User login

Dried blood spot tests show sensitivity as cCMV screen

Dried blood spot testing showed sensitivity comparable to saliva as a screening method for congenital cytomegalovirus infection in newborns, based on data from more than 12,000 newborns.

Congenital cytomegalovirus (cCMV) is a common congenital virus in the United States, but remains underrecognized, wrote Sheila C. Dollard, PhD, of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta, and colleagues.

“Given the burden associated with cCMV and the proven benefits of treatment and early intervention for some affected infants, there has been growing interest in universal newborn screening,” but an ideal screening strategy has yet to be determined, they said.

In a population-based cohort study published in JAMA Pediatrics, the researchers screened 12,554 newborns in Minnesota, including 56 with confirmed CMV infection. The newborns were screened for cCMV via dried blood spots (DBS) and saliva collected 1-2 days after birth. The DBS were tested for CMV DNA via polymerase chain reaction (PCR) at the University of Minnesota (UMN) and the CDC.

The overall sensitivity rate was 85.7% for a combination of laboratory results from the UMN and the CDC, which had separate sensitivities of 73.2% and 76.8%, respectively.

The specificity of the combined results was 100.0% (100% from both UMN and CDC), the combined positive predictive value was 98.0% (100.0% from UMN, 97.7% from CDC), and the combined negative predictive value was 99.9% (99.9% from both UMN and CDC).

By comparison, saliva swab test results showed sensitivity of 92.9%, specificity of 99.9%, positive predictive value of 86.7%, and negative predictive value of 100.0%.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the false-positive and false-negative results from saliva screening. Overall, the false-positive rate was 0.06%, which is comparable to rates from other screening techniques, the researchers said. “The recent Food and Drug Administration approval of a point-of-care neonatal saliva CMV test (Meridian Bioscience), underscores the importance of further clarifying the role of false-positive saliva CMV test results and underscores the requirement for urine confirmation for diagnosis of cCMV,” they added.

However, the study findings support the acceptability and feasibility of cCMV screening, as parents reported generally positive attitudes about the process, the researchers said.

The study is ongoing, and designed to follow infants with confirmed cCMV for up to age 4 years to assess clinical outcomes, they added. “Diagnostic methods are always improving, and therefore, our results show the potential of DBS to provide low-cost CMV screening with smooth integration of sample collection, laboratory testing, and follow-up,” they concluded.

Findings lay foundation for widespread use

“By using enhanced PCR methods, Dollard et al. have rekindled the hope that NBDBS [newborn dried blood spots] testing may be a viable method for large-scale, universal newborn screening for congenital CMV,” Gail J. Demmler-Harrison, MD, of Texas Children’s Hospital, Houston, wrote in an accompanying editorial. Congenital CMV is a common infection, but accurate prevalence remains uncertain because not all newborns are tested, she noted. Detection of CMV currently may involve urine, saliva, and blood, but challenges to the use of these methods include “a variety of constantly evolving DNA detection methods,” she said.

Although urine and saliva samples have been proposed for universal screening, they would require the creation of new sample collection and testing programs. “The routine of collecting the NBDBS samples on all newborns and the logistics of routing them to central laboratories and then reporting results to caregivers is already in place and are strengths of NBDBS samples for universal newborn screening,” but had been limited by a less sensitive platform than urine or saliva, said Dr. Demmler-Harrison.

“The results in the study by Dollard et al. may be a total game changer for the NBDBS proponents,” she emphasized. “Furthermore, scientists who have adapted even more sensitive DNA detection assays, such as the loop-mediated isothermal assay for detection of DNA in clinical samples from newborns, may be able to adapt loop-mediated isothermal assay methodology to detect CMV DNA in NBDBS,” she added.

“By adapting the collection methods, by using optimal filter paper to enhance DNA adherence, by improving DNA elution procedures, and by developing novel amplification and detection methods, NBDBS may soon meet the challenge and reach the sensitivity and specificity necessary for universal screening for congenital CMV,” she concluded.

The study was supported by the CDC, the Minnesota Department of Health, the National Vaccine Program Office (U.S. federal government), and the University of South Carolina Disability Research and Dissemination Center.

Dr. Dollard and Dr. Demmler-Harrison had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Dried blood spot testing showed sensitivity comparable to saliva as a screening method for congenital cytomegalovirus infection in newborns, based on data from more than 12,000 newborns.

Congenital cytomegalovirus (cCMV) is a common congenital virus in the United States, but remains underrecognized, wrote Sheila C. Dollard, PhD, of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta, and colleagues.

“Given the burden associated with cCMV and the proven benefits of treatment and early intervention for some affected infants, there has been growing interest in universal newborn screening,” but an ideal screening strategy has yet to be determined, they said.

In a population-based cohort study published in JAMA Pediatrics, the researchers screened 12,554 newborns in Minnesota, including 56 with confirmed CMV infection. The newborns were screened for cCMV via dried blood spots (DBS) and saliva collected 1-2 days after birth. The DBS were tested for CMV DNA via polymerase chain reaction (PCR) at the University of Minnesota (UMN) and the CDC.

The overall sensitivity rate was 85.7% for a combination of laboratory results from the UMN and the CDC, which had separate sensitivities of 73.2% and 76.8%, respectively.

The specificity of the combined results was 100.0% (100% from both UMN and CDC), the combined positive predictive value was 98.0% (100.0% from UMN, 97.7% from CDC), and the combined negative predictive value was 99.9% (99.9% from both UMN and CDC).

By comparison, saliva swab test results showed sensitivity of 92.9%, specificity of 99.9%, positive predictive value of 86.7%, and negative predictive value of 100.0%.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the false-positive and false-negative results from saliva screening. Overall, the false-positive rate was 0.06%, which is comparable to rates from other screening techniques, the researchers said. “The recent Food and Drug Administration approval of a point-of-care neonatal saliva CMV test (Meridian Bioscience), underscores the importance of further clarifying the role of false-positive saliva CMV test results and underscores the requirement for urine confirmation for diagnosis of cCMV,” they added.

However, the study findings support the acceptability and feasibility of cCMV screening, as parents reported generally positive attitudes about the process, the researchers said.

The study is ongoing, and designed to follow infants with confirmed cCMV for up to age 4 years to assess clinical outcomes, they added. “Diagnostic methods are always improving, and therefore, our results show the potential of DBS to provide low-cost CMV screening with smooth integration of sample collection, laboratory testing, and follow-up,” they concluded.

Findings lay foundation for widespread use

“By using enhanced PCR methods, Dollard et al. have rekindled the hope that NBDBS [newborn dried blood spots] testing may be a viable method for large-scale, universal newborn screening for congenital CMV,” Gail J. Demmler-Harrison, MD, of Texas Children’s Hospital, Houston, wrote in an accompanying editorial. Congenital CMV is a common infection, but accurate prevalence remains uncertain because not all newborns are tested, she noted. Detection of CMV currently may involve urine, saliva, and blood, but challenges to the use of these methods include “a variety of constantly evolving DNA detection methods,” she said.

Although urine and saliva samples have been proposed for universal screening, they would require the creation of new sample collection and testing programs. “The routine of collecting the NBDBS samples on all newborns and the logistics of routing them to central laboratories and then reporting results to caregivers is already in place and are strengths of NBDBS samples for universal newborn screening,” but had been limited by a less sensitive platform than urine or saliva, said Dr. Demmler-Harrison.

“The results in the study by Dollard et al. may be a total game changer for the NBDBS proponents,” she emphasized. “Furthermore, scientists who have adapted even more sensitive DNA detection assays, such as the loop-mediated isothermal assay for detection of DNA in clinical samples from newborns, may be able to adapt loop-mediated isothermal assay methodology to detect CMV DNA in NBDBS,” she added.

“By adapting the collection methods, by using optimal filter paper to enhance DNA adherence, by improving DNA elution procedures, and by developing novel amplification and detection methods, NBDBS may soon meet the challenge and reach the sensitivity and specificity necessary for universal screening for congenital CMV,” she concluded.

The study was supported by the CDC, the Minnesota Department of Health, the National Vaccine Program Office (U.S. federal government), and the University of South Carolina Disability Research and Dissemination Center.

Dr. Dollard and Dr. Demmler-Harrison had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Dried blood spot testing showed sensitivity comparable to saliva as a screening method for congenital cytomegalovirus infection in newborns, based on data from more than 12,000 newborns.

Congenital cytomegalovirus (cCMV) is a common congenital virus in the United States, but remains underrecognized, wrote Sheila C. Dollard, PhD, of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta, and colleagues.

