User login

Minidose edoxaban may safely cut AFib stroke risk in the frail, very elderly

suggests a randomized trial conducted in Japan.

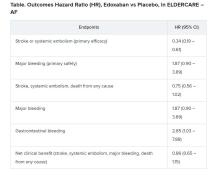

Many of the study’s 984 mostly octogenarian patients were objectively frail with poor renal function, low body weight, a history of serious bleeding, or other conditions that made them poor candidates for regular-dose oral anticoagulation. Yet those who took the factor Xa inhibitor edoxaban (Savaysa) at the off-label dosage of 15 mg once daily showed a two-thirds drop in risk for stroke or systemic embolism (P < .001), compared with patients who received placebo. There were no fatal bleeds and virtually no intracranial hemorrhages.

For such high-risk patients with nonvalvular AFib who otherwise would not be given an OAC, edoxaban 15 mg “can be an acceptable treatment option in decreasing the risk of devastating stroke”; however, “it may increase the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding, so care should be given in every patient,” said Ken Okumura, MD, PhD. Indeed, the rate of gastrointestinal bleeding tripled among the patients who received edoxaban, compared with those given placebo, at about 2.3% per year versus 0.8% per year.

Although their 87% increased risk for major bleeding did not reach significance, it hit close, with a P value of .09 in the trial, called Edoxaban Low-Dose for Elder Care Atrial Fibrillation Patients (ELDERCARE-AF).

Dr. Okumura, of Saiseikai Kumamoto (Japan) Hospital, presented the study August 30 during the virtual annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology. He is lead author of an article describing the study, which was simultaneously published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Many patients with AFib suffer strokes if they are not given oral anticoagulation because of “fear of major bleeding caused by standard OAC therapy,” Dr. Okumura noted. Others are inappropriately administered antiplatelets or anticoagulants at conventional dosages. “There is no standard of practice in Japan for patients like those in the present trial,” Dr. Okumura said. “However, I believe the present study opens a new possible path of thromboprophylaxis in such high-risk patients.”

Even with its relatively few bleeding events, ELDERCARE-AF “does suggest that the risk of the worst types of bleeds is not that high,” said Daniel E. Singer, MD, of Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston. “Gastrointestinal bleeding is annoying, and it will probably stop people from taking their edoxaban, but for the most part it doesn’t kill people.”

Moreover, he added, the trial suggests that low-dose edoxaban, in exchange for a steep reduction in thromboembolic risk, “doesn’t add to your risk of intracranial hemorrhage!”

ELDERCARE-AF may give practitioners “yet another reason to rethink” whether a low-dose DOAC such as edoxaban 15 mg/day may well be a good approach for such patients with AFib who are not receiving standard-dose OAC because of a perceived high risk for serious bleeding, said Dr. Singer, who was not involved in the study.

The trial randomly and evenly assigned 984 patients with AF in Japan to take either edoxaban 15 mg/day or placebo. The patients, who were at least 80 years old and had a CHADS2 score of 2 or higher, were judged inappropriate candidates for OAC at dosages approved for stroke prevention.

The mean age of the patients was 86.6, more than a decade older than patients “in the previous landmark clinical trials of direct oral anticoagulants,” and were 5-10 years older than the general AFib population, reported Dr. Okumura and colleagues.

Their mean weight was 52 kg, and mean creatinine clearance was 36.3 mL/min; 41% were classified as frail according to validated assessment tools.

Of the 303 patients who did not complete the trial, 158 voluntarily withdrew for various reasons. The withdrawal rate was similar in the two treatment arms. Outcomes were analyzed by intention to treat, the report noted.

The annualized rate of stroke or systemic embolism, the primary efficacy endpoint, was 2.3% for those who received edoxaban and 6.7% for the control group. Corresponding rates for the primary safety endpoint, major bleeding as determined by International Society on Thrombosis and Hemostasis criteria, were 3.3% and 1.8%, respectively.

“The question is, can the Food and Drug Administration act on this information? I doubt it can. What will be needed is to reproduce the study in a U.S. population to see if it holds,” Dr. Singer proposed.

“Edoxaban isn’t used much in the U.S. This could heighten interest. And who knows, there may be a gold rush,” he said, if the strategy were to pan out for the other DOACs, rivaroxaban (Xarelto), apixaban (Eliquis), and dabigatran (Pradaxa).

ELDERCARE-AF was funded by Daiichi Sankyo, from which Dr. Okumura reported receiving grants and personal fees; he also disclosed personal fees from Daiichi Sankyo, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Medtronic, Johnson & Johnson, and Bayer.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

suggests a randomized trial conducted in Japan.

Many of the study’s 984 mostly octogenarian patients were objectively frail with poor renal function, low body weight, a history of serious bleeding, or other conditions that made them poor candidates for regular-dose oral anticoagulation. Yet those who took the factor Xa inhibitor edoxaban (Savaysa) at the off-label dosage of 15 mg once daily showed a two-thirds drop in risk for stroke or systemic embolism (P < .001), compared with patients who received placebo. There were no fatal bleeds and virtually no intracranial hemorrhages.

For such high-risk patients with nonvalvular AFib who otherwise would not be given an OAC, edoxaban 15 mg “can be an acceptable treatment option in decreasing the risk of devastating stroke”; however, “it may increase the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding, so care should be given in every patient,” said Ken Okumura, MD, PhD. Indeed, the rate of gastrointestinal bleeding tripled among the patients who received edoxaban, compared with those given placebo, at about 2.3% per year versus 0.8% per year.

Although their 87% increased risk for major bleeding did not reach significance, it hit close, with a P value of .09 in the trial, called Edoxaban Low-Dose for Elder Care Atrial Fibrillation Patients (ELDERCARE-AF).

Dr. Okumura, of Saiseikai Kumamoto (Japan) Hospital, presented the study August 30 during the virtual annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology. He is lead author of an article describing the study, which was simultaneously published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Many patients with AFib suffer strokes if they are not given oral anticoagulation because of “fear of major bleeding caused by standard OAC therapy,” Dr. Okumura noted. Others are inappropriately administered antiplatelets or anticoagulants at conventional dosages. “There is no standard of practice in Japan for patients like those in the present trial,” Dr. Okumura said. “However, I believe the present study opens a new possible path of thromboprophylaxis in such high-risk patients.”

Even with its relatively few bleeding events, ELDERCARE-AF “does suggest that the risk of the worst types of bleeds is not that high,” said Daniel E. Singer, MD, of Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston. “Gastrointestinal bleeding is annoying, and it will probably stop people from taking their edoxaban, but for the most part it doesn’t kill people.”

Moreover, he added, the trial suggests that low-dose edoxaban, in exchange for a steep reduction in thromboembolic risk, “doesn’t add to your risk of intracranial hemorrhage!”

ELDERCARE-AF may give practitioners “yet another reason to rethink” whether a low-dose DOAC such as edoxaban 15 mg/day may well be a good approach for such patients with AFib who are not receiving standard-dose OAC because of a perceived high risk for serious bleeding, said Dr. Singer, who was not involved in the study.

The trial randomly and evenly assigned 984 patients with AF in Japan to take either edoxaban 15 mg/day or placebo. The patients, who were at least 80 years old and had a CHADS2 score of 2 or higher, were judged inappropriate candidates for OAC at dosages approved for stroke prevention.

The mean age of the patients was 86.6, more than a decade older than patients “in the previous landmark clinical trials of direct oral anticoagulants,” and were 5-10 years older than the general AFib population, reported Dr. Okumura and colleagues.

Their mean weight was 52 kg, and mean creatinine clearance was 36.3 mL/min; 41% were classified as frail according to validated assessment tools.

Of the 303 patients who did not complete the trial, 158 voluntarily withdrew for various reasons. The withdrawal rate was similar in the two treatment arms. Outcomes were analyzed by intention to treat, the report noted.

