User login

White Hispanic Mohs patients less informed about skin cancer risks

White Hispanic adults report a lower quality of life and less knowledge of skin cancer and sun protection behaviors than white non-Hispanic adults, survey results of 175 adults with nonmelanoma skin cancer show.

“The incidence of nonmelanoma skin cancer (NMSC) is lower in Hispanics when compared to Caucasians, but a high index of suspicion is needed given ethnic differences in presentation,” wrote Ali Rajabi-Estarabadi, MD, of the University of Miami, and colleagues.

Hispanic patients with NMSC tend to be younger than non-Hispanic white patients, and their basal cell carcinomas are more likely to be pigmented, the investigators noted. Although previous research suggests ethnic disparities in NMSC, factors including sun safety knowledge and quality of life after diagnosis have not been well studied, they said.

With this in mind, the investigators conducted a survey of white Hispanics and non-Hispanics treated for NMSC. The results were published as a research letter in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

The investigators recruited 175 consecutive patients being treated for NMSC with Mohs surgery at a single center. The average age of the patients was 67 years; 58 identified as white Hispanic, 116 identified as white non-Hispanic.

White Hispanic patients had significantly lower skin cancer knowledge scores, compared with white non-Hispanics (P = .003). White Hispanics were significantly more likely than white non-Hispanics to report never wearing hats (39% vs. 12%) and never wearing sunglasses (26% vs. 9%) for sun protection.

The findings were limited by the study population that included only residents of South Florida. However, the results highlight the need for “targeted patient education initiatives to bridge ethnic disparities regarding cancer knowledge and ultimately improve [quality of life] among Hispanic skin cancer suffers,” the investigators concluded.

The study received no outside funding. The investigators declared no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Rajabi-Estarabadi A et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020 Feb 4. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.01.063.

White Hispanic adults report a lower quality of life and less knowledge of skin cancer and sun protection behaviors than white non-Hispanic adults, survey results of 175 adults with nonmelanoma skin cancer show.

“The incidence of nonmelanoma skin cancer (NMSC) is lower in Hispanics when compared to Caucasians, but a high index of suspicion is needed given ethnic differences in presentation,” wrote Ali Rajabi-Estarabadi, MD, of the University of Miami, and colleagues.

Hispanic patients with NMSC tend to be younger than non-Hispanic white patients, and their basal cell carcinomas are more likely to be pigmented, the investigators noted. Although previous research suggests ethnic disparities in NMSC, factors including sun safety knowledge and quality of life after diagnosis have not been well studied, they said.

With this in mind, the investigators conducted a survey of white Hispanics and non-Hispanics treated for NMSC. The results were published as a research letter in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

The investigators recruited 175 consecutive patients being treated for NMSC with Mohs surgery at a single center. The average age of the patients was 67 years; 58 identified as white Hispanic, 116 identified as white non-Hispanic.

White Hispanic patients had significantly lower skin cancer knowledge scores, compared with white non-Hispanics (P = .003). White Hispanics were significantly more likely than white non-Hispanics to report never wearing hats (39% vs. 12%) and never wearing sunglasses (26% vs. 9%) for sun protection.

The findings were limited by the study population that included only residents of South Florida. However, the results highlight the need for “targeted patient education initiatives to bridge ethnic disparities regarding cancer knowledge and ultimately improve [quality of life] among Hispanic skin cancer suffers,” the investigators concluded.

The study received no outside funding. The investigators declared no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Rajabi-Estarabadi A et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020 Feb 4. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.01.063.

White Hispanic adults report a lower quality of life and less knowledge of skin cancer and sun protection behaviors than white non-Hispanic adults, survey results of 175 adults with nonmelanoma skin cancer show.

“The incidence of nonmelanoma skin cancer (NMSC) is lower in Hispanics when compared to Caucasians, but a high index of suspicion is needed given ethnic differences in presentation,” wrote Ali Rajabi-Estarabadi, MD, of the University of Miami, and colleagues.

Hispanic patients with NMSC tend to be younger than non-Hispanic white patients, and their basal cell carcinomas are more likely to be pigmented, the investigators noted. Although previous research suggests ethnic disparities in NMSC, factors including sun safety knowledge and quality of life after diagnosis have not been well studied, they said.

With this in mind, the investigators conducted a survey of white Hispanics and non-Hispanics treated for NMSC. The results were published as a research letter in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

The investigators recruited 175 consecutive patients being treated for NMSC with Mohs surgery at a single center. The average age of the patients was 67 years; 58 identified as white Hispanic, 116 identified as white non-Hispanic.

White Hispanic patients had significantly lower skin cancer knowledge scores, compared with white non-Hispanics (P = .003). White Hispanics were significantly more likely than white non-Hispanics to report never wearing hats (39% vs. 12%) and never wearing sunglasses (26% vs. 9%) for sun protection.

The findings were limited by the study population that included only residents of South Florida. However, the results highlight the need for “targeted patient education initiatives to bridge ethnic disparities regarding cancer knowledge and ultimately improve [quality of life] among Hispanic skin cancer suffers,” the investigators concluded.

The study received no outside funding. The investigators declared no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Rajabi-Estarabadi A et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020 Feb 4. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.01.063.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF DERMATOLOGY

