User login

Are operative vaginal delivery discharge instructions needed?

In order to identify the prevalence of concerns among postpartum women and the factors associated with them, the University of California–San Francisco (UCSF) began calling all of its obstetric patients through an automated phone call within 72 hours after hospital discharge.

Study details

All postpartum women from March to June 2017 were contacted after discharge via an automated call. Calls were considered successful if the woman engaged with the automated system; those who reported concerns were contacted by a nurse. UCSF researchers compared call success and presence of concerns by mode of delivery, insurance type (public or private), parity, pregnancy complication (diabetes, hypertension, hemorrhage), and neonatal intensive care (ICN) admission using univariate analyses and multivariable logistic regression.

A total of 881 women were called, and 730 (83%) were successfully contacted (meaning they engaged with the automated system through to the end of the call). About one-third of women (224 / 29%) reported a concern. Women with operative vaginal delivery were more likely to report an issue than spontaneous vaginal and cesarean delivery (42% vs 28%; P = .04). Nulliparous women also were more likely to report an issue (32% vs 25%; P = .05). They also were more likely to answer the call (86% vs 79%; P = .004). Women with public insurance were less likely to be successfully contacted (68% vs 84%; P = .003), but the frequency of concerns were equivalent (28% vs 29%). Women with neonates in the ICN were less likely to be successfully contacted. When controlling for confounders, nulliparity (odds ratio [OR], 1.5; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.1–2.2) and private insurance (OR, 1.9; 95% CI, 1.1–3.8) both were independently associated with successful contact.

What do the results mean for practice?

Nulliparous women and women with operative vaginal deliveries may benefit from additional discharge support, concluded the researchers. “For most patients we can’t predict in advance if they will have an operative vaginal delivery but I do think that we could do more counseling in the antepartum period about different options or mode of delivery and include operative vaginal deliveries in that bucket, especially as we are doing more of them,” said Dr. Molly Siegel, Resident at UCSF. “In the postpartum period we probably should be thinking more about our instructions to those patients because we have cesarean delivery and vaginal delivery discharge instructions, and I think there needs to be something specific for operative vaginal delivery. Ultimately the goal is to improve our counseling of patients so that they don’t have as many questions after they leave the hospital.”

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

In order to identify the prevalence of concerns among postpartum women and the factors associated with them, the University of California–San Francisco (UCSF) began calling all of its obstetric patients through an automated phone call within 72 hours after hospital discharge.

Study details

All postpartum women from March to June 2017 were contacted after discharge via an automated call. Calls were considered successful if the woman engaged with the automated system; those who reported concerns were contacted by a nurse. UCSF researchers compared call success and presence of concerns by mode of delivery, insurance type (public or private), parity, pregnancy complication (diabetes, hypertension, hemorrhage), and neonatal intensive care (ICN) admission using univariate analyses and multivariable logistic regression.

A total of 881 women were called, and 730 (83%) were successfully contacted (meaning they engaged with the automated system through to the end of the call). About one-third of women (224 / 29%) reported a concern. Women with operative vaginal delivery were more likely to report an issue than spontaneous vaginal and cesarean delivery (42% vs 28%; P = .04). Nulliparous women also were more likely to report an issue (32% vs 25%; P = .05). They also were more likely to answer the call (86% vs 79%; P = .004). Women with public insurance were less likely to be successfully contacted (68% vs 84%; P = .003), but the frequency of concerns were equivalent (28% vs 29%). Women with neonates in the ICN were less likely to be successfully contacted. When controlling for confounders, nulliparity (odds ratio [OR], 1.5; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.1–2.2) and private insurance (OR, 1.9; 95% CI, 1.1–3.8) both were independently associated with successful contact.

What do the results mean for practice?

Nulliparous women and women with operative vaginal deliveries may benefit from additional discharge support, concluded the researchers. “For most patients we can’t predict in advance if they will have an operative vaginal delivery but I do think that we could do more counseling in the antepartum period about different options or mode of delivery and include operative vaginal deliveries in that bucket, especially as we are doing more of them,” said Dr. Molly Siegel, Resident at UCSF. “In the postpartum period we probably should be thinking more about our instructions to those patients because we have cesarean delivery and vaginal delivery discharge instructions, and I think there needs to be something specific for operative vaginal delivery. Ultimately the goal is to improve our counseling of patients so that they don’t have as many questions after they leave the hospital.”

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

In order to identify the prevalence of concerns among postpartum women and the factors associated with them, the University of California–San Francisco (UCSF) began calling all of its obstetric patients through an automated phone call within 72 hours after hospital discharge.

Study details

All postpartum women from March to June 2017 were contacted after discharge via an automated call. Calls were considered successful if the woman engaged with the automated system; those who reported concerns were contacted by a nurse. UCSF researchers compared call success and presence of concerns by mode of delivery, insurance type (public or private), parity, pregnancy complication (diabetes, hypertension, hemorrhage), and neonatal intensive care (ICN) admission using univariate analyses and multivariable logistic regression.

A total of 881 women were called, and 730 (83%) were successfully contacted (meaning they engaged with the automated system through to the end of the call). About one-third of women (224 / 29%) reported a concern. Women with operative vaginal delivery were more likely to report an issue than spontaneous vaginal and cesarean delivery (42% vs 28%; P = .04). Nulliparous women also were more likely to report an issue (32% vs 25%; P = .05). They also were more likely to answer the call (86% vs 79%; P = .004). Women with public insurance were less likely to be successfully contacted (68% vs 84%; P = .003), but the frequency of concerns were equivalent (28% vs 29%). Women with neonates in the ICN were less likely to be successfully contacted. When controlling for confounders, nulliparity (odds ratio [OR], 1.5; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.1–2.2) and private insurance (OR, 1.9; 95% CI, 1.1–3.8) both were independently associated with successful contact.

What do the results mean for practice?

Nulliparous women and women with operative vaginal deliveries may benefit from additional discharge support, concluded the researchers. “For most patients we can’t predict in advance if they will have an operative vaginal delivery but I do think that we could do more counseling in the antepartum period about different options or mode of delivery and include operative vaginal deliveries in that bucket, especially as we are doing more of them,” said Dr. Molly Siegel, Resident at UCSF. “In the postpartum period we probably should be thinking more about our instructions to those patients because we have cesarean delivery and vaginal delivery discharge instructions, and I think there needs to be something specific for operative vaginal delivery. Ultimately the goal is to improve our counseling of patients so that they don’t have as many questions after they leave the hospital.”

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Making a difference: ACOG’s guidance on low-dose aspirin for preventing superimposed preeclampsia

Investigators at Thomas Jefferson University found that low-dose aspirin therapy in pregnant women with chronic hypertension—as recommended by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) in 20161—was associated with a 57% decrease in superimposed preeclampsia. Chaitra Banala, BS, presented the study’s results in a poster presentation at the ACOG 2018 annual meeting (April 27–30, 2018, Austin, Texas).2

The study’s goal was to evaluate the incidence of superimposed preeclampsia in women with chronic hypertension in the periods before and after the ACOG recommendation was published.

Study participants. Pregnant women with chronic hypertension who delivered at Thomas Jefferson University Hospital from January 2008 to July 2017 were included in this retrospective cohort study. Women with multiple gestations were excluded.

The cohort included 715 pregnant patients with chronic hypertension divided into 2 groups: 635 pre-ACOG patients and 80 post-ACOG patients (that is, patients who delivered before and after the ACOG recommendation). The investigators offered daily low-dose (81 mg) aspirin.

The cohort was further stratified by additional risk factors for superimposed preeclampsia, including a history of preeclampsia and pregestational diabetes.

Outcomes. The primary outcome was the incidence of superimposed preeclampsia. Secondary outcomes included the incidence of superimposed preeclampsia with severe features (SIPSF), small for gestational age, and preterm birth.

Findings. The incidence of superimposed preeclampsia in women with chronic hypertension was 20 (25%) in the post-ACOG group versus 232 (37%) in the pre-ACOG group (odds ratio [OR], 0.43; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.26–0.73).

