User login

When to Start Dialysis

Q) I sent a patient with a glomerular filtration rate (GFR) of 15 mL/min to nephrology to start dialysis. He came back to me and said they don’t start dialysis at 15. When do you start? Why?

There is considerable variation in the timing of dialysis initiation. Research suggests that sometimes earlier is not better.

IDEAL, a randomized controlled trial conducted in Australia and New Zealand, evaluated the advantages and disadvantages of earlier versus later dialysis initiation.1 Patients were randomly assigned to start any type of dialysis when their GFR was 8 or 11 mL/min. The results indicated that starting dialysis in a patient with a higher GFR did not lower the mortality or morbidity rate but did increase costs and complications (mostly for vascular access).1

Based on these findings, most of us start dialysis in a patient who has a GFR < 10 mL/min and symptoms of kidney failure. These include a metallic taste in mouth, weight gain (usually due to edema) or loss (cachexia), feeling “poorly,” hard-to-control hypertension, shortness of breath, confusion (uremic brain), odor, skin color changes, and insomnia. Symptomatic patients can be started on dialysis at a higher GFR (usually ≤ 18 mL/min), but there are many hoops to jump through with Medicare.

However, IDEAL was conducted outside the United States and included very few elderly (age > 75) patients with chronic kidney disease. In 2018, Kurella and colleagues published a study that analyzed age and kidney function in a US veteran population.2 Their results showed that age should be included in the “when to start dialysis” calculation. For older veterans, starting dialysis earlier—at a GFR of 10 mL/min—increased survival. However, the researchers pointed out that in this age group, survival is in months (not years) and does not necessarily equate to quality of life.

In conclusion, there is no compelling evidence that initiation of dialysis based solely on measurement of kidney function leads to improvement in clinical outcomes. In otherwise asymptomatic patients, there is no reason to begin dialysis based solely on GFR; age and fragility need to be considered in the equation. Earlier is not always better, and for the elderly patient with multiple comorbidities, dialysis is not always a better choice. —TH

Tricia Howard, MHS, PA-C, DFAAPA

Georgia Regional Medical Team, Savannah

1. Cooper BA, Branley P, Bulfone L, et al; for the IDEAL Trial. A randomized, controlled trial of early versus late initiation of dialysis. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(7):609-619.

2. Kurella Tamura M, Desai M, Kapphahn KI, et al. Dialysis versus medical management at different ages and levels of kidney function in veterans with advanced CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2018;29(8):2169-2177.

Q) I sent a patient with a glomerular filtration rate (GFR) of 15 mL/min to nephrology to start dialysis. He came back to me and said they don’t start dialysis at 15. When do you start? Why?

There is considerable variation in the timing of dialysis initiation. Research suggests that sometimes earlier is not better.

IDEAL, a randomized controlled trial conducted in Australia and New Zealand, evaluated the advantages and disadvantages of earlier versus later dialysis initiation.1 Patients were randomly assigned to start any type of dialysis when their GFR was 8 or 11 mL/min. The results indicated that starting dialysis in a patient with a higher GFR did not lower the mortality or morbidity rate but did increase costs and complications (mostly for vascular access).1

Based on these findings, most of us start dialysis in a patient who has a GFR < 10 mL/min and symptoms of kidney failure. These include a metallic taste in mouth, weight gain (usually due to edema) or loss (cachexia), feeling “poorly,” hard-to-control hypertension, shortness of breath, confusion (uremic brain), odor, skin color changes, and insomnia. Symptomatic patients can be started on dialysis at a higher GFR (usually ≤ 18 mL/min), but there are many hoops to jump through with Medicare.

However, IDEAL was conducted outside the United States and included very few elderly (age > 75) patients with chronic kidney disease. In 2018, Kurella and colleagues published a study that analyzed age and kidney function in a US veteran population.2 Their results showed that age should be included in the “when to start dialysis” calculation. For older veterans, starting dialysis earlier—at a GFR of 10 mL/min—increased survival. However, the researchers pointed out that in this age group, survival is in months (not years) and does not necessarily equate to quality of life.

In conclusion, there is no compelling evidence that initiation of dialysis based solely on measurement of kidney function leads to improvement in clinical outcomes. In otherwise asymptomatic patients, there is no reason to begin dialysis based solely on GFR; age and fragility need to be considered in the equation. Earlier is not always better, and for the elderly patient with multiple comorbidities, dialysis is not always a better choice. —TH

Tricia Howard, MHS, PA-C, DFAAPA

Georgia Regional Medical Team, Savannah

Q) I sent a patient with a glomerular filtration rate (GFR) of 15 mL/min to nephrology to start dialysis. He came back to me and said they don’t start dialysis at 15. When do you start? Why?

There is considerable variation in the timing of dialysis initiation. Research suggests that sometimes earlier is not better.

IDEAL, a randomized controlled trial conducted in Australia and New Zealand, evaluated the advantages and disadvantages of earlier versus later dialysis initiation.1 Patients were randomly assigned to start any type of dialysis when their GFR was 8 or 11 mL/min. The results indicated that starting dialysis in a patient with a higher GFR did not lower the mortality or morbidity rate but did increase costs and complications (mostly for vascular access).1

Based on these findings, most of us start dialysis in a patient who has a GFR < 10 mL/min and symptoms of kidney failure. These include a metallic taste in mouth, weight gain (usually due to edema) or loss (cachexia), feeling “poorly,” hard-to-control hypertension, shortness of breath, confusion (uremic brain), odor, skin color changes, and insomnia. Symptomatic patients can be started on dialysis at a higher GFR (usually ≤ 18 mL/min), but there are many hoops to jump through with Medicare.

However, IDEAL was conducted outside the United States and included very few elderly (age > 75) patients with chronic kidney disease. In 2018, Kurella and colleagues published a study that analyzed age and kidney function in a US veteran population.2 Their results showed that age should be included in the “when to start dialysis” calculation. For older veterans, starting dialysis earlier—at a GFR of 10 mL/min—increased survival. However, the researchers pointed out that in this age group, survival is in months (not years) and does not necessarily equate to quality of life.

In conclusion, there is no compelling evidence that initiation of dialysis based solely on measurement of kidney function leads to improvement in clinical outcomes. In otherwise asymptomatic patients, there is no reason to begin dialysis based solely on GFR; age and fragility need to be considered in the equation. Earlier is not always better, and for the elderly patient with multiple comorbidities, dialysis is not always a better choice. —TH

Tricia Howard, MHS, PA-C, DFAAPA

Georgia Regional Medical Team, Savannah

1. Cooper BA, Branley P, Bulfone L, et al; for the IDEAL Trial. A randomized, controlled trial of early versus late initiation of dialysis. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(7):609-619.

2. Kurella Tamura M, Desai M, Kapphahn KI, et al. Dialysis versus medical management at different ages and levels of kidney function in veterans with advanced CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2018;29(8):2169-2177.

1. Cooper BA, Branley P, Bulfone L, et al; for the IDEAL Trial. A randomized, controlled trial of early versus late initiation of dialysis. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(7):609-619.

2. Kurella Tamura M, Desai M, Kapphahn KI, et al. Dialysis versus medical management at different ages and levels of kidney function in veterans with advanced CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2018;29(8):2169-2177.

Newer antihyperglycemic drugs have distinctive CV, kidney benefits

The two newer classes of antihyperglycemic drugs that lower cardiovascular risk have different effects on specific cardiovascular and kidney disease outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes, results of a meta-analysis suggest. Sodium-glucose contransporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitors significantly reduced hospitalization from heart failure, whereas glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs) did not, according to the reported results.

The GLP-1–RA class reduced risk of kidney disease progression, largely driven by a reduction in macroalbuminuria, according to the authors, whereas only the SGLT2 inhibitors reduced adverse kidney disease outcomes in a composite excluding that biomarker.

“The prevention of heart failure and progression of kidney disease by SGLT2 [inhibitors] should be considered in the decision-making process when treating patients with type 2 diabetes,” study senior author Marc S. Sabatine, MD, MPH, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, and his coauthors wrote in a report on the study appearing in Circulation.

Both GLP-1 RAs and SGLT2 inhibitors significantly reduced major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) and, as shown in other recent findings, their benefits were confined to patients with established atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, Dr. Sabatine and his colleagues wrote.

The systematic review and meta-analysis of eight cardiovascular outcomes trials included 77,242 patients, of whom about 56% participated in GLP-1–RA studies and 44% in SGLT2-inhibitor trials. Just under three-quarters of the patients had established atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, while the remainder had multiple risk factors for it.

Relative risk of hospitalization for heart failure was reduced by 31% with SGLT2 inhibitors, but it was not significantly reduced by GLP-1 RAs, the authors noted.

Risk of kidney disease progression was reduced by 38% with SGLT2 inhibitors and by 18% with GLP-1 RAs when the researchers used a broad composite endpoint including macroalbuminuria, estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), end-stage kidney disease, and death due to renal causes.

