User login

Chronic opioid use linked to low testosterone levels

NEW ORLEANS – About two thirds of men who chronically use opioids have low testosterone levels, based on a literature search of more than 50 randomized and observational studies that examined endocrine function in patients on chronic opioid therapy.

Hypocortisolism, seen in about 20% of the men in these studies, was among the other potentially significant deficiencies in endocrine function, Amir H. Zamanipoor Najafabadi, PhD, reported at the annual meeting of the Endocrine Society.

Dr. Najafabadi of Leiden University in the Netherlands, and Friso de Vries, PhD, analyzed the link between opioid use and changes in the gonadal axis. Most of the subjects in their study were men (J Endocr Soc. 2019. doi. 10.1210/js.2019-SUN-489).

While the data do not support firm conclusions on the health consequences of these endocrine observations, Dr. Najafabadi said that a prospective trial is needed to determine whether there is a potential benefit from screening patients on chronic opioids for potentially treatable endocrine deficiencies.

NEW ORLEANS – About two thirds of men who chronically use opioids have low testosterone levels, based on a literature search of more than 50 randomized and observational studies that examined endocrine function in patients on chronic opioid therapy.

Hypocortisolism, seen in about 20% of the men in these studies, was among the other potentially significant deficiencies in endocrine function, Amir H. Zamanipoor Najafabadi, PhD, reported at the annual meeting of the Endocrine Society.

Dr. Najafabadi of Leiden University in the Netherlands, and Friso de Vries, PhD, analyzed the link between opioid use and changes in the gonadal axis. Most of the subjects in their study were men (J Endocr Soc. 2019. doi. 10.1210/js.2019-SUN-489).

While the data do not support firm conclusions on the health consequences of these endocrine observations, Dr. Najafabadi said that a prospective trial is needed to determine whether there is a potential benefit from screening patients on chronic opioids for potentially treatable endocrine deficiencies.

NEW ORLEANS – About two thirds of men who chronically use opioids have low testosterone levels, based on a literature search of more than 50 randomized and observational studies that examined endocrine function in patients on chronic opioid therapy.

Hypocortisolism, seen in about 20% of the men in these studies, was among the other potentially significant deficiencies in endocrine function, Amir H. Zamanipoor Najafabadi, PhD, reported at the annual meeting of the Endocrine Society.

Dr. Najafabadi of Leiden University in the Netherlands, and Friso de Vries, PhD, analyzed the link between opioid use and changes in the gonadal axis. Most of the subjects in their study were men (J Endocr Soc. 2019. doi. 10.1210/js.2019-SUN-489).

While the data do not support firm conclusions on the health consequences of these endocrine observations, Dr. Najafabadi said that a prospective trial is needed to determine whether there is a potential benefit from screening patients on chronic opioids for potentially treatable endocrine deficiencies.

REPORTING FROM ENDO 2019

Hanging by a Thread

ANSWER

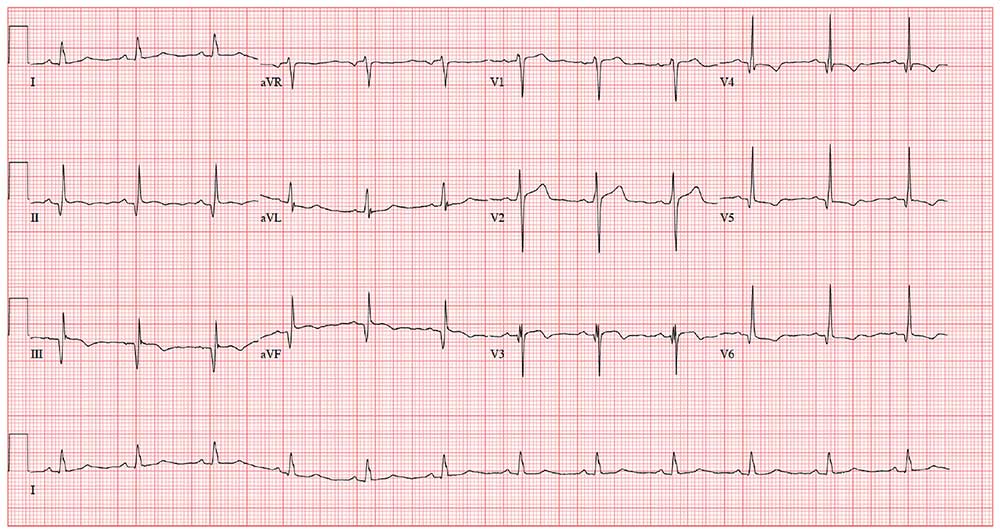

The correct interpretation incudes normal sinus rhythm, inferior MI, possible anterior MI, and ST-T wave abnormalit

Normal sinus rhythm is evidenced by a P wave for every QRS and a QRS for every P wave with a normal PR interval and a rate > 60 and < 100 beats/min.

An old inferior MI is indicated by the Q waves in inferior leads II, III, and aVF. The absence of ST-segment elevation in these leads also contributes to the diagnosis of an old rather than new MI. Possible anterior MI can be inferred from the poor R-wave progression in leads V1 through V3 with the absence of ST elevation.

ST-T wave abnormalities are evidenced by the chronic ST-segment elevation in V1 and V2 with T-wave inversions in leads V3 through V6 and in aVF. These may be due to remodeling and/or ECG lead placement.

The patient was subsequently cleared for his shoulder repair.

ANSWER

The correct interpretation incudes normal sinus rhythm, inferior MI, possible anterior MI, and ST-T wave abnormalit

Normal sinus rhythm is evidenced by a P wave for every QRS and a QRS for every P wave with a normal PR interval and a rate > 60 and < 100 beats/min.

An old inferior MI is indicated by the Q waves in inferior leads II, III, and aVF. The absence of ST-segment elevation in these leads also contributes to the diagnosis of an old rather than new MI. Possible anterior MI can be inferred from the poor R-wave progression in leads V1 through V3 with the absence of ST elevation.

ST-T wave abnormalities are evidenced by the chronic ST-segment elevation in V1 and V2 with T-wave inversions in leads V3 through V6 and in aVF. These may be due to remodeling and/or ECG lead placement.

The patient was subsequently cleared for his shoulder repair.

ANSWER

The correct interpretation incudes normal sinus rhythm, inferior MI, possible anterior MI, and ST-T wave abnormalit

Normal sinus rhythm is evidenced by a P wave for every QRS and a QRS for every P wave with a normal PR interval and a rate > 60 and < 100 beats/min.

An old inferior MI is indicated by the Q waves in inferior leads II, III, and aVF. The absence of ST-segment elevation in these leads also contributes to the diagnosis of an old rather than new MI. Possible anterior MI can be inferred from the poor R-wave progression in leads V1 through V3 with the absence of ST elevation.

ST-T wave abnormalities are evidenced by the chronic ST-segment elevation in V1 and V2 with T-wave inversions in leads V3 through V6 and in aVF. These may be due to remodeling and/or ECG lead placement.

The patient was subsequently cleared for his shoulder repair.

A 54-year-old man presents for preoperative workup for surgical repair of a partial tear of his right rotator cuff. He sustained the injury about 8 months ago, while rock climbing. His clinical work-up included MRI, magnetic resonance arthrogram, and dynamic musculoskeletal ultrasound. Initial treatment included physical therapy and 2 corticosteroid injections, without relief. A repeat arthrogram showed no resolution of the tear and revealed tendon retraction and muscular atrophy. The patient declined further physical therapy and opted for surgical intervention instead, because the injury is in his dominant shoulder and the pain continues to interfere with his job as a general contractor.

His medical history is positive for hypertension and hypercholesterolemia, which have been managed with medications. There is also a history of myocardial infarction (MI), which occurred 3 years ago when he was lifting a heavy truss at a job site; it manifested as acute chest pain, shortness of breath, and diaphoresis. He waited 3 days before seeking medical care because he “needed to get that project done.” He has had no further chest pain, but he‘s felt “a twinge” now and again in the past 2 months. He denies shortness of breath, dyspnea on exertion, or exertional chest pain. He has had no palpitations, syncope, or near-syncope.

His current medications include diltiazem, atorvastatin, and isosorbide. He tried metoprolol but did not like how he felt when taking it. He has no known drug allergies.

Family history is positive for familial hyperlipidemia on his father’s side. His father died of a heart attack at age 51. His mother has type 2 diabetes mellitus. His 2 older brothers have had MIs; his younger sister has no known health issues.

The patient is a self-employed general contractor. He has been married for 20 years and has a 21-year-old son who works for him. He smokes 1 to 1.5 packs a day and takes a shot of bourbon every night before dinner.

A review of systems reveals an 8-lb weight gain over the past 6 months. He denies fever, chills, and gastrointestinal and urologic symptoms. He believes he is depressed because his rotator cuff injury prevents him from doing what he would like.

Vital signs include a blood pressure of 138/88 mm Hg; pulse, 72 beats/min; respiratory rate, 14 breaths/min; O2 saturation, 98% on room air; and temperature, 97.4°F. His height is 70 in and his weight, 208 lb.

Physical exam reveals an anxious male in no distress wearing a sling on his right upper extremity. The HEENT exam is remarkable for corrective lenses. There are no lesions in the oropharynx, and his tobacco-stained teeth are in otherwise good repair. The neck is supple, and there are no carotid bruits, jugular venous distention, or thyromegaly. The pulmonary exam reveals coarse, scattered crackles with end-expiratory wheezing that clears with coughing.

Cardiac exam reveals a regular rate and rhythm of 72 beats/min. There are no murmurs, extra heart sounds, or rubs.

The abdomen is soft and nontender without palpable organomegaly or pulsatile masses. The lower extremities reveal no edema. The right upper extremity exam is deferred because the patient is very apprehensive about any movement of his shoulder. Peripheral pulses are strong and equal bilaterally. The neurologic exam is grossly intact.

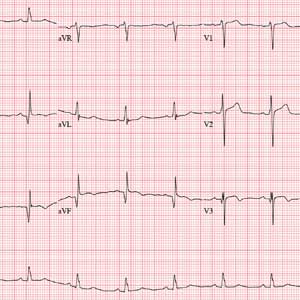

As part of the preoperative workup, an ECG is ordered. It shows a ventricular rate of 72 beats/min; PR interval, 158 ms; QRS duration, 106 ms; QT/QTc interval, 400/438 ms; P axis, 33°; R axis, 38°; and T axis, –15°. What is your interpretation of this ECG?

Lonely elderly patients suffer worse health outcomes

WASHINGTON – More lonely elderly patients suffered from health symptoms and received very aggressive end of life care than nonlonely elderly patients, according to a study presented at the annual meeting of the Society of General Internal Medicine.

“Loneliness and social isolation are very common problems, especially in older Americans, and inflict about 30%-40% of older Americans. But while we know that this may have implications for their quality [of] life and may actually lead to premature death, we know very little about the end of life experience,” said Nauzley Abedini, MD, MSc, a hospitalist in internal medicine at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

The study sought to determine the association between loneliness and end of life experience as measured by symptom burden, intensity of care, and advance care planning in adults. The pooled cohort study used data from the Health and Retirement Study (HRS) to analyze older Americans (aged 50 years or more) who died between 2004 and 2014. Investigators conducted postmortem “exit interviews” with the next of kin after each participant’s death. There were 2,896 participants included in the survey. Of these participants, 34% (942) were lonely; the remaining 1,954 of elderly adults were classified as nonlonely.

Loneliness was defined using the three-item Revised University of California, Los Angeles, Loneliness Scale score from a decedent’s last HRS interview prior to death. These items included feeling left out, feeling isolated, and lacking companionship. Investigators used this data to create a loneliness variable on previously established cutpoints for “lonely” and “nonlonely” participants. The data was used from the most recent survey prior to death.

Results showed more lonely older adults suffered from health symptoms in the last year of life, compared with nonlonely older adults (69.1% vs. 59.5%; odds ratio, 1.52; 95% confidence interval, 1.30-1.78). These symptoms included being troubled by pain, having difficulty breathing, experiencing severe fatigue, and having periodic confusion.

Patients with loneliness associated with intensity of health care at the end of life were more likely to die in a nursing home than at home, compared with nonlonely adults (OR, 1.68; 95% CI, 1.25-2.27). The lonely patients also were more likely to use life support during their last 2 years of life (OR, 1.41; 95% CI, 1.16-1.70).

“For clinicians, we need to identify end of life as an additional vulnerable time for people who are lonely. Currently, most of our interventions in terms of screening for loneliness are in the outpatient setting, but I would argue that working in hospitals, hospices, nursing homes, and community organizations, where these folks are living and dying, would be useful places to screen for this,” Dr. Abedini said.

The authors had no disclosures.