In the subgroup of women with chronic hypertension who did not have other risk factors, superimposed preeclampsia and SIPSF were significantly decreased: 4/41 (10%) versus 106/355 (30%) (OR, 0.25 [95% CI, 0.08–0.73]) and 2/41 (5%) versus 65/355 (18%) (OR, 0.22 [95% CI, 0.54–0.97]), respectively. The maternal demographics and secondary outcomes did not differ significantly.

After the ACOG guidance was released, low-dose aspirin decreased superimposed preeclampsia by 57% in all women with chronic hypertension. Of those with chronic hypertension without other risk factors, there were decreases of 75% in superimposed preeclampsia and 78% in SIPSF.

Final thoughts. Ms. Banala said in an interview with OBG Management following her presentation, “When we stratified the cohort based on their risk factors, we found that aspirin had the highest benefit in patients with only chronic hypertension, so without other risk factors. And we found that there was a benefit in patients with chronic hypertension who were not on antihypertensive medication. So overall our study concluded that this guideline has made a significant impact in decreasing the frequency of superimposed preeclampsia.”

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice advisory on low-dose aspirin and prevention of preeclampsia: updated recommendations. https://www.acog.org/Clinical-Guidance-and-Publications/Practice-Advisories/Practice-Advisory-Low-Dose-Aspirin-and-Prevention-of-Preeclampsia-Updated-Recommendations. Published July 11, 2016. Accessed May 3, 2018.

- Banala C, Cruz Y, Moreno C, Schoen C, Berghella V, Roman A. Impact of ACOG guideline regarding low dose aspirin for prevention of superimposed preeclampsia [abstract 27O]. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131(suppl 1):170S.

Investigators at Thomas Jefferson University found that low-dose aspirin therapy in pregnant women with chronic hypertension—as recommended by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) in 20161—was associated with a 57% decrease in superimposed preeclampsia. Chaitra Banala, BS, presented the study’s results in a poster presentation at the ACOG 2018 annual meeting (April 27–30, 2018, Austin, Texas).2

The study’s goal was to evaluate the incidence of superimposed preeclampsia in women with chronic hypertension in the periods before and after the ACOG recommendation was published.

Study participants. Pregnant women with chronic hypertension who delivered at Thomas Jefferson University Hospital from January 2008 to July 2017 were included in this retrospective cohort study. Women with multiple gestations were excluded.

The cohort included 715 pregnant patients with chronic hypertension divided into 2 groups: 635 pre-ACOG patients and 80 post-ACOG patients (that is, patients who delivered before and after the ACOG recommendation). The investigators offered daily low-dose (81 mg) aspirin.

The cohort was further stratified by additional risk factors for superimposed preeclampsia, including a history of preeclampsia and pregestational diabetes.

Outcomes. The primary outcome was the incidence of superimposed preeclampsia. Secondary outcomes included the incidence of superimposed preeclampsia with severe features (SIPSF), small for gestational age, and preterm birth.

Findings. The incidence of superimposed preeclampsia in women with chronic hypertension was 20 (25%) in the post-ACOG group versus 232 (37%) in the pre-ACOG group (odds ratio [OR], 0.43; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.26–0.73).

In the subgroup of women with chronic hypertension who did not have other risk factors, superimposed preeclampsia and SIPSF were significantly decreased: 4/41 (10%) versus 106/355 (30%) (OR, 0.25 [95% CI, 0.08–0.73]) and 2/41 (5%) versus 65/355 (18%) (OR, 0.22 [95% CI, 0.54–0.97]), respectively. The maternal demographics and secondary outcomes did not differ significantly.

After the ACOG guidance was released, low-dose aspirin decreased superimposed preeclampsia by 57% in all women with chronic hypertension. Of those with chronic hypertension without other risk factors, there were decreases of 75% in superimposed preeclampsia and 78% in SIPSF.

Final thoughts. Ms. Banala said in an interview with OBG Management following her presentation, “When we stratified the cohort based on their risk factors, we found that aspirin had the highest benefit in patients with only chronic hypertension, so without other risk factors. And we found that there was a benefit in patients with chronic hypertension who were not on antihypertensive medication. So overall our study concluded that this guideline has made a significant impact in decreasing the frequency of superimposed preeclampsia.”

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Investigators at Thomas Jefferson University found that low-dose aspirin therapy in pregnant women with chronic hypertension—as recommended by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) in 20161—was associated with a 57% decrease in superimposed preeclampsia. Chaitra Banala, BS, presented the study’s results in a poster presentation at the ACOG 2018 annual meeting (April 27–30, 2018, Austin, Texas).2

The study’s goal was to evaluate the incidence of superimposed preeclampsia in women with chronic hypertension in the periods before and after the ACOG recommendation was published.

Study participants. Pregnant women with chronic hypertension who delivered at Thomas Jefferson University Hospital from January 2008 to July 2017 were included in this retrospective cohort study. Women with multiple gestations were excluded.

The cohort included 715 pregnant patients with chronic hypertension divided into 2 groups: 635 pre-ACOG patients and 80 post-ACOG patients (that is, patients who delivered before and after the ACOG recommendation). The investigators offered daily low-dose (81 mg) aspirin.

The cohort was further stratified by additional risk factors for superimposed preeclampsia, including a history of preeclampsia and pregestational diabetes.

Outcomes. The primary outcome was the incidence of superimposed preeclampsia. Secondary outcomes included the incidence of superimposed preeclampsia with severe features (SIPSF), small for gestational age, and preterm birth.

Findings. The incidence of superimposed preeclampsia in women with chronic hypertension was 20 (25%) in the post-ACOG group versus 232 (37%) in the pre-ACOG group (odds ratio [OR], 0.43; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.26–0.73).

In the subgroup of women with chronic hypertension who did not have other risk factors, superimposed preeclampsia and SIPSF were significantly decreased: 4/41 (10%) versus 106/355 (30%) (OR, 0.25 [95% CI, 0.08–0.73]) and 2/41 (5%) versus 65/355 (18%) (OR, 0.22 [95% CI, 0.54–0.97]), respectively. The maternal demographics and secondary outcomes did not differ significantly.

After the ACOG guidance was released, low-dose aspirin decreased superimposed preeclampsia by 57% in all women with chronic hypertension. Of those with chronic hypertension without other risk factors, there were decreases of 75% in superimposed preeclampsia and 78% in SIPSF.

Final thoughts. Ms. Banala said in an interview with OBG Management following her presentation, “When we stratified the cohort based on their risk factors, we found that aspirin had the highest benefit in patients with only chronic hypertension, so without other risk factors. And we found that there was a benefit in patients with chronic hypertension who were not on antihypertensive medication. So overall our study concluded that this guideline has made a significant impact in decreasing the frequency of superimposed preeclampsia.”

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice advisory on low-dose aspirin and prevention of preeclampsia: updated recommendations. https://www.acog.org/Clinical-Guidance-and-Publications/Practice-Advisories/Practice-Advisory-Low-Dose-Aspirin-and-Prevention-of-Preeclampsia-Updated-Recommendations. Published July 11, 2016. Accessed May 3, 2018.

- Banala C, Cruz Y, Moreno C, Schoen C, Berghella V, Roman A. Impact of ACOG guideline regarding low dose aspirin for prevention of superimposed preeclampsia [abstract 27O]. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131(suppl 1):170S.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice advisory on low-dose aspirin and prevention of preeclampsia: updated recommendations. https://www.acog.org/Clinical-Guidance-and-Publications/Practice-Advisories/Practice-Advisory-Low-Dose-Aspirin-and-Prevention-of-Preeclampsia-Updated-Recommendations. Published July 11, 2016. Accessed May 3, 2018.

- Banala C, Cruz Y, Moreno C, Schoen C, Berghella V, Roman A. Impact of ACOG guideline regarding low dose aspirin for prevention of superimposed preeclampsia [abstract 27O]. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131(suppl 1):170S.

MDedge Daily News: How to handle opioid constipation

Bath emollients are a washout for childhood eczema. Does warfarin cause acute kidney injury? And there may be a new option for postpartum depression.

Listen to the MDedge Daily News podcast for all the details on today’s top news.

