User login

A Modified Anchor Taping Technique for Distal Onychocryptosis

Practice Gap

Onychocryptosis, colloquially known as an ingrown nail, most commonly affects the lateral folds of the toenails. It also can affect the fingernails and the distal aspect of the nail unit, though these presentations are not as well described in the literature. In onychocryptosis, the nail plate grows downward into the periungual skin, resulting in chronic pain and inflammation. Risk factors include overtrimming the nails with rounded edges, local trauma, nail surgery, wearing tight footwear, obesity, and onychomycosis.1

Although surgical intervention might be required for severe or refractory disease, conservative treatment options are first line and often curative. A variety of techniques have been designed to separate the ingrown portion of the nail plate from underlying skin, including placement of an intervening piece of dental floss, cotton, or plastic tubing.2

Anchor taping is another effective method of treating onychocryptosis; a strip of tape is used to gently pull and secure the affected nail fold away from the overlying nail plate. This technique has been well described for the treatment of onychocryptosis of the lateral toenail.3-5 In 2017, Arai and Haneke5 presented a modified technique for the treatment of distal disease.

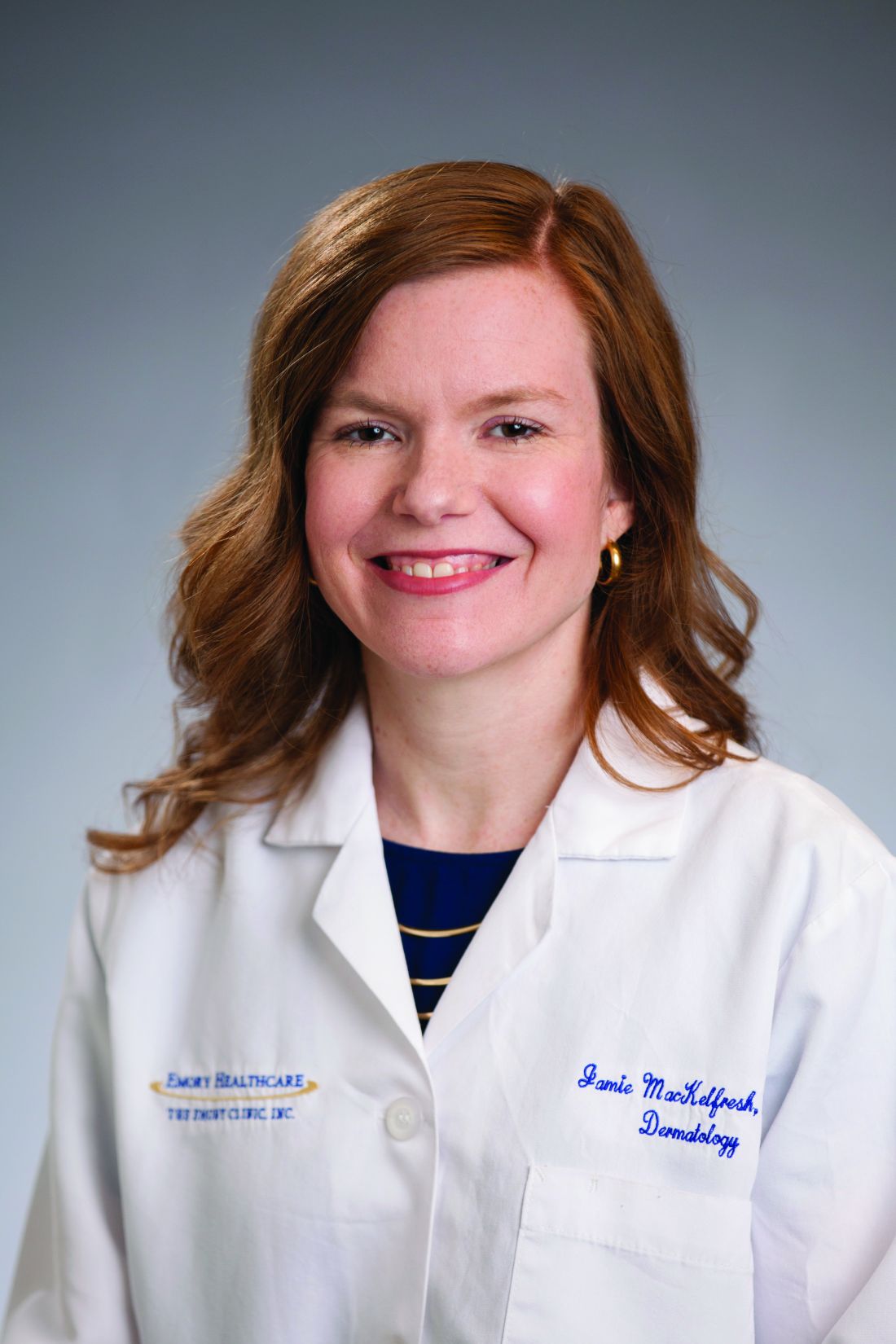

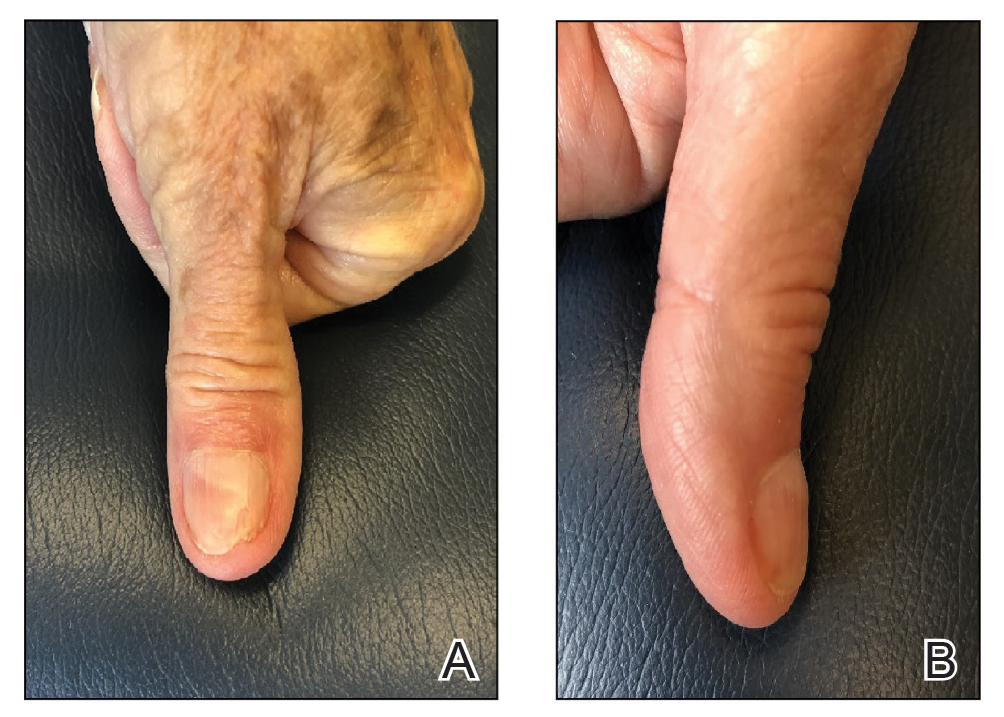

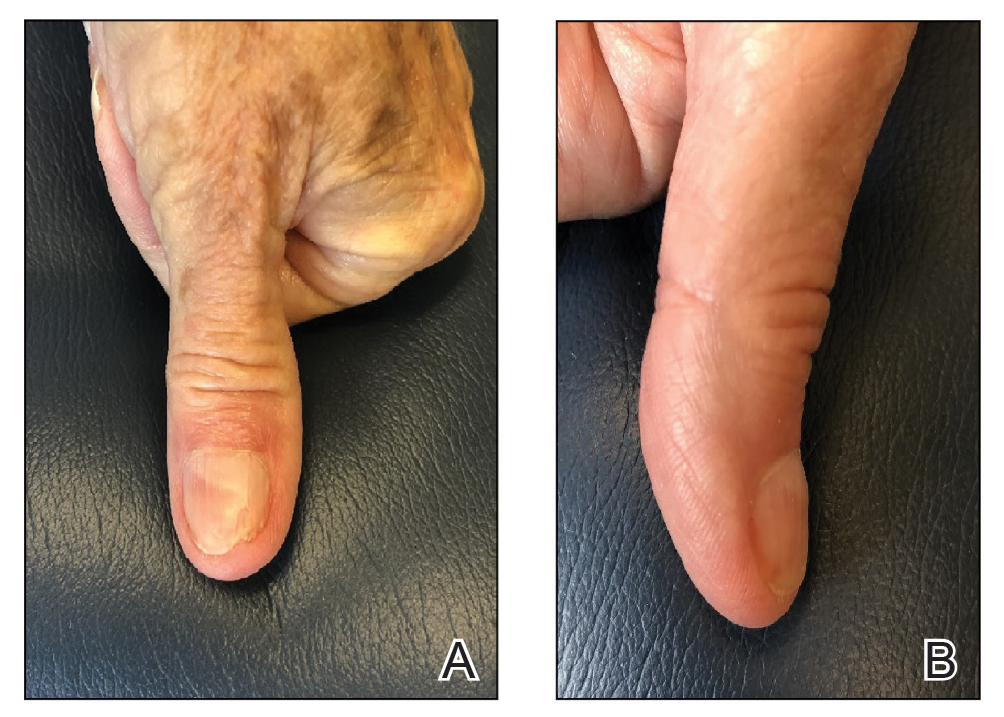

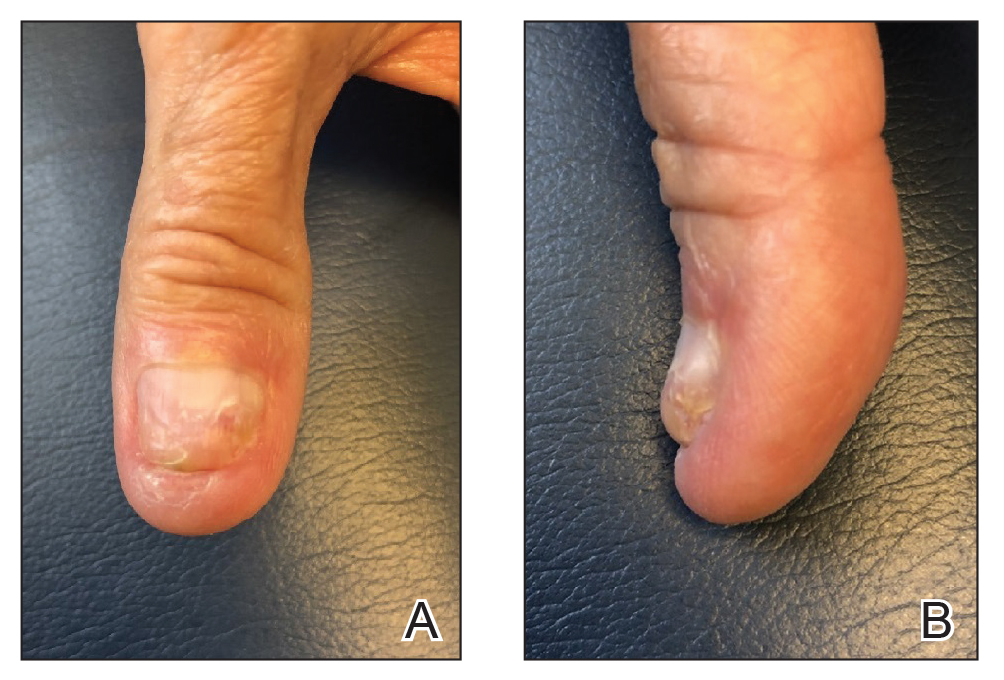

We present a simplified method that was used successfully in a case of distal onychocryptosis of the thumbnail that occurred approximately 4 months after complete nail avulsion with a nail matrix biopsy (Figure 1).

