User login

Infographic: Applications for the Ketogenic Diet in Dermatology

This infographic is available in the PDF above.

This infographic is available in the PDF above.

This infographic is available in the PDF above.

Sharp declines for lung cancer, melanoma deaths fuel record drop in cancer mortality

, the American Cancer Society says.

Lung cancer death rates, which were falling by 3% in men and 2% in women annually in 2008 through 2013, dropped by 5% in men and nearly 4% per year in women annually from 2013 to 2017, according to the society’s 2020 statistical report.

Those accelerating reductions in death rates helped fuel the biggest-ever single year decline in overall cancer mortality, of 2.2%, from 2016 to 2017, their report shows.

According to the investigators, the decline in melanoma death rates escalated to 6.9% per year among 20- to 49-year-olds over 2013-2017, compared with a decline of just 2.9% per year during 2006-2010. Likewise, the melanoma death rate decline was 7.2% annually for the more recent time period, compared with just 1.3% annually in the earlier time period. The finding was even more remarkable for those 65 years of age and older, according to investigators, since the declines in melanoma death rates reached 6.2% annually, compared with a 0.9% annual increase in the years before immunotherapy.

Smoking cessation has been the main driver of progress in cutting lung cancer death rates, according to the report, while in melanoma, death rates have dropped after the introduction of immune checkpoint inhibitors and targeted therapies.

By contrast, reductions in death rates have slowed for colorectal cancers and female breast cancers, and have stabilized for prostate cancer, Ms. Siegel and coauthors stated, adding that racial and geographic disparities persist in preventable cancers, including those of the lung and cervix.

“Increased investment in both the equitable application of existing cancer control interventions and basic and clinical research to further advance treatment options would undoubtedly accelerate progress against cancer,” said the investigators. The report appears in CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians.

While the decline in lung cancer death rates is good news, the disease remains a major killer, responsible for more deaths than breast, colorectal, and ovarian cancer combined, said Jacques P. Fontaine, MD, a thoracic surgeon at Moffitt Cancer Center in Tampa, Fla.

“Five-year survival rates are still around the 18%-20% range, which is much lower than breast and prostate cancer,” Dr. Fontaine said in an interview. “Nonetheless, we’ve made a little dent in that, and we’re improving.”

Two other factors that have helped spur that improvement, according to Dr. Fontaine, are the reduced incidence of squamous cell carcinomas, which are linked to smoking, and the increased use of lung cancer screening with low-dose computed tomography.

Squamous cell carcinomas tend to be a central rather than peripheral, which makes the tumors harder to resect: “Surgery is sometimes not an option, and even to this day in 2020, the single most effective treatment for lung cancer remains surgical resection,” said Dr. Fontaine.

Likewise, centrally located tumors may preclude giving high-dose radiation and may result in more “collateral damage” to healthy tissue, he added.

Landmark studies show that low-dose CT scans reduce lung cancer deaths by 20% or more; however, screening can have false-positive results that lead to unnecessary biopsies and other harms, suggesting that the procedures should be done in centers of excellence that provide high-quality, responsible screening for early lung cancer, Dr. Fontaine said.

While the drop in melanoma death rates is encouraging and, not surprising in light of new cutting-edge therapies, an ongoing unmet treatment need still exists, according to Vishal Anil Patel, MD, director of cutaneous oncology at the George Washington Cancer Center in Washington.

“We still have a lot to learn, and a way to go, because we’ve really just made the first breakthrough,” Dr. Patel said in an interview.

Mortality data for melanoma can be challenging to interpret, according to Dr. Patel, given that more widespread screening may increase the number of documented melanoma cases with a lower risk of mortality.

Nevertheless, it’s not surprising that advanced melanoma death rates have declined precipitously, said Dr. Patel, since the diseases carries a high tumor mutational burden, which may explain the improved efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitors.

“Without a doubt, the reason that people are living longer and doing better with this disease is because of these cutting-edge treatments that provide patients options that previously had no options at all, or a tailored option personalized to their tumor and focusing on what the patient really needs,” Dr. Patel said.

That said, response rates remain lower from other cancers, sparking interest in combining current immunotherapies with costimulatory molecules that may further improve survival rates, according to Dr. Patel.

In 2020, 606,000 cancer deaths are projected, according to the American Cancer Society statistical report. Of those deaths, nearly 136,000 are attributable to cancers of the lung and bronchus, while melanoma of the skin accounts for nearly 7,000 deaths.

The report notes that variation in cancer incidence reflects geographical differences in medical detection practices and the prevalence of risk factors, such as smoking, obesity, and other health behaviors. “For example, lung cancer incidence and mortality rates in Kentucky, where smoking prevalence was historically highest, are 3 to 4 times higher than those in Utah, where it was lowest. Even in 2018, 1 in 4 residents of Kentucky, Arkansas, and West Virginia were current smokers compared with 1 in 10 in Utah and California,” the investigators wrote.

Cancer mortality rates have fallen 29% since 1991, translating into 2.9 million fewer cancer deaths, the report says.

Dr. Siegel and coauthors are employed by the American Cancer Society, which receives grants from private and corporate foundations, and their salaries are solely funded through the American Cancer Society, according to the report.

SOURCE: Siegel RL et al. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70(1):7-30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21590.

, the American Cancer Society says.

Lung cancer death rates, which were falling by 3% in men and 2% in women annually in 2008 through 2013, dropped by 5% in men and nearly 4% per year in women annually from 2013 to 2017, according to the society’s 2020 statistical report.

Those accelerating reductions in death rates helped fuel the biggest-ever single year decline in overall cancer mortality, of 2.2%, from 2016 to 2017, their report shows.

According to the investigators, the decline in melanoma death rates escalated to 6.9% per year among 20- to 49-year-olds over 2013-2017, compared with a decline of just 2.9% per year during 2006-2010. Likewise, the melanoma death rate decline was 7.2% annually for the more recent time period, compared with just 1.3% annually in the earlier time period. The finding was even more remarkable for those 65 years of age and older, according to investigators, since the declines in melanoma death rates reached 6.2% annually, compared with a 0.9% annual increase in the years before immunotherapy.

Smoking cessation has been the main driver of progress in cutting lung cancer death rates, according to the report, while in melanoma, death rates have dropped after the introduction of immune checkpoint inhibitors and targeted therapies.

By contrast, reductions in death rates have slowed for colorectal cancers and female breast cancers, and have stabilized for prostate cancer, Ms. Siegel and coauthors stated, adding that racial and geographic disparities persist in preventable cancers, including those of the lung and cervix.

“Increased investment in both the equitable application of existing cancer control interventions and basic and clinical research to further advance treatment options would undoubtedly accelerate progress against cancer,” said the investigators. The report appears in CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians.

While the decline in lung cancer death rates is good news, the disease remains a major killer, responsible for more deaths than breast, colorectal, and ovarian cancer combined, said Jacques P. Fontaine, MD, a thoracic surgeon at Moffitt Cancer Center in Tampa, Fla.

“Five-year survival rates are still around the 18%-20% range, which is much lower than breast and prostate cancer,” Dr. Fontaine said in an interview. “Nonetheless, we’ve made a little dent in that, and we’re improving.”

Two other factors that have helped spur that improvement, according to Dr. Fontaine, are the reduced incidence of squamous cell carcinomas, which are linked to smoking, and the increased use of lung cancer screening with low-dose computed tomography.

Squamous cell carcinomas tend to be a central rather than peripheral, which makes the tumors harder to resect: “Surgery is sometimes not an option, and even to this day in 2020, the single most effective treatment for lung cancer remains surgical resection,” said Dr. Fontaine.

Likewise, centrally located tumors may preclude giving high-dose radiation and may result in more “collateral damage” to healthy tissue, he added.

Landmark studies show that low-dose CT scans reduce lung cancer deaths by 20% or more; however, screening can have false-positive results that lead to unnecessary biopsies and other harms, suggesting that the procedures should be done in centers of excellence that provide high-quality, responsible screening for early lung cancer, Dr. Fontaine said.

While the drop in melanoma death rates is encouraging and, not surprising in light of new cutting-edge therapies, an ongoing unmet treatment need still exists, according to Vishal Anil Patel, MD, director of cutaneous oncology at the George Washington Cancer Center in Washington.

“We still have a lot to learn, and a way to go, because we’ve really just made the first breakthrough,” Dr. Patel said in an interview.

Mortality data for melanoma can be challenging to interpret, according to Dr. Patel, given that more widespread screening may increase the number of documented melanoma cases with a lower risk of mortality.

Nevertheless, it’s not surprising that advanced melanoma death rates have declined precipitously, said Dr. Patel, since the diseases carries a high tumor mutational burden, which may explain the improved efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitors.

“Without a doubt, the reason that people are living longer and doing better with this disease is because of these cutting-edge treatments that provide patients options that previously had no options at all, or a tailored option personalized to their tumor and focusing on what the patient really needs,” Dr. Patel said.

That said, response rates remain lower from other cancers, sparking interest in combining current immunotherapies with costimulatory molecules that may further improve survival rates, according to Dr. Patel.

In 2020, 606,000 cancer deaths are projected, according to the American Cancer Society statistical report. Of those deaths, nearly 136,000 are attributable to cancers of the lung and bronchus, while melanoma of the skin accounts for nearly 7,000 deaths.

The report notes that variation in cancer incidence reflects geographical differences in medical detection practices and the prevalence of risk factors, such as smoking, obesity, and other health behaviors. “For example, lung cancer incidence and mortality rates in Kentucky, where smoking prevalence was historically highest, are 3 to 4 times higher than those in Utah, where it was lowest. Even in 2018, 1 in 4 residents of Kentucky, Arkansas, and West Virginia were current smokers compared with 1 in 10 in Utah and California,” the investigators wrote.

Cancer mortality rates have fallen 29% since 1991, translating into 2.9 million fewer cancer deaths, the report says.

Dr. Siegel and coauthors are employed by the American Cancer Society, which receives grants from private and corporate foundations, and their salaries are solely funded through the American Cancer Society, according to the report.

SOURCE: Siegel RL et al. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70(1):7-30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21590.

, the American Cancer Society says.

Lung cancer death rates, which were falling by 3% in men and 2% in women annually in 2008 through 2013, dropped by 5% in men and nearly 4% per year in women annually from 2013 to 2017, according to the society’s 2020 statistical report.

Those accelerating reductions in death rates helped fuel the biggest-ever single year decline in overall cancer mortality, of 2.2%, from 2016 to 2017, their report shows.

According to the investigators, the decline in melanoma death rates escalated to 6.9% per year among 20- to 49-year-olds over 2013-2017, compared with a decline of just 2.9% per year during 2006-2010. Likewise, the melanoma death rate decline was 7.2% annually for the more recent time period, compared with just 1.3% annually in the earlier time period. The finding was even more remarkable for those 65 years of age and older, according to investigators, since the declines in melanoma death rates reached 6.2% annually, compared with a 0.9% annual increase in the years before immunotherapy.

Smoking cessation has been the main driver of progress in cutting lung cancer death rates, according to the report, while in melanoma, death rates have dropped after the introduction of immune checkpoint inhibitors and targeted therapies.

By contrast, reductions in death rates have slowed for colorectal cancers and female breast cancers, and have stabilized for prostate cancer, Ms. Siegel and coauthors stated, adding that racial and geographic disparities persist in preventable cancers, including those of the lung and cervix.

“Increased investment in both the equitable application of existing cancer control interventions and basic and clinical research to further advance treatment options would undoubtedly accelerate progress against cancer,” said the investigators. The report appears in CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians.

While the decline in lung cancer death rates is good news, the disease remains a major killer, responsible for more deaths than breast, colorectal, and ovarian cancer combined, said Jacques P. Fontaine, MD, a thoracic surgeon at Moffitt Cancer Center in Tampa, Fla.

“Five-year survival rates are still around the 18%-20% range, which is much lower than breast and prostate cancer,” Dr. Fontaine said in an interview. “Nonetheless, we’ve made a little dent in that, and we’re improving.”