The annualized rate of stroke or systemic embolism, the primary efficacy endpoint, was 2.3% for those who received edoxaban and 6.7% for the control group. Corresponding rates for the primary safety endpoint, major bleeding as determined by International Society on Thrombosis and Hemostasis criteria, were 3.3% and 1.8%, respectively.

“The question is, can the Food and Drug Administration act on this information? I doubt it can. What will be needed is to reproduce the study in a U.S. population to see if it holds,” Dr. Singer proposed.

“Edoxaban isn’t used much in the U.S. This could heighten interest. And who knows, there may be a gold rush,” he said, if the strategy were to pan out for the other DOACs, rivaroxaban (Xarelto), apixaban (Eliquis), and dabigatran (Pradaxa).

ELDERCARE-AF was funded by Daiichi Sankyo, from which Dr. Okumura reported receiving grants and personal fees; he also disclosed personal fees from Daiichi Sankyo, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Medtronic, Johnson & Johnson, and Bayer.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

suggests a randomized trial conducted in Japan.

Many of the study’s 984 mostly octogenarian patients were objectively frail with poor renal function, low body weight, a history of serious bleeding, or other conditions that made them poor candidates for regular-dose oral anticoagulation. Yet those who took the factor Xa inhibitor edoxaban (Savaysa) at the off-label dosage of 15 mg once daily showed a two-thirds drop in risk for stroke or systemic embolism (P < .001), compared with patients who received placebo. There were no fatal bleeds and virtually no intracranial hemorrhages.

For such high-risk patients with nonvalvular AFib who otherwise would not be given an OAC, edoxaban 15 mg “can be an acceptable treatment option in decreasing the risk of devastating stroke”; however, “it may increase the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding, so care should be given in every patient,” said Ken Okumura, MD, PhD. Indeed, the rate of gastrointestinal bleeding tripled among the patients who received edoxaban, compared with those given placebo, at about 2.3% per year versus 0.8% per year.

Although their 87% increased risk for major bleeding did not reach significance, it hit close, with a P value of .09 in the trial, called Edoxaban Low-Dose for Elder Care Atrial Fibrillation Patients (ELDERCARE-AF).

Dr. Okumura, of Saiseikai Kumamoto (Japan) Hospital, presented the study August 30 during the virtual annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology. He is lead author of an article describing the study, which was simultaneously published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Many patients with AFib suffer strokes if they are not given oral anticoagulation because of “fear of major bleeding caused by standard OAC therapy,” Dr. Okumura noted. Others are inappropriately administered antiplatelets or anticoagulants at conventional dosages. “There is no standard of practice in Japan for patients like those in the present trial,” Dr. Okumura said. “However, I believe the present study opens a new possible path of thromboprophylaxis in such high-risk patients.”

Even with its relatively few bleeding events, ELDERCARE-AF “does suggest that the risk of the worst types of bleeds is not that high,” said Daniel E. Singer, MD, of Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston. “Gastrointestinal bleeding is annoying, and it will probably stop people from taking their edoxaban, but for the most part it doesn’t kill people.”

Moreover, he added, the trial suggests that low-dose edoxaban, in exchange for a steep reduction in thromboembolic risk, “doesn’t add to your risk of intracranial hemorrhage!”

ELDERCARE-AF may give practitioners “yet another reason to rethink” whether a low-dose DOAC such as edoxaban 15 mg/day may well be a good approach for such patients with AFib who are not receiving standard-dose OAC because of a perceived high risk for serious bleeding, said Dr. Singer, who was not involved in the study.

The trial randomly and evenly assigned 984 patients with AF in Japan to take either edoxaban 15 mg/day or placebo. The patients, who were at least 80 years old and had a CHADS2 score of 2 or higher, were judged inappropriate candidates for OAC at dosages approved for stroke prevention.

The mean age of the patients was 86.6, more than a decade older than patients “in the previous landmark clinical trials of direct oral anticoagulants,” and were 5-10 years older than the general AFib population, reported Dr. Okumura and colleagues.

Their mean weight was 52 kg, and mean creatinine clearance was 36.3 mL/min; 41% were classified as frail according to validated assessment tools.

Of the 303 patients who did not complete the trial, 158 voluntarily withdrew for various reasons. The withdrawal rate was similar in the two treatment arms. Outcomes were analyzed by intention to treat, the report noted.

The annualized rate of stroke or systemic embolism, the primary efficacy endpoint, was 2.3% for those who received edoxaban and 6.7% for the control group. Corresponding rates for the primary safety endpoint, major bleeding as determined by International Society on Thrombosis and Hemostasis criteria, were 3.3% and 1.8%, respectively.

“The question is, can the Food and Drug Administration act on this information? I doubt it can. What will be needed is to reproduce the study in a U.S. population to see if it holds,” Dr. Singer proposed.

“Edoxaban isn’t used much in the U.S. This could heighten interest. And who knows, there may be a gold rush,” he said, if the strategy were to pan out for the other DOACs, rivaroxaban (Xarelto), apixaban (Eliquis), and dabigatran (Pradaxa).

ELDERCARE-AF was funded by Daiichi Sankyo, from which Dr. Okumura reported receiving grants and personal fees; he also disclosed personal fees from Daiichi Sankyo, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Medtronic, Johnson & Johnson, and Bayer.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM ESC CONGRESS 2020

Nightmares: An independent risk factor for heart disease?

, new research shows. In what researchers describe as “surprising” findings, results from a large study of relatively young military veterans showed those who had nightmares two or more times per week had significantly increased risks for hypertension, myocardial infarction, or other heart problems.

“A diagnosis of PTSD incorporates sleep disturbance as a symptom. Thus, we were surprised to find that nightmares continued to be associated with CVD after controlling not only for PTSD and demographic factors, but also smoking and depression diagnosis,” said Christi Ulmer, PhD, of the department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, N.C.

The findings were presented at the virtual annual meeting of the Associated Professional Sleep Societies.

Unclear mechanism

The study included 3,468 veterans (77% male) with a mean age of 38 years who had served one or two tours of duty since Sept. 11, 2001. Nearly one-third (31%) met criteria for PTSD, and 33% self-reported having at least one cardiovascular condition, such as heart problems, hypertension, stroke, and MI.

Nightmare frequency and severity was assessed using the Davidson Trauma Scale. Nightmares were considered frequent if they occurred two or more times per week and moderate to severe if they were at least moderately distressing. About 31% of veterans reported having frequent nightmares, and 35% reported moderately distressing nightmares over the past week.

After adjusting for age, race, and sex, frequent nightmares were associated with hypertension (odds ratio, 1.51; 95% confidence interval, 1.28-1.78), heart problems (OR, 1.50; 95% CI, 1.11-2.02), and MI (OR, 2.32; 95% CI, 1.18-4.54).

Associations between frequent nightmares and hypertension (OR, 1.43; 95% CI, 1.17-1.73) and heart problems (OR, 1.43; 95% CI, 1.00-2.05) remained significant after further adjusting for smoking, depression, and PTSD.

“Our cross-sectional findings set the stage for future research examining the possibility that nightmares may confer cardiovascular disease risks beyond those conferred by PTSD diagnosis alone,” Dr. Ulmer said in a news release.

Dr. Ulmer also said that, because the study was based on self-reported data, the findings are “very preliminary.” Before doctors adjust clinical practices, it’s important that our findings be replicated using longitudinal studies, clinically diagnosed medical conditions, and objectively assessed sleep,” she said.

She added that more research is needed to uncover mechanisms explaining these associations and determine if reducing the frequency and severity of nightmares can lead to improved cardiovascular health.

Timely research

Reached for comment, Rajkumar (Raj) Dasgupta, MD, of the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, noted “the correlation between nightmares and heart disease is a timely topic right now with COVID-19 as more people may be having nightmares.”

“If a patient mentions nightmares, I do think it’s important not to just glaze over it, but to talk more about it and document it in the patient record, especially in patients with cardiovascular disease, atrial fibrillation, diabetes, and hypertension,” said Dr. Dasgupta, who wasn’t involved in the study.

