User login

Consider radiologic imaging for high-risk cutaneous SCC, expert advises

DENVER –

In a study published in 2020, Emily Ruiz, MD, MPH, and colleagues identified 87 CSCC tumors in 83 patients who underwent baseline or surveillance imaging primary at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital Mohs Surgery Clinic and the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute High-Risk Skin Cancer Clinic, both in Boston, from Jan. 1, 2017, to June 1, 2019. Of the 87 primary CSCCs, 48 (58%) underwent surveillance imaging. The researchers found that imaging detected additional disease in 26 patients, or 30% of cases, “whether that be nodal metastasis, local invasion beyond what was clinically accepted, or in-transit disease,” Dr. Ruiz, academic director of the Mohs and Dermatologic Surgery Center at Brigham and Women’s, said during the annual meeting of the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery. “But if you look at the 16 nodal metastases in this cohort, all were picked up on imaging and not on clinical exam.”

Since publication of these results, Dr. Ruiz routinely considers baseline radiologic imaging in T2b and T3 tumors; borderline T2a tumors (which she said they are now calling “T2a high,” for those who have one risk factor plus another intermediate risk factor),” and T2a tumors in patients who are profoundly immunosuppressed.

“My preference is to always do [the imaging] before treatment unless I’m up-staging them during surgery,” said Dr. Ruiz, who also directs the High-Risk Skin Cancer Clinic at Dana Farber. “We have picked up nodal metastases before surgery, which enables us to create a good therapeutic plan for our patients before we start operating. Then we image them every 6 months or so for about 2 years. Sometimes we will extend that out to 3 years.”

Some clinicians use sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) as a diagnostic test, but there are mixed results about its prognostic significance. A retrospective observational study of 720 patients with CSCC found that SLNB provided no benefit regarding further metastasis or tumor-specific survival, compared with those who received routine observation and follow-up, “but head and neck surgeons in the U.S. are putting together some prospective data from multiple centers,” Dr. Ruiz said. “I think in the coming years, you will have more multicenter data to inform us as to whether to do SLNB or not.”

Surgery may be the mainstay of treatment for resectable SCC, but the emerging role of neoadjuvant therapeutics is changing the way oncologists treat these tumors. For example, in a phase 2 trial recently published in the New England Journal of Medicine, 79 patients with stage II-IV CSCC received up to four doses of immunotherapy with the programmed death receptor–1 (PD-1) blocker cemiplimab administered every 3 weeks. The primary endpoint was a pathologic complete response, defined as the absence of viable tumor cells in the surgical specimen at a central laboratory. The researchers observed that 68% of patients had an objective response.

“These were patients with localized tumors that were either very aggressive or had nodal metastases,” said Dr, Ruiz, who was the site primary investigator at Dana Farber and a coauthor of the NEJM study. “This has altered the way we approach treating our larger tumors that could be resectable but have a lot of disease either locally or in the nodal basin. We think that we can shrink down the tumor and make it easier to resect, but also there is the possibility or improving outcomes.”

At Brigham and Women’s and the Dana Farber, she and her colleagues consider immunotherapy for multiple recurrent tumors that have been previously irradiated; cases of large tumor burden locally or in the nodal basin; tumors that have a complex surgical plan; cases where there is a low likelihood of achieving clear surgical margins; and cases of in-transit disease.

“We use two to four doses of immunotherapy prior to surgery and assess the tumor response after two doses both clinically and radiologically,” she said. “If the tumor continues to grow, we would do surgery sooner.”

The side-effect profile of immunotherapy is another consideration. “Some patients are not appropriate for a neoadjuvant immunotherapy approach, such as transplant patients,” she said.

According to the latest National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines, surgery with or without adjuvant radiation is the current standard of care for treating CSCC. These guidelines were developed without much data to support the use of radiation, but a 20-year retrospective cohort study at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and the Cleveland Clinic Foundation found that adjuvant radiation following margin resection in high T-stage CSCC cut the risk of local and locoregional recurrence in half.

“This is something that radiation oncologists have told us for years, but there was no data to support it, so it was nice to see that borne out in clinical data,” said Dr. Ruiz, the study’s lead author. The 10% risk of local recurrence observed in the study “may not be high enough for some of our older patients, so we wanted to see if we could identify a group of high tumors that had higher risk of local recurrence,” she said. They found that patients who had a greater than 20% risk of poor outcome were those with recurrent tumors, those with tumors 6 cm or greater in size, and those with all four BWH risk factors (tumor diameter ≥ 2 cm, poorly differentiated histology, perineural invasion ≥ 0.1 mm, or tumor invasion beyond fat excluding bone invasion).

“Those risks were also cut in half if you added radiation,” she said. “So, the way I now approach counseling patients is, I try to estimate their baseline risk as best I can based on the tumor itself. I tell them that if they want to do adjuvant radiation it would cut the risk in half. Some patients are too frail and want to pass on it, while others are very interested.”

Of patients who did not receive radiation but had a disease recurrence, just under half of tumors were salvageable, about 25% died of their disease, and 23% had persistent disease. “I think this does support using radiation earlier on for the appropriate patient,” Dr. Ruiz said. “I consider the baseline risks [and] balance that with the patient’s comorbidities.”

Limited data exists on adjuvant immunotherapy for CSCC, but two ongoing randomized prospective clinical trials underway are studying the PD-1 inhibitors cemiplimab and pembrolizumab versus placebo. “We don’t have data yet, but prior to randomization, patients undergo surgery with macroscopic gross resection of all disease,” Dr. Ruiz said. “All tumors receive ART [adjuvant radiation therapy] prior to randomization”

Dr. Ruiz disclosed that she is a consultant for Sanofi, Regeneron, Genentech, and Jaunce Therapeutics. She is also a member of the advisory board for Checkpoint Therapeutics and is an investigator for Merck, Sanofi, and Regeneron.

DENVER –

In a study published in 2020, Emily Ruiz, MD, MPH, and colleagues identified 87 CSCC tumors in 83 patients who underwent baseline or surveillance imaging primary at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital Mohs Surgery Clinic and the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute High-Risk Skin Cancer Clinic, both in Boston, from Jan. 1, 2017, to June 1, 2019. Of the 87 primary CSCCs, 48 (58%) underwent surveillance imaging. The researchers found that imaging detected additional disease in 26 patients, or 30% of cases, “whether that be nodal metastasis, local invasion beyond what was clinically accepted, or in-transit disease,” Dr. Ruiz, academic director of the Mohs and Dermatologic Surgery Center at Brigham and Women’s, said during the annual meeting of the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery. “But if you look at the 16 nodal metastases in this cohort, all were picked up on imaging and not on clinical exam.”

Since publication of these results, Dr. Ruiz routinely considers baseline radiologic imaging in T2b and T3 tumors; borderline T2a tumors (which she said they are now calling “T2a high,” for those who have one risk factor plus another intermediate risk factor),” and T2a tumors in patients who are profoundly immunosuppressed.

“My preference is to always do [the imaging] before treatment unless I’m up-staging them during surgery,” said Dr. Ruiz, who also directs the High-Risk Skin Cancer Clinic at Dana Farber. “We have picked up nodal metastases before surgery, which enables us to create a good therapeutic plan for our patients before we start operating. Then we image them every 6 months or so for about 2 years. Sometimes we will extend that out to 3 years.”

Some clinicians use sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) as a diagnostic test, but there are mixed results about its prognostic significance. A retrospective observational study of 720 patients with CSCC found that SLNB provided no benefit regarding further metastasis or tumor-specific survival, compared with those who received routine observation and follow-up, “but head and neck surgeons in the U.S. are putting together some prospective data from multiple centers,” Dr. Ruiz said. “I think in the coming years, you will have more multicenter data to inform us as to whether to do SLNB or not.”

Surgery may be the mainstay of treatment for resectable SCC, but the emerging role of neoadjuvant therapeutics is changing the way oncologists treat these tumors. For example, in a phase 2 trial recently published in the New England Journal of Medicine, 79 patients with stage II-IV CSCC received up to four doses of immunotherapy with the programmed death receptor–1 (PD-1) blocker cemiplimab administered every 3 weeks. The primary endpoint was a pathologic complete response, defined as the absence of viable tumor cells in the surgical specimen at a central laboratory. The researchers observed that 68% of patients had an objective response.

“These were patients with localized tumors that were either very aggressive or had nodal metastases,” said Dr, Ruiz, who was the site primary investigator at Dana Farber and a coauthor of the NEJM study. “This has altered the way we approach treating our larger tumors that could be resectable but have a lot of disease either locally or in the nodal basin. We think that we can shrink down the tumor and make it easier to resect, but also there is the possibility or improving outcomes.”

At Brigham and Women’s and the Dana Farber, she and her colleagues consider immunotherapy for multiple recurrent tumors that have been previously irradiated; cases of large tumor burden locally or in the nodal basin; tumors that have a complex surgical plan; cases where there is a low likelihood of achieving clear surgical margins; and cases of in-transit disease.

“We use two to four doses of immunotherapy prior to surgery and assess the tumor response after two doses both clinically and radiologically,” she said. “If the tumor continues to grow, we would do surgery sooner.”

The side-effect profile of immunotherapy is another consideration. “Some patients are not appropriate for a neoadjuvant immunotherapy approach, such as transplant patients,” she said.

According to the latest National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines, surgery with or without adjuvant radiation is the current standard of care for treating CSCC. These guidelines were developed without much data to support the use of radiation, but a 20-year retrospective cohort study at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and the Cleveland Clinic Foundation found that adjuvant radiation following margin resection in high T-stage CSCC cut the risk of local and locoregional recurrence in half.

“This is something that radiation oncologists have told us for years, but there was no data to support it, so it was nice to see that borne out in clinical data,” said Dr. Ruiz, the study’s lead author. The 10% risk of local recurrence observed in the study “may not be high enough for some of our older patients, so we wanted to see if we could identify a group of high tumors that had higher risk of local recurrence,” she said. They found that patients who had a greater than 20% risk of poor outcome were those with recurrent tumors, those with tumors 6 cm or greater in size, and those with all four BWH risk factors (tumor diameter ≥ 2 cm, poorly differentiated histology, perineural invasion ≥ 0.1 mm, or tumor invasion beyond fat excluding bone invasion).

“Those risks were also cut in half if you added radiation,” she said. “So, the way I now approach counseling patients is, I try to estimate their baseline risk as best I can based on the tumor itself. I tell them that if they want to do adjuvant radiation it would cut the risk in half. Some patients are too frail and want to pass on it, while others are very interested.”

Of patients who did not receive radiation but had a disease recurrence, just under half of tumors were salvageable, about 25% died of their disease, and 23% had persistent disease. “I think this does support using radiation earlier on for the appropriate patient,” Dr. Ruiz said. “I consider the baseline risks [and] balance that with the patient’s comorbidities.”

Limited data exists on adjuvant immunotherapy for CSCC, but two ongoing randomized prospective clinical trials underway are studying the PD-1 inhibitors cemiplimab and pembrolizumab versus placebo. “We don’t have data yet, but prior to randomization, patients undergo surgery with macroscopic gross resection of all disease,” Dr. Ruiz said. “All tumors receive ART [adjuvant radiation therapy] prior to randomization”

Dr. Ruiz disclosed that she is a consultant for Sanofi, Regeneron, Genentech, and Jaunce Therapeutics. She is also a member of the advisory board for Checkpoint Therapeutics and is an investigator for Merck, Sanofi, and Regeneron.

DENVER –

In a study published in 2020, Emily Ruiz, MD, MPH, and colleagues identified 87 CSCC tumors in 83 patients who underwent baseline or surveillance imaging primary at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital Mohs Surgery Clinic and the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute High-Risk Skin Cancer Clinic, both in Boston, from Jan. 1, 2017, to June 1, 2019. Of the 87 primary CSCCs, 48 (58%) underwent surveillance imaging. The researchers found that imaging detected additional disease in 26 patients, or 30% of cases, “whether that be nodal metastasis, local invasion beyond what was clinically accepted, or in-transit disease,” Dr. Ruiz, academic director of the Mohs and Dermatologic Surgery Center at Brigham and Women’s, said during the annual meeting of the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery. “But if you look at the 16 nodal metastases in this cohort, all were picked up on imaging and not on clinical exam.”

Since publication of these results, Dr. Ruiz routinely considers baseline radiologic imaging in T2b and T3 tumors; borderline T2a tumors (which she said they are now calling “T2a high,” for those who have one risk factor plus another intermediate risk factor),” and T2a tumors in patients who are profoundly immunosuppressed.

“My preference is to always do [the imaging] before treatment unless I’m up-staging them during surgery,” said Dr. Ruiz, who also directs the High-Risk Skin Cancer Clinic at Dana Farber. “We have picked up nodal metastases before surgery, which enables us to create a good therapeutic plan for our patients before we start operating. Then we image them every 6 months or so for about 2 years. Sometimes we will extend that out to 3 years.”

Some clinicians use sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) as a diagnostic test, but there are mixed results about its prognostic significance. A retrospective observational study of 720 patients with CSCC found that SLNB provided no benefit regarding further metastasis or tumor-specific survival, compared with those who received routine observation and follow-up, “but head and neck surgeons in the U.S. are putting together some prospective data from multiple centers,” Dr. Ruiz said. “I think in the coming years, you will have more multicenter data to inform us as to whether to do SLNB or not.”

Surgery may be the mainstay of treatment for resectable SCC, but the emerging role of neoadjuvant therapeutics is changing the way oncologists treat these tumors. For example, in a phase 2 trial recently published in the New England Journal of Medicine, 79 patients with stage II-IV CSCC received up to four doses of immunotherapy with the programmed death receptor–1 (PD-1) blocker cemiplimab administered every 3 weeks. The primary endpoint was a pathologic complete response, defined as the absence of viable tumor cells in the surgical specimen at a central laboratory. The researchers observed that 68% of patients had an objective response.

“These were patients with localized tumors that were either very aggressive or had nodal metastases,” said Dr, Ruiz, who was the site primary investigator at Dana Farber and a coauthor of the NEJM study. “This has altered the way we approach treating our larger tumors that could be resectable but have a lot of disease either locally or in the nodal basin. We think that we can shrink down the tumor and make it easier to resect, but also there is the possibility or improving outcomes.”

At Brigham and Women’s and the Dana Farber, she and her colleagues consider immunotherapy for multiple recurrent tumors that have been previously irradiated; cases of large tumor burden locally or in the nodal basin; tumors that have a complex surgical plan; cases where there is a low likelihood of achieving clear surgical margins; and cases of in-transit disease.

“We use two to four doses of immunotherapy prior to surgery and assess the tumor response after two doses both clinically and radiologically,” she said. “If the tumor continues to grow, we would do surgery sooner.”

The side-effect profile of immunotherapy is another consideration. “Some patients are not appropriate for a neoadjuvant immunotherapy approach, such as transplant patients,” she said.

According to the latest National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines, surgery with or without adjuvant radiation is the current standard of care for treating CSCC. These guidelines were developed without much data to support the use of radiation, but a 20-year retrospective cohort study at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and the Cleveland Clinic Foundation found that adjuvant radiation following margin resection in high T-stage CSCC cut the risk of local and locoregional recurrence in half.