Bath emollients are a washout for childhood eczema. Does warfarin cause acute kidney injury? And there may be a new option for postpartum depression.

Listen to the MDedge Daily News podcast for all the details on today’s top news.

Bath emollients are a washout for childhood eczema. Does warfarin cause acute kidney injury? And there may be a new option for postpartum depression.

Listen to the MDedge Daily News podcast for all the details on today’s top news.

Did unsafe oxytocin dose cause uterine rupture? $3.5M settlement

Did unsafe oxytocin dose cause uterine rupture? $3.5M settlement

When a mother presented to the hospital in labor, the on-call ObGyn ordered oxytocin with the dosage to be increased by 2 mU/min until she was receiving 30 mU/min or until an adequate contraction pattern was achieved and maintained. Over the next few hours, the labor and delivery nurse increased the dosage of the infusion several times.

As the patient began to push, a trickle of bright red blood was seen coming from her vagina and the baby's heart tones were temporarily lost. When the fetal heart tones were restored, his heart rate was approximately 50 bpm. After vaginal delivery was attempted using vacuum extraction and forceps, an emergency cesarean delivery was performed, leading to the finding that the mother's uterus had ruptured.

The baby suffered a permanent brain injury due to hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy.

PATIENT'S CLAIM: The mother sued the hospital and on-call ObGyn. She alleged that the health care providers breached the standard of care by negligently increasing and maintaining the oxytocin at unsafe levels, which caused the mother's uterus to be overworked and eventually rupture. The rupture led to the child's hypoxia. An expert ObGyn noted that the patient's contractions were adequate by the time the oxytocin dose reached 14 mU/min, but the dosage continued to be increased.

DEFENDANTS' DEFENSE: The case was settled during the trial.

VERDICT: A $3.5 million Kansas settlement was reached.

When did the bowel injury occur?

One day after undergoing a hysterectomy, a woman went to the emergency department (ED) because she was feeling ill. She received a diagnosis of a pulmonary embolism for which she was given anticoagulant medications. The patient's symptoms persisted. Computed tomography (CT) imaging showed a bowel injury, and, 17 days after the initial surgery, an emergency laparotomy was performed.

PATIENT'S CLAIM: The patient sued the surgeon and the hospital. The hospital settled before the trial and the case continued against the surgeon.

The patient's early symptoms after surgery were evidence of a bowel injury, but imaging was not undertaken for several days. If the imaging had been undertaken earlier, the bowel injury would have been detected before it caused a rectovaginal fistula. An expert pathologist testified that the microscopic findings he detected postlaparotomy could only exist if a bowel perforation had been there for a significant period of time before the fistula developed. The patient's experts argued that the injury was not a "free perforation," but had been contained by her body, preventing the spread of the infection.

DEFENDANTS' DEFENSE: The surgeon maintained that the injury did not occur during the hysterectomy but developed in the days just before it was discovered. Over time, a collection of infected fluid at the vaginal cuff eroded into the bowel above it, creating an entryway for stool to pass through. Continuous leakage from the bowel for 17 days (the length of time between development of symptoms and discovery of the bowel injury) would have likely resulted in the patient's death.

VERDICT: A Missouri defense verdict was returned.

Did improper delivery techniques caused brachial plexus injury? $950,000 settlement

In April, a woman began receiving prenatal care for her 7th pregnancy. Her history of maternal obesity and diabetes mellitus, physical examinations, and tests suggested that she was at increased risk for having a macrosomic baby and encountering shoulder dystocia during vaginal delivery.

At 37 weeks' gestation, the mother was admitted to the hospital for induction of labor. Shoulder dystocia was encountered during delivery. At birth, the baby weighed 9 lb 10 oz and her right arm was limp. She was found to have a right brachial plexus injury involving C5‒C8 nerve roots and muscles. Two nerve root avulsions were evident on MRI and visualized by the surgeon during an extensive nerve graft operation. Arm function and range of motion improved after surgery, but the child has not recovered normal use of her arm.

PARENTS' CLAIM: Under the standard of care, the ObGyn was required to obtain informed consent, including a discussion of the risks of vaginal delivery (shoulder dystocia and brachial plexus injury), and the option of cesarean delivery. The patient claimed that the ObGyn neither obtained informed consent nor discussed these risks with her.

The labor and delivery nurse reported that the ObGyn told her, before delivery, that he was expecting a large baby and, perhaps, shoulder dystocia.

The ObGyn deviated from the standard of care by applying more than gentle traction to the fetal head while the shoulder was still impacted. The injury to the baby's right brachial plexus resulted from excessive lateral traction used by the ObGyn. The injury would not have occurred if a cesarean delivery had been performed. The mechanism of maternal forces injuring a brachial plexus nerve has never been visualized by any physician and is an unproven hypothesis.

PHYSICIAN'S DEFENSE: The ObGyn reported using standard maneuvers to deliver the baby. He applied traction on the fetal head 3 times: once after McRoberts maneuver, once after suprapubic pressure, and once after delivery of the posterior arm. He dictated into his notes that "We had to be careful to avoid excessive tractive forces." He claimed that shoulder dystocia is an unpredictable and unpreventable obstetric emergency, and that the injury was caused by the maternal forces of labor.

VERDICT: A $950,000 Virginia settlement was reached.

Wrongful death claim

On March 13, a 76-year-old woman went to her primary care physician's office because of a vaginal discharge. A nurse practitioner (NP) diagnosed a urinary tract infection (UTI) and prescribed cefixime (Suprax). Four days later, the patient began to experience severe diarrhea and blamed the medication. At a follow-up visit on March 20, the NP switched the patient to sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim (Bactrim).

The following day, the patient was found unresponsive on her bathroom floor and was taken to the ED. It was determined that she had Clostridium difficile colitis (C difficile) and was admitted to the hospital. She developed acute renal failure, metabolic acidosis, hypovolemia, hypotension, and tachycardia. When she went into cardiac arrest, attempts to resuscitate her failed. She died on March 22.

ESTATE'S CLAIM: The estate sued the NP, claiming that the patient's symptoms did not meet the criteria for a UTI. If appropriate tests had been performed, the correct diagnosis would have been made and she could have received potentially life-saving treatment.

DEFENDANTS' DEFENSE: The NP claimed there was no negligence. Her diagnosis and treatment of the patient's condition were appropriate in all respects. The development of C difficile is a risk of any antibiotic.

VERDICT: An Indiana defense verdict was returned.

Nuchal cord: Undisclosed settlement

During delivery, the labor and delivery nurses lost the fetal heart-rate (FHR) monitor tracing, resulting in their being unaware of increasing signs of fetal intolerance to labor. The nurses continued to administer oxytocin to induce labor.

At birth, a nuchal cord was identified. The baby was born without signs of life but was successfully resuscitated by hospital staff.

The baby was found to have sustained severe brain damage as a result of profound fetal hypoxia. The child will require 24-hour nursing and supportive care for as long as she lives.

PARENTS' CLAIM: The nurses and ObGyn breached the standard of care resulting in her child's severe brain damage. The hospital nurses failed to continuously monitor the FHR. Profound brain damage was preventable in this case.

DEFENDANTS' DEFENSE: The nurses continuously monitored by listening to sounds coming out of the bedside monitor even though no taping of FHR was occurring on the central monitors or FHR monitor strip. A nuchal cord is an unforeseeable medical emergency; nothing different could have been done to change the outcome.

VERDICT: An undisclosed Texas settlement was reached.

Surgical needle left near bladder

The patient underwent a hysterectomy on July 9. Because of an injury sustained during the operation, bladder repair surgery was performed on July 19. After that surgery, she reported bleeding and urinary incontinence. Results of a computed tomography (CT) scan showed that the bladder repair was not successful, a vesicovaginal fistula had developed, and a 13-mm C-shaped needle was found near her bladder. A third operation to remove the needle from her abdomen took place on August 16.

PATIENT'S CLAIM: The needle left behind after the second surgery caused a fistula to develop. The patient suffered mental and emotional distress from knowing the needle was in her abdomen. Foreign objects left in a patient during surgery are strong evidence of negligence.