Two other factors that have helped spur that improvement, according to Dr. Fontaine, are the reduced incidence of squamous cell carcinomas, which are linked to smoking, and the increased use of lung cancer screening with low-dose computed tomography.

Squamous cell carcinomas tend to be a central rather than peripheral, which makes the tumors harder to resect: “Surgery is sometimes not an option, and even to this day in 2020, the single most effective treatment for lung cancer remains surgical resection,” said Dr. Fontaine.

Likewise, centrally located tumors may preclude giving high-dose radiation and may result in more “collateral damage” to healthy tissue, he added.

Landmark studies show that low-dose CT scans reduce lung cancer deaths by 20% or more; however, screening can have false-positive results that lead to unnecessary biopsies and other harms, suggesting that the procedures should be done in centers of excellence that provide high-quality, responsible screening for early lung cancer, Dr. Fontaine said.

While the drop in melanoma death rates is encouraging and, not surprising in light of new cutting-edge therapies, an ongoing unmet treatment need still exists, according to Vishal Anil Patel, MD, director of cutaneous oncology at the George Washington Cancer Center in Washington.

“We still have a lot to learn, and a way to go, because we’ve really just made the first breakthrough,” Dr. Patel said in an interview.

Mortality data for melanoma can be challenging to interpret, according to Dr. Patel, given that more widespread screening may increase the number of documented melanoma cases with a lower risk of mortality.

Nevertheless, it’s not surprising that advanced melanoma death rates have declined precipitously, said Dr. Patel, since the diseases carries a high tumor mutational burden, which may explain the improved efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitors.

“Without a doubt, the reason that people are living longer and doing better with this disease is because of these cutting-edge treatments that provide patients options that previously had no options at all, or a tailored option personalized to their tumor and focusing on what the patient really needs,” Dr. Patel said.

That said, response rates remain lower from other cancers, sparking interest in combining current immunotherapies with costimulatory molecules that may further improve survival rates, according to Dr. Patel.

In 2020, 606,000 cancer deaths are projected, according to the American Cancer Society statistical report. Of those deaths, nearly 136,000 are attributable to cancers of the lung and bronchus, while melanoma of the skin accounts for nearly 7,000 deaths.

The report notes that variation in cancer incidence reflects geographical differences in medical detection practices and the prevalence of risk factors, such as smoking, obesity, and other health behaviors. “For example, lung cancer incidence and mortality rates in Kentucky, where smoking prevalence was historically highest, are 3 to 4 times higher than those in Utah, where it was lowest. Even in 2018, 1 in 4 residents of Kentucky, Arkansas, and West Virginia were current smokers compared with 1 in 10 in Utah and California,” the investigators wrote.

Cancer mortality rates have fallen 29% since 1991, translating into 2.9 million fewer cancer deaths, the report says.

Dr. Siegel and coauthors are employed by the American Cancer Society, which receives grants from private and corporate foundations, and their salaries are solely funded through the American Cancer Society, according to the report.

SOURCE: Siegel RL et al. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70(1):7-30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21590.

FROM CA: A CANCER JOURNAL FOR CLINICIANS

New toxicity subscale measures QOL in cancer patients on checkpoint inhibitors

developed based on direct patient involvement, picks up on cutaneous and other side effects that would be missed using traditional quality of life questionnaires, investigators say.

The 25-item list represents the first-ever health-related quality of life (HRQOL) toxicity subscale developed for patients receiving checkpoint inhibitors, according to the investigators, led by Aaron R. Hansen, MBBS, of the division of medical oncology and hematology in the department of medicine at the University of Toronto.

The toxicity subscale is combined with the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–General (FACT-G), which measures physical, emotional, family and social, and functional domains, to form the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–Immune Checkpoint Modulator (FACT-ICM), Dr. Hansen stated in a recent report that describes initial development and early validation efforts.

The FACT-ICM could become an important tool for measuring HRQOL in patients receiving checkpoint inhibitors, depending on results of further investigations including more patients, the authors wrote in that report.

“Currently, we would recommend that our toxicity subscale be validated first before use in clinical care, or in trials with QOL as a primary or secondary endpoint,” wrote Dr. Hansen and colleagues in the report, which appears in Cancer.

The toxicity subscale asks patients to rate items such as “I am bothered by dry skin,” “I feel pain, soreness or aches in some of my muscles,” and “My fatigue keeps me from doing the things I want do” on a scale of 0 (not at all) to 4 (very much).

Development of the toxicity subscale was based on focus groups and interviews with 37 patients with a variety of cancer types who were being treated with a PD-1, PD-L1, and CTLA-4 immune checkpoint inhibitors. Sixteen physicians were surveyed to evaluate the patient input, while 11 of them also participated in follow-up interviews.

“At every step in this process, the patients were central,” the investigators wrote in their report.

According to the investigators, that approach is in line with guidance from the Food and Drug Administration, which has said that meaningful patient input should be used in the upfront development of patient-reported outcome (PRO) measures, rather than obtaining patient endorsement after the fact.

By contrast, an electronic PRO immune-oncology module recently developed, based on 19 immune-related adverse events from drug labels and clinical trial reports, had “no evaluation” of effects on HRQOL, according to Dr. Hansen and coauthors, who added that the tool “did not adhere” to the FDA call for meaningful patient input.

Some previous studies of quality of life in immune checkpoint inhibitor–treated patients have used tumor-specific PROs and the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire–Core 30 Items (EORTC-QLQ-C30).

The new, immune checkpoint inhibitor–specific toxicity subscale has “broader coverage” of side effects that reportedly affect HRQOL in patients treated with these agents, including taste disturbance, cough, and fever or chills, according to the investigators.

Moreover, the EORTC-QLQ-C30 and the EORTC head and neck cancer–specific-35 module (EORTC QLQ-H&N35), do not include items related to cutaneous adverse events such as itch, rash, and dry skin that have been seen in some checkpoint inhibitor clinical trials, they noted.

“This represents a clear limitation of such preexisting PRO instruments, which should be addressed with our immune checkpoint moduator–specific tool,” they wrote.

The study was supported by a grant from the University of Toronto. Authors of the study provided disclosures related to Merck, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Karyopharm, Boston Biomedical, Novartis, Genentech, Hoffmann La Roche, GlaxoSmithKline, and others.

SOURCE: Hansen AR et al. Cancer. 2020 Jan 8. doi: 10.1002/cncr.32692.

developed based on direct patient involvement, picks up on cutaneous and other side effects that would be missed using traditional quality of life questionnaires, investigators say.

The 25-item list represents the first-ever health-related quality of life (HRQOL) toxicity subscale developed for patients receiving checkpoint inhibitors, according to the investigators, led by Aaron R. Hansen, MBBS, of the division of medical oncology and hematology in the department of medicine at the University of Toronto.

The toxicity subscale is combined with the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–General (FACT-G), which measures physical, emotional, family and social, and functional domains, to form the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–Immune Checkpoint Modulator (FACT-ICM), Dr. Hansen stated in a recent report that describes initial development and early validation efforts.

The FACT-ICM could become an important tool for measuring HRQOL in patients receiving checkpoint inhibitors, depending on results of further investigations including more patients, the authors wrote in that report.

“Currently, we would recommend that our toxicity subscale be validated first before use in clinical care, or in trials with QOL as a primary or secondary endpoint,” wrote Dr. Hansen and colleagues in the report, which appears in Cancer.

The toxicity subscale asks patients to rate items such as “I am bothered by dry skin,” “I feel pain, soreness or aches in some of my muscles,” and “My fatigue keeps me from doing the things I want do” on a scale of 0 (not at all) to 4 (very much).

Development of the toxicity subscale was based on focus groups and interviews with 37 patients with a variety of cancer types who were being treated with a PD-1, PD-L1, and CTLA-4 immune checkpoint inhibitors. Sixteen physicians were surveyed to evaluate the patient input, while 11 of them also participated in follow-up interviews.

“At every step in this process, the patients were central,” the investigators wrote in their report.

According to the investigators, that approach is in line with guidance from the Food and Drug Administration, which has said that meaningful patient input should be used in the upfront development of patient-reported outcome (PRO) measures, rather than obtaining patient endorsement after the fact.

By contrast, an electronic PRO immune-oncology module recently developed, based on 19 immune-related adverse events from drug labels and clinical trial reports, had “no evaluation” of effects on HRQOL, according to Dr. Hansen and coauthors, who added that the tool “did not adhere” to the FDA call for meaningful patient input.

Some previous studies of quality of life in immune checkpoint inhibitor–treated patients have used tumor-specific PROs and the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire–Core 30 Items (EORTC-QLQ-C30).

The new, immune checkpoint inhibitor–specific toxicity subscale has “broader coverage” of side effects that reportedly affect HRQOL in patients treated with these agents, including taste disturbance, cough, and fever or chills, according to the investigators.

Moreover, the EORTC-QLQ-C30 and the EORTC head and neck cancer–specific-35 module (EORTC QLQ-H&N35), do not include items related to cutaneous adverse events such as itch, rash, and dry skin that have been seen in some checkpoint inhibitor clinical trials, they noted.

“This represents a clear limitation of such preexisting PRO instruments, which should be addressed with our immune checkpoint moduator–specific tool,” they wrote.

The study was supported by a grant from the University of Toronto. Authors of the study provided disclosures related to Merck, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Karyopharm, Boston Biomedical, Novartis, Genentech, Hoffmann La Roche, GlaxoSmithKline, and others.

SOURCE: Hansen AR et al. Cancer. 2020 Jan 8. doi: 10.1002/cncr.32692.

developed based on direct patient involvement, picks up on cutaneous and other side effects that would be missed using traditional quality of life questionnaires, investigators say.

The 25-item list represents the first-ever health-related quality of life (HRQOL) toxicity subscale developed for patients receiving checkpoint inhibitors, according to the investigators, led by Aaron R. Hansen, MBBS, of the division of medical oncology and hematology in the department of medicine at the University of Toronto.

The toxicity subscale is combined with the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–General (FACT-G), which measures physical, emotional, family and social, and functional domains, to form the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–Immune Checkpoint Modulator (FACT-ICM), Dr. Hansen stated in a recent report that describes initial development and early validation efforts.

The FACT-ICM could become an important tool for measuring HRQOL in patients receiving checkpoint inhibitors, depending on results of further investigations including more patients, the authors wrote in that report.

“Currently, we would recommend that our toxicity subscale be validated first before use in clinical care, or in trials with QOL as a primary or secondary endpoint,” wrote Dr. Hansen and colleagues in the report, which appears in Cancer.

The toxicity subscale asks patients to rate items such as “I am bothered by dry skin,” “I feel pain, soreness or aches in some of my muscles,” and “My fatigue keeps me from doing the things I want do” on a scale of 0 (not at all) to 4 (very much).

Development of the toxicity subscale was based on focus groups and interviews with 37 patients with a variety of cancer types who were being treated with a PD-1, PD-L1, and CTLA-4 immune checkpoint inhibitors. Sixteen physicians were surveyed to evaluate the patient input, while 11 of them also participated in follow-up interviews.

“At every step in this process, the patients were central,” the investigators wrote in their report.

According to the investigators, that approach is in line with guidance from the Food and Drug Administration, which has said that meaningful patient input should be used in the upfront development of patient-reported outcome (PRO) measures, rather than obtaining patient endorsement after the fact.

By contrast, an electronic PRO immune-oncology module recently developed, based on 19 immune-related adverse events from drug labels and clinical trial reports, had “no evaluation” of effects on HRQOL, according to Dr. Hansen and coauthors, who added that the tool “did not adhere” to the FDA call for meaningful patient input.

Some previous studies of quality of life in immune checkpoint inhibitor–treated patients have used tumor-specific PROs and the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire–Core 30 Items (EORTC-QLQ-C30).

The new, immune checkpoint inhibitor–specific toxicity subscale has “broader coverage” of side effects that reportedly affect HRQOL in patients treated with these agents, including taste disturbance, cough, and fever or chills, according to the investigators.

