User login

FDA approves first oral treatment for spinal muscular atrophy

This marks the first approval of an oral therapy for the rare and devastating condition.

Risdiplam, marketed by Roche and PTC Therapeutics, provides “an important treatment option for patients with SMA, following the approval of the first treatment for this devastating disease less than 4 years ago,” Billy Dunn, MD, director of the Office of Neuroscience in the Center for Drug Evaluation and Research at the FDA, said in a release from the agency.

The approval was based on the results from two trials. In the open-label FIREFISH study of infantile-onset SMA, 7 (41%) of the 17 participants (mean baseline age, 6.7 months) were able to sit independently for more than 5 seconds after 12 months of treatment with risdiplam. This was a “meaningful difference from the natural progression of the disease because all untreated infants with infantile-onset SMA cannot sit independently,” the FDA noted. In addition, 81% of the participants were alive after 23 or more months of treatment – and without need of permanent ventilation.

The second study was the randomized controlled trial known as SUNFISH and included 180 patients with SMA between the ages of 2 and 25 years. Those who received the study drug had an average 1.36 increase from baseline on a motor function measure versus a 0.19 decrease in function for those who received placebo.

The FDA noted that the most common treatment-related adverse events (AEs) include fever, diarrhea, rash, ulcers of the mouth, arthralgia, and urinary tract infections. Additional AEs reported in some patients with infantile-onset SMA included upper respiratory tract infection, pneumonia, constipation, and vomiting.

The drug received fast track designation and priority review from the FDA, as well as orphan drug designation.

‘Eagerly awaited’

“Today marks an incredibly important moment for the broader SMA patient community that had been in dire need of safe and effective treatment options,” Stuart W. Peltz, PhD, chief executive officer of PTC Therapeutics, said in a company statement.

“Given [that] the majority of people with SMA in the U.S. remain untreated, we believe Evrysdi, with its favorable clinical profile and oral administration, may offer meaningful benefits for many living with this rare neurological disease,” Levi Garraway, MD, PhD, chief medical officer and head of global product development for Genentech, added in the company’s press release. Genentech is a member of the Roche Group.

The drug is continuing to be studied in more than 450 individuals as part of a “large and robust clinical trial program in SMA,” the company reports. These participants are between the ages of 2 months and 60 years.

“The approval of Evrysdi is an eagerly awaited milestone for our community. We appreciate Genentech’s commitment to … developing a treatment that can be administered at home,” Kenneth Hobby, president of the nonprofit Cure SMA, said in the same release.

In May 2019, the FDA approved the first gene therapy for SMA – the infusion drug onasemnogene abeparvovec-xioi (Zolgensma, AveXis Inc).

Genentech announced that the new oral drug will be available in the United States within 2 weeks “for direct delivery to patients’ homes.”

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

This marks the first approval of an oral therapy for the rare and devastating condition.

Risdiplam, marketed by Roche and PTC Therapeutics, provides “an important treatment option for patients with SMA, following the approval of the first treatment for this devastating disease less than 4 years ago,” Billy Dunn, MD, director of the Office of Neuroscience in the Center for Drug Evaluation and Research at the FDA, said in a release from the agency.

The approval was based on the results from two trials. In the open-label FIREFISH study of infantile-onset SMA, 7 (41%) of the 17 participants (mean baseline age, 6.7 months) were able to sit independently for more than 5 seconds after 12 months of treatment with risdiplam. This was a “meaningful difference from the natural progression of the disease because all untreated infants with infantile-onset SMA cannot sit independently,” the FDA noted. In addition, 81% of the participants were alive after 23 or more months of treatment – and without need of permanent ventilation.

The second study was the randomized controlled trial known as SUNFISH and included 180 patients with SMA between the ages of 2 and 25 years. Those who received the study drug had an average 1.36 increase from baseline on a motor function measure versus a 0.19 decrease in function for those who received placebo.

The FDA noted that the most common treatment-related adverse events (AEs) include fever, diarrhea, rash, ulcers of the mouth, arthralgia, and urinary tract infections. Additional AEs reported in some patients with infantile-onset SMA included upper respiratory tract infection, pneumonia, constipation, and vomiting.

The drug received fast track designation and priority review from the FDA, as well as orphan drug designation.

‘Eagerly awaited’

“Today marks an incredibly important moment for the broader SMA patient community that had been in dire need of safe and effective treatment options,” Stuart W. Peltz, PhD, chief executive officer of PTC Therapeutics, said in a company statement.

“Given [that] the majority of people with SMA in the U.S. remain untreated, we believe Evrysdi, with its favorable clinical profile and oral administration, may offer meaningful benefits for many living with this rare neurological disease,” Levi Garraway, MD, PhD, chief medical officer and head of global product development for Genentech, added in the company’s press release. Genentech is a member of the Roche Group.

The drug is continuing to be studied in more than 450 individuals as part of a “large and robust clinical trial program in SMA,” the company reports. These participants are between the ages of 2 months and 60 years.

“The approval of Evrysdi is an eagerly awaited milestone for our community. We appreciate Genentech’s commitment to … developing a treatment that can be administered at home,” Kenneth Hobby, president of the nonprofit Cure SMA, said in the same release.

In May 2019, the FDA approved the first gene therapy for SMA – the infusion drug onasemnogene abeparvovec-xioi (Zolgensma, AveXis Inc).

Genentech announced that the new oral drug will be available in the United States within 2 weeks “for direct delivery to patients’ homes.”

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

This marks the first approval of an oral therapy for the rare and devastating condition.

Risdiplam, marketed by Roche and PTC Therapeutics, provides “an important treatment option for patients with SMA, following the approval of the first treatment for this devastating disease less than 4 years ago,” Billy Dunn, MD, director of the Office of Neuroscience in the Center for Drug Evaluation and Research at the FDA, said in a release from the agency.

The approval was based on the results from two trials. In the open-label FIREFISH study of infantile-onset SMA, 7 (41%) of the 17 participants (mean baseline age, 6.7 months) were able to sit independently for more than 5 seconds after 12 months of treatment with risdiplam. This was a “meaningful difference from the natural progression of the disease because all untreated infants with infantile-onset SMA cannot sit independently,” the FDA noted. In addition, 81% of the participants were alive after 23 or more months of treatment – and without need of permanent ventilation.

The second study was the randomized controlled trial known as SUNFISH and included 180 patients with SMA between the ages of 2 and 25 years. Those who received the study drug had an average 1.36 increase from baseline on a motor function measure versus a 0.19 decrease in function for those who received placebo.

The FDA noted that the most common treatment-related adverse events (AEs) include fever, diarrhea, rash, ulcers of the mouth, arthralgia, and urinary tract infections. Additional AEs reported in some patients with infantile-onset SMA included upper respiratory tract infection, pneumonia, constipation, and vomiting.

The drug received fast track designation and priority review from the FDA, as well as orphan drug designation.

‘Eagerly awaited’

“Today marks an incredibly important moment for the broader SMA patient community that had been in dire need of safe and effective treatment options,” Stuart W. Peltz, PhD, chief executive officer of PTC Therapeutics, said in a company statement.

“Given [that] the majority of people with SMA in the U.S. remain untreated, we believe Evrysdi, with its favorable clinical profile and oral administration, may offer meaningful benefits for many living with this rare neurological disease,” Levi Garraway, MD, PhD, chief medical officer and head of global product development for Genentech, added in the company’s press release. Genentech is a member of the Roche Group.

The drug is continuing to be studied in more than 450 individuals as part of a “large and robust clinical trial program in SMA,” the company reports. These participants are between the ages of 2 months and 60 years.

“The approval of Evrysdi is an eagerly awaited milestone for our community. We appreciate Genentech’s commitment to … developing a treatment that can be administered at home,” Kenneth Hobby, president of the nonprofit Cure SMA, said in the same release.

In May 2019, the FDA approved the first gene therapy for SMA – the infusion drug onasemnogene abeparvovec-xioi (Zolgensma, AveXis Inc).

Genentech announced that the new oral drug will be available in the United States within 2 weeks “for direct delivery to patients’ homes.”