The Technique

A strongly adhesive, soft cotton, elastic tape that is 1-inch wide, such as Elastikon Elastic Tape (Johnson & Johnson), is used to pull and secure the hyponychium away from the overlying nail plate. When this technique is used for lateral onychocryptosis, a single strip of tape is secured to the affected lateral nail fold, pulled obliquely and proximally, and secured to the base of the digit.3-5 In the Arai and Haneke5 method for the treatment of distal disease, a piece of tape is first placed at the distal nail fold, pulled proximally, and secured to the ventral aspect of the digit. Then, 1 or 2 additional strips of tape are applied to the lateral nail folds, pulled obliquely, and adhered to the base of the digit, as in the classic technique for lateral onychocryptosis.5

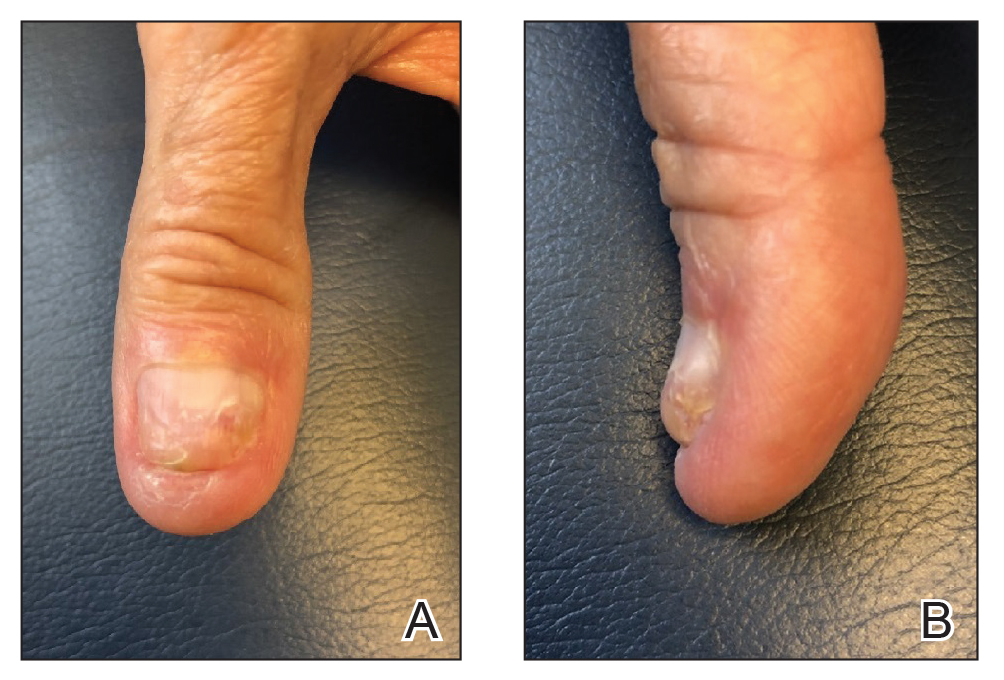

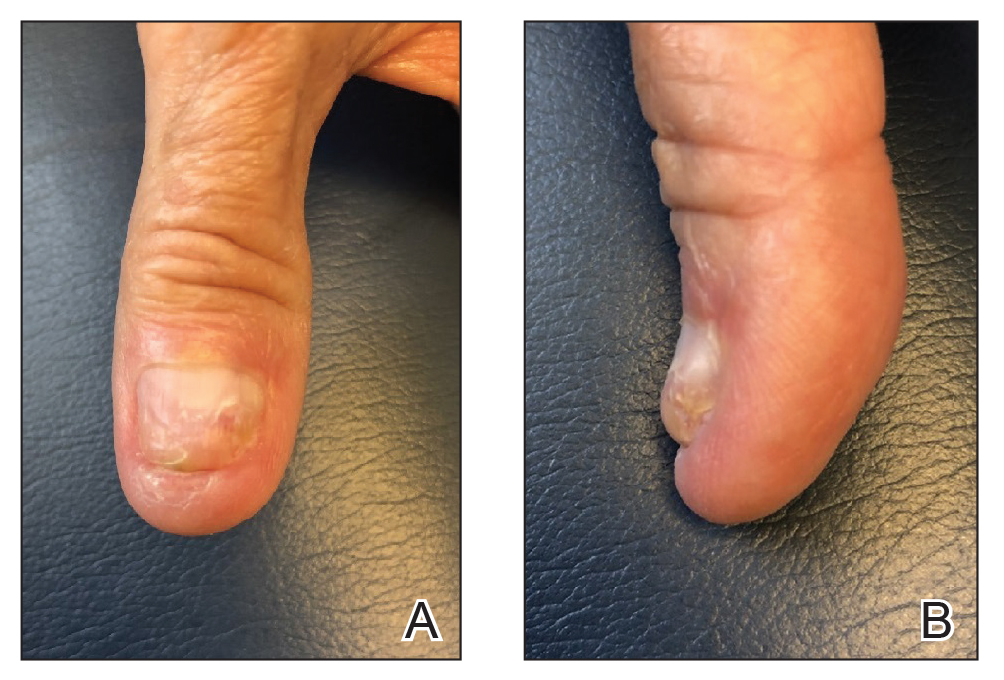

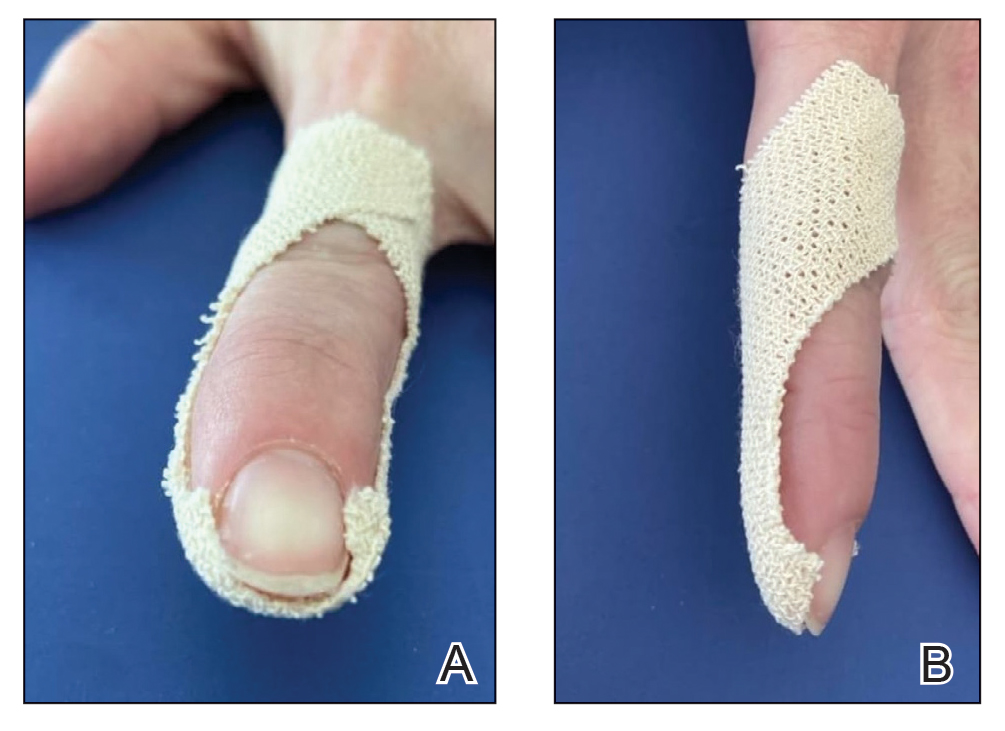

In our modification for the treatment of distal disease, only 2 strips of tape are required, each approximately 5-cm long. The first strip of tape is applied to the hyponychium parallel to the long axis of the finger, pulled away from the distal edge of the nail plate, and secured obliquely and proximally to the base of the finger on one side. The second strip of tape is applied to the hyponychium in the same manner, directly overlying the first strip, but is then pulled obliquely in the opposite direction and secured to the other side of the proximal finger (Figure 2). The 2 strips of tape are applied directly overlying each other at the distal nail fold but with opposing tension vectors to optimize pull on the distal nail fold. This modification eliminates the need to apply an initial strip of tape along the long axis of the digit, as described by Arai and Haneke.5

