User login

Vaginal cleansing protocol curbs deep SSIs after cesarean

reported Johanna Quist-Nelson, MD, of the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.

“Surgical site infections after a cesarean delivery are more common if the patient is in labor or has ruptured membranes,” she said at the 2020 virtual meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists..

Two options to decrease the risk of SSIs after cesarean for those patients in labor or with ruptured membranes are vaginal cleansing and azithromycin, given in addition to preoperative antibiotics, Dr. Quist-Nelson said. She and her colleagues conducted a quality improvement study of the effects of a stepwise implementation of vaginal cleansing and azithromycin to reduce SSIs at cesarean delivery in this high-risk population. The data were collected from 2016 to 2019 at Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia.

“We aimed to decrease our SSI rate by 30% by adopting an intervention of cleansing followed by azithromycin,” she said.

The researchers added vaginal cleansing to the SSI prevention protocol in January 2017, with the addition of azithromycin in March 2018. Vaginal cleansing involved 30 seconds of anterior to posterior cleaning prior to urinary catheter placement. Azithromycin was given at a dose of 500 mg intravenously in addition to preoperative antibiotics and within an hour of cesarean delivery.

A total of 1,033 deliveries qualified for the study by being in labor or with ruptured membranes; of these 291 were performed prior to the interventions, 335 received vaginal cleansing only, and 407 received vaginal cleansing and azithromycin. The average age of the participants was 30 years; approximately 42% were Black, and 32% were White.

Cleansing protocol reduces SSIs

Overall, the rate of SSIs was 22% in the standard care group, 17% in the vaginal cleansing group, and 15% in the vaginal cleansing plus azithromycin group. When broken down by infection type, no deep SSI occurred in the vaginal cleansing or cleansing plus azithromycin group, compared with 2% of the standard care group (P = .009). In addition, endometritis, which is an organ-space SSI, was significantly lower in the cleansing group (10%) and the cleansing plus azithromycin group (11%), compared with the standard care group (16%).

The study findings were limited by factors including the use of EMRs for collection of data, and given that it is a quality improvement study, there is a potential lack of generalizability to other institutions. The study focused on patients at high risk for SSI and the use of the Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) method of conducting the research, Dr. Quist-Nelson said. Compared with standard care, the implementation of vaginal cleansing reduced the SSI rate by 33%, with no significantly further change in SSI after the addition of azithromycin, she concluded.

Data sharing boosts compliance

In a question-and-answer session, Dr. Quist-Nelson noted that povidone iodine (Betadine) was chosen for vaginal cleansing because it was easily accessible at her institution, but that patients with allergies were given chlorhexidine. The cleansing itself was “primarily vaginal, not a full vulvar cleansing,” she clarified. The cleansing was performed immediately before catheter placement and included the urethra.

When asked about strategies to increase compliance, Dr. Quist-Nelson noted that sharing data was valuable, namely “reporting to our group the current compliance,” as well as sharing information by email and discussing it during multidisciplinary rounds.

The study was a quality improvement project and not a randomized trial, so the researchers were not able to tease out the impact of vaginal cleansing from the impact of azithromycin, Dr. Quist-Nelson said.

Based on her results, Dr. Quist-Nelson said she would recommend the protocol for use in patients who require cesarean delivery after being in labor or having ruptured membranes, and that “there are trials to support the use of both interventions.”

The results suggest opportunities for further randomized trials, including examination of the use of oral versus IV azithromycin, she added.

The study received no outside funding. Dr. Quist-Nelson had no financial conflicts to disclose.

reported Johanna Quist-Nelson, MD, of the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.

“Surgical site infections after a cesarean delivery are more common if the patient is in labor or has ruptured membranes,” she said at the 2020 virtual meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists..

Two options to decrease the risk of SSIs after cesarean for those patients in labor or with ruptured membranes are vaginal cleansing and azithromycin, given in addition to preoperative antibiotics, Dr. Quist-Nelson said. She and her colleagues conducted a quality improvement study of the effects of a stepwise implementation of vaginal cleansing and azithromycin to reduce SSIs at cesarean delivery in this high-risk population. The data were collected from 2016 to 2019 at Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia.

“We aimed to decrease our SSI rate by 30% by adopting an intervention of cleansing followed by azithromycin,” she said.

The researchers added vaginal cleansing to the SSI prevention protocol in January 2017, with the addition of azithromycin in March 2018. Vaginal cleansing involved 30 seconds of anterior to posterior cleaning prior to urinary catheter placement. Azithromycin was given at a dose of 500 mg intravenously in addition to preoperative antibiotics and within an hour of cesarean delivery.

A total of 1,033 deliveries qualified for the study by being in labor or with ruptured membranes; of these 291 were performed prior to the interventions, 335 received vaginal cleansing only, and 407 received vaginal cleansing and azithromycin. The average age of the participants was 30 years; approximately 42% were Black, and 32% were White.

Cleansing protocol reduces SSIs

Overall, the rate of SSIs was 22% in the standard care group, 17% in the vaginal cleansing group, and 15% in the vaginal cleansing plus azithromycin group. When broken down by infection type, no deep SSI occurred in the vaginal cleansing or cleansing plus azithromycin group, compared with 2% of the standard care group (P = .009). In addition, endometritis, which is an organ-space SSI, was significantly lower in the cleansing group (10%) and the cleansing plus azithromycin group (11%), compared with the standard care group (16%).

The study findings were limited by factors including the use of EMRs for collection of data, and given that it is a quality improvement study, there is a potential lack of generalizability to other institutions. The study focused on patients at high risk for SSI and the use of the Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) method of conducting the research, Dr. Quist-Nelson said. Compared with standard care, the implementation of vaginal cleansing reduced the SSI rate by 33%, with no significantly further change in SSI after the addition of azithromycin, she concluded.

Data sharing boosts compliance

In a question-and-answer session, Dr. Quist-Nelson noted that povidone iodine (Betadine) was chosen for vaginal cleansing because it was easily accessible at her institution, but that patients with allergies were given chlorhexidine. The cleansing itself was “primarily vaginal, not a full vulvar cleansing,” she clarified. The cleansing was performed immediately before catheter placement and included the urethra.

When asked about strategies to increase compliance, Dr. Quist-Nelson noted that sharing data was valuable, namely “reporting to our group the current compliance,” as well as sharing information by email and discussing it during multidisciplinary rounds.

The study was a quality improvement project and not a randomized trial, so the researchers were not able to tease out the impact of vaginal cleansing from the impact of azithromycin, Dr. Quist-Nelson said.

Based on her results, Dr. Quist-Nelson said she would recommend the protocol for use in patients who require cesarean delivery after being in labor or having ruptured membranes, and that “there are trials to support the use of both interventions.”

The results suggest opportunities for further randomized trials, including examination of the use of oral versus IV azithromycin, she added.

The study received no outside funding. Dr. Quist-Nelson had no financial conflicts to disclose.

reported Johanna Quist-Nelson, MD, of the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.

“Surgical site infections after a cesarean delivery are more common if the patient is in labor or has ruptured membranes,” she said at the 2020 virtual meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists..

Two options to decrease the risk of SSIs after cesarean for those patients in labor or with ruptured membranes are vaginal cleansing and azithromycin, given in addition to preoperative antibiotics, Dr. Quist-Nelson said. She and her colleagues conducted a quality improvement study of the effects of a stepwise implementation of vaginal cleansing and azithromycin to reduce SSIs at cesarean delivery in this high-risk population. The data were collected from 2016 to 2019 at Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia.

“We aimed to decrease our SSI rate by 30% by adopting an intervention of cleansing followed by azithromycin,” she said.

The researchers added vaginal cleansing to the SSI prevention protocol in January 2017, with the addition of azithromycin in March 2018. Vaginal cleansing involved 30 seconds of anterior to posterior cleaning prior to urinary catheter placement. Azithromycin was given at a dose of 500 mg intravenously in addition to preoperative antibiotics and within an hour of cesarean delivery.

A total of 1,033 deliveries qualified for the study by being in labor or with ruptured membranes; of these 291 were performed prior to the interventions, 335 received vaginal cleansing only, and 407 received vaginal cleansing and azithromycin. The average age of the participants was 30 years; approximately 42% were Black, and 32% were White.

