User login

DPP-4 drugs for diabetes may protect kidneys too

SAN DIEGO – Dipeptidyl peptidase–4 (DPP-4) inhibitors appear to delay the progression of chronic kidney disease (CKD) in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), a new study has found. Researchers also found that all-cause long-term mortality dropped by an astonishing 78% in patients who took the drugs for an average of more than 3 years.

While the reasons for the impressive mortality results are a mystery, “these medications could have a beneficial effect on the kidneys, and it begins to show after 3 years,” said lead author Mariana Garcia-Touza, MD, of the Kansas City (Missouri) Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center, in an interview. She presented the results at the meeting, sponsored by the American Society of Nephrology.

DPP-4 inhibitor drugs have been available for more than a decade in the United States. The medications, which include sitagliptin (Januvia) and linagliptin (Tradjenta), are used to treat patients with T2DM who are inadequately controlled by first-line treatments.

The drugs have critics. As UpToDate notes, they’re expensive and their effect on glucose levels is “modest.” In addition, UpToDate says, “some of the DPP-4 inhibitors have been associated with an increased risk of heart failure resulting in hospitalization.”

The authors of the new study sought to understand whether the drugs affect kidney function. As Dr. Garcia-Touza noted, metformin, which is processed in part by the kidneys, is considered harmful to certain patients with kidney disease. However, DPP-4 inhibitors are cleared through the liver. In fact, research has suggested the drugs may actually benefit the liver (Med Sci Monit. 2014 Sep 17;20:1662-7).

For the new study, researchers retrospectively analyzed 20,424 patients with T2DM in the VA system who took DPP-4 inhibitors (average age, 68 years) and compared them with a matched group of 52,118 patients with T2DM who didn’t take the drugs, tracking all patients for a mean of over 3 years.

T2DM control improved slightly in the DPP-4 group but remained worse than the non–DPP-4 group. However, “a significant reduction in progression of CKD was seen” in the DPP-4 group, she said.

The number of patients with creatinine levels above 1.5 mg/dL, 3 mg/dL, and 6 mg/dL was reduced by 7%, 41%, and 47%, respectively, in the DPP-4 group, compared with the other group (P less than .01). And the time to end-stage renal disease (creatinine above 6 mg/dL) was delayed by 144 days in the DPP-4 group (P less than .01).

All-cause mortality also fell by 78% in the DPP-4 group (P less than .0001). “Despite having worse glucose control [than the non–DPP-4 group], these patients have better overall mortality,” Dr. Garcia-Touza said.

The drugs may reduce the burden on the kidneys by decreasing inflammation, she said.

Could DPP-4 drugs be beneficial to patients with CKD even if they don’t have T2DM? Dr. Garcia-Touza wasn’t sure. However, she had a theory about why these kidney benefits didn’t show up in previous research. “My impression is that they didn’t go far enough [in time]. That was the main difference.”

Going forward, Dr. Garcia-Touza said her team plans to study the effects of the drugs on retinopathy and diabetic neuropathy.

The study was funded by the Midwest Biomedical Research Foundation and the VA. The study authors reported no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Garcia-Tourza M et al. Kidney Week 2018, Abstract TH-OR035.

SAN DIEGO – Dipeptidyl peptidase–4 (DPP-4) inhibitors appear to delay the progression of chronic kidney disease (CKD) in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), a new study has found. Researchers also found that all-cause long-term mortality dropped by an astonishing 78% in patients who took the drugs for an average of more than 3 years.

While the reasons for the impressive mortality results are a mystery, “these medications could have a beneficial effect on the kidneys, and it begins to show after 3 years,” said lead author Mariana Garcia-Touza, MD, of the Kansas City (Missouri) Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center, in an interview. She presented the results at the meeting, sponsored by the American Society of Nephrology.

DPP-4 inhibitor drugs have been available for more than a decade in the United States. The medications, which include sitagliptin (Januvia) and linagliptin (Tradjenta), are used to treat patients with T2DM who are inadequately controlled by first-line treatments.

The drugs have critics. As UpToDate notes, they’re expensive and their effect on glucose levels is “modest.” In addition, UpToDate says, “some of the DPP-4 inhibitors have been associated with an increased risk of heart failure resulting in hospitalization.”

The authors of the new study sought to understand whether the drugs affect kidney function. As Dr. Garcia-Touza noted, metformin, which is processed in part by the kidneys, is considered harmful to certain patients with kidney disease. However, DPP-4 inhibitors are cleared through the liver. In fact, research has suggested the drugs may actually benefit the liver (Med Sci Monit. 2014 Sep 17;20:1662-7).

For the new study, researchers retrospectively analyzed 20,424 patients with T2DM in the VA system who took DPP-4 inhibitors (average age, 68 years) and compared them with a matched group of 52,118 patients with T2DM who didn’t take the drugs, tracking all patients for a mean of over 3 years.

T2DM control improved slightly in the DPP-4 group but remained worse than the non–DPP-4 group. However, “a significant reduction in progression of CKD was seen” in the DPP-4 group, she said.

The number of patients with creatinine levels above 1.5 mg/dL, 3 mg/dL, and 6 mg/dL was reduced by 7%, 41%, and 47%, respectively, in the DPP-4 group, compared with the other group (P less than .01). And the time to end-stage renal disease (creatinine above 6 mg/dL) was delayed by 144 days in the DPP-4 group (P less than .01).

All-cause mortality also fell by 78% in the DPP-4 group (P less than .0001). “Despite having worse glucose control [than the non–DPP-4 group], these patients have better overall mortality,” Dr. Garcia-Touza said.

The drugs may reduce the burden on the kidneys by decreasing inflammation, she said.

Could DPP-4 drugs be beneficial to patients with CKD even if they don’t have T2DM? Dr. Garcia-Touza wasn’t sure. However, she had a theory about why these kidney benefits didn’t show up in previous research. “My impression is that they didn’t go far enough [in time]. That was the main difference.”

Going forward, Dr. Garcia-Touza said her team plans to study the effects of the drugs on retinopathy and diabetic neuropathy.

The study was funded by the Midwest Biomedical Research Foundation and the VA. The study authors reported no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Garcia-Tourza M et al. Kidney Week 2018, Abstract TH-OR035.

SAN DIEGO – Dipeptidyl peptidase–4 (DPP-4) inhibitors appear to delay the progression of chronic kidney disease (CKD) in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), a new study has found. Researchers also found that all-cause long-term mortality dropped by an astonishing 78% in patients who took the drugs for an average of more than 3 years.

While the reasons for the impressive mortality results are a mystery, “these medications could have a beneficial effect on the kidneys, and it begins to show after 3 years,” said lead author Mariana Garcia-Touza, MD, of the Kansas City (Missouri) Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center, in an interview. She presented the results at the meeting, sponsored by the American Society of Nephrology.

DPP-4 inhibitor drugs have been available for more than a decade in the United States. The medications, which include sitagliptin (Januvia) and linagliptin (Tradjenta), are used to treat patients with T2DM who are inadequately controlled by first-line treatments.

The drugs have critics. As UpToDate notes, they’re expensive and their effect on glucose levels is “modest.” In addition, UpToDate says, “some of the DPP-4 inhibitors have been associated with an increased risk of heart failure resulting in hospitalization.”

The authors of the new study sought to understand whether the drugs affect kidney function. As Dr. Garcia-Touza noted, metformin, which is processed in part by the kidneys, is considered harmful to certain patients with kidney disease. However, DPP-4 inhibitors are cleared through the liver. In fact, research has suggested the drugs may actually benefit the liver (Med Sci Monit. 2014 Sep 17;20:1662-7).

For the new study, researchers retrospectively analyzed 20,424 patients with T2DM in the VA system who took DPP-4 inhibitors (average age, 68 years) and compared them with a matched group of 52,118 patients with T2DM who didn’t take the drugs, tracking all patients for a mean of over 3 years.

T2DM control improved slightly in the DPP-4 group but remained worse than the non–DPP-4 group. However, “a significant reduction in progression of CKD was seen” in the DPP-4 group, she said.

The number of patients with creatinine levels above 1.5 mg/dL, 3 mg/dL, and 6 mg/dL was reduced by 7%, 41%, and 47%, respectively, in the DPP-4 group, compared with the other group (P less than .01). And the time to end-stage renal disease (creatinine above 6 mg/dL) was delayed by 144 days in the DPP-4 group (P less than .01).