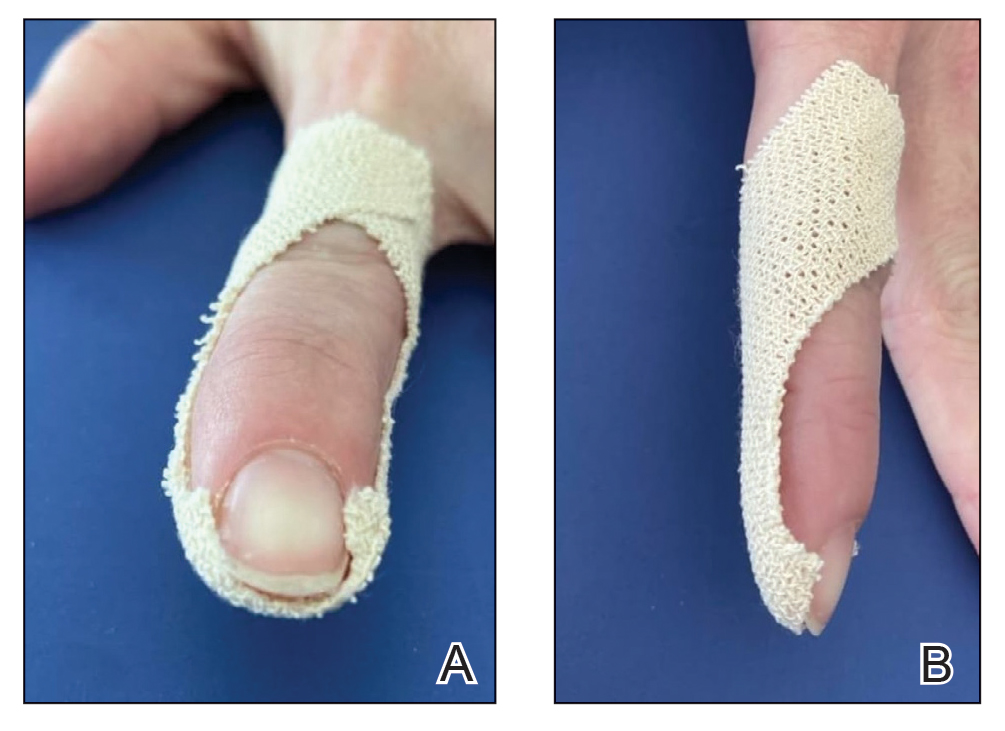

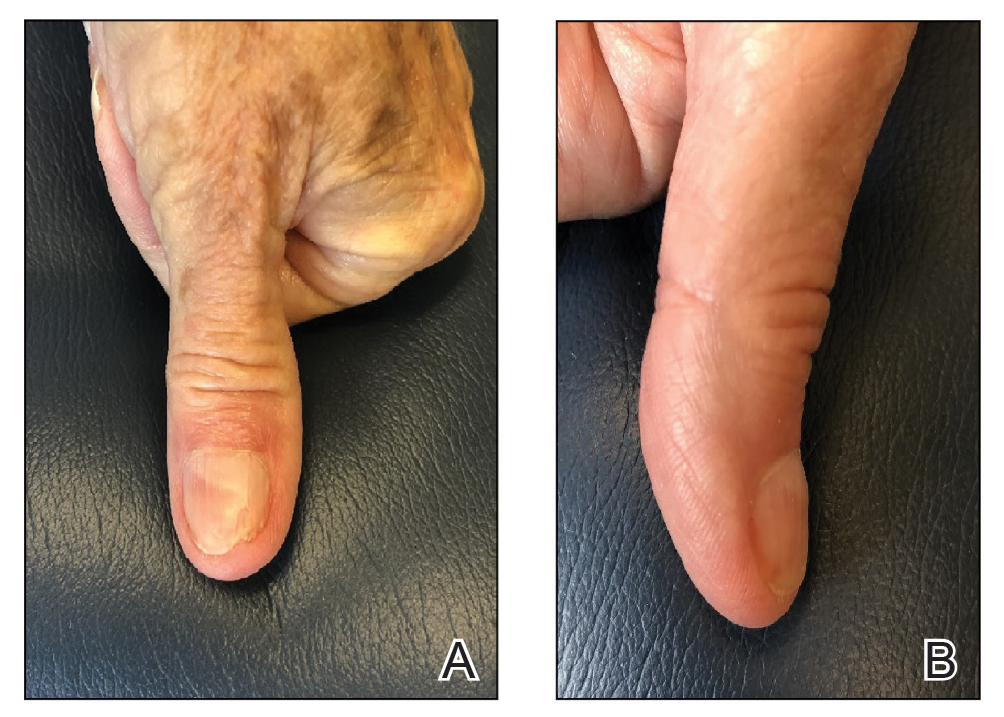

The patient is instructed on this method in the office and will change the tape at home daily for 2 to 6 weeks, until the nail plate has grown out over the hyponychium (Figure 3). This technique also can be combined with other modalities, such as dilute vinegar soaks performed daily after changing the tape to ease inflammation and prevent infection. Because strongly adhesive tape is used, it also is recommended that the patient soak the tape before removing it to prevent damage to underlying skin.

Practice Implications

Anchor taping is a common and effective treatment of onychocryptosis. Most techniques described in the literature are for lateral toenail cases, which often are managed by podiatry. A modification for the treatment of distal onychocryptosis has been previously described.5 We describe a similar modification using 2 tape strips pulled in opposite directions, which successfully resolved a case of distal onychocryptosis of the fingernail that developed following a nail procedure.

Because nail dystrophy is a relatively common complication of nail surgery, dermatologic surgeons should be aware of this simple, cost-effective, and noninvasive technique for the treatment of distal onychocryptosis.

- Geizhals S, Lipner SR. Review of onychocryptosis: epidemiology, pathogenesis, risk factors, diagnosis and treatment. Dermatol Online J. 2019;25:13030/qt9985w2n0

- Mayeaux EJ Jr, Carter C, Murphy TE. Ingrown toenail management. Am Fam Physician. 2019;100:158-164.

- Tsunoda M, Tsunoda K. Patient-controlled taping for the treatment of ingrown toenails. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12:553-555. doi:10.1370/afm.1712

- Watabe A, Yamasaki K, Hashimoto A, et al. Retrospective evaluation of conservative treatment for 140 ingrown toenails with a novel taping procedure. Acta Derm Venereol. 2015;95:822-825. doi:10.2340/00015555-2065

- Arai H, Haneke E. Noninvasive treatment for ingrown nails: anchor taping, acrylic affixed gutter splint, sculptured nail, and others. In: Baran R, Hadj-Rabia S, Silverman R, eds. Pediatric Nail Disorders. CRC Press; 2017:252-274.

Practice Gap

Onychocryptosis, colloquially known as an ingrown nail, most commonly affects the lateral folds of the toenails. It also can affect the fingernails and the distal aspect of the nail unit, though these presentations are not as well described in the literature. In onychocryptosis, the nail plate grows downward into the periungual skin, resulting in chronic pain and inflammation. Risk factors include overtrimming the nails with rounded edges, local trauma, nail surgery, wearing tight footwear, obesity, and onychomycosis.1

Although surgical intervention might be required for severe or refractory disease, conservative treatment options are first line and often curative. A variety of techniques have been designed to separate the ingrown portion of the nail plate from underlying skin, including placement of an intervening piece of dental floss, cotton, or plastic tubing.2

Anchor taping is another effective method of treating onychocryptosis; a strip of tape is used to gently pull and secure the affected nail fold away from the overlying nail plate. This technique has been well described for the treatment of onychocryptosis of the lateral toenail.3-5 In 2017, Arai and Haneke5 presented a modified technique for the treatment of distal disease.

We present a simplified method that was used successfully in a case of distal onychocryptosis of the thumbnail that occurred approximately 4 months after complete nail avulsion with a nail matrix biopsy (Figure 1).

The Technique

A strongly adhesive, soft cotton, elastic tape that is 1-inch wide, such as Elastikon Elastic Tape (Johnson & Johnson), is used to pull and secure the hyponychium away from the overlying nail plate. When this technique is used for lateral onychocryptosis, a single strip of tape is secured to the affected lateral nail fold, pulled obliquely and proximally, and secured to the base of the digit.3-5 In the Arai and Haneke5 method for the treatment of distal disease, a piece of tape is first placed at the distal nail fold, pulled proximally, and secured to the ventral aspect of the digit. Then, 1 or 2 additional strips of tape are applied to the lateral nail folds, pulled obliquely, and adhered to the base of the digit, as in the classic technique for lateral onychocryptosis.5

In our modification for the treatment of distal disease, only 2 strips of tape are required, each approximately 5-cm long. The first strip of tape is applied to the hyponychium parallel to the long axis of the finger, pulled away from the distal edge of the nail plate, and secured obliquely and proximally to the base of the finger on one side. The second strip of tape is applied to the hyponychium in the same manner, directly overlying the first strip, but is then pulled obliquely in the opposite direction and secured to the other side of the proximal finger (Figure 2). The 2 strips of tape are applied directly overlying each other at the distal nail fold but with opposing tension vectors to optimize pull on the distal nail fold. This modification eliminates the need to apply an initial strip of tape along the long axis of the digit, as described by Arai and Haneke.5

The patient is instructed on this method in the office and will change the tape at home daily for 2 to 6 weeks, until the nail plate has grown out over the hyponychium (Figure 3). This technique also can be combined with other modalities, such as dilute vinegar soaks performed daily after changing the tape to ease inflammation and prevent infection. Because strongly adhesive tape is used, it also is recommended that the patient soak the tape before removing it to prevent damage to underlying skin.

Practice Implications

Anchor taping is a common and effective treatment of onychocryptosis. Most techniques described in the literature are for lateral toenail cases, which often are managed by podiatry. A modification for the treatment of distal onychocryptosis has been previously described.5 We describe a similar modification using 2 tape strips pulled in opposite directions, which successfully resolved a case of distal onychocryptosis of the fingernail that developed following a nail procedure.

Because nail dystrophy is a relatively common complication of nail surgery, dermatologic surgeons should be aware of this simple, cost-effective, and noninvasive technique for the treatment of distal onychocryptosis.

Practice Gap

Onychocryptosis, colloquially known as an ingrown nail, most commonly affects the lateral folds of the toenails. It also can affect the fingernails and the distal aspect of the nail unit, though these presentations are not as well described in the literature. In onychocryptosis, the nail plate grows downward into the periungual skin, resulting in chronic pain and inflammation. Risk factors include overtrimming the nails with rounded edges, local trauma, nail surgery, wearing tight footwear, obesity, and onychomycosis.1

Although surgical intervention might be required for severe or refractory disease, conservative treatment options are first line and often curative. A variety of techniques have been designed to separate the ingrown portion of the nail plate from underlying skin, including placement of an intervening piece of dental floss, cotton, or plastic tubing.2

Anchor taping is another effective method of treating onychocryptosis; a strip of tape is used to gently pull and secure the affected nail fold away from the overlying nail plate. This technique has been well described for the treatment of onychocryptosis of the lateral toenail.3-5 In 2017, Arai and Haneke5 presented a modified technique for the treatment of distal disease.

We present a simplified method that was used successfully in a case of distal onychocryptosis of the thumbnail that occurred approximately 4 months after complete nail avulsion with a nail matrix biopsy (Figure 1).

The Technique

A strongly adhesive, soft cotton, elastic tape that is 1-inch wide, such as Elastikon Elastic Tape (Johnson & Johnson), is used to pull and secure the hyponychium away from the overlying nail plate. When this technique is used for lateral onychocryptosis, a single strip of tape is secured to the affected lateral nail fold, pulled obliquely and proximally, and secured to the base of the digit.3-5 In the Arai and Haneke5 method for the treatment of distal disease, a piece of tape is first placed at the distal nail fold, pulled proximally, and secured to the ventral aspect of the digit. Then, 1 or 2 additional strips of tape are applied to the lateral nail folds, pulled obliquely, and adhered to the base of the digit, as in the classic technique for lateral onychocryptosis.5

In our modification for the treatment of distal disease, only 2 strips of tape are required, each approximately 5-cm long. The first strip of tape is applied to the hyponychium parallel to the long axis of the finger, pulled away from the distal edge of the nail plate, and secured obliquely and proximally to the base of the finger on one side. The second strip of tape is applied to the hyponychium in the same manner, directly overlying the first strip, but is then pulled obliquely in the opposite direction and secured to the other side of the proximal finger (Figure 2). The 2 strips of tape are applied directly overlying each other at the distal nail fold but with opposing tension vectors to optimize pull on the distal nail fold. This modification eliminates the need to apply an initial strip of tape along the long axis of the digit, as described by Arai and Haneke.5

The patient is instructed on this method in the office and will change the tape at home daily for 2 to 6 weeks, until the nail plate has grown out over the hyponychium (Figure 3). This technique also can be combined with other modalities, such as dilute vinegar soaks performed daily after changing the tape to ease inflammation and prevent infection. Because strongly adhesive tape is used, it also is recommended that the patient soak the tape before removing it to prevent damage to underlying skin.