Cleansing protocol reduces SSIs

Overall, the rate of SSIs was 22% in the standard care group, 17% in the vaginal cleansing group, and 15% in the vaginal cleansing plus azithromycin group. When broken down by infection type, no deep SSI occurred in the vaginal cleansing or cleansing plus azithromycin group, compared with 2% of the standard care group (P = .009). In addition, endometritis, which is an organ-space SSI, was significantly lower in the cleansing group (10%) and the cleansing plus azithromycin group (11%), compared with the standard care group (16%).

The study findings were limited by factors including the use of EMRs for collection of data, and given that it is a quality improvement study, there is a potential lack of generalizability to other institutions. The study focused on patients at high risk for SSI and the use of the Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) method of conducting the research, Dr. Quist-Nelson said. Compared with standard care, the implementation of vaginal cleansing reduced the SSI rate by 33%, with no significantly further change in SSI after the addition of azithromycin, she concluded.

Data sharing boosts compliance

In a question-and-answer session, Dr. Quist-Nelson noted that povidone iodine (Betadine) was chosen for vaginal cleansing because it was easily accessible at her institution, but that patients with allergies were given chlorhexidine. The cleansing itself was “primarily vaginal, not a full vulvar cleansing,” she clarified. The cleansing was performed immediately before catheter placement and included the urethra.

When asked about strategies to increase compliance, Dr. Quist-Nelson noted that sharing data was valuable, namely “reporting to our group the current compliance,” as well as sharing information by email and discussing it during multidisciplinary rounds.

The study was a quality improvement project and not a randomized trial, so the researchers were not able to tease out the impact of vaginal cleansing from the impact of azithromycin, Dr. Quist-Nelson said.

Based on her results, Dr. Quist-Nelson said she would recommend the protocol for use in patients who require cesarean delivery after being in labor or having ruptured membranes, and that “there are trials to support the use of both interventions.”

The results suggest opportunities for further randomized trials, including examination of the use of oral versus IV azithromycin, she added.

The study received no outside funding. Dr. Quist-Nelson had no financial conflicts to disclose.

FROM ACOG 2020

Treating insomnia, anxiety in a pandemic

Since the start of the pandemic, we have been conducting an extra hour of Virtual Rounds at the Center for Women’s Mental Health. Virtual Rounds has been an opportunity to discuss cases around a spectrum of clinical management issues with respect to depression, bipolar disorder, and a spectrum of anxiety disorders like obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and generalized anxiety disorder. How to apply the calculus of risk-benefit decision-making around management of psychiatric disorder during pregnancy and the postpartum period has been the cornerstone of the work at our center for over 2 decades.

When we went virtual at our center in the early Spring, we decided to keep the format of our faculty rounds the way they have been for years and to sustain cohesiveness of our program during the pandemic. But we thought the needs of pregnant and postpartum women warranted being addressed in a context more specific to COVID-19, and also that reproductive psychiatrists and other clinicians could learn from each other about novel issues coming up for this group of patients during the pandemic. With that backdrop, Marlene Freeman, MD, and I founded “Virtual Rounds at the Center” to respond to queries from our colleagues across the country; we do this just after our own rounds on Wednesdays at 2:00 p.m.

As the pandemic has progressed, Virtual Rounds has blossomed into a virtual community on the Zoom platform, where social workers, psychologists, nurse prescribers, psychiatrists, and obstetricians discuss the needs of pregnant and postpartum women specific to COVID-19. Frequently, our discussions involve a review of the risks and benefits of treatment before, during, and after pregnancy.

Seemingly, week to week, more and more colleagues raise questions about the treatment of anxiety and insomnia during pregnancy and the postpartum period. I’ve spoken in previous columns about the enhanced use of telemedicine. Telemedicine not only facilitates efforts like Virtual Rounds and our ability to reach out to colleagues across the country and share cases, but also has allowed us to keep even closer tabs on the emotional well-being of our pregnant and postpartum women during COVID-19.

The question is not just about the effects of a medicine that a woman might take to treat anxiety or insomnia during pregnancy, but the experience of the pandemic per se, which we are measuring in multiple studies now using a variety of psychological instruments that patients complete. The pandemic is unequivocally taking a still unquantified toll on the mental health of Americans and potentially on the next generation to come.

Midcycle awakening during pregnancy

Complaints of insomnia and midcycle awakening during pregnancy are not new – it is the rule, rather than the exception for many pregnant women, particularly later in pregnancy. We have unequivocally seen a worsening of complaints of sleep disruption including insomnia and midcycle awakening during the pandemic that is greater than what we have seen previously. Both patients and colleagues have asked us the safest ways to manage it. One of the first things we consider when we hear about insomnia is whether it is part of an underlying mood disorder. While we see primary insomnia clinically, it really is important to remember that insomnia can be part and parcel of an underlying mood disorder.

With that in mind, what are the options? During the pandemic, we’ve seen an increased use of digital cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) for patients who cannot initiate sleep, which has a very strong evidence base for effectiveness as a first-line intervention for many.

If a patient has an incomplete response to CBT-I, what might be pursued next? In our center, we have a low threshold for using low doses of benzodiazepines, such as lorazepam or clonazepam, because the majority of data do not support an increased risk of major congenital malformations even when used in the first trimester. It is quite common to see medicines such as newer nonbenzodiazepine sedative hypnotics such as Ambien CR (zolpidem) or Lunesta (eszopiclone) used by our colleagues in ob.gyn. The reproductive safety data on those medicines are particularly sparse, and they may have greater risk of cognitive side effects the next day, so we tend to avoid them.

Another sometimes-forgotten option to consider is using low doses of tricyclic antidepressants (i.e., 10-25 mg of nortriptyline at bedtime), with tricyclics having a 40-year history and at least one pooled analysis showing the absence of increased risk for major congenital malformations when used. This may be a very easy way of managing insomnia, with low-dose tricyclics having an anxiolytic effect as well.

Anxiety during pregnancy

The most common rise in symptoms during COVID-19 for women who are pregnant or post partum has been an increase in anxiety. Women present with a spectrum of concerns leading to anxiety symptoms in the context of the pandemic. Earlier on in the pandemic, concerns focused mostly on how to stay healthy, and how to mitigate risk and not catch SARS-CoV-2 during pregnancy, as well as the very complex issues that were playing out in real time as hospital systems were figuring out how to manage pregnant women in labor and to keep both them and staff safe. Over time, anxiety has shifted to still staying safe during the pandemic and the potential impact of SARS-CoV-2 infection on pregnancy outcomes. The No. 1 concern is what the implications of COVID-19 disease are on mother and child. New mothers also are anxious about how they will practically navigate life with a newborn in the postpartum setting.

Early on in the pandemic, some hospital systems severely limited who was in the room with a woman during labor, potentially impeding the wishes of women during delivery who would have wanted their loved ones and/or a doula present, as an example. With enhanced testing available now, protocols have since relaxed in many hospitals to allow partners – but not a team – to remain in the hospital during the labor process. Still, the prospect of delivering during a pandemic is undoubtedly a source of anxiety for some women.

This sort of anxiety, particularly in patients with preexisting anxiety disorders, can be particularly challenging. Fortunately, there has been a rapid increase over the last several years of digital apps to mitigate anxiety. While many of them have not been systematically studied, the data on biobehavioral intervention for anxiety is enormous, and this should be used as first-line treatment for patients with mild to moderate symptoms; so many women would prefer to avoid pharmacological intervention during pregnancy, if possible, to avoid fetal drug exposure. For patients who meet criteria for frank anxiety disorder, other nonpharmacologic interventions such as CBT have been shown to be effective.

Frequently, we see women who are experiencing levels of anxiety where nonpharmacological interventions have an incomplete response, and colleagues have asked about the safest way to treat these patients. As has been discussed in multiple previous columns, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) should be thought of sooner rather than later, particularly with medicines with good reproductive safety data such as sertraline, citalopram, or fluoxetine.

We also reported over 15 years ago that at least 30%-40% of women presenting with histories of recurrent major depression at the beginning of pregnancy had comorbid anxiety disorders, and that the use of benzodiazepines in that population in addition to SSRIs was exceedingly common, with doses of approximately 0.5-1.5 mg of clonazepam or lorazepam being standard fare. Again, this is very appropriate treatment to mitigate anxiety symptoms because now have enough data as a field that support the existence of adverse outcomes associated with untreated anxiety during pregnancy in terms of both adverse obstetric and neonatal outcomes, higher rates of preterm birth, and other obstetric complications. Hence, managing anxiety during pregnancy should be considered like managing a toxic exposure – the same way that one would be concerned about anything else that a pregnant woman could be exposed to.