Friable Scalp Nodule

The Diagnosis: Adnexal Neoplasm Arising in a Nevus Sebaceus

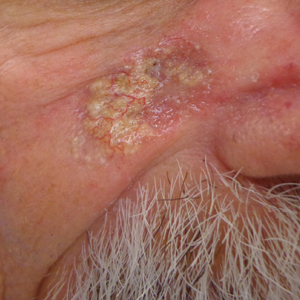

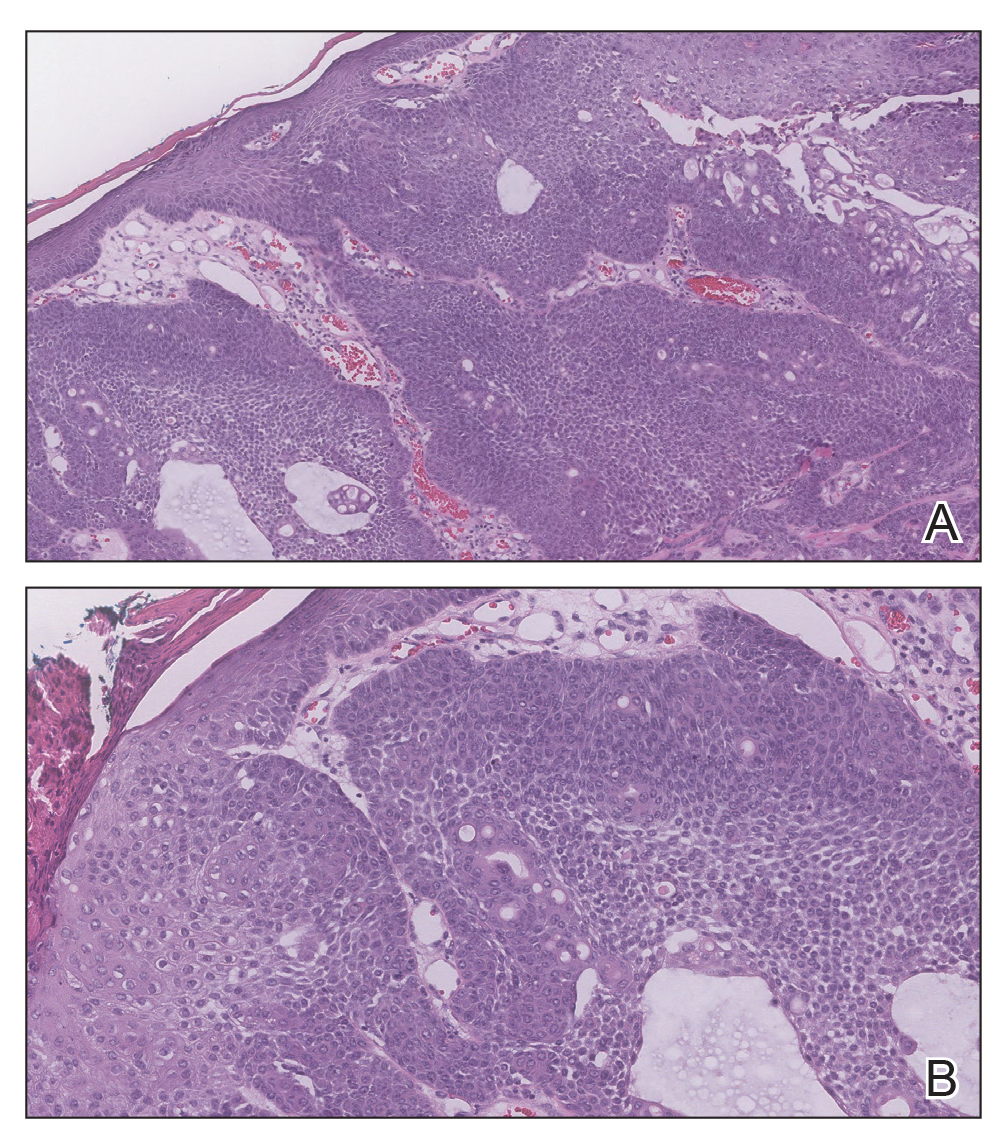

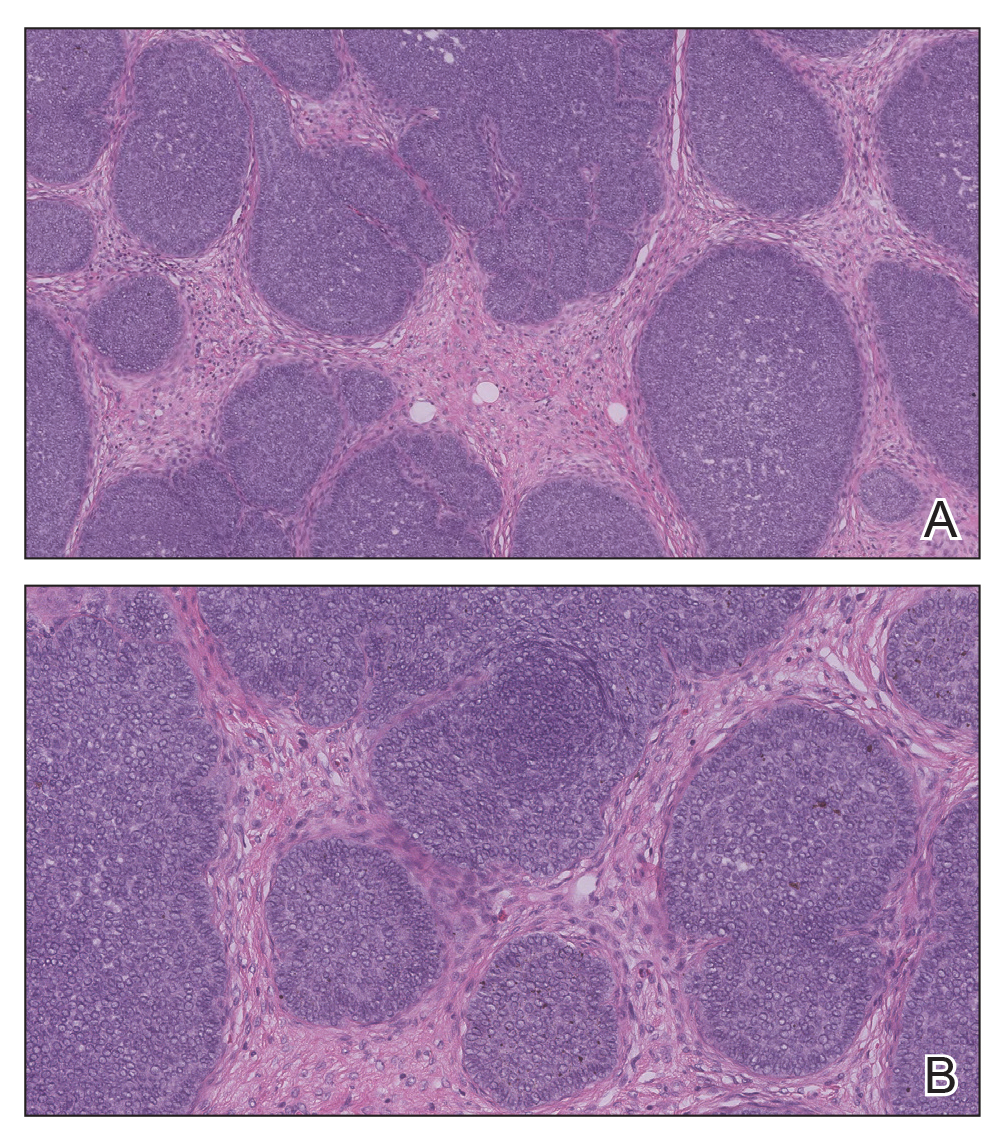

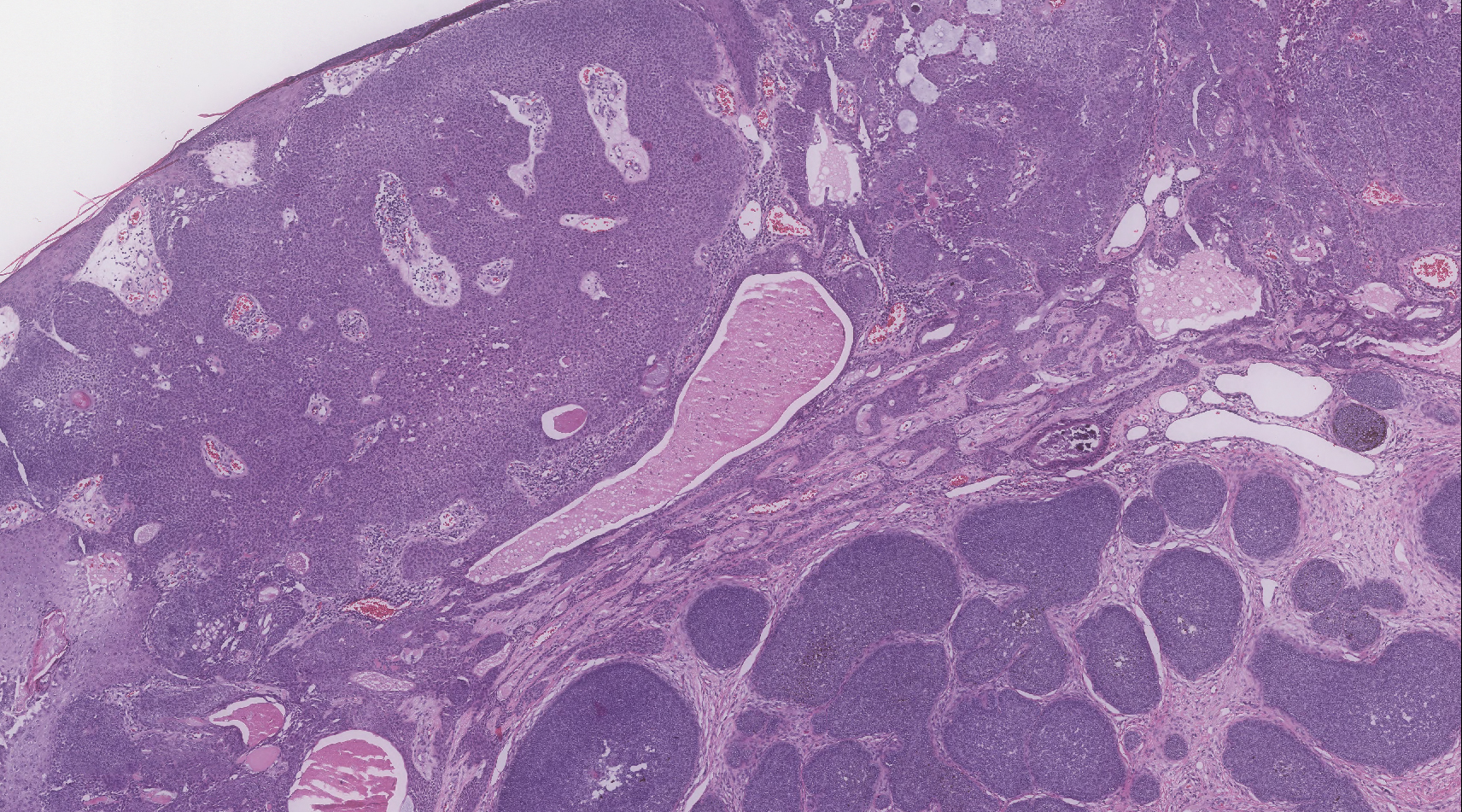

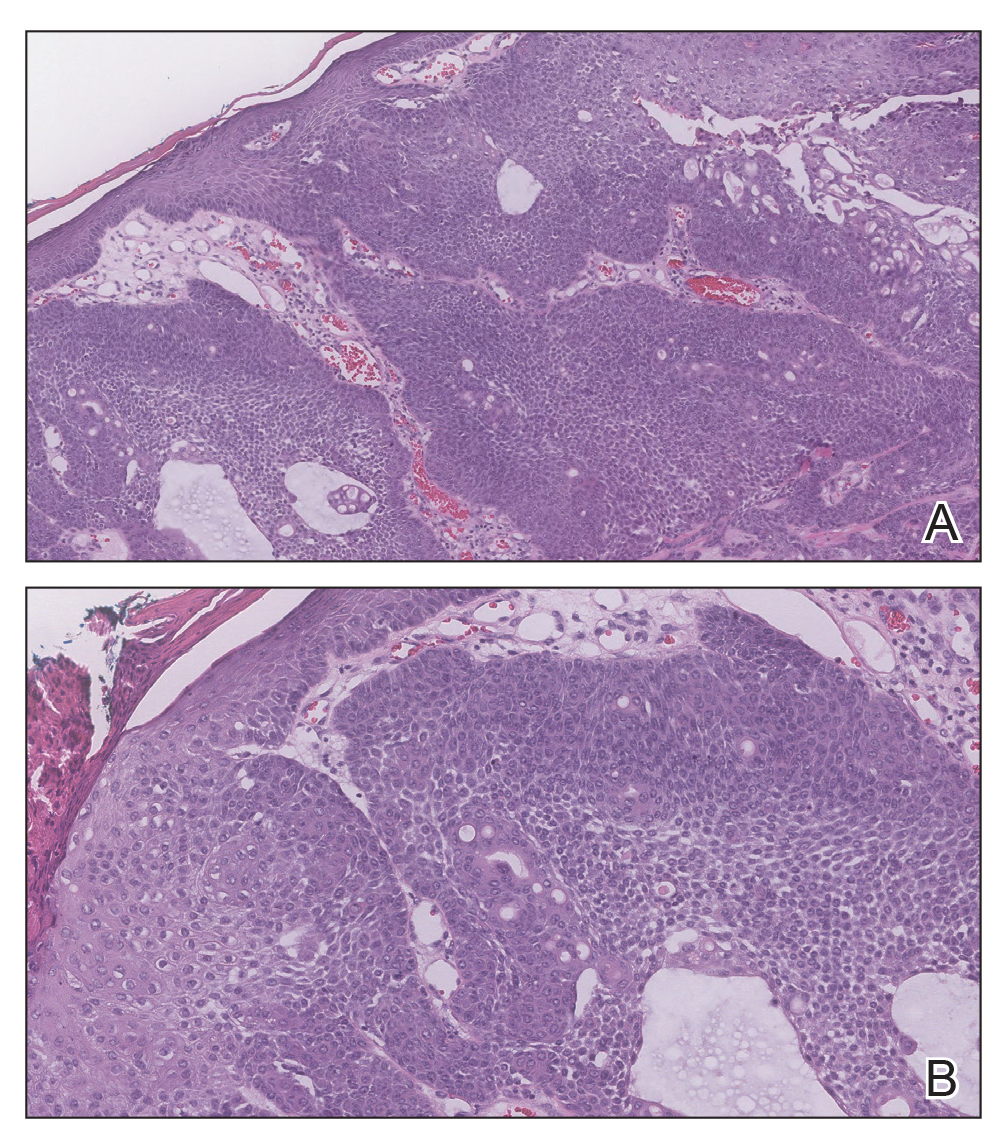

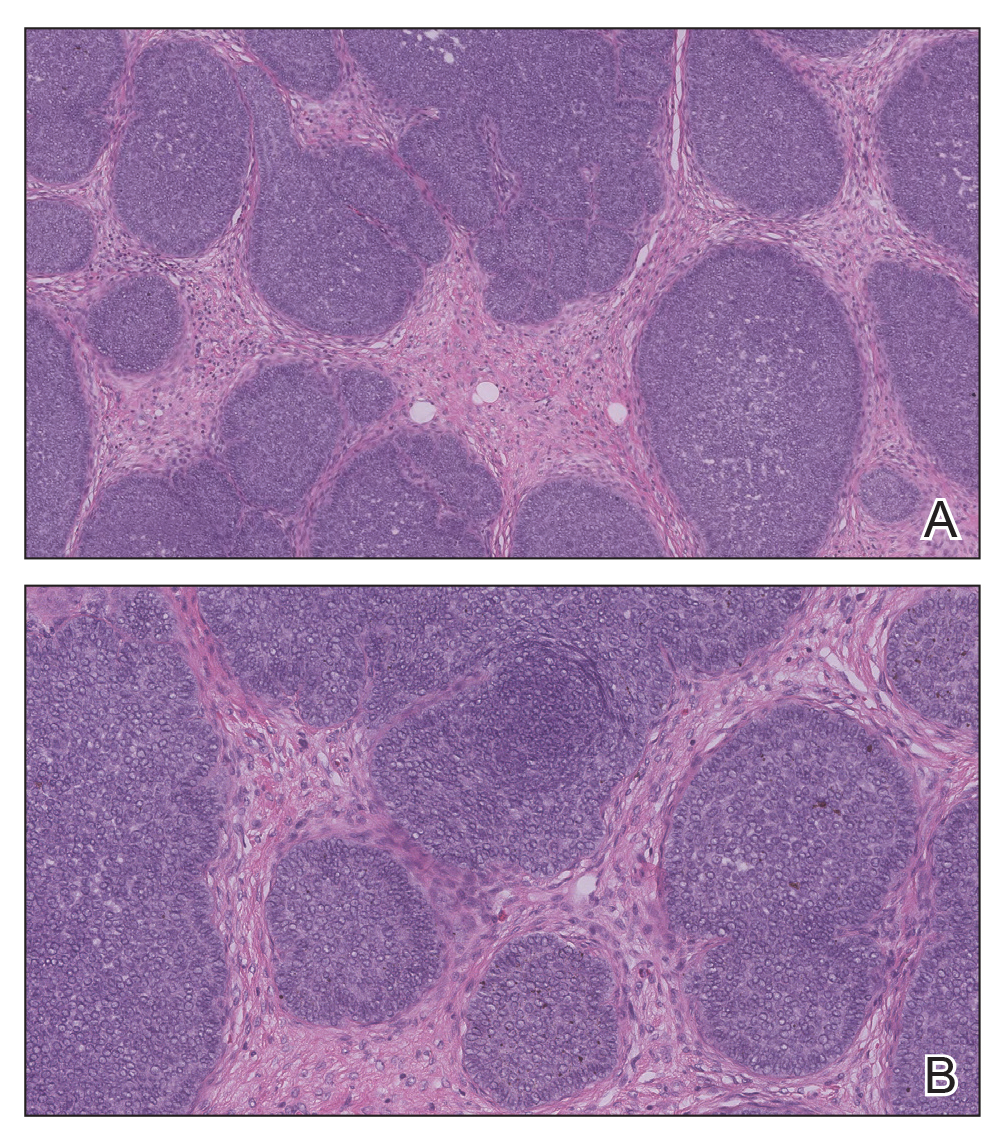

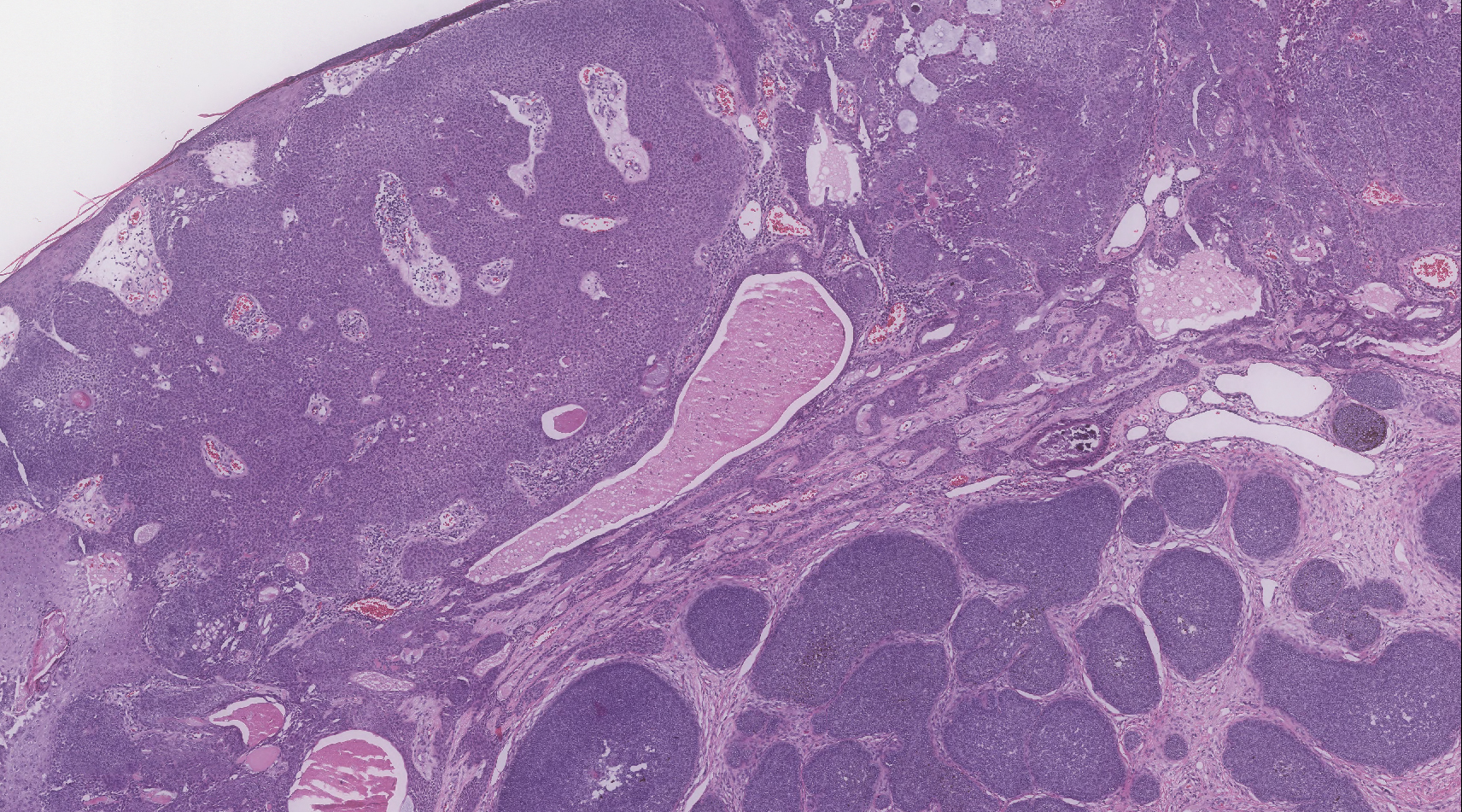

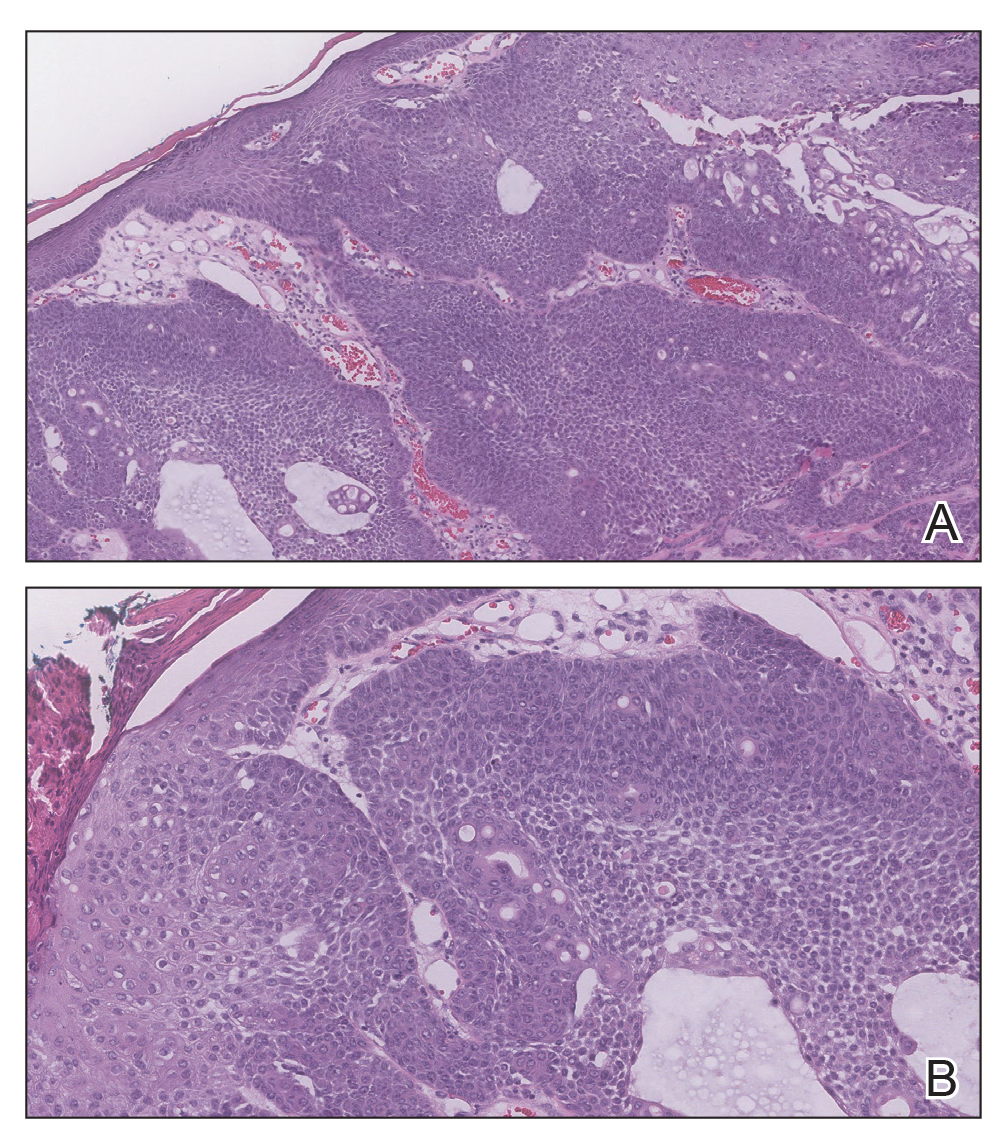

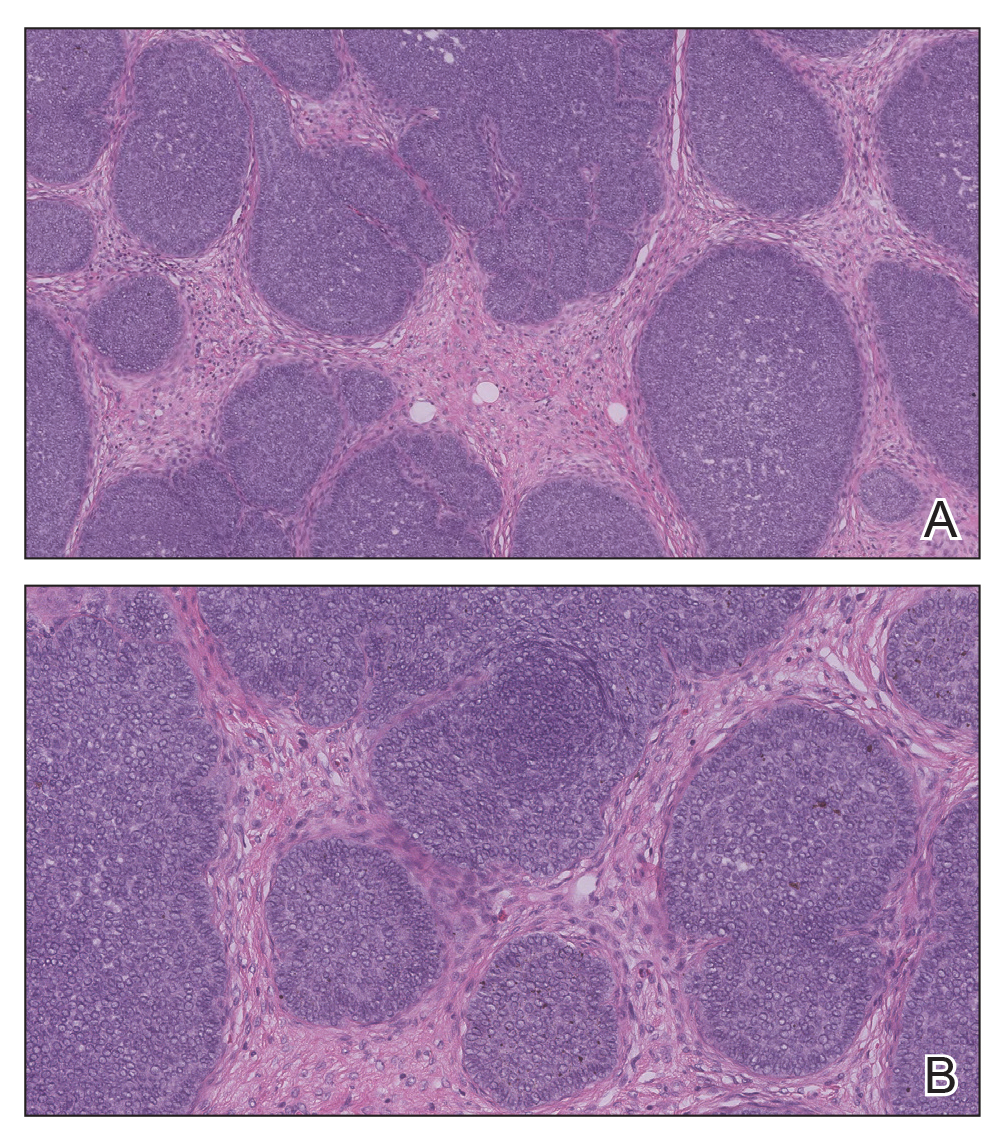

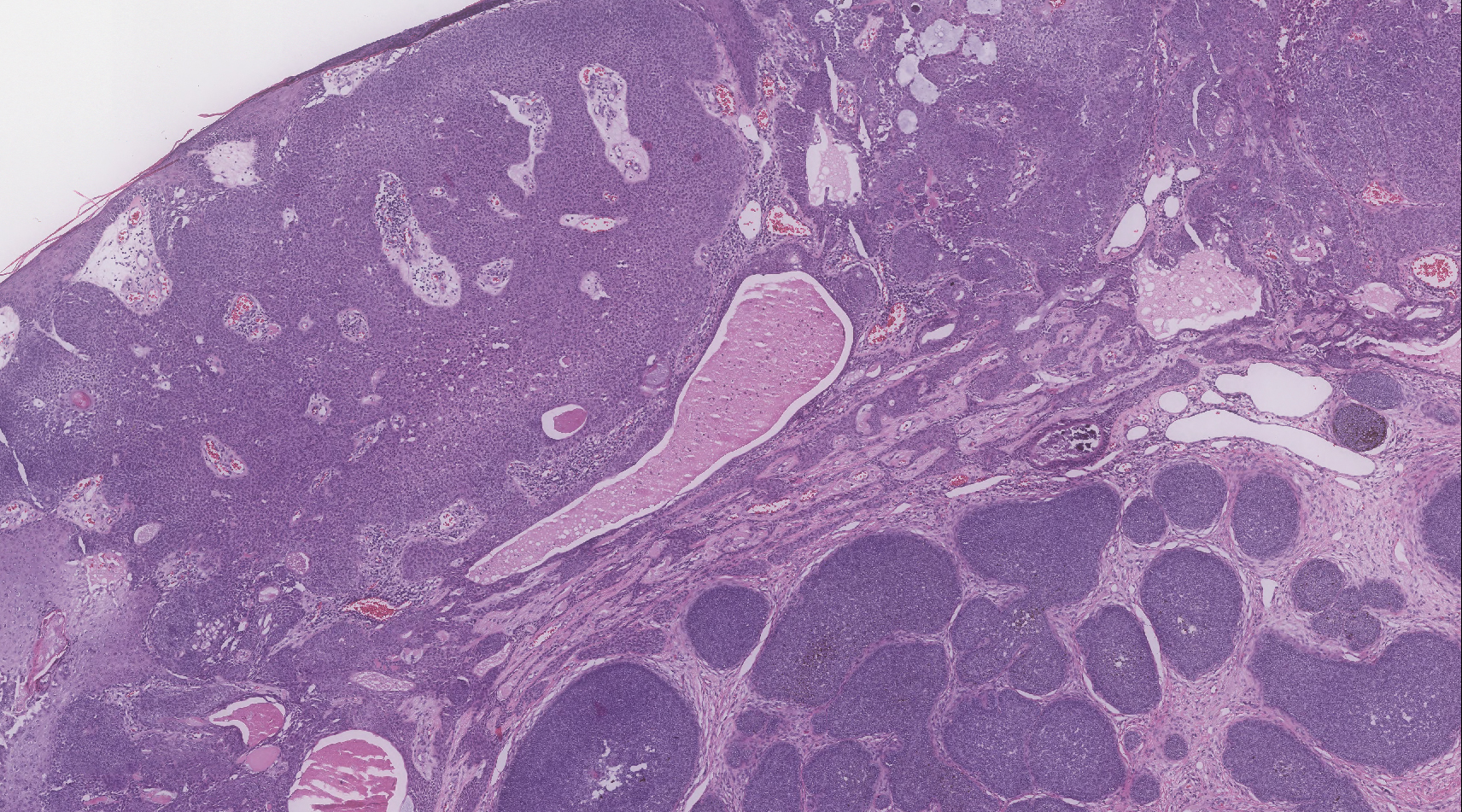

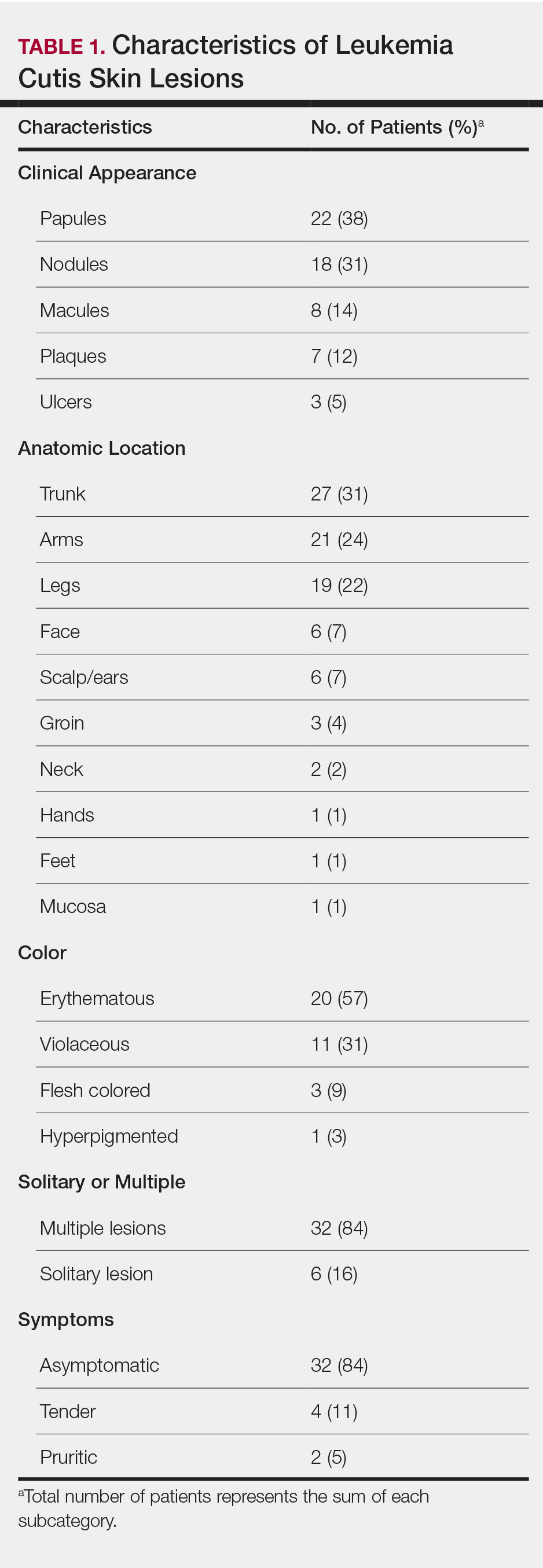

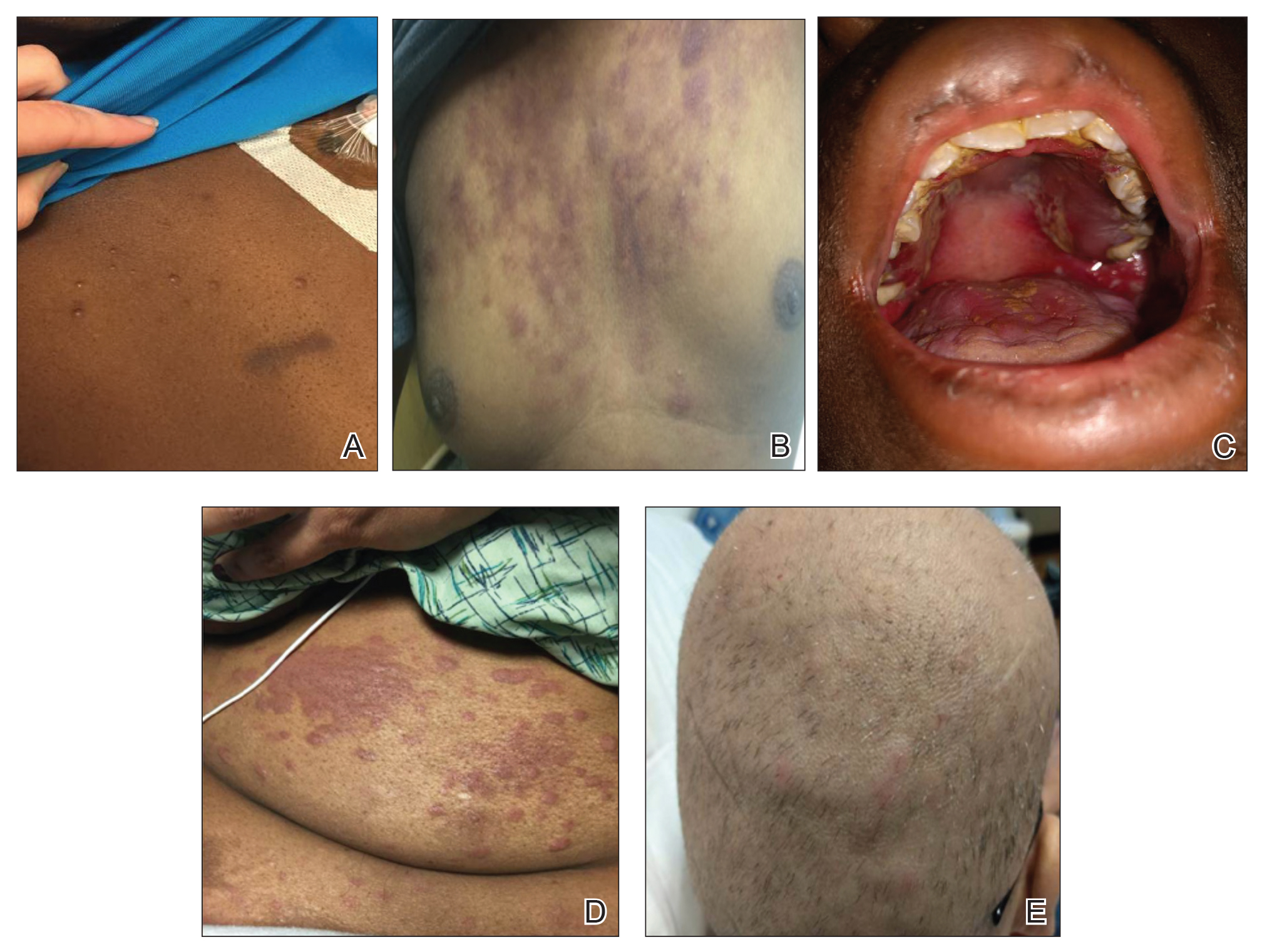

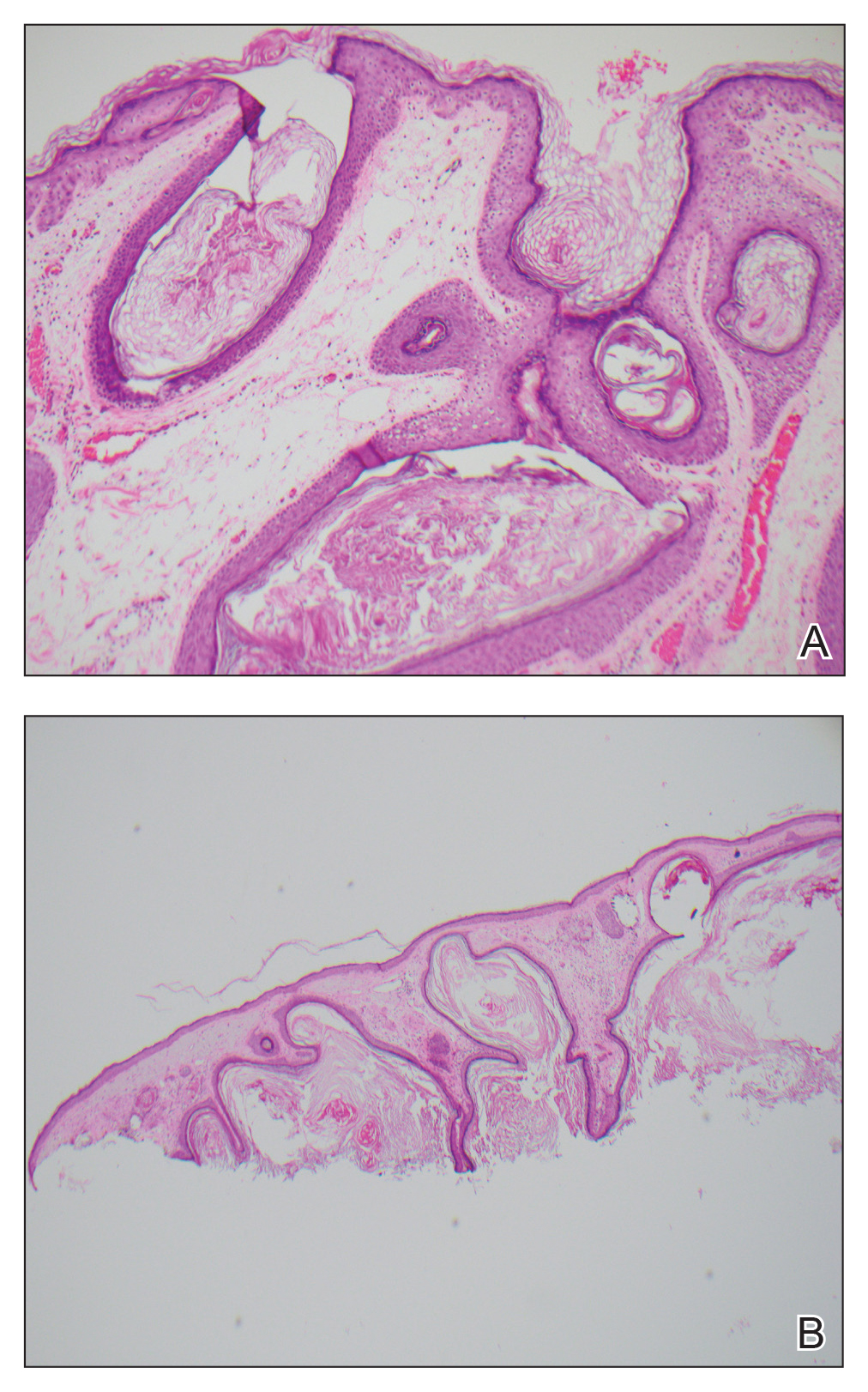

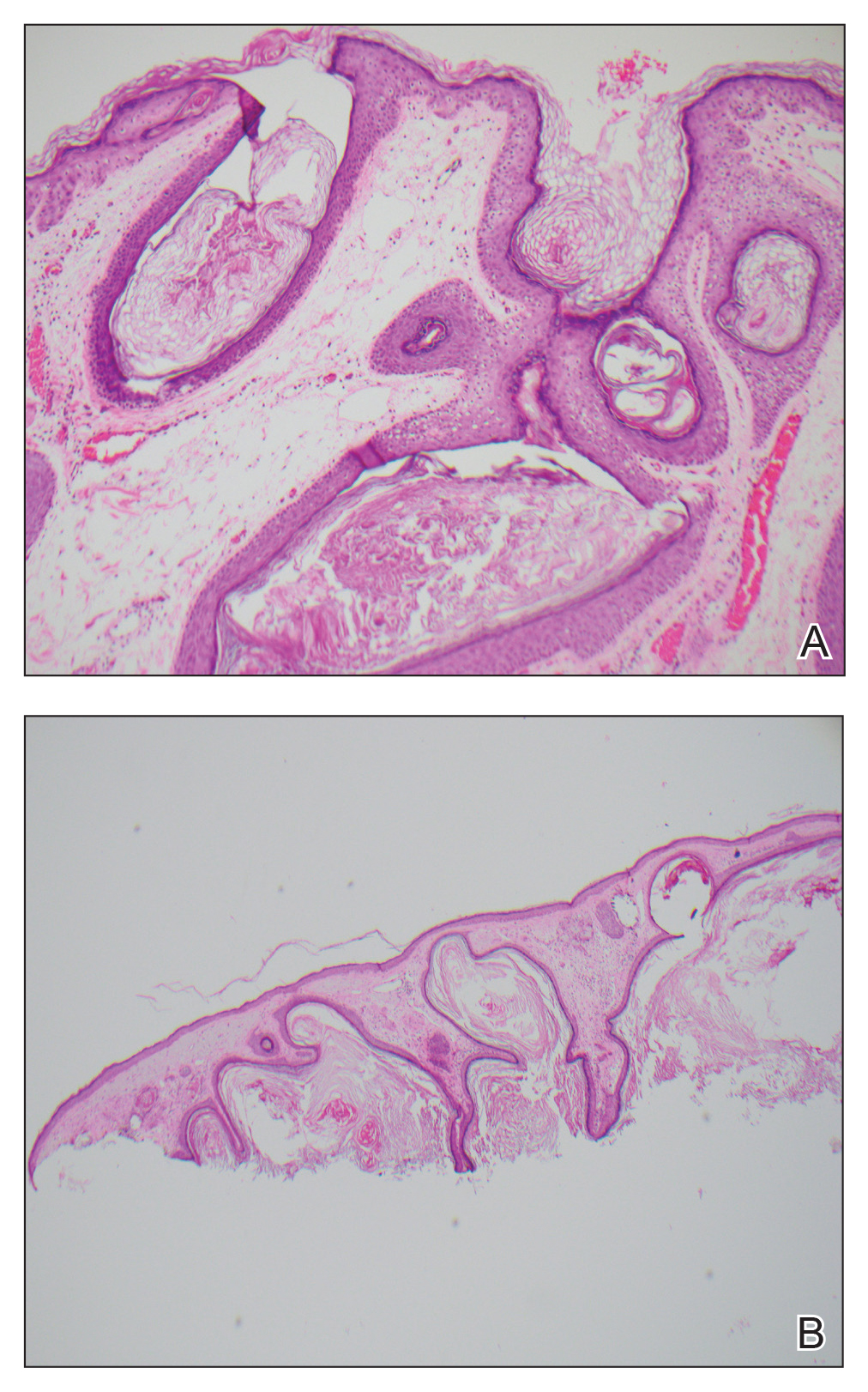

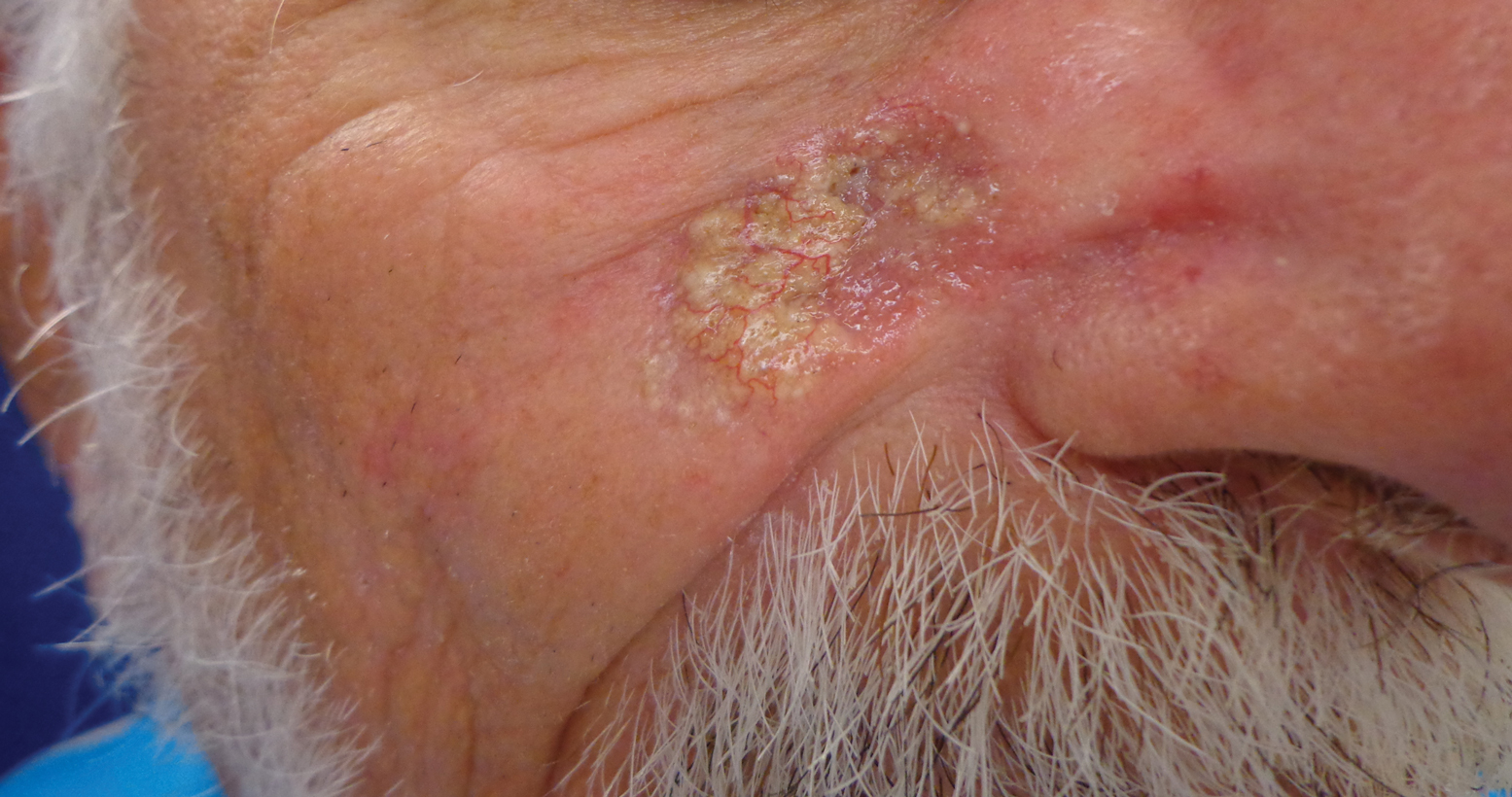

Biopsy of the lesion showed a proliferation of basaloid-appearing cells with focal ductal differentiation and ulceration consistent with poroma (Figure 1). Due to the superficial nature of the biopsy, the pathologist recommended excision to ensure complete removal and to rule out a well-differentiated porocarcinoma. Excision of the lesion showed large basaloid aggregates with a hypercellular