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Hypertension often goes undertreated in patients with a history of stroke

A new study of hypertension treatment trends found that “To our knowledge, the present study is the first to analyze and report national antihypertensive medication trends exclusively among individuals with a history of stroke in the United States,” wrote Daniel Santos, MD, and Mandip S. Dhamoon, MD, DrPH, of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York. Their study was published in JAMA Neurology.

To examine blood pressure control and treatment trends among stroke survivors, the researchers examined more than a decade of data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). The cross-sectional survey is conducted in 2-year cycles; the authors analyzed the results from 2005 to 2016 and uncovered a total of 4,971,136 eligible individuals with a history of both stroke and hypertension.

The mean age of the study population was 67.1 (95% confidence interval, 66.1-68.1), and 2,790,518 (56.1%) were women. Their mean blood pressure was 134/68 mm Hg (95% CI, 133/67–136/69), and the average number of antihypertensive medications they were taking was 1.8 (95% CI, 1.7-1.9). Of the 4,971,136 analyzed individuals, 4,721,409 (95%) were aware of their hypertension diagnosis yet more than 10% of that group had not previously been prescribed an antihypertensive medication.

More than 37% (n = 1,846,470) of the participants had uncontrolled high blood pressure upon examination (95% CI, 33.5%-40.8%), and 15.3% (95% CI, 12.5%-18.0%) were not taking any medication for it at all. The most commonly used antihypertensive medications included ACE inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers (59.2%; 95% CI, 54.9%-63.4%), beta-blockers (43.8%; 95% CI, 40.3%-47.3%), diuretics (41.6%; 95% CI, 37.3%-45.9%) and calcium-channel blockers (31.5%; 95% CI, 28.2%-34.8%).* Roughly 57% of the sample was taking more than one antihypertensive medication (95% CI, 52.8%-60.6%) while 28% (95% CI, 24.6%-31.5%) were taking only one.

Continued surveillance is key

“All the studies that have ever been done show that hypertension is inadequately treated,” Louis Caplan, MD, of Harvard Medical School and Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, both in Boston, said in an interview. “One of the reasons is that it can be hard to get some of the patients to seek treatment, particularly Black Americans. Also, a lot of the medicines to treat high blood pressure have side effects, so many patients don’t want to take the pills.

“Treating hypertension really requires continued surveillance,” he added. “It’s not one visit where the doctor gives you a pill. It’s taking the pill, following your blood pressure, and seeing if it works. If it doesn’t, then maybe you change the dose, get another pill, and are followed once again. That doesn’t happen as often as it should.”

In regard to next steps, Dr. Caplan urged that hypertension “be evaluated more seriously. Even as home blood pressure kits and monitoring become increasingly available, many doctors are still going by a casual blood pressure test in the office, which doesn’t tell you how serious the problem is. There needs to be more use of technology and more conditioning of patients to monitor their own blood pressure as a guide, and then we go from there.”

The authors acknowledged their study’s limitations, including the NHANES’s reliance on self-reporting a history of stroke and the inability to distinguish between subtypes of stroke. In addition, they noted that many antihypertensive medications have uses beyond treating hypertension, which introduces “another confounding factor to medication trends.”

The authors and Dr. Caplan reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Santos D et al. JAMA Neurol. 2020 Jul 27. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.2499.

Correction, 8/20/20: An earlier version of this article misstated the confidence interval for diuretics.

A new study of hypertension treatment trends found that “To our knowledge, the present study is the first to analyze and report national antihypertensive medication trends exclusively among individuals with a history of stroke in the United States,” wrote Daniel Santos, MD, and Mandip S. Dhamoon, MD, DrPH, of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York. Their study was published in JAMA Neurology.

To examine blood pressure control and treatment trends among stroke survivors, the researchers examined more than a decade of data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). The cross-sectional survey is conducted in 2-year cycles; the authors analyzed the results from 2005 to 2016 and uncovered a total of 4,971,136 eligible individuals with a history of both stroke and hypertension.

The mean age of the study population was 67.1 (95% confidence interval, 66.1-68.1), and 2,790,518 (56.1%) were women. Their mean blood pressure was 134/68 mm Hg (95% CI, 133/67–136/69), and the average number of antihypertensive medications they were taking was 1.8 (95% CI, 1.7-1.9). Of the 4,971,136 analyzed individuals, 4,721,409 (95%) were aware of their hypertension diagnosis yet more than 10% of that group had not previously been prescribed an antihypertensive medication.

More than 37% (n = 1,846,470) of the participants had uncontrolled high blood pressure upon examination (95% CI, 33.5%-40.8%), and 15.3% (95% CI, 12.5%-18.0%) were not taking any medication for it at all. The most commonly used antihypertensive medications included ACE inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers (59.2%; 95% CI, 54.9%-63.4%), beta-blockers (43.8%; 95% CI, 40.3%-47.3%), diuretics (41.6%; 95% CI, 37.3%-45.9%) and calcium-channel blockers (31.5%; 95% CI, 28.2%-34.8%).* Roughly 57% of the sample was taking more than one antihypertensive medication (95% CI, 52.8%-60.6%) while 28% (95% CI, 24.6%-31.5%) were taking only one.

Continued surveillance is key

“All the studies that have ever been done show that hypertension is inadequately treated,” Louis Caplan, MD, of Harvard Medical School and Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, both in Boston, said in an interview. “One of the reasons is that it can be hard to get some of the patients to seek treatment, particularly Black Americans. Also, a lot of the medicines to treat high blood pressure have side effects, so many patients don’t want to take the pills.

“Treating hypertension really requires continued surveillance,” he added. “It’s not one visit where the doctor gives you a pill. It’s taking the pill, following your blood pressure, and seeing if it works. If it doesn’t, then maybe you change the dose, get another pill, and are followed once again. That doesn’t happen as often as it should.”

In regard to next steps, Dr. Caplan urged that hypertension “be evaluated more seriously. Even as home blood pressure kits and monitoring become increasingly available, many doctors are still going by a casual blood pressure test in the office, which doesn’t tell you how serious the problem is. There needs to be more use of technology and more conditioning of patients to monitor their own blood pressure as a guide, and then we go from there.”

The authors acknowledged their study’s limitations, including the NHANES’s reliance on self-reporting a history of stroke and the inability to distinguish between subtypes of stroke. In addition, they noted that many antihypertensive medications have uses beyond treating hypertension, which introduces “another confounding factor to medication trends.”

The authors and Dr. Caplan reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Santos D et al. JAMA Neurol. 2020 Jul 27. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.2499.

Correction, 8/20/20: An earlier version of this article misstated the confidence interval for diuretics.

A new study of hypertension treatment trends found that “To our knowledge, the present study is the first to analyze and report national antihypertensive medication trends exclusively among individuals with a history of stroke in the United States,” wrote Daniel Santos, MD, and Mandip S. Dhamoon, MD, DrPH, of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York. Their study was published in JAMA Neurology.

To examine blood pressure control and treatment trends among stroke survivors, the researchers examined more than a decade of data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). The cross-sectional survey is conducted in 2-year cycles; the authors analyzed the results from 2005 to 2016 and uncovered a total of 4,971,136 eligible individuals with a history of both stroke and hypertension.

The mean age of the study population was 67.1 (95% confidence interval, 66.1-68.1), and 2,790,518 (56.1%) were women. Their mean blood pressure was 134/68 mm Hg (95% CI, 133/67–136/69), and the average number of antihypertensive medications they were taking was 1.8 (95% CI, 1.7-1.9). Of the 4,971,136 analyzed individuals, 4,721,409 (95%) were aware of their hypertension diagnosis yet more than 10% of that group had not previously been prescribed an antihypertensive medication.

More than 37% (n = 1,846,470) of the participants had uncontrolled high blood pressure upon examination (95% CI, 33.5%-40.8%), and 15.3% (95% CI, 12.5%-18.0%) were not taking any medication for it at all. The most commonly used antihypertensive medications included ACE inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers (59.2%; 95% CI, 54.9%-63.4%), beta-blockers (43.8%; 95% CI, 40.3%-47.3%), diuretics (41.6%; 95% CI, 37.3%-45.9%) and calcium-channel blockers (31.5%; 95% CI, 28.2%-34.8%).* Roughly 57% of the sample was taking more than one antihypertensive medication (95% CI, 52.8%-60.6%) while 28% (95% CI, 24.6%-31.5%) were taking only one.