“This is something that radiation oncologists have told us for years, but there was no data to support it, so it was nice to see that borne out in clinical data,” said Dr. Ruiz, the study’s lead author. The 10% risk of local recurrence observed in the study “may not be high enough for some of our older patients, so we wanted to see if we could identify a group of high tumors that had higher risk of local recurrence,” she said. They found that patients who had a greater than 20% risk of poor outcome were those with recurrent tumors, those with tumors 6 cm or greater in size, and those with all four BWH risk factors (tumor diameter ≥ 2 cm, poorly differentiated histology, perineural invasion ≥ 0.1 mm, or tumor invasion beyond fat excluding bone invasion).

“Those risks were also cut in half if you added radiation,” she said. “So, the way I now approach counseling patients is, I try to estimate their baseline risk as best I can based on the tumor itself. I tell them that if they want to do adjuvant radiation it would cut the risk in half. Some patients are too frail and want to pass on it, while others are very interested.”

Of patients who did not receive radiation but had a disease recurrence, just under half of tumors were salvageable, about 25% died of their disease, and 23% had persistent disease. “I think this does support using radiation earlier on for the appropriate patient,” Dr. Ruiz said. “I consider the baseline risks [and] balance that with the patient’s comorbidities.”

Limited data exists on adjuvant immunotherapy for CSCC, but two ongoing randomized prospective clinical trials underway are studying the PD-1 inhibitors cemiplimab and pembrolizumab versus placebo. “We don’t have data yet, but prior to randomization, patients undergo surgery with macroscopic gross resection of all disease,” Dr. Ruiz said. “All tumors receive ART [adjuvant radiation therapy] prior to randomization”

Dr. Ruiz disclosed that she is a consultant for Sanofi, Regeneron, Genentech, and Jaunce Therapeutics. She is also a member of the advisory board for Checkpoint Therapeutics and is an investigator for Merck, Sanofi, and Regeneron.

AT ASDS 2022

Update on high-grade vulvar interepithelial neoplasia

Vulvar squamous cell carcinomas (VSCC) comprise approximately 90% of all vulvar malignancies. Unlike cervical SCC, which are predominantly human papilloma virus (HPV) positive, only a minority of VSCC are HPV positive – on the order of 15%-25% of cases. Most cases occur in the setting of lichen sclerosus and are HPV negative.

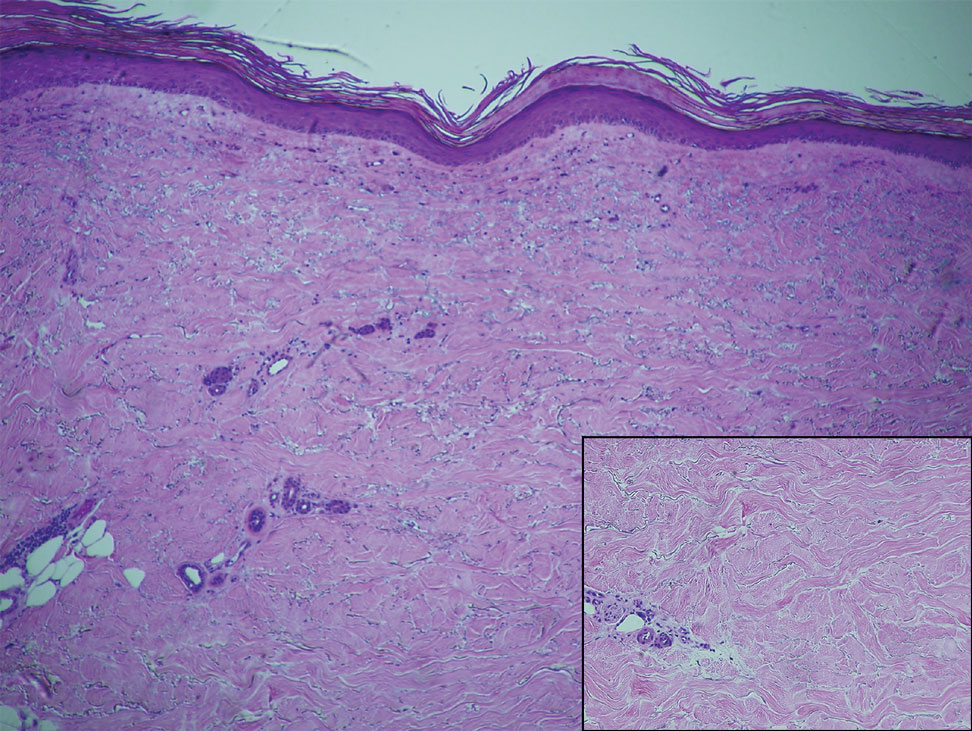

Lichen sclerosus is a chronic inflammatory dermatitis typically involving the anogenital area, which in some cases can become seriously distorted (e.g. atrophy of the labia minora, clitoral phimosis, and introital stenosis). Although most cases are diagnosed in postmenopausal women, LS can affect women of any age. The true prevalence of lichen sclerosus is unknown. Recent studies have shown a prevalence of 1 in 60; among older women, it can even be as high as 1 in 30. While lichen sclerosus is a pruriginous condition, it is often asymptomatic. It is not considered a premalignant condition. The diagnosis is clinical; however, suspicious lesions (erosions/ulcerations, hyperkeratosis, pigmented areas, ecchymosis, warty or papular lesions), particularly when recalcitrant to adequate first-line therapy, should be biopsied.

VSCC arises from precursor lesions or high-grade vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN). The 2015 International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disease nomenclature classifies high-grade VIN into high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HSIL) and differentiated VIN (dVIN). Most patients with high-grade VIN are diagnosed with HSIL or usual type VIN. A preponderance of these lesions (75%-85%) are HPV positive, predominantly HPV 16. Vulvar HSIL (vHSIL) lesions affect younger women. The lesions tend to be multifocal and extensive. On the other hand, dVIN typically affects older women and commonly develops as a solitary lesion. While dVIN accounts for only a small subset of patients with high-grade VIN, these lesions are HPV negative and associated with lichen sclerosus.

Both disease entities, vHSIL and dVIN, are increasing in incidence. There is a higher risk and shortened period of progression to cancer in patients with dVIN compared to HSIL. The cancer risk of vHSIL is relatively low. The 10-year cumulative VSCC risk reported in the literature is 10.3%; 9.7% for vHSIL and 50% for dVIN. Patients with vHSIL could benefit from less aggressive treatment modalities.

Patients present with a constellation of signs such as itching, pain, burning, bleeding, and discharge. Chronic symptoms portend HPV-independent lesions associated with lichen sclerosus while episodic signs are suggestive of HPV-positive lesions.

The recurrence risk of high-grade VIN is 46%-70%. Risk factors for recurrence include age greater than 50, immunosuppression, metasynchronous HSIL, and multifocal lesions. Recurrences occur in up to 50% of women who have undergone surgery. For those who undergo surgical treatment for high-grade VIN, recurrence is more common in the setting of positive margins, underlying lichen sclerosis, persistent HPV infection, and immunosuppression.

Management of high-grade VIN is determined by the lesion characteristics, patient characteristics, and medical expertise. Given the risk of progression of high-grade VIN to cancer and risk of underlying cancer, surgical therapy is typically recommended. The treatment of choice is surgical excision in cases of dVIN. Surgical treatments include CO2 laser ablation, wide local excision, and vulvectomy. Women who undergo surgical treatment for vHSIL have about a 50% chance of the condition recurring 1 year later, irrespective of whether treatment is by surgical excision or laser vaporization.

Since surgery can be associated with disfigurement and sexual dysfunction, alternatives to surgery should be considered in cases of vHSIL. The potential for effect on sexual function should be part of preoperative counseling and treatment. Women treated for VIN often experience increased inhibition of sexual excitement and increased inhibition of orgasm. One study found that in women undergoing vulvar excision for VIN, the impairment was found to be psychological in nature. Overall, the studies of sexual effect from treatment of VIN have found that women do not return to their pretreatment sexual function. However, the optimal management of vHSIL has not been determined. Nonsurgical options include topical therapies (imiquimod, 5-fluorouracil, cidofovir, and interferon) and nonpharmacologic treatments, such as photodynamic therapy.

Imiquimod, a topical immune modulator, is the most studied pharmacologic treatment of vHSIL. The drug induces secretion of cytokines, creating an immune response that clears the HPV infection. Imiquimod is safe and well tolerated. The clinical response rate varies between 35% and 81%. A recent study demonstrated the efficacy of imiquimod and the treatment was found to be noninferior to surgery. Adverse events differed, with local pain following surgical treatment and local pruritus and erythema associated with imiquimod use. Some patients did not respond to imiquimod; it was thought by the authors of the study that specific immunological factors affect the clinical response.

In conclusion, high-grade VIN is a heterogeneous disease made up of two distinct disease entities with rising incidence. In contrast to dVIN, the cancer risk is low for patients with vHSIL. Treatment should be driven by the clinical characteristics of the vulvar lesions, patients’ preferences, sexual activity, and compliance. Future directions include risk stratification of patients with vHSIL who are most likely to benefit from topical treatments, thus reducing overtreatment. Molecular biomarkers that could identify dVIN at an early stage are needed.

Dr. Jackson-Moore is associate professor in gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Tucker is assistant professor of gynecologic oncology at the university.

References

Cendejas BR et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015 Mar;212(3):291-7.

Lebreton M et al. J Gynecol Obstet Hum Reprod. 2020 Nov;49(9):101801.

Thuijs NB et al. Int J Cancer. 2021 Jan 1;148(1):90-8. doi: 10.1002/ijc.33198. .

Trutnovsky G et al. Lancet. 2022 May 7;399(10337):1790-8. Erratum in: Lancet. 2022 Oct 8;400(10359):1194.

Vulvar squamous cell carcinomas (VSCC) comprise approximately 90% of all vulvar malignancies. Unlike cervical SCC, which are predominantly human papilloma virus (HPV) positive, only a minority of VSCC are HPV positive – on the order of 15%-25% of cases. Most cases occur in the setting of lichen sclerosus and are HPV negative.

Lichen sclerosus is a chronic inflammatory dermatitis typically involving the anogenital area, which in some cases can become seriously distorted (e.g. atrophy of the labia minora, clitoral phimosis, and introital stenosis). Although most cases are diagnosed in postmenopausal women, LS can affect women of any age. The true prevalence of lichen sclerosus is unknown. Recent studies have shown a prevalence of 1 in 60; among older women, it can even be as high as 1 in 30. While lichen sclerosus is a pruriginous condition, it is often asymptomatic. It is not considered a premalignant condition. The diagnosis is clinical; however, suspicious lesions (erosions/ulcerations, hyperkeratosis, pigmented areas, ecchymosis, warty or papular lesions), particularly when recalcitrant to adequate first-line therapy, should be biopsied.

VSCC arises from precursor lesions or high-grade vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN). The 2015 International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disease nomenclature classifies high-grade VIN into high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HSIL) and differentiated VIN (dVIN). Most patients with high-grade VIN are diagnosed with HSIL or usual type VIN. A preponderance of these lesions (75%-85%) are HPV positive, predominantly HPV 16. Vulvar HSIL (vHSIL) lesions affect younger women. The lesions tend to be multifocal and extensive. On the other hand, dVIN typically affects older women and commonly develops as a solitary lesion. While dVIN accounts for only a small subset of patients with high-grade VIN, these lesions are HPV negative and associated with lichen sclerosus.

Both disease entities, vHSIL and dVIN, are increasing in incidence. There is a higher risk and shortened period of progression to cancer in patients with dVIN compared to HSIL. The cancer risk of vHSIL is relatively low. The 10-year cumulative VSCC risk reported in the literature is 10.3%; 9.7% for vHSIL and 50% for dVIN. Patients with vHSIL could benefit from less aggressive treatment modalities.

Patients present with a constellation of signs such as itching, pain, burning, bleeding, and discharge. Chronic symptoms portend HPV-independent lesions associated with lichen sclerosus while episodic signs are suggestive of HPV-positive lesions.

The recurrence risk of high-grade VIN is 46%-70%. Risk factors for recurrence include age greater than 50, immunosuppression, metasynchronous HSIL, and multifocal lesions. Recurrences occur in up to 50% of women who have undergone surgery. For those who undergo surgical treatment for high-grade VIN, recurrence is more common in the setting of positive margins, underlying lichen sclerosis, persistent HPV infection, and immunosuppression.

Management of high-grade VIN is determined by the lesion characteristics, patient characteristics, and medical expertise. Given the risk of progression of high-grade VIN to cancer and risk of underlying cancer, surgical therapy is typically recommended. The treatment of choice is surgical excision in cases of dVIN. Surgical treatments include CO2 laser ablation, wide local excision, and vulvectomy. Women who undergo surgical treatment for vHSIL have about a 50% chance of the condition recurring 1 year later, irrespective of whether treatment is by surgical excision or laser vaporization.

Since surgery can be associated with disfigurement and sexual dysfunction, alternatives to surgery should be considered in cases of vHSIL. The potential for effect on sexual function should be part of preoperative counseling and treatment. Women treated for VIN often experience increased inhibition of sexual excitement and increased inhibition of orgasm. One study found that in women undergoing vulvar excision for VIN, the impairment was found to be psychological in nature. Overall, the studies of sexual effect from treatment of VIN have found that women do not return to their pretreatment sexual function. However, the optimal management of vHSIL has not been determined. Nonsurgical options include topical therapies (imiquimod, 5-fluorouracil, cidofovir, and interferon) and nonpharmacologic treatments, such as photodynamic therapy.

Imiquimod, a topical immune modulator, is the most studied pharmacologic treatment of vHSIL. The drug induces secretion of cytokines, creating an immune response that clears the HPV infection. Imiquimod is safe and well tolerated. The clinical response rate varies between 35% and 81%. A recent study demonstrated the efficacy of imiquimod and the treatment was found to be noninferior to surgery. Adverse events differed, with local pain following surgical treatment and local pruritus and erythema associated with imiquimod use. Some patients did not respond to imiquimod; it was thought by the authors of the study that specific immunological factors affect the clinical response.

In conclusion, high-grade VIN is a heterogeneous disease made up of two distinct disease entities with rising incidence. In contrast to dVIN, the cancer risk is low for patients with vHSIL. Treatment should be driven by the clinical characteristics of the vulvar lesions, patients’ preferences, sexual activity, and compliance. Future directions include risk stratification of patients with vHSIL who are most likely to benefit from topical treatments, thus reducing overtreatment. Molecular biomarkers that could identify dVIN at an early stage are needed.

Dr. Jackson-Moore is associate professor in gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Tucker is assistant professor of gynecologic oncology at the university.

References

Cendejas BR et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015 Mar;212(3):291-7.

Lebreton M et al. J Gynecol Obstet Hum Reprod. 2020 Nov;49(9):101801.

Thuijs NB et al. Int J Cancer. 2021 Jan 1;148(1):90-8. doi: 10.1002/ijc.33198. .

Trutnovsky G et al. Lancet. 2022 May 7;399(10337):1790-8. Erratum in: Lancet. 2022 Oct 8;400(10359):1194.