stroma and a surrounding papillomatous epidermis with well-developed sebaceous lobules consistent with a trichoblastoma and a nevus sebaceus, respectively (Figure 2). There also was evidence of poroma; however, there were no findings concerning for porocarcinoma, which could lead to metastasis (Figure 3).

Nevus sebaceus is a benign, hamartomatous, congenital growth that occurs in approximately 1% of patients presenting to dermatology offices. It usually presents as a single asymptomatic plaque on the scalp (62.5%) or face (24.5%) that changes in morphology over its lifetime.1,2 In children, a nevus manifests as a yellowish, smooth, waxy skin lesion. As the sebaceous glands become more developed during adolescence, the lesion takes on more of a verrucous appearance and also can darken.

Although nevus sebaceus is benign, it may give rise to both benign and malignant neoplasms. In a 2014 study of 707 cases of nevus sebaceus, 21.4% developed secondary neoplasms, 88% of which were benign.2 The origins of these neoplasms can be epithelial, sebaceous, apocrine, and/or follicular. The 3 most common secondary neoplasms found in nevus sebaceus are trichoblastoma (34.7%), syringocystadenoma papilliferum (24.7%), and apocrine/eccrine adenoma (10%), all of which are benign.2 Trichoblastomas represent a type of hair follicle tumor. Malignant lesions manifest in approximately 2.5% of cases, with basal cell carcinoma (BCC) being the most common (5.3% of all neoplasms), followed by squamous cell carcinoma (2.7% of all neoplasms).2 Differentiating BCC from trichoblastoma can be difficult, but histologically BCCs usually have tumor stromal clefting while trichoblastomas do not.3 The incidence of secondary tumors in nevus sebaceus displays a strong correlation with age; thus, the highest proportion of neoplasms occur in adults.

Treatment of nevus sebaceus depends on the patient's age. In children, because of the low probability of secondary neoplasms, observation in lieu of surgical excision is a common approach. In adults, the approach typically is surgical excision or close follow-up, as there is a concern for secondary neoplasm and the potential for malignant degeneration.