WASHINGTON – More lonely elderly patients suffered from health symptoms and received very aggressive end of life care than nonlonely elderly patients, according to a study presented at the annual meeting of the Society of General Internal Medicine.

“Loneliness and social isolation are very common problems, especially in older Americans, and inflict about 30%-40% of older Americans. But while we know that this may have implications for their quality [of] life and may actually lead to premature death, we know very little about the end of life experience,” said Nauzley Abedini, MD, MSc, a hospitalist in internal medicine at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

The study sought to determine the association between loneliness and end of life experience as measured by symptom burden, intensity of care, and advance care planning in adults. The pooled cohort study used data from the Health and Retirement Study (HRS) to analyze older Americans (aged 50 years or more) who died between 2004 and 2014. Investigators conducted postmortem “exit interviews” with the next of kin after each participant’s death. There were 2,896 participants included in the survey. Of these participants, 34% (942) were lonely; the remaining 1,954 of elderly adults were classified as nonlonely.

Loneliness was defined using the three-item Revised University of California, Los Angeles, Loneliness Scale score from a decedent’s last HRS interview prior to death. These items included feeling left out, feeling isolated, and lacking companionship. Investigators used this data to create a loneliness variable on previously established cutpoints for “lonely” and “nonlonely” participants. The data was used from the most recent survey prior to death.

Results showed more lonely older adults suffered from health symptoms in the last year of life, compared with nonlonely older adults (69.1% vs. 59.5%; odds ratio, 1.52; 95% confidence interval, 1.30-1.78). These symptoms included being troubled by pain, having difficulty breathing, experiencing severe fatigue, and having periodic confusion.

Patients with loneliness associated with intensity of health care at the end of life were more likely to die in a nursing home than at home, compared with nonlonely adults (OR, 1.68; 95% CI, 1.25-2.27). The lonely patients also were more likely to use life support during their last 2 years of life (OR, 1.41; 95% CI, 1.16-1.70).

“For clinicians, we need to identify end of life as an additional vulnerable time for people who are lonely. Currently, most of our interventions in terms of screening for loneliness are in the outpatient setting, but I would argue that working in hospitals, hospices, nursing homes, and community organizations, where these folks are living and dying, would be useful places to screen for this,” Dr. Abedini said.

The authors had no disclosures.

WASHINGTON – More lonely elderly patients suffered from health symptoms and received very aggressive end of life care than nonlonely elderly patients, according to a study presented at the annual meeting of the Society of General Internal Medicine.

“Loneliness and social isolation are very common problems, especially in older Americans, and inflict about 30%-40% of older Americans. But while we know that this may have implications for their quality [of] life and may actually lead to premature death, we know very little about the end of life experience,” said Nauzley Abedini, MD, MSc, a hospitalist in internal medicine at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

The study sought to determine the association between loneliness and end of life experience as measured by symptom burden, intensity of care, and advance care planning in adults. The pooled cohort study used data from the Health and Retirement Study (HRS) to analyze older Americans (aged 50 years or more) who died between 2004 and 2014. Investigators conducted postmortem “exit interviews” with the next of kin after each participant’s death. There were 2,896 participants included in the survey. Of these participants, 34% (942) were lonely; the remaining 1,954 of elderly adults were classified as nonlonely.

Loneliness was defined using the three-item Revised University of California, Los Angeles, Loneliness Scale score from a decedent’s last HRS interview prior to death. These items included feeling left out, feeling isolated, and lacking companionship. Investigators used this data to create a loneliness variable on previously established cutpoints for “lonely” and “nonlonely” participants. The data was used from the most recent survey prior to death.

Results showed more lonely older adults suffered from health symptoms in the last year of life, compared with nonlonely older adults (69.1% vs. 59.5%; odds ratio, 1.52; 95% confidence interval, 1.30-1.78). These symptoms included being troubled by pain, having difficulty breathing, experiencing severe fatigue, and having periodic confusion.

Patients with loneliness associated with intensity of health care at the end of life were more likely to die in a nursing home than at home, compared with nonlonely adults (OR, 1.68; 95% CI, 1.25-2.27). The lonely patients also were more likely to use life support during their last 2 years of life (OR, 1.41; 95% CI, 1.16-1.70).

“For clinicians, we need to identify end of life as an additional vulnerable time for people who are lonely. Currently, most of our interventions in terms of screening for loneliness are in the outpatient setting, but I would argue that working in hospitals, hospices, nursing homes, and community organizations, where these folks are living and dying, would be useful places to screen for this,” Dr. Abedini said.

The authors had no disclosures.