Vulvar squamous cell carcinomas (VSCC) comprise approximately 90% of all vulvar malignancies. Unlike cervical SCC, which are predominantly human papilloma virus (HPV) positive, only a minority of VSCC are HPV positive – on the order of 15%-25% of cases. Most cases occur in the setting of lichen sclerosus and are HPV negative.

Lichen sclerosus is a chronic inflammatory dermatitis typically involving the anogenital area, which in some cases can become seriously distorted (e.g. atrophy of the labia minora, clitoral phimosis, and introital stenosis). Although most cases are diagnosed in postmenopausal women, LS can affect women of any age. The true prevalence of lichen sclerosus is unknown. Recent studies have shown a prevalence of 1 in 60; among older women, it can even be as high as 1 in 30. While lichen sclerosus is a pruriginous condition, it is often asymptomatic. It is not considered a premalignant condition. The diagnosis is clinical; however, suspicious lesions (erosions/ulcerations, hyperkeratosis, pigmented areas, ecchymosis, warty or papular lesions), particularly when recalcitrant to adequate first-line therapy, should be biopsied.

VSCC arises from precursor lesions or high-grade vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN). The 2015 International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disease nomenclature classifies high-grade VIN into high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HSIL) and differentiated VIN (dVIN). Most patients with high-grade VIN are diagnosed with HSIL or usual type VIN. A preponderance of these lesions (75%-85%) are HPV positive, predominantly HPV 16. Vulvar HSIL (vHSIL) lesions affect younger women. The lesions tend to be multifocal and extensive. On the other hand, dVIN typically affects older women and commonly develops as a solitary lesion. While dVIN accounts for only a small subset of patients with high-grade VIN, these lesions are HPV negative and associated with lichen sclerosus.

Both disease entities, vHSIL and dVIN, are increasing in incidence. There is a higher risk and shortened period of progression to cancer in patients with dVIN compared to HSIL. The cancer risk of vHSIL is relatively low. The 10-year cumulative VSCC risk reported in the literature is 10.3%; 9.7% for vHSIL and 50% for dVIN. Patients with vHSIL could benefit from less aggressive treatment modalities.

Patients present with a constellation of signs such as itching, pain, burning, bleeding, and discharge. Chronic symptoms portend HPV-independent lesions associated with lichen sclerosus while episodic signs are suggestive of HPV-positive lesions.

The recurrence risk of high-grade VIN is 46%-70%. Risk factors for recurrence include age greater than 50, immunosuppression, metasynchronous HSIL, and multifocal lesions. Recurrences occur in up to 50% of women who have undergone surgery. For those who undergo surgical treatment for high-grade VIN, recurrence is more common in the setting of positive margins, underlying lichen sclerosis, persistent HPV infection, and immunosuppression.

Management of high-grade VIN is determined by the lesion characteristics, patient characteristics, and medical expertise. Given the risk of progression of high-grade VIN to cancer and risk of underlying cancer, surgical therapy is typically recommended. The treatment of choice is surgical excision in cases of dVIN. Surgical treatments include CO2 laser ablation, wide local excision, and vulvectomy. Women who undergo surgical treatment for vHSIL have about a 50% chance of the condition recurring 1 year later, irrespective of whether treatment is by surgical excision or laser vaporization.

Since surgery can be associated with disfigurement and sexual dysfunction, alternatives to surgery should be considered in cases of vHSIL. The potential for effect on sexual function should be part of preoperative counseling and treatment. Women treated for VIN often experience increased inhibition of sexual excitement and increased inhibition of orgasm. One study found that in women undergoing vulvar excision for VIN, the impairment was found to be psychological in nature. Overall, the studies of sexual effect from treatment of VIN have found that women do not return to their pretreatment sexual function. However, the optimal management of vHSIL has not been determined. Nonsurgical options include topical therapies (imiquimod, 5-fluorouracil, cidofovir, and interferon) and nonpharmacologic treatments, such as photodynamic therapy.

Imiquimod, a topical immune modulator, is the most studied pharmacologic treatment of vHSIL. The drug induces secretion of cytokines, creating an immune response that clears the HPV infection. Imiquimod is safe and well tolerated. The clinical response rate varies between 35% and 81%. A recent study demonstrated the efficacy of imiquimod and the treatment was found to be noninferior to surgery. Adverse events differed, with local pain following surgical treatment and local pruritus and erythema associated with imiquimod use. Some patients did not respond to imiquimod; it was thought by the authors of the study that specific immunological factors affect the clinical response.

In conclusion, high-grade VIN is a heterogeneous disease made up of two distinct disease entities with rising incidence. In contrast to dVIN, the cancer risk is low for patients with vHSIL. Treatment should be driven by the clinical characteristics of the vulvar lesions, patients’ preferences, sexual activity, and compliance. Future directions include risk stratification of patients with vHSIL who are most likely to benefit from topical treatments, thus reducing overtreatment. Molecular biomarkers that could identify dVIN at an early stage are needed.

Dr. Jackson-Moore is associate professor in gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Tucker is assistant professor of gynecologic oncology at the university.

References

Cendejas BR et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015 Mar;212(3):291-7.

Lebreton M et al. J Gynecol Obstet Hum Reprod. 2020 Nov;49(9):101801.

Thuijs NB et al. Int J Cancer. 2021 Jan 1;148(1):90-8. doi: 10.1002/ijc.33198. .

Trutnovsky G et al. Lancet. 2022 May 7;399(10337):1790-8. Erratum in: Lancet. 2022 Oct 8;400(10359):1194.

Simplify Postoperative Self-removal of Bandages for Isolated Patients With Limited Range of Motion Using Pull Tabs

Practice Gap

A male patient presented with 2 concerning lesions, which histopathology revealed were invasive squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) on the right medial chest and SCC in situ on the right upper scapular region. Both were treated with wide local excision; margins were clear in our office the same day.

This case highlighted a practice gap in postoperative care. Two factors posed a challenge to proper postoperative wound care for our patient:

• Because of the high risk of transmission of SARS-CoV-2, the patient hoped to limit exposure by avoiding an office visit to remove the bandage.

• The patient did not have someone at home to serve as an immediate support system, which made it impossible for him to rely on others for postoperative wound care.

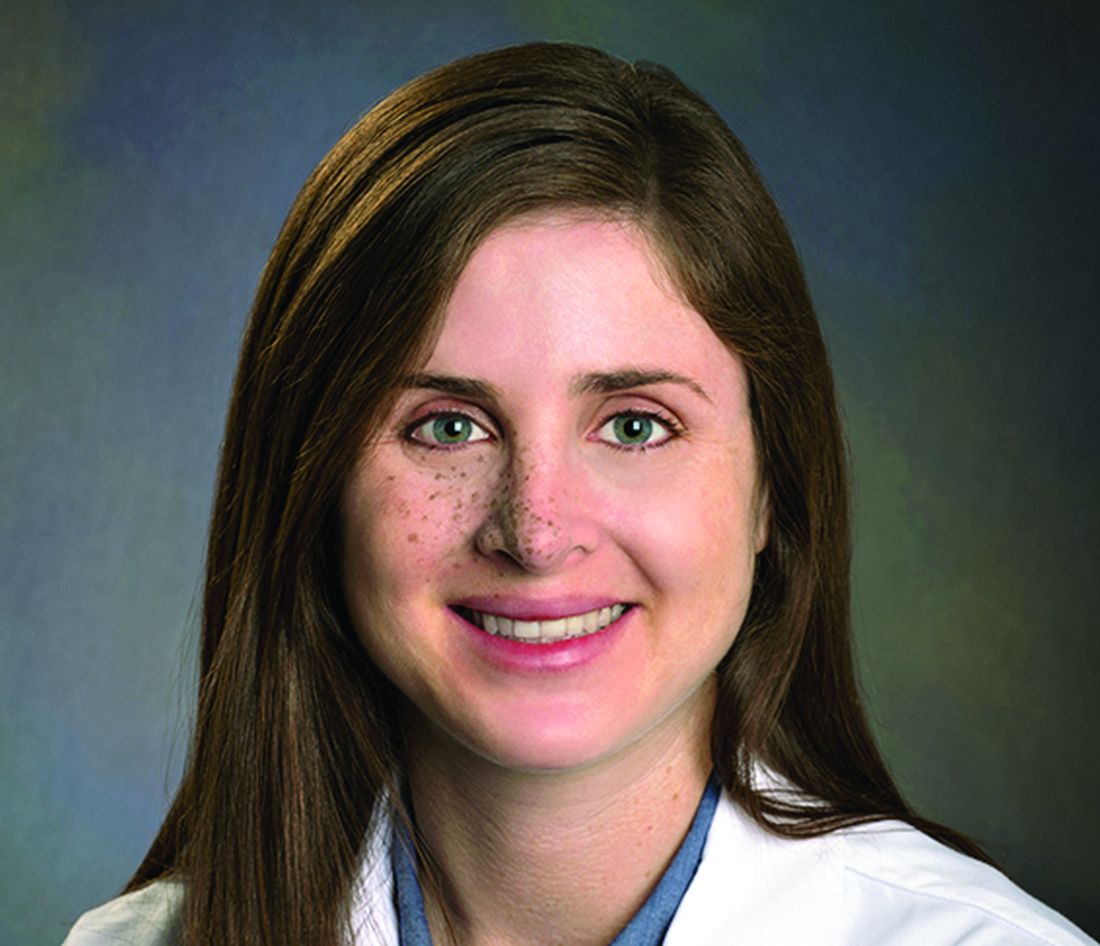

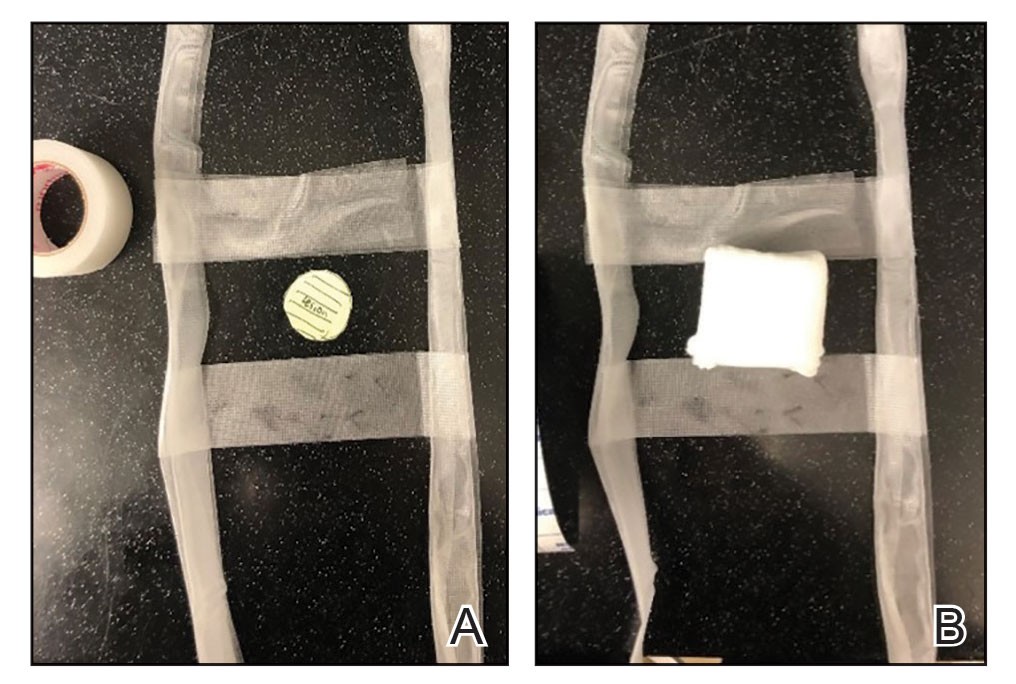

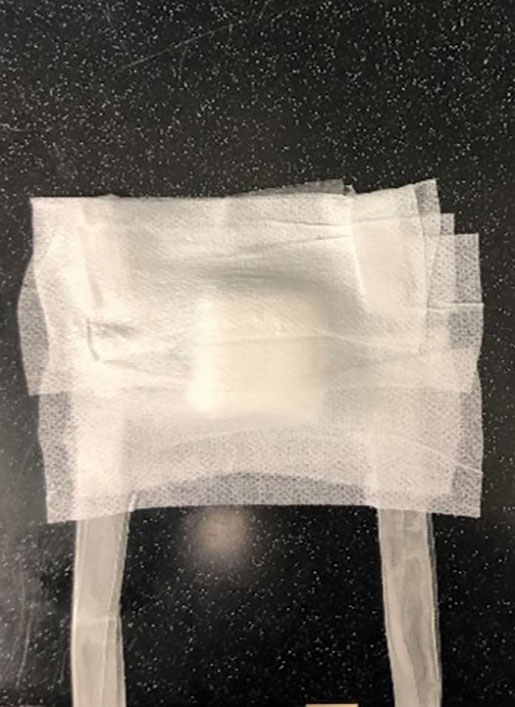

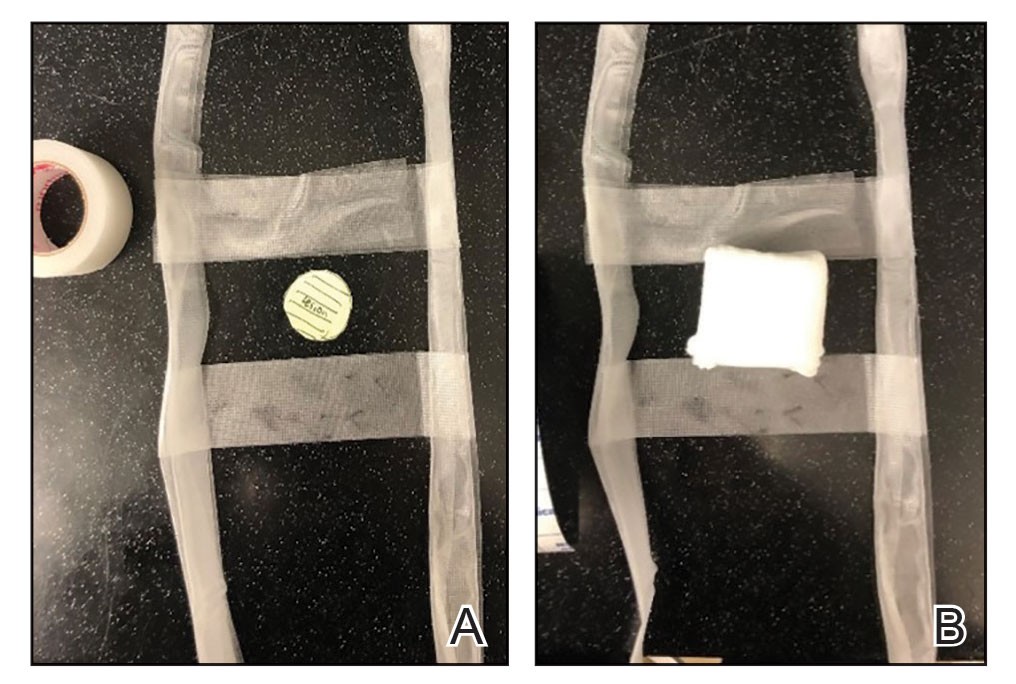

Previously, the patient had to ask a friend to remove a bandage for melanoma in situ on the inner aspect of the left upper arm. Therefore, after this procedure, the patient asked if the bandage could be fashioned in a manner that would allow him to remove it without assistance (Figure 1).