Lastly, although no atypical antipsychotic has been approved for the treatment of anxiety, its use off label is extremely common. More and more data support the absence of a signal of teratogenicity across the family of molecules including atypical antipsychotics. Beyond potential use of atypical antipsychotics, at Virtual Rounds last week, a colleague asked about the use of gabapentin in a patient who was diagnosed with substance use disorder and who had inadvertently conceived on gabapentin, which was being used to treat both anxiety and insomnia. We have typically avoided the use of gabapentin during pregnancy because prospective data have been limited to relatively small case series and one report, with a total of exposures in roughly the 300 range.

However, our colleagues at the Harvard School of Public Health have recently published an article that looked at the United States Medicaid Analytic eXtract (MAX) dataset, which has been used to publish other articles addressing atypical antipsychotics, SSRIs, lithium, and pharmacovigilance investigations among other important topics. In this study, the database was used to look specifically at 4,642 pregnancies with gabapentin exposure relative to 1,744,447 unexposed pregnancies, without a significant finding for increased risk for major congenital malformations.

The question of an increased risk of cardiac malformations and of increased risk for obstetric complications are difficult to untangle from anxiety and depression, as they also are associated with those same outcomes. With that said, the analysis is a welcome addition to our knowledge base for a medicine used more widely to treat symptoms such as anxiety and insomnia in the general population, with a question mark around where it may fit into the algorithm during pregnancy.

In our center, gabapentin still would not be used as a first-line treatment for the management of anxiety or insomnia during pregnancy. But these new data still are reassuring for patients who come in, frequently with unplanned pregnancies. It is an important reminder to those of us taking care of patients during the pandemic to review use of contraception, because although data are unavailable specific to the period of the pandemic, what is clear is that, even prior to COVID-19, 50% of pregnancies in America were unplanned. Addressing issues of reliable use of contraception, particularly during the pandemic, is that much more important.

In this particular case, our clinician colleague in Virtual Rounds decided to continue gabapentin across pregnancy in the context of these reassuring data, but others may choose to discontinue or pursue some of the other treatment options noted above.

Dr. Cohen is the director of the Ammon-Pinizzotto Center for Women’s Mental Health at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) in Boston, which provides information resources and conducts clinical care and research in reproductive mental health. He has been a consultant to manufacturers of psychiatric medications. Email Dr. Cohen at [email protected].

Since the start of the pandemic, we have been conducting an extra hour of Virtual Rounds at the Center for Women’s Mental Health. Virtual Rounds has been an opportunity to discuss cases around a spectrum of clinical management issues with respect to depression, bipolar disorder, and a spectrum of anxiety disorders like obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and generalized anxiety disorder. How to apply the calculus of risk-benefit decision-making around management of psychiatric disorder during pregnancy and the postpartum period has been the cornerstone of the work at our center for over 2 decades.

When we went virtual at our center in the early Spring, we decided to keep the format of our faculty rounds the way they have been for years and to sustain cohesiveness of our program during the pandemic. But we thought the needs of pregnant and postpartum women warranted being addressed in a context more specific to COVID-19, and also that reproductive psychiatrists and other clinicians could learn from each other about novel issues coming up for this group of patients during the pandemic. With that backdrop, Marlene Freeman, MD, and I founded “Virtual Rounds at the Center” to respond to queries from our colleagues across the country; we do this just after our own rounds on Wednesdays at 2:00 p.m.

As the pandemic has progressed, Virtual Rounds has blossomed into a virtual community on the Zoom platform, where social workers, psychologists, nurse prescribers, psychiatrists, and obstetricians discuss the needs of pregnant and postpartum women specific to COVID-19. Frequently, our discussions involve a review of the risks and benefits of treatment before, during, and after pregnancy.

Seemingly, week to week, more and more colleagues raise questions about the treatment of anxiety and insomnia during pregnancy and the postpartum period. I’ve spoken in previous columns about the enhanced use of telemedicine. Telemedicine not only facilitates efforts like Virtual Rounds and our ability to reach out to colleagues across the country and share cases, but also has allowed us to keep even closer tabs on the emotional well-being of our pregnant and postpartum women during COVID-19.

The question is not just about the effects of a medicine that a woman might take to treat anxiety or insomnia during pregnancy, but the experience of the pandemic per se, which we are measuring in multiple studies now using a variety of psychological instruments that patients complete. The pandemic is unequivocally taking a still unquantified toll on the mental health of Americans and potentially on the next generation to come.

Midcycle awakening during pregnancy

Complaints of insomnia and midcycle awakening during pregnancy are not new – it is the rule, rather than the exception for many pregnant women, particularly later in pregnancy. We have unequivocally seen a worsening of complaints of sleep disruption including insomnia and midcycle awakening during the pandemic that is greater than what we have seen previously. Both patients and colleagues have asked us the safest ways to manage it. One of the first things we consider when we hear about insomnia is whether it is part of an underlying mood disorder. While we see primary insomnia clinically, it really is important to remember that insomnia can be part and parcel of an underlying mood disorder.

With that in mind, what are the options? During the pandemic, we’ve seen an increased use of digital cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) for patients who cannot initiate sleep, which has a very strong evidence base for effectiveness as a first-line intervention for many.

If a patient has an incomplete response to CBT-I, what might be pursued next? In our center, we have a low threshold for using low doses of benzodiazepines, such as lorazepam or clonazepam, because the majority of data do not support an increased risk of major congenital malformations even when used in the first trimester. It is quite common to see medicines such as newer nonbenzodiazepine sedative hypnotics such as Ambien CR (zolpidem) or Lunesta (eszopiclone) used by our colleagues in ob.gyn. The reproductive safety data on those medicines are particularly sparse, and they may have greater risk of cognitive side effects the next day, so we tend to avoid them.

Another sometimes-forgotten option to consider is using low doses of tricyclic antidepressants (i.e., 10-25 mg of nortriptyline at bedtime), with tricyclics having a 40-year history and at least one pooled analysis showing the absence of increased risk for major congenital malformations when used. This may be a very easy way of managing insomnia, with low-dose tricyclics having an anxiolytic effect as well.

Anxiety during pregnancy

The most common rise in symptoms during COVID-19 for women who are pregnant or post partum has been an increase in anxiety. Women present with a spectrum of concerns leading to anxiety symptoms in the context of the pandemic. Earlier on in the pandemic, concerns focused mostly on how to stay healthy, and how to mitigate risk and not catch SARS-CoV-2 during pregnancy, as well as the very complex issues that were playing out in real time as hospital systems were figuring out how to manage pregnant women in labor and to keep both them and staff safe. Over time, anxiety has shifted to still staying safe during the pandemic and the potential impact of SARS-CoV-2 infection on pregnancy outcomes. The No. 1 concern is what the implications of COVID-19 disease are on mother and child. New mothers also are anxious about how they will practically navigate life with a newborn in the postpartum setting.

Early on in the pandemic, some hospital systems severely limited who was in the room with a woman during labor, potentially impeding the wishes of women during delivery who would have wanted their loved ones and/or a doula present, as an example. With enhanced testing available now, protocols have since relaxed in many hospitals to allow partners – but not a team – to remain in the hospital during the labor process. Still, the prospect of delivering during a pandemic is undoubtedly a source of anxiety for some women.

This sort of anxiety, particularly in patients with preexisting anxiety disorders, can be particularly challenging. Fortunately, there has been a rapid increase over the last several years of digital apps to mitigate anxiety. While many of them have not been systematically studied, the data on biobehavioral intervention for anxiety is enormous, and this should be used as first-line treatment for patients with mild to moderate symptoms; so many women would prefer to avoid pharmacological intervention during pregnancy, if possible, to avoid fetal drug exposure. For patients who meet criteria for frank anxiety disorder, other nonpharmacologic interventions such as CBT have been shown to be effective.

Frequently, we see women who are experiencing levels of anxiety where nonpharmacological interventions have an incomplete response, and colleagues have asked about the safest way to treat these patients. As has been discussed in multiple previous columns, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) should be thought of sooner rather than later, particularly with medicines with good reproductive safety data such as sertraline, citalopram, or fluoxetine.