By contrast, SGLT2 inhibitors reduced by 45% the relative risk of a narrower kidney outcome that excluded macroalbuminuria, whereas GLP-1 RAs had only a nonsignificant effect on the risk of doubling serum creatinine. That suggests the relative risk reduction of the kidney composite with GLP-1 RAs was driven mainly by a reduction in macroalbuminuria, the authors wrote.

Although albuminuria is an established biomarker for kidney and cardiovascular disease, it is a surrogate marker and can even be absent in patients with reduced eGFR, they said.

“Reduction in eGFR has emerged as a more meaningful endpoint of greater importance and is used in ongoing diabetes trials for kidney outcomes,” the authors said in a discussion of their results.

Relative risk of the composite MACE endpoint, including myocardial infarction, stroke, and cardiovascular death, was reduced by 12% for GLP-1 RAs and by 11% for SGLT2 [inhibitors], according to results of the analysis. However, the benefit was confined to patients with established cardiovascular disease, who had a 14% reduction of risk, compared with no treatment effect in patients who had multiple risk factors only.

Looking at individual MACE components, investigators found that both drug classes significantly reduced relative risk of myocardial infarction and of cardiovascular death, whereas only GLP-1 RAs significantly reduced relative risk of stroke.

Study authors provided disclosures related to AstraZeneca, Amgen, Daiichi-Sankyo, Eisai, GlaxoSmithKline, Intarcia, Janssen Research and Development, and Medimmune, among others.

SOURCE: Zelniker TA et al. Circulation. 2019 Feb 21. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.038868.

The two newer classes of antihyperglycemic drugs that lower cardiovascular risk have different effects on specific cardiovascular and kidney disease outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes, results of a meta-analysis suggest. Sodium-glucose contransporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitors significantly reduced hospitalization from heart failure, whereas glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs) did not, according to the reported results.

The GLP-1–RA class reduced risk of kidney disease progression, largely driven by a reduction in macroalbuminuria, according to the authors, whereas only the SGLT2 inhibitors reduced adverse kidney disease outcomes in a composite excluding that biomarker.

“The prevention of heart failure and progression of kidney disease by SGLT2 [inhibitors] should be considered in the decision-making process when treating patients with type 2 diabetes,” study senior author Marc S. Sabatine, MD, MPH, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, and his coauthors wrote in a report on the study appearing in Circulation.

Both GLP-1 RAs and SGLT2 inhibitors significantly reduced major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) and, as shown in other recent findings, their benefits were confined to patients with established atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, Dr. Sabatine and his colleagues wrote.

The systematic review and meta-analysis of eight cardiovascular outcomes trials included 77,242 patients, of whom about 56% participated in GLP-1–RA studies and 44% in SGLT2-inhibitor trials. Just under three-quarters of the patients had established atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, while the remainder had multiple risk factors for it.

Relative risk of hospitalization for heart failure was reduced by 31% with SGLT2 inhibitors, but it was not significantly reduced by GLP-1 RAs, the authors noted.

Risk of kidney disease progression was reduced by 38% with SGLT2 inhibitors and by 18% with GLP-1 RAs when the researchers used a broad composite endpoint including macroalbuminuria, estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), end-stage kidney disease, and death due to renal causes.

By contrast, SGLT2 inhibitors reduced by 45% the relative risk of a narrower kidney outcome that excluded macroalbuminuria, whereas GLP-1 RAs had only a nonsignificant effect on the risk of doubling serum creatinine. That suggests the relative risk reduction of the kidney composite with GLP-1 RAs was driven mainly by a reduction in macroalbuminuria, the authors wrote.

Although albuminuria is an established biomarker for kidney and cardiovascular disease, it is a surrogate marker and can even be absent in patients with reduced eGFR, they said.

“Reduction in eGFR has emerged as a more meaningful endpoint of greater importance and is used in ongoing diabetes trials for kidney outcomes,” the authors said in a discussion of their results.

Relative risk of the composite MACE endpoint, including myocardial infarction, stroke, and cardiovascular death, was reduced by 12% for GLP-1 RAs and by 11% for SGLT2 [inhibitors], according to results of the analysis. However, the benefit was confined to patients with established cardiovascular disease, who had a 14% reduction of risk, compared with no treatment effect in patients who had multiple risk factors only.

Looking at individual MACE components, investigators found that both drug classes significantly reduced relative risk of myocardial infarction and of cardiovascular death, whereas only GLP-1 RAs significantly reduced relative risk of stroke.

Study authors provided disclosures related to AstraZeneca, Amgen, Daiichi-Sankyo, Eisai, GlaxoSmithKline, Intarcia, Janssen Research and Development, and Medimmune, among others.

SOURCE: Zelniker TA et al. Circulation. 2019 Feb 21. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.038868.

The two newer classes of antihyperglycemic drugs that lower cardiovascular risk have different effects on specific cardiovascular and kidney disease outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes, results of a meta-analysis suggest. Sodium-glucose contransporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitors significantly reduced hospitalization from heart failure, whereas glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs) did not, according to the reported results.

The GLP-1–RA class reduced risk of kidney disease progression, largely driven by a reduction in macroalbuminuria, according to the authors, whereas only the SGLT2 inhibitors reduced adverse kidney disease outcomes in a composite excluding that biomarker.

“The prevention of heart failure and progression of kidney disease by SGLT2 [inhibitors] should be considered in the decision-making process when treating patients with type 2 diabetes,” study senior author Marc S. Sabatine, MD, MPH, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, and his coauthors wrote in a report on the study appearing in Circulation.

Both GLP-1 RAs and SGLT2 inhibitors significantly reduced major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) and, as shown in other recent findings, their benefits were confined to patients with established atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, Dr. Sabatine and his colleagues wrote.

The systematic review and meta-analysis of eight cardiovascular outcomes trials included 77,242 patients, of whom about 56% participated in GLP-1–RA studies and 44% in SGLT2-inhibitor trials. Just under three-quarters of the patients had established atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, while the remainder had multiple risk factors for it.

Relative risk of hospitalization for heart failure was reduced by 31% with SGLT2 inhibitors, but it was not significantly reduced by GLP-1 RAs, the authors noted.

Risk of kidney disease progression was reduced by 38% with SGLT2 inhibitors and by 18% with GLP-1 RAs when the researchers used a broad composite endpoint including macroalbuminuria, estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), end-stage kidney disease, and death due to renal causes.

By contrast, SGLT2 inhibitors reduced by 45% the relative risk of a narrower kidney outcome that excluded macroalbuminuria, whereas GLP-1 RAs had only a nonsignificant effect on the risk of doubling serum creatinine. That suggests the relative risk reduction of the kidney composite with GLP-1 RAs was driven mainly by a reduction in macroalbuminuria, the authors wrote.

Although albuminuria is an established biomarker for kidney and cardiovascular disease, it is a surrogate marker and can even be absent in patients with reduced eGFR, they said.

“Reduction in eGFR has emerged as a more meaningful endpoint of greater importance and is used in ongoing diabetes trials for kidney outcomes,” the authors said in a discussion of their results.

Relative risk of the composite MACE endpoint, including myocardial infarction, stroke, and cardiovascular death, was reduced by 12% for GLP-1 RAs and by 11% for SGLT2 [inhibitors], according to results of the analysis. However, the benefit was confined to patients with established cardiovascular disease, who had a 14% reduction of risk, compared with no treatment effect in patients who had multiple risk factors only.

Looking at individual MACE components, investigators found that both drug classes significantly reduced relative risk of myocardial infarction and of cardiovascular death, whereas only GLP-1 RAs significantly reduced relative risk of stroke.

Study authors provided disclosures related to AstraZeneca, Amgen, Daiichi-Sankyo, Eisai, GlaxoSmithKline, Intarcia, Janssen Research and Development, and Medimmune, among others.

SOURCE: Zelniker TA et al. Circulation. 2019 Feb 21. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.038868.

FROM CIRCULATION

A couple of little known side effects of medications

A 46-year-old woman with diabetes and seizure disorder presents with nausea and fatigue. Her physical exam is unremarkable.

Meds: Glyburide 5 mg daily, metformin 850 mg b.i.d., phenytoin 300 mg daily, topiramate 400 mg daily, pantoprazole 40 mg daily.

Labs: Na 133, K 3.9, Cl 112, HCO3 13, Glu 158, Bun 18, Cr 1.0.

What is the most likely cause of this patient’s acidosis?

A. Phenytoin

B. Topiramate

C. Metformin

D. Pantoprazole

The correct answer to this question is topiramate.

Metformin has had warnings about risk of lactic acidosis occurring in patients with kidney disease, but there is no evidence that metformin is associated with lactic acidosis or raised serum lactate levels in patients with diabetes with normal renal function.1 and its use may decrease CV risk in patients with stage 3 CKD.2 This patient has a non–anion gap acidosis (anion gap is 8).