Technique

In constructing a bandage that is easier to remove, some necessary pressure that is provided by the bandage often is sacrificed by making it looser. Considering that our patient had moderate bleeding during the procedure—in part because he took low-dose aspirin (81 mg/d)—it was important to maintain firm pressure under the bandage postoperatively to help prevent untoward bleeding. Furthermore, because of the location of the treated site and the patient’s limited range of motion, it was not feasible for him to reach the area on the scapula and remove the bandage.1

For easy self-removal, we designed a bandage with a pull tab that was within the patient’s reach. Suitable materials for the pull tab bandage included surgical tape, bandaging tape with adequate stretch, sterile nonadhesive gauze, fenestrated surgical gauze, and a topical emollient such as petroleum jelly or antibacterial ointment.

To clean the site and decrease the amount of oil that would reduce the effectiveness of the adhesive, the wound was prepared with 70% alcohol. The site was then treated with petroleum jelly.

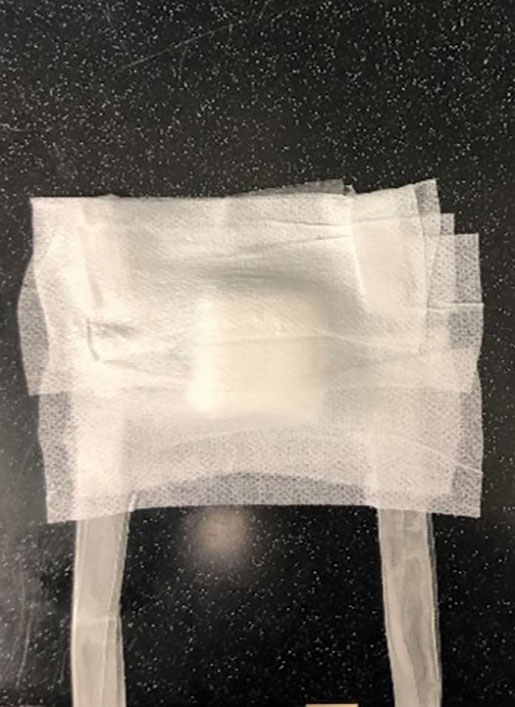

Next, we designed 2 pull tab bandage prototypes that allowed easy self-removal. For both prototypes, sterile nonadhesive gauze was applied to the wound along with folded and fenestrated gauze, which provided pressure. We used prototype #1 in our patient, and prototype #2 was demonstrated as an option.

Prototype #1—We created 2 tabs—each 2-feet long—using bandaging tape that was folded on itself once horizontally (Figure 2). The tabs were aligned on either side of the wound, the tops of which sat approximately 2 inches above the top of the first layer of adhesive bandage. An initial layer of adhesive surgical dressing was applied to cover the wound; 1 inch of the dressing was left exposed on the top of each tab. In addition, there were 2 “feet” running on the bottom.

The tops of the tabs were folded back over the adhesive tape, creating a type of “hook.” An additional final layer of adhesive tape was applied to ensure adequate pressure on the surgical site.

The patient was instructed to remove the bandage 2 days after the procedure. The outcome was qualified through a 3-day postoperative telephone call. The patient was asked about postoperative pain and his level of satisfaction with treatment. He was asked if he had any changes such as bleeding, swelling, signs of infection, or increased pain in the days after surgery or perceived postoperative complications, such as irritation. We asked the patient about the relative ease of removing the bandage and if removal was painful. He reported that the bandage was easy to remove, and that doing so was not painful; furthermore, he did not have problems with the bandage or healing and did not experience any medical changes. He found the bandage to be comfortable. The patient stated that the hanging feet of the prototype #1 bandage were not bothersome and were sturdy for the time that the bandage was on.

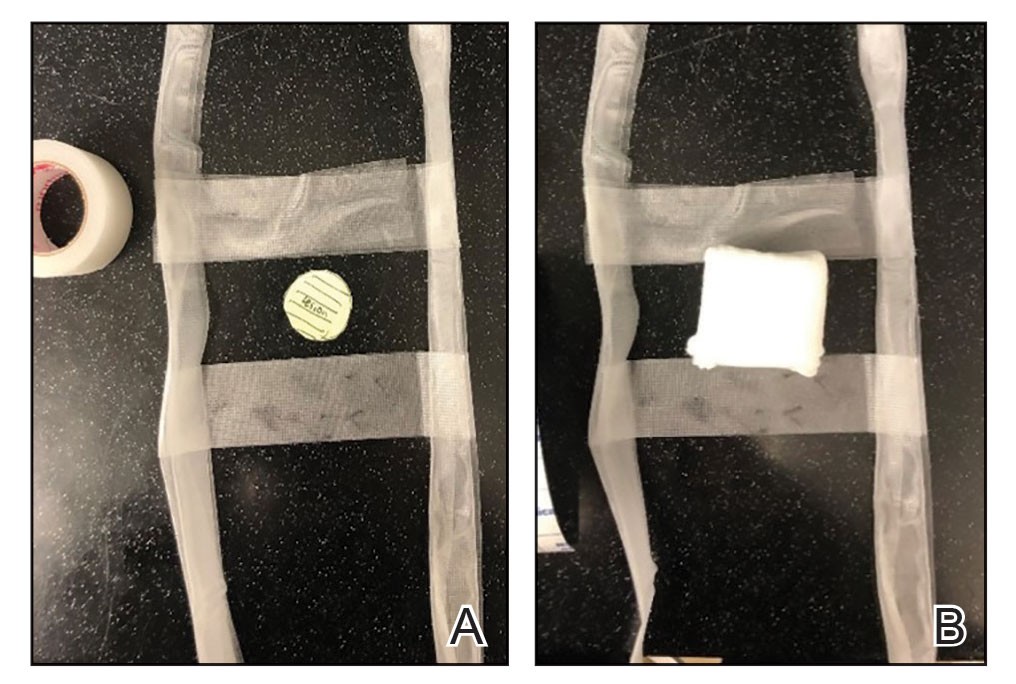

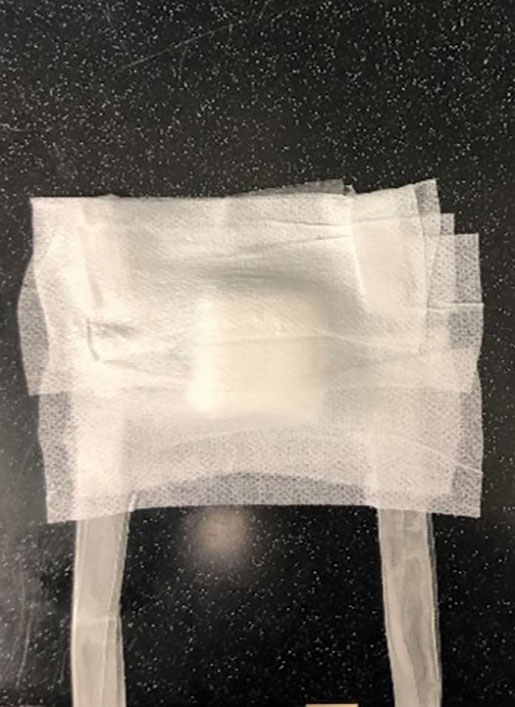

Prototype #2—We prepared a bandage using surgical packing as the tab (Figure 3). The packing was slowly placed around the site, which was already covered with nonadhesive gauze and fenestrated surgical gauze, with adequate spacing between each loop (for a total of 3 loops), 1 of which crossed over the third loop so that the adhesive bandaging tape could be removed easily. This allowed for a single tab that could be removed by a single pull. A final layer of adhesive tape was applied to ensure adequate pressure, similar to prototype #1. The same postoperative protocol was employed to provide a consistent standard of care. We recommend use of this prototype when surgical tape is not available, and surgical packing can be used as a substitute.

Practice Implications

Patients have a better appreciation for avoiding excess visits to medical offices due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The risk for exposure to SARS-CoV-2 infection is greater when patients who lack a support system must return to the office for aftercare or to have a bandage removed. Although protection offered by the COVID-19 vaccine alleviates concern, many patients have realized the benefits of only visiting medical offices in person when necessary.

The concept of pull tab bandages that can be removed by the patient at home has other applications. For example, patients who travel a long distance to see their physician will benefit from easier aftercare and avoid additional follow-up visits when provided with a self-removable bandage.

- Stathokostas, L, McDonald MW, Little RMD, et al. Flexibility of older adults aged 55-86 years and the influence of physical activity. J Aging Res. 2013;2013:1-8. doi:10.1155/2013/743843

Practice Gap

A male patient presented with 2 concerning lesions, which histopathology revealed were invasive squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) on the right medial chest and SCC in situ on the right upper scapular region. Both were treated with wide local excision; margins were clear in our office the same day.

This case highlighted a practice gap in postoperative care. Two factors posed a challenge to proper postoperative wound care for our patient:

• Because of the high risk of transmission of SARS-CoV-2, the patient hoped to limit exposure by avoiding an office visit to remove the bandage.

• The patient did not have someone at home to serve as an immediate support system, which made it impossible for him to rely on others for postoperative wound care.

Previously, the patient had to ask a friend to remove a bandage for melanoma in situ on the inner aspect of the left upper arm. Therefore, after this procedure, the patient asked if the bandage could be fashioned in a manner that would allow him to remove it without assistance (Figure 1).

Technique

In constructing a bandage that is easier to remove, some necessary pressure that is provided by the bandage often is sacrificed by making it looser. Considering that our patient had moderate bleeding during the procedure—in part because he took low-dose aspirin (81 mg/d)—it was important to maintain firm pressure under the bandage postoperatively to help prevent untoward bleeding. Furthermore, because of the location of the treated site and the patient’s limited range of motion, it was not feasible for him to reach the area on the scapula and remove the bandage.1

For easy self-removal, we designed a bandage with a pull tab that was within the patient’s reach. Suitable materials for the pull tab bandage included surgical tape, bandaging tape with adequate stretch, sterile nonadhesive gauze, fenestrated surgical gauze, and a topical emollient such as petroleum jelly or antibacterial ointment.

To clean the site and decrease the amount of oil that would reduce the effectiveness of the adhesive, the wound was prepared with 70% alcohol. The site was then treated with petroleum jelly.

Next, we designed 2 pull tab bandage prototypes that allowed easy self-removal. For both prototypes, sterile nonadhesive gauze was applied to the wound along with folded and fenestrated gauze, which provided pressure. We used prototype #1 in our patient, and prototype #2 was demonstrated as an option.

Prototype #1—We created 2 tabs—each 2-feet long—using bandaging tape that was folded on itself once horizontally (Figure 2). The tabs were aligned on either side of the wound, the tops of which sat approximately 2 inches above the top of the first layer of adhesive bandage. An initial layer of adhesive surgical dressing was applied to cover the wound; 1 inch of the dressing was left exposed on the top of each tab. In addition, there were 2 “feet” running on the bottom.

The tops of the tabs were folded back over the adhesive tape, creating a type of “hook.” An additional final layer of adhesive tape was applied to ensure adequate pressure on the surgical site.

The patient was instructed to remove the bandage 2 days after the procedure. The outcome was qualified through a 3-day postoperative telephone call. The patient was asked about postoperative pain and his level of satisfaction with treatment. He was asked if he had any changes such as bleeding, swelling, signs of infection, or increased pain in the days after surgery or perceived postoperative complications, such as irritation. We asked the patient about the relative ease of removing the bandage and if removal was painful. He reported that the bandage was easy to remove, and that doing so was not painful; furthermore, he did not have problems with the bandage or healing and did not experience any medical changes. He found the bandage to be comfortable. The patient stated that the hanging feet of the prototype #1 bandage were not bothersome and were sturdy for the time that the bandage was on.

Prototype #2—We prepared a bandage using surgical packing as the tab (Figure 3). The packing was slowly placed around the site, which was already covered with nonadhesive gauze and fenestrated surgical gauze, with adequate spacing between each loop (for a total of 3 loops), 1 of which crossed over the third loop so that the adhesive bandaging tape could be removed easily. This allowed for a single tab that could be removed by a single pull. A final layer of adhesive tape was applied to ensure adequate pressure, similar to prototype #1. The same postoperative protocol was employed to provide a consistent standard of care. We recommend use of this prototype when surgical tape is not available, and surgical packing can be used as a substitute.

Practice Implications

Patients have a better appreciation for avoiding excess visits to medical offices due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The risk for exposure to SARS-CoV-2 infection is greater when patients who lack a support system must return to the office for aftercare or to have a bandage removed. Although protection offered by the COVID-19 vaccine alleviates concern, many patients have realized the benefits of only visiting medical offices in person when necessary.

The concept of pull tab bandages that can be removed by the patient at home has other applications. For example, patients who travel a long distance to see their physician will benefit from easier aftercare and avoid additional follow-up visits when provided with a self-removable bandage.

Practice Gap

A male patient presented with 2 concerning lesions, which histopathology revealed were invasive squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) on the right medial chest and SCC in situ on the right upper scapular region. Both were treated with wide local excision; margins were clear in our office the same day.

This case highlighted a practice gap in postoperative care. Two factors posed a challenge to proper postoperative wound care for our patient:

• Because of the high risk of transmission of SARS-CoV-2, the patient hoped to limit exposure by avoiding an office visit to remove the bandage.

• The patient did not have someone at home to serve as an immediate support system, which made it impossible for him to rely on others for postoperative wound care.

Previously, the patient had to ask a friend to remove a bandage for melanoma in situ on the inner aspect of the left upper arm. Therefore, after this procedure, the patient asked if the bandage could be fashioned in a manner that would allow him to remove it without assistance (Figure 1).

Technique

In constructing a bandage that is easier to remove, some necessary pressure that is provided by the bandage often is sacrificed by making it looser. Considering that our patient had moderate bleeding during the procedure—in part because he took low-dose aspirin (81 mg/d)—it was important to maintain firm pressure under the bandage postoperatively to help prevent untoward bleeding. Furthermore, because of the location of the treated site and the patient’s limited range of motion, it was not feasible for him to reach the area on the scapula and remove the bandage.1

For easy self-removal, we designed a bandage with a pull tab that was within the patient’s reach. Suitable materials for the pull tab bandage included surgical tape, bandaging tape with adequate stretch, sterile nonadhesive gauze, fenestrated surgical gauze, and a topical emollient such as petroleum jelly or antibacterial ointment.

To clean the site and decrease the amount of oil that would reduce the effectiveness of the adhesive, the wound was prepared with 70% alcohol. The site was then treated with petroleum jelly.

Next, we designed 2 pull tab bandage prototypes that allowed easy self-removal. For both prototypes, sterile nonadhesive gauze was applied to the wound along with folded and fenestrated gauze, which provided pressure. We used prototype #1 in our patient, and prototype #2 was demonstrated as an option.

Prototype #1—We created 2 tabs—each 2-feet long—using bandaging tape that was folded on itself once horizontally (Figure 2). The tabs were aligned on either side of the wound, the tops of which sat approximately 2 inches above the top of the first layer of adhesive bandage. An initial layer of adhesive surgical dressing was applied to cover the wound; 1 inch of the dressing was left exposed on the top of each tab. In addition, there were 2 “feet” running on the bottom.