We also reported over 15 years ago that at least 30%-40% of women presenting with histories of recurrent major depression at the beginning of pregnancy had comorbid anxiety disorders, and that the use of benzodiazepines in that population in addition to SSRIs was exceedingly common, with doses of approximately 0.5-1.5 mg of clonazepam or lorazepam being standard fare. Again, this is very appropriate treatment to mitigate anxiety symptoms because now have enough data as a field that support the existence of adverse outcomes associated with untreated anxiety during pregnancy in terms of both adverse obstetric and neonatal outcomes, higher rates of preterm birth, and other obstetric complications. Hence, managing anxiety during pregnancy should be considered like managing a toxic exposure – the same way that one would be concerned about anything else that a pregnant woman could be exposed to.

Lastly, although no atypical antipsychotic has been approved for the treatment of anxiety, its use off label is extremely common. More and more data support the absence of a signal of teratogenicity across the family of molecules including atypical antipsychotics. Beyond potential use of atypical antipsychotics, at Virtual Rounds last week, a colleague asked about the use of gabapentin in a patient who was diagnosed with substance use disorder and who had inadvertently conceived on gabapentin, which was being used to treat both anxiety and insomnia. We have typically avoided the use of gabapentin during pregnancy because prospective data have been limited to relatively small case series and one report, with a total of exposures in roughly the 300 range.

However, our colleagues at the Harvard School of Public Health have recently published an article that looked at the United States Medicaid Analytic eXtract (MAX) dataset, which has been used to publish other articles addressing atypical antipsychotics, SSRIs, lithium, and pharmacovigilance investigations among other important topics. In this study, the database was used to look specifically at 4,642 pregnancies with gabapentin exposure relative to 1,744,447 unexposed pregnancies, without a significant finding for increased risk for major congenital malformations.

The question of an increased risk of cardiac malformations and of increased risk for obstetric complications are difficult to untangle from anxiety and depression, as they also are associated with those same outcomes. With that said, the analysis is a welcome addition to our knowledge base for a medicine used more widely to treat symptoms such as anxiety and insomnia in the general population, with a question mark around where it may fit into the algorithm during pregnancy.

In our center, gabapentin still would not be used as a first-line treatment for the management of anxiety or insomnia during pregnancy. But these new data still are reassuring for patients who come in, frequently with unplanned pregnancies. It is an important reminder to those of us taking care of patients during the pandemic to review use of contraception, because although data are unavailable specific to the period of the pandemic, what is clear is that, even prior to COVID-19, 50% of pregnancies in America were unplanned. Addressing issues of reliable use of contraception, particularly during the pandemic, is that much more important.

In this particular case, our clinician colleague in Virtual Rounds decided to continue gabapentin across pregnancy in the context of these reassuring data, but others may choose to discontinue or pursue some of the other treatment options noted above.

Dr. Cohen is the director of the Ammon-Pinizzotto Center for Women’s Mental Health at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) in Boston, which provides information resources and conducts clinical care and research in reproductive mental health. He has been a consultant to manufacturers of psychiatric medications. Email Dr. Cohen at [email protected].

Since the start of the pandemic, we have been conducting an extra hour of Virtual Rounds at the Center for Women’s Mental Health. Virtual Rounds has been an opportunity to discuss cases around a spectrum of clinical management issues with respect to depression, bipolar disorder, and a spectrum of anxiety disorders like obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and generalized anxiety disorder. How to apply the calculus of risk-benefit decision-making around management of psychiatric disorder during pregnancy and the postpartum period has been the cornerstone of the work at our center for over 2 decades.

When we went virtual at our center in the early Spring, we decided to keep the format of our faculty rounds the way they have been for years and to sustain cohesiveness of our program during the pandemic. But we thought the needs of pregnant and postpartum women warranted being addressed in a context more specific to COVID-19, and also that reproductive psychiatrists and other clinicians could learn from each other about novel issues coming up for this group of patients during the pandemic. With that backdrop, Marlene Freeman, MD, and I founded “Virtual Rounds at the Center” to respond to queries from our colleagues across the country; we do this just after our own rounds on Wednesdays at 2:00 p.m.

As the pandemic has progressed, Virtual Rounds has blossomed into a virtual community on the Zoom platform, where social workers, psychologists, nurse prescribers, psychiatrists, and obstetricians discuss the needs of pregnant and postpartum women specific to COVID-19. Frequently, our discussions involve a review of the risks and benefits of treatment before, during, and after pregnancy.

Seemingly, week to week, more and more colleagues raise questions about the treatment of anxiety and insomnia during pregnancy and the postpartum period. I’ve spoken in previous columns about the enhanced use of telemedicine. Telemedicine not only facilitates efforts like Virtual Rounds and our ability to reach out to colleagues across the country and share cases, but also has allowed us to keep even closer tabs on the emotional well-being of our pregnant and postpartum women during COVID-19.

The question is not just about the effects of a medicine that a woman might take to treat anxiety or insomnia during pregnancy, but the experience of the pandemic per se, which we are measuring in multiple studies now using a variety of psychological instruments that patients complete. The pandemic is unequivocally taking a still unquantified toll on the mental health of Americans and potentially on the next generation to come.

Midcycle awakening during pregnancy

Complaints of insomnia and midcycle awakening during pregnancy are not new – it is the rule, rather than the exception for many pregnant women, particularly later in pregnancy. We have unequivocally seen a worsening of complaints of sleep disruption including insomnia and midcycle awakening during the pandemic that is greater than what we have seen previously. Both patients and colleagues have asked us the safest ways to manage it. One of the first things we consider when we hear about insomnia is whether it is part of an underlying mood disorder. While we see primary insomnia clinically, it really is important to remember that insomnia can be part and parcel of an underlying mood disorder.

With that in mind, what are the options? During the pandemic, we’ve seen an increased use of digital cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) for patients who cannot initiate sleep, which has a very strong evidence base for effectiveness as a first-line intervention for many.

If a patient has an incomplete response to CBT-I, what might be pursued next? In our center, we have a low threshold for using low doses of benzodiazepines, such as lorazepam or clonazepam, because the majority of data do not support an increased risk of major congenital malformations even when used in the first trimester. It is quite common to see medicines such as newer nonbenzodiazepine sedative hypnotics such as Ambien CR (zolpidem) or Lunesta (eszopiclone) used by our colleagues in ob.gyn. The reproductive safety data on those medicines are particularly sparse, and they may have greater risk of cognitive side effects the next day, so we tend to avoid them.

Another sometimes-forgotten option to consider is using low doses of tricyclic antidepressants (i.e., 10-25 mg of nortriptyline at bedtime), with tricyclics having a 40-year history and at least one pooled analysis showing the absence of increased risk for major congenital malformations when used. This may be a very easy way of managing insomnia, with low-dose tricyclics having an anxiolytic effect as well.

Anxiety during pregnancy

The most common rise in symptoms during COVID-19 for women who are pregnant or post partum has been an increase in anxiety. Women present with a spectrum of concerns leading to anxiety symptoms in the context of the pandemic. Earlier on in the pandemic, concerns focused mostly on how to stay healthy, and how to mitigate risk and not catch SARS-CoV-2 during pregnancy, as well as the very complex issues that were playing out in real time as hospital systems were figuring out how to manage pregnant women in labor and to keep both them and staff safe. Over time, anxiety has shifted to still staying safe during the pandemic and the potential impact of SARS-CoV-2 infection on pregnancy outcomes. The No. 1 concern is what the implications of COVID-19 disease are on mother and child. New mothers also are anxious about how they will practically navigate life with a newborn in the postpartum setting.

Early on in the pandemic, some hospital systems severely limited who was in the room with a woman during labor, potentially impeding the wishes of women during delivery who would have wanted their loved ones and/or a doula present, as an example. With enhanced testing available now, protocols have since relaxed in many hospitals to allow partners – but not a team – to remain in the hospital during the labor process. Still, the prospect of delivering during a pandemic is undoubtedly a source of anxiety for some women.