All-cause mortality also fell by 78% in the DPP-4 group (P less than .0001). “Despite having worse glucose control [than the non–DPP-4 group], these patients have better overall mortality,” Dr. Garcia-Touza said.

The drugs may reduce the burden on the kidneys by decreasing inflammation, she said.

Could DPP-4 drugs be beneficial to patients with CKD even if they don’t have T2DM? Dr. Garcia-Touza wasn’t sure. However, she had a theory about why these kidney benefits didn’t show up in previous research. “My impression is that they didn’t go far enough [in time]. That was the main difference.”

Going forward, Dr. Garcia-Touza said her team plans to study the effects of the drugs on retinopathy and diabetic neuropathy.

The study was funded by the Midwest Biomedical Research Foundation and the VA. The study authors reported no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Garcia-Tourza M et al. Kidney Week 2018, Abstract TH-OR035.

REPORTING FROM KIDNEY WEEK 2018

Key clinical point: Dipeptidyl peptidase–4 (DPP-4) inhibitors may delay progression of chronic kidney disease in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and may dramatically reduce all-cause mortality.

Major finding: Compared with those who didn’t take the drugs, patients with T2DM who took DPP-4 inhibitors were much less likely to progress to creatinine levels above 1.5 mg/dL, 3 mg/dL, and 6 mg/dL (reduction of 7%, 41%, and 47%, respectively; P less than .01). All-cause mortality in the DPP-4 group fell by 78% (P less than .0001).

Study details: A retrospective study of 20,424 patients with T2DM in the Department of Veterans Affairs system who took DPP-4 inhibitors for mean of more than 3 years and a matched group of 52,118 patients with T2DM who didn’t take the drugs.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the Midwest Biomedical Research Foundation and the VA. The study authors reported no relevant disclosures.

Source: Garcia-Tourza M et al. Kidney Week 2018, Abstract TH-OR035.

In pediatric ICU, being underweight can be deadly

SAN DIEGO – Underweight people don’t get much attention amid the obesity epidemic. But a new analysis of worldwide data finds that underweight pediatric ICU patients worldwide face a higher risk of death within 28 days than all their counterparts, even the overweight and obese.

While the report suggests that underweight patients weren’t sicker than the other children and young adults, they also faced a higher risk of fluid accumulation and all-stage acute kidney injury, compared with overweight children, study lead author Rajit K. Basu, MD, MS, of Emory University and Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta, said in an interview. His team’s findings were released at Kidney Week 2018, sponsored by the American Society of Nephrology.

“Obesity gets the lion’s share of the spotlight, but there is a large and likely growing population of children who, for reasons left to be fully parsed out, are underweight,” Dr. Basu said. “These patients have increased attributable risks for poor outcome.”

The new report is a follow-up analysis of a 2017 prospective study by the same team that tracked acute kidney injury and mortality in 4,683 pediatric ICU patients at 32 clinics in Asia, Australia, Europe, and North America. The patients, aged from 3 months to 25 years, were recruited over 3 months in 2014 (N Engl J Med 2017;376:11-20).

The researchers launched the study to better understand the risk facing underweight pediatric patients. “There is a paucity of data linking mortality to weight classification in children,” Dr. Basu said. “There are only a few reports, and there is a suggestion that the ‘obesity paradox’ – protection from morbidity and mortality because of excessive weight – exists.”

For the new analysis, researchers tracked 3,719 patients: 29% were underweight, 44% had normal weight, 11% were overweight, and 16% were obese.

The 28-day mortality rate was 4% overall and highest in the underweight patients at 6%, compared with normal (3%), overweight (2%), and obese patients (2%) (P less than .0001). Underweight patients had a higher adjusted risk of mortality, compared with normal-weight patients (adjusted odds ratio, 1.8; 95% confidence interval, 1.2-2.8).

Underweight patients also had “a higher risk of fluid accumulation and a higher incidence of all-stage acute kidney injury, compared to overweight children,” Dr. Basu said.

The study authors also examined mortality rates in the 14% of patients (n = 542) who had sepsis. Again, underweight patients had the highest risk of 28-day mortality (15%), compared with normal weight (7%), overweight (4%), and obese patients (5%) (P = 0.003).

Who are the underweight children? “Analysis of the comorbidities reveals that nearly one-third of these children had some neuromuscular and/or pulmonary comorbidities, implying that these children were most likely static cerebral palsy children or had neuromuscular developmental disorder,” Dr. Basu said. “The demographic data also interestingly pointed out that the underweight population was predominantly Eastern Asian in origin.”

But there wasn’t a sign of increased illness in the underweight patients. “We can say that these kids were no sicker compared to the overweight kids as assessed by objective severity-of-illness scoring tools used in the critically ill population,” he said.

Is there a link between fluid overload and higher mortality numbers in underweight children? “There is a preponderance of data now, particularly in children, associating excessive fluid accumulation and poor outcome,” Dr. Basu said, who pointed to a 2018 systematic review and analysis that linked fluid overload to a higher risk of in-hospital mortality (OR, 4.34; 95% CI, 3.01-6.26) (JAMA Pediatr. 2018;172[3]:257-68).

Fluid accumulation disrupts organs “via hydrostatic pressure overregulation, causing an imbalance in local mediators of hormonal homeostasis and through vascular congestion,” he said. However, best practices regarding fluid are not yet clear.

“Fluid accumulation does occur frequently,” he said, “and it is likely a very important and relevant part of practice for bedside providers to be mindful on a multiple-times-a-day basis of what is happening with net fluid balance and how that relates to end-organ function, particularly the lungs and the kidneys.”

The National Institutes of Health provided partial funding for the study. One of the authors received fellowship funding from Gambro/Baxter Healthcare.

SAN DIEGO – Underweight people don’t get much attention amid the obesity epidemic. But a new analysis of worldwide data finds that underweight pediatric ICU patients worldwide face a higher risk of death within 28 days than all their counterparts, even the overweight and obese.

While the report suggests that underweight patients weren’t sicker than the other children and young adults, they also faced a higher risk of fluid accumulation and all-stage acute kidney injury, compared with overweight children, study lead author Rajit K. Basu, MD, MS, of Emory University and Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta, said in an interview. His team’s findings were released at Kidney Week 2018, sponsored by the American Society of Nephrology.

“Obesity gets the lion’s share of the spotlight, but there is a large and likely growing population of children who, for reasons left to be fully parsed out, are underweight,” Dr. Basu said. “These patients have increased attributable risks for poor outcome.”

The new report is a follow-up analysis of a 2017 prospective study by the same team that tracked acute kidney injury and mortality in 4,683 pediatric ICU patients at 32 clinics in Asia, Australia, Europe, and North America. The patients, aged from 3 months to 25 years, were recruited over 3 months in 2014 (N Engl J Med 2017;376:11-20).

The researchers launched the study to better understand the risk facing underweight pediatric patients. “There is a paucity of data linking mortality to weight classification in children,” Dr. Basu said. “There are only a few reports, and there is a suggestion that the ‘obesity paradox’ – protection from morbidity and mortality because of excessive weight – exists.”

For the new analysis, researchers tracked 3,719 patients: 29% were underweight, 44% had normal weight, 11% were overweight, and 16% were obese.

The 28-day mortality rate was 4% overall and highest in the underweight patients at 6%, compared with normal (3%), overweight (2%), and obese patients (2%) (P less than .0001). Underweight patients had a higher adjusted risk of mortality, compared with normal-weight patients (adjusted odds ratio, 1.8; 95% confidence interval, 1.2-2.8).

Underweight patients also had “a higher risk of fluid accumulation and a higher incidence of all-stage acute kidney injury, compared to overweight children,” Dr. Basu said.

The study authors also examined mortality rates in the 14% of patients (n = 542) who had sepsis. Again, underweight patients had the highest risk of 28-day mortality (15%), compared with normal weight (7%), overweight (4%), and obese patients (5%) (P = 0.003).

Who are the underweight children? “Analysis of the comorbidities reveals that nearly one-third of these children had some neuromuscular and/or pulmonary comorbidities, implying that these children were most likely static cerebral palsy children or had neuromuscular developmental disorder,” Dr. Basu said. “The demographic data also interestingly pointed out that the underweight population was predominantly Eastern Asian in origin.”

But there wasn’t a sign of increased illness in the underweight patients. “We can say that these kids were no sicker compared to the overweight kids as assessed by objective severity-of-illness scoring tools used in the critically ill population,” he said.