Moreover, the EORTC-QLQ-C30 and the EORTC head and neck cancer–specific-35 module (EORTC QLQ-H&N35), do not include items related to cutaneous adverse events such as itch, rash, and dry skin that have been seen in some checkpoint inhibitor clinical trials, they noted.

“This represents a clear limitation of such preexisting PRO instruments, which should be addressed with our immune checkpoint moduator–specific tool,” they wrote.

The study was supported by a grant from the University of Toronto. Authors of the study provided disclosures related to Merck, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Karyopharm, Boston Biomedical, Novartis, Genentech, Hoffmann La Roche, GlaxoSmithKline, and others.

SOURCE: Hansen AR et al. Cancer. 2020 Jan 8. doi: 10.1002/cncr.32692.

FROM CANCER

Cartilage Sutures for a Large Nasal Defect

Practice Gap

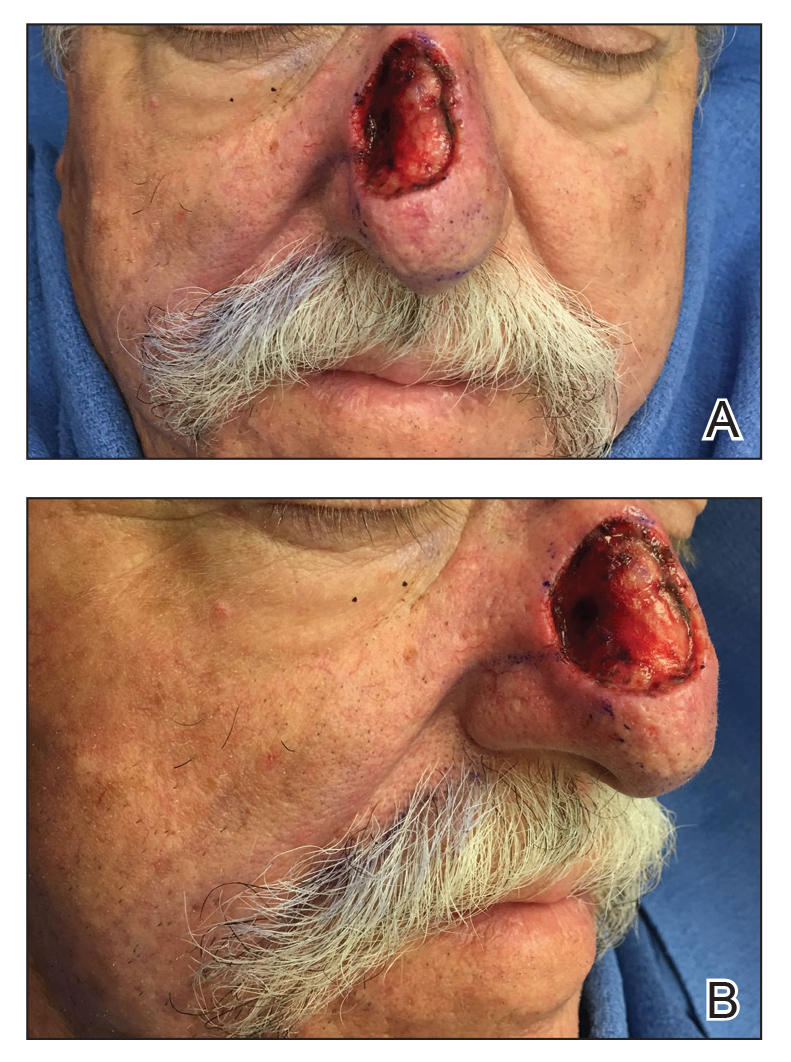

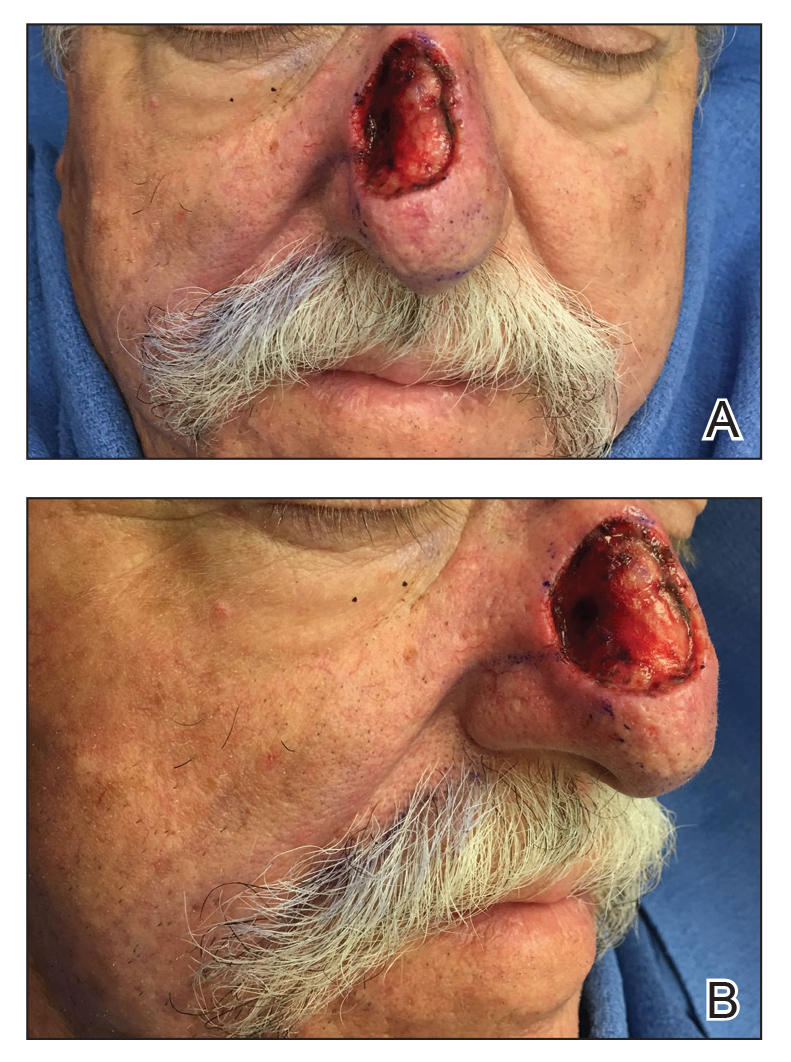

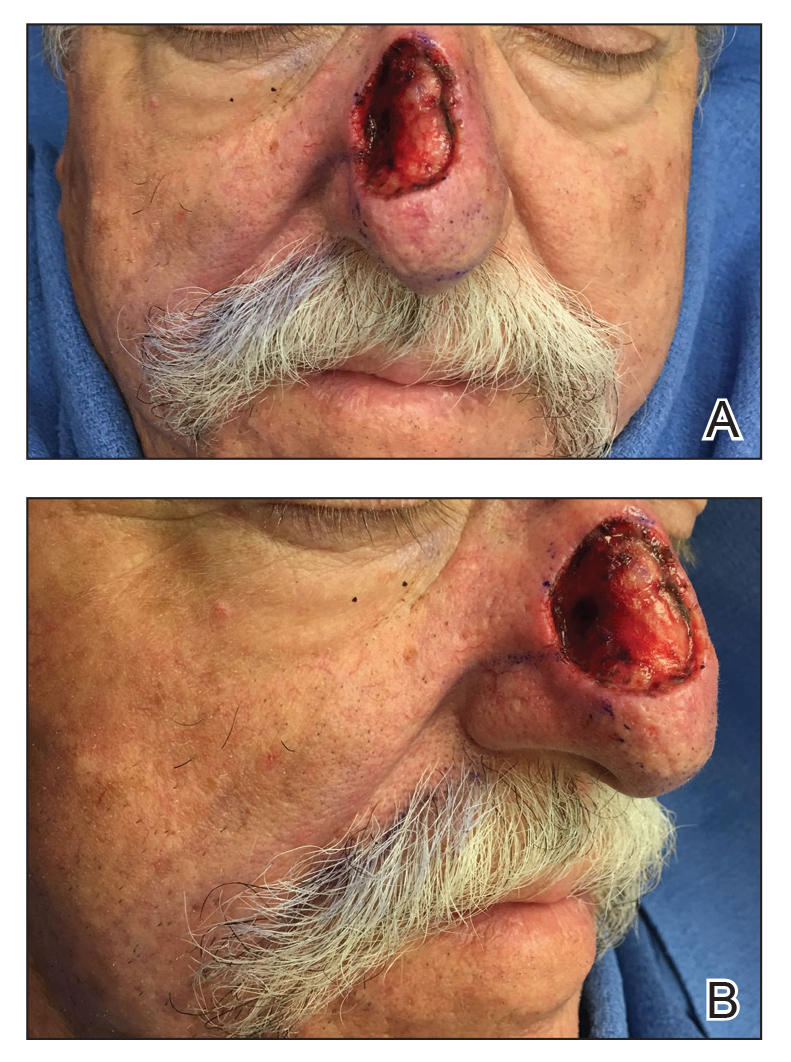

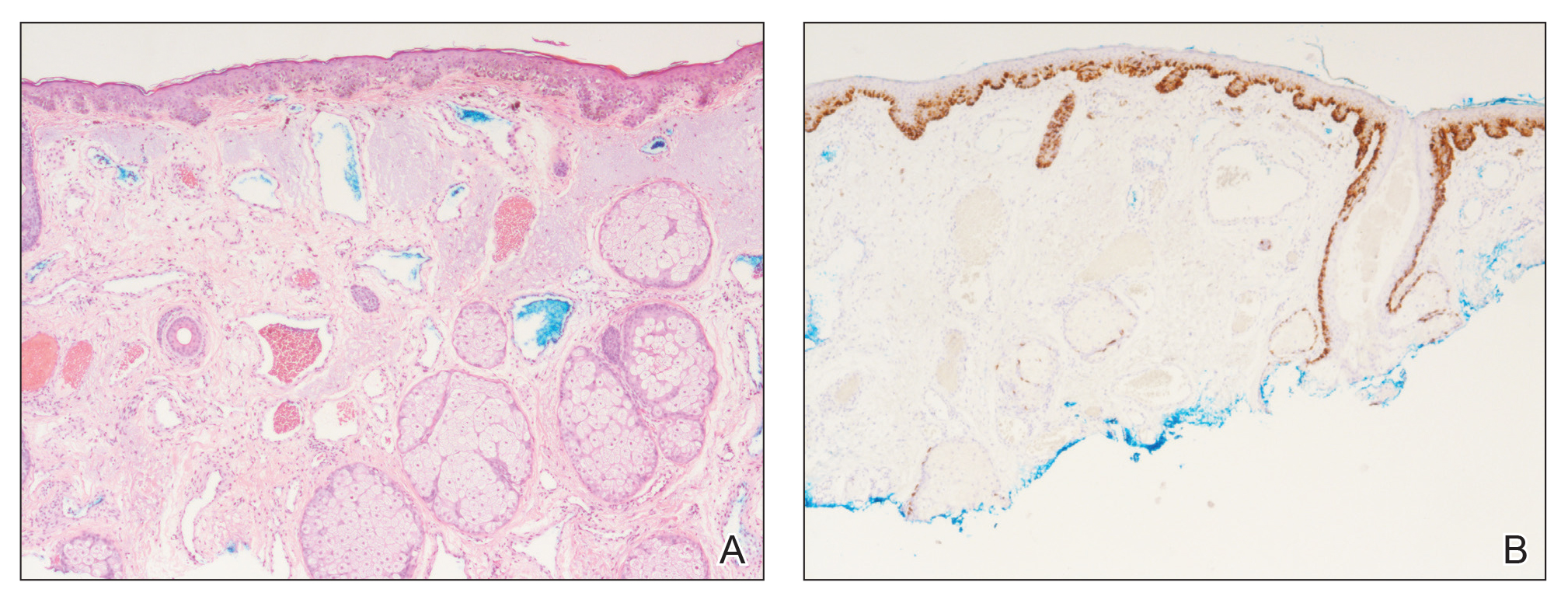

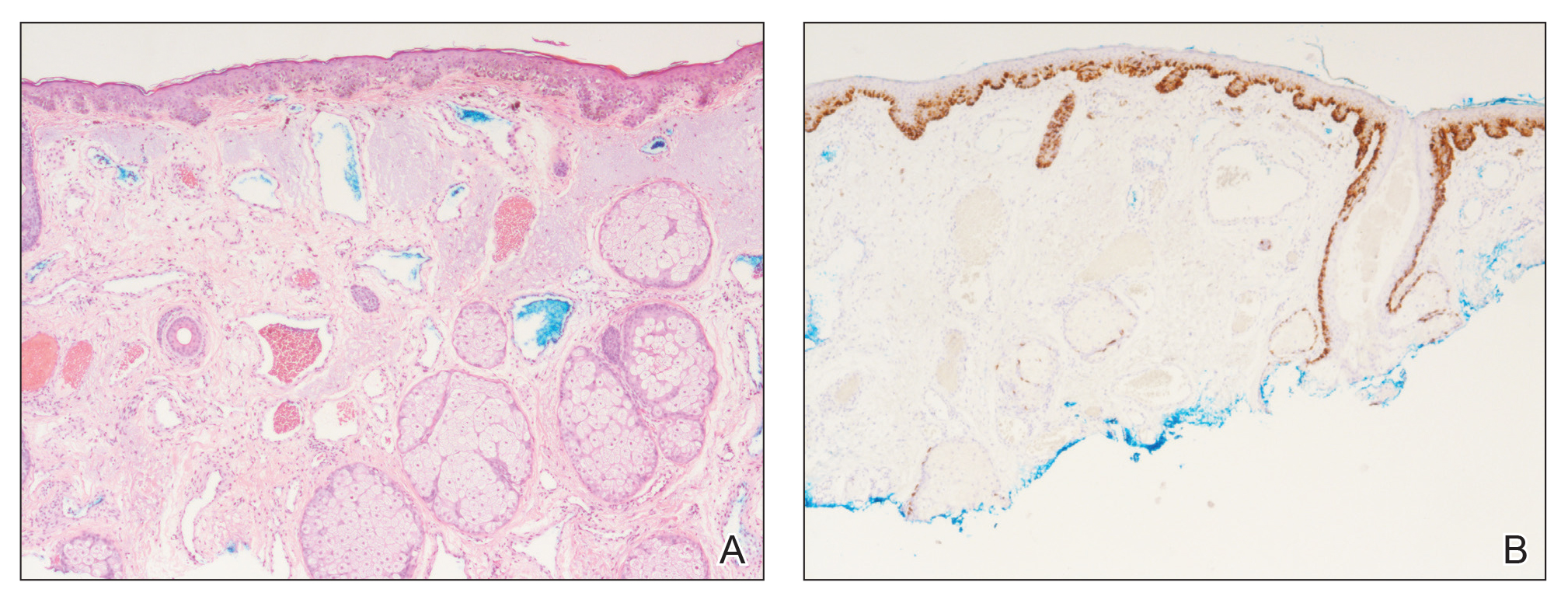

A 69-year-old man underwent staged excision for an invasive melanoma (0.4-mm Breslow depth; stage Ia) of the right dorsal nose. Two stages were required to achieve clear margins, leaving a 3.0×2.5-cm defect involving the nasal dorsum, right nasal sidewall, and nasal supratip (Figure 1). He declined any multistage repair and preferred a full-thickness skin graft (FTSG) over any interpolation flap.

Given the size of our patient’s defect, primary repair was not possible and second intention healing may have resulted in a suboptimal cosmetic outcome, potential alar distortion, and prolonged healing. No single local flap, such as the dorsal nasal rotation flap, crescentic advancement flap, bilobed flap, and Rintala flap, would have provided adequate coverage. A FTSG of the entire defect would not have been an ideal tissue match, and given the limited surrounding laxity, a Burow FTSG would have required the linear repair to extend well into the forehead with a questionable cosmetic outcome.

The Technique

We opted to repair the defect using a combination of local flaps for a single-stage repair. Using the right cheek reservoir, a crescentic advancement flap was performed to restore the right nasal sidewall as best as possible with a standing cone taken superiorly. To execute this flap, an incision was made extending from the alar sulcus into the nasolabial fold while preserving the apical triangle of the upper cutaneous lip. The flap was elevated submuscularly on the nose, and broad undermining was performed in the subcutaneous plane of the medial cheek. A crescentic redundancy above the alar sulcus was excised, and periosteal tacking sutures were placed to both help advance the flap and to recreate the nasofacial sulcus.1

Next, a nasal tip spiral/rotation flap was designed to restore the remaining nasal defect.2 An incision was made at the right inferiormost aspect of the defect and extended along the inferior border of the nasal tip as it crossed the midline to the left side of the nose. After incising and elevating the flap in the submuscular plane, there was not enough of a tissue reservoir to cover the entire remaining nasal defect.

To resolve this intraoperative conundrum, simple interrupted sutures were placed into the nasal cartilage at midline to narrow the structure of the nose (Figure 2). Three 4-0 polyglactin 910 sutures were placed beginning with the upper lateral cartilages and extending inferiorly to the lower lateral cartilages. Narrowing the nasal cartilages allowed for a smaller residual defect. The nasal tip rotation flap was then spiraled into place with adequate coverage. Some of the flap tip was trimmed after the superior aspect of the rotation flap was sutured to the inferior edge of the crescentic advancement flap. The immediate postoperative appearance is shown in Figure 3.

At 4-month follow-up, intralesional triamcinolone was injected into the slight induration at the right nasal tip. At 7-month follow-up, the patient was pleased with the cosmetic and functional result (Figure 4).

Practice Implications

Cartilage sutures highlight an underutilized technique in nasal reconstruction, with few cases reported

A combination of local flaps may be used to repair large nasal defects involving multiple subunits, especially in patients who decline multistage reconstruction. A nasal tip rotation/spiral flap can be considered for the appropriate nasal tip defect. Suturing the nasal cartilage with either permanent or long-lasting suture can narrow the cartilage and facilitate flap coverage for nasal defects while also improving the appearance of patients with wide prominent lower noses.

- Smith JM, Orseth ML, Nijhawan RI. Reconstruction of large nasal dorsum defects. Dermatol Surg. 2018;44:1607-1610.

- Snow SN. Rotation flaps to reconstruct nasal tip defects following Mohs surgery. Dermatol Surg. 1997;23:916-919.

- Malone CH, Hays JP, Tausend WE, et al. Interdomal sutures for nasal tip refinement and reduced wound size. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:E107-E108.

- Pelster MW, Behshad R, Maher IA. Large nasal tip defects-utilization of interdomal sutures before Burow’s graft for optimization of nasal contour. Dermatol Surg. 2019;45:743-746.

- Gruber RP, Chang E, Buchanan E. Suture techniques in rhinoplasty. Clin Plast Surg. 2010;37:231-243.

Practice Gap

A 69-year-old man underwent staged excision for an invasive melanoma (0.4-mm Breslow depth; stage Ia) of the right dorsal nose. Two stages were required to achieve clear margins, leaving a 3.0×2.5-cm defect involving the nasal dorsum, right nasal sidewall, and nasal supratip (Figure 1). He declined any multistage repair and preferred a full-thickness skin graft (FTSG) over any interpolation flap.