DEFENDANTS' DEFENSE: The primary defense claim was the absence of causation--any negligence did not cause the injury. Defense experts testified that the needle was on top of the bladder and did move anywhere to cause damage. The patient developed a vesicovaginal fistula due to complications from the bladder repair operation and not from the needle. In addition, there was testimony that the third surgery was unnecessary because the needle would eventually flush out of the abdomen without causing damage.

VERDICT: A Michigan defense verdict was returned.

Claims cancer diagnosis was delayed

On October 1, 2008, a woman saw her family physician (FP) for routine care. Blood work results showed an elevated white blood cell (WBC) count. The patient claimed that the FP did not inform her of these test results.

One year later, the patient went to an urgent care facility where blood work was performed; the results showed a high WBC count. After a work-up, the patient was given a presumptive diagnosis of mantel cell lymphoma. By December 9, she had undergone the first round of chemotherapy. Subsequent tests revealed that the presumptive diagnosis was incorrect; she actually had low-grade lymphoproliferative disorder.

In lieu of this new diagnosis, the medical team offered the patient the option of discontinuing chemotherapy. She decided, however, to continue the treatment. Chemotherapy was followed by 2 years of rituximab/hyaluronidase human maintenance therapy.

PATIENT'S CLAIM: The patient presented her case to a medical review board. The course of treatment (chemotherapy plus maintenance therapy) left her with permanent heart damage and an elevated risk of developing secondary cancer.

The patient claimed that none of this would have happened if her FP had informed her of the October 2008 test results and recommended appropriate follow-up studies. The results of those studies would have given her the correct diagnosis and allowed her to receive prompt, proper treatment. The medical review board responded unanimously that the FP's conduct constituted a breach of the standard of care, but concluded that the breach was not a factor in the patient's damages.

The patient filed suit against the FP. An expert in internal medicine commented that, based on the 2008 WBC count, the tests should have been repeated and the patient should have been referred to a hematologist/oncologist. Failure to do so increased the patient's risk of developing cancer in the future.

DEFENDANTS' DEFENSE: The FP denied any breach of standard of care. According to her notes, she had shared test results with the patient on November 26 and recommended following up with repeat blood work. The FP blamed the patient for failing to follow-up as recommended.

VERDICT: An Indiana defense verdict was returned.

These cases were selected by the editors of OBG Management from Medical Malpractice Verdicts, Settlements & Experts, with permission of the editor, Lewis Laska (www.verdictslaska.com). The information available to the editors about the cases presented here is sometimes incomplete. Moreover, the cases may or may not have merit. Nevertheless, these cases represent the types of clinical situations that typically result in litigation and are meant to illustrate nationwide variation in jury verdicts and awards.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Did unsafe oxytocin dose cause uterine rupture? $3.5M settlement

When a mother presented to the hospital in labor, the on-call ObGyn ordered oxytocin with the dosage to be increased by 2 mU/min until she was receiving 30 mU/min or until an adequate contraction pattern was achieved and maintained. Over the next few hours, the labor and delivery nurse increased the dosage of the infusion several times.

As the patient began to push, a trickle of bright red blood was seen coming from her vagina and the baby's heart tones were temporarily lost. When the fetal heart tones were restored, his heart rate was approximately 50 bpm. After vaginal delivery was attempted using vacuum extraction and forceps, an emergency cesarean delivery was performed, leading to the finding that the mother's uterus had ruptured.

The baby suffered a permanent brain injury due to hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy.

PATIENT'S CLAIM: The mother sued the hospital and on-call ObGyn. She alleged that the health care providers breached the standard of care by negligently increasing and maintaining the oxytocin at unsafe levels, which caused the mother's uterus to be overworked and eventually rupture. The rupture led to the child's hypoxia. An expert ObGyn noted that the patient's contractions were adequate by the time the oxytocin dose reached 14 mU/min, but the dosage continued to be increased.

DEFENDANTS' DEFENSE: The case was settled during the trial.

VERDICT: A $3.5 million Kansas settlement was reached.

When did the bowel injury occur?

One day after undergoing a hysterectomy, a woman went to the emergency department (ED) because she was feeling ill. She received a diagnosis of a pulmonary embolism for which she was given anticoagulant medications. The patient's symptoms persisted. Computed tomography (CT) imaging showed a bowel injury, and, 17 days after the initial surgery, an emergency laparotomy was performed.

PATIENT'S CLAIM: The patient sued the surgeon and the hospital. The hospital settled before the trial and the case continued against the surgeon.

The patient's early symptoms after surgery were evidence of a bowel injury, but imaging was not undertaken for several days. If the imaging had been undertaken earlier, the bowel injury would have been detected before it caused a rectovaginal fistula. An expert pathologist testified that the microscopic findings he detected postlaparotomy could only exist if a bowel perforation had been there for a significant period of time before the fistula developed. The patient's experts argued that the injury was not a "free perforation," but had been contained by her body, preventing the spread of the infection.

DEFENDANTS' DEFENSE: The surgeon maintained that the injury did not occur during the hysterectomy but developed in the days just before it was discovered. Over time, a collection of infected fluid at the vaginal cuff eroded into the bowel above it, creating an entryway for stool to pass through. Continuous leakage from the bowel for 17 days (the length of time between development of symptoms and discovery of the bowel injury) would have likely resulted in the patient's death.

VERDICT: A Missouri defense verdict was returned.

Did improper delivery techniques caused brachial plexus injury? $950,000 settlement

In April, a woman began receiving prenatal care for her 7th pregnancy. Her history of maternal obesity and diabetes mellitus, physical examinations, and tests suggested that she was at increased risk for having a macrosomic baby and encountering shoulder dystocia during vaginal delivery.

At 37 weeks' gestation, the mother was admitted to the hospital for induction of labor. Shoulder dystocia was encountered during delivery. At birth, the baby weighed 9 lb 10 oz and her right arm was limp. She was found to have a right brachial plexus injury involving C5‒C8 nerve roots and muscles. Two nerve root avulsions were evident on MRI and visualized by the surgeon during an extensive nerve graft operation. Arm function and range of motion improved after surgery, but the child has not recovered normal use of her arm.

PARENTS' CLAIM: Under the standard of care, the ObGyn was required to obtain informed consent, including a discussion of the risks of vaginal delivery (shoulder dystocia and brachial plexus injury), and the option of cesarean delivery. The patient claimed that the ObGyn neither obtained informed consent nor discussed these risks with her.

The labor and delivery nurse reported that the ObGyn told her, before delivery, that he was expecting a large baby and, perhaps, shoulder dystocia.

The ObGyn deviated from the standard of care by applying more than gentle traction to the fetal head while the shoulder was still impacted. The injury to the baby's right brachial plexus resulted from excessive lateral traction used by the ObGyn. The injury would not have occurred if a cesarean delivery had been performed. The mechanism of maternal forces injuring a brachial plexus nerve has never been visualized by any physician and is an unproven hypothesis.

PHYSICIAN'S DEFENSE: The ObGyn reported using standard maneuvers to deliver the baby. He applied traction on the fetal head 3 times: once after McRoberts maneuver, once after suprapubic pressure, and once after delivery of the posterior arm. He dictated into his notes that "We had to be careful to avoid excessive tractive forces." He claimed that shoulder dystocia is an unpredictable and unpreventable obstetric emergency, and that the injury was caused by the maternal forces of labor.

VERDICT: A $950,000 Virginia settlement was reached.

Wrongful death claim

On March 13, a 76-year-old woman went to her primary care physician's office because of a vaginal discharge. A nurse practitioner (NP) diagnosed a urinary tract infection (UTI) and prescribed cefixime (Suprax). Four days later, the patient began to experience severe diarrhea and blamed the medication. At a follow-up visit on March 20, the NP switched the patient to sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim (Bactrim).

The following day, the patient was found unresponsive on her bathroom floor and was taken to the ED. It was determined that she had Clostridium difficile colitis (C difficile) and was admitted to the hospital. She developed acute renal failure, metabolic acidosis, hypovolemia, hypotension, and tachycardia. When she went into cardiac arrest, attempts to resuscitate her failed. She died on March 22.