A nevus sebaceus leading to 2 or more tumors within the same lesion is rare (seen in only 4.2% of lesions). The most common combination is trichoblastoma with syringocystadenoma papilliferum (0.6% of all cases).2 Poromas represent sweat gland tumors that usually appear on the soles (65%) or palms (10%).4 It is uncommon for these neoplasms to manifest on the scalp or within a nevus sebaceus. Three independent studies (N=596; N=707; N=450) did not report any occurrences of eccrine poroma.1,2,5 Eccrine poroma in conjunction with nodular trichoblastoma arising in a nevus sebaceus is unusual, and definitive excision should be strongly considered because of the possibility to develop a porocarcinoma.6

Atypical fibroxanthoma presents on sun-exposed areas as an exophytic nodule or plaque that frequently ulcerates. Pathology of this tumor shows a spindled cell proliferation that can stain positively for CD10 and procollagen 1. Basal cell carcinoma presents as a pearly papule or nodule displaying basaloid-appearing aggregates with tumor stromal clefting and can stain with Ber-EP4. Cylindromas typically present on the scalp as large rubbery-appearing plaques and nodules. Cylindromas usually present as a solitary tumor, but in the familial form there can be clusters of multiple nodules. Metastatic renal cell carcinoma frequently appears as a bleeding nodule on the scalp in patients with known renal cell cancer or as the initial presentation.

- Cribier B, Scrivener Y, Grosshans E. Tumors arising in nevus sebaceus: a study of 596 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42(pt 1):263-268.

- Idriss MH, Elston DM. Secondary neoplasms associated with nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn: a study of 707 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:332-337.

- Wang E, Lee JS, Kazakov DV. A rare combination of sebaceoma with carcinomatous change (sebaceous carcinoma), trichoblastoma, and poroma arising from a nevus sebaceus. J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40:676-682.

- Bae MI, Cho TH, Shin MK, et al. An unusual clinical presentation of eccrine poroma occurring on the auricle. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60:523.

- Hsu MC, Liau JY, Hong JL, et al. Secondary neoplasms arising from nevus sebaceus: a retrospective study of 450 cases in Taiwan. J Dermatol. 2016;43:175-180.

- Takhan II, Domingo J. Metastasizing eccrine porocarcinoma developing in a sebaceous nevus of Jadassohn. report of a case. Arch Dermatol. 1985;121:413-415.

The Diagnosis: Adnexal Neoplasm Arising in a Nevus Sebaceus

Biopsy of the lesion showed a proliferation of basaloid-appearing cells with focal ductal differentiation and ulceration consistent with poroma (Figure 1). Due to the superficial nature of the biopsy, the pathologist recommended excision to ensure complete removal and to rule out a well-differentiated porocarcinoma. Excision of the lesion showed large basaloid aggregates with a hypercellular stroma and a surrounding papillomatous epidermis with well-developed sebaceous lobules consistent with a trichoblastoma and a nevus sebaceus, respectively (Figure 2). There also was evidence of poroma; however, there were no findings concerning for porocarcinoma, which could lead to metastasis (Figure 3).

Nevus sebaceus is a benign, hamartomatous, congenital growth that occurs in approximately 1% of patients presenting to dermatology offices. It usually presents as a single asymptomatic plaque on the scalp (62.5%) or face (24.5%) that changes in morphology over its lifetime.1,2 In children, a nevus manifests as a yellowish, smooth, waxy skin lesion. As the sebaceous glands become more developed during adolescence, the lesion takes on more of a verrucous appearance and also can darken.

Although nevus sebaceus is benign, it may give rise to both benign and malignant neoplasms. In a 2014 study of 707 cases of nevus sebaceus, 21.4% developed secondary neoplasms, 88% of which were benign.2 The origins of these neoplasms can be epithelial, sebaceous, apocrine, and/or follicular. The 3 most common secondary neoplasms found in nevus sebaceus are trichoblastoma (34.7%), syringocystadenoma papilliferum (24.7%), and apocrine/eccrine adenoma (10%), all of which are benign.2 Trichoblastomas represent a type of hair follicle tumor. Malignant lesions manifest in approximately 2.5% of cases, with basal cell carcinoma (BCC) being the most common (5.3% of all neoplasms), followed by squamous cell carcinoma (2.7% of all neoplasms).2 Differentiating BCC from trichoblastoma can be difficult, but histologically BCCs usually have tumor stromal clefting while trichoblastomas do not.3 The incidence of secondary tumors in nevus sebaceus displays a strong correlation with age; thus, the highest proportion of neoplasms occur in adults.

Treatment of nevus sebaceus depends on the patient's age. In children, because of the low probability of secondary neoplasms, observation in lieu of surgical excision is a common approach. In adults, the approach typically is surgical excision or close follow-up, as there is a concern for secondary neoplasm and the potential for malignant degeneration.

A nevus sebaceus leading to 2 or more tumors within the same lesion is rare (seen in only 4.2% of lesions). The most common combination is trichoblastoma with syringocystadenoma papilliferum (0.6% of all cases).2 Poromas represent sweat gland tumors that usually appear on the soles (65%) or palms (10%).4 It is uncommon for these neoplasms to manifest on the scalp or within a nevus sebaceus. Three independent studies (N=596; N=707; N=450) did not report any occurrences of eccrine poroma.1,2,5 Eccrine poroma in conjunction with nodular trichoblastoma arising in a nevus sebaceus is unusual, and definitive excision should be strongly considered because of the possibility to develop a porocarcinoma.6

Atypical fibroxanthoma presents on sun-exposed areas as an exophytic nodule or plaque that frequently ulcerates. Pathology of this tumor shows a spindled cell proliferation that can stain positively for CD10 and procollagen 1. Basal cell carcinoma presents as a pearly papule or nodule displaying basaloid-appearing aggregates with tumor stromal clefting and can stain with Ber-EP4. Cylindromas typically present on the scalp as large rubbery-appearing plaques and nodules. Cylindromas usually present as a solitary tumor, but in the familial form there can be clusters of multiple nodules. Metastatic renal cell carcinoma frequently appears as a bleeding nodule on the scalp in patients with known renal cell cancer or as the initial presentation.

The Diagnosis: Adnexal Neoplasm Arising in a Nevus Sebaceus

Biopsy of the lesion showed a proliferation of basaloid-appearing cells with focal ductal differentiation and ulceration consistent with poroma (Figure 1). Due to the superficial nature of the biopsy, the pathologist recommended excision to ensure complete removal and to rule out a well-differentiated porocarcinoma. Excision of the lesion showed large basaloid aggregates with a hypercellular stroma and a surrounding papillomatous epidermis with well-developed sebaceous lobules consistent with a trichoblastoma and a nevus sebaceus, respectively (Figure 2). There also was evidence of poroma; however, there were no findings concerning for porocarcinoma, which could lead to metastasis (Figure 3).

Nevus sebaceus is a benign, hamartomatous, congenital growth that occurs in approximately 1% of patients presenting to dermatology offices. It usually presents as a single asymptomatic plaque on the scalp (62.5%) or face (24.5%) that changes in morphology over its lifetime.1,2 In children, a nevus manifests as a yellowish, smooth, waxy skin lesion. As the sebaceous glands become more developed during adolescence, the lesion takes on more of a verrucous appearance and also can darken.

Although nevus sebaceus is benign, it may give rise to both benign and malignant neoplasms. In a 2014 study of 707 cases of nevus sebaceus, 21.4% developed secondary neoplasms, 88% of which were benign.2 The origins of these neoplasms can be epithelial, sebaceous, apocrine, and/or follicular. The 3 most common secondary neoplasms found in nevus sebaceus are trichoblastoma (34.7%), syringocystadenoma papilliferum (24.7%), and apocrine/eccrine adenoma (10%), all of which are benign.2 Trichoblastomas represent a type of hair follicle tumor. Malignant lesions manifest in approximately 2.5% of cases, with basal cell carcinoma (BCC) being the most common (5.3% of all neoplasms), followed by squamous cell carcinoma (2.7% of all neoplasms).2 Differentiating BCC from trichoblastoma can be difficult, but histologically BCCs usually have tumor stromal clefting while trichoblastomas do not.3 The incidence of secondary tumors in nevus sebaceus displays a strong correlation with age; thus, the highest proportion of neoplasms occur in adults.

Treatment of nevus sebaceus depends on the patient's age. In children, because of the low probability of secondary neoplasms, observation in lieu of surgical excision is a common approach. In adults, the approach typically is surgical excision or close follow-up, as there is a concern for secondary neoplasm and the potential for malignant degeneration.

A nevus sebaceus leading to 2 or more tumors within the same lesion is rare (seen in only 4.2% of lesions). The most common combination is trichoblastoma with syringocystadenoma papilliferum (0.6% of all cases).2 Poromas represent sweat gland tumors that usually appear on the soles (65%) or palms (10%).4 It is uncommon for these neoplasms to manifest on the scalp or within a nevus sebaceus. Three independent studies (N=596; N=707; N=450) did not report any occurrences of eccrine poroma.1,2,5 Eccrine poroma in conjunction with nodular trichoblastoma arising in a nevus sebaceus is unusual, and definitive excision should be strongly considered because of the possibility to develop a porocarcinoma.6

Atypical fibroxanthoma presents on sun-exposed areas as an exophytic nodule or plaque that frequently ulcerates. Pathology of this tumor shows a spindled cell proliferation that can stain positively for CD10 and procollagen 1. Basal cell carcinoma presents as a pearly papule or nodule displaying basaloid-appearing aggregates with tumor stromal clefting and can stain with Ber-EP4. Cylindromas typically present on the scalp as large rubbery-appearing plaques and nodules. Cylindromas usually present as a solitary tumor, but in the familial form there can be clusters of multiple nodules. Metastatic renal cell carcinoma frequently appears as a bleeding nodule on the scalp in patients with known renal cell cancer or as the initial presentation.

- Cribier B, Scrivener Y, Grosshans E. Tumors arising in nevus sebaceus: a study of 596 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42(pt 1):263-268.

- Idriss MH, Elston DM. Secondary neoplasms associated with nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn: a study of 707 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:332-337.

- Wang E, Lee JS, Kazakov DV. A rare combination of sebaceoma with carcinomatous change (sebaceous carcinoma), trichoblastoma, and poroma arising from a nevus sebaceus. J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40:676-682.

- Bae MI, Cho TH, Shin MK, et al. An unusual clinical presentation of eccrine poroma occurring on the auricle. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60:523.

- Hsu MC, Liau JY, Hong JL, et al. Secondary neoplasms arising from nevus sebaceus: a retrospective study of 450 cases in Taiwan. J Dermatol. 2016;43:175-180.

- Takhan II, Domingo J. Metastasizing eccrine porocarcinoma developing in a sebaceous nevus of Jadassohn. report of a case. Arch Dermatol. 1985;121:413-415.

- Cribier B, Scrivener Y, Grosshans E. Tumors arising in nevus sebaceus: a study of 596 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42(pt 1):263-268.

- Idriss MH, Elston DM. Secondary neoplasms associated with nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn: a study of 707 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:332-337.

- Wang E, Lee JS, Kazakov DV. A rare combination of sebaceoma with carcinomatous change (sebaceous carcinoma), trichoblastoma, and poroma arising from a nevus sebaceus. J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40:676-682.

- Bae MI, Cho TH, Shin MK, et al. An unusual clinical presentation of eccrine poroma occurring on the auricle. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60:523.

- Hsu MC, Liau JY, Hong JL, et al. Secondary neoplasms arising from nevus sebaceus: a retrospective study of 450 cases in Taiwan. J Dermatol. 2016;43:175-180.

- Takhan II, Domingo J. Metastasizing eccrine porocarcinoma developing in a sebaceous nevus of Jadassohn. report of a case. Arch Dermatol. 1985;121:413-415.

A 75-year-old woman presented with an enlarging plaque on the scalp of 5 years' duration. Physical examination revealed a 5.6.2 ×2.9-cm, tan-colored, verrucous plaque with an overlying pink friable nodule on the left occipital scalp. The lesion was not painful or pruritic, and the patient did not have any constitutional symptoms such as fever, night sweats, or weight loss. The patient denied prior tanning bed use and reported intermittent sun exposure over her lifetime. She denied any prior surgical intervention. There was no family history of similar lesions.

European marketing of Picato suspended while skin cancer risk reviewed

As a precaution, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) has recommended that patients stop using ingenol mebutate (Picato) while the agency continues to review the safety of the topical treatment, which is indicated for the treatment of actinic keratosis in Europe and the United States.

No such action has been taken in the United States.

The EMA’s Pharmacovigilance Risk Assessment Committee (PRAC) is reviewing data on skin cancer in patients treated with ingenol mebutate. In a trial comparing Picato and imiquimod, skin cancer was more common in the areas treated with Picato than in areas treated with imiquimod, the statement said.

“While uncertainties remain, the EMA said in a Jan. 17 news release. “The PRAC has therefore recommended suspending the medicine’s marketing authorization as a precaution and noted that alternative treatments are available.”

FDA is looking at the situation

LEO Pharma, the company that markets Picato, announced on Jan. 9 that it was initiating voluntary withdrawal of marketing authorization and possible voluntary withdrawal of Picato in the European Union (EU) and European Economic Area (EEA). The statement says, however, that “LEO Pharma has carefully reviewed the information received from PRAC, and the company disagrees with the ongoing assessment of PRAC.” There are “no additional safety data and it is LEO Pharma’s position that there is no evidence of a causal relationship or plausible mechanism hypothesis between the use of Picato and the development of skin malignancies.” An update added to the press release on Jan. 17 restates that the company disagrees with the assessment of PRAC.

“This matter does not affect Picato in the U.S., and there are no new developments in the [United States]. Picato continues to be available to patients in the U.S. We remain in dialogue with the U.S. Food and Drug Administration about Picato in the EU/EEA,” Rhonda Sciarra, associate director of global external communications for LEO Pharma, said in an email. “We remain committed to ensuring patient safety, rigorous pharmacovigilance monitoring, and transparency,” she added.

The FDA “is gathering data and information to investigate the safety concern related to Picato,” a spokesperson for the FDA told Dermatology News. “We are committed to sharing relevant findings when we have sufficient understanding of the situation and of what actions should be taken,” he added.

Examining the data

The EMA announcement described data about the risk of skin cancer in studies of Picato. A 3-year study in 484 patients found a higher incidence of skin malignancy with ingenol mebutate than with the comparator, imiquimod. In all, 3.3% of patients developed cancer in the ingenol mebutate group, compared with 0.4% in the comparator group.

In an 8-week vehicle-controlled trial in 1,262 patients, there were more skin tumors in patients who received ingenol mebutate than in those in the vehicle arm (1.0% vs. 0.1%).