Topiramate acts as a carbonic anhydrase inhibitor, which causes impairment of both the normal reabsorption of filtered HCO3 by the proximal renal tubule and the excretion of hydrogen ion by the distal tubule.3 Acidosis occurs in most patients who are treated with topiramate. Dr. Ture and colleagues did a cross-sectional study to assess the frequency of metabolic acidosis in patients who were taking topiramate.4 Eighty patients who were on topiramate for seizure prevention prior to elective craniotomy were studied. Metabolic acidosis was present in 71% of the patients. Patients treated with topiramate also have a higher risk for kidney stones and uric acid elevation.

A 60-year-old patient presents with right great toe pain. On exam he has warmth and erythema of the 1st MTP joint. Aspiration of the joint shows uric acid crystals. He has had BP’s of 150-160 mm Hg systolic on his home BP monitoring over the past 6 months. In clinic today BP is 156/90 mm Hg. Labs: Bun 10, Cr 1.0, K 3.8, Uric acid 7.4.

Which blood pressure medication would you recommend?

A. Hydrochlorothiazide

B. Chlorthalidone

C. Lisinopril

D. Losartan

E. Irbesartan

In a patient with gout, diuretics should be avoided if possible, as they increase uric acid levels. Of the other three options, losartan offers the added benefit of lowering uric acid levels. Losartan has uricosuric effects and lowers uric acid levels, a property that is unique to losartan of the angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) that have been studied.5-6 The uric acid lowering appears to be a probenecid-like effect. Losartan has also been evaluated to see whether using it in combination with a thiazide diuretic can reduce the rise in uric acid that occurs with thiazides. Dr. Matsumura et al. looked at data from the COMFORT trial, focusing on the effect of combining losartan with hydrochlorothiazide on uric acid levels.7 They looked at a group of 118 patients on an ARB other than losartan plus a diuretic, who were then randomly assigned to losartan 50 mg/hydrochlorothiazide 12.5 mg or continuation of another ARB plus a diuretic. Blood pressure control was the same between groups, but the patients who received the losartan combination had lower uric acid levels (P = .01).

Pearls: Topiramate acts as a cerbonic anhydrase inhibitor and can cause a non–anion gap acidosis. Losartan has a modest uricosuric effect and can modestly lower uric acid levels. This is a unique property of losartan and is not shared by other ARBs.

Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at the University of Washington. Contact Dr. Paauw at [email protected].

References

1. Salpeter SR et al. Risk of fatal and nonfatal lactic acidosis with metformin use in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;4:CD002967.

2. Charytan DM et al. Metformin use and cardiovascular events in patients with type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2019 Jan 22. doi: 10.1111/dom.13642.

3. Mirza N et al. Effect of topiramate on acid-base balance: extent, mechanism and effects. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2009 Nov;68(5):655-61.

4. Ture H et al. The frequency and severity of metabolic acidosis related to topiramate. J Int Med Res. 2016;44(6):1376-80.

5. Würzner G et al. Comparative effects of losartan and irbesartan on serum uric acid in hypertensive patients with hyperuricaemia and gout. J Hypertens. 2001 Oct;19(10):1855-60.

6. Puig JG et al. Effect of eprosartan and losartan on uric acid metabolism in patients with essential hypertension. J Hypertens. 1999 Jul;17(7):1033-9.

7. Matsumura K et al. Effect of losartan on serum uric acid in hypertension treated with a diuretic: the COMFORT study. Clin Exp Hypertens. 2015;37(3):192-6.

A 46-year-old woman with diabetes and seizure disorder presents with nausea and fatigue. Her physical exam is unremarkable.

Meds: Glyburide 5 mg daily, metformin 850 mg b.i.d., phenytoin 300 mg daily, topiramate 400 mg daily, pantoprazole 40 mg daily.

Labs: Na 133, K 3.9, Cl 112, HCO3 13, Glu 158, Bun 18, Cr 1.0.

What is the most likely cause of this patient’s acidosis?

A. Phenytoin

B. Topiramate

C. Metformin

D. Pantoprazole

The correct answer to this question is topiramate.

Metformin has had warnings about risk of lactic acidosis occurring in patients with kidney disease, but there is no evidence that metformin is associated with lactic acidosis or raised serum lactate levels in patients with diabetes with normal renal function.1 and its use may decrease CV risk in patients with stage 3 CKD.2 This patient has a non–anion gap acidosis (anion gap is 8).

Topiramate acts as a carbonic anhydrase inhibitor, which causes impairment of both the normal reabsorption of filtered HCO3 by the proximal renal tubule and the excretion of hydrogen ion by the distal tubule.3 Acidosis occurs in most patients who are treated with topiramate. Dr. Ture and colleagues did a cross-sectional study to assess the frequency of metabolic acidosis in patients who were taking topiramate.4 Eighty patients who were on topiramate for seizure prevention prior to elective craniotomy were studied. Metabolic acidosis was present in 71% of the patients. Patients treated with topiramate also have a higher risk for kidney stones and uric acid elevation.

A 60-year-old patient presents with right great toe pain. On exam he has warmth and erythema of the 1st MTP joint. Aspiration of the joint shows uric acid crystals. He has had BP’s of 150-160 mm Hg systolic on his home BP monitoring over the past 6 months. In clinic today BP is 156/90 mm Hg. Labs: Bun 10, Cr 1.0, K 3.8, Uric acid 7.4.

Which blood pressure medication would you recommend?

A. Hydrochlorothiazide

B. Chlorthalidone

C. Lisinopril

D. Losartan

E. Irbesartan

In a patient with gout, diuretics should be avoided if possible, as they increase uric acid levels. Of the other three options, losartan offers the added benefit of lowering uric acid levels. Losartan has uricosuric effects and lowers uric acid levels, a property that is unique to losartan of the angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) that have been studied.5-6 The uric acid lowering appears to be a probenecid-like effect. Losartan has also been evaluated to see whether using it in combination with a thiazide diuretic can reduce the rise in uric acid that occurs with thiazides. Dr. Matsumura et al. looked at data from the COMFORT trial, focusing on the effect of combining losartan with hydrochlorothiazide on uric acid levels.7 They looked at a group of 118 patients on an ARB other than losartan plus a diuretic, who were then randomly assigned to losartan 50 mg/hydrochlorothiazide 12.5 mg or continuation of another ARB plus a diuretic. Blood pressure control was the same between groups, but the patients who received the losartan combination had lower uric acid levels (P = .01).

Pearls: Topiramate acts as a cerbonic anhydrase inhibitor and can cause a non–anion gap acidosis. Losartan has a modest uricosuric effect and can modestly lower uric acid levels. This is a unique property of losartan and is not shared by other ARBs.

Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at the University of Washington. Contact Dr. Paauw at [email protected].

References

1. Salpeter SR et al. Risk of fatal and nonfatal lactic acidosis with metformin use in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;4:CD002967.

2. Charytan DM et al. Metformin use and cardiovascular events in patients with type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2019 Jan 22. doi: 10.1111/dom.13642.

3. Mirza N et al. Effect of topiramate on acid-base balance: extent, mechanism and effects. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2009 Nov;68(5):655-61.

4. Ture H et al. The frequency and severity of metabolic acidosis related to topiramate. J Int Med Res. 2016;44(6):1376-80.

5. Würzner G et al. Comparative effects of losartan and irbesartan on serum uric acid in hypertensive patients with hyperuricaemia and gout. J Hypertens. 2001 Oct;19(10):1855-60.

6. Puig JG et al. Effect of eprosartan and losartan on uric acid metabolism in patients with essential hypertension. J Hypertens. 1999 Jul;17(7):1033-9.

7. Matsumura K et al. Effect of losartan on serum uric acid in hypertension treated with a diuretic: the COMFORT study. Clin Exp Hypertens. 2015;37(3):192-6.

A 46-year-old woman with diabetes and seizure disorder presents with nausea and fatigue. Her physical exam is unremarkable.

Meds: Glyburide 5 mg daily, metformin 850 mg b.i.d., phenytoin 300 mg daily, topiramate 400 mg daily, pantoprazole 40 mg daily.

Labs: Na 133, K 3.9, Cl 112, HCO3 13, Glu 158, Bun 18, Cr 1.0.

What is the most likely cause of this patient’s acidosis?

A. Phenytoin

B. Topiramate

C. Metformin

D. Pantoprazole

The correct answer to this question is topiramate.

Metformin has had warnings about risk of lactic acidosis occurring in patients with kidney disease, but there is no evidence that metformin is associated with lactic acidosis or raised serum lactate levels in patients with diabetes with normal renal function.1 and its use may decrease CV risk in patients with stage 3 CKD.2 This patient has a non–anion gap acidosis (anion gap is 8).

Topiramate acts as a carbonic anhydrase inhibitor, which causes impairment of both the normal reabsorption of filtered HCO3 by the proximal renal tubule and the excretion of hydrogen ion by the distal tubule.3 Acidosis occurs in most patients who are treated with topiramate. Dr. Ture and colleagues did a cross-sectional study to assess the frequency of metabolic acidosis in patients who were taking topiramate.4 Eighty patients who were on topiramate for seizure prevention prior to elective craniotomy were studied. Metabolic acidosis was present in 71% of the patients. Patients treated with topiramate also have a higher risk for kidney stones and uric acid elevation.