Practice Implications

Anchor taping is a common and effective treatment of onychocryptosis. Most techniques described in the literature are for lateral toenail cases, which often are managed by podiatry. A modification for the treatment of distal onychocryptosis has been previously described.5 We describe a similar modification using 2 tape strips pulled in opposite directions, which successfully resolved a case of distal onychocryptosis of the fingernail that developed following a nail procedure.

Because nail dystrophy is a relatively common complication of nail surgery, dermatologic surgeons should be aware of this simple, cost-effective, and noninvasive technique for the treatment of distal onychocryptosis.

- Geizhals S, Lipner SR. Review of onychocryptosis: epidemiology, pathogenesis, risk factors, diagnosis and treatment. Dermatol Online J. 2019;25:13030/qt9985w2n0

- Mayeaux EJ Jr, Carter C, Murphy TE. Ingrown toenail management. Am Fam Physician. 2019;100:158-164.

- Tsunoda M, Tsunoda K. Patient-controlled taping for the treatment of ingrown toenails. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12:553-555. doi:10.1370/afm.1712

- Watabe A, Yamasaki K, Hashimoto A, et al. Retrospective evaluation of conservative treatment for 140 ingrown toenails with a novel taping procedure. Acta Derm Venereol. 2015;95:822-825. doi:10.2340/00015555-2065

- Arai H, Haneke E. Noninvasive treatment for ingrown nails: anchor taping, acrylic affixed gutter splint, sculptured nail, and others. In: Baran R, Hadj-Rabia S, Silverman R, eds. Pediatric Nail Disorders. CRC Press; 2017:252-274.

- Geizhals S, Lipner SR. Review of onychocryptosis: epidemiology, pathogenesis, risk factors, diagnosis and treatment. Dermatol Online J. 2019;25:13030/qt9985w2n0

- Mayeaux EJ Jr, Carter C, Murphy TE. Ingrown toenail management. Am Fam Physician. 2019;100:158-164.

- Tsunoda M, Tsunoda K. Patient-controlled taping for the treatment of ingrown toenails. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12:553-555. doi:10.1370/afm.1712

- Watabe A, Yamasaki K, Hashimoto A, et al. Retrospective evaluation of conservative treatment for 140 ingrown toenails with a novel taping procedure. Acta Derm Venereol. 2015;95:822-825. doi:10.2340/00015555-2065

- Arai H, Haneke E. Noninvasive treatment for ingrown nails: anchor taping, acrylic affixed gutter splint, sculptured nail, and others. In: Baran R, Hadj-Rabia S, Silverman R, eds. Pediatric Nail Disorders. CRC Press; 2017:252-274.

Review eyes nail unit toxicities secondary to targeted cancer therapy

while damage to other nail unit anatomic areas can be wide-ranging.

Those are key findings from an evidence-based literature review published on July 21, 2021, in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, as a letter to the editor. “Dermatologic toxicities are often the earliest-presenting and highest-incidence adverse events due to targeted anticancer therapies and immunotherapies,” corresponding author Anisha B. Patel, MD, of the department of dermatology at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, and colleagues wrote. “Nail unit toxicities due to immunotherapy are caused by nonspecific immune activation. Targeted therapies, particularly mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway inhibitors, lead to epidermal thinning of the nail folds and periungual tissue, increasing susceptibility to trauma and penetration by nail plate fragments. Although cutaneous toxicities have been well described, further characterization of nail unit toxicities is needed.”

The researchers searched the PubMed database using the terms nail, nail toxicity, nail dystrophy, paronychia, onycholysis, pyogenic granuloma, onychopathy, targeted therapy, and immunotherapy, and reviewed relevant articles for clinical presentation, diagnosis, incidence, outcomes, and references. They also proposed treatment algorithms for this patient population based on the existing literature and the authors’ collective clinical experience.

Dr. Patel and colleagues found that paronychia and periungual pyogenic granulomas were the most common nail unit toxicities caused by targeted therapy. “Damage to other nail unit anatomic areas includes drug induced or exacerbated lichen planus and psoriasis as well as pigmentary and neoplastic changes,” they wrote. “Onycholysis, onychoschizia, paronychia, psoriasis, lichen planus, and dermatomyositis have been reported with immune checkpoint inhibitors,” with the time of onset during the first week of treatment to several months after treatment has started.

According to National Cancer Institute criteria, nail adverse events associated with medical treatment include nail changes, discoloration, ridging, paronychia, and infection. The severity of nail loss, paronychia, and infection can be graded up to 3 (defined as “severe or medically significant but not life threatening”), while the remainder of nail toxicities may be categorized only as grade 1 (defined as “mild,” with “intervention not indicated”). “High-grade toxicities have been reported, especially with pan-fibroblast growth factor receptor inhibitors,” the authors wrote, referring to a previous study.

The review includes treatment algorithms for paronychia, periungual pyogenic granuloma, nail lichen planus, and psoriasis. “Long-acting and nonselective immunosuppressants are reserved for dose-limiting toxicities, given their unknown effects on already-immunosuppressed patients with cancer and on cancer therapy,” the authors wrote. “A discussion with the oncology department is essential before starting an immunomodulator or immunosuppressant.”

To manage onycholysis, Dr. Patel and colleagues recommended trimming the onycholytic nail plate to its attachment point. “Partial avulsion is used to treat a refractory abscess or painful hemorrhage,” they wrote. “A Pseudomonas superinfection is treated twice daily with a topical antibiotic solution. Brittle nail syndrome is managed with emollients or the application of polyureaurethane, a 16% nail solution, or a hydrosoluble nail lacquer,” they wrote, adding that biotin supplementation is not recommended.

Jonathan Leventhal, MD, who was asked to comment on the study, said that nail toxicity from targeted cancer therapy is one of the most common reasons for consultation in his role as director of the Yale University oncodermatology program at Smilow Cancer Hospital, New Haven, Conn. “When severe, these reactions frequently impact patients’ quality of life,” he said.

“This study is helpful for all dermatologists caring for cancer patients,” with strengths that include “succinctly summarizing the most prevalent conditions and providing a clear and practical algorithm for approaching these nail toxicities,” he said. In addition to targeted agents and immunotherapy, “we commonly see nail toxicities from cytotoxic chemotherapy, which was not reviewed in this paper. Multidisciplinary evaluation and dermatologic involvement is certainly beneficial to make accurate diagnoses and promptly manage these conditions, helping patients stay on their oncologic therapies.”

The researchers reported no financial disclosures. Dr. Leventhal disclosed that he is a member of the advisory board for Regeneron, Sanofi, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and La Roche–Posay. He has also received research funding from Azitra and OnQuality.

while damage to other nail unit anatomic areas can be wide-ranging.

Those are key findings from an evidence-based literature review published on July 21, 2021, in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, as a letter to the editor. “Dermatologic toxicities are often the earliest-presenting and highest-incidence adverse events due to targeted anticancer therapies and immunotherapies,” corresponding author Anisha B. Patel, MD, of the department of dermatology at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, and colleagues wrote. “Nail unit toxicities due to immunotherapy are caused by nonspecific immune activation. Targeted therapies, particularly mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway inhibitors, lead to epidermal thinning of the nail folds and periungual tissue, increasing susceptibility to trauma and penetration by nail plate fragments. Although cutaneous toxicities have been well described, further characterization of nail unit toxicities is needed.”

The researchers searched the PubMed database using the terms nail, nail toxicity, nail dystrophy, paronychia, onycholysis, pyogenic granuloma, onychopathy, targeted therapy, and immunotherapy, and reviewed relevant articles for clinical presentation, diagnosis, incidence, outcomes, and references. They also proposed treatment algorithms for this patient population based on the existing literature and the authors’ collective clinical experience.

Dr. Patel and colleagues found that paronychia and periungual pyogenic granulomas were the most common nail unit toxicities caused by targeted therapy. “Damage to other nail unit anatomic areas includes drug induced or exacerbated lichen planus and psoriasis as well as pigmentary and neoplastic changes,” they wrote. “Onycholysis, onychoschizia, paronychia, psoriasis, lichen planus, and dermatomyositis have been reported with immune checkpoint inhibitors,” with the time of onset during the first week of treatment to several months after treatment has started.

According to National Cancer Institute criteria, nail adverse events associated with medical treatment include nail changes, discoloration, ridging, paronychia, and infection. The severity of nail loss, paronychia, and infection can be graded up to 3 (defined as “severe or medically significant but not life threatening”), while the remainder of nail toxicities may be categorized only as grade 1 (defined as “mild,” with “intervention not indicated”). “High-grade toxicities have been reported, especially with pan-fibroblast growth factor receptor inhibitors,” the authors wrote, referring to a previous study.

The review includes treatment algorithms for paronychia, periungual pyogenic granuloma, nail lichen planus, and psoriasis. “Long-acting and nonselective immunosuppressants are reserved for dose-limiting toxicities, given their unknown effects on already-immunosuppressed patients with cancer and on cancer therapy,” the authors wrote. “A discussion with the oncology department is essential before starting an immunomodulator or immunosuppressant.”

To manage onycholysis, Dr. Patel and colleagues recommended trimming the onycholytic nail plate to its attachment point. “Partial avulsion is used to treat a refractory abscess or painful hemorrhage,” they wrote. “A Pseudomonas superinfection is treated twice daily with a topical antibiotic solution. Brittle nail syndrome is managed with emollients or the application of polyureaurethane, a 16% nail solution, or a hydrosoluble nail lacquer,” they wrote, adding that biotin supplementation is not recommended.

Jonathan Leventhal, MD, who was asked to comment on the study, said that nail toxicity from targeted cancer therapy is one of the most common reasons for consultation in his role as director of the Yale University oncodermatology program at Smilow Cancer Hospital, New Haven, Conn. “When severe, these reactions frequently impact patients’ quality of life,” he said.

“This study is helpful for all dermatologists caring for cancer patients,” with strengths that include “succinctly summarizing the most prevalent conditions and providing a clear and practical algorithm for approaching these nail toxicities,” he said. In addition to targeted agents and immunotherapy, “we commonly see nail toxicities from cytotoxic chemotherapy, which was not reviewed in this paper. Multidisciplinary evaluation and dermatologic involvement is certainly beneficial to make accurate diagnoses and promptly manage these conditions, helping patients stay on their oncologic therapies.”

