User login

Premature menopause a ‘warning sign’ for greater ASCVD risk

Premature menopause is well known to be linked to cardiovascular disease in women, but it may not carry as much weight as more traditional cardiovascular risk factors in determining a patient’s 10-year risk of having a heart attack or stroke in this population, a cohort study that evaluated the veracity of premature menopause found.

Premature menopause can serve as a “marker or warning sign” that cardiologists should pay closer attention to traditional atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) risk factors, lead study author Sadiya S. Khan, MD, MS, said in an interview. “When we looked at the addition of premature menopause into the risk-prediction equation, we did not see that it meaningfully improved the ability of the risk predictions of pooled cohort equations [PCEs] to identify who developed cardiovascular disease,” said Dr. Khan, a cardiologist at Northwestern University, Chicago.

The cohort study included 5,466 Black women and 10,584 White women from seven U.S. population-based cohorts, including the Women’s Health Initiative, of whom 951 and 1,039, respectively, self-reported early menopause. The cohort study researchers noted that the 2019 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guideline for prevention of CVD acknowledged premature menopause as risk-enhancing factor in the CVD assessment in women younger than 40.

The cohort study found that Black women had almost twice the rate of premature menopause than White women, 17.4% and 9.8%, respectively. And it found that premature menopause was significantly linked with ASCVD in both populations independent of traditional risk factors – a 24% greater risk for Black women and 28% greater risk for White women.

‘Surprising’ finding

However, when premature menopause was added to the pooled cohort equations per the 2013 ACC/AHA guideline, the researchers found no incremental benefit, a finding Dr. Khan called “really surprising to us.”

She added, “If we look at the differences in the characteristics of women who have premature menopause, compared with those who didn’t, there were slight differences in terms of higher blood pressure, higher body mass index, and slightly higher glucose. So maybe what we’re seeing – and this is more speculative – is that risk factors are developing after early menopause, and the focus should be earlier in the patient’s life course to try to prevent hypertension, diabetes, and obesity.”

Dr. Khan emphasized that the findings don’t obviate the value of premature menopause in assessing ASCVD risk in women. “We still know that this is an important marker for women and their risk for heart disease, and it should be a warning sign to pay close attention to those other risk factors and what other preventive measures can be taken,” she said.

Christie Ballantyne, MD, said it’s important to note that the study did not dismiss the relevance of premature menopause in shared decision-making for postmenopausal women. “It certainly doesn’t mean that premature menopause is not a risk,” Dr. Ballantyne said in an interview. “Premature menopause may cause a worsening of traditional CVD risk factors, so that’s one possible explanation for it. The other possible explanation is that women with worse ASCVD risk factors – who are more overweight, have higher blood pressure, and have more diabetes and insulin resistance – are more likely to have earlier menopause.” Dr. Ballantyne is chief of cardiology at Baylor College of Medicine and director of cardiovascular disease prevention at Methodist DeBakey Heart Center, both in Houston.

“You should still look very carefully at the patient’s risk factors, calculate the pooled cohort equations, and make sure you get a recommendation,” he said. “If their risks are up, give recommendations on how to improve diet and exercise. Consider if you need to treat lipids or treat blood pressure with more than diet and exercise because there’s nothing magical about 7.5%”, the threshold for lipid-lowering therapy in the ASCVD risk calculator.

Dr. Khan and coauthors disclosed receiving grants from the National Institutes of Health and the American Heart Association. One coauthor reported a financial relationship with HGM Biopharmaceuticals. Dr. Ballantyne is a lead investigator of the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study, one of the population-based cohorts used in the cohort study. He has no other relevant relationships to disclose.

Premature menopause is well known to be linked to cardiovascular disease in women, but it may not carry as much weight as more traditional cardiovascular risk factors in determining a patient’s 10-year risk of having a heart attack or stroke in this population, a cohort study that evaluated the veracity of premature menopause found.

Premature menopause can serve as a “marker or warning sign” that cardiologists should pay closer attention to traditional atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) risk factors, lead study author Sadiya S. Khan, MD, MS, said in an interview. “When we looked at the addition of premature menopause into the risk-prediction equation, we did not see that it meaningfully improved the ability of the risk predictions of pooled cohort equations [PCEs] to identify who developed cardiovascular disease,” said Dr. Khan, a cardiologist at Northwestern University, Chicago.

The cohort study included 5,466 Black women and 10,584 White women from seven U.S. population-based cohorts, including the Women’s Health Initiative, of whom 951 and 1,039, respectively, self-reported early menopause. The cohort study researchers noted that the 2019 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guideline for prevention of CVD acknowledged premature menopause as risk-enhancing factor in the CVD assessment in women younger than 40.

The cohort study found that Black women had almost twice the rate of premature menopause than White women, 17.4% and 9.8%, respectively. And it found that premature menopause was significantly linked with ASCVD in both populations independent of traditional risk factors – a 24% greater risk for Black women and 28% greater risk for White women.

‘Surprising’ finding

However, when premature menopause was added to the pooled cohort equations per the 2013 ACC/AHA guideline, the researchers found no incremental benefit, a finding Dr. Khan called “really surprising to us.”

She added, “If we look at the differences in the characteristics of women who have premature menopause, compared with those who didn’t, there were slight differences in terms of higher blood pressure, higher body mass index, and slightly higher glucose. So maybe what we’re seeing – and this is more speculative – is that risk factors are developing after early menopause, and the focus should be earlier in the patient’s life course to try to prevent hypertension, diabetes, and obesity.”

Dr. Khan emphasized that the findings don’t obviate the value of premature menopause in assessing ASCVD risk in women. “We still know that this is an important marker for women and their risk for heart disease, and it should be a warning sign to pay close attention to those other risk factors and what other preventive measures can be taken,” she said.

Christie Ballantyne, MD, said it’s important to note that the study did not dismiss the relevance of premature menopause in shared decision-making for postmenopausal women. “It certainly doesn’t mean that premature menopause is not a risk,” Dr. Ballantyne said in an interview. “Premature menopause may cause a worsening of traditional CVD risk factors, so that’s one possible explanation for it. The other possible explanation is that women with worse ASCVD risk factors – who are more overweight, have higher blood pressure, and have more diabetes and insulin resistance – are more likely to have earlier menopause.” Dr. Ballantyne is chief of cardiology at Baylor College of Medicine and director of cardiovascular disease prevention at Methodist DeBakey Heart Center, both in Houston.

“You should still look very carefully at the patient’s risk factors, calculate the pooled cohort equations, and make sure you get a recommendation,” he said. “If their risks are up, give recommendations on how to improve diet and exercise. Consider if you need to treat lipids or treat blood pressure with more than diet and exercise because there’s nothing magical about 7.5%”, the threshold for lipid-lowering therapy in the ASCVD risk calculator.

Dr. Khan and coauthors disclosed receiving grants from the National Institutes of Health and the American Heart Association. One coauthor reported a financial relationship with HGM Biopharmaceuticals. Dr. Ballantyne is a lead investigator of the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study, one of the population-based cohorts used in the cohort study. He has no other relevant relationships to disclose.

Premature menopause is well known to be linked to cardiovascular disease in women, but it may not carry as much weight as more traditional cardiovascular risk factors in determining a patient’s 10-year risk of having a heart attack or stroke in this population, a cohort study that evaluated the veracity of premature menopause found.

Premature menopause can serve as a “marker or warning sign” that cardiologists should pay closer attention to traditional atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) risk factors, lead study author Sadiya S. Khan, MD, MS, said in an interview. “When we looked at the addition of premature menopause into the risk-prediction equation, we did not see that it meaningfully improved the ability of the risk predictions of pooled cohort equations [PCEs] to identify who developed cardiovascular disease,” said Dr. Khan, a cardiologist at Northwestern University, Chicago.

The cohort study included 5,466 Black women and 10,584 White women from seven U.S. population-based cohorts, including the Women’s Health Initiative, of whom 951 and 1,039, respectively, self-reported early menopause. The cohort study researchers noted that the 2019 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guideline for prevention of CVD acknowledged premature menopause as risk-enhancing factor in the CVD assessment in women younger than 40.

The cohort study found that Black women had almost twice the rate of premature menopause than White women, 17.4% and 9.8%, respectively. And it found that premature menopause was significantly linked with ASCVD in both populations independent of traditional risk factors – a 24% greater risk for Black women and 28% greater risk for White women.

‘Surprising’ finding

However, when premature menopause was added to the pooled cohort equations per the 2013 ACC/AHA guideline, the researchers found no incremental benefit, a finding Dr. Khan called “really surprising to us.”