The research was supported by the Veterans Integrated Service Network 6 Mental Illness Research, Education and Clinical Center and the Department of Veterans Affairs HSR&D ADAPT Center at the Durham VA Health Care System. Dr. Ulmer and Dr. Dasgupta have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

, new research shows. In what researchers describe as “surprising” findings, results from a large study of relatively young military veterans showed those who had nightmares two or more times per week had significantly increased risks for hypertension, myocardial infarction, or other heart problems.

“A diagnosis of PTSD incorporates sleep disturbance as a symptom. Thus, we were surprised to find that nightmares continued to be associated with CVD after controlling not only for PTSD and demographic factors, but also smoking and depression diagnosis,” said Christi Ulmer, PhD, of the department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, N.C.

The findings were presented at the virtual annual meeting of the Associated Professional Sleep Societies.

Unclear mechanism

The study included 3,468 veterans (77% male) with a mean age of 38 years who had served one or two tours of duty since Sept. 11, 2001. Nearly one-third (31%) met criteria for PTSD, and 33% self-reported having at least one cardiovascular condition, such as heart problems, hypertension, stroke, and MI.

Nightmare frequency and severity was assessed using the Davidson Trauma Scale. Nightmares were considered frequent if they occurred two or more times per week and moderate to severe if they were at least moderately distressing. About 31% of veterans reported having frequent nightmares, and 35% reported moderately distressing nightmares over the past week.

After adjusting for age, race, and sex, frequent nightmares were associated with hypertension (odds ratio, 1.51; 95% confidence interval, 1.28-1.78), heart problems (OR, 1.50; 95% CI, 1.11-2.02), and MI (OR, 2.32; 95% CI, 1.18-4.54).

Associations between frequent nightmares and hypertension (OR, 1.43; 95% CI, 1.17-1.73) and heart problems (OR, 1.43; 95% CI, 1.00-2.05) remained significant after further adjusting for smoking, depression, and PTSD.

“Our cross-sectional findings set the stage for future research examining the possibility that nightmares may confer cardiovascular disease risks beyond those conferred by PTSD diagnosis alone,” Dr. Ulmer said in a news release.

Dr. Ulmer also said that, because the study was based on self-reported data, the findings are “very preliminary.” Before doctors adjust clinical practices, it’s important that our findings be replicated using longitudinal studies, clinically diagnosed medical conditions, and objectively assessed sleep,” she said.

She added that more research is needed to uncover mechanisms explaining these associations and determine if reducing the frequency and severity of nightmares can lead to improved cardiovascular health.

Timely research

Reached for comment, Rajkumar (Raj) Dasgupta, MD, of the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, noted “the correlation between nightmares and heart disease is a timely topic right now with COVID-19 as more people may be having nightmares.”

“If a patient mentions nightmares, I do think it’s important not to just glaze over it, but to talk more about it and document it in the patient record, especially in patients with cardiovascular disease, atrial fibrillation, diabetes, and hypertension,” said Dr. Dasgupta, who wasn’t involved in the study.

The research was supported by the Veterans Integrated Service Network 6 Mental Illness Research, Education and Clinical Center and the Department of Veterans Affairs HSR&D ADAPT Center at the Durham VA Health Care System. Dr. Ulmer and Dr. Dasgupta have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

, new research shows. In what researchers describe as “surprising” findings, results from a large study of relatively young military veterans showed those who had nightmares two or more times per week had significantly increased risks for hypertension, myocardial infarction, or other heart problems.

“A diagnosis of PTSD incorporates sleep disturbance as a symptom. Thus, we were surprised to find that nightmares continued to be associated with CVD after controlling not only for PTSD and demographic factors, but also smoking and depression diagnosis,” said Christi Ulmer, PhD, of the department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, N.C.

The findings were presented at the virtual annual meeting of the Associated Professional Sleep Societies.

Unclear mechanism

The study included 3,468 veterans (77% male) with a mean age of 38 years who had served one or two tours of duty since Sept. 11, 2001. Nearly one-third (31%) met criteria for PTSD, and 33% self-reported having at least one cardiovascular condition, such as heart problems, hypertension, stroke, and MI.

Nightmare frequency and severity was assessed using the Davidson Trauma Scale. Nightmares were considered frequent if they occurred two or more times per week and moderate to severe if they were at least moderately distressing. About 31% of veterans reported having frequent nightmares, and 35% reported moderately distressing nightmares over the past week.

After adjusting for age, race, and sex, frequent nightmares were associated with hypertension (odds ratio, 1.51; 95% confidence interval, 1.28-1.78), heart problems (OR, 1.50; 95% CI, 1.11-2.02), and MI (OR, 2.32; 95% CI, 1.18-4.54).

Associations between frequent nightmares and hypertension (OR, 1.43; 95% CI, 1.17-1.73) and heart problems (OR, 1.43; 95% CI, 1.00-2.05) remained significant after further adjusting for smoking, depression, and PTSD.

“Our cross-sectional findings set the stage for future research examining the possibility that nightmares may confer cardiovascular disease risks beyond those conferred by PTSD diagnosis alone,” Dr. Ulmer said in a news release.

Dr. Ulmer also said that, because the study was based on self-reported data, the findings are “very preliminary.” Before doctors adjust clinical practices, it’s important that our findings be replicated using longitudinal studies, clinically diagnosed medical conditions, and objectively assessed sleep,” she said.

She added that more research is needed to uncover mechanisms explaining these associations and determine if reducing the frequency and severity of nightmares can lead to improved cardiovascular health.

Timely research

Reached for comment, Rajkumar (Raj) Dasgupta, MD, of the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, noted “the correlation between nightmares and heart disease is a timely topic right now with COVID-19 as more people may be having nightmares.”

“If a patient mentions nightmares, I do think it’s important not to just glaze over it, but to talk more about it and document it in the patient record, especially in patients with cardiovascular disease, atrial fibrillation, diabetes, and hypertension,” said Dr. Dasgupta, who wasn’t involved in the study.

The research was supported by the Veterans Integrated Service Network 6 Mental Illness Research, Education and Clinical Center and the Department of Veterans Affairs HSR&D ADAPT Center at the Durham VA Health Care System. Dr. Ulmer and Dr. Dasgupta have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM SLEEP 2020

COVID-19 at home: What does optimal care look like?

Marilyn Stebbins, PharmD, fell ill at the end of February 2020. Initially diagnosed with multifocal pneumonia and treated with antibiotics, she later developed severe gastrointestinal symptoms, fatigue, and shortness of breath. She was hospitalized in early March and was diagnosed with COVID-19.

It was still early in the pandemic, and testing was not available for her husband. After she was discharged, her husband isolated himself as much as possible. But that limited the amount of care he could offer.

“When I came home after 8 days in the ICU, I felt completely alone and terrified of not being able to care for myself and not knowing how much care my husband could provide,” said Dr. Stebbins, professor of clinical pharmacy at the University of California, San Francisco.

“I can’t even imagine what it would have been like if I had been home alone without my husband in the house,” she said. “I think about the people who died at home and understand how that might happen.”

Dr. Stebbins is one of tens of thousands of people who, whether hospitalized and discharged or never admitted for inpatient care, needed to find ways to convalesce at home. Data from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services show that, of 326,674 beneficiaries who tested positive for COVID-19 between May 16 and June 11, 2020, 109,607 were hospitalized, suggesting that two-thirds were outpatients.

Most attention has focused on the sickest patients, leaving less severe cases to fall through the cracks. Despite fever, cough, difficulty breathing, and a surfeit of other symptoms, there are few available resources and all too little support to help patients navigate the physical and emotional struggles of contending with COVID-19 at home.

