was later changed to crusted scabies in 1976 by Parish and Lumholt2 because there was no inherent connection between Norway and Norwegian scabies. It is a skin infestation of Sarcoptes scabiei var hominis and more commonly is seen in immunocompromised individuals such as the elderly and malnourished patients as well as those with diabetes mellitus and alcoholism.3,4 Patients typically present with widespread hyperkeratosis, mostly involving the palms and soles. Subungual hyperkeratosis and nail dystrophy also can be seen when nail involvement is present, and the scalp rarely is involved.5 Unlike common scabies, skin burrows and pruritus may be minimal or absent, thus making the diagnosis of crusted scabies more difficult than normal scabies.6 Diagnosis of crusted scabies is confirmed by direct microscopy, which demonstrates mites, eggs, or feces. Strict isolation of the patient is necessary, as the disease is very contagious. Treatment with oral ivermectin (1–3 doses of 3 mg at 14-day intervals) in combination with topical permethrin is effective.7

We present a case of crusted scabies with nail involvement that presented with white superficial onychomycosislike lesions. The patient’s nails were successfully treated with a combination of oral ivermectin and topical permethrin occlusion of the nails. In cases with subungual hyperkeratosis, nonsurgical nail avulsion with 40% urea cream or ointment has been used to improve the penetration of permethrin. Partial nail avulsion may be necessary if subungual hyperkeratosis or nail dystrophy becomes extreme.8

To the Editor:

We report the case of an 83-year-old male nursing home resident with a history of end-stage renal disease who presented with multiple small white islands on the surface of the nail plate, similar to those seen in white superficial onychomycosis (Figure 1). Minimal subungual hyperkeratosis of the fingernails also was observed. Three digits were affected with no toenail involvement. Wet mount examination with potassium hydroxide 20% showed a mite (Figure 2A) and multiple eggs (Figure 2B). Treatment consisted of oral ivermectin 3 mg immediately and permethrin solution 5% applied under occlusion to each of the affected nails for 5 consecutive nights, which resulted in complete clearance of the lesion on the nail plate after 2 weeks.

Crusted scabies was first described as Norwegian scabies in 1848 by Danielsen and Boeck,1 and the name was later changed to crusted scabies in 1976 by Parish and Lumholt2 because there was no inherent connection between Norway and Norwegian scabies. It is a skin infestation of Sarcoptes scabiei var hominis and more commonly is seen in immunocompromised individuals such as the elderly and malnourished patients as well as those with diabetes mellitus and alcoholism.3,4 Patients typically present with widespread hyperkeratosis, mostly involving the palms and soles. Subungual hyperkeratosis and nail dystrophy also can be seen when nail involvement is present, and the scalp rarely is involved.5 Unlike common scabies, skin burrows and pruritus may be minimal or absent, thus making the diagnosis of crusted scabies more difficult than normal scabies.6 Diagnosis of crusted scabies is confirmed by direct microscopy, which demonstrates mites, eggs, or feces. Strict isolation of the patient is necessary, as the disease is very contagious. Treatment with oral ivermectin (1–3 doses of 3 mg at 14-day intervals) in combination with topical permethrin is effective.7

We present a case of crusted scabies with nail involvement that presented with white superficial onychomycosislike lesions. The patient’s nails were successfully treated with a combination of oral ivermectin and topical permethrin occlusion of the nails. In cases with subungual hyperkeratosis, nonsurgical nail avulsion with 40% urea cream or ointment has been used to improve the penetration of permethrin. Partial nail avulsion may be necessary if subungual hyperkeratosis or nail dystrophy becomes extreme.8

- Danielsen DG, Boeck W. Treatment of Leprosy or Greek Elephantiasis. JB Balliere; 1848.

- Parish L, Lumholt G. Crusted scabies: alias Norwegian scabies. Int J Dermatol. 1976;15:747-748.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Parasites: scabies. Updated November 2, 2010. Accessed January 17, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/scabies/

- Roberts LJ, Huffam SE, Walton SF, et al. Crusted scabies: clinical and immunological findings in seventy-eight patient and a review of the literature. J Infect. 2005;50:375-381.

- Dourmisher AL, Serafimova DK, Dourmisher LA, et al. Crusted scabies of the scalp in dermatomyositis patients: three cases treated with oral ivermectin. Int J Dermatol. 1998;37:231-234.

- Barnes L, McCallister RE, Lucky AW. Crusted (Norwegian) scabies: occurrence in a child undergoing a bone marrow transplant. Arch Dermatol. 1987;123:95-97.

- Huffam SE, Currie BJ. Ivermectin for Sarcoptes scabiei hyperinfestation. Int J Infect Dis. 1998;2:152-154.

- De Paoli R, Mark SV. Crusted (Norwegian) scabies: treatment of nail involvement. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;17:136-138.

- Danielsen DG, Boeck W. Treatment of Leprosy or Greek Elephantiasis. JB Balliere; 1848.

- Parish L, Lumholt G. Crusted scabies: alias Norwegian scabies. Int J Dermatol. 1976;15:747-748.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Parasites: scabies. Updated November 2, 2010. Accessed January 17, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/scabies/

- Roberts LJ, Huffam SE, Walton SF, et al. Crusted scabies: clinical and immunological findings in seventy-eight patient and a review of the literature. J Infect. 2005;50:375-381.

- Dourmisher AL, Serafimova DK, Dourmisher LA, et al. Crusted scabies of the scalp in dermatomyositis patients: three cases treated with oral ivermectin. Int J Dermatol. 1998;37:231-234.

- Barnes L, McCallister RE, Lucky AW. Crusted (Norwegian) scabies: occurrence in a child undergoing a bone marrow transplant. Arch Dermatol. 1987;123:95-97.

- Huffam SE, Currie BJ. Ivermectin for Sarcoptes scabiei hyperinfestation. Int J Infect Dis. 1998;2:152-154.

- De Paoli R, Mark SV. Crusted (Norwegian) scabies: treatment of nail involvement. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;17:136-138.

Practice Points

- Crusted scabies is asymptomatic; therefore, any white lesion at the surface of the nail should be scraped and examined with potassium hydroxide.

- Immunosuppressed patients are at risk for infection.

Unilateral Nail Clubbing in a Hemiparetic Patient

To the Editor:

Few cases of unilateral nail changes affecting only the hemiplegic side after a stroke have been reported. We present a case of acquired unilateral nail clubbing and longitudinal melanonychia in a hemiparetic patient.