REPORTING FROM SGIM 2019

Give Her a Shoulder to Cry on

ANSWER

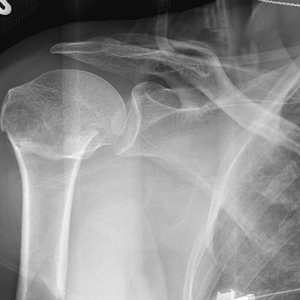

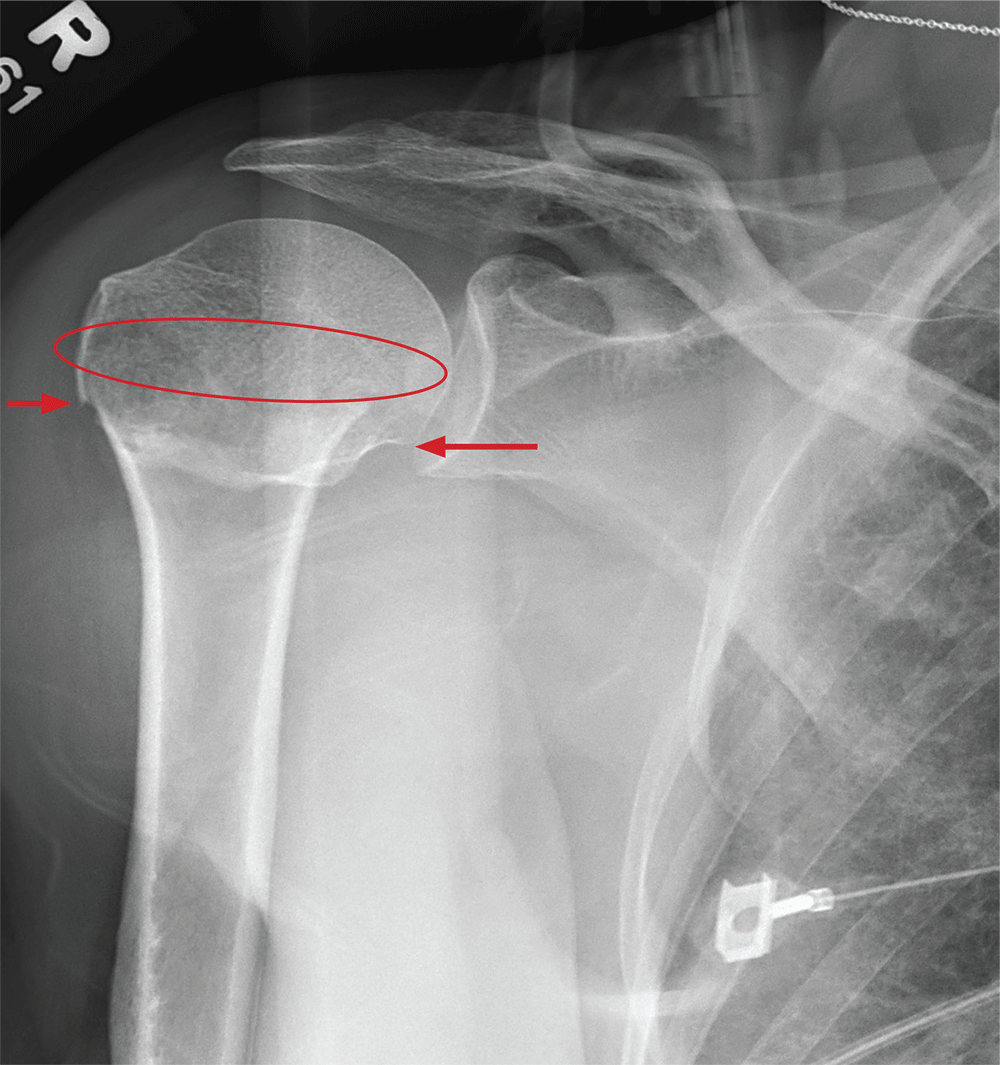

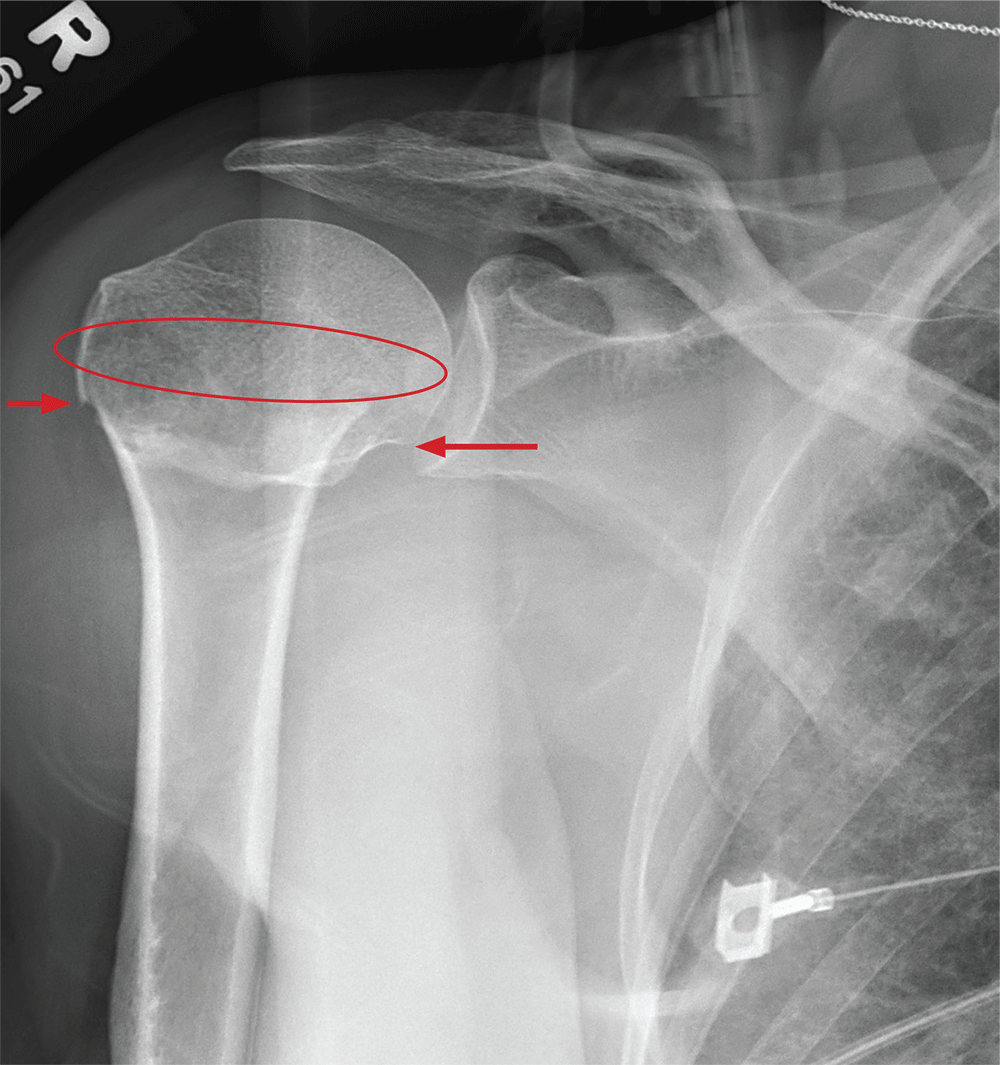

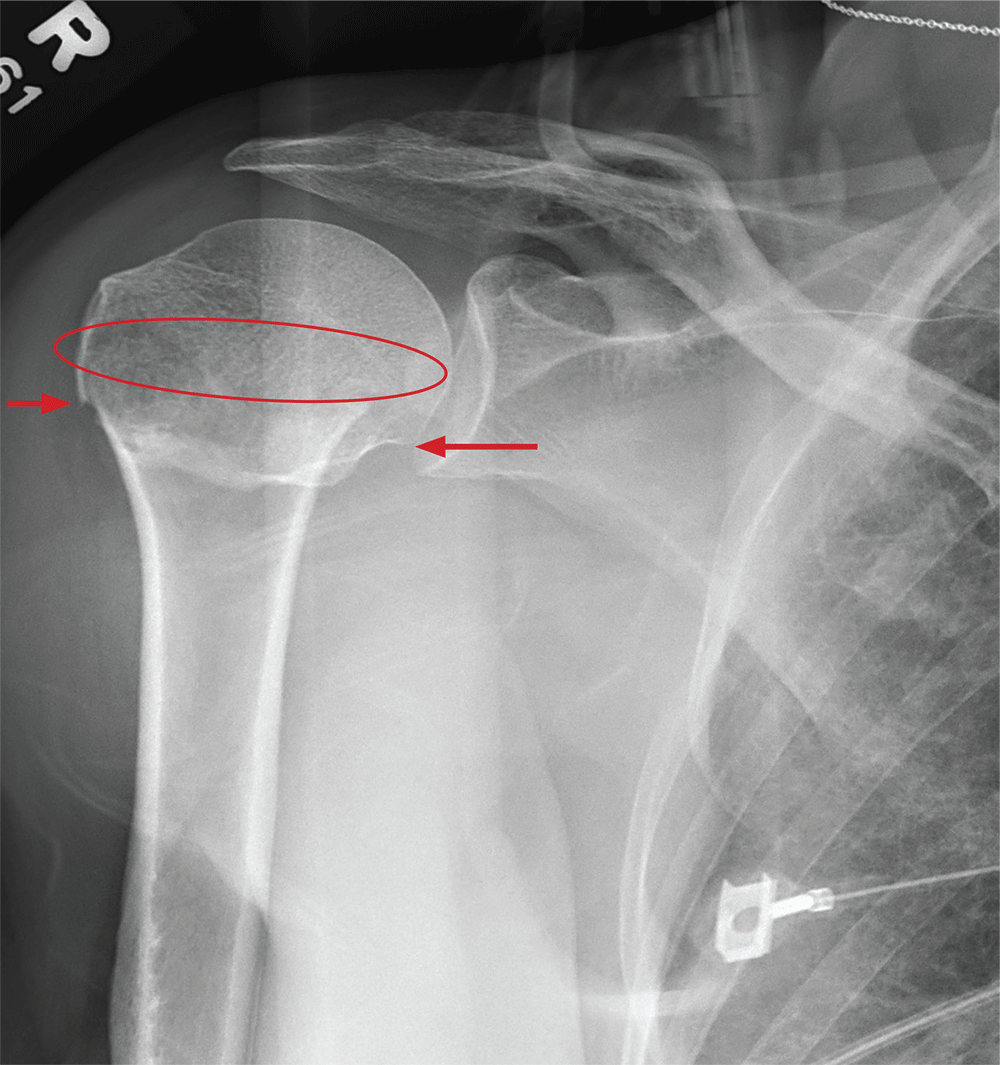

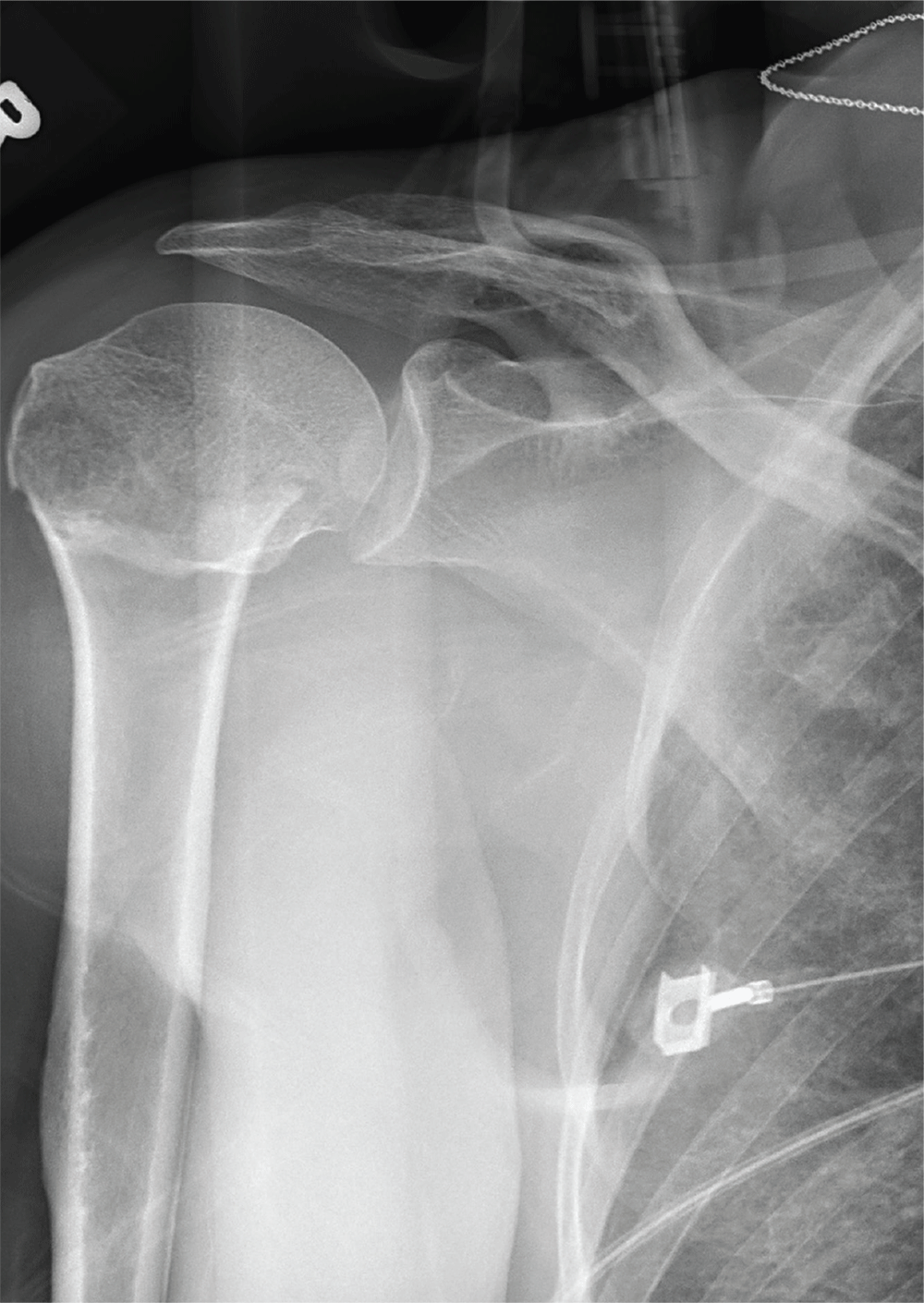

The radiograph demonstrates an acute horizontal fracture through the humeral neck. There is some slight lateral displacement of the fracture fragment.

The patient’s right arm was placed in a sling. Prompt orthopedic consultation was then obtained.

ANSWER

The radiograph demonstrates an acute horizontal fracture through the humeral neck. There is some slight lateral displacement of the fracture fragment.

The patient’s right arm was placed in a sling. Prompt orthopedic consultation was then obtained.

ANSWER

The radiograph demonstrates an acute horizontal fracture through the humeral neck. There is some slight lateral displacement of the fracture fragment.

The patient’s right arm was placed in a sling. Prompt orthopedic consultation was then obtained.

After a motor vehicle collision, a 70-year-old woman is brought to your emergency department by EMS personnel. She was a restrained driver in a vehicle crossing an intersection when she was broadsided by a tractor trailer traveling at high speed. Her airbags deployed, and she believes she briefly lost consciousness. Her biggest complaint is pain in her right shoulder.

Her medical history is significant for hypertension and hypothyroidism. On primary survey, you note an elderly woman who is in full cervical spine immobilization on a long backboard. Her Glasgow Coma Scale score is 15. She is in mild distress but has normal vital signs.

The patient has scattered abrasions and bruises on her body. Her right shoulder has mild to moderate tenderness to palpation and a decreased range of motion. Distally in that arm, she has good pulses and is neurovascularly intact.

You obtain a portable radiograph of the right shoulder (shown). What is your impression?

Green light therapy: A stop sign for pain?

MILWAUKEE – Exposure to green light therapy may significantly reduce pain in patients with chronic pain conditions, including migraine and fibromyalgia, an expert reported at the scientific meeting of the American Pain Society.

“There’s a subset of patients in every clinic whose pain doesn’t respond to medical therapies,” said Mohab M. Ibrahim, MD, PhD. “I always wonder what could be done with these patients.”

Dr. Ibrahim, who directs the chronic pain clinic at the University of Arizona, Tucson, walked attendees through an experimental process that began with an observation and has led to human clinical trials of green light therapy.

“Despite being a pharmacologist, I’m really interested in nonpharmacologic methods to manage pain,” he said.

Dr. Ibrahim said the idea for green light therapy came to him when he was speaking with his brother, who experiences migraines. His brother said his headaches were alleviated with time outside, in his back yard, or in one of the many parks in the city where he lives.

Knowing that spending time in nature had salutary effects in general, Dr. Ibrahim, an anesthesiologist and pain management specialist, wondered whether exposure to the sort of light found in nature, with blue skies and the green of a tree canopy, could help control pain.

To begin with, Dr. Ibrahim said, “the question was, do different colors have different behavior aspects on animals?”

Dr. Ibrahim and his collaborators exposed rats to light of various wavelengths across the color spectrum, as well as white and infrared light. They found that the rats who were exposed to blue and green light had a significantly longer latency period before withdrawing their hands and feet from a painfully hot stimulus, showing an antinociceptive effect with these wavelengths similar to that seen with analgesic medication.

“At that point, I decided to pursue green light and to forego blue, because blue can change the circadian rhythm,” said Dr. Ibrahim, adding, “Most pain patients have sleep disturbances to begin with, so to compound that issue is probably not a good idea.”

Dr. Ibrahim and his colleagues wanted to determine whether the analgesic effect had to do with rats seeing the green light or just being exposed to the light. Accordingly, the researchers fitted some rats with tiny, specially manufactured, completely opaque contact lenses. As a control, the researchers applied completely clear contact lenses to another group of rats. “I can’t tell you how many times we got bit, but by the end we got pretty good at it,” said Dr. Ibrahim.

Only the rats with clear lenses had prolonged latency in paw withdrawal to a noxious stimulus with green light exposure; for the rats with the blackout contact lenses, the effect was gone, “suggesting that the visual system is essential in mediating this effect,” noted Dr. Ibrahim.

This series of experiments also showed durable effects of green light exposure. In addition, the analgesic effect of green light did not wane over time, and higher “doses” were not required to achieve the same effect (as is the case with opioids, for example) (Pain. 2017 Feb;158[2]:347-60).

Clues to the mechanism of action came when Dr. Ibrahim and his colleagues administered naloxone to green light-exposed rats. “Naloxone reversed the effects of the green light, suggesting that the endogenous opioid system plays a role in this,” he said, adding that enkephalins were increased two- to threefold in the green light-exposed rats’ spinal cords, and astrocyte activation was reduced as well.

Similar experiments using a rat model of neuropathic pain showed a reversal of pain symptoms with green light exposure, offering promise that green light therapy could be effective in alleviating chronic as well as acute pain.

Moving to humans, Dr. Ibrahim enrolled a small group of individuals from his pain clinic who had refractory migraine into a study that exposed them either to white light or to green light. “These are patients who have failed everything…They have come to me, but I have nothing else to offer them,” he said.

The study had a crossover design. Participants in the small study had baseline pain scores of about 8/10, with no significant drop in pain with white light exposure. However, when the white light patients were crossed over to green light exposure, pain scores dropped to about 3/10. “That’s a greater than 50% reduction in the intensity of their migraine.”

Similar effects were seen in patients with fibromyalgia: “It was exactly the same story…When patients with white light exposure were crossed over [to green light], they had significant reductions in pain,” said Dr. Ibrahim.

“Their opioid use also decreased,” said Dr. Ibrahim. Medication use dropped in green light-exposed patients with migraine and fibromyalgia from an aggregate of about 280 morphine milligram equivalents (MME) to about 150 MME by the end of the study. The small size of the pilot study meant that those differences were not statistically significant.

“A multimodal approach to manage chronic pain patients is probably the best approach that we have so far,” said Dr. Ibrahim. An ongoing clinical trial randomizes patients with chronic pain to white light or green light therapy for two hours daily for 10 weeks, tracking pain scores, medication, and quality of life measures.

Future directions, said Dr. Ibrahim, include a study of the efficacy of green light therapy for patients with interstitial cystitis; another study will investigate green light for postoperative pain control. Sleep may also be improved by green light exposure, and Dr. Ibrahim and his colleagues plan to study this as well.

Dr. Ibrahim reported that his research was supported by the National Institutes of Health. He reported that he had no relevant conflicts of interest.

MILWAUKEE – Exposure to green light therapy may significantly reduce pain in patients with chronic pain conditions, including migraine and fibromyalgia, an expert reported at the scientific meeting of the American Pain Society.