She added, “If we look at the differences in the characteristics of women who have premature menopause, compared with those who didn’t, there were slight differences in terms of higher blood pressure, higher body mass index, and slightly higher glucose. So maybe what we’re seeing – and this is more speculative – is that risk factors are developing after early menopause, and the focus should be earlier in the patient’s life course to try to prevent hypertension, diabetes, and obesity.”

Dr. Khan emphasized that the findings don’t obviate the value of premature menopause in assessing ASCVD risk in women. “We still know that this is an important marker for women and their risk for heart disease, and it should be a warning sign to pay close attention to those other risk factors and what other preventive measures can be taken,” she said.

Christie Ballantyne, MD, said it’s important to note that the study did not dismiss the relevance of premature menopause in shared decision-making for postmenopausal women. “It certainly doesn’t mean that premature menopause is not a risk,” Dr. Ballantyne said in an interview. “Premature menopause may cause a worsening of traditional CVD risk factors, so that’s one possible explanation for it. The other possible explanation is that women with worse ASCVD risk factors – who are more overweight, have higher blood pressure, and have more diabetes and insulin resistance – are more likely to have earlier menopause.” Dr. Ballantyne is chief of cardiology at Baylor College of Medicine and director of cardiovascular disease prevention at Methodist DeBakey Heart Center, both in Houston.

“You should still look very carefully at the patient’s risk factors, calculate the pooled cohort equations, and make sure you get a recommendation,” he said. “If their risks are up, give recommendations on how to improve diet and exercise. Consider if you need to treat lipids or treat blood pressure with more than diet and exercise because there’s nothing magical about 7.5%”, the threshold for lipid-lowering therapy in the ASCVD risk calculator.

Dr. Khan and coauthors disclosed receiving grants from the National Institutes of Health and the American Heart Association. One coauthor reported a financial relationship with HGM Biopharmaceuticals. Dr. Ballantyne is a lead investigator of the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study, one of the population-based cohorts used in the cohort study. He has no other relevant relationships to disclose.

FROM JAMA CARDIOLOGY

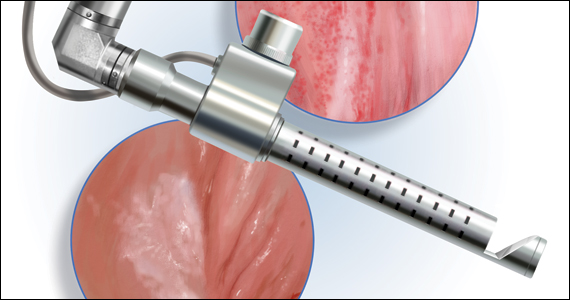

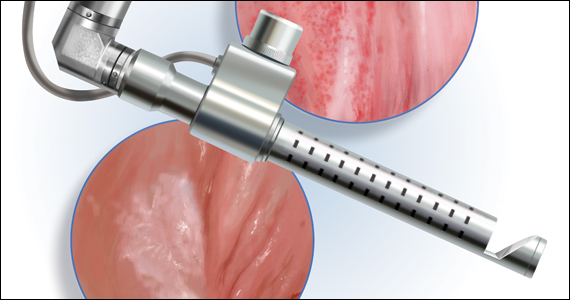

2021 Update on female sexual health

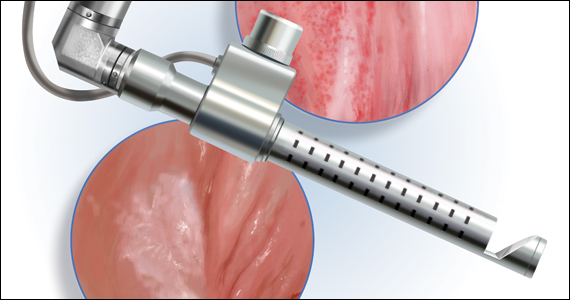

The approach to diagnosis and treatment of female sexual function continues to be a challenge for women’s health professionals. The search for a female “little blue pill” remains elusive as researchers struggle to understand the mechanisms that underlie the complex aspects of female sexual health. This Update will review the recent literature on the use of fractional CO2 laser for treatment of female sexual dysfunction and vulvovaginal symptoms. Bottom line: While the quality of the studies is poor overall, fractional CO2 laser treatment seems to temporarily improve symptoms of genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM). The duration of response, cost, and the overall long-term impact on sexual health remain in question.

A retrospective look at CO2 laser and postmenopausal GSM

Filippini M, Luvero D, Salvatore S, et al. Efficacy of fractional CO2 laser treatment in postmenopausal women with genitourinary syndrome: a multicenter study. Menopause. 2019;27:43-49. doi: 10.1097/GME. 0000000000001428.

Researchers conducted a retrospective, multicenter study of postmenopausal women with at least one symptom of GSM, including itching, burning, dyspareunia with penetration, and dryness.

Study details

A total of 171 of the 645 women (26.5%) were oncology patients. Women were excluded from analysis if they used any form of topical therapy within 15 days; had prolapse stage 2 or greater; or had any infection, abscess, or anatomical deformity precluding treatment with the laser.

Patients underwent gynecologic examination and were given a questionnaire to assess vulvovaginal symptoms. Exams occurred monthly during treatment (average, 6.5 months), at 6- and 12-months posttreatment, and then annually. No topical therapy was advised during or after treatment.

Patients received either 3 or 4 fractional CO2 laser treatments to the vulva and/or vagina depending on symptom location and type. Higher power settings of the same laser were used to treat vaginal symptoms (40W; 1,000 microseconds) versus vulvar symptoms (25W; 500 microseconds). Treatment sessions were 5 to 6 minutes. The study authors used a visual analog rating scale (VAS) for “atrophy and related symptoms,” tested vaginal pH, and completed the Vaginal Health Index Score. VAS scores were obtained from the patients prior to the initial laser intervention and 1 month after the final treatment.

Results

There were statistically significant improvements in dryness, vaginal orifice pain, dyspareunia, itching, and burning for both the 3-treatment and 4-treatment cohorts. The delta of improvement was then compared for the 2 subgroups; curiously, there was greater improvement of symptoms such as dryness (65% vs 61%), itching (78% vs 72%), burning (72% vs 67%), and vaginal orifice pain (67% vs 60%) in the group that received 3 cycles than in the group that received 4 cycles.

With regard to vaginal pH improvement, the 4-cycle group performed better than the 3-cycle group (1% improvement in the 4-cycle group vs 6% in the 3-cycle group). Although vaginal pH reduction was somewhat better in the group that received 4 treatments, and the pre versus posttreatment percentages were statistically significantly different, the clinical significance of a pH difference between 5.72 and 5.53 is questionable, especially since there was a greater difference in baseline pH between the two cohorts (6.08 in the 4-cycle group vs 5.59 in the 3-cycle group).

There were no reported adverse events related to the fractional laser treatments, and 6% of the patients underwent additional laser treatments during the followup timeframe of 8 to 20 months.

This was a retrospective study with no control or comparison group and short-term follow-up. The VAS scores were obtained 1 month after the final treatment. Failure to request additional treatment at 8 to 20 months cannot be used to infer that the therapeutic improvements recorded at 1 month were enduring. In addition, although the large number of patients in this study may lead to statistical significance, clinical significance is still questionable. Given the lack of a comparison group and the very short follow-up, it is hard to draw any scientifically valid conclusions from this study.

Continue to: Randomized data on CO2 laser vs Kegels for sexual dysfunction...

Randomized data on CO2 laser vs Kegels for sexual dysfunction

Lou W, Chen F, Xu T, et al. A randomized controlled study of vaginal fractional CO2 laser therapy for female sexual dysfunction. Lasers Med Sci. March 15, 2021. doi: 10.1007/s10103-021-03260-x.

In a small randomized controlled trial (RCT) conducted in China, Lou and colleagues identified premenopausal women at “high risk” for sexual dysfunction as determined by the Chinese version of the Female Sexual Function Index (CFSFI).

Details of the study

A total of 84 women (mean age, 36.5 years) were included in the study. All the participants were heterosexual and married or with a long-term partner. The domain of sexual dysfunction was not considered. Women were excluded if they had no current heterosexual partner; had genital malformation, urinary incontinence, or prolapse stage 2 or higher; a history of pelvic floor mesh treatment; current gynecologic malignancy; abnormal cervical cytology; or were currently pregnant or postpartum. In addition, women were excluded if they had been treated previously for sexual dysfunction or mental “disease.” The cohort was randomized to receive fractional CO2 laser treatments (three 15-minute treatments 1 month apart at 60W, 1,000 microseconds) or coached Kegel exercises (10 exercises repeated twice daily at least 3 times/week and monitored by physical therapists at biweekly clinic visits). Sexual distress was evaluated by using the Female Sexual Distress Scale-Revised (FSDSR). Outcomes measured were pelvic floor muscle strength and scores on the CFSFI and FSDSR. Data were obtained at 3, 6, 9, and 12 months after initiation of therapy.