No ‘cookie-cutter’ approach

The speed with which the pandemic progressed caught public health systems off guard, but now, “it is essential to put into place the infrastructure to care for the physical and mental health needs of patients at home because most are in the community and many, if not most, still aren’t receiving sufficient support at home,” said Dr. Stebbins.

said Gary LeRoy, MD, a family physician in Dayton, Ohio. He emphasized that there is “no cookie-cutter formula” for home care, because every patient’s situation is different.

“I begin by having a detailed conversation with each patient to ascertain whether their home environment is safe and to paint a picture of their circumstances,” Dr. LeRoy, who is the president of the American Academy of Family Physicians, said in an interview.

Dr. LeRoy suggested questions that constitute “not just a ‘medical’ checklist but a ‘whole life’ checklist.”

- Do you have access to food, water, medications, sanitation/cleaning supplies, a thermometer, and other necessities? If not, who might assist in providing those?

- Do you need help with activities of daily living and self-care?

- Who else lives in your household? Do they have signs and symptoms of the virus? Have they been tested?

- Do you have enough physical space between you and other household members?

- Do you have children? How are they being cared for?

- What type of work do you do? What are the implications for your employment if you are unable to work for an extended period?

- Do you have an emotional, social, and spiritual support system (e.g., family, friends, community, church)?

- Do you have concerns I haven’t mentioned?

Patients’ responses will inform the management plan and determine what medical and social resources are needed, he said.

Daily check-in

Dr. Stebbins said the nurse case manager from her insurance company called her daily after she came home from the hospital. She was told that a public health nurse would also call, but no one from the health department called for days – a situation she hopes has improved.

One way or another, she said, “health care providers [or their staff] should check in with patients daily, either telephonically or via video.” She noted that video is superior, because “someone who isn’t a family member needs to put eyes on a patient and might be able to detect warning signs that a family member without healthcare training might not notice.”

Dr. LeRoy, who is also an associate professor of medicine at Wright State University, Dayton, Ohio, said that, given his time constraints, a nurse or medical assistant in his practice conducts the daily check-ins and notifies him if the patient has fever or other symptoms.

“Under ordinary circumstances, when a patient comes to see me for some type of medical condition, I get to meet the patient, consider what might be going on, then order a test, wait for the results, and suggest a treatment plan. But these are anything but ordinary circumstances,” said Matthew Exline, MD, a pulmonary and critical care specialist at the Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, Columbus.

“That traditional structure broke down with COVID-19, when we may have test results without even seeing the patient. And without this interaction, it is harder to know as a physician what course of action to take,” he said in an interview.

Once a diagnosis has been made, the physician has at least some data to help guide next steps, even if there has been no prior meeting with the patient.

For example, a positive test raises a host of issues, not the least of which is the risk of spreading the infection to other household members and questions about whether to go the hospital. Moreover, for patients, positive tests can have serious ramifications.

“Severe shortness of breath at rest is not typical of the flu, nor is loss of taste or smell,” said Dr. Exline. Practitioners must educate patients and families about specific symptoms of COVID-19, including shortness of breath, loss of taste or smell, and gastrointestinal or neurologic symptoms, and when to seek emergency care.

Dr. LeRoy suggests buying a pulse oximeter to gauge blood oxygen levels and pulse rate. Together with a thermometer, a portable blood pressure monitor, and, if indicated, a blood glucose monitor, these devices provide a comprehensive and accurate assessment of vital signs.

Dr. LeRoy also educates patients and their families about when to seek medical attention.

Dr. Stebbins takes a similar approach. “Family members are part of, not apart from, the care of patients with COVID-19, and it’s our responsibility as healthcare providers to consider them in the patient’s care plan.”

Keeping family safe

Beyond care, family members need a plan to keep themselves healthy, too.

“A patient with COVID-19 at home should self-quarantine as much as possible to keep other family members safe, if they continue to live in the same house,” Dr. Exline said.

Ideally, uninfected family members should stay with relatives or friends. When that’s not possible, everyone in the household should wear a mask, be vigilant about hand washing, and wipe down all surfaces – including doorknobs, light switches, faucet handles, cellphones, and utensils – regularly with bleach or an alcohol solution.

Caregivers should also minimize the amount of time they are exposed to the patient.

“Set food, water, and medication on the night table and leave the room rather than spending hours at the bedside, since limiting exposure to viral load reduces the chances of contagion,” said Dr. Exline.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention offers guidance for household members caring for COVID-19 patients at home. It provides tips on how to help patients follow the doctor’s instructions and ways to ensure adequate hydration and rest, among others.

Patients with COVID-19 who live alone face more formidable challenges.

Dr. LeRoy says physicians can help patients by educating themselves about available social services in their community so they can provide appropriate referrals and connections. Such initiatives can include meal programs, friendly visit and financial assistance programs, as well as childcare and home health agencies.

He noted that Aunt Bertha, a social care network, provides a guide to social services throughout the United States. Additional resources are available on USA.gov.

Comfort and support

Patients with COVID-19 need to be as comfortable and as supported as possible, both physically and emotionally.

“While I was sick, my dogs curled up next to me and didn’t leave my side, and they were my saving grace. There’s not enough to be said about emotional support,” Dr. Stebbins said.

Although important, emotional support is not enough. For patients with respiratory disorders, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma, heart failure, or pneumonia, their subjective symptoms of shortness of breath, air hunger, or cough may improve with supplemental oxygen at home. Other measures include repositioning of the patient to lessen the body weight over the lungs or the use of lung percussion, Leroy said.

He added that improvement may also come from drainage of sputum from the airway passages, the use of agents to liquefy thick sputum (mucolytics), or aerosolized bronchodilator medications.

However, Dr. LeRoy cautioned, “one remedy does not work for everyone – an individual can improve gradually by using these home support interventions, or their respiratory status can deteriorate rapidly despite all these interventions.”

For this reason, he says patients should consult their personal physician to determine which, if any, of these home treatments would be best for their particular situation.

Patients who need emotional support, psychotherapy, or psychotropic medications may find teletherapy helpful. Guidance for psychiatrists, psychologists, and social workers regarding the treatment of COVID-19 patients via teletherapy can be found on the American Psychiatric Association, the American Psychological Association, and the National Association of Social Workers websites.

Pharmacists can also help ensure patient safety, Dr. Stebbins said.

If a patient has not picked up their usual medications, Dr. Stebbins said, “they may need a check-in call. Some may be ill and alone and may need encouragement to seek medical attention, and some may have no means of getting to the pharmacy and may need medications delivered.”

A home healthcare agency may also be helpful for homebound patients. David Bersson, director of operations at Synergy Home Care of Bergen County, N.J., has arranged in-home caregivers for patients with COVID-19.

The amount of care that professional caregivers provide can range from several hours per week to full-time, depending on the patient’s needs and budget, and can include companionship, Mr. Bersson said in an interview.

Because patient and caregiver safety are paramount, caregivers are thoroughly trained in protection and decontamination procedures and are regularly tested for COVID-19 prior to being sent into a client’s home.

Health insurance companies do not cover this service, Mr. Bersson noted, but the VetAssist program covers home care for veterans and their spouses who meet income requirements.

Caregiving and companionship are both vital pieces of the at-home care puzzle. “It was the virtual emotional support I got from friends, family, coworkers, and healthcare professionals that meant so much to me, and I know they played an important part in my recovery,” Dr. Stebbins said.

Dr. LeRoy agreed, noting that he calls patients, even if they only have mild symptoms and his nurse has already spoken to them. “The call doesn’t take much time – maybe just a 5-minute conversation – but it makes patients aware that I care.”

Dr. Stebbins, Dr. Exline, and Dr. LeRoy report no relevant financial relationships. Mr. Bersson is the director of operations at Synergy Home Care of Bergen County, New Jersey.

This story first appeared on Medscape.com.

Marilyn Stebbins, PharmD, fell ill at the end of February 2020. Initially diagnosed with multifocal pneumonia and treated with antibiotics, she later developed severe gastrointestinal symptoms, fatigue, and shortness of breath. She was hospitalized in early March and was diagnosed with COVID-19.