Continued surveillance is key

“All the studies that have ever been done show that hypertension is inadequately treated,” Louis Caplan, MD, of Harvard Medical School and Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, both in Boston, said in an interview. “One of the reasons is that it can be hard to get some of the patients to seek treatment, particularly Black Americans. Also, a lot of the medicines to treat high blood pressure have side effects, so many patients don’t want to take the pills.

“Treating hypertension really requires continued surveillance,” he added. “It’s not one visit where the doctor gives you a pill. It’s taking the pill, following your blood pressure, and seeing if it works. If it doesn’t, then maybe you change the dose, get another pill, and are followed once again. That doesn’t happen as often as it should.”

In regard to next steps, Dr. Caplan urged that hypertension “be evaluated more seriously. Even as home blood pressure kits and monitoring become increasingly available, many doctors are still going by a casual blood pressure test in the office, which doesn’t tell you how serious the problem is. There needs to be more use of technology and more conditioning of patients to monitor their own blood pressure as a guide, and then we go from there.”

The authors acknowledged their study’s limitations, including the NHANES’s reliance on self-reporting a history of stroke and the inability to distinguish between subtypes of stroke. In addition, they noted that many antihypertensive medications have uses beyond treating hypertension, which introduces “another confounding factor to medication trends.”

The authors and Dr. Caplan reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Santos D et al. JAMA Neurol. 2020 Jul 27. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.2499.

Correction, 8/20/20: An earlier version of this article misstated the confidence interval for diuretics.

FROM JAMA NEUROLOGY

Twelve risk factors linked to 40% of world’s dementia cases

according to an update of the Lancet Commission on Dementia Prevention, Intervention, and Care.

The original report, published in 2017, identified nine modifiable risk factors that were estimated to be responsible for one-third of dementia cases. The commission has now added three new modifiable risk factors to the list.

“We reconvened the 2017 Lancet Commission on Dementia Prevention, Intervention, and Care to identify the evidence for advances likely to have the greatest impact since our 2017 paper,” the authors wrote.

The 2020 report was presented at the virtual annual meeting of the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference (AAIC) 2020 and also was published online July 30 in the Lancet.

Alcohol, TBI, air pollution

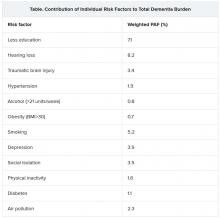

The three new risk factors that have been added in the latest update are excessive alcohol intake, traumatic brain injury (TBI), and air pollution. The original nine risk factors were not completing secondary education; hypertension; obesity; hearing loss; smoking; depression; physical inactivity; social isolation; and diabetes. Together, these 12 risk factors are estimated to account for 40% of the world’s dementia cases.

“We knew in 2017 when we published our first report with the nine risk factors that they would only be part of the story and that several other factors would likely be involved,” said lead author Gill Livingston, MD, professor, University College London (England). “We now have more published data giving enough evidence” to justify adding the three new factors to the list, she said.

The report includes the following nine recommendations for policymakers and individuals to prevent risk for dementia in the general population:

- Aim to maintain systolic blood pressure of 130 mm Hg or less in midlife from around age 40 years.

- Encourage use of hearing aids for hearing loss, and reduce hearing loss by protecting ears from high noise levels.

- Reduce exposure to air pollution and second-hand tobacco smoke.

- Prevent , particularly by targeting high-risk occupations and transport.

- Prevent alcohol misuse and limit drinking to less than 21 units per week.

- Stop smoking and support individuals to stop smoking, which the authors stress is beneficial at any age.

- Provide all children with primary and secondary education.

- Lead an active life into midlife and possibly later life.

- Reduce obesity and diabetes.

The report also summarizes the evidence supporting the three new risk factors for dementia.

TBI is usually caused by car, motorcycle, and bicycle injuries; military exposures; boxing, horse riding, and other recreational sports; firearms; and falls. The report notes that a single severe TBI is associated in humans and in mouse models with widespread hyperphosphorylated tau pathology. It also cites several nationwide studies that show that TBI is linked with a significantly increased risk for long-term dementia.

“We are not advising against partaking in sports, as playing sports is healthy. But we are urging people to take precautions to protect themselves properly,” Dr. Livingston said.

For excessive alcohol consumption, the report states that an “increasing body of evidence is emerging on alcohol’s complex relationship with cognition and dementia outcomes from a variety of sources including detailed cohorts and large-scale record-based studies.” One French study, which included more than 31 million individuals admitted to the hospital, showed that alcohol use disorders were associated with a threefold increased dementia risk. However, other studies have suggested that moderate drinking may be protective.

“We are not saying it is bad to drink, but we are saying it is bad to drink more than 21 units a week,” Dr. Livingston noted.

On air pollution, the report notes that in animal studies, airborne particulate pollutants have been found to accelerate neurodegenerative processes. Also, high nitrogen dioxide concentrations, fine ambient particulate matter from traffic exhaust, and residential wood burning have been shown in past research to be associated with increased dementia incidence.

“While we need international policy on reducing air pollution, individuals can take some action to reduce their risk,” Dr. Livingston said. For example, she suggested avoiding walking right next to busy roads and instead walking “a few streets back if possible.”

Hearing loss

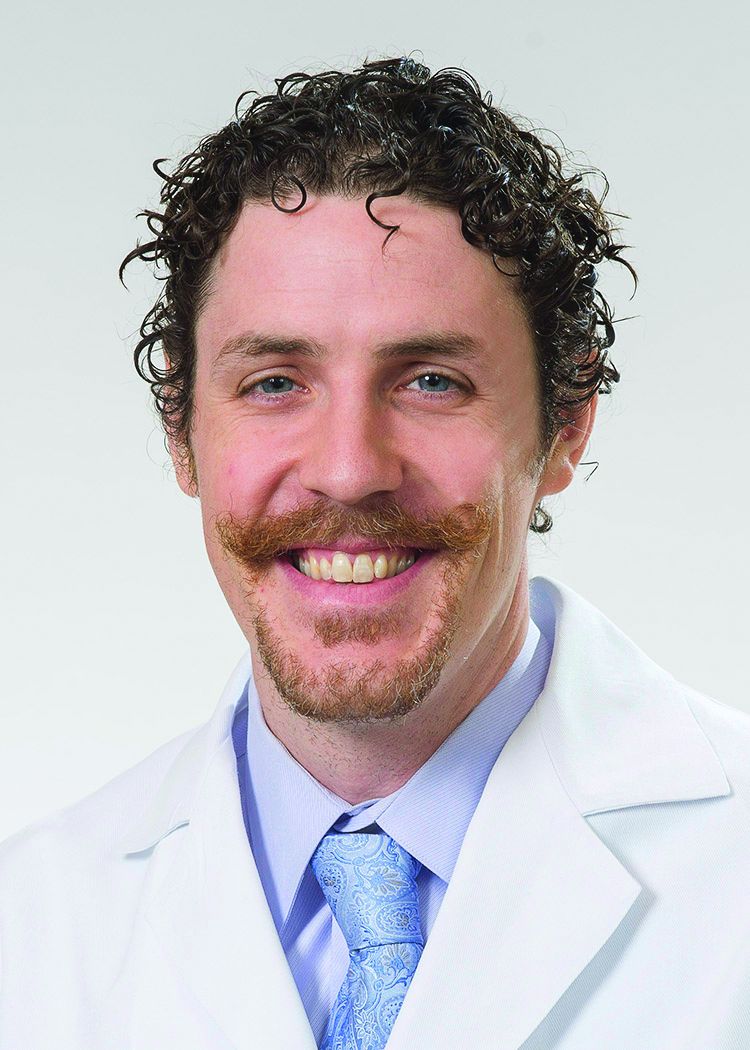

The researchers assessed how much each risk factor contributes to dementia, expressed as the population-attributable fraction (PAF). Hearing loss had the greatest effect, accounting for an estimated 8.2% of dementia cases. This was followed by lower education levels in young people (7.1%) and smoking (5.2%).