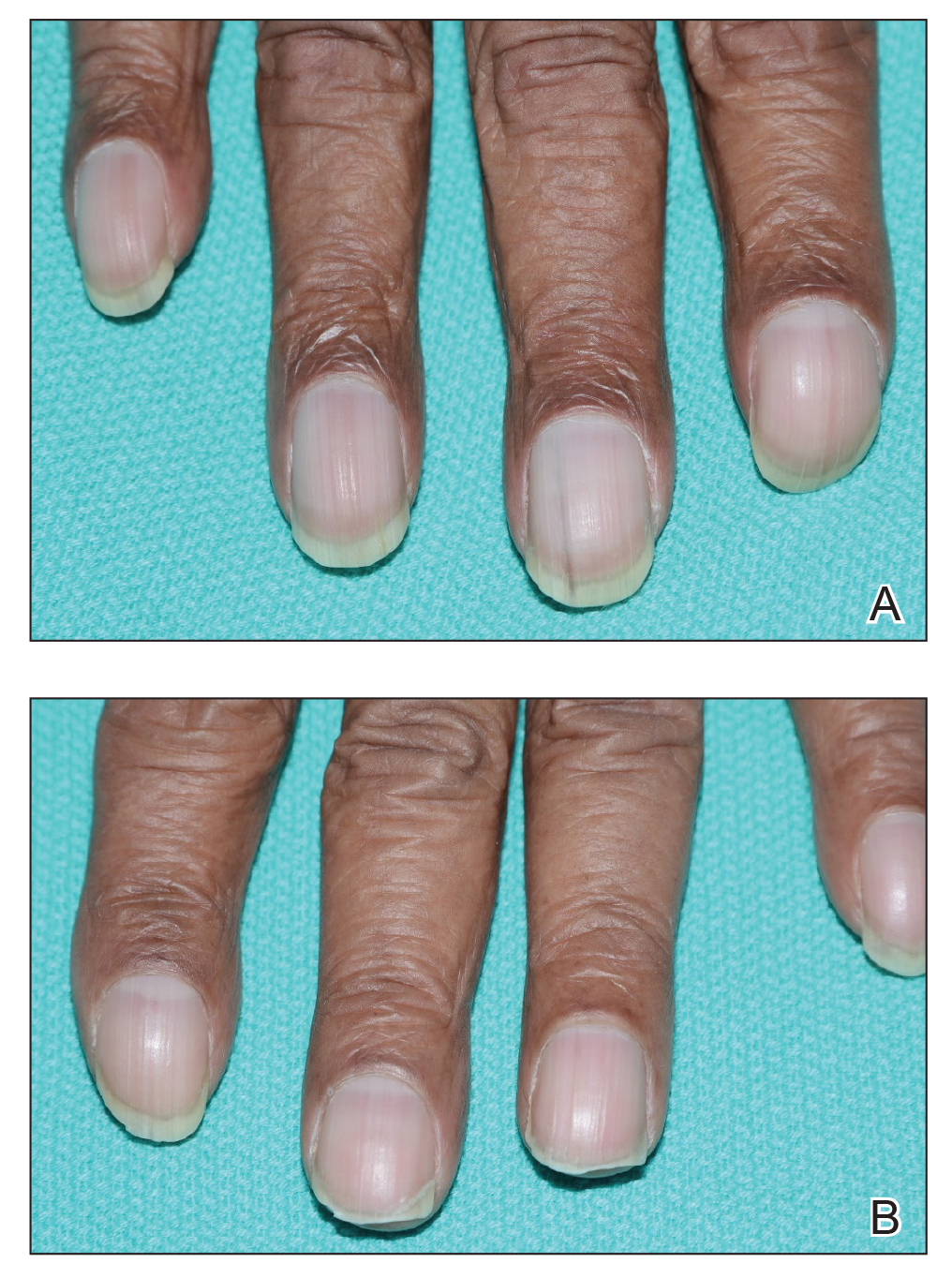

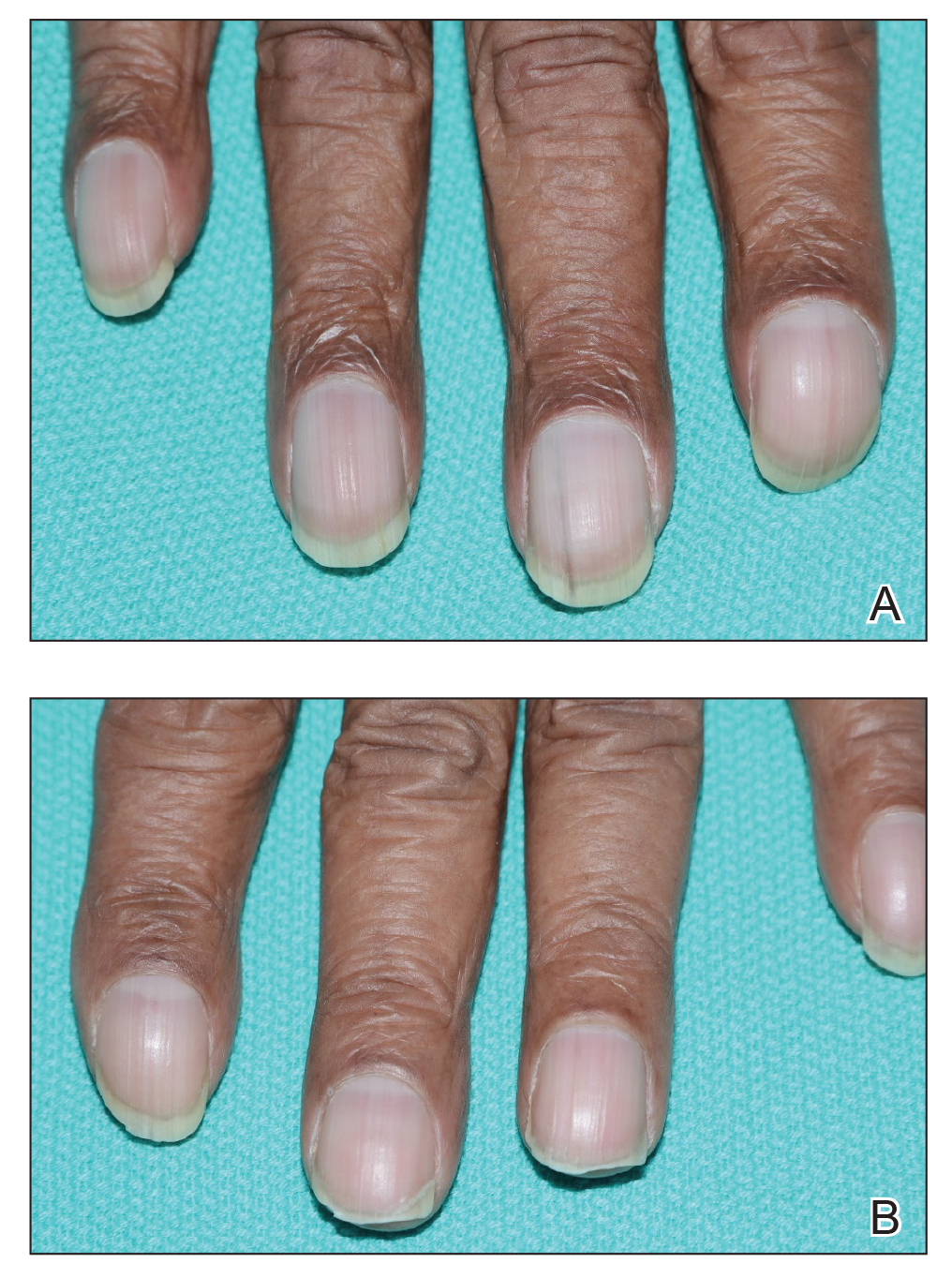

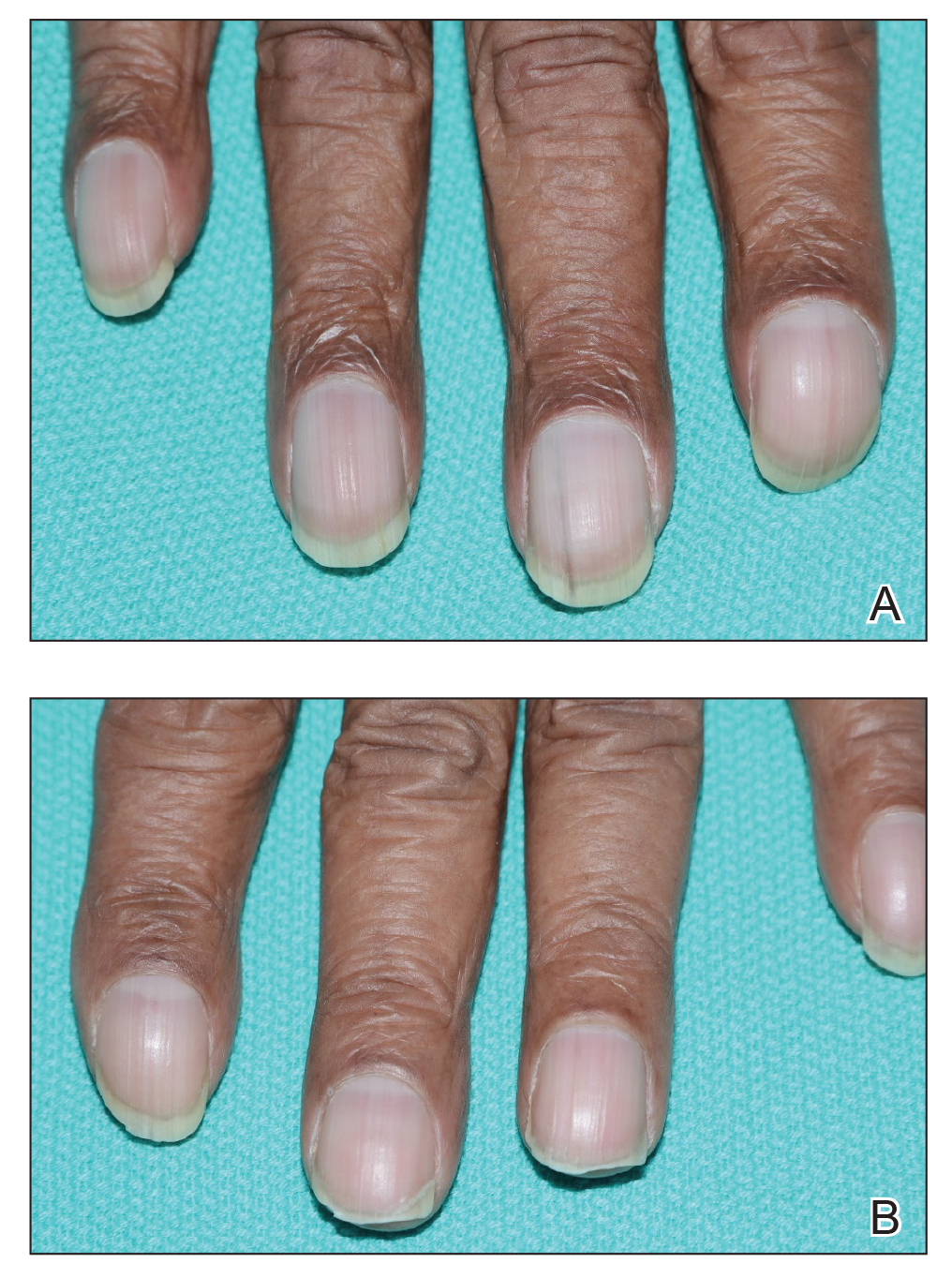

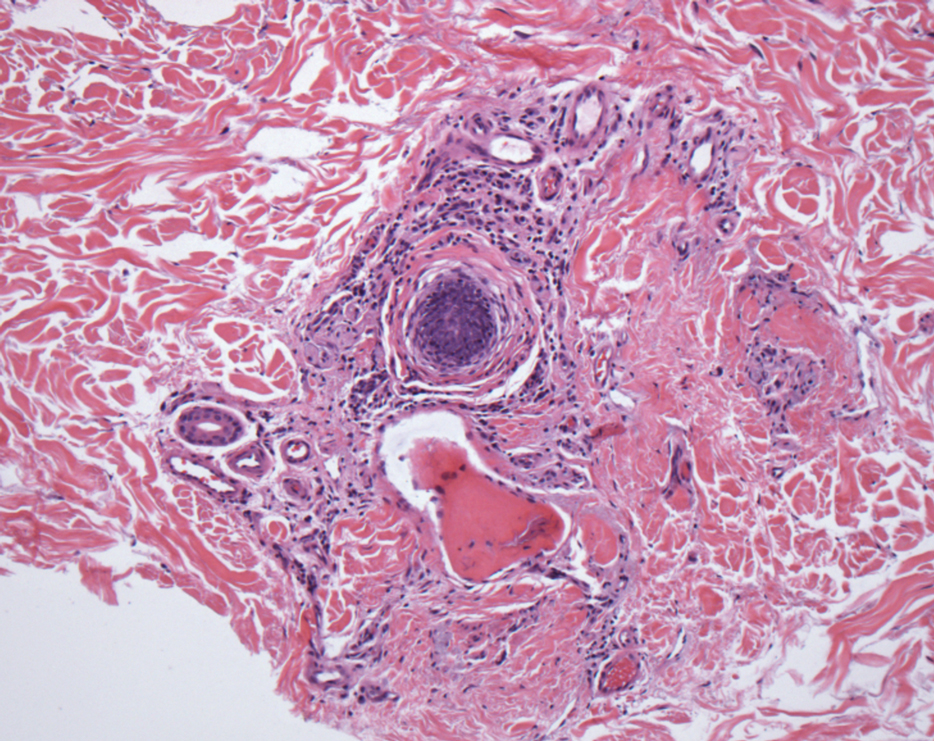

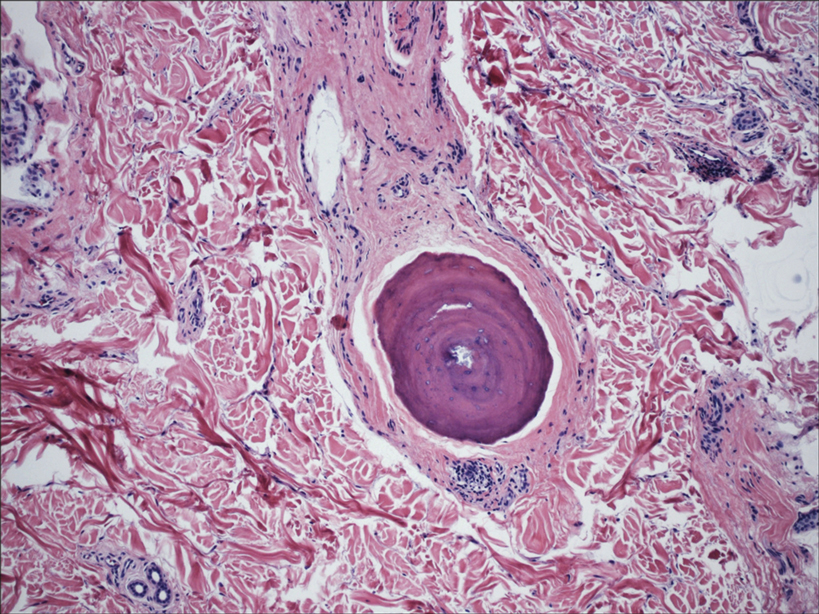

A 79-year-old Black man with a history of smoking and stroke presented with concerns of discoloration of the fingernails. His medical history was notable for congestive heart failure; hypertension; diabetes mellitus; hypercholesterolemia; and stroke 11 years prior, which resulted in right-sided hemiparesis. Physical examination revealed longitudinal, even hyperpigmentation of several fingernails on the hands, in addition to whitening of the nail beds, sparing the tips (Terry nails). Clubbing was noted only on the fingernails of the right hand; the fingernails of the left hand exhibited normal curvature (Figure). Pulse oximetry was conducted and demonstrated the following readings: unaffected left index finger, 98%; unaffected left middle finger, 100%; affected right index finger, 95%; and affected right middle finger, 97%. The patient was diagnosed with benign longitudinal melanonychia secondary to ethnic variation, Terry nails without underlying anemia or hypoalbuminemic state, and unilateral right-sided clubbing of the fingernails in the setting of right-sided hemiparesis.