The tops of the tabs were folded back over the adhesive tape, creating a type of “hook.” An additional final layer of adhesive tape was applied to ensure adequate pressure on the surgical site.

The patient was instructed to remove the bandage 2 days after the procedure. The outcome was qualified through a 3-day postoperative telephone call. The patient was asked about postoperative pain and his level of satisfaction with treatment. He was asked if he had any changes such as bleeding, swelling, signs of infection, or increased pain in the days after surgery or perceived postoperative complications, such as irritation. We asked the patient about the relative ease of removing the bandage and if removal was painful. He reported that the bandage was easy to remove, and that doing so was not painful; furthermore, he did not have problems with the bandage or healing and did not experience any medical changes. He found the bandage to be comfortable. The patient stated that the hanging feet of the prototype #1 bandage were not bothersome and were sturdy for the time that the bandage was on.

Prototype #2—We prepared a bandage using surgical packing as the tab (Figure 3). The packing was slowly placed around the site, which was already covered with nonadhesive gauze and fenestrated surgical gauze, with adequate spacing between each loop (for a total of 3 loops), 1 of which crossed over the third loop so that the adhesive bandaging tape could be removed easily. This allowed for a single tab that could be removed by a single pull. A final layer of adhesive tape was applied to ensure adequate pressure, similar to prototype #1. The same postoperative protocol was employed to provide a consistent standard of care. We recommend use of this prototype when surgical tape is not available, and surgical packing can be used as a substitute.

Practice Implications

Patients have a better appreciation for avoiding excess visits to medical offices due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The risk for exposure to SARS-CoV-2 infection is greater when patients who lack a support system must return to the office for aftercare or to have a bandage removed. Although protection offered by the COVID-19 vaccine alleviates concern, many patients have realized the benefits of only visiting medical offices in person when necessary.

The concept of pull tab bandages that can be removed by the patient at home has other applications. For example, patients who travel a long distance to see their physician will benefit from easier aftercare and avoid additional follow-up visits when provided with a self-removable bandage.

- Stathokostas, L, McDonald MW, Little RMD, et al. Flexibility of older adults aged 55-86 years and the influence of physical activity. J Aging Res. 2013;2013:1-8. doi:10.1155/2013/743843

- Stathokostas, L, McDonald MW, Little RMD, et al. Flexibility of older adults aged 55-86 years and the influence of physical activity. J Aging Res. 2013;2013:1-8. doi:10.1155/2013/743843