“Given the burden associated with cCMV and the proven benefits of treatment and early intervention for some affected infants, there has been growing interest in universal newborn screening,” but an ideal screening strategy has yet to be determined, they said.

In a population-based cohort study published in JAMA Pediatrics, the researchers screened 12,554 newborns in Minnesota, including 56 with confirmed CMV infection. The newborns were screened for cCMV via dried blood spots (DBS) and saliva collected 1-2 days after birth. The DBS were tested for CMV DNA via polymerase chain reaction (PCR) at the University of Minnesota (UMN) and the CDC.

The overall sensitivity rate was 85.7% for a combination of laboratory results from the UMN and the CDC, which had separate sensitivities of 73.2% and 76.8%, respectively.

The specificity of the combined results was 100.0% (100% from both UMN and CDC), the combined positive predictive value was 98.0% (100.0% from UMN, 97.7% from CDC), and the combined negative predictive value was 99.9% (99.9% from both UMN and CDC).

By comparison, saliva swab test results showed sensitivity of 92.9%, specificity of 99.9%, positive predictive value of 86.7%, and negative predictive value of 100.0%.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the false-positive and false-negative results from saliva screening. Overall, the false-positive rate was 0.06%, which is comparable to rates from other screening techniques, the researchers said. “The recent Food and Drug Administration approval of a point-of-care neonatal saliva CMV test (Meridian Bioscience), underscores the importance of further clarifying the role of false-positive saliva CMV test results and underscores the requirement for urine confirmation for diagnosis of cCMV,” they added.

However, the study findings support the acceptability and feasibility of cCMV screening, as parents reported generally positive attitudes about the process, the researchers said.

The study is ongoing, and designed to follow infants with confirmed cCMV for up to age 4 years to assess clinical outcomes, they added. “Diagnostic methods are always improving, and therefore, our results show the potential of DBS to provide low-cost CMV screening with smooth integration of sample collection, laboratory testing, and follow-up,” they concluded.

Findings lay foundation for widespread use

“By using enhanced PCR methods, Dollard et al. have rekindled the hope that NBDBS [newborn dried blood spots] testing may be a viable method for large-scale, universal newborn screening for congenital CMV,” Gail J. Demmler-Harrison, MD, of Texas Children’s Hospital, Houston, wrote in an accompanying editorial. Congenital CMV is a common infection, but accurate prevalence remains uncertain because not all newborns are tested, she noted. Detection of CMV currently may involve urine, saliva, and blood, but challenges to the use of these methods include “a variety of constantly evolving DNA detection methods,” she said.

Although urine and saliva samples have been proposed for universal screening, they would require the creation of new sample collection and testing programs. “The routine of collecting the NBDBS samples on all newborns and the logistics of routing them to central laboratories and then reporting results to caregivers is already in place and are strengths of NBDBS samples for universal newborn screening,” but had been limited by a less sensitive platform than urine or saliva, said Dr. Demmler-Harrison.

“The results in the study by Dollard et al. may be a total game changer for the NBDBS proponents,” she emphasized. “Furthermore, scientists who have adapted even more sensitive DNA detection assays, such as the loop-mediated isothermal assay for detection of DNA in clinical samples from newborns, may be able to adapt loop-mediated isothermal assay methodology to detect CMV DNA in NBDBS,” she added.

“By adapting the collection methods, by using optimal filter paper to enhance DNA adherence, by improving DNA elution procedures, and by developing novel amplification and detection methods, NBDBS may soon meet the challenge and reach the sensitivity and specificity necessary for universal screening for congenital CMV,” she concluded.

The study was supported by the CDC, the Minnesota Department of Health, the National Vaccine Program Office (U.S. federal government), and the University of South Carolina Disability Research and Dissemination Center.

Dr. Dollard and Dr. Demmler-Harrison had no financial conflicts to disclose.

FROM JAMA PEDIATRICS

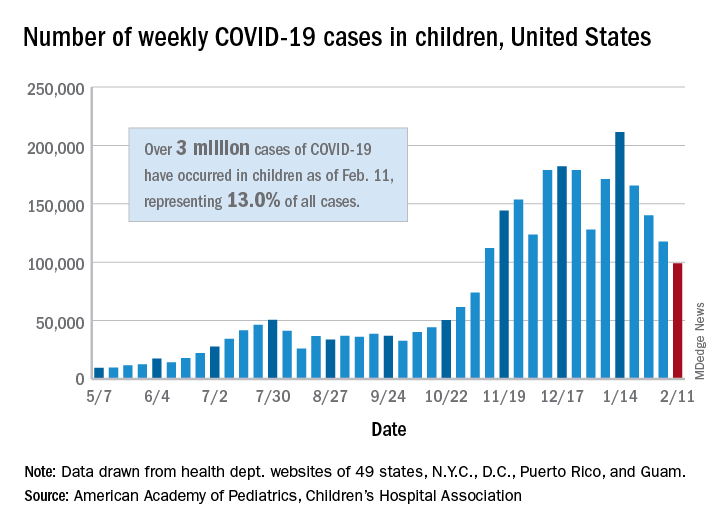

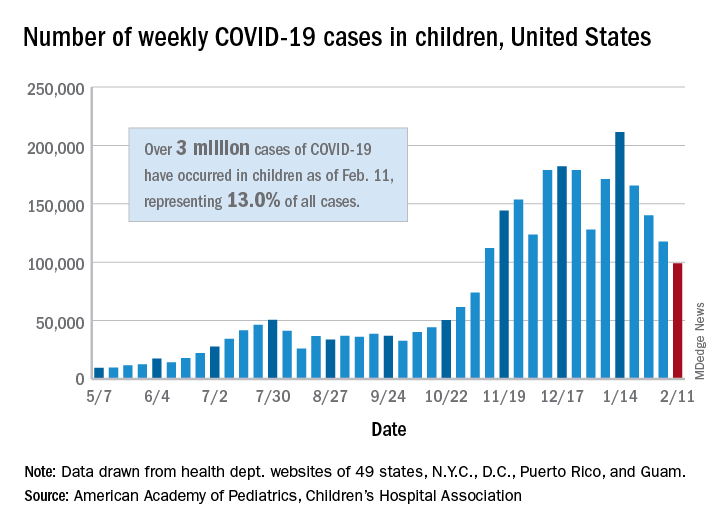

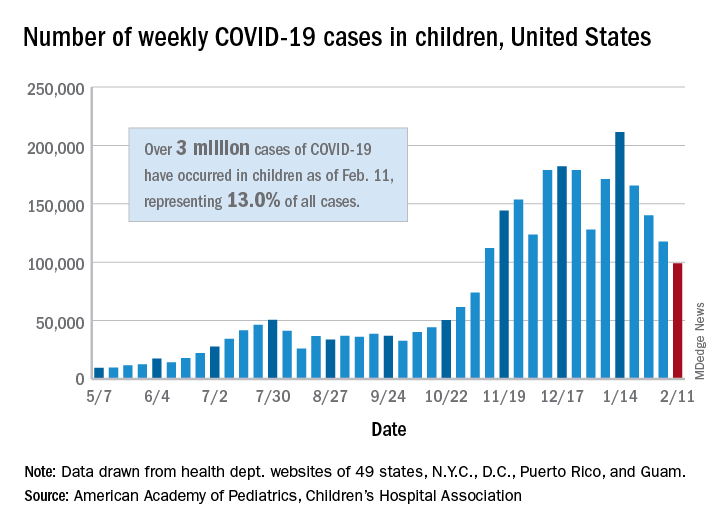

New child COVID-19 cases decline as total passes 3 million

New COVID-19 cases in children continue to drop each week, but the total number of cases has now surpassed 3 million since the start of the pandemic, according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

It was still enough, though, to bring the total to 3.03 million children infected with SARS-CoV-19 in the United States, the AAP and the CHA said in their weekly report.

The nation also hit a couple of other ignominious milestones. The cumulative rate of COVID-19 infection now stands at 4,030 per 100,000, so 4% of all children have been infected. Also, children represented 16.9% of all new cases for the week, which equals the highest proportion seen throughout the pandemic, based on data from health departments in 49 states (excluding New York), the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

There have been 241 COVID-19–related deaths in children so far, with 14 reported during the week of Feb. 5-11. Kansas just recorded its first pediatric death, which leaves 10 states that have had no fatalities. Texas, with 39 deaths, has had more than any other state, among the 43 that are reporting mortality by age, the AAP/CHA report showed.