Given the size of our patient’s defect, primary repair was not possible and second intention healing may have resulted in a suboptimal cosmetic outcome, potential alar distortion, and prolonged healing. No single local flap, such as the dorsal nasal rotation flap, crescentic advancement flap, bilobed flap, and Rintala flap, would have provided adequate coverage. A FTSG of the entire defect would not have been an ideal tissue match, and given the limited surrounding laxity, a Burow FTSG would have required the linear repair to extend well into the forehead with a questionable cosmetic outcome.

The Technique

We opted to repair the defect using a combination of local flaps for a single-stage repair. Using the right cheek reservoir, a crescentic advancement flap was performed to restore the right nasal sidewall as best as possible with a standing cone taken superiorly. To execute this flap, an incision was made extending from the alar sulcus into the nasolabial fold while preserving the apical triangle of the upper cutaneous lip. The flap was elevated submuscularly on the nose, and broad undermining was performed in the subcutaneous plane of the medial cheek. A crescentic redundancy above the alar sulcus was excised, and periosteal tacking sutures were placed to both help advance the flap and to recreate the nasofacial sulcus.1

Next, a nasal tip spiral/rotation flap was designed to restore the remaining nasal defect.2 An incision was made at the right inferiormost aspect of the defect and extended along the inferior border of the nasal tip as it crossed the midline to the left side of the nose. After incising and elevating the flap in the submuscular plane, there was not enough of a tissue reservoir to cover the entire remaining nasal defect.

To resolve this intraoperative conundrum, simple interrupted sutures were placed into the nasal cartilage at midline to narrow the structure of the nose (Figure 2). Three 4-0 polyglactin 910 sutures were placed beginning with the upper lateral cartilages and extending inferiorly to the lower lateral cartilages. Narrowing the nasal cartilages allowed for a smaller residual defect. The nasal tip rotation flap was then spiraled into place with adequate coverage. Some of the flap tip was trimmed after the superior aspect of the rotation flap was sutured to the inferior edge of the crescentic advancement flap. The immediate postoperative appearance is shown in Figure 3.

At 4-month follow-up, intralesional triamcinolone was injected into the slight induration at the right nasal tip. At 7-month follow-up, the patient was pleased with the cosmetic and functional result (Figure 4).

Practice Implications

Cartilage sutures highlight an underutilized technique in nasal reconstruction, with few cases reported

A combination of local flaps may be used to repair large nasal defects involving multiple subunits, especially in patients who decline multistage reconstruction. A nasal tip rotation/spiral flap can be considered for the appropriate nasal tip defect. Suturing the nasal cartilage with either permanent or long-lasting suture can narrow the cartilage and facilitate flap coverage for nasal defects while also improving the appearance of patients with wide prominent lower noses.

Practice Gap

A 69-year-old man underwent staged excision for an invasive melanoma (0.4-mm Breslow depth; stage Ia) of the right dorsal nose. Two stages were required to achieve clear margins, leaving a 3.0×2.5-cm defect involving the nasal dorsum, right nasal sidewall, and nasal supratip (Figure 1). He declined any multistage repair and preferred a full-thickness skin graft (FTSG) over any interpolation flap.

Given the size of our patient’s defect, primary repair was not possible and second intention healing may have resulted in a suboptimal cosmetic outcome, potential alar distortion, and prolonged healing. No single local flap, such as the dorsal nasal rotation flap, crescentic advancement flap, bilobed flap, and Rintala flap, would have provided adequate coverage. A FTSG of the entire defect would not have been an ideal tissue match, and given the limited surrounding laxity, a Burow FTSG would have required the linear repair to extend well into the forehead with a questionable cosmetic outcome.

The Technique

We opted to repair the defect using a combination of local flaps for a single-stage repair. Using the right cheek reservoir, a crescentic advancement flap was performed to restore the right nasal sidewall as best as possible with a standing cone taken superiorly. To execute this flap, an incision was made extending from the alar sulcus into the nasolabial fold while preserving the apical triangle of the upper cutaneous lip. The flap was elevated submuscularly on the nose, and broad undermining was performed in the subcutaneous plane of the medial cheek. A crescentic redundancy above the alar sulcus was excised, and periosteal tacking sutures were placed to both help advance the flap and to recreate the nasofacial sulcus.1

Next, a nasal tip spiral/rotation flap was designed to restore the remaining nasal defect.2 An incision was made at the right inferiormost aspect of the defect and extended along the inferior border of the nasal tip as it crossed the midline to the left side of the nose. After incising and elevating the flap in the submuscular plane, there was not enough of a tissue reservoir to cover the entire remaining nasal defect.