“There’s a subset of patients in every clinic whose pain doesn’t respond to medical therapies,” said Mohab M. Ibrahim, MD, PhD. “I always wonder what could be done with these patients.”

Dr. Ibrahim, who directs the chronic pain clinic at the University of Arizona, Tucson, walked attendees through an experimental process that began with an observation and has led to human clinical trials of green light therapy.

“Despite being a pharmacologist, I’m really interested in nonpharmacologic methods to manage pain,” he said.

Dr. Ibrahim said the idea for green light therapy came to him when he was speaking with his brother, who experiences migraines. His brother said his headaches were alleviated with time outside, in his back yard, or in one of the many parks in the city where he lives.

Knowing that spending time in nature had salutary effects in general, Dr. Ibrahim, an anesthesiologist and pain management specialist, wondered whether exposure to the sort of light found in nature, with blue skies and the green of a tree canopy, could help control pain.

To begin with, Dr. Ibrahim said, “the question was, do different colors have different behavior aspects on animals?”

Dr. Ibrahim and his collaborators exposed rats to light of various wavelengths across the color spectrum, as well as white and infrared light. They found that the rats who were exposed to blue and green light had a significantly longer latency period before withdrawing their hands and feet from a painfully hot stimulus, showing an antinociceptive effect with these wavelengths similar to that seen with analgesic medication.

“At that point, I decided to pursue green light and to forego blue, because blue can change the circadian rhythm,” said Dr. Ibrahim, adding, “Most pain patients have sleep disturbances to begin with, so to compound that issue is probably not a good idea.”

Dr. Ibrahim and his colleagues wanted to determine whether the analgesic effect had to do with rats seeing the green light or just being exposed to the light. Accordingly, the researchers fitted some rats with tiny, specially manufactured, completely opaque contact lenses. As a control, the researchers applied completely clear contact lenses to another group of rats. “I can’t tell you how many times we got bit, but by the end we got pretty good at it,” said Dr. Ibrahim.

Only the rats with clear lenses had prolonged latency in paw withdrawal to a noxious stimulus with green light exposure; for the rats with the blackout contact lenses, the effect was gone, “suggesting that the visual system is essential in mediating this effect,” noted Dr. Ibrahim.

This series of experiments also showed durable effects of green light exposure. In addition, the analgesic effect of green light did not wane over time, and higher “doses” were not required to achieve the same effect (as is the case with opioids, for example) (Pain. 2017 Feb;158[2]:347-60).

Clues to the mechanism of action came when Dr. Ibrahim and his colleagues administered naloxone to green light-exposed rats. “Naloxone reversed the effects of the green light, suggesting that the endogenous opioid system plays a role in this,” he said, adding that enkephalins were increased two- to threefold in the green light-exposed rats’ spinal cords, and astrocyte activation was reduced as well.

Similar experiments using a rat model of neuropathic pain showed a reversal of pain symptoms with green light exposure, offering promise that green light therapy could be effective in alleviating chronic as well as acute pain.

Moving to humans, Dr. Ibrahim enrolled a small group of individuals from his pain clinic who had refractory migraine into a study that exposed them either to white light or to green light. “These are patients who have failed everything…They have come to me, but I have nothing else to offer them,” he said.

The study had a crossover design. Participants in the small study had baseline pain scores of about 8/10, with no significant drop in pain with white light exposure. However, when the white light patients were crossed over to green light exposure, pain scores dropped to about 3/10. “That’s a greater than 50% reduction in the intensity of their migraine.”

Similar effects were seen in patients with fibromyalgia: “It was exactly the same story…When patients with white light exposure were crossed over [to green light], they had significant reductions in pain,” said Dr. Ibrahim.

“Their opioid use also decreased,” said Dr. Ibrahim. Medication use dropped in green light-exposed patients with migraine and fibromyalgia from an aggregate of about 280 morphine milligram equivalents (MME) to about 150 MME by the end of the study. The small size of the pilot study meant that those differences were not statistically significant.

“A multimodal approach to manage chronic pain patients is probably the best approach that we have so far,” said Dr. Ibrahim. An ongoing clinical trial randomizes patients with chronic pain to white light or green light therapy for two hours daily for 10 weeks, tracking pain scores, medication, and quality of life measures.

Future directions, said Dr. Ibrahim, include a study of the efficacy of green light therapy for patients with interstitial cystitis; another study will investigate green light for postoperative pain control. Sleep may also be improved by green light exposure, and Dr. Ibrahim and his colleagues plan to study this as well.

Dr. Ibrahim reported that his research was supported by the National Institutes of Health. He reported that he had no relevant conflicts of interest.

MILWAUKEE – Exposure to green light therapy may significantly reduce pain in patients with chronic pain conditions, including migraine and fibromyalgia, an expert reported at the scientific meeting of the American Pain Society.

“There’s a subset of patients in every clinic whose pain doesn’t respond to medical therapies,” said Mohab M. Ibrahim, MD, PhD. “I always wonder what could be done with these patients.”

Dr. Ibrahim, who directs the chronic pain clinic at the University of Arizona, Tucson, walked attendees through an experimental process that began with an observation and has led to human clinical trials of green light therapy.

“Despite being a pharmacologist, I’m really interested in nonpharmacologic methods to manage pain,” he said.

Dr. Ibrahim said the idea for green light therapy came to him when he was speaking with his brother, who experiences migraines. His brother said his headaches were alleviated with time outside, in his back yard, or in one of the many parks in the city where he lives.

Knowing that spending time in nature had salutary effects in general, Dr. Ibrahim, an anesthesiologist and pain management specialist, wondered whether exposure to the sort of light found in nature, with blue skies and the green of a tree canopy, could help control pain.

To begin with, Dr. Ibrahim said, “the question was, do different colors have different behavior aspects on animals?”

Dr. Ibrahim and his collaborators exposed rats to light of various wavelengths across the color spectrum, as well as white and infrared light. They found that the rats who were exposed to blue and green light had a significantly longer latency period before withdrawing their hands and feet from a painfully hot stimulus, showing an antinociceptive effect with these wavelengths similar to that seen with analgesic medication.

“At that point, I decided to pursue green light and to forego blue, because blue can change the circadian rhythm,” said Dr. Ibrahim, adding, “Most pain patients have sleep disturbances to begin with, so to compound that issue is probably not a good idea.”

Dr. Ibrahim and his colleagues wanted to determine whether the analgesic effect had to do with rats seeing the green light or just being exposed to the light. Accordingly, the researchers fitted some rats with tiny, specially manufactured, completely opaque contact lenses. As a control, the researchers applied completely clear contact lenses to another group of rats. “I can’t tell you how many times we got bit, but by the end we got pretty good at it,” said Dr. Ibrahim.

Only the rats with clear lenses had prolonged latency in paw withdrawal to a noxious stimulus with green light exposure; for the rats with the blackout contact lenses, the effect was gone, “suggesting that the visual system is essential in mediating this effect,” noted Dr. Ibrahim.

This series of experiments also showed durable effects of green light exposure. In addition, the analgesic effect of green light did not wane over time, and higher “doses” were not required to achieve the same effect (as is the case with opioids, for example) (Pain. 2017 Feb;158[2]:347-60).

Clues to the mechanism of action came when Dr. Ibrahim and his colleagues administered naloxone to green light-exposed rats. “Naloxone reversed the effects of the green light, suggesting that the endogenous opioid system plays a role in this,” he said, adding that enkephalins were increased two- to threefold in the green light-exposed rats’ spinal cords, and astrocyte activation was reduced as well.

Similar experiments using a rat model of neuropathic pain showed a reversal of pain symptoms with green light exposure, offering promise that green light therapy could be effective in alleviating chronic as well as acute pain.

Moving to humans, Dr. Ibrahim enrolled a small group of individuals from his pain clinic who had refractory migraine into a study that exposed them either to white light or to green light. “These are patients who have failed everything…They have come to me, but I have nothing else to offer them,” he said.

The study had a crossover design. Participants in the small study had baseline pain scores of about 8/10, with no significant drop in pain with white light exposure. However, when the white light patients were crossed over to green light exposure, pain scores dropped to about 3/10. “That’s a greater than 50% reduction in the intensity of their migraine.”

Similar effects were seen in patients with fibromyalgia: “It was exactly the same story…When patients with white light exposure were crossed over [to green light], they had significant reductions in pain,” said Dr. Ibrahim.

“Their opioid use also decreased,” said Dr. Ibrahim. Medication use dropped in green light-exposed patients with migraine and fibromyalgia from an aggregate of about 280 morphine milligram equivalents (MME) to about 150 MME by the end of the study. The small size of the pilot study meant that those differences were not statistically significant.

“A multimodal approach to manage chronic pain patients is probably the best approach that we have so far,” said Dr. Ibrahim. An ongoing clinical trial randomizes patients with chronic pain to white light or green light therapy for two hours daily for 10 weeks, tracking pain scores, medication, and quality of life measures.

Future directions, said Dr. Ibrahim, include a study of the efficacy of green light therapy for patients with interstitial cystitis; another study will investigate green light for postoperative pain control. Sleep may also be improved by green light exposure, and Dr. Ibrahim and his colleagues plan to study this as well.

Dr. Ibrahim reported that his research was supported by the National Institutes of Health. He reported that he had no relevant conflicts of interest.

REPORTING FROM APS 2019

Rimegepant dissolving tablets treat acute migraine in phase 3 trial

PHILADELPHIA – according to phase 3 trial results presented at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology. The treatment’s efficacy is sustained for 2-48 hours, researchers reported.

Rimegepant is a small molecule calcitonin gene–related peptide receptor antagonist. A 75-mg oral tablet formulation was effective in phase 3 trials. The present study evaluated a novel, orally dissolving tablet formulation that is intended to speed the drug’s onset. The tablet’s time to peak concentration is 1.50 hours, compared with 1.99 hours for the oral tablet.

Formulation preferences

“People with migraine prefer orally dissolving tablets to oral tablets, mainly for their convenience, onset of action, and ability to be taken without drinking liquids,” said first author Richard B. Lipton, MD, of Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New York, and colleagues.

To assess the formulation’s efficacy and safety, the investigators conducted a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, multicenter trial. Participants were aged at least 18 years and had migraine for at least 1 year. They had 2-8 moderate or severe migraine attacks and fewer than 15 headache days per month during the 3 months before the trial. Their preventive migraine medication doses, if any, had been stable for at least 3 months.

Coprimary efficacy endpoints were pain freedom 2 hours post dose and freedom from the most bothersome symptom at 2 hours post dose. The efficacy analyses included randomized subjects who had a qualifying migraine attack, took the study medication, and provided at least one postbaseline efficacy data point.

The investigators included 1,351 patients in their efficacy analysis – 669 who received rimegepant and 682 who received placebo. About 85% were female, and patients’ mean age was 40.2 years. They averaged 4.6 migraine attacks per month, and their most bothersome symptoms included photophobia (57%), nausea (23.5%), and phonophobia (19.3%). About 14% used preventive treatment.

Within 45 days of randomization, patients treated a migraine attack of moderate to severe intensity and completed an electronic diary predose to 48 hours post dose.

Less use of rescue medication

At 2 hours post dose, patients who received 75 mg rimegepant were more likely than patients who received placebo to achieve pain freedom (21.2% vs. 10.9%) and freedom from the most bothersome symptom (35.1% vs. 26.8%).

Numerical differences in the likelihood of pain relief between group began 15 minutes post dose, and the difference was statistically significant at 60 minutes (36.8% vs. 31.2%).

Various secondary endpoints, including ability to function normally at 2 hours post dose (38.1% vs. 25.8%), sustained pain relief from 2-48 hours (42.2% vs. 25.2%), and use of rescue medications within 24 hours (14.2% vs. 29.2%), also were statistically significant.

In the safety analysis, the most common adverse events were nausea (1.6% in the rimegepant group and 0.4% in the placebo group) and urinary tract infection (1.5% in the rimegepant group and 0.6% in the placebo group). There were no serious adverse events. “Safety and tolerability were similar to placebo,” Dr. Lipton and colleagues said.

Biohaven Pharmaceuticals, the developer of the drug, sponsored the study. Dr. Lipton has received honoraria and research support from Biohaven and holds stock in the company. Coauthors are employees of Biohaven.

PHILADELPHIA – according to phase 3 trial results presented at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology. The treatment’s efficacy is sustained for 2-48 hours, researchers reported.

Rimegepant is a small molecule calcitonin gene–related peptide receptor antagonist. A 75-mg oral tablet formulation was effective in phase 3 trials. The present study evaluated a novel, orally dissolving tablet formulation that is intended to speed the drug’s onset. The tablet’s time to peak concentration is 1.50 hours, compared with 1.99 hours for the oral tablet.