Both groups showed improvement

The laser cohort showed slightly more improvement in scale scores at 6 and 12 months. Specifically, the laser group had better scores on lubrication and overall satisfaction, with moderate effect size; neither group had improvements in arousal, desire, or orgasm. The Kegel group showed a significant improvement in pelvic floor strength and orgasm at 12 months, an improvement not seen in the laser cohort. Both groups showed gradual improvement in the FSDSR, with the laser group reporting a lower score (10.0) at 12 months posttreatment relative to the Kegel group (11.1). Again, these were modest effects as baseline scores for both cohorts were around 12.5. There were minimal safety signals in the laser group, with 22.5% of women reporting scant bloody discharge posttreatment and 72.5% describing mild discomfort (1 on a 1–10 VAS scale) during the procedure.

This study is problematic in several areas. Although it was a prospective, randomized trial, it was not blinded, and the therapeutic interventions were markedly different in nature and requirement for individual patient motivation. The experiences of sexual dysfunction among the participants were not stratified by type—arousal, desire, lubrication, orgasm, or pain. All patients had regular cyclic menses; however, the authors do not report on contraceptive methods, hormonal therapy, or other comorbid conditions that could impact sexual health. The cohorts may or may not have been similar in baseline types of sexual dissatisfaction.

CO2 laser for lichen sclerosus: Is it effective?

Pagano T, Conforti A, Buonfantino C, et al. Effect of rescue fractional microablative CO2 laser on symptoms and sexual dysfunction in women affected by vulvar lichen sclerosus resistant to long-term use of topic corticosteroid: a prospective longitudinal study. Menopause. 2020;27:418-422. doi: 10.1097 /GME.0000000000001482.

Burkett LS, Siddique M, Zeymo A, et al. Clobetasol compared with fractionated carbon dioxide laser for lichen sclerosus: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2021;137:968-978. doi: 10.1097 /AOG.0000000000004332.

Mitchell L, Goldstein AT, Heller D, et al. Fractionated carbon dioxide laser for the treatment of vulvar lichen sclerosus: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2021;137:979-987. doi: 10.1097 /AOG.0000000000004409.

High potency corticosteroid ointment is the current standard treatment for lichen sclerosus. Alternative options for disease that is refractory to steroids are limited. Three studies published in the past year explored the CO2 laser’s ability to treat lichen sclerosus symptoms and resultant sexual dysfunction—Pagano and colleagues conducted a small prospective study and Burkett and colleagues and Mitchell et al conducted small RCTs.

Details of the Pagano study

Three premenopausal and 37 postmenopausal women with refractory lichen sclerosus (defined as no improvement after 4 cycles of ultra-high potency steroids) were included in the study. Lichen sclerosus was uniformly biopsy confirmed. Women using topical or systemic hormones were excluded. VAS was administered prior to initial treatment and after each of 2 fractional CO2 treatments (25–30 W; 1,000 microseconds) 30 to 40 days apart to determine severity of vulvar itching, dyspareunia with penetration, vulvar dryness, sexual dysfunction, and procedure discomfort. Follow-up was conducted at 1 month after the final treatment. VAS score for the primary outcome of vulvar itching declined from 8 pretreatment to 6 after the first treatment and to 3 after the second. There was no significant treatment-related pain reported.

The authors acknowledged the limitations of their study; it was a relatively small sample size, nonrandomized and had short-term follow-up of a mixed patient population and no sham or control group. The short-term improvements reported in the study patients may not be sustained without ongoing treatment for a lifelong chronic disease, and the long-term potential for development of squamous cell carcinoma may or may not be ameliorated.

Continue to: Burkett et al: RCT study 1...

Burkett et al: RCT study 1

A total of 52 postmenopausal patients with biopsy-proven lichen sclerosus were randomly assigned to clobetasol or CO2 laser; 51 women completed 6-month follow-up. The outcomes were stratified by prior high-potency steroid use. The steroid cohort used clobetasol 0.05% nightly for 1 month, 3 times per week for 2 months, then as needed. The laser cohort received 3 treatments (26 W; 800 microseconds) 4 to 6 weeks apart. Overall adherence was only 75% in the clobetasol group, compared with 96% in the laser group. The authors found treatment efficacy of CO2 laser therapy only in the group of patients who had prior treatment with high potency topical corticosteroids. They conclude that, …“Despite previously optimistic results in well designed clinical trials of fractionated CO2 for genitourinary syndrome of menopause, and in noncontrolled case series for vulvar lichen sclerosus, our study failed to show any significant benefit of monotherapy of fractionated CO2 for vulvar lichen sclerosus. There may be a role for fractionated CO2 as an adjuvant therapy along with topical ultrapotent corticosteroids in vulvar lichen sclerosus.”

Mitchell et al: RCT study 2

This was a double blind, placebo-controlled, and histologically validated study of fractional CO2 for treatment of lichen sclerosus in 35 women; 17 in the treatment arm and 18 in the sham laser encounters. At least a 4-week no treatment period of topical steroids was required before monotherapy with CO2 laser was initiated.

The authors found no difference in their primary outcome—histopathology scale scores—after 5 treatments over 24 weeks. Secondary endpoints were changes in the CSS (Clinical Scoring System for Vulvar Lichen Sclerosus), a validated instrument that includes both a clinician’s examination of the severity of disease and a patient’s report of the severity of her symptoms. The patient score is the total of 4 domains: itching, soreness, burning, and dyspareunia. The clinician objective examination documents fissures, erosions, hyperkeratosis, agglutination, stenosis, and atrophy. At the conclusion of treatment there were no significant differences in the patient reported symptoms or the clinical findings between the active treatment and sham groups.

As a monotherapy, CO2 laser therapy is not effective in treating lichen sclerosus, although it may help improve symptoms as an adjunct to high potency steroid therapy when topical treatment alone has failed to provide adequate response.

Conclusion

The quality of evidence to support the use of the CO2 laser for improvement in sexual dysfunction is poor. Although patient satisfaction scores improved overall, and most specifically for symptoms related to GSM, the lack of blinding; inappropriate or no control groups; the very short-term outcomes; and for one of the studies, the lack of a clear definition of sexual dysfunction, make it difficult to draw meaningful conclusions for clinical care.

For GSM, we know that topical estrogen therapy works—and with little to no systemic absorption. The CO2 laser should be studied in comparison to this gold standard, with consideration of costs and potential long-term harms in addition to patient satisfaction and short-term measures of improvement. In addition, and very importantly, it is our professional responsibility to present the evidence for safety of topical estrogens to our professional colleagues as well as to our patients with estrogen-dependent cancers so that they understand the value of estrogen as a safe and appropriate alternative to expensive and potentially short-term interventions such as CO2 laser treatment. ●

Cheryl Iglesia, MD

Dr. Iglesia is Director, Section of Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgery, MedStar Washington Hospital Center, and Professor, Departments of ObGyn and Urology, Georgetown University School of Medicine, Washington, DC. She is a member of the OBG Management Board of Editors.

Barbara Levy, MD: Cheryl, you have more experience with use of the energy-based cosmetic laser than most ObGyns, and I thought that speaking with you about this technology would be of benefit, not only to me in learning more about the hands-on experience of a lead researcher and practitioner but also readers who are hearing more and more about the growth of cosmetic gynecology in general. Thank you for taking the time today.

Cheryl Iglesia, MD: I’m happy to speak about this with you, Barbara.

