User login

Emerging treatments for molluscum contagiosum and acne show promise

, but that could soon change, according to Leon H. Kircik, MD.

“The treatment of molluscum is still an unmet need,” Dr. Kircik, clinical professor of dermatology at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, said at the Orlando Dermatology Aesthetic and Clinical Conference. However, a proprietary drug-device combination of cantharidin 0.7% administered through a single-use precision applicator, which has been tested in phase 3 studies, is currently under FDA review. The manufacturer, Verrica Pharmaceuticals resubmitted a new drug application for the product, VP-102, in December 2020.

“VP-102 features a visualization agent so the injector can see which lesions have been treated, as well as a bittering agent to mitigate oral ingestion by children. Complete clearance at 12 weeks ranged from 46% to 54% of patients, while lesion count reduction compared with baseline ranged from 69% to 82%.”

Acne

In August, 2020, clascoterone 1% cream was approved for the treatment of acne in patients 12 years and older, a development that Dr. Kircik said “can be a game changer in acne treatment.” Clascoterone cream 1% exhibits strong, selective anti-androgen activity by targeting androgen receptors in the skin, not systemically. “It limits or blocks transcription of androgen responsive genes, but it also has an anti-inflammatory effect and an anti-sebum effect,” he explained.

According to results from two phase 3 trials of the product, a response of clear or almost clear on the IGA scale at week 12 was achieved in 18.4% of those on treatment vs. 9% of those on vehicle in one study (P less than .001) and 20.3% vs. 6.5%, respectively, in the second study (P less than .001). Clascoterone is also being evaluated for treating androgenetic alopecia.

In Dr. Kircik’s clinical experience, retinoids can be helpful for patients with moderate to severe acne. “We always use them for anticomedogenic effects, but we also know that they have anti-inflammatory effects,” he said. “They actually inhibit toll-like receptor activity. They also inhibit the AP-1 pathway by causing a reduction in inflammatory signaling associated with collagen degradation and scarring.”

The most recent retinoid to be approved for the topical treatment of acne was 0.005% trifarotene cream, in 2019, for patients aged 9 years and older. “But when we got the results, it was not that exciting,” a difference of about 3.6 (mean) inflammatory lesion reduction between the active and the vehicle arm, said Dr. Kircik, medical director of Physicians Skin Care in Louisville, Ky. “According to the package insert, treatment side effects included mild to moderate erythema in 59% of patients, scaling in 65%, dryness in 69%, and stinging/burning in 56%, which makes it difficult to use in our clinical practice.”

The drug was also tested for treating truncal acne. However, one comparative study showed that tazarotene 0.045% lotion spread an average of 36.7 square centimeters farther than the trifarotene cream, which makes the tazarotene lotion easier to use on the chest and back, he said.

Dr. Kircik also discussed 4% minocycline, a hydrophobic, topical foam formulation of minocycline that was approved by the FDA in 2019 for the treatment of moderate to severe acne, for patients aged 9 and older. In a 12-week study that involved 1,488 patients (mean age was about 20 years), investigators observed a 56% reduction in inflammatory lesion count among those treated with minocycline 4%, compared with 43% in the vehicle group.

Dr. Kircik, one of the authors of the study, noted that the hydrophobic composition of minocycline 4% allows for stable and efficient delivery of an inherently unstable active pharmaceutical ingredient such as minocycline. “It’s free of primary irritants such as surfactants and short chain alcohols, which makes it much more tolerable,” he said. “The unique physical foam characteristics facilitate ease of application and absorption at target sites.”

Dr. Kircik reported that he serves as a consultant and/or adviser to numerous pharmaceutical companies, including Galderma, the manufacturer of trifarotene cream.

[email protected]

, but that could soon change, according to Leon H. Kircik, MD.

“The treatment of molluscum is still an unmet need,” Dr. Kircik, clinical professor of dermatology at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, said at the Orlando Dermatology Aesthetic and Clinical Conference. However, a proprietary drug-device combination of cantharidin 0.7% administered through a single-use precision applicator, which has been tested in phase 3 studies, is currently under FDA review. The manufacturer, Verrica Pharmaceuticals resubmitted a new drug application for the product, VP-102, in December 2020.

“VP-102 features a visualization agent so the injector can see which lesions have been treated, as well as a bittering agent to mitigate oral ingestion by children. Complete clearance at 12 weeks ranged from 46% to 54% of patients, while lesion count reduction compared with baseline ranged from 69% to 82%.”

Acne

In August, 2020, clascoterone 1% cream was approved for the treatment of acne in patients 12 years and older, a development that Dr. Kircik said “can be a game changer in acne treatment.” Clascoterone cream 1% exhibits strong, selective anti-androgen activity by targeting androgen receptors in the skin, not systemically. “It limits or blocks transcription of androgen responsive genes, but it also has an anti-inflammatory effect and an anti-sebum effect,” he explained.

According to results from two phase 3 trials of the product, a response of clear or almost clear on the IGA scale at week 12 was achieved in 18.4% of those on treatment vs. 9% of those on vehicle in one study (P less than .001) and 20.3% vs. 6.5%, respectively, in the second study (P less than .001). Clascoterone is also being evaluated for treating androgenetic alopecia.

In Dr. Kircik’s clinical experience, retinoids can be helpful for patients with moderate to severe acne. “We always use them for anticomedogenic effects, but we also know that they have anti-inflammatory effects,” he said. “They actually inhibit toll-like receptor activity. They also inhibit the AP-1 pathway by causing a reduction in inflammatory signaling associated with collagen degradation and scarring.”

The most recent retinoid to be approved for the topical treatment of acne was 0.005% trifarotene cream, in 2019, for patients aged 9 years and older. “But when we got the results, it was not that exciting,” a difference of about 3.6 (mean) inflammatory lesion reduction between the active and the vehicle arm, said Dr. Kircik, medical director of Physicians Skin Care in Louisville, Ky. “According to the package insert, treatment side effects included mild to moderate erythema in 59% of patients, scaling in 65%, dryness in 69%, and stinging/burning in 56%, which makes it difficult to use in our clinical practice.”

The drug was also tested for treating truncal acne. However, one comparative study showed that tazarotene 0.045% lotion spread an average of 36.7 square centimeters farther than the trifarotene cream, which makes the tazarotene lotion easier to use on the chest and back, he said.

Dr. Kircik also discussed 4% minocycline, a hydrophobic, topical foam formulation of minocycline that was approved by the FDA in 2019 for the treatment of moderate to severe acne, for patients aged 9 and older. In a 12-week study that involved 1,488 patients (mean age was about 20 years), investigators observed a 56% reduction in inflammatory lesion count among those treated with minocycline 4%, compared with 43% in the vehicle group.

Dr. Kircik, one of the authors of the study, noted that the hydrophobic composition of minocycline 4% allows for stable and efficient delivery of an inherently unstable active pharmaceutical ingredient such as minocycline. “It’s free of primary irritants such as surfactants and short chain alcohols, which makes it much more tolerable,” he said. “The unique physical foam characteristics facilitate ease of application and absorption at target sites.”

Dr. Kircik reported that he serves as a consultant and/or adviser to numerous pharmaceutical companies, including Galderma, the manufacturer of trifarotene cream.

[email protected]

, but that could soon change, according to Leon H. Kircik, MD.

“The treatment of molluscum is still an unmet need,” Dr. Kircik, clinical professor of dermatology at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, said at the Orlando Dermatology Aesthetic and Clinical Conference. However, a proprietary drug-device combination of cantharidin 0.7% administered through a single-use precision applicator, which has been tested in phase 3 studies, is currently under FDA review. The manufacturer, Verrica Pharmaceuticals resubmitted a new drug application for the product, VP-102, in December 2020.

“VP-102 features a visualization agent so the injector can see which lesions have been treated, as well as a bittering agent to mitigate oral ingestion by children. Complete clearance at 12 weeks ranged from 46% to 54% of patients, while lesion count reduction compared with baseline ranged from 69% to 82%.”

Acne

In August, 2020, clascoterone 1% cream was approved for the treatment of acne in patients 12 years and older, a development that Dr. Kircik said “can be a game changer in acne treatment.” Clascoterone cream 1% exhibits strong, selective anti-androgen activity by targeting androgen receptors in the skin, not systemically. “It limits or blocks transcription of androgen responsive genes, but it also has an anti-inflammatory effect and an anti-sebum effect,” he explained.

According to results from two phase 3 trials of the product, a response of clear or almost clear on the IGA scale at week 12 was achieved in 18.4% of those on treatment vs. 9% of those on vehicle in one study (P less than .001) and 20.3% vs. 6.5%, respectively, in the second study (P less than .001). Clascoterone is also being evaluated for treating androgenetic alopecia.

In Dr. Kircik’s clinical experience, retinoids can be helpful for patients with moderate to severe acne. “We always use them for anticomedogenic effects, but we also know that they have anti-inflammatory effects,” he said. “They actually inhibit toll-like receptor activity. They also inhibit the AP-1 pathway by causing a reduction in inflammatory signaling associated with collagen degradation and scarring.”

The most recent retinoid to be approved for the topical treatment of acne was 0.005% trifarotene cream, in 2019, for patients aged 9 years and older. “But when we got the results, it was not that exciting,” a difference of about 3.6 (mean) inflammatory lesion reduction between the active and the vehicle arm, said Dr. Kircik, medical director of Physicians Skin Care in Louisville, Ky. “According to the package insert, treatment side effects included mild to moderate erythema in 59% of patients, scaling in 65%, dryness in 69%, and stinging/burning in 56%, which makes it difficult to use in our clinical practice.”