New COVID-19 cases in children continue to drop each week, but the total number of cases has now surpassed 3 million since the start of the pandemic, according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

It was still enough, though, to bring the total to 3.03 million children infected with SARS-CoV-19 in the United States, the AAP and the CHA said in their weekly report.

The nation also hit a couple of other ignominious milestones. The cumulative rate of COVID-19 infection now stands at 4,030 per 100,000, so 4% of all children have been infected. Also, children represented 16.9% of all new cases for the week, which equals the highest proportion seen throughout the pandemic, based on data from health departments in 49 states (excluding New York), the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

There have been 241 COVID-19–related deaths in children so far, with 14 reported during the week of Feb. 5-11. Kansas just recorded its first pediatric death, which leaves 10 states that have had no fatalities. Texas, with 39 deaths, has had more than any other state, among the 43 that are reporting mortality by age, the AAP/CHA report showed.

New COVID-19 cases in children continue to drop each week, but the total number of cases has now surpassed 3 million since the start of the pandemic, according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

It was still enough, though, to bring the total to 3.03 million children infected with SARS-CoV-19 in the United States, the AAP and the CHA said in their weekly report.

The nation also hit a couple of other ignominious milestones. The cumulative rate of COVID-19 infection now stands at 4,030 per 100,000, so 4% of all children have been infected. Also, children represented 16.9% of all new cases for the week, which equals the highest proportion seen throughout the pandemic, based on data from health departments in 49 states (excluding New York), the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

There have been 241 COVID-19–related deaths in children so far, with 14 reported during the week of Feb. 5-11. Kansas just recorded its first pediatric death, which leaves 10 states that have had no fatalities. Texas, with 39 deaths, has had more than any other state, among the 43 that are reporting mortality by age, the AAP/CHA report showed.

One-third of health care workers leery of getting COVID-19 vaccine, survey shows

Moreover, 54% of direct care providers indicated that they would take the vaccine if offered, compared with 60% of noncare providers.

The findings come from what is believed to be the largest survey of health care provider attitudes toward COVID-19 vaccination, published online Jan. 25 in Clinical Infectious Diseases.

“We have shown that self-reported willingness to receive vaccination against COVID-19 differs by age, gender, race and hospital role, with physicians and research scientists showing the highest acceptance,” Jana Shaw, MD, MPH, State University of New York, Syracuse, N.Y, the study’s corresponding author, told this news organization. “Building trust in authorities and confidence in vaccines is a complex and time-consuming process that requires commitment and resources. We have to make those investments as hesitancy can severely undermine vaccination coverage. Because health care providers are members of our communities, it is possible that their views are shared by the public at large. Our findings can assist public health professionals as a starting point of discussion and engagement with communities to ensure that we vaccinate at least 80% of the public to end the pandemic.”

For the study, Dr. Shaw and her colleagues emailed an anonymous survey to 9,565 employees of State University of New York Upstate Medical University, Syracuse, an academic medical center that cares for an estimated 1.8 million people. The survey, which contained questions intended to evaluate attitudes, belief, and willingness to get vaccinated, took place between Nov. 23 and Dec. 5, about a week before the U.S. Food and Drug Administration granted the first emergency use authorization for the Pfizer-BioNTech BNT162b2 mRNA vaccine.

Survey recipients included physicians, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, nurses, pharmacists, medical and nursing students, allied health professionals, and nonclinical ancillary staff.

Of the 9,565 surveys sent, 5,287 responses were collected and used in the final analysis, for a response rate of 55%. The mean age of respondents was 43, 73% were female, 85% were White, 6% were Asian, 5% were Black/African American, and the rest were Native American, Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, or from other races. More than half of respondents (59%) reported that they provided direct patient care, and 32% said they provided care for patients with COVID-19.

Of all survey respondents, 58% expressed their intent to receive a COVID-19 vaccine, but this varied by their role in the health care system. For example, in response to the statement, “If a vaccine were offered free of charge, I would take it,” 80% of scientists and physicians agreed that they would, while colleagues in other roles were unsure whether they would take the vaccine, including 34% of registered nurses, 32% of allied health professionals, and 32% of master’s-level clinicians. These differences across roles were significant (P less than .001).

The researchers also found that direct patient care or care for COVID-19 patients was associated with lower vaccination intent. For example, 54% of direct care providers and 62% of non-care providers indicated they would take the vaccine if offered, compared with 52% of those who had provided care for COVID-19 patients vs. 61% of those who had not (P less than .001).

“This was a really surprising finding,” said Dr. Shaw, who is a pediatric infectious diseases physician at SUNY Upstate. “In general, one would expect that perceived severity of disease would lead to a greater desire to get vaccinated. Because our question did not address severity of disease, it is possible that we oversampled respondents who took care of patients with mild disease (i.e., in an outpatient setting). This could have led to an underestimation of disease severity and resulted in lower vaccination intent.”

A focus on rebuilding trust

Survey respondents who agreed or strongly agreed that they would accept a vaccine were older (a mean age of 44 years), compared with those who were not sure or who disagreed (a mean age of 42 vs. 38 years, respectively; P less than .001). In addition, fewer females agreed or strongly agreed that they would accept a vaccine (54% vs. 73% of males), whereas those who self-identified as Black/African American were least likely to want to get vaccinated, compared with those from other ethnic groups (31%, compared with 74% of Asians, 58% of Whites, and 39% of American Indians or Alaska Natives).

“We are deeply aware of the poor decisions scientists made in the past, which led to a prevailing skepticism and ‘feeling like guinea pigs’ among people of color, especially Black adults,” Dr. Shaw said. “Black adults are less likely, compared [with] White adults, to have confidence that scientists act in the public interest. Rebuilding trust will take time and has to start with addressing health care disparities. In addition, we need to acknowledge contributions of Black researchers to science. For example, until recently very few knew that the Moderna vaccine was developed [with the help of] Dr. Kizzmekia Corbett, who is Black.”

The top five main areas of unease that all respondents expressed about a COVID-19 vaccine were concern about adverse events/side effects (47%), efficacy (15%), rushed release (11%), safety (11%), and the research and authorization process (3%).

“I think it is important that fellow clinicians recognize that, in order to boost vaccine confidence we will need careful, individually tailored communication strategies,” Dr. Shaw said. “A consideration should be given to those [strategies] that utilize interpersonal channels that deliver leadership by example and leverage influencers in the institution to encourage wider adoption of vaccination.”

Aaron M. Milstone, MD, MHS, asked to comment on the research, recommended that health care workers advocate for the vaccine and encourage their patients, friends, and loved ones to get vaccinated. “Soon, COVID-19 will have taken more than half a million lives in the U.S.,” said Dr. Milstone, a pediatric epidemiologist at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore. “Although vaccines can have side effects like fever and muscle aches, and very, very rare more serious side effects, the risks of dying from COVID are much greater than the risk of a serious vaccine reaction. The study’s authors shed light on the ongoing need for leaders of all communities to support the COVID vaccines, not just the scientific community, but religious leaders, political leaders, and community leaders.”

Addressing vaccine hesitancy

Informed by their own survey, Dr. Shaw and her colleagues have developed a plan to address vaccine hesitancy to ensure high vaccine uptake at SUNY Upstate. Those strategies include, but aren’t limited to, institution-wide forums for all employees on COVID-19 vaccine safety, risks, and benefits followed by Q&A sessions, grand rounds for providers summarizing clinical trial data on mRNA vaccines, development of an Ask COVID email line for staff to ask vaccine-related questions, and a detailed vaccine-specific FAQ document.

In addition, SUNY Upstate experts have engaged in numerous media interviews to provide education and updates on the benefits of vaccination to public and staff, stationary vaccine locations, and mobile COVID-19 vaccine carts. “To date, the COVID-19 vaccination process has been well received, and we anticipate strong vaccine uptake,” she said.

Dr. Shaw acknowledged certain limitations of the survey, including its cross-sectional design and the fact that it was conducted in a single health care system in the northeastern United States. “Thus, generalizability to other regions of the U.S. and other countries may be limited,” Dr. Shaw said. “The study was also conducted before EUA [emergency use authorization] was granted to either the Moderna or Pfizer-BioNTech vaccines. It is therefore likely that vaccine acceptance will change over time as more people get vaccinated.”

The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Milstone disclosed that he has received a research grant from Merck, but it is not related to vaccines.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Moreover, 54% of direct care providers indicated that they would take the vaccine if offered, compared with 60% of noncare providers.