Asymptomatic Umbilical Nodule

The Diagnosis: Sister Mary Joseph Nodule

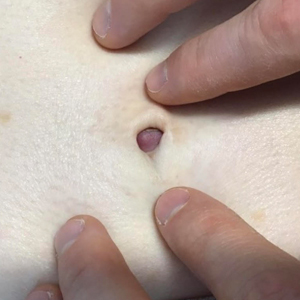

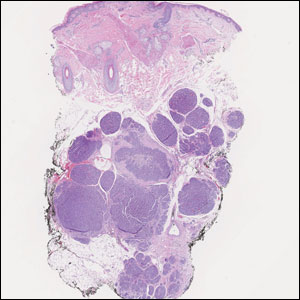

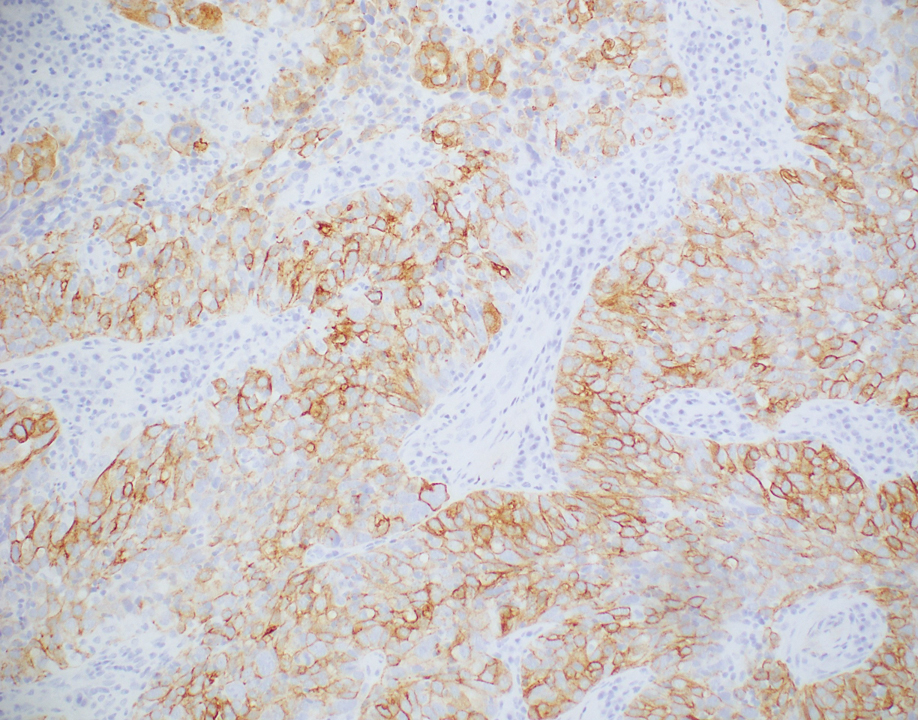

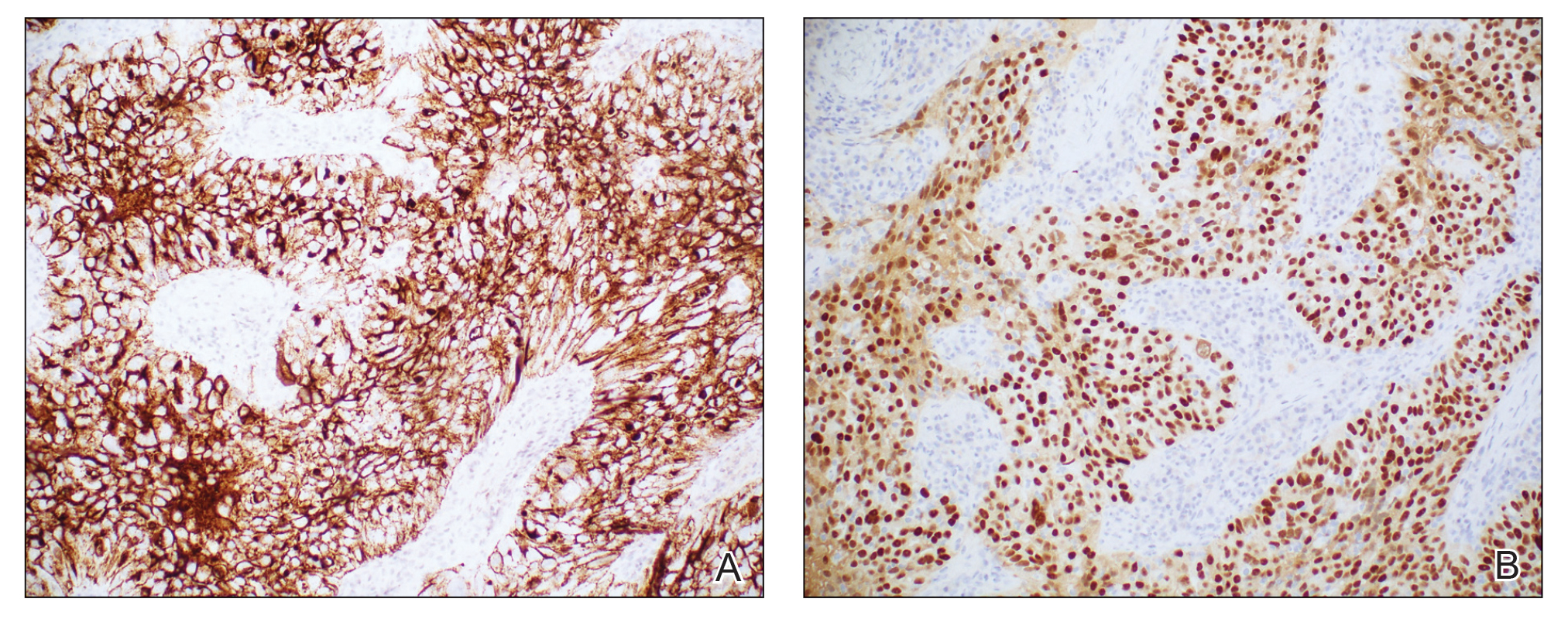

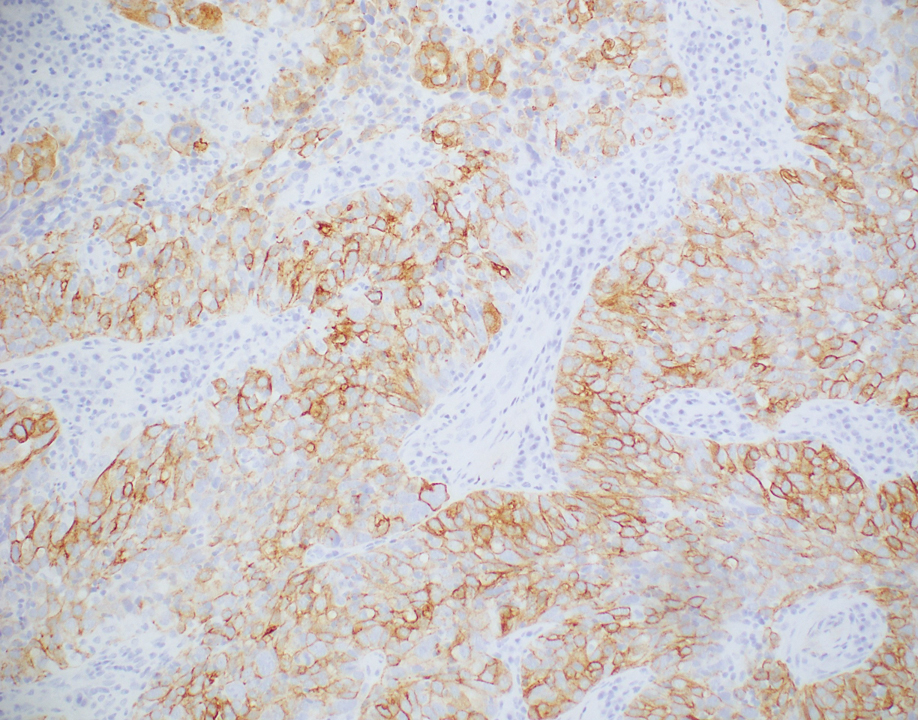

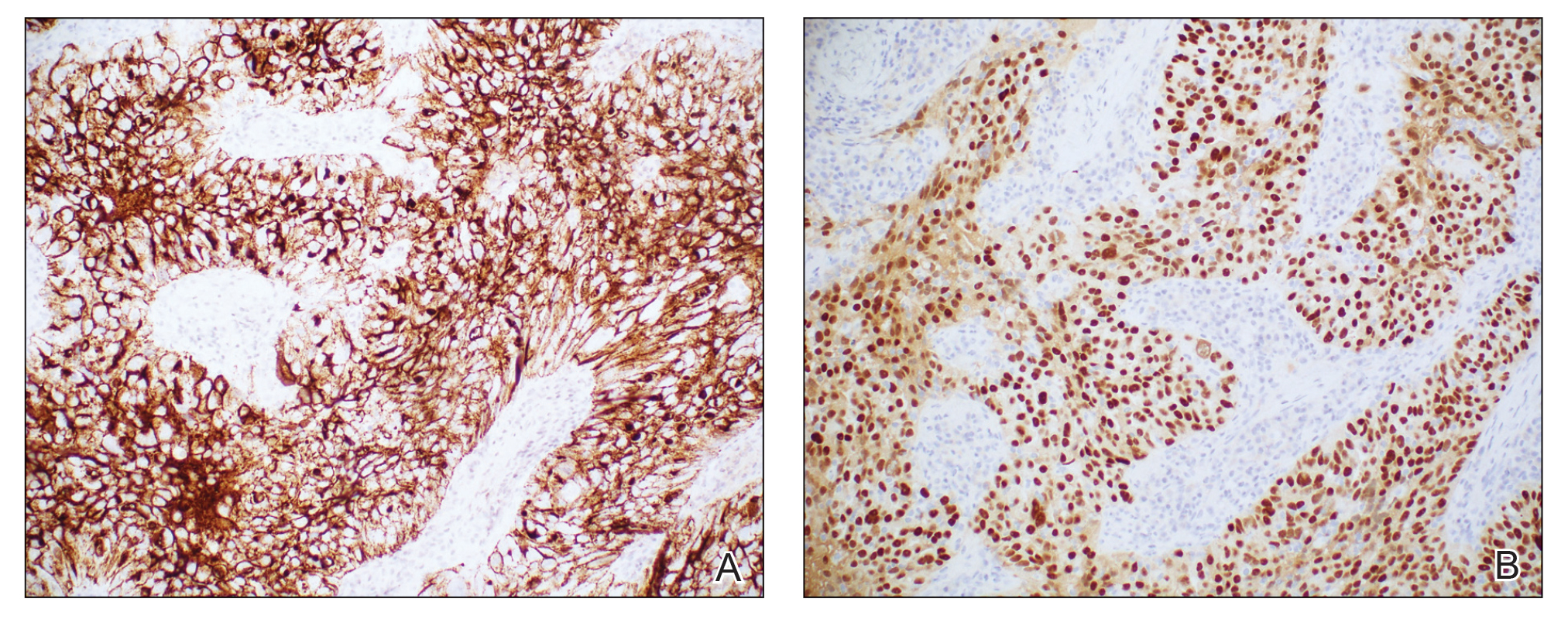

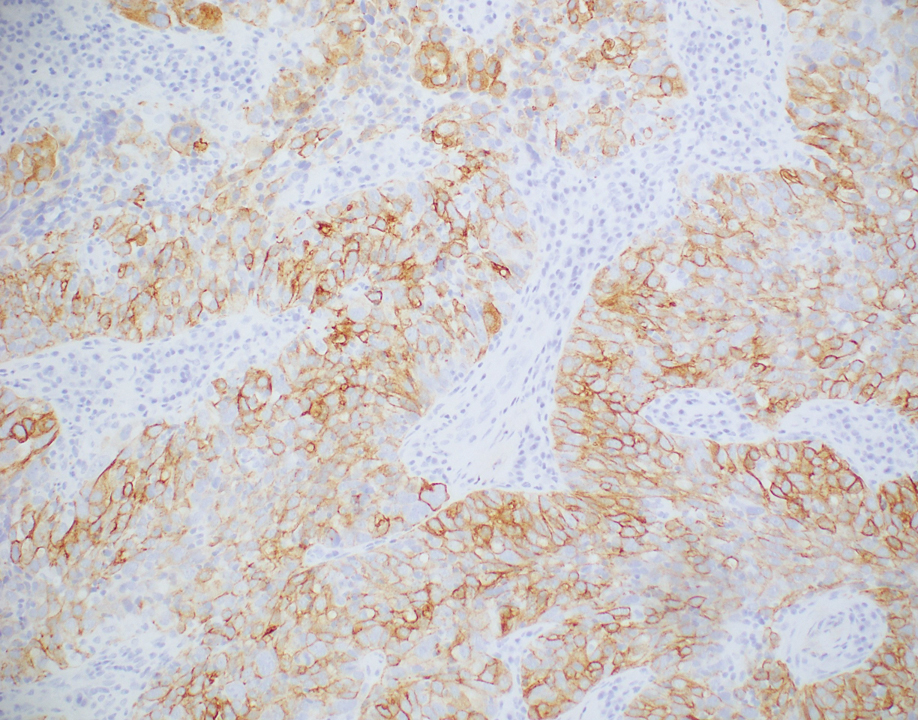

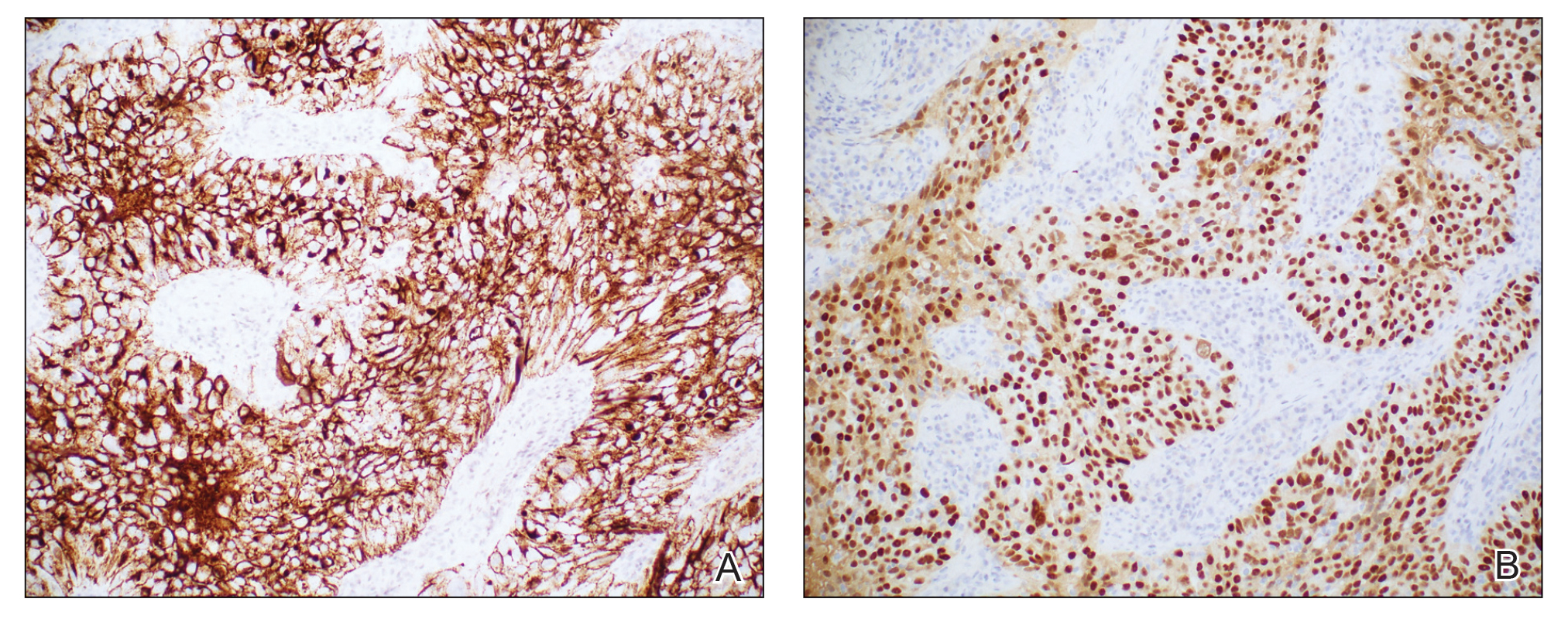

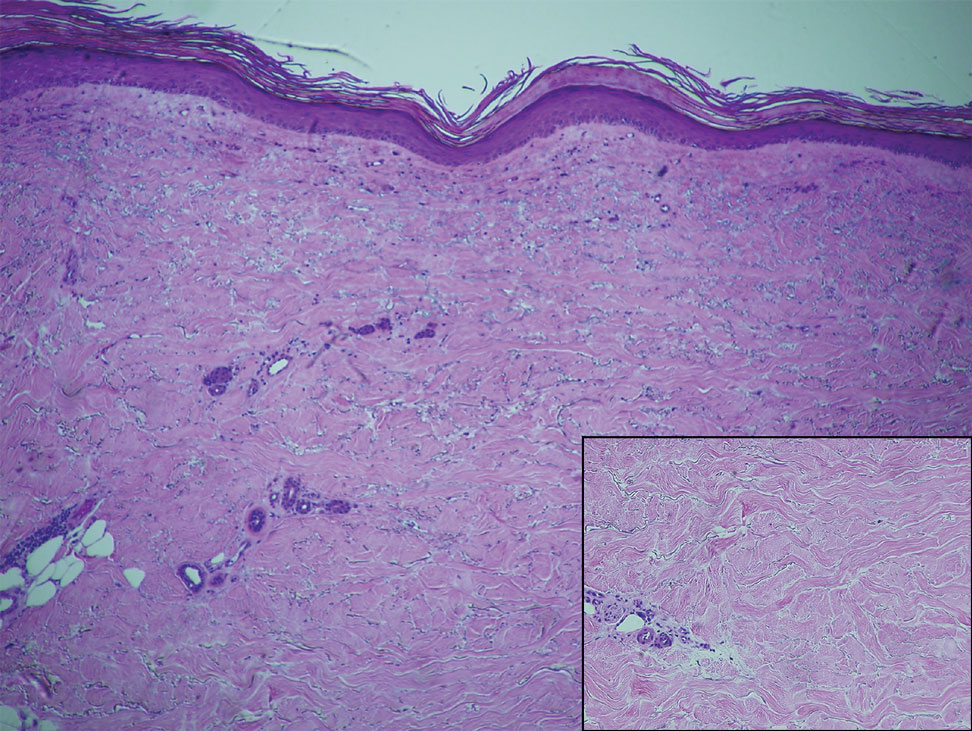

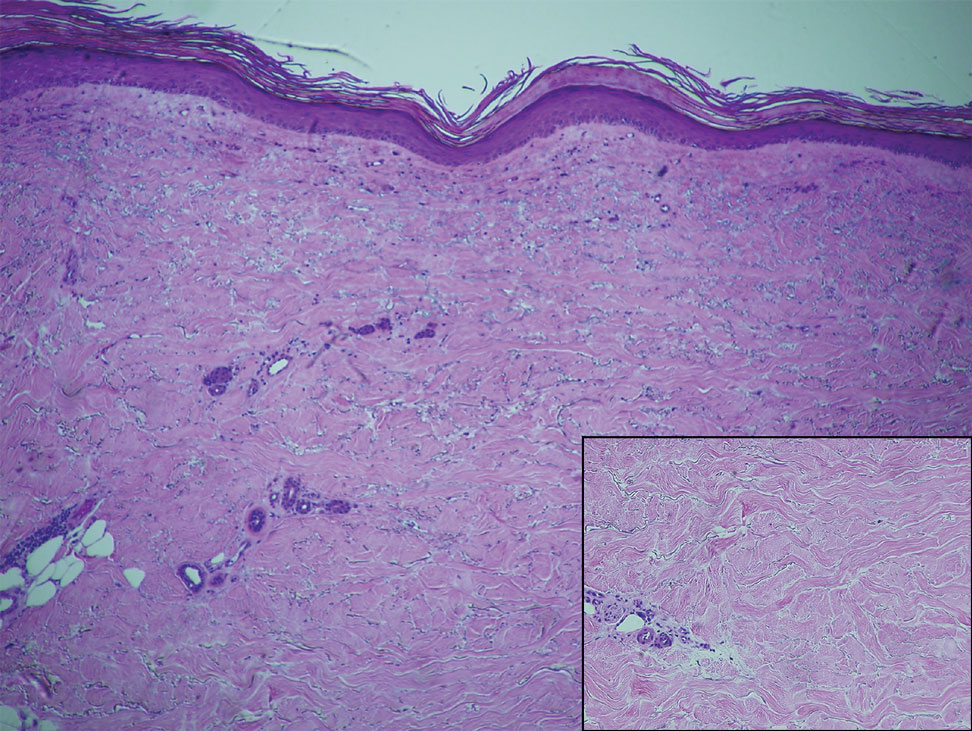

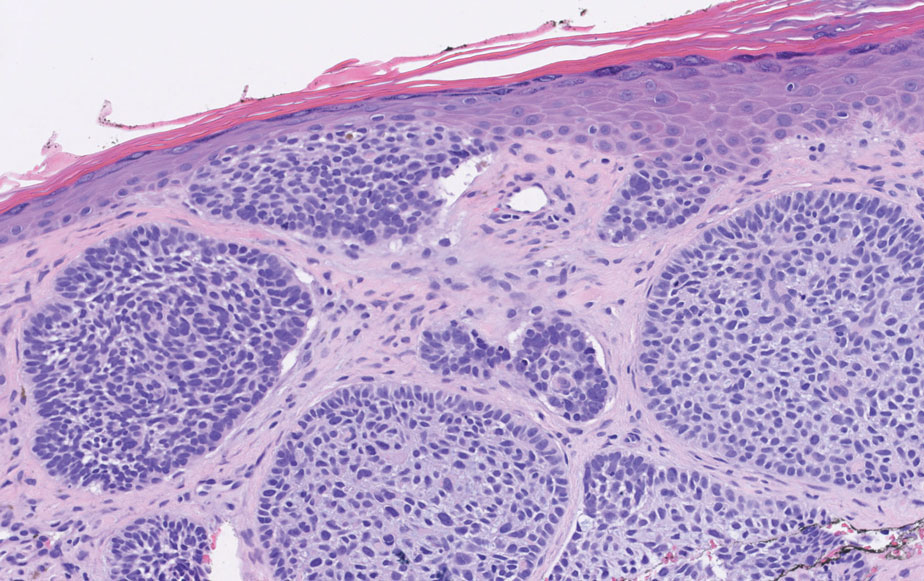

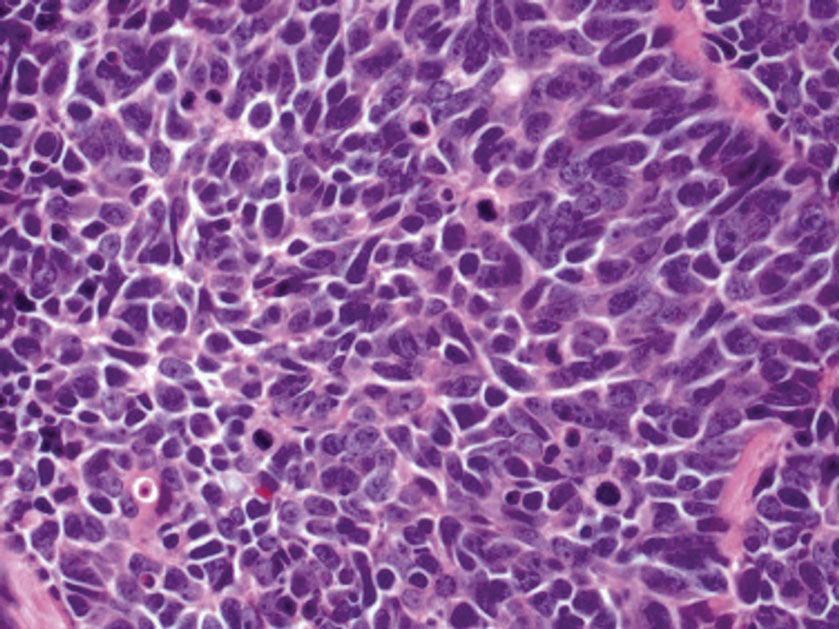

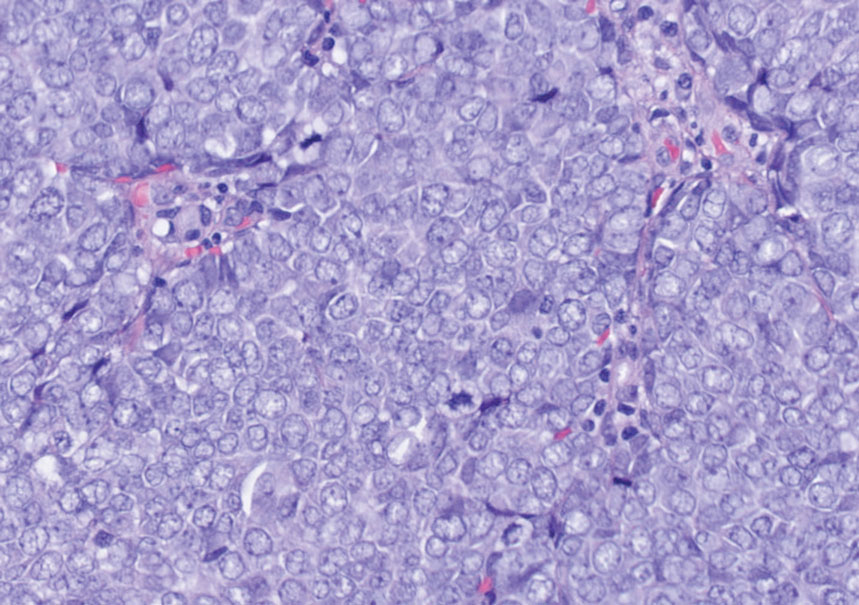

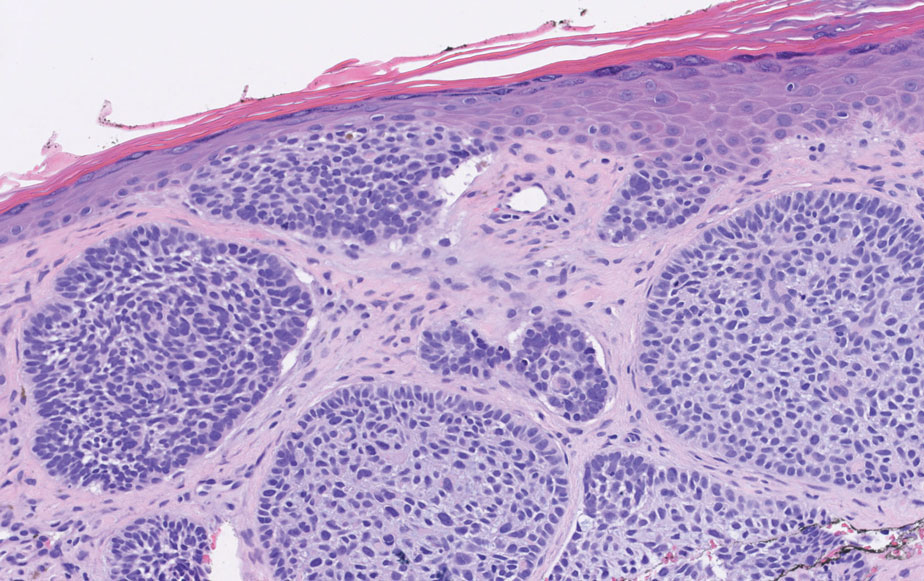

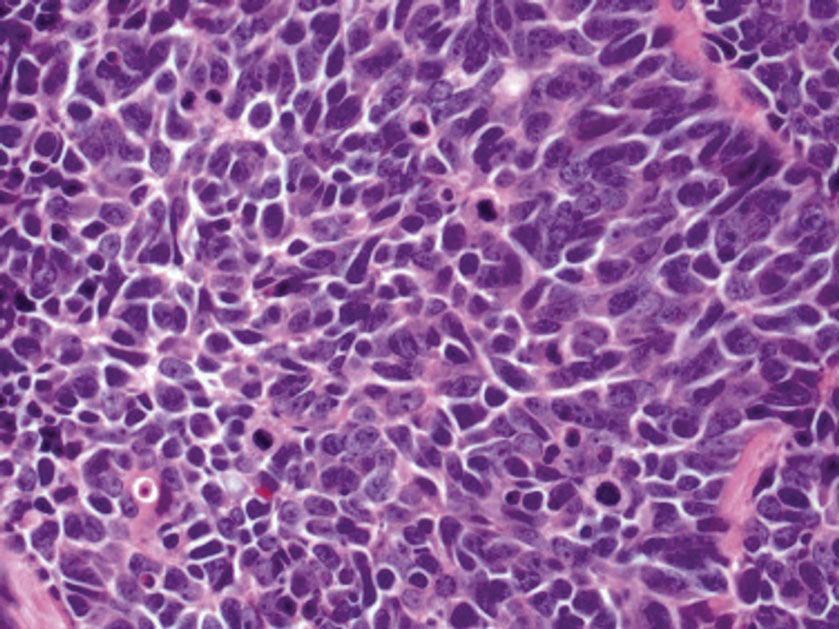

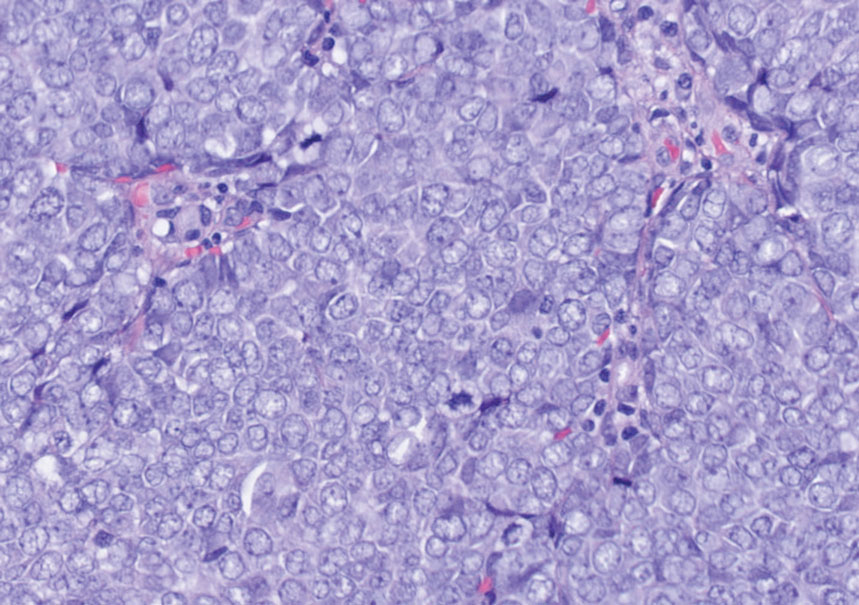

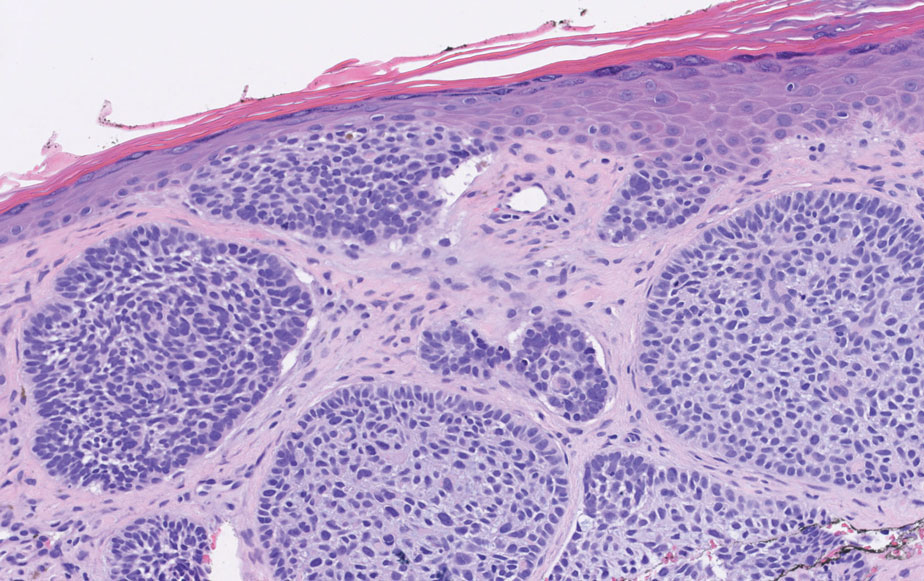

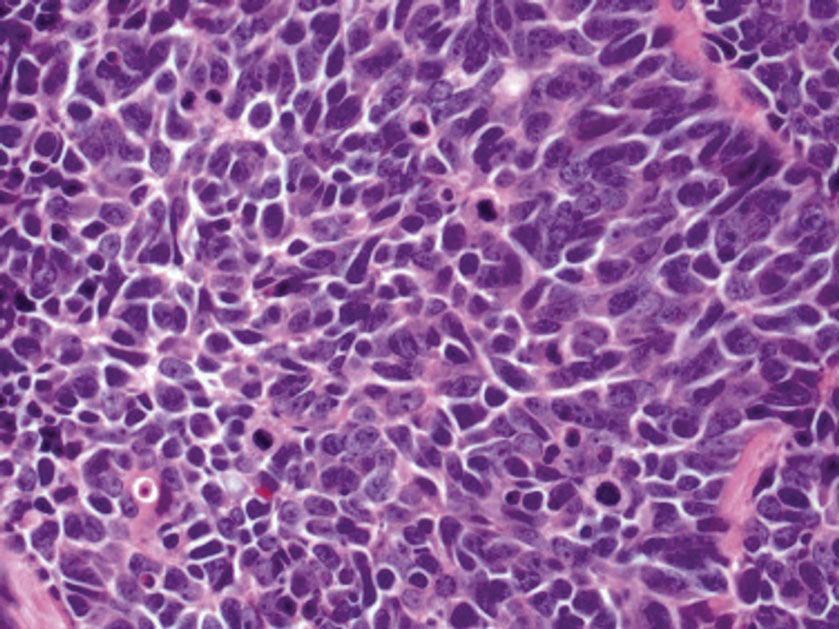

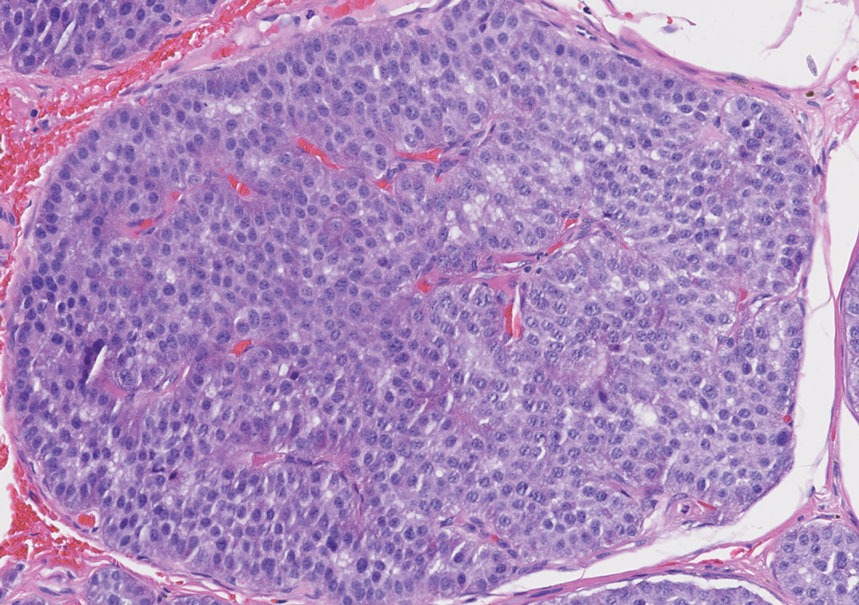

Histopathologic analysis of the biopsy specimen revealed a dense infiltrate of large, hyperchromatic, mucin-producing cells exhibiting varying degrees of nuclear pleomorphism (Figure 1). Immunohistochemical (IHC) staining was negative for cytokeratin (CK) 20; however, CK7 was found positive (Figure 2), which confirmed the presence of a metastatic adenocarcinoma, consistent with the clinical diagnosis of a Sister Mary Joseph nodule (SMJN). Subsequent IHC workup to determine the site of origin revealed densely positive expression of both cancer antigen 125 and paired homeobox gene 8 (PAX-8)(Figure 3), consistent with primary ovarian disease. Furthermore, expression of estrogen receptor and p53 both were positive within the nuclei, illustrating an aberrant expression pattern. On the other hand, cancer antigen 19-9, caudal-type homeobox 2, gross cystic disease fluid protein 15, and mammaglobin were all determined negative, thus leading to the pathologic diagnosis of a metastatic ovarian adenocarcinoma. Additional workup with computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis highlighted a large left ovarian mass with multiple omental nodules as well as enlarged retroperitoneal and pelvic lymph nodes.

The SMJN is a rare presentation of internal malignancy that appears as a nodule that metastasizes to the umbilicus. It may be ulcerated or necrotic and is seen in up to 10% of patients with cutaneous metastases from internal malignancy.1 These nodules are named after Sister Mary Joseph, the surgical assistant of Dr. William Mayo who first described the relationship between umbilical nodules seen in patients with gastrointestinal and genitourinary cancer. The most common underlying malignancies include primary gastrointestinal and gynecologic adenocarcinomas. In a retrospective study of 34 patients by Chalya et al,2 the stomach was found to be the most common primary site (41.1%). The presence of an SMJN affords a poor prognosis, with a mean overall survival of 11 months from the time of diagnosis.3 The mechanism of disease dissemination remains unknown but is thought to occur through lymphovascular invasion of tumor cells and spread via the umbilical ligament.1,4

Merkel cell carcinoma is a cutaneous neuroendocrine tumor that most commonly presents in elderly patients as red-violet nodules or plaques. Although Merkel cell carcinoma most frequently is encountered on sun-exposed skin, they also can arise on the trunk and abdomen. Positive IHC staining for CK20 would be expected; however, it was negative in our case.5