The researchers reported no financial disclosures. Dr. Leventhal disclosed that he is a member of the advisory board for Regeneron, Sanofi, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and La Roche–Posay. He has also received research funding from Azitra and OnQuality.

while damage to other nail unit anatomic areas can be wide-ranging.

Those are key findings from an evidence-based literature review published on July 21, 2021, in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, as a letter to the editor. “Dermatologic toxicities are often the earliest-presenting and highest-incidence adverse events due to targeted anticancer therapies and immunotherapies,” corresponding author Anisha B. Patel, MD, of the department of dermatology at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, and colleagues wrote. “Nail unit toxicities due to immunotherapy are caused by nonspecific immune activation. Targeted therapies, particularly mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway inhibitors, lead to epidermal thinning of the nail folds and periungual tissue, increasing susceptibility to trauma and penetration by nail plate fragments. Although cutaneous toxicities have been well described, further characterization of nail unit toxicities is needed.”

The researchers searched the PubMed database using the terms nail, nail toxicity, nail dystrophy, paronychia, onycholysis, pyogenic granuloma, onychopathy, targeted therapy, and immunotherapy, and reviewed relevant articles for clinical presentation, diagnosis, incidence, outcomes, and references. They also proposed treatment algorithms for this patient population based on the existing literature and the authors’ collective clinical experience.

Dr. Patel and colleagues found that paronychia and periungual pyogenic granulomas were the most common nail unit toxicities caused by targeted therapy. “Damage to other nail unit anatomic areas includes drug induced or exacerbated lichen planus and psoriasis as well as pigmentary and neoplastic changes,” they wrote. “Onycholysis, onychoschizia, paronychia, psoriasis, lichen planus, and dermatomyositis have been reported with immune checkpoint inhibitors,” with the time of onset during the first week of treatment to several months after treatment has started.

According to National Cancer Institute criteria, nail adverse events associated with medical treatment include nail changes, discoloration, ridging, paronychia, and infection. The severity of nail loss, paronychia, and infection can be graded up to 3 (defined as “severe or medically significant but not life threatening”), while the remainder of nail toxicities may be categorized only as grade 1 (defined as “mild,” with “intervention not indicated”). “High-grade toxicities have been reported, especially with pan-fibroblast growth factor receptor inhibitors,” the authors wrote, referring to a previous study.

The review includes treatment algorithms for paronychia, periungual pyogenic granuloma, nail lichen planus, and psoriasis. “Long-acting and nonselective immunosuppressants are reserved for dose-limiting toxicities, given their unknown effects on already-immunosuppressed patients with cancer and on cancer therapy,” the authors wrote. “A discussion with the oncology department is essential before starting an immunomodulator or immunosuppressant.”

To manage onycholysis, Dr. Patel and colleagues recommended trimming the onycholytic nail plate to its attachment point. “Partial avulsion is used to treat a refractory abscess or painful hemorrhage,” they wrote. “A Pseudomonas superinfection is treated twice daily with a topical antibiotic solution. Brittle nail syndrome is managed with emollients or the application of polyureaurethane, a 16% nail solution, or a hydrosoluble nail lacquer,” they wrote, adding that biotin supplementation is not recommended.

Jonathan Leventhal, MD, who was asked to comment on the study, said that nail toxicity from targeted cancer therapy is one of the most common reasons for consultation in his role as director of the Yale University oncodermatology program at Smilow Cancer Hospital, New Haven, Conn. “When severe, these reactions frequently impact patients’ quality of life,” he said.

“This study is helpful for all dermatologists caring for cancer patients,” with strengths that include “succinctly summarizing the most prevalent conditions and providing a clear and practical algorithm for approaching these nail toxicities,” he said. In addition to targeted agents and immunotherapy, “we commonly see nail toxicities from cytotoxic chemotherapy, which was not reviewed in this paper. Multidisciplinary evaluation and dermatologic involvement is certainly beneficial to make accurate diagnoses and promptly manage these conditions, helping patients stay on their oncologic therapies.”

The researchers reported no financial disclosures. Dr. Leventhal disclosed that he is a member of the advisory board for Regeneron, Sanofi, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and La Roche–Posay. He has also received research funding from Azitra and OnQuality.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF DERMATOLOGY

Microbiome: Gut dysbiosis linked to development of alopecia areata

presented at the annual meeting of the Society for Investigative Dermatology.

There have been reports of gut microbiome dysbiosis associated with autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, diabetes, and celiac disease. “It is now clear that these events not just shape the immune response in the gut, but also distant sites and immune-privileged organs,” Tanya Sezin, a doctor of natural science from the University of Lübeck (Germany) and Columbia University, New York, said in her presentation.

Whether the gut microbiome may also play a role as an environmental factor in alopecia areata, another T-cell–mediated autoimmune disease for which there are few available treatment options, is being evaluated at the Christiano Laboratory at Columbia University, Dr. Sezin noted. “Much of the difficulty underlying the lack of an effective treatment has been the incomplete understanding of the pathogenesis of AA.”

She also referred to several case reports describing hair growth in patients who received fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT), including a 20-year-old with alopecia universalis, who experienced hair growth after receiving FMT for Crohn’s disease.

Dr. Sezin and colleagues at the lab first performed a study in mice to test whether the gut microbiome was involved in the pathogenesis of AA. Mice given an antibiotic cocktail of ampicillin, neomycin, and vancomycin prior to or at the time of a skin graft taken from a mouse model of AA to induce AA were protected from hair loss, while mice given the antibiotic cocktail after skin grafting were not protected from hair loss.

“16S rRNA sequencing analysis of the gut microbiota revealed a significant shift in gut microbiome composition in animals treated with antibiotics and protected from hair loss, as reflected by significant changes in alpha and beta diversity,” Dr. Sezin explained. “In AA mice, we also observed differential abundance of families from the Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes phyla.” Specifically, Lactobacillus murinus and Muribaculum intestinale were overrepresented in mice with AA.

The investigators then performed 16S rRNA sequencing on 26 patients with AA, who stopped treatment for 30 days beforehand, and 9 participants who did not have AA as controls. “Though we did not observe difference in alpha and beta diversity, we see changes in the relative abundance of several families belonging to the Firmicutes phyla,” in patients with AA, Dr. Sezin said.

In another cohort of 30 patients with AA and 20 participants without AA, who stopped treatment before the study, Dr. Sezin and colleagues found “differences in the relative abundance of members of the Firmicutes and Bacteroides phyla,” including Bacteroides caccae, Prevotella copri, Syntrophomonas wolfei, Blautia wexlerae, and Eubacterium eligens, she said. “Consistent with our findings, there are previous reports in the literature showing gut dysbiosis in several other autoimmune diseases associated with differential regulation of some of the top species we have identified.”

Dr. Sezin said her group is recruiting patients for a clinical trial evaluating FMT in patients with AA. “We plan to study the association between changes in the gut microbiome and immune cell composition in AA patients undergoing FMT,” she said. “Additionally, functional studies in mice are also currently [being conducted] to further pinpoint the contribution of gut microbiome to the pathogenesis of AA.”

When asked during the discussion session if there was any relationship between the skin microbiome and AA, Dr. Sezin said there was no connection found in mice studies, which she and her colleagues are investigating further. “In the human samples, we are currently recruiting more patients and healthy controls to try to get a better understanding of whether we see differences in the skin microbiome,” she added.

Dr. Sezin explained that how the gut microbiota “is really remediated in alopecia areata” is not well understood. “We think that it is possible that we see intestinal permeability in the gut due to the gut dysbiosis that we see in alopecia areata patients, and this might lead to systemic distribution of bacteria, which might cross-react or present cross reactivity with the antigens” identified in AA, which is also being investigated, she said.

FMT not a ‘simple fix’ for AA

Leslie Castelo-Soccio, MD, PhD, a dermatologist at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, who was not involved with the research, said in an interview that the findings presented by Dr. Sezin show how AA shares similarities with other autoimmune diseases. “It does highlight how important the gut microbiome is to human disease, and that differences in relative abundance of bacteria play one part as a trigger in a genetically susceptible person.”

However, while some autoimmune diseases have a big difference in alpha and beta diversity, for example, “this has not been seen in people with alopecia areata,” Dr. Castelo-Soccio pointed out. “The differences are more subtle in terms of amounts of certain bacteria,” she said, noting that, in this study, the biggest differences were seen in the studies of mice.

Dr. Castelo-Soccio also said there may be also be differences in the gut microbiome in children and adults. “The gut microbiome shifts in very early childhood from a very diverse microbiome to a more ‘adult microbiome’ around age 4, which is the age we see the first peak of many autoimmune diseases, including alopecia areata. I think microbiome work in humans needs to focus on this transition point.”

As for the clinical trial at Columbia that is evaluating FMT in patients with AA, Dr. Castelo-Soccio said she is excited. “There is much to learn about fecal transplant for all diseases and about the role of the gut microbiome and environment. Most of what we know for fecal transplant centers on its use for Clostridium difficile infections.”

Patients and their families have been asking about the potential for FMT in alopecia area, Dr. Castelo-Soccio said, but some believe it is a “simple fix” when the reality is much more complex.

“When I speak to patients and families about this, I explain that currently the ‘active ingredient’ in fecal transplants is not definitively established. In any one donor, the community of bacteria is highly variable and can be from batch to batch. While the short-term risks are relatively low – cramping, diarrhea, discomfort, mode of delivery – there are reports of transmission of infectious bacteria from donors like [Escherichia] coli, which have led to severe infections.”

Long-term safety and durability of effects are also unclear, “so we do not know if a patient receiving one [FMT] will need many in the future. We do not know how changing the microbiome could affect the transplant recipient in terms of noninfectious diseases/disorders. We are learning about the role of microbiome in obesity, insulin resistance, mood disorders. We could be ‘fixing’ one trigger of alopecia but setting up [the] patient for other noninfectious conditions,” Dr. Castelo-Soccio said.

Dr. Sezin and Dr. Castelo-Soccio reported no relevant financial disclosures.

presented at the annual meeting of the Society for Investigative Dermatology.

There have been reports of gut microbiome dysbiosis associated with autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, diabetes, and celiac disease. “It is now clear that these events not just shape the immune response in the gut, but also distant sites and immune-privileged organs,” Tanya Sezin, a doctor of natural science from the University of Lübeck (Germany) and Columbia University, New York, said in her presentation.

Whether the gut microbiome may also play a role as an environmental factor in alopecia areata, another T-cell–mediated autoimmune disease for which there are few available treatment options, is being evaluated at the Christiano Laboratory at Columbia University, Dr. Sezin noted. “Much of the difficulty underlying the lack of an effective treatment has been the incomplete understanding of the pathogenesis of AA.”

She also referred to several case reports describing hair growth in patients who received fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT), including a 20-year-old with alopecia universalis, who experienced hair growth after receiving FMT for Crohn’s disease.