The drug was also tested for treating truncal acne. However, one comparative study showed that tazarotene 0.045% lotion spread an average of 36.7 square centimeters farther than the trifarotene cream, which makes the tazarotene lotion easier to use on the chest and back, he said.

Dr. Kircik also discussed 4% minocycline, a hydrophobic, topical foam formulation of minocycline that was approved by the FDA in 2019 for the treatment of moderate to severe acne, for patients aged 9 and older. In a 12-week study that involved 1,488 patients (mean age was about 20 years), investigators observed a 56% reduction in inflammatory lesion count among those treated with minocycline 4%, compared with 43% in the vehicle group.

Dr. Kircik, one of the authors of the study, noted that the hydrophobic composition of minocycline 4% allows for stable and efficient delivery of an inherently unstable active pharmaceutical ingredient such as minocycline. “It’s free of primary irritants such as surfactants and short chain alcohols, which makes it much more tolerable,” he said. “The unique physical foam characteristics facilitate ease of application and absorption at target sites.”

Dr. Kircik reported that he serves as a consultant and/or adviser to numerous pharmaceutical companies, including Galderma, the manufacturer of trifarotene cream.

[email protected]

FROM ODAC 2021

Strep A and tic worsening: Final word?

Exposure to Group A streptococcus (GAS) does not appear to worsen symptoms of Tourette syndrome and other chronic tic disorders (CTDs) in children and adolescents, new research suggests.

Investigators studied over 700 children and teenagers with CTDs, one-third of whom also had attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and one-third who had obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD).

The youngsters were followed for an average of 16 months and evaluated at 4-month intervals to see if they were infected with GAS. Tic severity was monitored through telephone interviews, in-person visits, and parental reports.

A little less than half the children experienced worsening of tics during the study period, but the researchers found no association between these exacerbations and GAS exposure.

There was also no link between GAS and worsening OCD. However, researchers did find an association between GAS exposure and an increase in hyperactivity and impulsivity in patients with ADHD.

“This study does not support GAS exposures as contributing factors for tic exacerbations in children with CTD,” the authors note.

“Specific work-up or active management of GAS infections is unlikely to help modifying the course of tics in CTD and is therefore not recommended,” they conclude.

The study was published online in Neurology.

‘Intense debate’

The association between GAS and CTD stems from the description of Pediatric Autoimmune Neuropsychiatric Disorders Associated with Streptococcal infection (PANDAS) – a condition that is now incorporated in the pediatric acute neuropsychiatric syndromes (PANS), the authors note. Tics constitute an “accompanying feature” of this condition.

However, neither population-based nor longitudinal clinical studies “could definitely establish if tic exacerbations in CTD are associated with GAS infections,” they note.

“The link between streptococcus and tics in children is still a matter of intense debate,” said study author Davide Martino, MD, PhD, director of the Movement Disorders Program at the University of Calgary (Alta.), in a press release.

“We wanted to look at that question, as well as a possible link between strep and behavioral symptoms like obsessive-compulsive disorder and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder,” he said.

The researchers followed 715 children with CTD (mean age 10.7 years, 76.8% male) who were drawn from 16 specialist clinics in nine countries. Almost all (90.8%) had a diagnosis of Tourette syndrome (TS); 31.7% had OCD, and 36.1% had ADHD.

Participants received a throat swab at baseline, and of these, 8.4% tested positive for GAS.

Participants were evaluated over a 16- to 18-month period, consisting of:

- Face-to-face interviews and collection of throat swabs and serum at 4-month intervals.

- Telephone interviews at 4-month intervals, which took place at 2 months between study visit.

- Weekly diaries: Parents were asked to indicate any worsening of tics and focus on detecting the earliest possible tic exacerbation.

Beyond the regularly scheduled visits, parents were instructed to report, by phone or email, any noticeable increase in tic severity and then attend an in-person visit.

Tic exacerbations were defined as an increase of greater than or equal to 6 points on the Yale Global Tic Severity Scale-Total Tic Severity Score (YGTSS-TTS), compared with the previous assessment.

OCD and ADHD symptoms were assessed according to the Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale and the parent-reported Swanson, Nolan, and Pelham-IV (SNAP-IV) questionnaire.

The researchers divided GAS exposures into four categories: new definite exposure; new possible exposure; ongoing definite exposure; and ongoing possible exposure.

Unlikely trigger

During the follow-up period, 43.1% (n = 308) of participants experienced tic exacerbations. Of these, 218 participants experienced one exacerbation, while 90 participants experienced two, three, or four exacerbations.

The researchers did not find a significant association between GAS exposure status and tic exacerbation.

Participants who did develop a GAS-associated exacerbation (n = 49) were younger at study exit (9.63 vs. 11.4 years, P < .0001) and were more likely to be male (46/49 vs. 210/259, Fisher’s = .035), compared with participants who developed a non-GAS-associated tic exacerbation (n = 259).

Additional analyses were adjusted for sex, age at onset, exposure to psychotropic medications, exposures to antibiotics, geographical regions, and number of visits in the time interval of interest. These analyses continued to yield no significant association between new or ongoing concurrent GAS exposure episodes and tic exacerbation events.

Of the children in the study, 103 had a positive throat swab, indicating a new definite GAS exposure, whereas 46 had a positive throat swab indicating an ongoing definite exposure (n = 149 visits). Of these visits, only 20 corresponded to tic exacerbations.

There was also no association between GAS exposure and OCD symptom severity. However, it was associated with longitudinal changes (between 17% and 21%, depending on GAS exposure definition) in the severity of hyperactivity-impulsivity symptoms in children with ADHD.

“It is known that immune activation may concur with tic severity in youth with CTDs and that psychosocial stress levels may predict short-term future tic severity in these patients,” the authors write.

“Our findings suggest that GAS is unlikely to be the main trigger for immune activation in these patients,” they add.

Brick or cornerstone?

Commenting on the study for this news organization, Margo Thienemann, MD, clinical professor of psychiatry, Stanford (Calif.) University, said that in the clinic population they treat, GAS, other pathogens, and other stresses can “each be associated with PANS symptom exacerbations.”

However, these “would not be likely to cause PANS symptoms exacerbations in the vast majority of individuals, only individuals with genetic backgrounds and immunologic dysfunctions creating susceptibility,” said Dr. Thienemann, who also directs the Pediatric Acute-Onset Neuropsychiatric Syndrome (PANS) Clinic at Stanford Children’s Health. She was not involved with the study.

In an accompanying editorial, Andrea Cavanna, MD, PhD, honorary reader in neuropsychiatry, Birmingham (England) Medical School and Keith Coffman, MD, director, Tourette Syndrome Center of Excellence, Children’s Mercy Hospital, Kansas City, Mo., suggest that perhaps the “interaction of psychosocial stress and GAS infections contributes more to tic exacerbation than psychosocial stress alone.”

“Time will tell whether this study stands as another brick – a cornerstone? – in the wall that separates streptococcus from tics,” they write.

The study was supported by the European Union’s Seventh Framework Program. Dr. Martino has received honoraria for lecturing from the Movement Disorders Society, Tourette Syndrome Association of America, and Dystonia Medical Research Foundation Canada; research funding support from Dystonia Medical Research Foundation Canada, the University of Calgary (Alta.), the Michael P. Smith Family, the Owerko Foundation, Ipsen Corporate, the Parkinson Association of Alberta, and the Canadian Institutes for Health Research; and royalties from Springer-Verlag. The other authors’ disclosures are listed in the original article. Dr. Cavanna, Dr. Coffman, and Dr. Thienemann have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Exposure to Group A streptococcus (GAS) does not appear to worsen symptoms of Tourette syndrome and other chronic tic disorders (CTDs) in children and adolescents, new research suggests.

Investigators studied over 700 children and teenagers with CTDs, one-third of whom also had attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and one-third who had obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD).

The youngsters were followed for an average of 16 months and evaluated at 4-month intervals to see if they were infected with GAS. Tic severity was monitored through telephone interviews, in-person visits, and parental reports.

A little less than half the children experienced worsening of tics during the study period, but the researchers found no association between these exacerbations and GAS exposure.

There was also no link between GAS and worsening OCD. However, researchers did find an association between GAS exposure and an increase in hyperactivity and impulsivity in patients with ADHD.

“This study does not support GAS exposures as contributing factors for tic exacerbations in children with CTD,” the authors note.

“Specific work-up or active management of GAS infections is unlikely to help modifying the course of tics in CTD and is therefore not recommended,” they conclude.

The study was published online in Neurology.

‘Intense debate’

The association between GAS and CTD stems from the description of Pediatric Autoimmune Neuropsychiatric Disorders Associated with Streptococcal infection (PANDAS) – a condition that is now incorporated in the pediatric acute neuropsychiatric syndromes (PANS), the authors note. Tics constitute an “accompanying feature” of this condition.

However, neither population-based nor longitudinal clinical studies “could definitely establish if tic exacerbations in CTD are associated with GAS infections,” they note.

“The link between streptococcus and tics in children is still a matter of intense debate,” said study author Davide Martino, MD, PhD, director of the Movement Disorders Program at the University of Calgary (Alta.), in a press release.

“We wanted to look at that question, as well as a possible link between strep and behavioral symptoms like obsessive-compulsive disorder and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder,” he said.

The researchers followed 715 children with CTD (mean age 10.7 years, 76.8% male) who were drawn from 16 specialist clinics in nine countries. Almost all (90.8%) had a diagnosis of Tourette syndrome (TS); 31.7% had OCD, and 36.1% had ADHD.