Is there a link between fluid overload and higher mortality numbers in underweight children? “There is a preponderance of data now, particularly in children, associating excessive fluid accumulation and poor outcome,” Dr. Basu said, who pointed to a 2018 systematic review and analysis that linked fluid overload to a higher risk of in-hospital mortality (OR, 4.34; 95% CI, 3.01-6.26) (JAMA Pediatr. 2018;172[3]:257-68).

Fluid accumulation disrupts organs “via hydrostatic pressure overregulation, causing an imbalance in local mediators of hormonal homeostasis and through vascular congestion,” he said. However, best practices regarding fluid are not yet clear.

“Fluid accumulation does occur frequently,” he said, “and it is likely a very important and relevant part of practice for bedside providers to be mindful on a multiple-times-a-day basis of what is happening with net fluid balance and how that relates to end-organ function, particularly the lungs and the kidneys.”

The National Institutes of Health provided partial funding for the study. One of the authors received fellowship funding from Gambro/Baxter Healthcare.

SAN DIEGO – Underweight people don’t get much attention amid the obesity epidemic. But a new analysis of worldwide data finds that underweight pediatric ICU patients worldwide face a higher risk of death within 28 days than all their counterparts, even the overweight and obese.

While the report suggests that underweight patients weren’t sicker than the other children and young adults, they also faced a higher risk of fluid accumulation and all-stage acute kidney injury, compared with overweight children, study lead author Rajit K. Basu, MD, MS, of Emory University and Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta, said in an interview. His team’s findings were released at Kidney Week 2018, sponsored by the American Society of Nephrology.

“Obesity gets the lion’s share of the spotlight, but there is a large and likely growing population of children who, for reasons left to be fully parsed out, are underweight,” Dr. Basu said. “These patients have increased attributable risks for poor outcome.”

The new report is a follow-up analysis of a 2017 prospective study by the same team that tracked acute kidney injury and mortality in 4,683 pediatric ICU patients at 32 clinics in Asia, Australia, Europe, and North America. The patients, aged from 3 months to 25 years, were recruited over 3 months in 2014 (N Engl J Med 2017;376:11-20).

The researchers launched the study to better understand the risk facing underweight pediatric patients. “There is a paucity of data linking mortality to weight classification in children,” Dr. Basu said. “There are only a few reports, and there is a suggestion that the ‘obesity paradox’ – protection from morbidity and mortality because of excessive weight – exists.”

For the new analysis, researchers tracked 3,719 patients: 29% were underweight, 44% had normal weight, 11% were overweight, and 16% were obese.

The 28-day mortality rate was 4% overall and highest in the underweight patients at 6%, compared with normal (3%), overweight (2%), and obese patients (2%) (P less than .0001). Underweight patients had a higher adjusted risk of mortality, compared with normal-weight patients (adjusted odds ratio, 1.8; 95% confidence interval, 1.2-2.8).

Underweight patients also had “a higher risk of fluid accumulation and a higher incidence of all-stage acute kidney injury, compared to overweight children,” Dr. Basu said.

The study authors also examined mortality rates in the 14% of patients (n = 542) who had sepsis. Again, underweight patients had the highest risk of 28-day mortality (15%), compared with normal weight (7%), overweight (4%), and obese patients (5%) (P = 0.003).

Who are the underweight children? “Analysis of the comorbidities reveals that nearly one-third of these children had some neuromuscular and/or pulmonary comorbidities, implying that these children were most likely static cerebral palsy children or had neuromuscular developmental disorder,” Dr. Basu said. “The demographic data also interestingly pointed out that the underweight population was predominantly Eastern Asian in origin.”

But there wasn’t a sign of increased illness in the underweight patients. “We can say that these kids were no sicker compared to the overweight kids as assessed by objective severity-of-illness scoring tools used in the critically ill population,” he said.

Is there a link between fluid overload and higher mortality numbers in underweight children? “There is a preponderance of data now, particularly in children, associating excessive fluid accumulation and poor outcome,” Dr. Basu said, who pointed to a 2018 systematic review and analysis that linked fluid overload to a higher risk of in-hospital mortality (OR, 4.34; 95% CI, 3.01-6.26) (JAMA Pediatr. 2018;172[3]:257-68).

Fluid accumulation disrupts organs “via hydrostatic pressure overregulation, causing an imbalance in local mediators of hormonal homeostasis and through vascular congestion,” he said. However, best practices regarding fluid are not yet clear.

“Fluid accumulation does occur frequently,” he said, “and it is likely a very important and relevant part of practice for bedside providers to be mindful on a multiple-times-a-day basis of what is happening with net fluid balance and how that relates to end-organ function, particularly the lungs and the kidneys.”

The National Institutes of Health provided partial funding for the study. One of the authors received fellowship funding from Gambro/Baxter Healthcare.

REPORTING FROM KIDNEY WEEK 2018

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Underweight patients had a higher adjusted risk of 28-day mortality than normal-weight patients (adjusted odds ratio, 1.8; 95% confidence interval, 1.2-2.8).

Study details: A follow-up analysis of 3,719 pediatric ICU patients, aged from 3 months to 25 years, recruited in a prospective study over 3 months in 2014 at 32 worldwide centers.

Disclosures: The National Institutes of Health provided partial funding for the study. One of the authors received fellowship funding from Gambro/Baxter Healthcare.

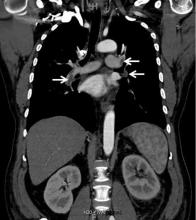

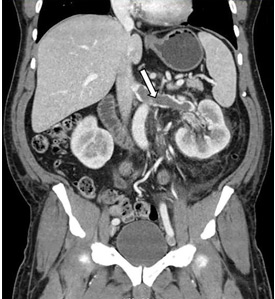

Renal vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism

A 49-year-old man developed nephrotic-range proteinuria (urine protein–creatinine ratio 4.1 g/g), and primary membranous nephropathy was diagnosed by kidney biopsy. He declined therapy apart from angiotensin receptor blockade.

Five months after undergoing the biopsy, he presented to the emergency room with marked dyspnea, cough, and epigastric discomfort. His blood pressure was 160/100 mm Hg, heart rate 95 beats/minute, and oxygen saturation by pulse oximetry 97% at rest on ambient air, decreasing to 92% with ambulation.

Initial laboratory testing results were as follows:

- Sodium 135 mmol/L (reference range 136–144)

- Potassium 3.9 mmol/L (3.7–5.1)

- Chloride 104 mmol/L (97–105)

- Bicarbonate 21 mmol/L (22–30)

- Blood urea nitrogen 14 mg/dL (9–24)

- Serum creatinine 1.1 mg/dL (0.73–1.22)

- Albumin 2.1 g/dL (3.4–4.9).

Urinalysis revealed the following:

- 5 red blood cells per high-power field, compared with 1 to 2 previously

- 3+ proteinuria

- Urine protein–creatinine ratio 11 g/g

- No glucosuria.

Electrocardiography revealed normal sinus rhythm without ischemic changes. Chest radiography did not show consolidation.

At 7 months after the thrombotic event, there was no evidence of residual renal vein thrombosis on magnetic resonance venography, and at 14 months his serum creatinine level was 0.9 mg/dL, albumin 4.0 g/dL, and urine protein–creatinine ratio 0.8 g/g.

RENAL VEIN THROMBOSIS: RISK FACTORS AND CLINICAL FEATURES

Severe hypoalbuminemia in the setting of nephrotic syndrome due to membranous nephropathy is associated with the highest risk of venous thromboembolic events, with renal vein thrombus being the classic complication.1 Venous thromboembolic events also occur in other nephrotic syndromes, albeit at a lower frequency.2

Venous thromboembolic events are estimated to occur in 7% to 33% of patients with membranous glomerulopathy, with albumin levels less than 2.8 g/dL considered a notable risk factor.1,2

While often a chronic complication, acute renal vein thrombosis may present with flank pain and hematuria.3 In our patient, the dramatic increase in proteinuria and possibly the increase in hematuria suggested renal vein thrombosis. Proximal tubular dysfunction, such as glucosuria, can be seen on occasion.

DIAGNOSIS AND TREATMENT

Screening asymptomatic patients for renal vein thrombosis is not recommended, and the decision to start prophylactic anticoagulation must be individualized.4

Although renal venography historically was the gold standard test to diagnose renal vein thrombosis, it has been replaced by noninvasive imaging such as computed tomography and magnetic resonance venography.