Dr. Levy: Specifically, I would like to talk about use of these technologies for sexual dysfunction. In the last few years some of the available data have been on the CO2 laser versus physical therapy, which is not an appropriate comparison.1

Dr. Iglesia: There have been limited data, and less randomized, controlled data, on laser and radiofrequency energies for cosmetic gynecology, and in fact these devices remain unapproved for any gynecologic indication. In 2018 the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued a Safety Communication about the use of energy-based devices to perform vaginal rejuvenation or cosmetic procedures. The International Urogynecological Association (IUGA) issued a consensus statement echoing concerns about the devices, and an International Continence Society/International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disease Best Practice Consensus Statement did not recommend the laser for “routine treatment of vaginal atrophy or urinary incontinence unless treatment is part of a well-designed trial or with special arrangements for clinical governance, consent, and audit.”2

In May 2020, as evidence remains limited (although 522 studies are ongoing in coordination with the FDA), the American Urogynecologic Society (AUGS) published a clinical consensus statement from a panel of experts in female pelvic medicine and reconstructive surgery. The panel had about 90% consensus that there is short-term efficacy for the laser with GSM and dyspareunia. But we only have outcomes data that lasts a maximum of 1 year.2

A problem with our VeLVET trial,3 which was published in Menopause, and the Cruz and colleagues’ trial from South America,4 both of which compared the CO2 laser to estrogen and had randomized groups, was that they were limited by the outcome measures used, none of which were consistently validated. But these studies also had small numbers of participants and short-term follow-up. So I don’t think there are much existing data that are promising for supporting energy-based treatment for GSM.

We also have just-published data on the laser for lichen sclerosus.5 For the AUGS panel, there was about 80% consensus for energy-based-device use and lichen sclerosus.2 According to Mitchell et al, who conducted a small, randomized, sham-controlled trial, CO2 laser resulted in no significant difference in histopathology scale score between active and sham arms.5

Future trials may want to assess laser as a mechanism for improved local drug delivery (eg, use of combined laser plus local estrogen for GSM or combined laser plus topical steroid for lichen sclerosus). I am also aware that properly designed laser versus sham studies are underway.

Dr. Levy: What about for stress urinary incontinence (SUI)? I don’t think these technologies are going to work.

Dr. Iglesia: For the AUGS panel, there was only about 70% consensus for energy-based-device use and SUI,2 and I’m one of the naysayers. The pathophysiology of SUI is so multifactorial that it’s hard to believe that laser or radiofrequency wand therapy could have sustained improvements, especially since prior radiofrequency therapy from the last decade (for instance, Renessa, Novasys Medical) did not show long-term efficacy.

Understanding lasers and coordinating care

Dr. Levy: We don’t know what the long-term outcomes are for the CO2 laser and GSM.

Dr. Iglesia: I agree with you, and I think there needs to be an understanding of the mechanism of how lasers work, whether it be erbium (Er:YAG), which is the most common, or CO2. Erbium and CO2 lasers, which are on the far-infrared spectrum, target the chromophore, water. My feeling is that, when you look at results from the Cruz trial,4 or even our trial that compared vaginal estrogen with laser,3 when there is severe GSM and high pH with virtually no water present in the tissues, that laser is not going to properly function. But I don’t think we know exactly what optimal pretreatment is necessary, and that is one of the problems. Furthermore, when intravaginal lasers are done and no adequate speculum exam is conducted prior to introducing the laser, there could be discharge or old creams present that block the mirrors necessary to adequately fire the fractionated laser beams.

Unfortunately, oftentimes these devices are marketed to women with breast cancer, who may be taking aromatase inhibitors, which cause the no-water problem; they dry out everything. They are effective for preventing breast cancer recurrence, but they cause severe atrophy (perhaps worse than many of the other selective estrogen-receptor modulators), with a resultant high vaginal pH. If we can bring that pH level down, closer to the normal 4.5 range so that we could have some level of moisture, and add estrogen first, the overall treatment approach will probably be more effective. We still do not know what happens after 1 year, though, and how often touch-ups need to be performed.

In fact, when working with a patient with breast cancer, I will speak with her oncologist; I will collaborate to put in place a treatment plan that may include initial pretreatment with low-dose vaginal estrogen followed by laser treatment for vaginal atrophy. But I will make sure I use the lowest dose. Sometimes when the patient comes back, the estrogen’s worked so well she’ll say, “Oh, I’m happy, so I don’t need the laser anymore.” A balanced conversation is necessary, especially with cancer survivors.

Informing patients and colleagues

Dr. Levy: I completely agree, and I think one of the key points here is that our purpose is to serve our patients. The data demonstrate that low doses of vaginal estrogen are not harmful for women who are being treated for or who have recovered from breast cancer. It is our ethical obligation to convince these women and their oncologists that ongoing treatment with vaginal estrogen not only will help their GSM but also their overactive bladder and their risk of urinary tract infections and other things. We could be exploiting patients who are really fearful of using any estrogen because of a perceived cancer risk. We could actually be validating their fear by telling them we have an alternative treatment for which they have to pay cash.

Treatment access

Dr. Iglesia: Yes, these are not cosmetic conditions that we are treating. So my goal when evaluating treatment for refractory GSM or lichen sclerosus is to find optimal energy-based therapies with the hope that one day these will be approved gynecologic conditions by the US FDA for laser and wand therapies and that they will ultimately not be out-of-pocket expenses but rather therapies covered by insurance.

Dr. Levy: Great. I understand that AUGS/IUGA have been working on a terminology algorithm to help distinguish between procedures being performed to resolve a medical problem such as prolapse or incontinence versus those designed to be cosmetic.

Dr. Iglesia: Yes, there is a big document from experts in both societies out for public comment right now. It will hopefully be published soon.

Outstanding questions remain

Dr. Levy: Really, we as ObGyns shouldn’t be quick to incorporate these things into our practices without high-quality studies demonstrating value. I have a major concern about these devices in the long term. When you look at fractional CO2 use on the face, for instance, which is a much different type of skin than the vagina, the laser builds collagen—but we don’t have long-term outcome results. The vagina is supposed to be an elastic tissue, so what is the risk of long-term scarring there? Yes, the laser builds collagen in the vaginal epithelium, but what does it do to scarring in the rest of the tissue? We don’t have answers to that.

Dr. Iglesia: And that is the question—how does histology equate with function? Well, I would go with what the patients are reporting.

Dr. Levy: Absolutely. But the thing about vaginal low-dose estrogen is that it is something that the oncologists or the ObGyns could be implementing with patients while they are undergoing cancer therapy, while in their menopausal transition, to preserve vulvovaginal function as opposed to trying to regain it.

Dr. Iglesia: Certainly, although it still needs to be determined when that type of approach would actually be contraindicated.

Dr. Levy: Thank you, Cheryl, for your valuable insights.

Dr. Iglesia: Of course. Thank you. ●

References

1. Lou W, Chen F, Xu T, et al. A randomized controlled study of vaginal fractional CO2 laser therapy for female sexual dysfunction. Lasers Med Sci. March 15, 2021. doi: 10.1007/s10103-021-03260-x.

2. Alshiek J, Garcia B, Minassian V, et al. Vaginal energy-based devices. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2020;26:287-298. doi: 10.1097 /SPV.0000000000000872.

3. Paraiso MF, Ferrando CA, et al. A randomized clinical trial comparing vaginal laser therapy to vaginal estrogen therapy in women with genitourinary syndrome of menopause: the VeLVET Trial. Menopause. 2020;27:50-56. doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000001416.

4. Cruz VL, Steiner ML, et al. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial for evaluating the efficacy of fractional CO2 laser compared with topical estriol in the treatment of vaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women. Menopause. 2018;25:21-28. doi: 10.1097 /GME.0000000000000955.

5. Mitchell L, Goldstein A, Heller D, et al. Fractionated carbon dioxide laser for the treatment of vulvar lichen sclerosus: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2021;137:979-987. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000004409.

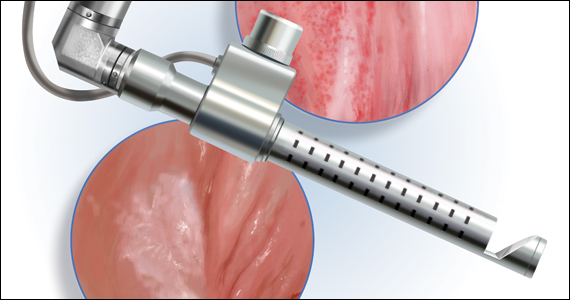

The approach to diagnosis and treatment of female sexual function continues to be a challenge for women’s health professionals. The search for a female “little blue pill” remains elusive as researchers struggle to understand the mechanisms that underlie the complex aspects of female sexual health. This Update will review the recent literature on the use of fractional CO2 laser for treatment of female sexual dysfunction and vulvovaginal symptoms. Bottom line: While the quality of the studies is poor overall, fractional CO2 laser treatment seems to temporarily improve symptoms of genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM). The duration of response, cost, and the overall long-term impact on sexual health remain in question.

A retrospective look at CO2 laser and postmenopausal GSM

Filippini M, Luvero D, Salvatore S, et al. Efficacy of fractional CO2 laser treatment in postmenopausal women with genitourinary syndrome: a multicenter study. Menopause. 2019;27:43-49. doi: 10.1097/GME. 0000000000001428.