In addition, according to the EMA statement, in four trials of a related ester that included 1,234 patients, a higher incidence of skin tumors occurred with the related drug, ingenol disoxate, than with a vehicle control (7.7% vs. 2.9%). PRAC considered these data because ingenol disoxate and ingenol mebutate are closely related, the EMA said.

“Health care professionals should stop prescribing Picato and consider different treatment options while authorities review the data,” according to the European agency. “Health care professionals should advise patients to be vigilant for any skin lesions developing and to seek medical advice promptly should any occur,” the statement adds.

Picato has been authorized in the EU since 2012, and the FDA approved Picato the same year. Patients have received about 2.8 million treatment courses in that time, according to the LEO Pharma press release.

As a precaution, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) has recommended that patients stop using ingenol mebutate (Picato) while the agency continues to review the safety of the topical treatment, which is indicated for the treatment of actinic keratosis in Europe and the United States.

No such action has been taken in the United States.

The EMA’s Pharmacovigilance Risk Assessment Committee (PRAC) is reviewing data on skin cancer in patients treated with ingenol mebutate. In a trial comparing Picato and imiquimod, skin cancer was more common in the areas treated with Picato than in areas treated with imiquimod, the statement said.

“While uncertainties remain, the EMA said in a Jan. 17 news release. “The PRAC has therefore recommended suspending the medicine’s marketing authorization as a precaution and noted that alternative treatments are available.”

FDA is looking at the situation

LEO Pharma, the company that markets Picato, announced on Jan. 9 that it was initiating voluntary withdrawal of marketing authorization and possible voluntary withdrawal of Picato in the European Union (EU) and European Economic Area (EEA). The statement says, however, that “LEO Pharma has carefully reviewed the information received from PRAC, and the company disagrees with the ongoing assessment of PRAC.” There are “no additional safety data and it is LEO Pharma’s position that there is no evidence of a causal relationship or plausible mechanism hypothesis between the use of Picato and the development of skin malignancies.” An update added to the press release on Jan. 17 restates that the company disagrees with the assessment of PRAC.

“This matter does not affect Picato in the U.S., and there are no new developments in the [United States]. Picato continues to be available to patients in the U.S. We remain in dialogue with the U.S. Food and Drug Administration about Picato in the EU/EEA,” Rhonda Sciarra, associate director of global external communications for LEO Pharma, said in an email. “We remain committed to ensuring patient safety, rigorous pharmacovigilance monitoring, and transparency,” she added.

The FDA “is gathering data and information to investigate the safety concern related to Picato,” a spokesperson for the FDA told Dermatology News. “We are committed to sharing relevant findings when we have sufficient understanding of the situation and of what actions should be taken,” he added.

Examining the data

The EMA announcement described data about the risk of skin cancer in studies of Picato. A 3-year study in 484 patients found a higher incidence of skin malignancy with ingenol mebutate than with the comparator, imiquimod. In all, 3.3% of patients developed cancer in the ingenol mebutate group, compared with 0.4% in the comparator group.

In an 8-week vehicle-controlled trial in 1,262 patients, there were more skin tumors in patients who received ingenol mebutate than in those in the vehicle arm (1.0% vs. 0.1%).

In addition, according to the EMA statement, in four trials of a related ester that included 1,234 patients, a higher incidence of skin tumors occurred with the related drug, ingenol disoxate, than with a vehicle control (7.7% vs. 2.9%). PRAC considered these data because ingenol disoxate and ingenol mebutate are closely related, the EMA said.

“Health care professionals should stop prescribing Picato and consider different treatment options while authorities review the data,” according to the European agency. “Health care professionals should advise patients to be vigilant for any skin lesions developing and to seek medical advice promptly should any occur,” the statement adds.

Picato has been authorized in the EU since 2012, and the FDA approved Picato the same year. Patients have received about 2.8 million treatment courses in that time, according to the LEO Pharma press release.

As a precaution, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) has recommended that patients stop using ingenol mebutate (Picato) while the agency continues to review the safety of the topical treatment, which is indicated for the treatment of actinic keratosis in Europe and the United States.

No such action has been taken in the United States.

The EMA’s Pharmacovigilance Risk Assessment Committee (PRAC) is reviewing data on skin cancer in patients treated with ingenol mebutate. In a trial comparing Picato and imiquimod, skin cancer was more common in the areas treated with Picato than in areas treated with imiquimod, the statement said.

“While uncertainties remain, the EMA said in a Jan. 17 news release. “The PRAC has therefore recommended suspending the medicine’s marketing authorization as a precaution and noted that alternative treatments are available.”

FDA is looking at the situation

LEO Pharma, the company that markets Picato, announced on Jan. 9 that it was initiating voluntary withdrawal of marketing authorization and possible voluntary withdrawal of Picato in the European Union (EU) and European Economic Area (EEA). The statement says, however, that “LEO Pharma has carefully reviewed the information received from PRAC, and the company disagrees with the ongoing assessment of PRAC.” There are “no additional safety data and it is LEO Pharma’s position that there is no evidence of a causal relationship or plausible mechanism hypothesis between the use of Picato and the development of skin malignancies.” An update added to the press release on Jan. 17 restates that the company disagrees with the assessment of PRAC.

“This matter does not affect Picato in the U.S., and there are no new developments in the [United States]. Picato continues to be available to patients in the U.S. We remain in dialogue with the U.S. Food and Drug Administration about Picato in the EU/EEA,” Rhonda Sciarra, associate director of global external communications for LEO Pharma, said in an email. “We remain committed to ensuring patient safety, rigorous pharmacovigilance monitoring, and transparency,” she added.

The FDA “is gathering data and information to investigate the safety concern related to Picato,” a spokesperson for the FDA told Dermatology News. “We are committed to sharing relevant findings when we have sufficient understanding of the situation and of what actions should be taken,” he added.

Examining the data

The EMA announcement described data about the risk of skin cancer in studies of Picato. A 3-year study in 484 patients found a higher incidence of skin malignancy with ingenol mebutate than with the comparator, imiquimod. In all, 3.3% of patients developed cancer in the ingenol mebutate group, compared with 0.4% in the comparator group.

In an 8-week vehicle-controlled trial in 1,262 patients, there were more skin tumors in patients who received ingenol mebutate than in those in the vehicle arm (1.0% vs. 0.1%).

In addition, according to the EMA statement, in four trials of a related ester that included 1,234 patients, a higher incidence of skin tumors occurred with the related drug, ingenol disoxate, than with a vehicle control (7.7% vs. 2.9%). PRAC considered these data because ingenol disoxate and ingenol mebutate are closely related, the EMA said.

“Health care professionals should stop prescribing Picato and consider different treatment options while authorities review the data,” according to the European agency. “Health care professionals should advise patients to be vigilant for any skin lesions developing and to seek medical advice promptly should any occur,” the statement adds.

Picato has been authorized in the EU since 2012, and the FDA approved Picato the same year. Patients have received about 2.8 million treatment courses in that time, according to the LEO Pharma press release.

The Ketogenic Diet and Dermatology: A Primer on Current Literature

The ketogenic diet has been therapeutically employed by physicians since the times of Hippocrates, primarily for its effect on the nervous system.1 The neurologic literature is inundated with the uses of this medicinal diet for applications in the treatment of epilepsy, neurodegenerative disease, malignancy, and enzyme deficiencies, among others.2 In recent years, physicians and scientists have moved to study the application of a ketogenic diet in the realms of cardiovascular disease,3 autoimmune disease,4 management of diabetes mellitus (DM) and obesity,3,5 and enhancement of sports and combat performance,6 all with promising results. Increased interest in alternative therapies among the lay population and the efficacy purported by many adherents has spurred intrigue by health care professionals. Over the last decade, there has seen a boom in so-called holistic approaches to health; included are the Paleo Diet, Primal Blueprint Diet, Bulletproof Diet, and the ketogenic/low-carbohydrate, high-fat diet. The benefits of ketones in these diets—through intermittent fasting or cyclical ketosis—–for cognitive enhancement, overall well-being, amelioration of chronic disease states, and increased health span have been promulgated to the lay population. But to date, there is a large gap in the literature on the applications of ketones as well as the ketogenic diet in dermatology and skin health and disease.

The aim of this article is not to summarize the uses of ketones and the ketogenic diet in dermatologic applications (because, unfortunately, those studies have not been undertaken) but to provide evidence from all available literature to support the need for targeted research and to encourage dermatologists to investigate ketones and their role in treating skin disease, primarily in an adjunctive manner. In doing so, a clearly medicinal diet may gain a foothold in the disease-treatment repertoire and among health-promoting agents of the dermatologist. Given the amount of capital being spent on health care, there is an ever-increasing need for low-cost, safe, and tolerable treatments that can be used for multiple disease processes and to promote health. We believe the ketogenic diet is such an adjunctive therapeutic option, as it has clearly been proven to be tolerable, safe, and efficacious for many people over the last millennia.

We conducted a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using varying combinations of the terms ketones, ketogenic, skin, inflammation, metabolic, oxidation, dermatology, and dermatologic and found 12 articles. Herein, we summarize the relevant articles and the works cited by those articles.

Adverse Effects of the Ketogenic Diet

As with all medical therapies, the ketogenic diet is not without risk of adverse effects, which should be communicated at the outset of this article and with patients in the clinic. The only known absolute contraindications to a ketogenic diet are porphyria and pyruvate carboxylase deficiency secondary to underlying metabolic derangements.7 Certain metabolic cytopathies and carnitine deficiency are relative contraindications, and patients with these conditions should be cautiously placed on this diet and closely monitored. Dehydration, acidosis, lethargy, hypoglycemia, dyslipidemia, electrolyte imbalances, prurigo pigmentosa, and gastrointestinal distress may be an acute issue, but these effects are transient and can be managed. Chronic adverse effects are nephrolithiasis (there are recommended screening procedures for those at risk and prophylactic therapies, which is beyond the scope of this article) and weight loss.7

NLRP3 Inflammasome Suppression

Youm et al8 reported their findings in Nature Medicine that β-hydroxybutyrate, a ketone body that naturally circulates in the human body, specifically suppresses activity of the NLRP3 inflammasome. The NLRP3 inflammasome serves as the activating platform for IL-1β.8 Aberrant and elevated IL-1β levels cause or are associated with a number of dermatologic diseases—namely, the autoinflammatory syndromes (familial cold autoinflammatory syndrome, Muckle-Wells syndrome, neonatal-onset multisystemic disease/chronic infantile neurological cutaneous articular syndrome), hyperimmunoglobulinemia D with periodic fever syndrome, tumor necrosis factor–receptor associated periodic syndrome, juvenile idiopathic arthritis, relapsing polychondritis, Schnitzler syndrome, Sweet syndrome, Behçet disease, gout, sunburn and contact hypersensitivity, hidradenitis suppurativa, and metastatic melanoma.7 Clearly, the ketogenic diet may be employed in a therapeutic manner (though to what degree, we need further study) for these dermatologic conditions based on the interaction with the NRLP3 inflammasome and IL-1β.

Acne

A link between acne and diet has long been suspected, but a lack of well-controlled studies has caused only speculation to remain. Recent literature suggests that the effects of insulin may be a notable driver of acne through effects on sex hormones and subsequent effects on sebum production and inflammation. Cordain et al9 discuss the mechanism by which insulin can worsen acne in a valuable article, which Paoli et al10 later corroborated. Essentially, insulin propagates acne by 2 known mechanisms. First, an increase in serum insulin causes a rise in insulinlike growth factor 1 levels and a decrease in insulinlike growth factor binding protein 3 levels, which directly influences keratinocyte proliferation and reduces retinoic acid receptor/retinoid X receptor activity in the skin, causing hyperkeratinization and concomitant abnormal desquamation of the follicular epithelium.9,10 Second, this increase in insulinlike growth factor 1 and insulin causes a decrease in sex hormone–binding globulin and leads to increased androgen production and circulation in the skin, which causes an increase in sebum production. These factors combined with skin that is colonized with Cutibacterium acnes lead to an inflammatory response and the disease known as acne vulgaris.9,10 A ketogenic diet could help ameliorate acne because it results in very little insulin secretion, unlike the typical Western diet, which causes frequent large spikes in insulin levels. Furthermore, the anti-inflammatory effects of ketones would benefit the inflammatory nature of this disease.

DM and Diabetic Skin Disease

Diabetes mellitus carries with it the risk for skin diseases specific to the diabetic disease process, such as increased risk for bacterial and fungal infections, venous stasis, pruritus (secondary to poor circulation), acanthosis nigricans, diabetic dermopathy, necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum, digital sclerosis, and bullosis diabeticorum.11 It is well established that better control of DM results in better disease state outcomes.12 The ketogenic diet has shown itself to be a formidable and successful treatment in the diseases of carbohydrate intolerance (eg, metabolic syndrome, insulin resistance, type 2 DM) because of several known mechanisms, including less glucose entering the body and thus less fat deposition, end-product glycation, and free-radical production (discussed below); enhanced fat loss and metabolic efficiency; increased insulin sensitivity; and decreased inflammation.13 Lowering a patient’s insulin resistance through a ketogenic diet may help prevent or treat diabetic skin disease.

Dermatologic Malignancy

A ketogenic diet has been of interest in oncology research as an adjunctive therapy for several reasons: anti-inflammatory effects, antioxidation effects, possible effects on mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) regulation,7 and exploitation of the Warburg effect.14 One article discusses how mTOR, a cell-cycle regulator of particular importance in cancer biology, can be influenced by ketones both directly and indirectly through modulating the inflammatory response.7 It has been shown that suppressing mTOR activity limits and slows tumor growth and spread. Ketones also may prove to be a unique method of metabolically exploiting cancer physiology. The Warburg effect, which earned Otto Warburg the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1931, is the observation that cancerous cells produce adenosine triphosphate solely through aerobic glycolysis followed by lactic acid fermentation.14 This phenomenon is the basis of the positron emission tomography scan. There are several small studies of the effects of ketogenic diets on malignancy, and although none of these studies are of substantial size or control, they show that a ketogenic diet can halt or even reverse tumor growth.15 The hypothesis is that because cancer cells cannot metabolize ketones (but normal cells can), the Warburg effect can be taken advantage of through a ketogenic diet to aid in the treatment of malignant disease.14 If further studies find it a formidable treatment, it most certainly would be helpful for the dermatologist involved in the treatment of cutaneous cancers.