A 60-year-old patient presents with right great toe pain. On exam he has warmth and erythema of the 1st MTP joint. Aspiration of the joint shows uric acid crystals. He has had BP’s of 150-160 mm Hg systolic on his home BP monitoring over the past 6 months. In clinic today BP is 156/90 mm Hg. Labs: Bun 10, Cr 1.0, K 3.8, Uric acid 7.4.

Which blood pressure medication would you recommend?

A. Hydrochlorothiazide

B. Chlorthalidone

C. Lisinopril

D. Losartan

E. Irbesartan

In a patient with gout, diuretics should be avoided if possible, as they increase uric acid levels. Of the other three options, losartan offers the added benefit of lowering uric acid levels. Losartan has uricosuric effects and lowers uric acid levels, a property that is unique to losartan of the angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) that have been studied.5-6 The uric acid lowering appears to be a probenecid-like effect. Losartan has also been evaluated to see whether using it in combination with a thiazide diuretic can reduce the rise in uric acid that occurs with thiazides. Dr. Matsumura et al. looked at data from the COMFORT trial, focusing on the effect of combining losartan with hydrochlorothiazide on uric acid levels.7 They looked at a group of 118 patients on an ARB other than losartan plus a diuretic, who were then randomly assigned to losartan 50 mg/hydrochlorothiazide 12.5 mg or continuation of another ARB plus a diuretic. Blood pressure control was the same between groups, but the patients who received the losartan combination had lower uric acid levels (P = .01).

Pearls: Topiramate acts as a cerbonic anhydrase inhibitor and can cause a non–anion gap acidosis. Losartan has a modest uricosuric effect and can modestly lower uric acid levels. This is a unique property of losartan and is not shared by other ARBs.

Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at the University of Washington. Contact Dr. Paauw at [email protected].

References

1. Salpeter SR et al. Risk of fatal and nonfatal lactic acidosis with metformin use in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;4:CD002967.

2. Charytan DM et al. Metformin use and cardiovascular events in patients with type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2019 Jan 22. doi: 10.1111/dom.13642.

3. Mirza N et al. Effect of topiramate on acid-base balance: extent, mechanism and effects. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2009 Nov;68(5):655-61.

4. Ture H et al. The frequency and severity of metabolic acidosis related to topiramate. J Int Med Res. 2016;44(6):1376-80.

5. Würzner G et al. Comparative effects of losartan and irbesartan on serum uric acid in hypertensive patients with hyperuricaemia and gout. J Hypertens. 2001 Oct;19(10):1855-60.

6. Puig JG et al. Effect of eprosartan and losartan on uric acid metabolism in patients with essential hypertension. J Hypertens. 1999 Jul;17(7):1033-9.

7. Matsumura K et al. Effect of losartan on serum uric acid in hypertension treated with a diuretic: the COMFORT study. Clin Exp Hypertens. 2015;37(3):192-6.

Laboratory tests in rheumatology: A rational approach

Laboratory tests are often ordered inappropriately for patients in whom a rheumatologic illness is suspected; this occurs in both primary and secondary care.1 Some tests are available both singly and as part of a battery of tests screening healthy people without symptoms.

The problem: negative test results are by no means always reassuring, and false-positive results raise the risks of unnecessary anxiety for patients and clinicians, needless referrals, and potential morbidity due to further unnecessary testing and exposure to wrong treatments.2 Clinicians should be aware of the pitfalls of these tests in order to choose them wisely and interpret the results correctly.

This article provides practical guidance on requesting and interpreting some common tests in rheumatology, with the aid of case vignettes.

RHEUMATOID FACTOR AND ANTICITRULLINATED PEPTIDE ANTIBODY

A 41-year-old woman, previously in good health, presents to her primary care practitioner with a 6-week history of pain and swelling in her hands and early morning stiffness lasting about 2 hours. She denies having any extraarticular symptoms. Physical examination reveals synovitis across her right metacarpophalangeal joints, proximal interphalangeal joint of the left middle finger, and left wrist. The primary care physician is concerned that her symptoms might be due to rheumatoid arthritis.

Would testing for rheumatoid factor and anticitrullinated peptide antibody be useful in this patient?

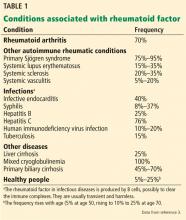

Rheumatoid factor is an antibody (immunoglobulin M, IgG, or IgA) targeted against the Fc fragment of IgG.3 It was so named because it was originally detected in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, but it is neither sensitive nor specific for this condition. A meta-analysis of more than 5,000 patients with rheumatoid arthritis reported that rheumatoid factor testing had a sensitivity of 69% and specificity of 85%.4

Anticitrullinated peptide antibody, on the other hand, is much more specific for rheumatoid arthritis (95%), as it is seldom seen in other conditions, but its sensitivity is similar to that of rheumatoid factor (68%).4–6 A positive result would thus lend strength to the diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis, but a negative result would not exclude it.

Approach to early arthritis

When faced with a patient with early arthritis, some key questions to ask include7,8:

Is this an inflammatory or a mechanical problem? Inflammatory arthritis is suggested by joint swelling that is not due to trauma or bony hypertrophy, early morning stiffness lasting longer than 30 minutes, and elevated inflammatory markers (erythrocyte sedimentation rate or C-reactive protein). Involvement of the small joints of the hands and feet may be suggested by pain on compression of the metacarpophalangeal and metatarsophalangeal joints, respectively.

Is there a definite identifiable underlying cause for the inflammatory arthritis? The pattern of development of joint symptoms or the presence of extraarticular symptoms may suggest an underlying problem such as gout, psoriatic arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, or sarcoidosis.

If the arthritis is undifferentiated (ie, there is no definite identifiable cause), is it likely to remit or persist? This is perhaps the most important question to ask in order to prognosticate. Patients with risk factors for persistent disease, ie, for development of rheumatoid arthritis, should be referred to a rheumatologist early for timely institution of disease-modifying antirheumatic drug therapy.9 Multiple studies have shown that patients in whom this therapy is started early have much better clinical, functional, and radiologic outcomes than those in whom it is delayed.10–12

The revised American College of Rheumatology and European League Against Rheumatism criteria13 include the following factors as predictors of persistence:

- Number of involved joints (with greater weight given to involvement of small joints)

- Duration of symptoms 6 weeks or longer

- Elevated acute-phase response (erythrocyte sedimentation rate or C-reactive protein level)

- A positive serologic test (either rheumatoid factor or anticitrullinated peptide antibody).

If both rheumatoid factor and anticitrullinated peptide antibody are positive in a patient with early undifferentiated arthritis, the risk of progression to rheumatoid arthritis is almost 100%, thus underscoring the importance of testing for these antibodies.5,6 Referral to a rheumatologist should, however, not be delayed in patients with negative test results (more than one-third of patients with rheumatoid arthritis may be negative for both), and should be considered in those with inflammatory joint symptoms persisting longer than 6 weeks, especially with involvement of the small joints (sparing the distal interphalangeals) and elevated acute-phase response.

Rheumatoid factor in healthy people without symptoms

In some countries, testing for rheumatoid factor is offered as part of a battery of screening tests in healthy people who have no symptoms, a practice that should be strongly discouraged.

Multiple studies, both prospective and retrospective, have demonstrated that both rheumatoid factor and anticitrullinated peptide antibody may be present several years before the clinical diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis.6,14–16 But the risk of developing rheumatoid arthritis for asymptomatic individuals who are rheumatoid factor-positive depends on the rheumatoid factor titer, positive family history of rheumatoid arthritis in first-degree relatives, and copresence of anticitrullinated peptide antibody. The absolute risk, nevertheless, is still very small. In some, there might be an alternative explanation such as undiagnosed Sjögren syndrome or hepatitis C.

In any event, no strategy is currently available that is proven to prevent the development of rheumatoid arthritis, and there is no role for disease-modifying therapy during the preclinical phase.16

Back to our patient

Blood testing in our patient reveals normal complete blood cell counts, aminotransferase levels, and serum creatinine concentration; findings on urinalysis are normal. Her erythrocyte sedimentation rate is 56 mm/hour (reference range 0–15), and her C-reactive protein level is 26 mg/dL (normal < 3). Testing is negative for rheumatoid factor and anticitrullinated peptide antibody.

Although her rheumatoid factor and anticitrullinated peptide antibody tests are negative, she is referred to a rheumatologist because she has predictors of persistent disease, ie, symptom duration of 6 weeks, involvement of the small joints of the hands, and elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein. The rheumatologist checks her parvovirus serology, which is negative.

The patient is given parenteral depot corticosteroid therapy, to which she responds briefly. Because her symptoms persist and continue to worsen, methotrexate treatment is started after an additional 6 weeks.