Dr. Livingston noted that the evidence that hearing loss is one of the most important risk factors for dementia is very strong. New studies show that correcting hearing loss with hearing aids negates any increased risk.

Hearing loss “has both a high relative risk for dementia and is a common problem, so it contributes a significant amount to dementia cases. This is really something that we can reduce relatively easily by encouraging use of hearing aids. They need to be made more accessible, more comfortable, and more acceptable,” she said.

“This could make a huge difference in reducing dementia cases in the future,” Dr. Livingston added.

Other risk factors for which the evidence base has strengthened since the 2017 report include systolic blood pressure, social interaction, and early-life education.

Dr. Livingston noted that the SPRINT MIND trial showed that aiming for a target systolic blood pressure of 120 mm Hg reduced risk for future mild cognitive impairment. “Before, we thought under 140 was the target, but now are recommending under 130 to reduce risks of dementia,” she said.

Evidence on social interaction “has been very consistent, and we now have more certainty on this. It is now well established that increased social interaction in midlife reduces dementia in late life,” said Dr. Livingston.

On the benefits of education in the young, she noted that it has been known for some time that education for individuals younger than 11 years is important in reducing later-life dementia. However, it is now thought that education to the age of 20 also makes a difference.

“While keeping the brain active in later years has some positive effects, increasing brain activity in young people seems to be more important. This is probably because of the better plasticity of the brain in the young,” she said.

Sleep and diet

Two risk factors that have not made it onto the list are diet and sleep. “While there has also been a lot more data published on nutrition and sleep with regard to dementia in the last few years, we didn’t think the evidence stacked up enough to include these on the list of modifiable risk factors,” Dr. Livingston said.

The report cites studies that suggest that both more sleep and less sleep are associated with increased risk for dementia, which the authors thought did not make “biological sense.” In addition, other underlying factors involved in sleep, such as depression, apathy, and different sleep patterns, may be symptoms of early dementia.

More data have been published on diet and dementia, “but there isn’t any individual vitamin deficit that is associated with the condition. The evidence is quite clear on that,” Dr. Livingston said. “Global diets, such as the Mediterranean or Nordic diets, can probably make a difference, but there doesn’t seem to be any one particular element that is needed,” she noted.

“We just recommend to eat a healthy diet and stay a healthy weight. Diet is very connected to economic circumstances and so very difficult to separate out as a risk factor. We do think it is linked, but we are not convinced enough to put it in the model,” she added.

Among other key information that has become available since 2017, Dr. Livingston highlighted new data showing that dementia is more common in less privileged populations, including Black and minority ethnic groups and low- and middle-income countries.

Although dementia was traditionally considered a disease of high-income countries, that has now been shown not to be the case. “People in low- and middle-income countries are now living longer and so are developing dementia more, and they have higher rates of many of the risk factors, including smoking and low education levels. There is a huge potential for prevention in these countries,” said Dr. Livingston.

She also highlighted new evidence showing that patients with dementia do not do well when admitted to the hospital. “So we need to do more to keep them well at home,” she said.

COVID-19 advice

The report also has a section on COVID-19. It points out that patients with dementia are particularly vulnerable to the disease because of their age, multimorbidities, and difficulties in maintaining physical distancing. Death certificates from the United Kingdom indicate that dementia and Alzheimer’s disease were the most common underlying conditions (present in 25.6% of all deaths involving COVID-19).

The situation is particularly concerning in care homes. In one U.S. study, nursing home residents living with dementia made up 52% of COVID-19 cases, yet they accounted for 72% of all deaths (increased risk, 1.7), the commission reported.

The authors recommended rigorous public health measures, such as protective equipment and hygiene, not moving staff or residents between care homes, and not admitting new residents when their COVID-19 status is unknown. The report also recommends regular testing of staff in care homes and the provision of oxygen therapy at the home to avoid hospital admission.

It is also important to reduce isolation by providing the necessary equipment to relatives and offering them brief training on how to protect themselves and others from COVID-19 so that they can visit their relatives with dementia in nursing homes safely when it is allowed.

“Most comprehensive overview to date”

Alzheimer’s Research UK welcomed the new report. “This is the most comprehensive overview into dementia risk to date, building on previous work by this commission and moving our understanding forward,” Rosa Sancho, PhD, head of research at the charity, said.

“This report underlines the importance of acting at a personal and policy level to reduce dementia risk. With Alzheimer’s Research UK’s Dementia Attitudes Monitor showing just a third of people think it’s possible to reduce their risk of developing dementia, there’s clearly much to do here to increase people’s awareness of the steps they can take,” Dr. Sancho said.

She added that, although there is “no surefire way of preventing dementia,” the best way to keep a brain healthy as it ages is for an individual to stay physically and mentally active, eat a healthy balanced diet, not smoke, drink only within the recommended limits, and keep weight, cholesterol level, and blood pressure in check. “With no treatments yet able to slow or stop the onset of dementia, taking action to reduce these risks is an important part of our strategy for tackling the condition,” Dr. Sancho said.

The Lancet Commission is partnered by University College London, the Alzheimer’s Society UK, the Economic and Social Research Council, and Alzheimer’s Research UK, which funded fares, accommodation, and food for the commission meeting but had no role in the writing of the manuscript or the decision to submit it for publication.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

according to an update of the Lancet Commission on Dementia Prevention, Intervention, and Care.

The original report, published in 2017, identified nine modifiable risk factors that were estimated to be responsible for one-third of dementia cases. The commission has now added three new modifiable risk factors to the list.

“We reconvened the 2017 Lancet Commission on Dementia Prevention, Intervention, and Care to identify the evidence for advances likely to have the greatest impact since our 2017 paper,” the authors wrote.

The 2020 report was presented at the virtual annual meeting of the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference (AAIC) 2020 and also was published online July 30 in the Lancet.

Alcohol, TBI, air pollution

The three new risk factors that have been added in the latest update are excessive alcohol intake, traumatic brain injury (TBI), and air pollution. The original nine risk factors were not completing secondary education; hypertension; obesity; hearing loss; smoking; depression; physical inactivity; social isolation; and diabetes. Together, these 12 risk factors are estimated to account for 40% of the world’s dementia cases.

“We knew in 2017 when we published our first report with the nine risk factors that they would only be part of the story and that several other factors would likely be involved,” said lead author Gill Livingston, MD, professor, University College London (England). “We now have more published data giving enough evidence” to justify adding the three new factors to the list, she said.

The report includes the following nine recommendations for policymakers and individuals to prevent risk for dementia in the general population:

- Aim to maintain systolic blood pressure of 130 mm Hg or less in midlife from around age 40 years.

- Encourage use of hearing aids for hearing loss, and reduce hearing loss by protecting ears from high noise levels.

- Reduce exposure to air pollution and second-hand tobacco smoke.

- Prevent , particularly by targeting high-risk occupations and transport.

- Prevent alcohol misuse and limit drinking to less than 21 units per week.

- Stop smoking and support individuals to stop smoking, which the authors stress is beneficial at any age.

- Provide all children with primary and secondary education.

- Lead an active life into midlife and possibly later life.

- Reduce obesity and diabetes.

The report also summarizes the evidence supporting the three new risk factors for dementia.

TBI is usually caused by car, motorcycle, and bicycle injuries; military exposures; boxing, horse riding, and other recreational sports; firearms; and falls. The report notes that a single severe TBI is associated in humans and in mouse models with widespread hyperphosphorylated tau pathology. It also cites several nationwide studies that show that TBI is linked with a significantly increased risk for long-term dementia.

“We are not advising against partaking in sports, as playing sports is healthy. But we are urging people to take precautions to protect themselves properly,” Dr. Livingston said.

For excessive alcohol consumption, the report states that an “increasing body of evidence is emerging on alcohol’s complex relationship with cognition and dementia outcomes from a variety of sources including detailed cohorts and large-scale record-based studies.” One French study, which included more than 31 million individuals admitted to the hospital, showed that alcohol use disorders were associated with a threefold increased dementia risk. However, other studies have suggested that moderate drinking may be protective.

“We are not saying it is bad to drink, but we are saying it is bad to drink more than 21 units a week,” Dr. Livingston noted.