Prior reports have documented the occurrence of nail pathologies after stroke and affecting hemiplegic limbs. Unilateral digital nail clubbing following a stroke was first reported in 19751; 2 reports concluded clubbing developed in all digits affected by the stroke, and the severity of clubbing was associated with the duration of the stroke.1,2 One study noted longitudinal reddish striation, Neapolitan nails, and unilateral clubbing more commonly in hemiplegic patients.3 Longitudinal reddish striation was the most frequent condition observed in this population, always affecting the entire thumbnail of the hemiplegic limb.3 A similar report observed clubbing only on the fingernails of the hemiplegic side.4

Digital clubbing describes an exaggerated nail curvature and bulbous overgrowth of the fingertips due to an expansion of connective tissue between the nail plate and the nail bed.3,5 Clubbed fingers are found in various chronic conditions affecting the heart, lungs, and liver. Although the pathogenesis of clubbing remains unknown, many hypothesize that it is a state of proliferation in response to digital hypoxia.5 Fittingly, our patient exhibited a relative hypoperfusion of the clubbed fingers in comparison to the unaffected side.

This case provides additional support for the phenomenon of unilateral nail changes limited to hemiplegic or hemiparetic limbs. The unique presentation of longitudinal melanonychia, clubbing, and a lowered pulse oximetry reading only affecting the hemiparetic side demonstrates the possible connection between hypoxia and nail clubbing in this patient population.

- Denham M, Hodkinson H, Wright B. Unilateral clubbing in hemiplegia. Gerontology Clin (Basel). 1975;17:7-12.

- Alveraz A, McNair D, Wildman J, et al. Unilateral clubbing of the fingernails in patients with hemiplegia. Gerontology Clin (Basel). 1975;17:1-6.

- Siragusa M, Schepis C, Cosentino F, et al. Nail pathology in patients with hemiplegia. Br J Dermatol. 2001;144:557-560.

- Gül Ü, Çakmak S, Özel S, et al. Skin disorders in patients with hemiplegia and paraplegia. J Rehabil Med. 2009;41:681-683.

- Sarkar M, Mahesh D, Madabhavi I. Digital clubbing. Lung India. 2012;29:354-362.

To the Editor:

Few cases of unilateral nail changes affecting only the hemiplegic side after a stroke have been reported. We present a case of acquired unilateral nail clubbing and longitudinal melanonychia in a hemiparetic patient.

A 79-year-old Black man with a history of smoking and stroke presented with concerns of discoloration of the fingernails. His medical history was notable for congestive heart failure; hypertension; diabetes mellitus; hypercholesterolemia; and stroke 11 years prior, which resulted in right-sided hemiparesis. Physical examination revealed longitudinal, even hyperpigmentation of several fingernails on the hands, in addition to whitening of the nail beds, sparing the tips (Terry nails). Clubbing was noted only on the fingernails of the right hand; the fingernails of the left hand exhibited normal curvature (Figure). Pulse oximetry was conducted and demonstrated the following readings: unaffected left index finger, 98%; unaffected left middle finger, 100%; affected right index finger, 95%; and affected right middle finger, 97%. The patient was diagnosed with benign longitudinal melanonychia secondary to ethnic variation, Terry nails without underlying anemia or hypoalbuminemic state, and unilateral right-sided clubbing of the fingernails in the setting of right-sided hemiparesis.

Prior reports have documented the occurrence of nail pathologies after stroke and affecting hemiplegic limbs. Unilateral digital nail clubbing following a stroke was first reported in 19751; 2 reports concluded clubbing developed in all digits affected by the stroke, and the severity of clubbing was associated with the duration of the stroke.1,2 One study noted longitudinal reddish striation, Neapolitan nails, and unilateral clubbing more commonly in hemiplegic patients.3 Longitudinal reddish striation was the most frequent condition observed in this population, always affecting the entire thumbnail of the hemiplegic limb.3 A similar report observed clubbing only on the fingernails of the hemiplegic side.4

Digital clubbing describes an exaggerated nail curvature and bulbous overgrowth of the fingertips due to an expansion of connective tissue between the nail plate and the nail bed.3,5 Clubbed fingers are found in various chronic conditions affecting the heart, lungs, and liver. Although the pathogenesis of clubbing remains unknown, many hypothesize that it is a state of proliferation in response to digital hypoxia.5 Fittingly, our patient exhibited a relative hypoperfusion of the clubbed fingers in comparison to the unaffected side.

This case provides additional support for the phenomenon of unilateral nail changes limited to hemiplegic or hemiparetic limbs. The unique presentation of longitudinal melanonychia, clubbing, and a lowered pulse oximetry reading only affecting the hemiparetic side demonstrates the possible connection between hypoxia and nail clubbing in this patient population.

To the Editor:

Few cases of unilateral nail changes affecting only the hemiplegic side after a stroke have been reported. We present a case of acquired unilateral nail clubbing and longitudinal melanonychia in a hemiparetic patient.

A 79-year-old Black man with a history of smoking and stroke presented with concerns of discoloration of the fingernails. His medical history was notable for congestive heart failure; hypertension; diabetes mellitus; hypercholesterolemia; and stroke 11 years prior, which resulted in right-sided hemiparesis. Physical examination revealed longitudinal, even hyperpigmentation of several fingernails on the hands, in addition to whitening of the nail beds, sparing the tips (Terry nails). Clubbing was noted only on the fingernails of the right hand; the fingernails of the left hand exhibited normal curvature (Figure). Pulse oximetry was conducted and demonstrated the following readings: unaffected left index finger, 98%; unaffected left middle finger, 100%; affected right index finger, 95%; and affected right middle finger, 97%. The patient was diagnosed with benign longitudinal melanonychia secondary to ethnic variation, Terry nails without underlying anemia or hypoalbuminemic state, and unilateral right-sided clubbing of the fingernails in the setting of right-sided hemiparesis.