The findings come from what is believed to be the largest survey of health care provider attitudes toward COVID-19 vaccination, published online Jan. 25 in Clinical Infectious Diseases.

“We have shown that self-reported willingness to receive vaccination against COVID-19 differs by age, gender, race and hospital role, with physicians and research scientists showing the highest acceptance,” Jana Shaw, MD, MPH, State University of New York, Syracuse, N.Y, the study’s corresponding author, told this news organization. “Building trust in authorities and confidence in vaccines is a complex and time-consuming process that requires commitment and resources. We have to make those investments as hesitancy can severely undermine vaccination coverage. Because health care providers are members of our communities, it is possible that their views are shared by the public at large. Our findings can assist public health professionals as a starting point of discussion and engagement with communities to ensure that we vaccinate at least 80% of the public to end the pandemic.”

For the study, Dr. Shaw and her colleagues emailed an anonymous survey to 9,565 employees of State University of New York Upstate Medical University, Syracuse, an academic medical center that cares for an estimated 1.8 million people. The survey, which contained questions intended to evaluate attitudes, belief, and willingness to get vaccinated, took place between Nov. 23 and Dec. 5, about a week before the U.S. Food and Drug Administration granted the first emergency use authorization for the Pfizer-BioNTech BNT162b2 mRNA vaccine.

Survey recipients included physicians, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, nurses, pharmacists, medical and nursing students, allied health professionals, and nonclinical ancillary staff.

Of the 9,565 surveys sent, 5,287 responses were collected and used in the final analysis, for a response rate of 55%. The mean age of respondents was 43, 73% were female, 85% were White, 6% were Asian, 5% were Black/African American, and the rest were Native American, Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, or from other races. More than half of respondents (59%) reported that they provided direct patient care, and 32% said they provided care for patients with COVID-19.

Of all survey respondents, 58% expressed their intent to receive a COVID-19 vaccine, but this varied by their role in the health care system. For example, in response to the statement, “If a vaccine were offered free of charge, I would take it,” 80% of scientists and physicians agreed that they would, while colleagues in other roles were unsure whether they would take the vaccine, including 34% of registered nurses, 32% of allied health professionals, and 32% of master’s-level clinicians. These differences across roles were significant (P less than .001).

The researchers also found that direct patient care or care for COVID-19 patients was associated with lower vaccination intent. For example, 54% of direct care providers and 62% of non-care providers indicated they would take the vaccine if offered, compared with 52% of those who had provided care for COVID-19 patients vs. 61% of those who had not (P less than .001).

“This was a really surprising finding,” said Dr. Shaw, who is a pediatric infectious diseases physician at SUNY Upstate. “In general, one would expect that perceived severity of disease would lead to a greater desire to get vaccinated. Because our question did not address severity of disease, it is possible that we oversampled respondents who took care of patients with mild disease (i.e., in an outpatient setting). This could have led to an underestimation of disease severity and resulted in lower vaccination intent.”

A focus on rebuilding trust

Survey respondents who agreed or strongly agreed that they would accept a vaccine were older (a mean age of 44 years), compared with those who were not sure or who disagreed (a mean age of 42 vs. 38 years, respectively; P less than .001). In addition, fewer females agreed or strongly agreed that they would accept a vaccine (54% vs. 73% of males), whereas those who self-identified as Black/African American were least likely to want to get vaccinated, compared with those from other ethnic groups (31%, compared with 74% of Asians, 58% of Whites, and 39% of American Indians or Alaska Natives).

“We are deeply aware of the poor decisions scientists made in the past, which led to a prevailing skepticism and ‘feeling like guinea pigs’ among people of color, especially Black adults,” Dr. Shaw said. “Black adults are less likely, compared [with] White adults, to have confidence that scientists act in the public interest. Rebuilding trust will take time and has to start with addressing health care disparities. In addition, we need to acknowledge contributions of Black researchers to science. For example, until recently very few knew that the Moderna vaccine was developed [with the help of] Dr. Kizzmekia Corbett, who is Black.”

The top five main areas of unease that all respondents expressed about a COVID-19 vaccine were concern about adverse events/side effects (47%), efficacy (15%), rushed release (11%), safety (11%), and the research and authorization process (3%).

“I think it is important that fellow clinicians recognize that, in order to boost vaccine confidence we will need careful, individually tailored communication strategies,” Dr. Shaw said. “A consideration should be given to those [strategies] that utilize interpersonal channels that deliver leadership by example and leverage influencers in the institution to encourage wider adoption of vaccination.”

Aaron M. Milstone, MD, MHS, asked to comment on the research, recommended that health care workers advocate for the vaccine and encourage their patients, friends, and loved ones to get vaccinated. “Soon, COVID-19 will have taken more than half a million lives in the U.S.,” said Dr. Milstone, a pediatric epidemiologist at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore. “Although vaccines can have side effects like fever and muscle aches, and very, very rare more serious side effects, the risks of dying from COVID are much greater than the risk of a serious vaccine reaction. The study’s authors shed light on the ongoing need for leaders of all communities to support the COVID vaccines, not just the scientific community, but religious leaders, political leaders, and community leaders.”

Addressing vaccine hesitancy

Informed by their own survey, Dr. Shaw and her colleagues have developed a plan to address vaccine hesitancy to ensure high vaccine uptake at SUNY Upstate. Those strategies include, but aren’t limited to, institution-wide forums for all employees on COVID-19 vaccine safety, risks, and benefits followed by Q&A sessions, grand rounds for providers summarizing clinical trial data on mRNA vaccines, development of an Ask COVID email line for staff to ask vaccine-related questions, and a detailed vaccine-specific FAQ document.

In addition, SUNY Upstate experts have engaged in numerous media interviews to provide education and updates on the benefits of vaccination to public and staff, stationary vaccine locations, and mobile COVID-19 vaccine carts. “To date, the COVID-19 vaccination process has been well received, and we anticipate strong vaccine uptake,” she said.

Dr. Shaw acknowledged certain limitations of the survey, including its cross-sectional design and the fact that it was conducted in a single health care system in the northeastern United States. “Thus, generalizability to other regions of the U.S. and other countries may be limited,” Dr. Shaw said. “The study was also conducted before EUA [emergency use authorization] was granted to either the Moderna or Pfizer-BioNTech vaccines. It is therefore likely that vaccine acceptance will change over time as more people get vaccinated.”

The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Milstone disclosed that he has received a research grant from Merck, but it is not related to vaccines.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Moreover, 54% of direct care providers indicated that they would take the vaccine if offered, compared with 60% of noncare providers.

The findings come from what is believed to be the largest survey of health care provider attitudes toward COVID-19 vaccination, published online Jan. 25 in Clinical Infectious Diseases.

“We have shown that self-reported willingness to receive vaccination against COVID-19 differs by age, gender, race and hospital role, with physicians and research scientists showing the highest acceptance,” Jana Shaw, MD, MPH, State University of New York, Syracuse, N.Y, the study’s corresponding author, told this news organization. “Building trust in authorities and confidence in vaccines is a complex and time-consuming process that requires commitment and resources. We have to make those investments as hesitancy can severely undermine vaccination coverage. Because health care providers are members of our communities, it is possible that their views are shared by the public at large. Our findings can assist public health professionals as a starting point of discussion and engagement with communities to ensure that we vaccinate at least 80% of the public to end the pandemic.”

For the study, Dr. Shaw and her colleagues emailed an anonymous survey to 9,565 employees of State University of New York Upstate Medical University, Syracuse, an academic medical center that cares for an estimated 1.8 million people. The survey, which contained questions intended to evaluate attitudes, belief, and willingness to get vaccinated, took place between Nov. 23 and Dec. 5, about a week before the U.S. Food and Drug Administration granted the first emergency use authorization for the Pfizer-BioNTech BNT162b2 mRNA vaccine.

Survey recipients included physicians, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, nurses, pharmacists, medical and nursing students, allied health professionals, and nonclinical ancillary staff.

Of the 9,565 surveys sent, 5,287 responses were collected and used in the final analysis, for a response rate of 55%. The mean age of respondents was 43, 73% were female, 85% were White, 6% were Asian, 5% were Black/African American, and the rest were Native American, Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, or from other races. More than half of respondents (59%) reported that they provided direct patient care, and 32% said they provided care for patients with COVID-19.