ESTATE'S CLAIM: The estate sued the NP, claiming that the patient's symptoms did not meet the criteria for a UTI. If appropriate tests had been performed, the correct diagnosis would have been made and she could have received potentially life-saving treatment.

DEFENDANTS' DEFENSE: The NP claimed there was no negligence. Her diagnosis and treatment of the patient's condition were appropriate in all respects. The development of C difficile is a risk of any antibiotic.

VERDICT: An Indiana defense verdict was returned.

Nuchal cord: Undisclosed settlement

During delivery, the labor and delivery nurses lost the fetal heart-rate (FHR) monitor tracing, resulting in their being unaware of increasing signs of fetal intolerance to labor. The nurses continued to administer oxytocin to induce labor.

At birth, a nuchal cord was identified. The baby was born without signs of life but was successfully resuscitated by hospital staff.

The baby was found to have sustained severe brain damage as a result of profound fetal hypoxia. The child will require 24-hour nursing and supportive care for as long as she lives.

PARENTS' CLAIM: The nurses and ObGyn breached the standard of care resulting in her child's severe brain damage. The hospital nurses failed to continuously monitor the FHR. Profound brain damage was preventable in this case.

DEFENDANTS' DEFENSE: The nurses continuously monitored by listening to sounds coming out of the bedside monitor even though no taping of FHR was occurring on the central monitors or FHR monitor strip. A nuchal cord is an unforeseeable medical emergency; nothing different could have been done to change the outcome.

VERDICT: An undisclosed Texas settlement was reached.

Surgical needle left near bladder

The patient underwent a hysterectomy on July 9. Because of an injury sustained during the operation, bladder repair surgery was performed on July 19. After that surgery, she reported bleeding and urinary incontinence. Results of a computed tomography (CT) scan showed that the bladder repair was not successful, a vesicovaginal fistula had developed, and a 13-mm C-shaped needle was found near her bladder. A third operation to remove the needle from her abdomen took place on August 16.

PATIENT'S CLAIM: The needle left behind after the second surgery caused a fistula to develop. The patient suffered mental and emotional distress from knowing the needle was in her abdomen. Foreign objects left in a patient during surgery are strong evidence of negligence.

DEFENDANTS' DEFENSE: The primary defense claim was the absence of causation--any negligence did not cause the injury. Defense experts testified that the needle was on top of the bladder and did move anywhere to cause damage. The patient developed a vesicovaginal fistula due to complications from the bladder repair operation and not from the needle. In addition, there was testimony that the third surgery was unnecessary because the needle would eventually flush out of the abdomen without causing damage.

VERDICT: A Michigan defense verdict was returned.

Claims cancer diagnosis was delayed

On October 1, 2008, a woman saw her family physician (FP) for routine care. Blood work results showed an elevated white blood cell (WBC) count. The patient claimed that the FP did not inform her of these test results.

One year later, the patient went to an urgent care facility where blood work was performed; the results showed a high WBC count. After a work-up, the patient was given a presumptive diagnosis of mantel cell lymphoma. By December 9, she had undergone the first round of chemotherapy. Subsequent tests revealed that the presumptive diagnosis was incorrect; she actually had low-grade lymphoproliferative disorder.

In lieu of this new diagnosis, the medical team offered the patient the option of discontinuing chemotherapy. She decided, however, to continue the treatment. Chemotherapy was followed by 2 years of rituximab/hyaluronidase human maintenance therapy.

PATIENT'S CLAIM: The patient presented her case to a medical review board. The course of treatment (chemotherapy plus maintenance therapy) left her with permanent heart damage and an elevated risk of developing secondary cancer.

The patient claimed that none of this would have happened if her FP had informed her of the October 2008 test results and recommended appropriate follow-up studies. The results of those studies would have given her the correct diagnosis and allowed her to receive prompt, proper treatment. The medical review board responded unanimously that the FP's conduct constituted a breach of the standard of care, but concluded that the breach was not a factor in the patient's damages.

The patient filed suit against the FP. An expert in internal medicine commented that, based on the 2008 WBC count, the tests should have been repeated and the patient should have been referred to a hematologist/oncologist. Failure to do so increased the patient's risk of developing cancer in the future.

DEFENDANTS' DEFENSE: The FP denied any breach of standard of care. According to her notes, she had shared test results with the patient on November 26 and recommended following up with repeat blood work. The FP blamed the patient for failing to follow-up as recommended.

VERDICT: An Indiana defense verdict was returned.

These cases were selected by the editors of OBG Management from Medical Malpractice Verdicts, Settlements & Experts, with permission of the editor, Lewis Laska (www.verdictslaska.com). The information available to the editors about the cases presented here is sometimes incomplete. Moreover, the cases may or may not have merit. Nevertheless, these cases represent the types of clinical situations that typically result in litigation and are meant to illustrate nationwide variation in jury verdicts and awards.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Did unsafe oxytocin dose cause uterine rupture? $3.5M settlement

When a mother presented to the hospital in labor, the on-call ObGyn ordered oxytocin with the dosage to be increased by 2 mU/min until she was receiving 30 mU/min or until an adequate contraction pattern was achieved and maintained. Over the next few hours, the labor and delivery nurse increased the dosage of the infusion several times.

As the patient began to push, a trickle of bright red blood was seen coming from her vagina and the baby's heart tones were temporarily lost. When the fetal heart tones were restored, his heart rate was approximately 50 bpm. After vaginal delivery was attempted using vacuum extraction and forceps, an emergency cesarean delivery was performed, leading to the finding that the mother's uterus had ruptured.

The baby suffered a permanent brain injury due to hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy.

PATIENT'S CLAIM: The mother sued the hospital and on-call ObGyn. She alleged that the health care providers breached the standard of care by negligently increasing and maintaining the oxytocin at unsafe levels, which caused the mother's uterus to be overworked and eventually rupture. The rupture led to the child's hypoxia. An expert ObGyn noted that the patient's contractions were adequate by the time the oxytocin dose reached 14 mU/min, but the dosage continued to be increased.

DEFENDANTS' DEFENSE: The case was settled during the trial.

VERDICT: A $3.5 million Kansas settlement was reached.

When did the bowel injury occur?

One day after undergoing a hysterectomy, a woman went to the emergency department (ED) because she was feeling ill. She received a diagnosis of a pulmonary embolism for which she was given anticoagulant medications. The patient's symptoms persisted. Computed tomography (CT) imaging showed a bowel injury, and, 17 days after the initial surgery, an emergency laparotomy was performed.

PATIENT'S CLAIM: The patient sued the surgeon and the hospital. The hospital settled before the trial and the case continued against the surgeon.

The patient's early symptoms after surgery were evidence of a bowel injury, but imaging was not undertaken for several days. If the imaging had been undertaken earlier, the bowel injury would have been detected before it caused a rectovaginal fistula. An expert pathologist testified that the microscopic findings he detected postlaparotomy could only exist if a bowel perforation had been there for a significant period of time before the fistula developed. The patient's experts argued that the injury was not a "free perforation," but had been contained by her body, preventing the spread of the infection.

DEFENDANTS' DEFENSE: The surgeon maintained that the injury did not occur during the hysterectomy but developed in the days just before it was discovered. Over time, a collection of infected fluid at the vaginal cuff eroded into the bowel above it, creating an entryway for stool to pass through. Continuous leakage from the bowel for 17 days (the length of time between development of symptoms and discovery of the bowel injury) would have likely resulted in the patient's death.

VERDICT: A Missouri defense verdict was returned.

Did improper delivery techniques caused brachial plexus injury? $950,000 settlement

In April, a woman began receiving prenatal care for her 7th pregnancy. Her history of maternal obesity and diabetes mellitus, physical examinations, and tests suggested that she was at increased risk for having a macrosomic baby and encountering shoulder dystocia during vaginal delivery.

At 37 weeks' gestation, the mother was admitted to the hospital for induction of labor. Shoulder dystocia was encountered during delivery. At birth, the baby weighed 9 lb 10 oz and her right arm was limp. She was found to have a right brachial plexus injury involving C5‒C8 nerve roots and muscles. Two nerve root avulsions were evident on MRI and visualized by the surgeon during an extensive nerve graft operation. Arm function and range of motion improved after surgery, but the child has not recovered normal use of her arm.