It was still early in the pandemic, and testing was not available for her husband. After she was discharged, her husband isolated himself as much as possible. But that limited the amount of care he could offer.

“When I came home after 8 days in the ICU, I felt completely alone and terrified of not being able to care for myself and not knowing how much care my husband could provide,” said Dr. Stebbins, professor of clinical pharmacy at the University of California, San Francisco.

“I can’t even imagine what it would have been like if I had been home alone without my husband in the house,” she said. “I think about the people who died at home and understand how that might happen.”

Dr. Stebbins is one of tens of thousands of people who, whether hospitalized and discharged or never admitted for inpatient care, needed to find ways to convalesce at home. Data from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services show that, of 326,674 beneficiaries who tested positive for COVID-19 between May 16 and June 11, 2020, 109,607 were hospitalized, suggesting that two-thirds were outpatients.

Most attention has focused on the sickest patients, leaving less severe cases to fall through the cracks. Despite fever, cough, difficulty breathing, and a surfeit of other symptoms, there are few available resources and all too little support to help patients navigate the physical and emotional struggles of contending with COVID-19 at home.

No ‘cookie-cutter’ approach

The speed with which the pandemic progressed caught public health systems off guard, but now, “it is essential to put into place the infrastructure to care for the physical and mental health needs of patients at home because most are in the community and many, if not most, still aren’t receiving sufficient support at home,” said Dr. Stebbins.

said Gary LeRoy, MD, a family physician in Dayton, Ohio. He emphasized that there is “no cookie-cutter formula” for home care, because every patient’s situation is different.

“I begin by having a detailed conversation with each patient to ascertain whether their home environment is safe and to paint a picture of their circumstances,” Dr. LeRoy, who is the president of the American Academy of Family Physicians, said in an interview.

Dr. LeRoy suggested questions that constitute “not just a ‘medical’ checklist but a ‘whole life’ checklist.”

- Do you have access to food, water, medications, sanitation/cleaning supplies, a thermometer, and other necessities? If not, who might assist in providing those?

- Do you need help with activities of daily living and self-care?

- Who else lives in your household? Do they have signs and symptoms of the virus? Have they been tested?

- Do you have enough physical space between you and other household members?

- Do you have children? How are they being cared for?

- What type of work do you do? What are the implications for your employment if you are unable to work for an extended period?

- Do you have an emotional, social, and spiritual support system (e.g., family, friends, community, church)?

- Do you have concerns I haven’t mentioned?

Patients’ responses will inform the management plan and determine what medical and social resources are needed, he said.

Daily check-in

Dr. Stebbins said the nurse case manager from her insurance company called her daily after she came home from the hospital. She was told that a public health nurse would also call, but no one from the health department called for days – a situation she hopes has improved.

One way or another, she said, “health care providers [or their staff] should check in with patients daily, either telephonically or via video.” She noted that video is superior, because “someone who isn’t a family member needs to put eyes on a patient and might be able to detect warning signs that a family member without healthcare training might not notice.”

Dr. LeRoy, who is also an associate professor of medicine at Wright State University, Dayton, Ohio, said that, given his time constraints, a nurse or medical assistant in his practice conducts the daily check-ins and notifies him if the patient has fever or other symptoms.

“Under ordinary circumstances, when a patient comes to see me for some type of medical condition, I get to meet the patient, consider what might be going on, then order a test, wait for the results, and suggest a treatment plan. But these are anything but ordinary circumstances,” said Matthew Exline, MD, a pulmonary and critical care specialist at the Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, Columbus.

“That traditional structure broke down with COVID-19, when we may have test results without even seeing the patient. And without this interaction, it is harder to know as a physician what course of action to take,” he said in an interview.

Once a diagnosis has been made, the physician has at least some data to help guide next steps, even if there has been no prior meeting with the patient.

For example, a positive test raises a host of issues, not the least of which is the risk of spreading the infection to other household members and questions about whether to go the hospital. Moreover, for patients, positive tests can have serious ramifications.

“Severe shortness of breath at rest is not typical of the flu, nor is loss of taste or smell,” said Dr. Exline. Practitioners must educate patients and families about specific symptoms of COVID-19, including shortness of breath, loss of taste or smell, and gastrointestinal or neurologic symptoms, and when to seek emergency care.

Dr. LeRoy suggests buying a pulse oximeter to gauge blood oxygen levels and pulse rate. Together with a thermometer, a portable blood pressure monitor, and, if indicated, a blood glucose monitor, these devices provide a comprehensive and accurate assessment of vital signs.

Dr. LeRoy also educates patients and their families about when to seek medical attention.

Dr. Stebbins takes a similar approach. “Family members are part of, not apart from, the care of patients with COVID-19, and it’s our responsibility as healthcare providers to consider them in the patient’s care plan.”

Keeping family safe

Beyond care, family members need a plan to keep themselves healthy, too.

“A patient with COVID-19 at home should self-quarantine as much as possible to keep other family members safe, if they continue to live in the same house,” Dr. Exline said.

Ideally, uninfected family members should stay with relatives or friends. When that’s not possible, everyone in the household should wear a mask, be vigilant about hand washing, and wipe down all surfaces – including doorknobs, light switches, faucet handles, cellphones, and utensils – regularly with bleach or an alcohol solution.

Caregivers should also minimize the amount of time they are exposed to the patient.

“Set food, water, and medication on the night table and leave the room rather than spending hours at the bedside, since limiting exposure to viral load reduces the chances of contagion,” said Dr. Exline.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention offers guidance for household members caring for COVID-19 patients at home. It provides tips on how to help patients follow the doctor’s instructions and ways to ensure adequate hydration and rest, among others.

Patients with COVID-19 who live alone face more formidable challenges.

Dr. LeRoy says physicians can help patients by educating themselves about available social services in their community so they can provide appropriate referrals and connections. Such initiatives can include meal programs, friendly visit and financial assistance programs, as well as childcare and home health agencies.

He noted that Aunt Bertha, a social care network, provides a guide to social services throughout the United States. Additional resources are available on USA.gov.

Comfort and support

Patients with COVID-19 need to be as comfortable and as supported as possible, both physically and emotionally.

“While I was sick, my dogs curled up next to me and didn’t leave my side, and they were my saving grace. There’s not enough to be said about emotional support,” Dr. Stebbins said.

Although important, emotional support is not enough. For patients with respiratory disorders, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma, heart failure, or pneumonia, their subjective symptoms of shortness of breath, air hunger, or cough may improve with supplemental oxygen at home. Other measures include repositioning of the patient to lessen the body weight over the lungs or the use of lung percussion, Leroy said.

He added that improvement may also come from drainage of sputum from the airway passages, the use of agents to liquefy thick sputum (mucolytics), or aerosolized bronchodilator medications.

However, Dr. LeRoy cautioned, “one remedy does not work for everyone – an individual can improve gradually by using these home support interventions, or their respiratory status can deteriorate rapidly despite all these interventions.”

For this reason, he says patients should consult their personal physician to determine which, if any, of these home treatments would be best for their particular situation.

Patients who need emotional support, psychotherapy, or psychotropic medications may find teletherapy helpful. Guidance for psychiatrists, psychologists, and social workers regarding the treatment of COVID-19 patients via teletherapy can be found on the American Psychiatric Association, the American Psychological Association, and the National Association of Social Workers websites.

Pharmacists can also help ensure patient safety, Dr. Stebbins said.

If a patient has not picked up their usual medications, Dr. Stebbins said, “they may need a check-in call. Some may be ill and alone and may need encouragement to seek medical attention, and some may have no means of getting to the pharmacy and may need medications delivered.”

A home healthcare agency may also be helpful for homebound patients. David Bersson, director of operations at Synergy Home Care of Bergen County, N.J., has arranged in-home caregivers for patients with COVID-19.

The amount of care that professional caregivers provide can range from several hours per week to full-time, depending on the patient’s needs and budget, and can include companionship, Mr. Bersson said in an interview.