Researchers conducted a retrospective, multicenter study of postmenopausal women with at least one symptom of GSM, including itching, burning, dyspareunia with penetration, and dryness.

Study details

A total of 171 of the 645 women (26.5%) were oncology patients. Women were excluded from analysis if they used any form of topical therapy within 15 days; had prolapse stage 2 or greater; or had any infection, abscess, or anatomical deformity precluding treatment with the laser.

Patients underwent gynecologic examination and were given a questionnaire to assess vulvovaginal symptoms. Exams occurred monthly during treatment (average, 6.5 months), at 6- and 12-months posttreatment, and then annually. No topical therapy was advised during or after treatment.

Patients received either 3 or 4 fractional CO2 laser treatments to the vulva and/or vagina depending on symptom location and type. Higher power settings of the same laser were used to treat vaginal symptoms (40W; 1,000 microseconds) versus vulvar symptoms (25W; 500 microseconds). Treatment sessions were 5 to 6 minutes. The study authors used a visual analog rating scale (VAS) for “atrophy and related symptoms,” tested vaginal pH, and completed the Vaginal Health Index Score. VAS scores were obtained from the patients prior to the initial laser intervention and 1 month after the final treatment.

Results

There were statistically significant improvements in dryness, vaginal orifice pain, dyspareunia, itching, and burning for both the 3-treatment and 4-treatment cohorts. The delta of improvement was then compared for the 2 subgroups; curiously, there was greater improvement of symptoms such as dryness (65% vs 61%), itching (78% vs 72%), burning (72% vs 67%), and vaginal orifice pain (67% vs 60%) in the group that received 3 cycles than in the group that received 4 cycles.

With regard to vaginal pH improvement, the 4-cycle group performed better than the 3-cycle group (1% improvement in the 4-cycle group vs 6% in the 3-cycle group). Although vaginal pH reduction was somewhat better in the group that received 4 treatments, and the pre versus posttreatment percentages were statistically significantly different, the clinical significance of a pH difference between 5.72 and 5.53 is questionable, especially since there was a greater difference in baseline pH between the two cohorts (6.08 in the 4-cycle group vs 5.59 in the 3-cycle group).

There were no reported adverse events related to the fractional laser treatments, and 6% of the patients underwent additional laser treatments during the followup timeframe of 8 to 20 months.

This was a retrospective study with no control or comparison group and short-term follow-up. The VAS scores were obtained 1 month after the final treatment. Failure to request additional treatment at 8 to 20 months cannot be used to infer that the therapeutic improvements recorded at 1 month were enduring. In addition, although the large number of patients in this study may lead to statistical significance, clinical significance is still questionable. Given the lack of a comparison group and the very short follow-up, it is hard to draw any scientifically valid conclusions from this study.

Continue to: Randomized data on CO2 laser vs Kegels for sexual dysfunction...

Randomized data on CO2 laser vs Kegels for sexual dysfunction

Lou W, Chen F, Xu T, et al. A randomized controlled study of vaginal fractional CO2 laser therapy for female sexual dysfunction. Lasers Med Sci. March 15, 2021. doi: 10.1007/s10103-021-03260-x.

In a small randomized controlled trial (RCT) conducted in China, Lou and colleagues identified premenopausal women at “high risk” for sexual dysfunction as determined by the Chinese version of the Female Sexual Function Index (CFSFI).

Details of the study

A total of 84 women (mean age, 36.5 years) were included in the study. All the participants were heterosexual and married or with a long-term partner. The domain of sexual dysfunction was not considered. Women were excluded if they had no current heterosexual partner; had genital malformation, urinary incontinence, or prolapse stage 2 or higher; a history of pelvic floor mesh treatment; current gynecologic malignancy; abnormal cervical cytology; or were currently pregnant or postpartum. In addition, women were excluded if they had been treated previously for sexual dysfunction or mental “disease.” The cohort was randomized to receive fractional CO2 laser treatments (three 15-minute treatments 1 month apart at 60W, 1,000 microseconds) or coached Kegel exercises (10 exercises repeated twice daily at least 3 times/week and monitored by physical therapists at biweekly clinic visits). Sexual distress was evaluated by using the Female Sexual Distress Scale-Revised (FSDSR). Outcomes measured were pelvic floor muscle strength and scores on the CFSFI and FSDSR. Data were obtained at 3, 6, 9, and 12 months after initiation of therapy.

Both groups showed improvement

The laser cohort showed slightly more improvement in scale scores at 6 and 12 months. Specifically, the laser group had better scores on lubrication and overall satisfaction, with moderate effect size; neither group had improvements in arousal, desire, or orgasm. The Kegel group showed a significant improvement in pelvic floor strength and orgasm at 12 months, an improvement not seen in the laser cohort. Both groups showed gradual improvement in the FSDSR, with the laser group reporting a lower score (10.0) at 12 months posttreatment relative to the Kegel group (11.1). Again, these were modest effects as baseline scores for both cohorts were around 12.5. There were minimal safety signals in the laser group, with 22.5% of women reporting scant bloody discharge posttreatment and 72.5% describing mild discomfort (1 on a 1–10 VAS scale) during the procedure.

This study is problematic in several areas. Although it was a prospective, randomized trial, it was not blinded, and the therapeutic interventions were markedly different in nature and requirement for individual patient motivation. The experiences of sexual dysfunction among the participants were not stratified by type—arousal, desire, lubrication, orgasm, or pain. All patients had regular cyclic menses; however, the authors do not report on contraceptive methods, hormonal therapy, or other comorbid conditions that could impact sexual health. The cohorts may or may not have been similar in baseline types of sexual dissatisfaction.

CO2 laser for lichen sclerosus: Is it effective?

Pagano T, Conforti A, Buonfantino C, et al. Effect of rescue fractional microablative CO2 laser on symptoms and sexual dysfunction in women affected by vulvar lichen sclerosus resistant to long-term use of topic corticosteroid: a prospective longitudinal study. Menopause. 2020;27:418-422. doi: 10.1097 /GME.0000000000001482.

Burkett LS, Siddique M, Zeymo A, et al. Clobetasol compared with fractionated carbon dioxide laser for lichen sclerosus: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2021;137:968-978. doi: 10.1097 /AOG.0000000000004332.

Mitchell L, Goldstein AT, Heller D, et al. Fractionated carbon dioxide laser for the treatment of vulvar lichen sclerosus: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2021;137:979-987. doi: 10.1097 /AOG.0000000000004409.

High potency corticosteroid ointment is the current standard treatment for lichen sclerosus. Alternative options for disease that is refractory to steroids are limited. Three studies published in the past year explored the CO2 laser’s ability to treat lichen sclerosus symptoms and resultant sexual dysfunction—Pagano and colleagues conducted a small prospective study and Burkett and colleagues and Mitchell et al conducted small RCTs.

Details of the Pagano study

Three premenopausal and 37 postmenopausal women with refractory lichen sclerosus (defined as no improvement after 4 cycles of ultra-high potency steroids) were included in the study. Lichen sclerosus was uniformly biopsy confirmed. Women using topical or systemic hormones were excluded. VAS was administered prior to initial treatment and after each of 2 fractional CO2 treatments (25–30 W; 1,000 microseconds) 30 to 40 days apart to determine severity of vulvar itching, dyspareunia with penetration, vulvar dryness, sexual dysfunction, and procedure discomfort. Follow-up was conducted at 1 month after the final treatment. VAS score for the primary outcome of vulvar itching declined from 8 pretreatment to 6 after the first treatment and to 3 after the second. There was no significant treatment-related pain reported.

The authors acknowledged the limitations of their study; it was a relatively small sample size, nonrandomized and had short-term follow-up of a mixed patient population and no sham or control group. The short-term improvements reported in the study patients may not be sustained without ongoing treatment for a lifelong chronic disease, and the long-term potential for development of squamous cell carcinoma may or may not be ameliorated.

Continue to: Burkett et al: RCT study 1...