Formulation preferences

“People with migraine prefer orally dissolving tablets to oral tablets, mainly for their convenience, onset of action, and ability to be taken without drinking liquids,” said first author Richard B. Lipton, MD, of Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New York, and colleagues.

To assess the formulation’s efficacy and safety, the investigators conducted a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, multicenter trial. Participants were aged at least 18 years and had migraine for at least 1 year. They had 2-8 moderate or severe migraine attacks and fewer than 15 headache days per month during the 3 months before the trial. Their preventive migraine medication doses, if any, had been stable for at least 3 months.

Coprimary efficacy endpoints were pain freedom 2 hours post dose and freedom from the most bothersome symptom at 2 hours post dose. The efficacy analyses included randomized subjects who had a qualifying migraine attack, took the study medication, and provided at least one postbaseline efficacy data point.

The investigators included 1,351 patients in their efficacy analysis – 669 who received rimegepant and 682 who received placebo. About 85% were female, and patients’ mean age was 40.2 years. They averaged 4.6 migraine attacks per month, and their most bothersome symptoms included photophobia (57%), nausea (23.5%), and phonophobia (19.3%). About 14% used preventive treatment.

Within 45 days of randomization, patients treated a migraine attack of moderate to severe intensity and completed an electronic diary predose to 48 hours post dose.

Less use of rescue medication

At 2 hours post dose, patients who received 75 mg rimegepant were more likely than patients who received placebo to achieve pain freedom (21.2% vs. 10.9%) and freedom from the most bothersome symptom (35.1% vs. 26.8%).

Numerical differences in the likelihood of pain relief between group began 15 minutes post dose, and the difference was statistically significant at 60 minutes (36.8% vs. 31.2%).

Various secondary endpoints, including ability to function normally at 2 hours post dose (38.1% vs. 25.8%), sustained pain relief from 2-48 hours (42.2% vs. 25.2%), and use of rescue medications within 24 hours (14.2% vs. 29.2%), also were statistically significant.

In the safety analysis, the most common adverse events were nausea (1.6% in the rimegepant group and 0.4% in the placebo group) and urinary tract infection (1.5% in the rimegepant group and 0.6% in the placebo group). There were no serious adverse events. “Safety and tolerability were similar to placebo,” Dr. Lipton and colleagues said.

Biohaven Pharmaceuticals, the developer of the drug, sponsored the study. Dr. Lipton has received honoraria and research support from Biohaven and holds stock in the company. Coauthors are employees of Biohaven.

PHILADELPHIA – according to phase 3 trial results presented at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology. The treatment’s efficacy is sustained for 2-48 hours, researchers reported.

Rimegepant is a small molecule calcitonin gene–related peptide receptor antagonist. A 75-mg oral tablet formulation was effective in phase 3 trials. The present study evaluated a novel, orally dissolving tablet formulation that is intended to speed the drug’s onset. The tablet’s time to peak concentration is 1.50 hours, compared with 1.99 hours for the oral tablet.

Formulation preferences

“People with migraine prefer orally dissolving tablets to oral tablets, mainly for their convenience, onset of action, and ability to be taken without drinking liquids,” said first author Richard B. Lipton, MD, of Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New York, and colleagues.

To assess the formulation’s efficacy and safety, the investigators conducted a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, multicenter trial. Participants were aged at least 18 years and had migraine for at least 1 year. They had 2-8 moderate or severe migraine attacks and fewer than 15 headache days per month during the 3 months before the trial. Their preventive migraine medication doses, if any, had been stable for at least 3 months.

Coprimary efficacy endpoints were pain freedom 2 hours post dose and freedom from the most bothersome symptom at 2 hours post dose. The efficacy analyses included randomized subjects who had a qualifying migraine attack, took the study medication, and provided at least one postbaseline efficacy data point.

The investigators included 1,351 patients in their efficacy analysis – 669 who received rimegepant and 682 who received placebo. About 85% were female, and patients’ mean age was 40.2 years. They averaged 4.6 migraine attacks per month, and their most bothersome symptoms included photophobia (57%), nausea (23.5%), and phonophobia (19.3%). About 14% used preventive treatment.

Within 45 days of randomization, patients treated a migraine attack of moderate to severe intensity and completed an electronic diary predose to 48 hours post dose.

Less use of rescue medication

At 2 hours post dose, patients who received 75 mg rimegepant were more likely than patients who received placebo to achieve pain freedom (21.2% vs. 10.9%) and freedom from the most bothersome symptom (35.1% vs. 26.8%).

Numerical differences in the likelihood of pain relief between group began 15 minutes post dose, and the difference was statistically significant at 60 minutes (36.8% vs. 31.2%).

Various secondary endpoints, including ability to function normally at 2 hours post dose (38.1% vs. 25.8%), sustained pain relief from 2-48 hours (42.2% vs. 25.2%), and use of rescue medications within 24 hours (14.2% vs. 29.2%), also were statistically significant.

In the safety analysis, the most common adverse events were nausea (1.6% in the rimegepant group and 0.4% in the placebo group) and urinary tract infection (1.5% in the rimegepant group and 0.6% in the placebo group). There were no serious adverse events. “Safety and tolerability were similar to placebo,” Dr. Lipton and colleagues said.

Biohaven Pharmaceuticals, the developer of the drug, sponsored the study. Dr. Lipton has received honoraria and research support from Biohaven and holds stock in the company. Coauthors are employees of Biohaven.

REPORTING FROM AAN 2019

Experts discuss what’s new in migraine treatment

PHILADELPHIA – At the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology, Alan M. Rapoport, MD, clinical professor of neurology at the University of California, Los Angeles, sat down with Stewart J. Tepper, MD, professor of neurology at the Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth, Hanover, N.H., to discuss in a video some of the new data presented at the meeting regarding the CGRP monoclonal antibodies, the small molecule receptor antagonists (gepants), and what Dr. Tepper described as “a real shift in paradigm and a watershed moment in migraine.”

The three gepants that are farthest along in clinical trials are ubrogepant, rimegepant, and atogepant. “Reassuring data” was presented, Dr. Tepper said, regarding liver toxicity, which has been a concern with earlier generations of the gepants. The Food and Drug Administration had mandated a close look at liver function with the use of these drugs, which are metabolized in the liver, and, to date, no safety signals have emerged.

The three CGRP monoclonal antibodies that are currently on the market are erenumab (Aimovig), fremanezumab (Ajovy), and galcanezumab (Emgality). Data from numerous open-label extension studies were presented. In general, it seems that “the monoclonal antibodies accumulate greater efficacy over time,” Dr. Tepper said. No safety concerns have emerged from 5 years of clinical trial data. With 250,000 patients on these drugs worldwide, that is “very reassuring,” Dr. Tepper said.

New data also show that the majority of patients with chronic migraine who are taking monoclonal antibodies convert from chronic migraine to episodic migraine. Additionally, new data show that use of monoclonal antibodies “dramatically reduce all migraine medication use,” Dr. Tepper said.

PHILADELPHIA – At the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology, Alan M. Rapoport, MD, clinical professor of neurology at the University of California, Los Angeles, sat down with Stewart J. Tepper, MD, professor of neurology at the Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth, Hanover, N.H., to discuss in a video some of the new data presented at the meeting regarding the CGRP monoclonal antibodies, the small molecule receptor antagonists (gepants), and what Dr. Tepper described as “a real shift in paradigm and a watershed moment in migraine.”

The three gepants that are farthest along in clinical trials are ubrogepant, rimegepant, and atogepant. “Reassuring data” was presented, Dr. Tepper said, regarding liver toxicity, which has been a concern with earlier generations of the gepants. The Food and Drug Administration had mandated a close look at liver function with the use of these drugs, which are metabolized in the liver, and, to date, no safety signals have emerged.

The three CGRP monoclonal antibodies that are currently on the market are erenumab (Aimovig), fremanezumab (Ajovy), and galcanezumab (Emgality). Data from numerous open-label extension studies were presented. In general, it seems that “the monoclonal antibodies accumulate greater efficacy over time,” Dr. Tepper said. No safety concerns have emerged from 5 years of clinical trial data. With 250,000 patients on these drugs worldwide, that is “very reassuring,” Dr. Tepper said.

New data also show that the majority of patients with chronic migraine who are taking monoclonal antibodies convert from chronic migraine to episodic migraine. Additionally, new data show that use of monoclonal antibodies “dramatically reduce all migraine medication use,” Dr. Tepper said.

PHILADELPHIA – At the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology, Alan M. Rapoport, MD, clinical professor of neurology at the University of California, Los Angeles, sat down with Stewart J. Tepper, MD, professor of neurology at the Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth, Hanover, N.H., to discuss in a video some of the new data presented at the meeting regarding the CGRP monoclonal antibodies, the small molecule receptor antagonists (gepants), and what Dr. Tepper described as “a real shift in paradigm and a watershed moment in migraine.”

The three gepants that are farthest along in clinical trials are ubrogepant, rimegepant, and atogepant. “Reassuring data” was presented, Dr. Tepper said, regarding liver toxicity, which has been a concern with earlier generations of the gepants. The Food and Drug Administration had mandated a close look at liver function with the use of these drugs, which are metabolized in the liver, and, to date, no safety signals have emerged.

The three CGRP monoclonal antibodies that are currently on the market are erenumab (Aimovig), fremanezumab (Ajovy), and galcanezumab (Emgality). Data from numerous open-label extension studies were presented. In general, it seems that “the monoclonal antibodies accumulate greater efficacy over time,” Dr. Tepper said. No safety concerns have emerged from 5 years of clinical trial data. With 250,000 patients on these drugs worldwide, that is “very reassuring,” Dr. Tepper said.

New data also show that the majority of patients with chronic migraine who are taking monoclonal antibodies convert from chronic migraine to episodic migraine. Additionally, new data show that use of monoclonal antibodies “dramatically reduce all migraine medication use,” Dr. Tepper said.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM AAN 2019

Could that back pain be caused by ankylosing spondylitis?

CASE

A 38-year-old man presents to your primary care clinic with chronic low back stiffness and pain. You have evaluated and treated this patient for this complaint for more than a year. His symptoms are worse in the morning upon wakening and improve with activity and anti-inflammatory medications. He denies any trauma or change in his activity level. His medical history includes chronic insertional Achilles pain and plantar fasciopathy, both for approximately 2 years. The patient reports no systemic or constitutional symptoms, and no pertinent family history.

How would you proceed with his work-up?

Ankylosing spondylitis (AS) is a form of arthritis that primarily affects the spine and sacroiliac joints. It is the most common spondyloarthropathy (SpA)—a family of disorders that also includes psoriatic arthritis; arthritis associated with inflammatory bowel disease; reactive arthritis; and juvenile SpA.1 AS is most prevalent in Caucasians and may affect 0.1% to 1.4% of the population.2

Historically, a diagnosis of AS required radiographic evidence of inflammation of the axial spine or sacrum that manifested as chronic stiffness and back pain. However, the disease can also be mild or take time for radiographic evidence to appear. So an umbrella term emerged—axial spondyloarthritis (axSpA)—that includes both AS and the less severe form, called nonradiographic axSpA (nr-axSpA). While patients with AS exhibit radiographic abnormalities consistent with sacroiliitis, patients with early, or nr-axSpA, do not have radiographic abnormalities of the sacroiliac (SI) joint or axial spine.

In clinical practice, the distinction between AS and nr-axSpA has limited impact on the management of individual patients. However, early recognition, intervention, and treatment in patients who do not meet radiographic criteria for AS can improve patient-oriented outcomes.

The family physician (FP)’s role. It is not necessary that FPs be able to make a definitive diagnosis, but FPs should:

- be able to recognize the symptoms of inflammatory back pain (IBP);

- know which radiographic and laboratory studies to obtain and when;

- know the Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society (ASAS) criteria3 that assist in identifying patients at risk for axSpA; and

- know when to refer moderate- to high-risk patients to rheumatologists for assistance with the diagnosis.

FPs should have a high index of suspicion in any patient who has chronic back pain (> 3 months) with other features of SpA, and should pay special attention to young adult patients (< 45 years) who have IBP features.

Continue to: Definitive data to show...

Definitive data to show what percentage of patients with nr-axSpA progress to AS are lacking. However, early identification of AS is important, as those who go undiagnosed have increased back pain, stiffness, progressive loss of mobility, and decreased quality of life. In addition, patients diagnosed after significant sacroiliitis is visible are less responsive to treatment.4

What follows is a review of what you’ll see and the tools that will help with diagnosis and referral.

The diagnosis dilemma

In the past, the modified New York criteria have been used to define AS, but they require the presence of both clinical symptoms and radiographic findings indicative of sacroiliitis for an AS designation.5,6 Because radiographic sacroiliitis can be a late finding in axSpA and nonexistent in nr-asSpA, these criteria are of limited clinical utility.