ANTINUCLEAR ANTIBODY

A 37-year-old woman presents to her primary care physician with the complaint of tiredness. She has a family history of systemic lupus erythematosus in her sister and maternal aunt. She is understandably worried about lupus because of the family history and is asking to be tested for it.

Would testing for antinuclear antibody be reasonable?

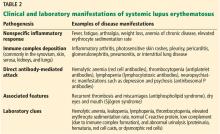

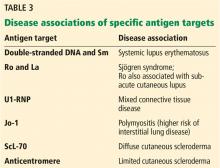

Antinuclear antibody is not a single antibody but rather a family of autoantibodies that are directed against nuclear constituents such as single- or double-stranded deoxyribonucleic acid (dsDNA), histones, centromeres, proteins complexed with ribonucleic acid (RNA), and enzymes such as topoisomerase.17,18

Protein antigens complexed with RNA and some enzymes in the nucleus are also known as extractable nuclear antigens (ENAs). They include Ro, La, Sm, Jo-1, RNP, and ScL-70 and are named after the patient in whom they were first discovered (Robert, Lavine, Smith, and John), the antigen that is targeted (ribonucleoprotein or RNP), and the disease with which they are associated (anti-ScL-70 or antitopoisomerase in diffuse cutaneous scleroderma).

Antinuclear antibody testing is commonly requested to exclude connective tissue diseases such as lupus, but the clinician needs to be aware of the following points:

Antinuclear antibody may be encountered in conditions other than lupus

These include19:

- Other autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, primary Sjögren syndrome, systemic sclerosis, autoimmune thyroid disease, and myasthenia gravis

- Infection with organisms that share the epitope with self-antigens (molecular mimicry)

- Cancers

- Drugs such as hydralazine, procainamide, and minocycline.

Antinuclear antibody might also be produced by the healthy immune system from time to time to clear the nuclear debris that is extruded from aging cells.

A study in healthy individuals20 reported a prevalence of positive antinuclear antibody of 32% at a titer of 1/40, 15% at a titer of 1/80, 7% at a titer of 1/160, and 3% at a titer of 1/320. Importantly, a positive result was more common among family members of patients with autoimmune connective tissue diseases.21 Hence, a positive antinuclear antibody result does not always mean lupus.

Antinuclear antibody testing is highly sensitive for lupus

With current laboratory methods, antinuclear antibody testing has a sensitivity close to 100%. Hence, a negative result virtually rules out lupus.

Two methods are commonly used to test for antinuclear antibody: indirect immunofluorescence and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA).22 While human epithelial (Hep2) cells are used as the source of antigen in immunofluorescence, purified nuclear antigens coated on multiple-well plates are used in ELISA.

Although ELISA is simpler to perform, immunofluorescence has a slightly better sensitivity (because the Hep2 cells express a wide range of antigens) and is still considered the gold standard. As expected, the higher sensitivity occurs at the cost of reduced specificity (about 60%), so antinuclear antibody will also be detected in all the other conditions listed above.23

To improve the specificity of antinuclear antibody testing, laboratories report titers (the highest dilution of the test serum that tested positive); a cutoff of greater than 1/80 is generally considered significant.

Do not order antinuclear antibody testing indiscriminately

To sum up, the antinuclear antibody test should be requested only in patients with involvement of multiple organ systems. Although a negative result would make it extremely unlikely that the clinical presentation is due to lupus, a positive result is insufficient on its own to make a diagnosis of lupus.

Diagnosing lupus is straightforward when patients present with a specific manifestation such as inflammatory arthritis, photosensitive skin rash, hemolytic anemia, thrombocytopenia, or nephritis, or with specific antibodies such as those against dsDNA or Sm. Patients who present with nonspecific symptoms such as arthralgia or tiredness with a positive antinuclear antibody and negative anti-dsDNA and anti-Sm may present difficulties even for the specialist.25–27

Back to our patient

Our patient denies arthralgia. She has no extraarticular symptoms such as skin rashes, oral ulcers, sicca symptoms, muscle weakness, Raynaud phenomenon, pleuritic chest pain, or breathlessness. Findings on physical examination and urinalysis are unremarkable.

Her primary care physician decides to check her complete blood cell count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and thyroid-stimulating hormone level. Although she is reassured that her tiredness is not due to lupus, she insists on getting an antinuclear antibody test.

Her complete blood cell counts are normal. Her erythrocyte sedimentation rate is 6 mm/hour. However, her thyroid-stimulating hormone level is elevated, and subsequent testing shows low free thyroxine and positive thyroid peroxidase antibodies. The antinuclear antibody is positive in a titer of 1/80 and negative for anti-dsDNA and anti-ENA.

We explain to her that the positive antinuclear antibody is most likely related to her autoimmune thyroid disease. She is referred to an endocrinologist.

ANTIPHOSPHOLIPID ANTIBODIES

A 24-year-old woman presents to the emergency department with acute unprovoked deep vein thrombosis in her right leg, confirmed by ultrasonography. She has no history of previous thrombosis, and the relevant family history is unremarkable. She has never been pregnant. Her platelet count is 84 × 109/L (reference range 150–400), and her baseline activated partial thromboplastin time is prolonged at 62 seconds (reference range 23.0–32.4). The rest of her blood counts and her prothrombin time, liver enzyme levels, and serum creatinine level are normal.

Should this patient be tested for antiphospholipid antibodies?

Antiphospholipid antibodies are important because of their association with thrombotic risk (both venous and arterial) and pregnancy morbidity. The name is a misnomer, as these antibodies are targeted against some proteins that are bound to phospholipids and not only to the phospholipids themselves.

According to the modified Sapporo criteria for the classification of antiphospholipid syndrome,28 antiphospholipid antibodies should remain persistently positive on at least 2 separate occasions at least 12 weeks apart for the result to be considered significant because some infections and drugs may be associated with the transient presence of antiphospholipid antibodies.

Screening for antiphospholipid antibodies should include testing for IgM and IgG anticardiolipin antibodies, lupus anticoagulant, and IgM and IgG beta-2 glycoprotein I antibodies.29,30

Anticardiolipin antibodies

Anticardiolipin (aCL) antibodies may be targeted either against beta-2 glycoprotein I (beta-2GPI) that is bound to cardiolipin (a phospholipid) or against cardiolipin alone; the former is more specific. Antibodies directed against cardiolipin alone are usually transient and are associated with infections and drugs. The result is considered significant only when anticardiolipin antibodies are present in a medium to high titer (> 40 IgG phospholipid units or IgM phospholipid units, or > 99th percentile).

Lupus anticoagulant

The antibody with “lupus anticoagulant activity” is targeted against prothrombin plus phospholipid or beta-2GPI plus phospholipid. The test for it is a functional assay involving 3 steps:

Demonstrating the prolongation of a phospholipid-dependent coagulation assay like the activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT). (This may explain the prolongation of aPTT in the patient described in the vignette.) Although the presence of lupus anticoagulant is associated with thrombosis, it is called an “anticoagulant” because of this in vitro prolongation of phospholipid-dependent coagulation assays.

Mixing study. The phospholipid-dependent coagulation assay could be prolonged because of either the deficiency of a coagulation factor or the presence of the antiphospholipid antibodies. This can be differentiated by mixing the patient’s plasma with normal plasma (which will have all the clotting factors) in a 1:1 ratio. If the coagulation assay remains prolonged after the addition of normal plasma, clotting factor deficiency can be excluded.

Addition of a phospholipid. If the prolongation of the coagulation assay is due to the presence of an antiphospholipid antibody, addition of extra phospholipid will correct this.

Beta-2 glycoprotein I antibody (anti-beta-2GPI)

The beta-2GPI that is not bound to the cardiolipin can be detected by separately testing for beta-2GPI (the anticardiolipin test only detects the beta-2GPI that is bound to the cardiolipin). The result is considered significant if beta-2GPI is present in a medium to high titer (> 99th percentile).

Studies have shown that antiphospholipid antibodies may be present in 1% to 5% of apparently healthy people in the general population.31 These are usually low-titer anticardiolipin or anti-beta-GPI IgM antibodies that are not associated with thrombosis or adverse pregnancy outcomes. Hence, the term antiphospholipid syndrome should be reserved for those who have had at least 1 episode of thrombosis or pregnancy morbidity and persistent antiphospholipid antibodies, and not those who have asymptomatic or transient antiphospholipid antibodies.

Triple positivity (positive anticardiolipin, lupus anticoagulant, and anti-beta-2GPI) seems to be associated with the highest risk of thrombosis, with a 10-year cumulative incidence of 37.1% (95% confidence interval [CI] 19.9–54.3) for a first thrombotic event,32 and 44.2% (95% CI 38.6–49.8) for recurrent thrombosis.33

The association with thrombosis is stronger for lupus anticoagulant than with the other 2 antibodies, with different studies34 finding an odds ratio ranging from 5 to 16. A positive lupus anticoagulant test with or without a moderate to high titer of anticardiolipin or anti-beta-2GPI IgM or IgG constitutes a high-risk profile, while a moderate to high titer of anticardiolipin or anti-beta-2GPI IgM or IgG constitutes a moderate-risk profile. A low titer of anticardiolipin or anti-beta-2GPI IgM or IgG constitutes a low-risk profile that may not be associated with thrombosis.35

Antiphospholipid syndrome is important to recognize because of the need for long-term anticoagulation to prevent recurrence.36 It may be primary, when it occurs on its own, or secondary, when it occurs in association with another autoimmune disease such as lupus.