Burkett et al: RCT study 1

A total of 52 postmenopausal patients with biopsy-proven lichen sclerosus were randomly assigned to clobetasol or CO2 laser; 51 women completed 6-month follow-up. The outcomes were stratified by prior high-potency steroid use. The steroid cohort used clobetasol 0.05% nightly for 1 month, 3 times per week for 2 months, then as needed. The laser cohort received 3 treatments (26 W; 800 microseconds) 4 to 6 weeks apart. Overall adherence was only 75% in the clobetasol group, compared with 96% in the laser group. The authors found treatment efficacy of CO2 laser therapy only in the group of patients who had prior treatment with high potency topical corticosteroids. They conclude that, …“Despite previously optimistic results in well designed clinical trials of fractionated CO2 for genitourinary syndrome of menopause, and in noncontrolled case series for vulvar lichen sclerosus, our study failed to show any significant benefit of monotherapy of fractionated CO2 for vulvar lichen sclerosus. There may be a role for fractionated CO2 as an adjuvant therapy along with topical ultrapotent corticosteroids in vulvar lichen sclerosus.”

Mitchell et al: RCT study 2

This was a double blind, placebo-controlled, and histologically validated study of fractional CO2 for treatment of lichen sclerosus in 35 women; 17 in the treatment arm and 18 in the sham laser encounters. At least a 4-week no treatment period of topical steroids was required before monotherapy with CO2 laser was initiated.

The authors found no difference in their primary outcome—histopathology scale scores—after 5 treatments over 24 weeks. Secondary endpoints were changes in the CSS (Clinical Scoring System for Vulvar Lichen Sclerosus), a validated instrument that includes both a clinician’s examination of the severity of disease and a patient’s report of the severity of her symptoms. The patient score is the total of 4 domains: itching, soreness, burning, and dyspareunia. The clinician objective examination documents fissures, erosions, hyperkeratosis, agglutination, stenosis, and atrophy. At the conclusion of treatment there were no significant differences in the patient reported symptoms or the clinical findings between the active treatment and sham groups.

As a monotherapy, CO2 laser therapy is not effective in treating lichen sclerosus, although it may help improve symptoms as an adjunct to high potency steroid therapy when topical treatment alone has failed to provide adequate response.

Conclusion

The quality of evidence to support the use of the CO2 laser for improvement in sexual dysfunction is poor. Although patient satisfaction scores improved overall, and most specifically for symptoms related to GSM, the lack of blinding; inappropriate or no control groups; the very short-term outcomes; and for one of the studies, the lack of a clear definition of sexual dysfunction, make it difficult to draw meaningful conclusions for clinical care.

For GSM, we know that topical estrogen therapy works—and with little to no systemic absorption. The CO2 laser should be studied in comparison to this gold standard, with consideration of costs and potential long-term harms in addition to patient satisfaction and short-term measures of improvement. In addition, and very importantly, it is our professional responsibility to present the evidence for safety of topical estrogens to our professional colleagues as well as to our patients with estrogen-dependent cancers so that they understand the value of estrogen as a safe and appropriate alternative to expensive and potentially short-term interventions such as CO2 laser treatment. ●

Cheryl Iglesia, MD

Dr. Iglesia is Director, Section of Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgery, MedStar Washington Hospital Center, and Professor, Departments of ObGyn and Urology, Georgetown University School of Medicine, Washington, DC. She is a member of the OBG Management Board of Editors.

Barbara Levy, MD: Cheryl, you have more experience with use of the energy-based cosmetic laser than most ObGyns, and I thought that speaking with you about this technology would be of benefit, not only to me in learning more about the hands-on experience of a lead researcher and practitioner but also readers who are hearing more and more about the growth of cosmetic gynecology in general. Thank you for taking the time today.

Cheryl Iglesia, MD: I’m happy to speak about this with you, Barbara.

Dr. Levy: Specifically, I would like to talk about use of these technologies for sexual dysfunction. In the last few years some of the available data have been on the CO2 laser versus physical therapy, which is not an appropriate comparison.1

Dr. Iglesia: There have been limited data, and less randomized, controlled data, on laser and radiofrequency energies for cosmetic gynecology, and in fact these devices remain unapproved for any gynecologic indication. In 2018 the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued a Safety Communication about the use of energy-based devices to perform vaginal rejuvenation or cosmetic procedures. The International Urogynecological Association (IUGA) issued a consensus statement echoing concerns about the devices, and an International Continence Society/International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disease Best Practice Consensus Statement did not recommend the laser for “routine treatment of vaginal atrophy or urinary incontinence unless treatment is part of a well-designed trial or with special arrangements for clinical governance, consent, and audit.”2

In May 2020, as evidence remains limited (although 522 studies are ongoing in coordination with the FDA), the American Urogynecologic Society (AUGS) published a clinical consensus statement from a panel of experts in female pelvic medicine and reconstructive surgery. The panel had about 90% consensus that there is short-term efficacy for the laser with GSM and dyspareunia. But we only have outcomes data that lasts a maximum of 1 year.2

A problem with our VeLVET trial,3 which was published in Menopause, and the Cruz and colleagues’ trial from South America,4 both of which compared the CO2 laser to estrogen and had randomized groups, was that they were limited by the outcome measures used, none of which were consistently validated. But these studies also had small numbers of participants and short-term follow-up. So I don’t think there are much existing data that are promising for supporting energy-based treatment for GSM.

We also have just-published data on the laser for lichen sclerosus.5 For the AUGS panel, there was about 80% consensus for energy-based-device use and lichen sclerosus.2 According to Mitchell et al, who conducted a small, randomized, sham-controlled trial, CO2 laser resulted in no significant difference in histopathology scale score between active and sham arms.5

Future trials may want to assess laser as a mechanism for improved local drug delivery (eg, use of combined laser plus local estrogen for GSM or combined laser plus topical steroid for lichen sclerosus). I am also aware that properly designed laser versus sham studies are underway.

Dr. Levy: What about for stress urinary incontinence (SUI)? I don’t think these technologies are going to work.

Dr. Iglesia: For the AUGS panel, there was only about 70% consensus for energy-based-device use and SUI,2 and I’m one of the naysayers. The pathophysiology of SUI is so multifactorial that it’s hard to believe that laser or radiofrequency wand therapy could have sustained improvements, especially since prior radiofrequency therapy from the last decade (for instance, Renessa, Novasys Medical) did not show long-term efficacy.

Understanding lasers and coordinating care

Dr. Levy: We don’t know what the long-term outcomes are for the CO2 laser and GSM.

Dr. Iglesia: I agree with you, and I think there needs to be an understanding of the mechanism of how lasers work, whether it be erbium (Er:YAG), which is the most common, or CO2. Erbium and CO2 lasers, which are on the far-infrared spectrum, target the chromophore, water. My feeling is that, when you look at results from the Cruz trial,4 or even our trial that compared vaginal estrogen with laser,3 when there is severe GSM and high pH with virtually no water present in the tissues, that laser is not going to properly function. But I don’t think we know exactly what optimal pretreatment is necessary, and that is one of the problems. Furthermore, when intravaginal lasers are done and no adequate speculum exam is conducted prior to introducing the laser, there could be discharge or old creams present that block the mirrors necessary to adequately fire the fractionated laser beams.

Unfortunately, oftentimes these devices are marketed to women with breast cancer, who may be taking aromatase inhibitors, which cause the no-water problem; they dry out everything. They are effective for preventing breast cancer recurrence, but they cause severe atrophy (perhaps worse than many of the other selective estrogen-receptor modulators), with a resultant high vaginal pH. If we can bring that pH level down, closer to the normal 4.5 range so that we could have some level of moisture, and add estrogen first, the overall treatment approach will probably be more effective. We still do not know what happens after 1 year, though, and how often touch-ups need to be performed.

In fact, when working with a patient with breast cancer, I will speak with her oncologist; I will collaborate to put in place a treatment plan that may include initial pretreatment with low-dose vaginal estrogen followed by laser treatment for vaginal atrophy. But I will make sure I use the lowest dose. Sometimes when the patient comes back, the estrogen’s worked so well she’ll say, “Oh, I’m happy, so I don’t need the laser anymore.” A balanced conversation is necessary, especially with cancer survivors.

Informing patients and colleagues

Dr. Levy: I completely agree, and I think one of the key points here is that our purpose is to serve our patients. The data demonstrate that low doses of vaginal estrogen are not harmful for women who are being treated for or who have recovered from breast cancer. It is our ethical obligation to convince these women and their oncologists that ongoing treatment with vaginal estrogen not only will help their GSM but also their overactive bladder and their risk of urinary tract infections and other things. We could be exploiting patients who are really fearful of using any estrogen because of a perceived cancer risk. We could actually be validating their fear by telling them we have an alternative treatment for which they have to pay cash.

Treatment access

Dr. Iglesia: Yes, these are not cosmetic conditions that we are treating. So my goal when evaluating treatment for refractory GSM or lichen sclerosus is to find optimal energy-based therapies with the hope that one day these will be approved gynecologic conditions by the US FDA for laser and wand therapies and that they will ultimately not be out-of-pocket expenses but rather therapies covered by insurance.