Prior reports have documented the occurrence of nail pathologies after stroke and affecting hemiplegic limbs. Unilateral digital nail clubbing following a stroke was first reported in 19751; 2 reports concluded clubbing developed in all digits affected by the stroke, and the severity of clubbing was associated with the duration of the stroke.1,2 One study noted longitudinal reddish striation, Neapolitan nails, and unilateral clubbing more commonly in hemiplegic patients.3 Longitudinal reddish striation was the most frequent condition observed in this population, always affecting the entire thumbnail of the hemiplegic limb.3 A similar report observed clubbing only on the fingernails of the hemiplegic side.4

Digital clubbing describes an exaggerated nail curvature and bulbous overgrowth of the fingertips due to an expansion of connective tissue between the nail plate and the nail bed.3,5 Clubbed fingers are found in various chronic conditions affecting the heart, lungs, and liver. Although the pathogenesis of clubbing remains unknown, many hypothesize that it is a state of proliferation in response to digital hypoxia.5 Fittingly, our patient exhibited a relative hypoperfusion of the clubbed fingers in comparison to the unaffected side.

This case provides additional support for the phenomenon of unilateral nail changes limited to hemiplegic or hemiparetic limbs. The unique presentation of longitudinal melanonychia, clubbing, and a lowered pulse oximetry reading only affecting the hemiparetic side demonstrates the possible connection between hypoxia and nail clubbing in this patient population.

- Denham M, Hodkinson H, Wright B. Unilateral clubbing in hemiplegia. Gerontology Clin (Basel). 1975;17:7-12.

- Alveraz A, McNair D, Wildman J, et al. Unilateral clubbing of the fingernails in patients with hemiplegia. Gerontology Clin (Basel). 1975;17:1-6.

- Siragusa M, Schepis C, Cosentino F, et al. Nail pathology in patients with hemiplegia. Br J Dermatol. 2001;144:557-560.

- Gül Ü, Çakmak S, Özel S, et al. Skin disorders in patients with hemiplegia and paraplegia. J Rehabil Med. 2009;41:681-683.

- Sarkar M, Mahesh D, Madabhavi I. Digital clubbing. Lung India. 2012;29:354-362.

- Denham M, Hodkinson H, Wright B. Unilateral clubbing in hemiplegia. Gerontology Clin (Basel). 1975;17:7-12.

- Alveraz A, McNair D, Wildman J, et al. Unilateral clubbing of the fingernails in patients with hemiplegia. Gerontology Clin (Basel). 1975;17:1-6.

- Siragusa M, Schepis C, Cosentino F, et al. Nail pathology in patients with hemiplegia. Br J Dermatol. 2001;144:557-560.

- Gül Ü, Çakmak S, Özel S, et al. Skin disorders in patients with hemiplegia and paraplegia. J Rehabil Med. 2009;41:681-683.

- Sarkar M, Mahesh D, Madabhavi I. Digital clubbing. Lung India. 2012;29:354-362.

Practice Points

- Unilateral nail changes can be limited to hemiplegic or hemiparetic limbs.

- Lowered pulse oximetry reading only affecting the hemiparetic side demonstrates the possible connection between hypoxia and nail clubbing in this patient population.

Increased risk of meningioma with cyproterone acetate use

.

Cyproterone acetate is a synthetic progestogen and potent antiandrogen that has been used in the treatment of hirsutism, alopecia, early puberty, amenorrhea, acne, and prostate cancer, and has also been combined with an estrogen in hormone replacement therapy.

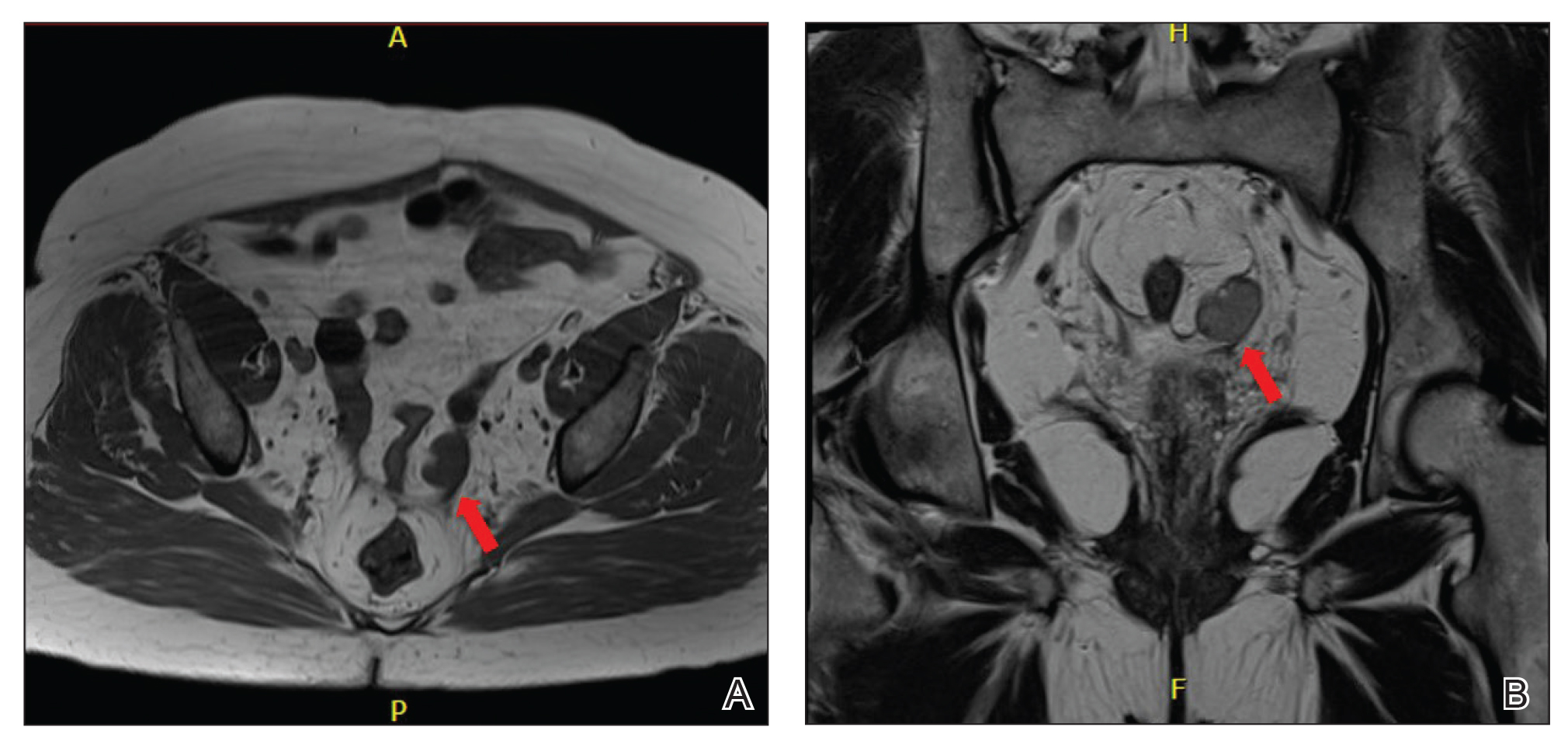

The new findings were published online in the BMJ. The primary analysis showed that, among women using cyproterone acetate, the rate of meningiomas was 23.8 per 100,000 person years vs. 4.5 per 100,000 in the control group. After adjusting for confounders, cyproterone acetate was associated with a sevenfold increased risk of meningioma.

These were young women – the mean age of participants was 29.4 years, and more than 40% of the cohort were younger than 25 years. The initial prescriber was a gynecologist for more than half (56.7%) of the participants, and 31.6% of prescriptions could correspond to the treatment of acne without hirsutism; 13.1% of prescriptions were compatible with management of hirsutism.