Oxidative Stress

Oxidative stress, a state brought about when reactive oxygen species (ROS) production exceeds the antioxidant capacity of the cell and causes damage, is known to be a central part of certain skin diseases (eg, acne, psoriasis, cutaneous malignancy, varicose ulcers, cutaneous allergic reactions, and drug-induced skin photosensitivity).7 There are 2 proven mechanisms by which a ketogenic diet can augment the body’s innate antioxidation capacity. First, ketones activate a potent antioxidant upregulating protein known as NRF2, which is bound in cytosol and remains inactive until activated by certain stimuli (ie, ketones).16 Migration to the nucleus causes transcriptional changes in DNA to upregulate, via a myriad of pathways, antioxidant production in the cell; most notably, it results in increased glutathione levels.17 NRF2 also targets several genes involved in chronic inflammatory skin diseases that cause an increase in the antioxidant capacity.18 As an aside, several foods encouraged on a ketogenic diet also activate NRF2 independently of ketones (eg, coffee, broccoli).19 Second, a ketogenic diet results in fewer produced ROS and an increase in the nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide ratio produced by the mitochondria; in short, it is a more efficient way of producing cellular energy while enhancing mitochondrial function. When fewer ROS are produced, there is less oxidative stress that needs to be attended to by the cell and less cellular damage. Feichtinger et al19 point out that mitochondrial inefficiency and dysfunction often are overlooked components in several skin diseases, and based on the studies discussed above, these diseases may be aided with a ketogenic diet.

Patient Applications

Clearly, a ketogenic diet is therapeutic, and there are many promising potential roles it may play in the treatment of a wide variety of health and disease states through hormonal normalization, antioxidant effects, anti-inflammatory effects, and improvement of metabolic risk factors. However, there are vast limitations to what is known about the ketogenic diet and how it might be employed, particularly by the dermatologist. First, the ketogenic diet lacks a firm definition. Although processed inflammatory vegetable oils and meats are low in carbohydrates and high in fat by definition, it is impossible to argue that they are healthy options for consumption and disease prevention and treatment. Second, nutrigenomics dictates that there must be an individual role in how the diet is employed (eg, patients who are lactose intolerant will need to stay away from dairy). Third, there are no clear proven clinical results from the ketogenic diet in the realm of dermatology. Fourth, as with everything, there are potential detrimental side effects of the ketogenic diet that must be considered for patients (though there are established screening procedures and prophylactic therapies that are beyond the scope of this article). Further, other diets have shown benefit for many other disease states and health promotion purposes (eg, the Mediterranean diet).20 We do not know yet if the avoidance of certain dietary factors such as processed carbohydrates and fats are more beneficial than adopting a state of ketosis at this time, and therefore we are not claiming superiority of one dietary approach over others that are proven to promote health.

Because there are no large-scale studies of the ketogenic diet, there is no verified standardization of initiating and monitoring it, though certain academic centers do have published methods of doing so.21 There are ample anecdotal methods of initiating, maintaining, and monitoring the ketogenic diet.22 In short, drastic restriction of carbohydrate intake and increased fat consumption are the staples of initiating the diet. Medium-chain triglyceride oil supplementation, coffee consumption, intermittent fasting, and low-level aerobic activity also are thought to aid in transition to a ketogenic state. As a result, a dermatologist may recommend that patients interested in this option begin by focusing on fat, fiber, and protein consumption while greatly reducing the amount of carbohydrates in the diet. Morning walks or more intense workouts for fitter patients should be encouraged. Consumption of serum ketone–enhancing foods (eg, coffee, medium-chain triglyceride oil, coconut products) also should be encouraged. A popular beverage known as Bulletproof coffee also may be of interest.23 A blood ketone meter can be used for biofeedback to reinforce these behaviors by aiming for proper β-hydroxybutyrate levels. Numerous companies and websites exist for supporting those patients wishing to pursue a ketogenic state, some hosted by physicians/researchers with others hosted by laypeople with an interest in the topic; discretion should be used as to the clinical and scientific accuracy of these sites. The dermatologist in particular can follow these patients and assess for changes in severity of skin disease, subjective well-being, need for medications and adjunctive therapies, and status of comorbid conditions.

For more information on the ketogenic diet, consider reading the works of the following physicians and researchers who all have been involved with or are currently conducting research in the medical use of ketones and ketogenic diets: David Perlmutter, MD; Thomas Seyfried, PhD; Dominic D’Agostino, PhD; Terry Wahls, MD; Jeff Volek, PhD; and Peter Attia, MD.

Conclusion

Based on the available data, there is potential for use of the ketogenic diet in an adjunctive manner for dermatologic applications, and studies should be undertaken to establish the efficacy or inefficacy of this diet as a preventive measure or treatment of skin disease. With the large push for complementary and alternative therapies over the last decade, particularly for skin disease, the time for research on the ketogenic diet is ripe. Over the coming years, it is our hope that larger clinical, randomized, controlled trials will be conducted for the benefit of dermatology patients worldwide.

- Wheless JW. History of the ketogenic diet. Epilepsia. 2008;49:3-5.

- Stafstrom CE, Rho JM. The ketogenic diet as a treatment paradigm for diverse neurological disorders. Front Pharmacol. 2012;3:59.

- Dashti HM, Mathew TC, Hussein T, et al. Long-term effects of a ketogenic diet in obese patients. Exp Clin Cardiol. 2004;9:200-205.

- Storoni M, Plant GT. The therapeutic potential of the ketogenic diet in treating progressive multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler Int. 2015;2015:681289. doi:10.1155/2015/681289.

- Yancy WS, Foy M, Chalecki AM, et al. A low-carbohydrate, ketogenic diet to treat type 2 diabetes. Nutr Metab (Lond). 2005;2:34.

- Phinney SD. Ketogenic diets and physical performance. Nutr Metab (Lond). 2004;1:2.

- J. The promising potential role of ketones in inflammatory dermatologic disease: a new frontier in treatment research. J Dermatol Treat. 2017;28:484-487.

- Youm YH, Nguyen KY, Grant RW, et al. The ketone metabolite β-hydroxybutyrate blocks NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated inflammatory disease. Nat Med. 2015;21:263-269.

- Cordain L, Lindeberg S, Hurtado M, et al. Acne vulgaris: a disease of western civilization. Arch Dermatol

- Nutrition and acne: therapeutic potential of ketogenic diets. Skin Pharmacol Physiol. 2012;25:111-117.

- American Diabetes Association. Skin complications. http://www.diabetes.org/diabetes/complications/skin-complications. Accessed December 18, 2019.

- Greenapple R. Review of strategies to enhance outcomes for patients with type 2 diabetes: payers’ perspective. Am Health Drug Benefits. 2011;4:377-386.

- Paoli A, Rubini A, Volek JS, et al. Beyond weight loss: a review of the therapeutic uses of very-low-carbohydrate (ketogenic) diets. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2013;67:789-796.

- Allen BG, Bhatia SK, Anderson CM, et al. Ketogenic diets as an adjuvant cancer therapy: history and potential mechanism. Redox Biol. 2014;2:963-970.

- Zhou W, Mukherjee P, Kiebish MA. The calorically restricted ketogenic diet, an effective alternative therapy for malignant brain cancer. Nutr Metab (Lond). 2007;4:5.

- Venugopal R, Jaiswal AK. Nrf1 and Nrf2 positively and c-Fos and Fra1 negatively regulate the human antioxidant response element-mediated expression of NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase1 gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:14960-14965.

- Milder JB, Liang LP, Patel M. Acute oxidative stress and systemic Nrf2 activation by the ketogenic diet. Neurobiol Dis. 2010:40:238-244.

- Vicente SJ, Ishimoto EY, Torres EA. Coffee modulates transcription factor Nrf2 and highly increases the activity of antioxidant enzymes in rats.J Agric Food Chem. 2014;62:116-122.

- Feichtinger R, Sperl W, Bauer JW, et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction: a neglected component of skin diseases. Exp Dermatol. 2014;23:607-614.

- Brandhorst S, Longo VD. Dietary restrictions and nutrition in the prevention and treatment of cardiovascular disease. Circ Res. 2019;124:952-965.

- Johns Hopkins Medicine. Ketogenic diet therapy for epilepsy. https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/neurology_neurosurgery/

centers_clinics/epilepsy/pediatric_epilepsy/ketogenic_diet.html. Accessed December 18, 2019. - Bergqvist AG. Long-term monitoring of the ketogenic diet: do’s and don’ts. Epilepsy Res. 2012;100:261-266.

- Bulletproof. Bulletproof coffee: everything you want to know. https://blog.bulletproof.com/how-to-make-your-coffee-bulletproof-and-your-morning-too/. Accessed December 18, 2019.

The ketogenic diet has been therapeutically employed by physicians since the times of Hippocrates, primarily for its effect on the nervous system.1 The neurologic literature is inundated with the uses of this medicinal diet for applications in the treatment of epilepsy, neurodegenerative disease, malignancy, and enzyme deficiencies, among others.2 In recent years, physicians and scientists have moved to study the application of a ketogenic diet in the realms of cardiovascular disease,3 autoimmune disease,4 management of diabetes mellitus (DM) and obesity,3,5 and enhancement of sports and combat performance,6 all with promising results. Increased interest in alternative therapies among the lay population and the efficacy purported by many adherents has spurred intrigue by health care professionals. Over the last decade, there has seen a boom in so-called holistic approaches to health; included are the Paleo Diet, Primal Blueprint Diet, Bulletproof Diet, and the ketogenic/low-carbohydrate, high-fat diet. The benefits of ketones in these diets—through intermittent fasting or cyclical ketosis—–for cognitive enhancement, overall well-being, amelioration of chronic disease states, and increased health span have been promulgated to the lay population. But to date, there is a large gap in the literature on the applications of ketones as well as the ketogenic diet in dermatology and skin health and disease.

The aim of this article is not to summarize the uses of ketones and the ketogenic diet in dermatologic applications (because, unfortunately, those studies have not been undertaken) but to provide evidence from all available literature to support the need for targeted research and to encourage dermatologists to investigate ketones and their role in treating skin disease, primarily in an adjunctive manner. In doing so, a clearly medicinal diet may gain a foothold in the disease-treatment repertoire and among health-promoting agents of the dermatologist. Given the amount of capital being spent on health care, there is an ever-increasing need for low-cost, safe, and tolerable treatments that can be used for multiple disease processes and to promote health. We believe the ketogenic diet is such an adjunctive therapeutic option, as it has clearly been proven to be tolerable, safe, and efficacious for many people over the last millennia.

We conducted a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using varying combinations of the terms ketones, ketogenic, skin, inflammation, metabolic, oxidation, dermatology, and dermatologic and found 12 articles. Herein, we summarize the relevant articles and the works cited by those articles.

Adverse Effects of the Ketogenic Diet

As with all medical therapies, the ketogenic diet is not without risk of adverse effects, which should be communicated at the outset of this article and with patients in the clinic. The only known absolute contraindications to a ketogenic diet are porphyria and pyruvate carboxylase deficiency secondary to underlying metabolic derangements.7 Certain metabolic cytopathies and carnitine deficiency are relative contraindications, and patients with these conditions should be cautiously placed on this diet and closely monitored. Dehydration, acidosis, lethargy, hypoglycemia, dyslipidemia, electrolyte imbalances, prurigo pigmentosa, and gastrointestinal distress may be an acute issue, but these effects are transient and can be managed. Chronic adverse effects are nephrolithiasis (there are recommended screening procedures for those at risk and prophylactic therapies, which is beyond the scope of this article) and weight loss.7

NLRP3 Inflammasome Suppression

Youm et al8 reported their findings in Nature Medicine that β-hydroxybutyrate, a ketone body that naturally circulates in the human body, specifically suppresses activity of the NLRP3 inflammasome. The NLRP3 inflammasome serves as the activating platform for IL-1β.8 Aberrant and elevated IL-1β levels cause or are associated with a number of dermatologic diseases—namely, the autoinflammatory syndromes (familial cold autoinflammatory syndrome, Muckle-Wells syndrome, neonatal-onset multisystemic disease/chronic infantile neurological cutaneous articular syndrome), hyperimmunoglobulinemia D with periodic fever syndrome, tumor necrosis factor–receptor associated periodic syndrome, juvenile idiopathic arthritis, relapsing polychondritis, Schnitzler syndrome, Sweet syndrome, Behçet disease, gout, sunburn and contact hypersensitivity, hidradenitis suppurativa, and metastatic melanoma.7 Clearly, the ketogenic diet may be employed in a therapeutic manner (though to what degree, we need further study) for these dermatologic conditions based on the interaction with the NRLP3 inflammasome and IL-1β.

Acne

A link between acne and diet has long been suspected, but a lack of well-controlled studies has caused only speculation to remain. Recent literature suggests that the effects of insulin may be a notable driver of acne through effects on sex hormones and subsequent effects on sebum production and inflammation. Cordain et al9 discuss the mechanism by which insulin can worsen acne in a valuable article, which Paoli et al10 later corroborated. Essentially, insulin propagates acne by 2 known mechanisms. First, an increase in serum insulin causes a rise in insulinlike growth factor 1 levels and a decrease in insulinlike growth factor binding protein 3 levels, which directly influences keratinocyte proliferation and reduces retinoic acid receptor/retinoid X receptor activity in the skin, causing hyperkeratinization and concomitant abnormal desquamation of the follicular epithelium.9,10 Second, this increase in insulinlike growth factor 1 and insulin causes a decrease in sex hormone–binding globulin and leads to increased androgen production and circulation in the skin, which causes an increase in sebum production. These factors combined with skin that is colonized with Cutibacterium acnes lead to an inflammatory response and the disease known as acne vulgaris.9,10 A ketogenic diet could help ameliorate acne because it results in very little insulin secretion, unlike the typical Western diet, which causes frequent large spikes in insulin levels. Furthermore, the anti-inflammatory effects of ketones would benefit the inflammatory nature of this disease.

DM and Diabetic Skin Disease

Diabetes mellitus carries with it the risk for skin diseases specific to the diabetic disease process, such as increased risk for bacterial and fungal infections, venous stasis, pruritus (secondary to poor circulation), acanthosis nigricans, diabetic dermopathy, necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum, digital sclerosis, and bullosis diabeticorum.11 It is well established that better control of DM results in better disease state outcomes.12 The ketogenic diet has shown itself to be a formidable and successful treatment in the diseases of carbohydrate intolerance (eg, metabolic syndrome, insulin resistance, type 2 DM) because of several known mechanisms, including less glucose entering the body and thus less fat deposition, end-product glycation, and free-radical production (discussed below); enhanced fat loss and metabolic efficiency; increased insulin sensitivity; and decreased inflammation.13 Lowering a patient’s insulin resistance through a ketogenic diet may help prevent or treat diabetic skin disease.