Of all survey respondents, 58% expressed their intent to receive a COVID-19 vaccine, but this varied by their role in the health care system. For example, in response to the statement, “If a vaccine were offered free of charge, I would take it,” 80% of scientists and physicians agreed that they would, while colleagues in other roles were unsure whether they would take the vaccine, including 34% of registered nurses, 32% of allied health professionals, and 32% of master’s-level clinicians. These differences across roles were significant (P less than .001).

The researchers also found that direct patient care or care for COVID-19 patients was associated with lower vaccination intent. For example, 54% of direct care providers and 62% of non-care providers indicated they would take the vaccine if offered, compared with 52% of those who had provided care for COVID-19 patients vs. 61% of those who had not (P less than .001).

“This was a really surprising finding,” said Dr. Shaw, who is a pediatric infectious diseases physician at SUNY Upstate. “In general, one would expect that perceived severity of disease would lead to a greater desire to get vaccinated. Because our question did not address severity of disease, it is possible that we oversampled respondents who took care of patients with mild disease (i.e., in an outpatient setting). This could have led to an underestimation of disease severity and resulted in lower vaccination intent.”

A focus on rebuilding trust

Survey respondents who agreed or strongly agreed that they would accept a vaccine were older (a mean age of 44 years), compared with those who were not sure or who disagreed (a mean age of 42 vs. 38 years, respectively; P less than .001). In addition, fewer females agreed or strongly agreed that they would accept a vaccine (54% vs. 73% of males), whereas those who self-identified as Black/African American were least likely to want to get vaccinated, compared with those from other ethnic groups (31%, compared with 74% of Asians, 58% of Whites, and 39% of American Indians or Alaska Natives).

“We are deeply aware of the poor decisions scientists made in the past, which led to a prevailing skepticism and ‘feeling like guinea pigs’ among people of color, especially Black adults,” Dr. Shaw said. “Black adults are less likely, compared [with] White adults, to have confidence that scientists act in the public interest. Rebuilding trust will take time and has to start with addressing health care disparities. In addition, we need to acknowledge contributions of Black researchers to science. For example, until recently very few knew that the Moderna vaccine was developed [with the help of] Dr. Kizzmekia Corbett, who is Black.”

The top five main areas of unease that all respondents expressed about a COVID-19 vaccine were concern about adverse events/side effects (47%), efficacy (15%), rushed release (11%), safety (11%), and the research and authorization process (3%).

“I think it is important that fellow clinicians recognize that, in order to boost vaccine confidence we will need careful, individually tailored communication strategies,” Dr. Shaw said. “A consideration should be given to those [strategies] that utilize interpersonal channels that deliver leadership by example and leverage influencers in the institution to encourage wider adoption of vaccination.”

Aaron M. Milstone, MD, MHS, asked to comment on the research, recommended that health care workers advocate for the vaccine and encourage their patients, friends, and loved ones to get vaccinated. “Soon, COVID-19 will have taken more than half a million lives in the U.S.,” said Dr. Milstone, a pediatric epidemiologist at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore. “Although vaccines can have side effects like fever and muscle aches, and very, very rare more serious side effects, the risks of dying from COVID are much greater than the risk of a serious vaccine reaction. The study’s authors shed light on the ongoing need for leaders of all communities to support the COVID vaccines, not just the scientific community, but religious leaders, political leaders, and community leaders.”

Addressing vaccine hesitancy

Informed by their own survey, Dr. Shaw and her colleagues have developed a plan to address vaccine hesitancy to ensure high vaccine uptake at SUNY Upstate. Those strategies include, but aren’t limited to, institution-wide forums for all employees on COVID-19 vaccine safety, risks, and benefits followed by Q&A sessions, grand rounds for providers summarizing clinical trial data on mRNA vaccines, development of an Ask COVID email line for staff to ask vaccine-related questions, and a detailed vaccine-specific FAQ document.

In addition, SUNY Upstate experts have engaged in numerous media interviews to provide education and updates on the benefits of vaccination to public and staff, stationary vaccine locations, and mobile COVID-19 vaccine carts. “To date, the COVID-19 vaccination process has been well received, and we anticipate strong vaccine uptake,” she said.

Dr. Shaw acknowledged certain limitations of the survey, including its cross-sectional design and the fact that it was conducted in a single health care system in the northeastern United States. “Thus, generalizability to other regions of the U.S. and other countries may be limited,” Dr. Shaw said. “The study was also conducted before EUA [emergency use authorization] was granted to either the Moderna or Pfizer-BioNTech vaccines. It is therefore likely that vaccine acceptance will change over time as more people get vaccinated.”

The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Milstone disclosed that he has received a research grant from Merck, but it is not related to vaccines.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Prospective data support delaying antibiotics for pediatric respiratory infections

For pediatric patients with respiratory tract infections (RTIs), immediately prescribing antibiotics may do more harm than good, based on prospective data from 436 children treated by primary care pediatricians in Spain.

In the largest trial of its kind to date, children who were immediately prescribed antibiotics showed no significant difference in symptom severity or duration from those who received a delayed prescription for antibiotics, or no prescription at all; yet those in the immediate-prescription group had a higher rate of gastrointestinal adverse events, reported lead author Gemma Mas-Dalmau, MD, of the Sant Pau Institute for Biomedical Research, Barcelona, and colleagues.

“Most RTIs are self-limiting, and antibiotics hardly alter the course of the condition, yet antibiotics are frequently prescribed for these conditions,” the investigators wrote in Pediatrics. “Antibiotic prescription for RTIs in children is especially considered to be inappropriately high.”

This clinical behavior is driven by several factors, according to Dr. Mas-Dalmau and colleagues, including limited diagnostics in primary care, pressure to meet parental expectations, and concern for possible complications if antibiotics are withheld or delayed.

In an accompanying editorial, Jeffrey S. Gerber, MD, PhD and Bonnie F. Offit, MD, of Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, noted that “children in the United States receive more than one antibiotic prescription per year, driven largely by acute RTIs.”

Dr. Gerber and Dr. Offit noted that some RTIs are indeed caused by bacteria, and therefore benefit from antibiotics, but it’s “not always easy” to identify these cases.

“Primary care, urgent care, and emergency medicine clinicians have a hard job,” they wrote.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, delayed prescription of antibiotics, in which a prescription is filled upon persistence or worsening of symptoms, can balance clinical caution and antibiotic stewardship.

“An example of this approach is acute otitis media, in which delayed prescribing has been shown to safely reduce antibiotic exposure,” wrote Dr. Gerber and Dr. Offit.

In a 2017 Cochrane systematic review of both adults and children with RTIs, antibiotic prescriptions, whether immediate, delayed, or not given at all, had no significant effect on most symptoms or complications. Although several randomized trials have evaluated delayed antibiotic prescriptions in children, Dr. Mas-Dalmau and colleagues described the current body of evidence as “scant.”

The present study built upon this knowledge base by prospectively following 436 children treated at 39 primary care centers in Spain from 2012 to 2016. Patients were between 2 and 14 years of age and presented for rhinosinusitis, pharyngitis, acute otitis media, or acute bronchitis. Inclusion in the study required the pediatrician to have “reasonable doubts about the need to prescribe an antibiotic.” Clinics with access to rapid streptococcal testing did not enroll patients with pharyngitis.

Patients were randomized in approximately equal groups to receive either immediate prescription of antibiotics, delayed prescription, or no prescription. In the delayed group, caregivers were advised to fill prescriptions if any of following three events occurred:

- No symptom improvement after a certain amount of days, depending on presenting complaint (acute otitis media, 4 days; pharyngitis, 7 days; acute rhinosinusitis, 15 days; acute bronchitis, 20 days).

- Temperature of at least 39° C after 24 hours, or at least 38° C but less than 39° C after 48 hours.

- Patient feeling “much worse.”

Primary outcomes were severity and duration of symptoms over 30 days, while secondary outcomes included antibiotic use over 30 days, additional unscheduled visits to primary care over 30 days, and parental satisfaction and beliefs regarding antibiotic efficacy.

In the final dataset, 148 patients received immediate antibiotic prescriptions, while 146 received delayed prescriptions, and 142 received no prescription. Rate of antibiotic use was highest in the immediate prescription group, at 96%, versus 25.3% in the delayed group and 12% among those who received no prescription upon first presentation (P < .001).

Although the mean duration of severe symptoms was longest in the delayed-prescription group, at 12.4 days, versus 10.9 days in the no-prescription group and 10.1 days in the immediate-prescription group, these differences were not statistically significant (P = .539). Median score for greatest severity of any symptom was also similar across groups. Secondary outcomes echoed this pattern, in which reconsultation rates and caregiver satisfaction were statistically similar regardless of treatment type.