On air pollution, the report notes that in animal studies, airborne particulate pollutants have been found to accelerate neurodegenerative processes. Also, high nitrogen dioxide concentrations, fine ambient particulate matter from traffic exhaust, and residential wood burning have been shown in past research to be associated with increased dementia incidence.

“While we need international policy on reducing air pollution, individuals can take some action to reduce their risk,” Dr. Livingston said. For example, she suggested avoiding walking right next to busy roads and instead walking “a few streets back if possible.”

Hearing loss

The researchers assessed how much each risk factor contributes to dementia, expressed as the population-attributable fraction (PAF). Hearing loss had the greatest effect, accounting for an estimated 8.2% of dementia cases. This was followed by lower education levels in young people (7.1%) and smoking (5.2%).

Dr. Livingston noted that the evidence that hearing loss is one of the most important risk factors for dementia is very strong. New studies show that correcting hearing loss with hearing aids negates any increased risk.

Hearing loss “has both a high relative risk for dementia and is a common problem, so it contributes a significant amount to dementia cases. This is really something that we can reduce relatively easily by encouraging use of hearing aids. They need to be made more accessible, more comfortable, and more acceptable,” she said.

“This could make a huge difference in reducing dementia cases in the future,” Dr. Livingston added.

Other risk factors for which the evidence base has strengthened since the 2017 report include systolic blood pressure, social interaction, and early-life education.

Dr. Livingston noted that the SPRINT MIND trial showed that aiming for a target systolic blood pressure of 120 mm Hg reduced risk for future mild cognitive impairment. “Before, we thought under 140 was the target, but now are recommending under 130 to reduce risks of dementia,” she said.

Evidence on social interaction “has been very consistent, and we now have more certainty on this. It is now well established that increased social interaction in midlife reduces dementia in late life,” said Dr. Livingston.

On the benefits of education in the young, she noted that it has been known for some time that education for individuals younger than 11 years is important in reducing later-life dementia. However, it is now thought that education to the age of 20 also makes a difference.

“While keeping the brain active in later years has some positive effects, increasing brain activity in young people seems to be more important. This is probably because of the better plasticity of the brain in the young,” she said.

Sleep and diet

Two risk factors that have not made it onto the list are diet and sleep. “While there has also been a lot more data published on nutrition and sleep with regard to dementia in the last few years, we didn’t think the evidence stacked up enough to include these on the list of modifiable risk factors,” Dr. Livingston said.

The report cites studies that suggest that both more sleep and less sleep are associated with increased risk for dementia, which the authors thought did not make “biological sense.” In addition, other underlying factors involved in sleep, such as depression, apathy, and different sleep patterns, may be symptoms of early dementia.

More data have been published on diet and dementia, “but there isn’t any individual vitamin deficit that is associated with the condition. The evidence is quite clear on that,” Dr. Livingston said. “Global diets, such as the Mediterranean or Nordic diets, can probably make a difference, but there doesn’t seem to be any one particular element that is needed,” she noted.

“We just recommend to eat a healthy diet and stay a healthy weight. Diet is very connected to economic circumstances and so very difficult to separate out as a risk factor. We do think it is linked, but we are not convinced enough to put it in the model,” she added.

Among other key information that has become available since 2017, Dr. Livingston highlighted new data showing that dementia is more common in less privileged populations, including Black and minority ethnic groups and low- and middle-income countries.

Although dementia was traditionally considered a disease of high-income countries, that has now been shown not to be the case. “People in low- and middle-income countries are now living longer and so are developing dementia more, and they have higher rates of many of the risk factors, including smoking and low education levels. There is a huge potential for prevention in these countries,” said Dr. Livingston.

She also highlighted new evidence showing that patients with dementia do not do well when admitted to the hospital. “So we need to do more to keep them well at home,” she said.

COVID-19 advice

The report also has a section on COVID-19. It points out that patients with dementia are particularly vulnerable to the disease because of their age, multimorbidities, and difficulties in maintaining physical distancing. Death certificates from the United Kingdom indicate that dementia and Alzheimer’s disease were the most common underlying conditions (present in 25.6% of all deaths involving COVID-19).

The situation is particularly concerning in care homes. In one U.S. study, nursing home residents living with dementia made up 52% of COVID-19 cases, yet they accounted for 72% of all deaths (increased risk, 1.7), the commission reported.

The authors recommended rigorous public health measures, such as protective equipment and hygiene, not moving staff or residents between care homes, and not admitting new residents when their COVID-19 status is unknown. The report also recommends regular testing of staff in care homes and the provision of oxygen therapy at the home to avoid hospital admission.

It is also important to reduce isolation by providing the necessary equipment to relatives and offering them brief training on how to protect themselves and others from COVID-19 so that they can visit their relatives with dementia in nursing homes safely when it is allowed.

“Most comprehensive overview to date”

Alzheimer’s Research UK welcomed the new report. “This is the most comprehensive overview into dementia risk to date, building on previous work by this commission and moving our understanding forward,” Rosa Sancho, PhD, head of research at the charity, said.

“This report underlines the importance of acting at a personal and policy level to reduce dementia risk. With Alzheimer’s Research UK’s Dementia Attitudes Monitor showing just a third of people think it’s possible to reduce their risk of developing dementia, there’s clearly much to do here to increase people’s awareness of the steps they can take,” Dr. Sancho said.

She added that, although there is “no surefire way of preventing dementia,” the best way to keep a brain healthy as it ages is for an individual to stay physically and mentally active, eat a healthy balanced diet, not smoke, drink only within the recommended limits, and keep weight, cholesterol level, and blood pressure in check. “With no treatments yet able to slow or stop the onset of dementia, taking action to reduce these risks is an important part of our strategy for tackling the condition,” Dr. Sancho said.

The Lancet Commission is partnered by University College London, the Alzheimer’s Society UK, the Economic and Social Research Council, and Alzheimer’s Research UK, which funded fares, accommodation, and food for the commission meeting but had no role in the writing of the manuscript or the decision to submit it for publication.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

according to an update of the Lancet Commission on Dementia Prevention, Intervention, and Care.

The original report, published in 2017, identified nine modifiable risk factors that were estimated to be responsible for one-third of dementia cases. The commission has now added three new modifiable risk factors to the list.

“We reconvened the 2017 Lancet Commission on Dementia Prevention, Intervention, and Care to identify the evidence for advances likely to have the greatest impact since our 2017 paper,” the authors wrote.

The 2020 report was presented at the virtual annual meeting of the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference (AAIC) 2020 and also was published online July 30 in the Lancet.

Alcohol, TBI, air pollution

The three new risk factors that have been added in the latest update are excessive alcohol intake, traumatic brain injury (TBI), and air pollution. The original nine risk factors were not completing secondary education; hypertension; obesity; hearing loss; smoking; depression; physical inactivity; social isolation; and diabetes. Together, these 12 risk factors are estimated to account for 40% of the world’s dementia cases.

“We knew in 2017 when we published our first report with the nine risk factors that they would only be part of the story and that several other factors would likely be involved,” said lead author Gill Livingston, MD, professor, University College London (England). “We now have more published data giving enough evidence” to justify adding the three new factors to the list, she said.

The report includes the following nine recommendations for policymakers and individuals to prevent risk for dementia in the general population:

- Aim to maintain systolic blood pressure of 130 mm Hg or less in midlife from around age 40 years.

- Encourage use of hearing aids for hearing loss, and reduce hearing loss by protecting ears from high noise levels.

- Reduce exposure to air pollution and second-hand tobacco smoke.

- Prevent , particularly by targeting high-risk occupations and transport.

- Prevent alcohol misuse and limit drinking to less than 21 units per week.

- Stop smoking and support individuals to stop smoking, which the authors stress is beneficial at any age.

- Provide all children with primary and secondary education.

- Lead an active life into midlife and possibly later life.

- Reduce obesity and diabetes.

The report also summarizes the evidence supporting the three new risk factors for dementia.

TBI is usually caused by car, motorcycle, and bicycle injuries; military exposures; boxing, horse riding, and other recreational sports; firearms; and falls. The report notes that a single severe TBI is associated in humans and in mouse models with widespread hyperphosphorylated tau pathology. It also cites several nationwide studies that show that TBI is linked with a significantly increased risk for long-term dementia.