Cutaneous endometriosis is a rare disease presentation and most commonly occurs as a secondary process due to surgical inoculation of the abdominal wall. Primary cutaneous endometriosis in which there is no history of abdominal surgery less frequently is encountered. Patients typically will report pain and cyclical bleeding with menses. Pathology demonstrates ectopic endometrial tissue with glands and uterine myxoid stroma.6

Amelanotic melanoma is an uncommon subtype of malignant melanoma that presents as nonpigmented nodules that have a propensity to ulcerate and bleed. Furthermore, the umbilicus is an exceedingly rare location for primary melanoma. However, one report does exist, and amelanotic melanoma should be considered in the differential for patients with umbilical nodules.7

Dermoid cysts are benign congenital lesions that typically present as a painless, slow-growing, and wellcircumscribed nodule, as similarly experienced by our patient. They most commonly are found on the testicles and ovaries but also are known to arise in embryologic fusion planes, and reports of umbilical lesions exist.8 Dermoid cysts are diagnosed based on histopathology, supporting the need for a biopsy to distinguish a malignant process from benign lesions.9

- Gabriele R, Conte M, Egidi F, et al. Umbilical metastases: current viewpoint. World J Surg Oncol. 2005;3:13.

- Chalya PL, Mabula JB, Rambau PF, et al. Sister Mary Joseph’s nodule at a university teaching hospital in northwestern Tanzania: a retrospective review of 34 cases. World J Surg Oncol. 2013;11:151.

- Leyrat B, Bernadach M, Ginzac A, et al. Sister Mary Joseph nodules: a case report about a rare location of skin metastasis. Case Rep Oncol. 2021;14:664-670.

- Yendluri V, Centeno B, Springett GM. Pancreatic cancer presenting as a Sister Mary Joseph’s nodule: case report and update of the literature. Pancreas. 2007;34:161-164.

- Uchi H. Merkel cell carcinoma: an update and immunotherapy. Front Oncol. 2018;8:48.

- Bittar PG, Hryneewycz KT, Bryant EA. Primary cutaneous endometriosis presenting as an umbilical nodule. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:1227.

- Kovitwanichkanont T, Joseph S, Yip L. Hidden in plain sight: umbilical melanoma [published online January 28, 2020]. Med J Aust. 2020;212:154-155.e1.

- Prior A, Anania P, Pacetti M, et al. Dermoid and epidermoid cysts of scalp: case series of 234 consecutive patients. World Neurosurg. 2018;120:119-124.

- Akinci O, Turker C, Erturk MS, et al. Umbilical dermoid cyst: a rare case. Cerrahpasa Med J. 2020;44:51-53.

The Diagnosis: Sister Mary Joseph Nodule

Histopathologic analysis of the biopsy specimen revealed a dense infiltrate of large, hyperchromatic, mucin-producing cells exhibiting varying degrees of nuclear pleomorphism (Figure 1). Immunohistochemical (IHC) staining was negative for cytokeratin (CK) 20; however, CK7 was found positive (Figure 2), which confirmed the presence of a metastatic adenocarcinoma, consistent with the clinical diagnosis of a Sister Mary Joseph nodule (SMJN). Subsequent IHC workup to determine the site of origin revealed densely positive expression of both cancer antigen 125 and paired homeobox gene 8 (PAX-8)(Figure 3), consistent with primary ovarian disease. Furthermore, expression of estrogen receptor and p53 both were positive within the nuclei, illustrating an aberrant expression pattern. On the other hand, cancer antigen 19-9, caudal-type homeobox 2, gross cystic disease fluid protein 15, and mammaglobin were all determined negative, thus leading to the pathologic diagnosis of a metastatic ovarian adenocarcinoma. Additional workup with computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis highlighted a large left ovarian mass with multiple omental nodules as well as enlarged retroperitoneal and pelvic lymph nodes.