While anticoagulation remains the treatment of choice, catheter-directed thrombectomy or surgical thrombectomy can be considered for some patients with acute renal vein thrombosis.5

- Couser WG. Primary membranous nephropathy. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2017; 12(6):983–997. doi:10.2215/CJN.11761116

- Barbour SJ, Greenwald A, Djurdjev O, et al. Disease-specific risk of venous thromboembolic events is increased in idiopathic glomerulonephritis. Kidney Int 2012; 81(2):190–195. doi:10.1038/ki.2011.312

- Lionaki S, Derebail VK, Hogan SL, et al. Venous thromboembolism in patients with membranous nephropathy. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2012; 7(1):43–51. doi:10.2215/CJN.04250511

- Lee T, Biddle AK, Lionaki S, et al. Personalized prophylactic anticoagulation decision analysis in patients with membranous nephropathy. Kidney Int 2014; 85(6):1412–1420. doi:10.1038/ki.2013.476

- Jaar BG, Kim HS, Samaniego MD, Lund GB, Atta MG. Percutaneous mechanical thrombectomy: a new approach in the treatment of acute renal-vein thrombosis. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2002; 17(6):1122–1125. pmid:12032209

A 49-year-old man developed nephrotic-range proteinuria (urine protein–creatinine ratio 4.1 g/g), and primary membranous nephropathy was diagnosed by kidney biopsy. He declined therapy apart from angiotensin receptor blockade.

Five months after undergoing the biopsy, he presented to the emergency room with marked dyspnea, cough, and epigastric discomfort. His blood pressure was 160/100 mm Hg, heart rate 95 beats/minute, and oxygen saturation by pulse oximetry 97% at rest on ambient air, decreasing to 92% with ambulation.

Initial laboratory testing results were as follows:

- Sodium 135 mmol/L (reference range 136–144)

- Potassium 3.9 mmol/L (3.7–5.1)

- Chloride 104 mmol/L (97–105)

- Bicarbonate 21 mmol/L (22–30)

- Blood urea nitrogen 14 mg/dL (9–24)

- Serum creatinine 1.1 mg/dL (0.73–1.22)

- Albumin 2.1 g/dL (3.4–4.9).

Urinalysis revealed the following:

- 5 red blood cells per high-power field, compared with 1 to 2 previously

- 3+ proteinuria

- Urine protein–creatinine ratio 11 g/g

- No glucosuria.

Electrocardiography revealed normal sinus rhythm without ischemic changes. Chest radiography did not show consolidation.

At 7 months after the thrombotic event, there was no evidence of residual renal vein thrombosis on magnetic resonance venography, and at 14 months his serum creatinine level was 0.9 mg/dL, albumin 4.0 g/dL, and urine protein–creatinine ratio 0.8 g/g.

RENAL VEIN THROMBOSIS: RISK FACTORS AND CLINICAL FEATURES

Severe hypoalbuminemia in the setting of nephrotic syndrome due to membranous nephropathy is associated with the highest risk of venous thromboembolic events, with renal vein thrombus being the classic complication.1 Venous thromboembolic events also occur in other nephrotic syndromes, albeit at a lower frequency.2

Venous thromboembolic events are estimated to occur in 7% to 33% of patients with membranous glomerulopathy, with albumin levels less than 2.8 g/dL considered a notable risk factor.1,2

While often a chronic complication, acute renal vein thrombosis may present with flank pain and hematuria.3 In our patient, the dramatic increase in proteinuria and possibly the increase in hematuria suggested renal vein thrombosis. Proximal tubular dysfunction, such as glucosuria, can be seen on occasion.

DIAGNOSIS AND TREATMENT

Screening asymptomatic patients for renal vein thrombosis is not recommended, and the decision to start prophylactic anticoagulation must be individualized.4

Although renal venography historically was the gold standard test to diagnose renal vein thrombosis, it has been replaced by noninvasive imaging such as computed tomography and magnetic resonance venography.

While anticoagulation remains the treatment of choice, catheter-directed thrombectomy or surgical thrombectomy can be considered for some patients with acute renal vein thrombosis.5

A 49-year-old man developed nephrotic-range proteinuria (urine protein–creatinine ratio 4.1 g/g), and primary membranous nephropathy was diagnosed by kidney biopsy. He declined therapy apart from angiotensin receptor blockade.

Five months after undergoing the biopsy, he presented to the emergency room with marked dyspnea, cough, and epigastric discomfort. His blood pressure was 160/100 mm Hg, heart rate 95 beats/minute, and oxygen saturation by pulse oximetry 97% at rest on ambient air, decreasing to 92% with ambulation.

Initial laboratory testing results were as follows:

- Sodium 135 mmol/L (reference range 136–144)

- Potassium 3.9 mmol/L (3.7–5.1)

- Chloride 104 mmol/L (97–105)

- Bicarbonate 21 mmol/L (22–30)

- Blood urea nitrogen 14 mg/dL (9–24)

- Serum creatinine 1.1 mg/dL (0.73–1.22)

- Albumin 2.1 g/dL (3.4–4.9).

Urinalysis revealed the following:

- 5 red blood cells per high-power field, compared with 1 to 2 previously

- 3+ proteinuria

- Urine protein–creatinine ratio 11 g/g

- No glucosuria.

Electrocardiography revealed normal sinus rhythm without ischemic changes. Chest radiography did not show consolidation.

At 7 months after the thrombotic event, there was no evidence of residual renal vein thrombosis on magnetic resonance venography, and at 14 months his serum creatinine level was 0.9 mg/dL, albumin 4.0 g/dL, and urine protein–creatinine ratio 0.8 g/g.

RENAL VEIN THROMBOSIS: RISK FACTORS AND CLINICAL FEATURES

Severe hypoalbuminemia in the setting of nephrotic syndrome due to membranous nephropathy is associated with the highest risk of venous thromboembolic events, with renal vein thrombus being the classic complication.1 Venous thromboembolic events also occur in other nephrotic syndromes, albeit at a lower frequency.2

Venous thromboembolic events are estimated to occur in 7% to 33% of patients with membranous glomerulopathy, with albumin levels less than 2.8 g/dL considered a notable risk factor.1,2

While often a chronic complication, acute renal vein thrombosis may present with flank pain and hematuria.3 In our patient, the dramatic increase in proteinuria and possibly the increase in hematuria suggested renal vein thrombosis. Proximal tubular dysfunction, such as glucosuria, can be seen on occasion.

DIAGNOSIS AND TREATMENT

Screening asymptomatic patients for renal vein thrombosis is not recommended, and the decision to start prophylactic anticoagulation must be individualized.4

Although renal venography historically was the gold standard test to diagnose renal vein thrombosis, it has been replaced by noninvasive imaging such as computed tomography and magnetic resonance venography.

While anticoagulation remains the treatment of choice, catheter-directed thrombectomy or surgical thrombectomy can be considered for some patients with acute renal vein thrombosis.5

- Couser WG. Primary membranous nephropathy. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2017; 12(6):983–997. doi:10.2215/CJN.11761116

- Barbour SJ, Greenwald A, Djurdjev O, et al. Disease-specific risk of venous thromboembolic events is increased in idiopathic glomerulonephritis. Kidney Int 2012; 81(2):190–195. doi:10.1038/ki.2011.312

- Lionaki S, Derebail VK, Hogan SL, et al. Venous thromboembolism in patients with membranous nephropathy. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2012; 7(1):43–51. doi:10.2215/CJN.04250511

- Lee T, Biddle AK, Lionaki S, et al. Personalized prophylactic anticoagulation decision analysis in patients with membranous nephropathy. Kidney Int 2014; 85(6):1412–1420. doi:10.1038/ki.2013.476

- Jaar BG, Kim HS, Samaniego MD, Lund GB, Atta MG. Percutaneous mechanical thrombectomy: a new approach in the treatment of acute renal-vein thrombosis. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2002; 17(6):1122–1125. pmid:12032209

- Couser WG. Primary membranous nephropathy. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2017; 12(6):983–997. doi:10.2215/CJN.11761116

- Barbour SJ, Greenwald A, Djurdjev O, et al. Disease-specific risk of venous thromboembolic events is increased in idiopathic glomerulonephritis. Kidney Int 2012; 81(2):190–195. doi:10.1038/ki.2011.312