“We are not advising against partaking in sports, as playing sports is healthy. But we are urging people to take precautions to protect themselves properly,” Dr. Livingston said.

For excessive alcohol consumption, the report states that an “increasing body of evidence is emerging on alcohol’s complex relationship with cognition and dementia outcomes from a variety of sources including detailed cohorts and large-scale record-based studies.” One French study, which included more than 31 million individuals admitted to the hospital, showed that alcohol use disorders were associated with a threefold increased dementia risk. However, other studies have suggested that moderate drinking may be protective.

“We are not saying it is bad to drink, but we are saying it is bad to drink more than 21 units a week,” Dr. Livingston noted.

On air pollution, the report notes that in animal studies, airborne particulate pollutants have been found to accelerate neurodegenerative processes. Also, high nitrogen dioxide concentrations, fine ambient particulate matter from traffic exhaust, and residential wood burning have been shown in past research to be associated with increased dementia incidence.

“While we need international policy on reducing air pollution, individuals can take some action to reduce their risk,” Dr. Livingston said. For example, she suggested avoiding walking right next to busy roads and instead walking “a few streets back if possible.”

Hearing loss

The researchers assessed how much each risk factor contributes to dementia, expressed as the population-attributable fraction (PAF). Hearing loss had the greatest effect, accounting for an estimated 8.2% of dementia cases. This was followed by lower education levels in young people (7.1%) and smoking (5.2%).

Dr. Livingston noted that the evidence that hearing loss is one of the most important risk factors for dementia is very strong. New studies show that correcting hearing loss with hearing aids negates any increased risk.

Hearing loss “has both a high relative risk for dementia and is a common problem, so it contributes a significant amount to dementia cases. This is really something that we can reduce relatively easily by encouraging use of hearing aids. They need to be made more accessible, more comfortable, and more acceptable,” she said.

“This could make a huge difference in reducing dementia cases in the future,” Dr. Livingston added.

Other risk factors for which the evidence base has strengthened since the 2017 report include systolic blood pressure, social interaction, and early-life education.

Dr. Livingston noted that the SPRINT MIND trial showed that aiming for a target systolic blood pressure of 120 mm Hg reduced risk for future mild cognitive impairment. “Before, we thought under 140 was the target, but now are recommending under 130 to reduce risks of dementia,” she said.

Evidence on social interaction “has been very consistent, and we now have more certainty on this. It is now well established that increased social interaction in midlife reduces dementia in late life,” said Dr. Livingston.

On the benefits of education in the young, she noted that it has been known for some time that education for individuals younger than 11 years is important in reducing later-life dementia. However, it is now thought that education to the age of 20 also makes a difference.

“While keeping the brain active in later years has some positive effects, increasing brain activity in young people seems to be more important. This is probably because of the better plasticity of the brain in the young,” she said.

Sleep and diet

Two risk factors that have not made it onto the list are diet and sleep. “While there has also been a lot more data published on nutrition and sleep with regard to dementia in the last few years, we didn’t think the evidence stacked up enough to include these on the list of modifiable risk factors,” Dr. Livingston said.

The report cites studies that suggest that both more sleep and less sleep are associated with increased risk for dementia, which the authors thought did not make “biological sense.” In addition, other underlying factors involved in sleep, such as depression, apathy, and different sleep patterns, may be symptoms of early dementia.

More data have been published on diet and dementia, “but there isn’t any individual vitamin deficit that is associated with the condition. The evidence is quite clear on that,” Dr. Livingston said. “Global diets, such as the Mediterranean or Nordic diets, can probably make a difference, but there doesn’t seem to be any one particular element that is needed,” she noted.

“We just recommend to eat a healthy diet and stay a healthy weight. Diet is very connected to economic circumstances and so very difficult to separate out as a risk factor. We do think it is linked, but we are not convinced enough to put it in the model,” she added.

Among other key information that has become available since 2017, Dr. Livingston highlighted new data showing that dementia is more common in less privileged populations, including Black and minority ethnic groups and low- and middle-income countries.

Although dementia was traditionally considered a disease of high-income countries, that has now been shown not to be the case. “People in low- and middle-income countries are now living longer and so are developing dementia more, and they have higher rates of many of the risk factors, including smoking and low education levels. There is a huge potential for prevention in these countries,” said Dr. Livingston.

She also highlighted new evidence showing that patients with dementia do not do well when admitted to the hospital. “So we need to do more to keep them well at home,” she said.

COVID-19 advice

The report also has a section on COVID-19. It points out that patients with dementia are particularly vulnerable to the disease because of their age, multimorbidities, and difficulties in maintaining physical distancing. Death certificates from the United Kingdom indicate that dementia and Alzheimer’s disease were the most common underlying conditions (present in 25.6% of all deaths involving COVID-19).

The situation is particularly concerning in care homes. In one U.S. study, nursing home residents living with dementia made up 52% of COVID-19 cases, yet they accounted for 72% of all deaths (increased risk, 1.7), the commission reported.

The authors recommended rigorous public health measures, such as protective equipment and hygiene, not moving staff or residents between care homes, and not admitting new residents when their COVID-19 status is unknown. The report also recommends regular testing of staff in care homes and the provision of oxygen therapy at the home to avoid hospital admission.

It is also important to reduce isolation by providing the necessary equipment to relatives and offering them brief training on how to protect themselves and others from COVID-19 so that they can visit their relatives with dementia in nursing homes safely when it is allowed.

“Most comprehensive overview to date”

Alzheimer’s Research UK welcomed the new report. “This is the most comprehensive overview into dementia risk to date, building on previous work by this commission and moving our understanding forward,” Rosa Sancho, PhD, head of research at the charity, said.

“This report underlines the importance of acting at a personal and policy level to reduce dementia risk. With Alzheimer’s Research UK’s Dementia Attitudes Monitor showing just a third of people think it’s possible to reduce their risk of developing dementia, there’s clearly much to do here to increase people’s awareness of the steps they can take,” Dr. Sancho said.

She added that, although there is “no surefire way of preventing dementia,” the best way to keep a brain healthy as it ages is for an individual to stay physically and mentally active, eat a healthy balanced diet, not smoke, drink only within the recommended limits, and keep weight, cholesterol level, and blood pressure in check. “With no treatments yet able to slow or stop the onset of dementia, taking action to reduce these risks is an important part of our strategy for tackling the condition,” Dr. Sancho said.

The Lancet Commission is partnered by University College London, the Alzheimer’s Society UK, the Economic and Social Research Council, and Alzheimer’s Research UK, which funded fares, accommodation, and food for the commission meeting but had no role in the writing of the manuscript or the decision to submit it for publication.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

From AAIC 2020

Inpatient pain management in the era of the opioid epidemic

Hospitalists continue to face challenges balancing appropriate management of acute pain in the inpatient setting with responsible opioid prescribing, particularly with the number of inpatients suffering from both pain and substance use disorders continuing to increase nationwide.

During my virtual session, “Inpatient Management in the Era of the Opioid Epidemic,” I will cover best practices on how to balance appropriate management of acute pain with responsible opioid prescribing and will examine which nonopioid analgesics and nonpharmacologic treatments have been demonstrated to be effective for management of acute pain in hospitalized patients, specifically risk-mitigation strategies designed to increase the number of patients to whom we can safely prescribe nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents.

Additionally, I will cover best practices in treating the hospitalized patient with chronic pain on long-term opioid therapy and managing acute pain in hospitalized patients with opioid use disorder. Real world patient scenarios will be the basis of the session.

Key points to be covered include the following:

- Tips for effective patient communication around pain management in the hospital.

- Responsible opioid prescribing in opioid naive patients, including time of discharge.

- Risk-mitigation strategies for use of NSAID medications for acute pain, including expanded use in patients with risk of GI complications, cardiovascular complications, and chronic kidney disease.

- Review of effective and available nonopioid and nonpharmacologic treatments for acute pain.

- Best practices in managing acute pain in patients with active opioid use disorder.

- Best practices in managing acute pain in patients with opioid use disorder who are treated with opioid agonists.