Venous events in antiphospholipid syndrome most commonly manifest as lower-limb deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism, while arterial events most commonly manifest as stroke or transient ischemic attack.37 Obstetric manifestations may include not only miscarriage and stillbirth, but also preterm delivery, intrauterine growth retardation, and preeclampsia, all occurring due to placental insufficiency.

The frequency of antiphospholipid antibodies has been estimated as 13.5% in patients with stroke, 11% with myocardial infarction, 9.5% with deep vein thrombosis, and 6% for those with pregnancy morbidity.38

Some noncriteria manifestations have also been recognized in antiphospholipid syndrome, such as thrombocytopenia, cardiac vegetations (Libman-Sachs endocarditis), livedo reticularis, and nephropathy.

Back to our patient

Our patient’s anticardiolipin IgG test is negative, while her lupus anticoagulant and beta-2GPI IgG are positive. She has no clinical or laboratory features suggesting lupus.

She is started on warfarin. After 3 months, the warfarin is interrupted for several days, and she is retested for all 3 antiphospholipid antibodies. Her beta-2GPI I IgG and lupus anticoagulant tests are again positive. Because of the persistent antiphospholipid antibody positivity and clinical history of deep vein thrombosis, her condition is diagnosed as primary antiphospholipid syndrome. She is advised to continue anticoagulant therapy indefinitely.

ANTINEUTROPHIL CYTOPLASMIC ANTIBODY

A 34-year-old man who is an injecting drug user presents with a 2-week history of fever, malaise, and generalized arthralgia. There are no localizing symptoms of infection. Notable findings on examination include a temperature of 38.0°C (100.4°F), needle track marks in his arms, nonblanching vasculitic rash in his legs, and a systolic murmur over the precordium.

His white blood cell count is 15.3 × 109/L (reference range 3.7–11.0), and his C-reactive protein level is 234 mg/dL (normal < 3). Otherwise, results of blood cell counts, liver enzyme tests, renal function tests, urinalysis, and chest radiography are normal.

Two sets of blood cultures are drawn. Transthoracic echocardiography and the antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA) test are requested, as are screening tests for human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C.

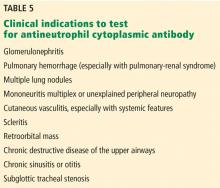

Was the ANCA test indicated in this patient?

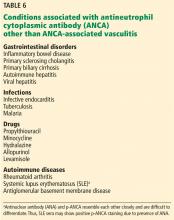

ANCAs are autoantibodies against antigens located in the cytoplasmic granules of neutrophils and monocytes. They are associated with small-vessel vasculitides such as granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA), microscopic polyangiitis (MPA), eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA), and isolated pauciimmune crescentic glomerulonephritis, all collectively known as ANCA-associated vasculitis (AAV).39

Laboratory methods to detect ANCA include indirect immunofluorescence and antigen-specific enzyme immunoassays. Indirect immunofluorescence only tells us whether or not an antibody that is targeting a cytoplasmic antigen is present. Based on the indirect immunofluorescent pattern, ANCA can be classified as follows:

- Perinuclear or p-ANCA (if the targeted antigen is located just around the nucleus and extends into it)

- Cytoplasmic or c-ANCA (if the targeted antigen is located farther away from the nucleus)

- Atypical ANCA (if the indirect immunofluorescent pattern does not fit with either p-ANCA or c-ANCA).

Indirect immunofluorescence does not give information about the exact antigen that is targeted; this can only be obtained by performing 1 of the antigen-specific immunoassays. The target antigen for c-ANCA is usually proteinase-3 (PR3), while that for p-ANCA could be myeloperoxidase (MPO), cathepsin, lysozyme, lactoferrin, or bactericidal permeability inhibitor. Anti-PR3 is highly specific for GPA, while anti-MPO is usually associated with MPA and EGPA. Less commonly, anti-PR3 may be seen in patients with MPA and anti-MPO in those with GPA. Hence, there is an increasing trend toward classifying ANCA-associated vasculitis into PR3-associated or MPO-associated vasculitis rather than as GPA, MPA, EGPA, or renal-limited vasculitis.40

Several audits have shown that the ANCA test is widely misused and requested indiscriminately to rule out vasculitis. This results in a lower positive predictive value, possible harm to patients due to increased false-positive rates, and increased burden on the laboratory.41–43 At least 2 separate groups have demonstrated that a gating policy that refuses ANCA testing in patients without clinical evidence of systemic vasculitis can reduce the number of inappropriate requests, improve the diagnostic yield, and make it more clinically relevant and cost-effective.44,45

The clinician should bear in mind that:

Current guidelines recommend using one of the antigen-specific assays for PR3 and MPO as the primary screening method.48 Until recently, indirect immunofluorescence was used to screen for ANCA-associated vasculitis, and positive results were confirmed by ELISA to detect ANCAs specific for PR3 and MPO,49 but this is no longer recommended because of recent evidence suggesting a large variability between the different indirect immunofluorescent methods and improved diagnostic performance of the antigen-specific assays.

In a large multicenter study by Damoiseaux et al, the specificity with the different antigen-specific immunoassays was 98% to 99% for PR3-ANCA and 96% to 99% for MPO-ANCA.50

ANCA-associated vasculitis should not be considered excluded if the PR3 and MPO-ANCA are negative. In the Damoiseaux study, about 11% to 15% of patients with GPA and 8% to 24% of patients with MPA tested negative for both PR3 and MPO-ANCA.50

If the ANCA result is negative and clinical suspicion for ANCA-associated vasculitis is high, the clinician may wish to consider requesting another immunoassay method or indirect immunofluorescence. Results of indirect immunofluorescent testing results may be positive in those with a negative immunoassay, and vice versa.

Thus, the ANCA result should always be interpreted in the context of the whole clinical picture.51 Biopsy should still be considered the gold standard for the diagnosis of ANCA-associated vasculitis. The ANCA titer can help to improve clinical interpretation, because the likelihood of ANCA-associated vasculitis increases with higher levels of PR3 and MPO-ANCA.52

Back to our patient

Our patient’s blood cultures grow methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus in both sets after 48 hours. Transthoracic echocardiography reveals vegetations around the tricuspid valve, with no evidence of valvular regurgitation. The diagnosis is right-sided infective endocarditis. He is started on appropriate antibiotics.

Tests for human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C are negative. The ANCA test is positive for MPO-ANCA at 28 IU/mL (normal < 10).

The positive ANCA is thought to be related to the infective endocarditis. His vasculitis is most likely secondary to infective endocarditis and not ANCA-associated vasculitis. The ANCA test need not have been requested in the first place.

HUMAN LEUKOCYTE ANTIGEN-B27

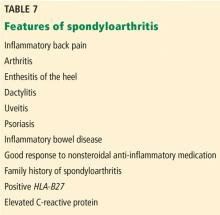

A 22-year-old man presents to his primary care physician with a 4-month history of gradually worsening low back pain associated with early morning stiffness lasting more than 2 hours. He has no peripheral joint symptoms.

In the last 2 years, he has had 2 separate episodes of uveitis. There is a family history of ankylosing spondylitis in his father. Examination reveals global restriction of lumbar movements but is otherwise unremarkable. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the lumbar spine and sacroiliac joints is normal.

Should this patient be tested for human leukocyte antigen-B27 (HLA-B27)?

The major histocompatibility complex (MHC) is a gene complex that is present in all animals. It encodes proteins that help with immunologic tolerance. HLA simply refers to the human version of the MHC.53 The HLA gene complex, located on chromosome 6, is categorized into class I, class II, and class III. HLA-B is one of the 3 class I genes. Thus, a positive HLA-B27 result simply means that the particular gene is present in that person.

HLA-B27 is strongly associated with ankylosing spondylitis, also known as axial spondyloarthropathy.54 Other genes also contribute to the pathogenesis of ankylosing spondylitis, but HLA-B27 is present in more than 90% of patients with this disease and is by far considered the most important. The association is not as strong for peripheral spondyloarthropathy, with studies reporting a frequency of up to 75% for reactive arthritis and inflammatory bowel disease-associated arthritis, and up to 50% for psoriatic arthritis and uveitis.55

About 9% of healthy, asymptomatic individuals may have HLA-B27, so the mere presence of this gene is not evidence of disease.56 There may be up to a 20-fold increased risk of ankylosing spondylitis among those who are HLA-B27-positive.57

Some HLA genes have many different alleles, each of which is given a number (explaining the number 27 that follows the B). Closely related alleles that differ from one another by only a few amino-acid substitutions are then categorized together, thus accounting for more than 100 subtypes of HLA-B27 (designated from HLA-B*2701 to HLA-B*27106). These subtypes vary in frequency among different racial groups, and the population prevalence of ankylosing spondylitis parallels the frequency of HLA-B27.58 The most common subtype seen in white people and American Indians is B*2705. HLA-B27 is rare in blacks, explaining the rarity of ankylosing spondylitis in this population. Further examples include HLA-B*2704, which is seen in Asians, and HLA-B*2702, seen in Mediterranean populations. Not all subtypes of HLA-B27 are associated with disease, and some, like HLA-B*2706, may also be protective.