In contrast, patients who received immediate antibiotic prescriptions had a significantly higher rate of gastrointestinal adverse events (8.8%) than those who received a delayed prescription (3.4%) or no prescription (2.8%; P = .037).

“Delayed antibiotic prescription is an efficacious and safe strategy for reducing inappropriate antibiotic treatment of uncomplicated RTIs in children when the doctor has reasonable doubts regarding the indication,” the investigators concluded. “[It] is therefore a useful tool for addressing the public health issue of bacterial resistance. However, no antibiotic prescription remains the recommended strategy when it is clear that antibiotics are not indicated, like in most cases of acute bronchitis.”

“These data are reassuring,” wrote Dr. Gerber and Dr. Offit; however, they went on to suggest that the data “might not substantially move the needle.”

“With rare exceptions, children with acute pharyngitis should first receive a group A streptococcal test,” they wrote. “If results are positive, all patients should get antibiotics; if results are negative, no one gets them. Acute bronchitis (whatever that is in children) is viral. Acute sinusitis with persistent symptoms (the most commonly diagnosed variety) already has a delayed option, and the current study ... was not powered for this outcome. We are left with acute otitis media, which dominated enrollment but already has an evidence-based guideline.”

Still, Dr. Gerber and Dr. Offit suggested that the findings should further encourage pediatricians to prescribe antibiotics judiciously, and when elected, to choose the shortest duration and narrowest spectrum possible.

In a joint comment, Rana El Feghaly, MD, MSCI, director of outpatient antibiotic stewardship at Children’s Mercy, Kansas City, and her colleague, Mary Anne Jackson, MD, noted that the findings are “in accordance” with the 2017 Cochrane review.

Dr. Feghaly and Dr. Jackson said that these new data provide greater support for conservative use of antibiotics, which is badly needed, considering approximately 50% of outpatient prescriptions are unnecessary or inappropriate .

Delayed antibiotic prescription is part of a multifaceted approach to the issue, they said, joining “communication skills training, antibiotic justification documentation, audit and feedback reporting with peer comparison, diagnostic stewardship, [and] the use of clinician education on practice-based guidelines.”

“Leveraging delayed antibiotic prescription may be an excellent way to combat antibiotic overuse in the outpatient setting, while avoiding provider and parental fear of the ‘no antibiotic’ approach,” Dr. Feghaly and Dr. Jackson said.

Karlyn Kinsella, MD, of Pediatric Associates of Cheshire, Conn., suggested that clinicians discuss these findings with parents who request antibiotics for “otitis, pharyngitis, bronchitis, or sinusitis.”

“We can cite this study that antibiotics have no effect on symptom duration or severity for these illnesses,” Dr. Kinsella said. “Of course, our clinical opinion in each case takes precedent.”

According to Dr. Kinsella, conversations with parents also need to cover reasonable expectations, as the study did, with clear time frames for each condition in which children should start to get better.

“I think this is really key in our anticipatory guidance so that patients know what to expect,” she said.

The study was funded by Instituto de Salud Carlos III, the European Union, and the Spanish Ministry of Health, Social Services, and Equality. The investigators and interviewees reported no conflicts of interest.

For pediatric patients with respiratory tract infections (RTIs), immediately prescribing antibiotics may do more harm than good, based on prospective data from 436 children treated by primary care pediatricians in Spain.

In the largest trial of its kind to date, children who were immediately prescribed antibiotics showed no significant difference in symptom severity or duration from those who received a delayed prescription for antibiotics, or no prescription at all; yet those in the immediate-prescription group had a higher rate of gastrointestinal adverse events, reported lead author Gemma Mas-Dalmau, MD, of the Sant Pau Institute for Biomedical Research, Barcelona, and colleagues.

“Most RTIs are self-limiting, and antibiotics hardly alter the course of the condition, yet antibiotics are frequently prescribed for these conditions,” the investigators wrote in Pediatrics. “Antibiotic prescription for RTIs in children is especially considered to be inappropriately high.”

This clinical behavior is driven by several factors, according to Dr. Mas-Dalmau and colleagues, including limited diagnostics in primary care, pressure to meet parental expectations, and concern for possible complications if antibiotics are withheld or delayed.

In an accompanying editorial, Jeffrey S. Gerber, MD, PhD and Bonnie F. Offit, MD, of Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, noted that “children in the United States receive more than one antibiotic prescription per year, driven largely by acute RTIs.”

Dr. Gerber and Dr. Offit noted that some RTIs are indeed caused by bacteria, and therefore benefit from antibiotics, but it’s “not always easy” to identify these cases.

“Primary care, urgent care, and emergency medicine clinicians have a hard job,” they wrote.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, delayed prescription of antibiotics, in which a prescription is filled upon persistence or worsening of symptoms, can balance clinical caution and antibiotic stewardship.

“An example of this approach is acute otitis media, in which delayed prescribing has been shown to safely reduce antibiotic exposure,” wrote Dr. Gerber and Dr. Offit.

In a 2017 Cochrane systematic review of both adults and children with RTIs, antibiotic prescriptions, whether immediate, delayed, or not given at all, had no significant effect on most symptoms or complications. Although several randomized trials have evaluated delayed antibiotic prescriptions in children, Dr. Mas-Dalmau and colleagues described the current body of evidence as “scant.”

The present study built upon this knowledge base by prospectively following 436 children treated at 39 primary care centers in Spain from 2012 to 2016. Patients were between 2 and 14 years of age and presented for rhinosinusitis, pharyngitis, acute otitis media, or acute bronchitis. Inclusion in the study required the pediatrician to have “reasonable doubts about the need to prescribe an antibiotic.” Clinics with access to rapid streptococcal testing did not enroll patients with pharyngitis.

Patients were randomized in approximately equal groups to receive either immediate prescription of antibiotics, delayed prescription, or no prescription. In the delayed group, caregivers were advised to fill prescriptions if any of following three events occurred:

- No symptom improvement after a certain amount of days, depending on presenting complaint (acute otitis media, 4 days; pharyngitis, 7 days; acute rhinosinusitis, 15 days; acute bronchitis, 20 days).

- Temperature of at least 39° C after 24 hours, or at least 38° C but less than 39° C after 48 hours.

- Patient feeling “much worse.”

Primary outcomes were severity and duration of symptoms over 30 days, while secondary outcomes included antibiotic use over 30 days, additional unscheduled visits to primary care over 30 days, and parental satisfaction and beliefs regarding antibiotic efficacy.

In the final dataset, 148 patients received immediate antibiotic prescriptions, while 146 received delayed prescriptions, and 142 received no prescription. Rate of antibiotic use was highest in the immediate prescription group, at 96%, versus 25.3% in the delayed group and 12% among those who received no prescription upon first presentation (P < .001).

Although the mean duration of severe symptoms was longest in the delayed-prescription group, at 12.4 days, versus 10.9 days in the no-prescription group and 10.1 days in the immediate-prescription group, these differences were not statistically significant (P = .539). Median score for greatest severity of any symptom was also similar across groups. Secondary outcomes echoed this pattern, in which reconsultation rates and caregiver satisfaction were statistically similar regardless of treatment type.

In contrast, patients who received immediate antibiotic prescriptions had a significantly higher rate of gastrointestinal adverse events (8.8%) than those who received a delayed prescription (3.4%) or no prescription (2.8%; P = .037).

“Delayed antibiotic prescription is an efficacious and safe strategy for reducing inappropriate antibiotic treatment of uncomplicated RTIs in children when the doctor has reasonable doubts regarding the indication,” the investigators concluded. “[It] is therefore a useful tool for addressing the public health issue of bacterial resistance. However, no antibiotic prescription remains the recommended strategy when it is clear that antibiotics are not indicated, like in most cases of acute bronchitis.”

“These data are reassuring,” wrote Dr. Gerber and Dr. Offit; however, they went on to suggest that the data “might not substantially move the needle.”

“With rare exceptions, children with acute pharyngitis should first receive a group A streptococcal test,” they wrote. “If results are positive, all patients should get antibiotics; if results are negative, no one gets them. Acute bronchitis (whatever that is in children) is viral. Acute sinusitis with persistent symptoms (the most commonly diagnosed variety) already has a delayed option, and the current study ... was not powered for this outcome. We are left with acute otitis media, which dominated enrollment but already has an evidence-based guideline.”