Dermatologic Malignancy

A ketogenic diet has been of interest in oncology research as an adjunctive therapy for several reasons: anti-inflammatory effects, antioxidation effects, possible effects on mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) regulation,7 and exploitation of the Warburg effect.14 One article discusses how mTOR, a cell-cycle regulator of particular importance in cancer biology, can be influenced by ketones both directly and indirectly through modulating the inflammatory response.7 It has been shown that suppressing mTOR activity limits and slows tumor growth and spread. Ketones also may prove to be a unique method of metabolically exploiting cancer physiology. The Warburg effect, which earned Otto Warburg the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1931, is the observation that cancerous cells produce adenosine triphosphate solely through aerobic glycolysis followed by lactic acid fermentation.14 This phenomenon is the basis of the positron emission tomography scan. There are several small studies of the effects of ketogenic diets on malignancy, and although none of these studies are of substantial size or control, they show that a ketogenic diet can halt or even reverse tumor growth.15 The hypothesis is that because cancer cells cannot metabolize ketones (but normal cells can), the Warburg effect can be taken advantage of through a ketogenic diet to aid in the treatment of malignant disease.14 If further studies find it a formidable treatment, it most certainly would be helpful for the dermatologist involved in the treatment of cutaneous cancers.

Oxidative Stress

Oxidative stress, a state brought about when reactive oxygen species (ROS) production exceeds the antioxidant capacity of the cell and causes damage, is known to be a central part of certain skin diseases (eg, acne, psoriasis, cutaneous malignancy, varicose ulcers, cutaneous allergic reactions, and drug-induced skin photosensitivity).7 There are 2 proven mechanisms by which a ketogenic diet can augment the body’s innate antioxidation capacity. First, ketones activate a potent antioxidant upregulating protein known as NRF2, which is bound in cytosol and remains inactive until activated by certain stimuli (ie, ketones).16 Migration to the nucleus causes transcriptional changes in DNA to upregulate, via a myriad of pathways, antioxidant production in the cell; most notably, it results in increased glutathione levels.17 NRF2 also targets several genes involved in chronic inflammatory skin diseases that cause an increase in the antioxidant capacity.18 As an aside, several foods encouraged on a ketogenic diet also activate NRF2 independently of ketones (eg, coffee, broccoli).19 Second, a ketogenic diet results in fewer produced ROS and an increase in the nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide ratio produced by the mitochondria; in short, it is a more efficient way of producing cellular energy while enhancing mitochondrial function. When fewer ROS are produced, there is less oxidative stress that needs to be attended to by the cell and less cellular damage. Feichtinger et al19 point out that mitochondrial inefficiency and dysfunction often are overlooked components in several skin diseases, and based on the studies discussed above, these diseases may be aided with a ketogenic diet.

Patient Applications

Clearly, a ketogenic diet is therapeutic, and there are many promising potential roles it may play in the treatment of a wide variety of health and disease states through hormonal normalization, antioxidant effects, anti-inflammatory effects, and improvement of metabolic risk factors. However, there are vast limitations to what is known about the ketogenic diet and how it might be employed, particularly by the dermatologist. First, the ketogenic diet lacks a firm definition. Although processed inflammatory vegetable oils and meats are low in carbohydrates and high in fat by definition, it is impossible to argue that they are healthy options for consumption and disease prevention and treatment. Second, nutrigenomics dictates that there must be an individual role in how the diet is employed (eg, patients who are lactose intolerant will need to stay away from dairy). Third, there are no clear proven clinical results from the ketogenic diet in the realm of dermatology. Fourth, as with everything, there are potential detrimental side effects of the ketogenic diet that must be considered for patients (though there are established screening procedures and prophylactic therapies that are beyond the scope of this article). Further, other diets have shown benefit for many other disease states and health promotion purposes (eg, the Mediterranean diet).20 We do not know yet if the avoidance of certain dietary factors such as processed carbohydrates and fats are more beneficial than adopting a state of ketosis at this time, and therefore we are not claiming superiority of one dietary approach over others that are proven to promote health.

Because there are no large-scale studies of the ketogenic diet, there is no verified standardization of initiating and monitoring it, though certain academic centers do have published methods of doing so.21 There are ample anecdotal methods of initiating, maintaining, and monitoring the ketogenic diet.22 In short, drastic restriction of carbohydrate intake and increased fat consumption are the staples of initiating the diet. Medium-chain triglyceride oil supplementation, coffee consumption, intermittent fasting, and low-level aerobic activity also are thought to aid in transition to a ketogenic state. As a result, a dermatologist may recommend that patients interested in this option begin by focusing on fat, fiber, and protein consumption while greatly reducing the amount of carbohydrates in the diet. Morning walks or more intense workouts for fitter patients should be encouraged. Consumption of serum ketone–enhancing foods (eg, coffee, medium-chain triglyceride oil, coconut products) also should be encouraged. A popular beverage known as Bulletproof coffee also may be of interest.23 A blood ketone meter can be used for biofeedback to reinforce these behaviors by aiming for proper β-hydroxybutyrate levels. Numerous companies and websites exist for supporting those patients wishing to pursue a ketogenic state, some hosted by physicians/researchers with others hosted by laypeople with an interest in the topic; discretion should be used as to the clinical and scientific accuracy of these sites. The dermatologist in particular can follow these patients and assess for changes in severity of skin disease, subjective well-being, need for medications and adjunctive therapies, and status of comorbid conditions.

For more information on the ketogenic diet, consider reading the works of the following physicians and researchers who all have been involved with or are currently conducting research in the medical use of ketones and ketogenic diets: David Perlmutter, MD; Thomas Seyfried, PhD; Dominic D’Agostino, PhD; Terry Wahls, MD; Jeff Volek, PhD; and Peter Attia, MD.

Conclusion

Based on the available data, there is potential for use of the ketogenic diet in an adjunctive manner for dermatologic applications, and studies should be undertaken to establish the efficacy or inefficacy of this diet as a preventive measure or treatment of skin disease. With the large push for complementary and alternative therapies over the last decade, particularly for skin disease, the time for research on the ketogenic diet is ripe. Over the coming years, it is our hope that larger clinical, randomized, controlled trials will be conducted for the benefit of dermatology patients worldwide.

The ketogenic diet has been therapeutically employed by physicians since the times of Hippocrates, primarily for its effect on the nervous system.1 The neurologic literature is inundated with the uses of this medicinal diet for applications in the treatment of epilepsy, neurodegenerative disease, malignancy, and enzyme deficiencies, among others.2 In recent years, physicians and scientists have moved to study the application of a ketogenic diet in the realms of cardiovascular disease,3 autoimmune disease,4 management of diabetes mellitus (DM) and obesity,3,5 and enhancement of sports and combat performance,6 all with promising results. Increased interest in alternative therapies among the lay population and the efficacy purported by many adherents has spurred intrigue by health care professionals. Over the last decade, there has seen a boom in so-called holistic approaches to health; included are the Paleo Diet, Primal Blueprint Diet, Bulletproof Diet, and the ketogenic/low-carbohydrate, high-fat diet. The benefits of ketones in these diets—through intermittent fasting or cyclical ketosis—–for cognitive enhancement, overall well-being, amelioration of chronic disease states, and increased health span have been promulgated to the lay population. But to date, there is a large gap in the literature on the applications of ketones as well as the ketogenic diet in dermatology and skin health and disease.

The aim of this article is not to summarize the uses of ketones and the ketogenic diet in dermatologic applications (because, unfortunately, those studies have not been undertaken) but to provide evidence from all available literature to support the need for targeted research and to encourage dermatologists to investigate ketones and their role in treating skin disease, primarily in an adjunctive manner. In doing so, a clearly medicinal diet may gain a foothold in the disease-treatment repertoire and among health-promoting agents of the dermatologist. Given the amount of capital being spent on health care, there is an ever-increasing need for low-cost, safe, and tolerable treatments that can be used for multiple disease processes and to promote health. We believe the ketogenic diet is such an adjunctive therapeutic option, as it has clearly been proven to be tolerable, safe, and efficacious for many people over the last millennia.

We conducted a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using varying combinations of the terms ketones, ketogenic, skin, inflammation, metabolic, oxidation, dermatology, and dermatologic and found 12 articles. Herein, we summarize the relevant articles and the works cited by those articles.

Adverse Effects of the Ketogenic Diet

As with all medical therapies, the ketogenic diet is not without risk of adverse effects, which should be communicated at the outset of this article and with patients in the clinic. The only known absolute contraindications to a ketogenic diet are porphyria and pyruvate carboxylase deficiency secondary to underlying metabolic derangements.7 Certain metabolic cytopathies and carnitine deficiency are relative contraindications, and patients with these conditions should be cautiously placed on this diet and closely monitored. Dehydration, acidosis, lethargy, hypoglycemia, dyslipidemia, electrolyte imbalances, prurigo pigmentosa, and gastrointestinal distress may be an acute issue, but these effects are transient and can be managed. Chronic adverse effects are nephrolithiasis (there are recommended screening procedures for those at risk and prophylactic therapies, which is beyond the scope of this article) and weight loss.7

NLRP3 Inflammasome Suppression

Youm et al8 reported their findings in Nature Medicine that β-hydroxybutyrate, a ketone body that naturally circulates in the human body, specifically suppresses activity of the NLRP3 inflammasome. The NLRP3 inflammasome serves as the activating platform for IL-1β.8 Aberrant and elevated IL-1β levels cause or are associated with a number of dermatologic diseases—namely, the autoinflammatory syndromes (familial cold autoinflammatory syndrome, Muckle-Wells syndrome, neonatal-onset multisystemic disease/chronic infantile neurological cutaneous articular syndrome), hyperimmunoglobulinemia D with periodic fever syndrome, tumor necrosis factor–receptor associated periodic syndrome, juvenile idiopathic arthritis, relapsing polychondritis, Schnitzler syndrome, Sweet syndrome, Behçet disease, gout, sunburn and contact hypersensitivity, hidradenitis suppurativa, and metastatic melanoma.7 Clearly, the ketogenic diet may be employed in a therapeutic manner (though to what degree, we need further study) for these dermatologic conditions based on the interaction with the NRLP3 inflammasome and IL-1β.

Acne

A link between acne and diet has long been suspected, but a lack of well-controlled studies has caused only speculation to remain. Recent literature suggests that the effects of insulin may be a notable driver of acne through effects on sex hormones and subsequent effects on sebum production and inflammation. Cordain et al9 discuss the mechanism by which insulin can worsen acne in a valuable article, which Paoli et al10 later corroborated. Essentially, insulin propagates acne by 2 known mechanisms. First, an increase in serum insulin causes a rise in insulinlike growth factor 1 levels and a decrease in insulinlike growth factor binding protein 3 levels, which directly influences keratinocyte proliferation and reduces retinoic acid receptor/retinoid X receptor activity in the skin, causing hyperkeratinization and concomitant abnormal desquamation of the follicular epithelium.9,10 Second, this increase in insulinlike growth factor 1 and insulin causes a decrease in sex hormone–binding globulin and leads to increased androgen production and circulation in the skin, which causes an increase in sebum production. These factors combined with skin that is colonized with Cutibacterium acnes lead to an inflammatory response and the disease known as acne vulgaris.9,10 A ketogenic diet could help ameliorate acne because it results in very little insulin secretion, unlike the typical Western diet, which causes frequent large spikes in insulin levels. Furthermore, the anti-inflammatory effects of ketones would benefit the inflammatory nature of this disease.

DM and Diabetic Skin Disease

Diabetes mellitus carries with it the risk for skin diseases specific to the diabetic disease process, such as increased risk for bacterial and fungal infections, venous stasis, pruritus (secondary to poor circulation), acanthosis nigricans, diabetic dermopathy, necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum, digital sclerosis, and bullosis diabeticorum.11 It is well established that better control of DM results in better disease state outcomes.12 The ketogenic diet has shown itself to be a formidable and successful treatment in the diseases of carbohydrate intolerance (eg, metabolic syndrome, insulin resistance, type 2 DM) because of several known mechanisms, including less glucose entering the body and thus less fat deposition, end-product glycation, and free-radical production (discussed below); enhanced fat loss and metabolic efficiency; increased insulin sensitivity; and decreased inflammation.13 Lowering a patient’s insulin resistance through a ketogenic diet may help prevent or treat diabetic skin disease.

Dermatologic Malignancy

A ketogenic diet has been of interest in oncology research as an adjunctive therapy for several reasons: anti-inflammatory effects, antioxidation effects, possible effects on mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) regulation,7 and exploitation of the Warburg effect.14 One article discusses how mTOR, a cell-cycle regulator of particular importance in cancer biology, can be influenced by ketones both directly and indirectly through modulating the inflammatory response.7 It has been shown that suppressing mTOR activity limits and slows tumor growth and spread. Ketones also may prove to be a unique method of metabolically exploiting cancer physiology. The Warburg effect, which earned Otto Warburg the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1931, is the observation that cancerous cells produce adenosine triphosphate solely through aerobic glycolysis followed by lactic acid fermentation.14 This phenomenon is the basis of the positron emission tomography scan. There are several small studies of the effects of ketogenic diets on malignancy, and although none of these studies are of substantial size or control, they show that a ketogenic diet can halt or even reverse tumor growth.15 The hypothesis is that because cancer cells cannot metabolize ketones (but normal cells can), the Warburg effect can be taken advantage of through a ketogenic diet to aid in the treatment of malignant disease.14 If further studies find it a formidable treatment, it most certainly would be helpful for the dermatologist involved in the treatment of cutaneous cancers.

Oxidative Stress

Oxidative stress, a state brought about when reactive oxygen species (ROS) production exceeds the antioxidant capacity of the cell and causes damage, is known to be a central part of certain skin diseases (eg, acne, psoriasis, cutaneous malignancy, varicose ulcers, cutaneous allergic reactions, and drug-induced skin photosensitivity).7 There are 2 proven mechanisms by which a ketogenic diet can augment the body’s innate antioxidation capacity. First, ketones activate a potent antioxidant upregulating protein known as NRF2, which is bound in cytosol and remains inactive until activated by certain stimuli (ie, ketones).16 Migration to the nucleus causes transcriptional changes in DNA to upregulate, via a myriad of pathways, antioxidant production in the cell; most notably, it results in increased glutathione levels.17 NRF2 also targets several genes involved in chronic inflammatory skin diseases that cause an increase in the antioxidant capacity.18 As an aside, several foods encouraged on a ketogenic diet also activate NRF2 independently of ketones (eg, coffee, broccoli).19 Second, a ketogenic diet results in fewer produced ROS and an increase in the nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide ratio produced by the mitochondria; in short, it is a more efficient way of producing cellular energy while enhancing mitochondrial function. When fewer ROS are produced, there is less oxidative stress that needs to be attended to by the cell and less cellular damage. Feichtinger et al19 point out that mitochondrial inefficiency and dysfunction often are overlooked components in several skin diseases, and based on the studies discussed above, these diseases may be aided with a ketogenic diet.

Patient Applications