Dr. Sezin and colleagues at the lab first performed a study in mice to test whether the gut microbiome was involved in the pathogenesis of AA. Mice given an antibiotic cocktail of ampicillin, neomycin, and vancomycin prior to or at the time of a skin graft taken from a mouse model of AA to induce AA were protected from hair loss, while mice given the antibiotic cocktail after skin grafting were not protected from hair loss.

“16S rRNA sequencing analysis of the gut microbiota revealed a significant shift in gut microbiome composition in animals treated with antibiotics and protected from hair loss, as reflected by significant changes in alpha and beta diversity,” Dr. Sezin explained. “In AA mice, we also observed differential abundance of families from the Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes phyla.” Specifically, Lactobacillus murinus and Muribaculum intestinale were overrepresented in mice with AA.

The investigators then performed 16S rRNA sequencing on 26 patients with AA, who stopped treatment for 30 days beforehand, and 9 participants who did not have AA as controls. “Though we did not observe difference in alpha and beta diversity, we see changes in the relative abundance of several families belonging to the Firmicutes phyla,” in patients with AA, Dr. Sezin said.

In another cohort of 30 patients with AA and 20 participants without AA, who stopped treatment before the study, Dr. Sezin and colleagues found “differences in the relative abundance of members of the Firmicutes and Bacteroides phyla,” including Bacteroides caccae, Prevotella copri, Syntrophomonas wolfei, Blautia wexlerae, and Eubacterium eligens, she said. “Consistent with our findings, there are previous reports in the literature showing gut dysbiosis in several other autoimmune diseases associated with differential regulation of some of the top species we have identified.”

Dr. Sezin said her group is recruiting patients for a clinical trial evaluating FMT in patients with AA. “We plan to study the association between changes in the gut microbiome and immune cell composition in AA patients undergoing FMT,” she said. “Additionally, functional studies in mice are also currently [being conducted] to further pinpoint the contribution of gut microbiome to the pathogenesis of AA.”

When asked during the discussion session if there was any relationship between the skin microbiome and AA, Dr. Sezin said there was no connection found in mice studies, which she and her colleagues are investigating further. “In the human samples, we are currently recruiting more patients and healthy controls to try to get a better understanding of whether we see differences in the skin microbiome,” she added.

Dr. Sezin explained that how the gut microbiota “is really remediated in alopecia areata” is not well understood. “We think that it is possible that we see intestinal permeability in the gut due to the gut dysbiosis that we see in alopecia areata patients, and this might lead to systemic distribution of bacteria, which might cross-react or present cross reactivity with the antigens” identified in AA, which is also being investigated, she said.

FMT not a ‘simple fix’ for AA

Leslie Castelo-Soccio, MD, PhD, a dermatologist at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, who was not involved with the research, said in an interview that the findings presented by Dr. Sezin show how AA shares similarities with other autoimmune diseases. “It does highlight how important the gut microbiome is to human disease, and that differences in relative abundance of bacteria play one part as a trigger in a genetically susceptible person.”

However, while some autoimmune diseases have a big difference in alpha and beta diversity, for example, “this has not been seen in people with alopecia areata,” Dr. Castelo-Soccio pointed out. “The differences are more subtle in terms of amounts of certain bacteria,” she said, noting that, in this study, the biggest differences were seen in the studies of mice.

Dr. Castelo-Soccio also said there may be also be differences in the gut microbiome in children and adults. “The gut microbiome shifts in very early childhood from a very diverse microbiome to a more ‘adult microbiome’ around age 4, which is the age we see the first peak of many autoimmune diseases, including alopecia areata. I think microbiome work in humans needs to focus on this transition point.”

As for the clinical trial at Columbia that is evaluating FMT in patients with AA, Dr. Castelo-Soccio said she is excited. “There is much to learn about fecal transplant for all diseases and about the role of the gut microbiome and environment. Most of what we know for fecal transplant centers on its use for Clostridium difficile infections.”

Patients and their families have been asking about the potential for FMT in alopecia area, Dr. Castelo-Soccio said, but some believe it is a “simple fix” when the reality is much more complex.

“When I speak to patients and families about this, I explain that currently the ‘active ingredient’ in fecal transplants is not definitively established. In any one donor, the community of bacteria is highly variable and can be from batch to batch. While the short-term risks are relatively low – cramping, diarrhea, discomfort, mode of delivery – there are reports of transmission of infectious bacteria from donors like [Escherichia] coli, which have led to severe infections.”

Long-term safety and durability of effects are also unclear, “so we do not know if a patient receiving one [FMT] will need many in the future. We do not know how changing the microbiome could affect the transplant recipient in terms of noninfectious diseases/disorders. We are learning about the role of microbiome in obesity, insulin resistance, mood disorders. We could be ‘fixing’ one trigger of alopecia but setting up [the] patient for other noninfectious conditions,” Dr. Castelo-Soccio said.

Dr. Sezin and Dr. Castelo-Soccio reported no relevant financial disclosures.

presented at the annual meeting of the Society for Investigative Dermatology.

There have been reports of gut microbiome dysbiosis associated with autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, diabetes, and celiac disease. “It is now clear that these events not just shape the immune response in the gut, but also distant sites and immune-privileged organs,” Tanya Sezin, a doctor of natural science from the University of Lübeck (Germany) and Columbia University, New York, said in her presentation.

Whether the gut microbiome may also play a role as an environmental factor in alopecia areata, another T-cell–mediated autoimmune disease for which there are few available treatment options, is being evaluated at the Christiano Laboratory at Columbia University, Dr. Sezin noted. “Much of the difficulty underlying the lack of an effective treatment has been the incomplete understanding of the pathogenesis of AA.”

She also referred to several case reports describing hair growth in patients who received fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT), including a 20-year-old with alopecia universalis, who experienced hair growth after receiving FMT for Crohn’s disease.

Dr. Sezin and colleagues at the lab first performed a study in mice to test whether the gut microbiome was involved in the pathogenesis of AA. Mice given an antibiotic cocktail of ampicillin, neomycin, and vancomycin prior to or at the time of a skin graft taken from a mouse model of AA to induce AA were protected from hair loss, while mice given the antibiotic cocktail after skin grafting were not protected from hair loss.

“16S rRNA sequencing analysis of the gut microbiota revealed a significant shift in gut microbiome composition in animals treated with antibiotics and protected from hair loss, as reflected by significant changes in alpha and beta diversity,” Dr. Sezin explained. “In AA mice, we also observed differential abundance of families from the Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes phyla.” Specifically, Lactobacillus murinus and Muribaculum intestinale were overrepresented in mice with AA.

The investigators then performed 16S rRNA sequencing on 26 patients with AA, who stopped treatment for 30 days beforehand, and 9 participants who did not have AA as controls. “Though we did not observe difference in alpha and beta diversity, we see changes in the relative abundance of several families belonging to the Firmicutes phyla,” in patients with AA, Dr. Sezin said.

In another cohort of 30 patients with AA and 20 participants without AA, who stopped treatment before the study, Dr. Sezin and colleagues found “differences in the relative abundance of members of the Firmicutes and Bacteroides phyla,” including Bacteroides caccae, Prevotella copri, Syntrophomonas wolfei, Blautia wexlerae, and Eubacterium eligens, she said. “Consistent with our findings, there are previous reports in the literature showing gut dysbiosis in several other autoimmune diseases associated with differential regulation of some of the top species we have identified.”

Dr. Sezin said her group is recruiting patients for a clinical trial evaluating FMT in patients with AA. “We plan to study the association between changes in the gut microbiome and immune cell composition in AA patients undergoing FMT,” she said. “Additionally, functional studies in mice are also currently [being conducted] to further pinpoint the contribution of gut microbiome to the pathogenesis of AA.”

When asked during the discussion session if there was any relationship between the skin microbiome and AA, Dr. Sezin said there was no connection found in mice studies, which she and her colleagues are investigating further. “In the human samples, we are currently recruiting more patients and healthy controls to try to get a better understanding of whether we see differences in the skin microbiome,” she added.

Dr. Sezin explained that how the gut microbiota “is really remediated in alopecia areata” is not well understood. “We think that it is possible that we see intestinal permeability in the gut due to the gut dysbiosis that we see in alopecia areata patients, and this might lead to systemic distribution of bacteria, which might cross-react or present cross reactivity with the antigens” identified in AA, which is also being investigated, she said.

FMT not a ‘simple fix’ for AA

Leslie Castelo-Soccio, MD, PhD, a dermatologist at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, who was not involved with the research, said in an interview that the findings presented by Dr. Sezin show how AA shares similarities with other autoimmune diseases. “It does highlight how important the gut microbiome is to human disease, and that differences in relative abundance of bacteria play one part as a trigger in a genetically susceptible person.”

However, while some autoimmune diseases have a big difference in alpha and beta diversity, for example, “this has not been seen in people with alopecia areata,” Dr. Castelo-Soccio pointed out. “The differences are more subtle in terms of amounts of certain bacteria,” she said, noting that, in this study, the biggest differences were seen in the studies of mice.

Dr. Castelo-Soccio also said there may be also be differences in the gut microbiome in children and adults. “The gut microbiome shifts in very early childhood from a very diverse microbiome to a more ‘adult microbiome’ around age 4, which is the age we see the first peak of many autoimmune diseases, including alopecia areata. I think microbiome work in humans needs to focus on this transition point.”

As for the clinical trial at Columbia that is evaluating FMT in patients with AA, Dr. Castelo-Soccio said she is excited. “There is much to learn about fecal transplant for all diseases and about the role of the gut microbiome and environment. Most of what we know for fecal transplant centers on its use for Clostridium difficile infections.”

Patients and their families have been asking about the potential for FMT in alopecia area, Dr. Castelo-Soccio said, but some believe it is a “simple fix” when the reality is much more complex.

“When I speak to patients and families about this, I explain that currently the ‘active ingredient’ in fecal transplants is not definitively established. In any one donor, the community of bacteria is highly variable and can be from batch to batch. While the short-term risks are relatively low – cramping, diarrhea, discomfort, mode of delivery – there are reports of transmission of infectious bacteria from donors like [Escherichia] coli, which have led to severe infections.”

Long-term safety and durability of effects are also unclear, “so we do not know if a patient receiving one [FMT] will need many in the future. We do not know how changing the microbiome could affect the transplant recipient in terms of noninfectious diseases/disorders. We are learning about the role of microbiome in obesity, insulin resistance, mood disorders. We could be ‘fixing’ one trigger of alopecia but setting up [the] patient for other noninfectious conditions,” Dr. Castelo-Soccio said.

Dr. Sezin and Dr. Castelo-Soccio reported no relevant financial disclosures.

FROM SID 2021

The Top 100 Most-Cited Articles on Nail Psoriasis: A Bibliometric Analysis

To the Editor:

Nail psoriasis is highly prevalent in patients with cutaneous psoriasis and also may present as an isolated finding. There is a strong association between nail psoriasis and development of psoriatic arthritis (PsA). However, publications on nail psoriasis are sparse compared with articles describing cutaneous psoriasis.1 Our objectives were to analyze the nail psoriasis literature for content, citations, and media attention.