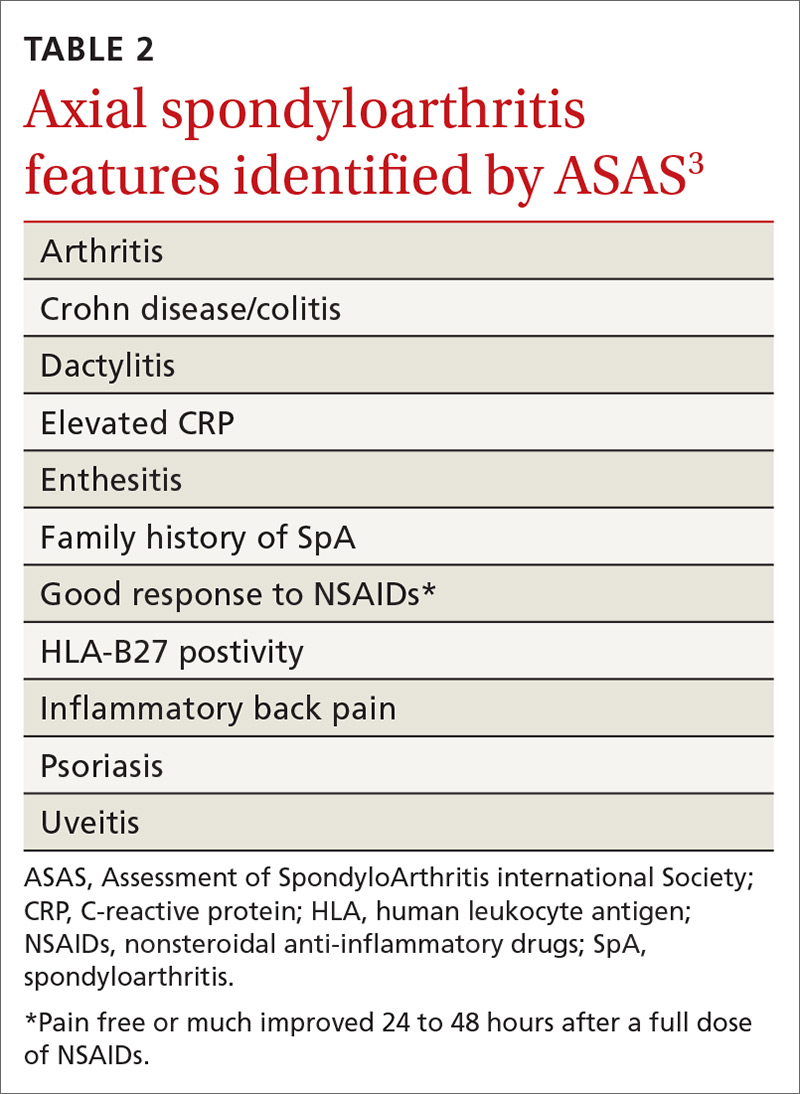

To assist in early identification, the ASAS published criteria to classify patients with early axSpA prior to radiographic manifestations.3 While not strictly diagnostic, these criteria combine patient history that includes evidence of IBP, human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-B27 positivity, and radiography to assist health care providers in identifying patients who may have axSpA and need prompt referral to a rheumatologist.

Easy to miss, even with evidence. It takes an average of 5 to 7 years for patients with radiographic evidence of AS to receive the proper diagnosis.7 There are several reasons for this. First, the axSpA spectrum encompasses a small percentage of patients who present to health care providers with back pain. In addition, many providers overlook the signs and symptoms of IBP, which are a hallmark of the condition. And finally, as stated earlier, true criteria for the diagnosis of axSpA do not exist.

Continue to: In addition...

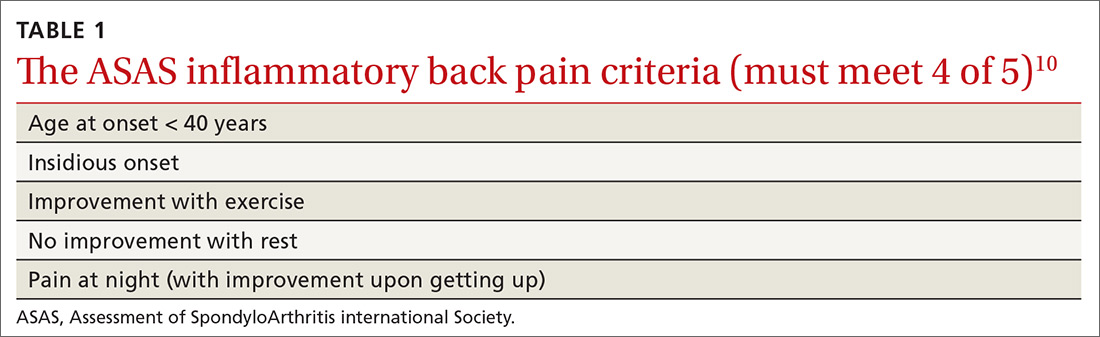

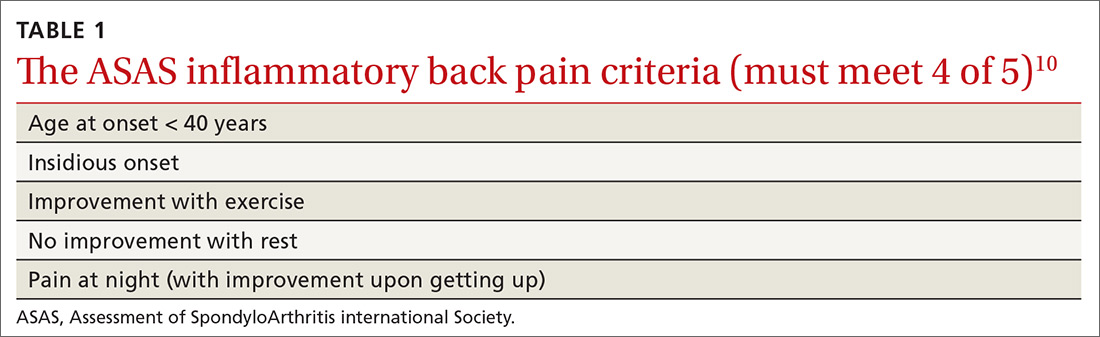

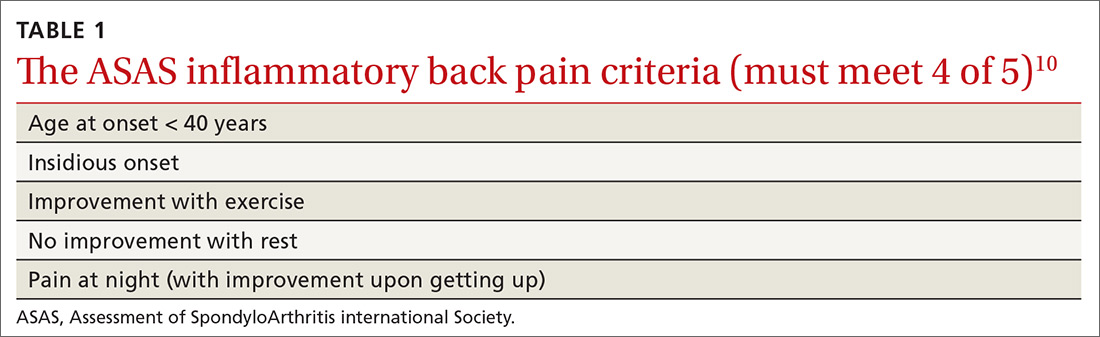

In addition, AS predominantly affects people in the third and fourth decades of life, but as many as 5% of patients of all ages with chronic back pain (> 3 months) can be classified as having AS.8 In patients who have IBP features, 14% can be classified as having axSpA.9 Therefore, it is important to recognize the features of IBP (TABLE 110). The presence of 4 of the 5 of IBP features has a sensitivity of 77% and a specificity of 91.7% for IBP.10

A different kind of back pain. The vast majority of patients presenting with low back pain will have features of mechanical back pain, which include improvement with rest, mild and short-lived morning stiffness and/or pain upon waking, and the absence of inflammatory markers. Those with axSpA, on the other hand, are more likely to report improvement of pain with exercise, no improvement with rest, and pain at night with improvement upon rising. While the presence of IBP features alone isn’t diagnostic for nr-axSpA or AS, such features should increase your suspicion, especially when such features are present in younger patients.

Physical exam findings

Physical exam findings are neither sensitive nor specific for the diagnosis of an axSpA disorder, but can help build a case for one. The physical exam can also assist in identifying comorbid conditions including uveitis, psoriasis, dactylitis, and enthesitis. Experts do not recommend using serial measurements of axial range of motion because they are time-consuming, and normative values are highly variable.

On examination of the peripheral joints and feet, note any swollen, tender, or deformed joints, as well as any dactylitis. Although any enthesis can be affected in axSpA, the insertional points of the Achilles and the plantar fascia are the most typical,1 so pay particular attention to these areas. On skin exam, note any evidence of psoriatic manifestations. Refer all patients with suspected uveitis to an ophthalmologist for confirmation of the diagnosis.