Participants received a throat swab at baseline, and of these, 8.4% tested positive for GAS.

Participants were evaluated over a 16- to 18-month period, consisting of:

- Face-to-face interviews and collection of throat swabs and serum at 4-month intervals.

- Telephone interviews at 4-month intervals, which took place at 2 months between study visit.

- Weekly diaries: Parents were asked to indicate any worsening of tics and focus on detecting the earliest possible tic exacerbation.

Beyond the regularly scheduled visits, parents were instructed to report, by phone or email, any noticeable increase in tic severity and then attend an in-person visit.

Tic exacerbations were defined as an increase of greater than or equal to 6 points on the Yale Global Tic Severity Scale-Total Tic Severity Score (YGTSS-TTS), compared with the previous assessment.

OCD and ADHD symptoms were assessed according to the Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale and the parent-reported Swanson, Nolan, and Pelham-IV (SNAP-IV) questionnaire.

The researchers divided GAS exposures into four categories: new definite exposure; new possible exposure; ongoing definite exposure; and ongoing possible exposure.

Unlikely trigger

During the follow-up period, 43.1% (n = 308) of participants experienced tic exacerbations. Of these, 218 participants experienced one exacerbation, while 90 participants experienced two, three, or four exacerbations.

The researchers did not find a significant association between GAS exposure status and tic exacerbation.

Participants who did develop a GAS-associated exacerbation (n = 49) were younger at study exit (9.63 vs. 11.4 years, P < .0001) and were more likely to be male (46/49 vs. 210/259, Fisher’s = .035), compared with participants who developed a non-GAS-associated tic exacerbation (n = 259).

Additional analyses were adjusted for sex, age at onset, exposure to psychotropic medications, exposures to antibiotics, geographical regions, and number of visits in the time interval of interest. These analyses continued to yield no significant association between new or ongoing concurrent GAS exposure episodes and tic exacerbation events.

Of the children in the study, 103 had a positive throat swab, indicating a new definite GAS exposure, whereas 46 had a positive throat swab indicating an ongoing definite exposure (n = 149 visits). Of these visits, only 20 corresponded to tic exacerbations.

There was also no association between GAS exposure and OCD symptom severity. However, it was associated with longitudinal changes (between 17% and 21%, depending on GAS exposure definition) in the severity of hyperactivity-impulsivity symptoms in children with ADHD.

“It is known that immune activation may concur with tic severity in youth with CTDs and that psychosocial stress levels may predict short-term future tic severity in these patients,” the authors write.

“Our findings suggest that GAS is unlikely to be the main trigger for immune activation in these patients,” they add.

Brick or cornerstone?

Commenting on the study for this news organization, Margo Thienemann, MD, clinical professor of psychiatry, Stanford (Calif.) University, said that in the clinic population they treat, GAS, other pathogens, and other stresses can “each be associated with PANS symptom exacerbations.”

However, these “would not be likely to cause PANS symptoms exacerbations in the vast majority of individuals, only individuals with genetic backgrounds and immunologic dysfunctions creating susceptibility,” said Dr. Thienemann, who also directs the Pediatric Acute-Onset Neuropsychiatric Syndrome (PANS) Clinic at Stanford Children’s Health. She was not involved with the study.

In an accompanying editorial, Andrea Cavanna, MD, PhD, honorary reader in neuropsychiatry, Birmingham (England) Medical School and Keith Coffman, MD, director, Tourette Syndrome Center of Excellence, Children’s Mercy Hospital, Kansas City, Mo., suggest that perhaps the “interaction of psychosocial stress and GAS infections contributes more to tic exacerbation than psychosocial stress alone.”

“Time will tell whether this study stands as another brick – a cornerstone? – in the wall that separates streptococcus from tics,” they write.

The study was supported by the European Union’s Seventh Framework Program. Dr. Martino has received honoraria for lecturing from the Movement Disorders Society, Tourette Syndrome Association of America, and Dystonia Medical Research Foundation Canada; research funding support from Dystonia Medical Research Foundation Canada, the University of Calgary (Alta.), the Michael P. Smith Family, the Owerko Foundation, Ipsen Corporate, the Parkinson Association of Alberta, and the Canadian Institutes for Health Research; and royalties from Springer-Verlag. The other authors’ disclosures are listed in the original article. Dr. Cavanna, Dr. Coffman, and Dr. Thienemann have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Exposure to Group A streptococcus (GAS) does not appear to worsen symptoms of Tourette syndrome and other chronic tic disorders (CTDs) in children and adolescents, new research suggests.

Investigators studied over 700 children and teenagers with CTDs, one-third of whom also had attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and one-third who had obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD).

The youngsters were followed for an average of 16 months and evaluated at 4-month intervals to see if they were infected with GAS. Tic severity was monitored through telephone interviews, in-person visits, and parental reports.

A little less than half the children experienced worsening of tics during the study period, but the researchers found no association between these exacerbations and GAS exposure.

There was also no link between GAS and worsening OCD. However, researchers did find an association between GAS exposure and an increase in hyperactivity and impulsivity in patients with ADHD.

“This study does not support GAS exposures as contributing factors for tic exacerbations in children with CTD,” the authors note.

“Specific work-up or active management of GAS infections is unlikely to help modifying the course of tics in CTD and is therefore not recommended,” they conclude.

The study was published online in Neurology.

‘Intense debate’

The association between GAS and CTD stems from the description of Pediatric Autoimmune Neuropsychiatric Disorders Associated with Streptococcal infection (PANDAS) – a condition that is now incorporated in the pediatric acute neuropsychiatric syndromes (PANS), the authors note. Tics constitute an “accompanying feature” of this condition.

However, neither population-based nor longitudinal clinical studies “could definitely establish if tic exacerbations in CTD are associated with GAS infections,” they note.

“The link between streptococcus and tics in children is still a matter of intense debate,” said study author Davide Martino, MD, PhD, director of the Movement Disorders Program at the University of Calgary (Alta.), in a press release.

“We wanted to look at that question, as well as a possible link between strep and behavioral symptoms like obsessive-compulsive disorder and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder,” he said.

The researchers followed 715 children with CTD (mean age 10.7 years, 76.8% male) who were drawn from 16 specialist clinics in nine countries. Almost all (90.8%) had a diagnosis of Tourette syndrome (TS); 31.7% had OCD, and 36.1% had ADHD.

Participants received a throat swab at baseline, and of these, 8.4% tested positive for GAS.

Participants were evaluated over a 16- to 18-month period, consisting of:

- Face-to-face interviews and collection of throat swabs and serum at 4-month intervals.

- Telephone interviews at 4-month intervals, which took place at 2 months between study visit.

- Weekly diaries: Parents were asked to indicate any worsening of tics and focus on detecting the earliest possible tic exacerbation.

Beyond the regularly scheduled visits, parents were instructed to report, by phone or email, any noticeable increase in tic severity and then attend an in-person visit.

Tic exacerbations were defined as an increase of greater than or equal to 6 points on the Yale Global Tic Severity Scale-Total Tic Severity Score (YGTSS-TTS), compared with the previous assessment.

OCD and ADHD symptoms were assessed according to the Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale and the parent-reported Swanson, Nolan, and Pelham-IV (SNAP-IV) questionnaire.

The researchers divided GAS exposures into four categories: new definite exposure; new possible exposure; ongoing definite exposure; and ongoing possible exposure.

Unlikely trigger

During the follow-up period, 43.1% (n = 308) of participants experienced tic exacerbations. Of these, 218 participants experienced one exacerbation, while 90 participants experienced two, three, or four exacerbations.

The researchers did not find a significant association between GAS exposure status and tic exacerbation.

Participants who did develop a GAS-associated exacerbation (n = 49) were younger at study exit (9.63 vs. 11.4 years, P < .0001) and were more likely to be male (46/49 vs. 210/259, Fisher’s = .035), compared with participants who developed a non-GAS-associated tic exacerbation (n = 259).

Additional analyses were adjusted for sex, age at onset, exposure to psychotropic medications, exposures to antibiotics, geographical regions, and number of visits in the time interval of interest. These analyses continued to yield no significant association between new or ongoing concurrent GAS exposure episodes and tic exacerbation events.

Of the children in the study, 103 had a positive throat swab, indicating a new definite GAS exposure, whereas 46 had a positive throat swab indicating an ongoing definite exposure (n = 149 visits). Of these visits, only 20 corresponded to tic exacerbations.

There was also no association between GAS exposure and OCD symptom severity. However, it was associated with longitudinal changes (between 17% and 21%, depending on GAS exposure definition) in the severity of hyperactivity-impulsivity symptoms in children with ADHD.

“It is known that immune activation may concur with tic severity in youth with CTDs and that psychosocial stress levels may predict short-term future tic severity in these patients,” the authors write.

“Our findings suggest that GAS is unlikely to be the main trigger for immune activation in these patients,” they add.

Brick or cornerstone?

Commenting on the study for this news organization, Margo Thienemann, MD, clinical professor of psychiatry, Stanford (Calif.) University, said that in the clinic population they treat, GAS, other pathogens, and other stresses can “each be associated with PANS symptom exacerbations.”

However, these “would not be likely to cause PANS symptoms exacerbations in the vast majority of individuals, only individuals with genetic backgrounds and immunologic dysfunctions creating susceptibility,” said Dr. Thienemann, who also directs the Pediatric Acute-Onset Neuropsychiatric Syndrome (PANS) Clinic at Stanford Children’s Health. She was not involved with the study.