When should the clinician consider testing for HLA-B27?

Peripheral spondyloarthropathy may present with arthritis, enthesitis (eg, heel pain due to inflammation at the site of insertion of the Achilles tendon or plantar fascia), or dactylitis (“sausage” swelling of the whole finger or toe due to extension of inflammation beyond the margins of the joint). Other clues may include psoriasis, inflammatory bowel disease, history of preceding gastrointestinal or genitourinary infection, family history of similar conditions, and history of recurrent uveitis.

For the initial assessment of patients who have inflammatory back pain, plain radiography of the sacroiliac joints is considered the gold standard.59 If plain radiography does not show evidence of sacroiliitis, MRI of the sacroiliac joints should be considered. While plain radiography can reveal only structural changes such as sclerosis, erosions, and ankylosis, MRI is useful to evaluate for early inflammatory changes such as bone marrow edema. Imaging the lumbar spine is not necessary, as the sacroiliac joints are almost invariably involved in axial spondyloarthropathy, and lesions seldom occur in the lumbar spine in isolation.60

The diagnosis of ankylosing spondylitis previously relied on confirmatory imaging features, but based on the new International Society classification criteria,61–63 which can be applied to patients with more than 3 months of back pain and age of onset of symptoms before age 45, patients can be classified as having 1 of the following:

- Radiographic axial spondyloarthropathy, if they have evidence of sacroiliitis on imaging plus 1 other feature of spondyloarthropathy

- Nonradiographic axial spondyloarthropathy, if they have a positive HLA-B27 plus 2 other features of spondyloarthropathy (Table 7).

These new criteria have a sensitivity of 82.9% and specificity of 84.4%.62,63 The disease burden of radiographic and nonradiographic axial spondyloarthropathy has been shown to be similar, suggesting that they are part of the same disease spectrum. Thus, the HLA-B27 test is useful to make a diagnosis of axial spondyloarthropathy even in the absence of imaging features and could be requested in patients with 2 or more features of spondyloarthropathy. In the absence of imaging features and a negative HLA-B27 result, however, the patient cannot be classified as having axial spondyloarthropathy.

Back to our patient

The absence of radiographic evidence would not exclude axial spondyloarthropathy in our patient. The HLA-B27 test is requested because of the inflammatory back pain and the presence of 2 spondyloarthropathy features (uveitis and the family history) and is reported to be positive. His disease is classified as nonradiographic axial spondyloarthropathy.

He is started on regular naproxen and is referred to a physiotherapist. After 1 month, he reports significant symptomatic improvement. He asks if he can be retested for HLA-B27 to see if it has become negative. We tell him that there is no point in repeating it, as it is a gene and will not disappear.

SUMMARY: CONSIDER THE CLINICAL PICTURE

When approaching a patient suspected of having a rheumatologic disease, a clinician should first consider the clinical presentation and the intended purpose of each test. The tests, in general, might serve several purposes. They might help to:

Increase the likelihood of the diagnosis in question. For example, a positive rheumatoid factor or anticitrullinated peptide antibody can help diagnose rheumatoid arthritis in a patient with early polyarthritis, a positive HLA-B27 can help diagnose ankylosing spondylitis in patients with inflammatory back pain and normal imaging, and a positive ANCA can help diagnose ANCA-associated vasculitis in a patient with glomerulonephritis.

Reduce the likelihood of the diagnosis in question. For example, a negative antinuclear antibody test reduces the likelihood of lupus in a patient with joint pains.

Monitor the condition. For example DNA antibodies can be used to monitor the activity of lupus.

Plan the treatment strategy. For example, one might consider lifelong anticoagulation if antiphospholipid antibodies are persistently positive in a patient with thrombosis.

Prognosticate. For example, positive rheumatoid factor and anticitrullinated peptide antibody increase the risk of erosive rheumatoid arthritis.

If the test was requested in the absence of a clear indication and the result is positive, it is important to bear in mind the potential pitfalls associated with that test and not attach a diagnostic label prematurely. None of the tests can confirm or exclude a condition, so the results should always be interpreted in the context of the whole clinical picture.

- American College of Rheumatology Ad Hoc Committee on Immunologic Testing Guidelines. Guidelines for immunologic laboratory testing in the rheumatic diseases: an introduction. Arthritis Rheum 2002; 47(4):429–433. doi:10.1002/art.10381

- Rang M. The Ulysses syndrome. Can Med Assoc J 1972; 106(2):122–123. pmid:5058884

- Ingegnoli F, Castelli R, Gualtierotti R. Rheumatoid factors: clinical applications. Dis Markers 2013; 35(6):727–734. doi:10.1155/2013/726598

- Nishimura K, Sugiyama D, Kogata Y, et al. Meta-analysis: diagnostic accuracy of anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibody and rheumatoid factor for rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Intern Med 2007; 146(11):797–808. pmid:17548411

- Taylor P, Gartemann J, Hsieh J, Creeden J. A systematic review of serum biomarkers anti-cyclic citrullinated Peptide and rheumatoid factor as tests for rheumatoid arthritis. Autoimmune Dis 2011; 2011:815038. doi:10.4061/2011/815038

- Rantapää-Dahlqvist S, de Jong BA, Berglin E, et al. Antibodies against cyclic citrullinated peptide and IgA rheumatoid factor predict the development of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2003; 48(10):2741–2749. doi:10.1002/art.11223

- Suresh E. Diagnosis of early rheumatoid arthritis: what the non-specialist needs to know. J R Soc Med 2004; 97(9):421–424. doi:10.1258/jrsm.97.9.421

- Emery P, Breedveld FC, Dougados M, Kalden JR, Schiff MH, Smolen JS. Early referral recommendation for newly diagnosed rheumatoid arthritis: evidence based development of a clinical guide. Ann Rheum Dis 2002; 61(4):290–297. pmid:11874828

- Combe B, Landewe R, Daien CI, et al. 2016 update of the EULAR recommendations for the management of early arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2017; 76(6):948–959. doi:10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-210602

- Egsmose C, Lund B, Borg G, et al. Patients with rheumatoid arthritis benefit from early 2nd line therapy: 5 year follow up of a prospective double blind placebo controlled study. J Rheumatol 1995; 22(12):2208–2213. pmid:8835550

- van der Heide A, Jacobs JW, Bijlsma JW, et al. The effectiveness of early treatment with “second-line” antirheumatic drugs. A randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med 1996; 124(8):699–707. pmid:8633829

- Andreson JJ, Wells G, Verhoeven AC, Felson DT. Factors predicting response to treatment in rheumatoid arthritis: the importance of disease duration. Arthritis Rheum 2000; 43(1):22–29. doi:10.1002/1529-0131(200001)43:1<22::AID-ANR4>3.0.CO;2-9

- Aletaha D, Neogi T, Silman AJ, et al. 2010 Rheumatoid arthritis classification criteria: an American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism collaborative initiative. Arthritis Rheum 2010; 62(9):2569–2581. doi:10.1002/art.27584

- Nielen MM, van Schaardenburg D, Reesink HW, et al. Specific autoantibodies precede the symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis: a study of serial measurements in blood donors. Arthritis Rheum 2004; 50(2):380–386. doi:10.1002/art.20018

- del Puente A, Knowler WC, Pettitt DJ, Bennett PH. The incidence of rheumatoid arthritis is predicted by rheumatoid factor titer in a longitudinal population study. Arthritis Rheum 1988; 31(10):1239–1244. pmid:3178905

- Deane KD, Norris JM, Holers VM. Preclinical rheumatoid arthritis: identification, evaluation, and future directions for investigation. Rheum Dis Clin North Am 2010; 36(2):213–241. doi:10.1016/j.rdc.2010.02.001

- Kavanaugh A, Tomar R, Reveille J, Solomon DH, Homburger HA. Guidelines for clinical use of the antinuclear antibody test and tests for specific autoantibodies to nuclear antigens. American College of Pathologists. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2000; 124(1):71–81. doi:10.1043/0003-9985(2000)124<0071:GFCUOT>2.0.CO;2

- Suresh E. Systemic lupus erythematosus: diagnosis for the non-specialist. Br J Hosp Med (Lond) 2007; 68(10):538–541. doi:10.12968/hmed.2007.68.10.27324

- Illei GG, Klippel JH. Why is the ANA result positive? Bull Rheum Dis 1999; 48(1):1–4. pmid:10028188