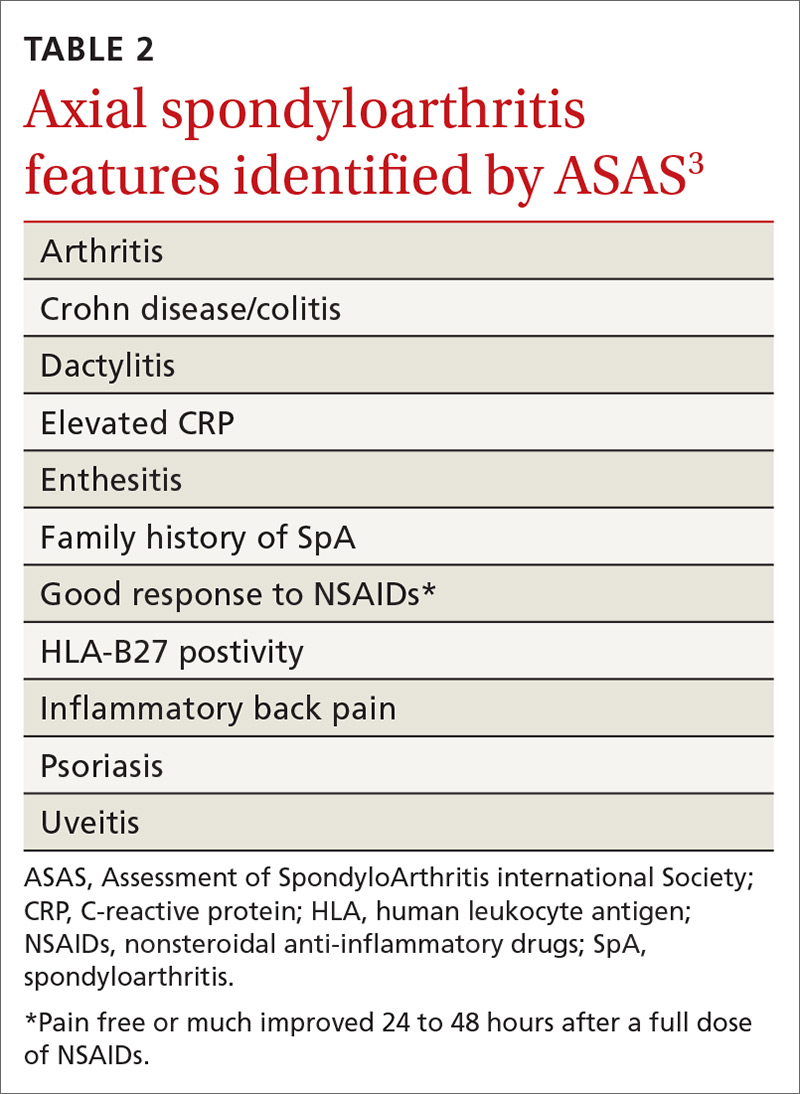

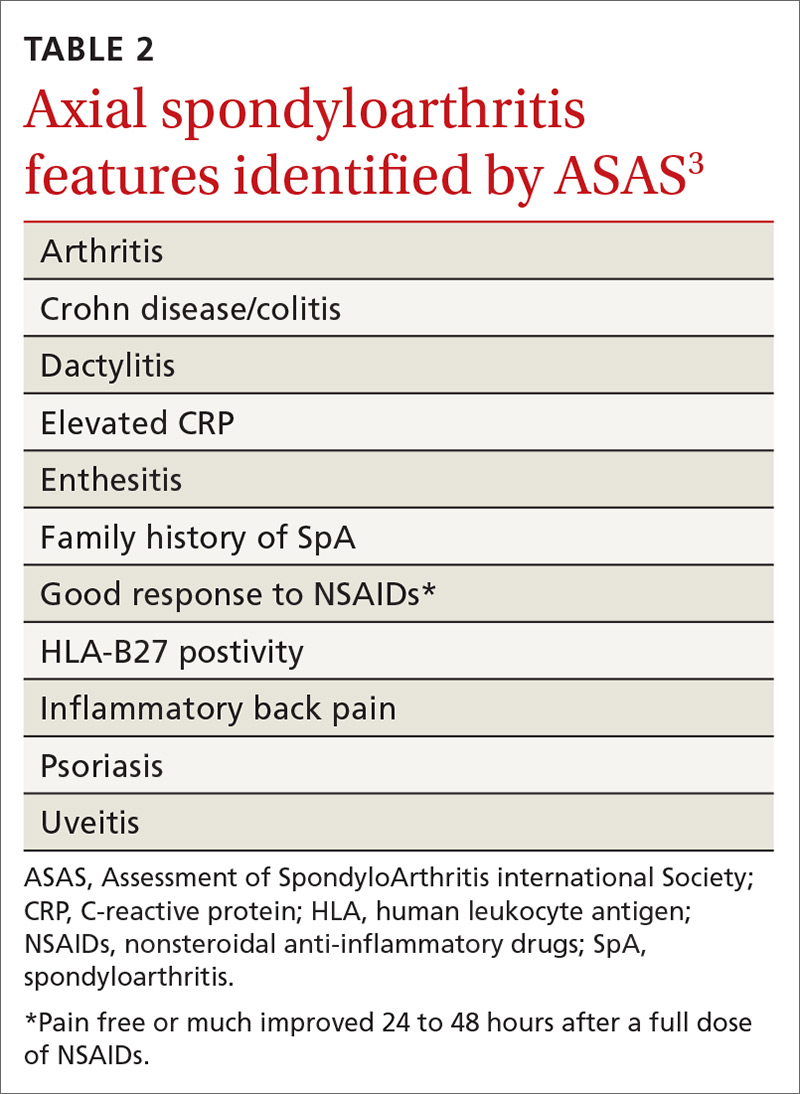

Lab studies: Not definitive, but helpful

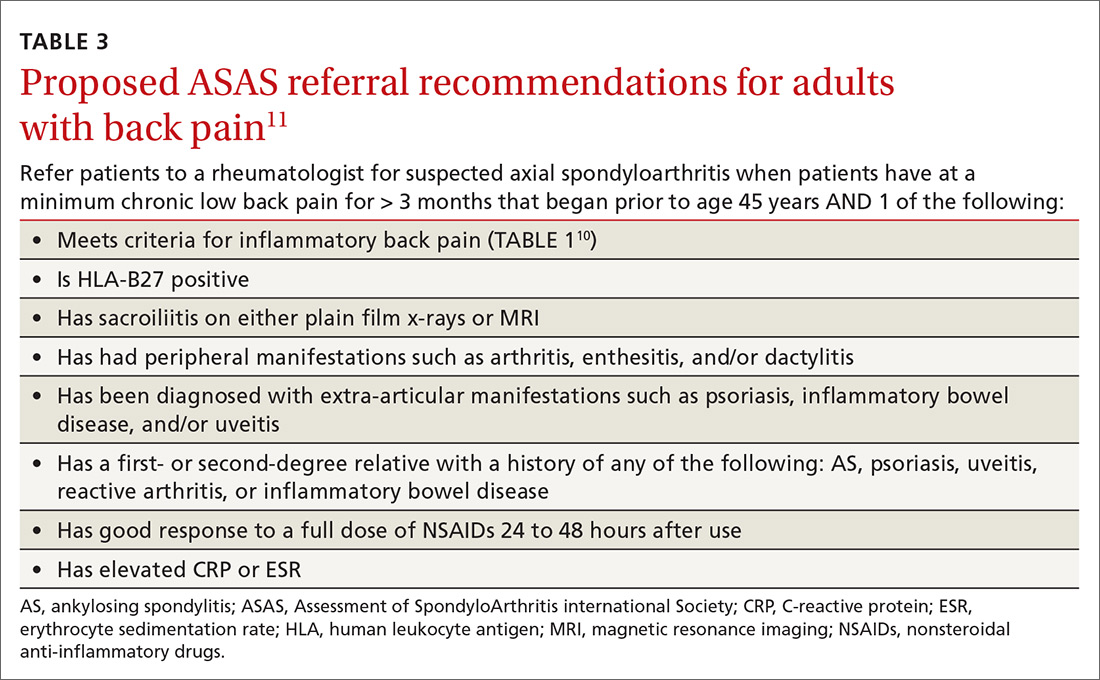

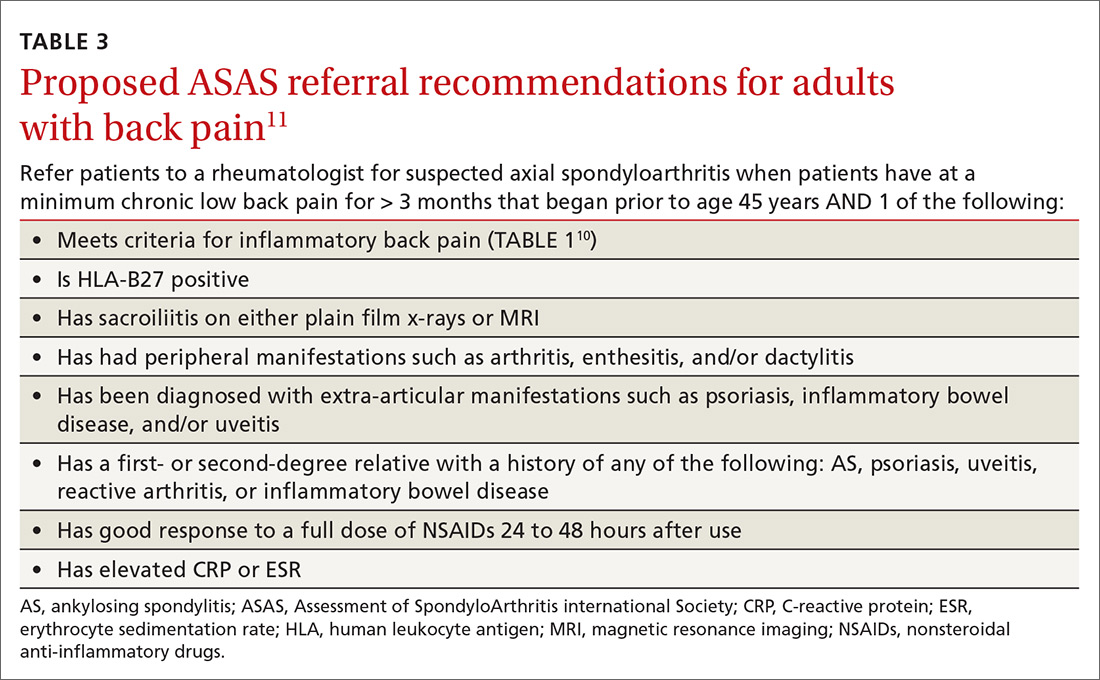

No laboratory studies confirm a diagnosis of nr-axSpA or AS; however, 2 studies—C-reactive protein (CRP) and HLA-B27—are important, as levels are listed as part of ASAS’s axSpA features (TABLE 23) and are factors that should be considered when deciding whether a referral is needed (TABLE 311). As such, HLA-B27 and CRP testing should be performed in all patients suspected of having an axSpA spectrum disorder.

Continue to: HLA-B27 is...

HLA-B27 is positive in 70% to 95% of patients with axSpA and can help build a case for the disorder.6,12 CRP is useful too, as an elevated CRP has important treatment implications (more on that in a bit).6

Other diagnoses in the differential include: degenerative disc disease, lumbar spondylosis, congenital vertebral anomalies, and osteoarthritis of the SI joint, bone metastasis, or primary bone tumors.1

Start with plain x-rays. The American College of Radiology (ACR) published appropriateness criteria for obtaining x-rays in patients suspected of having axSpA.13 Plain x-rays of the spine and SI joint are recommended for the initial evaluation. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the SI joint and/or spine should be obtained if the initial x-rays are negative or equivocal. Patient symptomology and/or exam findings determine whether to include the SI joint and/or spine. If the patient has subjective and objective findings concerning for pathology of both, then an MRI of the spine and SI joint is warranted.

Alternatively, computed tomography (CT) can be substituted if MRI is unavailable. In patients with known axSpA, surveillance radiography should not occur more often than every 2 years.6

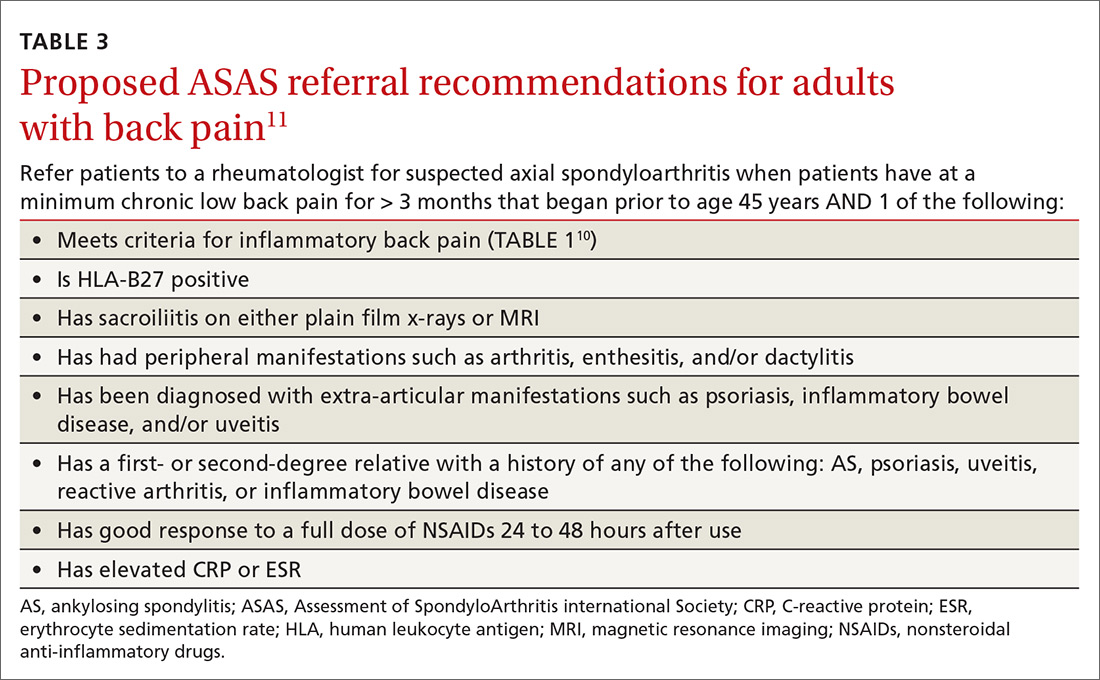

Timely referral is essential

Timely referral to a rheumatologist is an essential part of early diagnosis and treatment. Advances in treatment options for axSpA have become available in recent years and offer new hope for patients.

Continue to: As the presence of IBP...

As the presence of IBP features portends a 3-fold increase in the risk for axSpA,8 we propose an approach to the referral of patients with IBP features that deviates slightly from the ASAS algorithm. We believe it is within the scope of FPs to recognize IBP features, order appropriate ancillary studies, start a trial of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and follow-up with patients in 2 to 4 weeks to review results and evaluate treatment response. As such, all patients < 45 years old with IBP symptoms (TABLE 110) for 3 months or longer should be sent for laboratory workup (HLA-B27, CRP) and plain radiographs of the sacroiliac joints and lumbar spine.

Older patients, patients with IBP features for < 3 months, or patients < 45 years with IBP that have negative lab testing and negative radiographs should start an exercise program, be treated with an NSAID, and be assessed for ASAS spondyloarthritis features (TABLE 23).

Any patient with positive lab testing, positive radiographs, or ≥ 1 ASAS axSpA features should be referred to Rheumatology (TABLE 311). Patients with a negative radiograph should be evaluated with an MRI of the SI joints or spine (driven by pain location) and referred to Rheumatology if positive.

Keep in mind that not all patients fit neatly into an algorithm or a classification system. Therefore, we recommend that any patient with IBP features who fails to improve after 3 months of an exercise program, for whom you have a high index of suspicion for possible axSpA spectrum disease, receive appropriate ancillary studies and referral for expert consultation.