“Our study provides confirmation of the risk but also the measurement of the dose-effect relationship, the decrease in the risk after stopping use, and the preferential anatomical localization of meningiomas,” said lead author Alain Weill, MD, EPI-PHARE Scientific Interest Group, Saint-Denis, France.

“A large proportion of meningiomas involve the skull base, which is of considerable importance because skull base meningioma surgery is one of the most challenging forms of surgery and is associated with a much higher risk than surgery for convexity meningiomas,” he said in an interview.

Cyproterone acetate products have been available in Europe since the 1970s under various trade names and dose strengths (1, 2, 10, 50, and 100 mg), and marketed for various indications. These products are also marketed in many other industrialized nations, but not in the United States or Japan.

The link between cyproterone acetate and an increased risk of meningioma has been known for the past decade, and information on the risk of meningioma is already included in the prescribing information for cyproterone products.

Last year, the European Medicines Agency strengthened the warnings that were already in place and recommended that cyproterone products with daily doses of 10 mg or more be restricted because of the risk of developing meningioma.

“The recommendation from the EMA is a direct consequence of our study, that was sent to the EMA in summary form in 2018 and followed up with a very detailed with a report in summer 2019,” said Dr. Weill. “In light of this report, the European Medicines Agency recommended in February 2020 that drugs containing 10 mg or more of cyproterone acetate should only be used for hirsutism, androgenic alopecia, and acne and seborrhea once other treatment options have failed, including treatment with lower doses.”

Dr. Weill pointed out that two other epidemiologic studies have assessed the link between cyproterone acetate use and meningioma and showed an association. “Those studies and our own study are complementary and provide a coherent set of epidemiological evidence,” he said in the interview. “They show a documented risk for high-dose cyproterone acetate in men, women, and transgender people, and the absence of any observed risk for low-dose cyproterone acetate use in women.”

Strong dose-effect relationship

For their study, Dr. Weill and colleagues used data from the French administrative health care database. Between 2007 and 2014, 253,777 girls and women aged 7-70 years had begun using cyproterone acetate during that time period.

All participants had received at least one prescription for high-dose cyproterone acetate and did not have a history of meningioma, benign brain tumors, or long-term disease. They were considered to be exposed if they had received a cumulative dose of at least 3 g during the first 6 months (139,222 participants) and very slightly exposed (control group) when they had received a cumulative dose of less than 3 g (114,555 participants).

Overall, a total of 69 meningiomas were diagnosed in the exposed group (during 289,544 person years of follow-up) and 20 meningiomas in the control group (during 439,949 person years of follow-up). All were treated by surgery or radiotherapy.

When the analysis was done according to the cumulative dose, it showed a dose-effect relation, with a higher risk associated with a higher cumulative dose. The hazard ratio was not significant for exposure to less than 12 g of cyproterone acetate, but it jumped rapidly jumped as the dose climbed: The hazard ratio was 11.3 for 36-60 g and was 21.7 for 60 g or higher.

In a secondary analysis, the authors looked at the cohort who were already using cyproterone acetate in 2006 (n = 123,997). Women with long-term exposure were also taking estrogens more often (55.5% vs. 31.9%), and the incidence of meningioma in the exposed group was 141 per 100,000 person years, which was a risk greater than 20-fold (adjusted hazard ratio 21.2.) They also observed a strong dose-effect relationship, with adjusted hazard ratio ranging from 5.0 to 31.1.

However, the risk of meningioma decreased noticeably after treatment was stopped. At 1 year after discontinuing treatment, the risk of meningioma in the exposed group was 1.8-fold higher (1.0 to 3.2) than in the control group.

Dr. Weill noted the clinical implications of these findings: clinicians need to inform patients who have used high-dose cyproterone acetate for at least 3-5 years about the increased risk of intracranial meningioma, he said.

“The indication of cyproterone acetate should be clearly defined and the lowest possible daily dose used,” he said. “In the context of prolonged use of high-dose cyproterone acetate, magnetic resonance imaging screening for meningioma should be considered.”

“In patients with a documented meningioma, cyproterone acetate should be discontinued because the meningioma might regress in response to treatment discontinuation and invasive treatment could be avoided,” Dr. Weill added.

Use only when necessary

Weighing in on the research, Adilia Hormigo, MD, PhD, director of neuro-oncology at The Tisch Cancer Institute at Mount Sinai Health System in New York, noted that, “it is well known that there are sex differences in the incidence of meningiomas, as they are more frequent in women than men, and there is an association between breast cancer and the occurrence of meningiomas.”

Progesterone and androgen receptors have been found in meningiomas, she said in an interview, and there is no consensus regarding estrogen receptors. “In addition, hormonal therapy to inhibit estrogen or progesterone receptors has not produced any decrease in meningiomas’ growth,” she said.

The current study revealed an association between prolonged use of cyproterone acetate with an increased incidence of meningiomas, and the sphenoid-orbital meningioma location was specific for the drug use. “It is unclear from the study if all the meningiomas were benign,” she said. “Even if they are benign, they can cause severe morbidity, including seizures.”

Dr. Hormigo recommended that an MRI be performed on any patient who is taking a long course of cyproterone acetate in order to evaluate the development of meningiomas or meningioma progression. “And the drug should only be used when necessary,” she added.

This research was funded by the French National Health Insurance Fund and the Health Product Epidemiology Scientific Interest Group. Dr. Weill is an employee of the French National Health Insurance Fund, as are several other coauthors. The other authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Hormigo has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

.

Cyproterone acetate is a synthetic progestogen and potent antiandrogen that has been used in the treatment of hirsutism, alopecia, early puberty, amenorrhea, acne, and prostate cancer, and has also been combined with an estrogen in hormone replacement therapy.

The new findings were published online in the BMJ. The primary analysis showed that, among women using cyproterone acetate, the rate of meningiomas was 23.8 per 100,000 person years vs. 4.5 per 100,000 in the control group. After adjusting for confounders, cyproterone acetate was associated with a sevenfold increased risk of meningioma.

These were young women – the mean age of participants was 29.4 years, and more than 40% of the cohort were younger than 25 years. The initial prescriber was a gynecologist for more than half (56.7%) of the participants, and 31.6% of prescriptions could correspond to the treatment of acne without hirsutism; 13.1% of prescriptions were compatible with management of hirsutism.

“Our study provides confirmation of the risk but also the measurement of the dose-effect relationship, the decrease in the risk after stopping use, and the preferential anatomical localization of meningiomas,” said lead author Alain Weill, MD, EPI-PHARE Scientific Interest Group, Saint-Denis, France.

“A large proportion of meningiomas involve the skull base, which is of considerable importance because skull base meningioma surgery is one of the most challenging forms of surgery and is associated with a much higher risk than surgery for convexity meningiomas,” he said in an interview.

Cyproterone acetate products have been available in Europe since the 1970s under various trade names and dose strengths (1, 2, 10, 50, and 100 mg), and marketed for various indications. These products are also marketed in many other industrialized nations, but not in the United States or Japan.

The link between cyproterone acetate and an increased risk of meningioma has been known for the past decade, and information on the risk of meningioma is already included in the prescribing information for cyproterone products.

Last year, the European Medicines Agency strengthened the warnings that were already in place and recommended that cyproterone products with daily doses of 10 mg or more be restricted because of the risk of developing meningioma.