- Treatment of opioid use disorder in the hospital setting.

Inpatient management in the era of the opioid epidemic

Live Q&A: Wednesday, August 19, 1:00-2:00 p.m. ET

Dr. Vettese is associate professor in the Division of General Medicine and Geriatrics at Emory University School of Medicine.

Hospitalists continue to face challenges balancing appropriate management of acute pain in the inpatient setting with responsible opioid prescribing, particularly with the number of inpatients suffering from both pain and substance use disorders continuing to increase nationwide.

During my virtual session, “Inpatient Management in the Era of the Opioid Epidemic,” I will cover best practices on how to balance appropriate management of acute pain with responsible opioid prescribing and will examine which nonopioid analgesics and nonpharmacologic treatments have been demonstrated to be effective for management of acute pain in hospitalized patients, specifically risk-mitigation strategies designed to increase the number of patients to whom we can safely prescribe nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents.

Additionally, I will cover best practices in treating the hospitalized patient with chronic pain on long-term opioid therapy and managing acute pain in hospitalized patients with opioid use disorder. Real world patient scenarios will be the basis of the session.

Key points to be covered include the following:

- Tips for effective patient communication around pain management in the hospital.

- Responsible opioid prescribing in opioid naive patients, including time of discharge.

- Risk-mitigation strategies for use of NSAID medications for acute pain, including expanded use in patients with risk of GI complications, cardiovascular complications, and chronic kidney disease.

- Review of effective and available nonopioid and nonpharmacologic treatments for acute pain.

- Best practices in managing acute pain in patients with active opioid use disorder.

- Best practices in managing acute pain in patients with opioid use disorder who are treated with opioid agonists.

- Treatment of opioid use disorder in the hospital setting.

Inpatient management in the era of the opioid epidemic

Live Q&A: Wednesday, August 19, 1:00-2:00 p.m. ET

Dr. Vettese is associate professor in the Division of General Medicine and Geriatrics at Emory University School of Medicine.

Hospitalists continue to face challenges balancing appropriate management of acute pain in the inpatient setting with responsible opioid prescribing, particularly with the number of inpatients suffering from both pain and substance use disorders continuing to increase nationwide.

During my virtual session, “Inpatient Management in the Era of the Opioid Epidemic,” I will cover best practices on how to balance appropriate management of acute pain with responsible opioid prescribing and will examine which nonopioid analgesics and nonpharmacologic treatments have been demonstrated to be effective for management of acute pain in hospitalized patients, specifically risk-mitigation strategies designed to increase the number of patients to whom we can safely prescribe nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents.

Additionally, I will cover best practices in treating the hospitalized patient with chronic pain on long-term opioid therapy and managing acute pain in hospitalized patients with opioid use disorder. Real world patient scenarios will be the basis of the session.

Key points to be covered include the following:

- Tips for effective patient communication around pain management in the hospital.

- Responsible opioid prescribing in opioid naive patients, including time of discharge.

- Risk-mitigation strategies for use of NSAID medications for acute pain, including expanded use in patients with risk of GI complications, cardiovascular complications, and chronic kidney disease.

- Review of effective and available nonopioid and nonpharmacologic treatments for acute pain.

- Best practices in managing acute pain in patients with active opioid use disorder.

- Best practices in managing acute pain in patients with opioid use disorder who are treated with opioid agonists.

- Treatment of opioid use disorder in the hospital setting.

Inpatient management in the era of the opioid epidemic

Live Q&A: Wednesday, August 19, 1:00-2:00 p.m. ET

Dr. Vettese is associate professor in the Division of General Medicine and Geriatrics at Emory University School of Medicine.

Cognitive impairment in 9/11 responders tied to brain atrophy

, suggest results from the first structural neuroimaging study conducted in this population. The study clarifies that a neurodegenerative condition is present in first responders who experience cognitive impairment in midlife, which “is incredibly important to know,” said lead author Sean Clouston, PhD, of Stony Brook (N.Y.) University.

The findings were presented at the virtual annual meeting of the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference and were published online in Alzheimer’s and Dementia: Diagnosis, Assessment and Disease Monitoring.

Brain atrophy in midlife

During the 9/11 attack and in its aftermath, WTC responders were exposed to a range of inhaled neurotoxicants, as well as extreme psychosocial stressors. A growing number of WTC responders who are now in their 50s and early 60s are experiencing early cognitive impairment.

Using MRI, the investigators examined cortical thickness (CTX), a surrogate marker for neurodegeneration, in 99 mostly male WTC responders; 48 had cognitive impairment, and 51 did not. The age range of the participants was 45 to 65 years, a range during which cortical atrophy is uncommon in the general population, the researchers noted.

Compared with cognitively normal responders, those with cognitive impairment were found to have reductions in CTX across the whole brain and across 21 of 34 cortical regions, including frontal, temporal, and occipital lobes.

In both cognitively impaired and cognitively unimpaired WTC responders, CTX was reduced in the entorhinal and temporal cortices compared with normative data, but reductions were greater with cognitive impairment. Posttraumatic distress disorder (PTSD) status was not predictive of a reduction in CTX across groups.

Dr. Clouston said the level of reduction in CTX in many responders is similar to that commonly found in patients with dementia and may reflect early-stage dementia occurring in midlife.

Limitations of the study include the small sample size, the cross-sectional design, the unique nature of the exposure, and a lack of a non-WTC external control group.

‘Illuminating’ study

Keith N. Fargo, PhD, director of scientific engagement for the Alzheimer’s Association, called the findings “interesting and illuminating” but cautioned that it is not possible to show cause and effect with this type of study.

“We also don’t know when cortical thinning might have started or how quickly it might be progressing,” Dr. Fargo said in an interview.

He noted that the pattern of cortical thinning is “somewhat consistent with what we see among people who live with high levels of air pollution, which is an emerging risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias.”

The Lancet Commission on Dementia Prevention, Intervention, and Care added air pollution to its list of modifiable risk factors for dementia, which was recently updated.

Clinicians “need to be aware that their middle-aged 9/11 first responders are at a higher risk level for cognitive impairment, as well as PTSD and depression,” Dr. Fargo said.

The study was funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Institute on Aging. Dr. Clouston and Dr. Fargo have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

, suggest results from the first structural neuroimaging study conducted in this population. The study clarifies that a neurodegenerative condition is present in first responders who experience cognitive impairment in midlife, which “is incredibly important to know,” said lead author Sean Clouston, PhD, of Stony Brook (N.Y.) University.

The findings were presented at the virtual annual meeting of the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference and were published online in Alzheimer’s and Dementia: Diagnosis, Assessment and Disease Monitoring.

Brain atrophy in midlife

During the 9/11 attack and in its aftermath, WTC responders were exposed to a range of inhaled neurotoxicants, as well as extreme psychosocial stressors. A growing number of WTC responders who are now in their 50s and early 60s are experiencing early cognitive impairment.

Using MRI, the investigators examined cortical thickness (CTX), a surrogate marker for neurodegeneration, in 99 mostly male WTC responders; 48 had cognitive impairment, and 51 did not. The age range of the participants was 45 to 65 years, a range during which cortical atrophy is uncommon in the general population, the researchers noted.

Compared with cognitively normal responders, those with cognitive impairment were found to have reductions in CTX across the whole brain and across 21 of 34 cortical regions, including frontal, temporal, and occipital lobes.

In both cognitively impaired and cognitively unimpaired WTC responders, CTX was reduced in the entorhinal and temporal cortices compared with normative data, but reductions were greater with cognitive impairment. Posttraumatic distress disorder (PTSD) status was not predictive of a reduction in CTX across groups.

Dr. Clouston said the level of reduction in CTX in many responders is similar to that commonly found in patients with dementia and may reflect early-stage dementia occurring in midlife.

Limitations of the study include the small sample size, the cross-sectional design, the unique nature of the exposure, and a lack of a non-WTC external control group.

‘Illuminating’ study

Keith N. Fargo, PhD, director of scientific engagement for the Alzheimer’s Association, called the findings “interesting and illuminating” but cautioned that it is not possible to show cause and effect with this type of study.