- Lionaki S, Derebail VK, Hogan SL, et al. Venous thromboembolism in patients with membranous nephropathy. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2012; 7(1):43–51. doi:10.2215/CJN.04250511

- Lee T, Biddle AK, Lionaki S, et al. Personalized prophylactic anticoagulation decision analysis in patients with membranous nephropathy. Kidney Int 2014; 85(6):1412–1420. doi:10.1038/ki.2013.476

- Jaar BG, Kim HS, Samaniego MD, Lund GB, Atta MG. Percutaneous mechanical thrombectomy: a new approach in the treatment of acute renal-vein thrombosis. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2002; 17(6):1122–1125. pmid:12032209

Click for Credit: Short-term NSAIDs; endometriosis; more

Here are 5 articles from the November issue of Clinician Reviews (individual articles are valid for one year from date of publication—expiration dates below):

1. Short-term NSAIDs appear safe for high-risk patients

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2PgXKGx

Expires October 8, 2019

2. Chronic liver disease raises death risk in pneumonia patients

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2NPSXXA

Expires October 8, 2019

3. Half of outpatient antibiotics prescribed with no infectious disease code

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2pWEWxU

Expires October 6, 2019

4. Secondary fractures in older men spike soon after first, but exercise may help

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2OCNl8A

Expires October 3, 2019

5. Consider ART for younger endometriosis patients

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2NO1Sc4

Expires October 5, 2019

Here are 5 articles from the November issue of Clinician Reviews (individual articles are valid for one year from date of publication—expiration dates below):

1. Short-term NSAIDs appear safe for high-risk patients

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2PgXKGx

Expires October 8, 2019

2. Chronic liver disease raises death risk in pneumonia patients

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2NPSXXA

Expires October 8, 2019

3. Half of outpatient antibiotics prescribed with no infectious disease code

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2pWEWxU

Expires October 6, 2019

4. Secondary fractures in older men spike soon after first, but exercise may help

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2OCNl8A

Expires October 3, 2019

5. Consider ART for younger endometriosis patients

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2NO1Sc4

Expires October 5, 2019

Here are 5 articles from the November issue of Clinician Reviews (individual articles are valid for one year from date of publication—expiration dates below):

1. Short-term NSAIDs appear safe for high-risk patients

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2PgXKGx

Expires October 8, 2019

2. Chronic liver disease raises death risk in pneumonia patients

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2NPSXXA

Expires October 8, 2019

3. Half of outpatient antibiotics prescribed with no infectious disease code

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2pWEWxU

Expires October 6, 2019

4. Secondary fractures in older men spike soon after first, but exercise may help

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2OCNl8A

Expires October 3, 2019

5. Consider ART for younger endometriosis patients

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2NO1Sc4

Expires October 5, 2019

Acute kidney injury linked to later dementia

SAN DIEGO –

That’s according to a new study offering more evidence of a link between kidney disease and neurological problems.

“Clinicians should know that AKI is associated with poor long-term outcomes,” said lead author Jessica B. Kendrick MD, associate professor of medicine at the University of Colorado, Aurora. “We need to identify ways to prevent these long-term consequences.”

The findings were presented at Kidney Week 2018, sponsored by the American Society of Nephrology.

According to Dr. Kendrick, the acute neurological effects of AKI are well known. But no previous studies have examined the potential long-term cerebrovascular complications of AKI.

For the new study, Dr. Kendrick and her colleagues retrospectively analyzed 2,082 hospitalized patients in Utah from 1999 to 2009: 1,041 who completely recovered from AKI by discharge, and 1,041 who did not have AKI.

The average age was 61 years, and the average baseline creatinine was 0.9 ± 0.2 mg/dL. Over a median follow-up of 6 years, 97 patients developed dementia.

Those with AKI were more likely to develop dementia compared with the control group: 7% vs. 2% (hazard ratio, 3.4; 95% confidence interval, 2.14-5.40).

Other studies have linked kidney disease to cognitive impairment.

“There are a lot of theories as to why this is,” nephrologist Daniel Weiner, MD, of Tufts University, Boston, said in an interview. “It is most likely that the presence of kidney disease identifies individuals with a high burden of vascular disease, and that vascular disease, particularly of the small blood vessels, is an important contributor to cognitive impairment and dementia.”

That appears to be most notable in people who have protein in their urine, Dr. Weiner added. “The presence of protein in the urine identifies a severe enough process to affect the blood vessels in the kidney, and there is no reason to think that blood vessels elsewhere in the body, including in the brain, are not similarly affected.”

As for the current study, Dr. Weiner said it could support the vascular disease theory.

“People with vulnerable kidneys to acute injury also have vulnerable brains to acute injury,” he said. “People who get AKI usually have susceptibility to perfusion-related kidney injury. In other words, the small blood vessels that supply the kidney are unable to compensate to maintain sufficient blood flow during a time of low blood pressure or other systemic illness.”

That vulnerability “suggests to me that small blood vessels elsewhere in the body are less likely to be able to respond to challenges like low blood pressure,” Dr. Weiner explained. “If this occurs in the brain, it leads to microvascular disease and greater abnormal white-matter burden. This change in the brain anatomy is highly correlated with cognitive impairment.”

How can physicians put these finding to use? “These patients may require more monitoring,” Dr. Kendrick said. “For example, patients with AKI and complete recovery may not have any follow-up with a nephrologist, and perhaps they should.”

Moving forward, she said, “we are examining the association of AKI with cognitive dysfunction in different patient populations.” Researchers also are planning studies to better understand the mechanisms that are at work, she said.

The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute funded the study. The study authors had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Kendrick JB et al. Kidney Week 2018. Abstract TH-OR116.

SAN DIEGO –

That’s according to a new study offering more evidence of a link between kidney disease and neurological problems.

“Clinicians should know that AKI is associated with poor long-term outcomes,” said lead author Jessica B. Kendrick MD, associate professor of medicine at the University of Colorado, Aurora. “We need to identify ways to prevent these long-term consequences.”

The findings were presented at Kidney Week 2018, sponsored by the American Society of Nephrology.

According to Dr. Kendrick, the acute neurological effects of AKI are well known. But no previous studies have examined the potential long-term cerebrovascular complications of AKI.

For the new study, Dr. Kendrick and her colleagues retrospectively analyzed 2,082 hospitalized patients in Utah from 1999 to 2009: 1,041 who completely recovered from AKI by discharge, and 1,041 who did not have AKI.

The average age was 61 years, and the average baseline creatinine was 0.9 ± 0.2 mg/dL. Over a median follow-up of 6 years, 97 patients developed dementia.

Those with AKI were more likely to develop dementia compared with the control group: 7% vs. 2% (hazard ratio, 3.4; 95% confidence interval, 2.14-5.40).

Other studies have linked kidney disease to cognitive impairment.

“There are a lot of theories as to why this is,” nephrologist Daniel Weiner, MD, of Tufts University, Boston, said in an interview. “It is most likely that the presence of kidney disease identifies individuals with a high burden of vascular disease, and that vascular disease, particularly of the small blood vessels, is an important contributor to cognitive impairment and dementia.”

That appears to be most notable in people who have protein in their urine, Dr. Weiner added. “The presence of protein in the urine identifies a severe enough process to affect the blood vessels in the kidney, and there is no reason to think that blood vessels elsewhere in the body, including in the brain, are not similarly affected.”

As for the current study, Dr. Weiner said it could support the vascular disease theory.

“People with vulnerable kidneys to acute injury also have vulnerable brains to acute injury,” he said. “People who get AKI usually have susceptibility to perfusion-related kidney injury. In other words, the small blood vessels that supply the kidney are unable to compensate to maintain sufficient blood flow during a time of low blood pressure or other systemic illness.”

That vulnerability “suggests to me that small blood vessels elsewhere in the body are less likely to be able to respond to challenges like low blood pressure,” Dr. Weiner explained. “If this occurs in the brain, it leads to microvascular disease and greater abnormal white-matter burden. This change in the brain anatomy is highly correlated with cognitive impairment.”

How can physicians put these finding to use? “These patients may require more monitoring,” Dr. Kendrick said. “For example, patients with AKI and complete recovery may not have any follow-up with a nephrologist, and perhaps they should.”

Moving forward, she said, “we are examining the association of AKI with cognitive dysfunction in different patient populations.” Researchers also are planning studies to better understand the mechanisms that are at work, she said.