PARENTS' CLAIM: Under the standard of care, the ObGyn was required to obtain informed consent, including a discussion of the risks of vaginal delivery (shoulder dystocia and brachial plexus injury), and the option of cesarean delivery. The patient claimed that the ObGyn neither obtained informed consent nor discussed these risks with her.

The labor and delivery nurse reported that the ObGyn told her, before delivery, that he was expecting a large baby and, perhaps, shoulder dystocia.

The ObGyn deviated from the standard of care by applying more than gentle traction to the fetal head while the shoulder was still impacted. The injury to the baby's right brachial plexus resulted from excessive lateral traction used by the ObGyn. The injury would not have occurred if a cesarean delivery had been performed. The mechanism of maternal forces injuring a brachial plexus nerve has never been visualized by any physician and is an unproven hypothesis.

PHYSICIAN'S DEFENSE: The ObGyn reported using standard maneuvers to deliver the baby. He applied traction on the fetal head 3 times: once after McRoberts maneuver, once after suprapubic pressure, and once after delivery of the posterior arm. He dictated into his notes that "We had to be careful to avoid excessive tractive forces." He claimed that shoulder dystocia is an unpredictable and unpreventable obstetric emergency, and that the injury was caused by the maternal forces of labor.

VERDICT: A $950,000 Virginia settlement was reached.

Wrongful death claim

On March 13, a 76-year-old woman went to her primary care physician's office because of a vaginal discharge. A nurse practitioner (NP) diagnosed a urinary tract infection (UTI) and prescribed cefixime (Suprax). Four days later, the patient began to experience severe diarrhea and blamed the medication. At a follow-up visit on March 20, the NP switched the patient to sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim (Bactrim).

The following day, the patient was found unresponsive on her bathroom floor and was taken to the ED. It was determined that she had Clostridium difficile colitis (C difficile) and was admitted to the hospital. She developed acute renal failure, metabolic acidosis, hypovolemia, hypotension, and tachycardia. When she went into cardiac arrest, attempts to resuscitate her failed. She died on March 22.

ESTATE'S CLAIM: The estate sued the NP, claiming that the patient's symptoms did not meet the criteria for a UTI. If appropriate tests had been performed, the correct diagnosis would have been made and she could have received potentially life-saving treatment.

DEFENDANTS' DEFENSE: The NP claimed there was no negligence. Her diagnosis and treatment of the patient's condition were appropriate in all respects. The development of C difficile is a risk of any antibiotic.

VERDICT: An Indiana defense verdict was returned.

Nuchal cord: Undisclosed settlement

During delivery, the labor and delivery nurses lost the fetal heart-rate (FHR) monitor tracing, resulting in their being unaware of increasing signs of fetal intolerance to labor. The nurses continued to administer oxytocin to induce labor.

At birth, a nuchal cord was identified. The baby was born without signs of life but was successfully resuscitated by hospital staff.

The baby was found to have sustained severe brain damage as a result of profound fetal hypoxia. The child will require 24-hour nursing and supportive care for as long as she lives.

PARENTS' CLAIM: The nurses and ObGyn breached the standard of care resulting in her child's severe brain damage. The hospital nurses failed to continuously monitor the FHR. Profound brain damage was preventable in this case.

DEFENDANTS' DEFENSE: The nurses continuously monitored by listening to sounds coming out of the bedside monitor even though no taping of FHR was occurring on the central monitors or FHR monitor strip. A nuchal cord is an unforeseeable medical emergency; nothing different could have been done to change the outcome.

VERDICT: An undisclosed Texas settlement was reached.

Surgical needle left near bladder

The patient underwent a hysterectomy on July 9. Because of an injury sustained during the operation, bladder repair surgery was performed on July 19. After that surgery, she reported bleeding and urinary incontinence. Results of a computed tomography (CT) scan showed that the bladder repair was not successful, a vesicovaginal fistula had developed, and a 13-mm C-shaped needle was found near her bladder. A third operation to remove the needle from her abdomen took place on August 16.

PATIENT'S CLAIM: The needle left behind after the second surgery caused a fistula to develop. The patient suffered mental and emotional distress from knowing the needle was in her abdomen. Foreign objects left in a patient during surgery are strong evidence of negligence.

DEFENDANTS' DEFENSE: The primary defense claim was the absence of causation--any negligence did not cause the injury. Defense experts testified that the needle was on top of the bladder and did move anywhere to cause damage. The patient developed a vesicovaginal fistula due to complications from the bladder repair operation and not from the needle. In addition, there was testimony that the third surgery was unnecessary because the needle would eventually flush out of the abdomen without causing damage.

VERDICT: A Michigan defense verdict was returned.

Claims cancer diagnosis was delayed

On October 1, 2008, a woman saw her family physician (FP) for routine care. Blood work results showed an elevated white blood cell (WBC) count. The patient claimed that the FP did not inform her of these test results.

One year later, the patient went to an urgent care facility where blood work was performed; the results showed a high WBC count. After a work-up, the patient was given a presumptive diagnosis of mantel cell lymphoma. By December 9, she had undergone the first round of chemotherapy. Subsequent tests revealed that the presumptive diagnosis was incorrect; she actually had low-grade lymphoproliferative disorder.

In lieu of this new diagnosis, the medical team offered the patient the option of discontinuing chemotherapy. She decided, however, to continue the treatment. Chemotherapy was followed by 2 years of rituximab/hyaluronidase human maintenance therapy.

PATIENT'S CLAIM: The patient presented her case to a medical review board. The course of treatment (chemotherapy plus maintenance therapy) left her with permanent heart damage and an elevated risk of developing secondary cancer.

The patient claimed that none of this would have happened if her FP had informed her of the October 2008 test results and recommended appropriate follow-up studies. The results of those studies would have given her the correct diagnosis and allowed her to receive prompt, proper treatment. The medical review board responded unanimously that the FP's conduct constituted a breach of the standard of care, but concluded that the breach was not a factor in the patient's damages.

The patient filed suit against the FP. An expert in internal medicine commented that, based on the 2008 WBC count, the tests should have been repeated and the patient should have been referred to a hematologist/oncologist. Failure to do so increased the patient's risk of developing cancer in the future.

DEFENDANTS' DEFENSE: The FP denied any breach of standard of care. According to her notes, she had shared test results with the patient on November 26 and recommended following up with repeat blood work. The FP blamed the patient for failing to follow-up as recommended.

VERDICT: An Indiana defense verdict was returned.

These cases were selected by the editors of OBG Management from Medical Malpractice Verdicts, Settlements & Experts, with permission of the editor, Lewis Laska (www.verdictslaska.com). The information available to the editors about the cases presented here is sometimes incomplete. Moreover, the cases may or may not have merit. Nevertheless, these cases represent the types of clinical situations that typically result in litigation and are meant to illustrate nationwide variation in jury verdicts and awards.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

MDedge Daily News: Fewer smokes mean fewer strokes

Are biopsy’s days numbered for diagnosing celiac disease? The perils of endoscopic therapy for Barrett’s esophagus. And is your EHR preventing breastfeeding?

Listen to the MDedge Daily News podcast for all the details on today’s top news.

Are biopsy’s days numbered for diagnosing celiac disease? The perils of endoscopic therapy for Barrett’s esophagus. And is your EHR preventing breastfeeding?

Listen to the MDedge Daily News podcast for all the details on today’s top news.

Are biopsy’s days numbered for diagnosing celiac disease? The perils of endoscopic therapy for Barrett’s esophagus. And is your EHR preventing breastfeeding?

Listen to the MDedge Daily News podcast for all the details on today’s top news.

Maternal morbidity and BMI: A dose-response relationship

AUSTIN, TEX. – Women with the highest levels of obesity were at higher odds of experiencing a composite serious maternal morbidity outcome, while women at all levels of obesity experienced elevated risks of some serious complications of pregnancy, compared with women with a body mass index (BMI) in the normal range, according to a recent study.