The Web of Science database was searched for the term nail psoriasis on April 27, 2020, and publications by year, subject, and article type were compiled. Total and average yearly citations were calculated to create a list of the top 100 most-cited articles (eTable). First and last authors, sex, and Altmetric Attention Scores were then recorded. The Wilcoxon rank sum test was calculated to compare the relationship of Altmetric scores between nail psoriasis–specific references and others on the list.

In our data set, the average total number of citations was 134.09 (range, 42–1617), with average yearly citations ranging from 2 to 108. Altmetric scores—measures of media attention of scholarly work—were available for 58 of 100 papers (58%), with an average score of 33.2 (range, 1–509).

Of the top 100 most-cited articles using the search term nail psoriasis, only 20% focused on nail psoriasis, with the remainder concentrating on psoriasis/PsA. Only 32% and 24% of first and last authors, respectively, were female. Fifty-two percent and 31% of the articles were published in dermatology and arthritis/rheumatology journals, respectively. There was no statistically significant difference in Altmetric scores between nail psoriasis–specific and other articles in our data set (P=.7551).

For the nail psoriasis–specific articles, all 20 highlighted a lack of nail clinical trials, a positive association with PsA, and a correlation of increased cutaneous psoriasis body surface area with increased onychodystrophy likelihood.2 Three of 20 (15%) articles stated that nail psoriasis often is overlooked, despite the negative impact on quality of life,1 and emphasized the importance of patient compliance owing to the chronic nature of the disease. Only 1 of 20 (5%) articles focused on nail psoriasis treatments.3 There was no overlap between the 100 most-cited psoriasis articles from 1970 to 2012 and our top 100 articles on nail psoriasis.4

Treatment recommendations for nail psoriasis by consensus were published by a nail expert group in 2019.5 For 3 or fewer nails involved, suggested first-line treatment is intralesional matrix injections with triamcinolone acetonide. For more than 3 affected nails, systemic treatment with oral or biologic therapy is recommended.5 Although this article is likely to change clinical practice, it did not qualify for our list because it did not garner sufficient citations in the brief period between its publication date and our search (July 2019–April 2020).

This study is subject to several limitations. Only the Web of Science database was utilized, and only the term nail psoriasis was searched, potentially excluding relevant articles. Using total citations biases toward older articles.

Our bibliometric analysis highlights a lack of publications on nail psoriasis, with most articles focusing on psoriasis and PsA. This deficiency in highly cited nail psoriasis references is likely to be a barrier to physicians in managing patients with nail disease. There is a need for controlled clinical trials and better mechanisms to disseminate information on management of nail psoriasis to practicing physicians.

- Williamson L, Dalbeth N, Dockerty JL, et al. Extended report: nail disease in psoriatic arthritis—clinically important, potentially treatable and often overlooked. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2004;43:790-794. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/keh198

- Reich K. Approach to managing patients with nail psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23(suppl 1):15-21. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3083.2009.03364.x

- de Berker D. Management of nail psoriasis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2000;25:357-362. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2230.2000.00663.x

- Wu JJ, Choi YM, Marczynski W. The 100 most cited psoriasis articles in clinical dermatologic journals, 1970 to 2012. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7:10-19.

- Rigopoulos D, Baran R, Chiheb S, et al. Recommendations for the definition, evaluation, and treatment of nail psoriasis in adult patients with no or mild skin psoriasis: a dermatologist and nail expert group consensus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:228-240. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.01.072

To the Editor:

Nail psoriasis is highly prevalent in patients with cutaneous psoriasis and also may present as an isolated finding. There is a strong association between nail psoriasis and development of psoriatic arthritis (PsA). However, publications on nail psoriasis are sparse compared with articles describing cutaneous psoriasis.1 Our objectives were to analyze the nail psoriasis literature for content, citations, and media attention.

The Web of Science database was searched for the term nail psoriasis on April 27, 2020, and publications by year, subject, and article type were compiled. Total and average yearly citations were calculated to create a list of the top 100 most-cited articles (eTable). First and last authors, sex, and Altmetric Attention Scores were then recorded. The Wilcoxon rank sum test was calculated to compare the relationship of Altmetric scores between nail psoriasis–specific references and others on the list.

In our data set, the average total number of citations was 134.09 (range, 42–1617), with average yearly citations ranging from 2 to 108. Altmetric scores—measures of media attention of scholarly work—were available for 58 of 100 papers (58%), with an average score of 33.2 (range, 1–509).

Of the top 100 most-cited articles using the search term nail psoriasis, only 20% focused on nail psoriasis, with the remainder concentrating on psoriasis/PsA. Only 32% and 24% of first and last authors, respectively, were female. Fifty-two percent and 31% of the articles were published in dermatology and arthritis/rheumatology journals, respectively. There was no statistically significant difference in Altmetric scores between nail psoriasis–specific and other articles in our data set (P=.7551).

For the nail psoriasis–specific articles, all 20 highlighted a lack of nail clinical trials, a positive association with PsA, and a correlation of increased cutaneous psoriasis body surface area with increased onychodystrophy likelihood.2 Three of 20 (15%) articles stated that nail psoriasis often is overlooked, despite the negative impact on quality of life,1 and emphasized the importance of patient compliance owing to the chronic nature of the disease. Only 1 of 20 (5%) articles focused on nail psoriasis treatments.3 There was no overlap between the 100 most-cited psoriasis articles from 1970 to 2012 and our top 100 articles on nail psoriasis.4

Treatment recommendations for nail psoriasis by consensus were published by a nail expert group in 2019.5 For 3 or fewer nails involved, suggested first-line treatment is intralesional matrix injections with triamcinolone acetonide. For more than 3 affected nails, systemic treatment with oral or biologic therapy is recommended.5 Although this article is likely to change clinical practice, it did not qualify for our list because it did not garner sufficient citations in the brief period between its publication date and our search (July 2019–April 2020).

This study is subject to several limitations. Only the Web of Science database was utilized, and only the term nail psoriasis was searched, potentially excluding relevant articles. Using total citations biases toward older articles.

Our bibliometric analysis highlights a lack of publications on nail psoriasis, with most articles focusing on psoriasis and PsA. This deficiency in highly cited nail psoriasis references is likely to be a barrier to physicians in managing patients with nail disease. There is a need for controlled clinical trials and better mechanisms to disseminate information on management of nail psoriasis to practicing physicians.

To the Editor:

Nail psoriasis is highly prevalent in patients with cutaneous psoriasis and also may present as an isolated finding. There is a strong association between nail psoriasis and development of psoriatic arthritis (PsA). However, publications on nail psoriasis are sparse compared with articles describing cutaneous psoriasis.1 Our objectives were to analyze the nail psoriasis literature for content, citations, and media attention.

The Web of Science database was searched for the term nail psoriasis on April 27, 2020, and publications by year, subject, and article type were compiled. Total and average yearly citations were calculated to create a list of the top 100 most-cited articles (eTable). First and last authors, sex, and Altmetric Attention Scores were then recorded. The Wilcoxon rank sum test was calculated to compare the relationship of Altmetric scores between nail psoriasis–specific references and others on the list.

In our data set, the average total number of citations was 134.09 (range, 42–1617), with average yearly citations ranging from 2 to 108. Altmetric scores—measures of media attention of scholarly work—were available for 58 of 100 papers (58%), with an average score of 33.2 (range, 1–509).

Of the top 100 most-cited articles using the search term nail psoriasis, only 20% focused on nail psoriasis, with the remainder concentrating on psoriasis/PsA. Only 32% and 24% of first and last authors, respectively, were female. Fifty-two percent and 31% of the articles were published in dermatology and arthritis/rheumatology journals, respectively. There was no statistically significant difference in Altmetric scores between nail psoriasis–specific and other articles in our data set (P=.7551).

For the nail psoriasis–specific articles, all 20 highlighted a lack of nail clinical trials, a positive association with PsA, and a correlation of increased cutaneous psoriasis body surface area with increased onychodystrophy likelihood.2 Three of 20 (15%) articles stated that nail psoriasis often is overlooked, despite the negative impact on quality of life,1 and emphasized the importance of patient compliance owing to the chronic nature of the disease. Only 1 of 20 (5%) articles focused on nail psoriasis treatments.3 There was no overlap between the 100 most-cited psoriasis articles from 1970 to 2012 and our top 100 articles on nail psoriasis.4

Treatment recommendations for nail psoriasis by consensus were published by a nail expert group in 2019.5 For 3 or fewer nails involved, suggested first-line treatment is intralesional matrix injections with triamcinolone acetonide. For more than 3 affected nails, systemic treatment with oral or biologic therapy is recommended.5 Although this article is likely to change clinical practice, it did not qualify for our list because it did not garner sufficient citations in the brief period between its publication date and our search (July 2019–April 2020).

This study is subject to several limitations. Only the Web of Science database was utilized, and only the term nail psoriasis was searched, potentially excluding relevant articles. Using total citations biases toward older articles.

Our bibliometric analysis highlights a lack of publications on nail psoriasis, with most articles focusing on psoriasis and PsA. This deficiency in highly cited nail psoriasis references is likely to be a barrier to physicians in managing patients with nail disease. There is a need for controlled clinical trials and better mechanisms to disseminate information on management of nail psoriasis to practicing physicians.

- Williamson L, Dalbeth N, Dockerty JL, et al. Extended report: nail disease in psoriatic arthritis—clinically important, potentially treatable and often overlooked. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2004;43:790-794. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/keh198

- Reich K. Approach to managing patients with nail psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23(suppl 1):15-21. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3083.2009.03364.x

- de Berker D. Management of nail psoriasis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2000;25:357-362. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2230.2000.00663.x

- Wu JJ, Choi YM, Marczynski W. The 100 most cited psoriasis articles in clinical dermatologic journals, 1970 to 2012. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7:10-19.

- Rigopoulos D, Baran R, Chiheb S, et al. Recommendations for the definition, evaluation, and treatment of nail psoriasis in adult patients with no or mild skin psoriasis: a dermatologist and nail expert group consensus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:228-240. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.01.072

- Williamson L, Dalbeth N, Dockerty JL, et al. Extended report: nail disease in psoriatic arthritis—clinically important, potentially treatable and often overlooked. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2004;43:790-794. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/keh198

- Reich K. Approach to managing patients with nail psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23(suppl 1):15-21. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3083.2009.03364.x

- de Berker D. Management of nail psoriasis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2000;25:357-362. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2230.2000.00663.x

- Wu JJ, Choi YM, Marczynski W. The 100 most cited psoriasis articles in clinical dermatologic journals, 1970 to 2012. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7:10-19.