Exercise and NSAIDs form the basis of treatment

The purpose of treating patients with a suspected axSpA spectrum disorder is to decrease pain and stiffness, improve function and quality of life, and, ideally, halt or slow progression of disease. The only modifiable predictor of progression to axSpA is smoking; as such, encourage tobacco cessation if appropriate.14

Continue to: Nonpharmacologic treatment...

Nonpharmacologic treatment, such as regular aerobic exercise and strength training, should be prescribed for all patients with axSpA.6 Regular exercise is helpful in improving lower back pain, function, and spinal mobility. Combination endurance and strength-training programs are associated with the greatest benefits, and aquatic therapy is better than land-based therapy for pain.15 That said, recommend land-based exercises over no exercise when pool-based therapy is unavailable.

NSAIDs (eg, ibuprofen 200-800 mg at variable frequency, up to a maximum dose of 2400 mg/d; naproxen 250-500 mg bid) are the core treatment for patients with axSpA, as they improve pain, function, and quality of life.6 Both traditional NSAIDs and cyclooxygenase II (COX-II) inhibitors are effective; no differences in efficacy exist between the classes.6,15,16

NSAIDs have been shown to be as safe as placebo for up to 12 weeks of continuous use in patients without gastritis or renal disease.16 In patients with a gastrointestinal comorbidity, use NSAIDs cautiously.17

If adequate pain relief is not obtained after 2 to 4 weeks of NSAID use, try a different NSAID prior to escalating treatment.6 More research is needed to evaluate the effect of NSAIDs on spinal radiographic progression of disease because of conflicting results of existing studies.16

Unlike with other rheumatologic disorders, oral glucocorticoids and traditional disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs) are not effective in axSpA and should not be prescribed.18

Continue to: Other agents

Other agents. In patients who continue to have symptoms, or cannot tolerate 12 weeks of NSAIDs, newer biologic DMARDs may be considered. Tumor necrosis factor inhibitors (TNFi) and interleukin-17 inhibitors (IL-17i) have shown the best efficacy.18,19 In patients with AS, these medications improve pain and function, increase the chance of achieving partial remission of symptoms, and reduce CRP levels and MRI-detectable inflammation of the SI joint and/or spine.1,19 At this time, these medications are reserved for use in patients with clinical symptoms consistent with, and radiographic evidence of, axSpA, or in patients with nr-axSpA who have elevated CRP levels.18

For patients diagnosed with axSpA, an elevated CRP, short symptom duration (or young age), and inflammation noted on MRI seem to be the best predictors of a good response to TNFi.20 All patients in whom biologic DMARDS are considered should be referred to a rheumatologist because of cost, potential adverse effects, and stringent indications for use.

Surveil disease progression to prevent complications

We don’t yet know if progression of axSpA is linear or if the process can be slowed or halted with timely treatment. We do know that the natural history of structural progression is low in patients with early nr-axSpA.

Examples of validated online tools that can assist in measuring patient response to treatment and/or progression of disease follow.21 They can be used alone or in combination to help monitor treatment and progression of disease.

- The Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score (ASDAS) (https://www.asas-group.org/clinical-instruments/asdas-calculator/). This measure of disease activity uses a 5-item patient assessment and CRP level measurement.

- The Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index (BASFI) (http://basdai.com/BASFI.php). The BASFI consists of 8 items pertaining to everyday function and 2 items assessing the ability of patients to cope with everyday life.

- The Ankylosing Spondylitis Quality of Life Scale (ASQoL; http://oml.eular.org/sysModules/obxOml/docs/ID_32/ASQoL%20Questionnaire%20English.pdf).The ASQoL is an 18-item questionnaire related to the impact of disease on sleep, mood, motivation, and activities of daily living, among others.

Comorbidities. Patients with axSpA have an increased lifetime risk for cardiovascular disease, osteoporosis, fracture, inflammatory bowel disease, and iritis.6 Acute back pain in a patient with axSpA should be evaluated for a fracture and not automatically deemed an axSpA flare.13 Obtain a CT scan of the spine for all patients with known spine ankyloses who are suspected of having a fracture (because of the low sensitivity of plain radiography).13

Continue to: Prognosis

Prognosis. AS is a progressive long-term medical condition. Patients may experience progressive spinal deformity, hip joint or sacroiliac arthroses, or neurologic compromise after trauma. Reserve surgical referral for patients with spinal deformity that significantly affects quality of life and is severe or progressing despite nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic measures. Refer patients with an unstable spinal fracture for surgical intervention.6

Advise patients of available local, national, and international support groups. The National Ankylosis Spondylitis Society (NASS) based in the United Kingdom and the Spondylitis Association of America (SAA) are patient-friendly, nonprofit organizations that provide resources and information to people to help them learn about and cope with their condition.

CASE

You diagnose IBP in this patient and proceed with a work-up. You order x-rays of the back and SI joint, a CRP level, and an HLA-B27 test. X-rays and laboratory studies are negative. The patient is encouraged by your recommendation to start an aerobic and strength training home exercise program. In addition, you prescribe naproxen 500 mg bid and ask the patient to return in 1 month.

On follow-up he states that the naproxen is working well to control his pain. Upon further chart review and questioning, the patient confirms a history of chronic plantar fasciosis and psoriasis that he has controlled with intermittent topical steroids. He denies visual disturbances or gastrointestinal complaints. You refer him to a rheumatologist, where biologic agents are discussed but not prescribed at this time.

CORRESPONDENCE

Carlton J Covey, MD, FAAFP, Nellis Family Medicine Residency Program, 4700 Las Vegas Blvd. North, Nellis AFB, NV 89191; [email protected]

1. Sieper J, Poddubnyy D. Axial spondyloarthritis. Lancet. 2017;390:73-84.

2. Lawrence R, Helmick C, Arnett F, et al. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and selected musculoskeletal disorders in the United States. Arthritis Rheum. 1998;41:778-799.

3. Rudwaleit M, van der Heijde D, Landewe R, et al. The development of assessment of spondyloarthritis international society classification criteria for axial spondyloarthritis (part II); validation and final selection. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68:777-783.

4. Seo MR, Baek HL, Yoon HH, et al. Delayed diagnosis is linked to worse outcomes and unfavorable treatment responses in patients with axial spondyloarthritis. Clin Rheumatol. 2015;34:1397-1405.

5. van der Linden SM, Valkenburg HA, Cats A. Evaluation of diagnostic criteria for ankylosing spondylitis. A proposal for modification of the New York criteria. Arthritis Rheum. 1984;27:361-68.

6. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. NICE Guideline, No. 65. Spondyloarthritis in over 16s: diagnosis and management. February 2017. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmedhealth/PMH0091652/. Accessed April 24, 2019.

7. Dincer U, Cakar E, Kiralp MZ, et al. Diagnosis delay in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: possible reasons and proposals for new diagnostic criteria. Clin Rheumatol. 2008:27:457-462.

8. Underwood MR, Dawes P. Inflammatory back pain in primary care. Br J Rheumatol. 1995;34:1074-1077.

9. Strand V, Singh J. Evaluation and management of the patient with suspected inflammatory spine disease. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92:555-564.

10. Sieper J, van der Heijde D, Landewe R, et al. New criteria for inflammatory back pain in patients with chronic back pain: a real patient exercise by experts from the Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society (ASAS). Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68:784-788.

11. Poddubnyy D, van Tubergen A, Landewe R, et al. Development of ASAS-endorsed recommendation for the early referral of patients with a suspicion of axial spondyloarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74:1483-1487.

12. Rostom S, Dougados M, Gossec L. New tools for diagnosing spondyloarthropathy. Joint Bone Spine. 2010;77:108-114.

13. Bernard SA, Kransdorf MJ, Beaman FD, et al. ACR appropriateness criteria chronic back pain suspected sacroiliitis-spondyloarthropathy. J Am Coll Radiol. 2017;14:S62-S70.

14. Dougados M, Demattei C, van den Berg R, et al. Rate and predisposing factors for sacroiliac joint radiographic progression after a two-year follow-up period in recent-onset spondyloarthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68:1904-1913.

15. Regel A, Sepriano A, Baraliakos X, et al. Efficacy and safety of non-pharmacological treatment: a systematic literature review informing the 2016 update of the ASAS/EULAR recommendations for the management of axial spondyloarthritis. RMD Open. 2017;3:e000397.

16. Kroon FPB, van der Burg LRA, Ramiro S, et al. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) for axial spondyloarthritis (ankylosing spondylitis and non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;7:CD010952.

17. Radner H, Ramiro S, Buchbinder R, et al. Pain management for inflammatory arthritis (rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis and other spondyloarthritis) and gastrointestinal or liver comorbidity. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;1:CD008951.

18. van der Heijde D, Ramiro S, Landewe R, et al. 2016 update of the ASAS-EULAR management recommendations for axial spondyloarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76:978-991.

19. Maxwell LJ, Zochling J, Boonen A, et al. TNF-alpha inhibitors for ankylosing spondylitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;4:CN005468.

20. Sieper J, Poddubnyy D. New evidence on the management of spondyloarthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2016;12:282-295.

21. Zochling J. Measures of symptoms and disease status in ankylosing spondylitis. Arthritis Care Res. 2011;63:S47-S58.

CASE

A 38-year-old man presents to your primary care clinic with chronic low back stiffness and pain. You have evaluated and treated this patient for this complaint for more than a year. His symptoms are worse in the morning upon wakening and improve with activity and anti-inflammatory medications. He denies any trauma or change in his activity level. His medical history includes chronic insertional Achilles pain and plantar fasciopathy, both for approximately 2 years. The patient reports no systemic or constitutional symptoms, and no pertinent family history.

How would you proceed with his work-up?

Ankylosing spondylitis (AS) is a form of arthritis that primarily affects the spine and sacroiliac joints. It is the most common spondyloarthropathy (SpA)—a family of disorders that also includes psoriatic arthritis; arthritis associated with inflammatory bowel disease; reactive arthritis; and juvenile SpA.1 AS is most prevalent in Caucasians and may affect 0.1% to 1.4% of the population.2

Historically, a diagnosis of AS required radiographic evidence of inflammation of the axial spine or sacrum that manifested as chronic stiffness and back pain. However, the disease can also be mild or take time for radiographic evidence to appear. So an umbrella term emerged—axial spondyloarthritis (axSpA)—that includes both AS and the less severe form, called nonradiographic axSpA (nr-axSpA). While patients with AS exhibit radiographic abnormalities consistent with sacroiliitis, patients with early, or nr-axSpA, do not have radiographic abnormalities of the sacroiliac (SI) joint or axial spine.

In clinical practice, the distinction between AS and nr-axSpA has limited impact on the management of individual patients. However, early recognition, intervention, and treatment in patients who do not meet radiographic criteria for AS can improve patient-oriented outcomes.

The family physician (FP)’s role. It is not necessary that FPs be able to make a definitive diagnosis, but FPs should:

- be able to recognize the symptoms of inflammatory back pain (IBP);

- know which radiographic and laboratory studies to obtain and when;

- know the Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society (ASAS) criteria3 that assist in identifying patients at risk for axSpA; and

- know when to refer moderate- to high-risk patients to rheumatologists for assistance with the diagnosis.

FPs should have a high index of suspicion in any patient who has chronic back pain (> 3 months) with other features of SpA, and should pay special attention to young adult patients (< 45 years) who have IBP features.

Continue to: Definitive data to show...

Definitive data to show what percentage of patients with nr-axSpA progress to AS are lacking. However, early identification of AS is important, as those who go undiagnosed have increased back pain, stiffness, progressive loss of mobility, and decreased quality of life. In addition, patients diagnosed after significant sacroiliitis is visible are less responsive to treatment.4

What follows is a review of what you’ll see and the tools that will help with diagnosis and referral.

The diagnosis dilemma

In the past, the modified New York criteria have been used to define AS, but they require the presence of both clinical symptoms and radiographic findings indicative of sacroiliitis for an AS designation.5,6 Because radiographic sacroiliitis can be a late finding in axSpA and nonexistent in nr-asSpA, these criteria are of limited clinical utility.

To assist in early identification, the ASAS published criteria to classify patients with early axSpA prior to radiographic manifestations.3 While not strictly diagnostic, these criteria combine patient history that includes evidence of IBP, human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-B27 positivity, and radiography to assist health care providers in identifying patients who may have axSpA and need prompt referral to a rheumatologist.

Easy to miss, even with evidence. It takes an average of 5 to 7 years for patients with radiographic evidence of AS to receive the proper diagnosis.7 There are several reasons for this. First, the axSpA spectrum encompasses a small percentage of patients who present to health care providers with back pain. In addition, many providers overlook the signs and symptoms of IBP, which are a hallmark of the condition. And finally, as stated earlier, true criteria for the diagnosis of axSpA do not exist.

Continue to: In addition...