Dr. Levy: Great. I understand that AUGS/IUGA have been working on a terminology algorithm to help distinguish between procedures being performed to resolve a medical problem such as prolapse or incontinence versus those designed to be cosmetic.

Dr. Iglesia: Yes, there is a big document from experts in both societies out for public comment right now. It will hopefully be published soon.

Outstanding questions remain

Dr. Levy: Really, we as ObGyns shouldn’t be quick to incorporate these things into our practices without high-quality studies demonstrating value. I have a major concern about these devices in the long term. When you look at fractional CO2 use on the face, for instance, which is a much different type of skin than the vagina, the laser builds collagen—but we don’t have long-term outcome results. The vagina is supposed to be an elastic tissue, so what is the risk of long-term scarring there? Yes, the laser builds collagen in the vaginal epithelium, but what does it do to scarring in the rest of the tissue? We don’t have answers to that.

Dr. Iglesia: And that is the question—how does histology equate with function? Well, I would go with what the patients are reporting.

Dr. Levy: Absolutely. But the thing about vaginal low-dose estrogen is that it is something that the oncologists or the ObGyns could be implementing with patients while they are undergoing cancer therapy, while in their menopausal transition, to preserve vulvovaginal function as opposed to trying to regain it.

Dr. Iglesia: Certainly, although it still needs to be determined when that type of approach would actually be contraindicated.

Dr. Levy: Thank you, Cheryl, for your valuable insights.

Dr. Iglesia: Of course. Thank you. ●

References

1. Lou W, Chen F, Xu T, et al. A randomized controlled study of vaginal fractional CO2 laser therapy for female sexual dysfunction. Lasers Med Sci. March 15, 2021. doi: 10.1007/s10103-021-03260-x.

2. Alshiek J, Garcia B, Minassian V, et al. Vaginal energy-based devices. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2020;26:287-298. doi: 10.1097 /SPV.0000000000000872.

3. Paraiso MF, Ferrando CA, et al. A randomized clinical trial comparing vaginal laser therapy to vaginal estrogen therapy in women with genitourinary syndrome of menopause: the VeLVET Trial. Menopause. 2020;27:50-56. doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000001416.

4. Cruz VL, Steiner ML, et al. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial for evaluating the efficacy of fractional CO2 laser compared with topical estriol in the treatment of vaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women. Menopause. 2018;25:21-28. doi: 10.1097 /GME.0000000000000955.

5. Mitchell L, Goldstein A, Heller D, et al. Fractionated carbon dioxide laser for the treatment of vulvar lichen sclerosus: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2021;137:979-987. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000004409.

The approach to diagnosis and treatment of female sexual function continues to be a challenge for women’s health professionals. The search for a female “little blue pill” remains elusive as researchers struggle to understand the mechanisms that underlie the complex aspects of female sexual health. This Update will review the recent literature on the use of fractional CO2 laser for treatment of female sexual dysfunction and vulvovaginal symptoms. Bottom line: While the quality of the studies is poor overall, fractional CO2 laser treatment seems to temporarily improve symptoms of genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM). The duration of response, cost, and the overall long-term impact on sexual health remain in question.

A retrospective look at CO2 laser and postmenopausal GSM

Filippini M, Luvero D, Salvatore S, et al. Efficacy of fractional CO2 laser treatment in postmenopausal women with genitourinary syndrome: a multicenter study. Menopause. 2019;27:43-49. doi: 10.1097/GME. 0000000000001428.

Researchers conducted a retrospective, multicenter study of postmenopausal women with at least one symptom of GSM, including itching, burning, dyspareunia with penetration, and dryness.

Study details

A total of 171 of the 645 women (26.5%) were oncology patients. Women were excluded from analysis if they used any form of topical therapy within 15 days; had prolapse stage 2 or greater; or had any infection, abscess, or anatomical deformity precluding treatment with the laser.

Patients underwent gynecologic examination and were given a questionnaire to assess vulvovaginal symptoms. Exams occurred monthly during treatment (average, 6.5 months), at 6- and 12-months posttreatment, and then annually. No topical therapy was advised during or after treatment.

Patients received either 3 or 4 fractional CO2 laser treatments to the vulva and/or vagina depending on symptom location and type. Higher power settings of the same laser were used to treat vaginal symptoms (40W; 1,000 microseconds) versus vulvar symptoms (25W; 500 microseconds). Treatment sessions were 5 to 6 minutes. The study authors used a visual analog rating scale (VAS) for “atrophy and related symptoms,” tested vaginal pH, and completed the Vaginal Health Index Score. VAS scores were obtained from the patients prior to the initial laser intervention and 1 month after the final treatment.

Results

There were statistically significant improvements in dryness, vaginal orifice pain, dyspareunia, itching, and burning for both the 3-treatment and 4-treatment cohorts. The delta of improvement was then compared for the 2 subgroups; curiously, there was greater improvement of symptoms such as dryness (65% vs 61%), itching (78% vs 72%), burning (72% vs 67%), and vaginal orifice pain (67% vs 60%) in the group that received 3 cycles than in the group that received 4 cycles.

With regard to vaginal pH improvement, the 4-cycle group performed better than the 3-cycle group (1% improvement in the 4-cycle group vs 6% in the 3-cycle group). Although vaginal pH reduction was somewhat better in the group that received 4 treatments, and the pre versus posttreatment percentages were statistically significantly different, the clinical significance of a pH difference between 5.72 and 5.53 is questionable, especially since there was a greater difference in baseline pH between the two cohorts (6.08 in the 4-cycle group vs 5.59 in the 3-cycle group).

There were no reported adverse events related to the fractional laser treatments, and 6% of the patients underwent additional laser treatments during the followup timeframe of 8 to 20 months.

This was a retrospective study with no control or comparison group and short-term follow-up. The VAS scores were obtained 1 month after the final treatment. Failure to request additional treatment at 8 to 20 months cannot be used to infer that the therapeutic improvements recorded at 1 month were enduring. In addition, although the large number of patients in this study may lead to statistical significance, clinical significance is still questionable. Given the lack of a comparison group and the very short follow-up, it is hard to draw any scientifically valid conclusions from this study.

Continue to: Randomized data on CO2 laser vs Kegels for sexual dysfunction...

Randomized data on CO2 laser vs Kegels for sexual dysfunction

Lou W, Chen F, Xu T, et al. A randomized controlled study of vaginal fractional CO2 laser therapy for female sexual dysfunction. Lasers Med Sci. March 15, 2021. doi: 10.1007/s10103-021-03260-x.

In a small randomized controlled trial (RCT) conducted in China, Lou and colleagues identified premenopausal women at “high risk” for sexual dysfunction as determined by the Chinese version of the Female Sexual Function Index (CFSFI).

Details of the study

A total of 84 women (mean age, 36.5 years) were included in the study. All the participants were heterosexual and married or with a long-term partner. The domain of sexual dysfunction was not considered. Women were excluded if they had no current heterosexual partner; had genital malformation, urinary incontinence, or prolapse stage 2 or higher; a history of pelvic floor mesh treatment; current gynecologic malignancy; abnormal cervical cytology; or were currently pregnant or postpartum. In addition, women were excluded if they had been treated previously for sexual dysfunction or mental “disease.” The cohort was randomized to receive fractional CO2 laser treatments (three 15-minute treatments 1 month apart at 60W, 1,000 microseconds) or coached Kegel exercises (10 exercises repeated twice daily at least 3 times/week and monitored by physical therapists at biweekly clinic visits). Sexual distress was evaluated by using the Female Sexual Distress Scale-Revised (FSDSR). Outcomes measured were pelvic floor muscle strength and scores on the CFSFI and FSDSR. Data were obtained at 3, 6, 9, and 12 months after initiation of therapy.

Both groups showed improvement

The laser cohort showed slightly more improvement in scale scores at 6 and 12 months. Specifically, the laser group had better scores on lubrication and overall satisfaction, with moderate effect size; neither group had improvements in arousal, desire, or orgasm. The Kegel group showed a significant improvement in pelvic floor strength and orgasm at 12 months, an improvement not seen in the laser cohort. Both groups showed gradual improvement in the FSDSR, with the laser group reporting a lower score (10.0) at 12 months posttreatment relative to the Kegel group (11.1). Again, these were modest effects as baseline scores for both cohorts were around 12.5. There were minimal safety signals in the laser group, with 22.5% of women reporting scant bloody discharge posttreatment and 72.5% describing mild discomfort (1 on a 1–10 VAS scale) during the procedure.