Still, Dr. Gerber and Dr. Offit suggested that the findings should further encourage pediatricians to prescribe antibiotics judiciously, and when elected, to choose the shortest duration and narrowest spectrum possible.

In a joint comment, Rana El Feghaly, MD, MSCI, director of outpatient antibiotic stewardship at Children’s Mercy, Kansas City, and her colleague, Mary Anne Jackson, MD, noted that the findings are “in accordance” with the 2017 Cochrane review.

Dr. Feghaly and Dr. Jackson said that these new data provide greater support for conservative use of antibiotics, which is badly needed, considering approximately 50% of outpatient prescriptions are unnecessary or inappropriate .

Delayed antibiotic prescription is part of a multifaceted approach to the issue, they said, joining “communication skills training, antibiotic justification documentation, audit and feedback reporting with peer comparison, diagnostic stewardship, [and] the use of clinician education on practice-based guidelines.”

“Leveraging delayed antibiotic prescription may be an excellent way to combat antibiotic overuse in the outpatient setting, while avoiding provider and parental fear of the ‘no antibiotic’ approach,” Dr. Feghaly and Dr. Jackson said.

Karlyn Kinsella, MD, of Pediatric Associates of Cheshire, Conn., suggested that clinicians discuss these findings with parents who request antibiotics for “otitis, pharyngitis, bronchitis, or sinusitis.”

“We can cite this study that antibiotics have no effect on symptom duration or severity for these illnesses,” Dr. Kinsella said. “Of course, our clinical opinion in each case takes precedent.”

According to Dr. Kinsella, conversations with parents also need to cover reasonable expectations, as the study did, with clear time frames for each condition in which children should start to get better.

“I think this is really key in our anticipatory guidance so that patients know what to expect,” she said.

The study was funded by Instituto de Salud Carlos III, the European Union, and the Spanish Ministry of Health, Social Services, and Equality. The investigators and interviewees reported no conflicts of interest.

For pediatric patients with respiratory tract infections (RTIs), immediately prescribing antibiotics may do more harm than good, based on prospective data from 436 children treated by primary care pediatricians in Spain.

In the largest trial of its kind to date, children who were immediately prescribed antibiotics showed no significant difference in symptom severity or duration from those who received a delayed prescription for antibiotics, or no prescription at all; yet those in the immediate-prescription group had a higher rate of gastrointestinal adverse events, reported lead author Gemma Mas-Dalmau, MD, of the Sant Pau Institute for Biomedical Research, Barcelona, and colleagues.

“Most RTIs are self-limiting, and antibiotics hardly alter the course of the condition, yet antibiotics are frequently prescribed for these conditions,” the investigators wrote in Pediatrics. “Antibiotic prescription for RTIs in children is especially considered to be inappropriately high.”

This clinical behavior is driven by several factors, according to Dr. Mas-Dalmau and colleagues, including limited diagnostics in primary care, pressure to meet parental expectations, and concern for possible complications if antibiotics are withheld or delayed.

In an accompanying editorial, Jeffrey S. Gerber, MD, PhD and Bonnie F. Offit, MD, of Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, noted that “children in the United States receive more than one antibiotic prescription per year, driven largely by acute RTIs.”

Dr. Gerber and Dr. Offit noted that some RTIs are indeed caused by bacteria, and therefore benefit from antibiotics, but it’s “not always easy” to identify these cases.

“Primary care, urgent care, and emergency medicine clinicians have a hard job,” they wrote.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, delayed prescription of antibiotics, in which a prescription is filled upon persistence or worsening of symptoms, can balance clinical caution and antibiotic stewardship.

“An example of this approach is acute otitis media, in which delayed prescribing has been shown to safely reduce antibiotic exposure,” wrote Dr. Gerber and Dr. Offit.

In a 2017 Cochrane systematic review of both adults and children with RTIs, antibiotic prescriptions, whether immediate, delayed, or not given at all, had no significant effect on most symptoms or complications. Although several randomized trials have evaluated delayed antibiotic prescriptions in children, Dr. Mas-Dalmau and colleagues described the current body of evidence as “scant.”

The present study built upon this knowledge base by prospectively following 436 children treated at 39 primary care centers in Spain from 2012 to 2016. Patients were between 2 and 14 years of age and presented for rhinosinusitis, pharyngitis, acute otitis media, or acute bronchitis. Inclusion in the study required the pediatrician to have “reasonable doubts about the need to prescribe an antibiotic.” Clinics with access to rapid streptococcal testing did not enroll patients with pharyngitis.

Patients were randomized in approximately equal groups to receive either immediate prescription of antibiotics, delayed prescription, or no prescription. In the delayed group, caregivers were advised to fill prescriptions if any of following three events occurred:

- No symptom improvement after a certain amount of days, depending on presenting complaint (acute otitis media, 4 days; pharyngitis, 7 days; acute rhinosinusitis, 15 days; acute bronchitis, 20 days).

- Temperature of at least 39° C after 24 hours, or at least 38° C but less than 39° C after 48 hours.

- Patient feeling “much worse.”

Primary outcomes were severity and duration of symptoms over 30 days, while secondary outcomes included antibiotic use over 30 days, additional unscheduled visits to primary care over 30 days, and parental satisfaction and beliefs regarding antibiotic efficacy.

In the final dataset, 148 patients received immediate antibiotic prescriptions, while 146 received delayed prescriptions, and 142 received no prescription. Rate of antibiotic use was highest in the immediate prescription group, at 96%, versus 25.3% in the delayed group and 12% among those who received no prescription upon first presentation (P < .001).

Although the mean duration of severe symptoms was longest in the delayed-prescription group, at 12.4 days, versus 10.9 days in the no-prescription group and 10.1 days in the immediate-prescription group, these differences were not statistically significant (P = .539). Median score for greatest severity of any symptom was also similar across groups. Secondary outcomes echoed this pattern, in which reconsultation rates and caregiver satisfaction were statistically similar regardless of treatment type.

In contrast, patients who received immediate antibiotic prescriptions had a significantly higher rate of gastrointestinal adverse events (8.8%) than those who received a delayed prescription (3.4%) or no prescription (2.8%; P = .037).

“Delayed antibiotic prescription is an efficacious and safe strategy for reducing inappropriate antibiotic treatment of uncomplicated RTIs in children when the doctor has reasonable doubts regarding the indication,” the investigators concluded. “[It] is therefore a useful tool for addressing the public health issue of bacterial resistance. However, no antibiotic prescription remains the recommended strategy when it is clear that antibiotics are not indicated, like in most cases of acute bronchitis.”

“These data are reassuring,” wrote Dr. Gerber and Dr. Offit; however, they went on to suggest that the data “might not substantially move the needle.”

“With rare exceptions, children with acute pharyngitis should first receive a group A streptococcal test,” they wrote. “If results are positive, all patients should get antibiotics; if results are negative, no one gets them. Acute bronchitis (whatever that is in children) is viral. Acute sinusitis with persistent symptoms (the most commonly diagnosed variety) already has a delayed option, and the current study ... was not powered for this outcome. We are left with acute otitis media, which dominated enrollment but already has an evidence-based guideline.”

Still, Dr. Gerber and Dr. Offit suggested that the findings should further encourage pediatricians to prescribe antibiotics judiciously, and when elected, to choose the shortest duration and narrowest spectrum possible.

In a joint comment, Rana El Feghaly, MD, MSCI, director of outpatient antibiotic stewardship at Children’s Mercy, Kansas City, and her colleague, Mary Anne Jackson, MD, noted that the findings are “in accordance” with the 2017 Cochrane review.

Dr. Feghaly and Dr. Jackson said that these new data provide greater support for conservative use of antibiotics, which is badly needed, considering approximately 50% of outpatient prescriptions are unnecessary or inappropriate .

Delayed antibiotic prescription is part of a multifaceted approach to the issue, they said, joining “communication skills training, antibiotic justification documentation, audit and feedback reporting with peer comparison, diagnostic stewardship, [and] the use of clinician education on practice-based guidelines.”

“Leveraging delayed antibiotic prescription may be an excellent way to combat antibiotic overuse in the outpatient setting, while avoiding provider and parental fear of the ‘no antibiotic’ approach,” Dr. Feghaly and Dr. Jackson said.

Karlyn Kinsella, MD, of Pediatric Associates of Cheshire, Conn., suggested that clinicians discuss these findings with parents who request antibiotics for “otitis, pharyngitis, bronchitis, or sinusitis.”