Because patient and caregiver safety are paramount, caregivers are thoroughly trained in protection and decontamination procedures and are regularly tested for COVID-19 prior to being sent into a client’s home.

Health insurance companies do not cover this service, Mr. Bersson noted, but the VetAssist program covers home care for veterans and their spouses who meet income requirements.

Caregiving and companionship are both vital pieces of the at-home care puzzle. “It was the virtual emotional support I got from friends, family, coworkers, and healthcare professionals that meant so much to me, and I know they played an important part in my recovery,” Dr. Stebbins said.

Dr. LeRoy agreed, noting that he calls patients, even if they only have mild symptoms and his nurse has already spoken to them. “The call doesn’t take much time – maybe just a 5-minute conversation – but it makes patients aware that I care.”

Dr. Stebbins, Dr. Exline, and Dr. LeRoy report no relevant financial relationships. Mr. Bersson is the director of operations at Synergy Home Care of Bergen County, New Jersey.

This story first appeared on Medscape.com.

Marilyn Stebbins, PharmD, fell ill at the end of February 2020. Initially diagnosed with multifocal pneumonia and treated with antibiotics, she later developed severe gastrointestinal symptoms, fatigue, and shortness of breath. She was hospitalized in early March and was diagnosed with COVID-19.

It was still early in the pandemic, and testing was not available for her husband. After she was discharged, her husband isolated himself as much as possible. But that limited the amount of care he could offer.

“When I came home after 8 days in the ICU, I felt completely alone and terrified of not being able to care for myself and not knowing how much care my husband could provide,” said Dr. Stebbins, professor of clinical pharmacy at the University of California, San Francisco.

“I can’t even imagine what it would have been like if I had been home alone without my husband in the house,” she said. “I think about the people who died at home and understand how that might happen.”

Dr. Stebbins is one of tens of thousands of people who, whether hospitalized and discharged or never admitted for inpatient care, needed to find ways to convalesce at home. Data from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services show that, of 326,674 beneficiaries who tested positive for COVID-19 between May 16 and June 11, 2020, 109,607 were hospitalized, suggesting that two-thirds were outpatients.

Most attention has focused on the sickest patients, leaving less severe cases to fall through the cracks. Despite fever, cough, difficulty breathing, and a surfeit of other symptoms, there are few available resources and all too little support to help patients navigate the physical and emotional struggles of contending with COVID-19 at home.

No ‘cookie-cutter’ approach

The speed with which the pandemic progressed caught public health systems off guard, but now, “it is essential to put into place the infrastructure to care for the physical and mental health needs of patients at home because most are in the community and many, if not most, still aren’t receiving sufficient support at home,” said Dr. Stebbins.

said Gary LeRoy, MD, a family physician in Dayton, Ohio. He emphasized that there is “no cookie-cutter formula” for home care, because every patient’s situation is different.

“I begin by having a detailed conversation with each patient to ascertain whether their home environment is safe and to paint a picture of their circumstances,” Dr. LeRoy, who is the president of the American Academy of Family Physicians, said in an interview.

Dr. LeRoy suggested questions that constitute “not just a ‘medical’ checklist but a ‘whole life’ checklist.”

- Do you have access to food, water, medications, sanitation/cleaning supplies, a thermometer, and other necessities? If not, who might assist in providing those?

- Do you need help with activities of daily living and self-care?

- Who else lives in your household? Do they have signs and symptoms of the virus? Have they been tested?

- Do you have enough physical space between you and other household members?

- Do you have children? How are they being cared for?

- What type of work do you do? What are the implications for your employment if you are unable to work for an extended period?

- Do you have an emotional, social, and spiritual support system (e.g., family, friends, community, church)?

- Do you have concerns I haven’t mentioned?

Patients’ responses will inform the management plan and determine what medical and social resources are needed, he said.

Daily check-in

Dr. Stebbins said the nurse case manager from her insurance company called her daily after she came home from the hospital. She was told that a public health nurse would also call, but no one from the health department called for days – a situation she hopes has improved.

One way or another, she said, “health care providers [or their staff] should check in with patients daily, either telephonically or via video.” She noted that video is superior, because “someone who isn’t a family member needs to put eyes on a patient and might be able to detect warning signs that a family member without healthcare training might not notice.”

Dr. LeRoy, who is also an associate professor of medicine at Wright State University, Dayton, Ohio, said that, given his time constraints, a nurse or medical assistant in his practice conducts the daily check-ins and notifies him if the patient has fever or other symptoms.

“Under ordinary circumstances, when a patient comes to see me for some type of medical condition, I get to meet the patient, consider what might be going on, then order a test, wait for the results, and suggest a treatment plan. But these are anything but ordinary circumstances,” said Matthew Exline, MD, a pulmonary and critical care specialist at the Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, Columbus.

“That traditional structure broke down with COVID-19, when we may have test results without even seeing the patient. And without this interaction, it is harder to know as a physician what course of action to take,” he said in an interview.

Once a diagnosis has been made, the physician has at least some data to help guide next steps, even if there has been no prior meeting with the patient.

For example, a positive test raises a host of issues, not the least of which is the risk of spreading the infection to other household members and questions about whether to go the hospital. Moreover, for patients, positive tests can have serious ramifications.

“Severe shortness of breath at rest is not typical of the flu, nor is loss of taste or smell,” said Dr. Exline. Practitioners must educate patients and families about specific symptoms of COVID-19, including shortness of breath, loss of taste or smell, and gastrointestinal or neurologic symptoms, and when to seek emergency care.

Dr. LeRoy suggests buying a pulse oximeter to gauge blood oxygen levels and pulse rate. Together with a thermometer, a portable blood pressure monitor, and, if indicated, a blood glucose monitor, these devices provide a comprehensive and accurate assessment of vital signs.

Dr. LeRoy also educates patients and their families about when to seek medical attention.

Dr. Stebbins takes a similar approach. “Family members are part of, not apart from, the care of patients with COVID-19, and it’s our responsibility as healthcare providers to consider them in the patient’s care plan.”

Keeping family safe

Beyond care, family members need a plan to keep themselves healthy, too.

“A patient with COVID-19 at home should self-quarantine as much as possible to keep other family members safe, if they continue to live in the same house,” Dr. Exline said.

Ideally, uninfected family members should stay with relatives or friends. When that’s not possible, everyone in the household should wear a mask, be vigilant about hand washing, and wipe down all surfaces – including doorknobs, light switches, faucet handles, cellphones, and utensils – regularly with bleach or an alcohol solution.

Caregivers should also minimize the amount of time they are exposed to the patient.

“Set food, water, and medication on the night table and leave the room rather than spending hours at the bedside, since limiting exposure to viral load reduces the chances of contagion,” said Dr. Exline.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention offers guidance for household members caring for COVID-19 patients at home. It provides tips on how to help patients follow the doctor’s instructions and ways to ensure adequate hydration and rest, among others.

Patients with COVID-19 who live alone face more formidable challenges.

Dr. LeRoy says physicians can help patients by educating themselves about available social services in their community so they can provide appropriate referrals and connections. Such initiatives can include meal programs, friendly visit and financial assistance programs, as well as childcare and home health agencies.

He noted that Aunt Bertha, a social care network, provides a guide to social services throughout the United States. Additional resources are available on USA.gov.

Comfort and support

Patients with COVID-19 need to be as comfortable and as supported as possible, both physically and emotionally.

“While I was sick, my dogs curled up next to me and didn’t leave my side, and they were my saving grace. There’s not enough to be said about emotional support,” Dr. Stebbins said.

Although important, emotional support is not enough. For patients with respiratory disorders, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma, heart failure, or pneumonia, their subjective symptoms of shortness of breath, air hunger, or cough may improve with supplemental oxygen at home. Other measures include repositioning of the patient to lessen the body weight over the lungs or the use of lung percussion, Leroy said.