- Tan EM, Feltkamp TE, Smolen JS, et al. Range of antinuclear antibodies in “healthy” individuals. Arthritis Rheum 1997; 40(9):1601–1611. doi:10.1002/art.1780400909

- Langkilde H, Voss A, Heegaard N, Laustrup H. Autoantibodies persist in relatives to systemic lupus erythematosus patients during 12 years follow-up. Lupus 2017; 26(7):723–728. doi:10.1177/0961203316676378

- Rondeel JM. Immunofluorescence versus ELISA for the detection of antinuclear antigens. Expert Rev Mol Diagn 2002; 2(3):226–232. doi:10.1586/14737159.2.3.226

- Solomon DH, Kavanaugh AJ, Schur PH; American College of Rheumatology Ad Hoc Committee on Immunologic Testing Guidelines. Evidence-based guidelines for the use of immunologic tests: antinuclear antibody testing. Arthritis Rheum 2002; 47(4):434–444. doi:10.1002/art.10561

- Slater CA, Davis RB, Shmerling RH. Antinuclear antibody testing. A study of clinical utility. Arch Intern Med 1996; 156(13):1421–1425. pmid:8678710

- Maddison PJ. Is it SLE? Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2002; 16(2):167–180. doi:10.1053/berh.2001.0219

- Price E, Walker E. Diagnostic vertigo: the journey to diagnosis in systemic lupus erythematosus. Health (London) 2014; 18(3):223–239. doi:10.1177/1363459313488008

- Blumenthal DE. Tired, aching, ANA-positive: does your patient have lupus or fibromyalgia? Cleve Clin J Med 2002; 69(2):143–146, 151–152. pmid:11990644

- Miyakis S, Lockshin MD, Atsumi T, et al. International consensus statement on an update of the classification criteria for definite antiphospholipid syndrome (APS). J Thromb Haemost 2006; 4(2):295–306. doi:10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.01753.x

- Keeling D, Mackie I, Moore GW, Greer IA, Greaves M; British Committee for Standards in Haematology. Guidelines on the investigation and management of antiphospholipid syndrome. Br J Haematol 2012; 157(1):47–58. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2141.2012.09037.x

- Giannakopoulos B, Passam F, Iannou Y, Krillis SA. How we diagnose the antiphospholipid syndrome. Blood 2009; 113(5):985–994. doi:10.1182/blood-2007-12-129627

- Biggioggero M, Meroni PL. The geoepidemiology of the antiphospholipid antibody syndrome. Autoimmun Rev 2010; 9(5):A299–A304. doi:10.1016/j.autrev.2009.11.013

- Pengo V, Ruffatti A, Legnani C, et al. Incidence of a first thromboembolic event in asymptomatic carriers of high-risk antiphospholipid antibody profile: a multicenter prospective study. Blood 2011; 118(17):4714–4718. doi:10.1182/blood-2011-03-340232

- Pengo V, Ruffatti A, Legnani C, et al. Clinical course of high-risk patients diagnosed with antiphospholipid syndrome. J Thromb Haemost 2010; 8(2):237–242. doi:10.1111/j.1538-7836.2009.03674.x

- Galli M, Luciani D, Bertolini G, Barbui T. Lupus anticoagulants are stronger risk factors for thrombosis than anticardiolipin antibodies in the antiphospholipid syndrome: a systematic review of the literature. Blood 2003; 101(5):1827–1832. doi:10.1182/blood-2002-02-0441

- Garcia D, Erkan D. Diagnosis and management of the antiphospholipid syndrome. N Engl J Med 2018; 378(21):2010–2021. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1705454

- Garcia D, Akl EA, Carr R, Kearon C. Antiphospholipid antibodies and the risk of recurrence after a first episode of venous thromboembolism: a systematic review. Blood 2013; 122(5):817–824. doi:10.1182/blood-2013-04-496257

- Cervera R. Lessons from the “Euro-Phospholipid” project. Autoimmun Rev 2008; 7(3):174–178. doi:10.1016/j.autrev.2007.11.011

- Andreoli L, Chighizola CB, Banzato A, Pons-Estel GJ, Ramire de Jesus G, Erkan D. Estimated frequency of antiphospholipid antibodies in patients with pregnancy morbidity, stroke, myocardial infarction, and deep vein thrombosis: a critical review of the literature. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2013; 65(11):1869–1873. doi:10.1002/acr.22066

- Miller A, Chan M, Wiik A, Misbah SA, Luqmani RA. An approach to the diagnosis and management of systemic vasculitis. Clin Exp Immunol 2010; 160(2):143–160. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2249.2009.04078.x

- Cornec D, Cornec-Le-Gall E, Fervenza FC, Specks U. ANCA-associated vasculitis—clinical utility of using ANCA specificity to classify patients. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2016; 12(10):570–579. doi:10.1038/nrrheum.2016.123

- Edgar JD, McMillan SA, Bruce IN, Conlan SK. An audit of ANCA in routine clinical practice. Postgrad Med J 1995; 71(840):605–612. pmid:8545289

- McLaren JS, Stimson RH, McRorie ER, Coia JE, Luqmani RA. The diagnostic value of anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic testing in a routine clinical setting. QJM 2001; 94(11):615–621. pmid:11704691

- Mandl LA, Solomon DH, Smith EL, Lew RA, Katz JN, Shmerling RH. Using antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody testing to diagnose vasculitis: can test-ordering guidelines improve diagnostic accuracy? Arch Intern Med 2002; 162(13):1509–1514. pmid:12090888

- Sinclair D, Saas M, Stevens JM. The effect of a symptom related “gated policy” on ANCA requests in routine clinical practice. J Clin Pathol 2004; 57(2):131–134. pmid:14747434

- Arnold DF, Timms A, Luqmani R, Misbah SA. Does a gating policy for ANCA overlook patients with ANCA associated vasculitis? An audit of 263 patients. J Clin Pathol 2010; 63(8):678–680. doi:10.1136/jcp.2009.072504

- Savige J, Gills D, Benson E, et al. International consensus statement on testing and reporting of antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA). Am J Clin Pathol 1999; 111(4):507–513. pmid:10191771

- Robinson PC, Steele RH. Appropriateness of antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody testing in a tertiary hospital. J Clin Pathol 2009; 62(8):743–745. doi:10.1136/jcp.2009.064485

- Bossuyt X, Cohen Tervaert JW, Arimura Y, et al. Position paper: revised 2017 international consensus on testing of ANCAs in granulomatosis with polyangiitis and microscopic polyangiitis. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2017; 13(11):683–692. doi:10.1038/nrrheum.2017.140

- Hagen EC, Daha MR, Hermans J, et al. Diagnostic value of standardized assays for anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies in idiopathic systemic vasculitis. EC/BCR Project for ANCA Assay Standardization. Kidney Int 1998; 53(3):743–753. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1755.1998.00807.x

- Damoiseaux J, Csemok E, Rasmussen N, et al. Detection of antineutrophil antibodies (ANCAs): a multicentre European Vasculitis Study Group (EUVAS) evaluation of the value of indirect immunofluorescence (IIF) versus antigen specific immunoassays. Ann Rheum Dis 2017; 76(4):647–653. doi:10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-209507

- Suresh E. Diagnostic approach to patients with suspected vasculitis. Postgrad Med J 2006; 82(970):483–488. doi:10.1136/pgmj.2005.042648

- Vermeersch P, Blockmans D, Bossuyt X. Use of likelihood ratios can improve the clinical usefulness of enzyme immunoassays for the diagnosis of small-vessel vasculitis. Clin Chem 2009; 55(10):1886–1888. doi:10.1373/clinchem.2009.130583

- Bowness P. HLA-B27. Annu Rev Immunol 2015; 33:29–48. doi:10.1146/annurev-immunol-032414-112110

- Sieper J, Poddubnyy D. Axial spondyloarthritis. Lancet 2017; 390(10089):73–84. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31591-4

- Khan MA. Thoughts concerning the early diagnosis of ankylosing spondylitis and related diseases. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2002; 20(6 suppl 28):S6–S10. pmid:12463439

- Braun J, Bollow M, Remlinger G, et al. Prevalence of spondyloarthropathies in HLA-B27 positive and negative blood donors. Arthritis Rheum 1998; 41(1):58–67. doi:10.1002/1529-0131(199801)41:1<58::AID-ART8>3.0.CO;2-G

- van der Linden SM, Valkenburg HA, de Jongh BM, Cats A. The risk of developing ankylosing spondylitis in HLA-B27 positive individuals. A comparison of relatives of spondylitis patients with the general population. Arthritis Rheum 1984; 27(3):241–249. pmid:6608352

- Sheehan NJ. HLA-B27: what’s new? Rheumatology (Oxford) 2010; 49(4):621–631. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/kep450

- Baraliakos X, Maksymmowych WP. Imaging in the diagnosis and management of axial spondyloarthritis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2016; 30(4):608–623. doi:10.1016/j.berh.2016.09.011