To resolve this intraoperative conundrum, simple interrupted sutures were placed into the nasal cartilage at midline to narrow the structure of the nose (Figure 2). Three 4-0 polyglactin 910 sutures were placed beginning with the upper lateral cartilages and extending inferiorly to the lower lateral cartilages. Narrowing the nasal cartilages allowed for a smaller residual defect. The nasal tip rotation flap was then spiraled into place with adequate coverage. Some of the flap tip was trimmed after the superior aspect of the rotation flap was sutured to the inferior edge of the crescentic advancement flap. The immediate postoperative appearance is shown in Figure 3.

At 4-month follow-up, intralesional triamcinolone was injected into the slight induration at the right nasal tip. At 7-month follow-up, the patient was pleased with the cosmetic and functional result (Figure 4).

Practice Implications

Cartilage sutures highlight an underutilized technique in nasal reconstruction, with few cases reported

A combination of local flaps may be used to repair large nasal defects involving multiple subunits, especially in patients who decline multistage reconstruction. A nasal tip rotation/spiral flap can be considered for the appropriate nasal tip defect. Suturing the nasal cartilage with either permanent or long-lasting suture can narrow the cartilage and facilitate flap coverage for nasal defects while also improving the appearance of patients with wide prominent lower noses.

- Smith JM, Orseth ML, Nijhawan RI. Reconstruction of large nasal dorsum defects. Dermatol Surg. 2018;44:1607-1610.

- Snow SN. Rotation flaps to reconstruct nasal tip defects following Mohs surgery. Dermatol Surg. 1997;23:916-919.

- Malone CH, Hays JP, Tausend WE, et al. Interdomal sutures for nasal tip refinement and reduced wound size. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:E107-E108.

- Pelster MW, Behshad R, Maher IA. Large nasal tip defects-utilization of interdomal sutures before Burow’s graft for optimization of nasal contour. Dermatol Surg. 2019;45:743-746.

- Gruber RP, Chang E, Buchanan E. Suture techniques in rhinoplasty. Clin Plast Surg. 2010;37:231-243.

- Smith JM, Orseth ML, Nijhawan RI. Reconstruction of large nasal dorsum defects. Dermatol Surg. 2018;44:1607-1610.

- Snow SN. Rotation flaps to reconstruct nasal tip defects following Mohs surgery. Dermatol Surg. 1997;23:916-919.

- Malone CH, Hays JP, Tausend WE, et al. Interdomal sutures for nasal tip refinement and reduced wound size. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:E107-E108.

- Pelster MW, Behshad R, Maher IA. Large nasal tip defects-utilization of interdomal sutures before Burow’s graft for optimization of nasal contour. Dermatol Surg. 2019;45:743-746.

- Gruber RP, Chang E, Buchanan E. Suture techniques in rhinoplasty. Clin Plast Surg. 2010;37:231-243.

Is Artificial Intelligence Going to Replace Dermatologists?

Artificial intelligence (AI) is a loosely defined term that refers to machines (ie, algorithms) simulating facets of human intelligence. Some examples of AI are seen in natural language-processing algorithms, including autocorrect and search engine autocomplete functions; voice recognition in virtual assistants; autopilot systems in airplanes and self-driving cars; and computer vision in image and object recognition. Since the dawn of the century, various forms of AI have been tested and introduced in health care. However, a gap exists between clinician viewpoints on AI and the engineering world’s assumptions of what can be automated in medicine.

In this article, we review the history and evolution of AI in medicine, focusing on radiology and dermatology; current capabilities of AI; challenges to clinical integration; and future directions. Our aim is to provide realistic expectations of current technologies in solving complex problems and to empower dermatologists in planning for a future that likely includes various forms of AI.

Early Stages of AI in Medical Decision-making

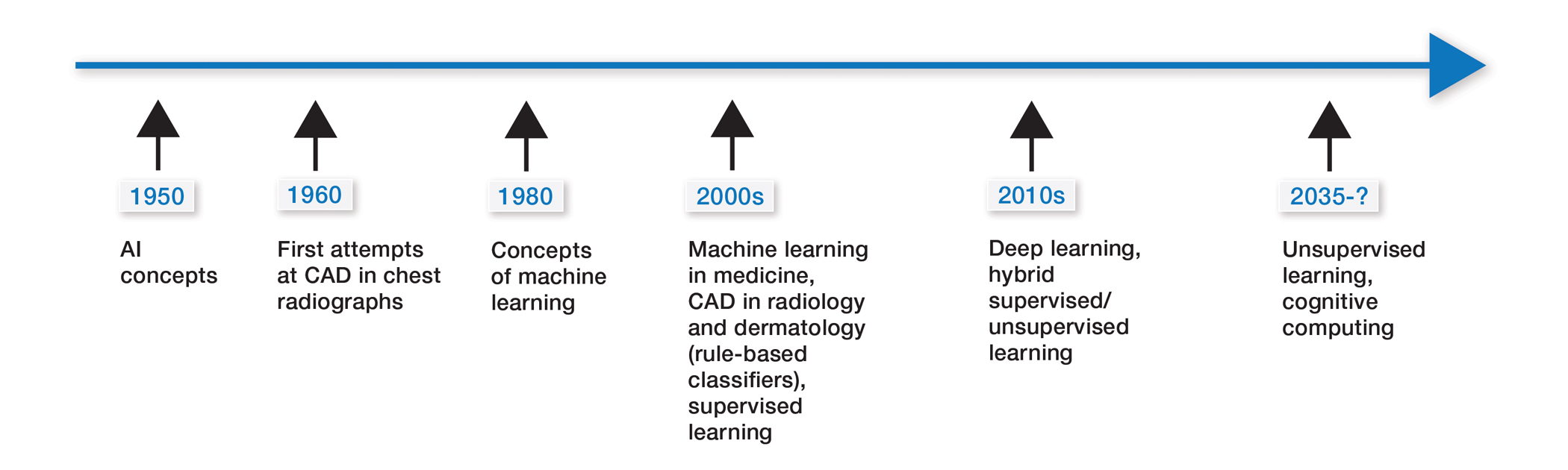

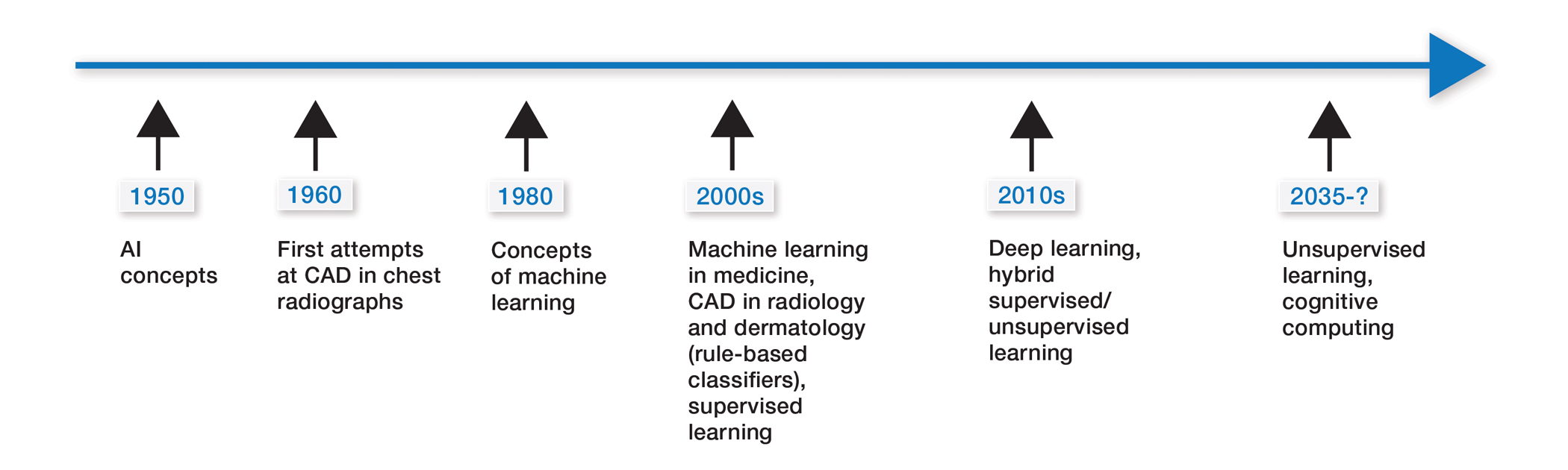

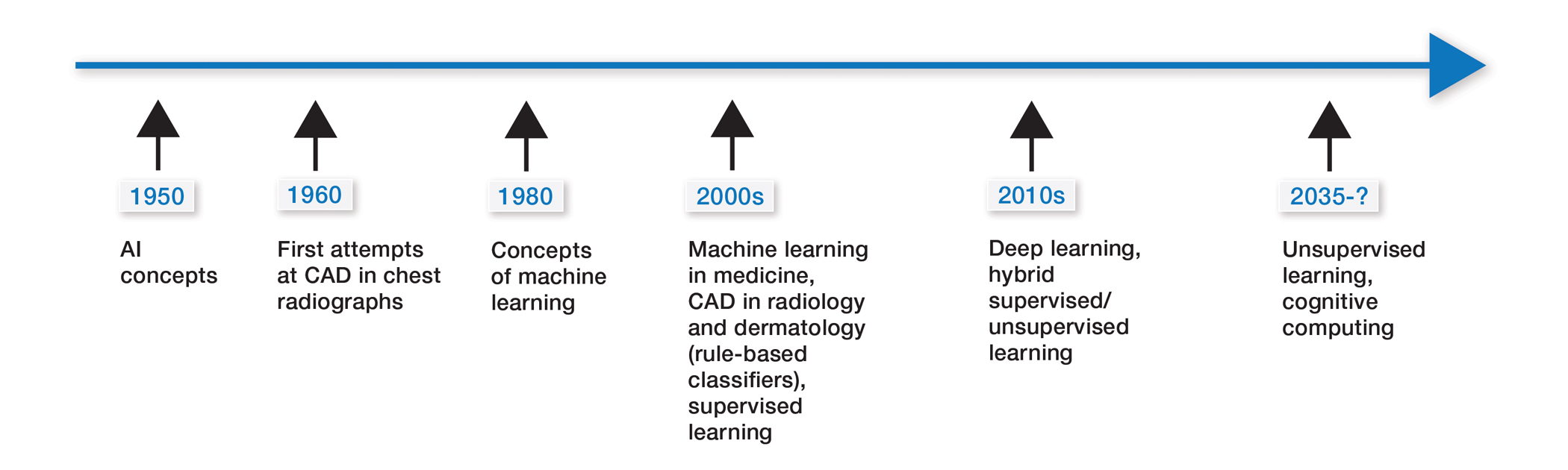

Some of the earliest forms of clinical decision-support software in medicine were computer-aided detection and computer-aided diagnosis (CAD) used in screening for breast and lung cancer on mammography and computed tomography.1-3 Early research on the use of CAD systems in radiology date to the 1960s (Figure), with the first US Food and Drug Administration–approved CAD system in mammography in 1998 and for Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services reimbursement in 2002.1,2