The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute funded the study. The study authors had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Kendrick JB et al. Kidney Week 2018. Abstract TH-OR116.

SAN DIEGO –

That’s according to a new study offering more evidence of a link between kidney disease and neurological problems.

“Clinicians should know that AKI is associated with poor long-term outcomes,” said lead author Jessica B. Kendrick MD, associate professor of medicine at the University of Colorado, Aurora. “We need to identify ways to prevent these long-term consequences.”

The findings were presented at Kidney Week 2018, sponsored by the American Society of Nephrology.

According to Dr. Kendrick, the acute neurological effects of AKI are well known. But no previous studies have examined the potential long-term cerebrovascular complications of AKI.

For the new study, Dr. Kendrick and her colleagues retrospectively analyzed 2,082 hospitalized patients in Utah from 1999 to 2009: 1,041 who completely recovered from AKI by discharge, and 1,041 who did not have AKI.

The average age was 61 years, and the average baseline creatinine was 0.9 ± 0.2 mg/dL. Over a median follow-up of 6 years, 97 patients developed dementia.

Those with AKI were more likely to develop dementia compared with the control group: 7% vs. 2% (hazard ratio, 3.4; 95% confidence interval, 2.14-5.40).

Other studies have linked kidney disease to cognitive impairment.

“There are a lot of theories as to why this is,” nephrologist Daniel Weiner, MD, of Tufts University, Boston, said in an interview. “It is most likely that the presence of kidney disease identifies individuals with a high burden of vascular disease, and that vascular disease, particularly of the small blood vessels, is an important contributor to cognitive impairment and dementia.”

That appears to be most notable in people who have protein in their urine, Dr. Weiner added. “The presence of protein in the urine identifies a severe enough process to affect the blood vessels in the kidney, and there is no reason to think that blood vessels elsewhere in the body, including in the brain, are not similarly affected.”

As for the current study, Dr. Weiner said it could support the vascular disease theory.

“People with vulnerable kidneys to acute injury also have vulnerable brains to acute injury,” he said. “People who get AKI usually have susceptibility to perfusion-related kidney injury. In other words, the small blood vessels that supply the kidney are unable to compensate to maintain sufficient blood flow during a time of low blood pressure or other systemic illness.”

That vulnerability “suggests to me that small blood vessels elsewhere in the body are less likely to be able to respond to challenges like low blood pressure,” Dr. Weiner explained. “If this occurs in the brain, it leads to microvascular disease and greater abnormal white-matter burden. This change in the brain anatomy is highly correlated with cognitive impairment.”

How can physicians put these finding to use? “These patients may require more monitoring,” Dr. Kendrick said. “For example, patients with AKI and complete recovery may not have any follow-up with a nephrologist, and perhaps they should.”

Moving forward, she said, “we are examining the association of AKI with cognitive dysfunction in different patient populations.” Researchers also are planning studies to better understand the mechanisms that are at work, she said.

The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute funded the study. The study authors had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Kendrick JB et al. Kidney Week 2018. Abstract TH-OR116.

REPORTING FROM KIDNEY WEEK 2018

Key clinical point: Patients with acute kidney injury seem to face a much higher risk of dementia.

Major finding: Hospitalized patients with AKI were 3.4 times more likely to develop dementia within a median of 6 years, compared with other hospitalized patients.

Study details: A retrospective study of 2,082 propensity-matched hospitalized patients, 1,041 who had AKI and fully recovered, and 1,041 who did not have AKI.

Disclosures: The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute funded the study. The authors had no disclosures.

Source: Kendrick JB et al. Kidney Week 2018. Abstract No. TH-OR116.

Case review: Posttransplant lupus nephritis recurrence rates declining

CHICAGO – Lupus nephritis recurrence rates in kidney transplant recipients declined over the past decade, compared with rates seen in earlier studies, according to a review of cases at the University of Tennessee Health Science Center (UTHSC).

The findings are likely related to improvements in posttransplant immunosuppressive regimens, and may have implications for the timing of transplant going forward, Debendra N. Pattanaik, MD, said at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

The biopsy-proven recurrence rate in 38 transplant recipients who received standard immunosuppression with prednisone, tacrolimus, and mycophenolate mofetil was 11%, and graft loss or death occurred in 26% at a median follow-up of 1,230 days, said Dr. Pattanaik, a rheumatologist at UTHSC, Memphis.

Patients with recurrence showed a trend for increased risk for graft loss or death, compared with recipients without recurrence (hazard ratio = 3.14), he noted during a press briefing at the meeting.

Lupus nephritis is a severe complication occurring in more than half of all patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), and despite a great deal of progress over the years, 10%-30% develop end-stage renal disease and require dialysis and/or transplant, he said, noting that studies have shown that transplant recipients do better over time than do those who remain on dialysis.

“So renal transplant is an important modality of treatment for end-stage renal disease from lupus nephritis,” he added.

However, recurrence of lupus nephritis in the graft is a concern, he said.

In previous eras – prior to improvements in immunosuppressive regimens for transplant recipients – studies showed variable rates of lupus nephritis recurrence, with some reporting rates up to 50% depending on the patient populations and protocols, he noted.

The rates in recent years at UTHSC seemed lower than that, so he and his colleagues looked more closely at the outcomes.

Case patients included all those with end-stage renal disease secondary to lupus nephritis who were transplanted between 2006 and 2017 at the center. Medical records of all 38 were reviewed along with information from the United Network for Organ Sharing Network. The mean age of the patients at baseline was 42 years, 89% were women, 89% were African American, and previous time on dialysis was a median of 4 years. Most (80%) received hemodialysis, and nearly one-third (31%) received living donor transplantation, Dr. Pattanaik said.

The main difference in the past decade compared with those previous eras is the use of posttransplant immunosuppressive regimens consisting of tacrolimus and mycophenolate mofetil rather than cyclosporine and azathioprine in addition to prednisone, he explained.

Previous reports showing higher recurrence rates were from studies in which patients received cyclosporine and azathioprine as part of the posttransplant regimen, he said.

“Our next question is whether patients can be transplanted early,” he said, explaining that transplant is often delayed for many months or years until SLE is in remission, but if the new regimens are reducing recurrence risk, early transplant may be feasible.

Dr. Pattanaik reported having no disclosures.

SOURCE: Pattanaik D et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2018;70(Suppl 10): Abstract 711.

CHICAGO – Lupus nephritis recurrence rates in kidney transplant recipients declined over the past decade, compared with rates seen in earlier studies, according to a review of cases at the University of Tennessee Health Science Center (UTHSC).

The findings are likely related to improvements in posttransplant immunosuppressive regimens, and may have implications for the timing of transplant going forward, Debendra N. Pattanaik, MD, said at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

The biopsy-proven recurrence rate in 38 transplant recipients who received standard immunosuppression with prednisone, tacrolimus, and mycophenolate mofetil was 11%, and graft loss or death occurred in 26% at a median follow-up of 1,230 days, said Dr. Pattanaik, a rheumatologist at UTHSC, Memphis.

Patients with recurrence showed a trend for increased risk for graft loss or death, compared with recipients without recurrence (hazard ratio = 3.14), he noted during a press briefing at the meeting.

Lupus nephritis is a severe complication occurring in more than half of all patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), and despite a great deal of progress over the years, 10%-30% develop end-stage renal disease and require dialysis and/or transplant, he said, noting that studies have shown that transplant recipients do better over time than do those who remain on dialysis.

“So renal transplant is an important modality of treatment for end-stage renal disease from lupus nephritis,” he added.

However, recurrence of lupus nephritis in the graft is a concern, he said.

In previous eras – prior to improvements in immunosuppressive regimens for transplant recipients – studies showed variable rates of lupus nephritis recurrence, with some reporting rates up to 50% depending on the patient populations and protocols, he noted.

The rates in recent years at UTHSC seemed lower than that, so he and his colleagues looked more closely at the outcomes.

Case patients included all those with end-stage renal disease secondary to lupus nephritis who were transplanted between 2006 and 2017 at the center. Medical records of all 38 were reviewed along with information from the United Network for Organ Sharing Network. The mean age of the patients at baseline was 42 years, 89% were women, 89% were African American, and previous time on dialysis was a median of 4 years. Most (80%) received hemodialysis, and nearly one-third (31%) received living donor transplantation, Dr. Pattanaik said.