In an accompanying editorial, Andrea Cavanna, MD, PhD, honorary reader in neuropsychiatry, Birmingham (England) Medical School and Keith Coffman, MD, director, Tourette Syndrome Center of Excellence, Children’s Mercy Hospital, Kansas City, Mo., suggest that perhaps the “interaction of psychosocial stress and GAS infections contributes more to tic exacerbation than psychosocial stress alone.”

“Time will tell whether this study stands as another brick – a cornerstone? – in the wall that separates streptococcus from tics,” they write.

The study was supported by the European Union’s Seventh Framework Program. Dr. Martino has received honoraria for lecturing from the Movement Disorders Society, Tourette Syndrome Association of America, and Dystonia Medical Research Foundation Canada; research funding support from Dystonia Medical Research Foundation Canada, the University of Calgary (Alta.), the Michael P. Smith Family, the Owerko Foundation, Ipsen Corporate, the Parkinson Association of Alberta, and the Canadian Institutes for Health Research; and royalties from Springer-Verlag. The other authors’ disclosures are listed in the original article. Dr. Cavanna, Dr. Coffman, and Dr. Thienemann have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Crusted Scabies Presenting as White Superficial Onychomycosislike Lesions

To the Editor:

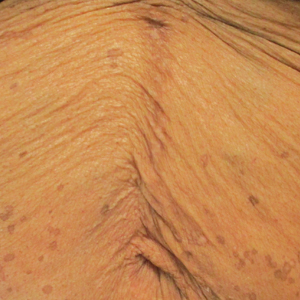

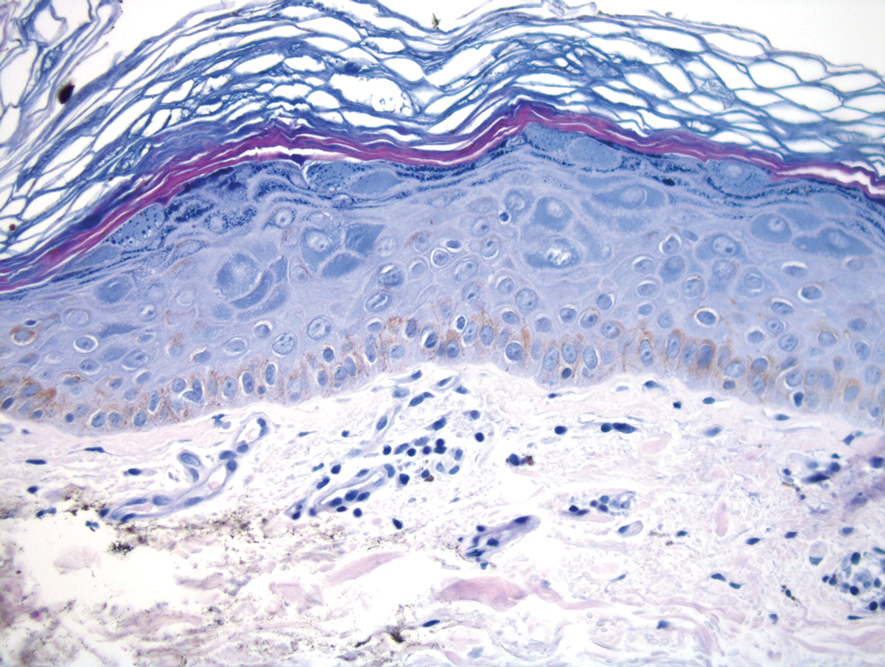

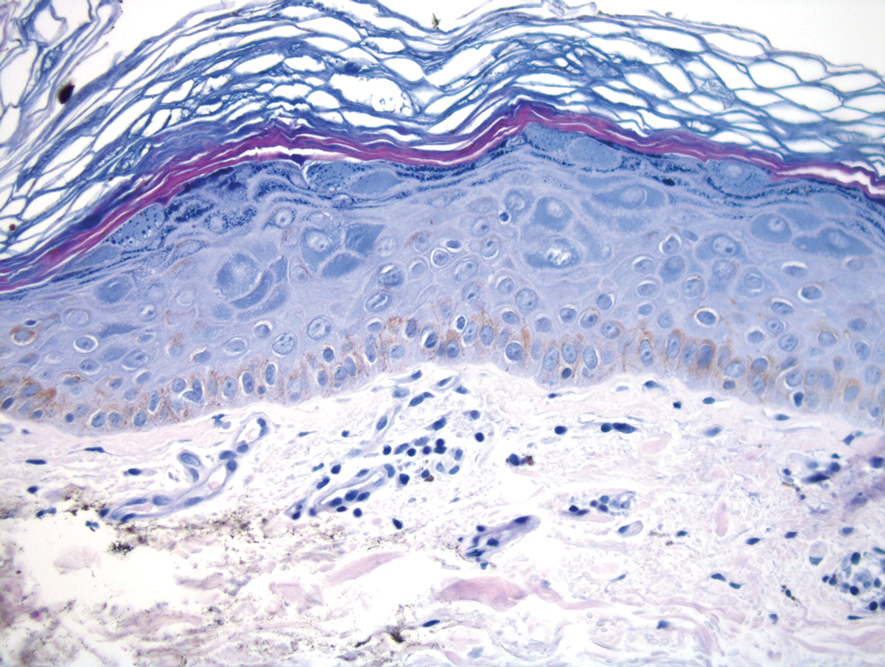

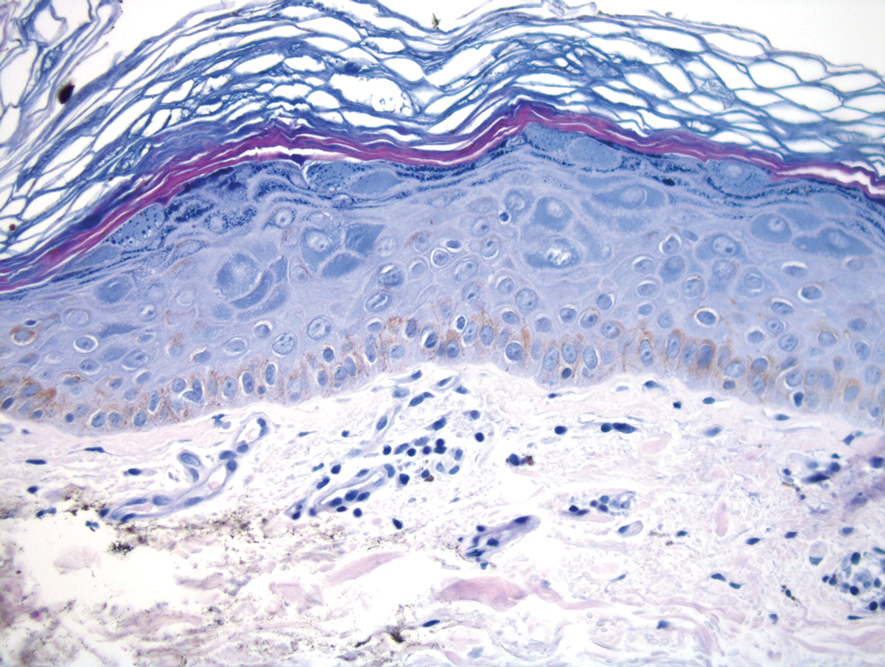

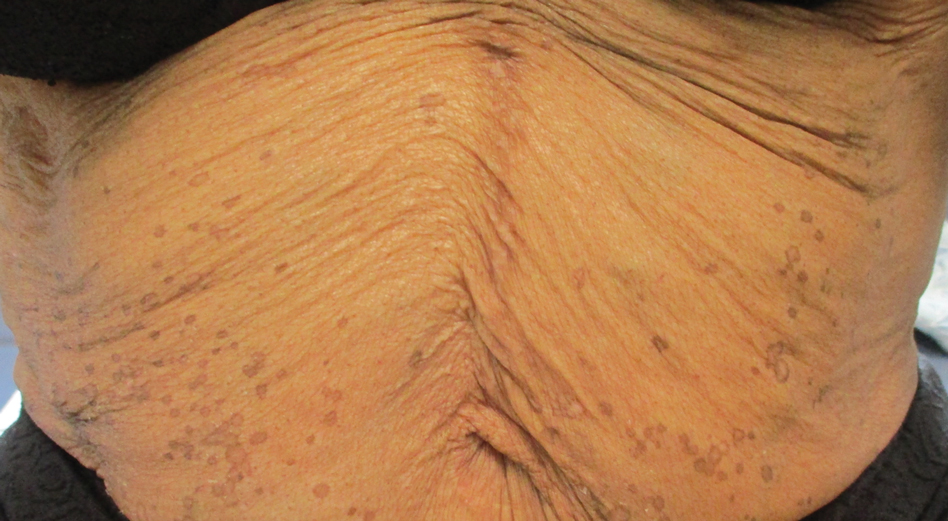

We report the case of an 83-year-old male nursing home resident with a history of end-stage renal disease who presented with multiple small white islands on the surface of the nail plate, similar to those seen in white superficial onychomycosis (Figure 1). Minimal subungual hyperkeratosis of the fingernails also was observed. Three digits were affected with no toenail involvement. Wet mount examination with potassium hydroxide 20% showed a mite (Figure 2A) and multiple eggs (Figure 2B). Treatment consisted of oral ivermectin 3 mg immediately and permethrin solution 5% applied under occlusion to each of the affected nails for 5 consecutive nights, which resulted in complete clearance of the lesion on the nail plate after 2 weeks.