“The recommendation from the EMA is a direct consequence of our study, that was sent to the EMA in summary form in 2018 and followed up with a very detailed with a report in summer 2019,” said Dr. Weill. “In light of this report, the European Medicines Agency recommended in February 2020 that drugs containing 10 mg or more of cyproterone acetate should only be used for hirsutism, androgenic alopecia, and acne and seborrhea once other treatment options have failed, including treatment with lower doses.”

Dr. Weill pointed out that two other epidemiologic studies have assessed the link between cyproterone acetate use and meningioma and showed an association. “Those studies and our own study are complementary and provide a coherent set of epidemiological evidence,” he said in the interview. “They show a documented risk for high-dose cyproterone acetate in men, women, and transgender people, and the absence of any observed risk for low-dose cyproterone acetate use in women.”

Strong dose-effect relationship

For their study, Dr. Weill and colleagues used data from the French administrative health care database. Between 2007 and 2014, 253,777 girls and women aged 7-70 years had begun using cyproterone acetate during that time period.

All participants had received at least one prescription for high-dose cyproterone acetate and did not have a history of meningioma, benign brain tumors, or long-term disease. They were considered to be exposed if they had received a cumulative dose of at least 3 g during the first 6 months (139,222 participants) and very slightly exposed (control group) when they had received a cumulative dose of less than 3 g (114,555 participants).

Overall, a total of 69 meningiomas were diagnosed in the exposed group (during 289,544 person years of follow-up) and 20 meningiomas in the control group (during 439,949 person years of follow-up). All were treated by surgery or radiotherapy.

When the analysis was done according to the cumulative dose, it showed a dose-effect relation, with a higher risk associated with a higher cumulative dose. The hazard ratio was not significant for exposure to less than 12 g of cyproterone acetate, but it jumped rapidly jumped as the dose climbed: The hazard ratio was 11.3 for 36-60 g and was 21.7 for 60 g or higher.

In a secondary analysis, the authors looked at the cohort who were already using cyproterone acetate in 2006 (n = 123,997). Women with long-term exposure were also taking estrogens more often (55.5% vs. 31.9%), and the incidence of meningioma in the exposed group was 141 per 100,000 person years, which was a risk greater than 20-fold (adjusted hazard ratio 21.2.) They also observed a strong dose-effect relationship, with adjusted hazard ratio ranging from 5.0 to 31.1.

However, the risk of meningioma decreased noticeably after treatment was stopped. At 1 year after discontinuing treatment, the risk of meningioma in the exposed group was 1.8-fold higher (1.0 to 3.2) than in the control group.

Dr. Weill noted the clinical implications of these findings: clinicians need to inform patients who have used high-dose cyproterone acetate for at least 3-5 years about the increased risk of intracranial meningioma, he said.

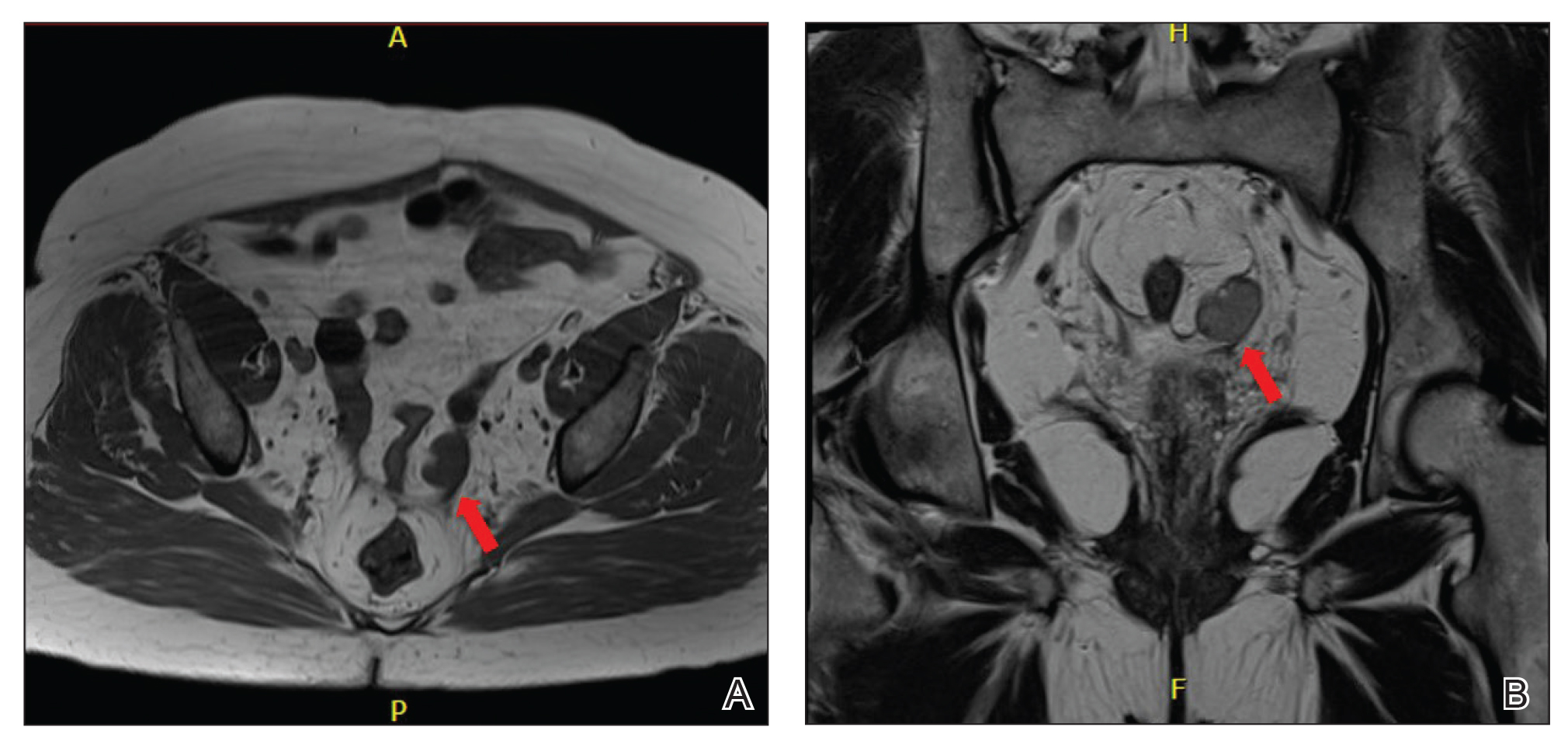

“The indication of cyproterone acetate should be clearly defined and the lowest possible daily dose used,” he said. “In the context of prolonged use of high-dose cyproterone acetate, magnetic resonance imaging screening for meningioma should be considered.”

“In patients with a documented meningioma, cyproterone acetate should be discontinued because the meningioma might regress in response to treatment discontinuation and invasive treatment could be avoided,” Dr. Weill added.

Use only when necessary

Weighing in on the research, Adilia Hormigo, MD, PhD, director of neuro-oncology at The Tisch Cancer Institute at Mount Sinai Health System in New York, noted that, “it is well known that there are sex differences in the incidence of meningiomas, as they are more frequent in women than men, and there is an association between breast cancer and the occurrence of meningiomas.”