This sort of anxiety, particularly in patients with preexisting anxiety disorders, can be particularly challenging. Fortunately, there has been a rapid increase over the last several years of digital apps to mitigate anxiety. While many of them have not been systematically studied, the data on biobehavioral intervention for anxiety is enormous, and this should be used as first-line treatment for patients with mild to moderate symptoms; so many women would prefer to avoid pharmacological intervention during pregnancy, if possible, to avoid fetal drug exposure. For patients who meet criteria for frank anxiety disorder, other nonpharmacologic interventions such as CBT have been shown to be effective.

Frequently, we see women who are experiencing levels of anxiety where nonpharmacological interventions have an incomplete response, and colleagues have asked about the safest way to treat these patients. As has been discussed in multiple previous columns, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) should be thought of sooner rather than later, particularly with medicines with good reproductive safety data such as sertraline, citalopram, or fluoxetine.

We also reported over 15 years ago that at least 30%-40% of women presenting with histories of recurrent major depression at the beginning of pregnancy had comorbid anxiety disorders, and that the use of benzodiazepines in that population in addition to SSRIs was exceedingly common, with doses of approximately 0.5-1.5 mg of clonazepam or lorazepam being standard fare. Again, this is very appropriate treatment to mitigate anxiety symptoms because now have enough data as a field that support the existence of adverse outcomes associated with untreated anxiety during pregnancy in terms of both adverse obstetric and neonatal outcomes, higher rates of preterm birth, and other obstetric complications. Hence, managing anxiety during pregnancy should be considered like managing a toxic exposure – the same way that one would be concerned about anything else that a pregnant woman could be exposed to.

Lastly, although no atypical antipsychotic has been approved for the treatment of anxiety, its use off label is extremely common. More and more data support the absence of a signal of teratogenicity across the family of molecules including atypical antipsychotics. Beyond potential use of atypical antipsychotics, at Virtual Rounds last week, a colleague asked about the use of gabapentin in a patient who was diagnosed with substance use disorder and who had inadvertently conceived on gabapentin, which was being used to treat both anxiety and insomnia. We have typically avoided the use of gabapentin during pregnancy because prospective data have been limited to relatively small case series and one report, with a total of exposures in roughly the 300 range.

However, our colleagues at the Harvard School of Public Health have recently published an article that looked at the United States Medicaid Analytic eXtract (MAX) dataset, which has been used to publish other articles addressing atypical antipsychotics, SSRIs, lithium, and pharmacovigilance investigations among other important topics. In this study, the database was used to look specifically at 4,642 pregnancies with gabapentin exposure relative to 1,744,447 unexposed pregnancies, without a significant finding for increased risk for major congenital malformations.

The question of an increased risk of cardiac malformations and of increased risk for obstetric complications are difficult to untangle from anxiety and depression, as they also are associated with those same outcomes. With that said, the analysis is a welcome addition to our knowledge base for a medicine used more widely to treat symptoms such as anxiety and insomnia in the general population, with a question mark around where it may fit into the algorithm during pregnancy.

In our center, gabapentin still would not be used as a first-line treatment for the management of anxiety or insomnia during pregnancy. But these new data still are reassuring for patients who come in, frequently with unplanned pregnancies. It is an important reminder to those of us taking care of patients during the pandemic to review use of contraception, because although data are unavailable specific to the period of the pandemic, what is clear is that, even prior to COVID-19, 50% of pregnancies in America were unplanned. Addressing issues of reliable use of contraception, particularly during the pandemic, is that much more important.

In this particular case, our clinician colleague in Virtual Rounds decided to continue gabapentin across pregnancy in the context of these reassuring data, but others may choose to discontinue or pursue some of the other treatment options noted above.

Dr. Cohen is the director of the Ammon-Pinizzotto Center for Women’s Mental Health at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) in Boston, which provides information resources and conducts clinical care and research in reproductive mental health. He has been a consultant to manufacturers of psychiatric medications. Email Dr. Cohen at [email protected].

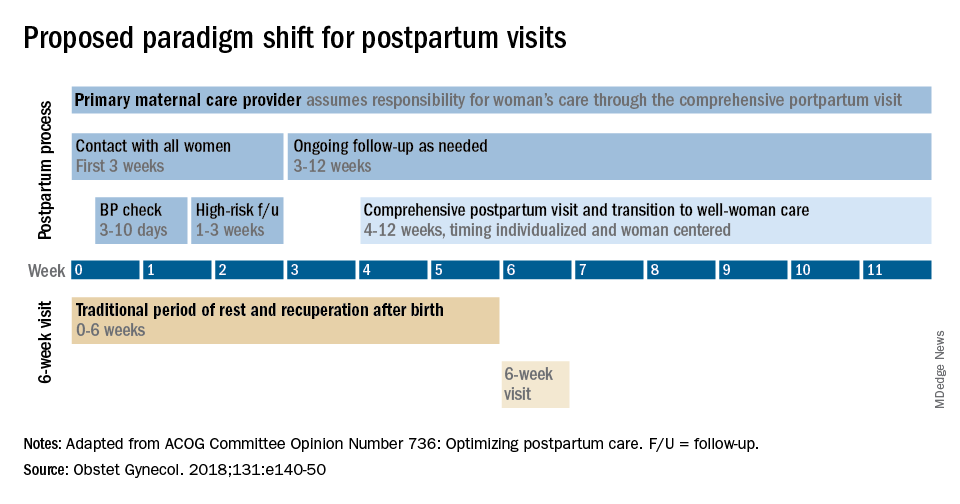

The fourth trimester: Achieving improved postpartum care

The field of ob.gyn. has long focused significantly more attention on the prenatal period – on determining the optimal frequency of ultrasound examinations, for instance, and on screening for diabetes and other conditions – than on women’s health and well-being after delivery.

The traditional 6-week postpartum visit has too often been a quick and cursory visit, with new mothers typically navigating the preceding postpartum transitions on their own.

The need to redefine postpartum care was a central message of Haywood Brown, MD, who in 2017 served as the president of the America College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Dr. Brown established a task force whose work resulted in important guidance for taking a more comprehensive and patient-centered approach to postpartum care.1

Improved care in the “fourth trimester,” as it has come to be known, is comprehensive and includes ensuring that our patients have a solid transition to health care beyond the pregnancy. We also hope that it will help us to reduce maternal mortality, given that more than half of pregnancy-related deaths occur after delivery.

Timing and frequency of contact

Historically, we’ve had a single 6-week postpartum visit, with little or no maternal support or patient contact before this visit unless the patient reported a complication. In the new paradigm, as described in the ACOG committee opinion on optimizing postpartum care, maternal care should be an ongoing process.1

so that any questions or concerns may be addressed and support can be provided.

This should be followed by individualized, ongoing care until a comprehensive postpartum visit covering physical, social, and psychological well-being is conducted by 12 weeks after birth – anytime between 4 and 12 weeks.

By stressing the importance of postpartum care during prenatal visits – and by talking about some of its key elements such as mental health, breastfeeding, and chronic disease management – we can let our patients know that postpartum care is not just an afterthought, but that it involves planning backed by evidence and expert opinion. Currently, as many as 40% of women do not attend a postpartum visit; early discussion, it is hoped, will increase attendance.

Certain high-risk groups should be seen or screened earlier than 3 weeks post partum. For instance, women who have hypertensive disorders of pregnancy should be evaluated no later than 7-10 days post partum, and women with severe hypertension should be seen within 72 hours, according to ACOG.

Early blood pressure checks – and follow-up as necessary – are critical for reducing the risk of postpartum stroke and other complications. I advocate uniformly checking blood pressure within several days after hospital discharge for all women who have hypertension at the end of their pregnancy.

Other high-risk conditions requiring early follow-up include diabetes and autoimmune conditions such as lupus, multiple sclerosis, and psoriasis that may flare in the postpartum period. Women with a history of postpartum depression similarly may benefit from early contact; they are at higher risk of having depression again, and there are clearly effective treatments, both medication and psychotherapy based.

In between the initial early contact (by 7-10 days post partum or by 3 weeks post partum) and the comprehensive visit between 4 and 12 weeks, the need for and timing of patient contact can be individualized. Some women will need only a brief contact and a visit at 8-10 weeks, while others will need much more. Our goal, as in all of medicine, is to provide individualized, patient-centered care.

Methods of contact

With the exception of the final comprehensive visit, postpartum care need not occur in person. Some conditions require an early office visit, but in general, as ACOG states, the usefulness of an in-person visit should be weighed against the burden of traveling to and attending that visit.