Crusted scabies was first described as Norwegian scabies in 1848 by Danielsen and Boeck,1 and the name was later changed to crusted scabies in 1976 by Parish and Lumholt2 because there was no inherent connection between Norway and Norwegian scabies. It is a skin infestation of Sarcoptes scabiei var hominis and more commonly is seen in immunocompromised individuals such as the elderly and malnourished patients as well as those with diabetes mellitus and alcoholism.3,4 Patients typically present with widespread hyperkeratosis, mostly involving the palms and soles. Subungual hyperkeratosis and nail dystrophy also can be seen when nail involvement is present, and the scalp rarely is involved.5 Unlike common scabies, skin burrows and pruritus may be minimal or absent, thus making the diagnosis of crusted scabies more difficult than normal scabies.6 Diagnosis of crusted scabies is confirmed by direct microscopy, which demonstrates mites, eggs, or feces. Strict isolation of the patient is necessary, as the disease is very contagious. Treatment with oral ivermectin (1–3 doses of 3 mg at 14-day intervals) in combination with topical permethrin is effective.7

We present a case of crusted scabies with nail involvement that presented with white superficial onychomycosislike lesions. The patient’s nails were successfully treated with a combination of oral ivermectin and topical permethrin occlusion of the nails. In cases with subungual hyperkeratosis, nonsurgical nail avulsion with 40% urea cream or ointment has been used to improve the penetration of permethrin. Partial nail avulsion may be necessary if subungual hyperkeratosis or nail dystrophy becomes extreme.8

- Danielsen DG, Boeck W. Treatment of Leprosy or Greek Elephantiasis. JB Balliere; 1848.

- Parish L, Lumholt G. Crusted scabies: alias Norwegian scabies. Int J Dermatol. 1976;15:747-748.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Parasites: scabies. Updated November 2, 2010. Accessed January 17, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/scabies/

- Roberts LJ, Huffam SE, Walton SF, et al. Crusted scabies: clinical and immunological findings in seventy-eight patient and a review of the literature. J Infect. 2005;50:375-381.

- Dourmisher AL, Serafimova DK, Dourmisher LA, et al. Crusted scabies of the scalp in dermatomyositis patients: three cases treated with oral ivermectin. Int J Dermatol. 1998;37:231-234.

- Barnes L, McCallister RE, Lucky AW. Crusted (Norwegian) scabies: occurrence in a child undergoing a bone marrow transplant. Arch Dermatol. 1987;123:95-97.

- Huffam SE, Currie BJ. Ivermectin for Sarcoptes scabiei hyperinfestation. Int J Infect Dis. 1998;2:152-154.

- De Paoli R, Mark SV. Crusted (Norwegian) scabies: treatment of nail involvement. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;17:136-138.

To the Editor:

We report the case of an 83-year-old male nursing home resident with a history of end-stage renal disease who presented with multiple small white islands on the surface of the nail plate, similar to those seen in white superficial onychomycosis (Figure 1). Minimal subungual hyperkeratosis of the fingernails also was observed. Three digits were affected with no toenail involvement. Wet mount examination with potassium hydroxide 20% showed a mite (Figure 2A) and multiple eggs (Figure 2B). Treatment consisted of oral ivermectin 3 mg immediately and permethrin solution 5% applied under occlusion to each of the affected nails for 5 consecutive nights, which resulted in complete clearance of the lesion on the nail plate after 2 weeks.

Crusted scabies was first described as Norwegian scabies in 1848 by Danielsen and Boeck,1 and the name was later changed to crusted scabies in 1976 by Parish and Lumholt2 because there was no inherent connection between Norway and Norwegian scabies. It is a skin infestation of Sarcoptes scabiei var hominis and more commonly is seen in immunocompromised individuals such as the elderly and malnourished patients as well as those with diabetes mellitus and alcoholism.3,4 Patients typically present with widespread hyperkeratosis, mostly involving the palms and soles. Subungual hyperkeratosis and nail dystrophy also can be seen when nail involvement is present, and the scalp rarely is involved.5 Unlike common scabies, skin burrows and pruritus may be minimal or absent, thus making the diagnosis of crusted scabies more difficult than normal scabies.6 Diagnosis of crusted scabies is confirmed by direct microscopy, which demonstrates mites, eggs, or feces. Strict isolation of the patient is necessary, as the disease is very contagious. Treatment with oral ivermectin (1–3 doses of 3 mg at 14-day intervals) in combination with topical permethrin is effective.7

We present a case of crusted scabies with nail involvement that presented with white superficial onychomycosislike lesions. The patient’s nails were successfully treated with a combination of oral ivermectin and topical permethrin occlusion of the nails. In cases with subungual hyperkeratosis, nonsurgical nail avulsion with 40% urea cream or ointment has been used to improve the penetration of permethrin. Partial nail avulsion may be necessary if subungual hyperkeratosis or nail dystrophy becomes extreme.8

To the Editor:

We report the case of an 83-year-old male nursing home resident with a history of end-stage renal disease who presented with multiple small white islands on the surface of the nail plate, similar to those seen in white superficial onychomycosis (Figure 1). Minimal subungual hyperkeratosis of the fingernails also was observed. Three digits were affected with no toenail involvement. Wet mount examination with potassium hydroxide 20% showed a mite (Figure 2A) and multiple eggs (Figure 2B). Treatment consisted of oral ivermectin 3 mg immediately and permethrin solution 5% applied under occlusion to each of the affected nails for 5 consecutive nights, which resulted in complete clearance of the lesion on the nail plate after 2 weeks.

Crusted scabies was first described as Norwegian scabies in 1848 by Danielsen and Boeck,1 and the name was later changed to crusted scabies in 1976 by Parish and Lumholt2 because there was no inherent connection between Norway and Norwegian scabies. It is a skin infestation of Sarcoptes scabiei var hominis and more commonly is seen in immunocompromised individuals such as the elderly and malnourished patients as well as those with diabetes mellitus and alcoholism.3,4 Patients typically present with widespread hyperkeratosis, mostly involving the palms and soles. Subungual hyperkeratosis and nail dystrophy also can be seen when nail involvement is present, and the scalp rarely is involved.5 Unlike common scabies, skin burrows and pruritus may be minimal or absent, thus making the diagnosis of crusted scabies more difficult than normal scabies.6 Diagnosis of crusted scabies is confirmed by direct microscopy, which demonstrates mites, eggs, or feces. Strict isolation of the patient is necessary, as the disease is very contagious. Treatment with oral ivermectin (1–3 doses of 3 mg at 14-day intervals) in combination with topical permethrin is effective.7

We present a case of crusted scabies with nail involvement that presented with white superficial onychomycosislike lesions. The patient’s nails were successfully treated with a combination of oral ivermectin and topical permethrin occlusion of the nails. In cases with subungual hyperkeratosis, nonsurgical nail avulsion with 40% urea cream or ointment has been used to improve the penetration of permethrin. Partial nail avulsion may be necessary if subungual hyperkeratosis or nail dystrophy becomes extreme.8

- Danielsen DG, Boeck W. Treatment of Leprosy or Greek Elephantiasis. JB Balliere; 1848.

- Parish L, Lumholt G. Crusted scabies: alias Norwegian scabies. Int J Dermatol. 1976;15:747-748.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Parasites: scabies. Updated November 2, 2010. Accessed January 17, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/scabies/

- Roberts LJ, Huffam SE, Walton SF, et al. Crusted scabies: clinical and immunological findings in seventy-eight patient and a review of the literature. J Infect. 2005;50:375-381.

- Dourmisher AL, Serafimova DK, Dourmisher LA, et al. Crusted scabies of the scalp in dermatomyositis patients: three cases treated with oral ivermectin. Int J Dermatol. 1998;37:231-234.

- Barnes L, McCallister RE, Lucky AW. Crusted (Norwegian) scabies: occurrence in a child undergoing a bone marrow transplant. Arch Dermatol. 1987;123:95-97.

- Huffam SE, Currie BJ. Ivermectin for Sarcoptes scabiei hyperinfestation. Int J Infect Dis. 1998;2:152-154.

- De Paoli R, Mark SV. Crusted (Norwegian) scabies: treatment of nail involvement. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;17:136-138.

- Danielsen DG, Boeck W. Treatment of Leprosy or Greek Elephantiasis. JB Balliere; 1848.

- Parish L, Lumholt G. Crusted scabies: alias Norwegian scabies. Int J Dermatol. 1976;15:747-748.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Parasites: scabies. Updated November 2, 2010. Accessed January 17, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/scabies/

- Roberts LJ, Huffam SE, Walton SF, et al. Crusted scabies: clinical and immunological findings in seventy-eight patient and a review of the literature. J Infect. 2005;50:375-381.

- Dourmisher AL, Serafimova DK, Dourmisher LA, et al. Crusted scabies of the scalp in dermatomyositis patients: three cases treated with oral ivermectin. Int J Dermatol. 1998;37:231-234.

- Barnes L, McCallister RE, Lucky AW. Crusted (Norwegian) scabies: occurrence in a child undergoing a bone marrow transplant. Arch Dermatol. 1987;123:95-97.

- Huffam SE, Currie BJ. Ivermectin for Sarcoptes scabiei hyperinfestation. Int J Infect Dis. 1998;2:152-154.

- De Paoli R, Mark SV. Crusted (Norwegian) scabies: treatment of nail involvement. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;17:136-138.

Practice Points

- Crusted scabies is asymptomatic; therefore, any white lesion at the surface of the nail should be scraped and examined with potassium hydroxide.

- Immunosuppressed patients are at risk for infection.

7 key changes: The 2021 child and adolescent immunization schedules

Each February, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, along with multiple professional organizations, releases an updated Recommended Child and Adolescent Immunization Schedule.