He added that improvement may also come from drainage of sputum from the airway passages, the use of agents to liquefy thick sputum (mucolytics), or aerosolized bronchodilator medications.

However, Dr. LeRoy cautioned, “one remedy does not work for everyone – an individual can improve gradually by using these home support interventions, or their respiratory status can deteriorate rapidly despite all these interventions.”

For this reason, he says patients should consult their personal physician to determine which, if any, of these home treatments would be best for their particular situation.

Patients who need emotional support, psychotherapy, or psychotropic medications may find teletherapy helpful. Guidance for psychiatrists, psychologists, and social workers regarding the treatment of COVID-19 patients via teletherapy can be found on the American Psychiatric Association, the American Psychological Association, and the National Association of Social Workers websites.

Pharmacists can also help ensure patient safety, Dr. Stebbins said.

If a patient has not picked up their usual medications, Dr. Stebbins said, “they may need a check-in call. Some may be ill and alone and may need encouragement to seek medical attention, and some may have no means of getting to the pharmacy and may need medications delivered.”

A home healthcare agency may also be helpful for homebound patients. David Bersson, director of operations at Synergy Home Care of Bergen County, N.J., has arranged in-home caregivers for patients with COVID-19.

The amount of care that professional caregivers provide can range from several hours per week to full-time, depending on the patient’s needs and budget, and can include companionship, Mr. Bersson said in an interview.

Because patient and caregiver safety are paramount, caregivers are thoroughly trained in protection and decontamination procedures and are regularly tested for COVID-19 prior to being sent into a client’s home.

Health insurance companies do not cover this service, Mr. Bersson noted, but the VetAssist program covers home care for veterans and their spouses who meet income requirements.

Caregiving and companionship are both vital pieces of the at-home care puzzle. “It was the virtual emotional support I got from friends, family, coworkers, and healthcare professionals that meant so much to me, and I know they played an important part in my recovery,” Dr. Stebbins said.

Dr. LeRoy agreed, noting that he calls patients, even if they only have mild symptoms and his nurse has already spoken to them. “The call doesn’t take much time – maybe just a 5-minute conversation – but it makes patients aware that I care.”

Dr. Stebbins, Dr. Exline, and Dr. LeRoy report no relevant financial relationships. Mr. Bersson is the director of operations at Synergy Home Care of Bergen County, New Jersey.

This story first appeared on Medscape.com.

Mortality burden of dementia may be greater than estimated

This burden may be greatest among non-Hispanic black older adults, compared with Hispanic and non-Hispanic whites. This burden also is significantly greater among people with less than a high school education, compared with those with a college education.

The study results underscore the importance of broadening access to population-based interventions that focus on dementia prevention and care, the investigators wrote. “Future research could examine the extent to which deaths attributable to dementia and underestimation of dementia as an underlying cause of death on death certificates might have changed over time,” wrote Andrew C. Stokes, PhD, assistant professor of global health at the Boston University School of Public Health, and colleagues.

The study was published online Aug. 24 in JAMA Neurology.

In 2019, approximately 5.6 million adults in the United States who were aged 65 years or older had Alzheimer’s disease, vascular dementia, or mixed-cause dementia. A further 18.8% of Americans in this age group had cognitive impairment without dementia (CIND). About one third of patients with CIND may develop Alzheimer’s disease or related dementias (ADRD) within 5 years.

Research suggests that medical examiners significantly underreport ADRD on death certificates. One community-based study, for example, found that only 25% of deaths in patients with dementia had Alzheimer’s disease listed on the death certificates. Other research found that deaths in patients with dementia were often coded using more proximate causes, such as cardiovascular disease, sepsis, and pneumonia.

Health and retirement study

Dr. Stokes and colleagues examined data from the Health and Retirement Study (HRS) to evaluate the association of dementia and CIND with all-cause mortality. The HRS is a longitudinal cohort study of adults older than 50 years who live in the community. Its sample is nationally representative. The HRS investigators also initiated the Aging, Demographics, and Memory study to develop a procedure for assessing cognitive status in the HRS sample.

In their study, Dr. Stokes and colleagues included adults who had been sampled in the 2000 wave of HRS. They focused on participants between ages 70 and 99 years at baseline, and their final sample included 7,342 older adults. To identify dementia status, the researchers used the Langa–Weir score cutoff, which is based on tests of immediate and delayed recall of 10 words, a serial 7-second task, and a backward counting task. They also classified dementia status using the Herzog–Wallace, Wu, Hurd, and modified Hurd algorithms.

At baseline, the researchers measured age, sex, race or ethnicity, educational attainment, smoking status, self-reported disease diagnoses, and U.S. Census division as covariates. The National Center for Health Statistics linked HRS data with National Death Index records. These linked records include underlying cause of death and any mention of a condition or cause of death on the death certificate. The researchers compared the percentage of deaths attributable to ADRD according to a population attributable fraction estimate with the proportion of dementia-related deaths according to underlying causes and with any mention of dementia on death certificates.

The sample of 7,342 older adults included 4,348 (60.3%) women. Data for 1,030 (13.4%) people were reported by proxy. At baseline, most participants (64.0%) were between ages 70 and 79 years, 31% were between ages 80 and 89, and 5% were between ages 90 and 99 years. The prevalence of dementia in the complete sample was 14.3%, and the prevalence of CIND was 24.7%. The prevalence of dementia (22.4%) and CIND (29.3%) was higher among decedents than among the full population.

The hazard ratio (HR) for mortality was 2.53 among participants with dementia and 1.53 among patients with CIND. Although 13.6% of deaths were attributable to dementia, the proportion of deaths assigned to dementia as an underlying cause on death certificates was 5.0%. This discrepancy suggests that dementia is underreported by more than a factor of 2.7.

The mortality burden of dementia was 24.7% in non-Hispanic black older adults, 20.7% in Hispanic white participants, and 12.2% in non-Hispanic white participants. In addition, the mortality burden of dementia was significantly greater among participants with less than a high school education (16.2%) than among participants with a college education (9.8%).

The degree to which the underlying cause of death underestimated the mortality burden of dementia varied by sociodemographic characteristics, health status, and geography. The burden was underestimated by a factor of 7.1 among non-Hispanic black participants, a factor of 4.1 among Hispanic participants, and a factor of 2.3 among non-Hispanic white participants. The burden was underestimated by a factor of 3.5 in men and a factor of 2.4 in women. In addition, the burden was underestimated by a factor of 3.0 among participants with less than a high school education, by a factor of 2.3 among participants with a high school education, by a factor of 1.9 in participants with some college, and by a factor of 2.5 among participants with a college or higher education.

One of the study’s strengths was its population attributable fraction analysis, which reduced the risk of overestimating the mortality burden of dementia, Dr. Stokes and colleagues wrote. Examining CIND is valuable because of its high prevalence and consequent influence on outcomes in the population, even though CIND is associated with a lower mortality risk, they added. Nevertheless, the investigators were unable to assess mortality for dementia subtypes, and the classifications of dementia status and CIND may be subject to measurement error.

Underestimation is systematic

“This study is eye-opening in that it highlights the systematic underestimation of deaths attributable to dementia,” said Costantino Iadecola, MD, Anne Parrish Titzell professor of neurology and director and chair of the Feil Family Brain and Mind Research Institute at Weill Cornell Medicine in New York. The study’s main strength is that it is nationally representative, but the data must be confirmed in a larger population, he added.

The results will clarify the effect of dementia on mortality for neurologists, and geriatricians should be made aware of them, said Dr. Iadecola. “These data should be valuable to rationalize public health efforts and related funding decisions concerning research and community support.”

Further research could determine the mortality of dementia subgroups, “especially dementias linked to vascular factors in which prevention may be effective,” said Dr. Iadecola. “In the older population, vascular factors may play a more preeminent role, and it may help focus preventive approaches.”

The study was supported by a grant from the National Institute on Aging. Dr. Stokes received grants from Ethicon that were unrelated to this study. Dr. Iadecola serves on the scientific advisory board of Broadview Venture.