For many women, in-person visits are difficult, and we must be creative in utilizing telemedicine and phone support, text messaging, and app-based support. Having practiced during this pandemic, we are better positioned than ever before to make it relatively easy for new mothers to obtain ongoing postpartum care.

Notably, research is demonstrating that the use of technology may allow us to provide improved care and monitoring of hypertension in the postpartum period. For example, a randomized trial published in 2018 of over 200 women with a hypertensive disorder of pregnancy found that text-based surveillance with home blood pressure monitoring was more effective than usual in-person blood pressure checks in meeting clinical guidelines for postpartum monitoring.2

Women in the texting group were significantly more likely to have a single blood pressure obtained in the first 10 days post partum than women in the office group.

Postpartum care is also not a completely physician-driven endeavor. Much of what is needed to help women successfully navigate the fourth trimester can be provided by certified nurse midwives, advanced practice nurses, and other members of our maternal care teams.

Components of postpartum care

The postpartum care plan should be comprehensive, and having a checklist to guide one through initial and comprehensive visits may be helpful. The ACOG committee opinion categorizes the components of postpartum care into seven domains: mood and emotional well-being; infant care and feeding; sexuality, contraception, and birth spacing; sleep and fatigue; physical recovery from birth; chronic disease management; and health maintenance.1

The importance of screening for depression and anxiety cannot be emphasized enough. Perinatal depression is highly prevalent: It affects as many as one in seven women and can result in adverse short- and long-term effects on both the mother and child.

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force has offered guidance for years, most recently in 2019 with its recommendations that clinicians refer pregnant and postpartum women who are at increased risk for depression to counseling interventions such as cognitive behavioral therapy and interpersonal therapy.3 There is evidence that some form of treatment for women who screen positive reduces the risk of perinatal depression.

Additionally, there is emerging evidence that postpartum PTSD may be as prevalent as postpartum depression.4 As ACOG points out, trauma is “in the eye of the beholder,” and an estimated 3%-16% of women have PTSD related to a traumatic birth experience. Complications like shoulder dystocia or postpartum hemorrhage, in which delivery processes rapidly change course, can be experienced as traumatic by women even though they and their infants are healthy. The risk of posttraumatic stress should be on our radar screen.

Interpregnancy intervals similarly are not discussed enough. We do not commonly talk to patients about how pregnancy and breastfeeding are nutritionally depleting and how it takes time to replenish these stores – yet birth spacing is so important.

Compared with interpregnancy intervals of at least 18 months, intervals shorter than 6 months were associated in a meta-analysis with increased risks of preterm birth, low birth weight, and small for gestational age.5 Optimal birth spacing is one of the few low-cost interventions available for reducing pregnancy complications in the future.

Finally, that chronic disease management is a domain of postpartum care warrants emphasis. We must work to ensure that patients have a solid plan of care in place for their diabetes, hypertension, lupus, or other chronic conditions. This includes who will provide that ongoing care, as well as when medical management should be restarted.

Some women are aware of the importance of timely care – of not waiting for 12 months, for instance, to see an internist or specialist – but others are not.

Again, certain health conditions such as multiple sclerosis and RA necessitate follow-up within a couple weeks after delivery so that medications can be restarted or dose adjustments made. The need for early postpartum follow-up can be discussed during prenatal visits, along with anticipatory guidance about breastfeeding, the signs and symptoms of perinatal depression and anxiety, and other components of the fourth trimester.

Dr. Macones has no relevant financial disclosures.

References

1. Obstet Gynecol. 2018 May;131(5):e140-50.

2. BMJ Qual Saf. 2018 Apr 27;27(11):871-7.

3. JAMA. 2019 Feb 12;321(6):580-7.

4. Clin Psychol Rev. 2014 Jul;34:389-401.JAMA. 2006 Apr 19;295(15):1809-23.

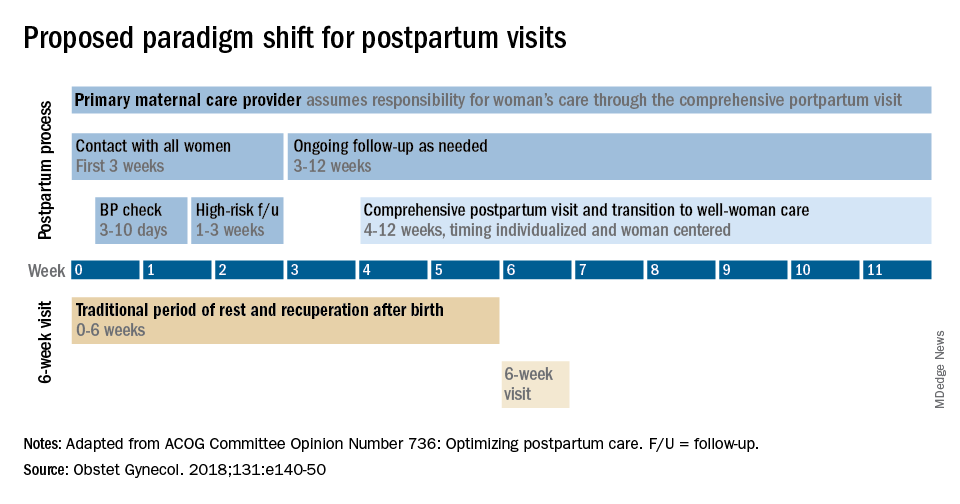

The field of ob.gyn. has long focused significantly more attention on the prenatal period – on determining the optimal frequency of ultrasound examinations, for instance, and on screening for diabetes and other conditions – than on women’s health and well-being after delivery.

The traditional 6-week postpartum visit has too often been a quick and cursory visit, with new mothers typically navigating the preceding postpartum transitions on their own.

The need to redefine postpartum care was a central message of Haywood Brown, MD, who in 2017 served as the president of the America College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Dr. Brown established a task force whose work resulted in important guidance for taking a more comprehensive and patient-centered approach to postpartum care.1

Improved care in the “fourth trimester,” as it has come to be known, is comprehensive and includes ensuring that our patients have a solid transition to health care beyond the pregnancy. We also hope that it will help us to reduce maternal mortality, given that more than half of pregnancy-related deaths occur after delivery.

Timing and frequency of contact

Historically, we’ve had a single 6-week postpartum visit, with little or no maternal support or patient contact before this visit unless the patient reported a complication. In the new paradigm, as described in the ACOG committee opinion on optimizing postpartum care, maternal care should be an ongoing process.1

so that any questions or concerns may be addressed and support can be provided.

This should be followed by individualized, ongoing care until a comprehensive postpartum visit covering physical, social, and psychological well-being is conducted by 12 weeks after birth – anytime between 4 and 12 weeks.

By stressing the importance of postpartum care during prenatal visits – and by talking about some of its key elements such as mental health, breastfeeding, and chronic disease management – we can let our patients know that postpartum care is not just an afterthought, but that it involves planning backed by evidence and expert opinion. Currently, as many as 40% of women do not attend a postpartum visit; early discussion, it is hoped, will increase attendance.

Certain high-risk groups should be seen or screened earlier than 3 weeks post partum. For instance, women who have hypertensive disorders of pregnancy should be evaluated no later than 7-10 days post partum, and women with severe hypertension should be seen within 72 hours, according to ACOG.

Early blood pressure checks – and follow-up as necessary – are critical for reducing the risk of postpartum stroke and other complications. I advocate uniformly checking blood pressure within several days after hospital discharge for all women who have hypertension at the end of their pregnancy.

Other high-risk conditions requiring early follow-up include diabetes and autoimmune conditions such as lupus, multiple sclerosis, and psoriasis that may flare in the postpartum period. Women with a history of postpartum depression similarly may benefit from early contact; they are at higher risk of having depression again, and there are clearly effective treatments, both medication and psychotherapy based.

In between the initial early contact (by 7-10 days post partum or by 3 weeks post partum) and the comprehensive visit between 4 and 12 weeks, the need for and timing of patient contact can be individualized. Some women will need only a brief contact and a visit at 8-10 weeks, while others will need much more. Our goal, as in all of medicine, is to provide individualized, patient-centered care.