Recent years have seen fewer changes in the vaccine schedule, mostly with adjustments based on products coming on or off the market, and sometimes with slight changes in recommendations. This year is no different, with mostly minor changes in store. As most practitioners know, having quick access to the tables that accompany the recommendations is always handy. Table 1 contains the typical, recommended immunization schedule. Table 2 contains the catch-up provisions, and Table 3 provides guidance on vaccines for special circumstances and for children with specific medical conditions.

2021 childhood and adolescent immunization schedule

One update is a recommendation that patients with egg allergies who had symptoms more extensive than hives should receive the influenza vaccine in a medical setting where severe allergic reactions or anaphylaxis can be recognized and treated, with the exclusion of two specific preparations, Flublok and Flucelvax.

In regard to the live attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV), there are several points of reinforcement. First, the nomenclature has generally been changed to “LAIV4” throughout the document because only quadrivalent preparations are available. There are specific recommendations that patients should not receive LAIV4 if they recently took antiviral medication for influenza, with “lockout” periods lasting from 2 days to 17 days, depending on the antiviral preparation used. In addition, there is an emphasis on not using LAIV4 for children younger than 2 years.

Two updates to the meningococcal group B vaccine are worth reviewing. The first is that children aged 10 years or older with complement deficiency, complement inhibitor use, or asplenia should receive a meningitis B booster dose beginning 1 year after completion of the primary series, with boosters thereafter every 2 or 3 years as long as that patient remains at greater risk. Another recommendation for patients 10 years or older is that, even if they have received a primary series of meningitis B vaccines, they should receive a booster dose in the setting of an outbreak if it has been 1 year or more since completion of their primary series.

Recommendations have generally been relaxed for tetanus prophylaxis in older children, indicating that individuals requiring tetanus prophylaxis or their 10-year tetanus booster after receipt of at least one Tdap vaccine can receive either tetanus-diphtheria toxoid or Tdap.

COVID-19 vaccines

Although childhood vaccination against COVID-19 is still currently limited to adolescents involved in clinical trials, pediatricians surely are getting peppered with questions from parents about whether they should be vaccinated and what to make of the recent reports about allergic reactions. Fortunately, there are several resources for pediatricians. First, two reports point out that true anaphylactic reactions to COVID-19 vaccines appear quite rare. The reported data on Pfizer-developed mRNA vaccine demonstrated an anaphylaxis rate of approximately 2 cases per 1 million doses administered. Among the 21 recipients who experienced anaphylaxis (out of over 11 million total doses administered), fully one third had a history of anaphylaxis episodes. The report also reviews vaccine reactions that were reported but were not classified as anaphylaxis, pointing out that when reporting vaccine reactions, we should be very careful in the nomenclature we use.

Reporting on the Moderna mRNA vaccine showed anaphylaxis rates of about 2.5 per 1 million doses, with 50% of the recipients who experienced true anaphylaxis having a history of anaphylaxis. Most of those who experienced anaphylaxis (90% in the Moderna group and 86% in the Pfizer group) exhibited symptoms of anaphylaxis within 30 minutes of receiving the vaccine. The take-home point, and the current CDC recommendation, is that many individuals, even those with a history of anaphylaxis, can still receive COVID-19 vaccines. The rates of observed anaphylaxis after COVID vaccination are far below population rates of a history of allergy or severe allergic reactions. When coupled with an estimated mortality rate of 0.5%-1% for SARS-CoV-2 disease, that CDC recommends that we encourage people, even those with severe allergies, to get vaccinated.

One clear caveat is that individuals with a history of severe anaphylaxis, and even those concerned about allergies, should be observed for a longer period after vaccination (at least 30 minutes) than the 15 minutes recommended for the general population. In addition, individuals with a specific anaphylactic reaction or severe allergic reaction to any injectable vaccine should confer with an immunologist before considering vaccination.

Another useful resource is a column published by the American Medical Association that walks through some talking points for providers when discussing whether a patient should receive COVID-19 vaccination. Advice is offered on answering patient questions about which preparation to get, what side effects to watch for, and how to report an adverse reaction. Providers are reminded to urge patients to complete whichever series they begin (get that second dose!), and that they currently should not have to pay for a vaccine. FAQ resource pages are available for patients and health care providers.

More vaccine news: HPV and influenza

Meanwhile, published vaccine reports provide evidence from the field to demonstrate the benefits of vaccination. A study published in the New England Journal of Medicine reported on the effectiveness of human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine in a Swedish cohort. The report evaluated females aged between 10 and 30 years beginning in 2006 and followed them through 2017, comparing rates of invasive cervical cancer among the group who received one or more HPV vaccine doses with the group who receive none. Even without adjustment, the raw rate of invasive cervical cancer in the vaccinated group was half of that in the unvaccinated group. After full adjustment, some populations experienced incident rate ratios that were greater than 80% reduced. The largest reduction, and therefore the biggest benefit, was among those who received the HPV vaccine before age 17.

A report from the United States looking at the 2018-2019 influenza season demonstrated a vaccine effectiveness rate against hospitalization of 41% and 51% against any ED visit related to influenza. The authors note that there was considerable drift in the influenza A type that appeared late in the influenza season, reducing the overall effectiveness, but that the vaccine was still largely effective.

William T. Basco Jr, MD, MS, is a professor of pediatrics at the Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, and director of the division of general pediatrics. He is an active health services researcher and has published more than 60 manuscripts in the peer-reviewed literature.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Each February, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, along with multiple professional organizations, releases an updated Recommended Child and Adolescent Immunization Schedule.

Recent years have seen fewer changes in the vaccine schedule, mostly with adjustments based on products coming on or off the market, and sometimes with slight changes in recommendations. This year is no different, with mostly minor changes in store. As most practitioners know, having quick access to the tables that accompany the recommendations is always handy. Table 1 contains the typical, recommended immunization schedule. Table 2 contains the catch-up provisions, and Table 3 provides guidance on vaccines for special circumstances and for children with specific medical conditions.

2021 childhood and adolescent immunization schedule

One update is a recommendation that patients with egg allergies who had symptoms more extensive than hives should receive the influenza vaccine in a medical setting where severe allergic reactions or anaphylaxis can be recognized and treated, with the exclusion of two specific preparations, Flublok and Flucelvax.

In regard to the live attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV), there are several points of reinforcement. First, the nomenclature has generally been changed to “LAIV4” throughout the document because only quadrivalent preparations are available. There are specific recommendations that patients should not receive LAIV4 if they recently took antiviral medication for influenza, with “lockout” periods lasting from 2 days to 17 days, depending on the antiviral preparation used. In addition, there is an emphasis on not using LAIV4 for children younger than 2 years.

Two updates to the meningococcal group B vaccine are worth reviewing. The first is that children aged 10 years or older with complement deficiency, complement inhibitor use, or asplenia should receive a meningitis B booster dose beginning 1 year after completion of the primary series, with boosters thereafter every 2 or 3 years as long as that patient remains at greater risk. Another recommendation for patients 10 years or older is that, even if they have received a primary series of meningitis B vaccines, they should receive a booster dose in the setting of an outbreak if it has been 1 year or more since completion of their primary series.

Recommendations have generally been relaxed for tetanus prophylaxis in older children, indicating that individuals requiring tetanus prophylaxis or their 10-year tetanus booster after receipt of at least one Tdap vaccine can receive either tetanus-diphtheria toxoid or Tdap.

COVID-19 vaccines

Although childhood vaccination against COVID-19 is still currently limited to adolescents involved in clinical trials, pediatricians surely are getting peppered with questions from parents about whether they should be vaccinated and what to make of the recent reports about allergic reactions. Fortunately, there are several resources for pediatricians. First, two reports point out that true anaphylactic reactions to COVID-19 vaccines appear quite rare. The reported data on Pfizer-developed mRNA vaccine demonstrated an anaphylaxis rate of approximately 2 cases per 1 million doses administered. Among the 21 recipients who experienced anaphylaxis (out of over 11 million total doses administered), fully one third had a history of anaphylaxis episodes. The report also reviews vaccine reactions that were reported but were not classified as anaphylaxis, pointing out that when reporting vaccine reactions, we should be very careful in the nomenclature we use.

Reporting on the Moderna mRNA vaccine showed anaphylaxis rates of about 2.5 per 1 million doses, with 50% of the recipients who experienced true anaphylaxis having a history of anaphylaxis. Most of those who experienced anaphylaxis (90% in the Moderna group and 86% in the Pfizer group) exhibited symptoms of anaphylaxis within 30 minutes of receiving the vaccine. The take-home point, and the current CDC recommendation, is that many individuals, even those with a history of anaphylaxis, can still receive COVID-19 vaccines. The rates of observed anaphylaxis after COVID vaccination are far below population rates of a history of allergy or severe allergic reactions. When coupled with an estimated mortality rate of 0.5%-1% for SARS-CoV-2 disease, that CDC recommends that we encourage people, even those with severe allergies, to get vaccinated.

One clear caveat is that individuals with a history of severe anaphylaxis, and even those concerned about allergies, should be observed for a longer period after vaccination (at least 30 minutes) than the 15 minutes recommended for the general population. In addition, individuals with a specific anaphylactic reaction or severe allergic reaction to any injectable vaccine should confer with an immunologist before considering vaccination.

Another useful resource is a column published by the American Medical Association that walks through some talking points for providers when discussing whether a patient should receive COVID-19 vaccination. Advice is offered on answering patient questions about which preparation to get, what side effects to watch for, and how to report an adverse reaction. Providers are reminded to urge patients to complete whichever series they begin (get that second dose!), and that they currently should not have to pay for a vaccine. FAQ resource pages are available for patients and health care providers.