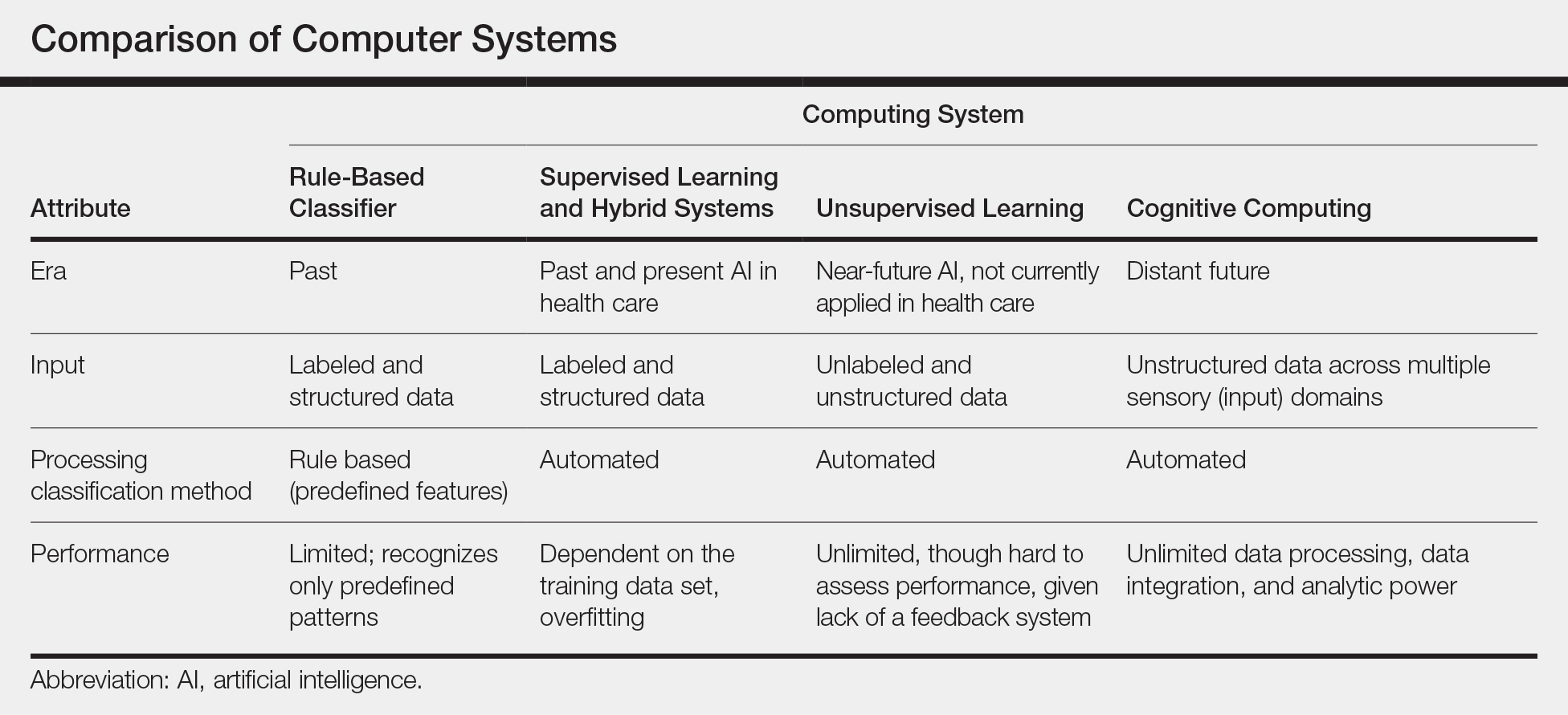

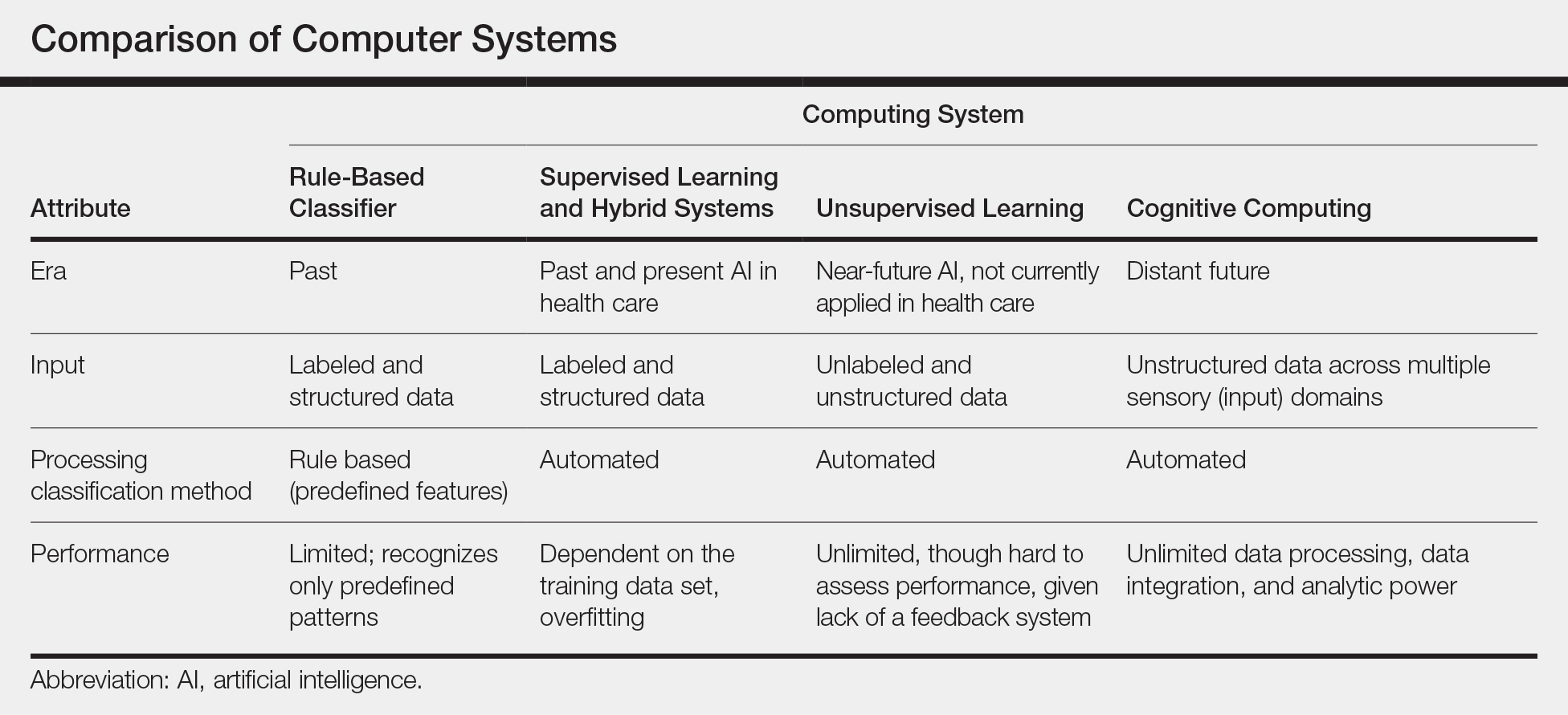

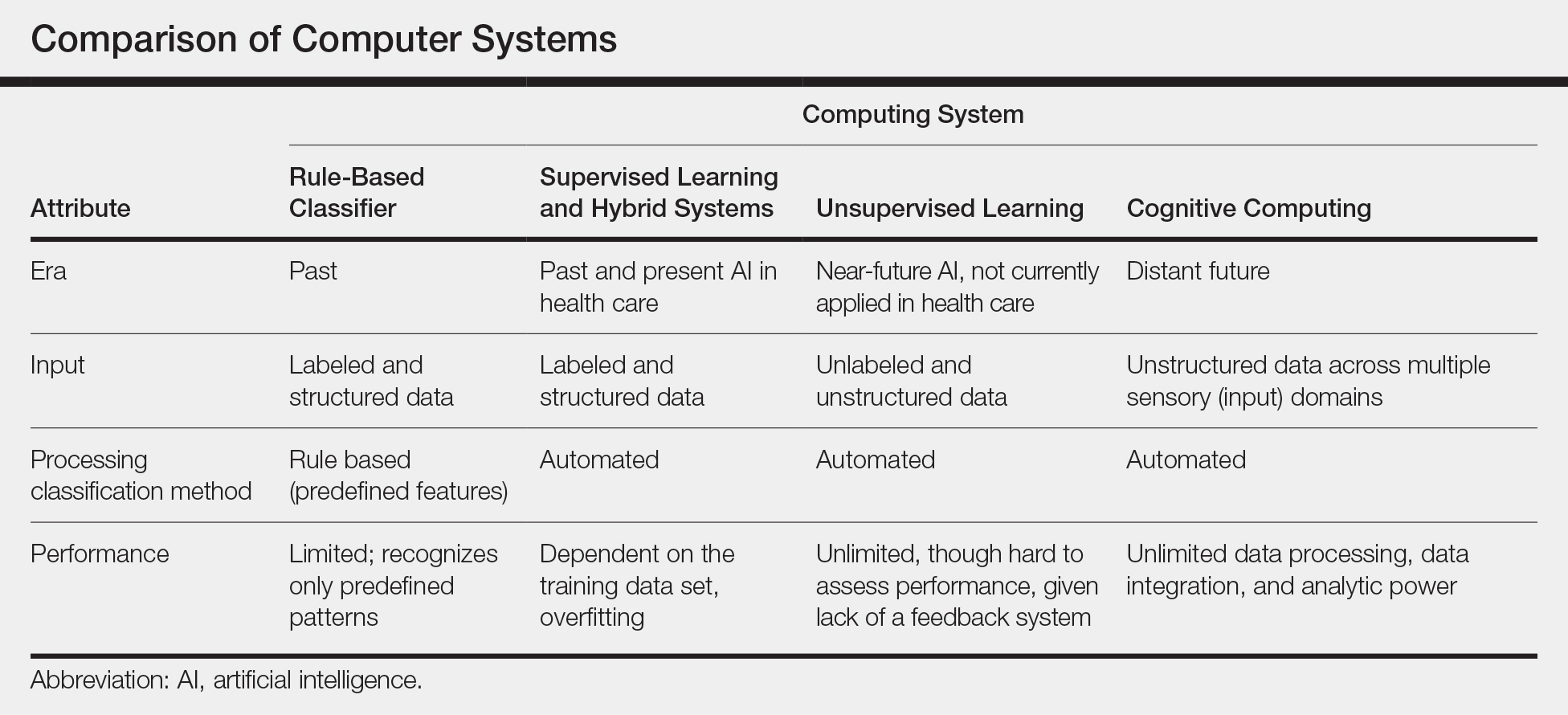

Early CAD systems relied on rule-based classifiers, which use predefined features to classify images into desired categories. For example, to classify an image as a high-risk or benign mass, features such as contour and texture had to be explicitly defined. Although these systems showed on par with, or higher, accuracy vs a radiologist in validation studies, early CAD systems never achieved wide adoption because of an increased rate of false positives as well as added work burden on a radiologist, who had to silence overcalling by the software.1,2,4,5

Computer-aided diagnosis–based melanoma diagnosis was introduced in early 2000 in dermatology (Figure) using the same feature-based classifiers. These systems claimed expert-level accuracy in proof-of-concept studies and prospective uncontrolled trials on proprietary devices using these classifiers.6,7 Similar to radiology, however, real-world adoption did not happen; in fact, the last of these devices was taken off the market in 2017. A recent meta-analysis of studies using CAD-based melanoma diagnosis point to study bias; data overfitting; and lack of large controlled, prospective trials as possible reasons why results could not be replicated in a clinical setting.8

Beyond 2010: Deep Learning

New techniques in machine learning (ML), called deep learning, began to emerge after 2010 (Figure). In deep learning, instead of directing the computer to look for certain discriminative features, the machine learns those features from the large amount of data without being explicitly programed to do so. In other words, compared to predecessor forms of computing, there is less human supervision in the learning process (Table). The concept of ML has existed since the 1980s. The field saw exponential growth in the last decade with the improvement of algorithms; an increase in computing power; and emergence of large training data sets, such as open-source platforms on the Web.9,10

Most ML methods today incorporate artificial neural networks (ANN), computer programs that imitate the architecture of biological neural networks and form dynamically changing systems that improve with continuous data exposure. The performance of an ANN is dependent on the number and architecture of its neural layers and (similar to CAD systems) the size, quality, and generalizability of the training data set.9-12

In medicine, images (eg, clinical or dermoscopic images and imaging scans) are the most commonly used form of data for AI development. Convolutional neural networks (CNN), a subtype of ANN, are frequently used for this purpose. These networks use a hierarchical neural network architecture, similar to the visual cortex, that allows for composition of complex features (eg, shapes) from simpler features (eg, image intensities), which leads to more efficient data processing.10-12

In recent years, CNNs have been applied in a number of image-based medical fields, including radiology, dermatology, and pathology. Initially, studies were largely led by computer scientists trying to match clinician performance in detection of disease categories. However, there has been a shift toward more physicians getting involved, which has motivated development of large curated (ie, expert-labeled) and standardized clinical data sets in training the CNN. Although training on quality-controlled data is a work in progress across medical disciplines, it has led to improved machine performance.11,12

Recent Advances in AI

In recent years, the number of studies covering CNN in diagnosis has increased exponentially in several medical specialties. The goal is to improve software to close the gap between experts and the machine in live clinical settings. The current literature focuses on a comparison of experts with the machine in simulated settings; prospective clinical trials are still lagging in the real world.9,11,13

We look at radiology to explore recent advances in AI diagnosis for 3 reasons: (1) radiology has the largest repository of digital data (using a picture archiving and communication system) among medical specialties; (2) radiology has well-defined, image-acquisition protocols in its clinical workflow14; and (3) gray-scale images are easier to standardize because they are impervious to environmental variables that are difficult to control (eg, recent sun exposure, rosacea flare, lighting, sweating). These are some of the reasons we think radiology is, and will be, ahead in training AI algorithms and integrating them into clinical practice. However, even radiology AI studies have limitations, including a lack of prospective, real-world clinical setting, generalizable studies, and a lack of large standardized available databases for training algorithms.