Methods of contact

With the exception of the final comprehensive visit, postpartum care need not occur in person. Some conditions require an early office visit, but in general, as ACOG states, the usefulness of an in-person visit should be weighed against the burden of traveling to and attending that visit.

For many women, in-person visits are difficult, and we must be creative in utilizing telemedicine and phone support, text messaging, and app-based support. Having practiced during this pandemic, we are better positioned than ever before to make it relatively easy for new mothers to obtain ongoing postpartum care.

Notably, research is demonstrating that the use of technology may allow us to provide improved care and monitoring of hypertension in the postpartum period. For example, a randomized trial published in 2018 of over 200 women with a hypertensive disorder of pregnancy found that text-based surveillance with home blood pressure monitoring was more effective than usual in-person blood pressure checks in meeting clinical guidelines for postpartum monitoring.2

Women in the texting group were significantly more likely to have a single blood pressure obtained in the first 10 days post partum than women in the office group.

Postpartum care is also not a completely physician-driven endeavor. Much of what is needed to help women successfully navigate the fourth trimester can be provided by certified nurse midwives, advanced practice nurses, and other members of our maternal care teams.

Components of postpartum care

The postpartum care plan should be comprehensive, and having a checklist to guide one through initial and comprehensive visits may be helpful. The ACOG committee opinion categorizes the components of postpartum care into seven domains: mood and emotional well-being; infant care and feeding; sexuality, contraception, and birth spacing; sleep and fatigue; physical recovery from birth; chronic disease management; and health maintenance.1

The importance of screening for depression and anxiety cannot be emphasized enough. Perinatal depression is highly prevalent: It affects as many as one in seven women and can result in adverse short- and long-term effects on both the mother and child.

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force has offered guidance for years, most recently in 2019 with its recommendations that clinicians refer pregnant and postpartum women who are at increased risk for depression to counseling interventions such as cognitive behavioral therapy and interpersonal therapy.3 There is evidence that some form of treatment for women who screen positive reduces the risk of perinatal depression.

Additionally, there is emerging evidence that postpartum PTSD may be as prevalent as postpartum depression.4 As ACOG points out, trauma is “in the eye of the beholder,” and an estimated 3%-16% of women have PTSD related to a traumatic birth experience. Complications like shoulder dystocia or postpartum hemorrhage, in which delivery processes rapidly change course, can be experienced as traumatic by women even though they and their infants are healthy. The risk of posttraumatic stress should be on our radar screen.

Interpregnancy intervals similarly are not discussed enough. We do not commonly talk to patients about how pregnancy and breastfeeding are nutritionally depleting and how it takes time to replenish these stores – yet birth spacing is so important.

Compared with interpregnancy intervals of at least 18 months, intervals shorter than 6 months were associated in a meta-analysis with increased risks of preterm birth, low birth weight, and small for gestational age.5 Optimal birth spacing is one of the few low-cost interventions available for reducing pregnancy complications in the future.

Finally, that chronic disease management is a domain of postpartum care warrants emphasis. We must work to ensure that patients have a solid plan of care in place for their diabetes, hypertension, lupus, or other chronic conditions. This includes who will provide that ongoing care, as well as when medical management should be restarted.

Some women are aware of the importance of timely care – of not waiting for 12 months, for instance, to see an internist or specialist – but others are not.

Again, certain health conditions such as multiple sclerosis and RA necessitate follow-up within a couple weeks after delivery so that medications can be restarted or dose adjustments made. The need for early postpartum follow-up can be discussed during prenatal visits, along with anticipatory guidance about breastfeeding, the signs and symptoms of perinatal depression and anxiety, and other components of the fourth trimester.

Dr. Macones has no relevant financial disclosures.

References

1. Obstet Gynecol. 2018 May;131(5):e140-50.

2. BMJ Qual Saf. 2018 Apr 27;27(11):871-7.

3. JAMA. 2019 Feb 12;321(6):580-7.

4. Clin Psychol Rev. 2014 Jul;34:389-401.JAMA. 2006 Apr 19;295(15):1809-23.

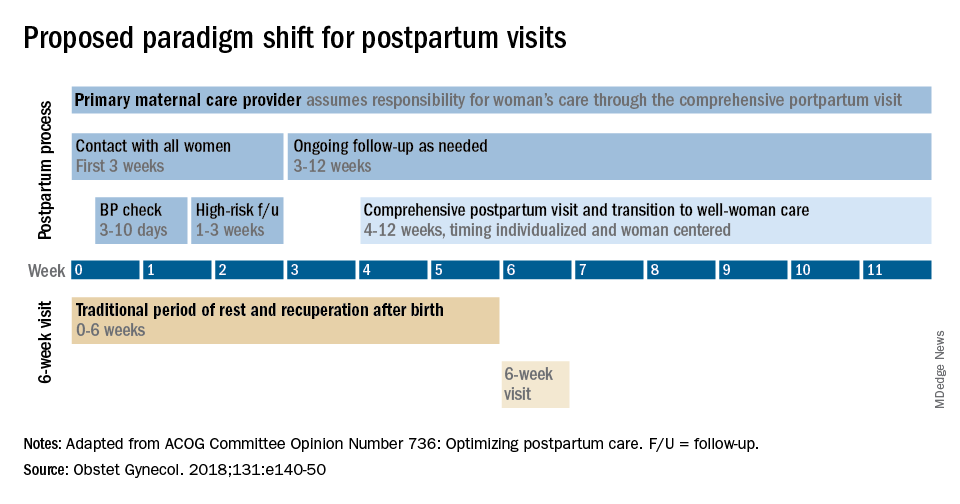

The field of ob.gyn. has long focused significantly more attention on the prenatal period – on determining the optimal frequency of ultrasound examinations, for instance, and on screening for diabetes and other conditions – than on women’s health and well-being after delivery.

The traditional 6-week postpartum visit has too often been a quick and cursory visit, with new mothers typically navigating the preceding postpartum transitions on their own.

The need to redefine postpartum care was a central message of Haywood Brown, MD, who in 2017 served as the president of the America College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Dr. Brown established a task force whose work resulted in important guidance for taking a more comprehensive and patient-centered approach to postpartum care.1

Improved care in the “fourth trimester,” as it has come to be known, is comprehensive and includes ensuring that our patients have a solid transition to health care beyond the pregnancy. We also hope that it will help us to reduce maternal mortality, given that more than half of pregnancy-related deaths occur after delivery.

Timing and frequency of contact

Historically, we’ve had a single 6-week postpartum visit, with little or no maternal support or patient contact before this visit unless the patient reported a complication. In the new paradigm, as described in the ACOG committee opinion on optimizing postpartum care, maternal care should be an ongoing process.1

so that any questions or concerns may be addressed and support can be provided.

This should be followed by individualized, ongoing care until a comprehensive postpartum visit covering physical, social, and psychological well-being is conducted by 12 weeks after birth – anytime between 4 and 12 weeks.

By stressing the importance of postpartum care during prenatal visits – and by talking about some of its key elements such as mental health, breastfeeding, and chronic disease management – we can let our patients know that postpartum care is not just an afterthought, but that it involves planning backed by evidence and expert opinion. Currently, as many as 40% of women do not attend a postpartum visit; early discussion, it is hoped, will increase attendance.

Certain high-risk groups should be seen or screened earlier than 3 weeks post partum. For instance, women who have hypertensive disorders of pregnancy should be evaluated no later than 7-10 days post partum, and women with severe hypertension should be seen within 72 hours, according to ACOG.

Early blood pressure checks – and follow-up as necessary – are critical for reducing the risk of postpartum stroke and other complications. I advocate uniformly checking blood pressure within several days after hospital discharge for all women who have hypertension at the end of their pregnancy.

Other high-risk conditions requiring early follow-up include diabetes and autoimmune conditions such as lupus, multiple sclerosis, and psoriasis that may flare in the postpartum period. Women with a history of postpartum depression similarly may benefit from early contact; they are at higher risk of having depression again, and there are clearly effective treatments, both medication and psychotherapy based.

In between the initial early contact (by 7-10 days post partum or by 3 weeks post partum) and the comprehensive visit between 4 and 12 weeks, the need for and timing of patient contact can be individualized. Some women will need only a brief contact and a visit at 8-10 weeks, while others will need much more. Our goal, as in all of medicine, is to provide individualized, patient-centered care.