Looking at individual indicators of severe maternal morbidity, Marissa Platner, MD, and her study coauthors saw that women who fell into the higher levels of obesity had significantly elevated odds of some complications.

“Those risks are really impressive, with odds ratios of two and three times that of a normal-weight patient,” said Dr. Platner in a video interview.

The adjusted odds ratio of acute renal failure for women with superobesity (BMI of 50 kg/m2 or more) was 3.62 (95% confidence interval, 1.75-7.52); odds ratios for renal failure were not significantly elevated for less-obese women.

Women with all levels of obesity had elevated risks of experiencing heart failure during a procedure or surgery, with adjusted odds ratios ranging from 1.68 (95% CI, 1.48-1.93) for women with class I obesity (BMI, 30-34.9 kg/m2) to 2.23 for women with superobesity (95% CI, 1.15-4.33).

Results from the retrospective cohort study were presented at the annual clinical and scientific meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

Dr. Platner and her colleagues examined 4 years of New York City delivery data that were linked to birth certificates, identifying those singleton live births for whom maternal prepregnancy BMI data were available.

From this group, they included women aged 15-50 years who delivered at 20-45 weeks’ gestational age. Women with prepregnancy BMIs less than 18.5 kg/m2 – those who were underweight – were excluded.

Dr. Platner and her coinvestigators used multivariable analysis to see what association the full range of obesity classes had with severe maternal morbidity, adjusting for many socioeconomic and demographic factors.

Of the 539,870 women included in the study, 3.3% experienced severe maternal morbidity, and 17.4% of patients met criteria for obesity. “Across all classes of obesity, there was a significantly greater risk of severe maternal morbidity, compared to nonobese women,” wrote Dr. Platner and her colleagues in the poster accompanying the presentation.

These risks climbed for women with the highest BMIs, however. “Women with higher levels of obesity, not surprisingly, are at increased risk” of severe maternal morbidity, said Dr. Platner. She and her colleagues noted in the poster that, “There is a significant dose-response relationship between increasing obesity class and risk of [severe maternal morbidity] at delivery hospitalization.”

It had been known that women with obesity are at increased risk of some serious complications of pregnancy, including severe maternal morbidity and mortality, and that those considered morbidly obese – with BMIs of 40 and above – are most likely to experience these complications, Dr. Platner said. However, she added, there’s a paucity of data to inform maternal risk stratification by level of obesity.

“We included the group of superobese women, which is significant in the surgical literature, and that’s a BMI of 50 and above ... we thought that would be an important subgroup to analyze in this population,” she said.

Dr. Platner said that she and her colleagues already had the clinical impressions that women with the highest BMIs were most likely to have serious complications. “I don’t think that these findings are particularly surprising,” she said. “This is what our hypothesis was in terms of why we did this study.”

The greater surprise, she said, was the magnitude of increased risk seen for serious morbidity with higher levels of obesity.

“Really, the risk is truly increased for those women with class III or superobesity, and when we start to stratify ... those are the women we need to be concerned about in terms of our prenatal counseling,” said Dr. Platner, a maternal-fetal medicine fellow at Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

“What can we do to intervene before we get there?” asked Dr. Platner. Although data are lacking about what specific interventions might be able to reduce the risk of these serious complications, she said she could envision such steps as acquiring predelivery baseline ECGs and cardiac ultrasounds in women with higher levels of obesity and being sure to follow renal function closely as well.

The findings also may help physicians provide more evidence-based preconception advice to women who are among the 35% of American adults who have obesity.

Dr. Platner reported no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Platner M et al. ACOG 2018, Abstract 39I.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

AUSTIN, TEX. – Women with the highest levels of obesity were at higher odds of experiencing a composite serious maternal morbidity outcome, while women at all levels of obesity experienced elevated risks of some serious complications of pregnancy, compared with women with a body mass index (BMI) in the normal range, according to a recent study.

Looking at individual indicators of severe maternal morbidity, Marissa Platner, MD, and her study coauthors saw that women who fell into the higher levels of obesity had significantly elevated odds of some complications.

“Those risks are really impressive, with odds ratios of two and three times that of a normal-weight patient,” said Dr. Platner in a video interview.

The adjusted odds ratio of acute renal failure for women with superobesity (BMI of 50 kg/m2 or more) was 3.62 (95% confidence interval, 1.75-7.52); odds ratios for renal failure were not significantly elevated for less-obese women.

Women with all levels of obesity had elevated risks of experiencing heart failure during a procedure or surgery, with adjusted odds ratios ranging from 1.68 (95% CI, 1.48-1.93) for women with class I obesity (BMI, 30-34.9 kg/m2) to 2.23 for women with superobesity (95% CI, 1.15-4.33).

Results from the retrospective cohort study were presented at the annual clinical and scientific meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

Dr. Platner and her colleagues examined 4 years of New York City delivery data that were linked to birth certificates, identifying those singleton live births for whom maternal prepregnancy BMI data were available.

From this group, they included women aged 15-50 years who delivered at 20-45 weeks’ gestational age. Women with prepregnancy BMIs less than 18.5 kg/m2 – those who were underweight – were excluded.

Dr. Platner and her coinvestigators used multivariable analysis to see what association the full range of obesity classes had with severe maternal morbidity, adjusting for many socioeconomic and demographic factors.

Of the 539,870 women included in the study, 3.3% experienced severe maternal morbidity, and 17.4% of patients met criteria for obesity. “Across all classes of obesity, there was a significantly greater risk of severe maternal morbidity, compared to nonobese women,” wrote Dr. Platner and her colleagues in the poster accompanying the presentation.

These risks climbed for women with the highest BMIs, however. “Women with higher levels of obesity, not surprisingly, are at increased risk” of severe maternal morbidity, said Dr. Platner. She and her colleagues noted in the poster that, “There is a significant dose-response relationship between increasing obesity class and risk of [severe maternal morbidity] at delivery hospitalization.”

It had been known that women with obesity are at increased risk of some serious complications of pregnancy, including severe maternal morbidity and mortality, and that those considered morbidly obese – with BMIs of 40 and above – are most likely to experience these complications, Dr. Platner said. However, she added, there’s a paucity of data to inform maternal risk stratification by level of obesity.

“We included the group of superobese women, which is significant in the surgical literature, and that’s a BMI of 50 and above ... we thought that would be an important subgroup to analyze in this population,” she said.

Dr. Platner said that she and her colleagues already had the clinical impressions that women with the highest BMIs were most likely to have serious complications. “I don’t think that these findings are particularly surprising,” she said. “This is what our hypothesis was in terms of why we did this study.”

The greater surprise, she said, was the magnitude of increased risk seen for serious morbidity with higher levels of obesity.

“Really, the risk is truly increased for those women with class III or superobesity, and when we start to stratify ... those are the women we need to be concerned about in terms of our prenatal counseling,” said Dr. Platner, a maternal-fetal medicine fellow at Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

“What can we do to intervene before we get there?” asked Dr. Platner. Although data are lacking about what specific interventions might be able to reduce the risk of these serious complications, she said she could envision such steps as acquiring predelivery baseline ECGs and cardiac ultrasounds in women with higher levels of obesity and being sure to follow renal function closely as well.

The findings also may help physicians provide more evidence-based preconception advice to women who are among the 35% of American adults who have obesity.

Dr. Platner reported no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Platner M et al. ACOG 2018, Abstract 39I.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

AUSTIN, TEX. – Women with the highest levels of obesity were at higher odds of experiencing a composite serious maternal morbidity outcome, while women at all levels of obesity experienced elevated risks of some serious complications of pregnancy, compared with women with a body mass index (BMI) in the normal range, according to a recent study.

Looking at individual indicators of severe maternal morbidity, Marissa Platner, MD, and her study coauthors saw that women who fell into the higher levels of obesity had significantly elevated odds of some complications.

“Those risks are really impressive, with odds ratios of two and three times that of a normal-weight patient,” said Dr. Platner in a video interview.

The adjusted odds ratio of acute renal failure for women with superobesity (BMI of 50 kg/m2 or more) was 3.62 (95% confidence interval, 1.75-7.52); odds ratios for renal failure were not significantly elevated for less-obese women.