Narrowing our discussion to studies of mammography—given the repetitive nature and binary output of this modality, which has made it one of the first targets of automation in diagnostic imaging1,2,5,13—AI-based CAD in mammography, much like its predecessor feature-based CAD, has shown promising results in artificial settings. Five key mammography CNN studies have reported a wide range of diagnostic accuracy (area under the curve, 69.2 to 97.8 [mean, 88.2]) compared to radiologists.15-19

In the most recent study (2019), Rodriguez-Ruiz et al15 compared machines and a cohort of 101 radiologists, in which AI showed performance comparability. However, results in this artificial setting were not followed up with prospective analysis of the technology in a clinical setting. First-generation, feature-based CADs in mammography also showed expert-level performance in artificial settings, but the technology became extinct because these results were not generalizable to real-world in prospective trials. To our knowledge, a limitation of radiology AI is that all current CNNs have not yet been tested in a live clinical setting.13-19

The second limitation of radiology AI is lack of standardization, which also applies to mammography, despite this subset having the largest and oldest publicly available data set. In a recent review of 23 studies on AI-based algorithms in mammography (2010-2019), clinicians point to one of the biggest flaws: the use of small, nonstandardized, and skewed public databases (often enriched for malignancy) as training algorithms.13

Standardization refers to quality-control measures in acquisition, processing, and image labeling that need to be met for images to be included in the training data set. At present, large stores of radiologic data that are standardized within each institution are not publicly accessible through a unified reference platform. Lack of large standardized training data sets leads to selection bias and increases the risk for overfitting, which occurs when algorithm models incorporate background noise in the data into its prediction scheme. Overfitting has been noted in several AI-based studies in mammography,13 which limits the generalizability of algorithm performance in the real-world setting.

To overcome this limitation, the American College of Radiology Data Science Institute recently took the lead on creating a reference platform for quality control and standardized data generation for AI integration in radiology. The goal of the institute is for radiologists to work collaboratively with industry to ensure that algorithms are trained on quality data that produces clinically useable output for the clinician and patient.11,20

Similar to initial radiology studies utilizing AI mainly as a screening tool, AI-driven studies in dermatology are focused on classification of melanocytic lesions; the goal is to aid in melanoma screening. Two of the most-recent, most-cited articles on this topic are by Esteva et al21 and Tschandl et al.22 Esteva et al21 matched the performance of 21 dermatologists in binary classification (malignant or nonmalignant) of clinical and dermoscopic images in pigmented and nonpigmented categories. A CNN developed by Google was trained on 130,000 clinical images encompassing more than 2000 dermatologist-labeled diagnoses from 18 sites. Despite promising results, the question remains whether these findings are transferrable to the clinical setting. In addition to the limitation on generalizability, the authors do not elaborate on standardization of training image data sets. For example, it is unclear what percentage of the training data set’s image labels were based on biopsy results vs clinical diagnosis.21

The second study was the largest Web-based study to compare the performance of more than 500 dermatologists worldwide.22 The top 3–performing algorithms (among a pool of 139) were at least as good as the performance of 27 expert dermatologists (defined as having more than 10 years’ experience) in the classification of pigmented lesions into 7 predefined categories.22 However, images came from nonstandardized sources gathered from a 20-year period at one European academic center and a private practice in Australia. Tschandl et al22 looked at external validation with an independent data set, outside the training data set. Although not generalizable to a real-world setting, looking at external data sets helps correct for overfitting and is a good first step in understanding transferability of results. However, the external data set was chosen by the authors and therefore might be tainted by selection bias. Although only a 10% drop in algorithmic accuracy was noted using the external data set chosen by the authors, this drop does not apply to other data sets or more importantly to a real-world setting.22

Current limitations and future goals of radiology also will most likely apply to dermatology AI research. In medicine and radiology, the goal of AI is to first help users by prioritizing what they should focus on. The concept of comparing AI to a radiologist or dermatologist is potentially shortsighted. Shortcomings of the current supervised or semisupervised algorithms used in medicine underscore the points that, first, to make their outputs clinically usable, it should be clinicians who procure and standardize training data sets and, second, it appears logical that the performance of these category of algorithms requires constant monitoring for bias. Therefore, these algorithms cannot operate as stand-alone diagnostic machines but as an aid to the clinician—if the performance of the algorithms is proved in large trials.

Near-Future Directions and Projections

Almost all recent state-of-the-art AI systems tested in medical disciplines fall under the engineering terminology of narrow or weak AI, meaning any given algorithm is trained to do only one specific task.9 An example of a task is classification of images into multiple categories (ie, benign or malignant). However, task classification only works with preselected images that will need substantial improvements in standardization.

Although it has been demonstrated that AI systems can excel at one task at a time, such as classification, better than a human cohort in simulated settings, these literal machines lack the ability to incorporate context; integrate various forms of sensory input such as visual, voice, or text; or make associations the way humans do.9 Multiple tasks and clinical context integration are required for predictive diagnosis or clinical decision-making, even in a simulated environment. In this sense, CNN is still similar to its antiquated linear CAD predecessor: It cannot make a diagnosis or a clinical decision but might be appropriate for triaging cases that are referred for evaluation by a dermatologist.

Medical AI also may use electronic health records or patient-gathered data (eg, apps). However, clinical images are more structured and less noisy and are more easily incorporated in AI training. Therefore, as we are already witnessing, earlier validation and adoption of AI will occur in image-based disciplines, beginning with radiology; then pathology; and eventually dermatology, which will be the most challenging of the 3 medical specialties to standardize.

Final Thoughts

Artificial intelligence in health care is in its infancy; specific task-driven algorithms are only beginning to be introduced. We project that in the next 5 to 10 years, clinicians will become increasingly involved in training and testing large-scale validation as well as monitoring narrow AI in clinical trials. Radiology has served as the pioneering area in medicine and is just beginning to utilize narrow AI to help specialists with very specific tasks. For example, a task would be to triage which scans to look at first for a radiologist or which pigmented lesion might need prompt evaluation by a dermatologist. Artificial intelligence in medicine is not replacing specialists or placing decision-making in the hands of a nonexpert. At this point, CNNs have not proven that they make us better at diagnosing because real-world clinical data are lacking, which may change in the future with large standardized training data sets and validation with prospective clinical trials. The near future for dermatology and pathology will follow what is already happening in radiology, with AI substantially increasing workflow efficiency by prioritizing tasks.

- Kohli A, Jha S. Why CAD failed in mammography. J Am Coll Radiol. 2018;15:535-537.

- Gao Y, Geras KJ, Lewin AA, Moy L. New frontiers: an update on computer-aided diagnosis for breast imaging in the age of artificial intelligence. Am J Roentgenol. 2019;212:300-307.

- Ardila D, Kiraly AP, Bharadwaj S, et al. End-to-end lung cancer screening with three-dimensional deep learning on low-dose chest computed tomography. Nat Med. 2019;25:954-961.

- Le EPV, Wang Y, Huang Y, et al. Artificial intelligence in breast imaging. Clin Radiol. 2019;74:357-366.

- Houssami N, Lee CI, Buist DSM, et al. Artificial intelligence for breast cancer screening: opportunity or hype? Breast. 2017;36:31-33.

- Cukras AR. On the comparison of diagnosis and management of melanoma between dermatologists and MelaFind. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:622-623.

- Gutkowicz-Krusin D, Elbaum M, Jacobs A, et al. Precision of automatic measurements of pigmented skin lesion parameters with a MelaFindTM multispectral digital dermoscope. Melanoma Res. 2000;10:563-570.

- Dick V, Sinz C, Mittlböck M, et al. Accuracy of computer-aided diagnosis of melanoma: a meta-analysis [published online June 19, 2019]. JAMA Dermatol. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.1375.

- Hosny A, Parmar C, Quackenbush J, et al. Artificial intelligence in radiology. Nat Rev Cancer. 2018;18:500-510.

- Gyftopoulos S, Lin D, Knoll F, et al. Artificial intelligence in musculoskeletal imaging: current status and future directions. Am J Roentgenol. 2019;213:506-513.

- Chan S, Siegel EL. Will machine learning end the viability of radiology as a thriving medical specialty? Br J Radiol. 2019;92:20180416.

- Erickson BJ, Korfiatis P, Kline TL, et al. Deep learning in radiology: does one size fit all? J Am Coll Radiol. 2018;15:521-526.

- Houssami N, Kirkpatrick-Jones G, Noguchi N, et al. Artificial Intelligence (AI) for the early detection of breast cancer: a scoping review to assess AI’s potential in breast screening practice. Expert Rev Med Devices. 2019;16:351-362.

- Pesapane F, Codari M, Sardanelli F. Artificial intelligence in medical imaging: threat or opportunity? Radiologists again at the forefront of innovation in medicine. Eur Radiol Exp. 2018;2:35.

- Rodriguez-Ruiz A, Lång K, Gubern-Merida A, et al. Stand-alone artificial intelligence for breast cancer detection in mammography: comparison with 101 radiologists. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2019;111:916-922.

- Becker AS, Mueller M, Stoffel E, et al. Classification of breast cancer in ultrasound imaging using a generic deep learning analysis software: a pilot study. Br J Radiol. 2018;91:20170576.

- Becker AS, Marcon M, Ghafoor S, et al. Deep learning in mammography: diagnostic accuracy of a multipurpose image analysis software in the detection of breast cancer. Invest Radiol. 2017;52:434-440.

- Kooi T, Litjens G, van Ginneken B, et al. Large scale deep learning for computer aided detection of mammographic lesions. Med Image Anal. 2017;35:303-312.

- Ayer T, Alagoz O, Chhatwal J, et al. Breast cancer risk estimation with artificial neural networks revisited: discrimination and calibration. Cancer. 2010;116:3310-3321.

- American College of Radiology Data Science Institute. Dataset directory. https://www.acrdsi.org/DSI-Services/Dataset-Directory. Accessed December 17, 2019.

- Esteva A, Kuprel B, Novoa RA, et al. Dermatologist-level classification of skin cancer with deep neural networks. Nature. 2017;542:115-118.

- Tschandl P, Codella N, Akay BN, et al. Comparison of the accuracy of human readers versus machine-learning algorithms for pigmented skin lesion classification: an open, web-based, international, diagnostic study. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20:938-947.