This study is problematic in several areas. Although it was a prospective, randomized trial, it was not blinded, and the therapeutic interventions were markedly different in nature and requirement for individual patient motivation. The experiences of sexual dysfunction among the participants were not stratified by type—arousal, desire, lubrication, orgasm, or pain. All patients had regular cyclic menses; however, the authors do not report on contraceptive methods, hormonal therapy, or other comorbid conditions that could impact sexual health. The cohorts may or may not have been similar in baseline types of sexual dissatisfaction.

CO2 laser for lichen sclerosus: Is it effective?

Pagano T, Conforti A, Buonfantino C, et al. Effect of rescue fractional microablative CO2 laser on symptoms and sexual dysfunction in women affected by vulvar lichen sclerosus resistant to long-term use of topic corticosteroid: a prospective longitudinal study. Menopause. 2020;27:418-422. doi: 10.1097 /GME.0000000000001482.

Burkett LS, Siddique M, Zeymo A, et al. Clobetasol compared with fractionated carbon dioxide laser for lichen sclerosus: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2021;137:968-978. doi: 10.1097 /AOG.0000000000004332.

Mitchell L, Goldstein AT, Heller D, et al. Fractionated carbon dioxide laser for the treatment of vulvar lichen sclerosus: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2021;137:979-987. doi: 10.1097 /AOG.0000000000004409.

High potency corticosteroid ointment is the current standard treatment for lichen sclerosus. Alternative options for disease that is refractory to steroids are limited. Three studies published in the past year explored the CO2 laser’s ability to treat lichen sclerosus symptoms and resultant sexual dysfunction—Pagano and colleagues conducted a small prospective study and Burkett and colleagues and Mitchell et al conducted small RCTs.

Details of the Pagano study

Three premenopausal and 37 postmenopausal women with refractory lichen sclerosus (defined as no improvement after 4 cycles of ultra-high potency steroids) were included in the study. Lichen sclerosus was uniformly biopsy confirmed. Women using topical or systemic hormones were excluded. VAS was administered prior to initial treatment and after each of 2 fractional CO2 treatments (25–30 W; 1,000 microseconds) 30 to 40 days apart to determine severity of vulvar itching, dyspareunia with penetration, vulvar dryness, sexual dysfunction, and procedure discomfort. Follow-up was conducted at 1 month after the final treatment. VAS score for the primary outcome of vulvar itching declined from 8 pretreatment to 6 after the first treatment and to 3 after the second. There was no significant treatment-related pain reported.

The authors acknowledged the limitations of their study; it was a relatively small sample size, nonrandomized and had short-term follow-up of a mixed patient population and no sham or control group. The short-term improvements reported in the study patients may not be sustained without ongoing treatment for a lifelong chronic disease, and the long-term potential for development of squamous cell carcinoma may or may not be ameliorated.

Continue to: Burkett et al: RCT study 1...

Burkett et al: RCT study 1

A total of 52 postmenopausal patients with biopsy-proven lichen sclerosus were randomly assigned to clobetasol or CO2 laser; 51 women completed 6-month follow-up. The outcomes were stratified by prior high-potency steroid use. The steroid cohort used clobetasol 0.05% nightly for 1 month, 3 times per week for 2 months, then as needed. The laser cohort received 3 treatments (26 W; 800 microseconds) 4 to 6 weeks apart. Overall adherence was only 75% in the clobetasol group, compared with 96% in the laser group. The authors found treatment efficacy of CO2 laser therapy only in the group of patients who had prior treatment with high potency topical corticosteroids. They conclude that, …“Despite previously optimistic results in well designed clinical trials of fractionated CO2 for genitourinary syndrome of menopause, and in noncontrolled case series for vulvar lichen sclerosus, our study failed to show any significant benefit of monotherapy of fractionated CO2 for vulvar lichen sclerosus. There may be a role for fractionated CO2 as an adjuvant therapy along with topical ultrapotent corticosteroids in vulvar lichen sclerosus.”

Mitchell et al: RCT study 2

This was a double blind, placebo-controlled, and histologically validated study of fractional CO2 for treatment of lichen sclerosus in 35 women; 17 in the treatment arm and 18 in the sham laser encounters. At least a 4-week no treatment period of topical steroids was required before monotherapy with CO2 laser was initiated.

The authors found no difference in their primary outcome—histopathology scale scores—after 5 treatments over 24 weeks. Secondary endpoints were changes in the CSS (Clinical Scoring System for Vulvar Lichen Sclerosus), a validated instrument that includes both a clinician’s examination of the severity of disease and a patient’s report of the severity of her symptoms. The patient score is the total of 4 domains: itching, soreness, burning, and dyspareunia. The clinician objective examination documents fissures, erosions, hyperkeratosis, agglutination, stenosis, and atrophy. At the conclusion of treatment there were no significant differences in the patient reported symptoms or the clinical findings between the active treatment and sham groups.

As a monotherapy, CO2 laser therapy is not effective in treating lichen sclerosus, although it may help improve symptoms as an adjunct to high potency steroid therapy when topical treatment alone has failed to provide adequate response.

Conclusion

The quality of evidence to support the use of the CO2 laser for improvement in sexual dysfunction is poor. Although patient satisfaction scores improved overall, and most specifically for symptoms related to GSM, the lack of blinding; inappropriate or no control groups; the very short-term outcomes; and for one of the studies, the lack of a clear definition of sexual dysfunction, make it difficult to draw meaningful conclusions for clinical care.

For GSM, we know that topical estrogen therapy works—and with little to no systemic absorption. The CO2 laser should be studied in comparison to this gold standard, with consideration of costs and potential long-term harms in addition to patient satisfaction and short-term measures of improvement. In addition, and very importantly, it is our professional responsibility to present the evidence for safety of topical estrogens to our professional colleagues as well as to our patients with estrogen-dependent cancers so that they understand the value of estrogen as a safe and appropriate alternative to expensive and potentially short-term interventions such as CO2 laser treatment. ●

Cheryl Iglesia, MD

Dr. Iglesia is Director, Section of Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgery, MedStar Washington Hospital Center, and Professor, Departments of ObGyn and Urology, Georgetown University School of Medicine, Washington, DC. She is a member of the OBG Management Board of Editors.

Barbara Levy, MD: Cheryl, you have more experience with use of the energy-based cosmetic laser than most ObGyns, and I thought that speaking with you about this technology would be of benefit, not only to me in learning more about the hands-on experience of a lead researcher and practitioner but also readers who are hearing more and more about the growth of cosmetic gynecology in general. Thank you for taking the time today.

Cheryl Iglesia, MD: I’m happy to speak about this with you, Barbara.

Dr. Levy: Specifically, I would like to talk about use of these technologies for sexual dysfunction. In the last few years some of the available data have been on the CO2 laser versus physical therapy, which is not an appropriate comparison.1

Dr. Iglesia: There have been limited data, and less randomized, controlled data, on laser and radiofrequency energies for cosmetic gynecology, and in fact these devices remain unapproved for any gynecologic indication. In 2018 the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued a Safety Communication about the use of energy-based devices to perform vaginal rejuvenation or cosmetic procedures. The International Urogynecological Association (IUGA) issued a consensus statement echoing concerns about the devices, and an International Continence Society/International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disease Best Practice Consensus Statement did not recommend the laser for “routine treatment of vaginal atrophy or urinary incontinence unless treatment is part of a well-designed trial or with special arrangements for clinical governance, consent, and audit.”2

In May 2020, as evidence remains limited (although 522 studies are ongoing in coordination with the FDA), the American Urogynecologic Society (AUGS) published a clinical consensus statement from a panel of experts in female pelvic medicine and reconstructive surgery. The panel had about 90% consensus that there is short-term efficacy for the laser with GSM and dyspareunia. But we only have outcomes data that lasts a maximum of 1 year.2

A problem with our VeLVET trial,3 which was published in Menopause, and the Cruz and colleagues’ trial from South America,4 both of which compared the CO2 laser to estrogen and had randomized groups, was that they were limited by the outcome measures used, none of which were consistently validated. But these studies also had small numbers of participants and short-term follow-up. So I don’t think there are much existing data that are promising for supporting energy-based treatment for GSM.

We also have just-published data on the laser for lichen sclerosus.5 For the AUGS panel, there was about 80% consensus for energy-based-device use and lichen sclerosus.2 According to Mitchell et al, who conducted a small, randomized, sham-controlled trial, CO2 laser resulted in no significant difference in histopathology scale score between active and sham arms.5