More vaccine news: HPV and influenza

Meanwhile, published vaccine reports provide evidence from the field to demonstrate the benefits of vaccination. A study published in the New England Journal of Medicine reported on the effectiveness of human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine in a Swedish cohort. The report evaluated females aged between 10 and 30 years beginning in 2006 and followed them through 2017, comparing rates of invasive cervical cancer among the group who received one or more HPV vaccine doses with the group who receive none. Even without adjustment, the raw rate of invasive cervical cancer in the vaccinated group was half of that in the unvaccinated group. After full adjustment, some populations experienced incident rate ratios that were greater than 80% reduced. The largest reduction, and therefore the biggest benefit, was among those who received the HPV vaccine before age 17.

A report from the United States looking at the 2018-2019 influenza season demonstrated a vaccine effectiveness rate against hospitalization of 41% and 51% against any ED visit related to influenza. The authors note that there was considerable drift in the influenza A type that appeared late in the influenza season, reducing the overall effectiveness, but that the vaccine was still largely effective.

William T. Basco Jr, MD, MS, is a professor of pediatrics at the Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, and director of the division of general pediatrics. He is an active health services researcher and has published more than 60 manuscripts in the peer-reviewed literature.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Each February, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, along with multiple professional organizations, releases an updated Recommended Child and Adolescent Immunization Schedule.

Recent years have seen fewer changes in the vaccine schedule, mostly with adjustments based on products coming on or off the market, and sometimes with slight changes in recommendations. This year is no different, with mostly minor changes in store. As most practitioners know, having quick access to the tables that accompany the recommendations is always handy. Table 1 contains the typical, recommended immunization schedule. Table 2 contains the catch-up provisions, and Table 3 provides guidance on vaccines for special circumstances and for children with specific medical conditions.

2021 childhood and adolescent immunization schedule

One update is a recommendation that patients with egg allergies who had symptoms more extensive than hives should receive the influenza vaccine in a medical setting where severe allergic reactions or anaphylaxis can be recognized and treated, with the exclusion of two specific preparations, Flublok and Flucelvax.

In regard to the live attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV), there are several points of reinforcement. First, the nomenclature has generally been changed to “LAIV4” throughout the document because only quadrivalent preparations are available. There are specific recommendations that patients should not receive LAIV4 if they recently took antiviral medication for influenza, with “lockout” periods lasting from 2 days to 17 days, depending on the antiviral preparation used. In addition, there is an emphasis on not using LAIV4 for children younger than 2 years.

Two updates to the meningococcal group B vaccine are worth reviewing. The first is that children aged 10 years or older with complement deficiency, complement inhibitor use, or asplenia should receive a meningitis B booster dose beginning 1 year after completion of the primary series, with boosters thereafter every 2 or 3 years as long as that patient remains at greater risk. Another recommendation for patients 10 years or older is that, even if they have received a primary series of meningitis B vaccines, they should receive a booster dose in the setting of an outbreak if it has been 1 year or more since completion of their primary series.

Recommendations have generally been relaxed for tetanus prophylaxis in older children, indicating that individuals requiring tetanus prophylaxis or their 10-year tetanus booster after receipt of at least one Tdap vaccine can receive either tetanus-diphtheria toxoid or Tdap.

COVID-19 vaccines

Although childhood vaccination against COVID-19 is still currently limited to adolescents involved in clinical trials, pediatricians surely are getting peppered with questions from parents about whether they should be vaccinated and what to make of the recent reports about allergic reactions. Fortunately, there are several resources for pediatricians. First, two reports point out that true anaphylactic reactions to COVID-19 vaccines appear quite rare. The reported data on Pfizer-developed mRNA vaccine demonstrated an anaphylaxis rate of approximately 2 cases per 1 million doses administered. Among the 21 recipients who experienced anaphylaxis (out of over 11 million total doses administered), fully one third had a history of anaphylaxis episodes. The report also reviews vaccine reactions that were reported but were not classified as anaphylaxis, pointing out that when reporting vaccine reactions, we should be very careful in the nomenclature we use.

Reporting on the Moderna mRNA vaccine showed anaphylaxis rates of about 2.5 per 1 million doses, with 50% of the recipients who experienced true anaphylaxis having a history of anaphylaxis. Most of those who experienced anaphylaxis (90% in the Moderna group and 86% in the Pfizer group) exhibited symptoms of anaphylaxis within 30 minutes of receiving the vaccine. The take-home point, and the current CDC recommendation, is that many individuals, even those with a history of anaphylaxis, can still receive COVID-19 vaccines. The rates of observed anaphylaxis after COVID vaccination are far below population rates of a history of allergy or severe allergic reactions. When coupled with an estimated mortality rate of 0.5%-1% for SARS-CoV-2 disease, that CDC recommends that we encourage people, even those with severe allergies, to get vaccinated.

One clear caveat is that individuals with a history of severe anaphylaxis, and even those concerned about allergies, should be observed for a longer period after vaccination (at least 30 minutes) than the 15 minutes recommended for the general population. In addition, individuals with a specific anaphylactic reaction or severe allergic reaction to any injectable vaccine should confer with an immunologist before considering vaccination.

Another useful resource is a column published by the American Medical Association that walks through some talking points for providers when discussing whether a patient should receive COVID-19 vaccination. Advice is offered on answering patient questions about which preparation to get, what side effects to watch for, and how to report an adverse reaction. Providers are reminded to urge patients to complete whichever series they begin (get that second dose!), and that they currently should not have to pay for a vaccine. FAQ resource pages are available for patients and health care providers.

More vaccine news: HPV and influenza

Meanwhile, published vaccine reports provide evidence from the field to demonstrate the benefits of vaccination. A study published in the New England Journal of Medicine reported on the effectiveness of human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine in a Swedish cohort. The report evaluated females aged between 10 and 30 years beginning in 2006 and followed them through 2017, comparing rates of invasive cervical cancer among the group who received one or more HPV vaccine doses with the group who receive none. Even without adjustment, the raw rate of invasive cervical cancer in the vaccinated group was half of that in the unvaccinated group. After full adjustment, some populations experienced incident rate ratios that were greater than 80% reduced. The largest reduction, and therefore the biggest benefit, was among those who received the HPV vaccine before age 17.

A report from the United States looking at the 2018-2019 influenza season demonstrated a vaccine effectiveness rate against hospitalization of 41% and 51% against any ED visit related to influenza. The authors note that there was considerable drift in the influenza A type that appeared late in the influenza season, reducing the overall effectiveness, but that the vaccine was still largely effective.

William T. Basco Jr, MD, MS, is a professor of pediatrics at the Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, and director of the division of general pediatrics. He is an active health services researcher and has published more than 60 manuscripts in the peer-reviewed literature.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

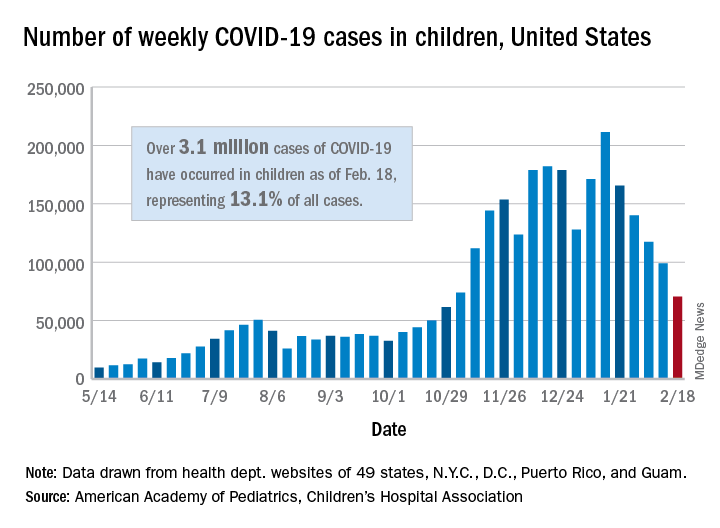

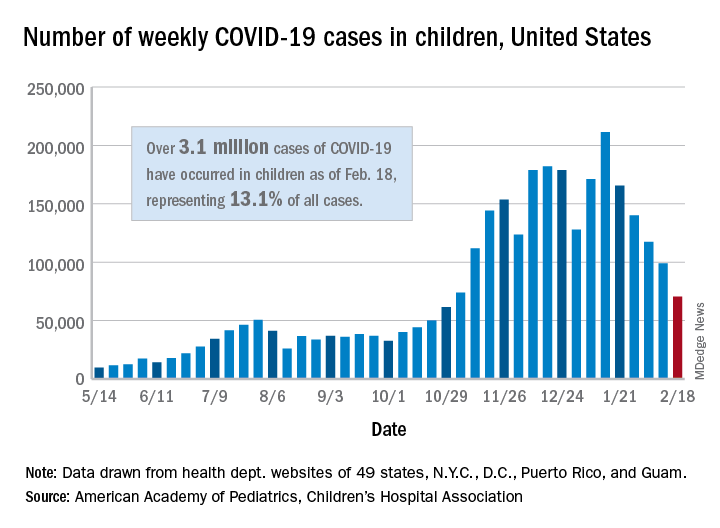

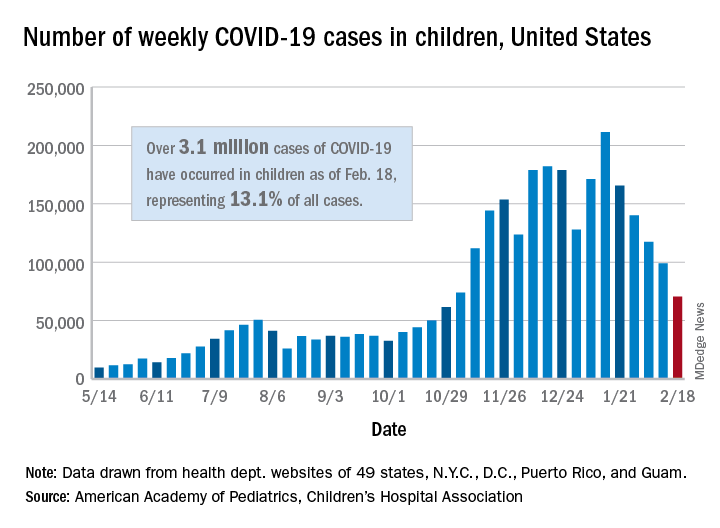

New cases of child COVID-19 drop for fifth straight week

The fifth consecutive week with a decline has the number of new COVID-19 cases in children at its lowest level since late October, according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

, when 61,000 cases were reported, the AAP and CHA said in their weekly COVID-19 report.