Artificial intelligence (AI) is a loosely defined term that refers to machines (ie, algorithms) simulating facets of human intelligence. Some examples of AI are seen in natural language-processing algorithms, including autocorrect and search engine autocomplete functions; voice recognition in virtual assistants; autopilot systems in airplanes and self-driving cars; and computer vision in image and object recognition. Since the dawn of the century, various forms of AI have been tested and introduced in health care. However, a gap exists between clinician viewpoints on AI and the engineering world’s assumptions of what can be automated in medicine.

In this article, we review the history and evolution of AI in medicine, focusing on radiology and dermatology; current capabilities of AI; challenges to clinical integration; and future directions. Our aim is to provide realistic expectations of current technologies in solving complex problems and to empower dermatologists in planning for a future that likely includes various forms of AI.

Early Stages of AI in Medical Decision-making

Some of the earliest forms of clinical decision-support software in medicine were computer-aided detection and computer-aided diagnosis (CAD) used in screening for breast and lung cancer on mammography and computed tomography.1-3 Early research on the use of CAD systems in radiology date to the 1960s (Figure), with the first US Food and Drug Administration–approved CAD system in mammography in 1998 and for Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services reimbursement in 2002.1,2

Early CAD systems relied on rule-based classifiers, which use predefined features to classify images into desired categories. For example, to classify an image as a high-risk or benign mass, features such as contour and texture had to be explicitly defined. Although these systems showed on par with, or higher, accuracy vs a radiologist in validation studies, early CAD systems never achieved wide adoption because of an increased rate of false positives as well as added work burden on a radiologist, who had to silence overcalling by the software.1,2,4,5

Computer-aided diagnosis–based melanoma diagnosis was introduced in early 2000 in dermatology (Figure) using the same feature-based classifiers. These systems claimed expert-level accuracy in proof-of-concept studies and prospective uncontrolled trials on proprietary devices using these classifiers.6,7 Similar to radiology, however, real-world adoption did not happen; in fact, the last of these devices was taken off the market in 2017. A recent meta-analysis of studies using CAD-based melanoma diagnosis point to study bias; data overfitting; and lack of large controlled, prospective trials as possible reasons why results could not be replicated in a clinical setting.8

Beyond 2010: Deep Learning

New techniques in machine learning (ML), called deep learning, began to emerge after 2010 (Figure). In deep learning, instead of directing the computer to look for certain discriminative features, the machine learns those features from the large amount of data without being explicitly programed to do so. In other words, compared to predecessor forms of computing, there is less human supervision in the learning process (Table). The concept of ML has existed since the 1980s. The field saw exponential growth in the last decade with the improvement of algorithms; an increase in computing power; and emergence of large training data sets, such as open-source platforms on the Web.9,10

Most ML methods today incorporate artificial neural networks (ANN), computer programs that imitate the architecture of biological neural networks and form dynamically changing systems that improve with continuous data exposure. The performance of an ANN is dependent on the number and architecture of its neural layers and (similar to CAD systems) the size, quality, and generalizability of the training data set.9-12

In medicine, images (eg, clinical or dermoscopic images and imaging scans) are the most commonly used form of data for AI development. Convolutional neural networks (CNN), a subtype of ANN, are frequently used for this purpose. These networks use a hierarchical neural network architecture, similar to the visual cortex, that allows for composition of complex features (eg, shapes) from simpler features (eg, image intensities), which leads to more efficient data processing.10-12

In recent years, CNNs have been applied in a number of image-based medical fields, including radiology, dermatology, and pathology. Initially, studies were largely led by computer scientists trying to match clinician performance in detection of disease categories. However, there has been a shift toward more physicians getting involved, which has motivated development of large curated (ie, expert-labeled) and standardized clinical data sets in training the CNN. Although training on quality-controlled data is a work in progress across medical disciplines, it has led to improved machine performance.11,12

Recent Advances in AI

In recent years, the number of studies covering CNN in diagnosis has increased exponentially in several medical specialties. The goal is to improve software to close the gap between experts and the machine in live clinical settings. The current literature focuses on a comparison of experts with the machine in simulated settings; prospective clinical trials are still lagging in the real world.9,11,13

We look at radiology to explore recent advances in AI diagnosis for 3 reasons: (1) radiology has the largest repository of digital data (using a picture archiving and communication system) among medical specialties; (2) radiology has well-defined, image-acquisition protocols in its clinical workflow14; and (3) gray-scale images are easier to standardize because they are impervious to environmental variables that are difficult to control (eg, recent sun exposure, rosacea flare, lighting, sweating). These are some of the reasons we think radiology is, and will be, ahead in training AI algorithms and integrating them into clinical practice. However, even radiology AI studies have limitations, including a lack of prospective, real-world clinical setting, generalizable studies, and a lack of large standardized available databases for training algorithms.

Narrowing our discussion to studies of mammography—given the repetitive nature and binary output of this modality, which has made it one of the first targets of automation in diagnostic imaging1,2,5,13—AI-based CAD in mammography, much like its predecessor feature-based CAD, has shown promising results in artificial settings. Five key mammography CNN studies have reported a wide range of diagnostic accuracy (area under the curve, 69.2 to 97.8 [mean, 88.2]) compared to radiologists.15-19

In the most recent study (2019), Rodriguez-Ruiz et al15 compared machines and a cohort of 101 radiologists, in which AI showed performance comparability. However, results in this artificial setting were not followed up with prospective analysis of the technology in a clinical setting. First-generation, feature-based CADs in mammography also showed expert-level performance in artificial settings, but the technology became extinct because these results were not generalizable to real-world in prospective trials. To our knowledge, a limitation of radiology AI is that all current CNNs have not yet been tested in a live clinical setting.13-19

The second limitation of radiology AI is lack of standardization, which also applies to mammography, despite this subset having the largest and oldest publicly available data set. In a recent review of 23 studies on AI-based algorithms in mammography (2010-2019), clinicians point to one of the biggest flaws: the use of small, nonstandardized, and skewed public databases (often enriched for malignancy) as training algorithms.13

Standardization refers to quality-control measures in acquisition, processing, and image labeling that need to be met for images to be included in the training data set. At present, large stores of radiologic data that are standardized within each institution are not publicly accessible through a unified reference platform. Lack of large standardized training data sets leads to selection bias and increases the risk for overfitting, which occurs when algorithm models incorporate background noise in the data into its prediction scheme. Overfitting has been noted in several AI-based studies in mammography,13 which limits the generalizability of algorithm performance in the real-world setting.

To overcome this limitation, the American College of Radiology Data Science Institute recently took the lead on creating a reference platform for quality control and standardized data generation for AI integration in radiology. The goal of the institute is for radiologists to work collaboratively with industry to ensure that algorithms are trained on quality data that produces clinically useable output for the clinician and patient.11,20

Similar to initial radiology studies utilizing AI mainly as a screening tool, AI-driven studies in dermatology are focused on classification of melanocytic lesions; the goal is to aid in melanoma screening. Two of the most-recent, most-cited articles on this topic are by Esteva et al21 and Tschandl et al.22 Esteva et al21 matched the performance of 21 dermatologists in binary classification (malignant or nonmalignant) of clinical and dermoscopic images in pigmented and nonpigmented categories. A CNN developed by Google was trained on 130,000 clinical images encompassing more than 2000 dermatologist-labeled diagnoses from 18 sites. Despite promising results, the question remains whether these findings are transferrable to the clinical setting. In addition to the limitation on generalizability, the authors do not elaborate on standardization of training image data sets. For example, it is unclear what percentage of the training data set’s image labels were based on biopsy results vs clinical diagnosis.21

The second study was the largest Web-based study to compare the performance of more than 500 dermatologists worldwide.22 The top 3–performing algorithms (among a pool of 139) were at least as good as the performance of 27 expert dermatologists (defined as having more than 10 years’ experience) in the classification of pigmented lesions into 7 predefined categories.22 However, images came from nonstandardized sources gathered from a 20-year period at one European academic center and a private practice in Australia. Tschandl et al22 looked at external validation with an independent data set, outside the training data set. Although not generalizable to a real-world setting, looking at external data sets helps correct for overfitting and is a good first step in understanding transferability of results. However, the external data set was chosen by the authors and therefore might be tainted by selection bias. Although only a 10% drop in algorithmic accuracy was noted using the external data set chosen by the authors, this drop does not apply to other data sets or more importantly to a real-world setting.22

Current limitations and future goals of radiology also will most likely apply to dermatology AI research. In medicine and radiology, the goal of AI is to first help users by prioritizing what they should focus on. The concept of comparing AI to a radiologist or dermatologist is potentially shortsighted. Shortcomings of the current supervised or semisupervised algorithms used in medicine underscore the points that, first, to make their outputs clinically usable, it should be clinicians who procure and standardize training data sets and, second, it appears logical that the performance of these category of algorithms requires constant monitoring for bias. Therefore, these algorithms cannot operate as stand-alone diagnostic machines but as an aid to the clinician—if the performance of the algorithms is proved in large trials.

Near-Future Directions and Projections

Almost all recent state-of-the-art AI systems tested in medical disciplines fall under the engineering terminology of narrow or weak AI, meaning any given algorithm is trained to do only one specific task.9 An example of a task is classification of images into multiple categories (ie, benign or malignant). However, task classification only works with preselected images that will need substantial improvements in standardization.

Although it has been demonstrated that AI systems can excel at one task at a time, such as classification, better than a human cohort in simulated settings, these literal machines lack the ability to incorporate context; integrate various forms of sensory input such as visual, voice, or text; or make associations the way humans do.9 Multiple tasks and clinical context integration are required for predictive diagnosis or clinical decision-making, even in a simulated environment. In this sense, CNN is still similar to its antiquated linear CAD predecessor: It cannot make a diagnosis or a clinical decision but might be appropriate for triaging cases that are referred for evaluation by a dermatologist.

Medical AI also may use electronic health records or patient-gathered data (eg, apps). However, clinical images are more structured and less noisy and are more easily incorporated in AI training. Therefore, as we are already witnessing, earlier validation and adoption of AI will occur in image-based disciplines, beginning with radiology; then pathology; and eventually dermatology, which will be the most challenging of the 3 medical specialties to standardize.

Final Thoughts

Artificial intelligence in health care is in its infancy; specific task-driven algorithms are only beginning to be introduced. We project that in the next 5 to 10 years, clinicians will become increasingly involved in training and testing large-scale validation as well as monitoring narrow AI in clinical trials. Radiology has served as the pioneering area in medicine and is just beginning to utilize narrow AI to help specialists with very specific tasks. For example, a task would be to triage which scans to look at first for a radiologist or which pigmented lesion might need prompt evaluation by a dermatologist. Artificial intelligence in medicine is not replacing specialists or placing decision-making in the hands of a nonexpert. At this point, CNNs have not proven that they make us better at diagnosing because real-world clinical data are lacking, which may change in the future with large standardized training data sets and validation with prospective clinical trials. The near future for dermatology and pathology will follow what is already happening in radiology, with AI substantially increasing workflow efficiency by prioritizing tasks.

Artificial intelligence (AI) is a loosely defined term that refers to machines (ie, algorithms) simulating facets of human intelligence. Some examples of AI are seen in natural language-processing algorithms, including autocorrect and search engine autocomplete functions; voice recognition in virtual assistants; autopilot systems in airplanes and self-driving cars; and computer vision in image and object recognition. Since the dawn of the century, various forms of AI have been tested and introduced in health care. However, a gap exists between clinician viewpoints on AI and the engineering world’s assumptions of what can be automated in medicine.

In this article, we review the history and evolution of AI in medicine, focusing on radiology and dermatology; current capabilities of AI; challenges to clinical integration; and future directions. Our aim is to provide realistic expectations of current technologies in solving complex problems and to empower dermatologists in planning for a future that likely includes various forms of AI.

Early Stages of AI in Medical Decision-making

Some of the earliest forms of clinical decision-support software in medicine were computer-aided detection and computer-aided diagnosis (CAD) used in screening for breast and lung cancer on mammography and computed tomography.1-3 Early research on the use of CAD systems in radiology date to the 1960s (Figure), with the first US Food and Drug Administration–approved CAD system in mammography in 1998 and for Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services reimbursement in 2002.1,2