The SMJN is a rare presentation of internal malignancy that appears as a nodule that metastasizes to the umbilicus. It may be ulcerated or necrotic and is seen in up to 10% of patients with cutaneous metastases from internal malignancy.1 These nodules are named after Sister Mary Joseph, the surgical assistant of Dr. William Mayo who first described the relationship between umbilical nodules seen in patients with gastrointestinal and genitourinary cancer. The most common underlying malignancies include primary gastrointestinal and gynecologic adenocarcinomas. In a retrospective study of 34 patients by Chalya et al,2 the stomach was found to be the most common primary site (41.1%). The presence of an SMJN affords a poor prognosis, with a mean overall survival of 11 months from the time of diagnosis.3 The mechanism of disease dissemination remains unknown but is thought to occur through lymphovascular invasion of tumor cells and spread via the umbilical ligament.1,4

Merkel cell carcinoma is a cutaneous neuroendocrine tumor that most commonly presents in elderly patients as red-violet nodules or plaques. Although Merkel cell carcinoma most frequently is encountered on sun-exposed skin, they also can arise on the trunk and abdomen. Positive IHC staining for CK20 would be expected; however, it was negative in our case.5

Cutaneous endometriosis is a rare disease presentation and most commonly occurs as a secondary process due to surgical inoculation of the abdominal wall. Primary cutaneous endometriosis in which there is no history of abdominal surgery less frequently is encountered. Patients typically will report pain and cyclical bleeding with menses. Pathology demonstrates ectopic endometrial tissue with glands and uterine myxoid stroma.6

Amelanotic melanoma is an uncommon subtype of malignant melanoma that presents as nonpigmented nodules that have a propensity to ulcerate and bleed. Furthermore, the umbilicus is an exceedingly rare location for primary melanoma. However, one report does exist, and amelanotic melanoma should be considered in the differential for patients with umbilical nodules.7

Dermoid cysts are benign congenital lesions that typically present as a painless, slow-growing, and wellcircumscribed nodule, as similarly experienced by our patient. They most commonly are found on the testicles and ovaries but also are known to arise in embryologic fusion planes, and reports of umbilical lesions exist.8 Dermoid cysts are diagnosed based on histopathology, supporting the need for a biopsy to distinguish a malignant process from benign lesions.9

The Diagnosis: Sister Mary Joseph Nodule

Histopathologic analysis of the biopsy specimen revealed a dense infiltrate of large, hyperchromatic, mucin-producing cells exhibiting varying degrees of nuclear pleomorphism (Figure 1). Immunohistochemical (IHC) staining was negative for cytokeratin (CK) 20; however, CK7 was found positive (Figure 2), which confirmed the presence of a metastatic adenocarcinoma, consistent with the clinical diagnosis of a Sister Mary Joseph nodule (SMJN). Subsequent IHC workup to determine the site of origin revealed densely positive expression of both cancer antigen 125 and paired homeobox gene 8 (PAX-8)(Figure 3), consistent with primary ovarian disease. Furthermore, expression of estrogen receptor and p53 both were positive within the nuclei, illustrating an aberrant expression pattern. On the other hand, cancer antigen 19-9, caudal-type homeobox 2, gross cystic disease fluid protein 15, and mammaglobin were all determined negative, thus leading to the pathologic diagnosis of a metastatic ovarian adenocarcinoma. Additional workup with computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis highlighted a large left ovarian mass with multiple omental nodules as well as enlarged retroperitoneal and pelvic lymph nodes.

The SMJN is a rare presentation of internal malignancy that appears as a nodule that metastasizes to the umbilicus. It may be ulcerated or necrotic and is seen in up to 10% of patients with cutaneous metastases from internal malignancy.1 These nodules are named after Sister Mary Joseph, the surgical assistant of Dr. William Mayo who first described the relationship between umbilical nodules seen in patients with gastrointestinal and genitourinary cancer. The most common underlying malignancies include primary gastrointestinal and gynecologic adenocarcinomas. In a retrospective study of 34 patients by Chalya et al,2 the stomach was found to be the most common primary site (41.1%). The presence of an SMJN affords a poor prognosis, with a mean overall survival of 11 months from the time of diagnosis.3 The mechanism of disease dissemination remains unknown but is thought to occur through lymphovascular invasion of tumor cells and spread via the umbilical ligament.1,4

Merkel cell carcinoma is a cutaneous neuroendocrine tumor that most commonly presents in elderly patients as red-violet nodules or plaques. Although Merkel cell carcinoma most frequently is encountered on sun-exposed skin, they also can arise on the trunk and abdomen. Positive IHC staining for CK20 would be expected; however, it was negative in our case.5

Cutaneous endometriosis is a rare disease presentation and most commonly occurs as a secondary process due to surgical inoculation of the abdominal wall. Primary cutaneous endometriosis in which there is no history of abdominal surgery less frequently is encountered. Patients typically will report pain and cyclical bleeding with menses. Pathology demonstrates ectopic endometrial tissue with glands and uterine myxoid stroma.6

Amelanotic melanoma is an uncommon subtype of malignant melanoma that presents as nonpigmented nodules that have a propensity to ulcerate and bleed. Furthermore, the umbilicus is an exceedingly rare location for primary melanoma. However, one report does exist, and amelanotic melanoma should be considered in the differential for patients with umbilical nodules.7

Dermoid cysts are benign congenital lesions that typically present as a painless, slow-growing, and wellcircumscribed nodule, as similarly experienced by our patient. They most commonly are found on the testicles and ovaries but also are known to arise in embryologic fusion planes, and reports of umbilical lesions exist.8 Dermoid cysts are diagnosed based on histopathology, supporting the need for a biopsy to distinguish a malignant process from benign lesions.9

- Gabriele R, Conte M, Egidi F, et al. Umbilical metastases: current viewpoint. World J Surg Oncol. 2005;3:13.

- Chalya PL, Mabula JB, Rambau PF, et al. Sister Mary Joseph’s nodule at a university teaching hospital in northwestern Tanzania: a retrospective review of 34 cases. World J Surg Oncol. 2013;11:151.

- Leyrat B, Bernadach M, Ginzac A, et al. Sister Mary Joseph nodules: a case report about a rare location of skin metastasis. Case Rep Oncol. 2021;14:664-670.

- Yendluri V, Centeno B, Springett GM. Pancreatic cancer presenting as a Sister Mary Joseph’s nodule: case report and update of the literature. Pancreas. 2007;34:161-164.

- Uchi H. Merkel cell carcinoma: an update and immunotherapy. Front Oncol. 2018;8:48.

- Bittar PG, Hryneewycz KT, Bryant EA. Primary cutaneous endometriosis presenting as an umbilical nodule. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:1227.

- Kovitwanichkanont T, Joseph S, Yip L. Hidden in plain sight: umbilical melanoma [published online January 28, 2020]. Med J Aust. 2020;212:154-155.e1.

- Prior A, Anania P, Pacetti M, et al. Dermoid and epidermoid cysts of scalp: case series of 234 consecutive patients. World Neurosurg. 2018;120:119-124.

- Akinci O, Turker C, Erturk MS, et al. Umbilical dermoid cyst: a rare case. Cerrahpasa Med J. 2020;44:51-53.

- Gabriele R, Conte M, Egidi F, et al. Umbilical metastases: current viewpoint. World J Surg Oncol. 2005;3:13.

- Chalya PL, Mabula JB, Rambau PF, et al. Sister Mary Joseph’s nodule at a university teaching hospital in northwestern Tanzania: a retrospective review of 34 cases. World J Surg Oncol. 2013;11:151.

- Leyrat B, Bernadach M, Ginzac A, et al. Sister Mary Joseph nodules: a case report about a rare location of skin metastasis. Case Rep Oncol. 2021;14:664-670.

- Yendluri V, Centeno B, Springett GM. Pancreatic cancer presenting as a Sister Mary Joseph’s nodule: case report and update of the literature. Pancreas. 2007;34:161-164.

- Uchi H. Merkel cell carcinoma: an update and immunotherapy. Front Oncol. 2018;8:48.

- Bittar PG, Hryneewycz KT, Bryant EA. Primary cutaneous endometriosis presenting as an umbilical nodule. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:1227.

- Kovitwanichkanont T, Joseph S, Yip L. Hidden in plain sight: umbilical melanoma [published online January 28, 2020]. Med J Aust. 2020;212:154-155.e1.

- Prior A, Anania P, Pacetti M, et al. Dermoid and epidermoid cysts of scalp: case series of 234 consecutive patients. World Neurosurg. 2018;120:119-124.

- Akinci O, Turker C, Erturk MS, et al. Umbilical dermoid cyst: a rare case. Cerrahpasa Med J. 2020;44:51-53.

A 64-year-old woman with no notable medical history was referred to our dermatology clinic with an intermittent eczematous rash around the eyelids of 3 months’ duration. While performing a total-body skin examination, a firm pink nodule with a smooth surface incidentally was discovered on the umbilicus. The patient was uncertain when the lesion first appeared and denied any associated symptoms including pain and bleeding. Additionally, a lymph node examination revealed right inguinal lymphadenopathy. Upon further questioning, she reported worsening muscle weakness, fatigue, night sweats, and an unintentional weight loss of 10 pounds. A 6-mm punch biopsy of the umbilical lesion was obtained for routine histopathology.

Atypical Localized Scleroderma Development During Nivolumab Therapy for Metastatic Lung Adenocarcinoma

To the Editor:

Immune checkpoint inhibitors such as anti–programmed cell death protein 1 (anti–PD-1) and anticytotoxic T lymphocyte–associated protein 4 therapies are a promising class of cancer therapeutics. However, they are associated with a variety of immune-related adverse events (irAEs), including cutaneous toxicity.1 The PD-1/programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) pathway is important for the maintenance of immune tolerance, and a blockade has been shown to lead to development of various autoimmune diseases.2 We present the case of a patient who developed new-onset localized scleroderma during treatment with the PD-1 inhibitor nivolumab.

A 65-year-old woman presented with a rash on the left thigh that was associated with pruritus, pain, and a pulling sensation. She had a history of stage IV lung adenocarcinoma, with a mass in the right upper lobe with metastatic foci to the left femur, right humerus, right hilar, and pretracheal lymph nodes. She received palliative radiation to the left femur and was started on carboplatin and pemetrexed. Metastasis to the liver was noted after completion of 6 cycles of therapy, and the patient’s treatment was changed to nivolumab. After 17 months on nivolumab therapy (2 years after initial diagnosis and 20 months after radiation therapy), she presented to our dermatology clinic with a cutaneous eruption on the buttocks that spread to the left thigh. The rash failed to improve after 1 month of treatment with emollients and triamcinolone cream 0.1%.

At the current presentation, which was 2 months after she initially presented to our clinic, dermatologic examination revealed erythematous and sclerotic plaques on the left lateral thigh (Figure 1A). Betamethasone cream 0.05% was prescribed, and nivolumab was discontinued due to progression of cutaneous symptoms. A punch biopsy from the left thigh demonstrated superficial dermal sclerosis that was suggestive of chronic radiation dermatitis; direct immunofluorescence testing was negative. The patient was started on prednisone 50 mg daily, which resulted in mild improvement in symptoms.

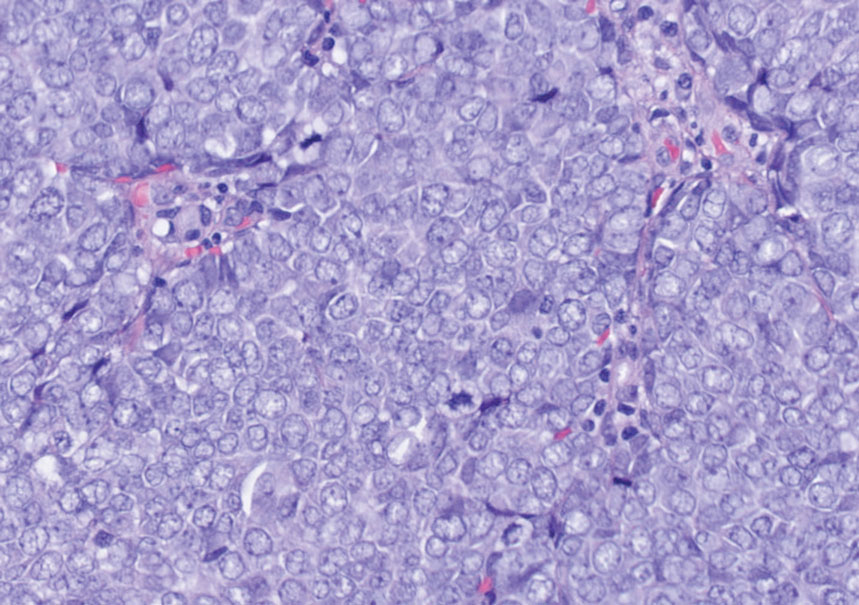

Within 6 months, new sclerotic plaques developed on the patient’s back and right thigh (Figure 1B). Because the lesions were located outside the radiation field of the left femur, a second biopsy was obtained from the right thigh. Histopathology revealed extensive dermal sclerosis and a perivascular lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate (Figure 2). An antinuclear antibody test was weakly positive (1:40, nucleolar pattern) with a negative extractable nuclear antigen panel result. Anti–double-stranded DNA, anti–topoisomerase 1, anti-Smith, antiribonucleoprotein, anti–Sjögren syndrome type A, anti–Sjögren syndrome type B, and anticentromere serology test results were negative. The patient denied decreased oral aperture, difficulty swallowing, or Raynaud phenomenon. Due to the atypical clinical presentation in the setting of PD-1 inhibitor therapy, the etiology of the eruption was potentially attributable to nivolumab. She was started on treatment with methotrexate 20 mg weekly and clobetasol cream 0.05% twice daily; she continued taking prednisone 5 mg daily. The cutaneous manifestations on the patient’s back completely resolved, and the legs continued to gradually improve on this regimen. Immunotherapy continued to be held due to skin toxicity.

Localized scleroderma is an autoimmune disorder characterized by inflammation and skin thickening. Overactive fibroblasts produce excess collagen, leading to the clinical symptoms of skin thickening, hardening, and discoloration.3 Lesions frequently develop on the arms, face, or legs and can present as patches or linear bands. Unlike systemic sclerosis, the internal organs typically are uninvolved; however, sclerotic lesions can be disfiguring and cause notable disability if they impede joint movement.

The PD-1/PD-L1 pathway is a negative regulator of the immune response that inactivates T cells and helps maintain self-tolerance. Modulation of the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway and overexpression of PD-L1 are seen in various cancers as a mechanism to help malignant cells avoid immune destruction.4 Conversely, inhibition of this pathway can be used to stimulate an antitumor immune response. This checkpoint inhibition strategy has been highly successful for the treatment of various cancers including melanoma and non–small cell lung carcinoma. There are several checkpoint inhibitors approved in the United States that are used for cancer therapy and target the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway, such as nivolumab, pembrolizumab, atezolizumab, durvalumab, and avelumab.4 A downside of checkpoint inhibitor treatment is that uncontrolled T-cell activation can lead to irAEs, including cutaneous eruptions, pruritus, diarrhea, colitis, hepatitis, endocrinopathies, pneumonitis, and renal insufficiency.5 These toxicities are reversible if treated appropriately but can cause notable morbidity and mortality if left unrecognized. Cutaneous eruption is one of the most common irAEs associated with anti–PD-1 and anti–PD-L1 therapies and can limit therapeutic efficacy, as the drug may need to be held or discontinued due to the severity of the eruption.6 Mid-potency to high-potency topical corticosteroids and systemic antihistamines are first-line treatments of grades 1 and 2 skin toxicities associated with PD-1 inhibitor therapy. For eruptions classified as grades 3 or 4 or refractory grade 2, discontinuation of the drug and systemic corticosteroids is recommended.7