Progesterone and androgen receptors have been found in meningiomas, she said in an interview, and there is no consensus regarding estrogen receptors. “In addition, hormonal therapy to inhibit estrogen or progesterone receptors has not produced any decrease in meningiomas’ growth,” she said.

The current study revealed an association between prolonged use of cyproterone acetate with an increased incidence of meningiomas, and the sphenoid-orbital meningioma location was specific for the drug use. “It is unclear from the study if all the meningiomas were benign,” she said. “Even if they are benign, they can cause severe morbidity, including seizures.”

Dr. Hormigo recommended that an MRI be performed on any patient who is taking a long course of cyproterone acetate in order to evaluate the development of meningiomas or meningioma progression. “And the drug should only be used when necessary,” she added.

This research was funded by the French National Health Insurance Fund and the Health Product Epidemiology Scientific Interest Group. Dr. Weill is an employee of the French National Health Insurance Fund, as are several other coauthors. The other authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Hormigo has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

.

Cyproterone acetate is a synthetic progestogen and potent antiandrogen that has been used in the treatment of hirsutism, alopecia, early puberty, amenorrhea, acne, and prostate cancer, and has also been combined with an estrogen in hormone replacement therapy.

The new findings were published online in the BMJ. The primary analysis showed that, among women using cyproterone acetate, the rate of meningiomas was 23.8 per 100,000 person years vs. 4.5 per 100,000 in the control group. After adjusting for confounders, cyproterone acetate was associated with a sevenfold increased risk of meningioma.

These were young women – the mean age of participants was 29.4 years, and more than 40% of the cohort were younger than 25 years. The initial prescriber was a gynecologist for more than half (56.7%) of the participants, and 31.6% of prescriptions could correspond to the treatment of acne without hirsutism; 13.1% of prescriptions were compatible with management of hirsutism.

“Our study provides confirmation of the risk but also the measurement of the dose-effect relationship, the decrease in the risk after stopping use, and the preferential anatomical localization of meningiomas,” said lead author Alain Weill, MD, EPI-PHARE Scientific Interest Group, Saint-Denis, France.

“A large proportion of meningiomas involve the skull base, which is of considerable importance because skull base meningioma surgery is one of the most challenging forms of surgery and is associated with a much higher risk than surgery for convexity meningiomas,” he said in an interview.

Cyproterone acetate products have been available in Europe since the 1970s under various trade names and dose strengths (1, 2, 10, 50, and 100 mg), and marketed for various indications. These products are also marketed in many other industrialized nations, but not in the United States or Japan.

The link between cyproterone acetate and an increased risk of meningioma has been known for the past decade, and information on the risk of meningioma is already included in the prescribing information for cyproterone products.

Last year, the European Medicines Agency strengthened the warnings that were already in place and recommended that cyproterone products with daily doses of 10 mg or more be restricted because of the risk of developing meningioma.

“The recommendation from the EMA is a direct consequence of our study, that was sent to the EMA in summary form in 2018 and followed up with a very detailed with a report in summer 2019,” said Dr. Weill. “In light of this report, the European Medicines Agency recommended in February 2020 that drugs containing 10 mg or more of cyproterone acetate should only be used for hirsutism, androgenic alopecia, and acne and seborrhea once other treatment options have failed, including treatment with lower doses.”

Dr. Weill pointed out that two other epidemiologic studies have assessed the link between cyproterone acetate use and meningioma and showed an association. “Those studies and our own study are complementary and provide a coherent set of epidemiological evidence,” he said in the interview. “They show a documented risk for high-dose cyproterone acetate in men, women, and transgender people, and the absence of any observed risk for low-dose cyproterone acetate use in women.”

Strong dose-effect relationship

For their study, Dr. Weill and colleagues used data from the French administrative health care database. Between 2007 and 2014, 253,777 girls and women aged 7-70 years had begun using cyproterone acetate during that time period.

All participants had received at least one prescription for high-dose cyproterone acetate and did not have a history of meningioma, benign brain tumors, or long-term disease. They were considered to be exposed if they had received a cumulative dose of at least 3 g during the first 6 months (139,222 participants) and very slightly exposed (control group) when they had received a cumulative dose of less than 3 g (114,555 participants).

Overall, a total of 69 meningiomas were diagnosed in the exposed group (during 289,544 person years of follow-up) and 20 meningiomas in the control group (during 439,949 person years of follow-up). All were treated by surgery or radiotherapy.

When the analysis was done according to the cumulative dose, it showed a dose-effect relation, with a higher risk associated with a higher cumulative dose. The hazard ratio was not significant for exposure to less than 12 g of cyproterone acetate, but it jumped rapidly jumped as the dose climbed: The hazard ratio was 11.3 for 36-60 g and was 21.7 for 60 g or higher.

In a secondary analysis, the authors looked at the cohort who were already using cyproterone acetate in 2006 (n = 123,997). Women with long-term exposure were also taking estrogens more often (55.5% vs. 31.9%), and the incidence of meningioma in the exposed group was 141 per 100,000 person years, which was a risk greater than 20-fold (adjusted hazard ratio 21.2.) They also observed a strong dose-effect relationship, with adjusted hazard ratio ranging from 5.0 to 31.1.

However, the risk of meningioma decreased noticeably after treatment was stopped. At 1 year after discontinuing treatment, the risk of meningioma in the exposed group was 1.8-fold higher (1.0 to 3.2) than in the control group.

Dr. Weill noted the clinical implications of these findings: clinicians need to inform patients who have used high-dose cyproterone acetate for at least 3-5 years about the increased risk of intracranial meningioma, he said.

“The indication of cyproterone acetate should be clearly defined and the lowest possible daily dose used,” he said. “In the context of prolonged use of high-dose cyproterone acetate, magnetic resonance imaging screening for meningioma should be considered.”

“In patients with a documented meningioma, cyproterone acetate should be discontinued because the meningioma might regress in response to treatment discontinuation and invasive treatment could be avoided,” Dr. Weill added.

Use only when necessary

Weighing in on the research, Adilia Hormigo, MD, PhD, director of neuro-oncology at The Tisch Cancer Institute at Mount Sinai Health System in New York, noted that, “it is well known that there are sex differences in the incidence of meningiomas, as they are more frequent in women than men, and there is an association between breast cancer and the occurrence of meningiomas.”

Progesterone and androgen receptors have been found in meningiomas, she said in an interview, and there is no consensus regarding estrogen receptors. “In addition, hormonal therapy to inhibit estrogen or progesterone receptors has not produced any decrease in meningiomas’ growth,” she said.

The current study revealed an association between prolonged use of cyproterone acetate with an increased incidence of meningiomas, and the sphenoid-orbital meningioma location was specific for the drug use. “It is unclear from the study if all the meningiomas were benign,” she said. “Even if they are benign, they can cause severe morbidity, including seizures.”

Dr. Hormigo recommended that an MRI be performed on any patient who is taking a long course of cyproterone acetate in order to evaluate the development of meningiomas or meningioma progression. “And the drug should only be used when necessary,” she added.

This research was funded by the French National Health Insurance Fund and the Health Product Epidemiology Scientific Interest Group. Dr. Weill is an employee of the French National Health Insurance Fund, as are several other coauthors. The other authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Hormigo has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Hair Follicle Bulb Region: A Potential Nidus for the Formation of Osteoma Cutis