SOURCE: Stokes AC et al. JAMA Neurol. 2020 Aug 24. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.2831.

This burden may be greatest among non-Hispanic black older adults, compared with Hispanic and non-Hispanic whites. This burden also is significantly greater among people with less than a high school education, compared with those with a college education.

The study results underscore the importance of broadening access to population-based interventions that focus on dementia prevention and care, the investigators wrote. “Future research could examine the extent to which deaths attributable to dementia and underestimation of dementia as an underlying cause of death on death certificates might have changed over time,” wrote Andrew C. Stokes, PhD, assistant professor of global health at the Boston University School of Public Health, and colleagues.

The study was published online Aug. 24 in JAMA Neurology.

In 2019, approximately 5.6 million adults in the United States who were aged 65 years or older had Alzheimer’s disease, vascular dementia, or mixed-cause dementia. A further 18.8% of Americans in this age group had cognitive impairment without dementia (CIND). About one third of patients with CIND may develop Alzheimer’s disease or related dementias (ADRD) within 5 years.

Research suggests that medical examiners significantly underreport ADRD on death certificates. One community-based study, for example, found that only 25% of deaths in patients with dementia had Alzheimer’s disease listed on the death certificates. Other research found that deaths in patients with dementia were often coded using more proximate causes, such as cardiovascular disease, sepsis, and pneumonia.

Health and retirement study

Dr. Stokes and colleagues examined data from the Health and Retirement Study (HRS) to evaluate the association of dementia and CIND with all-cause mortality. The HRS is a longitudinal cohort study of adults older than 50 years who live in the community. Its sample is nationally representative. The HRS investigators also initiated the Aging, Demographics, and Memory study to develop a procedure for assessing cognitive status in the HRS sample.

In their study, Dr. Stokes and colleagues included adults who had been sampled in the 2000 wave of HRS. They focused on participants between ages 70 and 99 years at baseline, and their final sample included 7,342 older adults. To identify dementia status, the researchers used the Langa–Weir score cutoff, which is based on tests of immediate and delayed recall of 10 words, a serial 7-second task, and a backward counting task. They also classified dementia status using the Herzog–Wallace, Wu, Hurd, and modified Hurd algorithms.

At baseline, the researchers measured age, sex, race or ethnicity, educational attainment, smoking status, self-reported disease diagnoses, and U.S. Census division as covariates. The National Center for Health Statistics linked HRS data with National Death Index records. These linked records include underlying cause of death and any mention of a condition or cause of death on the death certificate. The researchers compared the percentage of deaths attributable to ADRD according to a population attributable fraction estimate with the proportion of dementia-related deaths according to underlying causes and with any mention of dementia on death certificates.

The sample of 7,342 older adults included 4,348 (60.3%) women. Data for 1,030 (13.4%) people were reported by proxy. At baseline, most participants (64.0%) were between ages 70 and 79 years, 31% were between ages 80 and 89, and 5% were between ages 90 and 99 years. The prevalence of dementia in the complete sample was 14.3%, and the prevalence of CIND was 24.7%. The prevalence of dementia (22.4%) and CIND (29.3%) was higher among decedents than among the full population.

The hazard ratio (HR) for mortality was 2.53 among participants with dementia and 1.53 among patients with CIND. Although 13.6% of deaths were attributable to dementia, the proportion of deaths assigned to dementia as an underlying cause on death certificates was 5.0%. This discrepancy suggests that dementia is underreported by more than a factor of 2.7.

The mortality burden of dementia was 24.7% in non-Hispanic black older adults, 20.7% in Hispanic white participants, and 12.2% in non-Hispanic white participants. In addition, the mortality burden of dementia was significantly greater among participants with less than a high school education (16.2%) than among participants with a college education (9.8%).

The degree to which the underlying cause of death underestimated the mortality burden of dementia varied by sociodemographic characteristics, health status, and geography. The burden was underestimated by a factor of 7.1 among non-Hispanic black participants, a factor of 4.1 among Hispanic participants, and a factor of 2.3 among non-Hispanic white participants. The burden was underestimated by a factor of 3.5 in men and a factor of 2.4 in women. In addition, the burden was underestimated by a factor of 3.0 among participants with less than a high school education, by a factor of 2.3 among participants with a high school education, by a factor of 1.9 in participants with some college, and by a factor of 2.5 among participants with a college or higher education.

One of the study’s strengths was its population attributable fraction analysis, which reduced the risk of overestimating the mortality burden of dementia, Dr. Stokes and colleagues wrote. Examining CIND is valuable because of its high prevalence and consequent influence on outcomes in the population, even though CIND is associated with a lower mortality risk, they added. Nevertheless, the investigators were unable to assess mortality for dementia subtypes, and the classifications of dementia status and CIND may be subject to measurement error.

Underestimation is systematic

“This study is eye-opening in that it highlights the systematic underestimation of deaths attributable to dementia,” said Costantino Iadecola, MD, Anne Parrish Titzell professor of neurology and director and chair of the Feil Family Brain and Mind Research Institute at Weill Cornell Medicine in New York. The study’s main strength is that it is nationally representative, but the data must be confirmed in a larger population, he added.

The results will clarify the effect of dementia on mortality for neurologists, and geriatricians should be made aware of them, said Dr. Iadecola. “These data should be valuable to rationalize public health efforts and related funding decisions concerning research and community support.”

Further research could determine the mortality of dementia subgroups, “especially dementias linked to vascular factors in which prevention may be effective,” said Dr. Iadecola. “In the older population, vascular factors may play a more preeminent role, and it may help focus preventive approaches.”

The study was supported by a grant from the National Institute on Aging. Dr. Stokes received grants from Ethicon that were unrelated to this study. Dr. Iadecola serves on the scientific advisory board of Broadview Venture.

SOURCE: Stokes AC et al. JAMA Neurol. 2020 Aug 24. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.2831.

This burden may be greatest among non-Hispanic black older adults, compared with Hispanic and non-Hispanic whites. This burden also is significantly greater among people with less than a high school education, compared with those with a college education.

The study results underscore the importance of broadening access to population-based interventions that focus on dementia prevention and care, the investigators wrote. “Future research could examine the extent to which deaths attributable to dementia and underestimation of dementia as an underlying cause of death on death certificates might have changed over time,” wrote Andrew C. Stokes, PhD, assistant professor of global health at the Boston University School of Public Health, and colleagues.

The study was published online Aug. 24 in JAMA Neurology.

In 2019, approximately 5.6 million adults in the United States who were aged 65 years or older had Alzheimer’s disease, vascular dementia, or mixed-cause dementia. A further 18.8% of Americans in this age group had cognitive impairment without dementia (CIND). About one third of patients with CIND may develop Alzheimer’s disease or related dementias (ADRD) within 5 years.

Research suggests that medical examiners significantly underreport ADRD on death certificates. One community-based study, for example, found that only 25% of deaths in patients with dementia had Alzheimer’s disease listed on the death certificates. Other research found that deaths in patients with dementia were often coded using more proximate causes, such as cardiovascular disease, sepsis, and pneumonia.

Health and retirement study

Dr. Stokes and colleagues examined data from the Health and Retirement Study (HRS) to evaluate the association of dementia and CIND with all-cause mortality. The HRS is a longitudinal cohort study of adults older than 50 years who live in the community. Its sample is nationally representative. The HRS investigators also initiated the Aging, Demographics, and Memory study to develop a procedure for assessing cognitive status in the HRS sample.

In their study, Dr. Stokes and colleagues included adults who had been sampled in the 2000 wave of HRS. They focused on participants between ages 70 and 99 years at baseline, and their final sample included 7,342 older adults. To identify dementia status, the researchers used the Langa–Weir score cutoff, which is based on tests of immediate and delayed recall of 10 words, a serial 7-second task, and a backward counting task. They also classified dementia status using the Herzog–Wallace, Wu, Hurd, and modified Hurd algorithms.