The main difference in the past decade compared with those previous eras is the use of posttransplant immunosuppressive regimens consisting of tacrolimus and mycophenolate mofetil rather than cyclosporine and azathioprine in addition to prednisone, he explained.

Previous reports showing higher recurrence rates were from studies in which patients received cyclosporine and azathioprine as part of the posttransplant regimen, he said.

“Our next question is whether patients can be transplanted early,” he said, explaining that transplant is often delayed for many months or years until SLE is in remission, but if the new regimens are reducing recurrence risk, early transplant may be feasible.

Dr. Pattanaik reported having no disclosures.

SOURCE: Pattanaik D et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2018;70(Suppl 10): Abstract 711.

CHICAGO – Lupus nephritis recurrence rates in kidney transplant recipients declined over the past decade, compared with rates seen in earlier studies, according to a review of cases at the University of Tennessee Health Science Center (UTHSC).

The findings are likely related to improvements in posttransplant immunosuppressive regimens, and may have implications for the timing of transplant going forward, Debendra N. Pattanaik, MD, said at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

The biopsy-proven recurrence rate in 38 transplant recipients who received standard immunosuppression with prednisone, tacrolimus, and mycophenolate mofetil was 11%, and graft loss or death occurred in 26% at a median follow-up of 1,230 days, said Dr. Pattanaik, a rheumatologist at UTHSC, Memphis.

Patients with recurrence showed a trend for increased risk for graft loss or death, compared with recipients without recurrence (hazard ratio = 3.14), he noted during a press briefing at the meeting.

Lupus nephritis is a severe complication occurring in more than half of all patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), and despite a great deal of progress over the years, 10%-30% develop end-stage renal disease and require dialysis and/or transplant, he said, noting that studies have shown that transplant recipients do better over time than do those who remain on dialysis.

“So renal transplant is an important modality of treatment for end-stage renal disease from lupus nephritis,” he added.

However, recurrence of lupus nephritis in the graft is a concern, he said.

In previous eras – prior to improvements in immunosuppressive regimens for transplant recipients – studies showed variable rates of lupus nephritis recurrence, with some reporting rates up to 50% depending on the patient populations and protocols, he noted.

The rates in recent years at UTHSC seemed lower than that, so he and his colleagues looked more closely at the outcomes.

Case patients included all those with end-stage renal disease secondary to lupus nephritis who were transplanted between 2006 and 2017 at the center. Medical records of all 38 were reviewed along with information from the United Network for Organ Sharing Network. The mean age of the patients at baseline was 42 years, 89% were women, 89% were African American, and previous time on dialysis was a median of 4 years. Most (80%) received hemodialysis, and nearly one-third (31%) received living donor transplantation, Dr. Pattanaik said.

The main difference in the past decade compared with those previous eras is the use of posttransplant immunosuppressive regimens consisting of tacrolimus and mycophenolate mofetil rather than cyclosporine and azathioprine in addition to prednisone, he explained.

Previous reports showing higher recurrence rates were from studies in which patients received cyclosporine and azathioprine as part of the posttransplant regimen, he said.

“Our next question is whether patients can be transplanted early,” he said, explaining that transplant is often delayed for many months or years until SLE is in remission, but if the new regimens are reducing recurrence risk, early transplant may be feasible.

Dr. Pattanaik reported having no disclosures.

SOURCE: Pattanaik D et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2018;70(Suppl 10): Abstract 711.

REPORTING FROM THE ACR ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The biopsy-proven recurrence rate was 11%.

Study details: A review of 38 cases at one center.

Disclosures: Dr. Pattanaik reported having no disclosures.

Source: Pattanaik D et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2018;70(Suppl 10): Abstract 711.

Age, insurance type tied to delay in pediatric febrile UTI treatment

even after adjustment for confounders, according to a report in the Journal of Pediatrics.

Stephanie W. Hum and Nader Shaikh, MD, MPH, of the University of Pittsburgh, drew from data provided by two studies, Randomized Intervention for Children With Vesicoureteral Reflux and Careful Urinary Tract Infection Evaluation. Specifically, they extracted data regarding patients’ age, sex, history of UTIs, ethnicity, race, insurance, household size, and duration of fever before initiation of antimicrobial therapy, as well as primary caregivers’ level of education and income. Some factors were analyzed because of associations seen in adult studies, and others because of concerns about access to care. In this analysis, the researchers defined “treatment delay” as the number of hours between onset of fever and initiation of antimicrobial treatment and, after exclusion of afebrile children and those with missing data, included 660 patients.

In univariate analysis, both older age and commercial insurance were found to be significantly associated with delays in treatment. Compared with time to treatment seen with younger children, treatment was delayed by an average of 26.2 hours in children aged 12 months and older (P less than .001). Patients with commercial insurance were treated a mean of 12.6 hours later than were those with noncommercial insurance (P = .002). These associations remained significant even after adjustment in a multivariable regression model for sex, history of UTIs, ethnicity, race, primary caregivers’ level of education, insurance, and income level.

The finding regarding age is consistent with a previous study, and Ms. Hum and Dr. Shaikh suggested it may reflect parents experiencing reduced urgency regarding febrile illnesses among older children. However, the researchers also noted that greater rates of renal scarring are seen in older children, so “it seems important to educate physicians, parents, and triage nurses about the importance of early evaluation of children with fever,” even those older than 12 months.

The finding regarding insurance status, however, is contrary to what studies in adult populations have found, as well as those in pediatric EDs. The researchers suggested that perhaps parents with noncommercial insurance are more likely to take their children to EDs, where testing can be done on-site 24 hours a day, rather than to private clinics, which often have to send out testing to off-site laboratories.

One of the strengths of the study is its relatively large sample size, they said. Among its weaknesses is that treatment delays were self-reported by parents and might be inaccurate and that information regarding location of initial evaluation was not gathered and could not be examined with other factors.

This study was supported by a T35 training grant from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, sponsored by Tom R. Kleyman, MD, chief of the renal-electrolyte division at the University of Pittsburgh. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Hum SW et al. J Pediatr. 2018 Oct 16. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.09.029.

This article was updated 10/24/18.

even after adjustment for confounders, according to a report in the Journal of Pediatrics.

Stephanie W. Hum and Nader Shaikh, MD, MPH, of the University of Pittsburgh, drew from data provided by two studies, Randomized Intervention for Children With Vesicoureteral Reflux and Careful Urinary Tract Infection Evaluation. Specifically, they extracted data regarding patients’ age, sex, history of UTIs, ethnicity, race, insurance, household size, and duration of fever before initiation of antimicrobial therapy, as well as primary caregivers’ level of education and income. Some factors were analyzed because of associations seen in adult studies, and others because of concerns about access to care. In this analysis, the researchers defined “treatment delay” as the number of hours between onset of fever and initiation of antimicrobial treatment and, after exclusion of afebrile children and those with missing data, included 660 patients.

In univariate analysis, both older age and commercial insurance were found to be significantly associated with delays in treatment. Compared with time to treatment seen with younger children, treatment was delayed by an average of 26.2 hours in children aged 12 months and older (P less than .001). Patients with commercial insurance were treated a mean of 12.6 hours later than were those with noncommercial insurance (P = .002). These associations remained significant even after adjustment in a multivariable regression model for sex, history of UTIs, ethnicity, race, primary caregivers’ level of education, insurance, and income level.

The finding regarding age is consistent with a previous study, and Ms. Hum and Dr. Shaikh suggested it may reflect parents experiencing reduced urgency regarding febrile illnesses among older children. However, the researchers also noted that greater rates of renal scarring are seen in older children, so “it seems important to educate physicians, parents, and triage nurses about the importance of early evaluation of children with fever,” even those older than 12 months.

The finding regarding insurance status, however, is contrary to what studies in adult populations have found, as well as those in pediatric EDs. The researchers suggested that perhaps parents with noncommercial insurance are more likely to take their children to EDs, where testing can be done on-site 24 hours a day, rather than to private clinics, which often have to send out testing to off-site laboratories.

One of the strengths of the study is its relatively large sample size, they said. Among its weaknesses is that treatment delays were self-reported by parents and might be inaccurate and that information regarding location of initial evaluation was not gathered and could not be examined with other factors.

This study was supported by a T35 training grant from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, sponsored by Tom R. Kleyman, MD, chief of the renal-electrolyte division at the University of Pittsburgh. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Hum SW et al. J Pediatr. 2018 Oct 16. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.09.029.