The cumulative number of COVID-19 cases in children is now just over 3.1 million, which represents 13.1% of cases among all ages in the United States, based on data gathered from the health departments of 49 states (excluding New York), the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

More children in California (439,000) have been infected than in any other state, while Illinois (176,000), Florida (145,000), Tennessee (137,000), Arizona (127,000), Ohio (121,000), and Pennsylvania (111,000) are the only other states with more than 100,000 cases, the AAP/CHA report shows.

Proportionally, the children of Wyoming have been hardest hit: Pediatric cases represent 19.4% of all cases in the state. The other four states with proportions of 18% or more are Alaska, Vermont, South Carolina, and Tennessee. Cumulative rates, however, tell a somewhat different story, as North Dakota leads with just over 8,500 cases per 100,000 children, followed by Tennessee (7,700 per 100,000) and Rhode Island (7,000 per 100,000), the AAP and CHA said.

Deaths in children, which had not been following the trend of fewer new cases over the last few weeks, dropped below double digits for the first time in a month. The six deaths that occurred during the week of Feb. 12-18 bring the total to 247 since the start of the pandemic in the 43 states, along with New York City and Guam, that are reporting such data, according to the report.

The fifth consecutive week with a decline has the number of new COVID-19 cases in children at its lowest level since late October, according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

, when 61,000 cases were reported, the AAP and CHA said in their weekly COVID-19 report.

The cumulative number of COVID-19 cases in children is now just over 3.1 million, which represents 13.1% of cases among all ages in the United States, based on data gathered from the health departments of 49 states (excluding New York), the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

More children in California (439,000) have been infected than in any other state, while Illinois (176,000), Florida (145,000), Tennessee (137,000), Arizona (127,000), Ohio (121,000), and Pennsylvania (111,000) are the only other states with more than 100,000 cases, the AAP/CHA report shows.

Proportionally, the children of Wyoming have been hardest hit: Pediatric cases represent 19.4% of all cases in the state. The other four states with proportions of 18% or more are Alaska, Vermont, South Carolina, and Tennessee. Cumulative rates, however, tell a somewhat different story, as North Dakota leads with just over 8,500 cases per 100,000 children, followed by Tennessee (7,700 per 100,000) and Rhode Island (7,000 per 100,000), the AAP and CHA said.

Deaths in children, which had not been following the trend of fewer new cases over the last few weeks, dropped below double digits for the first time in a month. The six deaths that occurred during the week of Feb. 12-18 bring the total to 247 since the start of the pandemic in the 43 states, along with New York City and Guam, that are reporting such data, according to the report.

The fifth consecutive week with a decline has the number of new COVID-19 cases in children at its lowest level since late October, according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

, when 61,000 cases were reported, the AAP and CHA said in their weekly COVID-19 report.

The cumulative number of COVID-19 cases in children is now just over 3.1 million, which represents 13.1% of cases among all ages in the United States, based on data gathered from the health departments of 49 states (excluding New York), the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

More children in California (439,000) have been infected than in any other state, while Illinois (176,000), Florida (145,000), Tennessee (137,000), Arizona (127,000), Ohio (121,000), and Pennsylvania (111,000) are the only other states with more than 100,000 cases, the AAP/CHA report shows.

Proportionally, the children of Wyoming have been hardest hit: Pediatric cases represent 19.4% of all cases in the state. The other four states with proportions of 18% or more are Alaska, Vermont, South Carolina, and Tennessee. Cumulative rates, however, tell a somewhat different story, as North Dakota leads with just over 8,500 cases per 100,000 children, followed by Tennessee (7,700 per 100,000) and Rhode Island (7,000 per 100,000), the AAP and CHA said.

Deaths in children, which had not been following the trend of fewer new cases over the last few weeks, dropped below double digits for the first time in a month. The six deaths that occurred during the week of Feb. 12-18 bring the total to 247 since the start of the pandemic in the 43 states, along with New York City and Guam, that are reporting such data, according to the report.

Cellulitis treatment recommendations

He noticed discomfort today and saw that his left lower leg had redness and was warm. He does not recall scratches or injury to his leg. He has not had fever or chills. He has no other symptoms. His diabetes has been well controlled with diet and metformin.

On exam, his blood pressure is 120/70, pulse is 80, temperature is 37 degrees Celsius.

In the left lower extremity, the patient had 1+ edema at the ankle, with a 14-cm x 20-cm warm, erythematous area just above the ankle and extending proximally.

His labs found an HCT of 44 and a WBC of 12,000. What do you recommend?

A) Vascular duplex exam

B) 1st generation cephalosporin

C) 1st generation cephalosporin + TMP/Sulfa

D) Oral clindamycin

E) IV vancomycin

This patient has cellulitis and should receive a beta lactam antibiotic, which will have the best coverage and lowest minimal inhibitory concentration for the likely organism, beta hemolytic streptococci. Clindamycin would likely work, but it has greater side effects. This patient does not need coverage for methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). I know many of you, if not most, know this, but I want to go through relevant data and formal recommendations, because of a recent call I received from a patient.

My patient had a full body rash after receiving cephalexin + TMP/sulfa [trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole] treatment for cellulitis. In recent years the addition of TMP/sulfa to strep treatment to also cover MRSA has become popular, especially in emergency department and urgent care settings.

Moran and colleagues studied cephalexin + TMP/sulfa vs. cephalexin and placebo in patients with uncomplicated cellulitis.1 The outcome measured was clinical cure, and there was no difference between groups; clinical cure occurred in 182 (83.5%) of 218 participants in the cephalexin plus TMP/sulfa group vs. 165 (85.5%) of 193 in the cephalexin group (difference, −2.0%; 95% confidence interval, −9.7% to 5.7%; P = .50).

Jeng and colleagues studied patients admitted for a cellulitis, and evaluated the patients’ response to beta-lactam antibiotics.2 Patients had acute and convalescent serologies for beta hemolytic strep. Almost all evaluable patients with positive strep studies (97%) responded to beta-lactams, and 21 of 23 (91%) with negative studies responded to beta-lactams (overall response rate 95%). This study was done during a time of high MRSA prevalence.

The most recent Infectious Diseases Society of America guidelines for skin and soft tissue infections, recommend oral penicillin, cephalexin, dicloxacillin, or clindamycin for mild cellulitis, and IV equivalent if patients have moderate cellulitis.3 If abscesses are present, then drainage is recommended and MRSA coverage. Kamath and colleagues reported on how closely guidelines for skin and soft tissue infections were followed.4 In patients with mild cellulitis, only 36% received guideline-suggested antibiotics. The most common antibiotic prescribed that was outside the guidelines was trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole.

Myth: Cellulitis treatment should include MRSA coverage.

My advice: Stick with beta-lactam antibiotics, unless an abscess is present. There is no need to add MRSA coverage for initial treatment of mild to moderate cellulitis.

Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and he serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at the University of Washington. He is a member of the editorial advisory board of Internal Medicine News. Dr. Paauw has no conflicts to disclose. Contact him at [email protected].

References

1. Moran GJ et al. Effect of cephalexin plus trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole vs. cephalexin alone on clinical cure of uncomplicated cellulitis: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2017 May 23;317(20):2088-96.

2. Jeng Arthur et al. The role of beta-hemolytic streptococci in causing diffuse, nonculturable cellulitis. Medicine. 2010;July;89(4):217-26.

3. Stevens DL et al. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of skin and soft tissue infections: 2014 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59(2):e10-e52.

4. Kamath RS et al. Guidelines vs. actual management of skin and soft tissue infections in the emergency department. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2018 Jan 12;5(1):ofx188.

He noticed discomfort today and saw that his left lower leg had redness and was warm. He does not recall scratches or injury to his leg. He has not had fever or chills. He has no other symptoms. His diabetes has been well controlled with diet and metformin.

On exam, his blood pressure is 120/70, pulse is 80, temperature is 37 degrees Celsius.

In the left lower extremity, the patient had 1+ edema at the ankle, with a 14-cm x 20-cm warm, erythematous area just above the ankle and extending proximally.

His labs found an HCT of 44 and a WBC of 12,000. What do you recommend?

A) Vascular duplex exam

B) 1st generation cephalosporin

C) 1st generation cephalosporin + TMP/Sulfa

D) Oral clindamycin

E) IV vancomycin