“We can cite this study that antibiotics have no effect on symptom duration or severity for these illnesses,” Dr. Kinsella said. “Of course, our clinical opinion in each case takes precedent.”

According to Dr. Kinsella, conversations with parents also need to cover reasonable expectations, as the study did, with clear time frames for each condition in which children should start to get better.

“I think this is really key in our anticipatory guidance so that patients know what to expect,” she said.

The study was funded by Instituto de Salud Carlos III, the European Union, and the Spanish Ministry of Health, Social Services, and Equality. The investigators and interviewees reported no conflicts of interest.

FROM PEDIATRICS

Zika vaccine candidate shows promise in phase 1 trial

in a phase 1 study.

Although Zika cases have declined in recent years, “geographic expansion of the Aedes aegypti mosquito to areas where population-level immunity is low poses a substantial risk for future epidemics,” wrote Nadine C. Salisch, PhD, of Janssen Vaccines and Prevention, Leiden, the Netherlands, and colleagues in a paper published in Annals of Internal Medicine.

No vaccine against Zika is yet available, although more than 10 candidates have been studied in preclinical trials to date, they said.

The researchers randomized 100 healthy adult volunteers to an experimental Zika vaccine candidate known as Ad26.ZIKV.001 in either one-dose or two-dose regimens of 5x1010 viral particles (low dose) or 1x1011 viral particles (high dose) or placebo. Approximately half (55%) of the participants were women, and 72% were White.

Approximately 80% of patients in both two-dose groups showed antibody responses for a year after vaccination. Geometric mean titers (GMTs) reached peak of 823.4 in the low-dose/low-dose group and 961.5 in the high-dose/high-dose group. At day 365, the GMTs for these groups were 68.7 and 87.0, respectively.

A single high-dose vaccine achieved a similar level of neutralizing antibody titers, but lower peak neutralizing responses than the two-dose strategies, the researchers noted.

Most of the reported adverse events were mild to moderate, and short lived; the most common were injection site pain or tenderness, headache, and fatigue, the researchers said. After the first vaccination, 75% of participants in the low-dose groups, 88% of participants in high-dose groups, and 45% of participants receiving placebo reported local adverse events. In addition, 73%, 83%, and 40% of the participants in the low-dose, high-dose, and placebo groups, respectively, reported systemic adverse events. Reports were similar after the second vaccination. Two serious adverse events not related to vaccination were reported; one case of right lower lobe pneumonia and one case of incomplete spontaneous abortion.

The researchers also explored protective efficacy through a nonlethal mouse challenge model. “Transfer of 6 mg of IgG from Ad26.ZIKV.001 vaccines conferred complete protection from viremia in most recipient animals, with statistically significantly decreased breakthrough rates and cumulative viral loads per group compared with placebo,” they said.

The study findings were limited by the inability to assess safety and immunogenicity in an endemic area, the researchers noted. However, “Ad26.ZIKV.001 induces potent ZIKV-specific neutralizing responses with durability of at least 1 year, which supports further clinical development if an unmet medical need reemerges,” they said. “In addition, these data underscore the performance of the Ad26 vaccine platform, which Janssen is using for different infectious diseases, including COVID-19,” they noted.

Ad26 vector platform shows consistency

“Development of the investigational Janssen Zika vaccine candidate was initiated in 2015, and while the incidence of Zika virus has declined since the 2015-2016 outbreak, spread of the ‘carrier’ Aedes aegypti mosquito to areas where population-level immunity is low poses a substantial risk for future epidemics,” lead author Dr. Salisch said in an interview. For this reason, researchers say the vaccine warrants further development should the need reemerge, she said.

“Our research has found that while a single higher-dose regimen had lower peak neutralizing responses than a two-dose regimen, it achieved a similar level of neutralizing antibody responses at 1 year, an encouraging finding that shows our vaccine may be a useful tool to curb Zika epidemics,” Dr. Salisch noted. “Previous experience with the Ad26 vector platform across our investigational vaccine programs have yielded similarly promising results, most recently with our investigational Janssen COVID-19 vaccine program, for which phase 3 data show a single-dose vaccine met all primary and key secondary endpoints,” she said.

“The biggest barrier [to further development of the candidate vaccine] is one that we actually consider ourselves fortunate to have: The very low incidence of reported Zika cases currently reported worldwide,” Dr. Salisch said. “However, the current Zika case rate can change at any time, and in the event the situation demands it, we are open to alternative regulatory pathways to help us glean the necessary insights on vaccine safety and efficacy to further advance the development of this candidate,” she emphasized.

As for additional research, “there are still questions surrounding Zika transmission and the pathomechanism of congenital Zika syndrome,” said Dr. Salisch. “Our hope is that a correlate of protection against Zika disease, and in particular against congenital Zika syndrome, can be identified,” she said.

Consider pregnant women in next phase of research

“A major hurdle in ZIKV vaccine development is the inability to conduct large efficacy studies in the absence of a current outbreak,” Ann Chahroudi, MD, of Emory University, Atlanta, and Sallie Permar, MD, of Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, wrote in an accompanying editorial.

The current study provided some efficacy data using a mouse model, but “these data are obviously not conclusive for human protection,” they said.

“A further challenge for ZIKV vaccine efficacy trials will be to demonstrate fetal protection from [congenital Zika syndrome] after adult immunization. There should be a clear plan to readily deploy phase 3 trials for the most promising vaccines to emerge from phase 1 and 2 in the event of an outbreak, as was implemented for Ebola, including infant follow-up,” they emphasized.

The editorialists noted that the study did not include pregnant women, who represent a major target for immunization, but they said that vaccination of pregnant women against other neonatal pathogens such as influenza and tetanus has been effective. “Candidate ZIKV vaccines proven safe in phase 1 trials should immediately be assessed for safety and efficacy in pregnant women,” they said. Although Zika infections are not at epidemic levels currently, resurgence remains a possibility and the coronavirus pandemic “has taught us that preparedness for emerging infections is crucial,” they said.

Zika vaccine research is a challenge worth pursuing

“It is important to continue Zika vaccine research because of the unpredictable nature of that infection,” Kevin Ault, MD, of the University of Kansas, Kansas City, said in an interview. “Several times Zika has gained a foothold in unexposed and vulnerable populations,” Dr. Ault said. “Additionally, there are some data about using this vector during pregnancy, and eventually this vaccine may prevent the birth defects associated with Zika infections during pregnancy, he noted.

Dr. Ault said he was not surprised by the study findings. “This is a promising early phase vaccine candidate, and this adenovirus vector has been used in other similar trials,” he said. Potential barriers to vaccine development include the challenge of conducting late phase clinical trials in pregnant women, he noted. “The relevant endpoint is going to be clinical disease, and one of the most critical populations is pregnant women,” he said. In addition, “later phase 3 trials would be conducted in a population where there is an ongoing Zika outbreak,” Dr. Ault emphasized.

The study was supported by Janssen Vaccines and Infectious Diseases.

Dr. Chahroudi had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Permar disclosed grants from Merck and Moderna unrelated to the current study. Dr. Ault had no relevant financial conflicts to disclose; he has served as an adviser to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the World Medical Association, the National Vaccine Program Office, and the National Institute for Allergy and Infectious Diseases. He is a fellow of the Infectious Disease Society of American and a fellow of ACOG.

in a phase 1 study.

Although Zika cases have declined in recent years, “geographic expansion of the Aedes aegypti mosquito to areas where population-level immunity is low poses a substantial risk for future epidemics,” wrote Nadine C. Salisch, PhD, of Janssen Vaccines and Prevention, Leiden, the Netherlands, and colleagues in a paper published in Annals of Internal Medicine.

No vaccine against Zika is yet available, although more than 10 candidates have been studied in preclinical trials to date, they said.

The researchers randomized 100 healthy adult volunteers to an experimental Zika vaccine candidate known as Ad26.ZIKV.001 in either one-dose or two-dose regimens of 5x1010 viral particles (low dose) or 1x1011 viral particles (high dose) or placebo. Approximately half (55%) of the participants were women, and 72% were White.

Approximately 80% of patients in both two-dose groups showed antibody responses for a year after vaccination. Geometric mean titers (GMTs) reached peak of 823.4 in the low-dose/low-dose group and 961.5 in the high-dose/high-dose group. At day 365, the GMTs for these groups were 68.7 and 87.0, respectively.

A single high-dose vaccine achieved a similar level of neutralizing antibody titers, but lower peak neutralizing responses than the two-dose strategies, the researchers noted.