This article was updated 10/24/18.

even after adjustment for confounders, according to a report in the Journal of Pediatrics.

Stephanie W. Hum and Nader Shaikh, MD, MPH, of the University of Pittsburgh, drew from data provided by two studies, Randomized Intervention for Children With Vesicoureteral Reflux and Careful Urinary Tract Infection Evaluation. Specifically, they extracted data regarding patients’ age, sex, history of UTIs, ethnicity, race, insurance, household size, and duration of fever before initiation of antimicrobial therapy, as well as primary caregivers’ level of education and income. Some factors were analyzed because of associations seen in adult studies, and others because of concerns about access to care. In this analysis, the researchers defined “treatment delay” as the number of hours between onset of fever and initiation of antimicrobial treatment and, after exclusion of afebrile children and those with missing data, included 660 patients.

In univariate analysis, both older age and commercial insurance were found to be significantly associated with delays in treatment. Compared with time to treatment seen with younger children, treatment was delayed by an average of 26.2 hours in children aged 12 months and older (P less than .001). Patients with commercial insurance were treated a mean of 12.6 hours later than were those with noncommercial insurance (P = .002). These associations remained significant even after adjustment in a multivariable regression model for sex, history of UTIs, ethnicity, race, primary caregivers’ level of education, insurance, and income level.

The finding regarding age is consistent with a previous study, and Ms. Hum and Dr. Shaikh suggested it may reflect parents experiencing reduced urgency regarding febrile illnesses among older children. However, the researchers also noted that greater rates of renal scarring are seen in older children, so “it seems important to educate physicians, parents, and triage nurses about the importance of early evaluation of children with fever,” even those older than 12 months.

The finding regarding insurance status, however, is contrary to what studies in adult populations have found, as well as those in pediatric EDs. The researchers suggested that perhaps parents with noncommercial insurance are more likely to take their children to EDs, where testing can be done on-site 24 hours a day, rather than to private clinics, which often have to send out testing to off-site laboratories.

One of the strengths of the study is its relatively large sample size, they said. Among its weaknesses is that treatment delays were self-reported by parents and might be inaccurate and that information regarding location of initial evaluation was not gathered and could not be examined with other factors.

This study was supported by a T35 training grant from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, sponsored by Tom R. Kleyman, MD, chief of the renal-electrolyte division at the University of Pittsburgh. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Hum SW et al. J Pediatr. 2018 Oct 16. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.09.029.

This article was updated 10/24/18.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF PEDIATRICS

Pay attention to kidney disease risk in people living with HIV

The prevalence of chronic kidney disease (CKD) in people living with HIV varied widely, depending on population and criteria, according to a systematic literature review of the PubMed and PsycInfo databases for articles published from January 2000 through August 2016.

The review included all studies that involved adults older than 21 years of age, investigated people living with HIV with CKD, reported prevalence of CKD, and were published in a peer-reviewed journal, according to Jungmin Park, PhD, RN, of CHA University, Pocheon-Si, South Korea, and her colleague.

Out of an initial search yielding 1,960 citations in PubMed and 5,356 citations in PsycInfo, the results were pared down to 21 articles, which met all of the inclusion/exclusion criteria and were used for the final analysis.

The risk factors for CKD in people living with HIV cited most often in the studies consisted of medications, hypertension, older age, diabetes mellitus, hepatitis coinfection (with hepatitis C virus more prominent than hepatitis B virus), low CD4+ T-cell count, and race, Dr. Park and her colleague reported.

Of the various risk factors, the only ones unique to HIV were viral load and CD4+ T-cell count. One study reporting on 5,538 treatment-naive patients in mainland China suggested that HIV viral replication in renal cells may be the cause of renal damage in patients with high viral loads, meaning that viral suppression would improve renal function. However, all of these risk factors are intrinsically linked, according to Dr. Park and her colleague. They added that managing viral load alone would be ineffective in preventing CKD: “Therefore [people living with HIV] will need to effectively manage every aspect of their health, including metabolic and cardiovascular systems.”

Of the 43,114 people living with HIV across the 21 studies, 3,218 (7.3%) had CKD. The reported prevalence of CKD ranged from 2.3% to 53.3%, with the African population having the highest prevalence. Some of the wide variation was possibly attributable to differences in the definitions of CKD used across the various studies.

“The risk of under-diagnosis of CKD can lead to long-term health complications. Health care providers must monitor kidney function and treatment for renal damage carefully, especially for people living with HIV with additional diagnoses of diabetes and/or hypertension, and for those who are aging,” Dr. Park and her colleague concluded.

The authors reported that they had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Park, J et al. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2018;29:655-66.

The prevalence of chronic kidney disease (CKD) in people living with HIV varied widely, depending on population and criteria, according to a systematic literature review of the PubMed and PsycInfo databases for articles published from January 2000 through August 2016.

The review included all studies that involved adults older than 21 years of age, investigated people living with HIV with CKD, reported prevalence of CKD, and were published in a peer-reviewed journal, according to Jungmin Park, PhD, RN, of CHA University, Pocheon-Si, South Korea, and her colleague.

Out of an initial search yielding 1,960 citations in PubMed and 5,356 citations in PsycInfo, the results were pared down to 21 articles, which met all of the inclusion/exclusion criteria and were used for the final analysis.

The risk factors for CKD in people living with HIV cited most often in the studies consisted of medications, hypertension, older age, diabetes mellitus, hepatitis coinfection (with hepatitis C virus more prominent than hepatitis B virus), low CD4+ T-cell count, and race, Dr. Park and her colleague reported.

Of the various risk factors, the only ones unique to HIV were viral load and CD4+ T-cell count. One study reporting on 5,538 treatment-naive patients in mainland China suggested that HIV viral replication in renal cells may be the cause of renal damage in patients with high viral loads, meaning that viral suppression would improve renal function. However, all of these risk factors are intrinsically linked, according to Dr. Park and her colleague. They added that managing viral load alone would be ineffective in preventing CKD: “Therefore [people living with HIV] will need to effectively manage every aspect of their health, including metabolic and cardiovascular systems.”

Of the 43,114 people living with HIV across the 21 studies, 3,218 (7.3%) had CKD. The reported prevalence of CKD ranged from 2.3% to 53.3%, with the African population having the highest prevalence. Some of the wide variation was possibly attributable to differences in the definitions of CKD used across the various studies.

“The risk of under-diagnosis of CKD can lead to long-term health complications. Health care providers must monitor kidney function and treatment for renal damage carefully, especially for people living with HIV with additional diagnoses of diabetes and/or hypertension, and for those who are aging,” Dr. Park and her colleague concluded.

The authors reported that they had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Park, J et al. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2018;29:655-66.

The prevalence of chronic kidney disease (CKD) in people living with HIV varied widely, depending on population and criteria, according to a systematic literature review of the PubMed and PsycInfo databases for articles published from January 2000 through August 2016.

The review included all studies that involved adults older than 21 years of age, investigated people living with HIV with CKD, reported prevalence of CKD, and were published in a peer-reviewed journal, according to Jungmin Park, PhD, RN, of CHA University, Pocheon-Si, South Korea, and her colleague.

Out of an initial search yielding 1,960 citations in PubMed and 5,356 citations in PsycInfo, the results were pared down to 21 articles, which met all of the inclusion/exclusion criteria and were used for the final analysis.

The risk factors for CKD in people living with HIV cited most often in the studies consisted of medications, hypertension, older age, diabetes mellitus, hepatitis coinfection (with hepatitis C virus more prominent than hepatitis B virus), low CD4+ T-cell count, and race, Dr. Park and her colleague reported.

Of the various risk factors, the only ones unique to HIV were viral load and CD4+ T-cell count. One study reporting on 5,538 treatment-naive patients in mainland China suggested that HIV viral replication in renal cells may be the cause of renal damage in patients with high viral loads, meaning that viral suppression would improve renal function. However, all of these risk factors are intrinsically linked, according to Dr. Park and her colleague. They added that managing viral load alone would be ineffective in preventing CKD: “Therefore [people living with HIV] will need to effectively manage every aspect of their health, including metabolic and cardiovascular systems.”

Of the 43,114 people living with HIV across the 21 studies, 3,218 (7.3%) had CKD. The reported prevalence of CKD ranged from 2.3% to 53.3%, with the African population having the highest prevalence. Some of the wide variation was possibly attributable to differences in the definitions of CKD used across the various studies.