Methods of contact

With the exception of the final comprehensive visit, postpartum care need not occur in person. Some conditions require an early office visit, but in general, as ACOG states, the usefulness of an in-person visit should be weighed against the burden of traveling to and attending that visit.

For many women, in-person visits are difficult, and we must be creative in utilizing telemedicine and phone support, text messaging, and app-based support. Having practiced during this pandemic, we are better positioned than ever before to make it relatively easy for new mothers to obtain ongoing postpartum care.

Notably, research is demonstrating that the use of technology may allow us to provide improved care and monitoring of hypertension in the postpartum period. For example, a randomized trial published in 2018 of over 200 women with a hypertensive disorder of pregnancy found that text-based surveillance with home blood pressure monitoring was more effective than usual in-person blood pressure checks in meeting clinical guidelines for postpartum monitoring.2

Women in the texting group were significantly more likely to have a single blood pressure obtained in the first 10 days post partum than women in the office group.

Postpartum care is also not a completely physician-driven endeavor. Much of what is needed to help women successfully navigate the fourth trimester can be provided by certified nurse midwives, advanced practice nurses, and other members of our maternal care teams.

Components of postpartum care

The postpartum care plan should be comprehensive, and having a checklist to guide one through initial and comprehensive visits may be helpful. The ACOG committee opinion categorizes the components of postpartum care into seven domains: mood and emotional well-being; infant care and feeding; sexuality, contraception, and birth spacing; sleep and fatigue; physical recovery from birth; chronic disease management; and health maintenance.1

The importance of screening for depression and anxiety cannot be emphasized enough. Perinatal depression is highly prevalent: It affects as many as one in seven women and can result in adverse short- and long-term effects on both the mother and child.

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force has offered guidance for years, most recently in 2019 with its recommendations that clinicians refer pregnant and postpartum women who are at increased risk for depression to counseling interventions such as cognitive behavioral therapy and interpersonal therapy.3 There is evidence that some form of treatment for women who screen positive reduces the risk of perinatal depression.

Additionally, there is emerging evidence that postpartum PTSD may be as prevalent as postpartum depression.4 As ACOG points out, trauma is “in the eye of the beholder,” and an estimated 3%-16% of women have PTSD related to a traumatic birth experience. Complications like shoulder dystocia or postpartum hemorrhage, in which delivery processes rapidly change course, can be experienced as traumatic by women even though they and their infants are healthy. The risk of posttraumatic stress should be on our radar screen.

Interpregnancy intervals similarly are not discussed enough. We do not commonly talk to patients about how pregnancy and breastfeeding are nutritionally depleting and how it takes time to replenish these stores – yet birth spacing is so important.

Compared with interpregnancy intervals of at least 18 months, intervals shorter than 6 months were associated in a meta-analysis with increased risks of preterm birth, low birth weight, and small for gestational age.5 Optimal birth spacing is one of the few low-cost interventions available for reducing pregnancy complications in the future.

Finally, that chronic disease management is a domain of postpartum care warrants emphasis. We must work to ensure that patients have a solid plan of care in place for their diabetes, hypertension, lupus, or other chronic conditions. This includes who will provide that ongoing care, as well as when medical management should be restarted.

Some women are aware of the importance of timely care – of not waiting for 12 months, for instance, to see an internist or specialist – but others are not.

Again, certain health conditions such as multiple sclerosis and RA necessitate follow-up within a couple weeks after delivery so that medications can be restarted or dose adjustments made. The need for early postpartum follow-up can be discussed during prenatal visits, along with anticipatory guidance about breastfeeding, the signs and symptoms of perinatal depression and anxiety, and other components of the fourth trimester.

Dr. Macones has no relevant financial disclosures.

References

1. Obstet Gynecol. 2018 May;131(5):e140-50.

2. BMJ Qual Saf. 2018 Apr 27;27(11):871-7.

3. JAMA. 2019 Feb 12;321(6):580-7.

4. Clin Psychol Rev. 2014 Jul;34:389-401.JAMA. 2006 Apr 19;295(15):1809-23.

The fourth trimester

As we approach the end of this year, one of the most surreal times in human history, we will look back on the many things we taught ourselves, the many things we took for granted, the many things we were grateful for, the many things we missed, and the many things we plan to do once we can do things again. Among the many things 2020 taught us to appreciate was the very real manifestation of the old adage, “prevention is the best medicine.” To prevent transmission of SARS-CoV-2, we wore masks, we sanitized everything, we avoided crowds, we traded in-person meetings for virtual meetings, we learned how to homeschool our children, and we delayed seeing relatives and friends.

Ob.gyns. in small and large practices around the world had the tremendous challenge of balancing necessary in-person prenatal care services with keeping their patients and babies safe. Labor and delivery units had even greater demands to keep women and neonates free of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Practices quickly put into place new treatment protocols and new management strategies to maintain the health of their staff while ensuring a high quality of care.

While we have focused much of our attention on greater precautions during pregnancy and childbirth, an important component of care is the immediate postpartum period – colloquially referred to as the “fourth trimester” – which remains critical to maintaining physical and mental health and well-being.

Despite concerns regarding COVID-19 safety, we should continue monitoring our patients during these crucial first weeks after childbirth. This year of social isolation, financial strain, and incredible uncertainty has created additional stress in many women’s lives. The usual support that some women would receive from family members, friends, and other mothers in the early days post partum may not be available. The pandemic also has further highlighted inequities in access to health care for vulnerable groups. In addition, restrictions have increased the incidence of intimate partner violence as many women and children have needed to shelter with their abusers. Perhaps now more than any time previously, ob.gyns. must be attuned to their patients’ needs and be ready to provide compassionate and sensitive care.

In this final month of the year, we have invited George A. Macones, MD, professor and chair of the department of women’s health at the University of Texas, Austin, to address the importance of care in the final “trimester” of pregnancy – the first 3 months post partum.

Dr. Reece, who specializes in maternal-fetal medicine, is executive vice president for medical affairs at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, as well as the John Z. and Akiko K. Bowers Distinguished Professor and dean of the school of medicine. He is the medical editor of this column. He said he had no relevant financial disclosures. Contact him at [email protected].

*This version has been updated to correct an erroneous byline, photo, and bio.

As we approach the end of this year, one of the most surreal times in human history, we will look back on the many things we taught ourselves, the many things we took for granted, the many things we were grateful for, the many things we missed, and the many things we plan to do once we can do things again. Among the many things 2020 taught us to appreciate was the very real manifestation of the old adage, “prevention is the best medicine.” To prevent transmission of SARS-CoV-2, we wore masks, we sanitized everything, we avoided crowds, we traded in-person meetings for virtual meetings, we learned how to homeschool our children, and we delayed seeing relatives and friends.

Ob.gyns. in small and large practices around the world had the tremendous challenge of balancing necessary in-person prenatal care services with keeping their patients and babies safe. Labor and delivery units had even greater demands to keep women and neonates free of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Practices quickly put into place new treatment protocols and new management strategies to maintain the health of their staff while ensuring a high quality of care.

While we have focused much of our attention on greater precautions during pregnancy and childbirth, an important component of care is the immediate postpartum period – colloquially referred to as the “fourth trimester” – which remains critical to maintaining physical and mental health and well-being.

Despite concerns regarding COVID-19 safety, we should continue monitoring our patients during these crucial first weeks after childbirth. This year of social isolation, financial strain, and incredible uncertainty has created additional stress in many women’s lives. The usual support that some women would receive from family members, friends, and other mothers in the early days post partum may not be available. The pandemic also has further highlighted inequities in access to health care for vulnerable groups. In addition, restrictions have increased the incidence of intimate partner violence as many women and children have needed to shelter with their abusers. Perhaps now more than any time previously, ob.gyns. must be attuned to their patients’ needs and be ready to provide compassionate and sensitive care.

In this final month of the year, we have invited George A. Macones, MD, professor and chair of the department of women’s health at the University of Texas, Austin, to address the importance of care in the final “trimester” of pregnancy – the first 3 months post partum.

Dr. Reece, who specializes in maternal-fetal medicine, is executive vice president for medical affairs at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, as well as the John Z. and Akiko K. Bowers Distinguished Professor and dean of the school of medicine. He is the medical editor of this column. He said he had no relevant financial disclosures. Contact him at [email protected].

*This version has been updated to correct an erroneous byline, photo, and bio.