- Rigopoulos D, Baran R, Chiheb S, et al. Recommendations for the definition, evaluation, and treatment of nail psoriasis in adult patients with no or mild skin psoriasis: a dermatologist and nail expert group consensus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:228-240. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.01.072

Use of Complementary Alternative Medicine and Supplementation for Skin Disease

Complementary alternative medicine (CAM) has been described by the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Medicine as “health care approaches that are not typically part of conventional medical care or that may have origins outside of usual Western practice.”1 Although this definition is broad, CAM encompasses therapies such as traditional Chinese medicine, herbal therapies, dietary supplements, and mind/body interventions. The use of CAM has grown, and according to a 2012 National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health survey, more than 30% of US adults and 12% of US children use health care approaches that are considered outside of conventional medical practice. In a survey study of US adults, at least 17.7% of respondents said they had taken a dietary supplement other than a vitamin or mineral in the last year.1 Data from the 2007 National Health Interview Survey showed that the prevalence of adults with skin conditions using CAM was 84.5% compared to 38.3% in the general population.2 In addition, 8.15 million US patients with dermatologic conditions reported using CAM over a 5-year period.3 Complementary alternative medicine has emerged as an alternative or adjunct to standard treatments, making it important for dermatologists to understand the existing literature on these therapies. Herein, we review the current evidence-based literature that exists on CAM for the treatment of atopic dermatitis (AD), psoriasis, and alopecia areata (AA).

Atopic Dermatitis

Atopic dermatitis is a chronic, pruritic, inflammatory skin condition with considerable morbidity.4,5 The pathophysiology of AD is multifactorial and includes aspects of barrier dysfunction, IgE hypersensitivity, abnormal cell-mediated immune response, and environmental factors.6 Atopic dermatitis also is one of the most common inflammatory skin conditions in adults, affecting more than 7% of the US population and up to 20% of the total population in developed countries. Of those affected, 40% have moderate or severe symptoms that result in a substantial impact on quality of life.7 Despite advances in understanding disease pathology and treatment, a subset of patients opt to defer conventional treatments such as topical and systemic corticosteroids, antibiotics, nonsteroidal immunomodulators, and biologics. Patients may seek alternative therapies when typical treatments fail or when the perceived side effects outweigh the benefits.5,8 The use of CAM has been well described in patients with AD; however, the existing evidence supporting its use along with its safety profile have not been thoroughly explored. Herein, we will discuss some of the most well-studied supplements for treatment of AD, including evening primrose oil (EPO), fish oil, and probiotics.5

Oral supplementation with polyunsaturated fatty acids commonly is reported in patients with AD.5,8 The idea that a fatty acid deficiency could lead to atopic skin conditions has been around since 1937, when it was suggested that patients with AD had lower levels of blood unsaturated fatty acids.9 Conflicting evidence regarding oral fatty acid ingestion and AD disease severity has emerged.10,11 One unsaturated fatty acid, γ-linolenic acid (GLA), has demonstrated anti-inflammatory properties and involvement in barrier repair.12 It is converted to dihomo-GLA in the body, which acts on cyclooxygenase enzymes to produce the inflammatory mediator prostaglandin E1. The production of GLA is mediated by the enzyme delta-6 desaturase in the metabolization of linoleic acid.12 However, it has been reported that in a subset of patients with AD, a malfunction of delta-6 desaturase may play a role in disease progression and result in lower baseline levels of GLA.10,12 Evening primrose oil and borage oil contain high amounts of GLA (8%–10% and 23%, respectively); thus, supplementation with these oils has been studied in AD.13

EPO for AD

Studies investigating EPO (Oenothera biennis) and its association with AD severity have shown mixed results. A Cochrane review reported that oral borage oil and EPO were not effective treatments for AD,14 while another larger randomized controlled trial (RCT) found no statistically significant improvement in AD symptoms.15 However, multiple smaller studies have found that clinical symptoms of AD, such as erythema, xerosis, pruritus, and total body surface area involved, did improve with oral EPO supplementation when compared to placebo, and the results were statistically significant (P=.04).16,17 One study looked at different dosages of EPO and found that groups ingesting both 160 mg and 320 mg daily experienced reductions in eczema area and severity index score, with greater improvement noted with the higher dosage.17 Side effects associated with oral EPO include an anticoagulant effect and transient gastrointestinal tract upset.8,14 There currently is not enough evidence or safety data to recommend this supplement to AD patients.

Although topical use of fatty acids with high concentrations of GLA, such as EPO and borage oil, have demonstrated improvement in subjective symptom severity, most studies have not reached statistical significance.10,11 One study used a 10% EPO cream for 2 weeks compared to placebo and found statistically significant improvement in patient-reported AD symptoms (P=.045). However, this study only included 10 participants, and therefore larger studies are necessary to confirm this result.18 Some RCTs have shown that topical coconut oil, sunflower seed oil, and sandalwood album oil improve AD symptom severity, but again, large controlled trials are needed.5 Unfortunately, many essential oils, including EPO, can cause a secondary allergic contact dermatitis and potentially worsen AD.19

Fish Oil for AD

Fish oil is a commonly used supplement for AD due to its high content of the omega-3 fatty acids eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA). Omega-3 fatty acids exert anti-inflammatory effects by displacing arachidonic acid, a proinflammatory omega-6 fatty acid thought to increase IgE, as well as helper T cell (TH2) cytokines and prostaglandin E2.8,20 A 2012 Cochrane review found that, while some studies revealed mild improvement in AD symptoms with oral fish oil supplementation, these RCTs were of poor methodological quality.21 Multiple smaller studies have shown a decrease in pruritus, severity, and physician-rated clinical scores with fish oil use.5,8,20,22 One study with 145 participants reported that 6 g of fish oil once daily compared to isoenergetic corn oil for 16 weeks identified no statistically significant differences between the treatment groups.20 No adverse events were identified in any of the reported trials. Further studies should be conducted to assess the utility and dosing of fish oil supplements in AD patients.

Probiotics for AD

Probiotics consist of live microorganisms that enhance the microflora of the gastrointestinal tract.8,20 They have been shown to influence food digestion and also have demonstrated potential influence on the skin-gut axis.23 The theory that intestinal dysbiosis plays a role in AD pathogenesis has been investigated in multiple studies.23-25 The central premise is that low-fiber and high-fat Western diets lead to fundamental changes in the gut microbiome, resulting in fewer anti-inflammatory metabolites, such as short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs).23-25 These SCFAs are produced by microbes during the fermentation of dietary fiber and are known for their effect on epithelial barrier integrity and anti-inflammatory properties mediated through G protein–coupled receptor 43.25 Multiple studies have shown that the gut microbiome in patients with AD have higher proportions of Clostridium difficile, Escherichia coli, and Staphylococcus aureus and lower levels of Bifidobacterium, Bacteroidetes, and Bacteroides species compared to healthy controls.26,27 Metagenomic analysis of fecal samples from patients with AD have shown a reduction of Faecalibacterium prausnitzii species when compared to controls, along with a decreased SCFA production, leading to the hypothesis that the gut microbiome may play a role in epithelial barrier disruption.28,29 Systematic reviews and smaller studies have found that oral probiotic use does lead to AD symptom improvement.8,30,31 A systematic review of 25 RCTs with 1599 participants found that supplementation with oral probiotics significantly decreased the SCORAD (SCORing Atopic Dermatitis) index in adults and children older than 1 year with AD but had no effect on infants younger than 1 year (P<.001). They also found that supplementation with diverse microbes or Lactobacillus species showed greater benefit than Bifidobacterium species alone.30 Another study analyzed the effect of oral Lactobacillus fermentum (1×109 CFU twice daily) in 53 children with AD vs placebo for 16 weeks. This study found a statically significant decrease in SCORAD index between oral probiotics and placebo, with 92% (n=24) of participants supplementing with probiotics having a lower SCORAD index than baseline compared to 63% (n=17) in the placebo group (P=.01).31 However, the use of probiotics for AD treatment has remained controversial. Two recent systematic reviews, including 39 RCTs of 2599 randomized patients, found that the use of currently available oral probiotics made little or no difference in patient-rated AD symptoms, investigator-rated AD symptoms, or quality of life.32,33 No adverse effects were observed in the included studies. Unfortunately, the individual RCTs included were heterogeneous, and future studies with standardized probiotic supplementation should be undertaken before probiotics can be routinely recommended.

The use of topical probiotics in AD also has recently emerged. Multiple studies have shown that patients with AD have higher levels of colonization with S aureus, which is associated with T-cell dysfunction, more severe allergic skin reactions, and disruptions in barrier function.34,35 Therefore, altering the skin microbiota through topical probiotics could theoretically reduce AD symptoms and flares. Multiple RCTs and smaller studies have shown that topical probiotics can alter the skin microbiota, improve erythema, and decrease scaling and pruritus in AD patients.35-38 One study used a heat-treated Lactobacillus johnsonii 0.3% lotion twice daily for 3 weeks vs placebo in patients with AD with positive S aureus skin cultures. The S aureus load decreased in patients using the topical probiotic lotion, which correlated with lower SCORAD index that was statistically significant compared to placebo (P=.012).36 More robust studies are needed to determine if topical probiotics should routinely be recommended in AD.

Psoriasis

Psoriasis vulgaris is a chronic inflammatory skin condition characterized by pruritic, hyperkeratotic, scaly plaques.39,40 Keratinocyte hyperproliferation is central to psoriasis pathogenesis and is thought to be a T-cell–driven reaction to antigens or trauma in genetically predisposed individuals. Standard treatments for psoriasis currently include topical corticosteroids and anti-inflammatories, oral immunomodulatory therapy, biologic agents, and phototherapy.40 The use of CAM is highly prevalent among patients with psoriasis, with one study reporting that 51% (n=162) of psoriatic patients interviewed had used CAM.41 The most common reasons for CAM use included dissatisfaction with current treatment, adverse side effects of standard therapy, and patient-reported attempts at “trying everything to heal disease.”42 Herein, we will discuss some of the most frequently used supplements for treatment of psoriatic disease.39

Fish Oil for Psoriasis

One of the most common supplements used by patients with psoriasis is fish oil due to its purported anti-inflammatory qualities.20,39 The consensus on fish oil supplementation for psoriasis is mixed.43-45 Multiple RCTs have reported reductions in psoriasis area and severity index (PASI) scores or symptomatic improvement with variable doses of fish oil.44,46 One RCT found that using EPA 1.8 g once daily and DHA 1.2 g once daily for 12 weeks resulted in significant improvement in pruritus, scaling, and erythema (P<.05).44 Another study reported a significant decrease in erythema (P=.02) and total body surface area affected (P=.0001) with EPA 3.6 g once daily and DHA 2.4 g once daily supplementation compared to olive oil supplementation for 15 weeks.46 Alternatively, multiple studies have failed to show statistically significant improvement in psoriatic symptoms with fish oil supplementation at variable doses and time frames (14–216 mg daily EPA, 9–80 mg daily DHA, from 2 weeks to 9 months).40,47,48 Fish oil may impart anticoagulant properties and should not be started without the guidance of a physician. Currently, there are no data to make specific recommendations on the use of fish oil as an adjunct psoriatic treatment.

Curcumin for Psoriasis