“We also don’t know when cortical thinning might have started or how quickly it might be progressing,” Dr. Fargo said in an interview.

He noted that the pattern of cortical thinning is “somewhat consistent with what we see among people who live with high levels of air pollution, which is an emerging risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias.”

The Lancet Commission on Dementia Prevention, Intervention, and Care added air pollution to its list of modifiable risk factors for dementia, which was recently updated.

Clinicians “need to be aware that their middle-aged 9/11 first responders are at a higher risk level for cognitive impairment, as well as PTSD and depression,” Dr. Fargo said.

The study was funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Institute on Aging. Dr. Clouston and Dr. Fargo have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

, suggest results from the first structural neuroimaging study conducted in this population. The study clarifies that a neurodegenerative condition is present in first responders who experience cognitive impairment in midlife, which “is incredibly important to know,” said lead author Sean Clouston, PhD, of Stony Brook (N.Y.) University.

The findings were presented at the virtual annual meeting of the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference and were published online in Alzheimer’s and Dementia: Diagnosis, Assessment and Disease Monitoring.

Brain atrophy in midlife

During the 9/11 attack and in its aftermath, WTC responders were exposed to a range of inhaled neurotoxicants, as well as extreme psychosocial stressors. A growing number of WTC responders who are now in their 50s and early 60s are experiencing early cognitive impairment.

Using MRI, the investigators examined cortical thickness (CTX), a surrogate marker for neurodegeneration, in 99 mostly male WTC responders; 48 had cognitive impairment, and 51 did not. The age range of the participants was 45 to 65 years, a range during which cortical atrophy is uncommon in the general population, the researchers noted.

Compared with cognitively normal responders, those with cognitive impairment were found to have reductions in CTX across the whole brain and across 21 of 34 cortical regions, including frontal, temporal, and occipital lobes.

In both cognitively impaired and cognitively unimpaired WTC responders, CTX was reduced in the entorhinal and temporal cortices compared with normative data, but reductions were greater with cognitive impairment. Posttraumatic distress disorder (PTSD) status was not predictive of a reduction in CTX across groups.

Dr. Clouston said the level of reduction in CTX in many responders is similar to that commonly found in patients with dementia and may reflect early-stage dementia occurring in midlife.

Limitations of the study include the small sample size, the cross-sectional design, the unique nature of the exposure, and a lack of a non-WTC external control group.

‘Illuminating’ study

Keith N. Fargo, PhD, director of scientific engagement for the Alzheimer’s Association, called the findings “interesting and illuminating” but cautioned that it is not possible to show cause and effect with this type of study.

“We also don’t know when cortical thinning might have started or how quickly it might be progressing,” Dr. Fargo said in an interview.

He noted that the pattern of cortical thinning is “somewhat consistent with what we see among people who live with high levels of air pollution, which is an emerging risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias.”

The Lancet Commission on Dementia Prevention, Intervention, and Care added air pollution to its list of modifiable risk factors for dementia, which was recently updated.

Clinicians “need to be aware that their middle-aged 9/11 first responders are at a higher risk level for cognitive impairment, as well as PTSD and depression,” Dr. Fargo said.

The study was funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Institute on Aging. Dr. Clouston and Dr. Fargo have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

From AAIC 2020

Patent foramen ovale linked with increased risk of ischemic stroke in PE

Background: Studies have demonstrated the increased risk for ischemic stroke in patients diagnosed with acute PE, and data support the mechanism of paradoxical embolism via PFO. However, the frequency of this phenomenon is unknown and the strength of the association between PFO and ischemic stroke in patients with PE is unclear.

Study design: Prospective cohort study.

Setting: Four French hospitals.

Synopsis: 315 patients aged 18 years and older presenting with acute symptomatic PE were evaluated at the time of diagnosis for PFO with contrast transthoracic echocardiography and for ischemic stroke with cerebral magnetic resonance imaging. The overall frequency of ischemic stroke at the time of PE diagnosis was high (7.6%), and was nearly four times higher in the PFO group than the non-PFO group (21.4% vs. 5.5%; difference in proportions, 15.9 percentage points; 95% confidence interval, 4.7-30.7).

This study adds to the growing body of data which supports the association of ischemic stroke with PFO and PE. Given the moderate indication for indefinite anticoagulation in patients at high risk for recurrent PE and stroke, there may be a role for screening for PFO in patients with acute PE so that they can be appropriately risk stratified.

Bottom line: The presence of ischemic stroke in patients with acute pulmonary embolism is high, and there is a strong association with PFO.

Citation: Le Moigne E et al. Patent Foramen Ovale and Ischemic Stroke in Patients With Pulmonary Embolism: A Prospective Cohort Study. Ann Intern Med. 2019;170:756-63.

Dr. McIntyre is a hospitalist at Ochsner Health System, New Orleans.

Background: Studies have demonstrated the increased risk for ischemic stroke in patients diagnosed with acute PE, and data support the mechanism of paradoxical embolism via PFO. However, the frequency of this phenomenon is unknown and the strength of the association between PFO and ischemic stroke in patients with PE is unclear.

Study design: Prospective cohort study.

Setting: Four French hospitals.

Synopsis: 315 patients aged 18 years and older presenting with acute symptomatic PE were evaluated at the time of diagnosis for PFO with contrast transthoracic echocardiography and for ischemic stroke with cerebral magnetic resonance imaging. The overall frequency of ischemic stroke at the time of PE diagnosis was high (7.6%), and was nearly four times higher in the PFO group than the non-PFO group (21.4% vs. 5.5%; difference in proportions, 15.9 percentage points; 95% confidence interval, 4.7-30.7).

This study adds to the growing body of data which supports the association of ischemic stroke with PFO and PE. Given the moderate indication for indefinite anticoagulation in patients at high risk for recurrent PE and stroke, there may be a role for screening for PFO in patients with acute PE so that they can be appropriately risk stratified.

Bottom line: The presence of ischemic stroke in patients with acute pulmonary embolism is high, and there is a strong association with PFO.

Citation: Le Moigne E et al. Patent Foramen Ovale and Ischemic Stroke in Patients With Pulmonary Embolism: A Prospective Cohort Study. Ann Intern Med. 2019;170:756-63.

Dr. McIntyre is a hospitalist at Ochsner Health System, New Orleans.

Background: Studies have demonstrated the increased risk for ischemic stroke in patients diagnosed with acute PE, and data support the mechanism of paradoxical embolism via PFO. However, the frequency of this phenomenon is unknown and the strength of the association between PFO and ischemic stroke in patients with PE is unclear.

Study design: Prospective cohort study.

Setting: Four French hospitals.

Synopsis: 315 patients aged 18 years and older presenting with acute symptomatic PE were evaluated at the time of diagnosis for PFO with contrast transthoracic echocardiography and for ischemic stroke with cerebral magnetic resonance imaging. The overall frequency of ischemic stroke at the time of PE diagnosis was high (7.6%), and was nearly four times higher in the PFO group than the non-PFO group (21.4% vs. 5.5%; difference in proportions, 15.9 percentage points; 95% confidence interval, 4.7-30.7).

This study adds to the growing body of data which supports the association of ischemic stroke with PFO and PE. Given the moderate indication for indefinite anticoagulation in patients at high risk for recurrent PE and stroke, there may be a role for screening for PFO in patients with acute PE so that they can be appropriately risk stratified.

Bottom line: The presence of ischemic stroke in patients with acute pulmonary embolism is high, and there is a strong association with PFO.

Citation: Le Moigne E et al. Patent Foramen Ovale and Ischemic Stroke in Patients With Pulmonary Embolism: A Prospective Cohort Study. Ann Intern Med. 2019;170:756-63.

Dr. McIntyre is a hospitalist at Ochsner Health System, New Orleans.

FDA approves cannabidiol for tuberous sclerosis complex

The cannabidiol (CBD) oral solution Epidiolex has been approved by the Food and Drug Administration for the new indication of treatment of seizures associated with tuberous sclerosis complex in patients 1 year of age and older.

The drug was approved by the FDA in 2018 for the treatment of seizures associated with two rare and severe forms of epilepsy, Lennox-Gastaut syndrome and Dravet syndrome, as reported by Medscape Medical News.