Women with all levels of obesity had elevated risks of experiencing heart failure during a procedure or surgery, with adjusted odds ratios ranging from 1.68 (95% CI, 1.48-1.93) for women with class I obesity (BMI, 30-34.9 kg/m2) to 2.23 for women with superobesity (95% CI, 1.15-4.33).

Results from the retrospective cohort study were presented at the annual clinical and scientific meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

Dr. Platner and her colleagues examined 4 years of New York City delivery data that were linked to birth certificates, identifying those singleton live births for whom maternal prepregnancy BMI data were available.

From this group, they included women aged 15-50 years who delivered at 20-45 weeks’ gestational age. Women with prepregnancy BMIs less than 18.5 kg/m2 – those who were underweight – were excluded.

Dr. Platner and her coinvestigators used multivariable analysis to see what association the full range of obesity classes had with severe maternal morbidity, adjusting for many socioeconomic and demographic factors.

Of the 539,870 women included in the study, 3.3% experienced severe maternal morbidity, and 17.4% of patients met criteria for obesity. “Across all classes of obesity, there was a significantly greater risk of severe maternal morbidity, compared to nonobese women,” wrote Dr. Platner and her colleagues in the poster accompanying the presentation.

These risks climbed for women with the highest BMIs, however. “Women with higher levels of obesity, not surprisingly, are at increased risk” of severe maternal morbidity, said Dr. Platner. She and her colleagues noted in the poster that, “There is a significant dose-response relationship between increasing obesity class and risk of [severe maternal morbidity] at delivery hospitalization.”

It had been known that women with obesity are at increased risk of some serious complications of pregnancy, including severe maternal morbidity and mortality, and that those considered morbidly obese – with BMIs of 40 and above – are most likely to experience these complications, Dr. Platner said. However, she added, there’s a paucity of data to inform maternal risk stratification by level of obesity.

“We included the group of superobese women, which is significant in the surgical literature, and that’s a BMI of 50 and above ... we thought that would be an important subgroup to analyze in this population,” she said.

Dr. Platner said that she and her colleagues already had the clinical impressions that women with the highest BMIs were most likely to have serious complications. “I don’t think that these findings are particularly surprising,” she said. “This is what our hypothesis was in terms of why we did this study.”

The greater surprise, she said, was the magnitude of increased risk seen for serious morbidity with higher levels of obesity.

“Really, the risk is truly increased for those women with class III or superobesity, and when we start to stratify ... those are the women we need to be concerned about in terms of our prenatal counseling,” said Dr. Platner, a maternal-fetal medicine fellow at Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

“What can we do to intervene before we get there?” asked Dr. Platner. Although data are lacking about what specific interventions might be able to reduce the risk of these serious complications, she said she could envision such steps as acquiring predelivery baseline ECGs and cardiac ultrasounds in women with higher levels of obesity and being sure to follow renal function closely as well.

The findings also may help physicians provide more evidence-based preconception advice to women who are among the 35% of American adults who have obesity.

Dr. Platner reported no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Platner M et al. ACOG 2018, Abstract 39I.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

REPORTING FROM ACOG 2018

Inhaled nitrous oxide for labor analgesia: Pearls from clinical experience

Nitrous oxide, a colorless, odorless gas, has long been used for labor analgesia in many countries, including the United Kingdom, Canada, throughout Europe, Australia, and New Zealand. Recently, interest in its use in the United States has increased, since the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval in 2012 of simple devices for administration of nitrous oxide in a variety of locations. Being able to offer an alternative technique, other than parenteral opioids, for women who may not wish to or who cannot have regional analgesia, and for women who have delivered and need analgesia for postdelivery repair, conveys significant benefits. Risks to its use are very low, although the quality of pain relief is inferior to that offered by regional analgesic techniques. Our experience with its use since 2014 at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, Massachusetts, corroborates that reported in the literature and leads us to continue offering inhaled nitrous oxide and advocating that others do as well.1–7 When using nitrous oxide in your labor and delivery unit, or if considering its use, keep the following points in mind.

A successful inhaled nitrous oxide program requires proper patient selection

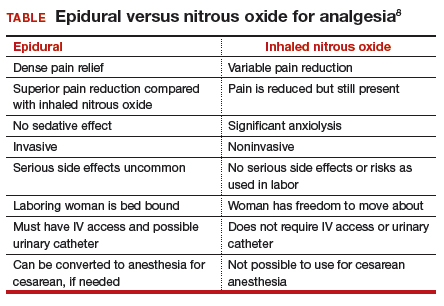

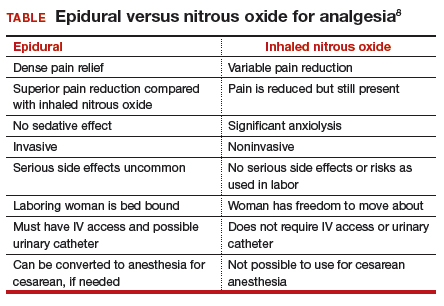

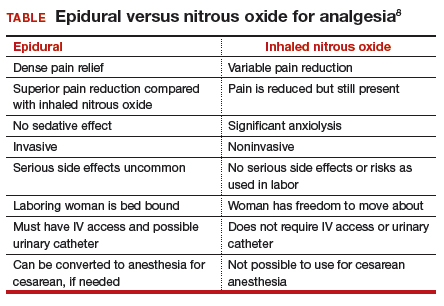

Inhaled nitrous oxide is not an epidural (TABLE).8 The pain relief is clearly inferior to that of an epidural. Inhaled nitrous oxide will not replace epidurals or even have any effect on the epidural rate at a particular institution.6 However, the use of inhaled nitrous oxide for labor analgesia has a long track record of safety (albeit with moderate efficacy for selected patients) for many years in many countries around the world. Inhaled nitrous oxide is a valuable addition to the options we can offer patients:

- who are poor responders to opioid medication or who have high opioid tolerance

- with certain disorders of coagulation

- with chronic pain or anxiety

- who for other reasons need to consider alternatives or adjuncts to neuraxial analgesia.

Although it is important to be realistic regarding the expectations of analgesia quality offered by this agent,7 compared with other agents we have tried, it has less adverse effects, is economically reasonable, and has no proven impact on neonatal outcomes.

No significant complications with inhaled nitrous oxide have been reported

Systematic reviews did not report any significant complications to either mother or newborn.1,2 Our personal experiences corroborate this, as no complications have been associated with its frequent use at Brigham and Women’s Hospital. Reported adverse effects are mild. The incidence of nausea is 13%, dizziness is 3% to 5%, and drowsiness is 4%; these rates are hard to detect over the baseline rates of those side effects associated with labor and delivery alone.1 Many other centers have now adopted the use of this agent, with several hundred locations now offering inhaled nitrous oxide for labor analgesia in the United States.

Practical use of inhaled nitrous oxide is relatively simple

Several vendors offer portable, user-friendly, cost-effective equipment that is appropriate for labor and delivery use. All devices are structured in demand-valve modality, meaning that the patient must initiate a breath in order to open a valve that allows gas to flow. Cessation of the inspiratory effort closes the valve, thus preventing the free flow of gas into the ambient atmosphere of the room. The devices generally include a tank with nitrous oxide as well as a source of oxygen. Most devices designed for labor and delivery provide a fixed mixture of 50% nitrous oxide and 50% oxygen, with fail-safe mechanisms to allow increased oxygen delivery in the event of failure or depletion of the nitrous supply. All modern, FDA–approved devices include effective scavenging systems, such that expired gases are vented outside (generally via room suction), which prevents occupational exposure to low levels of nitrous oxide.

Inhaled nitrous oxide for labor pain must be patient controlled

An essential feature of the use of inhaled nitrous oxide for labor analgesia is that it must be considered a patient-controlled system. Patients have an option to use either a mask or a mouthpiece, according to their preferences and comfort. The patient must hold the mask or mouthpiece herself; it is neither appropriate nor safe for anyone else, such as a nurse, family member, or labor support personnel, to assist with this task.